Hall, J.K et al., (2005)

国际小学科学教育的发展趋势

国际小学科学教育的发展趋势丁邦平作者工作单位:北京师大国际与比较教育研究所——兼谈我国小学自然课的若干问题一、小学科学教育的发展历程在西方,19世纪初,裴士泰洛齐就倡导在小学进行实物教学(obje-ct teaching)。

随着裴士泰洛齐教育思想19世纪中期在欧美各国逐渐传播,以及初等义务教育在这些国家的实施,实物教学形态的科学启蒙教育开始在工业化国家得到推广。

例如,19世纪50年代,实物教学的思想传到美国后,在全国教育协会发起和支持的澳滋威格计划(Oswego Pian)推动下,美国小学也盛行实物教学。

实物教学的主要作法是教儿童详细描述各种动物、植物和矿物,使其观察和学习自然现象。

通过实物教学,希望儿童学会观察和交流——两种“研究”科学的基本能力。

但在当时的实际教学过程中,由于绝大多数小学教师缺乏科学训练,实物教学多为对实物的机械描述和记忆。

到19世纪末期,这种实物教学法在美国便不再流行了。

19世纪90年代至20世纪头10年期间,美国教育开始摆脱欧洲教育传统的影响,进入教育理论和实践的创新时期。

当时,美国著名心理学家霍尔(S.Hall)的儿童研究和杜威的实用主义教育思想开始对美国教育产生影响。

此后小学科学教育发生了较大的变化。

首先是学科名称上的改变,即以“自然学习”(nature study)取代了实物教学。

其次是教学内容上的变化,这个时期科学启蒙教育注重儿童自身的需要,因而健康和卫生加入到小学科学教育内容中。

第三,强调科学方法的训练。

杜威认为,科学方法的训练与获得实际科学知识至少同样重要。

在奉行杜威实用主义教育哲学的学校里,科学教学还注重解决实际问题。

第四,这一时期美国科学教育研究工作在一些大学里开展起来,如1927年哥伦比亚大学克雷格(Gerald S.Craig)的博士论文被公认为小学科学教育发展中里程碑式著作。

(注:Esler,W.K.et al.(1993),Teaching Elementary,Science,Belmont,Califor nia:Wadsworth Publishing Company,pp.9-10.)克雷格指出了科学在卫生和安全等方面的实用价值,并认为科学对于一个公民的普通教育是至关重要的。

跨文化交际理论主要参考书目

跨文化交际理论主要参考书目LT跨文化交际理论主要参考书目Abrams, D.&Hogg, M. A. (eds.). Social Identity Theory: Constructive and Critical Advances, New York: Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., 1990.Ajzner, J. “Some problems of rationality, understanding, and universalistic ethics in the context of Habermas’s theory of communicative action”, in Philosophy of the Social Science, 1994,24, pp.468-474. Anderson, B. Imagined Communities (second edition), Lodon: Verso, 1991. Arasaratnam, L. A. & Doerfel, M. L. “Intercultural communication competence: in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2005, 29, pp. 137-142.Asher, H. B. et al.Theory-Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences, Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1984. Babbie, E.The Practice of Social Research, Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2003. Baghramian, M. & Ingram, A. (eds.) Pluralism:the Philosophy and Politics of Diversity, New York: Routledge, 2000.Ball, T. “From paradigms to research Program: Toward a post Kuhnian political science”, in H. B. Asher at al. (eds.) Theory Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences, Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1984, pp. 23-43. Beiner, R. et al. (eds.). Canadian Political Philosophy, New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.Benet-Martinez, V. et al. “Biculturalism and cognitive complexity: Expertise in cultural representations”, in Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 2006, 37, pp. 368-407.Bennett, M. “T owards ethnorelativism: A development model of intercultural sensitivity”, in M. Paige (ed.).Education for the Intercultural Experience (second edition) , Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 1986.Burgoon, J. K. “Interpersonal expectancy violations, and emotional communication”, in Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 1993, 12, pp. 30-48.Burgoon, J. K. “Cross-cultural and intercultural applications of expectancy violation theory”, in R. L. Wiseman (ed.), Intercultural Communication Theory, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1995, pp. 194-214.Burgoon, J. K. and Hubbard, A. S. E. “Cross-cultural and intercultural application of expectancy violation theory and interaction adaptation theory”, in W.B. Gudykunst (eds.).Theorizing about Intercultural Communication, Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2005, p. 164, pp. 161-166. Burns, E. M. Western Civilizations (eighth edition) (Vol.1), New York: W. W. Norton &Company, Inc., 1973.Carnoy, cation as Cultural Imperialism, New York: David McKay Company,Inc., 1974.Charon, J. M. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration, Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1998.Chen, G. M. “Intercultural communication competence: Some perspectives of research”, in The Howard Journal of Communications,1990, 2, pp. 243-261. Chen, G. M. &Starocta, W. J. “I ntercultural communication competence: A synthesis”, in Communication Yearbook, 19, 1996, pp. 353-383.Chen, G. M. &Starocta, W. J. Foundations of Intercultural Communication, Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1998.Chen, G. M. &Starocta, W. J. (eds). Communication and Global Society, New York: Peter Lang, 2000.Chen, G. M. “Toward transcultural understanding: A harmony theory of Chinese communication”, in V. H. Milhouse et al.(eds). Transcultural Realities: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Cross-cultural Relations, 2001, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp.55-70. Chen, G. M. “A model of global communication competence”, in China Media Research, 2005, 1, pp. 3-11.Chen, G. M. “Asian communication studies: What and where to now”, in The Review of Communication, 2006, 6, pp. 295-311. Chen, L. “Interaction involvement and partners of topical talk: A comparison of intercultural and intracultural dyads”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 19, 1995, pp.463-482. Christian, C. & Traber, M. (eds.). Communication Ethics and Universal Values, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1997. Chomsky, N. On Nature and Language, Beijing: Peking University Press, 2004.Condon, J. C. &Yousef, F. An Introduction to Intercultural Communication, Indianapolis:Bobbs-Merrill, 1975.Cornell, S. &Hartman, D. Ethnicity and Race: Making Identities in a Changing World, Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press, 1998. Craig, R. T. & Tracy, K. “Grounded practical theory: The case of intellectual discussion”, in Communication Theory, 1995, 8, pp. 248-254.Craig, R. T. & Muller, H. L. (eds). Theorizing Communication, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2007.Crain, S. “The interpretation of disjunction in universal grammar”, in Language ans Speech, 2008, 51(1&2), pp.152-169.Cronen, V. E. “Practical theory, practical art, and the pragmatic-systemic account of inquiry”, in Communication Theory, 2001, 11, pp.14-34.Cryderman, B. et al. (eds). Police, Race and Ethnicity: A Guide for Law Enforcement, Toronto: Butterworth &Co. (Cananda) Ltd.,1986.Cupach, W. R. & Imahori, T. “Identity management theory: Communication competence in intercultural episodes and relationships”, in R. L. Wiseman& J. Koester (eds.). Intercultural Communication Competence, Newbury Park: Sage, 1993, pp. 112-131.Dascal, M. (ed.). Cultural Relativism and Philosophy, New York: E. J. Brill, 1991. Delgado-Moreira, J. M.Multicultural Citizenship of the European Union, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2000.Doan, G. O. & Stephan, C. W. “The fuctions of ethnic identity: A New Mexico Hispanic example”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2005, 29, pp. 229-241.Dodd, C. H. Dynamics of Intercultural Communication, Madison: Brown & Benchmark, 1977.Dodd, C. H. Dynamics of Intercultural Communication(fifth edition), Shanghai Foreign Language Teaching Press, 2006. Duranti, A. (ed.).Key Terms in Language and Culture, Malden: Blackwell Publishers, 2001.Duranti, A. Linguistic Anthropology, Beijing:Beijing University Press, 2002. Duronto, P. M. et al. “Uncertainty, anxiety, and avoidance in communicating with strangers”,in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2005, 29, pp. 540-560.Earley, P. C. Face, Harmony, and Social Support: An Analysis of Organizational Behavior across Cultures, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.Ellis, J. M. Language, Thought, and Logic, Evanstom: Northwestern University Press, 1993.Erman, E. “Reconciling communicative action with recognition: Thickening the‘inter’of intersubjectivity”, in Philosophy and Social Criticism, 2006, 32, pp. 377-400.Evanoff, R. J. “Universalist, relativist, and constructivist approaches to intercultural ethics”,in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2004, 28, pp. 439-458.Foley, W. A. Anthropological Linguistics, Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2001.Freud, S.Interpretation of Dreams, Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Ge, G. “Book review on The Challenge of Facebook: Cross-Cultural and Interpersonal Issues”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 1995, 19, PP.455-462.Ge, G. “An initial analysis of the effects of face and concern for ‘other’in Chinese interpersonal communication”, inInternational Journal of Intercultural Relations , 1998, 22, pp.467-482. Geertz, C. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology, New York: Basic Boks, 1993.Geertz, C. Available Light: Anthropological Reflections on philosophical Topics, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.Giddeds, A. The Consequenced of Modernity, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990. Giles, H.& Noels, K. A. “Communication accommodation in intercultural encounters”, in J. N. Matin at al. (eds.). Readings in Cultural Contexts, Mountain View: Mayfeild Publishing Company, 2002. Glazer, N. et al. (eds.). Ethnicity: Theory and Experience, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975.Goffman, E. Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior, New York: Pantheon Books, 1967.Gorton, M. M. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origion, New York: Oxford University Press, 1964.Grace, G. W. The Linguistic Construction of Reality, New York: Groom Helm, 1987. Gudykunst, W. B. (ed.).Intercultural Communication Theory: Current Perspectives, Beverly Hills, Sage Publications, 1983. Gudykunst, W. B. “Anxiety/ uncertainty management(AUM) theory”in R. L. Wiseman(ed.). Intercultural Communication Theory,Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., 1995, pp.8-58.Gudykunst, W. B. “Applying anxiety/ uncertainty management(AUM) theory to intercultural adjustment training”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 1998, 22, pp.227-250. Gudykunst, W. B.& Nishida, T. “Anxiety, uncertainty, and perceiced effectiveness of communication across relationships andcultures”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2001, 25, pp.55-71.Gudykunst, W. B.& Mody, B. (eds). Handbook of International and Intercultural Communication (second edition), Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., 2002. Gudykunst, W. B. (ed.). Cross-Cultural and Intercultural Communication, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications,2003.Gudykunst, W. B. &Kim, Y. Y. Communicating with Strangers: An Approach to Intercultural Communication (forth edition), New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2003.Gudykunst, W. B. (ed.). Theorizing about Intercultural Communication, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.,2005.Guibernau, M. “National identity and modernity”, in A.Dieckoff& N. Gutierrez(eds.). Modern Roots: Studies of National Identity, Aldershot: AshgatePublishing Limited, 2001.Gullahorn, J. T. & Gullahorn J. E. “An extension of U-curve hypothesis”, in Journal of Social Issues, 1963, 19, pp.33-47.Gupta, C. & Chattopadhyaya, D. P. (eds.). Cultural Otherness and Beyond, Leiden: Brill, 1998.Habermas, J, Communication and the Evolution of Society(translated by T. McCarthy), Boston: Beacon Press, 1976. Habermas, J,On the Pragmatics of Communication( translated by M. Cook), Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1998.Hall, E. T. The Silent Language, Garden: Doubleday, 1959.Hall, E. T. The Hidden Dimension, Garden City: Doubleday, 1966.Hall, E. T. Beyond Culture, Garden City: Doubleday, 1976.Halliday, M. A. K. “Language and social man”, in J. J. Webster(ed.). Language andSociety, Beijing: Peking University Press, 2007, pp.65-130.Hampden-Turner, C. &Trompenaars, F. “Response to Geert Hofstede”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 1997, 21, pp.149-159.Hatch, E. Theories of Man and Culture, New York: Columbia University Press, 1973. Hattie, J. Self-Concept, Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associate, Publishers, 1992.Hawes, L. C. Pragmatics of Analoguing: Theory and Model Construction in Communication, Melo Park: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1975.Hickmann, M. “Linguistic relativity and linguistic determinism: Some new directions”, in Linguistic, 2000, 38, pp. 409-434.Ho,D. Y. “On the concept of face”, in American Journal of Sociology, 1976, 81, pp. 868-884.Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1991. Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., 2001. Hudson, R. A. Socialinguistics, Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2000.Hymes, D. “Two types of linguistic relativities”, in W. Bright (ed.). Sociolinguistics: Proceedings of the UCLA Sociolinguistics Conference, Hague: Mouton, 1966.Jandt, F. E. An Introduction to Intercultural Communication: Identities in a Global Community( fourth edition), Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2004. Jia, W. The Remaking of the Chinese Character and Identity in the 21th Century, Westport: Ablex Publishing, 2001.Kaplan, A. The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral Science, San Francisco: Chandler Publishing Company, 1964.Kim, Y. Y. “Toward an interactive theory of communication acculturation”, in D. Nimmo( ed.). Communication Yearbook 3, New Brunswick: Transaction, 1979, pp. 435-453. Kim, Y. Y.&Gudykunst, W. B. (eds.). Cross-Cultural Adaptation: Current Approaches, Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc.,1987.Kim, Y. Y.&Gudykunst, W. B. (eds.). Theories in Intercultural Communication, Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc., 1988. Kim, Y. Y. Becoming Intercultural: An Integrative Theory of Communication and Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., 2001.Kim, Y. Y. “Intercultural personhood: Globalization and a way of being”, in International Journal of InterculturalRelations,2008, 32, pp. 359-368. Klyukanov, I. E. Principles of Intercultural Communication, Boston: Pearson Education, Inc., 2005.Kottak, C. P. Cultural Anthropology (ninth edition), New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2002.Kuhn, T. The Structure of Scientific Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago University Press, 1970.Llayder, D. Social and Personal Identity: Understand Yourself, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2004.Littlejohn, S. W. Theories of Human Communication (seventh edition), Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2003. Lusting, M. W. & Koester, J. I ntercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures(fourth edition), Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2003.Lyon, J. Language and Linguistics: An Introduction, Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press, 1981.Marger, M. N. Race and Ethnic Relations: American and Global Perspectives(fifth edition), Belmont: Wadsworth, 2000. Markus, H. R. & Kitayama, S. “Implications for recognition, emotion and motivation: Culture and the self”, in Psychological Review, 1991, 98, pp. 224-253.Markus, H. R. & Kitayama, S. “The cultural psychology of personality”, in Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1998, 29, pp. 63-87.Marsella, A. J. et al. (eds.). Culture and Self: Asian and Western Perspectives, New York: Tavistock Publication, 1985. Martin. J. N. &Nakayama, T. K I ntercultural Communication in Contexts( second edition), Mountain View: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2000.Martin. J. N. et al. (eds.). Readings in Cultural Contexts, Mountain View: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2002.May, S. “Language rights: Moving the debate forward”, in Sociolinguistics, 2005,9, pp. 319-321.McLaren, M. C. Inetrpreting Cultural Difference: The Challenge of Intercultural Communication, Dereham: Peter Francis Publishers, 1998.Mead, G. H. Mind, Self, &Society: From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967. Miike, Y. “Theorizing culture and communication in the Asian context: An assumptive foundation”, in Intercultural Communication Studies, 2002, 11, pp. 1-12. Miike, Y. “Non-western theory in western research? An Asiacentric agenda for Asian communication studies”, in The Review of Communication, 2006, 6, pp. 4-31.Miller, D. Citizenship and National Identity, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000. Mowlana, H. Global Communication in Transition?, Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1996.Murray, S. O. American Sociolinguistics: Theories and Tteory Groups, Peking University Press, 2004.Navas, M. et al. “Relative acculturation extended model”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations,2005,29, pp. 21-37.Neuliep, J. W.Intercultural Communication: A Contextual Approach, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.Nevitte, N. &Kornberg, A.(eds.). Minorities and the Canadian State, Oakville: Mosaic Press, 1985.Nishida, H. et al. “Cognitive differences between Japanese and Americans in their perceptions of difficult social situations”, in Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1998, 29, pp. 499-524. Nishida, H. “A cognitive approach to intercultural communication based on schema theory”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 1999, 23, pp.753-777.Oberg, K. “Cultural shock: Adjustment to new cultural environments”, in Practical Anthropology, 1960, 7, pp. 177-182. Oliver, R. T. Culture and Communication, Springfield: Thomas, 1962.Padilla, A. (ed.). Acculturation: Theory, Models and Findings, Boulder: Westview, 1980.Pearce, W. B. & Pearce, K. A. “Extended theory of the coordinated management of meaning (CMM) through a community dialogue process”, in Communication Theory, 2000, 10, pp. 405-423.Phillipson, R. Linguistic Immperialism, Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2000.Picco, G. et al(eds.). Crossing the Devide: Dialogue among Civilizations, South Orange: School of Diplomacy and International Relations & Seton Hall University, 2001. Prosser, M. Cultural Dialogue, Boston:Houghton Miffilin.Prus, R. Symbolic Interactionism and Ethnographic Research: Intersubjectivity and the Study of Human Lived Experiences, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996.Rescher, N. Rationally: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Nature and the Rationale of Reason, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. Robins, R. H. A Short History of Linguistics (third edition), Lodon: Longman Group UK Limited, 1990.Samovar, L. A. &Porter, R. E. (eds.).I ntercultural Communication: A Reader, Belmont: Wadsworth, 1972.Samovar, L. A. et al. Communication between Cultures(third edition), Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Resaerch Press, 2000. Schiller, H. Mass Communications and American Empire, New York: Augustus M. Kelly, 1969.Schiller, H. Communication and CulturalDominance, New York: International Arts and Sciences Press, 1976.Schutz, A. The Phenomenology of the Social World( translated by G. Walsh et al.), Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1967.Searle, J. R. The Construction of Social Reality, New York: The Free Press, 1995. Severin, W. J. &Tankard, J. W. Jr Communication Theories: Origins, Methods, and Uses in the Mass Media( fourth edition), New York: Longman Publishers, 1997. Smith, A. D. National Identity, Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 1991.Smith, L. R. “Intercultural network theory: A cross-paradigmatic approach to acculturation”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 1999, 23, pp. 629-658.Smith, M. J. Contemporary Communication Research Metheods, Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1988.Splinder, G. D. Sociological and Psychological Processes in Menomini Acculturation, Berkley: University of California Press, 1955.Spiro, M. E.“The acculturation of American ethnic groups”, in American Anthropology, 1955, 57, pp. 1240-1252.Steinfatt, T. M. “Linguistic relativity: Toward a broader view”, in S. Ting-Toomey and F. Korzenny(eds.). Language, Communication, and Culture: Current Directions, Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1989.Tajfel, H. et al. “ Social categorization and intergroup behavior”, in European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol.1, 1971, pp. 149-178.Tajfel, H. (ed.). Social Identity and Intergroup Relations, London: Cambridge University Press, 1982.Ting-Toomey, S. “Towards a theory of conflict and culture”, in W. B. Gudykunst& S. Ting-Toomey (eds.). Communication, Culture, and Organizational Processes, Beverly Hills: Sage, 1985, pp. 71-86.Ting-Toomey, S.& Korzenny, F. (eds.). Cross-Cultural Interpersonal Communication, Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc., 1991.Ting-Toomey, S.& Kurogi, A. “Facework competence in intercultural conflict: An updated face-negotiation theory”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 1998, 22, pp. 187-225.Ting-Toomey, S. Communicating across Cultures, New York: The Guilford Press, 1999.Ting-Toomey, S. “Intercultural conflict competence”, in W. R. Cupach& D. J. Canary (eds.). Competence in Interpersonal Conflict, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997, pp. 120-147.Ting-Toomey, S.& Oetzel, J. G. Managing Intercultural Conflict Effectively,Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., 2001.Tomlinson, J. Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991. Tomlinson, J. Globalization and Culture, London Polity Press, 1999.Triandis, H. C. Individualism and Collctivism, Boulder: Westview, 1995. Tsukuba, Y. “English hegemony and English divide”, in China Media Research, 2008, 4, pp. 47-55.Tu, W. Conflict Thought: Selfhood as Creative Transformation, New York: State University of New York Press, 1985. Vago, J. M. (ed.). Culture Bound, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. Ward, C. “Thinking outside Berry boxes: New perspectives on identity, acculturation and intercultural relations”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32, 2008, pp. 105-114.White, S. K. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Habermas, Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2006.Willett, C. (ed.). Theorizing Multiculturalism: A Guide to the Current Debate, Malden: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 1998.Williams, R. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, London: Fontana Press, 1983.Wiseman, R. L. (ed.).Intercultural Communication Theory, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.,1995.Wood, J. T. Communication Theories in Action: An Introduction (second edition), Belmont: Wadsworth, 2000.Worchel, S. “Culture’s role in conflict and conflict management: Some suggestions, many questions”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2005, 29, pp. 739-757.Xiao, X. “Zhong (centrality): Aneverlasting subject of Chinese discourse”, in Intercultural Communication Studies, 2003, 12, pp. 137-149.Yang, R. P. et al. “Multiple routes to cross-cultural adaptation for international students: Mapping the paths between self-construals, English language confidence, and adjustment”, in International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2006, 30, pp. 478-506.Zilles, A. M. S. &King, K. “Self-presentation in sociolinguistic interviews: Identities and language variation in Panambi”, in Sociolinguistics, 2005, 9, pp. 74-75.中文参考书目【英】安德鲁·埃德加著,杨礼根与朱松峰译:《哈贝马斯:关键概念》,南京:江苏人民出版社,2009年版。

全皮下埋藏式心脏转复除颤器

全皮下埋藏式心脏转复除颤器:安全有效的心脏除颤器摘要:全皮下埋藏式心脏转复除颤器(Subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator,S—ICD)目前已在欧洲、新西兰、美国投入临床使用。

S-ICD主要由脉冲发生器、电极导线组成,与经静脉植入型心律转复除颤器(Transvenous implantable cardioverter defibrillator,TV—ICD)不同的是,S—ICD的脉冲发生器经皮下置于左侧胸壁,电极是由两个感知电极及一个电击线圈组成的,经皮下置于胸骨旁。

作为全皮下心脏除颤系统,S-ICD可在一定程度上避免与静脉导线相关的围手术期及长期并发症,且手术过程不需要在透视下进行.S-ICD的适应人群主要包括伴有静脉畸形或梗阻不适合经静脉行心脏转复除颤器的儿童、感染风险大以及有猝死风险的年轻心律失常患者(如Brugada综合症、长QT综合症及肥厚性心肌病)。

然而,由于缺乏腔内电极,S—ICD无起搏功能(除电击后短期起搏外),因此,I-SCD不适合缓慢性心律失常患者及有心脏再同步化治疗(Cardiac resynchronization therapy,CRT)适应症的患者.引言埋藏式心律转复除颤器(Implantable cardioverter—defibrillator,ICD)目前是心源性猝死的一级预防[1,2]及二级预防[3]的有效手段。

迄今为止,大部分ICD植入系统均通过传统植入方式,即经胸腔内大静脉将除颤电极置于右室,然而,TV—ICD具有较高的围手术期及远期并发症.最近的一项大规模研究表明,TV—ICD主要并发症的发生率大约为1。

5%,这些主要并发症包括:院内死亡、心脏骤停、心脏穿孔、心脏瓣膜损伤、冠状静脉损伤、血胸、气胸、深静脉炎、短暂性脑缺血发作、中风、心肌梗死、心包填塞以及动静脉瘘[4]。

同时,随着时间的推移,电极绝缘故障导致的电极故障的发生率日益增加,有研究显示,电极植入10年后电极故障的发生率约为20%[5].因此,尽管TV—ICD能够有效治疗快速性室性心律失常,它的缺点也是显而易见的。

植物内生菌的研究与应用

植物内生菌的研究与应用目录第一章植物内生菌的研究 (3)第二章分离过内生菌的植物种类 (17)第三章植物内生菌种类 (122)第三章相关作物内生菌的研究 (165)第四章植物内生菌研究参考文献 (166)第一章植物内生菌的研究1 内生菌的发现和定义植物体内普遍存在着内生菌,但是由于这些内生菌生活在没有外在感染症状的健康植物组织内部,所以内生菌的存在和作用长期以来被忽视。

直到20世纪30年代,发现造成畜牧业重大损失是由于牲畜食了感染内生真菌的牧草,这才开始对内生菌的深入研究(Leuchtmann A 1992)。

1886年,德国科学家Barry首先提出了内生菌一词“endophyte”(李能章彭远义2004)。

Carrol在1986年将内生菌阐述为生活在地上部分、活的植物组织内不引起明显症状的微生物(何劲刘蕴哲康冀川2006)。

1991年,Petrini提出内生菌是指生活史的一定阶段生活在活体植物组织内不引起植物明显病害的微生物(Petrini O 1986)。

1992年Kleopper等认为植物内生菌是指能够定殖在植物细胞间隙或细胞内,并与寄主植物建立和谐联合关系的一类微生物,并首次提出“植物内生细菌”的概念,他认为能在植物体内定殖的致病菌和菌根菌不属于内生菌(何红邱思鑫胡方平关雄2004)。

1997年Hallmann对植物内生细菌的概念进行补充,认为植物内生细菌是从表面消毒组织中分离得到或从植物内生细菌是从表面消毒的植物组织中分离得到或从植物内部汁液获得的,并对植物表观上无危害及明显症状的,但它们的存在并未使植物的表型特征和功能有任何改变的细菌(Hallmann J Kleopper J W Rodriguez-Kabana R 1997)。

目前,较被公认的定义为:指那些在其生活史的一定阶段或者全部阶段生活于健康植物的各种组织和器官内部的真菌或者细菌,被感染的宿主植物(至少是暂时)不表现出外在症状。

地铁车站PM2.5和PM10颗粒物浓度实测及分析

地铁车站 PM2.5 和 PM10颗粒物浓度实测及分析刘文龙 何垒 李懋中铁二院华东勘察设计有限责任公司摘 要: 为了进一步了解地铁车站内环境中的颗粒物浓度分布情况, 在 2015 年 11 月对上海市A 、 B 两个地铁车 站进行了实地监测,分析了PM2.5和PM10颗粒物浓度在一天中的变化规律及其影响因素。

测试结果显示站厅公 共区,站台公共区与轨行区的PM2.5浓度在监测时段内逐时变化规律相似。

站厅公共区,站台公共区PM10与 PM2.5在监测时段内逐时变化规律相似。

地铁车站站台内PM2.5/PM10质量浓度比值平均值为0.65~0.93, 颗粒物 污染主要为细颗粒物。

关键词: 站厅 站台 轨行区 PM2.5PM10 监测Site Monitoring and Analysis of Concentrationof PM2.5and PM10in Subway StationLIU Wenlong,HE Lei,LI MaoCREEC East China Survey and Design Co.,Ltd.Abstract: In order to get a better understanding of the Particle Concentration in subway station,in November 2015,two subway stations in Shanghai were monitored,and the changes of the concentration of PM2.5and PM10during the day and its influencing factors was analyzed.The results show that the changes of PM2.5concentration is similar at the public area of the station hall,the platform public area and the railroad area hour by hour;the changes of PM10and PM2.5at the public area of the station hall and the platform public area is similar hour by hour;the average mass concentration ratio of PM2.5/PM10in subway station platforms is 0.65~0.93,and the main particulate contaminant is fine particle.Keywords:station hall,platform,track area,PM2.5,PM10,monitoring收稿日期: 20201010作者简介: 刘文龙 (1988~), 男, 硕士, 工程师; 浙江省杭州市江干区三里亭路57号 (310004); Email:*********************0 引言PM2.5和PM10的浓度是影响地铁站站厅站台空气品质的主要参数之一, 有研究表明地铁车站内空气环境中所含的颗粒物与其他场合相比有较大区别 [12]。

布托啡诺复合舒芬太尼在乳腺癌根治术后静脉镇痛中的应用_骆喜宝

如芬太尼、舒芬太尼等历来占主导地位。 随着剂量 的增加,各种程度的疼痛能得到有效的控制, 静脉 自控镇痛效果确切,但其副作用多,不良反应发生 率高[3]。 近年来,多模式镇痛受到重视,采用不同镇 痛方案或不同镇痛药物作用的相加和协同,可以达 到充分的镇痛,同时因药物剂量的降低而使不良反 应 减 少 [4]。

2h 4.7 ± 1.4 1.6 ± 1.5* 1.5 ± 1.6*

4h 4.5 ± 1.3 1.5 ± 1.7* 1.7 ± 1.9*

8h 4.5 ± 1.8 1.9 ± 1.4* 2.0 ± 1.3*

12 h 4.6 ± 1. 4 1. Nhomakorabea ± 1.3* 1.8 ± 1.3*

24 h 4.5 ± 1.9 1.7 ± 1.6* 1.9 ± 1.5*

关键词 乳腺肿瘤; 布托啡诺; 舒芬太尼; 静脉镇痛

布托啡诺是一种典型的阿片受体兴奋-拮抗型 止痛药,镇痛效价是吗啡的 5 ~ 8 倍,而呼吸抑制仅 仅为吗啡的 1 / 5[1]。 舒芬太尼镇痛机制与吗啡相似, 为 μ 阿片受体激动剂,术后镇痛作用较强,安全范 围远远大于吗啡[2]。 本研究观察布托啡诺复合舒芬 太尼在乳腺癌改良根治手术后静脉镇痛中的效能和 不良反应,以寻求一种安全、有效的术后镇痛方法。 1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料 选 择 我 院 2009 年 1 月 至 2010 年 4 月全麻下择期行乳腺癌根治术患者 63 例, 年龄 38 ~ 68 岁,体重 45 ~ 65 kg,ASA Ⅰ~Ⅱ 级;无阿片 药物滥用史,无高血压及肝肾功能异常,无酗酒史; 所有受试者经医院伦理委员会同意并签署同意书 后进入研究。 63 例乳腺癌改良根治手术患者分为 A、B、C 组,3 组患者年龄、身高、体重、手术时间、麻 醉时间等差异均无统计学意义,见表 1。 1.2 麻醉方法 麻醉前肌注苯巴比妥钠 0.1 g、阿 托品 0.5 mg。 以咪达唑仑 0.05 ~ 0.1 mg / kg、丙泊酚 1 ~ 2 mg / kg、芬 太 尼 4 μg / kg、阿 曲 库 铵 0.5 mg / kg 诱导插管,术中丙泊酚维持 4 ~ 8 mg / (kg·h),异 氟 醚吸入维持麻醉。 1.3 镇痛方法 A 组:酒石酸布托啡诺 4 mg(江苏 恒瑞医药股份有限公司生产, 规格:1 mL;1 mg)加 生理盐水共 100 mL。 B 组:舒芬太尼 100 μg (宜昌 人福药业有限公司生产,规格:1 mL;50 μg)加生理 盐水共 100 mL。C 组:酒石酸布托啡诺 4 mg 复合舒 芬 太 尼 50 μg 加 生 理 盐 水 共 100 mL。 术 毕 清 醒 拔 管 后 接 静 脉 镇 痛 泵 行 静 脉 术 后 镇 痛 (PCIA)。 持 续

新视野大学英语读写教程(第二版)第二册课文及翻译

Unit 1Time-Conscious AmericansAmericans believe no one stands still. If you are not moving ahead, you are falling behind. This attitude results in a nation of people committed to researching, experimenting and exploring. Time is one of the two elements that Americans save carefully, the other being labor."We are slaves to nothing but the clock," it has been said. Time is treated as if it were something almost real. We budget it, save it, waste it, steal it, kill it, cut it, account for it; we also charge for it. It is a precious resource. Many people have a rather acute sense of the shortness of each lifetime. Once the sands have run out of a person's hourglass, they cannot be replaced. We want every minute to count.A foreigner's first impression of the US is likely to be that everyone is in a rush—often under pressure. City people always appear to be hurrying to get where they are going, restlessly seeking attention in a store, or elbowing others as they try to complete their shopping. Racing through daytime meals is part of the pace of life in this country. Working time is considered precious. Others in public eating-places are waiting for you to finish so they, too, can be served and get back to work within the time allowed. You also find drivers will be abrupt and people will push past you. You will miss smiles, brief conversations, and small exchanges with strangers. Don't take it personally. This is because people value time highly, and they resent someone else "wasting" it beyond a certain appropriate point.Many new arrivals in the States will miss the opening exchanges of a business call, for example. They will miss the ritual interaction that goes with a welcoming cup of tea or coffee that may be a convention in their own country. They may miss leisurely business chats in a restaurant or coffee house. Normally, Americans do not assess their visitors in such relaxed surroundings over extended small talk; much less do they take them out for dinner, or around on the golf course while they develop a sense of trust. Since we generally assess and probe professionally rather than socially, we start talking business very quickly. Time is, therefore, always ticking in our inner ear.Consequently, we work hard at the task of saving time. We produce a steady flow of labor-saving devices; we communicate rapidly through faxes, phone calls or emails rather than through personal contacts, which though pleasant, take longer—especially given our traffic-filled streets. We, therefore, save most personal visiting for after-work hours or for social weekend gatherings.To us the impersonality of electronic communication has little or no relation to the significance of the matter at hand. In some countries no major business is conducted without eye contact, requiring face-to-face conversation. In America, too, a final agreement will normally be signed in person. However, people are meeting increasingly on television screens, conducting "teleconferences" to settle problems not only in this country but also—by satellite—internationally.The US is definitely a telephone country. Almost everyone uses the telephone to conduct business, to chat with friends, to make or break social appointments, to say "Thank you", to shop and to obtain all kinds of information. Telephones save the feet and endless amounts of time. This is due partly to the fact that the telephone service is superb here, whereas the postal service is less efficient.Some new arrivals will come from cultures where it is considered impolite to work too quickly. Unless a certain amount of time is allowed to elapse, it seems in their eyes as if the task being considered were insignificant, not worthy of proper respect. Assignments are, consequently, given added weight by the passage of time. In the US, however, it is taken as a sign of skillfulness or being competent to solve a problem, or fulfill a job successfully, with speed. Usually, the more important a task is, the more capital, energy, and attention will be poured into it in order to "get it moving".美国人认为没有人能停止不前。

magneticcarriers:磁性载体

immobilized on magnetic carriers.Proceedings of European Congress of Chemical Engineering (ECCE-6)Copenhagen, 16-20 September 2007Application of magnetic nanostructures in biotechnological processes: Biodiesel production using lipase immobilized on magnetic carriersK. J. Dussán,a O. H. Giraldo,b C. A. Cardona,aa Department of Chemical Engineering, National University of Colombia at Manizales, Cra. 27 No. 64-60, Of. F-505, Manizales, Colombiab Department of Physics and Chemistry, National University of Colombia at Manizales, Cra. 27 No.64-60, Manizales, ColombiaAbstractMagnetic nanostructures have gained a remarkable interest in the last years both for basic research and applied studies. The use of magnetic nanostructures has been proven in biochemistry, biomedicine, and waste treatment among other fields. This broad range of applications is based on the fact that magnetic particles have very large magnetic moments, which allow them to be transported and driven by external magnetic fields. The magnetic nanostructures have also a great potential in biotechnological processes taking into account that they can be utilized as a carrier for enzymes during different biocatalytic transformations. In this way, the biocatalyst can be easily manipulated by a controlled magnetic field allowing it to be located permanently in the zone where the maximum concentration of reagents is present. In this work, some applications are presented. Particularly, the system composed of an immobilized lipase on a magnetic nanostructure for biodiesel production is analyzed. This system makes possible the intensification of the process due to the accomplishment of a reaction-extraction enzymatic process favoring the separation of the products formed during the transesterification reaction. In addition, the magnetic nature of the carrier permits the preferential location of the biocatalyst in the separation surface between the two liquid immiscible phases present in the system. Finally, techniques for the immobilization of different enzymes on magnetic carriers are described. This technology can offer innovative configurations allowing the intensification of enzymatic processes and the reduction of their costs.Keywords: Biodiesel, reaction-extraction process, magnetic nanostructure, lipase.1.IntroductionMagnetic particles (microspheres, nanospheres and ferrofluids) are widely studied for their applications in various fields in biology and medicine such as enzyme and protein immobilization, genes, radiopharmaceuticals, magnetic resonance imaging, diagnostics, immunoassays, RNA and DNA purification, magnetic cell separation and purification, magnetically controlled transport of anti-cancer drugs as well as hyperthermia generation (Ma, Zhang et al., 2003).Applications in biotechnology impose strict requirements on the particles physical, chemical and pharmacological properties, including chemical composition, granulometric uniformity, crystal structure, magnetic behavior, surface structure, adsorption properties, solubility and low own toxicity. The following parameters of the nanomagnets are critical: (a) particle size (small as possible to improve tissular diffusion and to have long sedimentation times and high effective surface areas), (b) surface characteristics (easy encapsulation of the magnetic nanoparticles protects them from degradation and endows biocompatibility), and (c) good magnetic response (possibility of decreasing nanomagnets concentration in blood and therefore diminishing the associated side effects) (Tartaj, Morales et al., 2005).On the other hand, the use of biocatalysts in transforming fats, oils, partial glycerides and fatty acids into higer-value-added derivates is well documented (Hsu, Jones et al., 2002). One area of interest is the utilization of immobilized lipases for catalyzing the synthesis of simple esters of vegetable oils (Clark, Wagner et al., 1984; Selmi and Thomas, 1998; Shimada, Watanabe et al., 1999) and other agricultural lipid feedstocks (Nelson, Foglia et al., 1996; Foglia, Nelson et al., 1997; Hsu, Jones et al., 2001) (Scheme 1).Some efforts have been made on the immobilization of lipase on the surface of ferromagnetic nanoparticles modified by polymer such as poly(ethylene glycol) and its copolymer with maleic acid (Tamaura, Takahashi et al., 1986; Mihama, Yoshimoto et al., 1988) and in magnetic sol-gel matrices (Kuncová and Sivel, 1997; Reetz, Zonta et al., 1998; Chen and Lin, 2003; Zeng, Luo et al., 2006). The former immobilization method seems to be more attractive because using magnetic nanoparticles as support not only yields a sufficiently large specific surface area for enzyme binding but also has no pore-diffusion resistance and fouling problem. Therefore, the system composed of an immobilized lipase on a magnetic nanostructure can be applicable in reaction-extraction processes. Because the magnetic nature of the carrier permits the preferential location of the biocatalyst in the separation surface between the two liquid immiscible phases present in the system and an easy recover the biocatalysts of medium.In the process reaction-extraction is used the immiscibility of liquid phase that can give naturally inside the reaction system or can be introduce with the addition of solvents (Samant, 1998), achieving the selective separation of intermediate compounds or products, prevent their later reaction. This in-situ separation carry to a reactive reconcentration which deceive (when are had reversible reactions) reach higher conversions. Besides the synergic effect reached by the reaction a separation combination, has the advantage of carry out the process in single equipment.immobilized on magnetic carriers.Scheme 1. Immobilized lipase-catalysed transesterification of triacylglycerols and etherification of fatty acids to simple alkyl esters (Hsu, Jones et al., 2002).2.Experimental2.1 Synthesis of magnetite nanoparticlesMagnetite was made according to the method of Zeng (Zeng, Luo et al., 2006). For the preparation of magnetic carriers, a mixture of FeCl2 (0.2 mol/l) and FeCl3 (0.3 mol/l) aqueous solution was added to a flask that containing stearic acid. Then the mixture was stirred vigorously for a while, and NaOH aqueous solution (4 mol/l) was dropped into the flask. A black precipitate was obtained. The precipitate was filtrated, washed and dried.2.2 Silane-coated magnetite nanoparticlesCertain amount of Fe3O4 (magnetic particle) was suspended in distilled water. A mixture of [3-(2-aminoethylamino)propyl]trimethoxysilane (APTS), methanol and NaF (1%) aqueous solution was stirring for 10 minutes. Then tetraethyl orthosilicate was dropped slowly into the flask and stirred vigorously at room temperature for 24 hours. The precipitate was collected, washed and dried.2.3 Lipase- immobilizedFor the immobilization of the enzyme, glutaraldehyde was added to certain amount of particles, and stirred at room temperature. Then, certain amount of lipase Candida Rugosa was added to phosphate buffer solution and stirred until all the lipase was dissolved. To this solution was added the solution prepared previously, and stirred for several minutes at room temperature. The immobilized lipase was separated bycentrifugation and washed with phosphate buffer and dried. All portions of centrifugation were retained for the determination of protein concentration.3. Results and discussion3.1 Uncoated and coated nanoparticles magnetic According to the XRD pattern (figure 1), the size of particle can be calculated in the following equation (Moore and Reynolds, 1997),θβλcos ··K L = (1) Where L is the mean diameter of particle, λ is the wavelength of copper anode (λ = 1.540562 Ǻ), K is a constant (K = 1), β is full width at half maximum-FWHM (β = 1.606). The calculation result is 12.3 nm.Figure 1. XRD pattern of the magnetite nanoparticles In the figure 2 shown FT-IR spectra of uncoated and coated Fe 3O 4 nanoparticles. It can be seen that, compared with the uncoated sample, the coated Fe 3O 4 nanoparticles posses adsorption bands in 1068 cm -1 due to the stretching vibration of Si-O bond, band in 792 cm -1 due to the bending vibration of –NH 2 group. All these reveal the existence of APTS. In addition, in figure 5 (a) and (b) the absorption bands near 3400 and 1630 cm -1 refer to the vibration of remainder H2O in the samples, bands near 2920 and 2850 cm -1 due to stretching vibration of C-H bond, bands near 570 cm -1 due to stretching vibration of Fe-O, bands near 1400 cm -1 due to stretching vibrations of N-H.immobilized on magnetic carriers.Figure 2. FT-IR spectra of the uncoated (a) and coated (b) magnetite nanoparticles3.2 Immobilization of LipaseThe magnetite as support was selected because it has some advantages (Huang, Liao et al., 2003): (i) higher specific surface area obtained for the binding of a larger amount of enzymes, (ii) lower mass transfer resistance and less fouling, and (iii) the selective separation of immobilized enzymes from a reaction mixture by the application of a magnetic field (Halling and Dunnill, 1980). Magnetite (Fe3O4) is one of the famous magnetic materials in common use. As a result of strong magnetic property and low toxicity, its applications in biotechnology and medicine have gained significant attention (Curtis and Wilkinson, 2001).In addition and with the interest to increase this resistance, the addition of glutaraldehyde as covalent link allows improving the properties already mentioned and it increases the degree of acetylation of the support which leads to a bigger fixation of lipase and also to a greater degree of hydrofobicity avoiding the possible catalyst and poisoning (Shao-Hua and Wen-Teng, 2004).Finally to carry out the fixation of the enzyme in the support has been used the impregnating technique, submerging the support with glutaraldehyde in a solution of known concentration and determining the percentage of immobilization of theenzyme by means of espectofotometric tests; the obtained results indicate that the percentage of immobilization of the enzyme is of 40%. These results are corroborated with the Kjeldhal method which determined the total nitrogen (5.84%) that multiply for a constant (k = 6.5) gives the percentage of immobilization (38%). This result is similar to calculated for espectofotometric test.4.ConclusionsLipase was directly bound to Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles via glutaraldehyde activation. The analyses of XRD indicated the resultant magnetic nanoparticles were pure Fe3O4 with a mean diameter of 12.3 nm. FTIR spectra were utilized to prove the formation of Fe-O-Si chemical bonds. The percentage of lipase immobilization was 40% and this data were calculated for Kjeldhal method and espectofotometric test. The enzyme-linked, it has been proved that these APTS-coated magnetite nanoparticles could significantly improve the protein immobilization.The process of extractive reaction is begins developed for biodiesel production from palm or castor oil with ethanol catalyzed for immobilized lipase on magnetic particle. This process can be modeling and simulated with the principles of processes intensification and the methodology that has been developed for the Group Investigation: Chemical, Catalytic and Biotechnology Processes of the National University of Colombia at Manizales. The obtained results in the modeling, simulation and experimentation will make part of future publications.Finally, this work will be helpful for the practical application of lipase and of other enzymes.AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the Direction of Investigations of the National University of Colombia at Manizales (DIMA).ReferencesClark, S. J., Wagner, L., et al., (1984) J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 61, 1632-1638. Curtis, A. and Wilkinson, C., (2001) Trends Biotechnol., 19, 97-101.Chen, J.-P. and Lin, W.-S., (2003) Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 32, 801-811. Foglia, T. A., Nelson, L. A., et al., (1997) J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 73, 1191–1195. Halling, P. J. and Dunnill, P., (1980) Enzyme Microb. Technol., 2, 2-10.Hsu, A.-F., Jones, K. C., et al., (2002) Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem., 36, 181-186. Hsu, A.-F., Jones, K. C., et al., (2001) J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 78, 585–588.Huang, S.-H., Liao, M.-H., et al., (2003) Biotechnol. Prog., 19, 1095-1100.immobilized on magnetic carriers.Kuncová , G. and Sivel, M., (1997) J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol., 8, 667-671.Ma, M., Zhang, Y., et al., (2003) Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects, 212, 219-226.Mihama, T., Yoshimoto, T., et al., (1988) J. Biotechnol., 7, 141-146.Moore, D. and Reynolds, R., X-Ray Diffraction and the Identification and Analysis of Clay Minerals, Oxford University Press, New York (1997).Nelson, L. A., Foglia, T. A., et al., (1996) J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 73, 1191–1195. Reetz, M., Zonta, A., et al., (1998) J. Mol. Catal. A 134, 251-258.Samant, K., (1998) AIChE J. , 44, 1363-1381.Selmi, B. and Thomas, D., (1998) J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 75, 691-695.Shao-Hua, C. and Wen-Teng, W., (2004) Biomaterials, 25, 197-204.Shimada, Y., Watanabe, Y., et al., (1999) J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 76, 517-521. Tamaura, Y., Takahashi, K., et al., (1986) Biotechnol. Lett., 8, 877-880.Tartaj, P., Morales, M. P., et al., (2005) Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 290-291, 28-34.Zeng, L., Luo, K., et al., (2006) Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 38, 24-30.。

尊严疗法的效果评价及其在我国的应用与研究

尊严疗法的效果评价及其在我国的应用与研究赵圣敏;闫翔宇;赵曼羽;方一安;陈慧平【摘要】“尊严疗法”是一种新兴的心理治疗方法,国外大量研究证实其在提升生命末期患者尊严感、减轻心理痛苦等方面具有显著效果.但尊严疗法在中国的临床应用和研究还处于起步阶段,在其具体的实施过程中仍存在一些问题,且由于东西方文化差异和社会经济发展水平不同,需从医护人员、生命末期患者及患者家属角度出发,进一步探索适合中国国情的生命朱期患者心理特征的实施方案,以改善他们的心理状况,提高他们的生命意义感和存在感,从而提升其生命质量.【期刊名称】《医学与哲学》【年(卷),期】2019(040)002【总页数】4页(P49-51,70)【关键词】尊严疗法;生命末期;心理治疗;生命质量【作者】赵圣敏;闫翔宇;赵曼羽;方一安;陈慧平【作者单位】四川大学华西公共卫生学院四川成都 610041;四川大学华西公共卫生学院四川成都 610041;四川大学华西公共卫生学院四川成都 610041;四川大学华西公共卫生学院四川成都 610041;四川大学华西第四医院四川成都 610041【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R-05相关研究显示,国外有3/4的临终患者遭受着身心折磨[1]。

孤独无助感和失落感是临终患者面临的两个主要的心理问题[2]。

进入临终期的患者,身体机能日益衰竭,基本技能逐渐丧失,很多事情都必须依赖他人完成,他们在遭受着躯体疼痛的同时,尊严感也会因此降低,甚至丧失生存欲望,出现自杀念头。

患者因常常想到死亡的不可抗拒而出现以绝望、恐惧、忧郁为主的心理特征[3]。

越来越多的学者及医护人员关注到了这个问题,临床上也开始不单以治疗身体疾病、延长生存时间为唯一目标,患者在治疗过程中心理、精神等方面的问题也不断地受到重视,维护临终患者的个人尊严逐渐成为临床治疗过程必不可少的任务。

在此背景下,如何提高临终患者的尊严,提升患者生命质量和生存欲望,让生命尊严落幕,成为一个医学界乃至全社会亟待解决的问题,也是医护领域一个重要的研究方向。

信息检索综合考查作业

层间氧化带砂岩型铀矿根据国际原子能机构(IAEA)报道,至2001年全世界现己探明的铀资源量中砂岩型铀矿位于各铀矿类型的第二位,占世界探明资源量的1/4强,仅次于在澳、加两国占统治地位的不整合面型铀矿(王正邦,2002;陈祖伊,2003),而其矿床数量占世界探明矿床数量的42.9%,分布范围最广泛(周维勋等,2000),占世界超大型铀矿床(储量大于5万吨)总数的1/3。

砂岩型铀矿根据成因和矿化特征主要分成晚期成岩表生后生渗入叠加型砂岩型铀矿、表生后生渗入型砂岩型铀矿、表生后生渗出渗入型砂岩型铀矿、后生热水叠造型砂岩型铀矿(王正邦,2002)。

层间氧化带砂岩型铀矿属于飙升后生渗入型砂岩型铀矿,具有埋藏浅、适宜地浸开采、分布较普遍和矿床规模大等最具开发价值。

目前,砂岩型铀矿床,特别是可地浸层间氧化带砂岩型铀矿床在世界铀资源中的地位举足轻重,己成为世界铀矿找矿和开发的主攻类型之一。

一、国内外研究现状1.1国外研究现状二十世纪五十年代以来,前苏联、美国等层间氧化带砂岩型铀矿勘查取得了巨大的成功,有关研究也各具特色,形成了―层间氧化带‖和―卷状‖砂岩型铀矿成矿理论两大流派。

成因类型上分为―整合型‖和―卷型‖两大类,形成著名的―卷型‖砂岩铀成矿理论。

在产铀盆地分析、成矿地质、地球化学环境、成矿物质来源、成矿作用机制、找矿判据等研究领域都取得了重要的研究成果,发表了大量的专著和论文。

代表性成果有:H.H.Adler和B.J.Sharp(1967)对卷型铀矿床的地质构造背景、含铀建造沉积环境和成因作了全面总结;R.L.Rackley(1976)对砂岩型铀矿的成因作了深入探讨;E.N.Harshman和S.S.Adams(1981)研究了美国陆相砂岩中卷型铀矿床的地质一地球化学模式和识别判据。

W.RKeefer(1970)对温得河盆地(Wind River Basin)构造背景的研究;J.W. King和S.R.Austin(1965, 1966)对怀俄明盆地气山(Gas Hills)卷型铀矿床的总结;R.E.Melin (1964,1969)对谢利盆地(Shirley Basin)铀矿床的成因研究;D.H.Earhle等(1961)对得克萨斯州东南部海岸平原铀矿床的形成及与油田断裂带中含硫化氢碳氢化合物之间关系进行了探讨;L.Jenson(1958)对砂岩型铀矿床成因与硫同位素的研究;K.R.Ludwig(1978,1979)关于铀矿化年龄的研究;M.F.Kashirtseva(1964)对砂岩型铀矿床中矿物与地球化学分带的研究;W.F.Galloway(1979,1984)对南得克萨斯砂岩型铀矿沉积环境和水文地质条件的研究;P.E.Hart, R.O.Duda和M.T. Einaudi(1978 )及J.Gaschaig (1980)利用计算机对铀矿勘探专家系统的研究;E. N.Harshman与S.S.Adams(1981)对砂岩型铀矿识别判据体系的研究和总结。

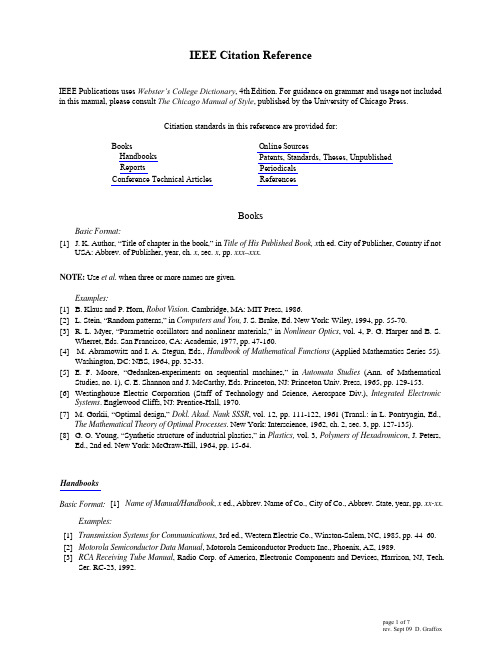

IEEE-certification of reference

IEEE Citation ReferenceIEEE Publications uses Webster’s College Dictionary , 4th Edition. For guidance on grammar and usage not included in this manual, please consult The Chicago Manual of Style , published by the University of Chicago Press.Citiation standards in this reference are provided for:BooksConference Technical ArticlesPeriodicals Handbooks ReferencesReportsBooksBasic Format:[1] J. K. Author, “Title of chapter in the book,” in Title of His Published Book, x th ed. City of Publisher, Country if notUSA: Abbrev. of Publisher, year, ch. x , sec. x , pp. xxx–xxx. Examples:[1] B. Klaus and P. Horn, Robot Vision. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986.[2] L. Stein, “Random patterns,” in Computers and You, J. S. Brake, Ed. New York: Wiley, 1994, pp. 55-70.[3] R. L. Myer, “Parametric oscillators and nonlinear materials,” in Nonlinear Optics , vol. 4, P. G. Harper and B. S.Wherret, Eds. San Francisco, CA: Academic, 1977, pp. 47-160.[4] M. Abramowitz and I. A. Stegun, Eds., Handbook of Mathematical Functions (Applied Mathematics Series 55).Washington, DC: NBS, 1964, pp. 32-33.[5] E. F. Moore, “Gedanken-experiments on sequential machines,” in Automata Studies (Ann. of MathematicalStudies, no. 1), C. E. Shannon and J. McCarthy, Eds. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1965, pp. 129-153.[6] Westinghouse Electric Corporation (Staff of Technology and Science, Aerospace Div.), Integrated ElectronicSystems . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970.[7] M. Gorkii, “Optimal design,” Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR , vol. 12, pp. 111-122, 1961 (Transl.: in L. Pontryagin, Ed.,The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes. New York: Interscience, 1962, ch. 2, sec. 3, pp. 127-135).[8] G. O. Young, “Synthetic structure of industrial plastics,” in Plastics, vol. 3, Polymers of Hexadromicon , J. Peters, Ed., 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964, pp. 15-64. [1] Name of Manual/Handbook , x ed., Abbrev. Name of Co., City of Co., Abbrev. State, year, pp. xx-xx. Examples:[1] Transmission Systems for Communications , 3rd ed., Western Electric Co., Winston-Salem, NC, 1985, pp. 44–60. [2] Motorola Semiconductor Data Manual , Motorola Semiconductor Products Inc., Phoenix, AZ, 1989.[3] RCA Receiving Tube Manual , Radio Corp. of America, Electronic Components and Devices, Harrison, NJ, Tech.Ser. RC-23, 1992.NOTE: Use et al. when three or more names are given.nline ourcesPatents, S tandards, Unpublished Theses, Basic Format:HandbooksReportsThe general form for citing technical reports is to place the name and location of the company or institution after the author and title and to give the report number and date at the end of the reference.Basic Format:[1] J. K. Author, “Title of report,” Abbrev. Name of Co., City of Co., Abbrev. State, Rep. xxx , year.Examples:[1] E. E. Reber absorption in the earth’s atmosphere,” Aerospace Corp., Los Angeles, CA, Tech. Rep. TR-0200 (4230-46)-3, Nov. 1988.[2] J. H. Davis and J. R. Cogdell, “Calibration program for the 16-foot antenna,” Elect. Eng. Res. Lab., Univ. Texas, Austin, Tech. Memo. NGL-006-69-3, Nov. 15, 1987.[3] R. E. Haskell and C. T. Case, “Transient signal propagation in lossless isotropic plasmas,” USAF Cambridge Res. Labs., Cambridge, MA, Rep. ARCRL-66-234 (II), 1994, vol. 2.[4] M. A. Brusberg and E. N. Clark, “Installation, operation, and data evaluation of an oblique-incidence ionosphere sounder system,” in “Radio Propagation Characteristics of the Washington-Honolulu Path,” Stanford Res. Inst., Stanford, CA, Contract NOBSR-87615, Final Rep., Feb. 1995, vol. 1.[5]P. Diament and W. L. Lupatkin, “V-line surface-wave radiation and scanning,” Dept. Elect. Eng., New York, Sci. Rep. 85, Aug. 1991.Conference Technical ArticlesThe general form for citing technical articles published in conference proceedings is to list the author/s and title of the paper, followed by the name (and location, if given) of the conference publication in italics using these standard abbreviations.When the word below appears in the conference publication title, abbreviate to Annals Ann. Annual Annu. Colloquium Colloq. Conference Conf. Congress Congr. Convention Conv. Digest Dig. Exposition Expo.International Int.National Nat.When the word below appears in theconference publication title, abbreviate toProceedings Proc. Record Rec. Symposium Symp. Technical Digest Tech. Dig. Technical Paper Tech. Paper First 1st Second Third 3rd Fourth/n th ...Write out all the remaining words, but omit most articles and prepositions like “of the” and “on.” That is, Proceedings of the 1996 Robotics and Automation Conference becomes Proc. 1996 Robotics and Automation Conf.Basic Format:[1] J. K. Author, “Title of paper,” in Unabbreviated Name of Conf., City of Conf., Abbrev. State (if given), year, pp.xxx-xxx. For an electronic conference article when there are no page numbers:J. K. Author [two authors: J. K. Author and A. N. Writer ] [three or more authors: J. K. Author et al.],“Title of Article,” in [Title of Conf. Record as ],[copyright year] © [IEEE or applicable copyright holder of the Conference Record]. doi: [DOI number] [1][1] J. K. Author, “Title of paper,” presented at the Unabbrev. Name of Conf., City of Conf., Abbrev. State, year.For an unpublished papr presented at a conference:it appears on the copyright page Angeles, CA, Tech. Rep.et al ., “Oxygen TR-0200 (4230-46)-3, Nov. 1988. Columbia Univ.,nline S ourcesThe basic guideline for citing online sources is to follow the standard citation for the source given previously and add the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) at the end of the citation, or add the DOI in place of page numbers if the source is not paginated. The DOI for each IEEE conference article is assigned when the article is processed for inclusion in the IEEE Xplore digital library and is included with the reference data of the article in Xplore. See The DOI System for more information about the benefits of DOI referencing.The following sources are unique in that they are electronic only sources.FTPBasic Format:[1]J. K. Author. (year). Title (edition) [Type of medium]. Available FTP: Directory: File:Example:[1]R. J. Vidmar. (1994). On the use of atmospheric plasmas as electromagnetic reflectors [Online]. Available FTP: Directory: pub/etext/1994 File: atmosplasma.txtWWWBasic Format:[1]J. K. Author. (year, month day). Title (edition) [Type of medium]. Available: http://www.(URL)Example:[1]J. Jones. (1991, May 10). Networks (2nd ed.) [Online]. Available: E-MailBasic Format:[1]J. K. Author. (year, month day). Title (edition) [Type of medium]. Available e-mail: Message:Example:[1]S. H. Gold. (1995, Oct. 10). Inter-Network Talk [Online]. Available e-mail: COMSERVE@RPIECS Message: GetNETWORK TALKTelnetBasic Format:[1]J. K. Author. (year, month day). Title (edition) [Type of medium]. Available Telnet: Directory: File:Example:[1]V. Meligna. (1993, June 11). Periodic table of elements [Online]. Available Telnet: Directory:Libraries/Reference Works File: Periodic Table of ElementsPatents, tandards, Theses, UnpublishedPatentsBasic Format:[1]J. K. Author, “Title of patent,” U.S. Patent x xxx xxx, Abbrev. Month, day, year.Example:[1]J. P. Wilkinson, “Nonlinear resonant circuit devices,” U.S. Patent 3 624 125, July 16, 1990.NOTE: Use “issued date” if several dates are given.StandardsBasic Format:[1]Title of Standard, Standard number, date.Examples:[1]IEEE Criteria for Class IE Electric Systems, IEEE Standard 308, 1969.[2]Letter Symbols for Quantities, ANSI Standard Y10.5-1968.Theses (M.S.) and Dissertations (Ph.D.)Basic Format:[1]J. K. Author, “Title of thesis,” M.S. thesis, Abbrev. Dept., Abbrev. Univ., City of Univ., Abbrev. State, year.[2]J. K. Author, “Title of dissertation,” Ph.D. dissertation, Abbrev. Dept., Abbrev. Univ., City of Univ., Abbrev. State,year.Examples:[1]J. O. Williams, “Narrow-band analyzer,” Ph.D. dissertation, Dept. Elect. Eng., Harvard Univ., Cambridge, MA,1993.[2]N. Kawasaki, “Parametric study of thermal and chemical nonequilibrium nozzle flow,” M.S. thesis, Dept. Electron.Eng., Osaka Univ., Osaka, Japan, 1993.[3]N. M. Amer, “The effects of homogeneous magnetic fields on developments of tribolium confusum,” Ph.D.dissertation, Radiation Lab., Univ. California, Berkeley, Tech. Rep. 16854, 1995. *** The state abbreviation is omitted if the name of the university includes the state name, i.e., “Univ. California, Berkeley.”***[4] C. Becle, These de doctoral d’etat, Univ. Grenoble, Grenoble, France, 1968.UnpublishedThese are the two most common types of unpublished references.Basic Format :[1]J. K. Author, private communication, Abbrev. Month, year.[2]J. K. Author, “Title of paper,” unpublished.Examples:[1] A. Harrison, private communication, May 1995.[2] B. Smith, “An approach to graphs of linear forms,” unpublished.[3] A. Brahms, “Representation error for real numbers in binary computer arithmetic,” IEEE Computer GroupRepository, Paper R-67-85.PeriodicalsWhen referencing IEEE Transactions, the issue number should be deleted and month carried.NOTE:Basic Format:[1]J. K. Author, “Name of paper,” Abbrev. Title of Periodical, vol. x, no. x, pp. xxx-xxx, Abbrev. Month, year.Examples:[1]R. E. Kalman, “New results in linear filtering and prediction theory,” J. Basic Eng., ser. D, vol. 83, pp. 95-108,Mar. 1961.[2][3][4][5][6]Ye. V. Lavrova, “Geographic distribution of ionospheric disturbances in the F2 layer,” Tr. IZMIRAN, vol. 19, no. 29, pp. 31–43, 1961 (Transl.: E. R. Hope, Directorate of Scientific Information Services, Defence Research Board of Canada, Rep. T384R, Apr. 1963).E. P. Wigner, “On a modification of the Rayleigh–Schrodinger perturbation theory,” (in German), Math. Naturwiss. Anz. Ungar. Akad. Wiss., vol. 53, p. 475, 1935.E. H. Miller, “A note on reflector arrays,” IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag..., to be published.**C. K. Kim, “Effect of gamma rays on plasma,” submitted for publication. **W. Rafferty, “Ground antennas in NASA’s deep space telecommunications,” Proc. IEEE vol. 82, pp. 636-640, May 1994.** Always use this style when the paper has not yet been accepted or scheduled for publication. Do not use “to appear in.”Abbreviations for IEEE PeriodicalsProceedings of the IEEE abbreviates to: Proc. IEEEProceedings of the IRE abbreviates to: Proc. IRE (until 1962)IEEE Journals IEEE J. Comput. Aid. Des. IEEE J. Solid-State CircuitsIEEE J. Ocean. Eng.IEEE Sensors J.IEEE J. Quantum Electron.IEEE Syst. J.IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. IEEE Transl. J. Magn. Jpn.IEEE J. Sel. Topics Signal Process. J. Lightw. Technol.IEEE J. Sel. Topics. Quantum Electron. J. Microelectromech. Syst.IEEE Letters IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett.IEEE Commun. Lett. IEEE Power Electron. Lett. (until 2005)IEEE Electron Device Lett. IEEE Signal Process. Lett.IEEE Magazines IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag.IEEE Annals Hist. Comput. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag.IEEE Antennas Propagat. Mag.IEEEIntell.Syst.IEEE ASSP Mag. (1984–1990)IEEE Internet Comput.IEEE Circuits Devices Mag. (1985–present)IEEE IT Prof.IEEE Circuits Syst. Mag. (1979–1984)IEEEMicroIEEE Commun. Mag. (1979–present)IEEEMicrowaveIEEE Commun. Soc. Mag. (until 1978)IEEEMultimediaIEEE Comput. Appl. Power IEEE Nanotechnol. Mag.IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. IEEE NetworkIEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. IEEE Pers. Commun.IEEE Comput. Sci. Eng. Mag. IEEE PotentialsIEEE Computer IEEE Power Eng. Rev.IEEE Concurrency IEEE Robot. Automat. Mag.IEEE Control. Syst. Mag. IEEE Signal Processing Mag. (1991–present)IEEE Des. Test Comput. IEEE Softw.IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. IEEE Spectr.IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag.IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag.IEEE Expert (until 1997)Today’sEng.IEEE Transactions abbreviationsIEEE Adv. Packag. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron.IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat.IEEE Human–Factors Electron. (until 1968)IEEE Trans. Inf. Forens. SecurityIEEE Man–Mach. Syst. (until 1970)IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed.IEEE Trans. Acoust., Speech, Signal Process. (1975–1990)IEEE Trans. Inf. TheoryIEEE Trans. Aeronaut. Navig. Electron.IEEE Trans. Instrum.IEEE Trans. Aerosp. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas.IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst.IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst.IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Navig. Electron. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng.IEEE Trans. Airbone Electron. IEEE Trans. Magn.IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. IEEE Trans. Manuf. Technol. (1972–1977)IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. IEEE Trans. Mechatron.IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. (until 1974)IEEE Trans. Med. Imag.IEEE Trans. Autom. Control IEEE Trans. Microw. Guid. Wave Lett. (1987–1999) IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech.IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. IEEE Trans. Microw. Wireless Compon. Lett. (until 2004) IEEE Trans. Broadcast. IEEE Trans. Mil. Electron.IEEE Trans. Broadcast. Technol. IEEE Trans. MultimediaIEEE Trans. Circuit Theory (until 1973)IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol.IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. (1974–1992)IEEE Trans. Neural Netw.IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, Fundam. Theory Appl. (until 2003)IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng.IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, Reg. Papers IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci.IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II, Analog Digit. Signal Process. (until2003)IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst.IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II, Exp. Briefs IEEE Trans. Parts, Hybrids, Packag. Technol. (June 1971–1977)IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. IEEE Trans. Parts, Mater. Packag.IEEE Trans. Commun. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.IEEE Trans. Commun. Technol. (until 1971)IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci.IEEE Trans. Compon. Hybrids, Manuf. Technol. (1978—1993) IEEE Trans. Power App. Syst. (until 1985)IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. A (1994–1998)IEEE Trans. Power Del.IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. B (1994–1998)IEEE Trans. Power Electron.IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. C (1996–1998)IEEE Trans. Power Syst.IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Technol. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun.IEEE Trans. Comput. IEEE Trans. Rehabil. Eng. (until 2000)IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. IEEE Trans. Reliab.IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom.IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf.IEEE Trans. Dev. Mat. Rel. IEEE Trans. Signal Process.IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng.IEEE Trans. Edu. IEEE Trans. Sonics Ultrason. (until 1985)IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. IEEE Trans. Speech Audio Process.IEEE Trans. Electron Devices IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. (1971–1995) IEEE Trans. Electron. Packag. Manuf. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A., Syst. Humans IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. B, Cybern.IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. C, Appl. Rev. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Eng.IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control IEEE Trans. Geosci. Electron. (1962–1979)IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol.IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. IEEE Trans. Image Process. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. GraphicsIEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun.ReferencesReferences in Text:References need not be cited in the text. When they are, they appear on the line, in square the punctuation.as shown by Brown [4], [5]; as mentioned earlier [2], [4]–[7], [9]; Smith [4] and Brown and Jones [5]; Wood et al. [7] NOTE: Use et al. when three or more names are given. or as nouns:as demonstrated in [3]; according to [4] and [6]–[9]. References Within a Reference:Check the reference list for ibid. or op. cit. These refer to a previous reference and reference section. In text, repeat the earlier reference number and renumber the reference ibid. gives a new page number, or other information, use the following forms:[3, Th. 1]; [3, Lemma 2]; [3, pp. 5-10]; [3, eq. (2)]; [3, Fig. 1]; [3, Appendix I]; [3, Sec. 4.5]; [3, Ch. 2, pp. 5-10]; [3, Algorithm 5].NOTE: Editing of references may entail careful renumbering of references, as well as the citations in text.Styletheir own, hanging out beyond the body of the reference. The reference numbers are on the line, enclosed in square brackets. In all references, the given name of the author or editor is abbreviated to the initial only and precedes the last name. Use commas around Jr., Sr., and III in names. If there Grammatically, they may be treated as if they were footnote numbers, e.g.,are many names, use et al. N ote that be kept, although it is normally deleted. Keep the day of the month when include all information; please obtain and include relevant information. Do not one reference with e ach number. If there is a URL included with the print reference, it can be included at the end of brackets, inside should be eliminated from the section accordingly. If theWhen the word below appears in the reference, abbreviate toAcoustics Acoust. Administration Admin. Administrative Administ. American Amer.Analysis Anal.Annals Ann.Annual Annu.Apparatus App.Applications Applicat.Applied Appl.Association Assoc.Automatic Automat.Broadcasting Broadcast.Business Bus.Communications Commun.Computer(s) Comput.Congress Congr.Convention Conv.Correspondence Corresp.Cybernetics Cybern.Department Dept. Development Develop. Digest Dig. Electrical Elect. Electronic Electron. Engineering Eng.Ergonomics Ergonom. Evolutionary Evol. Foundation Found. Geoscience Geosci. Graphics Graph. Industrial Ind. Industry Ind. Information Inform. Institute Inst. Intelligence Intell. International Int. Journal J. Letter(s) Lett. Machine Mach. Magazine Mag. Management Manage. Managing Manag. Mathematic(s) Math. Philosophical Philosph. Proceedings Proc. Processing Process. Production Prod. Productivity Productiv. Quarterly Quart. Record Rec. Reliability Rel. Report Rep. Royal Roy. Science Sci. Selected Select. Society Soc. Sociological Sociol. Statistics Stat. Studies Stud. Supplement Suppl. Symposium Symp. Systems Syst. Technical Tech.Telecommunication Telecommun.Transactions Trans. Vehicular Veh. Working Work.Econ. Economic(s) Education Educ. Mathematical Math.Mechanical Mech. National Nat. Newsletter Newslett.Nuclear Nucl. Occupation Occupat. month is not available, the number may referencing a patent. References may not combine references. There must be only w h en citing IEEE Transactions, if the Reference numbers are set flush left and form a column of the reference.。

Hall技术治疗乳磨牙龋齿的临床研究

Hall技术治疗乳磨牙龋齿的临床研究摘要:目的:评价乳磨牙龋病治疗中使用Hall技术的临床效果。

方法:选取在2022年1月~2023年2月于我院需行乳磨牙龋齿修复治疗的患儿83例,共133颗患牙,随机数字表法分为传统预成冠治疗组66颗,Hall技术治疗组67颗,随访6个月、12个月、18个月,观察远期临床疗效。

结果:6、12及18个月后Hall技术治疗组成功率为98.51%、98.51%和94.03%,传统预成冠治疗组成功率均为98.48%,两组比较差异无统计学意(P>0.05);Hall技术治疗组时间短于传统预成冠治疗组,家属满意度评分高于传统预成冠治疗组,差异均有统计学意(P<0.05)结论:Hall技术既具有无创特点又具有冠修复优势,缩短治疗时间,提高患者满意度,可以临床运用于乳磨牙龋齿治疗。

关键词:乳磨牙,Hall技术,预成冠乳磨牙龋损是儿童口腔牙病中最常见疾病之一。

传统的树脂充填技术已经逐渐被金属预成冠修复技术所取代,金属预成冠修复技术是局麻下去除腐质后充填后预成冠修复或者直接传统金属预成冠修复[1]。

2006年,苏格兰牙医NornaHall首次提到了Hall技术,Hall技术是基于金属预成冠技术提出的无须局麻、去腐及任何牙体预备,直接将冠用玻璃离子粘固到龋损的乳磨牙上,从而达到控制龋损的发展、保留乳磨牙的治疗方法。

本研究通过临床随机对照,比较Hall技术和普通金属预成冠技术治疗乳磨牙龋齿的效果。

现报告如下。

1一般资料1.1一般资料和方法选取2022年1月~2023年2月于我院需行乳磨牙龋齿修复治疗的患儿83例,男45人,女38人,共133颗患牙,上乳磨牙65颗,下乳磨牙68颗,随机数字表法分为传统预成冠治疗组66颗,Hall技术治疗组67颗,年龄范围4-9岁,平均年龄(7.10±2.89)岁。

本研究获得伦理委员会批准,且患儿及其家属均签署知情同意书。

电话回访并预约患儿及家属来我院进行复查。

风痛宁片中麻黄碱含量测定及其影响因素分析开题报告

2.1 对照品溶液制备 精密称取 105℃干燥至恒重的盐酸麻黄碱适量, 置量瓶中, 加水溶解稀释 至刻度,摇匀,即得。 2.2 供试品溶液制备 取风痛宁片适量,精密称定,研细,置蒸馏瓶中,加 20﹪氢氧化钠液适 量,水蒸汽蒸馏。收集馏出液,加水稀释至刻度,摇匀,即可。 2.3 波长选择 取对照品 0.8mL 溶液, 加水 4.2mL 及供试品溶液 5mL, 分别加入碳酸钠试 液 1mL,过碘酸钠试液 2mL,摇匀。放置 10min,分别精密加入正己烷 20mL。 振荡 30s,静置 10min 使分层。分取正己烷层,即得对照品和供试品测定液。 在 200-400nm 波长范围内进行光谱扫描。 2.4 含量测定 精密量取对照品溶液和供试品溶液适量,按 2.3 项下操作,在 242nm 波 长处测得麻黄碱的含量。按外标一点法计算风痛宁片中麻黄碱的含量。 2.5 稳定性试验

1

参考文献: [1] 柯长江,马辉明.紫外分光法测定半夏露口含片中麻黄碱的测定[J].药物分析 杂志,1999,19(1):47-54. [2] 姚新标,张文文.盐酸麻黄碱稳定性试验[J].新疆中医药,2005,23(2):10-11. [3] 莫明兴,费寿耆.紫外分光光度法测定麻黄素洗必泰滴鼻液的含量[J].海峡药 学,2002,14(1):42-52. [4] 李俐,陈坚.麻黄及其有效成分研究进展[J].新疆医科大学学报 2003,26(6): 6 06-608. [5] 李计萍.中药新药稳定性研究的现状及思考[J].江西中医学院学报,2004,6 (5):25-28. [6] 李继珩,王鲁燕,李平.铜离子络合法测定盐酸麻黄素含量[J].中国药科大学 学报,2000,3(4):27-31. [7] 陈叶琴.紫外分光光度法测定咳嗽合剂 I 中盐酸麻黄碱的含量[J].江苏药学与 临床研究,2004,12(2):18-19. [8] 陈桂新,李凤祥,曹顺林, 陈文成.息喘灵片中盐酸麻黄碱的含量测定[J].滨州 医学院学报,1999,22(2):97-101. [9] Jesper Hallas, Lars Bjerrum, Henrik Stvring, and e of a Scribed Ephedrine/Caffeine Combination and the Risk of Serious ardiovascular Events: A Registry-based Case-Crossover Study. 2008, 168(8): 123-154. [10] Guoyi Ma, Supriya A.Bavadekar, Yolande M.Davis, Shilpa lchandani, Phar macological Effects of Ephedrine Alkaloids on Human 1-and 2-Adrenergic Rece ptor Subtypes. 2007, 322(1): 214-221. [11] 廖昌军,杨拯.紫外分光光度法测定盐酸麻黄碱滴鼻液的含量[J].成都医学 院院报,2006,1(2):126-128. [12] 宋金英.哮灵片中盐酸麻黄碱的含量测定[J].长春中医药大学学报报, 2007, 12(6):66-67. [13] J.K.Dunnick, G.Kissling, D.K.Gerken, et al. Cardiotoxicity of Ma Huang/Caffein e or Ephedrine/Caffeine in a Rodent Model System. 2007, 35(5): 206-208.

四级硬度 缔造性福

四级硬度 缔造性福 1-4

1. Mulhall J, et al. J Sex Med. 2007;4(2):448-464. 2. King R, et al. Int J Impot Res. 2011;23(4):135-141. 3. Jünemann KP, et al. J Sex Med. 2006;3(suppl 3): 252. (full version) 4. Mulhall JP, et al. Urology. 2006;68(Suppl 3A):17-25.

本研究入选979名ED患者,进行长达4年的开放性研究,给予患者灵活剂量西地那非(25mg、50mg或 100mg)按需服用,并于每年末评估对勃起的治疗效果感到满意的ED患者比例。

McMurray JG, et al. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(6):975-981.

总结

4

*

4.2次

每月达到第4级勃起硬度 的次数

3

2

1

0.7次

0 安慰剂(n=205)

西地那非50mg(n=105)

这是一项为期24周的随机、双盲、安慰剂对照研究,532名ED患者接受西地那非(25mg、50mg 或100mg)或安慰剂治疗,观察勃起硬度的改善。

Goldstein I, et al. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(20):1397-1404.

3810100605121620所有治疗相关的不良事件头痛消化不良鼻炎潮红収生率05治疗相关不良事件本研究入选979名ed患者进行长达4年的开放性研究给予患者灵活剂量西地那非25mg50mg或100mg按需服用幵亍每年末评估对勃起的治疗效果感到满意的ed患者比例

铁离子对迟缓爱德华氏菌生物膜形成和基质组成的影响-湖南

铁离子对迟缓爱德华氏菌生物膜形成和基质组成的影响-湖南湖南省大学生研究性学习和创新性实验计划项目申报表项目名称: 铁离子对迟缓爱德华氏菌生物膜形成和基质组成的影响学校名称湖南农业大学学生姓名学号专业性别入学年份钟为铭201440566114 水族科学男2014级钟浪201440566118 水族科学男2014级叶涛201440566113 水族科学男2014级王雅琳201440566111 水族科学男2014级陈康勇201440566135 水族科学男2014级指导教师高志鹏职称讲师项目所属一级学科水产学学生曾经参与科研的情况参与学生均无参与科研的经历。

指导教师承担科研课题情况1、国家自然基金面上项目,鲶爱德华氏菌Ⅲ型与Ⅵ型分泌系统致病的分子机制研究,2010-2012,参与。

2、国家自然基金面上项目,鲶爱德华氏菌多拷贝质粒pEI1和pEI2编码的毒力蛋白的分子致病机理研究,2012-2015,参与。

-2-项目研究和实验的目的、内容和要解决的主要问题一、目的和意义迟缓爱德华氏菌作为重要的鱼类病原菌,其致病性与生物膜形成密切相关,而Fe3+又与细菌生物膜的形成、结构和基质组成密切相关。

因此,本研究拟通过结晶紫染色、CLSM、SEM和FilmTracer™ LIVE/DEAD® kit染色等方法,研究Fe3+在迟缓爱德华氏菌生物膜形成、结构和生物膜内细菌生存能力等方面的作用;通过利用聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳(SDS-PAGE)技术和SYPRO® Ruby 染色、FITC-ConA染色和DDAO染色等方法分别研究Fe3+对迟缓爱德华氏菌生物膜基质中蛋白质、多糖和胞外DNA的分布和形成的影响。

最终阐明Fe3+在迟缓爱德华氏菌生物膜形成中的作用机理,迟缓爱德华氏菌与耶尔森氏菌和沙门氏菌等人类病原菌同属于肠杆菌科,研究Fe3+在迟缓爱德华氏菌生物膜形成中的作用机理,可为人类主要肠道病原菌的相关研究提供重要的理论依据。

心理学学术论文:结构方程建模中的题目打包策略

心理学学术论文:结构方程建模中的题目打包策略吴艳/温忠麟 【内容提要】结构方程建模中题目打包法的优缺点包括:指标数据质量变好、模型拟合程度提高;估计偏差不大,可校正;估计稳定,但降低了敏感性与可证伪性。

打包法的前提条件是单维、同质,适合结构模型分析,不适合测量模型分析。

对于单维测验,给出了一个打包流程。

对于通常的多个子量表(多维结构)测验,推荐在子量表内打包,每个子量表打包成1个指标或者3个指标,用于结构方程建模。

【关键词】潜变量/结构方程/题目打包/题目小组 1、前言结构方程建模,对样本容量有一定的要求。

有建议说样本容量应当是题目(指标)数量的10倍以上,或者是自由参数的5倍以上(侯杰泰,温忠麟,成子娟,2004 )。

可见,题目越多,所需样本容量越大。

题目数量很多时,要估计的参数也多,若样本容量少,直接用原始题目建模容易产生较大的参数估计偏倚。

Bandalo s(2002)的模拟研究显示,在单维、样本容量为100,严重非正态的情况下,直接使用原始题目建模可产生高达29.5%的参数估计偏倚。

题目打包法(item parceling,也译为题目组合法或题目小组法)是解决此类问题的一种有效方法( Landis, Beal, & Tesluk, 2000)。

题目打包法是将同一量表的两个或以上题目打包成一个新指标,用合成分数(总分或均值)作为新指标的分数进行分析(Kishton& Widaman, 1994; Yang, Nay, & Hoyle, 2010)。

例如,一个量表原来有9个题目,可将每3个题目作为一个题目小组计算合成分数(小组内题目数也可以不相等),形成3个新指标,打包法直接用3个新指标进行分析(Little,Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002; Rogers &。

2.2打包法偏差不大、可校正应用研究者关心的一个重要问题是,使用打包法与直接使用原始题目相比,参数估计是否会产生偏差呢?Yuan,Bentler和Kano(1997)的研究显示,当题目在总体中单维、同质时,使用打包法与直接使用原始题目相比,结构参数估计不变(也见Sass& Smith, 2006)。

APA格式参考文献示例

APA格式参考文献示例期刊文章1.一位作者写的文章Hu, L. X. [胡莲香]. (2014). 走向大数据知识服务: 大数据时代图书馆服务模式创新. 农业图书情报学刊(2): 173-177.Olsher, D. (2014). Semantically-based priors and nuanced knowledge core for Big Data, Social AI, and language understanding. Neural Networks, 58, 131-147.2.两位作者写的文章Li, J. Z., & Liu, X. M. [李建中, 刘显敏]. (2013). 大数据的一个重要方面: 数据可用性. 计算机研究与发展(6): 1147-1162.Mendel, J. M., & Korjani, M. M. (2014). On establishing nonlinear combinations of variables from small to big data for use in later processing. Information Sciences, 280, 98-110.3. 三位及以上的作者写的文章Weichselbraun, A. et al. (2014). Enriching semantic knowledge bases for opinion mining in big data applications. Knowledge-Based Systems, 69, 78-85.Zhang, P. et al. [张鹏等]. (2013). 云计算环境下适于工作流的数据布局方法. 计算机研究与发展(3): 636-647.专著1.一位作者写的书籍Rossi, P. H. (1989). Down and out in America: The origins of homelessness. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Wang, B. B. [王彬彬]. (2002).文坛三户:金庸·王朔·余秋雨——当代三大文学论争辨析. 郑州: 大象出版社.2.两位作者写的书籍Plant, R., & Hoover, K. (2014). Conservative capitalism in Britain and the United States: A critical appraisal. London: Routledge.Yin, D., & Shang, H. [隐地, 尚海]. (2001).到绿光咖啡屋听巴赫读余秋雨. 上海: 上海世界图书出版公司.3. 三位作者写的书籍Chen, W. Z. et al. [陈维政等]. (2006).人力资源管理. 大连: 大连理工大学出版社. Hall, S. et al. (1991). Culture, media, language: Working papers in cultural studies, 1972-79 (Cultural studies Birmingham ). London: Routledge.4. 新版书Kail, R. (1990). Memory development in children (3rd ed.). New York: Freeman.编著1. 一位主编编撰的书籍Loshin, D. (Ed.). (2013a). Big data analytics. Boston: Morgan Kaufmann.Zhong, L. F. [钟兰凤] (编). (2014). 英文科技学术话语研究. 镇江: 江苏大学出版社.2. 两位主编编撰的书籍Hyland, K., & Diani, G. (Eds.). (2009). Academic evaluation: Review genres in university settings. London: Palgrave Macmillan.Zhang, D. L., & Zhang, G. [张德禄, 张国] (编). (2011). 英语文体学教程. 北京: 高等教育出版社.3. 三位及以上主编编撰的书籍Zhang, K. D. et al. [张克定等] (编). (2007). 系统评价功能. 北京: 高等教育出版社.Campbell, C. M. et al. (Eds.). (2003). Groups St Andrews 2001 in Oxford: Volume 2.New York: Cambridge University Press.4.书中的文章De la Rosa Algarín, A., & Demurjian, S. A. (2014). An approach to facilitate security assurance for information sharing and exchange in big-data applications. In B.Akhgar & H. R. Arabnia (Eds.), Emerging trends in ICT security(pp. 65-83).Boston: Morgan Kaufmann.He, J. M., & Yu, J. P. [何建敏, 于建平]. (2007). 学术论文引言部分的经验功能分析.张克定等. (编). 系统功能评价(pp. 93-101). 北京: 高等教育出版社.翻译的书籍Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays(C. Emerson & M.Holquist, Trans.). Austin: University of Texas Press.Le, D. L. [勒代雷]. (2001).释意学派口笔译理论(刘和平译). 北京: 中国对外翻译出版公司.Kontra, M. et al. (2014).语言: 权利和资源(李君, 满文静译). 北京: 外语教学与研究出版社.Wang, R. D., & Yu, Q. Y. [王仁定, 余秋雨]. (2001).吴越之间——余秋雨眼里的中国文化(彩图本)(梁实秋, 董乐天译). 上海: 上海文化出版社.硕博士论文Huan, C. P. (2015). Journalistic stance in Chinese and Australian hard news.Unpublished doctorial dissertation, Macquarie University, Sydney.Wang, X. Z. [王璇子]. (2014). 功能对等视角下的英语长句翻译.南京大学硕士学位论文.注:1.APA格式参考文献中的文章标题、书籍名称,冒号后第一个单词,括号里第一个单词和专有名词的首字母大写,其余单词首字母均小写。

有创足背动脉压与无创肱动脉压测量的对比研究

有创足背动脉压与无创肱动脉压测量的对比研究上官云芳段思源姚颖【摘要】目的探讨当有创收缩压(ABP)处于不同范围时无创收缩压(NIBP)与ABP 的关系。

方法选取我院2012年6月~2013年5月期间入院即将进行消化道肿瘤手术的患者50例,选用右侧肱动脉测量NIBP,选用足背动脉测量ABP。

所有患者均于静吸复合麻醉下进行手术,记录所有患者足背动脉穿刺诱导后1分钟(T1)、气管插管瞬间(T2)、插管后2分钟(T3)、手术切皮时(T4)各个时间点上的NIBP和相应的ABP,选取111mmHg为临界值,对ABP不同范围内不同时点ABP与NIBP之间的差异进行比较。

结果(1)当ABP<111mmHg 时,仅在插管后2分钟时ABP值大于NIBP,且差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);而在诱导后1分钟(T1)、气管插管瞬间(T2)和手术切皮时(T4)ABP与NIBP 之间的差异没有统计学差异(P>0.05)。

(2)当ABP≥111mmHg时,各个时间点上的ABP值均大于NIBP值,且差异均有统计学差异(P<0.0001);结论当消化道肿瘤手术患者足背ABP高于111 mmHg时,ABP高于NIBP,而当ABP低于111 mmHg时,ABP并不低于NIBP。

【关键词】消化道肿瘤手术;有创动脉血压;无创动脉血压;足背动脉Comparison of arterial blood pressure and non-invasive blood pressureShangguan yun-fang,Duan si-yuan, Yao yin[Abstract] Objective To investigate the relationship between NIBP and ABP when ABP in different range. Methods A self-control study was conducted among 50 cases of patients prepared to accept gastrointestinal tumor operation from June 2012 to May 2013. The blood pressure of brachial artery was measured as NIBP and the blood pressure of dorsalis pedis artery were measured as ABP simultaneously. All patients received under inhalation anesthesia during surgery, NIBP and ABP were recorded after one minute induction (T1), tracheal intubation moment (T2), two minutes after intubation(T3) and the skin incision moment(T4). Systolic pressure of 111mmHg was selected as cut-off point, differences between ABP and NIBP at various time points were compared. Results When ABP<111mmHg, ABP is higher than NIBP (P<0.05)at T2 time point, while no statistical difference between ABP and NIBP appears at other time points. When ABP≥111mmHg, ABP is higher than NIBP at each time points (P<0.0001). Conclusion ABP is higher than NIBP when ABP ≥110mmHg, while ABI is not lower than NIBP when ABP < 110mmHg among gastrointestinal tumor operation patients.Key words Gastrointestinal tumor operation, Arterial Blood Pressure, Non-Invasive Blood Pressure, Dorsalis Pedis Artery血压是反映人体循环系统机能的重要指标,也是临床上用于监测患者生命体征的重要参数之一。

纳米银颗粒在不同溶液中的聚集动力学

纳米银颗粒在不同溶液中的聚集动力学张强【摘要】采用Tollens还原反应用柠檬酸钠做分散剂制备了纳米银粒子(AgNP).利用透视电子显微镜(TEM)及动态光散射法(DLS)对纳米银的形貌、粒径分布及在不同盐溶液中的平均粒径进行了表征;同时采用TR-DLS技术对纳米银在不同自然水体中的聚集动力学进行了研究.结果表明:以柠檬酸钠为分散剂的纳米银主要呈球形,平均粒径为30 nm;实验表明,纳米银在海水中的聚集速率最快,在地下水中次之,在地表淡水中聚集速率最小.本研究对纳米银在环境水体中的环境危害评估有重要的借鉴意义.【期刊名称】《广州化工》【年(卷),期】2013(041)017【总页数】3页(P78-79,82)【关键词】纳米银;Tollens法;聚集动力学;聚集速率【作者】张强【作者单位】济南化工厂,山东济南250001【正文语种】中文【中图分类】O614.122统计数据表明,近些年,纳米银粒子(AgNP)被广泛应用于抗菌材料领域[1-9]。

纳米银材料已经占纳米材料市场总份额的23%以上[8]。

目前研究表明,制备AgNP的方法有化学还原法、生物法、及物理法等。

其中,化学还原法被广泛应用于科学研究及工业化生产等领域。

在化学还原法中,Tollens法因其简单的合成步骤及其环境友好性被广泛使用。

常用的纳米银稳定剂包含十二烷基硫酸钠(SDS)、吐温80(Tween-80),聚乙烯吡咯烷酮等作为分散剂常为Tollens法采用[10-11]。

本研究采用柠檬酸盐作为分散剂,柠檬酸盐的还原性有助于Tollens反应的进行,且其具有便宜易得及良好的生物降解性等优点。

作为有效的抗菌纳米材料,释放到环境中的纳米银的毒性与其物理化学性质如表面电荷与颗粒大小直接相关[10-15],因此,研究纳米银颗粒的聚集动力学对其颗粒粒径的预测有重要意义。

虽然已有大量文献研究了纳米银在不同电解质中的聚集速率,但是,对于纳米银在不同自然水体中的聚集动力学的研究报道却一直很少。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。