关于血液肿瘤二代测序报告单解读,您需要知道的。。。

肿瘤基因检测报告

肿瘤基因检测报告如何看懂肿瘤基因检测报告现在,随着科技的不断发展,肿瘤基因检测已经成为了癌症治疗的一项重要手段。

不过,对于一般人来说,肿瘤基因检测报告的语言和数据可能会有些难以理解,那么,接下来我们就来看看如何看懂肿瘤基因检测报告。

首先,我们需要了解一些基本概念。

肿瘤基因检测报告中最常见的一个概念就是“突变”。

简单来说,突变是指基因发生了异常改变,从而影响了基因所编码的蛋白质的功能,这种异常改变可能是遗传而来,也可能是后天因素所致。

肿瘤基因检测报告中还会出现“等位基因”、“基因型”等术语,它们是指个体的基因构成。

等位基因指的是位于同一基因位点上的两个基因,而基因型则是指一个个体在某一基因位点上,由该个体所拥有的两种等位基因所决定的遗传状态。

接下来,我们需要了解一些分析方法。

肿瘤基因检测报告中常见的分析方法有测序分析、芯片分析、FISH分析等。

测序分析是指对DNA序列进行测定,从而了解其中是否存在某种突变或基因序列异常;芯片分析则是通过对小片段DNA序列进行探针检测,从而判断其中是否存在某些变异情况;FISH分析则是检测染色体水平上的异常改变,例如染色体错位、缺失等。

在肿瘤基因检测报告中,可能会同时采用多种分析方法,以全面了解患者体内的肿瘤情况。

接下来,我们需要了解如何解读肿瘤基因检测报告。

对于每个患者而言,其肿瘤基因检测报告都是独一无二的。

正常情况下,基因突变一般被分为两种类型:良性突变和致病突变。

其中,良性突变指的是基因发生了异常改变,但并不一定会导致肿瘤的发生;而致病突变则是指基因突变恶化导致肿瘤细胞的增殖和扩散。

通过对肿瘤基因检测报告中出现的突变信息进行分析,医生可以制定针对性的治疗方案,从而提高治疗的效果。

此外,肿瘤基因检测报告中还可能出现一些阴性结果。

阴性结果指的是在检测样本中未出现致病突变的情况。

但是,阴性结果并不代表肿瘤不存在,因为肿瘤可能是由多个基因和信号通路的错乱所引起的,而这些基因和通路并未被检测到。

怎样看懂一份基因检测报告:报告解读常见问题答疑

怎样看懂一份基因检测报告:报告解读常见问题答疑# 怎样看懂一份基因检测报告 #随着靶向治疗和免疫治疗的发展,基因检测已经成为众多肿瘤治疗必不可少的检测项目。

尤其对于希望进行靶向药物或者免疫药物治疗的患者,绝大多数需要事先进行基因检测,从而了解自己是否能从靶向药物或者免疫药物中获益。

而当患者拿到检测报告后,由于对疾病和检测的专业知识了解不足,常常会遇到很多问题,亟需专业人士给出权威的解答。

今天在我们“六周年企划”的最后一期,由仁东医学遗传咨询部为大家进行基因检测报告中的常见问题答疑,帮助您更加了解自己的基因数据。

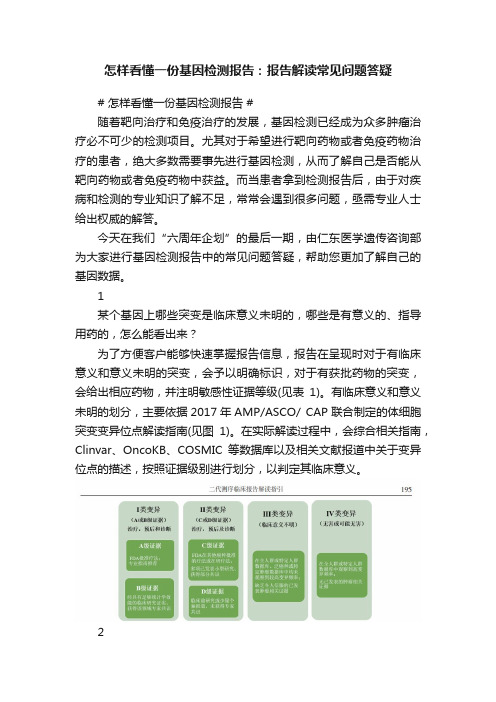

1某个基因上哪些突变是临床意义未明的,哪些是有意义的、指导用药的,怎么能看出来?为了方便客户能够快速掌握报告信息,报告在呈现时对于有临床意义和意义未明的突变,会予以明确标识,对于有获批药物的突变,会给出相应药物,并注明敏感性证据等级(见表1)。

有临床意义和意义未明的划分,主要依据2017年AMP/ASCO/ CAP联合制定的体细胞突变变异位点解读指南(见图1)。

在实际解读过程中,会综合相关指南,Clinvar、OncoKB、COSMIC等数据库以及相关文献报道中关于变异位点的描述,按照证据级别进行划分,以判定其临床意义。

2遗传方式为隐性遗传,合子类型为杂合的单核苷酸突变位点,致病性分类为什么是致病/疑似致病?对于遗传性变异,在解读时是严格按照ACMG遗传性变异分类指南进行分类(具体可回看“怎样看懂一份基因检测报告:给胚系突变分个类”),所分类的对象是“变异”,对应疾病的遗传模式是决定该疾病的表型是否会表现出来。

检测到常染色体隐性遗传的杂合致病/疑似致病变异,说明被检测者是变异的携带者,一般不会表现出相关疾病的症状,但是并不表示变异是不致病的,一般纯合或复合杂合变异时患者才可表现出相应疾病的症状。

3根据某个基因突变患者后续该如何用药?对于有用药提示的突变,报告中会给出相应的药物敏感证据等级,等级划分具体参考表1。

教你如何看懂肿瘤病理报告之

教你如何看懂肿瘤病理报告之教你如何看懂肿瘤病理报告之初步诊断肿瘤病理报告对于肿瘤患者来说是非常重要的,它提供了关于肿瘤类型、分级和分期等关键信息,有助于医生选择合适的治疗策略。

然而,对于大部分非医学专业的人来说,病理报告可能充满了术语和专业名词,不易理解。

本文将教你如何阅读和理解肿瘤病理报告的初步诊断部分。

一、了解报告的结构肿瘤病理报告通常由多个部分组成,包括患者信息、送检标本、镜下所见、特殊检查、免疫组化、诊断和建议等。

在阅读报告之前,先了解报告的结构可以帮助我们更好地理解其内容。

二、仔细阅读镜下所见镜下所见是病理报告最重要的部分,它描述了肿瘤组织在显微镜下的特征。

首先,我们需要了解肿瘤的组织类型,比如腺癌、鳞癌、肉瘤等。

然后,关注肿瘤的分级和分期,这对于确定肿瘤的严重程度以及患者的预后非常重要。

分级通常根据肿瘤细胞的异型性、增生速度和其在周围正常组织中的侵袭程度进行评估。

分期则是根据肿瘤的大小、转移情况和淋巴结受累情况等综合因素进行评估。

三、关注特殊检查与免疫组化结果有时,病理报告还会包括特殊检查和免疫组化结果。

特殊检查可以包括基因突变检测、染色体分析等,这些结果对于肿瘤的预后评估和治疗方案制定有重要意义。

而免疫组化则可以帮助鉴定肿瘤类型以及确定目标治疗药物的敏感性。

四、理解诊断和建议诊断部分是整个病理报告的核心内容,它提供了对肿瘤类型和严重性的正式诊断。

诊断通常会附带建议,比如手术切除范围、放疗或化疗等治疗方案。

仔细阅读诊断和建议部分可以帮助患者和医生共同决策,并选择最合适的治疗方案。

五、请教专业医生如果你在阅读病理报告的过程中有任何疑问或者不理解的地方,最好咨询专业医生的意见。

他们可以帮助你解答病理报告中的术语和专业名词,解释诊断结果以及提供进一步的诊疗建议。

总结起来,阅读肿瘤病理报告需要一定的医学知识和专业背景。

然而,通过了解报告结构、仔细阅读镜下所见、关注特殊检查和免疫组化结果、理解诊断和建议,我们可以更好地理解病理报告,为患者的治疗提供参考依据。

如何读懂肿瘤病理报告单

如何读懂肿瘤病理报告单发表时间:2019-08-14T09:24:38.213Z 来源:《健康世界》2019年7期作者:黄文[导读] 提起“肿瘤”,想必大家并不陌生,这些年,在多方面因素影响下,肿瘤的发病率呈现出逐年升高趋势,成为危害人们身心健康的一大疾病,甚至危及生命安全。

黄文新津县人民医院病理科提起“肿瘤”,想必大家并不陌生,这些年,在多方面因素影响下,肿瘤的发病率呈现出逐年升高趋势,成为危害人们身心健康的一大疾病,甚至危及生命安全。

然而,很多病人检查后拿到肿瘤病理报告单,看不懂检查结果,易出现焦急烦躁情绪,不利于身心健康。

什么是肿瘤?肿瘤(tumour),指的是机体在各种致瘤因子作用下,局部组织细胞增生所形成的新生物(neogrowth),因为这种新生物多呈占位性块状突起,也称赘生物(neoplasm)。

若是根据新生物的细胞特性与对机体造成的危害性,一般将其分成良性肿瘤和恶性肿瘤。

良性肿瘤:生长缓慢,多可见包膜,呈膨胀性生长状态,摸之会滑动,边界清楚,而且不会发生转移,预后一般较好,伴有局部压迫症状,一般情况下无全身症状,通常不会导致患者死亡。

恶性肿瘤:生长迅速,且呈现出侵袭性生长趋势,与周围组织呈粘连状态,摸之不会移动,边界欠清晰,容易发生转移,治疗后复发率高,早期多表现出低热、食欲下降、体重下降等症状,随着病情发展,晚期可能出现发热、贫血、严重消瘦等症状,若未能及时诊治,预后都较差。

近些年,很多报道都证实肿瘤的发病率逐年升高,对病人的身心健康造成了严重影响,降低患者生活质量,甚至危及患者的生命安全。

因此,早期诊治肿瘤,对病人的生命健康具有重要意义。

但是,很多人在病理检查后,拿着报告单也看不懂结论。

因此,如何看懂肿瘤病理报告单,成为人们关注的一个焦点问题。

病理报告单上的常见肿瘤信号有哪些?1,异型增生。

也可称其为不典型增生或者是非典型增生、间变等,指的是由于上皮细胞长期遭到慢性刺激所致的不正常增生现象。

如何读懂肿瘤病理报告单

如何读懂肿瘤病理报告单肿瘤防治的关键点在于“早”,早预防、早发现、早诊断、早治疗。

其中,早诊断中,关键在于病理学诊断。

但是,大多数普通群众对病理报告并不了解,看到报告单上面生涩难懂的文字,更加担心自己患病。

那么,我们应该如何读懂肿瘤病理报告单呢?希望通过本文分享,您能够读懂肿瘤病理报告单,正确获取报告单中的信息。

一:看懂异型增生异型增生,也称“不典型增生”、“间变”或者“非典型增生”等等,是指上皮细胞长期受到慢性刺激所表现出的不正常增生现象。

按照组织来源,可将异型增生分成以下几种:(1)腺瘤型异型增生,来源于肠型上皮,起于粘膜浅层,癌变后是高分化腺癌;(2)隐窝型异型增生,起源于隐窝,癌变后,呈现出中分化或者高分化腺癌;(3)再生型异型增生,见于粘膜缺损部位的再生上皮,癌变后,是低分化或者未分化腺癌。

异型增生,是一个动态过程,由轻度发展至重度,可保持不变或者逆转,单重度异型增生逆转难度大,可能发展至癌症。

例如,宫颈异型增生,就是说宫颈上皮细胞部分或者大部分出现异型与不典型增生。

病理报告单中,一般会看到“CIN”相关描述。

CIN大致分成3级,级别越高,提示发展成为浸润癌的几率越高。

故此,一旦发现是CINⅡ级以及更高级别异型增生,一定要定期随访,或者积极接受治疗。

同样的,若是支气管、肠道与乳腺等出现异型增生病变时,也要引起重视,以免导致严重后果。

二:看懂分化分化(differentiation)是指指在分裂基础上晚近获得的多细胞生物个体因生存行为分工而在个体体内细胞之间形成的形态与功能的差异。

简单来说,一种组织的细胞,由胚胎到发育成熟这一过程,需要经历各种分化阶段,分化的程度越高,提示成熟度越高。

肿瘤病理报告单中,一般需要对其分化程度进行描述,根据分化的程度,了解恶性程度,为判断预后提供信息。

三:看懂癌变趋势癌变趋势,就是“癌前病变”(precancerous lesion)。

癌前病变并非癌症,但是,若是继续发展下去,很有可能演变为癌症,故此,需警惕癌前病变。

教你如何看懂肿瘤病理报告之

教你如何看懂肿瘤病理报告之肿瘤病理报告是医学领域中对肿瘤组织进行详细分析和描述的重要文档。

这份报告包含了许多重要的信息,可以帮助医生了解肿瘤的类型、分级、扩散程度以及治疗选择。

然而,对非专业人士来说,肿瘤病理报告可能很难理解。

在以下内容中,我们将详细讨论如何看懂肿瘤病理报告,并提供一些实例和补充说明。

首先,肿瘤病理报告通常包含以下几个部分:1. 报告摘要:这部分会简要概述肿瘤的基本信息,如肿瘤类型、位置和大小等。

2. 组织学特征:这一部分会详细描述肿瘤组织的形态学特征。

其中包括肿瘤的细胞类型、组织结构和细胞核形态等。

3. 肿瘤扩散程度:这部分会评估肿瘤是否扩散到周围组织或淋巴结。

通过判断肿瘤细胞是否侵犯邻近结构和淋巴管道,可以确定其扩散程度。

4. 分级和分期:根据肿瘤的恶性程度和扩散情况,肿瘤病理报告会对其进行分级和分期。

分级通常使用数字(如1到4)来表示,数字越高表示恶性程度越高。

分期则会使用TNM系统(肿瘤大小、淋巴结是否受累和远处转移的存在)来进行标记。

了解这些基本部分后,下面是一些常见的病理报告补充说明和实例:1. 组织学特征的详细分析:报告中通常会提到肿瘤细胞的形态学特征,如细胞大小、染色质形态和细胞核变化等。

这些信息对于确定肿瘤类型和恶性程度至关重要。

例如,当报告中提到细胞呈现较大的异型性和异常核分裂时,表明可能存在高度恶性的肿瘤。

2. 分期和预后评估:分期是评估肿瘤扩散程度和临床预后的重要指标。

报告中可能会使用TNM系统来描述肿瘤的大小、淋巴结受累情况和远处转移。

举个例子,一个乳腺癌的报告中可能会提及T2N1M0,表示肿瘤大小为2,淋巴结受累为1,无远处转移。

3. 免疫组织化学(IHC)染色结果:免疫组织化学是一种通过特定抗体染色来检测肿瘤细胞标志物的方法。

在报告中,可能会提到肿瘤细胞染色阳性或阴性反应。

例如,一个肺癌的报告中可能会提及肿瘤细胞对肺特异性糖蛋白(TTF-1)染色呈阳性,这有助于确定肿瘤的起源。

肿瘤患者血液报告

肿瘤患者血液报告1. 引言肿瘤是一种严重的疾病,它对患者的身体健康产生了巨大的影响。

在肿瘤的诊断和治疗过程中,血液检测是一项非常重要的辅助手段。

通过分析肿瘤患者的血液报告,医生可以更好地了解患者的病情,制定有效的治疗方案。

本文将介绍肿瘤患者血液报告的步骤和相关内容。

2. 血液样本采集在进行血液检测之前,首先需要采集肿瘤患者的血液样本。

一般情况下,医生会选择静脉穿刺的方式获取血液样本。

在穿刺前,医生会对穿刺部位进行消毒,以确保采集的血液样本是干净的。

3. 血液参数检测获得血液样本后,接下来需要对样本进行一系列的血液参数检测。

这些参数包括但不限于以下几个方面:3.1 血细胞计数血细胞计数是一项重要的指标,它可以反映出肿瘤患者体内的血细胞数量。

通常包括红细胞计数、白细胞计数和血小板计数。

红细胞计数可以用来评估患者的贫血程度,白细胞计数可以反映患者的免疫功能,而血小板计数可以用于评估患者的凝血功能。

3.2 血红蛋白浓度血红蛋白是红细胞中的重要成分,它能携带氧气与二氧化碳。

通过测量血液中的血红蛋白浓度,可以了解患者的氧气输送情况。

血红蛋白浓度过低可能表明患者存在贫血。

3.3 血小板形态指数血小板形态指数是衡量血小板形态异常程度的指标。

通过观察血液中的血小板形态,可以判断患者是否存在血小板功能异常的情况。

3.4 白细胞分类计数白细胞分类计数可以分析血液中不同类型白细胞的数量。

这对于了解患者的免疫功能非常重要。

常见的白细胞分类计数包括中性粒细胞计数、淋巴细胞计数、单核细胞计数等。

3.5 肝功能指标肝功能指标可以用来评估患者的肝脏健康状况。

常见的肝功能指标包括谷丙转氨酶(ALT)、谷草转氨酶(AST)、总胆红素、直接胆红素等。

3.6 肾功能指标肾功能指标可以反映出患者的肾脏健康状态。

常见的肾功能指标包括血尿素氮(BUN)、肌酐等。

4. 结果分析在完成血液参数检测后,医生会对报告结果进行分析,并结合患者的病情进行综合评估。

ctc检查报告怎么看

ctc检查报告怎么看CTC(循环肿瘤细胞)检查已经成为肿瘤诊断和监测的重要方法之一。

正确阅读CTC检查报告对于了解自己的病情和选择正确的治疗方法非常重要。

但是,由于CTC检查报告中常涉及到专业术语和图像,对于大部分患者来说并不容易理解。

接下来,将会介绍如何正确阅读CTC检查报告。

一、检测方法首先要了解CTC检查的检测方法,一般包括细胞富集、荧光染色、图像获取和结果分析四个步骤。

报告中会给出检测方法的详细说明,患者可以看一下,了解自己的血液样本是如何被检测出来的。

二、检测结果CTC检查报告中会给出检测结果,一般包括CTC数目和CTC 范畴。

CTC数目是指在血液样本中检测到的癌细胞数量,数目越多,表示病情越严重。

CTC范畴则是指癌细胞的生物学特性,有助于判断癌细胞的侵袭性和毒性。

三、分析解读在CTC检查报告中会有一个分析解读部分,这是关键的部分,患者需要认真理解。

在分析解读部分,会针对患者的检测结果进行分析和评估,说明癌症的类型、分期和预后,可以根据报告中的分析解读部分来判断自己的病情发展和预后情况。

如果您不理解报告中的术语和图表,可以咨询您的医生或者专业的医疗机构。

四、注意事项在阅读CTC检查报告时,需要注意以下几个问题:1. 报告的准确性:CTC检查报告具有很高的准确性,但是仍然存在误差,需要结合医生的临床判断来决定是否需要进一步的诊断和治疗。

2. 时间戳:CTC检查报告中会附上时间戳,患者需要注意报告中时间戳和自己的就医时间是否一致。

3. 检测周期:CTC检测周期一般是3个月一次,有些患者需要每个月进行检测。

如果您不清楚自己的检测周期,可以咨询您的医生或医疗机构。

4. 治疗选择:CTC检测报告可以为患者提供治疗建议,但是最终的治疗选择还需要根据患者的具体情况和医生的建议进行决定。

从以上几个方面来看,患者可以更好地阅读CTC检查报告,了解自己的病情和选择正确的治疗方法。

但是需要强调的是,CTC检查报告还是需要结合其他检测和医生的临床判断来进行综合评估。

血液科检验报告解读技巧

血液科检验报告解读技巧血液检验是一种常见的医学检查手段,通过分析血液中的各种参数指标,可以帮助医生判断人体健康状况、诊断疾病,并指导治疗方案。

然而,对于一份血液科检验报告,很多人往往无法正确理解其中的意义和信息。

本文将介绍一些血液科检验报告解读的技巧,帮助您更好地理解和分析这些报告。

一、报告基本信息在解读血液科检验报告前,首先要对报告的基本信息进行了解。

主要包括患者的个人信息、采样时间和检验时间等。

这些信息可以帮助确认报告的准确性和及时性。

二、血红蛋白指标血红蛋白是血液中重要的组成成分,衡量了氧气在血液中的携带能力。

常见的血红蛋白指标有血红蛋白浓度、红细胞压积和红细胞计数等。

通过这些指标的检验结果,可以判断贫血程度、血液稠密度以及红细胞数量等信息。

三、白细胞指标白细胞是人体免疫系统的主要成分,对抵抗病原体起着重要作用。

白细胞指标包括总白细胞计数、不同类型白细胞比例和绝对值等。

这些指标能够反映机体的免疫功能、感染程度以及炎症反应情况。

四、血小板指标血小板是血液中的关键成分,参与止血和凝固过程。

常见的血小板指标有血小板计数和平均血小板体积等。

通过这些指标可以判断血小板数量是否正常,从而了解患者是否存在出血或凝血异常等问题。

五、肝功能指标肝功能是评估肝脏健康状况的重要指标,常见的肝功能指标有谷丙转氨酶、总胆红素和白蛋白等。

这些指标可以反映肝细胞损伤、胆红素代谢和肝功能代谢情况。

六、肾功能指标肾功能的评估对于判断肾脏状况和排除肾脏病变非常重要。

肾功能指标包括肌酐、尿素氮和尿酸等。

通过这些指标的变化可以了解肾脏的排泄功能和代谢情况。

七、血脂指标血脂异常是引发心脑血管疾病的危险因素之一。

血脂指标主要包括总胆固醇、甘油三酯和高密度脂蛋白等。

通过这些指标的变化可以判断血脂代谢情况,及时发现和控制异常情况。

八、血糖指标血糖是评估糖尿病的重要指标,常见的血糖指标有空腹血糖和餐后血糖等。

通过检测这些指标可以评估血糖水平是否正常。

如何正确看待肿瘤基因检测报告?教你如何解读!

如何正确看待肿瘤基因检测报告?教你如何解读!引言随着科学技术的不断进步,肿瘤基因检测已经成为了肿瘤诊断和治疗中的重要工具之一。

通过基因检测,可以发现肿瘤细胞的基因组变异情况,帮助医生确定患者的治疗方案,从而提高治疗的精准度和效果。

对于普通人来说,如何正确地看待和理解肿瘤基因检测报告却是一个挑战。

本文将教你如何正确解读肿瘤基因检测报告,帮助你更好地理解肿瘤基因检测结果。

一、了解基因检测的原理和意义在解读肿瘤基因检测报告之前,首先需要了解基因检测的原理和意义。

基因检测是通过对肿瘤细胞中的基因组进行测序,以发现其中的基因突变、基因重排、基因失活等情况,从而为肿瘤的诊断、预后评估和治疗提供依据。

基因检测可以帮助医生确定患者的治疗方案,包括化疗药物的选择、靶向药物的应用以及免疫治疗的指导,提高治疗的个体化和精准度。

二、了解检测报告的内容和格式通常情况下,肿瘤基因检测报告会包括肿瘤样本的信息、检测方法、基因变异情况以及相关的临床意义等内容。

在阅读报告时,需要了解每个部分的含义和格式,以便更好地理解报告的内容和结论。

一般来说,报告会包括基因突变的类型、变异的频率、临床意义和相关的治疗选项等信息,需要仔细阅读和理解每个部分。

三、正确理解基因突变的临床意义在肿瘤基因检测报告中,通常会包括肿瘤细胞中的基因突变情况。

基因突变的临床意义取决于突变的类型、频率以及相关的研究和临床资料。

在阅读报告时,需要注意理解每个基因突变的临床意义,并结合临床指南和最新研究成果进行综合分析。

有些基因突变可能会对治疗方案和预后评估产生重要影响,需要重点关注和理解。

四、与医生进行深入交流和讨论在解读肿瘤基因检测报告时,最重要的是与医生进行深入的交流和讨论。

医生会根据患者的个体情况和检测报告的结果,制定个性化的治疗方案,并解答患者可能有的疑问和担忧。

与医生进行良好的沟通和合作,可以帮助患者更加准确地理解检测报告的结果,以及可能的治疗选择和预后评估。

ctc报告解读

CTC报告解读CTC(循环肿瘤细胞)分析是一种用于癌症诊断和治疗的先进技术。

CTC报告是通过对患者血液中循环肿瘤细胞的分析得出的结果,对于癌症患者的诊断、治疗和预后具有重要意义。

以下是CTC报告的主要内容及其解读。

1. 细胞类型鉴定细胞类型鉴定是通过特定的抗体标记和图像分析等技术,对循环肿瘤细胞进行鉴定和分类。

CTC报告中的细胞类型鉴定通常包括腺癌细胞、鳞状细胞和其他类型的肿瘤细胞等。

通过对细胞类型的鉴定,可以初步确定肿瘤的组织来源,有助于医生对肿瘤进行准确的诊断和分类。

2. 细胞数量统计细胞数量统计是通过计数循环肿瘤细胞的数量,评估肿瘤负荷和疾病进展情况。

CTC报告中的细胞数量统计通常采用绝对计数和相对计数两种方式。

绝对计数是指报告中给出的具体细胞数量,而相对计数则是相对于其他血细胞的百分比来表示。

细胞数量越多,说明肿瘤负荷越大,病情越严重。

3. 细胞形态分析细胞形态分析是通过观察循环肿瘤细胞的形态特征,评估细胞的恶性程度和分化程度。

CTC报告中的细胞形态分析通常包括细胞的形状、大小、核质比例、染色质结构等方面。

不同形态的肿瘤细胞可能具有不同的恶性程度和生物学行为,对治疗的反应也不同。

因此,细胞形态分析有助于医生对肿瘤进行准确的病理学诊断和预后评估。

4. 细胞免疫表型分析细胞免疫表型分析是通过检测循环肿瘤细胞表面的免疫标志物,评估细胞的免疫表型和免疫反应性。

CTC报告中的细胞免疫表型分析通常包括肿瘤细胞的免疫标志物表达情况,如CD44、CD24等。

不同免疫表型的肿瘤细胞可能对免疫治疗的效果不同,因此,细胞免疫表型分析有助于医生选择合适的治疗方案和预测患者的预后情况。

5. 基因突变检测基因突变检测是通过检测循环肿瘤细胞中的基因突变,评估肿瘤的遗传学特征和致癌驱动因素。

CTC报告中的基因突变检测通常包括EGFR、KRAS、BRAF等基因的突变情况。

基因突变检测有助于医生了解肿瘤的生物学特征和抗药性机制,为患者提供更加精准的治疗方案。

如何读懂肿瘤病理报告单

如何读懂肿瘤病理报告单肿瘤病理报告单是病理学家在对患者进行病理分析后所生成的一份报告,其中包含了关于肿瘤组织的详细描述、诊断和其他补充信息。

对于患者及其家属来说,理解和读懂肿瘤病理报告单是至关重要的,因为它能够提供有关患者病情的关键信息,以及指导后续的治疗方案选择。

本文将为你介绍如何读懂肿瘤病理报告单,以便更好地应对肿瘤治疗过程。

1. 报告单概述肿瘤病理报告单通常包含以下几个主要部分:病理号码、患者信息、送检标本信息、诊断、病理特征描述、免疫组化(如有)、分级和分期、诊断者签名、报告日期等。

首先,要熟悉这些信息的含义和相关术语,以便更好地理解报告内容。

2. 送检标本信息病理报告单中的送检标本信息描述了所检测的组织类型和部位。

了解标本类型对于确定报告中描述的肿瘤类型至关重要。

例如,肺癌可以通过肺组织活检、切除或细针穿刺标本进行诊断。

3. 诊断肿瘤病理报告单中最重要的部分是诊断,其中提供了关于肿瘤类型、分级和分期的详细信息。

肿瘤类型描述了肿瘤的原始来源和细胞类型,例如乳腺癌、结肠癌等。

分级是根据肿瘤细胞的异型性程度和增殖活性来确定肿瘤的恶性程度,一般分为低分化、中分化和高分化。

分期则是根据肿瘤的大小、淋巴结转移和远处转移情况来评估肿瘤的严重程度,常采用TNM分期系统。

4. 病理特征描述病理特征描述了肿瘤组织的形态学特点,包括细胞学特征、组织结构、细胞分化程度、核分裂象等。

这些特征对于了解肿瘤的临床表现、预后以及指导治疗非常重要。

通过对报告中的特征描述进行学习和了解,可以帮助解读肿瘤是否具有侵袭性、预测肿瘤的预后以及选择合适的治疗方案。

5. 免疫组化免疫组化是一种病理学技术,通过检测肿瘤细胞中特定的蛋白质表达情况来帮助确定肿瘤类型。

免疫组化在肿瘤病理报告单中常常被用来确定一些难以鉴定的肿瘤类型,例如淋巴瘤亚型等。

了解免疫组化标记物的作用和结果对于对肿瘤报告进行综合分析和判断至关重要。

6. 分级和分期分级和分期是衡量肿瘤恶性程度和确定治疗方案的重要依据。

二代测序所测的肿瘤基因数据的分析

10.1101/gad.2017311Access the most recent version at doi: 2011 25: 534-555Genes Dev.Lynda Chin, William C. Hahn, Gad Getz, et al.Making sense of cancer genomic dataReferences/content/25/6/534.full.html#related-urls Article cited in:/content/25/6/534.full.html#ref-list-1This article cites 220 articles, 82 of which can be accessed free at:Open Access Freely available online through the Genes & Development Open Access option.serviceEmail alertingclick here top right corner of the article or Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at the CollectionsTopic(123 articles)Cancer and Disease ModelsArticles on similar topics can be found in the following collections Correction/content/26/9/1003.full.html online at:been appended to the original article in this reprint. The correction is also available have correction A correction has been published for this article. The contents of the/subscriptions go to: Genes & Development To subscribe to Copyright © 2011 by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory PressREVIEWMaking sense of cancer genomic dataLynda Chin,1,2,3William C.Hahn,1,2Gad Getz,2and Matthew Meyerson1,21Department of Medical Oncology,Dana-Farber Cancer Institute,Boston,Massachusetts02115,USA;2Broad Institute of Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology,Cambridge,Massachusetts02142,USAHigh-throughput tools for nucleic acid characterization now provide the means to conduct comprehensive anal-yses of all somatic alterations in the cancer genomes. Both large-scale and focused efforts have identified new targets of translational potential.The deluge of informa-tion that emerges from these genome-scale investigations has stimulated a parallel development of new analytical frameworks and tools.The complexity of somatic geno-mic alterations in cancer genomes also requires the de-velopment of robust methods for the interrogation of the function of genes identified by these genomics efforts. Here we provide an overview of the current state of can-cer genomics,appraise the current portals and tools for accessing and analyzing cancer genomic data,and dis-cuss emerging approaches to exploring the functions of somatically altered genes in cancer.The development of powerful and scalable methods to analyze nucleic acids has transformed biological inquiry and has the potential to alter the practice of medicine (Lander1996;Collins et al.2003).The application of such technologies,together with powerful computational methods in human disease and animal model systems, has facilitated the study of both normal and disease-affected tissues in a manner previously not possible.In-deed,the connection between basic inquiry and potential clinical translation has never been more intimate.This convergence is particularly evident in cancer, a complex multigenic disease characterized by a diversity of genetic and epigenetic alterations(Vogelstein and Kinzler1993;Weir et al.2004;Jones and Baylin2007; Stratton et al.2009).Early cancer genome analysis has already led to new targets for cancer therapy and new insights into the relationship of specific genetic muta-tions and clinical response,as well as new approaches useful for diagnosis and prognosis.These initial efforts have motivated large-scale coordinated cancer genomic efforts to obtain complete catalogs of the genomic alter-ations in specific cancer types(The Cancer Genome Atlas [TCGA],;Hudson et al.2010).Moreover,the current pace of technological ad-vances make it increasingly clear that the ability to perform prospective and comprehensive molecular pro-filing of tumors will become commonplace and enable genome-informed personalized cancer medicine. However,the bottlenecks along this path are formi-dable and numerous.For one,these large-scale genome characterization efforts involve the generation and in-terpretation of data at an unprecedented scale,which has brought into sharp focus the need for improved informa-tion technology infrastructure and new computational tools to render the data suitable for meaningful analyses. Moreover,exploiting this information to develop new therapeutic strategies depends on further biological in-sights derived from understanding the functional conse-quences of such genomic alterations.Thus,it is also clear that new approaches that permit the efficient validation of genomic data are required as a first step in distinguish-ing mutations responsible for disease pathogenesis from other mutations that are the consequence of genomic instability;defining genes involved in cancer initiation, progression,or maintenance;and identifying the optimal ways to exploit this information therapeutically.In this review,we provide an overview of the current state of cancer genomics,describe the types of data being gen-erated and where they can be accessed,and discuss recent progress in developing tools,models,and methods for analysis of gene functions in cancer,which is the requisite next step in the translation of cancer genome information. State of cancer genomicsNearly all cancer genomes contain many nucleotide se-quence changes compared with the germline of the can-cer patient(Vogelstein and Kinzler1993;Stratton et al. 2009).These variations include the genomic alterations that cause or promote cancer,often referred to colloqui-ally as‘‘drivers,’’as well as alterations present in the cancer genome but without obvious advantage to the can-cerous cells when they occurred,referred to as‘‘passen-gers’’(Davies et al.2005).The major known somatic alterations in the cancer genome include nucleotide sub-stitution mutations and small insertion/deletions(indels), copy number gains and losses,chromosomal rearrange-ments,and nucleic acids of foreign origin(e.g.,oncogenic viruses)(Weir et al.2004;Chin and Gray2008;Stratton et al.2009).In addition,alterations in the epigenetic[Keywords:functional validation;genomic data portal;integrative analysis;large-scale cancer genomics]3Corresponding author.E-MAIL lynda_chin@;FAX(617)582-8169.Article is online at /cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.2017311.Freely available online through the Genes&Development Open Accessoption.534GENES&DEVELOPMENT25:534–555Ó2011by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press ISSN0890-9369/11;mechanisms that regulate gene expression occur in most cancers;this subject has been covered elsewhere(Jones and Baylin2002,2007)and is not treated in detail here. All of these acquired changes occur in the setting of germline variations of copy number and nucleotide se-quence,which may influence the rate of occurrence and/or the effects of somatic genetic alterations(Balmain et al.2003).Moreover,although somatic mutations occur in tumor cells,it is increasingly clear that the tumor microenvironment mediates important heterotypic sig-nals between the tumor and stromal cells for growth and survival(Hanahan and Weinberg2000).In this respect, global gene expression encompassing the full tran-scriptome—including coding messenger RNAs(mRNAs) (Schena et al.1995)and noncoding microRNAs(miRNAs) (Lu et al.2005)—of the complex tumor tissue reflects the panoply of somatic and epigenomic alterations,together with the state of cell differentiation of the tumor and the admixture of noncancerous cells.Hence,transcriptional profiling can define a unique gene expression signature for each tumor that may prove useful for classification and prognosis(Golub et al.1999;Alizadeh et al.2000; van’t Veer et al.2002).Evolution of cancer genomicsOver the past decade,technologies for detection of each of these types of alterations have been developed and applied to analyses of the cancer genomes.The initial studies focused on a single technology platform and/or type of genetic alteration.For example,high-resolution copy number profiling has led to the discovery of novel oncogenes in ovarian cancer(Nanjundan et al.2007), melanoma(Garraway et al.2005;Kim et al.2006;Scott et al.2009),lung carcinoma(Weir et al.2007;Bass et al. 2009),and colon carcinoma(Firestein et al.2008),and tumor suppressor genes in leukemias(Mullighan et al. 2007,2008).Similarly,the application of directed se-quencing of specific classes of genes has identified novel genes involved in specific types of cancer(Davies et al. 2002;Lynch et al.2004;Paez et al.2004;Pao et al.2004; Samuels et al.2004;Stephens et al.2004;Baxter et al.2005; James et al.2005;Kralovics et al.2005;Levine et al.2005; Zhao et al.2005;Pollock et al.2007;Chen et al.2008;Dutt et al.2008;George et al.2008;Janoueix-Lerosey et al.2008; Mosse et al.2008).These observations underscore the contribution of different types of somatic genome alter-ations in different subsets of cancer,and that comprehen-sive profiling of the cancer genome will require interroga-tion of different types of genome alterations in diverse cancer types and subtypes.As technologies to perform comprehensive profiling of the cancer genome progressed,different technology plat-forms from microarrays to capillary sequencing were brought together on unified sample sets(The Cancer Genome Atlas Network2008;S Jones et al.2008;Parsons et al.2008).For example,Velculescu and colleagues(S Jones et al.2008)integrated sequencing with expression and copy number profiling to identify IDH1mutations in glioblastomas(GBM).The Cancer Genome Atlas pilot project applied targeted sequencing,copy number,and expression profiling,in addition to epigenetic assessment to a large number of stringently qualified tumor samples to define core pathways of deregulation in GBM(The Cancer Genome Atlas Network2008)and discover genomic and epigenomic definition of molecular subtypes(Noushmehr et al.2010;Verhaak et al.2010).Indeed,global com-prehensive analysis with complementary genome an-notation tools in statistically powered high-quality sample cohorts is a key aspect of the current consensus standard for large-scale cancer genomics efforts under the International Cancer Genome Consortium(ICGC) (Hudson et al.2010),now encompassing>20projects from14countries(Table1).Second-generation sequencing technologiesDuring the past several decades,continuous improve-ments in genomic technology have led to a series of breakthroughs in our understanding of cancer genetics. The advent of second-generation sequencing technolo-gies and their applications to cancer have already accel-erated the pace of genome discovery,as summarized in recent reviews(Shendure and Ji2008;Meyerson et al. 2010).During the last5years,a variety of array-based methods have been developed,including picotiter plate pyrosequencing(Margulies et al.2005;Wheeler et al. 2008),single-nucleotide fluorescent base extension with reversible terminators(Bentley et al.2008),and ligation-based sequencing(Shendure et al.2005;Drmanac et al. 2010).All of these second-generation methods involve the amplification of individual DNA molecules on arrays or beads prior to massively parallel sequence generation. The throughput limitation and cost of first-generation Sanger-based capillary sequencing technology had,until now,dictated two predominant study designs for cancer genome discovery:one in which large numbers of sam-ples were analyzed but only a small number of genes were interrogated(Greenman et al.2007;The Cancer Genome Atlas Network2008;Dalgliesh et al.2010;Kan et al. 2010),versus a second in which all coding genes were sequenced but in only a handful of discovery samples, followed by targeted sequencing of candidates in an ex-tension cohort comprised of an independent set of sam-ples(Sjoblom et al.2006;Wood et al.2007;S Jones et al. 2008;Parsons et al.2008).Second-generation sequencing technology enables the complete sequencing of entire genomes in a time-and cost-efficient manner.Today,a single sequencing run of an Illumina HiSeq2000se-quencer can generate;200gigabases of sequence data in8d—an output that easily exceeds the annual sequenc-ing production of a genome sequencing center a few years ago(/10001691).This astronom-ical increase in sequencing capacity,along with the rapid reduction in sequencing cost(which is faster than the doubling of semiconductor/computer capacity every18 mo,known as Moore’s law)(Pettersson et al.2009),has completely transformed cancer genome discovery science. Second-generation sequencing offers several advan-tages over previous technologies.It has the power toMaking sense of cancer genomic dataGENES&DEVELOPMENT535identify mutations in highly admixed samples by virtue of deep coverage(Thomas et al.2006),overcoming a major limitation of Sanger-based capillary sequencing technol-ogy.Whereas previous technologies could query one modality of cancer genome alteration(mutation,copy number,or expression)at a time,second-generation se-quencing analyses permit the identification of all such alterations simultaneously.For example,one can obtain high-resolution and accurate measurements of somatic copy number alterations(SCNAs)from whole-genome sequencing(Campbell et al.2008;Chiang et al.2009),and the same data can identify nucleotide substitutions.Fur-thermore,second-generation sequencing offers structural information never before available from other genomic platforms,thus enabling for the first time global assess-ment of chromosomal rearrangements in cancer(Campbell et al.2008;Mardis et al.2009;Stephens et al.2009;Ding et al.2010a;Pleasance et al.2010a,b).Similar approaches can be applied to cDNA,also known as RNA-seq,which permits accurate digital measurements of gene expression across the whole transcriptome.Importantly,this latter approach provides the means to measure known,and discover novel,splice variants as well as aberrant tran-scripts generated by somatic structural genome rear-rangements(Maher et al.2009a,b;Berger et al.2010; Palanisamy et al.2010).This type of data will undoubt-edly reveal new insights into the regulation of gene transcription and RNA processing.In the near future,sequencing-based approaches will be applied to nearly all aspects of cancer genome character-ization.For example,current TCGA projects involve the comprehensive sequencing of all protein-coding genes and transcripts by hybrid capture/whole-exome sequenc-ing in hundreds of tumor-and germline-matched pairs,Table1.ICGC cancer genome projects,committed or active,including37projects in12countries and two European consortia as of January2011Lead jurisdiction Organ sites Tumor subtypesAustralia Ovary Serous cystadenocarcinoma Pancreas Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomaCanada Pancreas Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma Prostate Prostate adenocarcinomaChina Stomach Intestinal-and diffuse-type gastric cancer European Union/France Kidney Renal cell carcinomaEuropean Union/United Kingdom Breast ER-positive,HER2-negative breast cancerFrance Breast HER2-amplified breast cancerLiver Hepatocellular carcinoma secondary to alcohol and adiposity Prostate Prostate adenocarcinomaGermany Blood Germinal center B-cell-derived lymphomaBrain Medulloblastoma and pediatric pilocytic astrocytoma Prostate Early onset prostate cancerIndia Oral cavity Gingivobuccal carcinomaItaly Pancreas Rare pancreatic subtypes,including enteropancreatic endocrinetumors and exocrine tumorsJapan Liver Virus-associated hepatocellular carcinomaMexico Multiple Common tumor types in MexicoSpain Hematopoietic Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with mutated and unmutated IgVHUnited Kingdom Bone Osteosarcoma/chondrosarcoma/rare bone cancersBreast Triple negative/lobular/other breast cancersHematopoietic Chronic myeloid disorders,including myelodysplastic syndrome,myeloproliferative neoplasms,and other chronic myeloidmalignanciesUnited States(TCGA)Brain GBM and low-grade gliomasBreast Ductal and lobular breast adenocarcinomasStomach Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinomaLiver Hepatocellular carcinomaIntestine Colon and rectal adenocarcinomasGynecologic Serous ovarian adenocarcinoma;endometrial carcinoma;cervicaladenocarcinoma;and squamous carcinomasProstate Prostate adenocarcinomaBladder Nonpapillary bladder cancerHead and neck Head and neck squamous cell and thyroid papillary carcinomas Hematopoietic Acute myeloid leukemiaSkin Metastatic cutaneous melanomaLung Non-small-cell lung cancer,adenocarcinoma,and squamous subtypes Kidney Renal clear cell and renal papillary carcinomasPancreas Pancreatic adenocarcinomaFor updated information,see and . Chin et al.536GENES&DEVELOPMENTcomplemented by deep sequencing of the whole genomes (WGS)(at>30-fold coverage)in10%of the samples. Given the rate at which sequencing capacity is increasing and cost is shrinking,it is highly likely that deep-coverage WGS will soon be applied to the majority of the discovery samples.In parallel,efforts to use low-coverage sequenc-ing to conduct structural and copy number analyses are likely to replace array-based technologies in the near future.Similar study designs are being adopted by ICGC projects.Accessing cancer genomics dataAlthough the data generated from these large-scale can-cer genome characterization efforts have been and will continue to be made publicly available,accessing and using these cancer genome data remains a major chal-lenge.In this section,we attempt to provide a framework for nongenomic noncomputational cancer biologists to become familiar with what data are available and where to download or query each of the major genomic data types.Specifically,we describe briefly the technology platform(s)used to generate each data type,followed by common public sites where cancer genome data can be downloaded and summarized results can be queried. We also point out basic open source analytical tools or computational algorithms for manipulation and analysis of cancer genome data.However,it should be noted that the tools described here are illustrative examples,rather than a complete survey of sites,data sources,or analytical tools,as these are rapidly evolving.Data structure and data access policiesGenerally speaking,cancer genomic data can be divided into(1)raw,(2)processed or normalized,(3)interpreted, and(4)summarized categories based on the degree of computational modification and integration applied to the data.These categories are sometimes referred to as Level I–Level IV data.Raw,processed,and interpreted (Level I–III)data apply to individual samples,while sum-marized(Level IV)data refer to analyses across sample sets.For example,normalized or processed data represent data that have been assigned to a genome reference,such as alignment of sequences to reference genome or map-ping of probes to chromosomal positions.For microarray-based platforms,normalization refers to combining mul-tiple probes measuring a single genomic locus to a single value and transforming the measured intensities such that the values can be compared between experiments; examples of normalization steps include correction for background noise and total brightness.Interpreted data represent meaningful biological results extracted from each specimen,such as genome-wide copy number pro-file,where copy number breakpoints have been statisti-cally defined,or gene expression profiles,where individ-ual gene expression levels have been collated from multiple loci across the gene.Summarized(Level IV)data represent analysis of interpreted data across a cohort of samples,where statistical methodologies can be applied to define significant events or molecular subtypes.This category of analyzed data is often presented as the findings of a genomic study in a publication.Major sites where these data sets can be accessed are listed in Table2 and are described in some detail below.Although cancer genomic data from various large-scale projects—including the Cancer Genome Project(CGP)at Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute(http://www.sanger.ac. uk/genetics/CGP),TCGA(/ dataportal),and ICGC()—are publi-cally available,for protection of patient privacy,access is either open or controlled.Prior to second-generation sequencing,most raw data and some type of normalized data(e.g.,single nucleotide polymorphism[SNP]profiles) are subjected to controlled-access restriction,while inter-preted and summarized data are openly accessible.With the transition to second-generation sequencing data,it is likely that raw and processed data,and possibly some interpreted data,will fall under the‘‘controlled-access’’category,since the level of resolution may provide the means to identify specific patients.Controlled-access data are restricted to qualified researchers(with certifi-cation by host institution)with a specific proposal of data use that is deemed compliant with the project’s data access policy,typically requiring preapproval by the in-stitutional review board of the requesting investigator. For TCGA,access to controlled data is obtained through dbGAP(/gap);for ICGC projects,access is obtained through its Data Access Compliance Office(/daco).In the case of the Sanger Institute’s Cancer Genome Project, genotyping and first-generation sequencing traces can be requested at its data archive(/ genetics/CGP/Archive),and its second-generation sequenc-ing data must be obtained through the European Genome-Phenome Archive(EGA,/ega).At present,downloading raw data from these sources is a technically and logistically challenging task that requires significant network infrastructure to handle the size of the data files.Nucleotide sequence mutationsNucleotide substitutions and small insertions/deletions are common mechanisms for activating oncogenes and inactivating tumor suppressor genes.The initial develop-ment of methods to determine the nucleotide sequence of DNA in1975(Sanger and Coulson1975)led to the discovery of cancer-specific somatic mutations in the RAS gene family in the early1980s(Parada et al.1982; Shimizu et al.1983;Santos et al.1984;Bos et al.1985)and, later,mutations in human tumor suppressor genes(Friend et al.1986;Hahn et al.1996).Subsequently,the invention of automated sequencing instruments(Hunkapiller et al. 1991)led to the initial sequencing of the human genome (Lander et al.2001;Venter et al.2001),and then to sys-tematic efforts to sequence gene families(Davies et al. 2005;Stephens et al.2005;Greenman et al.2007).These latter efforts identified several new oncogene mutations that are targets for cancer therapy—most notably theMaking sense of cancer genomic dataGENES&DEVELOPMENT537T a b l e 2.D a t a b a s e s f o r c a n c e r g e n o m i c s d a t aD a t a b a s eL i n kD a t a t y p e T y p e o f i n f o r m a t i o n A c c e s sI C G C h t t p ://d c c .i c g c .o r g /L e v e l s I –I VC o p y n u m b e r ,r e a r r a n g e m e n t ,e x p r e s s i o n ,a n d m u t a t i o n d a t a O p e n a n d c o n t r o l l e dT C G A h t t p ://c a n c e r g e n o m e .n i h .g o v /d a t a p o r t a lL e v e l s I –I I IC o p y n u m b e r ,e x p r e s s i o n (m R N A a n d m i R N A ),p r o m o t e r m e t h y l a t i o n ,a n d m u t a t i o n s e q u e n c i n g O p e n a n d c o n t r o l l e dN C B I d b G A P h t t p ://w w w .n c b i .n l m .n i h .g o v /g a pL e v e l s I –I IR a w s e q u e n c i n g t r a c e s ;s e c o n d -g e n e r a t i o n s e q u e n c i n g B A M f i l e s b y T C G A C o n t r o l l e dC O S M I C h t t p ://w w w .s a n g e r .a c .u k /g e n e t i c s /C G P /c o s m i cL e v e l s I I I –I VS o m a t i c m u t a t i o n s a n d c o p y n u m b e r a l t e r a t i o n s b y g e n e :a m i n o a c i d p o s i t i o n ,t u m o r t y p e ,l i t e r a t u r e r e f e r e n c e s O p e nC a n c e r G e n e C e n s u s h t t p ://w w w .s a n g e r .a c .u k /g e n e t i c s /C G P /C e n s u s L e v e l I V A n n o t a t i o n o f m u t a t e d o r g e n o m i c a l l y a l t e r e d g e n e s O p e n W T S I C G Ph t t p ://w w w .s a n g e r .a c .u k /g e n e t i c s /C G P /A r c h i v e L e v e l s I –I I F i r s t -g e n e r a t i o n t r a c e a r c h i v e ;S N P g e n o t y p e p r o f i l e s C o n t r o l l e dE G A h t t p ://w w w .e b i .a c .u k /e g aL e v e l s I –I IS e c o n d -g e n e r a t i o n s e q u e n c i n g B A M f i l e s g e n e r a t e d b y W T S I C G P C o n t r o l l e dT u m o r s c a p e h t t p ://w w w .b r o a d i n s t i t u t e .o r g /t u m o r s c a p eL e v e l s I –I VB r o w s a b l e ,s e a r c h a b l e c a n c e r c o p y n u m b e r v i e w e r u s i n g S N P a r r a y d a t a O p e nO n c o m i n e h t t p ://w w w .o n c o m i n e .o r gL e v e l I VG e n e e x p r e s s i o n a n d c o p y n u m b e r d a t a i n r e a d i l y s e a r c h a b l e a n d c o m p a r a b l e f a s h i o n P a s s w o r d -p r o t e c t e dG E O h t t p ://n c b i .n l m .n i h .g o v /g e o L e v e l I G e n e e x p r e s s i o n d a t a P a s s w o r d -p r o t e c t e d c a A r r a y h t t p ://c a a r r a y .n c i .n i h .g o v L e v e l I G e n e e x p r e s s i o n d a t a P a s s w o r d -p r o t e c t e d U C S C C a n c e r G e n o m e B r o w s e r h t t p s ://g e n o m e -c a n c e r .s o e .u c s c .e d uL e v e l s I I I –I VB r o w s a b l e v i e w e r f o r c a n c e r c o p y n u m b e r a n d e x p r e s s i o n d a t a O p e nT h e c B i o C a n c e r G e n o m i c s P o r t a l h t t p ://c b i o p o r t a l .o r gL e v e l s I I I –I VB r o w s a b l e a n d s e a r c h a b l e v i e w e r f o r c a n c e r c o p y n u m b e r a n d e x p r e s s i o n d a t a O p e nO M I Mh t t p ://w w w .n c b i .n l m .n i h .g o v /o m i mI n h e r i t e d s y n d r o m e s a n d c a u s a t i v e g e n e s f o r c a n c e r a n d o t h e r d i s e a s e s ,w i t h e x t e n s i v e l i t e r a t u r e r e v i e w O p e nM i t e l m a n h t t p ://c g a p .n c i .n i h .g o v /C h r o m o s o m e s /M i t e l m a nC o p y n u m b e r a l t e r a t i o n s a n d t r a n s l o c a t i o n s b a s e d o n c y t o g e n e t i c d a t aO p e n(L e v e l I )R a w ;(L e v e l I I )n o r m a l i z e d /p r o c e s s e d ;(L e v e l I I I )i n t e r p r e t e d ;(L e v e l I V )s u m m a r i z e d .Chin et al.538GENES &DEVELOPMENTCold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press on February 26, 2013 - Published by Downloaded fromBRAF and EGFR protein kinase genes and the PIK3CA phosphatidylinositol kinase gene(Davies et al.2002; Lynch et al.2004;Paez et al.2004;Pao et al.2004; Samuels et al.2004)—leading to approved and in-devel-opment targeted therapeutics for cancers.For sequencing data,the normalized data category represents sequencing reads that have been aligned to a specific version of the human reference genome.As the reference genome is refined and filled in with each new version,mapping data may change;thus,researchers should pay attention to and always note the specific reference genome build used in an analysis.Raw sequenc-ing reads from both Sanger-based capillary sequencing and second-generation platforms are stored at NCBI Sequence Read Archive and dbGAP(see Table2).Access to these sequencing data is restricted and requires data use approval by the appropriate data access committee. The interpreted category for mutation data includes the sequence variant calls,the types of sequence variants (such as synonymous versus nonsynonymous or mis-sense versus indel),and the location of the nucleotide change in relation to annotated gene structure;e.g.,in-tron versus exon and consequent amino acid changes. One aspect of this analysis includes an annotation of whether such sequence variants are reported in dbSNP, a database representing likely common SNPs.If not found in dbSNP and not observed in matched germline-derived sequences,such variants are generally considered so-matic in nature.Putative variants should be verified (e.g.,result reproduced in an independent assay using the same technology platform)or validated(e.g.,result observed by an orthogonal method)by methods including genotyping.For TCGA projects,all verified,validated,or putative somatic mutations and associated descriptions discovered in a sample or a cohort of samples can be found in the.MAF file,which is available on the TCGA data portal(/dataportal). Similar data files can be found at the ICGC Data Co-ordination Center()under the Down-load Data page.New file formats will likely emerge in the near future to support the increasing applications of next-generation sequencing platforms for data generation.A key downstream(Level IV)analysis of verified or validated mutations is the determination of significance, accounting for the background mutation rate and size as well as composition of a gene.Several methodologies have been developed for this purpose(Getz et al.2007; Greenman et al.2007).For example,in the MutSig algorithm,a P-value is calculated for each gene,testing the hypothesis that all of the observed mutations in that gene are a consequence of random background mutation processes,taking into account the list of bases that are successfully interrogated by sequencing(i.e.,‘‘covered’’) and the list of observed somatic mutations,as well as the length and composition of the gene in addition to the background mutation rates in different sequence con-texts.As in analyses of other genomic data,such calcu-lations must then be corrected for multiple hypothesis testing(see below).Using these types of significance analyses,the majority of the somatic mutations found in cancer genomes is likely to represent passenger events and only a minority is likely drivers.For example,of the 453validated nonsilent mutations in GBM scattered across223genes,only eight genes were considered having higher than background mutation frequency,suggestive of positive selection pressure(The Cancer Genome Atlas Network2008).However,it is worth noting that,as for any statistical test,the lack of statistical significance by MutSig or similar analyses does not preclude true cancer relevance,as,relatively speaking,the number of samples having been adequately sequenced is still low.Moreover, computational algorithms for mutation calling and sta-tistical frameworks for significance calculation are still being developed and refined.Beyond statistical analyses,there are various theoreti-cal and computational models designed to predict the likely functional consequences of specific nucleotide mutations,particularly for mutations in coding genes. These models are often based on the impact of specific amino acid substitutions on protein structure or known functional domains or evolutionarily conserved regions. For example,the PolyPhen(for polymorphism phenotyp-ing)tool predicts the possible impact of an amino acid substitution on the structure and function of a protein using a variety of structural and chemical parameters in addition to evolutionary conservation(Sunyaev et al. 2001;Ramensky et al.2002).Indeed,a recurring theme in analysis of genomic data is the leverage of evolutionary information.MutationAssessor(Reva et al.2007)is a re-cently published algorithm for predicting potential func-tional impact of a sequence mutation based heavily on the assumption that if a highly conserved residue is changed to a different residue type,the change is pre-sumed to have high functional impact on the function of the affected protein.By analyzing aligned sequence families of paralogous and orthologous proteins within the human genome and across many other species,this algorithm calculates the functional impact(FI)score for a mutation. Both of these tools are Web accessible(http://genetics.bwh. /pph;)and offer an intuitive and easy-to-use query interface as well as a batch processing feature.With MutationAssessor,in addition to the calculated FI score for each variance,users can inspect the placement of mutations in a multiple sequence align-ment relative to amino acid residues that are conserved globally or in a specific subfamily,as well as observe the consequences of the residue change in an interactive three-dimensional protein structure.Other examples of prediction algorithms include SIFT,CanPredict,and CHASM(Ng and Henikoff2001;Kaminker et al.2007; Carter et al.2009;Adzhubei et al.2010).In the end, beyond statistical analysis or the prediction of functional impact,the relevance of any mutational event to human cancer will require functional validation(see below). The COSMIC(Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Can-cer)site is the single most comprehensive source of curated analyzed somatic mutation data in cancers de-veloped and maintained by the Cancer Genome Project at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute(Futreal et al.2004; Forbes et al.2008).COSMIC is an open source,easilyMaking sense of cancer genomic dataGENES&DEVELOPMENT539。

肿瘤基因检测报告单解读

肿瘤基因检测报告单解读1. 嘿,你知道肿瘤基因检测报告单上那些密密麻麻的数字和符号都代表啥吗?就好比你拿到一张神秘地图,每个标记都让人好奇又困惑!比如,看到某个基因突变,你难道不想知道这到底意味着什么吗?2. 哇塞,肿瘤基因检测报告单解读可真是个大学问呢!就像破解一道超级复杂的谜题。

你看,这里一个指标升高,那里一个突变出现,这不是让人心里七上八下的嘛!比如看到那个“+”号,你心里会不会“咯噔”一下呀?3. 哎呀呀,拿到肿瘤基因检测报告单,简直就像面对一个充满未知的宝藏盒子!这里面的信息可太关键啦。

就像走迷宫,一个指标可能就是指引方向的关键呢!比如说,看到某个基因的状态,你不想赶紧搞清楚它是好是坏吗?4. 嘿,肿瘤基因检测报告单解读可不简单哟!这就像是在翻译一种神秘的语言。

你想想,那些专业术语,不搞明白能行吗?比如那个长长的基因名字,你难道不好奇它背后的故事?5. 哇哦,面对肿瘤基因检测报告单,是不是感觉有点懵?这可真是个挑战呢!就好像进入了一个陌生的领域,一切都要从头学起。

比如看到那些奇怪的符号,你不会想找个人问问到底是啥意思吧?6. 哎呀,肿瘤基因检测报告单里藏着好多秘密呀!就跟隐藏在树林里的小路一样。

你得仔细找才能发现关键信息呢!像看到某个基因的表述,你难道不想知道它对健康的影响有多大?7. 嘿哟,解读肿瘤基因检测报告单,这可是个精细活呢!就如同在拼凑一幅复杂的拼图。

每一块都很重要呢!比如说,看到某个指标的异常,你不会紧张起来吗?8. 哇呀,肿瘤基因检测报告单可真是让人又爱又恨呀!爱它能提供信息,恨它那么难懂。

就像一个调皮的小精灵,让人捉摸不透。

比如看到一个不熟悉的基因位点,你难道不想搞清楚它的作用?9. 哎呀妈呀,肿瘤基因检测报告单的解读真的好关键啊!这简直就是决定命运的钥匙。

你想想,一个小小的指标变化,可能影响巨大呢!像看到那个危险信号一样的标注,你不会心里一紧吗?10. 嘿,朋友们,肿瘤基因检测报告单就像是一本神秘的魔法书!里面充满了神奇的代码和信息。

二代测序原理及报告解读

二代测序原理

边 复 制 边 测 序

扩

复

增

制

二代测序原理

制复

增扩

边 复

制

边测序DNA的建立捕获目标片段二代测序

安捷伦捕 获试剂盒

illumima 测序平台

二代测序流程复杂,参数繁多

需要检测的基因序列 所有碱基数量之和

现在报告中使用的参数

目标区覆 目标区平

测序质量

盖度

均深度

2.1 基因变异所致疾病及遗传方式

使用孟德尔遗传数据库查找基因所致疾病及遗传方式

显性与隐性遗传共存在

多种遗传方式

不完全显性

2.结果具体分析

1)该基因突变致病疾病类型及遗传方式 2)该样本的此处突变是否为致病性突变 明确致病和可疑致病 3)该样本的突变型最终是否患病

2.2 查找突变位点的致病性

2.3 总结突变与患病的关系

• 从遗传方式看有没有患病的可能性 • 从突变类型看有没有患病的可能性

ACMG突变解析指南

未报道致病位点,致病可能性的评估指南,节选其中可能致病性很强列表如下:

3.基因与疾病背景介绍

• 基因介绍来自于Gene数据库 • 疾病介绍来自于OMIM、罕见病数据库或其他外文权威

99.8% 274.67

目标区平均深度 >20X比例

99.7%

报告结果中的数据意义

检测到与临床相 关发生突变的基 因

转录本 编号

Exon 编号

CLCN2

NM_0011710 Exon

88

21

同一个基因可有 不同的别名,使 用Gene数据库 统一名称

同一基因可有 外显 不同的转录本, 子 通过Gene数 据库查突变类 型时必须使用 或换算到同一 转录本的突变 点

二代测序临床报告解读指引

2020年8月第20卷第4期循证医学The Journal of Evidence-Based MedicineAug.2020Vol.20No.4二代测序临床报告解读指引二代测序临床报告解读专家组[摘要]二代测序(next generation sequencing,NGS)已成为中国临床肿瘤医生常用检测工具,而中国超90%临床医生需要NGS报告解读支持。

因此,为提升临床医生NGS报告解读能力,特编写了NGS临床报告解读指引,以帮助临床医生梳理NGS报告解读逻辑,快速抓取关键信息,同时尽可能规避过度解读基因组信息导致的潜在危害。

本文从临床靶点或驱动基因相关体细胞变异注释及解读、NGS报告解读及临床决策、可报告范围及质量控制等方面详细介绍了NGS报告解读应遵循的恰当的结构化循证原则,正确理解NGS报告的逻辑结构、抓取关键信息并综合分析,为肿瘤患者带来切实的临床获益。

帮助医生在综合浏览完一份样本检出的所有分子变异后,结合患者的基本临床信息以及既往或同期其他配对样本检测结果,综合判断患者疾病的全面分子特征谱及其演化过程,了解这些信息所提示的生物学意义和临床意义,最终做出正确的临床决策。

[关键词]二代测序;报告解读;指引[中图分类号]R446.7[文献标识码]A DOI:10.12019/j.issn.1671⁃5144.2020.04.001 Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Next GenerationSequencing Clinical ReportsNext Generation Sequencing Clinical Report Interpretation Expert GroupAbstract:In China,next generation sequencing(NGS)has became a common molecular testing tool used by clinical oncologists,however,NGS clinical reports could be overwhelming for some clinicians who are unfamiliar with NGS.Approximately90%of clinicians are dependent on external support for the interpretation of NGS reports.In order to improve the clinicians ability to interpret and derive more information from NGS reports,a working group comprised of clinical oncologists and NGS professionals from all over China have compiled relevant standards and guidelines to equip the clinicians with the knowledge to identify the key information and avoid the over⁃interpretation of genomic information from NGS clinical reports.This article provides a detailed introduction on the logically structured evidenced⁃based principles of NGS reports including the interpretation of somatic mutations related to clinical targets or driver genes,the proper interpretation of genomic results to inform clinical decision⁃making,reportable scope,sample quality control,and other relevant information included in NGS clinical reports.With a better grasp on the information from NGS reports,the clinicians should be able to integrate the basic clinical information,other past or present test results,and the molecular profile of the patient to comprehensively assess the patient s disease and tailor a treatment strategy that will benefit the patient.Key words:next generation sequencing;report interpretation;guideline背景目前二代测序(next generation sequencing,NGS)已成为中国临床肿瘤医生常用检测工具,中国临床肿瘤学会(Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology,CSCO)肿瘤生物标志物专家委员会发布的第1个NGS临床应用调研显示,大于30%的肿瘤科医生每月NGS检测量超5个,而中国超过90%临床医生需要NGS报告解读支持。

如何正确看待肿瘤基因检测报告?教你如何解读!

如何正确看待肿瘤基因检测报告?教你如何解读!摘要:一、肿瘤基因检测报告的重要性二、解读肿瘤基因检测报告的步骤1.了解报告的基本信息2.分析EGFR 和ALK 突变指标3.关注肿瘤基因检测报告的其他指标4.咨询专业医生进行解读三、正确看待肿瘤基因检测报告1.客观认识基因检测结果2.结合其他治疗手段3.积极面对疾病正文:肿瘤基因检测报告是诊断和治疗肿瘤的重要依据。

然而,对于普通患者来说,如何正确解读这份报告成为了一个难题。

本文将教你如何解读肿瘤基因检测报告,让你更好地了解自己的病情。

首先,我们需要了解肿瘤基因检测报告的基本信息。

报告通常包括患者的基本信息、检测方法、检测结果等。

其中,检测结果包括各种基因突变指标,如EGFR 和ALK 突变等。

接下来,我们要重点关注EGFR 和ALK 这两个突变指标。

EGFR 突变在肺癌患者中较为常见,而ALK 突变则主要出现在肺癌和淋巴瘤患者中。

了解这两个指标的状况,有助于医生为患者制定更精准的治疗方案。

此外,报告中还可能包括其他指标,如KRAS、BRAF 等,也需要留意。

当我们了解报告的基本信息并分析各项指标后,仍需要咨询专业医生进行解读。

因为肿瘤基因检测报告的解读涉及到医学专业知识,患者很难通过自学完全掌握。

而医生在诊断和治疗肿瘤方面具有丰富的经验,他们能够根据报告为患者提供针对性的治疗建议。

正确看待肿瘤基因检测报告是治疗肿瘤的关键。

首先,患者应客观认识基因检测结果,既不要过分担忧,也不要掉以轻心。

其次,肿瘤基因检测报告仅是诊断疾病的一个依据,患者还应结合其他治疗手段,如手术、放疗、化疗等。

最后,患者应积极面对疾病,保持良好的心态,以提高治疗效果。

总之,肿瘤基因检测报告对患者的诊断和治疗具有重要意义。

通过学会解读报告,患者可以更好地了解自己的病情,为治疗提供有力支持。

肿瘤二代测序临床报告解读共识

肿瘤二代测序临床报告解读共识

二代测序临床报告解读肿瘤学专家组;张绪超

【期刊名称】《循证医学》

【年(卷),期】2022(22)2

【摘要】随着新型治疗药物的研发以及多学科综合治疗模式的优化,传统的病理分型及检测方法已经不足以满足临床需求,二代测序(next generation sequencing,NGS)已成为中国肿瘤医生常用的检测手段。

为进一步协助临床医生理解临床靶点或驱动基因相关变异注释及解读、梳理NGS报告的逻辑、提升抓取关键信息,二代测序临床报告解读肿瘤学专家组对国内外NGS检测最新进展进行认真分析、讨论和总结,在《二代测序临床报告解读指引》基础上增加部分NGS报告解读示例,同源重组缺陷(homologous recombination deficiency,HRD)及微小/分子/可测量残留病灶(minimal/molecular/measurable residual disease,MRD)相关内容解读,制定了《肿瘤二代测序临床报告解读共识》,最终帮助临床医生做出正确的临床决策。

【总页数】15页(P65-79)

【作者】二代测序临床报告解读肿瘤学专家组;张绪超

【作者单位】不详;广东省人民医院

【正文语种】中文

【中图分类】R446.7

【相关文献】

1.专家共识解读:二代测序如何辅助血液肿瘤的临床诊治

2.二代测序临床报告解读指引

3.《中国宏基因组学第二代测序技术检测感染病原体的临床应用专家共识》解读

4.骨与软组织肿瘤二代测序中国专家共识(2021年版)

5.《循证医学》文章推荐:二代测序临床报告解读指引

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

关于血液肿瘤二代测序报告单解读,您需要知道的。

随着二代测序技术的发展,越来越多血液科医生都会开展二代测序项目,但是很多医生对报告单结果一头雾水。

所以今天我们简单谈谈如何看懂一份血液肿瘤二代测序报告。

鉴于大家对二代测序的相关知识了解程度参差不齐,我们总结出“一对二看三查四问”的四步法,大家可以作为参考来分析二代测序的结果。

“一对”:核对标本送检信息。

养成良好的核对习惯,确定我们手里拿的报告正好是我们需要的,病人信息没错,送检项目没错。

“二看”:看测序结果。

几乎所有报告单的测序结果都是分等级列表式呈现,通常会报出三类变异:强烈临床意义变异、可能临床意义变异以及意义未明变异。

推荐临床医生重点查看前两类突变,而“意义未明变异”鉴于目前尚不清楚其临床指导意义,不要过于纠结而浪费时间,只需记录积累,将来再进行回顾性分析即可。

测序结果通常以表格形式呈现,表头术语就是要交代清楚XX基因XX位置发生什么突变,突变频率是多少。

这些表头术语解释通常在报告单的末尾。

以下图为例,简洁明了地列出“基因”、“突变命名”和“突变频率”。

这个结果表示检测到I类变异有三个:其中DNMT3A发生了移码突变,SETBP1和SRSF2发生点突变;三类变异有一个:ETV6发生点突变。

其中“突变命名”均以人类基因组变异协会(HGVS)规范进行标准书写:

以DNMT3A为例进行移码突变的书写方式解释:

1. NM_175629.2是DNMT3A的一个转录本,

2. c.2374delC:c是cDNA序列,C是胞嘧啶,del是deletion

缩写,c.2374delC表示cDNA序列第2374位胞嘧啶缺失,

3. p.R792fs: p是蛋白序列,R是精氨酸, fs是framshift缩写,p.R792fs表示蛋白序列第792位精氨酸发生移码突变,

4. 30.6%:表示DNMT3A这个突变占野生+突变总和的30.6%,即突变频率为30.6%。

以SETBP1为例进行点突变的书写方式解释:

1. NM_015559.2是SETBP1的一个转录本,

2. c.2608G>A: c是cDNA序列,G是鸟嘌呤,A是腺嘌呤,

c.2608G>A表示cDNA序列地2608位鸟嘌呤突变为腺嘌呤,

3. p.G870S: p是蛋白序列,G是甘氨酸,S是丝氨酸,p.G870S 表示蛋白序列第870位甘氨酸突变为丝氨酸,

4. 23%:表示SETBP1这个突变频率为23%。

以上点突变及移码突变是最常见的两种变异方式,想知道其他复杂的变异书写方式可参阅2001年发表在Hum Genet的文献“Nomenclature for the description of human sequence variations”。

有的报告单会把基因的突变频率写成“丰度”“变异比例”“VAF(variant allele frequency)”“MAF(mutant allele frequency)”等,通过突变频率可初步判断一下突变是体细胞突变(后天获得的)还是胚系突变(先天可遗传的),一般胚系突变的理论值是50%(杂合)或者100%(纯合),但在实际分析中,会把50%左右(如40%-60%)认为是胚系的杂合突变,90%-100%认为是胚系的纯合突变,其他比例的突变是体细胞突变的可能性大。

但是判断是体细胞突变还是胚系突变,最好是有正常样本的对照,比如对口腔粘膜上皮细胞进行一代测序位点验证。

对于体细胞突变,突变频率可以反映当前样本肿瘤细胞的克隆比例,对于以后样本复查有重要的参考价值。

对于初诊标本,如存在多个基因突变,还可通过突变频率的高低大概判断一下基因突变发生的前后顺序,一般起始突变的突变频率都比较高,比如DNMT3A突变。

如果测序结果是常见的热点突变,那么对于有经验的临床医生到这一步就已经能够判断突变的临床意义了,但是一份样本的测序结果往往会出现很多不熟悉的突变,这时候我们就需要查找它们具体的临床意义。

“三查”:查找临床意义。

一份优秀的报告单会在结果解析部分对突变位点的临床意义给予充分的描述,包括诊断分型、预后评估以及指导治疗等,这些信息通常来自权威指南、共识,权威文献以及公认数据库等。

对于有多个基因突变的结果,他们的临床意义需要综合考虑,侧重突变频率高的有强烈临床意义的突变,侧重有预后不良意义的突变,侧重有靶药治疗的突变。

当然这些都是一些经验值,任何一种肿瘤的突变,都是一个谱系,要全面解读多基因突变的临床意义还需要不断地积累。

“四问”:问询。

如果完成了前三步,但结果与预期不相符,或者对于结果还有疑问,那么最好的办法就是找报告审核人员问询吧。