Moodys采矿业评级方法2006

采矿业中的矿产资源评估与经济效益分析方法研究

采矿业中的矿产资源评估与经济效益分析方法研究采矿业作为一项重要的经济活动,对于矿产资源的评估和经济效益的分析十分关键。

本文旨在研究采矿业中常用的矿产资源评估和经济效益分析方法,并探讨其优缺点以及适用范围。

一、矿产资源评估方法1. 储量评估法储量评估法是采矿业中最常用的方法之一。

它通过对矿床的地质勘探和数据分析,确定矿产资源的储量,包括已探明储量和潜在储量。

该方法的优点在于简单易行,能够提供初步的矿产资源量信息。

然而,储量评估法存在不确定性较高的问题,并且往往忽略了矿产资源质量的差异,不能提供详尽的信息。

2. 区域评价法区域评价法主要通过对采矿区域的地质特征和资源分布进行研究,评估矿产资源的分布范围和潜力。

该方法能够提供较为全面和综合的评估结果,但对于大规模采矿区域,数据收集和加工较为复杂,且评估结果受到样本选择和外推的影响。

3. 评价指标法评价指标法是一种定量的评估方法,通过建立评价指标体系,对矿产资源的各项指标进行测量和评估。

常用的评价指标包括资源量密度、丰度、回收率和经济价值等。

该方法能够提供较为精确和可比较的评估结果,但在构建评价指标体系和确定权重时存在主观性和不确定性。

二、经济效益分析方法1. 成本效益分析法成本效益分析法是一种常见的经济效益评估方法,通过比较投资成本与回报收益,评估矿产资源的经济可行性和盈利潜力。

该方法能够全面考虑投资和回报的关系,对于决策者来说具有重要的参考价值。

然而,成本效益分析法忽略了时间价值和风险因素的影响,可能导致评估结果不准确。

2. 效益成本比法效益成本比法是一种常用的经济效益分析方法,通过计算项目的效益与成本之比,评估矿产资源开发的经济效益。

该方法能够更好地考虑时间价值和风险因素,提供更准确的评估结果。

然而,效益成本比法对于所选评价指标和折现率的选择敏感,可能导致结果的误差。

3. 灵敏性分析法灵敏性分析法是一种用于评估矿产资源经济效益的敏感性和稳定性的方法。

采矿业中的矿业经济效益评估方法

采矿业中的矿业经济效益评估方法在采矿业中,矿业经济效益评估方法是十分重要的。

通过对矿业经济效益进行评估,不仅可以了解企业的盈利情况,还可以为决策者提供参考,指导采矿业的可持续发展。

本文将介绍几种常见的矿业经济效益评估方法。

一、成本法评估成本法评估是矿业经济效益评估的基础方法之一。

通过计算采矿企业的总成本和单位产量的成本,可以评估企业的经济效益。

具体方法如下:1. 计算总成本:将企业所有的生产成本,包括设备投资、人工成本、能源消耗、原材料采购等,加总计算得到。

2. 计算单位产量的成本:将总成本除以产量,得到单位产量的成本。

3. 进行效益评估:将单位产量的成本与市场价格进行比较,如果单位产量的成本小于市场价格,说明企业获得了正的经济效益。

二、收益法评估收益法评估是另一种常用的矿业经济效益评估方法。

它主要以企业的收益情况为评估指标,通过比较收益和成本的关系,以及与市场价格的比较,来评估企业的经济效益。

具体方法如下:1. 计算总收益:将企业所有的收入加总计算得到。

2. 计算净收益:将总收益减去总成本,得到净收益。

3. 进行效益评估:将净收益与投入的资本进行比较,如果净收益大于投入的资本,说明企业获得了正的经济效益。

三、动态评估方法动态评估方法考虑到了时间因素,更为综合和全面。

它重点关注企业的现金流量和资本收益率,通过对资本投入的折现和未来现金流量的估算,来评估企业的经济效益。

1. 折现:将未来的现金流量按照一定的折现率进行折算,得到现值。

2. 计算资本收益率:将净现值除以投入的资本,得到资本收益率。

3. 进行效益评估:根据资本收益率的高低来评估企业的经济效益,如果资本收益率大于一定的阈值(通常为企业的资本成本),说明企业获得了正的经济效益。

综上所述,对于采矿业中的矿业经济效益评估,成本法、收益法和动态评估方法是常见且有效的评估方法。

不同的方法适用于不同的情况,决策者可以根据实际情况选择适合的方法进行评估,以指导企业的经营和发展。

矿业权评估方法

矿业权评估方法概述:矿业权评估是对矿产资源进行评估和估值的过程,以确定其经济价值和投资潜力。

本文将详细介绍矿业权评估的方法和步骤,包括资源评估、产能评估、市场评估和财务评估等。

一、资源评估:资源评估是矿业权评估的基础,主要通过地质勘探和采样分析等方法来确定矿产资源的储量和品位。

常用的资源评估方法包括:1. 地质勘探:通过地质勘探工作,包括地质测量、地质钻探和地质调查等,获取地质信息,确定矿产资源的分布和性质。

2. 采样分析:对矿石进行采样,并通过化学分析、物理测试等方法,确定矿石的成分、品位和品质。

二、产能评估:产能评估是评估矿业权的生产潜力和可持续性的重要环节。

常用的产能评估方法包括:1. 设备评估:评估矿山所需的设备和机械设备的数量、规格和性能,以确定矿山的生产能力。

2. 工艺评估:评估矿山的选矿工艺和生产流程,以确定矿山的生产效率和生产能力。

3. 人力评估:评估矿山所需的人力资源,包括管理人员、技术人员和生产人员等,以确定矿山的生产能力和管理水平。

三、市场评估:市场评估是评估矿业权的市场价值和可行性的重要环节。

常用的市场评估方法包括:1. 市场调研:通过调研市场需求、供应和价格等信息,确定矿产品的市场潜力和竞争状况。

2. 市场模型:建立市场模型,预测矿产品的市场需求和价格变动趋势,以确定矿业权的市场价值和投资潜力。

3. 市场风险评估:评估市场风险和不确定性对矿业权价值的影响,以确定矿业权的可行性和投资回报率。

四、财务评估:财务评估是评估矿业权的财务状况和投资回报的重要环节。

常用的财务评估方法包括:1. 资本支出评估:评估矿山的建设投资和设备购置等资本支出,以确定投资额和资金回收期。

2. 运营成本评估:评估矿山的运营成本,包括人工成本、能源成本和原材料成本等,以确定矿山的盈利能力和现金流量。

3. 投资回报评估:评估矿业权的投资回报率和财务指标,包括净现值、内部收益率和投资回收期等,以确定矿业权的投资价值和可行性。

采矿业的矿产项目评估与决策

采矿业的矿产项目评估与决策在采矿业中,矿产项目评估与决策是非常重要的环节。

通过对矿产项目进行全面评估,可以为决策者提供决策依据,确保项目的可行性和效益。

本文将介绍矿产项目评估与决策的过程和方法,并探讨这一过程中的一些关键因素。

一、矿产项目评估过程1. 数据收集与准备在进行矿产项目评估前,首先需要收集和准备相关数据。

这些数据包括矿产资源的质量和数量、地质勘探报告、市场需求和价格等。

只有准备充分的数据,才能进行准确的评估。

2. 评估方法选择选择合适的评估方法是评估过程的重要一步。

常用的评估方法包括经济评估、环境评估和社会评估等。

根据矿产项目的具体情况,选择合适的评估方法是确保评估结果准确性的关键。

3. 评估指标建立评估指标的建立是评估过程中的核心工作。

评估指标应该包括经济效益、环境可持续性和社会影响等方面。

通过建立科学、全面的评估指标,可以对矿产项目的各方面进行客观、全面的评估。

4. 数据分析与评估在评估过程中,需要对收集到的数据进行分析和评估。

通过分析数据,可以得出关于矿产项目的各项指标和评估结果。

评估结果应该能够准确地反映出矿产项目的可行性和效益。

5. 结果报告与沟通评估结果应该以报告的形式进行呈现,并与相关人员进行沟通和交流。

通过报告,可以清晰地表达评估结果和决策建议。

同时,通过与相关人员的沟通,可以获得更多的反馈和建议,进一步完善评估结果。

二、矿产项目决策1. 决策过程在矿产项目决策过程中,需要综合考虑评估结果和各种因素,以制定决策方案。

决策过程应该是科学、公正、透明的,确保决策的合理性和可行性。

2. 决策依据评估结果是决策的主要依据。

决策者需要结合评估结果,考虑项目的可行性、效益和风险等因素,做出决策。

同时,决策者还应该参考相关法律法规和政策,确保决策符合国家和地方的要求。

3. 风险管理在矿产项目决策中,风险管理是一个重要的环节。

决策者需要对项目的风险进行评估,并制定相应的风险应对措施。

通过科学合理地管理风险,可以降低项目的风险和损失。

采矿业中的矿山资源评价与

采矿业中的矿山资源评价与管理矿山资源是采矿业的基础,对于矿山资源的评价和管理是保障矿业可持续发展的重要环节。

本文将探讨采矿业中的矿山资源评价与管理,并介绍相关的方法和策略。

一、矿山资源评价矿山资源评价是指对矿山资源进行综合评估,确定其储量、品质和经济价值等指标。

矿山资源评价可以帮助企业做出正确的决策,制定合理的开采方案,并为资源的开发利用提供科学依据。

1. 矿山资源评价方法目前,常用的矿山资源评价方法有静态评价法和动态评价法。

静态评价法主要是根据矿床地质特征和开采的信息,通过采样、分析和数据处理等手段,对矿床的储量和品质进行估算。

静态评价法适用于单一矿床的评价,能够提供较为准确的矿床开采潜力。

动态评价法则考虑了矿床开采过程中的因素,如开采技术、经济环境和市场需求等,对矿山资源进行全面评价。

动态评价法适用于多矿床、多期开采规划的评价,能够提供更全面的资源开发策略。

2. 矿山资源评价指标矿山资源评价指标包括储量、品位、勘探程度、开采条件和经济效益等。

其中,储量是指矿床中具有开采价值的矿石总量;品位是指矿石中有用成分的含量;勘探程度是指对矿床进行勘探工作的程度;开采条件是指矿床的地理、水文和气候等条件;经济效益是指通过开采和销售矿石所获得的收益。

二、矿山资源管理矿山资源管理是指对矿山资源进行规划、调度和监督,以实现资源的合理利用和可持续发展。

矿山资源管理需要考虑资源的有效开采、环境保护和社会效益等因素。

1. 矿山资源规划矿山资源规划是制定矿山资源开采的总体方向和目标。

在矿山资源规划中,需要考虑资源的分布情况、开采技术、环境要求和社会经济条件等因素,以制定合理的开采方案和时间表。

2. 矿山资源调度矿山资源调度是根据矿山的生产力、采矿设备和市场需求等因素,对矿石的开采和加工进行合理安排。

通过合理的资源调度,可以最大限度地提高资源的利用率和经济效益。

3. 矿山资源监督矿山资源监督是对矿山资源开采过程进行监测和管理。

矿业权评估方法

矿业权评估方法一、引言矿业权评估是矿产资源开发过程中的重要环节,对于确定矿产资源价值、保障矿产资源合理利用以及维护各方利益具有重要意义。

本文将全面阐述矿业权评估的七种主要方法,以期为矿业权评估工作提供参考。

二、七种评估方法成本逼近法(1)通过对矿产品成本费用的计算,评估出该矿产资源的最低价值。

(2)考虑到勘查成本、开采成本、税费等因素,确定合理的利润率和税费率。

(3)根据矿产资源的品质、储量、赋存条件等因素,对评估结果进行调整。

市场比较法(1)在市场调查基础上,选择与待评估矿业权类似的矿业权交易案例。

(2)对比分析类似案例的交易价格、交易条件、交易时间等因素。

(3)根据待评估矿业权的实际情况,调整比较因素,确定评估值。

收益还原法(1)估算矿业权的未来预期收益,包括矿产资源销售收入、加工收入等。

(2)考虑风险因素,预测未来收益的折现率。

(3)将未来预期收益折现至评估基准日,得出矿业权的价值。

地质要素评价法(1)综合分析矿产资源的品质、储量、赋存条件等因素。

(2)考虑矿床开采技术条件、矿床开采年限等因素。

(3)根据地质要素评价结果,确定矿业权的价值。

价值折算法(1)确定矿业权所对应的矿产资源的储量及品质。

(2)根据国内外市场行情和矿产资源用途,估算矿产资源的价值。

(3)根据矿业权的特性和剩余可采年限,对矿产资源价值进行调整。

实物期权法(1)识别矿业权所包含的实物期权类型,如扩张期权、延迟期权等。

(2)评估实物期权执行的条件和风险。

(3)利用实物期权定价模型计算实物期权的价值,并纳入矿业权价值中。

专家打分法(1)选定影响矿业权价值的因素,如矿床规模、矿石品位等。

(2)邀请专家对选定因素进行打分,并确定各因素的权重。

《矿业权评估指南》(2006修订)――矿业权评估收益途径评估方法和参数

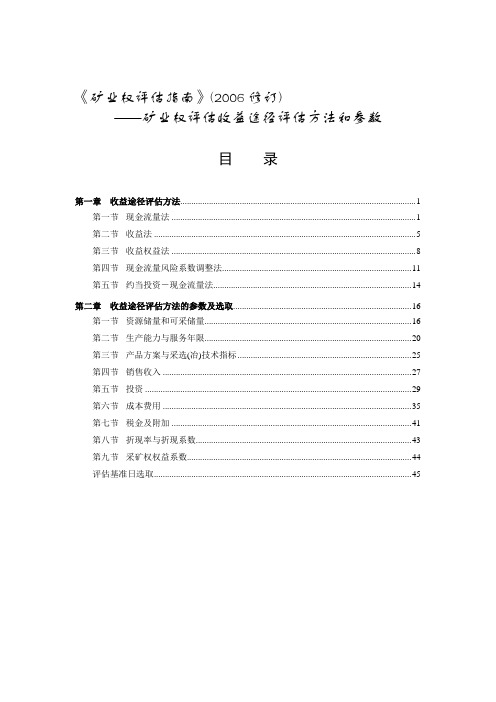

《矿业权评估指南》(2006修订)――矿业权评估收益途径评估方法和参数目录第一章收益途径评估方法 (1)第一节现金流量法 (1)第二节收益法 (5)第三节收益权益法 (8)第四节现金流量风险系数调整法 (11)第五节约当投资-现金流量法 (14)第二章收益途径评估方法的参数及选取 (16)第一节资源储量和可采储量 (16)第二节生产能力与服务年限 (20)第三节产品方案与采选(冶)技术指标 (25)第四节销售收入 (27)第五节投资 (29)第六节成本费用 (35)第七节税金及附加 (41)第八节折现率与折现系数 (43)第九节采矿权权益系数 (44)评估基准日选取 (45)矿业权评估收益途径评估方法和参数矿业权(探矿权和采矿权,下同)评估收益途径评估方法是指通过估算被评估矿业权所包括的矿产资源储量在未来开发预期收益的现值来确定被评估矿业权价值的一类评估方法。

收益途径是被较广泛采用的矿业权价值评估途径,易于为买卖双方所接受。

该途径评估方法是基于人们根据对矿业权价值的认识,通过将地质的、采矿的、选矿的和经济的等知识、经验和实践的综合运用,对矿业权价值做出评价和估算。

因此,合理地确定技术、经济等评估参数,是该途径评估方法应用的关键。

采用收益途径进行矿业权评估时,需要具备的前提条件和遵循的假设条件:一、前提条件1.评估对象未来的预期收益可以预测并可以用货币衡量;2.获得评估对象未来预期收益所承担的风险也可以预测并可以用货币衡量。

3.评估对象预期获利年限可以预测。

二、假设条件1.产销均衡原则,即生产的产品当期全部实现销售;2.评估设定的市场条件固定在评估基准日时点上,即矿业权评估时的市场环境、价格水平、矿山勘查和开发利用技术水平等以评估基准日的市场水平和设定的生产力为基点。

设定的生产力水平(以下相同)与评估目的相关,对于以收取矿业权价款为目的的出让评估以及以公平交易为目的的转让评估指社会平均生产力水平;对某些评估目的,如矿业权抵押贷款、上市或一般卖方的出价决策咨询,可以指矿业权人真实、实际的生产力水平。

穆迪esg评分方法

穆迪esg评分方法

穆迪(Moody's)ESG评分方法是指穆迪公司对企业的环境、社会和治理(ESG)表现进行评估和打分的方法。

ESG评分是指对企业在环境、社会和治理方面的表现进行评价,并给予相应的分数。

穆迪公司的ESG评分方法主要包括以下几个方面:

1. 数据收集,穆迪公司会收集关于企业ESG表现的数据,包括企业的环境管理、社会责任和治理结构等方面的信息。

2. 评分标准,穆迪公司根据一系列的评分标准对企业的ESG表现进行评价,这些标准可能涵盖环境保护、碳排放、劳工关系、董事会结构等多个方面。

3. 评分方法,穆迪公司可能采用定量和定性相结合的方法对企业的ESG表现进行评分,以确保评价的客观性和全面性。

4. 综合评定,穆迪公司会综合考虑企业在环境、社会和治理方面的表现,给出相应的ESG评分,这个评分可以帮助投资者和其他利益相关方更好地了解企业的可持续发展能力和风险。

总的来说,穆迪公司的ESG评分方法是通过收集数据、制定评

分标准、采用多种评分方法并进行综合评定,来评价企业在环境、

社会和治理方面的表现,为投资者和利益相关方提供全面的ESG信息。

这种评分方法有助于推动企业改善ESG表现,促进可持续发展。

中金公司—穆迪和标准普尔的信用评级方法介绍

中国固定收益证券:信用策略:2008 年 4 月 3 日

9 在投资实践中,评级公司的结果更多地并不是用于债券的实时交易,而是用于满足相关监管规则的要求和作为 资产组合构建的基础。

9 市场对评级公司的预期除了提供评级结果外,还希望评级公司在解决信息不对称性和透明化等方面发挥作用。 9 评级展望和评级观察名单是对评级结果的重要补充,如果投资者在投资时按照评级展望和评级观察对评级结果

9 评级公司的评级并不以特定的绝对违约率/预期损失率为目标,而是同一时间点对相对信用风险的排序。在同一 年或者平均来看,高评级公司的违约率/预期损失率低于低评级公司的违约率/预期损失率,但是在不同年度之间 不同级别之间的违约率/预期损失率之间并不具备绝对的可比较性。

9 对经济周期或者外部不利环境的承受能力是区分投资与投机级债券的关键,评级越低的债务,其偿还能力越依 赖于良好的外部条件;历史数据表明投资级债券对经济周期波动的抵御能力也确实远远高于投机级债券。

(如股价)波动而推出的隐含评级,在进行评级时我们主要分析和关注的仍然是影响发行人中长期信用基本面的因 素及其变化趋势。 ♦ 中金公司信用评分体系的内容和定义是什么? 9 中金公司信用评分的主要目标是区分发行人按时偿还债务能力和意愿相对风险的大小,也即发行人的违约概率。 9 中金公司信用评分目前暂分为 1 到 5 档,1 档表示信用状况最好、相对风险最低,5 档表示信用状况最差、相对 风险最高。 9 我们所指的违约率并不是特指发行人某一年的违约率,而是发行人所对应的一个违约率时间序列。因此,我们 的 5 级评级体系同时应用于短期(期限在一年以内)和长期信用产品。评级越高的债务人违约概率越低;随着 时间的增加,每个级别债务人的累积违约率都在增加,但级别低的累积违约率增加得更快。 9 我们的评级以发行人评级为基础,在确定具体债项的评级时,将分析债项的优先级和担保的具体情况,以及优 先级和担保等风险缓释条件对债项最终违约风险的影响。 ♦ 中金行业信用风险展望的定位和定义是什么? 9 国际历史经验表明不同行业的违约率存在巨大差异:政府管制、提供经济基础服务、可能引起经济系统性风险 的行业长期违约率低,而完全竞争行业的长期违约率高。 9 每个行业违约率的发生都具备“聚集性”和“传染性”的特征,并不是均匀地在每个年度发生,因此对经济周 期和行业周期的分析和展望是进行信用产品组合配置、避免绝对信用损失的关键因素之一。 9 为了给投资者提供更具前瞻性的信息,我们将对主要的行业引入“行业信用风险展望”,分为“正面”、“稳定”、 “负面”以及“发展中”四种评价结果。

采矿业中的矿产资源评估方法与技术

采矿业中的矿产资源评估方法与技术矿产资源评估在采矿业中扮演着重要的角色,它是为了评估矿产资源的潜力、价值和可开采性而进行的科学分析和判断。

本文将介绍一些常用的矿产资源评估方法与技术,旨在帮助采矿业从业者更好地了解和应用这些方法与技术。

一、资源调查与勘探资源调查与勘探是矿产资源评估的基础工作。

通过野外调查与勘探,可以获取矿床的地质信息、地球物理信息、地球化学信息等数据,从而帮助评估矿产资源的存在与储量。

1. 野外地质调查野外地质调查是资源评估工作的首要任务。

通过对矿区地质条件、地质构造、岩性组合、地层特征等进行详细观察和记录,可以初步了解矿产资源的分布情况和潜力。

2. 地球物理勘探地球物理勘探通过测量地球物理场,如重力场、磁场、电磁场等,获得与矿床有关的信息。

根据不同的地球物理方法,可以对矿床的形貌、尺寸、物性等进行综合解释和分析。

3. 地球化学勘探地球化学勘探通过采集和分析样品中的化学元素、同位素、矿物组成等数据,来识别和判断矿床的类型、成因以及矿物潜力。

二、资源评估与计算在完成资源调查与勘探工作后,需要进行资源评估与计算,以确定矿产资源的(可开采)储量和价值,以及进行开发计划和决策。

1. 储量评估储量评估是指通过收集和分析矿床地质数据,并运用相应的数学模型和计算方法,对矿产资源的储量进行估计和计算。

常用的储量计算方法包括等高线法、透镜法、多边形法等。

2. 价值评估价值评估是指对矿产资源进行经济评价,从而确定其开采的经济效益和投资回报。

通常考虑的因素包括矿石品位、开采成本、市场需求等。

3. 可开采性评估可开采性评估是指评估矿产资源在技术和经济条件下是否可以实际开采。

通过分析矿床的地质、工程和经济条件等因素,判断其开采的可行性和可持续性。

三、可视化分析与模拟为了更好地了解和展示矿产资源的空间分布和特征,可视化分析与模拟成为了评估中的重要环节。

1. 地理信息系统(GIS)地理信息系统是一种集成地理空间数据、空间分析和图形展示于一体的信息系统。

第一章采矿权评估方法

第一章采矿权评估方法1、贴现现金流量法定义、使用条件和适用范围。

答:贴现现金流量法,即DCF(Discounted Cash Flow)分析法,是采矿权评估广泛利用的基本方法之一。

由于采矿权是企业法人财产权,属企业资产,它具备独立的能够连续获得预期收益的能力,且资产未来的收益能够用货币来计算,资产未来的收益中包含风险收益等前提条件,所以该方法可用于采矿权评估。

国内通常将它称为“收益现值法”。

贴现现金流量法是指通过估算被评估资产的未来预期收益,并折算成现值,借以确定被评估资产价值的一种资产评估方法。

贴现现金流量法使用条件和适用范围(1)具有主管机构批准的地质勘探报告,储量审批机构审批的矿产储量报告。

已开采矿山还应用储审批机构审批的矿产储钽增减报告。

(2)采矿权转让和探矿权转让的目的是申请采矿权时要具备矿山建设项目可行性研究报告;具有完备的原探矿权人、采矿权人投资财务决算报表;适用范围:二级市场中的买断性转让;合资(合作)性转让(以采矿权作价作为合资股本);破产清算、出租、抵押采矿权;探矿权在勘查工作结束后放弃优先采矿权时的探矿权转让。

2、可比销售法的定义、使用条件和适用范围。

答:可比销售法是利用已知采矿权转让中的市场成交价,来评估未知采矿权志让价的评估方法。

①资源条件。

在市场调查中,要坚持寻找矿种相同,自然成因类型相同,工业类型大致相仿的参照采矿权,规模可以不要求一致。

同时,为了准确对比分析被评估采矿权与参照采矿权的差异,要求矿石品位,有用有害组分的构成,采选性能等参数清晰,准确。

②市场条件。

参照采矿权成交价是在正常交易下形成的,不存在任何行政干预,也不存在不利因素支配下形成的成交价。

同时要求参照采矿权的成交时间,成交地点,使用情况,预期效果以及有关资料完备,可靠。

③评判条件。

差异是素养评判是专家对被评估采矿权和参照采矿权交通条件、自然条件、经济条件、地质采选条件差异程序的主观判定。

如果专家人数较少和专业结构单一,往往做出的判断不容易接近客观实际。

采矿业的矿业企业绩效评估与提升

采矿业的矿业企业绩效评估与提升矿业企业绩效是评估企业经营管理水平、运营效益和发展潜力的重要指标,对于采矿业而言尤为重要。

本文将探讨采矿业的矿业企业绩效评估与提升,分析评估指标和提升方法,旨在帮助矿业企业提高竞争力和可持续发展。

一、矿业企业绩效评估指标矿业企业绩效评估指标的选择应与企业经营目标和战略相匹配,常见的指标包括生产效率、安全环保、财务管理、技术创新和人力资源等方面。

1. 生产效率生产效率是衡量企业生产经营状况的关键指标,包括矿石开采效率、矿石转化率和产品质量等。

企业应注重提高矿石开采和加工的效率,降低能耗和物资消耗。

2. 安全环保矿业企业应重视安全和环保工作,绩效评估指标包括事故率、环境影响评估等。

企业应加强安全生产管理,优化工艺流程,推行清洁生产,保护生态环境。

3. 财务管理财务管理是评估企业健康发展的重要依据,包括资产负债率、利润率、现金流量等指标。

企业应合理控制成本,提高资金利用效率,实施科学的财务管理策略。

4. 技术创新技术创新是矿业企业提升绩效的重要手段,包括矿山勘探技术、采矿设备的改进和自动化程度等。

企业应积极投入研发,引进和推广新技术,提高技术水平和核心竞争力。

5. 人力资源人力资源是矿业企业发展的核心和驱动力,包括员工素质、薪酬福利和人才培养等。

企业应加强人力资源规划,优化人员结构,注重员工培训和激励机制。

二、矿业企业绩效评估方法1. 指标体系建立针对具体企业的特点和经营目标,建立绩效评估指标体系,确保评估指标能够全面准确地反映企业的经营状况。

指标体系应考虑到不同环节和部门的需求,以及与行业和国家相关政策的要求。

2. 数据采集与分析通过收集企业的经营数据,如产量、收入、成本等,进行数据分析,找出影响企业绩效的主要问题和瓶颈,为企业提供决策依据。

同时,也可以通过市场调研、对竞争对手的分析等手段获取外部环境信息。

3. 绩效评估与对比将企业的绩效数据与既定的指标进行对比分析,评估企业在各项指标上的表现。

采矿权评估方法__收益途径评估法

何总您好:下面是我按今天下午所获资料(即刻发给您)计算所得采矿权价款的大至数字。

因暂时还不能确定我们矿山所产荒料的销售价格,同时,也无法确定矿山的开拓及采场布置等因素(无法确定回采率),所以,计算所得数字仅供参考。

不过,若能大体确定每立方米荒料的销售价格,代入下面第8小节的计算公式,则所得采矿权价款可基本接近实际。

附计算结果如下:按收益途径评估法计算的采矿权价款1.评估基准日可采储量可采储量=资源量-设计损失-采矿损失=资源量×设计利用率×开采回采率=180×80%×90%=129.6万立方米;2.生产规模(A)按地质、采矿、市场容量、投资规模及行业规范等确定,可大可小(但为减少采矿权价款并延长或取得更长时间的采矿权,应力求最小化。

下面的计算可见)。

本例选取两个数字做比较,即生产规模分别为1万立方米/年和2万立方米/年(荒料体积);3.服务年限(t)服务年限=可采量×荒料率/规模×(1+吊装损失率)=129.6×0.26/(1~2)×(1+0.05)=16.04~32.09(年);4.年销售收入(Sit)=年产量×荒料价格=(1~2)×(400~4000)=(400~8000)万元/年;5.采矿权权益系数(K)=(0.35~0.45)% 取低值有利;6.折现率(i)=(8~10)% 取高端值有利;7.采矿权价款(P)计算公式:P=∑〔SIt/(1+i)ª〕×K8.按不同生产规模(1万立方米/年、2万立方米/年)和不同销售价格(400元/立方米、4000元/立方米)计算所得采矿权价款分别为1)年产1万立方米荒料时,对上述采矿权价款计算公式整理后得:P=SIt×K×〔1/(1+i) + 1/(1+i)² + ……… +1/(1+i)ª〕 (注:此处a值等于32年,当生产规模为2万立方米/年a值取16年;Sit=(400~8000)万元/年;K=(3.5~4.5)%取平值为0.04;〔1/(1+i) + 1/(1+i)² + ……… +1/(1+i)ª〕=11.435)即 P=(400~8000)×0.4×11.435=(1829.6~16296)万元; 2)年产2万立方米荒料时,计算方法同上P=2×(400~8000)×0.4×8.445=(2702.4~27024)万元说明:从上面的计算可以看出1.采矿权权益系数和折现率等对采矿权价款的影响都不大。

采矿业中的矿产资源评估与经济效益分析

采矿业中的矿产资源评估与经济效益分析矿产资源评估是指对采矿业中的矿产资源进行定量化的评估和分析,以了解其潜在价值和可持续利用能力。

同时,矿产资源的经济效益分析则是评估采矿活动对经济的贡献和影响。

本文将对矿产资源评估的方法和矿产资源的经济效益进行详细探讨。

一、矿产资源评估的方法1. 地质勘查与探测技术地质勘查是矿产资源评估的重要手段之一。

通过采用地质勘查和探测技术,如地质剖面、物探雷达等,在地下构造和矿体分布上获取更多的数据,从而准确评估矿产资源的规模和品位。

2. 统计学方法统计学方法是进行矿产资源评估的一种常用手段。

通过抽样调查和统计分析,可以获取样本数据,并根据样本数据对整个矿产资源进行估算。

常用的统计学方法包括面积加权法、格点法等。

3. 数学模型与计算机模拟数学模型和计算机模拟技术也被广泛用于矿产资源评估中。

通过建立数学模型和模拟实验,可以对矿产资源进行多方面、多层次的评估。

常用的数学模型包括地质模型、矿体模型等。

二、矿产资源的经济效益分析1. 产出效益矿产资源的经济效益可以通过计算产出效益来评估。

产出效益主要体现在矿产资源的市场价格和生产量上。

通过比较开采成本与市场价格之间的差距,可以判断矿产资源的经济价值。

2. 就业效益采矿业的发展和运营,将直接或间接地创造就业机会。

就业效益是指通过采矿业所创造的就业机会对当地经济和社会的影响。

这些就业机会将提高当地人民的生活水平,促进当地经济的发展。

3. 环境效益与风险采矿活动对环境有一定的影响,包括土地破坏、水污染、大气污染等。

因此,评估矿产资源的经济效益时,也需要考虑其对环境的影响和风险。

通过引入环境保护措施和技术手段,可以减少采矿活动对环境的不利影响。

4. 社会效益矿产资源对当地社会的发展和福利有着重要的影响。

通过对采矿业的发展和运营的影响进行评估,可以综合考虑社会效益。

社会效益包括当地人民的收入、基础设施建设等方面的提升。

总结:采矿业中的矿产资源评估与经济效益分析是评估矿产资源潜力和对经济的贡献的重要手段。

采矿业中的矿业项目财务评估方法

采矿业中的矿业项目财务评估方法矿业项目的财务评估是对投资项目的经济可行性进行全面评估的过程。

在采矿业中,由于项目投资规模大、项目周期长、风险较高等特点,财务评估显得尤为重要。

本文将介绍几种常见的矿业项目财务评估方法。

一、投资回收期方法投资回收期是指项目从投资开始到收回全部投资及获得预期收益所需要的时间。

在矿业项目财务评估中,计算投资回收期可以帮助投资者判断投资项目的回报速度和投资风险。

一般来说,投资回收期越短,项目回报越快,风险越低。

通过计算投资回收期,投资者可以更好地把握投资时机,并决策是否投资该矿业项目。

二、净现值方法净现值是指将未来现金流折现到现在时间点,减去初始投资所得到的差额。

在矿业项目财务评估中,净现值是一种常用的评估方法。

计算净现值可以帮助投资者判断投资项目所获得的现金流量是否大于投资付出的成本。

净现值为正值时,说明项目具有经济效益;净现值为负值时,则意味着项目经济效益不佳。

三、内部收益率方法内部收益率是指使项目净现值等于零的贴现率。

在矿业项目财务评估中,内部收益率可以用来判断投资项目所能够带来的收益水平。

一般来说,内部收益率越高,说明项目回报越好,项目风险越低。

通过计算内部收益率,投资者可以比较不同矿业项目的投资回报率,选择最具吸引力的投资机会。

四、敏感性分析方法敏感性分析是在财务评估中常用的一种方法,它用来分析各种因素对项目经济效益的影响程度。

在矿业项目财务评估中,敏感性分析可以帮助投资者了解项目在不同市场条件下的风险和回报变化情况。

通过对关键变量进行敏感性分析,投资者可以更好地掌握投资项目的风险因素,并作出相应的决策调整。

综上所述,采矿业中的矿业项目财务评估方法包括投资回收期方法、净现值方法、内部收益率方法和敏感性分析方法等。

每种评估方法都有其独特的优缺点,投资者在进行项目财务评估时可以根据实际情况选用适合的方法。

通过合理的财务评估,投资者可以更好地判断矿业项目的可行性,降低投资风险,实现良好的投资回报。

采矿业的矿产资源开发效益评估指标体系

采矿业的矿产资源开发效益评估指标体系矿产资源是采矿业的核心资产,对于评估矿产资源开发效益的指标体系起着至关重要的作用。

本文将介绍采矿业的矿产资源开发效益评估指标体系,包括经济效益、环境效益和社会效益三个方面。

一、经济效益经济效益是评估矿产资源开发成果的重要指标之一。

下面将介绍几个常用的经济效益指标。

1. 产值产值是矿产资源开发所创造的货币价值总量。

它能够反映出矿产资源开发的规模和经济效益。

产值指标体系需要考虑矿产资源开发中的产量、价格和销售收入等关键因素。

2. 利润利润是评估矿产资源开发效益的重要指标,它是指矿产资源开发所获得的净利益。

利润指标体系需要综合考虑矿产资源开发中的成本、税收和利润率等因素。

3. 投资回报率投资回报率是指矿产资源开发所获得的投资收益相对于投资成本的比率。

投资回报率指标体系需要关注矿产资源开发中的投资规模和盈利能力。

二、环境效益环境效益是评估矿产资源开发成果的重要指标之一。

下面将介绍几个常用的环境效益指标。

1. 水资源利用率水资源是矿产资源开发过程中的重要环境因素,水资源利用率指标体系可以评估矿产资源开发对水资源的消耗情况。

2. 能源消耗强度能源消耗强度是评估矿产资源开发对能源的利用情况的指标,反映出矿产资源开发的资源利用效率。

3. 废弃物排放废弃物排放是矿产资源开发过程中产生的废物对环境造成的影响的重要指标。

废弃物排放指标体系需要考虑矿产资源开发中的废弃物处理和减排措施。

三、社会效益社会效益是评估矿产资源开发成果的重要指标之一。

下面将介绍几个常用的社会效益指标。

1. 就业机会矿产资源开发能够创造大量的就业机会,就业机会指标体系可以评估矿产资源开发对就业的促进作用。

2. 区域经济发展矿产资源开发对区域经济发展有着积极的推动作用,区域经济发展指标体系需要综合考虑矿产资源开发对经济增长、产业结构优化和区域收入等方面的影响。

总结:采矿业的矿产资源开发效益评估指标体系包括经济效益、环境效益和社会效益三个方面。

采矿业的矿产资源开发效益评估

采矿业的矿产资源开发效益评估在当今的社会发展进程中,矿产资源的开发与利用一直是一个备受关注的话题。

而采矿业中,对于矿产资源的开发效益评估显得尤为重要。

本文将从不同的角度探讨采矿业的矿产资源开发效益评估,并提出一些可行的方法和工具。

一、资源调查与勘探在进行矿产资源开发效益评估之前,首先要进行资源的调查与勘探工作。

只有准确了解矿产资源的分布情况、质量和数量,才能进行有效的评估工作。

资源调查与勘探需要依托于现代科学技术手段,包括测量、遥感、地质勘探等技术。

通过这些手段可以获得准确的矿产资源数据,并建立起评估的基础。

二、经济效益评估经济效益是评估矿产资源开发的一个重要因素。

在进行经济效益评估时,需要综合考虑多个因素,包括投资成本、生产效率、销售收入等。

通过对这些因素的评估,可以得出矿产资源开发对经济的贡献程度。

评估的结果可以帮助决策者确定是否值得进行矿产资源开发,以及在开发过程中应该采取何种策略和措施。

三、环境效益评估随着人们对环境问题的关注度不断提高,矿产资源开发对环境的影响也逐渐成为评估的一项重要内容。

环境效益评估需要考虑矿产资源开发对地质环境、水资源、大气环境等方面的影响。

通过综合评估这些影响,可以得出矿产资源开发对环境的影响程度。

评估的结果可以为开发者提供环保措施和管理方法,以减少对环境的负面影响。

四、社会效益评估除了经济效益和环境效益,矿产资源开发还对当地社会产生一定的影响。

社会效益评估需要考虑矿产资源开发对当地就业、经济发展、社会稳定等方面的影响。

通过综合评估这些影响,可以得出矿产资源开发对社会的贡献程度。

评估的结果可以帮助政府和社会各界更好地制定相关政策和规划,以实现资源开发和社会可持续发展的平衡。

总之,采矿业的矿产资源开发效益评估是一个综合考量的过程,需要综合考虑经济、环境和社会等多个方面的因素。

只有通过全面、科学地评估,才能真正实现矿产资源的可持续开发和利用。

因此,我们要不断提升评估水平,运用先进的方法和工具,为采矿业的矿产资源开发决策提供准确可靠的依据。

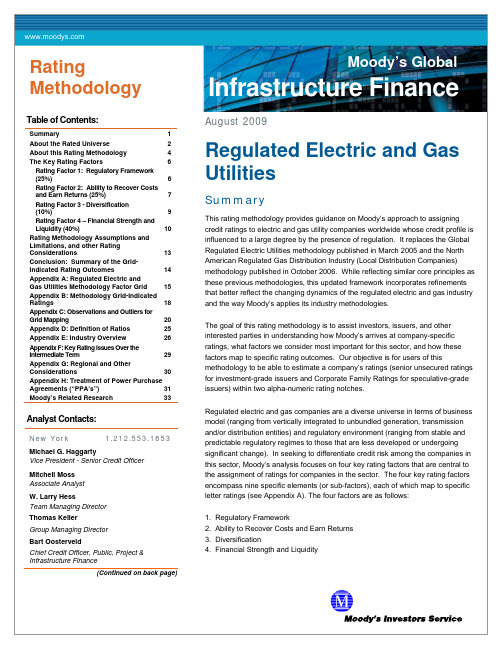

Regulated Electric and Gas Utilities (穆迪电力和天然气行业评级方法)

Infrastructure FinanceMoody’s GlobalRatingMethodologyTable of Contents:Summary 1 About the Rated Universe 2 August 2009Regulated Electric and GasThis methodology pertains to regulated electric and gas utilities and excludes regulated electric and gas networks (companies primarily engaged in the transmission and/or distribution of electricity and/or natural gas that do not serve retail customers) and unregulated utilities and power companies, which are covered by separate rating methodologies. Municipal utilities and electric cooperatives are also excluded and covered by separate rating methodologies.In Appendix A of this methodology, we have included a detailed rating grid for the companies covered by the methodology. For each company, the grid maps each of these key rating factors and shows an indicated alpha-numeric rating based on the results from the overall combination of the factors (see Appendix B). We note, however, that many companies will not match each dimension of the analytical framework laid out in the rating grid exactly and that from time to time a company’s performance on a particular rating factor may fall outside the expected range for a company at its rating level. These companies are categorized as “outliers” for that rating factor. We discuss some of the reasons for these outliers in this methodology as well as in published credit opinions and other company-specific analysis.The purpose of the rating grid is to provide a reference tool that can be used to approximate credit profiles within the regulated electric and gas utility sector. The grid provides summarized guidance on the factors that are generally most important in assigning ratings to the sector. While the factors and sub-factors within the grid are designed to capture the fundamental rating drivers for the sector, this grid does not include every rating consideration and does not fit every business model equally. Therefore, we outline additional considerations that may be appropriate to apply in addition to the four rating factors. Moody’s also assesses other rating factors that are common across all industries, such as event risk, off-balance sheet risk, legal structure, corporate governance, and management experience and credibility. Furthermore, most of our sub-factor mapping uses historical financial results to illustrate the grid while our ratings also consider forward looking expectations. As such, the grid-indicated rating is not expected to always match the actual rating of each company. The text of the rating methodology provides insights on the key rating considerations that are not represented in the grid, as well as the circumstances in which the rating effect for a factor might be significantly different from the weight indicated in the grid.Readers should also note that this methodology does not attempt to provide an exhaustive list of every factor that can be relevant to a utility’s ratings. For example, our analysis covers factors that are common across all industries (such as coverage metrics, debt leverage, and liquidity) as well as factors that can be meaningful on a company or industry specific basis (such as regulation, capital expenditure needs, or carbon exposure).This publication includes the following sections:About the Rated Universe: An overview of the regulated electric and gas industriesAbout the Rating Methodology: A description of our rating methodology, including a detailed explanation of each of the key factors that drive ratingsAssumptions and Limitations: Comments on the rating methodology’s assumptions and limitations, including a discussion of other rating considerations that are not included in the gridIn the appendices, we also provide tables that illustrate the application of the methodology grid to 30 representative electric and gas utility companies with explanatory comments on some of the more significant differences between the grid-implied rating and our actual rating (Appendix C). We also provide definitions of key ratios (Appendix D), an industry overview (Appendix E) and a discussion of the key issues facing the industry over the intermediate term (Appendix F) and regional considerations (Appendix G).About the Rated UniverseThe rating methodology covers investor-owned and commercially oriented government owned companies worldwide that are engaged in the production, transmission, distribution and/or sale of electricity and/or natural gas. It covers a wide variety of companies active in the sector, including vertically integrated utilities, transmission and distribution companies, some U.S. transmission-only companies, and local gas distribution companies (LDCs). For the LDCs, we note that this methodology is concerned principally with operating utilities regulated by their local jurisdictions and not with gas companies that have significant non-utilityAbout this Rating MethodologyMoody’s approach to rating companies in the regulated electric and gas utility sector, as outlined in this rating methodology, incorporates the following steps:1. Identification of the Key Rating FactorsIn general, Moody’s rating committees for the regulated electric and gas utility sector focus on a number of key rating factors which we identify and quantify in this methodology. A change in one or more of these factors, depending on its weighting, is likely to influence a utility’s overall business and financial risk. We have identified the following four key rating factors and nine sub-factors when assigning ratings to regulated electric and gas utility issuers:Rating Factor / Sub-Factor Weighting - Regulated UtilitiesBroad Rating FactorsBroad RatingFactor Weighting Rating Sub-FactorSub-Factor WeightingRegulatory Framework 25% 25% Ability to Recover Costs and Earn Returns 25% 25% 10%Market Position5%* Diversification Generation and Fuel Diversity 5%** 40%Liquidity10% CFO pre-WC + Interest/ Interest 7.5% CFO pre-WC / Debt7.5% CFO pre-WC – Dividends / Debt7.5% Financial Strength, Liquidity and Key Financial MetricsDebt/Capitalization or Debt / Regulated Asset Value 7.5% Total 100%100%*10% weight for issuers that lack generation; **0% weight for issuers that lack generationThese factors are critical to the analysis of regulated electric and gas utilities and, in most cases, can be benchmarked across the industry. The discussion begins with a review of each factor and an explanation of its importance to the rating.2. Measurement of the Key Rating FactorsWe next explain the elements we consider and the metrics we use to measure relative performance on each of the four factors. Some of these measures are quantitative in nature and can be specifically defined. However, for other factors, qualitative judgment or observation is necessary to determine the appropriate rating category. Moody’s ratings are forward looking and attempt to rate through the industry’s characteristic volatility, which can be caused by weather variations, fuel or commodity price changes, cost deferrals, or reasonable delays in regulatory recovery. The rating process also makes extensive use of historic financial statements. Historic results help us understand the pattern of a utility’s financial and operating performance and how a utility compares to its peers. While rating committees and the rating process use both historical and projected financial results, this document makes use only of historic data, and does so solely for illustrative purposes. All financial measures incorporate Moody’s standard adjustments to income statement, cash flow statement, and balance sheet amounts for (among other things) underfunded pension obligations and operating leases.3. Mapping Factors to Rating CategoriesAfter identifying the measurement criteria for each factor, we match the performance of each factor and sub-factor to one of Moody’s broad rating categories (Aaa, Aa, A, Baa, Ba, and B). In this report, we provide arange or description for each of the measurement criteria. For example, we specify what level of CFO pre-WC plus Interest/Interest is generally acceptable for an A credit versus a Baa credit, etc.4. Mapping Issuers to the Grid and Discussion of Grid OutliersFor each factor and sub-factor, we provide a table showing how a subset of the companies covered by the methodology maps within the specific factors and sub-factors. We recognize that any given company may perform higher or lower on a given factor than its actual rating level will otherwise indicate. These companies are identified as “outliers” for that factor. A company whose performance is two or more broad rating categories higher than its rating is deemed a positive outlier for that factor. A company whose performance is two or more broad rating categories below is deemed a negative outlier. We also discuss the general reasons for such outliers for each factor.5. Discussion of Assumptions, Limitations and Other RatingConsiderationsThis section discusses limitations in the use of the grid to map against actual ratings as well as limitations and key assumptions that pertain to the overall rating methodology.6. Determining the Overall Grid-Indicated RatingTo determine the overall rating, each of the factors and sub-factors is converted into a numeric value based on the following scale:Ratings ScaleAaa Aa A Baa Ba B1 3 6 9 12 15Each sub-factor’s numeric value is multiplied by an assigned weight and then summed to produce a composite weighted-average score. The total sum of the factors is then mapped to the ranges specified in the table below, and the indicated alpha-numeric rating is determined based on where the total score falls within the ranges.Factor NumericsComposite RatingIndicated Rating Aggregate Weighted Factor Score1.5Aaa <Aa1 1.5 < 2.5Aa2 2.5 < 3.5Aa3 3.5 < 4.5A1 4.5 < 5.5A2 5.5 < 6.5A3 6.5 < 7.5Baa1 7.5 < 8.5Baa2 8.5 < 9.5Baa3 9.5 < 10.5Ba1 10.5 < 11.5Ba2 11.5 < 12.5Ba3 12.5 < 13.5B1 13.5 < 14.5B2 14.5 < 15.5B3 15.5 < 16.5For example, an issuer with a composite weighting factor score of 8.2 would have a Baa1 grid-indicated rating.We use a similar procedure to derive the grid-indicated ratings in the tables embedded in the discussion ofeach of the four broad rating categories.The Key Rating FactorsMoody’s analysis of electric and gas utilities focuses on four broad factors:1. Regulatory Framework2. Ability to Recover Costs and Earn Returns3. Diversification4. Financial Strength and LiquidityRating Factor 1: Regulatory Framework (25%)Why it MattersFor a regulated utility, the predictability and supportiveness of the regulatory framework in which it operates isa key credit consideration and the one that differentiates the industry from most other corporate sectors. Themost direct and obvious way that regulation affects utility credit quality is through the establishment of prices orrates for the electricity, gas and related services provided (revenue requirements) and by determining a returnon a utility’s investment, or shareholder return. The latter is largely addressed in Factor 2, Ability to RecoverCost and Earn Returns, discussed below. However, in addition to rate setting, there are numerous other lessvisible or more subtle ways that regulatory decisions can affect a utility’s business position. These can includethe regulators’ ability to pre-approve recovery of investments for new generation, transmission or distribution;to allow the inclusion of generation asset purchases in utility rate bases; to oversee and ultimately approveutility mergers and acquisitions; to approve fuel and purchased power recovery; and to institute or increasering-fencing provisions.How We Measure It for the GridFor a regulated utility company, we consider the characteristics of the regulatory environment in which itoperates. These include how developed the regulatory framework is; its track record for predictability andstability in terms of decision making; and the strength of the regulator’s authority over utility regulatory issues.A utility operating in a stable, reliable, and highly predictable regulatory environment will be scored higher onthis factor than a utility operating in a regulatory environment that exhibits a high degree of uncertainty orunpredictability. Those utilities operating in a less developed regulatory framework or one that is characterizedby a high degree of political intervention in the regulatory process will receive the lowest scores on this factor.Consideration is given to the substance of any regulatory ring fencing provisions, including restrictions ondividends; restrictions on capital expenditures and investments; separate financing provisions; separate legalstructures; and limits on the ability of the regulated entity to support its parent company in times of financialdistress. The criteria for each rating category are outlined in the factor description within the rating grid.For regulated electric utilities with some unregulated operations, consideration will be given to the competitiveand business position of these unregulated operations3. Moody’s views unregulated operations that haveminimal or limited competition, large market shares, and statutorily protected monopoly positions as havingsubstantially less risk than those with smaller market shares or in highly competitive environments. Thosebusinesses with the latter characteristics usually face a higher likelihood of losing customers, revenues, ormarket share. For electric utilities with a significant amount of such unregulated operations, a lower scorecould be assigned to this factor than would be if the utility had solely regulated operations.Moody’s views the regulatory risk of U.S. utilities as being higher in most cases than that of utilities located insome other developed countries, including Japan, Australia, and Canada The difference in risk reflects ourview that individual state regulation is less predictable than national regulation; a highly fragmented market inthe U.S. results in stronger competition in wholesale power markets; U.S. fuel and power markets are more3For diversified gas companies, the “North American Diversified Natural Gas Transmission and Distribution Company” rating methodology is applied.volatile; there is a low likelihood of extraordinary political action to support a failing company in the U.S.;holding company structures limit regulatory oversight; and overlapping or unclear regulatory jurisdictionscharacterize the U.S. market. As a result, no U.S. utilities, except for transmission companies subject tofederal regulation, score higher than a single A in this factor.The scores for this factor replace the classifications we had been using to assess a utility’s regulatoryframework, namely, the Supportiveness of Regulatory Environment (SRE) framework, outlined in our previousrating methodology (Global Regulated Electric Utilities, March 2005), which we are phasing out. Generallyspeaking, an SRE 1 score from our previous methodology would roughly equate to Aaa or Aa ratings in thismethodology; an SRE 2 score to A or high Baa; an SRE 3 score to low Baa or Ba, and an SRE 4 score to a B.For U.S. and Canadian LDCs, this factor corresponds to the “Regulatory Support” and “Ring-fencing” factors inour previous methodology (North American Regulated Gas Distribution, October 2006).Factor 1 – Regulatory Framework (25%)Aaa Aa A Baa Ba BRegulatory framework is fully developed, has a long-track record of being predictable and stable, and is highly supportive of utilities. Utility regulatory body is a highly rated sovereign or strong independent regulator with unquestioned authority over utility regulation that is national in scope. Regulatory framework isfully developed, hasbeen mostly predictableand stable in recentyears, and is mostlysupportive of utilities.Utility regulatory bodyis a sovereign, sovereignagency, provincial, orindependent regulatorwith authority overmost utility regulationthat is national inscope.Regulatory frameworkis fully developed, hasabove averagepredictability andreliability, although issometimes lesssupportive of utilities.Utility regulatory bodymay be a statecommission ornational, state,provincial orindependent regulator.Regulatory framework isa) well-developed, withevidence of someinconsistency orunpredictability in theway framework hasbeen applied, orframework is new anduntested, but based onwell-developed andestablished precedents,or b) jurisdiction hashistory of independentand transparentregulation in othersectors. Regulatoryenvironment maysometimes bechallenging andpolitically charged.Regulatory framework isdeveloped, but there isa high degree ofinconsistency orunpredictability in theway the framework hasbeen applied.Regulatory environmentis consistentlychallenging andpolitically charged.There has been ahistory of difficult orless supportiveregulatory decisions, orregulatory authority hasbeen or may bechallenged or eroded bypolitical or legislativeaction.Regulatory framework isless developed, isunclear, is undergoingsubstantial change orhas a history of beingunpredictable oradverse to utilities.Utility regulatory bodylacks a consistent trackrecord or appearsunsupportive,uncertain, or highlyunpredictable. May behigh risk ofnationalization or othersignificant governmentintervention in utilityoperations or markets.Rating Factor 2: Ability to Recover Costs and Earn Returns (25% )Why It MattersUnlike Factor 1, which considers the general regulatory framework under which a utility operates and the overall business position of a utility within that regulatory framework, this factor addresses in a more specific manner the ability of an individual utility to recover its costs and earn a return. The ability to recover prudently incurred costs in a timely manner is perhaps the single most important credit consideration for regulated utilities as the lack of timely recovery of such costs has caused financial stress for utilities on several occasions. For example, in four of the six major investor-owned utility bankruptcies in the United States over the last 50 years, regulatory disputes culminated in insufficient or delayed rate relief for the recovery of costs and/or capital investment in utility plant. The reluctance to provide rate relief reflected regulatory commission concerns about the impact of large rate increases on customers as well as debate about the appropriateness of the relief being sought by the utility and views of imprudency. Currently, the utility industry’s sizable capital expenditure requirements for infrastructure needs will create a growing and ongoing need for rate relief for recovery of these expenditures at a time when the global economy has slowed.How We Measure It for the GridFor regulated utilities, the criteria we consider include the statutory protections that are in place to insure full and timely recovery of prudently incurred costs. In its strongest form, these statutory protections provide unquestioned recovery and preclude any possibility of legal or political challenges to rate increases or cost recovery mechanisms. Historically, there should be little evidence of regulatory disallowances or delays torate increases or cost recovery. These statutory protections are most often found in strongly supportive andprotected regulatory environments such as Japan, for example, where the utilities in that country receive ascore of Aa for this factor.More typically, however, and as is characteristic of most utilities in the U.S., the ability to recover costs andearn authorized returns is less certain and subject to public and sometimes political scrutiny. Where automaticcost recovery or pass-through provisions exist and where there have been only limited instances of regulatorychallenges or delays in cost recovery, a utility would likely receive a score of A for this factor. Where theremay be a greater tendency for a regulator to challenge cost recovery or some history of regulators disallowingor delaying some costs, a utility would likely receive a Baa rating for this factor. Where there are no automaticcost recovery provisions, a history of unfavorable rate decisions, a politically charged regulatory environment,or a highly uncertain cost recovery environment, lower scores for this factor would apply.For regulated electric utilities that have some unregulated operations, we assess the likelihood that the utilitywill be able to pass on costs of its unregulated businesses to unregulated customers. Among the criteria weuse to judge this factor include the number and types of different businesses the company is in; its marketshare in these businesses; whether there are significant barriers to entry for new competitors; and the degreeto which the utility is vertically integrated. Those utilities with several businesses with large market shares aregenerally in a better position to pass on their costs to unregulated customers. Those utilities that have lowermarket shares in their unregulated activities or are in businesses with few barriers to entry will likely be more atrisk in passing on costs, and thus would receive lower scores. A high proportion of unregulated businesses ora higher risk of passing on costs to unregulated customers could result in a lower score for this factor thanwould apply if the business was completely regulated.For U.S. and Canadian LDCs, this factor addresses the “Sustainable Profitability” and “Regulatory Support”assessments in the previous LDC rating methodology. While LDCs’ authorized returns are comparable tothose for their electric counterparts, the smaller, more mature LDCs tend to face less regulatory challenges.Purchased Gas Adjustment mechanisms are the norm and they have made strides in implementing alternativerate designs that decouple revenues from volumes sold.Factor 2 – Ability to Recover Costs and Earn Returns (25%)Aaa Aa A Baa Ba BRate/tariff formula allows unquestioned full and timely cost recovery, with statutory provisions in place to preclude any possibility of challenges to rate increases or cost recovery mechanisms. Rate/tariff formulagenerally allows fulland timely costrecovery. Fairreturn on allinvestments.Minimal challengesby regulators tocompanies’ costassumptions;consistent trackrecord of meetingefficiency tests.Rate/tariff reviewsand cost recoveryoutcomes are fairlypredictable (withautomatic fuel andpurchased powerrecovery provisions inplace whereapplicable), with agenerally fair returnon investments.Limited instances ofregulatory challenges;although efficiencytests may be morechallenging; limiteddelays to rate or tariffincreases or costrecovery.Rate/tariff reviewsand cost recoveryoutcomes are usuallypredictable, althoughapplication of tariffformula may berelatively unclear oruntested. Potentiallygreater tendency forregulatoryintervention, orgreater disallowance(e.g. challengingefficiencyassumptions) ordelaying of some costs(even whereautomatic fuel andpurchased powerrecovery provisionsare applicable).Rate/tariff reviews andcost recovery outcomesare inconsistent, withsome history ofunfavorable regulatorydecisions orunwillingness byregulators to maketimely rate changes toaddress marketvolatility or higher fuelor purchased powercosts.AND/ORTariff formula may nottake into account allcost components;investment are notclearly or fairlyremunerated.Difficult or highlyuncertain rate andcost recoveryoutcomes. Regulatorsmay engage insecond-guessing ofspending decisions ordeny rate increases orcost recovery neededby utilities to fundongoing operations, orhigh likelihood ofpolitically motivatedinterference in therate/tariff reviewprocess.AND/ORTariff formula maynot cover return oninvestments, onlycash operating costsmay be remunerated.Rating Factor 3 - Diversification (10%)Why It MattersDiversification of overall business operations helps to mitigate the risk that any one part of the company will have a severe negative impact on cash flow and credit quality. In general, a balance among several different businesses, geographic regions, regulatory regimes, generating plants, or fuel sources will diminish concentration risk and reduce the risk that a company will experience a sudden or rapid deterioration in its overall creditworthiness because of an adverse development specific to any one part of its operations.How We Measure It For the GridFor transmission and distribution utilities, local gas distribution companies, and other companies without significant generation, the key criterion we use is the diversity of their operations among various markets, geographic regions or regulatory regimes. For these utilities, the first set of criteria, labeled market diversification, account for the full 10% weighting for this factor. A predominately T&D utility with a high degree of diversification in terms of market and/or regulatory regime is less likely to be affected by adverse or unexpected developments in any one of these markets or regimes, and thus will receive the highest scores for this factor. Smaller T&D utilities operating in a limited market area or under the jurisdiction of a single regulatory regime will score lower on the factor, with those that are concentrated in an emerging market or riskier environment receiving the lowest scores.For vertically integrated utilities with generation, the diversification factor is broadened to include not only the criteria discussed above, but also takes into consideration the diversity of their generating assets and the type of fuel sources which they rely on. An additional but somewhat related consideration is the degree to which the utility is exposed to (or insulated from) commodity price changes. A utility with a highly diversified fleet of generating assets using different types of fuels is generally better able to withstand changes in the price of a particular fuel or additional costs required for particular assets, such as more stringent environmental compliance requirements, and thus would receive a higher rating for this sub-factor. Those utilities with more limited diversification or that are more reliant on a single type of generation and fuel source (measured by energy produced) will be scored lower on this sub-factor. Similarly, those utilities with a high reliance on coal and other carbon emitting generating resources will be scored lower on this factor due to their vulnerability to potential carbon regulations and accompanying carbon costs.Generally, only the largest vertically integrated utilities or transmission companies with substantial operations that are multinational or national in scope, or whose operations encompass a substantial region within a single country, will receive scores in the highest Aaa or Aa categories for this factor. In the U.S., most of the largest multi-state or multi-regional utilities are scored in the A category, most of the larger single state utilities are scored Baa, and smaller utilities operating in a single state or within a single city are scored Ba. A utility may also be scored higher if it is a combination electric and gas utility, which enhances diversification.The diversification factor was not included in the previous North American LDC methodology. Most LDCs are small and tend to have little geographic and regulatory diversity. However, they tend to be highly stable due to their customer base and margins that comprise primarily of a large number of residential and small commercial customers that are captive to the utility. This customer composition tends to result in a more stable operating performance than those that have concentrations in certain industrial customers that are prone to cyclicality or to bypassing the LDC to obtain gas directly from a pipeline. Pure LDCs are scored under the “Market Position” sub-factor for a full 100% under this factor. As with transmission and distribution utilities, no scores are given for “Fuel/Generation Diversification” as this sub-factor would not be applicable.。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

评级方法2005 年 9 月联系人多伦多电话号码Terry Marshall Fadwa Sahly泽西市1.416.214.1635Mark Gray Steve Oman纽约1.201.915.8750Carol Cowan James O’Shaughnessy悉尼1.212.553.1653Terry Fanous Ileria Chan伦敦61.2.9270.8100Francois Lauras Ruchi Gupta香港44.20.7772.5397Anna Ho852.2916.1110全球采矿业穆 迪 报 告 “Global Mining Industry” 的 中 文 翻 译 本 (中文为翻译稿,如有出入,以英文为准)评论摘要本评级方法报告针对穆迪向全球矿业公司授予信用评级的分析方法提供详细的说明。

就本方法而言, 我们将矿业发行人 定义为从事基础金属与贵金属、其他工业金属及煤炭的采矿、熔炼和精炼业务的公司。

大型铝业公司亦积极从事包装与 制造业务,这是唯一与上游和下游业务全面融合的矿业企业。

本评级方法报告的主要目的是帮助发行人、投资者和其他矿业参与者了解穆迪如何评估矿业公司的风险,并使我们 的委托人能够大概估测一家公司的评级。

本方法并非穆迪在授予矿业公司评级的过程中所考虑的全部因素, 但可以帮助 读者理解穆迪在评级过程中考虑的主要考虑因素、采用的财务比率及其权重。

穆迪评级的 40 家矿业发行人覆盖了矿业的多个界别(例如铜、铝、黄金、煤炭等) ,并展示出相近的业务基本及许 多共同的信用考虑因素。

整体而言,我们采用 5 大评级因素来衡量全球矿业公司的信用风险并授予评级。

我们将在本报 告中详细讨论各个评级因素,包括了多项具体要素与指标(或“次级因素”,5 个评级因素如下: ) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 储量 成本效率与盈利能力 财务政策 财务实力 业务多样性与规模此外,我们加入了“其他考虑因素”一节,讨论难以有意义地量化或预测,但对于矿业发行人的评级有显著影响的 因素(例如政治风险) 。

其它的适用于各行业的评级因素(尤其是公司治理、管理层实力和股东结构)对于全球矿业发行人的评级仍然是重 要的投入因素。

但这些因素并非是矿业公司所独具,而是适用于所有企业融资业,因此我们并未在本评级方法中深入探 讨此类问题。

为了提高透明度,我们亦提供了详细的评级表,反映各评级因素和财务指标与具体评级之间的映射关系。

最后,由于任何一家公司都不可能完全符合本分析方法的每个方面,所以我们在本评级方法中讨论了“异常值”的 问题,即指某一特定因素的评级与实际评级所隐含的情况有颇大分别的公司。

本报告的重点包括以下几方面:• • • • •全球矿业风险因素的概述 评级方法与推动矿业信用质量的 5 大因素(包括 15 项指标或次级因素)的介绍 评级框架对 16 家范例矿业公司的应用 其它评级因素的说明 我们的评级结果及其权重总结在分析全球矿业时,穆迪希望在金属和矿石价格上涨和下降期间评级保持一定的一致性。

此举表示我们亦认同在不 同经济环境下供需失衡导致金属价格变化,从而可能造成现金流的波动性以及债务保护措施。

但是在投机级别的评级类 别中,由于财务和运营杠杆及其所造成的受市场变化影响的程度普遍更高,因此维持评级一致性的能力有所下降的。

穆迪衡量比率的做法是利用过去 2-3 年的实际数据以及穆迪对未来 2-3 年的预期,并考虑平均值和高点与低点。

这便于我们了解该公司在不同价格条件下的运营能力。

为了在本方法中进行说明,我们仅用各范例公司的历史数据, 以代替穆迪在评级中考虑的不同价格环境。

我们使用的某些指标(例如息税前利润率(EBIT 利润率) )是以 5 年财务数据的平均值为基础。

其它指标(例如储 量和债务对资本值)则是某一固定时间的数据,该时间通常是有数据存在的最近一年的年底(储量)或最近的会计报告 期(EBIT 利润率) 。

我们在本报告中均会明确指出衡量各指标的基础。

全球受评矿业公司概况穆迪在全球对 40 家矿业公司授予评级,受评债务约为 1,040 亿美元,其中包括北美(25) 、南美(4) 、欧洲(6) 、澳大 利亚(2)和亚洲(2)的发行人。

上述发行人的评级范围广泛,从 Caa2(1)至 Aa3(2) 。

在所有受评发行人中,49% 是投机级别(主要是 Ba3 公司家族评级) ,其余多为 Baa3 公司家族评级(6) 。

上述评级反映了穆迪对于各家公司的相 对竞争地位、盈利能力和财务实力的意见。

全球矿业公共评级9 8 发行人数目 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Aa3 A1 A2 A3 Baa1 Baa2 Baa3 Ba1 Ba2 Ba3 B1 B2 B3 Caa2大概 87%的评级展望为稳定,2.5%为正面,不足 5%的评级展望为负面。

评级展望目前与任何特定的行业次级界别 或评级范围均无关联。

2穆迪评级方法行业概况行业风险因素全球矿业包括在单一地区从事单一金属或矿石的采矿、 熔炼、 精炼和选矿业务的公司以至在全球范围内生产多种金属和 矿石的公司。

如上文所述, 主要的铝业公司除了进行铝气石和氧化铝的采矿与精炼外, 亦在全球从事包装和制造业务 (汽 车与航空) 。

总体来看,矿业发行人具有下列多个相似特征:••••业务的商品特性及其造成的周期性。

各大铝业公司及其制造与包装业务在内的所有行业参与者的现金流 均具有周期性。

经济周期在其中发挥关键作用,各金属的基本供求关系亦有影响。

业务涉及一种金属的公 司的周期性集中,因此规模更大、更为多样化的公司相对压力较小;煤炭公司的合同具有滚动性质,所以 其周期性较为平稳。

不过,周期性仍是所有同业的一个重要风险因素。

补充储量和开发新矿产的需求而导致的资本密集性。

矿业是高度资本密集型业务,原因是该行业需要维 持现有运营以及找寻和 / 或收购并开发新的矿产。

若一家公司无法持续对业务的这个范畴来降低资本支 出的周期性, 其评级有时可能会受到不利影响。

持续地执行稳固的资本结构是帮助公司管理上述范畴的关 键因素。

对于投入成本上升的敏感性。

矿业十分依赖某些商品(能源、钢铁、爆炸品等),兼之该行业受汇率波 动影响(进而影响劳动力成本),因此更加影响现金流的周期性。

上述因素共同构成了矿业公司投入成本 的一个重要部分。

由于基础成本往往与金属价格的走势一致,这可能影响整体利润率,尤其是在商品价格 下跌时出现时间差的时候。

事件风险。

矿业公司的事件风险形式多样,包括运营、政治抑或是经济方面的风险。

鉴于该行业依赖发 展中国家作为最终市场,此类风险可能包括这些国家不时发生的经济冲击的风险。

未来 10 年的信用问题 • • • • • •不断需要通过扩大勘探与收购 / 整合来获得储量 可能利用高额的相关资本支出来开发新储量 金属价格颇可能仍主要关系于新兴市场经济,即提高政治与经济冲击所带来的价格波动性风险 环境 / 土地复原的责任可能会增加 投入成本居高不下(尤其是能源),这将支持更高的金属价格,但代价却是利润率的下降 全行业和多数地区劳动力持续短缺本评级方法介绍我们通过下列步骤帮助读者了解针对矿业公司的评级方法。

1. 明确指出主要评级因素穆迪负责矿业公司的评级委员会重点关注 5 个主要的评级因素,我们将在本报告中加以说明。

这些因素如下: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 储量 成本效率与盈利能力 财务政策 财务实力 业务多样性与规模除了本报告中讨论的 5 大因素外,穆迪亦考虑难以量化或难以有意义地来量化的其他定性因素。

但这些因素可能是 重要因素,甚至有时是最重要的考虑因素(例如政治风险) 。

我们将在“其他因素”一节进行说明。

2. 5 个主要评级因素的衡量在明确每个主要因素时,我们亦介绍用于量化该因素的指标和次级因素。

这些指标包括财务报表指标(例如债务对 EBITDA 比率)以及并非直接从财务报告分析中得出的其他指标(例如运营多样性) 。

上述因素在许可的情况下可能通 过下列方法之一或全部予以定义:穆迪评级方法3• • •纯定性评估(例如产品性质:商品与价值增值) 根据穆迪预测的等级或穆迪定义的广义定量措施进行的定性评估(例如地区性业务的数目) 可通过公开数据得出的纯定量或财务评估(例如 EBIT 利润率、收入等)共有 15 项指标用于衡量矿业评级的 5 个主要因素,其中 10 项是单纯的财务指标。

3. 与评级因素的映射之后,我们将 15 项指标逐一映射到评级类别(Aaa, Aa, A, Baa, Ba, B and Caa) 。

4. 说明评级方法 / 异常值讨论为说明全球评级方法,我们选择了北美、澳大拉西亚(Australasia)和欧洲这 3 大地区的 16 家具有代表性的公司,并将 各公司在每一因素的表现映射到其相关评级,同时列出各因素的评级与公司实际评级的比较。

我们亦指出正面或负面的“异常值”—即某一特定因素的评级比其现有评级高或低至少两个等级的公司(例如: 某公司的评级为 Ba,但其某一特定因素的评级属于 A 类) 。

此后我们说明可能有助于解释这种差异的信用因素。

最后,我们将每家范例公司各个因素的评级综合为该公司的整体评级。

在此过程中,我们对每一因素采用相同权重 及“穆迪”的权重。

五个主要评级因素评级因素一:储量其重要的原因储量是一家矿业公司的命脉,亦对于矿业公司的成败可能具有最重要的影响。

拥有高质量储量的供应,将对该公司提供 一个可符合经济效益地开发,而不会引致找寻与收购成本的运营平台。

影响储量质量的主要因素包括储量的级别与回采 率、 规模、 指示寿命、 位置、 以及所录得储量是否与现有矿业运营相关、 或是否需要棕地开发 (brownfield development) 或新建开发(greenfield development) 。

级别与回采率是决定质量的最重要因素,最终反映于某一矿井和公司的运营表 现。

一个矿床的基础冶金量也是影响回采率以及开发与运营成本的重要因素。

储量的位置也是另一个可连系到多个可变 因素的重要考虑, 这些可变因素包括露天和地底采矿、 高度、 与现有基建的接近程度、 以及一些政治、 监管和审批问题。

我们难以直接的或对不同金属的储量进行量化和将其质量排名,特别是在比较一些生产不同金属的公司的时候。

我们也知道某些矿石可能非常容易预测,所以探明储量的成本可能不必要且昂贵。

因此,探明和或有储量可能不能充份 反映地质上的实况。

穆迪亦会考虑一家公司的基础价格和成本假设来衡量未来储量修正的潜力。

最终, 储量质量是反映于某一家公司的盈利表现, 而盈利表现是反映于本评级方法内多个其它类别的一种衡量指标, 这些成其它类别包括成本效率与盈利能力、财务政策和财务实力。