《南洋问题研究》稿件格式要求

academic3

Journal of International Economic Law11(2),263–311doi:10.1093/jiel/jgn010.Advance Access publication26February2008EAST ASIAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS IN SERVICES:KEY ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS Carsten Fink*and Martı´n Molinuevo**ABSTRACTSince the mid-1990s East Asian countries have negotiated25free trade agreements(FTAs)with a services component.There are important archi-tectural differences in these agreements,which ultimately affect their value in promoting transparency,fostering the credibility of trade policies,and advancing market opening in services.This article reviews key architectural choices,focusing on the approach towards scheduling commitments,the treatment of investment and the movement of natural persons,rules of origin,provisions for the settlement of trade dispute,and selected deeper integration issues.In doing so,it assesses the advantages and drawbacks of different architectural approaches and discusses a number of lessons learned. INTRODUCTIONBilateral and regional free trade agreements(FTAs)are proliferating at an unprecedented pace.Most of the recently negotiated agreements are comprehensive in their coverage and extend their market opening ambition to international commerce in services.This trend is powered by underlying economic forces,such as technological progress which has expanded the scope for trading services internationally and increased private sector partici-pation in the provision of infrastructure services considered public mono-polies not too long ago.Have services FTAs actually served those economic forces?In particular, have they led to liberalization undertakings that go beyond those to which countries are committed under the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services(GATS)?Have they established stronger disciplines than the *Senior Economist at the World Bank Institute.E-mail:cfink_de@yahoo.de**Martı´n Molinuevo is a Research Fellow at the World Trade Institute and a Consultant to the World Bank.E-mail:martin.molinuevo@.This article is an output of a research project undertaken by the World Bank’s Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Department for East Asia.The authors are grateful to Rolf Adlung,Nasser Al Zubi,Daniel Crosby,Panos Delimatsis,Felipe Hees,Christoph Ko¨nig,Juan Marchetti,Se´bastien Miroudot,Christian Pauletto,Sebastia´n Sa´ez,Constantinos Stephanou,Carlos Gimeno Verdejo,and Mahani Zainal-Abidin for helpful comments and suggestions.The views expressed in this article are the authors’own and do not necessarily represent those of their respective institutions. Journal of International Economic Law V ol.11No.2ßOxford University Press2008,all rights reserved264Journal of International Economic Law(JIEL)11(2)GATS?Few studies exist to answer these questions.1This article seeks to answer the latter question by offering a review of key architectural elements of East Asian FTAs in services.2In another paper,we assess the liberaliza-tion content of these agreements and their compliance with WTO rules on regional integration.3The East Asia region offers an instructive case study of services FTAs. Figure1shows all25agreements that had been signed as of January2007. Twenty-four of those agreements were negotiated in this decade.Only the ASEAN-Framework Agreement on Trade in Services(AFAS)dates back to the mid-1990s.East Asian FTAs offer a wide variety in architectural approaches,with some being closely modeled on the GATS and others following the structure of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).In fact,the agreements concluded by East Asian countries offer an insightful window into global negotiating trends.The Singapore–US FTA, for instance,serves as a proxy for the FTA model promoted by the US in different regions of the world.Other NAFTA-inspired agreements in East Asia mirror the approaches adopted by many countries in the Western Hemisphere—including Canada,Chile,and Mexico.The region’s GATS-inspired agreements,in turn,show many commonalities with EU FTAs and the Mercosur services accord.Uniquely,a number of East Asian 1For a review some of the key architectural innovations of services FTAs,see OECD,‘The Relationship between Regional Trade Agreements and the Multilateral Trading System: Services’,Working Party of the Trade Committee,OECD document TD/TC/WP(2002)27/ FINAL,2002;and Sauve´Pierre,‘Adding Value at the Periphery:Elements of GATSþRegional Agreements in Services’,Paper prepared for the seminar Eyes Wide Shut?Beyond Market Access in North-South Regional Trade Arrangements,International Development Research Center,Ottawa2005.Stephenson Sherry,‘Examining APEC’s Progress towards Reaching the Bogor Goals for Services Liberalization’,Draft paper prepared for Pacific Economic Cooperation Council,2005.Available online at /content/apec/ documents_reports/committee_trade_investment/2006.html,visited September2006)and Roy et al.,Services Liberalization in the New Generation of Preferential Trade Agreements(PTAs):How Much Further than the GATS?,WTO Staff Working Paper No.ERSD-2006-07(Geneva:World Trade Organization,2006)evaluate the liberalization content of selected bilateral and regional agreements.On the negotiating experiences of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, see Stephenson Sherry(ed.)Services Trade in the W estern Hemisphere:Liberalization,Integration, and Reform.(Washington,DC:Organization of American States and Brookings Institution Press,2000);Sa´ez Sebastia´n,Trade in Services Negotiations:A Review of the Experience of the United States and the European Union in Latin America.SERIE Comercio Internacional,no.76, (Santiago,Chile:United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean,2005);Marconini Mario,Services in Regional Agreements between Latin American and Developed Countries.SERIE Comercio Internacional,no.71(Santiago,Chile:United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean,2006),and Pereira Goncalves et al.,Financial Services and Trade Agreements in Latin America and the Caribbean: an Overview,Policy Research Working Paper No.4181(Washington,DC:The World Bank,2007).2For the purposes of this article,we adopt the World Bank’s classification of East Asia,which encompasses countries in both Eastern Asia and Southeast Asia,as classified by the United Nations.3Fink Carsten and Molinuevo Martı´n,East Asian FTAs in Services:Liberalization Content and WTO rules,Mimeo,2007.East Asian Free Trade Agreements in Services265Figure1.East Asian FTAs with a services component.FTAs—notably the Trans-Pacific EPA and the Australia–Singapore FTA—have combined elements of different models,setting new standards which, in future,may be adopted by countries outside the region.Ultimately,trade agreements seek to promote international commerce. They can do so in three ways:by reducing barriers to foreign participation, by making trade policies more transparent,and by enhancing the credibility of the trade regime—the latter being defined as reducing the risk of policy becoming more restrictive.Architectural choices can make an important difference in this respect.In comparing the different approaches found in East Asia,we specifically seek to evaluate to what extent agreements promote trade along these three dimensions.266Journal of International Economic Law(JIEL)11(2)Due to space constraints,we cannot review all architectural elements of services FTAs,but rather focus on selected key elements that have not been discussed extensively in the previous literature and for which there is significant variation in East Asian agreements.In particular,our review starts with the scheduling approach adopted by FTAs(Section I)—one of the key distinguishing characteristics of trade agreements in services.We then consider the treatment of investment in services(Section II),the treatment of labor mobility(Section III),the rules of origin adopted(Section IV),and provisions for the settlement of trade disputes(Section V).In Section VI, we discuss to what extent East Asian FTAs have gone beyond the GATS on a number of deeper integration issues—notably recognition of professional qualifications,domestic regulation,and trade rules on government procure-ment,subsidies and emergency safeguards.In the conclusion(Section VII), we briefly discuss several lessons learned.I.SCHEDULING APPROACHNo services FTA has established immediate free trade in all service sectors.4 The East Asian FTAs make no exception in this regard.For a variety of reasons,governments wish to exempt certain activities from the coverage of trade disciplines or maintain certain trade-restrictive measures.A critical question in the design of an FTA is how these exemptions and limitations are inscribed into an agreement.As a first step,most FTAs allow for sectoral carve-outs that exempt one or more activities from the scope of the agreement.Activities falling under such an exemption are not subject to any of the disciplines established in the agreement.The most frequently encountered carve-out pertains to air transport.Twenty FTAs exempt core air transport services related to the exercise of air traffic rights.5This exemption is also found in the GATS and is explained by the fact that the provision of these services has historically been negotiated through separate bilateral treaties.Four FTAs also carve out cabotage in maritime transport—a sector in which foreign participation is often deemed sensitive.More significantly,four FTAs fully exempt financial services from the scope of the agreement—an issue to which we will return later.64Throughout the article and unless other terms are employed,we use the term‘FTA’loosely to also include other types of trade agreements that seek the liberalization of trade in services—such as bilateral trade agreements(BTAs)or economic partnership agreements(EPAs). Similarly,we refer to‘countries’in a broad sense,so as to encompass any geographical entity with international personality and capable of conducting an independent foreign economic policy.5However,this exception usually does not apply to aircraft repair and maintenance services,the selling and marketing of air transport services,and computer reservation system services.6In addition to the sectoral carve-outs found in the services chapters of FTAs,investment chapters may also exclude certain activities from the scope of investment disciplines.For example,under the Japan–Mexico EPA,Mexico scheduled a list of activities reserved to theEast Asian Free Trade Agreements in Services267 Five FTAs do not provide for any carve-out of service activities,making all service sectors subject to the agreements’underlying provisions.7However, it does not automatically follow that all sectors are subject to liberalization undertakings.The liberalization content of FTAs is detailed in country-specific market-opening schedules.A variety of approaches exist in drawing up these schedules.Fundamentally,these approaches differ along two dimensions:(i)the listing of service activities subject to liberalization com-mitments and(ii)the listing of levels of openness.Lists can either be drawn up on a positive basis—identifying what is covered or allowed—or on a negative basis—identifying what is not covered or not allowed,though mixed approaches are also possible.T able1indicates the scheduling approaches adopted by the East Asian FTAs.In what follows,we first describe key features of these scheduling approaches.We then compare and assess these approaches,focusing on the three dimensions outlined above:incentives for liberalization,transparency, and credibility.A.Agreements with a positive list of sectorsFifteen East Asian FTAs have adopted a positive list of sectors in which trade commitments are undertaken(T able1).In other words,only the sectors that parties have expressly identified are subject to market opening undertakings. Countries are free to maintain or impose trade-restrictive measures in non-scheduled sectors,although those measures may still be subject to an agree-ment’s general disciplines(such as on transparency).Once a sector is scheduled,the next question is how to set the level of openness in that sector.Interestingly,this question is not relevant for one of the East Asian FTAs—the Lao PDR–US Bilateral Trade Agreement(BTA). Under this agreement,Laos is committed to unrestricted market access and national treatment in listed sectors.8However,the Lao PDR–US BTA should be considered a special case and,indeed,is unparalleled in its ambition.All other trade agreements in services allow parties not to immediately commit to free trade in sectors subject to liberalization undertakings.For the remaining14East Asian FTAs with a positive list of state—including telegraph services,postal services,and electricity distribution—and for which foreign entry may be refused.7Namely,the Lao PDR–US BTA,the Mainland–Hong Kong CEPA,the Mainland–Macao CEPA,the New Zealand–Singapore FTA,and the Vietnam–US BTA.8In principle,the agreement specifies that‘each party’is not allowed to maintain any restriction on market access in the listed sectors and on national treatment.However,the agreement also provides that the obligations of the US are subject to the market access and national treatment limitations scheduled by the US under the GATS(see Articles32and33of the Lao PDR–US BTA).In addition,market access and national treatment do not apply to the United States with respect to the financial services sector(see Article35of the agreement).sectors,we observe two approaches for specifying levels of openness:pure positive lists and GATS-style hybrid lists.1.Pure positive list agreementsUnder a pure positive list,parties to an agreement specify for each listed service sector the level (and type)of foreign participation that is allowed.Only two East Asian FTAs follow this approach:the Mainland–Hong Kong and the Mainland–Macao Closer Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs).Interestingly,these two agreements do not establish binding disciplines,such as the ones created by the GATS market access and national treatment provisions.They also do not define any modes of supply,as is done for all other trade agreements in services (see subsequently).In fact,the legal disciplines established by the agreements’services chapters are arguably the weakest among all the East Asian FTAs.Y et,China’s marketT able 1.Scheduling approachesAgreement(s)Listing of sectors Listing of level ofopennessLao PDR–US BTA Positive Not applicable,asno trade-restrictivemeasures arescheduledMainland–Hong Kong CEPA,Mainland–Macao CEPA Positive PositiveAFAS,ASEAN–China TISAgreement,Australia–Thailand FTA,India–Singapore ECA,Japan–Malaysia EPA,Japan–PhilippinesEPA,Japan–Singapore EPA,EFTA–Korea FTA,EFTA–SingaporeFTA,Jordan–Singapore FTA,New Zealand–Singapore FTA,Vietnam–US BTAPositive Hybrid Australia–Singapore FTA,Chile–Korea FTA,Guatemala–T aiwan (China)FTA,Japan–MexicoEPA,Panama–T aiwan (China)FTA,Trans-Pacific EPANegative Negative Nicaragua–T aiwan (China)FTA,Singapore–Panama FTA,Singapore–US FTANegative,except for cross border trade in financial services for which a positive list is adopted Negative Korea–Singapore FTA Negative,except for finan-cial services for which apositive list is adopted Negative,except for financial services for which a hybrid listis adopted268Journal of International Economic Law (JIEL)11(2)East Asian Free Trade Agreements in Services269 opening undertakings under the two CEPAs grant service providers from Hong Kong and Macao substantial trade preferences.92.GATS-style hybrid list agreementsUnder a GATS-style hybrid list,parties may define the level of openness in listed sectors either on a positive or negative list basis.In particular, agreements following this approach typically adopt the market access and national treatment provisions of the GATS.Schedules of commitments then specify the market access‘terms,limitations and conditions’and national treatment‘conditions and qualifications’.10In other words,countries are free to describe either how trade is restricted or what type of services transac-tions are allowed in a listed sector.As a rule of thumb,an entry in a GATS schedule that takes the form‘None,except...’signifies a negative list of trade-restrictive measures,whereas an entry that takes the form‘Unbound, except...’signifies a positive list of market-opening concessions.11One clarifying remark is in order.The GATS approach to the scheduling of commitments has frequently been referred to in the literature as a positive list approach.This terminology focuses solely on the selection of sectors subject to trade commitments.For the purposes of this article,we refer to GATS-style agreements as hybrid list agreements,because the fixing of the level of openness under this approach involves elements of both negative and positive listing.12We use the term positive list agreements to describe all agreements that adopt a positive list of sectors subject to trade commitments, encompassing the special case of the Lao PDR–US BTA,the pure positive list agreements,and the hybrid list agreements.Several features associated with the GATS-style hybrid list approach are worth pointing out.First,commitments in each listed sector are made with respect to four different modes of supply:cross-border trade(mode1), consumption abroad(mode2),commercial presence(mode3),and movement of natural persons(MNP)(mode4).13In actual GATS schedules,most entries 9See Fink Carsten,‘A Macroeconomic Perspective on China’s Liberalization of Trade in Services’,in Henry Gao and Donald Lewis(eds),China’s Participation in the WTO(London: Cameron May,2005).10See GATS Articles XVI.1and XVII.1.11A negative list of trade-restrictive measures also prevails,when a scheduling member does not explicitly indicate‘None,except...’,but inscribes one or more limitations applying to a listed sector.For further details on the scheduling of GATS commitments,see WTO document S/CSC/W/19.12Other studies have also characterized GATS-style agreements as hybrid list agreements.See Hoekman Bernard and Sauve´Pierre,Liberalizing Trade in Services,Discussion Paper No.243 (Washington,DC:The World Bank,1994);OECD,above n1;and UNCTAD,‘National Treatment’,UNCTAD Series on Issues in International Investment Agreements(New Y ork and Geneva:United Nations,1999).13For a more comprehensive discussion of modes of supply,see Adlung Rudolf and Mattoo Aaditya,‘The GATS’,in Aaditya Mattoo et al.(eds),A Handbook of International Trade in Services(Washington,DC:The World Bank and Oxford University Press,2008).270Journal of International Economic Law(JIEL)11(2)for modes1,2,and3set the level of openness on a negative list basis,whereas the great majority of entries for mode4are made on a positive list basis. Eleven,of the12East Asian hybrid list FTAs follow the structure of the GATS by distinguishing between four modes of supply and between market access and national treatment measures.The only exception is the Australia–Thailand FTA,whose schedule does not differentiate between modes of supply nor between market access and national treatment measures.T o which mode and to which measures a particular commitment applies is determined by the nature of the scheduled pared to the GATS,this scheduling approach appears to reduce difficulties in scheduling measures that may be inconsistent with both market access and national treatment obligations.14 Second,several GATS-style hybrid list agreements adopt a most-favored nation(MFN)obligation which is subject to the scheduling of reservations. However,MFN reservations are always inscribed on a negative list basis in relation to both service activities and trade restrictive measures.Interestingly, some hybrid list agreements have not incorporated binding MFN disciplines in their text.15MFN obligations in an FTA context have a different meaning than the multilateral MFN principle under the GATS.They mainly take two forms.On the one hand,regional trade agreements involving more than two countries may wish to establish an MFN obligation to ensure non-discriminatory treatment between service providers from countries within the region.In East Asia,this is the case for the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services,which calls for preferential treatment to be accorded on an MFN basis.16On the other hand,some FTAs require non-discrimination between parties and non-parties.In other words,a non-party MFN clause guarantees FTA parties the best current and future treatment that the other party grants to services suppliers from any country.14The relationship between the GATS market access and national treatment disciplines has been subject to conflicting legal interpretations.See Mattoo Aaditya,‘National Treatment in the GATS:Corner-Stone or Pandora’s Box?’31(1)Journal of World Trade(1997),at 107–35;Pauwelyn Joost,‘Rien ne Va Plus?Distinguishing Domestic Regulation From Market Access in GATT and GATS’,4(2)World Trade Review(2005),at131–70;Delimatsis Panagiotis,‘Don’t Gamble with GATS—The Interaction Between Articles VI,XVI,XVII and XVIII in the Light of the US-Gambling Case’,40Journal of World Trade(2006),at 1059–80;and Molinuevo Martı´n,‘GATS Article XX—Schedules of Specific Commitments’, in R.Wolfrum et al.(eds),Max Planck GATS Commentary(Biggleswade,UK:Brill Publishers,forthcoming in October2008).15Namely,the ASEAN–China TIS,the Australia–Thailand FTA,the India–Singapore ECA,the Japan–Singapore EPA,the Jordan–Singapore FTA,and the New Zealand–Singapore FTA. 16However,a2003amendment to the AFAS allows for departure from MFN if two or more members agree to liberalize trade in services faster than the remaining ASEAN members.It is worth pointing out that an intra-regional MFN obligation may not be necessary for regional agreements involving WTO members,as FTA parties would already be bound by the MFN obligation under the GATS.It would only be needed if FTA parties wanted to eliminate at the regional level the application of MFN exemptions scheduled under the GATS or desired to make MFN subject to a regional dispute settlement mechanism.East Asian Free Trade Agreements in Services271 Third,GATS-style schedules allow for horizontal commitments.Measures scheduled in these horizontal commitments apply to all listed service sectors, unless the wording of a sectoral commitment unambiguously indicates other-wise.In assessing the level of openness of specific service sectors,it is therefore critical to take these horizontal commitments into account.Sometimes they can be far-reaching—for example,a joint venture requirement with foreign equity participation limited to49%,or an entry that limits the movement of individual service providers to specific types of intra-corporate transferees.In such cases, they effectively fix a low level of openness across all sectors.Fourth,GATS-style hybrid list agreements typically do not require signa-tories to make bindings at the level of actual openness.In fact,existing GATS commitments are often characterized as being less liberal than status quo policies—not least because substantial unilateral liberalization has taken place in many countries since the conclusion of the Uruguay Round of Trade Negotiations in1994.17A gap between bound and actual policies—a so-called binding overhang—may introduce uncertainty,because governments at any point can restrict foreign participation in their domestic service market,as long as they stay within their trade commitments.Most East Asian hybrid list FTAs similarly do not impose any requirement to bind at the actual level of openness. However,Japan’s Economic Partnership Agreements(EPAs)with Malaysia and the Philippines have introduced an innovation that serves to reduce the uncertainty associated with a binding overhang.18These agree-ments offer the possibility to identify in schedules those service sectors in which a party agrees to bind status quo policies.In addition,the identified service sectors are subject to upward ratcheting:once a party unilaterally eliminates a trade-restrictive measure,policy will automatically be bound at the more liberal level.19B.Negative list agreementsT en East Asian FTAs have adopted a negative list approach in scheduling their market opening commitments.Negative listing generally applies to both sectors and measures.In other words,trade is unrestricted across all covered service activities,unless scheduled limitations indicate otherwise.17For example,see Hoekman Bernard,‘Assessing the General Agreement on Trade in Services’,in Will Martin and L.Alan Winters(eds),The Uruguay Round and the Developing Countries(Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1996).18For example,Article99.3of the Japan–Malaysia EPA provides that‘[w]ith respect to sectors or sub-sectors where the specific commitments are undertaken[...]and which are indicated with‘‘SS’’,any terms,limitations,conditions and qualifications[...]other than those based on measures pursuant to immigration laws and regulations,shall be limited to those based on non-conforming measures,which are in effect on the date of entry into force of this Agreement’.19Even though upward ratcheting enhances the credibility of unilateral trade reforms,it arguably implies a loss of transparency in committed policies,because parties are not required to notify these reforms or periodically update their schedules.272Journal of International Economic Law(JIEL)11(2)Again,it is useful to review several key features of negative list agreements. First,these agreements typically establish separate disciplines for cross-border trade and investment in services.Cross-border trade in services in the negative list model covers the GATS equivalent of modes1,2,and4, although commitments do not formally distinguish between these three modes of supply.The GATS equivalent of mode3is covered by a horizontal investment chapter that applies to both goods and services,though the typical investment disciplines go beyond those established by the GATS.20 Second,trade in financial services receives separate treatment in several of the negative list FTAs.Four agreements revert to a positive list for trade in financial services,either by adopting a positive list for cross border trade in financial services(modes1,2,and4)or by entirely following GATS-style hybrid lists(T able1).Furthermore,four of the remaining six negative list FTAs21carve out trade in financial services entirely from the scope of the agreement,leaving only the Australia–Singapore FTA and the Panama–T aiwan(China)FTA for which the negative list applies,in principle,to financial services.Third,negative list agreements establish additional classes of measures for the scheduling of specific commitments.T able2lists the obligations identi-fied by the10negative list FTAs in the three areas subject to trade commit-ments:cross-border trade in services,investment,and trade in financial services.A number of patterns are worth pointing out:All10negative list FTAs feature obligations on national treatment, subject to sectoral reservations.22Only six negative list FTAs feature a market access discipline mirroring GATS Article XVI.23Three of the remaining four agreements follow20Two negative list agreements in East Asia depart from this basic model.The Trans-Pacific EPA does not establish separate investment disciplines,but services supplied through commercial presence are covered under the agreement’s services disciplines—reverting to the structure of the GATS.Similarly,the Australia–Singapore FTA covers commercial presence in the services chapter,but in this case separate investment disciplines still apply.21Namely,the Guatemala–T aiwan(China)FTA,the Korea–Chile FTA,the Trans-Pacific EPA, and the Japan–Mexico EPA.The latter agreement features a chapter on financial services.However,provisions in that chapter merely ratify existing multilateral and plurilateral commitments,and carve out financial services from the services,investment and dispute settlement chapters of the agreement.22The language of the national treatment provision mostly follows the NAFTA standard of providing for national treatment for services and services suppliers‘in like circumstances’.The only exception is the Australia–Thailand FTA,which incorporates the‘like services and service suppliers’language found in GATS Article XVII.For a discussion of the‘likeness’standard under the GATS,see Cossy Mireille,Determining‘Likeness’under the GATS: Squaring the Circle?WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2006-8(Geneva:World Trade Organization,2006).23The catalog of measures covered by these agreements is the same as the one adopted by the GATS,with the exception that all six agreements except the Australia–Singapore FTA do not cover restrictions on foreign equity participation under market access.In the case of the Korea–Singapore FTA,market access does not apply to investment in services and the。

《外语教育》投稿格式要求-new

外语教育投稿格式要求1. 稿件构成∙论文中文标题、中文摘要、中文关键词、英文标题、英文摘要、英文关键词、论文正文、尾注(如果有)、参考文献、附录等(如果有)。

∙请另页附论文标题、中文摘要、中文关键词、作者姓名、学位、职称、工作(学习)单位、详细地址、电话号码、E-mail等信息。

2.正文2.1 结构层次正文分为若干节(section),每节可分为若干小节(subsection)。

2.2 标题节标题、小节标题独占一行,顶左页边起头。

节号的形式为1、2、3…,节号加小数点,然后是节标题;或一、二、三…,节号后加顿号,然后是节标题。

小节号为阿拉伯数字,形式为1.1、1.2、1.3…,1.1.1、1.1.2、1.1.3…。

小节号后空1格,不加顿号或小数点,然后是小节标题。

小节之下可以采用字母A. B. C.,a. b. c.,(a) (b) (c)或罗马数字I. II. III.,i. ii. iii.,(i) (ii) (iii) 对需要编号的内容加以编号。

2.3 字体正文的默认字体为宋体五号。

中文楷体用于字词作为字词本身使用,如:“劣字怎么念?”英文倾斜字体的使用范围主要是:(1)词作为词本身使用,如:The most frequently used word in English is the.(2)拼写尚未被普遍接受的外来词,如:Jiaozi is a very popular food in China.(3)书刊等的名称。

图表的字体可根据需要换为较小的字号。

2.4 图表图标题置于图的下方,表标题置于表的上方。

图号/表号的格式为“图/表+带小数点的阿拉伯数字”。

图表的字体一般为宋体小五;如果需要,可以适当采用较小的字号。

图表的行距为单倍。

2.5 参引一切直接或间接引文以及论文所依据的文献均须通过随文圆括号参引标明其出处。

参引的内容和语言须与正文之后所列参考文献的内容和语言一致。

作者名字如果是英文或汉语拼音,不论该名字是本名还是译名,参引时都仅引其姓。

学位论文的“洋八股”写作方法!

学位论文的“洋八股”写作方法!展开全文这是社科学术圈推送的第1944篇文章社会学家彭玉生认为,社会科学研究属于“范式研究”,“自从托马斯·库恩发表了《科学革命的结构》一书,我们认识到了范式及其变革对学科发展的重要性。

根据库恩的定义,范式指被学术共同体奉为标准的一系列普遍性规则、方法、概念及理论。

”这种研究“都采用一种非常刻板、近乎迂腐的格式”。

于是,他“将这种结构戏称为‘洋八股’”,据此,“提炼出‘洋八股’的一般结构。

”即“经验社会科学研究的八个组成部分:问题、理论(文献)、假设、数据、测量、方法、发现和结论。

”硕士论文属于典型的“范式研究”,本文根据彭玉生提出的“社会科学研究的‘洋八股’规范”,并结合作者指导硕士研究生多年积累的经验,提出一种在实践中行之有效的“硕士论文写作‘洋八股’规范”,以期能为硕士生的学位论文写作提供一些有益的帮助。

一、开题报告逻辑框架图研究生是否掌握“硕士论文写作的‘洋八股’规范”是完成一篇合格硕士论文的关键。

从硕士论文写作流程看,选题是论文写作的第一步,而开题报告则是检验选题能否成立的首要环节。

因此,一个好的开题报告必然包括上述“经验社会科学研究的八个组成部分”,据此逻辑,笔者结合多年来指导研究生的经验,提出“硕士论文写作‘洋八股’规范暨开题报告逻辑框架图”如下:实践证明,硕士论文写作可以“按图索骥”,即用此“可视化”的方法将被广大研究生视为“畏途”的论文写作过程简化为若干必须严格遵循的“机械步骤”,进而依此展开有章可循、有标准可依的学术训练。

下面对其写作步骤和研究机理作详细剖析。

二、选题标准及常见问题学术研究始于选题,选题就是选择一个值得研究的问题。

“硕士论文写作‘洋八股’规范”的首要步骤是选题,选题有三大标准,现分述如下。

1.选题标准之一:选题必须是“真问题”“真问题”必须符合逻辑和事实。

劳凯生提出区别真假问题的几条经验:“我给真问题下了个定义:任何一个真问题必须满足两个条件:第一,逻辑上能自洽;第二,实践中能举证。

经管类CSSCI投稿经验与审稿时间

经管类CSSCI投稿经验与审稿时间2.经济学季刊:匿名审稿,注重论文质量。

是否刊登主要看编辑。

当然林毅夫的论文要不要匿名审稿,直接问编辑就可以了,哈哈。

如果中国有一大把林毅夫投稿,经济学水平倒是上了一个档次。

季刊编辑水平比经济研究高多了。

一旦有刊号,一定会把经济研究甩到二区。

以后一区就是一个了。

学生独发常见二区1.世界经济:对普通学生很公平,不会以名气定夺,是匿名审稿。

学生单独发表常见。

2.中国社会科学:其他社科类不说,但经济类论文良莠不齐,论文水准的方差很大,有些太差,有些还可以。

明显不是完全匿名审稿,人情避免不了。

学生一般不建议投,除非牛老板推荐。

3.经济学报:都是匿名审稿,不求数量,只求质量。

最近一段时间一直没有看到出版,说明稿件宁缺毋滥。

宁缺毋滥的刊物,一定不是看名气和地位,所以学生占优势,毕竟知识结构比老一代新。

4.金融研究:金融类的,看过没有投过,不过看似质量可以。

在子领域中算是一流。

好不好投,请大家补充。

5.世界经济文汇:最近几年上升很快,注重研究方法的规范化。

不规范的大话西游文章,乘早不要投。

几个编辑都很年轻,思维活跃。

学生单独发表常见。

6.经济科学:据稿也不给意见,很没有办刊的职业素养,不向国际一流看起,反而向国内三流看起,糟蹋了北大的牌子。

有人发过的补充下。

但学生单独有发。

7.数量经济技术经济研究:不知道什么审稿标准,据稿也不给意见,和经济科学一样。

有人发过的补充下。

但学生单独有发。

8.南开经济研究:做的不错,时间太长,审稿严谨。

但学生单独有发。

9.南方经济:具有真才实学的学生,发表首选,该杂志审稿严谨周到,仅以质量取胜,以后可能会进入一区,但是现在杂志名声不大,稿源不如一区。

学生单独常发。

10.管理世界:靠国研中心成为著名期刊,但是办刊选稿的宗旨居然是三流层次,实在难以理解,估计和编辑部素质有关。

AER、JPE、ECONOMETRICA上的论文在管理世界是不可能发表的,因为不符合它的三流标准。

《国际政治研究》稿约及注释体例

《国际政治研究》(季刊)稿约及注释体例说明一、本刊是由北京大学国际关系学院主办的、研究国际问题的综合类学术性刊物,内容涵盖国际政治、国际关系、国际组织与国际法、世界经济、中国外交、国际战略、国别和地区研究、世界社会主义运动、比较政治、台港澳研究、口述外交等方面,欢迎投稿。

二、来稿请用A4纸单面隔行打印,字体为5号字,同时提交Word格式的软盘。

一般不收手写稿件,请见谅。

三、论文稿件篇幅(包括注释在内)以六千字到八千字为宜,最长不宜超过一万字,书评稿件篇幅以四千到六千为宜,学术动态等稿件篇幅限制在三千字左右。

来稿请在正文之前附上简短的中文内容提要(一般在200字以内),以及关键词(三至五个)。

四、本刊编辑部有权对来稿作一定的修改或删节。

作者如不同意,请在投稿时声明。

五、凡在本刊发表的文章,一律文责自负,严禁一稿多投。

稿件寄出三个月内没有收到本刊用稿通知的,可改投他刊。

未被采用的稿件本刊不负责退稿,请作者自留底稿。

六、来稿请注明作者的真实姓名、工作单位、职务职称、通讯地址、电话及邮政编码,以便联系。

发表时可用笔名。

来稿一经采用,即付稿酬,并赠样刊两本。

七、来稿请寄北京大学国际关系学院《国际政治研究》编辑部收,电话:010-6275-5560,6275-9984,传真:010-6275-1639,电子邮件:yuankan@。

或直接将论文打印稿及软盘各一份送到北京大学国际关系学院院内“院刊编辑室”信箱。

凡以电子邮件方式投寄的稿件,无需再提交软盘,但仍需要提交论文打印稿一份。

八、文中第一次出现的不常见的外国人名、地名及机构名称或专业术语时,请在中文译文名称后加圆括号注出原文,其它常见人名、地名无须加注原文,但应为约定俗成的译名。

九、凡涉及引文或引证的观点,请注明出处。

本刊采用脚注形式,注释内容必须包括作者、书名或文章名、编者或译者(如果有的话)、城市及出版社、期刊名、出版日期、期刊的卷期数字、引用的页码等。

《外国文学研究》论文格式模版

论文格式模板□□□□□□论文题目□□□□□□( 文章题目:题名应简明、确切,能概括文章的要旨,一般不超过20个汉字,必要时可加副题。

)内容摘要(宋体5号字)□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□。

(宋体5号字,篇幅200-300字,摘要质量的高低,直接影响论文的被引用率。

请作者高度重视!)关键词:(宋体5号字)□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□(宋体5号字,关键词是反映论文最主要内容的词或词组,如人名、作品名、概念、术语等,一般3-5个,关键词之间用空格分隔。

)作者简介:□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□(宋体5号字,内容包括姓名、工作单位、职称、主要研究领域等。

如果论文属省部级以上科研立项的成果,也应在作者简介中标明。

)Title:□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□Abstract:□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□。

Key words:□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□Authors:□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□。

1975年出版的报刊

1975年出版的报刊、杂志、回忆录、译著一、报纸1、沈阳日报出版时间:1975-05期号:1975-05 1期至1975-05 31期总2592期至2622期2、解放军报出版单位:解放军报出版时间:1975期号:1975-09 1期至1975-09 30期总6443期至6472期3、解放日报责任人(主编):解放日报出版单位:解放日报出版时间:1975期号:1975-02 1期至1975-03 31期总9355期至9413期4、文汇报出版单位:文汇报出版社出版时间:1975-01-12期号:1975-01 1-31期至1975-12 1-31期总9929期至10293期5、人民日报责任人(主编):人民日报出版单位:人民日报出版时间:1975期号:1975-01 1期至1975-06 6期6、北京日报责任人(主编):北京日报社出版单位:北京日报社出版出版时间:1975-10期号:1975-10-02 3087期至1975-10-31 3116期总3087期至3116期二、杂志1、刊名:南洋问题研究主办:厦门大学南洋研究院周期:季刊出版地:福建省厦门市历史沿革:现用刊名:南洋问题研究Southeast Asian Affair 创刊时间:1974出版时间:1975年05期主要内容:主要从外国文献表明南海诸岛主权属于中国,某些国际条约和国际会议以及有关各国政府承认南海诸岛是中国的领土。

2、题名:技术标准简介发表时间:1975年3月2日主要内容:有关机械制图的标准刊名:汽车电器Auto Electric Parts 主办:长沙汽车电器研究所周期:月刊出版地:湖南省长沙市历史沿革:现用刊名:汽车电器创刊时间:1960 期刊荣誉:中科双效期刊、Caj-cd规范获奖期刊3、刊名:兰州大学学报 1975年02期题名:山黧豆中毒素分析与去毒方法的研究 1975年7月2日发表4、刊名:上海纺织动态 1975年09期题名:关于纤维、织物和整理方面研究的几项展望1975年7月2日发表5、题名:《石油化工设计给排水》70—74年文章总索引 1975年4月1日发表刊名:工业用水与废水Industrial Water & Wastewater主办:东华工程科技股份有限公司周期:双月出版地:安徽省合肥市历史沿革:现用刊名:工业用水与废水曾用刊名:化工给排水设计创刊时间:1970主要内容:该刊自1970年出版以来至1974年止共发行了17期,刊载了给水工程排水工程以及环境保护综合利用和各项报导、会议纪要思想评论、两报一刊元旦社论等共计195篇文章,为便于阅读参考,特将各期刊载论文分列为:一、两报一刊社论二、思想评论三、会议纪要和报导四、环境保护,综合利用五、给水工程六、排水工程给水排水工程又按各篇论文内容分类细目并注出所刊期号页数,以便索引查阅。

科研论文的写作规范(完整版本)

四、学术研究的基本规范

充分尊重他人成果是科学研究和文学创作中最重要的原则之一 。 违反这个基本原则将导致严重后果。

最极端的例子就是剽窃:作者将他人成果据为己有。 “在自己的写作中 使用他人的观点或措辞而不说明出处的即为剽窃” (MLA);

在国际学术界,剽窃行为一旦被发现,惩罚非常严厉。 哈佛大学校方每年都会颁发相关文件给所有新生,指导他们如何规范论

科研论文的写作规范

姜勋平 (华中农业大学)

内容

一、学术研究的基本策略 二、研究成果发布的必要性 三、学术研究成果形式 四、学术研究的基本规范 五、研究成果的书写格式

2020/3/20华中农业学一、学术研究的基本策略和定位

理论创新

挑战理论问题 探索科学规律

技术创新(科研与开发)

注意的问题

批评的眼光看前人的结果和理论 前人的理论都是有条件的,具体的 批评的眼光检验自己的结果-没有对照不做实验 实验结果必须及时分析,总结一般规律 观察、分析、归纳,上升为理论 总结重要创新点

课题的发展和变化

随时分析结果 关注相关研究动态 及时调整实验设计和课题方向

2、读文献、了解有关研究进展

学术研究成果的结构-正文

正文的章节与段落是有规则可循的。一般而言,理工方面的报告 是:

前言或导论:介绍自己的研究主题及目的,并作文献回顾。 方法章节:说明方法程序步骤。 结果与讨论:陈述主要的结果并作出合理的解释。 结论:作者自己所下的结论与研究心得。

而人文科学方面则是:

绪论:陈述问题、研究目的、范围,以及方法与步骤之说明。 文献分析:将有关的研究文献作重点说明,点出研究主题所在。 研究设计或调查结果分析。 结论与建议。

一、选题和构思 二、预实验和初步设想 三、实验研究和结果分析 四、根据结果调整课题设计和构思 五、整理数据、撰写论文 六、投稿 七、修改、补充数据 八、发表

南洋华侨教育研究(1927-1949)(历史专业毕业设计)

幸福的中考满分作文5篇无论是身处学校还是步入社会,大家都不可避免地要接触到作文吧,作文是人们把记忆中所存储的有关知识.经验和思想用书面形式表达出来的记叙方式.为了让您在写的过程中更加简单方便,一起来参考是怎么写的吧!下面给大家分享有关幸福的中考满分作文,欢迎阅读!有关幸福的中考满分作文1一天,我偶然得到一幅神秘的地图,上面烫着〝幸福〞两个字.我好奇地翻开它,顺着蜿蜒崎岖的路线,小心翼翼地踏上了寻找幸福宝藏的征途.第一站:家〝叮铃铃!叮铃铃!〞〝啪.〞我顶着浓重的睡意艰难地从被窝里爬出来.拉开窗帘,明媚的阳光穿过洁净的窗玻璃迅速照亮整个房间.走出房间,只见奶奶正忙碌地在厨房煮着美味的早餐,爷爷在厅里打理餐桌.不一会儿,迎着一股浓浓的香气,奶奶笑眯眯地端出营养可口的牛奶鸡蛋.我赶紧拉开椅子,屁股一坐,端起碗,狼吞虎咽地大吃起来,生怕早餐被人抢走了.爷爷看到我滑稽的吃相,笑着说:〝你好像非洲难民啊.〞我笑得差点呛出来.三人边聊天,边享用食物.一切都那么和谐,温馨.第二站:公交车每天上学,我都要乘公交车.上班高峰期,车厢总是塞得满满的,大家摩肩接踵,空气都因此变得稀薄.一位老奶奶提着菜篮子上了车,美好的一幕上演了:一位年轻人看到体弱的老奶奶,赶忙站起来快步走到老奶奶身边,右手搂着老奶奶的腰,左手扶住她的手,护送她到自己的座位上.车内的人瞬间产生了共鸣,大家都投去了赞许的目光.下了车,我的心情格外舒畅,鸟儿的歌声也显得动人悦耳.第三站:学校到了学校,同学们互相打招呼问好.瞧,小A正在位子上愁眉苦脸地找着自己的橡皮,小B看见了,用手拍了拍小A的肩膀,和气地说:〝我借你吧.〞说罢,递过自己的橡皮.小A的眸子一下灵动起来,头一偏,嘴角上扬,感激地说道:〝谢谢你.〞走廊上玩耍的小C看见手里抱满作业的语文老师,大步流星地上前接过重担.老师看着小C蹒跚的背影,会心笑了.我看到老师笑了,自己也不觉笑起来.……走完了地图,我耷拉着脑袋,因为我并没有在终点找到宝藏.可是回头一想,不禁释然,原来我在寻找宝藏的过程中已经收获了宝贵的幸福!家里.公交车.学校……这些看似平凡的地方都充满了幸福的元素.其实生活就是这样,每时每刻都令人感慨与激动.这些幸福的元素都是来自人们内心世界最真挚的情感.它们已经融入到社会的各个角落.生活的点点滴滴.好了,我的寻宝之旅就告一段落,如果你急着想要我手中的幸福地图,不要着急,告诉你一个秘诀——那就是拥有一双发现美的眼睛和一颗纯洁的心.有关幸福的中考满分作文2相信大多数人都有崇拜明星的情结吧,我也不例外,有许多明星都是我崇拜的对象,尤其是男明星,看他们帅帅的打扮,看万人迷的景象,我真是羡慕极了,觉得他们就是世界上最幸福的人.为什么他们就是幸福的呢?或许是他们打扮的阳光,富有朝气吧.自从我的脑袋里有了这个想法之后,为了幸福,我每天刻意打扮自己.可是几天过去了,除了我自己觉得变帅了点,没有一个人注意到我的打扮,一切还是原来的样子,这样的结果让我不禁有些失落,我觉得老天对我不公,我的幸福到底在哪里?有一天,我读到了这样一个故事:一只小狮子问妈妈:〝妈妈,幸福在哪里?〞妈妈笑着回答:〝幸福就在你的尾巴上.〞小狮子听后很高兴,急着想抓住尾巴上的幸福,但他转了很多圈,总是抓不到,于是它垂头丧气地问妈妈:〝妈妈,为什么我总是抓不住尾巴上的幸福?〞妈妈摸了摸小狮子的头说:〝孩子,不要刻意去追,只要你一直往前走,幸福就会永远跟在你的身后,不论你走到哪里,幸福都会一直伴随着你!〞小狮子似乎明白了妈妈的话,高兴地点了点头.此后,不管小狮子遇到什么样的困难,它都会这样想:有幸福在我身后,有幸福跟随着我,有什么困难我克服不了呢?由于总是这样想,小狮子渐渐变成了一只成熟稳重的大狮子,统领了狮子家族.通过这个故事我对幸福有了新的认识:其实,幸福就在我们身边,或许一个转身就能看见幸福,或许幸福一直伴随在我们的左右.每个人有每个人的幸福,明星有他们的山珍海味,我们有我们的粗茶淡饭;明星有他们的帅气打扮,我们有我们的朴素简洁.我的幸福就是做最好的自己.如果不能成为大海,就做晶莹的浪花;如果不能成为辉煌的宫殿,就做朴素的小屋.做最白的云朵,最亮的路灯,最红的花朵……幸福不需要刻意追求,因为幸福就在我们的身边.有关幸福的中考满分作文3还记得那是一个冬天,天气很冷,空中零零散散的飘着雪花.我打着伞拖着疲惫的身子,走在回家的路上.〝啊——〞我一个不小心便踏进水坑里.我的脚像触电般的缩回,寒冷以光速从我的脚掌直达大脑神经——整个人都精神了不少.〝我怎么这么倒霉啊?〞无奈,我踉踉跄跄的回家.终于到家了,我赶紧换上我干净的棉拖鞋,便悠哉悠哉地躺到沙发上看电视,谁知正享受着呢,〝咔哧〞一声,电视光一闪便停电了.〝我怎么还这么倒霉啊!〞更加无奈的,我不情愿的去写作业.〝嚓嚓嚓——〞我听见一阵刺耳的声音,便循着声音去找.当我走到浴室门口时,发现妈妈正蹲在地上给我刷鞋,妈妈系着蓝色的围裙,双手不停地在凉水里来回摆动.因为停电,没有热水,妈妈的手没凉水侵蚀的不成样子.手指肿的像粗大的香肠,手背也高高隆起,整个手红得像被开水灼烧过一般.我的心里充满了负罪感,喉咙也肿胀的要命,眼泪像洪水一样没有任何警告和提示决堤而下……我不知道如何开,口更不知道开口要说些什么.无奈的,我静静的回屋,更加认真的写我的作业.每次写完作业,妈妈都要检查.尽管,尽管她不懂什么数学公式,尽管她不懂什么欧姆定律.但是她唯一懂得的就是,这是一份谁也无法替代的爱.母亲双手在蓝围裙上使劲擦拭着,一双红肿的手拿起作业,认真的看了起来.我仔细的看着妈妈,仔仔细细的看着.我发现我已经好久都没这么认真的看妈妈了,妈妈的爱化作白色的游丝布在鬓旁,调皮的鱼游上眼角,还有那双原本好看的手如今也布满老茧……不觉的,数颗晶体从我眼中落下,重重的砸在地上,砸在我那颗忽略母亲的心上,狠狠地,毫不留情.夜深了,我躺在床上,久久的,无法入睡.我相信现在还不晚,还不晚去爱我的母亲,还不晚享受我所拥有的母爱.不能忽视你所拥有的幸福……有关幸福的中考满分作文4我现在是一名初三的中学生,每天早晨都要早早地到校,实在是忙得不行.现在已经是深秋了.每天早上六点,妈妈总是会把我从被窝中拉出来,看着我穿好衣服裤子,然后拍拍我的头:〝快点去洗漱.〞接着就跑去做早餐了.妈妈总是会问我想吃什么,各种各样的东西变着法儿给我做.今天是个半熟的鸡蛋加火腿和一杯〝爱心果汁〞;明天就是一个苹果沙拉拌生菜.天天不重样,味道好吃又有营养.当我走出家门时,天都才半亮,妈妈总是裹着大棉衣说那些让我觉得麻烦又心暖的叮嘱:〝你冷不冷,要不要多穿点?哎呀!你把帽子戴上!过马路要看车……〞而这时,我的头就会和小鸡啄米一般不停地点头〝知道啦知道了!〞路上,风呼呼从我脸上刮过,可我的心却是暖的.到了学校,忙碌又充实的一天又开始了.上课做好笔记,认真听讲.下课与同学们一起嬉戏打闹,聊着各种八卦,心里洋溢着一种快要溢出来的满足.有时想到,再过一年多就要和他们分离,又会觉得很遗憾.不过,很快就被眼前与同学们一起时的快乐所代替.晚自习结束后,我一个人走在回家的小道上.天空很黑,但是更突出了星星的亮,那颗北极星是多么的耀眼.微风把树上最后几片叶子吹了下来,金黄色在黑夜中格外闪眼,它们在空中转了又转,最后缓缓落在地上.很多人看到这景色常会涌出悲凉之感,可我却不,因为我知道,再见那绿叶时就是春天了.回到家做好一切后,躺在我的小床上,放空思想,让身体放松.我觉得自已真的很幸福,是一种发自内心的满足.我有关心我的老师,爱护我的同学,爱我的爸爸妈妈.他们在我困难时会帮助我,遇到坎坷时会鼓励我,受挫时会安慰我……月亮很亮,夜晚很静,我在月光之下沉沉睡去……我喜欢告诉别人我很幸福,我希望我身上的幸福可以带给他人快乐.有关幸福的中考满分作文5前阵子,我生病了,连续发了十多天的高烧,整天昏沉沉的,好难受!可是这些日子我很幸福,你知道为什么吗?听我慢慢道来吧!爸妈的疼爱是我的一大幸福.我一生病,爸爸就向单位请了假,全心全意地照顾我.白天,为了让我的体温下来,爸爸使劲让我多喝白开水,可我觉得白开水不好喝,爸爸就想办法给我榨橙汁.这下,我一口气就喝了一大碗.爸爸还变着法儿换一日三餐的口味,以满足我这个〝叼嘴〞.傍晚,妈妈一下课就往医院赶,为了逗我开心,妈妈就把学校里的趣事讲给我听,我仿佛又重新看到了同学们灿烂的笑脸.晚上,我一发起高烧,趴在旁边的爸爸妈妈一骨碌爬起来,又是给我喂水喂药,又是帮我擦身换衣服,折腾了好一会儿,我才安然入睡.爸爸妈妈呢,还得等半夜的盐水挂完才能睡下.我有这么爱我的爸妈,能不幸福吗?老师和同学的关爱更是我第二大幸福.同学们看我这么多天没来上学,就给我送来了一张张贺卡,贺卡上写满了大家对我的关心和祝福.老师们也送来了我喜爱的毛绒玩具,让它们陪伴在我身边,希望我的病快快好起来.看着可爱的小狗,翻阅着一张张贺卡,我的心里填满了甜甜的幸福.幸福其实很简单,不用住豪华别墅,不用吃山珍海味,只要身边有爱.同学们,你幸福吗?你也来晒晒你的幸福吧!有关幸福的中考满分作文。

高校智库专刊写作要求与规范格式

一、标题采用二号方正小标宋简体,作者及单位采用三号楷体字,加粗。

二、内容简介标题和作者下有250字以内旳【内容简介】。

三、格式及字数规定(一)正文采用三号仿宋字,单倍行距;(二)字数在3000字左右;(三)文章内各级标题要层次分明。

序号旳层次为“一、二、……;(一)(二)……;1.2.……;(1)(2)……。

”其中,一级标题采用黑体加粗,二级标题采用楷体加粗,三级标题仿宋字加粗;(四)文中关键信息点和结论性意见用黑体字。

四、工作思绪及内容规定专刊工作思绪:围绕“聚焦重大问题,服务国家战略”旳工作目旳,面向党和政府决策部门,充足发挥高校智库战略研究、政策建言、人才培养、舆论引导、公共外交旳重要功能,重点刊载高校专家学者着眼于战略研究、预测研究、应用对策研究旳政策提议,为党和政府科学决策提供高质量旳智力支持,推进高校新型智库建设。

内容规定:文字要简洁生动,防止过于学理化。

字数控制在3000字左右,对策提议部分原则上要占三分之一以上;淡化学理性说教,强化对策性研究;观点要科学理性,全面反应学术界旳最新声音;要有国家战略意识。

内容安排:文稿构造一般按照“提出问题、分析评价、对策提议”旳思绪谋篇布局。

一定要汇集问题,突出重点。

第一部分:提出问题(此部分重在指出所谈问题旳重大意义,或所谈问题旳严重性与紧迫性。

篇幅不适宜过长,要简要扼要地点出问题,阐明该问题对国家发展也许产生旳重要影响,以引起领导旳重视,尽量防止冗长旳历史性描述)第二部分:分析评价(此部分重在分析问题旳体现、原因与影响,不一样旳对策提议可以突出强化不一样旳部分)第三部分:对策提议(此部分重在提出处理问题旳对策提议,一般是整个专家提议旳关键部分,规定具有针对性、创新性、可操作性和科学性)五、作者简介文末有【作者简介】,写清单位、职称、职务、重要研究领域和代表性著作。

六、页面设置文稿页面设置一律采用A4纸默认版式、页边距。

科学文献

1

1. Find a deterministic rule for orienting the edges and analyze it on the the worst input sequence. 2. Suggest a rule and analyze it under some assumption on the distribution of the sequence, in particular that each edge in the sequence is chosen uniformly from all possible edges and independently of the rest of the sequence. 3. Suggest a randomized rule for orienting the edges and analyze its expected performance on the worst sequence. The greedy algorithm is the one where an edge is oriented from the node with the smaller di erence between the outdegree and indegree to the one with the larger di erence. In the deterministic version of the rule ties are broken according to the lexicographic order. In the randomized version of the rule ties are broken at random. We address the three avors of the problem and obtain the following results: 1. The optimal worst-case unfairness of a deterministic algorithm is linear. There is a method (the greedy algorithm) that achieves the bound n?1 on unfairness, and for any deterministic 2 1 rule there is a sequence where a di erence of 2 d n?1 e will occur. (In the broader setting of 2 the "carpool" problem, discussed below, a stronger lower bound of n?1 has been provided in 3 16].) These results are described in Section 2. p 2. There is a randomized rule (local greedy) with expected unfairness O( n log n) on any seplog n). These results are described in Section 3. quence. The lower bound is ( 3. The expected unfairness of the greedy algorithm on a uniform distribution on the edges is (log log n) and we derive a complete description of the process in this case. This is the main technical contribution of the paper. These results are described in Section 4. We view the edge orientation problem as a game played between an algorithm that chooses the edge orientations and an adversary that determines the sequence of edges. Each of the above cases corresponds to one of the three main types of adversaries treated in the literature: the adaptive, the oblivious, and the uniformly random, where the distinction is made according to the way the adversary determines which edges appear in the sequence. An adaptive adversary constructs the sequence on the y, making decisions that may depend on the whole previous history of the game. An oblivious adversary must x its sequence before the game starts, though it may choose this sequence based on knowledge of the algorithm. Finally, the uniformly random adversary produces a sequence in which each edge is chosen independently and uniformly at random. In addition, we investigate the relationship between the edge orientation problem and the vector rounding problem, a very general problem to which many problems in fair scheduling can be reduced. In this problem, we are given a real matrix column by column and should produce an integer matrix so that each column in the output matrix is a rounding of the corresponding column in the input matrix that preserves the sum. The goal is to minimize the maximum over all rows of the di erence between the sum of the rows in the integer and real matrix. (A formal de nition can be found in Section 5.) We show: 4. A general transformation from the vector rounding problem to the edge orientation problem, at the price of doubling the expected di erence. The transformation applies to both deterministic and randomized algorithms. It is described in Section 5.

《南洋问题研究》稿件格式要求

《南洋问题研究》稿件格式要求

佚名

【期刊名称】《南洋问题研究》

【年(卷),期】2006(000)002

【摘要】为适应学术期刊文献信息传播现代化的需要,本刊执行教育部在2000年

颁发的《中国高等学校社会科学学报编排规范》,特向投稿的作者强调以下事项:一、文章的作者应写明:姓名、出生年、性别、民族(汉族可省略)、籍贯、职称或学位等项目,其前以“作者简介:”作为标识,置于篇首页地脚。

二、在稿件应标明工作单位全称、所在省(区)、城市名、邮政编码。

【总页数】1页(P封3)

【正文语种】中文

【中图分类】D

【相关文献】

1.《南洋问题研究》稿件格式要求

2.《南洋问题研究》稿件格式要求

3.《南洋问题研究》稿件格式要求

4.《南洋问题研究》稿件格式要求

5.《南洋问题研究》稿件

格式要求

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

格式上的修改要求

“第六届软科学国际研讨会”论文格式为规范排版,请对照以下要求提供有关资料(数据):要求一:第一作者简介姓名(出生年-),性别,民族(汉族可省略),籍贯(具体到县级),职称职务,学位,研究方向(此项可省略)。

要求二:中、英文对照的标题、作者姓名、单位、地址、摘要(150字以内)、关键词(3-6个)。

1.英文标题统一为词首大写(介词、连词、定冠词除外),其它字母小写例如:Study of Target System and Empirical Analysis on Industrial Structure of Water Conservancy2.多个作者间用“,”连接。

一级单位与二级单位间有一个字的空格,省、市及邮编间各有一个字的空格。

例如:(作者是同一单位)经济政策模拟实验研究张世伟,邓创(吉林大学数量经济研究中心,吉林长春130012)The Simulation Experiments of Economic PoliciesZHANG Shi-wei,DENG Chuang(Center for Quantitative Economics, Jilin University, Changchun 130012, China)(作者是不同单位)国有森林资源产权制度变迁的理论与实证分析王兆君1,2,刘文燕2(1. 青岛科技大学经济与管理学院,山东青岛266061;2. 东北林业大学人文与社会科学学院,黑龙江哈尔滨150040 )Theoretical and Empirical Analysison Changes of State-owned Forest Resources Property Right SystemWANG Zhao-jun 1,2, LIU Wen-yan2(1.College of Econoomics &Management,QUST,Qingdao 266061,Cnina;2.College ofHumanities and Science,NEFU,Harbin 150040,China)要求三:在正文中用上角标标注参考文献批示序号,与文末的参考文献序号(方括号[1],[2],…)相对应.要求四:相关的时间、数目之间的连接号,统一用“-”。

盲样方案格式范文研究性课题书写格式

盲样方案格式范文研究性课题书写格式课题研究实施方案基本格式》课题名称一、目的、意义(问题提出)1、研究的背景、现状分析、碰到的问题。

2、目的、意义(为什么研究?价值是什么?解决什么问题?)二、研究目标本课题要解决的具体问题所要达到的目标要求。

三、研究内容实现研究目标要研究的具体问题,实验类课题还要研究假设。

四、研究范围1、对研究对象的总体范围界定;2、对研究对象模糊概念进行界定(例:“后进生”);3、对关键概念(变量)的界定。

五、研究对象课题研究的直接对象。

六、研究方法1、根据课题的性质、类型选择具体的一种或几种研究方法(例行动研究法、调查法、实验法);2、如何进行研究。

七、研究的程序设计研究步骤、时间规划、管理措施。

八、研究成果形式研究报告或论文,其他有关材料。

九、研究组成员及分工十、经费预算情况。

如何实施立项课题嘉兴市教科所朱建人一、课题立项的意义1、是对申报课题价值的认同。

2、是对科研课题进行规范管理的有效途径。

3、能对课题申报者的研究实施必要的指导与帮助。

4、是一份责任与使命而不是荣誉称号。

二、立项后的研究准备工作1、研讨修订方案——这是课题顺利完成的基础。

要点:集思广益;批判思维;精益求精。

方案的基本结构:⑴课题名称:语言最少化(指明对象、内容、研究方法)。

⑵目的、意义:回答为什么(对课题进行前瞻性思考和对真实问题的揭示)。

⑶国内外相关课题的研究综述:回答“谁在做”(广泛检索,择要阐述)。

⑷课题的界定:回答“是什么”(课题内涵的揭示与外延的框定以及操作路径的提炼)。

⑸课题研究的目标:回答“怎么样”(真实问题的对应面)。

⑹课题研究的方法和途径:回答“怎么做”的问题(技术创新)、策略或措施。

⑺课题研究的对象:确定被试。

⑻课题研究的步骤:准备——实施——总结。

⑼课题研究的成果形式:专著、研究报告、论文、产品等。

⑽课题研究的主要成员:专业、职称、职务等。

⑾经费预算:资料费、咨询费、差旅费、成果包装费等。

现代外语稿件的体例与格式2018新版

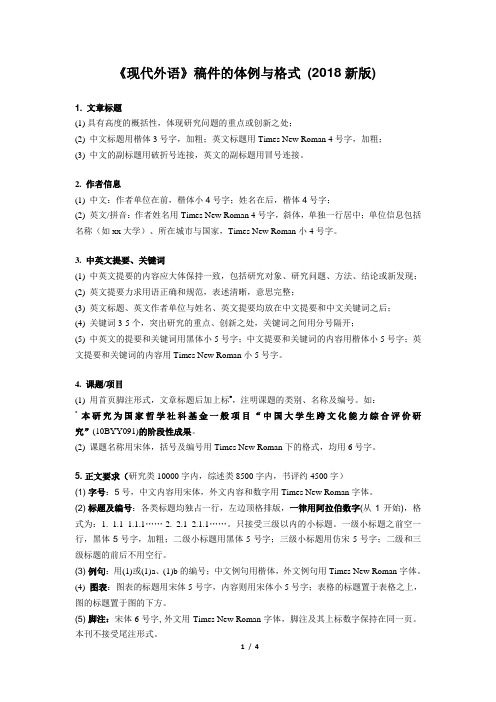

《现代外语》稿件的体例与格式(2018新版)1. 文章标题(1) 具有高度的概括性,体现研究问题的重点或创新之处;(2) 中文标题用楷体3号字,加粗;英文标题用Times New Roman 4号字,加粗;(3) 中文的副标题用破折号连接,英文的副标题用冒号连接。

2. 作者信息(1) 中文:作者单位在前,楷体小4号字;姓名在后,楷体4号字;(2) 英文/拼音:作者姓名用Times New Roman 4号字,斜体,单独一行居中;单位信息包括名称(如xx大学)、所在城市与国家,Times New Roman小4号字。

3. 中英文提要、关键词(1) 中英文提要的内容应大体保持一致,包括研究对象、研究问题、方法、结论或新发现;(2) 英文提要力求用语正确和规范,表述清晰,意思完整;(3) 英文标题、英文作者单位与姓名、英文提要均放在中文提要和中文关键词之后;(4) 关键词3-5个,突出研究的重点、创新之处,关键词之间用分号隔开;(5) 中英文的提要和关键词用黑体小5号字;中文提要和关键词的内容用楷体小5号字;英文提要和关键词的内容用Times New Roman小5号字。

4. 课题/项目(1) 用首页脚注形式,文章标题后加上标*,注明课题的类别、名称及编号。

如:* 本研究为国家哲学社科基金一般项目“中国大学生跨文化能力综合评价研究”(10BYY091)的阶段性成果。

(2) 课题名称用宋体,括号及编号用Times New Roman下的格式,均用6号字。

5. 正文要求(研究类10000字内,综述类8500字内,书评约4500字)(1) 字号:5号,中文内容用宋体,外文内容和数字用Times New Roman字体。

(2) 标题及编号:各类标题均独占一行,左边顶格排版,一律用阿拉伯数字(从1开始),格式为:1. 1.1 1.1.1……2. 2.1 2.1.1……。

只接受三级以内的小标题。

一级小标题之前空一行,黑体5号字,加粗;二级小标题用黑体5号字;三级小标题用仿宋5号字;二级和三级标题的前后不用空行。

郁达夫南洋时期政论文新探

郁达夫南洋时期政论文新探徐世建(厦门大学人文学院中文系2009级硕士研究生)摘要:郁达夫南洋时期的政论文,是其后期文学创作的一个重要方面。

以往的研究取得一些成果,但缺少全面性和系统性。

本文希望在以下几点上做进一步的探索:1、对郁达夫南洋时期政论文进行全面系统的归纳与分析;2、论述郁达夫南洋时期政论文的特色及成因;3、对郁达夫抗战“速胜论”的新看法;4、探求郁达夫战斗精神的来源。

关键词:郁达夫;南洋;政论文;速胜论;战斗精神应《星洲日报》的邀请,1938年12月18日,郁达夫离开福州远赴南洋。

正如他所说,此次南来的目的是“把南洋侨众的文化,和祖国的文化来作一个有计划的沟通”“在海外先筑起一个文化中继站来,好作将来建国急进时的一个后备队。

”[1]郁达夫南来后,主持过《星洲日报》的《晨星》、《繁星》、《文艺》,以及英国情报部创办的《华侨周报》等报纸副刊。

郁达夫对编辑工作充满热情,寄予了无限希望。

他希望借助报纸副刊,“发出新的力量来,助我们国家民族复兴的成功。

”[2]此时的郁达夫已不仅是一位功成名就的小说家、散文家、诗人和文艺评论家,更是一位杰出的政论家。

一、郁达夫南洋时期政论文的主要内容郁达夫在新加坡期间共写文章462篇,其中政论文104篇。

这些政论文内容涉及多个方面,本文主要从以下四点进行归纳与分析。

(一)对日本的侵略行径进行了义正词严的揭露与批判,通过敌我力量的分析,指出抗战时期应注意的问题。

郁达夫严厉的批判了日本帝国主义卑劣的侵略行径。

他写道:“敌阀自从发动对华侵略战争以来,三年之中,对我非武装平民,尤其是对我老幼妇孺之奸淫杀戮,已造成人类有史以来,最残酷、最恶毒之记录。

”“敌人的滥炸我不设防城市,及非军事要区,以及彻底破坏我文化机关,与第三国之教会,医院,使领馆等暴行,更为自有国际公法以来之绝无现象。

”[3]“最残酷、最恶毒、绝无”,可见他用词之重,痛恨之深。

军事上,主要有《抗战两年来的军事》、《敌在浙闽的攻势》、《第二期抗战的结果》等文。

《中国软科学》稿件格式要求

《中国软科学》稿件格式要求一、为了规范排版,请对照以下要求修改:要求一:第一作者简介1.格式:姓名(出生年-),性别,民族(汉族可省略),籍贯(具体到县级),职称职务,学位,研究方向(此项可省略)。

【示例】陈芳(1946-),女,壮族,广东佛山人,北京工业大学管理学院教授,博士,研究方向:风险投资与创业管理。

要求二:中、英文对照的标题、作者姓名、单位、地址、摘要(150字以内)、关键词(3-6个)。

1.英文标题统一为词首大写(介词、连词、定冠词除外),其它字母小写。

【示例】Study of Target System and Empirical Analysis on Industrial Structure of Water Conservancy2.多个作者间用“,”连接。

一级单位与二级单位间有一个字的空格,省、市及邮编间各有一个字的空格。

【示例】经济政策模拟实验研究张世伟,邓创(吉林大学数量经济研究中心,吉林长春130012)The Simulation Experiments of Economic PoliciesZHANG Shi-wei,DENG Chuang(Center for Quantitative Economics, Jilin University, Changchun 130012, China)要求三:在正文中引用的参考文献用上角标标注,与文末的参考文献序号(方括号[1],[2],…)相对应。

一篇文献如多次引用,文末参考文献列表中只出现一次,可注明每次引用的页码。

【示例】[1] 王鑫.区域循环经济发展[M].北京:社会科学文献出版社,2004.6,45-47,181-183.要求四:相关的时间、数目之间的连接号,统一用“-”。

【示例1】亩产1000公斤-1500公斤【示例2】以每年10%-20%的速度递增【示例3】1997-2002年要求五:英文格式1.英文标题统一为词首大写(介词、连词、定冠词除外),其它字母小写。

英文论文格式问题

题目A Contrastive Study between English and Chinese Idioms(题目:二号,黑体,加粗,居中,除了英语小词外,其他单词首字母都要大写;另外:除了题目外,论文中所有英文的字体均采用“Times New Roman”)(学院、专业、学号、作者姓名、指导教师姓名(小四号宋体字,加粗),依次排印在论文题目下,上空二行,居中)AbstractThis paper centers on the different expressions of …… (英文摘要:上空二行;题目采用五号“Times NewRoman”字体,加粗,置于粗体方括号【】内,顶格放置;随后的内容与前面的粗体方括号【】之间空一格,不用其他任何标点符号;采用五号“TimesNew Roman”字体,不加粗;单倍行距。

)Key Wordsidiom; comparison; English; Chinese(英文关键词:题目采用五号“Times NewRoman”字体,加粗,两个单词的首字母要大写,置于粗体方括号【】内,顶格放置;随后的内容与前面的粗体方括号【】之间空一格,不用任何其他标点符号,采用五号“Times New Roman”字体,不加粗,除了专有名词外,其他单词的首字母不大写,各单词之间用分号“;”隔开,分号之后空一格;最后一个关键词之后不用任何标点符号;单倍行距。

)Introduction(顶格,除了第一个单词及专有名词外,其他单词首字母都不要大写;标题最后不用任何标点符号,上空两行)In both English and Chinese, …. So, this essay is trying tofocus on the differences between Chinese and English idoms in termsof their essential meaning, customary usage and typical expression(Chang Liang, 1993:44; Li Guangling, 1999).(段落第一行缩进4个英文字符;夹注的标注法:出现在夹注中的作者必须与文后的参考文献形成一一对应关系;注意一个或多个作者间的标点符号,时间、页码等的标注法;另外,汉语参考文献的作者要以拼音形式出现,不能出现汉语姓氏;夹注出现在标点符号之前) 正文. The similarities between English idioms and Chinese idiomsIn English, …. And it can be clearly seen in the below examples:(1) I don’t know。

洛阳师范学院毕业论文格式

洛阳师范学院毕业论文格式史类样张(上边距30mm,下边距25mm,左边距30mm,右边距20mm)论孙中山利用外资的思想(二号,黑体,居中,与姓名行之间空一行)杨飞(政法学院思想政治教育专业学号:020314071 指导教师:王大洞副教授)(小四号,仿宋GB_2312,词与词之间空两格,姓名行与学号行之间不空行,学号行与摘要之间空一行)摘要:(小四号黑体,顶格)伟大的民主革命先行者孙中山在领导辛亥革命的同时创造性地提出了确保主权、利用外资、发展实业的经济思想,为救国救民设计了一条富强之路。

本文试从孙中山利用外资的动因,基本内容即外资的用途,利用外资的原则、方法,进而揭示其外资思想对中国社会所产生的巨大影响,以资能对我们今天的现代化建设和全面建设小康社会以启发和借鉴。

(小四号,仿宋_GB2312,摘要与关键词之间空一行)【一定是文章内容的概要】关键词:(小四号黑体,顶格)孙中山;利用外资;开放主义(小四号,仿宋GB_2312,词与词之用分号隔开,最后一个关键词后不打标点符号,关键词与正文之间空一行,)利用外资思想①是孙中山先生经济思想中的重要组成部分,同时也是中国近代对外开放思想的重要内容之一.特别是他提出的在确保国家主权的前提下利用外资并且要用于生产等基本原则对我们今天的经济建设和早日实现现代化仍具有重要的意义和借鉴作用。

(正文,宋体,小四号,1.5倍行距)一、孙中山利用外资思想形成的动因(黑体,小四号,标题居中)(一)利用外资是实现民生主义的必要条件(黑体,小四号,括号后面没有顿号)孙中山认为,辛亥革命后,“民族,民权,两层已经达到。

今日所急则在民生。

”[1]孙中山的民生主义概言之包括土地问题,资本问题及实业问题。

其中振兴实业,是中国摆脱贫困,走向富强的关键所在。

辛亥革命以后,中国百废待兴,发展实业需要大量的启动资金,而当时的中国在世界上是最穷最弱的国家,大部分百姓生活拮据,朝不保夕,从国家到民间都无法筹集到足够的发展资金。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

( )参考文献 ( 二 著者一 出版年 ) 体例

参考 文献 的标注项 目与上述 “ 注释体例 ”大致相 同 ,但参考文献 因页码 已在 正文中标注 ,故 没有页

码一项 ,而且 将出版年移至责任者之后 。

示例 :1亨廷顿 , 9 8 第三波——2 () 1 9 :《 0世纪后期 民主化浪潮 》, 军宁译 , 刘 上海 : 上海 三联 书店。

( ) K ig r 9 a a tr Q a tr ,o.() 2 W. r e, 4 , Ra e dP o ls n h i p ie” T e r s n u r l V 1 2 . e 1 a it P i F E e ey 4

I n By nT me(d . s & ra u r s ,H n b o iznh tde, o d n S GEP bi t n. i e ) a d o k fCtes i Su i L n o : A u l ai s o i p s c o

五 、页下 注 是对 正文 中某 一 内容 的进一 步解 释或 补充 说 明 ,置 于 当页地 脚 ,用 圈码 标识 。

( ) u e , y n S. 2 0 “ l i n a d P l i s Th l me tr o mso tz n hp, i g n 3 T r r Br a , 0 2, Rei o n o i c : e E e n a y F r fCi e s i ” nEn i n g t i

《 南洋 问题 研究 》稿 件格 式 要求

本 刊 自2 0 年第 1 08 期起采用 《 综合性期刊引证技术规范 》 ,特向投稿者强调以下事项 :

一

、

文章的作者应写明 : 姓名 、出生年 、 性别 、民族 ( 汉族可省略 ) 籍贯 、职称及学位等 、

项 目,其前 以 “ 作者简介 : ”作为标识 ,置于篇首页地脚。

示 例 :.o n , layP li n m cai t niId n s , o d nR ul g uz n 2 0 , .. J n aMitr oic a dDe o rtai o ei L n0 :o t d eC ro ,0 3 p9 H i ts z o nn a e

其格 式 为 :

( ) 一 注释体例

1 、专著 :责任者 ( 责任方式 )/ 题名 / 册/ 卷 译者 / 出版地/ 出版者 / 出版年 / 页码 。 示例 :张志建 :《 复思 想研究 》, 严 桂林 : 广西师 范大学出版社 ,9 9年 ,第 5 。 18 5页

2 、析 出文献 :析 出文献责任 者 / 析出文献题名 /( )文集责任者 ( 见 责任 方式 )/ 文集题名 / 卷册 / 出版 地/ 出版者 / 出版年/ 页码。

四、 注释或参考文献 ( 即引文 出处 ) 本 刊采用 “ : 注释 ” 体例和 “ 参考文献” 著者 一 ( 出版年 )

体例两种 ,各学科论文可视情况 自行选定这两种 引证体例中的一种。“ 注释”采用顺序编码制 ,

在引文处按论文中引用文献 出现的先后 以阿拉伯数字连续编码 , 序号置于方括号 内;参考文献” “ 则在正文中括注著者一 出版年及页码 ( 作者 ,出版年代 :页码 ) 。注释或参考文献一律置于文末 。

示例 : 王赓武 : 东南亚华人 的少数民族 》, 《 见姚楠编 : 东南亚与华人—— 王赓武教授论文选集 》, 《

北京: 中国友谊 出版社 ,9 6 , 1 6页。 18 年 第 9 3 、期 刊文章 :责任者/ 文章题名 / 刊题名 / 期 出版年 、卷期或 出版 日期 / 页码 。

六 、以上各项及其他的详细写法请参阅本刊。

示例 :刘 英德 :《 明清文学史 观散论 》,《 北京大学学报 》 ( 社会科 学版 ) 9 5 1 9 年第 3 , 3 期 第 2页。

4 、报纸文章 :责任者 / 文章题名 / 报纸题名 / 出版 日期或卷期 ( 出版年 月 )/ 附 版次 。 示例 :李 大伦 : 经济全球化 的重要性 》,《 《 光明 日报 》1 9 年 1 98 2月 2 7日, 3版 。 第 5 、外 文文献 : 责任者/ 题名 ( 斜体 , 出文献题名为正体加英 文引号 ) 出版 日期 / 析 / 责任方式 、卷册 、页码 等用英 文缩 略方式 。

二 、 件应 标 明工 作单 位 全称 、省 ( ) 城 市 名 、邮政 编码 ,加 圆括 号置 于作 者 署名 下方 。 稿 区 、

三、 来稿应附英文标题 、2 0 0 字左右的中英文摘要和 3 5 - 个中英文关键词 , 置于正文之前 。

获 得基 金 资助 的文 章应 署 “ 金项 目: ,注 明基 金项 目名称 ,并在 圆 括号 内注明 基 金项 目编 号 。 基 ”