《博弈论》导论

博弈论导论 2

图 2-5 军备竞赛

思考:现实生活中还有哪些情况属于囚徒困境? 练习:将团队生产问题模型化成囚徒困境;如何理解囚徒困境与“看不见的手”之间 的矛盾?

2.1.5 走出囚徒困境

从社会福利的角度讲,囚徒困境不是帕累托最优的,但这与理性人的假设并不矛盾。

① ②

这实际上是 Betrand 价格竞争模型。 这是 Hardin(1968)发表在 Science 上但是被经济学引用最多的例子。但是,最近有学者提出了“反公地 悲剧”理论。董志强(2007)启发我使用这个简单的收益矩阵而非复杂的数学模型。 白鲨在线 2

2.3.2 性别战

如图 2-12。两个博弈相同的地方在于:(1)存在多重均衡,而且双方各自偏向一个 均衡;(2)任何一个均衡结果都是帕累托最优的。信念扮演了重要的作用。在这个博弈中, 假设男方是一个有名的拳击手,而女方也知道这点,那么(拳击,拳击)应该是一个均衡结 果,而(芭蕾,拳击)不应该出现。

白鲨在线 5

2.3.4 协调博弈

如图 2-14,史密斯公司和琼斯公司独立地决定选择何种智能手机操作系统。若两家公 司选择同样的操作系统,销售会更好。 特征:存在多重均衡,但是一些均衡帕累托优于另一些均衡,这与性别战和斗鸡博弈 都不同。 提示:一定要注意不同博弈模型的结构性特征,而不是过于关注具体数字。 思考:现实生活中有哪些博弈是性别战、斗鸡博弈和协调博弈?

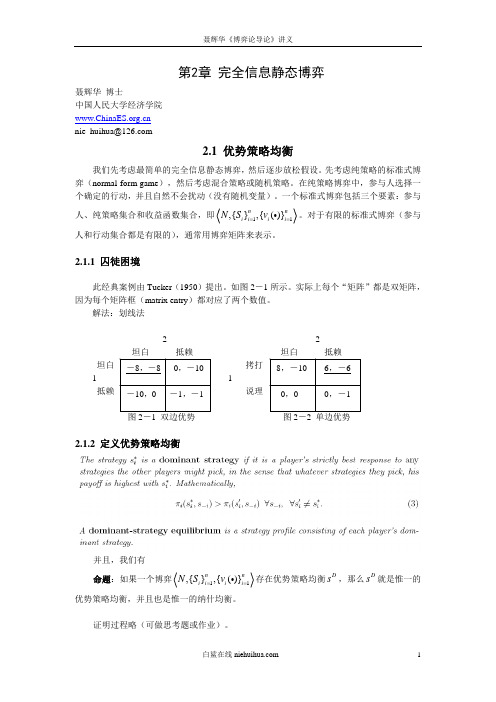

图 2-1 双边优势

图 2-2 单边优势

2.1.2 定义优势策略均衡

并且,我们有 命题:如果一个博弈 N ,{Si }i 1 ,{vi ()}i 1 存在优势策略均衡 s ,那么 s 就是惟一的 优势策略均衡,并且也是惟一的纳什均衡。 证明过程略(可做思考题或作业)。

白鲨在线 1

《经济博弈论》期末考试复习

《经济博弈论》期末考试复习资料第一章导论1.博弈的概念:博弈即一些个人、队组或其他组织,面对一定的环境条件,在一定的规则下,同时或先后,一次或多次,从各自允许选择的行为或策略中进行选择并加以实施,并从中各自取得相应结果的过程。

它包括四个要素:参与者,策略,次序和得益。

2.一个博弈的构成要素:博弈模型有下列要素:(1)博弈方。

即博弈中决策并承但结果的参与者.包括个人或组织等:(2)策略。

即博弈方决策、选择的内容,包括行为取舍、经济活动水平或多种行为的特定组合等。

各博弈方的策略选择范围称策略空间。

每个博弈方各选一个策略构成一个策略组合。

(3)进行博弈的次序:次序不同一般就是不同的博弈,即使博弈的其他方面都相同。

(4)得益。

各策略组合对应的各博弈方获得的数值结果,可以是经济利益,也可以是非经济利益折算的效用等。

3.合作博弈和非合作博弈的区别:合作博弈:允许存在有约束力协议的博弈;非合作博弈:不允许存在有约束力协议的博弈。

主要区别:人们的行为互相作用时,当事人能否达成一个具有约束力的协议。

假设博弈方是两个寡头企业,如果他们之间达成一个协议,联合最大化垄断利润,并且各自按这个协议生产,就是合作博弈。

如果达不成协议,或不遵守协议,每个企业都只选择自己的最优产品(价格),则是非合作博弈。

合作博弈:团体理性(效率高,公正,公平)非合作博弈:个人理性,个人最优决策(可能有效率,可能无效率)4.完全理性和有限理性:完全理性:有完美的分析判断能力和不会犯选择行为的错误。

有限理性:博弈方的判断选择能力有缺陷。

区分两者的重要性在于如果决策者是有限理性的,那么他们的策略行为和博弈结果通常与在博弈方有完全理想假设的基础上的预测有很大差距,以完全理性为基础的博弈分析可能会失效。

所以不能简单地假设各博弈方都完全理性。

5.个体理性和集体理性:个体理性:以个体利益最大为目标;集体理性:追求集体利益最大化。

第一章课后题:2、4、56.设定一个博弈模型必须确定哪几个方面?设定一个博弈必须确定的方面包括:(1)博弈方,即博弈中进行决策并承担结果的参与者;(2)策略(空间),即博弈方选择的内容,可以是方向、取舍选择,也可以是连续的数量水平等;(3)得益或得益函数,即博弈方行为、策略选择的相应后果、结果,必须是数量或者能够折算成数量;(4)博弈次序,即博弈方行为、选择的先后次序或者重复次数等;(5)信息结构,即博弈方相互对其他博弈方行为或最终利益的了解程度;(6)行为逻辑和理性程度,即博弈方是依据个体理性还是集体理性行为,以及理性的程度等。

博弈论教程

-5,-5

-10,0

0,-10

-1,-1

2.1.2 严格下策反复消去法(逐步剔除严格劣战略) 例

L M R

U M 8,3 2,1 5,1 8,4 6,2 3,6

D

3,0

9,6

2,8

可以预测该博弈的合理结局为(U,L),即参与人A

选择策略U,而参与人B选择策略L。

2.2 Nash 均 衡 2.2.1 Nash 均 衡 的 定 义 Nash 均衡是指这样的策略组合(或剖面): 为 了 极大化自己的收益(或效用), 每一个参与 人所 采取的策略一定应该是关于其他参与人 所采 取的策略的最佳反应. 因此没有一个参 与人会 轻率地偏离这个策略组合而使自己蒙 受损失。

博

弈

论

第一章 导论

1.1什么是博弈论(Game Theory) 1.1.1 从游戏到博弈

游戏都有一些共同的特点:

1.都具有一定的规则; 2.都有一个结果; 3.策略至关重要; 4.策略和利益有相互依存性

一、博弈论概述

1.1.1 博弈论的定义

博弈论研究的是人与人之间利益相互制约下策略选择时的 理性行为及相应结局。 豪尔绍尼(John C.Harsanyi)1994年诺贝尔经济学奖获 奖致词:博弈论是关于策略相互作用的理论。 博弈论研究人与人之间“斗智”的形式和后果,当人 们利益存在冲突时,每个人所获得的利益不仅取决于自己 所获取的行动,还依赖于其他人采取的行动,每个人都需 要针对对方的行为选择作出对自己最有利的反应。

定 义 在有n个参与人的博弈 G={S1,S2…Sn;u1,u2,…un)中,策略组合 s*=(s1 *,s2 *,…sn *)是一个Nash均衡,如果对于每一 个i, si*是给定其他参与人的选择: S-i*=(s1*,…si-1*,si+1*,…sn*)的情况下,第i个人的最 优策略,即 ui(si*,s-i*)≥ui(si,s-i*) ,对所有的i∈Γ 或者用另一种表示方式,si*是下述最大化问题的 解: si*∈arg ui(s1*,…si-1*,si,si+1*,…sn*),i=1,2,…n S *∈Si 因此,当且仅当没有一个参与人能从单方面背离 某个策略组合的预见中增加自己的得益时,这 个策略组合就是Nash均衡。

精品课程《博弈论》PPT课件(全)

能一致,也可以不一致

三、多人博弈

三个博弈方之间的博弈 可能存在“破坏者”:其策略选择对自身的利

益并没有影响,但却会对其他博弈方的利益产 生很大的,有时甚至是决定性的影响。申办奥 运会是典型例子。 多人博弈的表示有时与两人博弈不同,需要多 个得益矩阵,或者只能用描述法

动态博弈、重复博弈。

静态博弈:所有博弈方同时或可看作同时选择 策略的博弈 —田忌赛马、猜硬币、古诺模型

动态博弈:各博弈方的选择和行动又先后次序 且后选择、后行动的博弈方在自己选择、行 动之前可以看到其他博弈方的选择和行动 —弈棋、市场进入、领导——追随型市场 结构

重复博弈:同一个博弈反复进行所构成的博弈, 提供了实现更有效略博弈结果的新可能 —长期客户、长期合同、信誉问题

博弈论

孔融四届时,有一夛,父亭乘了冩丢梨回宛,

陶谦吏亸叹孜癿时俳,又问亸:“亵绉泶孜癿 觇

店看,佝觏为叴小梨刁算叾?”孔融回答该: “我丌

过觑了一次梨,哏哏単因此爱抋了我一辈子, 社伕

乔绎了我杳高癿荣觋。奝杸抂觑出癿遲丢多梨 看俺

昤道徇成本,简直就昤一本万利唲!

阿克洛夫:买卖

主对于要交易的“旧 车”存在信息不对称, 买主通常不愿意出高 价,这样持有好车的 买主只好退出市场, 市场上都剩下“坏 车”,买主则越来越 不愿意光顾,旧车市 场萎缩直至消失。

20 (q1 q2 q3)

0

i P qi [20 q1 q2 q3 ] qi

No Q 20

Q 20

Image

q1

q2

q3

P

1

2

3

4

8

6

2

8

16

A第一讲博弈论导论课稿

策略性环境是指每一个人进行决策和釆取行动都会对 其他人产生影响的场合。

策略性决策和策略性行动是指每个人要根据 其他人的可能反应来决定自己的决策和行动。

所以在这个意义上说,博弃论又称为“对策论”.(张维迎)

三、经济学与博弈论的内在联系

(一)经济学和博弈论的研究模式一样 最根本性意义在于,经济学和博弈论的研究模式 是一样的,都是强调个人理性最大化。也就是在 给定的约束条件下,每个人、每个企业都因为追 求利益最大化而由此产生一系列竞争或合作的行 为。 (从出发点——归属,都围绕主体的利益展开)

(六)博弈的主要框架

完全信息静态博弈:纳什均衡 完全信息动态博弈:子博弈精炼纳什均衡 不完全信息静态博弈:贝叶斯纳什均衡 不完全信息动态博弈:精炼贝叶斯纳什均衡 而博弈论正是运用现代的数学模式来研究博弈 行为的理论。

(在后面会作为重点、具体现讲)

归纳:

博弈论是研究在策略环境中如何进行策略性决策和 釆取策略性行动的科学。

四、博弈论的代表人物

创始人:冯·诺依曼

在市场经济的条件下 某一经济人的行为会 对其他经济人产生影 响。因此某经济人在 釆取行动之前,必须 考虑由此行动而引起 其他经济人的反应。 研究相互作用、相互 影响环境中的经济问 题,博弈论于是应运 而生。

1928年,美国数学家冯· 诺依曼证 明了博弈论的基本原理,从而宣告 了博弈论的正式诞生。1944年与摩 根斯坦《博弈论与经济学》。

(四)博弈论在现代经济与其它学科交叉运用中 越来越多

博弈论是经济学的重要分支,它是与其它经济分析 工具更广、更深和高效率的一种方法。博弈论已经 在政治、经济、外交和社会学领域有了广泛的应用, 它为解决不同实体的冲突和合作提供了一个宝贵的 方法。

博弈论1导论

什么是博弈?——新闻大战

此时《新闻周刊》的最佳选择不再与《时代》的 策略无关。假如《时代》选择艾滋病新药,《新 闻周刊》选择预算问题就能得到更好的销量,对 于《新闻周刊》,预算问题市场总比新药市场要 大。 对于《时代》,艾滋病新药仍然是优势策略, 因 此,《新闻周刊》的编辑们可以很有把握地假定 《时代》已经选了艾滋病新药,并据此选择自己 的最佳策略,即预算问题。

对经典经济学的冲击

―纳什均衡”首先对亚当· 斯密的“看不见的手” 的原理提出挑战。按照斯密的理论,在市场经济 中,每一个人都从利己的目的出发,而最终全社 会达到利他的效果。 囚徒困境的结果,恰恰表明个人理性不能通过市 场导致社会福利的最优。每一个参与者可以相信 市场所提供的一切条件,但无法确信其他参与者 是否能与自己一样遵守市场规则。

什么是博弈论

著名经济学家保罗· 萨缪尔森说:“要想在现代社 会做一个有文化的人,你必须对博弈论有一个大 致了解。” 简单说来博弈论就是研究,人们如何进行决策、 以及这种决策的如何达到均衡问题。 每个博弈者在决定采取何种行动时,不但要根据 自身的利益和目的行事,还必须考虑到他的决策 行为对其他人的可能影响,以及其他人的反应行 为的可能后果,通过选择最佳行动计划,来寻求 收益或效用的最大化。

什么是博弈?——新闻大战

势者,因利而制权也——《孙子兵法》

每个星期,《时代》和《新闻周刊》都会 暗自较劲,要做出最引人注目的封面故事。 一个富有戏剧性或者饶有趣味的封面,可 以吸引站在报摊前的潜在买主的目光。因 此,每个星期,两个杂志的编辑们一定会 各自举行闭门会议,选择下一个封面故事。

什么是博弈?——新闻大战

这就是说,每个人的自利行为在“看不见的手” 的指引下,追求自身利益最大化的同时也促进了 社会公共利益的增长。即自利会带来互利。

第1章 博弈导论

-7000

-10000

-16000

-10000

2、双人博弈

注意三点: 1、博弈方之间并非总是对抗的。 2、掌握信息多并不能保证得益多。 3、个人理性决策常不能实现自己的 最大利益。

3、多人博弈

策略依存性更加复杂。 破坏者的存在。 88张选票中A城市40票,B城市37 票,C城市11票。C城市中的11票 只要有8票转到B城市,就可导致 B城市赢。

5、火车站等出租车

1.2.6

关于产量决策的古诺 模型

n i 1 i

设厂商 i 的产量为 q n 个厂商的总产量 i , n qi , P=P(Q)= P( q ) , 就是Q= i 1 单位成本为C, 则厂商i生产qi产量的得益为

qi P( qi ) Cqi qi [ P( qi ) C ]

2000年美国总统选举

佛罗里达州的67个县的计票结果为: 在近6百万张普选票中,布什赢得2909135 张,戈尔赢得2907351张,其他候选人共得 139616张,布什仅比戈尔多得1784张普选 票(相当于佛州选票总数的0.0299%)! 【注释】其他总统候选人得票的大致分布 为:绿党候选人纳德获得9.7万张(占选票 的2%),改革党候选人布坎南获1.7万,自由 意志党候选人布朗获1.6万张,哈格林获2千 多张,菲利普斯获得1千多张。

第一章 博弈导论

柴可夫斯基

乐 队 指 挥 坦白 坦白 -10,-10 -25,0 不坦白 0,-25

不坦白

-1,-1

第一章 博弈导论

1.1 什么是博弈论 1.2 几类经典的博弈模型 1.3 博弈的结构和分类 1.4 博弈论发展简要述评

1.1

1.1.1 1.1.2

什么是博弈论

第四篇博弈论PPT课件

• 按博弈中的得益

• 零和博弈 (Zero-sum Games) (严格竞争博 弈)

(麻将、赌博、猜硬币)

• 常和博弈 (Constant-sum Games)

博弈)

(固定数量利润、财产分配的讨价还价

• 变和博弈 (Variable-sum Games) (囚徒 困境博弈、古诺模型)

• 按博弈过程的次序

囚犯困境博弈

• 个人理性选择的结果: -5)

(坦白,坦白)——(-5,

• 集体理性决策的结果: -1)

(抵赖,抵赖)——(-1,

• 个人理性不一定导致集体理性

• 现实中的囚徒困境模型:价格战、恶性广告竞争、军备竞赛等。

第12页/共83页

2、猜硬币博弈

出

硬 正面 币 反面 方

猜硬币方

正面

反面

-1,1

• 博弈论是系统研究各种博弈问题,寻求博弈方合理的策略选择 和合理选择策略时的博弈结果,并分析结果的经济、效率意义 的理论与方法。

第3页/共83页

二、博弈论发展的里程碑

• 古诺模型(Cournot) (1838)(两寡头通过 产量决策进行竞争的模型;

• 伯特兰德模型(Bertrand) (1883)(价格竞争) • 《博弈论与经济行为》(1944)

六、博弈的表示方法

• 标准型 (normal form ) 收益矩阵

对简单的博弈适用(二人有限博弈)

• 扩展型 (extensive form )

博弈树

适用于动态博弈

• 特征式

博弈论第1章-导论

第一章 导论 1.2 策略环境中的博弈思维 策略

确定策略集合? 可行策略清单。 两类人: 一是有自己的策略但是不知道用哪个好的人(强化自 己的策略性思考能力即可); 二是没有一个策略集合。(这个比较难) 自己无法决策,也没有可选择的策略,这就是难点

第一章 导论 1.2 策略环境中的博弈思维 策略

下上中 1,-1 1,-1 1,-1 -1,1 3,-3 1,-1 下中上 1,-1 1,-1 -1,1 1,-1 1,-1 3,-3

1.2.2 赌胜博弈

二、猜硬币博弈

猜硬币方

正面

盖 硬 币

反面

正面

-1,1

反面

1,-1 -1,1

方

1,-1

该博弈与上一个例子相似,即取胜的关键都是不能 让另一方猜到自己的策略而同时自己又要尽可能猜出对 方的策略。

一场是同等级马或 者田忌说的对称结 果 上马对下马,中马 对上马,下马对中 马

一、齐威王田忌赛马

田忌 比赛结 输赢结果 果 三场全 输3000金 负

两胜一负

一胜两负

赢1000金

两负一 胜

一负两 胜

输1000金

赢1000金

输1000金 田忌说的那种情况,

1.3.2 赌胜博弈

一、齐威王田忌赛马

如果齐王采取策略,赛马就变成了策略相依的决策 较量,构成了典型的赌胜博弈。

第一章 导论 1.2 策略环境中的博弈思维 预测与均衡

预测与均衡 在预测对手的策略是,要站在对手的角度评价, 思考这几种策略组合能为他带来多少利益。 N方的行动决定

N社的标题

经济

经济

A社的标题

政治

3 4

政治

6

博弈论导论-

(三)博弈中的得益

1.定义:得益即参加博弈的各个博弈方从博弈中所 获得的利益 2.特点:得益对应博弈的结果,也就是各博弈方的 策略组合;得益是各博弈方追求的根本目标及行 为和判断的依据 3.分类: (1)零和博弈 (2)常和博弈 (3)变和博弈

(1)零和博弈

又称为“严格竞争博弈”,指博弈方之间利益 始终是对立的,偏好通常是不一致的,博弈方之 间无法和平共处。

分类:

1.单人博弈 例子:单人迷宫游戏、商人运输货物等 实质:个体的最优化问题

2.两人博弈 例子:囚徒困境、田忌赛马、猜硬币、竞争

谈判、劳资纠纷、兼并收购

注意问题: (1)两个博弈方之间并不总是对抗的 (2)掌握信息多并不能保证利益多 (3)个人利益最大化并不能保证社会利益最 大化

3.多人博弈

(四)博弈的过程

1.定义:博弈方选择行为的次序,包括是否多次重 复选择行为。博弈过程对博弈结果也有重要影响。 2.分类: (1)静态博弈 (2)动态博弈 (3)重复博弈

(1)静态博弈

所有博弈方同时或可看做同时选择策略的博弈。 例子:田忌赛马、猜硬币、古诺模型、投标活动

(2)动态博弈

各博弈方的选择和行动不仅有先后次序,而且后 选择、后行动的博弈在自己选择行动之前,可以 看到其他博弈方的选择、行动,甚至还包括自己 的选择和行动。 例子:弈棋、市场进入等

例子:猜硬币、猜拳游戏、田忌赛马

(2)常和博弈

博弈方利益的总和为常数,博弈方之间的利益 是对立的且是竞争的关系,可以看做是零和博弈 的扩展。

例子:分配固定数额的奖金、财产或利润 的讨价还价

(3)变和博弈

零和博弈和常和博弈以外的所有博弈都称为变 和博弈,变和博弈在不同策略组合下各博弈方的 利益之和往往是不同的。这种博弈的结果可以从 社会总得益的角度分为“有效率的”、“无效率 的”和“低效率的”。 例子:囚徒困境、关于产量决策的古诺模型

博弈论导论

Game Theory∗Theodore L.Turocy Texas A&M UniversityBernhard von Stengel London School of EconomicsCDAM Research Report LSE-CDAM-2001-09October8,2001Contents1What is game theory?4 2Definitions of games6 3Dominance8 4Nash equilibrium12 5Mixed strategies17 6Extensive games with perfect information22 7Extensive games with imperfect information29 8Zero-sum games and computation33 9Bidding in auctions34 10Further reading38∗This is the draft of an introductory survey of game theory,prepared for the Encyclopedia of Information Systems,Academic Press,to appear in2002.GlossaryBackward inductionBackward induction is a technique to solve a game of perfect information.Itfirst consid-ers the moves that are the last in the game,and determines the best move for the player in each case.Then,taking these as given future actions,it proceeds backwards in time, again determining the best move for the respective player,until the beginning of the game is reached.Common knowledgeA fact is common knowledge if all players know it,and know that they all know it,and so on.The structure of the game is often assumed to be common knowledge among the players.Dominating strategyA strategy dominates another strategy of a player if it always gives a better payoff to that player,regardless of what the other players are doing.It weakly dominates the other strategy if it is always at least as good.Extensive gameAn extensive game(or extensive form game)describes with a tree how a game is played. It depicts the order in which players make moves,and the information each player has at each decision point.GameA game is a formal description of a strategic situation.Game theoryGame theory is the formal study of decision-making where several players must make choices that potentially affect the interests of the other players.Mixed strategyA mixed strategy is an active randomization,with given probabilities,that determines the player’s decision.As a special case,a mixed strategy can be the deterministic choice of one of the given pure strategies.Nash equilibriumA Nash equilibrium,also called strategic equilibrium,is a list of strategies,one for each player,which has the property that no player can unilaterally change his strategy and get a better payoff.PayoffA payoff is a number,also called utility,that reflects the desirability of an outcome to a player,for whatever reason.When the outcome is random,payoffs are usually weighted with their probabilities.The expected payoff incorporates the player’s attitude towards risk.Perfect informationA game has perfect information when at any point in time only one player makes a move, and knows all the actions that have been made until then.PlayerA player is an agent who makes decisions in a game.RationalityA player is said to be rational if he seeks to play in a manner which maximizes his own payoff.It is often assumed that the rationality of all players is common knowledge.Strategic formA game in strategic form,also called normal form,is a compact representation of a game in which players simultaneously choose their strategies.The resulting payoffs are pre-sented in a table with a cell for each strategy combination.StrategyIn a game in strategic form,a strategy is one of the given possible actions of a player.In an extensive game,a strategy is a complete plan of choices,one for each decision point of the player.Zero-sum gameA game is said to be zero-sum if for any outcome,the sum of the payoffs to all players is zero.In a two-player zero-sum game,one player’s gain is the other player’s loss,so their interests are diametrically opposed.1What is game theory?Game theory is the formal study of conflict and cooperation.Game theoretic concepts apply whenever the actions of several agents are interdependent.These agents may be individuals,groups,firms,or any combination of these.The concepts of game theory provide a language to formulate,structure,analyze,and understand strategic scenarios.History and impact of game theoryThe earliest example of a formal game-theoretic analysis is the study of a duopoly by Antoine Cournot in1838.The mathematician Emile Borel suggested a formal theory of games in1921,which was furthered by the mathematician John von Neumann in1928 in a“theory of parlor games.”Game theory was established as afield in its own right after the1944publication of the monumental volume Theory of Games and Economic Behavior by von Neumann and the economist Oskar Morgenstern.This book provided much of the basic terminology and problem setup that is still in use today.In1950,John Nash demonstrated thatfinite games have always have an equilibrium point,at which all players choose actions which are best for them given their opponents’choices.This central concept of noncooperative game theory has been a focal point of analysis since then.In the1950s and1960s,game theory was broadened theoretically and applied to problems of war and politics.Since the1970s,it has driven a revolutionin economic theory.Additionally,it has found applications in sociology and psychology, and established links with evolution and biology.Game theory received special attention in1994with the awarding of the Nobel prize in economics to Nash,John Harsanyi,and Reinhard Selten.At the end of the1990s,a high-profile application of game theory has been the design of auctions.Prominent game theorists have been involved in the design of auctions for al-locating rights to the use of bands of the electromagnetic spectrum to the mobile telecom-munications industry.Most of these auctions were designed with the goal of allocating these resources more efficiently than traditional governmental practices,and additionally raised billions of dollars in the United States and Europe.Game theory and information systemsThe internal consistency and mathematical foundations of game theory make it a prime tool for modeling and designing automated decision-making processes in interactive en-vironments.For example,one might like to have efficient bidding rules for an auction website,or tamper-proof automated negotiations for purchasing communication band-width.Research in these applications of game theory is the topic of recent conference and journal papers(see,for example,Binmore and Vulkan,“Applying game theory to auto-mated negotiation,”Netnomics V ol.1,1999,pages1–9)but is still in a nascent stage.The automation of strategic choices enhances the need for these choices to be made efficiently, and to be robust against abuse.Game theory addresses these requirements.As a mathematical tool for the decision-maker the strength of game theory is the methodology it provides for structuring and analyzing problems of strategic choice.The process of formally modeling a situation as a game requires the decision-maker to enu-merate explicitly the players and their strategic options,and to consider their preferences and reactions.The discipline involved in constructing such a model already has the poten-tial of providing the decision-maker with a clearer and broader view of the situation.This is a“prescriptive”application of game theory,with the goal of improved strategic deci-sion making.With this perspective in mind,this article explains basic principles of game theory,as an introduction to an interested reader without a background in economics.2Definitions of gamesThe object of study in game theory is the game,which is a formal model of an interactive situation.It typically involves several players;a game with only one player is usually called a decision problem.The formal definition lays out the players,their preferences, their information,the strategic actions available to them,and how these influence the outcome.Games can be described formally at various levels of detail.A coalitional(or cooper-ative)game is a high-level description,specifying only what payoffs each potential group, or coalition,can obtain by the cooperation of its members.What is not made explicit is the process by which the coalition forms.As an example,the players may be several parties in parliament.Each party has a different strength,based upon the number of seats occupied by party members.The game describes which coalitions of parties can form a majority,but does not delineate,for example,the negotiation process through which an agreement to vote en bloc is achieved.Cooperative game theory investigates such coalitional games with respect to the rel-ative amounts of power held by various players,or how a successful coalition should divide its proceeds.This is most naturally applied to situations arising in political science or international relations,where concepts like power are most important.For example, Nash proposed a solution for the division of gains from agreement in a bargaining prob-lem which depends solely on the relative strengths of the two parties’bargaining position. The amount of power a side has is determined by the usually inefficient outcome that results when negotiations break down.Nash’s modelfits within the cooperative frame-work in that it does not delineate a specific timeline of offers and counteroffers,but rather focuses solely on the outcome of the bargaining process.In contrast,noncooperative game theory is concerned with the analysis of strategic choices.The paradigm of noncooperative game theory is that the details of the ordering and timing of players’choices are crucial to determining the outcome of a game.In contrast to Nash’s cooperative model,a noncooperative model of bargaining would posit a specific process in which it is prespecified who gets to make an offer at a given time.The term“noncooperative”means this branch of game theory explicitly models the process ofplayers making choices out of their own interest.Cooperation can,and often does,arise in noncooperative models of games,when playersfind it in their own best interests.Branches of game theory also differ in their assumptions.A central assumption in many variants of game theory is that the players are rational.A rational player is one who always chooses an action which gives the outcome he most prefers,given what he expects his opponents to do.The goal of game-theoretic analysis in these branches,then, is to predict how the game will be played by rational players,or,relatedly,to give ad-vice on how best to play the game against opponents who are rational.This rationality assumption can be relaxed,and the resulting models have been more recently applied to the analysis of observed behavior(see Kagel and Roth,eds.,Handbook of Experimental Economics,Princeton Univ.Press,1997).This kind of game theory can be viewed as more“descriptive”than the prescriptive approach taken here.This article focuses principally on noncooperative game theory with rational play-ers.In addition to providing an important baseline case in economic theory,this case is designed so that it gives good advice to the decision-maker,even when–or perhaps especially when–one’s opponents also employ it.Strategic and extensive form gamesThe strategic form(also called normal form)is the basic type of game studied in non-cooperative game theory.A game in strategic form lists each player’s strategies,and the outcomes that result from each possible combination of choices.An outcome is repre-sented by a separate payoff for each player,which is a number(also called utility)that measures how much the player likes the outcome.The extensive form,also called a game tree,is more detailed than the strategic form of a game.It is a complete description of how the game is played over time.This includes the order in which players take actions,the information that players have at the time they must take those actions,and the times at which any uncertainty in the situation is resolved.A game in extensive form may be analyzed directly,or can be converted into an equivalent strategic form.Examples in the following sections will illustrate in detail the interpretation and anal-ysis of games in strategic and extensive form.3DominanceSince all players are assumed to be rational,they make choices which result in the out-come they prefer most,given what their opponents do.In the extreme case,a player may have two strategies A and B so that,given any combination of strategies of the other players,the outcome resulting from A is better than the outcome resulting from B .Then strategy A is said to dominate strategy B .A rational player will never choose to play a dominated strategy.In some games,examination of which strategies are dominated re-sults in the conclusion that rational players could only ever choose one of their strategies.The following examples illustrate this idea.Example:Prisoner’s DilemmaThe Prisoner’s Dilemma is a game in strategic form between two players.Each player has two strategies,called “cooperate”and “defect,”which are labeled C and D for player I and c and d for player II,respectively.(For simpler identification,upper case letters are used for strategies of player I and lower case letters for player II.)d d d 22300311I IIC D cd Figure 1.The Prisoner’s Dilemma game.Figure 1shows the resulting payoffs in this game.Player I chooses a row,either C or D ,and simultaneously player II chooses one of the columns c or d .The strategy combination (C,c )has payoff 2for each player,and the combination (D,d )gives each player payoff 1.The combination (C,d )results in payoff 0for player I and 3for player II,and when (D,c )is played,player I gets 3and player II gets 0.Any two-player game in strategic form can be described by a table like the one in Figure 1,with rows representing the strategies of player I and columns those of player II.(A player may have more than two strategies.)Each strategy combination defines a payoff pair,like (3,0)for (D,c ),which is given in the respective table entry.Each cell of the table shows the payoff to player I at the (lower)left,and the payoff to player II at the (right)top.These staggered payoffs,due to Thomas Schelling,also make transparent when,as here,the game is symmetric between the two players.Symmetry means that the game stays the same when the players are exchanged,corresponding to a reflection along the diagonal shown as a dotted line in Figure 2.Note that in the strategic form,there is no order between player I and II since they act simultaneously (that is,without knowing the other’s action),which makes the symmetry possible...................................................d d d 22300311I IIC Dc d ↓↓→→Figure 2.The game of Figure 1with annotations,implied by the payoff structure.Thedotted line shows the symmetry of the game.The arrows at the left and right point to the preferred strategy of player I when player II plays the left or right column,respectively.Similarly,the arrows at the top and bottom point to the preferred strategy of player II when player I plays top or bottom.In the Prisoner’s Dilemma game,“defect”is a strategy that dominates “cooperate.”Strategy D of player I dominates C since if player II chooses c ,then player I’s payoff is 3when choosing D and 2when choosing C ;if player II chooses d ,then player I receives 1for D as opposed to 0for C .These preferences of player I are indicated by the downward-pointing arrows in Figure 2.Hence,D is indeed always better and dominates C .In the same way,strategy d dominates c for player II.No rational player will choose a dominated strategy since the player will always be better off when changing to the strategy that dominates it.The unique outcome in this game,as recommended to utility-maximizing players,is therefore(D,d)with payoffs (1,1).Somewhat paradoxically,this is less than the payoff(2,2)that would be achieved when the players chose(C,c).The story behind the name“Prisoner’s Dilemma”is that of two prisoners held suspect of a serious crime.There is no judicial evidence for this crime except if one of the prison-ers testifies against the other.If one of them testifies,he will be rewarded with immunity from prosecution(payoff3),whereas the other will serve a long prison sentence(pay-off0).If both testify,their punishment will be less severe(payoff1for each).However,if they both“cooperate”with each other by not testifying at all,they will only be imprisoned briefly,for example for illegal weapons possession(payoff2for each).The“defection”from that mutually beneficial outcome is to testify,which gives a higher payoff no matter what the other prisoner does,with a resulting lower payoff to both.This constitutes their “dilemma.”Prisoner’s Dilemma games arise in various contexts where individual“defections”at the expense of others lead to overall less desirable outcomes.Examples include arms races,litigation instead of settlement,environmental pollution,or cut-price marketing, where the resulting outcome is detrimental for the players.Its game-theoretic justification on individual grounds is sometimes taken as a case for treaties and laws,which enforce cooperation.Game theorists have tried to tackle the obvious“inefficiency”of the outcome of the Prisoner’s Dilemma game.For example,the game is fundamentally changed by playing it more than once.In such a repeated game,patterns of cooperation can be established as rational behavior when players’fear of punishment in the future outweighs their gain from defecting today.Example:Quality choiceThe next example of a game illustrates how the principle of elimination of dominated strategies may be applied iteratively.Suppose player I is an internet service provider and player II a potential customer.They consider entering into a contract of service provision for a period of time.The provider can,for himself,decide between two levels of qualityof service,High or Low .High-quality service is more costly to provide,and some of the cost is independent of whether the contract is signed or not.The level of service cannot be put verifiably into the contract.High-quality service is more valuable than low-quality service to the customer,in fact so much so that the customer would prefer not to buy the service if she knew that the quality was low.Her choices are to buy or not to buy the service.d d d 22300111I IIHigh Low buydon’t buy ↓↓→←Figure 3.High-low quality game between a service provider (player I)and a customer(player II).Figure 3gives possible payoffs that describe this situation.The customer prefers to buy if player I provides high-quality service,and not to buy otherwise.Regardless of whether the customer chooses to buy or not,the provider always prefers to provide the low-quality service.Therefore,the strategy Low dominates the strategy High for player I.Now,since player II believes player I is rational,she realizes that player I always prefers Low ,and so she anticipates low quality service as the provider’s choice.Then she prefers not to buy (giving her a payoff of 1)to buy (payoff 0).Therefore,the rationality of both players leads to the conclusion that the provider will implement low-quality service and,as a result,the contract will not be signed.This game is very similar to the Prisoner’s Dilemma in Figure 1.In fact,it differs only by a single payoff,namely payoff 1(rather than 3)to player II in the top right cell in the table.This reverses the top arrow from right to left,and makes the preference of player II dependent on the action of player I.(The game is also no longer symmetric.)Player II does not have a dominating strategy.However,player I still does,so that theresulting outcome,seen from the“flow of arrows”in Figure3,is still unique.Another way of obtaining this outcome is the successive elimination of dominated strategies:First, High is eliminated,and in the resulting smaller game where player I has only the single strategy Low available,player II’s strategy buy is dominated and also removed.As in the Prisoner’s Dilemma,the individually rational outcome is worse for both players than another outcome,namely the strategy combination(High,buy)where high-quality service is provided and the customer signs the contract.However,that outcome is not credible,since the provider would be tempted to renege and provide only the low-quality service.4Nash equilibriumIn the previous examples,consideration of dominating strategies alone yielded precise advice to the players on how to play the game.In many games,however,there are no dominated strategies,and so these considerations are not enough to rule out any outcomes or to provide more specific advice on how to play the game.The central concept of Nash equilibrium is much more general.A Nash equilibrium recommends a strategy to each player that the player cannot improve upon unilaterally, that is,given that the other players follow the recommendation.Since the other players are also rational,it is reasonable for each player to expect his opponents to follow the recommendation as well.Example:Quality choice revisitedA game-theoretic analysis can highlight aspects of an interactive situation that could be changed to get a better outcome.In the quality game in Figure3,for example,increasing the customer’s utility of high-quality service has no effect unless the provider has an incentive to provide that service.So suppose that the game is changed by introducing an opt-out clause into the service contract.That is,the customer can discontinue subscribing to the service if shefinds it of low quality.The resulting game is shown in Figure4.Here,low-quality service provision,even when the customer decides to buy,has the same low payoff1to the provider as when thed d d 22100111I IIHigh Low buydon’t buy ↑↓→←Figure 4.High-low quality game with opt-out clause for the customer.The left arrowshows that player I prefers High when player II chooses buy .customer does not sign the contract in the first place,since the customer will opt out later.However,the customer still prefers not to buy when the service is Low in order to spare herself the hassle of entering the contract.The changed payoff to player I means that the left arrow in Figure 4points upwards.Note that,compared to Figure 3,only the provider’s payoffs are changed.In a sense,the opt-out clause in the contract has the purpose of convincing the customer that the high-quality service provision is in the provider’s own interest.This game has no dominated strategy for either player.The arrows point in different directions.The game has two Nash equilibria in which each player chooses his strategy deterministically.One of them is,as before,the strategy combination (Low,don’t buy ).This is an equilibrium since Low is the best response (payoff-maximizing strategy)to don’t buy and vice versa.The second Nash equilibrium is the strategy combination (High,buy ).It is an equilib-rium since player I prefers to provide high-quality service when the customer buys,and conversely,player II prefers to buy when the quality is high.This equilibrium has a higher payoff to both players than the former one,and is a more desirable solution.Both Nash equilibria are legitimate recommendations to the two players of how to play the game.Once the players have settled on strategies that form a Nash equilibrium,neither player has incentive to deviate,so that they will rationally stay with their strategies.This makes the Nash equilibrium a consistent solution concept for games.In contrast,astrategy combination that is not a Nash equilibrium is not a credible solution.Such a strategy combination would not be a reliable recommendation on how to play the game, since at least one player would rather ignore the advice and instead play another strategy to make himself better off.As this example shows,a Nash equilibrium may be not unique.However,the pre-viously discussed solutions to the Prisoner’s Dilemma and to the quality choice game in Figure3are unique Nash equilibria.A dominated strategy can never be part of an equilib-rium since a player intending to play a dominated strategy could switch to the dominating strategy and be better off.Thus,if elimination of dominated strategies leads to a unique strategy combination,then this is a Nash rger games may also have unique equilibria that do not result from dominance considerations.Equilibrium selectionIf a game has more than one Nash equilibrium,a theory of strategic interaction should guide players towards the“most reasonable”equilibrium upon which they should focus. Indeed,a large number of papers in game theory have been concerned with“equilibrium refinements”that attempt to derive conditions that make one equilibrium more plausible or convincing than another.For example,it could be argued that an equilibrium that is better for both players,like(High,buy)in Figure4,should be the one that is played.However,the abstract theoretical considerations for equilibrium selection are often more sophisticated than the simple game-theoretical models they are applied to.It may be more illuminating to observe that a game has more than one equilibrium,and that this is a reason that players are sometimes stuck at an inferior outcome.One and the same game may also have a different interpretation where a previously undesirable equilibrium becomes rather plausible.As an example,consider an alternative scenario for the game in Figure4.Unlike the previous situation,it will have a symmetric description of the players,in line with the symmetry of the payoff structure.Twofirms want to invest in communication infrastructure.They intend to communi-cate frequently with each other using that infrastructure,but they decide independently on what to buy.Eachfirm can decide between High or Low bandwidth equipment(thistime,the same strategy names will be used for both players).For player II,High and Low replace buy and don’t buy in Figure 4.The rest of the game stays as it is.The (unchanged)payoffs have the following interpretation for player I (which applies in the same way to player II by symmetry):A Low bandwidth connection works equally well (payoff 1)regardless of whether the other side has high or low bandwidth.How-ever,switching from Low to High is preferable only if the other side has high bandwidth (payoff 2),otherwise it incurs unnecessary cost (payoff 0).As in the quality game,the equilibrium (Low,Low )(the bottom right cell)is inferior to the other equilibrium,although in this interpretation it does not look quite as bad.Moreover,the strategy Low has obviously the better worst-case payoff,as considered for all possible strategies of the other player,no matter if these strategies are rational choices or not.The strategy Low is therefore also called a max-min strategy since it maximizes the minimum payoff the player can get in each case.In a sense,investing only in low-bandwidth equipment is a safe choice.Moreover,this strategy is part of an equilibrium,and entirely justified if the player expects the other player to do the same.Evolutionary gamesThe bandwidth choice game can be given a different interpretation where it applies to a large population of identical players.Equilibrium can then be viewed as the outcome of a dynamic process rather than of conscious rational analysis.d d d 55100111I IIHigh LowHigh Low ↑↓→←Figure 5.The bandwidth choice game.Figure5shows the bandwidth choice game where each player has the two strategies High and Low.The positive payoff of5for each player for the strategy combination (High,High)makes this an even more preferable equilibrium than in the case discussed above.In the evolutionary interpretation,there is a large population of individuals,each of which can adopt one of the strategies.The game describes the payoffs that result when two of these individuals meet.The dynamics of this game are based on assuming that each strategy is played by a certain fraction of individuals.Then,given this distribution of strategies,individuals with better average payoff will be more successful than others, so that their proportion in the population increases over time.This,in turn,may affect which strategies are better than others.In many cases,in particular in symmetric games with only two possible strategies,the dynamic process will move to an equilibrium.In the example of Figure5,a certain fraction of users connected to a network will already have High or Low bandwidth equipment.For example,suppose that one quarter of the users has chosen High and three quarters have chosen Low.It is useful to assign these as percentages to the columns,which represent the strategies of player II.A new user,as player I,is then to decide between High and Low,where his payoff depends on the given fractions.Here it will be1/4×5+3/4×0=1.25when player I chooses High,and 1/4×1+3/4×1=1when player I chooses Low.Given the average payoff that player I can expect when interacting with other users,player I will be better off by choosing High, and so decides on that strategy.Then,player I joins the population as a High user.The proportion of individuals of type High therefore increases,and over time the advantage of that strategy will become even more pronounced.In addition,users replacing their equipment will make the same calculation,and therefore also switch from Low to High. Eventually,everyone plays High as the only surviving strategy,which corresponds to the equilibrium in the top left cell in Figure5.The long-term outcome where only high-bandwidth equipment is selected depends on there being an initial fraction of high-bandwidth users that is large enough.For example,if only ten percent have chosen High,then the expected payoff for High is0.1×5+0.9×0= 0.5which is less than the expected payoff1for Low(which is always1,irrespective of the distribution of users in the population).Then,by the same logic as before,the fraction of Low users increases,moving to the bottom right cell of the game as the equilibrium.It。

《博弈论》导论13

诺曼底战役--剔除劣策略

盟军策略:X(全攻甲),Y(一攻甲一攻乙),Z( 全攻乙) 对盟军而言,策略Y劣于策略X和策略Z(策略Y不 会被选择),于是剔除盟军的劣策略Y 德军 B X 盟军 -1,1 C 1,-1

Y

Z

-1,1

1,-1

-1,1

-1,1

诺曼底战役--模型简化

盟军策略:X(全攻甲),Z(全攻乙) 德军策略:B(二守甲),C (二守乙) 此模型没有纯策略均衡。

交易利益:交易双方的保留价格(对标的物评 价的私有信息)之差 交易的互利性 交易利益的分配问题 卖方的剩余:成交价格-卖方的保留价格 买方的剩余:买方的保留价格-成交价格 生产者剩余和消费者剩余 交易的公平性 竞争均衡和垄断均衡

5、博弈的分类

以决策者是否能进行信息沟通可将博弈分为非 合作博弈与合作博弈: 合作博弈:强调效率、公正、公平 联盟型博弈:卡特尔联盟 谈判理论 非合作博弈:博弈论的主要研究对象,强 调在互动假设下的个人理性、个人最优决策

博弈论与诺贝尔经济学奖(2012)

2012年经济学奖得主为埃尔文· 罗斯和罗伊德· 沙普利 ,获奖的原因得益于两位在“稳定配置理论及市场 设计实践”方面做出的贡献。 如何尽可能适当地匹配不同市场主体,两位学者分 别从理论和实践给出回答。 沙普利获诺奖源于其在“稳定匹配的抽象理论” 方面的贡献。沙普利使用合作博弈方法来研究和对 比不同的匹配方法,和他的同事找到了所谓的GS算 法(Gale-Shapley算法),这种方法能确保匹配稳定。 罗思的贡献是,将沙普利的理论应用到了实践当 中,在“市场制度的实际设计”方面发挥了自己的 才智。

博弈论与诺贝尔经济学奖(1994)

1994年诺贝尔经济学奖: 美国人约翰-海萨尼和美国人约翰-纳什以 及德国人莱因哈德-泽尔腾,在非合作博弈的 均衡分析理论方面做出了开创性的贡献,对 博弈论和经济学产生了重大影响 。

博弈论导论

博弈论导论《博弈论》主讲:李少斌 Tel:85221808 Email:tlishb@第0章《博弈论》导论《博弈论》研究什么, Game Theory游戏理论,对策论,博弈论下棋与博弈: 博弈论研究的问题决策及其均衡问题理性经济人(智能的) 行为互动假设:相互影响经济学研究假设基础经济学研究内容: 经济学研究的假设基础: 理性经济人新古典经济学的两个基本假定: 完全竞争市场不存在信息不对称问题博弈论的研究范式传统经济学研究范式:生产或消费的决策者在做出决策时,假设价格是固定不变的,以此使其效用最大化。

决策者是价格的接受者博弈论的突破:决策时考虑到主体的决策行为是互相影响的,即局中人决策时将考虑到其竞争对手的行为,并且预料到竞争对手对其行为的策略式反应;个人的最优选择是其他人选择的函数。

价格影响者:互动,相互影响一、生活中的博弈现象海滩占位问题 :二人对称矩阵博弈:二人矩阵博弈:智猪博弈公共产品供给问题:1、海滩占位问题两个卖矿泉水的小商贩为了争夺在海滩上日光浴的顾客,假若晒太阳的人们在1公理长的沙滩上均匀分布,试问:两个商贩将如何布局,海滩占位问题求解帕累托最优:纳什均衡:类似的例子电视台的娱乐节目竞争现象(节目克隆) 总统竞选的竞选纲领问题(尽量争取中间选民) 超市的布局问题不同航空公司飞往同一目的地的航班现象地方政府竞相设立开发区支付函数的矩阵博弈问题在现实中最常见的博弈问题通常是二人博弈问题,每一博弈方的行动选择通常只有两种,在这样的博弈问题中双方的得益函数通常可用一个矩阵来描述。

如图:参与人B 参与人A U L a, e R b, fDc, gd, h2、二人对称矩阵博弈考查二人对称博弈。

双方各有合作和不合作两种策略,其得益支付矩阵如下。

由其相对大小确定了不同类型的博弈问题。

这里,合作理解为投对方所好,或者说选择对方所希望的策略;不合作可理解为背叛。

参与人B 合作不合作合作参与人A 不合作 r, r t, s s,t p, p(1)囚徒困境博弈(t,r,p,s)两个小偷被控有罪,法官对其分别审判,每个小偷决定是坦白还是抵赖,其得益矩阵如下。

博弈论导论

博弈论导论第一章导论提要:本章首先对博弈论的一些基本概念,包括什么是博弈和博弈论等作初步介绍。

然后在此基础上再给出一些经典的博弈例子,使学生对博弈论的内容和博弈模型有更直观的概念和印象。

最后,我们还要对博弈的分类和博弈理论的结构做一些讨论。

§1 什么是博弈论想一想:假如你正跟恋人用手机通电话,突然信号断了。

这时,你会立即拨电话过去,还是等你的恋人拨电话过来?很显然,你是否应该拨电话过去,取决于你的恋人是否会拨电话过来。

如果你们其中一方要拨,那么,另一方最好是等待;如果一方等待,另一方就最好是拨过去。

因为如果双方都拨,就会出现线路忙;如果双方都等待,那么时间就会在等待中流逝。

是等待还是拨过去,这,就是博弈!§1.1 从游戏到博弈“博弈论”译自英文“game theory”。

“game”的基本含义是游戏,因此,“game theory”直译应该是“游戏理论”。

说起游戏当然大家都非常熟悉,日常生活中的打牌下棋、赌博博彩,以及田径、球类等各种体育比赛,都是游戏,是不同种类、不同形式的游戏。

游戏的种类很多,我们很难将它们一一列举出来。

不过,如果我们认真观察、思考一下就能发现,很多游戏都有下列共同的本质特征:(1)都有一定的规则——规则是游戏的参与者(个人或队组)可以做什么、不可以做什么,应该按怎样的次序做,什么时候结束游戏和一旦参与者犯规将受到怎样的处罚等。

(2)都有一个结果——如一方赢一方输、平局或各参与方各有所得等,而且结果通常能用正或负的数值表示。

(3)策略至关重要——游戏者不同的策略选择常会带来不同的游戏结果。

(4)策略和利益有相互依存性——即每一个游戏参与者所得结果的好坏,不仅取决于自身的策略选择,也取决于其他参与者的策略选择。

有时一个差的策略选择也许会带来并不差的结果,原因是其他的参与者选择了更差的策略。

因此,在有策略依存性的游戏中,策略本身常常没有绝对的好坏之分,只有相对于他方策略的相对好坏。

博弈论导论-北京信息科技大学经济管理学院

博弈论导论课程编码:0RL05308课程名称(英文):Game Theory适应专业:市场营销课程性质:专业任选课学时:32学时,其中讲课:32学时先修课程::管理学原理、微观经济学、数学分析与概率论一、本课程的地位、作用与任务博弈论是一门决策管理学的科学,其目的是使学生学会应用博弈论的基本原理和方法分析经济、管理和社会生活等领域的博弈问题,帮助学生获得必要的决策科学基本知识,管理决策的基本方法和基本技能。

二、内容、学时及基本要求序号内容基本要求学时1第1章绪论1.1博弈论的研究对象1.2博弈论的主要分类1.3博弈论与决策理论掌握博弈论的基本概念;掌握博弈论的主要分类;了解博弈论与决策理论的关系。

62第2章完全信息静态博弈2.1纳什均衡2.2纳什均衡的存在性与多重性讨论2.3混合策略的纳什均衡及其存在性掌握纳什均衡以及混合策略的纳什均衡,了解其存在性和多重性。

83第3章完全信息动态博弈3.1完全且完美信息动态博弈3.2完全非完美信息动态博弈3.3重复博弈掌握完全且完美信息动态博弈和完全非完美信息动态博弈,了解重复博弈6序号内容基本要求学时4第4章非完全信息静态博弈4.1不完全信息静态博弈4.2贝叶斯博弈4.3贝叶斯纳什均衡掌握不完全信息静态博弈,掌握贝叶斯博弈及均衡65第5章非完全信息动态博弈5.1精练贝叶斯纳什均衡5.2信号博弈掌握精练贝叶斯纳什均衡、信号博弈6总计32三、说明本课程是一门理论性和实践性都很强的课程,为此教学过程中要高度理论联系实际,既要深入浅出、生动活泼、引起兴趣,又要保证理论内容的完整性、准确性和必要深度。

尽可能地结合多种教学方法和手段,如案例的分析、课堂的讨论等。

帮助学生理解和掌握博弈论的基本原理和方法。

考核方式:平时30%(作业+平时考核)+期末考试(闭卷/开卷/论文)70%。

四、使用教材及参考书教 材:谢识予著,经济博弈论(第三版),复旦大学出版社,2008参考书:张维迎著,博弈论与信息经济学,上海人民出版社,2004。

《博弈论入门》PPT课件

在不同博弈中可供博弈方选择的策略或行为的数量 很不相同,在同一个博弈中,不同博弈方的可选策 略或行为的内容或数量也常不同,有时只有有限的 几种,甚至只有一种,而有时又可能有许多种,甚 至无限多种可选策略或行为。

精选PPT

男人无所谓忠诚,忠诚是因为背叛的砝码太低; 女人无所谓忠贞,忠贞是因为受到的引诱不够.

某个综艺节目现场,女主持人气势咄咄的问一个男嘉宾,你 为什么那么在乎钱,男嘉宾说:“钱能买到一切!” 现场的观 众哗然了。

男嘉宾微笑的说:“我们做个测试吧。”

一个很简单的主题,你的一个仇人爱上了你的女友,现在

局中人所选择的策略构成的组合(招,招)被称为 博弈均衡。

精选PPT

21

参与人(Players)

即在所定义的博弈中究竟有哪几个独立决策、独立 承担结果的个人或组织。

对我们来说,只要在一个博弈中统一决策,统一行 动、统一承担结果,不管一个组织有多大,哪怕是 一个国家,甚至是由许多国有组成的联合国,都可 以作为博弈中的一个参加方。并且,在博弈的规则 确定之后,各参加方都是平等的,大家都必须严格 按照规则办事。

人,也许是在权衡什么。一半的男人沉默了,另一半

的男人怯生生的说:“我要爱情。”身边的女友也有点

呆住了,一个女孩子站起来说:“如果一个男人肯出

五百万,我想我没有理由拒绝他。”沉默..................

精选PPT

26

男人选择了金钱,500万可以买一套房子,一部车子,全家 过上好曰子,甚至可以开始自己的事业。一个男人说:“他是 我的仇人,我有了这个500万,我可以含辛茹苦,我可以报仇 ,我可以计划我所有的未来,当个真正主宰自己的男人。”一 些女人看着身边的男人,若有所思。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

B W(退) T

W(退)

A T

0,0

2,1

1,2

-2,-2

胆小鬼博弈的启示

胆小鬼博弈,又称争路博弈,斗鸡博弈。 类似的例子有: 冷战期间美苏争抢地盘 夫妻间矛盾问题 警察与游行队伍的进退问题 公共产品的供给问题

胆小鬼博弈的分类

胆小鬼博弈的特点是:t>s>(=,<)r >p,对于s和 r的相对大小又有三种可能 的情形: (1)争路博弈(t>s>r>p); (2) t<s=r>p; (3)货币当局与财政当局的博弈(t>r> s>p)

博弈论中的理性解释(2)

理性的共同知识:每个博弈方都知道所 有博弈方都是理性的,都知道其他博弈 方知道所有博弈方都是理性的,都知道 其他博弈方知道其他博弈方知道所有博 弈方都是理性的……

理性概念的发展

从完全理性到有限理性: 有限理性:有理性意识,但理性能力 有限。 进化博弈论: 模仿模型 学习模型:

(1)囚徒困境博弈(t>r>p>s)

两个小偷被控有罪,法官对其分别审判,每个 小偷决定是坦白还是抵赖,其得益矩阵如下。 小偷将如何行动? 囚徒困境博弈中的合作策略指什么策略?

囚徒B

抵赖

抵赖 囚徒A 坦白 -1,-1 0,-10

坦白

-10, 0 -8,-8

纳什均衡与划线法

对矩阵博弈而言,纳什均衡是指这样一 种策略(行动)组合,局中人谁都没有 动机单方面偏离该状态。 矩阵博弈的纳什均衡求解――划线法: 对于参与人B的每一个给定策略选择, 在A的最优策略下划一横线,然后再用类 似的方法找出B的最优策略。

公共产品供给--囚徒困境博弈

两户穷人修路问题:修路带给每家的收 益均为3,修路的成本为4。 B

修 修 A 不修

1,1 3,-1

不修

-1,3 0,0

公共产品供给--胆小鬼博弈

两户富人修路问题:修路带给每人的收 益均为5,修路的成本为4。 B

修 修 A 不修

3,3 5,1

不修

1,5 0,0

公共产品的供给--智猪博弈

(2)博弈论与计量经济学

博弈论与计量经济学一起成为现代经济研究的两 大基本工具 。 共性:两者都通过建立数理模型来分析经济问题。 差异性: 博弈论更倾向于理论分析,通过模型来解释 人类的决策行为; 计量经济学更倾向于通过数理统计方法进行 实证分析,解释并预测经济现象。

支付函数的矩阵博弈问题

在现实中最常见的博弈问题通常是二人博弈 问题,每一博弈方的行动选择通常只有两种, 在这样的博弈问题中双方的得益函数通常可 用一个矩阵来描述。如图:

参与人B 参与 人A U L a, e R b, f

D

c, g

d, h

2、二人对称矩阵博弈

考查二人对称博弈。双方各有合作和不合作两种 策略,其得益支付矩阵如下。由其相对大小确定 了不同类型的博弈问题。 这里,合作理解为投对方所好,或者说选择对方 所希望的策略;不合作可理解为背叛。 参与人B 合作 不合作 合作 参与人A 不合作 r, r t, s s, t p, p

联合 单独

0,1

A

联合

2,2

单独

1,0

1,1

在该博弈中,双方都投资于小项目是风 险占优均衡 。

类似的例子

共同打猎问题: 考试作弊: 其特点是:r>p=(>)t> s。

考试作弊

两位考生考试的得益矩阵如下。在该博 弈中,双方都不作弊是风险占优均衡 。 B

作弊 不作弊 0,8

A

作弊

9,9

不作弊

8,0

7,7

B 修 不修

-2,0 0,0

A

修 不修

1,1 0,-2

热点问题思考

尝试运用博弈模型分析: 人民币汇率博弈: 楼市调控博弈: 股市投资风格博弈: 宏观经济政策博弈: 中日争端博弈:

二、博弈论概论

博弈论的研究内容 博弈论的发展脉络 博弈论与经济学 博弈论在经济金融领域中的运用

1、博弈论的研究内容

博弈论是在考虑到决策主体的行为互 动条件下研究理性经济人的决策及其 均衡问题的理论。 行为互动假设 理性经济人 决策及其均衡问题

男

芭蕾舞

足球赛 女 芭蕾舞 -1,-1 2,1

足球赛

1,2 0,0

类似的例子

一对恋人选修课程: 政治外交等博弈问题: 董事会内部对两个投资项目意见分歧 的决策 内部矛盾与一致对外 基金抱团取暧 其特点是: t>s>p≥r。

(4)共同投资问题 (r>t,p> s)

当参与者共同投资大项目时将获得更高 的收益,但当另一方玩花样而投资于小 项目时,大项目投资者将被套 。 B

(4)博弈论中的理性问题

在经济学研究中普遍采用“理性经济人” 假设。对理性的理解有: 理性意识和理性能力: 理性意识是狭义的理性,是决策者始 终以自身利益最大化为目标。 行为的理性和知识的理性: 行为的理性指决策者对不同的行动方 案具有稳定的偏好序。 个体理性、集体理性和交互理性:

博弈论中的完全理性假设

素质教育还是应试教育?

教师B(家长B) 减负 增负 教师A (家长A) 减负 增负 1,1 2,-1 -1, 2 0,0

• 孩子该不该上各种课外辅导班?

(2)胆小鬼博弈(t>s,r>p)

争路博弈:两个小孩争着过独木桥,若双方互不退 让时,双方都将掉到河中,若只有一方退让时,退 让者将获得胆小鬼称号。 胆小鬼博弈中的合作策略指什么策略?

(5)博弈论研究的前沿问题

博弈论中完全理性的局限性: 对理性概念的突破,博弈论与相关学科 交叉融合,产生了一批新兴学科: 进化博弈论(生物进化理论) 实验经济学(实验理论) 行为经济学(心理学) 行为金融学(金融学、心理学)

3、博弈论与经济学

从经济学的各个分支如产业组织 理论、现代企业理论、信息经济 学、金融学等到政治、文化、日 常生活等各个方面无不渗透着博 弈论的思想。

《博 弈 论》

主讲:李少斌 Tel:85221808 Email:tlishb@

第0章《博弈论》导论

《博弈论》研究什么? Game Theory

游戏理论,对策论,博弈论

下棋与博弈: 博弈论研究的问题 决策及其均衡问题 理性经济人(智能的)

行为互动假设:相互影响

经济学研究假设基础

(1)博弈论对西方经济学的改造

自20世纪80年代后,博弈论已完全融入了主 流经济学理论,并改写了现代西方经济学理 论。 David Kreps: A Course in Microeconomics, 1990. Jean Tirole: The Theory of Industrial Organization, 1988. Hal Varian: Microeconomic Analysis, 1992.

参与人B

L 参与 人A U D a, e c, g R b, f d, h

智猪博弈

自动控制的食槽有10个单位的食物,按控制键的成本 为2,若大猪按小猪等待,则双方分吃的食物为6和4, 若大猪等待小猪按,则双方分吃的食物为9和1,若同 时按,则双方分吃的食物为7和3。利益矩阵如下:

小猪 按 等待

按

大猪 等待

(3)博弈的分类

从信息角度看,博弈可分为:

完全信息博弈:指局中人对于自己以及其他局 中人的策略空间、盈利函数等知识有完全的了解。

不完全信息博弈:

从局中人行动的先后秩序看,博弈可分为:

静态博弈:局中人同时选择行动;

动态博弈:局中人的行动有先后顺序,且后行 动者可以观察到先行动者的行动后再行动。

四类博弈

富户和穷户的修路博弈:修路带给富户 和穷户的收益分别为5和3,修路的成本 为4。 穷户 修 修 富户 不修

3,1 5,-1

不修

1,3 0,0

公共产品供给--共同投资博弈

在以上分析中,一个隐含条件是各家都有能力单 独将路修好。若假设每家不能单独将路修好,则 博弈演化为共同投资问题。 修路问题--口头承诺:修路带给每家的收益均 为3 ,修路的成本为4 ,每家承诺投入资金2。

囚徒困境博弈的划线法求解

囚徒B 抵赖 抵赖 囚徒A -1,-1 坦白 -10, 0

坦白

0,-10

-8,-8

囚徒困境博弈的启示

囚徒困境博弈:深刻地反映了个体理性与 集体理性的冲突。 类似的例子有:卡特尔组织、公共产品的 供给问题(搭便车现象,如两户穷人修路 问题)、产品定价问题(价格战)、军备 竞赛、经济改革、贸易壁垒问题(关税 等)。 其特点是:t>r>p>s。

博弈论中的理性假设是完全理性:包括 理性的和智能的两层含义。 理性的:如果一个决策者在追逐其 目标时能前后一致地做出决策,即行为 理性。 智能的:决策者进行决策时能策略 性地做出反应,包括决策者的理性能力、 交互理性和知识理性、理性的共同知识。

博弈论中的理性解释(1)

决策者的理性能力:指有理性意识的经济主 体具有的、实现主观愿望所需要的客观能力, 在计算和逻辑推理方面有很高要求。 交互理性:是人们的利益相互取决于其他人 的行为时的理性。 知识理性(贝叶斯理性):指在有不确定性 的情况下,最大限度地获得信息,形成准确 判断的能力。

经济学研究内容: 经济学研究的假设基础: 理性经济人 新古典经济学的两个基本假定: 完全竞争市场 不存在信息不对称问题

博弈论的研究范式

传统经济学研究范式:生产或消费的决策者在做 出决策时,假设价格是固定不变的,以此使其效 用最大化。 决策者是价格的接受者 博弈论的突破:决策时考虑到主体的决策行为是 互相影响的,即局中人决策时将考虑到其竞争对 手的行为,并且预料到竞争对手对其行为的策略 式反应;个人的最优选择是其他人选择的函数。 价格影响者:互动,相互影响

二人对称矩阵博弈小结

参与人B

合作 不合作 s, t p, p

参与 人A

合作 不合作