60秒读懂经济学概念(中英文对照)

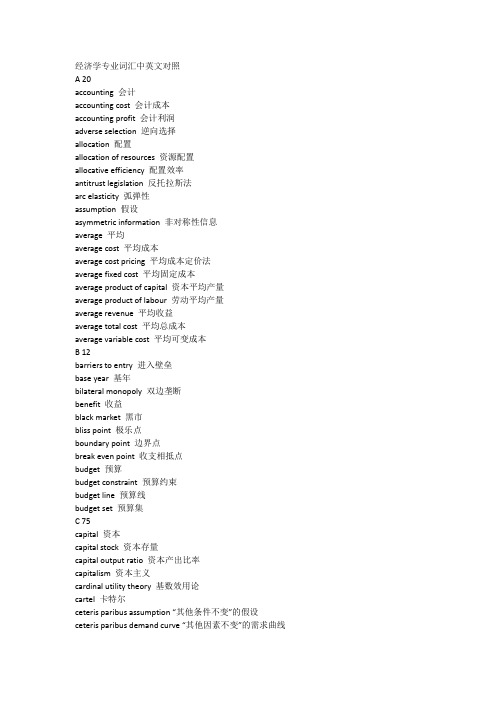

经济学专业词汇中英文对照

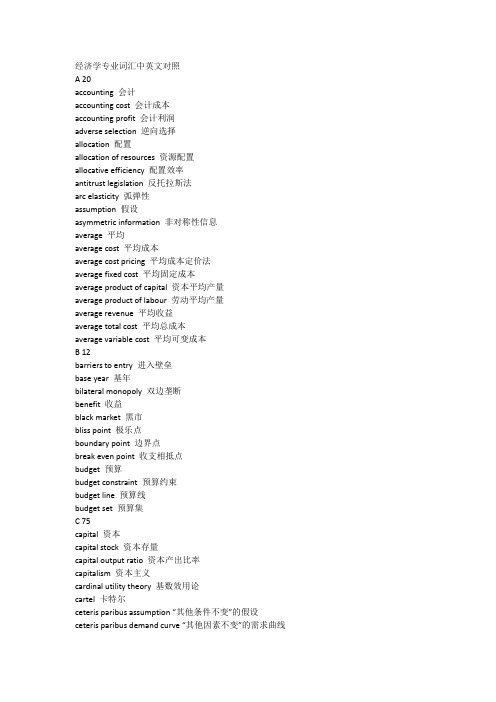

经济学专业词汇中英文对照A 20accounting 会计accounting cost 会计成本accounting profit 会计利润adverse selection 逆向选择allocation 配置allocation of resources 资源配置allocative efficiency 配置效率antitrust legislation 反托拉斯法arc elasticity 弧弹性assumption 假设asymmetric information 非对称性信息average 平均average cost 平均成本average cost pricing 平均成本定价法average fixed cost 平均固定成本average product of capital 资本平均产量average product of labour 劳动平均产量average revenue 平均收益average total cost 平均总成本average variable cost 平均可变成本B 12barriers to entry 进入壁垒base year 基年bilateral monopoly 双边垄断benefit 收益black market 黑市bliss point 极乐点boundary point 边界点break even point 收支相抵点budget 预算budget constraint 预算约束budget line 预算线budget set 预算集C 75capital 资本capital stock 资本存量capital output ratio 资本产出比率capitalism 资本主义cardinal utility theory 基数效用论cartel 卡特尔ceteris paribus assumption “其他条件不变”的假设ceteris paribus demand curve “其他因素不变”的需求曲线Chamberlain model 张伯伦模型change in demand 需求变化change in quantity demanded 需求量变化change in quantity supplied 供给量变化change in supply 供给变化choice 选择closed set 闭集Coase theorem 科斯定理Cobb-Douglas production function 柯布--道格拉斯生产函数cobweb model 蛛网模型collective bargaining 集体协议工资collusion 合谋command economy 指令经济commodity 商品commodity combination 商品组合commodity market 商品市场commodity space 商品空间common property 公用财产comparative static analysis 比较静态分析compensated budget line 补偿预算线compensated demand function 补偿需求函数compensation principles 补偿原则compensating variation in income 收入补偿变量competition 竞争competitive market 竞争性市场complement goods 互补品complete information 完全信息completeness 完备性condition for efficiency in exchange交换的最优条件condition for efficiency in production生产的最优条件concave 凹concave function 凹函数concave preference 凹偏好consistence 一致性constant cost industry 成本不变产业constant returns to scale 规模报酬不变constraints 约束consumer 消费者consumer behavior 消费者行为consumer choice 消费者选择consumer equilibrium 消费者均衡consumer optimization 消费者优化consumer preference 消费者偏好consumer surplus 消费者剩余consumer theory 消费者理论consumption 消费consumption bundle 消费束consumption combination 消费组合consumption possibility curve 消费可能曲线consumption possibility frontier 消费可能性前沿consumption set 消费集consumption space 消费空间continuity 连续性continuous function 连续函数contract curve 契约曲线convex 凸convex function 凸函数convex preference 凸偏好convex set 凸集corporation 公司cost 成本cost benefit analysis 成本收益分析cost function 成本函数cost minimization 成本最小化Cournot equilibrium 古诺均衡Cournot model 古诺模型cross-price elasticity 交叉价格弹性D 32dead-weights loss 重负损失decreasing cost industry 成本递减产业decreasing returns to scale 规模报酬递减deduction 演绎法demand 需求demand curve 需求曲线demand elasticity 需求弹性demand function 需求函数demand price 需求价格demand schedule 需求表depreciation 折旧derivative 导数derive demand 派生需求difference equation 差分方程differential equation 微分方程differentiated good 差异商品differentiated oligopoly 差异寡头diminishing marginal substitution 边际替代率递减diminishing marginal return 收益递减diminishing marginal utility 边际效用递减direct approach 直接法direct taxes 直接税discounting 贴水、折扣diseconomies of scale 规模不经济disequilibrium 非均衡distribution 分配division of labour 劳动分工duopoly 双头垄断、双寡duality 对偶durable goods 耐用品dynamic analysis 动态分析dynamic models 动态模型E 50economic agents 经济行为者economic cost 经济成本economic efficiency 经济效率economic goods 经济物品economic man 经济人economic mode 经济模型economic profit 经济利润economic regulation 经济调节economic rent 经济租金exchange 交换exchange efficiency 交换效率exchange contract curve 交换契约曲线economy of scale 规模经济Edgeworth box diagram 埃奇沃思图exclusion 排斥性、排他性Edgeworth contract curve 埃奇沃思契约线Edgeworth model 埃奇沃思模型efficiency 效率、效益efficiency parameter 效率参数elasticity 弹性elasticity of substitution 替代弹性endogenous variable 内生变量endowment 禀赋endowment of resources 资源禀赋Engel curve 恩格尔曲线entrepreneur 企业家entrepreneurship 企业家才能entry barriers 进入壁垒entry/exit decision 进出决策envelope curve 包络线equilibrium 均衡equilibrium condition 均衡条件equilibrium price 均衡价格equilibrium quantity 均衡产量equity 公平equivalent variation in income 收入等价变量excess-capacity theorem 过度生产能力定理existence 存在性existence of general equilibrium 总体均衡的存在性expansion paths 扩展径expectation 期望expected utility 期望效用expected value 期望值expenditure 支出explicit cost 显性成本external benefit 外部收益external cost 外部成本external economy 外部经济external diseconomy 外部不经济externalities 外部性F 24factor 要素factor demand 要素需求factor market 要素市场factors of production 生产要素factor substitution 要素替代factor supply 要素供给fallacy of composition 合成谬误final goods 最终产品firm 企业firms' demand curve for labour 企业劳动需求曲线firm supply curve 企业供给曲线first-degree price discrimination 第一级价格歧视first-order condition 一阶条件fixed costs 固定成本fixed input 固定投入fixed proportions production function 固定比例的生产函数flow 流量fluctuation 波动for whom to produce 为谁生产free entry 自由进入free goods 自由品、免费品free mobility of resources 资源自由流动free rider 搭便车、免费搭车者future value 未来值G 11game theory 博弈论、对策论general equilibrium 总体均衡、一般均衡general goods 一般商品Giffen goods 吉芬商品Giffen's Paradox 吉芬之谜Gini coefficient 吉尼系数golden rule 黄金规则government failure 政府失败government regulation 政府调控grand utility possibility curve 总效用可能曲线grand utility possibility frontier 总效用可能前沿H 9heterogeneous product 异质产品Hicks-kaldor welfare criterion 希克斯-卡尔多福利标准homogeneity 齐次性homogeneous demand function 齐次需求函数homogeneous product 同质产品homogeneous production function 齐次生产函数horizontal summation 水平和human capital 人力资本hypothesis 假说I 52identity 恒等式imperfect competition 不完全竞争implicit cost 隐性成本income 收入income compensated demand curve 收入补偿需求曲线income constraint 收入约束income consumption curve 收入消费曲线income distribution 收入分配income effect 收入效应income elasticity of demand 需求收入弹性increasing cost industry 成本递增产业increasing returns to scale 规模报酬递增index number 指数indifference 无差异indifference curve 无差异曲线indifference map 无差异族indifference relation 无差异关系indifference set 无差异集indirect approach 间接法individual analysis 个量分析individual demand curve 个人需求曲线individual demand function 个人需求函数induced variable 引致变量induction 归纳法industry 产业industry equilibrium 产业均衡industry supply curve 产业供给曲线inelastic 缺乏弹性的inferior goods 劣品inflection point 拐点information 信息information cost 信息成本initial condition 初始条件initial endowment 初始禀赋innovation 创新input 投入input-output 投入-产出institution 制度institutional economics 制度经济学insurance 保险intercept 截距interest 利息interest rate 利息率intermediate goods 中间产品internalization of externalities 外部性内部化invention 发明inverse demand function 反需求函数invisible hand 看不见的手isocost line 等成本线isoprofit curve 等利润曲线isoquant curve 等产量曲线isoquant map 等产量族K 1kinked-demand curve 弯折的需求曲线L 30labour demand 劳动需求labour supply 劳动供给labour theory of value 劳动价值论labour unions 工会laissez faire 自由放任Lagrangian function 拉格朗日函数Lagrangian multiplier 拉格朗日乘数law of demand and supply 供需法则law of diminishing marginal utility 边际效用递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution边际替代率递减法则law of increasing cost 成本递增法则law of one price 单一价格法则leader-follower model 领导者-跟随者模型least-cost combination of inputs最低成本的投入组合leisure 闲暇Leontief production function 里昂惕夫生产函数licenses 许可证linear demand function 线性需求函数linear homogeneity 线性齐次性linear homogeneous production function线性齐次生产函数long run 长期long run average cost 长期平均成本long run equilibrium 长期均衡long run industry supply curve 长期产业供给曲线long run marginal cost 长期边际成本long run total cost 长期总成本Lorenz curve 洛伦兹曲线loss minimization 损失极小化lump sum tax 一次性征税luxury 奢侈品M 45macroeconomics 宏观经济学marginal benefit 边际收益marginal cost 边际成本marginal cost pricing 边际成本定价marginal cost of factor 边际要素成本marginal period 市场期marginal physical productivity 边际实物生产率marginal product 边际产量marginal product of capital 资本的边际产量marginal product of labour 劳动的边际产量marginal productivity 边际生产率marginal rate of substitution 边际替代率marginal rate of transformation 边际转换率marginal returns 边际回报marginal revenue 边际收益marginal revenue product 边际收益产品marginal revolution 边际革命marginal social benefit 社会边际收益marginal social cost 社会边际成本marginal utility 边际效用marginal value products 边际价值产品market clearance 市场出清market economy 市场经济market equilibrium 市场均衡market failure 市场失灵market mechanism 市场机制market structure 市场结构market separation 市场分割market regulation 市场调节market share 市场份额markup pricing 加减定价法Marshallian demand function 马歇尔需求函数maximization 最大化microeconomics 微观经济学minimum wage 最低工资misallocation of resources 资源误置mixed economy 混合经济monopolistic competition 垄断竞争monopolistic exploitation 垄断剥削monopoly 垄断,卖方垄断monopoly equilibrium 垄断均衡monopoly pricing 垄断定价monopoly regulation 垄断调控monopoly rents 垄断租金monopsony 买方垄断N 17Nash equilibrium 纳什均衡natural monopoly 自然垄断natural resources 自然资源necessary condition 必要条件necessities 必需品net demand 净需求nonconvex preference 非凸性偏好nonconvexity 非凸性nonexclusion 非排斥性nonlinear pricing 非线性定价nonrivalry 非对抗性nonprice competition 非价格竞争nonsatiation 非饱和性non-zero-sum game 非零和对策normal goods 正常品normal profit 正常利润normative economics 规范经济学O 17objective function 目标函数oligopoly 寡头垄断oligopoly market 寡头市场oligopoly model 寡头模型opportunity cost 机会成本optimal choice 最佳选择optimal consumption bundle 消费束optimal resource allocation 最佳资源配置optimal scale 最佳规模optimal solution 最优解optimization 优化ordering of optimization (social) preference (社会)偏好排序ordinal utility 序数效用ordinary goods 一般品output 产出output elasticity 产出弹性output maximization 产出极大化P 68parameter 参数Pareto criterion 帕累托标准Pareto efficiency 帕累托效率Pareto improvement 帕累托改进Pareto optimality 帕累托优化Pareto set 帕累托集partial derivative 偏导数partial equilibrium 局部均衡patent 专利pay off matrix 收益矩阵、支付矩阵perceived demand curve 感觉到的需求曲线perfect competition 完全竞争perfect complement 完全互补品perfect monopoly 完全垄断perfect price discrimination 完全价格歧视perfect substitution 完全替代品perfect inelasticity 完全无弹性perfect elasticity 完全有弹性plant size 工厂规模point elasticity 点弹性positive economics 实证经济学Post Hoc Fallacy 后此谬误prediction 预测preference 偏好preference relation 偏好关系present value 现值price adjustment model 价格调整模型price ceiling 最高限价price consumption curve 价格消费曲线price control 价格管制price difference 价格差别price discrimination 价格歧视price elasticity of demand 需求价格弹性price elasticity of supply 供给价格弹性price floor 最低限价price maker 价格制定者price rigidity 价格刚性price seeker 价格搜求者price taker 价格接受者private benefit 私人收益principal-agent issues 委托-代理问题private cost 私人成本private goods 私人用品private property 私人财产producer equilibrium 生产者均衡producer theory 生产者论product transformation curve 产品转换曲线product differentiation 产品差异product group 产品集团production contract curve 生产契约曲线production efficiency 生产效率production function 生产函数production possibility curve 生产可能曲线productivity 生产率productivity of capital 资本生产率productivity of labour 劳动生产率profit function 利润函数profit maximization 利润最大化property rights 产权property rights economics 产权经济学proposition 定理proportional demand curve 成比例的需求函数public benefits 公共收益public choice 公共选择public goods 公共商品pure competition 纯粹竞争pure exchange 纯交换pure monopoly 纯粹垄断Q 3quantity-adjustment model 数量调整模型quantity tax 从量税quasi-rent 准租金R 18rate of product transformation 产品转换率rationality 理性reaction function 反应函数regulation 调节,调控relative price 相对价格rent 租金rent seeking 寻租rent seeking economics 寻租经济学resource 资源resource allocation 资源配置returns 报酬、回报returns to scale 规模报酬revealed preference 显示性偏好revenue 收益revenue curve 收益曲线revenue function 收益函数revenue maximization 收益最大化ridge line 脊线S 43satiation 饱和,满足saving 储蓄scarcity 稀缺性law of scarcity 稀缺法则second-degree price discrimination 二级价格歧视second derivative 二阶导数second-order condition 二阶条件service 劳务shadow prices 影子价格short-run 短期short-run cost curve 短期成本曲线short-run equilibrium 短期均衡short-run supply curve 短期供给曲线shut down decision 关闭决策shortage 短缺shut down point 关闭点single price monopoly 单一定价垄断slope 斜率social benefit 社会收益social cost 社会成本social indifference curve 社会无差异曲线social preference 社会偏好social security 社会保障social welfare function 社会福利函数socialism 社会主义solution 解space 空间stability 稳定性stable equilibrium 稳定的均衡Stackelberg model 斯塔克尔贝格模型static analysis 静态分析stock 存量stock market 股票市场strategy 策略subsidy 补贴substitutes 替代品substitution effect 替代效应substitution parameter 替代参数sufficient condition 充分条件supply schedule 供给表Sweezy model 斯威齐模型symmetry 对称性symmetry of information 信息对称T 16tangency 相切technical efficiency 技术效率technological constraints 技术约束technological progress 技术进步third-degree price discrimination 第三级价格歧视total cost 总成本total effect 总效应total expenditure 总支出total fixed cost 总固定成本total product 总产量total revenue 总收益total utility 总效用total variable cost 总可变成本traditional economy 传统经济transitivity 传递性transaction cost 交易费用U 8uncertainty 不确定性uniqueness 唯一性unit elasticity 单位弹性unstable equilibrium 不稳定均衡utility index 效用指数utility maximization 效用最大化utility possibility curve 效用可能性曲线utility possibility frontier 效用可能性前沿V 8value judge 价值判断value of marginal product 边际产量价值variable cost 可变成本variable input 可变投入variables 变量vector 向量visible hand 看得见的手vulgar economics 庸俗经济学W 8wage rate 工资率Walras general equilibrium 瓦尔拉斯总体均衡Walras's law 瓦尔拉斯法则Wants 需要Welfare criterion 福利标准Welfare economics 福利经济学Welfare loss triangle 福利损失三角形Welfare maximization 福利最大化Z 4zero cost 零成本zero elasticity 零弹性zero homogeneity 零阶齐次性zero economic profit 零利润。

经济学最全词典 中英对照

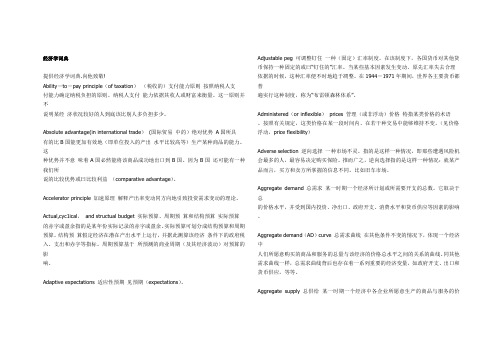

经济学词典提供经济学词典.向他致敬!Ability-to-pay principle(of taxation)(税收的)支付能力原则按照纳税人支付能力确定纳税负担的原则。

纳税人支付能力依据其收人或财富来衡量。

这一原则并不说明某经济状况较好的人到底该比别人多负担多少。

Absolute advantage(in international trade)(国际贸易中的)绝对优势A国所具有的比B国能更加有效地(即单位投入的产出水平比较高等)生产某种商品的能力。

这种优势并不意味着A国必然能将该商品成功地出口到B国。

因为B国还可能有一种我们所说的比较优势或曰比较利益(comparative advantage)。

Accelerator principle 加速原理解释产出率变动同方向地引致投资需求变动的理论。

Actual,cyc1ical,and structual budget 实际预算、周期预算和结构预算实际预算的赤字或盈余指的是某年份实际记录的赤字或盈余。

实际预算可划分成结构预算和周期预算。

结构预算假定经济在潜在产出水平上运行,并据此测算该经济条件下的政府税入、支出和赤字等指标。

周期预算基于所预测的商业周期(及其经济波动)对预算的影响。

Adaptive expectations 适应性预期见预期(expectations)。

Adjustable peg 可调整钉住一种(固定)汇率制度。

在该制度下,各国货币对其他货币保持一种固定的或曰“钉住的”汇率。

当某些基本因素发生变动、原先汇率失去合理依据的时候,这种汇率便不时地趋于凋整。

在1944-1971年期间,世界各主要货币都普遍实行这种制度,称为“布雷顿森林体系”。

Administered(or inflexible)prices 管理(或非浮动)价格特指某类价格的术语。

按照有关规定,这类价格在某一段时间内、在若干种交易中能够维持不变。

(见价格浮动,price flexibility)Adverse selection 逆向选择一种市场不灵。

经济学基础术语中英对照.

经济学基础术语中英对照经济学词汇Aaccounting:会计accounting cost :会计成本accounting profit :会计利润adverse selection :逆向选择allocation 配置allocation of resources :资源配置allocative efficiency :配置效率antitrust legislation :反托拉斯法arc elasticity :弧弹性Arrow's impossibility theorem :阿罗不可能定理Assumption :假设asymetric information :非对称性信息average :平均average cost :平均成本average cost pricing :平均成本定价法average fixed cost :平均固定成本average product of capital :资本平均产量average product of labour :劳动平均产量average revenue :平均收益average total cost :平均总成本average variable cost :平均可变成本Bbarriers to entry :进入壁垒base year :基年bilateral monopoly :双边垄断benefit :收益black market :黑市bliss point :极乐点boundary point :边界点break even point :收支相抵点budget :预算budget constraint :预算约束budget line :预算线budget set 预算集Ccapital :资本capital stock :资本存量capital output ratio :资本产出比率capitalism :资本主义cardinal utility theory :基数效用论cartel :卡特尔ceteris puribus assumption :“其他条件不变”的假设ceteris puribus demand curve :其他因素不变的需求曲线Chamberlin model :张伯伦模型change in demand :需求变化change in quantity demanded :需求量变化change in quantity supplied :供给量变化change in supply :供给变化choice :选择closed set :闭集Coase theorem :科斯定理Cobb—Douglas production function :柯布--道格拉斯生产函数cobweb model :蛛网模型collective bargaining :集体协议工资collusion :合谋command economy :指令经济commodity :商品commodity combination :商品组合commodity market :商品市场commodity space :商品空间common property :公用财产comparative static analysis :比较静态分析compensated budget line :补偿预算线compensated demand function :补偿需求函数compensation principles :补偿原则compensating variation in income :收入补偿变量competition :竞争competitive market :竞争性市场complement goods :互补品complete information :完全信息completeness :完备性condition for efficiency in exchange :交换的最优条件condition for efficiency in production :生产的最优条件concave :凹concave function :凹函数concave preference :凹偏好consistence :一致性constant cost industry :成本不变产业constant returns to scale :规模报酬不变constraints :约束consumer :消费者consumer behavior :消费者行为consumer choice :消费者选择consumer equilibrium :消费者均衡consumer optimization :消费者优化consumer preference :消费者偏好consumer surplus :消费者剩余consumer theory :消费者理论consumption :消费consumption bundle :消费束consumption combination :消费组合consumption possibility curve :消费可能曲线consumption possibility frontier :消费可能性前沿consumption set :消费集consumption space :消费空间continuity :连续性continuous function :连续函数contract curve :契约曲线convex :凸convex function :凸函数convex preference :凸偏好convex set :凸集corporatlon :公司cost :成本cost benefit analysis :成本收益分cost function :成本函数cost minimization :成本极小化Cournot equilihrium :古诺均衡Cournot model :古诺模型Cross—price elasticity :交叉价格弹性Ddead—weights loss :重负损失decreasing cost industry :成本递减产业decreasing returns to scale :规模报酬递减deduction :演绎法demand :需求demand curve :需求曲线demand elasticity :需求弹性demand function :需求函数demand price :需求价格demand schedule :需求表depreciation :折旧derivative :导数derive demand :派生需求difference equation :差分方程differential equation :微分方程differentiated good :差异商品differentiated oligoply :差异寡头diminishing marginal substitution :边际替代率递减diminishing marginal return :收益递减diminishing marginal utility :边际效用递减direct approach :直接法direct taxes :直接税discounting :贴税、折扣diseconomies of scale :规模不经济disequilibrium :非均衡distribution :分配division of labour :劳动分工distribution theory of marginal productivity :边际生产率分配论duoupoly :双头垄断、双寡duality :对偶durable goods :耐用品dynamic analysis :动态分析dynamic models :动态模型EEconomic agents :经济行为者economic cost :经济成本economic efficiency :经济效率economic goods :经济物品economic man :经济人economic mode :经济模型economic profit :经济利润economic region of production :生产的经济区域economic regulation :经济调节economic rent :经济租金exchange :交换economics :经济学exchange efficiency :交换效率economy :经济exchange contract curve :交换契约曲线economy of scale :规模经济Edgeworth box diagram :埃奇沃思图exclusion :排斥性、排他性Edgeworth contract curve :埃奇沃思契约线Edgeworth model :埃奇沃思模型efficiency :效率,效益efficiency parameter :效率参数elasticity :弹性elasticity of substitution :替代弹性endogenous variable :内生变量endowment :禀赋endowment of resources :资源禀赋Engel curve :恩格尔曲线entrepreneur :企业家entrepreneurship :企业家才能entry barriers :进入壁垒entry/exit decision :进出决策envolope curve :包络线equilibrium :均衡equilibrium condition :均衡条件equilibrium price :均衡价格equilibrium quantity :均衡产量eqity :公平equivalent variation in income :收入等价变量excess—capacity theorem :过度生产能力定理excess supply :过度供给exchange :交换exchange contract curve :交换契约曲线exclusion :排斥性、排他性exclusion principle :排他性原则existence :存在性existence of general equilibrium :总体均衡的存在性exogenous variables :外生变量expansion paths :扩展径expectation :期望expected utility :期望效用expected value :期望值expenditure :支出explicit cost :显性成本external benefit :外部收益external cost :外部成本external economy :外部经济external diseconomy :外部不经济externalities :外部性FFactor :要素factor demand :要素需求factor market :要素市场factors of production :生产要素factor substitution :要素替代factor supply :要素供给fallacy of composition :合成谬误final goods :最终产品firm :企业firms’demand curve for labor :企业劳动需求曲线firm supply curve :企业供给曲线first-degree price discrimination :第一级价格歧视first—order condition :一阶条件fixed costs :固定成本fixed input :固定投入fixed proportions production function :固定比例的生产函数flow :流量fluctuation :波动for whom to produce :为谁生产free entry :自由进入free goods :自由品,免费品free mobility of resources :资源自由流动free rider :搭便车,免费搭车function :函数future value :未来值Ggame theory :对策论、博弈论general equilibrium :总体均衡general goods :一般商品Giffen goods :吉芬晶收入补偿需求曲线Giffen's Paradox :吉芬之谜Gini coefficient :吉尼系数goldenrule :黄金规则goods :货物government failure :政府失败government regulation :政府调控grand utility possibility curve :总效用可能曲线grand utility possibility frontier :总效用可能前沿Hheterogeneous product :异质产品Hicks—kaldor welfare criterion :希克斯一卡尔多福利标准homogeneity :齐次性homogeneous demand function :齐次需求函数homogeneous product :同质产品homogeneous production function :齐次生产函数horizontal summation :水平和household :家庭how to produce :如何生产human capital :人力资本hypothesis :假说Iidentity :恒等式imperfect competion :不完全竞争implicitcost :隐性成本income :收入income compensated demand curve :收入补偿需求曲线income constraint :收入约束income consumption curve :收入消费曲线income distribution :收入分配income effect :收入效应income elasticity of demand :需求收入弹性increasing cost industry :成本递增产业increasing returns to scale :规模报酬递增inefficiency :缺乏效率index number :指数indifference :无差异indifference curve :无差异曲线indifference map :无差异族indifference relation :无差异关系indifference set :无差异集indirect approach :间接法individual analysis :个量分析individual demand curve :个人需求曲线individual demand function :个人需求函数induced variable :引致变量induction :归纳法industry :产业industry equilibrium :产业均衡industry supply curve :产业供给曲线inelastic :缺乏弹性的inferior goods :劣品inflection point :拐点information :信息information cost :信息成本initial condition :初始条件initial endowment :初始禀赋innovation :创新input :投入input—output :投入—产出institution :制度institutional economics :制度经济学insurance :保险intercept :截距interest :利息interest rate :利息率intermediate goods :中间产品internatization of externalities :外部性内部化invention :发明inverse demand function :逆需求函数investment :投资invisible hand :看不见的手isocost line :等成本线,isoprofit curve :等利润曲线isoquant curve :等产量曲线isoquant map :等产量族Kkinded—demand curve :弯折的需求曲线Llabour :劳动labour demand :劳动需求labour supply :劳动供给labour theory of value :劳动价值论labour unions :工会laissez faire :自由放任Lagrangian function :拉格朗日函数Lagrangian multiplier :拉格朗乘数,land :土地law :法则law of demand and supply :供需法law of diminishing marginal utility :边际效用递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution :边际替代率递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of technical substitution :边际技术替代率law of increasing cost :成本递增法则law of one price :单一价格法则leader—follower model :领导者--跟随者模型least—cost combination of inputs :最低成本的投入组合leisure :闲暇Leontief production function :列昂节夫生产函数licenses :许可证linear demand function :线性需求函数linear homogeneity :线性齐次性linear homogeneous production function :线性齐次生产函数long run :长期long run average cost :长期平均成本long run equilibrium :长期均衡long run industry supply curve :长期产业供给曲线long run marginal cost :长期边际成本long run total cost :长期总成本Lorenz curve :洛伦兹曲线loss minimization :损失极小化1ump sum tax :一次性征税luxury :奢侈品Mmacroeconomics :宏观经济学marginal :边际的marginal benefit :边际收益marginal cost :边际成本marginal cost pricing :边际成本定价marginal cost of factor :边际要素成本marginal physical productivity :实际实物生产率marginal product :边际产量marginal product of capital :资本的边际产量marginal product of 1abour :劳动的边际产量marginal productivity :边际生产率marginal rate of substitution :边替代率marginal rate of transformation 边际转换率marginal returns :边际回报marginal revenue :边际收益marginal revenue product :边际收益产品marginal revolution :边际革命marginal social benefit :社会边际收益marginal social cost :社会边际成本marginal utility :边际效用marginal value products :边际价值产品market :市场market clearance :市场结清,市场洗清market demand :市场需求market economy :市场经济market equilibrium :市场均衡market failure :市场失败market mechanism :市场机制market structure :市场结构market separation :市场分割market regulation :市场调节market share :市场份额markup pricing :加减定价法Marshallian demand function :马歇尔需求函数maximization :极大化microeconomics :微观经济学minimum wage :最低工资misallocation of resources :资源误置mixed economy :混合经济model :模型money :货币monopolistic competition :垄断竞争monopolistic exploitation :垄断剥削monopoly :垄断,卖方垄断monopoly equilibrium :垄断均衡monopoly pricing :垄断定价monopoly regulation :垄断调控monopoly rents :垄断租金monopsony :买方垄断NNash equilibrium :纳什均衡Natural monopoly :自然垄断Natural resources :自然资源Necessary condition :必要条件necessities :必需品net demand :净需求nonconvex preference :非凸性偏好nonconvexity :非凸性nonexclusion :非排斥性nonlinear pricing :非线性定价nonrivalry :非对抗性nonprice competition :非价格竞争nonsatiation :非饱和性non--zero—sum game :非零和对策normal goods :正常品normal profit :正常利润normative economics :规范经济学Oobjective function :目标函数oligopoly :寡头垄断oligopoly market :寡头市场oligopoly model :寡头模型opportunity cost :机会成本optimal choice :最佳选择optimal consumption bundle :消费束perfect elasticity :完全有弹性optimal resource allocation :最佳资源配置optimal scale :最佳规模optimal solution :最优解optimization :优化ordering of optimization(social) preference :(社会)偏好排序ordinal utility :序数效用ordinary goods :一般品output :产量、产出output elasticity :产出弹性output maximization 产出极大化Pparameter :参数Pareto criterion :帕累托标准Pareto efficiency :帕累托效率Pareto improvement :帕累托改进Pareto optimality :帕累托优化Pareto set :帕累托集partial derivative :偏导数partial equilibrium :局部均衡patent :专利pay off matrix :收益矩阵、支付矩阵perceived demand curve :感觉到的需求曲线perfect competition :完全竞争perfect complement :完全互补品perfect monopoly :完全垄断perfect price discrimination :完全价格歧视perfect substitution :完全替代品perfect inelasticity :完全无弹性perfectly elastic :完全有弹性perfectly inelastic :完全无弹性plant size :工厂规模point elasticity :点弹性post Hoc Fallacy :后此谬误prediction :预测preference :偏好preference relation :偏好关系present value :现值price :价格price adjustment model :价格调整模型price ceiling :最高限价price consumption curve :价格费曲线price control :价格管制price difference :价格差别price discrimination :价格歧视price elasticity of demand :需求价格弹性price elasticity of supply :供给价格弹性price floor :最低限价price maker :价格制定者price rigidity :价格刚性price seeker :价格搜求者price taker :价格接受者price tax :从价税private benefit :私人收益principal—agent issues :委托--代理问题private cost :私人成本private goods :私人用品private property :私人财产producer equilibrium :生产者均衡producer theory :生产者理论product :产品product transformation curve :产品转换曲线product differentiation :产品差异product group :产品集团production :生产production contract curve :生产契约曲线production efficiency :生产效率production function :生产函数production possibility curve :生产可能性曲线productivity :生产率productivity of capital :资本生产率productivity of labor :劳动生产率profit :利润profit function :利润函数profit maximization :利润极大化property rights :产权property rights economics :产权经济学proposition :定理proportional demand curve :成比例的需求曲线public benefits :公共收益public choice :公共选择public goods :公共商品pure competition :纯粹竞争rivalry :对抗性、竞争pure exchange :纯交换pure monopoly :纯粹垄断Qquantity—adjustment model :数量调整模型quantity tax :从量税quasi—rent :准租金Rrate of product transformation :产品转换率rationality :理性reaction function :反应函数regulation :调节,调控relative price 相对价格rent :租金rent control :规模报酬rent seeking :寻租rent seeking economics :寻租经济学resource :资源resource allocation :资源配置returns :报酬、回报returns to scale :规模报酬revealed preference :显示性偏好revenue :收益revenue curve :收益曲线revenue function :收益函数revenue maximization :收益极大化ridge line :脊线risk :风险satiation :饱和,满足saving :储蓄scarcity :稀缺性law of scarcity :稀缺法则second—degree price discrimination :二级价格歧视second derivative :--阶导数second—order condition :二阶条件service :劳务set :集shadow prices :影子价格short—run :短期short—run cost curve :短期成本曲线short—run equilibrium :短期均衡short—run supply curve :短期供给曲线shut down decision :关闭决策shortage 短缺shut down point :关闭点single price monopoly :单一定价垄断slope :斜率social benefit :社会收益social cost :社会成本social indifference curve :社会无差异曲线social preference :社会偏好social security :社会保障social welfare function :社会福利函数socialism :社会主义solution :解space :空间stability :稳定性stable equilibrium :稳定的均衡Stackelberg model :斯塔克尔贝格模型static analysis :静态分析stock :存量stock market :股票市场strategy :策略subsidy :津贴substitutes :替代品substitution effect :替代效应substitution parameter :替代参数sufficient condition :充分条件supply :供给supply curve :供给曲线supply function :供给函数supply schedule :供给表Sweezy model :斯威齐模型symmetry :对称性symmetry of information :信息对称tangency :相切taste :兴致technical efficiency :技术效率technological constraints ;技术约束technological progress :技术进步technology :技术third—degree price discrimination :第三级价格歧视total cost :总成本total effect :总效应total expenditure :总支出total fixed cost :总固定成本total product :总产量total revenue :总收益total utility :总效用total variable cost :总可变成本traditional economy :传统经济transitivity :传递性transaction cost :交易费用uncertainty :不确定性uniqueness :唯一性unit elasticity :单位弹性unstable equilibrium :不稳定均衡utility :效用utility function :效用函数utility index :效用指数utility maximization :效用极大化utility possibility curve :效用可能性曲线utility possibility frontier :效用可能性前沿Vvalue :价值value judge :价值判断value of marginal product :边际产量价值variable cost :可变成本variable input :可变投入variables :变量vector :向量visible hand :看得见的手vulgur economics :庸俗经济学Wwage :工资wage rate :工资率Walras general equilibrium :瓦尔拉斯总体均衡Walras's law :瓦尔拉斯法则Wants :需要Welfare criterion :福利标准Welfare economics :福利经学Welfare loss triangle :福利损失三角形welfare maximization :福利极大化Zzero cost :零成本zero elasticity :零弹性zero homogeneity :零阶齐次性zero economic profit :零利润。

经济学最全词典中英对照

经济学最全词典中英对照经济学词典提供经济学词典.向他致敬!Ability-to-pay principle(of taxation)(税收的)支付能力原则按照纳税人支付能力确定纳税负担的原则。

纳税人支付能力依据其收人或财富来衡量。

这一原则并不说明某经济状况较好的人到底该比别人多负担多少。

Absolute advantage(in international trade)(国际贸易中的)绝对优势A国所具有的比B国能更加有效地(即单位投入的产出水平比较高等)生产某种商品的能力。

这种优势并不意味着A国必然能将该商品成功地出口到B国。

因为B国还可能有一种我们所说的比较优势或曰比较利益(comparative advantage)。

Accelerator principle 加速原理解释产出率变动同方向地引致投资需求变动的理论。

Actual,cyc1ical,and structual budget 实际预算、周期预算和结构预算实际预算的赤字或盈余指的是某年份实际记录的赤字或盈余。

实际预算可划分成结构预算和周期预算。

结构预算假定经济在潜在产出水平上运行,并据此测算该经济条件下的政府税入、支出和赤字等指标。

周期预算基于所预测的商业周期(及其经济波动)对预算的影响。

Adaptive expectations 适应性预期见预期(expectations)。

Adjustable peg 可调整钉住一种(固定)汇率制度。

在该制度下,各国货币对其他货币保持一种固定的或曰“钉住的”汇率。

当某些基本因素发生变动、原先汇率失去合理依据的时候,这种汇率便不时地趋于凋整。

在1944-1971年期间,世界各主要货币都普遍实行这种制度,称为“布雷顿森林体系”。

Administered(or inflexible)prices 管理(或非浮动)价格特指某类价格的术语。

按照有关规定,这类价格在某一段时间内、在若干种交易中能够维持不变。

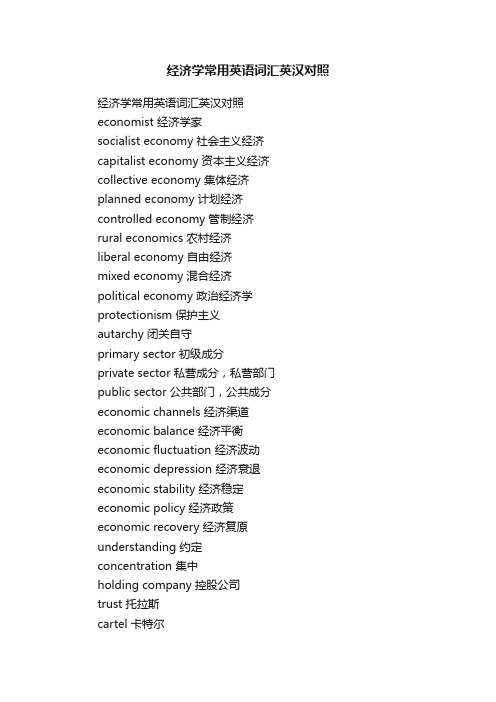

经济学常用英语词汇英汉对照

经济学常用英语词汇英汉对照经济学常用英语词汇英汉对照economist 经济学家socialist economy 社会主义经济capitalist economy 资本主义经济collective economy 集体经济planned economy 计划经济controlled economy 管制经济rural economics 农村经济liberal economy 自由经济mixed economy 混合经济political economy 政治经济学protectionism 保护主义autarchy 闭关自守primary sector 初级成分private sector 私营成分,私营部门public sector 公共部门,公共成分economic channels 经济渠道economic balance 经济平衡economic fluctuation 经济波动economic depression 经济衰退economic stability 经济稳定economic policy 经济政策economic recovery 经济复原understanding 约定concentration 集中holding company 控股公司trust 托拉斯cartel 卡特尔rate of growth 增长economic trend 经济趋势economic situation 经济形势infrastructure 基本建设standard of living 生活标准,生活水平purchasing power, buying power 购买力scarcity 短缺stagnation 停滞,萧条,不景气underdevelopment 不发达underdeveloped 不发达的` developing 发展中的。

经济学最全词典中英对照

经济学词典提供经济学词典.向他致敬!Ability-to-pay principle(of taxation)(税收的)支付能力原则按照纳税人支付能力确定纳税负担的原则。

纳税人支付能力依据其收人或财富来衡量。

这一原则并不说明某经济状况较好的人到底该比别人多负担多少。

Absolute advantage(in international trade)(国际贸易中的)绝对优势A国所具有的比B国能更加有效地(即单位投入的产出水平比较高等)生产某种商品的能力。

这种优势并不意味着A国必然能将该商品成功地出口到B国。

因为B国还可能有一种我们所说的比较优势或曰比较利益(comparative advantage)。

Accelerator principle 加速原理解释产出率变动同方向地引致投资需求变动的理论。

Actual,cyc1ical,and structual budget 实际预算、周期预算和结构预算实际预算的赤字或盈余指的是某年份实际记录的赤字或盈余。

实际预算可划分成结构预算和周期预算。

结构预算假定经济在潜在产出水平上运行,并据此测算该经济条件下的政府税入、支出和赤字等指标。

周期预算基于所预测的商业周期(及其经济波动)对预算的影响。

Adaptive expectations 适应性预期见预期(expectations)。

Adjustable peg 可调整钉住一种(固定)汇率制度。

在该制度下,各国货币对其他货币保持一种固定的或曰“钉住的”汇率。

当某些基本因素发生变动、原先汇率失去合理依据的时候,这种汇率便不时地趋于凋整。

在1944-1971年期间,世界各主要货币都普遍实行这种制度,称为“布雷顿森林体系”。

Administered(or inflexible)prices 管理(或非浮动)价格特指某类价格的术语。

按照有关规定,这类价格在某一段时间内、在若干种交易中能够维持不变。

(见价格浮动,price flexibility)Adverse selection 逆向选择一种市场不灵。

经济学专业词汇中英文对照

经济学专业词汇中英文对照经济学专业词汇中英文对照A 20accounting 会计accounting cost 会计成本accounting profit 会计利润adverse selection 逆向选择allocation 配置allocation of resources 资源配置allocativeefficiency 配置效率antitrustlegislation 反托拉斯法arc elasticity 弧弹性assumption 假设asymmetric information 非对称性信息average 平均average cost 平均成本average cost pricing 平均成本定价法average fixed cost 平均固定成本average product of capital 资本平均产量average product of labour 劳动平均产量average revenue 平均收益average total cost 平均总成本average variable cost 平均可变成本B 12barriers to entry 进入壁垒base year 基年bilateral monopoly 双边垄断benefit 收益black market 黑市bliss point 极乐点boundary point 边界点break even point 收支相抵点budget 预算budget constraint 预算约束budget line 预算线budget set 预算集C 75capital 资本capital stock 资本存量capital output ratio 资本产出比率capitalism 资本主义cardinal utility theory 基数效用论cartel 卡特尔ceteris paribus assumption “其他条件不变”的假设ceteris paribus demand curve “其他因素不变”的需求曲线Chamberlain model 张伯伦模型change in demand 需求变化change in quantity demanded 需求量变化change in quantity supplied 供给量变化change in supply 供给变化choice 选择closed set 闭集Coase theorem 科斯定理Cobb-Douglas production function 柯布--道格拉斯生产函数cobweb model 蛛网模型collective bargaining 集体协议工资collusion 合谋command economy 指令经济commodity 商品commodity combination 商品组合commodity market 商品市场commodity space 商品空间common property 公用财产comparative static analysis 比较静态分析compensated budget line 补偿预算线compensated demand function 补偿需求函数compensation principles 补偿原则compensating variation in income 收入补偿变量competition 竞争competitive market 竞争性市场complement goods 互补品complete information 完全信息completeness 完备性condition for efficiency in exchange交换的最优条件condition for efficiency in production生产的最优条件concave 凹concave function 凹函数concave preference 凹偏好consistence 一致性constant cost industry 成本不变产业constant returns to scale 规模报酬不变constraints 约束consumer 消费者consumer behavior 消费者行为consumer choice 消费者选择consumer equilibrium 消费者均衡consumer optimization 消费者优化consumer preference 消费者偏好consumer surplus 消费者剩余consumer theory 消费者理论consumption 消费consumption bundle 消费束consumption combination 消费组合consumption possibility curve 消费可能曲线consumption possibility frontier 消费可能性前沿consumption set 消费集consumption space 消费空间continuity 连续性continuous function 连续函数contract curve 契约曲线convex 凸convex function 凸函数convex preference 凸偏好convex set 凸集corporation 公司cost 成本cost benefit analysis 成本收益分析cost function 成本函数cost minimization 成本最小化Cournot equilibrium 古诺均衡Cournot model 古诺模型cross-price elasticity 交叉价格弹性D 32dead-weights loss 重负损失decreasing cost industry 成本递减产业decreasing returns to scale 规模报酬递减deduction 演绎法demand 需求demand curve 需求曲线demand elasticity 需求弹性demand function 需求函数demand price 需求价格demand schedule 需求表depreciation 折旧derivative 导数derive demand 派生需求difference equation 差分方程differential equation 微分方程differentiated good 差异商品differentiated oligopoly 差异寡头diminishing marginal substitution 边际替代率递减diminishing marginal return 收益递减diminishing marginal utility 边际效用递减direct approach 直接法direct taxes 直接税discounting 贴水、折扣diseconomies of scale 规模不经济disequilibrium 非均衡distribution 分配division of labour 劳动分工duopoly 双头垄断、双寡duality 对偶durable goods 耐用品dynamic analysis 动态分析dynamic models 动态模型E 50economic agents 经济行为者economic cost 经济成本economic efficiency 经济效率economic goods 经济物品economic man 经济人economic mode 经济模型economic profit 经济利润economic regulation 经济调节economic rent 经济租金exchange 交换exchange efficiency 交换效率exchange contract curve 交换契约曲线economy of scale 规模经济Edgeworth box diagram 埃奇沃思图exclusion 排斥性、排他性Edgeworth contract curve 埃奇沃思契约线Edgeworth model 埃奇沃思模型efficiency 效率、效益efficiency parameter 效率参数elasticity 弹性elasticity of substitution 替代弹性endogenous variable 内生变量endowment 禀赋endowment of resources 资源禀赋Engel curve 恩格尔曲线entrepreneur 企业家entrepreneurship 企业家才能entry barriers 进入壁垒entry/exit decision 进出决策envelope curve 包络线equilibrium 均衡equilibrium condition 均衡条件equilibrium price 均衡价格equilibrium quantity 均衡产量equity 公平equivalent variation in income 收入等价变量excess-capacity theorem 过度生产能力定理existence 存在性existence of general equilibrium 总体均衡的存在性expansion paths 扩展径expectation 期望expected utility 期望效用expected value 期望值expenditure 支出explicit cost 显性成本external benefit 外部收益external cost 外部成本external economy 外部经济external diseconomy外部不经济externalities 外部性F 24factor 要素factor demand 要素需求factor market 要素市场factors of production 生产要素factor substitution 要素替代factor supply 要素供给fallacy of composition 合成谬误final goods 最终产品firm 企业firms' demand curve for labour 企业劳动需求曲线firm supply curve 企业供给曲线first-degree price discrimination 第一级价格歧视first-order condition 一阶条件fixed costs 固定成本fixed input 固定投入fixed proportions production function 固定比例的生产函数flow 流量fluctuation 波动for whom to produce 为谁生产free entry 自由进入free goods 自由品、免费品free mobility of resources 资源自由流动free rider 搭便车、免费搭车者future value 未来值G 11game theory 博弈论、对策论general equilibrium 总体均衡、一般均衡general goods 一般商品Giffen goods 吉芬商品Giffen's Paradox 吉芬之谜Gini coefficient 吉尼系数golden rule 黄金规则government failure 政府失败government regulation 政府调控grand utility possibility curve 总效用可能曲线grand utility possibility frontier 总效用可能前沿H 9heterogeneous product 异质产品Hicks-kaldor welfare criterion 希克斯-卡尔多福利标准homogeneity 齐次性homogeneous demand function 齐次需求函数homogeneous product 同质产品homogeneous production function 齐次生产函数horizontal summation 水平和human capital 人力资本hypothesis 假说I 52identity 恒等式imperfect competition 不完全竞争implicit cost 隐性成本income 收入income compensated demand curve 收入补偿需求曲线income constraint 收入约束income consumption curve 收入消费曲线income distribution 收入分配income effect 收入效应income elasticity of demand 需求收入弹性increasing cost industry 成本递增产业increasing returns to scale 规模报酬递增index number 指数indifference 无差异indifference curve 无差异曲线indifference map 无差异族indifferencerelation 无差异关系indifference set 无差异集indirect approach 间接法individual analysis 个量分析individual demand curve 个人需求曲线individual demand function 个人需求函数induced variable 引致变量induction 归纳法industry 产业industry equilibrium 产业均衡industry supply curve 产业供给曲线inelastic 缺乏弹性的inferior goods 劣品inflection point 拐点information 信息information cost 信息成本initial condition 初始条件initial endowment 初始禀赋innovation 创新input 投入input-output 投入-产出institution 制度institutional economics 制度经济学insurance 保险intercept 截距interest 利息interest rate 利息率intermediate goods 中间产品internalization of externalities 外部性内部化invention 发明inverse demand function 反需求函数invisible hand 看不见的手isocost line 等成本线isoprofit curve 等利润曲线isoquant curve 等产量曲线isoquant map 等产量族K 1kinked-demand curve 弯折的需求曲线L 30labour demand 劳动需求labour supply 劳动供给labour theory of value 劳动价值论labour unions 工会laissez faire 自由放任Lagrangian function 拉格朗日函数Lagrangianmultiplier 拉格朗日乘数law of demand and supply 供需法则law of diminishing marginal utility 边际效用递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution边际替代率递减法则law of increasing cost 成本递增法则law of one price 单一价格法则leader-follower model 领导者-跟随者模型least-cost combination of inputs最低成本的投入组合leisure 闲暇Leontief production function 里昂惕夫生产函数licenses 许可证linear demand function 线性需求函数linear homogeneity 线性齐次性linear homogeneous production function 线性齐次生产函数long run 长期long run average cost 长期平均成本long run equilibrium 长期均衡long run industry supply curve 长期产业供给曲线long run marginal cost 长期边际成本long run total cost 长期总成本Lorenz curve 洛伦兹曲线loss minimization 损失极小化lump sum tax 一次性征税luxury 奢侈品M 45 macroeconomics 宏观经济学marginal benefit 边际收益marginal cost 边际成本marginal cost pricing 边际成本定价marginal cost of factor 边际要素成本marginal period 市场期marginal physical productivity 边际实物生产率marginal product 边际产量marginal product of capital 资本的边际产量marginal product of labour 劳动的边际产量marginalproductivity 边际生产率marginal rate of substitution 边际替代率marginal rate of transformation 边际转换率marginal returns 边际回报marginal revenue 边际收益marginal revenue product 边际收益产品marginal revolution 边际革命marginal social benefit 社会边际收益marginal social cost 社会边际成本marginal utility 边际效用marginal value products 边际价值产品market clearance 市场出清market economy 市场经济market equilibrium 市场均衡market failure 市场失灵market mechanism 市场机制market structure 市场结构market separation 市场分割market regulation 市场调节market share 市场份额markup pricing 加减定价法Marshallian demand function 马歇尔需求函数maximization 最大化microeconomics 微观经济学minimum wage 最低工资misallocation of resources 资源误置mixed economy 混合经济monopolistic competition 垄断竞争monopolistic exploitation 垄断剥削monopoly 垄断,卖方垄断monopoly equilibrium 垄断均衡monopoly pricing 垄断定价monopoly regulation 垄断调控monopoly rents 垄断租金monopsony 买方垄断N 17Nash equilibrium 纳什均衡natural monopoly 自然垄断natural resources 自然资源necessary condition必要条件necessities 必需品net demand 净需求nonconvex preference 非凸性偏好nonconvexity 非凸性nonexclusion 非排斥性nonlinear pricing 非线性定价nonrivalry 非对抗性nonprice competition 非价格竞争nonsatiation 非饱和性non-zero-sum game 非零和对策normal goods 正常品normal profit 正常利润normative economics 规范经济学O 17 objective function 目标函数oligopoly 寡头垄断oligopoly market 寡头市场oligopoly model 寡头模型opportunity cost 机会成本optimal choice 最佳选择optimal consumption bundle 消费束optimal resource allocation 最佳资源配置optimal scale 最佳规模optimal solution 最优解optimization 优化ordering of optimization (social)preference(社会)偏好排序ordinal utility 序数效用ordinary goods 一般品output 产出output elasticity 产出弹性output maximization 产出极大化P 68parameter 参数Pareto criterion 帕累托标准Pareto efficiency 帕累托效率Pareto improvement 帕累托改进Pareto optimality 帕累托优化Pareto set 帕累托集partial derivative 偏导数partial equilibrium 局部均衡patent 专利pay off matrix 收益矩阵、支付矩阵perceived demand curve 感觉到的需求曲线perfect competition 完全竞争perfect complement 完全互补品perfect monopoly 完全垄断perfect price discrimination 完全价格歧视perfect substitution 完全替代品perfect inelasticity 完全无弹性perfect elasticity完全有弹性plant size 工厂规模point elasticity 点弹性positive economics 实证经济学Post Hoc Fallacy 后此谬误prediction 预测preference 偏好preference relation 偏好关系present value 现值price adjustment model 价格调整模型price ceiling 最高限价price consumption curve 价格消费曲线price control 价格管制price difference 价格差别price discrimination 价格歧视price elasticity of demand 需求价格弹性price elasticity of supply 供给价格弹性price floor 最低限价price maker 价格制定者price rigidity 价格刚性price seeker 价格搜求者price taker 价格接受者private benefit 私人收益principal-agent issues 委托-代理问题private cost 私人成本private goods 私人用品private property 私人财产producer equilibrium 生产者均衡producer theory 生产者论product transformation curve 产品转换曲线product differentiation 产品差异product group 产品集团production contract curve 生产契约曲线productionefficiency 生产效率production function 生产函数production possibility curve 生产可能曲线productivity 生产率productivity of capital 资本生产率productivity of labour 劳动生产率profit function 利润函数profit maximization 利润最大化property rights 产权property rights economics 产权经济学proposition 定理proportional demand curve 成比例的需求函数public benefits 公共收益public choice 公共选择public goods 公共商品pure competition 纯粹竞争pure exchange 纯交换pure monopoly 纯粹垄断Q 3quantity-adjustment model 数量调整模型quantity tax 从量税quasi-rent 准租金R 18rate of product transformation 产品转换率rationality 理性reaction function 反应函数regulation 调节,调控relative price 相对价格rent 租金rent seeking 寻租rent seeking economics 寻租经济学resource 资源resource allocation 资源配置returns 报酬、回报returns to scale 规模报酬revealed preference 显示性偏好revenue 收益revenue curve 收益曲线revenue function 收益函数revenue maximization 收益最大化ridge line 脊线S 43satiation 饱和,满足saving 储蓄scarcity 稀缺性law of scarcity 稀缺法则second-degree price discrimination 二级价格歧视second derivative 二阶导数second-order condition 二阶条件service 劳务shadow prices 影子价格short-run 短期short-run cost curve 短期成本曲线short-run equilibrium 短期均衡short-run supply curve 短期供给曲线shut down decision 关闭决策shortage 短缺shut down point 关闭点single price monopoly 单一定价垄断slope 斜率social benefit 社会收益social cost 社会成本social indifference curve 社会无差异曲线social preference 社会偏好social security 社会保障social welfare function 社会福利函数socialism 社会主义solution 解space 空间stability 稳定性stable equilibrium 稳定的均衡Stackelberg model 斯塔克尔贝格模型static analysis 静态分析stock 存量stock market 股票市场strategy 策略subsidy 补贴substitutes 替代品substitution effect 替代效应substitution parameter 替代参数sufficient condition 充分条件supply schedule 供给表Sweezy model 斯威齐模型symmetry 对称性symmetry of information 信息对称T 16tangency 相切technical efficiency 技术效率technological constraints 技术约束technological progress 技术进步third-degree price discrimination 第三级价格歧视total cost 总成本total effect 总效应total expenditure 总支出total fixed cost 总固定成本total product 总产量total revenue 总收益total utility 总效用total variable cost 总可变成本traditional economy 传统经济transitivity 传递性transaction cost 交易费用U 8uncertainty 不确定性uniqueness 唯一性unit elasticity 单位弹性unstable equilibrium 不稳定均衡utility index 效用指数utility maximization 效用最大化utility possibility curve 效用可能性曲线utility possibility frontier 效用可能性前沿V 8value judge 价值判断value of marginal product 边际产量价值variable cost 可变成本variable input 可变投入variables 变量vector 向量visible hand 看得见的手vulgar economics 庸俗经济学W 8wage rate 工资率Walras general equilibrium 瓦尔拉斯总体均衡Walras's law 瓦尔拉斯法则Wants 需要Welfare criterion 福利标准Welfare economics 福利经济学Welfare loss triangle 福利损失三角形Welfare maximization 福利最大化Z 4zero cost 零成本zero elasticity 零弹性zero homogeneity 零阶齐次性zero economic profit 零利润。

经济学最全词典中英对照

经济学词典供给经济学词典.向他致敬 !Ability - to -pay principle ( of taxation )(税收的)支付能力原则依照纳税人支付能力确立纳税负担的原则。

纳税人支付能力依照其收人或财富来衡量。

这一原则并不说明某经济状况较好的人终归该比别人多负担多少。

Absolute advantage(in international trade)(国际贸易中的)绝对优势 A 国所具有的比 B 国能更加有效地(即单位投入的产出水平比较高等)生产某种商品的能力。

这种优势其实不意味着 A 国必然能将该商品成功地出口到 B 国。

由于 B 国还可能有一种我们所说的比较优势或曰比较利益( comparative advantage)。

Accelerator principle加速原理讲解产出率变动同方向地引致投资需求变动的理论。

Actual,cyc1ical , and structual budget本质估量、周期预算和结构估量本质估量的赤字或盈余指的是某年份本质记录的赤字或盈余。

本质估量可划分成结构估量和周期估量。

结构预算假设经济在潜藏产出水平上运行,并据此测算该经济条件下的政府税入、支出和赤字等指标。

周期估量基于所展望的商业周期(及其经济颠簸)对估量的影响。

Adaptive expectations适应性预期见预期(expectations)。

Adjustable peg 可调整钉住一种(固定)汇率制度。

在该制度下,各国钱币对其他钱币保持一种固定的或曰“钉住的”汇率。

当某些基本要素发生变动、本来汇率失去合理依照的时候,这类汇率便不时地趋于凋整。

在1944 - 1971 年时期,世界各主要钱币都普遍推行这类制度,称为“布雷顿森林系统”。

Administered ( or inflexible ) prices管理(或非浮动)价格特指某类价格的术语。

依照有关规定,这类价格在某一段时间内、在若干种交易中能够保持不变。

经济学概念总结

微观经济学关键概念中英文对照CHAPTER 1scarcity稀缺性economics经济学efficiency效率equity平等opportunity cost机会成本rational people理性人marginal changes边际变动incentive激励market economy市场经济property rights产权market failure市场失灵externality外部性market power市场势力productivity生产率inflation通货膨胀business cycle经济周期CHAPTER 2circular-flow diagram循环流向图production possibilities frontier生产可能性边界microeconomics微观经济学macroeconomics宏观经济学positive statements实证表述normative statements规范表述CHAPTER 3absolute advantage绝对优势opportunity cost机会成本comparative advantage比较优势imports进口exports出口CHAPTER 4market市场competitive market竞争市场quantity demanded需求量law of demand需求定理demand schedule需求表demand curve需求曲线normal good正常物品inferior good低档物品substitutes替代品complements互补品quantity supplied供给量law of supply供给定理supply schedule供给表supply curve供给曲线equilibrium均衡equilibrium price均衡价格equilibrium quantity均衡数量surplus过剩shortage短缺law of supply and demand供求定理CHAPTER 5elasticity弹性price elasticity of demand需求价格弹性total revenue总收益income elasticity of demand需求收入弹性cross-price elasticity of demand需求的交叉价格弹性price elasticity of supply供给价格弹性CHAPTER 6price ceiling价格上限price floor价格下限tax incidence税收归宿CHAPTER 7welfare economics福利经济学willingness to pay支付意愿consumer surplus消费者剩余cost成本producer surplus生产者剩余efficiency效率equity平等CHAPTER 8deadweight loss无谓损失CHAPTER 9world price世界价格tariff关税CHAPTER 10externality外部性internalizing the externality外部性的内在化Coase theorem科斯定理transaction costs交易成本corrective tax矫正税CHAPTER 11Excludability排他性rivalry in consumption消费中的竞争性private goods私人物品public goods公有物品common resources公有资源free rider搭便车者cost-benefit analysis成本收益分析Tragedy of the Commons公有地悲剧CHAPTER 12CHAPTER 13total revenue总收益total cost总成本profit利润explicit costs显性成本implicit costs隐性成本economic profit经济利润accounting profit会计利润production function生产函数marginal product边际产量diminishing marginal product边际产量递减fixed costs固定成本variable costs可变成本average total cost平均总成本average fixed cost平均固定成本average variable cost平均可变成本marginal cost边际成本efficient scale有效规模economies of scale规模经济diseconomies of scale规模不经济constant returns to scale规模收益不变CHAPTER 14competitive market竞争市场average revenue平均收益marginal revenue边际收益sunk cost沉没成本CHAPTER 15Monopoly垄断企业natural monopoly自然垄断price discrimination价格歧视CHAPTER 16Oligopoly寡头monopolistic competition垄断竞争collusion勾结cartel卡特尔Nash equilibrium纳什均衡game theory博弈论prisoners'dilemma囚徒困境dominant strategy占优策略CHAPTER 17monopolistic competition垄断竞争CHAPTER 18factors of production生产要素production function生产函数marginal product of labor劳动的边际产量diminishing marginal product边际产量递减value of the marginal product边际产量值capital资本CHAPTER 19compensating differential补偿性工资差别human capital人力资本union工会strike罢工efficiency wages效率工资discrimination歧视CHAPTER 20poverty rate贫困率poverty line贫困线in-kind transfers实物转移支付life cycle生命周期permanent income持久收入utilitarianism功利主义utility效用liberalism自由主义maximin criterion最大化标准social insurance社会保障libertarianism自由意志主义welfare福利negative income负所得税微观部分1.经济学:研究资源如何最佳配置使人类需要得到最大满足的一门社会科学。

微观经济学名词解释和中英文对照

【经济人】从事经济活动的人所采取的经济行为都是力图以自己的最小经济代价去获得自己的最大经济利益。

【需求】消费者在一定时期内在各种可能的价格水平愿意而且能够购置的该商品的数量。

【供应】生产者在一定时期内在各种价格水平下愿意并且能够提供出售的该种商品的数量。

【均衡价格】。

一种商品的均衡价格是指该种商品的市场需求量和市场供应量相等时的价格。

【供求定理】。

其他条件不变的情况下,需求变动分别引起均衡价格和均衡数量的同方向的变动,供应变动引起均衡价格的反方向变动,引起均衡数量的同方向变动。

【经济模型】。

经济模型是指用来描述所研究的经济事物的有关经济变量之间相关关系的理论构造。

【弹性】当一个经济变量发生1%的变动时,由它引起的另一个经济变量变动的百分比。

【弧弹性】表示某商品需求曲线上两点之间的需求量的变动对于价格的变动的反响程度。

【点弹性】表示需求曲线上某一点上的需求量变动对于价格变动的反响程度。

【需求的价格弹性】表示在一定时期内一种商品的需求量变动对于该商品的价格变动的反响程度。

或者说,表示在一定时期内当一种商品的价格变化百分之一时所引起的该商品的需求量变化的百分比。

【需求的穿插价格弹性】。

表示在一定时期内一种商品的需求量的变动相对于它的相关商品的价格变动的反响程度。

或者说,表示在一定时期内当一种商品的价格变化百分之一时所引起的另一种商品的需求量变化百分比。

【替代品】如果两种商品之间能够相互替代以满足消费者的某一种欲望,那么称这两种商品之间存在着替代关系,这两种商品互为替代品。

【需求的收入弹性】需求的收入弹性表示在一定时期内消费者对某种商品的需求量变动对于消费者收入量变动的反响程度。

或者说,表示在一定时期内当消费者的收入变化百分之一时所引起的商品需求量变化的百分比。

【恩格尔定律】。

在一个家庭或在一个国家中,食物支出在收入中所占的比例随着收入的增加而减少。

用弹性的概念来表述它那么可以是:对于一个家庭或一个国家来说,富裕程度越高,那么食物支出的收入弹性就越小;反之,那么越大。

(完整word版)60秒读懂经济学概念

60秒读懂经济学概念第一讲看不见的手经济是一个管理起来很头痛的系统,而政府总是尝试找到管理经济的方法。

1776年,经济学家亚当-斯密的观点让人震惊。

他认为政府要做的仅仅是什么都不做,让人们自由买卖。

如果政府让自负盈亏的交易主体充分参与竞争,市场就会导向积极的发展方向,“就像被一只看不见的手引导”。

如果有人卖的价格比你低,顾客自然会去买他们的东西。

这样你就只能降低价格,或者提高质量。

只要人们有足够的需求,市场就会满足他们,像娇惯的孩子一样,这样,人人都会满意。

后世的自由市场主义者,像哈耶克,这种“不干涉”政策实际上胜过任何的宏观调控。

但问题在于,经济需要很长的时间才能实现“均衡”,更有可能停滞不前。

市场调控期间,人们会失去信心。

这就是政府用“看得见的手”的原因。

第二节节约悖论就像小孩子拿到零花钱不知道怎么花一样,经济学最大的问题之一是,储蓄和消费哪个更好。

自由市场主义者,像哈耶克和弗里德曼认为,即使在经济困难时期,节约和储蓄仍然是最好的。

这样银行就能把储蓄用于投资,建立新工厂,发展新技术,提高生产力。

这样即使新技术可能减少工作岗位,降低薪水,新兴事业也会需要雇佣更多人手,最终失业率还是会下降。

逻辑很简单,至少从长期以来看是这样,但是另一个主张“人生苦短”的家伙——凯恩斯认为,长期来看我们都死了,因此,为了避免失业的阵痛,政府应该增加支出,创造工作机会。

如果政府勒紧腰带,而民众和企业也不愿花钱,消费就会下降,事业也会变得更严重。

这就是所谓的“节约悖论”。

因此政府要加大投入,当人们乐意时再收税。

尽管让人们乐意去交税,是连凯恩斯都完成不了的任务。

第三讲菲利普斯曲线新西兰鳄鱼猎手比尔—菲利普斯也是一位经济学家,他指出,当就业率高时,薪水就会涨的快。

人们有更多的钱去消费,于是价格上涨,通货膨胀出现。

反之,当失业率高时,投入消费的钱变少,通涨也会减退。

这就被称作为“菲利普斯曲线”。

政府甚至根据这个曲线制定政策,当加大投入创作工作机会时,会适当的容忍随之而来的通涨。

经济学名词英汉对照

生活费用

Cose of living

生活标准

Standarad of living

恩格尔系数

Engel coefficient

基尼系数

Gini coefficient

帕累托最优

Pareto optimality

领先于滞后

Leads and lags

公地的悲剧

Tragedy of the commons

路径依赖

Path dependence

博弈论

Game theory

囚徒困境

Prisoner’s dilemma

集体行动

Collective action

不确定性

Uncertainty

凯恩斯革命

Keynesian revolution

菜单成本

Menu cost

财政幻觉

Fiscal illusion

预算平衡

Balanced budget

宏观调控

Macro-economic control measures

转移支付

Transfer payment

资本利用程度

Capital utilization

排队配给

Rationing by queues

歧视

Discrimination

制度

Institution

交易成本

Transaction cost

激励

Incentive

产权

Property rights

基础设施

Infrastructure

多变贸易

经济学专业术语(中英文对照)

经济学专业术语(中英文对照)经济学专业术语(中英文对照)1.经济学原理经济:(economy)稀缺性:(scarcity)经济学:(economics)效率:(efficiency)同等:(equality)机遇本钱:(opporyunity cost)理性人:(rational people)边际变动:(marginal change)边沿收益:(marginal benefit)边沿本钱:(marginal cost)激励:(incentive)市场经济:(market XXX)产权:(property rights)市场失灵:(market failure)外部性:(externality)市场势力:(market power)生产率:(productivity)通货膨胀:(inflation)经济周期:(business cycle)2.像经济学家一样思考循环流量图:(circular-flow diagram)生产可能性边界:(production possibilities) 微观经济学:(microeconomics)宏观经济学:(macroeconomics)实证表述:(XXX)规范表述:(normative statements)有序数对:(ordered pair)3.相互依存性与贸易的好处绝对优势:(absolute advantage)机遇本钱:(apportunity cost)比力上风:(comparative advantage)入口品:(imports)出口品:(exports)4.供给与需求的市场力量市场:(market)竞争市场:(competitive market)需求量:(quantity XXX)需求定理:(law of demand)需求表:(demand schedule)需求曲线:(demand curve)正常物品:(normal good)低档物品:(inferior good)替代品:(substitutes)互补品:(complements)供给量:(quantity supplied)供给定理:(law of supply)供给表:(supply schedule)供给曲线:(supply curve)均衡:(equilibrium)均衡价格:(equilibrium price)均衡数量:(equilibrium quantity)多余:(surplus)短缺:(shortage)供求定理:(law of supply and demand)5.弹性及其使用弹性:(elasticity)需求代价弹性:(price elasticity of demand)总收益:(total revenue)需求收入弹性:(income elasticity)需求的交叉价格弹性:(cross-price elasticity)供给价格弹性:(price elasticity of supply)6.供给需求与政策价格上限:(price ceiling)代价下限:(price floor)税收归宿:(tax incidence)7.消费者、生产者与市场效率福利经济学:(XXX)领取志愿:(willingness to pay)消费者剩余:(consumer surplus)成本:(cost)出产者残剩:(producer surplus)效率:(efficiency)平等:(equality)8.钱粮的使用无谓损失:(deadweight loss)9.国际商业天下代价:(world price)关税:(tariff)10.外部性外部性:(externality)内部性内涵化:(internalizing XXX)改正税:(corrective taxes) 科斯定理:(coase XXX)生意业务本钱:(XXX cost)11.公共物品和公共资源排他性:(excludability)消耗中的合作性:(XXX)私人物品:(private goods)公共物品:(public goods)公共资源:(common resources)俱乐部物品:(XXX goods)搭便车者:(free rider)成本-收益分析:(cost-XXX)公地悲剧:(tragedy of commons)12.税制设想征税任务:(XXX)预算赤字:(budget defict)预算盈余:(budget surplus)平均税率:(average tax rate)边沿税率:(marginal tax rate)定额税:(lump-sum tax)受益准绳:(benefits principle)领取本领准绳:(ability-to-pay principle) 纵向同等:(XXX)横向同等:(XXX)比例税:(proportional tax)累退税:(regressive tax)累进税:(progressive tax)13.出产本钱总收益:(total revenue)总本钱:(total cost)利润:(profit)显性成本:(explicit costs)隐性本钱:(implicit costs)经济利润:(economic profit)会计利润:(counting profit)生产函数:(production function)边际产量:(marginal product)边沿产量递减:(diminishing marginal product)牢固本钱:(fixed costs)可变成本:(variable costs)平均总成本:(average total cost)平均固定成本:(average fixed costs)平均可变成本:(average variable costs)边沿本钱:(marginal cost)有效规模:(efficient scale)范围经济:(economies of scale)规模不经济:(diseconomies of scale)范围收益稳定:(constant returns to scale)14.竞争市场上的企业竞争市场:(competitive market)均匀收益:(average revenue)边际收益:(marginal revenue)漂浮本钱:(sunk revenue)15.把持垄断企业:(XXX)天然把持:(XXX)价格歧视:(price discrimination)16.垄断竞争寡头:(oligopoly)把持合作:(XXX)17.寡头博弈论:(game theory)勾搭:(collusion)XXX:(cartel)纳什均衡:(Nash equilibrium)囚徒困境:(prisoners’ dilemma)占优策略:(XXX)18.生产要素市场生产要素:(factors of production)出产函数:(production function)劳动的边沿产量:(marginal product of labor)边沿产量递减:(diminishing marginal product)边沿产量值:(value of the marginal product)本钱:(capital)19.收入与歧视抵偿性人为不同:(compensating differential)人力本钱:(human capital)工会:(union)罢工:(strike)效率工资:(efficiency)歧视:(discrimination)20.收入不平等与贫困贫困率:(poverty rate)贫困率:(poverty line)实物转移支付:(in-kind transfers) 生命周期:(life cycle)持久收入:(permanent income)功利主义:(utilitariansm)功效:(utilitariansm)自由主义:(liberalism)最大最小准则:(maximin criterion) 负所得税:(negative income tax)福利:(welfare)社会保险:(social insurance)自在至上主义:(libertarianism) 21.消耗者挑选实际预算约束线:(budget constraint)无不同曲线:(indiffernnce curve)边沿替换率:(marginal rate of subtitution) 完全替代品:(perfect substitudes)完全互补品:(perfect complements)一般物品:(normal good)低档物品:(inferior good)收入效应:(income effect)替代效应:(substitution effect)XXX物品:(Giffen good)22.微观经济学前沿道德风险:(moral hazard)代理人:(agent)委托人:(principal)逆向选择:(adverse selection)发旌旗灯号:(signaling)筛选:(screening)政治经济学:(political XXX)康多塞悖论:(condorcet paradox)XXX不成能性定理:(Arrow’XXX)中值选民定理:(XXX)行动经济学:(XXX)23.一国收入的衡量微观经济学:(microeconomics)宏观经济学:(macroeconomics)国内生产总值:(XXX,GDP)消费:(consumption) 投资:(investment)政府购买:(government purchase)净出口:(net export)名义GDP:(nominal GDP)真实GDP:(real GDP)GDP平减指数:(GDP deflator)XXX.糊口用度的衡量消耗物价指数:(consumer price index,CPI)通货收缩率:(inflation rate)出产品价指数:(produer price index,PPI)指数化:(indexation)生活费用津贴:(cost-of-living allowance,COLA)名义利率:(nominal interest rate)25.出产与增加生产率:(productivity)物资本钱:(physical capital)人力本钱:(XXX)自然资源:(natural resources)手艺常识:(XXX)收益递减:(diminishing returns)追逐效应:(catch-up effect)26.储蓄、投资和金融体系金融体系:(financial system)金融市场:(financial markets)债券:(bond)股票:(stock)金融中介机构:(financial intermediaries)配合基金:(mutual fund)国民储蓄:(national saving)公家储蓄:(private saving)大众储蓄:(public saving)预算盈余:(budget surplus)预算赤字:(budget deficit)可贷资金市场:(market for loanable funds)挤出:(crowding out)27.金融学的根本工具金融学:(finance)现值:(present value)终值:(future value)复利:(compounding)风险厌恶:(risk aversion)多元化:(diversification)企业特有风险:(firm-specific risk)市场风险:(market risk)基本面风险:(fundamental analysis)有效市场假说:(efficient XXX)信息有效:(informational efficiency)随机游走:(random walk)28.失业劳动力:(laborforce)赋闲率:(XXX)劳动力参与率:(labor-force participation rate)自然失业率:(natural rate of XXX)周期性失业:(cyclical unemployment) 失去信心的工人:(discouraged workers)磨擦性赋闲:(frictional unemployment)布局性赋闲:(structural XXX)寻找工作:(job search)失业保险:(XXX)工会:(union)个人商洽:(collective bargaining)罢工:(strike)效率工资:(essiciency wages)29.泉币制度货币:(money)交流序言:(medium of exchange)计价单位:(unit of account)价值储藏手段:(store of value)流动性:(liquidity)商品货币:(commodity money)法定货币:(fiat money)通货:(currency)活期存款:(demand deposits)XXX:(Federal Reserve)中心银行:(central bank)货币供给:(money supply)货币政策:(monetary policy)XXX:(reserves)局部筹办金银行:(fractional-reserve banking)筹办金率:(reserve ratio)货币乘数:(money multiplier)银行本钱:(bank capital)杠杆:(leverage)杠杆率:(leverage ratio)本钱需求量:(capital requirement)公布市场操纵:(open-market operations)贴现率:(discount rate)法定筹办金:(reserve requirements)弥补金融打算:(supplementary financing program)联邦基金利率:(federal funds rate)30.泉币增加与通货收缩铲除通胀:(whip Inflation Now)货币数量论:(XXX)名义变量:(nominal variables)实在变量:(real variables)古典二分法:(classiacl dichotomy)货币中性:(XXX)货币流通速度:(velocity of money)数目方程式:(XXX)通货膨胀税:(inflation tax)XXX效应:(Fisher effect)皮鞋本钱:(XXX)菜单成本:(menu costs)31.开放经济的宏观经济学封闭经济:(closed XXX)开放经济:(open XXX) 出口:(exports)净出口:(net exports)。

经济学最全词典 中英对照

经济学词典提供经济学词典.向他致敬!Ability-to-pay principle(of taxation)(税收的)支付能力原则按照纳税人支付能力确定纳税负担的原则。

纳税人支付能力依据其收人或财富来衡量。

这一原则并不说明某经济状况较好的人到底该比别人多负担多少。

Absolute advantage(in international trade)(国际贸易中的)绝对优势A国所具有的比B国能更加有效地(即单位投入的产出水平比较高等)生产某种商品的能力。

这种优势并不意味着A国必然能将该商品成功地出口到B国。

因为B国还可能有一种我们所说的比较优势或曰比较利益(comparative advantage)。

Accelerator principle 加速原理解释产出率变动同方向地引致投资需求变动的理论。

Actual,cyc1ical,and structual budget 实际预算、周期预算和结构预算实际预算的赤字或盈余指的是某年份实际记录的赤字或盈余。

实际预算可划分成结构预算和周期预算。

结构预算假定经济在潜在产出水平上运行,并据此测算该经济条件下的政府税入、支出和赤字等指标。

周期预算基于所预测的商业周期(及其经济波动)对预算的影响。

Adaptive expectations 适应性预期见预期(expectations)。

Adjustable peg 可调整钉住一种(固定)汇率制度。

在该制度下,各国货币对其他货币保持一种固定的或曰“钉住的”汇率。

当某些基本因素发生变动、原先汇率失去合理依据的时候,这种汇率便不时地趋于凋整。

在1944-1971年期间,世界各主要货币都普遍实行这种制度,称为“布雷顿森林体系”。

Administered(or inflexible)prices 管理(或非浮动)价格特指某类价格的术语。

按照有关规定,这类价格在某一段时间内、在若干种交易中能够维持不变。

(见价格浮动,price flexibility)Adverse selection 逆向选择一种市场不灵。

经济学专业词汇中英文对照

经济学专业词汇中英文对照A 20accounting 会计accounting cost 会计成本accounting profit 会计利润adverse selection 逆向选择allocation 配置allocation of resources 资源配置allocative efficiency 配置效率antitrust legislation 反托拉斯法arc elasticity 弧弹性assumption 假设asymmetric information 非对称性信息average 平均average cost 平均成本average cost pricing 平均成本定价法average fixed cost 平均固定成本average product of capital 资本平均产量average product of labour 劳动平均产量average revenue 平均收益average total cost 平均总成本average variable cost 平均可变成本B 12barriers to entry 进入壁垒base year 基年bilateral monopoly 双边垄断benefit 收益black market 黑市bliss point 极乐点boundary point 边界点break even point 收支相抵点budget 预算budget constraint 预算约束budget line 预算线budget set 预算集C 75capital 资本capital stock 资本存量capital output ratio 资本产出比率capitalism 资本主义cardinal utility theory 基数效用论cartel 卡特尔ceteris paribus assumption “其他条件不变”的假设ceteris paribus demand curve “其他因素不变”的需求曲线Chamberlain model 张伯伦模型change in demand 需求变化change in quantity demanded 需求量变化change in quantity supplied 供给量变化change in supply 供给变化choice 选择closed set 闭集Coase theorem 科斯定理Cobb-Douglas production function 柯布--道格拉斯生产函数cobweb model 蛛网模型collective bargaining 集体协议工资collusion 合谋command economy 指令经济commodity 商品commodity combination 商品组合commodity market 商品市场commodity space 商品空间common property 公用财产comparative static analysis 比较静态分析compensated budget line 补偿预算线compensated demand function 补偿需求函数compensation principles 补偿原则compensating variation in income 收入补偿变量competition 竞争competitive market 竞争性市场complement goods 互补品complete information 完全信息completeness 完备性condition for efficiency in exchange交换的最优条件condition for efficiency in production生产的最优条件concave 凹concave function 凹函数concave preference 凹偏好consistence 一致性constant cost industry 成本不变产业constant returns to scale 规模报酬不变constraints 约束consumer 消费者consumer behavior 消费者行为consumer choice 消费者选择consumer equilibrium 消费者均衡consumer optimization 消费者优化consumer preference 消费者偏好consumer surplus 消费者剩余consumer theory 消费者理论consumption 消费consumption bundle 消费束consumption combination 消费组合consumption possibility curve 消费可能曲线consumption possibility frontier 消费可能性前沿consumption set 消费集consumption space 消费空间continuity 连续性continuous function 连续函数contract curve 契约曲线convex 凸convex function 凸函数convex preference 凸偏好convex set 凸集corporation 公司cost 成本cost benefit analysis 成本收益分析cost function 成本函数cost minimization 成本最小化Cournot equilibrium 古诺均衡Cournot model 古诺模型cross-price elasticity 交叉价格弹性D 32dead-weights loss 重负损失decreasing cost industry 成本递减产业decreasing returns to scale 规模报酬递减deduction 演绎法demand 需求demand curve 需求曲线demand elasticity 需求弹性demand function 需求函数demand price 需求价格demand schedule 需求表depreciation 折旧derivative 导数derive demand 派生需求difference equation 差分方程differential equation 微分方程differentiated good 差异商品differentiated oligopoly 差异寡头diminishing marginal substitution 边际替代率递减diminishing marginal return 收益递减diminishing marginal utility 边际效用递减direct approach 直接法direct taxes 直接税discounting 贴水、折扣diseconomies of scale 规模不经济disequilibrium 非均衡distribution 分配division of labour 劳动分工duopoly 双头垄断、双寡duality 对偶durable goods 耐用品dynamic analysis 动态分析dynamic models 动态模型E 50economic agents 经济行为者economic cost 经济成本economic efficiency 经济效率economic goods 经济物品economic man 经济人economic mode 经济模型economic profit 经济利润economic regulation 经济调节economic rent 经济租金exchange 交换exchange efficiency 交换效率exchange contract curve 交换契约曲线economy of scale 规模经济Edgeworth box diagram 埃奇沃思图exclusion 排斥性、排他性Edgeworth contract curve 埃奇沃思契约线Edgeworth model 埃奇沃思模型efficiency 效率、效益efficiency parameter 效率参数elasticity 弹性elasticity of substitution 替代弹性endogenous variable 内生变量endowment 禀赋endowment of resources 资源禀赋Engel curve 恩格尔曲线entrepreneur 企业家entrepreneurship 企业家才能entry barriers 进入壁垒entry/exit decision 进出决策envelope curve 包络线equilibrium 均衡equilibrium condition 均衡条件equilibrium price 均衡价格equilibrium quantity 均衡产量equity 公平equivalent variation in income 收入等价变量excess-capacity theorem 过度生产能力定理existence 存在性existence of general equilibrium 总体均衡的存在性expansion paths 扩展径expectation 期望expected utility 期望效用expected value 期望值expenditure 支出explicit cost 显性成本external benefit 外部收益external cost 外部成本external economy 外部经济external diseconomy 外部不经济externalities 外部性F 24factor 要素factor demand 要素需求factor market 要素市场factors of production 生产要素factor substitution 要素替代factor supply 要素供给fallacy of composition 合成谬误final goods 最终产品firm 企业firms' demand curve for labour 企业劳动需求曲线firm supply curve 企业供给曲线first-degree price discrimination 第一级价格歧视first-order condition 一阶条件fixed costs 固定成本fixed input 固定投入fixed proportions production function 固定比例的生产函数flow 流量fluctuation 波动for whom to produce 为谁生产free entry 自由进入free goods 自由品、免费品free mobility of resources 资源自由流动free rider 搭便车、免费搭车者future value 未来值G 11game theory 博弈论、对策论general equilibrium 总体均衡、一般均衡general goods 一般商品Giffen goods 吉芬商品Giffen's Paradox 吉芬之谜Gini coefficient 吉尼系数golden rule 黄金规则government failure 政府失败government regulation 政府调控grand utility possibility curve 总效用可能曲线grand utility possibility frontier 总效用可能前沿H 9heterogeneous product 异质产品Hicks-kaldor welfare criterion 希克斯-卡尔多福利标准homogeneity 齐次性homogeneous demand function 齐次需求函数homogeneous product 同质产品homogeneous production function 齐次生产函数horizontal summation 水平和human capital 人力资本hypothesis 假说I 52identity 恒等式imperfect competition 不完全竞争implicit cost 隐性成本income 收入income compensated demand curve 收入补偿需求曲线income constraint 收入约束income consumption curve 收入消费曲线income distribution 收入分配income effect 收入效应income elasticity of demand 需求收入弹性increasing cost industry 成本递增产业increasing returns to scale 规模报酬递增index number 指数indifference 无差异indifference curve 无差异曲线indifference map 无差异族indifference relation 无差异关系indifference set 无差异集indirect approach 间接法individual analysis 个量分析individual demand curve 个人需求曲线individual demand function 个人需求函数induced variable 引致变量induction 归纳法industry 产业industry equilibrium 产业均衡industry supply curve 产业供给曲线inelastic 缺乏弹性的inferior goods 劣品inflection point 拐点information 信息information cost 信息成本initial condition 初始条件initial endowment 初始禀赋innovation 创新input 投入input-output 投入-产出institution 制度institutional economics 制度经济学insurance 保险intercept 截距interest 利息interest rate 利息率intermediate goods 中间产品internalization of externalities 外部性内部化invention 发明inverse demand function 反需求函数invisible hand 看不见的手isocost line 等成本线isoprofit curve 等利润曲线isoquant curve 等产量曲线isoquant map 等产量族K 1kinked-demand curve 弯折的需求曲线L 30labour demand 劳动需求labour supply 劳动供给labour theory of value 劳动价值论labour unions 工会laissez faire 自由放任Lagrangian function 拉格朗日函数Lagrangian multiplier 拉格朗日乘数law of demand and supply 供需法则law of diminishing marginal utility 边际效用递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution边际替代率递减法则law of increasing cost 成本递增法则law of one price 单一价格法则leader-follower model 领导者-跟随者模型least-cost combination of inputs最低成本的投入组合leisure 闲暇Leontief production function 里昂惕夫生产函数licenses 许可证linear demand function 线性需求函数linear homogeneity 线性齐次性linear homogeneous production function线性齐次生产函数long run 长期long run average cost 长期平均成本long run equilibrium 长期均衡long run industry supply curve 长期产业供给曲线long run marginal cost 长期边际成本long run total cost 长期总成本Lorenz curve 洛伦兹曲线loss minimization 损失极小化lump sum tax 一次性征税luxury 奢侈品M 45macroeconomics 宏观经济学marginal benefit 边际收益marginal cost 边际成本marginal cost pricing 边际成本定价marginal cost of factor 边际要素成本marginal period 市场期marginal physical productivity 边际实物生产率marginal product 边际产量marginal product of capital 资本的边际产量marginal product of labour 劳动的边际产量marginal productivity 边际生产率marginal rate of substitution 边际替代率marginal rate of transformation 边际转换率marginal returns 边际回报marginal revenue 边际收益marginal revenue product 边际收益产品marginal revolution 边际革命marginal social benefit 社会边际收益marginal social cost 社会边际成本marginal utility 边际效用marginal value products 边际价值产品market clearance 市场出清market economy 市场经济market equilibrium 市场均衡market failure 市场失灵market mechanism 市场机制market structure 市场结构market separation 市场分割market regulation 市场调节market share 市场份额markup pricing 加减定价法Marshallian demand function 马歇尔需求函数maximization 最大化microeconomics 微观经济学minimum wage 最低工资misallocation of resources 资源误置mixed economy 混合经济monopolistic competition 垄断竞争monopolistic exploitation 垄断剥削monopoly 垄断,卖方垄断monopoly equilibrium 垄断均衡monopoly pricing 垄断定价monopoly regulation 垄断调控monopoly rents 垄断租金monopsony 买方垄断N 17Nash equilibrium 纳什均衡natural monopoly 自然垄断natural resources 自然资源necessary condition 必要条件necessities 必需品net demand 净需求nonconvex preference 非凸性偏好nonconvexity 非凸性nonexclusion 非排斥性nonlinear pricing 非线性定价nonrivalry 非对抗性nonprice competition 非价格竞争nonsatiation 非饱和性non-zero-sum game 非零和对策normal goods 正常品normal profit 正常利润normative economics 规范经济学O 17objective function 目标函数oligopoly 寡头垄断oligopoly market 寡头市场oligopoly model 寡头模型opportunity cost 机会成本optimal choice 最佳选择optimal consumption bundle 消费束optimal resource allocation 最佳资源配置optimal scale 最佳规模optimal solution 最优解optimization 优化ordering of optimization (social) preference (社会)偏好排序ordinal utility 序数效用ordinary goods 一般品output 产出output elasticity 产出弹性output maximization 产出极大化P 68parameter 参数Pareto criterion 帕累托标准Pareto efficiency 帕累托效率Pareto improvement 帕累托改进Pareto optimality 帕累托优化Pareto set 帕累托集partial derivative 偏导数partial equilibrium 局部均衡patent 专利pay off matrix 收益矩阵、支付矩阵perceived demand curve 感觉到的需求曲线perfect competition 完全竞争perfect complement 完全互补品perfect monopoly 完全垄断perfect price discrimination 完全价格歧视perfect substitution 完全替代品perfect inelasticity 完全无弹性perfect elasticity 完全有弹性plant size 工厂规模point elasticity 点弹性positive economics 实证经济学Post Hoc Fallacy 后此谬误prediction 预测preference 偏好preference relation 偏好关系present value 现值price adjustment model 价格调整模型price ceiling 最高限价price consumption curve 价格消费曲线price control 价格管制price difference 价格差别price discrimination 价格歧视price elasticity of demand 需求价格弹性price elasticity of supply 供给价格弹性price floor 最低限价price maker 价格制定者price rigidity 价格刚性price seeker 价格搜求者price taker 价格接受者private benefit 私人收益principal-agent issues 委托-代理问题private cost 私人成本private goods 私人用品private property 私人财产producer equilibrium 生产者均衡producer theory 生产者论product transformation curve 产品转换曲线product differentiation 产品差异product group 产品集团production contract curve 生产契约曲线production efficiency 生产效率production function 生产函数production possibility curve 生产可能曲线productivity 生产率productivity of capital 资本生产率productivity of labour 劳动生产率profit function 利润函数profit maximization 利润最大化property rights 产权property rights economics 产权经济学proposition 定理proportional demand curve 成比例的需求函数public benefits 公共收益public choice 公共选择public goods 公共商品pure competition 纯粹竞争pure exchange 纯交换pure monopoly 纯粹垄断Q 3quantity-adjustment model 数量调整模型quantity tax 从量税quasi-rent 准租金R 18rate of product transformation 产品转换率rationality 理性reaction function 反应函数regulation 调节,调控relative price 相对价格rent 租金rent seeking 寻租rent seeking economics 寻租经济学resource 资源resource allocation 资源配置returns 报酬、回报returns to scale 规模报酬revealed preference 显示性偏好revenue 收益revenue curve 收益曲线revenue function 收益函数revenue maximization 收益最大化ridge line 脊线S 43satiation 饱和,满足saving 储蓄scarcity 稀缺性law of scarcity 稀缺法则second-degree price discrimination 二级价格歧视second derivative 二阶导数second-order condition 二阶条件service 劳务shadow prices 影子价格short-run 短期short-run cost curve 短期成本曲线short-run equilibrium 短期均衡short-run supply curve 短期供给曲线shut down decision 关闭决策shortage 短缺shut down point 关闭点single price monopoly 单一定价垄断slope 斜率social benefit 社会收益social cost 社会成本social indifference curve 社会无差异曲线social preference 社会偏好social security 社会保障social welfare function 社会福利函数socialism 社会主义solution 解space 空间stability 稳定性stable equilibrium 稳定的均衡Stackelberg model 斯塔克尔贝格模型static analysis 静态分析stock 存量stock market 股票市场strategy 策略subsidy 补贴substitutes 替代品substitution effect 替代效应substitution parameter 替代参数sufficient condition 充分条件supply schedule 供给表Sweezy model 斯威齐模型symmetry 对称性symmetry of information 信息对称T 16tangency 相切technical efficiency 技术效率technological constraints 技术约束technological progress 技术进步third-degree price discrimination 第三级价格歧视total cost 总成本total effect 总效应total expenditure 总支出total fixed cost 总固定成本total product 总产量total revenue 总收益total utility 总效用total variable cost 总可变成本traditional economy 传统经济transitivity 传递性transaction cost 交易费用U 8uncertainty 不确定性uniqueness 唯一性unit elasticity 单位弹性unstable equilibrium 不稳定均衡utility index 效用指数utility maximization 效用最大化utility possibility curve 效用可能性曲线utility possibility frontier 效用可能性前沿V 8value judge 价值判断value of marginal product 边际产量价值variable cost 可变成本variable input 可变投入variables 变量vector 向量visible hand 看得见的手vulgar economics 庸俗经济学W 8wage rate 工资率Walras general equilibrium 瓦尔拉斯总体均衡Walras's law 瓦尔拉斯法则Wants 需要Welfare criterion 福利标准Welfare economics 福利经济学Welfare loss triangle 福利损失三角形Welfare maximization 福利最大化Z 4zero cost 零成本zero elasticity 零弹性zero homogeneity 零阶齐次性zero economic profit 零利润总黄酮生物总黄酮是指黄酮类化合物,是一大类天然产物,广泛存在于植物界,是许多中草药的有效成分。

微观经济学概念中英对照

1. 经济人economic man 理性人Rational man从事经济活动的人所采取的经济行为都是力图以自己的最小经济代价去获得自己的最大经济利益。

两个假设条件是微观经济学中的基本假设条件:第一,合乎理性的人的假设条件(经济人)。

以利己为动机,力图以最小的经济代价去追逐和获取自身的最大的经济利益。

第二,完全信息。

市场上每一个从事经济活动的个体(即买者和卖者)都对有关的经济情况具有完全的信息。

西方经济学者承认,上述两个假设条件未必完全合乎事实,它们是为了理论分析的方便而设立的。

2. 需求demand消费者在一定时期内在各种可能的价格水平愿意而且能够购买的该商品的数量。

3. 需求函数demand function表示一种商品的需求数量和影响该需求数量的各种因素之间的相互关系的函数。

4. 供给supply生产者在一定时期内在各种价格水平下愿意并且能够提供出售的该种商品的数量。

5. 供给函数supply function供给函数表示一种商品的供给量和该商品的价格之间存在着一一对应的关系。

6. 均衡价格Equilibrium price一种商品的均衡价格是指该种商品的市场需求量和市场供给量相等时的价格。

7. 需求量的变动和需求的变动Changes in Quantity Demanded (movements along the demand curve) and Changes (Shifts) in Demand需求量的变动是指在其它条件不变时由某种商品的价格变动所应起的该商品需求数量的变动。

需求的变动是指在某商品价格不变的条件下,由于其它因素变动所引起的该商品需求数量的变动。

8. 供给量的变动和供给的变动Changes in Quantity supplied (movements along the supply curve) and Changes (Shifts) in supply供给量的变动是指在其它条件不变时由某种商品的价格变动所应起的该商品供给数量的变动。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

60秒读懂经济学概念第一讲看不见的手经济是一个管理起来很头痛的系统,而政府总是尝试找到管理经济的方法。

1776年,经济学家亚当-斯密的观点让人震惊。

他认为政府要做的仅仅是什么都不做,让人们自由买卖。

如果政府让自负盈亏的交易主体充分参与竞争,市场就会导向积极的发展方向,“就像被一只看不见的手引导”。

如果有人卖的价格比你低,顾客自然会去买他们的东西。

这样你就只能降低价格,或者提高质量。

只要人们有足够的需求,市场就会满足他们,像娇惯的孩子一样,这样,人人都会满意。

后世的自由市场主义者,像哈耶克,这种“不干涉”政策实际上胜过任何的宏观调控。

但问题在于,经济需要很长的时间才能实现“均衡”,更有可能停滞不前。

市场调控期间,人们会失去信心。

这就是政府用“看得见的手”的原因。

第二节节约悖论就像小孩子拿到零花钱不知道怎么花一样,经济学最大的问题之一是,储蓄和消费哪个更好。

自由市场主义者,像哈耶克和弗里德曼认为,即使在经济困难时期,节约和储蓄仍然是最好的。

这样银行就能把储蓄用于投资,建立新工厂,发展新技术,提高生产力。

这样即使新技术可能减少工作岗位,降低薪水,新兴事业也会需要雇佣更多人手,最终失业率还是会下降。

逻辑很简单,至少从长期以来看是这样,但是另一个主张“人生苦短”的家伙——凯恩斯认为,长期来看我们都死了,因此,为了避免失业的阵痛,政府应该增加支出,创造工作机会。

如果政府勒紧腰带,而民众和企业也不愿花钱,消费就会下降,事业也会变得更严重。

这就是所谓的“节约悖论”。

因此政府要加大投入,当人们乐意时再收税。

尽管让人们乐意去交税,是连凯恩斯都完成不了的任务。

第三讲菲利普斯曲线新西兰鳄鱼猎手比尔—菲利普斯也是一位经济学家,他指出,当就业率高时,薪水就会涨的快。

人们有更多的钱去消费,于是价格上涨,通货膨胀出现。

反之,当失业率高时,投入消费的钱变少,通涨也会减退。

这就被称作为“菲利普斯曲线”。

政府甚至根据这个曲线制定政策,当加大投入创作工作机会时,会适当的容忍随之而来的通涨。

但他们忘了劳动者也会看到这个曲线,所以失业率下降时,人们就会期待通涨出现,要求更高的薪水。

反而会导致失业率搞到原来的水平。

如果通胀率一直很高,就像70年代发生的一样,通胀和失业率同时升高。

而在90年代,失业率下降,通胀一直保持在低水平,好像摆脱了菲利普斯曲线的限制。

但至少菲利普斯曲线的部分影响还在继续,当经济的快速增长和高就业率恢复时,你保证有会看见通胀把事情搞的一团糟。

第四讲比较优势原则不管你认为让经济自由发展更好,还是认为政府应该插手调控经济,全球市场都是一个不可控因素。

对外国竞争的畏惧导致一些国家师徒自己生产所有必需品,提高关税,把外国货挡在门外。

但是,经济学家大卫李嘉图指出,国际贸易实际上可以使所有参与者受益,通过引进最伟大的早期经济模型之一。

李嘉图指出,即便一个国家能以最低的成本生产产品——这被经济学家成为“绝对优势”,专注于生产最高效的仍然是更好的选择,这样就放弃了少量其他非优势产品,国际市场中的各国都这样发挥比较优势,通过专业化的生产,各国互相出口富余产品,这样各方都能获利,这就是比较优势原理。

它说服了许多国家签署自由贸易协定,但不幸的是,对许多国家来说贸易致富需要很长时间。

因为当今财富的流动与聚集更加便捷,商品的跨国流动快速增长,人口的跨国流动也同样增长——一定程度上冲击了李嘉图的理论基础。

第五讲三元悖论大多数国家间的跨国贸易,对参与各方都有好处,这也同时意味着各国更难控制本国的财政和汇率。

各国政府热衷于三个目标。

首先,各国希望保持汇率稳定,这样进出口价格就不会忽升忽降;第二,政府希望能稳定利率,这样能保证企业更乐于借贷,而不是储蓄;第三,各国都希望资本的进入和流出不会有太多障碍。

但是当你试图同时实现这三个目标时,问题就来了。

举例说明,欧元区国家试图降低利率来加速投资,减少失业。

这样资本就会向其他利率更高的国家流出,于是汇率就会下降,导致通货膨胀。

最终欧元利率又被迫上升到原来的水平。

你要么只能稳定汇率,保证资本自由跨国流动,但同时也会失去对利率的控制,后者同时保证汇率和利率的稳定,但这样你就无法阻止资本的流入和流出。

就像参与铁人三项的运动员一样,你无法同时实现这三个目标。

第六讲理性选择理论在影响经济的所有因素中,最麻烦的就是人。

总体来说,认识理性的。

当某种商品的价格上升,人们就生产更多这样的商品,买的更少。

如果人们预期通胀率会上升,他们就会要求更高的薪水。

如果一国的利率或者汇率出现下降,拥有大量资本的人们就会试图把钱转出去,比你喊出“双底衰退”的数度更快。

各国政府制定经济政策正是奖励在“理性人”的假定之上。

这样很好,不过也会有意外。

有些讨厌鬼并不总能做出最好的选择,有时人们会误以为自己知道了真相,或者真相泰国复杂难以理解。

有时人们倾向于随大流,依靠他们才能了解自己真正在做什么。

比如2007年,房屋贷款利率普遍很低,很多人并不明白背后发生了什么。

更多人只是跟着大流贷款,一些放款方或者能够“理性的”思考,他们相信当信贷出现问题时,危机的严重性会迫使政府为他们买单。

对于银行,这是对的。

可惜对于他们的顾客来说不是这样。