Adaptive Control with a Nested Saturation Reference Model

Intelligent Excitation for Adaptive Control With Unknown

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AUTOMATIC CONTROL,VOL.52,NO.8,AUGUST 20071525[15]M.Johansson and A.Rantzer,“Computation of piecewise quadraticLyapunov functions for hybrid systems,”IEEE Trans.Autom.Control ,vol.43,no.4,pp.555–559,Apr.1998.[16]M.Mahmoud,P.Shi,and A.Ismail,“Robust Kalman filtering for dis-crete-time Markovian jump systems with Parameter Uncertainty,”put.Appl.Math.,vol.169,no.1,pp.53–69,2004.[17]C.Meyer,S.Schroder,and R.W.De Doncker,“Solid-state circuitsbreakers and current limiters for medium-voltage systems having dis-tributed power systems,”IEEE Trans.Power Electron.,vol.19,no.5,pp.1333–1340,Sep.2004.[18]M.C.de Oliverrira,J.C.Geromel,and J.Bernussu,“ExtendedH andH norm characterizations and controller parameterizations for dis-crete-time systems,”Int.J.Control ,vol.75,no.9,pp.666–679,2002.[19]P.Shi,M.Karan,and Y.Kaya,“Robust Kalman filter design for Mar-kovian jump linear systems with norm-bounded unknown nonlineari-ties,”Circuits Syst.Signal Process.,vol.24,no.2,pp.135–150,2005.[20]P.Shi,M.Mahmoud,and S.Nguang,“Robust filtering for jumpingsystems with mode-dependent delays,”Signal Process.,vol.86,no.1,pp.140–152,Jan.2006.[21]X.Sun,J.Zhao,and D.J.Hill,“Stability and L -gain analysis forswitched delay systems:A delay-dependent method,”Automatica ,vol.42,pp.1769–1774,2006.[22]H.Tshii and B.A.Francis,“Stabilizing a linear system by switchingcontrol with dwell-time,”IEEE Trans.Autom.Control ,vol.47,no.2,pp.1962–1973,Feb.2002.[23]Z.Wang and F.Yang,“Robust filtering for uncertain linear systemswith delayed states and outputs,”IEEE Trans.Circuits Syst.I,Fundam.Theory Appl.,vol.49,no.1,pp.125–130,Jan.2002.[24]L.Wu,P.Shi,C.Wang,and H.Gao,“Delay-dependent robustH andL 0L filtering for LPV systems with both discrete and distributed delays,”Inst.Electr.Eng.Proc.Control Theory Appl.,vol.153,no.4,pp.483–492,2006.[25]M.A.Wicks,P.Peleties,and R.A.De Carlo,“Construction of piece-wise Lyapunov functions for stabilizing switched systems,”in Proc.33rd Conf.Decision Control ,Dec.1994,pp.3492–3497.[26]G.Xie and L.Wang,“Quadratic stability and stabilization of discrete-time switched systems with state delay,”in Proc.43th IEEE Conf.De-cision Control ,Atlantis,Paradise Island,Bahamas,Dec.14–17,2004,pp.3235–3240.[27]L.Xie,“Output feedbackH control of systems with parameter un-certainty,”Int.J.Control ,vol.63,pp.741–750,1996.[28]H.Xu,Y.Zou,and S.Xu,“RobustH control for a class of uncertainnonlinear two-dimensional systems,”Int.J.Innovative Comput.Inf.Control ,vol.1,no.2,pp.181–191,2005.[29]G.Zhai,B.Hu,K.Yasuda,and A.N.Michel,“Disturbance attenuationproperties of time-controlled switched systems,”J.Franklin Inst.,vol.338,no.7,pp.765–779,2001.[30]G.Zhai,Y.Sun,X.Chen,and A.N.Michel,“Stability and L gainanalysis for switched symmetric systems with time delay,”in Proc.Amer.Control Conf.,Denver,CO,Jun.2003,pp.4–6.[31]B.Zhang and S.Xu,“RobustH filtering for uncertain discrete piece-wise time-delay systems,”Int.J.Control ,vol.80,no.4,pp.636–645,2007.[32]J.Zhao and G.M.Dimirovski,“Quadratic stability of a class ofswitched nonlinear systems,”IEEE Trans.Autom.Control ,vol.49,no.4,pp.574–578,Apr.2004.[33]S.Zhou and m,“Robust stabilization of delayed singular systemswith linear fractional parametric uncertainties,”Circuits Syst.Signal Process.,vol.22,no.6,pp.579–588,2003.Intelligent Excitation for Adaptive Control With UnknownParameters in Reference InputChengyu Cao,Naira Hovakimyan,and Jiang WangAbstract—Model reference adaptive control problem is considered for a class of reference inputs dependent upon the unknown parameters of the system.Due to the uncertainty in the reference input,the tracking objec-tive cannot be achieved without parameter convergence.The common ap-proach of injecting persistent excitation (PE)in the reference input leads to tracking of the excited reference input as opposed to the true one.A new technique,named intelligent excitation,is presented for introducing an ex-citation signal in the reference input and regulating its amplitude,depen-dent upon the convergence of the output tracking and parameter errors.Intelligent excitation ensures parameter convergence,similar to conven-tional PE;it vanishes as the errors converge to zero and reinitiates with every change in the unknown parameters.As a result,the regulated output tracks the desired reference input and not the excited one.Index Terms—Adaptive control,excitation,parameter convergence.I.I NTRODUCTIONThis note considers the framework of model reference adaptive con-trol (MRAC)architecture for the class of reference inputs dependent upon the unknown parameters of system dynamics.This problem for-mulation is motivated by practical applications,like visual guidance [1]or closed-coupled formation flight [10].In [1],the target tracking problem is considered with visual sensor (monocular camera),where the characteristic length of the target is unknown,and the relative range is not observable from available visual measurements.In [10],autopilot design is considered for a trailing aircraft that follows a lead aircraft in a closed-coupled formation.The trailing aircraft must constantly seek an optimal position relative to the leader to minimize the unknown drag effects introduced by the wing tip vortices of the lead aircraft.Both problems lead to definition of a reference system with a refer-ence input dependent upon the unknown parameters of the system.Fol-lowing the common approach of injecting persistent excitation (PE)in the reference input leads to parameter convergence [2],[11],[12]but the system output tracks the excited reference input and not the true one.A new technique,named intelligent excitation,is presented in this note to solve the output tracking problem while ensuring parameter convergence.The main feature of it is that it initiates excitation only when the tracking error exceeds a prespecified threshold,and it van-ishes as the parameter error converges to a neighborhood of the origin.The relationship between convergence of the parameter and the tracking errors,as well as between the conditions for convergence,has been extensively explored in the literature [2]–[8],[13].The well-known fact is that exponential parameter convergence leads to exponential tracking error convergence [2].We note that for a special set of regressor functions,like periodic ones,one can prove exponential convergence of tracking error to zero without the PEManuscript received August 5,2005;revised October 23,2006and May 1,2007.Recommended by Associate Editor M.Demetriou.This work was sup-ported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR)under Con-tract FA9550-05-1-0157and the Multidisciplinary University Research Initia-tive (MURI)under Subcontract F49620-03-1-0401.The authors are with the Department of Aerospace and Ocean Engineering,Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University,Blacksburg,V A 24061-0203USA (e-mail:chengyu@;nhovakim@;jwang005@).Color versions of one or more of the figures in this paper are available online at .Digital Object Identifier 10.1109/TAC.2007.9027800018-9286/$25.00©2007IEEEAuthorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT. Downloaded on February 12, 2009 at 09:44 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.1526IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AUTOMATIC CONTROL,VOL.52,NO.8,AUGUST 2007requirement or parameter convergence [4],[5],[9].However,in the problem of interest to us,namely when the reference input depends upon the unknown parameters of the system dynamics,the control objective cannot be met without parameter convergence.We further notice that in the presence of PE the exponential convergence of the tracking error to zero does not imply convergence of the system output to the desired reference input.Instead,the output tracks the excited reference input.In this note,we present a control design methodology that ensures simultaneous parameter convergence and tracking of the desired reference input.This note is organized as follows.Section II presents the problem for-mulation.Adaptive controller with intelligent excitation is introduced in Section III.Convergence of the regulated output within desired pre-cision in finite time is shown in Section IV.In Section V,simulation results are presented,and Section VI concludes this note.The proofs are included in the Appendix.II.P ROBLEM F ORMULATIONConsider the following single-input –single-output (SISO)system dynamics:_x (t )=A m x (t )+b m 1ru (t )0( 3x )>x (t);y (t )=c >x (t )(1)where x 2I R n is the system state vector (measurable),u 2I R is thecontrol signal,b m 2I R n and c 2I R n are known constant vectors,A mis known Hurwitz n 2n matrix, 3r2I R is an unknown constant with known sign, 3x 2I R nis the vector of unknown parameters,and y 2I Ris the regulated output.Let 3=[( 3x )> 3r ]>.The control objective is to regulate the output y so that it tracks r ( 3),where r is a known mapr :I R n 2IR !I R ,dependent upon the unknown parameters 3of the system.Let 23be the compact set,to which the unknown parameters belong,i.e., 3223.In case of a known reference signal r (t ),application of the conven-tional MRAC ensures that the tracking error between the desired ref-erence model and the system state goes to zero asymptotically,which consequently leads to output convergence y (t )!r (t ).Since r ( 3)depends upon the unknown parameters 3,it cannot be used in the feedforward component of the MRAC architecture,even if the map r :I R n 2I R !I R is known.III.A DAPTIVE C ONTROLLER U SING I NTELLIGENT E XCITATION In this section,we present a solution for solving the tracking problem in the presence of unknown r ( 3).We consider the following reference model:_x m (t )=A m x m (t )+b m k g ^r (t )y m (t )=c >x m (t )(2)where k g 1=lim s !0(1=(c >(sI 0A m )01b m )),and the following con-troller:u (t )=>x (t )x (t )+r (t )k g ^r (t )(3)in which ^r(t )is a bounded reference signal to be de fined shortly,and x (t )2I R n and r (t )2I R are the adaptive parameters governed by the following adaptive laws [15]:_ x (t )=0xProj x (t );0x (t )e >(t )P b sgn ( 3r)_ r (t )=0rProj r (t );0k g ^r (t )e >(t )Pb sgn ( 3r)(4)where e (t )=x (t )0x m (t ).In (4),0x >0and 0r >0are the adap-tation rates,P =P >>0is the solution of the algebraic Lyapunovequation A >m P +P A m =0Q for arbitrary Q >0,and Proj(1;1)denotes the projection operator de fined asProj( ;y )1=y;if f ( )<0y;if f ( ) 0and r f >y 0y 0r f r f >yjr f j 2f ( );if f ( ) 0and r f >y >0(5)where f:n!is the smooth convex function:f ( )=(( >0 2max )= ), max is the norm bound imposed on the parameter vector ,and >0denotes the convergence tolerance of our choice.Letx (t )=^r (t )x >m (t )>H (s )= x (s )=^r (s ):(6)It follows from (2)that x m (s )=^r(s )=(sI 0A m )01b m k g ,and hence H (s )=1(sI 0A m )01b m k g>>:(7)We de fine a (n +1)22m matrix with its p th row,q th column elementas=Re Hp j!de ;if q is oddIm Hp j!de;if q is evenq =1;2;111;m(8)where d q=2e denotes the smallest integer that is q=2and H p (s )is the p th element of H (s )de fined in (7).Lemma 1:There exist m and !1;...;!m such that has full row rank.Consider the following excitation signal over a finite time interval [0;T ]:e x (t )=mi =1sin(!i t );t 2[0;T ](9)where !1;...;!m ensure that has full row rank,and T >0is the first time instant for which e x (T )=0.The existence of finite T is straightforward for a linear combination of sinusoidal functions.Let(t )=[ >x (t ) r (t )]>.The reference signal ^r (t )is de fined as^r (t )=^r 0(t )+E x (t )(10)^r 0(t )=r ( (t ))(11)E x (t )=k (t )e x (t 0jT );if t 2[jT;(j +1)T );j =0;1;2...(12)and (13),shown at the bottom of the page,holds,where E x (t )is theintelligent excitation signal,e x (t )is de fined in (9),and 01>0,02>0,03>0,and k 0are design gains,subject to 03 k 0 02.It is straightforward to verify that 03 k (t ) 02,t 0.The complete controller with intelligent excitation consists of (2)–(4)and (10).We note that for the system in (1)the reference input r ( 3)is not available since 3is unknown.We can use (t ),the estimate of 3,to construct r ( (t )),for which MRAC can be applied.However,withoutk (t )=k 0;t 2[0;T )min 01jT(j 01)Te >( )Qe ( )d ;02003+03;t 2[jT;(j +1)T );j 1(13)Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT. Downloaded on February 12, 2009 at 09:44 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AUTOMATIC CONTROL,VOL.52,NO.8,AUGUST 20071527parameter convergence,there is no guarantee that r ( (t ))will con-verge to a neighborhood of r ( 3)in finite time.Therefore,we aug-ment r ( (t ))with the intelligent excitation signal E x (t ),which leads to the control objective as we prove in the following.First,we no-tice that though k (t )is piecewise constant over the time increments [jT;(j +1)T ),E x (t )is a continuous signal,since e x (T )=e x (0)=0.Thus,the rede fined reference input ^r(t )in (10)is continuous and bounded.Let e (t )=x (t )0x m (t )be the tracking error.Substituting (3)into (1),it follows from (2)that the dynamics of the tracking error can be rewritten_e (t )=A m e (t )+1 rbm ~ >x (t )x (t )+~ r (t )k g ^r (t)(14)where ~ x (t )= x (t )0 3x and ~ r (t )= r (t )0 3r denote parametricerrors.Let ~ (t )=[~ x (t )>~ r (t )]>.Using the candidate LyapunovfunctionV e (t );~ (t)=e >(t )P e (t )+1 3r~ >x (t )001x ~ x (t )+001r1 r~ 2r (t )(15)it can be veri fied easily that _V(t ) 0e >(t )Qe (t ) 0,t 0.Ap-plication of Barbalat ’s lemma yields lim t !1e (t )=0.Furthermore,itcan be veri fied easily that if ^r (t )= r ,where ris constant,one has lim t !1y (t )= r.From the de finition of asymptotic stability it follows that for any >0there exists finite T s >0such that j y (t )0 rj ,t T s .IV .C ONVERGENCE R ESULT OF A DAPTIVE C ONTROLLERW ITH I NTELLIGENT E XCITATIONWe note that the amplitude of the excitation signal in (13)is de fined via the integral of the tracking error over a time in-crement equal to the period of the excitation signal.To prove parameter convergence,we need to characterize the relationship between the unknown parameter error and the integral of thetracking error.Let 4(t )1=[x >(t )x >m (t ) >(t )]>2I R 3n +1be the state of the extended system dynamics (1),(2),and (4)with the reference input de fined in (10)and (13).Consider the compact set of all possible initial conditions of the system dy-namics and adaptive parameters 4(0)=402D 0 IR 3n +1.The Lyapunov function V (e (t );~(t ))in (15)can be equivalently rewritten in the phase space as V (e;~)=(x 0x m )>P (x 0x m )+j 1= 3rj ( x 0 3x )>001x ( x 0 3x )+001r j 1= 3r j ( r 0 3r )2and viewed as a map V (4; 3):IR 3n +1223![0;1).Since the error dynamics are globally asymptotically stable,the maximum of the Lyapunov function for every initial condition 402D 0is attained atthe initial time instant.Let V max =max 42D ; 22V (40; 3).Notice,however,that as time evolves,the system trajectory 4(t )can leaveD 0,but since the Lyapunov function is nonincreasing,there exists a compact set D c ,possibly larger than D 0,such that the system trajectory stays in it for all t 0.Since (14)implies that k (t )is constant over any time interval [jT;(j +1)T ],j =0;1;2...,we denote k j the value of k (t )over this interval.We note that the system trajectory over [jT;(j +1)T ],as well as the value of (j +1)T jTe >(t )Qe (t )dt is uniquely de fined by 4(jT )2D c ,k j 2(0;02],and 3223.We consider the following map g 4:D c 2(0;02]223![0;1)to characterize this relationship:(j +1)TjTe >(t )Qe (t )dt =g 4(4(jT );k j ; 3):(16)Fig.1.Illustration of maps g (v )and g (w ).We note that the entire systems (1),(2),and (4)de fining the trajec-tory of 4(t ),can be viewed as a time-invariant system with E x (t )as an external periodic input signal.Thus,the trajectory of 4(t )on t 2[j 1T;(j 1+1)T )is the same as on t 2[j 2T;(j 2+1)T ),if 4(j 1T )=4(j 2T )and k j =k j ,for any j 1;j 2.Hence,g 4(4(jT );k j ; 3)is independent of the choice of j and depends only upon the values of 4(jT )and k j .Moreover,since Q is positive de finite,g 4(4c ;k c ; 3):D c 2(0;02]223![0;1)is nonnegative,where 4c stands for the value of 4(jT ),and k c stands for k j to indicate the independence on j .We further de fine the map g v :[0;V max ]2(0;02]![0;1)as the solution of the following constrained optimization problem:g v (v;k c )=min42D ; 22;s :t :V (4; )=vg 4(4c ;k c ; 3)(17)where v 2[0;V max ].Notice that the constraint V (4c ; 3)=v de fines a nonempty compact set,hence the optimization problem (17)has at least one solution.Lemma 2:The map g v de fined in (17)has the following properties:1)g v (0;k c )=0;2)if k c >0and g v (v;k c )=0,then v =0.We de fine the map g k :[0;V max ]![0;1)asg k (v )=min0 k 0(g v (v;k c )=k c )(18)where g v is de fined in (17)and 02>03>0are design gains de fined in (14).The nonnegative property of g k (v )follows directly from the fact that g v (v;k c ) 0.Corollary 1follows from Lemma 2directly.Corollary 1:g k (v )=0if and only if v =0.It can be checked easily that g 4(4c ;k c ; 3)is a continuous function of its arguments.Therefore,g v (v;k c ),as well as g k (v ),continuously depend upon their arguments.Fig.1illustrates the function g k (v ).We note that g k (v )is a nonnegative function with a unique zero at v =0.Given the map g k (v ),which may not be monotonous,we de fine an “inverse-type ”map g i :[0;g k (V max )]![0;V max ]asg i (w )=max vf v 2[0;V max ]jg k (v )=w g :(19)Illustration of g i (w )for a possibly nonmonotonous g k (v )is shown in Fig.1for three different values of w .Since g k (v )is a continuous function and g k (0)=0,it can be checked easily that for any w 2[0;g k (V max )],the map g i (w )exists.Notice,however,that despite theAuthorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT. Downloaded on February 12, 2009 at 09:44 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.1528IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AUTOMATIC CONTROL,VOL.52,NO.8,AUGUST2007fact that the map g k(v)is continuous,g i(w),as defined in(19),is notguaranteed to be continuous.Lemma3:The map g i(w)has the following properties:1)limw!0g i(w)=0;(20)2)g i(0)=0;(21)3)for all v g i(w)one has g k(v) w:(22)For any constant >1,we define1(01; )=g i( =01)(23)j3=d(lg(02=03))( )e+1(24)where01;02,and03are the design gains defined in(14),and the no-tation d a e denotes the smallest integer greater than or equal to a.Itfollows from(20)thatlim0!11(01; )=0:(25)Theorem1:Given the system in(1)and the adaptive controller withintelligent excitation in(2),(3),(4),and(13),if for j3T,V( )1(01; ),then k x( )=02.Theorem1states that as long as the value of Lyapunov function isgreater than 1(01; ),the reference input will be subject to PE withconstant amplitude.Next,we prove that there exists afinite time instantsuch that the value of Lyapunov function will drop below 1(01; ).Inthat case,consequently,the amplitude of the excitation signal will beregulated dependent upon the integral of the tracking error to ensurethat the control objective can be met.Towards that end,let B~v=f~ jj1= 3r j~ >x001x~ x+001r j1= 3r j~ 2r~v g,where0 ~v V max.Let( ;~v)=max~2B r( 3+~ )0r( 3):(26)Let = max(cc>)= min(P),where min(P)is the minimum eigen-value of P>0,while max(cc>)is the maximum eigenvalue of cc>. We define 2(01;03; )=k G(s)k L( ( 3; 1(01; ))+03+ )+ + 1(01; );where >0and >1are arbitrary constants,and k G(s)k L is the L1gain of the system G(s)=y(s)=^r(s).Theorem2:For the system(1)and the adaptive controller with in-telligent excitation(2),(3),(4),and(13),there exists afinite T s>0 such thatj y(t)0r( 3)j 2(01;03; );t T s:(27) It can be verified easily that ( 3;~v)is a continuous function of~v and,therefore, ( 3;0)=0.Hence,it follows thatlim0!1;0!0; !02(01;03; )=0:(28)This implies that we can set01arbitrarily large and03and arbi-trarily small to obtain any desired precision of 1and 2in(25)and (28).Notice that 2can be set arbitrarily small by control design.Also, it is important to point out that a large value of01will not cause insta-bility,since the excitation signal E x(t)is always bounded by02. Thus,we proved that the adaptive controller with intelligent excita-tion regulates the system output infinite time.If there is any changein Fig.2.Illustration of time trajectories of V(t)and k(t).the unknown parameters of the system,then the desired reference tra-jectory changes correspondingly.If the interval in which the unknown parameters 3hold constant values is larger than thefinite settling time guaranteed by intelligent excitation,then the adaptive controller with intelligent excitation will achieve the control objective.Indeed,any change in the unknown parameters of the system results in an abrupt change of V(t).Theorem1ensures then that the intelligent excitation will reinitialize and lead to desired output tracking.Remark1:For practical implementation,due to the presence of noise and transient tracking errors,we can set03=0without wor-rying about premature disappearance of excitation.In that case,the ex-citation signal satisfies k(t) 02,where is a small positive number due to the noise in practical implementation.Furthermore,the definition of j3in(24)will change to j3=d lg(02= )=lg( )e+1.The constant gain01is inverse proportional to the bound of the parameter tracking error,so setting it large will increase the accuracy of parameter estimates.The gain02is the amplitude of the excitation signal,which controls the rate of convergence.Remark2:Fig.2illustrates the simultaneous change of V(t)and k(t).Let T be the time instant when V( T)= 1(01; ).Theorem1 states that k(t)is nondecreasing and increases to02before j3T for any initial k02[03;02],while k(t)=02;8t2[j3T; T].This im-plies a constant excitation signal,which leads to decrease of V(t)until it drops below 1(01; ).Once V(t) 1(01; ),Theorem2(Step1 in the proof)states that k(t)will decrease to03+ ,where can be arbitrarily small.Thus,Theorem1quantifies the performance of the intelligent excitation signal,while Theorem2consequently proves the output convergence.We further notice that Theorem1relates the pres-ence of constant excitation signal to the value of the Lyapunov function, which depends upon the unknown parameter errors.Thus,any change in the unknown parameters of the system,which leads to a new value for Lyapunov function,implies reinitialization of the excitation signal.Remark3:Wefinally note that adaptive control is not the only tool for controlling systems in the presence of uncertainties.Robust control literature offers alternative approaches,as high-gain controllers,vari-able structure controllers,to name just a few.However,for the output regulation problem discussed here,namely when the desired reference input depends on unknown parameters of the system,parameter identi-fication appears to be a required step for achieving the control objective. Intelligent excitation provides a solution for simultaneous parameter identification and output regulation.Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT. Downloaded on February 12, 2009 at 09:44 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AUTOMATIC CONTROL,VOL.52,NO.8,AUGUST20071529V.S IMULATIONWe consider the reference input dependent on piecewise constantunknown parameters.Consider the SISO system in(1)withA m=01:030:880:2502:96b m=00:0101:05c=1 03x(t)=[3:243310:7432]>;t 42sec[2:16227:1621]>;t>42sec3r(t)=6:18;t 42sec4;t>42sec:The reference signal isr( 3)=0[11]A m0b mr ( 3x)>[11]001:5rand the objective is to design control signal u(t)so that the system output y(t)tracks the reference input r( 3).We construct the adap-tive controller with intelligent excitation using the following parame-ters:Q=diag[100;10],0x=50I222,0r=10,01=10,T= =3, 02=1:5,and03=0.We choose!1=6and!2=9.It can be veri-fied that has full row rank with the chosen!i.Simulation results are given in Fig.3.Fig.3(a)plots the time history of y(t)and the ideal ref-erence signal r( 3).It demonstrates that with the change in unknown parameter 3r(t)the output y(t)converges to r( 3)with the help of in-telligent excitation.The trajectory of k(t),which defines the amplitude of the intelligent excitation,is plotted in Fig.3(b).Fig.3demonstrates the following:1)intelligent excitation vanishes as parameter conver-gence takes place and2)intelligent excitation reinitiates when a change occurs in unknown parameters.VI.C ONCLUSIONIn this note,we augment the traditional MRAC with an intelligent excitation signal to solve the output tracking for a reference input that depends upon the unknown parameters of the system.The main fea-ture of the new technique is that it initiates excitation only when nec-essary.We prove that intelligent excitation is a general technique for the class of problems,in which parameter convergence is needed to meet the control objective.It can also be used to enhance robustness of the adaptive controllers,when parameter drift may cause instability. Since intelligent excitation modifies only the reference input,while the proofs of convergence and reinitialization use only the properties of the Lyapunov function,it can be straightforwardly modified for different adaptive controllers,like backstepping,output feedback,etc.A PPENDIXProof of Lemma1:The transfer function(sI0A m)01b m k g can be expressed as(sI0A m)01b m k g=n(s)=d(s),where d(s)= det(sI0A m)is a n th order polynomial,and n(s)is a n21vector with its i th element being a polynomial functionn i(s)=nj=1n ij s j01:(29)Consider the matrix N with its entries n ij in(29).Wefirst prove that N is full rank.We note that(A m;b m)is controllable.Controllability of(A m;b m)for the linear time invariant(LTI)system in(2)implies that for arbitrary x t2I R n,x m(t0)=0,and arbitrary t1,there existsu( ); 2[t0;t1]such that x m(t1)=x t.If N is not full rank,then Fig.3.Simulation results.(a)Comparison of y(t)and r(t).(b)Trajectory of k(t).there exists a nonzero constant vector 2I R n,such that >n(s)=0. Then,( >n(s)=d(s))=( >x(s)=^r(s))=0,which implies that >x m(s)=0.If x m(t0)=0,for any u( ), >t0,we have >x m( )=0;8 >t0.This contradicts x m(t1)=x t,in which x t2I R n is assumed to be an arbitrary point.Therefore,N must be full rank.Since N is full rank,it follows that n(s)contains n linearly inde-pendent polynomials.We can rewrite the transfer function in(7)as H(s)=(1=d(s))[d(s)n1(s)111n n(s)]>.Since d(s)is an n th order polynomial,and n i(s)is(n01)th order polynomial,d(s)and n i(s) are linearly independent.Hence,H(s)contains n+1linearly inde-pendent functions of s,and,therefore,there exist!1;...;!m,which ensure that has full rowrank.Proof of Lemma2:The proof of thefirst statement is straightfor-ward.If v=0,then the optimization set is defined by V(4c; 3)=0. This is indeed a nonempty set,since the points of the hyperspace in I R3n+1223defined via the conditions x=x m; = 3sat-isfy V(4c; 3)=0.Notice that the computation of g4(4c;k c; 3) in(16)is done by starting the integration from4(jT)=4c.Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT. Downloaded on February 12, 2009 at 09:44 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.。

Advanced Control Systems

Advanced Control Systems Advanced Control Systems play a crucial role in modern engineering and technology, enabling precise and efficient control of complex systems across various industries. From aerospace and automotive to manufacturing and robotics, the application of advanced control systems has revolutionized the way we design, operate, and optimize processes and machinery. In this discussion, we will explore the significance of advanced control systems, their key components, challenges, and future prospects from multiple perspectives. From an engineering standpoint, advanced control systems encompass a wide range of methodologies and techniques aimed at regulating the behavior of dynamic systems. These systems can be as simple as a thermostat controlling room temperature or as complex as a self-driving car navigating through traffic. One of the fundamental components of advanced control systems is the use of mathematical models to describe the dynamics of the system and develop control algorithms. These algorithms can be implemented in hardware or software, utilizing sensors and actuators to measure and manipulate the system's behavior in real-time. In the field of aerospace, advanced control systems are instrumental in ensuring the stability and maneuverability of aircraft and spacecraft. Flight control systems utilize a combination of autopilots, gyroscopes, and control surfaces to maintain stability and respond to pilot commands. With the advent of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), advanced control systems have become even more critical in enabling autonomous flight and navigation, opening up new possibilities for surveillance, delivery, and exploration. In the automotive industry, advanced control systems have revolutionized vehicle dynamics and safety. Electronic stability control (ESC) systems use sensors to detect and prevent skidding and loss of traction, enhancing the overall safety of vehicles. Moreover, the development of autonomous vehicles relies heavily on advanced control systems, enabling cars to perceive their environment, make decisions, and navigate without human intervention. The integration of sensors, actuators, and control algorithms in modern vehicles represents a significant leap forward in the quest for safer and more efficient transportation. The manufacturing sector has also benefited significantly from advanced control systems, particularly in the realm of robotics and automation.Industrial robots equipped with advanced control systems can perform a wide array of tasks with precision and repeatability, ranging from assembly and welding to painting and inspection. The seamless integration of robots into manufacturing processes has not only improved efficiency but also created new opportunities for customization and flexibility in production lines. Despite the numerous advantages offered by advanced control systems, several challenges and considerations must be addressed to ensure their effective implementation and operation. One of the primary concerns is the robustness and reliability ofcontrol algorithms, especially in safety-critical applications such as autonomous vehicles and medical devices. The need to account for uncertainties, disturbances, and unforeseen events poses a significant challenge in the design and validation of advanced control systems. Another critical aspect is the ethical and societal implications of advanced control systems, particularly in the context of autonomous technologies. The deployment of autonomous vehicles, for instance, raises questions regarding liability, decision-making algorithms, and the impact on traditional modes of transportation. Furthermore, the potential displacement of human workers in various industries due to automation calls for a thoughtful and inclusive approach to the adoption of advanced control systems. Looking ahead, the future of advanced control systems holds immense potential for further innovation and integration across diverse domains. The emergence of cyber-physical systems, enabled by the Internet of Things (IoT) and cloud computing, presents new opportunities for interconnected and intelligent control systems. The ability to collect and analyze vast amounts of data in real-time opens up avenues for adaptive and predictive control strategies, enhancing performance and resilience in dynamic environments. In conclusion, advanced control systems represent a cornerstone of modern engineering and technology, driving advancements in aerospace, automotive, manufacturing, and beyond. The convergence of mathematical modeling, sensors, actuators, and computing has paved the way for unprecedented levels of precision, efficiency, and autonomy in controlling complex systems. As we continue to navigate the opportunities and challenges associated with advanced control systems, it is essential to prioritize safety, ethics, and inclusiveinnovation to realize their full potential in shaping the future of technology and society.。

adaptive control

Desired Performance ComparisonDecision

Adaptation Mechanism

Performance Measurement

Adaptation scheme

Adaptive Control – Landau, Lozano, M’Saad, Karimi

Adaptive Control versus Conventional Feedback Control

y

u

Plant

Desired Performance

Adaptation Scheme

Reference Controller

u

Plant

y

An adaptive control structure

Remark: An adaptive control system is nonlinear since controller parameters will depend upon u and y

Adaptive Control – Landau, Lozano, M’Saad, Karimi

Conventional Control – Adaptive Control - Robust Control

Conventional versus Adaptive

Conventional versus Robust

Adaptive Control – Landau, Lozano, M’Saad, Karimi

Conceptual Structures

Desired Performance Controller Design Method Plant Model

adaptive control

Adaptive control can help deliver both stability and good response. The approach changes the control algorithm coefficients in real time to compensate for variations in the environment or in the system itself. In general, the controller periodically monitors the system transfer function and then modifies the control algorithm. It does so by simultaneously learning about the process while controlling its behavior. The goal is to make the controller robust to a point where the performance of the complete system is as insensitive as possible to modeling errors and to changes in the environment.

Adaptive Control

The most recent class of control techniques to be used are collectively referred to as adaptive control. Although the basic algorithms have been known for decades, they have not been applied in many applications because they are calculation-intensive. However, the advent of special-purpose digital signal processor (DSP) chips has brought renewed interest in adaptive-control techniques. The reason is that DSP chips contain hardware that can implement adaptive algorithms directly, thus speeding up calculations.

自适应控制(Astrom著)Lecture1

stances. Any alteration in structure or function of an organism to make it better tted to survive and multiply in its environment. Change in response of sensory organs to changed environmental conditions. A slow usually unconscious modi cation of individual and social activity in adjustment to cultural surroundings. Learn to acquire knowledge or skill by study, instruction or experience. Problem: Adaptation and feedback?

c K. J. str m and B. Wittenmark

Dual Control

uc Nonlinear control law u Process y

The Adaptive Control Problem

Principles Certainty Equivalence Caution Dual Control Controller structure Linear Nonlinear State Model Input Output Model Control Design Method Parameter Adjustment Method Speci cations Situation dependent? Optimality

0

5

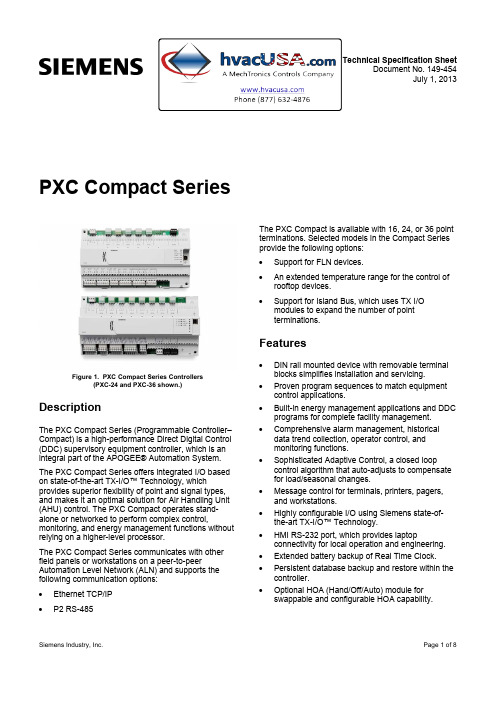

西门子PXCCompact系列控制器说明书

Technical Specification SheetDocument No. 149-454July 1, 2013 Siemens Industry, Inc. Page 1 of 8PXC Compact SeriesFigure 1. PXC Compact Series Controllers(PXC-24 and PXC-36 shown.)DescriptionThe PXC Compact Series (Programmable Controller–Compact) is a high-performance Direct Digital Control(DDC) supervisory equipment controller, which is anintegral part of the APOGEE® Automation System.The PXC Compact Series offers integrated I/O basedon state-of-the-art TX-I/O™ Technology, whichprovides superior flexibility of point and signal types,and makes it an optimal solution for Air Handling Unit(AHU) control. The PXC Compact operates stand-alone or networked to perform complex control,monitoring, and energy management functions withoutrelying on a higher-level processor.The PXC Compact Series communicates with otherfield panels or workstations on a peer-to-peerAutomation Level Network (ALN) and supports thefollowing communication options:∙ Ethernet TCP/IP∙P2 RS-485The PXC Compact is available with 16, 24, or 36 pointterminations. Selected models in the Compact Seriesprovide the following options:∙Support for FLN devices.∙An extended temperature range for the control ofrooftop devices.∙Support for Island Bus, which uses TX I/Omodules to expand the number of pointterminations.Features∙DIN rail mounted device with removable terminalblocks simplifies installation and servicing.∙Proven program sequences to match equipmentcontrol applications.∙Built-in energy management applications and DDCprograms for complete facility management.∙Comprehensive alarm management, historicaldata trend collection, operator control, andmonitoring functions.∙Sophisticated Adaptive Control, a closed loopcontrol algorithm that auto-adjusts to compensatefor load/seasonal changes.∙Message control for terminals, printers, pagers,and workstations.∙Highly configurable I/O using Siemens state-of-the-art TX-I/O™ Technology.∙HMI RS-232 port, which provides laptopconnectivity for local operation and engineering.∙Extended battery backup of Real Time Clock.∙Persistent database backup and restore within thecontroller.∙Optional HOA (Hand/Off/Auto) module forswappable and configurable HOA capability.∙Optional extended temperature range for rooftop installation.∙Optional peer-to-peer communications over industry-standard 10Base-T/100Base-TX Ethernet networks.∙Optional support for FLN devices.∙Optional support for P1 Wireless FLN.∙Optional operation as a P1 FLN device with default applications.∙Optional support for Virtual AEM.∙PXM10T and PXM10S support: Optional LCD Local user interface with HOA (Hand-off-auto)capability and point commanding and monitoringfeatures.The Compact SeriesIn addition to building and system management functions, the Compact Series includes several styles of controllers that flexibly meet application needs.PXC-16The PXC-16 provides control of 16 points, including 8 software-configurable universal points.Point count includes: 3 Universal Input (UI), 5 Universal I/O (U), 2 Digital Input (DI), 3 Analog Output (AOV), and 3 Digital Output (DO).PXC-24The PXC-24 provides control of 24 points, including 16 software-configurable universal points.Point count includes: 3 Universal Input (UI), 9 Universal I/O (U), 4 Super Universal I/O (X), 3 Analog Output (AOV), 5 Digital Output (DO).PXC-36The PXC-36 provides control of 36 local points, including 24 software-configurable universal points. Point count includes: 18 Universal I/O (U), 6 Super Universal I/O (X), 4 Digital Input (DI), and 8 Digital Output (DO).The PXC-36 offers the flexibility of expanding the total point count through a self-forming island bus. With the addition of a TX-I/O Power Supply, up to 4 TX-I/O modules can be supported. For more information, see the TX-I/O Product Range Technical Specification Sheet (149-476). Available OptionsThe following options are available to match the application:Ethernet or RS-485 ALNSupport for APOGEE P2 ALN through TCP/IP orRS-485 networks.FLN Support∙The PXC-24 “F32” models support up to 32 P1 FLN devices when the ALN is connected toTCP/IP.∙The PXC-24 “F” models with an FLN license support up to 32 P1 FLN devices when the ALN isconnected to TCP/IP.∙The PXC-36 with an FLN license supports up to 96 P1 FLN devices when the ALN is connected toRS-485 or TCP/IP.∙ A Wireless FLN may also be used to replace the traditional P1 FLN cabling with wirelesscommunication links that form a wireless meshnetwork. Additional hardware is required toimplement the Wireless FLN.For more information about FLN support, contact your local Siemens Industry representative.P1 FLN OperationThe PXC-16 and PXC-24 can be configured as a programmable P1 FLN device. In the P1 FLN mode, the PXC Compact functions as an equipment controller with customized programming and default applications.Virtual AEM SupportThe Virtual AEM license allows the PXC Compact to connect an RS-485 APOGEE Automation Level Network or individual field panels to a P2 Ethernet network without additional hardware.Extended Temperature OperationThe "R" models of the PXC Compact Series support extended temperature operation, allowing for rooftop installations.Field Panel GOThe PXC-36 supports Field Panel GO.The Field Panel GO license provides a Web-based user interface for your APOGEE® Building Automation System. It is an ideal solution for small or remote facilities with field panels on an Ethernet Automation Level Network (ALN).Page 2 of 8 Siemens Industry, Inc.HardwareThe PXC Compact Series consists of the following major components:∙ Input/Output Points∙ Power Supply∙ Controller ProcessorInput/Output Points∙The PXC Compact input/output points perform A/D or D/A conversion, signal processing, pointcommand output, and communication with thecontroller processor. The terminal blocks areremovable for easy termination of field wiring.∙The Universal and Super Universal points leverage TX-I/O™ Technology from SiemensIndustry to configure an extensive variety of pointtypes.∙Universal Input (UI) and Universal Input/Output (U) points are software-selectable to be:- 0-10V input-4-20 mA input- Digital Input-Pulse Accumulator inputs-1K Ni RTD @ 32°F (Siemens, JohnsonControls, DIN Standard)-1K Pt RTD (375 or 385 alpha) @ 32°F-10K NTC Thermistor (Type 2 and Type 3) @ 77°F-100K NTC Thermistor (Type 2) @ 77°F-0-10V Analog Output (Universal Input/Output (U) points only)∙Super Universal (X) points (PXC-24 and PXC-36 only) are software-selectable to be:- 0-10V input-4-20 mA input- Digital Input-Pulse Accumulator inputs-1K Ni RTD @ 32°F (Siemens, JohnsonControls, DIN Standard)-1K Pt RTD (375 or 385 alpha) @ 32°F-10K NTC Thermistor (Type 2 and Type 3) @ 77°F-100K NTC Thermistor (Type 2) @ 77°F- 0-10V Analog Output-4-20 mA Analog Output-Digital Output (using external relay)∙Dedicated Digital Input (DI) points (PXC-16 and PXC-36 only) are dry contact status sensing. ∙Digital Output (DO) points are 110/220V 4 Amp (resistive) Form C relays; LEDs indicate the status of each point.∙All PXC Compact Series models support 0-10 Vdc Voltage Analog Output circuits.∙On PXC-24 and PXC-36 models, the Super Universal circuits may be defined as 4-20 mAcurrent AO.Power Supply∙The 24 volt DC power supply provides regulated power to the input/output points and activesensors. The power supply is internal to the PXCCompact housing, eliminating the need forexternal power supply and simplifying installationand troubleshooting.∙The power supply works with the processor to ensure smooth power up and power downsequences for the equipment controlled by the I/O points, even through brownout conditions. Controller Processor∙The PXC Compact Series includes amicroprocessor-based multi-tasking platform forprogram execution and communications with theI/O points and with other PXC Compacts and field panels over the ALN.∙ A Human Machine Interface (HMI) port, with a quick-connect phone jack (RJ-45), uses RS-232protocol to support operator devices (such as alocal user interface or simple CRT terminal), and a phone modem for dial-in service capability.∙ A USB Device port supports a generic serial interface for an HMI or Tool connection.∙The program and database information stored in the PXC Compact RAM memory is battery-backed. This eliminates the need for time-consuming program and database re-entry in theevent of an extended power failure.∙The firmware, which includes the operating system, is stored in non-volatile flash ROMmemory; this enables firmware upgrades in thefield.∙Brownout protection and power recovery circuitry protect the controller board from powerfluctuations.∙LEDs provide instant visual indication of overall operation, network communication, and lowbattery warning.Siemens Industry, Inc. Page 3 of 8Programmable Control with Application FlexibilityThe PXC Compact Series of high performance controllers provides complete flexibility, which allows the owner to customize each controller with the exact program for the application.The control program for each PXC Compact is customized to exactly match the application. Proven Powers Process Control Language (PPCL), a text-based programming structure like BASIC, provides direct digital control and energy management sequences to precisely control equipment and optimize energy usage.Global Information AccessThe HMI port supports operator devices, such as a local user interface or simple CRT terminal, and a phone modem for dial-in service capability. Devices connected to the operator terminal port gain global information access.Multiple Operator AccessMultiple operators can access the network simultaneously. Multiple operator access ensures that alarms are reported to an alarm printer while an operator accesses information from a local terminal. When using the Ethernet TCP/IP ALN option, multiple operators may also access the controller through concurrent Telnet sessions and/or local operator terminal ports.Menu Prompted, English Language Operator InterfaceThe PXC Compact field panel includes a simple, yet powerful, menu-driven English Language Operator Interface that provides, among other things:∙Point monitoring and display∙ Point commanding∙Historical trend collection and display for multiple points∙ Event scheduling∙Program editing and modification via Powers Process Control Language (PPCL)∙Alarm reporting and acknowledgment∙Continual display of dynamic information Built-in Direct Digital Control RoutinesThe PXC Compact provides stand-alone Direct Digital Control (DDC) to deliver precise HVAC control and comprehensive information about system operation. The controller receives information from sensors in the building, processes the information, and directly controls the equipment. The following functions are available:∙Adaptive Control, an auto-adjusting closed loop control algorithm, which provides more efficient,adaptive, robust, fast, and stable control than thetraditional PID control algorithm. It is superior interms of response time and holding steady state,and at minimizing error, oscillations, and actuatorrepositioning.∙Closed Loop Proportional, Integral and Derivative (PID) control.∙ Logical sequencing.∙Alarm detection and reporting.∙ Reset schedules.Built-in Energy Management ApplicationsThe following applications are programmed in the PXC Compact Series and require simple parameter input for implementation:∙Automatic Daylight Saving Time switchover∙ Calendar-based scheduling∙ Duty cycling∙ Economizer control∙Equipment scheduling, optimization andsequencing∙ Event scheduling∙ Holiday scheduling∙Night setback control∙Peak Demand Limiting (PDL)∙Start-Stop Time Optimization (SSTO)∙ Temperature-compensated duty cycling∙Temporary schedule overridePage 4 of 8 Siemens Industry, Inc.SpecificationsDimensions (L × W × D)PXC-16 and PXC-2410.7 in. × 5.9 in. × 2.45 in. (272 mm × 150 mm × 62 mm)PXC-3611.5 in. × 5.9 in. × 3.0 in. (293 mm × 150 mm × 77 mm) Processor, Battery, and MemoryProcessor and Clock SpeedPXC-16 and PXC-24: Motorola MPC852T, 100 MHzPXC-36: Motorola MPC885, 133 MHz MemoryPXC-16 and PXC-24: 24 MB (16 MB SDRAM, 8 MB Flash ROM)PXC-36: 80 MB (64 MB SDRAM, 16 MB Flash ROM) Battery backup of Synchronous Dynamic (SD) RAM (field replaceable)Non-rooftop Models: 60 days (accumulated),AA (LR6) 1.5 Volt Alkaline (non-rechargeable)Rooftop (Extended Temperature) Models: 90 days (accumulated),AA (LR6) 3.6 Volt Lithium (non-rechargeable) Battery backup of Real Time ClockNon-rooftop Models: 10 yearsRooftop (Extended Temperature) Models: 18 months CommunicationA/D Resolution (analog in)16 bitsD/A Resolution (analog out)10 bitsEthernet/IP Automation Level Network (ALN)10Base-T or 100Base-TX compliant RS-485 Automation Level Network (ALN)1200 bps to 115.2 Kbps RS-485 P1 Field Level Network (FLN) on selected models, license required4800 bps to 38.4 Kbps Human-Machine Interface (HMI)RS-232 compliant, 1200 bps to 115.2 Kbps USB Device port (for non-smoke control applications only)Standard 1.1 and 2.0 USB device port, Type B female connector.USB Host port on selected models (for ancillary smoke control applications only)Standard 1.1 and 2.0 USB host port, Type A female connector. ElectricalPower Requirements24 Vac ±20% input @ 50/60 HzPower Consumption (Maximum)PXC-16: 18 VA @ 24 VacPXC-24: 20 VA @ 24 VacPXC-36: 35 VA @ 24 Vac Siemens Industry, Inc. Page 5 of 8AC Power and Digital OutputsNEC Class 1 Power Limited Communication and all other I/ONEC Class 2 Digital InputContact Closure SensingDry Contact/Potential Free inputs onlyDoes not support counter inputs Digital OutputClass 1 Relay Analog Output0 to 10 VdcUniversal Input (UI) and Universal Input/Output (U)Analog InputVoltage (0-10 Vdc)Current (4-20 mA)1K Ni RTD @ 32°F1K Pt RTD (375 or 385 alpha) @ 32°F10K NTC Type 2 or Type 3 Thermistor @ 77°F100K NTC Type 2 Thermistor @ 77°FDigital InputPulse AccumulatorContact Closure SensingDry Contact/Potential Free inputs onlySupports counter inputs up to 20 HzAnalog Output (Universal Input/Output (U) points only)Voltage (0-10 Vdc) Super Universal (X)Analog InputVoltage (0-10 Vdc)Current (4-20 mA)1K Ni RTD @ 32°F1K Pt RTD (375 or 385 alpha) @ 32°F10K NTC Type 2 or Type 3 Thermistor @ 77°F100K NTC Type 2 Thermistor @ 77°FDigital InputPulse AccumulatorContact Closure SensingDry Contact/Potential Free inputs onlySupports counter inputs up to 20 HzAnalog OutputVoltage (0-10 Vdc)Current (4-20 mA)Digital Output (requires an external relay)0 to 24 Vdc, 22 mA max. Operating EnvironmentAmbient operating temperature32°F to 122°F (0°C to 50°C) Ambient operating temperature with rooftop (extended temperature) option-40°F to 158°F (-40°C to 70°C) Relative HumidityPXC-16 and PXC-24: 5% to 95%, non-condensingPXC-36: 5% to 95%, non-condensing Page 6 of 8 Siemens Industry, Inc.Mounting SurfacePXC-16 and PXC-24: Direct equipment mount, building wall, or structural memberPXC-36: Building wall or a secure structure Agency ListingsULUL864 UUKL (except rooftop models)UL864 UUKL7 (except rooftop models)CAN/ULC-S527-M8 (except rooftop models)UL916 PAZX (all models)UL916 PAZX7 (all models) Agency ComplianceFCC ComplianceAustralian EMC FrameworkEuropean EMC Directive (CE)European Low Voltage Directive (LVD) OSHPD Seismic CertificationProduct meets OSHPD Special Seismic Preapproval certification(OSH-0217-10) under California Building Code 2010 (CBC2010) andInternational Building Code 2009 (IBC2009) when installed within thefollowing Siemens enclosure part numbers: PXA-ENC18, PXA-ENC19,or PXA-ENC34. Ordering InformationPXC Compact SeriesProduct Number DescriptionPXC16.2-P.A PXC Compact, 16 point, RS-485 ALNPXC16.2-PE.A PXC Compact, 16 point, Ethernet/IP ALNPXC24.2-P.A PXC Compact, 24 point, RS-485 ALNPXC24.2-PE.A PXC Compact, 24 point, Ethernet/IP ALNPXC24.2-PR.A PXC Compact, 24 point, RS-485 ALN, rooftop optionPXC24.2-PER.A PXC Compact, 24 point, Ethernet/IP ALN, rooftop optionPXC24.2-PEF.A PXC Compact, 24 point, Ethernet/IP or RS-485 ALN. P1 FLN or Remote Ethernet/IP(Virtual AEM) option.PXC24.2-PEF32.A PXC Compact, 24 point, Ethernet/IP or RS-485 ALN. P1 FLN enabledPXC24.2-PERF.A PXC Compact, 24 point, Ethernet/IP or RS-485 ALN, rooftop option. P1 FLN or RemoteEthernet/IP (Virtual AEM) option.PXC36-PE.A PXC Compact, 36 point, Ethernet/IP or RS-485 ALN.PXC36-PEF.A PXC Compact, 36 point, Ethernet/IP or RS-485 ALN, Island Bus, P1 FLN.Siemens Industry, Inc. Page 7 of 8Information in this document is based on specifications believed correct at the time of publication. The right is reserved to make changes as design improvements are introduced. APOGEE and Insight are registered trademarks of Siemens Industry, Inc. Other product or company names mentioned herein may be the trademarks of their respective owners. © 2013 Siemens Industry, Inc.Siemens Industry, Inc. Building Technologies Division 1000 Deerfield Parkway Buffalo Grove, IL 60089-4513 USA+ 1 847-215-1000Your feedback is important to us. If you havecomments about this document, please send them to***************************************.Document No. 149-454Printed in USAPage 8 of 8Optional LicensesProduct Number DescriptionLSM-FLN License to enable FLN support on PXC-16 or PXC-24 “F”modelsLSM-VAEM License to enable Virtual AEM support when the ALN is connected to RS-485LSM-FLN36.A License to enable FLN support on model PXC36-PE.ALSM-FPGO License to enable Field Panel GO on models PXC36-PE.A and PXC36-PEF.ALSM-IB36.A License to enable the Island Bus on model PXC36-PE.ALSM-36.A License to enable both FLN and Island Bus support on model PXC36-PE.AAccessoriesProduct Number DescriptionPXM10S Controller mounted Operator Display module with point monitor and optional blue backlight PXM10T Controller mounted Operator Display modulePXA8-M 8-switchHOA(UL864)PXA16-M 16-switchHOA(UL864)PXA16-MR 16-switch HOA (extended temp, UL 916) with HMI cablePXA-HMI.CABLEP5 Serial cable required for HOA or PXM10T/S connection to non-rooftop variants ofthe 16-point and 24-point Compact Series (pack of 5)TXA1.LLT-P100 Labels for HOA and TX-I/O Modules, pack of 100, letter formatService Boxes and EnclosuresProduct Number DescriptionPXA-SB115V192VA PX Series Service Box —115V, 24 Vac, 50/60 Hz, 192 VAPXA-SB115V384VA PX Series Service Box— 115V, 24 Vac, 50/60 Hz, 384 VAPXA-SB230V192VA PX Series Service Box— 230V, 24 Vac, 50/60 Hz, 192 VAPXA-SB230V384VA PX Series Service Box —230V, 24 Vac, 50/60 Hz, 384 VAPXA-ENC18 18" Enclosure (Utility Cabinet) (UL Listed NEMA Type 1 Enclosure)PXA-ENC19 19” Enclosure (UL Listed NEMA Type 1 Enclosure)PXA-ENC34 34” Enclosure (UL Listed NEMA Type 1 Enclosure)DocumentationProduct Number Description553-104 PXC Compact Series Owner’s Manual125-1896 Powers Process Control Language (PPCL) User’s Manual。

Adaptive tracking control of uncertain MIMO nonlinear systems with input constraints

article

info

abstract

In this paper, adaptive tracking control is proposed for a class of uncertain multi-input and multi-output nonlinear systems with non-symmetric input constraints. The auxiliary design system is introduced to analyze the effect of input constraints, and its states are used to adaptive tracking control design. The spectral radius of the control coefficient matrix is used to relax the nonsingular assumption of the control coefficient matrix. Subsequently, the constrained adaptive control is presented, where command filters are adopted to implement the emulate of actuator physical constraints on the control law and virtual control laws and avoid the tedious analytic computations of time derivatives of virtual control laws in the backstepping procedure. Under the proposed control techniques, the closed-loop semi-global uniformly ultimate bounded stability is achieved via Lyapunov synthesis. Finally, simulation studies are presented to illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed adaptive tracking control. © 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

基于强化学习的自主式水下潜器障碍规避技术