曼昆微观经济学英文版11public_goods

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》(第6版)课后习题详解(第11章 公共物品和公共资源)

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》(第6版)第11章公共物品和公共资源课后习题详解跨考网独家整理最全经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题解析资料库,您可以在这里查阅历年经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题,经济学考研参考书等内容,更有跨考考研历年辅导的经济学学哥学姐的经济学考研经验,从前辈中获得的经验对初学者来说是宝贵的财富,这或许能帮你少走弯路,躲开一些陷阱。

以下内容为跨考网独家整理,如您还需更多考研资料,可选择经济学一对一在线咨询进行咨询。

一、概念题1.排他性(excludability)答:排他性指一个人使用或消费一种产品或服务时可以阻止其他人使用或消费该种产品和服务的特性。

一种产品或服务具有排他性时,一个人使用或消费该产品或服务时可以阻止其他人使用或消费该种产品和服务。

排他性是区分公共物品和私人物品的标准之一。

生产者的排他原则有效时,生产者能够限制那些不为这种物品支付的消费者使用这种商品,消费者的排他性有效时,消费者在消费一种物品时,其他人能够被排除在外。

在排他性原则失效的地方,就会出现没有付出代价,却可以享受物品效用的“免费搭便车”现象。

2.消费中的竞争性(rivalry in consumption)答:消费中的竞争性指一种产品或服务被一个人消费从而减少了其他人消费的特性。

如果某人已经使用了某个商品(如某一火车座位),其他人就不能再同时使用该商品,则这种商品就具有消费中的竞争性。

市场机制只有在具备排他性和竞争性两个特点的私人物品的场合才真正起作用,才有效率。

3.私人物品(private goods)答:私人物品指既有排他性又有竞争性的物品,是供个人单独消费的物品。

私人物品是那种可得数量将随任何人对它的消费或使用的增加而减少的物品,它具有两个特征:第一是竞争性,如果某人已消费了某种商品,则其他人就不能再消费该商品;第二是排他性,对商品支付价格的人才能消费商品,其他人则不能。

4.公共物品(public goods)(西北大学2003研;北京师范大学2007研;华南理工大学2010研)答:公共物品与私人物品相对应,指既无排他性又无竞争性的物品。

曼昆经济学原理英文版第11章

Examine why people tend to use common r esour ces too much Consider some of the impor tant common r esour ces in our economyConsider some of the impor tant public goods in our economy Lear n t he def ini ng characteristics of public goods and common r esour ces Examine why private markets fail to pr ovide public goods See why the cost-benefit analysis of public goods is both necessar y and dif ficult An old song lyric maintains that “the best things in life are free.” A moment’s thought reveals a long list of goods that the songwriter could have had in mind. Na-ture provides some of them, such as rivers, mountains, beaches, lakes, and oceans.The government provides others, such as playgrounds, parks, and parades. In each case, people do not pay a fee when they choose to enjoy the benefit of the good.Free goods provide a special challenge for economic analysis. Most goods in our economy are allocated in markets, where buyers pay for what they receive and sellers are paid for what they provide. For these goods, prices are the signals that guide the decisions of buyers and sellers. When goods are available free of charge,however, the market forces that normally allocate resources in our economy are absent.In this chapter we examine the problems that arise for goods without market prices. Our analysis will shed light on one of the Ten Principles of EconomicsP U B L I C G O O D S A N DC O M M O N R E S O U R C ES225226PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTORin Chapter 1: Governments can sometimes improve market outcomes. When a good does not have a price attached to it, private markets cannot ensure that the good is produced and consumed in the proper amounts. In such cases, government policy can potentially remedy the market failure and raise economic well-being.How well do markets work in providing the goods that people want? The answer to this question depends on the good being considered. As we discussed in Chapter 7, we can rely on the market to provide the efficient number of ice-cream cones: The price of ice-cream cones adjusts to balance supply and demand, and this equilib-rium maximizes the sum of producer and consumer surplus. Yet, as we discussed in Chapter 10, we cannot rely on the market to prevent aluminum manufacturers from polluting the air we breathe: Buyers and sellers in a market typically do not take ac-count of the external effects of their decisions. Thus, markets work well when the good is ice cream, but they work badly when the good is clean air.In thinking about the various goods in the economy, it is useful to group them according to two characteristics:N Is the good excludable?Can people be prevented from using the good?N Is the good rival?Does one person’s use of the good diminish another person’s enjoyment of it?Using these two characteristics, Figure 11-1 divides goods into four categories:1.Private goods are both excludable and rival. Consider an ice-cream cone, for example. An ice-cream cone is excludable because it is possible to prevent someone from eating an ice-cream cone—you just don’t give it to him. An ice-cream cone is rival because if one person eats an ice-cream cone, another person cannot eat the same cone. Most goods in the economy are private goods like ice-cream cones. When we analyzed supply and demand in Chapters 4, 5, and 6 and the efficiency of markets in Chapters 7, 8, and 9, we implicitly assumed that goods were both excludable and rival.2.Public goods are neither excludable nor rival. That is, people cannot be prevented from using a public good, and one person’s enjoyment of a public good does not reduce another person’s enjoyment of it. For example, national defense is a public good. Once the country is defended from foreign aggressors, it is impossible to prevent any single person from enjoying the benefit of this defense. Moreover, when one person enjoys the benefit of national defense, he does not reduce the benefit to anyone mon resources are rival but not excludable. For example, fish in the ocean are a rival good: When one person catches fish, there are fewer fish for the next person to catch. Yet these fish are not an excludable good because itis difficult to charge fishermen for the fish that they catch.4.When a good is excludable but not rival, it is an example of a naturalmonopoly.For instance, consider fire protection in a small town. It is easy toexcluda b i l i t ythe property of a good whereby aperson can be prevented fromusing itrivalr ythe property of a good whereby oneperson’s use diminishes otherpeople’s usepr iv at e g o o d sgoods that are both excludableand rivalpubli c g o o d sgoods that are neither excludablenor rivalcom m o n r e so ur c e sgoods that are rival but notexcludableC H A P T E R 11P U B L I C G O OD S A N D C O M M O N RE S O U R C E S 227exclude people from enjoying this good: The fire department can just let their house burn down. Yet fire protection is not rival. Firefighters spend much of their time waiting for a fire, so protecting an extra house is unlikely to reduce the protection available to others. In other words, once a town has paid for the fire department, the additional cost of protecting one more house issmall. In Chapter 15 we give a more complete definition of naturalmonopolies and study them in some detail.In this chapter we examine goods that are not excludable and, therefore, are available to everyone free of charge: public goods and common resources. As we will see, this topic is closely related to the study of externalities. For both public goods and common resources, externalities arise because something of value has no price attached to it. If one person were to provide a public good, such as na-tional defense, other people would be better off, and yet they could not be charged for this benefit. Similarly, when one person uses a common resource, such as the fish in the ocean, other people are worse off, and yet they are not compensated for this loss. Because of these external effects, private decisions about consumption and production can lead to an inefficient allocation of resources, and government intervention can potentially raise economic well-being.QUICK QUIZ:Define public goods and common resources,and give anexample of each.To understand how public goods differ from other goods and what problems they present for society, let’s consider an example: a fireworks display. This good is not excludable because it is impossible to prevent someone from seeing fireworks, and it is not rival because one person’s enjoyment of fireworks does not reduce anyone else’s enjoyment of them.228PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTORTH E FR EE -RI D ER P ROB L EM The citizens of Smalltown, U.S.A., like seeing fireworks on the Fourth of July. Each of the town’s 500 residents places a $10 value on the experience. The cost of putting on a fireworks display is $1,000. Because the $5,000 of benefits exceed the $1,000 of costs, it is efficient for Smalltown residents to see fireworks on the Fourth of July.Would the private market produce the efficient outcome? Probably not. Imag-ine that Ellen, a Smalltown entrepreneur, decided to put on a fireworks display.Ellen would surely have trouble selling tickets to the event because her potential customers would quickly figure out that they could see the fireworks even without a ticket. Fireworks are not excludable, so people have an incentive to be free riders.A free rider is a person who receives the benefit of a good but avoids paying for it.One way to view this market failure is that it arises because of an externality.If Ellen did put on the fireworks display, she would confer an external benefit onthose who saw the display without paying for it. When deciding whether to put on the display, Ellen ignores these external benefits. Even though a fireworks dis-play is socially desirable, it is not privately profitable. As a result, Ellen makes the socially inefficient decision not to put on the display.Although the private market fails to supply the fireworks display demanded by Smalltown residents, the solution to Smalltown’s problem is obvious: The local government can sponsor a Fourth of July celebration. The town council can raise everyone’s taxes by $2 and use the revenue to hire Ellen to produce the fireworks.Everyone in Smalltown is better off by $8—the $10 in value from the fireworks mi-nus the $2 tax bill. Ellen can help Smalltown reach the efficient outcome as a pub-lic employee even though she could not do so as a private entrepreneur.The story of Smalltown is simplified, but it is also realistic. In fact, many local governments in the United States do pay for fireworks on the Fourth of July. More-over, the story shows a general lesson about public goods: Because public goods are not excludable, the free-rider problem prevents the private market from sup-plying them. The government, however, can potentially remedy the problem. If the government decides that the total benefits exceed the costs, it can provide the public good and pay for it with tax revenue, making everyone better off.SOME IMPOR TANT PUBLIC GOODSThere are many examples of public goods. Here we consider three of the most important.N at i onal Def ens e The defense of the country from foreign aggressors is a classic example of a public good. It is also one of the most expensive. In 1999 the U.S. federal government spent a total of $277 billion on national defense, or about $1,018 per person. People disagree about whether this amount is too small or too large, but almost no one doubts that some government spending for national de-fense is necessary. Even economists who advocate small government agree that the national defense is a public good the government should provide.B a s i c R e s e a r c h The creation of knowledge is a public good. If a mathe-matician proves a new theorem, the theorem enters the general pool of knowledgefr ee ridera person who receives the benefit of agood but avoids paying for itC H A P T E R11P U B L I C G O OD S A N D C O M M O N RE S O U R C E S229“I like the concept if we can do it with no new taxes.”that anyone can use without charge. Because knowledge is a public good, profit-seeking firms tend to free ride on the knowledge created by others and, as a result,devote too few resources to the creation of knowledge.In evaluating the appropriate policy toward knowledge creation, it is impor-tant to distinguish general knowledge from specific, technological knowledge.Specific, technological knowledge, such as the invention of a better battery, can bepatented. The inventor thus obtains much of the benefit of his invention, althoughcertainly not all of it. By contrast, a mathematician cannot patent a theorem; suchgeneral knowledge is freely available to everyone. In other words, the patent sys-tem makes specific, technological knowledge excludable, whereas general knowl-edge is not excludable.The government tries to provide the public good of general knowledge in var-ious ways. Government agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health and theNational Science Foundation, subsidize basic research in medicine, mathematics,physics, chemistry, biology, and even economics. Some people justify governmentfunding of the space program on the grounds that it adds to society’s pool ofknowledge. Certainly, many private goods, including bullet-proof vests and the in-stant drink Tang, use materials that were first developed by scientists and engi-neers trying to land a man on the moon. Determining the appropriate level ofgovernmental support for these endeavors is difficult because the benefits are hardto measure. Moreover, the members of Congress who appropriate funds for re-search usually have little expertise in science and, therefore, are not in the best po-sition to judge what lines of research will produce the largest benefits.F i g h t i n g P o v e r t y Many government programs are aimed at helping thepoor. The welfare system (officially called Temporary Assistance for Needy Fami-lies) provides a small income for some poor families. Similarly, the Food Stampprogram subsidizes the purchase of food for those with low incomes, and variousgovernment housing programs make shelter more affordable. These antipovertyprograms are financed by taxes on families that are financially more successful.230PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTORC ASE ST UD Y ARE LIGHTHOUSES PUBLIC GOODS?Some goods can switch between being public goods and being private goods depending on the circumstances. For example, a fireworks display is a public good if performed in a town with many residents. Yet if performed at a private amusement park, such as Walt Disney World, a fireworks display is more like a private good because visitors to the park pay for admission.Another example is a lighthouse. Economists have long used lighthouses as examples of a public good. Lighthouses are used to mark specific locations so that passing ships can avoid treacherous waters. The benefit that the lighthouse provides to the ship captain is neither excludable nor rival, so each captain has an incentive to free ride by using the lighthouse to navigate without paying for the service. Because of this free-rider problem, private markets usually fail to provide the lighthouses that ship captains need. As a result, most lighthouses today are operated by the government.Economists disagree among themselves about what role the government should play in fighting poverty. Although we will discuss this debate more fully in Chapter 20, here we note one important argument: Advocates of antipoverty pro-grams claim that fighting poverty is a public good.Suppose that everyone prefers to live in a society without poverty. Even if this preference is strong and widespread, fighting poverty is not a “good” that the pri-vate market can provide. No single individual can eliminate poverty because the problem is so large. Moreover, private charity is hard pressed to solve the problem:People who do not donate to charity can free ride on the generosity of others. In this case, taxing the wealthy to raise the living standards of the poor can make everyone better off. The poor are better off because they now enjoy a higher stan-dard of living, and those paying the taxes are better off because they enjoy living in a society with less poverty.U SE OF THE LIGHTHOUSE IS FREE TO THE BOAT OWNER . D OES THIS MAKE THE LIGHTHOUSE A PUBLIC GOOD?C H A P T E R11P U B L I C G O OD S A N D C O M M O N RE S O U R C E S231In some cases, however, lighthouses may be closer to private goods. On thecoast of England in the nineteenth century, some lighthouses were privatelyowned and operated. The owner of the local lighthouse did not try to chargeship captains for the service but did charge the owner of the nearby port. If theport owner did not pay, the lighthouse owner turned off the light, and shipsavoided that port.In deciding whether something is a public good, one must determine thenumber of beneficiaries and whether these beneficiaries can be excluded fromenjoying the good. A free-rider problem arises when the number of beneficiariesis large and exclusion of any one of them is impossible. If a lighthouse benefitsmany ship captains, it is a public good. Yet if it primarily benefits a single portowner, it is more like a private good.THE DIFFICULT JOB OF COST-BENEFIT ANALYSISSo far we have seen that the government provides public goods because the pri-vate market on its own will not produce an efficient quantity. Yet deciding that thegovernment must play a role is only the first step. The government must then de-termine what kinds of public goods to provide and in what quantities.Suppose that the government is considering a public project, such as buildinga new highway. To judge whether to build the highway, it must compare the totalbenefits of all those who would use it to the costs of building and maintaining it.To make this decision, the government might hire a team of economists and engi-neers to conduct a study, called a cost-benefit analysis,the goal of which is to es-timate the total costs and benefits of the project to society as a whole.Cost-benefit analysts have a tough job. Because the highway will be available to everyone free of charge, there is no price with which to judge the value of the highway. Simply asking people how much they would value the highway is not reliable. First, quantifying benefits is difficult using the results from a question-naire. Second, respondents have little incentive to tell the truth. Those who would use the highway have an incentive to exaggerate the benefit they receive to get the highway built. Those who would be harmed by the highway have an incentive to exaggerate the costs to them to prevent the highway from being built.The efficient provision of public goods is, therefore, intrinsically more difficult than the efficient provision of private goods. Private goods are provided in the market. Buyers of a private good reveal the value they place on it by the prices they are willing to pay. Sellers reveal their costs by the prices they are willing to accept. By contrast, cost-benefit analysts do not observe any price signals when evaluating whether the government should provide a public good. Their findings on the costs and benefits of public projects are, therefore, rough approximations at best.cost-benefit analysisa study that compares the costs and benefits to society of providing a public goodCASE STUDY HOW MUCH IS A LIFE WORTH?Imagine that you have been elected to serve as a member of your local town council. The town engineer comes to you with a proposal: The town can spend $10,000 to build and operate a traffic light at a town intersection that now has only a stop sign. The benefit of the traffic light is increased safety. The engineer232PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTORestimates, based on data from similar intersections, that the traffic light wouldreduce the risk of a fatal traffic accident over the lifetime of the traffic light from1.6 to 1.1 percent. Should you spend the money for the new light?To answer this question, you turn to cost-benefit analysis. But you quicklyrun into an obstacle: The costs and benefits must be measured in the same unitsif you are to compare them meaningfully. The cost is measured in dollars, butthe benefit—the possibility of saving a person’s life—is not directly monetary.To make your decision, you have to put a dollar value on a human life.At first, you may be tempted to conclude that a human life is priceless. Af-ter all, there is probably no amount of money that you could be paid to volun-tarily give up your life or that of a loved one. This suggests that a human lifehas an infinite dollar value.For the purposes of cost-benefit analysis, however, this answer leads tononsensical results. If we truly placed an infinite value on human life, weshould be placing traffic lights on every street corner. Similarly, we should all bedriving large cars with all the latest safety features, instead of smaller ones withfewer safety features. Yet traffic lights are not at every corner, and people some-times choose to buy small cars without side-impact air bags or antilock brakes.In both our public and private decisions, we are at times willing to risk our livesto save some money.Once we have accepted the idea that a person’s life does have an implicitdollar value, how can we determine what that value is? One approach, some-times used by courts to award damages in wrongful-death suits, is to look at thetotal amount of money a person would have earned if he or she had lived.Economists are often critical of this approach. It has the bizarre implication thatthe life of a retired or disabled person has no value.A better way to value human life is to look at the risks that people are vol-untarily willing to take and how much they must be paid for taking them. Mor-tality risk varies across jobs, for example. Construction workers in high-risebuildings face greater risk of death on the job than office workers do. By com-paring wages in risky and less risky occupations, controlling for education, ex-perience, and other determinants of wages, economists can get some senseabout what value people put on their own lives. Studies using this approachconclude that the value of a human life is about $10 million.EVERYONE WOULDLIKE TO AVOID THERISK OF THIS, BUTATWHATCOSTC H A P T E R 11P U B L I C G O OD S A N D C O M M O N RE S O U R C E S 233We can now return to our original example and respond to the town engi-neer. The traffic light reduces the risk of fatality by 0.5 percent. Thus, the ex-pected benefit from having the traffic light is 0.005 ϫ$10 million, or $50,000.This estimate of the benefit well exceeds the cost of $10,000, so you should ap-prove the project.I N T H E N E W SExistence ValueQUICK QUIZ:What is the free-rider problem?N Why does the free-rider problem induce the government to provide public goods?N How should the government decide whether to provide a public good?Common resources, like public goods, are not excludable: They are available free of charge to anyone who wants to use them. Common resources are, however, rival:234PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTOROne person’s use of the common resource reduces other people’s enjoyment of it.Thus, common resources give rise to a new problem. Once the good is provided,policymakers need to be concerned about how much it is used. This problem is best understood from the classic parable called the Tragedy of the Commons.THE TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONSConsider life in a small medieval town. Of the many economic activities that take place in the town, one of the most important is raising sheep. Many of the town’s families own flocks of sheep and support themselves by selling the sheep’s wool,which is used to make clothing.As our story begins, the sheep spend much of their time grazing on the land surrounding the town, called the Town Common. No family owns the land. In-stead, the town residents own the land collectively, and all the residents are al-lowed to graze their sheep on it. Collective ownership works well because land is plentiful. As long as everyone can get all the good grazing land they want, the Town Common is not a rival good, and allowing residents’ sheep to graze for free causes no problems. Everyone in town is happy.As the years pass, the population of the town grows, and so does the number of sheep grazing on the Town Common. With a growing number of sheep and a fixed amount of land, the land starts to lose its ability to replenish itself. Eventu-ally, the land is grazed so heavily that it becomes barren. With no grass left on the Town Common, raising sheep is impossible, and the town’s once prosperous wool industry disappears. Many families lose their source of livelihood.What causes the tragedy? Why do the shepherds allow the sheep population to grow so large that it destroys the Town Common? The reason is that social and private incentives differ. Avoiding the destruction of the grazing land depends on the collective action of the shepherds. If the shepherds acted together, they could reduce the sheep population to a size that the Town Common can support. Yet no single family has an incentive to reduce the size of its own flock because each flock represents only a small part of the problem.In essence, the Tragedy of the Commons arises because of an externality. When one family’s flock grazes on the common land, it reduces the quality of the land available for other families. Because people neglect this negative externality when deciding how many sheep to own, the result is an excessive number of sheep.If the tragedy had been foreseen, the town could have solved the problem in various ways. It could have regulated the number of sheep in each family’s flock, internalized the externality by taxing sheep, or auctioned off a limited num-ber of sheep-grazing permits. That is, the medieval town could have dealt with the problem of overgrazing in the way that modern society deals with the problem of pollution.In the case of land, however, there is a simpler solution. The town can divide up the land among town families. Each family can enclose its parcel of land with a fence and then protect it from excessive grazing. In this way, the land becomes a private good rather than a common resource. This outcome in fact occurred dur-ing the enclosure movement in England in the seventeenth century.The Tragedy of the Commons is a story with a general lesson: When one per-son uses a common resource, he diminishes other people’s enjoyment of it. Be-cause of this negative externality, common resources tend to be used excessively.Tra g edy of t he C o m m o nsa parable that illustrates whycommon resources get used morethan is desirable from the standpointof society as a wholeThe government can solve the problem by reducing use of the common resource through regulation or taxes. Alternatively, the government can sometimes turn the common resource into a private good.This lesson has been known for thousands of years. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle pointed out the problem with common resources: “What is common to many is taken least care of, for all men have greater regard for what is their own than for what they possess in common with others.”SOME IMPOR TANT COMMON RESOURCESThere are many examples of common resources. In almost all cases, the same prob-lem arises as in the Tragedy of the Commons: Private decisionmakers use the com-mon resource too much. Governments often regulate behavior or impose fees to mitigate the problem of overuse.Clean Air and Water As we discussed in Chapter 10, markets do not ad-equately protect the environment. Pollution is a negative externality that can be remedied with regulations or with Pigovian taxes on polluting activities. One can view this market failure as an example of a common-resource problem. Clean air and clean water are common resources like open grazing land, and excessive pol-lution is like excessive grazing. Environmental degradation is a modern Tragedy of the Commons.O i l P o o l s Consider an underground pool of oil so large that it lies under many properties with different owners. Any of the owners can drill and extract the oil, but when one owner extracts oil, less is available for the others. The oil is a common resource.Just as the number of sheep grazing on the Town Common was inefficiently large, the number of wells drawing from the oil pool will be inefficiently large. Be-cause each owner who drills a well imposes a negative externality on the other owners, the benefit to society of drilling a well is less than the benefit to the owner who drills it. That is, drilling a well can be privately profitable even when it is so-cially undesirable. If owners of the properties decide individually how many oil wells to drill, they will drill too many.To ensure that the oil is extracted at lowest cost, some type of joint action among the owners is necessary to solve the common-resource problem. The Coase theorem, which we discussed in Chapter 10, suggests that a private solution might be possible. The owners could reach an agreement among themselves about how to extract the oil and divide the profits. In essence, the owners would then act as if they were in a single business.When there are many owners, however, a private solution is more difficult. In this case, government regulation could ensure that the oil is extracted efficiently. Congested Roads Roads can be either public goods or common resources. If a road is not congested, then one person’s use does not affect anyone else. In this case, use is not rival, and the road is a public good. Yet if a road is congested, then use of that road yields a negative externality. When one person drives on the road, it becomes more crowded, and other people must drive more slowly. In this case, the road is a common resource.。

曼昆:《微观经济学》第十一章 公共物品和共有资源

第十一章公共物品和共有资源在本章中你将——了解公共物品和共有资源的定义考察为什么私人市场不能生产公共物品考虑我们经济中的一些重要的公共物品说明为什么公共物品的成本—收益分析既是必要的又是困难的考察为什么人们往往会过多的使用共有资源考虑我们经济中一些重要的共有资源一首老歌唱道:“生活中最美好的东西都是免费的。

”稍微思考一下就可以列出这首歌中所提到的物品的长长清单。

有一些东西是大自然提供的,比如,河流、山川、海岸、湖泊和海洋。

政府提供了另一些物品,比如,游览胜地、公园和节庆游行。

在每一种情况下,当人们选择享用这些物品的好处时,并不用花钱。

免费物品向经济分析提出了特殊的挑战。

在我们的经济中,大部分物品是在市场中配置的,买者为得到这些东西而付钱,卖者因提供这些东西而得到钱。

对这些物品来说,价格是引导买者与卖者决策的信号。

但是,当一些物品可以免费得到时,在正常情况下,经济中配置资源的市场力量就不存在了。

在本章中我们考察没有市场价格的物品所引起的问题。

我们的分析将要说明第一章中的经济学十大原理之一:政府有时可以改善市场结果。

当一种物品没有价格时,私人市场不能保证该物品生产和消费的适当数量。

在这种情况下,政府政策可以潜在地解决市场失灵,并增进经济福利。

不同类型的物品在提供人们需要的物品方面,市场如何完美地发挥作用呢?对这个问题的回答取决于所涉及到的物品。

正如我们在第七章中所讨论的,我们可以依靠市场提供有效率的冰激凌卷数量;冰激凌蛋卷的价格调整使供求平衡,而且,这种均衡使生产者和消费者剩余之大化。

但是,正如我们在第十章所讨论的,我们不能依靠市场来阻止铝产品制造者污染我们呼吸的空气:一般情况下市场上的买者与卖者不考虑他们决策的外部效应。

因此,当物品是冰激凌时,市场完美地发挥作用,当物品是清新的空气时,市场的作用很糟。

在考虑经济中的各种物品时,根据两个特点来对物品分类是有用的。

◎物品有排他性吗?可以阻止人们使用这些物品吗?◎物品有竞争性吗?一个人使用这种物品减少了其他人对该物品的享用吗?图11-l用这两个特点把物品分为四类:1.私人物品既有排他性又有竞争性。

曼昆经济学原理微观名词解释9-12(中英)

CHAPTER 9Application: International TradeWorld price: the price of a good that prevails in the world market for that good世界价格:一种物品在世界市场上通行的价格。

Tariff: a tax on goods produced abroad and sold domestically关税:对在国外生产而在国内销售的物品征收的一种税。

CHAPTER 10ExternalitiesExternality: the uncompensated impact of one person’s actions on the well-being of a bystander外部性:一个人的行为对旁观者福利的无补偿的影响Internalizing the externality: altering incentives so that people take into account the external effects of their actions外在性内部化:改变激励,以使人们考虑到自己行为的外部效应Corrective tax: a tax designed to induce private decision makers to take into account the social costs that arise from a negative externality矫正税:旨在引导私人决策者考虑负外部性引起的社会成本的税收Coase theorem: the proposition that if private parties canbargain without cost over the allocation of resources, they can solve the problem of externalities on their own科斯定理:认为如果私人各方可以无成本的就资源配置进行协商,那么他们就可以自己解决外部性问题的观点。

(微观经济学英文课件)Chap11 Public Goods and Common Resources

Excludability

People can be prevented from enjoying the good.(…can you prevent another one to use it?)

Rivalness

One person’s use of the good diminishes another person’s enjoyment of it.

To us?

Some students occupy the seats in the library How to solve traffic jam problem?

Yes

• •

•

Rival?

No

Natural Monopolies

• •

•

Excludable?

NoБайду номын сангаас

Common Resources Public Goods

•

•

•

•

•

•

Harcourt, Inc. items and derived items copyright © 2001 by Harcourt, Inc.

Harcourt, Inc. items and derived items copyright © 2001 by Harcourt, Inc.

The Different Kinds of Goods

group them according to two characteristics: Is the good excludable? Is the good rival?

(微观经济学英文课件)Chap11 Public Goods and Common Resources

微观经济ch11

chapter focuses on public goods and common resources. For both, externalities arise ause something of value has no price attached to it. So, private decisions about consumption and production can lead to an inefficient outcome. Public policy can potentially raise economic well-being.

If

good is not excludable, people have incentive to be free riders, because firms cannot prevent non-payers from consuming the good.

Result: The good is not produced, even if buyers collectively value the good higher than the cost of providing it.

Uncongested toll road: natural monopoly

Congested non-toll road: common resource

Congested toll road: private good

6

THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF GOODS

This

PUBLIC GOODS AND COMMON RESOURCES

What are public goods? What are common resources? Give examples of each. Why do markets generally fail to provide the efficient amounts of these goods? How might the government improve market outcomes in the case of public goods or common resources?

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》(第6版)笔记(第11章 公共物品和公共资源)

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》(第6版)第11章公共物品和公共资源复习笔记跨考网独家整理最全经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题解析资料库,您可以在这里查阅历年经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题,经济学考研参考书等内容,更有跨考考研历年辅导的经济学学哥学姐的经济学考研经验,从前辈中获得的经验对初学者来说是宝贵的财富,这或许能帮你少走弯路,躲开一些陷阱。

以下内容为跨考网独家整理,如您还需更多考研资料,可选择经济学一对一在线咨询进行咨询。

一、不同类型的物品1.相关概念:(1)排他性:一种物品具有的可以阻止一个人使用该物品的特性。

(2)消费者的竞争性:一个人使用一种物品将减少其他人对该物品的使用的特性。

(3)私人物品(private goods):消费中既有排他性又有竞争性的物品。

(4)公共资源:有竞争性但无排他性的物品。

(5)公共物品:既无排他性又无竞争性的物品。

(6)自然垄断:当一种物品在消费中有排他性但没有竞争性时,就是自然垄断的物品。

2.四种类型的物品根据物品的排他性和消费竞争性可以将物品分为四种类型,如图11-1所示。

物品在消费中有没有排他性或竞争性往往是一个程度问题,有时候界限模糊,难以区分。

图11-1 四种类型的物品二、公共物品1.搭便车者问题搭便车者:得到一种物品的利益但避开为此付费的人。

由于公共物品没有排他性,搭便车者问题的存在就使私人市场无法提供公共物品。

但是,政府可以潜在地解决这个问题。

如果政府确信一种公共物品的总利益大于成本,它就可以提供该公共物品,并用税收收入对其进行支付,从而可以使每个人的状况变好。

2.一些重要的公共物品考虑三种重要的公共物品:国防、基础研究、反贫困。

(1)国防国防既无排他性,也无竞争性。

国防是政府应该提供的公共物品。

(2)基础研究基础研究可以通过研究创造出知识。

知识可区分为一般性知识与特定知识:①特定技术知识可以申请专利,专利使发明者创造的知识具有了排他性,这将激励企业拿出资金用于新产品开发的研究中,以便获得专利并出售;②一般性知识是公共物品,既无排他性,也无竞争性,企业往往搭一般知识的便车,很少在上面投资。

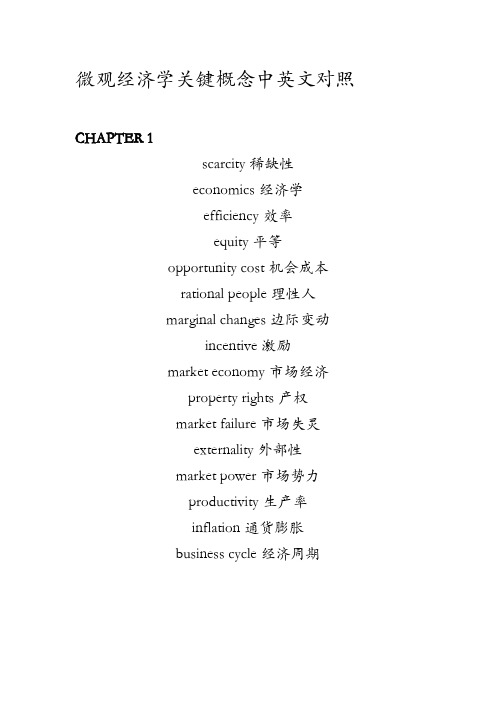

曼昆微观经济学第四版关键概念中英文对照

微观经济学关键概念中英文对照CHAPTER 1scarcity稀缺性economics经济学efficiency效率equity平等opportunity cost机会成本rational people理性人marginal changes边际变动incentive激励market economy市场经济property rights产权market failure市场失灵externality外部性market power市场势力productivity生产率inflation通货膨胀business cycle经济周期CHAPTER 2circular-flow diagram循环流向图production possibilities frontier生产可能性边界microeconomics微观经济学macroeconomics宏观经济学positive statements实证表述normative statements规范表述CHAPTER 3absolute advantage绝对优势opportunity cost机会成本comparative advantage比较优势imports进口exports出口CHAPTER 4market市场competitive market竞争市场quantity demanded需求量law of demand需求定理demand schedule需求表demand curve需求曲线normal good正常物品inferior good低档物品substitutes替代品complements互补品quantity supplied供给量law of supply供给定理supply schedule供给表supply curve供给曲线equilibrium均衡equilibrium price均衡价格equilibrium quantity均衡数量surplus过剩shortage短缺law of supply and demand供求定理CHAPTER 5elasticity弹性price elasticity of demand需求价格弹性total revenue总收益income elasticity of demand需求收入弹性cross-price elasticity of demand需求的交叉价格弹性price elasticity of supply供给价格弹性CHAPTER 6price ceiling价格上限price floor价格下限tax incidence税收归宿CHAPTER 7welfare economics福利经济学willingness to pay支付意愿consumer surplus消费者剩余cost成本producer surplus生产者剩余efficiency效率equity平等CHAPTER 8deadweight loss无谓损失CHAPTER 9world price世界价格tariff关税CHAPTER 10externality外部性internalizing the externality外部性的内在化Coase theorem科斯定理transaction costs交易成本corrective tax矫正税CHAPTER 11Excludability排他性rivalry in consumption消费中的竞争性private goods私人物品public goods公有物品common resources公有资源free rider搭便车者cost-benefit analysis成本收益分析Tragedy of the Commons公有地悲剧CHAPTER 12CHAPTER 13total revenue总收益total cost总成本profit利润explicit costs显性成本implicit costs隐性成本economic profit经济利润accounting profit会计利润production function生产函数marginal product边际产量diminishing marginal product边际产量递减fixed costs固定成本variable costs可变成本average total cost平均总成本average fixed cost平均固定成本average variable cost平均可变成本marginal cost边际成本efficient scale有效规模economies of scale规模经济diseconomies of scale规模不经济constant returns to scale规模收益不变CHAPTER 14competitive market竞争市场average revenue平均收益marginal revenue边际收益sunk cost沉没成本CHAPTER 15Monopoly垄断企业natural monopoly自然垄断price discrimination价格歧视CHAPTER 16Oligopoly寡头monopolistic competition垄断竞争collusion勾结cartel卡特尔Nash equilibrium纳什均衡game theory博弈论prisoners'dilemma囚徒困境dominant strategy占优策略CHAPTER 17monopolistic competition垄断竞争CHAPTER 18factors of production生产要素production function生产函数marginal product of labor劳动的边际产量diminishing marginal product边际产量递减value of the marginal product边际产量值capital资本CHAPTER 19compensating differential补偿性工资差别human capital人力资本union工会strike罢工efficiency wages效率工资discrimination歧视CHAPTER 20poverty rate贫困率poverty line贫困线in-kind transfers实物转移支付life cycle生命周期permanent income持久收入utilitarianism功利主义utility效用liberalism自由主义maximin criterion最大化标准social insurance社会保障libertarianism自由意志主义welfare福利negative income负所得税。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

Tragedy of the Commons

• The Tragedy of the Commons is a parable that illustrates why common resources get used more than is desirable from the standpoint of society as a whole.

• Private Goods

• Are both excludable and rival.

• Public Goods

• Are neither excludable nor rival.

• Common Resources

• Are rival but not excludable.

• Natural Monopolies

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF GOODS

• When thinking about the various goods in the economy, it is useful to group them according to two characteristics:

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

“The best things in life are free. . .”

• In such cases, government policy can potentially remedy the market failure that results, and raise economic well-being.

• Will the market protect me?

Private Ownership and the Profit Motive!

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

CONCLUSION: THE IMPORTANCE OF PROPERTY RIGHTS

• The market fails to allocate resources efficiently when property rights are not wellestablished (i.e. some item of value does not have an owner with the legal authority to control it).

• Common resources tend to be used excessively when individuals are not charged for their usage. • This is similar to a negative externality.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

Public Goods and Common Resource

11

Copyright©2004 South-Western

“The best things in life are free. . .”

• Free goods provide a special challenge for economic analysis. • Most goods in our economy are allocated in markets…

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

CONCLUSION: THE IMPORTANCE OF PROPERTY RIGHTS

• Four Types of Goods

• • • • Private Goods Public Goods Common Resources Natural Monopolies

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF GOODS

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

The Free-Rider Problem

• Solving the Free-Rider Problem

• The government can decide to provide the public good if the total benefits exceed the costs. • The government can make everyone better off by providing the public good and paying for it with tax revenue.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

“The best things in life are free. . .”

• When a good does not have a price attached to it, private markets cannot ensure that the good is produced and consumed in the proper amounts.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

COMMON RESOURCES

• Common resources are rival goods because one person’s use of the common resource reduces other people’s use.

• Is the good excludable? • Is the good rival?

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF GOODS

• Excludability

• Excludability refers to the property of a good whereby a person can be prevented from using it.

Some Important Common Resources

• Clean air and water • Congested roads • Fish, whales, and other wildlife

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

CASE STUDY: Why Isn’t the Cow Extinct?

• Rivalry

• Rivalry refers to the property of a good whereby one person’s use diminishes other people’s use.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF GOODS

The Free-Rider Problem

• Since people cannot be excluded from enjoying the benefits of a public good, individuals may withhold paying for the good hoping that others will pay for it. • The free-rider problem prevents private markets from supplying public goods.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

The Difficult Job of Cost-Benefit Analysis

• A cost-benefit analysis would be used to estimate the total costs and benefits of the project to society as a whole.

No

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

PUBLIC GOODS

• A free-rider is a person who receives the benefit of a good but avoids paying for it.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

“The best things in life are free. . .”

• When goods are available free of charge, the market forces that normally allocate resources in our economy are absent.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

Some Important Public Goods

• National Defense • Basic Research • Fighting Poverty

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

CASE STUDY: Are Lighthouses Public Goods?

• It is difficult to do because of the absence of prices needed to estimate social benefits and resource costs. • The value of life, the consumer’s time, and aesthetics are difficult to assess.

• Are excludable but not rival.