Herd Behavior and Investment

2013A decision tree model for herd behavior and empirical

Inf Syst E-Bus Manage(2013)11:141–160DOI10.1007/s10257-011-0182-4O R I G I N A L A R T I C L EA decision tree model for herd behavior and empirical evidence from the online P2P lending marketBinjie Luo•Zhangxi LinReceived:5July2011/Revised:20September2011/Accepted:12October2011/Published online:5November2011ÓSpringer-Verlag2011Abstract Herd behavior has been studied in a wide range of areas,such as fashion, online purchasing,and stock trading.However,to date,little attention has been paid to the herd behavior in online Peer-to-Peer lending market.With a decision tree,we model the formation of herding when decision makers with heterogeneous preferences are facing costly information acquiring and analyzing.Data from provides us with a good opportunity to explore empirical evidences for herd behavior.When herd behavior arises,individuals follow the behaviors of other people and generally ignore their own information which might cost them too much to obtain or analyze.Following this idea,we propose to detect herd behavior by focusing on investors’decision-making time variation.We observed that friend bids and bid counts impose significant effects on the decision-making time of investors,which is considered as the evidence of herding. We also conduct empirical analyses to address the impact of herd behavior on an individual’s benefit.We reveal that lenders are more likely to herd on listings with more bids and friend bid,but their benefit will be reduced as the consequence of the behavior.Keywords Herd behaviorÁSocial networkÁDecision treeÁP2P lending market 1IntroductionWith the innovative applicationa of IT technology in thefinancial industry,a new kind of lending market was inaugurated in2005.The online peer-to-peer(P2P) B.Luo(&)Sichuan Key Lab of Financial Intelligence and Financial Engineering,Southwestern University of Finance and Economics,Chengdu610074,Sichuan,Chinae-mail:luobinjie@B.LuoÁZ.LinCenter for Advanced Analytics and Business Intelligence,Texas Tech University,Lubbock,TX79409,USA142 B.Luo,Z.Lin lending market matches people who need small loans but are unable to get them from traditional lending markets,which are hosted primarily by banks and other financial institutions with willing lenders.The online P2P market allows these parties to communicate peer-to-peer directly.Without banks as intermediaries,the P2P lending market can theoretically bring significant benefits to both borrowers and lenders.The rapid growth and promising future of this market have also attracted considerable attentions(Everett2010;Freedman and Jin2008;Lopez et al. 2009;Lin et al.2009;Iyer et al.2009;Puro et al.2010).However,there is a dearth of research on human behavior in the online P2P lending market.The emergence of ,America’s largest peer-to-peer lending market provides us with a good opportunity tofill this gap.Herd behavior as a significant mode of human behavior has been documented in many academicfields:psychology(e.g.,Tard and Parsons1903;Hoffer1955),financial markets(e.g.,Brunnermeier2001;Hirshleifer and Teoh2003)and online auctions and purchasing(e.g.,Dholakia and Bagozzi2001;Chen2008).Herd behavior describes various social situations in which individuals are strongly influenced by the decisions of others(Asch1956).On a daily basis,most people appear to primarily use public information to infer the beliefs of others.Based on this interpretation,individuals form their own beliefs and make decisions.This tendency leads to herd behavior,where everyone follows what other people are doing regardless of the content of their private information(Banerjee1992).For animals,herd behavior is considered as a good way of reducing the chance of being caught by a predator(Hamilton1971).However,in human society,many cases have indicated that herd behavior is often correlated with undesired and inefficient results:herd behavior among investors has been believed to be one of the causes of the dot-com bubble in1990s(Phillips et al.2009);the‘‘Tequila effect’’refers to the herd behavior by global investors that resulted in a series of currency crises in South America in1994(Calvo and Mendoza2000);and in online auctions,herd behavior may lead to neither the seller nor the buyer receiving the best value(Dholakia and Bagozzi2001).Will herd behavior exist in the online P2P lending market?How could herd behavior form in such an environment?What is the impact of herd behavior on the investors exhibiting it?With data provided by the ,this paper is intended to investigate these questions.This paper is organized as follows.In Sect.2,we conduct a review of the literature on herd behavior and P2P lending market.The details of our proposed model are presented in Sect.3.We perform the empirical tests on the derived hypotheses in Sect.4.In Sec.5,we provide a summary and discussion about our work.2Background and literature reviewIn this section,wefirst introduce the process how a loan is obtained in . Based on the context,we review the prior research work on the online P2P lending market and those on herd behavior.A decision tree model1432.1The loan formation on The pricing model utilized by Prosper is a multi-unit reverse auction.Each potential borrower who wants to obtain money on Prosper has to registerfirst.During the registration process,each potential borrower will be asked to provide his/her personal information as a means of identification.Then,Prosper will check and retrieve the person’s credit score from a credit bureau(Experian).Based on this credit score,a Prosper Rating,which has seven levels from AA to HR in descending order,will be assigned to the person by directly translating his or her Experian credit score(e.g.,a 700credit score translates to a B credit grade).After registering,the borrower can create a customized listing,which is similar to a poster in a BBS(Bulletin Board System).This listing may include the borrower’s personal andfinancial situation (e.g.,sex,income,and job),a title and a short description regarding the purpose of the loan and the details of the borrower’s request(e.g.,the amount of money needed and the maximum interest rate that he or she is willing to accept).After creating a listing, the borrower can post it on the Prosper market and let lenders review it.At this point, the borrower hasfinished his or her work for obtaining a loan,and the market determines whether the listing can turn into a loan.Each listing is live for14days. During this period,the listing can be viewed by lenders(investor,lender,bidder,and decision maker are identical terms and interchangeable throughout the rest of this paper).After reviewing the listing,each lender will decide whether to bid.A listing can receive bids from different lenders,and the minimum amount of each bid is50 dollars.Each lender who bids on a listing must reveal his or her interest rate and the amount of money that he or she is willing to lend to the borrowers.While the listing is live,if a lender failed in his or her previous bids,then the lender can change his or her asking interest rate and the amount of money that he or she is willing to lend to the owner of the listing.After doing so,the lender can bid again.Thus,based on how fierce the competition is,the interest rate may change dynamically during the bidding process and only settle down at closing time.If a listing is fully funded,then it will become a loan,and the funds will be deposited directly into the borrower’s bank account within a few days.The borrower will also begin to make monthly payments to lenders per the agreement.Otherwise,the borrower can create another new listing and post it on Prosper again.2.2Research on P2P lending marketsIt is widely accepted thatfinancial intermediation exists primarily to mitigate the information asymmetry between borrowers and investors(Leland and Pyle1977).As it is a new way of investing and borrowing money,the anonymity of the online P2P lending market may cause borrowers to exhibit greater uncertainty,thus worsening the problem of information asymmetry.Indirectly,it reduces investor’s incentive to participate or may even lead to market failure,as described by Akerlof(1970).Social network services were introduced to the online P2P lending market to reduce the borrowers’level of uncertainty and to mitigate the problem of information asymmetry (Freedman and Jin2008).Thus,one of the research directions in the P2P lending market is to investigate the effect of social network on the loan default rate.Everett144 B.Luo,Z.Lin (2010)found that the loan default rate is significantly reduced only if membership holds the possibility of real-life personal connections.Similar evidence was reported by Freedman and Jin(2008).They said that loans with friend endorsements and friend bids have fewer missed payments and estimated returns of group loans are significantly lower than those of non-group loans.Additionally,Iyer et al.(2009) revealed that,on ,the credit score is a reliable proxy for creditworthiness and should play an important role in the decision making of lenders.After analyzing the determinants affecting the success rate of obtaining a loan,Puro et al.(2010) developed a decision aid system for improving borrowers’decision quality on .To date,the research has examined the determinants in decision making for both lenders and borrowers in the online P2P lending market.However,the existence of also provides us with a chance to observe the trading behavior of traders in a new lending model that may complement the traditional lending model used by banks and otherfinancial institutions.In this paper,we will investigate herd behavior on ,which has not yet been addressed.2.3Models for herd behaviorIn this section,we mainly review the economic literature that we consider relevant to our study.For a more extensive review of herd behavior not confined to the economic domain,we suggest reading Raafat et al.(2009).According to past theories,there are many reasons for us to behave like a herd,which have been used as a basis to develop different models.One of those reasons is‘‘conformity preference’’:individuals inherently wish to conform to the behavior of others(Jones 1984).Based on this,Bikhchandani et al.(1992)proposed a model named ‘‘Information Cascades’’to explain fads,fashions,customs,and cultural changes. Information cascades occur when the existing aggregated information becomes so overwhelming that an individual’s private information is not strong enough to reverse the resulting decision.Almost simultaneously,Banerjee(1992)and Welch (1992)both modeled herd behavior as cascades.Their initial contributions inspired many similar models(Lee1993;Banerjee and Fudenberg1995;Brandenburger and Polak1996)and formed one of the most important types of herd model.Banerjee(1992)proposed an easy-to-understand model that we want to introduce here to illustrate how herd behavior happens.The model utilizes a very common situation in which people have to choose between two restaurants that are generally unknown.The preceding probability that the people will choose restaurant A is higher than that for B at51%.People arrive at the restaurants in sequence,observe the choices made by the people before them,and decide on one of the two restaurants.In addition,each person also sends his or her own signal indicating a preference for A or B,and the quality of the signals is the same.Suppose that among 100people,99receive signals indicating that B is better,but the one person whose signal favors A movesfirst.By observing thefirst person’s action,the second person infers that his or her own signal favors A,even though the second person’s signal actually favors B.Because these signals are equal in quality,they cancel out,and the rational choice for the second person is to follow the preceding probability and go to restaurant A.The second person exhibits herding behavior and selects A regardlessA decision tree model145 of his or her own signal.The third person faces the exact same situation as the second person.Because the second person’s choice does not provide any new information to the next person,the third person then makes the same choice as the second person.AlthoughB is better in general,everyone ends up going to A.In this simple model,the second person’s decision,which ignores his or her own information and joins the herd,imposes a negative externality on the rest of the population.The latest model in this‘‘cascade’’stream was developed by Smith and Sorensen(2000).It models how Bayesian-rational individuals learn sequentially from the discrete actions of others,and it allows for individuals to possibly entertain different preferences over their actions,differentiating it from previous studies.Another reason for herd behavior is reputation concern.The representative model was introduced by Scharfstein and Stein(1990).Based on the‘‘The General Theory of Employment’’(Keynes1936),it explained why managers mimic others in investment decisions.The models of Trueman(1994),Graham(1999),Zwiebel (1995),and Prendergast and Stole(1996)also fall into this category but are devoted to different investment activities:analysts releasing forecasts(Trueman1994; Graham1999),managers adopting innovations(Zwiebel1995)and investment decisions(Prendergast and Stole1996).Due to limited space and a lack of representativeness,we will not delve into the details of each of these models here.Additionally,Froot et al.(1992)modeled how the trading horizon induces herd behavior.Avery and Chevalier(1999)presented a model predicting that older agents will herd less.Hirshleifer et al.(1994)demonstrated that the sequential nature of information arrival has a significant effect on herd behavior.Kultti and Miettinen(2007)modeled herd behavior with the cost of observation.After reviewing those models,wefind that they fail tofit the situations in the online P2P lending market because of the followings:(1)Most of the models assume that decision makers can obtain and study information for free except Kultti and Miettinen(2007).In our consideration,such kind of cost should play a key role in generating herd behavior in certain environments.(2)Most of previous models ignore individual information preference,although it may have an important effect on herding inclination(Welch1992;Smith and Sorensen2000).(3)They often assume that the succeeding decision makers observe perfect information from their predecessors.This is not applicable in the online P2P lending market,as only the predecessors who bid on a listing can be observed,while those who do not are not observed.This biased information display may impair the judgments of some inexperienced lenders.Being different from those reviewed models,we model the effect of personal preference on information and cost of obtaining and studying information on herd behavior simultaneously.Under the framework of decision tree, we analyze the optimal choice of decision maker and derive the conditions of herding.Based on that,we can see how information preference and costly information trigger herd behavior in an online P2P lending market.2.4Empirical works on herd behaviorAs pointed out by Graham(1999),the best way to test herd behavior is to compare an individual’s action with his private information because this would let us know146 B.Luo,Z.Lin whether an individual discard his private information to take the public action. However,there seems to be no such data source that could match this demand. Instead,other ways have been developed to empirically test herd behavior.The most frequently used phenomenon to identify herd behavior is‘‘action conformity’’: many people take the same action perhaps because some mimic the actions of others (Graham1999).For example,by a observing a disproportionate share of investors who engage in buying,or at other times selling,the same stock,Lakonishok et al. (1992)concluded that the money managers in their sample did not exhibit significant herding behavior.Similar approaches were also employed by Peles (1993),Falkenstein(1996),Nofsinger and Sias(1996),and Wylie(1996)to test herd behavior among pension funds,mutual funds,and institutional investors.The reasons behind this method are as follows:(1)An individual’s private information or belief is hard to observe,but his/her actions are easy to capture;and (2)The occurrence of herd behavior must lead to‘‘action conformity,’’which was suggested by many models(e.g.,Bikhchandani et al.1992;Banerjee1992;Smith and Sorensen2000;Welch1992).However,the observed‘‘action conformity’’may not result from herd behavior.For instance,many investors purchase‘hot’stocks only due to correlated information arrival from independently acting investors (Devenow and Welch1996).Grinblatt et al.(1995)and Wermers(1999)concluded that a large portion of herding behavior occurs when analysts‘‘momentum follow,’’that is,when they buy recent winners or sell recent losers.If both a leader and a follower choose to momentum follow,then it can look like the latter is herding on the former,when in fact both are simply mimicking the market movement.Thus,the way to test herd behavior by observing‘‘action conformity’’is a compromise between theory and data availability.Another deficiency of the previous empirical studies has been pointed out by Bikhchandani and Sharma(2001):empirical studies do not appear to be highly relevant to theoretical discussions;rather,the approach used in empirical studies is purely konishok et al.(1992)utilized a purely statistical technique to measure investors’herd behavior that has since been applied in many papers (Grinblatt et al.1995;Wermers1999).There seems to be no work that makes a good connection between the theoretical and empirical discussions,except that of Graham (1999).Following the style of Graham(1999),we willfirst model the formation of herd behavior and then test the implications with data from .3Decision tree modelIn this section,we use a decision tree to model the decision making process of investors and to explore how they herd on public information from .We depart from the previous models in the following ways:(1)There is a cost of information obtaining and studying.Profiles contain too much information,thus requiring a lender to spend time to read it and an additional click to access the details.However,bids by friends and the bid count are easier to access and understand for lenders.This is why we consider obtaining and studying profile to be a cost for lenders.(2)Integrating the concept of personal preference.In our model,A decision tree model147 we allow different people to respond differently to the same information.(3) Closely connected to empirical tests.Unlike most of the theoretical models,the implications of our model are closely connected with hypotheses that will be verified by real data from .3.1Model settingsOn a daily basis,people tend to infer others’signals or beliefs based on their observed actions(Frith and Frith2008).The same thing happens on , where each lender can infer the quality of the borrower and update their beliefs by utilizing the available information,such as bids from predecessors or the borrower’s friends.We assume that there is a sequence of lenders that will bid throughout the entire time period during which the listing is biddable.Each lender has to decide whether to bid.Simultaneously,the lender has to consider the interest rate that he/ she is willing to accept.Nonetheless,the analysis of interest rates is not the focus of this study.For simplicity,we assume that each lender sets the interest rate as the same as that of his predecessors,which is an optimal and applicable strategy on .We assume all of the lenders are rational,risk-neutral and expected payoff maximizers.On ,we assume there are two types of borrowers:high (H)and low(L).If a borrower’s type is H,then the payoff is V H.Otherwise,the loss will be V L.If a lender does not bid,then his or her payoff is0.In Prosper,lenders have information to make an inference about the borrower type.There are at least three kinds of information that can be utilized by lenders:friend bid,bid count and borrower’s profile.Lenders will study these types of information sequentially and update their beliefs about the borrower type in a step-by-step manner. Assumption1Lenders are allowed to infer different beliefs with the same information.When lender i and j observe the same information,such as a friend bid,as a consequence of assumption1,we can say that lender i’s belief about the borrower type is PðBorrower¼H friend bidjÞ¼P i which is not necessarily equal to lender j’s belief of PðBorrower¼H friend bidjÞ¼P j.We ascribe this to personal preferences for certain information.In contrast,in an information cascade model, Banerjee(1992)assumes that‘‘signals are equal in quality,’’which means that people respond identically to the same information.Assumption2The cost for obtaining and studying the information about the borrower’s friend bid and bid count are minimal and negligible,while the cost for obtaining and studying the borrower’s profile is significant.This assumption arises from the fact that,on ,information about a friend bid and bid count is easier to access and to understand.When a borrower’s profile contains more than20items,including whether a borrower has a car or not, the past behavior of this borrower(e.g.,whether this borrower owns a house),time and effort are needed to read it.Domain knowledge and experience are also requiredto have a better understanding of profiles.Figure 2is a snapshot of what a borrower’s profile contains.Because we have assumed that all lenders are rational,they will first study the easier information (friend bid and bid count)and then consider whether to obtain and study harder information (borrower’s profile).The cost for obtaining and studying a borrower’s profile is C .Assumption 3Lender’s belief regarding a borrower’s type will be affected by the number of bids on a listing.As the number of bids increases,the lender’s belief that the borrower is of a high type will become stronger.Based on assumption 3,we have P ðborrower ¼H bid count ¼n j Þwill increase as n increases but with a decreasing marginal effect until approximately 1.3.2Decision tree modelWe model the decision process of lender i on ,which is shown in Fig.1.Step 1At the start point of step 1,lender i has a prior belief regarding the whole market before seeing any listings.The prior belief (p 0)may be given by nature or inferred from a public action like a market administrator’s announcement.P ðBorrower ¼H Þ¼P 0P ðBorrower ¼L Þ¼1ÀP 0&ð1ÞIn step 1,lender i will probably observe a friend bid.If lender i sees it,he must update his belief from P 0to P 1.If not,his belief will remain as P 0.P ðBorrower ¼H friend bid j ¼yes Þ¼P 1P ðBorrower ¼L friend bid j ¼yes Þ¼1ÀP 1&ð2ÞStep 2In step 2,lender i will observe the others’bids,and his belief will be updated from P 1to P 2.148 B.Luo,Z.LinP ðBorrower ¼H friend bid j ¼yes ;bid count ¼n Þ¼P 2P ðBorrower ¼L friend bid j ¼yes ;bid count ¼n Þ¼1ÀP 2&ð3ÞAs consequence of assumption 3,n increases,P 2will increase.Additionally,if lender i favors more on the information of bid count,the positive effect of bid count might nullify any negative effect coming from previous information and P 2can approximate 1.The current expected payoff is EP 2=P 29V H -(1-P 2)9V L .Step 3In step 3,lender i has to make a choice of whether to study a borrower’s profile or not.If he chooses to do so,he has to pay a cost of C and the updated belief is:P ðBorrower ¼H friend bid j ¼yes ;bid count ¼n ;profile Þ¼P 3P ðBorrower ¼L friend bid j ¼yes ;bid count ¼n ;profile Þ¼1ÀP 3&ð4ÞThe conclusion inferred from a borrower’s profile can be good,bad or neutral.If lender i considers it as a good profile,we should have P 3[P 2.If not,P 3B P 2.When P 39V H -(1-P 3)9V L [0,the optimal choice for lender i is to bid.The expected payoff for studying a profile is EP 3=P 39V H -(1-P 3)9V L -C .If the following conditions are satisfied,EP study \EP not study P 3ÂV H Àð1ÀP 3ÞÂV L [0&ð5Þthe optimal choice for lender i is not to obtain and study the borrower’s profile but to follow the public in deciding whether to bid.When this happens,we say that lender i behaves like the herd.Based on Eq.5,we have the following propositions.Proposition 1Keeping the other factors invariant,if the cost for obtaining and studying information increases,the probability of lender i to herd will also increase .Proposition 2Keeping the other factors invariant,if lender i has a strong preference for public information,he/she is more likely to herd .The proof is as follows.First,we consider EP 3as a consequence of EP 2and a random variable .EP 3¼EP 2þ ÀC ð6ÞAccording to the decision tree model,we have EP study ¼P ðbid ÞÂEP 3Àð1ÀP ðbid ÞÞÂC ,and EP not study ¼EP 2.Thus,the probability of herding isP ðherd Þ¼P ðbid ÞÂP ðEP study \EP not study Þ¼P ðbid ÞÂP ðP ðbid ÞÞÂEP 3Àð1ÀP ðbid ÞÞÂC \EP 2ð7ÞBecause P ðbid Þ¼P ðEP 2þ [0Þand EP 3¼EP 2þ ÀC ,if we keep EP 2invariant,as C increases,P (bid )will stay the same,but P ðEP study \EP not study Þwill increase.The probability to herd will increase along with the cost of further study,and proposition 1is proved.A decision tree model 149Based on Eq.7,if we control C and let EP 2[0,we haveP ðbid ÞÂðEP 2þ ÀC ÞÀð1ÀP ðbid ÞÞÂC \EP 2)P ðbid ÞEP 2þP ðbid Þ ÀP ðbid ÞC ÀC þP ðbid ÞÂC \EP 2)P ðbid ÞEP 2þP ðbid Þ ÀC \EP 2ð8ÞBecause P (bid )B 1,as EP2j j j j increases (it is more likely to happen if assumptionsthree and four hold,which means lender i has a very strong preference for public information or the public information overwhelms as the bid count increases),P ðEP study \EP not study Þincreases.In the meantime,P (bid )will keep constant or increase.Therefore,we have proved proposition 2,in which lender i’s preference for public information will lead to herd with a higher probability.In real life,there are many causes that may lead people to have strong preference for public information,such as people not being confident with their information processing ability and being more willing to believe the information from experts or insiders.This kind of herding is similar to the reputation concern type herding (Scharfstein and Stein 1990):manager A has a stronger preference for manager B’s information.Although A’s evidence signals the opposite direction,he/she decides to herd.Corollary 1The propositions 1and 2imply that,borrower’s social relationship providing comparatively high-precision public information (friend bid)as well as the cost for obtaining and studying profile make lender’s belief towards adopting public action.Therefore,lenders are more likely to herd on the free public information.Corollary 2Proposition 2also implies that,an increased number of bids for a listing increases the probability of lenders’herding.Another question is how imperfect information affects the number of occurrences of herd behavior.Based on assumption 3,we derive that P ðBorrower ¼H bid count ¼n j Þincreases as n increases until approximately 1.If the perfect history about a listing is obtainable (the number of bids and the number of people who viewed a listing but without any bids),the speed of P ðBorrower ¼H bid count ¼n j Þapproaching 1would not be as rapid as in the situation in which only the bid count is available.In other words,perfect information about a listing history would help to reduce the number of occurrences of lender herding on .So far,we have modeled the formation of herding when lenders have heterogeneous preferences on information as well as costly information obtaining and studying.For the generalization of this model,we conjecture that it is not only confined to lenders in online lending market like Prosper,but is also applicable in predicating human behavior under other environments if assumption 1and 2are satisfied.At here,we give an illustrative example to see how to apply this model to other situation.Assume person A wants to buy a $10product at Walmart.When he was walking around in Walmart,he met one of his friends who said that he seemed to have seen the same product in another store is only $8.Now,A is facing the cost 150 B.Luo,Z.Lin。

资源配置、资源错配与生产率

中国经济分析

9

资源错配: Human capital

中国经济分析

10

Investment rates

• India: MPK 22%, (AU/AI) = 2, (yU/yI)=6.35

• 资源稀缺性

• 资源配置主体

• 企业、农民、消费者、劳动力(低技能、高技能劳动力)、资本所有者、政府、第 三方中介组织,。。。

• 资源配置的范围

• 企业层面、地区层面、国家层面、国际层面 • 静态、动态

• 资源配置的机制

中国经济分析

3

资源配置:基本原理

• 计划经济

• 计划、共有产权、政府主导

• 市场经济

• 农村改革 • 市场化和国有企业改革 • 资本市场、信贷市场与金融改革 • 劳动力市场 • 人力资本深化:教育、医疗 • 土地资源配置 • 市场开放、生产要素地区间流动、产业地区间分工和一体化 • 政府职能转变

中国经济分析

5

资源配置与生产率 • 资源配置:生产函数中的投入、产出和全要素生产率 • 新古典经济学中资源配置有效率的含义

• Marginal product in some firms is 50% or 100% or even more does not imply that the average of the marginal products across all firms is nearly as high

资源配置、资源错配与生产率

中国经济分析

1

目录

国外部分提供免费下载的经济学、管理学期刊、论文网址

国外部分提供免费下载的经济学、管理学期刊、论文网址一、经济学1.http://econpapers.hhs.se/article/专业的经济学论文网站,有多种Journal或working paper的链接,部分可免费下载。

2./经济学研究论文链接站点。

来自30个国家的100多名志愿者合作创立,该站点收录了118000篇工作论文、79000篇期刊论文、900个应用软件,并且还在不断增加中。

其中近100000篇论文可下载。

3.http://www.helsinki.fi/WebEc/journal2.html主要经济学期刊的链接地址4./社会科学研究网(英文简称SSRN)。

包括社会科学方面的研究论文,有8个专业研究网,分别是会计研究网、经济研究网、金融经济学研究网、法律研究网、管理研究网、信息系统研究网、市场营销研究网、谈判研究网。

许多经典论文在这儿也可以找到。

5./顶级学术期刊《经济学家》杂志的主页,部分文章免费下载。

6./顶级学术期刊《经济研究评论》网站,论文可免费下载。

二、管理学(均为优秀期刊)1./《管理科学》(Management Science)网站,论文可免费下载。

2. /《决策分析》(Decision Analysis)网站,论文可免费下载。

3./《信息系统研究》(Information Systems Research)网站,论文可免费下载。

4./《相互关系》(Interfaces)网站,论文可免费下载。

5. /《制造与服务运作管理》(Manufacturing & Service Operations Management)网站,论文可免费下载。

6./《营销科学》(Marketing Science)网站,论文可免费下载。

7./《运筹学数学》(Mathematics of Operations Research)网站,论文可免费下载。

7./《运筹学》(Operations Research)网站,论文可免费下载。

herd mentality英文解释

herd mentality英文解释Herd MentalityHuman behavior is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, shaped by a myriad of factors, both internal and external. One such influential aspect of human behavior is the concept of herd mentality, a psychological tendency that can have significant implications on individual and societal decision-making processes.Herd mentality, also known as crowd psychology or group think, refers to the tendency of individuals to align their thoughts, beliefs, and actions with those of the larger group or majority, often disregarding their own independent judgments or rational decision-making. This phenomenon is rooted in the innate human desire for belonging, social acceptance, and the avoidance of isolation or ostracization. In a herd-like environment, individuals may feel a sense of security and validation in conforming to the group's norms, even if those norms may not align with their personal beliefs or best interests.The underlying psychological mechanisms that drive herd mentality are multifaceted. One of the primary factors is the influence of socialproof, wherein individuals look to the actions and behaviors of others as a cue for appropriate or desirable conduct. When faced with uncertainty or ambiguity, people often turn to the majority's behavior as a guide, assuming that the collective wisdom of the group is superior to their own individual judgment. This reliance on social proof can lead to the perpetuation of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that may not necessarily be the most rational or beneficial.Another factor contributing to herd mentality is the desire for conformity and the fear of social rejection. Individuals may consciously or subconsciously suppress their own opinions or dissenting views in order to maintain group harmony and avoid the potential consequences of standing out or being perceived as different. This tendency is particularly prevalent in collectivist cultures, where the emphasis on group cohesion and the preservation of social harmony can override individual autonomy and critical thinking.The implications of herd mentality can be far-reaching and can manifest in various aspects of human behavior, from consumer purchasing decisions to political and social movements. In the realm of consumer behavior, herd mentality can lead to the rapid adoption of trends, fads, and products, often driven by the perceived social status or perceived benefits associated with these choices, rather than a rational evaluation of their actual merits.In the political and social spheres, herd mentality can contribute to the rise of populist movements, the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories, and the perpetuation of harmful ideologies. When individuals align their beliefs and actions with the perceived majority, they may become less inclined to critically examine the validity of the group's positions or to consider alternative perspectives. This can lead to the entrenchment of polarized views, the suppression of dissenting voices, and the erosion of democratic principles.Furthermore, herd mentality can have significant implications in crisis situations, such as natural disasters or pandemics. When faced with uncertainty and fear, individuals may be more inclined to follow the lead of the majority, even if the group's response is not necessarily the most effective or appropriate. This can lead to the perpetuation of misinformation, the adoption of ineffective coping strategies, and the exacerbation of the crisis itself.However, it is important to note that herd mentality is not inherently negative or detrimental. In certain contexts, the collective wisdom of the group can be valuable, providing a sense of security, support, and shared understanding. In situations where individual decision-making is limited or the stakes are low, herd mentality can serve as a functional and adaptive response.The challenge lies in striking a balance between the benefits of group cohesion and the importance of independent critical thinking. Encouraging individuals to develop a strong sense of self-awareness, to question the validity of group norms, and to consider alternative perspectives can help mitigate the potential pitfalls of herd mentality. Fostering a culture of open dialogue, intellectual curiosity, and a willingness to challenge the status quo can empower individuals to make more informed and rational decisions, ultimately leading to more positive societal outcomes.In conclusion, herd mentality is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that can have significant implications on individual and societal behavior. Understanding the underlying psychological mechanisms and the potential consequences of this tendency is crucial in navigating the complex landscape of human behavior and decision-making. By cultivating a mindset of critical thinking, self-awareness, and openness to diverse perspectives, individuals and communities can harness the benefits of group dynamics while mitigating the potential pitfalls of herd mentality.。

金融学研究生必读书

应用金融硕士研究生精读书目陈雨露、张杰、瞿强联合推荐2004-12-71、《经济学原理》N·格里高利·曼昆(N.Gregory Mankiw),中国人民大学出版社。

2、《应用经济计量学》拉姆·拉玛纳山(Ramu Ramanathan),机械工业出版社。

3、《货币金融学》弗雷德里克·S·米什金(Fredcric S.Mishkin),中国人民大学出版社。

4、《金融学》兹维·博迪、罗伯特·默顿,中国人民大学出版社。

5、《公司理财》斯蒂芬·A·罗斯,机械工业出版社。

6、《投资学精要》兹维·博迪,中国人民大学出版社。

7、《国际金融管理》Jeff.Madura,北京大学出版社。

8、《固定收入证券市场及其衍生产品》Suresh.M.Sundaresan,北京大学出版社。

9、《银行管理——教程与案例》(第五版),乔治·H·汉普尔,中国人民大学出版社。

10、《投资组合管理:理论及应用》小詹姆斯·法雷尔,机械工业出版社。

11、《衍生金融工具与风险管理》唐·M·钱斯(Don.M.Chanc),中信出版社攻读博士学位预备生精读书目陈雨露、张杰、瞿强联合推荐2004-12-71、《经济学原理》N·格里高利·曼昆(N.Gregory Mankiw),中国人民大学出版社。

2、《应用经济计量学》拉姆·拉玛纳山(Ramu Ramanathan),机械工业出版社。

3、《金融经济学》(德)于尔根·艾希贝格尔,西南财经大学出版社。

4、《货币金融学》弗雷德里克·S·米什金(Fredcric S.Mishkin),中国人民大学出版社。

5、《金融学》兹维·博迪、罗伯特·默顿,中国人民大学出版社。

6、《国际经济学》(美)保罗·克鲁德曼,中国人民大学出版社。

有关非理性行为的作文英语

有关非理性行为的作文英语Irrational behavior is a fascinating and complex topic that has long been the subject of study in fields such as psychology, sociology, and behavioral economics. At its core, irrational behavior refers to actions or decisions that deviate from what would be considered logical, reasonable, or in an individual's best interest. These behaviors can manifest in a variety of ways, from impulsive decision-making and risk-taking to biases and heuristics that lead to suboptimal choices.One of the key drivers of irrational behavior is the human tendency to rely on mental shortcuts or heuristics when making decisions. These cognitive biases, as they are often called, can lead individuals to make judgments and choices that are not aligned with objective reality or their own long-term interests. For example, the availability heuristic, which causes people to place more weight on information that is readily available or easily recalled, can lead to biased assessments of risk and probability. Similarly, the confirmation bias, which leads people to seek out and interpret information in a way that confirms their existing beliefs, can perpetuate irrational beliefs and behaviors.Another important factor in irrational behavior is the role of emotions. Emotions can have a powerful influence on our decision-making, often overriding more logical or rational considerations. For instance, the fear of losing something can lead to risk-averse behavior, even when the potential gains outweigh the risks. Conversely, the thrill of potential reward can lead to impulsive and reckless decision-making, as seen in gambling addictions and other forms of risky behavior.Interestingly, irrational behavior is not limited to individuals but can also manifest at the group or societal level. Phenomena such as herd mentality, where individuals conform to the actions of a group, and the bandwagon effect, where people are more likely to adopt a belief or behavior as it becomes more popular, can lead to the emergence of irrational collective behaviors. These group-level biases can have significant consequences, as seen in the formation of financial bubbles, the spread of misinformation, and the perpetuation of harmful social norms.Despite the prevalence of irrational behavior, it is important to note that it is not always a negative or undesirable phenomenon. In certain contexts, irrational behavior can actually serve a beneficial purpose. For example, the emotional attachment people have to their possessions, known as the endowment effect, can help foster asense of ownership and investment in their belongings, which can be valuable in personal and social contexts. Similarly, the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive events, known as the optimism bias, can provide individuals with the motivation and resilience to pursue their goals, even in the face of adversity.Moreover, the study of irrational behavior has led to important insights and advancements in fields such as behavioral economics and decision-making theory. By understanding the cognitive biases and emotional factors that influence human behavior, researchers and policymakers can develop more effective strategies for nudging individuals and organizations towards more rational and beneficial decision-making.In conclusion, irrational behavior is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that is deeply rooted in the human psyche. While it can lead to suboptimal decisions and undesirable outcomes, it is also a fundamental aspect of the human experience, with both positive and negative implications. By continuing to study and understand the mechanisms underlying irrational behavior, we can work towards developing more effective strategies for navigating the challenges and opportunities it presents.。

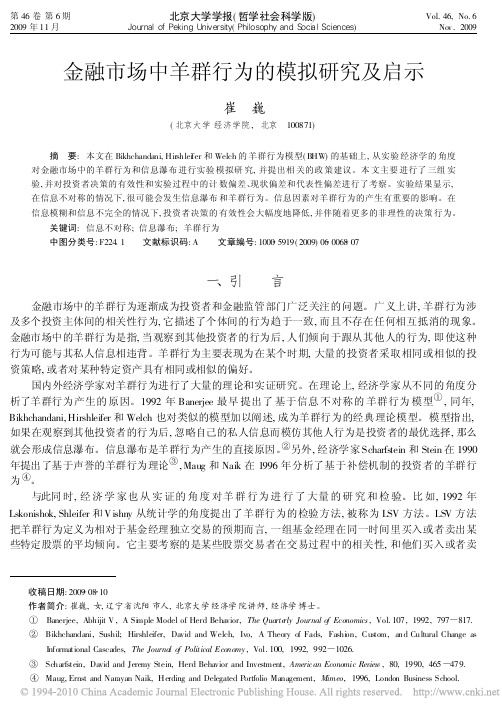

证券市场羊群效应研究文献述评

证券市场羊群效应研究文献述评陈锡娟摘㊀要:本文对国内外有关证券市场羊群效应的研究文献进行了分析,总结了关于证券市场羊群效应的理论研究过程及主要模型和观点,同时,对国内外羊群效应的实证模型和方法进行了归纳,此外,对我国证券市场羊群效应实证研究的进展进行了述评,并提出了我国证券市场羊群效应实证研究今后努力的方向㊂关键词:证券市场;羊群效应;理论;模型一㊁引言羊群效应这个词来源于自然界对动物的跟随行为的描述,后来被引入到金融市场,羊群效应是证券市场上一种异常现象,可能会造成信息追涨㊁信息得不到有效指示,严重的可能会引发金融危机㊂羊群效应的存在可能会破坏证券市场的平衡㊁使得证券市场的有效性大大降低,可能会造成证券市场紊乱㊁降低证券市场投资者的热情㊂研究羊群效应有利于引导相关部门对证券市场的调控,指引证券市场健康发展㊂二㊁证券市场羊群效应的理论研究最早提及到羊群效应在金融市场上表现的学者是宏观经济学鼻祖凯恩斯,他于1936年在‘就业㊁利息和货币通论“中提出 参与投资就像是参加选美只有跟随大众的品味才能有所斩获 这一 选美理论 ㊂这方面的理论研究在20世纪70年代开始大量涌现㊂主要的模型有㊂Scharftstein和Stein(1990)提出了声誉羊群效应模型㊂该模型是通过贝叶斯学习模型来研究基金经理的羊群行为,得出结论认为无论该决策是否正确所有基金经理都会倾向于羊群效应㊂此时,选择从众是一种维护声誉的安全措施㊂Banerjee(1992)提出了序列性羊群效应模型㊂该模型是最有代表性的羊群效应理论模型,当个体投资者按顺序做出投资决策,每个投资者在决策前参考的是顺序在自己之前的投资者的决策㊂序列性羊群效应模型证明了后面的决策者趋向于与前面的决策者做出相同的决策㊂但这种序列性有悖于金融市场的现实,因为区分先后顺序是不切实际的㊂Bikhchandani和Welch(1992)提出了信息流模型㊂该模型主要用于行为主体只可以观察到其他行为主体的行动,该模型假设个体之间不知道的他人拥有的私有信息,但可以通过观察他人的行动来端测他人所拥有的私有信息,如此反复引发羊群效应㊂Lee(1993)改进了提出的信息流模型,最后得出投资者买入或卖出的投资行为趋向于信息减少的过程的结论㊂目前主要形成两种不同的观点:第一,羊群行为的产生与投资者心理情绪等因素紧密相连,投资者会放弃理性而盲目跟随别人,出现非理性的投资行为;第二,羊群效应并不一定是我们所想象的非理性行为,而是符合效用最大化的㊂三㊁证券市场羊群效应的实证方法与模型研究国外学者对羊群效应的研究主要使用三种方法:LSV方法㊁CH方法和CCK方法㊂其他的研究绝大部分都是在这三种方法的基础上改进而来㊂Lakonishok,Shleifer和Vishny最早提出LSV方法,用于检验基金经理羊群效应,他们认为如果基金在一定时期内同时买入(或者卖出)某种股票的次数比基金在随机㊁独立的条件下买入(或者卖出)的次数还多时,那么说明基金经理之间发生了羊群效应㊂Christie和Huang(1995)提出了CH方法,用个股收益率的横截面标准偏离度(CSSD)来研究羊群效应,也就是说,在市场出现大幅变动时,可用市场个股收益率标准差的走势来测度羊群效应㊂Chang㊁Cheng和Khorana(2000)提出了检验羊群效应的CKK方法,采用个股收益率相对于市场收益率的横截面绝对偏离度(CSAD)指标㊂该方法通过检验偏离度与市场组合收益率之间是否存在非线性关系来判定羊群效应㊂国内的学者也主要采用LSV㊁CH和CCK这三种方法研究我国股票市场的羊群效应㊂吴福龙等(2004)使用LSV方法表明我国证券投资基金表现出较为显著的羊群效应㊂王燕华(2012)运用CH方法研究发现主板市场羊群效应程度强于创业板市场㊂孙培源(2002)都釆用CCK方法对我国股票市场进行了实证检验,证实我国股票市场存在这羊群效应㊂国内有的学者综合采用将两种方法结合来研究羊群效应㊂如:淳伟德,李晓燕和李曼(2011)综合运用CH和CCK方法检验我国股市在不同背景下的羊群效应,结果得32金融证券. All Rights Reserved.出熊市背景下存在羊群效应,而牛市背景下只有市场收益率下跌时的羊群效应较显著,市场收益率上涨时的羊群效应不明显㊂四㊁我国证券市场羊群效应的实证研究进展(一)按照不同投资主体的角度证券市场通常将投资主体分为个人投资者和机构投资者㊂由于个人投资者和与机构投资者在信息的获取和处理方面的能力和效率不同,可以按照不同投资主体来研究羊群效应㊂胡赫男(2006)以沪市和深市交易的基金数据为样本,发现基金的羊群效应的严重程度和规模正相关,熊市更为严重㊂刘成彦等(2007)研究了发现QFII之间有显著的羊群效应㊂程天笑等(2014)表明QFII群体内的羊群效应明显低于境内的机构投资者㊂周嘉樹(2012)㊁贾伶(2014)的研究也分析发现,基金经理间也存在理性的羊群效应㊂(二)按照不同市场㊁板块的角度由于我国的证券市场还不够成熟,而且我国不同市场在存在一些差异,从不同板块和不同市场研究羊群效应有一定的价值㊂董志勇㊁韩旭(2007)研究分为沪深两市,发现沪深两市中有相当比例的资产组合存在羊群效㊂顾荣宝(2012)以深圳成份股周收率研究了羊群效应㊂胡耀东(2009)研究沪深两市的B股数据,发现A㊁B股市场都存在显著的羊群效应㊂杨云龙(2013)对我国代办股份转让市场和台湾兴柜股票市场进行研究后发现我国场外交易市场存在着弱羊群效应的现象㊂五㊁证券市场羊群效应研究展望从二十世纪七八十年代到现在,已得到许多在理论和实证方面有价值的结论,但还有很多还未解决的问题值得深入研究㊂后续的研究方向归纳为以下几点㊂在未来的研究中,伴随着股市的发展,上市公司数量的壮大,应该釆用更长的样本区间和更大的样本量来对我国股市的羊群效应进行实证检验㊂我国学者大多是依据国外的羊群效应模型对我国证券市场进行实证研究,但由于我国证券市场还不及国外证券市场成熟,所以提出适应我国证券市场的实证模型,可以加快我国证券市场的步伐㊂此外,羊群行为对于价格波动影响的程度㊁如何准确的量化投资主体的心理过程和行为模式以及如何制定政策来有效的防范羊群行为等相关问题还有待进一步深入的研究㊂政府部门应该如何将理论模型和实证模型得出的有价值的理论结论,出台相应的政策来规范机构投资者和个体投资者的行为以及有效的控制市场的过度反应,引导我国证券市场健康发展㊂参考文献:[1]Scharfstein.Stein.HerdBehaviorandInvestment[J].AmericanEconomicReview.1990(80):465-679.[2]Banerjee.ASimpleModelofHerdBehavior[J].QuarterlyJournalofEconomics.1992(107):797-817.[3]Bikhchandani.Sushil.SushilSharma.HerdingBehaviorinFinancialMarkets[D].IMFStaffPapers.2001.47(3):279-310.[4]Lee.OntheConvergenceofInformationalCascades[J].JournalofEconomicsTheory.1993,61(2):395-411.[5]Lakonishok.J.,A.ShleiferandR.W.Vishny. TheIm⁃pactofInstitutionalTradingonStockPrices ,JournalofFi⁃nancialEconomics,1992.[6]Christie,Willian.GandHuang,Roger.D, FollowingthePiedPiper:DoIndividualReturnsHerdaroundtheMar⁃ket? ,FinancialAnalystsJournal,July1995.[7]ChangEricC,ChengJosephWandAjayKhorana: Anexaminationofherdbehaviorinequitymarkets:Aninter⁃nationalperspective ,Journalofbankingandfinance,2000.[8]吴福龙,曾勇,唐小我.中国证券投资基金的羊群行为分析[N].管理工程学报,2004(03):115-117.[9]王燕华.我国主板㊁创业板市场投资者羊群行为实证研究[J].中国外资,2012(10):155-156.[10]孙培源,施东晖.基于CAPM的中国股市羊群行为研究 兼与宋军㊁吴冲锋先生商榷[J].经济研究,2002(02):64-70+94.[11]淳伟德,李晓燕,李曼.基于分散度模型的股市羊群行为研究[J].预测,2011,30(05):25-30.[12]刘成彦,胡树,王暗.QFII也存在羊群行为吗?[J].金融研究,2007(10A):111-122.[13]程天笑,刘莉亚,关益众.QFII与境内机构投资者羊群行为的实证研究[J].管理科学,2014,27(4):110-122.[14]顾荣宝,蒋科学.深圳股票市场的羊群行为及其演化 基于一个改进的CCK模型[J].南方经济,2012,10:135-145.[15]胡耀东,陈玲.中国B股市场羊群行为实证检验新探[J].现代经济:现代物业中旬刊,2009,8(9):21-24.作者简介:陈锡娟,重庆市,西南大学经济与管理学院㊂42商讯. All Rights Reserved.。

2015年中国股灾的成因分析和对策思考

东华大学毕业论文论文题目2015年中国股灾的成因分析和对策思考学院旭日工商管理学院系别金融系专业金融学班级金融1205学号*********姓名范克俊指导老师李勇二零一六年三月至六月2015年中国股灾的成因分析和对策思考摘要2015年夏季中国的资本市场发生了异常波动,上证指数在短短的两个月时间内从5178.19点跌落至2850.71,期间A股市场上多次出现千股跌停的惨况,其中超过60%的中小盘股票被无情“腰斩”,中国资本市场上一时人心惶惶,草木皆兵,那么到底是什么原因导致A股出现这“过山车”似的行情?社会各界议论纷纷。

为此本文以2015年中国股灾为主要的研究对象,运用学术理论和数据分析推理的研究方式展开这一论题,希望能为广大投资者还原本轮股灾出现的本质原因,最终促进投资者投资观念的转变与升级。

本文首先对股灾的概念和本轮股灾的形成过程做了一个简单的介绍,第二部分是本文的核心部分,本文将以证券投资分析中技术分析和基本面分析两种不同的方法对本轮股灾的成因做一个形象的分析,其中前者引用了著名的艾略特波段理论和股指期货中期现套利理论进行分析推理;后者将会从全球经济的基本面出发,具体到我国经济基本面。

我们站在投资者和政府两个不同的立场上,从投资者新开户数和政府利率两方面数据出发进行探究,模拟暴跌出现之前我国资本市场上不断膨胀的“泡沫”,为之后的成因分析做好铺垫。

为本轮暴跌的出现做出一个合理的解释。

第三部分是对股灾出现之后我国金融监管机构提出的一系列救市措施的概述和评价。

期间我们将选取其中比较具有代表性的政策进行研讨,在对其经验总结的基础上为我国下一步资本市场的改革寻找出路和借鉴。

本文的最后是对本轮股灾的反思。

和第一部分的思路一样,我们还是站在投资者和监管机构两个方面进行反思。

这是一个循序渐进的过程,只有不断的改革,中国的资本市场才能持续的稳定与繁荣。

关键词:股灾;流动性泛滥;波段理论;杠杆资金;理性投资The Cause Analysis and Countermeasures of China'sstock market crash in 2015AbstractIn the summer of 2015,Abnormal fluctuations in China's capital market has undergone.The Shanghai Composite Index in just two months fell from 5178.19 points to 2850.71 points.A-share market hit bottom during the multiple occurrences of a thousand plight, of which more than 60% of small-cap stocks fell more than half. China's capital market momentary panic, then in the end what caused the A-shares this "roller coaster" like market? The community talked a lot. So the main research object of this paper is the 2015 stock market crash in China , using academic research methods and data analysis reasoning expand this topic, hoping to restore the essential reason for the majority of investors in the current round of stock market crash occurred, and ultimately promote the concept of investors transformation and upgrading.The article is divided into four sections, on the logical structure as the core cause analysis, theoretical analysis and research linked together to achieve the purpose of the study.The first part describes the process of the formation of the stock market crash, that is, before the stock market crash occurred on the specific situation of China's capital market. Reasons for which we stand on the position of the Government and investors, new investors and national accounts data from both interest rates starting to explore, simulate crash occurred before China's capital market, expanding the "bubble" for later pave the way.The second part is the core of this article, this article will focus on technical analysis and fundamental analysis are two different methods for analysis of causes of the current round of stock market crash, where the former refers to Eliot's famous band theory and stock index futures arbitrage deadline analyze reasoning; the latter will be departing from the fundamentals of the global economy, specifically to our country's economic fundamentals, the current round of the crash appeared to make a reasonable explanation.The third part is a series of rescue measures after the stock market crash of financial regulators appear presented an overview and evaluation. During which we will select one policy more representative to discuss, in its lessons learned on the basis of the next step for the reform of China's capital market find a way out and learn.Finally, this paper is a reflection of the current round of stock market crash. And ideas of the first part, we still stand both investors and regulators to rethink. The former investment philosophy much needed change, the latter's ruling needs to be improved, which is a gradual process, the only constant reform, China's capital market, in order to continued stability and prosperity.Keywords: stock market crash; the flood of liquidity; band theory; leveraged funds; rational investment目录第1章引言 (8)第2章2015中国股灾概述 (10)2.1 股灾概述 (10)2.1.1 股灾的特点 (10)2.1.2 引发股灾的一般原因 (10)2.1.3 中国历史上发生的两次股灾 (10)2.1.4 国内外研究概况 (11)2.2 2015年中国股灾记录 (12)第3章2015年中国股灾形成的原因分析 (13)3.1 技术层面:艾略特波段理论、期现套利理论 (13)3.2 基本面分析:虚实经济发展不协调 (19)3.2.1 投资者角度:股市上涨与新开户数的正向反馈 (20)3.2.2 政府角度:持续宽松货币政策下的“筹码”支持 (22)3.2.2.1 模型的建立 (23)3.2.2.2 数据的平稳性检验 (23)3.2.2.3 格兰杰检验 (24)4.2.2.4 实证分析结论 (25)4.2.2.5 实证分析结论的应用 (25)第4章关于政府救市的讨论 (27)4.1 政府救市措施概述 (27)4.2 政府救市手段评价 (28)4.2.1救市的必要性:反应过度 (28)第5章2015年中国股灾过后的反思 (31)结语32参考文献 (33)第1章引言自2014年6月起,A股一改常态,在券商板块的带领下一路上扬,期间权重板块轮番上阵,实现了有效的突破,指数节节日上,在此期间有人看多亦有人看空,但是A股却似乎不顾世人的眼光, 2015年6月12日达到最高点5178.19点,但此后一个月内三次暴跌,6月份A股收4277.22点,一个月期间暴跌900点;在接下来的两个月里,A股走势连绵日下,8月底跌破3000点,期间触底2850.71点。

金融学、经济学研究生和博士必读书目和经典文献

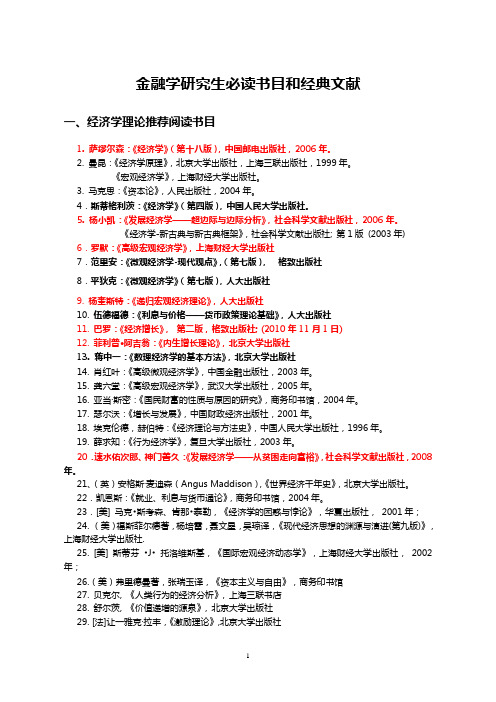

金融学研究生必读书目和经典文献一、经济学理论推荐阅读书目1. 萨缪尔森:《经济学》(第十八版),中国邮电出版社,2006年。

2. 曼昆:《经济学原理》,北京大学出版社,上海三联出版社,1999年。

《宏观经济学》,上海财经大学出版社。

3. 马克思:《资本论》,人民出版社,2004年。

4.斯蒂格利茨:《经济学》(第四版),中国人民大学出版社。

5. 杨小凯:《发展经济学——超边际与边际分析》,社会科学文献出版社,2006年。

《经济学-新古典与新古典框架》,社会科学文献出版社; 第1版(2003年) 6.罗默:《高级宏观经济学》,上海财经大学出版社7.范里安:《微观经济学-现代观点》,(第七版),格致出版社8.平狄克:《微观经济学》(第七版),人大出版社9. 杨奎斯特:《递归宏观经济理论》,人大出版社10. 伍德福德:《利息与价格——货币政策理论基础》,人大出版社11. 巴罗:《经济增长》,第二版,格致出版社; (2010年11月1日)12. 菲利普·阿吉翁:《内生增长理论》,北京大学出版社13. 蒋中一:《数理经济学的基本方法》,北京大学出版社14. 肖红叶:《高级微观经济学》,中国金融出版社,2003年。

15. 龚六堂:《高级宏观经济学》,武汉大学出版社,2005年。

16. 亚当·斯密:《国民财富的性质与原因的研究》,商务印书馆,2004年。

17. 瑟尔沃:《增长与发展》,中国财政经济出版社,2001年。

18. 埃克伦德,赫伯特:《经济理论与方法史》,中国人民大学出版社,1996年。

19. 薛求知:《行为经济学》,复旦大学出版社,2003年。

20.速水佑次郎、神门善久:《发展经济学——从贫困走向富裕》,社会科学文献出版社,2008年。

21、(英)安格斯·麦迪森(Angus Maddison),《世界经济千年史》,北京大学出版社。

22.凯恩斯:《就业、利息与货币通论》,商务印书馆,2004年。

小学上册B卷英语第4单元测验试卷

小学上册英语第4单元测验试卷英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1. A ______ is a special type of ant.2.Birds can fly in the ________________ (天空).3.I like to ride my ______ in the park.4.What do you call an animal that eats only meat?A. CarnivoreB. HerbivoreC. OmnivoreD. Insectivore5.I think that taking care of the environment is everyone's __________.6.I help my mom with __________. (家务)7.My friend is very _______ (形容词) when it comes to math. 她的表现一直很_______ (形容词).8. A ____(sustainable investment) supports eco-friendly businesses.9.What do you call a baby cat?A. PuppyB. KittenC. CubD. Chick10.Which fruit is known for having seeds on the outside?A. KiwiB. StrawberryC. BlackberryD. RaspberryB11.The _____ (海岸) is beautiful at sunset.12.The flowers are ________ and colorful.13.The process of heating a substance to separate components is called ______.14.I like to _______ outside.15.The symbol for ytterbium is _____.16.My __________ (玩具名) is a great __________ (名词) for my imagination.17.Which season comes after winter?A. AutumnB. SummerC. SpringD. FallC18.What is the fastest land animal?A. LionB. CheetahC. GazelleD. Horse19.What is the main ingredient in mayonnaise?A. MustardB. EggC. OilD. VinegarC20.What do we call the natural process of breaking down rocks?A. ErosionB. WeatheringC. DepositionD. SedimentationB21.Chlorine is commonly used as a _____ to disinfect water.22.I like to collect __________ because they are __________.23.How many stars are on the American flag?A. 50B. 48C. 51D. 4924.What is 7 + 7?A. 12B. 13C. 14D. 1525.The _______ (The Space Race) was a competition for supremacy in space exploration.26.How many days are in a week?A. FiveB. SixC. SevenD. Eight27.I love to watch the stars at ______ (夜晚). They twinkle like ______ (宝石).28.I have a new ___. (toy)29.The flowers are very ______. (pretty)30. A ______ often forages for food.31.What color do you get when you mix red and white?A. PinkB. PurpleC. OrangeD. Brown32.The ________ is the imaginary line that runs from the North Pole to the South Pole.33.The rabbit is ________ (跳) in the garden.34.They enjoy _____ (watching) movies.35.The __________ (花香) fills the air in spring.36.I can ______ (保持) good hygiene.37.The Earth's surface is covered by large bodies of ______.38.During a chemical reaction, bonds between atoms _____ (break) and new bonds form.39.The __________ is a famous area known for its vibrant markets.40.My teacher helps us understand __________ (数学问题).41.What is the name of the famous ancient city in Turkey?A. TroyB. EphesusC. CappadociaD. All of the above42.What is the name of the famous American holiday celebrated on July 4th?A. ThanksgivingB. Independence DayC. Labor DayD. Memorial DayB43. A ____ has a beautiful tail and dances in the wind.44.The first successful kidney-liver transplant was performed in ________.45. A __________ has a definite volume but no definite shape.46.The tiger stalks its _________. (猎物)47.I have a _____ (class/lesson) in the afternoon.48.What type of music do we dance to?A. ClassicalB. JazzC. PopD. Opera49.What is the opposite of 'happy'?A. SadB. JoyfulC. AngryD. ExcitedA50.The chemical symbol for europium is ______.51.My ________ (玩具名称) helps me learn about different cultures.52.What is the main purpose of a map?A. To show picturesB. To provide directionsC. To tell storiesD. To play gamesB53.What is 18 ÷ 2?A. 6B. 7C. 8D. 9D54.The _____ (小花) bloomed beautifully in the garden.55.The flowers in the garden are very ________ (美丽).56.What do you call a person who plays chess?A. Chess playerB. GambitC. StrategistD. PlayerA57.I watched a _______ (小鸟) build its nest.58.She is _______ (waiting) for the bus.59.How many states are there in Australia?A. 5B. 6C. 7D. 860.The chemical formula for mercury(II) chloride is _____.61.How many bones are in the human skull?A. 22B. 24C. 26D. 28A62.The ______ (老鼠) is afraid of cats.63.We will go ______ after school. (home)64.The _______ of an object can be tested using a force meter.65.What is the name of the famous singer known as the "King of Pop"?A. Elvis PresleyB. Michael JacksonC. PrinceD. Whitney HoustonB66.What is the name of the famous garden in Paris?A. Central ParkB. Jardin des TuileriesC. Kew GardensD. Brooklyn Botanic GardenB67.The __________ (大航海时代) changed global trade routes.68.What do you call the process of planting seeds?A. SowingB. HarvestingC. CultivatingD. TillingA69.My grandpa enjoys telling ____.70.The cake is _____ delicious. (very)71.The __________ was a major conflict in the history of the United States. (越南战争)72.I like ________ (solving) puzzles.73.The snake can be very ______.74.My uncle is a fantastic __________ (讲师).75.What is the opposite of "big"?A. SmallB. LargeC. TallD. HugeA76.I love to _____ (travel/stay) with my family.77.The waves are ___ (crashing) on the shore.78.What do you call a person who collects stamps?A. PhilatelistB. NumismatistC. CollectorD. ArchivistA79.The _____ (pen/pencil) is on the desk.80.What is the capital of the United Kingdom?A. LondonB. ParisC. RomeD. BerlinA81. A _______ can help improve the overall look of your yard.82.What is the name of the famous ancient wonder located in Egypt?A. Lighthouse of AlexandriaB. Hanging Gardens of BabylonC. Great Pyramid of GizaD. Statue of ZeusC83.What is the main ingredient in chocolate?A. SugarB. CocoaC. MilkD. Vanilla84.The _____ (fireplace) is warm.85.What is the main ingredient in jam?A. FruitB. SugarC. WaterD. Pectin86.Dolphins are known for their ______ behavior.87.The ______ is a type of plant that can survive in the desert.88.The kitten is ______ in a sunny spot. (sleeping)89.The __________ is a famous geographical feature in South America.90.The _____ (燕子) flies gracefully.91.My favorite season is ______ (春天) because of the flowers.92. A mineral's luster describes how it ______ light.93.What do we call the act of taking care of someone?A. CaringB. NurturingC. Looking afterD. All of the AboveD94.古代的________ (philosophers) 对科学和伦理的思考影响深远。

Herd mentality

Herd mentality第一段Come on-Everybody’s doing it.(来吧,每个人都这样做)That whispered message,half invitation and half goad,is what most of us think of when we hear the words peer pressure.(当我们听到“同侪压力”这个词,我们大部分人会想到,半邀请半煽动的窃窃私语的消息)It usually leads to no good-drinking,drugs and casual sex.(它通常会导致糟糕的事情—酗酒,吸毒和滥交)But in her new book Join the Club,Tina Rosenberg contends that peer pressure can also be a positive force through what she calls the social cure,(但在她的新书《加入俱乐部》里,蒂娜.罗森伯格辩称,“同侪压力”,也可以是一种积极的力量,通过她所说的社会治愈)In which organizations and officials use the power of group dynamics to help individuals improve their lives and possibly the world.(一些组织机构和官员们使用群体动力的力量来帮助个人改善他们的生活,甚至是世界)第二段Rosenberg,the recipient of a Pulitzer Prize,offers a host of examples of the social cure in action.(作为普利策奖的获得者,罗森伯格提供了大量关于社会治愈的例子)In south Carolina,a state-sponsored antismoking program called Rage Agains the Haze sets out to make cigarettes uncool.(在南卡罗来纳州,一个州发起的反吸烟计划,称为“愤怒反对阴霾”,使得香烟不再流行)In South Africa,an HIV-prevention initivative known as LoveLife recruits young people to promote safe sex among their peers.(在南非,一个预防艾滋病毒组织,最初称为“爱生命”,招募年轻人来倡导同龄人之间的安全性行为)The idea seems promising,and Rosenberg is a perceptive observer.(这个想法,似乎前景很光明,罗森柏格是位敏锐的观察员)Her critique of the lameness of many public-health campaigns is spot-on.(她对许多公共健康组织缺陷的批判是很准确的)They fail to moilize peer pressure for healthy habits,and they demonstrate a seriously flawed understanding of psychology.(他们没有调动同侪压力来促进健康的生活习惯,他们对心理认识有严重缺陷)“Dare to be different,please don’t smoke!”(“勇于不同,请不要抽烟”)Pleads one billboard campaign aimed at reducing smoking among teenagers-teenagers,who desire nothing more than fitting in .(一个广告运动宣传,旨在减少那些有从众心理青少年的吸烟行为)Rosenberg argues convincingly that public-health advocates ought to take a page from advertisers,so skilled at applying peer pressure.(罗柏森柏格认为令人信服的公共健康倡导者,应该学习广告商,他们能熟练运用同侪压力)第四段But on the general effectiveness of the social cure,Rosenberg is less persuasive.(但对社会治愈的总体效果,罗森伯格的想法不太具有说服力)Join the Club is filled with too much irrelevant detail and not enough exploration of the social and biological factors that make peer pressure so powerful.(《加入俱乐部》充满太多不相关的细节,并没有对那些使用同侪压力如此强大的社会和生物因素进行足够的探索)The most glaring flaw of the social cure as it’s presented that it doesn’t work very well for very long.(社会治愈,它最明显的缺陷是它并没有长时间生效)Rage Against the Haze failed once state funding was cut.(一旦国家财政拨款被消减,“愤怒反对阴霾”就失败了Evidence that the LoveLife program produces lasting changes is limited and mixed.(证据表明“爱生命”计划产生的持久的改变是有限的,而且是错杂的)There’s no doubt that our peer groups exert enormous influence on our behavior.(毫无疑问,我们的同龄群体会对我们的行为产生巨大的影响力)An emerging body of research shows that positive health habits-as well as negative ones-spread through networks of friends via social communication.(新兴的研究机构表明,积极的和消极的健康习惯都会通过社交传到朋友网里)This is a subtle form of peer pressure:we unconsciously imitate the behavior we see every day.(这是同侪压力的一个微妙的形式,我们不自觉地模仿那些我们每天都能看到的行为)第六段Far less certain,however,is how successfully experts and bureaucrats can select our peer groups and steer their activities in virtuous directions.(但是,不确定的是专家和官员会有多成功的来选择我们的同龄群体,并引导行为朝向着良性的方向)It’s like the teacher who breaks up the troublemakers in the back row by pairing them with better-behaved classmates.(这就像老师通过与表现好的学生做比较以便解决后排麻烦制造者的问题一样)The tactic never really works.(这个策略从来没有真正起作用)And that’s the problem with a social cure engineered from the outside:(这是从外面表现的一种社会治愈的问题:)In the real world,as in school,we insist on choosing our own friends.(在现实世界中,在学校里,我们坚持选择自己的朋友)9.22晚。

群体追逐现象的英语作文

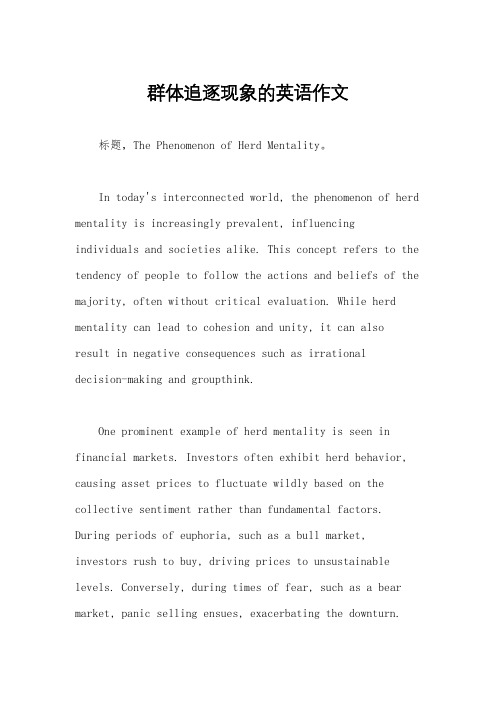

群体追逐现象的英语作文标题,The Phenomenon of Herd Mentality。

In today's interconnected world, the phenomenon of herd mentality is increasingly prevalent, influencingindividuals and societies alike. This concept refers to the tendency of people to follow the actions and beliefs of the majority, often without critical evaluation. While herd mentality can lead to cohesion and unity, it can alsoresult in negative consequences such as irrationaldecision-making and groupthink.One prominent example of herd mentality is seen in financial markets. Investors often exhibit herd behavior, causing asset prices to fluctuate wildly based on the collective sentiment rather than fundamental factors. During periods of euphoria, such as a bull market, investors rush to buy, driving prices to unsustainable levels. Conversely, during times of fear, such as a bear market, panic selling ensues, exacerbating the downturn.This herd behavior can amplify market volatility and lead to speculative bubbles or crashes.Similarly, herd mentality manifests in social and political movements. When a particular idea gains momentum, individuals may join the movement without fully understanding its implications or consequences. This blind allegiance to the group can stifle dissenting opinions and hinder critical thinking. Moreover, social media platforms have exacerbated this phenomenon by creating echo chambers where like-minded individuals reinforce each other's beliefs, further entrenching the herd mentality.Moreover, herd mentality can be observed in consumer behavior. Trends and fads spread rapidly through social networks, influencing people's purchasing decisions. Whether it's fashion, technology, or lifestyle choices, individuals often conform to what is popular or trendy within their social circles. This conformity can lead to homogenization of tastes and preferences, stiflingcreativity and innovation.In addition to its impact on financial markets, social movements, and consumer behavior, herd mentality also affects decision-making in organizations and institutions. Groupthink, a phenomenon where group members prioritize consensus over critical analysis, can lead to flawed decision-making and missed opportunities. Organizationsthat foster a culture of conformity may struggle to adapt to changing circumstances and innovate effectively.However, it is important to recognize that herd mentality is not inherently negative. In some cases, collective action can bring about positive change andsocial progress. For example, mass movements advocating for civil rights or environmental conservation have led to significant advancements in society. The key lies in striking a balance between collective action and individual autonomy, ensuring that critical thinking is not sacrificed in the pursuit of consensus.To mitigate the negative effects of herd mentality, individuals must cultivate a sense of independent thinking and skepticism. Rather than blindly following the crowd,individuals should question prevailing norms and seek out diverse perspectives. Education plays a crucial role in developing critical thinking skills and empowering individuals to resist the influence of herd mentality.Furthermore, fostering a culture of diversity and inclusion can help counteract the homogenizing effects of herd mentality. By embracing different viewpoints and experiences, organizations and societies can encourage innovation and creativity. Leaders have a responsibility to promote open dialogue and dissent within their organizations, challenging groupthink and fostering a culture of constructive debate.In conclusion, the phenomenon of herd mentality exerts a powerful influence on individuals and societies, shaping behavior and decision-making in various contexts. While herd mentality can facilitate cohesion and collective action, it also poses risks such as irrationality, conformity, and groupthink. By fostering independent thinking, promoting diversity, and encouraging opendialogue, we can mitigate the negative effects of herd mentality and harness its potential for positive change.。

金融术语对照表_修订版

金融术语对照表Abandonment o ption 放弃期权 Book-‐to-‐market r atio 账面市值比Accounts p ayable 应付账款 Break-‐even 盈亏平衡Accounts r eceivable 应收账款 Bridge l oan 过桥贷款Acquirer 收购方 Bulldogs 斗牛犬债券Acquisition p remium 收购溢价 Butterfly s pread 碟式跨价组合Adverse s election 逆向选择 Call d ate 赎回日Agency c osts 代理成本 Call o ption 看涨期权Aging s chedule 账龄分析表 Call p rice 赎回价American o ption 美式期权 Callable b onds 可赎回债券Amortization 摊销 Capital A sset P ricing M odel (CAPM) 资产定价模型 Amortizing l oan 分期贷款 Capital g ain 资本利得Angel i nvestors 天使投资者 Capital m arket l ine (CML) 资本市场线Annual p ercentage r ate 年度利率 Capital s tructure 资本结构Annuity 年金 Carryback 向后转回Arbitrage 套利 Carryforward 向前转结Arbitrage p ricing t heory (APT) 套利定价理论 Cash c onversion c ycle 现金周转期Ask p rice 卖价 Clientele e ffect (税收)客户效应Asset s ecuritization 资产证券化 Commercial p aper 商业票据Asset t urnover 资产易手 Committed l ine o f c redit 承诺的信贷额度Asset-‐backed b onds 资产支持债券 Compensating b alance 补偿性余额Asset-‐backed s ecurity (ABS) 资产支持证券 Competitive m arket 竞争性市场Asymmetric i nformation 不对称信息 Compound a nnual g rowth r ate 复合年率At-‐the-‐money 平价 Compound i nterest 复合利率Auction I PO 拍卖式IPO Consol 永续债券Auditor 审计 Convertible b onds 可转债Corporate g overnance 公司治理Backdating (期权)追溯 Coupon b onds 息票债券Balance s heet 资产负债表 Covenant 保护性条款Balloon p ayment 气球膨胀式偿付 Covered i nterest p arity e quation 抛补利率平价等式 Bearer b ond 无记名债券 Credibility p rinciple 置信原则Bid p rice 买价 Credit d efault s wap (CDS) 信用违约互换Bid-‐ask s pread 买卖价差 Credit r ating 信用评级Credit (default) s pread 信贷(违约)息差 Binomial O ption P ricing M odel 二项式期权定价模型Binomial t ree 二叉树 Cum d ividend 附息(含红利)Blanket l ien 总括留置权 Cumulative a bnormal r eturn 累计超常收益Book b uilding 询价圈购 Currency f orward c ontract 货币远期合约Book v alue 账面价值 Currency s wamp 货币互换Current a ssets 流动资产 Dividend y ield 股息率Current l iabilities 流动负债 Dividend-‐capture t heory 红利捕获理论 Current r atio 流动比率 Dividend-‐discount m odel 红利贴现理论Domestic b onds 国内债券Data s nooping b ias 数据探测偏差 Double-‐barreled 双重担保Dealer p aper 经纪商票据 Dual c lass s hare 双重表决权股票 Debentures 信用债券 DuPont i dentity 杜邦分析法Debt c apacity 借债能力 Duration m ismatch 久期错配Debt c ovenants 债务保护条款 Dutch a uction 荷兰式拍卖Debt o verhang 债务积压 Dynamic t rading s trategy 动态交易策略 Debt-‐equity r atio 权益负债率Debtor-‐in-‐procession f inancing (DIP) 破产保Earnings p er s hare (EPS) 每股收益护企业融资Decision n ode 决策点 Earnings y ield 收益率Decision t ree 决策树 EBIT 息税前收益Declaration d ate (分红)公告日 EBIT m argin 息税前利润率Deductible 可免除 EBITDA 息税折旧摊销前收益Deep i n-‐the-‐money 深度实值 Economic d istress 经济困境Deep o ut-‐of-‐the-‐money 深度虚值 Economies o f s cale 规模经济Default 违约 Economies o f s cope 范围经济Deferred t ax 递延税款 Effective a nnual r ate 有效年率 Depreciation 折旧 Effective d ividend t ax r ate 有效红利税率 Depreciation t ax s hield 折旧税盾 Efficient f rontier 有效边界Derivative s ecurity 衍生证券 Efficient m arket h ypothesis 有效市场假说 Diluted E PS 稀释每股收益 Efficient p ortfolio 有效投资组合Direct l ease 直接租赁 Empirical d istribution 经验分布Direct p aper 直接票据 Equal-‐ownership p ortfolio 等所有权投资组合 Dirty p rice (invoice p rice) (债券)发票价格 Equally w eighted p ortfolio 等权重投资组合 Disbursement f loat 付款浮动量 Equity 权益、股权Discount 贴现 Equity c ost o f c apital 股权资本成本 Discount f actor 贴现因子 Equity m ultiplier 股权乘数Discount r ate 贴现率 Equivalent a nnual b enefit (EAB) 等价年收益 Discounted f ree c ash f low m odel 现金流贴现EAB m ethod 等价年收益发模型Disposition e ffect 处置效应 European o ptions 欧式期权Distribution (payable) d ate 红利发放日 Evergreen c redit 长年信贷Diversifiable r isk 可分散风险 Ex-‐dividend d ate 除权除息日Dividend p ayout r ate 股息支付率 Excess r eturn 超额回报Dividend p uzzle 红利之谜 Exchange r atio 并购换股比率Exchange-‐traded f und (ETF) 交易所交易基金 Friendly t akeover 善意收购 Executive s tock o ption (ESO) 经理股票期权 Funding r isk 筹资风险Exercise (strike) p rice 行权价格 Future v alue 终值Exercising (an o ption) 行权 Future c ontract 期货合约Exit s trategy 退出策略Expected (mean) r eturn 期望回报 General l ien 一般留置权Expiration d ate 到期日 Gray d irectors 灰色董事General o bligation b onds 一般义务债券 Face v alue 面值 Global b onds 全球债券Factor b eta 因子贝塔 Golden p arachute 黄金降落伞Factor p ortfolios 因子组合 Goodwill 商誉Factoring o f a ccounts r eceivable 应收账款的保理 Generally A ccepted A ccounting P rinciples (GAAP) 公认会计原则Factors 保理商 Greenmail 绿邮Fair m arket v alue c ap l ease 公允价值封顶租赁 Greenshoe p rovision (over-‐allotment a llocation) 绿鞋条款(超额配售选择权)Familiarity b ias 熟悉度偏误 Gross m argin 毛利率Forward i nterest r ate (forward r ate) 远期利率Gross p rofit 毛利润Federal f unds r ate 联邦基金利率 Growing a nnuity 增长型年金Field w arehouse 就地仓库 Growing p erpetuity 增长型永续年金Final p rospectus 正式招股说明书 Growth o ption 增长期权Financial o ption 金融期权 Growth s tocks (shares) 成长股Financial s ecurity 金融证券Financial s tatement 财务报表 Hedge 对冲(套期保值)Firm c ommitment 包销 Herd b ehavior 羊群行为Fixed p rice l ease 固定价格租赁 Horizontal m erger 水平整合Floating l ien 浮动留置权 High-‐minus-‐low (HML) p ortfolio 高减低组合 Floating r ate 浮动利率 High-‐yield b onds 高收益债券Floor p lanning 最低限额计划 Homemade l everage 自制杠杆Flow t o e quity (FTE) 股权现金流 Homogeneous e xpectations 同质预期 Foreign b onds 外国债券 Hostile t akeover 敌意收购Forward e arnings 预期收益 Hurdle r ate 预设回报率Forward e xchange r ate 远期汇率Forward P/E 预期市盈率 Idiosyncratic r isk 非系统风险Free c ash f low 自由现金流 Immunized p ortfolio 免疫投资组合Free c ash f low t o e quity (FCFE) 股权自由现金流Impairment c harge 损失拨备Freezeout m erger 挤出合并 Informational c ascade e ffect 信息串流效应Implied v olatility 隐含波动率 Leverage (gearing) 杠杆Income s tatement 利润表 Leveraged b uyout (LBO) 杠杆收购 Incremental e arnings 增量收益 Leveraged l ease 杠杆租赁 Incremental I RR i nvestment r ule 增量IRR投资法Leveraged r ecapitalization 杠杆资本重整 Indenture 债券契约 Levered e quity 负债股权Independent (outside) d irectors 独立(外部)董事 London I nter-‐bank o ffered r ate (LIBOR) 伦敦银行同业拆借利率Independent r isk 独立风险 Limited p artnership 有限合伙企业Index f unds 指数基金 Line o f c redit 信贷额度Inefficient p ortfolio 无效投资组合 Liquid 流动的Information n ode 信息节点 Liquidating d ividend 清算红利Initial p ublic o ffering (IPO) 首次公开发行 Liquidation 清算Inside d irectors 内部董事 Liquidation v alue 清算价值Insider t rading 内幕交易 Liquidity r isk 流动性风险Insurance p remium 保费 Loan o rigination f ee 贷款发放费Intangible a ssets 无形资产 Lockup 锁定Interest c overage r atio 利息保障率 Limited l iability c ompany 有限责任公司Interest r ate f actor 利率因子 Long b onds 长期债权Interest r ate f orward c ontract 利率远期合约 Long p osition 多头Interest r ate s wap 利率互换 Long-‐term a ssets 长期资产Interest t ax s hield 利息税盾 Long-‐term d ebt 长期负债Internal r ate o f r eturn (IRR) 内含回报率 Long-‐term l iabilities 长期债务IRR i nvestment r ule 内含回报率投资法则Intrinsic v alue 内在价值 MACRS d epreciation 修正的加速成本回收系统折旧 Inventories 存货 Mail f loat 邮寄浮动量Investment-‐grade b onds 投资级债券 Management b uyout 管理层收购Management e ntrenchment 管理者壁垒 Jensen’s a lpha 詹森指数 Margin 保证金“just-‐in-‐time” (JIT) i nventory m anagement“适时”存货管理Market c apitalization 总市值Junk b onds 垃圾债券 Market i ndex 市场指数Market m akers 做市商Law o f O ne P rice 一价定律 Market p ortfolio 市场投资组合Lead u nderwriter 主承销商 Market p roxy 市场替代Lease-‐equivalent l oan 租赁等价贷款 Market r isk 市场风险Lemons p rinciple 柠檬原理 Market t iming h ypothesis 市场时机假说Lessee 承租方 Market v alue b alance s heet 市值资产负债表 Lessor 出租方 Market-‐to-‐book r atio (PB r atio) 市净率Marketable s ecurities 有价证券 Open m arket r epurchase 公开市场回购 Marking t o m arket 逐日盯市制度 Operating c ycle 营业周转期Martingale p rices 鞅价格 Operating i ncome (or p rofit) 营业利润 Matching p rinciple 匹配原则 Operating l ease 经营租赁Maturity d ate 到期日 Operating l everage 经营杠杆Method o f c omparables 可比公司估值法 Option p remium 期权标价Momentum s trategy 惯性策略 Operating m argin 经营利润率Moral h azard 道德风险 Opportunity c ost 机会成本Mortgage b onds 抵押债券 Opportunity c ost o f c apital 资本的机会成本Option d elta 期权对冲值Mortgage-‐backed s ecurity (MBS) 抵押支持证券Multifactor m odel 多因子模型 Option w riter 期权卖方Municipal b onds 市政债券 Out-‐of-‐the-‐money 虚值(价外)Mutually d ependent i nvestment 关联投资 Overconfidence h ypothesis 过度自信假设Overhead e xpenses 间接费用Naked s hort 裸卖空Natural h edge 自然避险 Price-‐earnings r atio (P/E) 市盈率Net d ebt 净负债 Paid-‐in c apital 实收资本Par 面值Net i ncome o r e arning o r p rofit 净收益(盈余或利润)Net i nvestment 净投资 Partnership 合伙企业Pass-‐through 过手Net o perating p rofit a fter t ax (NOPAT) 税后净运营收益Net p resent v alue (NPV) 净现值 Passive p ortfolio 被动投资组合NPV d ecision r ule 净现值投资法则 Payback i nvestment r ule 投资回收期法则Net p rofit m argin 销售净利润率 Payback p eriod 投资回收期Net w orking c apital 净运营资本 Payments p attern 付款模式No-‐arbitrage p rice 无套利价格 Payout p olicy 股利政策No-‐trade t heorem 无交易理论 Pecking o rder h ypothesis融资优序假说 Nominal i nterest r ate 名义利率 Perfect c apital m arkets 完没资本市场On-‐tax l ease 非节税租赁 Permanent w orking c apital 永久性运营资本 Normal m arket 正常市场 Perpetuity 永续年金Notes 票据(中期国债) Pledging o f a ccounts r eceivable 应收账款的抵押 Notional p rincipal 名义本金 Poison p ill 毒丸计划Policy l imits 保单限额Off-‐balance s heet t ransactions 表外交易 Pool (资产)池OID (original i ssue) d iscount 原始发行折价 Portfolio 投资组合On-‐the-‐run b onds 新发债券 Portfolio i nsurance 投资组合保险Open i nterest 未平仓合约数量 Portfolio w eights 投资组合权重Post-‐money v aluation 发行后股价 Real o ption 实物期权Precautionary b alance 预防性余额 Realized r eturn 已实现回报Preferred s tock 优先股 Record d ate 股权登记日Refinance 再融资Preliminary p rospectus (red h erring) 临时招股说明Premium 溢价 Registered b onds 记名公司债券 Prepackaged b ankruptcy 预包装破产重组 Registration s tatement 注册上市申请书 Prepayment r isk 预付风险 Relative w ealth c oncerns 相对财富考量 Present v alue (PV) 现值 Repatriated 收益返还Pretax W ACC 税前加权平均资本成本 Replicating p ortfolio 复制组合Price-‐weighted p ortfolio 价格加权组合 Required r eturn 必要回报率Primary m arket 一级市场 Residual i ncome v aluation m ethod 剩余收益股价模型Primary o ffering 首次发行 Residual v alue 剩余价值Primary s hare 新发股票 Retained e arning 留存收益Prime r ate 优惠利率 Retention r ate 留存收益率Prior o ne-‐year m omentum (PR1YR) p ortfolioReturn o n a sset (ROA) 资产收益率前一年惯性组合Private c ompany 私营公司 Return o n e quity (ROE) 股权收益率Private d ebt 私募债 Revenue b onds 收入担保债券Private e quity f irm 私人资本公司 Reverse s plit 股票合并Private p lacement 私募配售 Revolving l ine o f c redit 周转信贷Pro f orma 预测 Rights o ffer 配股发行Processing f loat 结算浮动量 Risk a version 风险厌恶Profitability i ndex 获利指数 Risk p remium 风险溢价Project e xternality 项目外部性 Risk-‐arbitrageurs 风险套利者Promissory n ote 本票 Risk-‐free i nterest r ate 无风险利率Property i nsurance 财产保险 Risk-‐neutral p robability 风险中性概率 Protective p ut 保护性看跌期权 Road s how 路演Proxy f ight 代理权争夺 Sale a nd l ease b ack 售后回租Public c ompanies 上市公司 Sales-‐type l ease 销售性租赁Public w arehouse 公共仓库 Samurai b onds 日本武士债券Pure d iscount (zero-‐coupon) b onds 零息债券 Scenario a nalysis 场景分析Put o ption 看跌期权 Seasoned e quity o ffering (SEO) 股票增发Put-‐call p arity 卖买权平价 Secondary m arket 二级市场Pyramid s tructure 金字塔结构 Secondary o ffering 二次发行Quick r atio 速动比率 Secondary s hares 增发股Raider 入侵者 Secured d ebt (loan) 有担保债务(贷款) Rational e xpectation 理性预期 Security i nterest 担保权益Real i nterest r ate 实际利率 Security m arket l ine (SML) 证券市场线Segmented c apital m arket 分割的资本市场 State p rices 状态价格Self-‐financing p ortfolio 自融资组合 State-‐contingent p rices 状态依存价格Semi-‐strong f orm e fficiency 半有效市场假说 Statement o f c ash f lows 现金流量表Seniority 优先权 Stop-‐out y ield 截止收益率Sensation s eeking 感觉寻求 Statement o f f inancial p osition 财务状况表 Sensitivity a nalysis 敏感性分析 Statement o f (comprehensive) i ncome (综合)收益表Separate T rading o f R egistered I nterest a ndPrincipal S ecurities (STRIPS) 本息分离式国债Step u p 调高Separation p rinciple 分离原理 Stock d ividend (stock s plit) 股票股利Serial b onds 分期偿还系列债权 Straddle 跨价式组合Share (stock) o ption g股票期权 Stock s wap 股票互换Share r epurchase 股票回购 Stock-‐out 库存耗竭Shareholder (stockholder o r e quity h older) 股东 Statement o f c hanges i n s hareholders’ e quity 股东权益变动表Shareholders’ (stockholders’) e quity 股东权益 Stock e xchange (stock m arkets) 证券交易所(股票市场)Sharpe r atio 夏普比率 Straight-‐line d epreciation 直线折旧法Short i nterest 卖空股票数额 Strangle 勒束式跨价组合Short p osition 空头头寸 Strategic i nvestor 策略投资者Short s ale 卖空 Strategic p artner 策略合伙人Signaling t heory o f d ebt 债务的信号传递理论 Stream o f c ash f lows 系列现金流Simple i nterest 单利 Stretching t he a ccounts p ayable 应付账款展期 Single-‐factor m odel 单因素模型 Strong f orm e fficiency 强有效市场假说 Sinking f und 偿债基金 Subordinated d ebenture 次级信用债券Size e ffect 规模效应 Subprime m ortgages 次级抵押贷款Small-‐minus-‐big (SMB) p ortfolio 小减大组合 Sunk c ost 沉没成本Sole p roprietorship 个人独资企业 Sunk c ost f allacy 沉没成本谬误Sovereign d ebt 国债 Syndicate 辛迪加(承销团、银团)Special d ividend 特别红利 Syndicated b ank l oan 银团贷款Special-‐purpose e ntity (SPE) 特殊目的实体 Synthetic l ease 合成租赁Specialists 专业证券商Speculate投机 Tailing t he h edge 跟踪套期保值 Speculative b onds 投机性债券 Takeover 并购Spin-‐off 分拆 Takeover s ynergies 并购协同效应Spot e xchange r ates 即期汇率 Tangent p ortfolio 切点投资组合Spot i nterest r ate 即期利率 Target l everage r atio 目标杠杆比率Staggered (classified) b oard 交叉(分级)董事会 Tax l oss c arryforwards a nd c arrybacks 纳税亏损递延和追溯Stakeholder m odel 利益相关者模型 Targeted r epurchase 目标定向回购TED (Treasury-‐Eurodollar) s pread 泰德价差 Unlevered P/E r atio 无杠杆市盈率Temporary w orking c apital 暂时性运营资本 Unsecured d ebt 无担保债券Tender o ffer 股权要约收购Term 期限 Valuation m ultiple 估值乘数Term l oan 定期贷款 Valuation p rinciple 估值原则Term s tructure 期限结构 Value a dditivity 价值可加性Terminal v alue 预测期期末价值 Value s tocks 绩优股Time v alue o f m oney 货币时间价值 Value-‐weighted p ortfolio 价值加权组合 Timeline 时间线 Venture c apital f irm 风险投资公司TIPS (Treasury-‐Inflation-‐ProtectedVenture c apitalist 风险投资家Securities) 国债通胀保值证券Toehold 立足点 Vertical i ntegration 纵向整合Total p ayout m odel 总支付模型 Volatility 波动率Trade c redit 商业信用Tradeoff t heory 权衡理论 Weighted a verage c ost o f c apital (WACC) 加权平均资本成本Trailing e arnings 历史收益 Warrant 认股权证Trailing P/E 追溯市盈率 Weak f orm e fficiency 弱市场有效假说 Tranches 贷款“种类” White k night 白衣骑士Transaction c ost 交易成本 White s quire 白衣护卫Transactions b alance 交易性余额 Winner’s c urse 赢者诅咒Treasury b ills 短期国债 With (without) r ecourse 有追索权Treasury b onds 长期国债 Workout 私下重组Treasury n otes 中期国债 Yield c urve 收益率曲线Treasury s tock m ethod Yield t o c all (YTC) 赎回收益率True l ease 真实租赁 Yield t o m aturity (YTM) 到期收益率True t ax l ease 真实课税租赁Trust r eceipts l oan 信托收据贷款 Zero-‐coupon y ield c urve 零息票债券收益率曲线 Tunneling 隧道效应 (利益输送)Uncommitted l ine o f c redit 无承诺的信贷额度Under-‐investment p roblem 投资不足问题Underwriter 承销商Underwriting s pread 承销价差Undiversifiable r isk 不可分散风险Unlevered b eta 无杠杆贝塔Unlevered c ost o f c apital 无杠杆资本成本Unlevered e quity 无杠杆股权Unlevered n et i ncome 无杠杆净收益。

托福口语素材:羊群效应