《宏观经济学》课后练习题参考答案9

宏观经济学习题及参考答案

第一章宏观经济学导论习题及参考答案一、习题1.简释下列概念:宏观经济学、经济增长、经济周期、失业、充分就业、通货膨胀、GDP、GNP、名义价值、实际价值、流量、存量、萨伊定律、古典宏观经济模型、凯恩斯革命。

2.宏观经济学的创始人是()。

A.斯密;B.李嘉图;C.凯恩斯;D.萨缪尔森。

3.宏观经济学的中心理论是()。

A.价格决定理论;B.工资决定理论;C.国民收入决定理论;D.汇率决定理论。

4.下列各项中除哪一项外,均被认为是宏观经济的“疾病”()。

A.高失业;B.滞胀;C.通货膨胀;D.价格稳定。

5.表示一国居民在一定时期内生产的所有最终产品和劳务的市场价值的总量指标是()。

A.国民生产总值;B.国内生产总值;C.名义国内生产总值;D.实际国内生产总值。

6.一国国内在一定时期内生产的所有最终产品和劳务的市场价值根据价格变化调整后的数值被称为()。

A.国民生产总值;B.实际国内生产总值;C.名义国内生产总值;D.潜在国内生产总值。

7.实际GDP等于()。

A.价格水平/名义GDP;B.名义GDP/价格水平×100;C.名义GDP乘以价格水平;D.价格水平乘以潜在GDP。

8.下列各项中哪一个属于流量?()。

A.国内生产总值;B.国民债务;C.现有住房数量;D.失业人数。

9.存量是()。

A.某个时点现存的经济量值;B.某个时点上的流动价值;C.流量的固体等价物;D.某个时期内发生的经济量值。

10. 下列各项中哪一个属于存量?()。

A. 国内生产总值;B. 投资;C. 失业人数;D. 人均收入。

11.古典宏观经济理论认为,利息率的灵活性使得()。

A.储蓄大于投资;B.储蓄等于投资;C.储蓄小于投资;D.上述情况均可能存在。

12.古典宏观经济理论认为,实现充分就业的原因是()。

A.政府管制;B.名义工资刚性;C.名义工资灵活性;D.货币供给适度。

13.根据古典宏观经济理论,价格水平降低导致下述哪一变量减少()。

《宏观经济学》课后练习题9(1)

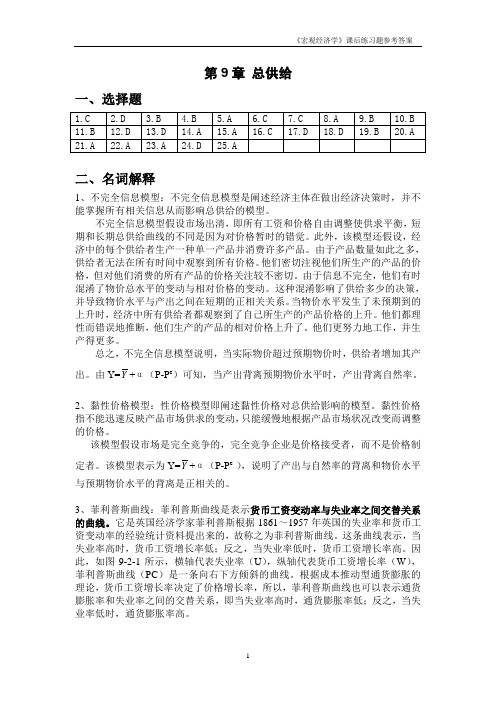

第9章总供给一、选择题1.教材所描述的二种短期总供给曲线模型是( C )A.粘性工资模型和工业的错觉模型B.粘性价格模型和工业的错觉模型C.粘性价格模型和不完全信息模型D.不完全信息模型和工业的错觉模型2.粘性价格模型中,价格在短期内具有粘性,因为( D )A.由长期合同确定的价格在短期内不会改变B.企业一旦印刷和发布了其目录或价目表,改变价格的成本昂贵C.企业往往根据产品的成本确定其价格,其成本中包括劳动力成本。

由于工资依赖于随着时间逐渐演变的社会规则,因而具有粘性D.以上全部正确3.如果经济中所有企业都有短期固定价格( B )A.短期总供给曲线垂直B.短期总供给曲线水平C.短期总供给曲线从左上向右下倾斜D.短期总供给曲线从左下向右上倾斜4.近期对不完全信息模型的研究( D )A.强调信息的获取日益受限B.强调个人在做决定时参考经济信息的能力有限C.发现人们不对相关价格作出预测D.强调以上所有答案5.根据不完全信息模型,当物价意外上涨,供应商推测相关价格会,这促使他们产出。

( A )A.上升;提高B.下降;减少C.上升;减少D.下降;提高6.在粘性价格模型中( C )A.所有企业都不时地调整价格以回应需求的变化。

B.没有企业不时地调整价格以回应需求的变化。

C.一些企业不时地调整价格以回应需求的变化。

但另一些并不这样。

D.产出是不变的。

7.如果经济中所有企业都有短期固定价格( C )A.短期与长期总供给曲线相同B.短期总供给曲线垂直C.短期总供给曲线水平D.以上全都不对8.在粘性价格模型中,公式p=P+a(Y-Y)描述了( A )A.具有弹性价格的企业在短期的行为B.具有粘性价格的企业在短期的行为C.所有企业在短期的行为D.所有的企业处于长期的行为,而没有企业处于短期9.在粘性价格模型中,公式p=P e+a(Y e-Y e)描述了( B )A.具有弹性价格的企业在短期的行为B.具有粘性价格的企业在短期的行为C.所有企业在短期的行为D.所有的企业处于长期的行为,而没有企业处于短期10.在粘性价格模型中,公式Y=Y +α(P-P e)描述了( B )A.处在长期和短期的每一个企业的行为B.处在长期和短期的这个经济体的行为C.A和B都正确D.小企业(不是大企业)的行为11.粘性价格模型可以解释为什么有着可变总需求的国家,其短期总供给曲线是( B )A.平缓的。

宏观经济学课后习题答案(1~9)

宏观经济学课后习题答案(1~9)第一章1.宏观经济学的研究对象是什么?它与微观经济学有什么区别?答:宏观经济学以整个国民经济活动作为研究对象,即以国内生产总值、国内生产净值和国民收入的变动及就业、经济周期波动、通货膨胀、财政与金融、经济增长等等之间的关系作为研究对象。

微观和宏观的区别在于:a研究对象不同;宏观的研究是整个国民经济的经济行为,微观研究的是个体经济行为。

b研究主题不同:宏观是资源利用以至充分就业;微观是资源配置最终到效用最大化。

c中心理论不同:宏观是国民收入决定理论;微观是价格理论。

2、宏观经济学的研究方法是什么?答:(1)三市场划分:宏观经济学把一个经济体系中的所有市场综合为三个市场:金融市场,产品和服务市场,以及要素市场。

(2)行为主体的划分:宏观经济学将行为主体主要分为:家庭、企业和政府。

(3)总量分析方法。

在宏观经济分析中,家庭和企业并不是作为分散决策的个体单位选择存在,而是最为一个统一的行动的总体存在。

宏观经济学把家庭和企业作为个别的选者行为加总,研究他们总体的选择行为,这就是总量分析。

(4)以微观经济分析为基础。

宏观经济学分析建立在微观经济主体行为分析基础上4、宏观经济政策的主要治理对象是什么?答:宏观经济政策的主要治理对象是:失业和通货膨胀。

失业为实际变量,通货膨胀为名义变量。

5、什么是GDP和GNP?它们之间的差别在什么地方?答:GDP是指一定时期内(通常是一年)一国境内所生产的全部最终产品和服务的价值总和。

GNP是指一国公民在一定时期内所产出的全部最终产品和服务的价值总和。

两者的差别:(1)GDP是个地域概念而GNP是个国民概念;(2)GNP衡量的是一国公民的总收入,而不管其收入是从国内还是从国外获取的;GDP衡量的是一国国境内所有产出的总价值,而不管其所有者是本国公民还是外国公民。

第二章1、试述国民生产总值(GNP)、国民生产净值(NNP)、国民收入(NI)、个人收入(PI)、和个人可支配收入(DPI)之间的关系。

宏观经济学第9章习题及答案.

第9章宏观经济政策一、名词解释财政政策自动稳定器货币政策公开市场业务法定准备金比率挤出效应财政政策乘数货币政策乘数二、判断题(正确标出“T”,错误标出“F”)1.紧缩性财政政策对经济的影响是抑制了通货膨胀但增加了政府债务。

()2.预算赤字财政政策是凯恩斯主义用于解决失业问题的有效需求管理的主要手段。

()3.扩张性货币政策使LM曲线右移,而紧缩性货币政策使LM曲线左移。

()4.政府的财政支出政策主要通过转移支付、政府购买和税收对国民经济产生影响。

()5.当政府同时实行紧缩性的财政政策和紧缩性货币政策时,均衡国民收入一定会下降,均衡的利率一定会上升。

()6.减少再贴现率和法定准备金比率可以增加货币供给量。

()7.由于现代西方财政制度具有自动稳定器功能,在经济繁荣时期自动抑制通货膨胀,在经济衰退时期自动减轻萧条,所以不需要政府采取任何行动来干预经济。

()8.宏观经济政策目标之一是价格稳定,价格稳定指价格指数相对稳定,而不是所有商品价格固定不变。

()9.财政政策的内在稳定器作用是稳定收入水平,但不稳定价格水平和就业水平。

()10.商业银行体系所能创造出来的货币数量与最初的存款和法定准备金比率都成正比。

()11.扩张性财政政策使IS曲线左移,而紧缩性财政政策使IS曲线右移。

()12.当一个国家出现恶性通货膨胀时,政府只能通过采取紧缩性货币政策加以遏制。

()13.在西方发达国家,由财政部、中央银行和商业银行共同运用货币政策来调节。

()14.当一个国家经济处于充分就业水平时,政府应采取紧缩性财政政策和货币政策。

()15.凯恩斯主义者奉行功能财政思想,而不是预算平衡思想。

()三、单项选择1.下列哪种情况增加货币供给不会影响均衡国民收入?()A. IS曲线陡峭而LM曲线平缓B. IS曲线垂直而LM曲线平缓C. IS曲线平缓而LM曲线陡峭D. IS曲线和LM曲线一样平缓2.下列哪种情况“挤出效应”可能会很大?()A. 货币需求对利率不敏感,私人部门支出对利率也不敏感B.货币需求对利率不敏感,而私人部门支出对利率敏感C. 货币需求对利率敏感,而私人部门支出对利率不敏感D. 货币需求对利率敏感,私人部门支出对利率也敏感3.挤出效应发生于下列哪种情况?()A. 私人部门增税,减少了私人部门的可支配收入和支出B. 减少政府支出,引起消费支出下降C. 增加政府支出,使利率提高,挤出了对利率敏感的私人部门支出D. 货币供给增加,引起消费支出增加4.政府支出增加使IS曲线右移,若要使均衡国民收入变动接近于IS曲线的移动量,则必须是()A. IS曲线陡峭而LM曲线陡峭B. IS曲线陡峭而LM曲线平缓C. IS曲线平缓而LM曲线陡峭D. IS曲线和LM曲线一样平缓5.货币供给变动如果对均衡国民收入有较大的影响,是因为()A. 私人部门支出对利率不敏感B. 支出系数小C.私人部门支出对利率敏感D.货币需求对利率敏感6.下列()不属于扩张性财政政策。

宏观经济学课后习题和答案

复习与思考题:1.名词解释宏观经济学实证分析规范分析存量分析流量分析事前变量分析事后变量分析2.宏观经济学的研究对象是什么?主要研究哪些问题?3.宏观经济学的研究方法主要有哪些?4.请谈谈宏观经济学和微观经济学的联系与区别?参考答案2.答:宏观经济学以整个国民经济作为研究对象,它考察总体经济的运行状况、发展趋势和内部各个组成部分之间的相互关系。

它涉及到经济中商品与劳务的总产量与收入、通货膨胀和失业率、国际收支和汇率、长期的经济增长和短期的经济波动等现象,揭示这些经济现象产生的原因及其相互关系。

3.答:实证分析方法与规范分析法、总量分析法、均衡分析与非均衡分析、事前变量分析与事后变量分析、存量分析与流量分析、即期分析与跨时期分析、静态、比较静态与动态分析、经济模型分析法。

4.答:参考第二节。

(撰稿:刘天祥)本章习题一、概念题国内生产总值、国民生产总值、国内生产净值、国民收入、个人可支配收入、名义GDP、实际GDP、GDP折算指数二、单项选择题1. 下列产品中不属于中间产品的是()A. 某造船厂购进的钢材B. 某造船厂购进的厂房C. 某面包店购进的面粉D. 某服装厂购进的棉布2. 在一个四部门经济模型中,GNP=()。

A. 消费十净投资十政府购买十净出口B. 消费十总投资十政府购买十净出口C. 消费十净投资十政府购买十总出口D. 消费十总投资十政府购买十总出口3. 下列各项中,属于要素收入的是()A. 企业间接税B. 政府的农产品补贴C. 公司利润税D. 政府企业盈余4. 经济学的投资是指()。

A. 企业增加一笔存货B. 建造一座厂房C. 购买一台机器D. 以上都是5. 已知在第一年名义GNP为500,如到第六年GNP核价指数增加一倍,实际产出上升40%,则第六年的名义GNP为()。

A. 2000B. 1400C. 1000D. 750三、判断题1.农民生产并用于自己消费的粮食不应计入GNP。

()2.在进行国民收入核算时,政府为公务人员加薪,应视为政府购买。

宏观经济学课后习题答案(共9篇)

宏观经济学课后习题答案(共9篇)宏观经济学课后习题答案(一): 这是曼昆的宏观经济学的24章的课后习题,求高手解答,我要详细的计算过程!答案我已经知道,是变动0.4美元在长期中,糖果的价格从0.10美元上升到0.60美元。

在同一时期中,消费物价指数从150上升到300。

根据整体通货膨胀进行调整后,糖果的价格变动了多少我要详细的解答过程,怎么算的就行了!由CPI可知,通货膨胀率=(300-150)/150*100%=100%糖果的原始价格P=0.1在这段时间通过通货膨胀变为0.1*(1+通货膨胀率)=0.2实际上糖果在后来卖到了0.6,所以糖果实际价格变动了0.6-0.2=0.4美元宏观经济学课后习题答案(二): 曼昆宏观经济学26章课后题答案是不是错了假设政府明年借债比今年多了200亿美元,对于可贷资金市场的利率和投资,供给和需求曲线的变动,答案是不是有错答案说是供给曲线不变,需求曲线右移,我认为是需求曲线不动,供给曲线左移……财政政策当然变动的是需求,供给怎么可能变动,你可能是总供给和总需求有些混淆,我开始的时候也不是很清楚,多看几遍就明白了,供给曲线可能因为劳动力变动,而合财政货币政策无关.这些政策变动的都是需求.另外右移就是借钱多了,就是投资需求多了,就是G多了,那就是需求曲线右移了宏观经济学课后习题答案(三): 谁有高鸿业版《西方经济学》宏观部分——第十七章课后题答案第十七章总需求——总供给模型1、(1)总需求是经济社会对产品和劳务的需求总量,这一需求总量通常以产出水平来表示.一个经济社会的总需求包括消费需求、投资需求、.政府购买和国外需求.总需求量受多种因素的影响,其中价格水平是一个重要的因素.在宏观经济学中,为了说明价格对总需求量的影响,引入了总需求曲线的概念,即总需求量与价格水平之间关系的几何表示.在凯恩斯主义的总需求理论中,总需求曲线的理论来源主要由产品市场均衡理论和货币市场均衡理论来反映.(2)在IS—LM模型中,一般价格水平被假定为一个常数(参数).在价格水平固定不变且货币供给为已知的情况下,IS曲线和LM曲线的交点决定均衡的收入水平.现用图1—62来说明怎样根据IS—LM图形推导总需求曲线.图1—62分上下两部.上图为IS—LM图.下图表示价格水平和需求总量之间的关系,即总需求曲线.当价格P的数值为时,此时的LM曲线与IS曲线相交于点 , 点所表示的国民收入和利率顺次为和 .将和标在下图中便得到总需求曲线上的一点 .现在假设P由下降到 .由于P的下降,LM曲线移动到的位置,它与IS曲线的交点为点. 点所表示的国民收入和利率顺次为和 .对应于上图的点 ,又可在下图中找到 .按照同样的程序,随着P的变化,LM曲线和IS曲线可以有许多交点,每一个交点都代表着一个特定的y和p.于是有许多P与的组合,从而构成了下图中一系列的点.把这些点连在一起所得到的曲线AD便是总需求曲线.从以上关于总需求曲线的推导中看到,总需求曲线表示社会中的需求总量和价格水平之间的相反方向的关系.即总需求曲线是向下方倾斜的.向右下方倾斜的总需求曲线表示,价格水平越高,需求总量越小;价格水平越低,需求总量越大.2、财政政策是政府变动税收和支出,以便影响总需求,进而影响就业和国民收入的政策.货币政策是指货币当局即中央银行通过银行体系变动货币供应量来调节总需求的政策.无论财政政策还是货币政策,都是通过影响利率、消费和投资进而影响总需求,使就业和国民收入得到调节的,通过对总需求的调节来调控宏观经济,所以称为需求管理政策.3、总供给曲线描述国民收入与一般价格水平之间的依存关系.根据生产函数和劳动力市场的均衡推导而得到.资本存量一定时,国民收入水平碎就业量的增加而增加,就业量取决于劳动力市场的均衡.所以总供给曲线的理论来源于生产函数和劳动力市场均衡的理论.4、总供给曲线的理论主要由总量生产函数和劳动力市场理论来反映的.在劳动力市场理论中,经济学家对工资和价格的变化和调整速度的看法是分歧的.古典总供给理论认为,劳动力市场运行没有阻力,在工资和价格可以灵活变动的情况下,劳动力市场得以出清,使经济的就业总能维持充分就业状态,从而在其他因素不变的情况下,经济的产量总能保持在充分就业的产量或潜在产量水平上.因此,在以价格为纵坐标,总产量为横坐标的坐标系中,古典供给曲线是一条位于充分就业产量水平的垂直线.凯恩斯的总供给理论认为,在短期,一些价格是粘性的,从而不能根据需求的变动而调整.由于工资和价格粘性,短期总供给曲线不是垂直的,凯恩斯总供给曲线在以价格为纵坐标,收入为横坐标的坐标系中是一条水平线,表明经济中的厂商在现有价格水平上,愿意供给所需的任何数量的商品.作为凯恩斯总供给曲线基础的思想是,作为工资和价格粘性的结果,劳动力市场不能总维持在充分就业状态,由于存在失业,厂商可以在现行工资下获得所需劳动.因而他们的平均生产成本被认为是不随产出水平变化而变化.一些经济学家认为,古典的和凯恩斯的总供给曲线分别代表着劳动力市场的两种极端的说法.在现实中工资和价格的调整经常介于两者之间.在这种情况下以价格为纵坐标,产量为横坐标的坐标系中,总供给曲线是向右上方延伸的,这即为常规的总需求曲线.总之,针对总量劳动市场关于工资和价格的不同假设,宏观经济学中存在着三种类型的总供给曲线.5、解答:宏观经济学在用总需求—总供给说明经济中的萧条,高涨和滞涨时,主要是通过说明短期的收入和价格水平的决定来完成的.如图1—63所示. 从图1—63可以看到,短期的收入和价格水平的决定有两种情况.第一种情况是,AD是总需求曲线, 使短期供给曲线,总需求曲线和短期供给曲线的交点E决定的产量或收入为y,价格水平为P,二者都处于很低的水平,第一种情况表示经济处于萧条状态.第二种情况是,当总需求增加,总需求曲线从AD向右移动到时,短期总供给曲线和新的总需求曲线的交点决定的产量或收入为 ,价格水平为 ,二者都处于很高的水平,第二种情况表示经济处于高涨状态.现在假定短期供给曲线由于供给冲击(如石油价格和工资等提高)而向左移动,但总需求曲线不发生变化.在这种情况下,短期收入和价格水平的决定可以用图1—64表示.在图1—64中,AD是总需求曲线,是短期总供给曲线,两者的交点E决定的产量或收入为,价格水平为P.现在由于出现供给冲击,短期总供给曲线向左移动到,总需求曲线和新的短期总供给曲线的交点决定的产量或收入为,价格水平为,这个产量低于原来的产量,而价格水平却高于原来的价格水平,这种情况表示经济处于滞涨状态,即经济停滞和通货膨胀结合在一起的状态.6、二者在“形式”上有一定的相似之处.微观经济学的供求模型主要说明单个商品的价格和数量的决定.宏观经济中的AD—AS模型主要说明总体经济的价格水平和国民收入的决定.二者在图形上都用两条曲线来表示,在价格为纵坐标,数量为横坐标的坐标系中,向右下方倾斜的为需求曲线,向右上方延伸的为供给曲线.但二者在内容上有很大的不同:其一,两模型涉及的对象不同.微观经济学的供求模型是微观领域的事物,而宏观经济中的AD—AS模型是宏观领域的事物.其二,各自的理论基础不同.微观经济学中的供求模型中的需求曲线的理论基础是消费者行为理论,而供给曲线的理论基础主要是成本理论和市场理论,它们均属于微观经济学的内容.宏观经济学中的总需求曲线的理论基础主要是产品市场均衡和货币市场均衡理论,而供给曲线的理论基础主要是劳动市场理论和总量生产函数,它们均属于宏观经济学的内容.其三,各自的功能不同.微观经济学中的供求模型在说明商品的价格和数量的决定的同时,还可以来说明需求曲线和供给曲线移动对价格和商品数量的影响,充其量这一模型只解释微观市场的一些现象和结果.宏观经济中的AD—AS模型在说明价格和产出决定的同时,可以用来解释宏观经济的波动现象,还可以用来说明政府运用宏观经济政策干预经济的结果.7、(1)由得;2023 + P = 2400 - P于是 P=200, =2200即得供求均衡点.(2)向左平移10%后的总需求方程为:于是,由有:2023 + P = 2160 – PP=80 , =2080与(1)相比,新的均衡表现出经济处于萧条状态.(3)向右平移10%后的总需求方程为:于是,由有:2023 + P = 2640 – PP=320 , =2320与(1)相比,新的均衡表现出经济处于高涨状态.(4)向左平移10%后的总供给方程为:于是,由有:1800 + P = 2400 – PP=300 , =2100与(1)相比,新的均衡表现出经济处于滞涨状态.(5)总供给曲线向右上方倾斜的直线,属于常规型.宏观经济学课后习题答案(四): 宏观经济学问题题号:11 题型:单选题(请在以下几个选项中选择唯一正确答案)本题分数:5内容:一般把经济周期分为四个阶段,这四个阶段为().选项:a、兴旺,停滞,萧条和复苏b、繁荣,停滞,萧条和恢复c、繁荣,衰退,萧条和复苏d、兴旺,衰退,萧条和恢复题号:12 题型:单选题(请在以下几个选项中选择唯一正确答案)本题分数:5内容:“面粉是中间产品”这一命题()选项:a、一定是对的b、一定是不对的c、可能是对的也可能是不对的d、以上三种说法全对.题号:13 题型:单选题(请在以下几个选项中选择唯一正确答案)本题分数:5内容:下列哪种情况下执行财政政策的效果较好(选项:a、LM陡峭而IS平缓b、LM平缓而IS陡峭c、LM和IS一样平缓d、LM和IS一样陡峭题号:14 题型:单选题(请在以下几个选项中选择唯一正确答案)本题分数:5内容:政府财政政策通过哪一个变量对国民收入产生影响().选项:a、进口b、消费支出c、出口d、政府购买.题号:15 题型:单选题(请在以下几个选项中选择唯一正确答案)本题分数:5内容:在国民收入核算体系中,计入GDP的政府支出是指().选项:a、政府购买物品的支出b、政府购买物品和劳务的支出c、政府购买物品和劳务的支出加上政府的转移支出之和d、政府工作人员的薪金和政府转移支出题号:16 题型:是非题本题分数:5内容:长期总供给曲线所表示的总产出是经济中的潜在产出水平选项:1、错2、对题号:17 题型:是非题本题分数:5内容:GDP中扣除资本折旧,就可以得到NNP选项:1、错2、对题号:18 题型:是非题本题分数:5内容:在长期总供给水平,由于生产要素等得到了充分利用,因此经济中不存在失业选项:1、错2、对题号:19 题型:是非题本题分数:5内容:个人收入即为个人可支配收入,是人们可随意用来消费或储蓄的收入选项:1、错2、对题号:20 题型:是非题本题分数:5内容:GNP折算指数是实际GDP与名义GDP的比率选项:1、错2、对C,C,A,D,B对,对(NNP国民生产净值),错(可能还有摩擦失业),错,错宏观经济学课后习题答案(五): 一道宏观经济学的习题,求答案及解析7、将一国经济中所有市场交易的货币价值进行加总a、会得到生产过程中所使用的全部资源的市场价值b、所获得的数值可能大于、小于或等于GDP的值c、会得到经济中的新增价值总和d、会得到国内生产总值`b 正确市场交易的可能有中间产品,如此中间产品加上最终产品,则重复计算的结果大于GDP;不在国内市场交易,出口销往国外的漏算,则计算结果会小于gdp;如果重复的和漏算的正好相等,则结果可能等于gdp。

曼昆《宏观经济学》(第6、7版)课后习题详解(第9章 经济波动导论)

腹有诗书气自华第4篇 经济周期理论:短期中的经济第9章 经济波动导论课后习题详解跨考网独家整理最全经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题解析资料库,您可以在这里查阅历年经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题,经济学考研参考书等内容,更有跨考考研历年辅导的经济学学哥学姐的经济学考研经验,从前辈中获得的经验对初学者来说是宝贵的财富,这或许能帮你少走弯路,躲开一些陷阱。

以下内容为跨考网独家整理,如您还需更多考研资料,可选择经济学一对一在线咨询进行咨询。

一、概念题1.奥肯定律(Okun ’s law )答:奥肯定律是表示失业率与实际国民收入增长率之间关系的经验统计规律,由美国经济学家奥肯在20世纪60年代初提出。

其主要内容是:失业率每高于自然失业率1个百分点,实际GDP 将低于潜在GDP 2个百分点。

奥肯定律的一个重要结论是:实际GDP 必须保持与潜在GDP 同样快的增长,以防止失业率的上升。

如果政府想让失业率下降,那么,该经济社会的实际GDP 的增长必须快于潜在GDP 的增长。

根据奥肯的研究,在美国,失业率每下降1%,实际国民收入增长2%。

但应该指出的是:①奥肯定律表明了失业率与实际国民收入增长率之间是反方向变动的关系;②两者的数量关系1∶2是一个平均数,在不同的时期,这一比率并不完全相同;③这一规律适用于经济没有实现充分就业时的情况。

在经济实现了充分就业时,这一规律所表示的自然失业率与实际国民收入增长率之间的关系要弱得多,一般估算是1∶0.76。

2.领先指标(leading indicators )答:领先指标是指一般先于整体经济变动的变量,可以帮助经济学家预测短期经济波动。

由于经济学家对前导指标可靠意见看法的不一致,导致经济学家给出不同的预测,其中就包括短期经济波动情况的预测。

领先指标的大幅度下降预示经济很可能会衰退,大幅度上升预示经济很可能会繁荣。

3.总需求(aggregate demand )答:总需求是指整个经济社会在任何一个给定的价格水平下对产品和劳务的需求总量。

《宏观经济学》课后练习题参考答案9

第9章总供给一、选择题二、名词解释1、不完全信息模型:不完全信息模型是阐述经济主体在做出经济决策时,并不能掌握所有相关信息从而影响总供给的模型。

不完全信息模型假设市场出清,即所有工资和价格自由调整使供求平衡,短期和长期总供给曲线的不同是因为对价格暂时的错觉。

此外,该模型还假设,经济中的每个供给者生产一种单一产品并消费许多产品。

由于产品数量如此之多,供给者无法在所有时间中观察到所有价格。

他们密切注视他们所生产的产品的价格,但对他们消费的所有产品的价格关注较不密切。

由于信息不完全,他们有时混淆了物价总水平的变动与相对价格的变动。

这种混淆影响了供给多少的决策,并导致物价水平与产出之间在短期的正相关关系。

当物价水平发生了未预期到的上升时,经济中所有供给者都观察到了自己所生产的产品价格的上升。

他们都理性而错误地推断,他们生产的产品的相对价格上升了。

他们更努力地工作,并生产得更多。

总之,不完全信息模型说明,当实际物价超过预期物价时,供给者增加其产出。

由Y=Y+α(P-P e)可知,当产出背离预期物价水平时,产出背离自然率。

2、黏性价格模型:性价格模型即阐述黏性价格对总供给影响的模型。

黏性价格指不能迅速反映产品市场供求的变动,只能缓慢地根据产品市场状况改变而调整的价格。

该模型假设市场是完全竞争的,完全竞争企业是价格接受者,而不是价格制定者。

该模型表示为Y=Y+α(P-P e ),说明了产出与自然率的背离和物价水平与预期物价水平的背离是正相关的。

3、菲利普斯曲线:菲利普斯曲线是表示货币工资变动率与失业率之间交替关系的曲线。

它是英国经济学家菲利普斯根据1861~1957年英国的失业率和货币工资变动率的经验统计资料提出来的,故称之为菲利普斯曲线。

这条曲线表示,当失业率高时,货币工资增长率低;反之,当失业率低时,货币工资增长率高。

因此,如图9-2-1所示,横轴代表失业率(U),纵轴代表货币工资增长率(W),菲利普斯曲线(PC)是一条向右下方倾斜的曲线。

宏观经济学(第四版)课后习题答案

第十二章国民收入核算1:政府转移支付不计入GDP,因为政府转移支付只是简单地通过税收(包括社会保障税)和社会保险及社会救济等把收入从一个人或一个组织转移到另一个人或另一个组织手中,并没有相应的货物或劳务的交换发生。

例如,政府给残疾人发放救济金,并不是因为残疾人创造了收入;相反,倒是因为他丧失了创造收入的能力从而失去生活来源才给予救济。

购买一辆用过的卡车不计入GDP,因为在生产时已经计入过。

购买普通股票不计入GDP,因为经济学上所讲的投资是增加或替换资本资产的支出,即购买新厂房、设备和存货的行为,而人们购买股票和债券只是一种证券交易活动,并不是实际的生产经营活动。

购买一块地产也不计入GDP,因为购买地产只是一种所有权的转移活动,不属于经济学意义的投资活动,故不计入GDP。

2:社会保险税实质上是企业和职工为得到社会保障而支付的保险金,它由政府有关部门(一般是社会保险局)按一定比率以税收形式征收。

社会保险税是从国民收入中扣除的,因此,社会保险税的增加并不影响GDP、NDP和NI,但影响个人收入PI。

社会保险税的增加并不直接影响可支配收入,因为一旦个人收入决定以后,只有个人所得税的变动才会影响个人可支配收入DPI。

3:如果甲乙两国合并一个国家,对GDP总和会有影响。

因为甲乙两国未合并成一个国家时,双方可能有贸易往来,但这种贸易只会影响甲国或乙国的GDP,对两国GDP总和不会有影响。

举例说,甲国向乙国出口10台机器,价值10万美元,乙国向甲国出口800套服装,价值8万美元,从甲国看,计入GDP的有净出口2万美元,计入乙国的GDP有净出口-2万美元;从两国GDP总和看,计入GDP的价值为零。

如果这两个国家并成一个国家,两国贸易变成两地区间的贸易。

甲地区出售给乙地区10台机器,从收入看,甲地区增加10万美元;从支出看,乙地区增加10万美元。

相反,乙地区出售给甲地区800套服装,从收入看,乙地区增加8万美元;从支出看,甲地区增加8万美元。

宏观经济学课后题答案

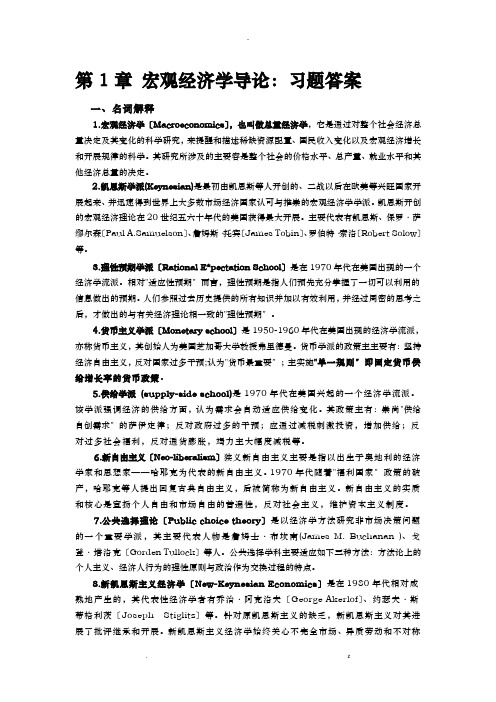

第1章宏观经济学导论:习题答案一、名词解释1.宏观经济学〔Macroeconomics〕,也叫做总量经济学,它是通过对整个社会经济总量决定及其变化的科学研究,来提醒和描述稀缺资源配置、国民收入变化以及宏观经济增长和开展规律的科学。

其研究所涉及的主要容是整个社会的价格水平、总产量、就业水平和其他经济总量的决定。

2.凯恩斯学派(Keynesian)是最初由凯恩斯等人开创的、二战以后在欧美等兴旺国家开展起来、并迅速得到世界上大多数市场经济国家认可与推崇的宏观经济学学派。

凯恩斯开创的宏观经济理论在20世纪五六十年代的美国获得最大开展。

主要代表有凯恩斯、保罗·萨缪尔森〔Paul A.Samuelson〕、詹姆斯·托宾〔James Tobin〕、罗伯特·索洛〔Robert Solow〕等。

3.理性预期学派〔Rational E*pectation School〕是在1970年代在美国出现的一个经济学流派。

相对"适应性预期〞而言,理性预期是指人们预先充分掌握了一切可以利用的信息做出的预期。

人们参照过去历史提供的所有知识并加以有效利用,并经过周密的思考之后,才做出的与有关经济理论相一致的"理性预期〞。

4.货币主义学派〔Monetary school〕是1950-1960年代在美国出现的经济学流派,亦称货币主义,其创始人为美国芝加哥大学教授弗里德曼。

货币学派的政策主主要有:坚持经济自由主义,反对国家过多干预;认为"货币最重要〞;主实施"单一规则〞即固定货币供给增长率的货币政策。

5.供给学派(supply-side school)是1970年代在美国兴起的一个经济学流派。

该学派强调经济的供给方面,认为需求会自动适应供给变化。

其政策主有:崇尚"供给自创需求〞的萨伊定律;反对政府过多的干预;应通过减税刺激投资,增加供给;反对过多社会福利,反对通货膨胀,竭力主大幅度减税等。

宏观经济学习题(附答案)

第一部分国民收入核算第二部分简单国民收入决定理论第三部分 IS-LM模型及政策分析与实践第四部分总供求+失业与通胀+经济周期与经济增长第一部分国民收入核算一、判断正误并改正1.国内生产总值等于各种最终产品和中间产品的价值总和。

(错)2.在国内生产总值的计算中,所谓商品只包括有形的物质产品。

(错)包括:物质产品与劳务(goods and services)3.不论是商品数量还是商品价格的变化都会引起实际国内生产总值的变化。

(错)只有商品数量的变化会引起实际国内生产总值的变化。

实际国内生产总值是以具有不变购买力的货币单位衡量的国内生产总值,通常是以现行货币单位来表现一国在一定时期(通常为一年)内的全部社会最终产品和劳务的总和。

但由于通货膨胀和通货紧缩会抬高或降低物价,因而会使货币的购买力随物价的波动而发生变化。

为了消除价格变动的影响,一般是以某一年为基期,以该年的价格为不变价格,然后用物价指数来矫正按当年价格计算的国内生产总值,而计算出实际国内生产总值。

实际国内生产总值能准确地反映产量的变动情况。

一般来说,在通货膨胀的情况下,实际国内生产总值小于按当年价格计算的国内生产总值;在通货紧缩的情况下,实际国内生产总值大于按当年价格计算的国内生产总值。

4.政府的转移支付是国内生产总值构成中的一部分。

(错)为什么政府转移支付不计入GDP?答:因为政府转移支付只是简单地通过税收(包括社会保险税)把收入从一个人或一个组织转移到另一个人或另一个组织手中,并没有相应的货物或劳务的交换发生。

例如,政府给残疾人发放救济金,并不是因为残疾人创造了收入;相反,倒是因为他丧失了创造收入的能力从而失去生活来源才给予救济。

失业救济金发放则是因为人们失去了工作从而丧失了取得收入的机会才给予救济。

政府转移支付和政府购买虽都属政府支出,但前者不计入GDP而后者计入GDP,因为后者发生了实在的交换活动。

比方说,政府给公立学校教师发薪水是因为教师提供了教育工作的服务。

曼昆-宏观经济经济学第九版-英文原版答案9

Answers to Textbook Questions and ProblemsCHAPTER 9 Economic Growth II: Technology, Empirics, and PolicyQuestions for Review1. In the Solow model, we find that only technological progress can affect the steady-state rate of growthin income per worker. Growth in the capital stock (through high saving) has no effect on the steady-state growth rate of income per worker; neither does population growth. But technological progress can lead to sustained growth.2. In the steady state, output per person in the Solow model grows at the rate of technological progress g.Capital per person also grows at rate g. Note that this implies that output and capital per effectiveworker are constant in steady state. In the U.S. data, output and capital per worker have both grown at about 2 percent per year for the past half-century.3. To decide whether an economy has more or less capital than the Golden Rule, we need to compare themarginal product of capital net of depreciation (MPK –δ) with the growth rate of total output (n + g).The growth rate of GDP is readily available. Estimating the net marginal product of capital requires a little more work but, as shown in the text, can be backed out of available data on the capital stock relative to GDP, the total amount o f depreciation relative to GDP, and capital’s share in GDP.4. Economic policy can influence the saving rate by either increasing public saving or providingincentives to stimulate private saving. Public saving is the difference between government revenue and government spending. If spending exceeds revenue, the government runs a budget deficit, which is negative saving. Policies that decrease the deficit (such as reductions in government purchases or increases in taxes) increase public saving, whereas policies that increase the deficit decrease saving. A variety of government policies affect private saving. The decision by a household to save may depend on the rate of return; the greater the return to saving, the more attractive saving becomes. Taxincentives such as tax-exempt retirement accounts for individuals and investment tax credits forcorporations increase the rate of return and encourage private saving.5. The legal system is an example of an institutional difference between countries that might explaindifferences in income per person. Countries that have adopted the English style common law system tend to have better developed capital markets, and this leads to more rapid growth because it is easier for businesses to obtain financing. The quality of government is also important. Countries with more government corruption tend to have lower levels of income per person.6. Endogenous growth theories attempt to explain the rate of technological progress by explaining thedecisions that determine the creation of knowledge through research and development. By contrast, the Solow model simply took this rate as exogenous. In the Solow model, the saving rate affects growth temporarily, but diminishing returns to capital eventually force the economy to approach a steady state in which growth depends only on exogenous technological progress. By contrast, many endogenous growth models in essence assume that there are constant (rather than diminishing) returns to capital, interpreted to include knowledge. Hence, changes in the saving rate can lead to persistent growth. Problems and Applications1. a. In the Solow model with technological progress, y is defined as output per effective worker, and kis defined as capital per effective worker. The number of effective workers is defined as L E (or LE), where L is the number of workers, and E measures the efficiency of each worker. To findoutput per effective worker y, divide total output by the number of effective workers:Y LE =K12(LE)12LEY LE =K12L12E12LEY LE =K12 L1E1Y LE =KLE æèççöø÷÷12y=k12b. To solve for the steady-state value of y as a function of s, n, g, and δ, we begin with the equationfor the change in the capital stock in the steady state:Δk = sf(k) –(δ + n + g)k = 0.The production function ycan also be rewritten as y2 = k. Plugging this production functioninto the equation for the change in the capital stock, we find that in the steady state:sy –(δ + n + g)y2 = 0.Solving this, we find the steady-state value of y:y* = s/(δ + n + g).c. The question provides us with the following information about each country:Atlantis: s = 0.28 Xanadu: s = 0.10n = 0.01 n = 0.04g = 0.02 g = 0.02δ = 0.04δ = 0.04Using the equation for y* that we derived in part (a), we can calculate the steady-state values of yfor each country.Developed country: y* = 0.28/(0.04 + 0.01 + 0.02) = 4Less-developed country: y* = 0.10/(0.04 + 0.04 + 0.02) = 12. a. In the steady state, capital per effective worker is constant, and this leads to a constant level ofoutput per effective worker. Given that the growth rate of output per effective worker is zero, this means the growth rate of output is equal to the growth rate of effective workers (LE). We know labor grows at the rate of population growth n and the efficiency of labor (E) grows at rate g. Therefore, output grows at rate n+g. Given output grows at rate n+g and labor grows at rate n, output perworker must grow at rate g. This follows from the rule that the growth rate of Y/L is equal to thegrowth rate of Y minus the growth rate of L.b. First find the output per effective worker production function by dividing both sides of theproduction function by the number of effective workers LE:Y LE =K 13(LE )23LE YLE =K 13L 23E 23LEY LE =K 13L 13E 13Y LE =K LE æèçöø÷13y =k 13To solve for capital per effective worker, we start with the steady state condition:Δk = sf (k ) – (δ + n + g )k = 0.Now substitute in the given parameter values and solve for capital per effective worker (k ):Substitute the value for k back into the per effective worker production function to find output per effective worker is equal to 2. The marginal product of capital is given bySubstitute the value for capital per effective worker to find the marginal product of capital is equal to 1/12.c. According to the Golden Rule, the marginal product of capital is equal to (δ + n + g) or 0.06. In the current steady state, the marginal product of capital is equal to 1/12 or 0.083. Therefore, we have less capital per effective worker in comparison to the Golden Rule. As the level of capital per effective worker rises, the marginal product of capital will fall until it is equal to 0.06. To increase capital per effective worker, there must be an increase in the saving rate.d. During the transition to the Golden Rule steady state, the growth rate of output per worker will increase. In the steady state, output per worker grows at rate g . The increase in the saving rate will increase output per effective worker, and this will increase output per effective worker. In the new steady state, output per effective worker is constant at a new higher level, and output per worker is growing at rate g . During the transition, the growth rate of output per worker jumps up, and then transitions back down to rate g .3. To solve this problem, it is useful to establish what we know about the U.S. economy: • A Cobb –Douglas production function has the form y = k α, where α is capital’s share of income.The question tells us that α = 0.3, so we know that the production function is y = k 0.3.• In the steady state, we know that the growth rate of output equals 3 percent, so we know that (n +g ) = 0.03.• The deprec iation rate δ = 0.04. • The capital –output ratio K/Y = 2.5. Because k/y = [K /(LE )]/[Y /(LE )] = K/Y , we also know that k/y =2.5. (That is, the capital –output ratio is the same in terms of effective workers as it is in levels.)a. Begin with the steady-state condition, sy = (δ + n + g)k. Rewriting this equation leads to a formulafor saving in the steady state:s = (δ + n + g)(k/y).Plugging in the values established above:s = (0.04 + 0.03)(2.5) = 0.175.The initial saving rate is 17.5 percent.b. We know from Chapter 3 that with a Cobb–Douglas production function, capital’s share ofincome α = MPK(K/Y). Rewriting, we haveMPK = α/(K/Y).Plugging in the values established above, we findMPK = 0.3/2.5 = 0.12.c. We know that at the Golden Rule steady state:MPK = (n + g + δ).Plugging in the values established above:MPK = (0.03 + 0.04) = 0.07.At the Golden Rule steady state, the marginal product of capital is 7 percent, whereas it is 12 percent in the initial steady state. Hence, from the initial steady state we need to increase k to achieve the Golden Rule steady state.d. We know from Chapter 3 that for a Cobb–Douglas production function, MPK = α (Y/K). Solvingthis for the capital–output ratio, we findK/Y = α/MPK.We can solve for the Golden Rule capital–output ratio using this equation. If we plug in the value0.07 for the Golden Rule steady-state marginal product of capital, and the value 0.3 for α, we findK/Y = 0.3/0.07 = 4.29.In the Golden Rule steady state, the capital–output ratio equals 4.29, compared to the current capital–output ratio of 2.5.e. We know from part (a) that in the steady states = (δ + n + g)(k/y),where k/y is the steady-state capital–output ratio. In the introduction to this answer, we showed that k/y = K/Y, and in part (d) we found that the Golden Rule K/Y = 4.29. Plugging in this value and those established above:s = (0.04 + 0.03)(4.29) = 0.30.To reach the Golden Rule steady state, the saving rate must rise from 17.5 to 30 percent. Thisresult implies that if we set the saving rate equal to the share going to capital (30 percent), we will achieve the Golden Rule steady state.4. a. In the steady state, we know that sy = (δ + n + g)k. This implies thatk/y = s/(δ + n + g).Since s, δ, n, and g are constant, this means that the ratio k/y is also constant. Since k/y =[K/(LE)]/[Y/(LE)] = K/Y, we can conclude that in the steady state, the capital–output ratio isconstant.b. We know that capital’s share of income = MPK ⨯ (K/Y). In the steady state, we know from part (a)that the capital–output ratio K/Y is constant. We also know from the hint that the MPK is afunction of k, which is constant in the steady state; therefore the MPK itself must be constant.Thus, capital’s share of income is constant. Labor’s share of income is 1 – [C apital’s Share].Hence, if capital’s share is constant, we see that labor’s share of income is also constant.c. We know that in the steady state, total income grows at n + g, defined as the rate of populationgrowth plus the rate of technological change. In part (b) we showed that labor’s and capital’s share of income is constant. If the shares are constant, and total income grows at the rate n + g, thenlabor income and capital income must also grow at the rate n + g.d. Define the real rental price of capital R asR = Total Capital Income/Capital Stock= (MPK ⨯K)/K= MPK.We know that in the steady state, the MPK is constant because capital per effective worker k isconstant. Therefore, we can conclude that the real rental price of capital is constant in the steadystate.To show that the real wage w grows at the rate of technological progress g, defineTLI = Total Labor IncomeL = Labor ForceUsing the hint that the real wage equals total labor income divided by the labor force:w = TLI/L.Equivalently,wL = TLI.In terms of percentage changes, we can write this asΔw/w + ΔL/L = ΔTLI/TLI.This equation says that the growth rate of the real wage plus the growth rate of the labor forceequals the growth rate of total labor income. We know that the labor force grows at rate n, and,from part (c), we know that total labor income grows at rate n + g. We, therefore, conclude that the real wage grows at rate g.5. a. The per worker production function is F (K, L )/L = AK α L 1–α/L = A (K/L )α = Ak α b. In the steady state, Δk = sf (k ) – (δ + n + g )k = 0. Hence, sAk α = (δ + n + g )k , or, after rearranging:k *=sA d +n +g éëêêùûúúa 1-a æèççöø÷÷.Plugging into the per-worker production function from part (a) givesy *=A a 1-a æèççöø÷÷s d +n +g éëêêùûúúa 1-a æèççöø÷÷.Thus, the ratio of steady-state income per worker in Richland to Poorland isy *Richland/y *Poorland ()=s Richland d +n Richland +g /s Poorlandd +n Poorland +g éëêêùûúúa1-a =0.320.05+0.01+0.02/0.100.05+0.03+0.02éëêêùûúúa1-c. If α equals 1/3, then Richland should be 41/2, or two times, richer than Poorland.d. If 4a 1-a æèççöø÷÷= 16, then it must be the case that a 1-a æèççöø÷÷, which in turn requires that α equals 2/3.Hence, if the Cobb –Douglas production function puts 2/3 of the weight on capital and only 1/3 on labor, then we can explain a 16-fold difference in levels of income per worker. One way to justify this might be to think about capital more broadly to include human capital —which must also be accumulated through investment, much in the way one accumulates physical capital.6. How do differences in education across countries affect the Solow model? Education is one factoraffecting the efficiency of labor , which we denoted by E . (Other factors affecting the efficiency of labor include levels of health, skill, and knowledge.) Since country 1 has a more highly educated labor force than country 2, each worker in country 1 is more efficient. That is, E 1 > E 2. We will assume that both countries are in steady state. a. In the Solow growth model, the rate of growth of total income is equal to n + g , which isindependent of the work force’s level of education. The two countries will, thus, have the same rate of growth of total income because they have the same rate of population growth and the same rate of technological progress.b. Because both countries have the same saving rate, the same population growth rate, and the samerate of technological progress, we know that the two countries will converge to the same steady-state level of capital per effective worker k *. This is shown in Figure 9-1.Hence, output per effective worker in the steady state, which is y* = f(k*), is the same in bothcountries. But y* = Y/(L E) or Y/L = y*E. We know that y* will be the same in both countries, but that E1 > E2. Therefore, y*E1 > y*E2. This implies that (Y/L)1 > (Y/L)2. Thus, the level of incomeper worker will be higher in the country with the more educated labor force.c. We know that the real rental price of capital R equals the marginal product of capital (MPK). Butthe MPK depends on the capital stock per efficiency unit of labor. In the steady state, bothcountries have k*1= k*2= k* because both countries have the same saving rate, the same population growth rate, and the same rate of technological progress. Therefore, it must be true that R1 = R2 = MPK. Thus, the real rental price of capital is identical in both countries.d. Output is divided between capital income and labor income. Therefore, the wage per effectiveworker can be expressed asw = f(k) –MPK • k.As discussed in parts (b) and (c), both countries have the same steady-state capital stock k and the same MPK. Therefore, the wage per effective worker in the two countries is equal.Workers, however, care about the wage per unit of labor, not the wage per effective worker.Also, we can observe the wage per unit of labor but not the wage per effective worker. The wageper unit of labor is related to the wage per effective worker by the equationWage per Unit of L = wE.Thus, the wage per unit of labor is higher in the country with the more educated labor force.7. a. In the two-sector endogenous growth model in the text, the production function for manufacturedgoods isY = F [K,(1 –u) EL].We assumed in this model that this function has constant returns to scale. As in Section 3-1,constant returns means that for any positive number z, zY = F(zK, z(1 –u) EL). Setting z = 1/EL,we obtainY EL =FKEL,(1-u)æèççöø÷÷.Using our standard definitions of y as output per effective worker and k as capital per effective worker, we can write this asy = F[k,(1 –u)]b. To begin, note that from the production function in research universities, the growth rate of laborefficiency, ΔE/E, equals g(u). We can now follow the logic of Section 9-1, substituting thefunction g(u) for the constant growth rate g. In order to keep capital per effective worker (K/EL) constant, break-even investment includes three terms: δk is needed to replace depreciating capital, nk is needed to provide capital for new workers, and g(u) is needed to provide capital for thegreater stock of knowledge E created by research universities. That is, break-even investment is [δ + n + g(u)]k.c. Again following the logic of Section 9-1, the growth of capital per effective worker is thedifference between saving per effective worker and break-even investment per effective worker.We now substitute the per-effective-worker production function from part (a) and the function g(u) for the constant growth rate g, to obtainΔk = sF [k,(1 –u)] – [δ + n + g(u)]kIn the steady state, Δk = 0, so we can rewrite the equation above assF [k,(1 –u)] = [δ + n + g(u)]k.As in our analysis of the Solow model, for a given value of u, we can plot the left and right sides of this equationThe steady state is given by the intersection of the two curves.d. The steady state has constant capital per effective worker k as given by Figure 9-2 above. We alsoassume that in the steady state, there is a constant share of time spent in research universities, so u is constant. (After all, if u were not constant, it wouldn’t be a ―steady‖ state!). Hence, output per effective worker y is also constant. Output per worker equals yE, and E grows at rate g(u).Therefore, output per worker grows at rate g(u). The saving rate does not affect this growth rate.However, the amount of time spent in research universities does affect this rate: as more time is spent in research universities, the steady-state growth rate rises.e. An increase in u shifts both lines in our figure. Output per effective worker falls for any givenlevel of capital per effective worker, since less of each worker’s time is spent producingmanufactured goods. This is the immediate effect of the change, since at the time u rises, thecapital stock K and the efficiency of each worker E are constant. Since output per effective worker falls, the curve showing saving per effective worker shifts down.At the same time, the increase in time spent in research universities increases the growth rate of labor efficiency g(u). Hence, break-even investment [which we found above in part (b)] rises at any given level of k, so the line showing breakeven investment also shifts up.Figure 9-3 shows these shifts.In the new steady state, capital per effective worker falls from k1 to k2. Output per effective worker also falls.f. In the short run, the increase in u unambiguously decreases consumption. After all, we argued inpart (e) that the immediate effect is to decrease output, since workers spend less time producingmanufacturing goods and more time in research universities expanding the stock of knowledge.For a given saving rate, the decrease in output implies a decrease in consumption.The long-run steady-state effect is more subtle. We found in part (e) that output per effective worker falls in the steady state. But welfare depends on output (and consumption) per worker, not per effective worker. The increase in time spent in research universities implies that E grows faster.That is, output per worker equals yE. Although steady-state y falls, in the long run the fastergrowth rate of E necessarily dominates. That is, in the long run, consumption unambiguously rises.Nevertheless, because of the initial decline in consumption, the increase in u is not unambiguously a good thing. That is, a policymaker who cares more about current generationsthan about future generations may decide not to pursue a policy of increasing u. (This is analogous to the question considered in Chapter 8 of whether a policymaker should try to reach the GoldenRule level of capital per effective worker if k is currently below the Golden Rule level.)8. On the World Bank Web site (), click on the data tab and then the indicators tab.This brings up a large list of data indicators that allows you to compare the level of growth anddevelopment across countries. To explain differences in income per person across countries, you might look at gross saving as a percentage of GDP, gross capital formation as a percentage of GDP, literacy rate, life expectancy, and population growth rate. From the Solow model, we learned that (all else the same) a higher rate of saving will lead to higher income per person, a lower population growth rate will lead to higher income per person, a higher level of capital per worker will lead to a higher level of income per person, and more efficient or productive labor will lead to higher income per person. The selected data indicators offer explanations as to why one country might have a higher level of income per person. However, although we might speculate about which factor is most responsible for thedifference in income per person across countries, it is not possible to say for certain given the largenumber of other variables that also affect income per person. For example, some countries may have more developed capital markets, less government corruption, and better access to foreign directinvestment. The Solow model allows us to understand some of the reasons why income per person differs across countries, but given it is a simplified model, it cannot explain all of the reasons why income per person may differ.More Problems and Applications to Chapter 91. a. The growth in total output (Y) depends on the growth rates of labor (L), capital (K), and totalfactor productivity (A), as summarized by the equationΔY/Y = αΔK/K + (1 –α)ΔL/L + ΔA/A,where α is capital’s share of output. We can look at the effect on output of a 5-percent increase in labor by setting ΔK/K = ΔA/A = 0. Since α = 2/3, this gives usΔY/Y = (1/3)(5%)= 1.67%.A 5-percent increase in labor input increases output by 1.67 percent.Labor productivity is Y/L. We can write the growth rate in labor productivity asD Y Y =D(Y/L)Y/L-D LL.Substituting for the growth in output and the growth in labor, we findΔ(Y/L)/(Y/L) = 1.67% – 5.0%= –3.34%.Labor productivity falls by 3.34 percent.To find the change in total factor productivity, we use the equationΔA/A = ΔY/Y –αΔK/K – (1 –α)ΔL/L.For this problem, we findΔA/A = 1.67% – 0 – (1/3)(5%)= 0.Total factor productivity is the amount of output growth that remains after we have accounted for the determinants of growth that we can measure. In this case, there is no change in technology, so all of the output growth is attributable to measured input growth. That is, total factorproductivity growth is zero, as expected.b. Between years 1 and 2, the capital stock grows by 1/6, labor input grows by 1/3, and output growsby 1/6. We know that the growth in total factor productivity is given byΔA/A = ΔY/Y –αΔK/K – (1 –α)ΔL/L.Substituting the numbers above, and setting α = 2/3, we findΔA/A = (1/6) – (2/3)(1/6) – (1/3)(1/3)= 3/18 – 2/18 – 2/18= – 1/18= –0.056.Total factor productivity falls by 1/18, or approximately 5.6 percent.2. By definition, output Y equals labor productivity Y/L multiplied by the labor force L:Y = (Y/L)L.Using the mathematical trick in the hint, we can rewrite this asD Y Y =D(Y/L)Y/L+D LL.We can rearrange this asD Y Y =D YY-D LL.Substituting for ΔY/Y from the text, we findD(Y/L) Y/L =D AA+aD KK+(1-a)D LL-D LL =D AA+aD KK-aD LL=D AA+aD KK-D LLéëêêùûúúUsing the same trick we used above, we can express the term in brackets asΔK/K –ΔL/L = Δ(K/L)/(K/L)Making this substitution in the equation for labor productivity growth, we conclude thatD(Y/L) Y/L =D AA+aD(K/L)K/L.3. We know the following:ΔY/Y = n + g = 3.6%ΔK/K = n + g = 3.6%ΔL/L = n = 1.8%Capital’s Share = α = 1/3Labor’s Share = 1 –α = 2/3Using these facts, we can easily find the contributions of each of the factors, and then find the contribution of total factor productivity growth, using the following equations:Output = Capital’s+ Labor’s+ Total FactorGrowth Contribution Contribution ProductivityD Y Y =aD KK+(1-a)D LL+D AA3.6% = (1/3)(3.6%) + (2/3)(1.8%) + ΔA/A.We can easily solve this for ΔA/A, to find that3.6% = 1.2% + 1.2% + 1.2%Chapter 9—Economic Growth II: Technology, Empirics, and Policy 81We conclude that the contribution of capital is 1.2 percent per year, the contribution of labor is 1.2 percent per year, and the contribution of total factor productivity growth is 1.2 percent per year. These numbers match the ones in Table 9-3 in the text for the United States from 1948–2002.Chapter 9—Economic Growth II: Technology, Empirics, and Policy 82。

宏观经济学课后答案(共10篇)

宏观经济学课后答案(共10篇)宏观经济学课后答案(一): 宏观经济学习题3 ,请大家帮忙做做!非常感谢!5、假设在两部门经济中,C=50+0.8Y,I=50。

(C为消费,I为投资)• (1)求均衡的国民收入Y、C、S分别为多少(2)投资乘数是多少• (3)如果投资增加20(即△I=20),国民收入将如何变化若充分就业的YF=800,经济存在紧缩还是膨胀其缺口是多少6、假如某人的边际消费倾向恒等于1/2,他的收支平衡点是8000美元,若他的收入为1万美元,试计算:他的消费和储蓄各为多少?7、假设经济模型为:C=20+0.75(Y-T);I=380;G=400;T=0.20Y;Y=C+I+G。

• (1)计算边际消费倾向。

(2)计算均衡的收入水平。

• (3)在均衡的收入水平下,政府预算盈余为多少?1 Y=C+I=0.8Y+50+50=0.8Y+100 ,Y=500,I=50,C=450,ki=1/(1-0.8)=5I增加20,Y增加100,紧缩,缺口800-500=3002 边际消费倾向1/2设消费函数c=a+0.5y收支平衡点80008000=a+4000,a=4000c=4000+0.5yy=10000,c=9000,s=10003 dc/dy=0.75*0.8=0.6y=c+i+g=20+0.75(y-0.2y)+380+400=0.6y+800,y=2023预算盈余bs=t-g=400-400=0宏观经济学课后答案(二): 宏观经济学习题:当政府通过提高税收来增加政府支出时的挤出效应是指:A.刺激了消费和储蓄,实际利率上升,投资下降B.抑制了消费和储蓄,实际利率下降,投资下降C.抑制了消费和储蓄,实际利率上升,投资上升D.抑制了消费和储蓄,实际利率下降,投资上升E.抑制了消费和储蓄,实际利率上升,投资下降帮帮忙啊~说明理由~分不多~麻烦了Y=C+G+I~G增加的挤出效应是C I减少因为y=c-s 税收增加后Y=C(1+T)100%-S(1+T)100%即储蓄消费同时下降.因为S=I 投资下降了当然利率就上升了所以答案是E楼下的对投资和消费的说明正确,但利率问题错了宏观经济学课后答案(三): 求解一道宏观经济学习题……已知C=200+0.25Yd,I=150+0.25Y-1000R,G=250,T=200,(L/P)^d=2Y-8000R,M/P=1600.试求:IS曲线方程LM曲线方程均衡的实际国民收入均衡利率水平均衡水平时的C和I,并将C、I和G相加来检验均衡的实际国民收入Y.【宏观经济学课后答案】IS曲线:y=c+i+t=200+0.25(y-t)+150+0.25y-1000r+200,t=200LM曲线:2y-8000r=1600自己化简方程,然后两方程联立,解得y,r.分别代入就好了···宏观经济学课后答案(四): 宏观经济学习题在某国,自发消费支出是500亿美元,边际消费倾向是0.8.投资是3000亿美元,政府购买是2500亿美元,税收T=3000+0.1Y(亿美元,假定没有转移支付等项,税收为净税收),出口为100亿美元,进口M=0.12Y.1.消费函数是什么2.总支出曲线的方程式是什么3.均衡支出是多少4.政府购买乘数是多少消费函数C=500+0.8*(Y-3000-0.1Y)自己化简就行了总支出 AE=Y=C+I+GP+(出口-进口) Y就是NI国名收入 C用第一题的式子带入 GP是政府购买带进去就行了均衡支出就是吧y求出来就行了政府购买乘数与税收乘数相差一个负号购买乘数是正的税收乘数=-MPC*MULT MULT=1/(1-MPC)算出来的是负的把符号除了就是购买乘数宏观经济学课后答案(五): 一道宏观经济学的习题,求答案及解析7、将一国经济中所有市场交易的货币价值进行加总a、会得到生产过程中所使用的全部资源的市场价值b、所获得的数值可能大于、小于或等于GDP的值c、会得到经济中的新增价值总和d、会得到国内生产总值`b 正确市场交易的可能有中间产品,如此中间产品加上最终产品,则重复计算的结果大于GDP;不在国内市场交易,出口销往国外的漏算,则计算结果会小于gdp;如果重复的和漏算的正好相等,则结果可能等于gdp。

曼昆 宏观经济经济学第九版 英文原版答案9(完整资料).doc

【最新整理,下载后即可编辑】Answers to Textbook Questions and ProblemsCHAPTER 9 Economic Growth II: Technology, Empirics, and Policy Questions for Review1. In the Solow model, we find that only technological progress canaffect the steady-state rate of growth in income per worker. Growth in the capital stock (through high saving) has no effect on the steady-state growth rate of income per worker; neither does population growth.But technological progress can lead to sustained growth.2. In the steady state, output per person in the Solow model grows at the rate of technological progress g. Capital per person also grows at rate g. Note that this implies that output and capital per effective worker are constant in steady state. In the U.S. data, output and capital per worker have both grown at about 2 percent per year for the past half-century.3. To decide whether an economy has more or less capital than theGolden Rule, we need to compare the marginal product of capital net of depreciation (MPK –δ) with the growt h rate of total output (n + g). The growth rate of GDP is readily available. Estimating the netmarginal product of capital requires a little more work but, as shown in the text, can be backed out of available data on the capital stockrelative to GDP, the total amount of depreciation relative to GDP, and capital’s share in GDP.4. Economic policy can influence the saving rate by either increasingpublic saving or providing incentives to stimulate private saving. Public saving is the difference between government revenue and government spending. If spending exceeds revenue, the government runs a budget deficit, which is negative saving. Policies that decrease the deficit (such as reductions in government purchases or increases in taxes) increase public saving, whereas policies that increase the deficit decrease saving.A variety of government policies affect private saving. The decision bya household to save may depend on the rate of return; the greater thereturn to saving, the more attractive saving becomes. Tax incentives such as tax-exempt retirement accounts for individuals and investment tax credits for corporations increase the rate of return and encourage private saving.5. The legal system is an example of an institutional difference betweencountries that might explain differences in income per person.Countries that have adopted the English style common law systemtend to have better developed capital markets, and this leads to more rapid growth because it is easier for businesses to obtain financing. The quality of government is also important. Countries with moregovernment corruption tend to have lower levels of income per person.6. Endogenous growth theories attempt to explain the rate oftechnological progress by explaining the decisions that determine the creation of knowledge through research and development. By contrast, the Solow model simply took this rate as exogenous. In the Solowmodel, the saving rate affects growth temporarily, but diminishingreturns to capital eventually force the economy to approach a steady state in which growth depends only on exogenous technologicalprogress. By contrast, many endogenous growth models in essenceassume that there are constant (rather than diminishing) returns tocapital, interpreted to include knowledge. Hence, changes in the saving rate can lead to persistent growth.Problems and Applications1. a. In the Solow model with technological progress, y is defined asoutput per effective worker, and k is defined as capital per effective worker. The number of effective workers is defined as L E (orLE), where L is the number of workers, and E measures theefficiency of each worker. To find output per effective worker y,divide total output by the number of effective workers:Y LE =K12(LE)12LEY LE =K12L12E12LEY LE =K12 L12E12Y LE =KLE æèççöø÷÷12y=k1b. To solve for the steady-state value of y as a function of s, n, g, andδ, we begin with the equation for the change in the capital stock in the steady state:Δk = sf(k) –(δ + n + g)k = 0.The production function ycan also be rewritten as y2 = k.Plugging this production function into the equation for the changein the capital stock, we find that in the steady state:sy –(δ + n + g)y2 = 0.Solving this, we find the steady-state value of y:y* = s/(δ + n + g).c. The question provides us with the following information about each country:Atlantis: s = 0.28 Xanadu: s = 0.10n = 0.01 n = 0.04g = 0.02 g = 0.02δ = 0.04δ = 0.04Using the equation for y* that we derived in part (a), we cancalculate the steady-state values of y for each country.Developed country: y* = 0.28/(0.04 + 0.01 + 0.02) = 4Less-developed country: y* = 0.10/(0.04 + 0.04 + 0.02) = 1 2. a. In the steady state, capital per effective worker is constant, and thisleads to a constant level of output per effective worker. Given that the growth rate of output per effective worker is zero, this means the growth rate of output is equal to the growth rate of effective workers (LE). We know labor grows at the rate of population growth n and the efficiency of labor (E) grows at rate g. Therefore, output grows at rate n+g. Given output grows at rate n+g and labor grows at rate n,output per worker must grow at rate g. This follows from the rule that the growth rate of Y/L is equal to the growth rate of Y minus the growth rate of L.b. First find the output per effective worker production function by dividing both sides of the production function by the number of effective workers LE:Y LE =K13(LE)23LEYLE=K13L23E23LEYLE=K13L13E13YLE=KLEæèçöø÷13y=k13To solve for capital per effective worker, we start with the steady state condition:Δk = sf(k) –(δ + n + g)k = 0.Now substitute in the given parameter values and solve for capital per effective worker (k):Substitute the value for k back into the per effective workerproduction function to find output per effective worker is equal to2. The marginal product of capital is given bySubstitute the value for capital per effective worker to find themarginal product of capital is equal to 1/12.c. According to the Golden Rule, the marginal product of capital isequal to (δ + n + g) or 0.06. In the current steady state, the marginal product of capital is equal to 1/12 or 0.083. Therefore, we have less capital per effective worker in comparison to the Golden Rule. Asthe level of capital per effective worker rises, the marginal product of capital will fall until it is equal to 0.06. To increase capital pereffective worker, there must be an increase in the saving rate.d. During the transition to the Golden Rule steady state, the growth rateof output per worker will increase. In the steady state, output perworker grows at rate g. The increase in the saving rate will increaseoutput per effective worker, and this will increase output pereffective worker. In the new steady state, output per effective worker is constant at a new higher level, and output per worker is growing at rate g. During the transition, the growth rate of output per workerjumps up, and then transitions back down to rate g.3. To solve this problem, it is useful to establish what we know about the U.S. economy:• A Cobb–Douglas production function has the form y = kα, where α is capital’s share of income. The question tells us that α = 0.3,so we know that the production function is y = k0.3.•In the steady state, we know that the growth rate of output equals 3 percent, so we know that (n + g) = 0.03.•The deprec iation rate δ = 0.04.•The capital–output ratio K/Y = 2.5. Because k/y =[K/(LE)]/[Y/(LE)] = K/Y, we also know that k/y = 2.5. (That is, the capital–output ratio is the same in terms of effective workers as it is in levels.)a. Begin with the steady-state condition, sy = (δ + n + g)k. Rewritingthis equation leads to a formula for saving in the steady state:s = (δ + n + g)(k/y).Plugging in the values established above:s = (0.04 + 0.03)(2.5) = 0.175.The initial saving rate is 17.5 percent.b. We know from Chapter 3 that with a Cobb–Douglas production function, capital’s share of income α = MPK(K/Y). Rewriting, we haveMPK = α/(K/Y).Plugging in the values established above, we findMPK = 0.3/2.5 = 0.12.c. We know that at the Golden Rule steady state:MPK = (n + g + δ).Plugging in the values established above:MPK = (0.03 + 0.04) = 0.07.At the Golden Rule steady state, the marginal product of capital is 7 percent, whereas it is 12 percent in the initial steady state. Hence, from the initial steady state we need to increase k to achieve theGolden Rule steady state.d. We know from Chapter 3 that for a Cobb–Douglas production function, MPK = α (Y/K). Solving this for the capital–outputratio, we findK/Y = α/MPK.We can solve for the Golden Rule capital–output ratio using this equation. If we plug in the value 0.07 for the Golden Rule steady-state marginal product of capital, and the value 0.3 for α, we findK/Y = 0.3/0.07 = 4.29.In the Golden Rule steady state, the capital–output ratio equals4.29, compared to the current capital–output ratio of 2.5.e. We know from part (a) that in the steady states = (δ + n + g)(k/y),where k/y is the steady-state capital–output ratio. In theintroduction to this answer, we showed that k/y = K/Y, and in part(d) we found that the Golden Rule K/Y = 4.29. Plugging in thisvalue and those established above:s = (0.04 + 0.03)(4.29) = 0.30.To reach the Golden Rule steady state, the saving rate must risefrom 17.5 to 30 percent. This result implies that if we set the saving rate equal to the share going to capital (30 percent), we will achieve the Golden Rule steady state.4. a. In the steady state, we know that sy = (δ + n + g)k. This implies thatk/y = s/(δ + n + g).Since s, δ, n, and g are constant, this means that the ratio k/y is also constant. Since k/y = [K/(LE)]/[Y/(LE)] = K/Y, we can conclude that in the steady state, the capital–output ratio is constant.b. We know that capital’s share of income = MPK (K/Y). In thesteady state, we know from part (a) that the capital–output ratioK/Y is constant. We also know from the hint that the MPK is afunction of k, which is constant in the steady state; therefore theMPK itself must be constant. Thus, capital’s share of income isconstant. Labor’s share of income is 1 – [C apital’s Share].Hence, if capital’s share is constant, we see that labor’s share of income is also constant.c. We know that in the steady state, total income grows at n + g,defined as the rate of population growth plus the rate oftechnological change. In part (b) we showed that labor’s andcapital’s share of income is constant. If the shares are constant,and total income grows at the rate n + g, then labor income andcapital income must also grow at the rate n + g.d. Define the real rental price of capital R asR = Total Capital Income/Capital Stock= (MPK K)/K= MPK.We know that in the steady state, the MPK is constant becausecapital per effective worker k is constant. Therefore, we canconclude that the real rental price of capital is constant in the steady state.To show that the real wage w grows at the rate of technological progress g, defineTLI = Total Labor IncomeL = Labor ForceUsing the hint that the real wage equals total labor income divided by the labor force:w = TLI/L.Equivalently,wL = TLI.In terms of percentage changes, we can write this asΔw/w + ΔL/L = ΔTLI/TLI.This equation says that the growth rate of the real wage plus thegrowth rate of the labor force equals the growth rate of total labor income. We know that the labor force grows at rate n, and, frompart (c), we know that total labor income grows at rate n + g. We, therefore, conclude that the real wage grows at rate g.5. a. The per worker production function isF(K, L)/L = AKαL1–α/L = A(K/L)α = Akαb. In the steady state, Δk = sf(k) –(δ + n + g)k = 0. Hence, sAkα = (δ + n + g)k, or, after rearranging:k*=sAd+n+géëêêùûúúa1-aæèççöø÷÷.Plugging into the per-worker production function from part (a) givesy *=A a 1-a æèççöø÷÷s d +n +g éëêêùûúúa 1-a æèççöø÷÷.Thus, the ratio of steady-state income per worker in Richland to Poorland isy *Richland /y *Poorland ()=s Richland d +n Richland +g /s Poorland d +n Poorland +g éëêêùûúúa 1-a=0.320.05+0.01+0.02/0.100.05+0.03+0.02éëêêùûúúa 1-ac. If α equals 1/3, then Richland should be 41/2, or two times, richer than Poorland.d. If 4a 1-æèççöø÷÷= 16, then it must be the case that a 1-a æèççöø÷÷, which in turnrequires that α equals 2/3. Hence, if the Cobb –Douglasproduction function puts 2/3 of the weight on capital and only 1/3 on labor, then we can explain a 16-fold difference in levels ofincome per worker. One way to justify this might be to think about capital more broadly to include human capital —which must also be accumulated through investment, much in the way one accumulates physical capital.6. How do differences in education across countries affect the Solowmodel? Education is one factor affecting the efficiency of labor , which we denoted by E . (Other factors affecting the efficiency of laborinclude levels of health, skill, and knowledge.) Since country 1 has amore highly educated labor force than country 2, each worker in country 1 is more efficient. That is, E1 > E2. We will assume that both countries are in steady state.a. In the Solow growth model, the rate of growth of total income is equal to n + g, which is independent of the work force’s level of education. The two countries will, thus, have the same rate ofgrowth of total income because they have the same rate ofpopulation growth and the same rate of technological progress. b. Because both countries have the same saving rate, the samepopulation growth rate, and the same rate of technological progress, we know that the two countries will converge to the same steady-state level of capital per effective worker k*. This is shown in Figure 9-1.Hence, output per effective worker in the steady state, which is y* = f(k*), is the same in both countries. But y* = Y/(L E) or Y/L = y* E. We know that y* will be the same in both countries, but that E1> E2. Therefore, y*E1 > y*E2. This implies that (Y/L)1 > (Y/L)2.Thus, the level of income per worker will be higher in the countrywith the more educated labor force.c. We know that the real rental price of capital R equals the marginalproduct of capital (MPK). But the MPK depends on the capitalstock per efficiency unit of labor. In the steady state, both countries have k*1= k*2= k* because both countries have the same saving rate, the same population growth rate, and the same rate of technological progress. Therefore, it must be true that R1 = R2 = MPK. Thus, the real rental price of capital is identical in both countries.d. Output is divided between capital income and labor income.Therefore, the wage per effective worker can be expressed asw = f(k) –MPK • k.As discussed in parts (b) and (c), both countries have the samesteady-state capital stock k and the same MPK. Therefore, the wage per effective worker in the two countries is equal.Workers, however, care about the wage per unit of labor, not the wage per effective worker. Also, we can observe the wage per unitof labor but not the wage per effective worker. The wage per unitof labor is related to the wage per effective worker by the equationWage per Unit of L = wE.Thus, the wage per unit of labor is higher in the country with the more educated labor force.7. a. In the two-sector endogenous growth model in the text, theproduction function for manufactured goods isY = F [K,(1 –u) EL].We assumed in this model that this function has constant returns to scale. As in Section 3-1, constant returns means that for anypositive number z, zY = F(zK, z(1 –u) EL). Setting z = 1/EL, we obtainY EL =FKEL,(1-u)æèççöø÷÷.Using our standard definitions of y as output per effective worker and k as capital per effective worker, we can write this asy = F[k,(1 –u)]b. To begin, note that from the production function in research universities, the growth rate of labor efficiency, ΔE/E, equals g(u).We can now follow the logic of Section 9-1, substituting the function g(u) for the constant growth rate g. In order to keep capital per effective worker (K/EL) constant, break-even investment includes three terms: δk is needed to replace depreciating capital, nk is needed to provide capital for new workers, and g(u) is needed to provide capital for the greater stock of knowledge E created by research universities. That is, break-even investment is [δ +n + g(u)]k.c. Again following the logic of Section 9-1, the growth of capital pereffective worker is the difference between saving per effectiveworker and break-even investment per effective worker. We now substitute the per-effective-worker production function from part (a) and the function g(u) for the constant growth rate g, to obtainΔk = sF [k,(1 –u)] – [δ + n + g(u)]kIn the steady state, Δk = 0, so we can rewrite the equation above assF [k,(1 –u)] = [δ + n + g(u)]k.As in our analysis of the Solow model, for a given value of u, we can plot the left and right sides of this equationThe steady state is given by the intersection of the two curves. d. The steady state has constant capital per effective worker k as givenby Figure 9-2 above. We also assume that in the steady state, there is a constant share of time spent in research universities, so u is constant. (After all, if u were not constant, it wouldn’t be a“steady” state!). Hence, output per effective worker y is also constant. Output per worker equals yE, and E grows at rate g(u). Therefore, output per worker grows at rate g(u). The saving ratedoes not affect this growth rate. However, the amount of timespent in research universities does affect this rate: as more time is spent in research universities, the steady-state growth rate rises.e. An increase in u shifts both lines in our figure. Output per effectiveworker falls for any given level of capital per effective worker, since less of each worker’s time is spent producing manufactured goods. This is the immediate effect of the change, since at the time u rises, the capital stock K and the efficiency of each worker E are constant.Since output per effective worker falls, the curve showing savingper effective worker shifts down.At the same time, the increase in time spent in research universities increases the growth rate of labor efficiency g(u). Hence, break-even investment [which we found above in part (b)] rises at any given level of k, so the line showing breakeven investment also shifts up.Figure 9-3 shows these shifts.In the new steady state, capital per effective worker falls from k1 to k2. Output per effective worker also falls.f. In the short run, the increase in u unambiguously decreasesconsumption. After all, we argued in part (e) that the immediateeffect is to decrease output, since workers spend less timeproducing manufacturing goods and more time in researchuniversities expanding the stock of knowledge. For a given saving rate, the decrease in output implies a decrease in consumption.The long-run steady-state effect is more subtle. We found in part(e) that output per effective worker falls in the steady state. But welfare depends on output (and consumption) per worker, not per effective worker. The increase in time spent in research universities implies that E grows faster. That is, output per worker equals yE. Although steady-state y falls, in the long run the faster growth rate of E necessarily dominates. That is, in the long run, consumption unambiguously rises.Nevertheless, because of the initial decline in consumption, theincrease in u is not unambiguously a good thing. That is, apolicymaker who cares more about current generations than aboutfuture generations may decide not to pursue a policy of increasing u.(This is analogous to the question considered in Chapter 8 ofwhether a policymaker should try to reach the Golden Rule level ofcapital per effective worker if k is currently below the Golden Rulelevel.)8. On the World Bank Web site (), click on the datatab and then the indicators tab. This brings up a large list of dataindicators that allows you to compare the level of growth anddevelopment across countries. To explain differences in income per person across countries, you might look at gross saving as a percentage of GDP, gross capital formation as a percentage of GDP, literacy rate, life expectancy, and population growth rate. From the Solow model, we learned that (all else the same) a higher rate of saving will lead to higher income per person, a lower population growth rate will lead to higher income per person, a higher level of capital per worker will lead to a higher level of income per person, and more efficient orproductive labor will lead to higher income per person. The selected data indicators offer explanations as to why one country might have a higher level of income per person. However, although we mightspeculate about which factor is most responsible for the difference in income per person across countries, it is not possible to say for certain given the large number of other variables that also affect income per person. For example, some countries may have more developed capital markets, less government corruption, and better access to foreigndirect investment. The Solow model allows us to understand some of the reasons why income per person differs across countries, but givenit is a simplified model, it cannot explain all of the reasons why income per person may differ.More Problems and Applications to Chapter 91. a. The growth in total output (Y) depends on the growth rates oflabor (L), capital (K), and total factor productivity (A), assummarized by the equationΔY/Y = αΔK/K + (1 –α)ΔL/L + ΔA/A, where α is capital’s share of output. We can look at the effect onoutput of a 5-percent increase in labor by setting ΔK/K = ΔA/A =0. Since α = 2/3, this gives usΔY/Y = (1/3)(5%)= 1.67%.A 5-percent increase in labor input increases output by 1.67 percent.Labor productivity is Y/L. We can write the growth rate in labor productivity asD Y Y =D(Y/L)Y/L-D LL.Substituting for the growth in output and the growth in labor, we findΔ(Y/L)/(Y/L) = 1.67% – 5.0%= –3.34%.Labor productivity falls by 3.34 percent.To find the change in total factor productivity, we use the equationΔA/A = ΔY/Y –αΔK/K – (1 –α)ΔL/L.For this problem, we findΔA/A = 1.67% – 0 – (1/3)(5%)= 0.Total factor productivity is the amount of output growth that remains after we have accounted for the determinants of growththat we can measure. In this case, there is no change in technology, so all of the output growth is attributable to measured input growth.That is, total factor productivity growth is zero, as expected.b. Between years 1 and 2, the capital stock grows by 1/6, labor inputgrows by 1/3, and output grows by 1/6. We know that the growthin total factor productivity is given byΔA/A = ΔY/Y –αΔK/K – (1 –α)ΔL/L.Substituting the numbers above, and setting α = 2/3, we findΔA/A = (1/6) – (2/3)(1/6) – (1/3)(1/3)= 3/18 – 2/18 – 2/18= – 1/18= –0.056.Total factor productivity falls by 1/18, or approximately 5.6 percent.2. By definition, output Y equals labor productivity Y/L multiplied by the labor force L:Y = (Y/L)L.Using the mathematical trick in the hint, we can rewrite this asD Y Y =D(Y/L)Y/L+D LL.We can rearrange this asD Y Y =D YY-D LL.Substituting for ΔY/Y from the text, we findD(Y/L) Y/L =D AA+aD KK+(1-a)D LL-D LL =D AA+aD KK-aD LL=D AA+aD KK-D LLéëêêùûúúUsing the same trick we used above, we can express the term in brackets asΔK/K –ΔL/L = Δ(K/L)/(K/L) Making this substitution in the equation for labor productivity growth, we conclude thatD(Y/L) Y/L =D AA+aD(K/L)K/L.3. We know the following:ΔY/Y = n + g = 3.6%ΔK/K = n + g = 3.6%ΔL/L = n = 1.8%Capital’s Share = α = 1/3Labor’s Share = 1 –α = 2/3Using these facts, we can easily find the contributions of each of the factors, and then find the contribution of total factor productivitygrowth, using the following equations:Output = Capital’s+ Labor’s+ Total FactorGrowth Contribution ContributionProductivityD Y Y = aD KK+ (1-a)D LL+ D AA3.6% = (1/3)(3.6%) + (2/3)(1.8%) +ΔA/A.We can easily solve this for ΔA/A, to find that3.6% = 1.2% + 1.2% + 1.2%We conclude that the contribution of capital is 1.2 percent per year, the contribution of labor is 1.2 percent per year, and the contribution of total factor productivity growth is 1.2 percent per year. These numbers match the ones in Table 9-3 in the text for the United States from 1948–2002.。

《宏观经济学》教材--书后习题参考答案

《宏观经济学》教材:书后习题参考答案第九章宏观经济的基本指标及其衡量1.何为GDP?如何理解GDP?答案要点:GDP是指一定时期内在一国(或地区)境内生产的所有最终产品和服务的市场价值总和。

对于GDP的理解,以下几点要注意:(1)GDP是一个市场价值的概念。

为了解决经济中不同产品和服务的实物量一般不能加总的问题,人们转而研究它们的货币价值,这就意味着,GDP一般是用某种货币单位来表示的。

(2)GDP衡量的是最终产品和服务的价值,中间产品和服务价值不计入GDP。

最终产品和服务是指直接出售给最终消费者的那些产品和服务,而中间产品和服务是指由一家企业生产来被另一家企业当作投入品的那些服务和产品。

(3)GDP是一国(或地区)范围内生产的最终产品和服务的市场价值。

也就是说,只有那些在指定的国家和地区生产出来的产品和服务才被计算到该国或该地区的GDP中。

(4)GDP衡量的是一定时间内的产品和服务的价值,这意味着GDP属于流量,而不是存量。

2.说明核算GDP的支出法。

答案要点:支出法核算GDP的基本依据是:对于整个经济体来说,收入必定等于支出。

具体说来,该方法将一国经济从对产品和服务需求的角度划分为了四个部门,即家庭部门、企业部门、政府部门和国际部门。

对家庭部门而言,其对最终产品和服务的支出称为消费支出,用字母C表示;对企业部门而言,其支出称为投资支出,用字母I表示;对政府部门而言,将各级政府购买产品和服务的支出定义为政府购买,用字母G表示;对于国际部门,引入净出口NX来衡量其支出,净出口被定义为出口额与进口额的差额。

将上述四部门支出项目加总,用Y表示GDP,则支出法核算GDP 的国民收入核算恒等式为:Y=C+I+G+NX。

3.说明GDP这一指标的缺陷。

答案要点:(1)GDP并不能反映经济中的收入分配状况。

GDP 高低或人均GDP高低并不能说明一个经济体中的收入分配状况是否理想或良好。

(2)由于GDP只涉及与市场活动有关的那些产品和服务的价值,因此它忽略了家庭劳动和地下经济因素。

宏观经济学第9章作业答案

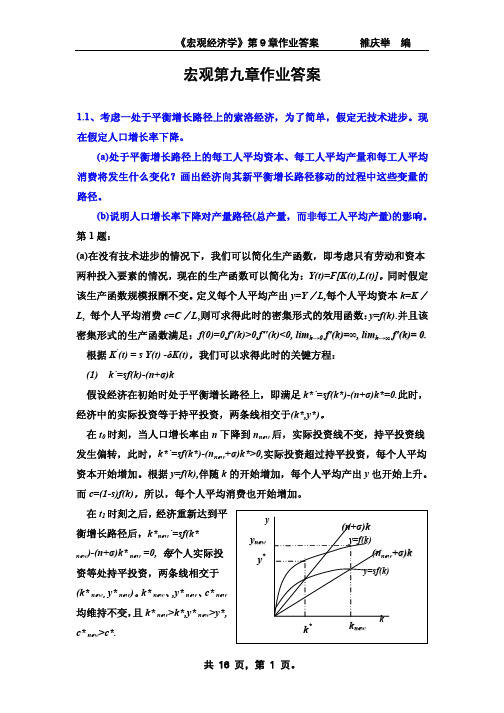

宏观第九章作业答案1.1、考虑一处于平衡增长路径上的索洛经济,为了简单,假定无技术进步。

现在假定人口增长率下降。

(a)处于平衡增长路径上的每工人平均资本、每工人平均产量和每工人平均消费将发生什么变化?画出经济向其新平衡增长路径移动的过程中这些变量的路径。

(b)说明人口增长率下降对产量路径(总产量,而非每工人平均产量)的影响。

第1题:(a)在没有技术进步的情况下,我们可以简化生产函数,即考虑只有劳动和资本两种投入要素的情况,现在的生产函数可以简化为:Y(t)=F[K(t),L(t)]。

同时假定该生产函数规模报酬不变。

定义每个人平均产出y=Y/L,每个人平均资本k=K/L, 每个人平均消费c=C/L,则可求得此时的密集形式的效用函数:y=f(k).并且该密集形式的生产函数满足:f(0)=0,f′(k)>0,f″(k)<0,l i m k→0f′(k)=∞,l i m k→∞f′(k)=0.根据K˙(t) = s Y(t) -δK(t),我们可以求得此时的关键方程:(1) k˙=sf(k)-(n+σ)k假设经济在初始时处于平衡增长路径上,即满足k*˙=sf(k*)-(n+σ)k*=0.此时,经济中的实际投资等于持平投资,两条线相交于(k*,y*)。

在t0时刻,当人口增长率由n下降到n new后,实际投资线不变,持平投资线发生偏转,此时,k*˙=sf(k*)-(n new+σ)k*>0,实际投资超过持平投资,每个人平均资本开始增加。

根据y=f(k),伴随k的开始增加,每个人平均产出y也开始上升。

而c=(1-s)f(k),所以,每个人平均消费也开始增加。

在t1时刻之后,经济重新达到平衡增长路径后,k*new˙=sf(k*new)-(n+σ)k* new =0, 每个人实际投资等处持平投资,两条线相交于(k* new,y* new)。

k* new、,y* new、c* new 均维持不变,且k* new>k*,y* new>y*, c* new>c*.y=f(k)y=sf(k)(n+σ)kkk n e wk*y n e wy*y(n new+σ)k在t 0时刻到t 1时刻之间,由于k ˙>0,所以每个人平均资本逐步增长。

萨缪尔森《宏观经济学》(第19版)习题详解(含考研真题)(第9章--货币和金融体系)

3. 主 要 金 融 资 产 或 工 具 ( The mainly financial assets or instruments)

答:(1)商品货币也称实值或实质货币,它是指商品价值与货币价 值相等的货币。

(2)纸币是由国家依法发行的、作为法定流通手段的货币符号。它 本身没有价值,而是代替金属货币来执行流通手段的职能,充当商品 交换的媒介。商品流通中所需要的纸币数量,相当于所需要的金属货 币数量。如果纸币发行过量,将会使其贬值,导致物价上涨。

经济学历年考研真题及详解

11.普通股票(公司股权)[common stocks(corporate equities)] 答:普通股票是“优先股”的对称,指股东享有平等权利和义务、不 加特别限制、股利不固定的股票。其股息随公司盈利多少而变动。它 是股份公司发行股票时采用最多的一种形式。普通股股金构成股份公 司资金的基础。普通股持有人是公司的基本股东,享有广泛的权利,如 表决权、选举与被选举权、优先认股权、资产分配权、参与经营权等。 但普通股股东也比优先股股东承担更多的义务和更大的风险。普通股 的股息必须在先支付债券利息、优先股股息后才能分配。普通股的收 益无充分保障,公司盈利多时,分到的股利便多;公司盈利少时,分到 的股利便少,甚至没有股利。在公司清算时,普通股对公司剩余资产 的索取权排在债权人和优先股之后。

以保证储户提款,其余的存款才能用于放贷或投资,这部分提留的存 款称之为银行准备金。

9.部分准备金银行(fractional reserve banking) 答:部分准备金银行指银行只把它们的部分存款作为准备金的制 度。在这种制度下,银行将部分存款作为准备金,而将其余存款用于 向企业或个人发放贷款或者投资。若得到贷款的人再将贷款存入其他 银行,从而使其他银行增加了发放贷款或者投资的资金,这一过程持 续下去,使得更多的货币被创造出来了。因此,部分准备金的银行制 度是银行能够进行多倍货币创造的前提条件,在百分之百准备金银行 制度下,银行不能进行多倍货币创造。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

第9章总供给一、选择题二、名词解释1、黏性工资模型:黏性工资模型即阐述黏性名义工资对总供给影响的模型。

黏性工资指不能迅速地反映劳动力市场供求的变动,只能缓慢地根据劳动力市场状况改变而调整的工资。

工人的名义工资通常不能随着经济条件的变化而迅速调整,在短期内表现为“迟钝的”或“黏性的”。

该模型假设劳动力的需求数量决定就业,以及工人和企业根据目标实际工资和对价格水平的预期来确定名义工资水平。

当名义工资是黏性的时候,价格水平提高会降低实际工资,促使企业多雇佣劳动力,从而生产更多的产品,总供给增加,所以短期总供给曲线是向上倾斜的。

新凯恩斯学派提出工资黏性的理由:(1)合同的长期性。

(2)合同分批到期的性质。

(3)效率工资论。

(4)长期劳动合同论。

新凯恩斯主义黏性工资论认为,无论是通过合同制还是理性预期机制来稳定工资水平,都会导致膨胀和失业并存。

因此有必要对工资制度进行改革。

努力降低劳动力成本,刺激企业生产和用人的积极性。

这就要求建立完整而有效的劳动力市场,工资完全由劳动力市场的供求和劳动者提供劳动的质和量来决定,工资是调节劳动力资源配置和流动的惟一手段。

2、不完全信息模型:不完全信息模型是阐述经济主体在做出经济决策时,并不能掌握所有相关信息从而影响总供给的模型。

不完全信息模型假设市场出清,即所有工资和价格自由调整使供求平衡,短期和长期总供给曲线的不同是因为对价格暂时的错觉。

此外,该模型还假设,经济中的每个供给者生产一种单一产品并消费许多产品。

由于产品数量如此之多,供给者无法在所有时间中观察到所有价格。

他们密切注视他们所生产的产品的价格,但对他们消费的所有产品的价格关注较不密切。

由于信息不完全,他们有时混淆了物价总水平的变动与相对价格的变动。

这种混淆影响了供给多少的决策,并导致物价水平与产出之间在短期的正相关关系。

当物价水平发生了未预期到的上升时,经济中所有供给者都观察到了自己所生产的产品价格的上升。

他们都理性而错误地推断,他们生产的产品的相对价格上升了。

他们更努力地工作,并生产得更多。

总之,不完全信息模型说明,当实际物价超过预期物价时,供给者增加其产出。

由Y=Y+α(P-P e)可知,当产出背离预期物价水平时,产出背离自然率。

3、黏性价格模型:性价格模型即阐述黏性价格对总供给影响的模型。

黏性价格指不能迅速反映产品市场供求的变动,只能缓慢地根据产品市场状况改变而调整的价格。

该模型假设市场是完全竞争的,完全竞争企业是价格接受者,而不是价格制定者。

该模型表示为Y=Y+α(P-P e ),说明了产出与自然率的背离和物价水平与预期物价水平的背离是正相关的。

4、菲利普斯曲线:菲利普斯曲线是表示货币工资变动率与失业率之间交替关系的曲线。

它是英国经济学家菲利普斯根据1861~1957年英国的失业率和货币工资变动率的经验统计资料提出来的,故称之为菲利普斯曲线。

这条曲线表示,当失业率高时,货币工资增长率低;反之,当失业率低时,货币工资增长率高。

因此,如图9-2-1所示,横轴代表失业率(U ),纵轴代表货币工资增长率(W ),菲利普斯曲线(PC )是一条向右下方倾斜的曲线。

根据成本推动型通货膨胀的理论,货币工资增长率决定了价格增长率,所以,菲利普斯曲线也可以表示通货膨胀率和失业率之间的交替关系,即当失业率高时,通货膨胀率低;反之,当失业率低时,通货膨胀率高。

新古典综合派经济学家把菲利普斯曲线作为调节经济的依据,即当失业率高时,实行扩张性财政政策与货币政策,以承受一定通货膨胀率为代价换取较低的失业率;当通货膨胀率高时,实行紧缩性的财政政策与货币政策,借助提高失业率以降低通货膨胀率。

货币主义者对菲利普斯曲线所表示的通货膨胀率与失业率之间的交替关系提出了质疑,并进一步论述了短期菲利普斯曲线、长期菲利普斯曲线和附加预期的菲利普斯曲线,以进一步解释在不同条件下,通货膨胀率与失业率之间的关系。

理性预期学派一步以理性预期为依据解释了菲利普斯曲线。

他们既反对凯恩斯主义的观点,也不同意货币主义的说法,他们认为,由于人们的预期是理性的,预期的通货膨胀率与以后实际发生的通货膨胀率总是一致的,不会出现短期内实际通货膨胀率大于预期通货膨胀率的情况,所以,无论在短期或长期中,菲利普斯曲线所表示的失业与通货膨胀之间都不存在稳定的交替关系,菲利普斯曲线只能是一条垂直线。

5、适应性预期:适应性预期是根据以前的预期误差来修正以后的预期的方式,“适应性预期”这一术语由菲利普·卡甘于20世纪50年代在一篇讨论恶性通货膨胀的文章中提出。

由于它比较适用于当时的经济形势,因而很快在宏观经济学中得到了应用。

适应性预期模型中的预期变量依赖于该变量的历史信息。

例如,某个时点的适应性预期价格P 等于上一个时期的预期价格加上常数C 以及上期价格的误差。

适应性预期在物价较为稳定的时期能较好地反映经济现实,西方国家的经济在20世纪50~60年代正好如此,因此适应性预期非常广泛地流行起来了。

适应性预期后来受到新古典宏观经济学的批判,认为它缺乏微观经济学基础。

适应性预期的权数分布是既定的几何级数,没有利用与被测变量相关的其他变量,对经济预期方程的确定基本上是随意的,没有合理的经济解释。

因此新古典宏观经济W U图9-2-1学派的“理性预期”逐渐取代了“适应性预期”。

6、需求拉动型通货膨胀:需求拉动型通货膨胀,又称为超额需求通货膨胀,指总需求超过总供给所引起的一般价格水平的持续显著上涨,可解释为“过多货币追求过少的商品”。

需求拉动型通货膨胀的原因:在总产量达到一定水平后,当需求增加时,供给增加一部分,但供给的增加会遇到生产过程中的瓶颈现象,即由于劳动、原料、生产设备的不足使成本提高,从而引起价格上升。

或者在产量达到最大时,即为充分就业的产量时,当需求增加,供给也不会增加,总需求增加只会引起价格的上涨。

消费需求、投资需求或来自政府的需求、国外需求都会导致需求拉动型通货膨胀,需求方面的原因或冲击主要包括财政政策、货币政策、消费习惯的改变、国际市场的需求变动等等。

引起需求扩大的因素有两大类:一类是消费需求、投资需求的扩大,政府支出的增加、减税,净出口增加等(通过IS曲线右移),它们都会导致总需求的增加,需求曲线右移,称为实际因素;另一类是货币因素,即货币供给量的增加或实际货币需求量的减少(通过LM曲线右移),导致总需求增加。

7、成本推动型通货膨胀:成本推动型通货膨胀,又称为成本通货膨胀或供给通货膨胀,指在没有超额需求的情况下,由于供给方面成本的提高所引起的一般价格水平持续和显著地上涨。

成本推动型通货膨胀又可以分为工资推动通货膨胀和利润推动通货膨胀(这里的利润通常为垄断利润)。

工资推动通货膨胀指不完全竞争的劳动市场造成的过高工资所导致的一般价格水平的上涨。

据西方学者解释,在完全竞争的劳动市场上,工资率完全决定于劳动的供求,工资的提高不会导致通货膨胀;而在不完全竞争的劳动力市场上,由于强大的工会组织的存在,工资不再是竞争的工资,而是工会和雇主集体议价的工资,并且由于工资的增长率超过生产率增长速度,工资的提高就导致成本提高,从而导致一般价格水平上涨。

西方经济学者进而认为,工资提高价格水平上涨之间存在因果关系:工资提高引起价格上涨,价格上涨又引起工资提高。

这样,工资提高和价格上涨形成了螺旋式的上升运动,即所谓工资一价格螺旋。

利润推动通货膨胀是指垄断企业和寡头企业利用市场势力谋取过高利润所导致的一般价格水平的上涨。

西方学者认为,就像不完全竞争的劳动市场是工资推动通货膨胀的前提一样,不完全竞争的产品市场是利润推动通货膨胀的前提。

在完全竞争的产品市场上,价格完全决定于商品的供求,任何企业都不能通过控制产量来改变市场价格;而在不完全竞争的产品市场上,垄断企业和寡头企业为了追求更大的利润,可以操纵价格,把产品价格定得很高,致使价格上涨的速度超过成本增长的速度。

8、牺牲率:牺牲率是指通货膨胀率每降低一个百分点所必须放弃的一年实际GDP的百分比。

由菲利普斯曲线得知,在短期,通货膨胀和失业之间有取舍关系,低通货膨胀率意味着高失业;又由奥肯定理得知,失业增加,产出减少,也即降低通货膨胀是有成本的,牺牲率就是用来衡量降低通货膨胀成本的。

适应性预期理论认为通货膨胀引发通货膨胀预期,而通货膨胀预期又引发更高的通货膨胀率,因此,降低通货膨胀的成本是巨大的。

而理性预期学派则认为,如果政府能够可信地承诺降低通货膨胀,公众理解这种承诺,并相应降低通货膨胀预期的话,那么降低通货膨胀不必须经历一个高失业、低产出的时期,牺牲率是可以为零的。

尽管牺牲率的估算差别很大,但典型的估算基本在5%左右:通货膨胀每下降一个百分点,一年的GDP必须牺牲5%。

9、理性预期:理性预期又称合理预期,是现代经济学中的预期概念之一,指人们可以最好地利用所有可以获得的信息,包括关于现在政府政策的信息来形成自己的预期。

由约翰·穆思在其《合理预期和价格变动理论》(1961年)一文中首先提出。

它的含义有三个:首先,做出经济决策的经济主体是有理性的;其次,为正确决策,经济主体会在做出预期时为图获得一切有关的信息;最后,经济主体在预期时不会犯系统错误,即使犯错误,他也会及时有效地进行修正,使得在长期而言保持正确。

它是新古典宏观经济理论攻击凯恩斯主义的重要武器。

10、自然率假说:自然率假说是卢卡斯在“自然失业率”的基础上,提出的一种关于就业、产出、物价等经济变量存在着一种由政府政策支配的实际因素(如生产、技术等)决定的自然水平的理论观点。

自然率主要指自然失业率。

自然率假说认为,自由竞争可以使整个经济处于充分就业状态,并且认为这种趋势是完全竞争的市场经济本身固有的属性,而经济活动出现非充分就业的原因不在于市场制度本身,而在于外界的干扰或者人们对经济变量所作预期的误差。

根据自然率假说,任何一个资本主义社会都存在一个自然失业率,其大小取决于社会的技术水平、资源数量和文化传统。

长期而言,经济总是趋向于自然失业率。

尽管短期内,经济政策能够使得实际失业率不同于自然失业率。

它是货币主义的重要理论基础,也是新古典主义的重要基本假说。

“自然率”的存在使货币政策的作用只有在造成非预期的通货膨胀时才能奏效。

“自然率假说”从理论上论述了政策作用的有限性,为理性预期学说确立了重要的理论前提。

11、滞后性:滞后性是用来描述历史自然率的长期影响的术语。

滞后性是一些经济学家向自然率提出挑战的一种机制。

自然率假说认为:总需求的波动仅仅在短期中影响产出与就业。

而在长期中,经济回到古典模型所描述的产出、就业和失业水平。

但一些经济学家通过提出总需求甚至在长期中也能影响产出和就业而向自然率假说提出了挑战。

他们指出存在若干机制,通过这些机制衰退可能通过改变自然失业率而给经济留下长期伤害。