各国破案率

洗冤集录,《洗冤录》,洗冤录

洗冤集录,《洗冤录》,洗冤录《洗冤集录》拼音:xǐyuān jílù (xiyuan jilu)同义词条:洗冤集录,《洗冤录》,洗冤录目录[ 显示 ]宋提刑洗冤集录五卷(元刻本)《洗冤集录》是中国古代法医学著作。

南宋宋慈著,刊于宋淳祐七年(1247),由其从事司法刑狱工作所积累之丰富验尸经验为基础,并结合当时传世的尸伤检验诸书,加以综合、核定和提炼,是世界上现存第一部系统的法医学专著。

《洗冤集录》是中国古代一部比较系统地总结尸体检查经验的法医学名著。

它自南宋以来,成为历代官府尸伤检验的蓝本,曾定为宋、元、明、清各代刑事检验的准则。

在中国古代司法实践中,起过重大作用。

本书曾被译成多种外国文字,深受世界各国重视,在世界法医学史上占有十分重要的地位。

该书的最早版本,当属宋淳祐丁未宋慈于湖南宪治的自刻本,继又奉旨颁行天下,但均已不传。

现存最早的版本是元刻本《宋提刑洗冤集录》;兰陵孙星衍元椠重刊本或称《岱南阁丛书》本;此外又有从《永乐大典》中辑出的2卷本;清代多种刻本与元刻本完全相同。

还有1937年商务印书馆的《丛书集成(初编)》本。

现较通行的有:法律出版社1958年的《洗冤集录点校本》;群众出版社 1980 年出版杨奉琨校译本《洗冤录校译》;上海科学技术出版社1981年出版贾静涛点校本。

编辑本段作品概述《洗冤集录》中的绘图《洗冤集录》成书于淳祐七年(1247年),有五卷,53条,有检验总论、验尸、验骨、验伤、中毒、救死方六大题材。

以目录来看,本书的主要项目包括:宋代的检验尸伤法令;验尸方法和注意事项;尸体现象;各种机械性窒息死;各式钝器损伤;锐器损伤;交通事故损伤;高温致死;中毒;病死和急死;尸体发掘等项。

主要的涵盖验尸的检验方法、死因的判断,例如对于被火烧死与死后焚尸的差别、生前溺死与死后弃尸入水,都有精辟的见解。

《洗冤集录》中所称呼的“血坠”也就是现代法医学中的“尸斑”。

《洗冤集录》是宋慈集前人验尸经验大成之著作。

世界各国警察死亡率排行

世界各国警察死亡率排行第十名:阿富汗-人均gdp美元阿富汗也许是唯一一个不用介绍的世界穷国。

这要感谢9·11撞击事件和随后美国对其进行的制裁,这让全世界都知道了这个南亚的内陆国。

他们也许是世界上最穷的人,但是他们很懂得怎么去打仗。

他们常用小股的游击队而非正规军将敌人拖得无可奈何。

大概超过70%的阿富汗人每天的消费不超过2美元。

为了赚钱很多人在做着非法的交易。

阿富汗是世界上最大的海洛因输出国。

毒品问题是这个国家的不能承受之重,一项对阿富汗警方的调查表明大概这个国家17%的警察最近都吸过毒。

甚至更糟-仅有30%的警察识字!难怪阿富汗是世界上最穷的国家之一。

第九名:中非共和国-人均gdp美元这个非独立命名的国名告诉我们这是一个位于中非的原法国殖民地。

作为世界上最穷的国家中的一员,意味着这个国家政府的管理能力是相当弱的。

这个国家的福利完全依赖于外国的支援以及其他的非利益性组织的帮助。

这些友善的救援者的支援是这个国家收入的主要来源。

大概40%的进口收入来源于该国钻石的输出。

和本文中将要提到的其它贫困的非洲国家一样,中非共和国基本靠自己来满足粮食需求,但是还是有很多人要忍受营养不良和饥荒的折磨。

这是因为,那些富有的农场主往往会选择将自己的粮食卖给国外来换取金钱,他们不愿意低价将粮食卖给本国的国民。

年反政府武装因为对此不满而开始袭击政府,这导致了5万人的死亡或者挨饿。

第八位:塞拉利昂-人均年gdp美元塞拉利昂是西非的一个贫穷的国家,官方语言是英语。

在经历了数年之后当地人从英语中衍生出了自己的语言,他们称该语言为krio。

这种语言使用英语的词汇但是语法来自于12个不同的非洲语言。

作为世界上最穷的国家之一,塞拉利昂也是世界上最大的钻石出口国之一。

如果你看过电影《血钻》你一定知道这个电影的背景便是塞拉利昂。

到这10年间有人死于内战,活下来的人生活变得更加穷困。

至少有人逃到了他们的邻国几内亚和利比亚。

环境应急资源调查报告精选全文

可编辑修改精选全文完整版1.调查概要1.1环境应急资源调查背景近年来,为了预防和减少突发环境事件的发生,控制、减轻和消除突发环境事件引起的严重社会危害,规范突发事件应对活动,保护人民生命财产安全,维护国家安全、公共安全、环境安全和社会秩序,国家颁布了《中华人民共和国突发事件应对法》,发布了《国家突发环境事件应急预案》,原国家环保总局组织编写了《环境应急响应实用手册》,生态环境部编制了《环境应急资源调查指南(试行)》。

在任何工业活动中都有可能发生事故,尤其是随着现代化工业的发展,生产过程中存在的巨大能量和有害物质,一旦发生重大事故,往往造成惨重的生命、财产损失和环境破坏。

由于自然或人为、技术等原因,当事故或灾害不可能完全避免的时候,建立重大事故环境应急救援体系,组织及时有效的应急救援行动,已成为抵御事故风险或控制灾害蔓延、降低危害后果的关键手段之一。

为确保我公司发生突发环境事件后,能最大限度利用各种应急资源,迅速、有序有效地开展应急处置行动,阻止和控制污染物向周边环境的无序排放,尽最大可能避免对公共环境(大气、水体、土壤等)造成污染冲击。

本公司开展环境应急资源调查,收集和掌握本公司第一时间可以调用的环境应急资源状况,建立健全环境应急资源信息库,加强环境应急资源储备管理,促进环境应急预案质量和环境应急能力提升。

1.2调查原则环境应急资源调查应遵循客观、专业、可靠的原则。

“客观”是指针对已经储备的资源和已经掌握的资源信息进行调查。

“专业”是指重点针对环境应急时的专用资源进行调查。

“可靠”是指调查过程科学、调查结论可信、资源调集可保障。

1.3调查主体和调查对象环境应急资源调查主体为XXXX公司,调查对象为本公司发生或可能发生突发环境事件时,第一时间可以调用的环境应急资源情况,包括可以直接使用或可以协调使用的环境应急资源,并对环境应急资源的管理、维护、获得方式与保存时限等进行调查。

1.4调查信息的基准时间和调查工作的起止时间公司调查信息的基准时间为2021年1月1日。

绕不开中国刑法的阿克毛

绕不开中国刑法的阿克毛作者:杨静来源:《中国检察官·经典案例版》2010年第02期编者按:随着经济全球化的发展,世界各国在政治、经济和社会文化交往上日趋频繁。

各种犯罪活动也逐渐表现出一种有组织的国际化态势。

为此,以联合国为代表的政府组织和一些非政府组织,提出了很多具有开创意义的积极建议并付诸卓有成效的实践。

各国政府也逐步通过缔结国际公约、参加国际组织等方式,强化国际刑事司法合作,共同打击刑事犯罪,维护国家安全与稳定。

1997年,联合国专门设立了联合国毒品和犯罪问题办公室(UNDOC,United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime),旨在加强各国在反腐败、毒品犯罪、艾滋病、人口买卖、非法移民、刑事司法、监狱制度改革、犯罪预防、洗钱、有组织犯罪、隐私保护和反恐等领域的合作。

从本期开始,《中国检察官》“域外案牍”栏目将立足于中国检察的实际案例,从涉外刑事案件审判、国际刑事司法协助等方面,重点探讨和分析对我国检察制度发展具有重要意义的国际刑事法律制度。

2009年12月29日,拥有英国国籍的什肯·阿克毛(Akmal Shaikh,以下简称“阿克毛”)在经过最高人民法院死刑复核程序后,在新疆乌鲁木齐市被注射执行死刑。

从而,阿克毛成为新中国成立后第一个在中国境内被处以死刑的英国人。

【浪子的漫漫不归路】2007年9月12日凌晨,一架从塔吉克斯坦共和国杜尚别市出发的国际航班抵达中国新疆乌鲁木齐国际机场。

一名神色慌张的外国乘客在机场不住的游移徘徊,这引起了海关人员的特别关注,而这名外国乘客就是具有英国国籍的阿克毛。

在接下来的例行检查中,海关工作人员发现阿克毛随身只带了100美元和100元人民币,行李箱中只有几件衣服。

但在他随身携带的行李箱的夹层里,工作人员发现了4包海洛因,每包1000多克。

后来通过检验人员的鉴定,海洛因的纯度为84.2%,共4030克,价值约25万英镑。

辛普森涉嫌杀人案

辛普森涉嫌杀人案程序公正与世纪审判——the people of the state of California v. O. J. Simpson(1995)橄榄球超级明星Orenthal James Simpson涉嫌杀人案,震惊全美,堪称20世纪美国社会中最具争议的世纪大案之一。

不少人认为,Simpson腰缠万贯,不惜花费重金,聘请了号称天下无敌的“dream team”(梦幻律师队)为自己开脱罪名。

这帮律师唯利是图,凭着三寸不烂之舌,利用美国社会中的种族矛盾以及刑事诉讼程序中的漏洞,把“血证如山”的检察官和警方证人驳得目瞪口呆,最后说服了陪审员全体成员,把杀人凶手无罪开释。

这场为全球媒体瞩目一时的“trial of the century”(世纪审判),无疑是对美国司法制度的极大讽刺和嘲弄。

然而,事过多年之后,根据已公布的Simpson案档案和涉案当事人的回忆,人们惊奇地发现,Los Angeles警方在调查案情过程中,未能严格遵循正当程序,出现了一系列严重失误。

致使Simpson的律师团能够以比较充足的证据向陪审团证明,Simpson未必就是杀人元凶,很有可能有人伪造罪证,用栽赃手法嫁祸Simpson。

(一)有钱未必能使鬼推磨谈起Simpson一案,无论黑人白人都承认,假如Simpson是个雇不起一流律师的穷光蛋,那他非进大狱不可。

这就叫“有钱能使鬼推磨”,古今中外都是一个理儿。

可是,如果细琢磨一下,这个理儿好像又有点儿说不通。

原因在于,若是论有钱,大名鼎鼎的拳王Mike Tyson 比淡出体坛多年的Simpson有钱得多。

可是,1997年Tyson因涉嫌强奸遭到起诉后,尽管他同样花费天文价格,聘请了一帮名律师出庭辩护,但仍然无法摆脱被定罪的命运,在大狱里结结实实地蹲了好几年。

那么,何以Tyson落入正义之网,而Simpson却能逍遥法外呢?有一种解释是,Tyson案陪审团以白人为主,而Simpson案陪审团成员多为黑人。

世界上犯罪率最高的国家或地区是哪里

?(2012-03-18)谁能想到富足安定的瑞士10个人里面有1.3个人就是罪犯呢?饱暖生淫欲,这句中国古话看来很是实用啊!刑事犯罪率最高的10个国家:(1)xx13679xx的约38倍(2)xx12053约33倍(3)xx11598约32倍(4)xx10345约28倍(5)xx9834约27倍(6)xx8621约24倍(7)xx8397约23倍(8)xx7627约21倍(9)xx7419约20倍(10)xx7235约20倍中国363(十万人口犯罪363件,以上也是)在瑞士这样一个安定富足的国家,每小时会发生72起犯罪,听起来让人震惊,然而这却是一个铁的事实,2011年3月下旬,瑞士联邦统计局公布了2010年的警方提供的犯罪统计数字。

生活在xx的外国人也可以长舒一口气:调查结果显示,他们并不是人们想像中的那样是造成瑞士高犯罪率的“罪魁”。

2010年瑞士警方共经手了656858起各类犯罪案件。

尽管这个数字触目惊心,但这份统计结果对于瑞士人来说却是一个好消息:xx去年的犯罪率从整体上有所减少。

青少年的犯罪率也有了明显的减少,但是谋杀案件有所增加,盗窃案则在一定程度上有所下降。

谋杀案有所增加2010年在瑞士发生的触犯法律案件比2009年减少了2%,青少年犯罪率更是降低了8%。

在所有发生的案件中,240件为谋杀案,其中189件企图谋杀,比2009年增加2%。

将近半数的谋杀案的作案武器为利器,只有17%动用了枪支。

谋杀案件属于“严重的暴力案件”,而该类案件2010年下降了12%。

强奸和伤害他人案件也有所减少,分别发生了543起和487起。

针对儿童的性侵案件也在明显减少,但依然发生了1133起,其中50%发生在家中,该类案件被侦破。

侵害财产案有所减少在去年所有发生的案件中,72%为侵害财产案件,其中包括盗窃案。

2010年瑞士共发生了62000起入室盗窃案,比前一年减少了3%。

偷窃案共发生183386起,比2009年减少4%。

计算机病毒发展的现状

计算机病毒发展的现状随着电脑不断地影响我们的生活,电脑病毒也随着各种网络,磁盘等等日新月异的方式企图入侵我们的家用电脑、公司电脑,严重影响了我们使用计算机与网络。

下面是店铺收集整理的计算机病毒发展的现状,希望对大家有帮助~~计算机病毒发展的现状计算机病毒(Computer Virus)是指编制或在计算机程序中插入破坏计算机功能或毁坏数据,影响计算机使用并能自我复制的一种指令或程序代码。

它具有可隐藏性、可传播性、可潜伏性、可激发性和巨大危害性等特征。

特别是在网络环境下,计算机病毒更易于传播,其危害性更大。

因而,本文试图从这一角度出发探讨在网络环境下制作、传播计算机病毒犯罪的现状、成因及因此应采取的立法对策。

一、网络环境下制作、传播计算机病毒犯罪的现状计算机病毒最早产生于美国电报电话公司的贝尔实验室,目前全世界已发现的计算机病毒已达上万种之多。

我国自1989年发现病毒,迄今已发现的病毒数以千计,其中也有许多“国产”病毒。

随着计算机网络技术的发展,网络在提供信息共享与便捷的同时,也为计算机病毒的传播提供了良好的环境,因而其破坏性更为巨大。

在当今网络环境下计算机病毒的犯罪趋势主要表现为:1.计算机病毒犯罪在网络环境下带来的经济损失呈上升趋势。

计算机病毒产生之初,人们对其危害性往往认识不清,自1988年下半年莫里斯(Morris)制作的“因特网蠕虫”病毒致使美国军方计算机网络全面瘫痪,其经济损失达六千万美元后,人们才开始关注它。

随着网络的民用化,网络取得了突飞猛进的发展,给人们带来信息的便利,展示了21世纪信息社会的巨大魅力。

但计算机病毒似乎与网络“形影相连”,给人们巨大的警示:网络不是净土。

1999年“曼里沙”(Melissa)病毒借助英特网通过电子邮件而造成全世界大批网络瘫痪。

同年4月26日爆发的“CIH”病毒对全球六千多万台计算机造成严重损害,仅我国的经济损失便超过亿元人民币。

2000年5月4日“爱虫”病毒再次泛滥全球,其经济损失高达百亿美元。

FBI

美国联邦调查局,英文全称Federal Bureau of Investigation,英文缩写FBI。

但―F BI‖也不仅是局称的缩写,还代表着联邦调查局坚持贯彻的信条——忠诚Fidelity,勇敢Bravery和正直Integrity,是联邦警察。

[编辑本段]FBI总括美国联邦调查局是美国司法部的主要调查机构,俗称为事务所,它的职责是调查具体的犯罪。

美国联邦调查局也被授权提供其他执法机构的合作服务,如指纹识别,实验室检查,和警察培训。

根据美国法典第28条533款,授权司法部长―委任官员侦测反美国的罪行‖,另外其它联邦的法令给予FBI权力和职责调查特定的罪行。

FBI 现有的调查司法权已经超过200种联邦罪行。

十大通缉犯清单从1930年起就已经公布于众了。

FBI的任务是调查违反联邦犯罪法,支持法律。

保护美国调查来自于外国的情报和恐怖活动,在领导阶层和法律执行方面对联邦,州,当地和国际机构提供帮助,同时在响应公众需要和忠实于美国宪法前提下履行职责。

对内,全权负责维护国家安全和防范有组织的恐怖主义活动;对外,积极协助美国国防部军事情报局(M.I.A., Milit ary Intelligence Agency, U.S. Department of Defense) 及美国中央情报局(C.I. A., Central Intelligence Agency),防范并打击一切可能危害到美国国家安全的情报和军事活动。

FBI的官方使命是:通过调查违反联邦刑法的行为来维护法律,保护美国免受外国间谍和恐怖分子活动的威胁,为联邦、州、地方或国际机构提供领导和执法帮助,并且能按照公众的需要且在遵守美国宪法的前提下履行上述职责。

在FBI每次调查的情报资料后,递交适当的美国律师或者美国司法部官员,由他们决定是否批准起诉或其它行动。

其中五大影响社会的方面享有最高优先权:反暴行,毒品/有组织犯罪,外国反间谍活动,暴力犯罪,和白领阶层犯罪。

GTD全球恐怖主义数据库中文译本

关于社会治安综合治理工作的论文

做好社会治安工作,是维护我国社会稳定、保障改革开放深入进行的重要之举。

下面是为大家整理的关于社会治安的论文,供大家参考。

社会治安的论文篇一:《浅谈社会治安制度的完善策略》摘要:社会治安是维护国家长治久安,保障人民安居乐业的重要一环,十八届四中全会强调了社会治安的重要性,提出完善立体化社会治安的要求,对各项具体内容都做出了明确指示,因此,本文从各项具体要求出发,阐述笔者所认为的浅薄观念。

关键词:立体化;依法办事;严格执法十八届四中全会决定中对社会治安提出了新的要求,要求完善立体化社会治安防控体系,有效防范化解影响社会安定的问题,保障人民生命财产安全。

依法严厉打击暴力恐怖、涉黑犯罪、邪教和黄赌毒等违法犯罪活动,绝不允许其形成气候。

依法强化危害食品药品安全、影响安全生产、损害生态环境、破坏网络安全等重点问题治理。

从这些要求中,我们可以提炼出以下几点。

一、完善立体化社会治安防控体系什么是立体化社会治安防控体系,这对于现代管理模式是十分常见的描述,立体化,意味着要多层次,全方位。

那么如何使社会治安防控体系立体化,将是这一点要求的立足之本。

一多层次社会治安是需要多个部门来协调配合达成的,比如110接警中心与交警,派出所之间的指挥关系。

然而,想要立体化的社会治安防控体系,就必须确立有多少层次来构成该立体化的体系。

第一,基层。

基层是面对治安问题等突发状况的维护者,因此,保证基层人员充足,素质过硬是必不可少的要求。

在招收基层执行人员时,标准要相对于其他岗位做一点改变,对于专业知识需要过硬,而对于法律就更需要精通了。

基层人员处理治安问题时必须依照法律规定,这是最基本的要求。

在此基础之上,基层工作人员还需根据不同的情形,来采取不同的方式以达到解决问题,维持社会安定的治安目的。

基层的组织机构必须时时刻刻保持思想的先进性,跟上社会的步伐。

基层的工作人员还需保持通讯畅通,因为基层治安组织属于第一线的组织,必须在第一时间到达现场,保证人民群众生命财产安全。

OMEN Command Center 用户指南说明书

用户指南©Copyright 2019 HP Development Company, L.P.本文档中包含的信息如有更改,恕不另行通知。

随 HP 产品和服务附带的明确有限保修声明中阐明了此类产品和服务的全部保修服务。

本文档中的任何内容均不应理解为构成任何额外保证。

HP 对本文档中出现的技术错误、编辑错误或遗漏之处不承担责任。

第一版:2019 年 7 月文档部件号:L49473-AA1目录1 使用入门 (1)下载软件 (1)打开软件 (1)2 使用软件 (2)耳机菜单 (2)OMEN 音频实验室 (2)音频设置 (2)修改均衡器预设 (3)创建用户均衡器预设 (3)灯光 (3)静态模式 (4)动画模式 (4)散热 (4)设置 (4)3 辅助功能 (5)辅助功能 (5)查找所需技术工具 (5)HP 承诺 (5)国际无障碍专业人员协会(International Association of Accessibility Professionals,IAAP) (5)查找最佳的辅助技术 (6)评估您的需求 (6)HP 产品的辅助功能 (6)标准和法规 (7)标准 (7)指令 376 – EN 301 549 (7)Web 内容无障碍指南 (WCAG) (7)法规和规定 (7)美国 (7)《21 世纪通信和视频无障碍法案》(CVAA) (8)加拿大 (8)欧洲 (8)英国 (8)iii澳大利亚 (9)全球 (9)相关无障碍资源和链接 (9)组织 (9)教育机构 (9)其他残障资源 (10)HP 链接 (10)联系支持部门 (10)iv1使用入门下载软件注:该软件可能预安装在部分计算机上。

该软件需要 Windows®10 操作系统(64 位),1709 或更高版本。

1.在您的计算机上,选择开始按钮,然后选择 Microsoft Store。

2.搜索 OMEN Command Center,然后下载应用程序。

犯罪术语(中英对照)

例句:

Businesses are losing millions of dollars, and products are more expensive due to white-collar crime.

由于白领犯罪,企业界每年损失数百万美元,产品也因之更贵

擅于从别人口袋里偷取物品的窃贼。

例句:

I had my wallet stolen by a pickpocket while I was on the subway.

被用来从一地到另一地运送毒品或违禁品的人。

例句:

Security officials in airports are finding an astounding number of people who are being used as mules.

机场的安检人员发现数目十分庞大的旅客充当贩运私货的人。

发生在洛杉矶的不光彩的罗德尼?金毒打案向公众展示了警察暴行是多少猖狂。

police corruption警察腐败

The misuse of police power in return for favors of gain.

警察滥用权力以换取好处和利益。

例句:

The mayor is working to put an end to police corruption in this city.

院外集团的说客用贿金拉拢政府官员。

statutory rape法定强奸罪

Sexual intercourse with a female who has consented, but who is legally incapable of consent because she is underage.

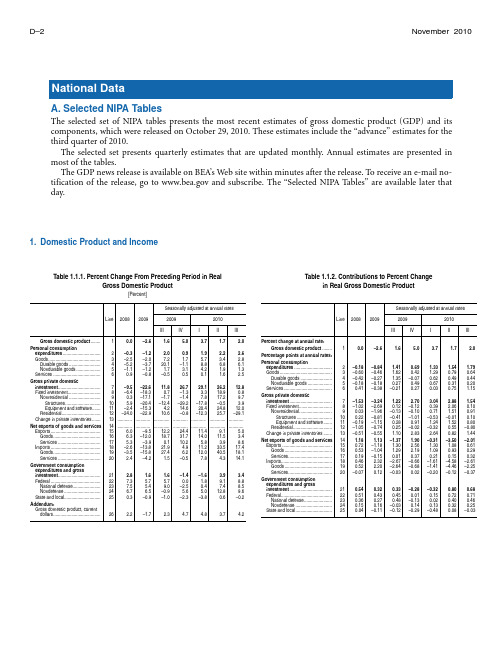

美国近年宏观经济数据

D–2 November 2010National DataA. Selected NIPA Tables The selected set of NIPA tables presents the most recent estimates of gross domestic product (GDP) and i tscomponents, which were released on October 29, 2010. These estimates include the “advance” estimates for the third quarter of 2010.The selected set presents quarterly esti mates that are updated monthly. Annual esti mates are presented i n most of the tables.The GDP news release is available on BEA’s Web site within minutes after the release. To receive an e-mail notification of the release, go to and subscribe. The “Selected NIPA Tables” are available later that day.1. Domestic Product and IncomeTable 1.1.1. Percent Change From Preceding Period in Real Table 1.1.2. Contributions to Percent Change Gross Domestic Productin Real Gross Domestic Product[Percent]Line 20082009Seasonally adjusted at annual rates20092010 IIIIV I II III Gross domestic product ........ Personal consumption1 0.0 –2.6 1.6 5.0 3.7 1.7 2.0 expenditures ...............................2 –0.3 –1.2 2.0 0.9 1.9 2.2 2.6 Goods........................................... 3 –2.5 –2.0 7.2 1.7 5.7 3.4 2.8 Durable goods .......................... 4 –5.2 –3.7 20.1 –1.1 8.8 6.8 6.1 Nondurable goods ....................5 –1.1 –1.2 1.7 3.1 4.2 1.9 1.3 Services .......................................Gross private domestic60.9–0.8–0.5 0.50.11.62.5investment ................................... 7 –9.5 –22.6 11.8 26.7 29.1 26.2 12.8 Fixed investment........................... 8 –6.4 –18.3 0.7 –1.3 3.3 18.9 0.8 Nonresidential .......................... 9 0.3 –17.1 –1.7 –1.4 7.8 17.2 9.7 Structures............................. 10 5.9 –20.4 –12.4 –29.2 –17.8 –0.5 3.9 Equipment and software....... 11 –2.4 –15.3 4.2 14.6 20.4 24.8 12.0 Residential................................ 12 –24.0 –22.9 10.6 –0.8 –12.3 25.7 –29.1 Change in private inventories ....... 13 ............ ............ ............. ............ ............ ............. ............ Net exports of goods and services 14 ............ ............ ............. ............ ............ ............. ............ Exports ......................................... 15 6.0 –9.5 12.2 24.4 11.4 9.1 5.0 Goods....................................... 16 6.3 –12.0 18.7 31.7 14.0 11.5 3.4 Services ................................... 17 5.3 –3.9 0.1 10.2 5.8 3.9 8.6 Imports ......................................... 18 –2.6 –13.8 21.9 4.9 11.2 33.5 17.4 Goods....................................... 19 –3.5 –15.8 27.4 6.2 12.0 40.5 18.1 Services ................................... Government consumption expenditures and gross 20 2.4 –4.2 1.5 –0.5 7.8 4.3 14.1 investment ................................... 21 2.8 1.6 1.6 –1.4 –1.6 3.9 3.4 Federal ......................................... 22 7.3 5.7 5.7 0.0 1.8 9.1 8.8 National defense....................... 23 7.5 5.4 9.0 –2.5 0.4 7.4 8.5 Nondefense .............................. 24 6.7 6.5 –0.9 5.6 5.0 12.8 9.6 State and local.............................. Addendum:Gross domestic product, current 25 0.3 –0.9 –1.0 –2.3 –3.8 0.6 –0.2 dollars.......................................262.2–1.72.34.74.83.74.2Line 20082009Seasonally adjusted at annual rates20092010 IIIIV I II III Percent change at annual rate: Gross domestic product (1)0.0–2.61.6 5.03.71.72.0Percentage points at annual rates: Personal consumption expenditures ............................... 2 –0.18 –0.84 1.41 0.69 1.33 1.54 1.79 Goods ........................................... 3 –0.60 –0.46 1.62 0.42 1.29 0.79 0.64 Durable goods .......................... 4 –0.42 –0.27 1.35 –0.07 0.62 0.49 0.44 Nondurable goods .................... 5 –0.18 –0.18 0.27 0.49 0.67 0.31 0.20 Services........................................Gross private domestic6 0.41 –0.38 –0.21 0.27 0.03 0.75 1.15 investment ................................... 7 –1.53 –3.24 1.22 2.70 3.04 2.88 1.54 Fixed investment........................... 8 –1.02 –2.69 0.12 –0.12 0.39 2.06 0.10 Nonresidential........................... 9 0.03 –1.96 –0.13 –0.10 0.71 1.51 0.91 Structures .............................10 0.22 –0.81 –0.41 –1.01 –0.53 –0.01 0.10 Equipment and software.......11 –0.19 –1.15 0.28 0.91 1.24 1.52 0.80 Residential................................ 12 –1.05 –0.74 0.25 –0.02 –0.32 0.55 –0.80 Change in private inventories .......13 –0.51 –0.55 1.10 2.83 2.64 0.82 1.44 Net exports of goods and services14 1.18 1.13 –1.37 1.90 –0.31 –3.50 –2.01 Exports ......................................... 15 0.72 –1.18 1.30 2.56 1.30 1.08 0.61 Goods ....................................... 16 0.53 –1.04 1.29 2.19 1.09 0.93 0.29 Services.................................... 17 0.19 –0.15 0.01 0.37 0.21 0.15 0.32 Imports.......................................... 18 0.46 2.32 –2.67 –0.66 –1.61 –4.58 –2.61 Goods ....................................... 19 0.52 2.20 –2.64 –0.68 –1.41 –4.46 –2.25 Services.................................... 20 –0.07 0.12 –0.03 0.02 –0.20 –0.12 –0.37 Government consumption expenditures and gross investment ................................... 21 0.54 0.32 0.33 –0.28 –0.32 0.80 0.68 Federal.......................................... 22 0.51 0.43 0.45 0.01 0.15 0.72 0.71 National defense....................... 23 0.36 0.27 0.48 –0.13 0.02 0.40 0.46 Nondefense .............................. 24 0.15 0.16 –0.03 0.14 0.13 0.32 0.25 State and local..............................250.04–0.11–0.12–0.29–0.480.08–0.03November 2010S URVEY OF C URRENT B USINESSD–3Table 1.1.3. Real Gross Domestic Product, Quantity IndexesTable 1.1.4. Price Indexes for Gross Domestic Product[Index numbers, 2005=100][Index numbers, 2005=100]Line20082009Seasonally adjusted20092010 IIIIVIIIIIIGross domestic productPersonal consumption1 104.672 101.917 101.760 103.012 103.960 104.403 104.924 expenditures ....................... 2 105.057 103.797 103.885 104.126 104.608 105.178 105.846 Goods................................... 3 103.462 101.416 102.092 102.533 103.952 104.837 105.565 Durable goods .................. 4 102.798 99.011 101.159 100.870 103.025 104.735 106.304 Nondurable goods ............ 5 103.698 102.487 102.460 103.247 104.321 104.823 105.160 Services ...............................Gross private domestic6 105.870105.006104.797104.936104.952105.366106.006investment ........................... 7 90.105 69.778 68.800 73.000 77.811 82.474 84.986 Fixed investment................... 8 94.096 76.835 76.447 76.198 76.826 80.219 80.383 Nonresidential .................. 9 115.532 95.804 95.216 94.879 96.677 100.592 102.957 Structures..................... 10 131.976 105.064 103.911 95.310 90.761 90.649 91.515 Equipment and software 11 108.681 92.035 91.716 94.895 99.408 105.067 108.085 Residential........................12 57.324 44.220 44.185 44.092 42.670 45.177 41.455 Change in private inventories Net exports of goods and13 .............. .............. ............. .............. .............. ............. .............. services ............................... 14 .............. .............. ............. .............. .............. ............. .............. Exports ................................. 15 126.255 114.228 114.174 120.569 123.858 126.592 128.138 Goods............................... 16 127.649 112.377 112.474 120.484 124.495 127.939 129.014 Services ........................... 17 123.095 118.303 117.933 120.822 122.533 123.708 126.292 Imports ................................. 18 106.113 91.418 92.752 93.874 96.401 103.613 107.859 Goods............................... 19 105.189 88.615 90.324 91.691 94.321 102.690 107.056 Services ........................... 20 111.167 106.461 105.915 105.772 107.766 108.916 112.572 Government consumption expenditures and gross investment ........................... 21 105.605 107.287 107.991 107.613 107.185 108.228 109.125 Federal ................................. 22 110.900 117.266 119.085 119.091 119.634 122.276 124.891 National defense............... 23 111.653 117.648 120.237 119.477 119.582 121.732 124.229 Nondefense ...................... 24 109.326 116.467 116.687 118.283 119.738 123.410 126.271 State and local......................25102.611101.688101.770101.179100.213100.367100.310Line20082009Seasonally adjusted20092010 IIIIVIIIIIIGross domestic product Personal consumption 1 108.598 109.618 109.759 109.693 109.959 110.485 111.108 expenditures ....................... 2 109.061 109.258 109.598 110.333 110.901 110.888 111.166 Goods ................................... 3 106.262 103.634 104.403 105.120 105.784 104.812 105.064 Durable goods .................. 4 95.340 93.782 93.450 93.603 93.121 92.755 92.234 Nondurable goods ............ 5 112.484 109.262 110.624 111.651 112.949 111.638 112.325 Services................................ Gross private domestic 6 110.566 112.233 112.355 113.102 113.620 114.116114.408investment ........................... 7 106.977 104.873 103.656 103.466 102.952 102.765 102.875 Fixed investment................... 8 107.053 105.260 104.294 104.030 103.661 103.487 103.539 Nonresidential................... 9 106.984 105.700 104.768 104.144 103.639 103.636 103.730 Structures ..................... 10 125.460 122.187 119.654 119.017 119.291 119.887 120.665 Equipment and software 11 100.083 99.620 99.344 98.721 97.954 97.764 97.651 Residential ........................ 12 106.361 102.736 101.637 102.712 102.869 102.030 101.907 Change in private inventories Net exports of goods and 13 .............. ............. .............. ............. .............. ............. .............. services ............................... 14 .............. ............. .............. ............. .............. ............. .............. Exports ................................. 15 111.874 105.877 106.212 107.424 108.771 110.060 110.180 Goods ............................... 16 111.970 104.403 104.892 106.072 107.565 108.965 109.098 Services............................ 17 111.643 109.172 109.164 110.437 111.451 112.480 112.568 Imports.................................. 18 118.685 105.987 105.879 111.222 114.514 112.234 109.936 Goods ............................... 19 119.603 104.908 104.680 110.650 114.497 111.653 109.033 Services............................ 20 113.921 110.711 111.179 113.650 114.351 114.813 114.152 Government consumption expenditures and gross investment ........................... 21 115.009 114.644 114.635 115.067 116.358 116.606 116.734 Federal.................................. 22 111.119 110.895 110.716 111.141 112.375 112.615 112.718 National defense............... 23 112.109 111.342 111.153 111.590 113.046 113.377 113.489 Nondefense ...................... 24 109.077 109.984 109.822 110.222 110.997 111.053 111.138 State and local ......................25117.349116.892116.998117.434118.760119.014119.158Table 1.1.5. Gross Domestic ProductTable 1.1.6. Real Gross Domestic Product, Chained Dollars[Billions of dollars][Billions of chained (2005) dollars]Line20082009Seasonally adjusted at annual rates20092010 IIIIVIIIIIIGross domestic productPersonal consumption1 14,369.1 14,119.0 14,114.7 14,277.3 14,446.4 14,578.7 14,730.2 expenditures ....................... 2 10,104.5 10,001.3 10,040.7 10,131.5 10,230.8 10,285.4 10,376.7 Goods................................... 3 3,379.5 3,230.7 3,276.1 3,312.9 3,380.0 3,377.5 3,409.0 Durable goods .................. 4 1,083.5 1,026.5 1,045.2 1,043.9 1,060.7 1,074.1 1,084.1 Nondurable goods ............ 5 2,296.0 2,204.2 2,231.0 2,269.0 2,319.3 2,303.4 2,325.0 Services ...............................Gross private domestic6 6,725.06,770.66,764.66,818.66,850.96,907.96,967.6investment ........................... 7 2,096.7 1,589.2 1,548.5 1,637.7 1,739.7 1,841.8 1,896.1 Fixed investment................... 8 2,137.8 1,716.4 1,691.8 1,681.9 1,689.8 1,761.4 1,765.9 Nonresidential .................. 9 1,665.3 1,364.4 1,343.8 1,330.9 1,349.6 1,404.2 1,438.5 Structures..................... 10 582.4 451.6 436.6 398.2 380.1 381.5 387.7 Equipment and software 11 1,082.9 912.8 907.2 932.7 969.5 1,022.7 1,050.9 Residential........................12 472.5 352.1 348.0 351.0 340.2 357.2 327.4 Change in private inventories Net exports of goods and13 –41.1 –127.2 –143.3 –44.2 50.0 80.4 130.2 services ............................... 14 –710.4 –386.4 –408.3 –426.4 –479.9 –539.3 –561.5 Exports ................................. 15 1,843.4 1,578.4 1,582.1 1,689.9 1,757.8 1,817.9 1,842.1 Goods............................... 16 1,295.1 1,063.1 1,068.6 1,157.6 1,213.0 1,262.8 1,274.9 Services ........................... 17 548.3 515.3 513.6 532.3 544.8 555.1 567.1 Imports ................................. 18 2,553.8 1,964.7 1,990.5 2,116.3 2,237.6 2,357.1 2,403.5 Goods............................... 19 2,148.8 1,587.8 1,613.8 1,731.8 1,843.5 1,957.2 1,992.5 Services ........................... Government consumptionexpenditures and gross20405.0376.9376.6384.5394.1400.0411.0investment ........................... 21 2,878.3 2,914.9 2,933.8 2,934.5 2,955.7 2,990.8 3,018.9 Federal ................................. 22 1,079.9 1,139.6 1,155.4 1,159.9 1,178.1 1,206.7 1,233.6 National defense............... 23 737.3 771.6 787.3 785.4 796.3 813.0 830.5 Nondefense ...................... 24 342.5 368.0 368.1 374.5 381.8 393.7 403.1 State and local......................25 1,798.5 1,775.3 1,778.4 1,774.7 1,777.6 1,784.1 1,785.3Line20082009Seasonally adjusted at annual rates20092010 IIIIVIIIIIIGross domestic product Personal consumption 1 13,228.8 12,880.6 12,860.8 13,019.0 13,138.8 13,194.9 13,260.7 expenditures ....................... 2 9,265.0 9,153.9 9,161.6 9,182.9 9,225.4 9,275.7 9,334.6 Goods ................................... 3 3,180.3 3,117.4 3,138.2 3,151.8 3,195.4 3,222.6 3,245.0 Durable goods .................. 4 1,136.4 1,094.6 1,118.3 1,115.1 1,138.9 1,157.8 1,175.2 Nondurable goods ............ 5 2,041.2 2,017.4 2,016.9 2,032.3 2,053.5 2,063.4 2,070.0 Services................................ Gross private domestic 6 6,082.36,032.76,020.76,028.76,029.66,053.46,090.1investment ........................... 7 1,957.3 1,515.7 1,494.5 1,585.7 1,690.2 1,791.5 1,846.1 Fixed investment................... 8 1,997.0 1,630.7 1,622.4 1,617.1 1,630.5 1,702.5 1,706.0 Nonresidential................... 9 1,556.6 1,290.8 1,282.9 1,278.3 1,302.6 1,355.3 1,387.2 Structures ..................... 10 464.2 369.6 365.5 335.3 319.3 318.9 321.9 Equipment and software 11 1,082.0 916.3 913.1 944.7 989.7 1,046.0 1,076.1 Residential ........................ 12 444.2 342.7 342.4 341.7 330.7 350.1 321.3 Change in private inventories Net exports of goods and 13 –37.6 –113.1 –128.2 –36.7 44.1 68.8 115.5 services ............................... 14 –504.1 –363.0 –390.8 –330.1 –338.4 –449.0 –514.9 Exports ................................. 15 1,647.7 1,490.7 1,490.0 1,573.5 1,616.4 1,652.1 1,672.3 Goods ............................... 16 1,156.6 1,018.2 1,019.1 1,091.7 1,128.0 1,159.2 1,169.0 Services............................ 17 491.1 472.0 470.5 482.0 488.9 493.6 503.9 Imports.................................. 18 2,151.7 1,853.8 1,880.8 1,903.6 1,954.8 2,101.1 2,187.2 Goods ............................... 19 1,796.6 1,513.5 1,542.7 1,566.1 1,611.0 1,753.9 1,828.5 Services............................ Government consumption expenditures and gross 20355.5340.5338.7338.3344.6348.3360.0investment ........................... 21 2,502.7 2,542.6 2,559.3 2,550.3 2,540.2 2,564.9 2,586.1 Federal.................................. 22 971.8 1,027.6 1,043.5 1,043.6 1,048.4 1,071.5 1,094.4 National defense............... 23 657.7 693.0 708.3 703.8 704.4 717.1 731.8 Nondefense ...................... 24 314.0 334.6 335.2 339.8 344.0 354.5 362.7 State and local ...................... 25 1,532.6 1,518.8 1,520.0 1,511.2 1,496.8 1,499.1 1,498.2 Residual....................................26 16.2 37.8 40.4 33.8 26.5 15.2 13.5N OTE . Chained (2005) dollar series are calculated as the product of the chain-type quantity index and the 2005 current-dollar value of the corresponding series, divided by 100. Because the formula for the chain-type quantity indexes uses weights of more than one period, the corresponding chained-dollar estimates are usually not additive. The residual line is the difference between the first line and the sum of the most detailed lines.D–4 National Data November 2010Table 1.1.7. Percent Change From Preceding Period Table 1.1.8. Contributions to Percent Change in the in Prices for Gross Domestic Product Gross Domestic Product Price Index[Percent]Line20082009Seasonally adjusted at annual rates 20092010 IIIIV I II III Gross domestic productPersonal consumption1 2.2 0.9 0.7 –0.2 1.0 1.9 2.3 expenditures (2)3.3 0.2 2.9 2.7 2.1 0.0 1.0 Goods................................... 3 3.2 –2.5 5.7 2.8 2.6 –3.6 1.0 Durable goods .................. 4 –1.4 –1.6 –2.5 0.7 –2.0 –1.6 –2.2 Nondurable goods ............ 5 5.6 –2.9 9.7 3.84.7 –4.6 2.5 Services ...............................Gross private domestic63.41.51.72.71.81.81.0investment ........................... 7 0.7 –2.0 –6.0 –0.7 –2.0 –0.7 0.4 Fixed investment................... 8 0.8 –1.7 –4.8 –1.0 –1.4 –0.7 0.2 Nonresidential .................. 9 1.4 –1.2 –5.1 –2.4 –1.9 0.0 0.4 Structures..................... 10 4.7 –2.6 –10.5 –2.1 0.9 2.0 2.6 Equipment and software 11 –0.2 –0.5 –2.4 –2.5 –3.1 –0.8 –0.5 Residential........................ 12 –1.2 –3.4 –3.3 4.3 0.6 –3.2 –0.5 Change in private inventories Net exports of goods and 13 .............. ............. .............. ............. ............. .............. ............. services ............................... 14 .............. ............. .............. ............. ............. .............. ............. Exports ................................. 15 4.7 –5.4 4.6 4.6 5.1 4.8 0.4 Goods............................... 16 4.8 –6.8 4.8 4.6 5.8 5.3 0.5 Services ........................... 17 4.2 –2.2 4.0 4.7 3.7 3.7 0.3 Imports ................................. 18 10.4 –10.7 8.6 21.8 12.4 –7.7 –7.9 Goods............................... 19 11.3 –12.3 9.2 24.8 14.6 –9.6 –9.1 Services ........................... Government consumption expenditures and gross 20 5.7 –2.8 6.2 9.2 2.5 1.6 –2.3 investment ........................... 21 4.7 –0.3 0.4 1.5 4.6 0.9 0.4 Federal ................................. 22 3.1 –0.2 –0.1 1.5 4.5 0.9 0.4 National defense............... 23 3.6 –0.7 0.3 1.6 5.3 1.2 0.4 Nondefense ...................... 24 2.2 0.8 –1.0 1.5 2.8 0.2 0.3 State and local...................... Addenda:25 5.6 –0.4 0.8 1.5 4.6 0.90.5Gross national product ......... Implicit price deflators: 26 2.2 0.9 0.8 –0.2 1.0 1.9 ............. Gross domestic product 127 2.2 0.9 0.7 –0.3 1.1 2.0 2.2 Gross national product 1 282.20.90.7–0.31.01.9 .............Line20082009Seasonally adjusted at annual rates 20092010 IIIIVIIIIIIPercent change at annualrate:Gross domestic product 1 2.2 0.9 0.7 –0.2 1.0 1.9 2.3Percentage points at annualrates:Personal consumptionexpenditures ....................... 2 2.31 0.13 1.98 1.87 1.46 –0.03 0.72 Goods ................................... 3 0.76 –0.58 1.22 0.62 0.59 –0.86 0.23 Durable goods ..................4 –0.12 –0.12 –0.19 0.04 –0.15 –0.12 –0.17 Nondurable goods ............ 5 0.88 –0.46 1.41 0.58 0.74 –0.74 0.39 Services................................Gross private domestic6 1.55 0.71 0.76 1.25 0.87 0.83 0.49 investment ........................... 7 0.11 –0.25 –0.63 –0.05 –0.23 –0.09 0.06 Fixed investment...................8 0.12 –0.23 –0.61 –0.13 –0.17 –0.08 0.03 Nonresidential...................9 0.16 –0.13 –0.53 –0.23 –0.18 0.00 0.04 Structures ..................... 10 0.18 –0.10 –0.37 –0.07 0.02 0.05 0.07 Equipment and software 11 –0.02 –0.03 –0.16 –0.17 –0.21 –0.05 –0.03 Residential ........................ 12 –0.05 –0.10 –0.08 0.10 0.01 –0.08 –0.01 Change in private inventories Net exports of goods and 13 0.00 –0.02 –0.01 0.07 –0.07 –0.01 0.03 services ............................... 14 –1.16 1.13 –0.69 –2.37 –1.17 1.87 1.41 Exports ................................. 15 0.57 –0.66 0.48 0.52 0.60 0.58 0.06 Goods ............................... 16 0.41 –0.58 0.34 0.35 0.46 0.44 0.04 Services............................ 17 0.15 –0.08 0.14 0.17 0.14 0.14 0.01 Imports.................................. 18 –1.73 1.79 –1.17 –2.88 –1.77 1.28 1.35 Goods ............................... 19 –1.58 1.71 –1.00 –2.64 –1.70 1.33 1.29 Services............................ 20 –0.15 0.08 –0.17 –0.24 –0.07 –0.04 0.06 Government consumption expenditures and gross investment ........................... 21 0.90 –0.07 0.08 0.31 0.92 0.18 0.09 Federal.................................. 22 0.22 –0.02 0.00 0.13 0.36 0.07 0.03 National defense............... 23 0.17 –0.04 0.02 0.09 0.29 0.07 0.02 Nondefense ...................... 24 0.05 0.02 –0.02 0.04 0.07 0.01 0.01 State and local ......................250.68–0.050.080.180.560.110.061. The percent change for this series is calculated from the implicit price deflator in NIP A table 1.1.9.Table 1.1.9. Implicit Price Deflators for Gross Domestic Product Table 1.1.10. Percentage Shares of Gross Domestic Product[Index numbers, 2005=100][Percent]Line20082009Seasonally adjusted20092010 IIIIVIIIIIIGross domestic product Personal consumption1 108.619 109.615 109.750 109.665 109.952 110.488 111.082 expenditures ....................... 2 109.061 109.258 109.596 110.330 110.899 110.886 111.163 Goods................................... 3 106.263 103.634 104.394 105.113 105.777 104.805 105.056 Durable goods .................. 4 95.340 93.782 93.459 93.615 93.133 92.767 92.246 Nondurable goods ............ 5 112.484 109.262 110.617 111.645 112.942 111.632 112.319 Services ............................... Gross private domestic 6 110.566112.233112.356113.102 113.621 114.117 114.409 investment ........................... 7 107.122 104.848 103.613 103.278 102.929 102.807 102.710 Fixed investment................... 8 107.052 105.260 104.274 104.006 103.637 103.463 103.515 Nonresidential .................. 9 106.984 105.700 104.745 104.116 103.611 103.608 103.702 Structures..................... 10 125.460 122.187 119.439 118.782 119.055 119.650 120.427 Equipment and software 11 100.083 99.620 99.352 98.727 97.961 97.770 97.657 Residential........................ 12 106.361 102.737 101.635 102.717 102.874 102.035 101.912 Change in private inventories Net exports of goods and 13 .............. ............. .............. ............. ............. .............. ............. services ............................... 14 .............. ............. .............. ............. ............. .............. ............. Exports ................................. 15 111.875 105.877 106.182 107.398 108.745 110.033 110.153 Goods............................... 16 111.970 104.403 104.852 106.038 107.531 108.930 109.063 Services ........................... 17 111.643 109.171 109.154 110.426 111.438 112.467 112.556 Imports ................................. 18 118.685 105.987 105.829 111.178 114.468 112.189 109.892 Goods............................... 19 119.603 104.908 104.609 110.586 114.432 111.588 108.970 Services ........................... 20 113.921 110.711 111.191 113.662 114.362 114.824 114.164 Government consumption expenditures and gross investment ........................... 21 115.008 114.644 114.635 115.067 116.358 116.607 116.734 Federal ................................. 22 111.119 110.895 110.717 111.142 112.376 112.616 112.719 National defense............... 23 112.109 111.342 111.157 111.594 113.051 113.381 113.494 Nondefense ...................... 24 109.077 109.984 109.820 110.220 110.995 111.050 111.135 State and local...................... Addendum:25117.348116.892116.999117.435118.762119.016119.160Gross national product .........26 108.626 109.609 109.744 109.664 109.950 110.479 .............Line2008 2009 2009 2010 III IV I II III Gross domestic product Personal consumption 1 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 expenditures ....................... 2 70.3 70.8 71.1 71.0 70.8 70.6 70.4 Goods ................................... 3 23.5 22.9 23.2 23.2 23.4 23.2 23.1 Durable goods .................. 4 7.5 7.3 7.4 7.3 7.3 7.4 7.4 Nondurable goods ............ 5 16.0 15.6 15.8 15.9 16.1 15.8 15.8 Services................................Gross private domestic6 46.8 48.0 47.9 47.8 47.4 47.4 47.3 investment ...........................7 14.6 11.3 11.0 11.5 12.0 12.6 12.9 Fixed investment...................8 14.9 12.2 12.0 11.8 11.7 12.1 12.0 Nonresidential................... 9 11.6 9.7 9.5 9.3 9.3 9.6 9.8 Structures ..................... 10 4.1 3.2 3.1 2.8 2.6 2.6 2.6 Equipment and software 11 7.5 6.5 6.4 6.5 6.7 7.0 7.1 Residential ........................ 12 3.3 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.4 2.5 2.2 Change in private inventories Net exports of goods and 13 –0.3 –0.9 –1.0 –0.3 0.3 0.6 0.9 services ............................... 14 –4.9 –2.7 –2.9 –3.0 –3.3 –3.7 –3.8 Exports ................................. 15 12.8 11.2 11.2 11.8 12.2 12.5 12.5 Goods ............................... 16 9.0 7.5 7.6 8.1 8.4 8.7 8.7 Services............................ 17 3.8 3.6 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.8 3.9 Imports.................................. 18 17.8 13.9 14.1 14.8 15.5 16.2 16.3 Goods ............................... 19 15.0 11.2 11.4 12.1 12.8 13.4 13.5 Services............................ Government consumptionexpenditures and gross20 2.8 2.7 2.7 2.7 2.7 2.7 2.8 investment ........................... 21 20.0 20.6 20.8 20.6 20.5 20.5 20.5 Federal.................................. 22 7.5 8.1 8.2 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 National defense............... 23 5.1 5.5 5.6 5.5 5.5 5.6 5.6 Nondefense ...................... 24 2.4 2.6 2.6 2.6 2.6 2.7 2.7 State and local ......................2512.512.612.612.412.312.212.1November 2010 S URVEY OF C URRENT B USINESS D–5 Table 1.1.11. Real Gross Domestic Product: Percent Change From Quarter One Year Ago[Percent]Line2009 2010III IV I II IIIGross domestic product.............................................................................................. 1 –2.7 0.2 2.4 3.0 3.1 Personal consumption expenditures ................................................................................. 2 –0.9 0.2 0.8 1.7 1.9 Goods................................................................................................................................. 3 –1.0 2.3 3.2 4.5 3.4 Durable goods................................................................................................................ 4 –1.3 4.8 5.8 8.4 5.1 Nondurable goods.......................................................................................................... 5 –0.9 1.1 2.1 2.7 2.6 Services ............................................................................................................................. 6 –0.8 –0.8 –0.4 0.4 1.2 Gross private domestic investment.................................................................................... 7 –24.0 –9.6 10.5 23.3 23.5 Fixed investment ................................................................................................................ 8 –18.6 –12.9 –2.0 5.1 5.1 Nonresidential ................................................................................................................ 9 –17.8 –12.7 –0.8 5.2 8.1 Structures................................................................................................................... 10 –21.7 –26.5 –20.1 –15.6 –11.9 Equipment and software ............................................................................................ 11 –15.8 –4.9 9.515.717.8 Residential ..................................................................................................................... 12 –21.4 –13.4 –6.3 4.8 –6.2 Change in private inventories............................................................................................. 13 ................................ ................................. ................................ ................................ ................................. Net exports of goods and services .................................................................................... 14 ................................ ................................. ................................ ................................ .................................Exports............................................................................................................................... 15 –11.0 –0.1 11.4 14.1 12.2 Goods ............................................................................................................................ 16 –13.8 –0.2 14.4 18.7 14.7 Services ......................................................................................................................... 17 –4.6 0.3 5.1 4.9 7.1 Imports ............................................................................................................................... 18 –14.1 –7.2 6.2 17.4 16.3 Goods ............................................................................................................................ 19 –16.0 –7.3 7.9 20.8 18.5 Services ......................................................................................................................... 20 –4.3 –7.0 –0.8 3.2 6.3 Government consumption expenditures and gross investment ..................................... 21 1.5 0.8 1.1 0.6 1.1 Federal ............................................................................................................................... 22 5.7 3.6 5.5 4.1 4.9 National defense ............................................................................................................ 23 5.2 3.3 5.6 3.4 3.3 Nondefense.................................................................................................................... 246.74.55.15.58.2 State and local ................................................................................................................... 25 –1.1 –1.0 –1.5 –1.6 –1.4 Addenda:Final sales of domestic product.......................................................................................... 26 –2.0 –0.3 0.9 1.1 1.1 Gross domestic purchases................................................................................................. 27 –3.6 –0.9 1.9 3.8 4.0 Final sales to domestic purchasers.................................................................................... 28 –2.9 –1.40.51.92.1 Gross national product ....................................................................................................... 29 –2.9 0.5 2.8 3.4 .................................Real disposable personal income ...................................................................................... 30 1.1 0.4 0.70.31.6 Price indexes (Chain–type):Gross domestic purchases ............................................................................................ 31 –1.1 0.5 1.51.41.3 Gross domestic purchases excluding food and energy 1 ............................................... 32 0.2 0.6 1.1 1.1 1.1 Gross domestic product ................................................................................................. 33 0.2 0.5 0.5 0.8 1.2 Gross domestic product excluding food and energy 1.................................................... 34 0.3 0.8 1.1 1.2 1.2 Personal consumption expenditures .............................................................................. 35 –0.7 1.5 2.4 1.9 1.4 Personal consumption expenditures excluding food and energy 1................................. 36 1.3 1.7 1.8 1.5 1.3 Market-based PCE 2 ...................................................................................................... 37 –0.6 1.5 2.2 1.7 1.2 Market-based PCE excluding food and energy 2 ........................................................... 38 1.8 1.7 1.4 1.1 1.01. Food excludes personal consumption expenditures for purchased meals and beverages, which are classified in food services.2. Market-based PCE is a supplemental measure that is based on household expenditures for which there are observable price measures. It excludes most imputed transactions (for example, financial services furnished without payment) and the final consumption expenditures of nonprofit institutions serving households.N OTE. Percent changes for real estimates are calculated from corresponding quantity indexes presented in NIP A tables 1.1.3, 1.2.3, 1.4.3, and 1.7.3. Percent changes in price estimates are calculated from corresponding price indexes presented in NIPA tables 1.1.4, 1.6.4, and 2.3.4.Table 1.2.1. Percent Change From Preceding Period in RealGross Domestic Product by Major Type of Product[Percent]Line 2008 2009Seasonally adjusted at annual rates2009 2010III IV I II IIIGross domestic product.............................................................................................. 1 0.0 –2.6 1.6 5.0 3.7 1.7 2.0 Final sales of domestic product ................................................................................. 2 0.5 –2.1 0.4 2.1 1.1 0.9 0.6 Change in private inventories..................................................................................... 3 ...................... ...................... ....................... ...................... ...................... ...................... ....................... Goods.................................................................................................................................... 4 –0.5 –3.8 6.8 23.9 19.5 –0.8 3.6 Final sales...................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 –1.6 2.0 11.0 8.6 –3.7 –1.7 Change in private inventories......................................................................................... 6 ...................... ...................... ....................... ...................... ...................... ...................... ....................... Durable goods.................................................................................................................... 7 –0.9 –10.0 15.2 16.3 33.3 11.2 7.0 Final sales...................................................................................................................... 8 0.9 –5.4 5.9 4.0 11.2 5.3 3.0 Change in private inventories 1 ...................................................................................... 9 ...................... ...................... ....................... ...................... ...................... ...................... ....................... Nondurable goods.............................................................................................................. 10 0.0 3.2 –0.6 31.7 7.4 –11.8 0.1 Final sales...................................................................................................................... 11 2.1 2.6 –1.9 18.5 6.0 –12.2 –6.4 Change in private inventories 1 ...................................................................................... 12 ...................... ...................... ....................... ...................... ...................... ...................... ....................... Services 2.............................................................................................................................. 13 1.5 –0.2 –0.2 0.8 0.0 1.9 2.4 Structures ............................................................................................................................. 14 –7.9 –16.6 –0.1 –15.9 –15.2 10.6 –7.2 Addenda:Motor vehicle output........................................................................................................... 15 –18.6 –24.7 145.5 13.7 42.3 –2.7 21.2 Gross domestic product excluding motor vehicle output.................................................... 16 0.5 –2.1 0.0 4.8 3.0 1.8 1.6 Final sales of computers 3 ................................................................................................. 17 26.5 5.0 –4.0 17.3 19.2 5.3 55.4 Gross domestic product excluding final sales of computers .............................................. 18 –0.1 –2.7 1.6 5.0 3.7 1.7 1.8 Gross domestic purchases excluding final sales of computers to domestic purchasers.... 19 –1.3 –3.7 2.8 2.6 3.9 4.9 3.9 Final sales of domestic product, current dollars................................................................. 20 2.7 –1.1 1.2 1.82.12.92.81. Estimates for durable goods and nondurable goods for 1996 and earlier periods are based on the 1987 Standard Industrial Classification (SIC); later estimates for these industries are based on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).2. Includes government consumption expenditures, which are for services (such as education and national defense) produced by government. In current dollars, these services are valued at their cost of production.3. Some components of final sales of computers include computer parts.。

利用人工智能打击网络恐怖主义:南亚和东南亚执法和反恐机构概述

COUNTERING TERRORISM ONLINE WITH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCEAn Overview for Law Enforcement and Counter-Terrorism Agencies in South Asia and South-East AsiaA Joint Report by UNICRI and UNCCT3DisclaimerThe opinions, findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Unit-ed Nations, the Government of Japan or any other national, regional or global entities involved. Moreover, reference to any specific tool or application in this report should not be considered an endorsement by UNOCT-UNCCT, UNICRI or by the United Nations itself.The designation employed and material presented in this publication does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoev-er on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.Contents of this publication may be quoted or reproduced, provided that the source of information is acknowledged. The au-thors would like to receive a copy of the document in which this publication is used or quoted.AcknowledgementsThis report is the product of a joint research initiative on counter-terrorism in the age of artificial intelligence of the Cyber Security and New Technologies Unit of the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Centre (UNCCT) in the United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNOCT) and the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) through its Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics. The joint research initiative was funded with generous contributions from Japan.Copyright© United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNOCT), 2021United Nations Office of Counter-TerrorismS-2716United Nations405 East 42nd StreetNew York, NY 10017Website: /counterterrorism/© United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), 2021Viale Maestri del Lavoro,10, 10127 Torino – ItalyWebsite: http://www.unicri.it/E-mail:************************4FOREWORDArtificial intelligence (AI) can have, and already is having, a profound impact on our society, from healthcare, agri-culture and industry to financial services and education. However, as the United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres stated in his 2018 Strategy on New Technologies, “[w]hile these technologies hold great promise, they are not risk-free, and some inspire anxiety and even fear. They can be used to malicious ends or have unintended negative consequences”. AI embodies this duality perhaps more than any other emerging technology today. While it can bring improvements to many sectors, it also has the potential to obstruct the enjoyment of human rights and fundamen-tal freedoms – in particular the rights to privacy, freedom of thought and expression, and non-discrimination. Thus, any exploration of the use of AI-enabled technologies must always go hand-in-hand with efforts to prevent potential infringement upon human rights. In this context, we have observed many international and regional organizations, national authorities and civil society organizations working on initiatives aimed at putting in place ethical guidelines regarding the use of AI, as well as the emergence of proto-legal frameworks.This duality is most obviously prevalent online, where increased terrorist activity is a growing challenge that is be-coming almost synonymous with modern terrorism. Consider that as part of 2020 Referral Action Day, Europol and 17 Member States identified and assessed for removal as many as 1,906 URLs linking to terrorist content on 180 platforms and websites in one day. Facebook has indicated that over the course of two years it removed more than 26 million pieces of content from groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and Al-Qaida. The Internet and social media are proving to be powerful tools in the hands of such groups, enabling them to communicate, spread their messages, raise funds, recruit supporters, inspire and coordinate attacks, and target vulnerable persons.In the United Nations Global-Counter Terrorism Strategy (A/RES/60/288), Member States resolved to work with the United Nations with due regard to confidentiality, respecting human rights and in compliance with other obligations under international law, to explore ways to coordinate efforts at the international and regional levels to counter ter-rorism in all its forms and manifestations on the Internet and use the Internet as a tool for countering the spread of terrorism. At the same time, the Strategy recognizes that Member States may require assistance to meet these com-mitments.Through the present report – a product of the partnership between the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Centre in the United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism and the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute through its Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics – we seek to explore how AI can be used to combat the threat of terrorism online.5Recognizing the threat of terrorism, growing rates of digitalization and burgeoning young, vulnerable and online pop-ulations in South Asia and South-East Asia, this report provides guidance to law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies in South Asia and South-East Asia on the potential application of AI to counter terrorism online, as well as on the many human rights, technical and political challenges they will need to consider and address should they opt to do so.Our work does not end here. Addressing the challenges identified in this report and unlocking the potential for using AI to counter terrorism will require further in-depth analysis. Our Offices stand ready to support Member States and other counter-terrorism partners to prevent and combat terrorism, in all its forms and manifestations, and to exploreinnovative and human rights-compliant approaches to do so.Vladimir VoronkovUnder-Secretary-GeneralUnited Nations Office of Counter-TerrorismExecutive DirectorUnited Nations Counter-Terrorism CentreAntonia Marie De MeoDirectorUnited Nations Interregional Crimeand Justice Research Institute6EXECUTIVE SUMMARYThe integration of digital technologies into everyday life has increased at an extraordinary pace in South Asia and South-East Asia in recent years, with the use of social media by the regions’ notably young population surpassing the global average. While this trend offers a wide range of opportunities for development, the freedom of expression, polit-ical participation, and civic action, it also increases the risk of potentially vulnerable youths being exposed to terrorist online content produced by terrorist and violent extremist groups online. Additionally, given an established terrorist and violent extremist presence in South Asia and South-East Asia, law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies in these regions are increasingly pressed to adapt to transformations in criminal and terrorist activities, as well as to how investigations into these activities are carried out.Artificial intelligence (AI) has received considerable attention globally as a tool that can process vast quantities of data and discover patterns and correlations in the data unseen to the human eye, which can enhance effectiveness and ef-ficiency in the analysis of complex information. As a general-purpose technology, such benefits can also be leveraged in the field of counter-terrorism. In light of this, there is growing interest amongst law enforcement and counter-ter-rorism agencies globally in exploring how the transformative potential of AI can be unlocked.Considering the aforementioned trends and developments, this report serves as an introduction to the use of AI to counter terrorism online for law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies in the regions of South Asia and South-East Asia. This report is introductory in nature as a result of the limited publicly available information on the degree of technological readiness of law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies in these regions, which is considered likely to be indicative of limited experience with this technology. In this regard, the report provides a broad assessment of different use cases of AI, demonstrating the opportunities of the technology, as well as curbing out the challenges. The report is intended to serve as an initial mapping of AI, contextualizing possible use cases of the technology that could theoretically be deployed in the regions, whilst juxtaposing this with the key challenges that authorities must overcome to ensure the use of AI is responsible and human rights compliant. Give its introductory nature, this report is by no means intended to be an exhaustive overview of the application of AI to counter terrorism online.The report is divided into five chapters. The first chapter provides a general introduction to the context of terrorism, Internet usage in South Asia and South-East Asia and AI. The second chapter introduces and explains some key terms, technologies, and processes relevant for this report from a technical perspective. The third chapter maps applica-tions of AI in the context of countering the terrorist use of the Internet and social media, focusing on six identified use cases, namely: i) Predictive analytics for terrorist activities; ii) Identifying red flags of radicalization; iii) Detecting mis- and disinformation spread by terrorists for strategic purposes; iv) Automated content moderation and takedown; v) Countering terrorist and violent extremist narratives; and vi) Managing heavy data analysis demands. The fourth chapter examines the challenges that law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies must be prepared to address in their exploration of the technology, in particular specific political and legal challenges, as well as technical issues. The report concludes with the fifth and final chapter, which provides high-level recommendations for law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies in South Asia and South-East Asia to take onboard to support them to navigate the challenges described in terms of the use of AI to counter terrorism online.7CONTENTSI. INTRODUCTION 10 II. KEY CONCEPTS, TECHNOLOGIES, AND PROCESSES 15i.Artificial intelligence 15 ii. Data 17 iii. Machine learning 18 iv. Deep learning 19 v. Generative adversarial network 19 vi. Natural language processing 20 vii. Object recognition 20 viii. Predictive analytics 20 ix. Social network analysis 21 x. Content matching technology 21 xi. Data anonymization and pseudonymization 22 xii. Open-source intelligence and social media intelligence 23 xiii. Disinformation and misinformation 23 III. PROBING THE POTENTIAL OF AI23i. Predictive analytics for terrorist activities 24ii. Identify red flags of radicalization 2689iii.Detecting mis- and disinformation spread by terrorists for strategic purposes iv.Automated content moderation and takedown v.Countering terrorist and violent extremist narratives vi.Managing heavy data analysis demands IV.THE GREATER THE OPPPORTUNITY, THE GREATER THE CHALLENGE 35i. Legal and political challengesa.Human rights concerns 35b.Admissibility of AI-generated evidence in court 39c.A fragmented landscape of definitions 40d.AI governance 41e. Public-private relations 42ii. Technical challenges in using AI toolsa.False positives and false negatives 43b.Bias in the data 43c.Explainability and the black box problem 44d. The complexity of human-generated content 45V. MOVING FORWARD WITH AI47I. INTRODUCTIONSouth Asia and South-East Asia, like many parts of the world, grapple with the threat of terrorism and violent extrem-ism. This includes both home-grown organized violent extremist groups such as Jemaah Islamiyah and internation-ally-oriented groups such as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as Da’esh) and Al-Qaida, which includes local affiliated groups such as the Abu Sayyaf Group.These regions have become important areas of focus for terrorist and violent extremist groups in terms of recruitment. At its height in 2015, over 30,000 foreign terrorist fighters, from more than 100 States, were believed to have joined ISIL.1 Of this, more than 1,500 persons from South Asia and South-East Asia alone are believed to have travelled to ISIL-controlled territory.2 By July 2017, at which point ISIL had begun to lose significant percentages of its territory, the regions of South Asia and South-East Asia saw significant numbers of foreign fighters returning to their home coun-tries, as well as significant numbers of foreign fighters not originally from these regions relocating to South Asia and South-East Asia instead of returning to their home countries.3 Radicalization poses an increasing threat in the regions. For example, the Ministry of Home Affairs and Law of Singapore recently indicated that the timeframe for recruitment has been reduced from approximately twenty-two to nine months.4 The terrorist landscape in South-East Asia has also notably witnessed a growing number of women in terrorism.5 This rising number of women in terrorism is believed to be linked with broader trends of increasingly self-directed terrorist attacks perpetrated by lone terrorist actors or groups.6 The COVID-19 pandemic has also had an effect on the radicalization and recruitment-related phenomenon, with many Member States – including from South Asia and South-East Asia – raising concerns about radicalization in the context of the large numbers of people connected to the Internet for extended periods of time.7The presence of terrorist and violent extremists in South Asia and South-East Asia is, however, not a new development, with these regions each having their own experience with diverse forms of national, regional and international violent extremism and having developed extensive experience in countering terrorism. The bombing of the Colombo World Trade Centre in October 1997,8 the Bali bombings in October 2002,9 the bombing of Super Ferry 14 in the Manila Bay in February 2004,10 and the Mumbai attacks in November 2008 are all testament to the trials the regions have faced.11 Another global trend that the regions of South Asia and South-East Asia have faced in recent years is that of “digitiza-tion”. Indeed, the integration of digital technologies into everyday life in South Asia and South-East Asia is something that has been increasing at an extraordinary pace. While there is no single driver, a key factor often acknowledged is the large percentages of youths throughout the regions. Notably, more than 70.2% of the population in South Asia and1 Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee. (2021). Foreign terrorist fighters. Accessible at https:///securitycouncil/ctc/content/foreign-terrorist-fighters.2 Richard Barrett. (2017). Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees. The Soufan Centre, 10. Accessible athttps:///wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Beyond-the-Caliphate-Foreign-Fighters-and-the-Threat-of-Returnees-TSC-Report-October-2017-v3.pdf.3 Ibid.4 Valerie Koh. (Sept. 2017). Time taken for people to be radicalised has been shortened: Shanmugam. Today. Accessible at https://www./singapore/time-taken-people-be-radicalised-has-been-shortened-shanmugam.5 The Soufan Center. (Jun. 2021). Terrorism and Counterterrorism in Southeast Asia: Emerging Trends and Dynamics. The Soufan CentreAccessible at https:///wp-content/uploads/2021/06/TSC-Report_Terrorism-and-Counterterrorism-in-South-east-Asia_June-2021.pdf.6 Ibid.7 Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida andassociated individuals and entities, Twenty-seventh report, S/2021/68 (3 February 2021).8 Agence France-Presse. (Oct. 1997). 17 Die, 100 Wounded by Huge Bomb and Gunfire in Sri Lanka. The New York Times. Accessible athttps:///1997/10/15/world/17-die-100-wounded-by-huge-bomb-and-gunfire-in-sri-lanka.html.9 BBC News. (Oct. 2012). The 12 October 2002 Bali bombing plot. BBC News. Accessible at https:///news/world-asia-19881138.10 BBC News. (Oct 2004). Bomb caused Philippine ferry fire. BBC News. Accessible at /2/hi/asia-pacific/3732356.stm11 Gethin Chamberlain. (Nov. 2008). Mumbai terror attacks: Nightmare in the lap of luxury. The Guardian. Accessible at https://n.com/2013/09/18/world/asia/mumbai-terror-attacks/index.html10South-East Asia are under 40 years old. This young population is exceptionally active online with “more than 55% using social media extensively, which is 13% more than the world’s average”.12 As with younger generations across the globe, many are so-called “digital natives” – persons born or brought up during the digital age and possessing high-levels of familiarity with computers, the Internet and digital technology from an early age – and, thus, have a higher acceptance of Internet-related services and are enthusiastic users of social media. In line with this, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is, tellingly, the fastest-growing Internet market in the world, with 125,000 new users joining the Internet every day.13,14 It was reported that almost 60% of the global social media users in 2020 were located in Asia.15 The COVID-19 pandemic has equally played a role in expediting the process of digitization in the regions, with youths in South Asia and South-East Asia expanding their digital footprint throughout 2020 and more than 70% believ-ing that their increased use of social media will last beyond the pandemic.16 The use of social media grew the most in comparison with other online services, according to the respondents of the ASEAN Youth Survey 2020 conducted by the World Economic Forum.17Photo by camilo jimenez on UnsplashNaturally, these developments present a wide range of opportunities – if they are leveraged appropriately. The Internet and social media have demonstrated their beneficial potential in South Asia and South-East Asia on many occasions, for instance, as an accelerator of grassroots activism. Studies in South-East Asia over the last decade have demon-strated a positive correlation between social media use, political participation, and civic action in both democratic and authoritarian systems.18 Unfortunately, however, the advantages of the Internet and social media that support civil society movements also make them appealing to actors with malicious intent and present a plethora of challenges for authorities in South Asia and South-East Asia, as well as globally.12 UNCCT-CTED. (2021). Misuse of the Internet for Terrorist Purposes in Selected Member States in South Asia and Southeast Asia andResponses to the Threat, 3.13 WEF. (2021). Digital ASEAN. Accessible at https:///projects/digital-asean.14 WEF, in collaboration with Sea. (Jul. 2020). COVID-19 – The True Test of ASEAN Youth´s Resilience and Adaptability, Impact of SocialDistancing on ASEAN Youth, 8. Accessible at /docs/WEF_ASEAN_Youth_Survey_2020_Report.pdf15 Jordan Newton, Yasmira Moner, Kyaw Nyi NyI, Hari Prasad. (2021) Polarising Narratives and Deepening Fault Lines: Social Media, Intol-erance and Extremism in Four Asian Nations. GNET, 5. Accessible at https:///wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GNET-Re-port-Polarising-Narratives-And-Deepening-Fault-Lines.pdf.16 WEF. (Jul. 2020). COVID-19 – The True Test of ASEAN Youth´s Resilience and Adaptability, Impact of Social Distancing on ASEAN Youth, 9.Accessible at: /docs/WEF_ASEAN_Youth_Survey_2020_Report.pdf17 Ibid.18 Aim Signpeng & Ross Tapsell. (2020). From Grassroots Activism to disinformation; Social Media Trends in Southeast Asia. ISEAS-YusofIshak Institute.Terrorists and violent extremists around the world have adapted to the new digital paradigms of the 21st Century, learning to use information and communications technologies, and in particular online spaces and the multitude of interactive applications and social media platforms, to further their objectives – for instance, to spread hateful ideolo-gy and propaganda, recruit new members, organize financial support and operational tactics and manage supportive online communities. The use of such technologies in South Asia and South-East Asia parallels the use in other parts of the world, with social media and highly localized content tailored to local grievances and available in local languages playing a particularly important role in radicalization and recruitment. For instance, according to the former Home Affairs Minister of Malaysia, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, social media was responsible for approximately 17 percent of ISIL recruitment in the country.19 Similarly, in Singapore, of 21 nationals held for terrorism-related activities under the Internal Security Act between 2015 and 2018, 19 were radicalized by ISIL propaganda online, with the other two being radicalized by other online content encouraging participation in the Syrian conflict.20 The relevance of such information and communications technologies throughout these regions in recent years can also be seen in national responses. For example, in Indonesia, the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology petitioned the encrypted mes-saging app Telegram to set up a specialized team of moderators familiar with Indonesian languages to specifically moderate terrorist content being spread in Indonesia.21In addition to having to understand a widening threat landscape beyond the physical domain, law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies are being tested and challenged to deal with extensive and complex investigations in in-creasingly data-heavy environments that fall outside their traditional areas of expertise. Large cases can take several years of work to search through and cross-check relevant case information, meaning that finding one key piece of information or being able to single out the most important leads for the purposes of an investigation has never been so difficult.22 Law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies across the globe therefore find themselves being pressed to keep up with the digital transformation.Confronted by the reality that an inability to keep up may result in failing to obstruct a terrorist plot and lead to the loss of lives, there is increasing interest in exploring tools, techniques, or processes to fill operational and capacity gaps of law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies in combatting terrorism online.23 One field that is receiving considerable interest globally from both public and private sector entities con-fronting similar “informational overloads” is artificial intelligence (AI). As will be explained in the following chapter, AI is the field of computer science aimed at developing computer systems capable of performing tasks that would normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, trans-lation between languages, decision-making, and problem-solving. Much of the appeal of AI lies in its ability to analyze vast amounts of data – also referred to as “big data” – faster and with greater ease than a human analyst or even a team of analysts can do, and, in doing so, to discover patterns and correlations unseen to the human eye. Moreover, AI can extrapolate likely outcomes of a given scenario based on available data.24 Seen for a long time as little more than science fiction, AI is already being used throughout the public and private sector for a range of beneficial purposes. For instance, AI has played a role in helping to significantly speed up the development of messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA)-based vaccines, such as those now being used to rein in the COV-ID-19 pandemic,25 and is being deployed to help broker peace deals in war-torn Libya and Yemen.26 The United Nations19 Ibid20 Kimberly T’ng. (Apr. 2019). Down the Rabbit Hole: ISIS on the Internet and How It Influences Singapore Youth. Accessible at https://www..sg/docs/hta_libraries/publications/final-home-team-journal-issue-8-(for-web).pdf21 James Hookway. (Jul. 2017). Messaging App Telegram to Boost Efforts to Remove Terror-Linked Content. Accessible at https://www.wsj.com/articles/messaging-app-telegram-to-boost-efforts-to-remove-terror-linked-content-1500214488?mg=prod/accounts-wsj22 Jo Cavan & Paul Killworth. (Oct. 10, 2019). GCHQ embraces AI but not as a black box. About Intel. Accessible at https://aboutintel.eu/gchq-embraces-ai/.23 INTERPOL & UNICRI. (2020). Towards Responsible AI Innovation for Law Enforcement. Accessible at:http://unicri.it/towards-responsible-artificial-intelligence-innovation24 Whether those predictions are accurate or not and how that impacts the use of AI to combat the terrorist use of the Internet is analyzedin the third and fourth chapters.25 Hannah Mayer et al. (Nov. 24, 2020). AI puts Moderna within striking distance of beating COVID-19. Digital Initiative. Accessible at https:///artificial-intelligence-machine-learning/ai-puts-moderna-within-striking-distance-of-beating-covid-19/.26 Dalvin Brown. (Apr. 23, 2021) The United Nations is turning to artificial intelligence in search for peace in war zones. The WashingtonPost. Accessible at https:///technology/2021/04/23/ai-un-peacekeeping/.Secretary-General, António Guterres, has indicated that, if harnessed appropriately and anchored in the values and obligations defined by the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, AI can play a role in the fulfilment of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, by contributing to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure peace and prosperity for all.27AI can be a powerful tool in counter-terrorism, enabling law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies to realize game-changing potential, enhancing effectiveness, augmenting existing capacities and enabling them to manage with the massive increase in data. AI can support law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies, for example, by auto-mating highly repetitive tasks to reduce workload; assisting analysts through predictions of future terrorist scenarios for well-defined, narrow settings; identifying suspicious financial transactions that may be indicative of the financing of terrorism; as well as monitoring Internet spaces for terrorist activity at a scale and speed beyond traditionally avail-able human capabilities.Excitement about the potential for societal advancement with AI is, however, tempered by growing concerns about possible adverse impacts and unintended consequences that may flow from the deployment of this technology. As a result, AI is currently the subject of extensive debate among technologists, ethicists, and policymakers worldwide. With counter-terrorism – and particularly pre-emptive forms of counter-terrorism – already at the forefront of debates about human rights protection, the development and deployment of AI raises acute human rights concerns in these contexts.28Photo by Shahadat Rahman on UnsplashNevertheless, from a security perspective, the need for law enforcement and counter-terrorism agencies to adapt to the digital transformation certainly exists. It could even be said to be particularly pressing for South Asia and South-East Asia, given the increased rate of digitalization and the growing presence of younger, potentially vulnerable, ele-27 António Guterres. (Sept. 2018). Secretary-General’s Strategy on New Technologies. United Nations. Accessible at https:///en/newtechnologies/images/pdf/SGs-Strategy-on-New-Technologies.pdf28 Although these issues will be touch upon in this report, for further analysis see: OHCHR, UNOCT-UNCCT & UNICRI. (2021). Human RightsAspects to the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Counter-Terrorism.。

犯罪率最高的国家

犯罪率最高的国家大家都渴望生活在一个比较和平的环境里,和平的环境下才能过的更开心。

但是在国际环境中有很多国家充满了不安定的因素,很多犯罪每天都会发生,如果问世界十大犯罪率最高的国家排行榜,你会想到什么国家,估计是美国,接下来看看世界上犯罪率最高的十个国家,看看犯罪率居高不下的原因是什么?世界上犯罪率最高国家排行2022最新排名前十名1、美国美国排在这个榜单的首位,当然这并不是一件值得庆祝的事情。

尽管美国在其他方面处于世界领先的地位,但是这个国家的犯罪率也是居高不下,而且犯罪率每年还有上升的势头。

这里的街头犯罪很常见,还有就是交通事故和走私等,是世界上犯罪率最高的国家之一。

2、加拿大加拿大是一个经济高度发达的资本主义国家,是世界领先的国家之一,在国际上享有声誉。

不过这个国家犯罪率也非常的高。

居民也会遇到谋杀,抢劫,强奸和走私的问题。

这个国家的走私也非常让国际方面头痛,是世界上犯罪率最高的国家之一。

3、德国尽管德国是欧盟经济总量最高的国家,有着许多高科技安全产品,德国拥有着超级汽车跑车和优雅的宝马,德国车凭借独特的气质征服着很多消费者。

但是实际上德国的犯罪案件也是比较频繁的,其犯罪案件也逐年增加,是世界上犯罪率最高的国家之一。

其实这和被臭名昭着的纳粹统治的历史有一定的关联。

4、韩国尽管韩国的教育在世界范围内有一定地位,但是犯罪率还是居高不下,100个人中有近20人有犯罪记录,是世界上犯罪率最高的国家之一。

5、乌干达乌干达是非洲东部的国家,其实这里的谋杀率却非常高,曾有报道称,谋杀率高达到92%。

报纸上也有街头犯罪,涉及到盗窃和强奸,是世界上犯罪率最高的国家之一。

6、南非作为非洲的第二大经济体,丰富的旅游资源吸引着大量的游客。

与过去几年相比,街头抢劫,流氓强奸和盗窃袭击事件增加了70%以上。

街头犯罪的受害者往往是来这个国家的游客。

这里常见的犯罪是盗窃、强奸和抢劫,其犯罪率有显著上升的趋势。

其谋杀,袭击,强奸和其他暴力犯罪的发生率非常高。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

美国

该国破案率:约40%

美国电影最常见的题材便是警匪片,《猫鼠游戏》、《犯罪现场调查》等,网络上更是流传着FBI 的破案案例、犯罪心理测试题,看片同时不得不为各种高科技缉凶手段啧啧称奇。其实,这些电影素材均不是幻想,美国警察破案时也确实有高科技手段。根据神探李昌钰书里所写,美国将破案的几率分为了10 个等级:第一是现场逮捕、第二是有直接证人、第三是有间接证据如录像带、第四则是验DNA……越往后证据越少,破案率也最低。美国对每一个案子都很重视,必要时出动直升机也不是不可能,当然,并不是这样就能百分百破案,还有一奇特现象是,虽说现在动用的都是高科技,破案率却在不断下降,近10 年来几乎没有上升过。

中国香港

该地区破案率:40%

“你有权保持沉默,但你说的每句话都将成为呈堂证供。”这句台词再熟悉不过,每一部警匪港片里都有,这也是香港警察逮到犯人后必须说的一句话。虽然香港近几年的破案率已远不如十多年前的75% 以上那样惊人,香港警署、扑灭罪行委员仍不遗余力地为灭罪、破案努力着。比如拍摄灭罪宣传片或定期召开新闻发布会给公众宣传灭罪知识,港剧,也是香港宣传灭罪的途径之一。警察办案运用物理学、心理学等学科知识,DNA 检测、人脸识别、解剖等技术,在实际生活中警察办案时亦是如此。

文中资料来源:维基百科、《神探李昌钰破案实录》、BBC、星期日泰晤士报、法制日报、环球时报、京华时报等

巴西

该国破案率:约8%

巴西贫富差距极大,是当地犯罪率高的原因之一,国内的某些贫民窟甚至连警察都不敢靠近,而有些警察更与黑帮勾搭一气,共同犯罪。在巴西最大的城市圣保罗有这样一句话:“你如果从来没被抢过,那就算不得一位真正的圣保罗人。”听着就已让人肝儿颤,而2016 奥林匹克运动会的举办地里约热内卢竟有“流弹之都”的称号,把警察的直升机从天上打下来对当地黑帮来说实属小儿科,政府为了防止流弹竟要建设一座高3 米的防弹墙!同时,巴西政府为了降低犯案率,甚至推出以枪换世界杯票的奇招,真是让人满头黑线,也不得不为2014 年去巴西看世界杯的观众们捏一把汗。

各国破案率

尽管各国破案率有高有低,但总归法网恢恢疏而不漏,如果没有《猫鼠游戏》中弗兰克的智商或者不是生在南非、巴西这样的国家,还是别存有侥幸心理,踏踏实实工作,老老实实做人。

英国

该国破案率:约36%

英国的治安差已经不是什么新闻了,尽管英国政府近十年来拨款数十亿英镑给英国警察,尽管英国警方积极动用高科技手段破案,比如引进人脸识别系统、DNA 对比系统等,也都不能改变英国民众对本国治安差的看法。这不,就连英国的内政大臣也不敢一个人走夜路。当然,说他们破案效率低也不是完全没道理的,最出名的要数十几年前的邓奕新被杀案件,前几年翻出来重新调查,高额悬赏,至今也未见结果。更有数据表明,英国近十年来的破案率不是下降便是停滞不前,这也引起了民众对执政党的不满。

日本

该国破案率:约59.9%

旅行者河源启一郎在武汉丢了自行车被三天内找回的事情传遍整个日本,在他们惊呼中国破案效率奇高的同时,我们来看一下日本的破案率。日本也曾经有过发案率高、破案率低的年代,2001年日本内阁批准发布的《犯罪白皮书》就打破了日本的治安神话。不过,经过日本警察多年的不懈努力,同时引进高科技手段,日本近年来的破案率也在不断飙升,当然,如果日本警察中多几个金田一、柯南这样的破案高手,相信他们的破案率有望高居世界榜首。

德国

该国破案率:约56%

德国每年记录在案的刑事案件数以百万计,警方为降低案发率提高破案率也是伤透了脑筋。2006 年,德国引进一种新的DNA计算系统,其准确率比之前的提高了15%,这套系统在德国大展拳脚,抓获不少犯罪分子,光是靠它协助破案的比例就达63% 之多。不过,值得欣慰的是,德国青少年的犯罪率非常之少,大多是网络犯罪或酒后犯罪。同时,作为汽车工业大国,德国的汽车也被犯罪分子视为摇钱树,盗窃汽车的案件时有发生,占整个德国犯罪比例的1/3。

菲律宾

该国破案率:约30Байду номын сангаас

有些西方媒体称菲律宾为亚洲的“绑架之都”,菲律宾层出不穷的绑架事件确实让这个国家名誉受损,政府不得不下令打击绑架犯罪,以求扔掉这顶破帽子。压力还是有用的,

菲律宾近年来就绑架案的破案率已提高到55% 以上。不过,也不能怪菲律宾警察办事效率低,他们中1/5 的同仁甚至都没有配枪! OMG,你能想象没有配枪的警察如何逮捕悍匪吗?况且这还是一个允许私人拥有枪支的国家!菲律宾预算和管理部长阿瓦德为此向政府申请五百多万美金的拨款以改良警察装备,他愤愤地表示无法忍受一支打不过犯罪分子的警察队伍!