中文版-柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制

“柠檬”的市场质量的不确定性和市场机制【外文翻译】

外文翻译原文The market for "lemons": quality uncertainty and the marketmechanismMaterial Source: The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1970Author:GEORGE A. AKERLOFI. INTRODUCTIONThis paper relates quality and uncertainty. The existence of goods of many grades poses interesting and important problems for the theory of markets. On the one hand, the interaction of quality differences and uncertainty may explain important institutions of the labor market. On the other hand, this paper presents a struggling attempt to give structure to the statement: "Business in underdeveloped countries is difficult"; in particular, a structure is given for determining the economic costs of dishonesty. Additional applications of the theory include comments on the structure of money markets, on the notion of "insurability," on the liquidity of durables, and on brand-name goods.There are many markets in which buyers use some market statistic to judge the quality of prospective purchases. In this case there is incentive for sellers to market poor quality merchandise, since the returns for good quality accrue mainly to the entire group whose statistic is affected rather than to the individual seller. As a result there tends to be a reduction in the average quality of goods and also in the size of the market. It should also be perceived that in these markets social and private returns differ, and therefore, in some cases, governmental intervention may increase the welfare of all parties. Or private institutions may arise to take advantage of the potential increases in welfare which can accrue to all parties. By nature, however, these institutions are non atomistic, and therefore concentrations of power with ill consequences of their own can develop.The automobile market is used as a finger exercise to illustrate and developthese thoughts. It should be emphasized that this market is chosen for its concreteness and ease in understanding rather than for its importance or realism.II. THE MODEL WITH AUTOMOBILES AS AN EXAMPLEA.The Automobiles MarketThe example of used cars captures the essence of the problem. From time to time one hears either mention of or surprise at the large price difference between new cars and those which have just left the showroom. The usual lunch table justification for this phenomenon the pure joy of owning a "new" car. We offer a different explanation. Suppose (for the sake of clarity rather than reality) that there are just four kinds of cars. There are new cars and used cars. There are good cars and bad cars (which in America are known as "lemons"). A new car may be a good car or a lemon, and of course the same is true of used cars.The individuals in this market buy a new automobile without knowing whether the car they buy will be good or a lemon. But they do know that with probability q it is a good car and with probability (1-q) it is a lemon; by assumption, q is the proportion of good cars produced and (1-q) is the proportion of lemons.After owning a specific car, however, for a length of time, the car owner can form a good idea of the quality of this machine; i.e., the owner assigns a new probability to the event that his car is a lemon. This estimate is more accurate than the original estimate. An asymmetry in available information has developed: for the sellers now have more knowledge about the quality of a car than the buyers. But good cars and bad cars must still sell at the same price since it is impossible for a buyer to tell the difference between a good car and a bad car. It is apparent that a used car cannot have the same valuation as a new car .if it did have the same valuation, it would clearly be advantageous to trade a lemon at the price of new car, and buy another new car, at a higher probability q of being good and a lower probability of being bad. Thus the owner of a good machine must be locked in. Not only is it true that he cannot receive the true value of his car, but he cannot even obtain the expected value of a new car.Gresham's law has made a modified reappearance. For most cars traded will bethe "lemons," and good cars may not be traded at all. The "bad" cars tend to drive out the good (in much the same way that bad money drives out the good). But the analogy with Gresham's law is not quite complete: bad cars drive out the good because they sell at the same price as good cars; similarly, bad money drives out good because the exchange rate is even. But the bad cars sell at the same price as good cars since it is impossible for a buyer to tell the difference between a good and a bad car; only the seller knows. In Gresham's law, however, presumably both buyer and seller can tell the difference between good and bad money. So the analogy is instructive, but not complete .B. Asymmetrical InformationIt has been seen that the good cars may be driven out of the market by the lemons. But in a more continuous case with different grades of goods, even worse pathologies can exist. For it is quite possible to have the bad driving out the not-so-bad driving out the medium driving out the not-so-good driving out the good in such a sequence of events that no market exists at all. One can assume that the demand for used automobiles depends most strongly upon two variables the price of the automobile p and the average quality of used cars traded, a, or Q = D (p, A). Both the supply of used cars and also the average quality p will depend upon the price, or p=j (p) and S=S(p). And in equilibrium the supply must equal the demand for the given average quality, or S(p) = D (p, p (p)). As the price falls, normally the quality will also fall. And it is quite possible that no goods will be traded at any price level.Such an example can be derived from utility theory. Assume that there are just two groups of traders: groups one and two. Give group one a utility functionnU1= M+ ∑X ii=1where M is the consumption of goods other than automobiles, X1 is the quality of the I.T.H automobile, and N is the number of automobiles. Similarly, letnU2= M+ ∑X3/2X ii=1where M, X1, and N are defined as before. Three comments should be made about these utility functions: (1) without linear utility (say with logarithmic utility) one gets needlessly mired in algebraic complication. (2) The use of linear utility allows a focus on the effects of asymmetry of information; with a concave utility function we would have to deal jointly with the usual risk variance effects of uncertainty and the special effects we wish to discuss here. (3) U1 and U2 have the odd characteristic that the addition of a second car, or indeed a KTH car, adds the same amount of utility as the first. Again realism is sacrificed to avoid a diversion from the proper focus.To continue, it is assumed (1) that both type one traders and type two traders are V on Neumann Morgenstern maximizers of expected utility; (2) that group one has N cars with uniformly distributed quality x, 0<x <2, and group two has no cars; (3) that the price of "other goods" M is unity.Denote the income (including that derived from the sale of automobiles) of all type one traders as Y1 and the income of all type two traders as Y2. The demand for used cars will be the sum of the demands by both groups. When one ignores indivisibility, the demand for automobiles by type one traders will be D1=Y1/p μ/p>lD1=O μ/ p<l.And the supply of cars offered by type one traders isS2= PN/2 p≤2with average qualityi= p/2.(To derive (1) and (2), the uniform distribution of automobile quality is used.) Similarly the demand of type two traders isD2 = Y2/P 3μ/2 > pD2 =0 3μ/2 < pandS2 =0.Thus total demand D (p, μ) isD (p, μ) = (Y2+ Y1)/P if p <μD (p, μ) = Y2/p if μ< p <3μ/2D(p, μ)=0 if p>3μ/2.However, with price p, average quality is p/2 and therefore at no price will anytrade take place at all: in spite of the fact that at any given price between 0 and 3 there are traders of type one who are willing to sell their automobiles at a price which traders of type two are willing to pay.C. Symmetric Information The foregoing is contrasted with the case of symmetric information. Suppose that the quality of all cars is uniformly distributed, O<x<2. Then the demand curves and supply curves can be written as follows SupplyS(p) =N p>1S(p)=O p<1.And the demand curves areD(p) = (Y2+M ay)/P p<1D(p) = (Y2/p) l<p<3/2D(p) = 0 p > 3/2.In equilibriump=1 if Y2<NP=Y2/N if 2Y2/3<N<Y2p =3/2 if N<2Y2/3.If N <Y2 there is a gain in utility over the case of asymmetrical information of N/2. (If N> Y2, in which case the income of type two traders is insufficient to buy all N automobiles, there is a gain in utility of Y2/2 units.Finally, it should be mentioned that in this example, if traders of groups one and two have the same probabilistic estimates about the quality of individual automobiles though these estimates may vary from automobile to automobile(3), (4), and (5) will still describe equilibrium with one slight change: p will then represent the expected price of one quality unit.III. EXAMPLES AND APPLICATIONSA.InsuranceIt is a well-known fact that people over 65 have great difficulty in buying medical insurance. The natural question arises: why doesn't the price rise to match the risk?Our answer is that as the price level rises the people who insure themselves will be those who are increasingly certain that they will need the insurance; for error in medical check-ups, doctors' sympathy with older patients, and so on make it much easier for the applicant to assess the risks involved than the insurance company. The result is that the average medical condition of insurance applicants deteriorates as theprice level rises with the result that no insurance sales may take place at any price.' This is strictly analogous to our automobiles case, where the average quality of used cars supplied fell with a corresponding fall in the price level. This agrees with the explanation in insurance textbooks:Generally speaking policies are not available at ages materially greater than sixty-five.... The term premiums are too high for any but the most pessimistic (which is to say the least healthy) insureds to find attractive. Thus there is a severe problem of adverse selection at these ages.The statistics do not contradict this conclusion. While demands for health insurance rise with age, a 1956 national sample survey of 2,809 families with 8,898 persons shows that hospital insurance coverage drops from 63 per cent of those aged 45 to 54, to 31 per cent for those over 65. And surprisingly, this survey also finds average medical expenses for males aged 55 to 64 of $88, while males over 65 pay an average of $77.3 While non insured expenditure rises from $66 to $80 in these age groups, insured expenditure declines from $105 to $70. The conclusion is tempting that insurance companies are particularly wary of giving medical insurance to older people.The principle of "adverse selection" is potentially present in all lines of insurance. The following statement appears in an insurance textbook written at the What's School:There is potential adverse selection in the fact that healthy term insurance policy holders may decide to terminate their coverage when they become older and premiums mount. This action could leave an insurer with an undue proportion of below average risks and claims might be higher than anticipated. Adverse selection "appears (or at least is possible) whenever the individual or group insured has freedom to buy or not to buy, to choose the amount or plan of insurance, and to persist or to discontinue as a policy holder."Group insurance, which is the most common form of medical insurance in the United States, picks out the healthy, for generally adequate health is a precondition for employment. At the same time this means that medical insurance is least available to those who need it most, for the insurance companies do their own "adverse selection."This adds one major argument in favor of medicare. On a cost benefit basis medicare may pay off: for it is quite possible that every individual in the market would be willing to pay the expected cost of his medicare and buy insurance, yet no insurance company can afford to sell him a policy for at any price it will attract toomany "lemons." The welfare economics of medicare, in this view, is exactly analogous to the usual classroom argument for public expenditure on roads.B. The Employment of MinoritiesThe Lemons Principle also casts light on the employment of minorities. Employers may refuse to hire members of minority groups for certain types of jobs. This decision may not reflect irrationality or prejudice but profit maximization. For race may serve as a good statistic for the applicant's social background, quality of schooling, and general job capabilities.Good quality schooling could serve as a substitute for this statistic; by grading students the schooling system can give a better indicator of quality than other more superficial characteristics. As T. W. Schultz writes, "The educational establishment discovers and cultivates potential talent. The capabilities of children and mature students can never be known until found and cultivated." An untrained worker may have valuable natural talents, but these talents must be certified by "the educational establishment" before a company can afford to use them. The certifying establishment, however, must be credible; the unreliability of slum schools decreases the economic possibilities of their students.This lack may be particularly disadvantageous to members of already disadvantaged minority groups. For an employer may make a rational decision not to hire any members of these groups in responsible positions because it is difficult to distinguish those with good job qualifications from those with bad qualifications. This type of decision is clearly what George Stigler had in mind when he wrote, "in a regime of ignorance Enrico Fermi would have been a gardener, V on Neumann a checkout clerk at a drugstore."As a result, however, the rewards for work in slum schools tend to accrue to the group as a whole in raising its average quality rather than to the individual. Only insofar as information in addition to race is used is there any incentive for training.An additional worry is that the Office of Economic Opportunity is going to use cost-benefit analysis to evaluate its programs. For many benefits may be external. The benefit from training minority groups may arise as much from raising the average quality of the group as from raising the quality of the individual trainee; and, likewise, the returns may be distributed over the whole group rather than to the individual.C. The Costs of DishonestyThe Lemons model can be used to make some comments on the costs of dishonesty. Consider a market in which goods are sold honestly or dishonestly;quality may be represented, or it may be misrepresented. The purchaser's problem, of course, is to identify quality. The presence of people in the market who are willing to offer inferior goods tends to drive the market out of existence as in the case of our automobile "lemons." It is this possibility that represents the major costs of dishonesty for dishonest dealings tend to drive honest dealings out of the market. There may be potential buyers of good quality products and there may be potential sellers of such products in the appropriate price range; however, the presence of people who wish to pawn bad wares as good wares tends to drive out the legitimate business. The cost of dishonesty, therefore, lies not only in the amount by which the purchaser is cheated; the cost also must include the loss incurred from driving legitimate business out of existence.Dishonesty in business is a serious problem in underdeveloped countries. Our model gives a possible structure to this statement and delineates the nature of the "external" economies involved. In particular, in the model economy described, dishonesty, or the misrepresentation of the quality of automobiles, costs 1/2 unit of utility per automobile; furthermore, it reduces the size of the used car market from N to 0. We can, consequently, directly evaluate the costs of dishonesty at least in theory.There is considerable evidence that quality variation is greater in underdeveloped than in developed areas. For instance, the need for quality control of exports and State Trading Corporations can be taken as one indicator. In India, for example, under the Export Quality Control and Inspection Act of 1963, "about 85 per cent of Indian exports are covered under one or the other type of quality control." Indian housewives must carefully glean the rice of the local bazaar to sort out stones of the same color and shape which have been intentionally added to the rice. Any comparison of the heterogeneity of quality in the street market and the canned qualities of the American supermarket suggests that quality variation is a greater problem in the East than in the West.In one traditional pattern of development the merchants of the preindustrial generation turn into the first entrepreneurs of the next. The best documented case is Japan,but this also may have been the pattern for Britain and America.In our picture the important skill of the merchant is identifying the quality of merchandise; those who can identify used cars in our example and can guarantee the quality may profit by as much as the difference between type two traders' buying price and type one traders' selling price. These people are the merchants. In production these skills are equally necessary both to be able to identify the quality of inputs and to certify the quality ofoutputs. And this is one (added) reason why the merchants may logically become the first entrepreneurs.The problem, of course, is that entrepreneurship may be a scarce resource; no development text leaves entrepreneurship unemphasized. Some treat it as central.Given, then, that entrepreneurship is scarce, there are two ways in which product variations impede development. First, the pay-off to trade is great for would be entrepreneurs, and hence they are diverted from production; second, the amount of entrepreneurial time per unit output is greater, the greater are the quality variations.MARKET FOR "LEMONS": AND MARKET MECHANISM 497 D. Credit Marketing Underdeveloped Countries(1)Credit markets in underdeveloped countries often strongly reflect the operation of the Lemons Principle. In India a major fraction of industrial enterprise is controlled by managing agencies (according to a recent survey, these "managing agencies" controlled 65.7 per cent of the net worth of public limited companies and 66 per cent of total assets).3 Here is a historian's account of the function and genesis of the "managing agency system":The management of the South Asian commercial scene remained the function of merchant houses, and a type of organization peculiar to South Asia known as the Managing Agency. When a new venture was promoted (such as a manufacturing plant, a plantation, or a trading venture), the promoters would approach an established managing agency. The promoters might be Indian or British, and they might have technical or financial resources or merely a concession. In any case they would turn to the agency because of its reputation, which would encourage confidence in the venture and stimulate investment.In turn, a second major feature of the Indian industrial scene has been the dominance of these managing agencies by caste (or, more accurately, communal) groups. Thus firms can usually be classified according to communal origin.5 In this environment, in which outside investors are likely to be bilked of their holdings, either (1) firms establish a reputation for "honest" dealing, which confers upon them a monopoly rent insofar as their services are limited in supply, or (2) the sources of finance are limited to local communal groups which can use communal and possibly familial ties to encourage honest dealing within the community. It is, in Indian economic history, extraordinarily difficult to discern whether the savings of rich landlords failed to be invested in the industrial sector (1) because of a fear to invest in ventures con-trolled by other communities, (2) because of inflated propensities toconsume, or (3) because of low rates of return. At the very least, however, it is clear that the British-owned managing agencies tended to have an equity holding whose communal origin was more hetero-gorgeous than the Indian-controlled agency houses, and would usually include both Indian and British investors.(2)A second example of the workings of the Lemons Principle concerns the extortionate rates which the local moneylender charges his clients. In India these high rates of interest have been the lead-mon factor in landless; the so-called "Cooperative Movement" was meant to counteract this growing landless by setting up banks to compete with the local moneylenders.While the large banks in the central cities have prime interest rates of 6, 8, and 10 per cent, the local moneylender charges 15, 25, and even 50 per cent. The answer to this seeming paradox is that credit is granted only where the granter has (1) easy means of enforcing his contract or (2) personal knowledge of the character of the borrower. The middleman who tries to arbitrage between the rates of the moneylender and the central bank is apt to attract all the "lemons" and thereby make a loss.This interpretation can be seen in Sir Malcolm Darling's interpretation of the village moneylender's power:It is only fair to remember that in the Indian village the moneylender is often the one thrifty person amongst a generally thriftless people; and that his methods of business, though demoralizing under modern conditions, suit the happy-go-lucky ways of the peasant. He is always accessible, even at night; dispenses with troublesome formalities, asks no inconvenient questions, advances promptly, and if interest is paid, does not press for repay-meet of principal. He keeps in close personal touch with his clients, and in many villages shares their occasions of weal or woe. With his intimate knowledge of those around him he is able, without serious risk, to finance those who would otherwise get no loan at all.Or look at Barbara Ward's account:A small shopkeeper in a Hong Kong fishing village told me: "I give credit to anyone who anchors regularly in our bay; but if it is someone I don't know well, then I think twice about it unless I can find out all about him.Or, a profitable sideline of cotton ginning in Iran is the loaning of money for the next season, since the ginning companies often have a line of credit from Teheran banks at the market rate of interest. But in the first years of operation large losses are expected from unpaid debts due to poor knowledge of the local scene.IV. COUNTERACTING INSTITUTIONSNumerous institutions arise to counteract the effects of quality uncertainty.One obvious institution is guarantees. Most consumer durables carry guarantees to ensure the buyer of some normal expected quality. One natural result of our model is that the risk is borne by the seller rather than by the buyer.A second example of an institution which counteracts the effects of quality uncertainty is the brand-name good. Brand names not only indicate quality but also give the consumer a means of retaliation if the quality does not meet expectations. For the con-sumer will then curtail future purchases. Often too, new products are associated with old brand names. This ensures the prospective consumer of the quality of the product.consumer of the quality of the product. Chains such as hotel chains or restaurant chains are similar to brand names. One observation consistent with our approach is the chain restaurant. These restaurants, at least in the United States, most often appear on interurban highways. The customers are seldom local. The reason is that these well-known chains offer a better hamburger than the average local restaurant; at the same time, the local customer, who knows his area,can usually choose a place he prefers.place he prefers. Licensing practices also reduce quality uncertainty. For in-stance, there is the licensing of doctors, lawyers, and barbers. Most skilled labor carries some certification indicating the attainment of certain levels of proficiency. The high school diploma, the Dacca-laureate degree, the Ph.D., even the Nobel Prize, to some degree, serve this function of certification. And education to some degree, serve this function of certification. And education and labor mar-bets themselves have their own "brand names."V. CONCLUSIONWe have been discussing economic models in which "trust" is important. Informal unwritten guaranteed re preconditioning r trade and production. Where these guarantees are indefinite, business will suffer -as indicated by our generalized Gresham's law. This aspect of uncertainty has been explored by game theorists, as in the Prisoner's Dilemma, but usually it has not been incorporated in the more traditional Arrow-Dealer approach to june-dainty.2 But the difficulty of distinguishing good quality from bad is inherent in the business world; this may indeed explain many economic institutions and may in fact be one of the more important aspects of uncertainty.译文“柠檬”的市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制资料来源:《经济学季刊》,1970 作者:乔治•a•阿克尔洛夫 I介绍本文认为质量和不确定性有着某种联系,许多不同东西的存在提出了关于市场理论的有趣和重要的问题来讨论。

柠檬市场存在的问题(一)

柠檬市场存在的问题(一)柠檬市场存在的问题问题一:产品质量问题•柠檬市场存在着产品质量参差不齐的问题,部分柠檬质量不合格。

•柠檬在运输过程中易受压力和温度影响,导致部分柠檬变质。

问题二:信息不对称•卖家发布的柠檬信息与实际情况不符,欺骗消费者。

•柠檬市场上缺乏对产品品质的准确描述,消费者难以做出明智的购买决策。

问题三:价格不透明•柠檬市场价格变动频繁,价格不稳定。

•柠檬市场存在着价格垄断、价格操纵等不正当行为,导致价格不透明。

问题四:生产者和消费者沟通不畅•柠檬市场缺乏可靠的供应链管理系统,生产者和消费者之间缺乏有效沟通渠道。

•生产者无法及时了解消费者的需求和反馈,消费者也无法得到及时的售后服务。

解决方案解决方案一:建立质量监控体系•加强对柠檬质量的把关,建立质量监控体系,确保市场上柠檬的质量符合标准。

•加强柠檬运输过程中的保鲜措施,减少柠檬变质的情况发生。

解决方案二:加强信息公开和监管•加强对柠檬信息的真实性审核,禁止虚假宣传,保证消费者获得准确的产品信息。

•建立柠檬市场监管机构,加强对市场的监管,严厉打击欺诈行为。

解决方案三:建立价格监测机制•建立柠檬市场价格监测机制,定期公布柠檬价格指导价,增加价格透明度。

•加强对价格垄断和价格操纵行为的打击,维护市场价格秩序。

解决方案四:建立供应链管理系统•建立可靠的柠檬供应链管理系统,实现生产者和消费者之间的信息共享和沟通。

•提供有效的售后服务渠道,保障消费者的权益,加强生产者和消费者之间的信任和合作关系。

通过以上解决方案的实施,能够有效解决柠檬市场存在的问题,提升市场的良性发展。

柠檬市场存在的问题及解决对策

柠檬市场存在的问题及解决对策

柠檬市场存在的主要问题包括信息不对称和逆向选择。

信息不对称是指交易双方对有关交易的信息掌握的程度不同,有些一方掌握的信息比另一方更多。

在这种情况下,信息多的一方可能会利用自己的信息优势来获取更多的利益,而信息少的一方则可能会因为缺乏信息而受到损失。

逆向选择是指由于信息不对称,市场上的优质产品难以得到认可,而低质量的产品则容易占据市场,导致市场上的产品质量下降。

这可能导致市场失灵,投资者和消费者失去信心,进而导致市场萎缩。

为了解决柠檬市场的问题,需要加强信息披露和监管,提高市场透明度,同时加强产品质量监管和认证,以减少信息不对称和逆向选择的风险。

此外,还可以采用其他机制如拍卖、反向拍卖、协商和中介等来减少信息不对称和逆向选择对市场的影响。

读《柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制》兼议如何解决市场信息不对称问题

读《柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制》兼议如何解决市场信息不对称问题一、《柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制》概述和观后感柠檬市场,也称次品市场,也叫做阿克洛夫模型。

它是是指在信息不对称的市场中,产品的卖方对产品的质量拥有比买方更多的信息。

而在极端情况下,市场会止步萎缩和不存在,这其实就是信息经济学中的逆向选择问题。

柠檬市场效应则是指在信息不对称的情况下,质量好的商品遭受淘汰,而质量差的商品会逐渐占领市场,从而取代质量好的商品,从而导致市场之中充斥着劣质商品。

这和一个经济学名词“劣币驱逐良币”异曲同工,在远古的铸币时代,当那些质量和成色低于法定铸币的货币——“劣币”进入流通领域之后,人们就倾向于将那些价值高的货币——“良币”收藏起来。

最后,良币将被劣币驱逐,市场上就只流通下劣币了。

交易当事人的信息不对称是“劣币驱逐良币”现象存在的基础。

因为如果交易双方对货币的成色或者真伪都已经十分地了解,劣币持有者就很难将手中的劣币用出去,或者,即使能够用出去也只能按照劣币的“实际”而非“法定”价值与对方进行交易。

一般说来,货币是作为一般等价物的特殊商品,当货币的接受方对货币的成色或真伪缺乏信息的时候,就会想办法提供价值更低的交易物,而交易物的需求方也就是支付货币的一方相应地也会想办法用更不足值的货币来进行支付,最终导致整个市场充斥劣币。

在产品市场上,显然卖家比买家拥有更多的信息,因此两者之间的信息是非对称的。

买者肯定不会相信卖者的话,但即使卖家说的天花乱坠。

买者唯一拥有的办法只有压低价格以避免信息不对称带来的风险损失。

因此这样买者出过低的价格也使得卖者不愿意提供高质量的产品,从而使得低质量产品充斥市场,高品质产品被逐出市场,最后整个产业产品市场萎缩退步。

为了更清楚地说明这个现象,我们假设市场中好车与坏车并存,每100 辆二手车中有50 辆质量较好的、50 辆质量较差,质量较好的车在市场中的价值是50 万元,质量较差的价值10万元。

柠檬市场:质量的不确定性与市场机制

2001年诺贝尔经济学奖得主—乔治·阿克洛夫经济学思想述评瑞典皇家科学院于10月10日宣布,将本年度诺贝尔经济学奖授予美国经济学家乔治·阿克洛夫、迈克尔·斯宾塞和约瑟夫·斯蒂格利茨,以表彰他们运用不对称信息理论研究市场经济所取得的成就。

众所周知,诺贝尔经济学奖认可的都是经过实践检验的理论成果,而经济学理论成果经过实践检验被认为是正确的,通常需要20、30年。

此次获奖三人的理论成果主要集中在20世纪70年代。

他们的获奖意味着国际上正式承认其理论具有广泛的应用价值。

瑞典皇家科学院在其新闻公报中称,许多市场都存在信息不对称现象:买卖的一方往往掌握比另一方更多的信息。

借款人比贷款人更了解自己的还贷潜力,企业经理和董事会比股民更了解企业的未来,客户比保险公司更了解他们发生事故的风险率。

而一个市场经济的有效运作,需要买者和卖者之间拥有充分的共同信息。

如果信息不对称现象非常严重,那么就有可能限制市场功能的发挥,在极端情况下,会使整个市场不存在。

此次获奖的三位经济学家分别从产品市场、劳动力市场、保险及资金市场等领域探讨了信息不对称问题,指出市场体制需要完善、设计。

这是对传统经济学的重大突破。

他们的研究揭示了当代信息经济的核心问题,奠定了关于市场经济不对称信息理论的基础,其分析理论用途广泛,既适用于对传统的农业市场的分析研究,也适用于对现代金融的分析研究。

本文主要是对乔治·阿克洛夫的一些主要经济思想进行简单的评述,以便大家更深刻地了解这位世界一流的经济学家。

一、乔治·阿克洛夫生平简介乔治·阿克洛夫(George A.Akerlof)1940年出生于美国康涅狄州纽黑文,现年61岁;1962年,在耶鲁大学获得学士学位;4年后在麻省理工学院获得博士学位。

他曾担任伦敦经济学院货币银行专业的经济学教授、经济顾问委员会高级经济学家、布鲁金斯小组(Brooking Panel)经济问题高级顾问和美国经济联合会副主席;现任加州大学伯克利分校经济学教授。

柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制(中英对照)

The Markets for “Lemons”:Quality uncertainty and The Market Mechanism柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制Geogre A. Akerlof 阿克洛夫一、引言This paper relates quality and uncertainty. The existence of goods of many grades poses interesting and important problems for the theory of markets.(本文论述的是质量和不确定性问题。

现实中存在大量多种档次的物品给市场理论提出了饶有趣味而十分重大的难题)On the one hand, the interaction of quality differences and uncertainty may explain important institutions of the labor market.(一方面,质量差异和不确定性的相互作用可以解释劳动力的重要机制)On the other hand, this paper presents a struggling attempt to give structure to the statement: "Business in under-developed countries is difficult"; in particular, a structure is given for determining the economic costs of dishonesty.(另一方面,本文试图通过讨论获得这样的结论:在不发达国家,商业交易是困难的,其中,特别论及了欺骗性交易的经济成本)Additional applications of the theory include comments on the structure of money markets, on the notion of "insurability," on the liquidity of durables, and on brand-name goods.(本文的理论还可以用来研究货币市场、保险可行性、耐用品的流动性和名牌商品等问题)There are many markets in which buyers use some market statistic to judge the quality of prospective purchases.(在许多市场中,买者利用市场的统计数据来判断他们将要购买的商品的质量)In this case there is incentive for sellers to market poor quality merchandise, since the returns for good quality accrue mainly to the entire group whose statistic is affected rather than to the individual seller. As a result there tends to be a reduction in the average quality of goods and also in the size of the market.(在这种情况下,卖者有动力提供低质量商品,因为某种商品的价格主要取决于所有同类商品质量的统计数据而非该商品的实际质量。

the market for lemons解读

the market for lemons解读

柠檬市场(The Market for Lemons)是一个经济学概念,它指的是信息不对称的市场,即买卖双方对商品或服务的真实信息了解程度不同。

柠檬市场中的买家通常对商品或服务的质量不确定,因此他们可能会根据平均质量来决定价格,从而使得高质量的产品或服务因为价格过高而难以出售,而低质量的产品或服务则可能以高价出售。

这个概念来源于美国俚语中的“柠檬”,表示“次品”或“不中用的东西”。

在柠檬市场中,由于信息不对称,买家往往难以判断商品或服务的质量,因此他们可能会采取平均质量的预期来决定价格。

这种平均质量的预期价格可能会使得高质量的商品或服务难以出售,因为他们无法与低质量的商品或服务区分开来。

柠檬市场的存在对经济效率和市场秩序产生了一定的影响。

它可能导致市场上的优质商品或服务被排挤出市场,而低质量的产品或服务则可能占据主导地位。

这不仅影响了市场的公平性和竞争性,还可能导致市场的萎缩和消失。

为了解决柠檬市场的问题,需要采取一些措施来增加市场的透明度和信息对称性。

例如,政府可以加强监管和信息披露要求,提高市场的透明度;卖家也可以采取一些措施来增加商品或服务的可追溯性和质量保证,从而增强买家的信心。

此外,买家也可以通过提高自身的信息获取能力和风险意识,来降低信息不对称的影响。

柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制(中英对照)

The Markets for “Lemons”:Quality uncertainty and The Market Mechanism柠檬市场:质量的不确定性与市场机制Geogre A、Akerlof 阿克洛夫一、引言This paper relates quality and uncertainty、The existence of goods of many grades poses interesting and important problems for the theory of markets、(本文论述的就是质量与不确定性问题。

现实中存在大量多种档次的物品给市场理论提出了饶有趣味而十分重大的难题)On the one hand, the interaction of quality differences and uncertainty may explain important institutions of the labor market、(一方面,质量差异与不确定性的相互作用可以解释劳动力的重要机制)On the other hand, this paper presents a struggling attempt to give structure to the statement: "Business in under-developed countries is difficult"; in particular, a structure is given for determining the economic costs of dishonesty、(另一方面,本文试图通过讨论获得这样的结论:在不发达国家,商业交易就是困难的,其中,特别论及了欺骗性交易的经济成本)Additional applications of the theory include comments on the structure of money markets, on the notion of "insurability," on the liquidity of durables, and on brand-name goods、(本文的理论还可以用来研究货币市场、保险可行性、耐用品的流动性与名牌商品等问题)There are many markets in which buyers use some market statistic to judge the quality of prospective purchases、(在许多市场中,买者利用市场的统计数据来判断她们将要购买的商品的质量)In this case there is incentive for sellers to market poor quality merchandise, since the returns for good quality accrue mainly to the entire group whose statistic is affected rather than to the individual seller、As a result there tends to be a reduction in the average quality of goods and also in the size of the market、(在这种情况下,卖者有动力提供低质量商品,因为某种商品的价格主要取决于所有同类商品质量的统计数据而非该商品的实际质量。

柠檬市场:质量的不确定性与市场机制

2001年诺贝尔经济学奖得主—乔治·阿克洛夫经济学思想述评瑞典皇家科学院于10月10日宣布,将本年度诺贝尔经济学奖授予美国经济学家乔治·阿克洛夫、迈克尔·斯宾塞和约瑟夫·斯蒂格利茨,以表彰他们运用不对称信息理论研究市场经济所取得的成就。

众所周知,诺贝尔经济学奖认可的都是经过实践检验的理论成果,而经济学理论成果经过实践检验被认为是正确的,通常需要20、30年。

此次获奖三人的理论成果主要集中在20世纪70年代。

他们的获奖意味着国际上正式承认其理论具有广泛的应用价值。

瑞典皇家科学院在其新闻公报中称,许多市场都存在信息不对称现象:买卖的一方往往掌握比另一方更多的信息。

借款人比贷款人更了解自己的还贷潜力,企业经理和董事会比股民更了解企业的未来,客户比保险公司更了解他们发生事故的风险率。

而一个市场经济的有效运作,需要买者和卖者之间拥有充分的共同信息。

如果信息不对称现象非常严重,那么就有可能限制市场功能的发挥,在极端情况下,会使整个市场不存在。

此次获奖的三位经济学家分别从产品市场、劳动力市场、保险及资金市场等领域探讨了信息不对称问题,指出市场体制需要完善、设计。

这是对传统经济学的重大突破。

他们的研究揭示了当代信息经济的核心问题,奠定了关于市场经济不对称信息理论的基础,其分析理论用途广泛,既适用于对传统的农业市场的分析研究,也适用于对现代金融的分析研究。

本文主要是对乔治·阿克洛夫的一些主要经济思想进行简单的评述,以便大家更深刻地了解这位世界一流的经济学家。

一、乔治·阿克洛夫生平简介乔治·阿克洛夫(George A.Akerlof)1940年出生于美国康涅狄州纽黑文,现年61岁;1962年,在耶鲁大学获得学士学位;4年后在麻省理工学院获得博士学位。

他曾担任伦敦经济学院货币银行专业的经济学教授、经济顾问委员会高级经济学家、布鲁金斯小组(Brooking Panel)经济问题高级顾问和美国经济联合会副主席;现任加州大学伯克利分校经济学教授。

“柠檬”市场:质量不确定和市场机制

《“柠檬”市场:质量不确定性与市场机制》一、课堂讲解作者乔治·阿克洛夫的写作风格很鲜明,他喜欢用简单模型、简单事例说明重要的经济学问题。

他毕业于麻省理工大学,在学期间十分关注种族歧视问题、心理学以及人类学,他的这些关注点在文中也有一些体现,例如,少数民族就业、道德风险等。

我们在学习这篇文章时,不仅要了解作者观点,还要与前一篇文章《信息经济学》联系起来读。

其实无论阅读那篇经济学文章,我们都应该将文章中的理论与客观实际相联系,将文中理论放置于整个经济学框架中,带着全局观去看问题。

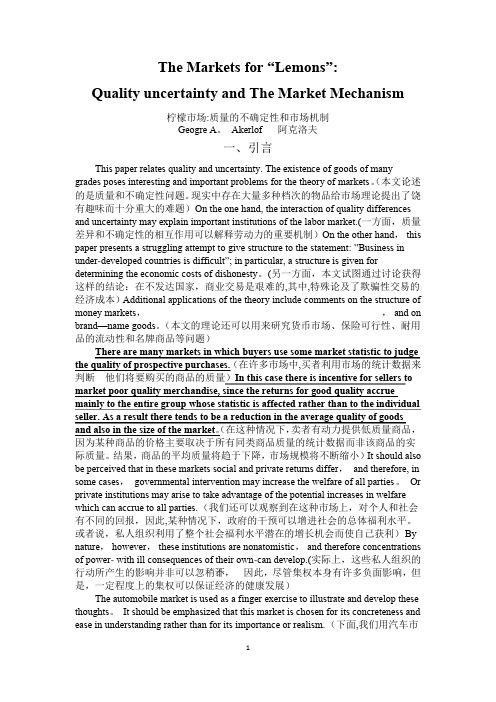

乔治从在引言中就阐明观点:质量不确定性光靠市场机制是无法解决的,还需要其他补充机制。

这其实就是一个假说,作者接下来要为自己的假说进行证实。

我们先关注这样几个问题:这篇论文的题目中“柠檬”是什么?柠檬就是低质量的商品;那什么是“柠檬”市场?它就是市场中充斥着低质量商品,而高质量商品不被交易的情形。

他首先举出一个二手车市场的例子。

二手车市场中汽车质量参差不齐,但由于买者在买车时无法区分汽车质量,所以无论高质量车还是“柠檬”出同样价格购买。

但卖者对汽车质量情况了于指掌,这就产生了信息不对称,此时卖者肯定先卖出质量低的车,高质量车根本不会卖出。

这样,低质量车就将高质量车逐出市场,最终二手车市场将不复存在。

这是为什么呢?因为低质量车会继而将质量较好、质量中等、质量再稍差的汽车依次逐出市场。

如图所示,一般来说,质量越好价格越高,但由于信息不对称,所有质量高于Q1的汽车,即质量差的车将质量高于Q1的车逐降到P2,同上次一样,质量在Q1到Q2之间的汽车逐出市无法成交,该市场最终不复存在。

本文还举出很多“柠檬”市场的例证。

如,保险,无论在哪一价格水平上,保险合同的购买者都有太多“柠檬”,导致保险公司的承担的过多本不应由它承担的风险,保险公司将不会继续开展此类保险业务;再如,少数民族就业问题,招聘公司由于不了解少数民族求职者的工作能力、社会背景、道德素质等方面信息,故为少数民族求职者提供同一薪酬,这使其中能力强者放弃进入该公司的机会,而能力弱者或许留在这个人才市场中寻找职位。

柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制(中英对照)

The Markets for “Lemons”:Quality uncertainty and The Market Mechanism柠檬市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制Geogre A。

Akerlof 阿克洛夫一、引言This paper relates quality and uncertainty. The existence of goods of many grades poses interesting and important problems for the theory of markets。

(本文论述的是质量和不确定性问题。

现实中存在大量多种档次的物品给市场理论提出了饶有趣味而十分重大的难题)On the one hand, the interaction of quality differences and uncertainty may explain important institutions of the labor market.(一方面,质量差异和不确定性的相互作用可以解释劳动力的重要机制)On the other hand,this paper presents a struggling attempt to give structure to the statement: ”Business in under-developed countries is difficult”; in particular, a structure is given for determining the economic costs of dishonesty。

(另一方面,本文试图通过讨论获得这样的结论:在不发达国家,商业交易是艰难的,其中,特殊论及了欺骗性交易的经济成本)Additional applications of the theory include comments on the structure of money markets,,and on brand—name goods。

柠檬市场的名词解释

柠檬市场的名词解释在日常生活中,我们经常听到柠檬市场这个词语,但很多人可能并不了解它的具体含义。

柠檬市场是一个常用的经济术语,用来形容市场的供求关系和价格波动。

柠檬市场一词最早由美国经济学家乔治·阿克罗夫特(George Akerlof)在1970年的一篇学术论文中首次提出。

他通过研究二手车市场发现,由于信息不对称,卖家往往了解比买家更多有关二手车质量的信息。

这样一来,卖家有可能故意隐瞒车辆的问题,诱使买家购买质量较差的车辆,从而导致市场交易不公平。

柠檬市场中的“柠檬”一词在此处并非指柠檬水或柠檬果实,而是指商品市场中存在问题的物品。

这些物品可能存在有缺陷、低质量或隐藏问题等情况。

卖家往往会有动机出售这些产品或信息,以获取利润,而买家则很难辨别真相。

在柠檬市场中,由于买家很难判断商品的真实价值,他们更容易支付比产品真实价值更高的价格。

这种供求机制的扭曲导致柠檬市场的不公平和低效。

当柠檬市场存在时,买家往往会变得谨慎,对市场失去信心,降低交易的频率,从而影响整个市场的运作和发展。

为了解决柠檬市场问题,商家和政府采取了一系列措施。

例如,商家可以通过质量认证、产品保修和退换货政策来增加产品质量的透明度和可信度。

此外,政府可以颁布法律法规,规范市场行为,保护消费者权益,防止柠檬市场的形成。

柠檬市场的概念也可应用于金融市场和劳动力市场等领域。

在金融市场中,柠檬市场指的是存在对金融产品和服务信息不对称的情况。

例如,股票市场中,内幕交易者可能会利用未公开信息获取不公正利益,从而损害其他投资者的利益。

在劳动力市场中,雇主可能有更多关于潜在雇员的信息,而雇员可能对工作条件和薪酬待遇了解不足,使得劳动力市场存在信息不对称的情况,导致资源配置不均衡。

柠檬市场的名词解释告诉我们,市场中信息的不对称性可能导致供求关系扭曲,阻碍交易的顺利进行。

为了提高市场效率和公平性,我们需要加强信息透明度,通过建立有效的监管机制和消费者保护措施来减少信息不对称所带来的不利影响。

我国市场经济中的“柠檬市场”问题分析

我国市场经济中的“柠檬市场”问题分析引言柠檬市场问题是指在市场经济中存在信息不对称的情况下,卖方因对自己所出售的商品或服务的质量、性能等信息了解更多,而买方知之甚少,从而导致市场失灵的现象。

这种信息的不平衡使得卖方有可能通过欺诈行为获取不当利益,而买方在交易后发现所购商品的质量低于预期或者存在其他问题,从而造成损失。

在我国市场经济中,柠檬市场问题十分突出,尤其在一些非标准化产品或服务的交易中,买方往往难以获取到足够的信息来做出明智的选择。

因此,本文将对我国市场经济中的柠檬市场问题进行分析,探讨其原因和可能的解决方案。

问题的原因1.信息不对称:在我国市场经济中,买方往往无法获取到充足的关于商品或服务质量、性能等方面的信息。

卖方往往会以虚假宣传、隐瞒信息等手段误导买方,使得买方无法准确评估商品或服务的价值。

2.法律法规不健全:我国市场监管体系尚不完善,相关法律法规还存在一些漏洞。

一些不法商家可以利用这些漏洞规避法律责任,从而得以继续从事欺诈行为。

3.缺乏有效的监管和执法:尽管我国有一定的市场监管和执法机构,但由于资源有限和执法效率低下,很多欺诈行为得不到及时的制止和处罚。

影响和后果柠檬市场问题给我国的经济发展和市场信心造成了一定的负面影响。

1.损害消费者权益:柠檬市场问题使得消费者往往购买到质量不合格的商品或服务,导致消费者的利益受损。

2.扭曲市场竞争:市场失灵导致商家没有足够的动力去提供优质的商品和服务,从而扭曲了市场竞争环境。

3.抑制消费需求:消费者对于市场中存在柠檬问题的担忧,降低了他们对于购买商品和服务的需求,进一步抑制了消费活动。

解决方案针对柠檬市场问题,我国应采取以下解决方案:1.健全监管体系:完善市场监管机制,加大对于市场欺诈行为的监管力度,加强对商家的监督检查和处罚力度。

2.加强信息公开:建立商品和服务质量信息的公开透明平台,让消费者能够更加准确地了解商品和服务的质量和性能。

3.建立信誉评价体系:推动建立消费者对商家信誉的评价体系,鼓励消费者进行评价和投诉,提高商家的信誉风险。

柠檬模型概述

《柠檬市场:产品质量的不确定性与市场机制》阿科洛夫1.柠檬市场(The Market for Lemons)的定义也称次品市场,也称阿克洛夫模型。

是指信息不对称的市场,即在市场中,产品的卖方对产品的质量拥有比买方更多的信息。

在极端情况下,市场会止步萎缩和不存在,这就是信息经济学中的逆向选择。

柠檬市场效应则是指在信息不对称的情况下,往往好的商品遭受淘汰,而劣等品会逐渐占领市场,从而取代好的商品,导致市场中都是劣等品。

2.柠檬市场的表现。

柠檬市场的存在是由于交易一方并不知道商品的真正价值,只能通过市场上的平均价格来判断平均质量,由于难以分清商品好坏,因此也只愿意付出平均价格。

由于商品有好有坏,对于平均价格来说,提供好商品的自然就要吃亏,提供坏商品的便得益。

于是好商品便会逐步退出市场。

由于平均质量有因此下降,于是平均价格也会下降,真实价值处于平均价格以上的商品也逐渐退出市场,最后就只剩下坏商品。

在这个情况下,消费者便会认为市场上的商品都是坏的,就算面对一件价格较高的好商品,都会持怀疑态度,为了避免被骗,最后还是选择坏商品。

这就是柠檬市场的表现。

乔治·阿克尔罗夫在其发表的《柠檬市场:产品质量的不确定性与市场机制》的论文中举了一个二手车市场的案例。

指出在二手车市场,显然卖家比买家拥有更多的信息,两者之间的信息是非对称的。

买者肯定不会相信卖者的话,即使卖家说的天花乱坠。

买者唯一的办法就是压低价格以避免信息不对称带来的风险损失。

买者过低的价格也使得卖者不愿意提供高质量的产品,从而低质品充斥市场,高质品被逐出市场,最后导致二手车市场萎缩。

(假设)阿克洛夫用一个简单的例子来说明他的观点。

假设一种产品以不可分割的单位进行买卖,并且具有固定比例λ和1-λ的低和高两种质量。

每个买者潜在地有兴趣购买一辆汽车,但在购买时无法识别两种质量之间的区别。

所有的买者对两种质量作出相同的估价:对买者来说低质量的车值WL美元,而高质量的车值WH美元,且WH>WL。

《“柠檬市场”质量的不确定性和市场机制》读书笔记

Akerlof ——《“柠檬市场”:质量的不确定性和市场机制》读书笔记本文试图将商品质量和不确定性联系在一起,考察不诚信行为的经济成本。

利用简单的均衡模型推导,在格雷欣法则基础上解释二手车柠檬市场中,买卖双方由于信息不对称最终导致市场消失的情况。

引言作者主要试图讲述本文的主要内容和观点:由于买家往往会通过市场统计数据得到对该市场中商品的预期质量,因此卖家就有降低自己产品质量浑水摸鱼的动机,但这样的想法最终会带来市场中整体商品质量的下降和市场规模的萎缩;社会回报不同于私人回报,因此政府干预以集中力量可能是有效的;选择汽车市场作为研究对象的原因;理论基础作者认为,“劣币驱逐良币”的格雷欣法则是基于买卖双方都知晓两种商品质量的基础之上的,而在二手车市场中,二手车的质量好坏只有卖方知道,买方只能评价市场的平均水平(如假设市场中好车的概率是q ),以相同的价格面对包含好车坏车的市场。

前提假设新车比旧车质量高——否则不会有二手车交易需求与供给函数:假设一个人对于二手车的需求强烈地依赖于汽车价格p 和二手车市场的平均质量 µ Q d =D(p,μ)而卖方对于二手车的供应和平均质量均取决于价格S =S(p)μ=μ(p)因此有:S(p)=D(p,μ(p))当价格下降平均质量也会下降,最终没有任何交易发生效用函数:假设有两组交易者,组1和组2,各自的效用函数分别为:U 1=M +∑x i n i=1U 2=M +∑32⁄x i n i=1此效用函数可以将买卖双方相区分,拥有二手车的边际效用高的组2即买方。

其中M 是除汽车以外的消费,x i 是i 车的质量对于该效用函数有几点假设基础假设:1.为使分析简便采取线性效用函数;2.U 的边际效用不变,即增加一辆车的消费带来的效用是相同的;3.消费者追求期望效用最大化;模型假设:4.交易者1拥有N 辆质量为x 并且服从均匀分布的汽车,交易者2没有汽车(这意味着1为卖方,2为买方)5.将其他商品M 的价格视为1信息不对称情况Y 为收入,则D 1=Y 1p ⁄,μp ⁄>1 ;D 1=0,μp ⁄<1表示当车的价值(质量)高于出价时,卖方组会收回所有汽车;当车的价值低于出价时,此时卖方卖车是获利的,因此会把旧车全都变卖,故需求为0。

柠檬市场原理

柠檬市场原理

柠檬市场原理,也被称为阻碍市场,是指在信息不对称的情况下,市场上出现低质量产品的现象。

柠檬市场原理最早由经济学家乔治·阿克洛夫和迈克尔·斯佩尔

曼提出。

在柠檬市场中,买方对于商品的质量了解有限,而卖方则掌握了更多的信息。

卖方往往会选择把低质量的商品推向市场,而买方则对此一无所知。

这种信息不对称会导致市场的失败和资源浪费。

买方无法判断商品的真实价值,因此会对所有商品的价值进行平均估计,而卖方则会因此而放弃创造高质量的商品。

最终,市场上的商品质量会不断下降,买方也会逐渐失去信心,从而导致市场的衰退。

为了解决柠檬市场问题,可以采取一些策略。

例如,政府可以设立监管机构来监督市场,提供公正的信息和评估机制。

此外,消费者也可以通过评论、评分和口碑来共享自己的购买经验,以增加市场的透明度。

总体来说,柠檬市场原理揭示了信息不对称对市场运行的影响,提出了解决市场失灵问题的方向。

通过增加信息的透明度和强化监管措施,可以减少柠檬市场的发生,促进市场的正常运行。

柠檬市场理论

柠檬市场理论"柠檬"在美国俚语中表示"次品"或"不中用的东西"."柠檬"市场是次品市场的意思.当产品的卖方对产品质量比买方有更多信息时.柠檬市场会出现,低质量产品会不断驱逐高质量产品。

著名经济学家乔治·阿克尔罗夫以一篇关于"柠檬市场"的论文摘取了2001年的诺贝尔经济学奖,并与其他两位经济学家一起奠定了"非对称信息学"的基础。

该论文曾经因为被认为“肤浅”,先后遭到三家权威的经济学刊物拒绝。

几经周折,该论文才得以在哈佛大学的《经济学季刊》上发表,结果立刻引起巨大反响。

柠檬市场也称次品市场,是指信息不对称的市场,即在市场中,产品的卖方对产品的质量拥有比买方更多的信息。

在极端情况下,市场会止步萎缩和不存在,这就是信息经济学中的逆向选择。

柠檬市场效应则是指在信息不对称的情况下,往往好的商品遭受淘汰,而劣等品会逐渐占领市场,从而取代好的商品,导致市场中都是劣等品. [编辑本段]二手车市场的案例阿克罗夫在其1970年发表的《柠檬市场:产品质量的不确定性与市场机制》中举了一个二手车市场的案例。

指出在二手车市场,显然卖家比买家拥有更多的信息,两者之间的信息是非对称的。

买者肯定不会相信卖者的话,即使卖家说的天花乱坠。

买者惟一的办法就是压低价格以避免信息不对称带来的风险损失。

买者过低的价格也使得卖者不愿意提供高质量的产品,从而低质品充斥市场,高质品被逐出市场,最后导致二手车市场萎缩。

[编辑本段]信息不对称与柠檬市场要削减信息不对称,沟通是惟一的手段。

在信息社会中,诚实也是一种工具。

因为信息不完整和信息不对称,人与人之间需要沟通对话,以取得信息。

而且,因为不知道别人提供的信息是真是假,只好借着“对方是否诚实”来间接地解读对方所提供的信息。

因此,“诚实”这种人性中的德性,成为了人际交往中的一种“工具”。

柠檬市场

1970年,31岁的著名经济学家乔治·阿克尔洛夫发表了《柠檬市场:质量不确定和市场机制》的论文,成为研究信息不对称理论的最经典文献之一,开创了逆向选择理论的先河。

他凭着该论文摘取了2001年的诺贝尔经济学奖,并与其他两位经济学家一起奠定了"非对称信息学"的基础。

在论文里,阿克尔洛夫首次提出了“柠檬市场”的概念(柠檬一词在美国俚语中意思为“次品”或不中用的东西),现在“柠檬”已成为每位经济学家最为熟知的一个隐喻。

柠檬市场也称次品市场,是指信息不对称的市场,即在市场中,产品的卖方对产品的质量拥有比买方更多的信息。

在极端情况下,市场会止步萎缩和不存在,这就是信息经济学中的逆向选择。

阿克罗夫在其发表的《柠檬市场:产品质量的不确定性与市场机制》中举了一个二手车市场的案例。

指出在二手车市场,显然卖家比买家拥有更多的信息,两者之间的信息是非对称的。

买者肯定不会相信卖者的话,即使卖家说的天花乱坠。

买者惟一的办法就是压低价格以避免信息不对称带来的风险损失。

买者过低的价格也使得卖者不愿意提供高质量的产品,从而低质品充斥市场,高质品被逐出市场,最后导致二手车市场萎缩。

柠檬市场的存在是由于交易一方并不知道商品的真正价值,只能通过市场上的平均价格来判断平均质量,由于难以分清商品好坏,因此也只愿意付出平均价格。

由于商品有好有坏,对于平均价格来说,提供好商品的自然就要吃亏,提供坏商品的便得益。

于是好商品便会逐步退出市场。

由于平均质量有因此下降,于是平均价格也会下降,真实价值处于平均价格以上的商品也逐渐退出市场,最后就只剩下坏商品。

在这个情况下,消费者便会认为市场上的商品都是坏的,就算面对一件价格较高的好商品,都会持怀疑态度,为了避免被骗,最后还是选择坏商品。

这就是柠檬市场的表现。

[编辑]信息不对称与柠檬市场信息不对称是造成柠檬市场上诸多不良现象的原因,但是怎样解决这个问题,“柠檬市场”上要削减信息不对称,沟通是惟一的手段。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

“柠檬”市场:质量的不确定性和市场机制乔治·阿克洛夫关键词:信息经济学;质量不确定性;市场机制;“柠檬市场”;信息不对称一. 引言本文论述的是质量和不确定性问题。

多种档次的物品给市场理论提出了有趣而又重要的问题。

一方面,质量差异和不确定性的相互作用可以解释某些重要的劳动市场制度。

另一方面,本文力求对如下主张,即“在不发达国家做生意是因难的”给出一个模型。

尤其是要给出一个用于确定不诚实的经济成本的模型。

理论的应用还包括对货币市场结构、不可保险性、耐用品的流动性以及品牌产品的评论。

在许多市场中,购买者总是利用某些市场统计数据来判断欲购商品的质量。

在这种情况下,销售者就有动机销售劣质商品,因为从优质商品中受益的主要是其统计数据受影响的销售者整体而不是单个销售者。

结果是,产品的平均质量往往会下降,市场规模相缩小。

还应该看到的是,在这些市场中,社会收益和私人收益是有差别的,因此,在某些情况下,政府干预可以增加各方的福利。

或者是,私人制度可能会产生,以利用各方潜在的福利增长。

但是,这些制度并不是孤立分散的(Nonatomistic)。

因此,权力的集中有可能形成——这就是制度本身带来的不良后果。

本文试图用汽车市场来阐述上述思想。

应该强调的是,之所以选择汽车市场,是因为它非常具体并且易于理解,而不是因为它的重要性或现实性。

二. 以汽车为例的模型1.汽车市场旧车市场的例子说明了问题的本质。

用以解释这种现象的常见理由是,拥有一辆新车可以带来快乐,而我们却给出了另一种解释。

假定(为了说明问题,而不是现实情况)市场中只有4种汽车,即新车和旧车,好车和次品车(在美国,也称之为“柠檬”)。

新车有可能是好车,也有可能是次品车;当然,旧车也是如此。

人们在上述市场中购买一辆新车时,并不知道他所购买的汽车是好车还是次品车。

但是,假定在生产出来的汽车中,好车的比例为q, 次品车的比例为1-q. 则买主必定知道买到好车的概率为q, 买到次品车的概率为1-q.然而。

在对某辆汽车拥有一段时间后,车主就可以了解该车的质量,也就是说,车主会重新估计其汽车的概率是次品车,这一估计要比原来的估计更准确。

这就形成了一种可得信息的不对称:现在卖主比买主更了解汽车的质量。

但是,好车和次品车仍然以相同的价格出售——因为买主不能区别好车和次品车。

显然,旧车与新车的价值不会一样——如果旧车的价值和新车的一样,那么,在好车的概率更高,次品车的概率更低的情况下,以新车的价格出售一辆次品车,然后买回一辆新车肯定是有利可图的。

因此,好车的车主被锁定(Locked in)了。

实际上,他不仅得不到其汽车的真实价值,而且也得不到新车的预期价值。

格雷欣法则以另一种方式出现了。

绝大多数出售的汽车可能是次品车,好车的买卖可能根本就不存在。

次品车倾向于将好车挤出市场(这与劣币驱逐良币极其相依)。

但是,与格雷欣法则不尽相同的是,次品车挤掉好车的原因在于它们的售价与好车的售价一样。

类似地,劣币驱逐良币的原因是这两种货币的交换率是一样的。

但是,次品车的售价与好车的售价一样是因为买主不能区分好车和次品车,然而在格雷欣法则中,买主和卖主部有可能可以区分劣币和良币。

因此,上述两种情况极其相像,但并不完全相同。

2.不对称信息由上可见,好车有可能被次品车挤出市场。

但是,在有不同档次商品的连续市场中,甚至更糟贱的异常现象也会存在。

一个很有可能出现的现象是,次品格不太差的产品挤出市场,不太差的产品又将中档产品挤出市场,中档产品则将不太好的产品挤出市场,不太好的产品格高档产品挤出市场,依次类推,最终不会有任何市场存在。

我们可以假定,如果对旧车的需求严格地取决于两个变量——汽车的价格p 和旧车的平均质量,则旧车的需求函数可以表述如下:.旧车的供给和平均质量将取决于价格,也即=, S=S(p).在均衡状态中,给定旧车的平均质量,则其供给必定等于需求,即S (P)=D(p,u(P)).如果价格下降,平均质量通常也将下降。

很有可能在任何价格水平上,不会有物品买卖。

上述例子可以从效用理论中推导出来。

假定只有两组交易商,组1和组2。

让组1的效用函数为:. 式中的M表示除汽车以外的其他消费品,表示i辆汽车的质量,n表示汽车的数量。

同样地,让组2的效用函数为, 式中的M,和n的含义与上式相同。

上述效用因数有三点需要加以说明:(1) 如果不使用线性效用(比如说使用对数函数),我们就无需处理代数方面的复杂问题。

(2) 使用线性效用使得我们可以集中讨论信息不对称的影响;由于效用函数是凹的,我们将不得不同时处理不确定性对风险变化的一般影响以及我们希望在这里进行讨论的特殊影响。

(3) U1和U2都有奇次的特征(Odd Characteristic),即增加第二辆汽车或者说第k辆汽车带来的效用与增加第一辆汽车带来的效用是一样的。

为了不偏离小心论题,我们再次忽略了现实情况。

为了进一步展开讨论.假定:(1) 两组交易商都是预期效用的冯·诺依曼-摩根斯特恩最大化者(Von Neumann-Morgenstern Maximizers);(2) 组1有N辆汽车,这些汽车的质量x呈均匀分布,其中0≤x≤2,组2没有汽车;(3) 其他消费品M的价格为1。

用Y1和Y2分别表示组1和组2中所有交易商的收入(包括汽车的销售收入)。

对旧车的需求将等于两组交易商的需求之和。

如果忽略不可分性(Indivisibilities),则组1的交易商对汽车的需求将是:D1=Y1/P, u/P>1D1=0, u/P<1组1中的交易商提供的汽车供给为S2=pN/2, P≤2(1)这些汽车的平均质量为:L1=P/2 (2)(为了推导出等式(1)和(2),我们假定汽车质量是均匀分布的)。

同样地,组2中的交易商对旧车的需求为:D2=Y2/p, 3u/2>pD2=0, 3u/2<p供给为:S2=0.因此,总需求D(p,u)为:如果u<p<3u/2,则D(p, u)=Y2/p;如果p>3u/2,则D(p,u)=0.但是,如果价格为p, 平均质量为p/2, 在任何价格水平下都不会有交易发生:尽管在0-3之间的任何给定的价格水平下,组1的交易商愿意以组2的交易商愿意购买的价格出售汽车。

3.对称信息我们可以将上述情况与对称信息的情况比较一下。

假定所有汽车的质量都是均匀分布的,且. 此时,需求曲线和供给曲线可以表述如下:供给曲线为:S(p)=N, p>1S(p)=0, p<1需求曲线为:D(p)=(Y2+Y1)/p, p<1D(p)=(Y2/p) , 1<p<3/2D(p)=0 , p>3/2在均衡状态中,如果Y2<N, p=1 (3)如果2Y2/3<N<Y2/3, p=Y2 (4)如果N<2Y2/3, p=3/2 (5)如果N<Y2,在信息不对称的情况下,效用可以增加N/2单位(如果N>Y2组2的交易商拥有的收入足以购买所有的汽车,此时,效用可以增加Y2/2单位)。

最后,应当提出的是,在上述例子中,如果组1和组2的交易商对单个汽车的质量打相同的概率估计——尽管这些估计在各辆汽车之间有所不同——那么,等式(3),(4)和(5)仍可以说明均衡状态的轻微变化:此时,p将等于某一特定质量的汽车的预期价格。

三. 案例和应用1.保险一个众所用知的事实是,65岁以上的人很难买到医疗保险。

这自然引发了人们的疑问:为什么保费不上升以与其风险相匹配呢?我们的答案是,如果保费上升,那些为自己投保的人将是越来越确信自己需要保险的人。

体检中的错误,医生对老年病人的同情.等等,都使保险申请人比保险公司更容易评估相关风险。

结果是保险申请人的平均健康状况将随保费的上升而恶化——这可能导致在任何保费水平下都不会有保险交易(Insurance Sales)。

这与上述汽车的例子极其相似,在那里,供应的旧车平均质量随价格的下降而下降。

这也与保险教科书中的解释相吻合;一般来说.年龄实际上超过65岁的人买不到保单。

定期保费(Term Premiums)是如此之高,只有那些最悲观(也即健康状况最差)的被保险人才会认为这样的保费是有吸引力的。

因此,在上述年龄的人群中存在着严重的逆向选择问题。

②统计数据与上述结论并不矛盾。

对健康保险的需求随年龄的增大而上升,1956年对2809户家庭的98人所做的全国抽样调查表明,45-54岁人群的医院保险覆盖范围为63%,而65岁以上人群的医院保险覆盖范围为31%。

而且令人吃惊的是,这一调查还发现,55—64岁的男性其平均医疗支出为朋美元,65岁以上的男性其平均医疗支出为77美元。

③但是,这两个人群的非保险医疗支出分别为105美元和80美元,保险医疗支出分别为105美元和70美元。

结论是饶有兴味的,保险公司在向老年人提供保险时特别谨慎。

“逆向选择”理论在各种保险中部有可能存在。

在沃顿商学院的一本保险教科书中有这样一段叙述:潜在的逆向选择存在于如下事实中:定期健康保险保单的持有人可能因年龄的增大和保费的增加而决定终止他们的保险条款(coverage)。

这一行动可施舍使保险人面临着低于平均风险的束到期风险比例和未到期索赔比例都可能高于预期。

只要个人或团体被保险人有决定是否购买保险的自由,有选择保险金额或保险计划的自由,以及作为保单的持有人有维持或停止保险的自由,逆向选择就会出现(或者至少是有可能出现)。

④团体保险(Group Insurance)是美国最普通的医疗保险形式,其服务对象是身体健康的人,因为通常来说,充分健康是就业的前提条件。

同时.这也意味着那些最需要医疗保险的人几乎得不到医疗保险,因为保险公司也有他们自己的“逆向选择”。

这是支持老年保健医疗制度(Medicare)的一个主要理由。

⑤从成本收益(Cost Benefit)的角度来看,老年保健医疗制度有可能取得成功(Pay off):因为很有可能的是,该市场中的每个人都愿意支付其预期的保健医疗费用并购买保险,但是没有任何保险公司愿意出售保单——因为不管保费的水平如何,都会有大量健康状况不佳的人购买保单。

从这一观点来看,老年医疗保健制度的福利经济学分析完全类似于我们在澡堂上对公路公共支出的分析。

2.少数民族的就业次品理论还可用来说明少数民族的就业问题。

雇主可以拒绝雇用少数民族的人就任某些工作。

这种决策可能不是非理性的或者是有偏见的,相反它可能是出于利润最大比的需要。

因为种族可以作为一种良好的统计数据(Statistic),用来判断求职者的社会背景,学历以及一般工作能力。

良好的学历可以替代种族这种统计数据。

通过将学生按年级排列,学历制度(Schooling System) 可以比其他表面特征更好地反映一个人的素质*正如T.w.舒尔茨论述的那样,“教育机构发现并培养未来的人才。