THE_NEW_CRITICISM

新批评(New

新批評(New Criticism)新批評是二、三0年付形成於英美的文學批評流派,五0年付成為美國文學批評的主流。

反對把文學當成文獻、傳記、史料,注重文學本身的價值。

認為文學不同於科學,不是實用性的。

新批評強調文學內緣的研究(意象、格律、文體),主張細讀(close reading)。

新批評常用的術語:歧義(ambiguity,含混、模稜、多義)、反諷(irory)、矛盾語法(language of paradox)〃張力(tension),肌理(texture、紋理,質地)無我(impersonality),客觀相應物(objective correlative)。

敘事觀點、敘事語氣為小說討論的重點。

提出敘事者不等於作者。

詩及小說的批評重視文字、意象、結構、肌理、語氣。

強調作品必須包含各種複雜而互相矛盾的因素,只有這樣才能‚掌握人類經驗範圍的各面‛。

反對詩作為宣傳,反對大眾語言(mass language)。

新批評三0年付興起,至五、六0年付英美學術界影響仍然很大。

但也有視野較闊的批評家,如特里林(Leonard Trilling)和威爾森(Edmund Wilson)等人對他們提出批評。

在中國方面,四0年付的袁可嘉,五、六0年付香港的葉維廉、李英豪、王敬羲,美國的夏志清,台灣的歐陽子、顏元叔,八0年付的黃維樑,都受新批評的影響。

林以亮編選的《美國文學批評選》(1961)有艾略特、布魯克斯、泰德等論文。

這種批評方法,在反對載道或泛政治的批評方面有其意義,產生於特殊的歷史斷層的處境有其必然性,對文章細讀有幫助,個別評論家有進一步發展(袁可嘉、夏志清、葉維廉),亦各有盲點,如顏元叔談古詩,黃維樑談新詩,弊端特別顯著。

新批評(New Criticism) 的起源休姆(T.E. Hulme):〈古典主義與浪漫主義〉;意象派詩Imagism龐德(Ezra Pound)詩“In a Station of the Metro”在地鐵車站(1914):The apparition of these faces in the crowd:Petals on a wet, black bough.受俳句(Haiku)影響、受中國詩影響。

论“新批评”文本细读

摘 要文本细读是一种细致的阅读文本的一种文学研究方法。

本文意在强调,新批评的文本细读是从文学自身研究文学的文学研究方式,在各种文学批评理论纷呈眼前时,我们应该认识到,文学研究应该拥有自己的范畴和方法;在文学研究之中,学习并应用某种其他学科的理论时,不应该放弃了文学研究的独立性。

除前言部分,本文共分为四个部分。

第一部分主要阐明新批评文本细读的理论基础,交待了文本细读的根据。

第一节分析了新批评的以文本为中心文本中心主义,梳理了新批评否定了其它文学批评流派把现实,作家和读者的感受作为批评文学作品的依据;第二节指出新批评派试图建立一种专业的文学批评,这种专业的文学批评就是他们奉行的文本细读。

第二部分指出新批评的文本细读所关注的因素。

动机和目的决定了方法和价值标准,他们所关注的就成为了文学批评预设的价值标准。

第三部分分析了文本细读的实践。

因为新批评主要是对诗歌进行细读,所以这部分主要考察了燕卜荪和布鲁克斯的关于诗歌的文本细读,而简单的总结了布鲁克斯和华伦的小说阅读。

第四个部分讨论了新批评与中国文学的联系,以及从文学的发展和文艺学本身的发展出发,提出当下的文学批评要借鉴学习新批评的文本细读。

关键字:新批评;文本细读;文本AbstractClose reading is a technique which is used for full reading literature text. In this paper, it is emphasized that close reading is a technique of studying works in the own way of literature, and that we should know that the literature studies should have its own category and method when other literary criticism theories appear in our literature criticism. During the literature researches, the literature research independence should not be given up when we study and apply some other disciplines on works. Except the foreword part, this article altogether is divided into four parts. The foreword limits the new criticism and the close reading. The first part mainly expounded the rationale of the new criticism for close reading, and transferred the basis for close reading. It is analysed that the new criticism take the text as the central, and described that New Criticism rejected the other schools of literary criticismes which take the reality, the feelings of writers and readers as the foundation for literature criticism in the first section. It is pointed out that the New Criticism trying to set up a professional literary criticism,close reading, which they pursued in the second section. In the second part, the factors are pointed that the close reading concerns. Because motive and purpose determines the methods and values, the factors become default values for the literary criticism. The practice of close reading is analysed in the third part. Since the main criticism of the New Criticism is on poetry, it is investigated in the most part that Empson and Brooks' poetry reading, and their story reading is mentioned slightly. It is discussed that the relationship between the New Criticism and Chinese literature. It is initiated that the modern Chinese literature criticism should learn from close reading.Key words:the New Criticism; close reading; text学位论文独创性声明本人郑重声明:1、坚持以“求实、创新”的科学精神从事研究工作。

专四词汇题 undermine

专四词汇题 undermine一、词汇题。

1. The constant criticism from his parents began to ____ his self - confidence.A. undermine.B. underlie.C. understand.D. undertake.解析:A。

“undermine”有“逐渐削弱(损害)”的意思,父母不断的批评开始损害他的自信心;“underlie”表示“位于…之下;构成…的基础”;“understand”是“理解”;“undertake”为“承担;从事”。

2. Repeated failures in the experiment have ____ the researchers' enthusiasm.A. undermined.B. enhanced.C. strengthened.D. fortified.解析:A。

实验中的屡次失败削弱了研究者们的热情。

“enhance”“strengthen”“fortify”都有“加强、增强”的意思,与句子语境不符,“undermine”符合表示消极影响的语境。

3. His bad habits, such as smoking and drinking too much, will eventually ____ his health.A. undermine.B. promote.C. improve.D. maintain.解析:A。

他吸烟和酗酒等不良习惯最终会损害他的健康。

“promote”“improve”“maintain”分别是“促进”“改善”“保持”,与句子要表达的损害健康的意思相反,所以选A。

4. The scandal has seriously ____ public trust in the government.A. undermined.B. built.C. established.D. created.解析:A。

Unit 12 the two cultures

The Two CulturesC. P. Snow(查尔斯·珀西·斯诺Charles Percy Snow)作者:斯诺最值得人们注意的是他关于他“两种文化”这一概念的讲演与书籍。

这一概念在他的《两种文化与科学变革》(The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution,1959年出版)。

在这本书中,斯诺注意到科学与人文中联系的中断对解决世界上的问题是一个主要障碍。

斯诺特别提到如今世界上教育的质量正在逐步地降低。

比如说,很多科学家从未读过查尔斯·狄更斯的作品,同样,艺术工作者对科学也同样的不熟悉。

他写道:斯诺的演讲在发表之时引起了很多的骚动,一部分原因是他在陈述观点时不愿妥协的态度。

他被文学评论家F·R·利维斯(F. R. Leavis)强烈地抨击。

这一激烈的争辩甚至使夫兰达斯与史旺创作了一首主题是热力学第一与第二定律的喜剧歌曲,并起名为《第一与第二定律》(First and Second Law)。

斯诺写到:斯诺同时注意到了另一个分化,即富国与穷国之间的分化。

1 “It’s rather odd,” said G. H. Ha rdy, one afternoon in the early Thirties, “but when we hear about intellectuals nowadays, it doesn’t include people like me and J. J. Thomson and Rutherford.” Hardy was the first mathematician of his generation, J. J. Thomson the first physicist of his; as for Rutherford, he was one of the greatest scientists who have ever lived. Some bright young literary person (I forget the exact context) putting them outside the enclosure reserved for intellectuals seemed to Hardy the best joke for some time. It does not seem quite such a good joke now. The separation between the two cultures has been getting deeper under our eyes;there is now precious little communication between them, little but different kinds of incomprehension1 and dislike.2 The traditional culture, which is, of course, mainly literary, is behaving like a state whose power is rapidly declining—standing on its precarious2 dignity, spending far too much energy on Alexandrian intricacies, [1] occasionally letting fly in fits of aggressive pique3 quite beyond its means, [2] too much on the defensive4 to show any generous imagination to the forces, which must inevitably reshape it. Whereas the scientific culture is expansive, not restrictive, confident at the roots, the more confident after its bout5 of Oppenheimerian self-criticism, certain that history is on its side, impatient, intolerant, and creative rather than critical, good-natured and brash6. Neither culture knows the virtues of the other; often it seems they deliberately do not want to know. [3] The resentment, which the traditional culture feels for the scientific, is shaded with fear; from the other side, the resentment is not shaded so much as brimming7 with irritation. When scientists are faced with an expression of the traditional culture, it tends (to borrow Mr. William Cooper’s eloquent phrase) to make their feet ache.3 It does not need saying that [4]generalizations of this kind are bound to look silly at the edges. There are a good many scientists indistinguishable from literary persons, and vice versa. Even the stereotype generalizations about scientists are misleading without some sort of detail—e.g., the generalization that scientists as a group stand on the political Left. This is only partly true. A very high proportion of engineers is almost as conservative as doctors; of pure scientists; the same would apply to chemists. It is only among physicists and biologists that one finds the Left in strength. If one compared the whole body of scientists with their opposite numbers of the traditional culture (writers, academics, and so on), the total result might be a few per cent, more towards the Left wing, but not more than that. [5]Nevertheless, as a first approximation, the scientific culture is real enough, and so is its difference from the traditional. For anyone like myself, by education a scientist, by calling a writer, at one time moving between groups of scientists and writers in the same evening, the difference has seemed dramatic.4 The first thing, impossible to miss, is that scientists are on the up and up; they have the strength of a social force behind them. If theyare English, they share the experience common to us all—of being in a country sliding economically downhill—but in addition (and to many of them it seems psychologically more important) they belong to something more than a profession, to something more like a directing class of a new society. [6]In a sense oddly divorced from politics, they are the new men. Even the steadiest and most politically conservative of scientific veterans, [7] lurking8 in dignity in their colleges, has some kind of link with the world to come. They do not hate it as their colleagues do; part of their mind is open to it;[8]almost against their will, there is a residual glimmer of kinship there. The young English scientists may and do curse their luck; increasingly they fret9 about the rigidities of their universities, about the ossification10 of the traditional culture which, to the scientists, makes the universities cold and dead; they violently envy their Russian counterparts who have money and equipment without discernible11 limit, who have the whole field wide open. But still they stay pretty resilient12: the same social force sweeps them on. Harwell and Winscale have just as much spirit as Los Alamos and Chalk River: the neat petty bourgeois houses, the tough and clever young, the crowds of children: they are symbols, frontier towns.5 There is a touch of the frontier qualities, in fact, about the whole scientific culture. Its tone is, for example, steadily heterosexual. The difference in social manners between Harwell and Hampstead or as far as that goes between Los Alamos and Greenwich Village, would make an anthropologist blink. [9]About the whole scientific culture, there is an absence—surprising to outsiders—of the feline13 and oblique14. Sometimes it seems that scientists relish15 speaking the truth, especially when it is unpleasant. The climate of personal relations is singularly bracing16, not to say harsh: it strikes bleaklyo n those unused to it, who suddenly find that [10] the scientists’ way of deciding on action is by a full-dress argument, with no regard for sensibilities and no holds barred17. No body of people ever believed more in dialectic as the primary method of attaining sense; [11]and if you want a picture of scientists in their off-moments, it could be just one of a knock-about18 argument. Under the argument there glitter egotisms as rapacious19 as any of ours: but, unlike ours, the egotisms are driven by a common purpose.6 How much of the traditional culture gets through to them? The answer is not simple. A good many scientists, including some of the most gifted, have the tastes of literary persons, read the same things,and lead as much. Broadly, though, [12] the infiltration20 is much less . History gets across to a certain extent, in particular social history: the sheer mechanics21 of living, how men ate, built, traveled, worked, touches a good many scientific imaginations, and so they have fastened on22 such works as Trevelyan’s Social History, and Professor Gordon Childe’s books. Philosophy, the scientific culture view with indifference, especially metaphysics. As Rutherford said cheerfully to Samuel Alexander: “When you think of all the years you’ve been tal king about those things, Alexander, and what does it all add up to? Hot air, nothing but hot air.” A bit less exuberantly23, that is what contemporary scientists would say. They regard it as a major intellectual virtue, to know what not to think about. [13]They might touch their hats to24 linguistic analysis, as a relatively honorable way of wasting time; not so to existentialism25.7 The arts? The only one which is cultivated among scientists is music. It goes both wide and deep; there may possibly be a greater density of musical appreciation than in the traditional culture. In comparison, the graphic arts (except architecture) score little, and poetry not at all. [14]Some novels work their way through, but not as a rule the novels which literary persons set most value on. [15]Thetwo cultures have so few points of contact that the diffusion26 of novels shows the same sort of delay, and exhibits the same oddities, as though they were getting into translation in a foreign country. It is only fairly recently, for instance, that Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh has become more than names. And, just as it is rather startling to find that in Italy Bruce Marshall is by a long shot the best-known British novelist, so it jolts27 one to hear scientists talking with attention of the works of Nevil Shute. In fact, there is a good reason for that: Mr. Shute was himself a high-class engineer, and a book like No Highway is packed with technical stuff that is not only accurate but often original. Incidentally, there are benefits to be gained from listening to intelligent men, [16]utterly removed from the literary scene and unconcerned as to who’s in and who’s out. One can pick up such a comment as a scientist once made, that it looked to him as though the current preoccupations28 of the New Criticism, the extreme concentration on a tiny passage, had made us curiously insensitive to the total flavor of a work, to itscumulative29 effects, to the epic qualities in literature. But, on the other side of the coin, one is just as likely to listen to three of the most massive intellects in Europe happily discussing the merits of The Wallet of Kai-Lung.8 When you meet the younger rank-and-file30 of scientists, it often seems that they do not read at all. The prestige of the traditional culture is high enough for some of them to make a gallant31 shot at it. [17]Oddly enough, the novelist whose name to them has become a token of esoteric32 literary excellence is that difficult highbrow33 Dickens. [18]They approach him in a grim and dutiful spirit as though tackling Finnegan’s Wake, and feel a sense of achievement if they manage to read a book through. But most young techniciansdo not fly so high when you ask them what they read—“As a married man,” one says, “I prefer the garden.” Another says: “I always like just to use my books as tools.” (Difficult to resist speculating what kind of tool a book would make. A sort of hammer?A crude digging instrument?)9 That, or something like it, is a measure of the incommunicabilityof the two cultures. On their side the scientists are losing a great deal. Some of that loss is inevitable: it must and would happen in any society at our technical level. [19]But in this country we make it quite unnecessarily worse by our educational patterns. On the other side, how much does the traditional culture lose by the separation?10 I am inclined to think, even more. Not only practically—we are familiar with those arguments by now—but also intellectually and morally. The intellectual loss is a little difficult to appraise34. Most scientists would claim that you couldn’t comprehend the world unless you know the structure of science, in particular of physical science. In a sense, and a perfectly genuine sense, that is true. Not to have read War and Peace and La Cousine Bette and La Chartreuse de Parme is not to be educated; but so is not to have a glimmer of the Second Law of Thermodynamics35. Yet that case ought not to be pressed too far. It is more justifiable to say that those without any scientific understanding miss a whole body of experience: they are rather like the tone deaf, from whom all musical experience is cut off and who have to get on without it. The intellectual invasions of science are, however, penetrating deeper. Psycho-analysis once looked like a deep invasion, but that was a false alarm; cybernetics may turn out to be the real thing, driving down into the problems of will and cause and motive. If so, those who do not understand the method will not understand the depths of their own cultures.11 But the greatest enrichment the scientific culture could give us is—though it does not originate like that—a moral one. Among scientists, deep-natured men know, as starkly36 as any men have known, that the individual human condition is tragic; [20]for all its triumphs and joys, the essence of it is loneliness and the end death. But what they will not admit is that, because the individual condition is tragic, therefore the social condition must be tragic, too.[21]Because a man must die, that is no excuse for his dying before his time and after a servile37 life. The impulse behind the scientists drives them to limit the area of tragedy, to take nothing as tragic that can conceivably38 lie within men’s will. [22] They have nothing but contempt for those representatives of the traditional culture who use a deep insight into man’s fate to obscure39 the truth, justto hang on to a few perks40. Dostoevski sucking up to the Chancellor Pobedonostsev, who thought the only thing wrong with slavery was that there was not enough of it; the political decadence of the avant-garde41 of 1914, with Ezra Pound finishing up broadcasting for the fascists; Claudel agreeing sanctimoniously42 with the Marshal about the virtue in others’ suffering; Faulkner giving sentimental reasons for treating Negroes as a different species. They are all symptoms of the deepest temptation of the clerks—which is to say: “[23]Because man’s condition is tragic,everyone ought to stay in their place, with mine as it happens somewhere near the top.” From that particular temptation, made up of defeat, self-indulgence, and moral vanity, the scientific culture is almost totally immune. It is that kind of moral health of the scientists, which, in the last few years, the rest of us have needed most; and of which, because the two cultures scarcely touch, we have been most deprived.。

芬芳的玫瑰悲伤的恋歌——《献给爱米丽的玫瑰》的新历尖主义解读

19

万方数据

作者简介:黄薇,1981.6,女,武汉人,研究生,讲师,主要研究方向:英美文学

[中图分类号]:106[文献标识码】:A[文章编号】:1002-2139(2011)一08-0018_02

引育 新历史主义批评认为,文本属于特定时期的历史,它植根 于一定的社会制度之中并受其制约。要认识文学文本的意义和 作用,就要了解它产生和形成的条件和方式。新历史主义不仅 提供了一种解读文本评价作品的新方法,而且还启发了人们对 待文学,理解历史,把握处理历史与文学,历史与文化之间复 杂关系的新概念。 威廉・福克纳作为美国南方文艺复兴中的一员,其许多小说 作品都描述了南方兴衰枯荣的历史。他笔下的约克纳帕塔法世 界里有种植园主世家子弟的苦闷身影,也有黑人奴隶苦苦挣扎 的凄惨画面:有南方过去的辉煌和荣耀,也有旧南方的罪恶与 腐朽,详尽生动地为我们演绎了一部南方社会二百多年的历史 剧。其短篇小说《献给爱米丽的玫瑰》描写了约克纳帕塔法县

View be

to

a

new a

replaeement position of

objectiwe

it

view,and be

hi story

wiIl

put

subjectiwe

remodeling the ellltural

interpretation,and and dialogue between when

evade

as a

the influence of

nat

the Southern htst01-y

restrained

ive Southerner.

am

Key

WOrds:Willi

FaUlkner:Emily:New background;

英美新批评

反讽。布鲁克斯对反讽作了最详备的解释。 他把反讽定义为“语境对一个陈述语的明 显的歪曲”。语境能使一句话的含混意颠 倒,这就是反讽。诗歌中的所有语词都得 受到语境的约束,它们的意义都受到语境 的影响,因而都存在着一定程度的反讽。 反讽可以表现在语言技巧上,如故意把话 说轻,但听者却知其分量。反讽也可以表 现在整个作品结构之中。 鲁迅的小说:《祝福》《啊Q正传》

三、基本概念: 意义含混 反讽 张力 悖论 隐喻 细读法

意义含混。该术语由燕卜逊引入新批评, 指文学语言的多义形成的复合意义。换句 话说,意义含混指的是一个语言单位(字、 词)包含两种或两种以上的意义,一句话 可以有多种理解的现象,是指某种修辞手 段所产生的多种效果。意义含混以往被视 为文学创作的一大弊病,而新批评则把它 视为诗歌语言的基本特征,使之大致接近 “丰富”、“巧智”的意思。意义含混这 一术语的提出和运用将使我们从语言学的 角度更好地对诗歌的复杂性和幽微曲折性 加以解释,从而丰富诗歌的意蕴。

Although there were antecedents from Plato

through James, a systematic and methodological formalistic approach to literary criticism appeared only with the rise in

它们所共有、所推广的观点有:把文学看作

是一个有机的“传统”,强调严格遵守形式 的 重要性,在古典价值方面坚持保守主义,怀 有创立一个提倡秩序和传统的社会的理想, 偏于仪式,主张对文学文本进行严密分析的 读解方法。

二、基本理论主张: 1、文学本体论:意图谬见和感受谬见 2、结构—肌质论。 3、语境理论。

第2讲,西方文论

第一、本体论批评

• 艾略特的非个人化理论 • 兰瑟姆的本体论批评 • 维姆萨特与比尔兹利的《意图谬误》、《情感 谬误》

艾略特的“非个人化”理论 (depersonalization)

诗不是放纵感情, 而是逃避感情,不是 表现个性,而是逃避 个性。

《传统与个人才能》

• 整个文学是个有机整体每一部具体的作品也是一个有机整体文 学家受到文学传统的深刻影响,不可能脱离文学传统而真正具 有个性 • 文学家应当消灭个性。 “艺术家的过程就是不停的自我牺牲,持续的个性泯灭。” “艺术家越高明,他个人的情感和创作的大脑之间分离得就越 彻底”。 “在氧气和二氧化硫发生化学反应生成硫酸的过程中,白金作 为催化剂,既不可或缺又本身不受任何影响。诗人创作时他的 思想犹如白金,既是创作的源泉又不介入作品中去。” • 非个人化还应当逃避文学家个人的情感。诗和其它文学作品是 表现情感的, “这种感情只活在诗里,而不存在于诗人的经历中。艺术的感 情是非个人的。”

俄国形式主义

时间: • 1915-1930 两个中心: • 莫斯科语言学学会 • 诗歌语言研究会 (奥波亚兹) 历史沿革: 俄国形式主义——捷克布拉格学派——法国结 构主义

两个重要代表人物

罗曼· 雅各布森 1896-1982

Viktor Shklovsky 1893-1984

文学性(literariness)

• 诗歌语言VS.实用语言 用新的术语置换西方传统文论中形式与内容的二元对立 材料和手法 故事和情节 彻底颠覆了西方传统文论中形式与内容的二元对立。 形式主义者认为:文学是形式的艺术。第一、内容不能 决定形式,内容不能创造形式;第二、形式有不受内 容支配的独立自主性;第三、形式可以决定内容,创 造内容。内容是形式的内容。

20世纪西方文论讲义 第二章英美新批评文论

第二章英美新批评文论一、发展概述新批评(TheNewCriticism)是关注文学文本主体的形式主义批评,认为文学的本体即作品,文学研究应以作品为中心,对作品的语言、构成、意象等进行认真细致的分析。

新批评20世纪在英美流行,一度在文学研究中占统治地位。

大致讲,新批评分三个阶段。

第一阶段是20年代,英国的T. S. 艾略特、I. A. 理查兹和威廉·燕卜荪以及美国的约翰·克罗·兰瑟姆和艾伦·泰特等人,开始提出一些新批评的基本观点并付诸实践。

30年代和40年代为第二阶段,这一时期认同并支持新批评这种形式主义的人大量增加,新批评的观点迅速扩展,直接影响到文学期刊、大学教学和课程设置。

主要代表人物除上述五人外,还有R. P. 布莱克默、科林斯·布鲁克斯、雷内·韦勒克和W. K.韦姆萨特等。

第三个阶段从40年代末延续到50年代后期,这一时期新批评占据了主流地位,形成了制度化的批评模式,失去了“革命的”气息,批评家的著作大多阐述新批评的原则而缺乏创新。

到50年代末,新批评失去了它的生命力,虽然在大学教学中仍被应用,但许多人认为它已经过时,开始以新的理论观念对它进行批判和超越。

新批评与俄国形式主义有许多相似之处,主要目的都是探讨独特的文学性所在,都否认后期浪漫主义诗学中“软弱的”精神性,一味主张经验主义阅读方式。

但新批评与俄国形式主义又有许多不同,它有自身的特性。

布鲁克斯把新批评的特征概括为五点:(1)把文学批评从渊源研究中分离出来,使其脱离社会背景、思想史、政治和社会效果,寻求不考虑“外在”因素的纯文学批评,只集中注意文学客体本身;(2)集中探讨作品的结构,不考虑作者的思想或读者的反应;(3)主张一种“有机统一”的文学理论,不赞成形式和内容划分的二元论观念,强调探讨作品中词语与整个作品语境的关系,认为每个词对独特的语境都有其作用,并由它在语境中的地位产生意义;(4)强调对单个作品的细读,特别注意词的细微差别、修辞方式以及意义的微小差异,力图具体说明语境的统一性和作品的意义;(5)把文学与宗教和道德区分开来——这主要是因为新批评的许多支持者具有确定的宗教观而又不想把它放弃,也不想以它取代道德或文学。

literary-theory-and-criticism

Literary Theory and CriticismLiterary theory and literary criticism are interpretive tools that help us think more deeply and insightfully about the literature that we read. Over time, different schools of literary criticism have developed, each with its own approaches to the act of reading.Schools of InterpretationCambridge School (1920s–1930s): A group of scholars at Cambridge University who rejected historical and biographical analysis of texts in favor of close readings of the texts themselves.Chicago School (1950s): A group, formed at the University of Chicago in the 1950s, that drew on Aristotle’s distinctions between the various elements within a narrative to analyze the relation between form and structure. Critics and Criticisms: Ancient and Modern (1952) is the major work of the Chicago School.Deconstruction (1967–present): A philosophical approach to reading, first advanced by Jacques Derrida that attacks the assumption that a text has a single, stable meaning. Derrida suggests that all interpretation of a text simply constitutes further texts, which means there is no “outside the text” at all. Therefore, it is impossible for a text to have stable meaning. The practice of deconstruction involves identifying the contradictions within a text’s claim to have a single, stable meaning, and showing that a text can be taken to mean a variety of things that differ significantly from what it purports to mean. Feminist criticism (1960s–present): An umbrella term for a number of different critical approaches that seek to distinguish the human experience from the male experience. Feminist critics draw attention to the ways in which patriarchal social structures have marginalized women and male authors have exploited women in their portrayal of them. Althou gh feminist criticism dates as far back as Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and had some significant advocates in the early 20th century, such as Virginia Woolf and Simone de Beauvoir, it did not gain widespread recognition as a theoretical and political movement until the 1960s and 1970s.Psychoanalytic criticism: Any form of criticism that draws on psychoanalysis, the practice of analyzing the role of unconscious psychological drives and impulses in shaping human behavior or artistic production. The three main schools of psychoanalysis are named for the three leading figures in developing psychoanalytic theory: Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and Jacques Lacan.•Freudian criticism (c. 1900–present): The view of art as the imagined fulfillment of wishes that reality denies. According to Freud, artists sublimate their desiresand translate their imagined wishes into art. We, as an audience, respond to thesublimated wishes that we share with the artist. Working from this view, anar tist’s biography becomes a useful tool in interpreting his or her work. “Freudian criticism” is also used as a term to describe the analysis of Freudian images withina work of art.•Jungian criticism (1920s–present): A school of criticism that draws on Car l Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, a reservoir of common thoughts andexperiences that all cultures share. Jung holds that literature is an expression ofthe main themes of the collective unconscious, and critics often invoke his workin discussions of literary archetypes.•Lacanian criticism (c. 1977–present): Criticism based on Jacques Lacan’s view that the unconscious, and our perception of ourselves, is shaped in the “symbolic”order of language rather than in the “imaginary” order of preling uistic thought.Lacan is famous in literary circles for his influential reading of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Purloined Letter.”Marxist criticism: An umbrella term for a number of critical approaches to literature that draw inspiration from the social and economic theories of Karl Marx. Marx maintained that material production, or economics, ultimately determines the course of history, and in turn influences social structures.These social structures, Marx argued, are held in place by the dominant ideology, which serves to reinforce the interests of the ruling class. Marxist criticism approaches literature as a struggle with social realities and ideologies.•Frankfurt School (c. 1923–1970): A group of German Marxist thinkers associated with the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt. These thinkersapplied the principles of Marxism to a wide range of social phenomena, including literature. Major members of the Frankfurt School include Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, and Jürgen Habermas.New Criticism (1930s–1960s):Coined in John Crowe Ransom’s The New Criticism (1941), this approach discourages the use of history and biography in interpreting a literary work. Instead, it encourages readers to discover the meaning of a work through a detailed analysis of the text itself. This approach was popular in the middle of the 20th century, especially in the United States, but has since fallen out of favor.New Historicism (1980s–present): An approach that breaks down distinctions between “literature” and “historical context” by examining the contemporary production and reception of literary texts, including the dominant social, political, and moral movements of the time. Stephen Greenblatt is a leader in this field, which joins the careful textual analysis of New Criticism with a dynamic model of historical research.New Humanism (c. 1910–1933): An American movement, led by Irving Babbitt and Paul Elmer More, that embraced conservative literary and moral values and advocated a return to humanistic education.Post-structuralism (1960s–1970s): A movement that comprised, among other things, Deconstruction, Lacanian criticism, and the later works of Roland Barthes and MichelFoucault. It criticized structuralism for its claims to scientific objectivity, including its assumption that the system of signs in which language operates was stable.Queer theory (1980s–present):A “constructivist” (as opposed to “essentialist”) approach to gender and sexuality that asserts that gender roles and sexual identity are social constructions rather than an essential, inescapable part of our nature. Queer theory consequently studies literary texts with an eye to the ways in which different authors in different eras construct sexual and gender identity. Queer theory draws on certain branches of feminist criticism and traces its roots to the first volume of Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality (1976).Russian Formalism (1915–1929): A school that attempted a scientific analysis of the formal literary devices used in a text. The Stalinist authorities criticized and silenced the Formalists, but Western critics rediscovered their work in the 1960s. Ultimately, the Russian Formalists had significant influence on structuralism and Marxist criticism. Structuralism (1950s–1960s): An intellectual movement that made significant contributions not only to literary criticism but also to philosophy, anthropology, sociology, and history. Structuralist literary critics, such as Roland Barthes, read texts as an interrelated system of signs that refer to one another rather than to an external “meaning” that is fixed either by author or reader. Structuralist literary theory draws on the work of the Russian Formalists, as well as the linguistic theories of Ferdinand de Saussure and C. S. Peirce.Literary Terms and TheoriesLiterary theory is notorious for its complex and somewhat inaccessible jargon. The following list defines some of the more commonly encountered terms in the field. Anxiety of influence: A theory that the critic Harold Bloom put forth in The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry(1973). Bloom uses Freud’s idea of the Oedipus complex (see below) to suggest that poets, plagued by anxiety that they have nothing new to say, struggle against the influence of earlier generations of poets. Bloom suggests that poets find their distinctive voices in an act of misprision, or misreading, of earlier influences, thus refiguring the poetic tradition. Although Bloom presents his thesis as a theory of poetry, it can be applied to other arts as well.Canon: A group of literary works commonly regarded as central or authoritative to the literary tradition. For example, many critics concur that the Western canon—the central literary works of Western civilization—includes the writings of Homer, Shakespeare, Tolstoy, and the like. A canon is an evolving entity, as works are added or subtracted as their perceived value shifts over time. For example, the fiction of W. Somerset Maugham was central to the canon during the middle of the 20th century but is read less frequently today. In recent decades, the idea of an authoritative canon has come under attack, especially from feminist and postcolonial critics, who see the canon as a tyranny of dead white males that marginalizes less mainstream voices.Death of the author: A post-structuralist theory, first advanced by Roland Barthes, that suggests that the reader, not the author, creates the meaning of a text. Ultimately, the very idea of an author is a fiction invented by the reader.Diachronic/synchronic: Terms that Ferdinand de Saussure used to describe two different approaches to language. The diachronic approach looks at language as a historical process and examines the ways in which it has changed over time. The synchronic approach looks at language at a particular moment in time, without reference to history. Saussure’s structuralist approach is synchronic, for it studies language as a system of interrelated signs that have no reference to anything (such as history) outside of the system.Dialogic/monologic: Terms that the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin used to distinguish works that are controlled by a single, authorial voice (monologic) from works in which no single voice predominates (dialogic or polyphonic). Bakhtin takes Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky as examples of monologic and dialogic writing, respectively.Diegesis/Mimesis:Terms that Aristotle first used to distinguish “telling” (diegesis) from “showing” (mimesis). In a play, for instance, most of the action is mimetic, but moments in which a character recounts what has happened offstage are diegetic.Discourse: A post-structuralist term for the wider social and intellectual context in which communication takes place. The implication is that the meaning of works is as dependent on their surrounding context as it is on the content of the works themselves.Exegesis: An explanation of a text that clarifies difficult passages and analyzes its contemporary relevance or application.Explication: A close reading of a text that identifies and explains the figurative language and forms within the work.Hermeneutics: The study of textual interpretation and of the way in which a text communicates meaning.Intertextuality: The various relationships a text may have with other texts, through allusions, borrowing of formal or thematic elements, or simply by reference to traditional literary forms. The term is important to structuralist and poststructuralist critics, who argue that texts relate primarily to one another and not to an external reality. Linguistics: The scientific study of language, encompassing, among other things, the study of syntax, semantics, and the evolution of language.Logocentrism: The desire for an ultimate guarantee of meaning, whether God, Truth, Reason, or something else. Jacques Derrida criticizes the bulk of Western philosophy as being based on a logocentric “metaphysics of presence,” which insists on the presence ofsome such ultimate guarantee. The main goal of deconstruction is to undermine this belief.Metalanguage: A technical language that explains and interprets the properties of ordinary language. For example, the vocabulary of literary criticism is a metalanguage that explains the ordinary language of literature. Post-structuralist critics argue that there is no such thing as a metalanguage; rather, they assert, all language is on an even plane and therefore there is no essential difference between literature and criticism.Metanarrative: A larger framework within which we understand historical processes. For instance, a Marxist metanarrative sees history primarily as a history of changing material circumstances and class struggle. Post-structuralist critics draw our attention to the ways in which assumed met narratives can be used as tools of political domination.Mimesis:See diegesis/mimesis, above.Monologic:See dialogic/monologic, above.Narratology: The study of narrative, encompassing the different kinds of narrative voices, forms of narrative, and possibilities of narrative analysis.Oedipus complex: Sigmund Freud’s theory that a male child feels unconscious jealousy toward his father and lust for his mother. The name comes from Sophocles’ play Oedipus Rex, in which the main character unknowingly kills his father and marries his mother. Freud applies this theory in an influential reading of Hamlet, in which he sees Hamlet as struggling with his admiration of Claudius, who fulfilled Hamlet’s own desire of murdering Hamlet’s father and marrying his mother.Semantics: The branch of linguistics that studies the meanings of words.Semiotics or semiology: Terms for the study of sign systems and the ways in which communication functions through conventions in sign systems. Semiotics is central to structuralist linguistics.Sign/signifier/signified: Terms fundamental to Ferdinand de Saussure’s structuralism linguistics. A sign is a basic unit of meaning—a word, picture, or hand gesture, for instance, that conveys some meaning. A signifier is the perceptible aspect of a sign (e.g., the word “car”) while the signified is the conceptual aspect of a sign (e.g., the concept of a car). A referent is a physical object to which a sign system refers (e.g., the physical car itself).。

美国文学复习资料

American Literature Lecture One 060511/2, 9th Nov. 2009Part I. IntroductionPart I: introduction questions1.Teaching schemes, examination, requirements, advice, contacts, and so on2.What is literature?3.How to define American Literature?4.How to study literature?1. What is literature?1)The definition of 14th century:It means polite learning through reading. A man of literature or a man of letters = a man of wide reading, “literacy”2)The definition of 18th century:practice and profession of writing3)The definition of 19th century:the high skills of writing in the special context of high imagination4)Robert Frost’s definition:performance in words5)Modern definition:We can define literature as language artistically used to achieve identifiable literary qualities and to convey meaningful messages. Literature is characterized by beauty of expression and form and by universality intellectual and emotional appeal.2. How to define the American literatureAmerican literature mainly refers to literature produced in American English by the people living in the United States.3. How to study literatureHistorical Perspectives: Biographical-Historical and Moral-Philosophical.(Diverse Types of Historicisms: including Feminist, Sociological or Marxian Studies of Language, Literature and Translation)Structuralist Perspectives: Looking for Systematic Deep Structures both in Form and Content.(Semiotics, TG Grammar, Systematic/Functional Grammar, Narratology, Freudian psycho-analysis, Russian Formalism, Anglo-American New Criticism, Archetypalism, Myth Criticism, Structural Marxism, Ideology)Poststructuralist or Postmodern Perspectives: Deconstructing Structuring Binaries (No Clear Distinction between Form and Content)[Postmodern Feminism, Postcolonialism, Postmodern Narratologies, New Historicism, Ideological Studies, Discourse Analysis, Reception Theories, Trauma Studies, Trans-Atlantic Studies, Transnationalism, Eco-criticism, Cultural Pathology, and other Postmodernisms]Approaches on Literature1. The Traditional Approaches:1)Analytical ApproachBe familiar with the elements of a literary work, eg: plot, character, setting, point of view, structure, style, atmosphere, theme, etc; answer some basic questions about the text itself.2)Thematic Approach“What is the story, the poem, the play or the essay about?”3)Historical - Biographical Approach4)Moral - Philosophical Approach.2.The Formalistic AppoachStructuralism, Poststructuralism, Semiotics3.The Psychological Approach: Freud4.Mythological and Archetypal Approach5.Feminist Approaches6.Sociological Approach7.Deconstruction8.Phenomenology, Hermeneutics, Reception Theory9.Cultural CriticismAmerican MulticultualismThe New Historicism, British Cultural Materialism10.Additional Approaches:①Aristotlian Criticism②Genre Criticism③Rhetoric, Linguistics, and Stylistics④The Marxist Approach⑤Ecological Criticism⑥Post ColonialismLecture Two 060511/2, 10th Nov. 2009Part II. The periods of American literature①The colonial period (约1607 - 1765)②The period of Enlightenment and the Independence War (1765 -1800)③The romantic period (1800 - 1865)④The realistic period (1865 - 1914)⑤The period of modernism (1914 - 1945)⑥The Contemporary Literature (1945 - 2000)1.The colonial period (约1607 - 1765)The main featuresPuritanism2.The period of Enlightenment and the Independence War (1765 -1800)Benjamin Franklin3.The romantic period (1800 - 1865)1)The early romanticismWashington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper2)“New England Transcendentalism” or “American Renaissance (1836 - 1855)”Emerson, Thoreau/ Whitman, Dickinson/ Hawthorne, Melville , Allan Poe3)“New England Poets” or “Schoolroom Poets”Bryant/ Longfellow/ Lowell/ Holmes/ Whittier4) The Reformers and AbolitionistsBeecher Stowe/ Frederick Douglass4.The realistic period (1865 - 1914)1)Midwestern RealismWilliam Dean Howells2)Cosmopolitan NovelistHenry James3)Local ColorismMark Twain4)NaturalismStephen Crane/ Jack London/ Theodore Dreiser5)The “Chicago School” of PoetryMasters/ Sandburg/ Lindsay/ Robinson6)The Rise of Black American LiteratureWashington/ Du Bois/ Chestnutt5.The period of modernism (1914 - 1945)1)Modern poetry: experiments in form (Imagism)Ezra Pound/ T.S.Eliot/ Robert Frost/ Wallace Stevens/ Carlos Williams2)Prose Writing: modern realism (the Lost Generation)F.Scott Fitzgerald/ Ernest Hemingway/ William Faulkner3)Novels of Social AwarenessSinclair Lewis/ Dos Passos/ John Steinbeck/ Richard Wright4)The Harlem RenaissanceLangston Hughes/ Zora Neals Hurston5)The Fugitives and New Criticism6)The 20th Century American DramaEugene O’ Neil6.The Contemporary Literature (1945 - 2000)I.American Poetry Since 1945: the Anti-traditionII.American Prose Since 1945: Realism and Experimentation.I. Poetry:1)Traditionalism2)Idiosyncratic poets3)Experimental poetry4)Surrealism and Existentialism5)Women and Multiethnic poets6)Chicano / Hispanic / Latino poetry7)Native American poetry8)African-American poetry9)Asian-American poetry10)New DirectionsExperimental Poetry:1)The Black Mountain School2)The San Francisco School3)Beat Poets4)The New York SchoolII. Prose:1.The Realist Legacy and the Late 1940s2.The Affluent but Alienated 1950s3.The Turbulent but Creative 1960s4.The 1970s and 1980s: New Directions1.The Realist Legacy and the Late 1940s1)Robert Penn Warren2)Arthur Miller3)Tennessee Williams4)Katherine Anne Porter5)Eudora Welty2.The Affluent But Alienated 1950s1)John O’Hara2) James Baldwin3) Ralph Waldo Ellison4) Flannery O’Conner5) Saul Bellow6) Bernard Malamud7) Isaac Bashevis Singer8) Vladimir Nabokov9) John Cheever10) John Updike11) J.D.Salinger12) Jack Kerouac3. The Turbulent but Creative 1960s1) Thomas Pynchon2) John Barth3) Norman Mailer4. The 1970s and 1980s: New Directions1) John Gardner2) Toni Morrison3) Alice WalkerPart II. Early American and Colonial Period to 17651. Introduction1. Instead of beginning with folk tales and songs the American literature began with abstractions and proceededfrom philosophy to fiction because there were no written literature among the more than 500 different Indian languages and tribal cultures that existed in North America before the first Europeans arrived there and set up the first colony Jamestown in about 1607.2. American writing began with the work of English adventurers and colonists in the New World chiefly for thebenefit of readers in the mother country. Some of these early works reached the level of literature, as in the robust and perhaps truthful account of his adventures by Captain John Smith and the sober, tendentious journalistic histories of John Winthrop and William Bradford in New England. From the beginning, however, the literature of New England was also directed to the edification and instruction of the colonists themselves, intended to direct them in the ways of the godly.3. Therefore the writing in this period was essentially two kinds: (1) practical matter-of-fact accounts of farming,hunting, travel, etc. designed to inform people “at home” what life was like in the new world, and, often, to induce their immigration; (2) highly theoretical, generally polemical, discussions of religious questions.4. Furthermore, the influential Protestant work ethic, reinforced by the practical necessities of a hard pioneer life,inhibited the development of any reading matter designed simply for leisure-time entertainment.It is the belief that work itself is good in addition to what it achieves; that time saved by efficiency or goodfortune should not be spent in leisure but in doing further work; that idleness is always immoral and likely to lead to even worse sin since “the devil finds work for idle hands to do”. This belief late r developed into the American philosophic idea Puritanism.5. divines who wrote furiously to set forth their views was to defend and promote visions of the religious state. They set forth their visions —in effect the first formulation of the concept of national destiny —in a series ofimpassioned histories and jeremiads from Providence (1654) to Cotton Mather ’s epic Magnalia Christi Americana6. Even Puritan poetry was offered uniformly to the service of God. Michael Wigglesworth ’s Day of Doom (1662) wasuncompromisingly theological, and Anne Bradstreet ’s poems, issued as The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America (1650), were reflective of her own piety. The best of the Puritan poets, Edward Taylor , whose work was not published until two centuries after his death, wrote metaphysical verse,Sermons and tracts poured forth until austere Calvinism found its last utterance in the words of Jonathan Edwards . In the other colonies writing was usually more mundane and on the whole less notable, though the journal of the Quaker John Woolman is highly esteemed, and some critics maintain that the best writing of the colonial period is found in the witty and urbane observations of William Byrd , a gentleman planter of Westover, Virginia.2. The Main Features of this period1) American literature grew out of humble origins. diaries, histories, journals, letters, commonplace books, travelbooks, sermons, in short, personal literature in its various forms, occupy a major position in the literature of the early colonial period.2) In content these early writings served either God or colonial expansion or both. In form, if there was any format all, English literary traditions were faithfully imitated and transplanted.3) The Puritanism formed in this period was one of the most enduring shaping influences in American thought andAmerican literature.3. Puritanism1) Simply speaking, American Puritanism just refers to the spirit and ideal of puritans who settled in the NorthAmerican continent in the early part of the seventeenth century because of religious persecutions. In content it means scrupulous moral rigor, especially hostility to social pleasures and indulgences, that is strictness,sternness and austerity in conduct and religion.2) With time passing it became a dominant factor in American life, one of the most enduring shaping influences inAmerican thought and American Literature. To some extent it is a state of mind, a part of the national cultural atmosphere that the American breathes, rather than a set of tenets.3) Actually it is a code of values, a philosophy of life and a point of view in American minds, also a two-facetedtradition of religious idealism and level-headed common sense.Part III. The period of Enlightenment and the Independence War (1765 -1800)I. Introduction1) The 18th-century American enlightenment as a movement marked by an emphasis on rationality rather thantradition, scientific inquiry instead of unquestioning religious dogma, and representative government in place of monarchy.2) Enlightenment thinkers and writers, such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine, were devoted to the idealsof justice, liberty, and equality as the natural rights of man.3) In these period with the exception of outstanding political writing, such as Common sense, Declaration ofIndependence, The Federalist Papers and so on, few works of note appeared. Even if there appeared poetry and fiction, they were full of imitativeness and vague universality. So most Americans were painfully aware of their excessive dependence on English literary models. The search for a native literature became a national obsession.4) Despite these we should pay attention to several points in this period:William Hill Brown (1765-1793) published the first American novel The Power of Sympathy in 1789.Charles Brockden Brown (1771-1810) was the first American author to attempt to live from his writing. Hedeveloped the genre of American Gothic.The Dictionary edited by Noah Webster (1758-1843) based the American lexicography. Updated Webster’sdictionaries are still standard today.Philip Freneau’s (1752-1832) was known as "the poet of the American Revolution". His major themes are death, nature, transition, and the human in nature. All of these themes become important in 19th century writing. All the while...in romanticizing the wonders of nature in his writings...he searched for an American idiom in verse. II. Benjamin Franklin1706 - 1790(An Extraordinary Life and An Electric Mind)1. His Life1)Born the tenth of fifteen children in a poor candle and soap maker’s family, he had to leave school before he waseleven.2)At twelve he was apprenticed to an older brother, James, a printer in Boston.3)As a voracious reader he managed to make up for the deficiency by his own effort and began at 16 to publishessays under the pseudonym, Silence Dogood, essays commenting on social life in Boston.4)When he was 17 he ran away to Philadelphia to make his own fortune marking the beginning of a long successstory of an archetypal kind.5)He set himself up as an independent printer and publisher, found the Junto Club and subscription library,issued the immensely popular Poor Richard’s Almanac.6)Retired around forty-two, he did what was to him a great happiness: read, make scientific experiments and dogood to his fellowmen. He helped to find the Pennsylvania Hospital, an academy which led to the University of Pennsylvania, and the American Philosophical Society.7)At the same time he did a lot of famous experiments and invented many things such as volunteer firedepartments, effective street lighting, the Franklin Stove, bifocal glasses, efficient heating devices, lightning-rod and so on.8)Beginning his public career in the early fifties, he became a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly, the DeputyPostmaster-General for the colonies, and for some eighteen years served as representative of the colonies in London.9)During the War of Independence, he was made a delegate to the Continental Congress and a member of thecommittee to write the Declaration of Independence. One of the makers of the new nation, he was instrumental in bringing France into an alliance with America against England, and played a decisive role at the Constitutional Convention.2. Major Works1)Poor Richard’s AlmanacMaxims(谚语,格言)and axioms(哲理,格言)a)Lost time is never found again.b) A penny saved is a penny earned.c)God help them that help themselves.d)Fish and visitors stink in three days.e)Early to bed, and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.f)Ale in, truth out.g)Eat not to dullness. Drink not to elevation.h)Diligence is the Mother of Good Luck.i)One Today is worth two tomorrow.j)Industry pays debts. Despair encreaseth them.2)Autobiographya.It is perhaps the first real post-revolutionary American writing as well as the first real autobiography in English.b.It gives us the simple yet immensely fascinating record of a man rising to wealth and fame from a state ofpoverty and obscu rity into which he was born, the faithful account of the colorful career of America’s first self-made man.c.First of all, it is a puritan document. The most famous section describes his scientific scheme of self-examinationand self-improvement.d.It is also an eloquent elucidation of the fact that Franklin was spokesman for the new order of eighteenthcentury enlightenment, and that he represented in America all its ideas, that man is basically good and free, by nature endowed by God with certain inalienable rights of liberty and the pursuit of happiness.e.It is the pattern of Puritan simplicity, directness, and concision. The plainness of its style, the homeliness ofimagery, the simplicity of diction, syntax and expression are some of the salient features we cannot mistake.3. Evaluation1)He was a rare genius in human history. Nature seemed particularly lavish and happy when he was shaped.Everything seems to meet in this one man, mind and will, talent and art, strength and ease, wit and grace, and he became almost everything: a printer, postmaster, citizen, almanac maker, essayist, scientist, inventor, orator, statesman, philosopher, political economist, ambassador, musician and parlor man.2)He was the first great self-made man in America, a poor democrat born in an aristocratic age that his fineexample helped to liberalize.3)Politically he brought the colonial era to a close. For quite some time he was regarded as the father of allYankees, even more than Washington was. He was the only American to sign the four documents that created the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the treaty of alliance with France, the treaty of peace with England, and the constitution.4)Scientifically, as the symbol of America in the Age of Enlightenment, he invented a lot of useful implements. Hisresearch on electricity, his famous experiment with his kite line and many others made him the preeminent scientist of his day.5)Literally, he really opened the story of American literature. D. H. Lawrance agreed that Franklin waseverything but a poet. In the Scottish philosopher David Hume’s eyes he was America’s “first great man of letters”.Assignment: Please read the material by Ralph Waldo EmersonLecture Three 060511/2, 16th Nov. 2009The American Romanticism(I)I. What is RomanticismSimply speaking, Romanticism is a literary movement flourished as a cultural force throughout the 19th C and it can be divided into the early period and the late period. Also it remains powerful in contemporary literature and art.Romanticism, a term that is associated with imagination and boundlessness, as contrasted with classicism, which is commonly associated with reason and restriction. A romantic attitude may be detected in literature of any period, but as an historical movement it arose in the 18th and 19th centuries, in reaction to more rational literary, philosophic, artistic, religious, and economic standards.... The most clearly defined romantic literary movement in the U. S. was Transcendentalism.The representatives of the early period includes Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper, and those of the late period contain Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe.II. The reasons on the rise of American RomanticismInternal causes:1)American burgeoned into a political, economic and cultural independence. Democracy and political equalitybecame the ideals of the new nation. Radical changes came about in the political life of the country. Parties began to squabble and scramble for power, and new system was in the making.2)The spread of industrialism, the sudden influx of immigration, and the pioneers pushing the frontier furtherwest, all these produced something of an economic boon and, with it, a tremendous sense of optimism and hope among the people.3)Ever-increasing magazines played an important role in facilitating literary expansion in the country.External causes:1)Foreign influences added incentive to the growth of romanticism in America.2)The influence of Sir Walter Scott was particularly powerful and enduring.III. Characteristics of American Romanticism (b)1)Sentimentalism, primitivism and the cult of the noble savage2)Political liberalism3)The celebration of natural beauty and the simple life4)Introspection5)The idealization of the common man, uncorrupted by civilization6)Interest in the picturesque past and remote places7)Antiquarianism8)Individualism9)Morbid melancholy10)Historical romanceIV. The Representatives of the early American romanticismA. Washington Irving(1783-1859 )1. About the Author1)Washington Irving was born in New York City on April 3, 1783 as the youngest of 11 children. His parents,Scottish-English immigrants, were great admirers of General George Washington, and named their son after their hero.2)Early in his life Irving developed a passion for books. He studied law privately but practiced only briefly. From1804 to 1806 he travelled widely in Europe. After returning to the United States, Irving was admitted to the New York bar in 1806.3)He was a partner with his brothers in the family hardware business and representative of the business inEngland until it collapsed in 1818. During the war of 1812 Irving was a military aide to New York Governor Tompkins in the U.S. Army.4)Irving's career as a writer started in journals and newspapers. His success in social life and literature wasshadowed by a personal tragedy because his engaged love died at the age of seventeen. So he never married or had children.5)After the death of his mother, Irving decided to stay in Europe, where he remained for seventeen years from1815 to 1832.6)In 1832 Irving returned to New York to an enthusiastic welcome as the first American author to have achievedinternational fame. Between the years 1842-45 Irving was the U.S. Ambassador to Spain.7)Irving spent the last years of his life in Tarrytown. From 1848 to 1859 he was President of Astor Library, laterNew York Public Library. Irving's later publications include Mahomet And His Successors(1850), Wolfert's Roost(1855), and his five-volume The Life of George Washington(1855-59). Irving died in Tarrytown on November 28, 1859.2. His Major Works1)His earliest work was a sparkling, satirical History of New York (1809) under the Dutch, ostensibly written byDiedrich Knickbo cker (hence the name of Irving’s friends and New York writers of the day, the “Knickbocker School”.)2)The Sketch Book (1819-20 as Geoffrey Crayon) - contains 'Rip Van Winkle' and 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow'3)The Life of George Washington (1855-59, five volumes)3. Evaluation to him1)American author, short story writer, essayist, poet, travel book writer, biographer, and columnist. Irving hasbeen called the father of the American short story. He is best known for 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,' in which the schoolmaster Ichabold Crane meets with a headless horseman, and 'Rip V an Winkle,' about a man who falls asleep for 20 years.2)The first American writer of imaginative literature to gain international fame, so he was regarded as father ofAmerican literature.3)The short story as a genre in American literature probably began with Irving’s The Sketch Book, ACOLLECTION OF ESSAYS, SKETCHES, AND TALES. It also marked the beginning of American Romanticism.B. James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851)1. His Major WorksIn his life Cooper wrote over thirty novels which can be divided into frontier novels, detective novels and reference novels. He considered The Pathfinder (1840) and The Deerslayer (1841) his best works.The unifying thread of the five novels collectively known as the Leather-Stocking Tales is the life of Natty Bumppo. Cooper’s finest achievement, they constitute4 a vast prose epic with the North American continent as setting. Indian tribes as Characters, and great wars and westward migration as social background. The novels bring to life frontier America from 1740 to 1804.1)The Pioneers(1823): Natty Bumppo first appears as a seasoned scout in advancing years, with the dyingChingachgook, the old Indian chief and his faithful comrade, as the eastern forest frontier begins to disappear and Chingachgook dies.2)The Last of the Mohicans(1826): An adventure of the French and Indian Wars in the Lake George county.3)The Prairie(1827): Set in the new frontier where the Leatherstocking dies.4)The Pathfinder(1840): Continuing the same border warfare in the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario county.5)The Deerslayer(1841): Early adventures with the hostile Hurons on Lake Otsego, NY.2. Contributions of CooperThe creation of the famous Leatherstocking saga has cemented his position as our first great national novelist and his influence pervades American literature. In his thirty-two years (1820-1851) of authorship, Cooper produced twenty-nine other long works of fiction and fifteen books - enough to fill forty-eight volumes in the new definitive edition of his Works. Among his achievements:1)The first successful American historical romance in the vein of Sir Walter Scott (The Spy, 1821).2)The first sea novel (The Pilot, 1824).3)The first attempt at a fully researched historical novel (Lionel Lincoln, 1825).4)The first full-scale History of the Navy of the United States of America (1839).5)The first American international novel of manners (Homeward Bound and Home as Found, 1838).6)The first trilogy in American fiction (Satanstoe, 1845; The Chainbearer, 1845; and The Redskins, 1846).7)The first and only five-volume epic romance to carry its mythic hero - Natty Bumppo - from youth to old age. 3. His Skills1)He is good at making plots.2)All his novels are full of myths.3)He had never been to the frontier and among the Indians and yet could write five huge epic books about them isan eloquent proof of the richness of his imagination.4)He created the first Indians to appear in American fiction and probably the first group of noble savages.5)He hi t upon the native subject of frontier and wilderness, and helped to introduce the “Western” tradition intoAmerican literature.V. American Renaissance1. The Concept1)It also called New England Renaissance period from the 1830s roughly until the end of the American CivilWar in which American literature, in the wake of the Romantic movement, came of age as an expression of a national spirit.2)The literary scene of the period was dominated by a group of New England writers, the “Brahmins”. They werearistocrats, steeped in foreign culture, active as professors at Harvard College, and interested in creating a genteel American literature based on foreign models.3)One of the most important influences in the period was that of the Transcendentalists, including Emerson,Thoreau and so on.4)The Transcendentalists contributed to the founding of a new national culture based on native elements. Theyadvocated reforms in church, state, and society, contributing to the rise of free religion and the abolition movement and to the formation of various utopian communities, such as Brook Farm. The abolition movement was also bolstered by other New England writers, including the Quaker poet Whittier and the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) dramatized the plight of the black slave.5)Apart from the Transcendentalists, there emerged during this period great imaginative writers—NathanielHawthorne, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman—whose novels and poetry left a permanent imprint on American literature. Contemporary with these writers but outside the New England circle was the Southern genius Edgar Allan Poe, who later in the century had a strong impact on European literature.Lecture Four The American Romanticism(II)TranscendentalismIt is a 19th-century movement of writers and philosophers in New England who were loosely bound together by adherence to an idealistic system of thought.Emerson defined it as “idealism” simply. In reality it was far more complex collection of beliefs: that the spark of divinity lies within man; that everything in the world is a microcosm of existence; that the individual soul is identical to the world soul, or Over-Soul. By meditation, by communing with nature, through work and art, man could transcend his senses and attain an understanding of beauty and goodness and truth.In application, American transcendentalism urged a reform in society, and that such a reform may be reached if individuals resist customs and social codes, and rely rather on reason to learn what is right. Ultimately, transcendentalists believed that one should transcend society's code of ethics and rely on personal intuition in order to reach absolute goodness, or Absolute Truth.It was indebted to the dual heritage of American Puritanism. That is to say, it was in actuality romanticism on the puritan soil.Transcendentalism dominated the thinking of the American Renaissance, and its resonance reverberated through American life well into the 20th century. In one way or another American most creative minds were drawn into its thrall, attracted not only to its practicable messages of confident self-identity, spiritual progress and social justice, but also by its aesthetics, which celebrated, in landscape and mindscape, the immense grandeur of the American soul.The Representativesof American RenaissanceI. The Essayists1)Ralph Waldo Emerson2)Henry David ThoreauRalph Waldo Emerson(1803 - 1882)1.His philosophy:1)Strongly he felt the need for a new national vision.2)He firmly believes in the transcendence of the Oversoul and thought that the universe was composed of Nature。

耶鲁学派

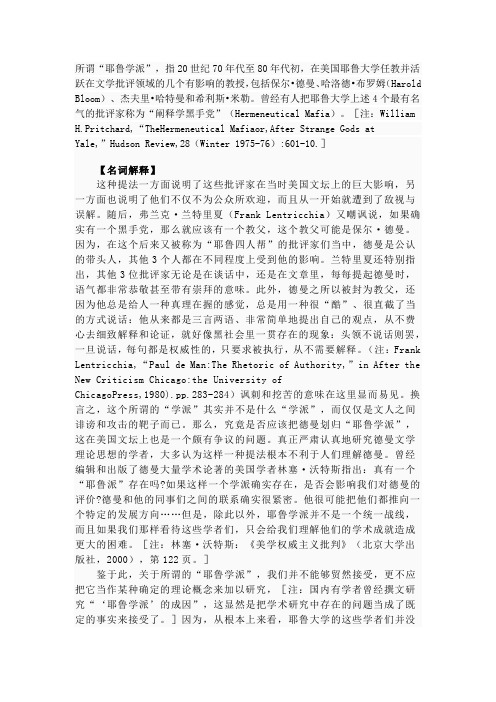

所谓“耶鲁学派”,指20世纪70年代至80年代初,在美国耶鲁大学任教并活跃在文学批评领域的几个有影响的教授,包括保尔•德曼、哈洛德•布罗姆(Harold Bloom)、杰夫里•哈特曼和希利斯•米勒。

曾经有人把耶鲁大学上述4个最有名气的批评家称为“阐释学黑手党”(Hermeneutical Mafia)。

[注:William H.Pritchard,“TheHermeneutical Mafiaor,After Strange Gods atYale,”Hudson Review,28(Winter 1975-76):601-10.]【名词解释】这种提法一方面说明了这些批评家在当时美国文坛上的巨大影响,另一方面也说明了他们不仅不为公众所欢迎,而且从一开始就遭到了敌视与误解。

随后,弗兰克·兰特里夏(Frank Lentricchia)又嘲讽说,如果确实有一个黑手党,那么就应该有一个教父,这个教父可能是保尔·德曼。

因为,在这个后来又被称为“耶鲁四人帮”的批评家们当中,德曼是公认的带头人,其他3个人都在不同程度上受到他的影响。

兰特里夏还特别指出,其他3位批评家无论是在谈话中,还是在文章里,每每提起德曼时,语气都非常恭敬甚至带有崇拜的意味。

此外,德曼之所以被封为教父,还因为他总是给人一种真理在握的感觉,总是用一种很“酷”、很直截了当的方式说话:他从来都是三言两语、非常简单地提出自己的观点,从不费心去细致解释和论证,就好像黑社会里一贯存在的现象:头领不说话则罢,一旦说话,每句都是权威性的,只要求被执行,从不需要解释。

(注:Frank Lentricchia,“Paul de Man:The Rhetoric of Authority,”in After the New Criticism Chicago:the University ofChicagoPress,1980).pp.283-284)讽刺和挖苦的意味在这里显而易见。

Literarytheory