微观经济学讲义(05本科)

(完整word版)范里安微观经济学现代观点讲义

Chapter one:Introduction一、资源的稀缺性与合理配置对于消费者和厂商等微观个体来说,其所拥有的经济资源的稀缺性要求对资源进行合理的配置,从而产生微观经济学的基本问题。

资源配置有两种方式,微观经济学研究市场是如何配置资源,并且认为在一般情况下市场的竞争程度决定资源的配置效率。

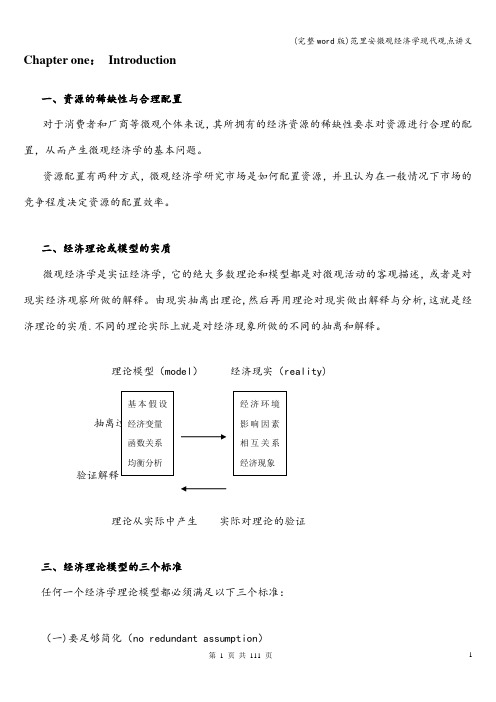

二、经济理论或模型的实质微观经济学是实证经济学,它的绝大多数理论和模型都是对微观活动的客观描述,或者是对现实经济观察所做的解释。

由现实抽离出理论,然后再用理论对现实做出解释与分析,这就是经济理论的实质.不同的理论实际上就是对经济现象所做的不同的抽离和解释。

理论模型(model)经济现实(reality)验证解释理论从实际中产生实际对理论的验证三、经济理论模型的三个标准任何一个经济学理论模型都必须满足以下三个标准:(一)要足够简化(no redundant assumption)指假设的必要性。

假设越少模型的适用面越宽。

足够简化还意味着应当使用尽可能简单的方法来解释和说明实际问题,应当将复杂的问题简单化而不是将简单的问题复杂化。

应当正确看待数学方法在经济学中的应用,奠定必要的数学基础.熟练的运用三种经济学语言.(二)内部一致性(internal consistency)这是对理论模型的基本要求,即在一种假设下只能有一种结论。

比如根据特定假设建立的模型只能有唯一的均衡(比如供求模型);在比较静态分析中,一个变量的变化也只能产生一种结果。

内在一致性保证经济学的科学性,而假设的存在决定了理论模型的局限性。

经济学家有几只手?(三)是否能解决实际问题(relevance)经济学不是理论游戏,任何经济学模型都应当能够解决实际问题。

在这方面曾经有关于经济学本土化问题的讨论。

争论的核心在于经济学是建立在完善的市场经济的基础上的,而中国的市场经济是不完善的,因此能不能运用经济学的理论体系和方法来研究和解决中的问题。

两种观点:一种观点认为经济理论是一个参照系,可以用来对比和发现问题,因此具有普遍的适用性;另一种观点认为中国有自己的国情,需要对经济学进行改造或者使之本土化,甚至有人提出要建立有中国特色的经济学体系。

《微观经济学》教学大纲

单选 判断 名词解释

支撑 分值

目标 目标1 目标2 10 目标3

目标1 目标2 20 目标3

目标1 目标2 20 目标3

目标1 目标2 10 目标3

目标1 目标2 10 目标3

目标1 目标2 15 目标3

目标1 目标2 5 目标3

目标1 5

目标2

目标1 5

目标3

难点: 边际效用递减规律

听讲,做好

思政元素:用马克思主义的劳动价值论正确对待

目标1

三、需求

笔记

4 效用价值论

目标2

理论

课后:复习

教学方法与策略:线下教学。在课堂上主要运用讲

目标3

巩固重点

授法和案例法开展教学,辅以启发式提问以提高学

和难点问

生学习兴趣并拓宽学生学习思路。

题

重点:生产函数;边际产量递减规律;最佳生产 课前:预习

金融与贸易学院

二、课程简介

《微观经济学》是高等本科院校国际经济与贸易和电子商务专业的一门学科基础必修课, 是学习经济学理论的入门课程。《微观经济学》通过对个体经济单位的经济行为的研究,来 说明现代西方经济社会市场机制的运行和作用,及其改善途径。研究内容包括供求与价格、 消费者选择、企业的生产和成本、完全竞争市场、不完全竞争市场、生产要素市场和收入分 配、一般均衡和效率、市场失灵和微观经济政策等。本课程在教学设计上强调专业基础知识 的学习,要求学生能够理解与掌握微观经济学的基本概念、基本理论与基本分析方法,能够 运用微观经济理论进行经济问题的思考和分析,并理解微观经济政策及其影响。

目 象的观察和分析能力,训练经济学直觉, 的能力

力

标 学会经济学思维方式。

微观经济学讲义

微观经济学教案主讲:柳治国目录第一章导言第一节(西方)经济学涵义第二节经济学的研究对象第三节经济学的十大原理第四节微观经济学的研究方法第五节(西方)经济学的由来和演变第二章供求理论第一节需求第二节供给第三节均衡价格和价格机制第三章弹性理论第一节需求价格弹性第二节其他弹性第四章消费者行为理论第一节欲望与效用第二节边际效用分析法第三节无差异分析法第五章生产理论第一节生产与生产函数第二节一种要素的合理投入第三节多种要素的合理投入(1):规模经济第四节多种要素的合理投入(2):最佳组合第六章成本与收益第一节成本函数分析第二节几个重要的成本概念第三节收益与利润最大法原则第七章厂商均衡理论第一节完全竞争条件下的厂商均衡第二节完全垄断条件下的厂商均衡第三节垄断竞争条件下的企业行为模式第四节寡头垄断市场条件下企业行为模式第八章分配理论第一节分配的基本原理第二节工资第三节利息第四节地租第五节利润第六节收入分配均等程度的度量第九章市场失灵与微观经济政策第一章导论第一节(西方)经济学涵义教学重点:介绍经济学的定义教学难点:西方经济学与政治经济学的区别与联系教学方法:讲授法,比较法教学安排:2课时教学过程:一、(西方)经济学的定义经济学是一门实践性的社会科学,内容博大庞杂,分支众多,研究者阵营强大,因而难以有标准的定义。

这里给出若干定义,以见其内涵。

1.定义一:经济学是研究国民财富生产的。

( 亚当·斯密)2.定义二:经济学是研究人类日常生活事物的科学。

(阿尔弗雷德·马歇尔)3.定义三:经济学是对经济理论的研究和考察。

4.定义四:经济学是“研究如何利用稀缺的资源以生产有价值的商品,并将它们分配给不同的个人”的科学(萨谬尔森)。

5.其他含义:“企事业的经营管理方法和经验,对某一经济部门或问题的集中研究成果。

”二、经济学是一门理论科学1.经济科学是一个庞大的学科体系科学分为理论学科和应用学科,如物理学与各种工程技术学。

微观经济学课件_微观经济学

29/09/2015 33

均衡价格(图示)

P

D Pe E S

o

Qe

Q

34

29/09/2015

均衡价格的形成(图示)

29/09/2015

5

经济学产生

生产可能性曲线

大炮(Y) A Y1 Y2 O

29/09/2015

机会成本

B

C

X1

X2 D

黄油(X)

6

机会成本

机会成本:用一定资源生产X产品的机会 成本是所放弃的Y产品的数量。或者,一 定资源选择某种用途的机会成本是所放 弃的其它用途中代价最高的那种。

谁言寸草心,报得三春晖 夫妻店 项目投资决策

29/09/2015

36

支持价格与限制价格(图示)

P

D P1 Pe P2 短缺 o Q1 Qe Q2 Q

37

过剩 E

S

29/09/2015

四、均衡价格的变动

供给不变,需求的变动引起均衡价格和 均衡数量的同方向变动。 需求不变,供给的变动引起均衡价格的 反方向变动和均衡数量的同方向变动。 供求定理。 需求、供给同时变动。

点弹性公式与计算

dQ/Q dQ P Ed = —— 或 = —×— dP/P

弧弹性计算

某杂志价格为2元时销售量为5万册,价 格为3元时销售量为3万册,则需求价格 弹性为多少?

解:价格从2元上涨至3元,Ed= -0.8

价格从3元下降至2元,Ed= -2

弧弹性=1.25

微观经济学教学课件ppt

厂商在生产过程中需要最小化成本、最大化收益,从而实现利润最大化。厂商需要寻求最优的生产规模,以达到成本最小化与利润最大化的平衡。

成本最小化与利润最大化

市场结构与竞争策略

市场结构类型与竞争策略对厂商行为和产量有着重要影响。

总结词

市场结构类型对厂商行为和产量有着重要影响。完全竞争市场中,厂商只能被动接受市场价格,而在垄断市场中,厂商可以通过控制产量来影响市场价格。厂商需要根据市场结构类型制定相应的竞争策略以获得最大利润。

收入效应与替代效应

当价格变化时,消费者的预算约束也会发生变化,从而产生收入效应和替代效应。

消费者最优选择是指在给定预算约束下,选择最优的商品组合以获得最大效用。

消费者最优选择:边际效用理论

定义

随着消费量的增加,边际效用逐渐减少。

边际效用递减规律

在最优选择点处,无差异曲线与预算约束线相切,即边际替代率等于价格之比。

06

微观经济学的发展动态

行为经济学

研究在复杂的心理和社会环境下,经济主体如何做出并执行决策的科学。

神经经济学

利用神经科学的方法,研究大脑如何处理信息并做出决策,以揭示经济行为的神经基础。

行为经济学与神经经济学

产业组织理论

研究企业与市场之间的相互关系,以及市场结构、企业行为和政府规制对企业和市场的影响。

要点一

要点二

偏好公理

偏好具有完备性、反身性、传递性和无差异曲线凸性等公理性质。

效用函数

对于每个消费者,都存在一个效用函数,该函数表示消费者对于不同商品组合的偏好程度。

要点三

定义

消费者预算约束是指消费者在一定收入水平下,可以购买的商品组合的集合。

消费者预算约束

微观经济学概述PPT课件

(2)古典经济学革命

《国富论》的出版被称为经济学史上的第 一次革命,即古典经济学革命。其标志着微观 经济的诞生,以斯密为代表的古典经济学的贡 献是建立了以自由放任的市场经济为中心的经 济学体系。

13

古典经济学自由放任的思想反映了自由 竞争时期经济发展的要求。古典经济学家把经 济研究从流通领域转移到生产领域,使经济学 真正成为有独立体系的学科。

31

1.动态分析

动态分析则对经济变动的实际过程进行 分析,其中包括分析有关的经济总量在一定时 间过程中的变动,这些经济总量在变动过程中 的相互影响和彼此制约的关系,以及它们在每 一时点上变动的速率等等。这种分析考察时间 因素的影响,并把经济现象的变化当作一个连 续的过程来看待。

32

三、边际分析方法

一、微观经济学发展简况 二、微观经济学及其体系

9

一、微观经济学发展简况

1.古典经济学时期——微观经济学的形成时期 2.新古典经济学时期——微观经济学的建立时期

10

1.古典经济学时期

(1)对古典经济学的说明 (2)古典经济学革命

11

(1)对古典经济学的说明

我们这里所说的古典经济学是从17世纪 中期开始,到19世纪70年代前为止,其代表人 物包括英国经济学家亚当•斯密、大卫•李嘉图、 西尼尔、约翰•缪勒、马尔萨斯。其中最重要 的代表人物是亚当•斯密,其代表作是1776年 出版的《国富论》

管理者必须学会告别过去的失误,做到 立足于现实,面向未来地进行决策。

37

3.边际分析方法的深化

边际分析法要求正确处理好增量与存量的 关系

(1)通过增量,激活存量,实现总量的共同 发展。

(2)控制增量,而盘活存量。

38

微观经济学导论

微观经济学讲义

微观经济学讲义第一节西方经济学概论一、稀缺性1.相对于人类社会的无穷欲望而言,经济物品,或者说生产这些物品所需要的资源总是不足的。

这种资源的相对有限性就是稀缺性。

2.稀缺性的相对性是指相对于无限的欲望而言,再多的资源也是稀缺的。

3.稀缺性的绝对性是指它存在于人类历史的各个时期和一切社会。

稀缺性是人类社会永恒的问题,只要有人类社会,就会有稀缺性。

4.经济学产生于稀缺性的存在。

5.稀缺性的存在决定了一个社会和个人必须作出选择。

二、选择1.稀缺性的存在决定了一个社会和个人必须作出选择。

2.选择就是用有限的资源去满足什么欲望的决策。

它包括“生产什么”、“如何生产”和“为谁生产”三个问题。

这三个问题被称为资源配置问题。

三、机会成本1.经济学是研究选择的,要选择就要有所舍弃,舍弃的东西就是机会成本。

2.机会成本并不是实际上的支出,而是一种观念上的支出。

四、微观经济学与宏观经济学微观经济学以单个经济单位为研究对象,通过研究单个经济单位的经济行为和相应的经济变量单项数值的决定,来说明价格机制如何解决社会的资源配置问题。

宏观经济学以整个国民经济为研究对象,通过研究经济中各有关总量的决定及其变化,来说明资源如何才能得到充分利用。

微观经济学与宏观经济学的区别:第一,研究的对象不同。

微观经济学的研究对象是单个经济单位的经济行为,宏观经济学的研究对象是整个经济。

第二,解决的问题不同。

微观经济学解决的问题是资源配置,宏观经济学解决的问题是资源利用。

第三,中心理论不同。

微观经济学的中心理论是价格理论,宏观经济学的中心理论是国民收入决定理论。

第四,研究方法不同。

微观经济学的研究方法是个量分析,宏观经济学的研究方法是总量分析。

微观经济学与宏观经济学的联系:第一,微观经济学与宏观经济学是互相补充的。

第二,微观经济学与宏观经济学的研究方法都是实证分析。

第三,微观经济学是宏观经济学的基础。

五、理论(一)理论的内容一个完整的理论包括定义、假设、假说和预测。

微观经济学介绍课件

03

预算约束: 消费者在购 买商品时受 到收入和价 格的限制

04

消费者均衡: 消费者在预 算约束下, 实现效用最 大化的状态

生产者行为理论

生产者行为理论是微观经济学的核心 理论之一,主要研究生产者在市场中 的行为和决策。

生产者行为理论的主要内容包括:生 产函数、成本函数、利润最大化原则、 市场均衡等。

生产函数是生产者行为理论的基础, 它描述了生产者在给定的投入和技术 条件下,所能生产的最大产量。

成本函数是生产者行为理论的关键, 它描述了生产者在生产过程中所付出 的成本与产量之间的关系。

利润最大化原则是生产者行为理论的 目标,生产者在市场中追求利润最大 化,从而实现资源的最优配置。

市场均衡是生产者行为理论的结果, 在完全竞争的市场中,生产者的利润 最大化和市场的均衡状态是一致的。

能够购买的商品数量

供给:生产者在一定时期内, 在一定价格水平下愿意并且

能够提供的商品数量

均衡价格:需求与供给相 等时的价格

市场均衡:需求与供给相等 时的市场状态

需求曲线:表示需求与价格 关系的曲线

供给曲线:表示供给与价格 关系的曲线

需求弹性:需求量对价格变 动的反应程度

供给弹性:供给量对价格变 动的反应程度

微观经济学的基本假设

01 理性人假设:经济主体都是理 性的,追求自身利益最大化

02 完全信息假设:经济主体拥有 完全信息,能够做出最优决策

03 市场出清假设:市场价格能够 迅速调整,实现供需平衡

04 均衡假设:市场在长期和短期 中都能达到均衡状态

微观经济学的基 本概念

需求与供给

需求:消费者在一定时期内, 在一定价格水平下愿意并且

微观经济学介绍课件

《微观经济学》课程教学大纲

《微观经济学》课程教学大纲一、课程基本信息课程代码:16143103课程名称:西方经济学(微观部分)英文名称:Microeconomics课程类型:学科基础课学时:48学时学分:3学分适应对象:全院经济管理类各本科专业考核方式:考试先修课程:高等数学二、课程简介中文简介:(附内容结构图)微观经济学研究单个经济单位的活动规律。

具体地说,微观经济学研究单个消费者、单个生产者、单个市场的的经济行为,其对单个经济单位的考察,是在三个逐步深入的层次上进行:第一层次考察单个消费者、单个生产者的均衡;第二层次考察单个的市场均衡;第三层次考察所有单个市场均衡价格的决定。

正因为其分析涉及的变量都是经济个量,它才被称为微观经济学。

价格分析是微观经济学分析的核心,微观经济学也被称为价格理论。

本书关于价格理论的讲述是按以下层次展开:开篇简介西方经济学;第二章介绍价格的确定是由于供需两种因素均衡的结果,当然,作为必备知识,本章也介绍了供给、需求函数及相关曲线、供求的各种弹性;第三章介绍了决定商品价格的需求因素,需求曲线之所以向右下方倾斜,是由于效用最大化原则的要求;为说明供给曲线,第四章、第五章介绍了生产函数和成本函数,得到了一定产量时厂商成本最小化的条件和长短期成本曲线。

通过第六章的学习,可以得到完全竞争的市场条件下,厂商的商品供给曲线即是其边际成本线(高于平均可变成本最低点以上部分)。

第七章介绍了三种不完全竞争市场条件下都不存在规律的供给曲线。

至此,商品的供求及价格决定的内容已完整。

第八章、第九章介绍了要素的供求,从而确定了要素均衡时的价格。

第十章将单个市场均衡推广到多个市场,并讨论了生产和交换的最优条件;第十一章则从价格失灵的角度讨论其失灵原因及相应的对策。

英文简介:The conomics behaviors of single unit are studies in the subject of Microeconomics.In details,a cosumer、a poductor or a market is studied.Three contends are included in the book.The first one describes the conomics equilibrium behaviors of single cosumer andsingle cosumer;the second part explains how some market turning equilibrium;the equilibrium price and quantity of all markets was discussed in the third one.Because single unit is discussed,the subject was called as Microeconomics.The price analyses is the core of Microeconomics.What is Economics is introduced in the first chaptes;how the price deing decided is explained in the second chapter;demanding is described in the third;how to get supply curve is the main contend from the fourthchapter to the seventh one.The discussion about the factors demand and supply was introduced.The contend of the tenth chapter is market equilibrium and the production optimization and exchange optimization;Externalities、public goods、asymmetric information and Microeconomics policy are discussed in the eleventh.微观经济学内容结构图第一章:引论第四章:生产论第三章:效用论第二章:需求曲线和供给曲线概述以及有关的基本概念第十章:一般均衡论和福利经济学第九章:生产要素价格决定的供给方面第五章:成本论第六章:完全竞争市场第七章:不完全竞争市场第八章:生产要素价格决定的需求方面第十一章:市场失灵和微观经济政策在本课程体系中的功能章次及内容简介“西方经济学”范畴价格的形成机制——供求均衡的结果商品需求曲线的形成:消费者效用最大化的结果完全竞争时商品供给曲线的形成:生产者利润最大化的结果生产函数成本函数利润最大化条件不完全竞争条件下无有规律的商品供给曲线商品价格的形成:供求均衡生产要素的需求因素:边际要素收益=边际要素成本生产要素的供给因素:要素自用效用=要素供给效用所有市场的均衡价要素价格的形成:供求均衡价格失灵,不能起资源调配作用,采用相关经济政策生产和交换的最优条件实证经济学规范经济学三、课程性质与教学目的课程性质:作为西方经济学的组成部分,微观经济学是对西方发达资本主义国家二百多年市场经济发展中的单个经济单位活动规律的一般抽象和概括。

华中科技大学费剑平 高级微观经济学课程讲义 Lecture05

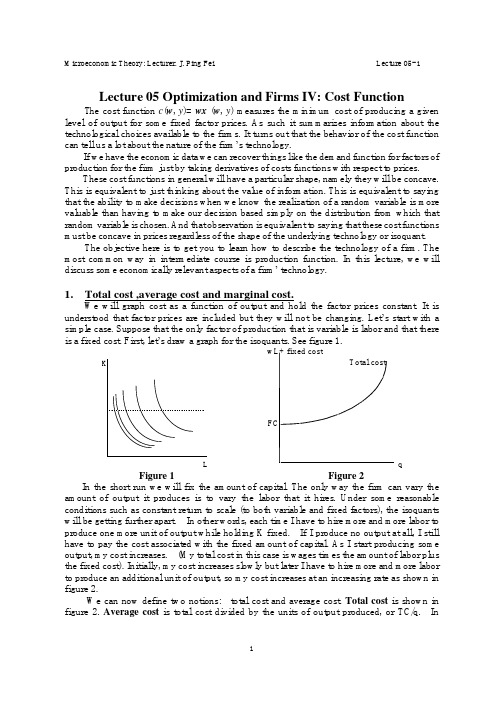

Microeconomic Theory: Lecturer. J. Ping FeiLecture 05- 1Lecture 05 Optimization and Firms IV: Cost FunctionThe cost function c(w, y)= wx (w, y) measures the minimum cost of producing a givenlevel of output for some fixed factor prices. As such it summarizes information about the technological choices available to the firms. It turns out that the behavior of the cost function can tell us a lot about the nature of the firm’s technology.If we have the economic data we can recover things like the demand function for factors of production for the firm just by taking derivatives of costs functions with respect to prices.These cost functions in general will have a particular shape, namely they will be concave. This is equivalent to just thinking about the value of information. This is equivalent to saying that the ability to make decisions when we know the realization of a random variable is more valuable than having to make our decision based simply on the distribution from which that random variable is chosen. And that observation is equivalent to saying that these cost functions must be concave in prices regardless of the shape of the underlying technology or isoquant.The objective here is to get you to learn how to describe the technology of a firm. The most common way in intermediate course is production function. In this lecture, we will discuss some economically relevant aspects of a firm’ technology.1. Total cost ,average cost and marginal cost.We will graph cost as a function of output and hold the factor prices constant. It is understood that factor prices are included but they will not be changing. Let’s start with asimple case. Suppose that the only factor of production that is variable is labor and that there is a fixed cost. First, let’s draw a graph for the isoquants. See figure 1.wL+ fixed costKTotal costFCLqFigure 1Figure 2In the short run we will fix the amount of capital. The only way the firm can vary theamount of output it produces is to vary the labor that it hires. Under some reasonableconditions such as constant return to scale (to both variable and fixed factors), the isoquantswill be getting further apart. In other words, each time I have to hire more and more labor toproduce one more unit of output while holding K fixed. If I produce no output at all, I stillhave to pay the cost associated with the fixed amount of capital. As I start producing someoutput, my cost increases. (My total cost in this case is wages times the amount of labor plusthe fixed cost). Initially, my cost increases slowly but later I have to hire more and more laborto produce an additional unit of output, so my cost increases at an increasing rate as shown infigure 2.We can now define two notions: total cost and average cost. Total cost is shown infigure 2. Average cost is total cost divided by the units of output produced, or TC/q. In1Microeconomic Theory: Lecturer. J. Ping FeiLecture 05- 2terms of figure 2, average cost is the slope of the ray from the origin to the total cost curve.This would be the slope of the diagonal lines in Figure 2. When output is close to zero,average cost is really big (the slope is really steep). If my total cost is $10,000 and I produceone unit of output, my average cost is $10,000. If I only produce 1/2 unit of output, my average cost is $20,000, assuming the variable cost of ½ unit and 1 unit are the same. Asoutput increases, the slope decreases until it reaches a minimum. Beyond that minimum,average cost starts to rise again. So, my average cost curve might be expected to have somekind of a U-shape (see figure 3).Marginal cost. Marginal cost is the cost of producing one more unit of output. Marginalcost is the derivative of total cost with respect to output (q). As output increases, the slope ofmarginal cost gets steeper. Since capital is fixed (say capital is the amount of machines Ihave), the only way I can increase my output is by hiring more unit of labor. However, themore people I hire to work with the same number of machines, the less additional output Iwill be getting from each additional unit of labor. Eventually, I will run into some capacitylimitation and my output will be very difficult to increase.MCACTotal cost for the small factoryTotal cost for the large factoryqFigure 3Figure 4The marginal cost curve goes through the minimum of the average cost curve (see figure 3)because the minimum average cost is where the average cost is tangent to total cost (seefigure 2), and the slope of the tangent to total cost is marginal cost.For the intuition, think about bowling scores. You know that if you score less than youraverage, then you lower your average and if you score more than your average, then you raiseyou average. If your average stays the same, it must be because your score on the last gamewas the same as your average.Long run total cost and short run total cost. In the long run I can choose the amount ofthe fixed input, capital in this case. For example, I can choose between a small factory and alarge one. In terms of the graph, the total cost curve of a small factory will have a lower levelof fixed cost than the large factory. However, the total cost curve of the small factory willrise faster than the total cost curve of the larger factory (see figure 4).Which factory would I rather have? It would depend on how much I want to produce. IfI want to produce any amount up to where the short run total cost curves intersect, I wouldrather have the smaller factory because it produces it more cheaply. On the other hand, if Iwant to produce a large amount of output, then I want to have the larger factory because itproduces that level of output at a lower cost. If these two factories are my only alternatives,in the long run my total cost curve would look like the thick line in figure 4.If we have more alternatives in terms of size of factories (each alternative has a differenttotal cost curve), in the long run the cost of any particular level of output is going to be thecost associated with the cheapest means of producing that level of output. The long run totalcost curve will be the lower bound of all the short run total cost curves (see figure 5).2Microeconomic Theory: Lecturer. J. Ping FeiLecture 05- 3SRTCSRTC (1) SRTC LRTCAC (1)AC (3) AC (2)LRACqq11Figure 5Figure 6The LRTC curve is just the lower ‘envelope’ of all the SRTC curves. The LRTC curvedoes not have to start at the origin if there are fixed costs. For any particular set of fixedfactors, short run total cost is the minimum total cost over all of the factors that are variable.Long run total cost for a given level of output is the minimum of short run total cost overfixed factors of production given the level of output. And this is equal to the minimum (overfixed factors) of the minimum (over variable factors) of total cost given q.The question is in what order we are doing the minimization. We turned this into atwo-stage problem. My costs depend not only on the level of output but also on how much ofthe variable factors I hire and how much of the fixed factors I hire. We are defining short runcost as what you get when you minimize over the variable factors. And we are defining longrun cost as what you get when you minimize the short run cost over the fixed factor. What weend up with is a long run total cost obtained by minimizing costs over both fixed and variablefactors. The order of the minimization does not matter.Long run average cost and short run average cost. Figure 6 shows the average costcurves corresponding to the total cost curves in figure 5.short-run total cost=STC=wv xv (w, y, xf ) + wf x fshort-run average cost=SAC=c(w, y, xf ) / yshort-run average variable cost=SAVC=wv xv (w, y, xf ) / yshort-run average fixed cost=SAFC=wf x f / yshort-run marginal cost=SMC=∂c(w, y, x f ) / ∂ylong-run average cost=LAC=c(w, y) / ∂ylong-run marginal cost=LMC=∂c(w, y) / ∂yTo derive the long run and short run average cost curves, suppose we choose a certain level of output, say q1. At output level q1, long run total cost was obtained by choosing the minimum of all ways of producing q1. Output level q1 was produced at lowest cost by factory 1. At q1, the average total costs are the same in the short run and the long run. If factory 1 produces at any level of output different from q1, short run total costs are higher than long run total costs, and hence short run average costs are higher than long run average costs.We can repeat this analysis with factories 2 and 3. So the long run average cost curve is the envelope of the short run average cost curves, in the same way that my long run cost curve is the envelope of the short run total cost curves. Also, long run and short run average costs will be the same for the output level for which the particular factory is the least costly at producing the given level of output.3Microeconomic Theory: Lecturer. J. Ping FeiLecture 05- 4Note that the place where the SRAC curves and the LRAC curve are tangent is notnecessarily the minimum of each SRAC curve. When the LRAC curve is declining thetangency point occurs before the minimum of the SRAC curve and where the LRAC curve isincreasing, the tangency point occurs beyond the minimum of the SRAC curve. The onlypoint where the tangency point occurs at the minimum of a SRAC curve is at the minimum ofthe LRAC curve.This may sound confusing because we are saying that to produce a level of output q1, the best plant to use is plant 1. However, q1 is not the best level of output for that particular plant. Plant 1 could produce a higher level of output at a lower average cost. But if we want toproduce at that higher level of output, plant 1 would not be the best plant to use.We are not interested in the level of output that a plant produces most cheaply for itself.Instead, we are interested in how well that plant produces a particular level of output, relativeto other plants.If I want to produce 100 units of output and plant 1 produces the 100 units of output atthe lowest cost, I do not care if plant 1 can produce 110 units at a lower average cost. What Icare about is which plant produces 100 units in the cheapest way.A baseball analogy: I am interested in putting the best second baseman at second base.The fact that he may be a better third baseman does not interest me if I have a guy who playsthird base still better than he. The fact that you do third base best does not interest me if youhappen to be the best second base player I have and if I have a guy who can play third basebetter than you can.To summarize, what is important to you is not running a plant at its minimum averagecost. What is important to you is deciding what level of output you want to produce anddeciding how to produce that level of output in the cheapest way.How do we decide what level of output I want to produce? Suppose I can sell myoutput at price p per unit of output. If I sell q units, my revenue is pq. My profit is my revenueminus my cost. Graphically, my profit is the vertical difference between the revenue line andthe total cost curve (it does not matter if it is short run total cost or long run total cost) (seefigure 7).$TC Revenue (pq)LRMC LRACNegative profitsPPositive profitsqq*q*Figure 7Figure 8If I want to maximize my profit, I have to choose the point where the curves are thefurthest apart, that is, where the slopes are the same. Since the slope of the revenue line is theprice of output, and the slope of the total cost curve is marginal cost, I maximize my profitwhere price equals marginal cost (where output = q* in figure 7). If I produce less than that,price is greater than marginal cost and I can make more money by producing more. If Iproduce at a point where marginal cost is greater than price, then I can make more money byproducing less.4Microeconomic Theory: Lecturer. J. Ping FeiLecture 05- 5In figure 8, I maximize my profit if I produce at the level of output where the LRMC is equal to the price (at q*).So, I want to produce a level of output q*, and I want to produce it in the cheapest way. The factory associated with the SRAC curve in figure 8 is the factory that produces q* in the cheapest way. In this case, q* is at a point beyond the minimum for that factory.2.Examples:1). The short-run Cobb-Douglas cost functions. min w1x1 + w2 x2 s.t. x2 = k and y = x1a x12−a1−a⇒ SAC = w1( y / k) a + w2k / y1−aSMC=w1( y / k) a / a Proposition 1: Constant returns to scale. If the production function exhibits constant returns to scale, the cost function may be written as c(w, y)= y c(w,1).Proof: let x* be a cheapest way to produce one unit of output at prices w. Notice that yx* is feasible to produce y since the technology is constant returns to scale. Suppose it does not minimize cost; instead let x′ be the cost-minimizing bundle to produce y at w so wx′/y<wyx*/y. Then x′/y can produce 1 since the technology is constant returns to scale.Proposition 2: Marginal costs equal average costs at the point of minimum average costs.Proof: Let y* denote the point of minimum average cost, then to the left of y* averagecosts are declining so that for y≤y* d (c( y) / y) / dy ≤ 0 which implies c′( y) ≤ c( y) / y ∀y ≤ y * . A similar analysis shows that c′( y) ≥ c( y) / y ∀y ≥ y * .Proposition 3:limy→0cv( y) y= cv′ (0)2). CD cost curves1c( y) = Ky a+b1− a −bAC( y) = Ky a+bMC( y) = c′( y) =K1−a −by a+ba+bProposition 4: The long- and short run (average) cost curves are tangent.3. Factor prices and cost functionsProperties of the cost function (1) Non-decreasing in prices. If w′≥w, then c(w′, y) ≥c(w, y). (2) Homogeneous of degree 1 in w. c(tw, y)= t c(w, y) for t>0. (3) Concave in w. c(tw + (1− t)w′, y) ≥ tc(w, y) + (1− t)c(w′, y) ∀0 ≤ t ≤ 1(4) Continuous in w. c(w, y) is continuous as a function of w for w ? 0. (5) Shephard’s lemma. (the derivative property.) Let xi(w, y)be the firm’s conditional factor demand for input i. Then if the cost function is differentiable at (w, y), and wi>0 for i=1, …, n,5Microeconomic Theory: Lecturer. J. Ping FeiLecture 05- 6then xi (w, y) = ∂c(w, y) / ∂wi i = 1,L, n . Proof: Construct g(w)= c(w, y)−wx*, since is thecheapest way to produce y, ∂g(w)/∂wi=0. We can also prove it by the definition of c(w, y)= wx(w, y) or directly by the envelopetheorem. The concavity of the cost function is also a nice geometrical argument.4. The envelope theorem for constrained optimizationdM (a) = ∂L(x, a)da∂ax= x(a )=∂g ∂ax=x(a)−λ∂h ∂aApplications: Shephard’s lemma⇒∂c(w, ∂wiy)=xixi = xi ( w, y )=xi (w,y),marginal cost L = w1x1 + w2 x2 − λ[ f (x1, x2 ) − y] ∂c(w1, w2 , y) / ∂y = λ5. Comparative statics using the cost function1) The cost function is nondecreasing in factor prices⇔ Factor demand x(w,y) is nonnegative. 2) The cost function is homogeneous of degree 1 in w ⇔ x(w,y) is homogeneous of degree 0. 3) The cost function is concave in w has the following implications.a) the cross-price effects are symmetric. b) the own-price effects are nonpositive. c) dwdx≤06。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

反垄断的谬误:关于市场竞争形成的垄断与政府管制而形成的垄断之间的区别

15价格歧视

垄断厂商没有达到pareto efficiency)的原因:交易费用

价格歧视:垄断厂商的帕累托改善

一级价格歧视

二级价格歧视

三级价格歧视

16经济租金与寻租

经济租金的来源

各种寻租的行为

17要素市场理论

30道德风险与委托-代理问题

道德风险的定义

委托-代理问题

激励机制设计:一个简单例子

31企业理论前沿简介为来自么会存在企业企业的边界在哪里

企业的产权属于谁

32总结与展望

我们已经知道的

我们尚未知道的

参考书目

《微观经济学》,平狄克/鲁宾费尔德,第四版,张军等人译,中国人民大学出版社,1996

《微观经济学十八讲》,平新乔,北京大学出版社

逆向归纳法

19贯序博弈的应用

Stackelberg模型——先走者的优势(产量的领导-追随模型)

价格领导模型

22完全信息动态博弈:重复博弈(repeated games)

囚徒的无限次重复博弈

如何重塑信用机制

23合作博弈

窜通与卡特尔

卡特尔的稳定性(违约冲动)

24一般均衡分析与埃奇沃斯盒

局部均衡分析与一般均衡分析的区别

埃奇沃斯盒

Pareto efficiency与契约线

25效率与公平

福利经济学第一定理

福利经济学第二定理

26外在性与科斯定理

外在性与庇古税

科斯定理

27公共物品

公共物品的严格定义

市场失灵

政府失灵

28逆向选择

旧车市场

保险市场中的逆向选择

信贷市场

逆向选择的克服:声誉与标准化

29信号模型

价格作为质量的信号

文凭信号模型

竞争性要素市场

买方垄断的要素市场

卖方垄断的要素市场

失业的解释

企业家人力资本

18完全信息静态博弈

囚徒困境模型

纳什均衡

现实中的囚徒困境案例

19完全信息静态博弈的应用

古诺模型(产量博弈)

Bertrand模型(价格博弈)

21完全信息动态博弈:贯序博弈(sequentialgames)

房地产开发博弈模型

子博弈精练纳什均衡

微观经济学讲义(05本科)

均衡——马歇尔大剪刀的交点

均衡点的移动

均衡模型的应用初步

12厂商行为

利润最大化假设

厂商成本

生产函数

最佳利润的确定

13完全竞争厂商模型与行业供给曲线

完全竞争的定义

短期均衡

长期均衡

市场供给曲线的推导

14垄断厂商模型

垄断的定义

垄断厂商的产量决定

帕累托改善与帕累托效率(pareto efficiency)

《微观经济学:现代观点》,范里安,上海三联书店

《博弈论与信息经济学》,张维迎,上海三联书店