英语(二)——大学英语自学教程(下册)——电子版教材

大学英语自学教程(上下合本)课文英文原文

大学英语自学教程(上下合本)课文英文原文Lesson 1: Introduction to College EnglishIn this first lesson, we will introduce you to the basic structure of the course and provide you with some tips on how to study effectively. We will also discuss the importance of setting goals and creating a study plan.Lesson 2: Grammar BasicsIn this lesson, we will cover the basic rules of English grammar. We will discuss nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions. We will also provide you with some examples of how to use these parts of speech in sentences.Lesson 3: Vocabulary BuildingLesson 4: Reading ComprehensionLesson 5: Writing SkillsWriting is an important skill for academic and professional success. In this lesson, we will provide you with some tips on how to improve your writing skills. We will also provide you with some practice exercises to help you develop your writing skills.Lesson 6: Listening SkillsListening is an important skill for learning English. In this lesson, we will provide you with some tips on how toimprove your listening skills. We will also provide you with some practice exercises to help you develop your listening skills.Lesson 7: Speaking SkillsLesson 8: Review and AssessmentWe hope that you find this course helpful and enjoyable. Good luck on your journey to mastering the English language!Lesson 9: Cultural AwarenessLesson 10: Advanced GrammarIn this lesson, we will cover more advanced aspects of English grammar, including verb tenses, modal verbs, and passive voice. We will provide you with examples and exercises to help you understand and practice these grammar points.Lesson 11: Academic WritingAcademic writing is an important skill for success in higher education. In this lesson, we will discuss the structure and conventions of academic writing, including essay organization, citation styles, and plagiarism. We will also provide you with some practice exercises to help you develop your academic writing skills.Lesson 12: Pronunciation and Accent ReductionPronunciation is an important aspect of spoken English. In this lesson, we will discuss the phonetic system ofEnglish and provide you with some tips on how to improve your pronunciation and reduce your accent. We will also provide you with some practice exercises to help you develop your pronunciation skills.Lesson 13: English for Specific PurposesEnglish is used in a wide range of fields, including business, medicine, and law. In this lesson, we will explore some specialized vocabulary and expressions used in these fields. We will also provide you with some practice exercises to help you develop your English skills for specific purposes.Lesson 14: Conversation PracticeLesson 15: Final ProjectLesson 16: Advanced Reading StrategiesLesson 17: Public SpeakingPublic speaking is a valuable skill in many professional settings. In this lesson, we will discuss techniques for effective public speaking, including speech organization, delivery, and audience engagement. We will provide you with opportunities to practice delivering speeches and receive feedback to improve your public speaking skills.Lesson 18: Advanced Listening ComprehensionLesson 19: English for Travel and TourismLesson 20: English for Job InterviewsLesson 21: Advanced Writing TechniquesIn this lesson, we will explore advanced writing techniques, such as persuasive writing, argumentative writing, and creative writing. We will provide you with writingprompts and guidelines to help you develop your writingskills in different genres.Lesson 22: English for Social MediaLesson 23: English for Academic ResearchConducting academic research requires strong English language skills. In this lesson, we will discuss techniquesfor reading and understanding academic articles, as well as how to write research papers and cite sources correctly. Wewill provide you with practice exercises to enhance your academic research skills.Lesson 24: English for International RelationsIf you are interested in pursuing a career ininternational relations, this lesson will be beneficial. Wewill explore the language used in diplomacy, negotiations,and international conferences. We will provide you with examples and exercises to help you develop your Englishskills in this specialized field.Lesson 25: Final ReflectionWe hope that this College English SelfStudy Course has equipped you with the necessary tools and knowledge to excelin your English language abilities. Remember to practiceregularly, seek opportunities for language immersion, and never stop learning. Good luck in all your endeavors!。

自考英语(二)00015教程课后试题答案

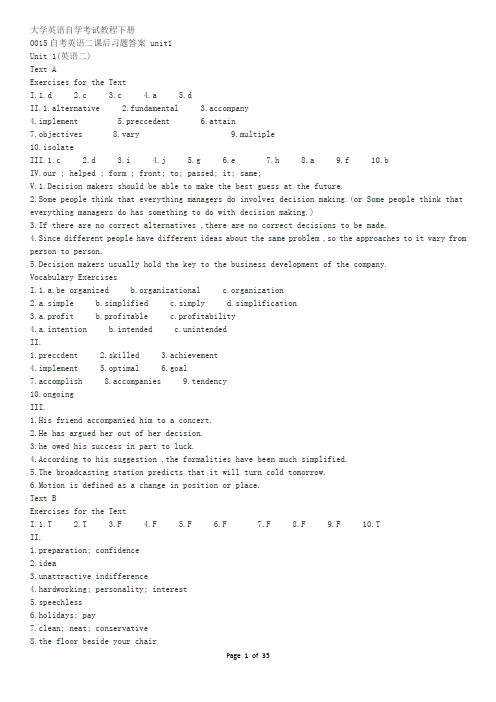

大学英语自学考试教程下册0015自考英语二课后习题答案unit1Unit 1(英语二)Text AExercises for the Text; helped ; form ; front; to; passed; it; same;makers should be able to make the best guess at the future.people think that everything managers do involves decision making.(or Some people think that everything managers do has something to do with decision making.)there are no correct alternatives ,there are no correct decisions to be made.different people have different ideas about the same problem ,so the approaches to it vary from person to person. makers usually hold the key to the business development of the company.Vocabulary ExercisesorganizedII.III.friend accompanied him to a concert.has argued her out of her decision.owed his success in part to luck.to his suggestion ,the formalities have been much simplified.broadcasting station predicts that it will turn cold tomorrow.is defined as a change in position or place.Text BExercises for the TextII.; confidenceindifference; personality; interest; pay; neat; conservativefloor beside your chairI.a disadvantagesuredown your advantagethe trouble toGrammar ExercisesI.1.连词;让步状语从句。

自考英语二课后习题答案

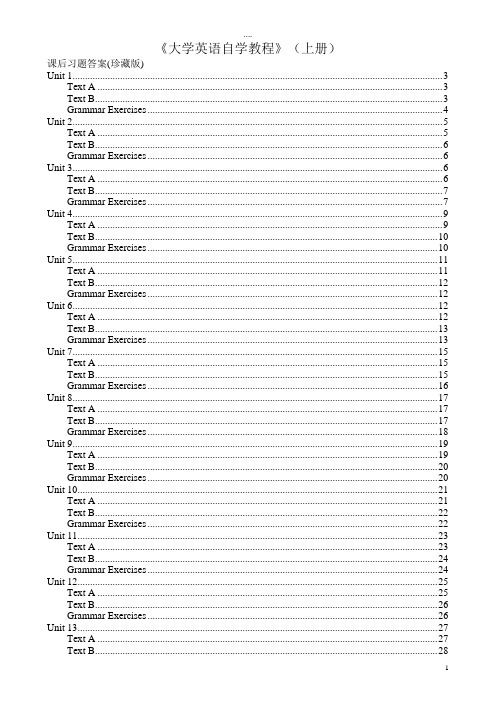

《大学英语自学教程》(上册)课后习题答案(珍藏版)Unit 1 (3)Text A (3)Text B (3)Grammar Exercises (4)Unit 2 (5)Text A (5)Text B (6)Grammar Exercises (6)Unit 3 (6)Text A (6)Text B (7)Grammar Exercises (7)Unit 4 (9)Text A (9)Text B (10)Grammar Exercises (10)Unit 5 (11)Text A (11)Text B (12)Grammar Exercises (12)Unit 6 (12)Text A (12)Text B (13)Grammar Exercises (13)Unit 7 (15)Text A (15)Text B (15)Grammar Exercises (16)Unit 8 (17)Text A (17)Text B (17)Grammar Exercises (18)Unit 9 (19)Text A (19)Text B (20)Grammar Exercises (20)Unit 10 (21)Text A (21)Text B (22)Grammar Exercises (22)Unit 11 (23)Text A (23)Text B (24)Grammar Exercises (24)Unit 12 (25)Text A (25)Text B (26)Grammar Exercises (26)Unit 13 (27)Text A (27)Text B (28)Grammar Exercises (28)Unit 14 (28)Text A (28)Text B (29)Grammar Exercises (30)Unit 15 (31)Text A (31)Text B (32)Grammar Exercises (32)Unit 16 (33)Text A (33)Text B (34)Grammar Exercises (34)Unit 17 (35)Text A (35)Text B (36)Grammar Exercises (37)Unit 18 (38)Text A (38)Text B (39)Grammar Exercises (39)Unit 19 (39)Text A (39)Text B (40)Grammar Exercises (41)Unit 20 (42)Text A (42)Text B (43)Grammar Exercises (43)Unit 21 (44)Text A (44)Text B (44)Unit 22 (45)Text A (45)Text B (46)Unit 23 (46)Text A (46)Text B (47)Unit 24 (49)Text A (49)Text B (50)Unit 25 (50)Text A (50)Text B (51)Unit 1Text AExercises for the TextI.1.d2.a3.c4.d5.dII.1.task2.intelligent3.research4.clue5.conclusion6.repeatmunicate8.purpose9. probably 10.outlineIII.1.Instead of2.therefore3.more...than4.even5.First of all6.because7.on the otherhand 8.finally 9.looking for 10.ConverselyIV.1.Research shows that successful language learners are similar in many ways.nguage learning is active learning.Therefore,successful learners should look for every chance to use the language.nguage learning should be active,independent and purposeful.4.Learning a language is different from learning maths.5.The teacher often imparts successfull language learning experiences to us.Vocabulary ExercisesI.1.a.success b.successful c.successfully2.a.indepence b.depend c.dependent3.a.covered b.uncover c.discovered4.a.purposeful b.purposefully c.purposeII.1.inexact2.technique3.outlinedmunicate5.regularly6.clues7.intelligent 8.incomplete 9.similar10.statementIII.1.disagree2.independent3.incomplete4.inexact5.uncoverIV.1.They find it hard to master a foreign language.2.The research shows that successful men are similar in many ways.3.Successful language learners do not only depend on the book or the teacher.4.We are willingto help our friends.5.We should learn new things independently,actively,and purposefully.Text BExercises for the TextI.1.T2.F3.T4.F5.T6.F7.F8.F9.T 10.FII.1.With the help of their fingers2."I am thirsty."3.tea,coffee,wine,beer and soda-water4.Put his hands on his stomach5.nothing but drinks6.much more exact7.meanings and can be put together into sentences8.form new sentences9.talk10.speakVocabulary ExercisesI.1.b2.a3.c4.e5.dII.1.B2.A3.B4.D5.A6.A7.C8.C9.C 10.BGrammar ExercisesI.whether 连词 towards 介词second 数词 hour 名词repeat 动词 successful 形容词not 副词 probably 副词than 连词 because 连词which 连词 even 副词intelligent 形容词 differ 动词regular 形容词 some 形容词/代词/副词into 介词 oh 感叹词seem 系动词 communicate 动词II.1.Let 动词 round 介词2.fresh 形容词 for 介词3.leave 名词 call 动词 on 介词 if 连词 spare 动词4.Even 副词 it 代词5.Where 连接副词 will 名词6.after 介词 calm 名词7.seem 系动词 those 代词 makes 名词8.without 介词 return 名词9.strict 形容词 work 动词10.news 名词 live 形容词 meeting 名词III.(斜体为主语,带下划线的为谓语)1.Most adults would disagree with this statement.2.How much time did they allow you for doing the work.3. I had a visit from Mary yesterday.4. China's stand on this questionis clear to all.5.Warm clothes protest against the cold of winter.6.What we need is more practice.7.There doesn't seem to be much chance of my getting job.8.In those days the cost of living rose by nearly 4 percent.9.There are a number of people interested in the case.10.Every means has been tried but without much result.IV.1.a magazine (宾语)last night (状语)2.in need (定语)indeed (定语)3.outside your area (定语)telephoning long distance (主语补足语)4.your children (宾语)all day (状语)5.his direction (宾语)French (宾语)6.me (宾语)plenty of exercises (不定式宾语)7.long (宾语)to London (状语)8.those (宾语)who help themselves (从句作定语)9.her (宾语)above others (宾语补足语)10.to build a hotel in the village (定语)of the foreigners (定语)Unit 2Text AExercises for the TextI.1.a2.c3.a4.a5.cII.1. Income tax is a certain percentage of the salaries paid to the goverment.2. Graduated income tax means the percentage of the tax(14 to 70 percent) increases as a person's income increase.3. Property tax is that people who own a home have to pay taxes on it.4. Exercise tax is charged on cars in a city.5. Sales tax is a percentage charged to any item which you buy in that state.III.1.due2.depends on3.diverse4.consists of5.simila6.tends toplaining about8.In addition to9.issue 10.agreed onIV.1.How much do you charge for a haircut.2.We are trying to use funds for the Red Cross.3.He has earned a good reputation for honsety.4.We pay taxes in exchange for government services.5.An open letter protests the government's foreign policy.V.1.Every citizen is obliged to pay taxes.(It is obligatory on every citizen to pay taxes)(It is every citizen's duty to pay taxes.)2.Americans often say that there are two things they can be sure of in life.3.There are generally three levels of government in the United States; therefore,there are three types of taxes.4.Some states charge income tax in addition to a sales tax.5.Americans complain that taxes are too high and the government uses them in the wrong way. Vocabulary ExercisesI.1.a. percent b. percentage c. percent2.a. adds b. addition c. additional3.a. confused b. confusing c. confusion4.a. complained b. complain c. complaintII.1.charge2.departmen3.due4.diverse5.earns6.vary7.property8.leading9.funds 10.tends III.1.China leads the world with silk products.2.In addition to an income tax some states charge a sales tax.3.The sales tax varies from price to price of any item you buy.4.People often complain about the increasing price.5.His mother says that he spends too much time on TV every day.Text BExercises for the TextI.1.F2.F3.F4.T5.T6.T7.T8.F9.T 10.FII.1.attracts2.leisure3.available4.limited5.estimateIII.1.decided on2.approved3.estimate4.carried over5.put up with6.characteristic ofIV.1.B2.C3.B4.A5.C6.DGrammar ExercisesI.1.SV2.SVO3.SVOC4.SVC5.SVO6.SVOC7.SVOC8.SVO9.SVOO 10.SVOC11.SVOC 12.SVC 13.SVOC 14.SVOO 15.SVCII.1.prefer2.insisted3.need4.make5.remember6.look7.worked8.was9.sounds 10.gaveIII.1.B2.C3.D4.A5.B6.C7.A8.D9.A 10.DIV.1.The two languages are different/not similar in many way.2.The deaf and dumb can neigher speak nor hear.3.The Englishman speaks a very good Italian.4.Could you pass me a cup of coffee.5.At this time he felt thirsty and hungry.6.Yesterday evening she asked me to wait for her at the gate of the restaurant.7.When did you get up this morning.8.The story sounds interesting,but it is not true.9.The meat and macaroni cost me 25 yuan.10.She oftern teaches the children to sing English songs.Unit 3Text AExercises for the TextI.1.d2.d3.c4.b5.dII.1.long/wide2.across3.deep4.around5.highIII.1.The,/,/2.The3.the,the4./5./,a6./,the7./ 8.The,the,the 9.The,the10./IV.1.unwilling2.avarage3.take4.runs5.SupposeV.1.On the avarage there are 1,000 vistors a day.2.The Atlantic Ocean is only as half as the Pacific,but it is moar than 4,000 miles wide.st night it took him a long time to get to sleep.4.There are so many ads on TV that it is to remember how many there are.5.Many wrong ideas about the Atlantic made the people in Columbus'days unwilling to sail westward.Vocabulary ExercisesI.1.a.sailed b.sailor c.sail(n.)2.a.willing b.unwillingly c.unwilling3.a.unusual ual ually4.a.average(n.) b.average(a.) c.averaged(v.)II.1.peak2.crew3.average4.blils5.unusual6.highway7.narrow 8.salty 9.spot10.affectedIII.1.The sailors were afraid that might meet bad weather.2.The mountain is half as high as Mount Tai.3.On the average there are 45 students in every class of the school.4.The climate affects the growth of plants.5.My work keeps pilling up.Text BExercises for the TextI.1.T2.T3.F4.T5.F6.T7.T8.T9.F 10.TII.1.three2.the earth's gravitational pull.3.it is near4.29.55.its own/reflects6.disc7.the old moon in the new moon's arms.8.outline9.the old earth in the new earth's arms10.nightVocabulary ExercisesI.1.d2.b3.a4.c5.eII.1.C2.C3.B4.A5.D6.C7.B8.B9.B 10.DGrammar ExercisesI.depend--dependence explain--explanationform--formation conclude--conclusioninform--information move--movementmean--meaning govern--governmentgraduate--graduation similar--aimilarityconfuse--confusion pay--paymentagree--agreement advertise--advertisementannounce--announcement add--additiondecide--decision use--usefulnessattract--attraction mix--mixtureII.science--scientific sulless--sullessfulresponse--responsible color--colorfulnation--national revolution--revolutionaryaddition--additional help--helpfulperson--personal meaning--meaningfulaccept--acceptable use--usefulwood--wooden act--activeIII.disagree eimpractical independentuncover inexact incompletedisorder unhappy informalinpossible inactive uncertaindischarge dishonest impoliteIV.1.try n. 尝试;试验经过许多次尝试后,他们终于取得了成功。

0015自考--英语(二)《大学英语自学教程》(上下册) 精品词汇(音序排序)

vt.禁止,取缔 n.禁止;禁令 n.一帮,一群;带,带形物;波段 n.障碍;障碍物 a.基本的,基础的 ad.基本上,从根本上说 n.基础,根据;主要成份;军事基地 n.海湾,口岸,湾 vt.忍受,容忍;承担;结(果实),生育 n.啤酒 n.行为,举止;运转情况,表现情况 n.相信;信念,信仰 n.[常 pl.]所有物;行李 prep.在…下面(或底下),低于 a.有益的,有利的 n.益处,好处 vt.有益于 vi.得益 a.生物学(上)的 vt./vi./n.咬,叮,蜇 n.疾风,强风;爆炸 vt.炸,炸掉 n.布鲁斯;慢四步舞 n.边缘;边界 vt./vi.接壤,毗邻;接近 a.一定的,必然的;受约束的,有义务的 n.分界线,边界 vt.繁殖;饲养 n.品种,种类 n.新娘 a.简短的;简洁的 vt.作简要的介绍 a.宽的,阔的;广泛的 n./vt./vi.广播,播音 n.预算 vt.把…编入预算;安排,预定 n.(北美)野牛;(亚洲)水牛 n.负担;责任,义务 vt.使负重担;麻烦 n.钙(化学符号 Ca) n.照相机,摄影机 n.战役;运动 v.参加运动,参加竞选活动 n.癌 n.候选人,候补者;应试者 a.有能力的,有才能的;能…的(of) n.容量,容积;能力 vt.捕获;夺得,占领 n.捕获,捕获物 n.碳 n.生涯,经历;职业,事业 - 3 -

n.同伴,同事; [天]伴星(=~star) n.公司;同伴,陪伴 n.罗盘; [pl.]圆规 n.补偿,赔偿;补偿物,赔偿费 vi.竞争,比赛 n.竞争;比赛 a.竞争的,比赛的 a.复杂的,组合的 n.综合体 n.(组)成(部)分;部件 a.组成的,构成的 n.作曲家 n.计算机,电脑 n.专注,专心;集中;浓度 n.概念;观念 n.关心,挂念;关系 vt.涉及;使关心 a.有关的;关切的,担心的 n.结论,推论 a.具体的;混凝土的 n.混凝土 vt.使凝固 vt.处理;指挥;传导 n.举止,行为 n.信任,信心 n.争论,抵触,冲突 vi.冲突,抵触 n.连接,关系 n.保存;保护 a.保存的,防腐的;保守的,守旧的 vt.考虑,细想;认为 vi.考虑,细想 a.值得考虑的,重要的;相当大或多的 vi.组成(of) a.永恒的,经久不变的;经常的 n.常数,恒量 ad.经常地;不断地;时常地 a.宪法上规定的;组成的,构成的 n.消费者;顾客,用户 n.接触,联系 vt.与…接触,使联系 vt.包含,容纳 n.内容,目录 a.满意(足)的 vt.使满意(足) n.竞争,比赛;争夺,竞争;争论,争辩 ad.不停地,频频地 a.继续的,连续的 a.连续不断的,不停歇的 n.合同,契约 vt./vi.订合同;收缩 n.对比,对照 vi.形成对比 vt.把…与…对比 vt./vi.贡献;捐献;投稿;有助于 - 4 -

00015自考英语二教程电子版

大学英语自学教程(下)01-A. What Is a Decision?A decision is a choice made from among alternative courses of action that are available. The purpose of making a decision is to establish and achieve organizational goals and objectives. The reason for making a decision is that a problem exists, goals or objectives are wrong, or something is standing in the way of accomplishing them.Thus the decision-making process is fundamental to management. Almost everything a manager does involves decisions, indeed, some suggest that the management process is decision making. Although managers cannot predict the future, many of their decisions require that they consider possible future events. Often managers must make a best guess at what the future will be and try to leave as little as possible to chance, hut since uncertainty is always there, risk accompanies decisions. Sometimes the consequences of a poor decision are slight; at other times they are serious.Choice is the opportunity to select among alternatives. If there is no choice, there is no decision to be made. Decision making is the process of choosing, and many decisions have a broad range of choice. For example, a student may be able to choose among a number of different courses in order to implement the decision to obtain a college degree. For managers, every decision has constraints based on policies, procedures, laws, precedents, and the like. These constraints exist at all levels of the organization.Alternatives are the possible courses of action from which choices can be made. If there are no alternatives, there is no choice and, therefore, no decision. If no alternatives are seen, often it means that a thorough job of examining the problems has not been done. For example, managers sometimes treat problems in an either/or fashion; this is their way of simplifying complex problems. But the tendency to simplify blinds them to other alternatives.At the managerial level, decision making includes limiting alternatives as well as identifying them, and the range is from highly limited to practically unlimited.Decision makers must have some way of determining which of several alternatives is best -- that is, which contributes the most to the achievement of organizational goals. An organizational goal is an end or a state of affairs the organization seeks to reach. Because individuals (and organizations) frequently have different ideas about how to attain the goals, the best choice may depend on who makes the decision. Frequently, departments or units within an organization make decisions that are good for them individually but that are less than optimal for the larger organization. Called suboptimization, this is a trade-off that increases the advantages to one unit or function but decreases the advantages to another unit or function. For example, the marketing manager may argue effectively for an increased advertising budget. In the larger scheme of things, however, increased funding for research to improve the products might be more beneficial to the organization.These trade-offs occur because there are many objectives that organizations wish to attainsimultaneously. Some of these objectives are more important than others, but the order and degree of importance often vary from person to person and from department to department. Different managers define the same problem in different terms. When presented with a common case, sales managers tend to see sales problems, production managers see production problems, and so on.The ordering and importance of multiple objectives is also based, in part, on the values of the decision maker. Such values are personal; they are hard to understand, even by the individual, because they are so dynamic and complex. In many business situations different people's values about acceptable degrees of risk and profitability cause disagreement about the correctness of decisions.People often assume that a decision is an isolated phenomenon. But from a systems point of view, problems have multiple causes, and decisions have intended and unintended consequences. An organization is an ongoing entity, and a decision made today may have consequences far into the future. Thus the skilled manager looks toward the future consequences of current decisions. 01-B. Secrets of Success at an InterviewThe subject of today's talk is interviews.The key words here are preparation and confidence, which will carry you far.Do your homework first.Find out all you can about the job you are applying for and the organization you hope to work for.Many of the employers I interviewed made the same criticism of candidates. "They have no idea what the day to day work of the job brings about. They have vague notions of "furthering the company's prospects’ or of 'serving the community', but have never taken the trouble to find out the actual tasks they will be required to do.”Do not let this be said of you. It shows an unattractive indifference to your employer and to your job.Take the time to put yourself into the interviewer's place. He wants somebody who is hard-working with a pleasant personality and a real interest in the job.Anything that you find out about the prospective employer can be used to your advantage during the interview to show that you have bothered to master some facts about the people who you hope to work for.Write down (and remember) the questions you want to ask the interviewer(s) so that you are not speechless when they invite your questions. Make sure that holidays and pay are not the first things you ask about. If all your questions have been answered during the interview, reply: "In fact, I did have several questions, but you have already answered them all.”Do not be afraid to ask for clarification of something that has been said during the interview if you want to be sure what was implied, but do be polite.Just before you go to the interview, look again at the original advertisement that you answered,any correspondence from your prospective employer, photocopies of your letter of application or application form and your resume.Then you will remember what you said and what they want. This is very important if you have applied for many jobs in a short time as it is easy to become confused and give an impression of inefficiency.Make sure you know where and when you have to report for the interview. Go to the building (but not inside the office) a day or two before, if necessary, to find out how long the journey takes and where exactly the place is.Aim to arrive five or ten minutes early for the actual interview, then you will have a little time in hand and you will not panic if you are delayed. You start at a disadvantage if you arrive worried and ten minutes late.Dress in clean, neat, conservative clothes. Now is NOT the time to experiment with the punk look or (girls) to wear low-cut dresses with miniskirts. Make sure that your shoes, hands and hair (and teeth) are clean and neat.Have the letter inviting you for an interview ready to show in case there is any difficulty in communication.You may find yourself facing one interviewer or a panel. The latter is far more intimidating, but do not let it worry you too much. The interviewer will probably have a table in front of him/her. Do not put your things or arms on it.If you have a bag or a case, put it on the floor beside your chair. Do not clutch it nervously or, worse still, drop it, spilling everything.Shake hands if the interviewer offers his hand first. There is little likelihood that a panel of five wants to go though the process of all shaking hands with you in turn. So you do not be upset if no one offers.Shake hands firmly -- a weak hand suggests a weak personality, and a crushing grip is obviously painful. Do not drop the hand as soon as yours has touched it as this will seem to show you do not like the other person.Speak politely and naturally even if you are feeling shy. Think before you answer any questions. If you cannot understand, ask: "Would you mind rephrasing the question, please?" The question will then be repeated in different words.If you are not definitely accepted or turned down on the spot, ask: "When may I expect to hear the results of this interview?"If you do receive a letter offering you the job, you must reply by letter (keep a photocopy) as soon as possible.Good luck!02-A. Black HolesWhat is a black hole? Well, it's difficult to answer this question, since the terms we would normally use to describe a scientific phenomenon are inadequate here. Astronomers andscientists think that a black hole is a region of space (not a thing ) into which matter has fallen and from which nothing can escape ?not even light. So we can't see a black hole. A black hole exerts a strong gravitational pull and yet it has no matter. It is only space -- or so we think. How can this happen?The theory is that some stars explode when their density increases to a particular point; they collapse and sometimes a supernova occurs. From earth, a supernova looks like a very bright light in the sky which shines even in the daytime. Supernovae were reported by astronomers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Some people think that the Star of Bethlehem could have been a supernova. The collapse of a star may produce a White Dwarf or a neutron star -- a star, whose matter is so dense that it continually shrinks by the force of its own gravity. But if the star is very large (much bigger than our sun) this process of shrinking may be so intense that a black hole results. Imagine the earth reduced to the size of a marble, but still having the same mass and a stronger gravitational pull, and you have some idea of the force of a black hole. Any matter near the black hole is sucked in. It is impossible to say what happens inside a black hole. Scientists have called the boundary area around the hole the "event horizon." We know nothing about events which happen once objects pass this boundary. But in theory, matter must behave very differently inside the hole.For example, if a man fell into a black hole, he would think that he reached the center of it very quickly. However an observer at the event horizon would think that the man never reached the center at all. Our space and time laws don't seem to apply to objects in the area of a black hole. Einstein's relativity theory is the only one which can explain such phenomena. Einstein claimed that matter and energy are interchangeable, so that there is no "absolute" time and space. There are no constants at all, and measurements of time and space depend on the position of the observer. They are relative. We do not yet fully understand the implications of the relativity theory; but it is interesting that Einstein's theory provided a basis for the idea of black holes before astronomers started to find some evidence for their existence. It is only recently that astronomers have begun specific research into black holes. In August 1977, a satellite was launched to gather data about the 10 million black holes which are thought to be in the Milky Way. And astronomers are planning a new observatory to study the individual exploding stars believed to be black holes,The most convincing evidence of black holes comes frown research into binary star systems. Binary stars, as their name suggests, are twin stars whose position in space affects each other. In some binary systems, astronomers have shown that there is an invisible companion star, a "partner" to the one which we can see in the sky. Matter from the one which we can see is being pulled towards the companion star. Could this invisible star, which exerts such a great force, be a black hole? Astronomers have evidence of a few other stars too, which might have black holes as companions.The story of black holes is just beginning. Speculations about them. are endless. There might bea massive black hole at the center of our galaxy swallowing up stars at a very rapid rate. Mankind may one day meet this fate. On the other hand, scientists have suggested that very advanced technology could one day make use of the energy of black holes for mankind. These speculations sound like science fiction. But the theory of black holes in space is accepted by many serious scientists and astronomers. They show us a world which operates in a totally different way from our own and they question our most basic experience of space and time.02-B. Worlds within WorldsFirst of all let us consider the earth (that is to say, the world) as a planet revolving round the sun. The earth is one of nine planets which move in orbit round the sun. These nine planets, together with the sun, make up what is called our solar system. How this wonderful system started and what kept it working with such wonderful accuracy is largely a mystery but astronomers tell us that it is only one of millions of similar systems in space, and one of the smallest.The stars which we see glittering in the sky on a dark and cloudless night are almost certainly the suns of other solar systems more or less like our own, but they are so far away in space that it is unlikely that we shall ever get to know very much about them. About our own solar system, however, we are learning more every day.Before the American and Russian astronauts made their thrilling journeys into outer space it was difficult for us to realise what our earth looked like from hundreds of thousands of miles away, but the photographs which the astronauts were able to take show us the earth in space looking not very different from what the moon looks like when we look at it from the earth. The earth is, however, very different from the moon, which the American astronauts have found to be without life or vegetation, whereas our earth is very much alive in every respect. The moon, by the way, is called a satellite because it goes round our earth as well as round the sun. In other words, it goes round the sun with our earth.The surface of our earth is covered by masses of land and larger areas of water. Let us consider the water areas first. The total water area is about three times as large as the land area. The very large separate areas of water are called "oceans” and the lesser areas are called "seas.”In most of the oceans and seas some of the water is found to be flowing in a particular direction -- that is to say, from one part towards another part of the ocean or sea concerned. The water which is flowing in this manner is said to be moving as a "current." There are many thousands of currents in the waters of the oceans and seas, but only certain of the stronger and better marked currents are specially named and of great importance. These currents are important because they affect the climate of the land areas close to where they flow and also because they carry large quantities of microscopic animal and vegetable life which forms a large part of the food for fishes.The nature and characteristics of the surface of the land areas of the earth vary a great deal from area to area and from place to place. The surface of some areas consists largely of high mountains and deep valleys whilst, in other areas, most of the surface consists of plains. If onemade a journey over the Continents one would find every kind of surface including mountain ranges, plains, plateaux, deserts, tropical forestlands and empty areas covered permanently by ice and snow.When thinking and learning about the world we should not forget that our world is the home of a very great many different people -- peoples with different coloured skins, living very different lives and having very different ideas about a great many important things such as religion, government, education and social behaviour.The circumstances under which different people live make a great difference between the way in which they live and the way in which we live, and it ought to be our business to try to understand those different circumstances so that we can better understand people of other lands. Above all, we should avoid deciding what we think about people different from ourselves without first having learned a great deal about them and the kind of lives they have to live. It is true to say that the more we learn about other people, the better we understand their ideas and, as a rule, the better we like those people themselves.03-A. Euthanasia: For and Against"We mustn't delay any longer ... swallowing is difficult ... and breathing, that's also difficult. Those muscles are weakening too ... we mustn't delay any longer.”These were the words of Dutchman Cees van Wendel de Joode asking his doctor to help him die. Affected with a serious disease, van Wendel was no longer able to speak clearly and he knew there was no hope of recovery and that his condition was rapidly deteriorating.Van Wendel's last three months of life before being given a final, lethal injection by his doctor were filmed and first shown on television last year in the Netherlands. The programme has since been bought by 20 countries and each time it is shown, it starts a nationwide debate on the subject.The Netherlands is the only country in Europe which permits euthanasia, although it is not technically legal there. However, doctors who carry out euthanasia under strict guidelines introduced by the Dutch Parliament two years ago are usually not prosecuted. The guidelines demand that the patient is experiencing extreme suffering, that there is no chance of a cure, and that the patient has made repeated requests for euthanasia. In addition to this, a second doctor must confirm that these criteria have been met and the death must be reported to the police department.Should doctors be allowed to take the lives of others? Dr. Wilfred van Oijen, Cees van Wendel's doctor, explains how he looks at the question:"Well, it's not as if I'm planning to murder a crowd of people with a machine gun. In that case, killing is the worst thing I can imagine. But that's entirely different from my work as a doctor. I care for people and I try to ensure that they don't suffer too much. Th at's a very different thing.”Many people, though, are totally against the practice of euthanasia. Dr. Andrew Ferguson, Chairman of the organisation Healthcare Opposed to Euthanasia, says that "in the vast majorityof euthanasia cases, what the patient is actually asking for is something else. They may want a health professional to open up communication for them with their loved ones or family -- there's nearly always another question behind the question.”Britain also has a strong tradition of hospices -- special hospitals which care only for the dying and their special needs. Cicely Saunders, President of the National Hospice Council and a founder member of the hospice movement, argues that euthanasia doesn't take into account that there are ways of caring for the dying. She is also concerned that allowing euthanasia would undermine the need for care and consideration of a wide range of people: "It's very easy in society now for the elderly, the disabled and the dependent to feel that they are burdens, and therefore that they ought to opt out. I think that anything that legally allows the shortening of life does make those people more vulnerable.”Many find this prohibition of an individual's right to die paternalistic. Although they agree that life is important and should be respected, they feel that the quality of life should not be ignored. Dr. van Oijen believes that people have the fundamental right to choose for themselves if they want to die: "What those people who oppose euthanasia are telling me is that dying people haven't the right. And that when people are very ill, we are all afraid of their death. But there are situations where death is a friend. And in those cases, why not?But "why not?" is a question which might cause strong emotion. The film showing Cees van Wendel's death was both moving and sensitive. His doctor was clearly a family friend; his wife had only her husband's interests at heart. Some, however, would argue that it would be dangerous to use this particular example to support the case for euthanasia. Not all patients would receive such a high level of individual care and attention.03-B. Advantage UnfairAccording to the writer Walter Ellis, author of a book called the Oxbridge Conspiracy, Britain is still dominated by the old-boy network: it isn't what you know that matters, but who you know. He claims that at Oxford and Cambridge Universities (Oxbridge for short) a few select people start on an escalator ride which, over the years, carries them to the tops of British privilege and power. His research revealed that the top professions all continue to be dominated, if not 90 per cent, then 60 or 65 per cent, by Oxbridge graduates.And yet, says Ellis, Oxbridge graduates make up only two per cent of the total number of students who graduate from Britain's universities. Other researches also seem to support his belief that Oxbridge graduates start with an unfair advantage in the employment market. In the law, a recently published report showed that out of 26 senior judges appointed to the High Court last year, all of them went to private schools and 21 of them went to Oxbridge.But can this be said to amount to a conspiracy? Not according to Dr. John Rae, a former headmaster of one of Britain's leading private schools, Westminster:"I would accept that there was a bias in some key areas of British life, but that bias has now gone. Some time ago -- in the 60s and before ?entry to Oxford and Cambridge was not entirely onmerit. Now, there's absolutely no question in any objective observer's mind that, entry to Oxford and Cambridge is fiercely competitive."However, many would disagree with this. For, although over three-quarters of British pupils are educated in state schools, over half the students that go to Oxbridge have been to private, or "public" schools. Is this because pupils from Britain's private schools are more intelligent than those from state schools, or are they simply better prepared?On average, about $ 5,000 a year is spent on each private school pupil, more than twice the amount spent on state school pupils. So how can the state schools be expected to compete with the private schools when they have far fewer resources? And how can they prepare their pupils for the special entrance exam to Oxford University, which requires extra preparation, and for which many public school pupils traditionally stay at school and do an additional term?Until recently, many blamed Oxford for this bias because of the university's special entrance exam (Cambridge abolished its entrance exam in 1986). But last February, Oxford University decided to abolish the exam to encourage more state school applicants. From autumn 1996, Oxford University applicants, like applicants to other universities, will be judged only on their A level results and on their performance at interviews, although some departments might still set special tests.However, some argue that there's nothing wrong in having elite places of learning, and that by their very nature, these places should not be easily accessible. Most countries are run by an elite and have centres of academic excellence from which the elite are recruited. Walter Ellis accepts that this is true:"But in France, for example, there are something like 40 equivalents of university, which provide this elite through a much broader base. In America you've got the Ivy League, centred on Harvard and Yale, with Princeton and Stanford and others. But again, those universities together -- the elite universities -- are about ten or fifteen in number, and are being pushed along from behind by other great universities like, for example, Chicago and Berkeley. So you don't have just this narrow concentration of two universities providing a constantly replicating elite.”When it comes to Oxford and Cambridge being elitist because of the number of private school pupils they accept, Professor Stone of Oxford University argues that there is a simple fact he and his associates cannot ignore:"If certain schools do better than others then we just have to accept it. We cannot be a place for remedial education. It's not what Oxford is there to do.”However, since academic excellence does appear to be related to the amount of money spent per pupil, this does seem to imply that Prime Minister John Major's vision of Britain as a classless society is still a long way off. And it may be worth remembering that while John Major didn't himself go to Oxbridge, most of his ministers did.04-A. Slavery on Our DoorstepThere are estimated to be more than 20,000 overseas domestic servants working in Britain (theexact figure is not known because the Home Office, the Government department that deals with this, does not keep statistics). Usually, they have been brought over by foreign businessmen, diplomats or Britons returning from abroad. Of these 20,000, just under 2,000 are being exploited and abused by their employers, according to a London-based campaigning group which helps overseas servants working in Britain.The abuse can take several forms. Often the domestics are not allowed to go out, and they do not receive any payment. They can be physically, sexually and psychologically abused. And they can have their passports removed, making leaving or "escaping" virtually impossible.The sad condition of women working as domestics around the world received much media attention earlier this year in several highly publicised cases. In one of them, a Filipino maid was executed in Singapore after being convicted of murder, despite protests from various quarters that her guilt had not been adequately established. Groups like Anti-Slavery International say other, less dramatic, cases are equally deserving of attention, such as that of Lydia Garcia, a Filipino maid working in London:"I was hired by a Saudi diplomat directly from the Philippines to work in London in 1989. I was supposed to be paid $ 120 but I never received that amount. They always threatened that they would send me back to my country.”Then there is the case of Kumari from Sri Lanka. The main breadwinner in her family, she used to work for a very low wage at a tea factory in Sri Lanka. Because she found it difficult to feed her four children, she accepted a job working as a domestic in London. She says she felt like a prisoner at the London house where she worked:"No days off -- ever, no breaks at all, no proper food. I didn't have my own room; I slept on a shelf with a spad0 of only three feet above me. I wasn't allowed to talk to anybody. I wasn't even allowed to open the window. My employers always threatened to report me to the Home Office or the police.”At the end of 1994 the British Government introduced new measures to help protect domestic workers from abuse by their employers. This included increasing the minimum age of employees to 18, getting employees to read and, understand an advice leaflet, getting employers to agree to provide adequate maintenance and conditions, and to put in writing the main terms and conditions of the job (of which the employees should see a copy).However, many people doubt whether this will successfully reduce the incidence of abuse. For the main problem facing overseas maids and domestics who try to complain about cruel living and working conditions is that they do not have independent immigrant status and so cannot change employer. (They are allowed in the United Kingdom under a special concession in the immigration rules which allows foreigners to bring domestic staff with them.) So if they do complain, they risk being deported.Allowing domestic workers the freedom to seek the same type of work but with a different employer, if they so choose, is what groups like Anti-Slavery International are campaigning the。

00015英语二_下册课后讲解_(自考)

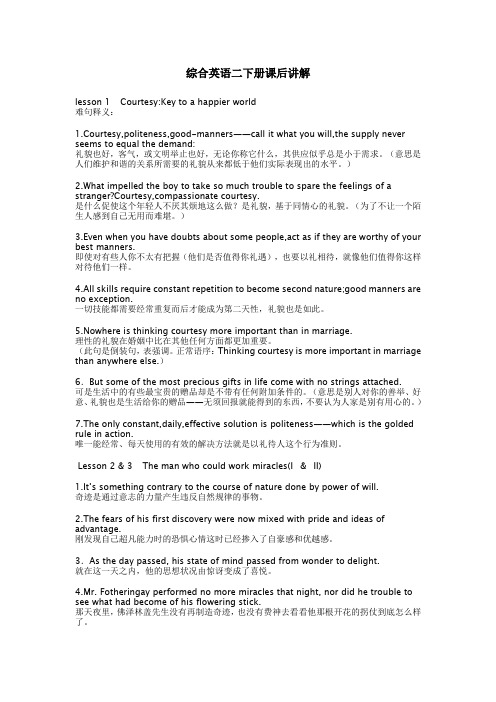

综合英语二下册课后讲解lesson 1 Courtesy:Key to a happier world难句释义:1.Courtesy,politeness,good-manners——call it what you will,the supply never seems to equal the demand:礼貌也好,客气,或文明举止也好,无论你称它什么,其供应似乎总是小于需求。

(意思是人们维护和谐的关系所需要的礼貌从来都低于他们实际表现出的水平。

)2.What impelled the boy to take so much trouble to spare the feelings of a stranger?Courtesy,compassionate courtesy.是什么促使这个年轻人不厌其烦地这么做?是礼貌,基于同情心的礼貌。

(为了不让一个陌生人感到自己无用而难堪。

)3.Even when you have doubts about some people,act as if they are worthy of your best manners.即使对有些人你不太有把握(他们是否值得你礼遇),也要以礼相待,就像他们值得你这样对待他们一样。

4.All skills require constant repetition to become second nature;good manners are no exception.一切技能都需要经常重复而后才能成为第二天性,礼貌也是如此。

5.Nowhere is thinking courtesy more important than in marriage.理性的礼貌在婚姻中比在其他任何方面都更加重要。

(此句是倒装句,表强调。

正常语序:Thinking courtesy is more important in marriage than anywhere else.)6.But some of the most precious gifts in life come with no strings attached.可是生活中的有些最宝贵的赠品却是不带有任何附加条件的。

大学英语自学教程含课文翻译注释答案(上下合订)

Unit 1第一部分 Text A【课文译文】怎样成为一名成功的语言学习者“学习一门语言很容易,即使小孩也能做得到。

”大多数正在学习第二语言的成年人会不同意这种说法。

对他们来说,学习一门语言是非常困难的事情。

他们需要数百小时的学习与练习,即使这样也不能保证每个成年语言学习者都能学好。

语言学习不同于其他学习。

许多人很聪明,在自己的领域很成功,但他们发现很难学好一门语言。

相反,一些人学习语言很成功,但却发现很难在其他领域有所成就。

语言教师常常向语言学习者提出建议:“要用新的语言尽量多阅读”,“每天练习说这种语言”,“与说这种语言的人住在一起”,“不要翻译——尽量用这种新的语言去思考”,“要像孩子学语言一样去学习新语言”,“放松地去学习语言。

”然而,成功的语言学习者是怎样做的呢?语言学习研究表明,成功的语言学习者在许多方面都有相似之处。

首先,成功的语言学习者独立学习。

他们不依赖书本和老师,而且能找到自己学习语言的方法。

他们不是等待老师来解释,而是自己尽力去找到语言的句式和规则。

他们寻找线索并由自己得出结论,从而做出正确的猜测。

如果猜错,他们就再猜一遍。

他们都努力从错误中学习。

成功的语言学习是一种主动的学习。

因此,成功的语言学习者不是坐等时机而是主动寻找机会来使用语言。

他们找到(说)这种语言的人进行练习,出错时请这些人纠正。

他们不失时机地进行交流,不怕重复所听到的话,也不怕说出离奇的话,他们不在乎出错,并乐于反复尝试。

当交流困难时,他们可以接受不确切或不完整的信息。

对他们来说,更重要的是学习用这种语言思考,而不是知道每个词的意思。

最后,成功的语言学习者学习目的明确。

他们想学习一门语言是因为他们对这门语言以及说这种语言的人感兴趣。

他们有必要学习这门语言去和那些人交流并向他们学习。

他们发现经常练习使用这种语言很容易,因为他们想利用这种语言来学习。

你是什么样的语言学习者?如果你是一位成功的语言学习者,那么你大概一直在独立地、主动地、目的明确地学习。

英语(一)、英语(二)——大学英语自学教程(上册)——电子版教材

英语(一)、英语(二)——大学英语自学教程(上册)——电子版教材大学英语自学教程(上)01-A. How to be a successful language learner?―Learning a language is easy, even a child can do it!‖Most adults who are learning a second language would disagree with this statement. For them, learning a language is a very difficult task. They need hundreds of hours of study and practice, and even this will not guarantee success for every adult language learner.Language learning is different from other kinds of learning. Some people who are very intelligent and successful in their fields find it difficult to succeed in language learning. Conversely, some people who are successful language learners find it difficult to succeed in other fields.Language teachers often offer advice to language learners: “Read as much as you can in the new language.”“ Practice speaking the languageevery day. ”“Live with people who speak the language.”“Don‘t translate-try to think in the new language.”“ Learn as a child would learn;play with the language.”But what does a successful language learner do? Language learning research shows that successful language learners are similar in many ways.First of all, successful language learners are independent learners. They do not depend on the book or the teacher; they discover their own way to learn the language. Instead of waiting for the teacher to explain, they try to find the patterns and the rules for themselves. They are good guessers who look for clues and form their own conclusions. When they guess wrong, they guess again. They try to learn from their mistakes.Successful language learning is active learning. Therefore,successful learners do not wait for a chance to use the language; they look for such a chance. They find people who speak the language and they ask these people to correct them when they make a mistake. They will try anything to communicate. They are not afraid to repeat what they hear or1to say strange things; they are willing to make mistakes and try again. When communication is difficult, they can accept information that is inexact or incomplete. It is more important for them to learn tothink in the language than to know the meaning of every word.Finally, successful language learners are learners with a purpose. They want to learn the language because they are interested in the language and the people who speak it. It is necessary for them to learn the language in order to communicate with these people and to learn fromthem. They find it easy to practice using the language regularly because they want to learn with it.What kind of language learner are you? If you are a successful language learner, you have probably been learning independently,actively, and purposefully. On the other hand, if your language learning has been less than successful, you might do well to try some of the techniques outlined above.01-B. LanguageWhen we want to tell other people what we think, we can do it notonly with the help of words, but also in many other ways. For instance, we sometimes move our heads up and d own when we want to say "yes‖and we move our heads from side to side when we want to say "no." People who can neither hear nor speak (that is, deaf and dumb people) talk to each other with the help of their fingers. People who do not understand each other's language have to do the same. The following story shows how they sometimes do it.An Englishman who could not speak Italian was once traveling inItaly. One day he entered a restaurant and sat down at a table. When the waiter came, the Englishman opened his mouth, put his fingers in it,took them out again and moved his lips. In this way he meant to say, "Bring me something to eat." The waiter soon brought him a cup of tea. The Englishman shook his head and the waiter understood that he didn't want tea, so he took it away and brought him some coffee. The Englishman, who was very hungry by this time and not at all thirsty, looked very sad.He shook his head each time the waiter brought him something to drink.2The waiter brought him wine, then beer, then soda-water, but that wasn‘tfood, of course. He was just going to leave the restaurant when another traveler came in. When this man saw the waiter, he put his hands on his stomach. That was enough: in a few minutes there was a largeplate of macaroni and meat on the table before him.As you see, the primitive language of signs is not always very clear. The language of words is much more exact.Words consist of sounds, but there are many sounds which have ameaning and yet are not words. For example, we may say "Sh-sh-sh‖ when we mean "keep silent.‖ When babies laugh, we know they arehappy, and when they cry, we know they are ill or simply want something.It is the same with animals. When a dog says ―G-r-r‖ or a cat says "F-f-f‖ we know they are angry.But these sounds are not language. Language consists of words which we put together into sentences. But animals can not do this: a dog can say ―G-r-r‖ when he means "I am angry,‖ but he cannot say first "I‖ and then "am‖ and then "angry.‖ A parrot can talk like a man; it can repeat whole sentences and knows what they mean. We may say that aparrot talks, but cannot say that it really speaks, because it cannotform new sentences out of the words it knows. Only man has the power to do this.02-A. Taxes, Taxes, and More TaxesAmericans often say that there are only two things a person can be sure of in life: death and taxes, Americans do not have a corner on the "death" market, but many people feel that the United States leadsthe world with the worst taxes.Taxes consist of the money which people pay to support their government. There are generally three levels of government in the United States: federal, state, and city; therefore, there are three types of taxes.Salaried people who earn more than a few thousand dollars must pay3a certain percentage of their salaries to the federal government. The percentage varies from person to person. It depends on their salaries. The federal government has a graduated income tax, that is, the percentage of the tax (14 to 70 percent) increases as a person's income increases. With the high cost of taxes, people are not very happy on April 15, when the federal taxes are due.The second tax is for the state government: New York, California, North Dakota, or any of the other forty-seven states. Some states have an income tax similar to that of the federal government. Of course, the percentage for the state tax is lower. Other states have a sales tax, which is a percentage charged to any item which you buy in that state.For example, a person might want to buy a packet of cigarettes for twenty-five cents. If there is a sales tax of eight percent in that state, then the cost of the cigarettes is twenty-seven cents. Thisfigure includes the sales tax. Some states use income tax in addition to sales tax to raise their revenues. The state tax laws are diverse and confusing.The third tax is for the city. This tax comes in two forms: property tax (people who own a home have to pay taxes on it) and excise tax, which is charged on cars in a city. The cities use these funds for education, police and fire departments, public works and municipal buildings.Since Americans pay such high taxes, they often feel that they are working one day each week just to pay their taxes. People always complain about taxes. They often protest that the government uses their tax dollars in the wrong way. They say that it spends too much on useless and impractical programs. Although Americans have different views on many issues, they tend to agree on one subject: taxes are too high.02-B. AdvertisingAdvertising is only part of the total sales effort, but it is the part that attracts the most attention. This is natural enough because advertising is designed for just that purpose. In newspapers, in magazines, in the mail, on radio and television, we constantly see andhear the messages for hundreds of different products and services. For the most part, they arethe kinds of things that we can be persuaded to buy – food and drinks,4cars and television sets, furniture and clothing, travel and leisure time activities.The simplest kind of advertising is the classified ad. Every day the newspapers carry a few pages of these ads; in the large Sunday editions there may be several sections of them. A classified ad is usually only a few lines long. It is really a notice or announcement that something is available.Newspapers also carry a large amount of display advertising. Most of it is for stores or for various forms of entertainment. Newspapers generally reach an audience only in a limited area. To bring their message to a larger audience, many who want to put out their ads use nationalmagazines. Many of the techniques of modern advertising were developed in magazine ads. The use of bright colors, attractive pictures, and short messages is all characteristic of magazine ads. The most . The message itself is usually short, important purpose is to catch the eyeoften no more than a slogan which the public identifies with theproduct.The same techniques have been carried over into televisionadvertising. Voices and music have been added to color and pictures to catch the ear as well as the eye. Television ads are short –usually only15,30, or 60 seconds, but they are repeated over and over again so that the audience sees and hears them many times. Commercial television has mixed entertainment and advertising. If you want the entertainment, you have to put up with the advertising-and millions of people want the entertainment.The men and women in the sales department are responsible for the company‘s advertising, They must decide on the audience they want to reach. They must also decide on the best way to get their message to their particular audience. They also make an estimate of the costs before management approves the plan. In most large companies management is directly involved in planning the advertising.03-A. The Atlantic OceanThe Atlantic Ocean is one of the oceans that separate the Old World5from the New. For centuries it kept the Americas from being discoveredby the people of Europe.Many wrong ideas about the Atlantic made early sailors unwilling to sail far out into it. One idea was that it reached out to "the edge ofthe world." Sailors were afraid that they might sail right off the earth. Another idea was that at the equator the ocean would be boiling hot.The Atlantic Ocean is only half as big as the Pacific, but it isstill very large. It is more than 4,000 miles (6,000 km) wide where Columbus crossed it. Even at its narrowest it is about 2, 000 miles(3,200 km) wide. This narrowest place is between the bulge of south America and the bulge of Africa.Two things make the Atlantic Ocean rather unusual. For so large an ocean it has very few islands. Also, it is the world's saltiest ocean.There is so much water in the Atlantic that it is hard to imaginehow much there is. But suppose no more rain fell into it and no more water was brought to it by rivers. It would take the ocean about 4,000 years to dry up. On the average the water is a little more than twomiles (3.2 km) deep, but in places it is much deeper. The deepest spotis near Puerto Rico. This "deep" 30, 246 feet - almost six miles (9.6 km).One of the longest mountain ranges of the world rises the floor ofthe Atlantic. This mountain range runs north and south down the middleof the ocean. The tops of a few of the mountains reach up above the sea and make islands. The Azores are the tops of peaks in the mid-Atlantic mountain range.Several hundred miles eastward from Florida there is a part of the ocean called the Sargasso Sea. Here the water is quiet, for there islittle wind. In the days of sailing vessels the crew were afraid they would be becalmed here. Sometimes they were.Ocean currents are sometime called "rivers in the sea." One of these "river" in the Atlantic is called the Gulf Stream. It is a current of warm water. Another is the Labrador Current - cold water coming downfrom the Arctic. Ocean currents affect the climates of the lands near which they flow.The Atlantic furnishes much food for the people on its shores. Oneof its most famous fishing regions, the Grand Banks, is near6Newfoundland.Today the Atlantic is a great highway. It is not, however, always a smooth and safe one. Storms sweep across it and pile up great waves. Icebergs float down from the Far North across the paths of ships.We now have such fast ways of traveling that this big ocean seems to have grown smaller. Columbus sailed for more than two months to cross it.A fast modern steamship can make the trip in less than four days. Airplanes fly from New York to London in only eight hours and from South America to Africa in four!03-B. The MoonWe find that the moon is about 239,000 miles (384,551km) away fromthe earth, and, to within a few thousand miles, its distance always remains the same. Yet a very little observation shows that the moon is not standing still. Its distance from the earth remains the same, butits direction continually changes. We find that it is traveling in a circle - or very nearly a circle - round the earth, going completely round once a month, or, more exactly, once every 27 1/3 days. It is our nearest neighbour in space, and like ourselves it is kept tied to the earth by the earth's gravitational pull.Except for the sun, the moon looks the biggest object in the sky. Actually it is one of the smallest, and only looks big because it is so near to us. Its diameter is only 2, 160 miles (3,389 km), or a little more than a quarter of the diameter of the earth.Once a month, or, more exactly, once every 29 1/2 days, at the time we call "full moon," its whole disc looks bright. At other times only part of it appears bright, and we always find that this is the partwhich faces towards the sun, while the part facing away from the sun appears dark. Artists could make their pictures better if they kept in mind -- only those parts of the moon which are lighted up by the sun are bright. This shows that the moon gives no light of its own. It merely reflects the light of the sun, like a huge mirror hung in the sky.Yet the dark part of the moon‘s surface is not absolutely black;7generally it is just light enough for us to be able to see its outline, so that we speak of seeing "the old moon in the new moon's arms." The light by which we see the old moon does not come from the sun, but from the earth. we knows well how the surface of the sea or of snow, or even of a wet road, may reflect uncomfortably much of the sun's lighton to our faces. In the same way the surface of the whole earth reflects enough of the sun's light on to the face of the moon for us to be able to see the parts of it which would otherwise be dark.If there were any inhabitants of the moon, they would see our earth reflecting the light of the sun, again like a huge mirror hung in the sky. They would speak of earthlight just as we speak of moonlight. "The oldmoon in the new moon's arms" is nothing but that part of the moon's surface on which it is night, lighted up by earth light. In the same way, the lunar inhabitants would occasionally see part of our earth in full sunlight, and the rest lighted only by moonlight; they might call this "the old earth in the new earth's arms.‖04-A. Improving Your MemoryPsychological research has focused on a number of basic principles that help memory: meaningfulness, organization, association, and visualization. It is useful to know how these principles work.Meaningfulness affects memory at all levels. Information that does not make any sense to you is difficult to remember. There are several ways in which we can make material more meaningful. Many people, for instance, learn a rhyme to help them remember. Do you know the rhyme―Thirty days has September, April, June, and November…? ‖ It helps many people remember which months of the year have 30 days.Organization also makes a difference in our ability to remember. How useful would a library be if the books were kept in random order?Material that is organized is better remembered than jumbled information. One example of organization is chunking. Chunking consists of grouping separate bits of information. For example, the number 4671363 is more easily remembered if it is chunked as 467,13,63. Categorizing is another means of organization. Suppose you are asked to remember the following8list of words: man, bench, dog, desk, woman, horse, child, cat, chair. Many people will group the words into similar categories and remember them as follows: man, woman, child; cat, dog, horse; bench, chair, desk. Needless to say, the second list can be remembered more easily than the first one.Association refers to taking the material we want to remember and relating it to something we remember accurately. In memorizing a number, you might try to associate it with familiar numbers or events. For example, the height of Mount Fuji in Japan - 12, 389 feet - might be remembered using the following associations: 12 is the number of months in the year, and 389 is the number of days in a year(365) added to the number of months twice (24).The last principle is visualization. Research has shown striking improvements in many types of memory tasks when people are asked to visualize the items to be remembered. In one study, subjects in onegroup were asked to learn some words using imagery, while the second group used repetition to learn the words. Those using imagery remembered 80 to 90 percent of the words, compared with 30 to 40 percent of thewords for those who memorized by repetition. Thus forming an integrated image with all the information placed in a single mental picture can help us to preserve a memory.04-B. Short-term MemoryThere are two kinds of memory: shore-term and long-term. Information in long-term memory can be recalled at a later time when it is needed. The information may be kept for days or weeks. Sometimes information in the long-term memory is hard to remember. Students taking exam often have this experience. In contrast, information in shore-term memory is kept for only a few seconds, usually by repeating the information over and over. For example, you look up a number in the telephone book, and before you dial, you repeat the number over and over. If someone interrupts you, you will probably forget the number. In laboratory studies, subjects are unable to remember three letters after eighteen seconds if they are not allowed to repeat the letters to9themselves.Psychologists study memory and learning with both animal and human subjects. The two experiments here show how short-term memory has been studied.Dr. Hunter studied short-term memory in rats. He used a special apparatus which had a cage for the rat and three doors, There was alight in each door. First the rat was placed in the closed cage. Next, one of the lights was turned on and then off. There was food for the ratonly at this door. After the light was turned off, the rat had to wait a short time before it was released from its cage. Then, if it went to the correct door, it was rewarded with the food that was there. Hunter did this experiment many times. He always turned on the lights in a random order. The rat had to wait different intervals before it was released from the cage. Hunter found that if the rat had to wait more than ten seconds, it could not remember the correct door. Hunter's results show that rats have a short-term memory of about ten seconds.Later, Dr. Henning studied how students who are learning English asa second language remember vocabulary. The subjects in his experiment were 75 students at the University of California in Los Angeles. They represented all levels of ability in English; beginning, intermediate, advanced, and native-speaking students.To begin, the subjects listened to a recording of a native speaker reading a paragraph in English. Following the recording, the subjects took a 15-question test to see which words they remembered. Each question had four choices. The subjects had to circle the word they had heard in the recording. Some of the questions had four choices that sound alike. For example, weather, whether, wither, and wetter are four words thatsound alike. Some of the questions had four choices that have the same meaning. Method, way, manner, and system would be four words with thesame meaning. Some of them had four unrelated choices. For instance,weather, method, love, and result could be used as four unrelated words.Finally the subjects took a language proficiency test.Henning found that students with a lower proficiency in English made more of their mistakes on words that sound alike; students with a higher proficiency made more of their mistakes on words that have the same meaning. Henning‘s results suggest that beginning students hold the10sound of words in their short-term memory, while advanced studentshold the meaning of words in their short-term memory.05-A. Fallacies about FoodMany primitive peoples believed that by eating an animal they couldget some of the good qualities of that animal for themselves. They thought, for example, that eating deer would make them run as fast asthe deer. Some savage tribes believed that eating enemies that had shown bravery in battle would make them brave. Man-eating may have started because people were eager to become as strong and brave as their enemies.Among civilized people it was once thought that ginger root by some magical power could improve the memory. Eggs were thought to make the voice pretty. Tomatoes also were believed to have magical powers. They were called love apples and were supposed to make people who ate themfall in love.Later another wrong idea about tomatoes grew up - the idea that they were poisonous. How surprised the people who thought tomatoes poisonouswould be if they could know that millions of pounds of tomatoes were supplied to soldiers overseas during World War II.Even today there are a great many wrong ideas about food. Some of them are very widespread.One such idea is that fish is the best brain food. Fish is good brain food just as it is good muscle food and skin food and bone food. But no one has been able to prove that fish is any better for the brain than manyother kinds of food.Another such idea is that you should not drink water with meals. Washing food down with water as a substitute for chewing is not a good idea, but some water with meals has been found to be helpful. It makes the digestive juices flow more freely and helps to digest the food.Many of the ideas which scientists tell us have no foundation have to11do with mixtures of foods. A few years ago the belief became general that orange juice and milk should never be drunk at the same meal. The reason given was that the acid in the orange juice would make the milk curdle and become indigestible. As a matter of fact, milk always meets in the stomach a digestive juice which curdles it; the curdling of the milk is the first step in its digestion. A similar wrong idea is that fish and ice cream when eaten at the same meal form a poisonous combination.Still another wrong idea about mixing foods is that proteins and carbohydrates should never be eaten at the same meal. Many people think of bread, for example, as a carbohydrate food. It is chiefly a carbohydrate food, but it also contains proteins. In the same way, milk, probably the best single food, contains both proteins and carbohydrates. It is just as foolish to say that one should never eat meat and potatoes together as it is to say that one should never eat bread or drink milk.05-B. Do Animals Think?The question has often been asked, Do animals think? I believe that some of them think a great deal. Many of them are like children in their sports. We notice this to be true very often with dogs and cats; but it is true with other animals as well.Some birds are very lively in their sports; and the same is truewith some insects. The ants, hardworking as they are, have their times for play. They run races; they wrestle; and sometimes they have mock fights together. Very busy must be their thoughts while engaged in these sports.There are many animals, however, that never play; their thoughts seem to be of the more sober kind. We never see frogs engaged in sport. They all the time appear to be very grave. The same is true of the owl, who always looks as if he were considering some important question.Animals think much while building their houses. The bird searchesfor what it can use in building its nest, and in doing this it thinks. Thebeavers think as they build their dams and their houses. They think in getting their materials, and also in arranging them, and inplastering them12together with mud. Some spiders build houses which could scarcely have been made except by some thinking creature.As animals think, they learn. Some learn more than others. Theparrot learns to talk, though in some other respects it is quite stupid. The mocking bird learns to imitate a great many different sounds. The horse is not long in learning many things connected with the work which he has to do. The shepherd dog does not know as much about most things as some other dogs , and yet he understands very well how to take care of sheep.Though animals think and learn, they do not make any real improvement in their ways of doing things, as men do. Each kind of bird has its own way of building a nest, and it is always the same way. And so of other animals. They have no new fashions, and learn none from each other. But men, as you know, are always finding new ways of building houses, and improved methods of doing almost all kinds of labor.Many of the things that animals know how to do they seem to know either without learning, or in some way which we cannot understand. They are said to do such things by instinct; but no one can tell whatinstinct is. It is by this instinct that birds build their nests and beavers their dam and huts. If these things were all planned and thoughtout just as men plan new houses. there would be some changes in the fashions of them, and some improvements.I have spoken of the building instinct of beavers. An English gentleman caught a young one and put him at first in a cage. After a while he let him out in a room where there was a great variety of things. As soon as he was let out he began to exercise his building instinct. He gathered together whatever he could find, brushes, baskets, boots, clothes, sticks, bits of coal, etc., and arranged them as if to build a dam. Now, if he had had his wits about him, he would have known that there was no use in building a dam where there was no water.It is plain that, while animals learn about things by their sensesas we do, they do not think nearly as much about what they learn, andthis is the reason why they do not improve more rapidly. Even the wisest of them, as the elephant and the dog, do not think very much about what they see and hear. Nor is this all. There are some thing that we understand,but about which animals know nothing. They have no knowledge of13anything that happens outside of their own observation. Their minds are so much unlike ours that they do not know the difference betweenrightand wrong.06-A. Diamonds。

大学英语自学教程(下)讲义

Unit 1第一部分 Text A【课文译文】怎样成为一名成功的语言学习者决策是从可供挑选的行动方案中作出选择,目的在于确定并实现组织机构的目标或目的。

之所以要决策是因为存在问题,或是目标或目的不对,或某种东西妨碍目标或目的实现。

因此,决策过程对于管理人员非常重要。

管理者所做的一切几乎都与决策有关,事实上,有人甚至认为管理过程就是决策过程。

虽然决策者不能预测未来,但他们的许多决策要求他们必须考虑未来可能会发生的情况。

管理者必须对未来的事情作出最佳的猜测,并使偶然性尽可能少地发生。

但因为总是存在着未知情况,所以决策往往伴随着风险。

有时失误的决策带来的后果不很严重,但有时就会不堪设想。

选择就是从多种选项中进行取舍,没有选择,就没有决策。

决策本身就是一个选择的过程,许多决策有着很广的选择范围。

例如,学生为了实现自己获得学位的目标,可能会从多门课程中进行选择,对于管理者来说,每一个决策都受到政策、程序、法律、惯例等方面的制约,这些制约存在于一个组织的各个部门里。

选项就是可供选择的种种可行的行动方案。

没有选项,就没有选择,因而也就没有决策。

如果看不到任何选项,这意味着还没有对问题进行彻底的研究。

例如,管理者有时会用“非此即彼”的方式处理问题,这是他们简化问题的方法。

这种简化问题的习惯常常使他们看不到其他的选项。

在管理这个层次上,制定决策包括:识别选项和缩小选项范围,其范围小到微乎其微,大到近乎无限。

决策者必须有某种方法来断定几种选项中的最佳选项,即哪个选项最有利于实现其组织的目标。

组织的目标是指该组织努力完成或达到的目标或现状。

由于个人(或组织)对于怎样实现其目标的方式都有不同的见解,最佳的选择就在于决策者了。

常常是一个组织的下属部门做出的决策对自己有利,而对上一级的部门来说,就不是较佳选择了。

这种增加部门的局部利益而减少其他部门的局部利益所作出的权衡,叫做局部优化。

例如,市场营销经理为增加广告预算可能会讲得头头是道,但从更大的布局来看,增加优化产品的研究经费也许对组织更有利。

大学英语自学考试英语二(下册)unit1教(学)案

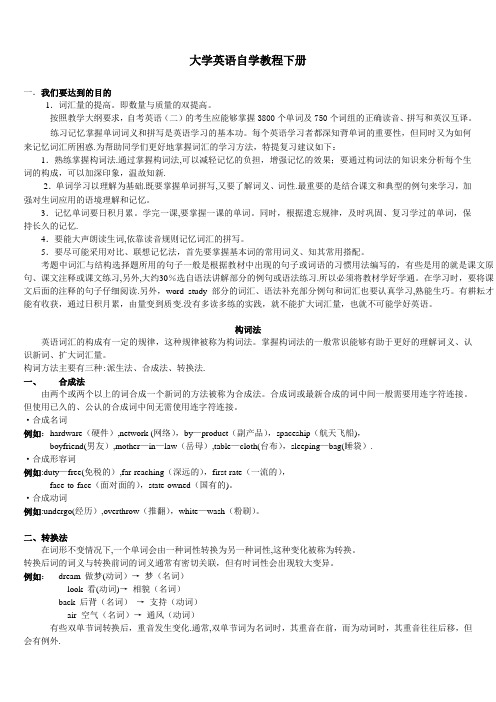

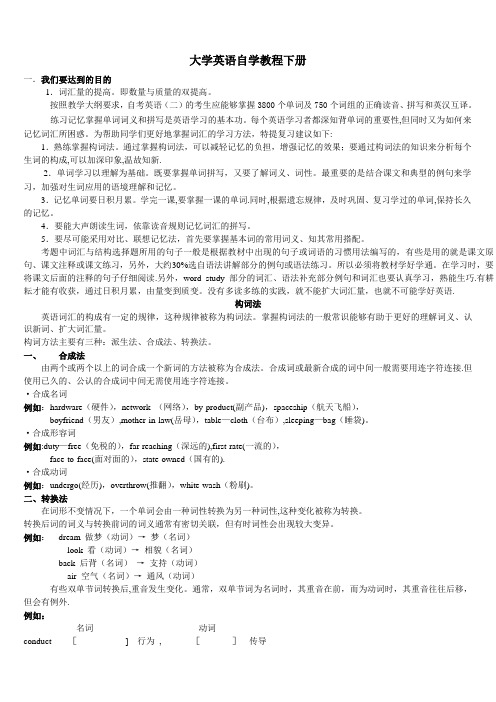

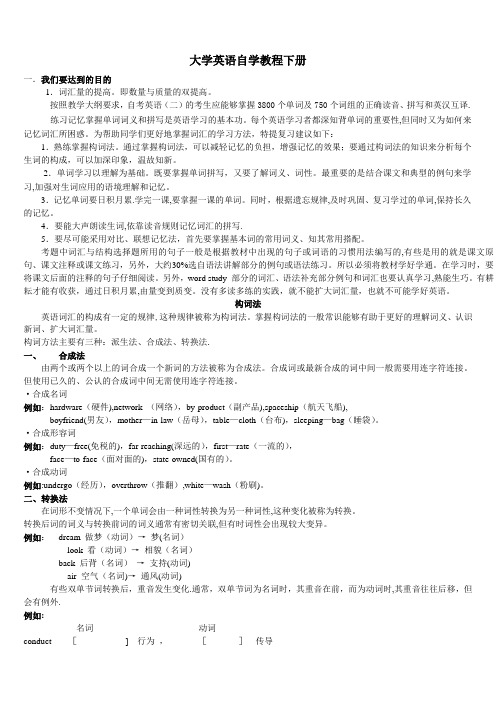

大学英语自学教程下册一.我们要达到的目的1.词汇量的提高。

即数量与质量的双提高。

按照教学大纲要求,自考英语(二)的考生应能够掌握3800个单词及750个词组的正确读音、拼写和英汉互译。

练习记忆掌握单词词义和拼写是英语学习的基本功。

每个英语学习者都深知背单词的重要性,但同时又为如何来记忆词汇所困惑。

为帮助同学们更好地掌握词汇的学习方法,特提复习建议如下:1.熟练掌握构词法。

通过掌握构词法,可以减轻记忆的负担,增强记忆的效果;要通过构词法的知识来分析每个生词的构成,可以加深印象,温故知新。

2.单词学习以理解为基础。

既要掌握单词拼写,又要了解词义、词性。

最重要的是结合课文和典型的例句来学习,加强对生词应用的语境理解和记忆。

3.记忆单词要日积月累。

学完一课,要掌握一课的单词。

同时,根据遗忘规律,及时巩固、复习学过的单词,保持长久的记忆。

4.要能大声朗读生词,依靠读音规则记忆词汇的拼写。

5.要尽可能采用对比、联想记忆法,首先要掌握基本词的常用词义、知其常用搭配。

考题中词汇与结构选择题所用的句子一般是根据教材中出现的句子或词语的习惯用法编写的,有些是用的就是课文原句、课文注释或课文练习,另外,大约30%选自语法讲解部分的例句或语法练习。

所以必须将教材学好学通。

在学习时,要将课文后面的注释的句子仔细阅读。

另外,word study 部分的词汇、语法补充部分例句和词汇也要认真学习,熟能生巧。

有耕耘才能有收获,通过日积月累,由量变到质变。

没有多读多练的实践,就不能扩大词汇量,也就不可能学好英语。

构词法英语词汇的构成有一定的规律,这种规律被称为构词法。

掌握构词法的一般常识能够有助于更好的理解词义、认识新词、扩大词汇量。

构词方法主要有三种:派生法、合成法、转换法。

一、合成法由两个或两个以上的词合成一个新词的方法被称为合成法。

合成词或最新合成的词中间一般需要用连字符连接。

但使用已久的、公认的合成词中间无需使用连字符连接。

自考英语二电子教材_0

---------------------------------------------------------------最新资料推荐------------------------------------------------------自考英语二电子教材01 -A. What Is a Decision? A decision is a choice made from among alternative courses of action that are available. The purpose of making a decision is to establish and achieve organizational goals and objectives. The reason for making a decision is that a problem exists, goals or objectives are wrong, or something is standing in the way of accomplishing them. Thus the decision-making process is fundamental to management. Almost everything a manager does involves decisions, indeed, some suggest that the management process is decision making. Although managers cannot predict the future, many of their decisions require that they consider possible future events. Often managers must make a best guess at what the future will be and try to leave as little as possible to chance, hut since uncertainty is always there, risk accompanies decisions. Sometimes the consequences of a poor decision are slight; at other times they are serious. Choice is the opportunity to select among alternatives. If there is no choice, there is no decision to be made. Decision making is the process of choosing, and many decisions have a broad range of choice. For example, a student may be able to choose among a number of different1/ 2courses in order to implement the decision to obtain a college degree. For managers, every decision has constraints based on policies, procedures, laws, precedents, and the like. These constraints exist at all levels of the organization. Alternatives are the possible courses of action from which choices can be made. If there are no alternatives, there is no choice and, therefore, no decision. If no alternatives are seen, often it means that a thorough job of examining the problems has not been done. For example, managers sometimes treat problems in an either/or fashion; this is their way of simplifying complex problems. But the tendency to simplify blinds them to other alternatives. At the managerial level, decision making includes limiting alternatives as well as identifying them, and the range is from highly limi...。

00015自考英语(二)教程课后试题答案

大学英语自学考试教程下册0015自考英语二课后习题答案 unit1Unit 1(英语二)Text AExercises for the TextI.1.d 2.c 3.c 4.a 5.dII.1.alternative 2.fundamental 3.accompany4.implement5.preccedent6.attain7.objectives 8.vary 9.multiple10.isolateIII.1.c 2.d 3.i 4.j 5.g 6.e 7.h 8.a 9.f 10.bIV.our ; helped ; form ; front; to; passed; it; same;V.1.Decision makers should be able to make the best guess at the future.2.Some people think that everything managers do involves decision making.(or Some people think that everything managers do has something to do with decision making.)3.If there are no correct alternatives ,there are no correct decisions to be made.4.Since different people have different ideas about the same problem ,so the approaches to it vary from person to person.5.Decision makers usually hold the key to the business development of the company.Vocabulary ExercisesI.1.a.be organized anizational anization2.a.simple b.simplified c.simply d.simplification3.a.profit b.profitable c.profitability4.a.intention b.intended c.unintendedII.1.preccdent2.skilled3.achievement4.implement5.optimal6.goal7.accomplish 8.accompanies 9.tendency10.ongoingIII.1.His friend accompanied him to a concert.2.He has argued her out of her decision.3.he owed his success in part to luck.4.According to his suggestion ,the formalities have been much simplified.5.The broadcasting station predicts that it will turn cold tomorrow.6.Motion is defined as a change in position or place.Text BExercises for the TextI.1.T 2.T 3.F 4.F 5.F 6.F 7.F 8.F 9.F 10.TII.1.preparation; confidence2.idea3.unattractive indifference4.hardworking; personality; interest5.speechless6.holidays; pay7.clean; neat; conservative9.politely; naturally10."I beg your pardon?" or "Could you please repeat it?" etc. Vocabulary ExercisesI.1.at a disadvantage2.conservative3.indifference4.make sure5.vague6.clutched7.turned down 8.to your advantage 9.neat10.prospects 11.take the trouble to 12.place Grammar ExercisesI.1.连词;让步状语从句。

大学英语自学考试英语二下册unit1教案

大学英语自学教程下册一.我们要达到的目的二.1.词汇量的提高。

即数量与质量的双提高。

按照教学大纲要求,自考英语(二)的考生应能够掌握3800个单词及750个词组的正确读音、拼写和英汉互译。

练习记忆掌握单词词义和拼写是英语学习的基本功。