English住吉的长屋

住吉的长屋案例分析

住吉的长屋案例分析住吉的长屋是一座位于日本大阪的历史悠久的建筑,也是日本国宝级别的建筑,其独特的建筑风格和丰富的历史内涵吸引着众多游客和建筑学者前来参观和研究。

本文将对住吉的长屋进行深入分析,探讨其建筑特点、历史价值以及对当代建筑的启示。

住吉的长屋建筑风格独特,其采用了传统的日本古建筑风格,包括木质结构、斜屋顶、榻榻米等元素。

长屋的建筑结构非常坚固,经得起数百年的风吹雨打,展现出了日本古代建筑师的高超技艺和智慧。

同时,长屋的内部布局合理,起居空间与储藏空间相互配合,使得整个建筑既实用又美观。

这种建筑风格不仅展现了日本古代建筑的特点,也为当代建筑提供了宝贵的借鉴。

除了建筑风格,住吉的长屋还承载着丰富的历史价值。

据历史记录,长屋建于日本奈良时代,距今已有数百年的历史。

在这漫长的岁月中,长屋见证了日本社会的变迁,承载了许多历史事件和文化传统。

长屋的建筑风格、装饰图案、传统习俗等都反映了当时社会的风貌,对于研究日本古代社会和文化具有重要的参考价值。

因此,长屋被列为日本国宝,并受到了国家和社会的重视和保护。

住吉的长屋对当代建筑也有着重要的启示。

首先,长屋的木质结构和斜屋顶设计在抗震方面具有独特优势,这为当代建筑提供了宝贵的经验。

其次,长屋的内部布局合理,充分利用了空间,这对于当代城市建筑的空间规划和设计具有借鉴意义。

另外,长屋的传统装饰图案和建筑风格也为当代建筑注入了新的灵感和创意,使得建筑更加具有文化底蕴和艺术价值。

总之,住吉的长屋作为日本国宝级别的建筑,其建筑风格、历史价值以及对当代建筑的启示都具有重要意义。

通过对长屋的深入分析和研究,我们可以更好地理解古代建筑的精髓,同时也可以为当代建筑的发展提供宝贵的经验和启示。

希望长屋的价值能够得到更多人的关注和重视,为保护和传承历史文化做出更多的努力。

住吉的长屋详细资料概要

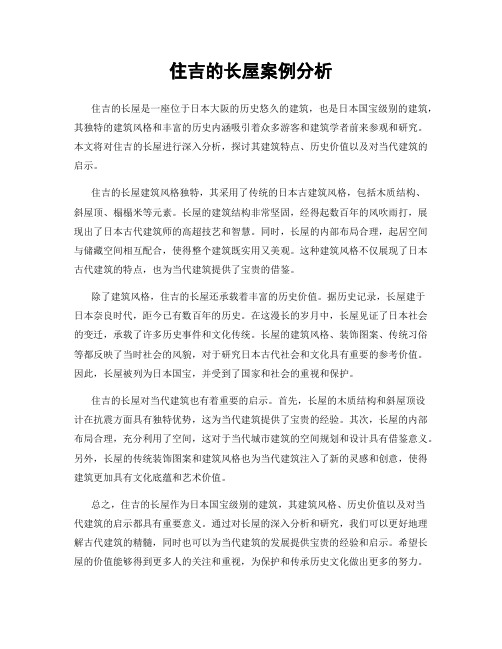

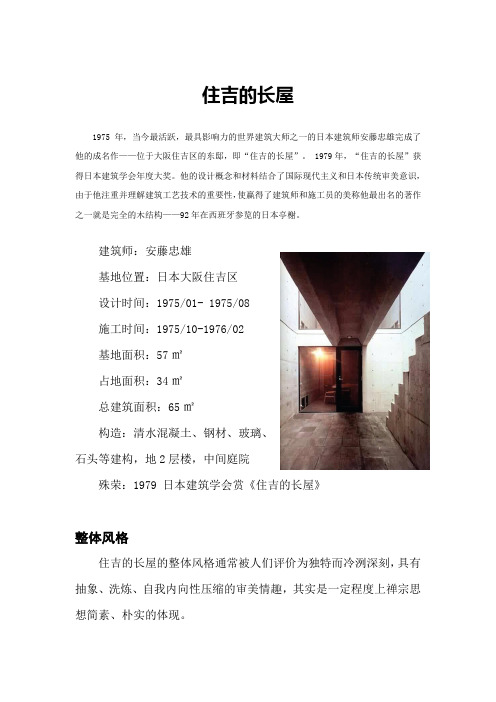

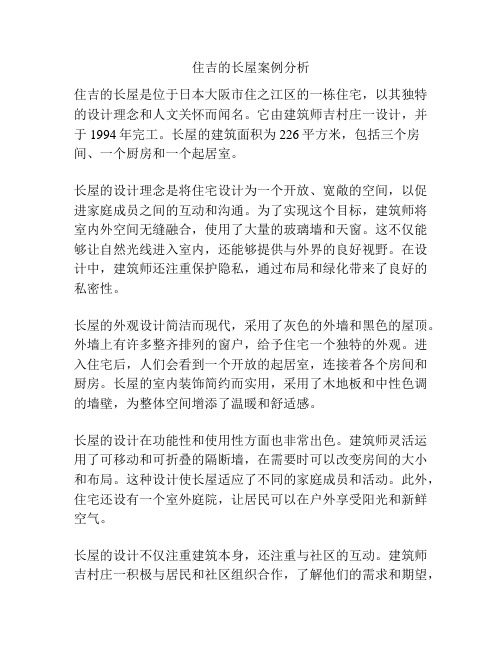

住吉的长屋1975年,当今最活跃,最具影响力的世界建筑大师之一的日本建筑师安藤忠雄完成了他的成名作——位于大阪住吉区的东邸,即“住吉的长屋”。

1979年,“住吉的长屋”获得日本建筑学会年度大奖。

他的设计概念和材料结合了国际现代主义和日本传统审美意识,由于他注重并理解建筑工艺技术的重要性,使赢得了建筑师和施工员的美称他最出名的著作之一就是完全的木结构——92年在西班牙参览的日本亭榭。

建筑师:安藤忠雄基地位置:日本大阪住吉区设计时间:1975/01- 1975/08施工时间:1975/10-1976/02基地面积:57㎡占地面积:34㎡总建筑面积:65㎡构造:清水混凝土、钢材、玻璃、石头等建构,地2层楼,中间庭院殊荣:1979 日本建筑学会赏《住吉的长屋》整体风格住吉的长屋的整体风格通常被人们评价为独特而冷洌深刻,具有抽象、洗炼、自我内向性压缩的审美情趣,其实是一定程度上禅宗思想简素、朴实的体现。

平面布局住吉的长屋的平面布局上,建筑师首先用混凝土的墙壁把狭窄而细长的基地围合了起来,从而限定了内部空间作为一个特别的场所和栖居的场所。

接下来,把这一似长方形的箱子进行了三等分,前和后为两层,中间部分为向天空开放的庭院。

前后部分的二层用无顶的桥连接起来,并有楼梯通向底层庭院。

建成平面占地面积34平方米,总建筑面积65平方米。

立面处理在立面处理上:住吉的长屋继承了传统长屋狭长的特点,但在立面处理时,较传统长屋要封闭。

住吉的长屋对外没有设置一个窗户,面向街道的墙壁是一个四角形的没有分割的立面,除了入口以外没有任何的装饰性元素。

从外部看似乎内部是没有光线的黑房子,且与外部缺乏交流,其实不然:长屋凹入处的墙板将光线反射到街道上,光线成为这座内向式住宅与街道相联系的调节器。

让进入内部的来访者感到惊讶,因为有了庭院而感到非常明亮。

其次,其立面的严格对称,一使建筑有均衡感,二使处于传统长屋区的建筑保留一定传统观念。

此外,通过将宅基地的三分之一设计为庭院,建筑覆盖率也可以达到60% ,充分合理的运用了用地。

住吉的长屋详细资料全

住吉的长屋1975年,当今最活跃,最具影响力的世界建筑大师之一的日本建筑师安藤忠雄完成了他的成名作一一位于大阪住吉区的东邸,即“住吉的长屋”。

1979年,“住吉的长屋”获得日本建筑学会年度大奖。

他的设计概念和材料结合了国际现代主义和日本传统审美意识,由于他注重并理解建筑工艺技术的重要性,使赢得了建筑师和施工员的美称他最出名的著作之一就是完全的木结构——92年在西班牙参览的日本亭榭。

建筑师:安藤忠雄基地位置:日本大阪住吉区设计时间:1975/01- 1975/08施工时间:1975/10-1976/02基地面积:57 m2占地面积:34 m2总建筑面积:65 m构造:清水混凝土、钢材、玻璃、石头等建构,地2层楼,中间庭院殊荣:1979日本建筑学会赏《住吉的长屋》整体风格住吉的长屋的整体风格通常被人们评价为独特而冷洌深刻,具有抽象、洗炼、自我向性压缩的审美情趣,其实是一定程度上禅宗思想简素、朴实的体现。

中间部分为向天空开放的庭院。

前后部分的二层用无顶的桥连接起来,并有楼梯通向底层庭院。

建成平面占地面积34平方米,总建筑 面积65平方米。

平面布局 住吉的长屋的 平面布局上,建筑师 首先用混凝土的墙 壁把狭窄而细长的 基地围合了起来,从 而限定了部空间作 为一个特别的场所 和栖居的场所。

接下 来,把这一似长方形 的箱子进行了三等 分,前和后为两层,1卄山|口叫 ■ 匚i ~ )立面处理在立面处理上:住吉的长屋继承了传统长屋狭长的特点, 但在立 面处理时,较传统长屋要封闭。

住吉的长屋对外没有设置一个窗户, 面向街道的墙壁是一个四角形的没有分割的立面, 除了入口以外没有 任何的装饰性元素。

从外部看似乎部是没有光线的黑房子, 且与外部 缺乏交流,其实不然:长屋凹入处的墙板将光线反射到街道上 ,光线 成为这座向式住宅与街道相联系的调节器。

让进入部的来访者感到惊 讶,因为有了庭院而感到非常明亮。

其次,其立面的严格对称,一使W— j 仙— T ~ ~ i F" . 的■WL KIiCwl建筑有均衡感,二使处于传统长屋区的建筑保留一定传统观念。

住吉的长屋案例分析

住吉的长屋案例分析住吉的长屋是位于日本大阪市住之江区的一栋住宅,以其独特的设计理念和人文关怀而闻名。

它由建筑师吉村庄一设计,并于1994年完工。

长屋的建筑面积为226平方米,包括三个房间、一个厨房和一个起居室。

长屋的设计理念是将住宅设计为一个开放、宽敞的空间,以促进家庭成员之间的互动和沟通。

为了实现这个目标,建筑师将室内外空间无缝融合,使用了大量的玻璃墙和天窗。

这不仅能够让自然光线进入室内,还能够提供与外界的良好视野。

在设计中,建筑师还注重保护隐私,通过布局和绿化带来了良好的私密性。

长屋的外观设计简洁而现代,采用了灰色的外墙和黑色的屋顶。

外墙上有许多整齐排列的窗户,给予住宅一个独特的外观。

进入住宅后,人们会看到一个开放的起居室,连接着各个房间和厨房。

长屋的室内装饰简约而实用,采用了木地板和中性色调的墙壁,为整体空间增添了温暖和舒适感。

长屋的设计在功能性和使用性方面也非常出色。

建筑师灵活运用了可移动和可折叠的隔断墙,在需要时可以改变房间的大小和布局。

这种设计使长屋适应了不同的家庭成员和活动。

此外,住宅还设有一个室外庭院,让居民可以在户外享受阳光和新鲜空气。

长屋的设计不仅注重建筑本身,还注重与社区的互动。

建筑师吉村庄一积极与居民和社区组织合作,了解他们的需求和期望,并将这些考虑融入了设计中。

通过定期举办社区活动和开放日,长屋与周围社区建立了紧密的联系,并成为社区的重要组成部分。

总的来说,住吉的长屋是一栋独特而实用的住宅,以其开放的空间设计、精心布局和与社区的紧密互动而备受赞誉。

它是建筑师吉村庄一智慧与创意的结晶,同时也是人文关怀和社会责任的典范。

这个案例提供了一个很好的参考,为我们今后的住宅设计提供了启示。

大师作品之住吉的长屋

打磨的像镜面一样光滑的 打放水泥

END

材料的选择 清水混凝土 带圆孔的清水混凝土墙面是安藤建筑的显著外表, 安藤的建筑一般全部或局部采用清水混凝土墙面 作为室外或室内墙面,这种墙面不加任何装饰, 墙面上的圆孔是残留的模板螺栓。清水混凝土演 奏一曲光与影的旋律。在清水混凝土的施工中, 传统手工艺和现代建筑之间并不矛盾,高超的木 模制造工艺、优质的混凝土铸造以及严格的工程 管理,共同造就了“安氏混凝土美学”。

配色方案

中庭也巧妙的引用了安腾建筑 三要素之一的“自然”,将四 季变化的自然,引入曰常的生 活空间。安藤将自然还原成光、

风、水空气等元素引入中 庭,在有限的混凝土空间中完

成了一个“微型的宇宙”。

安藤对光线的运用源于日本传 统的数寄屋茶室,喜欢用一束 不经意的光线刺破昏暗变幻莫 测的光从庭院投入室内、地下 产生幽静的美。光影是组织空 间的重要因素,让光撒向墙与 柱的间隙,直接塑造空间,取 得神圣而亲密的效果。墙体在

材料的选择

我乐于把混凝土看成一种明朗 安宁的无机材料,赋予它一种 幽雅的表达。 ——安藤忠雄

主体构造以最简朴的清水混凝 土,给人坚固之安全感,不花 俏的外观给人统一、简洁的美 感,厚实的墙面可以阻绝东西 晒的阳光,降低室内的温度以 节省能源。

长屋还使用了玻璃、石材、 钢材等建构 安腾将门设计为玻璃门,在保 证不影响各个空间私密性的同 时,又使人不被封闭在小的长 方体盒子里,也扩大了人的视 觉空间

住吉的长屋详细资料

住吉的长屋详细资料平面布局上,建筑师首先用混凝土的墙壁把狭窄而细长的基地围合了起来,从而限定了内部空间作为一个特别的场所和栖居的场所。

接下来,把这一似长方形的箱子进行了三等分,前和后为两层,中间部分为向天空开放的庭院。

前后部分的二层用无顶的桥连接起来,并有楼梯通向底层庭院。

建成平面占地面积34平方米,总建筑面积65平方米。

立面处理在立面处理上:住吉的长屋继承了传统长屋狭长的特点,但在立面处理时,较传统长屋要封闭。

住吉的长屋对外没有设置一个窗户,面向街道的墙壁是一个四角形的没有分割的立面,除了入口以外没有任何的装饰性元素。

从外部看似乎内部是没有光线的黑房子,且与外部缺乏交流,其实不然:长屋凹入处的墙板将光线反射到街道上,光线成为这座内向式住宅与街道相联系的调节器。

让进入内部的来访者感到惊讶,因为有了庭院而感到非常明亮。

其次,其立面的严格对称,一使建筑有均衡感,二使处于传统长屋区的建筑保留一定传统观念。

此外,通过将宅基地的三分之一设计为庭院,建筑覆盖率也可以达到60% ,充分合理的运用了用地。

住吉的长屋的立面处理,一方面大大降低了周围嘈杂环境的不利影响,满足了地处中心城区的住宅对私密性的要求,同时凸现了内部光线的丰富性。

中庭——空间流动的枢纽长屋在大阪是比较普遍的一种住宅形式。

近些年来,由于大量旧建筑的更新,大都改建成了独家独户的组装式住宅或集合式住宅,长屋就越来越少。

普通的长屋大约是以2间的宽度为一户的住宅,然后将其连续着排列而成的。

进入住宅里面有中庭或通道,以及后院。

中庭或过庭中有一些小的自然景色的空间。

由于我们的生活需要采光、通风、日照等,住吉的长屋的设计,安藤忠雄认为即使再小的房子,也要在中间设置一个庭院空间。

“无论是多么小的物质空间,其小宇宙中都应该有其不可替代的自然景色。

”为什么向自然开放的庭院是必须的呢?在高度工业化的社会里,环境污染、环境破坏都成为常态,在城市中,已经不存在无垢的自然。

小建筑分析--住吉的长屋

─ 住吉的长屋

林鹏 建筑学

目录

住吉的长屋简介 空间布局 结构分析 光色分析 设计特点、风格分 析

住吉的长屋简介

基地位置:日本大阪住吉区 基地面积:57㎡ 占地面积:34㎡ 总建筑面积:65㎡ 结构:清水混泥土

长屋是关西地区特有的一种住宅形式,其为 竖长条形,数家住房紧密依靠在一起,共用 同一地基。安藤在保留传统长屋住宅样式的 基础上大胆加以现代的改造,引入自然的气 息。虽然该建筑由于居住时的不方便引起了 诸多非议,但其设计思想仍是值得肯定的。

楼梯交接处

一 层 设 计

结构分析

平面图

N

与隔壁房屋间距:10cm

二层平面图 一层平面图 剖面图

透视图

取代了原来的 一座连排长屋, 中间的一座,它 的地基、粱与 旁边的长屋是 共用的.

外部空间是内部空间的 反映,长方体体形决定 内部的空间形状统一的 长方体块. 五个长方体空间组成大 的长方体块.使建筑本 身也内外取得统一.

谢谢

整体风格

住吉的长屋的整 体风格通常被人 们评价为独特而 冷洌深刻,具有 抽象、洗炼、自 我内向性压缩的 审美情趣,其实 是一定程度上禅 宗思想简素、朴 实的体现。

空间布局

小孩卧室

天窗

中庭

主卧

小地窗 门厅

起居室

共用地基

厨房

厕所

主卧

内部各空间相对独立, 保证了各功能空间的私 密性.

小孩卧室

厨房 卫生间

光色分析

长屋还有一个十分显著的特点:对外没有设 置一个窗户。从外部来看就像一个封闭式的 火柴盒,似乎内部是没有光线的黑洞。但是 进入内部就会发现,因为中间有一个庭院 而感到十分明亮,足可以让来者大吃一惊。 并不是推开门就可以见到起居室,还要转一 个弯,这使建筑中光的效果更加显著。

建筑赏析之住吉的长屋

结构形式

有和

构住

明 显 的 传 承 关 系

日 本 关 西 的

庭 院 式

天 井 式 与 自 然 式

成吉 手长 法屋

中 庭 院 的 两 种

住

吉

的

长 • 清水混凝土材

继 承 与

____

屋

料以及简约的 几何构成,营 造出静谧、明 朗的空间效果

发 展

• 比传统长屋封 闭,来突显内

部光的丰富性

住吉的长屋建筑的概况

处理,自然与建筑既对立又并存。

• 最后一个因素是”自然”;在这儿所指的自然并非是原始的自然,而是人所 安排过的一种无序的自然或从自然中概括而来的有序的自然--人工化自然! 安藤所谓的自然,并非泛指植栽化的概念,而是指被人工化的自然、或者说 是建筑化的自然。他认为植栽只不过是对现实的一种美化方式,仅以造园及 其中植物之季节变化作为象征的手段极为粗糙。抽象化的光、水、风。这样 的自然是由素材与以几何为基础的建筑体同时被导入所共同呈现的。

旧街 日本大阪住吉区 二战后随处可见的木构建筑

住吉的长屋

结构形式

住吉的长屋的形体特征

建筑的平面分析和功能组织

建筑的平面分析和功能组织

• 卫浴·餐厅·厨房 • 中庭 • 起居室·门厅

• 两个卧室(私人空间) • 儿童房 • 主人房

建筑流线

• 安藤忠雄的住吉长屋是位于三幢连排长屋中间的 独立住宅,基地非常狭窄,他通过把各种房间向 两端尽量压缩从而在住宅的中心争取出一个室外 的中庭。厨房和起居室、卧室和预备室分别安置 于中庭的两端。晴天时,中庭的存在使整个住宅 充满了阳光,而雨天时,即使从一个房间走到另 一个房间也必须撑起雨伞。安藤忠雄通过这种看 似功能布置极不合理的设计,却使住户在拥挤的 都市住宅中具有了一处属于自己的能够随时感觉 到自然四季变化的精神世界。在这里,随时随地 能够感受自然的内省式中庭成为超越生理性居住 层次到达精神性居住层次的催化装置

内省的居所--安藤忠雄住吉的长屋阅读分析

内省的居所——安藤忠雄作品住吉的长屋阅读关键词:现代性与地域性比较阅读内省摘要:通过比较阅读,以及对远近历史环境的分析,试寻找出安藤所受日本传统的影响、对待历史的态度,和他应对现代性与地域性关系的策略。

1.历史背景与长屋设计理念的形成:20世纪初,密斯将建筑的普遍性追求到了极致。

他作为理想提出的“万能空间”与材料的工业化同时并进,通过极其简易的形态将它传播到了全世界。

60年代实现了经济高速增长的日本,城市中出现了大量生产的毫无个性的方盒子。

建筑不能使人感受到差异,人的欲望或思想没有进入的余地,人们对现代建筑的“崇高理想”渐渐反感。

60年代现代主义进入转折时期,安藤此时二十出头,正在形成自己的建筑观。

在60年代日本的经济增长中,新的思维模式逐渐形成。

以前人们认为是好的传统,如对物的珍惜,重视与近邻的关系,重视家庭和睦,与自然共生等传统正在消失。

经历了变革激烈的60年代后,安藤开始思考“运用现代建筑的材料和语言、几何学构成原理,使建筑同时具有时代精神和普遍性,将风光水等自然要素引入建筑的方法”,从而创造出根植于建筑场所的气候风土,又表现出其固有文化传统的建筑。

住吉的长屋,就是安藤这些思考的完整体现。

通过这样一个美丽的小住宅,安藤向导致“人的规格化、平均化”的标准化现代主义建筑宣战,实践着他关于人居理想的追求。

正因如此,Frampton 将安藤看做批判地域主义的成功实践者。

2.几何-场所-自然——长屋的总体理念住吉的长屋改造,基地在大阪住吉区,用地拥挤紧张,周围存在大片日本关西近代住宅形式——长屋。

具体用地宽2间、进深7间,共14坪左右,覆盖率限制在六成,在如此紧张的用地上,安藤却创造了充满诗意的栖居场所。

他切掉部分长屋,插入了表现抽象艺术的混凝土盒子,将关西人常年居住的长屋要素置换成现代建筑。

尽管有很多争议,令安藤骄傲的是,他“在完全抽象化的几何四方盒子中,将关西居民继承下来的传统居住方式,以及对自然的认识等全部装了进去”。

住吉长屋作品分析

住吉长屋注重人性化设计,从空间布局、采光、通风等方面充分考虑 人的需求和感受,提高了居住的舒适度和幸福感。

对未来建筑发展的启示与影响

01

重视传统文化的传承与创新

住吉长屋的成功经验告诉我们,在建筑设计中应重视传统文化的传承与

创新,将传统文化元素与现代技术、审美相结合。

02

注重人性化设计和可持续性发展

瓦片

用于屋顶的覆盖,具有良 好的防水性能和耐久性。

建筑结构与功能布局

结构形式

采用传统的长屋形式,以适应日本气 候和地形特点。

功能布局

空间利用

通过设置阁楼和储物间等空间,充分 利用建筑内部空间,满足家庭成员的 生活需求。

内部空间根据家庭成员的需求进行合 理布局,如客厅、卧室、厨房等。

03

住吉长屋的建筑风格与美学

04

住吉长屋的社会与文化意义

对当地社区的影响与贡献

促进当地经济发展

01

住吉长屋的建设为当地提供了就业机会,吸引了外来游客,增

加了地方财政收入。

提升当地居民生活品质

02

住吉长屋提供了舒适的居住环境,改善了当地居民的生活质量。

传承和弘扬地域文化

03

住吉长屋的设计融入了当地传统建筑元素,展现了地域文化的

03

04

05

采用了传统的木结构和 瓦屋顶,与周围的环境 相协调。

在室内设计中,注重自 然采光和通风,营造出 舒适宜人的居住环境。

在空间布局上,采用了 开放式的设计,使得室 内空间与外部环境相互 渗透,增强了建筑与自 然的互动性。

02

住吉长屋的构造与材料

构造方式与技术

01

02

03

木结构

长屋文字资料集4页

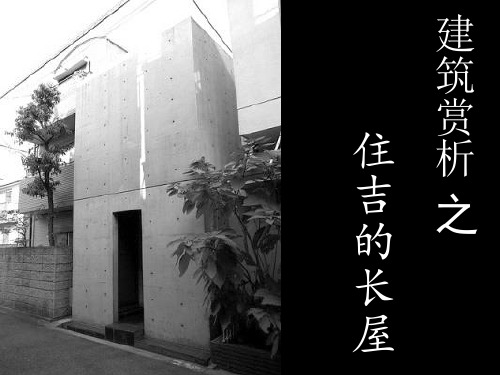

关于“住吉的长屋”的一些资料垒书主人整理建筑设计者:安藤忠雄基地位置:日本大阪住吉区基地面积:57㎡占地面积:34㎡总建筑面积:65㎡概况住吉的长屋设计于1975年,它取代了一片密集住宅区内三座木制连排长屋之中的一座。

宽约3.5m、全长约14m、高约6m,共2层,总建筑面积仅有65㎡。

但其封闭的长方体块结构使得有限的地基得到了充分利用。

住吉长屋继承了传统长屋狭长的特点,但在立面的处理上,较传统长屋要封闭。

同时立面严格地对称,使整栋建筑有均衡感,也使得处于长屋内部的建筑保留了一定的传统观念。

住吉的长屋可以说是安藤建筑生涯中最重要的作品,,他曾坦言,其以后建筑作品的理念,几乎都已经在住吉的长屋中进行过思考.在创造这个有极度限制的的空间的过程中,安藤领悟到在这种近乎极端的条件中存在一种丰富性,以及与日常生活有关的一种限制性。

由等垮的框架结构营造的均质空间是现代建筑的首要基础,而安藤则倾向于创造一种看似简单而实际尚远不止于此的空间——那就是在单纯化中产生的复杂空间。

安藤的不连续的空间为建筑平添了许多生机和乐趣,给参观者以意外的惊喜,但非连续的空间在功能和人的情感效应上是连续的,并不使人感到突兀。

在住宅中,室外庭院是室内起居室的延续,它与日常生活密切相关,是必不可少的环节.庭院这座建筑对外没有设置一个窗户,从外部看似乎内部没有光线的黑盒子。

但是进入内部就会发现,因为有庭院而感到非常明亮,甚至使来访者感到吃惊。

建筑的庭院占据了三人之一的基地面积,并布置在建筑的中央。

中庭巧妙的引用了安藤建筑三要素之一的“自然”,将四季变化的自然,引入日常的生活空间。

安藤将自然还原成光、风、水、空气等元素引入中庭,在有限的混凝土空间中完成了一个“微型的宇宙”。

它提供了一种与自然的接触,并揭示出自然的各个方面,是住宅生活的中心,也是一个引入正在现代城市日趋消逝的光、风、雨等自然物的一种装置。

光线从天空渗入院中,在墙上和院子里投下深深的阴影。

住吉的长屋浅析

东南大学成贤学院建筑学系2010级05310119 卢方舟住吉长屋位于大阪南部,设计于1975年。

取代了一片密集住宅区内三座木制连排长屋之中的一座。

宽约3.5m、全长约14m、高约6m,共2层,总建筑面积仅有65平方米。

但其封闭的长方体块结构使得有限的地基得到了充分利用。

住吉的长屋尝试在通过对原有建筑形式内涵进行提炼升华的前提下,在原位置建立一个与周边环境协调,空间利用率高效,居住环境更加宜人的建筑。

在这样一个狭窄的空间内,安藤试图引入天光,风,雷,雨,雪等自然元素堪称一种挑战。

建筑的外墙面左右后紧邻其它住宅,前里面外即使交通道路,可以说,尝试拓展室外空间是十分困难的,然而安藤大胆的在建筑内部开辟出一块室外空间,在对室内空间合理简约布局的前提下,这样的处理不仅不显拥挤,反而创造了一种宁静,和谐的建筑内涵。

建筑在延轴线方向均分为三分,中间为无遮蔽内院,内设垂直交通楼梯。

在竖直方向上分为两层。

考虑到街道拥挤嘈杂,视野及其有限,建筑外立面开窗极少,相反将上下四个主要房间均采用面向内院开落地窗及玻璃门,这一方面解决了采光问题,另一方弱化里室内外空间界限,充分将自然元素引入室内,并且并未妨碍隐私要求。

建筑内交通流动以内院为核心,这种室内外空间感的频繁转换可一说大大地削减了长屋这种建筑形式固有的狭小拥挤的特性。

有人也许会怀疑,就连上厕所也要打着雨伞经过内院的建筑空间真得有借鉴意义吗?我认为,这栋建筑或许正是对日本人文特点的一种诠释,即使是在有限的空间内也要为自然留出位置,这大概就是日本人的生活哲学吧,毕竟,到如今,长屋的主人一家还居住在这里。

安藤把他对自然与建筑的深刻理解与他对日本传统文化的辩证的继承,融合灌注在这样一个精巧的建筑中,渺小中足见伟大。

作为建筑师,我想我们要学习的并非他一钉一铆的细节之处,而是扎根于民族文化,人民生活的哲学态度,杰作不因惊世骇俗,天马行空出色,而因对生活本质的理解而深刻,因为建筑是关于人的建筑,关于生命的建筑,关于自然的建筑。

住吉的长屋

住吉的长屋:一.基本资料:外文名:Azuma House设计师:安藤忠雄设计时间:1975.1-1975.8施工时间:1975.10-1976.2基地面积:57㎡占地面积:大约34㎡总建筑面积:大约65㎡尺寸:宽约3.5m、全长约14m、高约6m,共2层建筑位置:日本大阪住吉区的东邸获奖情况:1979年,“住吉的长屋”获得日本建筑学会年度大奖。

二.建筑师简介:安藤忠雄,日本大阪人,曾任货车司机及职业拳手,其后在没有经过正统训练下成为职业建筑师。

正因为此,安腾素有“没文化的日本鬼才”之称。

安藤在大阪府立城东工业高校毕业后,前往世界各地旅行,并自学建筑。

1969年成立安藤忠雄建筑研究所。

1976年完成位于大阪府的住吉长屋,是两层高的混凝土住宅,已显现其设计风格。

其后获得日本建筑学会赏。

1980年代参与关西周边地区(神户北野大阪心斋桥)的商业建筑设计,1990年代以后,参与公共建筑美术馆建筑等大型计划。

安藤成名后接连发表了以清水混凝土建造的住宅和商业建筑,引起风潮和讨论。

从博物馆娱乐设施宗教设施办公室等,通常都是大规模的设计。

安藤忠雄是位难得的建筑师,他集艺术和智慧的天赋于一身,他所建的房屋无论大小,都是那么实用,有灵性,他有超强的洞察力,超脱了当今最盛行的运动学派或风格。

他的建筑是形式与将要生活那里的人们的综合统一。

在大多数建筑师位正开始着手于最正统的作品时,安藤已经完成了一件杰出作品的主体部分,尤其是在他本土日本,这也正是他与众不同的一点。

有了光滑如丝的混凝土,安藤创造的空间都是那么富有表现力,而他使用的墙体都是那么富有表现力,而他使用的墙体正是他所称的建筑最基本的元件。

长期以来,尽管他使用的材料和构件都是柱、墙、拱等,但这些元件一经过他不同的组合,又总是充满了活力与动态感。

他成功地完成了强加给自己的使命,即恢复房屋与自然的统一,通过最基本的几何形式,他用不断变幻的光图成功地营造了个人的微观世界。

住吉的长屋

住吉的长屋简介 • 长屋建于1975-1976间 • 长屋位于大阪市住吉区老街连续的三间长屋之中。他的地基与梁与其他两家 共用 • 正中间的那间被改建成了宽两间,深八间的箱型混凝土房子。 • 约3.5m宽、全长约14m、高约6m,共2层,总建筑面积仅有65平方米。 • 长屋长向被三等分,中间的三分之一是中庭。 • 长屋的建筑材料—清筑的庭院式的明 显传承。

完全敞开的中庭在竖直方向上将自 然毫无保留的引向室内,是室内与 室外沟通的装置。

所有的房间都面向中庭,以之为中 型。中庭加强了各个空间水平与竖 向的空间联系。楼梯加强了向上的 空间联系。

建筑中所有的活动都有中庭的参与,中庭是空间的枢纽,也是人情的枢纽。 中庭是组织空间的向心,也是人情空间的向心。

时代背景 长屋建于20世纪70年代,1971年日本住宅产业兴起。二战后的25年,憧憬美 式生活的而一直拼命的日本人,总算有余力可以建造自己的家了。 那时大家所追求的,自然是设备齐全的美式住宅,宣传着亮丽时尚居家样式 的公寓、新楼房以惊人的态势不断兴建。 虽然大阪等地的新兴住宅区不断被许多新楼房淹没,但是以传统工法建造的 木材房屋为主流,密集排列的住宅才是现实的风景,和时尚居家扯不上关系。 但是与地面广博的美国不同,地狭人稠的日本国土追求美式住宅毕竟不切合 实际,日本社会应该思考的是如何选择更加符合自己的生活状态。

住吉的长屋

---------从社会批评模式 历史文化角度解读

长屋 长屋是关西的一种比较普遍的住宅形式。普通的长屋大约是以2 间的宽度为一 户的住宅,然后将其连续着排列而成的。住宅里面有中庭或通道,以及后庭。中 庭或过庭中有一些小的自然景色的空间。因此,长屋是一种空间狭长、但充满 生活情趣的住宅形式。住吉的长屋继承了长屋的传统,在极度限制的条件下 创造出了丰富的空间。

住吉的长屋

建筑师:安藤忠雄基地位置:日本大阪住吉区设计时间:1975/01- 1975/08施工时间:1975/10-1976/02基地面积:57㎡占地面积:34㎡总建筑面积:65㎡1976年大阪市住吉区,安藤忠雄的成名作,也是其代表作之一。

安藤先生自己对这座建筑也有一番评价“这个小住宅是我后来作品的起点,它是我值得纪念的建筑,也是我所钟爱的建筑之一。

这栋房子是三幢联立住宅中间的一个矩形插入体。

我的基本构思是楔入一个混凝土盒子,并在其间创造一处世外桃源,和一个由多样化空间和动态直线组合的简洁构成”。

住吉的长屋是在日本大阪传统民居的基础上引入现代住宅的概念,而又在这个利用西方发明的混凝土和钢材为主要建筑材料的住宅中充分体现出日本人的生活习惯和民族特点。

而且是在一个十分小的空间内完成的,又要考虑到与四周民居的统一。

因为所要做改建的长屋与其他长屋是一个整体,地基和大梁都是通用的。

一般的建筑师可能只是将其内部做一些改造,装饰一下而已,而安藤不仅成功解决以上各种问题,而且是安藤早期最优秀的作品,正是它使他日后逐步走向了世界。

使其成为经典建筑之一,并获得1979年日本建筑学会奖奖。

所以不能简单的观赏建筑外形,还要深刻的体会其建筑内涵和建筑风格。

1,住吉的长屋采用的建筑材料是非常普通的混凝土和钢材,其受力体系十分清楚简单。

钢筋混凝土现浇板,和钢筋混凝土现浇得二层过道,经混凝土剪力墙传到基础,十分经济。

现浇模拆除后会留下很多矩形图形,安藤就将这些巨型图案作一些简单处理而使其成为内外????? 墙的饰面,淡雅、朴素。

2,? 屋内则采用自然材料,地板为木材或者石材,家具全部采用木质材料,充分体现出日本人对自然的热爱,让住户得到精神上的慰藉。

3,? 长屋的所有墙面都开有为了通风的小地窗,与相邻的住宅间留有十厘米的缝隙用以通风,是一座没有空调设备也可以生活的节能型空间,这一细微的设计可谓是独具匠心,别出心裁。

从其剖面图可以看出地窗位置 ??4,??长屋还有一个十分显著的特点:对外没有设置一个窗户。

安藤忠雄之一住吉的长屋

安藤忠雄之一住吉的长屋〖普利茨克建筑奖:住吉的长屋〗1.作品名称:住吉长屋2.建造时间:19763.基地:日本.大阪市住吉区4.面积:3.3基地面积:57㎡占地面积:34㎡总建筑面积:65㎡5.构造:清水混凝土、钢材、玻璃、石头等建构,地上2层楼,中间庭院。

6.住吉长屋位于大阪南部,设计于1975年。

取代了一片密集住宅区内三座木制连排长屋之中的一座。

宽约3.5m、全长约14m、高约6m,共2层,总建筑面积仅有65平方米。

但其封闭的长方体块结构使得有限的地基得到了充分利用。

〖作品分析〗(1).考量周遭环境:考量不破坏巷弄之整体感,消除突兀感,而让此建筑物依旧设计为2层楼之建筑。

(2).排除基地限制:此基地本身位於小巷弄内,左右两旁皆是2层楼的住家,此基地为一个狭长的空间,原本在狭长的空间会有光线引进不均的状况,如前後光线较充足而中间较幽暗的情形产生,然而安藤为了解决上述问题,而将空间约三等分的分割,将中央留设天井,巧妙引进光线。

(3).质朴的素材:主体构造以最简朴的清水混凝土,给人坚固之安全感,不花俏的外观给人统一、简洁的美感,厚实的墙面可以阻绝东西方向晒的阳光,墙上还开有小地窗,用作房间通风换气,调节室内的温度以节省能源。

(4).简单的几何:在一个长方体里以垂直分割成上下2层楼,水平的分割约3等分,中间留设天井形成前後两个空间,再以天桥连接前後空间,形成简单明了的动线。

把杂乱的都市景像排除在视线外,围砌出排除与外界的连结,由个人内在的经验与感知,塑造属於自己的"情感空间",这是对日渐杂乱的都市景观之反讽。

(5).强调引进自然:一楼形成中庭并试图在住宅空间内巧妙地引进安藤所强调的建筑三要素之一的"自然",将四季变化的自然,引导至日常的生活空间。

(6).延续文脉,继承当地的传统居住方式:Ando采用的手法不是直接引用对这些小住宅的空间、生活及历史的记忆,和传统材料、做法等不可缺少的要素来继承传统,而是像里查德.塞拉和盖里的绘画一样在完全抽象化的几何四方盒中,将关西居民继承下的传统居住方式,以及对自然的认识等全部装进去的手法。

English住吉的长屋

English住吉的长屋a course-long investigation of inveterate systems, sites, and buildings09Nov 20114CommentsAzuma Row House by Tadao Ando | Designing Architecture to Purposefully Make PeopleFeel uNCoMfoRTabLEThe Azuma Row House (Sumiyoshi, Osaka, Japan) was designed by Tadao Ando in 1976. Built in an old post WWII neighborhood of wooden row houses, his project replaced its predecessor with a modern interpretation of the urban context. Cast in concrete, Ando’s austere and functional design divides the site into three parts – two equally sized enclosed interior volumes flanking an open-air courtyard. Centralizing the courtyard makes it an integral part of circulation and the focus of everyday life. What makes this setup particularly unique is that there is no way to cross to either side of the house without passing through exterior and ultimately confronting nature. Despite the hardships that this may enforce on the inhabitants, Ando defends his design:At the time [mid-1970s], I thought of residential design as the creation of a place where people can dwell as they themselves intend. If they feel cold, they can put on an additional layer of clothing. If they feel warm, they can discard extraneous clothing. What is important is the space be, not a device for environmental control, but something definite and responsive to human life… No matter how advanced society becomes, institutionally or technologically, a house in which nature can be sensed represents for me the ideal environment in which to live.With subtle and careful presentation Ando forces occupants to experience the dynamic flows of nature every single day. Despite the advent of highly thermally controlled architecture, the environment’s energy flows are somehow an inherent experience in inhabiting the house. I’d like to explor e how this seemingly anachronistic and modest design approach affects the comfort and lifestyle of its victims, oops I mean tenants ;-)Tadao Ando is actually one of my favorite architects, and is world renowned for his stunning manipulation of air, light, and water. This project, his first residential commission, explores issues we’ve discussed in class regarding heat transfer, air flow, and light.Thermally Active Surfaces and flows: What kind of environment does Ando create?The building envelope of the Azuma Row House is simple and uniform — a continuous fa?ade with no apertures, except for one small skylight. Apart from its inward –facing glass walls and minimal wood finish, the majority of the envelope is cast concrete, which has a very high specific heat capacity (0.880 J/(gK)), and therefore capable of absorbing a lot of heat energy. This trait affects the heating and cooling of the interior and courtyard in various waysCourtyard_ Constantly exposed to the sun, the concrete and stone slabsre ceive heat energy from the sun’s direct radiation, diffused sky radiation, and any rays reflected off of surrounding buildings.They cannot easily conduct or release this energy and stores it throughout the day, gradually increasing in temperature. The ground can retain a large amount of heat for hours, which can make standing in that space uncomfortable – think of asphalt on a summer day. Also since hot air molecules rise, the occupant space air temperature can become overheated and uncomfortable as well. This is a greater concern in the summer time when exposure and temperatures are high. Furthermore, by placing the exterior space at the center of the row house the building envelope’s surface area almost doubles,which can be a crucial matter for skin-loaded or envelope dominated structures. Expanding the threshold for hot or cool air to transfer across makes the thermal environment asymmetrical, less predictable, and uncomfortable.The Interior_ In each room there are four surfaces of exposed concrete. Although the floors are covered with wood slats providing insulation between the foot and slab, there is still conduction of heat energy through the walls. Bearing in mind the house’s small scale, there is likely considerable contact with the building envelope which prompts measurable heat loss from the human body – comfortable during warm seasons, frustrating during cold.The sixth surface of every room is a floor-to-ceiling plane of glass with a glass door. Although certain types of glass have relatively high heat capacities, the metal mullions that support the panes are highly conductive –not to mention that a building cannot be perfectly sealed. A significant temperature difference across this barrier will cause a convection current that will easily circulate warm air into a cooler courtyard, and vice versa, causing fluctuations in the room’s temperature.In addition, without any apertures to penetrate, radiation waves reflect off of the house’s exterior facade or are absorbed by it. Unlike the courtyard, this heat exchange occurs on the side the occupants do not have contact with. Since the thick thermal mass absorbs all of the heat, the interior remains cool. Again, despite the benefit in the summer, this kind of passive radiant heating could be very useful during the winter.Thermal Comfort_ After reading Heating, Cooling, and Lighting by Lechner we discussed the body’s thermal response to any environment, or its relationship with the space’s temperature profile. Many of the thermally dynamic characteristics of the Azuma House are beneficial during one season, and a burden during another. However, some issues like convection across thermal surfaces can always work against your desired comfort zone. Ando includes many conductive and convective thermal surfaces in his construction and few radiant sources. The volatility of convection patterns make air flow, heat transfer, and therefore room temperature asymmetrical and unpredictable.Natural Ventilation: How does Ando achieve reasonable comfort through passive design?As a skin-load or envelope dominated structure – with climate dependent cooling requirements– passive solar heating is a reliable method to keep the structure reasonably comfortable because it is an efficient transfer of heat energy between the climate and envelope that requires no fluid medium like in convection. Part of what makes these structures so easily influenced by their envelopes, are their large surface area-to-volume ratio, which creates a large gateway for heat loss. It’s interesting to see what fluid dynamics principles, if any, Ando utilized to make the space more comfortable by modern standards. To start, there are no mechanical systems in the structure for heating or cooling.Cross Ventilation_ Again, the building envelope is a continuous and uniform surface. There aren’t proper inlets or outlets to let wind through the interior spaces, as there no apertures at all. Therefore, no cross ventilation can occur.Stack Effect_ However, high-speed winds redirected over the row house can create a region of lower temperature that draws out the warm air from the courtyard. It produces something similar to a stack effect. When air in the courtyard gains heat energy due to high air temperature or thermal radiation, its buoyancy will decrease, causing it to rise up out of the courtyard.This is what prompts the convection of cool air from the interior to the exterior through the glass pane, as I mentioned above under Interior thermal flows. The rising warm air molecules leave a region of low pressure that draws the high pressure cool air into the void – as molecules always flow form groups of greater energy to groups of lower energy.High Mass Cooling_ The Azuma row house is a great example of Night ventilation of a thermal mass. The concrete slabs have a great capacity to hold heat that accumulated during the day and is gradually released as the surrounding environment cools in the evening. More specifically, at night, cool air circulates through the building and the heat in the thermal mass is released to the space above it, keeping it warm and renewing its own ability to re-absorb more energy the following day. This prevents sudden swings in hot and cold temperature.Why not more natural ventilation? _ There are several cons or obstacles that come about when utilizing certain types of natural ventilation, which is why Ando might have under-utilized these methods. Noise, pollutants, and harsh winds are a side effect of any kind of ventilation system that passes through a structure at occupant level, which — considering the scale of this project — was unavoidable. Although I think that these system characteristics could in some way support Ando’s thesis regarding bringing the house’s inhabitants closer with nature, cross ventilation in addition to such a large open-air courtyard,would form a setting too abrasive for his clients, especially considering the urban conditions. Furthermore the penetrating sounds, smells, and contents of street’s cross breeze would also undermine his idea of the ―inward looking‖ house.In Conclusion: Would I have the courage to live here?Is Tadao Ando successful in creating a thermally appropriate environment for humans. Well, that’s a difficult question to answer, as it can be interpreted from many of his works and from his own words that hisintention was to make his occupants slightly uncomfortable. Ando has said that walls have often separated us from the outside world in a way that has ―bordered on violent.‖ Through his design it seems he allows light and air to enter into the daily lifestyle of humans in order to disrupt the stale inertia of the modernist lifestyle. As we have discussed in class, humans are historically and genetically outdoor animals, and that our bodies thrive considerably more when we expand our temporal zone of comfort. Ando does exactly that, challenging the widespread momentum towards thermally controlled environments in residential architecture that was simultaneously taking place in America during the 1970’s. I agree with the general principles Ando implies in his design — that we should stop relying on mechanical heating/cooling systems to moderate every environment we occupy, and that a little compromise on our end can go a long way in terms of conserving energy and minimizing waste. On the other hand, I’d also appreciate not having to use an umbrella in my own house. Tadao Ando caught the world’s attention with his extreme manifestation of nature’s intervention in the modern home — and he successfully and succinctly made his point. But if I were to follow his footsteps in my personal practice, I’d most likely prefer a more mode rate approach.。

住吉的长屋案例分析

安 藤 忠 雄

1975

东 西

34 57 65

, 10

属

性

房 屋 间 距 :

: 传 统 与 现 代

厘 米

空 间 与

形

式

的

完

美

结

合

主

要

材 向朝

质

向

:

:

清

长

水

度

混

方

凝

向

土

上

、

东

铁

西

玻

璃

条

总

建基

筑 面 积 :

地 面 积 :

占 地 面 积

:

坪坪

坪

日本关西地区的1种传统住宅形 式,多出现在京东、大阪

“在这种情况下,我认为与自然接触比生活便利更为重要 ”

“我觉得自己并没有什么过错,并为在这么小的用地中,能建造出这么大的住宅而 感到自豪,我采用的手法不是直接引用这些小住宅的空间,生活以及历史的记忆和 传统的材料,做法等不可缺少的要素来继承传统,而是在4方盒子中,将关西居民继 承下来的传统居住方式,以及对自然的认识等全部装进去的手法 ”

大约是4米宽为1户住宅,然后将 其连续排列而成

在这种狭长的住宅形制中,内部 会有中庭和过道

中庭中设置了小的自然景观,体 现了日本的文化观念

2层截面

1层截面

为什么要设计出如此不好用的住宅

下雨的时候需要打伞去上厕所 要么把中庭打扫地非常干净,要么去吃饭或者睡觉都要换鞋 冷 孤寂

功能 保温隔热 光线

安藤自己写的书上面说,住吉长屋做出来以后,他拜托当时的人家,希望他们可以 忍受1下

“安藤的书中1直写到他在不停地反抗着日本青年人中流行的美式公寓住宅,舒 适,快捷,时尚,便利的建筑理念 我的理解是安藤想要回归的是日式住宅空寂,简朴, 清心寡欲的生活方式 ”

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

a course-long investigation of inveterate systems, sites, and buildings09Nov 20114CommentsAzuma Row House by Tadao Ando | Designing Architecture to Purposefully Make PeopleFeel uNCoMfoRTabLEThe Azuma Row House (Sumiyoshi, Osaka, Japan) was designed by Tadao Ando in 1976. Built in an old post WWII neighborhood of wooden row houses, his project replaced its predecessor with a modern interpretation of the urban context. Cast in concrete, Ando’s austere and functional design divides the site into three parts – two equally sized enclosed interior volumes flanking an open-air courtyard. Centralizing the courtyard makes it an integral part of circulation and the focus of everyday life. What makes this setup particularly unique is that there is no way to cross to either side of the house without passing through exterior and ultimately confronting nature. Despite the hardships that this may enforce on the inhabitants, Ando defends his design:At the time [mid-1970s], I thought of residential design as the creation of a place where people can dwell as they themselves intend. If they feel cold, they can put on an additional layer of clothing. If they feel warm, they can discard extraneous clothing. What is important is the space be, not a device for environmental control, but something definite and responsive to human life… No matter how advanced society becomes, institutionally or technologically, a house in which nature can be sensed represents for me the ideal environment in which to live.With subtle and careful presentation Ando forces occupants to experience the dynamic flows of nature every single day. Despite the advent of highly thermally controlled architecture, the environment’s energy flows are somehow an inherent experience in inhabiting the house. I’d like to explor e how this seemingly anachronistic and modest design approach affects the comfort and lifestyle of its victims, oops I mean tenants ;-)Tadao Ando is actually one of my favorite architects, and is world renowned for his stunning manipulation of air, light, and water. This project, his first residential commission, explores issues we’ve discussed in class regarding heat transfer, air flow, and light.Thermally Active Surfaces and flows: What kind of environment does Ando create?The building envelope of the Azuma Row House is simple and uniform — a continuous façade with no apertures, except for one small skylight. Apart from its inward –facing glass walls and minimal wood finish, the majority of the envelope is cast concrete, which has a very high specific heat capacity (0.880 J/(gK)), and therefore capable of absorbing a lot of heat energy. This trait affects the heating and cooling of the interior and courtyard in various waysCourtyard_ Constantly exposed to the sun, the concrete and stone slabsre ceive heat energy from the sun’s direct radiation, diffused sky radiation, and any rays reflected off of surrounding buildings. They cannot easily conduct or release this energy and stores it throughout the day, gradually increasing in temperature. The ground can retain a large amount of heat for hours, which can make standing in that space uncomfortable – think of asphalt on a summer day. Also since hot air molecules rise, the occupant space air temperature can become overheated and uncomfortable as well. This is a greater concern in the summer time when exposure and temperatures are high. Furthermore, by placing the exterior space at the center of the row house the building envelope’s surface area almost doubles,which can be a crucial matter for skin-loaded or envelope dominated structures. Expanding the threshold for hot or cool air to transfer across makes the thermal environment asymmetrical, less predictable, and uncomfortable.The Interior_ In each room there are four surfaces of exposed concrete. Although the floors are covered with wood slats providing insulation between the foot and slab, there is still conduction of heat energy through the walls. Bearing in mind the house’s small scale, there is likely considerable contact with the building envelope which prompts measurable heat loss from the human body – comfortable during warm seasons, frustrating during cold.The sixth surface of every room is a floor-to-ceiling plane of glass with a glass door. Although certain types of glass have relatively high heat capacities, the metal mullions that support the panes are highly conductive –not to mention that a building cannot be perfectly sealed. A significant temperature difference across this barrier will cause a convection current that will easily circulate warm air into a cooler courtyard, and vice versa, causing fluctuations in the room’s temperature.In addition, without any apertures to penetrate, radiation waves reflect off of the house’s exterior facade or are absorbed by it. Unlike the courtyard, this heat exchange occurs on the side the occupants do not have contact with. Since the thick thermal mass absorbs all of the heat, the interior remains cool. Again, despite the benefit in the summer, this kind of passive radiant heating could be very useful during the winter.Thermal Comfort_ After reading Heating, Cooling, and Lighting by Lechner we discussed the body’s thermal response to any environment, or its relationship with the space’s temperature profile. Many of the thermally dynamic characteristics of the Azuma House are beneficial during one season, and a burden during another. However, some issues like convection across thermal surfaces can always work against your desired comfort zone. Ando includes many conductive and convective thermal surfaces in his construction and few radiant sources. The volatility of convection patterns make air flow, heat transfer, and therefore room temperature asymmetrical and unpredictable.Natural Ventilation: How does Ando achieve reasonable comfort through passive design?As a skin-load or envelope dominated structure – with climate dependent cooling requirements– passive solar heating is a reliable method to keep the structure reasonably comfortable because it is an efficient transfer of heat energy between the climate and envelope that requires no fluid medium like in convection. Part of what makes these structures so easily influenced by their envelopes, are their large surface area-to-volume ratio, which creates a large gateway for heat loss. It’s interesting to see what fluid dynamics principles, if any, Ando utilized to make the space more comfortable by modern standards. To start, there are no mechanical systems in the structure for heating or cooling.Cross Ventilation_ Again, the building envelope is a continuous and uniform surface. There aren’t proper inlets or outlets to let wind through the interior spaces, as there no apertures at all. Therefore, no cross ventilation can occur.Stack Effect_ However, high-speed winds redirected over the row house can create a region of lower temperature that draws out the warm air from the courtyard. It produces something similar to a stack effect. When air in the courtyard gains heat energy due to high air temperature or thermal radiation, its buoyancy will decrease, causing it to rise up out of the courtyard. This is what prompts the convection of cool air from the interior to the exterior through the glass pane, as I mentioned above under Interior thermal flows. The rising warm air molecules leave a region of low pressure that draws the high pressure cool air into the void – as molecules always flow form groups of greater energy to groups of lower energy.High Mass Cooling_ The Azuma row house is a great example of Night ventilation of a thermal mass. The concrete slabs have a great capacity to hold heat that accumulated during the day and is gradually released as the surrounding environment cools in the evening. More specifically, at night, cool air circulates through the building and the heat in the thermal mass is released to the space above it, keeping it warm and renewing its own ability to re-absorb more energy the following day. This prevents sudden swings in hot and cold temperature.Why not more natural ventilation? _ There are several cons or obstacles that come about when utilizing certain types of natural ventilation, which is why Ando might have under-utilized these methods. Noise, pollutants, and harsh winds are a side effect of any kind of ventilation system that passes through a structure at occupant level, which — considering the scale of this project — was unavoidable. Although I think that these system characteristics could in some way support Ando’s thesis regarding bringing the house’s inhabitants closer with nature, cross ventilation in addition to such a large open-air courtyard, would form a setting too abrasive for his clients, especially considering the urban conditions. Furthermore the penetrating sounds, smells, and contents of street’s cross breeze would also undermine his idea of the ―inward looking‖ house.In Conclusion: Would I have the courage to live here?Is Tadao Ando successful in creating a thermally appropriate environment for humans. Well, that’s a difficult question to answer, as it can be interpreted from many of his works and from his own words that hisintention was to make his occupants slightly uncomfortable. Ando has said that walls have often separated us from the outside world in a way that has ―bordered on violent.‖ Through his design it seems he allows light and air to enter into the daily lifestyle of humans in order to disrupt the stale inertia of the modernist lifestyle. As we have discussed in class, humans are historically and genetically outdoor animals, and that our bodies thrive considerably more when we expand our temporal zone of comfort. Ando does exactly that, challenging the widespread momentum towards thermally controlled environments in residential architecture that was simultaneously taking place in America during the 1970’s. I agree with the general principles Ando implies in his design — that we should stop relying on mechanical heating/cooling systems to moderate every environment we occupy, and that a little compromise on our end can go a long way in terms of conserving energy and minimizing waste. On the other hand, I’d also appreciate not having to use an umbrella in my own house. Tadao Ando caught the world’s attention with his extreme manifestation of nature’s intervention in the modern home — and he successfully and succinctly made his point. But if I were to follow his footsteps in my personal practice, I’d most likely prefer a more mode rate approach.。