2016年澳洲国立大学商学院

澳洲最好的大学排名前十

澳洲最好的大学排名前十澳大利亚各著名城市都有哪些知名大学?对于一些赫赫有名的大学,你应该听说过。

在澳洲著名大学中,哪一所学校的排名是位居榜首的呢?下面是小编给大家整理的澳洲著名的大学排名,欢迎阅读。

澳洲著名的大学排名榜澳洲著名的大学排名1:澳大利亚国立大学澳大利亚国立大学是今年澳大利亚排名第1以及世界排名第22位的学校,澳大利亚国立大学位于澳大利亚的首都城市堪培拉。

澳大利亚国立大学是唯一一所由澳大利亚议会创建的大学,不同于澳大利亚其它的公立大学是由各地州议会立法设立。

澳大利亚国立大学有超过22,500名学生在此就读,并且在澳大利亚国立大学的校友和教师间已经产生了六位诺贝尔奖得主。

澳大利亚国立大学是澳大利亚八大名校之一,在大洋洲享有特殊的学术地位。

澳大利亚国立大学有人文艺术和社会科学院、物理和数学科学院、医学生物和环境学院、工商和经济学院、工程和计算机科学学院、亚洲和太平洋学院和法律学院这七大学院。

在澳大利亚国立大学的学生中,本科生较少,以研究生为主,学生总数不多,但学术气氛浓厚,学术水平极高。

澳洲著名的大学排名2:墨尔本大学墨尔本大学继续保持了其位于世界排名第42位的位置,墨尔本大学成立于1853年,是澳大利亚第二古老的大学。

墨尔本大学的校友包括四位澳大利亚总理,并且墨尔本大学也产生了九位诺贝尔奖获得者。

墨尔本大学也是澳大利亚八校联盟中唯一不认可中国高考成绩的大学。

是不是犹豫如何在澳大利亚国立大学和墨尔本大学这两所顶尖大学之间进行选择?你可以查看店铺为大家进行的澳大利亚国立大学和墨尔本大学的比较。

墨尔本大学位于澳大利亚城市墨尔本,墨尔本连续多年被联合国人居署评为“全球最适合人类居住的城市”。

墨尔本大学的优势专业包括有法学、医学、金融与会计、建筑学、工程学、计算机科学等等,这些专业全部都位于世界前50名中,这也是澳大利亚唯一一所能够做到这些的大学。

澳洲著名的大学排名3:悉尼大学悉尼大学今年位列澳大利亚大学排名第3位,并且与美国的纽约大学一起并列世界大学排名第46位。

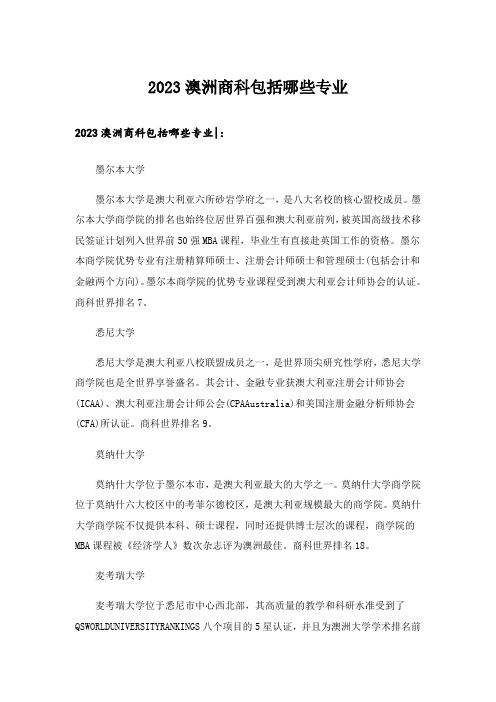

2023大学_澳洲商科包括哪些专业

2023澳洲商科包括哪些专业2023澳洲商科包括哪些专业|:墨尔本大学墨尔本大学是澳大利亚六所砂岩学府之一,是八大名校的核心盟校成员。

墨尔本大学商学院的排名也始终位居世界百强和澳大利亚前列,被英国高级技术移民签证计划列入世界前50强MBA课程,毕业生有直接赴英国工作的资格。

墨尔本商学院优势专业有注册精算师硕士、注册会计师硕士和管理硕士(包括会计和金融两个方向)。

墨尔本商学院的优势专业课程受到澳大利亚会计师协会的认证。

商科世界排名7。

悉尼大学悉尼大学是澳大利亚八校联盟成员之一,是世界顶尖研究性学府,悉尼大学商学院也是全世界享誉盛名。

其会计、金融专业获澳大利亚注册会计师协会(ICAA)、澳大利亚注册会计师公会(CPAAustralia)和美国注册金融分析师协会(CFA)所认证。

商科世界排名9。

莫纳什大学莫纳什大学位于墨尔本市,是澳大利亚最大的大学之一。

莫纳什大学商学院位于莫纳什六大校区中的考菲尔德校区,是澳大利亚规模最大的商学院。

莫纳什大学商学院不仅提供本科、硕士课程,同时还提供博士层次的课程,商学院的MBA课程被《经济学人》数次杂志评为澳洲最佳。

商科世界排名18。

麦考瑞大学麦考瑞大学位于悉尼市中心西北部,其高质量的教学和科研水准受到了QSWORLDUNIVERSITYRANKINGS八个项目的5星认证,并且为澳洲大学学术排名前8。

麦考瑞大学是澳大利亚第一所开设精算课程的大学,麦考瑞大学在以金融,精算,会计为代表的商科领域享有盛名。

其中会计学硕士是麦考瑞大学的优势专业,每年都会有大批中国留学生到麦考瑞大学攻读这一专业,商科世界排名51~100。

迪肯大学迪肯大学位于澳大利亚维多利亚州墨尔本市,是一所大型的综合性学府,尤其在教育学、心理学、信息技术、传媒学、建筑学等领域在澳大利亚处于领先地位。

迪肯大学商学院开设会计(CPA课程)、市场营销、金融、国际商务、MBA、电子商务、保险、CPA/MBA课程。

澳洲商科热门专业有哪些:市场营销市场营销专业的澳洲毕业生几乎在所有行业都能找到大量的职位需求,尤其在房地产、快速消费品、健康保健、休闲食品、通讯、消费电子、电子商务等行业大量需要一流的市场营销人才。

UNIDROIT_Principles of International Commercial Contracts -blackletter2016-chinese

应仅影响代理人和第三方之间的关系。

第 2.2.4 条 (隐名代理) (1)如果代理人在其权限范围内行事,但第三方既不知道也不应知道代理 人是以代理人身份行事,则代理人的行为仅影响代理人与第三方之间的关系。 (2)然而,如果代理人代表一个企业与第三方达成合同,并声称是该企业 的所有人,则第三方在发现该企业的真实所有人后,亦可以向后者行使其对代理 人的权利。

第 1.11 条 (定义) 通则中: ——“法院”,包括仲裁庭; ——“长期合同”是指在一定期间内履行,并且通常不同程度上涉及交易复 杂性以及当事人之间持续关系的合同; ——在当事人有一个以上的营业地时,考虑到在合同订立之前任何时候或合 同订立之时各方当事人所知晓或期待的情况,相关的“营业地”是指与合同和其 履行具有最密切联系的营业地; ——“债务人”是指履行义务的一方当事人;“债权人”是指有权要求履行 义务的一方当事人; ——“书面”是指能为所含信息保存记录,并能以有形方式再现的任何通信 方式。

第 2.1.10 条 (承诺的撤回) 承诺可以撤回,但撤回通知要在承诺本应生效之前或同时送达要约人。

第 2.1.11 条 (变更的承诺) (1)对要约意在表示承诺但载有添加、限制或其他变更的答复,即为对要 约的拒绝,并构成反要约。 (2)但是,对要约意在表示承诺但载有添加或不同条件的答复,如果所载 的添加或不同条件没有实质性地改变要约的条件,则除非要约人毫不迟延地表示 拒绝这些不符,此答复仍构成承诺。如果要约人不做出拒绝,则合同的条款应以 该要约的条款以及承诺所载有的变更为准。 合同的订立 第 2.1.1 条 (订立方式) 合同可通过对要约的承诺或通过能充分表明合意的当事人各方的行为而订 立。

第 2.1.2 条 (要约的定义) 一项订立合同的建议,如果十分确定,并表明要约人在得到承诺时受其约束 的意思,即构成一项要约。

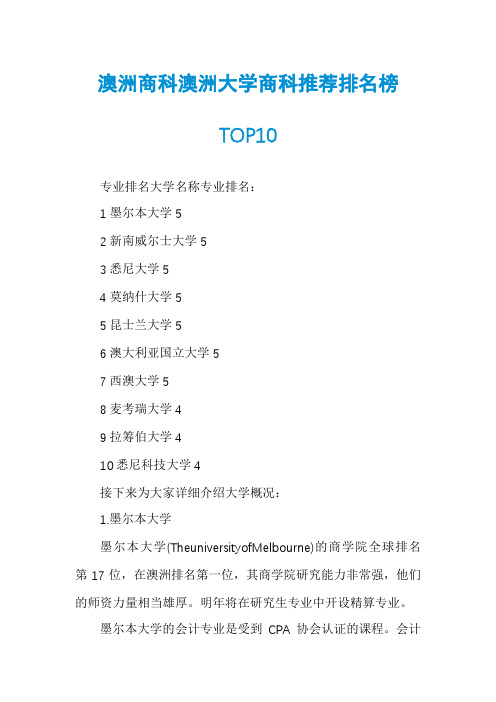

澳洲商科澳洲大学商科推荐排名榜TOP10

澳洲商科澳洲大学商科推荐排名榜TOP10专业排名大学名称专业排名:1墨尔本大学52新南威尔士大学53悉尼大学54莫纳什大学55昆士兰大学56澳大利亚国立大学57西澳大学58麦考瑞大学49拉筹伯大学410悉尼科技大学4接下来为大家详细介绍大学概况:1.墨尔本大学墨尔本大学(TheuniversityofMelbourne)的商学院全球排名第17位,在澳洲排名第一位,其商学院研究能力非常强,他们的师资力量相当雄厚。

明年将在研究生专业中开设精算专业。

墨尔本大学的会计专业是受到CPA协会认证的课程。

会计专业是由一个系部,两名诺贝尔奖教授、七名澳大利亚社会科学院院士组成,他们以最广泛的课程设置、质量的商科教育、秀的师资和最出色的毕业生闻名,其毕业生的就业率和起薪点远高于国内平均水平。

墨尔本大学的会计专业的毕业生为四大会计师事务所抢聘;而且它的保险精算研究教学中心也排名澳洲前三,科研力量雄厚,教学支持和学习辅导有口皆碑。

墨尔本大学的商学院连续三年被评为澳洲第一的商学院。

2.新南威尔士大学一提起这所学校,相信很多中国的学生都会说这所学校就是工程类的专业出色。

但是他们不知道很多当地的学生是很喜欢去新南威尔士大学(UNSW)去读商科的。

也许是因为它的工程太出色了,导致了信息相对封闭的中国学生与家长对学校其专业了解甚少。

其实新南威尔士大学金融方向的硕士项目和墨尔本一样齐全(CommerceinFinance),适合没有商科背景的孩子,但是有个别专业课程,比如说金融分析(FinanceAnalysis)适合有金融或者会计背景的;金融学(Finance)适合已经具有金融本科学历的学生,希望进一步深造的;另外还有金融数学(FinancialMathematics)课程,就适合数学底子好的学生。

3.悉尼大学悉尼大学商学院(TheUniversityofSydneyBusinessSchool)是澳州的商学院之一,他的商学院也是高考入学分数的大学之一。

202XTimes世界大学商学院排名Top200.doc

202XTimes世界大学商学院排名Top200.doc202XTimes世界大学商学院排名Top200 利用《泰晤士报高等教育》的全球大学排名数据,找出最适合攻读商科学位的大学。

无论是本科还是研究生阶段,攻读商学学位都是进入一系列职业的第一步。

跟随了解下排名前200的商学院。

一、简介对于未来的学生来说,在哪里学习商科是一个重要的决定,因此《泰晤士报高等教育》发布了一份全球商科和经济学学位排名。

该榜单涵盖了62个国家的500多所大学。

在商业排名的前20所大学中,大多数是美国大学,其中麻省理工学院和斯坦福大学位居榜首。

尽管美国在排行榜上占据主导地位,但英国和亚洲各地的大学也表现得尤为出色。

英国有四所大学进入前20名,还有2所亚洲的院校。

加拿大、荷兰和澳大利亚的商学院在商业和经济学位方面也表现出色。

该排名采用了与世界大学排名相同的方法,但在教学和研究指标上的权重略高,而在引用上的权重略低。

完整的方法可以在这里找到。

二、202X年商学院排名前200的大学202X世界大学商学院排名大学国家/地区1麻省理工学院美国2斯坦福大学美国3牛津大学英国4剑桥大学英国5杜克大学美国6加州大学伯克利分校美国7哈佛大学美国8伦敦政治经济学院英国9耶鲁大学美国10宾夕法尼亚大学美国11芝加哥大学美国12西北大学美国13哥伦比亚大学美国14加州大学洛杉矶分校美国=15密歇根大学美国=15纽约大学美国17新加坡国立大学新加坡18清华大学中国19伦敦大学学院英国20苏黎世联邦理工学院瑞士21康奈尔大学美国22香港科技大学中国香港23北京大学中国24卡内基梅隆大学美国25英属哥伦比亚大学加拿大26东京大学日本27香港大学中国香港=28蒂尔堡大学荷兰=28多伦多大学加拿大30加州大学圣地亚哥分校美国31明尼苏达大学双城分校美国32鹿特丹伊拉斯姆斯大学荷兰=33曼海姆大学德国=33华威大学英国35哥本哈根商学院丹麦36威斯康星大学麦迪逊分校美国37曼彻斯特大学英国38华盛顿大学美国38香港理工大学中国香港39约翰霍普金斯大学美国41达特茅斯学院美国42苏黎世大学瑞士43墨尔本大学澳大利亚44宾夕法尼亚州立大学美国45密歇根州立大学美国46德克萨斯大学奥斯汀分校美国47南加州大学美国48首尔国立大学韩国49爱丁堡大学英国50澳大利亚国立大学澳大利亚51佐治亚理工学院美国52香港中文大学中国香港53图卢兹联邦大学法国53浙江大学中国55俄亥俄州立大学美国56波士顿大学美国=57伊利诺伊大学香槟分校美国=57庞培法布拉大学西班牙59亚利桑那州立大学美国=60鲁汶大学比利时=60苏塞克斯大学英国62阿尔托大学芬兰63波士顿学院美国64印第安纳大学美国65新加坡南洋理工大学新加坡66维吉尼亚大学美国67马里兰大学帕克分校美国68马斯特里赫特大学荷兰69北卡罗莱纳大学教堂山分校美国70新南威尔士大学澳大利亚71京都大学日本72德州农工大学美国=73昆士兰大学澳大利亚=73圣加伦大学瑞士75巴黎综合理工学院法国=76格罗宁根大学荷兰=76圣路易斯的华盛顿大学美国78香港城市大学中国香港79高丽大学韩国80隆德大学瑞典81莱斯大学美国82阿姆斯特丹大学荷兰83维也纳大学奥地利=84麦吉尔大学加拿大=84上海交通大学中国=84西部大学加拿大87诺丁汉大学英国88巴黎综合文理大学法国89复旦大学中国90兰开斯特大学英国91耶路撒冷希伯来大学以色列92韩国成均馆大学韩国92南京大学中国93米兰理工大学意大利=94佛罗里达大学美国=94天主教鲁汶大学比利时=94莫纳什大学澳大利亚97伦敦国王学院英国99昆士兰理工大学澳大利亚=100伦敦大学城市分校英国=100瑞士洛桑大学瑞士101–125阿尔伯塔大学加拿大101–125阿斯顿大学英国101–125巴塞罗那自治大学西班牙101–125凯斯西储大学美国101–125埃默里大学美国101–125埃克塞特大学英国101–125柏林自由大学德国101–125乔治华盛顿大学美国101–125俄罗斯国立高等经济学院俄罗斯101–125庆熙大学韩国101–125利兹大学英国101–125莫斯科国立大学俄罗斯101–125马萨诸塞大学美国101–125蒙特利尔大学加拿大101–125国立台湾大学中国台湾省101–125中国人民大学中国101–125新泽西州立罗格斯大学美国101–125圣安娜高等研究学院意大利101–125圣安德鲁斯大学英国101–125萨里大学英国101–125悉尼大学澳大利亚101–125特文特大学荷兰101–125厦门大学中国101–125约克大学加拿大126–150奥尔堡大学丹麦126–150亚利桑那大学美国126–150英国巴斯大学英国126–150加州大学欧文分校美国126–150卡迪夫大学英国126–150科罗拉多大学博尔德分校美国126–150英国杜伦大学英国126–150瑞士日内瓦大学瑞士126–150乔治亚州立大学美国126–150格拉斯哥大学英国126–150汉堡大学德国126–150爱荷华州立大学美国126–150迈阿密大学美国126–150东北大学美国126–150巴黎大学法国126–150罗彻斯特大学美国126–150伦敦大学皇家霍洛威学院英国126–150谢菲尔德大学英国126–150西蒙弗雷泽大学加拿大126–150南澳大利亚大学澳大利亚126–150斯德哥尔摩大学瑞典126–150中山大学中国126–150悉尼科技大学澳大利亚126–150特拉维夫大学以色列126–150天普大学美国126–150阿姆斯特丹自由大学荷兰126–150约克大学英国151–175奥尔胡斯大学丹麦151–175安特卫普大学比利时151–175奥克兰大学新西兰151–175博洛尼亚大学意大利151–175布里斯托大学英国151–175坎特伯雷大学新西兰151–175查默斯理工大学瑞典151–175科隆大学德国151–175埃塞克斯大学英国151–175乔治敦大学美国151–175根特大学比利时151–175康斯坦茨大学德国151–175布鲁塞尔自由大学比利时151–175马来亚大学马来西亚151–175国立台湾科技大学中国台湾省151–175西班牙纳瓦拉大学西班牙151–175圣母大学美国151–175大阪大学日本151–175匹兹堡大学美国151–175拉德堡德大学荷兰151–175世宗大学韩国151–175斯特拉思克莱德大学英国151–175德克萨斯大学达拉斯分校美国151–175都柏林三一学院爱尔兰共和国176–200开普敦大学南非176–200马德里卡洛斯三世大学西班牙176–200德乌斯托大学西班牙176–200都柏林大学学院爱尔兰共和国176–200东英吉利大学英国176–200埃尔兰根-纽伦堡大学德国176–200佐治亚大学美国176–200格里菲斯大学澳大利亚176–200伊利诺斯大学芝加哥分校美国176–200沙特国王大学沙特阿拉伯176–200韩国科学技术院韩国176–200纽卡斯尔大学澳大利亚176–200纽卡斯尔大学英国176–200里斯本诺瓦大学葡萄牙176–200皇后大学加拿大176–200雷丁大学英国176–200南安普顿大学英国176–200南卡罗莱纳大学美国176–200南丹麦大学丹麦176–200同济大学中国176–200乌普萨拉大学瑞典176–200范德比尔特大学美国176–200华盛顿州立大学美国176–200西澳大利亚大学澳大利亚176–200伍伦贡大学澳大利亚176–200延世大学韩国三、202X年商学院排名前5的大学1.麻省理工学院斯隆管理学院也被称为麻省理工学院斯隆管理学院,在该校开设商业课程。

国际商务 企业社会责任CSR

•

School of International Business-SWUFE

Education

•

Formal education – The medium through which individuals learn many of the language, conceptual, and mathematical skills. – Supplements the family’s role in socialising the young into the values and norms of a society. – Teaches basic facts about the social and political nature of a society.

School of International Business-SWUFE

Enhancing your intercultural sensitivity -- THE CONCEPT OF CULTURE

Symbols Attitudes

Shared System

Values

Priorities Attitudes Rules

School of International Business-SWUFE

Exporting Jobs or Abusing People?

• •

Nestle-Powdered Milk Issue Nike (low wages, child labor and unsafe working conditions)

School of International Business-SWUFE

Ethics/CSR

Does investment efficiency improve after the disclosure of material weaknesses in internal control..

Does investment efficiency improve after the disclosure of material weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting?$Mei Cheng a ,Dan Dhaliwal a ,b ,Yuan Zhang c ,naThe University of Arizona,Tucson,AZ 85721,United StatesbKorea University Business School,Seoul 136-701,Republic of Korea cUniversity of Texas at Dallas,Richardson,TX 75080,United Statesa r t i c l e i n f oArticle history:Received 23September 2009Received in revised form 1March 2013Accepted 5March 2013Available online 16March 2013JEL classifications:G31G38M41M48Keywords:Effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting Investment efficiency Disclosurea b s t r a c tWe provide more direct evidence on the causal relation between the quality of financial reporting and investment efficiency.We examine the investment behavior of a sample of firms that disclosed internal control weaknesses under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.We find that prior to the disclosure,these firms under-invest (over-invest)when they are financially constrained (unconstrained).More importantly,we find that after the disclosure,these firms ’investment efficiency improves significantly.&2013Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.1.IntroductionPrior literature shows that firms with a lower quality of financial reporting under-invest (over-invest)when they are financially constrained (unconstrained)(Biddle et al.,2009).These results are important because they suggest that the quality of a firm 's financial reporting has an association with real investment efficiency.However,the literature does not establish a causal relation for this association.In this study,we provide more direct evidence for this causal relation by taking advantage of a provision in the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX)Act that requires a firm to disclose if it has a material internal control weakness (ICW)in its financial reporting (U.S.Congress,2002).Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirectjournal homepage:/locate/jaeJournal of Accounting and Economics0165-4101/$-see front matter &2013Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved./10.1016/j.jacceco.2013.03.001☆We thank the editor,John Core,and an anonymous referee for their invaluable suggestions.We also thank seminar participants at Columbia University,Nanyang Technological University,the University of Illinois at Chicago,and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for helpful comments.All errors are ourown.nCorresponding author.E-mail addresses:meicheng@ (M.Cheng),dhaliwal@ (D.Dhaliwal),yuan.zhang2@ (Y.Zhang).Journal of Accounting and Economics 56(2013)1–18An ICW suggests that there is an information problem in the firm 's financial reporting system.Given this information problem and the findings from Biddle et al.(2009),we predict that firms that disclose ICWs (ICW firms)exhibit inefficient investment behavior prior to the disclosure.More importantly,because an ICW provides an adverse public signal,these firms are expected to address their past financial reporting problems subsequent to the disclosure.Thus,firms should show an increase in the quality of their financial reporting from the pre-disclosure period to the post-disclosure period.If the improvement in the quality of financial reporting increases investment efficiency,we predict that the pre-disclosure inefficiency in investment by the ICW firms will be mitigated or eliminated in the post-disclosure period.We test these predictions by examining the investment behavior of a sample of ICW firms surrounding their first disclosure of ICWs.Following Biddle et al.(2009),we focus on the relation between the effectiveness of the internal control and investment levels conditional on a given firm 's likelihood of over-investing or under-investing.We start our analyses with a pooled sample of ICW firms and control firms with effective internal control.Regression analyses show that in the year prior to the first disclosure of an ICW,relative to control firms with similar financial conditions,financially constrained ICW firms under-invest by about 1.79%(2.89%)of total assets,while financially unconstrained ICW firms over-invest by about 2.53%(2.76%)of total assets based on the pooled sample (pooled sample of survivors).These numbers represent about 14–23%of average investment levels of the sample (which is about 12.80%of total assets),suggesting that the magnitudes of the effects are economically significant.Most importantly,we find that after the initial disclosure of material weaknesses,the investment inefficiency of ICW firms becomes small and insignificant relative to control firms.Regression analyses based on both the pooled sample and the pooled sample of survivors show that in the second year after the disclosure,the investment levels of ICW firms are no longer significantly different from those of the control firms with similar financial conditions.Further statistical tests also formally confirm significant reductions in both over-investment and under-investment.Following Armstrong et al.(2010),we also employ a propensity-score matching procedure to generate a different control sample.This procedure provides a control sample that has similar characteristics to the ICW firms,but different levels of internal control effectiveness and hence financial reporting quality.When we examine all matched firms,regression analyses support both sets of our hypotheses:(1)in the year prior to disclosure,ICW firms significantly under-invest (over-invest)when firms are financially constrained (unconstrained);and (2)after the disclosure,there are significant reductions in both under-investment and over-investment.Two-sample statistical tests that compare ICW firms and control firms within groups of firms with high ex ante likelihood of over-and under-investment respectively are largely consistent with the regression analyses except that we find little evidence of decreases in under-investment.We also focus on a matched sample of surviving ICW and control firms.The survivorship requirement ensures that the ICW firms remain constant in our event period,which makes it more sensible for inferring over-time changes in investment efficiency.Both two-sample tests of the differences and regression tests based on this sample provide support for both sets of our hypotheses.Taken together,these results suggest that SOX disclosures of ICWs and the changes that follow reduce investment inefficiency.Our study contributes to several streams of literature.First,we contribute to the emerging literature on the relation between the quality of financial reporting and investment efficiency (Bens and Monahan,2004;Biddle and Hilary,2006;McNichols and Stubben,2008;Biddle et al.,2009;Francis and Martin,2010;Bushman et al.,2011).By examining the changes around disclosures of ICWs,we are able to provide more direct evidence of the causal relation between financial reporting quality and investment efficiency than research based on cross-sectional analyses (e.g.,Biddle et al.,2009;Francis and Martin,2010;Bushman et al.,2011).1Second,we shed light on the debate regarding the costs and benefits of SOX and,in particular,of the increased disclosure requirement under Section 404.The popular press and practitioners both argued that the requirement to disclose ICWs under Section 404is burdensome to corporate shareholders as well as to corporate managers and might lead to the misallocation of corporate resources (American Bankers ’Association (ABA),2005;Charles River Associates,2005).In line with these concerns,Berger et al.(2005),Zhang (2007),and Li et al.(2008)document the costs of implementing the SOX requirements with regard to auditing and reporting on internal controls.However,other studies document the benefits of these requirements such as providing information to the executive labor market (Li et al.,2010),improving the quality of financial reporting (Altamuro and Beatty,2010),and reducing the cost of capital for firms (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al.,2009;Dhaliwal et al.,2011).We add to this debate by showing that the changes following ICW disclosures increase real investment efficiency.The remainder of the study proceeds as follows.Section 2provides background on Sections 302and 404of the SOX and develops our empirical predictions.Section 3introduces our research design and describes the samples.Section 4presents our empirical results.Section 5concludes.1Hope and Thomas (2008)also provide a time-series analysis of the effects of disclosure on investment efficiency.There are at least two important differences between our study and theirs.First,we focus on investment efficiency in terms of both over-investment and under-investment,while their focus is on over-investment (“empire building ”)only.Second,we examine the effects of disclosing internal control weaknesses while they examine the effects of geographic earnings disclosure.M.Cheng et al./Journal of Accounting and Economics 56(2013)1–182M.Cheng et al./Journal of Accounting and Economics56(2013)1–183 2.Background and hypotheses2.1.Background on Sections302and404of the Sarbanes Oxley ActThe Sarbanes Oxley Act(SOX)became effective on July29,2002.Prior to the act,firms were only required to publicly disclose deficiencies in their internal control if they changed auditors(Doyle et al.,2007a).With the enactment of SOX, public firms were required to assess and disclose the effectiveness of their internal control systems.Specifically,Section302 mandates that a firm's CEO and CFO certify in periodic(interim and annual)SEC filings that they have“evaluated and presented in the report their conclusions about the effectiveness of their internal controls based on their evaluation.”Section404further requires that each annual report contains an internal control report that includes an assessment of the effectiveness of the issuer's internal control structure and procedures with respect to financial reporting.22.2.Hypothesis developmentWhether suboptimal investments take the form of over-investment or under-investment depends not only on the managers’incentives and the monitoring environment,but also on the availability of capital.Firms with abundant financial resources are more likely to over-invest,while firms with constrained financial resources are more likely to under-invest (Jensen,1986;Myers,1997).Therefore,following Biddle et al.(2009),our prediction of the effects of ICWs on firms’investment is conditional on the availability of financial resources to the firm.2.2.1.ICW and investment levelsWe identify the year in which a firm first discloses an ICW as Year T.Our first set of hypotheses examines investment efficiency in the year immediately prior to the first disclosure(i.e.,Year T−1).3Researchers have documented that the reporting of internal control weakness/effectiveness is associated with accrual quality(e.g.,Doyle et al.,2007b),and they have used ICW reporting as a proxy for poor financial reporting quality(e.g.,Costello and Wittenberg-Moerman,2011).Thus, in the year prior to the first disclosure of an ICW,the firm is expected to have poor financial reporting quality.In a world without frictions(as described in Modigliani and Miller,1958),funds flow such that the marginal product of capital is equal across all projects in the economy,leading to an optimal investment level.However,the literature recognizes that frictions do exist in the economy and documents,both theoretically and empirically,that these frictions can lead to investment inefficiency.Among these frictions,perhaps the most pervasive and important ones are those that arise from information asymmetry(Stein,2003).Information asymmetry between managers and outside suppliers of capital can result in adverse selection and moral hazard,both of which can affect investment efficiency.We argue that a weak internal control system can increase information asymmetry and exacerbate both of these problems,leading to inefficient investment.Under adverse selection,managers are better informed than outside investors as to the true value of the firm's assets and growth opportunities.Managers are thus likely to issue capital when their firm is overvalued.Given that ICW firms have lower financial reporting quality than control firms(Doyle et al.,2007b),information asymmetry is higher and managers have greater incentives to time the issuance of capital.If these timing strategies are successful,managers can then over-invest the proceeds from these capital issuances(Biddle et al.,2009).On the other hand,rational investors anticipate this tendency and are likely to increase the firms’cost of capital.Ashbaugh-Skaife et al.(2009)and Dhaliwal et al.(2011) document that ICW firms have a higher cost of capital than control firms.In this case,we expect that the increased cost of capital associated with ICWs leads financially constrained firms to under-invest,compared with equally financially constrained control firms,because these firms have more difficulty raising the capital needed to fund their projects.Moral hazard,on the other hand,suggests that when managers’and investors’interests are not well aligned,managers have incentives to over-invest so as to maximize their personal welfare(Williamson,1974;Jensen,1986).Without effective monitoring and control,managers of ICW firms have greater opportunities to provide upward-biased information to the board or to shareholders when seeking support for their investment plans.For example,managers might over-state revenue or under-state cost in order to depict a high-growth trend or strong competitive advantage in segments they hope to expand.Thus,under moral hazard,we expect ICW firms without financial constraints to over-invest.However,if outside suppliers of capital are able to anticipate this problem and can ration capital ex ante,moral hazard might lead ICW firms with significant financial constraints to under-invest ex post(Stiglitz and Weiss,1981).To summarize,we expect that,in the year prior to the first disclosure of the ICWs(i.e.,Year T−1),the ICW firms have poor information quality.Given this low information quality and the findings of the literature(Biddle et al.,2009),we expect an ICW firm to invest inefficiently.Following Biddle et al.(2009),we formulate our first set of hypotheses regarding the effects of an ICW,conditional on a given firm's underlying financial condition,as follows:2Section404came into effect for firms with market values greater than or equal to$75million(accelerated filers)for fiscal years ending on or after November15,2004.For smaller public companies(non-accelerated filers),the SEC extended the effective date to fiscal years ending on or after December 15,2007.On September15,2010,the SEC issued rule33–9142that permanently exempts registrants that are non-accelerated filers from the Section404(b) requirement for an internal control audit.3Our empirical tests assume that the disclosed ICW also exists in the year immediately prior to that disclosure.This assumption is consistent with Doyle et al.(2007a),Ashbaugh-Skaife et al.(2008),and Dhaliwal et al.(2011).H1a.Financially constrained ICW firms are more likely to under-invest in the year prior to the disclosures of their ICWs.H1b.Financially unconstrained ICW firms are more likely to over-invest in the year prior to the disclosures of their ICWs.2.2.2.Disclosure of ICW and investment levelsOur second,and more innovative,set of hypotheses relates to the changes in a firm 's investment efficiency around their first disclosure of an ICW.We predict that disclosures of ICWs lead the disclosing firms to undergo important changes.These changes are expected to improve financial reporting quality and mitigate the agency problems of adverse selection and moral hazard,which,in turn,increases investment efficiency.First,we expect a firm 's disclosure of an ICW to mitigate adverse selection.The disclosure of an ICW provides a signal to the board,shareholders,and other stakeholders that the firm has low information quality.The ICW firm is likely to improve its internal control systems over financial reporting subsequent to the disclosure,which should increase the quality of its financial information (Nicolaisen,2004).Consistent with this view,Altamuro and Beatty (2010)find that the requirements to report internal control effectiveness decrease earnings management and increase the validity of the loan-loss provision,persistence of earnings,and the predictability of cash flow.Furthermore,once investors and the board of directors recognize their internal control system is weak,they are likely to demand more and higher-quality disclosures from the managers (Feng et al.,2009).Thus,with both the enhanced disclosures and the improved quality of information,the extent of information asymmetry and hence adverse selection is expected to decrease.As a result,securities are less likely to be overpriced and managers are less likely to time the issuance of capital,which,in turn,decreases the amount of over-investment.On the other hand,in anticipation of these changes,investors are likely to reduce the cost of capital they demand from these firms (Lambert et al.,2007).This lower cost decreases the amount of under-investment because managers have better access to funding when there are good investment opportunities (Myers and Majluf,1984).Second,the ICW disclosure should induce the board of directors,as well as market intermediaries such as credit rating agencies and financial analysts,to increase their level of monitoring,which,in turn,reduces the problem of moral hazard.Importantly,these monitoring entities are likely to increase their scrutiny not only of the financial information managers provide but also of the operating,investing,and financing decisions managers make.For example,the board of directors might seek more independent information,might crosscheck financial information,and might challenge managerial proposals more than they previously had.This enhanced scrutiny helps to reduce the amount of bias or the number of errors in financial reporting and to reduce possible empire-building investment activities.The possibility also exists that managers,now aware of the enhanced scrutiny,will make fewer investment decisions that are not aligned with investors ’interests.As investors anticipate this decrease in managers ’incentives to over-invest,their tendency to ration capital ex ante will also decrease,which will lead to less under-investment ex post in ICW firms with financial constraints.To summarize,the identification and disclosure of an ICW is expected to mitigate the problems of adverse selection and moral hazard.Thus,we use an ICW disclosure as an instrument for an improvement in the quality of financial reporting and examine whether investment efficiency improves following the disclosure of ICWs.This setting helps us shed light on the causal relation between financial reporting quality and investment efficiency and leads to our second set of hypotheses:H2a.Financially constrained ICW firms under-invest less in the years following the disclosures of their ICWs.H2b.Financially unconstrained ICW firms over-invest less in the years following the disclosures of their ICWs.It is important to note that while a firm 's disclosure of the material weaknesses might improve investment efficiency,the timing and extent of that improvement are not clear ex ante.For example,the board of directors and outside shareholders might not effectively detect and stop all over-investment or under-investment activities immediately,in which case ICW firms can still over-invest or under-invest,although to a lesser extent.3.Research design and sample selection 3.1.Research designWe use two different procedures to obtain control samples to compare with the ICW sample.The first procedure obtains control samples based on all firms that make no ICW disclosures around the ICW firms ’first disclosure of an ICW.We refer to this comparison as the pooled sample analysis.Our second method is based on a propensity-score matching procedure.We refer to this comparison as the matched sample analysis.3.1.1.Pooled sample analysisTo test our two sets of hypotheses for the pooled sample,we examine investment efficiency for Years T −1,T þ1,and T þ2separately.We cluster the standard errors at both the firm and year levels to obtain standard errors that are robust to heteroskedasticity,serial correlation,and cross-sectional correlation (Petersen,2009;Gow et al.,2010).Specifically,ourM.Cheng et al./Journal of Accounting and Economics 56(2013)1–184M.Cheng et al./Journal of Accounting and Economics56(2013)1–185 regression model is as follows(firm subscripts are suppressed):Investment t¼a0þa1ÂWeakþa2ÂWeakÂOverFirm t−1þa3ÂOverFirm t−1þ∑b iÂWeakDetermin ant i,t−1þ∑c iÂINVDetermin ant i,t−1þ∑d1i GOV i,t−1þ∑d2i GOV i,t−1ÂOverFirm t−1þe t:ð1ÞThe dependent variable Investment is the total investment measured as the sum of research and development,capital, and acquisition expenditures less the sale of property,plant,and equipment multiplied by100and scaled by the lagged total assets.Weak is an indicator variable,which is set to one for firms that disclosed an ICW and zero for the control firms.Consistent with Biddle et al.(2009),we measure Investment in Year t,and our control variables at the end of Year t−1. As our hypotheses are conditional on the respective ex ante likelihoods of over-investment and under-investment(Opler et al.,1999;Biddle et al.,2009),we use a variable OverFirm to distinguish between situations in which a given firm is more likely to over-invest or under-invest.To construct OverFirm,we follow prior studies that suggest cash-rich and low-leverage firms are more likely to over-invest,and rank each of our sample firms’cash balances and negative leverage at the end of Year t−1into two decile ranks.We then average these two decile ranks and scale the average so that it ranges from zero to one.By focusing our analysis on firms that are prone to specific forms of suboptimal investment,we increase the power of our tests.To test hypotheses H1a and H1b,we estimate Model(1)for Year T−1and focus on the indicator variable Weak and its interaction with OverFirm.Before the firms’initial disclosures of ICWs,if OverFirm equals zero,then firms are financially constrained and thus,ex ante,are more likely to under-invest.Under this scenario,if constrained ICW firms indeed under-invest more than control firms do as predicted in H1a,then the coefficient on Weak(i.e.,a1)is expected to be negative.On the other hand,if OverFirm equals one,then firms are financially unconstrained and thus,ex ante,are more likely to over-invest.Under this scenario,if unconstrained ICW firms over-invest more than control firms do as predicted in H1b,then the sum of the coefficients on Weak and WeakÂOverFirm(i.e.,a1þa2)is expected to be positive.In our second set of hypotheses,we focus on Years Tþ1and Tþ2instead of Year T itself.We choose this focus because how soon after the disclosure the board of directors and other stakeholders of the firm become aware of and respond to the ICWs is unclear.If a firm's disclosure of an ICW leads to elimination(reduction)of the under-investment and over-investment,then a1and a1þa2should be insignificant(of lower magnitude).The control variables we include in Model(1)can be categorized into one of three groups:(1)determinants of material ICW(WeakDeterminant);(2)determinants of investment level(INVDeterminant);and(3)other governance mechanisms (GOV).We base our first group of control variables on Doyle et al.(2007a),who find that smaller(LogAsset),4younger(Age), financially weaker(Losses,Z-score),and more complex(Nseg,Foreign)firms,as well as firms that are growing more rapidly (Extrgrow)or are undergoing restructuring(Rest),are more likely to have a material ICW.We base our second and third groups of control variables on Biddle et al.(2009),who examine the cross-sectional relation between the quality of financial reporting and investment efficiency.Our determinants for investment levels comprise Tobin's Q(Q),cash flow(CFOsale),the standard deviation of cash flow(s(CFO)),the standard deviation of sales(s(Sales)),the standard deviation of investments(s(Investment)),the market-to-book ratio(Mkt-to-book), tangibility(Tangibility),market leverage(Leverage),industry market leverage(Ind Leverage),dividends(Dividend), operating cycle(OperatingCycle),firm age(Age),financial bankruptcy risk(Z-score),firm size(LogAsset),and a loss indicator(Loss).Our third group of control variables captures other monitoring or governance mechanisms that could affect investment efficiency,and comprises the corporate governance index(G-score),5institutional holdings(Institutions),and analyst coverage(Analysts)(Jensen and Meckling,1976;Shleifer and Vishny,1997;Bhojraj and Sengupta,2003).More importantly, we also include the main proxy for the quality of financial reporting used in Biddle et al.(2009),namely,accrual quality (AQ).6,7The addition of these variables ensures that our findings are robust to their effects.To control for the differential effects of these variables on over-investment and under-investment,we include in the model these variables(i.e.,our monitoring/governance variables,particularly the accrual quality variable)as well as their interactions with OverFirm.All variables are defined in detail in the appendix.Further,consistent with Biddle et al.(2009),in addition to the above control variables,we add industry fixed effects using the Fama-French(1997)48-industry classification to control for industry-specific effects on investments.4Doyle et al.(2007a)use Logmv to capture firm size.However,Logmv is highly correlated with LogAsset,which is a control variable in Biddle et al. (2009).We use LogAsset in our models.Replacing it with Logmv does not affect the inferences of this paper.5To avoid a significant reduction in our sample size due to a missing G-score,we follow Biddle et al.(2009)and set the G-score to zero if missing and add an indicator variable for the availability of the corporate governance index(G-score dummy).6Following Biddle et al.(2009),our AQ measure is measured as of Year t−2instead of Year t−1because of the requirement for one leading year of data in calculating AQ.7We choose the accrual quality measure based on Dechow and Dichev(2002)as it is consistently the most significant measure in Biddle et al.(2009). Nonetheless,in additional robustness tests we use two alternative measures of earnings quality:a measure of discretionary revenue used in McNichols and Stubben(2008)and a dummy variable that indicates whether the firm-year's financial statements are subsequently restated according to AuditAnalytics data.Our results are generally robust to these alternative measures.3.1.2.Propensity-score matched sample analysisFor our matched sample analysis,we follow Armstrong et al.(2010)and adopt the method of propensity-score matching to more effectively control for differences in relevant dimensions between the treatment and control samples.We attempt to match each ICW firm with a control firm that is similar across all observable relevant variables.Specifically,we include in the first stage of our regression all determinants of ICW and investment levels,and our governance variables.We estimate the following model for the first stage (firm subscripts are suppressed)by year:Weak ¼a 0þa 1ÂOverFirm t −1þ∑b i ÂWeakDetermin ant i ,t −1þ∑c i ÂINVDetermin ant i ,t −1þ∑d 1i GOV i ,t −1þe t :ð2ÞThe variables used in Model (2)are defined as in Model (1).We also add industry-fixed effects to Model (2)to account for industry-specific factors.We obtain the propensity score for each firm-year as the predicted value in Model (2).We then match each treatment firm (with no replacement)with the control firm that has the closest score in the same year within a distance of 0.01from the treatment firm 's propensity score.If the propensity-score matching is successful,then each ICW firm and its matching control firm are similar in all observable dimensions (including OverFirm ),with the exception of the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting.Accordingly,in the second stage of our analyses,we compare the investment levels between the ICW firms and the control firms conditional on the ex ante likelihood of over-and under-investing separately to test H1a and H1b .We also examine the changes of the investment differences between ICW firms and control firms from Year T −1to Year T þ2to test H2a and H2b .In addition,we estimate the following model to test our hypotheses:Investment t ¼a 0þa 1ÂWeak þa 2ÂWeak ÂOverFirm t −1þa 3ÂOverFirm t −1þe tð3ÞWe include OverFirm and its interaction with Weak because our identification of investment inefficiency is conditional on the ex ante likelihood that a given firm over-invests or under-invests.Similar to the design of the pooled sample,we expect a 1(a 1þa 2)to be significantly negative (positive)for the under-investment (over-investment)prediction in Year T −1under H1a and H1b ,but insignificant in Years T þ1and T þ2under H2a and H2b .3.2.Sample selectionFollowing recent academic studies (Ogneva et al.,2007;Li et al.,2010;Costello and Wittenberg-Moerman,2011),we obtain information on firms ’disclosures of their internal control from the AuditAnalytics database.This database keeps track of SEC filings in interim and annual reports for both Sections 302and 404disclosures.While there are some differences between the types of disclosures Sections 302and 404require,many firms integrate the two procedures and,hence,reach similar assessments for both.Thus,following the literature (Doyle et al.,2007a,2007b;Ashbaugh-Skaife et al.,2008),we do not differentiate between the assessments of effectiveness under Section 302and those under Section 404.We restrict the disclosures to those occurring between 2004and 2007because disclosures occurring between 2002and 2003are scarce.8Under SOX,internal control deficiencies can take the form of a significant deficiency or a material weakness,with the latter considered as the more severe one (Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC),2003).Consistent with Doyle et al.(2007a),we focus on firms ’disclosures of material ICWs in order to identify more severe deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting and provide greater power for our tests.Accordingly,we code each firm-year as containing material ICWs if (1)AuditAnalytics 302data identify the disclosure of material ICWs in any of its quarterly or annual reports;or (2)AuditAnalytics 404data identify the disclosure of ineffective internal control during that fiscal year.We focus on a firm 's first disclosure of an ICW only.We exclude disclosures made through Form 20-F or Form 10-K/QSB,because foreign or small firms have limited financial data available for our analyses.After merging this data with Compustat data using CIK identifiers,we obtain an initial sample of 1696firms that disclosed material ICWs for the first time between 2004and 2007(i.e.,Year T )via Form 10-K or Form 10-Q.We further require the availability of the investment variable and various control variables used in Model (1).We obtain information on these variables from Compustat (for financial information and earnings quality variables),CRSP (for firm age),RiskMetrics (for corporate monitoring/governance variables),IBES (for analyst coverage),and Thomson Reuters (for institutional holding).Requiring these variables substantially reduces our sample of ICW firms to 545,439,and 388for Years T −1,T þ1,and T þ2respectively.Our main analyses also require a control sample of firms with effective internal control.We use two alternative sample selection procedures.The first procedure obtains all firms covered by AuditAnalytics that (1)disclosed no ICWs between 2004and 2007and (2)have information available for all variables used in our analyses.This leads to 4999,4050,and 3145control firms for the Years T −1,T þ1,and Year T þ2respectively.This sample is larger than the matched sample described below and hence offers greater testing power.8The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)(2003)also requires auditors to provide an independent opinion on the effectiveness of the internal control system.Analyses of the AuditAnalytics data show that auditors ’assessments are predominantly consistent with managers ’assessments.For our sample,there are only four cases wherein these two opinions are inconsistent with each other.M.Cheng et al./Journal of Accounting and Economics 56(2013)1–186。

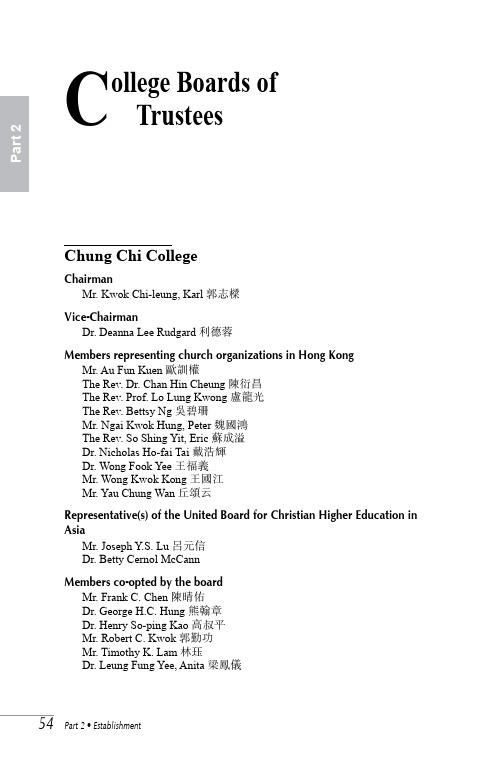

College Boards ofTrustees

2C ollege Boards of TrusteesChung Chi CollegeChairmanMr. Kwok Chi-leung, Karl 郭志樑Vice-ChairmanDr. Deanna Lee Rudgard 利德蓉Members representing church organizations in Hong Kong Mr. Au Fun Kuen 歐訓權The Rev. Dr. Chan Hin Cheung 陳衍昌The Rev. Prof. Lo Lung Kwong 盧龍光The Rev. Bettsy Ng 吳碧珊Mr. Ngai Kwok Hung, Peter 魏國鴻The Rev. So Shing Yit, Eric 蘇成溢Dr. Nicholas Ho-fai Tai 戴浩輝Dr. Wong Fook Yee 王福義Mr. Wong Kwok Kong 王國江Mr. Yau Chung Wan 丘頌云Representative(s) of the United Board for Christian Higher Education in AsiaMr. Joseph Y.S. Lu 呂元信Dr. Betty Cernol McCannMembers co-opted by the boardMr. Frank C. Chen 陳晴佑Dr. George H.C. Hung 熊翰章Dr. Henry So-ping Kao 高叔平Mr. Robert C. Kwok 郭勤功Mr. Timothy K. Lam 林珏Dr. Leung Fung Yee, Anita 梁鳳儀2Mr. Aubrey Kwok-sing Li 李國星Mr. John K.H. Li 李國謙Mr. Pang Yuk Wing, Joseph 彭玉榮Mr. S.H. Sung 宋常康College academics and othersProf. Leung Yuen-sang 梁元生 (Head of College )The Rev. Dr. Ng Wai Man 伍渭文 (Chaplain )Prof. Cheung Yuet Wah 張越華 (Fellow )Prof. Leung Yee 梁怡 (Fellow )Mr. Leung Kwong Lam 梁廣林 (Chinese Christian Universities Alumni Association )Mr. Alfred Hau Wun Fai 侯運輝 (College Alumni Association ) Mr. Ma Siu Leung 馬紹良 (College Alumni Association )SecretaryMrs. Angeline K.Y . Kwok 郭譚潔瑩New Asia CollegeChairmanDr. Charles Y .W. Leung 梁英偉Vice-ChairmanMs. Leung Hung Kee 梁雄姬ex officio MemberProf. Henry N.C. Wong 黃乃正 (Head of College )Members nominated by the Yale Club of Hong KongMr. Randolph C. Kwei 桂徵麒Mr. Nelson L. Miu 繆亮Member nominated by The Chinese University of Hong KongDr. Fung Kwok-lun, William 馮國綸Member nominated by the University of Hong KongProf. K.S. Cheng 鄭廣生Members nominated by the College Alumni AssociationMr. Heung Shu-fai 香樹輝Mr. Anthony T.T. Yuen 阮德添Members nominated by the Assembly of Fellows of New Asia CollegeProf. Daniel T.L. Shek 石丹理Prof. David Tai-wai Yew 姚大衛2Members of the community-at-large nominated by the board Mr. Chan Chi-sun 陳志新Dr. Cheng Shing-lung, Edwin 鄭承隆Dr. Vincent H.C. Cheng 鄭海泉Dr. Chow Kwen-lim 周君廉Mr. Fung Shing 馮昇Mr. Dennis Y.K. Hui 許耀君Mr. Bankee Pak-hoo Kwan 關百豪Dr. Kwok Siu-ming, Simon 郭少明Mr. Bill W.T. Lam 林榮德Mr. David Y.M. Lam 林耀明Mr. Dick M.K. Lee 李明逵Ms. Lee Kit-lan 李潔蘭Dr. Li Dak-sum 李達三Mr. Liu Lit-man 廖烈文Mr. Liu Shang Chien, Richard 劉尚儉Mr. Akihiro Nagahara 長原彰弘Mr. Anthony Hung-gun So 蘇洪根Mr. Franklin Tat-fai To 杜達輝Dr. Tong Yun-kai 湯恩佳Dr. Wong Kwai-lam 黃桂林Mr. Michael Y.K. Wong 黃奕鑑Mr. K.K. Yeung 楊國佳SecretaryDr. Peter Jic-leung Man 文直良United CollegeHonorary ChairmanDr. the Honourable Run Run Shaw 邵逸夫ChairmanMr. Shum Choi-sang 岑才生Vice-ChairmanDr. Thomas H.C. Cheung 張煊昌MembersDr. Peter Chan Po-fun 陳普芬Prof. Chang Song-hing 張雙慶Prof. Chau Kwai-cheong 鄒桂昌Dr. Thomas T.T. Chen 陳曾燾Mr. Cheng Kar-shing 鄭家成2Dr. Cheng Yu Tung 鄭裕彤Mrs. Irene Cheung 張玉麟夫人The Rev. Cheung King-man 張景文Dr. Choi Koon-shum 蔡冠深Prof. Chung Yu-to 鍾汝滔Mr. Glenn Fok 霍經麟Mr. David Man-hung Fong 方文雄Dr. Fong Yun-wah 方潤華Mr. Kenneth H.C. Fung 馮慶鏘Prof. Fung Kwok-pui 馮國培 (Head of College )Mr. Ho Man-sum 何萬森Prof. Alaster H.Y . Lau劉行榕Prof. Arthur K.C. Lee 李國章Prof. Lee Cheuk-yu 李卓予Dr. Lee Shau Kee 李兆基Mr. Simon K.C. Lee 李國忠Dr. Liu Lit-mo 廖烈武Dr. Lui Che-woo 呂志和Ms. Ng Chu Lien Fan 吳朱蓮芬Mr. Robert K.K. Shum 岑啟基Dr. Samson W.H. Tam 譚偉豪Mr. Tsang Wing-hong 曾永康Dr. Dickson K.T. Wong 王啟達Prof. Wong Kwan-yiu 黃鈞堯Mr. Ricky W.K. Wong 王維基Mr. Ronald S.L. Wong 王緒亮Mr. S.T. Wong 黃紹曾Ms. Lina H.Y . Yan 殷巧兒Mr. Anthony Y .C. Yeh 葉元章SecretaryMrs. Christina P.L. Li 李雷寶玲Shaw CollegeChairmanProf. Ma Lin 馬臨First Vice-ChairmanMr. Lee Woo-sing 李和聲Second Vice-ChairmanMr. Clement S.T. Fung 馮兆滔2ex officio MemberProf. Joseph J.Y. Sung 沈祖堯 (Head of College) MembersProf. Andrew C.F. Chan 陳志輝Prof. Chan Sin-wai 陳善偉Mr. Che Yueh-chiao 車越喬Ms. Kelly K.Y. Cheng 鄭潔賢Prof. Gordon W.H. Cheung 張偉雄Sir C.K. Chow 周松崗Dr. Peter K.L. Chu 朱嘉樂Prof. Chung Yue-ping 鍾宇平Mr. Hamen S.H. Fan 范思浩 (Hon. Treasurer)Mrs. Helen Fong 方劉小梅Ms. Mona Fong 方逸華Mr. Michael Y.S. Fung 馮鈺聲Prof. Hau Kit-tai 侯傑泰Prof. Ho Pui-yin 何佩然Mr. William V.M. King 金維明Mr. Daniel S.C. Koo 古勝祥Prof. Lee Kin-hong 李健康Prof. Paul S.N. Lee 李少南Prof. Leung Wing-por 梁永波Ms. Venus W. Liu 廖慧Mr. Lok Chi-hung 駱志鴻Ms. Jenny W.Y. Lu 盧文韻Prof. Lui Tai-lok 呂大樂Mr. Pang Kam-chun 彭錦俊Prof. Michael S.C. Tam 譚兆祥Dr. Tan Siu-lin 陳守仁Mr. Tsui Yiu-kwong 徐耀光Prof. Norman Y.S. Woo 胡應劭Prof. John H.K. Yeung 楊鶴強Dr. Nelson Y.C. Yu 余銳超Prof. Yum Tak-shing 任德盛SecretaryMiss Bonnie L.S. Kan 簡麗嫦。

the new issues puzzle

The New Issues Puzzle:Testing the Investment-Based ExplanationEvgeny Lyandres ∗Jones Graduate School of ManagementRice UniversityLe Sun †William E.Simon Graduate School of Business AdministrationUniversity of Rochester and GSAMLu Zhang ‡Stephen M.Ross School of BusinessUniversity of Michigan and NBERNovember 2006§AbstractAn investment factor,long in low investment stocks and short in high investment stocks,helpsexplain the new issues puzzle.Adding this factor into standard factor regressions reduces sub-stantially the magnitude of the underperformance following equity and debt offerings and thecomposite issuance effect.The reason is that issuers invest more than nonissuers,and the low-minus-high investment factor earns a significant average return of 0.57%per month.Our evi-dence lends support to the real options theory,in which investment extinguishes risky expansionoptions,and the q -theory of investment,in which firms with low costs of capital invest more.i li1IntroductionEquity and debt issuers underperform matching nonissuers with similar characteristics during the three tofive post-issue years(e.g.,Ritter1991;Loughran and Ritter1995;and Spiess and Affleck-Graves1995,1999).We explore empirically the investment-based hypothesis of this underper-formance.The q-theory of investment and real options theory imply a negative relation between investment and expected returns.If the proceeds from equity and debt issues are used tofinance in-vestment,then issuers should invest more and earn lower average returns than matching nonissuers.Our centralfinding is that a new investment factor,long in low investment stocks and short in high investment stocks,explains a substantial part of the new issues puzzle.Specifically:•We construct the investment factor by buying stocks with the bottom30%investment-to-asset ratios and selling stocks with the top30%investment-to-asset ratios,while using a triple sort to control for size and book-to-market.From January1970to December2005,the investment factor earns an average return of0.57%per month(t-statistic=7.13).•Most importantly,adding the investment factor into standard factor regressions reduces the magnitude of the underperformance for new equity issues portfolios.The equally-weighted portfolio offirms that have conducted seasoned equity offerings(SEOs)in the prior36months earns an alpha of−0.41%per month(t-statistic=−2.43).Adding the investment factor makes the CAPM alpha insignificant and reduces its magnitude by82%to−0.07%per month.The equally-weighted portfolio offirms that have conducted initial public offerings(IPOs)in the prior36months earn an alpha of−0.71%per month(t-statistic=−2.60).Adding the investment factor makes the CAPM alpha insignificant and reduces its magnitude by59%to −0.29%.The results from the Fama-French(1993)model are quantitatively similar.•The investment factor also helps explain the underperformance following debt offerings.The equally-weighted portfolio offirms that have conducted convertible debt offerings in the prior 36months earn an alpha of−0.63%per month(t-statistic=−4.20).Adding the invest-ment factor makes reduces the CAPM alpha by46%in magnitude to−0.34%,albeit still significant(t-statistic=−2.04).The underperformance following straight debt offerings is largely insignificant in our sample.The only exception is the equally-weighted alpha from the Fama-French(1993)model,−0.26%per month(t-statistic=−2.35).Controlling for the investment factor makes the alpha weakly positive,0.029%per month(t-statistic=0.27).•The results from using buy-and-hold abnormal returns(BHARs)are largely consistent with factor regressions.The BHARs of the SEO portfolio from matching on size and book-to-market over thefirst two and three post-issue years are−21.9%and−34.6%,respectively.Matching further on investment-to-asset ratios reduces the BHARs to−16.1%and−25.2%, respectively,about26%drop in magnitude.The BHARs of the IPO portfolio from matching on size and book-to-market are significantly negative after about six post-issue months,and the BHARs of the convertible debt portfolio are significantly negative after about18post-issue months.Matching on investment-to-asset makes this underperformance largely insignificant.•The investment factor also explains part of Daniel and Titman’s(2006)finding.A zero-cost portfolio that buys stocks in the bottom30%and sells stocks in the top30%of their composite equity issuance measure earns an equally-weighted alpha of−0.56%per month (t-statistic=−4.38)from the CAPM.Adding the investment factor reduces the alpha to −0.40%(t-statistic=−3.18),a drop in magnitude of28%.The value-weighted alpha from the Fama-French(1993)model is−0.36%per month(t-statistic=−3.57),and it drops by 57%in magnitude to−0.16%(t-statistic=−1.49)when we include the investment factor.Our evidence lends support to the investment-based explanation of the new issues puzzle(e.g., Zhang2005;Carlson,Fisher,and Giammarino2006).In their real options model,Carlson et al. argue thatfirms have expansion options and assets in place prior to equity issuance.This compo-sition is levered and risky.If real investment isfinanced by equity,then risk and expected returns must decrease because investment extinguishes the risky expansion options.2Inspired by the negative relation between real investment and expected returnsfirst derived by Cochrane(1991),Zhang(2005)argues that investment is likely to be the main driving force of the new issues puzzle.Intuitively,real investment increases with the net present values(NPVs)of new projects(e.g.,Brealey,Myers,and Allen2006,chapter6).The NPVs of new projects are inversely related to their costs of capital or expected returns,controlling for their expected cashflows.If the costs of capital are high,then the NPVs are low,giving rise to low investment.If the costs of capital are low,then the NPVs are high,giving rise to high investment.The average costs of equity forfirms that take many new projects are reduced by the low costs of capital for the new projects.Further,firms’balance-sheet constraint implies that the sources of funds must equal the uses of funds.Therefore,firms raising capital are likely to invest more and earn lower expected returns,andfirms distributing capital are likely to invest less and earn higher expected returns.Consistent with this theoretical prediction,we document that issuers invest more than matching nonissuers.The investment-to-asset spread between issuers and nonissuers is the highest in the IPO sample,followed by the SEO and convertible debt sample,and is the lowest in the straight debt sample.The relative magnitudes of the investment-to-asset spreads are consistent with the relative magnitudes of the underperformance across the four samples.We alsofind that high composite issuancefirms invest more than low composite issuancefirms.Our paper brings the insights from the literature on investment-based asset pricing to the liter-ature on the new issues puzzle.Our use of investment-to-asset as a key matching characteristic is motivated by the partial equilibrium models of Cochrane(1991,1996)and Berk,Green,and Naik (1999).Our use of the investment factor as a common factor of stock returns is motivated by the general equilibrium models of Gala(2005)and P´a stor and Veronesi(2005a,b).Several papers document the negative relation between investment and average returns.Cochrane (1991)is among thefirst to show this relation in the time series.Titman,Wei,and Xie(2004) and Cooper,Gulen,and Schill(2006)find a similar relation in the cross section but interpret the evidence as investors underreacting to overinvestment.Xing(2005)shows that real investment3helps explain the value effect.Anderson and Garcia-Feij´o o(2006)find that investment growth classifiesfirms into size and book-to-market portfolios.Anderson and Garcia-Feij´o o also anticipate our analysis:“Many studies examine long-run returns tofirms subsequent to new security offerings and report negative abnormal returns.Benchmarking long-run returns to changes in investment spending that may coincide withfinancing events might attenuate abnormal returns(p.191).”Brav and Gompers(1997)and Brav,Geczy,and Gompers(2000)document that equity issuers are concentrated among small-growthfirms,and suggest that their underperformance reflects the Fama-French(1993)size and book-to-market factors.Our evidence supports this argument because both equity issuers and small-growthfirms invest more than other types offirms.We suggest that real investment is likely to be the common link and the more fundamental driving force of their underperformance.Eckbo,Masulis,and Norli(2000)show that a six-factor model can explain the new issues puzzle,but we show that controlling for the investment factor is often sufficient.The rest of the paper is organized as follows.Section2develops the testable hypothesis.Section 3describes our data.Section4reports our empirical results,and Section5concludes.2Hypothesis DevelopmentThe investment-based explanation of the new issues puzzle argues that the post-issue underperfor-mance arises from the negative relation between real investment and expected returns.First,the relation between real investment and expected returns is negative.Second,iffirms issue new equity and debt tofinance real investment,then issuers should earn lower expected returns than nonissuers.2.1Theoretical MotivationFigure1illustrates the negative relation between real investment and expected returns,a central prediction in recent theoretical literature on investment-based asset pricing.Cochrane(1991,1996) derives the negative investment-return relation from the q theory of investment.In his models,firms invest more when their marginal q—the net present value of future cashflows generated from4one additional unit of capital—is high.Controlling for expected cashflows,a high marginal q is associated with a low cost of capital.In the real options model of Berk,Green,and Naik(1999),firms invest more when they have access to many low risk projects.Investing in these projects lowersfirm level risk and expected returns.In Carlson,Fisher,and Giammarino(2004),expansion options are riskier than assets in place.Real investment transforms riskier expansion options into less risky assets in place,thereby reducing risk and expected returns.1Figure1:The Investment-Based Explanation of the New Issues PuzzleTExpected return1The basic mechanisms in the real options and the q-theory models are similar because the two approaches are equivalent(e.g.,Abel,Dixit,Eberly,and Pindyck1996).5Gala(2005)constructs a general equilibrium production economy with heterogeneousfirms.In his model,afirm’s ability to provide consumption insurance depends on its ability to mitigate ag-gregate business cycle shocks through capital investment.In bad times,low investment,valuefirms want to disinvest and sell offtheir capital stocks.But they are prevented from doing so because of binding irreversibility constraints.Thesefirms thus earn high expected returns because their returns covary more with economic downturns.In contrast,in the face of negative shocks,high investment, growthfirms can easily lower their positive investment without facing the irreversibility constraints. Thesefirms thus earn low expected returns as they provide consumption insurance to investors.P´a stor and Veronesi(2005a)develop a general equilibrium model of optimal timing of initial public offerings,in which IPO waves are partially caused by declines in expected market returns.In their model,entrepreneurs choose the optimal timing of taking their privatefirms public,and then immediately investing part of the equity proceeds.Entrepreneurs prefer to postpone their IPOs until favorable market conditions such as low expected market return and high expected aggregate profitability.As a result,real investment of IPOfirms can serve as a state variable:high investment suggests low expected market returns,high aggregate profitability,or both.P´a stor and Veronesi(2005b)develop a general equilibrium model in which returns offirms investing in new technologies can define new systematic factors.Their model has two sectors:the “new economy”and the“old economy.”The old economy implements existing technologies on a large scale and its output determines a representative agent’s terminal wealth.The new economy implements the new technology on a small scale that does not affect the terminal wealth.The agent optimally chooses to experiment with the new technology on a small scale to learn about its unobservable productivity.If the productivity turns out to be sufficiently high,the new technology is adopted on a large scale.The nature of the risk associated with new technologies changes over time.The risk is initially idiosyncratic because of the small scale of production.Once adopted on a large scale,the risk becomes systematic because the new economy now affects the terminal wealth.6Figure1also shows that issuers are located at the right end of the curve,where expected re-turns are low,and nonissuers are located at the left end of the curve,where expected returns are high.Intuitively,the balance-sheet constraint requires that the uses of funds must equal the sources of funds,implying that issuers are likely to invest more than nonissuers.Based on this insight, Zhang(2005)and Carlson,Fisher,and Giammarino(2006)argue that SEOfirms must earn lower expected returns than matching nonissuers.The same intuition also applies to the underperfor-mance following IPOs(e.g.,Ritter1991)and convertible and straight debt offerings(e.g.,Spiess and Affleck-Graves1999),as well as the composite issuance effect(e.g.,Daniel and Titman2006).The investment-based explanation of the new issues puzzle,and more generally,the negative investment-return relation are conditional on a given level of profitability.High investment can be caused not only by low costs of capital,but also by high expected cashflows(profitability). More profitablefirms earn higher average returns than less profitablefirms(e.g.,Piotroski2000; Fama and French2006).Our results show that the difference in investment between issuers and nonissuers,rather than the difference in profitability,drives the new issues puzzle.2.2Empirical DesignOur choice of empirical methods echoes the theme of the theoretical motivation by complementing the use of a zero-cost low-minus-high investment factor as a common factor of stock returns and the use of investment as a matching characteristic.Motivated by the partial equilibrium models(e.g.,Cochrane1991;Berk,Green,and Naik1999), we examine the performance of security issuers relative to matchingfirms with similar characteris-tics including prior investment-to-asset ratios.The theoretical prior is that matching on investment should reduce the magnitude of buy-and-hold abnormal returns documented in previous studies(in which investment is not one of the control characteristics).Motivated by the general equilibrium models(e.g.,Gala2005;P´a stor and Veronesi2005a,b),we augment standard factor regressions with the investment factor constructed by sortingfirms on their investment-to-asset ratios.The7theoretical prior is that doing so should reduce the magnitude of the post-issue underperformance.Following Fama and French(1993,1996),we interpret the investment factor as a common fac-tor.While Fama and French go further and interpret their similarly constructed SMB and HML factors as risk factors motivated from ICAPM or APT,we do not take a stance on the risk inter-pretation of our investment factor.Arguments supporting the risk interpretation are clear.None of the theoretical papers that we use to motivate the investment factor assumes any form of over-and under-reaction.And unlike size and book-to-market,investment-to-asset does not involve the market value of equity,and is less likely to be affected by mispricing,at least directly.However,general equilibrium models with behavioral biases(e.g.,Barberis,Huang,and Santos 2001)can also motivate the investment factor.2Moreover,investor sentiment can presumably affect investment policy through shareholder discount rates(e.g.,Polk and Sapienza2006).Perhaps more importantly,covariance-based and characteristic-based explanations of the average-return variations are not mutually exclusive,in contrast to the position taken by Daniel and Titman(1997) and Davis,Fama,and French(2000).Under certain conditions,there exists a one-to-one mapping between covariances and characteristics,implying that they can both serve as sufficient statistics for expected returns(e.g.,Zhang2005).Our goal is thus to search for a theoretically motivated and empirically parsimonious factor specification that can explain anomalies in asset pricing tests. 3DataWe examine four types of security offerings:IPOs,SEOs,convertible debt issues,and straight debt issues.All four samples are obtained from Thomson Financial’s SDC database.The samples of the IPOs,SEOs,and convertible debt offerings are from1970to2005.Due to data availability,the sample of the straight debt offerings is from1983to2005.We obtain monthly returns from the Center for Research in Security Prices(CRSP).The monthly returns of Fama and French’s(1993)three factors and the risk-free rate are from Kenneth French’s website.Accounting information is from the COMPUSTAT Annual Industrial Files.Our sample selection largely follows previous studies.3To be included in a sample,a security offering must be performed by a U.S.firm that has returns on CRSP at some point during the three post-issuance years.We exclude unit offerings and secondary offerings of SEOs,in which new shares are not issued.For SEOs,our results are also robust to the exclusion of mixed offerings.4We also exclude equity and debt offerings offirms that trade on exchanges other than NYSE,AMEX, and NASDAQ.Similar to Brav,Geczy,and Gompers(2000)and Eckbo,Masulis,and Norli(2000), but different from Loughran and Ritter(1995)and Spiess and Affleck-Graves(1995,1999),we include utilities in our sample.Following Loughran and Ritter,we define utilities asfirms with SIC codes ranging between4,910and4,949.Excluding utilities does not materially impact our results,likely because the fraction of utilities in each sample is small:6%for SEOs,0.4%for IPOs, 2%for convertible debt issues,and8%for straight debt issues.Further,manyfirms issue multiple tranches of debt on the same date.We deal with this issue by aggregating the amount issued on a given day but separating straight and convertible debt issues.Table1reports for each of the four samples the number of offerings for each year,the number of offerings by non-utilities,and the number of offerings with valid data on size,book-to-market,and investment-to-asset ratio.These characteristics are used to select matching nonissuers.Our samples include10,084SEOs,7,732IPOs,1,215convertible debt offerings,and2,969straight debt offerings. Because of the long sample period(22years for straight debt offerings and36years for all others), our samples are among the largest in the literature.For comparison,Eckbo,Masulis,and Norli’s (2000)sample includes4,766SEOs,Loughran and Ritter’s(1995)sample consists of3,702SEOs and 4,753IPOs,and Brav,Geczy,and Gompers’s(2000)sample includes4,526SEOs and4,622IPOs.Inaddition,Spiess and Affleck-Graves’s(1995)sample consists of1,247SEOs,and Spiess and Affleck-Graves’s(1999)samples contain1,557straight debt offerings and672convertible debt offerings.To study the frequency distribution of issuers across size and book-to-market quintiles,we as-sign issuers to quintiles using the breakpoints from Kenneth French’s website.Forfirms that have issued in the period from July of year t to June of year t+1,we determine the size and book-to-market quintiles at thefiscal yearend of calendar year t−1.If size or book-to-market is missing at that time(frequently in the IPO sample),we use thefirst available size and book-to-market if the available date is no later than12months after the offering(24months for IPOs).We measure the market value as the share price at the end of June times shares outstanding. Book equity is stockholder’s equity(item216)minus preferred stock plus balance sheet deferred taxes and investment tax credit(item35)if available,minus post-retirement benefit asset(item330) if available.If stockholder’s equity is missing,we use common equity(item60)plus preferred stock par value(item130).If these variables are missing,we use book assets(item6)less liabilities(item 181).Preferred stock is preferred stock liquidating value(item10),or preferred stock redemption value(item56),or preferred stock par value(item130)in that order of availability.To compute the book-to-market equity,we use December closing price times number of shares outstanding.Table2presents the frequency distribution of issuingfirms and the relative amount of capital raised in the offerings.From the left four panels,smallfirms are more likely than largefirms to issue equity and convertible debt,but are less likely to issue straight debt.Growthfirms are more likely than valuefirms to issue equity and convertible debt,and to a lesser extent,straight debt. From Panel A,small-growthfirms perform19%of SEOs,while big-valuefirms account for only 0.52%of SEOs.The spread in issuing frequency is even wider for IPOs:32%of IPOs are conducted by small-growthfirms,in contrast to only0.11%by big-valuefirms.The frequency distribution of the convertible debt offerings sample is similar to that of the SEO sample.12%of the convertible debt issues are performed by small-growthfirms,in contrast to only0.58%undertaken by big-value firms.Prior studies show that small-growthfirms have higher investment-to-asset ratios than other10firms(e.g.,Xing2005;Anderson and Garcia-Feijoo2006).Our evidence that small-growthfirms are also the most frequent equity and convertible debt issuers is therefore suggestive of the role of real investment in explaining the underperformance following the offerings.5The right four panels of Table2report the median new issue-to-asset ratios of issuers by size and book-to-market quintiles.We measure the new issue-to-asset ratio as the proceeds of a new issue from SDC divided by the book value of assets at thefiscal yearend preceding an SEO or convertible or straight debt offering.Because of data limitations,we use the book value of assets at thefiscal yearend of an IPO.The distribution of the median new issue-to-asset across size and book-to-market quintiles is similar to the frequency distribution reported in the left panels of the table.Not only small-growthfirms issue securities much more frequently than big-valuefirms,but they also issue much more as a percentage of their book assets.From Panel A,the median new seasoned equity-to-asset ratio of small-growthfirms is0.89.In contrast,the median ratio of big-valuefirms is only 0.01.Dispersions of similar magnitudes are also evident in the convertible and straight debt samples (Panels C and D).From Panel B,the IPO sample displays an even wider spread:the median new equity-to-asset ratio for small-growthfirms is1.75,much higher than that for big-valuefirms,0.05. 4Empirical ResultsWe study the role of investment in driving the new issues puzzle using factor regressions(Section 4.1)and buy-and-holding abnormal returns(Section4.2).Section4.3examines the investment and profitability behavior for issuers and matching nonissuers.Inspired by Daniel and Titman(2006), Section4.4studies the link between investment and the returns of composite issuance portfolios.4.1Factor RegressionsEvidence on the New Issues PuzzleWe measure the post-issue underperformance as Jensen’s alphas in factor regressions.Lyon,Barber and Tsai(1999)argue that factor regressions are one of the two methods that yield well-specifiedtest statistics.(The other approach is Buy-and-Hold Abnormal Returns,see Section4.2.) We use the CAPM and the Fama and French(1993)three-factor model.The dependent variables in the factor regressions are the new issues portfolio returns in excess of the one-month Treasury bill rate.The new issues portfolios,including the SEO,IPO,convertible debt,and straight debt portfolios,consist of allfirms that have issued seasoned equity,gone public,issued convertible debt, and issued straight debt in the past36months,respectively.6Loughran and Ritter(2000)argue that the power of the tests can be increased if we weight eachfirm equally,instead of weighting each period equally.Following Spiess and Affleck-Graves(1999),we thus estimate factor regressions using Weighted Least Squares(WLS),where the weight of each month corresponds to the number of eventfirms having non-missing returns during that month.7Table3reports strong evidence of underperformance following equity issuance(Panels A and B).From Panel A,the equally-weighted alpha from the CAPM regression of the SEO portfolio is −0.41%per month(t-statistic=−2.43),and that from the Fama-French(1993)model is−0.39% per month(t-statistic=−3.52).The value-weighted alphas are similar in magnitude.From Panel B,the post-issue underperformance of IPOs from the CAPM is larger in magnitude than that of SEOs.The equally-weighted and value-weighted CAPM alphas of the IPO portfolio are−0.71% and−0.82%per month with t-statistics−2.60and−3.03,respectively.The alphas of the IPO portfolios from the Fama-French model are close to those of the SEO portfolios.Table3also reports reliable evidence of post-issue underperformance of convertible debt issuers, but not of straight debt issuers(Panels C and D).Convertible debt issuers show comparable under-performance to equity issuers.The convertible debt portfolio earns equally-weighted alphas from the CAPM and the Fama-French(1993)model of−0.63%and−0.54%per month,respectively. Both have t-statistics above four.The value-weighted alphas are smaller in magnitude,−0.44% and−0.26%,but still significant(t-statistics−3.38and−2.00),respectively.In contrast,only the equally-weighted alpha from the Fama-French model,−0.26%,is significant for the straight debtportfolio(t-statistic=−2.35).All the other alphas are insignificantly different from zero.Our evidence that convertible debt issuers display higher post-issue underperformance than straight debt issuers is consistent with Spiess and Affleck-Graves(1999).The Investment FactorAs a direct test of the investment hypothesis,we augment traditional factor models with a common factor based on real investment.We construct the investment factor as the zero-cost portfolio from buying stocks with the lowest30%investment-to-asset ratios and selling stocks with the highest 30%investment-to-asset ratios,while controlling for size and book-to-market.We measure investment-to-asset as the annual change in gross property,plant,and equipment (COMPUSTAT annual item7)plus the annual change in inventories(item3)divided by the lagged book value of assets(item6).We use property,plant,and equipment to measure real investment in long-lived assets used in operations over many years such as buildings,machinery,furniture, computers,and other equipment.We use inventories to measure real investment in short-lived assets used in a normal operating cycle such as merchandise,raw materials,supplies,and work in process.We do a triple sort on size,book-to-market,and investment-to-asset`a la Fama and French (1993).We independently sort stocks in each June on size,book-to-market,and investment-to-asset into three groups,the top30%,the medium40%,and the bottom30%.By taking intersections of these nine portfolios,we classify stocks into27portfolios.The investment factor,denoted INV, is defined as the average return of the nine low investment-to-asset portfolios minus the average return of the nine high investment-to-asset portfolios.8In untabulated results,the investment factor earns an average return of0.57%per month (t-statistic=7.13)from January1970to December2005.This average return is economically meaningful.For comparison,the average market excess return over the same period is0.50%per month(t-statistic=2.28)and the average HML return is0.48%per month(t-statistic=3.24).。

澳大利亚留学简介

【导语】澳⼤利亚的⾼等教育和美国有着⽐较⼤的区别,他更倾向于英国式的传统精英养成⽅式。

虽然也有私⽴⼤学,但是最知名的学府⼏乎都是政府的国⽴⼤学。

与世界同等排名的⼤学相⽐,澳⼤利亚的⼤学申请周期较短,申请难度也有所降低,⽽且留学签证的审理更为简化,⽽毕业之后澳⼤利亚还提供2-4年的毕业⼯作签证,因此确实是更受学⽣和家长的青睐。

下⾯是⽆忧考分享的澳⼤利亚留学简介。

欢迎阅读参考!澳⼤利亚留学简介 1.墨尔本⼤学 是澳⼤利亚第⼆古⽼的⼤学,仅仅⽐悉尼⼤学⼩三岁。

它是澳⼤利亚⼤学在泰晤⼠榜单⾥的多年的第⼀名,18年世界排名第32位,师⽣⽐在1:7左右,虽然总排名不是前三⼗,但是墨尔本⼤学基本上所有学科在世界排名都在前30。

其中最厉害的学院是教育学和法学院,世界排名经常出现在前⼗的位置上,商科和医学也是很有名的。

墨尔本⼤学感觉像是哈利波特的霍格沃兹,除了没有那顶神奇的分院帽,在校园内有⼗三所住宿学院,学⽣被分配到这⼗三所住宿学院,在教学区⼀起上课但是⽣活在各⾃的学院区内,各学院拥有社团活动,有着⾃⼰的传统和院徽。

其申请条件要求雅思6.5以上,托福79以上,同级别⼤学的雅思⼀般都是7分以上。

在这⾥你可以感受和吸收从150年前就开始聚集在这⾥的智慧。

2.澳⼤利亚国⽴⼤学 它是澳⼤利亚的国⽴⼤学(其它澳⼤利亚公⽴⼤学都是州⽴的)很明显⾼了⼀级。

在泰晤⼠排⾏榜⾥低于墨尔本⼤学,⽽他在19年的QS⼤学排⾏榜⾥世界排名第24位,QS⼤学排⾏榜评分项是学术互评,这说明澳洲国⽴⼤学虽然创建的历史⽐较短,但在世界上⼝碑很不错。

创校初期,ANU致⼒于尖端科技的研发,因此仅招收研究⽣。

直到1960年,才开始本科的招⽣。

国⽴⼤学的宿舍有的附⾷堂并供餐,住宿费⽤较⾼;有些宿舍则不供餐,但提供⾃炊的厨房设施。

其中⼈⽂学科、社会科学和⾃然科学领域更是堪称世界顶尖。

ANU典型的学术型⼤学,很适合以后想做学者的⼈来读⼀下。

⽽且学校在堪培拉,跟悉尼和墨尔本⽐,没那么繁华和安逸。

澳大利亚课程论文

澳大利亚五大名校摘要:澳大利亚的教育在当今世界居于一流水平,每年都会吸引大量世界各地的留学生前往澳大利亚深造。

走入澳大利亚五大名校,我们会发现澳大利亚大学教育既融合了美国式的开放校风,又延续了英国式的传统教育,为培养人才提供了宽松的学习空间、良好的学术氛围。

多年来,世界大学学术排名500强中不乏澳大利亚大学的身影。

澳大利亚的教育在当今世界居于一流水平,每年都会吸引大量世界各地的留学生前往澳大利亚深造。

是什么原因,使得澳大利亚大学的水平得到了世人的肯定?走入澳大利亚五大名校,我们一起探究其中的秘密。

一、澳大利亚国立大学(Australian National University )澳大利亚国立大学(Australian National University )于1946年由澳大利亚联邦政府创建,坐落在澳大利亚首都堪培拉,校园占地226公顷,四周被国家自然保护区、伯利•格芬湖和市中心区环抱。

该校连续数年在澳洲大学排名榜上夺魁。

它的光学研究中心,凭借着光纤通讯方面的研究成果,曾荣获马科尼国际奖;雷达与核物理的领头人奥利芬、青霉素发现者之一的弗洛里、杰出的历史学家汉考克、经济学家库姆斯,以及新一代众多知名学者让它熠熠生辉。

澳大利亚国立大学有花园般美丽的校园,四周被国家自然保护区,伯利格里芬湖和市中心区环抱。

其理想的地理位置、优美的自然环境使校园的学习和生活充满友好、和平的气氛,是大学生学习、生活和旅游的最佳选择。

学生会是大学的交流中心,包括商店、会面场所、学生会办公室、饭厅、酒吧、活动室和游戏室等。

体育协会组织各项体育活动,成立了包括武术、柔道、瑜伽等项目的俱乐部。

这里提供了室内健身房、网球场、足球场、橄榄球场、体育娱乐中心、划船俱乐部和航海俱乐部等体育设施。

本校的艺术中心,如大学美术训练馆、堪培拉艺术、美术学校、图像美术馆、堪培拉Llewellgn音乐学校等组织丰富的文化活动。

这里还有大约100个俱乐部和社团,包括亚洲电影协会、堪培拉海外学生咨询会,及Ha re Krishna Vegetarian社团。

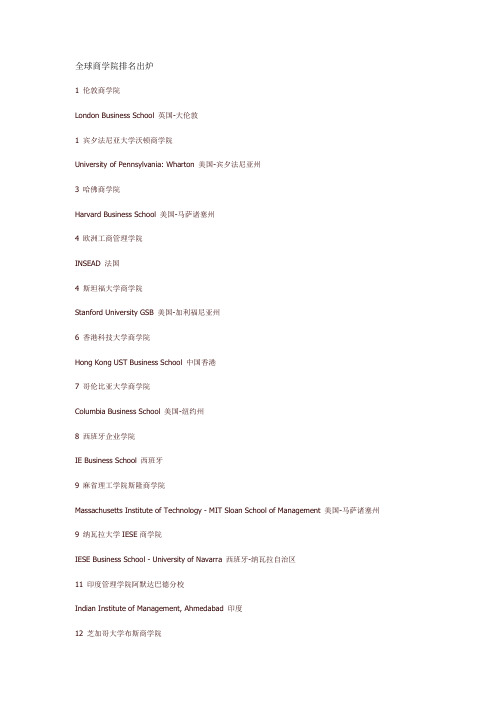

全球商学院排名出炉