1.2 Chapter 6 Memory Language and writing 每课一练(上海牛津九年级上)

计算机英语教程第六版

计算机英语教程第六版Computer English Tutorial, 6th EditionComputer English Tutorial, 6th Edition, provides a comprehensive guide to learning English in the context of computers and technology. This edition covers the fundamentals of computer terminology, programming, networking, and cybersecurity, making it suitable for both beginners and intermediate learners. With a practical approach and engaging exercises, this tutorial is designed to enhance the English language skills of computer enthusiasts and professionals alike.The tutorial begins with an introduction to basic computer terminology. It covers essential terms such as hardware, software, operating systems, peripherals, and input/output devices. Each term is explained in clear and concise language, accompanied by relevant examples, making it easier for learners to grasp the concepts. The tutorial also includes exercises to reinforce understanding and aid in memorization.Moving on, the tutorial delves into the world of programming. It provides a step-by-step guide to understanding programming concepts, including variables, data types, conditionals, loops, and functions. Learners are introduced to popular programming languages such as Python and Java, and are encouraged to practice writing their own code. The tutorial also includes coding exercises and quizzes to assess the learners' progress.The networking section of the tutorial is dedicated to familiarizing learners with the basics of computer networks. Topics coveredinclude local area networks (LANs), wide area networks (WANs), routers, switches, and protocols. Learners will also gain an understanding of IP addresses, subnetting, and network troubleshooting. Real-world examples and case studies are used to illustrate networking concepts and enhance comprehension.In today's digital age, cybersecurity is of paramount importance. The tutorial covers essential cybersecurity principles, including threat identification, risk assessment, and vulnerability management. Learners will gain knowledge in areas such as encryption, authentication, firewalls, and intrusion detection systems. The tutorial also provides guidance on security best practices and emphasizes the importance of ethical hacking and responsible online behavior.At the end of each chapter, the tutorial offers a comprehensive review to reinforce the learned material. These reviews include multiple-choice questions, fill-in-the-blanks exercises, and practical scenarios, allowing learners to assess their progress and identify areas for improvement.In addition to the main content, the tutorial includes a glossary of computer terms and a list of recommended resources for further learning. Learners can refer to the glossary for quick reference and use the recommended resources to deepen their understanding of specific topics.Computer English Tutorial, 6th Edition, is an invaluable resource for anyone seeking to enhance their English language skills in the domain of computers and technology. Whether you are a student, aprofessional, or simply an enthusiast, this tutorial provides a solid foundation in both English language and computer concepts. With its practical approach and comprehensive coverage, it is an essential guide for mastering computer English.。

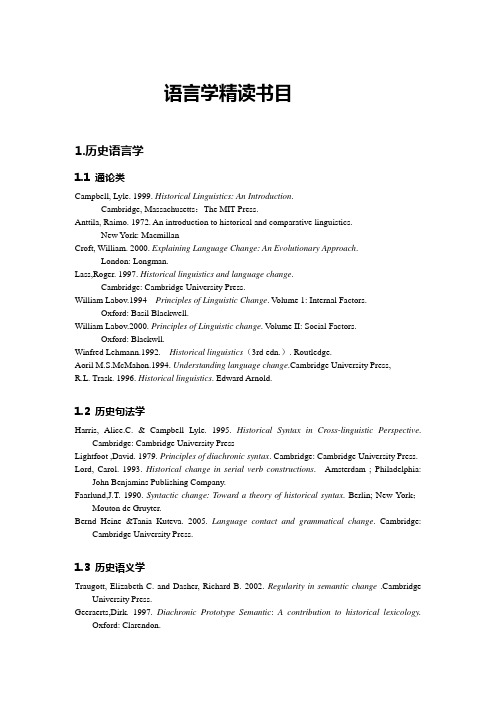

语言学精读书目(英文)

语言学精读书目1.历史语言学1.1 通论类Campbell, Lyle. 1999. Historical Linguistics: An Introduction.Cambridge, Massachusetts:The MIT Press.Anttila, Raimo. 1972. An introduction to historical and comparative linguistics.New York: MacmillanCroft, William. 2000. Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach.London: Longman.Lass,Roger. 1997. Historical linguistics and language change.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.William Labov.1994 Principles of Linguistic Change. V olume 1: Internal Factors.Oxford: Basil Blackwell.William Labov.2000. Principles of Linguistic change. V olume II: Social Factors.Oxford: Blackwll.Winfred Lehmann.1992. Historical linguistics(3rd edn.). Routledge.Aoril M.S.McMahon.1994. Understanding language change.Cambridge University Press,R.L. Trask. 1996. Historical linguistics. Edward Arnold.1.2 历史句法学Harris, Alice.C. & Campbell Lyle. 1995. Historical Syntax in Cross-linguistic Perspective.Cambridge: Cambridge University PressLightfoot ,David. 1979. Principles of diachronic syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lord, Carol. 1993. Historical change in serial verb constructions. Amsterdam ; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Faarlund,J.T. 1990. Syntactic change: Toward a theory of historical syntax. Berlin; New York;Mouton de Gruyter.Bernd Heine &Tania Kuteva. 2005. Language contact and grammatical change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.1.3 历史语义学Traugott, Elizabeth C. and Dasher, Richard B. 2002. Regularity in semantic change .Cambridge University Press.Geeraerts,Dirk. 1997. Diachronic Prototype Semantic:A contribution to historical lexicology.Oxford: Clarendon.Sweetser, Eve E.1990. From etymology to pragmatics: Metaphorical and cultural aspects of semantic structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 19901.4 历史语用学Arnovick,Lesliek. 1999. Diachronic Pragmatics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Brinton, Laurel J. 1996. Pragmatic markers in English: Grammaticalization and discourse function. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.2.语法化研究Givo n, Talmy. 1979. On Understanding Grammar. New York: Academic Press.Heine, Bernd & Kuteva ,Tania. 2002 .World lexicon of grammaticalization.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Heine , Bernd, Ulrike Claudi & Friederike Hu nnemeyer. 1991. Grammaticalization : Aconceptual Framework. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Bybee, Joan. , Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect and modality in the languages of the world. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hopper, Paul J .&Traugott, Elizabeth C. 2003. Grammaticalization, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Lehmann, Christian. 1995[1982]. Thoughts on Grammaticalization. Munich: Lincom Europa.Xiu-Zhi Zoe WU.2004. Grammaticalization and Language Change in Chinese : A formal view London and New York: RoutledgeCurzonElly van Gelderen. 2004.Grammaticalization as Economy. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing CompanyBernd Heine and Tania Kuteva. 2005 Language Contact and Grammatical Change. Cambridge University Press.Ian Roberts and Anna Roussou.2003. SyntacticChange: A minimalist approach to grammaticaliza- tion. Canbridge:Cambridge University Press.Regine Eckardt. 2006. Meaning change in grammaticalization: an enquiry into semantic reanalysis New York : Oxford University Press.3.认知语言学Taylor, John R. 2005. Cognitive grammar.Oxford: Oxford University Press.Croft,William and D. A. Cruse.2004. Cognitive linguistics. (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Langacker,Ronald W. 1987/1991. Foundations of cognitive grammar,vol.1-2, Stanford: Stanford University Press.Lakoff, George.1987. Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Talmy, L. 2000, Toward a Cognitive Semantics. V ol.1& 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.4.语言类型学Croft, William. 2003. Typology and Universals, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Song, Jae Jung. 2001. Linguistic Typology: Morphology and syntax. Longman.Whaley, Linndsay J. 1997. Introduction to Typology: the unity and diversity of language. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.L.J.Whaley. 1997. Introduction to typology: The unity and diversity of language. Sage. Bernard Comrie. 1989. Languge universals and linguistic typology(2nd edition), University of Chicago Press.J.A.Hawkins. 1983. Word order universals. Academic Press.5.语用学、句法学与语义学5.1 句法学:Payne,Thomas E. 1997. Describing Morphosyntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thomas E. Payne.2006. Exploring language Structure: A student’s guide. Cambridge University Press.Timothy Shopen. 1985. Language typology and syntactic Description. Cambridge University Press.Givo n, Talmy. 1984/1991. Syntax: A functional-typological introduction, V ol.I.II, Amsterdam: Benjamins,1984.5.2 语义学:Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Saeed,John. 1997. Sementics. Blackwell Publishers.5.3 语用学:Levinson,Stephen C. 1983. Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Green,Georgia M. 1989. Pragmatics and natural language understanding .Hillsdale,NJ:Erlbaum Associates.5.4 其他:Schiffrin, Deborah. 1987. Discourse markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Karin Aijmer. 2002. English Discourse Particles: Evidence from a corpus. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia : John Benjamins Publishing Company.Verhagen, Arie. 2005. Constructions of intersubjectivity: Discourse, syntax,and cognition. Oxford:Oxford University Press.Dahl, Osten. 1985.Tense and aspect systems. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.Kemmer,Suzanne. 1993. The middle voice: A typological and diachronic study.Amsterdam: Benjamins.Bybee, Joan. 1985. Morphology: A study of the relation between meaning and form. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Newmeyer, Fredrick J. Language form and language function. Cambridge;MA: MIT Press,1998 Croft,William. Syntactic categories and grammatical relations.Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991Haiman, John. Natural syntax: Iconicity and erosion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect: An introduction to the study of verbal aspect and related problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Comrie ,Bernard. 1985.Tense. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Palmer,F.R.2001. Mood and Modality. Second Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Smith,Carlotta S.1991. The Parameter of Aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer.Goldberg, A. E. 1995,Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure.Chicago: Chicago University Press.6.接触语言学:Thomason, Sarah G. 2001. Language contact: An introduction. Edinburgh University Press. Thomason, Sarah G. & Kaufman,Terrence.1988. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.Dixon, R.M.W. 1997. The rise and fall of languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Holm, J. 2004. Languages in contact. The partial restructuring of vernaculars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Myers-Scotton, C. 2003. Contact linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Winford,Donald. 2003. An introduction to contact linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell.Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2002. Language contact in Amazonia. New York: Oxford University Press.Enfield, N. J. 2003. Linguistic epidemiology: semantics and grammar of language contact in mainland Southeast Asia. London: Routledge Curzon.。

语言学教程Chapter 6. Language and Cognition课件

语言学教程Chapter 6. Language and Cognition

(1) Access to words

• Steps involved in the planning of words: • 1. processing step, called conceptualization,…… • 2.to select a word that corresponds to the chosen concept. • 3.morpho-phonological encoding • Generally, morphemes are accessed in sequence, according to

• 1). Serial models…… • 2). Parallel models…… • Structural factors in comprehension of sentences • 1). minimal attachment which defines “structural simpler” • 2).“Garden path” • Lexical factors in comprehension • Information about specific words is stored in the lexicon.

语言学教程Chapter 6. Language and Cognition

6.2.3 language production

• Language production involves…… • 1. generation of single words • 2. generation of simple utterances • Different mappings in language comprehension and in language production • Discussions: • A. production of words orally, • B. production of longer utterances, • C. the different representations and processes involved in spoken production

Chapter4.ThepsychologyofSecondLanguage

Chapter4.ThepsychologyofSecondLanguageChapter 4. The psychology of Second Language Acquisition1)Languages and the brainBroca’s area – to be responsible for the ability to speak.Wernicke’s area - located in the left temporal lobe, result in excessivespeech and loss of language comprehension.Brain lateralization – specialization of the two halves of the brain. Methods for gathering data:Correlations of location of brain damage with patterns of loss/recoveryin cases where languages are affected differentially.Presentation of stimuli from different languages to the right versus theleft visual or auditory fields.Mapping the brain surface during surgery by using electrical stimulationat precise points and recording.Positron Emission Tomography and other non-invasive imagingtechniques.Some researches and questions in this area:How independent are the languages of multilingual speakers?How are multiple language structures organized in relation to oneanother in the brain? Are both languages stored in the same areas?Does the organization of the brain for L2 in relation to L1 differ withage of acquisition, how it is learned, or level of proficiency?Do two or more languages show the same sort of loss or disruption afterbrain damage? When there is differential impairment or recovery, whic hlanguage recovers first?2)Learning processesPsychology provides us with two major frameworks for the focus onlearning processes: Information Processing and Connectionism.Information Processing (IP)(1)Perception and the input of new information.(2)The formation, organization, and regulation of internal representations.(3)Retrieval and output strategies.Assumptions:Second language learning is the acquisition of a complex cognitive skill.Complex skills can be reduced to sets of simpler component skills.Le arning of a skill initially demands learners’ attention.Controlled processing requires considerable mental “space”.Humans are limited-capacity processors.Learners go from controlled to automatic processing with practice.Learning essentially involves development from controlled to automaticprocessing of component skills.Along with development from controlled to automatic processing.Reorganizing mental representations as part of learning makes structuresmore coordinated, integrated, and efficient, including a faster responsetime when they are activated.In SLA, restructuring of internal L2 representations, along with largerstores in memory, accounts for increasing levels of L2 proficiency.Theories regarding order of acquisitionLearners acquire certain grammatical structures in a developmentalsequence.Developmental sequences reflect how learners overcome processinglimitations.Language instruction which targets developmental features will besuccessful only if learners have already mastered the p rocessingoperations which are associated with the previous stage of acquisition.Competition M odelCoined by Bates and MacWhinney: this is a functional approach which assumes that all linguistic performance involves mapping between external form and internal function.Form-function mapping is basic for L1 acquisitionTask frequency.Contrastive availability.Conflict reliability.Connectionist approachesFocus on the increasing strength of associations between stimuli and responses rather than on t he inferred abstraction of “rules” or on restructuring.The best-known connectionist approach in SLA is Parallel Distributed Processing (PDP)Attention is not viewed as a central mechanism.Information processing is not serial in nature.Knowledge is not stored in memory or retrieved as patterns.3)Differences in learnersAge factorAge differences in SLAYounger advantage:Brain plasticity.Not analytical.Fewer inhibitions.Weaker group identity.Simplified input more likely.Older advantage:Learning capacity.Analytic ability.Pragmatic skills.Greater knowledge of L1.Real-world knowledge.Sex factor:Females tend to be better L2 learners than males.Aptitude factor:Phonemic coding ability.Inductive language learning ability and grammatical sensitivity.Associative memory capacity.M otivation factor:Significant goal or need.Desire to attain the goal.Perception that learning L2 is relevant to fulfilling the goal or meetingthe need.Belief in the likely success or failure of learning L2.Value of potential outcomes/rewards.Cognitive style factor:Field-dependent - Field-independentGlobal - ParticularHolistic - AnalyticDeductive - InductiveFocus on meaning – Focus on formPersonality factor:(1)Anxious – Self – confidence(2)Risk avoiding – Risk trying(3)Shy – Advertisement(4)Introverted – Extroverted(5)Inner directed – Other directed(6)Reflective – Impulsive(7)Imaginative – Uninquisitive(8)Creative – Uncreative(9)Empathetic – Insensitive to others(10)Referent of ambiguity – Closure orientedLearning strategies:Differential L2 outcomes may also be affected by individualslearning strategies.(1)Meta cognitive.(2)Cognitive.(3)Social/affective.The major traits good learners have:Concern for language formConcern for communicationActive task approachAwareness of the learning process.Capacity to use strategies flexibly in accordance with task requirements.4)The effects of multilingualism(1)Bilingual children show consistent advantages in tasks of both verbaland nonverbal abilities.(2)Bilingual children show advanced meta-linguistic abilities.(3)Cognitive and meta-linguistic advantages appearing bilingual situations.(4)The cognitive effects of bilingualism appear relatively early in theprocess of becoming bilingual and do not require high levels ofbilingual proficiency nor the achievement of balanced bilingualism.。

精品课件-新视野大学英语第三版读写教程第二册Unit6

2. What is the proper way to deal with this dilemma? Is more always better than less?

Evidences show that people feel less happy and more depressed when given an overabundance of choice. The tendency to keep all our doors of choices open might have damaged our life, and we can get greater pleasure and more satisfaction by focusing our energy and attention on fewer options and things. More is not necessarily better in life. We should close some doors in order to allow for the right windows of opportunity and happiness to open.

Just as all people have to make decisions in their everyday lives, college students are always faced with the dilemma of making right choices. Faced with an abundance of options to choose from, they can’t bear the pain to lose any opportunity and have a strong desire to keep all the options open. They try to avoid such an emotional loss, and would rather pay the high cost to keep all the doors of opportunity open.

The Science of Memory

The Science of MemoryMemory is a fascinating and complex aspect of human cognition, and it has been the subject of extensive scientific study. The science of memory encompasses various disciplines such as psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science, and it seeks to understand the processes involved in encoding, storing, and retrieving information. Memory plays a crucial role in shaping our identities, guiding our decision-making, and allowing us to learn from past experiences. However, it is also prone to errors and distortions, which can have significant implications for our daily lives. In this response, we will delve into the science of memory from multiple perspectives, exploring its mechanisms, functions, and potential limitations. From a psychological perspective, memory can be categorized into different types based on the duration of retention and the nature of the information being stored. Short-term memory refers to the temporary storage of information, typically lasting for a few seconds to a minute. This type of memory is essential for tasks such as remembering a phone number long enough to dial it or recalling a person's name in a conversation. On the other hand, long-term memory involves the storage of information over an extended period, ranging from minutes to a lifetime. Long-term memory can be further divided into explicit (or declarative) memory, which involves conscious recollection of facts and events, and implicit (or procedural) memory, which pertains to the retention of skills and habits without conscious awareness. Understanding these distinctions is crucialfor comprehending the intricacies of memory and how it influences our behavior and cognition. Neuroscience offers valuable insights into the biological underpinnings of memory, shedding light on the neural circuits and mechanisms involved in memory formation and retrieval. The hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure located in the brain's temporal lobe, is widely recognized as a key player in the formation of new memories. It acts as a sort of "gateway" for incoming information, facilitating its consolidation into long-term memory. Additionally, various neurotransmitters and synaptic connections within the brain contribute to the encoding and storage of memories. For example, the neurotransmitter dopamine has been implicated in the formation of reward-related memories, highlighting the intricate interplay between brain chemistry and memoryprocesses. By unraveling the neural basis of memory, neuroscientists strive to develop a deeper understanding of conditions such as amnesia and dementia, as well as potential interventions to enhance memory function. Cognitive science approaches memory from a broader perspective, examining how memory interacts with other cognitive processes such as attention, perception, and language. One influential model in this field is the multi-store model of memory, proposed by Atkinson and Shiffrin in 1968. This model posits the existence of three memory stores – sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory – and outlines the flow of information between these stores. While the multi-store model has been refined and expanded upon over the years, it laid the groundwork for subsequent research on memory and provided a framework for understanding memory processes ina holistic manner. Cognitive scientists also investigate the factors thatinfluence memory performance, such as mnemonic techniques, context-dependent retrieval, and the role of schemas in organizing and interpreting information. By integrating insights from various disciplines, cognitive science contributes to a comprehensive understanding of memory and its implications for human cognition.In addition to its cognitive and neurological dimensions, memory holds significant emotional and personal significance for individuals. Memories shape ourperceptions of the world, inform our sense of self, and influence our emotional responses to past events. The recollection of cherished memories can evokefeelings of joy, nostalgia, and gratitude, while traumatic memories may trigger anxiety, grief, or distress. Moreover, memory plays a pivotal role in maintaining social bonds and relationships, as it enables us to remember significant events shared with loved ones and to empathize with others by recalling similar experiences. The emotional impact of memory is evident in phenomena such as flashbulb memories, which are vivid and enduring recollections of emotionally charged events, such as the assassination of a public figure or a natural disaster. These memories are often characterized by their clarity and emotional salience, underscoring the profound intertwining of memory and emotion in human experience. Despite its many virtues, memory is not immune to imperfections and fallibility. Human memory is susceptible to various forms of distortion, including forgetting, misattribution, and false memories. For instance, the misinformation effect, asdemonstrated in studies by Loftus and Palmer, illustrates how the introduction of misleading information can alter one's memory of an event. This phenomenon has significant implications for eyewitness testimony in legal contexts, as it underscores the potential for memory malleability and suggestibility. Moreover, memory biases and heuristics, such as the availability heuristic and confirmation bias, can influence our perceptions and decision-making by shaping the way we retrieve and interpret information. These cognitive pitfalls highlight the needfor critical reflection on the reliability and accuracy of our memories, as well as the importance of corroborating evidence in situations where memory is the primary source of information. In conclusion, the science of memory encompasses a rich tapestry of psychological, neurological, cognitive, and emotional dimensions. It is a fundamental aspect of human cognition, shaping our identities, informing our decisions, and connecting us to the past. By examining memory from multiple perspectives, we gain a deeper appreciation of its mechanisms, functions, and potential limitations. From the intricate neural processes underlying memory formation to the emotional resonance of cherished recollections, memory permeates every facet of human experience. While memory is susceptible to errors and distortions, it remains a cornerstone of our cognitive architecture, enabling us to navigate the complexities of the world and construct meaningful narratives of our lives. As we continue to unravel the mysteries of memory, we are poised to gain new insights into the human mind and the intricate interplay between memory, cognition, and emotion.。

Chapter 1-2剖析

10

#

(i) Arbitrariness (Saussure)

B. However arbitrariness of language is not absolute and there seems to be different levels of arbitrariness.

• Book •书 • ほん

5

#

• ③vocal: the primary medium is sound for all

languages, no matter how well developed are

their writing systems. All evidence shows that

• The features that define our human languages can be called design features.

9

#

(i) Arbitrariness (Saussure)

A. definition • It refers to the fact that the forms of

13

#

C. Significance of arbitrariness

• Arbitrariness of language makes it potentially creative, makes it possible to have unlimited sources of expressions. We can use new sets of sounds or coin new words to represent newly invented things or new ideas.

新编英语词汇学教程第二版Chapter6Major ApproachestoWord Meaning

6.1 The naming theory

Problems

• This theory seems to apply to nouns only. • Even within the category of nouns, this theory cannot account

for the meaning of some fictional, mythical, or abstract entities, let alone the meanings of polysemous words. • This theory cannot be used to account for the phenomenon that the same object in the real world can be referred to by different expressions which are both meaningful.

6.2 Componential analysis

Componential analysis is often seen as a process of breaking down the sense of a word into its minimal components, which are known as semantic features or sense components. This analysis is based on semantic contrast. These minimal components can be symbolized in terms of binarity or binary opposition, i.e. they can be X or not X (indicated by +/–) such as [+ADULT] for “adult”, [–ADULT] for “young”.

Principles-of-Language-Learning-and-Teaching

Terminology: Discourse/Text

Distictions Between Discourse and Text

First, people often talk of spoken discourse versus written text. Discourse often is naturally occuring spoken language, as found in such discourses as conversations, interviews, commentaries, and speeches, which implies interactive discourse; whereas text is wriiten language, as found in such texts as essays, notices, newspaper articles and chapters, which implies noninteractive monologue, whether intended to be spoken aloud or not. For example people can speak of an academic paper, meaning what is delivered or read to an audience, or its printed version. For instance, a lecture may refer to a whole social event, or only to the main spoken text or its written version. One talk of a written text of a speech. So such ambiguities arise in the previous examples.

英语unit 6单元

Multiple Choice

Listening to a recording and choosing the correct answer from a set of options

Tense voice

Simple future

01

used to refer to a future action or event

Subjunctive Mood

02

used to express a wish, likelihood, or condition

Past effect

03

used to refer to an action that had happened before

Claims starting with "after", "before", "until", or "since" can have some functions as advertisements

Noun claim: used as the subject or object of a verb

First person regular subject: verbs use "we"

form

Second person regular subject: verbs use "you"

form

Third person plural subject: verbs use "they"

form

Usage of claims

Understand the meaning and usage of new words and phrases

Chapter 6章

2.1 Performatives and constatives (P247)

Austin’s first shot at the theory is the claim that there are two types of sentences: performatives and constatives. 2.1.1 Constatives A constative is a sentence which describes or states something; it is either true or false. Example: Tom is taller than John.

Obviously, ‘context’ is a basic notion in pragmatic studies. Context is generally considered as constituted by the knowledge shared by the speaker and the hearer, including encyclopedic knowledge of the world, knowledge specific to the situation of communication, knowledge about the participants, and knowledge of the language they use, and so on.

Chapter Six

Pragmatics

1.2.2 Utterance-meaning An utterance is a piece of language actually used in a particular context. It is often a sentence in a certain context, but may not always be so. Once said in a certain context, a sentence may convey something more than its sentence-meaning, i.e. its literal meaning. Ex. 1

高级语言1 Unit 6 Mark Twain-Mirror of America课后练习答案

Unit 6Mark Twain --- Mirror of America课后习题答案Ⅲ. Paraphrase:1.Mark Twain is known to most Americans as theauthor of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Huck Finn is noted for his simple and pleasant journey through his boyhood which seems eternal and Tom Sawyer is famous for his free roam of the country and his adventure in one summer which seems never to end.The youth and summer are eternal because this is the only age and time we knew them. They are frozen in that age/season for all readers.2.His work on the boat made it possible for him tomeet a large variety of people. It is a world of all types of characters.3.All would reappear in his books, written in thecolorful language that he seemed to be able to remember and record as accurately as a phonograph.4.Steamboat decks were filled with people who explored and prepared the way for others and also lawless people or social outcasts such as hustlers, gamblers and thugs.5.He took a horse-drawn public vehicle and went west to Nevada, following the flow of people in the gold rush.6.Mark Twain began to work hard as a newspaper reporter and humorist to become well-known locally.7.Those who came pioneering out west were energetic, courageous and reckless people, because those who stayed at home were the slow, dull and lazy people.8.That’s typical of California.9.If we relaxed, rested or stayed away from all thiscrazy struggle for success occasionally and kept the daring and enterprising spirit, we would be able to remain strong and healthy and continue to produce great thinkers.10.At the end of his life, he lost the last bit of hispositive view of man and the world.IV. Practice with Words and ExpressionsA.1. starry-eyed: romantic, dreamy; with the eyessparkling in a glow f wonderacid-tongued: sharp, sarcastic in speech2. medicine shows: shows given by entertainers whotravel from town to town, accompanied by quacks and fake Indians, selling cure-alls, snake-bite medicine, etc.3. flirt: originally meaning pretending love withoutserious intention, here meaning trying but not hard or persistently enough4. strike: the sudden discovery of some mineral ores5. hotbed: a place that fosters rapid growth orextensive activity, often used of sth. Evil6. ring: to produce, as by sounding, a specifiedimpression on the hearertrend-setting: taking the lead in starting a new trend or new ways of doing things7. project: propose or make plan for8. entry: an item in his notebook9. shot: quantity of tiny balls of lead used in a sportinggun against birds or small animals10. sorely: greatly or extremely11. shots: critical remarks12. bowl: a hollow land formationB:1: romantic意为“浪漫的”;sentimental意为“伤感的”或“易感伤的”;humorous意为“幽默的”或“风趣的”;witty意为“机智的”或“聪颖的”。

全新版大学英语第二册 unit 6 A woman can learna nything a manc an全新版大学英语(第二版)

men

VS

women

superwomen

IRON LADY– Margaret Thatcher

She is the first female leader of British Conservative Party in British history, created for the three consecutive terms, a term of up to 11 years of recording female prime minister. In addition, early before she became prime minister, because of her high profile against communism, and by Soviet media dubbed “the Iron Lady”, the nickname has ever become her main mark.

Old standards for women

1.Men for the field and women for the hearth.

2.Men for the sword and women for the needle.

3.Men with the head and women with the heart.

Dream: be loaded the magazine" Times” Evaluation: Desires to manipulative from childhood, had the ambitious to be a leader

Chinese Iron lady ----Wu Yi

A Brief Introduction to Feminism

数据库英文版第六版课后答案

数据库英文版第六版课后答案Chapter 1: IntroductionQuestions1.What is a database?A database is a collection of organized and structured data stored electronically in a computer system. It allows users to efficiently store, retrieve, and manipulate large amounts of data.2.What are the advantages of using a database system?–Data sharing and integration: A database system allows multiple users to access and share data simultaneously.–Data consistency and integrity: A database system enforces rules and constraints to maintain the accuracy and integrity of the data.–Data security: A database system provides access control mechanisms to ensure that data is accessed by authorized users only.–Data independence: A database system separates the data from the application programs that use it, allowing for easier applicationdevelopment and maintenance.Exercises1.Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of using a database system.Advantages:–Data sharing and integration–Data consistency and integrity–Data security–Data independenceDisadvantages:–Cost: Database systems can be expensive to set up and maintain.–Complexity: Database systems require a certain level of expertise to design, implement, and manage.–Performance overhead: Database systems may introduce some overhead in terms of storage and processing.Overall, the advantages of using a database system outweigh the disadvantages in most cases, especially for large-scale applications with multiple users and complex data requirements.Chapter 2: Relational Model and Relational Algebra Questions1.What is a relation? How is it represented in the relational model?A relation is a table-like structure that represents a set of related data. It is represented as a two-dimensional table with rows and columns, where each row corresponds to a record and each column corresponds to a attribute or field.2.What is the primary key of a relation?The primary key of a relation is a unique identifier for each record in the relation. It is used to ensure the uniqueness and integrity of the data.Exercises1.Consider the following relation:Employees (EmpID, Name, Age, Salary)–EmpID is the primary key of the Employees relation.–Name, Age, and Salary are attributes of the Employees relation.2.Write a relational algebra expression to retrieve the names of all employees whose age is greater than 30.π Name (σ Age > 30 (Employees))Chapter 3: SQLQuestions1.What is SQL?SQL (Structured Query Language) is a programming language designed for managing and manipulating relational databases. It provides a set of commands and statements that allow users to create, modify, and query databases.2.What are the main components of an SQL statement?An SQL statement consists of the following main components:–Keywords: SQL commands and instructions.–Clauses: Criteria and conditions that specify what data to retrieve or modify.–Expressions: Values, variables, or calculations used in SQL statements.–Operators: Symbols used to perform operations on data. Exercises1.Write an SQL statement to create a table called。

Finley_Benjamin_Hays_RBjork_Kornell_2011

Benefits of accumulating versus diminishing cues in recallJason R.Finley a ,⇑,Aaron S.Benjamin a ,Matthew J.Hays b ,1,Robert A.Bjork b ,Nate Kornell b ,caDepartment of Psychology,University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,USA bDepartment of Psychology,University of California,Los Angeles,USA cDepartment of Psychology,Williams College,USAa r t i c l e i n f o Article history:Received 12August 2010revision received 6January 2011Available online 4March 2011Keywords:Cued recall Retrieval cuesRetrieval difficulty Retrieval practice Testing effecta b s t r a c tOptimizing learning over multiple retrieval opportunities requires a joint consideration of both the probability and the mnemonic value of a successful retrieval.Previous research has addressed this trade-off by manipulating the schedule of practice trials,suggesting that a pattern of increasingly long lags—‘‘expanding retrieval practice’’—may keep retrievals successful while gradually increasing their mnemonic value (Landauer &Bjork,1978).Here we explore the trade-off issue further using an analogous manipulation of cue informative-ness.After being given an initial presentation of English–Iñupiaq word pairs,participants received practice trials across which letters of the target word were either accumulated (AC),diminished (DC),or always fully present.Diminishing cues yielded the highest perfor-mance on a final test of cued recall.Additional analyses suggest that AC practice promotes potent (effortful)retrieval at the cost of success,and DC practice promotes successful retrieval at the cost of potency.Experiment 2revealed that the negative effects of AC prac-tice can be partly ameliorated by providing feedback after each practice trial.Ó2011Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.IntroductionEffortful retrieval enhances long-term learning (Bjork,1975;Gardiner,Craik,&Bleasdale,1973;Glover,1989;Pyc &Rawson,2009).This principle underlies the concept of desirable difficulties (Bjork,1994),whereby durable and flexible gains are thought to result from conditions that make learning effortful (Schmidt &Bjork,1992).These conditions include spaced repetitions of learning events (Cepeda,Pashler,Vul,Wixted,&Rohrer,2006),interleaved practice of contextually interfering tasks (Shea &Morgan,1979),a reduction in the frequency of feedback (Schmidt,1991),and the use of tests as learning events (Roediger &Karpicke,2006).But,in each of these cases,difficulties are only desirable to the extent that they are overcome.That is,practice can be sub-optimal not only when condi-tions are too easy,but also when they are too hard.Thus,harnessing difficulties to enhance learning is a matter of determining and implementing the appropriate amount of retrieval difficulty for a given learner and a given set of materials.Desirable difficulties in the spacing of practiceThe manipulation of retrieval difficulty that has re-ceived the most empirical attention is the scheduling of re-peated practice.It is well established that longer lags (i.e.,more spacing)between practice trials can impair perfor-mance during training but enhance it at a delay (cf.Bah-rick,1979;Dempster,1988;Greene,2008;Schmidt &Bjork,1992).When the practice trials are tests,rather than re-study opportunities,spacing must be calibrated with re-spect to forgetting in order to take advantages of desirable difficulty.If the lag between trials is too short,forgetting is minimal,retrieval is trivial,and the benefits of successful retrieval are small.However,if the lag between trials is0749-596X/$-see front matter Ó2011Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.jml.2011.01.006⇑Corresponding author.Address:Department of Psychology,Univer-sity of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,603E.Daniel St.,Champaign,IL 61820,USA.E-mail address:jrfinley@ (J.R.Finley).1Present address:Institute for Creative Technologies,University of Southern California,United States.too long,forgetting is considerable,retrieval is unlikely, and the benefits of successful retrieval are unrealized (Cepeda,Vul,Rohrer,Wixted,&Pashler,2008).Thus,hit-ting the‘‘sweet spot’’on the trade-off between the amount of forgetting and the magnitude of the benefit requires considerable calibration,not just for the level of difficulty on each individual practice trial,but also for the overall dif-ficulty schedule(e.g.,increasing,decreasing,or constant).A prediction of this view is that an optimally difficult spacing schedule must provide shorter lags early in prac-tice when levels of learning are low,and longer lags later in practice when levels of learning are higher.This predic-tion was tested by Landauer and Bjork(1978),who demon-strated that a schedule of expanding spaced intervals produced superiorfinal test performance when compared to uniformly spaced or contracting spaced intervals.The logic behind an expanding schedule is compelling. The best time to retrieve an item—the sweet spot of max-imal potency—is just before that item is forgotten(i.e., after the longest manageable interval).As an item becomes better learned because of each successive retrieval,the maximum interval at which the learner can successfully retrieve that item increases,moving the sweet spot further away in time.A schedule of expanding retrieval practice should provide the best chances offitting this pattern, offering successive retrieval opportunities that are neither too easy(as they may be with later practice trials in con-tracting or uniform spacing)nor too hard(as they may be with the early trials of contracting or uniform spacing).Many prior studies have examined the theoretical underpinnings and the applied potential of expanding re-trieval practice(for reviews,see Balota,Duchek,&Logan, 2007;Storm,Bjork,&Storm,2010),and Pavlik and Ander-son(2008)developed a spacing optimization model that produced expanding schedules.It is important to note, however,that expanding schedules are not guaranteed to always optimally promote long-term retention.In fact,sev-eral studies have demonstrated conditions in which an expanding schedule may be equivalent or inferior to a uni-form one(cf.Karpicke&Roediger,2007,2010).One inter-esting point this work has highlighted is the importance of pinpointing the optimal amount of spacing for the very first interval.If thefirst interval is too long then retrieval will fail,and the subsequent difficulty schedule matters lit-tle as learners are unlikely to recover the item(assuming there is no feedback during practice).If thefirst interval is too short then retrieval will succeed but may provide so lit-tle benefit that the expanding schedule is inferior to a uni-form lag schedule with an equivalent amount of overall spacing that offers a longer initial interval.Thus,implementing an optimally difficult practice plan hinges on determining the optimal initial amount of spac-ing,for a given learner studying a given item.Unfortu-nately,this is impossible.Empirically establishing whether a learner can retrieve an item after a particular lag requires testing that item.If the participant success-fully retrieves the item,it is consequently strengthened, thereby invalidating the lag estimation.Conversely,if the participant fails to retrieve the item,the experimenter knows only that the lag was too long.This is an inherent limitation in the use of spacing to optimize learning,and may explain why results based on expanding practice schedules have been mixed(Balota et al.,2007):the initial interval used in a particular study will vary in how close it is to what would be optimal for a given learner and item, and this proximity will influence the effectiveness of any subsequent lag schedule.Furthermore,there are practical limitations on the total time available during studying as well as difficulties that arise from the complexity of co-scheduling massive numbers of items at different stages of learning.However,even in the face of these limitations, Pavlik and Anderson(2008)developed an impressive mod-el that makes ongoing estimates of optimal spacing sched-ules for practice of a large number of items,based on history of practice during a study session(for a given lear-ner and item),and parameters estimated from prior data. Although the optimality of interval estimates must logi-cally be limited for the earliest trials for each item,the model nevertheless produced effective overall schedules. Cue informativeness as an alternative manipulation of difficultyAn alternative way of manipulating difficulty is to vary the amount of information provided by the retrieval cue (e.g.,the number of letters of a to-be-remembered word; Benjamin,2005;Carpenter&DeLosh,2006;Carroll&Nel-son,1993).In spacing paradigms,difficulty increases with lag;in cue informativeness paradigms,difficulty increases with the poverty of the cue.Varying cue informativeness across practice trials,or fading cues,in order to enhance learning,is an idea that dates back to Skinner(1958)and includes variants such as the vanishing cues procedure(Gli-sky,Schacter,&Tulving,1986),which we address further in the general discussion.These approaches to the strategic regulation of diffi-culty are conceptually similar to common procedures of computerized adaptive testing(cf.Weiss&Kingsbury, 1984),which attempt to pinpoint a person’s general ability or achievement in some domain by dynamically adminis-tering items of varying normative difficulty according to the person’s successive responses.In contrast to such test-ing for the sake of assessment,our goal here was to exploit the powerful effects of testing as a learning event(cf. Roediger&Karpicke,2006)in order to optimize learning of specific materials.In the present study,we adopted this difficulty manip-ulation and examined two basic schedules for varying cue informativeness:accumulating cues(AC),and diminishing cues(DC).The effectiveness of both schedules was com-pared against a study-only control condition in which the entire target was presented on all trials.In the DC condition,the informativeness of cues de-creases across trials:initially easy practice becomes more difficult.In this way,DC is analogous to expanding retrie-val practice;it minimizes the probability of retrieval fail-ure while also ensuring that later trials are more difficult than early trials.We therefore predicted it would produce the greatestfinal recall performance of all the conditions.In the AC condition,the informativeness of cues in-creases across trials:initially difficult practice becomes290J.R.Finley et al./Journal of Memory and Language64(2011)289–298more easy.Although AC is similar to the oft-dismissed con-dition of contracting retrieval practice,it differs in an important way:it offers learners a chance for recovery from retrieval failure on preceding trials.Furthermore,AC also offers greater opportunity than DC for more potent ret-rievals;the less well-learned an item is,and the more effortful its retrieval is,the greater the boost it will receive upon successful retrieval(Bjork&Bjork,1992;Carpenter& DeLosh,2006).This reasoning is also consistent with work by Gardiner,Smith,Richardson,Burrows,and Williams (1985),who found that thefinal-free-recall benefits of gen-erating versus reading a word increased as a linear func-tion of the number of letters omitted.AC,which presents the most difficult trials earliest in practice,is better suited than DC to allow such powerful retrievals.In other words, AC is more likely to hit the learner’s sweet spot at least once.DC,by presenting the easiest trials earliest,may sell learners short of the opportunity to make high-yield effort-ful retrievals,while at the same time maximizing the num-ber of overall successes.In short,accumulating cues should promote potent re-trieval at the cost of success;diminishing cues should pro-mote successful retrieval at the cost of potency. Diminishing cues,like expanding retrieval practice,are ex-pected to lead to an overall advantage infinal recall. Experiment1Experiment1was designed with two goals:to evaluate the prediction that diminishing cues would promote supe-rior long-term retention;and to explore the trade-off be-tween the potency and success of retrieval.An initial presentation of English–Iñupiaq word pairs was followed by practice trials(with no feedback)across which letters of the target word were either accumulated,diminished, or always present.Afinal test of cued recall measured the learning benefits of the three practice conditions. MethodParticipantsEighty undergraduates participated for course credit. MaterialsMaterials were12English–Iñupiaq word pairs(e.g., dust–apyuq),all nouns.The Iñupiaq words were all5letters long,and the English words varied in length from3to7 letters.See the Appendix for the complete list.DesignThe experiment used a within-subjects design with one independent variable,practice condition,which had three levels:accumulating cues(AC),diminishing cues(DC), and study-only.The dependent measure was performance on afinal cued recall test.ProcedureParticipants were run individually on computers pro-grammed with Matlab using the Psychophysics Toolbox extensions(Brainard,1997).The procedure consisted of three phases:initial presentation,practice,andfinal test. Initial presentation phaseParticipants studied all12English–Iñupiaq word pairs, three times each,for4s per presentation,with no inter-stimulus intervals.The12word pairs were separated into three groups of four words each.Each group was rotated through the three practice conditions every three partici-pants.For each participant,a random presentation order was generated for the initial presentation of the word pairs,and this order was repeated three times.Initial pre-sentation was followed by a1.5min distractor task con-sisting of arithmetic problems and judgments about which of two circles was a darker shade of gray.Practice phaseParticipants completed six practice trials for each word pair.Each practice trial displayed an English word along with0–5(all)letters of the corresponding Iñupiaq word. Participants were instructed to type the full Iñupiaq word on each trial(even if all5letters of that word were pro-vided),or to type a question mark if they did not know the word.There was no time limit and no feedback was given.The three practice conditions are illustrated in Table1. For word pairs in the AC condition,thefirst practice trial showedfive underscores for the Iñupiaq word(e.g.,dust-_____),and each subsequent trial incrementally added one letter,until the sixth trialfinally showed all letters. The order in which letters were added was determined randomly,with each added letter persisting on subsequent trials.Letters were always shown in their correct position, and underscores were spaced so as to clearly show the number of missing letters.The DC condition was the re-verse of the AC condition:thefirst practice trial showed the entire Iñupiaq word,and each subsequent trial re-moved one letter.The study-only condition showed the entire Iñupiaq word on each trial,and instructed partici-pants to type that word.Practice trials were presented according to one of two fixed randomized orders(one of which was the reverse of the other).These orders were structured such that partici-pants completed all practice trials for half of the pairs(an equal number from each condition)before moving on to practice trials for the other half of the pairs.Within these halves of practice,each pair received itsfirst trial before any other pair received its second,and so on with later tri-als.The mean lag between successive practice trials for a given pair was5intervening trials(range:3–7).The prac-tice phase was followed by10min of the same distractor task described above.Final test phaseAll word pairs were tested using cued recall in an order that was randomized for each participant.Each test trial showed an entire English word along withfive underscores (e.g.,dust-_____)and participants were instructed to type the full Iñupiaq word,or to type a question mark if they did not know the word.There was no time limit and no feedback was given.J.R.Finley et al./Journal of Memory and Language64(2011)289–298291Results and discussionAn alpha level of.05was used for all tests of statistical significance.No corrections for multiple comparisons were made because comparisons were few and were pre-planned.Effect sizes for comparisons of means are re-ported as Cohen’s d calculated using pooled standard devi-ations(Olejnik&Algina,2000,Box1Option B).Effect sizes for ANOVAs are reported as^x2(for one-way)or^x2partial,cal-culated using the formulae provided by Maxwell and Del-aney(2004,pp.547,598).All within-subjects and mixed ANOVAs used uncorrected degrees of freedom,as Mau-chly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was met in all instances.Effectiveness of practice onfinal recall performance Final recall performance as a function of practice condi-tion is shown in Fig.1(left side),and in Table2along with practice performance.A one-way ANOVA revealed a reli-able effect of practice condition,F(2,158)=9.02,MS e= .057,p<.001,^x2¼:043.DC recall was reliably greater than study-only recall,t(79)=2.99,p=.004,d=.37.There was no reliable difference between AC recall and study-only recall,t(79)=1.28,p=.205,d=.17.Of key interest, DC recall was reliably greater than AC recall,t(79)=3.92, p=.001,d=.53.This result supports the hypothesis that,subject comparison of total number of successful practice retrievals for AC versus DC confirmed that successful prac-tice retrieval was indeed reliably less frequent in AC than in DC(M AC=5.8,SD AC=4.3,M DC=11.5,SD DC=6.0), t(79)=9.34,p<.001,d=1.09.Second,the consistently higher vertical positions of the gray bubbles(AC)over the white bubbles(DC)indicate that successful AC practice retrievals yielded greaterfinal test performance than suc-cessful DC practice retrievals.A comparison of the mean of participant means across number of successful practice retrievals(n=6,as in Fig.2)for AC versus DC showed that successful practice retrieval in AC was marginally more effective at enhancingfinal recall performance than was successful practice retrieval in DC(M AC=.45,SD AC=.29, M DC=.27,SD DC=.26),t(5)=2.20,p=.079,d=0.66.These results illustrate the delicate balance between in-creased difficulty and increased probability of retrieval success(cf.Pyc&Rawson,2009).The DC schedule provides a way of increasing the number of successful practice ret-rievals,but it also attenuates the benefits of these suc-cesses because earlier trials may be too easy.The AC schedule provides a way of maximizing the benefit of an initial successful practice retrieval because thefirst suc-cessful retrieval will necessarily be near the maximum le-vel of difficulty at which a participant is capable ofTable1Examples of practice trials for the three practice conditions.Practice trial English word displayed Iñupiaq word displayedAccumulating cues(AC)Diminishing cues(DC)Study-onlyFig.1.Meanfinal recall performance as a function of practice conditionand experiment.Error bars represent the standard error of the mean ofeach condition.3As shown in Table1,both AC and DC practice conditions include onetrial that amounts to a copy task.We exclude these trials from analysis. 292J.R.Finley et al./Journal of Memory and Language64(2011)289–298successfully retrieving that item.But this maximized ben-efit comes at the cost of diminishing benefits of further successes(because subsequent trials get easier)and at the cost of fewer overall successes than in the DC schedule.The results considered so far suggest that the advantage of DC is due exclusively to the greater number of successful practice retrievals it promotes.That is,the greater proba-bility of success under DC appears to outweigh the greater potency afforded by retrievals in AC.To evaluate this hypothesis more directly,we performed a mediation anal-ysis based on the three-variable model illustrated in Fig.3, with number of successful practice retrievals as a mediator between practice condition andfinal recall performance (cf.MacKinnon,Fairchild,&Fritz,2007;MacKinnon,Krull,practice condition(AC=0,DC=1,Study-only condition ex-cluded from analysis),Y isfinal test performance(0,1),and Z is the number of successful practice retrievals(0–5).Table3shows the estimated parameter ing the Sobel(1982)method of estimating the indirect effect, and the Aroian(1944)method of estimating the standard error for this effect,we found that the number of successful practice retrievals indeed reliably mediated the effect of practice condition onfinal test performance(indirect effec-t=a b)such that DC practice yielded superiorfinal test per-formance overall(total effect=s),but AC practice yielded superiorfinal test performance when the number of suc-cessful practice retrievals was accounted for(direct effect=s0).The opposite sign of the coefficients for the to-tal and direct effects indicates an inconsistent mediation (MacKinnon et al.,2000)and more specifically,that theTable2Means and standard deviations of performance across practice trials and onfinal test.Practice condition Practice trial Final test 123456 Experiment1Fig.2.Final recall performance(mean of participant means)as a functionof practice condition(AC versus DC)and number of successful practiceretrievals during practice for a given item(1–6).Bubble diameterrepresents mean number of items in each category,across participants(range:0.15–1.95;Experiment1).Fig.3.Three-variable mediation model.J.R.Finley et al./Journal of Memory and Language64(2011)289–298293number of successful retrievals is acting asiable that changes the direction ofother variables(MacKinnon,2008,p.7;p.102).These results suggest thatevals were more potent under ACditions,but thatfinal test performancebecause it permitted sufficiently moreattempts to offset their reduced potency.AC practice offers you more bang forbuck.Experiment2In Experiment1,recall in the ACvided an advantage relative to DC whenmance was conditionalized on thepractice retrievals.It is thereforenot yield an advantage over thetion.In Experiment2,we evaluated whether providingparticipants with correct-response feedback after each practice trial would decrease the costs of retrieval failure but maintain the benefits of retrieval success.If so,the AC condition should be superior to the study-only control, in which no opportunities for effortful retrieval were pro-vided(i.e.,participants merely copied the correct re-sponse).In addition,the advantage of DC over AC should be less than it was when no feedback was provided(as in Experiment1);feedback provides a failsafe,enabling par-ticipants to more quickly recover from early failed retrieval attempts(Kornell,Hays,&Bjork,2009)and thus capitalize on more of the potent early AC trials.MethodParticipants,materials,and designEighty undergraduates participated for course credit, and the materials and design were identical to those em-ployed in Experiment1.ProcedureThe procedure was identical to that used in Experiment 1,with the following addition:on each practice trial,after a participant’s response was made,the complete correct Iñu-piaq word appeared on the screen for4s.Such feedback was supplied in all three practice conditions(including study-only)and was not contingent on participants’responses.Results and discussionEffectiveness of practice onfinal recall performance Final recall performance as a function of practice condi-tion is shown in Fig.1(right side),and in Table2along with practice performance.A one-way ANOVA revealed a reliable effect of practice condition,F(2,158)=12.77, MS e=.049,p<.001,^x2¼:047.DC recall was again reliably greater than study-only recall,t(79)=4.90,p<.001,d=.56. As predicted—and unlike in Experiment1—AC recall was also reliably greater than study-only recall,t(79)=3.22, p=.002,d=.36.This effect was in contrast to the pattern in Experiment1,as confirmed by a two-way ANOVA (Experiment1versus2;AC versus.study-only)which re-vealed a reliable interaction,F(1,158)=9.88,MS e=.051, p=.002,^x2partial¼:016.This result supports our prediction about the effects of feedback in ameliorating some of the negative consequences of accumulating cues.In Experiment2,DC recall was only marginally greater than AC recall,t(79)=1.81,p=.075,d=.20.To assess whether the advantage of DC practice over AC practice is reduced with feedback,we conducted a two-way ANOVA (Experiment1versus2;AC versus DC),which revealed a marginally reliable interaction(F(1,158)=3.15, MS e=.056,p=.078,^x2partial¼:004),providing some sup-port for our prediction that feedback would increase the efficacy of the AC schedule relative to the DC schedule. Differential potency of successful retrievalFig.4illustrates the benefit tofinal recall performance yielded by different numbers of successful practice retri-evals for the AC and DC conditions in Experiment2.Suc-cessful practice retrieval was again reliably less frequent in AC than in DC(M AC=15.0,SD AC=4.3,M DC=16.2, SD DC=3.7),t(79)=3.14,p=.002,d=0.29,but this disparity was reliably smaller than it had been in Experiment1, t(158)=À6.36,p<.001,d=À1.01.As one would expect from the effects of feedback,and unlike the results in Experiment1,successful practice retrieval was not more potent in the AC than in the DC condition(M AC=.32, SD AC=.26,M DC=.39,SD DC=.23),t(5)=0.09,p=.94, d=.28.Thus,it appears that feedback,by making all prac-tice trials less difficult,indeed increased the number of successful AC retrievals,but also attenuated the relative potency of these retrievals.As with Experiment1,we next turn to a mediation anal-ysis in order to elucidate the relationship between practice condition,number of successful practice retrievals,andfi-nal recall performance(see Fig.3and Table3).We again found that the number of successful practice retrievals reli-ably mediated the effect of practice condition onfinal test performance(indirect effect=)such that DC practice yielded marginally superiorfinal test performance overall Fig.4.Final recall performance(mean of participant means)as a function of practice condition(AC versus DC)and number of successful practice retrievals during practice for a given item(1–6).Bubble diameter represents mean number of items in each category,across participants (range:0.00–2.15;Experiment2).294J.R.Finley(total effect=s),but the effect of practice condition was not reliable when the number of successful practice retri-evals was accounted for(direct effect=s0).Thus,although number of successful practice retrievals still mediated the effect of practice condition onfinal test performance, it did not reverse that effect as in Experiment1.This was likely due to the presence of feedback in Experiment2both diluting the potency and increasing the prevalence of suc-cessful AC practice retrievals.General discussionA major challenge in implementing desirable difficul-ties in learning is effectively calibrating that difficulty across trials.An optimal design strategy would account for individual variations in learners and in materials, such that each retrieval is neither so difficult that it fails nor so easy that it provides negligible benefit.Toward this end,we have demonstrated here a manipulation of difficulty that is a useful alternative to spacing:cue informativeness.A schedule of accumulating cues (increasing cue informativeness across practice trials) automatically locates the highest level of difficulty at which a certain learner canfirst retrieve a certain item. Furthermore,unlike difficulty schedules based on spacing (e.g.,expanding versus contracting retrieval practice), there are potential benefits to both accumulating and diminishing cues.Accumulating cues practice promotes effortful retrieval and its consequent mnemonic benefits, at the cost of likely success;diminishing cues practice promotes successful retrieval,at the cost of those benefits.An additional possible benefit afforded by AC practice is suggested by recent work by Kornell et al.(2009;see also Izawa,1970;Richland,Kornell,&Kao,2009).They found that a failed retrieval attempt can enhance the benefits of subsequent opportunities to study the item in question.Thus,presenting a learner with a trial that is too difficult(as may be the case for early AC trials) is not necessarily a waste of time and effort,as long as it is remedied by further information to ultimately en-sure a subsequent successful retrieval,either in the form of greater cue informativeness on later trials or in the form of feedback.Such an effect may have contributed to the AC potency advantage we have observed here, but confirming the presence of this effect requires fur-ther study.Further study should also investigate perfor-mance at longer retention intervals(e.g.,days rather than minutes),as any benefits of AC practice may be-come more apparent at a longer delay(cf.Karpicke& Roediger,2007).Finally,it is worth noting that the discrete nature of accumulating/diminishing individual letters offers a coar-ser adjustment of difficulty than would spacing,which can be varied on a muchfiner scale.However this does not eliminate the advantage that cue informativeness can better be used to identify appropriate levels of difficulty. Furthermore,higher-precision manipulations of cue infor-mativeness are possible,such as varying the focus or occlu-sion of picture stimuli for a recognition task.Individual differences in relative benefits of practice conditionsRiley and Heaton(2000)explored the benefits of a sim-ilar paradigm for patients with a history of head injuries and how those benefits varied with an individual’s current performance.They found that decreasing assistance(anal-ogous to diminishing cues)was more effective than increasing assistance(analogous to accumulating cues) for patients with poorer memory,but the opposite was true for those with better memory.In a similar vein, McDaniel,Hines,and Guynn(2002)found that studying text passages with some letters deleted improved recall of propositions for skilled readers,but impaired recall for unskilled readers(compared to a control condition with no deleted letters).We reasoned that the relative benefits of practice con-dition in our paradigm should similarly vary as a func-tion of individual differences in initial learning, considering that retrieval difficulties are beneficial only to the extent that they can be overcome.Participants who did not learn the material well by the end of the initial presentation phase likelyfloundered with AC prac-tice and benefited from the early assistance provided by DC.Conversely,participants who learned the material well enough to meet the early challenge of AC should have shown a lesser advantage of DC over AC.We inves-tigated this possibility by calculating correlations be-tween mean performance on thefirst practice trials of the AC condition(our best available indicator of initial learning)and the difference infinal test performance for DC versus AC.These correlations were reliably nega-tive for Experiment1,r=À.32,t(78)=À3.03,p=.003, and for Experiment2,r=À.24,t(78)=À2.11,p=.038. These results suggest that individual differences in initial learning moderated the extent to which participants were able to capitalize on the opportunity for potent ret-rievals provided by AC practice.Related prior work using cue informativenessAlthough learners may themselves employ some desirable difficulties during self-directed learning,the management and optimization of complex difficulty schedules(whether based on spacing,cue informative-ness or some other manipulation)are likely best imple-mented through well-designed learning environments, which can themselves serve to improve learners’meta-cognition as well as their learning(Finley,Tullis,&Ben-jamin,2010).A framework from educational research that encompasses this approach is that of scaffolding: shaping instruction to assist a learner to perform beyond the level s/he is currently independently capable,with the goal of ultimately removing this assistance(-joie,2005;Linn,1995;Pea,2004;Wood,Bruner,&Ross, 1976).The research we have described here can be con-sidered an instance of scaffolding,as can other studies that have used cue informativeness,which we will now review.A little-known set of efforts have been made to apply a strategy of progressive letter deletion(analogous to DC)toJ.R.Finley et al./Journal of Memory and Language64(2011)289–298295。

English Book6 课文翻译

Philosophers Among the Carrots几天前,当我在擦冰箱时,我深思熟虑地想着有关妇女解放运动,我问我自己,是否可能以家庭主妇为乐趣,同时又不是妇女解放运动事业的背叛者。

我的大学教育是否真正有用呢?大一A系的哲学导论对我来说有什么帮助呢?我想到Socrates的一句话,“那些混混噩噩的生活不值得过”,是该决定我生活的时候了。

当我站着吃苹果、桔子以及皮发褐色的香蕉,凝望着冰箱的深处的同时,脑中想到了大学教育的家庭主妇之间的关系,我看到了一个伟大、形而上学的真理的出现。

“就像能量一样,物质是按比例下降的——从烤到炖到烧汤再到成为猫食”。

当我停下吃东西,往猫碗里盛了点汤,我很博学的对猫咕哝了一句,“昨天的菜豆哪去了?”当然,今天已把它们做成菜汤了。

如果我没上过大学,我就不会看出这有意义的类推,当我做完色拉后,我自鸣得意地把一个桔子放在水槽中(也许我这是在中学学过的?)。

我沉思地打量着一碗烧好的胡萝卜,是把它做成胡萝卜蛋糕呢还是泡菜色拉?我知道如果选择做胡萝卜蛋糕的话就会得到我丈夫和三个儿子的支持。

我沿着我的思路,即我思想的火车轰隆隆地开进了阿基米德所领导的哲学领域,他曾说过“任何物体放入液体中,就会转移它的重量;一个被浸泡的物体就会转移它的体积”,这个原则指导我,我按食谱上的把块状的胡萝卜浸入牛奶中,发现这正好成为一杯。

重复爱默生的一句话“愚蠢的一致性是人类思想的妖怪”(即墨守成规的做法是愚蠢的)。

我加了几勺苹果酱使之更加好。

蛋糕在炉上烤着,我带着我新发现的关于家庭主妇与哲学之间关系的启迪(释加牟尼有他的菩提树,我有我的冰箱)走进了洗漱室,在这里,我面对着一条由脏的T-恤、汗淋淋的短袜、睡衣裤、和内衣组成的一条永无止境的河流,引用Heraclitus的一句话“你不能两次踏进同一条河流(世界是不断变化的,你再次踏进同一条河流,水已不是原来的水了)”,我自言自语着,我捡起一条牛仔裤,把其口袋中的泡泡糖纸、铅笔和硬币拿出来,我似乎看到了美术教授提到的变化中的统一和统一中的变化。

新视野大学英语读写教程第二版第一册课文中英对译

Unit1Learning a foreign language was one of the most difficult yet most rewarding experiences of my life.学习外语是我一生中最艰苦也是最有意义的经历之一。

Although at times learning a language was frustrating, it was well worth the effort.虽然时常遭遇挫折,但却非常有价值。

My experience with learning a foreign language began in <4>junior</4> middle school, when I took my first English class.我学外语的经历始于初中的第一堂英语课。

I had a kind and patient teacher who often praised all of the students.老师很慈祥耐心,时常表扬学生。

Because of this positive method, I eagerly answered all the questions I could, never worrying much about making mistakes.由于这种积极的教学方法,我踊跃回答各种问题,从不怕答错。

I was at the top of my class for two years.两年中,我的成绩一直名列前茅When I went to senior middle school, I was eager to continue studying English; however, my experience in senior middle school was very different from before.到了高中后,我渴望继续学习英语。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

CHAPTER 6 检测题听力原文及参考答案

听力原文:

第一题情景反应这一大题共有5个小题,每小题你将听到一组对话。

请你从每小题所给的A、B、C三幅图片中,选出与你所听到的信息相关联的一项。

每组对话读一遍。

1. W:Do you like science fiction films?

M:Yes, I do. They are exciting!

2. M:Let’s get some popcorn.

W:Sounds good. I’ll buy the popcorn. Wait for me here.

3. W:Jack,is the documentary about robots?

M:Yes,it is.

4. M:Jane will play the role of a clever doctor in the new movie.

W:How lucky she is! It must be an interesting movie.

5. M: Jane, do you go back to your hometown for the Spring Festival every year?

W: Yes. I usually go by train.

第二题对话理解这一大题共有5个小题,每小题你将听到一组对话和一个问题。

请你从每小题所给的A、B、C三个选项中,选出一个最佳选项。

每组对话读两遍。

6. M: Have you seen the film Avatar?

W: Yes, it’s wonderful.

Q: What does the woman think of the film?

7. M: Are you ready, Alice? Hurr y up, or we’ll be late.

W: Don’t worry. Now it’s half past six. The film will begin in thirty minutes.

Q: When will the film begin?

8. M: I usually go to the cinema twice a month. Do you often go to the cinema, Mary?

W: Oh, I seldom watch films at the cinema. Perhaps twice a year, I guess.

Q: How often does Mary go to the cinema?

9. W: I don’t think we should buy a new car.

M: But our car is too old to drive, and it only has three wheels. I can’t drive it to work.

Q: What does the man want to do?

10. M: Excuse me. Is there a cinema near here?

W: Yes. It’ s in front of the bookshop. If you walk through the market, it will be much nearer.

Q: What is the man looking for?

第三题语篇理解这一大题你将听到一篇短文。

请你根据短文内容,完成下面的表格,并将获取的信息填到相应的位置上。

短文读两遍。

Hospital rules

This hospital can hold 900 patients. There are eight beds in each room. You are allowed to visit patients twice a day. Only two people can see you at a time. We wake you up at 6:00 am. You are not allowed to smoke. If you need to smoke, two smoking rooms are provided (提供) for you.

参考答案:

1~5BCAAB 6~10 CBCAB 11. 900 12. twice 13. two 14. 6:00 am

15. smoking rooms

16. B “make+宾语+动词原形”意为“让……做……”。

17. A 句意为“我想知道我能帮母亲做点什么”。

宾语从句中要用陈述语序。

18. B 关系代词that 或which在定语从句中作动词的宾语时,that 或which可以省略。

19. A 先行词是物,选用which引导定语从句,which在定语从句中作主语,不能省略。

20. A because引导原因状语从句,句意为“他今天没在这儿,因为他生病了”。

21. B exactly作副词,意为“恰恰,正是”。

22. D on/at weekends在周末;be strict with sb.对某人要求严格。

23. A stay up熬夜。

24. B need to do sth.需要做某事。

25. C 本题考查含有情态动词的被动语态。

26.C 借书应该是到图书馆(library)的。

27.B with和……一起。

28.D 本句为否定句,故用any。

29.C one of the+可数名词复数。

30.D 由转折词but可知,这个机器人不工作。

31.B What’s wrong with…?……出了什么毛病?

32.A want后接动词不定式作宾语。

33.B 情态动词must后跟动词原形。

34.A 祈使句以动词原形开头,故用give。

35.C so表示结果,意为“因此,所以”。

36. D 由第一段中的More than fifty years ago…He called his mouse Mickey Mouse.可确定D

项为正确选项。

37. D 由第二段第一句“年轻人和老人都喜欢米老鼠”可知。

38. C 由第一段中的An American man called Walt Disney…可知。

39. A 由第二段中的People were very angry…want Mickey to do silly things.可知。

40. B 由第二段最后两句话可知。

41. A

42. D 由第二段的第二句话可知。

43. D 由第二段的第三句话可知。

44. A 由第二段的最后一句话可知。

45. C

46.A 由第一条建议中“You should not walk alone outside.”可知。

47.C 由第二条建议中“Y our bag should be carried towards the front of your body…”可知。

48.D 由第三条建议中“If you are followed by someone you don’t know, cross the street and

go to the other way…”可知。

49.A 由最后一条建议中“Sit behind the driver or with other people. Don’t sleep.”可知。

50.B 通读全文可知,本文主要讲述“如何在你的日常生活中保持安全”。

51~55 CABED

56. helpful 57. from 58. wasting 59. earlier 60. if

61. received 62. my 63. but 64. years 65. third

One possible version:

Dear Jane,

Thank you for telling me so much about cartoon characters from America. Some of the characters you told me are also familiar to Chinese kids. For example, Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, Tom and Jerry are well known to almost every child in China.

China has also produced many cartoon TV plays or movies. Among all the Chinese cartoon characters, I like Monkey King and Nezha best because they are brave and clever. They can beat all their enemies, no matter how ferocious they are. I believe you will fall in love with them if you see them one day.

Yours,

Lingling。