ACR-RA治疗指南-2008-v4.3

类风湿关节炎治疗指南

类风湿关节炎治疗指南

一、引言

非特异性多发性类风湿关节炎(polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis,RA)是一种复杂的全身性炎症性疾病,可引起关节肿胀、疼

痛和功能障碍。

RA可导致严重的结构性与功能性损害,对病人的生活质

量产生显著影响。

RA的全程管理旨在维持完全活动,减少慢性炎症的发

作频率,并降低伴随症状的发生率。

二、诊断

RA的诊断主要依据病史、体格检查以及实验室检查结果。

体格检查

应检测关节软骨、滑膜和肌肉的炎症,以及关节脱位的可能。

此外,实验

室检查通常包括血液学检查(血常规、白细胞计数和C反应蛋白水平)、

尿常规检查和免疫分析(尤其是抗环瓜氨酸抗体测定)。

三、治疗

RA的治疗可以分为有效控制炎症反应和改善功能失调两个主要目标。

有效地控制炎症反应的有效药物主要包括非甾体类抗炎药(NSAIDs)、心

血管预防药物和免疫抑制剂,如抗TNF-α类药物,抗CD20类药物,抗

IL-6类药物等,以及激素类药物,如可的松(dexamethasone)等。

改善功能失调的策略包括药物治疗、物理治疗、康复治疗以及手术治疗,病人应根据具体病情接受相应的治疗。

2008抗心律失常药物治疗指南

2008抗心律失常药物治疗指南中华医学会心血管病学分会中华心血管病杂志编辑委员会抗心律失常药物治疗专题组一、抗心律失常药物分类、作用机制和用法药物一直是防治快速心律失常的主要手段,奎尼丁应用已近百年,普鲁卡因胺应用也有50年历史。

60年代,利多卡因在心肌梗死室性心律失常中得到广泛的应用。

到80年代,普罗帕酮、氟卡尼等药物的应用,使Ⅰ类药物发展到了顶峰。

90年代初,CAST结果公布[2],人们注意到在心肌梗死后伴室性期前收缩的患者中,应用Ⅰ类药物虽可使室性期前收缩减少,但总死亡率上升。

由此引起了人们重视抗心律失常药物治疗的效益与风险关系,并开始注意Ⅲ类药物的发展。

(一)抗心律失常药物分类抗心律失常药物现在广泛使用的是改良的VaughanWilams分类,根据药物不同的电生理作用分为四类(表1)。

一种抗心律失常药物的作用可能不是单一的,如索他洛尔既有β受体阻滞(Ⅱ类)作用,又有延长QT间期(Ⅲ类)作用;胺碘酮同时表现Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ、Ⅳ类的作用,还能阻滞α、β受体;普鲁卡因胺属Ⅰa类,但它的活性代谢产物N-乙酰普鲁卡因胺(NAPA)具Ⅲ类作用;奎尼丁同时兼具Ⅰ、Ⅲ类的作用。

可见以上的分类显得过于简单,同时还有一些其他抗心律失常药物未能包括在内。

因此,在1991年国外心律失常专家在意大利西西里岛制定了一个新的分类,称为“西西里岛分类”(Siciliangambit)。

该分类突破传统分类,纳入对心律失常药物作用与心律失常机制相关的新概念。

“西西里岛分类”根据药物作用的靶点,表述了每个药物作用的通道、受体和离子泵,根据心律失常不同的离子流基础、形成的易损环节,便于选用相应的药物。

在此分类中,对一些未能归类的药物也找到了相应的位置。

该分类有助于理解抗心律失常药物作用的机理,但由于心律失常机制的复杂性,因此西西里岛分类难于在实际中应用,临床上仍习惯地使用VaughanWilams分类。

药物作用的通道、受体及主要电生理作用见表1。

RA病情评估及缓解标准

目前 DAS44 评分 >1.2 >0.6 且≤1.2

≤ 2.4

优良反应 中等反应

≤0.6 无反应

> 2.4 且≤3.7

> 3.7

DAS28 自基线变化值

目前 DAS28 评分 >1.2 >0.6 且≤1.2 ≤0.6

≤ 3.2

优良反应 中等反应 无反应

> 3.2 且 ≤ 5.1

> 5.1

1. van Gestel AM, et al. Arthritis Rheum.1998;41:1845-50. 2. van Gestel AM, et al. Arthritis Rheum.1996;39:34-40.

• CDAI= TJC(28个关节中的肿胀关节 数)+SJC(28个关节中的压痛关节 数)+PGA(患者的总体评价0-10)+MDGA(医 生的总体评价0-10)

资料仅供参考,不当之处,请联系改正。

2012 ACR RA诊断治疗指南

A.加MTX、HCQ或LEF

再评价

B.加或转其他DMARD

再评价

有严重不良反应

再评价或有非FDA规定的严 重不良反应

F.转换另外一种TNF拮抗剂或非TNF拮抗剂 再评价 G.转换成另一种TNF拮抗剂或者非TNF拮抗剂

长病程RA: ≥6个月或符合1987 ACR分类标准

Singh JA, Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(5):625-39

高

中

无

预后不良因素

有

无

预后不良因素

有

DMARD 单药治疗 早期RA (病程<6个月)

DMARD联合 (二或三联)治疗

DMARD单药或 HCQ+MTX

TNF拮抗剂+/-MTX 或DMARD联合 (二联或三联) 治疗

2012 ACR RA指南推荐:TNF拮抗剂是 中重度长病程RA,DMARDs治疗无效后最佳方案

2012 ACR RA指南定义的预后不良因素包括: 基线期存在骨侵蚀、类风湿因子或抗CCP抗2 ACR RA指南推荐:TNF拮抗剂联合MTX是 高疾病活动度伴预后不良因素早期RA的一线治疗方案

低

以 达 到 低 疾 病 活 动 度 或 者 缓 解 为 目 标

疾病活动度

以 达 到 低 疾 病 活 动 度 或 者 缓 解 为 目 标

E.换成非TNF生物制剂 C.加或转换为TNF拮抗剂 D.加或转为 阿巴西普或利妥昔 再评价或有任何不良 反应 DMARD单药 再评价 MTX单药或包括MTX在内的DMARD联合治疗 再评价 低疾病活动度无预后不良因素 低疾病活动度有预后不良因素或至少中活动度

11 ~ 26 >26

112008年严重脓毒症与脓毒性休克治疗国际指南(摘译)

0020拯救脓毒症运动(SSC)2008年严重脓毒症与脓毒性休克治疗国际指南(摘译)2004年,全球11个专业组织的专家代表对感染与脓毒症的诊断及治疗发表了第一个被国际广泛接受的指南。

指南代表了拯救脓毒症运动的第二阶段,即进一步改善患者预后及对脓毒症进行再认识。

这些专家分别在2006年与2007年应用新的循证医学系统方法对证据质量及推荐级别进行再次评价,对指南内容进行了更新。

这些建议旨在为临床医生提供治疗严重脓毒症或脓毒性休克的指南,但不能取代医生面对患者病情独特变化而做出的临床决定。

指南中大部分建议适用于ICU及非ICU中的严重脓毒症。

专家们相信,对非ICU科室及紧急情况下医师如何救治严重脓毒症患者的培训有助于改善患者预后。

当然,不同国家或救治机构资源的有限性可能会限制内科医生对某些指南建议的实施。

本报特邀首都医科大学北京朝阳医院急诊科李春盛教授主持,摘译了新版指南的重要内容。

第一部分严重脓毒症的治疗严重脓毒症(继发于感染)和脓毒性休克(严重脓毒症伴经液体复苏仍难以逆转的低血压)每年影响成千上万患者,其中1/4患者甚至更多患者死亡,且病死率不断升高。

严重脓毒症发病第一时间治疗的及时程度及具体措施极可能影响患者预后。

A 早期复苏1、脓毒症所致休克的定义为组织低灌注,表现为经过最初的液体复苏后持续低血压或血乳酸浓度≥4mmol/L。

此时应按照本指南进行早期复苏,并应在确定存在低灌注第一时间、而不是延迟到患者入住ICU后实施。

在早期复苏最初6小时内的复苏目标包括:①中心静脉压(CVP)8-12mmHg;②平均动脉压(MAP)≥65mmHg;③尿量≥0.5ml/(kg·h);④中心静脉(上腔静脉)氧饱和度(S cv O2)≥70%,混合静脉氧饱和度(S v O2)≥65%(1C)。

2、严重脓毒症或脓毒性休克在最初6小时复苏过程中,尽管CVP已达到目标,但对应的S cv O2与S v O2未达到70%或65%时,可输入浓缩红细胞达到红细胞压积≥30%,同时/或者输入多巴酚丁胺[最大剂量为20μg/(kg·min)]来达到目标(2C)。

2008_慢性阻塞性肺疾病治疗指南的解读 (1)

继教讲堂

慢性阻塞性肺疾病治疗指南的解读

刘超

慢 性 阻 塞 性 肺 疾 病 ( Chronic objective pul m ona ry d isease , COPD ) 是一种常见病、 多发病 , 患病率和 病死率均高 , 目前 居全 球死亡原因的第 4 位。世界卫生组织 (WHO ) 公布 , 至 2020 年 , COPD 将位居世界疾病经济负担的第 5 位。在我国 , CO PD 同样 是严重危害人民身体 健康的重要慢性呼吸系统疾病。 为了促 使社会政府 和患者对 CO PD 的 关注 , 提高 COPD 的 诊疗水平 , 降低 CO PD 的患 病率 和病 死率 , 国内 外呼 吸病 学学 术界近期发表了一系 列关于 COPD 诊 断和治 疗的新指 南 : 2006 年慢性阻塞性肺疾病 全球倡议 ( G loba l In itia tive for Chron ic O b structive L ung D isease , GOLD ) 和我国慢性 阻塞性 肺疾病诊 治指 南 ( 2007 年修订版 ) 。本文对 CO PD 的治疗指南做如下解 读。 1 COPD 的定义 2006 年 , GO LD 将 COPD 定义 如下 : CO PD 是一 种可 以预 防、 可以治疗的疾病 , 伴有一些 显著的肺外 效应 , 这些肺外 效应 与患者疾病的 严重性 相关。肺 部病 变的特 点为 不完 全可 逆性 气流受限 , 这种气流 受限 通常进 行性 发展 , 与肺 部对 有害 颗粒 或气体的异常炎症反 应有关 。明确 强调了 COPD 是可预 防和 可治疗的 , 目的是呈 现给 患者一 个积 极的前 景 ; 对医 务人 员在 COPD 预防和治疗措施的制定 发挥 了更为 积极 的作用 , 有 助于 克服 COPD 防治领域中的消极、 悲 观情绪。 肺功能检查对 确定 气流 受限有 重要 意义。 在吸 入支 气管 舒张剂后 , 第 1 秒用力呼气容 积 ( FEV 1) /用力 肺活量 ( FVC ) ﹤ 70% 表明存在气流受限 , 并且不能完全逆转。 慢性咳嗽咳痰常 先于气流受限许多年 存在 ; 但不是所 有有 咳嗽、 咳痰症状的患者 均发展 为 COPD。部分 患者可 仅有 不可 逆气流受限改变而无 慢性咳嗽、 咳痰症状。 COPD 与慢性支气管炎 和肺 气肿密 切相 关。通常 , 慢 性支 气管炎是指在除外慢 性咳嗽的其他已知 原因后 , 患者每年 咳嗽 咳痰 3 个月以上 , 并连续 2 年者。肺气肿 则指肺 部终末支 气管 远端气腔出现异常持 久的扩张 , 并伴 有肺泡壁和 细支气管 的破 坏而无明显的肺纤维 化。 当慢性支气管 炎、 肺气肿 患者 肺功 能检 查出 现气 流受 限 , 并且不能完全可逆时 , 则诊断为 COPD。如患者只有 慢性支气 管炎 和或 肺气肿 , 而无气流受限 , 则不能诊断为 CO PD。 虽然支气管哮喘 与 COPD 都是慢 性气道 炎症性 疾病 , 但二 者的发病机制不同 , 临床表现以及对 治疗的反应 性也有明 显差 异。大多数支气管哮喘患者的 气流受限具 有显著的 可逆性 , 是 其不同于 COPD 的一个 关键 特征 ; 但 是 , 部 分支 气管 哮喘 患者 随着病程延长 , 可出 现较 明显的 气道 重塑 , 导致 气流 受限 的可 逆性明显减 小 , 临 床很 难与 COPD 相 鉴别。 COPD 和 支气 管哮 喘可以发生于同一位患者 ; 而且 , 由于二者都 是常见 病多发病 , 这种概率并不低。 一些已知病因或具有特征病 理表现的气 流受限 性疾病 , 如 支气管扩张症肺 结核纤 维化 病变肺 囊性 纤维化 弥漫 性泛 细支 气管炎以及闭塞性细支气管炎等 , 均不属于 COPD。 2 诊断与严重程度分级 2 1 病史 我国 COPD 诊 治指南 ( 2007 年修 订版 ) 特 别强调 : 诊断 COPD 时 , 首先应全面采集 病史 , 包括症 状、 既 往史和 系统 回顾、 接触史。症状包 括 : 慢性 咳嗽、 咳 痰、 气 短。既往 史和 系 统回顾应注意 : 童年时期有无哮喘 , 变态反应 性疾病 , 感染 及其 他呼吸道疾 病 , 如 结核 , COPD 和 呼 吸系 统 疾 病家 族 史 , CO PD 急性加重和住院治疗病史 , 有相同危险因素 ( 吸烟 ) 的其 他疾病 ( 如 心脏、 外周血管和神经系统疾病 ) , 不能解释的 体重下降 , 其 他非特异性症状 ( 喘息、 胸闷、 胸痛和晨起头痛 ), 要注意 吸烟史 ( 以 包年计算 ) 及职业、 环 境有害物质接触史等。 2 2 诊断 COPD 的诊 断 应根 据吸 烟 等高 危因 素 史、 临床 症 状、 体征及肺功能检 查等 资料 , 综合 分析 确定。不 完全 可逆 的 气流受 限 是 诊 断 CO PD 的 必 备 条 件。吸 入 支 气 管 扩 张 剂 后 FEV 1 /FVC < 70% 及 FEV1% pred< 80% 可确定为不完全可逆性 气流受限。 肺功能检查是诊断 COPD 的金标准。 COPD 早期轻 度气流 受限时可有或无临床症状。因此 , 凡具有吸烟史和 ( 或 ) 环境职 业污染接触史 , 咳嗽、 咳痰或呼吸 困难史者 , 均应进 行肺功 能检 查。胸部 X 线检查有助于确 定肺过 度充 气的程 度及 与其 他肺 部疾病鉴别。 2 3 严重程 度分 级 在 COPD 病 情严 重程 度 分级 方面 , 2006 年 GOLD 和 我 国 CO PD 诊 治 指 南 ( 2007 年 修 订 版 ) 均 取 消 CO PD 病情严重 程度分级 中的 0 级 ( 危险 期 , 见表 1) 。因 为到 目前为止 , 尚无充分的证据表明 0 级 COPD ( 危险期 ) 患者 , 即表 现为慢性咳嗽和咳痰、 而肺功能正常者 , 必然会进 展到 级 ( 轻 度 ) COPD。新 指南也指 出肺 功能 在诊 断 COPD 时 起了 至关 重 要的作用 , COPD 的诊断应 该得 到肺功 能检 查的证 实。肺 功能 检查应在吸入 足够剂 量的 支气管 舒张 剂 ( 如吸入 400 g的 沙 丁胺 醇 ) 后 进行 , 如 果第 1 秒 用力 呼气 容积 /用力 肺活 量比 值 ( FEV1 /FV C) < 70% , 表 明 有 气 流 受限 , 且 不 可 逆 , 可 以 诊 断 CO PD。 2 4 CO PD 病程分 期 急性加重期 : 指患者出 现超越日 常状况 的持续恶化 , 并需改 变基 础 COPD 的 常规 用药 者 , 通常 在疾 病 过程中 , 患者短期内咳嗽咳痰气短和 ( 或 ) 喘息加重 , 痰量增多 , 呈脓性或黏液性 , 可伴发热等炎症明 显加重的表 现 ; 稳定期 : 指

2015年ACR类风湿关节炎治疗指南(翻译)

2015年ACR类风湿关节炎治疗指南(翻译)美国风湿病学会(ACR)制定和/或认可的指南和建议旨在为特定实践模式提供指导,而不指导特定患者的照护。

ACR认为遵守本指南中的建议是自愿的,最终决定由医生根据患者的个人情况提出。

指南和建议旨在促进有益或有价值的结果,但不能保证任何具体结果。

由于医学知识、技术和实践的发展,ACR制定和认可的指南和建议需要定期修订。

ACR建议并非旨在规定付款或保险决策。

这些建议无法充分传达患者照护的所有不确定性和细微差别。

ACR是一个独立的、专业的、医学和科学的协会,不对任何商业产品或服务做承诺、保证或认可。

目的制定新的基于证据的类风湿关节炎(RA)药物治疗指南。

方法我们综合各种治疗选择益处和危害的证据进行了系统评价。

我们使用GRADE方法对证据质量进行评级。

我们采用了一个小组共识流程来评估建议的强度(强烈的或有条件的)。

强烈推荐表明临床医生确信干预的好处远大于危害(反之亦然)。

条件推荐表示对患者获益和危害权衡的不确定性和/或患者价值受益上具有更显著的可变性。

结果该指南涵盖了早期(<6个月)和确诊(6个月)RA的传统改善病情抗风湿药(DMARDs)、生物制剂、托法替尼和糖皮质激素的使用。

此外,它还提供了关于使用目标治疗策略、逐渐减少和停止使用药物、以及在肝炎、充血性心力衰竭、恶性肿瘤和严重感染患者中使用生物制剂和DMARDs的建议。

该指南强调了在开始/接受DMARDs或生物制剂的患者中使用疫苗、筛选开始/接受生物制剂或托法替尼的结核病住院患者,以及传统DMARDs的实验室监测。

该指南包括74条建议:23%是强有力的,77%是有条件的。

结论该RA指南应作为临床医生和患者(我们的两个目标受众)在常见临床情况下进行药物治疗决策的工具。

这些建议不是强制性的,治疗决策应由医生和患者通过共同的决策过程来综合考虑患者的价值观、偏好和合并症。

这些建议不适用于限制或拒绝治疗。

介绍类风湿关节炎(RA)是成人中最常见的自身免疫性炎性关节炎。

最新类风湿性关节炎治疗指南

类风湿关节炎的治疗指南(总结)2019年07月20日ACR小组委员会RA简介类风湿关节炎(RA)是一种病因不明的自身免疫性疾病,以对称性、侵蚀性滑膜炎为特征,有些病例还有关节外受累。

即便接受治疗,大多数病人都要经历一个慢性的反复的病程,有可能导致进展性关节损害、残疾、劳动能力丧失,甚至过早死亡。

每年因RA就诊人数超过9百万次,住院人数超过25万次。

RA造成的劳动能力丧失导致巨大的经济损失并给家庭带来沉重的负担。

约1%的成年人群会罹患类风湿关节炎,较低的发病率意味着普通的内科大夫常常缺乏对RA的诊断及治疗经验。

以下提及的关于RA的治疗指南均假设其诊断已经成立,当然这在疾病的早期或许比较困难。

诊断RA的复杂性要远大于本指南所论述的范围。

RA的治疗指南和药物治疗的监测始于1996年。

从那时起,RA的治疗已经取得了重大的进展。

现在,有证据表明在疾病早期治疗是有益的,同样有证据显示治疗可以改善预后。

这些修订的指南尽可能遵循循证医学。

然而,因为在我们的知识层次仍存在显著差异,某些推荐治疗是来自实践检验并获得专业委员会认可的。

这些指南经过风湿病学专家、从事风湿病基础治疗的开业医师,以及其它从事关节炎健康研究的相关职业人员,包括专业治疗医师,理疗医师,社会工作者以及病人教育专家的评审。

风湿病治疗的目标RA治疗的最终目标是防止和控制关节破坏,阻止功能丧失及减少疼痛。

表1总结了RA治疗的途径。

RA治疗的初始步骤是明确诊断,进行基础状况的评估,以及估计预后。

如果基层医疗工作者对评估的初始步骤不熟悉,强烈建议风湿病专科医生来进行评估。

治疗开始时要向病人开展有关疾病的教育,以及关节损害和功能丧失的危害,同时也要告诉病人现有治疗的好处以及风险。

病人将在同理疗科医师、职业病医师、社会工作者以及病人教育者进行交流中得到益处。

为控制症状,可适当选用非甾类消炎药(NSAIDs)、关节注射糖皮质激素、并用或单用小剂量泼尼松。

大多数新近诊断为RA的病人应该在明确诊断3个月内开始缓解疾病的抗风湿药物(DMARDs)治疗。

2008ESC急性肺动脉栓塞诊断治疗指南

2008ESC急性肺动脉栓塞诊断治疗指南引言篇指南和专家共识是针对解决某一特定问题目前所获得的所有证据的总结和评价,旨在帮助临床医师针对患有某种疾病的典型患者选择最佳的诊疗策略,同时要考虑到其对结果的影响以及该诊断和治疗措施的风险/效益比值。

指南并不能代替教科书,临床指南的法律效力也已经讨论过。

近年来,欧洲心脏病学会(European Society of Cardiology, ESC) 及其它学会和机构陆续出版了一系列指南和专家共识。

考虑到其对临床实践的影响,同时保证决策的形成对使用者是透明的,已经建立了指南形成的质量标准。

在ESC网站上可以看到对指南和专家共识形成和出版的介绍(http:\\www.escar /guidelines)。

ESC邀请了各专业领域的专家,这些专家承担了对已发表的治疗策略进行综合评价并对某种特定疾病进行预防的工作,同时完成了对诊断和治疗过程的最终评价,包括风险—效益比值的评定。

对于大规模群体的健康预测也包括在内,并附以数据说明。

工作组根据以前制定的标准对某种治疗措施的证据水平进行评价及分级(表1、2)。

专家组成员已就其可能涉及到的目前或潜在的利益冲突关系发表了公开的声明,这些声明以档案的形式保存在ESC总部,欧洲心脏病学大厦。

ESC始终关注着撰写期间可能发生的利益冲突变化。

指南是由欧洲心脏病学会对专门工作组拨款资助的,无任何商业组织介入。

ESC实践委员会(ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines, CPG)指导和组织了由工作组、专家组承担的新指南和专家共识的准备工作。

委员会还负责这些指南和共识的认证过程。

专家组所有成员均完成指南一系列版本的起草和编辑后,该版本由工作组以外的专家进行评阅。

在经由CPG修改、批准后,指南对外出版。

出版之后的推广传播是至关重要的。

宣传手册和网上可以下载的电子版本有助于此。

一些调查显示预期的最终用户有时并没有意识到指南的存在,或者并没有将它出版之后的推广传播是至关重要的。

RA诊治指南

实验室 ESR/CRP RF* 全血细胞计数** 血肌酐** 肝酶(AST、ALT、白蛋白)** 尿常规** 关节滑液检查*** 粪便检查** 其他 用标准问卷进行功能状况或生活质量评估

• RA最终治疗目标是达到完全缓解,完全 缓解的定义如下:1炎症性关节疼痛消失 (并非机械性疼痛);2无晨僵;3无疲劳; 4关节检查中未发现滑膜炎;5影象学资料 不提示骨关节进行性破坏;6ESR及CRP 水平正常。如病情不能完全缓解,则应控 制疾病的活动性尽可能的减轻患者的关节 疼痛、维持从事日常活动的能力和改善生 活质量。缓解疼痛的治疗中要避免麻醉性 止痛药物的依赖。

ESR或CRP升高 受累关节的影像学进展 评价治疗效果的其他参数 医师对疾病活动的整体评估 患者对疾病活动的整体评估 标准问卷评估功能状况或生活质量

RA预后的评估

• ACR制定了RA的病情改善及临床缓解的标准。 临床改善20%的ACR标准(ACR20)要求肿胀 及触痛关节计数改善达20%,且下列5个参数中 有3个改善达20%:病人的整体评估、医师的整 体评估、病人对疼痛程度的评估、功能丧失的 程度、急性期反应物的水平。这些标准被扩展 用于50%及70%(ACR50,ACR70标准)临床 改善评估。也有用包括Paulus标准在内的其他 标准进行临床评估。影像学的进展(如Sharp评 分)也被用于评估预后。

• 4、糖皮质激素

三、RA的手术治疗

• 包括腕管松解术、滑膜切除术、趾指切 除术、关节成形术以及关节融合。

RA的治疗

• 一、非药物治疗 • 非药物治疗是指对患者进行健康教育, 是患者积极参与制订治疗方案。指导其 如何保护关节、如何保持体能、如何进 行适度的关节运动以及增力训练等。

2008脓毒血症治疗指引

2008脓毒血症治疗指南严重脓毒症和脓毒症休克治疗指南2008A初期复苏1.脓毒症导致休克(定义为存在组织低灌注:经过初期的补液试样后仍持续低血压或血乳酸浓度三4mmol/L)的患者应该制定复苏计划。

一旦证实存在组织低灌注后应该尽早开始实施复苏计划,而且不应该因为等待入住1(^而延迟复苏。

在复苏的前6小时,脓毒症引起组织低灌注的早期复苏目标应该包括以下所有指标:中心静脉压(CVP): 8〜12mmHg平均动脉压(MAP)三65mmHg尿量三0.5mL/ (kg?h)中心静脉(上腔静脉)或混合静脉血氧饱和度分别三70%或65%2.在重症脓毒血症或脓毒血症休克复苏的前6小时,如果通过液体复苏使CVP达到复苏目标而SCVO2或SVO2未能达到70%或65%,此时可以输注浓缩红细胞使红细胞压积三30%和/或输注多巴酚丁胺(最大可达20ug/ (kg?min))以达到治疗目标。

B诊断1.只要不会导致抗生素治疗的显著延迟,在使用抗生素之前应该进行合适的细菌培养。

为了更好地识别病原菌,至少要获得两份血培养,其中至少一份经外周静脉抽取,另一份经血管内每个留置导管抽取,除非导管是在近期(<48h)留置的。

只要不会导致抗生素治疗的显著延迟,对于可能是感染源的其他部位,也应该获取标本进行培养,如尿液、脑脊液、伤口分泌物、呼吸道分泌物或者其他体液(最好在合适的部位获得足量的标本)。

2.为明确可能的感染源,应尽快进行影像学检查。

应该对可能的感染源进行取样,以便明确诊断。

但是部分患者可能病情不稳定以至于不能接受某些有创操作或搬运至ICU以外。

在这种情况下,一些床旁检查(如超声检查)比较有效。

C 抗生素治疗1.在认识到发生脓毒症休克和尚无休克的重症脓毒症的最初1小时内,应该尽可能早的静脉输注抗生素。

在使用抗生素前应该进行适当的培养,但是不能因此而延误抗生素的给药。

2a.初始的经验性抗生素治疗应该包括一种或多种药物,其应该对所有可能的病原体(细菌和/或真菌)有效,而且能够在可能的感染部位达到足够的血药浓度。

2008欧洲抗风湿协会系统性红斑狼疮治疗指南

doi:10.1136/ard.2007.0703672008;67;195-205; originally published online 15 May 2007; Ann Rheum DisVollenhoven, C Gordon and D T Boumpas Khamashta, J C Piette, M Schneider, J Smolen, G Sturfelt, A Tincani, R van Font, I M Gilboe, F Houssiau, T Huizinga, D Isenberg, C G M Kallenberg, M G Bertsias, J P A Ioannidis, J Boletis, S Bombardieri, R Cervera, C Dostal, JTherapeutics International Clinical Studies Including Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task EULAR recommendations for the management of/cgi/content/full/67/2/195Updated information and services can be found at:These include:References /cgi/content/full/67/2/195#otherarticles 1 online articles that cite this article can be accessed at:/cgi/content/full/67/2/195#BIBL This article cites 143 articles, 52 of which can be accessed free at: Open Access This article is free to access Rapid responses/cgi/eletter-submit/67/2/195You can respond to this article at:service Email alertingthe top right corner of the articleReceive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at Topic collections(114 articles)UnlockedArticles on similar topics can be found in the following collectionsNotes/cgi/reprintform To order reprints of this article go to:/subscriptions/ go to: Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases To subscribe toEULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus.Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee forInternational Clinical Studies Including TherapeuticsG Bertsias,1J P A Ioannidis,2J Boletis,3S Bombardieri,4R Cervera,5C Dostal,6J Font,5I M Gilboe,7F Houssiau,8T Huizinga,9D Isenberg,10C G M Kallenberg,11M Khamashta,12J C Piette,13M Schneider,14J Smolen,15G Sturfelt,16A Tincani,17R van Vollenhoven,18C Gordon,19D T Boumpas 11Internal Medicine,andRheumatology,Clinical Immunology and Allergy,University of Crete School of Medicine,Heraklion,Greece;2Clinical Trials and Evidence-Based Medicine Unit,Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology,University of Ioannina School of Medicine,Ioannina,Greece;3Department of Nephrology and Transplantation Medicine,Laiko Hospital,Athens,Greece;4Cattedra di Reumatologia,Universita di Pisa,Pisa,Italy;5Department of AutoimmuneDiseases,Hospital Clinic,Barcelona,Spain;6Institute of Rheumatology,Prague,Czech Republic;7Department of Rheumatology,Rikshospitalet,Oslo,Norway;8Rheumatology Department,Universite ´catholique de Louvain,Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc,Brussels,Belgium;9Department of Rheumatology Leiden University Medical Center,Leiden,The Netherlands;10Centre forRheumatology,University College London Hospitals,London,UK;11Department of ClinicalImmunology,University Medical Center Groningen,Groningen,The Netherlands;12Lupus Research Unit,The Rayne Institute,St Thomas’Hospital,London,UK;13Service de Me ´decine Interne,Groupe Hospitalier Pitie ´-Salpe ˆtrie `re,Paris,France;14Rheumatolology,Clinic of Endocrinology,Diabetology and Rheumatology,Heinrich-Heine-University,Dusseldorf,Germany;15Department of Rheumatology,Medical University of Vienna,Austria;16Department of Rheumatology,University Hospital of Lund,Lund,Sweden;17Rheumatologia eImmunologia Clinica,Ospedale Civile di Brescia,Italy;18Rheumatology Unit,Department of Medicine,Karolinska Institutet,Karolinska University Hospital,Solna,Sweden;19Centre for Immune Regulation,Division of Immunity and Infection,The University of Birmingham,Birmingham,UKCorrespondence to:D T Boumpas,Departments of Internal Medicine andRheumatology,University of Crete School of Medicine,71003,Heraklion,Greece;boumpasd@med.uoc.gr This is an abbreviated version of the recommendations.The full-text version is available online ()Dr Font died on 26July 2006.Accepted 30April 2007Published Online First 5July2007This paper is freely available online under the BMJ Journals unlocked scheme,see /info/unlocked.dtlABSTRACTObjective:Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)is a complex disease with variable presentations,course and prognosis.We sought to develop evidence-based recommendations addressing the major issues in the management of SLE.Methods:The EULAR Task Force on SLE comprised 19specialists and a clinical epidemiologist.Key questions for the management of SLE were compiled using the Delphi technique.A systematic search of PubMed and Cochrane Library Reports was performed using McMaster/Hedges clinical queries’strategies for questions related to the diagnosis,prognosis,monitoring and treatment of SLE.For neuropsychiatric,pregnancy and antiphospholipid syn-drome questions,the search was conducted using an array of relevant terms.Evidence was categorised based on sample size and type of design,and the categories of available evidence were identified for each recommen-dation.The strength of recommendation was assessed based on the category of available evidence,andagreement on the statements was measured across the 19specialists.Results:Twelve questions were generated regarding the prognosis,diagnosis,monitoring and treatment of SLE,including neuropsychiatric SLE,pregnancy,the antipho-spholipid syndrome and lupus nephritis.The evidence to support each proposition was evaluated and scored.After discussion and votes,the final recommendations were presented using brief statements.The average agreement among experts was 8.8out of 10.Conclusion:Recommendations for the management of SLE were developed using an evidence-based approach followed by expert consensus with high level of agreement among the experts.Approximately half a million people in Europe and a quarter of a million people in the USA (projec-tions based on prevalence rates of 30–50per 100000)have systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1The great majority of these patients are women in their childbearing years.SLE is a complex disease with variable presentations,course and prognosis characterised by remissions and flares.23Because of the systemic nature of the disease,multiple medical specialties are involved in the care of these patients.To avoid fragmentation and optimise management,there is a presentlyunmet need to establish an integrated approach based on widely accepted principles and evidence-based recommendations.Recommendations and/or guidelines represent a popular way of integrating evidence-based medi-cine to clinical practice.These are systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances.4To this end and under the auspices of EULAR,we undertook the task of developing guidelines for the management of various aspects of SLE.To ensure a high level of intrinsic quality and comparability of this approach,we used the EULAR standard operating procedures.5We present here 12key recommenda-tions,selected from a panel of experts,for the management (diagnosis,treatment,monitoring)of SLE using a combination of research-based evi-dence and expert consensus.METHODSThe EULAR standardised operating procedures suggest a discussion among experts in the field about the focus,the target population and an operational definition of the term ‘‘management’’,followed by consensus building based on the currently available literature (evidence-based),combined with expert opinion,as needed,to arrive at consensus for a set of recommendations.5The expert committee agreed on 12topics,including general management of SLE (5questions),neuro-psychiatric lupus (2questions),pregnancy in lupus (1question),antiphospholipid syndrome (1ques-tion)and lupus nephritis (3questions).A syste-matic search of PubMed the Cochrane library was performed,and retrieved items were screened for eligibility based on their title,abstract and/or full content.Evidence was categorised according to study design using a traditional rating scale,and the strength of the evidence was graded combining information on the design and vali-dity of the available data (see the full-text version for more details).The results of the literature search were summarised,aggregated and distrib-uted to the expert committee.Following dis-cussion,voting and adjusting the formulation,the expert committee arrived at 12final recom-mendations for the management of SLE (table 1).Further,the expert committee proposed topics for a Research Agenda.RESULTS(TABLES1AND2)PrognosisSLE runs a highly variable clinical course,and determination of prognosis together with the development of reliable indicators of active disease,disease severity and damage accrual is important.Several clinical manifestations(discoid lesions,6 arthritis,7serositis,8renal involvement,910psychosis or sei-zures611),laboratory tests(anaemia,81213thrombocytopenia,14leucopenia,15serum cretatinine9),immunological tests(anti-dsDNA,101416anti-C1q,17antiphospholipid,18–20anti-RNP,18anti-Ro/SSA,2122anti-La/SSB antibodies,23serum complement con-centrations121423),brain MRI7and renal biopsy2425correlate with outcome in terms of development of major organ involvement(nephritis,neuropsychiatric lupus),end-stage renal disease(ESRD),and damage accrual or decreased survival. The small size and large number of candidate predictors tested represent significant problems and raise the possibility for selective reporting of significant associations.Moreover,these prognostic variables have not been uniformly informative acrossTable1Summary of the statements and recommendations on the management of systemic lupus erythematosus based on evidence and expert opinionGeneral managementPrognosisIn patients with SLE,new clinical signs(rashes,arthritis,serositis,neurological manifestations and seizures/psychosis),routine laboratory(CBC,serum creatinine,proteinuria and urinary sediment),and immunological tests(serum C3,anti-dsDNA,anti-Ro/SSA,anti-La/SSB,antiphospholipid,anti-RNP),may provide prognostic information for the outcome in general and involvement of major organs,and thus should be considered in the evaluation of these patients.Confirmation by imaging(brain MRI),and pathology(renal biopsy)may add prognostic information and should be considered in selected patients.MonitoringNew clinical manifestations such as number and type of skin lesions,or arthritis,serositis,and neurological manifestations(seizures/psychosis),laboratory tests(CBC), immunological tests(serum C3/C4,anti-C1q,anti-dsDNA),and validated global activity indices have diagnostic ability for monitoring for lupus activity and flares,and may be used in the monitoring of lupus patients.Co-morbiditiesSLE patients are at increased risk for certain co-morbidities,due to the disease and/or its treatment.These co-morbidities include infections(urinary-tract infections,other infections),atherosclerosis,hypertension,dyslipidaemias,diabetes,osteoporosis,avascular necrosis,malignancies(especially non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma).Minimisation of risk factors together with a high-index of suspicion,prompt evaluation,and diligent follow-up of these patients is recommended.TreatmentIn the treatment of SLE without major organ manifestations,antimalarials and/or glucocorticoids are of benefit and may be used.NSAIDs may be used judiciously for limited periods of time at patients at low risk for their complications.In non-responsive patients or patients not being able to reduce steroids below doses acceptable for chronic use, immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine,mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate should also be considered.Adjunct therapyPhoto-protection may be beneficial in patients with skin manifestations and should be considered.Lifestyle modifications(smoking cessation,weight control,exercise)are likely to be beneficial for patient outcomes and should be encouraged.Depending on the individual medication and the clinical situation,other agents(low-dose aspirin,calcium/vitamin D, biphosphonates,statins,antihypertensives(including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors))should be considered.Oestrogens(oral contraceptives,hormone-replacement therapy)may be used,but accompanying risks should be assessed.Neuropsychiatric lupusDiagnosisIn SLE patients,the diagnostic work-up(clinical,laboratory,neuropsychological,and imaging tests)of neuropsychiatric manifestations should be similar to that in the general population presenting with the same neuropsychiatric manifestations.TreatmentSLE patients with major neuropsychiatric manifestations considered to be of inflammatory origin(optic neuritis,acute confusional state/coma,cranial or peripheral neuropathy, psychosis,and transverse myelitis/myelopathy)may benefit from immunosuppressive therapy.Pregnancy in lupusPregnancy affects mothers with SLE and their offspring in several ways.(a)Mother.There is no significant difference in fertility in lupus patients.Pregnancy may increase lupus disease activity,but these flares are usually mild.Patients with lupus nephritis and antiphospholipid antibodies are more at risk of developing pre-eclampsia and should be monitored more closely.(b)Fetus.SLE may affect the fetus in several ways,especially if the mother has a history of lupus nephritis,antiphospholipid,anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies.These conditions are associated with an increase in the risk of miscarriage,stillbirth,premature delivery,intrauterine growth restriction and fetal congenital heart block.Prednisolone,azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine and low-dose aspirin may be used in lupus pregnancies.At present,evidence suggests that mycophenolate mofetil,cyclophosphamide and methotrexate must be avoided.Antiphospholipid syndromeIn patients with SLE and antiphospholipid antibodies,low-dose aspirin may be considered for primary prevention of thrombosis and pregnancy loss.Other risk factors for thrombosis should also be assessed.Oestrogen-containing drugs increase the risk for thrombosis.In non-pregnant patients with SLE and APS-associated thrombosis,long-term anticoagulation with oral anticoagulants is effective for secondary prevention of thrombosis.In pregnant patients with SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome combined unfractionated or LMW heparin and aspirin reduce pregnancy loss and thrombosis and should be considered.Lupus nephritisMonitoringRenal biopsy,urine sediment analysis,proteinuria,and kidney function may have independent predictive ability for clinical outcome in therapy of lupus nephritis but need to be interpreted in conjunction.Changes in immunological tests(anti-dsDNA,serum C3)have only limited ability to predict the response to treatment and may be used only as supplemental information.TreatmentIn patients with proliferative lupus nephritis,glucocorticoids in combination with immunosuppressive agents are effective against progression to end-stage renal disease.Long-term efficacy has been demonstrated only for cyclophosphamide-based regimens,which are however associated with considerable adverse effects.In short-and medium-term trials, mycophenolate mofetil has demonstrated at least similar efficacy compared with pulse cyclophosphamide and a more favourable toxicity profile:failure to respond by6months should evoke discussions for intensification of therapy.Flares following remission are not uncommon and require diligent follow-up.End-stage renal diseaseDialysis and transplantation in SLE have rates for long-term patient and graft-survival comparable with those observed in non-diabetic non-SLE patients,with transplantation being the method of choice.Table2Category of evidence and strength of statementsRecommendation/item No.of studies evaluated Category of evidence Strength of statement Mean level of agreement*Prognosis.Prognostic value of:Clinical featuresRashes44B8.6Arthritis44B8.7Serositis64B8.6Seizures/psychosis94B9.0Laboratory findingsSevere anaemia104B8.0Leucopenia/lymphopenia45C8.0 Thrombocytopenia154B8.0Serum creatinine204B9.2Proteinuria/urinary sediment244B9.3C3/C4134B8.4Anti-dsDNA174B8.7Anti-Ro/SSA64B7.7Anti-La/SSB15C7.7Antiphospholipid194B8.5Anti-RNP34B7.6ImagingBrain MRI74B8.7PathologyRenal biopsy334B9.5Monitoring.Diagnostic ability of:Rashes15C8.8Anaemia14B8.3Lymphopenia14BThrombocytopenia15CC3/C4134B8.8Anti-C1q84B7.7Anti-dsDNA154B8.7Comorbidities.Increased risk for:Infections135C8.6Urinary-tract infections14B8.9Atherosclerosis144B8.8Hypertension74B9.4Dyslipidaemia74B9.2Diabetes35C8.9Osteoporosis65C9.1Avascular necrosis85C8.6Neoplasms8.7Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas64BOther104BTherapy of uncomplicated SLEAntimalarials42A9.4NSAIDs1–D8.8Glucocorticoids32A9.1Azathioprine14B9.3Mycophenolate mofetil46D 6.9Methotrexate32A8.0Adjunct therapy in SLEPhotoprotection14B9.2Smoking cessation––D9.3Weight control––DExercise––DLow-dose aspirin14D{9.0Calcium/vitamin D52A9.2Biphosphonates22A8.5Statins––D8.9Antihypertensives––D8.9Oral contraceptives(safe use)22A9.1Hormone-replacement therapy32A9.1Table2ContinuedRecommendation/item No.of studies evaluated Category of evidence Strength of statement Mean level of agreement*Diagnosis of neuropsychiatric lupus8.1{Clinical featuresHeadache(not related)13AAnxiety15CDepression15CCognitive impairment34BLaboratory testsEEG34BAnti-P64BAntiphopholipid44BNeuropsychological tests35CImaging testsCT34BMRI94BPET24BSPECT55CMTI55CDWI15CMRS35CT2relaxation time25CTreatment of neuropsychiatric lupusImmunosuppressants(CY)in combination with102A9.2glucocorticoidsPregnancyFertility not impaired45C8.8Increased lupus activity/flares113B8.8Increased risk for pre-eclampsia64B9.8Increased risk for miscarriage/stillbirth/premature delivery304B9.4Increased risk for intrauterine growth restriction65CIncreased risk for fetal congenital heart block74BTherapy during pregnancyPrednisolone66D9.6Azathioprine56D9.2HCQ92A9.5Low-dose aspirin16D9.3Antiphospholipid syndromePrimary prevention of thrombosis/pregnancy lossLow-dose aspirin––D8.7Secondary prevention of thrombosis/pregnancy lossOral anticoagulants(non-pregnant patients)82A9.0141A9.1Unfractionated/LMW heparin and aspirin(pregnantpatients)Nephritis:monitoringRepeat renal biopsy64B9.5Urinary sediment24BProteinuria104BSerum creatinine84BAnti-dsDNA34B8.7C324BNephritis:treatmentCombined glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants are211A9.3effective against ESRD82A9.2MMF has similar efficancy to pulse CY in short-/medium-term trialsCY efficacy in long-term trials131A9.5End-stage renal disease in SLEDialysis is safe in SLE73B8.8Transplantation is safe in SLE93BTransplantation is superior to dialysis25C19.4*Mean level of agreement of the Task Force members on each sub-item/statement;{in elderly SLE patients,low-dose aspirin is associated with improved cognitive function(4/B); {this refers to the statement that‘‘in SLE patients,the diagnostic work-up(clinical,laboratory,neuropsychological and imaging tests)of neuropsychiatric manifestations should be similar to that in the general population presenting with the same neuropsychiatric manifestations’’;1non-SLE studies.patients in various clinical settings or backgrounds.Most importantly,perhaps,no single predicting factor has emerged that could accurately predict the outcome.Thus,the various prognostic factors in a single patient need to be evaluated in conjunction.In general,involvement of major organs denotes a worse prognosis.MonitoringSLE is often complicated by exacerbations and flares of varying severity.Several global and organ-specific activity indices are used in the evaluation of SLE patients in routine clinical prac-tice and in clinical trials.26–28More commonly used are the British Isles Lupus Assessement Group Scale(BILAG),European Consensus Lupus Activity Measure(ECLAM),and the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index(SLEDAI).These indices have been developed in the context of long-term obser-vational studies,are good predictors of damage and morta-lity,and reflect changes in disease activity.29–31The committee encourages the use of at least one of these indices for the monitoring of disease activity.In addition,new clinical manifestations(skin lesions,32anaemia,lymphopenia,or thrombocytopenia,3334low serum C3and/or C4concentra-tions,3536anti-dsDNA,333738and anti-C1q titres39)correlate with disease severity and can predict future flares.While these indices and diagnostic tests may have some diagnostic ability for monitoring disease,none of them has been evaluated in randomised trials for the ability to alter manage-ment and patient outcome.The level of changes that should trigger changes in management is also unknown.For example, intensification of therapy based on serological activity alone, especially a rise in anti-dsDNA titres,374041runs a risk of overtreating patients,although it has been shown to prevent relapses in a randomized clinical trial(RCT).42In these cases, most experts advise a closer follow-up for clinical disease activity.Co-morbiditiesSLE patients may be at increased risk for several co-morbidities, and treatment-related morbidity may not be easily separable from disease-related morbidity,thus raising the issue of whether the two may have an additive or synergistic effect.Patients with SLE have an almost5-fold increased risk of death compared with the general population.4344Several observational cohorts and case-control studies have identified infections,104546hyperten-sion,47dyslipidaemia,4748diabetes mellitus,47atherosclerosis,4849 coronary heart disease,50osteoporosis,51avascular bone necro-sis1052and certain types of cancer(non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lung cancer,hepatobiliary cancer)53as a common cause of morbidity and mortality in SLE patients.However,no randomised trials exist to suggest that intensified screening for these comorbidities would improve outcome.Moreover,many of these data originate from tertiary referral centres that usually provide care to the most severe cases of lupus raising the possibility of spectrum of disease bias.Suboptimal selection of controls may also inflate the reported strength of some of these associations.Neverthless,clinical experience and available data suggest that comorbities are a major component of the disease. The committee therefore recommends a high index of suspicion and diligent follow-up.Treatment of non-major organ involvement Glucocorticoids,4254antimalarials,5556non-steroid anti-inflam-matory drugs(NSAIDs)and,in severe,refractory cases,immunosuppressive agents57–59are used in the treatment of SLE patients without major-organ involvement.Despite their widespread use,there are only a few RCTs with variable outcome criteria demonstrating their efficacy in SLE.Moreover, while most studies have shown improvement,it is not apparent whether patients were left with residual disease activity and its extent.The evidence is typically limited to small sample sizes, even when randomisation has been used.The committee recommends judicious use of these agents,taking into consideration the potential harms associated with each of these drugs.Adjunct-therapyIn a double-blind,intra-individual comparative study,the use of sunscreens could prevent the development of skin lesions following photoprovocation.60Although no data are available in SLE specifically,the committee felt that low-dose aspirin may be considered in adult lupus patients receiving corticosteroids,in those with antiphospholipid antibodies and in those with at least one traditional risk factor for atherosclerotic disease.61In patients receiving long-term glucocorticoid therapy, calcium and vitamin D may protect from bone mass loss.62 Two other studies have demonstrated beneficial effects of biphosphonates in mixed population of patients with SLE and other inflammatory diseases.6364Pregnancy should be postponed for6months after withdrawal of biphosphonates.65Although oestrogen use has been associated with increased risk for developing SLE,66two RCTs have concluded that oral oestrogen contraceptives do not increase the risk for flare in stable disease.6768Hormone-replacement therapy results in a signifi-cantly better change in bone mass density compared with placebo or calcitriol,without increasing the risk for flares.6970 These results may not be generalised to patients with increased risk for thombo-occlusive incidents,and accompanying risks should be assessed before oestrogen therapy is prescribed. Despite the lack of SLE-specific literature,weight control, physical exercise and smoking cessation are recommended, especially for SLE patients with increased CVD risk.Statins and antihypertensives(ACE inhibitors)should also be considered in selected patients.Diagnosis of neuropsychiatric lupusNeurological and/or psychiatric manifestations occur often in SLE patients and may be directly related to disease itself (primary neuropsychiatric lupus)or to complications of the disease or its treatment(secondary neuropsychiatric lupus). There are several clinical,laboratory/immunological,neuropsy-chological and imaging tests2071–78which have been used in SLE patients presenting with neuropsychiatric manifestations. Altogether,these studies suggest that no single clinical, laboratory,neuropsychological and imaging test can be used to differentiate neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE)from non-NPSLE patients with similar neuropsychia-tric manifestations.A combination of the aforementioned tests may provide useful information in assessment of selected SLE patients presenting with neuropsychiatric symptoms.The diagnostic evaluation should be similar to what the evaluation would be in patients without SLE who exhibit the same neuropsychiatric manifestations.Treatment of severe,inflammatory neuropsychiatric lupus Primary neuropsychiatric lupus occurs in the setting of lupus activity in other organs and involves a variety of pathogenicmechanisms including immune-mediated neuronal excitation/ injury/death or demyelination(which is usually managed with immunosuppressive therapy)and/or ischaemic injury due to impaired perfusion(due to microangiopathy,thrombosis or emboli)commonly associated with the antiphospholipid anti-bodies which may require anticoagulation.2We found a single RCT conducted in32SLE patients presenting with active NPSLE manifestations such as periph-eral/cranial neuropathy,optic neuritis,transverse myelitis, brainstem disease or coma.79Induction therapy with intrave-nous methylprednisolone(MP)was followed by either intrave-nous monthly cyclophosphamide(CY)versus intravenous MP every4months for1year and then intravenous CY or intravenous MP every3months for another year.Eighteen out of19patients receiving CY versus7/13patients receiving MP(p=0.03)responded to treatment.Beneficial effects of CY in treatment of severe NPSLE have also been suggested in non-randomised controlled studies.8081Pregnancy in lupusThe management of a pregnant SLE patient has always been a challenge for the practising physician,since lupus may affect pregnancy and vice versa.There is not enough evidence to support a deleterious effect of SLE on fertility.82–84Pregnancy may increase lupus disease activity and cause mild-to-moderate flares,involving mostly skin,joints and blood.85–87Lupus nephritis8889and antiphospholipid antibodies9091have been identified as a risk factor for hypertensive complications and pre-eclampsia.SLE patients—especially those with nephri-tis or antiphospholipid antibodies—are at risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes,including miscarriage,stillbirth and premature delivery(relative risks ranging from2.2to5.8).8792–95Antiphospholipid antibodies and nephritis are also associated with low birth weight and intra-uterine growth restriction.9697 Fetal congenital heart block is another complication of SLE pregnancies(2–4.5%),9899and it is associated with anti-Ro/SSA or anti-La/SSB autoantibodies.Prednisolone and other non-fluorinated glucocorticoids, azathioprine,ciclosporin A and low-dose aspirin have been used in lupus pregnancy,but their efficacy and safety have not been demonstrated in randomised trials.The efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine in lupus pregnancy have been evaluated in one RCT.100These recommendations may differ from the ratings of the United States Food&Drug Administration which,in their current form,are often not helpful for the clinician treating patients with chronic disease during preg-nancy and lactation.65There is no evidence to support the use of mycophenolate mofetil or CY,and methotrexate and these agents must be avoided during pregnancy.101102 Antiphospholipid syndrome in lupusAntiphospholipid antibodies are commonly encountered in SLE patients and are associated with increased risk for thrombo-occlusive incidents.In such patients,primary and/or secondary prevention of thrombosis is warranted,but the clinical decision is often hampered by accompanying risks for treatment-related adverse effects(ie,major bleeding).Despite the lack of evidence for primary prevention of thombosis and pregnancy loss,the expert committee recommends the use of low-dose aspirin in SLE patients with antiphospholipid antibodies,especially when other risk factors for thrombosis coexist.The effectiveness of oral anticoagulation over aspirin alone in prevention of thrombosis in(non-pregnant)SLE patients with antiphospholipid antibodies and thrombosis has been estab-lished in retrospective controlled studies.103–106Two RCTs107108 have demonstrated no superiority of high-intensity(target INR 3.1–4.0)over moderate-intensity warfarin(INR 2.0–3.0)for secondary prevention,and increased risk for minor bleeding in the high-intensity arm(28%vs11%).108Their results,however, are limited in that most patients(.70%)had history of venous—rather than arterial—thrombosis,and that patients who had already had recurrent events on oral anticoagulation were excluded.Conversely,retrospective studies including more patients with previous arterial thrombosis or stroke have concluded that high-intensity warfarin is more efficacious in secondary prevention of thrombosis without increasing the risk for major bleeding.103–105109110The committee proposes that in patients with APS and a first event of venous thrombosis,oral anticoagulation should target INR2.0–3.0.In the case of arterial or recurrent thrombosis,high-intensity anticoagulation(target INR3.0–4.0)is warranted.As for pregnant SLE patients with APS,a recent Cochrane Review concluded that combined unfractionated heparin and aspirin may reduce the risk for pregnancy loss(RR0.46,95%CI: 0.29to0.71).111The combination of low-molecular-weight heparin and aspirin also seems to be effective(RR0.78,95% CI:0.39to1.57).There are no randomised trials assessing the usefulness of anticoagulation in prevention of recurrent thrombosis during pregnancy.The committee recommends the use of aspirin and heparin for the prevention of APS-related thrombosis during pregancy.Lupus nephritis:diagnosis and monitoringIn patients with suspected lupus nephritis,renal biopsy may be used to confirm the diagnosis,evaluate disease activity, chronicity/damage,and determine prognosis and appropriate therapy.The predictive value of second renal biopsy(ie,after treatment initiation)has been assessed in one prospective112and a few retrospective studies.113114It was found that some pathology findings were associated with clinical response and outcome in lupus nephritis.Nevertheless,repeat renal biopsies pose a risk to the patient and may not be feasible for all patients.There is some evidence to support the predictive ability of urine sediment analysis in monitoring lupus nephritis therapy.115116Changes in proteinuria,117serum creati-nine,2236113117anti-dsDNA and serum C3concentations36118119 correlate with renal flares and outcome.It should be empha-sised,however,that these studies were not specifically designed to evaluate the efficacy of various tests in monitoring response to therapy of lupus nephritis.There are no randomised trials evaluating the benefits from various monitoring strategies. Lupus nephritis:treatmentThe treatment of lupus nephritis often consists of a period of intensive immunosuppressive therapy(induction therapy) followed by a longer period of less intensive maintenance therapy.In a recent Cochrane Review,CY plus steroids reduced the risk for doubling of serum creatinine level compared with steroids alone(RR=0.6),but had no impact on overall mortality.120121Azathioprine plus steroids reduced the risk for all-cause mortality compared with steroids alone(RR=0.6), but had no effect on renal outcomes.CY was superior to azathioprine and/or corticosteroids with high-dose,intermit-tent administration of CY(pulse therapy)demonstrating a more favourable efficacy-to-toxicity ratio than oral CY.122In a long-term follow-up(median11years)of an RCT combination。

解读2008esc急性肺栓塞诊治指南_熊长明

血液供应:肺动脉、支气管动脉、肺循环和支气管血管 之间交通、肺泡氧弥散。 肺梗死常发生于外周小肺动脉阻塞时,中心肺动脉阻塞 一般不引起肺梗死。 既往有心肺疾病者易发生肺梗死。

静脉血栓栓塞易患因素

易患因素

患者相关

化疗

慢性心衰或呼衰

✓

激素替代治疗

✓

恶性肿瘤

✓Байду номын сангаас

口服避孕药治疗

✓

中风发作

✓

怀孕/产后

既往下肢静脉血栓

✓

血栓形成倾向

✓

环境相关 ✓ ✓ ✓

✓

2000年ESC急性肺栓塞临床分型

大面积肺栓塞(massive PTE):临床上以休克和低血压 为主要表现,即体循环动脉收缩压<90mmHg或较基础 值下降幅度>40mmHg,持续15分钟以上。须除外新发生 的心律失常,低血容量或感染中毒症所致血压下降。

抗凝治疗时程

急性肺栓塞的抗凝时间长短应个体化,一般至少需要3 个月。

如果急性肺栓塞(0.5%-5%患者)发展成慢性血栓 栓塞性肺动脉高压者应长期抗凝治疗。

如果急性肺栓塞治疗成功,症状基本消失,无右心压 力负荷,影像学检查肺栓塞基本消失者应根据血栓形 成的诱发因素类型决定抗凝时程。

抗凝治疗时程

抗凝治疗

普通肝素应用指征

血流动力学不稳定的高危肺栓塞患者(因为目前一些比较普通肝 素和低分子量肝素的抗凝效果和安全性的临床试验中并不包括这 些高危患者)。

肾功能不全患者(因普通肝素经网状内皮系统清除,不经肾脏代 谢)。

高出血风险患者(因普通肝素抗凝作用可迅速被中和)。

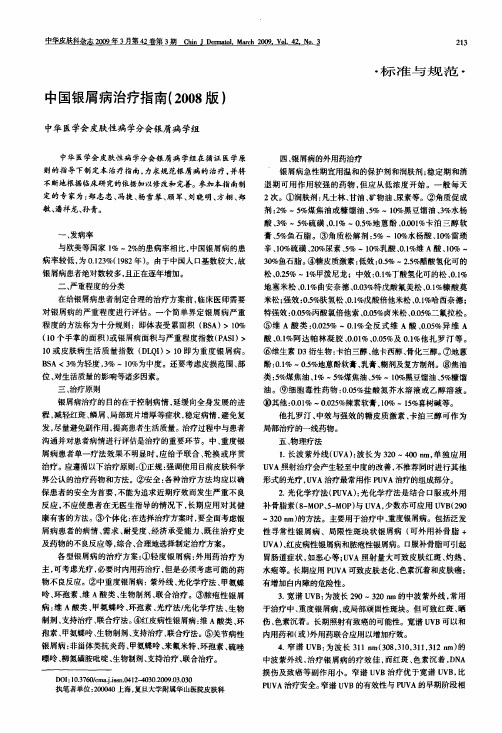

中国银屑病治疗指南(2008版)

PUVA治疗安全。窄谱UVB的有效性与PUVA的早期阶段相 损伤及致癌等副作用小。窄谱UVB治疗优于宽谱UVB,比 中波紫外线。治疗银屑病的疗效佳,而红斑、色素沉着,DNA am)的 rim(308,310,311,312 4.窄谱UVB:为波长311 内用药和(或)外用药联合应用以增加疗效。 伤、色素沉着。长期照射有致癌的可能性。宽谱UVB可以和 于治疗中、重度银屑病,或局部顽固性斑块。但可致红斑、晒 nm的中波紫外线。常用 3.宽谱UVB:为波长290~320 有增加白内障的危险性。 水疱等。长期应用PUVA可致皮肤老化、色素沉着和皮肤癌; 胃肠道症状,如恶心等;UVA照射量大可致皮肤红斑、灼热、 UVA)、红皮病性银屑病和脓疱性银屑病。口服补骨脂可引起 性寻常性银屑病、局限性斑块状银屑病(可外用补骨脂+ rim)的方法。主要用于治疗中、重度银屑病。包括泛发 —320 补骨脂素(8-MOP、5一MOP)与UVA,少数亦可应用UVB(290 2.光化学疗法(PUVA):光化学疗法是结合口服或外用 形式的光疗,UVA治疗最常用作PUVA治疗的组成部分。 UVA照射治疗会产生轻至中度的改善,不推荐同时进行其他 nm,单独应用 1.长波紫外线(UVA):波长为320—400 五、物理疗法 局部治疗的一线药物。 他扎罗汀、中效与强效的糖皮质激素、卡泊三醇可作为 ⑩其他:0.01%一0.025%辣素软膏,10%一15%喜树碱等。 油。⑨细胞毒性药物:0.05%盐酸氮芥水溶液或乙醇溶液。 类:5%煤焦油、l%一5%煤焦油、5%~10%黑豆馏油、5%糠馏 酚:0.1%一0.5%地蒽酚软膏、乳膏、糊剂及复方制剂。⑧焦油 ⑥维生素D3衍生物:卡泊三醇、他卡西醇、骨化三醇。⑦地蒽 酸、0.1%阿达帕林凝胶、0.01%、0.05%及0.1%他扎罗汀等。 ⑤维A酸类:0.025%一0.1%全反式维A酸、0.05%异维A 特强效:0.05%丙酸氯倍他索、0.05%卤米松、0.05%二氟拉松。 米松;强效:0.5%肤氢松、0.1%戊酸倍他米松、0.1%哈西奈德; 地塞米松、0.1%曲安奈德、0.03%特戊酸氟美松、0.1%糠酸莫 松、0.25%~l%甲泼尼龙;中效:0.1%丁酸氢化可的松、0.1% 30%鱼石脂。④糖皮质激素:低效:0.5%一2.5%醋酸氢化可的 辛、10%硫磺、20%尿素、5%一lo%孚L酸、o.1%维A酸、10%~ 膏、5%鱼石脂。③角质松解剂:5%一10%水杨酸、10%雷琐 酸、3%一5%硫磺、0.1%一0.5%地蒽酚、0.001%卡泊三醇软 剂:2%~5%煤焦油或糠馏油、5%~10%黑豆馏油、3%水杨 2次。①润肤剂:凡士林、甘油、矿物油、尿素等。②角质促成 退期可用作用较强的药物,但应从低浓度开始。一般每天 银屑病急性期宜用温和的保护剂和润肤剂;稳定期和消 四、银屑病的外用药治疗 213 执笔者单位:200040上海,复旦大学附属华山医院皮肤科 DOI:10.37601cma.j.issn.0412-4030.2009.03.030 嘌呤、柳氮磺胺吡啶、生物制剂、支持治疗、联合治疗。 银屑病:非甾体类抗炎药、甲氨蝶呤、来氟米特、环孢素、硫唑 孢素、甲氨蝶呤、生物制剂、支持治疗、联合疗法。⑤关节病性 制剂、支持治疗、联合疗法。④红皮病性银屑病:维A酸类、环 病:维A酸类、甲氨蝶呤、环孢素、光疗法/光化学疗法、生物 呤、环孢素、维A酸类、生物制剂、联合治疗。③脓疱性银屑 物不良反应。②中重度银屑病:紫外线、光化学疗法、甲氨蝶 主,可考虑光疗,必要时内用药治疗,但是必须考虑可能的药 各型银屑病的治疗方案:①轻度银屑病:外用药治疗为 及药物的不良反应等,综合、合理地选择制定治疗方案。 屑病患者的病情、需求、耐受度、经济承受能力、既往治疗史 康有害的方法。③个体化:在选择治疗方案时,要全面考虑银 反应.不应使患者在无医生指导的情况下,长期应用对其健 保患者的安全为首要,不能为追求近期疗效而发生严重不良 界公认的治疗药物和方法。②安全:各种治疗方法均应以确 治疗。应遵循以下治疗原则:①正规:强调使用目前皮肤科学 屑病患者单一疗法效果不明显时,应给予联合、轮换或序贯 沟通并对患者病情进行评估是治疗的重要环节。中、重度银 发,尽量避免副作用,提高患者生活质量。治疗过程中与患者 程,减轻红斑、鳞屑、局部斑片增厚等症状,稳定病情,避免复 银屑病治疗的目的在于控制病情,延缓向全身发展的进 三、治疗原则 位、对生活质量的影响等诸多因素。 BSA<3%为轻度,3%~10%为中度。还要考虑皮损范围、部 lO或皮肤病生活质量指数(DLQI)>10即为重度银屑病。 (10个手掌的面积)或银屑病面积与严重程度指数(PASI)> 程度的方法称为十分规则:即体表受累面积(BSA)>10% 对银屑病的严重程度进行评估。一个简单界定银屑病严重 在给银屑病患者制定合理的治疗方案前,临床医师需要 二、严重程度的分类 银屑病患者绝对数较多,且正在逐年增加。 病率较低,为0.123%(1982年)。由于中国人口基数较大,故 与欧美等国家l%~2%的患病率相比,中国银屑病的患 一、发病率 敏、潘祥龙、孙青。 定的专家为:郑志忠、冯捷、杨雪琴、顾军、刘晓明、方栩、郑 不断地根据临床研究的依据加以修改和完善。参加本指南制 则的指导下制定本治疗指南,力求规范银屑病的治疗,并将 中华医学会皮肤性病学分会银屑病学组在循证医学原 中华医学会皮肤性病学分会银屑病学组 2Q堕,坠!!丝:盥Q:3 主堡麈隧型塞盍至Q螋生3旦筮垒2鲞筮3期£h地j坠塑坠趔,丛§醴h

不同病程RA的治疗PPT

Colebatch AN, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;0:1–11.

MRI和超声可监测炎症,以预测关 节损伤,即使在临床缓解时也可用 于评估持续存在的炎症

目录

治疗目标

什么影响治疗 策略的选择

影响治疗策略选择因素

疾病活动 度

预后不良 因素

患者的 意愿

功能活动 受限

(HAQ-DI)

52周

达标治疗策略研究

临床研 时 设定的 试验设计

究

间 目标

平均病 结果(临床

程

缓解)

STEN 199 ⊿CRP≥ 前瞻、历史

GER 8 50%

数据配对,

n=139

危险因素分

(89)

层研究,

24 月

7.5m

No data

TICOR 200 ∆DAS>1 单盲、随机 19m

A

4 .2

对照试验,n=11165432

*

1

0

3

Grigor C, et al. Lancet. 2004;364:263-269

Routine Intensive

*P < 0.001

*

*

*

*

*

6

9

12

15

18

Months

TICORA试验: 强化治疗方案放射学进展缓慢

Median change in erosion, joint space narrowing and total Sharp score

结果(影像学)

无危险因素的 无差异 有危 险因素, 目 标治疗优于 常规治疗 目标治疗优于 常规治疗†

No-data

RAMRIS无差 异,仅CRP 目 标组有差 异 无差异

2015ACR类风湿关节炎治疗指南正式发布

2015ACR类风湿关节炎治疗指南正式发布2015ACR会议在美国隆重召开啦!今天小编为大家带来新鲜出炉的2015ACR类风湿关节炎治疗指南!来源:中华风湿以下两个表格简述了2015版美国风湿病学学院(ACR)针对类风湿关节炎(RA)的治疗推荐。

背景绿色和加粗字体代表强推荐。

强推荐意味着建议编制小组相信遵循推荐所带来的期望效应远超非期望效应(反之亦然), 所以相应的治疗过程应适用于绝大多数患者, 不能遵循相应推荐者进展很少部分。

背景黄色和斜体字代表有条件推荐, 即遵循推荐所带来的期望效应可能远超非期望效应, 所以相应的治疗过程应该适合于大部分患者, 但有一部分不愿意遵循推荐。

有鉴于此, 有条件推荐是对医生和/或患者的偏好敏感的, 医患共同决策常能取得双方满意。

有偏向性的治疗推荐意味着某种偏好治疗会被推荐为首选项, 而非偏好者就可能成为次要选择。

某种治疗的偏好重于于另一种治疗, 并不意指非偏好治疗存在禁忌, 它仍是一种可选项。

相应的治疗药物按照字母顺序排列; 硫唑嘌呤、金制剂和环孢素曾被考虑过但未包括纳入本指南。

改善病情抗风湿药((DMARD)包括羟氯喹、来氟米特、甲氨蝶呤(MTX)和柳氮磺吡啶。

PICO =群体, 干预, 参比药和临床结局。

TNFi=肿瘤坏死因子抑制剂。

相关定义和描述请参加原文的表1。

一、针对早期RA症状的患者的药物治疗建议治疗建议证据等级(已评估的证据)1. 无论患者处于何等疾病活动水平,均遵循目标治疗策略而非无目标治疗方案(PICO A1)低等(17)2. 低疾病活动度且尚未接受任何DMARD治疗的患者:l 先尝试DMARD单药(首选MTX),之后尝试两联治疗(PICO A .2)l 先尝试DMARD单药,之后尝试三联治疗(PICO A. 3)低等(18-21)低级 (22-25)3. 中、高疾病活动度且尚未接受任何DMARD治疗的患者:l 先尝试DMARD单药,之后尝试两联治疗(PICO A .4)l 先尝试DMARD单药,之后尝试三联治疗(PICO A. 5)中等(18,20,2 1)高等 (22-25)4. DMARD单药治疗无效的中、高疾病活动度患者(伴随/不伴糖皮质激素),后续治疗方案可选择DMARD联合或TNFi 或其他非TNF生物制剂(上述方案无先后顺序,可联合或不联合MTX),而非继续DMARD单药治疗( PICO A. 7)低等(26-28)5. DMARDs经治患者,仍处于中、高疾病活动度l 先尝试TNFi ,之后尝试托法替尼单药 (PICO A. 8)l 先尝试TNFi+MTX,之后尝试托法替尼+MTX(PICO A. 9)低等(29)低等(30)6. 如DMARD( PICO A.6)或生物制剂( PICO A.12)治疗后,疾病仍处于中、高度活动,可适当加用低剂量糖皮质激素中等(31-37)低等(31-37)7. 如疾病复发,加用最低起效剂量糖皮质激素进行很低(38-43)最短疗程治疗(PICO A.10, A.11)。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

MIN

SSZ MTX+HCQ MTX+LEF HCQ+SSZ MTX+ +HCQ+SSZ

病程小于6个月

起始点 低

不良预后 特征 ‡ 疾病 活动度 †

中或高

不良预后 特征 ‡

有

LEF MTX SSZ

无

HCQ MIN

有

LEF MTX MTX+SSZ+HCQ MTX+HCQ MTX+SSZ§

无

SSZ

2A

无

不良预 后特征‡

有

阿贝西普 或 TNF 拮 抗剂 或 利妥昔§

3C

禁忌症总目

• • • • • • • • 感染性疾病和/或肺炎方面的禁忌 血液系统疾病和肿瘤方面的禁忌症 心脏方面禁忌 肝脏方面禁忌 肾脏禁忌症 神经系统禁忌症 妊娠和哺乳的禁忌 围手术期感染的风险

感染性疾病和/或肺炎方面的禁忌

海选10696篇,最终入选295篇文献

非生物制剂DMARDs 生物制剂DMARDs

3878篇

共检索到文献

6818篇

515篇

符合文章入选标准

286篇

142篇

排除: 综述、非英语、 非适应症等

153篇

纳入文章质量的评价

• 随机对照临床试验(randomized and controlled trials, RCT)

工作组以及 核心专家小组(CEP)

数据库的选择

检索数据库

非生物制剂 DMARDs:

生物制剂 DMARDs: PubMed

PubMed

1966/1/12007/1/31

1998/1/12007/2/14

生物制剂DMARDs还检索的数据库:EMBASE、SCOPUS、科学网、 国际药学文摘、电子书目录。 未使用FDA不良反应报告系统的数据。

感染性疾病和/或肺炎方面的禁忌

• 禁用甲氨蝶呤

– 临床出现与类风湿关节炎相关的间质性肺炎 – 或不明原因的肺间质病变

• 在开始甲氨蝶呤治疗之前是否需要进行胸 部放射学检查,没有提出建议

感染性疾病和/或肺炎方面的禁忌

器官系统和禁忌证 ABA TNFα拮抗剂 RIT HCQ LEF MTX MIN SSZ

• 成立相关组织

– 核心专家小组:由临床专家和方法学专家组成 – 任务小组:有国际知名临床专家、方法学专家、 患者代表组成

建议制订方法流程图

系统文献复习 制定证 据报告 分析第一次评估 拟构临床 适用条件

评审报告 评价临床适用条件

分析第二次评估 建议草案 评估建议 最终建议

小组间互动会议和 专责小组(TFP) 网络远程会议; RAND-UCLA 审核评价, 讨论证 适用性检验方法 据,再次评价

确定影响治疗决策的重要临床因素

• 在RA诊断确立后,对危险性进行评估是指 导最佳治疗选择的重要因素

• 危险性评估:

– 对RA的病程 – 病情活动度

– 预后不良的相关因素

RA病程

非生物DMARDs

<6月

相当于 疾病 早期

6-24月

相当于中期病程

>24月

相当于 长期慢 性病程

≤3 3-6

生物DMARDs

适应症-说明

• 本适应症讨论的目标人群:

– 既往曾经进行过适当的非药物治疗(例如理疗 及职业疗法)以及抗炎药物治疗(例如非甾体 类抗炎药、关节内注射及口服糖皮质激素)的 主要关注RA患者 类风湿关节炎患者

初始药物治疗 • 如果被同等推荐用于某一特定临床情况, 或 顺序是按字母先后顺序,并非按照选择的 恢复药物治疗的适应症 优劣排序

– – – – – MTX+HCQ MTX+SSZ MTX+LEF SSZ+HCQ SSZ+HCQ+MTX

• 曾考虑过增加或者转换非生物性DMARDs的问题, 但没有达成共识

非生物制剂DMARD治疗建议

预后不良指征 有 否 <6 病程(月) ≥6且≤24 >24 低 疾病活动度 中 高

MTX LEF HCQ

• 用于MTX联合或续以其它DMARDs治疗反应不佳

– 同时病情至少中度活动的患者,不管这些患者有无预 后不良的因素

• 专家小组认为用其它非生物制剂DMARDs代替 MTX应该与原联合治疗方案之间没有显著性差异

其他生物制剂

• 阿贝西普(abatacept)

– 曾经甲氨蝶呤与其它DMARDs联合或续以其它 DMARDs治疗反应不佳,同时至少中度病情活动性、 具有预后不良特征的患者

X

X X X

X

X X X

X

X X X

-

X

X

X

X

-

-

X X -

X X -

X X -

-

X X -

X X X

-

-

血液系统疾病和肿瘤方面的禁忌症

• 禁用或停用来氟米特和甲氨蝶呤

– 白细胞计数<3,000/mm3 – 骨髓异常增生(如白血病前期)病史 – 5年内新诊断或曾经治疗过淋巴增殖性疾病

• 停用来氟米特、甲氨蝶呤和柳氮磺胺吡啶

• 用RAND/UCLA方法,评价2000种具体临 床方案的适当性程度 • 将评级为“适当”的临床方案转化成ACR 关于类风湿关节炎的治疗建议 • 评估类风湿关节炎治疗建议中证据的强度 • ACR对治疗建议进行审查 • 定期重新审阅和更新建议

ACR关于应用非生物制剂及生物 制剂DMARDs治疗类风湿关节炎 的建议

ACR关于使用非生物和生物 DMARDs治疗RA的建议

Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Care & Research) Vol. 59, No. 6, June 15, 2008, pp 762–784

建议的制订方法

• 基于循证医学的证据

– 运用改良的研究开发程序对数据进行评分和分 类

文献检索限制条件和文章入选标准

• 限制条件:研究对象是人,有摘要,原创性研究 • 排除文献的条件

– 报告是会议摘要、病例系列、少于30例的病例报道或 研时间不足6个月 – 非生物制剂DMARDs用于RA以外的疾病(如银屑病关 节炎、系统性红斑狼疮) – 生物制剂DMARDs用于FDA批准适应征以外的其它疾 病(如Wegener肉芽肿) – 生物制剂DMARDs在风湿病疾病以外的使用(如 rituximab治疗淋巴瘤)

#

患者活动评分(Patient Activity Scale, 0-10 PAS)或PASII 常 规 患 者 评 估 指 标 数 据 (Routine Assessment Patient Index Data) 0-30

< 1.9 <6

>1.9 且 5.3 >6 且≤ 12

> 5.3 > 12

• 不能使用来氟米特、甲氨蝶呤或生物制剂

– 活动性细菌感染(或者目前需要抗生素治疗的细菌感 染) – 活动性结核感染(或潜在的结核感染进行预防性治疗 之前) – 活动性带状疱疹病毒感染 – 活动性危及生命的真菌感染时

• 不要使用生物制剂

– 有严重上呼吸道感染(细菌性或病毒性) – 皮肤感染性溃疡未愈合时

• 建议应用TNFα拮抗剂联合MTX治疗

– 从未接受过DMARDs治疗 – 病情高度活动 – 病程不超过3个月 – 具有预后不良的特征 – 同时患者没有治疗费用限制

TNFα拮抗剂在中-长期RA的应用

• 对MTX单药治疗反应不佳

– 同时病情高度活动、有预后不良特征的患者 – 或者病情高度活动、不论有无预后不良因素患者。

– 当血小板计数<50,000/mm3

• 禁用TNFα拮抗剂

– 5年内新诊断或曾经治疗过淋巴细胞增殖性疾 病的患者

血液系统疾病和肿瘤方面的禁忌症

• 白细胞减少时需除外与RA相关的Felty综合 征和大颗粒淋巴细胞综合症,因为后两者 情况并非用药禁忌症 • 除淋巴细胞增殖性疾病外,使用非生物制 剂或生物制剂DMARDs与其它恶性肿瘤的 相关性方面不做任何特异建议。

检索药物

非生物DMARDs 生物DMARDs

•硫唑嘌呤 •羟基氯喹 •来氟米特 •MTX •米诺环素 •金制剂 •柳氮磺吡啶

•依那西普 •英福利昔 •阿达木单抗 •阿那白滞素 •阿贝西普 (Abatacept) •利妥昔单抗

研究领域

1. 用药指征 2. 结核感染的筛查(仅限于生物制剂 DMARDs) 3. 不良反应的监测 4. 临床反应评价 5. 治疗费用和患者喜好在治疗决策中的作用 (仅限于生物制剂DMARDs)

急性严重的细菌感染或正在使用 抗生素治疗的感染

上呼吸道感染(假设为病毒性) 伴有发热(>101º ) F 未愈合的皮肤感染性溃疡 在开始抗结核治疗之前的潜在性 结核感染,或活动性结核在完成 标准抗结核治疗之前† 危及生命的活动性真菌感染 活动性带状疱疹病毒感染 间质性肺炎(由于类风湿关节炎 或未知原因)或临床明显的肺间 质纤维化

– Jadad量表进行评价,得分越高意味着试验的质量越好,最高得分 为5分 – 非生物制剂DMARDs文章的Jadad平均评分为3分

•

生物制剂的临床试验 观察性研究(病例对照研究和队列研究) 质量优于非生物DMARDs

– 关生物制剂DMARDs的文章Jadad评分为5分 – Newcastle-Ottawa评分系统(Newcastle-Ottawa scale, NOS)分 值范围为0 ~ 9 ,分数高提示质量好。 – 非生物制剂DMARDs的文章,平均NOS得分为3分(IQR2.253.75), – 生物制剂的NOS得分为7分(IQR5-8)

适应症-讨论的药物

• 非生物制剂

– 羟基氯喹 – 来氟米特 – 甲氨喋呤 – 米诺环素 – 柳氮磺胺吡啶