MIT-SCIENCE-Lectures-william_julius_wilson

MIT-SCIENCE-Lectures-fa01lec08 (2)

24.00: Problems of PhilosophyProf. Sally HaslangerOctober 15, 2001Personal Identity IThere are several questions that might arise concerning personal identity. When we ask "Who am I?" we might be wondering about what "makes us tick", what we ultimately value, what matters to us. We might also be asking what sort of being we are, what our possibilities are, under what conditions "I" would continue to exist. We'll begin our discussion of personal identity with the latter set of questions.Consider a parallel set of questions:(Id) Under what conditions are baseball-events events in the same game? E.g., under what conditions are aparticular batter batting and a particular runner running parts of the same game?Break (I) into two questions. First, the question of synchronic identity:(SI) Under what conditions are simultaneous baseball-events events in the same game?Let a baseball "stage" consist of all the events at a given time that are part of a single game. Then we can formulate the question of diachronic identity as follows:(DI) Under what conditions are two baseball stages stages in the same game? E.g., what makes the beginning of the third inning and the end of the eighth inning stages of the very same baseball game?Restate the questions for persons:Synchronic identity: under what conditions are two simultaneous person-events events in the life of the same person? Diachronic identity: under what conditions are two person-stages stages in the life of a single person. In particular, what makes a particular person-stage a continuation of me as I am right now?Synchronic unity relation: the relation that unites simultaneous person-events into a stage of a single person.Diachronic unity relation: the relation that unites person-stages into a single temporally-extended person.Perry Dialogue, First Night:1. (Weirob) Is survival of death possible?ï What we want is survival of me (not the molecules of my body...).ï What survives must do justice to possibility of anticipation and memory.2. (Miller) Postulation of soul.Soul criterion: x is the same person as y iff x and y have the same soul.ï What is a soul? The subject of consciousness? A spiritual/disembodied self? The ghost in the machine?3. (Weirob) Practical applicability condition on adequate response:ï An adequate account of the survival/identity of persons must also be able to justify our practices of recognizing and identifying each other.4. (Weirob) The soul not a good basis for recognition.ï We can recognize each othersí bodies, but not each othersí souls.5. (Miller) Body-soul correlations provide a basis for recognition.ï We do observe the soul indirectly by observing the behavior of each others' bodies.6. (Weirob) But how do you know that there is a body-soul correlation? By observation?ï Chocolate example shows that correlation between body and soul untestable; if not testable, it must just be a matter of faith.7. (Miller) Personality-Soul correlations provide a basis for body-soul correlations.ï If the soul is the subject of mental states, the soul must be what explains the pattern of mental states, i.e., it must be what provides us with our personality or character. So there must be a correlation between soul and personality.8. (Weirob) But even if soul does account for personality, thereís no reason that one must have the same soul to exhibit the same personality.ï We can't infer from sameness/similarity of personality to sameness/similarity of soul.ï River analogy: rivers have the same appearance even though the water molecules are constantly changing; better example: Martians/God/mad scientist could make a duplicate of you with the same personality, but without the same soul. ï [Also, don't people sometimes undergo changes in their personality, e.g., after a conversion, a tragic experience, falling in love, etc.?]9. (Miller) But maybe the relevant correlations must be established by 1st person observations.ï I know of myself that there is a body-personality-soul correlation.10. (Weirob) But how do you know that even in your own case?ï All that you introspect is thoughts and feelings, but isnít this compatible with a sequence of souls passing through? How do you know that God doesnít give your body a new soul each morning? How would you tell if when you woke up there was a new soul responsible for your thoughts, or just the old one?11. (Weirob) Does the postulation of soul really help? Doesnít it push the question back?ï E.g., suppose I say that a flower blooming in my garden is the same one that was blooming yesterday; someone asks: on what basis do you say that? I say that it has the same flower-spirit as the previous one. Doesnít the question arise: what are the identity conditions for flower spirits? What does it take for a flower-spirit to continue to exist?12. Gretchenís bodily solution:ï Do I doubt my own soul? Not in the sense of doubting that Iím conscious. But my consciousness is a property of a body, and that body is me. But if I am my body, then the destruction of my body is the destruction of me. So:Body criterion: x is the same person as y iff x and y have the same living human body.In other words:Person-stage x is part of the same person as person-stage y iff x and y are person stages linked by bodily continuity (where bodily continuity is understood in terms of the continuity of a living human body).。

MIT-SCIENCE-Lectures-essay

Prof. SmithGUIDELINES FOR PREPARING A SCHOLARLY ESSAYDue date: April 14First, the choice of topic is up to you. The subject may be a biography of a famous inventor (e.g. Thomas Edison, Elmer Sperry, Edwin Land, John Bardeen, et al.), an influential engineer or system builder (e.g. Vannevar Bush), the development of an important invention, improved design, and/or innovation (e.g. the DC-3 airplane, the laser, industrial research lab), the development of a technological system (e.g. telephony, electric power, telegraphy, the “American system of manufacturing”), a medical advance (e.g. penicillin, the artificial heart), or it can be about broader subjects like depiction of technology in art, literature, and/or modern advertising, technology and the advent of “consumer society” . . . and so on.Whatever topic you choose, remember that you are expected to address it from three angles of vision and analysis: the technical “nuts and bolts” aspect of the subject (technology as knowledge, if you will), the subject’s impact on society (technology as social force), and how the subject reflected the society, politics, and culture in which it emerged and/or existed (technology as social product).Second, once you have decided on a subject, you must clear it either with Professor Smith or Shane Hamilton. If you have trouble identifying a topic, Professor Smith and Shane Hamilton are willing to help you do so.Third, the paper you write should be a footnoted scholarly essay. The text should be 1112 pages long, double-spaced. Like the book review, it should be an example of your best work. Remember to proof-read and correct your paper before handing it in. The paper should go through at least three drafts before you give it to us. Doing so will save a lot of extra work later on.If you need help with writing the paper, remember that Jessica Weintraub is available for consultation.Fourth, the paper will be graded on four levels: content, organization, insight/perception, and writing style. Each student will receive two grades, one for the first submission; a second for the revised submission.Fifth, source materials. Whatever topic you select, you must consult at least four source materials beyond the required textbooks for this class. In other words, some basic research is required before you write the paper. Books, articles from scholarly journals, newspaper and magazine articles are acceptable sources. The use of primarymanuscript/archival sources is encouraged but not required. Encyclopedias like the World Book do not count, nor will special websites unless they are discussed first and approved by Professor Smith or Shane Hamilton. Your use of source materials will be taken into account by the instructors and will comprise part of the grade assigned for the “content” portion of the essay. You are strongly encouraged to consult with Shane Hamilton about finding good sources. Oftentimes the best materials are tucked away in publications that are very hard to find. Shane is ready and willing to help you with your search.Finally, footnoting. The purpose of a footnote is to indicate to the reader where you acquired the information you are using. You don’t have to footnote everything. However, direct quotations must always be footnoted. So should important pieces of information that are critical to your argument, as should anything you believe the reader might want to know more about upon reading your essay. In other words, footnotes should be used to document your essay and to point the reader to the sources you are using in case s/he wants to check your facts and/or consult them for further information. Some example footnotes follow.Example FootnotesBooksBook by a Single Author, First Edition:1. Donald N. McCloskey, Enterprise and Trade in Victorian Britain:Essays in Historical Economics (London: George Allen and Unwin,1981), 54.Book by a Single Author, Later Edition:2. Donald N. McCloskey, The Applied Theory of Price, 2nd ed. (NewYork: Macmillan, 1985), 24.Book by Two or Three Authors:3. Donald A. Lloyd and Harry R. Warfel, American English and ItsCultural Setting (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1956), 12.[If there is a third author, follow this example: James Smith, Donald Marc,and Jack Jones.]Book by More than Three Authors:4. Martin Greenberger et al., eds., Networks for Research and Education:Sharing of Computer and Information Resources Nationwide(Cambridge: MIT Press, 1974), 50.Book by an Unknown Author:5. College Bound Seniors (Princeton: College Board Publications, 1979),1.Book with Both an Author and an Editor or Translator:6. Helmut Thielicke, Man in God's World, trans. and ed. John W.Doberstein (New York: Harper and Row, 1963), 12.An Anthology:7. Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, ed. E. de Selincourt and H.Darbishire, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952), 10.Chapter in an Edited Collection:8. Ernest Kaiser, "The Literature of Harlem," in Harlem: A Community inTransition, ed. J. H. Clarke (New York: Citadel Press, 1964), 64.Reprinted Book:9. Gunnar Myrdal, Population: A Problem for Democracy (Cambridge:Harvard University Press, 1940; reprint, Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith,1956), 9.ArticlesArticle in a Journal:10. Louise M. Rosenblatt, "The Transactional Theory: AgainstDualisms," College English 54 (1993): 380.Book Review:11. Steven Spitzer, review of The Limits of Law Enforcement, by HansZeisel, American Journal of Sociology 91 (1985): 727.Newspaper Article:12. Tyler Marshall, "200th Birthday of Grimms Celebrated," Los AngelesTimes, 15 March 1985, sec. 1A, p. 3.["p." is used to make clear the difference between the page and sectionnumbers.]OtherGovernment Document:13. Congressional Record, 71st Cong., 2nd sess., 1930, 72, pt.10:10828:30.Unpublished Material (Dissertation or Thesis):14. James E. Hoard, "On the Foundations of Phonological Theory" (Ph.D.diss., University of Washington, 1967), 119.Interview by Writer of Research Paper:15. Charles M. Vest, interview by author, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1December 1992.For more examples see:Kate L. Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).Dewey Library - Reference Collection | LB2369.T929 1996Humanities Library - Reference Collection | LB2369.T929 1996Humanities Library - Ready Reference Collection | LB2369.T929 1996Rotch Library - Reserve Stacks | LB2369.T929 1996Science Library - Reference Collection | LB2369.T929 1996。

MIT天才发明“第六感”

身通信测试 的应用范围, 而扩展到如嵌入式 系

统 测 试 和一 般 软 件测 试 等 新 的领 域 。此 次大 会 的 目的是 联 合 全 球 在 软 件 测 试 、通 信 系 统 测 试 、嵌 入式 系统 测试 等 领 域 的从 业 者 、开 发 商

欧洲电信标准协会(uoenT l o muia E rpa ee m nc— c

t n tnad si t简 称 E S ) 建 于 18 年 , i s a drs ntue o S I t T I创 98

是独立的非赢利性的欧洲地 区性信息和通信技术

Sn s r a gt 对他们采集的流量 和 D R A e A P 传统 的9/9 89 离线测试数据进行了对 比, 指

量数据存在以下 问题 :过时 、 使用 了模拟 、 不能代表今 天的攻击技术 ,而 C X竞赛采 D

用 真 实 的 网络 拓 扑 ,红 蓝 两 队 都 是 真 实 人

势以及现实物体。软件则分析 由摄像头视频流的

数据 并 追踪 用 户彩 色 的指 尖 ( 准点 )这 些 基准 基 。 点 的 移 动 和排列 会 被 翻译 成 手势 ,为 被投 影 的应 用 程 序充 当接 口交 互指 示 。追 踪手 指 的最 大数 目 只 受 被 基 准 点 的 数 量 的 限 制 。 因 此 ,第 六 感

界就 是一 个 硬 盘 。

第六感(ihes ) S t ne 是一种便携式 xS

实验工具

P y f s d I vau ton a o Ba e DS E l a i

手势界面,可以增加我们所处的现实

MIT-SCIENCE-Lectures-fa01lec04 (2)

24.00: Problems of PhilosophyProf. Sally HaslangerSeptember 26, 2001Evidentialism v. Pragmatism1. The "Wager" and the Practical Rationality PrinciplePractical Rationality Principle: The practically rational thing to do is the thing with the highest expected value (or "utility").Version A: Do the thing with higher expected value than all its competitors.--In the case of a tie, neither action/belief is permitted.Version B: Find the actions with highest expected value and perform whichever of them you like.--In the case of a tie, Theism is practically rational. (Just like choosing pie over cake.)2. Evidentialism (Clifford)"It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence" (p. 124)First objection: Problem is not with evidence, but with falsity of beliefs.Clifford's response: There is an all-important difference between the beliefs we are entitled to hold and those we arenít. The beliefs we are entitled to hold are the ones supported by the evidence, i.e., the supported beliefs. Nothing else is relevant..Second objection: Clifford's examples all involve beliefs that matter, i.e., ones that have consequences for the welfare of others. This suggests that maybe what's wrong is holding unsupported beliefs that can reasonably be expected to cause harm. What about harmless beliefs?Note distinction between actions that are intrinsically wrong, and ones that are instrumentally wrong. Instrumental wrongs are not wrong in themselves, but only insofar as they cause harm. If unsupported belief is intrinsically wrong, then it would be clear that it is always wrong. But if only instrumentally wrong, then it would seem that there are all sorts of cases in which no bad consequences could reasonably be expected. In fact, there seem to be cases in which unsupported beliefs are instrumentally good, i.e., they have good or positive consequences.You'd expect Clifford, given his uncompromising position, would not be happy simply with the idea that the wrong of unsupported belief is merely instrumental. And he does sometimes suggest otherwise. But he has no argument for the intrinsic wrongness of unsupported belief. Instead he puts together a questionable argument that unsupported belief always has bad consequences, and so is always instrumentally wrong.But forasmuch as no belief held by one man, however seemingly trivial the belief, and however obscure thebeliever, is ever actually insignificant or without its effects on the fate of mankind, we have no choice but toextend our judgement to all cases of belief whatever. (123)His argument seems to be (roughly):1) All beliefs influence action in some way or another.2) Actions based on unjustified beliefs either cause harm directly, or they promote credulity which results in broad social ills.3) Therefore it is always wrong to hold unjustified beliefs.Both premise (1) and (2) seem questionable. Here are three questions for you to think about:ï Is it really plausible that all unsupported beliefs, i.e., beliefs based on weak evidence, have, or may be expected to have, bad consequences?ï Is it possible to have a belief that has no effect whatsoever on action?ï Is it ever wrong in itself to believe without sufficient evidence? Could it always be wrong in itself to believe without sufficient evidence?3. Pragmatism (James)There are many different kinds of circumstances in which we are faced with the decision about what to believe. James offers a view about when unsupported belief is permitted. Options:living v. dead: living "make an electric connection with your nature"forced v. avoidable: forced leave no other alternativesmomentous v. trivial: momentous have big stakes and the chance is uniquegenuine: living, forced, momentousPragmatism: Faced with a genuine choice about what to believe, and where evidence does not decide the matter, we are free to decide it however we want.As James puts it, "our passional nature not only lawfully may, but must, decide an option between propositions, whenever it is a genuine option that cannot by its nature be decided on intellectual grounds." (129)4. James's response to CliffordHow does Clifford know that Evidentialism is true? Argument for it is unconvincing.James' suggestion: Clifford is not convinced of evidentialism by evidence, but rather a feeling--Quite simply, Clifford is afraid. Of what? Of making a mistake, of falling into error. His demand that we believe only what is based on the evidence is based on no more than his "preponderant private horror of becoming a dupe"(129).Won't Clifford have a response: that we should avoid error is not my own private obsession--isn't it a real and objective danger? James replies: Reading Clifford one might think that only evidentialists are concerned with truth. But:There are two ways of looking at our duty in the matter of opinion: we must know the truth and we must avoid error. These are our first and great commandments as would-be knowers; but there are not two ways of stating an identical commandment, they are two separable laws. (129)So, James concludes, we must be guided by two principles: (i) KNOW TRUTH, (ii) AVOID ERROR. We need both, otherwise we should believe everything, or nothing. On James's view, the evidentialist is one who ignores one commandment in obsessive pursuit of the other. So, in the end, James maintains that evidentialism is based simply on afeeling, not on evidence.How might we turn this into an argument against Clifford? Consider the idea of a self-defeating claim. It is best captured by examples: Never say "never". No one can construct a grammatical English sentence. I don't exist. [Written:] I am illiterate. One's claim is self-defeating if something in the act of making the claim contradicts the message being put forward. Try:1) Clifford's belief in evidentialism is based not on evidence but on passion.2) Evidentialism forbids beliefs not based on evidence.3) Therefore, Evidentialism forbids Clifford's belief in evidentialism.This doesn't show Evidentialism is wrong, just that Clifford is inconsistent. (Maybe it is true, but lacking evidence, he shouldn't believe it.)Can we develop this into an argument that evidentialism is wrong? One could use the self-defeat argument if one could show that any commitment (not just Clifford's) to evidentialism must be based in passion, i.e., that any absolute commitment to the commandment avoid error, would have to be passional. But this isn't promising.5. Other arguments for Pragmatism?Remember, James not saying that we can believe anything we like. There are special contexts where passion is permitted. Examples: friendship, love, faith.The desire for a certain kind of truth here brings about that special truthís existence...And where faith in a fact can help create the fact, that would be an insane logic which would say that faith running ahead of evidence is[wrong]. (131)Consider religious faith:One who would shut himself up in snarling logicality and try to make the gods extort his recognition willy-nilly or not get it at all, might cut himself off forever from his only opportunity of making the godsí acquaintance. (132) St. Augustine:How can you believe if you don't know? Answer: I believe in order that I may know.Possible Pragmatist principle: "A rule of thinking which would absolutely prevent me from acknowledging certain kinds of truth if those kinds of truth were really there, would be an irrational rule." (132)So, (1) By following evidentialism, we are completely shut off from certain kinds of truth.(2) A rule which completely shuts us off from certain kinds of truth is wrong.(3) So evidentialism is wrong. (1,2)Is (2), our "possible pragmatist principle", plausible? Problem: We should accept rules that shut us off from some kinds of truths--e.g., we should accept rules that shut us off from beliefs about exactly how many dinosaurs there were. We want to limit belief in cases where evidence is not forthcoming or where only guesswork is possible; So (2) seems like it too strong. Yet, we wouldn't want a rule that blocked us from all belief about the past, or about distant places, or about otherpeople, etc. So (2) may be on the right track, but it needs to be refined to get at what James is looking for. (Exercise: can you refine it?)However, note that where Clifford's view is self-defeating (assuming we don't have conclusive evidence for it), James's is self-endorsing. The decision between evidentialism and pragmatism seems to be genuine, and so we are entitled, by pragmatism to endorse whichever we want; so James's pragmatism entitles him to endorse pragmatism, but does not require it.RECAP:Mackie: Theism is irrational (because belief in God is inconsistent with the recognition of evil).Pascal: Theism is (pragmatically) rationally required (because the EV of theism swamps the alternatives).Clifford: Theism is not warranted by the Wager (because belief must be based on sufficient evidence).James: Theism is rationally permissible but not required (because it is a genuine option).。

MIT-SCIENCE-Lectures-fa01lec06 (2)

24.00: Problems of PhilosophyProf. Sally HaslangerOctober 3, 2001RacismsI. Racist PropositionsAppiah distinguishes three importantly different ideas relevant to race and racism:Racialism:...there are heritable characteristics, possessed by members of our species, that allow us to divide them into a small set of races, in such a way that all the members of these races share certain traits and tendencies with each other that they do not share with members of any other race. These traits and tendencies characteristic of a raceconstitute, on the racialist view, a sort of racial essence; and it is part of the content of racialism that the essential heritable characteristics...account for more than the visible morphological characteristicsskin color, hair type,facial featureson the basis of which we make our informal classifications. (5)In other words: A racialist is one who maintains that people who appear similar on the basis of certain inherited physical characteristics (such as skin color, hair type, facial features) share a distinctive "racial essence" that is responsible for a range of psychological and behavioral traits and tendencies.ï Appiah argues (elsewhere) that racialism is false: There is no "racial essence" (genetic or otherwise) underlying the morphological features shared by members of what we count as races that is responsible for (supposed) similarities in traits and tendencies among members of racial groups. In other words, even if there are what we might call superficial races,i.e., groups of people who share certain inherited visible features, there are no racial kinds, i.e., groups unified by sharing a racial essence.ï A consequence of Appiah's denial of racialism is that if there are any psychological/behavioral similarities ("common traits and tendencies") among members of "superficial races", this is due either to historical/cultural/social causes, or it is due to contingent natural correlations, e.g., it might be that the members of genetically isolated groups are similar in many ways, both visibly and psychologically, but in such cases one cannot assume that there is an underlying "nature" or "essence" that explains all the similarities. The correlation of visible and psychological features may be accidental, or due to contextual features, and may break down immediately when the group disperses or when the group's genetic isolation ends.ï Appiah maintains that racialists are wrong in the sense that the hold a false or incorrect view, but because racialism makes no moral or evaluative claims (it doesn't say anything about what's good or bad, what we ought to do or not do), there is nothing wrong morally speaking in being a racialist. As he puts it, racialism "seems to be a cognitive rather than a moral problem." (5)Extrinsic racism:...extrinsic racists make moral distinctions between members of different races because they believe that the racial essence entails certain morally relevant qualities. The basis for the extrinsic racists' discrimination between people is their belief that members of different races differ in respects that warrant the differential treatment,respectssuch as honesty or courage or intelligencethat are uncontroversially held...to be acceptable as a basis fortreating people differently. (5)In other words: An extrinsic racist maintains that people of racial group X tend to have the property P, and P is a morally objectionable property (such as dishonesty, laziness, irrationality, etc.) So we are warranted in treating people of racial group X differently (i.e., worse) than others (for at least some apparent racial group X).Intrinsic racism:intrinsic racists..are people who differentiate morally between members of different races because they believe that each race has a different moral status, quite independent of the moral characteristics entailed by its racialessence....an intrinsic racist holds that the bare fact of being the same race is a reason for preferring one person to another. (5-6)In other words: An intrinsic racists maintains that people of racial group X are inherently morally inferior (for at least some apparent racial group X).ï Appiah points out, however, that it would be "odd" to call someone a "racist" if they just happened to be ignorant of all the facts. E.g., someone brought up in a remote location might have only false information about X's and so come to hold what look like racist beliefs; but if in the face of new (and better) evidence she easily corrects her beliefs, then even if she holds some racist beliefs, there is a sense in which she is not a racist.ï So, he suggests, racism is not just a matter of what you believe, but how you believe it: does your belief rest on the evidence you have available to you (or could easily get), or are you unable or unwilling to take advantage of the available evidence? Those who exhibit a pattern in their inadequate attention to the evidence have a "cognitive incapacity"on Appiah's view this is a form of irrationality--and this "cognitive incapacity" is the source of their racism. They exhibit "distortions of judgement" (8) possibly due to self-interest, self-deception, internalized racist stereotypes, etc.II. Racial PrejudiceGiven these observations, Appiah defines "racial prejudice" as follows:Racial prejudice consists in "the deformation of rationality in judgment [viz., their systematic "incapacity" to collect and assess evidence responsibly] that characterizes those whose racism is more than a theoretical attachment to certain propositions about race." (8) On this view, racial prejudice is a kind of cognitive flaw. For those who are ignorant and hold racist propositions because they have not been exposed to all the evidence, there is hope that more information will lead them to see the error in their views. But those who suffer from racial prejudice need more than information; they need to learn skills of critical reflection that enable them to see through the distortions of ideology and self-interest. (9-10)III. Racism and MoralityAppiah suggests that racism is symptomatic of a kind of irrationality. In the case of extrinsic racists, it consists in a failure to be responsive to evidence concerning the (supposedly inferior) racial group in question, e.g., to evidence whether they really have the questionable property P, and to reasoning concerning the link between generalizations about the group and moral judgements.In the case of intrinsic racists, however, the racism does not lie in the incorrect attribution of certain observable properties to members of a group (it is not like miscalculating whether Whites can jump, or whether Blacks "have rhythm"); the attribution in question concerns moral worth. The intrinsic racist asserts that some groups have greater moral worth than others (or that some individuals, because of their race alone, are more worthy of my regard or loyalty, etc.). Is the intrinsicracist's failing, if it is a failing, a cognitive error? Is it a failure of rationality? Or is it, as Appiah sometimes suggests, (also?) a kind of moral failure?Appiah suggests that the intrinsic racist exhibits a kind of distorted rationality insofar as he under the influence of an ideology that serves the dominant group (8) and uses the racist beliefs "as a basis for inflicting harm" (10). Sometimes intrinsic racism is not used as a basis for harm and is not connected to the power of the dominant group, in which case it is not clearly racism, and not clearly irrational. For example, racially subordinate groups sometimes build solidarity with each otherAppiah mentions Zionists and Black Nationalistsby maintaining that race, in and of itself, is morally significant. Although one might argue that at least some members of these groups use race as a basis for inflicting harm, the relevant question is whether it is ever permissible to hold views that are intrinsically racist. Appiah suggests that it is. Do you agree? Are intrinsic racist beliefs less problematic for some groups than others?But the "distorted rationality" Appiah is trying to point out in the case of intrinsic racists is nothing like a failure to appreciate evidence. Ultimately Appiah's argument is that intrinsic racists misunderstand the nature of public morality. It may be that we are allowed to form special attachments to others, attachments that are based on arbitrary likes and dislikes, in the private domain, e.g., of family. But these special attachments are not allowed to influence us in contexts where morality is at stake. It may be OK to give a birthday gift to your mother and not your professor; but it is not OK to keep your promise to your mother and not to your professor. You must keep all your promises. What the intrinsic racist fails to understand is that from the moral point of view, race is not a legitimate basis for making distinctions between individuals. So the intrinsic racist, on Appiah's view, doesn't simply exhibit a cognitive failure, but also a moral failure.Questions:ï On what basis does Appiah claim that race is not morally relevant? He suggests that it to deny this is to go "against the mainstream of the history of Western moral philosophy" (14). But does he have an argument for it? Does he have evidence for it? How could one go about arguing that race is not morally relevant?ï Could an intrinsic racist charge that Appiah's reliance on the idea that race is morally irrelevant is itself a bit of ideology, i.e., that it is the articulation of a particular "practical consciousness" found in the West? Does saying this show that the idea is false or distorted or problematic?IV. Return to PragmatismIs Pragmatism a good guide to what is epistemically justified? Is it a good guide to what is practically justified? Consider first epistemic justification, using this instance of the Pragmatist principle:Faced with a genuine choice about whether or not to believe extrinsic racism, where there is no compellingevidence in favor of either extrinsic racism or not, we are "free" to decide whether or not to believe extrinsicracism.When is there "no compelling evidence" to settle the matter?(a) when I lack compelling evidence?(b) when no one has found compelling evidence (so far)?(c) when there is, in principle, no compelling evidence?If (a) or (b), then it would seem that the lack of compelling evidence may be due to systematic distortion (my irrationality, or the ideological influences in society that prevent evidence from being properly collected and evaluated). But if systematic distortion is a plausible hypothesis, shouldn't we say that we should withhold belief, and that belief either way is not rationally permissible? However, if we strengthen the Pragmatist principle to require that we withhold belief until all possible evidence is collected (so going for (c)), then we would miss out on many of the advantages James mentions (e.g.,in love) and it isn't clear how far Pragmatism offers an improvement over Evidentialism. Thus it seems that Pragmatism is not a good guide to what's rationally permissible, understood as a matter of epistemic rationality, i.e., how we should proceed in our search for knowledge.Consider pragmatic justification using a different instance of the principle:Faced with a genuine choice (at time t) about whether or not to believe intrinsic racism, where there is nocompelling evidence (at t) in favor of either intrinsic racism or not, we are "free" to decide whether or not tobelieve intrinsic racism.According to Appiah, intrinsic racism is not refutable by (scientific) evidence (8). On his view, however, it is a distorted ideology that can be used to support injustice. If it is sometimes a genuine choice whether to accept intrinsic racism, and if there is no compelling evidence one way or the othereven in principlethen it would seem that according to Pragmatism it is rationally permissible to accept intrinsic racism. But to continue with Appiah, one who endorses this sort of intrinsic racism can be charged with a deep moral failing. Appiah suggests this is not a "cognitive incapacity", but a "moral error"(12). If the intrinsic racist holds the racist beliefs "unthinkingly" then it is unclear that we have a case of autonomous rational behavior at all (see Appiah, 9). Alternatively, if the intrinsic racist is autonomous in this choice of belief (and harmful action based on it), then we should say that Pragmatism allows that morally reprehensible beliefs (and the actions they justify?) are rationally permitted. Is this enough to show that Pragmatism is not a good guide to what's rationally permissible, understood as a matter of practical rationality, i.e., of how we should proceed in our efforts to act rationally?Question: Is there some way to understand or modify Pragmatism to avoid these conclusions?Summary: The phenomena of wishful thinking, ideological distortion, irrational adherence to unfounded beliefs, all call into question our ability to determine if and when we have come to a point when we can be confident there is no evidence to settle the matter and that we're permitted to just choose what to believe. Even if we do reach such a point, we must be aware that our choice of what to believe may have problematic moral consequences. So Pragmatism is not without problems. All things considered is Evidentialism the better choice? Are there further alternatives to these two approaches?。

MIT-SCIENCE-Lectures-f02handout2

Handout #2Parfit's Reasons and Persons (1st of 4)Reading (for the next few weeks): Perry's Dialogue and all of part III of Reasons and Persons, giving special attention to sections 75-80, 87-97.Identity is the relation everything bears to itself, and itself only; it's the relation symbolized by `=' in '2+2=4' or 'Superman = Clark Kent'. Our topic in the first third of the course is often called "personal identity," and we will use that term too. But the term is misleading. Really we shall be enquiring into the nature of things like ourselves: persons. One way of conducting this enquiry is to ask what sorts of changes we can undergo and survive; "personal persistence" then might be a better name.Questions of persistence, it turns out, are conveniently formulated in terms of identity. What sorts of changes can a person A undergo such that after those changes, there is a person B such that A=B? What does it take for person B to be A's future self? What does it take for a person B existing at time t2 to be identical to A existing at time t1?Qualitative identity:(i) I would not be the same person if I had grown up in Mongolia;(ii) Mary Kate and Ashley are exactly the same. Our topic is numerical identity. The two are connected byLeibniz's Law: x = y iff: for all properties P, x is P iff y is P.['iff' is an abreviation for 'if and only if'.] Is this true? How if so can the girl be identical to the woman?Parfit's argument can be split into two parts. First, an argument for the sorts of things we are. Second, an argument that draws various startling consequences about "what matters" from the conclusion of the first argument. This week and next week we will concentrate on the first part.A criterion of personal identity is an informative and necessarily true completion of:Person A who exists at time t1 = person B who exists at t2 (t1 < t2) if and onlyif_____________Likewise for other things. A criterion of set identity is: set A = set B iff A has the same members as B. Notice that this tells you something about the nature of sets.An example from John LockeMass of matter m1 which exists at t1 = mass of matter m2 which exists at t2 iff the atoms that compose m1 at t1 are the same atoms as those that compose m2 at t2.Locke noted that a criterion like this cannot be given for animals or vegetables (why?). What about artefacts?The Cartesian criterionPerson A who exists at t1 = Person B who exists at t2 iff A's (immaterial!) soul at t1 = B's soul at t2If we make the assumption that immaterial souls can survive any sort of psychological change the Cartesian criterion becomes what Parfit calls the Featureless Cartesian view. The Bodily criterionPerson A who exists at t1 = person B who exists at t2 iff A's body at t1 = B's body at t2. The Brain criterionPerson A who exists at t1 = person B who exists at t2 iff A's brain at t1 = B's brain at t2.。

MIT-SCIENCE-Lectures-2004b_l_fore_5

21w.777 BOOKS FOR BOOK REVIEW ASSIGNMENT (Essay 5)Marcia Bartusiak. Einstein’s Unfinished Symphony: Listening to the Sounds of Space-Time.Science Library - Stacks | QC173.59.S65.B39 2000 249 p.Won the 2001 American Institute of Physics Science Writing Award.“A new generation of observatories, now being completed worldwide, will give astronomers not just a new window on the cosmos but a whole new sense with which to explore and experience the heavens aboveus. . . . These vibrations in space-time--or gravity waves--are the last prediction of Einstein's generaltheory of relativity yet to be observed directly. They are his unfinished symphony, waiting nearly a centuryto be heard . . .”Greene, Brian. The elegant universe. Approx. 400 p. Science Library – Stacks QC794.6.S85.G75 1999. A well received discussion of superstring theory.Evelyn Fox Keller. The Century of the Gene. Humanities Library - Stacks | QH428.K448 2000Makes an argument about how the concept of the gene has shaped research in recent decades andsuggests limits of that concept.Stephen Hall. Invisible Frontiers: the race to synthesize a human gene. 334 p.Humanities Library - Stacks | TP248.6.H35 1987“From the spring of 1976 to the fall of 1978, three laboratories competed in a feverish race to clone ahuman gene for the first time, a feat that ultimately produced the world's first genetically engineered drug--the life-sustaining hormone insulin. Invisible Frontiers gives us a behind-the-scenes look at the threemain groups at Harvard University, the University of California-San Francisco, and a team of upstartscientists at Genentech, the first company devoted to the use of genetic engineering in the creation of pharmaceuticals.”James Watson. The double helix: a personal account of the discovery of the structure of DNA approx. 300 p.Science Library - Stacks | Q143.W339.A3 1981& other locationsA classic, this book is available in a Norton Critical edition, which includes reviews and a bibliography.Richard Dawkins. The selfish gene352 p.Science Library - Stacks | QH437.D38 1989“A genetics classic.” “Dawkins shows that the selfish gene is also the subtle gene. And he holds out thehope that our species - alone on earth - has the power to rebel against the designs of the selfish gene.This book is a call to arms.”Edward O. Wilson. The future of Life.229 p. Humanities Library - Stacks | QH75.W535 2002Author of Sociobiology and The Ants; honorary curator at Harvard MuseumNatalie Angier. Woman: an intimate geography. 398 p. Humanities Library – Women’s Studies Reading Room. QP38.A54 1999. “ Written with whimsy and eloquence, [Angier’s] investigation intofemale physiology draws its inspiration not only from scientific and medical sources but also frommythology, history, art, and literature, layering biological factoids with her own personal encounters andarcane anecdotes from the history of science.” (from a review)Roger Lewin. Bones of Contention: controversies in the search for human origins348p. Humanities Library - Stacks | GN281.L487 1987“a behind-the-scenes look at the search for human origins. Analyzing how the biases and preconceptionsof paleoanthropologists shaped their work, Roger Lewin's detective stories about the discovery ofNeanderthal Man, the Taung Child, Lucy, and other major fossils provide insight into this most subjectiveof scientific endeavors. The new afterword looks at ways in which paleoanthropology, while becomingmore scientific in many ways, remains contentious.”Clifford Stoll. Silicon snake oil: second thoughts on the information highway249 p.Humanities Library - Stacks | QA76.9.C66.S88 1996“the first book that intelligently questions where the Internet is leading us. Stoll looks at our network as itis, not as it's promised to be.”Gleick, James. Isaac Newton. 272 p.Humanities Library - Stacks | QC16.N7.G55 2003Well-received biography of the great scientist.Contents: 1. What imployment is he fit for -- 2. Some philosophical questions -- 3. To resolve problems by motion -- 4. Two great orbs -- 5. Bodys & senses --6. The oddest if not the most considerable detection --7. Reluctancy and rection -8. In the midst of a whirlwind --9. All things are corruptible -- 10. Heresy, blasphemy, idolatry -- 11. First principles --12. Every body perseveres -- 13. Is he like other men -- 14. No man is a witness in his own cause -- 15.The marble index of a mind.Kanigel, Robert. The man who knew infinity: A life of the genius Ramanujan. approx. 400 p. Humanities Library – Stacks; and Science Library – Stacks. QA29.R3.K36 1991 Biography of the Indian mathematician Ramanujan (1887-1920), who was “discovered” by the English mathematician G.H. Hardy and came to England to study. Considered one of the finest books ever written about mathematics.Barry Mazur. Imagining Numbers (Particularly the square root of minus fifteen). 288 p. "A clear, accessible, beautifully written introduction not only to imaginary numbers, but to the role of imagination in mathematics." (from a review). (Not in MIT library)Atul Gawande. Complications: a surgeon's notes on an imperfect science269 p.Humanities Library - Stacks | RD27.35.G39.A3 2002Gawande wrote up his experiences and observations as a young surgeon in training in a series ofarticles, some of which originally appeared in the New Yorker. He is especially compelling on the way surgeons respond to and learn from errors.Simon Winchester. The Map that Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth ofModern Geology. 329 p. Humanities Library - Stacks | QE22.S6.W55 2001“the fascinating story of William Smith, a 19th-century engineer who became the father of moderngeology by discovering the various fossil layers under the earth and creating the world's first map of the various strata. Before he could receive any such acclaim, however, he was forced to overcome alandslide of adversity . . .”Stephen Jay Gould. Time's arrow, time's cycle : myth and metaphor in the discovery of geological time. 222 p. Humanities Library - Stacks | QE508.G68 1987“In [this book], Gould has turned to the history of geology, a field very close to his main concerns as a paleontologist. He offers a revisionist historical account of the discovery of geological time.”John McPhee. Basin and range215 p.Humanities Library - Stacks | QE79.M28 1981Geology of the American West, by a great writer.Thomas Kuhn. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.Science Library - Stacks | Q175.I612 v.2 no.2 1970 & Dewey & HumanitiesA seminal work whose influence is everywhere visible today; changed the way we look at scientific discovery, emphasizing the importance of cultural context and introducing the concept of the paradigminto everyday speech.Henry Petroski. Invention by Design: How Engineers Get from Thought to Thing. 242 p. Dewey Library - Stacks | TA174.P4735 1996“case studies of engineers who, by dint of ingenuity and persistence, have created important newstructures or devices. Whether designing something as small as a pencil or as large as the World Trade Center, successful engineers must not only devise new technology but also find a way to situate that technology within the existing economic, social, and ecological order.”---.Remaking the World: Adventures in Engineering. 256 p. [n.i.B.]A collection of magazine essays. “Petroski dismantles the image of the engineer as an analyticalautomaton . . . as less important than the pure scientist.” Pieces cover such topics as the Panama Canal,the Ferris Wheel, and the Hoover Dam.Krogh, David. Smoking: The Artificial Passion. [not catalogued in Barton]。

物理学专业英语

华中师范大学物理学院物理学专业英语仅供内部学习参考!2014一、课程的任务和教学目的通过学习《物理学专业英语》,学生将掌握物理学领域使用频率较高的专业词汇和表达方法,进而具备基本的阅读理解物理学专业文献的能力。

通过分析《物理学专业英语》课程教材中的范文,学生还将从英语角度理解物理学中个学科的研究内容和主要思想,提高学生的专业英语能力和了解物理学研究前沿的能力。

培养专业英语阅读能力,了解科技英语的特点,提高专业外语的阅读质量和阅读速度;掌握一定量的本专业英文词汇,基本达到能够独立完成一般性本专业外文资料的阅读;达到一定的笔译水平。

要求译文通顺、准确和专业化。

要求译文通顺、准确和专业化。

二、课程内容课程内容包括以下章节:物理学、经典力学、热力学、电磁学、光学、原子物理、统计力学、量子力学和狭义相对论三、基本要求1.充分利用课内时间保证充足的阅读量(约1200~1500词/学时),要求正确理解原文。

2.泛读适量课外相关英文读物,要求基本理解原文主要内容。

3.掌握基本专业词汇(不少于200词)。

4.应具有流利阅读、翻译及赏析专业英语文献,并能简单地进行写作的能力。

四、参考书目录1 Physics 物理学 (1)Introduction to physics (1)Classical and modern physics (2)Research fields (4)V ocabulary (7)2 Classical mechanics 经典力学 (10)Introduction (10)Description of classical mechanics (10)Momentum and collisions (14)Angular momentum (15)V ocabulary (16)3 Thermodynamics 热力学 (18)Introduction (18)Laws of thermodynamics (21)System models (22)Thermodynamic processes (27)Scope of thermodynamics (29)V ocabulary (30)4 Electromagnetism 电磁学 (33)Introduction (33)Electrostatics (33)Magnetostatics (35)Electromagnetic induction (40)V ocabulary (43)5 Optics 光学 (45)Introduction (45)Geometrical optics (45)Physical optics (47)Polarization (50)V ocabulary (51)6 Atomic physics 原子物理 (52)Introduction (52)Electronic configuration (52)Excitation and ionization (56)V ocabulary (59)7 Statistical mechanics 统计力学 (60)Overview (60)Fundamentals (60)Statistical ensembles (63)V ocabulary (65)8 Quantum mechanics 量子力学 (67)Introduction (67)Mathematical formulations (68)Quantization (71)Wave-particle duality (72)Quantum entanglement (75)V ocabulary (77)9 Special relativity 狭义相对论 (79)Introduction (79)Relativity of simultaneity (80)Lorentz transformations (80)Time dilation and length contraction (81)Mass-energy equivalence (82)Relativistic energy-momentum relation (86)V ocabulary (89)正文标记说明:蓝色Arial字体(例如energy):已知的专业词汇蓝色Arial字体加下划线(例如electromagnetism):新学的专业词汇黑色Times New Roman字体加下划线(例如postulate):新学的普通词汇1 Physics 物理学1 Physics 物理学Introduction to physicsPhysics is a part of natural philosophy and a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through space and time, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic disciplines, perhaps the oldest through its inclusion of astronomy. Over the last two millennia, physics was a part of natural philosophy along with chemistry, certain branches of mathematics, and biology, but during the Scientific Revolution in the 17th century, the natural sciences emerged as unique research programs in their own right. Physics intersects with many interdisciplinary areas of research, such as biophysics and quantum chemistry,and the boundaries of physics are not rigidly defined. New ideas in physics often explain the fundamental mechanisms of other sciences, while opening new avenues of research in areas such as mathematics and philosophy.Physics also makes significant contributions through advances in new technologies that arise from theoretical breakthroughs. For example, advances in the understanding of electromagnetism or nuclear physics led directly to the development of new products which have dramatically transformed modern-day society, such as television, computers, domestic appliances, and nuclear weapons; advances in thermodynamics led to the development of industrialization; and advances in mechanics inspired the development of calculus.Core theoriesThough physics deals with a wide variety of systems, certain theories are used by all physicists. Each of these theories were experimentally tested numerous times and found correct as an approximation of nature (within a certain domain of validity).For instance, the theory of classical mechanics accurately describes the motion of objects, provided they are much larger than atoms and moving at much less than the speed of light. These theories continue to be areas of active research, and a remarkable aspect of classical mechanics known as chaos was discovered in the 20th century, three centuries after the original formulation of classical mechanics by Isaac Newton (1642–1727) 【艾萨克·牛顿】.University PhysicsThese central theories are important tools for research into more specialized topics, and any physicist, regardless of his or her specialization, is expected to be literate in them. These include classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics and statistical mechanics, electromagnetism, and special relativity.Classical and modern physicsClassical mechanicsClassical physics includes the traditional branches and topics that were recognized and well-developed before the beginning of the 20th century—classical mechanics, acoustics, optics, thermodynamics, and electromagnetism.Classical mechanics is concerned with bodies acted on by forces and bodies in motion and may be divided into statics (study of the forces on a body or bodies at rest), kinematics (study of motion without regard to its causes), and dynamics (study of motion and the forces that affect it); mechanics may also be divided into solid mechanics and fluid mechanics (known together as continuum mechanics), the latter including such branches as hydrostatics, hydrodynamics, aerodynamics, and pneumatics.Acoustics is the study of how sound is produced, controlled, transmitted and received. Important modern branches of acoustics include ultrasonics, the study of sound waves of very high frequency beyond the range of human hearing; bioacoustics the physics of animal calls and hearing, and electroacoustics, the manipulation of audible sound waves using electronics.Optics, the study of light, is concerned not only with visible light but also with infrared and ultraviolet radiation, which exhibit all of the phenomena of visible light except visibility, e.g., reflection, refraction, interference, diffraction, dispersion, and polarization of light.Heat is a form of energy, the internal energy possessed by the particles of which a substance is composed; thermodynamics deals with the relationships between heat and other forms of energy.Electricity and magnetism have been studied as a single branch of physics since the intimate connection between them was discovered in the early 19th century; an electric current gives rise to a magnetic field and a changing magnetic field induces an electric current. Electrostatics deals with electric charges at rest, electrodynamics with moving charges, and magnetostatics with magnetic poles at rest.Modern PhysicsClassical physics is generally concerned with matter and energy on the normal scale of1 Physics 物理学observation, while much of modern physics is concerned with the behavior of matter and energy under extreme conditions or on the very large or very small scale.For example, atomic and nuclear physics studies matter on the smallest scale at which chemical elements can be identified.The physics of elementary particles is on an even smaller scale, as it is concerned with the most basic units of matter; this branch of physics is also known as high-energy physics because of the extremely high energies necessary to produce many types of particles in large particle accelerators. On this scale, ordinary, commonsense notions of space, time, matter, and energy are no longer valid.The two chief theories of modern physics present a different picture of the concepts of space, time, and matter from that presented by classical physics.Quantum theory is concerned with the discrete, rather than continuous, nature of many phenomena at the atomic and subatomic level, and with the complementary aspects of particles and waves in the description of such phenomena.The theory of relativity is concerned with the description of phenomena that take place in a frame of reference that is in motion with respect to an observer; the special theory of relativity is concerned with relative uniform motion in a straight line and the general theory of relativity with accelerated motion and its connection with gravitation.Both quantum theory and the theory of relativity find applications in all areas of modern physics.Difference between classical and modern physicsWhile physics aims to discover universal laws, its theories lie in explicit domains of applicability. Loosely speaking, the laws of classical physics accurately describe systems whose important length scales are greater than the atomic scale and whose motions are much slower than the speed of light. Outside of this domain, observations do not match their predictions.Albert Einstein【阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦】contributed the framework of special relativity, which replaced notions of absolute time and space with space-time and allowed an accurate description of systems whose components have speeds approaching the speed of light.Max Planck【普朗克】, Erwin Schrödinger【薛定谔】, and others introduced quantum mechanics, a probabilistic notion of particles and interactions that allowed an accurate description of atomic and subatomic scales.Later, quantum field theory unified quantum mechanics and special relativity.General relativity allowed for a dynamical, curved space-time, with which highly massiveUniversity Physicssystems and the large-scale structure of the universe can be well-described. General relativity has not yet been unified with the other fundamental descriptions; several candidate theories of quantum gravity are being developed.Research fieldsContemporary research in physics can be broadly divided into condensed matter physics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; particle physics; astrophysics; geophysics and biophysics. Some physics departments also support research in Physics education.Since the 20th century, the individual fields of physics have become increasingly specialized, and today most physicists work in a single field for their entire careers. "Universalists" such as Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and Lev Landau (1908–1968)【列夫·朗道】, who worked in multiple fields of physics, are now very rare.Condensed matter physicsCondensed matter physics is the field of physics that deals with the macroscopic physical properties of matter. In particular, it is concerned with the "condensed" phases that appear whenever the number of particles in a system is extremely large and the interactions between them are strong.The most familiar examples of condensed phases are solids and liquids, which arise from the bonding by way of the electromagnetic force between atoms. More exotic condensed phases include the super-fluid and the Bose–Einstein condensate found in certain atomic systems at very low temperature, the superconducting phase exhibited by conduction electrons in certain materials,and the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases of spins on atomic lattices.Condensed matter physics is by far the largest field of contemporary physics.Historically, condensed matter physics grew out of solid-state physics, which is now considered one of its main subfields. The term condensed matter physics was apparently coined by Philip Anderson when he renamed his research group—previously solid-state theory—in 1967. In 1978, the Division of Solid State Physics of the American Physical Society was renamed as the Division of Condensed Matter Physics.Condensed matter physics has a large overlap with chemistry, materials science, nanotechnology and engineering.Atomic, molecular and optical physicsAtomic, molecular, and optical physics (AMO) is the study of matter–matter and light–matter interactions on the scale of single atoms and molecules.1 Physics 物理学The three areas are grouped together because of their interrelationships, the similarity of methods used, and the commonality of the energy scales that are relevant. All three areas include both classical, semi-classical and quantum treatments; they can treat their subject from a microscopic view (in contrast to a macroscopic view).Atomic physics studies the electron shells of atoms. Current research focuses on activities in quantum control, cooling and trapping of atoms and ions, low-temperature collision dynamics and the effects of electron correlation on structure and dynamics. Atomic physics is influenced by the nucleus (see, e.g., hyperfine splitting), but intra-nuclear phenomena such as fission and fusion are considered part of high-energy physics.Molecular physics focuses on multi-atomic structures and their internal and external interactions with matter and light.Optical physics is distinct from optics in that it tends to focus not on the control of classical light fields by macroscopic objects, but on the fundamental properties of optical fields and their interactions with matter in the microscopic realm.High-energy physics (particle physics) and nuclear physicsParticle physics is the study of the elementary constituents of matter and energy, and the interactions between them.In addition, particle physicists design and develop the high energy accelerators,detectors, and computer programs necessary for this research. The field is also called "high-energy physics" because many elementary particles do not occur naturally, but are created only during high-energy collisions of other particles.Currently, the interactions of elementary particles and fields are described by the Standard Model.●The model accounts for the 12 known particles of matter (quarks and leptons) thatinteract via the strong, weak, and electromagnetic fundamental forces.●Dynamics are described in terms of matter particles exchanging gauge bosons (gluons,W and Z bosons, and photons, respectively).●The Standard Model also predicts a particle known as the Higgs boson. In July 2012CERN, the European laboratory for particle physics, announced the detection of a particle consistent with the Higgs boson.Nuclear Physics is the field of physics that studies the constituents and interactions of atomic nuclei. The most commonly known applications of nuclear physics are nuclear power generation and nuclear weapons technology, but the research has provided application in many fields, including those in nuclear medicine and magnetic resonance imaging, ion implantation in materials engineering, and radiocarbon dating in geology and archaeology.University PhysicsAstrophysics and Physical CosmologyAstrophysics and astronomy are the application of the theories and methods of physics to the study of stellar structure, stellar evolution, the origin of the solar system, and related problems of cosmology. Because astrophysics is a broad subject, astrophysicists typically apply many disciplines of physics, including mechanics, electromagnetism, statistical mechanics, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, relativity, nuclear and particle physics, and atomic and molecular physics.The discovery by Karl Jansky in 1931 that radio signals were emitted by celestial bodies initiated the science of radio astronomy. Most recently, the frontiers of astronomy have been expanded by space exploration. Perturbations and interference from the earth's atmosphere make space-based observations necessary for infrared, ultraviolet, gamma-ray, and X-ray astronomy.Physical cosmology is the study of the formation and evolution of the universe on its largest scales. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity plays a central role in all modern cosmological theories. In the early 20th century, Hubble's discovery that the universe was expanding, as shown by the Hubble diagram, prompted rival explanations known as the steady state universe and the Big Bang.The Big Bang was confirmed by the success of Big Bang nucleo-synthesis and the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964. The Big Bang model rests on two theoretical pillars: Albert Einstein's general relativity and the cosmological principle (On a sufficiently large scale, the properties of the Universe are the same for all observers). Cosmologists have recently established the ΛCDM model (the standard model of Big Bang cosmology) of the evolution of the universe, which includes cosmic inflation, dark energy and dark matter.Current research frontiersIn condensed matter physics, an important unsolved theoretical problem is that of high-temperature superconductivity. Many condensed matter experiments are aiming to fabricate workable spintronics and quantum computers.In particle physics, the first pieces of experimental evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model have begun to appear. Foremost among these are indications that neutrinos have non-zero mass. These experimental results appear to have solved the long-standing solar neutrino problem, and the physics of massive neutrinos remains an area of active theoretical and experimental research. Particle accelerators have begun probing energy scales in the TeV range, in which experimentalists are hoping to find evidence for the super-symmetric particles, after discovery of the Higgs boson.Theoretical attempts to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity into a single theory1 Physics 物理学of quantum gravity, a program ongoing for over half a century, have not yet been decisively resolved. The current leading candidates are M-theory, superstring theory and loop quantum gravity.Many astronomical and cosmological phenomena have yet to be satisfactorily explained, including the existence of ultra-high energy cosmic rays, the baryon asymmetry, the acceleration of the universe and the anomalous rotation rates of galaxies.Although much progress has been made in high-energy, quantum, and astronomical physics, many everyday phenomena involving complexity, chaos, or turbulence are still poorly understood. Complex problems that seem like they could be solved by a clever application of dynamics and mechanics remain unsolved; examples include the formation of sand-piles, nodes in trickling water, the shape of water droplets, mechanisms of surface tension catastrophes, and self-sorting in shaken heterogeneous collections.These complex phenomena have received growing attention since the 1970s for several reasons, including the availability of modern mathematical methods and computers, which enabled complex systems to be modeled in new ways. Complex physics has become part of increasingly interdisciplinary research, as exemplified by the study of turbulence in aerodynamics and the observation of pattern formation in biological systems.Vocabulary★natural science 自然科学academic disciplines 学科astronomy 天文学in their own right 凭他们本身的实力intersects相交,交叉interdisciplinary交叉学科的,跨学科的★quantum 量子的theoretical breakthroughs 理论突破★electromagnetism 电磁学dramatically显著地★thermodynamics热力学★calculus微积分validity★classical mechanics 经典力学chaos 混沌literate 学者★quantum mechanics量子力学★thermodynamics and statistical mechanics热力学与统计物理★special relativity狭义相对论is concerned with 关注,讨论,考虑acoustics 声学★optics 光学statics静力学at rest 静息kinematics运动学★dynamics动力学ultrasonics超声学manipulation 操作,处理,使用University Physicsinfrared红外ultraviolet紫外radiation辐射reflection 反射refraction 折射★interference 干涉★diffraction 衍射dispersion散射★polarization 极化,偏振internal energy 内能Electricity电性Magnetism 磁性intimate 亲密的induces 诱导,感应scale尺度★elementary particles基本粒子★high-energy physics 高能物理particle accelerators 粒子加速器valid 有效的,正当的★discrete离散的continuous 连续的complementary 互补的★frame of reference 参照系★the special theory of relativity 狭义相对论★general theory of relativity 广义相对论gravitation 重力,万有引力explicit 详细的,清楚的★quantum field theory 量子场论★condensed matter physics凝聚态物理astrophysics天体物理geophysics地球物理Universalist博学多才者★Macroscopic宏观Exotic奇异的★Superconducting 超导Ferromagnetic铁磁质Antiferromagnetic 反铁磁质★Spin自旋Lattice 晶格,点阵,网格★Society社会,学会★microscopic微观的hyperfine splitting超精细分裂fission分裂,裂变fusion熔合,聚变constituents成分,组分accelerators加速器detectors 检测器★quarks夸克lepton 轻子gauge bosons规范玻色子gluons胶子★Higgs boson希格斯玻色子CERN欧洲核子研究中心★Magnetic Resonance Imaging磁共振成像,核磁共振ion implantation 离子注入radiocarbon dating放射性碳年代测定法geology地质学archaeology考古学stellar 恒星cosmology宇宙论celestial bodies 天体Hubble diagram 哈勃图Rival竞争的★Big Bang大爆炸nucleo-synthesis核聚合,核合成pillar支柱cosmological principle宇宙学原理ΛCDM modelΛ-冷暗物质模型cosmic inflation宇宙膨胀1 Physics 物理学fabricate制造,建造spintronics自旋电子元件,自旋电子学★neutrinos 中微子superstring 超弦baryon重子turbulence湍流,扰动,骚动catastrophes突变,灾变,灾难heterogeneous collections异质性集合pattern formation模式形成University Physics2 Classical mechanics 经典力学IntroductionIn physics, classical mechanics is one of the two major sub-fields of mechanics, which is concerned with the set of physical laws describing the motion of bodies under the action of a system of forces. The study of the motion of bodies is an ancient one, making classical mechanics one of the oldest and largest subjects in science, engineering and technology.Classical mechanics describes the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, as well as astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. Besides this, many specializations within the subject deal with gases, liquids, solids, and other specific sub-topics.Classical mechanics provides extremely accurate results as long as the domain of study is restricted to large objects and the speeds involved do not approach the speed of light. When the objects being dealt with become sufficiently small, it becomes necessary to introduce the other major sub-field of mechanics, quantum mechanics, which reconciles the macroscopic laws of physics with the atomic nature of matter and handles the wave–particle duality of atoms and molecules. In the case of high velocity objects approaching the speed of light, classical mechanics is enhanced by special relativity. General relativity unifies special relativity with Newton's law of universal gravitation, allowing physicists to handle gravitation at a deeper level.The initial stage in the development of classical mechanics is often referred to as Newtonian mechanics, and is associated with the physical concepts employed by and the mathematical methods invented by Newton himself, in parallel with Leibniz【莱布尼兹】, and others.Later, more abstract and general methods were developed, leading to reformulations of classical mechanics known as Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics. These advances were largely made in the 18th and 19th centuries, and they extend substantially beyond Newton's work, particularly through their use of analytical mechanics. Ultimately, the mathematics developed for these were central to the creation of quantum mechanics.Description of classical mechanicsThe following introduces the basic concepts of classical mechanics. For simplicity, it often2 Classical mechanics 经典力学models real-world objects as point particles, objects with negligible size. The motion of a point particle is characterized by a small number of parameters: its position, mass, and the forces applied to it.In reality, the kind of objects that classical mechanics can describe always have a non-zero size. (The physics of very small particles, such as the electron, is more accurately described by quantum mechanics). Objects with non-zero size have more complicated behavior than hypothetical point particles, because of the additional degrees of freedom—for example, a baseball can spin while it is moving. However, the results for point particles can be used to study such objects by treating them as composite objects, made up of a large number of interacting point particles. The center of mass of a composite object behaves like a point particle.Classical mechanics uses common-sense notions of how matter and forces exist and interact. It assumes that matter and energy have definite, knowable attributes such as where an object is in space and its speed. It also assumes that objects may be directly influenced only by their immediate surroundings, known as the principle of locality.In quantum mechanics objects may have unknowable position or velocity, or instantaneously interact with other objects at a distance.Position and its derivativesThe position of a point particle is defined with respect to an arbitrary fixed reference point, O, in space, usually accompanied by a coordinate system, with the reference point located at the origin of the coordinate system. It is defined as the vector r from O to the particle.In general, the point particle need not be stationary relative to O, so r is a function of t, the time elapsed since an arbitrary initial time.In pre-Einstein relativity (known as Galilean relativity), time is considered an absolute, i.e., the time interval between any given pair of events is the same for all observers. In addition to relying on absolute time, classical mechanics assumes Euclidean geometry for the structure of space.Velocity and speedThe velocity, or the rate of change of position with time, is defined as the derivative of the position with respect to time. In classical mechanics, velocities are directly additive and subtractive as vector quantities; they must be dealt with using vector analysis.When both objects are moving in the same direction, the difference can be given in terms of speed only by ignoring direction.University PhysicsAccelerationThe acceleration , or rate of change of velocity, is the derivative of the velocity with respect to time (the second derivative of the position with respect to time).Acceleration can arise from a change with time of the magnitude of the velocity or of the direction of the velocity or both . If only the magnitude v of the velocity decreases, this is sometimes referred to as deceleration , but generally any change in the velocity with time, including deceleration, is simply referred to as acceleration.Inertial frames of referenceWhile the position and velocity and acceleration of a particle can be referred to any observer in any state of motion, classical mechanics assumes the existence of a special family of reference frames in terms of which the mechanical laws of nature take a comparatively simple form. These special reference frames are called inertial frames .An inertial frame is such that when an object without any force interactions (an idealized situation) is viewed from it, it appears either to be at rest or in a state of uniform motion in a straight line. This is the fundamental definition of an inertial frame. They are characterized by the requirement that all forces entering the observer's physical laws originate in identifiable sources (charges, gravitational bodies, and so forth).A non-inertial reference frame is one accelerating with respect to an inertial one, and in such a non-inertial frame a particle is subject to acceleration by fictitious forces that enter the equations of motion solely as a result of its accelerated motion, and do not originate in identifiable sources. These fictitious forces are in addition to the real forces recognized in an inertial frame.A key concept of inertial frames is the method for identifying them. For practical purposes, reference frames that are un-accelerated with respect to the distant stars are regarded as good approximations to inertial frames.Forces; Newton's second lawNewton was the first to mathematically express the relationship between force and momentum . Some physicists interpret Newton's second law of motion as a definition of force and mass, while others consider it a fundamental postulate, a law of nature. Either interpretation has the same mathematical consequences, historically known as "Newton's Second Law":a m t v m t p F ===d )(d d dThe quantity m v is called the (canonical ) momentum . The net force on a particle is thus equal to rate of change of momentum of the particle with time.So long as the force acting on a particle is known, Newton's second law is sufficient to。

当代研究生英语 第七单元 B课文翻译

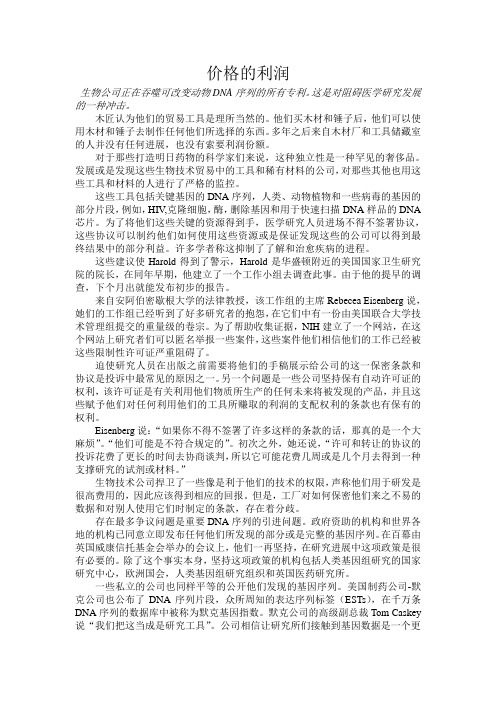

价格的利润生物公司正在吞噬可改变动物DNA序列的所有专利。

这是对阻碍医学研究发展的一种冲击。

木匠认为他们的贸易工具是理所当然的。

他们买木材和锤子后,他们可以使用木材和锤子去制作任何他们所选择的东西。

多年之后来自木材厂和工具储藏室的人并没有任何进展,也没有索要利润份额。

对于那些打造明日药物的科学家们来说,这种独立性是一种罕见的奢侈品。

发展或是发现这些生物技术贸易中的工具和稀有材料的公司,对那些其他也用这些工具和材料的人进行了严格的监控。

这些工具包括关键基因的DNA序列,人类、动物植物和一些病毒的基因的部分片段,例如,HIV,克隆细胞,酶,删除基因和用于快速扫描DNA样品的DNA 芯片。

为了将他们这些关键的资源得到手,医学研究人员进场不得不签署协议,这些协议可以制约他们如何使用这些资源或是保证发现这些的公司可以得到最终结果中的部分利益。

许多学者称这抑制了了解和治愈疾病的进程。

这些建议使Harold得到了警示,Harold是华盛顿附近的美国国家卫生研究院的院长,在同年早期,他建立了一个工作小组去调查此事。

由于他的提早的调查,下个月出就能发布初步的报告。

来自安阿伯密歇根大学的法律教授,该工作组的主席Rebecea Eisenberg说,她们的工作组已经听到了好多研究者的抱怨,在它们中有一份由美国联合大学技术管理组提交的重量级的卷宗。

为了帮助收集证据,NIH建立了一个网站,在这个网站上研究者们可以匿名举报一些案件,这些案件他们相信他们的工作已经被这些限制性许可证严重阻碍了。

迫使研究人员在出版之前需要将他们的手稿展示给公司的这一保密条款和协议是投诉中最常见的原因之一。

另一个问题是一些公司坚持保有自动许可证的权利,该许可证是有关利用他们物质所生产的任何未来将被发现的产品,并且这些赋予他们对任何利用他们的工具所赚取的利润的支配权利的条款也有保有的权利。

Eisenberg说:“如果你不得不签署了许多这样的条款的话,那真的是一个大麻烦”。

MIT-SCIENCE-Lectures-1_introduction