2012 REO consumption projection - page 6

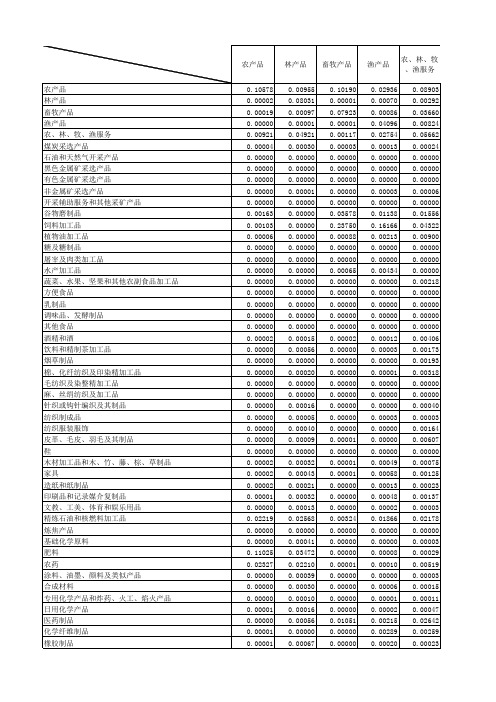

2012年中国投入产出直接消耗系数表

渔产品 0.02936 0.00070 0.00086 0.04096 0.02754 0.00013 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00003 0.00000 0.01138 0.16166 0.00213 0.00000 0.00000 0.00434 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00012 0.00003 0.00000 0.00001 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00003 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00049 0.00058 0.00013 0.00048 0.00002 0.01866 0.00000 0.00000 0.00008 0.00010 0.00000 0.00006 0.00001 0.00002 0.00215 0.00289 0.00020

0.01390 0.00001 0.00000 0.00001 0.00000 0.00001 0.00001 0.00001 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00014 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00001 0.00000 0.00001 0.00000 0.00000 0.00878 0.00000 0.00000 0.00025 0.00000 0.00000 0.00003 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00002 0.00000 0.00000 0.01576 0.00000 0.00000 0.00005 0.00002 0.00000 0.00000 0.00979 0.00121

m2012

M2012IntroductionM2012 is an advanced software system that provides a wide range of tools and features for businesses and individuals. This document will provide an overview of the capabilities and benefits of M2012, explaining how it can be used to simplify everyday tasks and improve overall efficiency.FeaturesM2012 offers a comprehensive set of features that cater to various needs. Some of the key features include:1. Task ManagementM2012 provides a powerful task management system that enables users to create, assign, and track tasks. With customizable priority levels and due dates, users can easily manage their workload and ensure timely completion of tasks. The intuitive user interface allows for seamless navigation and quick access to task details, making the overall process more efficient.2. Customer Relationship Management (CRM)M2012 includes a robust CRM module that helps businesses maintain and nurture their customer relationships. The CRM module allows users to store customer information, track interactions, manage sales leads, and generate reports. By centralizing customer data and providing valuable insights, M2012 enhances customer engagement and helps in driving business growth.3. Document ManagementM2012 offers a comprehensive document management system that enables users to securely store, organize, and share files. With version control and permissions management, users can collaborate effectively and have full control over access to sensitive documents. The search functionality allows for quick retrieval of documents, eliminating the need for manual searching and saving valuable time.4. Project CollaborationM2012 facilitates seamless collaboration on projects through its dedicated project management module. Users can create and assign tasks, track progress, and communicate with team members all within the system. The real-time notification feature ensures that everyone stays updated on project developments, enhancing coordination and improving overall project efficiency.5. Reporting and AnalyticsM2012 includes a robust reporting and analytics module that provides valuable insights into business performance. Users can generate customized reports, visualize data through charts and graphs, and analyze trends. By leveraging these features, businesses can make data-driven decisions and optimize their operations for better results.BenefitsImplementing M2012 into your business workflow can result in several key benefits, including:1. Increased ProductivityBy streamlining various processes and providing a centralized platform, M2012 eliminates the need for multiple tools and systems. This consolidation allows users to save time and focus on their core responsibilities, ultimately driving productivity improvements.2. Enhanced CollaborationM2012’s collaborati on features enable team members to easily communicate, share files, and collaborate on projects in real-time. This eliminates delays caused by the exchange of emails or the use of separate collaboration tools, fostering a more seamless and efficient work environment.3. Improved Customer EngagementThe CRM module in M2012 helps businesses deliver personalized experiences to their customers. By storing crucial customer information and tracking interactions, businesses can better understand customer needs and preferences, leading to improved customer engagement and loyalty.4. Data-Driven Decision MakingThe reporting and analytics module in M2012 provides valuable insights into business performance. By analyzing trends and visualizing data, businesses can make informed decisions and optimize their strategies for better results.5. Time and Cost SavingsM2012 eliminates the need for manual and repetitive tasks, saving users valuable time. By reducing administrative overhead and improving process efficiency, businesses can achieve cost savings and allocate resources more effectively.ConclusionM2012 is a powerful software system that offers a wide range of features to streamline workflows and enhance productivity. With its task management, CRM, document management, project collaboration, and reporting capabilities, businesses can simplify everyday tasks, improve customer engagement, and make data-driven decisions. By implementing M2012, businesses can unlock new levels of efficiency and achieve better results in less time.。

上海2012年投入产出表

513 2835671 232159 666033 192422 3740 3969 180417 233722 15035 20681 402135 12292 308624 17242 227 12694 1712 0 1644 2771 19049731 601213 581851 578648 1172724 2934436 21984167

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

247 0 264080 209473 55982 15331 17990 767706 358526 78074 58387 197533 5706 965304 68950 644 137936 8289 0 4176 459 9892841 2013326 5023648 560656 1688352 9285981 19178822

1353 29697 203788 389056 54046 20271 10866 414771 248741 41853 121476 135124 26631 171160 17643 693 70830 7110 0 3895 658 8249362 1100858 471256 309467 850605 2732185 10981548

化学产品

12 326940 250536 1110344 1 20695 312582 306237 42160 123485 561476 6651019 19036627 560630 256728 147983 195985 16441 2165 20117 7360 4546

65 2012 EC

COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) No 65/2012of 24 January 2012implementing Regulation (EC) No 661/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council asregards gear shift indicators and amending Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament andof the Council(Text with EEA relevance)THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,Having regard to Regulation (EC) No 661/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning type- approval requirements for the general safety of motor vehicles, their trailers and systems, components and separate technical units intended therefor ( 1 ) and in particular Article 14(1)(a) thereof,Whereas:(1) Regulation(EC) No 661/2009 requires the installation of gear shift indicators (GSI) on all vehicles, which are fittedwith a manual gearbox, of category M 1 with a reference mass not exceeding 2 610 kg and vehicles to which type- approval is extended in accordance with Article 2(2) of Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2007 on type-approval of motor vehicles with respect to emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6) and on access to vehicle repair and maintenance information ( 2 ).(2) Regulation(EC) No 661/2009 requires the technical details of its provisions on GSI to be defined by imple menting legislation. It is now necessary to set out the specific procedures, tests and requirements for such type- approval of GSI.(3) Directive2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 September 2007 establishing aframework for the approval of motor vehicles and their trailers, and of systems, components and separate technical units intended for such vehicles (Framework Directive) ( 3 ) should therefore be amended accordingly.(4) The measures provided for in this Regulation are in accordance with the opinion of the Technical Committee — Motor Vehicles,HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION:Article 1 ScopeThis Regulation applies to vehicles of category M 1 which comply with the following requirements:— they are fitted with a manual gearbox,— they have a reference mass not exceeding 2 610 kg or type- approval is extended to them in accordance with Article 2(2) of Regulation (EC) No 715/2007. This Regulation does not apply to ‘vehicles designed to fulfil specific social needs’ as defined in Article 3(2)(c) of Regulation (EC) No 715/2007.Article 2 DefinitionsFor the purposes of this Regulation, the following definitions shall apply in addition to the definitions set out in Regulation (EC) No 661/2009:(1) ‘vehicle type with regard to the GSI’ means a group ofvehicles, which do not differ with respect to functional characteristics of the GSI and the logic used by the GSI to determine when to indicate a gearshift point. Examples of different logics include, but are not limited to:(i) upshifts indicated at specified engine speeds;(ii) upshifts indicated when specific fuel consumptionengine maps show that a specified minimum fuel consumption improvement will be delivered in the higher gear; (iii) upshifts indicated when torque demand can be met inthe higher gear;(2) ‘functional characteristics of the GSI’ means the set of inputparameters, such as engine speed, power demand, torque and their variation in time, determining the GSI indicationand the functional dependence of the GSI indications on these parameters; (3) ‘operational mode of the vehicle’ means a state of thevehicle, in which shifts between at least two forward gears may occur;( 1 ) OJ L 200, 31.7.2009, p. 1. ( 2 ) OJ L 171, 29.6.2007, p. 1. ( 3 ) OJ L 263, 9.10.2007, p. 1.(4) ‘manual mode’ means an operational mode of the vehicle,where the shift between all or some of the gears is always an immediate consequence of an action of the driver;(5) ‘tailpipe emissions’ means tailpipe emissions as defined inArticle 3(6) of Regulation (EC) No 715/2007.Article 3Assessment of manual gearboxFor the purpose of assessing whether a gearbox meets the definition according to Article 3(16) of Regulation (EC) No 661/2009, a gearbox having at least one manual mode according to Article 2(4) of this Regulation shall be considered as a ‘manual gearbox’. For this assessment, automatic changes between gears, which are performed not to optimise the operation of the vehicle but only under extreme conditions for reasons such as protecting or avoiding the stalling of the engine, are not considered.Article 4EC type-approval1. Manufacturers shall ensure that vehicles placed on the market, which are covered by Article 11 of Regulation (EC) No 661/2009, are equipped with GSI in accordance with the requirements of Annex I to this Regulation.2. To obtain an EC type-approvalfor the vehiclescoveredby Article 11 of Regulation (EC) No 661/2009, the manufacturer shall fulfil the following obligations:(a) draw up and submit to the type-approval authority aninformation document in accordance with the model set out in Part 1 of Annex II to this Regulation;(b) submit to the type-approval authority a declaration layingdown that, according to the manufacturer’s assessment, the vehicle complies with the requirements set out in this Regulation;(c) present to the type-approval authority a certificate established in accordance with the model set out in Part 2 of Annex II to this Regulation; (d) either(i) submit to the type-approval authority the GSI gear shiftpoints determined analytically as provided for in the lastparagraph of point 4.1 to Annex I; or(ii) submit to the technical service responsible for conducting the type-approval tests a vehicle which isrepresentative of the vehicle type to be approved toenable the test described in point 4 of Annex I to becarried out.3. Based on the elements provided by the manufacturer under points (a), (b) and (c) of paragraph 2 and the results of the type-approval test referred to in point (d) of paragraph 2, the type-approval authority shall assess compliance with the requirements of Annex I.It shall issue an EC type-approval certificate according to the model set out in Part 3 of Annex II to this Regulation for the vehicles covered by Article 11 of Regulation (EC) No 661/2009 only if such compliance is established.Article 5Monitoring the effects of legislationFor the purpose of monitoring the effects of this Regulation and evaluating the need for further developments, manufacturers and type-approval authorities shall make available to the Commission, upon request, the information set out in Annex II. This information shall be treated in a confidential manner by the Commission and its delegates.Article 6Amendments to Directive 2007/46/EC Annexes I, III, IV, VI and XI to Directive 2007/46/EC are amended in accordance with Annex III to this Regulation.Article 7Entry into forceThis Regulation shall enter into force on the 20th day following its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States. Done at Brussels, 24 January 2012.For the CommissionThe PresidentJosé Manuel BARROSOANNEX ISPECIAL REQUIREMENTS FOR VEHICLES EQUIPPED WITH GEAR SHIFT INDICATORS (GSI)GSItheappearanceof1. Characteristic1.1. The shift recommendation shall be provided by means of a distinct visual indication, for example a clear indicationto shift up or up/down or a symbol that identifies the gear into which the driver should shift. The visible indication may be complemented by other indications, including audible ones, provided that these do not compromise safety.1.2. The GSI must not interfere with or mask the identification of any tell-tale, control or indicator, which is mandatedor supports the safe operation of the vehicle. Notwithstanding point 1.3, the signal shall be designed so that it does not distract the driver’s attention and to avoid interfering with proper and safe vehicle operation.1.3. The GSI shall be located in compliance with paragraph 5.1.2 of UNECE Regulation No 121. It shall be designedsuch that it can not be confused with any other tell-tale, control or indicator the vehicle is equipped with.1.4. An information display device may be used to display GSI indications provided that they are sufficiently differentfrom other indications so as to be clearly visible and identifiable by the driver.1.5. Temporarily, the GSI indication may be automatically overridden or deactivated in exceptional situations. Suchcircumstances are those that may compromise the safe operation or integrity of the vehicle, including activation of traction or stability control systems, temporary displays from driver assistance systems or events relating to vehicle malfunctioning. The GSI shall resume normal operation after the exceptional situations ceased to exist, and withina delay of 10 seconds or longer, if justified by specific technical or behavioural reasons.toallmodes)(applicablemanualGSIrequirements2. Functionalfor2.1. The GSI shall suggest changing the gear when the fuel consumption with the suggested gear is estimated to belower than the current one giving consideration to the requirements laid down in points 2.2 and 2.3.2.2. The GSI shall be designed to encourage an optimised fuel efficient driving style under reasonably foreseeabledriving conditions. Its main purpose is to minimise the fuel consumption of the vehicle when the driver follows its indications. However, regulated tailpipe emissions shall not be disproportionately increased with respect to the initial state when following the indication of the GSI. In addition, following the GSI strategy should not have any negative effect on the timely functioning of pollution control devices, such as catalysts, after a cold start. For this purpose vehicle manufacturers should provide technical documentation to the type-approval authority, which describes the impact of the GSI strategy on the vehicle’s regulated tailpipe emissions, under at least steady vehicle speed.2.3. Following the indication of the GSI must not compromise the safe operation of the vehicle, e.g. to prevent stallingof the engine, insufficient engine braking or insufficient engine torque in the case of high power demand.providedbe3. Informationto3.1. The manufacturer shall provide the following information to the type-approval authority. The information shall bemade available in the following two parts:(a) the ‘formal documentation package’ that may be made available to interested parties upon request;(b) the ‘extended documentation package’ that shall remain strictly confidential.3.1.1. The formal documentation package shall contain:(a) a description of the complete set of appearances of the GSIs which are fitted on vehicles being part of thevehicle type with regard to GSI, and evidence of their compliance with the requirements of point 1;(b) evidence in the form of data or engineering evaluations, for example modelling data, emission or fuelconsumption maps, emission tests, which adequately demonstrate that the GSI is effective in providing timely and meaningful shift recommendations to the driver in order to comply with the requirements ofpoint 2;(c) an explanation of the purpose, use and functions of the GSI in a ‘GSI section’ of the user manual accompanying the vehicle.3.1.2. The extended documentation package shall contain the design strategy of the GSI, in particular its functionalcharacteristics.3.1.3. Notwithstanding the provisions of Article 5, the extended documentation package shall remain strictly confidentialbetween the type-approval authority and the manufacturer. It may be kept by the type-approval authority, or, at the discretion of the type-approval authority, may be retained by the manufacturer. In the case the manufacturer retains the documentation package, that package shall be identified and dated by the type-approval authority once reviewed and approved. It shall be made available for inspection by the approval authority at the time of approval or at any time during the validity of the approval.3.2. The manufacturer shall provide an explanation of the purpose, use and functions of the GSI in a ‘GSI section’ ofthe user manual accompanying the vehicle.beshallpointsshiftdeterminedthetoaccordingoffuel4. ThegeareconomyimpactrecommendedGSIfollowing procedure:4.1.Determination of vehicle speeds at which GSI recommends shifting up gearsThis test is to be performed on a warmed up vehicle on a chassis dynamometer according to the speed profile described in Appendix 1 to this Annex. The advice of the GSI is followed for shifting up gears and the vehicle speeds, for which the GSI recommends shifting, are recorded. The test is repeated 3 times.V n GSI shall denote the average speed at which the GSI recommends shifting up from gear n (n = 1, 2, …, #g) into gear n + 1, determined from the 3 tests, where #g shall denote the vehicle’s number of forward gears. For this purpose only GSI shift instructions in the phase before the maximum speed is reached are taken into account and any GSI instruction during the deceleration is ignored.For the purposes of the following calculations V0 GSI is set to 0 km/h and V#g GSI is set to 140 km/h or the maximum vehicle speed, whichever is smaller. Where the vehicle cannot attain 140 km/h, the vehicle shall be driven at its maximum speed until it rejoins the speed profile in Figure I.1.Alternatively, the recommended GSI shift speeds may be analytically determined by the manufacturer based on the GSI algorithm contained in the extended documentation package provided according to point 3.1.4.2. Standard gear shift pointsV n std shall denote the speed at which a typical driver is assumed to shift up from gear n into gear n + 1 without GSI recommendation. Based on the gear shift points defined in the type 1 emission test (1) the following standard gear shift speeds are defined:V0 std= 0 km/h;V1 std= 15 km/h;V2 std= 35 km/h;V3 std= 50 km/h;V4 std= 70 km/h;V5 std= 90 km/h;V6 std= 110 km/h;V7 std= 130 km/h;V8 std= V#g GSI;V n min shall denote the minimum vehicle speed the vehicle can be driven in the gear n without stalling of the engine and V n max the maximum vehicle speed the vehicle can be driven in the gear n without creating damage to the engine.If V n std derived from this list is smaller than V n + 1 min, then V n std is set to be V n + 1 min. If V n std derived from this list is greater than V n max, then V n std is set to be V n max(n = 1, 2, …, #g – 1).If V#g std determined by this procedure is smaller than V#g GSI, it shall be set to V#g GSI.(1) Defined in Annex 4a of UNECE Regulation No 83, 05 series of amendments.4.3. Fuel consumption speed curvesThe manufacturer shall supply the type-approval authority with the functional dependence of the vehicle’s fuel consumption on the steady vehicle speed when driving with gear n according to the following rules.FC n i shall denote the fuel consumption in terms of kg/h (kilograms per hour) when the vehicle is driven with the constant vehicle speed v i= i × 5 km/h – 2,5 km/h (where i is a positive integer number) in the gear n. These data shall be provided by the manufacturer for each gear n (n = 1, 2, …, #g) and v n min≤v i≤v n max. These fuel consumption values shall be determined under identical ambient conditions corresponding to a realistic driving situation that may be defined by the vehicle manufacturer, either by a physical test or by an appropriate calculation model agreed between the approval authority and the manufacturer.4.4. Vehicle speed distributionThe following distribution should be used for the probability P i that the vehicle drives with a speed v, where v i– 2,5 km/h < v ≤v i+ 2,5 km/h (i = 1, …, 28):Where the maximum speed of the vehicle corresponds to step i and i < 28, the values of P i + 1to P28shall be added to P i.4.5. Determination of the model fuel consumptionFC GSI shall denote the fuel consumption of the vehicle when the driver follows the advice of the GSI:FC GSI i= FC n i, where V n – 1 GSI≤v i< V n GSI(for n = 1, …, #g) and FC GSI i= 0 if v i≥V#g GSIFC GSI¼Σ28 i¼1P iÜ FC GSI i=100FC std shall denote the fuel consumption of the vehicle when standard gear shift points are used:FC std i= FC n i, where V n – 1 std≤v i< V n std(for n = 1, …, #g) and FC std i= 0 if v i≥V#g GSIFC std¼Σ28 i¼1P iÜ FC std i=100The relative saving of fuel consumption by following the advice of the GSI of the model is calculated as:FC rel. Save= (1 – FC GSI/FC std) × 100 %4.6. Data recordsThe following information shall be recorded:— the values of V n GSI as determined according to point 4.1,— the values FC n i of the fuel consumption speed curve as communicated by the manufacturer according to point 4.3,— the values FC GSI, FC std and FC rel. Save as calculated according to point 4.5.Description of vehicle speed profile referred to in point 4.1The tolerances for deviation from this speed profile are defined in point 6.1.3.4 of Annex 4a of UNECE Regulation No83, 05 series of amendments.Graphical representation of the speed profile referred to in point 4.1; solid line: speed profile; dashed lines:tolerances for deviation from this speed profileThe following table provides a second by second description of the speed profile. Where the vehicle is unable to attain 140 km/h, it shall be driven at its maximum speed until it rejoins the above speed profile.ANNEX IIPART 1Information documentMODELInformation document No … relating to EC type-approval of a vehicle with regard to gear shift indicators.The following information, if applicable, must be supplied in triplicate and include a list of contents. Any drawings must be supplied in appropriate scale and in sufficient detail on size A4 or on a folder of A4 format. Photographs, if any, must show sufficient detail.If the systems, components or separate technical units have electronic controls, information concerning their performance shall be supplied.Information set out in points 0, 3 and 4 of Appendix 3 to Annex I of Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 (1):4.11. Gear shift indicator (GSI)4.11.1. Acoustic indication available yes/no (2). If yes, description of sound and sound level at the driver’s ear in dB(A).(Acoustic indication always switchable on/off): ...........................................................................................................................4.11.2. Information according to point 4.6 of Annex I (manufacturer’s declared value): ...........................................................4.11.3. Information according to point 3.1.1 of Annex I: ....................................................................................................................4.11.4. Information according to point 3.1.2 of Annex I: ....................................................................................................................4.11.5. Photographs and/or drawings of the gear shift indicator instrument and brief description of the systemcomponents and operation: ...............................................................................................................................................................4.11.6. Information on the GSI in the vehicle’s user manual: .............................................................................................................(1) OJ L 199, 28.7.2008, p. 1.(2) Delete where not applicableMODELEC type-approval certificateMODEL(maximum format: A4 (210 × 297 mm))EC TYPE-APPROVAL CERTIFICATEStamp of EC type-approval authority Communication concerning the— EC type-approval (1)— extension of EC type-approval (1)— refusal of EC type-approval (1)— withdrawal of EC type-approval (1)of a type of a vehicle with regard to gear shift indicatorwith regard to Regulation (EU) No 65/2012 as last amended by Regulation (EU) No …/2012 (1)EC type-approval number: ................................................................................................................................................................................. Reason for extension: ..........................................................................................................................................................................................SECTION I0.1. Make (trade name of manufacturer): .................................................................................................................................................0.2. Type: ............................................................................................................................................................................................................0.2.1. Commercial name(s), (if available): .....................................................................................................................................................0.3. Means of identification of type, if marked on the vehicle ........................................................................................................0.3.1. Location of that marking: .....................................................................................................................................................................0.4. Category of vehicle: .................................................................................................................................................................................0.5. Name and address of manufacturer: ..................................................................................................................................................0.8. Name(s) and address(es) of assembly plant(s) .................................................................................................................................0.9. Name and address of the manufacturer’s representative (if any) .............................................................................................(1) Delete where not applicable1. Additional information (where applicable): see addendum2. Technical service responsible for carrying out the test and evaluations:3. Date of test report:4. Number of test report:5. Information according to point 4.6 of Annex I to Regulation (EU) No 65/2012 (determined at type-approval):6. Remarks (if any): see addendum7. Place:8. Date:9. Signature:Attachments: Information packageTest reportAdditional information: …Addendum to EC type-approval certificate No … concerning …AMENDMENTS TO FRAMEWORK DIRECTIVE 2007/46/ECDirective 2007/46/EC is amended as follows:1. In Annex I the following points are inserted:‘4.11. Gear shift indicator (GSI)4.11.1. Acoustic indication available yes/no (1). If yes, description of sound and sound level at the driver’s ear in dB(A).(Acoustic indication always switchable on/off)4.11.2. Information according to point 4.6 of Annex I to Regulation (EU) No 65/2012 (manufacturer’s declared value)4.11.3. Photographs and/or drawings of the gear shift indicator instrument and brief description of the systemcomponents and operation:’2. In Annex III the following points are inserted:‘4.11. Gear shift indicator (GSI)4.11.1. Acoustic indication available yes/no (1). If yes, description of sound and sound level at the driver’s ear in dB(A).(Acoustic indication always switchable on/off)4.11.2. Information according to point 4.6 of Annex I to Regulation (EU) No 65/2012 (determined at type-approval)’3. Part I of Annex IV is amended as follows:(a) in the table, the following point 63.1 is inserted:(b) in the Appendix, in the table, the following point 63.1 is inserted:4. In the Appendix to Annex VI, in the table, the following point 63.1 is inserted:5. Annex XI is amended as follows:(a) In Appendix 1, in the table, the following point 63.1 is inserted:(b) In Appendix 2, in the table, the following point 63.1 is inserted:(c) In Appendix 3, in the table, the following point 63.1 is inserted:(d) In Appendix 4, in the table, between the columns headed ‘Regulatory act reference’ and ‘M2’ a column ‘M1’ isadded and the following point 63.1 is inserted:。

美国2012年EPA

2012 Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories2012 Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health AdvisoriesEPA 822-S-12-001Office of WaterU.S. Environmental Protection AgencyWashington, DCSpring 2012Date of update: April, 2012Recycled/RecyclablePrinted on paper that containsat least 50% recycled fiber.Spring 2012 Page iii of vi The Health Advisory (HA) Program, sponsored by the EPA’s Office of Water (OW), publishes concentrations of drinking water contaminants at Drinking Water Specific Risk Level Concentration for cancer (10-4 Cancer Risk) and concentrations of drinking water contaminants at which noncancer adverse health effects are not anticipated to occur over specific exposure durations - One-day, Ten-day, and Lifetime - in the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories (DWSHA) tables. The One-day and Ten-day HAs are for a 10 kg child and the Lifetime HA is for a 70 kg adult. The daily drinking water consumption for the 10 kg child and 70 kg adult are assumed to be 1 L/day and 2 L/day, respectively. The Lifetime HA for the drinking water contaminant is calculated from its associated Drinking Water Equivalent Level (DWEL), obtained from its RfD, and incorporates a drinking water Relative Source Contribution (RSC) factor of contaminant-specific data or a default of 20% of total exposure from all sources. Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) for some regulated drinking water contaminants are also published.HAs serve as the informal technical guidance for unregulated drinking water contaminants to assist Federal, State and local officials, and managers of public or community water systems in protecting public health as needed. They are not to be construed as legally enforceable Federal standards. EPA’s OW has provided MCL, MCLGs, RfDs, One-Day HAs, Ten-day HAs, DWELs, and Lifetime HAs. Drinking Water Specific Risk Level Concentration for cancer (10-4 Cancer Risk), and Cancer Descriptors in the DWSHA tables. HAs are intended to protect against noncancer effects. The 10-4 Cancer Risk level provides information concerning cancer effects. The MCL values for specific drinking water contaminants must be used for regulated contaminants in public drinking water systems.The DWSHA tables are revised periodically by the OW so that the benchmark values are consistent with the most current Agency assessments. Reference dose (RfD) values are updated to reflect the values in the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) and the Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) Reregistration Eligibility Decisions (REDs) documents. The associated DWEL is recalculated accordingly.A Lifetime noncancer benchmark is made available to risk assessment managers for comparison to the cancer risk level drinking water concentration (10-4 Cancer Risk) and to determine whether the noncancer Lifetime HA or the cancer risk level drinking water concentration provides a more meaningful scenario-specific risk reduction. In this regard, the Office of Water defines the Lifetime HA as the concentration in drinking water that is not expected to cause any adverse noncarcinogenic effects for a lifetime of exposure, whereas the 10-4 Cancer Risk is the concentration of the chemical contaminant in drinking water that is associated with a specific probability of cancer. The Office of Water also advises consideration of the more conservative cancer risk levels (10-5, 10-6), found in the IRIS or OPP RED source documents, if it is considered more appropriate for exposure-specific risk assessment.iiiSpring 2012 Page iv of vi Many of the values on the DWSHA tables have been revised since the original HAs were published. Revised RfDs, 10-4 Cancer Risk values, and cancer designations or descriptors obtained from Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS), and One-day and Ten-dayHealth Advisories are presented in BOLD type. Revised RfDs, 10-4 Cancer Risk values, and cancer designations or descriptors obtained from Office of Pesticide Program’sRegistration Eligibility Decision (OPP RED) are presented in BOLD ITALICS type.The summaries of IRIS Toxicological Reviews from which the RfDs and cancerbenchmarks, as well as the associated narratives and references can be accessed at:/IRIS. Those from OPP REDs can be accessed at:/pesticides/reregistration/status.htm.In some cases, there is an HA value for a contaminant but there is no reference to an HA document. Such HA values can be found in the Drinking Water Criteria Document forthe contaminant.With a few exceptions, the RfDs, Health Advisories, and Cancer Risk values have beenrounded to one significant figure following the convention adopted by IRIS.For unregulated chemicals with current IRIS or OPP REDs RfDs, the Lifetime HealthAdvisories are calculated from the associated DWELs, using the RSC values published in the HA documents for the contaminants.The DWSHA tables may be reached from the Water Science home page at:/waterscience/. The DWSHA tables are accessed under the Drinking Water icon.Copies the Tables may be ordered free of charge fromSAFE DRINKING WATER HOTLINE1-800-426-4791Monday thru Friday, 9:00 AM to 5:30 PM ESTivSpring 2012 Page v of vi DEFINITIONSThe following definitions for terms used in the DWSHA tables are not all-encompassing, and should not be construed to be “official” definitions. They are intended to assist the user in understanding terms used in the DWSHA tables.Action Level: The concentration of a contaminant which, if exceeded, triggers treatment or other requirements which a water system must follow. For example, it is the level of lead or copper which, if exceeded in over 10% of the homes tested, triggers treatment for corrosion control. Cancer Classification: A descriptive weight-of-evidence judgment as to the likelihood that an agent is a human carcinogen and the conditions under which the carcinogenic effects may be expressed. Under the 2005 EPA Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment, Cancer Descriptors replace the earlier alpha numeric Cancer Group designations (US EPA 1986 guidelines). The Cancer Descriptors in the 2005 EPA Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment are as follows: •“carcinogenic to humans” (H)•“likely to be carcinogenic to humans” (L)•“likely to be carcinogenic above a specified dose but not likely to be carcinogenic below that dose because a key event in tumor formation does not occur below that dose” (L/N) •“suggestive evidence of carcinogenic potential” (S)•“inadequate information to assess carcinogenic potential” (I)•“not likely to be carcinogenic to humans” (N)The letter abbreviations provided parenthetically above are now used in the DWSHA tables in place of the prior alpha numeric identifiers for chemicals that have been evaluated under the new guidelines (the 2005 guidelines or the 1996 and 1999 draft guidelines) or whose records in the DWSHA tables have been revised.Cancer Group: A qualitative weight-of-evidence judgment as to the likelihood that a chemical may be a carcinogen for humans. Each chemical was placed into one of the following five categories (US EPA 1986 guidelines). The Cancer Group designations are given in the Tables for chemicals that have not yet been evaluated under the new guidelines or whose records in the DWSHA tables have been revised.Group CategoryA Human carcinogenB Probable human carcinogen:B1 indicates limited human evidencevSpring 2012 Page vi of vi B2 indicates sufficient evidence in animals and inadequate or no evidence in humansC Possible human carcinogenD Not classifiable as to human carcinogenicityE Evidence of noncarcinogenicity for humans10-4 Cancer Risk: The concentration of a chemical in drinking water corresponding to an excess estimated lifetime cancer risk of 1 in 10,000.Drinking Water Advisory: A nonregulatory concentration of a contaminant in water that is likely to be without adverse effects on health and aesthetics for the period it is derived.DWEL: Drinking Water Equivalent Level. A DWEL is a drinking water lifetime exposure level, assuming 100% exposure from that medium, at which adverse, noncarcinogenic health effects would not be expected to occur.HA: Health Advisory. An estimate of acceptable drinking water levels for a chemical substance based on health effects information; an HA is not a legally enforceable Federal standard, but serves as technical guidance to assist Federal, State, and local officials.One-Day HA: The concentration of a chemical in drinking water that is not expected to cause any adverse noncarcinogenic effects for up to one day of exposure. The One-Day HA is intended o protect a 10-kg child consuming 1 liter of water per day.Ten-Day HA: The concentration of a chemical in drinking water that is not expected to cause any adverse noncarcinogenic effects for up to ten days of exposure. The Ten-Day HA is also intended to protect a 10-kg child consuming 1 liter of water per day.Lifetime HA: The concentration of a chemical in drinking water that is not expected tocause any adverse noncarcinogenic effects for a lifetime of exposure, incorporating adrinking water RSC factor of contaminant-specific data or a default of 20% of totalexposure from all sources. The Lifetime HA is based on exposure of a 70-kg adultconsuming 2 liters of water per day. For Lifetime HAs developed for drinking watercontaminants before the Lifetime HA policy change to develop Lifetime HAs for alldrinking water contaminants regardless of carcinogenicity status in this DWSHA update, the Lifetime HA for Group C carcinogens, as indicated by the 1986 Cancer Guidelines,includes an uncertainty adjustment factor of 10 for possible carcinogenicity.MCLG: Maximum Contaminant Level Goal. A non-enforceable health benchmark goal which is set at a level at which no known or anticipated adverse effect on the health of persons is expected to occur and which allows an adequate margin of safety.viSpring 2012 Page vii of vi MCL: Maximum Contaminant Level. The highest level of a contaminant that is allowed in drinking water. MCLs are set as close to the MCLG as feasible using the best available analytical and treatment technologies and taking cost into consideration. MCLs are enforceable standards. Oral cancer slope factor: The slope factor is the result of application of a low-dose extrapolation procedure and is presented as the risk per (mg/kg)/day.RfD: Reference Dose. An estimate (with uncertainty spanning perhaps an order of magnitude) of a daily oral exposure to the human population (including sensitive subgroups) that is likely to be without an appreciable risk of deleterious effects during a lifetime.Risk Specific Level Concentration: The concentration of the chemical contaminant in drinking water or air providing cancer risks of 1 in 10,000, 1 in 100,000, or 1 in 100,000,000.SDWR: Secondary Drinking Water Regulations. Non-enforceable Federal guidelines regarding cosmetic effects (such as tooth or skin discoloration) or aesthetic effects (such as taste, odor, or color) of drinking water.TT: Treatment Technique. A required process intended to reduce the level of a contaminant in drinking water.Unit Risk: The unit risk is the quantitative estimate in terms of either risk per µg/L drinking water or risk per µg/m3 air breathed.viiSpring 2012 Page viii of vi ABBREVIATIONSD DraftDWEL Drinking Water Equivalent LevelDWSHA Drinking Water Standards and Health AdvisoriesF FinalHA Health AdvisoryI InterimIRIS Integrated Risk Information SystemMCL Maximum Contaminant LevelMCLG Maximum Contaminant Level GoalNA Not ApplicableNOAEL No-Observed-Adverse-Effect LevelOPP Office of Pesticide ProgramsOW Office of WaterP ProposedPv ProvisionalRED Registration Eligibility DecisionReg RegulationRfD Reference DoseTT Treatment Techniqueviii。

微软Volume Licensing 消费化IT指南说明书

B r i e fMICROSOFT LICENSING FOR THE CONSUMERIZATION OF IT May 2012All Volume License ProgramsContents Summary (1)Introduction (1)Key Questions to Ask in Any Scenario (1)Common Scenarios (2)Scenario 1: Bringing a Tablet Device Not Running Windows to Work (2)Scenario 2: Working Remotely (3)Scenario 3: Bring Your Own PC (4)Scenario 4: The Road Warrior (6)Coming Enhancements with Windows 8 (7)Additional Resources (7)SummaryThe purpose of this brief is to guide users on Microsoft Volume Licensing requirements for common scenarios related to their using various personal devices at work. This brief applies to Windows 7 and prior versions. IntroductionWhether you refer to it as the “Consumerization of IT (CoIT)” or “Bring Your Own Device (BYOD),” one thing is certain: The proliferation of personal devices and users expecting that they can use them for work-related purposes presents new opportunities—and new challenges. The anytime, anywhere access to information and people opens up new avenues for user collaboration and productivity. However, this has left many IT departments scrambling to accommodate user expectations and determine how they will support new technologies while maintaining control over their IT data and network. One challenge is ensuring that users and devices are properly licensed. Microsoft licensing is continually evolving to meet this challenge. The keys to determining proper licensing are to ask the right questions and understand the scenario and requirements. The following information will guide you on what questions to ask and some common scenarios to help you determine your licensing needs.Key Questions to Ask in Any ScenarioWhen determining the licensing requirements for a given scenario, consider some key questions about the user, the device, and the location that will inform your decision.User Device LocationCommon ScenariosThe following hypothetical scenarios are designed to illustrate the licensing requirements for five common CoIT scenarios.Scenario 1: Bringing a Tablet Device Not Running Windows to Worksituationkey questionsrequired licensesrecommended approachScenario 2: Working Remotelysituationkey questionsrequired licensesrecommended approach Scenario 3: Bring Your Own PCsituationkey questionsrequired licensesrecommended approachScenario 4: The Road Warriorsituationkey questionsrequired licensesrecommended approachComing Enhancements with Windows 8Windows 8 licensing will offer even more flexibility for addressing the consumerization of IT. For a preview, refer to this Windows Team Blog post.Additional ResourcesFor more information, please refer to the following Microsoft Volume Licensing briefs:∙Licensing Windows 7 for Use in Virtual Environments∙Licensing the Core CAL Suite and Enterprise CAL Suite∙Licensing Windows Server 2008 R2 Remote Desktop Services and Terminal Services∙Licensing Microsoft Desktop Application Software for Use with Windows Server Remote Desktop Services© 2012 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.This document is for informational purposes only. MICROSOFT MAKES NO WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IN THIS DOCUMENT. This information is provided to help guide your authorized use of products you license; it is not your agreement. Your use of products licensed under your volume license agreement is governed by the terms and conditions of that agreement. In the case of any conflict between this information and your agreement, the terms and conditions of your agreement control. Prices for licenses acquired through Microsoft resellers are determined by the reseller.。

Product-design and pricingstrategies with remanufacturing

Production,Manufacturing and LogisticsProduct-design and pricing strategies with remanufacturingCheng-Han Wu ⇑Department of Industrial Engineering and Management,National Yunlin University of Science and Technology,Yunlin 64002,Taiwan,ROCa r t i c l e i n f o Article history:Received 20April 2011Accepted 24April 2012Available online 5May 2012Keywords:Supply chain management Product design PricingRemanufacturing Game theorya b s t r a c tIn this paper,we consider a supply chain that consists of an original equipment manufacturer (OEM)pro-ducing new products and a remanufacturer recovering the used items.The OEM often faces a strategic dilemma when determining the degree of disassemblability of its product design,as high disassemblabil-ity decreases the OEM’s production costs as well as the remanufacturer’s recovery costs.However,high disassemblability may be harmful to the OEM in a market in which the remanufacturer is encouraged to intensify price competition with the OEM because design for high disassemblability leads to larger cost savings in remanufacturing.We first formulate a two-period model to investigate the OEM’s product-design strategy and the remanufacturer’s pricing strategy in an extensive-form game,in which the equilibrium decisions of the resulting scenarios are derived.Next,we show the thresholds that determine whether remanufacturing is constrained by collection,the thresholds for the remanufacturer’s choice of a profitable pricing strategy,and the thresholds for determining the OEM’s product-design strategy.Finally,we expand the model for a multiple-period problem to show that the main insights obtained from the two-period model can be applied.Ó2012Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.1.IntroductionRemanufacturing is important for consumers who desire lower-priced but environmentally friendly products.The prevalence of environmental awareness has encouraged remanufacturers to col-lect and recover end-of-life products produced by original equip-ment manufacturers (OEMs)through the remanufacturing process,which includes disassembly,cleaning,inspection,recondi-tioning,and reassembly.Because of the decrements in raw materials demanded and production processes,remanufacturing systems reduce not only the burdens on the environment but also produc-tion costs.Moreover,the supervision of non-governmental organi-zations and legislative pressure has also accelerated the growth of the remanufacturing industry.For example,according to a recent report conducted by Global Industry Analysts (2010),the global automotive remanufacturing industry is rapidly growing and is forecasted to reach US$104.8billion in 2015.Even if remanufactur-ing proves to be profitable,the other critical issue is the market po-sition of the remanufactured product.Some surveys have indicated that green consumers are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products.The remanufacturer may choose to either sell their product at a high price to obtain high margins from the green market segment or penetrate the whole market at a low price.As defined by Mok et al.(1997),we consider disassemblability as to be the degree to which the product can be disassembled without force.Designing product with high disassemblability is a contributing factor in the success of remanufacturing because of the decrease of the difficulty in recovery.As shown in various sur-veys,the profitability of remanufacturing is related to product de-sign (Kerr and Ryan,2001),and it is difficult and costly to recover used items from assemblies or equipment not designed for reman-ufacturing (Graedel and Allenby,1996).Design for disassembly may also be beneficial for OEMs,as it allows for ease of repair,inspection,handling,and cleaning.Thus,the design for disassembly appears to be a ‘‘win–win’’strategy if the OEM and remanufacturer are not in direct competition with each other.When this is not the case,some OEMs may adjust their design strategies by decreasing the degree of disassemblability to hinder remanufacturers (Shu and Flowers,1993).For example,in the printer-cartridge industry,a Gartner report (Tripathi et al.,2009)indicates that printer OEMs are losing revenue,which may exceed $13billion in 2010,because of competition from low-cost remanufactured products.In the face of such a great threat of remanufacturing,Hewlett–Packard (HP)Inc.still insists on producing only single-use cartridges and not offering remanufactured cartridges (HP Inc.,2009).However,some reports,e.g.,(Gell,2008;Gray and Charter,2007),indicate that printer OEMs try to deter remanufacturers by using the sonic weld-ing technique or adhesive tape in assembly process,which de-creases the disassemblability of components,in order to prevent remanufacturing their products.From the OEM’s perspective,the entry of remanufacturers into the market results in a competition between new and remanufactured products.To respond to the threat of competition from remanufactured products,the OEM0377-2217/$-see front matter Ó2012Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved./10.1016/j.ejor.2012.04.031Tel.:+88655342601;fax:+88655312073.E-mail address:wuchan@.twmay or may not utilize a product design with a low degree of dis-assemblability to increase the remanufacturer’s costs,and thus, prevent penetration by the remanufactured products.As a result, investigation of the interaction between the OEM’s product design strategy and the remanufacturer’s pricing strategy is interesting and insightful.In this study,we discuss the strategic interaction between an OEM and a remanufacturer,and provide the conditions for their strategies that lead to higher profits.Wefirst develop a two-period problem,and derive the conditions that bring about the remanu-facturer’s pricing regime.Then,we develop thresholds of the pro-portion of green consumers in the market that render focusing on the green segment with a high price more profitable for the remanufacturer than penetrating the whole market with a low price.Secondly,we obtain the thresholds of the market scale for the OEM’s equilibrium strategy(i.e.,above a level of the market scale,the high degree of disassemblability is economic for the OEM because the market is sufficiently large to achieve economies of scale).Some insights associated with the equilibrium choices of product design and pricing strategy are discovered from the numerical analysis.We further extend the model with a multi-ple-period planning horizon,in which the equilibrium prices of the OEM and the remanufacturer are characterized.We show that the OEM and the remanufacturer behave similarly within the two-period and multiple-period planning horizons.For instance,even if the high degree of disassemblability is profitable,the OEM may adopt low disassemblability due to concern about competition from the remanufacturer.However,when recovery costs increase, the OEM will profit by choosing the design with high disassembla-bility.Moreover,in some cases,the OEM can use a high degree of disassemblability to avoid competition with the remanufacturer that is encouraged to focus on green consumers,e.g.,when con-sumers highly value the remanufactured product(except at the ex-treme)and when the cost savings from disassemblability are significant.The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.Section2 surveys the related literature while comparing with our work.In Section3,we derive the market demand of the new and remanu-factured products from the utilities of the customers,and formu-late thefirms’profit functions of the considered scenarios in a two-period problem.Section4obtains the equilibrium operational decisions and profits under the two-period model.Based on these equilibrium results,the thresholds for determining thefirms’stra-tegic choices are derived,and some examples are provided for illustration.Section5conducts numerical studies under the two-period model,and discusses the effects of market and cost param-eters on the thresholds of remanufacturing and on thefirms’stra-tegic choices.In Section6,we extend the model to a multiple-period problem,and show that the chain members behave analo-gously in the two-period and multiple-period models.Thefinal section concludes the study with a brief summary,and points to potential research directions.2.Literature reviewThere are two streams of literature related to this study:one examines market segmentation in the face of competition between OEMs and remanufacturers,and the other examines product de-sign for remanufacturing/disassembly.The studies in thefirst stream argued that the market is differentiated based on new and remanufactured products when the consumers are heteroge-neous and have distinct valuations for new and remanufactured products(Atasu et al.,2008;Debo et al.,2005;Ferrer and Swaminathan,2006;Ferrer and Swaminathan,2010;Ferguson and Toktay,2006;Ray et al.,2005;Majumder and Groenevelt,2001).Majumder and Groenevelt(2001)investigated the competi-tion between an OEM and a local remanufacturer while consider-ing that remanufacturing in the second period was constrained by the availability of used cores from the OEM’s products,which were sold during thefirst period.Majumder and Groenevelt (2001)also outlined the impacts of costs and availability of returns on the chain members’equilibrium decisions and profits consider-ing various reverse logistics configurations.Such relationships be-tween new and remanufactured products are commonly adopted in the later studies.For example,Debo et al.(2005)examined the conditions that enable the OEM to determine product technology, which,in turn,influences the level of remanufacturability and then determined the joint pricing decisions in an infinite-horizon setting.Ferrer and Swaminathan(2006)studied monopoly and duopoly competitions in two-period,multiple-period,and infi-nite-horizon models,in which a fraction of the used items were collected by the OEM for free,and the rest were available to the remanufacturer;their work analyzed and characterized the equi-librium prices and quantities under such conditions.Ferguson and Toktay(2006)considered situations in which remanufacturing and preemptive collection strategies could be treated as entry (remanufacturer)deterrent strategies for the OEM;afterwards, they identified the cost conditions under which the preemptive collection strategy is profitable to the OEM and mathematically incorporated the unit costs,which are varied by volume and the fixed costs of the strategies.In this paper,we examine the concept that the OEM may more aggressively hinder the remanufacturer before the selling season by changing its disassemblability in prod-uct design.Furthermore,Atasu et al.(2008)expended thefindings of previous studies by considering a market composed of primary and green segments,in which the green consumers always prefer to buy the remanufactured product and give it the same value as the new product.They also considered market growth in the sec-ond period,which allows demand to expand or shrink based on the state of the product life cycle,and further specified the impacts of the market growth and the green segment on the remanufac-turer’s profitability.However,Atasu et al.(2008)focused on pricing competition between the chain members,regardless of the strate-gic interaction between them.Our study is distinct from the afore-mentioned studies,as it is in accordance with(Atasu et al.,2008)in its consideration of different market structure and Ferguson and Toktay(2006)in its examination of the strategic interaction be-tween the chain members,and moreover,we investigate the equi-librium behavior of the chain members’strategies and pricing decisions.Therefore,our model enables the investigation of how the OEM’s product-design strategy affects a remanufacturer’s pric-ing strategy in different market structures.We also show that mar-ket structure has significant impacts on the OEM’s product-design strategy as well as the remanufacturer’s pricing strategy.The second stream of literature primarily examined product design,especially the success principles of product design for remanufacturing(Chen,2001;Chung and Wee,2008;Gray and Charter,2007;Hoetker et al.,2007;Kim and Chhajed,2000; Maukhopadhyay and Setoputro,2005;Sundin,2004;Shu and Flowers,1993;Ulrich,1995).Sundin(2004)identified the goal of remanufacturing as the creation of value from end-of-life products, but found that some products may not be designed for this pur-pose,which increased the barriers and costs for remanufacturers during their rebuilding processes(e.g.,disassembly,replacement, and reassembly).Sundin also argued that design for disassembly is a key factor in achieving success in remanufacturing. Maukhopadhyay and Setoputro(2005)proposed the use of modu-lar product design as a solution for retaining the large salvageable value of returned products that were built for specific orders,i.e., returned products are easily dismantled and reused,so the products experience smaller value reduction.Kim and ChhajedC.-H.Wu/European Journal of Operational Research222(2012)204–215205(2000)indicated that the interchangeability of product design also creates cost savings during production because of lowered assem-bly costs and more easily achieved economies of scale.However, these studies considered product design as a given and focused on other purposes(e.g.,quality improvement,production cost sav-ings,and the reuse of return items);moreover,they did not con-sider the impact of product design on pricing decisions.Shu and Flowers(1993)noted that OEMs may discourage remanufacturing of their products by not sharing product specifications and manu-facturing processes or,more aggressively,by changing product de-sign to hinder remanufacturing.Gray and Charter(2007)surveyed the empirical data related to recent developments in remanufac-turing,and concluded that product design enablesfirms to resolve inefficiencies in remanufacturing and increase their own profit margins.Thus,products designed for the environment are impor-tant for the success of remanufacturing.Several studies(Graedel and Allenby,1996;Gray and Charter,2007;Kerr and Ryan,2001; Sundin,2004)showed the importance of product design to reman-ufacturing through qualitative data analysis.This study explicitly models the interaction between the OEM’s disassemblability in product design and the remanufacturer’s pricing strategy in a com-petitive environment.In contrast to the works of previous studies,the model of this paper shows that an OEM can design a product with low or high disassemblability to deter direct competition from the remanufac-turer in the sequent period.Furthermore,previous works on remanufacturing focused exclusively on operational decisions or the OEM’s strategic choices(Ferguson and Toktay,2006).In this study,we consider both the OEM’s and the remanufacturer’s stra-tegic choices and operational decisions(i.e.,sales prices)in a sequential game,and explore their behavior according to the stra-tegic choices presented to them.3.The modelWe consider a supply chain with two chain members:an OEM produces and sells a new product to the market during two periods (we extend the model to multiple periods in§6),and a remanufac-turer recovers the used products sold in thefirst period and sells them as remanufactured products during the second period.Thus, remanufacturing is constrained by the collected quantity of the items used in thefirst period.The price competition between the OEM and the remanufacturer arises in the second period.More-over,due to growing environmental awareness,a high-priced remanufactured product is usually accepted by green consumers. Therefore,the remanufacturer must make a strategic choice with regard to price:a high-pricing strategy that focuses only on the green market segment or a low-pricing strategy that penetrates the whole market.In thefirst period,the OEM usually must make a strategic choice in product design:high or low disassemblability.A product designed with high disassemblability will be easier to both assemble as a new product and disassemble for recovery than a product with low disassemblability,which leads to lower recov-ery costs.In accordance with the literature on remanufacturing (Atasu et al.,2008;Ferrer and Swaminathan,2006;Ferguson and Toktay,2006;Ray et al.,2005;Majumder and Groenevelt,2001), wefirst consider a two-period model for analyzingfirms’strategic and operational interactions with the consideration of remanufac-turing.Moreover,we extend the model with afinite multiple-per-iod planning horizon to examine the statics of the chain members’equilibrium behavior.Let r and n denote the remanufactured and new products, respectively.The OEM and the remanufacturer compete on both the strategic level and operational level.On the strategic level, the OEM chooses its product design’s disassemblability in thefirst period,and the remanufacturer chooses its pricing strategy in the subsequent period.High disassemblability is represented as Strat-egy H,low disassemblability as Strategy L,the remanufacturer’s high-pricing strategy as Strategy G,and the remanufacturer’s low-pricing strategy as Strategy S.As a result,four possible sub-games emerge based on thefirms’strategic choices.Each subgame is an operational level game in which the OEM determines its unit sales prices p1of thefirst period,and chooses p n for the subsequent period,while the remanufacture determines the unit sales price p r. Thefirms’pricing decisions of each selling period must be made prior to the start of sales.Therefore,the chain members’strategic choices are determined in consideration of their own profits ob-tained from the equilibrium decisions of the possible operational games.Throughout the paper,we focus on the cases in which the unit sales price of the remanufactured product is lower than the new product’s sales price(i.e.,p r<p n).Such scenarios have oc-curred in reality;for example,Dell sold refurbished PCs at10–30%less than the prices of new PCs on average(Kandra,2002). Due to energy and material cost savings,remanufactured products could be(and sometimes were)sold at30–70%of the prices of new products(Gray and Charter,2007).Based on the common assumptions of two-period models (Atasu et al.,2008;Ferguson and Toktay,2006;Majumder and Groenevelt,2001),we assume that the new product bought in thefirst period cannot provide positive utility for customers in the second period;therefore,without remanufacturing,the product has a useful lifetime of only one sales period.This assumption allows us to claim that consumers’purchase behaviors across the periods are independent(i.e.,a consumer does not determine the purchase decision in consideration of the utility of the product that was previously purchased).Furthermore,we assume that in the first period,the OEM behaves as a monopolist,and after thefirst period,the twofirms engage in duopolistic competition.Other products in the dedicated market and other markets have no effect on the demand of the products under consideration.Such an assumption allows us to shed light on the competition between the remanufactured and new products.We also consider thefirms to be risk-neutral and profit maximizing and to have complete information in the games.3.1.Consumer preference and market demandIn accordance with Atasu et al.(2008),we consider the market in thefirst period to consist of A consumers and the market size of the second period to be dependent on the product’s position in its life cycle.We use D A to represent the market size of the second period,where D is a scale parameter.When the product is in the growth(decline)phase of its life cycle,the market size of the sec-ond period expands(shrinks),so that D>1(<1).The market is composed of two types of consumers:primary consumers and green consumers.The primary consumers give the remanufactured products a lower value than the new products(Atasu et al.,2008; Debo et al.,2005;Ferguson and Toktay,2006).However,the green consumers focus more on recycling and prefer to purchase prod-ucts less harmful to the environment.Thus,these consumers equally value the remanufactured and new products.Please refer to Atasu et al.(2008)for more details on the discussion of the green segment of the market.Although in thefirst period,the pri-mary and green consumers cannot be differentiated due to the ab-sence of a remanufactured product in the market,when the remanufactured product becomes available,the green consumers’proportion of the market becomes b<1(i.e.,the green segment in-cludes b D A consumers,and the primary segment has(1Àb)D A consumers).Consumers are heterogenous in their willingness to pay for the products.We denote each consumer’s willingness to pay by h,and206 C.-H.Wu/European Journal of Operational Research222(2012)204–215capture the heterogeneity of h by assuming that h is uniformly distributed between 0and 1,i.e.,f (h )$Uniform[0,1](Atasu et al.,2008;Cattani et al.,2006;Ferguson and Toktay,2006;Ray et al.,2005).Because the consumer’s utility is sensitive to the prices,the utility of the consumers in Period 1is formulated as U 1=h Àp 1.It is easy to derive the demand quantity of Period 1as q 1=A (1Àp 1).In Period 2,the market can be divided into pri-mary and green segments,as (Atasu et al.,2008).In the primary segment,the consumers have lower valuations for the remanufac-tured products than the new ones by setting the primary consumer’s willingness to pay for a remanufactured product as a fraction q (0<q <1)of his or her willingness to pay for a new product.Hence,the primary consumer receives the utility U n =h Àp n from the new product and the utility U r =q h Àp r from the remanufactured product.Each primary consumer buys a prod-uct if and only if he or she receives a nonnegative utility,and each primary customer chooses which product to buy by comparing the utilities between the two products.More specifically,Let H n and H r be the sets of primary customer types who buy a new and remanufactured product,respectively.Then,H n ={h :U n P max{U r ,0}}and H r ={h :U r P max{U n ,0}}.The OEM’s market shareof the primary segment is m n ¼Rh 2H n f ðh Þd h and the remanufac-turer’s market share of the primary segment is m r ¼Rh 2H r f ðh Þd h .We assume q 61À(p n Àp r )such that q n >0(see Ferrer and Swaminathan (2006)),indicating that the OEM would not exit the market.When p r 6q p n ,the demand quantity of the remanufac-tured and new products from the primary consumers can be calculated as follows:q r ¼A m r ¼ð1Àb ÞD A q p n Àp rq ð1Àq Þ ;if p r 6q p n ;q n ¼A m n ¼ð1Àb ÞD A1Àq Àp n þp r1Àq:When p r >q p n ,the primary consumers do not purchase the reman-ufactured product,and the OEM grabs all the primary consumers:^q r ¼0;and ^q n ¼ð1Àb ÞD A ð1Àp n Þ;if p r >q p n :The utilities that green (environmentally conscious)consumersreceive from new and remanufactured products are U n =h Àp n and U r =h Àp r ,respectively.Because p r <p n ,the green consumer only purchases the remanufactured product,and the demand quan-tities are calculated as qr ¼b D A ð1Àp r Þand q n ¼0.In summary,there are two demand scenarios based on the remanufacturer’s pricing strategy (i.e.,low-pricing p r 6q p n or high pricing strategy p r >q p n ).Under the low-pricing strategy,the demand quantities of the new and remanufactured products in Period 2are q S n ¼q nand q S r ¼q r þ q r ,respectively;whereas,under the high pricingstrategy,q G n ¼^q n and q G r ¼ q r ,respectively.3.2.Problem formulationEach firm is endowed with two strategies:The OEM uses thenotation i and takes the two strategies L and H ,while the remanu-facturer takes the notation j and takes the two strategies S and G .Four subgames emerge as follows:HS ,LS ,HG ,and LG ,where the first and second letters signify the OEM’s and remanufacturer’s strategic choices,respectively.In each subgame,the firms compete with each other’s prices.We use P ij y to denote firm y ’s profit in Sub-game ij .As is typical of the strategic form game,the equilibrium strategy is obtained by examining the firms’equilibrium profits in the subgames.In each subgame,the firms play in a two-period noncooperative game (with no collusion);the OEM acts as the first mover and the remanufacturer as the second mover (i.e.,a Stackel-berg game).The OEM will decide its prices,p 1and p n ,while consid-ering the remanufacturer’s best response,p r .We now formulate the firms’profit functions.In our model,the OEM needs to carry the production costs and the fixed costs asso-ciated with disassemblability.The difficulty in assembly and disas-sembly of cores and parts is critical for determining the ease of recycling,replacing,and remanufacturing.Design for disassembly benefits the OEM by increasing production flexibility,saving pro-duction energy,and decreasing processing time and cost;however,it is also accompanied by greater fixed costs,such as the invest-ment costs of purchasing new equipment or updating facilities.Let c L and c H be the OEM’s unit production cost with low and high disassemblability,respectively.Note that c i must satisfy c i <1be-cause the consumer’s maximum willingness to pay equals 1.Low disassemblability may incur additional costs for the OEM (such as unnecessary adhesive tape (Gell,2008),difficulty of repair)and contrarily,high degree of disassemblability may cause the products to be produced efficiently,so that c L >c H .However,man-ufacturing a product with higher disassemblability incurs a higher fixed cost,which is represented by T i ,so that T L <T H .(Note that for simplicity,we let T L =0and T H =T in the following analysis.)More-over,the fixed cost is considered a one-time investment,which means that the fixed cost is only incurred in the first period,be-cause it is reasonable to assume that the equipment or facilities can be used during the planning periods.Following (Debo et al.,2005,Ferrer and Swaminathan,2006,Ferrer and Swaminathan,2010),we let d (06d 61)denote the value-discount factor over the periods,which means that a value decreases (1Àd )in compar-ison with that in the previous period.The OEM’s objective can be written as follows:max p 1;p n P 0P ij n ¼½ðp 1Àc i Þq 1ÀT i þd ðp n Àc i Þq jn ÂÃ;ð1Þwhere i ={L ,H }and j 2{S ,G }.The first term of Eq.(1)is the profit obtained in Period 1,and the second term is the profit obtained in Period 2.In the second period,the remanufacturer’s cost of remanufac-turing is associated with the OEM’s product design.Let w i repre-sent the remanufacturer’s recovery cost associated with the OEM’s Strategy i (i ={L ,H }).The high degree of disassemblability al-lows the remanufacturer to easily disassemble,clean,test,and re-place parts,thus reducing recovery costs,so that w L >w H .We consider that remanufacturing leads to cost savings in production,i.e.,w i <c i ,which drives the remanufacturer to enter the market.Without loss of generality,we do not explicitly formulate the cost structure with respect to the degree of disassemblability until Sec-tion 5.3,in which the relationship between cost and disassembla-bility is provided for illustration.The remanufacturer collects the used products at the end of Period 1for remanufacturing.In gen-eral,not all products can be remanufactured,or can be collected at the end of their life cycle.We conjecture that c q 1can be col-lected at the beginning of Period 2,where c is the collection rate with the acknowledgment that only a proportion of the used prod-ucts are obtained or available to be remanufactured.The remanu-facturing problem is constrained by the collected units,given bymax p r P 0P ij r ¼d ðp r Àw i Þq jr ;s :t :q j r <c q 1;ð2Þwhere i ={L ,H }and j 2{S ,G }.4.The equilibrium decisions and strategiesWe proceed to determine the subgame-perfect Nash equilibrium (SPE)decisions and profits of the four subgames.Throughout the pa-per,the proofs of the propositions are included in the electroniccompanion,and for the sake of simplicity, q1Àq ; b 1Àb ,and v b= q .Proposition 1characterizes the firms’profit functions and is essential for deriving the firms’unique decisions.C.-H.Wu /European Journal of Operational Research 222(2012)204–215207。

2012年美国消费物价指数概况(CPI)