SIBO IBS Psychological Factors

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征陈坚* 邱志兵 张会禄 汤子慧 杨冬琴(复旦大学附属华山医院消化内科 上海 200040)摘要本文概要介绍小肠细菌过度生长(small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, SIBO)和低度炎症在肠易激综合征患者中的发生率、SIBO的致病作用、利福昔明治疗伴有SIBO的肠易激综合征患者的疗效以及对利福昔明治疗失败的患者的补救治疗方法。

关键词 肠易激综合征小肠细菌过度生长乳果糖呼气试验 低度炎症 利福昔明中图分类号:R574.4; R363.21文献标志码:A文章编号:1006-1533(2019)15-0007-04Small intestinal bacteria overgrowth and irritable bowel syndromeCHEN Jian*, QIU Zhibing, ZHANG Huilu, TANG Zihui, YANG Dongqin(Department of Digestive Disease, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China)ABSTRACT The incidence and pathogenesis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and low-grade inflammatory response in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients are introduced. The effects of rifaximin on IBS patients with SIBO and the remedial treatment for rifaximin-resistant IBS patients are also discussed.KEy WORDS irritable bowel syndrome; small intestinal bacterial overgrowth; lactulose breath test; low-grade inflammation; rifaximin肠易激综合征(irritable bowel syndrome, IBS)是一种常见的功能性胃肠病,临床上主要表现为腹痛、腹胀以及腹泻或便秘等,全球人口的患病率为3% ~ 25%[1],亚洲地区人口的患病率为4% ~ 10%[2]。

Psychosocial Factors in IBS

Psychosocial Factors in IBS: Toward a More Comprehensive Understanding and Approach to TreatmentYehuda Ringel, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division Digestive Diseases University of North Carolina at Chapel HillDouglas A. Drossman, MD, Co-director, UNC Center for Functional GI & Motility Disorders,University of North Carolina at Chapel HillEdited by Donna Swantkowski, M.Ed., Coordinator, UNC Center for Functional GI & MotilityDisorders, University of North Carolina at Chapel HillThe treatment of functional GI disorders must include not only traditional physical clinical care but also an assessment of and focus on the psychological issues that may relate to these disorders. Studies at DDW 2003 have looked at the following aspects.THE RELEVANCE OF PSYCHOLOGICAL ISSUESAlthough most patients with IBS do not meet criteria for psychological disorders, considerably higher rates of IBS are found in patients with psychiatric diagnosis. However, it is not clear whether psychiatric disorders precede a diagnosis of IBS or is a consequence of it. Dr. Stuart C. Howell and colleagues at the University of Sydney performed a study of Australian subjects for their first 26 years of life to determine the connection between psychiatric disorders and IBS. By age, 16.7% met the Manning criteria for IBS. IBS was not found to be more common among individuals with 26 chronic psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. The study concluded that in young adults IBS is related to personality but not to a history of psychiatric disorder. There are, however, some limitations to consider. The study followed 869 subjects, but since only 145 of those met the IBS criteria, the actual number of patients that could be studied was relatively small. This could lead to findings that lack statistical power. IBS was defined categorically and from a population database, where subjects are more likely to have a milder illness. It is probable that psychiatric disorder would be found more often in those with more severe symptoms and a higher usage of health care. In addition, other psychological factors such as social support and coping style were not studied.POSSIBLE MECHANISMSSeveral studies at DDW offered insights on possible mechanisms by which psychological distress may affect patients' illness and behavior. Britta Dikhaus and colleagues, from UCLA conducted a study that looked at the effect of auditory induced psychological stress on sensitivity and emotional responses to rectal balloon distension in the esophagus. The study tested IBS patients whose predominant symptom is diarrhea as well as normal individuals who do not have IBS. In the IBSgroup, relatively to controls, the induced psychological stress was associated with increased sensitivity and a stronger emotional response. In the control group of normal subjects, this association was not observed.In another study, Lloyd J. Gregory from the United Kingdom looked at changes in brain activation in response to esophageal distension when given either of two tasks: a) a visual (distracting) task and b) focusing attention to the esophageal stimulus. There was greater brain activation when subjects were asked to concentrate on the esophageal stimulus rather when they did the visual task. The study concluded that conscious selective attention to the esophagus during esophageal stimulation results in more brain activation than when the esophageal stimulus is present but the person is distracted. The effect of psychological factors on IBS sufferers (on patient status, illness severity, and outcome of their disorder) provides the rationalization for using treatments directed towards modifying attention to gastrointestinal sensations and changing the way they are interpreted, as occurs in cognitive behavior therapy.PSYCHOTROPIC DRUG TREATMENTThe effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in IBS patients has recently been reported. Antidepressants are also frequently used for a variety of other functional GI symptomsand/syndromes. A meta-analysis by Dr. Ray E. Clouse from the University of Washington, St. Louis has shown a significant beneficial effect of antidepressants for the following functional gastrointestinal disorders: IBS, functional esophageal symptoms, functional dyspepsia, and abdominal pain. The odds ratio (the percentage of people on active drug who get better divided by the percent on placebo) benefit exceeds 4 when compared with placebo. Nevertheless, comparative, controlled studies between the different antidepressant classes are still missing. PSYCHOLOGICAL TREATMENTSSeveral psychological treatment interventions have been suggested for the treatment of IBS. These include active psychotherapeutic treatments (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Dynamic or interpersonal therapy) as well as more passive treatments (hypnosis or Progressive Muscle Relaxation). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) involves the patient working with a therapist to address specific concerns and perceptions about their functional gastrointestinal symptoms. These are then modified in ways that lead to changes in cognitive appraisal of stress, which in turn impacts, the patient's bowel symptoms. Phillip M. Boyce et al reported the results of a study that compared the benefit of CBT, Relaxation Therapy, and Routine Medical Care in IBS patients. A significant improvement in The Bowel Symptoms Severity Scale, Hospital Anxiety, and SF-36 Physical Scores were found at the end of eight weeks. Also, additional improvement occurred at 10 months of follow up with no treatment. Interestingly there were no differences between the three treatment groups, meaning all three were equally effective. The investigators concluded thatroutine medical care, with an emphasis on education and reassurance, could be as effective as CBT and relaxation in reducing symptoms and improving quality of life. This conclusion should be regarded with caution since these results are not consistent with several recently published papers showing a beneficial effect of CBT in patients with IBS. The discrepancies between studies might be related to the different patient populations with regard to their illness severity or to a failure of the particular therapy done in this study to be effective. No process measures were reported to determine if there was indeed evidence that the CBT Treatment to more effective thinking. Additional studies with larger samples of patients selected by their severity, and using standardized CBT treatments along with measures to assess CBT effect are needed. Dr. Francis H. Creed from the University of Manchester, in the United Kingdom, conducted a study to explore the cost-effectiveness of combining psychotherapy and SSRI antidepressants treatment for severe irritable bowel syndrome. Patients were randomized into one of three treatments: a) 7 sessions of individual psychotherapy, b) 20mgs daily of paroxetine, c) or routine medical care. After one year, psychotherapy and antidepressant were superior to routine care in reducing disability in IBS patients. However, there were no differences, among the groups, in terms of GI symptoms themselves after 3 month or one year follow-ups. In Creed's study, health related quality of life improved during treatment more for psychological and SSRI antidepressants groups than for the routine care group. All groups showed improvement in quality of life at the one-year follow-up. Finally, health care costs were similar for all groups by 3 months follow-up, but by the end of one year, the psychotherapy group consumed significantly fewer health costs than the other two groups. This suggests that patients continue to benefit with psychotherapy over time, and this is related to reduced health care costs. Hypnotherapy is another non-pharmacological treatment for IBS. Peter Whorwell's group at the University of South Manchester have shown the efficacy of hypnotherapy in improving symptoms, quality of life, and more recently the long term treatments of functional dyspepsia. The results of a randomized controlled study, by Emma L. Calvert, in which patients either received hypnotherapy, conventional treatment with ranitidine150mg twice daily, or supportive therapy for 16 weeks showed that the improvements in functional dyspepsia were similar between the 3 groups. However, long-term hypnotherapy was superior to other treatments in improving the quality of life and in reducing the need for medication. Another study presented by Giuseppe Chiarioni from Verona, Italy showed increased gastric emptying in response to hypnotic relaxation with gut-oriented suggestions in healthy controls and patients with functional dyspepsia. Again the effect was greater in patients who received hypnotherapy than with Cisapride. The efficacy of hypnotherapy warrants additional studies. The variety of studies presented at DDW 2003 reflects the continuo us change in the way functional disorders are conceptualized and the growing acceptance and understanding of these disorders. Continued researches in this area will contribute to the improvement of our care for patients with functional disorders.。

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征小肠细菌过度生长(SIBO)是一种肠道疾病,它与肠易激综合征(IBS)有很强的关联。

SIBO是指小肠内细菌种类、数量或位置异常增长,可能导致腹泻、便秘、腹痛等症状。

和IBS一样,SIBO也非常常见,影响着全球数百万的人。

SIBO的发生原因有很多,其中包括感染、长期使用抗生素药物、胃酸分泌异常等因素。

研究表明,SIBO也与消化系统神经调节、免疫功能、肠黏膜屏障损伤等相关。

而IBS的发生原因则包括环境因素、遗传因素、肠道菌群失衡、肠道运动异常等多种因素。

SIBO与IBS的联系非常紧密,因为两者有许多相同的症状,如腹痛、腹泻、便秘等。

此外,研究表明,SIBO患者约有60%-80%同时患有IBS,而IBS患者中也有很高比例存在SIBO。

SIBO和IBS的共同点并不止于症状上,还包括治疗方法。

治疗SIBO、IBS的方法主要包括饮食改变、抗生素药物、益生菌等。

对SIBO患者而言,抗生素药物是常用的治疗方法,因为可以有效清除肠道内的细菌。

但患者需要继续注意饮食改变和肠道菌群调节。

对IBS患者而言,饮食调节即为重要,一些炎症性食物和刺激性食物,如糖类、乳制品、咖啡、酒精等,会加重症状,而高纤维食物则有助于改善症状。

与SIBO和IBS相关的另一个因素是肠道菌群失衡。

肠道内有大量的细菌,这些细菌可以帮助消化和吸收食物中的营养物质,同时也可以抑制一些有害细菌的生长。

但如果菌群失衡,即某些有益细菌数量过少,或者有害细菌数量过多,就会引发一系列肠道问题,如SIBO和IBS等。

因此,维持肠道菌群平衡非常重要,可以适当使用益生菌和益生元来调节肠道菌群。

总之,SIBO和IBS是两种常见的肠道疾病,二者之间有很多相似之处。

治疗SIBO和IBS的方法也很相似,重点在于饮食调节和肠道菌群的调节。

了解SIBO和IBS的病因和治疗方法,有助于我们更好地预防和治疗这些疾病,提高生活质量。

罗马iv诊断标准

罗马iv诊断标准

罗马IV诊断标准是指一组确定常见胃肠道疾病的标准,该标准由世界

胃肠病学会于2016年发布。

罗马IV诊断标准旨在为胃肠科医生提供一种综合性的诊疗方法,以诊

断和管理不同类型的胃肠道疾病。

该标准将胃肠道疾病分为以下四类:1. 功能性胃肠道紊乱(FGID)

FGID包括一系列不明原因的胃肠道症状和疾病,如腹痛、腹泻、便秘、消化不良等。

FGID的诊断基于症状的类型、出现时间和程度,同时还

需排除其他胃肠道疾病的可能性。

2. 肠易激综合征(IBS)

IBS是一种常见的FGID,其特点是反复发作的腹痛和改变排便习惯的

症状。

IBS的诊断基于运动过程、疼痛类型和严重程度等症状。

3. 小肠综合征(SIBO)

SIBO是一种胃肠道疾病,其特点是肠道内过度增殖的细菌。

SIBO的

诊断基于氫气呼气试验、甲烷呼气试验或小肠细菌定植试验。

4. 慢性便秘

慢性便秘是口服治疗无效而持续超过3个月的排便困难。

慢性便秘的诊断需排除其他身体疾病的可能性,并评估便秘的类型、持续时间和症状程度等。

罗马IV诊断标准的主要优点在于它提供了一种标准化的诊断方法,可以帮助医师为FGID和相关胃肠道疾病的患者制定个性化的治疗方案。

此外,该标准还为临床试验和研究提供了统一的参照标准。

靶向药物的不良反应

靶向药物的不良反应(综述)2015-04-16 15:50 来源:丁香园作者:月下荷花字体大小- | +第39届ESMO大会于2014年9月26-30日在马德里召开,在大会特别论坛“靶向药物的毒性”中,来自世界各国的专家们分别介绍了新出现的靶向治疗的各种不良反应,现简要介绍如下:心脏毒性皇家玛格丽特癌症中心Siu医生对分子靶向药物的心脏毒性进行了总述,包括左心功能衰竭、高血压和QT间期(QTc)延长。

药物诱导左心功能衰竭机制各有不同,例如细胞毒蒽环类药物产生I型损伤,而分子靶向药物如曲妥珠单抗则产生II型损伤。

血管生成抑制剂和MEK抑制剂会诱发高血压,血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)抑制剂诱导高血压以剂量依赖方式,应使用血管紧张素转化酶抑制剂和/钙离子通道阻断剂治疗血压增高,尽可能维持VEGF抑制剂剂量。

QTc间期延长是组蛋白去乙酰化酶抑制剂、ABL抑制剂、MET抑制剂和多靶点酪氨酸激酶抑制剂的副反应,易患因素包括遗传学因素如先天性长QT综合征,或是后天原因,具体如下:(1)心脏:左心室射血功能下降、左心室肥大、心脏缺血、房室结阻滞、二尖瓣脱垂、窦房结功能不全。

(2)代谢:电解质紊乱如低钾、低镁、低钙,营养不良,甲状腺功能减低。

(3)药物诱导:抗心律失常药如奎尼丁、甲磺胺心定、胺碘酮,精神病用药如阿米替林、文拉法辛,抗生素如阿奇霉素、莫西沙星,抗组胺药如阿司米唑、特非那唑,其它药物如多潘立酮和枢复宁。

靶向HER2的新药Siu医生对靶向HER2新药的心脏毒性进行了总结。

拉帕替尼减低左心室射血分数(LVEF)作用低于曲妥珠单抗;帕妥珠单抗与曲妥珠单抗合用不增加心脏毒性;TDM1减低LVEF作用低于曲妥珠单抗。

血管生成抑制剂血管生成抑制剂也能降低LVEF,导致CHF和高血压,另有一罕见风险是可逆性后部脑病综合征和血栓性微血管病。

多靶点酪氨酸激酶抑制剂可使QTc延长,还可导致腹泻并继发电解质紊乱及动脉血栓事件。

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征是两种与肠道健康相关的疾病。

小肠细菌过度生长(SIBO)是一种病情严重的疾病,其特征是小肠中的细菌数量过多,远超过正常水平。

而肠易激综合征(IBS)是一种功能性肠道紊乱,其特征包括腹痛、腹泻和便秘等症状。

本文将详细介绍小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征的症状、原因、诊断和治疗方法。

小肠细菌过度生长的症状包括腹胀、腹泻、腹痛和消化不良等,这些都是由于细菌过多产生过多气体而引起的。

一旦小肠中的细菌过多,它们就会吸收食物中的营养物质,导致人体无法获得营养的充分吸收。

在一些情况下,SIBO还可能导致营养不良和贫血等症状。

小肠细菌过度生长的原因是多方面的。

其中最常见的原因是肠蠕动异常。

肠蠕动是指食物在肠道中的运动,以促进食物的消化和吸收。

如果肠蠕动异常,食物会停滞在小肠中,提供了细菌生长的温床。

其他可能的原因包括胃酸减少、肠道解剖异常和免疫系统缺陷。

诊断小肠细菌过度生长一般采用呼气氢试验或呼气甲烷试验。

这些测试通过测量呼气中的氢气或甲烷气体来检测细菌过度生长。

还可以通过肠镜检查或抽取小肠液体样本来确诊。

小肠细菌过度生长的治疗方法主要包括抗生素治疗和饮食调整。

抗生素可以杀死过多的细菌,但会导致肠道菌群紊乱。

在使用抗生素的还应考虑使用益生菌来调节肠道菌群。

饮食调整也很重要,应避免吃含有高纤维和难以消化的食物,例如豆类、大蒜和洋葱等。

分餐、小餐多餐、避免吃辛辣刺激性食物等也是一些调整饮食的方法。

肠易激综合征是一种功能性肠道紊乱,其症状包括腹痛、腹泻和便秘等。

尽管肠易激综合征的病因尚不清楚,但许多研究表明,小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征之间存在一定的关联。

有研究指出,肠易激综合征患者中约有50%的人也同时存在小肠细菌过度生长。

肠易激综合征的诊断主要基于病史和临床症状的鉴别。

医生可能会基于罗马Ⅳ标准对患者进行评估,并排除其他肠道疾病,如炎症性肠病或肠道感染。

肠易激综合征的治疗方法主要包括药物治疗和生活方式改变。

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征小肠细菌过度生长(SIBO)是一种疾病,其特点是小肠内细菌数量过多。

这些细菌通常生长于结肠,但如果它们进入小肠,就可能引起一系列问题。

小肠细菌过度生长的症状包括腹痛、腹胀、腹泻、便秘、胃灼热、恶心和呕吐。

患有这种疾病的患者通常会出现吸收不良,因为细菌会消耗食物中的营养物质。

SIBO也可能导致维生素和矿物质缺乏,从而引发其他健康问题。

SIBO通常是由于肠道蠕动迟缓或功能紊乱造成的。

这些问题可能是由多种原因引起的,包括食物不耐受、神经系统疾病、器官移位和结构异常等。

SIBO还可能与肠易激综合征(IBS)有关。

肠易激综合征是一种常见的慢性肠道疾病,其主要症状包括腹痛、腹泻、便秘和腹胀。

研究表明,SIBO与IBS的发生率很高,因此科学家们开始探究两者之间的关联。

研究发现,SIBO患者中有相当一部分同时患有IBS。

SIBO的治疗也可能有助于缓解IBS的症状。

了解SIBO与IBS的关系对于诊断和治疗这两种疾病至关重要。

一些研究表明,SIBO与IBS之间存在着因果关系。

SIBO可能导致IBS的发生,因为细菌过度生长可能导致肠道炎症和黏膜受损,进而引发IBS的症状。

SIBO还会干扰肠道蠕动,增加罹患IBS的风险。

一些研究还发现,IBS患者中存在较高的SIBO患病率。

这可能是由于IBS患者的食管括约肌功能紊乱,导致胃酸逆流,细菌逆行进入小肠。

目前,治疗SIBO的方法主要包括抗生素疗法和膳食调整。

抗生素可以有效清除肠道内的细菌过多,但也会破坏肠道内有益细菌,因此需要在医生的指导下使用。

膳食调整也是治疗SIBO的重要手段,避免食物中的碳水化合物和纤维摄入过多,有助于减少细菌过度生长。

对于IBS的治疗,主要包括膳食调整、药物治疗和生活方式改变。

膳食调整可以帮助改善消化不良和腹泻等症状,包括限制乳糖、防止过度摄入蔬菜和水果中的难消化碳水化合物等。

药物治疗方面,常用的药物包括抗生素、益生菌和粘膜保护剂等。

SIBO and IBS

SIDDS 2009 Seoul International Digestive Disease Symposium 2009S5-3 Irritable Bowel Syndrome and SmallIntestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)Oh Young Lee, M.D., Ph.D.Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is characterized by bowel habit change and abdominal pain relieved with defecation.1 Although the exact mechanisms of IBS are unclear, the pathogenesis is known to be due to multifactorial factors which include visceral hypersensitivity, altered brain-gut axis, dysmotilities, and genetic influence. Therefore, IBS is diagnosed and managed based on the clinical criteria with exclusion of organic causes. Recently the relatively objective factor of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) sharing similar symptoms with IBS has been suggested as a pathogenetic factor of IBS.SIBO is a condition defined by the presence of abnormally high number of bacteria or the growth of colon-type bacteria in the small intestine.2 As anatomical or functional impairment of the small intestine as well as systemic conditions could develop SIBO, there are many conditions predisposing to SIBO such as resection of an ileocecal valve which would normally prevent colonic bacteria from entering the ileum, intestinal stasis caused by small bowel dysmotility, reduced secretion of gastric acid which inhibits bacterial overgrowth, and systemic diseases like liver cirrhosis or scleroderma. By fermenting undigested carbohydrates within the small intestine, SIBO could impair the digestion and absorption of nutrients resulting similar symptoms of IBS, such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence.Many studies have reported the higher prevalence of SIBO in patients with IBS than healthy controls (HC). About 80% of IBS patients were reported to have SIBO compared with only 20% of HC,3 and their IBS symptoms improved after antibiotic treatment with normalization of SIBO test.4 However, other studies concluded that IBS patients had low prevalence of SIBO and the prevalence of SIBO in IBS was not significantly different from HC.5 These discrepancies might be influenced by variable methods and different criteria used to diagnose SIBO. Currently lactulose breath test (LBT) is most commonly used to diagnose SIBO, but actually it was a method measuring colon transit time at first. LBT detects hydrogen or methane gas in expired air which is produced from fermentation of lactulose by intestinal bacteria and then absorbed through the intestinal mucosa. There are three different criteria for SIBO by LBT; when expired air was collected every 15 to 20 min for 3 h after ingestion of 10 g of lactulose, double peaks during LBT can be considered as a positive result, or increase of hydrogen within 90 min, or increase >20 particles per million (ppm) within 180 min can also be regarded as positive. In addition, glucose has been used as a substrate for breath test substitute for lactulose, and direct culture of aspirates from proximal small bowel has been also used to diagnose SIBO. However, glucose breath test has a high false negative result when glucose is absorbed from the proximal small bowel and direct culture methods can underestimate bacterial overgrowth in the distal small intestine. Even LBT has a false positive result when subjects34 | Seoul International Digestive Disease Symposium 2009Symposium 5: Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)have a rapid intestinal transit time. Therefore, it can be said that there is no gold standard to diagnose SIBO yet and it is controversial that SIBO plays a definite role in the pathogenesis of IBS. However, fecal DNA fingerprinting could be used as an objective and direct method to qualify intestinal bacteria but the difficulty of anaerobes culture may elucidate the association between bacterial overgrowth and gastrointestinal symptoms.6 One of the main physiologic functions of gastric acid is inactivation of ingested micro-organism. Majority of ingested micro-biological pathogens never reach the intestine due to gastric barrier. PPIs may lead to gastrointestinal bacterial overgrowth. As we know, overlaps between IBS and GERD are common in the general population. Therefore, possible link among SIBO, IBS and PPI should be investigated, based on the following facts that IBS patients take PPI more likely than controls, PPI may contribute to SIBO by inhibiting gastric acid secretion, and studies exhibiting the association between IBS and SIBO did not exclude the PPI users.7In spite of all these uncertainties, it is still intriguing and worthwhile to study the quality and quantity of variable intestinal bacteria that could alter the intestinal function and develop gastrointestinal symptoms associated with functional alterations. The manipulation of these intestinal bacteria might improve the gastrointestinal symptoms and furthermore the general health of human being.References1.Longstreth GF, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480-1491.2.Donaldson RM Jr. Normal Bacterial Populations of the Intestine and Their Relation to Intestinal Function. NewEngland Journal of Medicine 1964;270:1050-1056 CONCL.3.Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement inirritable bowel syndrome. a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2003;98: 412-419.4.Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowelsyndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2000;95:3503-3506.5.Walters B, Vanner SJ. Detection of bacterial overgrowth in IBS using the lactulose H2 breath test: Comparisonwith14C-D-xylose and healthy controls. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2005;100:1566-1570.6.Kassinen A, et al. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthysubjects. Gastroenterology 2007;133:24-33.7.Spiegel BM, Chey WD, Chang L. Bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome: unifying hypothesis or aspurious consequence of proton pump inhibitors? American Journal of Gastroenterology 2008;103:2972-2976.Towards New Horizons in Gastroenterology: Focused on Translational Research| 35。

211256960_小肠细菌过度生长的检测及其在肠易激综合征诊治中的临床意义

小肠细菌过度生长的检测及其在肠易激综合征诊治中的临床意义陈坚张会禄邱志兵(复旦大学附属华山医院消化内科上海 200040)摘要小肠细菌过度生长(small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, SIBO)是肠道菌群失调的一种特殊表现,可引起肠道局部炎症和免疫变化,进而引发多种消化系统症状,如腹泻、腹痛、腹胀和营养吸收障碍等。

目前,SIBO在肠易激综合征发病中的作用已越来越受到关注。

本文就SIBO的健康危害、SIBO检测方法和SIBO检测在肠易激综合征诊治中的临床意义作一综述。

关键词小肠细菌过度生长肠易激综合征呼气试验中图分类号:R574.5; R574.4 文献标志码:A 文章编号:1006-1533(2023)09-0020-06引用本文 陈坚, 张会禄, 邱志兵. 小肠细菌过度生长的检测及其在肠易激综合征诊治中的临床意义[J]. 上海医药, 2023, 44(9): 20-25.Detection of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and its clinical significance in diagnosis and treatment of irritable bowel syndromeCHEN Jian, ZHANG Huilu, QIU Zhibing(Department of Gastroenterology, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China) ABSTRACT Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a specific form of intestinal microbiome disorder that can cause local inflammatory-immune response in the intestinal tract, resulting in a variety of digestive symptoms (such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating and nutrition malabsorption). The role of SIBO in the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a highlight in the recent years. The present review will focus on the hazards of SIBO in human, various methods for the detection of SIBO, the clinical significance of SIBO in the diagnosis and treatment of IBS.KEY WORDS small intestinal bacterial overgrowth; irritable bowel syndrome; breath test小肠细菌过度生长(small intestinal bacterial over-growth, SIBO)又称小肠淤积综合征、小肠污染综合征或盲袢综合征,是指小肠内菌群数量和(或)种类改变已达到一定程度并引起一系列症状这样一种临床综合征[1]。

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征(SIBO与IBS)患有肠易激综合征(irritable bowel syndrome,IBS)的人在日常生活中经常面临着腹痛、腹胀、恶心、便秘或腹泻等症状的折磨。

而在近年来,研究学者们发现了一种与IBS密切相关的疾病——小肠细菌过度生长(small intestinal bacterial overgrowth,SIBO)。

SIBO是指人体的小肠内过度繁殖了细菌,这些细菌正常情况下应该寄居于结肠内。

SIBO与IBS之间的联系引起了医学界的广泛关注,对于患有IBS的患者来说,这项发现可能会为他们的治疗带来新的突破。

一、 SIBO与IBS的关系SIBO与IBS的关系是如何产生的呢?研究表明,小肠内的细菌过度生长可能导致食物在肠道内的快速分解和吸收,进而对小肠黏膜屏障造成破坏,破坏后的小肠黏膜屏障可能导致肠道内的细菌和毒素通过黏膜屏障,进而引起肠道发炎,产生IBS的临床表现。

SIBO与IBS也存在一定的相互诱发关系。

在一些研究中,患有IBS的患者在肠镜检查中发现了小肠黏膜炎症,这可能为SIBO提供了生存的环境,从而使得SIBO对IBS的发生和发展起到一定的促进作用。

由于SIBO与IBS之间的关系非常密切,所以对于IBS患者来说,SIBO可能成为一个重要的治疗靶点。

目前,SIBO已经成为IBS治疗中的重要一环,而且SIBO的治疗可能对IBS 的症状改善起到关键作用。

二、SIBO的病因SIBO发生的原因可能有很多,其中主要的原因可能包括:1. 胃酸分泌不足:胃酸是一种对胃内的细菌具有较强杀菌作用的物质,如果胃酸分泌不足,就容易导致胃中的细菌经过胃进入到小肠内,从而引发SIBO。

2. 肠骨间膜松弛:肠骨间膜是一种连接小肠和腹壁的组织,如果这个膜的功能受损了,就会导致小肠内的细菌进入到腹腔内,从而引发SIBO。

3. 肠道蠕动减弱:肠道的正常蠕动是将食物颗粒从小肠向结肠移动的重要保证,而如果蠕动减弱了,就会导致食物在小肠内停留的时间过长,从而为细菌的过度繁殖提供了机会。

肠道微生态参与肠易激综合征发病的相关机制

肠道微生态参与肠易激综合征发病的相关机制庄晓君;陈旻湖;熊理守【摘要】肠易激综合征(IBS)的病因和发病机制尚未明了,近年认为肠道微生态可能发挥重要作用.有研究表明IBS患者存在肠道菌群改变,干预肠道微生态对IBS有一定的治疗作用.本文就肠道微生态通过改变黏膜通透性、激活免疫反应、改变胃肠动力和影响脑-肠轴等参与IBS发病的相关机制作一综述.%The etiology and pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are not fully understood, and intestinal microbiota had been assumed as a possible factor in the pathogenesis of IBS.Increasing evidences have shown that alterations of gut microbiota were found in IBS patients and modulation of intestinal microbiota might be effective in the treatment of IBS.This article reviewed the mechanism of involvement of intestinal microbiota in pathogenesis of IBS by altering mucosal permeability, activating immune reaction, disturbing gastrointestinal motility and affecting brain-gut axis.【期刊名称】《胃肠病学》【年(卷),期】2017(022)003【总页数】3页(P181-183)【关键词】肠易激综合征;肠道菌群;通透性;免疫;胃肠活动;微生物-脑-肠轴【作者】庄晓君;陈旻湖;熊理守【作者单位】中山大学附属第一医院消化内科,510080;中山大学附属第一医院消化内科,510080;中山大学附属第一医院消化内科,510080【正文语种】中文肠易激综合征(IBS)是一种以腹痛或腹部不适伴有排便习惯改变和(或)粪便性状异常为主要特征的功能性肠病,其缺乏可解释症状的形态学改变和生化异常。

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征小肠细菌过度生长(SIBO)是指正常生活在大肠内的细菌过多地滋生在小肠。

小肠是人体消化系统中起主要作用的一部分,其主要功能是吸收营养物质和水分。

由于各种原因,小肠细菌可能会从大肠中迁移到小肠,导致细菌在小肠内过度繁殖。

SIBO的症状包括腹胀、腹痛、恶心、消化不良、腹泻和便秘等。

这些症状与肠易激综合征(IBS)的症状非常相似,使得两者很难区分。

事实上,一些研究发现,SIBO是IBS的一个常见原因。

研究表明,在IBS患者中,SIBO的患病率达到60-80%。

造成SIBO的原因是多方面的。

一是胃酸不足,胃酸可以杀灭许多进入胃部的细菌,如果胃酸分泌不足,细菌进入小肠的机会就增加了。

二是肠蠕动功能障碍,正常情况下,肠道的蠕动可以将细菌推进向结肠,但是如果蠕动功能不正常,细菌就会在小肠内滞留。

三是某些疾病的影响,如炎症性肠病、肠道瘤、糖尿病等都会增加SIBO的患病风险。

四是长期使用抗生素,抗生素可以杀灭细菌,但同时也会破坏正常肠道菌群的平衡,导致细菌过度生长。

治疗SIBO的方法主要包括使用抗生素和改善肠道菌群平衡。

抗生素可以杀灭细菌,但是抗生素治疗对于SIBO的长期效果并不理想,因为抗生素也会破坏正常肠道菌群。

一些研究表明,使用益生菌和益生元可以帮助改善肠道菌群的平衡,减少细菌过度生长的风险。

一些研究还发现,低碳水化合物饮食可以减少SIBO的症状,因为细菌在小肠中主要通过碳水化合物进行繁殖。

饮食调整对于SIBO的治疗非常重要。

建议患者避免高碳水化合物食物,如面包、米饭、面条、糖果等。

同时增加高蛋白食物和健康脂肪的摄入,如鱼类、禽类、坚果、橄榄油等。

多食用富含纤维的食物,如蔬菜、水果、全谷物等,纤维可以促进肠道蠕动,减少细菌滞留的机会。

SIBO与肠易激综合征有着密切的关联,而且是IBS患者中常见的一种病症。

治疗SIBO 需要综合考虑患者的具体情况,包括使用抗生素、改善肠道菌群平衡和调整饮食习惯。

抗生素对肠易激综合征患者肠道菌群的影响

抗生素对肠易激综合征患者肠道菌群的影响摘要:肠易激综合征(IBS)是目前最常见的肠道功能性肠病。

发病机制尚不明确,与多种因素有关,其中,肠道菌群的紊乱是潜在的病理生理学发病机制;同时,关于其的治疗也涉及多方面,近几年,抗生素对IBS的肠道菌群的治疗引起广大学者的关注,本文就抗生素对肠易激综合征患者肠道菌群的影响作一综述。

关键词:肠易激综合征肠道菌群抗生素1、肠易激综合征(IBS)IBS是一种胃肠道功能紊乱性疾病,主要有腹痛、腹胀、腹泻、便秘或混合的排便习惯改变等症状,但缺乏生化、影像、内镜等异常改变。

该病发病率较高,在美国和欧洲发病率9%—22%,亚洲国家为4%—20%[1]。

以年轻女性患病率高[2],病程长,易反复,已严重影响了患者的生活质量,同时给社会带来了巨大的经济负担。

根据Bristol粪便性状量表不同,主要被分为腹泻型(IBS-D)、便秘型(IBS-C)、混合型(IBS-M),目前罗马III为诊断金标准,因其发病机制尚不明确,可涉及心理、生理、社会等因素;治疗根据患者本身症状特点制定治疗方案,以得到症状的缓解,最近,抗生素的应用逐渐得到了广泛的关注。

2、 IBS与肠道菌群肠道菌群是一个复杂的微生态系统,包括细菌、病毒、真菌及其它微生物,细菌多达1000余种[1],正常情况下,肠道的细菌按照一定比例、数量与宿主处于相互依赖、相互制约的动态平衡,贯穿于人体生理和病理过程中,肠道的菌群主要分为3类:即共生菌,如双歧杆菌、乳酸杆菌等;条件致病菌,如肠球菌、肠杆菌等;病原菌。

对人体的健康有着重要影响。

2.1 IBS与小肠菌群正常小肠的菌落小于104 U/ml,主要为革兰氏阳性需氧菌,小肠的上段运动强,细菌很难附着,所以,十二指肠和空肠内细菌较少,但当肠道动力失调时,进入小肠的细菌增多大于104 U/ml 或有革兰氏阴性菌或厌氧菌生长时,即可视为小肠细菌过度生长(SIBO)[3]。

与SIBO相关的症状可表现为腹泻、便秘、贫血、消化不良等。

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征小肠细菌过度生长(Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth,SIBO)是指小肠内的细菌数量超过正常范围,导致肠道菌群失衡。

正常情况下,小肠内的菌群数量应该较少,而大量细菌聚集在结肠中。

当小肠的清洁机制受损时,细菌就有可能大量繁殖在小肠内。

造成这种菌群失衡的原因有很多,常见的有胃酸减少、胃肠蠕动减弱、胆道功能异常等。

小肠细菌过度生长会引起一系列症状,其中最常见的就是肠易激综合征(Irritable Bowel Syndrome,IBS)。

肠易激综合征是一种常见的慢性肠道疾病,其特点是腹痛、腹部不适、腹胀、腹泻或便秘等症状。

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征之间存在着相互影响的关系。

小肠细菌过度生长可以引起肠道内细菌产生大量的氢气和甲烷气体,进而导致腹胀、腹泻等症状。

小肠细菌过度生长还可以干扰小肠正常吸收和运输营养物质的功能,导致营养物质的摄取不足。

这些营养物质的不足会影响肠道黏膜的正常功能,进一步加重肠易激综合征的症状。

而肠易激综合征患者由于消化功能的紊乱,易导致小肠细菌过度生长。

治疗小肠细菌过度生长和肠易激综合征的关键是恢复肠道菌群平衡。

可以通过服用抗生素来控制细菌数量。

常用的抗生素有利福平、替硝唑等,可以有效杀灭小肠内的细菌,缓解症状。

还可以通过饮食调节来改善菌群失衡。

一方面,可以适量增加益生菌的摄入,如酸奶、发酵豆制品等,帮助恢复肠道微生态平衡。

可以避免摄入过多的淀粉和纤维,因为这些食物容易被细菌分解,产生大量气体,加重症状。

还可以采用中药治疗,如中药合剂、草药浸膏等,具有较好的疗效。

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征之间存在着相互影响的关系。

治疗的关键是恢复肠道菌群平衡,可以通过抗生素、饮食调节和中药治疗等方式进行。

肠易激综合征患者中小肠细菌过度生长的研究

临床研究3肠易激综合征是一种以腹痛或腹部不适伴排便习惯改变和(或)大便性状异常为主要特征的慢性功能性肠道疾病。

小肠道细菌过度生长(Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth,SIBO)定义为必定的条件下小肠细菌超出105CFU/mL,IBS患者中SIBO发生率为4%~78%[1]。

本文对肠易激综合征患者小肠细菌过度生长情况进行了分析。

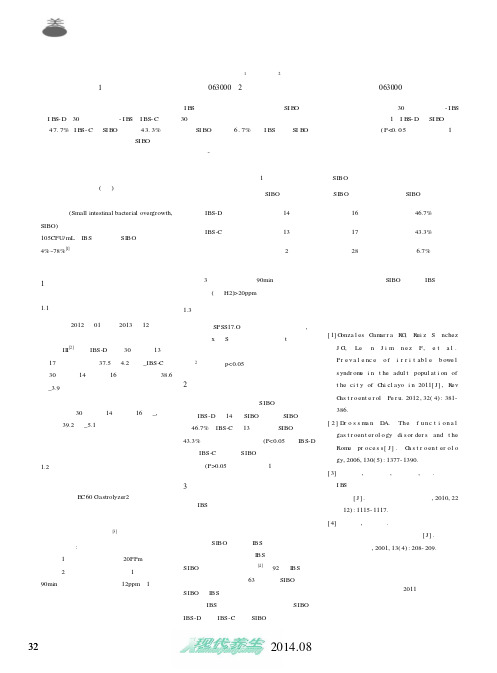

1材料与方法1.1研究对象选取2012年01月至2013年12月在迁安市人民医院消化内科病房或门诊就诊的符合罗马III[2]标准IBS-D患者30例,男13例,女17例,平均年龄37.5士4.2岁,_IBS-C患者30例,男14例,女16例,平均年龄38.6士_3.9岁,所有病人均已行常规体检,结肠镜、肝肾功能、血糖及血常规检查,无异常变化。

健康志愿者30例,女14例,男16例_,平均年龄为39.2士_5.1岁,符合以下条件:没有糖尿病,甲状腺功能疾病,非结缔组织疾病,排便频率和特征均正常。

1.2方法全部受试者行乳果糖氢呼气试验,采用英国进口的EC60Gastrolyzer2胃肠氢气检测仪进行检查,按照其操作过程进行操作。

判断标准:小肠细菌过度生长[3]:符合以下三者之一者为阳性:(1)空腹基础呼气氢≥20PPm。

(2)出现双峰图形,第1峰起始点在90min之前出现,上升至少12ppm,1小时后出现第二个更高的氢气水平,双峰可能会合并出现一个早期上升平台。

肠易激综合征患者中小肠细菌过度生长的研究郑秀丽1 莫艳波21河北联合大学 河北省唐山市 063000 2河北联合大学附属医院 河北省唐山市 063000【摘 要】目的:分析肠易激综合征(I B S)患者小肠细菌过度生长(SI B O)情况。

方法:选取正常对照30人;腹泻型-I B S (I B S-D)30人,便秘型-I B S(I BS-C)患者30人;测定小肠细菌过度生长情况,并将结果加以比较。

可能引起消化问题的无害食物

FODMAPs:可能引起消化问题的无害食物低发酵饮食对于许多功能性胃肠病(比如)患者(包括成人和儿童)是非常有效的。

也有少量研究表明,低发酵饮食对炎症性肠病(IBD)能起到一定的积极作用。

什么是发酵(FODMAPs)?发酵(FODMAPs)是存在于食物或食品添加剂中的一些短链碳水化合物和糖醇,包括:低聚糖、二糖、单糖和多元醇。

这些短链碳水化合物在人体肠道中无法被完全消化,因而能被肠道的细菌发酵利用。

其中的一些糖类具有渗透作用。

什么是发酵不耐受?(FODMAP intolerance)许多常见的食物含有很高的发酵,尽管在大多数情况下这些食物被认为是健康的,但它们仍旧可能造成肠易激综合征(IBS)以及炎症性肠病(IBD)患者的症状。

来自乳制品的乳糖,来自某些水果的果糖或糖醇,以及来自蔬菜的果聚糖都可能会诱发或加重这些病人的问题,比如会引起腹痛、腹部不适、胀气、大便频率的改变(便秘、腹泻或两者交替进行)。

这些病人的不良反应即统称为发酵不耐受。

虽然绝大数肠易激综合征的患者都存在发酵不耐受的问题,但发酵本身并不会造成肠易激综合征。

它仅仅是诱发或加剧症状。

所以,许多人可以吃大量富含发酵的食物而不存在任何反应,但那些肠道失调的患者摄入少量这类食物就可能引起极大的不适。

虽然所有的发酵都可能引起IBS 患者的症状,但不同的人群对不同类型的发酵的反应是不一样的,并且对于发酵的耐受程度也是因人而异的。

比如一个人可以较好地耐受果糖,但乳糖会使他腹泻;而另一个人可以吃少量的乳糖,但吃太多也会出问题。

什么造成了发酵不耐受?有以下几个可能的原因。

在某些情况下,(SIBO)会引起IBS的症状以及发酵不耐受。

病人小肠中过度生长的细菌提前发酵了这些人体无法完全消化的碳水化合物,使得病人小肠内聚集大量的气体,从而引起各种症状。

在另一些患者中,由于病人缺少足够的消化液来预分解这些可发酵的糖,大肠中的细菌会异常发酵,从而影响肠道功能的正常运行,引起腹泻或便秘。

利福昔明对SIBO^+腹泻型肠易激综合征患者NF-κB及炎性因子的影响

试 验 (SIBO )的IBS D患者 (满 足罗 马 Ⅲ标 准)78例 ,随 机分成试 验组 与对 照组 (”=39)。 试验 组给予 利福昔 明(0.2g/次 ,

4次 /d,共 1 4d)治 疗 ,对 照 组 给 予 安 慰 剂 2周 。 观 察 治 疗 前 后 各 组 症 状 评 分 及 白介 素 .8(IL一8)、肿 瘤 坏 死

Graduate School,Army M ilitary M edical University,Chongqing 400038,China

Department of Gastroenterology ̄Chinese Navy General Hospital,Beqing 1 00048,China

clinical sym ptom s ofIBS—D .Rifaxim in m ay have a good ef i cacy in treatment ofIBS-D.

clarify the pathogenesis of IBS·D.M ethods Seventy—eight IBS-D patients.met Rome Ⅲ criteria with SIBO and admitted in our hospital from Jun.20 1 6 to Dec.20 1 7,were enrolled in the present study,and randomly divided into experimental group and control

improved in control group(P>0.0S),W hile the symptom score,IL一8,TNF-OL and NF—KB were obviously improved in experimental group after treatment with rifaximin(P<0.0s).Conclusions SIBO may lead heightening of NF—KB level and then aggravate the

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征

小肠细菌过度生长与肠易激综合征导语:肠易激综合征(IBS)是一种常见的胃肠道疾病,主要表现为腹痛、腹泻和便秘等症状。

而小肠细菌过度生长(SIBO)也是一个近年来备受关注的胃肠道问题,研究发现SIBO与IBS之间存在着密切的关联。

本文将从SIBO的定义、病因、临床表现及诊断等方面进行介绍,以帮助读者更好地了解SIBO与IBS这两种疾病之间的关系。

一、SIBO的定义小肠细菌过度生长(SIBO)是指正常情况下寄生在人体消化道内的细菌在数量或者种类上出现异常增加,并且从正常的消化道定位上进入到小肠内。

SIBO的发病机理可能与小肠蠕动减弱、消化道解剖结构异常、胃肠动力紊乱、免疫功能低下等因素有关。

SIBO的临床症状包括腹痛、腹泻、腹胀、胃灼热等,与IBS有许多相似之处。

二、SIBO的病因SIBO的发病机制至今尚未完全明了,但已经有不少研究表明SIBO可能与以下因素有关:1. 小肠蠕动障碍:小肠的蠕动功能是将食物从胃部推向结肠的关键环节。

一旦小肠的蠕动功能受到影响,就会造成食物在小肠内停留时间过长,为细菌提供了生长的有利条件。

2. 消化道解剖结构异常:例如十二指肠的返流、狭窄等情况会导致小肠内环境的改变,从而促进SIBO的发生。

3. 胃肠动力紊乱:例如胃排空功能减弱、胃肠道的传输功能障碍等都会增加小肠细菌过度生长的风险。

4. 长期使用抗生素或者免疫抑制剂:这些药物会在一定程度上破坏人体内部的微生物平衡,为细菌过度生长创造了条件。

5. 免疫功能低下:免疫系统的功能下降会使肠道对外界病原物质产生较差的识别和清除能力,为细菌生长提供了便利条件。

SIBO的发病原因可能是多种多样的,需要根据个体情况进行分析。

三、SIBO的临床表现SIBO主要症状为腹痛、腹泻和腹胀。

部分患者还可能伴有恶心、呕吐、食欲不振等症状。

腹泻和腹胀是SIBO的两种主要表现,腹泻多表现为稀便,并伴有腹痛和不适感;而腹胀则是由于肠道内过多气体和液体积聚所引起的。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

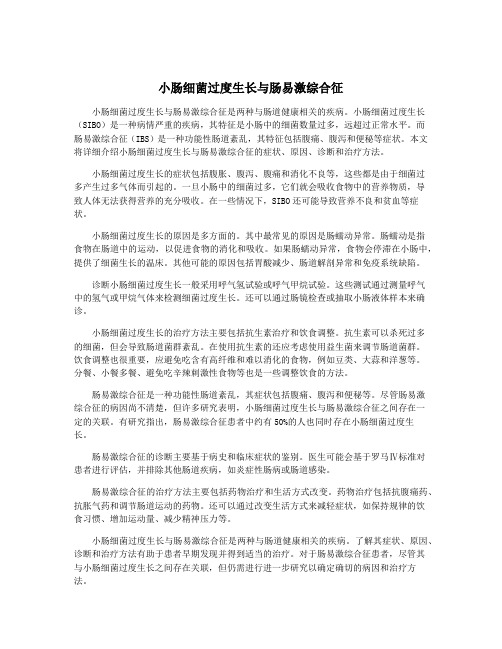

Research ArticleSmall Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patientswith Irritable Bowel Syndrome:Clinical Characteristics, Psychological Factors,and Peripheral CytokinesHua Chu,1Mark Fox,2,3Xia Zheng,1Yanyong Deng,1Yanqin Long,1Zhihui Huang,1Lijun Du,1Fei Xu,1and Ning Dai11Department of Gastroenterology,Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital,School of Medicine,Zhejiang University,Hangzhou310016,China2Division of Gastroenterology&Hepatology,University Hospital Z¨u rich,Z¨u rich,Switzerland3Z¨u rich Centre for Integrative Human Physiology(ZIHP),University of Z¨u rich,Z¨u rich,SwitzerlandCorrespondence should be addressed to Ning Dai;ndaicn@Received4March2016;Accepted17April2016Academic Editor:Qasim AzizCopyright©2016Hua Chu et al.This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License,whichpermits unrestricted use,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,provided the original work is properly cited.Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth(SIBO)has been implicated in the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome(IBS).Psychosocial factors and low-grade colonic mucosal immune activation have been suggested to play important roles in thepathophysiology of IBS.In total,94patients with IBS and13healthy volunteers underwent a10g lactulose hydrogen breathtest(HBT)with concurrent99m Tc scintigraphy.All participants also completed a face-to-face questionnaire survey,includingthe Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,Life Event Stress(LES),and general information.Serum tumour necrosis factor-α,interleukin-(IL-)6,IL-8,and IL-10levels were measured.The89enrolled patients with IBS and13healthy controls had no differences in baseline characteristics.The prevalence of SIBO in patients with IBS was higher than that in healthy controls(39%versus8%,resp.;p=0.026).Patients with IBS had higher anxiety,depression,and LES scores,but anxiety,depression,and LESscores were similar between the SIBO-positive and SIBO-negative groups.Psychological disorders were not associated with SIBOin patients with IBS.The serum IL-10level was significantly lower in SIBO-positive than SIBO-negative patients with IBS.1.IntroductionIrritable bowel syndrome(IBS)is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder(FGID)characterised by recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort associated with alterations in stool frequency and/or consistency,for which there is no apparent physical or biochemical cause to explain the symp-toms.About10–20%[1]of adults in western countries and 5–10%[2–4]of Asian adults are affected by IBS.It seriously affects quality of life and consumes vast medical resources. The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of IBS are complex and remain incompletely understood.Visceral hypersensitiv-ity and abnormal gastrointestinal motility are possible major pathophysiologies,but other factors may include brain-gut dysfunction,psychological disorders,dietary issues,gastroin-testinal infections,and genetics.Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth(SIBO)has received increasing attention,and many studies have shown that the frequency of SIBO in patients with IBS is higher than that in a healthy population[5–8].SIBO is a condition in which the small bowel is colonised by colonic bacteria,resulting in symptoms ranging from bloating and diarrhoea to weight loss and nutritional deficiencies.However,the diagnostic tests for SIBO remain controversial.Direct aspiration and culture of organisms are the gold standard for diagnosing SIBO, formally defined as the presence of>105colony-forming units in jejunal aspirate;however,this approach is obviously invasive and difficult to perform,and aspirates from the proximal jejunum lack sensitivity in all but the most severe cases of enteric dysfunction.The lactulose hydrogen breath test(LHBT)is the most commonly used method to diagnose SIBO,but its accuracy has been questioned by many scholarsHindawi Publishing Corporation Gastroenterology Research and Practice Volume 2016, Article ID 3230859, 8 pages /10.1155/2016/3230859because of individual variations in small intestinal transit [9].We published a paper confirming that LHBT alone is not a valid test for SIBO[10];however,LHBT combined with scintigraphic measurements of the orocaecal transit time (OCTT)provides an accurate and reproducible diagnostic test for SIBO.In the present study,we used this method to diagnose SIBO.The main mechanisms of the development of SIBO are thought to include structural changes in the gastrointestinal tract,disordered gastric and/or small intestinal peristalsis, and disruption of normal mucosal small intestinal defences [11].Abnormally low intestinal motility and immune acti-vation may explain SIBO in a patient with IBS.Bacterial products,such as endotoxins,can affect gut motility[12]. Gut bacteria are also important for activating an immune response.Immune-mediated cytokines have multiple actions, including altered epithelial secretion,exaggerated nocicep-tive signalling,and abnormal motility[13].Together,these changes may lead to IBS.There is also considerable evidence that psychological and social influences can affect the perception of symptoms, healthcare-seeking behaviours,and outcomes in patients with FGIDs,particularly those with IBS[14,15].Little infor-mation is available about anxiety or depression in patients with IBS and SIBO.However,there is a large body of work demonstrating that patients with IBS have low-grade immune activation,and associations between psychological state and stress and immune activation have been detected in mucosa [16–19].Results from animal experiments suggest that low-grade gut inflammation can alter gastrointestinal tract motor function[20]and that gut motility abnormalities can further predispose to bacterial overgrowth.However,the relationships among SIBO,psychologi-cal factors,and proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines have not been established in patients with IBS. Thus,this study was designed to examine the clinical char-acteristics,psychological states,and serum cytokine levels in patients with IBS and SIBO to better understand the pathology of IBS.2.Materials and MethodsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital(reference number,20070823-2).All par-ticipants provided written informed consent before the study.2.1.Participants.Data from94consecutive patients who met the Rome III criteria for IBS and13healthy volunteers with no history of gastrointestinal symptoms were studied. Patients had no alarm symptoms and no evidence of relevant organic diseases on colonoscopy,routine blood tests,or faecal microbiology.The participants were from the same population as those used in a previous study[10].2.2.Assessment of Psychosocial Status and General Informa-tion.Psychological status was assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score(HADS),and psychosocial stress was assessed by the Life Event Stress(LES)scale of Miller and Rahe,as modified and validated for use in Chinese populations[21].A HADS score of≥11was considered torepresent clinically significant anxiety or depression,witha cut-off score of≥8for diagnosing borderline neurosis.Anxiety and depression were defined as scores of≥8oneach respective scale for the categorical analysis.The subject’sdemographic data(age,sex,marital status,education,profes-sion,and income range),smoking,alcohol consumption,andmedical and surgical history were recorded.bined LHBT and Scintigraphic Orocaecal Transit(SOCT)Study.The subjects were instructed to avoid foodscontaining incompletely absorbed carbohydrates,such asbread,corn,pasta,and potatoes,on the evening beforethe breath test and then underwent a minimum12h fastto minimise basal hydrogen excretion[22].Immediatelybefore the procedure,the subjects used30mL of antisepticmouthwash(1.5%compound borax solution;Winguidehp,Shanghai,China)to eliminate lactulose fermentation dueto oropharyngeal bacteria.Other extraintestinal influenceson breath hydrogen concentrations,such as cigarette smoke,physical exercise,and hyperventilation[23],were avoidedduring the test.Subjects fasted for the duration of the test.After determining the baseline H2breath concentration,all subjects underwent combined LHBT/scintigraphy.Asdescribed previously[24],10g of lactulose(15mL;Dupha-lac Solvay Pharmaceuticals B.V.,Weesp,The Netherlands) labelled with37MBq99m Tc-diethylene triamine pentaaceticacid(HTA Co.Ltd.,Beijing,China)was ingested with100mLof water.The subjects were placed in the supine positionwith a gamma camera(Millennium VG;General Elec-tric,Milwaukee,WI,USA)monitoring the abdomen.End-expiratory breath samples were collected concurrently withscintigraphic images after the meal and then every15minfor up to3h using a portable analyser with a sensitivity of ±1ppm(Micro H2Meter;Micro Medical Limited,Chatham, UK).The geometric mean of the anterior and posteriorvalues was used for scintigraphy to correct for depth changes(geometric mean counts=square root[anterior counts×posterior counts])corrected for radioisotope decay[25].Thescintigraphy images were reviewed independently and in ablinded manner by two investigators to determine the arrivalof the tracer in the caecal region of interest.The OCTT wasdefined as the time at which at least5%of the administeredisotope dose had accumulated in the caecal region[9,24].Thetemporal association between increased breath H2and arrivalof the marker in the caecum was assessed.2.4.Diagnostic Criteria.The diagnostic criterion for SIBOwas an initial H2increase involving at least two consecutivevalues of≥5ppm above baseline,beginning at least15minbefore an increase in radioactivity(≥5%of administereddose)in the caecal region.In previous publication[10],wehave demonstrated that combined LHBT/SOCT is a validmethod for noninvasive diagnosis of SIBO.A5ppm increasein breath H2prior to the arrival of cecal contrast may identifya subset of IBS patients that have good clinical outcomesfollowing antibiotic therapy.Figure1showed the results thathad been published.Health controls 77%30%38%8%0%0%C r i t e r i o n 6C r i t e r i o n 5C r i t e r i o n 4C r i t e r i o n 3C r i t e r i o n 2C r i t e r i o n 1Figure 1:SIBO prevalence in IBS patients and healthy controls as determined by six published diagnostic criteria.Only Criterion 4for the combined lactulose HBT/SOCT indicated a higher prevalence of SIBO in patients than controls (which has been published).Criterion 1:a H 2rise of ≥20ppm within 180min;Criterion 2:a H 2rise of ≥20ppm within 90min;Criterion 3:dual breath H 2peaks,a 12ppm increase in breath H 2over baseline with a decrease of ≥5ppm before the second peak;Criterion 4:initial H 2rise,involving at least two consecutive values ≥5ppm above baseline,commenced at least 15min before an increase of radioactivity (≥5%of administered dose)in the caecal region;Criterion 5:initial H 2rise,involving at least two consecutive values ≥10ppm above baseline,commenced at least 15min before an increase of radioactivity (≥5%of administered dose)in the caecal region;Criterion 6:initial H 2rise,involving at least two consecutive values ≥20ppm above baseline,commenced at least 15min before an increase of radioactivity (≥5%of administered dose)in the caecal region;∗p <0.05.2.5.Serum Cytokine Tests.Twelve-hour fasting venous blood samples were drawn from patients.Whole-blood samples (2mL)were collected in tubes containing ethylenediaminete-traacetic acid.The samples were centrifuged immediately,and serum was frozen at −80∘C until further use.Serum tumour necrosis factor-(TNF-)α,interleukin-(IL-)6,IL-8,and IL-10levels were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (eBioscience,San Diego,CA,USA)according to the manufacturer’s protocols.Optical density was measured at a wavelength of 450nm.Density values were correlated linearly with the concentrations of cytokine standards.2.6.Statistical Analysis.All statistical analyses were per-formed using SPSS version 19.0for Windows software (SPSS Inc.,Chicago,IL,USA).All variables are expressed as means ±standard deviations or medians with quartiles,as appro-priate.Student’s t -test was used to compare means,and the Mann-Whitney U test was used as a nonparametric statistical test.We used the χ2test for qualitative data comparisons.Alpha values of <0.05were considered statistically significant.3.Results3.1.Study Population.In total,94patients with IBS and 13healthy volunteers with no history of gastrointestinal symptoms were analysed.Five patients were excluded (n =4hydrogen nonproducers,n =1pancreatic cancer diagnosed after study entry).The patients and healthy controls were similar in age and sex (Table 1).Among the 89subjects,most of the patients with IBS had diarrhoea-predominant IBS (IBS-D;70.8%)or mixed type IBS (IBS-M;23.6%);very few had constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C;3.4%)or the unsubtyped types (IBS-U;2.2%)(Table 2).According to the diagnostic criterion,35/89(39%)patients and 1/13(8%)were diagnosed as SIBO-positive,whereas the others were SIBO-negative.The prevalence of SIBO in patients with IBS was higher than that in healthy controls (p =0.026),as we showed previously.The demo-graphic and clinical characteristics were similar in patients with IBS with and without SIBO,except marital status (Table 3).Figure 1had showed the reason that we selected these criteria and the paper had been published in the Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility [10].3.2.Psychological State Reflected by HADS and Life Event Stress (LES).Patients with IBS had higher anxiety,depression,and LES scores than did healthy controls (Table 1).However,the SIBO-positive and SIBO-negative patients exhibited similar scores for anxiety (5.37±3.61versus 5.04±2.85,resp.;p =0.628)and depression (5.86±3.90versus 5.30±2.87,resp.;p =0.437)(Table 4).Similarly,LES scores of patients with IBS and SIBO were comparable to those of patients without SIBO.3.3.Serum Cytokines.The IL-10level was significantly lower in SIBO-positive than SIBO-negative patients with IBS (mean,12.92pg/mL [range,11.40–14.85pg/mL],versus mean,14.03pg/mL [range,12.66–16.33pg/mL],resp.;p =0.026).No differences were observed in TNF-α,IL-6,or IL-8levels between the groups (Table 5).4.DiscussionSIBO has been suggested to play a role in the pathophysiology of IBS,but the reported prevalence of SIBO in patients with IBS varies widely depending on the geographical origin of the study population,methods for detection,and crite-ria for diagnosing SIBO.Our results demonstrate that the prevalence of SIBO was higher in patients with IBS than in healthy controls,as we showed previously [10].The diagnostic criterion for SIBO by combining LHBT with scintigraphic measurement is certificated in our previous study [10].We found no relationship between SIBO and age,sex,BMI,or alcohol consumption.Many studies have demonstrated that older age and female sex are predictors of SIBO [26–29].More females than males are diagnosed with IBS,and SIBO is more common in older individuals,likely due to reduced intestinal motility with advancing age [29].However,consistent with Rana’s report,we found no relationship between SIBO and old age or sex [30].In a retrospective review,Gabbard et al.[31]reported that moderate alcohol consumption is a strong risk factor for SIBO.Previous studies [32,33]have demonstrated that alcoholics have higher rates of SIBO.The main mechanisms for the development of SIBO include structural changes in the gastrointestinal tract,disorderedTable1:Baseline demographic factors of the patients and controls.Patients with IBS Healthy controlsp value(n=89)(n=13)Age in years,mean±SD45.7±12.943.3±8.60.595 Sex,male/female47/429/40.266 BMI,kg/m222.1±5.824.5±2.90.245 Anxiety,mean±SD 5.17±3.16 2.77±1.640.009 Depression,mean±SD 5.52±3.30 3.54±2.500.041 LES40.0(11.0–75.0)8.0(0.0–35.0)<0.001Table2:Baseline comparison of the small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-(SIBO-)positive and negative patients.SIBO(+)(n=35)SIBO(−)(n=54)p value Age in years,mean±SD43.5±12.547.2±13.10.187 Sex,male/female21/1426/280.274 BMI,kg/m223.2±7.721.4±4.00.139 IBS-D28350.124 IBS-C12 1.000 IBS-M6150.248 IBS-U020.517Table3:General characteristics of the small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-(SIBO-)positive and negative patients with irritable bowel syndrome.Variables Levels SIBO(+)(n=35)SIBO(−)(n=54)p value Age,years Mean±SD43.5±12.547.2±13.10.187Sex,n(%)Male21(60.0%)26(48.1%)Female14(40.0%)28(51.9%)0.274BMI,kg/m2Mean±SD23.2±7.721.4±4.00.139Marital status,n(%)Married29(82.9%)52(96.3%)Single6(17.1%)2(3.7%)0.030Education,n(%)≤Primary8(22.9%)11(20.4%)Middle school10(28.6%)19(35.2%)High school9(25.7%)15(27.8%)0.848≥College8(22.9%)9(16.7%)Average family income,n(%)<10003(8.6%)2(3.7%)≥100018(51.4%)35(64.8%)0.470≥500010(28.6%)10(18.5%)≥100004(11.4%)7(13.0%)Job,n(%)Office work4(11.4%)6(11.1%)Physical work22(62.9%)36(66.7%)0.924 Housework9(25.7%)12(22.2%)Cigarette smoking,n(%)Never24(68.6%)44(81.5%)≥17(20.0%)7(13.0%)0.520≥102(5.7%)1(1.9%)≥202(5.7%)2(3.7%)Alcohol drinking,n(%)Never16(45.7%)25(46.3%)Sometimes17(48.6%)26(26.1%)0.840 Often0(0.0%)1(1.9%)Always2(5.7%)2(3.7%)Medical history,n(%)No27(77.1%)39(72.2%)0.604 Y es8(22.9%)15(27.8%)Table4:Hospital anxiety and depression scale and life event stress scores in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with and without small intestinal bacterial overgrowth(SIBO).SIBO(+)(n=35)SIBO(−)(n=54)Healthy controls(n=13) Anxiety(mean±SD) 5.37±3.61∗ 5.04±2.85∗ 2.77±1.64 Depression(mean±SD) 5.86±3.90∗ 5.30±2.87∗ 3.54±2.50Life event stress42.0(11.0–99.0)∗39.50(0.0–69.25)∗8.0(0.0–35.0)∗p<0.05compared with healthy controls.Table5:Serum cytokine levels in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-(SIBO-)positive and negative patients(pg/mL).SIBO(+)(n=35)SIBO(–)(n=54)p value TNF-α9.77(5.16–15.24)9.41(6.09–13.49)0.938 IL-6 6.84(6.69–7.07) 6.76(6.65–7.13)0.678 IL-817.67(5.30–36.19)12.49(5.94–48.96)0.911 IL-1012.92(11.40–14.85)14.03(12.66–16.33)0.026gastric and/or small intestinal peristalsis,and disruption of the normal mucosal defences of the small intestine[11]. However,we found no association between SIBO and alcohol consumption in the present study.Previous studies[14,34]have confirmed that anxiety and depression are more common in patients with FGIDs than in the healthy population,particularly in patients with IBS, as confirmed here.Anxiety,depression,and life event stress were more prevalent in patients with IBS than in healthy controls.However,whether patients IBS and SIBO have more severe psychological disorders is unknown.Our study showed similar levels of anxiety and depression,including life event stress experience.A possible explanation may be that the symptoms of SIBO are similar to those of IBS,such as bloating,diarrhoea,abdominal pain,and malabsorption. Thus,SIBO does not further aggravate the psychological status in patients with IBS.This finding was consistent with Grover et al.[35],who reported no difference in psychological distress between SIBO-positive and SIBO-negative patients with IBS.Thus,it seems unlikely that psychological distress mediates the association between SIBO and bowel symptoms. However,one study found an increase in the number of positive breath tests in patients with fibromyalgia,suggesting an association between psychological distress factors,such as somatisation,and SIBO[36].Another study demonstrated that state anxiety is related to SIBO[37].No study has investigated psychological distress as a moderating variable in patients with SIBO.Many studies have demonstrated that some patients with IBS display persistent signs of low-grade mucosal inflamma-tion,with activated T lymphocytes,B lymphocytes,and mast cells and increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-αand IL-6[38–41].We found that serum IL-10level was significantly lower in SIBO-positive than SIBO-negative patients with IBS,whereas the TNF-α,IL-6,and IL-8levels were similar in both groups.IL-10is an anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by T cells,B cells,and monocytes and inhibits synthesis of other cytokines.Thus, a decrease in the IL-10level could predispose a patient to increased mucosal cytokine production during infections or other mucosal insults[42].Intestinal inflammation andactivation of the immune response can cause a cytokineimbalance.Experimental data suggest that inflammation,even if mild,can lead to persistent changes in gastrointestinalnerve and smooth muscle function,resulting in colonicdysmotility,hypersensitivity,and dysfunction[43].It hasalso been reported from animal experiments that low-gradegut inflammation alters gastrointestinal tract motor function[20,44].Gut motility abnormalities can further predisposeto bacterial overgrowth.Many studies have reported thata delayed OCTT is associated with SIBO in patients withdiabetes mellitus,ulcerative colitis,and several other diseases[45–47].This is the first report of lower peripheral serum IL-10levels in SIBO-positive than SIBO-negative patients with IBS.Many studies have reported that IL-10expression is lower inpatients with IBS than in healthy controls[48–50],but studieson changes in peripheral cytokines in patients with IBS withor without SIBO are rare.Riordan et al.[51]investigatedpatients with SIBO by culturing proximal small intesti-nal luminal secretions and measuring luminal interferon-γ,IL-6,and TNF-αconcentrations.They found increased mucosal production of IL-6in SIBO-positive subjects.Thesubjects they recruited were patients with pure SIBO,notpatients with IBS,and cytokines were assessed from intestinalluminal secretions,which may reflect cytokine levels moreaccurately than peripheral blood.In animal experiments,German et al.[52]examined the role of cytokines in theimmunopathogenesis of SIBO in German shepherd dogs.Duodenal mucosal biopsies were taken,and mRNA expres-sion of various cytokines was determined by semiquantitativereverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.IL-2,IL-5,IL-12p40,TNF-α,and transforming growth factor-β1mRNAlevels in SIBO-positive dogs were significantly greater thanthose in SIBO-negative dogs.This study had some limitations.First,relatively smallnumbers of patients and controls were recruited.Second,wedid not test cytokine profiles in the healthy controls.Third,weassessed cytokine profiles in peripheral blood rather than inmucosa or tissue.Measuring cytokine levels in the intestineor colon may be more appropriate.Future studies will assess activation of the immune response in the mucosa of SIBO-positive patients with IBS and healthy controls.In summary,we conclude that SIBO is unlikely to be associated with older age,sex,alcohol consumption,or psychological disorders.Our results suggest that lower serum production of IL-10occurs in SIBO-positive than SIBO-negative patients with IBS.Future studies will assess low-grade inflammation and immune activation status by deter-mining the imbalance of cytokines and immune cell changes from intestinal biopsies in patients with IBS and SIBO.Such data will be valuable to develop a better understanding of the role of SIBO in the pathogenesis of IBS.Additional PointsSmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth(SIBO)has been impli-cated in the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome(IBS), although the issue remains controversial.Psychosocial factors and low-grade colonic mucosal immune activation have been suggested to play important roles in the pathophysiology of IBS.Our results suggest that lower serum production of IL-10occurs in SIBO-positive than SIBO-negative patients with IBS.DisclosureThe English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors,both native speakers of English. Competing InterestsThe authors have no competing interests.FundingThis study was funded by the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province,China(no.2009C14016) and was supported by the National Natural Science Founda-tion of China(no.81200274).AcknowledgmentsThe authors are very grateful for the technical support provided by Cen Lou,Liang Chen,Huacheng Huang,and Bucheng Zhang.References[1]Y.A.Saito,P.Schoenfeld,and G.R.Locke III,“The epidemiol-ogy of irritable bowel syndrome in North America:a systematic review,”American Journal of Gastroenterology,vol.97,no.8,pp.1910–1915,2002.[2]S.H.Han,O.Y.Lee,S.C.Bae et al.,“Prevalence of irritablebowel syndrome in Korea:population-based survey using the Rome II criteria,”Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol.21,no.11,pp.1687–1692,2006.[3]F.-Y.Chang and C.-L.Lu,“Irritable bowel syndrome in the21stcentury:perspectives from Asia or South-east Asia,”Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology,vol.22,no.1,pp.4–12,2007.[4]Y.Zhao,D.Zou,R.Wang et al.,“Dyspepsia and irritable bowelsyndrome in China:a population-based endoscopy study of prevalence and impact,”Alimentary Pharmacology and Thera-peutics,vol.32,no.4,pp.562–572,2010.[5]M.L.Anderson,T.M.Pasha,and J.A.Leighton,“Eradication ofsmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irri-table bowel syndrome,”American Journal of Gastroenterology, vol.95,no.12,pp.3503–3506,2000.[6]M.Pimentel,E.J.Chow,and H.C.Lin,“Normalization oflactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome:a double-blind,randomized, placebo-controlled study,”The American Journal of Gastroen-terology,vol.98,no.2,pp.412–419,2003.[7]A.Lupascu,M.Gabrielli,uritano et al.,“Hydrogen glu-cose breath test to detect small intestinal bacterial overgrowth:a prevalence case-control study in irritable bowel syndrome,”Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics,vol.22,no.11-12, pp.1157–1160,2005.[8]S.Peralta, C.Cottone,T.Doveri,P.L.Almasio,and A.Craxi,“Small intestine bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome-related symptoms:experience with Rifax-imin,”World Journal of Gastroenterology,vol.15,no.21,pp.2628–2631,2009.[9]D.Yu,F.Cheeseman,and S.Vanner,“Combined oro-caecalscintigraphy and lactulose hydrogen breath testing demonstrate that breath testing detects oro-caecal transit,not small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with IBS,”Gut,vol.60,no.3,pp.334–340,2011.[10]J.Zhao,X.Zheng,H.Chu et al.,“A study of the methodologicaland clinical validity of the combined lactulose hydrogen breath test with scintigraphic oro-cecal transit test for diagnosing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS patients,”Neurogastroen-terology and Motility,vol.26,no.6,pp.794–802,2014. [11]A.C.Dukowicz,cy,and G.M.Levine,“Small intestinalbacterial overgrowth:a comprehensive review,”Gastroenterol-ogy and Hepatology,vol.3,no.2,pp.112–122,2007.[12]G.Barbara,V.Stanghellini,G.Brandi et al.,“Interactionsbetween commensal bacteria and gut sensorimotor function in health and disease,”The American Journal of Gastroenterology, vol.100,no.11,pp.2560–2568,2005.[13]U.C.Ghoshal and D.Srivastava,“Irritable bowel syndrome andsmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth:meaningful association or unnecessary hype,”World Journal of Gastroenterology,vol.20, no.10,pp.2482–2491,2014.[14]P.Jerndal,G.Ringstr¨o m,P.Agerforz et al.,“Gastrointestinal-specific anxiety:an important factor for severity of GI symp-toms and quality of life in IBS,”Neurogastroenterology and Motility,vol.22,no.6,pp.e646–e179,2010.[15]R.L.Levy,K.W.Olden,B.D.Naliboff et al.,“Psychosocialaspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders,”Gastroen-terology,vol.130,no.5,pp.1447–1458,2006.[16]B.Braak,T.K.Klooker,M.M.Wouters et al.,“Mucosal immunecell numbers and visceral sensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome:is there any relationship?”The American Journal of Gastroenterology,vol.107,no.5,pp.715–726,2012.[17]G.Barbara,B.Wang,V.Stanghellini et al.,“Mast cell-dependentexcitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome,”Gastroenterology,vol.132,no.1,pp.26–37, 2007.。