乔治奥威尔 Why I Write 共35页

animal-farm动物农场-乔治奥威尔

Old Major-Pig, the founder of the animal rightist, symbolize Marx and Lenin

Napoleon- Pig, a leader and commander of the revolution, symbolize Joseph Stalin

Benjamin - donkey, doubt but protect himself only, symbolize Intellectuals with independent thinking and Orwell himself

The Dogs - the tool for ruling and violence, symbolize the Secret Police

Main Characters

Snowball- Pig, a leader and enemy of the revolution , symbolize Trotsky

Boxer-horse, the loyal follower of the animal rightist, symbolize the masses

The Plot of Animal Farm

However, the leaders ——pigs took advantage of new system to benefit themselves. They slept on the bed and drunk milk. The two leaders-Snowball and Napoleon wanted to be the only leader. Snowball was driven out because Napoleon let some fierce dog to chase him. And then Napoleon declared Snowball was spy and the enemy of Animal Farm. In the past, Snowball put forward to build windmill and Napoleon push others to build it since Snowball’s departure. Though it was wrecked twice but it finally was accomplished through years of hard work.

Why I Write

I had the lonely child's habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued.

我想写大部头的自然主义小说,以悲剧结局,充满细致的描写和惊人的比喻,而且不乏文才斐然的段落,字词的使用部分要求其音响效果。

I wanted to write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their sound.

我在不同时期崇仰风格各异的作家。我想,从这些“故事”一定能看出这些作家的文笔风格的痕迹。但是我记得,这些描述又总是一样地细致入微,纤毫毕现。

The "story" must, I suppose, have reflected the styles of the various writers I admired at different ages, but so far as I remember it always had the same meticulous descriptive quality.

Marrakech——乔治欧威尔

From one perspective the implied argument is that they are no more But clearly this is not Orwell’s view. In fact, it is this inhuman, exploitative view that this essay criticizes. Orwell attacks a viewpoint that many of his readers would subscribe to. They, of course, would not see imperialism as responsible for causing or even contributing to the problems he describes. Orwell, however, aims to make clear that colonialism, founded on a view of human beings as material to be exploited, perpetuates the misery he describes.

Understanding the text

Structure: This essay is divided into 5 parts: 1) By telling his readers how the people of Marrakech are buried, the author accentuates the extreme poverty of Marrakech and the little regard in which human life is held. Thesis statement appears in this part: All colonial empires are in reality founded upon the fact that people here are treated as animals.

乔治奥威尔

Orwell next explored his overseas experiences in Burmese Days, which offered a dark look at British colonialism in Burma, then part of the country's Indian empire. Orwell's interest in political matters grew rapidly after this novel was published.

In December 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out. Orwell traveled to Spain, where he joined one of the groups fighting against General Francisco Franco who was supported by facisits and Nazi. Orwell was badly injured during his time with a militia, getting shot in the throat and arm. For several weeks, he was unable to speak. Later, in 1937, after having fought in Barcelona against communists who were trying to suppress their political opponents, he was forced to flee Spain in fear of his life. The experience left him with a lifelong dread of communism and he predicted that Spain would fall under fascist totalitarianism.

奥威尔英文介绍ppt课件

Orwell's Contribution to Liter

Creating critical reality

Orwell's works are an important representative of critical reality in English literature His works are full of social and political criticism, analyzing the social problems and political issues of the time, and pointing out the direction for solving these problems

Critical thinking

Orwell's works often involve critical thinking, analyzing and critiquing the social problems and political issues of the time His works are full of irony, sarcasm and sentiment, but also contain profounded social ideas

01

Orwell Background Introduction

Orwell Historical Background

01

02

03

04

1903

Born in India, but his family moved to England when he was still a baby

1917

Enrolled in Eton College, a preliminary private school

乔治·奥威尔

四、斯奎拉不断强调外在的假想敌,当内部矛盾激

化时,就利用外敌一直是严重威胁,随时可能入侵 来转移民众视线。

五、运用语言“忽悠”技巧移花接木、颠倒黑白。

“吱嘎”的软实力与拿破仑的硬实力里外 结合,从精神到肉体完全控制了动物庄园。这 种结合方式正是奥威尔最为担忧的现代极权主 义统治方式。

乔治· 奥威尔

(George Orwell,1903~1950)

卡玛在文革记录片《八九点钟的太阳》中 有着这样解说“在无数人心目中,革命已 死,乌托邦的美景正以新的面貌展现,但 毛的幽灵仍在徘徊,每当人们受到压迫并 感到绝望,每当异议或抗议被视为非法, 毛泽东的身影就可能化为希望的象征 ”。

体性,精神特权以及精神财产丧失,所有的人变成了 一种精神空白或精神缺损。”(詹姆逊) 所以,唯有通过对乌托邦的反面构建(反乌托 邦),通过一种绝望的悲凉对人类生命的冲击,才能 给人予刺激和警醒。

ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ

何为“极权主义”?

“极权主义兴起,首先得力于建立在一整套意识形态 的运作上。

这种意识形态以种族、阶级斗争为前提,用一种先念 未来进行通盘解释,声称发现了‘历史必然性’之规 律,并将其目标定在建立一个人间天堂式的社会理想

第二次世界大战(一九三九——一九四 五),是当时的“三国演义”。英美、苏联 和德国是世界的三极,就像中国的抗战,国 民党、共产党和日本,也是三极。三极变两 极,都是敌人之中选朋友。

这就是政治。

《动物农场》

Animal Farm

何为“反乌托邦”?

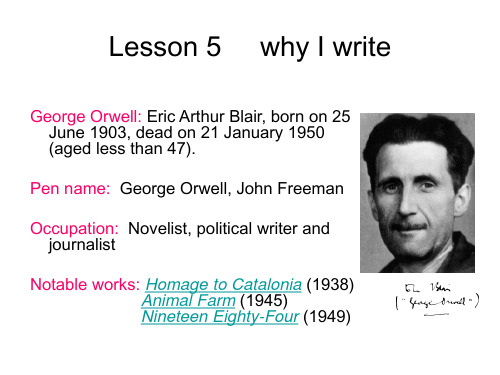

Lesson 5 why I write1

1. Orwell liked to provoke argument by challenging the status quo, but he was also a traditionalist with a love of old English values. 2. His works are concerned with the sociopolitical conditions of his time, notably with the problem of human freedom. 3. He was a left-wing Labour-supporting democratic socialist. 4. He had a few close friends with a similar background or with a similar level of literary ability. He wasUngregarious (不合群的 ),out of place in a crowd with real working people.

The square in Barcelona renamed in Orwell's honour

什么时候缺乏政治目的,什么时候我就会写出毫无生气的书,就会坠入华 而不实的篇章,写出毫无意义的句子,卖弄矫饰的形容词和堆砌一大堆空 话废话。

• Blair family home at Shiplake

5. He was explaining that "it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally."

George-Orwell-简介

His Works

• 1931 A Hanging essay • 1933 Down And OutI In Paris And London

• Orwell's influence on popular and political culture endures, and several of his neologisms, along with the term Orwellian — a byword for totalitarian or manipulative social practices — have entered the vernacular.

• Orwell decided to follow family tradition and, in 1922, went to Burma as assistant district superintendent in the Indian Imperial Police. In 1927 Orwell, on leave to England, decided not to return to Burma.

• After that he bad been a vagabondage for four years.

• In 1936, he went to Barcelona as a journalist to report the Spanish Civil War(西班牙内战 1936~1939).

The Achievement

英语散文why I write

WHY I WRITE (1946)From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up I should be a writer. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.I was the middle child of three, but there was a gap of five years on either side, and I barely saw my father before I was eight. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays. I had the lonely child’s habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life. Nevertheless the volume of serious—i.e. seriously intended—writing which I produced all through my childhood and boyhood would not amount to half a dozen pages. I wrote my first poem at the age of four or five, my mother taking it down to dictation. I cannot remember anything about it except that it was about a tiger and the tiger had ‘chair-like teeth’—a good enough phrase, but I fancy the poem was a plagiarism of Blake’s ‘Tiger, Tiger’. At eleven, when the war or 1914-18 broke out, I wrote a patriotic poem which was printed in the local newspaper, as was another, two years later, on the death of Kitchener. From time to time, when I was a bit older, I wrote bad and usually unfinished ‘nature poems’ in the Georgian style. I also attempted a short story which was a ghastly failure. That was the totalof the would-be serious work that I actually set down on paper during all those years.However, throughout this time I did in a sense engage in literary activities. To begin with there was the made-to-order stuff which I produced quickly, easily and without much pleasure to myself. Apart from school work, I wrote VERS D’OCCASION, semi-comic poems which I could turn out at what now seems to me astonishing speed—at fourteen I wrote a whole rhyming play, in imitation of Aristophanes, in about a week—and helped to edit a school magazines, both printed and in manuscript. These magazines were the most pitiful burlesque stuff that you could imagine, and I took far less trouble with them than I now would with the cheapest journalism. But side by side with all this, for fifteen years or more, I was carrying out a literary exercise of a quite different kind: this was the making up of a continuous ‘story’ about myself, a sort of diary existing only in the mind. I believe this is a common habit of children and adolescents. As a very small child I used to imagine that I was, say, Robin Hood, and picture myself as the hero of thrilling adventures, but quite soon my ‘story’ ceased to be narcissistic in a crude way and became more and more a mere description of what I was doing and the things I saw. For minutes at a time this kind of thing would be running through my head: ‘He pushed the door open and entered the room. A yellow beam of sunlight, filtering through the muslin curtains, slanted on to the table, where a match-box, half-open, lay beside the inkpot. With his right hand in his pocket he moved across to the window. Down in the street a tortoiseshell cat was chasing a dead leaf’, etc. etc. This habit continued until I was about twenty-five, right through my non-literary years. Although I had to search, and did search, for the right words, I seemed to be making this descriptive effort almost against my will, under a kind of compulsion from outside. The ‘story’ must, I suppose, have reflected the styles of the various writers I admired at different ages,but so far as I remember it always had the same meticulous descriptive quality.When I was about sixteen I suddenly discovered the joy of mere words, i.e. the sounds and associations of words. The lines from PARADISE LOST,So hee with difficulty and labour hard Moved on: with difficulty and labour hee.which do not now seem to me so very wonderful, sent shivers down my backbone; and the spelling ‘hee’ for ‘he’ was an added pleasure. As for the need to describe things, I knew all about it already. So it is clear what kind of books I wanted to write, in so far as I could be said to want to write books at that time. I wanted to write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their own sound. And in fact my first completed novel, BURMESE DAYS, which I wrote when I was thirty but projected much earlier, is rather that kind of book.I give all this background information because I do not think one can assess a writer’s motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject matter will be determined by the age he lives in —at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own — but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, in some perverse mood; but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write. Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen—in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all—and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.(iv) Political purpose.—Using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other peoples’ idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinionthat art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time. By nature—taking your ‘nature’ to be the state you have attained when you are first adult—I am a person in whom the first three motives would outweigh the fourth. In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer. First I spent five years in an unsuitable profession (the Indian Imperial Police, in Burma), and then I underwent poverty and the sense of failure. This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism: but these experiences were not enough to give me an accurate political orientation. Then came Hitler, the Spanish Civil War, etc. By the end of 1935 I had still failed to reach a firm decision. I remember a little poem that I wrote at that date, expressing my dilemma:A happy vicar I might have been Two hundred years ago To preach upon eternal doom And watch my walnuts grow;But born, alas, in an evil time, I missed that pleasant haven, For the hair has grown on my upper lip And the clergy are all clean-shaven.And later still the times were good, We were so easy to please, We rocked our troubled thoughts to sleep On the bosoms of the trees.All ignorant we dared to own The joys we now dissemble; The greenfinch on the apple bough Could make my enemies tremble.But girl’s bellies and apricots, Roach in a shaded stream, Horses, ducks in flight at dawn, All these are a dream.It is forbidden to dream again; We maim our joys or hide them: Horses are made of chromium steel And little fat men shall ride them.I am the worm who never turned, The eunuch without a harem; Between the priest and the commissar I walk like Eugene Aram;And the commissar is telling my fortune While the radio plays, But the priest has promised an Austin Seven, For Duggie always pays.I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls, And woke to find it true; I wasn’t born for an age like this; Was Smith? Was Jones? Were you?The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, AGAINST totalitarianism and FOR democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. Everyone writes of them in one guise or another. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows. And the more one is conscious of one’s political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one’s aesthetic and intellectual integrity.What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art’. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article, if it were not also an aesthetic experience. Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able,and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.It is not easy. It raises problems of construction and of language, and it raises in a new way the problem of truthfulness. Let me give just one example of the cruder kind of difficulty that arises. My book about the Spanish civil war, HOMAGE TO CATALONIA, is of course a frankly political book, but in the main it is written with a certain detachment and regard for form. I did try very hard in it to tell the whole truth without violating my literary instincts. But among other things it contains a long chapter, full of newspaper quotations and the like, defending the Trotskyists who were accused of plotting with Franco. Clearly such a chapter, which after a year or two would lose its interest for any ordinary reader, must ruin the book. A critic whom I respect read me a lecture about it. ‘Why did you put in all that stuff?’ he said. ‘You’ve turned what might have been a good book into journalism.’ What he said was true, but I could not have done otherwise. I happened to know, what very few people in England had been allowed to know, that innocent men were being falsely accused. If I had not been angry about that I should never have written the book.In one form or another this problem comes up again. The problem of language is subtler and would take too long to discuss. I will only say that of late years I have tried to write less picturesquely and more exactly. In any case I find that by the time you have perfected any style of writing, you have always outgrown it. ANIMAL FARM was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse politicalpurpose and artistic purpose into one whole. I have not written a novel for seven years, but I hope to write another fairly soon. It is bound to be a failure, every book is a failure, but I do know with some clarity what kind of book I want to write.Looking back through the last page or two, I see that I have made it appear as though my motives in writing were wholly public-spirited. I don’t want to leave that as the final impression. All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand. For all one knows that demon is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a POLITICAL purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.。

Why I Write

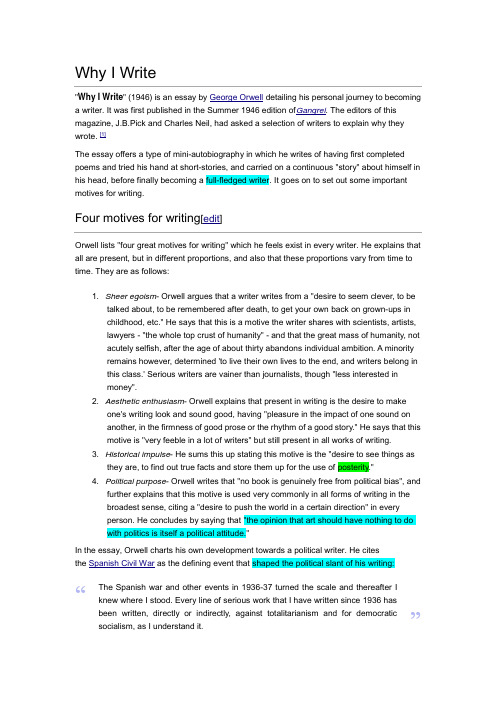

Why I Write"Why I Write" (1946) is an essay by George Orwell detailing his personal journey to becoming a writer. It was first published in the Summer 1946 edition of Gangrel. The editors of this magazine, J.B.Pick and Charles Neil, had asked a selection of writers to explain why they wrote. [1]The essay offers a type of mini-autobiography in which he writes of having first completed poems and tried his hand at short-stories, and carried on a continuous "story" about himself in his head, before finally becoming a full-fledged writer. It goes on to set out some important motives for writing.Orwell lists "four great motives for writing" which he feels exist in every writer. He explains that all are present, but in different proportions, and also that these proportions vary from time to time. They are as follows:1. Sheer egoism- Orwell argues that a writer writes from a "desire to seem clever, to betalked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups inchildhood, etc." He says that this is a motive the writer shares with scientists, artists,lawyers - "the whole top crust of humanity" - and that the great mass of humanity, not acutely selfish, after the age of about thirty abandons individual ambition. A minorityremains however, determined 'to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong inthis class.' Serious writers are vainer than journalists, though "less interested inmoney".2. Aesthetic enthusiasm- Orwell explains that present in writing is the desire to makeone's writing look and sound good, having "pleasure in the impact of one sound onanother, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story." He says that this motive is "very feeble in a lot of writers" but still present in all works of writing.3. Historical impulse- He sums this up stating this motive is the "desire to see things asthey are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity."4. Political purpose- Orwell writes that "no book is genuinely free from political bias", andfurther explains that this motive is used very commonly in all forms of writing in thebroadest sense, citing a "desire to push the world in a certain direction" in everyperson. He concludes by saying that "the opinion that art should have nothing to dowith politics is itself a political attitude."In the essay, Orwell charts his own development towards a political writer. He citesthe Spanish Civil War as the defining event that shaped the political slant of his writing: “The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 hasbeen written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it. ”Orwell, who is considered to be a very political writer, says that by nature, he is "a person in whom the first three motives would outweigh the fourth", and that he "might have remained almost unaware of [his] political loyalties", - but that he had been "forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer" because his era was not a peaceful one. In the decade since 1936-37 his desire had been to "make political writing into an art". He concludes the essay explaining that "it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally."2.原文:Why I Writeby George OrwellGangrel, [No. 4, Summer] 1946From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up I should be a writer. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.I was the middle child of three, but there was a gap of five years on either side, and I barely saw my father before I was eight. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays. I had the lonely child's habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life. Nevertheless the volume of serious — i.e. seriously intended — writing which I produced all through my childhood and boyhood would not amount to half a dozen pages. I wrote my first poem at the age of four or five, my mother taking it down to dictation. I cannot remember anything about it except that it was about a tiger and the tiger had 'chair-like teeth'— a good enough phrase, but I fancy the poem was a plagiarism of Blake's 'Tiger, Tiger'. At eleven, when the war or 1914-18 broke out, I wrote a patriotic poem which was printed in the local newspaper, as was another, two years later, on the death of Kitchener. From time to time, when I was a bit older, I wrote bad and usually unfinished'nature poems' in the Georgian style. I also attempted a short story which was a ghastly failure. That was the total of the would-be serious work that I actually set down on paper during all those years.However, throughout this time I did in a sense engage in literary activities. To begin with there was the made-to-order stuff which I produced quickly, easily and without much pleasure to myself. Apart from school work, I wrote vers d’occasion, semi-comic poems which I could turn out at what now seems to me astonishing speed — at fourteen I wrote a whole rhyming play, in imitation of Aristophanes, in about a week — and helped to edit a school magazines, both printed and in manuscript. These magazines were the most pitiful burlesque stuff that you could imagine, and I took far less trouble with them than I now would with the cheapest journalism. But side by side with all this, for fifteen years or more, I was carrying out a literary exercise of a quite different kind: this was the making up of a continuous 'story' about myself, a sort of diary existing only in the mind. I believe this is a common habit of children and adolescents. As a very small child I used to imagine that I was, say, Robin Hood, and picture myself as the hero of thrilling adventures, but quite soon my 'story' ceased to be narcissistic in a crude way and became more and more a mere description of what I was doing and the things I saw. For minutes at a time this kind of thing would be running through my head: 'He pushed the door open and entered the room. A yellow beam of sunlight, filtering through the muslin curtains, slanted on to the table, where a match-box, half-open, lay beside the inkpot. With his right hand in his pocket he moved across to the window. Down in the street a tortoiseshell cat was chasing a dead leaf', etc. etc. This habit continued until I was about twenty-five, right through my non-literary years. Although I had to search, and did search, for the right words, I seemed to be making this descriptive effort almost against my will, under a kind of compulsion from outside. The 'story' must, I suppose, have reflected the styles of the various writers I admired at different ages, but so far as I remember it always had the same meticulous descriptive quality.When I was about sixteen I suddenly discovered the joy of mere words, i.e. the sounds and associations of words. The lines from Paradise Lost—So hee with difficulty and labour hardMoved on: with difficulty and labour hee.which do not now seem to me so very wonderful, sent shivers down my backbone; and the spelling 'hee' for 'he' was an added pleasure. As for the need to describe things, I knew all about it already. So it is clear what kind of books I wanted to write, in so far as I could be said to want to write books at that time.I wanted to write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their own sound. And in fact my first completed novel, Burmese Days, which I wrote when I was thirty but projected much earlier, is rather that kind of book.I give all this background information because I do not think one can assess a writer's motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject matter will be determined by the age he lives in — at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own — but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, in some perverse mood; but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write. Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen — in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all — and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are onthe whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.(iv) Political purpose.— Using the word 'political' in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other peoples' idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time. By nature — taking your 'nature' to be the state you have attained when you are first adult — I am a person in whom the first three motives would outweigh the fourth. In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer. First I spent five years in an unsuitable profession (the Indian Imperial Police, in Burma), and then I underwent poverty and the sense of failure. This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism: but these experiences were not enough to give me an accurate political orientation. Then came Hitler, the Spanish Civil War, etc. Bythe end of 1935 I had still failed to reach a firm decision. I remember a little poem that I wrote at that date, expressing my dilemma:I am the worm who never turned,The eunuch without a harem;Between the priest and the commissarI walk like Eugene Aram;And the commissar is telling my fortuneWhile the radio plays,But the priest has promised an Austin Seven,For Duggie always pays.I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls,And woke to find it true;I wasn't born for an age like this;Was Smith? Was Jones? Were you?The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. Everyone writes of them in one guise or another. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows. And the more one is conscious of one's political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one's aesthetic and intellectual integrity.What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, 'I am going to produce a work of art'. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article, if it were not also an aesthetic experience. Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant.I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.It is not easy. It raises problems of construction and of language, and it raises in a new way the problem of truthfulness. Let me give just one example of the cruder kind of difficulty that arises. My book about the Spanish civil war, Homage to Catalonia, is of course a frankly political book, but in the main it is written with a certain detachment and regard for form. I did try very hard in it to tell the whole truth without violating my literary instincts. But among other things it contains a long chapter, full of newspaper quotations and the like, defending the Trotskyists who were accused of plotting with Franco. Clearly such a chapter, which after a year or two would lose its interest for any ordinary reader, must ruin the book. A critic whom I respect read me a lecture about it. 'Why did you put in all that stuff?' he said. 'You've turned what might have been a good book into journalism.' What he said was true, but I could not have done otherwise. I happened to know, what very few people in England had been allowed to know, that innocent men were being falsely accused. If I had not been angry about that I should never have written the book.In one form or another this problem comes up again. The problem of language is subtler and would take too long to discuss. I will only say that of late years I have tried to write less picturesquely and more exactly. In any case I find that by the time you have perfected any style of writing, you have always outgrown it. Animal Farm was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole.I have not written a novel for seven years, but I hope to write another fairly soon. It is bound to be a failure, every book is a failure, but I do know with some clarity what kind of book I want to write.Looking back through the last page or two, I see that I have made it appear as though my motives in writing were wholly public-spirited. I don't want to leavethat as the final impression. All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand. For all one knows that demon is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one's own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.。

乔治奥威尔-Why-I-Write-PPT

unmediated way and tells the truth

about it.” 2024/1/2

----Rushbrook Williams

“垂死的肺病患者,三十三年前自己的喘息都 已不继,就咳尽你一腔的热血。”

---《致奥威尔》余光中

“西方文学自伊索寓言以来,历代都有以动物 为主的童话和寓言,但对20世纪后期的读者来 说,此类作品中没有一种比《动物庄园》更中 肯地道出当今人类的处境了。”

---夏志清

奥威尔以锐目观察,批判以斯大林时代的苏联为首、 掩盖在社会主义名义下的极权主义,以辛辣的笔触讽刺 泯灭人性的极权主义社会和追逐权力者。小说中对极权 主义政权的预言在之后的五十年中也不断地为历史印证, 所以两部作品堪称世界文坛政治讽喻小说的经典之作, 他因此被称为“一代人的冷峻良知”。

2024/1/2

merchant in Burma(缅甸)

2024/1/2

Childhood

•In 1914, 11-year-old Orwell published a poem Wake up, the boys in the local newspaper for the first time •He studied in the most famous school Eton College(1917) •morose,unsociable and disobedient

2024/1/2

Evaluations

2024/1/2

Orwell was “the best English essayist since Hazlitt.”

---- Irving Howe

“ A successful impersonation of a plain

乔治奥威尔和他的《动物农场》英文作文

乔治奥威尔和他的《动物农场》英文作文George Orwell and His "Animal Farm"George Orwell, a renowned British writer and journalist, is best known for his dystopian novel "Animal Farm". Published in 1945, the novel is a satirical allegory of the Russian Revolution and the rise of Stalinism. Through the use of animal characters and a farm as the setting, Orwell criticizes the corruption of power and the betrayal of the socialist ideals.Set on a farm where the animals revolt against their human owner Mr. Jones, "Animal Farm" follows the animals' journey towards self-governance and equality. Led by the pigs, especially Napoleon and Snowball, the animals establish their own rules and work towards a utopian society. However, as time passes, the pigs begin to manipulate and oppress the other animals, eventually turning into the very tyrants they once rebelled against.One of the most striking features of "Animal Farm" is Orwell's use of allegory to illustrate the events of the Russian Revolution. Napoleon represents Stalin, Snowball represents Trotsky, and the other animals represent various factions of society. Through these characters, Orwell shows how powercorrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The manipulation and brainwashing of the animals by the pigs mirror the totalitarian regime of Stalin and the Communist Party.Moreover, Orwell's choice of animals as characters adds another layer of complexity to the novel. By using animals to represent humans, Orwell highlights the universal nature of power struggles and oppression. The pigs' gradual transformation into human-like figures demonstrates how even the most noble ideals can be corrupted by greed and ambition.In addition to its political themes, "Animal Farm" also explores the nature of truth and propaganda. The pigs' manipulation of language and rewriting of history mirrors the propaganda tactics used by totalitarian regimes. The famous quote "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others" illustrates the hypocrisy and double standards of those in power.Overall, "Animal Farm" is a powerful and timeless work that continues to resonate with readers around the world. Orwell's critique of totalitarianism, corruption, and propaganda remains relevant in today's society, where the abuse of power and distortion of truth are still prevalent. Through the story of the animals' rebellion and subsequent downfall, Orwell warnsagainst the dangers of unchecked authority and the importance of remaining vigilant in the face of injustice.In conclusion, George Orwell's "Animal Farm" is a literary masterpiece that serves as a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of power and the fragility of freedom. By using animals to symbolize human behavior and political ideologies, Orwell creates a compelling narrative that exposes the darker side of human nature. As we reflect on the lessons of "Animal Farm", we are reminded of the importance of remaining vigilant and standing up for justice in the face of oppression.。

1984乔治奥威尔英文epub

1984乔治奥威尔英文epub全文共10篇示例,供读者参考篇1One day, I read a super cool book called "1984" by George Orwell! It's like a futuristic story about a guy named Winston who lives in a super strict society where Big Brother watches everything you do.In the book, Winston starts to question the rules of the society and tries to rebel against Big Brother. But oh no, he gets caught and has to go through all kinds of crazy stuff like brainwashing and torture. It's so intense!But Winston is super brave and he never gives up. Even when things get super tough, he keeps fighting for his freedom and for the truth. He's like a superhero, but in a regular guy way.The book talks about how powerful governments can control people and manipulate the truth. It's a reminder to always question authority and to stand up for what's right, even when it's hard.I really loved reading "1984" because it made me think about the world in a different way. It's like a warning about what could happen if we're not careful. Plus, there are so many twists and turns that keep you on the edge of your seat!If you like exciting stories with a deeper meaning, then you should definitely check out "1984". It's a classic book that will make you think and feel all sorts of emotions. So grab a copy and join Winston on his epic journey against Big Brother!篇2Hey guys, today I'm gonna tell you about this super cool book called "1984" by George Orwell. It's like a story set in the future, but it was actually written a long time ago. The book talks about this guy named Winston who lives in a world where the government controls everything. They even control what people think and feel!So, Winston doesn't really like the government and he starts thinking about rebelling against them. He meets this girl named Julia, and they fall in love and try to rebel together. But things get super intense and they have to be really careful not to get caught by the government.There's this guy called Big Brother who is like the leader of the government, and everyone has to worship him. It's kinda creepy, but it makes the story really interesting. Winston and Julia try to fight against Big Brother and the government, but they face a lot of challenges along the way.I won't spoil the ending for you guys, but let me tell you, it'sa real rollercoaster of emotions. The book makes you think about freedom, power, and the importance of thinking for yourself. It's a real eye-opener, even though it was written so long ago.Overall, "1984" is a must-read for anyone who loves a good dystopian story. It's full of suspense, drama, and some really deep themes. So, if you're looking for a book that will make you think and feel all kinds of emotions, give "1984" a try. You won't be disappointed!篇3Title: My Thoughts on George Orwell's 1984Hey guys, have you ever read the book 1984 by George Orwell? It's a super cool book that talks about a society where Big Brother is always watching you. I want to share with you my thoughts about this book.First of all, the main character Winston is really brave. He doesn't like the way the government controls everything and he wants to rebel against it. He even starts a secret diary to write down his thoughts, even though it's super dangerous. I think Winston is really cool for standing up for what he believes in.But oh my gosh, the Party is so scary in this book. They control everything, even what people think and feel. They even have this thing called the Thought Police that can read your mind! Can you imagine living in a world like that? It's so creepy.One thing that really surprised me in the book is how the Party uses technology to control people. They have these telescreens everywhere that watch your every move. It made me think about how much we rely on technology today and how it could be used to control us in the future. It's a little bit scary to think about.Overall, I think 1984 is a really important book to read. It makes you think about freedom, privacy, and the power of the government. It's a little bit scary, but it's also really interesting. I would definitely recommend it to all my friends.So, have you guys read 1984? What did you think about it? Let me know in the comments! Thanks for listening to my thoughts, guys. See you next time!篇4Once upon a time, there was a book called "1984" written by George Orwell. It's a super cool book that tells the story of a guy named Winston who lives in a place called Oceania. In Oceania, Big Brother is always watching and controlling everything. It's kind of scary but also really interesting.Winston works for the government and he starts to question the rules and the surveillance that Big Brother imposes on everyone. He meets a girl named Julia and they fall in love, but they have to keep their relationship a secret because love is not allowed in Oceania. They try to rebel against the government and the Party, but things get really intense and dangerous.The Party uses a lot of propaganda and manipulation to control the people in Oceania. They change history, control information, and brainwash everyone into believing in Big Brother. It's really creepy how they can control people's thoughts and feelings.Winston and Julia try to resist the Party's control, but they get caught and tortured by the Thought Police. They are forced to betray each other and give up their love and beliefs. It's so sadand heartbreaking to see them suffer because they just wanted to be free and happy.In the end, Winston becomes completely brainwashed and he accepts Big Brother's control over his mind and soul. He betrays Julia and loses everything he ever believed in. It's a really dark and depressing ending, but it makes you think about the power of the government and the importance of freedom and individuality."1984" is a super thought-provoking book that raises important questions about society, government, and human nature. It's a classic that everyone should read and think about. Just remember, Big Brother is watching you, so be careful and stay true to yourself.篇5Hi everyone, today I want to talk to you about a book called "1984" by George Orwell. It's a really cool book that talks about a world where the government controls everything and people's thoughts, feelings, and actions are all monitored.In the book, there is a guy named Winston who doesn't really like the way things are in this society. He rebels against the government by writing in a secret diary and falling in love with agirl named Julia. They try to fight against the oppressive government but end up getting caught and punished.The government in this book is super controlling and manipulative. They use things like surveillance cameras, propaganda, and mind control to keep everyone in line. It's a scary world where freedom of speech and independent thought are not allowed.I think this book is really important because it shows us how powerful governments can become if we're not careful. It's a warning about what could happen if we let our freedoms slip away. It's a reminder to always question authority and fight for our rights.So if you're into dystopian stories and like thinking about the future of society, definitely check out "1984" by George Orwell. It's a wild ride that will make you think about the world in a whole new way.篇6Once upon a time, there was a book called "1984" by George Orwell. This book is super famous and lots of people like to read it. It's all about a guy named Winston who lives in a world wherethe government controls everything, even what you think and feel.Winston doesn't like the government and he starts to rebel against them. He falls in love with a girl named Julia and they do some sneaky things to try and take down the government. But, spoiler alert, things don't end too well for them.One of the scariest parts of the book is Big Brother. He's like a super creepy dictator who watches everyone all the time. Imagine if your teacher could see everything you did, even when you were at home! That's how Big Brother is in "1984."The government in "1984" is also really good at changing history. They have this thing called the Ministry of Truth, which is actually all about lies. They rewrite history books and newspapers to make people believe whatever they want them to believe.Reading "1984" makes you think a lot about freedom and privacy. It's kind of a scary book because it feels like some of the things in it could actually happen in real life. That's why it's so popular and people still talk about it today.So, if you want to read a book that's exciting, a little bit scary, and makes you think about the world we live in, check out "1984" by George Orwell. Just remember, Big Brother is watching!篇7Title: My Thoughts on "1984" by George OrwellHey guys! Today I want to talk about this super cool book called "1984" by George Orwell. It's a classic book that was written a long time ago, but it's still really awesome and I learned a lot from reading it.So, "1984" is a dystopian novel, which means it's set in a really dark and scary future world. In this world, there is a government called the Party that controls everything and everyone. They spy on people all the time and even control what they think and feel. It's pretty crazy!The main character in the book is a guy named Winston. He doesn't like the Party and he starts to rebel against them. He meets a girl named Julia and together they try to fight back against the government. It's really exciting to read about their adventures and see how they try to break free from the Party's control.One of the scariest things about the book is the concept of Big Brother. Big Brother is like the leader of the Party, but no one really knows who he is. He's always watching everyone, and the Party uses him to scare people into obeying them. It's super creepy!I won't spoil the ending for you, but let me tell you, it's really intense and will make you think a lot. The book raises a lot of questions about power, freedom, and the importance of standing up for what you believe in. It's a really deep book that will make you think about society and politics in a whole new way.I really recommend reading "1984" if you haven't already. It'sa classic for a reason and it's definitely worth checking out. Plus, it's a great book to discuss with your friends and classmates. You'll have a lot to talk about and think about together.Well, that's all for now. I hope you guys enjoyed my little review of "1984" by George Orwell. Go pick up a copy and start reading, you won't regret it! See you next time!篇8Hello everyone! Today I want to talk about the book "1984" by George Orwell. This book is super cool and also super scary at the same time.In the book, there is this guy named Winston who lives in a world where everything is controlled by this dude called Big Brother. Big Brother is like the boss of everything and he watches everyone all the time. It's kind of like having a super strict parent who never lets you do anything fun.Winston doesn't like living in this world because he wants to be free and do things on his own. He meets this girl named Julia and they start to rebel against Big Brother together. It's like a super secret club where they do things that they're not supposed to do, like falling in love and reading banned books.But of course, Big Brother finds out and things get really intense. Winston and Julia get caught and they have to face the consequences of going against the rules. It's really sad and makes you think about how important it is to have freedom and privacy.I think this book is really cool because it shows us what could happen if we let someone control every aspect of our lives. It's a scary thought but also a reminder that we should always fight for our rights and not let anyone take them away from us.So if you like books that make you think and challenge the way you see the world, definitely check out "1984" by George Orwell. It's a classic for a reason and will make you appreciate the freedom we have today. Remember, Big Brother is watching, so stay alert!篇9Hey guys, today I wanna talk about this super cool book called "1984" by George Orwell. It's like a really old book but it's still so awesome! It's all about this guy named Winston who lives in a crazy world where the government is like always watching you.So basically, in this world, everyone has to follow these strict rules and they can't even think for themselves. It's so unfair! Winston is like tired of it and he starts questioning everything. He meets this girl named Julia and together they try to rebel against the government.But uh-oh, things start to get really intense and they have to be super sneaky. There are secret spies everywhere and they have to be careful not to get caught. It's like a big adventure full of danger and suspense.The government in "1984" is like so powerful and they control everything. They even change history to make themselves look good. It's so creepy! Winston and Julia are like fighting against this huge system and it's so inspiring.The ending of the book is like whoa, I won't spoil it for you guys but let's just say it's a real rollercoaster of emotions. "1984" really makes you think about freedom and independence. It's a classic for a reason!So yeah, if you're into dystopian worlds and thrilling adventures, you should totally check out "1984". It's a must-read for sure!篇10Title: My Thoughts on George Orwell's 1984Hey guys, have you ever heard of a book called "1984" by George Orwell? Well, I just finished reading it and I wanted to share my thoughts with you all!First of all, let me tell you, this book is super cool but also super scary. It's about this guy named Winston who lives in a world where the government controls everything. They watchyou all the time, they control what you think, and they even change history so that you can't trust anything you know.Winston starts to rebel against the government and tries to think for himself, but he gets caught and has to face some serious consequences. It's really intense and makes you think about how important freedom and privacy are.One of the scariest parts of the book is the concept of "Big Brother", which is the government's symbolic leader who is always watching everyone. It's like having a giant eye in the sky that sees everything you do. It's so creepy!But even though it's scary, I think this book is really important because it shows us how dangerous it can be if we let the government have too much power. It's a reminder to always question authority and fight for our rights.Overall, I really enjoyed reading "1984" and I think you guys should check it out too. It's a classic book that will make you think and maybe even change the way you see the world. Just remember to be careful, Big Brother might be watching!That's all for now, see you guys next time!。

乔治·奥威尔:我为什么写作

乔治·奥威尔:我为什么写作文:乔治·奥威尔我从很小的时候起——约莫五六岁光景,就知道自己长大以后会成为一个作家。

大概17岁到24岁那几年,我曾试图打消这个念头,但同时深知这样做是在抹杀自己的秉赋,或早或晚,我是一定会安下心来埋头写作的。

我家有三个孩子,我排行老二,比老大小五岁,比老三大五岁,因此我和他们之间都有点隔膜,此外八岁之前我没怎么见过父亲。

由于这样的家庭环境和其它一些原因,我那时不怎么合群,岁数再大点时更是浑身讨嫌的怪癖,使得我在整个学生时代都不受欢迎。

和任何一个孤僻的孩子一样,我终日沉浸在自己编织的故事世界中,喋喋不休地与想象中的人物对话,因而,我想,我的文学梦从一开始就夹杂着这种被冷落的屈辱感,以及不被看重的挫折感。

我知道自己有驾驭文字的才能,也能承受现实中的种种不快,我意识到这为我打开了一扇通向某个隐秘世界的大门,在那里我可以对日常生活中遭到的失败进行回击,直至反败为胜。

不过,在整个儿童时期和少年时期,我全部的严肃作品——其实毋宁说是煞有介事地写下的东西,加起来也超不过半打纸。

大约在四岁,或者五岁时,我就作出了我的第一首诗,母亲替我把它听写下来。

我现在已经完全不记得那首诗是怎么写的了,只记得写的是一只老虎,它长着“椅子一样的牙齿”,这个比喻还算不赖,不过我有些疑心,我的处女作多半是布莱克那首《虎》的学步之作[译注1]。

十一岁那年,战争爆发(1914-18战争[译注2]),我写了一首讴歌祖国的诗,在一份地方报纸上发表;两年后基钦纳[译注3]去世,我作的悼念诗再次被这家报纸刊载。

之后几年,我陆陆续续写过一些乔治王时代风格的“自然派诗歌”,大多半途而废,能坚持写完的,也莫不是拙劣蹩脚之作。

此外我还曾尝试写一部短篇小说,那是一场惨败的记录,不提也罢。

以上就是我在那些年间一本正经地写在纸上的全部成果。

然而从某种意义上讲,我在这一阶段的确也从事过一些文学活动。

其中首推毫无乐趣可言的命题作文,我可以一挥而就,不必费吹灰之力。

乔治·奥威尔的“反极权斗士”之路

校园英语 / 大视野乔治·奥威尔的“反极权斗士”之路唐山师范学院外语系/唐翠云【摘要】西班牙内战期间,奥威尔对这里呈现的社会主义社会雏形感到欣喜,但将西班牙革命失败归咎于苏联,对苏联产生了极大的愤恨。

这种愤恨在冷战中被西方意识形态所利用,“反极权斗士”称号的背后是奥威尔被刻意忽略的社会主义者的身份。

【关键词】奥威尔 西班牙内战 冷战乔治·奥威尔在二十世纪的国际影响不言而喻。

冷战背景之下,奥威尔在西方被誉为反极权斗士、预言家,在意识形态彼岸的社会主义国家,却以“反动作家”的恶名遭到封杀。

这样一冷一热截然相反的待遇不免令人疑惑:为什么自称是社会主义者的奥威尔,居然受到敌对的西方意识形态的支持与热捧,而被社会主义国家抛弃呢?他的“反极权斗士”之路是如何成行的呢?一、社会主义理想的西班牙雏形1936年西班牙内战爆发。

苏联共产国际组织全球50多个国家的志愿者,编成著名的国际纵队前往西班牙抗击法西斯。

奥威尔在英国左翼反法西斯宣传的感召下,成为国际纵队志愿者的一员。

西班牙内战的经历对奥威尔来说是至关重要的转折点。

内战一方是由西班牙共产党、社会党和劳动者总同盟等组织的人民阵线左翼共和军政府,另一方则是法西斯分子佛朗哥的国民军。

奥威尔凭借英国独立工党的介绍信,到巴塞罗那后偶然加入了左翼共和军政府中的马克思主义统一工人党的民兵组织。

奥威尔本人一生对党派毫无兴趣,党派意识非常淡薄。

他曾说,“如果你问我为什么要参加民兵,我的回答是:‘反抗法西斯主义’;如果你问我为什么而战,我的回答是:‘为了人类共同的尊严’”。

在巴塞罗那,奥威尔惊喜地发现,巴塞罗那就是他心目中的社会主义社会的雏形。

当时,反法西斯分子佛朗哥的主要力量是处于统治地位的工人阶级,他们武装起来,建立起苏维埃政权的雏形,施行土地公有化,经济上实现了人人平等。

这里看不到极端贫困的人,没有失业者,没有流浪汉,没有乞丐,富人也都脱下华服,小心翼翼地混入民众,仿佛一夜之间消失了。

Why I write-George Orwell

George OrwellWhy I Write1.From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up I should be a writer. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.2.I was the middle child of three, but there was a gap of five years on either side, and I barely saw my father before I was eight. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays. I had the lonely child's habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life. Nevertheless the volume of serious — i.e. seriously intended — writing which I produced all through my childhood and boyhood would not amount to half a dozen pages.I wrote my first poem at the age of four or five, my mother taking it down to dictation. I cannot remember anything about it except that it was about a tiger and the tiger had ‘chair-like teeth’ — a good enough phrase, but I fancy the poem was a plagiarism of Blake's ‘Tiger, Tiger’. At eleven, when the war or 1914-18 broke out, I wrote a patriotic poem which was printed in the local newspaper, as was another, two years later, on the death of Kitchener. From time to time, when I was a bit older, I wrote bad and usually unfinished ‘nature poems’ in the Georgian style. I also attempted a short story which was a ghastly failure. That was the total of the would-be serious work that I actually set down on paper during all those years.3.However, throughout this time I did in a sense engage in literary activities. To begin with there was the made-to-order stuff which I produced quickly, easily and without much pleasure to myself. Apart from school work, I wrote vers d'occasion, semi-comic poems which I could turn out at what now seems to me astonishing speed — at fourteen I wrote a whole rhyming play, in imitation of Aristophanes, in about a week — and helped to edit a school magazines, both printed and in manuscript. These magazines were the most pitiful burlesque stuff that you could imagine, and I took far less trouble with them than I now would with the cheapest journalism. But side by side with all this, for fifteen years or more, I was carrying out a literary exercise of a quite different kind: this was the making up of a continuous ‘story’ about myself, a sort of diary existing only in the mind. I believe this is a common habit of children and adolescents. As a very small child I used to imagine that I was, say, Robin Hood, and picture myself as the hero of thrilling adventures, but quite soon my ‘story’ ceased to be na rcissistic in a crude way and became more and more a mere description of what I was doing and the things I saw. For minutes at a time this kind of thing would be running through my head: ‘He pushed the door open and entered the room. A yellow beam of sunlight, filtering through the muslin curtains, slanted on to the table, where a match-box, half-open, lay beside the inkpot. With his right hand in his pocket he moved across to the window. Down in the street a tortoiseshell cat was chasing a dead leaf’, etc. etc. This habit continued until I was about twenty-five, right through my non-literary years. Although I had to search, and did search, for the right words, I seemed to be making this descriptive effort almost against my will, under a kind of compulsion f rom outside. The ‘story’ must, I suppose, have reflected the styles ofthe various writers I admired at different ages, but so far as I remember it always had the same meticulous descriptive quality.4.When I was about sixteen I suddenly discovered the joy of mere words, i.e. the sounds and associations of words. The lines from Paradise Lost —So hee with difficulty and labour hardMoved on: with difficulty and labour hee.which do not now seem to me so very wonderful, sent shivers down my backbone; and the spelling ‘hee’ for ‘he’ was an added pleasure. As for the need to describe things, I knew all about it already. So it is clear what kind of books I wanted to write, in so far as I could be said to want to write books at that time. I wanted to write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their own sound. And in fact my first completed novel, Burmese Days, which I wrote when I was thirty but projected much earlier, is rather that kind of book.I give all this background information because I do not think one can assess a writer's motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject matter will be determined by the age he lives in — at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own — but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, in some perverse mood; but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write. Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen —in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all —and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.(iv) Political purpose. —Using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain dire ction, to alter other peoples’ idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time. By nature —taking your ‘nature’ to be the state you have attained when you are first adult — I am a person in whom the first three motives would outweigh the fourth. In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer. First I spent five years in an unsuitable profession (the Indian Imperial Police, in Burma), and then I underwent poverty and the sense of failure. This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism: but these experiences were not enough to give me an accurate political orientation. Then came Hitler, the Spanish Civil War, etc. By the end of 1935 I had still failed to reach a firm decision. I remember a little poem that I wrote at that date, expressing my dilemma: A happy vicar I might have beenTwo hundred years agoTo preach upon eternal doomAnd watch my walnuts grow;But born, alas, in an evil time,I missed that pleasant haven,For the hair has grown on my upper lipAnd the clergy are all clean-shaven.And later still the times were good,We were so easy to please,We rocked our troubled thoughts to sleepOn the bosoms of the trees.All ignorant we dared to ownThe joys we now dissemble;The greenfinch on the apple boughCould make my enemies tremble.But girl's bellies and apricots,Roach in a shaded stream,Horses, ducks in flight at dawn,All these are a dream.It is forbidden to dream again;We maim our joys or hide them:Horses are made of chromium steelAnd little fat men shall ride them.I am the worm who never turned,The eunuch without a harem;Between the priest and the commissarI walk like Eugene Aram;And the commissar is telling my fortuneWhile the radio plays,But the priest has promised an Austin Seven,For Duggie always pays.I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls,And woke to find it true;I wasn't born for an age like this;Was Smith? Was Jones? Were you?The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. Everyone writes of them in one guise or another. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows. And the more one is conscious of one's political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one's aesthetic and intellectual integrity.What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art’. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article, if it were not also an aesthetic experience. Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.It is not easy. It raises problems of construction and of language, and it raises in a new way the problem of truthfulness. Let me give just one example of the cruder kind of difficulty that arises. My book about the Spanish civil war, Homage to Catalonia, is of course a frankly political book, but in the main it is written with a certain detachment and regard for form. I did try very hard in it to tell the whole truth without violating my literary instincts. But among other things it contains a long chapter, full of newspaper quotations and the like, defending the Trotskyists who were accused of plotting with Franco. Clearly such a chapter, which after a year or two would lose its interest for any ordinary reader, must ruin the book. A critic whom I respect read me a lecture about it. ‘Why did you put in all that stuff?’ he said. ‘You've turned what might have been a good book into journalism.’ What he said was true, but I could not have done otherwise. I happened to know, what very few people in England had been allowed to know, that innocent men were being falsely accused. If I had not been angry about that I should never have written the book.In one form or another this problem comes up again. The problem of language is subtler and would take too long to discuss. I will only say that of late years I have tried to write lesspicturesquely and more exactly. In any case I find that by the time you have perfected any style of writing, you have always outgrown it. Animal Farm was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole. I have not written a novel for seven years, but I hope to write another fairly soon. It is bound to be a failure, every book is a failure, but I do know with some clarity what kind of book I want to write. Looking back through the last page or two, I see that I have made it appear as though my motives in writing were wholly public-spirited. I don't want to leave that as the final impression. All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand. For all one knows that demon is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one's own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.1946THE END。

奥威尔英文介绍ppt课件

Down and Out in Paris and London (1933)

A memory of the author's experiences as a trap and a dismissed teacher in Paris and London

Animal Farm (1945)

A political stability about the Russian Revolution and the risk of communication

Nineteen Eighty Four (1949)

A dystopian novel about a future society controlled by a totalitarian regime

Orwell's works often reflect his concerns about the impact of technology on society He worries about the loss of human values in a technical age and the potential for technology to be used for aggressive purposes

Orwell's exploration of these themes also allowed him to critique social justice and political corruption, calling for greater individual responsibility and social change

Orwell English Introduction PPT Courseware

乔治奥威尔:我为什么要写作

乔治奥威尔:我为什么要写作大约在我很小也许是五六岁的时候,我就知道了我在长大以后要当一个作家。

在大约十七到二十四岁之间,我曾经想放弃这个念头,但是我心里很明白:我这么做有违我的天性,或迟或早,我会安下心来写作的。

在三个孩子里我居中,与两边的年龄差距都是五岁,我在八岁之前很少见到我的父亲。

由于这个以及其他原因,我的性格有些不太合群,我很快就养成了一些不讨人喜欢的习惯和举止,这使我在整个学生时代都不太受人欢迎。

我有性格古怪的孩子的那种倾心于编织故事和同想象中的人物对话的习惯,我想从一开始起我的文学抱负就同无人搭理和不受重视的感觉交织在一起。

我知道我有话语的才能和应付不愉快事件的能力,我觉得这为我创造了一种独特的隐私天地,我在日常生活中遭到的挫折都可以在这里得到补偿。

不过,我在整个童年和少年时代所写的全部认真的或曰真正象一回事的作品,加起来不会超过五六页。

我在四岁或者五岁时,写了第一首诗,我母亲把它录了下来。

我已几乎全忘了,除了它说的是关于一只老虎,那只老虎有“椅子一般的牙齿”,不过我想这首不太合格的诗是抄袭布莱克的《老虎,老虎》的。

十一岁的时候,爆发了1914—1918年的战争,我写了一首爱国诗,发表在当地报纸上,两年后又有一首悼念克钦纳伯爵逝世的诗,也刊登在当地报纸上。

长大一些以后,我不时写些蹩脚的而且常常是写了一半的乔治时代风格的“自然诗”。

我也曾尝试写短篇小说,但两次都以失败告终,几乎不值一提。

这就是我在那些理想年代里实际上用笔写下来的全部的作品。

但是,从某种意义上来说,在这期间,我确也参与了与文学有关的活动。

首先是那些我不花什么力气就能写出来的但是并不能为我自己带来很大乐趣的应景之作。

除了为学校唱赞歌以外,我还写些带有应付性质半开玩笑的打油诗,我能够按今天看来是惊人的速度写出来。

比如说我在十四岁的时候,曾花了大约一个星期的时间,模仿阿里斯托芬的风格写了一部押韵的完整的诗剧。

我还参加了编辑校刊的工作,这些校刊都是些可笑到可怜程度的东西,有铅印稿,也有手稿。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

2019/7/20

1931 A Hanging 《行刑》 1933 Down and Out in Paris and London

《巴黎伦敦落魄记》 1934 Burmese Days 《在缅甸的日子》 1935 A Clergyman’s Daughter 《牧师的女儿》 1936 Keep the Aspidistra Flying 《让叶兰在风中飞舞》 1938 Homage to Catalonia 《向加泰罗尼亚致敬》 1938 Marrakech 《马拉喀什》 1939 Coming up for Air 《上来透口气》 1940 Inside the Whale 《鲸鱼之中》

BBC

In August 1941 Orwell began to work for the Eastern Service of the BBC at the beginning of the WWII .

2019/7/20

Frameworks

Major Works

2019/7/20

A List of his works

Civil Service.(印度总督府鸦片局) • his mother---French parentage, daughter of a timber

merchant in Burma(缅甸)

2019/7/20

Childhood

•In 1914, 11-year-old Orwell published a poem Wake up, the boys in the local newspaper for the first time •He studied in the most famous school Eton College(1917) •morose,unsociable and disobedient

• 1941 The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius 《狮子与独角兽》 • 1945 Animal Farm 《动物庄园》 • 1945 Notes on Nationalism 《民族主义的基本特

2019/7/20

Spain

When the Spanish Civil War broke out, he went to Spain and joined the Republican militia in fighting against the Fascist forces of Franco. The experience in Spain was described by him in Homage to Catalonia(1938)

2019/7/20

Parentage Career Major works Evaluations

Parentage

• born in West Bengal(西孟加拉邦), India • his father---worked in the Opium Department of the Indian

Burma

France

2019/7/20

CONTENTS

career

England

BBC Spain

• Burma (1922~1927)

Orwell joined the Indian Imperial Police for five years and eventually resigned the post in 1927. His experience in Burma, which made him recognize the evil side of colonialism and thus left the colonial police force.

• In 1933, his first novel Down and Out in Paris and London was published under the pennames of George Orwell. It described his experiences as a struggling writer.

2019/7/20

Why I Write

张雅君 张姚海岛

Why I Writee article

Literature works

Comments

Writer

outline

Orwell's press card portrait, taken in 1933

• France(1928~1929)

He began his wandering life and lived in Paris. During this time, he used to wash the dishes in a luxury hotel.

2019/7/20

•England