线性代数课件1.3

高等数学线性代数极大线性无关组的性质于应用教学ppt(3)

向量组 B :1, ,m ,m1 也线性相关.反言之,

若向量组B 线性无关,则向量组A也线性无关 .

证

1,2 ,

,

线性相关,

m

存在不全为0的数x1, x2 , , xm,使

x11 x22 xmm =0,

从而存在不全为0的数x1, x2, , xm,0,使

x11 x22 xmm +0m+1=0.

ann xn 0,

a11 a12

a1n

当 a21 a22

a2n 0, 方程组(1)只有零解.

an1 an2

ann

定理2

向量组 1, 2, , m (m 2)线性相关

1, 2,

,

中至少有一个向量可

m

由其余向量线性表示.

证明 充分性

设 a1 , a2 ,, am 中有一个向量(比如 am)

能由其余向量线性表示. 即有

向量组线性表示.

例4 将向量 (1, 0, 4)T 用向量组1 (0,1,1)T ,

2 (1, 0,1)T ,3 (1,1, 0)T 线性表出.

解 设x11 x22 x33 , 即

0x1 1x2 1x1 0x2

1x3 1x3

1, 0,

1x1 1x2 0x3 4,

解得x1

l11 l22 lmm ,

(k1 l1)1 (k2 l2 )2 (km lm )m 0,

1,2 ,

,

线性无关,

m

表示式唯一. Page56 例6; Page57. 例8; Page59. 例9

四、小结

1. 线性组合与线性表示的概念;

2. 线性相关与线性无关的概念;(重点)

3. 线性相关与线性无关的判定方法:定义, 两个定理.(难点)

线性代数全套教学课件

aa2111xx11

a12 x2 a22 x2

a13 x3 a23 x3

b1 , b2 ,

a31x1 a32 x2 a33 x3 b3;

a11 b1 a13

得

D2 a21 b2 a23 ,

a31 b3 a33

aa2111xx11

a12 x2 a22 x2

a13 x3 a23 x3

当 a11a22 a12a21 0 时, 方程组的解为

x1

b1a22 a11a22

a12b2 , a12a21

x2

a11b2 a11a22

b1a21 . a12a21

(3)

由方程组的四个系数确定.

定义 由四个数排成二行二列(横为行、竖为列) 的数表

a11 a12

a21 a22

(4)

表达式 a11a22 a12a21称为数表(4)所确定的二阶

a31x1 a32 x2 a33 x3 b3;

a11 b1 a13

得

D2 a21 b2 a23 ,

a31 b3 a33

aa2111xx11

a12 x2 a22 x2

a13 x3 a23 x3

b1 , b2 ,

a31x1 a32 x2 a33 x3 b3;

a11 a12 a13 D a21 a22 a23

a31 a32 a33

aa2111xx11

a12 x2 a22 x2

a13 x3 a23 x3

b1 , b2 ,

a31x1 a32 x2 a33 x3 b3;

若记 或

b1 b2 b1

b1 a12 a13 D1 b2 a22 a23 ,

b3 a32 a33 a11 a12 a13 D a21 a22 a23 a31 a32 a33

《线性代数讲义》课件

在工程学中,性变换也得到了广泛的应用。例如,在图像处理中,可

以通过线性变换对图像进行缩放、旋转等操作;在线性控制系统分析中

,可以通过线性变换对系统进行建模和分析。

THANKS

感谢观看

特征向量的性质

特征向量与特征值一一对应,不同的 特征值对应的特征向量线性无关。

特征值与特征向量的计算方法

01

定义法

根据特征值的定义,通过解方程 组Av=λv来计算特征值和特征向 量。

02

03

公式法

幂法

对于某些特殊的矩阵,可以利用 公式直接计算特征值和特征向量 。

通过迭代的方式,不断计算矩阵 的幂,最终得到特征值和特征向 量。

矩阵表示线性变换的方法

矩阵的定义与性质

矩阵是线性代数中一个基本概念,它可以表示线性变 换。矩阵具有一些重要的性质,如矩阵的加法、标量 乘法、乘法等都是封闭的。

矩阵表示线性变换的方法

通过将线性变换表示为矩阵,可以更方便地研究线性 变换的性质和计算。具体来说,如果一个矩阵A表示 一个线性变换L,那么对于任意向量x,有L(x)=Ax。

特征值与特征向量的应用

数值分析

在求解微分方程、积分方程等数值问题时, 可以利用特征值和特征向量的性质进行求解 。

信号处理

在信号处理中,可以利用特征值和特征向量的性质 进行信号的滤波、降噪等处理。

图像处理

在图像处理中,可以利用特征值和特征向量 的性质进行图像的压缩、识别等处理。

05

二次型与矩阵的相似性

矩阵的定义与性质

数学工具

矩阵是一个由数字组成的矩形阵列,表示为二维数组。矩阵具有行数和列数。矩阵可以进行加法、数 乘、乘法等运算,并具有相应的性质和定理。矩阵是线性代数中重要的数学工具,用于表示线性变换 、线性方程组等。

线性代数1.3按行(列)展开

VS

$x = frac{D_x}{D} = 2$,$y = frac{D_y}{D} = 0$,$z = frac{D_z}{D} = -1$

06

总结与展望

课程总结

掌握了按行(列)展开的基本概念和性质,能 够灵活运用行列式的性质进行化简和计算。

学会了使用克拉默法则求解线性方程组,并能 够理解其几何意义。

深入理解了矩阵的秩、逆矩阵等概念,并能够 运用相关知识解决实际问题。

对未来的展望

进一步探索线性代数在各个领域 的应用,如机器学习、图像处理、

密码学等。

学习更高级的线性代数知识,如 特征值、特征向量、二次型等, 为未来的学习和工作打下坚实基

础。

将线性代数的知识与其他数学分 支相结合,如微积分、概率论等, 以更全面地理解和应用数学知识。

举例分析

01

2&5

02

1&1

03

end{array} right| = -3$

举例分析

举例分析

2. 示例二:三元一次方程组

$$left{ begin{array}{l}

举例分析

x+y+z=6

1

x-y+z=2

2

x+y-z=4

3

举例分析

end{array} right.$$

系数行列式为 $D = left| begin{array}{ccc}

2. 利用初等行变换将增广 矩阵化为行阶梯形矩阵

4. 利用行阶梯形矩阵求解 未知量

举例分析

1. 示例一:二元一次方程组 $$left{ begin{array}{l}

举例分析

01

2x + y = 5

《线性代数》1.3行列式的性质

a1n ain ka jn D1 a jn ann

n 2 ka j1 an1ai1 a a j1 an1

证 由行列式性质4 以及性质3 的推论2 可得到

a11 ai1 D1 a j1 an1 a j2 an 2 a jn ann a12 ai 2 a1n ain a j1 an1 a j2 an 2 a jn ann a11 ka j1 a12 ka j 2 a1n ka jn

x n 1 a r2 , r3 rn都减去r1 0 0

a xa 0

a 0 xa

x n 1 a x a

n 1

ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ

练习 计算

a1 0 Dn 1 0 1

a1 a2 0 1

0

0 0

0 0 an 1

a2 0 1

an 1

c2 c1后c3 c2 类推 1 a1a2

n

a1 0 0 a2 0 1 0 2

0 0 0 3

0 0 an n

0 0 0 n 1

an n 1

例4

计算 2 n 阶行列式(行列式的空白处为零)

a a a b b a b b a a b b

D2 n

同理 ci c j ; kci ; ci kc j 分别表示行列式互换第 i列与第 j

列;数k乘以第 i列;第 i列的各元素加上第 j列对应元素 的k倍.

例1 计算

1 2 D 1 1 3 2 2 1 1 4 0 3 2 1 0 1 2 3 1 5 1

3 1 2 1 1 2 0 3

b

a b

小结: 本次课我们学习了行列式的性质,重点要掌握如何 灵活应用行列式的性质来计算行列式。 作业: P26 习题一:5⑥⑦,6①②

《线性代数电子教案》课件

《线性代数电子教案》PPT课件第一章:线性代数简介1.1 线性代数的意义和应用解释线性代数的概念和重要性探讨线性代数在工程、物理、计算机科学等领域的应用1.2 向量和空间定义向量及其几何表示介绍向量的运算,如加法、减法、数乘和点积1.3 矩阵和矩阵运算介绍矩阵的定义和基本性质探讨矩阵的运算,如加法、减法、数乘和乘法第二章:线性方程组2.1 线性方程组的定义和性质解释线性方程组的含义和基本性质探讨线性方程组的解的存在性和唯一性2.2 高斯消元法介绍高斯消元法的原理和步骤演示高斯消元法的具体操作过程2.3 矩阵的逆定义矩阵的逆及其性质探讨矩阵的逆的求法和应用第三章:矩阵的特征值和特征向量3.1 特征值和特征向量的定义解释特征值和特征向量的概念探讨特征值和特征向量的性质和关系3.2 矩阵的特征值和特征向量的求法介绍求解矩阵的特征值和特征向量的方法演示求解矩阵的特征值和特征向量的具体过程3.3 矩阵的对角化定义矩阵的对角化及其条件探讨矩阵对角化的方法和应用第四章:向量空间和线性变换4.1 向量空间的概念和性质解释向量空间的概念和基本性质探讨向量空间的基、维数和维度4.2 线性变换的定义和性质定义线性变换及其性质探讨线性变换的矩阵表示和特征值4.3 线性变换的图像和应用介绍线性变换的图像和性质探讨线性变换在图像处理等领域的应用第五章:行列式和矩阵的秩5.1 行列式的定义和性质解释行列式的概念和基本性质探讨行列式的计算方法和性质5.2 矩阵的秩的定义和性质定义矩阵的秩及其性质探讨矩阵的秩的求法和应用5.3 矩阵的逆和行列式的关系探讨矩阵的逆和行列式之间的关系演示利用行列式和矩阵的秩解决实际问题的方法第六章:二次型和正定矩阵6.1 二次型的定义和性质解释二次型的概念和基本性质探讨二次型的标准形和判定方法6.2 矩阵的正定性和二次型的应用定义正定矩阵及其性质探讨正定矩阵的判定方法和应用6.3 二次型的最小二乘法介绍最小二乘法的原理和步骤演示最小二乘法在实际问题中的应用第七章:特征值和特征向量的应用7.1 特征值和特征向量在控制理论中的应用探讨特征值和特征向量在控制理论中的重要作用演示利用特征值和特征向量分析线性系统的稳定性7.2 特征值和特征向量在信号处理中的应用解释特征值和特征向量在信号处理中的重要性探讨利用特征值和特征向量进行信号降噪等处理的方法7.3 特征值和特征向量在图像处理中的应用介绍特征值和特征向量在图像处理中的作用演示利用特征值和特征向量进行图像降维和特征提取的方法第八章:向量空间的同构和商空间8.1 向量空间的同构定义向量空间的同构及其性质探讨同构的判定方法和性质8.2 向量空间的商空间解释向量空间的商空间的概念和性质探讨商空间的构造和运算规则8.3 向量空间的同构和商空间的应用探讨向量空间的同构和商空间在数学和物理学中的应用演示利用同构和商空间解决实际问题的方法第九章:线性代数在优化问题中的应用9.1 线性代数在线性规划中的应用解释线性规划问题的概念和基本性质探讨利用线性代数方法解决线性规划问题的方法9.2 线性代数在非线性优化中的应用介绍非线性优化问题的概念和基本性质探讨利用线性代数方法解决非线性优化问题的方法9.3 线性代数在机器学习中的应用解释机器学习中的线性代数方法探讨利用线性代数方法进行数据降维、特征提取和模型构建的方法第十章:总结和拓展10.1 线性代数的核心概念和定理总结线性代数的核心概念和定理强调其在数学和科学研究中的重要性10.2 线性代数的拓展学习和研究方向介绍线性代数的拓展学习和研究方向鼓励学生积极探索线性代数的应用和创新10.3 线性代数的练习和参考资源提供线性代数的练习题和解答推荐相关的参考书籍和在线资源,供学生进一步学习和参考重点和难点解析重点一:向量和空间的概念及运算向量是线性代数的基本元素,其运算包括加法、减法、数乘和点积。

线性代数课件第三节 行列式

0 0 1 0

3 0 0 1 0 0 1 2

1 (1)11 1

11

0 0 1 0 0 1

2 0 1 0 2

0 3 (1)13 3 1 0 0 2

当然,按照第二列展开是最简单的计算方法!

用首行展开法Байду номын сангаас以证明

a11 a21 M an1 0 L 0 0 M ann a22 L M O an 2 L

性质1.10 如果行列式的某一行(列)的元素都是两项 的和,则可以把该行列式拆成相应的两个行列 式之和。 a a L a

11 12 1n

a21 M bi1 ci1 M

a22 M bi 2 ci 2 M an 2 a11

L M

a2 n M

L bin cin M M L

a11 a21 M bi1 M an1

下三角形 行列式

a11a22 L

下三角 形行列式 之值等于 ann 主对角线 元素之积

后面还可以证明

a11 a12 0 a22 M M 0 0 L L O L a1n a2 n M ann

上三角形 行列式

a11a22 L

上三角 形行列式 之值等于 ann 主对角线 元素之积

计算

观察哪一行或 列的零最多

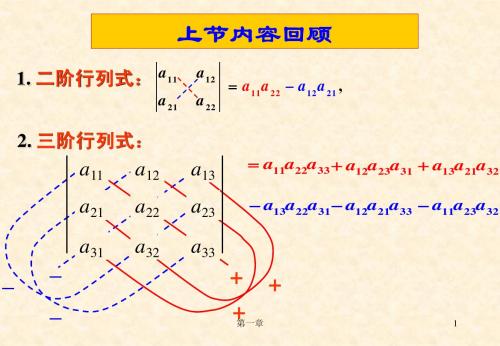

即:主对角线元素之积减去副对角线元素之积。

a11 a12 a13 对于3阶方阵 A a21 a22 a23 , 定义其行列式|A|为 a a32 a33 31 a11 a12 a13 a11a22 a33 a12 a23a31 a13a21a32 A a21 a22 a23 a13a22 a31 a12 a21a33 a11a23a32 a31 a32 a33

线性代数1-3

0aL MM 0 0L b(1)2n1 0 0 L MM 0cL c 0L

0 0L MM a bL cdL MM 0 0L 0 0L

00 MM 00 00 MM 0d 00

ad (1)2n12n1 D2n2 bc(1)2n1 (1)12n1 D2n2

(ad bc)D2n2

x y z x 31 r2 r3 3 0 2 y 0 1 1.

1 1 1 z 21

例5 解方程 解 方法一

11 1L 1 1 x 1 L 1 1 2x L MM M 11 1L

1 1 1 0. M n x

11 1L 1 1 x 1 L 1 1 2x L MM M 11 1L

解 将行列式按第一列展开

00 00 00

. MM 75 27

7 5L 27L Dn 7 M M 0 0L 0 0L

00 50L 00 27L M M 2 M M 75 00L 27 00L

00 00 MM 75 27

50L 00

27L 00

7Dn1 2 M M

MM

00L 75

00L 27

即

D2n (ad bc)D2(n1) .

所以

D2n (ad bc)D2(n1) (ad bc)2 D2(n2) L

(ad

bc)n1

D2

(ad

bc)n1

a c

b (ad bc)n . d

例8 计算行列式

7 5 0L 2 7 5L 0 2 7L Dn M M M 0 0 0L 0 0 0L

0 2 3 3

0 0 7 5

1 2 1 0

1 2 1 0

大学线性代数课件1.3-PPT精品文档

性质2

互换行列式的两行(列),行列式的值变号。

推论 如果行列式中有两行(列)的对应元素相同,则 此行列式的值为零。

性质3 用数k乘以行列式的某一行(列),等于用数k 乘以此行列式。

推论1 如果行列式中某一行(列)的所有元素有公因 子,则公因子可以提到行列式符号的外面。 推论2 如果行列式有两行(列)的对应元素成比例, 则此行列式的值为零。

首页

上页

返回

性质 下页3

结束

性质2

互换行列式的两行(列),行列式的值变号。

推论 如果行列式中有两行(列)的对应元素相同,则 此行列式的值为零。

性质3 用数k乘以行列式的某一行(列),等于用数k 乘以此行列式。即 a11 a12 … a1n a11 a12 … a1n … … … … … … … … ka31 ka32 … ka3n =k a31 a32 … a3n 。 … … … … … … … … an1 an2 … ann an1 an2 … ann

N ( j j j ) 1 2 n ( 1 ) a b a 。 1 j ij n 1 i n

首页

上页

返回

性质 下页5

结束

性质5 将行列式的某一行(列)的所有元素同乘以数 k后加到另一行(列)对应位置的元素上,行列式的值不变。

它与D的一般项相差一个负号,所以D 1=D。

首页 上页 返回 列),行列式的值变号。

推论 如果行列式中有两行(列)的对应元素相同,则 此行列式的值为零。 这是因为,将行列式 D 中具有相同元素的两行互换 后所得的行列式仍为D,但由性质2,D=D,所以D=0。

证明:记D=|aij|,D T=| bij |, D T的一般项为

《线性代数》课件第3章

定义1.4对于一组m × n矩阵A1,..., At和数c1,...,ct , 矩阵 c1A1 + + ctAt

⎛⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎝

a11 a 21

am1

a12 a 22

am 2

a 1n a 2n

amn

⎞⎠⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟

称为S

上一个m

×

n矩阵,通常简记为

(aij

) m

×n

或

(aij

).

一个n × n矩阵称为n阶矩阵或n阶方阵.在一个n阶矩阵中,从

左上角至右下角的一串元素a11, a22 ,..., ann称为矩阵的对角线.

+

a2

⎛⎝⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜

0 1 0

0

⎞⎠⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟

+

+

an

⎛⎝⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜

0 0

0 1

⎞⎠⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟

= a 1ε1 + a 2ε2 +

+ anen .

§3.2 矩阵的乘法

( ) ( ) 定义2.1(矩阵的乘法)设A = aij 是一个m×n矩阵, B = bij 是一个

1. 把A整个分成一块,此时A就是一个1×1的分快矩阵;

2. 把A的每一行(列)或若干行(列)看成一块.比如,把A按列分

线性代数1.3

′ ′

′

第一章

确定5阶行列式 的符号. 例4 确定 阶行列式 |aij| 中项 a 43 a 21 a 34 a 15 a 52 的符号 解 (方法1) 方法 ) Q N ( 42315 ) + N ( 31452 ) = 5 + 4 = 9

负号。 ∴ 负号。

(方法2) 方法 ) Q a 43 a 21 a 34 a 15 a 52 = a 15 a 21 a 34 a 43 a 52

( − 1) N ( i1 i 2 L i n ) + N ( j1 j 2 L j n ) a i1 j1 a i 2 j 2 L a i n j n

其中i 均为n级排列 级排列. 其中 1i2…in , j1j2…jn均为 级排列 证

a i1 j1 a i2 j 2 L a in j n = a 1 j1′ a 2 j 2′ L a n j n ′

a1 n a2 n L an − 1 n ann

的值. 的值

( − 1) N ( j1 j 2 L j n ) a 1 j1 a 2 j 2 L a nj n , 解 D 的一般项为

第n行元素中,只有 nn可能不为 ,其余全为 , 行元素中, 行元素中 只有a 可能不为0,其余全为0, 故只考虑 j n = n , 外全为0, 行元素中, 第n-1行元素中,除 a ( n − 1 )( n − 1 ) , a ( n − 1 ) n 外全为 , 行元素中 故只考虑 jn-1=n-1或 n, 又因为 j n = n , 故 j n − 1 = n − 1, 或 , 依此类推, 依此类推,还有 所以 D = (− 1 )

a11 a 22 a 33 a 44 + (− 1)N (1243 ) a11 a 22 a 34 a 43

线性代数_课件

2020/3/1

22

五、关于等价定义的说明

对于行列式中的任一项

(1) a1p1...aipi ...a jpj ...anpn

(1)

其中 1...i... j...n为自然排列, 为列下标排

列 p1...pi...p j... pn 的逆序数。对换 (1) 中元

素a

与

ip i

a jp

j

成:

(1) a1p1...a jpj ...aipi ...anpn

解:∵ 排列p1 p2 p3…pn与排列 pn…p3 p2 p1的逆序

数之和等于1~ n 这 n 个数中任取两个数的组合

数即 :

(

p1 p2... pn )

(

pn

pn1... p1)

Cn2

n(n 1) 2

(

pn

pn1... p1)

n(n 1) 2

k

2020/3/1

9

例4 求排列(2k)1(2k 1)2(2k 2)...(k 1)k

a22 ...

... a2n ... ...

a11a22...ann

0 0 ... ann

2020/3/1

16

3) 次上三角行列式

a1,1 ... a1,n1 a1,n

a2,1 ... a2,n1 ... ... ...

0 ...

n ( n 1)

(1) 2 a1,na2,n1...an,n

例6 若 a13a2ia32a4k , a11a22a3ia4k , ai2a31a43ak 4 为四阶行列式的项,试确定i与k,使前两项带正号, 后一项带负号。

大学线性代数课件1.3

011 101 110

11 ① 1

②

1 0 1

0 1 1④① 1

1 1

1 0

1 1

③

①

0 0

0 1 1

1 1 1

1 1 0

1110

1110

0 1 0 1

④② 1 0 1 1

10 1 1

③②

0 0

1 0

1 2

1 ③④ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้1

0 0

1 0

1 1

1 2

0 0 1 2

0 0 2 1

10 1 1

④ 2③ 0 0

… …… … …… x(n1)a a a … x a x(n1)a a a … a x

②①(1)

③①(1)

x(n1)a a 0 xa 00 …… 00 00

a…a a 0…0 0 xa … 0 0 … … …… 0 … xa 0 0 … 0 xa

=[x(n1)a](xa)n1。

首页

上页

返回

下例页4

首页

上页

返回

下解页答

结束

首页

上页

返回

下页

结束

首页

上页

返回

下页

结束

首页

上页

返回

下页

结束

例3. n 阶行列式

x a a…a a a x a…a a a a x…a a ……… … …… a a a…x a a a a… a x

①② ①③

x(n1)a a a … a a x(n1)a x a … a a x(n1)a a x … a a

3a31 a32 5a33

(3)① 5③

2(3)5

线性代数1.3

Math1229A/BUnit3: Lines and Planes(text reference:Section1.3)c V.Olds201030Unit33Lines and PlanesLines inℜ2You are already familiar with equations of lines.In previous courses you will have written equations of lines in slope-point form,in slope-intercept form,and probably also in standard form for a line inℜ2.Recall that:y−y1=m(x−x1)is the slope-point form equation of the line through point(x1,y1)with slope m y=mx+b is the slope-intercept form equation of the line with slope m and y-intercept b ax+by=c is the standard form equation which either of the others can be rearranged to In this course,we don’t use the slope-point or slope-intercept forms of equations of lines.Instead, we use various other,vector-based,forms of equations.But we do still use the standard form.You already know that given any2distinct points,whether inℜ2or inℜ3,there is exactly one line which passes through both points.Suppose we have2points,P and Q.Letℓbe the line that passes through these two points.Both point P and point Q lie on lineℓ,and so do all the points between them.In fact,the directed line segment−−→P Q lies on lineℓ.When this directed line segment is translated to the origin,the resulting vector most likely doesn’t lie on lineℓ(unless the originhappens to lie on lineℓ),but if not,it does lie on a line which is parallel to lineℓ.It lies on the line parallel toℓwhich passes through the origin.So this vector does give us some information about the line.(Similar to the information given by knowing the slope of a line inℜ2,although it’s not quite the same information.)If a vector v lies on a particular line,or on a line parallel to that line,we say that v is parallel to, or is collinear with that line.And we call v a direction vector for the line.Not that the line actually has a direction associated with it.It doesn’t.It extends in both directions,but has no particular “forwards along the line”or“backwards along the line”associated with it.So don’t read too much meaning into the term direction vector.If v is a direction vector for lineℓ,then so is− v.And so is every other scalar multiple of v,except for0 v.Because of course0 v= 0which has no direction information.But every other scalar multiple of v starts at the origin,and goes either the same or the opposite direction as v and therefore also lies on the line parallel toℓwhich passes through the origin.So any such vector would be considered a direction vector for lineℓ.Definition:Any non-zero vector which is parallel to a lineℓis called a direction vectorfor lineℓ.For instance,consider the line x+y=2.The points(1,1),(2,0),(0,2),(−1,3),(3,−1),(−2,4), (4,−2),etc.,all lie on this line.So do(1/2,3/2)and(3/2,1/2)and infinitely many other points. Pick any2of these points,andfind the vector which is the translation to the origin of the directed line segment between them,and you have a direction vector for the line.And we know that for any points P and Q,letting p=−−→OP denote the vector from the origin to point P and q=−−→OQ denote the vector from the origin to point Q,the vector v= q− p is the translation of directed line segment −−→P Q to the origin.So for instance for points P(1,1)and Q(0,2),we have p=(1,1)and q=(0,2), and we see that v= q− p=(0,2)−(1,1)=(−1,1)is a direction vector for the line x+y=2.And other choices of P and Q give other direction vectors which are scalar multiples of this one.(Go ahead,pick some other points,and see what vectors you get.)Unit331 Point-Parallel Form32Unit3 Parametric EquationsUnit333 Example3.3.Write a point-parallel form equation for the line with parametric equationsx=1+5ty=2Solution:We use the x equation tofind thefirst components for our point-parallel equation,and the y equation tofind the second components.We need to recognize that in each equation,the number on the right hand side that isn’t multiplied by t is the coordinate of the known point,P,and that the number that is multiplied by t is the component of the direction vector, v.So from thefirst equation,i.e. the x-equation,we see that p1=1and v1=5.And from the second equation,since there’s no t multiplying it,the2must be p2.So where’s the t?It’s invisible,which means it must have a0 multiplier.That is,v2=0.So we have the point P(1,2)and the direction vector v=(5,0),which when we put it in the form x(t)= p+t v gives the point-parallel form equationx(t)=(1,2)+t(5,0)Two-Point Form-34Unit 3But nothing that we did here really required being in between P and Q .We could do something similar for any point on the line containing P and Q .The only difference is that t would no longer necessarily be between 0and 1.That is,for any point X on the line containing the points P and Q ,we could travel from the origin to point P ,and then travel some scalar multiple of the vector u to end up at the point X .For instance,consider the diagram shown below.As before,we have x = p +t u ,but now t is bigger than 1.Or if we needed to go the other direction along the line,from P ,then t would be negative.6X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X ¡¡¡¡¡¡!P p Q q ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨B X x And so for any point X on the line,we havex = p +t u = p +t ( q − p )= p +t q −t p =(1−t ) p +t qfor some value t .That is,we can express the line containing two points P and Q as the line containing all points X (x,y )such that x =(1−t ) p +t q for some value t .And so we have another form of equation for the line.We call this the two-point form,and as before,we write x (t )instead of just x .Definition:The two-point form of equation for the line through points P and Q is:x (t )=(1−t ) p +t qExample 3.4.Write equations in two-point form for each of the lines in Example 3.1.Solution:(a)The line here is the line through the points P (3,1)and Q (0,6),so we have p =(3,1)andq =(0,6)and we get the two-point form x (t )=(1−t )(3,1)+t (0,6)(b)This time,we have the line through P (1,2)with direction vector v =(2,−1).We don’t know two points on the line,so we need to find a second point.We saw in Example 3.1(b)that a point-parallel form equation for this line is x (t )=(1,2)+t (2,−1).We can choose any value of t other than 0to get another point on the line.(Notice:We don’t want to use t =0,because that will just give us the point we already know.But any other value of t will do.)For instance,using t =1we have x (1)=(1,2)+1(2,−1)=(1,2)+(2,−1)=(3,1),so we see that Q (3,1)is another point on the same line.Now that we know two points on the line,we can find a two-point form equation.Notice,though,that since we have already been using t as the parameter for the point-parallel form equation,we should use a different name for the parameter in the two-point form equation.(Especially since we gave t a specific value.We wouldn’t want to get confused and think the parameter in the two-point form equation was supposed to have that value too.)Notice also that it doesn’t matter in the least what letter we use to represent the parameter (which is just a scalar multiplier).So we can use s instead.We get:x (s )=(1−s )(1,2)+s (3,1)Unit335 (c)This time,we have the line through the origin with direction vector(0,1).We know that the point(0,0)is on the line,and clearly the point(0,1)is also on the line(because the vector(0,1)is on the line,since the line does pass through the origin).So a two-point form equation for this line isx(t)=(1−t)(0,0)+t(0,1)Point-Normal Form36Unit3 Example3.6.(a)Find an equation in point-normal form for the line x(t)=(0,1)+t(2,−1).(b)Write an equation in point-parallel form for the line from Example3.5.(c)Write a point-normal form equation for the line with parametric equationsx=3+t and y=2t−4Solution:(a)We have x(t)=(0,1)+t(2,−1),which we recognize as a point-parallel form equation for the line through point(0,1)parallel to the vector(2,−1).Since the vector(2,−1)is parallel to the line,then the vector(1,2),obtained by switching the components and changing one of the signs, is perpendicular to the line.That is, n=(1,2)is a normal for this line.So a point-normal form equation for the line is(1,2)•( x−(0,1))=0(b)In Example3.5we found the point-normal form equation(−1,1)•( x−(1,2))=0for a particular line.Since(−1,1)is a normal for this line,and the vector(1,1)is orthogonal to(−1,1),then the vector(1,1)is parallel to the line,i.e.is a direction vector for the line.And of course(1,2)is a point on the line.So a point-parallel form equation for this line isx(t)=(1,2)+t(1,1)(c)From the parametric equations of the line we can identify both a point on the line and a direction vector for the line.Remember,the multiplier on t is the component of the direction vector,while the number without a t is the coordinate of the known point.Keeping this in mind allows us to correctly identify both the known point and the direction vector from the parametric equations, even when they look a bit different than we expect.Here,the parametric equations are given asx=3+ty=2t−4We’re more accustomed to seeing the form we have in the x equation.The form in the y equation, with the t term coming before the non-t term,is different.This is just done to avoid having a “leading negative”.Equations look less tidy when thefirst thing on one side of the equation is a negative sign,so mathematicians often avoid writing things that way.That is,the given parametric equations are just a tidier form ofx=3+ty=−4+2tIn this form we see that the corresponding point-parallel form equation is x(t)=(3,−4)+t(1,2). So(1,2)is a direction vector for the line and therefore(2,−1)is a normal for the line.Thus we can write a point-normal form equation as(2,−1)•( x−(3,−4))=0Unit337 Standard Form38Unit3 Example3.8.Write a point-normal form equation for the line x−2y=5.Solution:We use the coefficients of x and y as the components of a normal vector for the line.Of course, x−2y=1x+(−2)y,so the coefficients are1and−2.That is,we get n=(1,−2)as a normal vector for the line.Now,we just need tofind any point on the line.We plug in any convenient x-value and solve for y.Or we plug in any convenient y-value and solve for x.For instance,when y=0we have x−2(0)=5,so x−0=5.That is,we see that when y=0we must have x=5.So P(5,0)is a point on the line.Now we can write the point-normal form equation:(1,−2)•( x−(5,0))=0Example3.9.Write a standard form equation of the line x(t)=(3,2)+t(2,7).Solution:From the given point-parallel form equation,we see that P(3,2)is a point on the line and v=(2,7) is a direction vector for the line,i.e.is parallel to the line.And so n=(7,−2)is a normal vector to the line,so the standard form equation has7x−2y=c for some value c.And we canfind c usingc=(7,−2)•(3,2)=7(3)+(−2)(2)=21−4=17Therefore the standard form equation is7x−2y=17.Lines inℜ3Of course,we can have lines in3-space,as well as in the plane.And there’s a lot that’s the same inℜ3as it was inℜ2,so we use the same terminology and notation.For instance,when we move from2dimensions to3,it’s still true that given any2points,there is exactly one line that passes through both those points.And the vector equivalent to the directed line segment between those points is parallel to that line,so we still call it a direction vector for the line.That is,we define the term direction vector the same way inℜ3as we did inℜ2.Definition:If v∈ℜ3is parallel to some lineℓinℜ3,we say that v is a directionvector forℓ.As inℜ2,we can use a direction vector for a line(i.e.a vector parallel to the line)and any one point on the line to write a point-parallel equation for the line.And from that we can write parametric equations.Or we could write a2-point form equation,instead.The only difference is that now the points have3coordinates and the vectors have3components. Of course,for parametric equations this means that we have a third equation,corresponding to the z components of the vectors.These observations are summarized in the following definitions.Unit339 Definition:Let P(p1,p2,p3)and Q(q1,q2,q3)be any points inℜ3and let v=(v1,v2,v3)be any vector inℜ3.Then:1.Ifℓis the line which passes through P parallel to v(so that v is a direction vectorforℓ),thenx(t)=(p1,p2,p3)+t(v1,v2,v3)is an equation for lineℓin point-parallel form.2.If lineℓpasses through point P and v is a direction vector forℓ,then parametricequations of lineℓare:x=p1+tv1y=p2+tv2z=p3+tv33.If points P and Q are both on lineℓthen a two-point form equation forℓisx(t)=(1−t)(p1,p2,p3)+t(q1,q2,q3)Example3.10.Letℓbe the line which passes through the points P(1,2,3)and Q(1,−1,1).Write equations of lineℓin two-point form and in point-parallel form.Solution:In two-point form,we get the equation forℓ:x(t)=(1−t)(1,2,3)+t(1,−1,1)For a point-parallel form equation of lineℓwefirst need tofind a direction vector forℓ.The directed line segment−−→P Q is equivalent tov= q− p=(1,−1,1)−(1,2,3)=(0,−3,−2)which is parallel to(and hence is a direction vector for)ℓ.Using this direction vector and the point P which we know is on the line,we getx(t)=(1,2,3)+t(0,−3,−2)(Of course,we could have used point Q instead of point P to write the point-parallel form equation. Likewise,we could have used p− q=(0,3,2)as the direction vector.And in the two-point form equation,we could have switched the roles of P and Q.)Example3.11.Write parametric equations for the line through the point(0,1,−1)which is parallel to v=(2,1,0).Solution:An equation of the line in point-parallel form is x(t)=(0,1,−1)+t(2,1,0).This tells us that a point(x,y,z)is on this line if there is some value of t for which(x,y,z)=(0,1,−1)+t(2,1,0).So it must be true that,for the same value of t,we havex=0+2ty=1+1tz=−1+0t40Unit3 That is,we can write parametric equations of the line asx=2ty=1+tz=−1Example3.12.ℓ1is the line x(t)=(1−t)(2,1,−1)+t(0,1,2).ℓ2is the line with parametric equa-tions x=2t−2,y=1,z=5−3t.Areℓ1andℓ2the same line?Solution:Hmm.That’s different.Let’s see.Forℓ1we recognize that what we’ve been given is a two-point form equation.(We can tell because of the(1−t)multiplier.)From it we can see that P(2,1,−1) and Q(0,1,2)are two points on lineℓ1.This also tells us that the vectorv=−−→P Q= q− p=(0,1,2)−(2,1,−1)=(−2,0,3)is parallel to lineℓ1.Forℓ2we’re given parametric equations.It may be helpful to write these equations all the same way,with“constant+multiple of t”on the right hand side.We have:x=2t−2x=−2+2ty=1⇒y=1+0tz=5−3t y=5+(−3)tFrom the rearranged set of equations,using our knowledge of the form of parametric equations,we see that the point onℓ2used to write these parametric equations is R(−2,1,5).Also,the direction vector used for these equations is u=(2,0,−3).Since u=(2,0,−3)=−(−2,0,3)=− v,we see that these vectors are scalar multiples of one an-other,so they are collinear.That is,the direction vector u used to write the equation ofℓ2is parallel to the vector which we know is parallel toℓ1.Therefore u is also parallel toℓ1,and thus linesℓ1 andℓ2are parallel to one another.It’s possible that they could be the same line.How can we tell whether they are?Sinceℓ1andℓ2are parallel,then either they have no points in common or else they are the same line and have all points in common.So all we need to do is determine whether any point which is known to be on one line is also on the other.If it is,then they are actually the same line.But if it isn’t,then they must be different,but parallel,lines.We know that the point P(0,1,2)is on lineℓ1.Is it also on lineℓ2?If it is,then(x,y,z)=(0,1,2) must satisfy the parametric equations forℓ2,using the same value of t for each component(equation). Since the second coordinate of P is1,the equation y=1is satisfied.For thefirst coordinate,we see that we need to have x=2t−2satisfied for x=0.This gives0=2t−2⇒0+2=2t⇒2t=2⇒t=1Now,if we substitute t=1into the third of the parametric equations,we getz=5−3(1)=5−3=2Since z=2is the third coordinate of point P,we see that the point(x,y,z)=(0,1,2)does satisfy the parametric equations ofℓ2.That is,we have(0,1,2)=(−2,1,5)+1(2,0,−3)Unit341 so(x,y,z)=(0,1,2)satisfies x=−2+2t,y=1+0t and z=5−3t with t=1.Because the point (0,1,2)does satisfy the equations forℓ2,it is a point on lineℓ2.So now we know thatℓ1andℓ2are parallel lines,with a point in common,which means that they must have all points in common and be the same line.That is,sinceℓ1andℓ2are parallel and intersect at point P(0,1,2),they must intersect at all other points as well,and actually be the same line.Planes inℜ3We know that inℜ2,something of the form ax+by=c is the standard form of an equation of a line.What about the3-dimensional equivalent,ax+by+cz=d.Is that an equation of a line? Well,let’s see.Let’s think about a specific,uncomplicated,example.Consider the equation x+y+z=0. This equation is satisfied by the point P(2,−2,0)(because2+(−2)+0=0)and also by the point Q(3,−3,0).And we know that there’s a unique line that passes through those2points.Let’s call that lineℓing v= q− p=(3,−3,0)−(2,−2,0)=(1,−1,0)as a vector which is parallel toℓ1, we can write an equation ofℓ1asx(t)=(2,−2,0)+t(1,−1,0)Notice that for any point(x,y,z)on lineℓ1we havex=2+ty=−2−tz=0and so x+y+z=(2+t)+(−2−t)+0=2−2+t−t=0.That is,every point onℓ1satisfies the equation x+y+z=0.But those aren’t the only points which satisfy that equation.For instance,the point R(1,0,−1) also satisfies this equation.And this point is not onℓ1.The easiest way to tell is because from the parametric equations ofℓ1we can see that every point onℓ1has z=0,but the third coordinate of point R isn’t0,so it is not a point onℓ1.Hmm.Every point on lineℓ1satisfies x+y+z=0,but it’s not true that every point that satisfies x+y+z=0is on lineℓ1.So x+y+z=0cannot be an equation of lineℓ1.Then what is it?Well,actually,it’s the equation of a plane.ℜ2(i.e.2-space)is just a single plane.Butℜ3, which is to say3-space,contains infinitely many planes.(For instance,think of the walls,ceilings andfloors of the building you’re in.And also every other building you ever have been or ever could be in.And all the ramps you’ve ever seen.And what those ramps would look like if they were knocked offkilter.And...Each of those things lies in some particular plane inℜ3,and there are many other planes besides those.)So x+y+z=0is an equation of a plane.Let’s call it the planeΠ.(Planes are often named Π,which is just the Greek letter P,just like lines are namedℓ.ℓfor line,Πfor plane.Same idea.) Any plane contains infinitely many lines.One of the lines that lies in the particular planeΠwe’ve been talking about is the lineℓ1.But there are many others.For instance,we saw that P(2,−2,0) and R(1,0,−1)both lie on this plane,so the line on which those points lie is another line in plane Π.We can call that oneℓ2.And the vector r− p=(1,0,−1)−(2,−2,0)=(−1,2,−1)is parallel to ℓ2so we can expressℓ2as x(t)=(1,0,−1)+t(−1,2,−1).42Unit3 Notice that x+y+z=(1,1,1)•(x,y,z).Let’s think about the vector(1,1,1)whose components are the coefficients in the equation of the planeΠ.We know that(1,−1,0)is parallel to lineℓ1, which lies in planeΠ.Notice that(1,1,1)•(1,−1,0)=1(1)+1(−1)+1(0)=1−1+0=0, so the vector(1,1,1)is a normal for(i.e.is perpendicular to)lineℓ1.Likewise,we know that (−1,2,−1)is parallel to lineℓ2,which also lies in planeΠ.Notice that(1,1,1)•(−1,2,−1)= 1(−1)+1(2)+1(−1)=−1+2−1=0,so the vector(1,1,1)is also a normal for(perpendicular to) lineℓ2.However(1,−1,0)is not a scalar multiple of(−1,2,−1),so those vectors aren’t orthogonal (i.e.parallel)and therefore linesℓ1andℓ2aren’t parallel to one another.How can the same vector be perpendicular to both?Well,by being perpendicular to the whole plane in which both lines lie. This vector(1,1,1)is actually perpendicular to,i.e.a normal for,the planeΠ.Definition:A vector which is perpendicular to a particular plane inℜ3is said to benormal to the plane,and is called a normal for that plane,or a normal vector forthe plane.Point-Normal Form of an Equation of a PlaneUnit343 How do wefind a normal for the plane?Well,we know from the equation ofℓ1that the vector u=(1,−1,0)is parallel toℓ1,and likewise from the equation ofℓ2that the vector v=(−1,2,−1) is parallel toℓ2.Of course any vector n which is a normal forΠ(i.e.is perpendicular to this plane) must be perpendicular to any line that lies withinΠ.So if n is a normal forΠ,then n is perpen-dicular to bothℓ1andℓ2and therefore must be orthogonal to both u and v.(That is,any vector which is perpendicular toℓ1is also perpendicular to(orthogonal to)every vector that is parallel to ℓ1.And similarly forℓ2.)So how do wefind a vector which is perpendicular to both u and v?Well that’s easy.We know that the vector u× v is perpendicular to both u and v.So we can usen= u× v=(1,−1,0)×(−1,2,−1)=((−1)(−1),(0)(−1),(1)(2))−((2)(0),(−1)(1),(−1)(−1))=(1,0,2)−(0,−1,1)=(1,1,1)(Recall that we discussed previously that the vector(1,1,1)was a normal for the plane containing these linesℓ1andℓ2.)Now we know both a normal vector forΠand a point in planeΠso we can write the point-normal form equation.We get(1,1,1)•( x−(2,−2,0))=0Standard Form Equation of a Plane44Unit3 Example3.15.Write an equation in standard form for the plane with normal vector n=(1,2,3) which contains the point P(0,−1,2).Solution:Since n=(1,2,3)is a normal vector for the plane,then the standard form equation must have the form1x+2y+3z=d for some scalar d.But of course we would write that as x+2y+3z=d. How can wefind the value of d?Well,we know that the point P(0,−1,2)lies on the plane,so (x,y,z)=(0,−1,2)must satisfy this equation.That is,we plug in x=0,y=−2and z=2tofind the value of d.We get:x+2y+3z=d⇒0+2(−1)+3(2)=d⇒−2+6=d⇒d=6−2=4So a standard form equation of the plane is x+2y+3z=4.Notice:We could have used n• p=d,from rearranging the point-normal equation for the plane. What we did here is just another explanation of the exact same arithmetic.(Look back at the ex-amples in which we found point-normal equations of lines.We could have described the arithmetic we did there as“let x=p1and y=p2”instead of“find x• p”.)The Plane Determined by Three PointsUnit345 Example3.16.Find both a point-normal form equation and a standard form equation of the plane determined by the points P(−1,0,1),Q(1,2,3)and R(2,−1,5).Solution:The line passing through points P and Q lies in this plane,and so any vector parallel to that line is also parallel to the plane.And if we let u= q− p,then u is such a vector.Similarly,the vector v= r− p is parallel to the line which passes through both P and R,and since that line also lies in the plane, v is another vector which is parallel to the plane we need to describe.Also,we haveu= q− p=(1,2,3)−(−1,0,1)=(1−(−1),2−0,3−1)=(2,2,2)v= r− p=(2,−1,5)−(−1,0,1)=(2−(−1),−1−0,5−1)=(3,−1,4)and we can see that since u and v are not scalar multiples of one another then they are not collinear. We use these two non-collinear vectors which are both parallel to the plane tofind a normal for the plane:n= u× v=(8−(−2),6−8,−2−6)=(10,−2,−8)Now we use this normal vector and any one of the three points to write a point-normal equation of the plane.For instance,using point P,the form n•( x− p)=0gives:(10,−2,−8)•( x−(−1,0,1))=0Finally,we can also rearrange this equation to standard form.Letting x=(x,y,z),we get:(10,−2,−8)•((x,y,z)−(−1,0,1))=0⇒(10,−2,−8)•(x,y,z)−(10,−2,−8)•(−1,0,1)=0⇒10x−2y−8z=(10,−2,−8)•(−1,0,1)⇒10x−2y−8z=−10+0−8⇒10x−2y−8z=−18(Note:We might prefer to divide through the equation by2.That is,this plane would often be expressed as5x−y−4z=−9.)Determining the Distance between a Point and a Plane|| n||46Unit3That is,we simply need tofind the dot product of any normal vector to the plane with the vector equivalent to the directed line segment between the point P and any known point on the plane,discard the negative sign(if there is one),and divide by the magnitude of the normal vector used.(Notice:We have not explained why this gives −−→P′P ,so you should not be trying to understand that from the above.If you’re interested,look at the explanation given in the text.All we’ve done here is to assert that it can be shown that this is true.)Theorem3.3.Consider any planeΠ.Let n be any normal vector for planeΠand let Q be any point on planeΠ.Consider any other point P which is not on the planeΠ.Then the distance between point P and planeΠis given by:distance=| n•( q− p)|√612+22+12=and so the distance from P to the plane isdistance=| n•( q− p)|√√|(1,1,−1)•((5,0,0)−(0,0,0))| √|| n||=Unit347 Finding the Distance Between a Point and a Line|| n||Example3.19.Find the distance between the point P(1,2)and the lineℓdescribed by2x+y=1. Solution:Lineℓhas normal n=(2,1).We need tofind some point Q on lineℓ.Letting x=0we get 2(0)+y=1,so y=1.That is,the point on lineℓwhich has x-coordinate0has y-coordinate1,so the point Q(0,1)is a point on lineℓ.(Notice that for(x,y)=(1,2)we have2x+y=2(1)+2=4=1, so P(1,2)is not on lineℓ.)The distance between P andℓis| n•( q− p)|||(2,1)||=|(2,1)•(−1,−1)|22+12=|−2−1|4+1=35Finding the Intersection of Two Lines48Unit3 Example3.20.Find the point of intersection of the lineℓ1: x(t)=(1,0)+t(2,1)with the lineℓ2: x(s)=(1,1)+s(−1,0).Solution:Forℓ1we have parametric equations x=1+2ty=tand forℓ2we havex=1−sy=1.If some point P(x,y)is on both these lines,then it must be true that there are some values of t and s which give the same values of x and y.So we must have1+2t=1−s and t=1.Since t=1, then1+2t=3,so1−s=3and we see that s=1−3=−2.Notice that we’ve found values of the parameters,s and t,but we have not yet found the point on the line which corresponds to these values.That is,we know the value of t that gives the point on lineℓ1at which the two lines intersect,and likewise we know the value of s that gives that same point on lineℓ2.But we were asked tofind the actual point at which the two lines intersect.We’re notfinished until we’ve done that.And we have more information than we need tofind the point, since we know two ways to get it.So we can use the value of t we found,in the equation forℓ1,to get the point P.And then we can use the value of s we found,in the equation ofℓ2,to check our work.We get:t=1⇒(x,y)=(1,0)+t(2,1)=(1,0)+1(2,1)=(3,1)as the point onℓ1which we were looking for.We check that the point onℓ2is the same point: s=−2⇒(x,y)=(1,1)+s(−1,0)=(1,1)+(−2)(−1,0)=(1,1)+(2,0)=(3,1) Since we didfind the same point on each line,this is the point we were looking for.We see thatℓ1 andℓ2intersect at the point P(3,1).Note:As we observed above,we found values of both parameters,but really we only need one. As we have seen,the other allows us to check our work.We’re just checking that we didn’t make an arithmetic error.If we got a different point onℓ2than the one onℓ1that would tell us that somewhere in our calculations we made an arithmetic mistake.Either infinding the points,or(more likely)infinding the values of the parameters.We would need to re-do our calculations until we find the mistake,and thenfinish the problem(including the check)again.Example3.21.Find the point of intersection of the lineℓ1: x(t)=(1,1,2)+t(2,1,−1)with the line ℓ2: x(s)=(0,1,2)+s(1,−1,1).Solution:Forℓ1we have x=1+2ty=1+tz=2−tand forℓ2we havex=sy=1−sz=2+s.The point of intersection ofℓ1andℓ2is a point P(x,y,z)which satisfies both sets of equations at the same time,so we must have:1+2t=s(1)1+t=1−s(2)2−t=2+s(3) Equation(1)says that s=1+2t,so that1−s=1−(1+2t)=0−2t=−2t.Therefore equation (2)gives1+t=−2t,so1=−3t and thus t=−13into s=1+2t。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

7 6 3 2 1 3 5 0 , 5 1 0 9

求A+B, A-B。 解 根据矩阵加法定义:

1 7 3 6 1 3 4 2 A+B= 1 1 3 3 2 5 1 0 0 5 5 1 2 0 7 9

4)k(AB)=(kA)B=A(kB)=(AB)k.

选择节次

第一章

根据矩阵乘法:令 A=(aij) m×n, x=(x1, x2, x3, …, xn)T, b=(b1, b2, b3, …, bm)T, 则线性方程组(1.9)可以表示为:

Ax=b (1.13)

此形式称为线性方程组(1.9)的矩阵形式。

0 a 0 a k 1 0 0 b k 1 k b 0 a

也成立, 故由数学归纳法知:

an An= 0

选择节次

0 n b

第一章

二、矩阵的一元运算 1、转置运算

a11 a12 a21 a22 定义1.9 设矩阵A=(aij)m×n= a31 a32 a m1 am 2 a13 a23 a33 am 3 a1n a2 n a3n , amn

试求3A-2B。 解

1 3 5 3 9 15 3A=3 2 1 0 6 3 0 4 0 1 2 0 2 2B=2 7 2 5 14 4 10

3 9 15 0 2 4 3 7 11 3A-2B 14 4 10 6 3 0 20 1 10

选择节次

第一章

• 矩阵的加法有下列性质: • 性质1.1 设A、B、C都是m×n矩阵, O是 m×n零矩阵, 则有 • 1)A-A=O; • 2)A+O=A; • 3)A+B=B+A; • 4)(A+B)+C=A+(B+C)

选择节次

第一章

1 3 1 4 例1.6 已知矩阵A= 1 3 2 1 , B= 0 5 2 7

试求AB和BA。 解 根据定义:

0 1 1 2 , B= 1 1 2 1 , 2 3 1 0

1 0 3 0 1 1 2 6 8 2 2 1 1 2 1 2 1 2 5 5 2 5 AB= 2 3 1 0

选择节次

a12 b12 a22 b22 a32 b32 am 2 bm 2

a13 b13 a23 b23 a33 b33

am 3 bm 3

a1n b1n a2n b2n a3n b3n amn bmn

选择节次

第一章

2、数乘运算

定义1.6 数k与矩阵Am×n的乘积记作kAm×n或者Am×nk, 规定

a11 a12 a21 a22 a a32 31 a m1 am 2 a13 a23 a33 am 3 a1n k a11 a2 n k a21 a3n k a31 amn k am1

因为矩阵B的列数是4而矩阵A的行数是2, 两者不 相等, 故BA没有意义。

选择节次

第一章

1 0 例1.9 设有矩阵A=(2 1 0 3), B= , 试求AB和BA。 2 1 解 根据定义:

AB=A1×4B4×1=(1×2+0×1+2×0+1×3)=(5)=5 1 2 1 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 BA=B4×1A1×4=C4×4= (2 1 0 3) 4 2 0 6 2 2 1 0 3 1

选择节次

a a

j 1 s j 1 j 1 s

s

1j

bj2 bj2

2j

a

mj

bj2

a1 j b jn j 1 s a2 j b jn j 1 s amj b jn j 1

s

称为A左乘B或者称为B右乘 A。

第一章

选择节次

第一章

因此, 一般情况下矩阵相乘不满足交换律, 即AB不一 定等于BA。 如果矩阵AB=BA, 那么我们称矩阵A、B可交换。如

1 0 1 0 A= 1 1 , B= 2 1

1 0 1 0 1 0 AB= 1 1 2 1 3 1

证明 用数学归纳法。

an 0

0 . bn

a 0 当n=1时, A1= 0 b , 显然成立;

假设当n=k时, 等式成立, 即

选择节次

ak Ak= 0

0 k b

第一章

当n=k+1时,

ak Ak+1=AkA= 0

选择节次

1 0 1 0

0 0

1 2 1 2

2 2

第一章

在例1.8中, A与B相乘有意义, 但若交换相乘乘法没 意义;

在例1.9中, A与B相乘有意义, 且AB是1×1的矩阵, B 与A相乘也有意义, 但BA是4×4的矩阵, 则AB不等于BA; 在例1.10中, AB、BA都有意义, 且阶数相等, 但AB 也不等于BA。 在例1.10中, AB=0, 并不代表矩阵A或者矩阵B是零 阵。因此一般情况下, 矩阵相乘也不满足消去律, 即 AB=CB, 并不一定表示A=C。

a11 a12 B=(bij)n×m= a13 a 1n 选择节次

则称矩阵

a21 a22 a23 a2 n

a31 am1 a32 am 2 是矩阵A的转置, a33 am 3 记作B=AT。 a3n amn

选择节次

1 0 1 0 2 1 1 1 =BA

第一章

矩阵的乘法运算具有下列性质: 性质1.3 设A、B、C是矩阵, k是数, 下列运算有意义, 则有

1)结合律:(AB)C=A(BC)

2)分配律:A(B+C)=AB+AC, (B+C)A=BA+CA 3)单位矩阵交换律:Am×n=EmAm×n =Am×nEn=Am×n

k a12 k a22 k a32 k am 2

k a13 k a23 k a33 k am3

kAm×n=k

k a1n k a2 n k a3n k amn

称矩阵Am×n数乘k, 简称数乘。

选择节次

第一章

矩阵的数乘运算满足下列性质:

性质1.2 设下列运算有意义, k为数

第一章

• 矩阵A的负矩阵记作-A, 规定 -A=(-aij)m×n • 根据矩阵加法的定义有 A+(-A)=A-A=(aij-aij)m×n=Om×n • 矩阵的减法定义为: A-B=A+(-B)=(aij-bij)m×n • 显然, 只有同型矩阵才能进行矩阵的加法与 减法运算。

选择节次

第一章

• 例如 在第二节的引例1.4中, 我们看到: • 某一种物资如果有s个产地和n个销地, 那么 一个调运方案就可以表示为一个s×n矩阵, 矩阵中的元素其中aij表示由产地Ai运到销地 Bj的这种物资的数量, 比如说吨数。 • 如果从这些产地还有另一种物资要运到这 些销地, 那么, 这种物资的调运方案也可以 表示为一个s×n矩阵。 • 于是从产地到销地的总的运输量也可以表 示为一个矩阵。显然, 这个矩阵就等于上面 两个矩阵的和。

选择节次

8 9 4 6 2 6 7 1 5 4 2 16

第一章

1 7 3 6 1 3 4 2 11 3 3 2 5 1 0 A B 0 0 3 1 5 6 2 2

选择节次

第一章

1 2 如果存在列矩阵= 3 , 使得(1.13)成立, 则称 n

是线性方程组(1.13)的解。有了线性方程组的矩阵

形式, 线性方程组(1.9)的求解, 则可直接转换为矩阵方 程Ax=b的求解, 这样将线性方程组的求解与矩阵理论 联系起来, 书写方便、简洁, 为讨论线性方程组的解 带来极大的方便。

选择节次

第一章

3、乘法运算

定义1.7 设两个矩阵A=(aik)m×s, B=(bik)s×n, 两个矩 阵的乘积是C, 即AB=C=(cik)m×n, 且

s a1 j b j1 j 1 s C=(cik)m×n= a2 j b j1 j 1 s amj b j1 j 1

第一章

第三节

矩阵的运算

一、矩阵的二元运算

二、矩阵的一元运算

选择节次

第一章

•一、矩阵的二元运算 •1、加法与减法运算 •定义1.5 设有两个矩阵A=(aij)m×n, B=(bij)m×n, 两个矩阵的加法表示为A+B, 定义为

a11 b11 a21 b21 A B a31 b31 a b m1 m1

根据矩阵乘法定义, 只有当矩阵A的列数和矩阵B的

行数相等时, AB才有意义, 且cij=

a

l 1

s

il lj

b (i=1, 2, 3, …,

m;j=1, 2, 3, …, n):表示矩阵C第i行第j列的元素是矩阵 A第i行和矩阵B第j列对应元素乘积之和。否则两个矩 阵不能相乘。

选择节次

第一章

1 0 3 例1.8 设矩阵A= 2 1 2

1)lA=A;