head start

HeadStart计划对我国弱势群体儿童教育的启示

jc对美 国幼儿教育有着十分 重要 的影 响, et 而且 对于解决 我 国 贫 困儿童学前教育 问题提供一个新 的思路 。

一

、

开 端 0年代 , 美国人 注意到有大约 2 的美 国家庭处 O 于贫困状态 中, 他们在获得 高质量的教育、 工作 、 卫生 、 保健等社 会服务方 面受到不公平的待遇 。2美 国政府 为了解 决这一 问题 _ ] 的对策是增加教育机会, 制定 教育培训计划 。而 在当时很 多的 家庭 由于无力支付孩子的学前保育与教育费用 , 了顺应民意, 为 美国政府决定在短期 内设法消除贫 困现象 , 让贫 困家庭的孩子 也获得学前教育 , 使他们 能够不输在起跑线上 。为此 , 美国政府 于 16 9 4年提出“ 向贫 困宣战” 的战略思想 ,开端计划” “ 则是这个 战略思想的重要组成部分 。1 6 9 5年, 该计划正式实施。

( ) 端 计 划 的 目标 与 内容 二 开

书的资格认定过程需要 以实际的操作为依据。最后 , 把幼儿园、 社 区与获权机构结合起来 , 共同致力 于解决贫 困问题 。

( ) 端计 划存 在 的 问题 四 开

首先 , 参加开端计划的儿童在学业成绩 方面低 于国家平均 水平 。联邦政府 的许多相关研究 的报告都显示参加开端计划 的 儿童学习成绩落后于同龄儿童, 未能实现 开端计划促进 儿童人 学准备的 目标 。 ] [ 其次 , 童教育 与保育割 裂的状 况阻碍 了开 儿

第 9期 ( 第 4 总 5期 )

No 9 Ge e a . 5 . n r lN0 4

哲 理

P i sp y hl o h o

21 0 0年第 9期

NO. 0 0 92 1

H a tr 计划 对 我 国弱 势群 体儿 童 教 育的 启示 edSat

start的用法总结大全

start的用法总结大全1. Start作为动词,用来表示开始或开启某个活动、过程或状态:- We will start the meeting at 9 o'clock.- He started the car and drove away.- The singer started the concert with her latest hit.2. Start可以用来表示开始做某事,或开始从事某个职业或活动:- She started studying French when she was in high school.- He started working as a teacher after he graduated.3. Start还可以表示开始使用或启动某个机器、设备或系统:- I start my computer every morning.- He started the washing machine to do the laundry.4. Start也可以表示开始存在或发生某种情况或事件:- The rain started at noon and didn't stop until evening.- The war started in 1939.5. Start可以作为名词,表示开始的时间或地点:- The start of the race is at the park.- The start of the party is at 7 pm.6. Start还可以表示开始的信号或动作:- The referee blew the whistle to signal the start of the game. - She gave a nod to indicate the start of the dance performance.7. Start常用于一些固定搭配中:- Start over: 重新开始- Start up: 启动(公司、项目等)- Start off: 开始,出发- Start with: 以…开始- Start from scratch: 白手起家,从零开始这只是start的一些常见用法总结,并不涵盖所有情况。

start的用法总结大全

start的用法总结大全1. 作为动词使用:- 表示开始、开启某个活动或过程:We should start working on this project.- 表示开始、发动某个行动或运动:He started running as soon as the race began.- 表示开始使用或操作某个装置或系统:Please start the engine.- 表示出发、启程或开始旅程:We started our journey early in the morning.- 表示开始生效或实施:The new policy will start next month.2. 作为名词使用:- 表示某个活动或过程的开始:The start of the race was delayed due to bad weather. - 表示某个事物或位置的起点:We reached the start of the hiking trail.3. 作为形容词使用:- 表示最初的、起始的:In the start of the project, we encountered several difficulties.- 表示初步的、初始的:She made a start on her homework, but still has a lot to do.4. 作为副词使用:- 表示从开始的时刻或地点起:They left the concert early, before it had even started. - 表示开始行动或操作:Start by cutting the vegetables into small pieces.5. 另外,start还有一些固定搭配和短语用法,例如:- start over:重新开始- start from scratch:从零开始- start a conversation:开始对话- start a fire:点燃火焰- get off to a good/bad start:有一个好/不好的开端- start with:以...开始- startle someone:使某人吃惊需要注意的是,start这个词还有其他一些特定用法和短语,上述总结只是其中的一部分。

Australia Trading Mark申请流程

Application methods availableThere are two methods you can use to apply for a trade mark. Each methodmeets slightly different needs and has slightly different fees.The methods are:All applications must include the following:∙your name/ownership details and contact details∙ a representation of the trade mark - see our image requirements for online services∙ a description of the goods and/or services to which it will apply∙ a list of the relevant classes - what you are offering as goods or services∙ a translation/transliteration of any part of your mark that is in another language and the required fee.When you can't use TM HeadstartThe following types of marks can’t use TM Headstart:∙special kinds of signs∙series trade marks∙certification trade marks∙collective trade marks∙defensive trade marks∙divisional applications.If you request a series we will call you and ask you choose one representation (otherwise we can't proceed).TM Headstart process1. Submit your request through our online services.2. A trade mark examiner will assess your request against registration criteria andcontact you within five working days.3. If you choose email you will be sent the results report electronically with theexaminer’s contact details s hould you want to discuss the results.4. Based on the pre-application assessment you can then choose to continue withyour request, make amendments, or decide not to continue your request.5. To continue with your request, pay the Part 2 fee online within five working daysof the date of your results report.6. Your TM Headstart request converts to a standard trade mark application atthat time.7. only once this fee is paid that your request becomes a trade mark application, ispublished and allocated a filing date.有两种申请Trademark(注册商标)的方式:一、TM Headstart (可以在客户正式提交在线申请前提供评估和帮助)这种方式会在我们正式提交申请前,一位专业的评估人员提前帮我们检查并且修改申请材料,使其细节上可以更符合审批要求。

英语特殊的常用字眼

特殊的常用字眼1.H ead Starthead[ ♒♏♎ ]n.头, 头脑, 领袖, (队伍, 名单等)最前的部分, 人, 顶点vt.作为...的首领, 朝向, 前进, 用头顶vi.成头状物, 出发adj.头的, 主要的start[ ♦♦♦ ]n.动身, 出发点, 开始, 惊起, 惊跳, 赛跑的先跑权, 优先地位v.出发, 起程, 开始, 着手, 惊动, 惊起, 起动, 发动如果这两个字开头的字母是大写,则连在一起是一个专有名词,指的是美国政府为贫穷或弱智的儿童设立的一种训练机构,帮助他们,希望他们在进小学之前能赶上教学进度。

也就是:U.S. government tries to give extra -help for those underprivileged children before entering first grade. (underprivileged 比poor 更委婉些)underprivileged [ ✈⏹♎☜☐❒♓♓●♓♎✞♎ ]adj.被剥夺基本权力的,穷困的,下层社会的poor [ ☐◆☜ ]adj.贫穷的, 可怜的, 乏味的, 卑鄙的例如:Many poor parents send their children to Head Start.但是如果head start的字母是小写,那么就是普通名词了,是指比別人早着手,或领先、有利,即:advance start or advantageadvance [☜♎⏹♦]n.前进, 提升, 预付款v.前进, 提前, 预付adj.前面的, 预先的预付(款项)advantage [☜♎⏹♦♓♎✞] n.优势, 有利条件, 利益例如:To know more colloquial expressions is a head start in learning English. (了解更多的俗语对学习英语有好处。

启蒙计划(Head Start):简介教育:启蒙计划是正确的开始健康和启蒙计划

啟蒙計劃(Head Start):簡介啟蒙計劃為年齡三至五歲的兒童提供教育方案,並且也為他們的家庭提供各種各樣的機會和支持服務。

自1965年以來,我們偕同來自數以百計不同背景,數以百萬計人數的低收入家長,一齊幫助孩子成功地求學,以致有個美滿的人生。

兒童服務管理局(Administration for Children’s Services -ACS)在整個紐約市的社區內贊助超過250個啟蒙計劃中心。

每個中心皆為兒童與家長們提供一個安全與關懷的環境,讓他們都能來學習、成長和實現。

還有,每個啟蒙計劃方案都是完全免費的。

有興趣的家庭可致電212-232-0966或311查詢啟蒙計劃的細節,以及如何找到在自己社區內的啟蒙計劃中心。

教育:啟蒙計劃是正確的開始當孩子們愛學習,其他各方面便會水到渠成,成長茁壯。

每天在啟蒙計劃受教育的兒童歡喜學習各種為他們設計的活動和遊戲,教導他們從數字和字母,以至如何分享和與他人相處。

他們學會愛書本並奠定良好的閱讀基礎。

透過有趣的實際操作,他們學習自然與科學。

他們畫畫、扮家家酒、玩樂器,以鼓勵他們童年特有的好奇心、想像力與歡樂的本質。

而這僅僅只是個開始!所有啟蒙計劃都會帶學童到公園、遊樂場遊玩及遠足參觀,足跡可遍及當地社區和整個紐約市。

所有的課程都是多語教學,並包括不同種族和文化背景的兒童和家庭。

啟蒙計劃樂見並教導種族多元化的事實,不僅是教室內的學習並且延伸到教室外的活動,甚至午餐時供應各種不同傳統的美食。

每天在當地的啟蒙計劃中心會準備美味營養餐點,供應給啟蒙計劃的兒童。

當他們要升級時,啟蒙計劃的兒童帶著滿滿的信心與技能,幫助他們成功地在幼稚園、一年級及未來的學程中學習。

健康和啟蒙計劃啟蒙計劃協助兒童和家庭在自己的社區內獲得高質量、免費的醫療服務。

在進入啟蒙計劃之後的45天內,專業醫療人員會為兒童做一項初步檢查,由此可以迅速解決任何問題。

啟蒙計劃家庭全年可獲得經常性的醫療照顧,包括體檢、牙科保健和心理健康服務。

“开始,启动”用英语怎么说?

2018年即将结束,在最后的十几天里也不能松懈,让我们“动”起来!在英语当中,想要表达“启动项目”、“开启活动”等的意思,需要不同的“开始、启动”的词语表达,我们一起来学习一下吧!1. launch 启动(计划或者项目)launch 有推行,开始实施,发起,发动的意思,指“启动新计划或者新产品”。

The new model will be launched in May.新型号产品将在五月推出。

2. start/begin 开始,启动(项目;程序;机器)动词start和begin是近义词,在表示“启动”的意思时可作及物动词。

比如“启动某个项目、软件程序、机器”。

He's just started a new job.他刚刚着手一项新工作。

We began work on the project in July.我们于七月份启动这个项目。

3. turn/switch on 启动(机器)当我们说启动机器,尤其是电器的时候,会用“turn on”或者“switch on”。

比如说“turn on the computer”打开电脑。

It's too cold in here, could you turn on the air-conditioning?这里太冷了,你能把空调打开吗?She stepped forward and switched on the light in the living room.她走上前,打开客厅里的灯。

4. inaugurate 开始,正式启用inaugurate可以表示“正式启用,开始某个行动”,是一个比较正式的表达。

The classic period of the first cold war runs from 1947 through the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, which finally inaugurated an era of detente.第一次冷战的经典时期从1947年到1962年古巴导弹危机,最终开启了一个停留的时代。

start和begin的用法总结

start和begin的用法总结Start和begin的用法总结Start和begin都是英语中常用的动词,它们的意思都是“开始”,但在不同的场合下,它们有着不同的用法和含义。

本文将详细介绍start 和begin的用法。

一、start和begin的基本意思1. startstart作为动词,主要表示“开始”,可以表示一个动作或过程的开始。

例如:- The meeting will start at 10 o'clock.- I always start my day with a cup of coffee.此外,start还可以表示“启动”、“开动”等含义。

例如:- He started the car and drove away.- She started the washing machine and went to do somethingelse.2. beginbegin也是表示“开始”的动词,与start基本相同。

例如:- Let's begin our discussion.- The concert began at 8 o'clock.二、start和begin用法区别虽然start和begin都表示“开始”,但在一些情况下它们有着不同的用法和含义。

1. 表示某个活动或事件开始时如果要描述某个活动或事件刚刚开始时,通常使用start。

例如:- The movie just started.- The game has already started.2. 表示一个过程中某个阶段开始时如果要描述一个过程中某个阶段刚刚开始时,则通常使用begin。

例如:- We are about to begin the second phase of the project.- He began to feel tired after working for two hours.3. 表示开始进行某个动作或行为如果要描述开始进行某个动作或行为,则通常使用start。

start分类法的陈述

start分类法的陈述

start作动词使用时,有开始,开动,开始进行等含义;作名词使用时,有开端,良好的基础条件等含义;start后面既可以加动名词和不定式;接动名词表示经常性习惯性行为,接不定式指一次性具体的某一次的行为。

作为及物动词,后面可跟动名词或不定式,但一般跟动名词形式的比较多。

一、start to do

开始做;开始去做某事;开始做某事

1、the machines start to wear down, they don't make as many nuts and bolts as they used to

机器开始出现磨损,螺母和螺钉的产量不如从前了。

2、as the plants grow and start to bear fruit they will need a lot of water.

当植物生长并开始结果的时候,它们需要大量的水。

二、start doing something

开始做某事

you can't get very far until you start doing something for somebody else.

当你为他人做了些事情,你才能走得更远。

一种简便的ID卡曼彻斯特解码方法

一种简便的ID卡曼彻斯特解码方法我这里介绍的是常用的125KHz的ID卡。

ID卡内固化了64位数据,由5个区组成:9个引导位、10个行偶校验位“PO~P9′’、4个列偶校验位“PC0~PC3”、40个数据位“D00~D93”和1个停止位S0。

9个引导位是出厂时就已掩膜在芯片内的,其值为“111111111”,当它输出数据时,首先输出9个引导位,然后是10组由4个数据位和1个行偶校验位组成的数据串,其次是4个列偶校验位,最后是停止位“0”。

“D00~D13”是一个8位的晶体版本号或ID识别码。

“D20~D93”是8组32位的芯片信息,即卡号。

注意校验位都是偶校验,网上有些资料写的是奇校验,很明显是错的,如果是奇校验的话,在一个字节是FF 的情况下,很容易就出现9个1,这样引导位就不是唯一的了,也就无法判断64位数据的起始位了。

数据结构如下图:我读的一个ID卡数据是111111111 10001 00101 00000 00011 00000 01010 00000 11011 00110 01100 01100,对应的ID卡号是01050d36。

ID卡数据采用曼彻斯特编码,1对应着电平下跳,0对应着电平上跳。

每一位数据的时间宽度都是一样的(1T)。

由于电路参数的差别,时间宽度要实际测量。

解码芯片采用U2270B,单片机采用89S52。

U2270B的输出脚把解码得到的曼彻斯特码输出到89S52的INT脚。

在89S52的外部中断程序中完成解码。

在没有ID卡在读卡器射频范围内时,U2270B的输出脚会有杂波输出,ID卡进入读卡器射频范围内后,会循环发送64位数据,直到ID卡离开读卡器的有效工作区域。

根据ID卡的数据结构,64位数据的最后一位停止位是0。

最开始的9位引导位是1,可以把0111111111做为引导码。

也就是说在ID卡进入读卡器工作范围后,丢掉ID卡发送的第一个64位码,检测最后1位0,然后检测ID卡发送的第2个64位码的9个引导码111111111,引导码检测成功后,解码剩余的55位码。

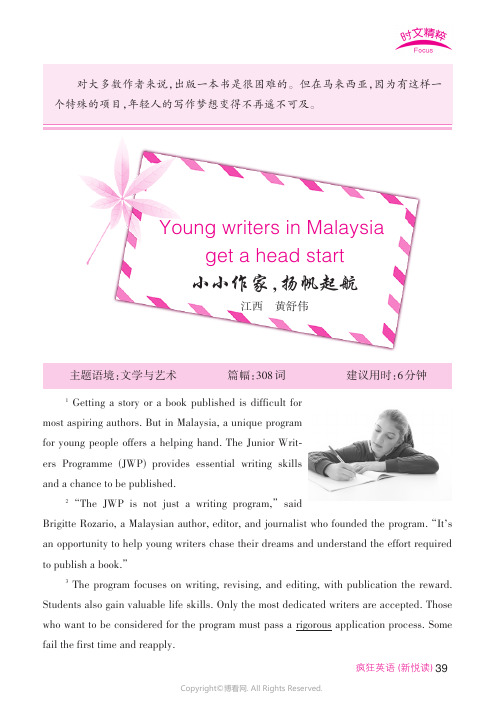

Young_writers_in_Malaysia_get_a_head_start_小小作家,扬帆

疯狂英语(新悦读)Young writers in Malaysiaget a head start小小作家,扬帆起航江西黄舒伟主题语境:文学与艺术篇幅:308词建议用时:6分钟1Getting a story or a book published is difficult for most aspiring authors.But in Malaysia,a unique programfor young people offers a helping hand.The Junior Writ⁃ers Programme (JWP)provides essential writing skills and a chance to be published.2“The JWP is not just a writing program,”saidBrigitte Rozario,a Malaysian author,editor,and journalist who founded the program.“It s an opportunity to help young writers chase their dreams and understand the effort required to publish a book.”3The program focuses on writing,revising,and editing,with publication the reward.Students also gain valuable life skills.Only the most dedicated writers are accepted.Those who want to be considered for the program must pass a rigorous application process.Somefail the first time andreapply.对大多数作者来说,出版一本书是很困难的。

开端计划与确保开端计划的异同

• 1、政府重视对学前教育方案工程的资金投 入;

• 2、出台相关政策法规来促进方案工程的顺 利开展;

3〕、支持家长参与与家长培训;

不同点

一、 “确保开端〞英国联邦政府在1998年开始投资实施的一项依靠社区而向学前儿童和父母的学前教育综合性方案,此方案采取提供均等

的学前教育、更完善儿童保育、家庭支持和医疗卫生等方式为儿童提供一生开展提供适当的条件,旨在确保每个儿童都有一个良好的 开端并为儿童及其他家庭创造更美好的生活。

相同点

• 一、工程根本特征的共性

• 1〕、对处境不利儿童的关注;

• 2〕、重视对学前儿童认知、语言及社会方 面的开展;

• 3〕、支持家长参与与家长培训;

3〕、支持家长参与与家长培训; “开端方案〞〔Head Start〕与“确保开端〞〔Sure Start〕分别作为美国和英国一项为处境不利儿童提供学前教育和健康效劳的综合

性方案,在两国学前教育的开展与改革中有着重要的地位。

3〕、支持家长参与与家长培训;

对象是3—6岁处境不利的家庭儿童

1、政府重视对学前教育方案工程的资金投入;

对象是3—6岁处境不利的家庭儿童 5〕、重视对方案实施质量的评估;

1、政府重视对学前教育方案工程的资金投入;

对象是3—6岁处境不利的家庭儿童

确保开端方案 “确保开端〞英国联邦政府在1998年开始投资实施的一项依靠社区而向学前儿童和父母的学前教育综合性方案,此方案采取提供均等

确保开端方案

• “确保开端〞英国联邦政府在1998年开 始投资实施的一项依靠社区而向学前儿童和 父母的学前教育综合性方案,此方案采取提 供均等的学前教育、更完善儿童保育、家庭 支持和医疗卫生等方式为儿童提供一生开展 提供适当的条件,旨在确保每个儿童都有一 个良好的开端并为儿童及其他家庭创造更美 好的生活。

英语学习资料:关于“head”的趣味俚语表达~

英语学习资料:关于“head”的趣味俚语表达~下列习语和表达中会使用到名词‘head’,每个习语或表达后都有一个定义和两个例句,来帮助你理解这些常用的‘head’习语表达。

Able to do something standing on one's head做某事轻而易举Definition: do something very easily and without effort定义:很轻易地完成某事He's able to count backward standing on his head.倒着数数对他而言轻而易举。

Don't worry about that. I can do it standing on my head.别担心。

这对我来说是小菜一碟。

Bang your head against a brick wall做不可能成功的事情Definition: do something without any chance of it succeeding定义:做丝毫没有成功把握的事I've been banging my head against a brick wall when it es to finding a job.我根本就找不到工作。

Trying to convince Kevin is like banging your head against a brick wall.想要说服凯文是不可能的事。

Beat something into someone's head通过不断的重复来教某人做某事Definition: teach someone something by repeating it over and over again定义:通过反复重复的方式来教会某人某事Sometimes you just need to beat grammar into your head.有时候,你只需要通过不断地重复来学习语法。

Giving_Head_Start_a_Fresh_Start_07_0629A

Giving Head Start a Fresh StartDouglas J. BesharovandCaeli A. HigneyJune 29, 2007Welfare Reform AcademyUniversity of MarylandAmerican Enterprise Institute1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W.Washington, D.C. 20036Douglas J. Besharov is the Joseph J. and Violet Jacobs Scholar in Social Welfare Studies at the American Enterprise Institute, and a professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Policy. Caeli A. Higney was a research assistant at the American Enterprise Institute/Welfare Reform Academy, and is now a student at Stanford Law School. This paper will appear in Handbook of Families and Poverty, eds. Russell Crane and Tim Heaton (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, forthcoming, 2007).© Douglas J. Besharov 2007Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon B. Johnson, 1968-69, Book II (Washington,1D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1970), p. 973.Sargent Shriver quoted in Edward Zigler and Susan Muenchow, Head Start: The Inside Story of America’s 2Most Successful Educational Experiment (New York: BasicBooks, 1992), p. 26.The Westinghouse report in 1969 reviewed 58 previous studies on Head Start. Westinghouse Learning 3From its earliest days, Head Start has been an extremely popular program because it is based on a simple idea that makes great intuitive sense: A child’s early learning experiences are the basis of later development and, given the connections between poverty and low academic achievement, a compensatory preschool program should help disadvantaged children catch up with more fortunate children.Who could be against a relatively low-cost, voluntary program that children and parents seem to love? Especially if evaluations show that it “works”? But the attractiveness of Head Start’s underlying concept should not make it immune from constructive criticism. Given the results of recent evaluations, the program’s continued defensiveness has becomecounterproductive. Head Start cannot be improved without an honest appreciation of its weaknesses (as well as strengths) followed by real reform.The original Head Start model consisted of a few hours a day of center-based education during the summer before kindergarten. After its first summer of operation, relatively informal evaluations suggested that Head Start raised the IQs of poor children. In the face of so many other programmatic disappointments, the Johnson administration latched onto these earlyfindings. For example, in a September 1968 Rose Garden speech highlighting the “success” of Head Start, President Lyndon B. Johnson said “Project Head Start, which only began in 1965,has actually already raised the IQ of hundreds of thousands of children in this country.” And 1Sargent Shriver, who headed the War on Poverty, testified before Congress that Head Start “has had great impact on children—in terms of raising IQs, as much as 8 to 10 IQ points in a six-week period.”2No wonder that Head Start quickly expanded to every state and almost everycongressional district. This early emphasis on improved IQ scores, however, proved to be a doubled-edged sword. In 1969, the results of the first rigorous evaluation of the national Head Start program were released. Echoing the findings of many future evaluations, this Office of Economic Opportunity-commissioned (OEO) study conducted by the Westinghouse Learning Corporation and Ohio University concluded that Head Start children made relatively small cognitive gains that quickly “faded out.” (This was, to program advocates, the notorious“Westinghouse Study.”) In the words of the report: “The research staff for this project failed to find any evidence in the published literature or in prior research that compensatory intervention efforts had produced meaningful differences on any significant scale or over an extended period of time.”3U.S. Government Accountability Office, Head Start: Research Provides Little Information on Impact of4Current Program GAO/HEHS-97-59 (Washington, DC: GAO, April 15, 1997), p. 8.U.S. Government Accountability Office, Head Start: Research Provides Little Information on Impact of5Current Program GAO/HEHS-97-59 (Washington, DC: GAO, April 15, 1997), p. 20.As a result, support for the program waned, and there followed a period of uncertaintyabout Head Start’s future. Because the Westinghouse Study found that the academic-year version of the program had some measurable effects, the summer program was phased out and Head Start took on its current shape: four to seven hours a day from early September to mid-June.By the early 1970s, Head Start advocates had regrouped. Ignoring the negativeWestinghouse findings, they pointed to the apparent successes of other early childhood education programs, especially the Perry Preschool Project, and, later, the Abecedarian Project. And,indeed, the public’s impression that Head Start works stems largely from the widely trumpeted results of these two small and richly funded experimental programs from thirty and forty years ago. Some advocates describe these programs as “Head Start-like,” but that is an exaggeration:They cost as much as $15,000 a year in today’s dollars (50 percent more than Head Start), often involved multiple years of services, had well-trained teachers, and instructed parents on effective child rearing. These programs are more accurately seen as hothouse programs that, in total,served fewer than 200 children. Significantly, they tended to serve low-IQ children or children with low-IQ parents.Most careful evaluations of actual Head Start programs are much less rosy. They haverepeatedly shown either small effects or effects that, like those in the 1969 Westinghouse Study,fade out within a few years. No scientifically rigorous study has ever found that Head Start itself has a meaningful and lasting impact on disadvantaged young people. Upon reflection, this should not come as any surprise, given the large cognitive and social deficits that Head Start children evidence even after being in the program for two years (unless one thinks these children would be much worse off without Head Start).After reviewing the full body of this research, a 1997 U.S. Government AccountabilityOffice (GAO) report concluded that there was “insufficient” research to determine Head Start’s impact. “The body of research on current Head Start is insufficient to draw conclusions about the impact of the national program.” The GAO added: “Until sound impact studies are conducted on 4the current Head Start program, fundamental questions about program quality will remain.”5The Head Start Impact StudyResponding to the GAO report, in 1998, Congress required the U.S. Department ofHealth and Human Services to conduct another national evaluation of Head Start. To its credit,the Clinton Administration took this mandate seriously and initiated a 383-site, randomizedU.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Head Start6Impact Study: First Year Findings (Washington, DC: HHS, June 2005),/programs/opre/hs/impact_study/ (accessed January 23, 2006).Personal communication from Jean Layzer to Caeli Higney, July 29, 2005. The Impact Study itself also7notes that vocabulary tests are “strongly predictive of children’s general knowledge at the end of kindergarten and first grade.” See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Head Start Impact Study: First Year Findings (Washington, DC: HHS, June 2005), pp. 5–7.experiment (the gold-standard of evaluation) involving about 4,600 children. (In fact, throughout his presidency, Clinton and his appointees were strongly supportive of efforts to improve Head Start, even to the point of defunding especially mismanaged local programs.)Sadly, the first-year findings from this Head Start Impact Study, released in June 2005,6showed little meaningful impact on disadvantaged children.For four-year-olds (half the program), statistically significant gains were detected in only six of thirty measures of social and cognitive development and family functioning (itself astatistically suspect result). Of these six measures, only three measures—the Woodcock Johnson Letter-Word Identification test, the Spelling test and the Letter Naming Task—directly testcognitive skills and show a slight improvement in one of three major predictors of later reading ability (letter identification). Head Start four-year-olds were able to name about two more letters than their non-Head Start counterparts, but they did not show any significant gains on much more important measures such as early math learning, vocabulary, oral comprehension (moreindicative of later reading comprehension), motivation to learn, or social competencies, including the ability to interact with peers and teachers.Results were somewhat better for three-year-olds, with statistically significant gains onfourteen out of thirty measures; however, the measures that showed the most improvement tended to be superficial as well. Head Start three-year-olds were able to identify one and a half more letters and they showed a small, statistically significant gain in vocabulary. However, they came only 8 percent closer to the national norm in vocabulary tests—a very small relative gain—and showed no improvement in oral comprehension, phonological awareness, or early math skills.For both age groups, the actual gains were in limited areas and disappointingly small.Some commentators have expressed the hope that these effects will lead to later increases inschool achievement; however, based on past research, it does not seem likely that they will do so.As Jean Layzer of Abt Associates points out, vocabulary and oral comprehension skills tend to be more indicative of later reading comprehension than the small increase in letter recognition.7These weak impacts come as a tremendous disappointment. They simply don’t do enough to close the achievement gap between poor children (particularly minority children) and theU.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, “HHS Releases 8Head Start Impact Study,” HHS News, June 9, 2005, /news/press/2005/headstart_study.htm (accessed May 22, 2006). In this statement concerning the study’s findings, HHS said that despite the gains shown in several areas, the Head Start programs “did not close the gap” between poor children and the general population.“The study found that Head Start produced small to moderate impacts in areas such as pre-reading, pre-writing,vocabulary and in health and parent practice domains. However these impacts did not close the gap betweenlow-income children in the Head Start program and the general population of three- and four-year olds. There were no significant impacts for three- and four-year olds in areas of early mathematics, oral comprehension and social competencies.”The Head Start Bureau reports an annual per child cost of $7,222. However, that figure (1) does not9include all funds allocated to or spent by the program, (2) ignores the cost differences between part-day and full-day,center-based and home-based care, as well as between Early Head Start and regular Head Start.Total Head Start spending : For the 2003/2004 program year, total Head Start expenditures (including support activities not counted by the Bureau when calculating annual per child costs) were $6.774 billion ($6.074 billion excluding Early Head Start costs). In addition, the Head Start Act requires that grantees provide an additional 20percent to annual spending, which brings total spending to $8.129 billion ($7.289 excluding Early Head Start costs).The children in center-based Head Start also receive an additional subsidy through the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) of about $1,106. This brings the total spent on Head Start to $9.015 billion (8.175 billion excluding Early Head Start costs). In addition, various medical and other services are provided that are not quantified. We make no adjustments to our costs for these additional expenditures.Cost differences for part-day and full-day, center-based and home-based care, as well as between Early Head Start and regular Head Start : Head Start data do not identify the different costs for these types of care, but it is possible to estimate them by deriving hourly costs for each. First, we assume that hourly costs are the same for part-day and full-day care, and are 25 percent lower for home-based care compared to center-based care. We then derive anapproximate hourly cost by taking estimated expenditures for part-day and full-day care (derived from the portion of spending on children in each, 29 percent and 71 percent, respectively) and dividing them by their respectivedurations (four hours and seven hours for 156 and 197 days, respectively, multiplied by the number of children for each category). After adjusting for the cost difference between center-based and home-based care, this results in annual per child costs of $6,081 for part-day and $13,438 for full-day center-based care. The respective figures for home-based care are $3,731 and $9,249. For Early Head Start, which is about seven hours a day, we simply divide total expenditures ($677 million) by the number of children in the program (52,487) without including the pregnant mothers (5,896). The result is a 2004 estimated per child cost for Early Head Start of $12,899 .By applying these per child annual costs, we find a weighted average per Head Start child of $10,156 ($9,980 for part-day and full-day children), compared to the Head Start Bureau’s estimate of $7,222.[For Head Start’s calculation of annual per child costs, see: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,Administration for Children and Families, Child Care Bureau, “Head Start Program Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2004,”(Washington, DC: HHS, 2005), /programs/hsb/research/2005.htm (accessed June 28, 2006);for Head Start’s total expenditures, authors’ calculation based on: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,Administration for Children and Families, Child Care Bureau, “Head Start Program Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2004”;general population. And the absence of better short-term results is alarming, for it suggests that 8the quality of Head Start programs has deteriorated. In the past, the story of Head Start’s impact was always one of fade out. But the Impact Study indicates that there are now few initial impacts to fade out. We should expect more of a program that spends about $9,980 a year on each child.9for the 20 percent matching funds requirement under the Head Start Act, see: Melinda Gish, Child Care Issues in the 108 Congress, CRS Report RL31817 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, July 20, 2004); for the th CACFP subsidy, authors’ calculation based on: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Child & Adult Care Food Program: National Average Payment Rates, Day Care Home Food Service Payment Rates, and Administrative Reimbursement Rates for Sponsoring Organizations of Day Care Homes for the Period July 1,2004–June 30, 2005,” Federal Register, Vol. 69, No. 135 (July 15, 2004), pp. 42413–42415,/cnd/Care/Publications/pdf/2005notice.pdf (accessed June 28, 2006).]National Head Start Association, “New Head Start Impact Study Shows ‘Very Promising’ Early Results,10Points to Success of Program Boosting School Readiness of America’s Most At-Risk Children,” Press Release, June 9, 2005, /press/index_news_060905.htm (accessed January 18, 2006).Michelle R. Davis, “Head Start Has Modest Impact,” June 15, 2005,11/issues/education/details.cfm?id=32351 (accessed May 15, 2006).Instead of acknowledging the troubling significance of these findings, the Head Startestablishment and its allies immediately went on the offensive—perhaps because the reported impacts imply that the program needs a major overhaul that would threaten vested interests. The Head Start Association, for example, claimed that the study is “good news for Head Start” and warned that “those who have resolved to trash Head Start at every turn will twist this data to their ends” as part of their “continued attempts to dismantle the program.”10Whatever might be the motivations of the enemies of Head Start, many friends of low-income children find these results heartbreaking. is a collaboration between the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights Education Fund, and 180 allied organizations. The best it could say about the study was that Head Start has a “modest impact.”11Sadly, the Head Start establishment’s stonewalling seems to be working. Evenresponsible critics have been cowed into silence, or at least relegated to private muttering on the sidelines. As a result, instead of galvanizing action to improve the program, this most recent study will likely be ignored.The same thing happened in 2001 when the equally heartbreaking results of theevaluation of Early Head Start were released. Started in 1995, Early Head Start is a two-generation program intended to enhance children’s development and help parents to educate theirU.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Program Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2004.12U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Head Start13Bureau, Early Head Start Almanac (Washington, DC: Head Start Information and Publication Center, October 2004), /programs/hsb/programs/ehs/ehsalmanac.htm (accessed January 17, 2005).U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Program Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2004.14John Love, Ellen Eliason Kisker, Christine M. Ross, Peter Z. Schochet, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Diane15Paulsell, Kimberly Boller, Jill Constantine, Cheri Vogel, Allison Sidle Fuligni, and Christy Brady-Smith, Making a Difference in the Lives of Infants and Toddlers and Their Families: The Impacts of Early Head Start. Volume 1:Final Technical Report (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Commissioner’s Office of Research and Evaluation and Head Start Bureau, June 2002), /PDFs/ehsfinalvol1.pdf (accessed December 30, 2002), p. xxv.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families Press Office,16“Early Head Start Shows Significant Results for Low Income Children and Parents,” HHS News , January 11, 2001,/news/press/2001/ehs112.html (accessed January 18, 2006).young children. In 2004, it served about 62,000 children in about 1,300 centers, at a cost of 12about $10,500 per child. The program’s total annual cost was about $677 million.1314The evaluation of Early Head Start, involving about 3,000 families, was also based on arigorous random assignment design. Unfortunately, the effect sizes for virtually all importantoutcomes fell below levels that have traditionally been considered educationally meaningful. For instance, at age three, Early Head Start children achieved a statistically significant, but small, two point gain on the Bayley MDI, a standardized assessment of infant and toddler cognitivedevelopment (91.4 vs. 89.9 for control group children). In addition, a smaller percentage of Early Head Start children fell in the “at-risk” range of developmental functioning on the Bayley MDI (27.3 percent compared to 32.0 percent for the control group) (only statistically significant at the 10 percent level). But these impacts are small, with the effect sizes just 0.12 and -0.10.The HHS evaluation contractor’s report was carefully worded to avoid claiming largegains while still making the program seem a success: “The Early Head Start research programs stimulated better outcomes along a range of dimensions (with children, parents, and home environments) by the time children’s eligibility ended at age 3.” A press release about these 15findings issued by then Secretary of HHS, Donna Shalala, was not as careful. It was titled: “Early Head Start Shows Significant Results for Low Income Children and Parents.”16Both were misleading overstatements, but the tactic worked. There was no public dissent from this unjustifiably rosy interpretation of the findings—either from within the early childhood education community or even from more skeptical conservative observers. (After five years in office, the Bush administration has done little to provide a more realistic understanding of these disappointing findings.)U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Bureau, “Head Start Program Information17Report for the 1999–2000 Program Year” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,undated); and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Bureau, “Head Start Program Information Report for the 2003–2004 Program Year” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,undated).U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Bureau, “Head Start Program Information18Report for the 1999–2000 Program Year” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,undated); and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Bureau, “Head Start Program Information Report for the 2003–2004 Program Year” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,So, don’t count on the politicians to do much on their own to improve Head Start.Republicans, worn down by years of battling, are reluctant to raise Head Start’s problems, for fear that Democrats and liberal advocates will paint them, yet again, as being against poorchildren. And Democrats are afraid that honesty about Head Start’s weaknesses will sharpen the knives of conservative budget cutters. In fact, even after the release of the Impact Study results,the relevant committees in both Houses of Congress voted unanimously to expand eligibility for Head Start. The Senate bill would raise the income-eligibility cap from the poverty line to 130percent of poverty (a roughly 35 percent increase in eligible children), and the House bill would allow programs to enroll more one- and two-year-olds, rather than their traditional target group of three and four-year-olds (ultimately doubling the number of eligible children). At this writing, no final action has been taken, but it appears likely that the Senate will adopt the House provision.Not what parents wantNo single evaluation, of course, should decide the fate of an important program like Head Start, but this new study reinforces a developing professional consensus about Head Start’s limitations. Many liberal foundations have already shifted their support away from Head Start and toward the expansion of preschool or prekindergarten (“preK”) services—which siphon off hundreds of thousands of children from Head Start programs. Many states have likewise begun funding expanded prekindergarten programs, again at Head Start’s expense.Perhaps the best indication of Head Start’s slumping reputation comes from low-income parents themselves, who often chose not to place their children in Head Start. One can see this in the declining proportional enrollment of four-year-olds, Head Start’s prime age group. Between 1997 and 2004, even as Head Start’s funded enrollment increased by 22 percent, the number of four-year-olds in the program increased by only 2 percent.17To compensate for this drop-off in the proportional enrollment of four-year-olds, HeadStart grantees are signing up more three-year-olds and encouraging them to stay in the program for a second year. Between 1997 and 2004, the number of three-year-olds in the programincreased by 38 percent, and their proportion of total enrollment increased from 30 percent to 34percent. HHS strongly encourages grantees to serve four-year-olds before serving other age18undated).Douglas J. Besharov and Jeffrey S. Morrow, Is Head Start Fully Funded? Income-eligible enrollment,19coverage rates, and program implications (College Park, MD: Welfare Reform Academy, 2006).Douglas J. Besharov and Jeffrey S. Morrow, Is Head Start Fully Funded? Income-eligible enrollment,20coverage rates, and program implications (College Park, MD: Welfare Reform Academy, 2006).U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Bureau, “Head Start Today,” Creating a 21st21Century Head Start: Executive Summary of the Final Report of the Advisory Committee on Head Start Quality and Expansion (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1993),/programs/hsb/research/21_century/part1.htm (accessed April 3, 2005), stating: “Head Start must now fit into a diverse set of early childhood programs and resources at the federal, state, and local level. Some of the most dramatic changes in communities since the beginning of Head Start are reflected in the increased number and variety of programs sponsored by states and local education agencies, the increase in resources and mandates for serving children with disabilities, and the expansion and demand for full day services.”For 1996–2000: unpublished tables from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 15: Presence and Age of22Own Children of Civilian Women 16 Years and Over, by Employment Status and Marital Status;” and for 2001:unpublished tables from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 3: Employment Status of the Civilian Noninstitutional Population by Sex, Age, Presence and Age of Youngest Child, Marital Status, Race, and Hispanic Origin.”groups. So, these age allocations, largely in the control of local grantees (except for Early Head Start), presumably reflect local needs and preferences.This explains, by the way, why Head Start allies have pushed for an expansion ofeligibility even in the absence of more funding. The program has essentially run out of eligible four-year-olds to enroll. There has already been a notable loosening in the application of19income-eligibility rules. By our calculation, about a quarter of the children in Head Start would not be income eligible if their income were measured at the time of enrollment or reenrollment.20A major reason for this shift away from Head Start is the increase in the employment,especially full-time employment, of low-income mothers. When Head Start was first21conceptualized in the 1960s, few low-income mothers (for that matter, few mothers in general)were in the paid labor force. So Head Start’s part-time, part-year program was not an obstacle to participation. Since then, and especially after welfare reform, many more low-income mothers are working. Between 1996 and 2001, for example, the percentage of never-married mothers working full time rose from 36 percent to 52 percent. In almost all places, though, Head Start 22remains a part-time, part-year program, with half-day classes usually beginning in September and ending in mid-June.The Head Start Bureau has actively encouraged grantees to provide more assistance forworking parents, including targeted expansions for full-day programs and collaborations with child care agencies. It has had real, but limited success. Some Head Start grantees haveresponded to the needs of working mothers by obtaining additional funding for “wrap-around”U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Bureau, “Head Start Program Information23Report for the 2003–2004 Program Year” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,undated). This is up from 41 percent in 1998/1999, although we have some questions about the accuracy of these data.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Bureau, “Head Start Program Information24Report for the 2003–2004 Program Year” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,undated).Even though child care for low-income families is subsidized, most states require copayments that can be25substantial, even for families under the poverty line. As of FY 2000, many states imposed copayments for poorfamilies as high as 10 percent of family income [U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, National Child Care Information Center, “Sliding Fee Scale,” Part III, Section 3.5 in Child Care and Development Fund Report of State Plans for the Period of 10/01/99 to 9/30/01 (Washington, DC: U.S.Department of Health and Human Services, 2002), /pubs/CCDFStat.pdf (accessed June 30,2005), stating: “Co-payments are typically based on a percentage of family income, a percentage of the price of the child care, or a percentage of the State reimbursement rate.” Thirty-eight states set copayments on a percentage of the family income, often as much as 10 percent; five states set them as a percentage of the price of the child care; six states set them as a percentage of the state reimbursement rate; and one state allows but does not require counties to set copayments at between 9 and 15 percent of the family’s gross income, with the average, in FY 2001, being about3.4 percent of family income. For a family of three (a mother and two children at the poverty line ($14,128) that would be a copayment of about $480 per year.] [Craig Turner, Director of Program Management, Head Start Bureau,U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, e-mail message to Douglas Besharov, June 22, 2005, stating: “In FFY 2001, the average co-payment as a percentage of income for families with incomes below the poverty line was3.4%. In FFY 2002, it was 3.6% and in FFY 2003 3.8%.” (These average payments include families with zero copayment.)]Douglas J. Besharov and Jeffrey S. Morrow, Is Head Start Fully Funded? Income-eligible enrollment,26coverage rates, and program implications (College Park, MD: Welfare Reform Academy, 2006). child care services. But only about half of the Head Start children whose parents say that they “need” full-time/full-year care obtained it from Head Start in 2003/2004. Hence, the other half 23of mothers who work full-time and use Head Start must find some other child care for the rest of the day and the summer. About 230,000 mothers do just that.24The issue runs deeper, however. The evidence suggests that some parents simply do notwant to use Head Start. Most income-eligible mothers who work full-time do not use Head Start,even though that means that they must spend more on child care (because of an often substantial copayment)—over 200,000 children in 2001. Or, instead, they rely on relatives to care for their 25children (another 200,000 plus children in 2001).26Even many mothers who do not work, or who only work part-time and thus could useHead Start as a form of child care while they work, use relative care. In fact, we are told by a number of directors of local agencies that, when offered free Head Start in the summer, manyparents who used Head Start during the school year prefer to leave their children home with older siblings.。

start的短语有哪些

start的短语有哪些start表示开始; 动身; 开动; 起点的意思,那么你知道start的短语有哪些吗?接下来小编为大家整理了start的短语搭配,希望对你有帮助哦!start的短语:don't start (或 don't you start)1. (非正式)告诉(某人)不要发牢骚(或指责)不要发牢骚,我做我应该做的那一份。

don't start—I do my fair share.for a start1. (非正式)首先;一开始这一边处于优势,首先是他们人更多。

this side are at an advantage—for a start, there are more of them.get the start of1. (旧)比…居先,比…占优势start a family1. 开始怀第一个孩子start something1. (非正式)惹是生非start in1. (非正式)开始做(尤指开始说)当她开始表达当演员的志向时,人们报以不满的哼哼声。

people groan when she starts in about her acting ambitions.start off (或 start someone/thing off)1. (使)开始;(使)从事治疗首先应该从注意饮食开始。

treatment should start off with attention to diet.是什么使你开始这项研究的。

what started you off on this search?.start on1. 开始进行;着手处理我正开始写一本新书。

I'm starting on a new book .2. (非正式)开始吵架;开始用言语抨击她开始指责我没有合适的家具。

she started on about my not having proper furniture.start over1. (北美)重新开始你能面对返回学校重新开始读书吗。

start的用法总结大全2篇

start的用法总结大全start的用法总结大全精选2篇(一)1. Start作为动词,用来表示开始或开启某个活动、过程或状态:- We will start the meeting at 9 o'clock.- He started the car and drove away.- The singer started the concert with her latest hit.2. Start可以用来表示开始做某事,或开始从事某个职业或活动:- She started studying French when she was in high school.- He started working as a teacher after he graduated.3. Start还可以表示开始使用或启动某个机器、设备或系统:- I start my computer every morning.- He started the washing machine to do the laundry.4. Start也可以表示开始存在或发生某种情况或事件:- The rain started at noon and didn't stop until evening.- The war started in 1939.5. Start可以作为名词,表示开始的时间或地点:- The start of the race is at the park.- The start of the party is at 7 pm.6. Start还可以表示开始的信号或动作:- The referee blew the whistle to signal the start of the game. - She gave a nod to indicate the start of the dance performance.7. Start常用于一些固定搭配中:- Start over: 重新开始- Start up: 启动(公司、项目等)- Start off: 开始,出发- Start with: 以…开始- Start from scratch: 白手起家,从零开始这只是start的一些常见用法总结,并不涵盖所有情况。

开始的英文怎么写

1.开始的英文单词怎么写开始的英文单词是start。

英式读法是[stɑːt];美式读法是[stɑrt]。

可做名词和动词使用,作不及物动词时意思是出发、启程、发生等;作及物动词是意思是使开始、使流出等;作名词是意思是出发、开动、启动等。

相关例句:用作动词(v.)1、It started to rain.下起雨来了.2、I used to start work at 9 o'clock every day.我过去常在每天9:00开始工作。

用作名词(n.)1、He knew from the start the idea was hopeless.一开始他就知道这主意行不通。

2、What a start you gave me!你吓了我一大跳!单词解析:1、变形:过去式: started过去分词: started现在分词: starting第三人称单数: starts2、用法:v. (动词)1)start的基本意思是“从静止状态转移到运动状态”,可指工作、活动等的开始;战争、火灾等的发生;也可指人开始工作,着手某项活动;还可指人、事物使某事情发生或引起某事情。

2)start可用作不及物动词,也可用作及物动词。

用作及物动词时,可接名词、代词、动名词、动词不定式作宾语,也可接以现在分词充当补足语的复合宾语。

start偶尔还可用作系动词,接形容词作表语。

3)start可用一般现在时或现在进行时来表示将来。

n. (名词)1)start用作可数名词的基本意思是“开始,出发,起点”,可指做某件事情的开始,也可指某件事情的开始地点,是可数名词。

2)start也可用于表示某件事开始时就有“领先地位,有利条件”,通常用作不可数名词,但可用不定冠词a修饰。

3)start还可作“惊动,惊起”解,一般为可数名词,经常用单数形式,与不定冠词a连用。

百度百科-start2.开始的英语怎么写利用begin造句如:Everything had to be begun over again.意思是:一切都得重新开始。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Infants&Young ChildrenVol.18,No.1,pp.16–24c 2005Lippincott Williams&Wilkins,Inc.Head Start’s Lasting BenefitsW.Steven Barnett,PhD;Jason T.Hustedt,PhDThe benefits of Head Start are under increased scrutiny as Congress debates its reauthorization.How effective is Head Start,and how can it be improved?We provide a current overview and crit-ical evaluation of Head Start research and discuss implications of this research with an eye toward informing debate.There has been a good deal of controversy over whether Head Start produces lasting benefits,dating back to its early years.Our review finds mixed,but generally positive,evi-dence regarding Head Start’s long-term benefits.Although studies typically find that increases in IQ fade out over time,many other studies also find decreases in grade retention and special education placements.Sustained increases in school achievement are sometimes found,but in other cases flawed research methods produce results that mimic fade-out.In recent years,the federal govern-ment has funded large-scale evaluations of Head Start and Early Head Start.Results from the Early Head Start evaluation are particularly informative,as study participants were randomly assigned to either the Early Head Start group or a control group.Early Head Start demonstrated modest improvements in children’s development and parent beliefs and behavior.The ongoing National Head Start Impact Study,which is also using random assignment,should yield additional insight into Head Start’s effectiveness.We conclude with suggestions for future research.key words: early education,Head Start,long-term benefits,policyH EAD START is our nation’s foremost fed-erally funded provider of educational services to young children in poverty.Since 1965,more than21million children have par-ticipated in this comprehensive child develop-ment program(U.S.Department of Health and Human Services,2003a).As a comprehensive program,in addition to its educational ser-vices,Head Start also provides social,health, and nutritional services to children and their low-income parents.When Early Head Start was established in1994,the program was ex-panded to serve even younger children(from birth to age3)and their families.By2002, the Head Start program reported funding more than910,000children with a budget of $6.5billion(U.S.Department of Health andFrom the National Institute for Early Education Research,Rutgers,The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick.We extend our thanks to the anonymous reviewers of this article for their helpful suggestions. Corresponding author:W.Steven Barnett,PhD,Na-tional Institute for Early Education Research,Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey,120Albany St, Suite500,New Brunswick,NJ08901(e-mail:sbarnett@ ).Human Services,2003a).However,Head Start remains a promise unfulfilled.Nearly10years after Congress authorized full-funding,Head Start’s budget is still insufficient to serve all eligible children or deliver uniformly high-quality services to all enrolled.As one of the most prominent educational and social programs in the United States, Head Start has attracted both proponents and detractors.How effective is Head Start as an early education program for disad-vantaged children?What are the long-term benefits associated with participation in Head Start?These are questions that are reconsidered in each authorization cycle, when the program’s benefits come under increased public scrutiny.Head Start was most recently reauthorized by Congress in 1998and was scheduled for reauthorization again in2003,although this process has not yet been completed.This article critically reviews the research on Head Start and other early education programs for at-risk children.We also discuss the implications of this research for issues that are likely to arise during reauthorization.Finally,we present recommendations for future studies of Head Start.16Head Start’s Lasting Benefits17THE WESTINGHOUSE STUDY Controversy over the benefits of Head Start dates back to its earliest years,when a study by Westinghouse Learning Corpora-tion and Ohio University(1969)reported that the program produced few sustained effects. This was the first prominent effort to inves-tigate Head Start’s impacts over time.For-mer Head Start children identified in first, second,and third grades were compared to schoolmates within the same grades who had not participated in Head Start,with a focus on cognitive and social-emotional develop-ment.Children from the Head Start and com-parison groups were matched within grades on other important characteristics including ethnic group,gender,socioeconomic status (SES),and kindergarten attendance.The Westinghouse study was immediately and widely criticized on methodological grounds(Condry,1983).However,no one ap-pears to have noticed at the time the most se-rious methodological flaw.The post hoc se-lection of the2groups literally equated the children on grade level.This biases between-group comparisons to the extent that differ-ences in grade retention rates and special ed-ucation placements truncated the samples, thereby eliminating the higher percentage of lower performing children from the com-parison groups.The most obvious evidence that the comparison group does not repre-sent comparable cohorts is that an increas-ing age gap is found moving across the grades with children in the third-grade comparison group significantly older than the third-grade Head Start children.Despite this and other evi-dence of methodological problems,the West-inghouse study continues to be cited in pol-icy debates as evidence that Head Start does not produce sustained educational benefits for children in poverty.FINDINGS FROM SHORT-ANDLONG-TERM STUDIES OF HEAD START Since the publication of the Westinghouse study,Head Start has continued to draw re-searchers’attention.A number of longitudi-nal studies have followed former participants over time to gather more information about the benefits associated with Head Start.This research can be divided into2general cate-gories:short-term and long-term studies.For the purposes of this review,we consider stud-ies with immediate outcome measures and longitudinal studies with outcome measures taken earlier than third grade to be short-term studies,and consider studies with outcomes measured in third grade or later to be long-term studies.A brief summary of the key findings from the short-term studies follows,since our primary interest is in Head Start’s long-term benefits.Evidence of short-term ben-efits of preschool programs including Head Start has been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere (Barnett,2004;McKey et al.,1985;Nelson, Westhues,&MacLeod,2003;Ramey,Bryant, &Suarez,1985;White&Casto,1985).Studies have generally shown that programs for chil-dren at risk,including Head Start,result in in-creases of0.5standard deviations in IQ and achievement.Estimated impacts on measures of social behavior,self-esteem,and academic motivation typically are slightly smaller.A recent short-term study by Abbott-Shim, Lambert,and McCarty(2003)is particularly notable for using random assignment of eli-gible4-year-olds who had applied to a large Head Start program with a waiting list.This procedure allowed the researchers to rule out selection bias as an influence on results. Abbott-Shim et al.(2003)found that Head Start participants benefited substantially com-pared to nonparticipants in the areas of recep-tive vocabulary and phonemic awareness and had more positive health-related outcomes, for example,they were more likely to be cur-rent on their immunizations.And the parents of Head Start children reported more posi-tive health and safety habits than the parents whose children did not attend Head Start.Be-cause of the strength of the research design used in this study,these outcomes provide strong support for the short-term effective-ness of Head Start.18I NFANTS&Y OUNG C HILDREN/J ANUARY–M ARCH2005Some past reviewers(Haskins,2004; McKey et al.,1985;White&Casto,1985) have found that positive impacts of Head Start and early childhood programs for dis-advantaged children decrease over time and eventually fade altogether.However,recent meta-analyses of longitudinal studies(Gorey, 2001;Nelson et al.,2003)suggest that effects persist over time although there may be some diminution of effects over the long term. These findings are consistent with the work done by Barnett,Young,and Schweinhart (1998),who used causal modeling to show that long-term effects of early childhood education are built upon short-term effects. Reviews focused on long-term studies of early education programs serving econom-ically disadvantaged children(eg,Barnett, 1998,2004)find that the evidence regard-ing Head Start’s long-term outcomes is mixed. In a recent examination of Head Start’s long-term cognitive effects,Barnett(2004)identi-fied only39studies in which educational pro-grams included treatment and control groups, served children from low-income families,be-gan during or before the preschool years, and were followed up with cognitive or aca-demic measures at least through third grade, of which15were studies of“model”programs and24were studies of large-scale public pro-grams.Twelve of the public program stud-ies focused on Head Start,and an additional 4included both Head Start and public school programs.Several of the model pro-gram studies,but none of the large-scale public program studies,employed random assignment.Studies of model programs typically show initial gains in children’s IQ scores that fade out over time(Barnett,2004).Studies of large-scale programs have less often measured IQ, although the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test has sometimes been used as a proxy for ver-bal IQ,making it more difficult to evalu-ate whether Head Start produces persistent IQ gains.However,it is likely that initial in-creases in IQ scores by Head Start children also fade out over time.Findings regarding other types of benefits are more promising.Studies of both model and large-scale pro-grams find achievement effects.In some stud-ies the effects persist,in others effects on achievement cease to be statistically signifi-cant over time.Fade-out is frequently asso-ciated with high attrition over time or with other design flaws that affect the collection of achievement test data.Yet,decreases in chil-dren’s later rates of grade retention and spe-cial education placements are found in most studies of model and large-scale programs. This apparent inconsistency often can be ex-plained by differences in data collection pro-cedures that lead to greater,more-biased attri-tion for achievement test data(Barnett,2004). Few studies have measured impacts on high school graduation,but those with the largest samples reported statistically significant posi-tive impacts(Barnett,1998).Overall,it appears that model programs and large-scale programs such as Head Start have similar types of effects,but the studies of model programs found effects of greater magnitude(Barnett,2004).Given the varia-tion in populations,programs,and contexts across studies,it is difficult to identify a sin-gle cause for this difference in effectiveness. Yet,it seems highly plausible that programs such as Head Start lack the type of fund-ing necessary to produce the levels of in-tensity and quality achieved in better funded model programs with the direct result that they are less effective.Several studies provide direct evidence in support of this argument (Barnett,1998).Some of this is discussed be-low in the context of findings from key studies of non–Head Start preschool interventions. OUTCOMES FROM OTHER PRESCHOOL INTERVENTION PROJECTSThe Carolina Abecedarian Project (Campbell&Ramey,1994,1995)is one of the most notable studies of a model program to provide high-quality early education services to at-risk children.Participants were identified in the1970s as infants,on the basis of their parents’low-income status as well as other risk factors predictive of cognitive difficultiesHead Start’s Lasting Benefits19in childhood.The sample(N=111),which was primarily African American,was divided into experimental and control groups by random assignment.Experimental group children attended the full-day,year-round Abecedarian program until age 5.Another randomization took place before children started school,with half the members of both the control and the experimental groups receiving an additional3-year intervention. Thus,participants in this study received from 0to8years of intervention services,with vari-ation in its timing.Follow-up results have now been reported through age21(Campbell, Pungello,Miller-Johnson,Burchinal,&Ramey, 2001;Campbell,Ramey,Pungello,Sparling, &Miller-Johnson,2002).Findings from the Abecedarian Project show that the program produced large ini-tial effects that persisted long after the inter-vention ended(Campbell et al.,2001,2002; Campbell&Ramey,1994,1995).At the age 21follow-up,Campbell et al.(2002)found that program effects were strongest for young adults who had taken part in the(5-year) preschool phase of the intervention.When compared to the preschool control group, these adults showed stronger performance on measures of academic skills and IQ.At age 21,they also were more likely to be enrolled in4-year colleges,were better educated over-all,and were more likely to hold skilled em-ployment.Further,cost-benefit analysis of the Abecedarian Project(Masse&Barnett,2002) shows that its overall benefits outweigh its costs,on the order of$4saved for every dollar spent on the preschool intervention(present value discounted at a real rate of3%). Research on the Chicago Child-Parent Cen-ters(CPC;Reynolds,Temple,Robertson, &Mann,2002)provides evidence of the long-term effects of a public-school–operated preschool program.The CPC program began in1967and classrooms are located in or near public schools in Chicago’s highest poverty neighborhoods.From age3until age5,par-ticipants attend 2.5hour classes5days a week during the school year and a6-week summer program is also generally provided.After attending kindergarten,participants re-ceive less intensive services through the pub-lic schools until age9.Longitudinal follow-ups of the CPC cohort born in1980have been completed through age21,on the basis of2 study groups created beginning in1985:for-mer participants in the preschool and kinder-garten phases of the CPC program(N=989) and a comparison group of nonparticipants (N=550).Members of the comparison group were matched to former preschool partici-pants using SES and other demographic fac-tors.Reynolds and colleagues(2002)report positive long-term outcomes from CPC across a wide range of domains.These include per-sistent gains in reading achievement(age14), lower rates of grade retention and special ed-ucation,lower rates of reported child mal-treatment(ages4–17),lower rates of juvenile arrests,and higher rates of educational attain-ment.A cost-benefit analysis estimates that the CPC preschool program yields an eco-nomic return far exceeding its cost(Reynolds et al.,2002).RECENT RESEARCH ON HEAD START’S LONG-TERM OUTCOMESAlthough long-term longitudinal evalua-tions of benefits associated with the Head Start program have been rare,several re-cent studies have sought new evidence.In a follow-up to the Head Start Planned Vari-ation study conducted from1969to1972, Oden,Schweinhart,Weikart,Marcus,and Xie (2000)compare22-year-olds who attended Head Start at age4to others who had not at-tended,in2communities,1in Florida(N= 424)and1in Colorado(N=198).Former Head Start participants were located as young adults,and a post hoc comparison group was constructed using young adults who had lived on the same streets or in the same high-poverty neighborhoods(Census tracts)as the Head Start participants.Members of the com-parison group had not attended Head Start or any other early education program.However, perhaps because many children from the com-munities’lowest SES families had attended20I NFANTS&Y OUNG C HILDREN/J ANUARY–M ARCH2005Head Start,the Head Start group was slightly lower in SES than the non–Head Start compar-ison group.Statistical adjustments for these and other differences were made in the data analysis,to facilitate the process of drawing meaningful conclusions from comparisons be-tween the2groups.Few statistically significant differences were found between the Head Start and non–Head Start comparison groups(Oden et al., 2000).However,the direction and pattern of results suggests possible long-term benefits. Most notably,in the Florida sample,girls who had attended Head Start were significantly more likely to graduate high school or earn a GED(95%vs81%)and significantly less likely to have been arrested at age22(5%vs 15%)than were girls in the non–Head Start comparison group.The lack of strong results in this study may be due to methodological limitations that led to difficulties in adequately controlling for preexisting differences between the Head Start group and the non–Head Start group.All of the initial advantages of the comparison group may not be captured by the difference in socioeconomic status,and the statistical ad-justments cannot be guaranteed to produce an unbiased estimate of the impact of Head Start on the more disadvantaged participant group.Oden and colleagues recommend that more rigorously designed studies be devel-oped to obtain stronger evidence.Janet Currie and colleagues have employed creative statistical approaches to estimate the long-term effects of Head Start from national data sets with self-reported Head Start partici-pation(Currie&Thomas,1995,1999;Garces, Thomas,&Currie,2000).These studies esti-mate within family differences among siblings where one child is reported to have attended Head Start and another not.One strength of these studies is that they employ data col-lected across the nation.Limitations include error in self-reported participation and highly restrictive assumptions about the reasons for, and the consequences of,differences in Head Start participation among siblings(Barnett& Camilli,2002;Currie,2001).Most of the lim-itations seem likely to lead to an underesti-mation of long-term benefits(Currie,2001). For example,they assume that Head Start has no benefit for siblings and that parents en-gage in no compensating behaviors to gen-erate more equal outcomes among siblings. These assumptions are unlikely to be true and thus bias downward the estimated effects from comparing siblings(Barnett&Camilli, 2002).Currie and colleagues find long-term effects for subpopulations:higher long-term Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test scores,less grade rep-etition,and more high school graduation and college attendance for whites and Latinos and fewer criminal charges and convictions for African Americans.This variation by eth-nicity is not predicted a priori,and the lack of persistent academic improvements for African Americans is inconsistent with the findings of randomized trials of other in-terventions with African American samples. Barnett and Camilli(2002)conducted similar analyses with one data set employed by Currie and Thomas(1995)and found no persistent gains for either white non-Latino or African American children.They caution that limita-tions of the data and the potential for substan-tive violations of the analytical assumptions are so serious that such estimates of Head Start’s long-term effects should not be relied upon for public policy purposes.RECENT FEDERALLY SPONSORED EVALUATIONS OF HEAD STARTThe federal government has renewed its emphasis on funding large-scale scientific evaluations of Head Start and Early Head Start in recent years.These national,longitudinal studies have been sponsored by the Admin-istration on Children,Youth,and Families to provide more details about the services pro-vided by these programs,as well as better in-formation regarding the progress made by par-ticipants and their families.The Family and Child Experiences Survey (FACES;Zill et al.,2001)of Head Start childrenHead Start’s Lasting Benefits21and their families was the first of these studies, beginning in1997.Of primary interest in FACES1997were Head Start’s impact on chil-dren’s development and readiness for school; the quality of education,nutrition,and health services provided to children;the relation-ships between quality in the classroom and child outcomes;and the program’s impact in strengthening families.One problem with this study,however,is that its design does not allow for comparisons between Head Start participants and demographically similar chil-dren who did not attend Head Start.There-fore,although it is possible to conclude that middle-income children continue to outscore Head Start participants,the scope for finer grained conclusions about the gains made by Head Start children in comparison to eligi-ble nonparticipants is quite limited(Barnett& Hustedt,2003).Results have recently become available for an additional FACES cohort of children who entered Head Start beginning in 2000(Zill et al.,2003).However,like the ini-tial FACES study,FACES2000lacks a compar-ison group of non–Head Start children.The modest initial effects estimated by Barnett and Camilli(2002)appear to be consistent with re-sults from the FACES studies.A second large-scale study is the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation project(Love et al.,2002),which began shortly after Early Head Start was established.At the outset of this study,families were randomly assigned to a participant group that received services from the Early Head Start program or to a control group that did not receive these ser-vices.Results suggest that this program has a wide range of important short-term impacts, both for2-and3-year-old Early Head Start participants and for their parents.When com-pared to nonparticipants,participating chil-dren were less aggressive and more success-ful on measures of cognitive and language development.Parents of Early Head Start chil-dren became more self-sufficient,as they were more likely to participate in job training and educational programs.Furthermore,they showed improvements on assessments of parenting.Finally,data collection began in2002for a third large-scale longitudinal study,which was mandated by Congress during Head Start’s most recent reauthorization in1998.The Na-tional Head Start Impact Study(Puma et al., 2001)will focus on the effects of Head Start participation on children,especially their school readiness,and will also examine the impacts associated with variations in types of services and settings.Children will be fol-lowed in this study from age3or4until the spring of their first grade year.Unlike the FACES studies,the Impact Study employs ran-dom assignment of at-risk children to exper-imental(Head Start)and control(non–Head Start)groups.Although results are not yet available,the use of random assignment gives this study greater promise of producing valid estimates of the effects of Head Start pro-grams on children and their parents.The Im-pact Study is the most promising evaluation of Head Start’s benefits to date. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE HEAD START RESEARCH Despite the fact that Head Start has been extensively studied since it began nearly4 decades ago,the answers to some critical questions remain incomplete.The long-term benefits of Head Start rarely have been stud-ied,and never with sufficiently strong re-search designs.Research on Head Start and similar programs has found substantial long-term benefits in educational achievement and attainment,employment,and social behavior. It is reasonable to conclude that Head Start has positive benefits for school readiness and at least some educational benefits are sustained over time.Less is known about the magnitude of the benefits,the full range of benefits(so-cial,emotional,and physical as well as cogni-tive),the benefits to parents and siblings of children in Head Start,and the effectiveness of Head Start’s various components.The strongest evidence for a broad range of large long-term benefits comes from stud-ies of other preschool programs in which key aspects of both the research designs and22I NFANTS&Y OUNG C HILDREN/J ANUARY–M ARCH2005programs are of higher quality.This compli-cates the interpretation of differences in find-ings between studies of Head Start and other programs.One constant is that initial gains in IQ fade over time.Gains on subject-matter–specific achievement tests are more likely to be maintained.Decreased grade retention and special education rates and increased high school graduation rates are common.Flawed research methods frequently produced results that mimic fade-out with achievement tests, producing an unnecessarily confusing pattern of results.Head Start also seems likely to im-prove social behavior(eg,reducing crime), but direct evidence is quite limited.Across all domains,Head Start’s benefits for children seem likely to be modest in size,smaller than the effects of such well-known interventions as the Perry Preschool and Abecedarian programs.The most obvious reason for the relatively small size of Head Start and Early Head Start effects is the qual-ity and intensity of key aspects of the pro-grams.The programs producing larger effects had much better educated teachers,smaller classes,stronger supervision,and other re-source advantages.Head Start’s broad mission to the family may result in smaller impacts on children because its budget is not sufficient to provide intensive services across the board. Head Start Program Information Report data (U.S.Department of Health and Human Ser-vices,2003b)suggest another possible reason for smaller effects.A substantial number of children appear to pass through the program in a given year so that the total number served during the course of the year is considerably larger than the number served for an entire year.And,only about half the children served by Head Start attend the program prior to age 4enabling them to receive more than a year of Head Start.An important related question for future re-search is the relative costs and benefits of the broad array of services mandated to be part of Head Start.Evidence regarding these is spotty,although this includes such bright spots as very large increases in access to den-tal care(Barnett&Brown,2000).Results from the Early Head Start study(Love et al., 2002)are promising as they show positive, though small,impacts on a range of outcomes for both children and their parents.In ad-dition,benefits transmitted through parents seem likely to diffuse to siblings,as well.How can the potential to enhance program effec-tiveness through services to parents be bet-ter realized?How can Head Start be reshaped in terms of social,health,and related ser-vices?Should its overall budget be increased so that it can increase the intensity of all its ser-vices?Should the intensity of selected compo-nents be increased,and should this be accom-plished by reducing the scope of Head Start’s services and goals?The past offers some lessons for future research on these questions.IQ tests and their proxies,which include the Peabody Pic-ture Vocabulary Test,may provide reasonable guides to the magnitude of initial cognitive gains,but subject-matter–specific tests are re-quired to more fully assess Head Start’s long-term effects on cognitive abilities.Social and emotional development should be assessed, and studies should not neglect attitudes and behavior in and out of school including moti-vation,prosocial activities,aggression,delin-quency,and crime.Physical development and nutrition seem all too often neglected at a time of increasing concern regarding obe-sity in children.If such outcomes are ne-glected in research and evaluation,Head Start policy will be made without much relevant information.It is particularly important that researchers seek answers to these questions to inform policy decisions that will shape the future of the Head Start program.For example,in2003 and2004Congress considered proposals for a variety of changes in Head Start.The pres-ident and others have proposed that Head Start should focus more intensely on liter-acy,and there are indications that Head Start needs improvement in this area(eg,McGill-Franzen,Lanford,&Adams,2002;Zill et al., 2001).However,such a focus could lead Head Start away from an integrated curriculum with broader educational goals and draw down。