Phase Diagram of the Two Dimensional Lattice Coulomb Gas

std22安休茨22型电罗经说明书

std22安休茨22型电罗经说明书RaytheonAnschützGmbHPostfach1166D--24100KielGermanyTel+49--431--3019--0Fax+49--431--3019--501EmailService@www.raytheon--anschuetz.deSTD22CompactGYROCOMPASSandSTD22GYROCOMPASSType110--233InstallationandServicemanual3646/110--233.DOC010302Edition:Revision:Revision:Revision:Revision:May20,2005Oct.12,2006Feb.05,2007March27,2007Oct.05,2007 WeitergabeMitteilungzugestanden.ihressowieZuwiderhandlungenInhaltesVervielf?ltigungnichtgestattet,dieserverpflichtensoweitUnterlage,zunichtVerwertungundSchadenersatz.ausdrücklichToutecommunicationoureproductiondecedocument,touteexploitationou communicationdesoncontenusontinterdites,saufautorisationexpresse.To utmanquementàcetterègleestilliciteetexposesonauteurauversementded ommagesetintérêts.Copyingofthisdocument,andgivingittoothersandtheu seorcommunicationofthecontentsthereof,areforbiddenwithoutexpressau thority.Offendersareliabletothepaymentofdamages.Sinnuestraexpresaau torización,quedaterminantementeprohibidalareproduccióntotaloparciald eestedocumento,asícomosuusoindebidoy/osuexhibiciónocomunicacióna terceros.Delosinfractoresseexigiráelcorrespondienteresarcimientodeda? osyperjuicios.InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCompassSTD22MaintenanceplanDeclarationofConformitySafetynotes..............................................11.122.12.22.32.3.12.3.1.12.42.4.12.4.1.12.4.1.22.4.1.32.4.1.42.52.5.12.5.1.12.5.1.22.5.1.32.5.1.42.5.1.52.62.6.12.6.22.6.32.6.3.12.6.42.6.4.12.6.4.22.6.4.32.6.4.42.6.4.52.6.4.62.6.4.7Generalinformation......................................CANbus(CAN=ControllerArea Network)...................PreparingtoinstalltheSTD22CompactGyroCompass... .STD22CompactCompass–ScopeofSupply................Generalinformationco ncerninginstallationoftheSTD22CompactCompass...........................Creatingcableconnections. ................................Generalinformationconcerningon-boardwiring........... ....Generalinformationaboutcreatinganearthconnection........Installingthe compassandputtingitintooperation.............Removethetransportationsup portwithoutersphere,supportingliquidanddistilledwater...........................Assemblingthecompas senclosure..........................Installationofthegyrosphere............................. ...Fillingwithdistilledwaterandsupportingliquid................Insertingtheoute rsphereinthecompassenclosure...........Creatingcableconnectionsandplugc onnections..............OverviewofplugconnectionsandfusesonPCB‘s............. ConnectingthecoursereceiverintheSTD22CompactGyroCompass.......................ConnectingstatusandcontrolsignaloutputsintheSTD22CompactGyroCompass.......................Connectingsignalinputsf orQSandSECintheSTD22CompactGyrocompass.......................Connectingthepowersup plycable..........................Connectingthecompasstoearth............................ Installationandcommissioningofoptionalfeatures............Installationandco mmissioningoftheAdditionalOutputBox143--103..........................Installationandcommis sioningoftheAC/DCConverter121--062InstallationandcommissioningoftheOperatorUnitQuickSettling(QS)130--606..............InstallingtheOpera torUnitQuickSettling....................Switchingon,settlingandadjustment....... .................Switchingonthecompass..................................Checksonthecom pass....................................SettingtheSTD22CompactCompassintooperati on..........Settingthecompasszero(referencecourse).................Readingthea lignmenterror................................SettingChannel1andChannel2............... .............SettingtheinformationsourceforSpeedErrorCorrection.......I1313151516171720212122252729313133353739404141434647494949 5153565760Edition:Oct.05,20073646/110--233.DOC010302InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact2.6.4.82.6.4.933.13.1.13.23.2.13.2.1.13.33.3.13.3.1.13.3.1.23.3.1.33.3.1.43.43.4.13.4.23.4.2.13.4.2.23.4.2.33.4.2.43.4.2.53.4.33.4.3.13.4.3.23.4.3.33.4.3.43.4.3.53.4.3.63.4.3.7455.15.1.15.1.25.1.35.1.45.1.566.16.1.16.1.1.16.2Adjustmentofessentialoperatingmodes.....................F unctioncheckonexternallyconnectedcoursereceivers.......Preparingtoinsta lltheSTD22GyroCompass.............STD22Compass–ScopeofSupply............... ..........GeneralinformationconcerninginstallationoftheSTD22Compass....... .............................Creatingcableconnections.................................Generalinformationconcerningon-boardwiring...............Generalinformationabout creatinganearthconnection........Installingthecompassandputtingitintoop eration.............Removethetransportationsupportwithoutersphere,suppo rtingliquidanddistilledwater..........................Assemblingthecompassenclo sure..........................Installationofthegyrosphere................................Fillin gwithdistilledwaterandsupportingliquid................Insertingtheouterspher einthecompassenclosure...........Creatingcableconnectionsandplugconnec tions..............OverviewofplugconnectionsandfusesonPCB‘s.............CreatingacableconnectionfromSTD22Compass→DistributionUnit........................Connectingtothepowersupply(Distributio nUnit).............ConnectingtheCANbusplug...............................Settingtheju mpersfortheCANbus.........................Switchingtheterminationresistorsfort heCANbus(E10only)..Connectingthecompasstoearth............................Swi tchingon,settlingandadjustment........................Checksonthecompass....... .............................Switchingonthecompass..................................Settingth ecompasszero(referencecourse)..................Readingthealignmenterror...... ..........................SettingtheCANbusaddress...............................Adjustment sofessentialoperatingmodes....................Functioncheckonexternallyconn ectedcoursereceivers,FunctioncheckofRoT.....................................Fuses,ju mper,LED‘s,buttonsandplugs...................DIPSWITCHsettings...................... ...............OverviewoffunctionsofallDIPswitchsettings................Adjustmen tsofparameters(inascendingorderoffunction).....Adjustmentsofparameters(inascendingorderoftheirappearance)......................7segmentdisplaysan dtheirmeaning........................FunctionaldescriptionofDIPswitchsettings(f orgeneraluse)...FunctionaldescriptionofDIPswitchsettings(SEC)............Tas kstobeperformedregularly...........................Changingthesupportingliquida nddistilledwater..............Removingtheouterspherefromthecompassenclo sure.......Drainingout/fillinginthesupportingliquidanddistilledwater....Clea ningofthegyrosphereandtheoutersphere.. (6771737374757578797)9808385878989919293949596979799101103105106113115117118122 1241261271641841841841861893646/110--233.DOC010302IIEdition:Fe b.05,2007InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCo mpassSTD2277.17.27.2.17.2.27.2.37.2.47.2.58Errormessagesandwarnings.............................Errormessages.................. .........................Warnings.................................................Warning1“Fanfail ure”.....................................Warning2“Heaterfailure”.................................. Warning3“Supportingliquid>60°C”.........................Warning4“Supporti ngliquidleveltoolow”....................Warning5“Voltagecut-off”....................... ...........NMEA--Formats..........................................ET--Catalogue(Pages1to4)Annex1--8(PCBwithcomponentviewanddesignations)1921921941951961 96197197198Drawings:GyroCompassDimensionalDrawing110D233HP005GyroCompassCablean dConnectionDiagram110--233HP009Sheets1to3GyroCompassCableandConnectionDiagram(E10)110--233.HP029Sheets1to3GyroCompassCableandConnectionDiagram110--233HP010AdditionalOutputBoxDimensionalDrawing146--103.HP005AdditionalOutputBoxWiringDiagram146--103.HP007AC/DCConverterDimensionalDrawing121--062.HP005OperatorUnitQuickSettlingDimensionalDrawing130E606HP005GyroCompassSTD22,WiringDiagram110--233.HP008Sheets1+2TerminalStripPCB,CircuitDiagram110--233.HP016Edition:Feb.05,2007III3646/110--233.DOC010302InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compactintentionallyleftblank3646/110--233.DOC010302IVEdition:May20,2005InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCo mpassSTD22Edition:Oct.05,2007V3646/110--233.DOC010302InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compactintentionallyleftblank3646/110--233.DOC010302VIEdition:May20,2005InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCo mpassSTD22Edition:March27,2007VII3646/110--233.DOC010302InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact3646/110--233.DOC010302VIIIEdition:March27,2007InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCo mpassSTD22Edition:March27,2007IX3646/110--233.DOC010302InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactIntentionallyleftblank3646/110--233.DOC010302XEdition:May20,2005InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCo mpassSTD22Edition:March27,2007XI3646/110--233.DOC010302InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact3646/110--233.DOC010302XIIEdition:March27,2007InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCo mpassSTD22Edition:March27,2007XIII3646/110--233.DOC010302InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact3646/110--233.DOC010302XIVEdition:March27,2007InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCo mpassSTD22SafetynotesCaution:--Maintenanceandrepairworkshouldbecarriedoutonlybytrainedandqualifiedstaffwhoarewellversedinnationalsafetyregulations.--Afterthegyrocompasshasbeenswitchedoffitisnecessarytowaitatleast15minutesbeforeaccessingtheinteriorofthegyrocompass.Otherwisethespherecouldbedamaged!--Neverswitchoffthecompassatsea,thespherecouldbedamaged.------Itisadvisabletoleavethegyrocompassswitchedonwhenlyinginportforperi odsofuptooneweek.Ifwarningsoccur,theoperationofthegyroequipmentisn otrestricted.Ifthecauseoftheproblemisrectifiedquickly,itispossibletopreve nttheequipmentfrombreakingdown.Pleaseinformtheauthorisedservicest aff(viathehotline).Refertotheservicemanualasappropriate.Whenerrormes sagesappear,theheadingisnolongerdisplayedonthecompass;theheadingisnotfolloweduponaconnectedcoursereceiver.Thecompassmustberepairedbywelltrainedstaff.Pleaseno tethatallship‘sof500grosstonnageandupwardsaccor-dingtoSOLA Sregulationsmustbeequippedwithagyrocompass.Thegyrocompassmustbe operational.Forthisreasonitisnotallo-wedtohaveaswitched--offgyroduring voyages.Aswitched--offgyrocompassduringvoyagescouldcausedamagetothegyros phere.Edition:May20,200513646/110--233.DOC010302InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCausedbytechnicalprogressthePC--BoardsoftheGyroCompassarechanged.Du etothatsomepicturesand/orprocedureshavebeenchanged.Respectivecha ngesaremarkedwith“E10”.TheACsupplyvoltage(shipsmains)maydropout.Thisleadstoarestartofthegy rocompassandanewsettlingstage.Theheadinginformationduringthissettlin gstagehasareducedaccuracy.Thereforeacontinouslysupplywith24VDCsho uldbeguar-anteed.Itisrecommendedtoactivatespeederrorcorrectioninordertoobtainaccurat eheadinginformation.ThisappliesalsoiftheheadinginformationisusedbyDP systems.PleasepayattentiontotherequirementsoftheDPsystem manufacturer.Supportingliquidshouldbestoredinacold,dryanddarkplace.Pleasepourawa yliquidleftovers.Donotmixsupportingliquids.Thereisareducedaccuracyofthecompassduringthesettlingstage.Thecompa ssshowsrequiredaccuracyafterendingofthesettlingstage(appr.4hoursafter switchingON).3646/110--233.DOC0103022Edition:Sept.12,2006InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22CompactCo mpassSTD221GeneralinformationTheSTD22CompactCompassandtheSTD22Compassareidenticalgyrocomp asses.ThedifferencebetweenthetwogyrocompassesisthattheSTD22GyroCompa sscanbeoperatedviaaCANbussystemwithanOperatorUnitandaDistribution Unit.InthecaseoftheSTD22CompactGyroCompass,theCANbusisnotenable d.Thefollowingdiagramsprovideanoverviewofthepossibleapplicationsofth eSTD22CompactandSTD22GyroCompasses.Edition:May20,200533646/110--233.DOC0103023646/110--233.DOC010302s--NMEASpeed--NMEAPosition--PulseLog--PulseLogDirection--StatusQuickSettlingOperatorUnit(Option)STD22CompactCompassNG001--2xHeading RMGcoursebusorNMEA--1xstatussignal--1xRMGCoursebusforOutputbox Outputbox--1xNMEA0183superfast50Hz--1xstep(6steps/degree) InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact4Edition:Feb.17,2006STD22CompactGyroCompassEdition:Feb.17,2006InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact5ebusDistributionUnitcompactxoutputs,separateadjustable:therCoursebus,NMEA1orNMEA2atussignals :ystemfailureompassfailureompassavaailable--1xROTorheadinganalogue--1xCourseprinter--3xStepSTD22Compass3646/110--233.DOC0103023646/110--233.DOC010302MEASpeed--NMEAPosition--PulseLog--PulseLogDirectionDistributionUnit:--8xHeadingRMGcoursebusorNMEA--3xStep(6steps/deg ree),24/35VDC,max.10W--1xRS232serialinterfaceforprinter--1xrateofturn +/--10Vfor30/100/300degrees/min--12xStatus(potentialfree) .:3647manualno.:3648InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact622GMGyroCompassSystem*=Gyro/Magnet)Edition:Feb.17,20061xRS232forprinterAC/DCconvertersdependsontheneces-sarymax.powero fallsupplieddevices*ThenumberofnecessaryEdition:May20,2005--NMEASpeed--NMEAPosition--PulseLog--PulseLogDirectionDistributionUnit:--8xHeadingRMGcoursebusorNMEA--3xStep(6steps/deg ree),24/35VDC,max.10W--1xRS232serialinterfaceforprinter--1xrateofturn +/--10Vfor30/100/300degrees/min--12xStatus(potentialfree) MaInstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact715forprinterGGMGyroCompassSystem*Gyro/Gyro/Magnet)AC/DCconvertersdependsontheneces-sarymax.powerofallsupplieddevice s*ThenumberofnecessarySTD22Compass3646/110--233.DOC0103023646/110--233.DOC010302eedsitionDirection2CompactCompassNG001adingRMGcoursebusorNME AtussignalUnitadingRMGcoursebusorNMEAp(6steps/degree),24/35VDC, max.10W232serialinterfaceforprintereofturn+/--10Vfor30/100/300degrees/mintatus(potentialfree)anualno.:3648InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact8Edition:Feb.17,2006AC/DCconvertersdependsontheneces-sarymax.powerofallsupplieddevice sThenumberofnecessaryompassSystem*agnet)Edition:Feb.17,2006ing(12x)busorNMEA3xStepofturnxRS232forprinterebusorNMEAe),24/35VDC,max.10Wceforprinterfor30/100/300degrees/ minee)InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact9puts(Deviation)hastobetributionUnits3646/110--233.DOC010302STD22CompassbusorNMEA,24/35VDC,max.10Wforprinterr30/100/300degrees/min) 3646/110--233.DOC010302manualno.:3648InstallationandServicemanualCompassSTD22CompassSTD22Compact101xRS232forprinterEdition:Feb.17,2006AC/DCconvertersdependsontheneces-sarymax.powerofallsupplieddevice syroCompassSystem*lite/Magnet)Edition。

crystal_melt_phase_diagrams晶体-熔体相图

• Learning Objectives: – How are crystal-melt equilibria displayed graphically as phase diagrams? – What are the different types of phase relations commonly observed in igneous systems? – How can we use phase diagrams to learn about crystallization and melting? – How do intensive variables affect rock-forming mineral stabilities?

Enstatite melting yields liquid richer in silica.

Equilibrium vs. Fractional Crystallization

Equilibrium Crystallization: crystals continuously react and re-equilibrate with the melt at P-T-X conditions change. Melt-xtal reactions are reversible Fractional Crystallization: Crystals are immediately isolated, removed, or fractionated from the residual melt so that no further reactions can occur. Melt-xtal reactions are irreversible.

材料科学基础名词解释中英

《材料科学基础》名词解释AOrowan mechanism (奥罗万机制)位错绕过第二相粒子,形成包围第二相粒子的位错环的机制。

Austenite(奥氏体)碳在γ-Fe中形成的间隙固溶体称为奥氏体。

B布拉菲点阵除考虑晶胞外形外,还考虑阵点位置所构成的点阵。

Half-coherent interface(半共格相界)两相邻晶体在相界面处的晶面间距相差较大,则在相界面上不可能做到完全一一对应,于是在界面上将产生一些位错,以降低界面弹性应变能。

这时两相原子部分保持匹配,这样的界面称为半共格界面。

Sheet texture(板织构)轧板时形成的组织的择优取向。

Peritectic reaction(包晶反应)固相和液相生成另一成分的固溶体的反应Peritectic segregation(包晶偏析)新生成的固相的芯部保留残余的原有固相,新相本身成分也不均匀。

Peritectic phase diagram(包晶相图)具有包晶反应的相图Peritectoid reaction(包析反应)由两个固相反应得到一个固相的过程为包析反应。

Cellular structure(胞状结构)成分过冷区很小时,固相突出部分局限在很小区域内,不生成侧向枝晶。

Intrinstic diffusion coefficient(本征扩散系数)依赖热缺陷进行的扩散的扩散系数。

Transformed ledeburite(变态莱氏体)渗碳体和奥氏体组成的莱氏体冷却至727℃时奥氏体发生共析反应转变为珠光体,此时称变态莱氏体。

Deformation twins(变形孪晶)晶体通过孪生方式发生塑性变形时产生的孪晶(BCC,HCP)Chill zone(表层细晶区)和低温铸模模壁接触,强烈过冷形成的细小的方向杂乱的等轴晶粒细晶区。

Burger’s vector(柏氏矢量)表征位错引起的晶格点阵畸变大小和方向的物理量。

Asymmetric tilt boundary(不对称倾斜晶界)晶界两侧晶粒不对称的小角度晶界,界面含两套垂直的刃型位错。

锂离子电池基础科学问题(Ⅷ)——负极材料

万方数据万方数据万方数据万方数据万方数据万方数据万方数据万方数据锂离子电池基础科学问题(Ⅷ)——负极材料作者:罗飞, 褚赓, 黄杰, 孙洋, 李泓, LUO Fei, CHU Geng, HUANG Jie, SUN Yang, LI Hong作者单位:中国科学院物理研究所,北京,100190刊名:储能科学与技术英文刊名:Energy Storage Science and Technology年,卷(期):2014,3(2)1.Armand M;Murphy D;Broadhead J Materials for Advanced Batteries 19802.Garreau M;Thevenin J;Fekir M On the processes responsible for the degradation of the aluminum lithium electrode used as anode material in lithium aprotic electrolyte batteries 1983(3-4)3.Yazami R;Touzain P A reversible graphite-lithium negative electrode for electrochemical generators 1983(3)4.Tarascon J MorSe6:A new solid-state electrode for secondary lithium batteries 1985(9)5.Scrosati B Non aqueous lithium cells 1981(11)6.Abraham K Ambient temperature secondary lithium batteries using LiA1 lithium insertion anodes 19877.Hrold A Recherches sur les composes d'insertion du graphite 1955(7-8)8.Dey A;Sullivan B The electrochemical decomposition of propylene carbonate on graphite 1970(2)9.SONY Non-aqueous electrolyte secondary cell 198910.Nagaura T;Tozawa K Lithium ion rechargeable battery 199011.Endo M;Kim C;Nishimura K Recent development of carbon materials for Li ion batteries 2000(2)12.Mabuchi A A survey on the carbon anode materials for rechargeable lithiumbatteries 199413.Yamaura J;Ozaki Y;Morita A High voltage,rechargeable lithium batteries using newly-developed carbon for negative electrode material 1993(1)14.Tarascon J M;Armand M Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium battefies 2001(6861)15.Van S W;gcrosati B Advances in Lithium-Ion Batteries 200216.Kang B;Ceder G Battery materials for ultrafast charging and diseharging 2009(7235)17.Armand M;Tarascon J M Building better batteries 2008(7179)18.Jansen A;Kahaian A;Kepler K Development of a high-power lithium-ion battery 199919.Smith K;Wang C Y Power and thermal characterization of a lithium-ion battery pack for hybrid-electric vehicles 2006(1)20.Zhang X;Ross P;Kostecki R Diagnostic characterization of high power lithium-ion batteries for use in hybrid electric vehicles 2001(5)21.Zhou H H;Ci L C;Liu C Y Progress in studies of the electrode materials for Li ion batteries 1998(1)22.Hao R R;Fang X Y;Niu S C Chemistry of the Elements (Ⅲ) 199823.Ohzuku T;Ueda A;Yamamoto N Zero-strain insertion material of Li(Li1/3Ti5/3)O4 for rechargeable lithium cells 1995(5)24.Woo K C;Mertwoy H;Fischer J Experimental phase diagram of lithium-intercalated graphite 1983(12)25.Dahn J Phase diagram of LixC6 1991(17)26.Nalamova V;Guerard D;Lelaurain M X-ray investigation of highly saturated Li-graphite intercalation compound 1995(2)27.Feng Z Z;Song S Q Preparation and application of mesophase pitch 201328.Honda H;Yamada Y Meso-carbon microbeads 197329.Xu B;Chen E Intermediate development phase carbon microbeads (MCMB),properties and applications 1996(3)30.Niu Y J;Zhang H G;ZhouA M Non-Ferrous Progress:1996-2005 200731.Choi W C;Byun D;Lee J K Electrochemical characteristics of silver-and nickel-coated synthetic graphite preparedby a gas suspension spray coating method for the anode of lithium secondary batteries 2004(2)32.Lee H Y;Baek J K;Lee S M Effect of earbon coating on elevated temperature performance of graphite as lithium-ion battery anode material 2004(1)33.Tanaka H;Osawa T;Moriyoshi Y Improvement of the anode performance of graphite particles through surface modification in RF thermal plasma 2004(1)34.Guoping W;Bolan Z;Min Y A modified graphite anode with high initial efficiency and excellent cycle life expectation 2005(9)35.Lee J H;Lee S;Paik U Aqueous processing of natural graphite particulates for lithium-ion battery anodes andtheir electrochemical performance 2005(1)36.Yamauchi Y;Hino T;Ohzeki K Gas desorption behavior of graphite anodes used for lithium ion secondary batteries 2005(6)37.Zhao X;Hayner C M;Kung M C In-plane vacancy-enabled high-power Si-graphene composite electrode for lithium-ion batteries 2011(6)38.王广驹世界石墨生产,消费及国际贸易 2006(1)39.Jonker G H Magnetic compounds with perovskite structure Ⅳ conducting and non-conducting compounds 195640.Murphy D;Cava R;Zahurak S Ternary LixTiO2 phases from insertion reactions 198341.Ferg E;Gummow R;De K A Spinel anodes for lithium-ion batteries 1994(11)42.Robertson A;Trevino L;Tukamoto H New inorganic spinel oxides for use as negative electrode materials in future lithium-ion batteries 199943.Peramunage D;Abraham K Preparation of micron-sized Li4Ti5O12 and its electrochemistry in polyacrylonitrile electrolyte-based lithium cells 1998(8)44.Julien C;Massot M;Zaghib K Structural studies of Li4/3Me5/3O4 (Me=Ti,Mn) electrode materials:Local structure and electrochemical aspects 2004(1)45.Scharner S;Weppner W;Schmid B E Evidence of two-phase formation upon lithium insertion into the Li1.33Ti1.67O4 spinel 1999(3)46.Zaghib K;Simoneau M;Armand M Electrochemical study of Li4Ti5O12 as negative electrode for Li-ion polymer rechargeable batteries 199947.Pecharroman C;Amarilla J Thermal evolution of infrared vibrational properties of Li4/3Ti5/3O4 measured by specular reflectance 2000(18)48.Guerfi A;Charest P;Kinoshita K Nano electronically conductive titanium-spinel as lithium ion storage negative electrode 2004(1)49.Gao L;Qiu W;Zhao H L Lithiated titanium complex oxide as negative electrode 2005(1)50.Bach S;Pereira R J;Baffier N Electrochemical properties of sol-gel Li4/3Ti5/3O4 199951.Kavan L;Grtzel M Facile synthesis of nanocrystalline Li4Ti5O12 (spinel) exhibiting fast Li insertion 2002(2)52.Hao Y;Lai Q Y;Liu D Synthesis by citric acid sol-gel method and electrochemical properties of Li4Ti5O12 anode material for lithium-ion battery 2005(2-3)53.王虹微波法制备钛酸锂的方法 200854.白莹一种用于锂二次电池负极材料尖晶石钛酸锂的制各方法 200655.Li J;Tang Z;Zhang Z Controllable formation and electrochemical properties of one-dimensional nanostructured spinel Li4Ti5O12 2005(9)56.杨立一种应用于锂离子电池的钛酸锂负极材料的制备方法中国 200857.Huang S;Wen Z;Zhu X Effects of dopant on the electrochemical performance of Li4Ti5O12 as electrode material for lithium ion batteries 2007(1)58.Tian B;Xiang H;Zhang L Niobium doped lithium titanate as a high rate anode material for Li-ion batteries2010(19)59.Huang Y;Qi Y;Jia D Synthesis and electrochemical properties of spinel Li4Ti5Ol2-xClx anode materials forlithium-ion batteries 2012(5)60.Venkateswarlu M;Chen C;Do J Electrochemical properties of nano-sized Li4Ti5O12 powders synthesized by a sol-gel process and characterized by X-ray absorption spectroscopy 2005(1)61.Cai R;Yu X;Liu X Li4Ti5O12/Sn composite anodes for lithium-ion batteries:Synthesis and electrochemical performance 2010(24)62.Yuan T;Yu X;Cai R Synthesis of pristine and carbon-coated Li4Ti5O12 and their low-temperature electrochemical performance 2010(15)63.Hu X;Lin Z;Yang K Effects of carbon source and carbon content on electrochemical performances of Li4Ti5O12/C prepared by one-step solid-state reaction 2011(14)64.Martha S K;Haik O;Borgel V Li4Ti5O12/LiMnPO4 lithium-ion battery systems for load leveling application 2011(7)65.Huang K L;Wang Z X;Liu S Q Lithium-Ion Battery Technology and Key Principles 200866.Xu K;Wang X Y;Xiao L X Lithium Ion Battery 200267.Wang Q;Li H;Chen L Novel spherical microporous carbon as anode material for Li-ion batteries 200268.Li H;Wang Q;Shi L Nanosized SnSb alloy pinning on hard non-graphitic carbon spherules as anode materials for aLi ion battery 2002(1)69.Hu J;Li H;Huang X Influence of micropore structure on Li-storage capacity in hard carbon spherules 2005(11)70.Fey G T K;Chen C L High-capacity carbons for lithium-ion batteries prepared from rice husk 200171.Yin G P;Zhou D R;Xia B J Preparation of phosphorus-doped carbon and its performance Lithium intercalation2000(4)72.Schnfelder H H;Kitoh K;Nemoto H Nanostructure criteria for lithium intercalation in non-doped and phosphorus-doped hard carbons 1997(2)73.Buiel E;Dahn J Li-insertion in hard carbon anode materials for Li-ionbatteries 1999(1)74.Rosamaria F;Ulrich V S;Dahn J R Studies of lithium intercalation into carbons using nonaqueous electrochemical-cells 1990(7)75.Stevens D;Dahn J The mechanisms of lithium and sodium insertion in carbon materials 2001(8)76.Bonino F;Brutti S;Piana M Structural and electrochemical studies of a hexaphenylbenzene pyrolysed soft carbon as anode material in lithium batteries 2006(17)77.Guo M;Wang J C;Wu L B Study of carbon nanofibers as negative materials for Li-ion batteries 2004(5)78.Sato Y;Kikuchi Y;Kawai T Characteristics of coke carbon modified with mesophase-pitch as a negative electrodefor lithium ion batteries 199979.Yoshio M;Tsumura T;Dimov N Electrochemical behaviors of silicon based anode material 2005(1)i S C Solid lithium-silicon electrode 197681.Sharma R A;Seefurth R N Thermodynamic properties of the lithium-silicon system 1976(12)82.Seefurth R N;Sharma R A Investigation of lithium utilization from a lithium-silicon electrode 1977(8)83.Seefurth R N;Sharma R A Dependence of lithium-silicon electrode potential and lithium utilization on reference electrode location 1980(5)84.Wen C J;Huggins R A Chemical diffusion in intermediate phases in the lithium-silicon system 1981(3)85.Boukamp B A;Lesh G C;Huggins R A All-solid lithium electrodes with mixed-conductor matrix 1981(4)86.Weydanz W J;Wohlfahrt M M;Huggins R A A room temperature study of the binary lithium-silicon and the ternary lithium-chromium-silicon system for use in rechargeable lithium batteries 199987.Gao B;Sinha S;Fleming L Alloy formation in nanostructured silicon 2001(11)88.Li H;Huang X J;Chen L Q A high capacity nano-Si composite anode material for lithium rechargeable batteries 1999(11)89.Li H;Huang X J;Chen L Q The crystal structural evolution of nano-Si anode caused by lithium insertion and extraction at room temperature 2000(1-4)90.Limthongkul P;Jang Y I;Dudney N J Electrochemically-driven solid-state amorphization in lithium-silicon alloys and implications for lithium storage 2003(4)91.Hatchard T D;Dahn J R In situ XRD and electrochemical study of the reaction of lithium with amorphous silicon 2004(6)92.Key B;Bhattacharyya R;Grey C P Real-time NMR investigations of structural changes in silicon electrodes for lithium-ion batteries 2009(26)93.Key B;Morcrette M;Grey C P Pair distribution function analysis and solid State NMR studies of silicon electrodes for lithium ion batteries:Understanding the (De) lithiation mechanisms 2011(3)94.Beaulieu L Y;Hatchard T D;Bonakdarpour A Reaction of Li with alloy thin films studied by in situ AFM 2003(11)95.Baggetto L;Danilov D;Notten P H L Honeycomb-structured silicon:Remarkable morphological changes induced by electrochemical (De)lithiation 2011(13)96.Lee S W;Mcdowell M T;Choi J W Anomalous shape changes of silicon nanopillars by electrochemical lithiation2011(7)97.Lee S W;Mcdowell M T;Berla L A Fracture of crystalline silicon nanopillars during electrochemical lithium insertion 2012(11)98.He Y;Yu X Q;Wang Y H Alumina-coated patterned amorphous silicon as the anode for a lithium-ion battery with high coulombic effficiency 2011(42)99.He Y;Wang Y H;Yu X Q Si-Cu thin film electrode with kirkendall voids structure for lithium-ion batteries2012(12)100.He Y;Yu X Q;Li G Shape evolution of patterned amorphous and polycrystalline silicon microarray thin film electrodes caused by lithium insertion and extraction 2012101.Wang Y;He Y;Xiao R Investigation of crack patterns and cyclic performance of Ti-Si nanocomposite thin film anodes for lithium ion batteries 2012102.Notten P H L;Roozeboom F;Niessen R A H3-D integrated all-solid-state rechargeable batteries 2007(24)103.Baggetto L;Oudenhoven J F M;Van D T On the electrochemistry of an anode stack for all-solid-state 3D-integrated batteries 2009(1)104.Chan C K;Ruffo R;Hong S S Surface chemistry and morphology of the solid electrolyte interphase on silicon nanowire lithium-ion battery anodes 2009(2)105.Zheng J Y;Zheng H;Wang R An investigation on the sold electrolyte interphase of silicon anode for Li-ion batteries through force curve method 2013(6)106.Zhang X W;Patil P K;Wang C S Electrochemical performance of lithium ion battery,nano-silicon-based,disordered carbon composite anodes with different microstructures 2004(2)107.Chan C K;Ruffo R;Hong S S Structural and electrochemical study of the reaction of lithium with silicon nanowires 2009(1)108.Cui L F;Ruffo R;Chan C K Crystalline-amorphous core-shell silicon nanowires for high capacity and high current battery electrodes 2009(1)109.Mcdowell M T;Lee S W;Ryu I Novel size and surface oxide effects in silicon nanowires as lithium battery anodes 2011(9)110.Ryu I;Choi J W;Cui Y Size-dependent fracture of Si nanowire battery anodes 2011(9)111.Xu W L;Vegunta S S S;Flake J C Surface-modified silicon nanowire anodes for lithium-ion batteries 2011(20) 112.Yue L;Wang S Q;Zhao X Y Nano-silicon composites using poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):Poly (styrenesulfonate) as elastic polymer matrix and carbon source for lithium-ion battery anode 2012(3)113.Zang J L;Zhao Y P Silicon nanowire reinforced by single-walled carbon nanotube and its applications to anti-pulverization electrode in lithium ion battery 2012(1)114.Yoshio M;Wang H Y;Fukuda K Carbon-coated Si as a lithium-ion battery anode material 2002(12)115.Qu J;Li H Q;henry J J Self-aligned Cu-Si core-shell nanowire array as a high-performance anode for Li-ion batteries 2012116.Jia H P;Gao P F;Yang J Novel three-dimensional mesoporous silicon for high power lithium-ion battery anode material 2011(6)117.Yao Y;Mcdowell M T;Ryu I Interconnected silicon hollow nanospheres for lithium-ion battery anodes with long cycle life 2011(7)118.Fu K;Yildiz O;Bhanushali H Aligned carbon nanotube-silicon sheets:A novel nano-architecture for flexiblelithium ion battery electrodes 2013(36)119.Min J H;Bae Y S;Kim J Y Self-organized artificial SEI for improving the cycling ability of silicon-basedbattery anode materials 2013(4)120.Choi N S;Yew K H;Lww K Y Effect of fluoroethylene carbonate additive on interfacial properties of silicon thin-film electrode 2006(2)121.Chakrapani V;Rusli F;Filler M A Quaternary ammonium ionic liquid electrolyte for a silicon nanowire-based lithium ion battery 2011(44)122.Etacheri V;Haik O;Goffer Y Effect of fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) on the performance and surface chemistry of Si-nanowire Li-ion battery anodes 2011(1)123.Buddie M C High performance silicon nanoparticle anode in fluoroethylene carbonate-based electrolyte for Li-ion batteries 2012(58)124.Profatilova I A;Stock C;Schmitz A Enhanced thermal stability of a lithiated nano-silicon electrode by fluoroethylene carbonate and vinylene carbonate 2013125.Leung K;Rempe S B;Foster M E Modeling electrochemical decomposition of fluoroethylene carbonate on silicon anode surfaces in lithium ion batteries 2014(3)126.Kovalenko I;Zdyrko B;Magasinski A A major constituent of brown algae for use in high-capacity Li-ion batteries 2011(6052)127.Ryou M H;Kim J;Lee I Mussel-inspired adhesive binders for high-performance silicon nanoparticle anodes in lithium-ion batteries 2012(11)128.Li J;Lewis R;Dahn J Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose a potential binder for Si negative electrodes for Li-ion batteries 2007(2)129.Bridel J S;Azais T;Morcrette M Key parameters governing the reversibility of Si/carbon/CMC electrodes for Li-ion batteries 2009(3)130.Mazouzi D;Lestriez B;Roue L Silicon composite electrode with high capacity and long cycle life 2009(11)131.Guo J C;Wang C S A polymer scaffold binder structure for high capacity silicon anode of lithium-ion battery 2010(9)132.Liu W R;Yang M H;Wu H C Enhanced cycle life of Si anode for Li-ion batteries by using modified elastomeric binder 2005(2)133.Park H K;Kong B S;Oh E S Effect of high adhesive polyvinyl alcohol binder on the anodes of lithium ionbatteries 2011(10)134.Magasinski A;Zdyrko B;Kovalenko I Toward efficient binders for Li-ion battery Si-based anodes:Polyacrylic acid 2010(11)135.Yun J B;Soo K J;Tae L K Aphoto-cross-linkable polymeric binder for silicon anodes in lithium ion batteries 2013(31)136.Han Z J;Yabuuchi N;Hashimoto S Cross-linked poly (acrylic acid) with polycarbodiimide as advanced binder for Si/graphite composite negative electrodes in Li-ion batteries 2013(2)137.Koo B;Kim H;Cho Y A highly cross-linked polymeric binder for high-performance silicon negative electrodes in lithium ion batteries 2012(35)138.Bae J;Cha S H;Park J A new polymeric binder for silicon-carbon nanotube composites in lithium ion battery 2013(7)139.Yim C H;Abu L Y;Courtel F M High capacity silicon/graphite composite as anode for lithium-ion batteries using low content amorphous silicon and compatible binders 2013(28)140.Erk C;Brezesinski T;Sommer H Toward silicon anodes for next-generation lithium ion batteries:A comparative performance study of various polymer binders and silicon nanopowders 2013(15)141.Kim J S;Choi W;Cho K Y Effect of polyimide binder on electrochemical characteristics of surface-modified silicon anode for lithium ion batteries 2013142.Li J;Christensen L;Obrovac M Effect of heat treatment on Si electrodes using polyvinylidene fluoride binder 2008(3)143.Kim Y L;Sun Y K;Lee S M Enhanced electrochemical performance of silicon-based anode material by using current collector with modified surface morphology 2008(13)144.Guo J C;Sun A;Wang C S A porous silicon-carbon anode with high overall capacity on carbon fiber current collector 2010(7)145.Choi J Y;Lee D J;Lee Y M Silicon nanofibrils on a flexible current collector for bendable lithium-ion battery anodes 2013(17)146.Hang T;Nara H;Yokoshima T Silicon composite thick film electrodeposited on a nickel micro-nanocones hierarchical structured current collector for lithium batteries 2013147.Luais E;Sakai J;Desploban S Thin and flexible silicon anode based on integrated macroporous silicon film onto electrodeposited copper current collector 2013148.Tang X X;Liu W;Ye B Y Preparation of current collector with blind holes and enhanced cycle performance of silicon-based anode 2013(6)149.Kim H;Han B;Choo J Three-dimensional porous silicon particles for use in high-performance lithium secondary batteries 2008(52)150.Bang B M;Kim H;Song H K Scalable approach to multi-dimensional bulk Si anodes via metal-assisted chemical etching 2011(12)151.Kasavajjula U;Wang C;Appleby A J Nano-and bulk-silicon-based insertion anodes for lithium-ion secondary cells 2007(2)152.Magasinski A;Dixon P;Hertzberg B High-performance lithium-ion anodes using a hierarchical bottom-up approach 2010(4)153.Liu G;Xun S;Vukmirovic N Polymers with tailored electronic structure for high capacity lithium battery electrodes 2011(40)154.Chan C K;Peng H;Liu G High-performance lithium battery anodes using silicon nanowires 2007(1)155.Idota Y;Kubota T;Matsufiti A Tin-based amorphous oxide:A high-capacity lithium-ion-storage material 1997(5317)156.Courtney I A;Dahn J Key factors controlling the reversibility of the reaction of lithium with SnO2 and Sn2BPO6 glass 1997(9)157.Li H;Huang X J;Chen L Q Direct imaging of the passivating film and microstructure of nanometer-scale SnO anodes in lithium rechargeable batteries 1998(6)158.Liu W;Huang X J;Wang Z Studies of stannic oxide as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries 1998(1)159.Li H;Wang Z;Chen L Research on advanced materials for Li-ion batteries 2009(45)160.David M New materials extend Li-ion performance 2006(5)161.Ogisu K R&D activities & results for sony batteries 2005162.索尼公司索尼成功开发3.5 A·h高容量锂离子电池"Nexelion" 2011163.Dahn J;Mar R;Abouzeid A Combinatorial study of Sn1-xCox (0《x《 0.6) and (Sn0 55Co0 45)1-yCy (0《 y《 0 5)alloy negative electrode materials for Li-ion battaries 2006(2)164.Todd A;Mar R;Dahn J Tin-transition metal-carbon systems for lithium-ion battery negative electrodes 2007(6) 165.Ferguson P;Martine M;Dunlap R Structural and electrochemical studies of (SnxCo1-x)60C40 alloys prepared by mechanical attriting 2009(19)166.Ferguson P;Rajora M;Dunlap R(Sn0.5Co0 5)1-yCy alloy negative electrode materials prepared by mechanical attriting 2009(3)167.Ferguson P;ToddA;Dahn J Comparison of mechanically alloyed and sputtered tin-cobalt-carbon as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries 2008(1)168.Hassoun J;Mulas G;Panero S Ternary Sn-Co-C Li-ion battery electrode material prepared by high energy ball milling 2007(8)vela P;Nacimiento F;Ortiz G F Sn-Co-C composites obtained from resorcinol-formaldehyde gel as anodes in lithium-ion batteries 2010(1)170.Liu B;Abouimrane A;Ren Y New anode material based on SiO-SnxCoyCz for lithium batteries 2012(24)171.Zhong X C;Jiang F Q;Xin P A Preparation and electrochemical performance of Sn-Co-C composite as anode material for Li-ion batteries 2009(1)172.Yang S;Li Q;Shen D Influence of Fe on electrochemical performance of SnxCoy/C anode materials 2011(2)173.Shaobin Y;Ding S;Qiang L Synthesis and electrochemical properties of Sno.35-0 5xCoo 35-0 5xZnxCo 3o composite 2010(1)174.YangSB;ShenD;WuXG Effects of Cu on structures and electrochemical properties of Sn-Co/C composite 2012(4)175.Cui W;Wang F;Wang J Nanostructural CoSnC anode prepared by CoSnO3 with improved cyclability for high-performance Li-ion batteries 2011(13)176.Li M Y;Liu C L;Shi M R Nanostructure Sn-Co-C composite lithium ion battery electrode with unique stability and high electrochemical performance 2011(8)177.Xin L;Jing Y X;Hai L Z Synthesis and properties of Sn30Co30C40 ternary alloy anode material for lithium ion battery 2013(7)178.Lee S I;Yoon S;Park C M Reaction mechanism and electrochemical characterization of a Sn-Co-C composite anodefor Li-ion batteries 2008(2)179.Fauteux D;Koksbang R Rechargeable lithium battery anodes:Alternatives to metallic lithium 1993(1)180.Rahner D;Machill S;Schlorb H Intercalation materials for lithium rechargeable batteries 1996181.Besenhard J;Hess M;Komenda P Dimensionally stable Li-alloy electrodes for secondary batteries 1990182.Maxfield M;Jow T;Gould S Composite electrodes containing conducting polymers and Li alloys 1988(2)183.Winter M;Besenhard J O Electrochemical lithiation of tin and tin-based intermetallics and composites 1999(1) 184.Du C W;Chen Y B;Wu M S Advances in lithium-ion battery anode materials for non-carbon 2000185.Wu Y P;Wan C R Study on materials for lithium-ion batteries tin-based negative 1999(3)186.Kepler K D;Vaughey J T;Thackeray M M LixCu6Sn5(0《x《13):An intermetallic insertion electrode for rechargeable lithium batteries 1999(7)187.Mao O;Dunlap R;Dahn J Mechanically alloyed Sn-Fe(-C) powders as anode materials for Li-ion batteries:Ⅰ.TheSn2Fe-C system 1999(2)rcher D;Beaulieu L;Macneil D In situ X-ray study of the electrochemical reaction of Li with η'-Cu6Sn52000(5)189.Li H;Zhu G;Huang X Synthesis and electrochemical performance of dendrite-like nanosized SnSb alloyprepared by co-precipitation in alcohol solution at low temperature 2000(3)190.Kim H;Kim Y J;Kim D Mechanochemical synthesis and electrochemical characteristics of Mg2Sn as an anode material for Li-ion batteries 2001(1)191.Wang L;Kitamura S;Sonoda T Electroplated Sn-Zn alloy electrode for Li secondary batteries 2003(10)192.Yin J;Wada M;Yoshida S New Ag-Sn alloy anode materials for lithium-ion batteries 2003(8)193.Tamura N;Fujimoto M;Kamino M Mechanical stability of Sn-Co alloy anodes for lithium secondary batteries2004(12)194.Wang L;Kitamura S;Obata K Multilayered Sn-Zn-Cu alloy thin-film as negative electrodes for advanced lithium-ion batteries 2005(2)195.Beauleiu L;Hewitt K;Turner R The electrochemical reaction of Li with amorphous Si-Sn alloys 2003(2)196.Besenhard J;Yang J;Winter M Will advanced lithium-alloy anodes have a chance in lithium-ion batteries 1997(1) 197.Yang J;Winter M;Besenhard J Small particle size multiphase Li-alloy anodes for lithium-ionbatteries 1996(1) 198.Mukaibo H;Sumi T;Yokoshima T Electrodeposited Sn-Ni alloy film as a high capacity anode material for lithium-ion secondary batteries 2003(10)199.Photo F Nonaqueous secondary battery 1995200.Photo F Nonaqueous secondary battery 1995201.Goodenough J;Manthiram A;James A Lithium insertion compounds 1988202.Aydinol M;Kohan A;Ceder G Abinitio calculation of the intercalation voltage of lithium-transition-metal oxide electrodes for rechargeable batteries 1997(2)203.三星SDI株式会社用于非水电解液电池的负极活性材料,其制备方法和非水电解液电池 2005204.Song J H;Park H J;Kim K J Electrochemical characteristics of lithium vanadate,Li1+xVO2,new anode materials for lithium ion batteries 2010(18)205.Chang J J Synthesis and electrochemical:Properties of lithium-ion battery anode material Li1+xVO2 2012206.Armstrong A R;Lyness C;Panchmatia P M The lithium intercalation process in the low-voltage lithium battery anode Li1+xV1-xO2 2011(3)207.Chen H;Xiang K X;Hu Z L Synthesis and electrochemical performance of new anode materials Li1.1V0 9O2 forlithium ion batteries 2012(5)208.Choi N S;Kim J S;Yin R Z Electrochemical properties of lithium vanadium oxide as an anode material for lithium-ion battery 2009(2)zzari M;Scrosati B A cyclable lithium organic electrolyte cell based on two intercalation electrodes 1980(3) 210.Dipietro B;Patriarco M;Scrosati B On the use of rocking chair configurations for cyelabte lithium organic electrolyte batteries 1982(2)211.Ktakata H O;Meri T;Koshita N Procedures of the symposium onprimary and secondary lithium batteries 1988212.Poizot P;Laurelle S;Grugeon S Nano-sized ttansition-metal oxides as negative-electrode materials for lithium-ion batteries 2000(6803)213.Debart A;Dupont L;Poizot P A transmission electron microscopy study of the reactivity mechanism of tailor-made CuO particles toward lithium 2001(11)214.Dedryvere R;Laruelle S;Grugeon S Contribution of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy to the study of the electrochemical reactivity of CoO toward lithium 2004(6)215.Xin C;Naiqing Z;Kening S3d transition-metal oxides as anode micro/nano-materials for lithium ion batteries 2011(10)216.Li H;Richter G;Maier J Reversible formation and decomposition of LiF clusters using transition metal fluorides as precursors and their application in rechargeable Li batteries 2003(9)217.Badway F;Mansour A;Pereira N Structure and electrochemistry of copper fluoride nanocomposites utilizing mixed conducting matrices 2007(17)218.Dbart A;Dupont L;Patrice R Reactivity of transition metal (Co,Ni,Cu) sulphides versus lithium:The intriguing case of the copper sulphide 2006(6)219.Gillot F;Boyanov S;Dupont L Electrochemical reactivity and design of NiP2 negative electrodes for secondary Li-ion batteries 2005(25)220.Pereira N;Dupont L;Tarascon J Electrochemistry of Cu3N with lithium a complex system with parallel processes 2003(9)221.Zhang W M;Wu X L;Hu J S Carbon coated Fe3O4 nanospindles as a superior anode material for lithium-ion batteries 2008(24)222.Rahman M;Chou S L;Zhong C Spray pyrolyzed NiO-C nanocomposite as an anode material for the lithium-ion battery with enhanced capacity retention 2010(40)223.Wang Y;Zhang H J;Lu L Designed functional systems from peapod-like Co@carbon to Co3O4@carbon nanocomposites 2010(8)224.Zhou G;Wang D W;Li F Graphene-wrapped Fe3O4 anode material with improved reversible capacity and cyclicstability for lithium ion batteries 2010(18)225.Wang Y;Zhang L Simple synthesis of CoO-NiO-C anode materials for lithium-ion batteries and investigation on its electrochemical performance 2012226.Zhang P;Guo Z;Kang S Three-dimensional Li2O-NiO-CoO composite thin-film anode with network structure forlithium-ion batteries 2009(1)227.Zhu X J;Guo Z P;Zhang P Highly porous reticular tin-cobalt oxide composite thin film anodes for lithium ion batteries 2009(44)228.Wang C;Wang D;Wang Q Fabrication and lithium storage performance of three-dimensional porous NiO as anode for lithium-ion battery 2010(21)229.Xia Y;Zhang W;Xiao Z Biotemplated fabrication of hierarchically porous NiO/C composite from lotus pollen grains for lithium-ion batteries 2012(18)230.Yu Y;Chen C H;Shi Y A tin-based amorphous oxide composite with a porous,spherical,multideck-cage morphology as a highly reversible anode material for lithium-ion batteries 2007(7)231.Li F;Zou Q Q;Xia Y Y Co-loaded graphitable carbon hollow spheres as anode materials for lithium-ion battery 2008(2)232.Wu Z S;Ren W;Wen L Graphene anchored with Co3O4 nanoparticles as anode of lithium ion batteries with enhanced reversible capacity and cyclic performance 2010(6)引用本文格式:罗飞.褚赓.黄杰.孙洋.李泓.LUO Fei.CHU Geng.HUANG Jie.SUN Yang.LI Hong锂离子电池基础科学问题(Ⅷ)——负。

Ternary_Phase_Diagrams

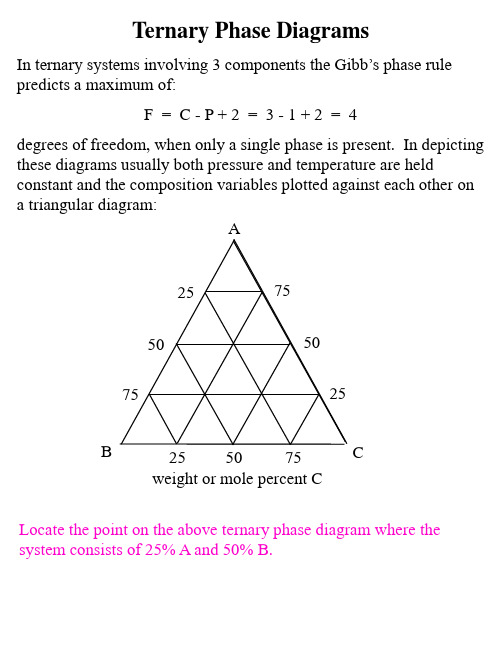

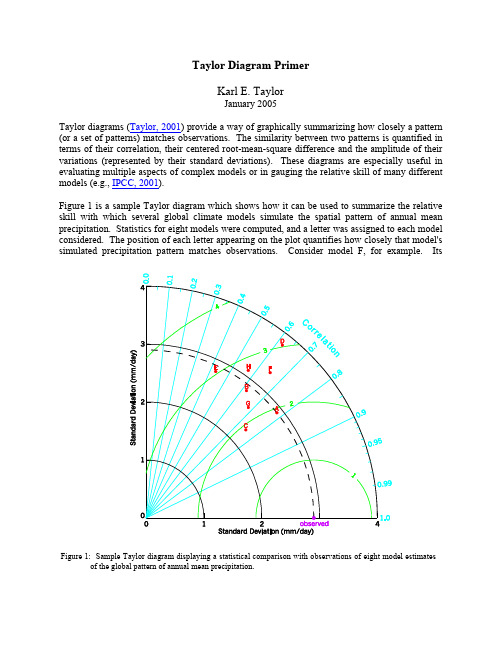

When the system is at an overall composition described by point j in the evaporative sequence: What mass of water remains in the syer has evaporated?

What is the mass of the liquid solution of composition b that remains?

How many grams of KCl and NaCl remain dissolved in this liquid?

How many grams of solid KCl and solid NaCl have precipitated from the solution

The mass of KCl that has precipitated by the time the system has reached point e can be calculated by applying the lever law to a tie line (line gf) that passes through point e and intersects the pure solid KCl corner: mKCl (s) = mtotal (ef / gf) = (mH2O remaining + mKCl + mNaCl ) (ef / gf) = (32 g + 20 g + 10 g) (10 / 152) = 4 grams What is the composition of the liquid solution that is in equilibrium with this 4 grams of precipitated pure solid KCl? When the system has reached point h in the evaporative sequence, it is saturated in NaCl as well as KCl and pure solid NaCl will begin to precipitate from solution. How many degrees of freedom are present at point h? What are the 3 phases that are in equilibrium at point h and what are their compositions? By the time the system composition has reached point j, substantial pure solid NaCl has precipitated from the solution, as well as more pure solid KCl. The solution composition remains fixed at b. When the system has overall composition j, the masses of liquid of composition b and solid mixture that has precipitated can be calculated from a the tie line constructed through segment bj that intesects the pure solid KCl pure solid NaCl axis at point k. Once the mass of the solid mixture at point k is known, another application of the lever law along the tie line that extends along the pure solid KCl pure solid NaCl axis and passes through point k can be used to calculate the masses of pure solid KCl and NaCl that have precipitated from the solution and comprise the solid mixture at point k.

4_bond

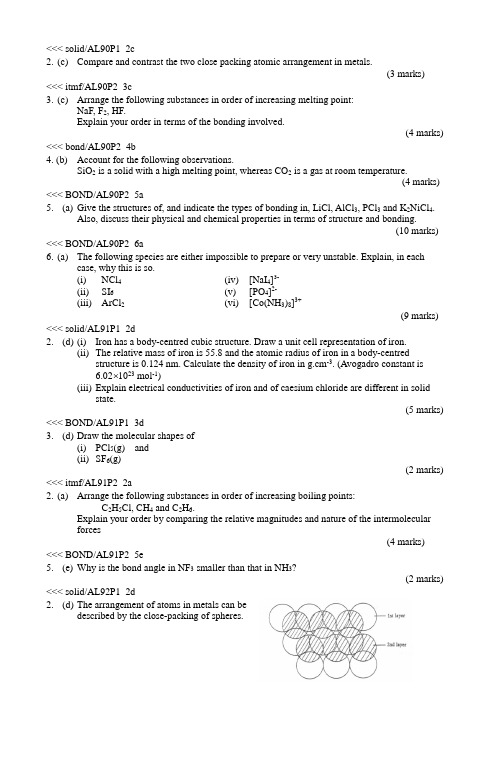

<<< solid/AL90P1_2c2. (c) Compare and contrast the two close packing atomic arrangement in metals.(3 marks)<<< itmf/AL90P2_3c3. (c) Arrange the following substances in order of increasing melting point:NaF, F2, HF.Explain your order in terms of the bonding involved.(4 marks) <<< bond/AL90P2_4b4. (b) Account for the following observations.SiO2 is a solid with a high melting point, whereas CO2 is a gas at room temperature.(4 marks) <<< BOND/AL90P2_5a5. (a) Give the structures of, and indicate the types of bonding in, LiCl, AlCl3, PCl3 and K2NiCl4.Also, discuss their physical and chemical properties in terms of structure and bonding.(10 marks) <<< BOND/AL90P2_6a6. (a) The following species are either impossible to prepare or very unstable. Explain, in eachcase, why this is so.(i) NCl4 (iv) [NaI4]3-(ii) SI6 (v) [PO4]2-(iii) ArCl2 (vi) [Co(NH3)8]3+(9 marks) <<< solid/AL91P1_2d2. (d) (i)Iron has a body-centred cubic structure. Draw a unit cell representation of iron.(ii)The relative mass of iron is 55.8 and the atomic radius of iron in a body-centred structure is 0.124 nm. Calculate the density of iron in g.cm-3. (Avogadro constant is6.02 1023 mol-1)(iii)Explain electrical conductivities of iron and of caesium chloride are different in solid state.(5 marks) <<< BOND/AL91P1_3d3. (d) Draw the molecular shapes of(i)PCl5(g) and(ii)SF6(g)(2 marks) <<< itmf/AL91P2_2a2. (a) Arrange the following substances in order of increasing boiling points:C2H5Cl, CH4 and C2H6.Explain your order by comparing the relative magnitudes and nature of the intermolecularforces(4 marks)<<< BOND/AL91P2_5e5. (e) Why is the bond angle in NF3 smaller than that in NH3?(2 marks) <<< solid/AL92P1_2d2. (d) The arrangement of atoms in metals can bedescribed by the close-packing of spheres.(i)Which close-packed structure does abcabcabc... describe? Indicate on the diagrambelow one tetrahedral hole (marking it T) and one octahedral hole (marking it O).(ii)Describe the bonding in metallic crystals.(iii)Of the three energy ranges in kJ mol -1 given below:5 - 100200 - 700800 - 1500which is the most likely energy range for the change M(s) --> M(g), where M is ametal?(4 marks) <<< BOND/AL92P1_3g3. (g) Draw diagrams showing the shapes of the following molecules. Indicate the lone pairs (if any)on each central atom.(i) ICl (ii) XeOF4(3 marks) <<< BOND/AL92P2_2b2. (b) Give a brief account of the electron density of the hydrogen molecule. Your answer shouldinclude an electron density map.(4 marks) <<< itmf/AL92P2_3a3. (a) (i)Describe the bonding and intermolecular forces in ice and in SiO2 solid.(ii)What type of interactions must be overcome to melt these solids?(4 marks) <<< BOND/AL92P2_3b3. (b) (i)Define the covalent radius of an atom.(ii)State and explain the trends in the covalent radius on going down any group and going across a short period of the periodic table.(iii)The covalent radius of carbon is 0.077 nm. The measured carbon-carbon bond length in benzene is 0.139 nm. Estimate the carbon-carbon bond length in ethane. Explain anydifference in the carbon-carbon bond lengths in these two molecules.(6 marks) <<< BOND/AL93P1_1b1. (b) For each of the following molecules, draw a three-dimensional structure and state themolecular geometry.(i)SiF4(ii)OF2(4 marks) <<< \PM\SOLID AL94 IA 1b1. (b) The crystal structure of a compound A, B, can be described as a simple cubic lattice of A atomswith B atoms at the middle of all the edges.(i)What is the empirical formula of this compound?(ii)What are the coordination numbers of an A atom and a B atom respectively.(2 marks) <<< BOND/AL94P1_1c1. (c) For each of the following molecules, draw a three-dimensional structure showing the positionsof the bond electron pairs and lone electron pairs (if any). In each case, state the moleculargeometry and whether the molecule possesses a non-zero dipole moment.(i)BF3(ii)ClF3(4 marks) <<< itmf/AL94P1_2d2. (d) (i)Explain the term "hydrogen bonding".(ii)Draw a diagram of the structure of a compound which has hydrogen bonds. Indicate the hydrogen bond(s) clearly.(iii)Explain why(I)the boiling point of CH4 is lower than that of SiH4, and(II)the boiling point of NH3 is higher than that of PH3.(5 marks)<<< itmf/AL94P2_2B2. (b) Account for each of the following:(i)Concentrated H3PO4 has a high viscosity.(ii)The melting point of ice decreases with an increase in pressure.(5 marks) <<< BOND/AL95P1_1c1. (c) Account for the fact that the carbon oxygen bond lengths in CO, CO2 and CO32- are 0.113, 0.116and 0.129 nm respectively.(3 marks) <<< BOND/AL95P1_2a2. (a) Explain why phosphorus can form PCl3 and PCl5, while nitrogen can form only NCl3.(2 marks) <<< BOND/AL95P1_2e2. (e) For each of the following species, draw a three-dimensional structure showing the bond electronpairs and lone electron pairs of the central atom. State the shape of the species in each case.(i)ICl4-(ii)SCl2(3 marks) <<< bond/AL96P1_2b2.(b) For each of the following chemical species, draw a three-dimensional structure showing thebond electron pairs and lone electron pair(s) of the central atom underlined. State the shape of the species in each case.(i)ClO3-(ii)NOF(3 marks) <<solid/AL97P1_1a>>Answer ALL questions in this section. Write your answers in the spaces provided.1. (a) At room temperature, iron has a body-centred cubic structure.(i)Draw the unit cell represenation of iron.(ii)Deduce the number of atoms in one unit cell of iron.(2 marks) <<itmf/AL97P1_1d>>1. (d) Explain why(i)the boiling point of HF is higher than that of HCl;(ii)the boiling point of HI is higher than that of HBr.(2 marks) <<bond/AL97P1_3b>>3. (b) For each of the following sulphur-containing chemical species, state its shape and the oxidationstate of sulphur.(i)H2S(ii)SO2(iii)SO42-(3 marks) <<< itmf/AL97P2_1a1. (a) (i)Explain the terms 'dipole' and 'dipole moment', using HBr as an example.(ii)Explain why the dipole moment of HF is greater than that of HI.(iii)State the effect of an electric field on molecules of the following compounds and explain the effect in terms of dipole moment.(7 marks) <<itmf/AL98P1_2b>>2. (b) Which compound, H2O or F2O, would you expect to have a higher boiling point? Explain youranswer.(2 marks) <<BOND/AL98P1_1b>>1. (b) (i) An iodine molecule can be represented by the diagram in theright, with each dot ' ' representing an atomic nucleus.(I) Uisng one or more diagram of this kind, illustrate your understanding of the twoterms 'covalent radius' and van der Waals' radius'.(II) Account for the difference between the covalent radius and van der Waals' radius for iodine.(ii) Explain why the carbon-oxygen bond lengths in CO and CO2 are different.<<bond/AL98P1_3a>>3. (a) For each of the nitrogen-containing chemical species below, state its shape and the oxidation stateof nitrogen(i) NO2-(ii) NH3(iii) NO3-(3 marks) <<< BOND/AL98P2_1c>>1.(c) (i)Draw the three-dimensional structure of BF3.(ii)BF3 reacts with NH3 to form an adduct, BF3.NH3. Account for the formation of the adduct and draw its three-dimensional structure.(4 marks) <<< BOND/AL98P2_2a>>2. (a) The structure of two allotropes of carbon, diamond and graphite, are shown below.(i)Comment on the three different carbon-carbon distances as indicated in the abovestructures.(ii)With reference to the above structures, explain why diamond is hard whereas graphite is soft enough to be used as lubricant.(6 marks) <<< BOND/AL98P2_5a>>5. (a) Consider the following compound F.(i)Give the hybridization states of the carbon atoms, a, b, c and d.(ii)Draw all possible three-dimensional structures for F, indicating the expected bond angles around the carbon atoms, a, b, c and d in one of the structures.<<< bond/AL99P1_1b1-31.(b) Account for each of the following:(i) At 298 K and 1 atm pressure, carbon dioxide is a gas whereas silicon dioxide is a solid..(iii) At 273 K, ice has a smaller density than water.(5 marks) <<< solid/AL99P2_2c>>2 (c) (i) Consider the unit cell of calcium fluoride shown below:(I)State the respective coordination numbers of each calcium ion and each fluorideion.(II)Describe the lattice of calcium ions and that of fluoride ions.(ii) (I)Draw the unit cell of caesium chloride.(II)Describe the lattice of caesium ions and that of chloride ions in caesium chloride.(6 marks) <<< BOND/AL00P1_1a>>1. (a) The diagrams below show the arrangements of atoms, ions or molecules in four crystallinesubstances: graphite, ice, iodine and sodium chloride.(i)Write the name of the substance for each structure in the space provided.(ii)Label, on the diagrams, the type of interactions that are present in these substances.(6 marks) <<< BOND/AL00P1_1b>>1. (b) Explain why nitrogen forms only one chloride, NCl3, whereas phosphorus forms two chlorides,PCl3 and PCl5.(2 marks) <<< itmf/AL00P1_1c>>1. (c) A ccount for the order of boiling point for the two series of compound below:(I)H2O > C2H5OH > C2H5OC2H5(II)H2S > C2H5SH > C2H5SC2H5(3 marks) <<< BOND/AL00P2_2d>>2. (d) Draw three-dimensional structures for methane and carbon dioxide. Give the hybridization stateof the carbon atom in each molecule.(3 marks) <<< BOND/AL00P2_4b>>4. (b) (i)Both argon and xenon (Xe) are Group 0 elements in the Periodic Table. Explain whycompounds of xenon and fluorine exist, whereas compounds of argon and fluorine areunknown.(ii)Draw the three-dimensional structure of xenon(IV) fluoride, showing the bond electron pairs and lone electron pairs of the central atom.(3 marks) <<< BOND/AL01P1_2c>>2. (c) Draw the three-dimensional structure for each molecule below, showing the lone electronpiar(s), if any, of the central atom. State the shape of each molecule.(i) BF3(ii) ClF3(3 marks) <<< BOND/AL01P1_2d>>2. (d) The lattice structure of BaO(s) is described as the interpenetration of two simple cubiclattices, one of Ba2+ ions and the other of O2- ions.(i) Draw the unit cell of BaO(s), labelling the Ba2+ and O2- ions.(ii) What is the coordinaiton number of each O2- ion in the structure?(2 marks) <<< Itmf/AL02P1_3c>>3. (c) (i) Account for the fact that CO2 is a gas while SiO2 is a high melting solid under roomtemperature and atmospheric pressure.(ii) Give the hybridization state of carbon in CO2 and of silicon in SiO2.(4 marks)<<< BOND/AL02P2_1d>>1. (d) Ammonia (NH3) and phosphine (PH3) are hydrides of nitrogen and phosphorusrespectively. Account for each of the following phenomena:(i) The bond angle between two N-H bonds in NH3 (about 107o) is greater than thatbetween two P-H bonds in PH3 (about 94o).(ii) NH3 is very soluble in water but PH3 is sparingly soluble.(4 marks)<<< itmf/AL02P2_2c>>2. (c) The graph below shows the variations of melting points and boiling points of the Period 3elements.Explain why(i) Silicon, metalloid, has a very high melting point;(ii) the boiling points of the metals are in the order:Al > Mg > Na(iii) there is generally a larger difference between the melting point and the boiling point for metals than for non-metals;(iv) the melting point of sulphur is the highest among the non-metals.(9 marks)<<< solid/AL02P2_4b>>4. (b) Both MgO(s) and NaF(s) have a face-centred cubic structure. The table below lists themelting points and solubilities in water of the two compounds.(i) Draw the unit cell of MgO(s)(ii) Account for the following phenomena:(I) The melting point of MgO(s) is higher than that of NaF(s)(II) The solubility of NaF(s) is higher than that of MgO(s)(6 marks)。

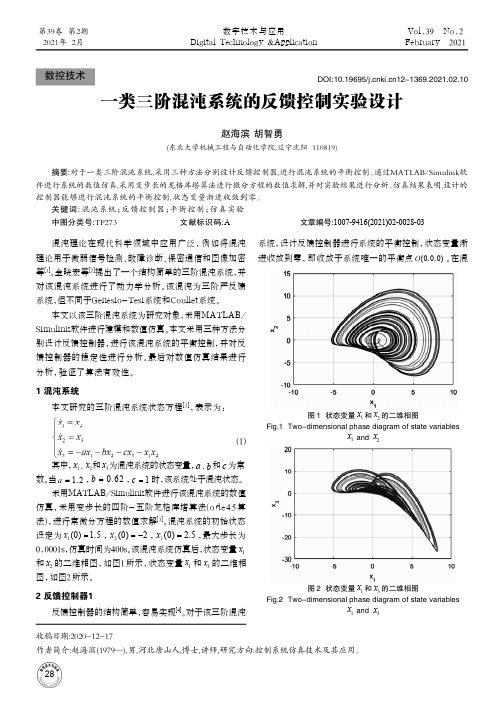

基于平衡力矩法的二维弹道修正引信摩擦力矩测试方法

Vol.4"No.1Feb.2021第43卷第1期2021年2月探测与控制学报JournalofDetecton & Control基于平衡力矩法的二维弹道修正引信摩擦力矩测试方法何江杨,高铭泽,霍鹏飞,柳海斌(西安机电信息技术研究所,陕西西安710065)扌商要:针对目前文献未披露二维弹道修正引信摩擦力矩测试方法,仅是在选取的特定条件下对轴承摩擦力矩进行测试,不能满足轴承在二维弹道修正引信中作用时高过载、高转速的工况要求,无法得到轴承在二维弹道修正引信全寿命周期摩擦力矩值的问题,提出了基于平衡力矩法的二维弹道修正引信摩擦力矩测试方法&该方法考虑了轴承装配、高转速和高过载对摩擦力矩的影响,将轴承装配在二维弹道修正引信中,使用马歇特 锤和高速转台分别模拟引信高过载和高转速的环境,通过所设计的装置实现摩擦力矩测试。

试验验证表明,该 方法可有效测得不同转速、经受轴向和径向高过载后二维弹道修正引信摩擦力矩值,测试操作性强,测量条件 范围广。

由数据分析可知转速和径向过载对二维弹道修正引信摩擦力矩值影响较大,轴向过载对摩擦力矩值影响并不明显。

与理论计算值相比,结果更加符合实际,接近真实值&关键词:二维弹道修正引信;摩擦力矩测试;平衡力矩法;高过载;高转速中图分类号:TJ431.3文献标识码:A 文章编号:1008-1194(2021)01-0008-05Two-dimentional Trajectory Correction Fuze Friction MomentTesting Method Based on Balance MomentHE Jiangyang ,GAO Mingze ,HUO Pengfei ,LIU Haibin(Xi'an Institute of Electromechanical Information Technology ,Xi'an 710065,China)Abstract : In view of the fact that the test method of friction moment of the two-dimentional trajectory correc tion fuze is not disclosed in the current literature ,it only tests the friction moment of bearing under the selected specific conditions ,which can not meet the requirements of high overload and high speed when the bearing acts in the two-dimentional trajectory correction fuze and can not get the friction value of bearing in the whole life cy cle of the two-dimensional trajectory correction fuze. For that ,a test method of friction moment of the two-di mensional trajectory correction fuze based on the balance moment method was proposed. In this method ,the influence of bearing assembly ,high speed and high overload on friction moment is considered. The bearings wereassembled in the two-dimensional trajectory correction fuze. The environment of high overload and high speedwas simulated by the Machete hammer and high speed turntable respectively. The friction moment test was real ized by the designed deviceSThe test result showed that the method could e f ectively measure the friction mo ment of the two-dimensional correction fuze in the condition of different speed and high axial and radial overload.The test has strong operability and a wide range of measurement conditions. It could be got from the dada analy-sisOhaOroOaionspeedandradialovercomehadagreaOinfluenceonfricionmomenOvalueofOheOwo-dimensional correction fuze ,while the axial overload had no obvious influence on friction moment value. Compared with the theoretical value ,the result was more practical and close to the real value.Keywords I wo-dimensionalOrajecOorycorrecionfuze ; fricion momenOOesO ; Ohebalance momenOmeOhod ;highoverload ; highspeed"收稿日期:20200926作者简介:何江杨(1991—),男,陕西米脂人,硕士,研究方向:弹道修正引信。

磁共振中一些常用的简化及缩写用语

熔焊原理-4.5 Solidification Path

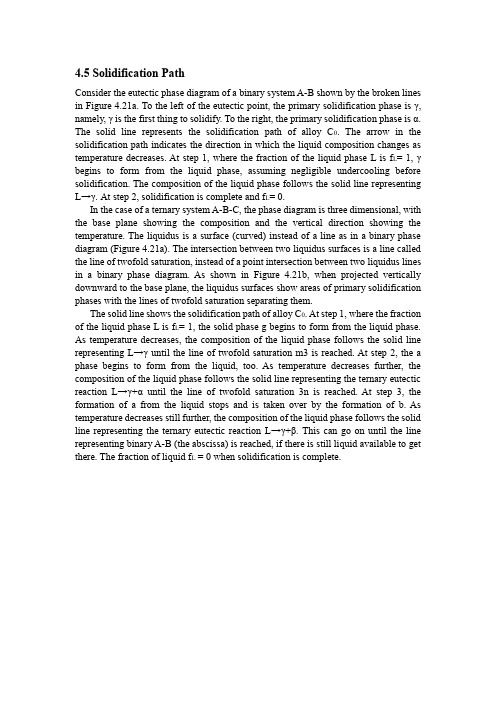

4.5 Solidification PathConsider the eutectic phase diagram of a binary system A-B shown by the broken lines in Figure 4.21a. To the left of the eutectic point, the primary solidification phase is γ, namely, γ is the first thing to solidify.To the right, the primary solidification phase is α. The solid line represents the solidification path of alloy C0. The arrow in the solidification path indicates the direction in which the liquid composition changes as temperature decreases. At step 1, where the fraction of the liquid phase L is f L= 1, γ begins to form from the liquid phase, assuming negligible undercooling before solidification. The composition of the liquid phase follows the solid line representing L→γ. At step 2, solidification is complete and f L= 0.In the case of a ternary system A-B-C, the phase diagram is three dimensional, with the base plane showing the composition and the vertical direction showing the temperature. The liquidus is a surface (curved) instead of a line as in a binary phase diagram (Figure 4.21a). The intersection between two liquidus surfaces is a line called the line of twofold saturation, instead of a point intersection between two liquidus lines in a binary phase diagram. As shown in Figure 4.21b, when projected vertically downward to the base plane, the liquidus surfaces show areas of primary solidification phases with the lines of twofold saturation separating them.The solid line shows the solidification path of alloy C0. At step 1, where the fraction of the liquid phase L is f L= 1, the solid phase g begins to form from the liquid phase. As temperature decreases, the composition of the liquid phase follows the solid line representing L→γ until the line of twofold saturation m3 is reached. At step 2, the a phase begins to form from the liquid, too. As temperature decreases further, the composition of the liquid phase follows the solid line representing the ternary eutectic reaction L→γ+αuntil the line of twofold saturation 3n is reached. At step 3, the formation of a from the liquid stops and is taken over by the formation of b. As temperature decreases still further, the composition of the liquid phase follows the solid line representing the ternary eutectic reaction L→γ+β. This can go on until the line representing binary A-B (the abscissa) is reached, if there is still liquid available to get there. The fraction of liquid f L = 0 when solidification is complete.Figure 4.21 Solidification paths: (a) a binary A-B system; (b) a ternary A-B-C system.。

CrystGrowthDes晶体生长英文文献