Cetuximab for the Treatment of CRC

西妥昔单抗注射液Cetuximab-详细说明书与重点

西妥昔单抗注射液Cetuximab商品名:爱必妥英文名:Cetuximab Solution for Infusion汉语拼音:Xi Tuo Xi Dan Kang Zhu She Ye【警示语】警告:严重的输液反应。

在大约3%的患者中发生了严重的输液反应,其中一些为致命性的。

注意:因本品目前尚缺乏中国人应用的安全性、有效性数据,故必须在有相关产品应用经验的三级以上医院内(建议在国家临床肿瘤研究基地使用) ,与伊立替康联合用药试用于治疗表达表皮生长因子受体(EGFR) 、经含伊立替康细胞毒治疗失败后的转移性结直肠癌;本品必须在有经验医师的指导下使用。

【成份】本品每20ml溶液含:活性成分:西妥昔单抗100mg其他成分:氯化钠116.88mg,甘氨酸150.14mg,聚山梨酯80 2mg,一水合柠檬酸42.02mg,氢氧化钠(1M)调节pH值至5.5,注射用水加至20ml。

【性状】本品为注射用无色、澄清、透明溶液。

【适应症】西妥昔单抗用于治疗表达表皮生长因子受体(EGFR) 、RAS基因野生型的的转移性结直肠癌:与伊立替康联合用于经含伊立替康治疗失败后的患者。

西妥昔单抗联合FOLFOX(奥沙利铂+亚叶酸钙+5-氟尿嘧啶[5-FU])或FOLFIRI(伊立替康+亚叶酸钙+5-FU)一线治疗RAS野生型(wt)转移性结直肠癌(mCRC)患者、或联合伊立替康(irinotecan)用于对伊立替康化疗无效的患者。

与铂类和氟尿嘧啶化疗联合,用于一线治疗复发和/或转移性头颈部鳞癌。

【规格】100mg(20ml)/瓶【用法用量】西妥昔单抗必须在有使用抗癌药物经验的医师指导下使用。

在用药过程中及用药结束后1小时内,需密切监测患者的状况,并必须配备复苏设备。

在首次滴注本品之前至少1小时,患者必须接受抗组胺药物和皮质类固醇药物的预防用药。

建议在在后续治疗中,每次使用本品之前都对患者进行上述预防用药。

本品每周给药一次。

211113621_脊髓损伤患者脊髓神经刺激器植入术后康复治疗1例报告

·专家论坛·脊髓损伤患者脊髓神经刺激器植入术后康复治疗1例报告陈楠 陈婵 顾雨薇 凌骏麒 白玉龙(复旦大学附属华山医院康复医学科 上海 200040)摘要目的:观察硬膜外脊髓神经电刺激结合康复训练对1例脊髓损伤患者肢体功能恢复的效果。

方法:采用常规康复训练方法治疗脊髓损伤后植入脊髓神经刺激器的截瘫患者,每周6次共3周。

治疗前、后和1个月随访时通过美国脊髓损伤协会脊髓损伤分级、Lovett肌力分级、改良Barthel指数量表、Berg平衡功能量表和改良Ashworth量表评估患者的肢体功能和日常生活活动能力。

结果:治疗3周后,患者的运动、感觉、平衡功能和日常生活活动能力均获得明显改善,且这些改善在1个月随访时仍得以保留。

结论:康复训练能改善脊髓损伤后植入脊髓神经刺激器的截瘫患者的肢体功能,是此类患者不可或缺的治疗手段,但要获得良好的效果,患者须长期坚持康复训练。

关键词 脊髓损伤硬膜外脊髓神经电刺激康复训练中图分类号:R493; R651.2 文献标志码:B 文章编号:1006-1533(2023)07-0008-03引用本文陈楠, 陈婵, 顾雨薇, 等. 脊髓损伤患者脊髓神经刺激器植入术后康复治疗1例报告[J]. 上海医药, 2023, 44(7): 8-10; 36.Postoperative rehabilitation of spinal cord nerve stimulator implantationin a patient with spinal cord injury: a case reportCHEN Nan, CHEN Chan, GU Yuwei, LING Junqi, BAI Yulong(Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China) ABSTRACT Objective: To observe the effect of epidural spinal cord stimulation combined with rehabilitation training on the recovery of limb function in a patient with spinal cord injury. Methods: The paraplegic patients with spinal cord nerve stimulator implanted after spinal cord injury was treated with routine rehabilitation training, 6 times a week for 3 weeks. The limb function and the abilities of daily living were assessed by the American Spinal Cord Injury Association spinal cord injury scale, Lovett muscle strength scale, modified Barthel index scale, Berg balance function scale, and modified Ashworth scale at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-month follow-up. Results: After 3 weeks of treatment, the patient showed significant improvements in motor, sensory, balance, and daily living, and these improvements were maintained at 1-month follow-up.Conclusion: Rehabilitation training can improve the limb function of paraplegic patients with spinal cord nerve stimulator implantation after spinal cord injury, and is an indispensable treatment for such patients. However, patients must adhere to long-term rehabilitation training to obtain good results.KEY WORDS spinal cord injury; epidural spinal cord stimulation; rehabilitation training脊髓损伤是指由于各种原因引起的脊髓结构和功能的破坏,多继发于外伤[1],可导致损伤平面以下运动、感觉和自主神经功能障碍。

西妥昔单抗CRC关键临床研究及策略解读

西妥昔单抗 + 伊立替康 (共218例患者)

西妥昔单抗 (共111例患者)

Cunningham D, et al. N Engl J Med 2004;351:337–345

BOND 研究-既往治疗

既往治疗线数 1 2

>3 既往使用奥沙利铂治疗

ERBITUX % (n=111)

24 37 39 64

安全性和毒性反应

thereafter plus . . .

Wilke et al. Cetuximab + irinotecan in mCRC (MABEL). Abstract 3549

MABEL研究-疗效

有效率 疾病控制率 无进展生存率:

Week 12 Week 24 中位总生存期

爱必妥放性、无对照、多中心研究

EGFR表达阳性、伊立替康治疗后进展的 mCRC患者

爱必妥 + 伊立替康 治疗直至疾病进展

n=1147

2006. ESMO. Abstract

MABEL研究-患者入选标准、治疗方案、研究终点

患者入选标准:

EGFR阳性 在伊立替康治疗6个月内疾病进展的 mCRC

治疗方案(治疗直至疾病进展):

• KRAS突变是CRC早 期发生的事件,在40– 45%的CRC患者会出 现

• KRAS突变与不良预 后相关

免疫效应细胞

EGFR信号途径抑制策略

EGFR 酪氨酸激酶 抗EGFR单抗 抑制剂

抗EGFR 配体单抗

双特异性抗体

ATP

TK

TK

--

TK

TK

--

EGFR信号途径抑制药物

❖ Gefitinib ❖ Erlotinib

吉西他滨及顺铂经动脉、静脉注射后血浆、组织药物浓度的变化

吉西他滨及顺铂经动脉、静脉注射后血浆、组织药物浓度的变化目的分析不同化療药物通过动脉及静脉途径注射后血浆及组织内药物浓度的变化情况。

方法40只带瘤裸大鼠,随机分为8组,其中4组为动脉组,另4组为静脉组,带瘤裸大鼠分别经动脉及静脉注射吉西他滨及顺铂。

于注射后5、10、20、40、80、120、360、720 min采血液标本,注射后10、40、120、720 min取组织标本,以高效液相色谱法测定血浆及肿瘤组织中吉西他滨浓度,ICP-MS法测定血浆及肿瘤组织中的铂含量,计算药代动力学参数。

结果经动脉及静脉注射两种药物后,血浆及肿瘤组织中的药物浓度出现规律性变化,其变化过程均可用两室模型来描述。

动脉注射两组药物的药代动力学参数与静脉注射的药代动力学参数不同,动脉组注射药物后,血浆药物峰浓度[吉西他滨:(20.84±10.11)μg/mL,顺铂:(15.13±7.12)μg/mL]均低于静脉组[吉西他滨:(28.96±7.02)μg/mL,顺铂:(21.64±9.72)μg/mL],靶组织内药物峰浓度[吉西他滨:(20.18±9.43)μg/mL,顺铂:(6.98±0.31)μg/mL]均高于静脉组[吉西他滨:(18.19±10.30)μg/mL,顺铂:(3.04±0.11)μg/mL],靶组织内药物曲线下面积[吉西他滨:(2641±411)μg/(min·mL),顺铂:(6025±870)μg/(min·mL)]均明显高于静脉组[吉西他滨:(1663±568)μg/(min·mL),顺铂:(1780±883)μg/(min·mL)],差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05或P < 0.01)。

结论动脉注射吉西他滨和顺铂较静脉注射有不同程度的优势,这种优势与药物的药理特性有关。

2008年转移性结直肠癌个体化治疗进展回顾

(<中国癌症杂志》2009年第19卷第6期CHINAONCOLOGY2009V01.19No.6刘云鹏,中国医科大学附属第一医院教授、博士生导师、肿瘤内科主任、肿瘤中心副主任、大内科副主任,辽宁省肿瘤药物与生物治疗重点实验室主任。

主要从事胃肠肿瘤和淋巴瘤的化疗与免疫生物治疗的机制研究。

中国版NccN胃癌和结直肠癌诊治标准制定委员;中国抗癌协会CSCO执行委员;中国抗癌协会肿瘤标志专业委员会委员;中国生物工程学会生物治疗专业委员会委员;辽宁省抗癌协会常务理事;辽宁省抗癌协会化疗专业委员会、大肠癌专业委员会、淋巴瘤专业委员会副主任委员;美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)会员;《世界华人消化杂志》编委;《中国肿瘤临床》杂志特邀编委;《中国实用内科杂志》常务编委;《中国进修医师杂志》、《临床肿瘤学杂志》编委。

先后获得国家自然科学基金2项;卫生部和辽宁省基金课题多项及辽宁省科技进步二等奖和沈阳市科技进步二等奖各一项,发表论文100余篇,培养硕、博士研究生40余人。

2008年转移性结直肠癌个体化治疗进展回顾[摘要】含草酸铂或伊立替康的化疗方案作为晚期结直肠癌的标准治疗方案,使得患者总生存期超过20个月,靶向治疗药物西妥昔单抗和贝伐单抗的加入进一步提高了疗效。

2008年结直肠癌治疗的重要进展是确定KRAS基凶状态与抗EGFR抗体疗效的相关性。

CRYSTAL、OPUS和CELIM等随机研究显示,通过K—ras检测可筛选出能从分子靶向治疗药物中获益的人群,西妥昔单抗无论是联合以奥沙利铂为基础、还是联合以伊立替康为基础的一线化疗方案,都能使KRAS野生型患者疗效显著提高,显示出西妥昔单抗在mcRc一线治疗中的优势。

【关键词】结直肠癌;西妥昔单抗;KliAS;草酸铂;伊立替康中图分类号:R735:3;R730.53文献标识码:A文章编号:1007—3639(2009)06—0406—03Reviewofadvances1‘1theindividualizedtreatmentofmetastaticcolorectalcancerin2008LIUYun—peng(DepartmentofMedicalOncology,theFirstHospitalofChinaMedicalUniversity,ShenyangLiaoning110001,China)Correspondenceto:LIUYun-pengE-taail:liuyunpengOmedmail.co皿册[Abstract]Oxaliplatinoririnotecancontainingchemotherapeuticregimenisthestandardtreatmentformetastaticcolorectalcancer(mCRC),whichachievesmorethan20monthsofoverallSHrVival.Theadditionofcetuximaborbevacizumabtothechemotherapyfurtherimprovestheoutcome.11hemajorachievementforthetherapyofmCRCin2008isthecorrelationbetweenK-rasstatusandtheefficacyofanti.EGFRtherapy.DatafromthreerandomizedclinicaltrialsCRYSl’AL.OPUSandCELlMhavedemonstratedthattheanalysisofK-rasstatuscallhetpselectpatientswhomaybenefitfromanti.EGFRantibodytreatment.11”additionofcetuximabtoeitheroxalipllatinoririnotecancontainingregimenscanbenefitmCRCpatientswithwild-typeK-rastumors,whichshowsthegreatofcetuximabinthefirst-linetreatmentofmCRC.superiority[Keywords]colorectalcancer;,cetuximab;K-ras;oxaliplatin;irinotecan通讯作者:刘云鹏E-mail:liuyunpeng◎medmail.toulon万方数据《中国癌症毒志》2009年第19卷第6期407结直肠癌是常见的恶性肿瘤之一。

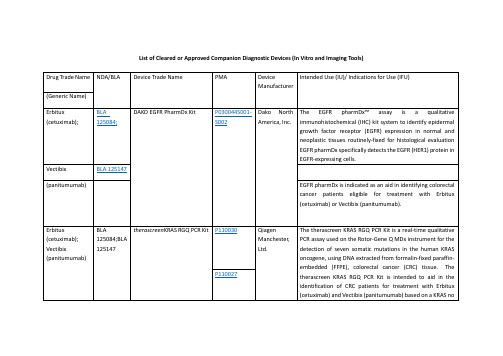

FDA批准的精准医疗诊断体外器械一览表List of Cleared or Approved Companion Diagnostic Devices

Drug Trade Name

NDA/BLA

Device Trade Name

PMA

Device Manufacturer

Intended Use (IU)/ Indications for Use (IFU)

(imatinibmesylate)

NDA 021588

The c-KitpharmDxis indicated as an aid in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). After diagnosis of GIST, results from c-KitpharmDxmay be used as an aid in identifying those patients eligible for treatment withGleevec/Glivec(imatinibmesylate).

(deferasirox)

Gilotrif

NDA 201292

therascreenEGFR RGQ PCR Kit

P120022

QiagenManchester, Ltd.

ThetherascreenEGFR RGQ PCR Kit is a real-time PCR test for the qualitative detection of exon 19 deletions and exon 21 (L858R) substitution mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene in DNA derived from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumor tissue. The test is intended to be used to select patients with NSCLC for whom GILOTRIF (afatinib), an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), is indicated. Safety and efficacy of GILOTRIF (afatinib) have not been established in patients whose tumors have L861Q, G719X, S768I, exon 20 insertions, and T790M mutations, which are also detected by thetherascreenEGFR RGQ PCR Kit.

不可切除胰腺癌的分子靶向药物治疗进展

不可切除胰腺癌的分子靶向药物治疗进展胡润,李俊蒽,姚沛,桂仁捷,段华新湖南师范大学附属第一医院,湖南省人民医院肿瘤科,长沙 410005通信作者:段华新,****************(ORCID: 0000-0001-9596-5013)摘要:胰腺癌作为消化系统最常见的恶性肿瘤之一,其发病率及死亡率正逐年上升,大多数胰腺癌患者因分期较晚而失去了手术机会。

尽管以吉西他滨、氟尿嘧啶为主的化疗方案在一定程度上延长了患者的生存期,但仍有部分患者因无法耐受化疗而失去治疗机会。

随着精准医疗时代的来临,分子靶向药物治疗展现出的优异疗效使其成为对抗肿瘤的重要治疗手段之一,但由于胰腺癌高度的异质性及复杂的免疫微环境,针对胰腺癌的分子靶向治疗并未取得显著效果,因此亟需探寻新的治疗靶点及药物攻克这一难题。

本综述基于胰腺癌常见分子靶点及肿瘤免疫相关靶点探究在不可切除胰腺癌中分子靶向药物治疗研究的最新进展,为胰腺癌患者提供新的治疗策略。

关键词:胰腺肿瘤;分子靶向治疗;免疫疗法基金项目:湖南省自然科学基金(2020JJ8084)Advances in molecular-targeted therapy for unresectable pancreatic cancerHU Run,LI Junen,YAO Pei,GUI Renjie,DUAN Huaxin.(Department of Oncology,The First Affiliated Hospital of Hunan Normal University, Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital, Changsha 410005, China)Corresponding author: DUAN Huaxin,****************(ORCID: 0000-0001-9596-5013)Abstract:Pancreatic cancer is one of the most prevalent malignant tumors of the digestive system, and its incidence and mortality rates are increasing year by year. Most patients with pancreatic cancer are unable to receive surgery due to the advanced stage. Although chemotherapy regimens based on gemcitabine and fluorouracil have prolonged the survival time of patients to some extent,some patients cannot tolerate chemotherapy and hence lose the opportunity for treatment. With the advent of the era of precision medicine, molecular-targeted therapy has exhibited an excellent therapeutic efficacy and has thus become one of the most important treatment techniques for tumors; however, due to the high heterogeneity of pancreatic cancer and its complicated tumor microenvironment, molecular-targeted therapy for pancreatic cancer has not achieved notable results. Therefore, it is imperative to seek new therapeutic targets and medications to overcome this issue. This article reviews the latest advances in the research on molecular-targeted therapy for unresectable pancreatic cancer based on common molecular targets and tumor immunity-related therapeutic targets, in order to provide new treatment strategies for patients with pancreatic cancer.Key words:Pancreatic Neoplasms; Molecular Targeted Therapy; ImmunotherapyResearch funding:Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (2020JJ8084)胰腺癌是一种起病隐匿、进展迅速、疗效及预后极差的恶性肿瘤,大多数患者确诊时已经属于晚期。

分子靶向抗肿瘤药物的作用机制及临床研究进展

分子靶向抗肿瘤药物的作用机制及临床研究进展胡宏祥, 王学清, 张华*, 张强(北京大学药学院, 北京100191)摘要: 肿瘤分子靶向药物因其特异性强、耐受性好等特点, 在肿瘤治疗中占有越来越重要的地位。

分子靶向治疗药物的种类很多, 包括单克隆抗体和小分子激酶抑制剂等, 从1997年首个单抗药物利妥昔单抗上市到目前为止, 已被批准上市的药物达50多种, 抗肿瘤靶点也趋于多样化。

以肿瘤细胞特异性分子靶点为导向的药物研发已经成为现代抗肿瘤药物发展的主流趋势。

本文对FDA批准上市的分子靶向药物进行总结, 按照作用靶点的不同进行分类, 并对各类药物的分子机制及临床使用情况作一概述。

关键词: 分子靶向治疗; 单克隆抗体; 蛋白酪氨酸激酶; 抗肿瘤中图分类号: R943 文献标识码:A 文章编号: 0513-4870 (2015) 10-1232-08 Mechanism and clinical progress of molecular targeted cancer therapy HU Hong-xiang, WANG Xue-qing, ZHANG Hua*, ZHANG Qiang(School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100191, China)Abstract: Molecular target-based cancer therapy is playing a more and more important role in cancer therapy because of its high specificity, good tolerance and so on. There are different kinds of molecular targeted drugs such as monoclonal antibodies and small molecular kinase inhibitors, and more than 50 drugs have been approved since 1997. When the first monoclonal antibody, rituximab, was on the market. The development of molecular target-based cancer therapeutics has become the main approach. Based on this, we summarized the drugs approved by FDA and introduced their mechanism of actions and clinical applications. In order to incorporate most molecular targeted drugs and describe clearly various characteristics, we divided them into four categories: drugs related to EGFR, drugs related to antiangiogenesis, drugs related to specific antigen and other targeted drugs. The purpose of this review is to provide a current status of this field and discover the main problems in the molecular targeted therapy.Key words: molecular targeted therapy; monoclonal antibody; protein-tyrosine kinases; anti-cancer肿瘤分子靶向治疗(molecular targeted therapy) 与激素治疗、免疫治疗和细胞毒化疗药治疗共同构成了现代肿瘤药物治疗的主要治疗手段。

大肠癌化疗进展

28

36 P=0.01

mPFS(wks)

53

56

CR+PR(%)

51

54

PR(%)

2

2

CR(%)

OPTIMOX 2

OPTIMOX 1

方案

21.0

68

Tournigand 2001

19.4

60

Giacchetti 2000

19.5

60

Goldberg 2002

20.1

54

Koehne 2003

16.2

29

De Gramont 2000

17.4

16

Douilard 2000

14.8

mCRC :有效药物

5FU/LV

XELODA

CPT-11

L-OHP

mCRC化疗 :二药联合

*可用于一线或二线治疗

CAPIRI

IFL

XELIRI

FOLFIRI

Irinotecan

CAPOX

bFOL

XELOX

FOLFOX

Oxaliplatin

给药方式:CI 5-FU vs bolus 5-FU ( JCO 1998 1611:301-308 )

6项共1219例mCRC的meta分析 CIV 5-FU i.v bolus 5-FU RR 22% 14% mTTP(mo) 7.1 6.7 mOS(mo) 12.1 11.3

CONcePT试验: 间歇和 连续Oxal的比较

Oxal使用

Intermittent(IO)

Continueing(CO)

P值

失败:毒性 PD mTTF (wk)

晚期结直肠癌整体治疗策略优化教程文件

CALGB/ SWOG 80405†

CALGB/ SWOG 80405†

中位 OS(月)

单纯化疗

靶向治疗

Bev=bevacizumab; cetux=cetuximab; pan=panitumumab; *FIRE-3 did not meet its primary endpoint of significantly improving ORR in patients with KRAS (exon 2) wt mCRC based on investigators’ read5 †CALGB/SWOG 80405 did not meet its primary endpoint of significantly improving OS in the cetuximab + FOLFOX/FOLFIRI vs bevacizumab + FOLFOX/FOLFIRI arm in patients with KRAS (exon 2) wt mCRC7 ‡Cetuximab is approved in patients with RAS wt mCRC.8 Cetuximab is not indicated for the treatment of patients with mCRC whose tumors have RAS mutations or for whom RAS tumor status is unknown8

发展中国家

亚洲结直肠癌的流行病学

男性

女性

转移性结直肠癌药物治疗的发展

CRC的化疗和生存期

35 30

25

252例结直肠癌组织中KRAS、NRAS、 BRAF、PIK3CA的基因突变分析

252例结直肠癌组织中KRAS、NRAS、 BRAF、PIK3CA的基因突变分析刘影;郑细闰;朱亚珍;何青莲;郑广娟【摘要】目的分析结直肠癌(colorectal cancer,CRC)组织中KRAS、NRAS、BRAF和PIK3CA基因的常见突变类型及其与临床病理指标的关系.方法对252例CRC石蜡包埋组织进行DNA提取,采用Sanger测序法对KRAS、NRAS、BRAF和PIK3CA基因进行检测,分析各个基因的突变率与临床病理特征的关系,并统计各个基因的突变类型.结果 252例CRC中,KRAS、BRAF、NRAS和PIK3CA突变发生率在性别、年龄、肿瘤部位、病理分期和有无淋巴结转移上差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05);检测阳性突变共140例(55.5%),其中KRAS 113例(44.8%),NRAS 1例(0.4%),BRAF 19例(7.5%),PIK3CA 28例(11.1%),包括PIK3 CA与KRAS、NRAS、BRAF基因发生双突变21例(8.3%);KRAS的主要突变类型包括G12A、G12C、G12D、G12R、G12S、G12V、G13D、T20M、A59T、Q61H、Q61L、Q61P;NRAS仅有1例突变为G12D;BRAF的主要突变类型为V600E、D594G、K601E;PIK3CA的主要突变类型包括E542K、E545K、Q546K、Q546P、Q546R、M1043I、H1047R.PIK3CA与KRAS、NRAS、BRAF之间会发生交叉突变,但KRAS、NRAS、BRAF三者之间基本不存在交叉突变.结论 CRC中KRAS阳性突变率居高,PIK3CA次之,BRAF、NRAS突变率最低,且PIK3CA常与KRAS、NRAS、BRAF发生交叉突变.对CRC患者行KRAS、NRAS、BRAF、PIK3CA等多基因检测,可正确指导并选择抗EGFR单抗药,从而实现真正意义上的个体化靶向治疗.【期刊名称】《临床与实验病理学杂志》【年(卷),期】2016(032)008【总页数】6页(P851-855,859)【关键词】结直肠肿瘤;Sanger测序;KRAS;PIK3CA;靶向治疗【作者】刘影;郑细闰;朱亚珍;何青莲;郑广娟【作者单位】广东省中医院病理科,广州510120;广东省中医院病理科,广州510120;广东省中医院病理科,广州510120;广东省中医院病理科,广州510120;广东省中医院病理科,广州510120【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R735.3美国最新癌症统计结果显示,结直肠癌(colorectal cancer, CRC)发病率居全球常见恶性肿瘤的第3位,病死率居第4位[1]。

c-225cetuximab,西妥昔单抗)(也称C-225)

美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)已批准cetuximab作为治疗晚期结肠癌的药物上市。

Cetuximab 是迄今第一个获得批准治疗结肠癌的单克隆抗体药物。

瑞士已批准了MerckKgaA公司的抗癌药物Erbitux(cetuximab,西妥昔单抗)(也称C-225),用于对irinotecan (伊立替康)标准疗法不再响应的结肠癌患者。

这是Erbitux在全球的首次获批。

【作用机制】Cetuximab为IgG1单克隆抗体,是表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)阻止剂。

Cetuximab主要通过干扰癌细胞表面一种名为“表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)”的蛋白质生长,通过抑制表皮生长因子受体,减少癌细胞进入正常组织的几率,控制癌细胞的转移,达到抗癌目的。

它虽然不能延长结肠癌患者生命,但是能够部分缩减已扩散至身体其他部位的癌细胞。

临床试验结果显示,同时接受新药和另一种化疗药物治疗的患者中,有近23%的人结肠肿瘤不同程度地缩减。

只接受新药治疗的患者中也有约11%的人结肠肿瘤出现缩减。

Cetuximab是一种人和鼠的EGFR单克隆抗体的嵌合体,由鼠抗EGFR抗体和人IgG1的重链和轻链的恒定区域组成,Cetuximab可以竞争性的抑制EGF及其它配体的结合,阻断了受体的相关酶的磷酸化,进而抑制细胞生长,诱导调亡,减少基质金属蛋白酶和血管表皮生长因子(VEGF)的生成,体外实验和动物实验显示ERBITUX可以抑制过度表达EGFR的肿瘤细胞的生长,而对缺乏EGFR表达的人肿瘤细胞则没有抗肿瘤活性,此外还发现Cetuximab 与化疗联合应用要优于单独化疗。

>【药代动力学】【适应症】晚期结肠癌肺癌【禁忌症】【用法与用量】intravenous use only联合OXALIPLATIN的方案:Cetuximab 400 mg/m2 loading one dose week #1 of cycle #1250 mg/m2 weekly starting on week #2andoxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 dl,LV 200 mg/m2, d1 & d2,5-FU 400 mg/m2 bolusthen 600 mg/m2 CI (22 hours)d1 & d2 (FOLFOX4)every 2 weeks【不良反应】最常见的非血液毒性包括痤疮状皮疹,感染及疲劳。

《结核病患者外周血淋巴细胞亚群检测及临床应用专家共识》解读

•专论•《结核病患者外周血淋巴细胞亚群检测及临床应用专家共识》解读梁建琴吴雪琼【摘要】结核病的发生、发展及转归与机体免疫力关系密切。

检测结核病患者外周血淋巴细胞亚群是评估免 疫功能的方法之一,但该检测项目在结核病的临床应用有限,认识不统一。

发表于《中国防痨杂志>2020年第10期 的《结核病患者外周血淋巴细胞亚群检测及临床应用专家共识》,就淋巴细胞亚群检测结果的正确判读和临床应用 提出了具体建议并达成共识。

本解读强调要关注结核病患者外周血淋巴细胞亚群检测方法的标准化和规范化,重 视全面正确客观分析检测结果,并就存在的问题提出简要建议,以供我国结核病临床工作者借鉴和参考。

【关键词】结核;淋巴细胞亚群;实验室技术和方法;总结性报告(主题);评论;基于问题的学习Interpretation of Expert consensus on detection and clinical application of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in patients with tuberculosis LIANG Jia n-q in, W U Xue-qiong. Army Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Key Laboratory,Beijing Key Laboratory o f New Techniques o f Tuberculosis Diagnosis and Treatment,Institute for Tuberculosis Research , the 8th Medical Center o f Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100091, ChinaCorresponding author :W U Xue-qiong 9 Email : xueqiongwu@ 139. com【Abstract】The occurrence,development and prognosis of tuberculosis (TB) are closely related to immune resistance. The detection of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in TB patients is one of the methods to evaluate immune function, but the clinical application of this detection in TB is limited and the understanding is not uniform.^Expert consensus on detection and clinical application o f peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in patients with tuberculosis^ published in No. 10 of 2020 in Chinese J ournal o f A nti t uberculosis proposed specific suggevStions and reached consensus on correct interpretation and clinical application of lymphocyte subsets detection results. This interpretation emphasizes that we should pay attention to the standardization and normalization of detection methods for peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in TB patients, pay attention to the comprehensive, correct and objective analysis of the detection results»and put forward brief suggestions on the existing problems, to provide the reference of TB clinical workers of our country.【Key words】Tuberculosis; Lymphocyte subsets;Laboratory techniques and procedures;Consensus development conferences as topic;Comment;Problem-based learning结核病是威胁全球公共卫生健康的传染病之一。

西妥昔单抗和贝伐单抗在晚期结直肠癌一二线治疗中的研究进展

西妥昔单抗和贝伐单抗在晚期结直肠癌一二线治疗中的研究进展在我国,结直肠癌患者正呈现逐年上升的趋势,其治疗方法以手术为主,辅以放化疗,但效果却不甚理想。

对于晚期结直肠癌的患者,已无法进行根治性手术切除,而放、化疗本身带来的毒副作用也严重影响患者的生活质量。

近10年来,随着人们对西妥昔单抗和贝伐单抗等靶向药物的研究越来越深入,晚期结直肠癌患者再次迎来的新的曙光。

在原有化疗药物的基础上使用靶向药物以进一步提高疗效也成為晚期结直肠癌一二线治疗新的发展趋势。

此外,随着研究的不断深入,原发瘤部位的不同对靶向药物疗效的影响也成为医学界关注的焦点话题之一。

本文就西妥昔单抗和贝伐单抗在晚期结直肠癌一二线治疗的研究进展以及左、右半结肠对靶向药物疗效的影响进行综述。

[Abstract] In China,the incidence of CRC is reportedly increasing over time. The treatment options including surgery,chemotherapy and radiotherapy,which are available depending mostly on disease stage. However,patients with advanced CRC have lost the chance of surgery,may also have a worse life because of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. With more and more studies on targeted therapy,such as Bevacizumab and Cetuximab,may shines a light for the patients with CRC. Chemotherapy combined with targeted therapy has become a new direction for the treatment of advanced CRC. Moreover,the association between tumor location and targeted therapy has become a hot topic. This review focuses on the progress of monoclonal antibody in the first-and second-tier treatment of advanced CRC and the effect of the left and right half colon on the efficacy of targeted drugs.[Key words] Advanced colorectal cancer;Cetuximab;Bevacizumab根據最近的数据,我国结直肠癌(CRC)发病率较以往有显著提高,年发病增长率为4.2%,已远远超过发达国家的平均水平,并呈现逐年增长的趋势,且发病患者趋于年轻化[1-2]。

爱必妥联合介入治疗在mCRC中的应用

J Clin Oncol 29: 2011 (suppl; abstr e14102)

研究结果

A median of 4 protocol courses (1-12) was given. Main grade 34 toxicities per patient were neutropenia (39%), abdominal pain (30%), fatigue (22%), and leukopenia (17%). An objective tumor response was achieved in 10/23 patients (43.4%). Seven patients underwent liver surgery (30.4%). 17 pts are alive with a median follow up of 16 months.

J Clin Oncol 29: 2011 (suppl; abstr e14102)

结论

•作为新辅助治疗,爱必妥联合介入动脉灌注化疗是可行 的,肿瘤反应率高,提高了转移灶的切除率。

中位TTP(月)

8

7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 7.4 Patients (%)

60

50 40 30 20 10 0 62

•中位OS在文章发表时还未达到 •其中有四位患者CEA降低超过50%多达4周

毒副反应(1)

•爱必妥相关的不良反应主要有:1个3级的皮肤反应,1个间质性肺炎(并发 链球菌败血症),2个囊性胆管扩张(其中一人伴发肝动脉胆管瘘)。

爱必妥联合介入治疗 在mCRC中的应用

研究简介

这是一个单中心的探索性研究,主要看静脉输注爱必妥 联合介入下肝动脉灌注化疗的可行性与安全性。

一例犬细小病毒病的治疗与体会

第3卷第5期 高原农业 V ol.3 No.5 2019年10月 Journal of Plateau Agriculture Oct. 2019 收稿日期:2019-07-08作者简介:常振宇(1989-),男。

汉族,河南林州人,讲师,硕士。

研究方向:从事畜禽营养代谢病与中毒病方面的研究。

通讯作者:吴庆侠(1973-),女,汉族,陕西固城人,副教授,博士。

研究方向:从事动物病理方面的研究。

基金项目:2018年兽医学创新创业平台建设(503118005);西藏自治区厅校联合基金(XZ2018ZRG-26(Z))。

一例犬细小病毒病的治疗与体会常振宇 陈文 张笑冰 周欣燃 李鑫宇 吴庆侠* (西藏农牧学院 动物科学学院,西藏林芝860000)摘要 犬细小病毒病是一种在犬中非常容易发生的急性传染病,由感染的犬细小病毒(CPV )引起,也称犬出血性肠炎、病毒性肠炎,致死率非常之高。

作者在北京某宠物医院实习期间遇到一例有呕吐症状,排便稀且有腥臭味的患犬,通过实验室检查、临床观察和试纸条检测等方法对病犬进行诊断。

结果表明,病犬血液中红细胞数、血红蛋白、红细胞压积数目降低,平均血红蛋白浓度、红细胞分布宽度增加,犬细小病毒试纸检测为阳性,再根据临床症状观察,最终确诊为犬细小病毒病,该研究为犬细小病毒病的临床治疗和综合防治提供理论依据。

关键词 犬;细小病毒病;治疗;体会中图分类号:S858.2 文献标识码:A 文章编号:2096-4781(2019)05-0533-06 DOI: 10.19707/ki.jpa.2019.05.011Treatment and Experience of a Case of Canine Parvovirus DiseaseCHANG Zhenyu, CHEN Wen, ZHANG Xiaobing, ZHOU Xinran, LI Xinyu, WU Qingxia*(Animal Science College, Tibet Agriculture & Animal Husbandry University, Nyingchi Tibet, 860000, China )Abstract: Canine parvovirus disease is a susceptible acute infectious disease in dogs, caused by canine parvovirus (CPV), also known as hemorrhagic enteritis and viral enteritis in dogs with a high fatality rate. The case dog was diagnosed by laboratory examination, clinical observation and strip test. The results showed that the red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin (Hb) and hematocrit (HCT) in the blood of case were decreased, the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), red blood cell distribution width (RDW) were increased, and dipstick test of the canine parvovirus was positive. Finally, the case was confirmed as canine parvovirus disease by clinical examination. This study will provide the theoretical basis for the clinical treatment, and comprehensive prevention and treatment of canine parvovirus disease.Key words: Dogs, Parvovirus disease, Treatment, Experience 犬细小病毒病的主要特征是白细胞数显著减少、心肌炎、剧烈呕吐以及出血性肠炎,该病毒最初在1977年由美国学者Eugster 通过电镜在患腹泻的幼犬粪便中分离得到,1983年我国正式确认该病的流行[1-3]。

西妥昔单抗疗效与mCRC原发位置的相关性

FOLFIRI Cetuximab+FOLF (n=289) IRI (n=277)

p

42.6

61.0

<0.001

8.8

10.9

0.0013

21.6

25.1

0.093

2020/5/16

mCRC原发位置是OS独立预后因素

2020/5/16

如何定义左右半结/直肠癌?

• 右半结肠癌:盲肠、升结 肠、横结肠近端2/3

KRAS Wild-Type (n=666)

FOLFIRI (n=350)

39.7

Cetuximab+FOLF IRI (n=316)

p

57.3

<0.001

8.4

9.9

0.0012

20

23.5

0.093

ORR (%) PFS (mo) OS (mo)

KRAS Wild-Type/BRAF Wild-Type (n=566)

Saltz1 Douillard2

Saltz1 Douillard2 Goldberg3

Hurwitz4 Falcone5

Saltz6

5-FU/LV 推注

12.6

5-FU/LV 静注

14.1

IFL

14.8

FOLFIRI

17.4

FOLFOX

19.5

IFL + 贝伐珠单抗

AVF2107g

20.3

FOLFOXIRI

左右半结直肠癌的区别

流行病学 胚胎来源 解剖结构 临床特征 分子特征 预后结局

均不同

2020/5/16

流行病学

从全球范围看,左半结肠癌的发病率高于右半 结肠癌,而且左半结肠癌中男性的发病率较女性高 ,但右半结肠癌中女性的发病率较男性高,并且右 半结肠癌的平均发病年龄明显高于左半结肠。

Panitumumab 和 Cetuximab 毒性管理指南说明书

Panitumumab and CetuximabToxicity ManagementGuideline Resource Unit ***********Accompanies: Clinical Practice Guideline GI-003The assessment, prevention, rehabilitation and management strategies outlined in this summary and accompanying guideline apply to adult cancer patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Refer to the full clinical practice guideline for a detailed description of the clinical questions, recommendations, guideline development methodology, and references.BackgroundThis resource has been created to ensure the safe administration of panitumumab or cetuximab (anti-EGFR therapy) to patients with advanced colorectal cancer in Alberta.For more information on recommended regimens please see the Metastatic Colorectal Cancer clinical practice guideline.Adverse EventsStandard monitoring for adverse effects should occur through each cycle. The following adverse effects warrant specific attention:Cutaneous Toxicities (e.g., erythema, rash, follicular eruption, desquamation, xerosis, pruritus):E r y t h e m a , R a s h ,F o l l i c u l a r E r u p t i o n , D e s q u a m a t i o n , a n d /o r U l c e r a t i o nPainless erythema Painful erythemaGeneralized erythrodermaLife threatening or disabling Macular or papular follicular eruption without associated symptoms Macular or papular follicular eruption with associated symptoms (e.g.: pruritus, pain) Severe macular or papular follicular eruptionLocalized desquamation (<50% body surface area) Generalized desquamation (≥50% body surface area) —sloughing not just dry flakingGeneralized exfoliation or ulcerationSuperficial ulceration < 2 cmUlceration ≥ 2 cmProvide symptomatic careProvide symptomatic and local skin care Provide symptomatic care, debridement,primary closure, etc.Provide supportive care, skin grafting, tissue reconstruction, etc. Continue anti-EGFR therapyContinue anti-EGFR therapy Withhold anti-EGFR therapy and reassess intwo weeksIf cutaneous toxicities regress to grade ≤2, then resume with 20% dose reduction Permanentlydiscontinue anti-EGFR therapyX e r o s i s (D r y Sk i n ) a n d P r u r i t u sAsymptomatic xerosisSymptomatic xerosis, but not interfering with activities of daily livingXerosis or pruritus that interferes with activities of daily living Not applicableMild or localized pruritus Intense or widespreadpruritusApply moisturizing creamsApply moisturizing creamsSuggest oral anti-histamineApply moisturizing creamsSuggest oral anti-histamineWithhold panitumumab and reassess in two weeksNot applicableOther cutaneous toxicities include hair alteration (e.g.: thinning, trichomegaly), telangiectasiae, and nasal mucositis.The STEPP trial suggests that, when compared to reactive skin treatment, “pre-emptive” skin treatment (started twenty-four hours before the first dose of panitumumab) reduces the incidence of grade 2, 3, and 4 skin toxicities from 62% to 29%, delays the development of severe skin toxicities, and improves the patient’s quality of life during the period of prophylactic use.1 Patients should be encouraged to: • Apply moisturizing creams frequently to prevent skin dryness, fissures, or pulpitis sicca • Use sunscreens and limit sun exposure• Avoid the excessive use of soaps and bathing•Avoid medications for acne vulgaris (benzoyl peroxide, antibiotic gels, and retinoids can irritate the skin, result in excessive dryness, and aggravate the rash and pruritus).Further information about rash management can be found in the clinical practice guideline for Prevention and Treatment of Acneiform Rash in Patients Treated with EGFR Inhibitor Therapies . Painful inflammation around the nails (paronychia) may lead to painful fissures and pyogenic granulomas. Patients should be encouraged to avoid wearing tight- or ill-fitting shoes. Relief can oftenbe achieved by the use of Epsom salt soaks. Secondary infections warrant the use of a topical (or, if severe, systemic) antibiotic or antifungal agents (e.g., mupirocin ointment).Ocular irritation (e.g., dry eyes, conjunctivitis, crusting, hyperemia, lacrimation) may require moisturizing eye drops, warm soaks, and/or ophthalmic antibiotics. Diarrhea:D i a r r h e aIncrease of one to three stools per day or mild increase in ostomy output over baselineIncrease of four to six stools per day or moderate increase in ostomy output over base-line that fails to interfere with activities of daily livingIncrease of seven or more stools per day or severe increase in ostomy output over baseline or interferes with activities of daily livingLife threateningconsequences (e.g.: hemodynamic collapse)Consider Loperamide Provide symptomatic careConsider Loperamide Provide symptomatic care and intravenous hydrationConsider Loperamide Provide intravenous hydration and hospitalization for supportive careProvide intensive careContinue anti-EGFR therapy Continue anti-EGFR therapyWithhold anti-EGFR therapy and reassess in two weeksIf diarrhea regresses to grade ≤1, then resume with 20% dose reductionPermanently discontinue anti-EGFR therapyHypomagnesemia: Monitor electrolyte, magnesium, and calcium levels during and for eight weeks beyond completion of therapy. See appendix for further details.H y p o m a g n e s e m i aMagnesium: 0.50 to 0.70 mM Magnesium: 0.40 to 0.49 mMMagnesium: 0.30 to 0.39 mMMagnesium: <0.30 mM If asymptomatic, continue anti-EGFR therapyIf asymptomatic, continue anti-EGFR therapyIf symptomatic,withhold anti-EGFR therapy and reassess in two weeks Withhold anti-EGFR therapy and reassess in two weeks Consider pre-emptive oral supplementation Consider pre-emptive oral supplementation Provide oralsupplementation Provide oralsupplementation See appendixSee appendixSee appendix See appendixContraindications to magnesium replacement: · Pre-existing diarrhea· Acute abdominal pain, nausea, or emesis · Heart block· Renal impairment· Myasthenia gravis or other neuromuscular diseaseIf hypokalemia and/or QT intervalprolongation co-exist, considermagnesium sulfate 4,000 mg over at least two hoursIf hypokalemia and/or QT interval prolongation co-exist, considermagnesium sulfate 4,000 mg over at least two hoursIf toxicity regresses to grade ≤2, resume anti -EGFR therapy If toxicity regresses to grade ≤2, resume anti -EGFR therapyFatigue, Asthenia, Lethargy, or Malaise:F a t i g u e , A s t h e n i a , L e t h a r g y , o r M a l a i s eMild fatigue over baselineCauses difficulty performing someactivities of daily living Interferes with activities of daily livingDisabling Exclude laboratory and other confounding abnormalitiesProvide symptomatic careExclude laboratory and other confounding abnormalitiesProvide symptomatic careExclude laboratory and other confounding abnormalitiesProvide symptomatic careExclude laboratory and other confounding abnormalitiesProvide symptomatic care Continue anti-EGFR therapyContinue anti-EGFR therapyWithhold anti-EGFR therapy and reassess in two weeksIf fatigue regresses to grade ≤1, then resume with 20% dose reductionPermanently discontinue anti-EGFR therapyHypersensitivity Reactions: Infusion reactions have been reported at a rate of about 1%. Remain vigilant for fever, chills, rash, urticaria, bronchospasm, hypotension, and anaphylactic reactions. For more information, refer to the Acute Infusion Related Adverse Events to Chemotherapy and Monoclonal Antibodies clinical practice guideline.Interstitial Lung Disease: Represents a rare (0.5%), rapidly progressive, and potentially fatal complication. Assess respiratory symptoms, especially during the first few months of therapy. Initial signs include dyspnea with or without a cough or low-grade fever.I n t e r s t i t i a l L u n g D i s e a s eAsymptomatic (no dyspnea or cough)Dyspnea, low-grade fever, or cough that fails to interfere with activities of daily livingDyspnea, low-grade fever, or cough that interferes with activities of daily livingLife threateningPatchy radiologicchanges that involve less than 25% of lung volume Patchy radiologicchanges that involve 25 to 49% of lung volumeWidespread infiltrates that involve 50 to 74% of lung volumeWidespread infiltrates that involve ≥75% of lung volumeProvide symptomatic care (e.g.: oxygen if S a O 2 ≤89%) Provide symptomatic care (e.g.: oxygen if S a O 2 ≤89%) Provide intensive care for ventilatory support Exclude confounding etiologyExclude confounding etiologyExclude confounding etiologyPermanently discontinue anti-EGFR therapyPermanently discontinue anti-EGFR therapyPermanently discontinue anti-EGFR therapyPermanently discontinue anti-EGFR therapyConstitutional Toxicities and Pain: Provide the usual supportive management for anorexia, nausea, emesis, pain, constipation, and fever (neutropenia is not expected with anti-EGFR therapy).References1. Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B, Pillai MV, Shearer H, Iannotti N, et al. Skin toxicity evaluation protocol withpanitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-Emptive Skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010 Mar 10;28(8):1351-1357.2. Jahnen-Dechent W, Ketteler M. Magnesium basics. Clinical Kidney Journal 2012 02/01;5:i3-i14.3. de Baaij, Jeroen H. F., Hoenderop JGJ, Bindels RJM. Regulation of magnesium balance: lessons learned fromhuman genetic disease. Clinical Kidney Journal 2012 02/01;5:i15-i24.4. Petrelli F, Borgonovo K, Cabiddu M, Ghilardi M, Barni S. Risk of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody-relatedhypomagnesemia: systematic review and pooled analysis of randomized studies. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2012 May;11 Suppl 1:S9-19.5. Vickers MM, Karapetis CS, Tu D, O'Callaghan CJ, Price TJ, Tebbutt NC, et al. Association of hypomagnesemia withinferior survival in a phase III, randomized study of cetuximab plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone: NCIC CTG/AGITG CO.17. Ann Oncol 2013 Apr;24(4):953-960.6. Ranade VV, Somberg JC. Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of magnesium after administration of magnesium saltsto humans. Am J Ther 2001 Sep-Oct;8(5):345-357.7. Reed BN, Zhang S, Marron JS, Montague D. Comparison of intravenous and oral magnesium replacement inhospitalized patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2012 Jul 15;69(14):1212-1217.8.National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Magnesium Fact Sheet for Health Professionals.Available at: https:///factsheets/Magnesium-HealthProfessional/#en10. Updated June 2, 2022;Accessed August 12, 2022.Appendix: HypomagnesemiaMagnesium is an important electrolyte that functions as a cofactor for enzymatic reactions involved in glucose utilization, muscle contraction and nerve conduction, and the synthesis of fat, proteins, nucleic acids, and coenzymes.2 Hypomagnesemia contributes to a broad range of clinical problems; they range from anorexia, nausea, emesis, weakness, paraesthesias, and muscle cramps to ataxia, seizures, neuropsychiatric disturbances (e.g.: depression, delirium, psychosis), dysrhythmias, and respiratory failure.2Hypomagnesemia results from protracted emesis or diarrhea, the chronic use of diuretics and proton pump inhibitors, diabetes mellitus type 2 and alcoholism, malabsorption or resection/bypass of the small intestine (especially the ileum), renal injury (e.g.: aminoglycosides, Cisplatin, Carboplatin, etc.), and defective renal tubular magnesium reabsorption. Anti-EGFR therapies induce hypomagnesemia by this latter mechanism3 with an overall relative risk for all-grade hypomagnesemia of 5.83 and an overall relative risk for severe hypomagnesemia of 10.51.4 Although the evidence is inconsistent in the literature, Vickers and colleagues5 suggests that hypomagnesemia correlates with an inferior median overall survival. Given all of these factors, it is important to optimally manage this common problem. Ingestion of magnesium salts predisposes to diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal cramps; however, catharsis generally occurs with elemental doses over 1,000 mg per day. In addition, oral magnesium interferes with the absorption of oral bisphosphonates (e.g.: Alendronate), antibiotics (e.g.: tetracyclines, quinolones), azole antifungals, levothyroxine, and other drugs.6Please refer to specialized references for drug interaction information.A rapid increase in the serum levels is rarely required in the absence of life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias. Further, doses of intravenous magnesium to correct low serum magnesium concentrations in the acute setting remain unlikely to correct chronic hypomagnesemia. Therefore, when rapid change is not required, oral magnesium provides a suitable option, especially for chronic replacement.7Recommendations:As there is limited evidence available regarding magnesium supplementation and anti-EGFR therapy the recommendations included are based on consideration of the available evidence and consensus of the GI Provincial Tumour Team.1. Ensure optimal management of emesis, diarrhea, and diabetes2. Address alcoholism3. Curtail the use of loop and thiazide diuretics, where possible4. Curtail the use of proton pump inhibitors, where possible5. Avoid nephrotoxic agents (e.g.: aminoglycosides, cisplatin, etc.)6. Encourage a diet high in magnesium (see Sources of Magnesium table)7. Provide magnesium supplementationProduct/dosing examples*:•Magnesium oxide 420-840 mg once daily to three times daily•Magnesium glucoheptonate (Magnesium Rougier®) 15-75 mL four times daily•Magnesium gluconate (Maglucate®) 500-1000 mg three times daily•Magnesium complex 250 mg twice daily•Magnesium hydroxide (Milk of Magnesia®)** 5-15 mL once daily to 4 times daily* This is not an all-inclusive list of products or dosing recommendations. Starting with lower doses and daily divided doses may improve tolerance and reduce diarrhea. Monitor for magnesium levels and toxicity.** Consider antacid activity of magnesium hydroxide may alter gastric and urinary pH and affect bioavailability or renal elimination of concurrent medications.Sources of Magnesium8Pumpkin seeds, roasted (1 oz) 156 mg 37% Oatmeal, instant (1 packet) 36 mg9% Chia seeds (1 oz) 111 mg 26% Kidney beans, canned (1/2 cup) 35 mg8% Almonds, dry roasted (1 oz) 80 mg19% Banana (1 medium) 32 mg 8%26 mg 6% Spinach, boiled (1/2 cup) 78 mg19% Salmon, Atlantic farmed andcooked (3 oz)6% Cashews, dry roasted (1 oz) 74 mg 18%Milk (1 cup) 24-27mgPeanuts, oil roasted (1/4 cup) 63 mg 15% Halibut, cooked (3 oz) 24 mg 6%61 mg 15% Raisins (1/2 cup) 23 mg 6% Cereal, shredded wheat (2 largebiscuits)Soymilk, plain or vanilla (1 cup) 61 mg 15% Bread, whole wheat (1 slice) 23 mg 5% Black beans, cooked (1/2 cup) 60 mg 14% Avocado, cubed (1/2 cup) 22 mg 5%50 mg 12% Chicken breast, roasted (3 oz) 22 mg 5% Edamame, shelled & cooked (1/2cup)20 mg 5% Peanut butter, smooth (2 tbsp) 49 mg 12% Beef, ground 90% lean pan broiled(3 oz)Potato, baked with skin (3.5 oz) 43 mg 10% Broccoli, cooked (1/2 cup) 12 mg 3% Rice, brown, cooked (1/2 cup) 42 mg 10% Rice, white, cooked (1/2 cup) 10 mg 2% Yogurt, plain low fat (8 oz) 42 mg 10% Apple (1 medium) 9 mg 2% Breakfast cereals, fortified with42 mg10%Carrot, raw (1 medium) 7 mg 2% 10% of the DV for magnesium, 1servingNational Institutes of Health (https:///factsheets/Magnesium-HealthProfessional/) Based upon Recommended Dietary Allowances。

CPT治疗CRC的优势与不良反应处理图文

Group 1

Potentially resectable metastases

Group 2

nonresectable metastases, high tumor

burden, tumor-related

symptoms

FOLFOX /XELOX

FOLFOX+CET /FOLFIRI+CET

FOLFIRI+CET

XELOX

Median OS, mo

19.8

19.6

11பைடு நூலகம்9

12.5

Median PFS, mo

8.5

8.0

4.8

4.7

RR, %

49

46

20

17

Saltz J et al Clin Oncol 2008; Rothenberg et al J Clin Oncol 2008.

CAPIRI疗效与FOLFIRI无差异,但 腹泻发生率增加

改变给药方式与剂量强度?

Hong-hua Ding,et al. Tumor Biol. 2014

临床诊疗中不同方案的选择

• FOLFIRI = FOLFOX = XELOX • CAPIRI 适合给药方式与剂量在探索中 • 伊立替康治疗不受累积性神经毒性的影响 • 依据不同方案的不良反应结合患者临床特征进行

Tumor shrinkage at 8weeks ≧20%

30.0 months

HR=0.643, p=0.003

Long survival

Van Cutsem E, et al. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2011–2019 Piessevaux H, et al. ESMO 2010; abstract 596P, Mansmann UR et al. ASCO GI 2012, abstract 580

结直肠癌肺转移

– 5-10%结直肠癌患者有肝肺转移

– 肝肺转移同时出现发生率 6.9%--30.8%

– 同时肝肺转移且均能切除者少,仅占肝肺转移的5%不到

– 影响预后因素:DFI-2、术前CEA、胸部LN侵犯

– 先期肝转移切除生存率% 30 42

结直肠癌肺转移的手术治疗: 结节数目,可手术次数?

手术治疗

• 手术入路

正中胸骨劈开,后外侧剖胸切除,横断胸骨切口 同期双肺肿瘤楔形切除术,分期后外侧切口 – 不同手术入路对预后无影响

• 手术方式

肺组织楔形切除及肺段切除

– Vogelsang等:楔形切除优于解剖学肺切除(39% vs 25%) – 余13项研究均未显示术式对预后有影响

手术治疗在孤立性肺 转移中占主导地位

根据4项OS预后因子, 对所有患者分成3类统计总体生存率

4项预后因子包括: 除结肠或肾脏以 外的原发疾病病, DFI小于或等于1 年,肿瘤尺寸大 于2厘米,两个以

上的肺转移

2021/2/20

肺部进展与局部不可切除的肺部进展

2021/2/20

结论:

这份报告证明,对肺转移灶行射频消融治疗与既往手 术切除所报道的生存率之间,具有可比性,同时二者 也存在着一些重叠的预测因素;

结直肠癌肺转移灶立体定向放疗的临床疗效

A total of 79 metastatic lung lesions from 50 patients who underwent curative resection for their primary colorectal cancer or salvage treatment at a recurrent site were included. 研究对象:50例行直肠癌原发灶根治术或转移灶解救治疗患者的79个肺部转灶

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

T h e ne w engl a nd jour na l o f medicinen engl j med 357;20 november 15, 20072040Cetuximab for the Treatmentof Colorectal CancerDerek J. Jonker, M.D., Chris J. O’Callaghan, Ph.D., Christos S. Karapetis, M.D.,John R. Zalcberg, M.D., Dongsheng Tu, Ph.D., Heather-Jane Au, M.D., Scott R. Berry, M.D., Marianne Krahn, M.D., Timothy Price, M.D., R. John Simes, M.D., Niall C. Tebbutt, M.D., Guy van Hazel, M.D.,Rafal Wierzbicki, M.D., Christiane Langer, M.D., and Malcolm J. Moore, M.D.*From Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa (D.J.J.); Na-tional Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group, Queen’s University, Kings-ton, ON (C.J.O., D.T.); Flinders Medical Centre, Adelaide, Australia (C.S.K.); Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Depart-ment of Medicine, University of Mel-bourne, Melbourne, Australia (J.R.Z.); Cross Cancer Institute, Edmonton, AB, Canada (H.-J.A.); Toronto–Sunnybrook Re-gional Cancer Centre, Toronto (S.R.B.); St. Boniface General Hospital, Winnipeg, MB, Canada (M.K.); Queen Elizabeth Hos-pital, Adelaide, Australia (T.P.); National Health and Medical Research Council Clin-ical Trials Centre, University of Sydney, Sydney (R.J.S.); Austin Health, Melbourne, Australia (N.C.T.); Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, Australia (G.H.); Lake-ridge Health, Oshawa, ON, Canada (R.W.); Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wallingford, CT (C.L.); and Princess Margaret Hospital, Toronto (M.J.M.). Address reprint requests to Dr. Jonker at the Ottawa Hospital Regional Cancer Centre, University of Ottawa, 501 Smyth Rd., Box 912, Ottawa, ON K1H 8L6, Canada, or at djonker@ ottawahospital.on.ca.Drs. Jonker and O’Callaghan contributed equally to this article.*Other participants in the CO.17 Trial from the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group and the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group are listed in the Appendix.N Engl J Med 2007;357:2040-8.Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.ABSTR ACTBackgroundCetuximab, an IgG1 chimeric monoclonal antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), has activity against colorectal cancers that express EGFR.MethodsFrom December 2003 to August 2005, 572 patients who had colorectal cancer express-ing immunohistochemically detectable EGFR and who had been previously treated with a fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin or had contraindications to treat-ment with these drugs underwent randomization to an initial dose of 400 mg of cetuximab per square meter of body-surface area followed by a weekly infusion of 250 mg per square meter plus best supportive care (287 patients) or best supportive care alone (285 patients). The primary end point was overall survival.ResultsIn comparison with best supportive care alone, cetuximab treatment was associated with a significant improvement in overall survival (hazard ratio for death, 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64 to 0.92; P = 0.005) and in progression-free survival (haz-ard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.80; P<0.001). These benefits were robust after adjustment in a multivariable Cox proportional-hazards model. The median overall survival was 6.1 months in the cetuximab group and 4.6 months in the group assigned to supportive care alone. Partial responses occurred in 23 patients (8.0%) in the cetuximab group but in none in the group assigned to sup-portive care alone (P<0.001); the disease was stable in an additional 31.4% of patients assigned to cetuximab and in 10.9% of patients assigned to supportive care alone (P<0.001). Quality of life was better preserved in the cetuximab group, with less dete-rioration in physical function and global health status scores (both P<0.05). Cetux-imab treatment was associated with a characteristic rash; a rash of grade 2 or higher was strongly associated with improved survival (hazard ratio for death, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.50; P<0.001). The incidence of any adverse event of grade 3 or higher was 78.5% in the cetuximab group and 59.1% in the group assigned to supportive care alone (P<0.001).ConclusionsCetuximab improves overall survival and progression-free survival and preserves qual-ity-of-life measures in patients with colorectal cancer in whom other treatments have failed. ( number, NCT00079066.)Cetuximab for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancern engl j med 357;20 november 15, 20072041Colorectal cancer has a worldwide annual incidence of 917,000 and is the sec-ond leading cause of cancer-related death in Western nations.1 The cytotoxic agents irinote-can, oxaliplatin, and the fluoropyrimidines, as well as bevacizumab, the antibody against vascular en-dothelial growth factor A, have increased the me-dian survival of patients with advanced colorectal cancer,2-9 but in most patients the disease is in-curable.Recent advances have led to the development of agents that specifically inhibit tumor growth. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is often up-regulated in colorectal cancer. Cetuximab, a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to the extracellular domain of EGFR, blocks ligand-induced receptor signaling and modulates tumor-cell growth. Immune-mediated antitumor mech-anisms, such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, may also contribute to the activity of cetuximab.10,11 Cetuximab has activity in colorec-tal cancer 12 and can reverse drug resistance in patients with colorectal cancer when administered with irinotecan.13,14 However, to our knowledge, no trials have demonstrated an effect of cetuximab on survival or quality of life in patients with ad-vanced colorectal cancer. We report a randomized trial that was conducted by the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG) in collaboration with the Australasian Gas-tro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG).MethodsThe study was designed by a protocol committee that included members of the NCIC CTG and the AGITG. The NCIC CTG collected, managed, and analyzed the data. Employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb and all the other authors reviewed the final manuscript and provided comments on it. NCIC CTG maintains full unrestricted rights to publi-cation of the study data. Prepublication confiden-tiality of results was maintained by both the NCIC CTG and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The relevant insti-tutional review boards approved the protocol, and all participants gave written informed consent.Eligible patients had advanced colorectal can-cer expressing EGFR that was detectable by im-munohistochemical methods in a central reference laboratory. The patients either had been treated with a fluoropyrimidine (e.g., fluorouracil orcapecitabine), irinotecan, and oxaliplatin with no response to treatment (as defined by unacceptable adverse events or progression of the tumor within 6 months of completion of treatment) or had contraindications to treatment with these drugs. The patients had disease that could be measured or otherwise evaluated; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 2; adequate bone marrow, kidney, and liver function; and no serious concurrent illness. Pa-tients were ineligible if they had received any agent that targets the EGFR pathway (e.g., cetux-imab, erlotinib, gefitinib, or panitumumab) or treatment with a murine monoclonal antibody. Previous bevacizumab therapy was permitted but not required.RandomizationEligible patients were stratified according to cen-ter and ECOG performance status (0 or 1 vs. 2) and randomly assigned between December 2003 and August 2005 at a 1:1 ratio to cetuximab plus best supportive care or best supportive care alone. Randomization was performed by the NCIC CTG central office with the use of a minimization meth-od that dynamically balanced patients according to stratification factors.15 The database was main-tained by the NCIC CTG.TreatmentsAll patients received best supportive care, which was defined as those measures designed to pro-vide palliation of symptoms and improve quality of life as much as possible. Because the patients had cancer that was refractory to all recommend-ed chemotherapy, further chemotherapy or other antineoplastic therapy was not intended, although some patients did receive therapy after the com-pletion of protocol procedures.Cetuximab was given intravenously as an initial dose of 400 mg per square meter of body-surface area, administered over a period of 120 minutes, followed by a weekly maintenance infusion of 250 mg per square meter, administered over a period of 60 minutes. An antihistamine was given 30 to 60 minutes before each dose of cetuximab. Treat-ment was continued until death, in the absence of the occurrence of unacceptable adverse events, tumor progression, worsening symptoms of the cancer, or request by the patient, with or without the withdrawal of consent for continued follow-up.T h e ne w engl a nd jour na l o f medicinen engl j med 357;20 november 15, 20072042ASSESSMENTSAll patients were assessed every 4 weeks. Telephone monitoring was conducted until death for patients unable to attend the clinic. Chest radiographs and cross-sectional imaging were performed at base-line and every 8 weeks in both study groups until tumor progression occurred. Quality of life was assessed by the European Organization for Re-search and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality-of-life questionnaire (QLQ-C30) at baseline and at 4, 8, 16, and 24 weeks after randomization.16,17Statistical AnalysisThe primary end point of this study was overall survival, defined as the time from randomization until death from any cause. It was estimated a pri-ori that 445 deaths would provide a statistical pow-er of 90% and a two-sided alpha of 5% to detect an absolute increase of 9.6% in the 1-year overall survival from the predicted 1-year overall survival of 14.1% in the group assigned to supportive care alone (hazard ratio, 0.74). The final analysis was conducted after at least 445 patients were known to have died; March 6, 2006, was established as the data cutoff date.The secondary end points were progression-free survival, defined as the time from randomization until the first objective observation of disease pro-gression or death from any cause; response rates, defined according to the Modified Response Eval-uation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST); and quality of life, assessed by mean changes in scores of physical function and global health status at 8 and 16 weeks. The safety profile of cetuximab was assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC), version 2.0.All patients who underwent randomization were included in the efficacy analyses on the basis of the group to which they were assigned. Safety analysis was conducted on an on-treatment basis, contrasting patients who had at least one dose of cetuximab (including those who crossed over) with patients assigned to supportive care alone, and omitting patients who withdrew consent before any intervention. Time-to-event variables were summarized with the use of Kaplan–Meier plots. Primary comparisons of the treatment groups were made with the use of the stratified log-rank test adjusted for ECOG performance status at ran-domization. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence* ECOG denotes Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.Cetuximab for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancern engl j med 357;20 november 15, 20072043intervals were calculated from stratified Cox re-gression models with treatment group as the sin-gle factor.18 Quality-of-life scores for physical func-tion and global health status were standardized to range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indi-cating better quality of life.14 Deterioration in these quality-of-life scores was defined a priori as a decline of 10 points or more from baseline. Dis-crete variables were compared with the use of Fisher’s exact test, and continuous and ordinal categorical variables with the use of the Wilcoxon test. An exploratory analysis of the effect of other potential prognostic factors specified a priori in the protocol was conducted by a multivariable Cox regression model stratified according to ECOG performance status at randomization. All P values were two-sided, and no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. The final analysis was con-ducted by the NCIC CTG.R esultsWe randomly assigned 572 patients to treatment: 287 to cetuximab plus best supportive care and 285 to best supportive care alone. Four patients as-signed to the cetuximab group never received the drug, and five patients assigned to receive support-ive care alone subsequently received cetuximab off protocol. Six patients assigned to supportive care alone immediately withdrew their consent. Four patients (two in each group) were ineligible because of elevated bilirubin levels, other cancer, refusal to complete a quality-of-life assessment at baseline, or death on the date of randomization. All were included in the analyses. The two groups were similar with respect to baseline characteristics (Table 1). The median duration of follow-up was 14.6 months.TreatmentThe median duration of cetuximab treatment was 8.1 weeks (range, 1 to 60). Thirty-three patients(11.5%) had at least one dose reduction; rash, char-acteristically an acneiform papulopustular rash in-volving the face and trunk, was the most frequent reason (3.5%). One or more dose omissions oc-curred in 136 patients; intercurrent illness, rash, and patient request were the most common rea-sons. In 45 patients (15.7%), the infusion rate was decreased or infusion was interrupted at least once, most often because of a hypersensitivity reaction. The median dose intensity of cetuximab infusionEFFICACYFigure 1A shows overall survival in the two groups. A total of 456 deaths (222 in the cetuximab groupT h e ne w engl a nd jour na l o f medicine2044and 234 in the supportive-care group) had occurred by the date of analysis. All except 6 of these 456 patients died of colorectal cancer. The addition of cetuximab to supportive care resulted in longer overall survival than did supportive care alone (haz-ard ratio for death, 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64 to 0.92; P = 0.005). The median survival was 6.1 months in the cetuximab group and 4.6 months in the supportive-care group. The propor-tions of patients surviving at 6 and 12 months were 50% and 21%, respectively, in the cetuximab group and 33% and 16%, respectively, in the supportive-care group. This difference remained statistically significant after adjustment for other protocol-specified potential prognostic factors with the use of a multivariable Cox regression model (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.95; P = 0.01). Factors other than treatment that were associated with sur-vival in the multivariable analysis were sex; base-line levels of lactic dehydrogenase, alkaline phos-phatase, and hemoglobin; and number of disease sites.In a planned subgroup analysis, no significant differences in the relative benefit of cetuximab were seen across subgroups defined on the basis of ECOG performance status at baseline, age, or sex (Fig. 2). An unplanned landmark-type analy-sis that excluded all patients who died within 28 days after the start of the study demonstrated that the grade of rash in patients receiving cetuximab was strongly correlated with overall survival, with median survival of 2.6 months in patients with no rash, as compared with 4.8 months in patients with grade 1 rash and 8.4 months in patients with grade 2 rash (P<0.001) (Fig. 3). The median time to the onset of a rash in patients who received ce-tuximab was 10 days; in 90% of patients with a rash, the rash developed within 29 days.Objective progression of the tumor was ob-served in 402 patients (224 in the cetuximab group and 178 in the supportive-care group), and 140 patients (49 in the cetuximab group and 91 in the supportive-care group) died without documented objective progression. Treatment with cetuximab resulted in a significant improvement in progres-sion-free survival (hazard ratio for disease progres-sion or death, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.80; P<0.001) (Fig. 1B). This difference remained statistically significant after adjustment for other protocol-specified potential prognostic factors (hazard ra-tio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.85; P<0.001). Similar relative benefits of cetuximab in terms of progres-sion-free survival were seen in subgroups defined on the basis of ECOG performance status at base-line, age, and sex. The estimated proportions of patients who were alive without documented ob-jective progression of disease at 3 and 6 months were 41% and 15%, respectively, in the cetuximab group and 24% and 3%, respectively, in the sup-portive-care group.Cetuximab for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancern engl j med 357;20 november 15, 20072045Twenty-three patients (8.0%) in the cetuximab group and none in the supportive-care group had partial responses (P<0.001). Stable disease was observed in 90 patients in the cetuximab group (31.4%) and 31 patients in the supportive-care group (10.9%, P<0.001).Compliance with the quality-of-life question-naire was 94% at baseline in both groups, 81% at 8 weeks and 67% at 16 weeks in the cetuximab group, and 62% at 8 weeks and 43% at 16 weeks in the supportive-care group. As compared with supportive care alone, cetuximab treatment was associated with less deterioration in physical func-tion at 8 weeks (mean change score, –3.9 vs. –8.6; P<0.05 by the Wilcoxon test) and 16 weeks (mean change score, –5.9 vs. –12.5; P = 0.03). Cetuximab treatment was also associated with less deterio-ration in global health status at 8 weeks (mean change score, –0.5 vs. –7.1; P = 0.008) and 16 weeks (mean change score, –3.6 vs. –15.2; P<0.001).Safety Adverse events of interest or with an incidence of at least 5% at grade 3 or higher, according to the NCI-CTC, version 2.0, are summarized in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences between the cetuximab group and the supportive-care group in the incidence of grade 3 or higheradverse events, with the exception of rash (11.8% for cetuximab vs. 0.4% for supportive care, P<0.001), infection without neutropenia (12.8% vs. 5.5%,P = 0.003), confusion (5.6% vs. 2.2%, P = 0.05), andpain defined as “other” according to the NCI-CTC (14.9% vs. 7.3%, P = 0.005). Hematologic adverseevents were uncommon, and there were no signifi-cant differences between the groups in grade 3 orhigher (according to the NCI-CTC) serum chemicalvalues or other laboratory measurements, with the exception of hypomagnesemia, which was more common in the cetuximab group than in the group receiving supportive care alone (5.8% vs. 0.0%,P<0.001). Grade 3 or 4 infusion reactions (hyper-sensitivity) occurred in 4.5% of patients assigned to cetuximab.As compared with patients in the supportive-care group, patients in the cetuximab group had a higher incidence of rash of any grade (88.6% vs. 16.1%, P<0.001), hypomagnesemia of any grade (53.3% vs. 15.1%, P<0.001), and infusion reactions of any grade (20.5% vs. 0.0%, P<0.001).Fifty-nine patients died within 30 days after thelast date of the cetuximab infusion. All died of colorectal cancer except one patient who had a pulmonary embolus. Eleven patients had adverse events leading to discontinuation of cetuximab, most frequently because of an infusion reaction.DiscussionThis study showed that cetuximab can improve overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer in whom other treatments have failed. Cetuximab alone — not in combination with other agents — improved survival. This trial was not blinded, which raises the possibility of bias in the assess-ment of progression-free survival but not overall survival. The hazard ratios for death (0.77) and disease progression or death (0.68) suggest min-imal bias.The interpretation of quality-of-life data is com-plicated by differences in compliance rates be-tween the two groups; rapid disease progressionin the group assigned to supportive care alone is likely to have resulted in a lower compliance rate. The tumor response rates were similar to rates reported in previous studies of cetuximab andT h e ne w engl a nd jour na l o f medicinen engl j med 357;20 november 15, 20072046other anti-EGFR antibodies.12,13 Our results sug-gest that stabilization of disease and response to the treatment contribute to the prolongation of survival but that tumor response alone may not be a useful surrogate outcome.Initial studies of the treatment of colorectal cancer with cetuximab were performed in patients whose tumors had immunohistochemically detect-able EGFR, but there is evidence that the intensity of staining of the tumor section for EGFR corre-lates poorly with the response to cetuximab. More-over, responses have been reported in patients with tumors without immunohistochemically detect-able EGFR.19,20 Although it is unknown whether the improvements in survival can be extrapolated to the patients with EGFR-negative tumors, im-munohistochemically detectable EGFR is no lon-ger considered a clinically useful biomarker.21This study further validates the use of EGFR as a biologic target in colorectal cancer; however, not all EGFR inhibitors are equally efficacious against this disease. The EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors erlotinib and gefitinib have less activ-ity against EGFR than do monoclonal antibod-ies.22,23 A study that compared the human anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody panitumumab with supportive care found a decrease in the time to progression of the disease but no improvement in overall survival with panitumumab.24Cetuximab has the ability to reverse resistance* Grades were determined according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC), version 2.0.† This category excludes arthralgia; myalgia; earache; headache; and abdominal, bone, chest, hepatic, neuropathic, pelvic, pleuritic, rectal, perirectal, and tumor pain.‡ The P values, calculated with the use of Fisher’s exact test, are for the difference in the incidence of adverse events between the two treat-ment groups.§ The results for hypomagnesemia are based on 259 patients in the cetuximab group and 198 patients in the supportive-care group.Cetuximab for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancern engl j med 357;20 november 15, 20072047to irinotecan.13 Studies in which cetuximab was combined with irinotecan in the treatment of colorectal cancer found improvements in response rates and progression-free survival but not in over-all survival.13,25-27 The uncoupling of overall sur-vival benefits from progression-free survival ben-efits in these combination studies is probably due in part to intentional or unintentional crossover, whereby patients assigned initially to a group with-out cetuximab eventually received cetuximab after progression. If the absolute survival benefit of ce-tuximab is similar whether it is given earlier or later in the course of treatment for advanced colorectal cancer, no survival difference will be seen in studies with substantial crossover. In con-trast to the findings of these combination studies, only 7.0% of patients in our trial who were receiv-ing supportive care alone subsequently received cetuximab, and only 27.5% of patients in the cetux-imab group, versus 23.2% of patients in the sup-portive-care group, received any anticancer treat-ment after progression of the disease. The collective data suggest that cetuximab can benefit patients with advanced colorectal cancer, whether their disease is resistant or sensitive to chemotherapy.Tumor progression had occurred in more than50% of patients in both groups of our study by the time of the first computed tomographic scan, and the median progression-free survival did not dif-fer between the groups (1.8 months in the sup-portive-care group vs. 1.9 months in the cetuximab group). However, the hazard ratio of 0.68 for dis-ease progression or death is reflected in a clear separation of the curves after the median.The disease was stable or responded to therapy in only 39.4% of the patients in the cetuximab group, a result indicating a need for predictive biomarkers to identify patients who could benefit from such treatment. Rash related to EGFR inhi-bition, which is due to alteration of the mediation of epidermal basal keratinocytes by EGFR, is one such potential biomarker. Analysis of the incidence of the rash suggests that it may be a predictive marker, but this point has not been validated.Supported by the National Cancer Institute of Canada, ImClone Systems, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.Drs. O’Callaghan and Tu are employees of the National Can-cer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group, which has received grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Amgen Canada. Drs. Simes and Zalcberg report receiving research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb; and Dr. Zalcberg, consulting fees from Amgen. Dr. Langer owns equity in and is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.AppendixIn addition to the authors, the following committee members, site investigators, data managers, and key trial staff participated in the CO.17 study from the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG) and the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG). NCIC CTG investigators in Canada: Dr. H. Bliss Murphy Cancer Centre, St. John’s, NB — J. Siddiqui; QEII Health Sciences Center, Halifax, NS — B. Colwell; Atlantic Health Sciences Corporation, St. John’s, NB — M. Burnell; Moncton Hospital, Moncton, NB — S. Rubin; Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal, Montreal — R. Whittom; Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Mon-tréal–Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal — D. Charpentier; Hôpital Charles LeMoyne, Greenfield Park, QC — B. Samson; Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario, Kingston — A. Tomiak; Quinte Healthcare Corporation, Belleville, ON — R. Levesque; Niagara Health System, Ontario — B. Findlay; Toronto East General Hospital, Toronto — J. Meharchand; St. Joseph’s Health Centre, Toronto — J. Blondal; Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto — R. Burkes; St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto — R. Haq; Grand River Regional Cancer Centre, Kitch-ener, ON — G. Knight; London Regional Cancer Program, Ontario — I. Kerr; Windsor Regional Cancer Centre, Ontario — J. Mathews; Thunder Bay Regional Health Science Centre, North Bay, ON — D. Dueck; Allan Blair Cancer Centre, Regina, SK — H. Chalchal; Sas-katoon Cancer Centre, Saskatoon, SK — S. Yadav; Cross Cancer Institute, Edmonton, AB — S. Koski; BC Cancer Agency–Vancouver Cancer Centre, Vancouver, BC — H. Kennecke; BC Cancer Agency–Cancer Centre for the Southern Interior, Kelowna, BC — M. Taylor; BC Cancer Agency–Vancouver Island Cancer Centre, Victoria, BC — H. Anderson; BC Cancer Agency–Fraser Valley Cancer Centre, Sur-rey, BC — U. Lee. NCIC CTG central office staff, Kingston, ON: S. Robitaille, N. Magoski, S. Hunt, A. Lewis, D. Nomikos, J. Ottaway, A. Hung, A. Sargeant, V. Classen, J. Baran, L. Pho, A. Garrah, L. Zhu. Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG) investigators in Australia: Newcastle Mater Misericordiae Hospital, New South Wales — S. Ackland; Port Macquarie Base Hospital, New South Wales — S. Begbie; St. Vincent’s Hospital, Victoria — I. Burns; Launceston General Hospital, Tasmania — I. Byard; Fremantle Hospital, Western Australia — P. Claringbold; Royal Melbourne Hospital, Victoria — P. Gibbs; Prince of Wales Hospital, New South Wales — D. Goldstein; Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Victoria — M. Jefford; St. George Hospital, New South Wales — M. Links; Royal Hobart Hospital, Tasmania — R. Lowenthal; Brisbane Adult Mater, Queensland — P. Mainwaring; Royal North Shore Hospital, New South Wales — N. Pavlakis; St. John of God Subiaco, Western Australia — D. Ransom; Nepean Hospital, New South Wales — J. Shannon; Cabrini Hospital, Victoria, and Alfred Hospital, Victoria — J. Shapiro; Monash Medical Centre, Victoria — A. Strickland; Royal Perth Hospital, Western Australia — J. Trotter; Border Medical Oncology, Victoria — C. Underhill; Royal Brisbane Hospital, Queensland — D. Wyld; Canberra Hospital, Australian Capital Territory — D. Yip. AGITG investigators in New Zealand: Palmerston North Hospital, Palmerston North — R. Isaacs; Christchurch Hospital, Christchurch — M. Jeffrey. AGITG investigator in Singapore: National Cancer Centre Singapore — K.F. Foo. Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Clinical Trials Centre (AGITG Coor-dinating Centre) staff: B. Cakir, A. Pearce, C. Aiken, J. Simard-Lebrun, J. Shoulder, F. Howard. Bristol-Myers Squibb: J. Dechamplain, N. Gustafson.。