石墨烯的发现与发展历程

石墨烯 发现过程

石墨烯发现过程摘要:一、石墨烯的概述二、石墨烯的发现过程1.原子力显微镜的发明2.单层石墨烯的实验制备3.诺贝尔奖得主安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫的贡献三、石墨烯的特性及应用1.机械强度2.导电性3.热传导性4.应用领域四、我国在石墨烯研究方面的进展五、石墨烯的未来发展前景正文:石墨烯,一种仅有一层原子厚度的二维材料,自2004年被安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫成功实验制得,逐渐成为材料科学领域的热点。

石墨烯的发现过程可分为以下几个阶段。

首先,我们要了解石墨烯的来源。

石墨烯是碳的同素异形体之一,存在于自然界中的石墨中。

石墨是一种常见的矿物,具有良好的导电性和热传导性。

然而,在自然界中,石墨是以多层结构存在的,而石墨烯则是单层结构。

如何将多层石墨剥离成单层石墨烯成为科学家们面临的挑战。

石墨烯的发现过程可以追溯到20世纪80年代,当时原子力显微镜(AFM)的发明为科学家们提供了观测和操作单个原子级别的物质的新工具。

借助原子力显微镜,研究人员首次成功观察到单层石墨烯的结构。

这一发现为后续的研究奠定了基础。

2004年,安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫利用胶带剥离法成功制备出单层石墨烯,这一突破性成果使他们荣获2010年诺贝尔物理学奖。

这一发现标志着石墨烯研究进入一个新的阶段。

石墨烯的特性使其在众多领域具有广泛的应用前景。

首先,石墨烯具有极高的机械强度,是迄今为止发现的强度最高的材料。

其次,石墨烯具有良好的导电性和热传导性,可应用于电子器件、散热器和柔性显示屏等领域。

此外,石墨烯还具有优异的光学性能,可用于开发高性能的光学器件。

在我国,石墨烯研究也取得了显著的进展。

众多科研团队在石墨烯的制备、性能研究和应用开发方面取得了世界领先的成绩。

政府也对石墨烯产业给予了高度重视,制定了一系列政策扶持措施。

如今,我国已成为全球石墨烯产业的重要基地。

中国石墨烯的发展

中国石墨烯的发展1.引言1.1 概述石墨烯作为一种具有革命性的二维材料,在科学界引起了广泛的兴趣和关注。

它由只有一个原子厚度的碳原子构成,具有出色的导电性、热传导性和机械强度。

这些优异的性能使得石墨烯在许多领域具有巨大的应用潜力。

中国作为世界上最大的石墨烯生产国之一,在石墨烯领域也取得了长足的发展。

自2004年英国科学家安德鲁·盖门和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫首次成功分离出石墨烯以来,中国科学家们便开始了对石墨烯的深入研究和应用探索。

中国石墨烯的发展历程可以追溯到2006年,当时中国科学院物理研究所的研究团队成功地在石墨烯的制备和应用方面取得了重要突破。

随后,中国各大高校和科研机构纷纷投入到石墨烯研究中,并在材料制备、性能测试和应用开发等方面取得了一系列的成果。

目前,中国已建立了一批具备自主知识产权的石墨烯制备技术和核心设备。

石墨烯产业链也逐渐形成,包括石墨烯材料的生产、加工、应用等环节。

中国在石墨烯相关领域的科研和产业化水平在国际上处于领先地位。

然而,中国石墨烯产业仍然面临一些挑战和问题。

首先,石墨烯的大规模生产和应用仍然存在技术门槛和成本限制。

其次,石墨烯的应用开发和商业化步伐较慢,需要进一步的市场推广和应用示范。

此外,石墨烯产业还需要加强与其他相关领域的协同创新,以满足实际应用需求。

展望未来,中国石墨烯的发展前景仍然广阔。

可以预见的是,随着石墨烯制备技术的不断成熟和改进,石墨烯将在能源、材料、电子、生物医药等诸多领域得到更广泛的应用。

同时,政府、企业和科研机构需要加强合作,共同推动石墨烯产业的发展,为我国经济转型升级和可持续发展做出更大的贡献。

总之,中国石墨烯的发展已经取得了令人瞩目的成就,但仍然面临一些挑战和机遇。

我们有理由相信,在多方共同努力下,中国石墨烯必将实现更大范围的应用和产业化,为我国科技创新和经济发展注入新的活力。

1.2 文章结构文章结构部分主要用来介绍整篇文章的组成和内容安排。

石墨烯发展历程

石墨烯发展历程石墨烯是一种由碳原子构成的二维晶体结构,具有极高的导电性、导热性和机械强度,被誉为“未来材料之王”。

石墨烯的发现和研究历程可以追溯到20世纪60年代,但直到2004年才被成功分离出来,随后引起了全球科学界的广泛关注和研究。

石墨烯的发现石墨烯的发现可以追溯到20世纪60年代,当时科学家们通过电子显微镜观察到了一种由碳原子构成的薄膜结构,但由于当时技术条件的限制,无法对其进行深入的研究和应用。

直到2004年,英国曼彻斯特大学的安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫成功地将石墨烯从石墨中分离出来,并发现了其独特的物理和化学性质,这一发现被誉为“二十一世纪最重要的科学发现之一”。

石墨烯的研究自石墨烯被发现以来,全球科学界对其进行了广泛的研究和探索。

研究表明,石墨烯具有极高的导电性、导热性和机械强度,可以应用于电子器件、传感器、储能材料等领域。

此外,石墨烯还具有良好的光学性质和化学稳定性,可以应用于光电器件、催化剂等领域。

石墨烯的应用随着石墨烯的研究不断深入,其应用领域也在不断扩展。

目前,石墨烯已经应用于电子器件、传感器、储能材料、光电器件、催化剂等领域。

其中,石墨烯在电子器件领域的应用最为广泛,可以用于制造高性能的晶体管、集成电路等器件。

此外,石墨烯还可以用于制造柔性电子器件,具有广阔的应用前景。

石墨烯的未来石墨烯作为一种具有广泛应用前景的新型材料,其未来发展前景十分广阔。

随着石墨烯的研究不断深入,其应用领域也将不断扩展。

未来,石墨烯有望应用于更多的领域,如生物医学、环境保护等领域。

此外,石墨烯的制备技术也将不断改进和完善,使其在工业化生产中得到更广泛的应用。

总结石墨烯的发现和研究历程可以追溯到20世纪60年代,但直到2004年才被成功分离出来。

自此以后,全球科学界对石墨烯进行了广泛的研究和探索,发现了其独特的物理和化学性质,并将其应用于电子器件、传感器、储能材料、光电器件、催化剂等领域。

石墨烯的发展历程

石墨烯的发展历程

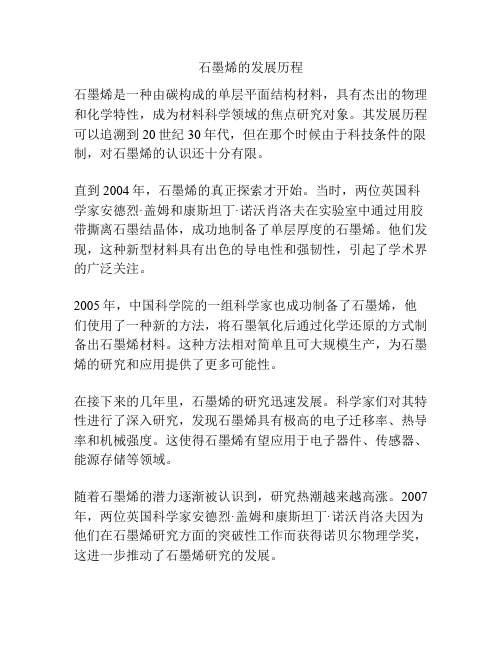

石墨烯是一种由碳构成的单层平面结构材料,具有杰出的物理和化学特性,成为材料科学领域的焦点研究对象。

其发展历程可以追溯到20世纪30年代,但在那个时候由于科技条件的限制,对石墨烯的认识还十分有限。

直到2004年,石墨烯的真正探索才开始。

当时,两位英国科学家安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫在实验室中通过用胶带撕离石墨结晶体,成功地制备了单层厚度的石墨烯。

他们发现,这种新型材料具有出色的导电性和强韧性,引起了学术界的广泛关注。

2005年,中国科学院的一组科学家也成功制备了石墨烯,他们使用了一种新的方法,将石墨氧化后通过化学还原的方式制备出石墨烯材料。

这种方法相对简单且可大规模生产,为石墨烯的研究和应用提供了更多可能性。

在接下来的几年里,石墨烯的研究迅速发展。

科学家们对其特性进行了深入研究,发现石墨烯具有极高的电子迁移率、热导率和机械强度。

这使得石墨烯有望应用于电子器件、传感器、能源存储等领域。

随着石墨烯的潜力逐渐被认识到,研究热潮越来越高涨。

2007年,两位英国科学家安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫因为他们在石墨烯研究方面的突破性工作而获得诺贝尔物理学奖,这进一步推动了石墨烯研究的发展。

如今,石墨烯的应用领域已经相当广泛。

除了科学研究领域外,石墨烯还已应用于可穿戴设备、柔性电子器件、环境监测等领域。

科学家们仍在不断研究、探索石墨烯的新特性和新应用,相信它将在未来的科技领域中发挥重要作用。

石墨烯发现的故事

石墨烯发现的故事

摘要:

一、石墨烯的发现背景

二、石墨烯的特性与应用

三、石墨烯发现的意义和前景

正文:

石墨烯是一种只有一个原子层厚的二维材料,具有令人惊叹的物理特性。

它的强度、导电性和透明度等都超越了其他材料。

这个神奇的材料的发现,开启了一个全新的科技时代。

石墨烯的发现源于对石墨的研究。

石墨是一种常见的碳的同素异形体,具有良好的导电性和热稳定性。

科学家们一直对石墨的导电机制感兴趣,希望找到一种能够解释这种现象的理论。

2004年,安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫成功地在实验中分离出单层石墨,并证实了石墨烯的存在。

这一发现为他们赢得了2010年诺贝尔物理学奖。

石墨烯的特性使其在众多领域具有广泛的应用前景。

首先,石墨烯是一种优秀的导电材料,可用于制造更高效的电子器件。

其高强度和柔韧性使其成为的理想材料,可用于制造柔性显示屏、太阳能电池板等。

此外,石墨烯的超高热导率使其在散热领域具有巨大的潜力。

石墨烯的发现对我国科技发展具有重要意义。

我国政府高度重视石墨烯产业的发展,将其列为战略性新兴产业。

目前,我国在石墨烯研究和应用方面取得了世界领先的成果。

例如,我国科学家成功研发出石墨烯电池,其充电速度

远超传统电池。

此外,石墨烯在医疗、能源、环保等领域也取得了显著的应用。

总之,石墨烯的发现开启了二维材料研究的新篇章。

它所带来的创新技术和应用前景无法估量。

石墨烯发现的故事

石墨烯发现的故事

石墨烯,一种只有一个原子层厚的二维材料,近年来在全球范围内备受关注。

其独特的光滑表面、高强度、导电性和超薄特性使其在科学研究和应用领域具有广泛的前景。

石墨烯的发现故事充满了传奇色彩,今天我们就来回顾一下这一重要的科学历程。

石墨烯的发现可以追溯到2004年,当时安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫成功实验制得石墨烯。

他们采用胶带剥离法制备出这种只有一个原子层厚的材料,这一突破性成果使他们荣获2010年诺贝尔物理学奖。

石墨烯的发现为全球科学家打开了一个全新的研究领域,激发了人们对二维材料的研究热情。

石墨烯的特性使其在众多领域具有广泛应用。

首先,石墨烯具有极高的强度和韧性,是目前已知强度最高的材料。

这一特性使其在航空航天、汽车制造等高强度结构件领域具有巨大潜力。

其次,石墨烯具有良好的导电性,可以应用于高性能电子器件的制造。

此外,石墨烯还具有优异的热传导性能,有望解决现代电子设备散热问题。

石墨烯的发现对于我国科技发展具有重要意义。

我国政府高度重视石墨烯产业的发展,将其列为战略性新兴产业。

近年来,我国石墨烯研究取得了世界领先的成果,推动了石墨烯材料的产业化进程。

在新能源、智能制造、生物医疗等领域,石墨烯的应用正在逐步改变我们的生活。

总之,石墨烯的发现不仅为科学研究提供了新的方向,也为我国科技发展带来了前所未有的机遇。

石墨烯的研究历史

石墨烯的研究历史石墨烯是一种由碳原子组成的二维材料,具有出色的物理和化学性质,因此引起了广泛的关注和研究。

本文将介绍石墨烯的研究历史。

石墨烯的发现石墨烯最早是由安德烈·赫姆(A.K. Geim)和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫(K.S. Novoselov)在2004年发现的。

他们使用的方法是利用普通的黏着带,将一些石墨片剥离成非常薄的层,最终得到了一片厚度仅为一个原子的石墨烯。

这项发现因为其高度的新颖性和创新性而获得了2010年的诺贝尔物理学奖。

石墨烯的早期研究石墨烯的发现以后,引起了极大的科学兴趣。

科学家们开始探究这种新型材料的特殊性质和实际应用。

最初,人们主要研究了其电子性质和力学性质。

在2005年,科学家就发现了石墨烯的电导率比银还高,并且在极低的温度下(约为4.2K),其电子运动方式也非常特殊。

此外,人们还发现,尽管石墨烯只有单层,但其刚度比钢还高,同时又具有弹性,展现出了无与伦比的物理特性。

石墨烯的应用研究在石墨烯的研究过程中,科学家们还开始考虑其实际应用。

石墨烯的高导电性能和更广泛的带隙,使其成为新一代电子器件(例如晶体管)的一个有很大潜力的替代品。

石墨烯的力学性质也使其成为用于航空和航天应用的强度材料。

此外,石墨烯的化学稳定性和高比表面积使其成为高效的电池、传感器和催化剂的备选材料。

石墨烯的世界研究热潮自石墨烯发现以来,世界各地的研究人员都投入了大量精力,对石墨烯进行了广泛的研究。

可以说,石墨烯研究的确是一个世界性的热潮。

科学家们不仅在探求石墨烯的性质和应用方面取得了许多重要的成果,还提出了许多新的想法和建议,为后来的石墨烯研究带来了深远的影响。

石墨烯的未来前景石墨烯的研究历史虽然还很短,但是石墨烯已经成为了一个重要的而又有很大前景的研究领域。

未来,科学家们将继续在石墨烯的性质和应用方面进行深入的研究,希望能够更好地利用石墨烯的出色特性,为我们的物质生活和科学研究带来更多的可能性。

石墨烯行业发展历程

石墨烯行业发展历程石墨烯是一种由碳原子构成的二维材料,具有出色的导电性、热导性和机械性能,被公认为是材料科学的突破性发现。

下面将简要介绍石墨烯行业发展历程。

石墨烯的发现源于2004年的一项重要科学研究。

英国曼彻斯特大学的科学家安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫等人在实验中使用胶带剥离法成功剥离出了最早的石墨烯薄片,并发现了石墨烯的独特性质。

这项研究成果于2004年发表在《科学》杂志上,引起了国际学术界的极大关注和热议,被认为是材料科学的重大突破。

自石墨烯发现后,全球范围内的科学家和工程师投入了大量的研究工作,以探索石墨烯的潜在应用领域。

石墨烯的导电性能使其在电子器件领域具有巨大的应用潜力。

石墨烯可以制备成柔性的薄膜电子器件,如柔性显示屏、柔性太阳能电池等。

石墨烯的高导热性也使其被广泛应用于热管理领域,如散热材料、高效热导材料等。

此外,石墨烯还具有优异的力学性能,可以用于制备轻量、高强度的材料,如复合材料、强化材料等。

在石墨烯的研究和应用过程中,科学家们面临了许多技术难题。

例如,如何大规模制备石墨烯薄片、如何控制石墨烯的结构和性质、如何将石墨烯与其他材料结合等。

经过多年的研究和探索,科学家们逐渐攻克了这些技术难题,并取得了一系列重要的科研成果。

随着石墨烯技术的不断进步,石墨烯产业逐渐开始崛起。

全球范围内涌现了大量的石墨烯技术企业和创业公司。

这些企业通过自主研发或技术引进,推动了石墨烯产业的快速发展。

目前,石墨烯已经得到了广泛应用。

石墨烯薄膜在电子、光电、能源等领域具有重要的应用前景。

石墨烯复合材料可以用于航空航天、汽车制造等高端领域。

此外,石墨烯还可以应用于生物医药领域,如石墨烯纳米药物传输系统、石墨烯生物传感器等。

然而,石墨烯产业的发展也面临一些挑战。

首先,石墨烯的制备工艺相对复杂,制备成本较高,限制了其规模化生产。

其次,石墨烯在某些应用领域的商业化进程较慢,市场需求尚未完全释放出来。

石墨烯 发现过程

石墨烯发现过程

摘要:

一、石墨烯的发现背景

二、石墨烯的发现过程

三、石墨烯的重要性和应用前景

正文:

石墨烯是一种由单层碳原子构成的二维材料,自2004年被发现以来,一直备受关注。

它的发现者是英国曼彻斯特大学的物理学家安德烈·海姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫,他们因为这一突破性的实验而共同获得了2010年的诺贝尔物理学奖。

石墨烯的发现过程颇具偶然性。

当时,海姆和诺沃肖洛夫在实验室中研究石墨的性质时,意外地发现了一种简单易行的新途径来制备石墨烯。

他们强行将石墨分离成较小的碎片,从碎片中剥离出较薄的石墨薄片,然后用普通的塑料胶带将薄片粘在金属箔上,最后撕开胶带,就能把石墨片一分为二。

这一方法使得单层石墨烯得以分离出来,从而证实了石墨烯可以单独存在。

石墨烯的重要性和应用前景非常广阔。

它是世上最薄也是最坚硬的纳米材料,具有很高的导电性和热导性。

石墨烯几乎是完全透明的,只吸收2.3%的光,因此它具有很好的光学性能。

这些优异的性能使得石墨烯在多个领域都有广泛的应用前景,如能源、催化、生物医药、复合材料等。

目前,石墨烯已经被广泛用于制备多功能分离膜、高导高强纤维、超轻超弹性气凝胶等多种功能材料,并且在电化学储能、催化、生物医药、复合材料等方面表现出良好的应

用前景。

总的来说,石墨烯的发现是一个充满偶然性的过程,但其背后是科学家们对石墨性质的长期研究和探索。

石墨烯制备

3、化学气相沉积法(CVD):将碳氢气体吸附于具有催化活性的非金属 或金属表面,通过加热使碳氢气体脱氢使其在衬底表面形成石墨烯结构。

三ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱCVD举例

利用甲烷作为碳源,铜箔作为衬底制备单层或多层石墨烯薄膜。石墨烯薄膜的面积 和质量主要受生长温度、甲烷碳源的浓度、生长时间的影响。

1. 生长温度的影响

生长温度在800-1000℃时都有石墨 烯生成,800℃时D峰较大,说明石 墨烯晶格缺陷较多,石墨烯数量较 少;随着温度的升高,D峰逐渐变小, 2D峰逐渐变强,说明石墨烯的质量 逐渐变好。

不同温度下所得石墨烯薄膜的Raman图谱

铜箔在800℃时生长的石墨烯薄膜SEM图

铜箔在1000℃时生长的石墨烯薄膜SEM图

2004年,英国曼彻斯特大学物理学家安德烈· 海姆(Andre Geim)和康斯坦丁· 诺沃 肖洛夫(Konstantin Novoselov),成功地在实验中从石墨中分离出石墨烯,而证 实它可以单独存在,两人也因“在二维石墨烯材料的开创性实验”,共同获得 2010年诺贝尔物理学奖。

二、石墨烯的制备方法

生长温度越高,石墨烯面积越大,均匀性越好,且在铜箔表面覆盖率更高

2. 生长时间的影响

随着生长时间的增加2D峰与G峰的 峰值比值降低,2D峰峰位红移,表 明石墨烯的层数随时间的延长而变 厚。

不同生长时间所得石墨烯的Raman图谱

2D峰对比

3. 甲烷浓度的影响

生长温度为1000℃时,不同甲烷浓度条件下石墨烯薄膜的拉曼光谱。随着甲烷浓度 的增加2D峰与G峰的比值减小,说明石墨烯的层数变厚。

石墨烯是由碳原子构成的单层片状结构新材料,厚度仅为一个碳原子,是目 前已知的世界上最薄的材料,也是迄今被证实的最坚硬的材料,其强度是钢的100 多倍。同时石墨烯也是已知材料中电子传导速率最快的材料,其还具有97.7%的透 光率,并具有优良的热导率。由于制备困难,目前石墨烯比黄金还贵15~20倍。

石墨烯技术发展史

石墨烯技术发展史石墨烯是一种由石墨片层组成的二维材料。

它具有许多独特的物理特性,如高的电导率、极薄的层厚度、高强度和超高的比表面积等。

自从2004年石墨烯首次被制备出来,这一领域的研究进展非常迅速,开发出了许多新的制备方法和应用领域。

下面将简要介绍石墨烯技术的发展史。

2004年,安德烈·海姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫通过机械削离的方法首次制备出了石墨烯。

他们用胶带从普通石墨中剥离出单层石墨烯,并通过电子显微镜证实了单层结构。

这一重大发现为石墨烯研究打下了基础,并在同年发表于《科学》杂志,成为新颖材料领域里的里程碑。

随着石墨烯的制备方法不断发展,石墨烯的应用领域也不断扩大。

2006年,路易斯·布拉格等人发明了一种新的制备方法,即化学气相沉积法(CVD)。

这种方法可以在大面积的基底上制备出石墨烯,因此非常适合于电子学、传感器和太阳能电池等领域的应用。

2009年,斯蒂芬·霍普金斯等人证实了石墨烯具有极高的电导率和强烈的电子色散。

这些特性使得石墨烯成为了新型的电子和光学器件材料的最佳选择,并引发了各种基于石墨烯的电子器件的研究。

除了电子学方面的应用外,石墨烯还具有很多其他应用领域。

2010年,瓦图·穆尔等人成功地将石墨烯应用于电池领域,制造出了石墨烯复合材料,这些材料具有较高的导电性和耐用性,可用于高性能电池的制造。

2012年,康奈尔大学研究团队成功地将石墨烯应用于滤水器领域。

他们发现,石墨烯膜具有极高的通量和选择性,可用于高效和环保的水处理技术的制造。

近年来,随着石墨烯的不断发展,石墨烯在能源、材料、生物医学等领域中的应用也越来越广泛。

人们相信,随着石墨烯技术不断的突破,它将在未来的许多领域中发挥更大的作用。

石墨烯

石墨烯石墨烯声明:百科词条人人可编辑,词条创建和修改均免费,绝不存在官方及代理商付费代编,请勿上当受骗。

详情>> 石墨烯(二维碳材料)编辑本词条由“科普中国”百科科学词条编写与应用工作项目审核。

石墨烯(Graphene)是一种由碳原子以sp2杂化方式形成的蜂窝状平面薄膜,是一种只有一个原子层厚度的准二维材料,所以又叫做单原子层石墨。

英国曼彻斯特大学物理学家安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫,用微机械剥离法成功从石墨中分离出石墨烯,因此共同获得2010年诺贝尔物理学奖。

石墨烯常见的粉体生产的方法为机械剥离法、氧化还原法、SiC外延生长法,薄膜生产方法为化学气相沉积法(CVD)。

[1] 由于其十分良好的强度、柔韧、导电、导热、光学特性,在物理学、材料学、电子信息、计算机、航空航天等领域都得到了长足的发展。

作为目前发现的最薄、强度最大、导电导热性能最强的一种新型纳米材料,石墨烯被称为“黑金”,是“新材料之王”,科学家甚至预言石墨烯将“彻底改变21世纪”。

极有可能掀起一场席卷全球的颠覆性新技术新产业革命。

中文名石墨烯外文名Graphene 发现时间2004年主要制备方法机械剥离法、气相沉积法、氧化还原法、SiC外延法主要分类单层、双层、少层、多层(厚层)基本特性强度柔韧性、导热导电、光学性质应用领域物理、材料、电子信息、计算机等目录1 研究历史2 理化性质? 物理性质? 化学性质3 制备方法? 粉体生产方法? 薄膜生产方法4 主要分类? 单层石墨烯? 双层石墨烯? 少层石墨烯? 多层石墨烯5 主要应用? 基础研究? 晶体管? 柔性显示屏? 新能源电池? 航空航天? 感光元件? 复合材料6 发展前景? 中国? 美国? 欧洲? 韩国? 西班牙? 日本研究历史编辑实际上石墨烯本来就存在于自然界,只是难以剥离出单层结构。

石墨烯一层层叠起来就是石墨,厚1毫米的石墨大约包含300万层石墨烯。

石墨烯发展历程

石墨烯发展历程石墨烯是一种由碳原子构成的二维蜂窝状晶格结构的材料。

它的发展历程可以追溯到2004年,当时两位科学家安德烈·海姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫在使用普通胶带剥离石墨时发现了这种材料。

在他们进行实验时,他们注意到普通胶带从石墨表面剥离时形成了非常薄的薄膜。

通过进一步的研究,他们发现这些薄膜是由一个原子层的石墨组成,这就是后来被称为石墨烯的材料。

他们的发现在科学界引起了巨大的轰动,因为石墨烯具有许多独特的性质。

它是一个单层的纳米材料,但非常坚固和耐热。

石墨烯的电导率很高,且能够承受非常高的电流密度。

此外,石墨烯还具有优异的光学性质,对于光的吸收和发射具有高效率。

从2004年开始,石墨烯的研究就迅速发展起来。

科学家们开始研究如何大规模制备石墨烯,并发现了一种称为化学气相沉积的方法。

这种方法将碳气体在高温下沉积在基底上,形成石墨烯薄膜。

这种方法可以实现大规模生产,并且薄膜的质量相对较高。

随着对石墨烯的研究不断深入,科学家们发现了更多的应用潜力。

石墨烯被用于制造超级电容器、柔性电子器件和导热材料等。

它还可以用作传感器、催化剂和给药系统等。

虽然石墨烯有很多独特的性质和应用潜力,但要将其应用到实际中仍然面临一些挑战。

其中之一是大规模制备的问题,目前还没有实现低成本高质量的生产方法。

此外,石墨烯的集成和封装也是一个挑战,这对于将其应用到电子器件中非常重要。

鉴于石墨烯的独特性质和应用潜力,科学家们对其进行的研究仍在不断发展。

未来,有望看到更多的石墨烯应用于电子、能源和生物医学领域,并带来革命性的变化。

石墨烯的发展、结构及性能简介

石墨烯的发展、结构及性能简介一、石墨烯的发展1934年,朗道和佩尔斯就指出了准二维晶体材料由于其自身的热力学不稳定,在常温常压下会迅速分解。

菲利普·华莱士1947年就开始研究石墨烯的电子结构。

麦克鲁1956年推导出了相应的波函数方程,林纳斯·鲍林1960年曾质疑过石墨烯的导电性。

1966年,大卫·莫明和赫伯特·瓦格纳提出Mermin-Wagner理论,指出表面起伏会破坏二维晶体的长程有序。

谢米诺夫1984年得出与波函数方程类型的狄拉克方程。

直到1987年,穆拉斯才首次使用“graphene”这个名称来指定石墨稀。

2004年,英国曼彻斯特大学物理学家安德烈·海姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫,从石墨中成功分离出石墨烯,而他们分离的方法也极为简单,他们把石墨薄片粘在胶带上,把有粘性的一面对折,再把胶带撕开,这样石墨薄片就被一分为二。

通过不断地重复这个过程,片状石墨越来越薄,最终就可以得到一定数量的石墨烯,从而证实石墨烯可以单独存在,两人也因“在二维石墨烯材料的开创性实验”共同获得2010年诺贝尔物理学奖。

十余年来,各国科研人员针对石墨烯开展了大量研究工作,试图研制出高效、可控的制备石墨烯纳米带的技术工艺。

基于法国SOLEIL同步加速器X射线等实验的研究成果,法美科学团队成功研制出一种用于生产石墨烯纳米带半导体的方法。

科研人员在碳化硅表面刻蚀凹槽,并以此作为基板,通过控制基板的几何形状,在其上形成仅有几纳米宽的石墨烯纳米带。

该项技术可在常温下进行,其制备的石墨烯半导体仅为此前IBM公司所制纳米带的五分之一宽。

该技术可高效、可控地制备石墨烯半导体,为石墨烯规模化工业生产带来可能,同时也使新一代高密度集成电路的制备不再遥不可及。

二、石墨烯的结构石墨稀是由碳六元环组成的两维周期蜂窝状点阵结构,它可以翘曲成零维的富勒稀,卷成一维的碳纳米管或者堆垛成三维的石墨,因此石墨稀是构成其他石墨材料的基元。

石墨烯发现的故事

石墨烯发现的故事

摘要:

1.石墨烯的发现背景

2.石墨烯的发现过程

3.石墨烯的独特性质

4.石墨烯的应用前景

5.石墨烯在我国的研究进展

正文:

石墨烯是一种由单层碳原子构成的二维材料,其发现源于英国曼彻斯特大学物理学家安德烈·盖姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫的一次实验。

他们使用胶带剥离法制备出单层石墨烯,并因此获得了2010 年诺贝尔物理学奖。

石墨烯的发现过程并不容易,两位科学家经过多次尝试,最终成功剥离出单层石墨烯。

这一突破性成果使他们能够对石墨烯的独特性质进行研究。

石墨烯具有许多独特的性质,如高强度、高导电性、透明性和柔韧性等,这使得它在许多领域都有广泛的应用前景。

石墨烯的应用前景非常广阔,包括柔性显示器、高速计算机、新型电池、传感器等。

石墨烯的高强度和柔韧性使其在制造柔性电子产品方面具有巨大潜力。

此外,石墨烯的高导电性也有助于提高计算机的运行速度。

在我国,石墨烯研究取得了显著进展。

政府高度重视石墨烯产业发展,出台了一系列政策和措施支持石墨烯研究。

我国石墨烯产业逐渐形成了从原材料、制备、应用到终端产品的完整产业链。

此外,我国在石墨烯基超级电容

器、石墨烯散热材料、石墨烯改性沥青等领域取得了重要突破。

总之,石墨烯的发现是一个充满挑战和惊喜的过程。

作为一种具有巨大潜力的二维材料,石墨烯将为人类社会带来许多创新和变革。

石墨烯的研究进展及应用前景概述

石墨烯的研究进展及应用前景概述石墨烯是一种由碳原子构成的单层二维晶体结构,在2004年被诺贝尔物理学奖得主安德烈·海姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫首次成功制备出来。

石墨烯具有出色的电子、热传导性能和机械强度,以及在纳米尺度下的光学性质,因此被认为是一种拥有广泛应用前景的材料。

1.制备技术:最早的石墨烯制备技术是机械剥离法,通过对石墨晶体进行力学剥离,得到石墨烯。

随后,还出现了化学气相沉积法、还原氧化石墨烯法、剥离法等制备方法,使得石墨烯的制备更为成熟和可控。

2.物性研究:石墨烯具有极高的电子迁移率和热导率,以及优异的光学特性。

研究者们通过实验和模拟等手段,深入探究了石墨烯的电子结构、光学性质和热传导机制,为进一步的应用开发奠定了基础。

3.功能化研究:为了进一步拓展石墨烯的应用领域,研究者们对石墨烯进行了各种功能化改性,如在石墨烯上引入杂原子或对石墨烯进行掺杂,以实现特定的电子、磁学或光学性质。

石墨烯的应用前景广阔,以下是几个重要领域的应用概述:1.电子学:由于石墨烯独特的电子特性,可应用于高速电子器件、柔性显示器件和传感器等领域。

石墨烯晶体管的特性使其成为下一代电子器件的理想候选材料。

2.光学与光电子学:石墨烯具有宽带吸收和强光学非线性特性,在传感器、光电转换器和光电子器件等领域有着重要应用。

石墨烯的光电转换效率高,可用于太阳能电池的制备。

3.储能技术:石墨烯的高比表面积和优异的电化学性能使其成为超级电容器和锂离子电池等储能设备的理想材料。

石墨烯的应用能够提高储能设备的能量密度和循环稳定性。

4.测量和传感:石墨烯对外界环境的微小变化非常敏感,因此可用于高灵敏度的传感器和检测器。

石墨烯传感器在气体传感、流体传感和生物传感等领域有着广泛的应用潜力。

5.材料增强:添加石墨烯可以显著提高材料的机械强度和导热性能,可应用于制备高强度复合材料和导热材料。

石墨烯的应用使得材料的性能得到大幅度提升。

石墨烯发展史

石墨烯发展史

石墨烯是一种由碳原子构成的二维材料,具有出色的导电性、热导性和力学性能。

以下是石墨烯发展的主要历程:

1947年:

•基础石墨烯概念首次出现在《The Chemistry of Graphene》一书中,但当时并未引起广泛注意。

1986年:

•石墨烯的基本结构被苏联物理学家Andrey Geim和Konstantin Novoselov首次绘制,但并没有引起广泛关注。

2004年:

•Geim和Novoselov再次在它们的实验中分离出石墨烯,并通过在硅衬底上用普通胶带剥离石墨层的方法,成功地制备了单层

石墨烯。

他们的研究发表在《Science》杂志上,引起了科学界

的广泛关注。

2005年:

•Geim和Novoselov因在石墨烯研究方面的贡献而获得诺贝尔物理学奖。

这一时刻被认为是石墨烯领域的重要突破。

2006年:

•美国科学家成功合成出石墨烯纳米带(graphene nanoribbons),这是一种石墨烯的窄条形结构,具有特殊的电学性质。

2008年:

•科学家首次在石墨烯上制造出晶体管,这一技术为未来的电子

器件提供了潜在应用。

2010年:

•石墨烯的研究逐渐扩展到其他领域,如光学、生物医学、能源存储等。

2014年:

•石墨烯领域的商业化逐渐加速,各种石墨烯应用产品开始进入市场。

未来:

•石墨烯仍然是一个活跃的研究领域,科学家们正在探索更多潜在的应用,并努力解决在大规模生产和应用中面临的挑战。

总体而言,石墨烯的发展历程表明它是一种具有巨大潜力的材料,有望在未来改变许多领域的技术和产业。

石墨烯的发展历程

石墨烯的发展历程石墨烯是一种由碳原子组成的单层二维晶体结构,具有超强的导电性、热导性和机械性能,以及出色的光学和电子特性。

石墨烯的发展历程可以追溯到20世纪40年代早期,当时科学家们首次理论上预测了石墨烯的存在。

然而,由于缺乏实验证据和制备方法,直到最近几十年才有了石墨烯的真正突破。

石墨烯的实验发现可以追溯到2004年,由英国曼彻斯特大学的安德烈·海姆和康斯坦丁·诺沃肖洛夫等科学家发现。

他们使用一种简单的“黏性带状法”制备出了石墨烯。

通过将碳原子从石墨晶体中剥离出来,他们成功地获得了具有二维结构的石墨烯材料,并在实验中发现了它的独特性质。

随着石墨烯的发现,科学家们开始对其进行深入研究。

在随后的几年里,他们进一步发展了一系列制备石墨烯的方法,包括机械剥离法、化学还原法和化学气相沉积法等。

这些方法极大地推动了石墨烯的研究和应用领域的发展。

石墨烯的发展历程中还面临了许多挑战和困难。

首先,石墨烯的单层结构非常难以制备和稳定,容易在制备过程中出现损伤和结构缺陷。

其次,长期以来,科学家们一直没有找到一种有效的方法来大规模制备石墨烯材料。

这对于实际应用来说是一个巨大的障碍。

然而,随着时间的推移,科学家们逐渐克服了这些困难。

他们发展出了一系列新的制备方法和处理技术,使得石墨烯的质量和稳定性得到了极大的提高。

同时,科学家们还发现了石墨烯的许多新特性和应用领域。

石墨烯的发展也引起了广泛的关注和兴趣。

它被认为是一种具有广阔应用前景的新材料,可以应用于电子、光电、能源存储和传感器等领域。

石墨烯的独特性能使得它成为了科学界和工业界的研究热点。

在未来,石墨烯的发展仍将面临许多挑战和困难。

科学家们需要进一步了解石墨烯的物理和化学性质,寻找新的应用领域,并开发更有效的制备和处理方法。

同时,科学家们也需要考虑石墨烯的环境和安全性问题,以确保其可持续发展和应用。

总之,石墨烯的发展历程经历了多年的努力和研究。

石墨烯的发现和研究为科学界带来了许多新的发现和突破,在许多领域都具有广阔的应用前景。

石墨烯综述

石墨烯综述概要:自2004年石墨烯横空出世,便引起全世界科学家的关注。

随着研究的一步步深入,石墨烯的各项有点更是引起世界的惊叹。

第一次成功制备出石墨烯的两位科学家安德烈·K·海姆和康斯坦丁·沃肖洛夫也在2010年夺得诺贝尔物理学奖。

本文从石墨烯的发现,结构,特性,制备及应用几个方面出发,对石墨烯做了一次比较简单,全面的综述。

关键字:石墨烯,发现,结构,特性,制备,应用一,发现及研究进展斯哥尔摩2010年10月5日电瑞典皇家科学院5日宣布,将2010年诺贝尔物理学奖授予英国曼彻斯特大学科学家安德烈·K·海姆和康斯坦丁·沃肖洛夫,以表彰他们在石墨烯材料方面的卓越研究。

2004年,英国曼彻斯特大学的安德烈·K·海姆(Andre K. Geim)等利用胶带法制备出了石墨烯。

一问世,就受到广泛关注,对石墨烯的研究也越来越深入,石墨烯独特的碳二维结构,优越的性能,广泛的应用前景更是吸引了全世界科学家的目光。

可以说自2004年石墨烯横空出世,便轰动了整个世界,引起了全世界的研究热潮。

如今已过去五年,对石墨烯的研究热度却依然不减。

在短短的五年时间内,仅在Nature 和Science 上发表的与石墨烯相关的科研论文就达40 余篇。

新闻发布会上,美联社记者问及石墨烯的应用前景,海姆回答,他无法作具体预测,但以塑料作比,推断石墨烯“有改变人们生活的潜力”。

二,石墨烯的结构石墨是三维(或立体)的层状结构,石墨晶体中层与层之间相隔340pm,距离较大,是以范德华力结合起来的,即层与层之间属于分子晶体。

但是,由于同一平面层上的碳原子间结合很强,极难破坏,所以石墨的溶点也很高,化学性质也稳定,其中一层就是石墨烯。

石墨烯是由单层碳原子组成的六方蜂巢状二维结构,即石墨烯是一种从石墨材料中剥离出的单层碳原子面材料,是碳的二维结构。

这种石墨晶体薄膜的厚度只有0.335纳米,把20万片薄膜叠加到一起,也只有一根头发丝那么厚。

石墨烯的发现与发展

石墨烯的发现与发展摘要:2004 年,石墨烯横空出世,轰动世界。

如今已过去五年,对石墨烯的研究热度依然不减。

本文诣在回顾石墨烯的发现与发展,论述石墨烯目前面临的机遇与挑战,并展望石墨烯有可能带给我们的更加光明的未来关键词:石墨烯,电子迁移率,能隙,晶体管,非电子效应,功能化一、石墨烯的发现关于石墨烯存在的可能性,科学界一直有争论。

早在1934年,Peierls就提出准二维晶体材料由于其本身的热力学不稳定性,在室温环境下会迅速分解或拆解。

1966年,Mermin和Wagner提出Mermin-Wagner理论,指出长的波长起伏也会使长程有序的二维晶体受到破坏。

因此二维晶体石墨烯只是作为研究碳质材料的理论模型,一直未受到广泛关注。

直到2004年,来自曼彻斯特大学的Andre Geim和Konstantin Novoselov 首次成功分离出稳定的石墨烯,而他们分离的方法也极为简单,他们把石墨薄片粘在胶带上,把有粘性的一面对折,再把胶带撕开, 这样石墨薄片就被一分为二。

通过不断地重复这个过程,片状石墨越来越薄, 最[1,2,3]终就可以得到一定数量的石墨烯。

二、石墨烯的结构理想的石墨烯结构是平面六边形点阵,可以看作是一层被剥离 2的石墨分子,每个碳原子均为sp 杂化,并贡献剩余一个p轨道上的电子形成大π键,π电子可以自由移动,赋予石墨烯良好的导电性。

[1]二维石墨烯结构可以看是形成所有sp2杂化碳质材料的基本组成单元图。

例如,石墨可以看成是多层石墨烯片堆垛而成,而前面介绍过的碳纳米管可以看作是卷成圆筒状的石墨烯。

当石墨烯的晶格中存在五元环的晶格时,石墨烯片会发生翘曲,富勒球可以便看成通过多个六元环和五元环按照适当顺序排列得到的。

实际中的石墨烯并不能有如此完美的晶形。

2007年, J. C. Meyer等人在TEM中利用电子衍射对Graphene进行研究时, 发现了一个有趣的现象:当电子束偏离Graphene表面法线方向入射时, 可以观察到样品的衍射斑点随着入射角的增大而不断展宽。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

RANDOM WALK TO GRAPHENENobel Lecture, December 8, 2010byANDRE K. GEIMSchool of Phys i cs and Astronomy, The Un i vers i ty of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, Un i ted K i ngdom.If one wants to understand the beaut i ful phys i cs of graphene, they w i ll be spo i led for cho i ce w i th so many rev i ews and popular sc i ence art i cles now ava i lable. I hope that the reader w i ll excuse me i f on th i s occas i on I recommend my own wr i t i ngs [1–3]. Instead of repeat i ng myself here, I have chosen to descr i be my tw i sty sc i ent ific road that eventually led to the Nobel Pr i ze. Most parts of th i s story are not descr i bed anywhere else, and i ts t i me-l i ne covers the per i od from my PhD i n 1987 to the moment when our 2004 paper, recogn i sed by the Nobel Comm i ttee, was accepted for publ i cat i on. The story naturally gets denser i n events and explanat i ons towards the end. Also, i t prov i des a deta i led rev i ew of pre-2004 l i terature and, w i th the benefit of h i nds i ght, attempts to analyse why graphene has attracted so much i nter-est. I have tr i ed my best to make th i s art i cle not only i nformat i ve but also easy to read, even for non-phys i c i sts.ZOMBIE MANAGEMENTMy PhD thes i s was called “Invest i gat i on of mechan i sms of transport relaxa-t i on i n metals by a hel i con resonance method”. All I can say i s that the stuff was as i nterest i ng at that t i me as i t sounds to the reader today. I publ i shed five journal papers and fin i shed the thes i s i n five years, the offic i al durat i on for a PhD at my i nst i tut i on, the Inst i tute of Sol i d State Phys i cs.Web of Sc i ence so-berly reveals that the papers were c i ted tw i ce, by co-authors only. The subject was dead a decade before I even started my PhD. However, every cloud has i ts s i lver l i n i ng, and what I un i quely learned from that exper i ence was that I should never torture research students by offer i ng them “zomb i e” projects. After my PhD, I worked as a staff sc i ent i st at the Inst i tute of M i cro-electron i cs Technology, Chernogolovka, wh i ch belongs to the Russ i an Academy of Sc i ences. The Sov i et system allowed and even encouraged jun i or staff to choose the i r own l i ne of research. After a year of pok i ng i n d i fferent d i rect i ons, I separated research-w i se from my former PhD superv i sor, V i ctor Petrashov, and started develop i ng my own n i che. It was an exper i mental system that was both new and doable, wh i ch was nearly an oxymoron, tak i ng i nto account the scarce resources ava i lable at the t i me at Sov i et researchi nst i tutes. I fabr i cated a sandw i ch cons i st i ng of a th i n metal film and a super-conductor separated by a th i n i nsulator. The superconductor served only to condense an external magnet i c field i nto an array of vort i ces, and th i s h i ghly i nhomogeneous magnet i c field was projected onto the film under i nvest i ga-t i on. Electron transport i n such a m i croscop i cally i nhomogeneous field (vary i ng on a subm i cron scale) was new research terr i tory, and I publ i shed the first exper i mental report on the subject [4], wh i ch was closely followed by an i ndependent paper from S i mon Bend i ng [5]. It was an i nterest i ng and reasonably i mportant n i che, and I cont i nued study i ng the subject for the next few years, i nclud i ng a spell at the Un i vers i ty of Bath i n 1991 as a postdoctoral researcher work i ng w i th S i mon.Th i s exper i ence taught me an i mportant lesson: that i ntroduc i ng a new exper i mental system i s generally more reward i ng than try i ng to find new phenomena w i th i n crowded areas. The chances of success are much h i gher where the field i s new. Of course, the fantast i c results one or i g i nally hopes for are unl i kely to mater i al i se, but, i n the process of study i ng any new system, someth i ng or i g i nal i nev i tably shows up.ONE MAN’S JUNK, ANOTHER MAN’S GOLDIn 1990, thanks to V i taly Ar i stov, d i rector of my Inst i tute i n Chernogolovka at the t i me, I rece i ved a s i x month v i s i t i ng fellowsh i p from the Br i t i sh Royal Soc i ety. Laurence Eaves and Peter Ma i n from Nott i ngham Un i vers i ty k i ndly agreed to accept me as a v i s i tor. S i x months i s a very short per i od for exper i mental work, and c i rcumstances d i ctated that I could only study de-v i ces read i ly ava i lable i n the host laboratory. Ava i lable were subm i cron GaAs w i res left over from prev i ous exper i ments, all done and dusted a few years earl i er. Under the c i rcumstances, my exper i ence of work i ng i n a poverty-str i cken Sov i et academy was helpful. The samples that my hosts cons i dered pract i cally exhausted looked l i ke a gold ve i n to me, and I started work i ng 100 hours per week to explo i t i t. Th i s short v i s i t led to two Phys. Rev. Letters of decent qual i ty [6,7], and I often use th i s exper i ence to tease my younger colleagues. When th i ngs do not go as planned and people start compla i n i ng, I provoke them by procla i m i ng ‘there i s no such th i ng as bad samples; there are only bad postdocs/students’. Search carefully and you w i ll always find someth i ng new. Of course, i t i s better to avo i d such exper i ences and explore new terr i tor i es, but even i f one i s fortunate enough to find an exper i mental system as new and exc i t i ng as graphene, met i culousness and perseverance allow one to progress much further.The pace of research at Nott i ngham was so relentless and, at the same t i me so i nsp i r i ng, that a return to Russ i a was not an opt i on. Sw i mm i ng through Sov i et treacle seemed no less than wast i ng the rest of my l i fe. So at the age of th i rty-three and w i th an h-i ndex of 1 (latest papers not yet publ i shed), I entered the Western job market for postdocs. Dur i ng the next four years I moved between d i fferent un i vers i t i es, from Nott i ngham to Copenhagen to Bath and back to Nott i ngham. Each move allowed me to get acqua i nted w i thyet another top i c or two, s i gn ificantly broaden i ng my research hor i zons. The phys i cs I stud i ed i n those years could be broadly descr i bed as mesoscop i c and i nvolved such systems and phenomena as two-d i mens i onal electron gases (2DEGs), quantum po i nt contacts, resonant tunnell i ng and the quantum Hall effect (QHE), to name but a few. In add i t i on, I became fam i l i ar w i th GaAlAs heterostructures grown by molecular beam ep i taxy (MBE) and i mproved my expert i se i n m i crofabr i cat i on and electron-beam l i thography, technolog i es I had started learn i ng i n Russ i a. All these elements came together to form the foundat i on for the successful work on graphene a decade later.DUTCH COMFORTBy 1994 I had publ i shed enough qual i ty papers and attended enough con-ferences to hope for a permanent academ i c pos i t i on. When I was offered an assoc i ate professorsh i p at the Un i vers i ty of N i jmegen, I i nstantly se i zed upon the chance of hav i ng some secur i ty i n my new post-Sov i et l i fe. The first task i n N i jmegen was of course to establ i sh myself. To th i s end, there was no start-up and no m i crofabr i cat i on to cont i nue any of my prev i ous l i nes of re-search. As resources, I was offered access to magnets, cryostats and electron i c equ i pment ava i lable at N i jmegen’s H i gh F i eld Magnet Laboratory, led by Jan Kees Maan. He was also my formal boss and i n charge of all the money. Even when I was awarded grants as the pr i nc i pal i nvest i gator (the Dutch fund i ng agency FOM was generous dur i ng my stay i n N i jmegen), I could not spend the money as I w i shed. All funds were d i str i buted through so-called ‘work i ng groups’ led by full professors. In add i t i on, PhD students i n the Netherlands could formally be superv i sed only by full professors. Although th i s probably sounds strange to many, th i s was the Dutch academ i c system of the 1990s. It was tough for me then. For a couple of years, I really struggled to adjust to the system, wh i ch was such a contrast to my joyful and product i ve years at Nott i ngham. In add i t i on, the s i tuat i on was a b i t surreal because outs i de the un i vers i ty walls I rece i ved a warm-hearted welcome from everyone around, i nclud i ng Jan Kees and other academ i cs.St i ll, the research opportun i t i es i n N i jmegen were much better than i n Russ i a and, eventually, I managed to surv i ve sc i ent ifically, thanks to help from abroad. Nott i ngham colleagues (i n part i cular Mohamed Hen i n i) prov i ded me w i th 2DEGs that were sent to Chernogolovka, where Sergey Dubonos, a close colleague and fr i end from the 1980s, m i crofabr i cated requested dev i ces. The research top i c I eventually found and later focused on can be referred to as mesoscop i c superconduct i v i ty. Sergey and I used m i cron-s i zed Hall bars made from a 2DEG as local probes of the magnet i c field around small superconduct i ng samples. Th i s allowed measurements of the i r magnet i sat i on w i th accuracy suffic i ent to detect not only the entry and ex i t of i nd i v i dual vort i ces but also much more subtle changes. Th i s was a new exper i mental n i che, made poss i ble by the development of an or i g i nal techn i que of ball i st i c Hall m i cromagnetometry [8]. Dur i ng the next fewyears, we explo i ted th i s n i che area and publ i shed several papers i n Nature and Phys. Rev. Letters wh i ch reported a paramagnet i c Me i ssner effect, vort i ces carry i ng fract i onal flux, vortex configurat i ons i n confined geometr i es and so on. My w i fe Ir i na Gr i gor i eva, an expert i n vortex phys i cs [9], could not find a job i n the Netherlands and therefore had plenty of t i me to help me w i th conquer i ng the subject and wr i t i ng papers. Also, Sergey not only made the dev i ces but also v i s i ted N i jmegen to help w i th measurements. We establ i shed a very product i ve modus operand i where he collected data and I analysed them w i th i n an hour on my computer next door to dec i de what should be done next.A SPELL OF LEVITYThe first results on mesoscop i c superconduct i v i ty started emerg i ng i n 1996, wh i ch made me feel safer w i th i n the Dutch system and also more i nqu i s i-t i ve. I started look i ng around for new areas to explore. The major fac i l i ty at N i jmegen’s H i gh F i eld Lab was powerful electromagnets. They were a major headache, too. These magnets could prov i de fields up to 20 T, wh i ch was somewhat h i gher than 16 to 18 T ava i lable w i th the superconduct i ng magnets that many of our compet i tors had. On the other hand, the elec-tromagnets were so expens i ve to run that we could use them only for a few hours at n i ght, when electr i c i ty was cheaper. My work on mesoscop i c super-conduct i v i ty requ i red only t i ny fields (< 0.01T), and I d i d not use the electro-magnets. Th i s made me feel gu i lty as well as respons i ble for com i ng up w i th exper i ments that would just i fy the fac i l i ty’s ex i stence. The only compet i t i ve edge I could see i n the electromagnets was the i r room temperature (T) bore. Th i s was often cons i dered as an extra d i sadvantage because research i n condensed matter phys i cs typ i cally requ i res low, l i qu i d-hel i um T. The con-trad i ct i on prompted me, as well as other researchers work i ng i n the lab, to ponder on h i gh-field phenomena at room T. Unfortunately, there were few to choose from.Eventually, I stumbled across the mystery of so-called magnet i c water. It i s cla i med that putt i ng a small magnet around a hot water p i pe prevents format i on of scale i ns i de the p i pe. Or i nstall such a magnet on a water tap, and your kettle w i ll never suffer from chalky depos i ts. These magnets are ava i lable i n a great var i ety i n many shops and on the i nternet. There are also hundreds of art i cles wr i tten on th i s phenomenon, but the phys i cs beh i nd i t rema i ns unclear, and many researchers are scept i cal about the very ex i stence of the effect [10]. Over the last fifteen years I have made several attempts to i nvest i gate “magnet i c water” but they were i nconclus i ve, and I st i ll have noth i ng to add to the argument. However, the ava i lab i l i ty of ultra-h i gh fields i n a room T env i ronment i nv i ted lateral th i nk i ng about water. Bas i cally, i f magnet i c water ex i sted, I thought, then the effect should be clearer i n 20 T rather than i n typ i cal fields of <0.1 T created by standard magnets.W i th th i s i dea i n m i nd and, allegedly, on a Fr i day n i ght, I poured water i ns i de the lab’s electromagnet when i t was at i ts max i mum power. Pour i ngwater i n one's equ i pment i s certa i nly not a standard sc i ent ific approach, and I cannot recall why I behaved so ‘unprofess i onally’. Apparently, no one had tr i ed such a s i lly th i ng before, although s i m i lar fac i l i t i es ex i sted i n several places around the world for decades. To my surpr i se, water d i d not end up on the floor but got stuck i n the vert i cal bore of the magnet. Humberto Carmona, a v i s i t i ng student from Nott i ngham, and I played for an hour w i th the water by break i ng the blockage w i th a wooden st i ck and chang i ng the field strength. As a result, we saw balls of lev i tat i ng water (F i gure 1). Th i s was awesome. It took l i ttle t i me to real i se that the phys i cs beh i nd was good old d i amagnet i sm. It took much longer to adjust my i ntu i t i on to the fact that the feeble magnet i c response of water (~10–5), b i ll i ons of t i mes weaker than that of i ron, was suffic i ent to compensate the earth’s grav i ty. Many colleagues, i nclud i ng those who worked w i th h i gh magnet i c fields all the i r l i ves, were flabbergasted, and some of them even argued that th i s was a hoax.I spent the next few months demonstrat i ng magnet i c lev i tat i on to colleagues and v i s i tors, as well as try i ng to make a ‘non-boffin’i llustrat i on for th i s beaut i ful phenomenon. Out of the many objects that we had float i ng i ns i de the magnet, i t was the i mage of a lev i tat i ng frog (F i gure 1) that started the med i a hype. More i mportantly, though, beh i nd all the med i a no i se, th i s i mage found i ts way i nto many textbooks. However qu i rky, i t has become a beaut i ful symbol of ever-present d i amagnet i sm, wh i ch i s no longer perce i ved to be extremely feeble. Somet i mes I am stopped at conferences by people excla i m i ng “I know you! Sorry, i t i s not about graphene. I start my lectures w i th show i ng your frog. Students always want to learn how i t could fly.” The frog story, w i th some i ntr i cate phys i cs beh i nd the stab i l i ty of d i amagnet i c lev i tat i on, i s descr i bed i n my rev i ew i n Phys i cs Today [11].F i gure 1. Lev i tat i ng moments i n N i jmegen. Left – Ball of water (about 5 cm i n d i ameter) freely floats i ns i de the vert i cal bore of an electromagnet. R i ght – The frog that learned to fly. Th i s i mage cont i nues to serve as a symbol show i ng that magnet i sm of ‘nonmagnet i c th i ngs’, i nclud i ng humans, i s not so negl i g i ble. Th i s exper i ment earned M i chael Berry and me the 2000 Ig Nobel Pr i ze. We were asked first whether we dared to accept th i s pr i ze, and I take pr i de i n our sense of humour and self-deprecat i on that we d i d.FRIDAY NIGHT EXPERIMENTSThe lev i tat i on exper i ence was both i nterest i ng and add i ct i ve. It taught me the i mportant lesson that pok i ng i n d i rect i ons far away from my i mmed i ate area of expert i se could lead to i nterest i ng results, even i f the i n i t i al i deas were extremely bas i c. Th i s i n turn i nfluenced my research style, as I started mak i ng s i m i lar exploratory detours that somehow acqu i red the name ‘Fr i day n i ght exper i ments’. The term i s of course i naccurate. No ser i ous work can be accompl i shed i n just one n i ght. It usually requ i res many months of lateral th i nk i ng and d i gg i ng through i rrelevant l i terature w i thout any clear i dea i n s i ght. Eventually, you get a feel i ng – rather than an i dea – about what could be i nterest i ng to explore. Next, you g i ve i t a try, and normally you fa i l. Then, you may or may not try aga i n. In any case, at some moment you must dec i de (and th i s i s the most d i fficult part) whether to cont i nue further efforts or cut losses and start th i nk i ng of another exper i ment. All th i s happens aga i nst the backdrop of your ma i n research and occup i es only a small part of your t i me and bra i n.Already i n N i jmegen, I started us i ng lateral i deas as under- and post-graduate projects, and students were always exc i ted to buy a p i g i n a poke. Kostya Novoselov, who came to N i jmegen as a PhD student i n 1999, took part i n many of these projects. They never lasted for more than a few months, i n order not to jeopard i se a thes i s or career progress i on. Although the enthus i asm i nev i tably van i shed towards the end, when the pred i ctable fa i lures mater i al i sed, some students later confided that those exploratory detours were i nvaluable exper i ences.Most surpr i s i ngly, fa i lures somet i mes fa i led to mater i al i se. Gecko tape i s one such example. Acc i dentally or not, I read a paper descr i b i ng the mechan i sm beh i nd the amaz i ng cl i mb i ng ab i l i ty of geckos [12]. The phys i cs i s rather stra i ghtforward. Gecko’s toes are covered w i th t i ny ha i rs. Each ha i r attaches to the oppos i te surface w i th a m i nute van der Waals force (i n the nN range), but b i ll i ons of ha i rs work together to create a form i dable attract i on suffic i ent to keep geckos attached to any surface, even a glass ce i l i ng. In part i cular, my attent i on was attracted by the spat i al scale of the i r ha i rs. They were subm i cron i n d i ameter, the standard s i ze i n research on mesoscop i c phys i cs. After toy i ng w i th the i dea for a year or so, Sergey Dubonos and I came up w i th procedures to make a mater i al that m i m i cked a gecko’s ha i ry feet. He fabr i cated a square cm of th i s tape, and i t exh i b i ted notable adhes i on [13]. Unfortunately, the mater i al d i d not work as well as a gecko’s feet, deter i orat i ng completely after a couple of attachments. St i ll, i t was an i mportant proof-of-concept exper i ment that i nsp i red further work i n the field. Hopefully, one day someone w i ll develop a way to repl i cate the h i erarch i cal structure of gecko’s setae and i ts self-clean i ng mechan i sm. Then gecko tape can go on sale.BETTER TO BE WRONG THAN BORINGWh i le prepar i ng for my lecture i n Stockholm, I comp i led a l i st of my Fr i day n i ght exper i ments. Only then d i d I real i se a stunn i ng fact. There were two dozen or so exper i ments over a per i od of approx i mately fifteen years and, as expected, most of them fa i led m i serably. But there were three h i ts: lev i tat i on, gecko tape and graphene. Th i s i mpl i es an extraord i nary success rate: more than 10%. Moreover, there were probably near-m i sses, too. For example, I once read a paper [14] about g i ant d i amagnet i sm i n FeGeSeAs alloys, wh i ch was i nterpreted as a s i gn of h i gh-T superconduct i v i ty. I asked Lamarches for samples and got them. Kostya and I employed ball i st i c Hall magnetometry to check for g i ant d i amagnet i sm but found noth i ng, even at 1 K. Th i s happened i n 2003, well before the d i scovery of i ron pn i ct i de superconduct i v-i ty, and I st i ll wonder whether there were any small i nclus i ons of a supercon-duct i ng mater i al wh i ch we m i ssed w i th our approach. Another m i ss was an attempt to detect “heartbeats” of i nd i v i dual l i v i ng cells. The i dea was to use 2DEG Hall crosses as ultrasens i t i ve electrometers to detect electr i cal s i gnals due to phys i olog i cal act i v i ty of i nd i v i dual cells. Even though no heartbeats were detected wh i le a cell was al i ve, our sensor recorded huge voltage sp i kes at i ts “last gasp” when the cell was treated w i th excess alcohol [15]. Now I attr i bute th i s near-m i ss to the unw i se use of yeast, a very dormant m i cro-organ i sm. Four years later, s i m i lar exper i ments were done us i ng embryon i c heart cells and – what a surpr i se – graphene sensors, and they were successful i n detect i ng such b i oelectr i cal act i v i ty [16].Frankly, I do not bel i eve that the above success rate can be expla i ned by my lateral i deas be i ng part i cularly good. More l i kely, th i s tells us that pok i ng i n new d i rect i ons, even randomly, i s more reward i ng than i s generally perce i ved. We are probably d i gg i ng too deep w i th i n establ i shed areas, leav i ng plenty of unexplored stuff under the surface, just one poke away. When one dares to try, rewards are not guaranteed, but at least i t i s an adventure.THE MANCUNIAN WAYBy 2000, w i th mesoscop i c superconduct i v i ty, d i amagnet i c lev i tat i on and four Nature papers under my belt, I was well placed to apply for a full professorsh i p. Colleagues were rather surpr i sed when I chose the Un i vers i ty of Manchester, decl i n i ng a number of seem i ngly more prest i g i ous offers. The reason was s i mple.M i ke Moore, cha i rman of the search comm i ttee, knew my w i fe Ir i na when she was a very successful postdoc i n Br i stol rather than my co-author and a part-t i me teach i ng lab techn i c i an i n N i jmegen. He suggested that Ir i na could apply for the lecturesh i p that was there to support the professorsh i p. After s i x years i n the Netherlands, the i dea that a husband and w i fe could offic i ally work together had not even crossed my m i nd. Th i s was the dec i s i ve factor. We apprec i ated not only the poss i b i l i ty of sort i ng out our dual career problems but also felttouched that our future colleagues cared. We have never regretted the move.So i n early 2001, I took charge of several d i lap i dated rooms stor i ng anc i ent equ i pment of no value, and a start-up grant of £100K. There were no central fac i l i t i es that I could explo i t, except for a hel i um l i quefier. No problem. I followed the same rout i ne as i n N i jmegen, comb i n i ng help from other places, espec i ally Sergey Dubonos. The lab started shap i ng up surpr i s i ngly qu i ckly. W i th i n half a year, I rece i ved my first grant of £500K, wh i ch allowed us to acqu i re essent i al equ i pment. Desp i te be i ng consumed w i th our one year old daughter, Ir i na also got her start i ng grant a few months later. We i nv i ted Kostya to jo i n us as a research fellow (he cont i nued to be offic i ally reg i stered i n N i jmegen as a PhD student unt i l 2004 when he defended h i s thes i s there). And our group started generat i ng results that led to more grants that i n turn led to more results.By 2003 we publ i shed several good-qual i ty papers i nclud i ng Nature, Nature Mater i als and Phys. Rev. Letters, and we cont i nued beefing up the labora-tory w i th new equ i pment. Moreover, thanks to a grant of £1.4M (research i nfrastructure fund i ng scheme masterm i nded by the then sc i ence m i n i ster Dav i d Sa i nsbury), Ern i e H i ll from the Department of Computer Sc i ences and I managed to set up the Manchester Centre for Mesosc i ence and Nanotechnology. Instead of pour i ng the w i ndfall money i nto br i cks-and-mortar, we ut i l i sed the ex i st i ng clean room areas (~250 m2) i n Computer Sc i ences. Those rooms conta i ned obsolete equ i pment, and i t was thrown away and replaced w i th state-of-the-art m i crofabr i cat i on fac i l i t i es, i nclud i ng a new electron-beam l i thography system. The fact that Ern i e and I are most proud of i s that many groups around the world have more expens i ve fac i l i t i es but our Centre has cont i nuously, s i nce 2003, been produc i ng new structures and dev i ces. We do not have a posh horse here that i s for show, but rather a draft horse that has been work i ng really hard.Whenever I descr i be th i s exper i ence to my colleagues abroad, they find i t d i fficult to bel i eve that i t i s poss i ble to establ i sh a fully funct i onal labora-tory and a m i crofabr i cat i on fac i l i ty i n less than three years and w i thout an astronom i cal start-up grant. If not for my own exper i ence, I would not bel i eve i t e i ther. Th i ngs progressed unbel i evably qu i ckly. The Un i vers i ty was support i ve, but my greatest thanks are reserved spec ifically for the respons i ve mode of the UK Eng i neer i ng and Phys i cal Sc i ences Research Counc i l (EPSRC). The fund i ng system i s democrat i c and non-xenophob i c. Your pos i t i on i n an academ i c h i erarchy or an old-boys network counts for l i ttle. Also, ‘v i s i onary i deas’ and grand prom i ses to ‘address soc i al and econom i c needs’ play l i ttle role when i t comes to the peer rev i ew. In truth, the respons i ve mode d i str i butes i ts money on the bas i s of a recent track record, whatever that means i n d i fferent subjects, and the fund i ng normally goes to researchers who work both effic i ently and hard. Of course, no system i s perfect, and one can always hope for a better one. However, paraphras i ng W i nston Church i ll, the UK has the worst research fund i ng system, except for all the others that I am aware of.THREE LITTLE CLOUDSAs our laboratory and Nanotech Centre were shap i ng up, I got some spare t i me for th i nk i ng of new research detours. Gecko tape and the fa i led attempts w i th yeast and quas i-pn i ct i des took place dur i ng that t i me. Also, Serge Morozov, a sen i or fellow from Chernogolovka, who later became a regular v i s i-tor and i nvaluable collaborator, wasted h i s first two v i s i ts on study i ng magnet i c water. In the autumn of 2002, our first Manchester PhD student, Da J i ang, arr i ved, and I needed to i nvent a PhD project for h i m. It was clear that for the first few months he needed to spend h i s t i me learn i ng Engl i sh and gett i ng acqua i nted w i th the lab. Accord i ngly, as a starter, I suggested to h i m a new lateral exper i ment. It was to make films of graph i te ‘as th i n as poss i ble’ and, i f successful, I prom i sed we would then study the i r ‘mesoscop i c’ propert i es. Recently, try i ng to analyse how th i s i dea emerged, I recalled three badly shaped thought clouds.One cloud was a concept of ‘metall i c electron i cs’. If an external electr i c field i s appl i ed to a metal, the number of charge carr i ers near i ts surface changes, so that one may expect that i ts surface propert i es change, too. Th i s i s how modern sem i conductor electron i cs works. Why not use a metal i nstead of s i l i con? As an undergraduate student, I wanted to use electr i c field effect (EFE) and X-ray analys i s to i nduce and detect changes i n the latt i ce constant. It was naïve because s i mple est i mates show that the effect would be negl i g i ble. Indeed, no d i electr i c allows fields much h i gher than 1V/nm, wh i ch translates i nto max i mum changes i n charge carr i er concentrat i on n at the metal surface of about 1014 per cm2. In compar i son, a typ i cal metal (e.g., Au) conta i ns ~1023 electrons per cm3 and, even for a 1 nm th i ck film, th i s y i elds relat i ve changes i n n and conduct i v i ty of ~1%, leav i ng as i de much smaller changes i n the latt i ce constant.Prev i ously, many researchers asp i red to detect the field effect i n metals. The first ment i on i s as far back as 1902, shortly after the d i scovery of the electron. J. J. Thomson (1906 Nobel Pr i ze i n Phys i cs) suggested to Charles Mott, the father of Nev i ll Mott (1977 Nobel Pr i ze i n Phys i cs), to look for the EFE i n a th i n metal film, but noth i ng was found [17]. The first attempt to measure the EFE i n a metal was recorded i n sc i ent ific l i terature i n 1906 [18]. Instead of a normal metal, one could also th i nk of sem i metals such as b i smuth, graph i te or ant i mony wh i ch have a lot fewer carr i ers. Over the last century, many researchers used B i films (n ~1018 cm–3) but observed only small changes i n the i r conduct i v i ty [19,20]. Aware of th i s research area and w i th exper i ence i n GaAlAs heterostructures, I was cont i nuously, albe i t casually, look i ng for other cand i dates, espec i ally ultra-th i n films of superconductors i n wh i ch the field effect can be ampl ified i n prox i m i ty to the superconduct i ng trans i t i on [21,22]. In N i jmegen, my enthus i asm was once sparked by learn i ng about nm-th i ck Al films grown by MBE on top of GaAlAs heterostructures but, after est i mat i ng poss i ble effects, I dec i ded that the chances of success were so poor i t was not worth try i ng.Carbon nanotubes were the second cloud hang i ng around i n the late。