医学英文文献学习

医学英文文献 (1)

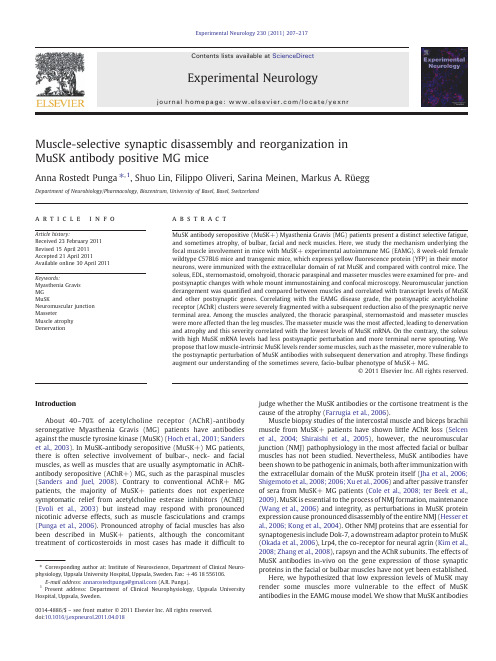

Muscle-selective synaptic disassembly and reorganization in MuSK antibody positive MG miceAnna Rostedt Punga ⁎,1,Shuo Lin,Filippo Oliveri,Sarina Meinen,Markus A.RüeggDepartment of Neurobiology/Pharmacology,Biozentrum,University of Basel,Basel,Switzerlanda b s t r a c ta r t i c l e i n f o Article history:Received 23February 2011Revised 15April 2011Accepted 21April 2011Available online 30April 2011Keywords:Myasthenia Gravis MG MuSKNeuromuscular junction MasseterMuscle atrophy DenervationMuSK antibody seropositive (MuSK+)Myasthenia Gravis (MG)patients present a distinct selective fatigue,and sometimes atrophy,of bulbar,facial and neck muscles.Here,we study the mechanism underlying the focal muscle involvement in mice with MuSK+experimental autoimmune MG (EAMG).8week-old female wildtype C57BL6mice and transgenic mice,which express yellow fluorescence protein (YFP)in their motor neurons,were immunized with the extracellular domain of rat MuSK and compared with control mice.The soleus,EDL,sternomastoid,omohyoid,thoracic paraspinal and masseter muscles were examined for pre-and postsynaptic changes with whole mount immunostaining and confocal microscopy.Neuromuscular junction derangement was quanti fied and compared between muscles and correlated with transcript levels of MuSK and other postsynaptic genes.Correlating with the EAMG disease grade,the postsynaptic acetylcholine receptor (AChR)clusters were severely fragmented with a subsequent reduction also of the presynaptic nerve terminal area.Among the muscles analyzed,the thoracic paraspinal,sternomastoid and masseter muscles were more affected than the leg muscles.The masseter muscle was the most affected,leading to denervation and atrophy and this severity correlated with the lowest levels of MuSK mRNA.On the contrary,the soleus with high MuSK mRNA levels had less postsynaptic perturbation and more terminal nerve sprouting.We propose that low muscle-intrinsic MuSK levels render some muscles,such as the masseter,more vulnerable to the postsynaptic perturbation of MuSK antibodies with subsequent denervation and atrophy.These findings augment our understanding of the sometimes severe,facio-bulbar phenotype of MuSK+MG.©2011Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.IntroductionAbout 40–70%of acetylcholine receptor (AChR)-antibody seronegative Myasthenia Gravis (MG)patients have antibodies against the muscle tyrosine kinase (MuSK)(Hoch et al.,2001;Sanders et al.,2003).In MuSK-antibody seropositive (MuSK+)MG patients,there is often selective involvement of bulbar-,neck-and facial muscles,as well as muscles that are usually asymptomatic in AChR-antibody seropositive (AChR+)MG,such as the paraspinal muscles (Sanders and Juel,2008).Contrary to conventional AChR+MG patients,the majority of MuSK+patients does not experience symptomatic relief from acetylcholine esterase inhibitors (AChEI)(Evoli et al.,2003)but instead may respond with pronounced nicotinic adverse effects,such as muscle fasciculations and cramps (Punga et al.,2006).Pronounced atrophy of facial muscles has also been described in MuSK+patients,although the concomitant treatment of corticosteroids in most cases has made it dif ficult tojudge whether the MuSK antibodies or the cortisone treatment is the cause of the atrophy (Farrugia et al.,2006).Muscle biopsy studies of the intercostal muscle and biceps brachii muscle from MuSK+patients have shown little AChR loss (Selcen et al.,2004;Shiraishi et al.,2005),however,the neuromuscular junction (NMJ)pathophysiology in the most affected facial or bulbar muscles has not been studied.Nevertheless,MuSK antibodies have been shown to be pathogenic in animals,both after immunization with the extracellular domain of the MuSK protein itself (Jha et al.,2006;Shigemoto et al.,2008;2006;Xu et al.,2006)and after passive transfer of sera from MuSK+MG patients (Cole et al.,2008;ter Beek et al.,2009).MuSK is essential to the process of NMJ formation,maintenance (Wang et al.,2006)and integrity,as perturbations in MuSK protein expression cause pronounced disassembly of the entire NMJ (Hesser et al.,2006;Kong et al.,2004).Other NMJ proteins that are essential for synaptogenesis include Dok-7,a downstream adaptor protein to MuSK (Okada et al.,2006),Lrp4,the co-receptor for neural agrin (Kim et al.,2008;Zhang et al.,2008),rapsyn and the AChR subunits.The effects of MuSK antibodies in-vivo on the gene expression of those synaptic proteins in the facial or bulbar muscles have not yet been established.Here,we hypothesized that low expression levels of MuSK may render some muscles more vulnerable to the effect of MuSK antibodies in the EAMG mouse model.We show that MuSK antibodiesExperimental Neurology 230(2011)207–217⁎Corresponding author at:Institute of Neuroscience,Department of Clinical Neuro-physiology,Uppsala University Hospital,Uppsala,Sweden.Fax:+4618556106.E-mail address:annarostedtpunga@ (A.R.Punga).1Present address:Department of Clinical Neurophysiology,Uppsala University Hospital,Uppsala,Sweden.0014-4886/$–see front matter ©2011Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.04.018Contents lists available at ScienceDirectExperimental Neurologyj o u r n a l h o me p a g e :w w w.e l s e v i e r.c om /l o c a t e /y e x n rinduce severe fragmentation of the postsynaptic AChR clusters in particular in the masseter and thoracic paraspinal muscles,with less fragmentation in the limb muscles.The severe postsynaptic pertur-bation results in subsequent denervation of musclefibers,not previously described in EAMG or MG.We propose that one underlying mechanism for the severe involvement of the facial masseter muscle, with severely impaired NMJ architecture,atrophy and denervation,is its low intrinsic levels of MuSK.Moreover,muscles respond to the partial denervation caused by MuSK antibodies in two different ways: (1)terminal nerve sprouting in muscles with high intrinsic levels of MuSK(i.e.soleus,sternomastoid)and(2)no nerve sprouting in muscles with low intrinsic MuSK levels(i.e.masseter,omohyoid).MethodsProduction of recombinant rat MuSKpCEP-PU vector containing the His-tagged extracellular domain of recombinant rat MuSK(aa21-491;(Jones et al.,1999))was transfected(Lipofectamine2000;Invitrogen)into HEK293EBNA cells.The overexpressed protein was purified from the cell superna-tant over a Ni-NTA superflow column(Qiagen)and was subsequently dialyzed against PBS.Protein concentration was determined at OD 280nm and purity was ensured by SDS-PAGE.Experimental animalsC57BL6mice and mice expressing yellowfluorescence protein (YFP)in their motor neurons under Thy-1promoter(Feng et al., 2000)were originally supplied from Jackson Laboratories(Bar Harbor, Maine,US).For immunization,8week-old female mice were used.All mice were housed in the Animal Facility of Biozentrum,University of Basel,where they had free access to food and water in a room with controlled temperature and a12hour alternating light–dark cycle.All animal procedures complied with Swiss animal experimental regu-lations(ethical application approval no.2352)and EC Directive 86/609/EEC.ImmunizationThe immunization procedure has been described previously(Jha et al.,2006).Briefly,eleven C57BL6and seven Thy1-YFP female mice aged8weeks were anesthetized(Ketamine:111mg/kg and Xylazine: 22mg/kg)and immunized with10μg of MuSK emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant(CFA,Difco laboratories,Detroit,Michigan,US) subcutaneously in the hind foot pads,at the base of the tail and dorsolateral on the back.At day28post-injection,immunization was repeated.A3rd immunization was given to mice that did not show any myasthenic weakness after56days.Control mice(8female mice) were immunized with PBS/CFA.Clinical and neurophysiological examinationMuscle weakness was graded every week,as described(Nakayashiki et al.,2000).Briefly,mice were exercised by20consecutive paw grips on a grid and were then placed on an upside-down grid.The time they could hold on to the grid reflected the grade of fatigue and muscle weakness.EAMG grades were as follows:grade0,no weakness;grade1, mild muscle fatigue after exercise;grade2,moderate muscle fatigue; and grade3,severe generalized weakness.Evaluation of the response to AChEIs was performed by i.p.injection of a mix of neostigmine bromide (0.0375mg/kg)and atropine sulfate(0.015mg/kg)in mice with EAMG grades2and3(Berman and Patrick,1980).Repetitive stimulation of the sciatic nerve and recording from the gastrocnemius muscle with monopolar needle electrodes was performed under anesthesia,in mice with EAMG grades2(n=2)and3(n=2),using a Saphire1L EMG machine(Medelec).Decrement was calculated as percent amplitude change between the1st and4th compound motor action potentials evoked by a train of10impulses where10%was considered as pathological.ELISASera were obtained from tail vein blood on day0(preimmune sera)and day35post-immunization.ELISA plates(Nunc MaxiSorp, Fisher Thermo Scientific,Rockford,IL,US)were coated with250ng/ ml of His-labeled rat MuSK(50μl/well),blocked with3%BSA/PBS and then incubated with a sera dilution row(1:3000–1:2,000,000).Pre-immune sera constituted negative and rabbit-anti-MuSK antibody (Scotton et al.,2006)positive controls.After washing,plates were incubated with secondary HRPO-conjugated goat-anti-mouse (1:2000)and goat anti-rabbit antibodies(1:2000;both from Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories,Westgrove,PA,US).HRPO activation by a TMB substrate was terminated with1N HCl after5min. Absorbance was read at450nm.Non-specific binding,determined by incubation of plates with pre-immune serum,was subtracted.The data were displayed as“half maximum MuSK immunoreactivity”,which represents the immunore-activity at a dilution of1:27,000,where the majority of sera obtained50% of maximum absorbance(in the linear range of the absorption at450nm).Western blotWestern blot of masseter muscles was conducted as described (Bentzinger et al.,2008).10μg of protein was resolved on a4–12%Nu-PAGE Bis–Tris gel(Invitrogen,Eugene,OR,US),transferred to nitrocellulose membrane,probed with rat monoclonal anti-NCAM (CD56;1:100;GeneTex)and rabbit polyclonal anti-pan-actin(1:1000; cell signaling)and then recognized with HRPO-conjugated antibodies (1:5000;Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories,Westgrove,PA,US). Quantitative RT-PCR analysisMouse muscle RNA was extracted and purified as previously described(Punga et al.,2011).RT-PCR reactions(triplicates)were carried out with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix reagent(Applied Biosystems,Warrington,UK).β-actin was used as endogenous control (Punga et al.,2011;Murphy et al.,2003;Yuzbasioglu et al.,2010).The following primer sets were used:MuSK:5′-GCCTTCAGCGGGACTGAG-3′and5′-GAGGCGTGGTGA-CAGG-3′Lrp4:5′-GGATGGCTGTACGCTGCCTA-3′and5′-TTGCCGTTGTCA-CAGTGGA-3′Dok-7:5′-CTCGGCAGTTACAGGAGGTTG-3′and5′-GCAATGC-CACTGTCAGAGGA-3′A C h Rα1:5′-G C C A T T A A C C C G G A A AG T G A C-3′a n d5′-CCCCGCTCTCCATGAAGTT-3′AChRε:5′-CTGTGAACTTTGCTGAG-3′and5′-GGAGATCAG-GAACTTGGTTG-3′AChRγsubunit:5′-AACGAGACTCGGATGTGGTC-3′and5′-GTCGCACCACTGCATCTCTA-3′Rapsyn:5′-AGGTTGGCAATAAGCTGAGCC-3′and5′-TGCTCTCACT-CAGGCAATGC-3′MuRF-1:5′-ACC TGC TGG TGG AAA ACA-3′and5′-AGG AGC AAG TAG GCA CCT CA-3′β-actin:5′-CAGCTTCTTTGCAGCTCCTT-3′and5′-GCAGCGA-TATCGTCATCCA-3′A C h E:5′-G G G C T C C T A C T T T C T G G T T T A C G-3′a n d5′-GGGCCCGGCTGATGAG-3′208 A.R.Punga et al./Experimental Neurology230(2011)207–217NMJ whole mount analysisAlexa Fluor555-conjugatedα-bungarotoxin(1μg/ml;Invitrogen) was injected into soleus,EDL,sternomastoid,omohyoid,masseter and the thoracic paraspinal muscles as described(Bezakova and Lomo, 2001).At least12images of each muscle per mouse(6MuSK-immunized YFP-transgenic mice and4CFA-immunized control mice) were collected with a confocal laser-scanning microscope(Leica TCS SPE).Laser gain and intensity were equal for all images.Quantification of pre-and postsynaptic area was performed in ImageJ(http://imagej. /ij/index.html).NMJs containing terminal nerve sprouts(processes with YFP expression)were counted in muscles fromfive MuSK+EAMG mice with disease grades1–3.At least275NMJs per muscle were analyzed. The number of postsynapse fragments per NMJ was counted using a fluorescence microscope(Leica DM5000B)in at least50NMJs per muscle deriving fromfive MuSK+EAMG grades1–2and from four control mice(Supplemental Fig.1).Fragmentation was classified as follows:1)normal pretzel-like NMJ;2)slight to moderate fragmen-tation;and3)severe fragmentation or absent postsynapse.The degree of postsynaptic perturbation per muscle was judged based on the percentage of NMJs belonging to each postsynaptic class and was further subdivided into number of postsynapse fragments per NMJ:1–3,4–6,7–9,10–12and more than12.Each NMJ was given the median score for that subgroup.The fragmentation score was obtained by taking the ratio of the score between the EAMG mice and control mice.Statistical analysisIndependent,2-sample t-test was performed for parametric data. For ordinal data(ELISA),the non-parametric test Spearman Rank Correlation was applied.A p-value b0.05was considered significant.Fig.1.(A)Development of EAMG after immunization with recombinant rat MuSK.Progress of clinical EAMG grade at the time points week4,5,7and10.*The mice with EAMG grade 3were sacrificed after week7(hence no new grade3mice week10)and the remaining mice were sacrificed andfinally evaluated at week10.(B)One mouse,representative of the most severely affected MuSK+EAMG mice,withflaccid paralysis and pronounced kyphosis.(C)Repetitive nerve stimulation performed in the same mouse.Stimulation of the sciatic nerve and recording of the gastrocnemius muscle demonstrated a35%decrement between the1st and4th compound motor action potentials at low frequency3Hz stimulation.(D)Correlation of clinical EAMG grade with MuSK antibody titer.Half of maximum MuSK immunoreactivity(1:27,000dilution)in sera from MuSK immunized mice was assessed by Elisa at450nm.R=0.483(Spearman's Rank Correlation);p b0.05.209A.R.Punga et al./Experimental Neurology230(2011)207–217ResultsMuSK+EAMG presents with prominent kyphosis,paralysis and weight lossOut of the18mice immunized with MuSK,thefinal EAMG grade 0was seen in3mice(17%),grade1in8mice(44%),grade2in4mice (22%)and grade3in3mice(17%)(Fig.1A).No difference in disease incidence was found between the groups of C57BL6mice and the YFP-transgenic mice.Based on this,the data were pooled in the current study.The most severe phenotype of EAMG(grade3)includedflaccid paralysis,pronounced kyphosis and weight loss(Fig.1B).In-vivo nerve stimulation at3Hz with recording from the gastrocnemius muscle revealed a decrement of10–40%in the MuSK+EAMG mice (Fig.1C),whereas the control mice had normal neuromuscular transmission(data not shown).MuSK immunoreactivity in sera(day 35)correlated with clinical severity(Fig.1D;Spearman Rank Correlation;R=0.483;p b0.05),although some mice developed measurable MuSK antibodies without showing obvious muscle weakness or fatigue.Bulbar symptoms underlying weight loss in MuSK+EAMG The MuSK immunized mice steadily decreased significantly in body weight after the2nd immunization(Fig.2A),in contrast to the control mice,and thefinal body weight of the MuSK+mice was significantly smaller(p b0.001;Fig.2B).This severe weight loss was slowed but not stopped after introduction of wet food(data not shown).Since the timeline of the weight drop also correlated with development of muscle fatigue,the weight loss was assumed to be indicative of chewing and swallowing difficulties,some of the cardinal symptoms of MuSK+MG.To determine whether loss of muscle weight significantly contributed to the overall lower body weight in the MuSK+EAMG mice,the weight offive different muscles was assessed.The masseter was the only muscle with a significant weight reduction(p b0.01;Fig.2C),implying that this muscle is atrophic and further indicating chewing difficulties.Adverse effects of AChEIs in MuSK+EAMGTo elucidate whether AChEIs have any beneficial effect on fatigue or weakness in MuSK+EAMG,a neostigmine test was performed in the mice with EAMG grade3(n=3).No apparent improvement in weakness at rest or exercise-induced fatigue was seen;instead the mice experienced shivering and constant twitching of the tail,trunk and limbs starting after approximately13min(Supplemental Video1).This effect wore off after40min and was interpreted as nicotinic side effects and neuromuscular hyperactivity,usually seen after an overdose of AChEIs.Thus,this intolerance towards AChEIs in MuSK+EAMG indicates an abnormal sensitivity to acetylcholine.Impairment of NMJs in different musclesBecause muscle groups in the bulbar/facial/back region are selectively involved in the MuSK+EAMG model,we next examined the morphological changes of NMJs in the thoracic paraspinal muscles, masseter,omohyoid and sternomastoid and compared them with those in two limb muscles(EDL and soleus).Typical features of postsynaptic impairment were a fainting of AChRfluorescence,areas lacking AChRs(holes)and disassembly of AChR clusters.To quantify these impairments,we classified NMJs into three classes as illustrated in Fig.3A.All muscles from MuSK+EAMG mice displayeddifferentFig.2.Weight loss in MuSK+EAMG.(A)The course of weight loss in two MuSK+mice with EAMG grade3compared to control(Ctrl CFA)mice(n=8).Initial body weight was comparable and weight loss started after the2nd immunization and weight kept dropping even though wet food was provided ad libitum.(B)Mean body weight was dramatically reduced in the MuSK immunized mice(MuSK+;n=18),compared to the control mice.Results shown as mean±SEM(gram);***p b0.001.(C)Muscles were weighed and compared between control mice(n=8)and MuSK+EAMG mice(n=18).Results displayed as mean muscle weight±SEM(mg).The only muscle which was significantly lighter in the MuSK+mice was the masseter.**p b0.01.210 A.R.Punga et al./Experimental Neurology230(2011)207–217degrees of NMJ impairment (Fig.3B).Moreover,we also observed that the postsynapses were often fragmented into two to three non-continuous fragments (see illustration in Fig.3A),which is in strong contrast to non-interrupted,pretzel-like shape of AChRs in non-immunized mice.This fragmentation was also quanti fied (Supplemental Fig.1)and expressed as “fragmentation score ”.Because fragmentation differs between muscles,this “fragmentation score ”was normalized to the control.As shown in Fig.3C,the fragmentation score varied between a minimum of 2.0in the soleus muscle and a maximum of 3.3in the masseter muscle.The postsynaptic labeling was markedly reduced in the MuSK+EAMG mice compared to control mice (Fig.4A).In the mild to moderately affected mice,AChR cluster area was reduced signi ficantly by 40–50%in all muscles (p b 0.01),except for the soleus,which had a remaining area of 85%(p b 0.05;Fig.4B).In the most severely affected mice,the postsynaptic area was also lost in the soleus muscle and less than 10%of the α-bungarotoxin staining remained in the masseter,sternomastoid and thoracic paraspinal muscles (p b 0.001).In the soleus,the nerve terminal area was unchanged in the severely affected mice,although in the other muscles the presynaptic area was reduced to about 80%in the mild to moderate cases and to 50%in the most severely affected mice (p b 0.01)(Fig.4C).Thus,both the pre-and postsynaptic data suggest that the masseter is the most affected muscle by MuSK antibodies whereas the soleus is the least affected.mRNA transcript expression of NMJ proteins in different muscles in MuSK+EAMGThe mRNA levels of MuSK differ signi ficantly between muscles,with the highest levels in the soleus muscle and lowest levels in the omohyoid muscle (Punga et al.,2011).Consequently,we additionally analyzed MuSK transcript levels in the masseter and these were even lower,with less than 20%of the mRNA levels detected in the soleus muscle (Supplemental Fig.2;p b 0.01).In the MuSK+EAMG mice,MuSK mRNA levels were signi ficantly reduced to 45%of control in the EDL (p b 0.05)and to 25%in the omohyoid muscle (p b 0.001;Fig.5A).Conversely,MuSK mRNA expression was signi ficantly increased in the masseter muscle (p b 0.01)and remained unchanged in the soleus and sternomastoid muscles.The expression of the AChR αsubunit was unchanged (Fig.5B),whereas the AChR εsubunit transcript was downregulated in the soleus and sternomastoid muscles and conversely a trend towards upregulation was seen in the masseter muscle (Fig.5C).The fetal AChR γsubunit mRNA was upregulated up to 1000-fold in the masseter (p b 0.001)and 5-fold in the soleus (p b 0.05;Fig.5D).The transcript levels of rapsyn,Lrp4and Dok-7were not signi ficantly altered (Fig.5E to G).Finally,the transcript levels of acetylcholine esterase (AChE)were signi ficantly down-regulated only in the sternomastoid and omohyoid muscles (p b 0.05;Fig.5H).Fig.3.Postsynaptic fragmentation of NMJs.(A)Examples from each postsynaptic classi fication.AChRs stained for alfa-bungarotoxin.(B)At least 275neuromuscular junctions (NMJs)per muscle were assessed in a total of 5MuSK+EAMG mice with moderate to severe disease.The appearance of NMJ postsynapses were divided into 3classes as indicated.Sol:soleus;EDL:extensor digitorum longus;STM:sternomastoid muscle;omo:omohyoid;mass:masseter.(C)Postsynapses were analyzed in at least 50NMJs per muscle in a total of 5MuSK+EAMG mice with slight to moderate disease grade and in 4control mice.Each NMJ in a certain subclass (for details see Supplemental Fig.1)was given the median score for that subclass.The fragmentation score for each muscle is the ratio in score between the EAMG mice and control mice.211A.R.Punga et al./Experimental Neurology 230(2011)207–217In summary,particularly the massive upregulation of MuSK transcripts and AChR γin conjunction with the overall trend for upregulation of mRNA for the other postsynaptic genes in the masseter muscle most likely re flects the severely disturbed neuro-muscular transmission in this muscle as a result of the MuSK antibodyattack.Fig.4.Pronounced reduction of postsynaptic and presynaptic area in different muscles in MuSK+EAMG.(A)Whole mount staining of single fiber layer bundles from the paraspinal muscle (ps),sternomastoid (STM),masseter (mass),omohyoid (omo),extensor digitorum longus (EDL)and soleus (sol)muscles from one control mouse immunized with CFA/PBS and one mouse with severe MuSK+EAMG.AChRs are visualized by alexa-555-bungarotoxin (red)and the motor nerve terminals by YFP expression (green).The AChRs are almost completely gone from the paraspinal muscles,STM and masseter.Confocal images of 100×magni fication,scale bar is 10μm.Quanti fication of (B)postsynapse (AChR clusters)and (C)presynaptic area in the different muscles;soleus (sol),extensor digitorum longus (EDL),omohyoid (omo),masseter (mass),sternomastoid (STM)and paraspinal muscles (ps).Results are given as %of ctrl area±SEM and at least 12NMJs in each muscle/mouse was measured in mice with EAMG grades 1–2(N =4),in mice with severe grade 3(N =2)and in control mice (N =4).**p b 0.01;#p b 0.001.212 A.R.Punga et al./Experimental Neurology 230(2011)207–217Denervation induced muscle atrophy in MuSK+EAMGThe masseter muscle lost weight and consequently we examined the mRNA levels of the atrophy marker muscle-speci fic RING finger protein 1(MuRF-1)and assessed signs of denervation.For this analysis we included the same muscles as previously examined,with the addition of thoracic paraspinal muscles due to the pronounced kyphosis of the MuSK+EAMG mice.MuRF-1mRNA levels were signi ficantly upregulated in the masseter muscle (p b 0.05;Fig.6A)and on the contrary MuRF-1transcript levels were strongly reduced in the soleus muscle (p b 0.01)in the MuSK+EAMG mice.Further,the protein levels of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM),a marker for denervation,were increased in the masseter muscle as detected by Western blot analysis.This is thus additional evidence of denervation in this particular muscle (Fig.6B).Absence of nerve sprouting may contribute to the severe denervation phenotypePresynaptic nerve terminals were visualized by transgenic YFP expression,allowing observation also of NMJs with absent post-synapses.In the masseter,the nerve terminals were still present although many postsynaptic AChRs were partially or completely lost.Intriguingly,no or little nerve sprouting was observed in these cases (Fig.7).This finding raised the possibility that postsynaptic perturbation in this muscle did not elicit any nerve sprouting response.To test this hypothesis,we examined ≥450NMJs in each of the muscles for such sprouting response.The quantitative examination of 4MuSK+EAMG mice revealed terminal nerve sprouting in approximately 20%of NMJs in the soleus and in 15%of endplates in the sternomastoid (Fig.7).On the contrary,theFig.5.mRNA levels of postsynaptic proteins in MuSK+EAMG.C:control mice immunized with CFA/PBS.MG:EAMG mice immunized with MuSK.mRNA levels in the control mice are set to 100%and levels in the EAMG mice are relative to the control levels.n=6control mice;n=6MuSK+EAMG mice.Genes of interest are relative to the house keeping gene β-actin.*p b 0.05;***p b 0.001.213A.R.Punga et al./Experimental Neurology 230(2011)207–217omohyoid,EDL,thoracic paraspinal muscles and masseter,showed terminal sprouting at only a few NMJs.In most samples no sprouting was observed,which differed signi ficantly from the soleus (p b 0.001)and the sternomastoid muscle (p b 0.05).Interestingly,the degree of nerve sprouting in each muscle correlates with their endogenous levels of MuSK,suggesting that MuSK levels regulate the nerve sprouting response and consequently reorganization of NMJs (Punga et al.,2011).DiscussionMuSK+MG patients often present with focal weakness of facial,bulbar,neck and respiratory muscles and sometimes also of paraspinal and upper esophageal muscles (Sanders and Juel,2008).The pathopysiological role of MuSK antibodies has been questioned based on the normal levels of MuSK and AChRs at the NMJ in cross-sections of the intercostal muscle and biceps brachii muscle of MuSK+MG patients (Selcen et al.,2004;Shiraishi et al.,2005).Further studies in mice have now shown that MuSK antibodies deplete MuSK from the NMJ,which results in disassembly of the postsynaptic apparatus and a reduced packing of AChRs (Jha et al.,2006;Shigemoto et al.,2006;Cole et al.,2010).Nevertheless,the exact mechanism of how MuSK antibodies affect muscles has so far not been revealed.Here we report that MuSK antibodies cause a severe pre-and postsynaptic disassembly in the facial,bulbar and paraspinal muscles but only a slight disruption in the limb muscles (i.e.soleus and EDL).The most affected muscle was the masseter and intriguingly this muscle expressed less than 20%of MuSK transcripts than the least affected soleus muscle.Considering that fast-twitch muscle fibers require larger depolarization to initiate contraction compared to slow-twitch fibers,we propose that the superfast twitch pattern of the masseter in combination with its critically low MuSK levels makes this muscle extra vulnerable to the synaptic perturbation following the MuSK antibody attack (Laszewski and Ruff,1985).Hence,over-expression of MuSK in vulnerable muscles could potentially alleviate the effects of the antibody-mediated attack against MuSK.Earlier studies of AChR+EAMG rats have been shown to respond to rapsyn-overexpression in the tibialis anterior muscle with no loss of AChRs and almost normal postsynaptic folds,whereas the NMJs of untreated muscles showed typical AChR loss and morphological damage (Losen et al.,2005).Nevertheless,we did not find any changes in rapsyn mRNA levels across the examined muscles.Additionally,our findings underline the importance of examining the clinically affected muscles in MuSK+MG in order to draw the right conclusions regarding NMJ morphology.In the MuSK+EAMG model,the mice exhibited obvious bulbar and thoracospinal muscle weakness,similar to the mouse model of congenital myasthenic syndrome with MuSK mutation (Chevessier et al.,2008).This implies a common clinical phenotype in mice with impaired MuSK function and corresponds well with the phenotype of human MuSK+MG.In contrast,we have noticed in parallel rounds with immunization of C57BL6mice with AChR from Torpedo californica that the AChR-antibody seropositive mice did not develop signi ficant weight loss,neck muscle weakness or kyphosis and also that their flaccid paralysis was reversible with AChEI treatment (Punga et al.,unpublished observations).The adverse effect of AChEIs in MuSK+EAMG resembles the neuromuscular hyperactivity reported in MuSK+MG patients (Punga et al.,2006).We hypothesize that the underlying reason for the hypersensitivity in the muscles to the additional amount of available ACh at the NMJ is a consequence of (1)the denervation of the muscle fibers with extensive AChR fragmentation and (2)the downregulation of AChE in some muscles (e.g.omohyoid and sternomastoid),which may result in AChEI overdose-like phenotype.The downregulation of AChE mRNA is most probably a direct consequence to the loss of MuSK,since MuSK binds collagen Q,an interaction that is thought to be largely responsible for the synaptic localization of AChE-collagen Q complex at the NMJ (Cartaud et al.,2004).The fragmentation and spatial dispersion of AChRs most likely inhibits the response to the increased ACh at the NMJ induced by AChEIs in the most clinically affected muscles.This study also investigated the possibility of MuSK antibodies to initiate a cascade that results in denervation-induced atrophy.MRI studies of newly diagnosed MuSK+patients have con firmed early muscle atrophy in the temporal,masseter and lingual muscles with fatty replacement (Zouvelou et al.,2009;Farrugia et al.,2006).We observed that,particularly in the masseter and paraspinal muscles,some NMJs were completely depleted of AChRs,and the subsequent loss of synaptic transmission most probably resulted in functional denervation.This explanation is further supported by the fact that pharmacological denervation arises after injection of botulinum toxin A (BotA),which also blocks the cholinergic synaptic transmission,and it is sometimes dif ficult to distinguish this from a surgical denervation due to the similarities in pattern,extent and time course (Drachman and Johnston,1975).Previous studies of passively induced AChR+EAMG in rats have shown an upregulation of the AChR ε,but not the γsubunits;thus suggesting that newly expressed AChRs in the case of antibody mediated AChR loss are of the adult type (Asher et al.,1993).However,our observed massive upregulation of AChR γtranscript in the masseter implies that,except for disturbed neuromuscular transmission,denervation is also ongoing since this usually correlates with the predominant expression of embryonic type receptors and re-expression of the fetal type occurs after experimental denervation (Witzemann et al.,1989).Levels of AChR γmRNA are normally extremely low in all muscles except for the extraocular muscles (Kaminski et al.,1996;MacLennan et al.,1997).Concomitantly with the very prominent increase in transcripts encoding AChR γ,MuSKFig.6.Atrophy-and denervation related markers in MuSK+EAMG mice.(A)mRNA levels of MuRF-1expressed as %of control in relation to β-actin.n=6control mice (C)and n=5MuSK+EAMG mice (MG).*p b 0.05.(B)Western blot of NCAM in the masseter muscle of one MuSK+EAMG mice with disease grade 3(MG)and in one CFA-immunized control mouse (Ctrl).NCAM was detected as 3bands at levels 120,140and 180kD and the loading control β-actin (45kD).An equal amount of protein was loaded.**p b 0.01.214 A.R.Punga et al./Experimental Neurology 230(2011)207–217。

英文文献(医学生学习策略)

Norwegian nursing and medical students’ perception ofinterprofessional teamworkInterprofessional teamwork in healthcare has gained increasing recognition worldwide as a way to increase patient safety and to foster collaborative and effective teams. The World Health Organization (WHO) has highlighted the importance of interprofessional teamwork and recommended educational programs that equip health care students with the necessary skills and competence to become effective team players.International research corroborates the position taken by the WHO, but studies also reveal difficulties in implementing interprofessional educational efforts and suggest that undergraduate education largely fails to address key elements, such as the understanding of professional roles, authority, hierarchy and gender related dimensions of teamwork.Of interest for the current study is the fact that Norwegian authorities have taken steps to promote interprofessional teamwork and education. The National Health Plan acknowledges interprofessional collaboration as a critical element for ensuring quality in health care services. In a White Paper submitted to the Norwegian Parliament the Ministry of Education sets requirements for the inclusion of interprofessional teamwork in health education. Reviewing lessons learned from the Norwegian initiatives, Clark concluded that the emerging positive outcomes have been somewhat impaired by lack of resources.Previous studies by Kyrkjebø and Bjørke noted that Norwegian students are not sufficiently exposedto interprofessional teamwork during their clinical training. Other Norwegian studies reported similar results. Aase found that theoretical lectures on interprofessional teamwork were not followed-up in clinical training, especially in nursing schools. Medical schools exposed their students to more interprofessional training, but still fell short of full compliance with the WHO recommendations. The reasons for this are partly because of structural constraints, such as resources, and partly because of faculty and students’ attitudes.Saroo et al. argue that successful interprofessional training should take advantage of the students’ psychosociological determinants, such as professional role behavior, hierarchy, and power relations. Based on this information, we surmise that a thorough understanding of the students’ perspective is imperative for designing successful interprofessional training. The current study analyses data from focus group interviews with nursing and medical students who had been exposed to interprofessional teamwork during their clinical training in Norway. Grounded in the students’ perceptions, the analysis aims at describing patterns and recommendations for the design of future interprofessional training. Note that the qualitative framework allowed the students to include reflections on the group processes –i.e., the focus group interviews –that were part of the current study.。

医学英语文献分类 PPT课件

An Evidence Based Approach

There is an apparent misconception about evidence based medicine that it should take the place of traditional medical education. Unfortunately, you still have to do background reading. When you solve a clinical problem, you will see that you need to use a lot of background knowledge (pathophysiology, pathology, pharmacology) in addition to foreground knowledge about your patient’s specific problem.

三.医学英语阅读的准备及注意事项:

1.语法:字法,句法. 2.词汇:单词,短语. 3.专业知识: 4.辞典:<牛津英语双解辞典>, <英汉医学词汇>, 专业辞典. 5.快速阅读:题目,摘要 / 结论,每一段的起始句. 6.准确理解:多读,泛读与精读相结合.

After you have refined a question for research, you can search for the relevant journal articles. In order to be successful, you need to be aware of the resources available and you need to have a good search strae-Based Medicine" is a recent trend which aims to make medical decisionmaking more deliberate and methodical. Most descriptions of the evidence based approach contain the following four steps:

医学英文文献

RAPSYN CARBOXYL TERMINAL DOMAINS MEDIATE MUSCLE SPECIFIC KINASE–INDUCED PHOSPHORYLATION OFTHE MUSCLE ACETYLCHOLINE RECEPTORY. LEE, J. RUDELL, S. YECHIKHOV, R. TAYLOR,S. SWOPE AND M. FERNS*Departments of Anesthesiology and Physiology and Membrane Biol-ogy, One Shields Avenue, University of California Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USAAbstract—At the developing vertebrate neuromuscular junc-tion, postsynaptic localization of the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) is regulated by agrin signaling via the muscle specific kinase (MuSK) and requires an intracellular scaffolding pro-tein called rapsyn. In addition to its structural role, rapsyn is also necessary for agrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the AChR, which regulates some aspects of receptor local-ization. Here, we have investigated the molecular mechanism by which rapsyn mediates AChR phosphorylation at the ro-dent neuromuscular junction. In a heterologous COS cell system, we show that MuSK and rapsyn induced phosphor-ylation of  subunit tyrosine 390 (Y390) and ␦ subunit Y393, as in muscle cells. Mutation of  Y390 or ␦ Y393 did not inhibit MuSK/rapsyn-induced phosphorylation of the other subunit in COS cells, and mutation of  Y390 did not inhibit agrin-induced phosphorylation of the ␦ subunit in Sol8 muscle cells; thus, their phosphorylation occurs independently, downstream of MuSK activation. In COS cells, we further show that MuSK-induced phosphorylation of the  subunit was mediated by rapsyn, as MuSK plus rapsyn increased Y390 phosphorylation more than rapsyn alone and MuSK alone had no effect. Intriguingly, MuSK also induced tyrosine phosphorylation of rapsyn itself. We then used deletion mu-tants to map the rapsyn domains responsible for activation of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases that phosphorylate the AChR subunits. We found that rapsyn C-terminal domains (amino acids 212– 412) are both necessary and sufficient for activa-tion of tyrosine kinases and induction of cellular tyrosine phosphorylation. Moreover, deletion of the rapsyn RING do-main (365– 412) abolished MuSK-induced tyrosine phosphor-ylation of the AChR  subunit. Together, these findings sug-gest that rapsyn facilitates AChR phosphorylation by activat-ing or localizing tyrosine kinases via its C-terminal domains.© 2008 IBRO. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Key words: neuromuscular junction, synaptogenesis, agrin, postsynaptic membrane.At the developing neuromuscular junction in vertebrates, several nerve-derived signals combine to localize the ace-tylcholine receptor at postsynaptic sites (Sanes and Lich-tman, 2001; Burden, 2002; Kummer et al., 2006). One essential factor is agrin, which signals via the muscle specific kinase (MuSK) and induces and/or stabilizes clus-tering of the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) in the postsyn-aptic membrane (reviewed in Kummer et al., 2006). Inter-estingly, embryonic muscle is prepatterned and AChR clusters occur in the central region of the muscle prior to and even in the absence of neural innervation (Lin et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001). However, upon innervation, agrin is required for stable aggregation of AChR at nerve–mus-cle contacts, counteracting an acetylcholine-driven dis-persal of AChR that eliminates aneural aggregates (Lin et al., 2005; Misgeld et al., 2005). Indeed, in agrin and MuSK knockout mice, AChR clusters are largely eliminated by birth and the mice die due to an inability to move and breathe (DeChiara et al., 1996; Gautam et al., 1996). Downstream of MuSK activation, an important mediator of AChR clustering is the intracellular, peripheral membrane protein, rapsyn, which associates with the AChR in the postsynaptic membrane in approximately 1:1 stoichiom-etry (Froehner, 1991). When expressed in heterologous cells, rapsyn self-aggregates and is sufficient to cluster, anchor and stabilize the AChR (Froehner et al., 1990; Phillips et al., 1991, 1993, 1997; Wang et al., 1999). More-over, in rapsyn null mice, there is a complete absence of AChR clusters at developing synaptic sites (Gautam et al., 1995). Together, these findings suggest that rapsyn binds the receptor, clustering and anchoring it in the postsynaptic membrane.Although rapsyn mediates AChR localization, it is un-clear how this is regulated by agrin signaling in muscle cells. Potentially, protein interactions underlying localiza-tion could be regulated via posttranslational modifications of the AChR, rapsyn, or additional binding proteins. Con-sistent with the first possibility, agrin/MuSK signaling in-duces rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the AChR  and ␦subunits (Mittaud et al., 2001; Mohamed et al., 2001), mediated by an intervening cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase (Fuhrer et al., 1997), perhaps of the src and/or abl families (Mohamed and Swope, 1999; Finn et al., 2003). Phosphor-ylation correlates closely with reduced mobility and deter-gent extractability of the AChR(Meier et al.,1995;Borges and Ferns,2001),suggesting that it regulates linkage to the cytoskeleton.In addition,it precedes AChR clustering (Ferns et al.,1996)and tyrosine kinase inhibitors that block phosphorylation also block clustering(Wallace et al.,1991; Ferns et al.,1996).Consistent with thesefindings,muta-tion of the tyrosine phosphorylation site in thesubunit abolishes agrin-induced cytoskeletal anchoring of mutant AChR and impairs its aggregation in muscle cells(Borges*Corresponding author.Tel:ϩ1-530-754-4973;fax:ϩ1-530-752-5423.E-mail address: mjferns@ (M. Ferns).Abbreviations:aa,amino acid;AChR,acetylcholine receptor;BuTX,␣-bungarotoxin;C-terminal,carboxyl terminal;HA,hemagglutinin;MuSK,muscle specific kinase;N-terminal,amino terminal.Neuroscience153(2008)997–10070306-4522/08$32.00ϩ0.00©2008IBRO.Published by Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.009997and Ferns,2001).Moreover,mice with targeted mutations of thesubunit intracellular tyrosines have neuromuscular junctions that are simplified and reduced in size,with de-creased density and total numbers of AChRs(Friese et al., 2007).Phosphorylation of thesubunit contributes to AChR localization,therefore,but it is unclear whether it does so by regulating rapsyn interaction(Fuhrer et al., 1999;Marangi et al.,2001;Moransard et al.,2003).In addition to its structural role,rapsyn also functions in agrin signaling.Notably,agrin-induced phosphorylation of the AChRand␦subunits is significantly decreased in rapsyn null myotubes(Apel et al.,1997;Mittaud et al., 2001),and rapsyn activates src family kinases in heterol-ogous cells(Qu et al.,1996;Mohamed and Swope,1999), resulting in tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple cellular proteins.Thus,rapsyn may facilitate MuSK-induced phos-phorylation of the AChR by activating and/or localizing the relevant cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases.In this study,we have investigated how rapsyn mediates the functionally important tyrosine phosphorylation of the AChR and have mapped the COOH-terminal domains required for tyrosine kinase activation and receptor phosphorylation.EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES Expression constructsRat MuSK that was myc-tagged at the amino terminal(N-terminus)was expressed in the pRcRSV vector(provided by S. Burden,NYU,New York,NY,USA).Mouse muscle nAChR subunits(␣,,,␦)were expressed using the pcDNA3vectorwith a CMV promoter(Invitrogen;Carlsbad,CA,USA).To epitope tag the-subunit,a Kpn I site was introduced at thecarboxyl terminal(C-terminal)extracellular tail,and double-stranded oligonucleotides that coded for the hemagglutinin (HA)or142epitopes(Das and Lindstrom,1991)were ligated into this site.To tag the␦-subunit,a Cla I site was introducedand the142epitope ligated into this site.Tyrosine390of thesubunit and393of the␦subunit were mutated to phenylala-nines using polymerase chain reaction-based site-directed mu-tagenesis(Quickchange Kit,Stratagene;La Jolla,CA,USA). Mouse rapsyn was expressed using the pcDNA3vector. Rapsyn deletion mutants that were His6-tagged at the C-termi-nus were generated through PCR and ligated into the pMT23 vector;rapsyn C-terminal deletion constructs retained the N-terminal myristoylation sequence whereas C-terminal frag-ments lacked this sequence.All constructs were confirmed by sequencing.Assaying phosphorylation of AChRCOS cells were grown on10cm dishes in DMEM-HI containing 10%fetal bovine serum and penicillin–streptomycin.When the cells reached85–90%confluency they were transfected overnight with20g of plasmid DNA encoding the AChR subunits(␣,,,␦)using the calcium phosphate method(Profection kit,Promega; Madison,WI,USA).For these experiments,theand␦subunitswere tagged with HA and142epitopes,respectively.After2days of expression,the live cells were surface labeled with biotin-conjugated␣-bungarotoxin(BuTX)(Molecular Probes;Eugene, OR,USA)for1h,rinsed,and then scraped off and pelleted in Ca2ϩ/Mg2ϩ-free PBS containing1mM sodium vanadate.Cells were then resuspended in buffer containing1%Triton X-100and 25mM Tris–glycine pH7.5,150mM NaCl,5mM EDTA,1mM sodium vanadate,50mM sodiumfluoride and the protease inhib-itors:1mM bisbenzimidine,1mM sodium tetrathionate,and1mM PMSF.After extraction on ice for10min,the detergent soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation at 16,000ϫg for4min.The insoluble pellet fraction was resus-pended directly in200l of SDS-PAGE loading buffer.The solu-ble lysates were incubated with streptavidin–agarose beads(Mo-lecular Probes)for1h to isolate AChR pre-labeled with biotin-conjugated BuTX.MuSK was then immunoprecipitated with anti-MuSK polyclonal antibody(gift of J.Sugiyama and Z.Hall,UCSF San Francisco,CA,USA)and protein G beads.In both cases, proteins isolated on the beads were eluted in30l of2ϫSDS-PAGE loading buffer.Sol8muscle cells were grown on10cm dishes and trans-fected with142-taggedsubunit using the calcium phosphate method as previously described(Borges and Ferns,2001).After treatment with agrin for1h(200pM C-Ag4,8),the cells were extracted as described above.AChR containing taggedsubunit was immunoprecipitated with mAb142and then the remaining AChR was pulled down using biotin-conjugated BuTX and strepta-vidin-agarose beads(Molecular Probes).For immunoblotting,samples were electrophoretically sepa-rated on10%SDS-PAGE gels,and transferred onto PVDF mem-branes.To detect phosphorylated AChRand␦subunits,the proteins were probed with polyclonal antibodies JH-1360and JH-1358,respectively(Mohamed and Swope,1999)in buffer containing4%Blotto,20mM Tris–HCl,pH7.6,150mM NaCl, 0.5%NP40,and0.1%Tween-20.The blots were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG second-ary antibody(Amersham Corporation;Arlington Heights,IL,USA) and bound antibody was visualized by chemiluminescence(ECL, Amersham Corporation).To identify theand␦subunit phos-phorylation bands,the immunoblots were reprobed for taggedand␦subunits with monoclonal antibodies anti-HA(Roche;Indi-anapolis,IN,USA)or mAb142(Sigma-Aldrich;St.Louis,MO, USA).The identity of the bands was also confirmed via mutations ofY390and␦Y393,which eliminate phosphorylation of the respective subunits.Blots were also reprobed for the␣subunit using mAb210(Babco;Berkley,CA,USA)to compare levels of expression of the AChR.Rapsyn immunoblots were performed using monoclonal antibody mAb1234(gift of S.Froehner,Univ. Washington,Seattle,WA,USA),polyclonal antibody B5668(gen-erated against amino acids(aa)133–153of rapsyn)or anti-His6 for tagged versions of rapsyn.Reprobes for tagged MuSK were performed using anti-myc monoclonal antibody9E10.To quantify levels of tyrosine phosphorylation,we carried out densitometric analysis of theand␦subunit bands in both soluble and pellet fractions using Sci-Scan5000Bioanalysis software(USB;Cleveland,OH,USA).As only20%of the pellet fraction was used for immunoblotting,these values were mul-tiplied byfive and added to the corresponding value for the soluble fraction in order to give total AChR subunit phosphor-ylation.The data were also normalized to the level of AChR, detected by immunoblotting for the taggedsubunit(anti-HA or 142).In order to average several independent transfection experiments,all values were expressed as a percentage of the maximal signal,which was obtained in COS cells co-expressing AChR,MuSK and rapsyn,or in Sol8muscle cells treated with agrin.Assaying total cellular phosphorylationCOS cells grown on6cm dishes were transfected overnight with 9g of plasmid DNA.After1day of expression,cells were rinsed, scraped off and pelleted in Ca2ϩ/Mg2ϩ-free PBS containing1mM sodium vanadate.The cells were then lysed in100l of extraction buffer(1%Triton X-100,25mM Tris–glycine pH7.5,150mM NaCl,5mM EDTA,1mM sodium vanadate,50mM sodium fluoride,1mM bisbenzimidine,1mM sodium tetrathionate,and 1mM PMSF),and after centrifugation,the residual pellets wereY.Lee et al./Neuroscience153(2008)997–1007 998resuspended in 100l of SDS loading buffer and boiled.To assay cellular protein tyrosine phosphorylation,10l of the pellet frac-tion were separated on 10%acrylamide gels and immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies 4G10and PY20.The inten-sity of the phosphotyrosine signal was quantified using Sci-Scan 5000Bioanalysis software (USB)where we performed a line scan through all the bands in each lane,from the top of the separating gel to ϳ45kD in order to avoid rapsyn.To average independent transfection experiments,we normalized the data in each exper-iment by subtracting the background in COS cells transfected with empty vector (i.e.0%)and expressing levels of cellular phosphor-ylation as a percentage of that in COS cells expressing wild type rapsyn (i.e.100%).This best controls for the variation in transfec-tion efficiency (and resulting cellular phosphorylation)between experiments,by comparing rapsyn versus rapsyn plus MuSK,or rapsyn deletion mutants to full-length rapsyn.Phosphorylation of rapsyn was measured independently and rapsyn levels were as-sayed by blotting duplicate gels with mAb1234or anti-His6.Phos-phorylation of rapsyn was also confirmed by immunoprecipitating with polyclonal anti-rapsyn antibodies B5668and B6766(gener-ated against aa 133–153and 402–412of rapsyn,respectively),and immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal anti-bodies 4G10and PY20.Assaying AChR extractabilityCOS cells growing in six well plates were transfected with AChR and rapsyn deletion mutants using Fugene (Roche).After 2days of expression,the live cells were incubated with 10nM I 125-BuTX for 1h to label surface AChR and rinsed 3ϫwith PBS.Cells were then lysed in 200l of extraction buffer (as above)for 10min on ice and the detergent soluble and insoluble fractions separated by centrifugation at 16,000ϫg for 4min.Both lysate and pellet fractions were counted with a gamma counter to assay rapsyn’s effect on detergent extract-ability of the AChR (i.e.anchoring).RESULTSMuSK/rapsyn-induced phosphorylation of AChR and ␦subunitsAgrin/MuSK signaling in muscle cells induces a rapid ty-rosine phosphorylation of the AChR,which contributes to its postsynaptic localization.Surprisingly,receptor phos-phorylation is dependent on rapsyn,a scaffolding protein that clusters and anchors the AChR in the postsynaptic membrane.To investigate the mechanism by which rapsyn mediates the functionally important phosphorylation of the receptor,we first recapitulated MuSK-induced AChR phos-phorylation in a simplified,heterologous cell system.To do this,we transiently expressed the AChR subunits (␣,,,␦)in COS cells in combination with rapsyn and MuSK.To assay phosphorylation,surface AChR was labeled with biotin-conjugated ␣-BuTX,pulled down from cell lysates and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for the phos-phorylated (Y390)and ␦(Y393)subunits (Wagner et al.,1991;Mohamed and Swope,1999).AChR retained in the detergent-insoluble pellet fraction was also immunoblot-ted,as previous studies have shown that rapsyn anchors significant amounts of receptor to the cytoskeleton (Phillips et al.,1993;Mohamed and Swope,1999).In agreement with previous work (Gillespie et al.,1996),we find that coexpression of MuSK and rapsyn significantly increased phosphorylation of the AChR and ␦subunits (Fig.1A,B).The MuSK/rapsyn-induced increase in phosphorylation was greatest for the subunit,whereas basal phosphory-lation was highest for the ␦subunit;these findings in heterologous cells mirror previous observations in muscle cells (Meier et al.,1995;Mittaud et al.,2001).Moreover,Fig.1.Phosphorylation of AChR and ␦subunits is not interdependent.AChR was transiently expressed in COS cells with either wild type or tyrosine-mutated and ␦subunits (Y390F and ␦Y393F).(A)After detergent extraction,we assayed MuSK/rapsyn-induced phosphorylation of surface AChR isolated from the soluble lysate (100%of BuTX pull-down)and also AChR retained in the insoluble pellet (20%of pellet)by immunoblotting with and ␦subunit phospho-specific antibodies (JH-1360and JH-1358,respectively).The blots were reprobed with anti-HA antibody to detect HA-tagged subunit and levels of AChR expression.Arrows indicate the and ␦subunit phosphorylation bands and *marks a nonspecific band present in the pellet fraction.(B)Quantification of total AChR phosphorylation in both soluble and pellet fractions shows that rapsyn plus MuSK induced significant phosphorylation of the and ␦subunits (P Ͻ0.00001and P Ͻ0.05,respectively;n ϭ5,Student’s t -test).Mutation of subunit Y390(Y390F)did not block ␦subunit phosphorylation (78Ϯ6%of wild type levels,mean ϮS.E.M.;n ϭ5;ns,difference not significant;Student’s t -test),nor did ␦subunit Y393F mutation block subunit phosphorylation (89Ϯ3.5%of wild type levels;n ϭ5,difference not significant).Thus,rapsyn/MuSK-induced phosphorylation of the two sites occurs independently.Y.Lee et al./Neuroscience 153(2008)997–1007999most phosphorylated AChR was found in the pellet frac-tion,consistent with previous findings in both heterologous and muscle cells (Meier et al.,1995;Borges and Ferns,2001).Several studies have shown and ␦subunit phosphor-ylation to be closely linked,both temporally and in their sensitivity to kinase blockers (Mohamed and Swope,1999;Mittaud et al.,2001).This could reflect parallel phosphor-ylation of the two sites by the same—or a similar—kinase.Alternatively,phosphorylation might be sequential,with phosphorylation at one site recruiting a kinase that then phosphorylates the second subunit.To distinguish these possibilities,we expressed AChR with subunit Y390F or ␦subunit Y393F mutations and tested the effect on MuSK/rapsyn-induced phosphorylation of the other subunit (Fig.1A,B).We find that mutation of Y390did not block ␦subunit phosphorylation,and similarly,mutation of ␦Y393did not abolish phosphorylation of the subunit,suggest-ing that their phosphorylation is independent.To confirm that AChR phosphorylation occurs via a similar mechanism in muscle cells,we transfected Sol8myotubes with 142-tagged,wild type or Y390F subunit,which we have shown previously to be incorporated into AChR that is expressed on the myotube surface (Borges and Ferns,2001).After agrin treatment,the cells were extracted and AChR containing tagged subunit was se-lectively immunoprecipitated using anti-142antibodies and assayed for and ␦phosphorylation (Fig.2A,B).Consis-tent with our results in COS cells we find that subunit Y390F mutation did not block ␦phosphorylation in muscle cells (85Ϯ6%of wild-type levels;mean ϮS.E.M.).We were unable to test the effect of ␦Y393F mutation on phos-phorylation due to low expression of the introduced ␦sub-unit.Together with the results from COS cells,however,these findings demonstrate that phosphorylation of the and ␦subunits is independent and occurs in parallel,downstream of MuSK activation.Rapsyn facilitates MuSK-induced phosphorylation of the AChR subunitAgrin/MuSK-induced phosphorylation of the AChR is sig-nificantly impaired in rapsyn null muscle cells (Apel et al.,1997;Mittaud et al.,2001).To confirm that rapsyn is also required in our heterologous cell system,we expressed the AChR in combination with rapsyn and/or MuSK,and as-sayed phosphorylation as described above.As in muscle cells,basal phosphorylation of the ␦subunit was higher than the subunit.Rapsyn co-expression increased both and ␦subunit phosphorylation,whereas MuSK alone did not affect phosphorylation.Moreover,co-expression of rapsyn plus MuSK increased phosphorylation above that with rapsyn or MuSK alone (Fig.3A,B;n ϭ6;P ϭ0.002and Ͻ0.0001respectively;Student’s t -test).Thus,in agree-ment with previous work,we find that rapsyn facilitates MuSK-induced phosphorylation of the AChR subunit (Gillespie et al.,1996).Rapsyn C-terminus is necessary and sufficient for activation of cellular tyrosine kinasesRapsyn likely mediates MuSK-induced phosphorylation of the AChR by activating and/or localizing cytoplasmic ty-rosine kinases that phosphorylate the and ␦subunits.Indeed,rapsyn activates src family kinases in heterolo-gous cells,resulting in increased tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple cellular proteins (Qu et al.,1996;Mohamed and Swope,1999).Moreover,agrin specifically activates src-family kinases associated with the AChR in musclecellsFig.2.Phosphorylation of AChR ␦subunit is not dependent on subunit phosphorylation in muscle cells.(A,B)Sol 8muscle cells were transfected with 142-tagged wild-type or Y390F subunit.After detergent extraction,AChR containing tagged subunit was immunoprecipitated with mAb142(142IP),followed by isolation of the remaining AChR with ␣BuTX (BuTX pull-down).Isolates were then immunoblotted with and ␦subunit phospho-specific antibodies (JH-1360and JH-1358,respectively).The blots were reprobed with anti-142antibody to detect tagged subunit and with mAb 210to determine AChR levels.For AChR containing tagged wild type subunit (142IP),agrin induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the and ␦subunits,similar to endogenous AChR (BuTX pull-down).In AChR containing Y390F subunit,absence of phosphorylation did not inhibit agrin-induced phosphorylation of the ␦subunit (85Ϯ6%of wild type level;n ϭ3;ns,difference not significant,Student’s t -test).Y.Lee et al./Neuroscience 153(2008)997–10071000and this occurs in a rapsyn-dependent manner (Mittaud et al.,2001).We examined,therefore,whether rapsyn’s activation of kinases is enhanced by MuSK and which do-mains in rapsyn are responsible.First,we expressed rapsyn and/or MuSK in COS cells and after detergent extraction,assayed phosphorylation in the pellet fraction by immunoblot-ting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies 4G10and PY20.As previously reported (Qu et al.,1996;Mohamed and Swope,1999),rapsyn alone significantly increased cellular tyrosine phosphorylation compared with controls transfected with empty vector (by ϳ250%;Fig.4A,B).In contrast,MuSK alone did not increase phosphorylation significantly and MuSK coexpression with rapsyn did not increase overall cel-lular phosphorylation beyond the levels found with rapsyn alone (Fig.4A,B).One interesting exception was that MuSK increased tyrosine phosphorylation of rapsyn itself.In immunoblots of the pellet fraction,we found ϳ350%increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of a 43kD band corresponding to rapsyn (Fig.4A,C;arrowed band).This was confirmed in immu-noblots of rapsyn deletion mutants,where a strong phos-photyrosine signal corresponded exactly to the different-sized rapsyn mutants (see Fig.5).In addition,we detected tyrosine phosphorylation of rapsyn that was specifically immunoprecipitated from the soluble fraction (Fig.4D),although interestingly,the level of tyrosine phosphorylation was significantly lower than in rapsyn anchored in the pellet fraction.The MuSK-induced phosphorylation of rapsyn suggests that its function might also be regulated by agrin-induced phosphorylation during synaptogenesis.To then map the domains in rapsyn responsible for kinase activation (Fig.5A),we tested a series of deletionmutants for their ability to induce cellular tyrosine phos-phorylation.Full-length wild type and His6-tagged rapsyn increased levels of overall cellular tyrosine phosphoryla-tion by approximately 2.5-to threefold (Fig.5B).In con-trast,three different rapsyn C-terminal deletion mutants failed to increase tyrosine phosphorylation above back-ground levels,despite being expressed at levels equiva-lent to wild type rapsyn.Indeed,deletion of just the RING domain and following 10aa (rapsyn 1–365)abolished kinase activation (Fig.5C).We then tested whether the rapsyn C-terminus alone activated kinases and increased tyrosine phosphorylation.Strikingly,we found that two different rapsyn C-terminal fragments (rapsyn 158–412and 212–412)both increased cellular tyrosine phosphorylation to levels similar to that seen with wild type rapsyn (Fig.5D,E).In an effort to map the responsible domains further,we tested two additional GFP-tagged C-terminal fragments (GFP-rapsyn 200–284and 255–412);despite being highly expressed,neither increased cellular phosphorylation (data not shown).To-gether,these results demonstrate that the C-terminal half of rapsyn is sufficient for activation of cellular tyrosine kinases,and within this region,the RING domain and following 10aa are necessary for activation.Rapsyn C-terminus is required but not sufficient for AChR phosphorylationNext,we investigated whether rapsyn’s C-terminal do-mains mediate MuSK-induced phosphorylation of the AChR,focusing on the functionally important phosphory-lation of the subunit (Borges and Ferns,2001;FrieseFig.3.Rapsyn mediates MuSK-induced phosphorylation of AChR subunit.(A)AChR was transiently expressed in COS cells alone or with rapsyn and/or MuSK.After detergent extraction,we assayed phosphorylation of surface AChR isolated from the soluble lysate (100%of BuTX pull-down)and also AChR retained in the insoluble pellet (20%of pellet)by immunoblotting with and ␦subunit phospho-specific antibodies (JH-1360and JH-1358,respectively).Levels of AChR were determined by blotting for HA-tagged subunit,and expression of MuSK and rapsyn confirmed by blotting with anti-MuSK and mAb1234antibodies,respectively.(B)Quantification of total AChR phosphorylation (in both soluble and pellet fractions)shows that rapsyn co-expression increased and ␦subunit phosphorylation,whereas MuSK alone had no effect (n ϭ3–6).Co-expression of both rapsyn and MuSK increased the levels of subunit phosphorylation above that with rapsyn or MuSK alone (P ϭ0.002and P Ͻ0.0001,respectively;Student’s t -test),indicating that rapsyn facilitates MuSK-induced subunit phosphorylation.Y.Lee et al./Neuroscience 153(2008)997–10071001et al.,2007).To do this,we co-expressed AChR and MuSK together with rapsyn C-and N-terminal deletion mutants and then assayed tyrosine phosphorylation of the sub-unit.Consistent with our previous results,we found that all three rapsyn C-terminal deletions abolished MuSK-in-duced subunit phosphorylation (Fig.6A,B).Thus,the RING domain and following 10aa is required for rapsyn’s ability to mediate AChR tyrosine phosphorylation.The C-terminus of rapsyn was not sufficient for AChR phosphor-ylation,however,as subunit phosphorylation was unde-tectable with either of the rapsyn C-terminal fragments (rapsyn 158–412and 212–412;Fig.6C,D).Fig.4.Rapsyn activates cellular tyrosine kinases independent of MuSK.(A)COS cells transfected with rapsyn and/or MuSK were extracted and the pellet fractions immunoblotted with monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies,4G10and PY20to assay levels of phosphorylation.Rapsyn expression increased tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple cellular proteins,indicating that it activates cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases.MuSK expression did not increase general cellular phosphorylation,either alone or in combination with rapsyn.However,it did increase phosphorylation of the 43kD band corresponding to rapsyn (arrow).(B)Quantification of relative phosphotyrosine levels in the COS pellet fractions,expressed as a percentage of the level with rapsyn alone.MuSK expression did not increase phosphorylation above control levels or enhance the effect of rapsyn (123Ϯ35%of rapsyn alone,mean ϮS.E.M.;n ϭ3;difference not significant,Student’s t -test).(C)MuSK co-expression significantly increased the tyrosine phos-phorylation of rapsyn (360Ϯ31%of rapsyn alone,mean ϮS.E.M.;n ϭ3;P ϭ0.01,Student’s t -test).(D)COS cells transfected with rapsyn and/or MuSK were extracted and rapsyn was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and immunoblotted along with the residual pellet with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies,4G10and PY20.Rapsyn immunoprecipitated from the soluble lysate is tyrosine-phosphorylated,although to a lesser extent than rapsyn anchored in the insoluble pellet.Reprobing with mAb1234shows the relative levels of rapsyn in the soluble and insoluble fractions,and immunoblotting with mAb 9E10confirms expression of myc-tagged MuSK.Y.Lee et al./Neuroscience 153(2008)997–10071002。

医学英语文献带读

医学英语文献带读English:Medical English literature is a crucial component in the field of healthcare as it provides valuable research and information for healthcare professionals. Reading medical English literature allows healthcare practitioners to stay updated with the latest advancements, evidence-based practices, and treatment options. It helps in enhancing and expanding their knowledge base, which ultimately leads to improved patient care and outcomes. Additionally, medical English literature plays a vital role in fostering critical thinking and problem-solving skills among healthcare professionals. By analyzing different studies, research papers, and clinical trials, clinicians can develop a comprehensive understanding of various diseases, their pathophysiology, diagnostic techniques, and therapeutic interventions. Moreover, medical English literature aids healthcare professionals in staying abreast of current guidelines and protocols, ensuring their clinical practice aligns with the best practices and standards.By reading medical English literature, healthcare professionals also gain access to a vast network of experts and researchers, enabling them to collaborate and share knowledge with peers globally. It facilitates discussions and debates on emerging topics, leading to advancements in medical practices. Furthermore, medical English literature encourages evidence-based practice, as it provides reliable and validated information to support clinical decision-making. Healthcare practitioners depend on this literature to evaluate the efficacy and safety of different treatment modalities and interventions, ensuring optimal patient outcomes. In addition, medical English literature encompasses various specialties and sub-specialties, allowing healthcare professionals to stay current with advancements in their specific fields. Whether it's cardiology, oncology, neurology, or any other discipline, medical English literature covers a wide range of topics, ensuring practitioners have access to the latest research and knowledge specific to their respective areas of expertise.In conclusion, medical English literature plays a vital role in the healthcare industry by providing a wealth of research, information, and knowledge. It enhances the clinical skills of healthcareprofessionals, promotes evidence-based practice, fosters collaboration and global networking, and ensures the delivery ofhigh-quality patient care. Reading medical English literature is an essential activity for healthcare practitioners, enabling them to stay abreast of the advancements in medical science and apply the best practices in their clinical practice.中文翻译:医学英语文献在医疗保健领域起着重要作用,为医护专业人员提供了可贵的研究和信息。

医学英语文献入门

医学英语文献入门English:Medical English literature provides an extensive and essential resource for healthcare professionals and researchers. It encompasses a wide range of topics including clinical trials, case reports, systematic reviews, and original research articles. To navigate the world of medical English literature, it is crucial to develop a systematic approach. Firstly, it is important to understand the structure and components of scientific articles. This includes familiarizing oneself with the abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion sections. Each section has a specific purpose and provides different types of information. Additionally, understanding the terminology used in medical literature is vital. Medical English utilizes a specialized language that can be complex and challenging to comprehend. To overcome this, the use of medical dictionaries, glossaries, and online resources can be beneficial. Another important aspect is learning how to critically appraise scientific articles. This involves evaluating the study design, methodology, statistical analysis, and validity of the results.Assessing the strength of evidence presented in the literature helps healthcare professionals make informed decisions. Moreover, staying updated with the latest medical research is crucial for evidence-based practice. Numerous online platforms and journal subscriptions provide access to current medical literature. It is important to prioritize credible sources and reputable journals. Additionally, joining medical societies and attending conferences can facilitate knowledge exchange and networking opportunities. Finally, developing effective reading strategies can enhance the efficiency of literature review. Techniques such as skimming, scanning, and summarizing can help locate relevant information efficiently. Taking notes and organizing them systematically are also vital for future reference. In conclusion, mastering medical English literature requires a systematic approach including familiarizing oneself with the structure, terminology, critical appraisal skills, staying updated, utilizing effective reading strategies, and engaging in professional networks.中文翻译:医学英语文献为医护专业人员和研究者提供了广泛而重要的资源。

免费的英文文献资料网站

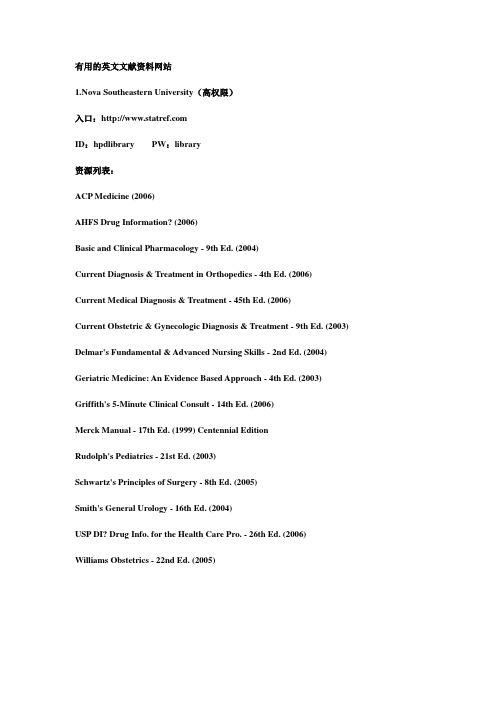

有用的英文文献资料网站1.Nova Southeastern University(高权限)入口:ID:hpdlibrary PW:library资源列表:ACP Medicine (2006)AHFS Drug Information? (2006)Basic and Clinical Pharmacology - 9th Ed. (2004)Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics - 4th Ed. (2006)Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment - 45th Ed. (2006)Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment - 9th Ed. (2003) Delmar's Fundamental & Advanced Nursing Skills - 2nd Ed. (2004) Geriatric Medicine: An Evidence Based Approach - 4th Ed. (2003) Griffith's 5-Minute Clinical Consult - 14th Ed. (2006)Merck Manual - 17th Ed. (1999) Centennial EditionRudolph's Pediatrics - 21st Ed. (2003)Schwartz's Principles of Surgery - 8th Ed. (2005)Smith's General Urology - 16th Ed. (2004)USP DI? Drug Info. for the Health Care Pro. - 26th Ed. (2006)Williams Obstetrics - 22nd Ed. (2005)还有一些免费外文文献网站。

生物医学英文文献导读

生物医学英文文献导读Title: Biomedical Applications of Nanoparticles: An OverviewAuthors: John Smith, Emily Johnson, David Wilson Journal: Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part AYear: 2018Summary:This review article provides an overview of the biomedical applications of nanoparticles. Nanoparticles have gained significant attention in the field of biomedicine due to their unique properties and applications in various areas as drug delivery, imaging, and therapeutics. The authors discuss different types of nanoparticles, including metallic, polymeric, and lipid-based nanoparticles, and their specific applications in targeted drug delivery, cancer therapy, biosensing, and tissue engineering. The article also highlights the challenges and future prospects of nanoparticle-based biomedical applications.Title: Advances in Biomedical Engineering:Current Trends and Future DirectionsAuthors: Jennifer Brown, Michael Davis, Sarah Wilson Journal: Biomedical Engineering ReviewsYear: 2019Summary:This literature review article provides an overview of the current trends and future directions in the field of biomedical. The authors discuss recent advancements in various areas of biomedical engineering, such as biomaterials, medical imaging, tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and artificial intelligence in healthcare. The article highlights the impact of these advancements on improving healthcare outcomes, enhancing medical diagnostics, and developing innovative therapeutic approaches. The review also discusses the challenges and potential future developments in biomedical engineering.Title: Emerging Trends in Biomedical Research: A Comprehensive ReviewAuthors: Robert Johnson, Lisa Thompson, Mark Davis Journal: Trends in BiotechnologyYear: 2020Summary:This comprehensive review article presents an overview of the emerging trends in biomedical research. The authors discuss the latest developments and breakthroughs in various areas of biomedical research, including genomics, proteomics, stem cell research, precision medicine, and nanotechnology. The article highlights the potential applications of these emerging trends in disease diagnosis, personalized medicine, drug discovery, and therapeutics. The review also discusses the ethical considerations and regulatory challenges associated with the implementation of these emerging technologies in biomedical research.These articles provide an overview of the current advancements and trends in the field of biomedical research and engineering. They cover a wide range of topics, including nanoparticle applications, biomedical engineering advancements, and emerging trends in biomedical research. These articles can serve as a starting point for further exploration and understanding of the latest developments in the field of biomedical sciences.。

医药学类文献双语版_汉译英

介导性shRNA能抑制肺癌细胞中livin沉默基因的表达从而促进SGC-7901细胞凋亡背景—由于肿瘤细胞抑制凋亡增殖,特定凋亡的抑制因素会对于发展新的治疗策略提供一个合理途径。

Livin是一种凋亡抑制蛋白家族成员,在多种恶性肿瘤的表达中具有意义。

但是, 在有关胃癌方面没有可利用的数据。

在本研究中,我们发现livin基因在人类胃癌中的表达并调查了介导的shRNA能抑制肺癌细胞中livin沉默基因的表达,从而促进SGC-7901细胞凋亡。

方法—mRNA及蛋白质livin基因的表达用逆转录聚合酶链反应技术及西方吸干化验进行了分析。

小干扰RNA真核表达载体具体到livin基因采用基因重组、测序核酸。

然后用Lipofectamin2000转染进入SGC-7901细胞。

逆转录聚合酶链反应技术和西方吸干化验用来验证的livin基因在SGC-7901细胞中使沉默基因生效。

所得到的稳定的复制品用G418来筛选。

细胞凋亡用应用流式细胞仪(FCM)来评估。

细胞生长状态和5-FU的50%抑制浓度(IC50)和顺铂都由MTT比色法来决定。

结果—livin mRNA和蛋白质的表达检测40例中有19例(47.5%)有胃癌和SGC-7901细胞。

没有livin基因表达的是在肿瘤邻近组织和良性胃溃疡病灶。

相关发现在livin基因的表达和肿瘤的微小分化和淋巴结转移一样(P < 0.05)。

4个小干扰RNA真核表达矢量具体到基因重组的livin基因建立。

其中之一,能有效地减少livin基因的表达,抑制基因不少于70%(P < 0.01)。

重组的质粒被提取和转染到胃癌细胞。

G418筛选所得到的稳定的复制品被放大讲究。

当livin基因沉默,胃癌细胞的生殖活动明显低于对照组(P < 0.05)。

研究还表明,IC50上的5-Fu 和顺铂在胃癌细胞的治疗上是通过shRNA减少以及刺激这些细胞(5-Fu proapoptotic和顺铂)(P < 0.01)。

《临床常见疾病:医学英语文献阅读》读书笔记模板

Section Five: Cancer第五部分恶性肿瘤

66. Breast Cancer乳腺癌 67. Esophagus Cancer食管癌 68. Liver Cancer肝癌 69. Stomach Cancer胃癌 70. Colorectal Cancer结直肠癌 71. Lung Cancer肺癌 72. Cervical Cancer宫颈癌 73. Ovarian Cancer卵巢癌 74. Bladder Cancer膀胱癌

A good relaxation during commuting hours。

比较基础的医学科普文。

This is a collection of patient leaflets explaining common diseases in layman's terms (except for infectious disease and ophthalmology). I recommend converting the measurements, such as inches into centimetres and Fahrenheit into Celsius, as well as avoiding the use of 911 as the service number for emergencies. Thorough proofreading is necessary before publication in case of a second version since numerous errors were made in spelling or using lookalike words.。

84. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Hypopnoea Syndrome (OSAHS)阻塞性睡眠 呼吸暂停低通气综合征

医学英文翻译文献

英文文献翻译第1 篇 Effects of sevoflurane on dopamine, glutamate and aspartate release in an vitro model of cerebral ischaemia七氟醚对离体脑缺血模型多巴胺、谷氨酸和天冬氨酸释放的影响兴奋性氨基酸和多巴胺的释放在脑缺血后神经损伤中起重要作用。

在当前的研究中,采用离体脑缺血模型观察七氟醚对大鼠皮质纹状体脑片中多巴胺、谷氨酸和天冬氨酸释放量的影响。

脑片以34℃人工脑脊液灌流,缺血发作以去除氧气和降低葡萄糖浓度(从4mmol/l至2mmol/l)≤30分钟模拟。

多巴胺释放量用伏特法原位监测,灌流样本中的谷氨酸和天冬氨酸浓度用带有荧光检测的高效液相色谱法测定。

脑片释放的神经递质在有或无4%七氟醚下测定。

对照组脑片诱导缺血后,平均延迟166s(n=5)后细胞外多巴胺浓度达最大77.0μmol/l。

缺血期4%七氟醚降低多巴胺释放速率,(对照组和七氟醚处理组脑片分别是6.9μmol/l/s和4.73μmol/l/s,p<0.05),没有影响它的起始或量。

兴奋性氨基酸的释放更缓慢。

每个脑片基础(缺血前)谷氨酸和天冬氨酸是94.8nmol/l和69.3nmol/l,没有明显被七氟醚减少。

缺血大大地增加了谷氨酸和天冬氨酸释放量(最大值分别是对照组的244%和489%)。

然而,4%七氟醚明显减少缺血诱导的谷氨酸和天冬氨酸释放量。

总结,七氟醚的神经保护作用与其可以减少缺血引起的兴奋性氨基酸的释放有关,较小程度上与多巴胺也有关。

第2篇The Influence of Mitochondrial K ATP-Channels in the Cardioprotection of Proconditioning and Postconditioning by Sevoflurane in the Rat In Vivo线粒体K ATP通道在离体大鼠七氟醚预处理和后处理中心肌保护作用中的影响挥发性麻醉药引起心肌预处理并也能在给予再灌注的开始保护心脏——一种实践目前被称为后处理。

医学英语文献阅读(二)

医学英语文献阅读(二)Medical English Literature Reading (Part II)。

In the field of medicine, staying updated with the latest research and advancements is crucial for healthcare professionals. Reading medical literature is an essential skill that allows practitioners to access and understand scientific studies, clinical trials, and expert opinions. In this article, we will delve deeper into the process of reading medical English literature and explore various strategies to enhance comprehension and critical analysis.1. Understanding the Structure of Medical Articles。

Medical articles generally follow a specific structure, consisting of the title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Familiarizing yourself with this structure can greatly facilitate your reading process. The title provides a concise overview of the study, while the abstract summarizes the key findings and conclusions. The introduction introduces the research question and provides background information, while the methods section outlines the study design, sample size, and data collection methods. The results section presents the findings, often in the form of tables, figures, and statistical analyses. The discussion section interprets the results, compares them with existing literature, and highlights the study's limitations. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the main findings and their implications.2. Skimming and Scanning Techniques。

医学医学英文文献汇报讲解PPT培训课件

Case description

在入院前4个月,经胸超声心动图提示病人有轻中度肺动脉 高压,肺动脉收缩压大约40mmHg并且房间隔变扁。随后的 进行左、右心脏导管插入术提示PA 50/19(平均31)且其 患有非梗阻性冠状动脉疾病。尽管积极使用速尿利尿以及使 用西地那非血管扩张剂治疗,患者呼吸困难仍然继续加剧且 伴有心悸。

该病人诊疗经过十分复杂,既需要血管升压药来治疗低血压,又有逐渐恶化的 右心室功能障碍和急性肾损伤。在移植评估过程中,她决定不想再继续接受那 些试图稳定其进行性多器官功能障碍的治疗,并改为安适疗法。在撤去支持治 疗后数小时她便去世了。

2

Background

Background

肺静脉闭塞性疾病(PVOD)是一种罕见的肺动脉高血压(PAH) 病因,其肺小静脉和微静脉纤维化,逐渐导致肺动脉高压、 肺间质、胸膜水肿和右心衰。

Discussion

使用PAH特殊疗法在治疗PVOD时,因为容易引起肺动脉扩张,进而引 起肺水肿,所以需要密切的临床监测。曾有PVOD的个案报道称,一个 病人由于使用了小剂量的前列环素后死于急性肺水肿和呼吸衰竭。最近 发现,前列环素谨慎使用可以暂时改善某些PVOD患者临床和血流动力学 参数,继而可以进行肺移植手术。尽管所有种类PAH相关血管舒张治疗 都会增加PVOD患者肺水肿的风险,但另一份报告却介绍了一个病人在 使用了前列环素后发生了进行性恶化的低氧血症,但在使用了其他血管 舒张剂后,这种症状却改善了。同样,我们的病人尽管在使用了强心治 疗后仍表现为低血压并且对前列环素不耐受。如果继续使用前列环素, 那么她的心肺功能可能会处于失代偿状态甚至更糟。然而,在她大部分 住院治疗中,吸入一氧化氮和口服西地那非治疗贯穿始终。尽管有证据 表明输注前列环素可以改善某些PVOD患者病情,但是我们这个病例和 之前报道的其他病例却表明,并不是所有的PVOD患者都会从环前列腺 素治疗中获益。

医学英文文献阅读技巧

医学英文文献阅读技巧Baisonfield医学文献阅读心得医学论文段落摘抄分析下面文字来源于《生殖与不孕》杂志2008年一篇关于子宫内膜的文献,是方法部分的2段。