2020北京西城高三二模英语(1)

2020届北京市西城区实验中学高三英语二模试题及答案解析

2020届北京市西城区实验中学高三英语二模试题及答案解析第一部分阅读(共两节,满分40分)第一节(共15小题;每小题2分,满分30分)阅读下列短文,从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中选出最佳选项APeople in the Middle Ages did eat with their hands. Personal utensils (餐具) were mostly unheard of, especially forks. There were spoons to help serve, but only special guests would receive a knife from the host. Everyone else would be expected to bring their own. Of course, eating with one's hands can be quite a sticky situation, so towels were provided to help diners stay at least somewhat clean as they ate.Still, dining was often a messy affair. At special occasions in the wealthiest households, women tended to dine alone, separate from the men. Women were expected to uphold a quality of grace. Eating greasy meat by hand would certainly not help! Once the men and women had finished their meals, they would come together to socialize.Dietary scholars of the Middle Ages believed that the foods in a meal needed to be served and eaten in order of heaviness. The lightest and most easily digested foods, such as fruits and cheeses, were eaten first to help the digestive (消化) system get started. Once digestion was underway, greens and light meats, such as lettuce, cabbage and chicken, could be eaten. Last came the heavier vegetables and meats, such as carrots, beans, beef, pork, and mutton. This method was considered the most healthful way to eat.The main and largest meal of the day was supper, and it was eaten at midday. Dinner was a light meal, and many of those in nobility (贵族) -the highest levels of the Middle Ages society-skipped breakfast altogether. Breakfast was considered unnecessary for those who did not perform physical work. Snacks and any other eating during the day were viewed the same way. Commoners, or the working class, were allowed to eat breakfast and small meals throughout the day.1. What did people in the Middle Ages usually do at the dinner table?A. They cleaned hands before meals.B. They used personal utensils.C. They had to use knives at dinner.D. They ate mostly with hands.2. What is the third paragraph mainly about?A. The order of eating foods.B. The weight of various foods.C. The principles of digesting foods.D. The list of healthy foods.3. Why did the nobility avoid eating breakfast?A. Breakfast was wasted for the nobility.B. Breakfast was viewed as unnecessary.C. Breakfast was considered as a light meal.D. Breakfast was saved for commoners.BThe English language is changing, and you are responsible! Whether we consider changes in grammar, spelling, pronunciation, or the very vocabulary of the language, you have played your part and continue to do so.When we first learned basic grammar and spelling, perhaps in elementary school, we might have gotten the impression that these things were sacred. The rules that apply to such things might have been presented as unchanging and unchangeable. While this way might be helpful for teaching children, it is far from accurate.The English language, like many others, is a living, growing, ever-evolving thing. Like it or not, you are involved in this change. These changes take many forms. Grammar and spelling have changed greatly over the years and centuries, with the spelling differences in different countries today a reflection of this. While the language of a thousand years ago might be called English, most of us would hardly recognize it today as the same language.The first involves changes in the pronunciation of words. Many are familiar with the differences between the British and American ways of pronouncing certain words. In addition to these differences, the pronunciation of many words has changed over the years because of how you have decided to pronounce them. For example, consider the word "err." The traditional pronunciation of this word rhymes with the word "her." Older dictionaries show this to be the primary or only pronunciation. However, in recent years, more and more people have been pronouncing it so that it sounds like "air." Another change in the language involves the addition and removal of words. The makers of dictionaries decide which words deserve to be officially adopted as part of the English language. Through the centuries, many words have come from other languages. In fact, English has probably done this more than any other language in the world, which is why spelling and pronunciation rules for English have so many exceptions.Of course, many slang words have been just short-lived fashions that have died out quickly. Others, though,have been adopted by mainstream society and become respectable, as have many technical terms. So then remember, the next time you repeat the newest expression to hit the street, or make up your own words, you may be contributing to the future of the English language.4. When we begin to learn English, we think _________.A. it is interesting to pick up a new languageB. English rules are wrongly presented in factC. grammar and spelling rules are unchangeableD. only adults have the ability to affect a language5. From paragraph 3 we can know that_________.A. we can change the English languageB. many languages are changing over yearsC. English has changed little in the past 1,000 yearsD. there were main changes in grammar and pronunciation6. Why is the pronunciation of words changing?A. people speak in different waysB. people have adopted foreign wordsC. it has been affected by American EnglishD. makers of dictionaries often change them7. Which of the following is the best title for the passage?A. Foreign words involved in English.B. The British speaks differently from Americans.C. English language is changing over years.D. You can change the English language.CA crew(全体成员)of six teenage girls completed a nine-day sailing trip in the US recently, after having seasickness and strong winds.For the past three years, the Sea Cadet teenagers whoset sail were all male. Roger Noakes, who captained(担任队长)the boat, said this was the first time he’d taken out an all-female crew.The girls asked for an all-girls trip in August this year. The crew set sail along with three adults, Noakes and two Sea Cadet representatives. The original plan was for the girls to sail 24 hours a day in rotating shifts(轮流换班)along the coast and then return. Things turned out differently, however. “The first night was difficult because the wind was really hard. The waves were going up and down,” said Abby Fairchild,16. “Everybody got seasick.” Noakes gave the girls the choice of just sailing in the bay and not going into open water. “But they decided they were going.”The teenagers then sailed a long way overnight and slept in shifts. “We’ve learned everything from controlling the boat to putting up the sails while we have rough seas,” said 15-year-old Olivia Wilcox.The teenagers stopped on land in Massachusetts. They didn’t make it to their original destination(目的地)in Maine, where they were supposed to have a celebratory dinner, due to the weather and winds. They said they weren’t disappointed, however, as they’d learned a lot. “They learned about boating, and above all, they built confidence and character,” said Noakes.8. What was special about the Sea Cadet trip this year?A. It was the longest sailing trip ever.B. It was the first all-female-crew sailing trip.C. It was the most dangerous sailing trip ever.D. It was the first sailing trip for teenagers.9. What happened on the crew’s first day of the trip?A. They all felt sick on the boat.B. Some of them were hurt.C. Their boat was out of control.D. They went into open water by mistake.10. Which of the following best describes these young sailors?A. Strong-minded and having a strong sense of teamwork.B. Hard-working and having great leadership skills.C. Understanding and creative.D. Adventurous and skillful.11. According to Noakes, what was the sailors’ greatest benefit from the trip?A. They knew the sea better.B. They made many friends.C. They got excellent sailing skills.D. They developed good personalities.D“We are running out of space and the only places to go to are other worlds... Spreading out may be the only thing that saves us from ourselves. I am convinced that humans need to leave Earth.” These are the words of the famous scientist Stephen Hawking, spoken at a science festival inNorwayin 2017, a year before his death.Hawking was not alone in this view. Many experts feel that the only way for humanity to last far into the future is to colonize other planets. That way, if an asteroid, a terrible disease, nuclear war, or some other disasterstrikes Earth, civilization as we know it would still have a chance. Mars is one of the most tempting destinations. NASA, theUnited Arab Emirates, the private company SpaceX, and the organization Mars One all have plans to send humans there. “Either we spread Earth to other planets, or we risk going extinct, SpaceX founder Elon Musk said at a conference in 2013.But not everyone agrees that colonizing Mars or any other planet is such a great plan. The most common argument against going is that it’s just too expensive or dangerous. It will take huge amounts of money and other resources just to get people there, let alone set up a place for them to live. It’s not even clear if humans could survive on Mars. One of the biggest dangers there is deadly radiation that bombards the planet.Maybe all the time and money people would pour into a Mars mission would be better spent on more urgent projects here on Earth, like dealing with poverty or climate change. Some experts argue that handling a problem like an asteroid strike or disease outbreak while staying here on Earth would be much easier and less expensive than surviving on a new planet.In addition, moving to a new planet could harm or destroy anything that already lives there. Mars seems uninhabited, but it could possibly host microbial life. Human visitors may destroy this life or permanently change or damage the Martian environment. Some feel that’s too much of a risk to take.What do you think? Should humans colonize outer space or stay home?12. What can be inferred from the passage?A. Many experts insist that humans should take the risk.B. Mars is the most attractive destinations for human beings.C. Hawking firmly believes the only way to save humans is moving to Mars.D. All the other experts don’t agree with Hawking’s idea.13. Why do some experts disagree with the plan to colonize Mars?A. It will cost much more money to settle on Mars than on Earth.B. It is too long a distance from the Earth to the Mars.C. Human visitors will bring diseases to Martian environment.D. The deadly radiation that bombards the planet is the biggest danger.14. What’s the writing purpose of the passage?A. To raise people’s awareness of protecting the environment.B. To present different opinions on whether to move to the Mars.C. To arouse readers’ reflection on whether to colonize outer space.D. To inspire people to deal with the environmental problems.15. In which section of a magazine is the passage most likely from?A. Fiction.B. Current affairs.C. Social Studies.D. Science.第二节(共5小题;每小题2分,满分10分)阅读下面短文,从短文后的选项中选出可以填入空白处的最佳选项。

2020年北京市西城区实验中学高三英语二模试卷及参考答案

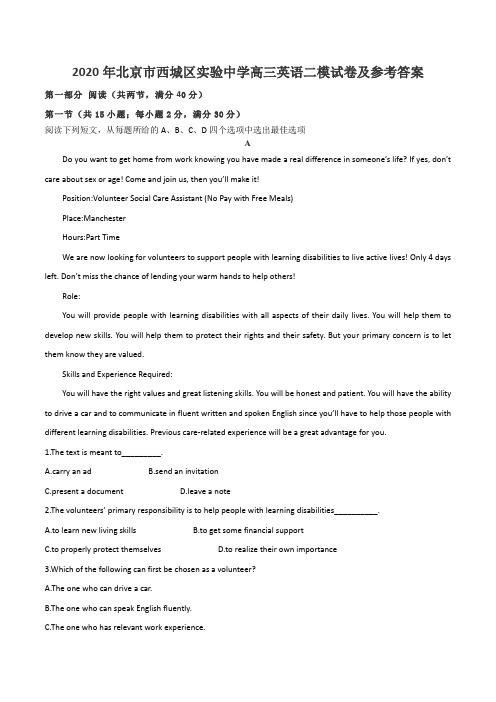

2020年北京市西城区实验中学高三英语二模试卷及参考答案第一部分阅读(共两节,满分40分)第一节(共15小题;每小题2分,满分30分)阅读下列短文,从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中选出最佳选项ADo you want to get home from work knowing you have made a real difference in someone’s life? If yes, don’t care about sex or age! Come and join us, then you’ll make it!Position:Volunteer Social Care Assistant (No Pay with Free Meals)Place:ManchesterHours:Part TimeWe are now looking for volunteers to support people with learning disabilities to live active lives! Only 4 days left. Don’t miss the chance of lending your warm hands to help others!Role:You will provide people with learning disabilities with all aspects of their daily lives. You will help them to develop new skills. You will help them to protect their rights and their safety. But your primary concern is to let them know they are valued.Skills and Experience Required:You will have the right values and great listening skills. You will be honest and patient. You will have the ability to drive a car and to communicate in fluent written and spoken English since you’ll have to help those people with different learning disabilities. Previous care-related experience will be a great advantage for you.1.The text is meant to_________.A.carry an adB.send an invitationC.present a documentD.leave a note2.The volunteers’ primary responsibility is to help people with learning disabilities__________.A.to learn new living skillsB.to get some financial supportC.to properly protect themselvesD.to realize their own importance3.Which of the following can first be chosen as a volunteer?A.The one who can drive a car.B.The one who can speak English fluently.C.The one who has relevant work experience.D.The one who has the patience to listen to others.BHappiness is not a warm phone, according to anew study exploring the link between young life satisfaction and screen time. The study was led by professor of psychology Jean M. Twenge at San Diego State University (SDSU).To research this link, Twenge, along with colleagues Gabrielle Martin at SDSU and W. Keith Campbell at the University of Georgia, dealt with data from the Monitoring the Future (MtF) study, a nationally representative survey of more than a million U. S. 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-graders. The survey asked students questions about how often they spent time on their Phones, tablets and computers, as well as questions about their face-to-face social interactions and their overall happiness.On average found that teens who spent more time in front of screen devices — playing computer games, using social media, texting and video chatting — were less happy than those who invested more time in non-screen activities like sports, reading newspapers and magazines, and face-to-face social interactions."The key to digital media use and happiness is limited use," Twenge said. "Aim to spend no more than two hours a day on digital media, and try to increase the amount of time you spend seeing friends face-to-face and exercising — two activities reliably linked to greater happiness."Looking at historical trends from the same age groups since the 1990s, it's easy to find that the increase of screen devices over time happened at the same time as a general drop-off in reported happiness inU. S.teens. Specifically, young peopled life satisfaction and happiness declined sharply after 2012. That's the year when the percentage of Americans who owned a smartphone rose above 50 percent. By far the largest change in teens' lives between 2012 and 2016 was the increase in the amount of time they spent on digital media, and the following decline in in-person social activities and sleep.4. Which method did Twenge's team use for the study?A. Calculating students' happiness.B. Asking students certain questions.C. Analyzing data from a survey.D. Doing experiments on screen time.5. How does the author develop the finding of the study in paragraph 3?A. By making a comparison.B. By giving an example.C. By making an argument.D. By introducing a concept.6. What is the purpose of the last paragraph?A. To draw a conclusion from the study.B. To offer some advice to the readers.C. To prove social activities' importance.D. To support the researchers' finding.7. Which of the following can be the best title for the text?A. Quitting Phones Equals HappinessB. Screen Time Should Be BannedC. Teens' Lives Have Changed SharplyD. Screen-addicted Teens Are UnhappierCIn the old days, when you had to drive to a movie theater to get some entertainment, it was easy to see how your actions could have an impact(影响)on the environment. After all, you were jumping into your car, driving across town, coughing out emissions(产生排放)and using gas all the way. But now that we're used to staying at home and streaming movies, we might get a littleproud. After all, we're just picking up our phones and maybe turning on the TV. You're welcome. Mother Nature.Not so fast, says a recent report from the French-based Shift Project. According to "Climate Crisis: The Unsustainable Use of Online Video", digital technologies are responsible for 4% of greenhouse gas emissions, and that energy use is increasing by 9% a year. Watching a half-hour show would cause 1. 6 kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions. That's like driving 6. 28 kilometers. And in the European Union, the Eureca project found that data centers(where videos are stored)there used 25% more energy in 2017 compared to just three years earlier, reports the BBC.Streaming is only expected to increase as webecome more enamored ofour digital devices(设备)and the possibility of enjoying entertainment where and when we want it increases. Online video use is expected to increase by four times from 2017 to 2022 and account for 80% of all Internet traffic by 2022. By then, about 60% of the world's population will be online.You're probably not going to give up your streaming services, but there're things you can do to help lessen the impact of your online use, experts say. For example, according to Lutz Stobbe, a researcher from theFraunhofer Institute in Berlin, we have no need to upload 25 pictures of the same thing to the cloud because it consumes energy every time. If instead you delete a few things here and there, you can save energy. Moreover, it's also a good idea to stream over Wi-Fi, watch on the smallest screen you can, and turn off your Wi-Fi in your home if you're not using your devices.8. What topic is the first paragraph intended to lead in?A. The environmental effects of driving private cars.B. The improvements on environmental awareness.C. The change in the way people seek entertainment.D The environmental impacts of screaming services.9. What does the underlined phrase become more enamored of" in paragraph 3 probably mean?A. Get more skeptical of.B. Become more aware of.C. Feel much crazier about.D. Get more worried about.10. What can we infer about the use of streaming services?A. It is being reduced to protect the planet.B. Its environmental effects are worsening.C. It is easily available to almost everyone.D. Its side effects have drawn global attention.11. Which of the following is the most environmentally-friendly?A. Watching downloaded movies on a mobile phone.B. Downloading music on a personal computer.C. Uploading a lot of images of the same thing.D. Playing online games over mobile networks.DBrian Hamilton's life changed in a prison when he went there with his friend, Reverend Robert J. Harris, who often went to local prisons to do ministry work. During the visit,Hamiltonstarted talking to one of the prisoners and asked what he was going to do when he got out. “He said he was going to get a job,”Hamiltonrecalls. “I thought to myself, wow, that’s going to be difficult with a criminal background.”The conversation madeHamiltonconsider how to help those who came out from prison. Finally in 2008, 16 years after that initial conversation,Hamiltoncreated Inmates to Entrepreneurs, a nonprofit organization that helps people with criminal backgrounds start their own small businesses.At the time,Hamiltonwas building his own company, a software technology company for the banking industry. As his company grew, so didHamilton’s time devoted to giving lessons to prisoners. He averaged three to four courses a month at prisons throughoutNorth Carolina.Eventually,Hamiltondecided to shift his focus to his true passion. In May 2019, he sold his company and focused on helping those who were imprisoned. His online courses will be set next year. “By March 1, 2022, anyone will be able to access the courses, either to become a certificated instructor or to access it for themselves as a prisoner or part of the general population,”Hamiltonexplained. In addition, he visits middle schools and presents the course to at-risk students as a preventative measure against crime.The free course is funded by the recently established Brian Hamilton Foundation, which offers assistance to military members as they return to civilian life and provides loans o small businesses. “Starting up a business isn't for everyone, but if we make opportunities available, and let people know that other people care about them, it makes a difference.”Hamiltonsaid.12. Why did Brian Hamilton went to a prison?A. He accompanied his friend.B. He took lessons in the prison.C. He wanted to get a job in the prison.D. He had a friend who was in prison.13. What can be inferred about Inmates to Entrepreneurs?A. It often assists military members.B It provides loans to small businesses.C. Its course has been largely broadened.D. It is an organization intended for business men.14. According to the author, which of the following best describesHamilton?A. He is a man who always changes his mind.B. He has a sense of social responsibility.C. He is good at running a big company.D. He makes money by giving lessons.15. What is the main idea of the text?A. A man made a fruitless visit to the prison.B. A man sold his business to teach prisoners.C. A man realized his dream of being a teacher.D. A man successfully created two organizations.第二节(共5小题;每小题2分,满分10分)阅读下面短文,从短文后的选项中选出可以填入空白处的最佳选项。

2020届北京市西城区高考英语二模试卷含答案

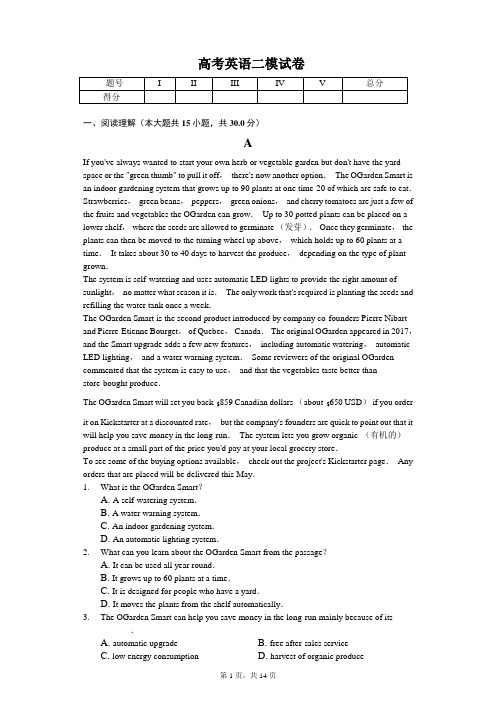

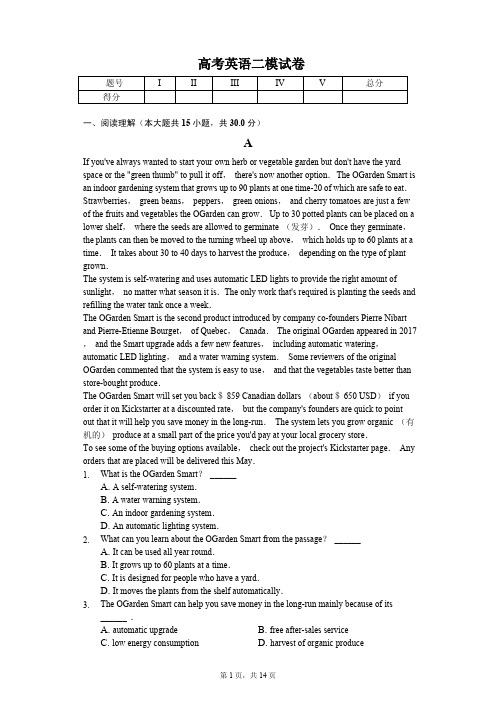

高考英语二模试卷一、阅读理解(本大题共15小题,共30.0分)AIf you've always wanted to start your own herb or vegetable garden but don't have the yard space or the "green thumb" to pull it off,there's now another option.The OGarden Smart is an indoor gardening system that grows up to 90 plants at one time-20 of which are safe to eat.Strawberries,green beans,peppers,green onions,and cherry tomatoes are just a few of the fruits and vegetables the OGarden can grow.Up to 30 potted plants can be placed on a lower shelf,where the seeds are allowed to germinate (发芽).Once they germinate,the plants can then be moved to the turning wheel up above,which holds up to 60 plants at a time.It takes about 30 to 40 days to harvest the produce,depending on the type of plant grown.The system is self-watering and uses automatic LED lights to provide the right amount of sunlight,no matter what season it is.The only work that's required is planting the seeds and refilling the water tank once a week.The OGarden Smart is the second product introduced by company co-founders Pierre Nibart and Pierre-Etienne Bourget,of Quebec,Canada.The original OGarden appeared in 2017,and the Smart upgrade adds a few new features,including automatic watering,automatic LED lighting,and a water warning system.Some reviewers of the original OGarden commented that the system is easy to use,and that the vegetables taste better thanstore-bought produce.The OGarden Smart will set you back ﹩859 Canadian dollars (about ﹩650 USD)if you orderit on Kickstarter at a discounted rate,but the company's founders are quick to point out that it will help you save money in the long-run.The system lets you grow organic (有机的)produce at a small part of the price you'd pay at your local grocery store.To see some of the buying options available,check out the project's Kickstarter page.Any orders that are placed will be delivered this May.1.What is the OGarden Smart?______A. A self-watering system.B. A water warning system.C. An indoor gardening system.D. An automatic lighting system.2.What can you learn about the OGarden Smart from the passage?______A. It can be used all year round.B. It grows up to 60 plants at a time.C. It is designed for people who have a yard.D. It moves the plants from the shelf automatically.3.The OGarden Smart can help you save money in the long-run mainly because of its______ .A. automatic upgradeB. free after-sales serviceC. low energy consumptionD. harvest of organic produceBAs the Camp Fire continued,killing at least 85 people and displacing thousands more in Northern California,Madison waited there.Gaylord,the Anatolian shepherd mix's owner,was not able to get to her home in Paradise,when the fire began to spread,meaning Madison was left behind.For weeks,all Gaylord could do was pray for Madison's safety,according to California-based animal rescue organization Paw Print Rescue.Sullivan,a volunteer with the organization,had already helped locate Madison's brother Miguel in a different city.But Madison was even more difficult to find.Sullivan spotted Madison a few times in a canyon (峡谷),apparently guarding his land,and put out fresh food and water regularly in hopes that the dog would turn up,according to a Facebook post by Sullivan.She even placed an article of clothing that smelled like Gaylord near the home "to keep Madison's hope alive until his people could return," Sullivan wrote.When the evacuation (疏散)order was lifted last week and Gaylord went back to her home-which had been ruined by the fire-her prayers were answered:Madison was there,seemingly protecting what little remained of his family's home."Well,I'm so happy to report that Gaylord was allowed to return to her home today and THERE MADISON WAS!!!! He had stayed to protect what was left of his home,and never gave up on his people!" Sullivan wrote in the comment on her Facebook post."I'm so happy I'm crying as I write this! He didn't give up through the storms or the fire!" she added.Soon afterward,Madison was reunited with Miguel for the first time since the fire broke out.An emotional Gaylord said in an interview with the network that she was overcome with joy to see Madison waiting for her.She also expressed how grateful she was to Sullivan.Gaylord said fighting through tears,"You could never ask for better animals.He is the best dog."4.What did Madison do during the Camp Fire?______A. He rescued Sullivan.B. He waited for Gaylord.C. He stayed with Miguel.D. He ran away from Paradise.5.Why did Sullivan place an article of clothing smelling like Gaylord near the home?______A. To keep Madison warm.B. To get Madison to turn up.C. To help Madison remember his owner.D. To encourage Madison not to give up.6.Where was Madison finally found?______A. In a different city.B. In a canyon.C. At a camp.D. At his home.7.What quality is emphasized in this story?______A. Patience.B. Unity.C. Devotion.D. Wisdom.CChoosing to forget something might take more mental effort than trying to remember it,researchers at The University of Texas at Austin discovered through neuroimaging (神经成像).These findings,published in the Journal of Neuroscience,suggest that in order to forget an unwanted experience,more attention should be focused on it.This surprising result continues previous research on intentional forgetting,which focused on reducing attention tothe unwanted information through redirecting attention away from unwanted experiences or holding back the memory's retrievals (恢复)."We may want to get rid of memories that cause nonadaptive responses,such as upsetting memories,so that we can respond to new experiences in more adaptive ways," said Jarrod Lewis-Peacock,the study's senior author and an assistant professor of psychology at UT Austin."Decades of research has shown that we have the ability to voluntarily forget something,but how our brains do that is still being questioned.Once we can figure out how memories are weakened and design ways to control this,we can design treatment to help people rid themselves of unwanted memories."Using neuroimaging to track patterns of brain activity,the researchers showed a group of healthy adults images of scenes and faces,instructing them to either remember or forget each image.Their findings not only confirmed that humans have the ability to control what they forget,but that successful intentional forgetting required "moderate (适中的)levels" of brain activity in these sensory and perceptual areas (感官区域)-more activity than what was required to remember."A moderate level of brain activity is critical to this forgetting mechanism.Too strong,and it will strengthen the memory;too weak,and you won't change it," said Tracy Wang,lead author of the study and a psychology postdoctoral fellow at UT Austin."Importantly,it's the intention to forget that increases the activation of the memory,and when this activation hits the ‘moderate level' sweet spot,that's when it leads to later forgetting of that experience." The researchers also found that participants were more likely to forget scenes than faces,which can carry much more emotional information,the researchers said."We're learning how these mechanisms in our brain respond to different types of information,and it will take a lot of further research and replication (重复)of this work before we understand how to control our ability to forget," said Lewis-Peacock,who has begun a new study using neurofeedback to track how much attention is given to certain types of memories."This will make way for future studies on how we process,and hopefully get rid of,those really strong,sticky emotional memories,which can have a powerful effect on our health and well-being," Lewis-Peacock said.8.Previous studies on intentional forgetting researched ______ .A. the pattern of brain activityB. the process of recovering a memoryC. the way to reduce attention to unwanted informationD. the amount of attention required by intentional forgetting9.According to Tracy Wang,forgetting is possible when ______ .A. people respond to new experiences in an adaptive wayB. the activation of the memory reaches a certain levelC. people have the strongest intention to forgetD. the information involves more emotion10.Lewis continues his study to find out ______ .A. how to control people's ability to forgetB. where to apply the findings of his team's latest studyC. what effects upsetting memories have on people's healthD. if different types of information requires different levels of attention11.What is the best title of the article?______A. Where does forgetting take place?B. How does attention affect memory?C. Forgetting uses more brain power than rememberingD. Forgetting is far more difficult than we once imaginedDThe new social robots,including Jibo,Cozmo,Kuri and Meccano M.A.X.,bear some resemblance to assistants like Apple's Siri,but these robots come with something more.They are designed to win us over not with their smarts but with their personality.They are sold as companions that do more than talk to us.Time magazine hailed (称赞)the robots that "could fundamentally reshape how we interact with machines." But is reshaping how we interact with machines a good thing,especially for children?Some researchers in favor of the robots don't see a problem with this.People have relationships with many kinds of things.Some say robots are just another thing with which we can have relationships.To support their argument,roboticists sometimes point to how children deal with toy dolls.Children animate (赋予…生命)dolls and turn them into imaginary friends.Jibo,in a sense,will be one more imaginary friend,and arguably a more intelligent and fun one.Getting attached to dolls and sociable machines is different,though.Today's robots tell children that they have emotions,friendships,even dreams to share.In reality,the whole goal of the robots is emotional trickery.For instance,Cozmo the robot needs to be fed,repaired and played with.Boris Sofman,the chief executive of Anki,the company behind Cozmo,says that the idea is to create "a deeper and deeper emotional connection …And if you neglect him,you feel the pain of that." What is the point of this,exactly?What does it mean to feel the pain of neglecting something that feels no pain at being neglected,or to feel anger at being neglected by something that doesn't even know it is neglecting you?This should not be our only concern.It is troubling that these robots try to empathize with children.Empathy allows us to put ourselves in the place of others,to know what they are feeling.Robots,however,have no emotions to share,and they cannot put themselves in our place.No matter what robotic creatures "say" or squeak,they don't understand our emotional lives.They present themselves as empathy machines,but they are missing the essential equipment.They have not been born,they don't know pain,or death,or fear.Robot thinking may be thinking,but robot feeling is never feeling,and robot love is never love.What is also troubling is that children take robots' behavior to indicate feelings.When the robots interact with them,children take this as evidence that the robots like them,and when robots don't work when needed,children also take it personally.Their relationships with the robots affect their self-esteem (自尊).In one study,an 8-year-old boy concluded that the robot stopped talking to him because the robot liked his brothers better.For so long,we dreamed of artificial intelligence offering us not only simple help but conversation and care.Now that our dream is becoming real,it is time to deal with the emotional downside of living with robots that "feel."12.How are the new social robots different from Siri?______A. They are intended to teach children how to talk.B. They are designed to attract people with their smarts.C. Their main function is to evaluate children's personality.D. They have a new way to communicate with human beings.13.In Paragraph 3 Cozmo is used as an example to show that the social robots ______ .A. are deeply connected with human beingsB. are unable to build a real relationship with childrenC. are so advanced that they can feel the pain of human beingsD. are not good enough to carry out the instructions of children14.The underlined phrase "essential equipment" in Paragraph 4 refers to ______ .A. emotionB. painC. fearD. thinking15.Which of the following shows the development of ideas in the passage?______A.B.C.D. I:Introduction P:Point Sp:Sub-point (次要点)C:Conclusion二、阅读七选五(本大题共5小题,共10.0分)Healthy See,Healthy Do Visit the grocery store on an empty stomach,and you will probably come home with a few things you did not plan to buy.But hunger is not the only cause of additional purchases.The location of store displays (摆放)also influences our shopping choices.(1)The checkout area is a particular hotspot for junk food.Studies have found that the products most commonly found there are sugary and salty snacks.(2) A 2012 study in the Netherlands found that hospital workers were more likely to give up junk food for healthy snacks when the latter were more readily available on canteen shelves,for example.In 2014 Norwegian and Icelandic researchers also found that replacing unhealthy foods with healthy ones in the checkout area significantly increased last-minute sales of healthier foods.(3) It has been working with more than 1,000 store owners to encourage them to order and promote nutritious foods."We know that the stores are full of cues (暗示)meant to encourage consumption," says Tamar Adjoian,a research scientist at the department,"Making healthy foods more convenient or appealing can lead to increased sales of those products."Adjoian and her colleagues wondered if such findings would apply to their city's crowded urban checkout areas,so they selected three Bronx supermarkets for their own study.(4) Then they recorded purchases over six three-hour periods in each store for two weeks.Of the more than 2,100 shoppers they observed,just 4 percent bought anything from the checkout area.Among those who did,however,customers in the healthy lines purchased nutritious foods more than twice as often as those in the standard lines.(5) The findings were reported in September in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.The potential influence may seem small,but Adjoian believes that changing more checkout lines would open customers' eyes to nutritious,lower-calorie foods.Health department officials are now exploring ways to expand healthy options at checkout counters throughout New York City.A.These foods give people more energy.B.They bought unhealthy foods 40 percent less often.C.And it may make or break some healthy eating habits.D.The supermarkets began to offer nutritious,lower-calorie foods.E.These findings caught the attention of New York City Department of Health.F.They replaced candies and cookies with fruits and nuts near the checkout counter.G.And a few studies have suggested that simply swapping in healthier options can change customer behavior.16. A. A B. B C. C D. D E.E F.F G. G17. A. A B. B C. C D. D E.E F.F G. G18. A. A B. B C. C D. D E.E F.F G. G19. A. A B. B C. C D. D E.E F.F G. G20. A. A B. B C. C D. D E.E F.F G. G三、完形填空(本大题共20小题,共30.0分)The Gift of Forgiveness The summer I turned 16,my father gave me his old 69 Chevy Malibu convertible.What did I know about classic cars?For me,the important thing was that Hannah and I could (21)around Tucson with the top down.Hannah was my best friend,a year younger but much (22).That summer she (23)with a modeling agency,doing catalog and runway work.A month after my birthday,Hannah and I went to the movies.On the way home,we (24)at the McDonald's drive-through,putting the fries in the space between us to (25)."Let's ride around awhile," I said.It was a clear night,hot,full moon hanging low over the desert.Taking a curve (弯)too (26),I ran over some dirt and fishtailed.I then moved quickly through a neighbor's landscape wall and drove into a full-grown palm tree.The front wheel came to rest halfway(27)the tree trunk.There were French fries on the floor,the dash (仪表盘)and my lap.An impossible amount of (28) was on Hannah's face,pieces of skin hanging around her eyes.We were taken in separate ambulances.In the emergency room,my parents spoke quietly:"Best plastic surgeon (整容医生)in the city…but it is more likely the(29)of her modeling career…"We'd been wearing lap belts,(30)the car didn't have shoulder belts.I'd broken my cheekbone on the steering wheel;Hannah's (31)had split wide open on the dash.What would I say to her?When her mother,Sharon,came into my hospital room,I started to cry,preparing myself for her (32).She sat beside me and took my hand."I drove into the back of the car of my best friend when I was your age," she said."I completely (33)her car and mine.""I'm so sorry," I said."You're both (34)," she said."Everything else doesn't matter." I started to explain,and Sharon stopped me."I(35)you.Hannah will too."Sharon's forgiveness allowed Hannah and me to get back in the car together that summer,to stay (36)throughout high school and college,to be in each other's weddings.I think of her gift of forgiveness every time I tend to feel angry about someone for a perceived(可感知到的)(37),and whenever I see Hannah.The scars (伤疤)are now(38)and no one else would notice,but in the sunlight I can still (39)the faint,shiny skin just below her hairline-for(40),a sign of forgiveness.21. A. drive B. run C. wander D. march22. A. stronger B. healthier C. taller D. smaller23. A. competed B. chatted C. signed D. bargained24. A. stopped B. ate C. aimed D. stood25. A. catch B. share C. hold D. spare26. A. fast B. seriously C. softly D. slow27. A. across B. up C. below D. along28. A. blood B. petrol C. water D. sweat29. A. path B. base C. point D. end30. A. and B. but C. or D. so31. A. shoulders B. arms C. chest D. forehead32. A. anger B. regret C. sorrow D. concern33. A. attacked B. dragged C. damaged D. removed34. A. alike B. relieved C. injured D. alive35. A. help B. love C. understand D. forgive36. A. sisters B. friends C. classmates D. colleagues37. A. need B. effort C. wrong D. threat38. A. left B. marked C. shown D. faded39. A. touch B. see C. feel D. learn40. A. them B. you C. me D. her四、语法填空(本大题共1小题,共15.0分)41. A When I was in high school our physics teacher gave us a challenge (1) involved makinga paper airplane of any shape.The only objective was to get it to fly as far as possible.(2)(stand)at the starting line,one of my classmates took a piece of flat paper,crumpled (把…捏成一团)it up,and (3) (throw)it down the way.He beat the class withease.Some of the students got mad and said that he cheated,but the physics teacher (4) (clear)explained it could be any shape and that a paper ball was indeed a shape.B Buildings around the world (5) (go)dark for 60 minutes this evening in a voluntaryevent known as Earth Hour.This grassroots effort started in 2007 in Sydney,Australia,and has since grown into (6) global movement to raise awareness of our energyconsumption and the effects of climate change on our planet.Anyone can participate in this movement (7) switching off the lights at 8:30 PM local time.Last year close to 18,000 landmark buildings switched off their lights in 188 countries.Will you dim your lights tonight?C The story of Chinese fashion began in 2011 when Feiyue and Huili,both Chinesesneaker brands,suddenly gained international attention.Their products (8) (see)on models all over the world then.Last year,Chinese sportswear brand LI-NING was at the New York Fashion Week in September with new designs (9) (decorate)withChinese characters.Now the Chinese brands are impressive and ambitious and can go head to head with foreign brands.And this ambition may be due to the fact that China's young people are now more confident about (10) (they)own culture.五、书面表达(本大题共2小题,共35.0分)42.假设你是红星中学高三学生李华.你的英国朋友Jim来信说他在英国学校参加了中国书法俱乐部.擅长书法的你决定写一幅书法作品寄给他,并附上一封信.信的内容包括:1.该作品的内容;2.送该作品的原因;3.表示愿意提供帮助.注意: 1.词数不少于50;2.开头和结尾已给出,不计入总词数.提示词:书法 calligraphyDear Jim,Yours,Li Hua43.假设你是红星中学高三学生李华.毕业之际,你们班开展了感谢学校教职员工的活动.请根据下面四幅图的先后顺序,写一篇英文周记,记述活动的全过程.注意:词数不少于60.提示词:教职员工 teachers and staff答案和解析1.【答案】【小题1】C 【小题2】A 【小题3】D【解析】1.C.细节理解题.根据文章第一段The OGarden Smart is an indoor gardening system that grows up to 90 plants at one time-20 of which are safe to eat可知OgarySmart是一个室内园艺系统;故选C.2.A.细节理解题.根据文章第二段The system is self-watering and uses automatic LED lights to provide the right amount of sun light, no matter what season it is可知花园智能它可以全年使用;故选A.3.D.细节理解题.根据文章第四段The system lets you grow organic (有机的) produce at a small part of the price you'd pay at your local grocery store可知OGarden Smart能帮助你长期省钱,主要是因为有机产品收获;故选D本文属于说明文阅读,作者通过这篇文章主要向我们描述了一个室内园艺系统OgarySmart的优点.考察学生的细节理解和推理判断能力,做细节理解题时一定要找到文章中的原句,和题干进行比较,再做出正确的选择.在做推理判断题不要以个人的主观想象代替文章的事实,要根据文章事实进行合乎逻辑的推理判断.4.【答案】【小题1】B 【小题2】D 【小题3】D 【小题4】C【解析】1.B.细节理解题.根据文章第二段Gaylord, the Anatolian shepherd mix's owner, was not able to get to her home in Paradise , when the fire began to spread, meaning Madison was left behind盖洛德,安纳托利亚牧羊人的主人,当火开始蔓延时,他无法到达她在天堂的家,这意味着麦迪逊被抛在后面.可知麦迪逊在野营之火期间他在等盖洛德;故选B.2.D.细节理解题.根据文章第三段She even placed an article of clothing that smelled like Gaylord near the home "to keep Madis on's hope alive until his people could return她甚至在家里放了一件闻起来像盖洛德的衣服,"以保持麦迪逊的希望,直到他的人民回来.可知沙利文在家里附近放了一件带有盖洛德味道的衣服为了鼓励麦迪逊不要放弃;故选D.3.D.细节理解题.根据文章第四段Well, I'm so happy to report that Gaylord was allowed to return to her home today and THE RE MADISON WAS!!!! He had stayed to protect what was left of his home好吧,我很高兴地告诉大家,盖洛德今天被允许回到她的家,麦迪逊就在那里!他留下来保护家里剩下的东西.可知麦迪逊最终在他的家被找到;故选D.4.C.细节理解题.根据文章最后一段 She also expressed how grateful she was to Sullivan. Gaylord said fighting through tears , "You could never ask for better animals. He is the best dog她还表达了她对沙利文的感激之情.盖洛德热泪盈眶地说:"你永远不能要求更好的动物,他是最好的狗."可知这个故事强调奉献的品质;故选C本文属于说明文阅读,作者通过这篇文章主要向我们描述了主人和狗在火灾中的感情升华.考察学生的细节理解和推理判断能力,做细节理解题时一定要找到文章中的原句,和题干进行比较,再做出正确的选择.在做推理判断题不要以个人的主观想象代替文章的事实,要根据文章事实进行合乎逻辑的推理判断.8.【答案】【小题1】C 【小题2】B 【小题3】A 【小题4】C【解析】1.C.细节理解题.根据文章第二段This surprising result continues previous research on intentional forgetting, which focused o n reducing attention to the unwanted information through redirecting attention away from un wanted experiences or holding back the memory's retrievals 这一令人惊讶的结果延续了以往关于有意遗忘的研究,该研究的重点是通过将注意力从不想要的经历中转移或阻止记忆的检索来减少对不需要的信息的关注.可知已有的关于故意遗忘的研究了减少对不想要的信息的注意的方法;故选C.2.B.细节理解题.根据文章第五段Too strong, and it will strengthen the memory; too weak, and you won't change it," said Tracy Wang, lead author of the study and a psychology postdoctoral fellow at UT Au stin. "Importantly, it's the intention to forget that increases the activation of the memory, and when this activation hits the ‘moderate level' sweet spot这项研究的主要作者、奥斯丁大学心理学博士后特蕾西•王说:"太强了,就会增强记忆力;太弱了,你也改变不了它.重要的是,它的意图是要忘记,增加记忆的激活,当这种激活达到‘中等水平'的甜蜜点时.可知根据TracyWang,遗忘是可能的当存储器的激活达到某个级别;故选B.3.A.细节理解题.根据文章第六段We're learning how these mechanisms in our brain respond to different types of information, and it will take a lot of further research and replication (重复) of this work before we understand how to control our ability to forget我们正在学习大脑中的这些机制是如何对不同类型的信息作出反应的,在我们了解如何控制我们忘记的能力之前,我们需要对这项工作进行大量的研究和复制.可知刘易斯继续进行研究发现如何控制人忘记的能力;故选A.4.C.细节理解题.根据文章最后一段This will make way for future studies on how we process, and hopefully get rid of, those r eally strong, sticky emotional memories, which can have a powerful effect on our health a nd well-being," Lewis-Peacock said这将为我们如何处理并希望摆脱那些对我们的健康和幸福有着强大影响的真正强烈的、粘稠的情感记忆的未来研究让路,"lewis-peacock 说.可知文章的最佳标题是遗忘比记住需要更多的大脑力量;故选C本文属于说明文阅读,作者通过这篇文章主要向我们描述了关于遗忘记忆的研究成果.考察学生的细节理解和推理判断能力,做细节理解题时一定要找到文章中的原句,和题干进行比较,再做出正确的选择.在做推理判断题不要以个人的主观想象代替文章的事实,要根据文章事实进行合乎逻辑的推理判断.12.【答案】【小题1】D 【小题2】B 【小题3】A 【小题4】B【解析】考察学生的细节理解和推理判断能力,做细节理解题时一定要找到文章中的原句,和题干进行比较,再做出正确的选择.在做推理判断题不要以个人的主观想象代替文章的事实,要根据文章事实进行合乎逻辑的推理判断.16.【答案】【小题1】C 【小题2】G 【小题3】E 【小题4】F 【小题5】B【解析】1-5 CGEFB1.C.细节理解题.根据前文"The location of store displays (摆放)also influences our shopping choices商店陈列的位置也会影响我们的购物选择".可知此处应填"它可能会形成或打破一些健康的饮食习惯".故选C.2.G.细节理解题.根据前文"Studies have found that the products most commonly found there are sugary and salty snacks研究发现,最常见的产品有甜味和咸味小吃".可知此处应填"一些研究表明,简单地更换更健康的食物就能改变顾客的行为".故选G.3.E.细节理解题.根据下文"It has been working with more than 1,000 store owners to encourage them to order and promote nutritious foods该公司已与1000多名店主合作,鼓励他们订购和推广营养食品".可知此处应填"这些发现引起了纽约市卫生局的注意".故选E.4.F.推理判断题.根据前文"Adjoian and her colleagues wondered if such findings would apply to their city's crowded urban checkout areas,so they selected three Bronx supermarkets for their own studyAdjoian和她的同事想知道这些发现是否适用于他们城市拥挤的收银台区域,所以他们选择了布朗克斯的三家超市作为自己的研究对象".可知此处应填"他们把糖果和饼干换成了收银台附近的水果和坚果".故选F.5.B.推理判断题.根据下文"The findings were reported in September in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior该研究结果发表在9月份的《营养教育与行为》杂志上".可知此处应填"他们购买不健康食品的频率降低了40%".故选B.本文是一篇选句填空,文章主要介绍了空着肚子去杂货店,你可能会带着一些你不打算买的东西回家.但饥饿并不是额外购买的唯一原因.商店陈列的位置也会影响我们的购物选择.此题主要考查学生的细节理解和推理判断能力.做细节理解题时一定要找到文章中的原句,和题干进行比较,再做出正确选择.在做推理判断题时不要以个人的主观想象代替文章的事实,要根据文章事实进行合乎逻辑的推理判断.21.【答案】略【解析】A12.C13.C14.A 15.B=16.A17.B 18.A19.D20.B=21.D22.A 23.C 24.D 25.D=26.B27.C28.D29.B30.C41.【答案】【小题1】that/which 【小题2】Standing【小题3】threw 【小题4】clearly【小题5】willgo【小题6】a 【小题7】by 【小题8】wereseen【小题9】decorated【小题10】their【解析】1.that/which.考查连词,先行词是challenge,在定语从句中做主语,故填关系代词which或that.2.Standing.考查非谓语,one of my classmates与stand是主动关系,故填现在分词做状语,故填standing.3.threw.考查动词,and并列动词took,crumpled以及threw,时态保持一致,故填threw.4.clearly.考查副词,修饰动词explain,故填clearly.5.will go.考查时态,将会熄灯一个小时,表示将来,故填will go.6.a.考查冠词,表示泛指,变成一个全球的行动,故填a.7.by.考查介词,通过熄灯,表示:通过,故填介词by.8.were seen.考查被动,主语是products,被看见,根据then可知使用一般过去时,故填were seen.9.decorated.考查非谓语,decorate与designs是动宾关系,故填过去分词做后置定语,故填decorated.10.their.考查代词,他们自己的文化,修饰名词使用形容词性物主代词,故填their.A:文章讲述了作者高中物理课扔纸飞机的故事;B:讲述了地球日的熄灯活动;C:中国时装品牌正在世界舞台走红.语法填空是通过语篇在语境中考查语法知识的运用能力,在解题前应快速浏览短文掌握大意,在读懂短文的基础上,结合短文提供的特定的语言环境去逐句分析.要解决好语法填空,离不开坚实的语法知识,有了坚实的语法知识才能对语言进行正确的分析和判断,从而答对题目.42.【答案】Dear Jim,I am glad to know that you have joined your school's calligraphy club. The calligraphy piece I sent to you was written by myself. I really hope you will like it.【要点一,表达愿意提供帮助】The Chinese characters on the piece are "天道酬勤" (Tian Dao Chou Qin), meaning "Hard work pays off." It is a well-known Chinese idi om, widely adopted as a motto by Chinese people. There is a similar calligraphy piece ha nging in the study at my home, which was written by my grandfather【高分句型一,which 引导非限制性定语从句】. He gave it to me when I started to learn calligraphy at age six in hopes that I would pr actise it often and learn it well【高分句型二,that引导同位语从句】. You see now my efforts have paid off. I hope it can serve as an encouragement to y ou at all times. I wrote this piece in the calligraphic style of my favorite calligrapher, Yan Zhenqing, a renowned master of the Tang Dynasty. His style is Kaishu, a standard script , suitable for beginners. I guess maybe it is the style that you are practising【高分句型三,it is…that强调句型】.【要点二,表达作品内容和送该作品的原因】I know it is not easy to learn Chinese calligraphy. If you have any problems during you r study, I would be happy to help you. I sincerely hope you enjoy learning Chinese calligr aphy!Yours,Li Hua【解析】【高分句型一】 There is a similar calligraphy piece hanging in the study at my home, which was writt en by my grandfather.我家书房里挂着一幅类似的书法作品,是我祖父写的.which引导非限制性定语从句.【高分句型二】 He gave it to me when I started to learn calligraphy at age six in hopes that I would prac tise it often and learn it well.我六岁开始学书法时,他给了我,希望我能经常练习,学好书法.that引导同位语从句.【高分句型三】 I guess maybe it is the style that you are practising.我想可能是你练习的风格吧.it is…that强调句型.。

2020届北京市西城区高三二模英语试题(带答案解析)

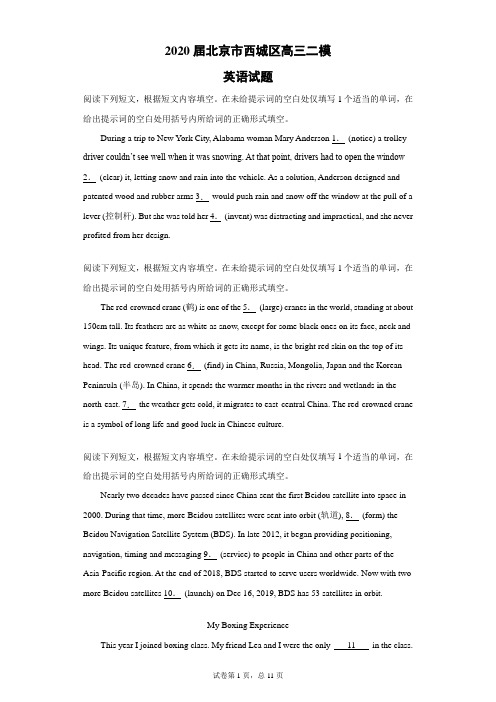

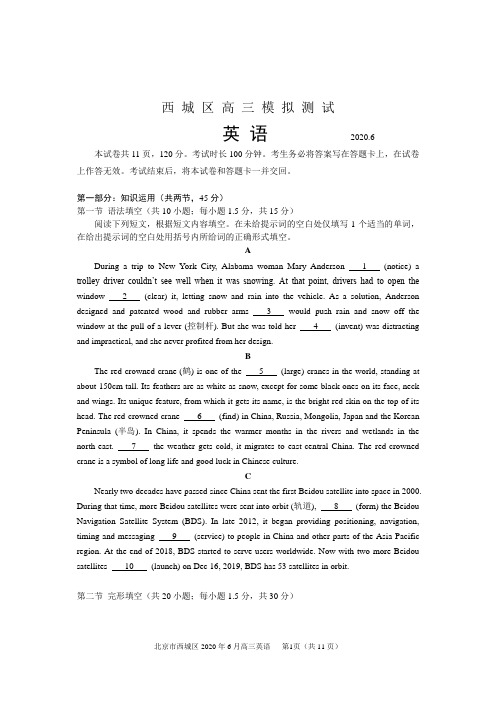

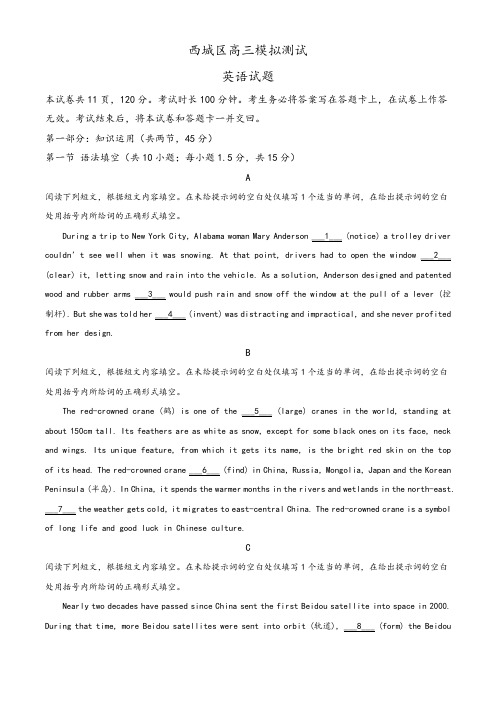

Nearly two decades have passed since China sent the first Beidou satellite into space in 2000. During that time, more Beidou satellites were sent into orbit (轨道),8.(form) the Beidou Navigation Satellite System (BDS). In late 2012, it began providing positioning, navigation, timing and messaging9.(service) to people in China and other parts of the Asia-Pacific region. At the end of 2018, BDS started to serve users worldwide. Now with two more Beidou satellites10.(launch) on Dec 16, 2019, BDS has 53 satellites in orbit.

阅读下列短文,根据短文内容填空。在未给提示词的空白处仅填写1个适当的单词,在给出提示词的空白处用括号内所给词的正确形式填空。

The red-crowned crane (鹤) is one of the5.(large) cranes in the world, standing at about 150cm tall. Its feathers are as white as snow, except for some black ones on its face, neck and wings. Its unique feature, from which it gets its name, is the bright red skin on the top of its head. The red-crowned crane6.(find) in China, Russia, Mongolia, Japan and the Korean Peninsula (半岛). In China, it spends the warmer months in the rivers and wetlands in the north-east.7.the weather gets cold, it migrates to east-central China. The red-crowned crane is a symbol of long life and good luck in Chinese culture.

2020年西城实验学校高三英语二模试题及参考答案

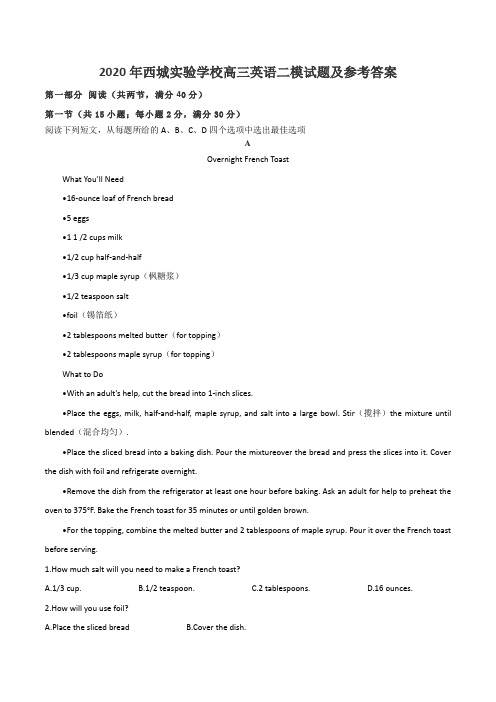

2020年西城实验学校高三英语二模试题及参考答案第一部分阅读(共两节,满分40分)第一节(共15小题;每小题2分,满分30分)阅读下列短文,从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中选出最佳选项AOvernight French ToastWhat You’ll Need•16-ounce loaf of French bread•5 eggs•1 1 /2 cups milk•1/2 cup half-and-half•1/3 cup maple syrup(枫糖浆)•1/2 teaspoon salt•foil(锡箔纸)•2 tablespoons melted butter(for topping)•2 tablespoons maple syrup(for topping)What to Do•With an adult’s help, cut the bread into 1-inch slices.•Place the eggs, milk, half-and-half, maple syrup, and salt into a large bowl. Stir(揽拌)the mixture until blended(混合均匀).•Place the sliced bread into a baking dish. Pour the mixtureover the bread and press the slices into it. Cover the dish with foil and refrigerate overnight.•Remove the dish from the refrigerator at least one hour before baking. Ask an adult for help to preheat the oven to 375°F. Bake the French toast for 35 minutes or until golden brown.•For the topping, combine the melted butter and 2 tablespoons of maple syrup. Pour it over the French toast before serving.1.How much salt will you need to make a French toast?A.1/3 cup.B.1/2 teaspoon.C.2 tablespoons.D.16 ounces.2.How will you use foil?A.Place the sliced breadB.Cover the dish.C.Remove the dish.D.Eat the French toast.3.Who is the passage written for?A.Teachers.B.Parents.C.Cooks.D.Kids.BShanghairesidents passing through the city’s eastern Huangpu district in Octobermight have astonished at an unusual sight: a “walking” building. An 85-year-old primary school has been lifted off the ground in its entirety and relocated using new technology named the “walking” machine.In the city’s latest effort to preserve historic structures, engineers used nearly 200 mobile supports under the five-story building. The supports act like robotic legs. They’re split into two groups which in turns rise up and down, imitating the human step. Attached sensors help control how the building moves forward.TheLagenaPrimary School, which weighs 7,600 tons, faced a new challenge — it’s T-shaped, while previously relocated structures were square or rectangular. Experts and technicians met to discuss possibilities and test a number of different technologies before deciding on the “walking machine”.Over the course of 18 days, the building was rotated 21degrees and moved 62 meters away to its new location. The old school building is set to become a center for heritage protection and cultural protection. The project marks the first time this “walking machine” method has been used inShanghaito relocate a historical building.In recent years,China’s rapid modernization has seen many historic buildingsrazedto clear land for skyscrapers and office buildings. But there has been growing concern about the architectural heritage loss as a result of destruction across the country.Shanghaihas beenChina’s most progressive city when it comes to heritage preservation. The survival of a number of 1930s buildings in the famous Bund district and 19th-century “Shikumen” houses in the repaired Xintiandi neighborhood has offered examples of how to give old buildings new life. The city also has a track record of relocating old buildings. In 2018, the city relocated a 90-year-old building in Hongkou district, which was then considered to beShanghai’s most complex relocation project to date.4. How did the primary school get moved?A. By reducing the weight of it.B. By using movable supports.C. By dividing it into several parts.D. By using robotic legs.5. What does the underlined word “razed” probably mean in Paragraph 5?A. Replaced.B. Burnt.C. Protected.D. Destroyed.6. What can we infer about the heritage preservation inChina?A. The use of advanced technology leads to growing concern.B. Shanghai is the pioneer in preserving architectural heritage.C.A number of old buildings have been given new life.D. Many historic buildings will be relocated.7. What is the passage mainly about?A. New preservation campaigns are launched inChina.B. New technology gives new life to historic buildings.C. A building inShanghai“walks” to a new location.D. “Walking machine” makes heritage protection simpler.CBecoming famous is the dream of many, and Tian is getting closer to that dream.Tian, 30, is a white-collar worker inBeijing. On short video application Douyin, Tian has more than 2,000 fans. So far, she has received more than 50,000 likes on the Dubsmash-like app. On her page on Douyin, Tian shares everything, from her son’s daily activities, to her pet dogs, to little skits (段子) made up by her and her husband. “Making funny videos, and combining them with music is really interesting,” Tian said. “Of course, I make the videos for fun because it is quite relaxing.”China’s short video market has seen great growth, according to areport. The report said thatChina’s short video market was valued at 5.73 billion yuan ($900 million) in 2017, an increase of 184 percent. The industry value is expected to go up to the 30 billion mark in 2020. Companies like Tencent, Sohu and Iqiyi have all started providing short video content.“Short videos are popular because they are an addition to traditional audio and video content on the internet,” said Sun Jiashan with the Chinese National Academy of Arts.Fans say that the short videos help them “chill out” from a stressed-out lifestyle. “My favorite videos are all about pets,” said Zhou Na, a nurse inHefei, capital of East China’sAnhuiprovince. “After a whole day’s work,watching the 15-second videos makes me laugh, which reduces my pressure.”8. Why does Tian make short videos in Douyin?A. To get fun.B. To become a well-known person.C. To attract fans.D. To record her family’s routine.9. What’s Sun Jiashan’s opinion about short videos?A. They have huge value.B. They greatly reduce people’s pressure.C. They make people’s star dreams come true.D. They enrich internet audio and video content.10. What does the underlined words “chill out” probably mean?A. Catch a cold.B. Feel cold.C. Calm down.D. Become concerned.11. What does the passage mainly tell us?A. Every Chinese is using Douyin.B. China’s short video market is open.C. Douyin brings the Chinese great happiness.D.China’s short video market has developed rapidly.DDogs are often referred to as “man's best friend”. But MacKenzie, a four-pound Chihuahua (奇瓦瓦狗), who was named winner of the 2020 American Hero Dog competition, is making the world a better place for humans and animals alike. Often called the “Oscars for dogs”, the award recognizes dogs who make great contributions to society.This year's competition attracted over 400 competitors from across the country. While all were impressive, it was tiny MacKenzie who won the judges' hearts. Born at a rescue shelter in Hilton, New York, in 2013, she had a cleft palate (腭裂) that required her to be tube fed for the first year of her life. A life-saving operation, performed in 2014, gave her the ability to eat and drink independently, enabling the tiny dog to focus on doing what she loved most: taking care of others.The seven-year-old Chihuahua is now gainfully “employed” by the Mid Foundation, a Rochester, New York-based non-profit organization that shelters and cares for animals born with disabilities. MacKenzie's official job is “to provide love and care for baby rescue animals born with birth defects”. The Chihuahua is good at her joband hasnurturedmany different species-from puppies to kittens to turkeys, squirrels, birds and even a goat. She acts as their mother and teaches them how to socialize, play, and have good manners.In addition to her role as an animal caretaker, MacKenzie also has the important job of greeting the foundation's volunteers and friends. The incredible dog, who has lost her ability to bark, also visits area schools to help children understand physical disabilities in both animals and people. Her heart-warming and inspiring story makes MacKenzie worthy of America's top dog honor!12. What made MacKenzie American Hero Dog?A. Being man's best friend.B. Her struggle with disabilities.C. Rescuing animals with disabilities.D. Her contributions to a better world.13. What can we infer about MacKenzie from Paragraph 2?A. Her growth path was not easy.B. She was deserted by her owner.C. She was operated on at two years old.D. She still needs taking care of by others.14. What does the underlined word “nurtured” in Paragraph 3 mean?A. Trained.B. Comforted.C. Tended.D. Abused.15. Which can be a suitable title for the text?A. MacKenzie—The Most Hard-working DogB. MacKenzie—America's “Most Heroic Dog”C. Chihuahua—Inspiration of Positive EnergyD. Chihuahua—Appeal for Animals' Protection第二节(共5小题;每小题2分,满分10分)阅读下面短文,从短文后的选项中选出可以填入空白处的最佳选项。

2020届北京市西城区高考英语二模试卷解析版