评析 the American Scholar

《美国文学赏析》试题

Group 1Column A Column B( e ) 1. T. S. Eliot a. Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening ( d ) 2. Wallace Stevens b. Sister Carrie( b ) 3. Theodore Dreiser c.The Oversoul( c ) 4. Ralph Waldo Emerson d. Anecdote of the Jar( a ) 5. Robert Frost e. The Waste LandGroup 2Column A Column B( b ) 1. Benjy a. Sister Carrie( a ) 2. George Hurstwood b. The Sound and the Fury( d ) 3. Emily c. Mrs Warren’s Profession( c ) 4. Vivie d. A Rose for Emily( e ) 5. Jim e. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn“God help men that help themselves” is found in ________ work.A.PaineB. FranklinC. FreneauD. JeffersonFrom 1732 to 1758, Benjamin Franklin wrote and published his famous _____, an annal(年表、编年史) collection of proverbs.(谚语)A.The AutobiographyB. Poor Richard’s AlmanacC. Common Sense D .The General Magazine______ was the most leading spirit of the Transcendental Club.A.Henry David ThoreauB. Ralph Waldo EmersonC. Nathanial HawthorneD. Walt WhitmanTranscendentalists(超验主义者)recognized ________ as the “highest power of the soul”.A. IntuitionB. logicC. data of the sensesD. thinkingThe common thread throughout American literature has been emphasis on the ________.A.RevolutionB. ReasonC. IndividualismD. RationalismThe publication of ________ established Emerson as the most eloquent spokesman of New England Transcendentalism.A. NatureB. Self-relianceC.The American ScholarD. The Over-soulThere is a good reason to state that New England Transcendentalism was actually ______ on the Puritan soil.A. RomanticismB. Puritanism (清教主义)C. Mysticism (神秘主义)D. Unitarianism (实用主义)In the history of literature, Romanticism is regarded as _______.A.the thought that designates(标出、定名为)a literary and philosophical theory which tends tosee the individual as the very center of all life and all experience.B.The thought that designates man as a social animalC.The orientation that emphasizes those features which men have in commoD.The modes of thinkingMark Twain wrote most of his literary works with a ______ language.A.GrandB. pompousC. simpleD. vernacularMark Twain, one of the greatest 19th century American writers, is well known for his _______. A. international theme B. waste-land imageryC. local colorD. symbolismThe Age of Realism is also what Mark Twain referred to as ______.A.the golden ageB. the silver ageC.the gilded ageD. the roaring ageThe impact of Darwin’s evolutionary theory on the American thought and the influence of the 19th century French literature on the American men of letters gave rise to yet another school of realism: American _________.A. modernismB. NaturalismC. VernacularismD. local colorismWhich of the following figures does not belong to “The Lost Generation”?A. Ezra PoundB. William Carlos WilliamsC. Robert FrostD. Theodore DreiserThe following writers were awarded Nobel Prize for literature except ______.A. William FaulknerB. F. Scott. FitzgeraldC. John SteinbeckD. Ernest HemingwayWho, one of the most import poets in his time, is a leading spokesman of the “Imagist Movement”?A. J. D. SalingerB. Ezra PoundC. Richard WrightD. Ralph EllisonTheodore Dreiser is generally regarded as one of American’s ____________.A. naturalistsB. realistsC. modernistsD. romanticistsThe book from which “all modern American literature comes” refers to _____.A. The Great GatsbyB. The Sun Also RisesC. The Adventure of Huckleberry FinnD. Moby DickThe American “Thirties”, lasted from the Crash(股市崩盘), through the ensuing Great Depression, until the outbreak (开始) of the Second World War in 1939. This was a period of ______.A. povertyB. important social movementsC. a new social consciousness (意识)D. all of the above“The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough.” This is the shortest poem written by _________.A.T. S. EliotB. Robert FrostC. Ezra PoundD.E. E. CummingsEarly in the 20th century, _______ published works that would change the nature of American poetry.A. Ezra PoundB. T. S. EliotC. Robert FrostD. Both A and BThe imagist writers followed three principles; they respectively are direct treatment, economy of expression and ____________.A. clear rhythmB. blank verseC. free verseD. heroic couplet“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood and sorry I could not travel both…” In the above two lines of Robert Frost’s The Road Not Taken, the poet, by implication, was referring to __________.A. a travel experienceB. a marriage decisionC. a middle-age crisisD. on e’s course of lifeIn Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, he used a technique called ________ in which the whole story was told through the thoughts of one character.A. stream of consciousnessB. imagismC. symbolismD. naturalismYoknapatawpha county is an imagery land invented by _________.A. William FaulknerB. Thomas HardyC. BalzacD. Theodore Dreiser_______ wrote about the society in the South by inventing families which represented different social forces: the old decaying (衰败的) upper class; the rising, ambitious, unscrupulous(厚颜无耻的)class of the “poor Whites”; and the Negroes who labored for both of them.A. FaulknerB. FitzgeraldC. HemmingwayD. Steinbeck1.Who is your favorite American writer? What is his/her masterwork? Why do you likehim/her? ( The writers and the works are not confined to (局限于) those we havementioned in class.) (15 points)2.What is the relationship between wars and American literature? (U.S. has gone throughthe Independence War, the civil war, WWI, WWII, and the anti-terrorist war, you can choose one particular period to analyze or interpret it from a bird’s view.) (15 points)3.What have you leaned from this elective(选修课)this term? And do you have anysuggestions for this class? (10 points)你最喜欢哪一位美国作家?他(她)的代表作品是什么?为什么喜欢?简述美国文学与战争的关系。

美国文学选读及赏析名词解释

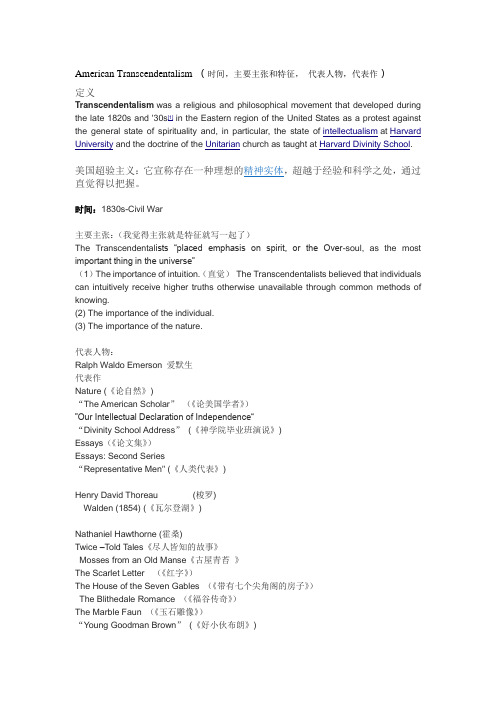

American Transcendentalism (时间,主要主张和特征,代表人物,代表作)定义Transcendentalism was a religious and philosophical movement that developed during the late 1820s and '30s[1] in the Eastern region of the United States as a protest against the general state of spirituality and, in particular, the state of intellectualism at Harvard University and the doctrine of the Unitarian church as taught at Harvard Divinity School.美国超验主义:它宣称存在一种理想的精神实体,超越于经验和科学之处,通过直觉得以把握。

时间:1830s-Civil War主要主张:(我觉得主张就是特征就写一起了)The Transcendental ists “placed emphasis on spirit, or the Over-soul, as the most important thing in the universe”(1)The importance of intuition.(直觉)The Transcendentalists believed that individuals can intuitively receive higher truths otherwise unavailable through common methods of knowing.(2) The importance of the individual.(3) The importance of the nature.代表人物:Ralph Waldo Emerson 爱默生代表作Nature (《论自然》)“The American Scholar”(《论美国学者》)”Our Intellectual Declaration of Independence““Divinity School Address”(《神学院毕业班演说》)Essays(《论文集》)Essays: Second Series“Representative Men" (《人类代表》)Henry David Thoreau (梭罗)Walden (1854) (《瓦尔登湖》)Nathaniel Hawthorne (霍桑)Twice –Told Tales《尽人皆知的故事》Mosses from an Old Manse《古屋青苔》The Scarlet Letter (《红字》)The House of the Seven Gables (《带有七个尖角阁的房子》)The Blithedale Romance (《福谷传奇》)The Marble Faun (《玉石雕像》)“Young Goodman Brown”(《好小伙布朗》)Henry Wadsworth Longfellow亨利.华兹沃斯.朗费罗Voices of the Night (1839) 《夜籁集》-- catch the attentionBallads and Other Poems (1841) 《歌谣及其它》Evangeline (1847) 《伊凡吉林》Hiawatha or The Song of Hiawatha (1855)《海华莎之歌》Imagism (时间,对Image 的定义,主要主张和特征,代表人物,代表作)定义Imagism was poetic movement of England and the united states, flourishing from 1909-1917. Its credo, expressed in some imagist poets, includes the use of precise language, the creation of new rhythms, absolute freedom in choice of subject matter, and the evocation of concrete images.时间:between the years 1909 and 1917特征:(1) “Direct treatment of the 'thing' whet h er subjective or objective;”(2) “To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation;”(3) “As regarding rhythm: to compose in the sequence of musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome(节拍器).”主张:It came into being as a reaction to the traditional English poetry characterized by cloudy verbiage, and aimed instead at a new clarity and exactness in the short lyric poem.代表人物:Ezra Pound“The Cantos”。

专八美国文学~~~

美国文学主要分为四个时期:㈠The Literature Around the Revolution of Independence(独立革命前后的文学)。

一.殖民地时期(The Literature of Colonial American Colonial Period 1607---1775)1、约翰·史密斯(John Smith):早期英国殖民者、探险家,在弗吉尼亚建立了第一个永久英国殖民地。

被誉为美国文学的第一位作家。

(注:Jamestown, Virginia, was the first permanent English settlement in North America on May, 1607.)代表作:《关于弗吉尼亚的真实叙述》(A True Relation of Virginia)是美国文学第一书。

2、纳撒尼尔·沃德(Nathaniel Ward):被誉为“北美讽刺文学第一笔”。

代表作:《北美的阿格瓦姆鞋匠》(The Simple Cobbler of Aggawam in America)。

3、威廉·布拉福德(William Bradford):被誉为“美国历史之父”。

说起美国人的祖先,一般人都会说是“五月花”号(Mayflower)。

威廉·布拉福特(William Bradford)就是“五月花”号上的领导者,《五月花号公约》Mayflower Compact的主要起草人,后来成为普利茅斯殖民地的总督。

现在,美国的第二号节日“感恩节”就是由他提出来的。

代表作:《普利茅斯种植园史》(History of Plymouth Plantation)。

4、安妮·布拉德斯特里特(Anne Bradstreet):殖民地时期的第一位诗人。

代表作:《最近在北美出现的第十位缪斯》(The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America)。

L01-1 The American Scholar

A Reading List for American Literature (II)

Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie 《嘉莉妹妹》(1900) Jack London, Martin Eden 《马丁·伊登》(1909) Willa Cather, My Antonia《我的安东尼娅》(1918) Sherwood Anderson, Winesburg, Ohio 《小镇畸人》(1919) Sinclair Lewis, Main Street《大街》(1920) Eugene O’ Neil, Desire under the Elms 《榆树下的欲望》(1924) William Faulkner, Light in August 《八月之光》(1932) Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind 《乱世佳人》(1936) F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby 《了不起的盖茨比》) John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath 《愤怒的葡萄》(1939) Richard Wright, Native Son《土生子》(1940) Tennessee Williams, The Streetcar Named Desire《欲望号街车》(1947) Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea《老人与海》(1952) J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye 《麦田里的守望者》(1951) Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man 《看不见的人》(1952)

Maxine Hong Kingston, Amy Tan

美国文学论文原创全英文版《美国三部曲》的主题

邯郸学院本科毕业论文题目析《“美国”三部曲》的主题思想—以《赚大钱》为例学生 ***学号20100120021005指导教师 ****教授年级 2010级专业英语(师范类)二级学院外国语学院*******外国语学院2014年5月B.A. ThesisOn the Themes of U. S. A. —A Case Study ofThe Big MoneyByXie WenpingSupervisor: Professor. Sun HongyanA Thesis Submitted to School of Foreign LanguagesOf Handan College in Partial FulfillmentOf the Requirement for the DegreeOf Bachelor of ArtsHandan, ChinaMay, 2014郑重声明本人的毕业论文是在指导教师孙红艳的指导下独立撰写完成的。

如有剽窃、抄袭、造假等违反学术道德、学术规范和侵权的行为,本人愿意承担由此产生的各种后果,直至法律责任,并愿意通过网络接受公众的监督。

特此郑重声明。

毕业论文作者:年月日AcknowledgementsIt is really a laborious task to accomplish this B.A. thesis. A lot of people have offered me friendly support and help in the process of writing the thesis. I would like to express my heart felt gratitude to all the respectable professors who have taught and helped me in my undergraduate study and given me much nourishment and inspiration for further study.Special thanks go to my supervisor, Professor Sun Hongyan. She has been available at all times with helpful advice and a helping hand throughout my whole writing process of the thesis. Her erudition and strictness as supervisors, kindness and consideration and tolerance as friends make my study here more meaningful. She teaches me not merely how to conduct research on literature but also how to be an upright person.I would like to express my heart-felt thanks to my family and my dear friends whose encouragement always helps me to carry on.Many thanks to all!AbstractJohn Dos Passos is a member of the extraordinary literary generation. His novel , U. S. A. Trilogy , which is John Dos Passos’s masterpiece, mirrors the dark side of America and revals the essence of the society, marking a higher level of John Dos Passos’s artistic achievements.This thesis tends to explore the themes of U. S. A. Trilogy from three chapters. Chapter one deliberates the theme—the pursuit of money, which is mainly formed by Charley’s pursuit of money and Moorehouse’s pursuit of money. Chapter two elaborates the theme—the protest against the society from two angles—Savage’s p rotest and Mary’s protest.Chapter three investigates the theme—the compromise on the destiny including Charley’s compromise on career and spirit and Margo’s compromise on dream and life.In conclusion, in U. S. A. Trilogy, employing the unique narrative art, John Dos Passos creates insightful themes—the pursuit of money, the protest against the society and the compromise on the destiny. Themes reflect the distorted effects of capitalism on the American people, which is of great realistic significance in modern society. Consequently, U. S. A. Trilogy enlightens that people should be brave, hard-working and hopeful so as to fabricate a more harmonious society.Key Words: John Dos Passos money protest compromise摘要约翰•多斯•帕索斯,是一位美国杰出的的文学家。

12.The American Scholar

The American ScholarI read with joy of the auspicious signs of the coming days, as they glimmer already through poetry and art, through philosophy and science, through church and state.One of these signs is the fact that the same movement which affected the elevation of what was called the lowest class in the state, assumed in literature a very marked and as benign an aspect. Instead of the sublime and beautiful; the near, the low, the common, was explored and poetized. That which had been negligently trodden under foot by those who were harnessing and provisioning themselves for long journeys into far countries, is suddenly found to be richer than all foreign parts. The literature of the poor, the feelings of the child, the philosophy of the street, the meaning of household life, are the topics of the time. It is a great stride. It is a sign, is it not? of new vigor, when the extremities (foot, hand, limb,) are made active, when currents of warm life run into the hands and feet. I ask not for the great, the remote, the romantic; what is doing in Italy or Arabia; what is Greek art or Provençalminstrelsy (吟游诗艺,ballad); I embrace the common, I explore and sit at the feet of the familiar, the low. Give me insight into to-day, and you may have the antique and future worlds. What would we really know the meaning of? The meal in the firkin, the milk in the pan, the ballad in the street, the news of the boat, the glance of the eye, the form and the gait of the body,—show me the ultimate reason of these matters; show me the sublime presence of the highest spiritual cause lurking, as always it does lurk, in these suburbs and extremities of nature; let me see every trifle bristling with the polarity that ranges it instantly on an eternal law; and the shop, the plough, and the ledger, referred to the like cause by which light undulates and poets sing;—and the world lies no longer a dull miscellany and lumber-room, but has form and order; there is no trifle, there is no puzzle, but one design unites and animates the farthest pinnacle and the lowest trench.This idea has inspired the genius of Goldsmith, Burns, Cowper, and, in a newer time, of Goethe, Wordsworth, and Carlyle. This idea they have differently followed and with various success. Incontrast with their writing, the style of Pope, of Johnson, of Gibbon, looks cold and pedantic. This writing is blood-warm. Man is surprised to find that things near are not less beautiful and wondrous than things remote. The near explains the far. The drop is a small ocean. A man is related to all nature. This perception of the worth of the vulgar is fruitful in discoveries. Goethe, in this very thing the most modern of the moderns, has shown us, as none ever did, the genius of the ancients.There is one man of genius who has done much for this philosophy of life, whose literary value has never yet been rightly estimated; I mean Emanuel Swedenborg. The most imaginative of men, yet writing with the precision of a mathematician, he endeavored to engraft a purely philosophical Ethics on the popular Christianity of his time. Such an attempt, of course, must have difficulty which no genius could surmount. But he saw and showed the connection between nature and the affections of the soul. He pierced the emblematic or spiritual character of the visible, audible, tangible world. Especially did his shade-loving muse hoverover and interpret the lower parts of nature; he showed the mysterious bond that allies moral evil to the foul material forms, and has given in epical parables a theory of insanity, of beasts, of unclean and fearful things.Another sign of our times, also marked by an analogous political movement, is the new importance given to the single person. Everything that tends to insulate the individual—to surround him with barriers of natural respect, so that each man shall feel the world is his and man shall treat with man as a sovereign state with a sovereign state—tends to true union as well as greatness. “I learned,” said the melancholy Pestalozzi, “that no man in God’s wide earth is either willing or able to help any other man.” Help must come from the bosom alone. The scholar is that man who must take up into himself all the ability of the time, all the contributions of the past, all the hopes of the future. He must be a university of knowledges. If there be one lesson more than another which should pierce his ear, it is, The world is nothing, the man is all; in yourself is the law of all nature, and you know not yet how a globule of sapascends; in yourself slumbers the whole of Reason; it is for you to know all, it is for you to dare all. Mr. President and Gentlemen, this confidence in the unsearched might of man belongs, by all motives, by all prophecy, by all preparation, to the American Scholar. We have listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe. The spirit of the American freeman is already suspected to be timid, imitative, tame. Public and private avarice make the air we breathe thick and fat. The scholar is decent, indolent, complaisant. See already the tragic consequence. The mind of this country, taught to aim at low objects, eats upon itself. There is no work for any but the decorous and the complaisant. Young men of the fairest promise, who begin life upon our shores, inflated by the mountain winds, shined upon by all the stars of God, find the earth below not in unison with these, but are hindered from action by the disgust which the principles on which business is managed inspire, and turn drudges or die of disgust—some of them suicides. What is the remedy? They did not yet see, and thousands of young men as hopeful now crowding to the barriers for the career do not yet see, that if the single man planthimself indomitably on his instincts, and there abide, the huge world will come round to him. Patience, patience; with the shades of all the good and great for company; and for solace, the perspective of your own infinite life; and for work, the study and the communication of principles, the making those instincts prevalent, the conversion of the world. Is it not the chief disgrace in the world not to be a unit, not to be reckoned one character, not to yield that peculiar fruit; which each man was created to bear; but to be reckoned in the gross, in the hundred, or the thousand, of the party, the section, to which we belong; and our opinion predicted geographically, as the north, or the south? Not so, brothers and friends,—please God, ours shall not be so. We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds. The study of letters shall be no longer a name for pity, for doubt, and for sensual indulgence. The dread of man and the love of man shall be a wall of defence and a wreath of joy around all. A nation of men will for the first time exist, because each believes himself inspired by the Divine Soul which also inspires all men.我喜悦地读到了那未来日子的吉兆,他们闪烁于诗歌和艺术中,体现在哲学和科学里,表现在教堂和政府里。

The_American_Scholar

The American Scholar,国外论知识和做学问写的最好的文章Emerson:The American Scholar1837年8月31日,爱默生在美国大学生联谊会上以《论美国学者》为题发表演讲,抨击美国社会中灵魂从属于金钱的拜金主义和资本主义的劳动分工使人异化为物的现象,强调人的价值;他提出学者的任务是自由而勇敢地从表相中揭示真实,以鼓舞人、提高人和引导人;他号召发扬民族自尊心,反对一味追随外国学说。

这一演讲轰动一时,对美国民族文化的兴起产生了巨大影响,被誉为是美国“思想上的独立宣言”。

这是Bantom classic 的版本,也可以算国外论知识和做学问写的最好的文章-----------------------------------------------------------------------------Mr. President and Gentlemen,I greet you on the re-commencement of our literary year. Our anniversary is one of hope, and, perhaps, not enough of labor. We do not meet for games of strength or skill, for the recitation of histories, tragedies, and odes, like the ancient Greeks; for parliaments of love and poesy, like the Troubadours; nor for the advancement of science, like our contemporaries in the British and European capitals. Thus far, our holiday has been simply a friendly sign of the survival of the love of letters amongst a people too busy to give to letters any more. As such, it is precious as the sign of an indestructible instinct. Perhaps the time is already come, when it ought to be, and will be, something else; when the sluggard intellect of this continent will look from under its iron lids, and fill the postponed expectation of the world with something better than the exertions of mechanical skill. Our day of dependence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close.The millions, that around us are rushing into life, cannot always be fed on the sere remains of foreign harvests. Events, actions arise, that must be sung, that will sing themselves. Who can doubt, that poetry will revive and lead in a new age, as the star in the constellation Harp, which now flames in our zenith, astronomers announce, shall one day be the pole-star for a thousand years?In this hope, I accept the topic which not only usage, but the nature of our association, seem to prescribe to this day,--the AMERICAN SCHOLAR. Year by year, we come up hither to read one more chapter of his biography. Let us inquire what light new days and events have thrown on his character, and his hopes.It is one of those fables, which, out of an unknown antiquity, convey an unlooked-for wisdom, that the gods, in the beginning, divided Man into men, that he might be more helpful to himself; just as the hand was divided into fingers, the better to answer its end.The old fable covers a doctrine ever new and sublime; that there is One Man,--present to all particular men only partially, or through one faculty; and that you must take the whole society to find the whole man. Man is not a farmer, or a professor, or an engineer, but he is all. Man is priest, and scholar, and statesman, and producer, and soldier. In the divided or social state, these functions are parceled out to individuals, each of whom aims to do his stint of the joint work, whilst each other performs his. The fable implies, that the individual, to possess himself, must sometimes return from his own labor to embrace all the other laborers. But unfortunately, this original unit, this fountain of power, has been so distributed to multitudes, has been so minutely subdivided and peddled out, that it is spilled into drops, and cannot be gathered. The state of society is one in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk, and strut about so many walking monsters,--a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man.Man is thus metamorphosed into a thing, into many things. The planter, who is Man sent out into the field to gather food, is seldom cheered by any idea of the true dignity of his ministry. He sees his bushel and his cart, and nothing beyond, and sinks into the farmer, instead of Man on the farm. The tradesman scarcely ever gives an ideal worth to his work, but is ridden by the routine of his craft, and the soul is subject to dollars. The priest becomes a form; the attorney, a statute-book; the mechanic, a machine; the sailor, a rope of a ship.In this distribution of functions, the scholar is the delegated intellect. In the right state, he is, Man Thinking. In the degenerate state, when the victim of society, he tends to become a mere thinker,or, still worse, the parrot of other men's thinking.In this view of him, as Man Thinking, the theory of his office is contained. Him nature solicits with all her placid, all her monitory pictures; him the past instructs; him the future invites.Is not, indeed, every man a student, and do not all things exist for the student's behoof? And, finally, is not the true scholar the only true master? But the old oracle said, `All things have two handles: beware of the wrong one.' In life, too often, the scholar errs with mankind and forfeits his privilege. Let us see him in his school, and consider him in reference to the main influences he receives.I. The first in time and the first in importance of the influences upon the mind is that of nature. Every day, the sun; and, after sunset, night and her stars. Ever the winds blow; ever the grass grows. Every day, men and women, conversing, beholding and beholden. The scholar is he of all men whom this spectacle most engages. He must settle its value in his mind. What is nature to him? There is never a beginning, there is never an end, to the inexplicable continuity of this web of God, but always circular power returning into itself. Therein it resembles his own spirit, whose beginning, whose ending, he never can find,--so entire, so boundless. Far, too, as her splendors shine, system on system shooting like rays, upward, downward, without centre, without circumference,--in the mass and in the particle, nature hastens to render account of herself to the mind. Classification begins. To the young mind, every thing is individual, stands by itself. By and by, it finds how to join two things, and see in them one nature; then three, then three thousand; and so, tyrannized over by its own unifying instinct, it goes on tying things together, diminishing anomalies, discovering roots running under ground, whereby contrary and remote things cohere, and flower out from one stem. It presently learns, that, since the dawn of history, there has been a constant accumulation and classifying of facts. But what is classification but the perceiving that these objects are not chaotic, and are not foreign, but have a law which is also a law of the human mind? The astronomer discovers that geometry, a pure abstraction of the human mind, is the measure of planetary motion. The chemist finds proportions and intelligible method throughout matter; and science is nothing but the finding of analogy, identity, in the most remoteparts. The ambitious soul sits down before each refractory fact; one after another, reduces all strange constitutions, all new powers, to their class and their law, and goes on for ever to animate the last fibre of organization, the outskirts of nature, by insight.Thus to him, to this school-boy under the bending dome of day, is suggested, that he and it proceed from one root; one is leaf and one is flower; relation, sympathy, stirring in every vein. And what is that Root? Is not that the soul of his soul?--A thought too bold,--a dream too wild. Yet when this spiritual light shall have revealed the law of more earthly natures,--when he has learned to worship the soul, and to see that the natural philosophy that now is, is only the first gropings of its gigantic hand, he shall look forward to an ever expanding knowledge as to a becoming creator. He shall see, that nature is the opposite of the soul, answering to it part for part. One is seal, and one is print. Its beauty is the beauty of his own mind. Its laws are the laws of his own mind. Nature then becomes to him the measure of his attainments. So much of nature as he is ignorant of, so much of his own mind does he not yet possess. And, in fine, the ancient precept, "Know thyself," and the modern precept, "Study nature," become at last one maxim.II. The next great influence into the spirit of the scholar, is, the mind of the Past,--in whatever form, whether of literature, of art, of institutions, that mind is inscribed. Books are the best type of the influence of the past, and perhaps we shall get at the truth,--learn the amount of this influence more conveniently,--by considering their value alone.The theory of books is noble. The scholar of the first age received into him the world around; brooded thereon; gave it the new arrangement of his own mind, and uttered it again. It came into him, life; it went out from him, truth. It came to him, short-lived actions; it went out from him, immortal thoughts. It came to him, business; it went from him, poetry. It was dead fact; now, it is quick thought. It can stand, and it can go. It now endures, it now flies, it now inspires. Precisely in proportion to the depth of mind from which it issued, so high does it soar, so long does it sing.Or, I might say, it depends on how far the process had gone, of transmuting life into truth. In proportion to the completeness of the distillation, so will the purity and imperishableness of theproduct be. But none is quite perfect. As no air-pump can by any means make a perfect vacuum, so neither can any artist entirely exclude the conventional, the local, the perishable from his book, or write a book of pure thought, that shall be as efficient, in all respects, to a remote posterity, as to contemporaries, or rather to the second age. Each age, it is found, must write its own books; or rather, each generation for the next succeeding. The books of an older period will not fit this.Yet hence arises a grave mischief. The sacredness which attaches to the act of creation,--the actof thought,--is transferred to the record. The poet chanting, was felt to be a divine man: henceforth the chant is divine also. The writer was a just and wise spirit: henceforward it is settled, the book is perfect; as love of the hero corrupts into worship of his statue. Instantly, the book becomes noxious: the guide is a tyrant. The sluggish and perverted mind of the multitude, slow to open to the incursions of Reason, having once so opened, having once received this book, stands upon it, and makes an outcry, if it is disparaged. Colleges are built on it. Books are written on it by thinkers, not by Man Thinking; by men of talent, that is, who start wrong, who set out from accepted dogmas, not from their own sight of principles. Meek young men grow up in libraries, believing it their duty to accept the views, which Cicero, which Locke, which Bacon, have given, forgetful that Cicero, Locke, and Bacon were only young men in libraries, when they wrote these books.Hence, instead of Man Thinking, we have the bookworm. Hence, the book-learned class, who value books, as such; not as related to nature and the human constitution, but as making a sort of Third Estate with the world and the soul. Hence, the restorers of readings, the emendators, the bibliomaniacs of all degrees.Books are the best of things, well used; abused, among the worst. What is the right use? What is the one end, which all means go to effect? They are for nothing but to inspire. I had better never see a book, than to be warped by its attraction clean out of my own orbit, and made a satellite instead of a system. The one thing in the world, of value, is the active soul. This every man is entitled to; this every man contains within him, although, in almost all men, obstructed, and as yet unborn. The soul active sees absolute truth; and utters truth, or creates. In this action, it is genius;not the privilege of here and there a favorite, but the sound estate of every man. In its essence, it is progressive. The book, the college, the school of art, the institution of any kind, stop with some past utterance of genius. This is good, say they,--let us hold by this. They pin me down. They look backward and not forward. But genius looks forward: the eyes of man are set in his forehead, not in his hindhead: man hopes: genius creates. Whatever talents may be, if the man create not, the pure efflux of the Deity is not his;--cinders and smoke there may be, but not yet flame. There are creative manners, there are creative actions, and creative words; manners, actions, words, that is, indicative of no custom or authority, but springing spontaneous from the mind's own sense of good and fair.On the other part, instead of being its own seer, let it receive from another mind its truth, though it were in torrents of light, without periods of solitude, inquest, and self-recovery, and a fatal disservice is done. Genius is always sufficiently the enemy of genius by over influence. The literature of every nation bear me witness. The English dramatic poets have Shakspearized nowfor two hundred years.Undoubtedly there is a right way of reading, so it be sternly subordinated. Man Thinking must not be subdued by his instruments. Books are for the scholar's idle times. When he can read God directly, the hour is too precious to be wasted in other men's transcripts of their readings. But when the intervals of darkness come, as come they must,--when the sun is hid, and the stars withdraw their shining, --we repair to the lamps which were kindled by their ray, to guide our steps to the East again, where the dawn is. We hear, that we may speak. The Arabian proverb says, "A fig tree, looking on a fig tree, becometh fruitful."It is remarkable, the character of the pleasure we derive from the best books. They impress us with the conviction, that one nature wrote and the same reads. We read the verses of one of the great English poets, of Chaucer, of Marvell, of Dryden, with the most modern joy,--with a pleasure, I mean, which is in great part caused by the abstraction of all time from their verses. There is some awe mixed with the joy of our surprise, when this poet, who lived in some past world, twoor three hundred years ago, says that which lies close to my own soul, that which I also hadwellnigh thought and said. But for the evidence thence afforded to the philosophical doctrine of the identity of all minds, we should suppose some preestablished harmony, some foresight of souls that were to be, and some preparation of stores for their future wants, like the fact observed in insects, who lay up food before death for the young grub they shall never see.I would not be hurried by any love of system, by any exaggeration of instincts, to underrate the Book. We all know, that, as the human body can be nourished on any food, though it were boiled grass and the broth of shoes, so the human mind can be fed by any knowledge. And great and heroic men have existed, who had almost no other information than by the printed page. I only would say, that it needs a strong head to bear that diet. One must be an inventor to read well. As the proverb says, "He that would bring home the wealth of the Indies, must carry out the wealth of the Indies." There is then creative reading as well as creative writing. When the mind is braced by labor and invention, the page of whatever book we read becomes luminous with manifold allusion. Every sentence is doubly significant, and the sense of our author is as broad as the world. We then see, what is always true, that, as the seer's hour of vision is short and rare among heavy days and months, so is its record, perchance, the least part of his volume. The discerning will read, in his Plato or Shakespeare, only that least part,--only the authentic utterances of the oracle;-- all the rest he rejects, were it never so many times Plato's and Shakespeare's.Of course, there is a portion of reading quite indispensable to a wise man. History and exact science he must learn by laborious reading. Colleges, in like manner, have their indispensable office,--to teach elements. But they can only highly serve us, when they aim not to drill, but to create; when they gather from far every ray of various genius to their hospitable halls, and, by the concentrated fires, set the hearts of their youth on flame. Thought and knowledge are natures in which apparatus and pretension avail nothing. Gowns, and pecuniary foundations, though of towns of gold, can never countervail the least sentence or syllable of wit. Forget this, and our American colleges will recede in their public importance, whilst they grow richer every year.III. There goes in the world a notion, that the scholar should be a recluse, a valetudinarian,--as unfit for any handiwork or public labor, as a penknife for an axe. The so-called 'practical men'sneer at speculative men, as if, because they speculate or see, they could do nothing. I have heard it said that the clergy,--who are always, more universally than any other class, the scholars of their day,--are addressed as women; that the rough, spontaneous conversation of men they do not hear, but only a mincing and diluted speech. They are often virtually disfranchised; and, indeed, there are advocates for their celibacy. As far as this is true of the studious classes, it is not just and wise. Action is with the scholar subordinate, but it is essential. Without it, he is not yet man. Without it, thought can never ripen into truth. Whilst the world hangs before the eye as a cloud of beauty, we cannot even see its beauty. Inaction is cowardice, but there can be no scholar without the heroic mind. The preamble of thought, the transition through which it passes from the unconscious to the conscious, is action. Only so much do I know, as I have lived. Instantly we know whose words are loaded with life, and whose not.The world,--this shadow of the soul, or other me, lies wide around. Its attractions are the keys which unlock my thoughts and make me acquainted with myself. I run eagerly into this resounding tumult. I grasp the hands of those next me, and take my place in the ring to suffer and to work, taught by an instinct, that so shall the dumb abyss be vocal with speech. I pierce its order; I dissipate its fear; I dispose of it within the circuit of my expanding life. So much only of life as I know by experience, so much of the wilderness have I vanquished and planted, or so far have I extended my being, my dominion. I do not see how any man can afford, for the sake of his nerves and his nap, to spare any action in which he can partake. It is pearls and rubies to his discourse. Drudgery, calamity, exasperation, want, are instructors in eloquence and wisdom. The true scholar grudges every opportunity of action past by, as a loss of power.It is the raw material out of which the intellect moulds her splendid products. A strange process too, this, by which experience is converted into thought, as a mulberry leaf is converted into satin. The manufacture goes forward at all hours.The actions and events of our childhood and youth, are now matters of calmest observation. They lie like fair pictures in the air. Not so with our recent actions,--with the business which we now have in hand. On this we are quite unable to speculate. Our affections as yet circulate through it.We no more feel or know it, than we feel the feet, or the hand, or the brain of our body. The new deed is yet a part of life,--remains for a time immersed in our unconscious life. In some contemplative hour, it detaches itself from the life like a ripe fruit, to become a thought of the mind. Instantly, it is raised, transfigured; the corruptible has put on incorruption. Henceforth it is an object of beauty, however base its origin and neighborhood. Observe, too, the impossibility of antedating this act. In its grub state, it cannot fly, it cannot shine, it is a dull grub. But suddenly, without observation, the selfsame thing unfurls beautiful wings, and is an angel of wisdom.So is there no fact, no event, in our private history, which shall not, sooner or later, lose its adhesive, inert form, and astonish us by soaring from our body into the empyrean. Cradle and infancy, school and playground, the fear of boys, and dogs, and ferules, the love of little maids and berries, and many another fact that once filled the whole sky, are gone already; friend and relative profession and party, town and country, nation and world, must also soar and sing.Of course, he who has put forth his total strength in fit actions, has the richest return of wisdom. I will not shut myself out of this globe of action, and transplant an oak into a flower-pot, there to hunger and pine; nor trust the revenue of some single faculty, and exhaust one vein of thought, much like those Savoyards, who, getting their livelihood by carving shepherds, shepherdesses, and smoking Dutchmen, for all Europe, went out one day to the mountain to find stock, and discovered that they had whittled up the last of their pine-trees. Authors we have, in numbers, who have written out their vein, and who, moved by a commendable prudence, sail for Greece or Palestine, follow the trapper into the prairie, or ramble round Algiers, to replenish their merchantable stock. If it were only for a vocabulary, the scholar would be covetous of action. Life is our dictionary. Years are well spent in country labors; in town,--in the insight into trades and manufactures; in frank intercourse with many men and women; in science; in art; to the one end of mastering in all their facts a language by which to illustrate and embody our perceptions. I learn immediately from any speaker how much he has already lived, through the poverty or the splendor of his speech. Life lies behind us as the quarry from whence we get tiles and copestones for the masonry of to-day. This is the way to learn grammar. Colleges and books only copy the language which the field and the work-yard made.But the final value of action, like that of books, and better than books, is, that it is a resource. That great principle of Undulation in nature, that shows itself in the inspiring and expiring of the breath; in desire and satiety; in the ebb and flow of the sea; in day and night; in heat and cold; and as yet more deeply ingrained in every atom and every fluid, is known to us under the name of Polarity,--these "fits of easy transmission and reflection," as Newton called them, are the law of nature because they are the law of spirit.The mind now thinks; now acts; and each fit reproduces the other. When the artist has exhausted his materials, when the fancy no longer paints, when thoughts are no longer apprehended, and books are a weariness,--he has always the resource to live. Character is higher than intellect. Thinking is the function. Living is the functionary. The stream retreats to its source. A great soul will be strong to live, as well as strong to think. Does he lack organ or medium to impart his truths? He can still fall back on this elemental force of living them. This is a total act. Thinking is a partial act. Let the grandeur of justice shine in his affairs. Let the beauty of affection cheer his lowly roof. Those 'far from fame,' who dwell and act with him, will feel the force of his constitution in the doings and passages of the day better than it can be measured by any public and designed display. Time shall teach him, that the scholar loses no hour which the man lives. Herein he unfolds the sacred germ of his instinct, screened from influence. What is lost in seemliness is gained in strength. Not out of those, on whom systems of education have exhausted their culture, comesthe helpful giant to destroy the old or to build the new, but out of unhandselled savage nature,out of terrible Druids and Berserkirs, come at last Alfred and Shakespeare.I hear therefore with joy whatever is beginning to be said of the dignity and necessity of labor to every citizen. There is virtue yet in the hoe and the spade, for learned as well as for unlearned hands. And labor is everywhere welcome; always we are invited to work; only be this limitation observed, that a man shall not for the sake of wider activity sacrifice any opinion to the popular judgments and modes of action.I have now spoken of the education of the scholar by nature, by books, and by action. It remainsto say somewhat of his duties. They are such as become Man Thinking. They may all be comprised in self-trust. The office of the scholar is to cheer, to raise, and to guide men by showing them facts amidst appearances. He plies the slow, unhonored, and unpaid task of observation. Flamsteed and Herschel, in their glazed observatories, may catalogue the stars with the praise of all men, and, the results being splendid and useful, honor is sure. But he, in his private observatory, cataloguing obscure and nebulous stars of the human mind, which as yet no man has thought of as such, --watching days and months, sometimes, for a few facts; correcting still his old records;--must relinquish display and immediate fame. In the long period of his preparation, he must betray often an ignorance and shiftlessness in popular arts, incurring the disdain of the able who shoulder him aside. Long he must stammer in his speech; often forego the living for the dead. Worse yet, he must accept,--how often! poverty and solitude. For the ease and pleasure of treading the old road, accepting the fashions, the education, the religion of society, he takes the cross of making his own, and, of course, the self-accusation, the faint heart, the frequent uncertainty and loss of time, which are the nettles and tangling vines in the way of the self-relying and self-directed; and the state of virtual hostility in which he seems to stand to society, and especially to educated society. For all this loss and scorn, what offset? He is to find consolation in exercising the highest functions of human nature. He is one, who raises himself from private considerations, and breathes and lives on public and illustrious thoughts. He is the world's eye.He is the world's heart. He is to resist the vulgar prosperity that retrogrades ever to barbarism, by preserving and communicating heroic sentiments, noble biographies, melodious verse, and the conclusions of history. Whatsoever oracles the human heart, in all emergencies, in all solemn hours, has uttered as its commentary on the world of actions,--these he shall receive and impart. And whatsoever new verdict Reason from her inviolable seat pronounces on the passing men and events of to-day,--this he shall hear and promulgate.These being his functions, it becomes him to feel all confidence in himself, and to defer never to the popular cry. He and he only knows the world. The world of any moment is the merest appearance. Some great decorum, some fetish of a government, some ephemeral trade, or war, or man, is cried up by half mankind and cried down by the other half, as if all depended on thisparticular up or down. The odds are that the whole question is not worth the poorest thought which the scholar has lost in listening to the controversy. Let him not quit his belief that a popgun is a popgun, though the ancient and honorable of the earth affirm it to be the crack of doom. In silence, in steadiness, in severe abstraction, let him hold by himself; add observation to observation, patient of neglect, patient of reproach; and bide his own time,--happy enough, if he can satisfy himself alone, that this day he has seen something truly. Success treads on every right step. For the instinct is sure, that prompts him to tell his brother what he thinks. He then learns, that in going down into the secrets of his own mind, he has descended into the secrets of all minds. He learns that he who has mastered any law in his private thoughts, is master to that extent of all men whose language he speaks, and of all into whose language his own can be translated. The poet, in utter solitude remembering his spontaneous thoughts and recording them, is found to have recorded that, which men in crowded cities find true for them also. The orator distrusts at first the fitness of his frank confessions, --his want of knowledge of the persons he addresses,--until he finds that he is the complement of his hearers;--that they drink his words because he fulfill for them their own nature; the deeper he dives into his privatest, secretest presentiment, to his wonder he finds, this is the most acceptable, most public, and universally true. The people delight in it; the better part of every man feels, This is my music; this is myself.In self-trust, all the virtues are comprehended. Free should the scholar be,--free and brave. Free even to the definition of freedom, "without any hindrance that does not arise out of his own constitution." Brave; for fear is a thing, which a scholar by his very function puts behind him. Fear always springs from ignorance. It is a shame to him if his tranquility, amid dangerous times, arise from the presumption, that, like children and women, his is a protected class; or if he seek a temporary peace by the diversion of his thoughts from politics or vexed questions, hiding his head like an ostrich in the flowering bushes, peeping into microscopes, and turning rhymes, as a boy whistles to keep his courage up. So is the danger a danger still; so is the fear worse. Manlike let him turn and face it. Let him look into its eye and search its nature, inspect its origin,--see the whelping of this lion,--which lies no great way back; he will then find in himself a perfect comprehension of its nature and extent; he will have made his hands meet on the other side, and can henceforth defy it, and pass on superior. The world is his, who can see through its pretension.。

泛读The_American_Character翻译

要是让国外来客描述美国人的性格,结果常常令美国人感到奇怪。

一个人说:“所有的美国人都是清教徒;所以他们与众不同。

”另一个人说:“他们总是想方设法让自己开心。

”一位尊贵的客人告诉我们:“他们花在工作上的时间太多。

他们不懂如何玩乐。

”另一个人反驳说:“他们不懂什么是工作。

因为机器替他们做了一切。

”“美国女人是不知廉耻的,妖艳而危险的女人。

”--“不,她们假正经。

”“这里的孩子真好--外向,自然。

”----“象小小的野兽一样自然。

他们没礼貌,不尊敬长辈。

”当然,世上既没有单一模式的美国人性格,也没有单一的英国人性格或土耳其人性格或是中国人性格。

个性的定义在美国变得更为复杂,因为我们有不同的种族和文化背景,因为来自世界各地连续不断的移民浪潮,因为我们区域的多样性。

个性的定义变得复杂,因为几百种不同的宗教信仰及其对各自的信奉者的影响不同。

个性的定义也由于每个人所处的年代不同而趋多样化--第一代是移民,第二代是移民的孩子,一直照此延续下去。

强大的吸引力把众多的美国人聚集在了一起。

然而那些想再了解深入一点的人弄不懂美国人生活中各种似乎自相矛盾的东西。

的确,美国人总体上工作努力。

但他们也拼命地玩。

他们去旅游、露营、打猎、看体育比赛、喝酒、抽烟、看电影电视、读报纸杂志,花的时间和金钱比世界任何地方的人都多。

而他们还把更多的时间花在教会、社会服务、医院和各种各样的慈善活动上。

他们总是忙来忙去,又总是花更多的时间休闲。

他们十分在乎个人的权利,又习惯于墨守陈规。

他们崇拜大人物,也把小人物理想化,不论他是和大商人形成对照的小商人,还是和大权在握的人形成对照的平民百姓。

Success as a Goal 成功作为目标包括美国人在内几乎每一个人都会赞同的一点是,美国人极为看重成功。

成功不一定是物质上的回报,而是得到某种认可,最好是可以衡量的那种。

如果一个男孩后来没有从商,而是做了布道的教士,那也没什么。

但是他的教堂规模越大,教堂会众越多,别人就认为他越成功。

The American Scholar 整体版

His father passed away when he was 8 (in1811) and he was left to support his four other brothers. Despite the hardships, all the Emerson boys, except one, graduated from Harvard University

+ Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a novel, The

Blithedale Romance (1852), satirizing the movement, and based it on his experiences at Brook Farm, a short-lived utopian community founded on transcendental principles . + Edgar Allan Poe had a deep dislike for transcendentalism, calling its followers "Frogpondians" after the pond on Boston Common. He ridiculed their writings in particular by calling them "metaphor-run," lapsing into "obscurity for obscurity's sake" or "mysticism for mysticism's sake

Emerson went on to become a famous lecturer sharing his transcendental philosophy throughout the country. Upset in the 1860s by the coming of the Civil War, he lived a quiet life with his family. His house was burnt to the ground in 1872. He died quietly of pneumonia on April 27th, 1882.

读赫钦斯的《美国高等教育》有感

读赫钦斯的《美国高等教育》有感作者:苏美娜来源:《中国证券期货》2013年第09期【摘要】西方自由教育的主要倡导者赫钦斯在其著作《美国高等教育》中记录了其对美国高等教育的担忧和冀望,此书中的许多观点很有见解性,本文作者读过该书后就自己看法谈谈对理智与经验,课程开设,理想学院模式的构建的看法,以期参考。

【关键词】高等教育;理智;课程;三种学院赫钦斯的《美国高等教育》具有批判性的分析了美国高等教育存在的两难困境——专业主义、孤立主义、反理智主义,并从普通教育和高等教育的角度阐述了走出困境的相应对策,例如:学习经典名著的方法和意义;大学应当注重思辨思维的培养;研究性研究所机构独立于高校;三种学院理念——形而上学、社会科学学院、自然科学学院;理智的训练和发展等等。

我国高等教育发展到现在阶段,同样面临着美国在书中那个年代出现的类似的两难困境,深刻分析文中批判性的观点及对策,对于改变我国高等教育现状具有重要启示。

从中世纪开始,高等教育追求自由的呼声从未停止。

学术自由、高校自治、教授治校、去行政化政治化,这些名词历历在目,并出现在各种学术论文中,可见学者对于大学自由的关注程度。

大学的主要职能是什么,上大学是为了追求真理还是为未来生活做准备,大学课程的开设,教师如何引导学生学习……种种反思,醍醐灌顶。

从赫钦斯的观点中更是读到大学对于人的理智培养的首要性、大学中课程开设的重要性以及三级学院模式的可行性。

亚里斯多德在《政治学》中说:“现在,对于人而言,理性和心智是大自然为之奋斗的目标。

因此,应该从公民的角度出发进行公民的培养和道德训练。

”理性和心智,即为理智。

高校要培养社会人,首先应培养使其成为一个理智的人。

拥有批判思维和理性心智的人才是自由的,思想在无任何羁绊的状态下能够促成创新果实的萌芽和成长。

一、理智与经验相对于理智,现代社会人更看重经验。

经验是由一系列历史数据资料来体现的,虽然会束缚思辨的广度和效度,但是一定程度上说明或者证实了一些有用原则的真理性,可见其工具性的作用。

TEM8美国文学串讲及试卷评析(下)

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) 埃米莉•迪金森

代表作品:Poems by Emily Dickinson (1890) — collection This is My Letter to the World I Heard a Fly Buzz When I Died

英语专业八级考试在线课堂

Philip Freneau (1752-1832)菲利普•弗伦诺

作品:The Rising Glory of America (1772) The Wild Honey Suckle (1786) – one of his best lyrics (抒情诗)

英语专业八级考试在线课堂

三、American Romanticism 美国浪漫主义文学(十八世纪末—十九世纪中后期)

英语专业八级考试在线课堂

四、Literature of Realism 美国现实主义文学 (十九世纪中期—二十世纪初)

美国现实主义文学三个组成部分:

Realism 现实主义 Local Color Fiction 地方色彩小说

Naturalism 自然主义

作家作品

D. Ernest

例:The novel For Whom the Bell Tolls is written by ____. A. Scott Fitzgerald B. William Faulkner C. Eugene O’Neil Hemingway

文学评论

例:____ is defined as an expression of human emotion which is condensed into fourteen lines. A. Free Verse B. Sonnet C. Ode D. Epigram (以上例题均为2006年英语专八人文知识真题。答案分别为:A,D, B。)

美国文学常识

美国文学常识美国文学常识1.乔纳森。

爱德华兹:(Jonathan Edwards)主要作品:自述(Personal Narrative).意志的自由(Freedom of the Will).原罪说辩(The Doctrine of Original Sin Defended)和神灵的形影(Images or Shadows of Divine Things)真正的美德(the Nature of True Virtue)他是北美殖民地时期最富创见的神学家。

爱德华兹的思想是清教传统中虔诚精神一面的代表。

是19世纪新英格兰超验主义的先驱。

即:one of the most important figures in Puritan tradition.Influenced by the new ideas of Enlightenment, such as empiricism.First modern American and the country’s last medieval man.孤独(solitude)禁欲(asceticism)2.本杰明。

富兰克林:(Benjamin Franklin)重点:十三戒条。

主要作品:富兰克林自传(The Autobiography)A famous statesman. (the only American who once signed all the four documents that created the new country).An example who made American Dream come true.He was the first great self-man in American.独立宣言(Declaration of Independence)3.菲利普。

福瑞诺:(Philip Freneau)主要作品:(野金银花the Wild Honey Suckle)美国诗歌之父(Father of American poetry)获得美国革命诗人的光荣称号(英国囚船The British Prisonship)民族之声(National Gazette)4.华盛顿。

美国文学期末复习笔记 (1)

美国文学笔记III. The Romantic period (浪漫主义时期): (1800-1865)American Transcendentalism(美国超验主义)(1830s- Civil War)Summit of Romanticism/ American Renaissance1. Appearance1836, ―Nature‖ by Emerson2. Features of Transcendentalism(1). Spirit(思想)/Oversoul(超灵)(2). importance of individualism(3). nature – symbol of spirit/God;garment of the oversoul(4). focus in intuition (irrationalism and subconsciousness)IV. The American Realism 现实主义时期(1865-1918)1. Three Giants in Realistic PeriodWilliam Dean Howells –―Dean of American Realism‖Henry JamesMark Twain2. Comparison:Theme:Howells –middle classJames –upper classTwain –lower classTechnique:Howells –smiling/genteel realismJames –psychological realismTwain –local colourism and colloquialismMark Twain (1835-1910):1. Summary:American writer, short story writer/Humorist2. Major works:The Celebrated jumping Frog of Calaveras County (1865)《卡拉维拉县弛名的跳蛙》Innocents Abroad (1869) 《傻子国外旅行记》The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) 《汤姆.索亚历险记》Life on the Mississippi (1883) 《密西西比河上》The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1886)《哈克贝里.费恩历险记》: All modern American literature comes from his masterpiece ―The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.‖——Ernest Hemingway3. Style:(1). colloquial language(口语), vernacular (本土的)language, dialects(2). local colour(3). syntactic feature: sentences are simple, brief, and sometimes ungrammatical(4). humour(5). tall tales (highly exaggerated) (荒诞不经的故事)(6). social criticism (satire on the different ugly things in society)4. ContributionOne of Mark Twain’s significant contributions to American literature lies in the fact that he made colloquial speech an accepted, respectable literary medium in the literary history of the country.Henry James (1843-1916)1. Summary:An American and British novelist, literary criticFounder of psychological realismFirst of the modern psychological novelistInitiator of the international theme: American innocence in face of European sophistication2. Major works:Daisy Miller (1878)《戴茜·米勒》The Portrait of a Lady (1881) 《贵妇的肖像》The Wings of the Dove (1902)《鸽翼》The Ambassadors (1903)《专使》The Golden Bowl (1904)《金碗》The Art of Fiction(1884)《小说的艺术》3. His Point of view(1). Psychological analysis, forefather of stream of consciousness(2).Psychological realism(3). Highly-refined language4. Style –“stylist”(1). Language: highly-refined, polished, insightful, and accurate(2).V ocabulary: large(3). Construction: complicated, intricateNaturalism(自然主义)1. Background:(1). Dar win’s theory: ―natural selection‖(2).Spenser’s idea: ―social Darwinism‖(3). French Naturalism: Zora2. Features(1). environment and heredity(2). scientific accuracy and a lot of details(3). general tone: ironic and pessimistic, hopelessness, despair, gloom, ugly side of the societySt ephen Crane (1881-1900)1. Summary:Novelist, poetPioneer in the naturalistic traditionPrecursors(先驱)of Imagist poetry2. Major Works:Maggie: A Girl of the Streets 《街头女郎麦姬》: the first naturalistic novel in AmericaThe Red Badge of Courage 《红色英勇勋章》The Open Boat《海上扁舟》V. AMERICAN MODERNISM (1918-1945)(美国现代主义)F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940)1. Summary:Famous American novelist, short story writer, and essayistthe representative of the 1920sthe spokesman for the Jazz Ageone of the“lost generation”writers2. Major WorksThis Side of Paradise (1920) 《人间天堂》Tales of the Jazz Age (1922) 《爵士乐时代的故事》Tender Is the Night (1934) 《夜色温柔》The Great Gatsby (1925) 《了不起的盖茨比》:Narrative point of view – Nick CarrawayTheme: The decline of the American Dream3. His Point of view(1). He expressed what the young people believed in the 1920s, the so-called ―American Dream‖ is false innature.(2). He had always been critical of the rich and tried to show the integrating effects of money on theemotional make-up of his character. He found that wealth altered people’s characters, making them mean and distrusted. He thinks money brought only tragedy and remorse.(3). His novels follow a pattern: dream – lack of attraction – failure and despair.4. His ideas of “American Dream”It is false to most young people. Only those who were dishonest could become rich.William Faulkner (1897-1962)1. Sumary:An American novelist and poetInitiator of American Southern RenaissanceOne of the most influential modern novelists of 20th centuryNobel Prize winner for literature in 19492. Major Works:The Sound and the Fury 《喧哗与骚动》As I Lay Dying 《在我弥留之际》Light in August 《八月之光》Absalom, Absalom 《押沙龙,押沙龙!》Go Down, Moses 《去吧,摩西》Barn Burning 《烧牲口棚》Yoknapatawpha County(约克纳帕塔法县):--- A fictional county in northern Mississippi, the setting for most of William Faulkner’s novels and short stories, and patterned upon Faulkner’s actual home in Lafayette County, Mississippi.3. Major Themes of his Works(1). history and race(2). Deterioration(3). Conflicts between generations, classes, races, man and environment(4). Horror, violence and the abnormal4. Faulkner's narrative technique(1).Withdrawal of the author as a controlling narrator(2). Dislocation of the narrative time: The most characteristic way of structuring his stories is to fragment thechronological time.(3). the modern stream-of-consciousness(意识流)technique and the interior monologue(内心独白):(4). Multiple points of view(多重视角)(5). symbolism and mythological and biblical(圣经的)allusionsErnest Hemingway (1899—1961)1. Summary:Novelist and short-story writerOne of the great American writers of the 20th centuryThe Spokesman of the ―Lost Generation‖Nobel Prize winner for literature in 19542. Major worksThe Sun Also Rises 《太阳照常升起》A Farewell to Arms《永别了,武器》For Whom the Bell Tolls 《丧钟为谁而鸣》/ 《战地钟声》The Old Man and the Sea 《老人与海》A Clean, Well-lighted Place 《一个干净,明亮的地方》3. Major Themes(1).The ―Nada‖(虚无) Concept(2).Grace under pressure(压力下的优雅)―Man is not made for defeats. A man can be destroyed but not defeated.‖------The Old Man and the Sea(3). Code Hero(准则英雄/ 硬汉)a. The Hemingway hero is not a thinker; he is a man of action.b.―Grace under pressure is their motto.c.The Hemingway code heroes are best remembered for their indestructible(不可毁灭的)spirit.4. Artistic features(1) .The iceberg(冰山)techniqueThe dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.(2). Language stylea. simple and naturalb.direct, clear and freshc. lean and economicald.simple, conversational, common found, fundamental wordse. simple sentencesf. Iceberg principle: understatement, implied thingsg.SymbolismEzra Pound (1885—1972)1. Summary:A leading spokesman of the ―Imagist Movement‖(意象主义运动)One of the most influential American poets and critic2. Major works:Cathay:《华夏集》《神州集》《中国诗章》Hugh Selwyn Mauberley《休·赛尔温·毛伯利》Cantos /《诗章》3. Imagism (1909-1917)(1) .Background:Imagism was influenced by French symbolism, ancient Chinese poetry and Japaneseliterature ―haiku‖(2). Defintion : The imagists, with Ezra Pound leading the way, hold that the most effective means to expressthe these momentary impressions is through the use of one dominant image.(3): Manifesto of Imagism:•Direct treatment•Economy of expression•New rhythmIn a station of the Metro《在一个地铁站》: a quintessential(典型的)imagist textRobert Frost(1847-1963)1. Summary:the most popular American poetWon Pulitzer Prize four timesReceived honorary degrees from forty-four colleges and universitiesRead ― The Gift Outright‖ at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy in 19612. Famous Poems:F ire and Ice《火与冰》The Road Not Taken 《未选择的路》Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening 《雪夜伫立林边有感》Mending Wall《补墙》After Apple-Picking《摘罢苹果》3. Frost’s writing featureHis combination of the traditional verse pattern and a colloquial distinctive language (New England Speech)Eugene O’Neil (1888-1953)1. Summary:America's greatest playwrightWon the Pulitzer Prize four timesWon Nobel Prize in 1936Founder of the American drama2. Major WorksBeyond the Horizon (1920) 《天边外》The Emperor Jones(1920) 《琼斯皇帝》The Hairy Ape (1922)《毛猿》Desire under the Elms (1924) 《榆树下的欲望》美国文学笔记整理完整版18世纪末-19世纪中后浪漫主义时期Romanticism1. 早期浪漫主义华盛顿·欧文美国文学之父father of American Literature(为美国文学第一次赢得世界声誉)Washington Irving 以笔记小说和历史传厅闻名,humor1783-1859 The Sketch Book见闻札记(标志浪漫主义开始)A History of New York纽约史---美国人写的第一部诙谐文学杰作;----The Legend of Sleepy Hollow睡谷的传说---成为美国第1个获国际声誉作家-----Rip Van Winkle里普·万·温克尔(李伯大梦)The Alhambra阿尔罕伯拉2.超验主义New England Transcendentalism埃德加·爱伦·坡侦探小说之父Father of western detective stories and psychoanalytic criticism精神批Edgar Allan Poe 评,首开近代侦探小说先河,又是法国象征主义运动的源头1809-1849 Novelist小说家, poet, critic批评家good at writing Gothic(哥特式)and detective fictionPoetryThe Raven《乌鸦》To Helen《献给海伦》Short storiesHorror ( suspense, terror, Insanity, death,Revenge and rebirth)The Fall of the House of Usher《厄舍古屋的倒塌》The Masque of the Red Death 《红色死亡的化妆舞会》The Black Cat《黑猫》The Cask of Amontillado《一桶白葡萄酒》Ligeia《丽姬娅》Detective /ratiocinative(推理的)(originator)The Purloined Letter 《窃信案》The Muder in the Rue Morgue 《莫格街谋杀案》The Mystery of Marie Rog《玛丽.罗热疑案》The Gold Bug 《金甲虫》拉尔夫·沃尔多·爱默生Nature论自然-----新英格兰超验主义者的宣言书manifestoRalf Waldo Emerson The American Scholar论美国学者;American essayist,lecturer, poetThe Founder of Transcendentalism1803-1882 Self-reliance论自立The Transcendentalist超验主义者Representative Men代表人物School Address神学院演说Days日子-首开自由诗之先河free verseRalph Waldo Emerson was an American philosopher, essayist, and poet, best remembered for leading the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism个人主义.纳撒尼尔·霍桑subject: human soul first great American writer of fiction 虚构Nathaniel Hawthorne 象征主义大师American novelist and short story writer1804-1864 The Scarlet Letter红字Twice-told Tales尽人皆知的故事Mosses from an Old Manse古屋青苔The House of the Seven Gables有七个尖角阁的房子The Marble Faun玉石雕像The Blithedale Romance福谷传奇Young Goodman Brown年轻的布朗The Birthmark胎记His point of view : Hawthorne is influenced by Puritanism(清教主义)deeply.(1). Evil is at the core of human life 邪恶是人类生活的中心(2).whenever there is sin 罪恶, there is punishment 惩罚. Sin or evil can be passed from generation to generation 代代相传(3). Evil educates. 邪恶的教育(4). He has disgust in science科学. One source of evil is overweening (自负的) (too proud of oneself) intellect . His intellectual characters聪明的特征are villains反派角色, dreadful可怕的and cold-blooded冷血的赫尔曼·迈尔维尔擅长航海奇遇和异域风情Herman Melville Moby Dick/The White Whale白鲸(first American prose epic史诗)1819-1891 Main characters: Ishmael(以实玛利): the narrator 叙述者Ahab(埃哈伯): the protagonist 主要人物Moby DickTypee泰比Omoo奥穆Mardi玛地White Jacket白外衣Pierre皮尔埃; Billy Budd比利·巴德沃尔特·惠特曼Father of free verse自由诗之父Walt Whitman Leaves of Grass草叶集(the birth of truly American poetry and the1819-1892 end of romanticism)共和圣经Democratic Bible 美国史诗American EpicAmerican poet, essayist散文家, journalist新闻工作者, and humanist人道主义学家The father of free verse(自由诗)Song of Myself自我之歌Democratic Vistas 民主的前景One’s Self I Sing 《我歌唱一个人的自己》O Captain! My Captain! 《噢,我的船长!我的船长!》3.Writing themes (almost everything):equality of things and beings 平等的事情和人divinity 神学of everythingImmanence(无所不在)of GodDemocracy 民主evolution of cosmos(宇宙的演化)multiplicity 多样性of natureself-reliant spirit 自力更生的精神death, beauty of deathexpansion of America 美国的扩张brotherhood 手足情谊and social solidarity(社会团结)(unity of nations in the world世界统一的国家) pursuit 追求of love and happiness4.S tyle: “free verse(自由诗): the verse that does not follow a fixed metrical pattern固定的韵律模式, the verse without a fixed beat 固定的节拍or regular rhyme scheme规律的格律.(1).Parallelism(排比)(2).phonetic recurrence(同字起句法)(the repetition重复of words or phrases at the beginning of the line, inthe middle or at the end)(3).the use of a certain pronoun ―I‖ (the first person narrator)(4).strong tendency to use oral English使用英语口语的强烈倾向(5).the habit of using snapshots 生活小照(6).a looser and more open-ended syntactic structure语法结构(7).use of conventional image 传统的想象(8).vocabulary – powerful, colourful, rarely used words of foreign origins, some even wrong(9). sentences – catalogue目录technique: long list of names, long poem lines5. Significance of Leaves of GrassLeaves of Gras s, either in content or in form, is an epoch-making work in American literature:无论是在内容还是在形式上,是一个划时代的作品在美国文学→Its democratic content marked the shift from Romanticism to Realism. 其民主内容标志着从浪漫主义到现实主义的转变→Its free-verse form broke from old poetic conventions to open a new way for American poetry.其生发的形式从旧的诗意的约定了打开新的思路对美国诗歌。

美国文学选读期末名词解释

美国文学选读期末名词解释1.American Romanticism(美国浪漫主义)①Romanticism refers to an artistic and intellectual movement originating in Europe in the late 18th century and characterized by a heightened interest in nature, emphasis on the individual’s expression of emotion and imagination, departure from the attitudes and forms of classicism, and rebellion against established social rules and conventions.②The romantic period in American literature stret ches from the end of the 18th century through the outbreak of the Civil war.③Irving, Whitman and Thoreau are the representatives.Background(1)Political background and economic development(2)Romantic movement in European countriesDerivative – foreign influencefeatures(1)American romanticism was in essence the expression of ―a real newexperience and contained ―an alien quality‖ for the simple reason that ―thespirit of the place‖ was radically new and alien.(2)There is American Puritanism as a cultural heritage to consider. Americanromantic authors tended more to moralize. Many American romanticwritings intended to edify more than they entertained.(3)The ―newness‖ of Americans as a nation is in connection with AmericanRomanticism.(4)As a logical result of the foreign and native factors at work, Americanromanticism was both imitative and independent.浪漫主义两大主题:爱和大自然的力量The social and cultural background of Romanticism:---The young Republic was flourishing into a politically, economically and culturally independent country.---The Romantic writings revealed unique characteristics of their own in their works and they grew on the native lands.---The desire for an escape from society and a return to nature became a permanent convention of American literature.---The American Puritanism as a cultural heritage exerted great influences over American moral values.Romantics frequently shared certain general characteristics: moral enthusiasm, faith in value of individualism and intuitive perception, and a presumption that the natural world wa s a source of goodness and man’s societies as a source of corruption.2. Transcendentalism (超验主义、先验主义) : It was a group of new ideas in literature, religion, culture and philosophy that emerged in New England in the middle 19th century. It began as a protest against the general state of culture and society. Among transcendentalist’s core beliefs was an ideal spiritual state that “transcends”the physical and empirical(以观察或实验为依据的) and is only realized through the individua l’s intuition, rather than through the doctrines of established religions. Prominent transcendentalists included Ralph Waldo Emerson(爱默生), Henry David Thoreau(梭罗), Walt Whitman(惠特曼), etc. It is a kind of philosophy that stresses belief in transcendental things and the importanceof spiritual rather than material existence. (相信超凡的事物,认为精神存在比物质存在更重要).American Transcendentalism(美国超验主义)①Transcendentalism is the summit of the Romantic Movement in the history of American literature in the 19th century, which flourished from about 1835 to 1860.②Transcendentalists place emphasis on the importance of the Oversoul, the individual and nature. Specifically, they stressed intuitive understanding of God, without the help of the church, and advocated independence of the mind.③The most important representatives are Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.Ralph Waldo Emerson①Ralph Waldo Emerson was an American essayist, philosopher and poet, best remembered for leading the Transcendentalist movement of the mid 19th century.②He expressed the philosophy of Transcendentalism in his 1836 essay, Nature.③Besides, his The American Scholar was considered to be American’s ―Intellectual Declaration of Independence‖.Oversoul①It is an all-pervading power for goodness from which all things come of which all things are a part.②It is a key doctrine for Transcendentalists.Self-reliance①Self-reliance is an essay written by American Transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson.②It contains the most solid statement of one of his repeating themes, the need for each individual to avoid conformity and false consistency, and follow his or her own instincts and ideas.③These ideas are considered a reaction to a commercial identify. Emerson calls for a return to individual identity.Individualism(个人主义)①Individualism is a moral, political, and social philosophy, which emphasizes individual liberty, the primary importance of the individual, and the “virtues of self-reliance”.②It is thus directly opposed to collectivism, social psychology and sociology, which consider the individual’s rapport to the society or communit y.③It is often confused with ―egoism‖, but an individualist need not be an egoist. Walden①It is one of the American classics written by Henry David Thoreau.②It records his experiment in living at Walden pond, his sympathetic understanding of nature, his meditation on the meanings of life and his social criticism.③Compared with Emerson’s Nature, it is more radical and social-minded.3.Free verse (自由体诗歌)①Free ver se is a general term referring to the modern form of verse with no fixed foot, rhythm or rime schemes.②It was first written and labeled by a group of French poets of the late 19th century.③Free verse has been characteristic of the work of many American poets, includingWalt Whitman, Ezra Pound and Carl Sandburg.“The Song of Myself”①It is the best known poem in Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman.②It is a celebration of the individual as well as the commonpeople.4.American Realism(美国现实主义)①The period rang ing from 1865 to 1914 has been preferred to as the age of Realism.②It was a literary doctrine that called for ―reality and truth‖ in the depiction of ordinary life. It is, in literature, an approach that attempts to describe life without idealization or romantic subjectivity.③Three dominant figures are William Dean Howells, Mark Twain and Henry James. Local Colorism/ Regionalism (地方特色主义)①Local Colorism is popular in the late 19th century, particularly among authors in the south of the U.S.②This style re lied heavily on using words, phrases, and slang that were native to the particular region in which the story took place. The term has come to mean any device which implies a specific focus, whether it is geographical or temporal.③A well-know local colorism author was Mark Twain with his book The Adventure of Huckleberry Finn.5.Jazz Age(爵士乐时代)①The Jazz Age refers to the 1920s, a time marked by hedonism and excitement in the life of flaming youth.②With the rise of the Great Depression, materially rich, spiritually lost, the generation felt frustrated with life and indulged in pleasure.③Perhaps the most representative literary work of the age is American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, highlighting what some describe as the decadence and hedonism, as well as the growth of individualism.6.Yoknapatawpha(约克纳帕塔法)①Most of Faulkner’s literary works were set in the small county of American South. It is the fictional modification of his hometown, Oxford, Mississippi.②To Faulkner, this small piece of land was worth a life’s work in literary writing and here Faulkner created a world of imagination.③Yoknapatawpha has become an allegory of the Old South, with which Faulkner has managed successfully to show a panorama of the experience of the whole Southern society.7.Southern Renaissance(南方文艺复兴)①It is the revival of American Southern literature that began in the 1920s until the 1950s.②The writers affirmed their position on the superiority of the Southern lifestyle over that of the industrialized north.③William Faulkner and Katherine Anne Porter are writers of this type.Avant-garde (先锋派)①It is a French military and political term for the vanguard of an army or political movement.②This term extended since the late 19th century in literature, which refers to the innovative writer who is ahead of the time both in themes and style.③In the 20th century American literature, writers like Faulkner and e.e.cummings can be called avant-garde writers.8 Imagism:it’s a poetic movement of England and the U.S f lourished from 1909 to 1917. The movement insists on the creation of images in poetry by ―the direct treatment of the thing‖ and the economy of wording. The leaders of this mov ement were Ezra Pound and Amy Lowell艾米?洛威尔.Imagism:It came into being in Britain and U.S around 1910 as a reaction to the traditional English poetry to express the sense of fragmentation and dislocation. The imagists, with Ezra Pound leading the way, hold that the most effective means to express these momentary impressions is through the use of one dominant image. Imagism is characterized by the following three poetic principles: direct treatment of subject matter; economy of expression; as regards rhythm, to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of metronome节拍器. Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro”is a well-known imagist poem.Imagism (意象派)①Imagism was a poetic school at the beginning of the 20th century.②Imagist poets strived for a simple, clear and vivid image, which in itself is the expression of art and meaning. The imagist poetry is a kind of free verse shaking of conventional metres and emphasizing the use of common speech and new rhythms.③This movement was led by Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot.Imagery (意象)①Imagery means words and phrases that create pictures ,or images in the readers’mind.②In a literary text, it occurs when an author uses an object that is not really there, in order to create a comparison between one that is, usually evoking a more meaningful visual experience for the reader.③It is useful as it allows an author to add depth and understanding to his work, like a sculptor adding layer and layer to his statue, building it up into a beautiful work of art.9.Black humor:To deal with tragic things in comic ways to make it more powerful and more tragic.It refers to the use of morbid病态的and absurd荒谬的for darkly comic purpose. It carries the tone of anger, bitterness in the grotesque situation of suffering, anxiety, and death. It makes the reader laugh at the blackness of modern life. The writers usually do not laugh at the characters.代表人物:Thomas Pynchon + Joseph HelleJoseph Heller:Catch-22 第22条军规It is not only a war novel, but also a novel about people’s life in peaceful time. This novel attacked the dehumanization of all contemporary institutions and corruptions of individuals who gain power in institutions. Armed-forces are the most outrageous example of the two evils.It is a combination of humor with resentment(怨恨), gloom, anger, and despair. Seeing all that is unreasonable, hypocritical, ugly, and even frenzied(狂乱的),writers of black humor nurse a grievance(不平) against their society which, according to them, is full of institutionalized(制度化的) absurdity. Yet they are cynical. They laugh a morbid(病态的) laugh when facing the hideous(丑恶的). In hopeless indignation(愤慨)they take up freezing irony and burning satire as their weapons. Their novels are often in the form of anti-novel(反传统小说), devoid of(缺乏) completeness of plot and characterized by fragmentation(零碎的)and dislocation(混乱).10.The Lost Generation(迷失的一代)①It is a term first used by Gertrude Stein to describe the post-World I generation of American writers: men and women haunted by a sense of betrayal and emptiness brought about bythe destructiveness of the war.②Full of youthful ideali sm, these individuals sought the meaning of life, drank excessively, had love affairs and created some of the finest American literature to date.③The three best-known representatives of Lost Generation are F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos.Beat Generation/ The Beat Writers (垮掉的一代)①It refers to a loosely-knit group of poets and novelists, writing in the second-half of the 1950s and early 1960s.②They shared a set of social attitudes—anti-established, anti-political, anti-intellectual, opposed to the prevailing cultural, literary, and moral values, and were in favor of unfettered self-realization and self-expression.③Representatives of the group were Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs. And the most famous literary cr eations produced by this group should be Allen Ginsberg’s long poem Howl(嚎叫) and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road(在路上).。

评析 the American Scholar