新概念_英音_4

新概念英语第四册知识点整理

新概念英语第四册知识点整理第一部分:语法点1. 一般现在时和现在进行时一般现在时用于描述经常性的、习惯性的动作或状态,现在进行时则用于描述正在进行的动作。

例如:- I usually go to the park on Sundays. (我通常在星期天去公园。

)- She is watching TV right now. (她正在看电视。

)2. 祈使句祈使句用于表达命令、建议、请求等,一般省略主语"you"。

例如:- Sit down. (坐下。

)- Please close the window. (请关窗。

)3. 定冠词和不定冠词定冠词 "the" 用于特指某个人或物,不定冠词 "a" 或 "an" 用于泛指一个人或物。

例如:- The dog is barking. (那只狗在叫。

)- I saw a cat in the garden. (我在花园里看见了一只猫。

)4. 可数名词和不可数名词可数名词表示可以计数的事物,可以用数词修饰;不可数名词表示不可分割的事物,不能用数词修饰。

例如:- There are three books on the table. (桌子上有三本书。

)- I have some milk in the fridge. (冰箱里有一些牛奶。

)5. 过去式和过去分词过去式用于过去的单一事件,过去分词用于完成时态和被动语态中。

例如:- He did his homework yesterday. (他昨天做了作业。

)- The letter was sent by him. (这封信是他寄的。

)第二部分:词汇点1. 常见动词短语- take off(脱下)- put on(穿上)- look after(照顾)- give up(放弃)- look for(寻找)2. 常见形容词和副词- happy(快乐的)- sad(悲伤的)- beautiful(美丽的)- quickly(快速地)- slowly(慢慢地)3. 人称代词的主格和宾格形式- 主格形式:I,you,he,she,it,we,you,they- 宾格形式:me,you,him,her,it,us,you,them 4. 常见连词- and(和)- but(但是)- or(或者)- because(因为)- so(所以)5. 常见短语和惯用表达- How are you?(你好吗?)- Thank you.(谢谢。

新概念英语第二册英音版04:An Exciting Trip

新概念英语第二册英音版04:An Exciting Trip Lesson 4第4课An Exciting Trip激动人心的旅行First listen and then answer the question.听录音,然后回答以下问题。

Why is Tim finding this trip exciting?为什么蒂姆觉得这次旅行很激动人心?I have just received a letter from my brother, Tim.我刚刚收到弟弟蒂姆的来信,He is in Australia.他正在澳大利亚。

He has been there for six months.他在那儿已经住了6个月了。

Tim is an engineer.蒂姆是个工程师,He is working for a big firm and he has already visited a great number of different places in Australia.正在为一家大公司工作,并且已经去过澳大利亚的很多地方了。

He has just bought an Australian car and has gone to Alice Springs, a small town in the centre of Australia.他刚买了一辆澳大利亚小汽车,现在去了澳大利亚中部的小镇艾利斯斯普林斯。

He will soon visit Darwin.他不久还将到达尔文去,From there, he will fly to Perth.从那里,他再飞往珀斯。

My brother has never been abroad before, so he is finding this trip very exciting.我弟弟以前从未出过国,所以,他觉得这次旅行非常激动人心。

新概念英语第四册:Education教育

【导语】学习英语并不难啊。

你还在为英语成绩低拖后腿⽽烦恼吗?不要着急,⼩编为⼤家提供了“新概念英语第四册:Education教育”。

相信加⼊学习当中的你,很快便不再受英语的困扰!还在等什么?和⼩编⼀起来学习吧! First listen and then answer the following question.听录⾳,然后回答以下问题。

Why is education democratic in bookless, tribal societies? Education is one of the key words of our time. A man without an education, many of us believe, is an unfortunate victim of adverse circumstances, deprived of one of the greatest twentieth-century opportunities. Convinced of the importance of education, modern states 'invest' in institutions of learning to get back 'interest' in the form of a large group of enlightened young men and women who are potential leaders. Education, with its cycles of instruction so carefully worked out, punctuated by textbooks —— those purchasable wells of wisdom-what would civilization be like without its benefits? So much is certain: that we would have doctors and preachers, lawyers and defendants, marriages and births ——but our spiritual outlook would be different. We would lay less stress on 'facts and figures' and more on a good memory, on applied psychology, and on the capacity of a man to get along with his fellow-citizens. If our educational system were fashioned after its bookless past we would have the most democratic form of 'college' imaginable. Among tribal people all knowledge inherited by tradition is shared by all; it is taught to every member of the tribe so that in this respect everybody is equally equipped for life. It is the ideal condition of the 'equal start' which only our most progressive forms of modern education try to regain. In primitive cultures the obligation to seek and to receive the traditional instruction is binding to all. There are no 'illiterates' ——if the term can be applied to peoples without a sc ript —— while our own compulsory school attendance became law in Germany in 1642, in France in 1806, and in England in 1876, and is still non-existent in a number of 'civilized' nations. This shows how long it was before we deemed it necessary to make sure that all our children could share in the knowledge accumulated by the 'happy few' during the past centuries. Education in the wilderness is not a matter of monetary means. All are entitled to an equal start. There is none of the hurry which, in our society, often hampers the full development of a growing personality. There, a child grows up under the ever-present attention of his parent; therefore the jungles and the savannahs know of no 'juvenile delinquency'. No necessity of making a living away from home results in neglect of children, and no father is confronted with his inability to 'buy' an education for his child. JULIUS E. LIPS The Origin of Things New words and expressions ⽣词和短语 adverse adj. purchasable adj.可买到的preacher n. 传教⼠defendant n. 被告outlook n. 视野capacity n. 能⼒democratic adj. 民主的tribal n. 部落的tribe n. 部落illiterate n. ⽂盲compulsory adj. 义务的deem v. 认为means n. ⽅法,⼿段,财产,资⼒hamper v. 妨碍savannah n. ⼤草原juvenile adj. 青少年delinquency n. 犯罪 参考译⽂ 教育是我们这个时代的关键词之⼀。

新概念英语第四册课文word版

Lesson1We can read of things that happened 5,000 years ago in the , where people first learned to write. But there are some parts of the world where even now people cannot write. The only way that they can preserve their history is to recount it as sagas--legends handed down from one generation ofstory-tellers to another. These legends are useful because they can tell us something about migrations of people who lived long ago, but none could write down what they did. Anthropologists wondered where the remote ancestors of the Polynesian peoples now living in the came from. The sagas of these people explain that some of them came from about 2,000 years ago.But the first people who were like ourselves lived so long ago that even their sagas, if they had any, are forgotten. So archaeologists have neither history nor legends to help them to find out where the first 'modern men' came from.Fortunately, however, ancient men made tools of stone, especially flint, because this is easier to shape than other kinds. They may also have used wood and skins, but these have rotted away. Stone does not decay, and so the tools of long agohave remained when even the bones of the men who made them have disappeared without trace.Lesson2Why, you may wonder, should spiders be our friends ? Because they destroy so many insects, and insects include some of the greatest enemies of the human race. Insects would make it impossible for us to live in the world; they would devour all our crops and kill our flocks and herds, if it were not for the protection we get from insect-eating animals. We owe a lot to the birds and beasts who eat insects but all of them put together kill only a fraction of the number destroyed by spiders. Moreover, unlike some of the other insect eaters, spiders never do the least harm to us or our belongings.Spiders are not insects, as many people think, nor even nearly related to them. One can tell the difference almost at a glance for a spider always has eight legs and an insect never more than six.How many spiders are engaged in this work on our behalf ? One authority on spiders made a census of the spiders in a grassfield in the south of , and he estimated that there were more than one acre, that is something like 6,000,000 spiders of different kinds on a football pitch. Spiders are busy for at least half the year in killing insects. It is impossible to make more than the wildest guess at how many they kill, but they are hungry creatures, not content with only three meals a day. It has been estimated that the weight of all the insects destroyed by spiders in in one year would be greater than the total weight of all the human beings in the country.Lesson3Modern alpinists try to climb mountains by a route which will give them good sport, and the more difficult it is, the more highly it is regarded. In the pioneering days, however, this was not the case at all. The early climbers were looking for the easiest way to the top because the summit was the prize they sought, especially if it had never been attained before. It is true that during their explorations they often faced difficulties and dangers of the most perilous nature, equipped in a manner which would make a modern climber shudder at thethought, but they did not go out of their way to court such excitement. They had a single aim, a solitary goal--the top!It is hard for us to realize nowadays how difficult it was for the pioneers. Except for one or two places such as Zermatt and Chamonix, which had rapidly become popular, Alpine villages tended to be impoverished settlements cut off from civilization by the high mountains. Such inns as there were were generally dirty and flea-ridden; the food simply local cheese accompanied by bread often twelve months old, all washed down with coarse wine. Often a valley boasted no inn at all, and climbers found shelter wherever they could--sometimes with the local priest (who was usually as poor as his parishioners), sometimes with shepherds or cheese-makers. Invariably the background was the same: dirt and poverty, and very uncomfortable. For men accustomed to eating seven-course dinners and sleeping between fine linen sheets at home, the change to themust have been very hard indeed.Lesson4In the several cases have been reported recently of people who can read and detect colours with their fingers, and even see through solid doors and walls. One case concerns an'eleven-year-old schoolgirl, Vera Petrova, who has normal vision but who can also perceive things with different parts of her skin, and through solid walls. This ability was first noticed by her father. One day she came into his office and happened to put her hands on the door of a locked safe. Suddenly she asked her father why he kept so many old newspapers locked away there, and even described the way they were done up in bundles.Vera's curious talent was brought to the notice of a scientific research institute in the town of , near where she lives, and in April she was given a series of tests by a special commission of the Ministry of Health of the . During these tests she was able to read a newspaper through an opaque screen and, stranger still, by moving her elbow over a child's game of Lotto she was able to describe the figures and colours printed on it; and, in another instance, wearing stockings and slippers, to make out with her foot the outlines and colours of a picture hidden under a carpet. Other experiments showed that her knees and shoulders had a similar sensitivity. During all these testsVera was blindfold; and, indeed, except when blindfold she lacked the ability to perceive things with her skin. It was also found that although she could perceive things with her fingers this ability ceased the moment her hands were wet.Lesson5The gorilla is something of a paradox in the African scene. One thinks one knows him very well. For a hundred years or more he has been killed, captured, and imprisoned, in zoos. His bones have been mounted in natural history museums everywhere, and he has always exerted a strong fascination upon scientists and romantics alike. He is the stereotyped monster of the horror films and the adventure books, and an obvious (though not perhaps strictly scientific) linkwith our ancestral past.Yet the fact is we know very little about gorillas. No really satisfactory photograph has ever been taken of one in a wild state, no zoologist, however intrepid, has been able to keep the animal under close and constant observation in the dark jungles in which he lives. Carl Akeley, the American naturalist,led two expeditions in the nineteen-twenties, and now lies buried among the animals heloved so well. But even he was unable to discover how long the gorilla lives, or how or why it dies, nor was he able to define the exact social pattern of the family groups, or indicate the final extent of their intelligence. All this and many other things remain almost as much a mystery as they were when the French explorer Du Chaillu first described the animal to the civilized world a century ago. The Abominable Snowman who haunts the imagination of climbers in the is hardly more elusive.Lesson6People are always talking about' the problem of youth '. If there is one—which I take leave to doubt--then it is older people who create it, not the young themselves. Let us get down to fundamentals and agree that the young are after all human beings--people just like their elders. There is only one difference between an old man and a young one: the young man has a glorious future before him and the old one has a splendid future behind him: and maybe that is where the rub is.When I was a teenager, I felt that I was just young and uncertain--that I was a new boy in a huge school, and I would have been very pleased to be regarded as something so interesting as a problem. For one thing, being a problem gives you a certain identity, and that is one of the things the young are busily engaged in seeking.I find young people exciting. They have an air of freedom, and they have not a dreary commitment to mean ambitions or love of comfort. They are not anxious social climbers, and they have no devotion to material things. All this seems to me to link them with life, and the origins of things. It's as if they were in some sense cosmic beings in violent an lovely contrast with us suburban creatures. All that is in my mind when I meet a young person. He may be conceited, ill- mannered, presumptuous of fatuous, but I do not turn for protection to dreary cliches about respect for elders--as if mere age were a reason for respect. I accept that we are equals, and I will argue with him, as an equal, if I think he is wrong.Lesson7I am always amazed when I hear people saying that sport creates goodwill between the nations, and that if only the common peoples of the world could meet one another at football or cricket, they would have no inclination to meet on the battlefield. Even if one didn't know from concrete examples (the 1936 Olympic Games, for instance) that international sporting contests lead to orgies of hatred, one could deduce it from general principles.Nearly all the sports practised nowadays are competitive. You play to win, and the game has little meaning unless you do your utmost to win. On the village green, where you pick up sides and no feeling of local patriotism is involved, it is possible to play simply for the fun and exercise: but as soon as the question of prestige arises, as soon as you feel that you and some larger unit will be disgraced if you lose, the most savage combative instincts are aroused. Anyone who has played even in a school football match knows this. At the international level sport is frankly mimic warfare. But the significant thing is not the behaviour of the players but the attitude of the spectators: and, behind the spectators, of the nations. who work themselves into furies over these absurd contests, andseriously believe--at any rate for short periods--that running, jumping and kicking a ball are tests of national virtue.Lesson8Parents have to do much less for their children today than they used to do, and home has become much less of a workshop. Clothes can be bought ready made, washing can go to the laundry, food can be bought cooked, canned or preserved, bread is baked and delivered by the baker, milk arrives on the doorstep, meals can be had at the restaurant, the works' canteen, and the school dining-room.It is unusual now for father to pursue his trade or other employment at home, and his children rarely, if ever, see him at his place of work. Boys are therefore seldom trained to follow their father's occupation, and in many towns they have a fairly wide choice of employment and so do girls. The young wage-earner often earns good money, and soon acquires a feeling of economic independence. In textile areas it has long been customary for mothers to go out to work, but thispractice has become so widespread that the working mother is now a not unusual factor in a child's home life, the number of married women in employment having more than doubled in the last twenty-five years. With mother earning and his older children drawing substantial wages father is seldom the dominant figure that he still was at the beginning of the century. When mother workseconomic advantages accrue, but children lose something of great value if mother's employment prevents her from being home to greet them when they return from school.Lesson9Not all sounds made by animals serve as language, and we have only to turn to that extraordinary discovery ofecho-location in bats to see a case in which the voice plays a strictly utilitarian role.To get a full appreciation of what this means we must turn first to some recent human inventions. Everyone knows that if he shouts in the vicinity of a wall or a mountainside, an echo will come back. The further off this solid obstruction thelonger time will elapse for the return of the echo. A sound made by tapping on the hull of a ship will be reflected from the sea bottom, and by measuring the time interval between the taps and the receipt of the echoes the depth of the sea at that point can be calculated. So was born the echo-sounding apparatus, now in general use in ships. Every solid object will reflect a sound, varying ac- cording to the size and nature of the object. A shoal of fish will do this. So it is a comparatively simple step from locating the sea bottom to locating a shoal of fish. With experience, and with improved apparatus, it is now possible not only to locate a shoal but to tell if it is herring, cod, or other well-known fish, by the pattern of its echo .A few years ago it was found that certain bats emit squeaks and by receiving the echoes they could locate and steer clear of obstacles--or locate flying insects on which they feed. This echo-location in bats is often compared with radar, the principle of which is similar.Lesson10In our new society there is a growing dislike of original, creative men. The manipulated do not understand them; themanipulators fear them. The tidy committee men regard them with horror, knowing that no pigeonholes can be found for them. We could do with a few original, creative men in our political life—if only to create some enthusiasm, release someenergy--but where are they? We are asked to choose between various shades of the negative. The engine is falling to pieces while the joint owners of the car argue whether the footbrake or the handbrake should be applied. Notice how the cold, colourless men, without ideas and with no other passion but a craving for success, get on in this society, capturing one plum after another and taking the juice and taste out of them. Sometimes you might think the machines we worship make all the chief appointments, promoting the human beings who seem closest to them. Between mid-night and dawn, when sleep will not come and all the old wounds begin to ache, I often have a nightmare vision of a future world in which there are billions of people, all numbered and registered, with not a gleam of genius anywhere, not an original mind, a rich personality, on the whole packed globe. The twin ideals of our time, organization and quantity, will have won for ever.Lesson11Alfred the Great acted as his own spy, visiting Danish camps disguised as a minstrel. In those days wandering minstrels were welcome everywhere. They were not fighting men, and their harp was their passport. Alfred had learned many of their ballads in his youth, and could vary his programme with acrobatic tricks and simple conjuring.While Alfred's little army slowly began to gather at Athelney, the king himself set out to penetrate the camp of Guthrum, the commander of the Danish invaders. These had settled down for the winter at Chippenham: thither Alfred went. He noticed at once that discipline was slack: the Danes had the self-confidence of conquerors, and their security precautions were casual. They lived well, on the proceeds of raids on neighbouring regions. There they collected women as well as food and drink, and a life of ease had made them soft.Alfred stayed in the camp a week before he returned to Athelney. The force there assembled was trivial compared with the Danish horde. But Alfred had deduced that the Danes were no longer fit for prolonged battle : and that their commissariat had no organization, but depended on irregular raids.So, faced with the Danish advance, Alfred did not risk open battle but harried the enemy. He was constantly on the move, drawing the Danes after him. His patrols halted the raiding parties: hunger assailed the Danish army. Now Alfred began a long series of skirmishes--and within a month the Danes had surrendered. The episode could reasonably serve as a unique epic of royal espionage!Lesson12What characterizes almost all pictures is their inner emptiness. This is compensated for by an outer impressiveness. Such impressiveness usually takes the form of truly grandiose realism. Nothing is spared to make the setting, the costumes, all of the surface details correct. These efforts help to mask the essential emptiness of the characterization, and the absurdities and trivialities of the plots. The houses look like houses, the streets look like streets; the people look and talk like people; but they are empty of humanity, credibility, and motivation. Needless to say, the disgraceful censorship code is an important factor in predetermining the content of these pictures. But the code does not disturb the profits, nor theentertainment value of the films; it merely helps to prevent them from being credible. It isn't too heavy a burden for the industry to bear. In addition to the impressiveness of the settings, there is a use of the camera, which at times seems magical. But of what human import is all this skill, all this effort, all this energy in the production of effects, when the story, the representation of life is hollow, stupid, banal, childish ?Lesson13has been ruined by the motor industry. The peace which Oxford once knew, and which a great university city should always have, has been swept ruthlessly away; and no benefactions and research endowments can make up for the change in character which the city has suffered. At six in the morning the old courts shake to the roar of buses taking the next shift to Cowley and Pressed Steel, great lorries with a double deck cargo of cars for export lumber past Magdalen and the . Loads of motor-engines are hurried hither and thither and the streets are thronged with a population which has no interest in learningand knows no studies beyond servo-systems and distributors, compression ratios and camshafts.Theoretically the marriage of an old seat of learning and tradition with a new and wealthy industry might be expected to produce some interesting children. It might have been thought that the culture of the university would radiate out and transform the lives of the workers. That this has not happened may be the fault of the university, for at both and the colleges tend tolive in an era which is certainly not of the twentieth century, and upon a planet which bears little resemblance to the war-torn Earth. Wherever the fault may lie the fact remains that it is the theatre at Oxford and not at Cambridge which is on the verge of extinction, and the only fruit of the combination of industry and the rarefied atmosphere of learning is the dust in the streets, and a pathetic sense of being lost which hangs over some of the colleges.Lesson14Some old people are oppressed by the fear of death. In the young there is a justification for this feeling. Young men who have reason to fear that they will be killed in battle may justifiably feel bitter in the thought that they have been cheated of the best things that life has to offer. But in an old man who has known human joys and sorrows, and has achieved whatever work it was in him to do, the fear of death is somewhat abject and ignoble. The best way to overcome it- so at least it seems to me----is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river--small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past boulders and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The man who, in old age, can see his life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things he cares for will continue. And it, with the decay of vitality, weariness increases, the thought of rest will be not unwelcome. I should wish to die while still at work, knowing that others will carryon what I can no longer do, and content in the thought that what was possible has been done.Lesson15When anyone opens a current account at a bank, he is lending the bank money, repayment of which he may demand at any time, either in cash or by drawing a cheque in favour of another person. Primarily, the banker-customer relationship is that of debtor and creditor--who is which depending on whether the customer's account is in credit or is overdrawn. But, in addition to that basically simple concept, the bank and its customer owe a large number of obligations to one another. Many of these obligations can give rise to problems and complications but a bank customer, unlike, say, a buyer of goods, cannot complain that the law is loaded against him.The bank must obey its customer's instructions, and not those of anyone else. When, for example, a customer first opens an account, he instructs the bank to debit his account only in respect of cheques drawn by himself. He gives the bank specimens of his signature, and there is a very firm rule that the bank has no right or authority to pay out a customer's money on acheque on which its customer's signature has been forged. It makes no difference that the forgery may have been a very skilful one: the bank must recognize its customer's signature. For this reason there is no risk to the customer in the modern practice, adopted by some banks, of printing the customer's name on his cheques. If this facilitates forgery it is the bank which will lose, not the customer.Lesson16The deepest holes of all are made for oil, and they go down to as much as 25,000 feet. But we do not need to send men down to get the oil out, as we must with other mineral deposits. The holes are only borings, less than a foot in diameter. My particular experience is largely in oil, and the search for oil has done more to improve deep drilling than any other mining activity. When it has been decided where we are going to drill, we put up at the surface an oil derrick. It has to be tall because it is like a giant block and tackle, and we have to lower into the ground and haul out of the ground great lengths of drill pipe which are rotated by an engine at the top and are fitted with a cutting bit at the bottom.The geologist needs to know what rocks the drill has reached, so every so often a sample is obtained with a coring bit. It cuts a clean cylinder of rock, from which can be seen he strata the drill has been cutting through. Once we get down to the oil, it usually flows to the surface because great pressure, either from gas or water, is pushing it. This pressure must be under control, and we control it by means of the mud which we circulate down the drill pipe. We endeavour to avoid the old, romantic idea of a gusher, which wastes oil and gas. We want it to stay down the hole until we can lead it off in a controlled manner.Lesson17The fact that we are not sure what 'intelligence' is, nor what is passed on, does not prevent us from finding it a very useful working concept, and placing a certain amount of reliance on tests which 'measure' it.In an intelligence test we take a sample of an individual's ability to solve puzzles and problems of various kinds, and if we have taken a representative sample it will allow us to predict successfully the level of performance he will reach in a wide variety of occupations.This became of particular importance when, as a result of the 1944 Education Act, secondary schooling for all became law, and grammar schools, with the exception of a small number of independent foundation schools, became available to the whole population. Since the number of grammar schools in the country could accommodate at most approximately 25 per cent of the total child population of eleven-plus, some kind of selection had to be made. Narrowly academic examinations and tests were felt, quite rightly, to be heavily weighted in favour of children who had had the advantage of highly-academic primary schools and academically biased homes. Intelligence tests were devised to counteract this narrow specialization, by introducing problems which were not based on specifically scholastically-acquired knowledge. The intelligence test is an attempt to assess the general ability of any child to think, reason, judge, analyse and synthesize by presenting him with situations, both verbal and practical, which are within his range of competence and understanding.Lesson18Two factors weigh heavily against the effectiveness of scientific in industry. One is the general atmosphere of secrecy in which it is carried out, the other the lack of freedom of the individual research worker. In so far as any inquiry is a secret one, it naturally limits all those engaged in carrying it out from effective contact with their fellow scientists either in other countries or in universities, or even , often enough , in other departments of the same firm. The degree of secrecy naturally varies considerably. Some of the bigger firms are engaged in researches which are of such general and fundamental nature that it is a positive advantage to them not to keep them secret. Yet a great many processes depending on such research are sought for with complete secrecy until the stage at which patents can be taken out. Even more processes are never patented at all but kept as secret processes. This applies particularly to chemical industries, where chance discoveries play a much larger part than they do in physical and mechanical industries. Sometimes the secrecy goes to such an extent that the whole nature of the research cannot be mentioned. Many firms, for instance, have great difficulty in obtaining technical or scientific books from libraries because they are unwilling to have their names entered as having takenout such and such a book for fear the agents of other firms should be able to trace the kind of research they are likely to be undertaking.Lesson19A gentleman is, rather than does. He is interested in nothing in a professional way. He is allowed to cultivate hobbies, even eccentricities, but must not practise a vocation. He must know how to ride and shoot and cast a fly. He should have relatives in the army and navy and at least one connection in the diplomatic service. But there are weaknesses in the English gentleman's ability to rule us today. He usually knows nothing of political economy and less about how foreign countries are governed. He does not respect learning and prefers 'sport '. The problem set for society is not the virtues of the type so much as its adequacy for its function, and here grave difficulties arise. He refuses to consider sufficiently the wants of the customer, who must buy, not the thing he desires but the thing the English gentleman wants to sell. He attends inadequately to technological development. Disbelieving in the necessity of large-scale production in the modern world, he ispassionately devoted to excessive secrecy, both in finance and method of production. He has an incurable and widespread nepotism in appointment, discounting ability and relying upon a mystic entity called 'character,' which means, in a gentleman's mouth, the qualities he traditionally possesses himself. His lack of imagination and the narrowness of his social loyalties have ranged against him one of the fundamental estates of the realm. He is incapable of that imaginative realism which admits that this is a new world to which he must adjust himself and his institutions, that every privilege he formerly took as of right he can now attain only by offering proof that it is directly relevant to social welfare.Lesson20In the organization of industrial life the influence of the factory upon the physiological and mental state of the workers has been completely neglected. Modern industry is based on the conception of the maximum production at lowest cost, in order that an individual or a group of individuals may earn as much money as possible. It has expanded without any idea of the true nature of the human beings who run the machines, and without。

新概念英语第4册课文及译文

sgnieb nam uh eht lla fo thgiew latot eht naht retaerg eb dluow raey eno ni niatirB ni sredips yb deyortsed stcesni eht lla fo thgiew eht fo sre dips 000,000,6 ekil gnihtemos si taht ;erca eno ni 000,052,2 naht erom erew ereht taht detamitse eh dna ,dnalgnE fo htuos eht ni dleif ssarg ni sredips eht fo susnec a edam sredips no ytirohtua enO ?flaheb ruo on krow siht ni degagne era sredips ynam woH a rof ,e cnalg a ta tsomla ecnereffid eht llet nac enO .meht ot detaler ylraen neve ron ,kniht elpoep ynam sa ,stcesni ton era sredipS eht naht erom ekam ot elbissopmi si tI .stcesni gnillik ni raey eht flah tsael ta rof ysub era sredipS .hctip llabtoof a no sdnik tnereffid

sredluohs dna seenk reh taht dewohs stnemirepxe rehtO .teprac a rednu neddih erutcip a fo sruoloc dna seniltuo eht toof reh htiw tuo

新概念英语第4册课文及译文

新概念英语第4册课文及译文。

量重总的口人家国个这过超消中年一们它。

虫昆吃于忙在年半有少至蛛蜘。

蛛蜘的类种同不只万006 有约上场球足个一在说是就这。

蛛蜘只多万522 有里坪草亩英每计估他。

查调次一了作蛛蜘的上坪草块一部南国英对威权的蛛蜘究研位一呢力效们我为在蛛蜘少多有8 是都蛛蜘为因异差的者二出看能就眼一乎几们人。

系关无毫虫昆与至甚虫昆是不们它但虫昆是蛛蜘为认人多许。

条6 过超不从腿的虫昆而腿条量重的虫昆灭消所里年一蛛蜘国英在计估据。

餐三日一意满不物动的饱不吃是们它测猜法无直简们我虫昆少多了灭。

物财的们我和们我害危不毫丝们它物动虫食他其于同不蛛蜘外此。

分部小一的灭消所蛛蜘于当相只也起一在加部全虫昆的死杀所们它把而然兽和鸟的虫昆吃些那谢感分十要们我。

羊牛的群成的们我死杀稼庄部全的们我食吞会虫昆去下活生上球地在法无们我使会就虫昆护保的物动虫食些一受类人是不要敌大的类人些一括包中其虫昆的多么那灭消能们它为因呢友朋的们我是会么怎蛛蜘怪奇得觉会能可你 .yrtnuoc eht ni 文译考参sgnieb nam uh eht lla fo thgiew latot eht naht retaerg eb dluow raey eno ni niatirB ni sredips yb deyortsed stcesni eht lla fo thgiew eht fo sre dips 000,000,6 ekil gnihtemos si taht ;erca eno ni 000,052,2 naht erom erew ereht taht detamitse eh dna ,dnalgnE fo htuos eht ni dleif ssarg ni sredips eht fo susnec a edam sredips no ytirohtua enO ?flaheb ruo on krow siht ni degagne era sredips ynam woH a rof ,e cnalg a ta tsomla ecnereffid eht llet nac enO .meht ot detaler ylraen neve ron ,kniht elpoep ynam sa ,stcesni ton era sredipS eht naht erom ekam ot elbissopmi si tI .stcesni gnillik ni raey eht flah tsael ta rof ysub era sredipS .hctip llabtoof a no sdnik tnereffidtaht detam itse neeb sah tI .yad a slaem eerht ylno htiw tnetnoc ton ,serutaerc yrgnuh era yeht tub ,llik yehtynam woh ta sseug tsedliw.xis naht erom reven tcesni dna sgel thgie sah sy awla redipsdna sporc ruo lla ruoved dluow yeht ;dlrow eht ni evil ot su rof elbissopmi ti ekam dluow stcesnI .ecar namuh eht fo seimene tsetaerg eht fo emos edulcni stcesni dna ,stcesni ynam os yortsed yeht esuaceB ?sdneirf ruo eb sredips dluohs ,rednow yam uoy ,y hW 蛛蜘害伤要不redips taht erapS 2 nosseLohw stsaeb dna sdrib eht ot tol a ewo eW .slamina gnitae-tcesni morf teg ew noitcetorp eht rof ton erew ti fi ,sdreh dna skcolf ruo llikrehto e ht fo emos ekilnu ,revoeroM .sredips yb deyortsed rebmun eht fo noitcarf a ylno llik rehtegot tup meht fo lla tub stcesni tae.sgnignoleb ruo ro su ot mrah eht od reven sredips ,sretae tcesni。

(完整版)新概念英语第四册(中英对译)

$课文1 发现化石人1. We can read of things that happened 5,000 years ago in the Near East, where people first learned to write.我们从书籍中可读到5,000 年前近东发生的事情,那里的人最早学会了写字。

2. But there are some parts of the world where even now people cannot write.但直到现在,世界上有些地方,人们还不会书写。

3. The only way that they can preserve their history is to recount it as sagas -- legends handed down from one generation of story tales to another.他们保存历史的唯一办法是将历史当作传说讲述,由讲述人一代接一代地将史实描述为传奇故事口传下来。

4. These legends are useful because they can tell us something about migrations of people who lived long ago,这些传说是有用的,因为他们告诉我们很久以前生活在这里的移民的一些事情。

5. but none could write down what they did.但是没有人能写下来。

6. Anthropologists wondered where the remote ancestors of the Polynesian peoples now living in the Pacific Islands came from.人类学家过去不清楚如今生活在太平洋诸岛上的波利尼西亚人的祖先来自何方,7. The sagas of these people explain that some of them came from Indonesia about 2,000 years ago.当地人的传说却告诉人们:其中一部分是约在2,000年前从印度尼西亚迁来的。

新概念英语4 蓝思指数

新概念英语4 蓝思指数

新概念英语4(New Concept English 4)是新概念英语系列教材中的第四册,适用于英语学习的中高级阶段。

蓝思指数(Bloom's Taxonomy)是一个教育目标分类体系,用于描述学习者在认知、情感和心理动力三个领域的发展水平。

蓝思指数将认知目标分为六个层次,从低到高依次为:记忆、理解、应用、分析、评价和创造。

新概念英语4的蓝思指数如下:

1. 记忆:学习者需要记忆大量的词汇、短语和句型,以便在实际交流中能够熟练运用。

2. 理解:学习者需要理解课文内容,包括对文章主旨、细节和隐含意义的把握。

3. 应用:学习者需要将所学知识应用于实际情境,如写作、口语表达等。

4. 分析:学习者需要分析课文中的语言现象,如词汇搭配、句子结构等,以提高自己的语言运用能力。

5. 评价:学习者需要对自己的学习过程和成果进行评价,以便找出

问题并加以改进。

6. 创造:学习者需要运用所学知识进行创造性的表达,如撰写文章、发表演讲等。

综上所述,新概念英语4涵盖了蓝思指数的六个层次,有助于学习者全面提高英语能力。

电子书新概念英语第四册课文 中英

课文1 发现化石人1. We can read of things that happened 5,000 years ago in the Near East, where people first learned to write.我们从书籍中可读到5,000 年前近东发生的事情,那里的人最早学会了写字。

2. But there are some parts of the world where even now people cannot write.但直到现在,世界上有些地方,人们还不会书写。

3. The only way that they can preserve their history is to recount it as sagas -- legends handed down from one generation of story tales to another.他们保存历史的唯一办法是将历史当作传说讲述,由讲述人一代接一代地将史实描述为传奇故事口传下来。

4. These legends are useful because they can tell us something about migrations of people who lived long ago,这些传说是有用的,因为他们告诉我们很久以前生活在这里的移民的一些事情。

5. but none could write down what they did.但是没有人能写下来。

6. Anthropologists wondered where the remote ancestors of the Polynesian peoples now living in the Pacific Islands came from.人类学家过去不清楚如今生活在太平洋诸岛上的波利尼西亚人的祖先来自何方,7. The sagas of these people explain that some of them came from Indonesia about 2,000 years ago.当地人的传说却告诉人们:其中一部分是约在2,000年前从印度尼西亚迁来的。

新概念英语第四册课文翻译及学习笔记:Lesson4

新概念英语第四册课文翻译及学习笔记:Lesson4【课文】First listen and then answer the following question.听录音,然后回答以下问题。

How does the writer like to treat young people?People are always talking about 'the problem of youth'.If there is one--which I take leave to doubt -- then it is older people who create it, not the young themselves. Let us get down to fundamentals and agree that the young are afterall human beings--people just like their elders. There isonly one difference between an old man and a young one: the young man has a glorious future before him and the old onehas a splendid future behind him: and maybe that is wherethe rub is.When I was a teenager, I felt that I was just young and uncertain--that I was a new boy in a huge school, and I would have been very pleased to be regarded as something so interesting as a problem. For one thing, being a problemgives you a certain identity, and that is one of the thingsthe young are busily engaged in seeking.I find young people exciting. They have an air of freedom, and they have not a dreary commitment to mean ambitions orlove of comfort. They are not anxious social climbers, andthey have no devotion to material things. All this seems tome to link them with life, and the origins of things. It's as if they were, in some sense, cosmic beings in violent and lovely contrast with us suburban creatures. All that is in mymind when I meet a young person. He may be conceited, ill-mannered, presumptuous or fatuous, but I do not turn for protection to dreary cliches about respect for elders -- as if mere age were a reason for respect. I accept that we are equals, and I will argue with him, as an equal, if I think he is wrong.FIELDEN HUGHES from Out of the Air, The Listene【New words and expressions 生词和短语】leave n. 允许fundamentals n. 基本原则glorious adj. 光辉灿烂的splendid adj. 灿烂的rub n. 难题identity n. 身份dreary adj. 沉郁的commitment n. 信奉mean adj. 吝啬,小气social climber 追求更高社会地位的,向上爬的人devotion n. 热爱cosmic adj. 宇宙的suburban adj. 见识不广的,偏狭的conceited adj. 自高自大的presumptuous adj. 自以为是的,放肆的fatuous adj. 愚蠢的cliche n. 陈词滥调【课文注释】1. which I take leave to doubt,这是一个插入成分,用两个破折号与句子的主要部分分开。

新概念英语第四课

Lesson 4 10 His ______ kept his secret. (1. 12) a.brothers b.workmates c.companions d.comrades

Lesson 4

11 His rise in status more than ______ the loss of money. (11. 14-15)

a.pays back b.rewards c.makes for d.values

Lesson 4

12 He wanted to be ______ ‘Mr. Bloggs’, not‘Alf’. (11. 15-16)

a.addressed as b.named c.cried out d.shouted

Ellesmere Corporation? (He was a dustman.) 7 Was Alf married? (Yes, he was.) 8 What did Alf fail to tell his wife? (That he was a dustman.)

Lesson 4 9 How did he dress every morning? (In a smart black suit.) 10 What did he change into when he got to

New Concept English

Lesson Four

The double life of Alfred Bloggs

Lesson 4 The double life of Alfred Bloggs

Lesson 4

新版新概念英语音频资料英音版、美音版下载

新版新概念英语全四册CD转128 Kbps高音质MP3(英音版)下载大家都知道《新概念英语》。

新概念英语英音版比较好听,比平淡无节奏的美音版更有抑扬顿挫之感.新版新概念英语英音版全套MP3为2007年北京外语音像出版社出版的全4册11张CD无损转换而成,为网络上最清晰的版本。

打开Web迅雷,点击左侧的[新建]按钮会弹出"新的下载"对话框.然后在"网址(URL)"文本框处添加以下网址即可.新版新概念英语第一册(英音)MP3文件大小:85.13MBURL:thunder://QUFmdHA6Ly8yMTAuNTEuMTgwLjI1Mi9jbHViL25jZS/QwrDm0MK4xcTu06 LT78irNLLh06LS9ENE16pNUDMv0MKw5tDCuMXE7tOi0++12tK7suEo06LS9ClNUDNbd3d3 LlRvcFNhZ2UuY29tXS5yYXJaWg==新版新概念英语第二册(英音)MP3文件大小:137.01MBURL:thunder://QUFmdHA6Ly8yMTAuNTEuMTgwLjI1Mi9jbHViL25jZS/QwrDm0MK4xcTu06 LT78irNLLh06LS9ENE16pNUDMv0MKw5tDCuMXE7tOi0++12rb+suEo06LS9ClNUDNbd3d3 LlRvcFNhZ2UuY29tXS5yYXJaWg==新版新概念英语第三册(英音)MP3文件大小:134.87MBURL:thunder://QUFmdHA6Ly8yMTAuNTEuMTgwLjI1Mi9jbHViL25jZS/QwrDm0MK4xcTu06 LT78irNLLh06LS9ENE16pNUDMv0MKw5tDCuMXE7tOi0++12sj9suEo06LS9ClNUDNbd3d3 LlRvcFNhZ2UuY29tXS5yYXJaWg==新版新概念英语第四册(英音)MP3文件大小:129.14MBURL:thunder://QUFmdHA6Ly8yMTAuNTEuMTgwLjI1Mi9jbHViL25jZS/QwrDm0MK4xcTu06 LT78irNLLh06LS9ENE16pNUDMv0MKw5tDCuMXE7tOi0++12svEsuEo06LS9ClNUDNbd3d3 LlRvcFNhZ2UuY29tXS5yYXJaWg==128 Kbps高音质MP3,毫无杂音!!!强烈推荐!!!请大家用Web迅雷下载。

新概念英语4答案

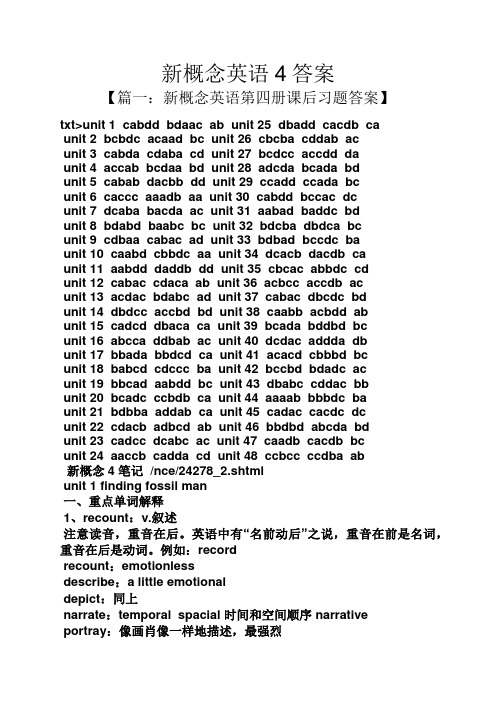

新概念英语4答案【篇一:新概念英语第四册课后习题答案】txt>unit 1 cabdd bdaac ab unit 25 dbadd cacdb caunit 2 bcbdc acaad bc unit 26 cbcba cddab acunit 3 cabda cdaba cd unit 27 bcdcc accdd daunit 4 accab bcdaa bd unit 28 adcda bcada bdunit 5 cabab dacbb dd unit 29 ccadd ccada bcunit 6 caccc aaadb aa unit 30 cabdd bccac dcunit 7 dcaba bacda ac unit 31 aabad baddc bdunit 8 bdabd baabc bc unit 32 bdcba dbdca bcunit 9 cdbaa cabac ad unit 33 bdbad bccdc baunit 10 caabd cbbdc aa unit 34 dcacb dacdb caunit 11 aabdd daddb dd unit 35 cbcac abbdc cdunit 12 cabac cdaca ab unit 36 acbcc accdb acunit 13 acdac bdabc ad unit 37 cabac dbcdc bdunit 14 dbdcc accbd bd unit 38 caabb acbdd abunit 15 cadcd dbaca ca unit 39 bcada bddbd bcunit 16 abcca ddbab ac unit 40 dcdac addda dbunit 17 bbada bbdcd ca unit 41 acacd cbbbd bcunit 18 babcd cdccc ba unit 42 bccbd bdadc acunit 19 bbcad aabdd bc unit 43 dbabc cddac bbunit 20 bcadc ccbdb ca unit 44 aaaab bbbdc baunit 21 bdbba addab ca unit 45 cadac cacdc dcunit 22 cdacb adbcd ab unit 46 bbdbd abcda bdunit 23 cadcc dcabc ac unit 47 caadb cacdb bcunit 24 aaccb cadda cd unit 48 ccbcc ccdba ab新概念4 笔记 /nce/24278_2.shtmlunit 1 finding fossil man一、重点单词解释1、recount:v.叙述注意读音,重音在后。

新概念第四册课文翻译及学习笔记【Lesson4、5、6】

【导语】新概念英语作为⼀套世界闻名的英语教程,以其全新的教学理念,有趣的课⽂内容和全⾯的技能训练,深受⼴⼤英语学习者的欢迎和喜爱。

为了⽅便同学们的学习,为⼤家整理了⾯的新概念第四册课⽂翻译及学习笔记,希望为⼤家的新概念英语学习提供帮助!Lesson4【课⽂】First listen and then answer the following question.听录⾳,然后回答以下问题。

How did Vera discover she had this gift of second sight?Several cases have been reported in Russia recently of people who can read and detect colours with their fingers, and even see through solid doors and walls. One case concerns an eleven-year-old schoolgirl, Vera Petrova, who has normal vision but who can also perceive things with different parts of her skin, and through solid walls. This ability was first noticed by her father. One day she came into his office and happened to put her hands on the door of a locked safe. Suddenly she asked her father why he kept so many old newspapers locked away there, and even described the way they were done up in bundles.Vera's curious talent was brought to the notice of a scientific research institute in the town of Ulyanovsk, near where she lives, and in April she was given a series of tests by a special commission of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federal Republic. During these tests she was able to read a newspaper through an opaque screen and, stranger still, by moving her elbow over a child's game of Lotto she was able to describe the figures and colours printed on it; and, in another instance, wearing stockings and slippers, to make out with her foot the outlines and colours of a picture hidden under a carpet. Other experiments showed that her knees and shoulders had a similar sensitivity. During all these tests Vera was blindfold; and, indeed, except when blindfold she lacked the ability to perceive things with her skin. It was also found that although she could perceive things with her fingers this ability ceased the moment her hands were wet.ERIC DE MAUNY Seeing hands from The Listener【New words and expressions ⽣词和短语】solid adj. 坚实的safe n. 保险柜ulyanovsk n. 乌⾥扬诺夫斯克commission n. 委员会opaque adj. 不透明的lotto n. ⼀种有编号的纸牌slipper n. 拖鞋blindfold adj.& adv. 被蒙上眼睛的【课⽂注释】1. of people who can read...,这个定语从句⽤来修饰主语cases,由于太长,因此被移⾄谓语之后。

新概念英语4

He worked _f_o_r_/__in__ a middle school. He worked ___a__s___ a teacher in a middle school.

2. Where is he now? He is in _A__l_i_c_e___S__p__r_i_n_g__s____ now.

Text

1. I have just received a letter from my brother, Tim.

语法:have just received 为本课重点学习时态: __现__在__完__成__时___(详见重点语法)

have been there 表示___待__在__那__里__

4. Tim is an engineer. He is working for a big firm and he has already visited a great number of different places in Australia.

翻译: 我们刚刚寄掉这些明信片。 _W__e__h_a_v_e__ju__s_t_s_e_n_t__th_e__s_e_p__o_s_tc_a__rd__s_. _ 他已经把所有词典都借给你了。 _H_e__h_a_s__a_lr_e_a_d_y__l_e_n_t_a_l_l_h_i_s_d__ic_t_i_o_n_a_r_ie__s_t_o__y_o_u. 我之前从未见过你。 _I_h_a__v_e_n__e_v_e_r_s_e_e_n__y_o__u_b__e_f_o_r_e_. _

新概念4单词Word完整版+音标+词意

新概念4单词Word完整版+音标+词意fossil man adj. /ˈfɒsl/ /mæn/化石人recount v. /ˌriːˈkaʊnt/叙述saga n. /ˈsɑːgə/英雄故事legend n. /ˈlɛʤənd/传说,传奇migration n. /maɪˈgreɪʃən/迁移,移居anthropologist n. /ˌænθrəˈpɒləʤɪst/人类学家archaeologist n. /ˌɑːkɪˈɒləʤɪst/考古学家ancestor n. /ˈænsɪstə/祖先Polynesian adj. /ˌpɒlɪˈniːʒən/波利尼西亚(中太平洋之一群岛)的Indonesia n. /ˌɪndəˈnɪzɪə/印度尼西亚flint n. /flɪnt/燧石rot n. /rɒt/烂掉beast n. /biːst/野兽census n. /ˈsɛnsəs/统计数字acre n. /ˈeɪkə/英亩content adj. /ˈkɒntɛnt/满足的Matterhorn n. Matterhorn马特霍恩峰(阿尔卑斯山之一,在意大利和瑞士边境)alpinist n. /ˈælpɪnɪst/登山运动员pioneer v. n. /ˌpaɪəˈnɪə/开辟,倡导;先锋,开辟者summit n. /ˈsʌmɪt/顶峰attain v. /əˈteɪn/到达perilous adj. /ˈpɛrɪləs/危险的shudder v. /ˈʃʌdə/不寒而栗court v. /kɔːt/追求solitary adj. /ˈsɒlɪtəri/唯一的impoverish v. /ɪmˈpɒvərɪʃ/使贫困Alpine adj. /ˈælpaɪn/阿尔卑斯山的flea-ridden adj. /fliː/-/ˈrɪdn/布满跳蚤的coarse adj. /kɔːs/粗劣的boast v. /bəʊst/自恃有parishioner n. /pəˈrɪʃənə/教区居民shepherd n. /ˈʃɛpəd/牧羊人linen n. /ˈlɪnɪn/亚麻布床单the Alps n. /ði/ /ælps/阿尔卑斯山脉solid adj. /ˈsɒlɪd/坚实的safe n. /seɪf/保险柜Ulyanovsk n. /ʊˈljɑːnəfsk/乌里扬诺夫斯克commission n. /kəˈmɪʃən/委员会opaque adj. /əʊˈpeɪk/不透明的lotto n. /ˈlɒtəʊ/一种有编号的纸牌slipper n. /ˈslɪpə/拖鞋blindfold adj.& adv. /ˈblaɪndfəʊld/被蒙上眼睛的leave n. /liːv/允许fundamentals n. /ˌfʌndəˈmɛntlz/基本原则glorious adj. /ˈglɔːrɪəs/光辉灿烂的splendid adj. /ˈsplɛndɪd/灿烂的rub n. /rʌb/难题identity n. /aɪˈdɛntɪti/身份dreary adj. /ˈdrɪəri/沉郁的commitment n. /kəˈmɪtmənt/信奉mean adj. /miːn/吝啬,小气social climber /ˈsəʊʃəl/ /ˈklaɪmə/追求更高社会地位的,向上爬的人devotion n. /dɪˈvəʊʃən/热爱cosmic adj. /ˈkɒzmɪk/宇宙的suburban adj. /səˈbɜːbən/见识不广的,偏狭的conceited adj. /kənˈsiːtɪd/自高自大的presumptuous adj. /prɪˈzʌmptjʊəs/自以为是的,放肆的fatuous adj. /ˈfætjʊəs/愚蠢的cliche n. /ˈkliːʃeɪ/陈词滥调goodwill n. /ˈgʊdˈwɪl/友好cricket n. /ˈkrɪkɪt/板球inclination n. /ˌɪnklɪˈneɪʃən/意愿contest n. /ˈkɒntɛst/比赛orgy n. /ˈɔːʤi/无节制的,放荡deduce v. /dɪˈdjuːs/推断competitive adj. /kəmˈpɛtɪtɪv/竞争性的patriotism n. /ˈpætrɪətɪzm/地方观念,爱国主义disgrace v. /dɪsˈgreɪs/使丢脸savage adj. /ˈsævɪʤ/野性的combative adj. /ˈkɒmbətɪv/好斗的mimic warfare /ˈmɪmɪk/ /ˈwɔːfeə/模拟战争behaviour n. /bɪˈheɪvjə/行动,举止absurd adj. /əbˈsɜːd/荒唐的bat n. /bæt/蝙蝠strictly adv. /ˈstrɪktli/明确地utilitarian adj./ˌjuːtɪlɪˈteərɪən/实用的appreciation n. /əˌpriːʃɪˈeɪʃ(ə)n/评价,感激elapse v. /ɪˈlæps/消逝hull n. /hʌl/船体interval n. /ˈɪntəvəl/间隔receipt n. /rɪˈsiːt/收到apparatus n. /ˌæpəˈreɪtəs/仪器shoal n. /ʃəʊl/鱼群herring n. /ˈhɛrɪŋ/鲱(又称青鱼)cod n. /kɒd/鳕鱼squeak n. /skwiːk/尖叫声slaughter v. /ˈslɔːtə/屠宰fit adj. /fɪt/适合grace v. /greɪs/...给增光tariff n. /ˈtærɪf/关税standard n. /ˈstændəd/标准dialysis n. /daɪˈælɪsɪs/分离,分解;透析,渗析electrocute v. /ɪˈlɛktrəkjuːt/使触电身亡eliminate v. /ɪˈlɪmɪneɪt/消灭accord n. /əˈkɔːd/协议device n. /dɪˈvaɪs/仪器,器械hammer out v. /ˈhæmər/ /aʊt/推敲pact n. /pækt/合同,条约,公约espionage n. /ˌɛspɪəˈnɑːʒ/间谍活动Alfred /ˈælfrəd/公元871-899年间任英国国王Danish adj. /ˈdeɪnɪʃ/丹麦的,丹麦人的,丹麦语的minstrel n. /ˈmɪnstrəl/中世纪的吟游歌手wandering adj. /ˈwɒndərɪŋ/漫游的harp n. /hɑːp/坚琴ballad n. /ˈbæləd/民歌acrobatic adj. /ˌækrəʊˈbætɪk/杂技的conjuring n. /ˈkʌnʤərɪŋ/魔术Athelney n. Athelney阿塞尔纳(英国一个小岛)Chippenham n. Chippenham切本哈姆(英国一个城市)thither adv. /ˈðɪðə/向那里Dane n. /deɪn/丹麦人slack adj. /slæk/涣散的conqueror n. /ˈkɒŋkərə/征服者casual adj. /ˈkæʒjʊəl/马虎的,随便的precaution n. /prɪˈkɔːʃən/预防,警惕proceeds n. /ˈprəʊsiːdz/所得assemble v. /əˈsɛmbl/集合trivial adj. /ˈtrɪvɪəl/微不足道的prolonged adj. /prəʊˈlɒŋd/持久的commissariat n. /ˌkɒmɪˈseərɪət/军粮供应episode n. /ˈɛpɪsəʊd/一个事件,片断epic n. /ˈɛpɪk/史诗harry v. /ˈhæri/骚扰assail v. /əˈseɪl/袭击skirmish n. /ˈskɜːmɪʃ/小规模战斗silicon n. /ˈsɪlɪkən/硅integrated adj. /ˈɪntɪgreɪtɪd/综合的circuit n. /ˈsɜːkɪt/线路,电路California n. /ˌkæləˈfɔːniə/加利福尼亚(美国州名)workstation n. /ˈwɜːkˌsteɪʃ(ə)n/工作站chip n. /ʧɪp/芯片,集成电路片,集成块newsletter n. /ˈnjuːzˌlɛtə/时事通讯Macintosh n. /ˈmækɪntɒʃ/苹果机,一种个人电脑penalize v. /ˈpiːnəlaɪz/处罚,惩罚customize v. /ˈkʌstəˌmaɪz/按顾客具体需要制造spawn v. /spɔːn/引起,酿成thrive v. /θraɪv/兴旺,繁荣anarchy n. /ˈænəki/无政府状态,混乱oriental n. /ˌɔːrɪˈɛnt(ə)l/东方人constitute v. /ˈkɒnstɪtjuːt/构成drove n. /drəʊv/群innovator n. /ˈɪnəʊveɪtə/发明者forge v. /fɔːʤ/发展memory-chip n. /ˈmɛməri/-/ʧɪp/内存条AT & T/æt/&/tiː/美国电话电报公司() Kansas n. /ˈkænzəs/堪萨斯(美国州名)Missouri n. /mɪˈzʊəri/密苏里(美国州名)oppress v. /əˈprɛs/忧郁,压抑justification n. /ˌʤʌstɪfɪˈkeɪʃən/正当理由justifiably adv. /ˈʤʌstɪfaɪəbli/无可非议地cheat v. /ʧiːt/欺骗abject adj. /ˈæbʤɛkt/可怜的ignoble adj. /ɪgˈnəʊbl/不体面的,可耻的impersonal adj. /ɪmˈpɜːsnl/超脱个人感情影响的ego n. /ˈɛgəʊ/自我receded v. /ri(ː)ˈsiːdɪd/退去increasing adv. /ɪnˈkriːsɪŋ/日益,不断passionately adv. /ˈpæʃənɪtli/激昂地painlessly adv. /ˈpeɪnlɪsli/毫无痛苦地vitality n. /vaɪˈtælɪti/精力weariness n. /ˈwɪərɪnɪs/疲惫感current adj. /ˈkʌrənt/通用的,流行的account n. /əˈkaʊnt/账户cash n. /kæʃ/现金debtor n. /ˈdɛtə/支票debtor n. /ˈdɛtə/借方creditor n. /ˈkrɛdɪtə/贷方obligation n. /ˌɒblɪˈgeɪʃən/义务complication n. /ˌkɒmplɪˈkeɪʃən/纠纷debit v. .../ˈdɛbɪt/把记入借方specimen n. /ˈspɛsɪmɪn/样本forge v. /fɔːʤ/伪造forgery n. /ˈfɔːʤəri/伪造(文件,签名等)adopt v. /əˈdɒpt/采用facilitate v. /fəˈsɪlɪteɪt/使便利mineral adj. /ˈmɪnərəl/矿物的boring n. /ˈbɔːrɪŋ/钻孔derrick n. /ˈdɛrɪk/井架block and tackle /blɒk/ /ænd/ /ˈtækl/滑轮组haul v. /hɔːl/拖,拉rotate v. /rəʊˈteɪt/使转动cutting bit /ˈkʌtɪŋ/ /bɪt/钻头geologist n. /ʤɪˈɒləʤɪst/地质学家coring /ˈkɔːrɪŋ/取芯钻头cylinder n. /ˈsɪlɪndə/圆柱体strata n. /ˈstrɑːtə/岩层[复]([单]或[误用]) circulate v. /ˈsɜːkjʊleɪt/注入,环流gusher n. /ˈgʌʃə/喷油井forecast n. /ˈfɔːkɑːst/预报speculative adj. /ˈspɛkjʊlətɪv/推测的blizzard n. /ˈblɪzəd/暴风雪deteriorate v. /dɪˈtɪərɪəreɪt/变坏multiply v. /ˈmʌltɪplaɪ/增加cascade v. /kæsˈkeɪd/瀑布似地落下turbulent adj. /ˈtɜːbjʊlənt/狂暴的dust devil /dʌst/ /ˈdɛvl/小尘暴,尘旋风squall n. /skwɔːl/暴风eddy n. /ˈɛdi/旋涡grid n. /grɪd/坐标方格sensor n. /ˈsɛnsə/传感器humidity n. /hju(ː)ˈmɪdɪti/温度meteorologist n. /ˌmiːtiəˈrɒləʤɪst/气象学家Princeton n. /ˈprɪnstən/普林斯顿(美国城市名)New Jersey n. /njuː/ /ˈʤɜːzi/新泽西(美国州名)fluctuation n. /ˌflʌktjʊˈeɪʃən/起伏,波动deviation n. /ˌdiːvɪˈeɪʃən/偏差secrecy n. /ˈsiːkrɪsi/秘密effectiveness n. /ɪˈfɛktɪvnəs/成效,效力inquiry n. /ɪnˈkwaɪəri/调查研究positive adj. /ˈpɒzətɪv/确实的process n. /ˈprəʊsɛs/过程patent n. v. /ˈpeɪtənt/专利;得到专利权agent n. /ˈeɪʤənt/情报人员physiological adj. /ˌfɪzɪəˈlɒʤɪkəl/生理的maximum adj. /ˈmæksɪməm/最大限度的consideration n. /kənˌsɪdəˈreɪʃən/考虑descendant n. /dɪˈsɛndənt/子孙,后代artificial n. /ˌɑːtɪˈfɪʃ(ə)l/人工的impose v. /ɪmˈpəʊz/强加dimension n. /dɪˈmɛnʃən/直径skyscraper n. /ˈskaɪˌskreɪpə/摩天大楼tenant n. /ˈtɛnənt/租户civilized adj. /ˈsɪvɪlaɪzd/文明的banal adj. /bəˈnɑːl/平庸luxury n. /ˈlʌkʃəri/豪华deprive v. /dɪˈpraɪv/剥夺monstrous adj. /ˈmɒnstrəs/畸形的edifice n. /ɛˈdɪfɪs/大厦toxic adj. /ˈtɒksɪk/有毒的ceaselessly adv. /ˈsiːslɪsli/不停地throng v. /θrɒŋ/挤满,壅塞settlement n. /ˈsɛtlmənt/新拓居地enterprising adj. /ˈɛntəpraɪzɪŋ/有事业心的settler n. /ˈsɛtlə/移居者Antipodes n. /ænˈtɪpədiːz/新西兰和澳大利亚(英)promiscuous adj. /prəˈmɪskjʊəs/杂乱的abandon n. /əˈbændən/放任,纵情overrun v. /ˌəʊvəˈrʌn/蔓延,泛滥devastation n. /ˌdɛvəsˈteɪʃən/破坏,劫掠burrow v. /ˈbɜːrəʊ/挖、掘susceptible adj. /səˈsɛptəbl/易受感染的virus n. /ˈvaɪərəs/病毒myxomatosis n. myxomatosis多发性粘液瘤infect v. /ɪnˈfɛkt/传染epidemic n. /ˌɛpɪˈdɛmɪk/流行病mosquito n. /məsˈkiːtəʊ/蚊虫carrier n. /ˈkærɪə/带菌者exterminate v. /ɪksˈtɜːmɪneɪt/消灭ironically adv. /aɪˈrɒnɪkəli/具有讽刺意味地bequeath v. /bɪˈkwiːð/...把传给pest n. /pɛst/害虫,有害动物pestilence n. /ˈpɛstɪləns/瘟疫confine n. /kənˈfaɪn/范围domesticate v. /dəʊˈmɛstɪkeɪt/驯养porpoise n. /ˈpɔːpəs/海豚mariner n. /ˈmærɪnə/水手shark n. /ʃɑːk/鲨鱼formation n. /fɔːˈmeɪʃən/队形dolphin n. /ˈdɒlfɪn/海豚科动物unconscious adj. /ʌnˈkɒnʃəs/不省人事beaver n. /ˈbiːvə/海狸ashore adv. /əˈʃɔː/上岸waterlogged adj. /ˈwɔːtəlɒgd/浸满水的scent n. /sɛnt/香味ensue v. /ɪnˈsjuː/接着发生intrigue v. /ɪnˈtriːg/引起兴趣indignity n. /ɪnˈdɪgnɪti/侮辱snout n. /snaʊt/口鼻部shove v. /ʃʌv/硬推aquaplane n. /ˈækwəpleɪn/驾浪滑水板oceanarium n. oceanarium水族馆swoop v. /swuːp/猛扑belly n. /ˈbɛli/腹部equilibrium n. /ˌiːkwɪˈlɪbrɪəm/平衡butt v. /bʌt/碰撞crack n. /kræk/重击speculation n. /ˌspɛkjʊˈleɪʃən/推测literally adv. /ˈlɪtərəli/确实odd adj. /ɒd/奇特的tissue n. /ˈtɪʃuː/组织plausible adj. /ˈplɔːzəbl/似乎有理的hypothesis n. /haɪˈpɒθɪsɪs/假说electroencephalograph n. /ɪ,lektrəʊɪn'sef(ə)ləgrɑːf/ 脑电图仪electrode n. /ɪˈlɛktrəʊd/电极scalp n. /skælp/头皮psychiatrist n. /saɪˈkaɪətrɪst/精神病学家punctuate v. /ˈpʌŋktjʊeɪt/不时介入jerky adj. /ˈʤɜːki/急动的disorder n. /dɪsˈɔːdə/失调implication n. /ˌɪmplɪˈkeɪʃən/表明saliva n. /səˈlaɪvə/唾液digestive adj. /dɪˈʤɛstɪv/助消化的defy v. /dɪˈfaɪ/使不可能analysis n. /əˈnæləsɪs/分析prey n. /preɪ/被捕食的动物fierce adj. /fɪəs/凶猛的tussle n. /ˈtʌsl/扭打carnivore n. /ˈkɑːnɪvɔː/食肉动物vertebrate n. /ˈvɜːtɪbrɪt/脊椎动物lizard n. /ˈlɪzəd/蜥蜴concoct v. /kənˈkɒkt/调制potency n. /ˈpəʊtənsi/效力conversion n. /kənˈvɜːʃən/转变arsenic n. /ˈɑːsnɪk/砒霜strychnine n. /ˈstrɪkniːn/马钱子碱mamba n. /ˈmæmbə/树眼镜蛇cobra n. /ˈkəʊbrə/眼镜蛇venom n. /ˈvɛnəm/毒液neurotoxic adj. neurotoxic毒害神经的viper n. /ˈvaɪpə/蝰蛇adder n. /ˈædə/蝮蛇rattlesnake n. /ˈrætlsneɪk/响尾蛇haemolytic adj. haemolytic溶血性的viperine adj. viperine毒蛇Supreme adj. /sju(ː)ˈpriːm/首屈一指protagonist n. /prəʊˈtægənɪst/主角outlaw n. /ˈaʊtlɔː/逃犯,亡命之徒framed adj. /freɪmd/遭到陷害的vicious adj. /ˈvɪʃəs/恶毒的mythology n. /mɪˈθɒləʤi/神话vanished adj. /ˈvænɪʃt/消失了的absurdly adv. /əbˈsɜːdli/荒诞地arena n. /əˈriːnə/竞技场在encroaching adj. /ɪnˈkrəʊʧɪŋ/渐渐渗入的Indian n. /ˈɪndiən/印第安人bewilder v. /bɪˈwɪldə/使手足无措alien adj. /ˈeɪliən/外来的taboo n. /təˈbuː/戒律disinherit v. /ˌdɪsɪnˈhɛrɪt/剥夺继承权undeclared adj. /ˌʌndɪˈkleəd/未经宣布的hypocrisy n. /hɪˈpɒkrəsi/伪善chicanery n. /ʃɪˈkeɪnəri/诈骗impending adj. /ɪmˈpɛndɪŋ/迫近的,近在眉睫的immolation n. /ˌɪməʊˈleɪʃən/杀戮code n. /kəʊd/准则loom v. /luːm/赫然耸起manifest adj./ˈmænɪfɛst/明显的morality n. /məˈrælɪti/道德communicate v. /kəˈmjuːnɪkeɪt/交流,交际compound adj. /ˈkɒmpaʊnd/复合的enhance v. /ɪnˈhɑːns/增进tempo n. /ˈtɛmpəʊ/速率trickle n. /ˈtrɪkl/涓涓细流torrent n. /ˈtɒrənt/滔滔洪流humanity n. /hju(ː)ˈmænɪti/人类indifferently adv. /ɪnˈdɪfrəntli/不在乎地grimly adv. /ˈgrɪmli/可怖地whimsical adj. /ˈwɪmzɪkəl/怪诞的shatter v. /ˈʃætə/毁坏twofold adj. /ˈtuːfəʊld/双重的albatross n. /ˈælbətrɒs/信天翁sustenance n. /ˈsʌstɪnəns/支撑力glider n. /ˈglaɪdə/滑翔者harness v. /ˈhɑːnɪs/利用endow v. /ɪnˈdaʊ/赋有ply v. /plaɪ/不断地供给gale n. /geɪl/大风partridge n. /ˈpɑːtrɪʤ/鹧鸪like adj. /laɪk/类似的propulsion n. /prəˈpʌlʃən/推进力utter adj. /ˈʌtə/完全的slip v. /slɪp/滑行adverse adj. /ˈædvɜːs/逆的,相反的omen n. /ˈəʊmɛn/预兆intense adj. /ɪnˈtɛns/强烈的aesthetic adj. /iːsˈθɛtɪk/审美的realm n. /rɛlm/世界serenity n. /sɪˈrɛnɪti/静谧undeniable adj. /ˌʌndɪˈnaɪəbl/不可否认的indefinable adj. /ˌɪndɪˈfaɪnəbl/模糊不清的vulgar adj. /ˈvʌlgə/平庸的radiance n. /ˈreɪdiəns/发光intimation n. /ˌɪntɪˈmeɪʃən/暗示unutterable adj. /ʌnˈʌtərəbl/不可言传的invest v. /ɪnˈvɛst/赋予auditory adj. /ˈɔːdɪtəri/听觉的inadequate adj. /ɪnˈædɪkwɪt/不适当的plea n. /pliː/要求abatement n. /əˈbeɪtmənt/减少discredit v. /dɪsˈkrɛdɪt/怀疑allegation n. /ˌælɪˈgeɪʃ(ə)n/断言caption n. /ˈkæpʃən/插图说明wreck n. /rɛk/残废人snag n. /snæg/疑难之处,障碍anecdote n. /ˈænɪkdəʊt/轶闻slander v. /ˈslɑːndə/诽谤persecute v. /ˈpɜːsɪkjuːt/迫害squadron n. /ˈskwɒdrən/中队psychiatric adj. /ˌsaɪkɪˈætrɪk/精神病学的diagnosis n. /ˌdaɪəgˈnəʊsɪs/诊所orphanage n. /ˈɔːfənɪʤ/孤儿院preservation n. /ˌprɛzə(ː)ˈveɪʃən/保存silt n. /sɪlt/淤泥scavenger n. /ˈskævɪnʤə/食腐动物vole n. /vəʊl/野鼠,鼹鼠decompose v. /ˌdiːkəmˈpəʊz/腐烂inaccessible adj. /ˌɪnækˈsɛsəbl/不能到达的crevasse n. /krɪˈvæs/缝隙Siberian adj./saɪˈbɪərɪən/西伯利亚的palaeontological adj. palaeontological古生物学的St. Petersburg n. St./ˈpiːtəzˌbɜːg/圣彼得堡sabre-toothed adj. /ˈseɪbə/-/tuːθt/长着锐利的长牙venture v. /ˈvɛnʧə/冒险bogged adj. /bɒgd/陷入泥沼的,陷入要困境的galleon n./ˈgælɪən/大型帆船Stockholm n./ˈstɒkhəʊm/斯德哥尔摩flagship n./ˈflægʃɪp/旗舰imperial a./ɪmˈpɪərɪəl/帝国的hurricane n./ˈhʌrɪkən/飓风might n./maɪt/力量ferment n./ˈfɜːmɛnt/激动不安ornament v./ˈɔːnəmənt/装饰riot n./ˈraɪət/丰富demon n./ˈdiːmən/恶魔mermaid n./ˈmɜːmeɪd/美人鱼cherub n./ˈʧɛrəb/小天使zoomorphic a.zoomorphic兽形的ablaze a./əˈbleɪz/光彩的portray v./pɔːˈtreɪ/绘制drifting a./ˈdrɪftɪŋ/弥漫的churn v./ʧɜːn/翻滚pennant n./ˈpɛnənt/三角旗superstructure n./ˈsjuːpəˌstrʌkʧə/上部结构armament n./ˈɑːməmənt/军械triple a./ˈtrɪpl/三层的mount v. /maʊnt/登上bronze n./brɒnz/青铜cannon n./ˈkænən/加农炮majestic a./məˈʤɛstɪk/威严的muzzle n. /ˈmʌzl/炮口freshen v./ˈfrɛʃn/变强squall n./skwɔːl/暴风list v./lɪst/倾斜port n./pɔːt/(船、飞机的)左舷ordnance n./ˈɔːdnəns/军械heave v./hiːv/拖starboard n./ˈstɑːbəd/(船、飞机的)右舷counteract v./ˌkaʊntəˈrækt/抵消steepen v./ˈstiːpən/变得更陡峭ballast n./ˈbæləst/压舱物inrush n./ˈɪnrʌʃ/水的涌入Baltic n./ˈbɔːltɪk/波罗的海sceptical adj. /ˈskɛptɪkəl/怀疑的forefathers n. /ˈfɔːˌfɑːðəz/祖先fervently adv. /ˈfɜːvəntli/热情地curative adj. /ˈkjʊərətɪv/治病的astronomical adj. /ˌæstrəˈnɒmɪkəl/天文学的tangible adj./ˈtænʤəbl/实实在在的remedy n. /ˈrɛmɪdi/药物ointment n. /ˈɔɪntmənt/药膏prescribe v. /prɪsˈkraɪb/开药方indisposition n. /ˌɪndɪspəˈzɪʃən/小病inconvenience n. /ˌɪnkənˈviːniəns/令人讨厌的inconvenience n. /ˌɪnkənˈviːniəns/不便hovercraft n. /ˈhɒvəkrɑːft/气垫船Norfolk Broads n. /ˈnɔːfək/ /brɔːdz/诺福克郡的湖泊地区cushion n. /ˈkʊʃən/座垫ring v. /rɪŋ/围Solent n. (英国的)苏伦特海峡sensation n. /sɛnˈseɪʃən/轰动dune n. /djuːn/沙丘plantation n. /plænˈteɪʃən/种植园hovertrain n. hovertrain气垫火车navigation n. /ˌnævɪˈgeɪʃən/航海sounding n. /ˈsaʊndɪŋ/水深度fathom n./ˈfæðəm/寻(1寻等于18米)porcupine n. /ˈpɔːkjʊpaɪn/箭猪dredge v. /drɛʤ/挖掘expedition n. /ˌɛkspɪˈdɪʃən/远征physicist n. /ˈfɪzɪsɪst/物理学家magnitude n. /ˈmægnɪtjuːd/很多topography n. /təˈpɒgrəfi/地形crust n. /krʌst/地壳rugged adj./ˈrʌgɪd/崎岖不平tableland n. /ˈteɪbllænd/高地sediment n. /ˈsɛdɪmənt/沉淀物terrace n. /ˈtɛrəs/阶地erode v. /ɪˈrəʊd/侵蚀colour-blind adj. /ˈkʌlə/-/blaɪnd/色盲的perception n. /pəˈsɛpʃən/知觉comprehend v. /ˌkɒmprɪˈhɛnd/理解spatial adj. /ˈspeɪʃəl/空间visualize v. /ˈvɪzjʊəlaɪz/使具形象,设想reminiscence n. /ˌrɛmɪˈnɪsns/回忆,联想tadpole n. /ˈtædpəʊl/蝌蚪mushroom n. /ˈmʌʃrʊm/蘑菇carrot n. /ˈkærət/胡萝卜bud n. /bʌd/花蕾lark n. /lɑːk/云雀ladybird n. /ˈleɪdɪbɜːd/瓢虫bulrush n. /ˈbʊlrʌʃ/芦苇controversy n. /ˈkɒntrəvɜːsi/争议,争论dust n. /dʌst/纠纷,骚动clash n. /klæʃ/冲突Inquisition n. /ˌɪnkwɪˈzɪʃən/(罗马天主教的)宗教法庭perspective n. /pəˈspɛktɪv/观点,看法despise v. /dɪsˈpaɪz/蔑视generalize v. /ˈʤɛnərəlaɪz/归纳undercurrent n. /ˈʌndəˌkʌrənt/潜流theoretical adj. /θɪəˈrɛtɪkəl/理论上的potentiality n. /pəʊˌtɛnʃɪˈælɪti/潜能intimate adj. /ˈɪntɪmɪt/详尽的familiarity n. /fəˌmɪlɪˈærɪti/熟悉的culpable adj. /ˈkʌlpəbl/应受遣责的Aristotelian n. /ˌærɪstɒˈtiːljən/亚里士多德学派的人Aristotle n. /ˈærɪˌstɒt(ə)l/亚里士多德(公元前384-322,古希腊哲学家)Ptolemy n./ˈtɒlɪmi/托勒密(公元90-168,古希腊天文学家)Leaning Tower of Pisa /ˈliːnɪŋ/ /ˈtaʊər/ /ɒv/ /ˈpiːzə/比萨斜塔spiral adj. /ˈspaɪərəl/螺旋状的nebula n. /ˈnɛbjʊlə/星云scratch n. /skræʧ/擦痕contrivance n. /kənˈtraɪvəns/器械distort v. /dɪsˈtɔːt/歪曲adverse adj. /ˈædvɜːs/不利的purchasable adj./ˈpɜːʧəsəbl/可买到的preacher n. /ˈpriːʧə/传教士defendant n. /dɪˈfɛndənt/被告outlook n. /ˈaʊtlʊk/视野capacity n. /kəˈpæsɪti/能力democratic adj. /ˌdɛməˈkrætɪk/民主的tribal n. /ˈtraɪbəl/部落的tribe n. /traɪb/部落illiterate n. /ɪˈlɪtərɪt/文盲compulsory adj. /kəmˈpʌlsəri/义务的deem v. /diːm/认为means n. /miːnz/方法,手段,财产,资力hamper v. /ˈhæmpə/妨碍savannah n. /səˈvænə/大草原juvenile adj. /ˈʤuːvɪnaɪl/青少年delinquency n. /dɪˈlɪŋkwənsi/犯罪adolescence n. /ˌædəʊˈlɛsns/青春期slur n./slɜː/诋毁adolescent n. /ˌædəʊˈlɛsnt/底毁disloyalty n./ˌdɪsˈlɔɪəlti/青少年(12-18岁)spiteful adj. /ˈspaɪtfʊl/恶意的,怀恨的disillusionment n. /ˌdɪsɪˈluːʒənmənt/幻灭感evaluation n. /ɪˌvæljʊˈeɪʃən/评价infallibility n. /ɪnˌfæləˈbɪlɪti/一贯正确resent v. /rɪˈzɛnt/怨恨sincerity n. /sɪnˈsɛrɪti/诚挚victorian adj. /vɪkˈtɔːrɪən/维多利亚式的retreat v. /rɪˈtriːt/后退unreasoning adj. /ʌnˈriːznɪŋ/不凭理智的authoritarian adj. /ɔːˌθɒrɪˈteərɪən/专制的cow v. /kaʊ/吓唬hub n. /hʌb/(活动的)中心lunar adj. /ˈluːnə/月球的oxygen n. /ˈɒksɪʤən/氧气Apollo n. /əˈpɒləʊ/阿波罗accelerate v. /əkˈsɛləreɪt/加速terrestrial adj. /tɪˈrɛstrɪəl/地球的permanently adv. /ˈpɜːmənəntli/永远地fascination n. /ˌfæsɪˈneɪʃən/魅力senior adj. /ˈsiːnjə/资历深的,年长的chasm n. /kæzm/断层,裂口canyon n. /ˈkænjən/峡谷disunited adj. /ˌdɪsjuːˈnaɪtɪd/分裂的correspondingly adv. /ˌkɒrɪsˈpɒndɪŋli/相应地backward adj. /ˈbækwəd/落后的incur v. /ɪnˈkɜː/承担administer v. /ədˈmɪnɪstə/管理adminstrative adj. adminstrative行政管理的analogous adj. /əˈnæləgəs/类似的overheads n. /ˈəʊvɛhɛdz/一般费用initiative n. /ɪˈnɪʃɪətɪv/主动,积极性checker n. /ˈʧɛkə/检查人员foreman n. /ˈfɔːmən/监工dividend n. /ˈdɪvɪdɛnd/红利unduly adv. /ʌnˈdjuːli/ /æd/过度地likelihood n. /ˈlaɪklɪhʊd/可能性infant n. /ˈɪnfənt/婴儿vulnerable adj. /ˈvʌlnərəbl/脆弱imperceptible adj. /ˌɪmpəˈsɛptəbl/感觉不到的steep adj. /stiːp/急转直下ageing n. /ˈeɪʤɪŋ/老化odds n. /ɒdz/可能性virtual adj. /ˈvɜːtjʊəl/实际上的robust adj. /rəʊˈbʌst/强健的organism n. /ˈɔːgənɪzm/有机体thermodynamics n. /ˌθɜːməʊdaɪˈnæmɪks/热力学moot adj. /muːt/争论未决的run-down adj. /rʌn/-/daʊn/破旧的friction n. /ˈfrɪkʃən/摩擦contamination n. /kənˌtæmɪˈneɪʃən/污染sanitation n. /ˌsænɪˈteɪʃən/卫生,卫生设备sewage n. /ˈsju(ː)ɪʤ/污水leakage n. /ˈliːkɪʤ/泄漏intermittent adj. /ˌɪntə(ː)ˈmɪtənt/间歇的,断断续续的carbonated adj. /ˈkɑːbənɪtɪd/碳化的,碳酸的acidic adj. /əˈsɪdɪk/酸的,酸性的alcohol n. /ˈælkəhɒl/酒精disinfectant n. /ˌdɪsɪnˈfɛktənt/消毒剂sterilize v. /ˈstɛrɪlaɪz/消毒ethanol n. /ˈɛθənɒl/乙醇bactericidal adj. bactericidal杀菌的negligible adj. /ˈnɛglɪʤəbl/可以忽略的,微不足道的methylated adj. methylated加入甲醇的confess v. /kənˈfɛs/承认inspiration n. /ˌɪnspəˈreɪʃən/灵感Kashmir n. /ˈkæʃmɪə/克什米尔interweave v. /ˌɪntə(ː)ˈwiːv/交织afresh adv. /əˈfrɛʃ/重新discern v. /dɪˈsɜːn/辨明,领悟indescribable adj. /ˌɪndɪsˈkraɪbəbl/无法描述的blur v. .../blɜː/使模糊不清yeast n. /jiːst/激动fathom v. /ˈfæðəm/领悟,彻底了解interminably adv. /ɪnˈtɜːmɪnəbli/没完没了地winkle v. /ˈwɪŋkl/挖掘incidentally adv. /ˌɪnsɪˈdɛntli/顺便说一下pertinent adj. /ˈpɜːtɪnənt/中肯的flirt v. /flɜːt/调情inmost adj. /ˈɪnməʊst/内心深处signature n. /ˈsɪgnɪʧə/签名,标记infinity n. /ɪnˈfɪnɪti/无穷ray n. /reɪ/光线energize v. /ˈɛnəʤaɪz/给与能量rhythm n. /ˈrɪðəm/节奏transmit v. /trænzˈmɪt/传送exquisite adj. /ˈɛkskwɪzɪt/高雅的phenomena n. /fɪˈnɒmɪnə/现象crest n. /krɛst/浪峰trough n. /trɒf/波谷vertical adj. /ˈvɜːtɪkəl/垂直的horizontal adj. /ˌhɒrɪˈzɒntl/水平的actuality n. /ˌækʧʊˈælɪti/现实catastrophic adj. /ˌkætəˈstrɒfɪk/大灾难的particle n. /ˈpɑːtɪkl/微粒maturity n. /məˈtjʊərɪti/成熟undulate v. /ˈʌndjʊleɪt/波动,形成波浪tremor n. /ˈtrɛmə/震颤gravitational adj. /ˌgrævɪˈteɪʃən(ə)l/地心吸力的technique n. /tɛkˈniːk/技术tough adj. /tʌf/强硬的resentful adj. /rɪˈzɛntfʊl/忿恨不满的assign v. /əˈsaɪn/分配,指派mahout n. /məˈhaʊt/驯象人calf n. /kɑːf/幼仔pine v. /paɪn/消瘦underline v. /ˈʌndəlaɪn/着重说明,强调keep n. /kiːp/生计subservient adj. /səbˈsɜːviənt/屈从的plunge v. /plʌnʤ/向前冲tame adj. /teɪm/养驯服了的tether v. /ˈtɛðə/(用绳)拴ticklish adj. /ˈtɪklɪʃ/难对付的,棘手的alarming adj. /əˈlɑːmɪŋ/引起惊恐的accompaniment n. /əˈkʌmpənɪmənt/伴奏soothe v. /suːð/镇定chant n. /ʧɑːnt/单调的歌reinforce v. /ˌriːɪnˈfɔːs/加强endearing adj./ɪnˈdɪərɪŋ/惹人喜爱的epithet n. /ˈɛpɪθɛt/称呼susceptible adj. /səˈsɛptəbl/易受感动的blandishment n. /ˈblændɪʃmənt/奉承lash v. /læʃ/猛烈地甩curl v. /kɜːl/使卷曲earthquaken./ˈɜːθkweɪk/地震slumberv./ˈslʌmbə/睡眠ninepinn.ninepin九柱戏中的木柱rigidadj./ˈrɪʤɪd/坚硬的delicateadj./ˈdɛlɪkɪt/灵感的seismometern.seismometer地震仪penholdern./ˈpɛnˌhəʊldə/笔杆legiblyadv./ˈlɛʤəbli/字迹清楚地drumn./drʌm/鼓状物wrigglev./ˈrɪgl/扭动bluebottlen./ˈbluːˌbɒtl/绿头苍蝇graphn./grɑːf/图表graphicadj./ˈgræfɪk/图示的longitudinaladj./ˌlɒnʤɪˈtjuːdɪnl/纵向的transverseadj./ˈtrænzvɜːs/横向的Mercury n. /ˈmɜːkjʊri/水星hydrogen n. /ˈhaɪdrɪʤən/氢气prevailing adj. /prɪˈveɪlɪŋ/普遍的radio astronomer /ˈreɪdɪəʊ/ /əsˈtrɒnəmə/射电天方学家uniquely adv. /juːˈniːkli/唯一地rational adj. /ˈræʃənl/合理的radio frequency /ˈreɪdɪəʊ/ /ˈfriːkwənsi/无线电频率cm n. /ˈsentɪmiːtə(r)/厘米megacycle n. /ˈmɛgəˈsaɪkl/兆周emission n. /ɪˈmɪʃən/散发intersteller adj.intersteller星际的rendezvous n. /ˈrɒndɪvuː/约会地点encounter n./ɪnˈkaʊntə/相遇commonplace adj. /ˈkɒmənpleɪs/平凡的aberrant adj. /æˈbɛrənt/脱离常轨的,异常的trivial adj. /ˈtrɪvɪəl/微不足道的,琐细的predominant adj. /prɪˈdɒmɪnənt/占优势的,起支配作用的manifest v. /ˈmænɪfɛst/表明pristine adj. /ˈprɪstaɪn/纯洁的,质朴的stereotype n. /ˈstɪərɪətaɪp/陈规vernacular n. /vəˈnækjʊlə/方言accommodation n. /əˌkɒməˈdeɪʃ(ə)n/适应incumbent adj. /ɪnˈkʌmbənt/义不容辞的,有责任的preliminary adj. /prɪˈlɪmɪnəri/初步的proposition n. /ˌprɒpəˈzɪʃən/主张preferrential adj. preferrential优先的controversial adj. /ˌkɒntrəˈvɜːʃəl/引起争论的cactus n. /ˈkæktəs/仙人掌termite n. /ˈtɜːmaɪt/白蚁nebula adj. /ˈnɛbjʊlə/星云variant n. /ˈveərɪənt/不同的barbarian n. /bɑːˈbeərɪən/野蛮人pagan n. /ˈpeɪgən/异教徒sophistication n. /səˌfɪstɪˈkeɪʃən/老练premise n. /ˈprɛmɪs/前提supernatural adj. /ˌsjuːpəˈnæʧrəl/超自然的dispute v. /dɪsˈpjuːt/争夺mosquito n. /məsˈkiːtəʊ/蚊子subdue v. /səbˈdjuː/征服drainage n. /ˈdreɪnɪʤ/下水系统envision n. /ɪnˈvɪʒən/预想Morocco n. /məˈrɒkəʊ/摩洛哥latitude n. /ˈlætɪtjuːd/纬度heretic n. /ˈhɛrətɪk/异教徒,异端邪说conceive v. /kənˈsiːv/想像suffice v. /səˈfaɪs/足够nuclear adj. /ˈnjuːklɪə/原子弹的original adj./əˈrɪʤənl/有独到见解的gifted adj. /ˈgɪftɪd/有天才的psychologist n. /saɪˈkɒləʤɪst/心理学家spasm n. /ˈspæzm/一阵(感情)发作futile adj. /ˈfjuːtaɪl/无用的insinuate v. /ɪnˈsɪnjʊeɪt/便潜入,暗示convulsive adj. /kənˈvʌlsɪv/起痉挛的illumination n. /ɪˌljuːmɪˈneɪʃən/启发,照明undue adj. /ʌnˈdjuː/不造当的grip n. /grɪp/紧张recuperation n. /rɪˌkjuːpəˈreɪʃən/休息improvise v. /ˈɪmprəvaɪz/临时作成sedulously adv. /ˈsɛdjʊləsli/孜孜不倦地vivify v. /ˈvɪvɪfaɪ/使生气勃勃aggravate v. /ˈægrəveɪt/加剧trifling adj. /ˈtraɪflɪŋ/微小的gratify v. /ˈgrætɪfaɪ/便满意caprice n. /kəˈpriːs/任性satiation n. /ˌseɪʃɪˈeɪʃən/满足frantically adv. /ˈfræntɪk(ə)li/狂乱地avenge v. /əˈvɛnʤ/替…报复boredom n. /ˈbɔːdəm/厌烦clatter n. /ˈklætə/喧闹的谈话sustenance n. /ˈsʌstɪnəns/生计appetite n. /ˈæpɪtaɪt/欲望grudge v. /grʌʤ/怨恨absorbing adj. /əbˈsɔːbɪŋ/引人入胜的banish v. /ˈbænɪʃ/排除,放弃assumption n./əˈsʌmpʃ(ə)n/假定manoeuvre v./məˈnuːvə/(驱车)移动myriad adj./ˈmɪrɪəd/无数的paradox n./ˈpærədɒks/自相矛盾的呈cynic n./ˈsɪnɪk/愤世嫉俗者sociologist n./ˌsəʊsɪˈɒləʤɪst/社会学家shun v. /ʃʌn/避开affluent adj./ˈæflʊənt/富有的chambermaid n./ˈʧeɪmbəmeɪd/女招待员boo b./buː/ /biː/呸的一声maitre d'hotel n.'[法语]总管snobbery n./ˈsnɒbəri/势利hierarchy n. /ˈhaɪərɑːki/等级制度entail v./ɪnˈteɪl/便成为必要inclement adj. /ɪnˈklɛmənt/险恶的package tour /ˈpækɪʤ/ /tʊə/由旅行社安排一切的一揽子诱游insularity n./ˌɪnsjʊˈlærɪti/偏狭cater v./ˈkeɪtə/迎合exclusively adv./ɪksˈkluːsɪvli/排他地cosmopolitan adj./ˌkɒzməʊˈpɒlɪtən/世界的preponderance n./prɪˈpɒndərəns/优势overwhelmingly adv. /ˌəʊvəˈwɛlmɪŋli/以压倒优势地,清一色地patronage n. /ˈpætrənɪʤ/恩惠,惠顾sauerkraut n./ˈsaʊəkraʊt/泡菜vie v./vaɪ/竞争municipality n. /mju(ː)ˌnɪsɪˈpælɪti/市政当局itinerant n. /ɪˈtɪnərənt/巡回者heath v. /hiːθ/荒地alienate v. /ˈeɪliəneɪt/便疏远eternal adj. /i(ː)ˈtɜːnl/永久的portfolio n. /pɔːtˈfəʊliəʊ/投资组合tipster n. /ˈtɪpstə/(以提供证券投机等内部消息为主的)情报贩子Las Vegas n. /lɑːz/ /ˈveɪgəs/拉斯韦加斯fritter v. /ˈfrɪtə/挥霍,浪费reputable n. /ˈrɛpjʊtəbl/享有声望的broker n. /ˈbrəʊkə/经纪人finance n. /faɪˈnæns/资金,财源mortgage n. /ˈmɔːgɪʤ/抵押贷款pension n. /ˈpɛnʃən/养老金priority n. /praɪˈɒrɪti/优先权gilt n. /gɪlt/金边证券(高度可靠的证券)convertible n. /kənˈvɜːtəbl/可换证券sanguine adj. /ˈsæŋgwɪn/乐观的heady adj. /ˈhɛdi/令人陶醉的alongside prep. /əˈlɒŋˈsaɪd/在……旁边,和……一起pedestrian adj. /pɪˈdɛstrɪən/平淡无奇的,乏味的。

新概念英语第四册听力原文:Knowledgeandprogress

新概念频道为⼤家整理的新概念英语第四册听⼒原⽂:Knowledge and progress,供⼤家参考。

更多阅读请查看本站频道。

Knowledge and progress 知识和进步 First listen and then answer the following question. 听录⾳,然后回答以下问题。

In what two areas have people made no 'progress' at all? Why does the idea of progress loom so large in the modern world? Surely because progress of a particular kind is actually taking place around us and is becoming more and more manifest. Although mankind has undergone no general improvement in intelligence or morality, it has made extraordinary progress in the accumulation of knowledge. Knowledge began to increase as soon as the thoughts of one individual could be communicated to another by means of speech. With the invention of writing, a great advance was made, for knowledge could then be not only communicated but also stored. Libraries made education possible, and education in its turn added to libraries: the growth of knowledge followed a kind of compound interest law, which was greatly enhanced by the invention of printing. All this was comparatively slow until, with the coming of science, the tempo was suddenly raised. Then knowledge began to be accumulated according to a systematic plan. The trickle became a stream; the stream has now become a torrent. Moreover, as soon as new knowledge is acquired, it is now turned to practical account. What is called 'modern civilization' is not the result of a balanced development of all man's nature, but of accumulated knowledge applied to practical life. The problem now facing humanity is: What is going to be done with all this knowledge? As is so often pointed out, knowledge is a two-edged weapon which can be used equally for good or evil. It is now being used indifferently for both. Could any spectacle, for instance, be more grimly whimsical than that of gunners using science to shatter men's bodies while, close at hand, surgeons use it to restore them? We have to ask ourselves very seriously what will happen if this twofold use of knowledge, with its ever-increasing power, continues. G.N.M.TYRRELL The Personality of Man New words and expressions ⽣词与短语 loom v. 赫然耸起 manifest adj.明显的 morality n. 道德 communicate v. 交流,交际 compound adj. 复合的 enhance v. 增进 tempo n. 速率 trickle n. 涓涓细流 torrent n. 滔滔洪流 humanity n. ⼈类 indifferently adv. 不在乎地 grimly adv. 可怖地 whimsical adj. 怪诞的 shatter v. 毁坏 twofold adj. 双重的 本⽂参考译⽂ 为什么进步这个概念在现代世界显得如此突出?⽆疑是因为有⼀种特殊的进步实际上正在我们周围发⽣,⽽且变得越来越明显。