罗素 我为什么而活着 英文原文

英语美文翻译技巧欣赏

The Road Not Taken

• • • • • • • Then took the other, as just as fair , And having perhaps the better claim , Because it was grassy and wanted wear 但我却选择了另外一条路 它荒草萋萋,十分幽寂 显得更诱人,更美丽 翻译方法:增词法、引申法

The Road Not Taken

• • • • • • • And be one traveler,long I stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth 我在那路口久久伫立 我向着一条路极目望去 只见小径拐进灌木 翻译技巧:分句法、增词法

What I Have Lived Fቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱr

• And I have tried to apprehend the Pythagorean power by which number holds sway above the flux. • 我也曾经努力理解毕达哥拉斯学派的理论, 他们认为数字主载着万物的此消彼长。 • 翻译技巧:分句法、增词法

What I Have Lived For

• I long to alleviate the evil, but I cannot, and I too suffer. • 我渴望能够消除人世间的邪恶,可是力 不从心,我自己也同样遭受着它们的折磨。 翻译技巧:增词法

What I Have Lived For

• This has been my life.I have found it worth living, and I would gladly live it again if the chance were offered to me. • 这就是我的一生。我已经找到了它的价值。 如果有机会的话,我愿意开心地,再活一 次。 • 翻译技巧:被动句翻译成无主句

罗素名言中英文

罗素名言中英文导读:本文是关于罗素名言中英文,如果觉得很不错,欢迎点评和分享!1、我们两次出生于这个世界,第一次是为了存在,第二次是为了生存。

Two times we were born in this world, for the first time in order to exist, the second is to survive.2、使我们无法自由和高尚地活着的最主要原因是对财富的迷恋。

We are unable to make free and noble living is the main reason for the fascination with wealth.3、许多人宁愿死,也不愿思考,事实上他们也确实至死都没有思考。

Many people would rather die than think, in fact they do not have to think.4、无聊,对于道德家来说是一个严重的问题,因为人类的罪过半数以上都是源于对它的恐惧。

Boredom is a serious problem for the moral home, because more than half of the sins of mankind are derived from the fear of it.5、爱国就是为一些很无聊的理由去杀人或被杀。

Patriotism is for some very boring reason to kill or be6、倘若一个人不依靠温暖的神话就无法面对生活中的不幸,那么他可就有点软弱和可鄙了。

If a person does not rely on the warmth of the myth cannot face the misfortunes in life, so he is a little weak and despicable.7、中国是一切规则的例外。

罗素名言中英文对照赏析

罗素名言中英文对照赏析罗素名言中英文对照赏析罗素伯特兰·罗素伯爵,二十世纪英国哲学家、数学家、逻辑学家、历史学家,1950年诺贝尔文学奖获得者,分析哲学创始人之一。

以下是罗素名言盘点:罗素名言一Beggars do not envy millionaires, though of course they will envy other beggars who are more successful.乞丐并不羡慕百万富翁,尽管他们一定会羡慕比他们乞讨得多的乞丐。

罗素名言二To be without some of the things you want is an indispensable part of happiness.得不到渴望得到的一些东西是幸福的一个必不可少的组成部分。

罗素名言三Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly controlling my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.有三种质朴而又十分强烈的*** 一直支配着我的人生——对爱之渴望,对知识的求索,对人类苦难的无限怜悯。

罗素名言四One of the symptoms of approaching nervous breakdown is the belief that one's .work is terribly important, and that to take a holiday would bring all kinds of disaster, If I were a medical man , I should precribe a holiday to many patient who consicered his work important.神经即将崩溃的症状之一是相信自己的工作极端重要,休假将会带来种种灾难。

罗素我为什么而活中英文

罗素我为什么而活中英文罗素我为什么而活中英文来源:任炜的日志有三种简单然而无比强烈的激情左右了我的一生:对爱的渴望,对知识的探索和对人类苦难的难以忍受的怜悯。

这些激情象飓风,无处不在、反复无常地吹拂着我,吹过深重的苦海,濒于绝境。

我寻找爱,首先是因为它使人心醉神迷,这种陶醉是如此的美妙,使我愿意牺牲所有的余生去换取几个小时这样的欣喜。

我寻找爱,还因为它解除孤独,在可怕的孤独中,一颗颤抖的灵魂从世界的边缘看到冰冷、无底、死寂的深渊。

最后,我寻找爱,还因为在爱的交融中,神秘而又具体而微地,我看到了圣贤和诗人们想象出的天堂的前景。

这就是我所寻找的,而且,虽然对人生来说似乎过于美妙,这也是我终于找到了的。

以同样的激情我探索知识。

我希望能够理解人类的心灵。

我希望能够知道群星为何闪烁。

我试图领悟毕达哥拉斯所景仰的数字力量,它支配着此消彼涨。

仅在不大的一定程度上,我达到了此目的。

爱和知识,只要有可能,通向着天堂。

但是怜悯总把我带回尘世。

痛苦呼喊的回声回荡在我的内心。

忍饥挨饿的孩子,惨遭压迫者摧残的受害者,被儿女们视为可憎的负担的无助的老人,连同这整个充满了孤独、贫穷和痛苦的世界,使人类所应有的生活成为了笑柄。

我渴望能够减少邪恶,但是我无能为力,而且我自己也在忍受折磨。

这就是我的一生。

我发现它值得一过。

如果再给我一次机会,我会很高兴地再活它一次。

What I have Lived For ------Bertrand Russell Three passions,simple but overwhelmingly strong,have governed my life:the longing for love,the search for knowledge,and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.These passions,like great winds,have blown me hither and thither,in a wayward course,over a deep ocean of anguish,reaching to the very verge of despair. I have sought love,first,because it brings ecstasy--ecstasy so great that I would often have sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of this joy.I have sought it,next,because it relieves loneliness--that terrible loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss.I have sought it,finally,because in the union of love I have seen,in a mystic miniature,the prefiguring vision of the heaven that saints and poets have imagined.This is what I sought,and though it might seem too good for human life, this is what--at last--I have found. With equal passion I have sought knowledge.I have wished to understand the hearts of men.I have wished to know why the stars shine.And I have tried to apprehend the Pythagorean power by which number holds sway above the flux.A little of this,but not much,I have achieved. Love and knowledge,so far as they were possible,led upward toward the heavens.But always pity brought me back to earth.Echoes of cries of pain reverberate in my heart.Children in famine,victims tortured by oppressors,helpless old people a hated burden to their sons,and the whole world of loneliness,poverty,and pain make a mockery of what human life should be.I long to alleviate the evil, but I can’t ,and I too suffer. This has been my life.I have found it worth living,and would gladly live itagain if the chance were offered me.。

HOW-TO-GROW-OLD罗素

HOW TO GROW OLDBy Bertrand Russell罗素(1872-1970),是一个活了99岁的哲学家。

然而,他最大的魅力却不是哲学,而是文学。

曾经获得诺贝尔文学奖——文学中最高奖项的他,用自己的朴实优美的语言为你讲述怎样才能度过一个成功的晚年。

1. In spite of the title, this article will really be on how not to grow old, which, at my time of life, is a much more important subject. My first advice would be to choose your ancestors carefully. Although both my parents died young, I have done well in this respect as regards my other ancestors. My maternal grandfather, it is true, was cut off in the flower of his youth at the age of sixty-seven, but my other three grandparents all lived to be over eighty. Of remoter ancestors I can only discover one who did not live to a great age, and he died of a disease which is now rare, namely, having his head cut off.2. A great grandmother of mine, who was a friend of Gibbon, lived to the age of ninety-two, and to her last day remained a terror to all her descendants. My maternal grandmother, after having nine children who survived, one who died in infancy, and many miscarriages, as soon as she became a widow, devoted herself towoman’s higher education. She was one of the founders of Girton College, and worked hard at opening the medical profession to women. She used to relate how she met in Italy an elderly gentleman who was looking very sad. She inquired the cause of his melancholy and he said that he had just parted from his two grandchildren. “Good gracious”, she exclaimed, “I haveseventy-two grandchildren, and if I were sad each time I parted from one of them, I should have a di smal existence!” “Madre snaturale,” he replied. But speaking as one of the seventy-two, I prefer her recipe. After the age of eighty she found she had some difficulty in getting to sleep, so she habitually spent the hours from midnight to 3 a.m. in reading popular science. I do not believe that she ever had time to notice that she was growing old. This, I think, is proper recipe for remaining young. If you have wide and keen interests and activities in which you can still be effective, you will have no reason to think about the merely statistical fact of the number of years you have already lived, still less of the probable brevity of you future.3. As regards health I have nothing useful to say since I have little experience of illness. I eat and drink whatever I like, and sleep when I cannot keep awake. I never do anything whatever on the ground that it is good for health, though in actual fact the things Ilike doing are mostly wholesome.4. Psychologically there are two dangers to be guarded against in old age. One of these is undue absorption in the past. It does not do to live in memories, in regrets for the good old days, or in sadness about friends who are dead. One’s thoughts must be directed to the future and to things about which there is something to be done. This is not always easy: one’s own past is gradually increasing weight. It is easy to think to oneself that one’s emotions used to be more vivid than they are, and one’s mind keener. If this is true it should be forgotten, and if it is forgotten it will probably not be true.5. The other thing to be avoided is clinging to youth in the hope of sucking vigor from its vitality. When your children are grown up they want to live their own lives, and if you continue to be as interested in them as you were when they were young, you are likely to become a burden to them, unless they are unusually callous. I do not mean that one should be without interest in them, but one’s interest should be contemplative and, if possible, philanthropic, but not unduly emotional. Animals become indifferent to their young as soon as their young can look after themselves, but human beings, owing to the length of infancy, find this difficult.6. I think that a successful old age is easiest for those who havestrong impersonal interests involving appropriate activities. It is in this sphere that long experience is really fruitful, and it is in this sphere that the wisdom born of experience can be exercised without being oppressive. It is no use telling grown-up children not to make mistakes, both because they will not believe you, and because mistakes are an essential part of education. But if you are one of those who are incapable of impersonal interests, you may find that your life will be empty unless you concern yourself with you children and grandchildren. In that case you must realize that while you can still render them material services, such as making them an allowance or knitting them jumpers, you must not expect that they will enjoy your company.7. Some old people are oppressed by the fear of death. In the young there is a justification for this feeling. Young men who have reason to fear that they will be killed in battle may justifiably feel bitter in the thought that they have been cheated of the best things that life has to offer. But in an old man who has known human joys and sorrows, and has achieved whatever work it was in him to do, the fear of death is somewhat abject and ignoble. The best way to overcome it – so at least it seems to me – is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in theuniversal life. An individual human existence should be like a river –small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The man who, in old age, can see his life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things he cares for will continue. And if, with the decay of vitality, weariness increases, the thought of rest will not be unwelcome. I should wish to die while still at work, knowing that others will carry on what I can no longer do and content in the thought that what was possible has been done.大聪明和小聪明都是罗素的特色。

英语美文欣赏how+to+grow+old(new)

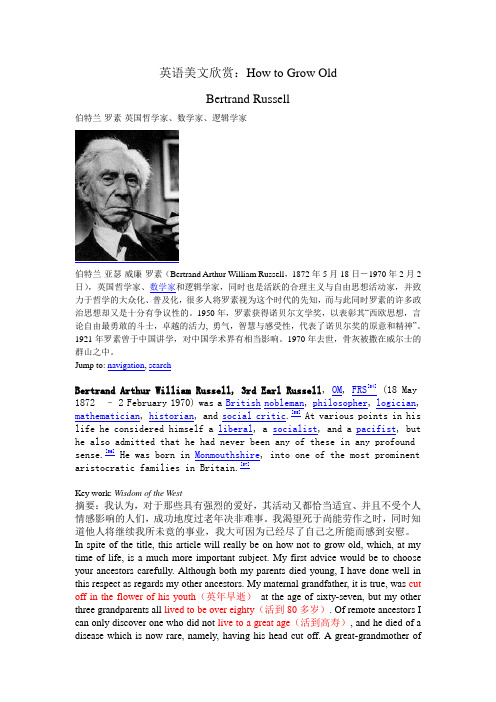

英语美文欣赏:How to Grow OldBertrand Russell伯特兰·罗素-英国哲学家、数学家、逻辑学家伯特兰·亚瑟·威廉·罗素(Bertrand Arthur William Russell,1872年5月18日-1970年2月2日),英国哲学家、数学家和逻辑学家,同时也是活跃的合理主义与自由思想活动家,并致力于哲学的大众化、普及化,很多人将罗素视为这个时代的先知,而与此同时罗素的许多政治思想却又是十分有争议性的。

1950年,罗素获得诺贝尔文学奖,以表彰其“西欧思想,言论自由最勇敢的斗士,卓越的活力, 勇气,智慧与感受性,代表了诺贝尔奖的原意和精神”。

1921年罗素曾于中国讲学,对中国学术界有相当影响。

1970年去世,骨灰被撒在威尔士的群山之中。

Jump to: navigation, searchBertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS[54] (18 May 1872 –2 February 1970) was a British nobleman, philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic.[55] At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these in any profound sense.[56] He was born in Monmouthshire, into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in Britain.[57]Key work: Wisdom of the West摘要:我认为,对于那些具有强烈的爱好,其活动又都恰当适宜、并且不受个人情感影响的人们,成功地度过老年决非难事。

散文两篇我为什么而活着

鉴赏课文

永久的生命

这几种追求的内在联系是:“对人类苦难不可遏制的同 情”是追求爱情、知识的真正动力,这体现了一个伟大 的思想家拯救人类苦难的良知。

由此可以看出全文的脉络: 总提人生追求—分述追求 理由—总结表明态度

品味语言

这三种感情就像飓风一样, 在深深的苦海上,肆意地把 我吹来吹去,吹到濒临绝望 的边缘。

鉴赏课文

永久的生命

你从全文中体会到作者具有怎样崇高而伟大的情操?

他追求爱情,是因为那里有人类所梦想的仙境的缩影;追求 知识,是因为他愿意把自己所有的智慧、力量奉献给人类, 这一切都源于他心中一个辉煌的梦:关爱人类,救民于水火。

永久的生命

鉴赏课文

永久的生命

罗素生于1872年,死于1970年,他一生都在热诚地为公众 的良知辩护。积极参加社会政治活动,为维护世界和平,多次发 表声明和演讲,反对侵略战争。1961年,因反战静坐示威,89 岁的罗素和他的妻子一起被判两个月的监禁。他认为值得,是因 为他一直把关爱人类、救民于水火作为自己的梦想,而且他一直 也是这样做的。

我寻找爱情。

详细内容……点击输入本栏的具体文 字,简明扼要的说明分项内容。

Text here

我以同样的热情寻 求知识。

Text here

再读课文, 理清情感脉络

Text here

爱情和知识,尽其 可能地把我引向云 霄,但是同情心总 把我带回尘世。 Text here

我渴望减轻这些不幸。

详细内容……点击输入本栏的具体文 字,简明扼要的说明分项内容。

鉴赏课文

永久的生命

✓ 爱情和知识,尽其可能地把我引向云霄,但是同情心总把我带回尘世。

✓ 爱情和知识把罗素引向美好的理想境界,而对于人类苦难的同情又使 他把目光投向了现实世界,这体现了一个伟大的思想家拯救人类苦难 的良知。

罗素经典英语散文

罗素经典英语散文:Education and DisciplineAny serious educational theory must consist of two parts: a conception of the ends of life, and a science of psychological dynamics, i.e., of the laws of mental change. Two men who differ as to the ends of life cannot hope to agree about education. The educational machine, throughout Western civilization, is dominated by two ethical theories: that of Christianity, and that of nationalism. These two, when taken seriously, are incompatible, as is becoming evident in Germany. For my part, I hold that where they differ, Christianity is preferable, but where they agree, both are mistaken. The conception which I should substitute as the purpose of education is civilization, a term which, as I meant it, has a definition which is partly individual, partly social. It consists, in the individual, of both intellectual and moral qualities: intellectually, a certain minimum of general knowledge, technical skill in one's own profession, and a habit of forming opinions on evidence; morally, of impartiality, kindliness, and a modicum of self-control. I should add a quality which is neither moral nor intellectual, but perhaps physiological: zest and joy of life. In communities, civilization demands respect for law, justice as between man and man, purposes not involving permanent injury to any section of the human race, and intelligent adaptation of means to ends.If these are to be the purpose of education, it is a question for the science of psychology to consider what can be done towards realizing them, and, in particular, what degree of freedom is likely to prove most effective.On the question of freedom in education there are at present three main schools of thought, deriving partly from differences as to ends and partly from differences in psychological theory. There are those who say that children should be completely free, however bad they may be; there are those who say they should be completely subject to authority, however good they may be; and there are those who say they should be free, but in spite of freedom they should be always good. This last party is larger than it has any logical right to be; Children, like adults, will not all be virtuous if they are all free. The belief that liberty will insure moral perfection is a relic of Rousseauism, and would not survive a study of animals and babies. Those who hold this belief think that education should have no positive purpose, but should merely offer an environment suitable for spontaneous development. I cannot agree with this school, which seems too individualistic, and unduly indifferent to the importance of knowledge. We live in communities which require cooperation, and it would be utopian to expect all the necessary cooperation to result from spontaneous impulse. The existence of a large population on a limited area is only possible owing to science and technique; education must, therefore, hand on the necessary minimum of these. The educators who allow most freedom are men whose success depends upon a degree of benevolence, self-control, and trained intelligence which can hardly be generated where every impulse is left unchecked; their merits, therefore, are not likely to be perpetuated if their methods are undiluted. Education, viewed from a social standpoint, must be something more positive than a mere opportunity for growth. It must, of course, provide this, but it must also provide a mental and moral equipment which children cannot acquire entirely for themselves.The arguments in favor of a great degree of freedom in education are derived not from man's natural goodness, but from the effects of authority, both on those who suffer it and on those who exercise it. Those who are subject to authority become either submissive or rebellious, and each attitude has its drawbacks.The submissive lose initiative, both in thought and action; moreover, the anger generated by the feeling of being thwarted tends to find an outlet in bullying those who are weaker. That is why tyrannical institutions are self-perpetuating: what a man has suffered from his father he inflicts upon his son, and the humiliations which he remembers having endured at his public school he passes on to "natives" when he becomes an empire-builder. Thus an unduly authoritative education turns the pupils into timid tyrants, incapable of either claiming or tolerating originality in word or deed. The effect upon the educators is even worse: they tend to become sadistic disciplinarians, glad to inspire terror, and content to inspire nothing else. As these men represent knowledge, the pupils acquire a horror of knowledge, which, among the English upper class, is supposed to be part of human nature, but is really part of the well-grounded hatred of the authoritarian pedagogue.Rebels, on the other hand, though they may be necessary, can hardly be just to what exists. Moreover, there are many ways of rebelling, and only a small minority of these are wise. Galileo was a rebel and was wise; believers in the flat-earth theory are equally rebels, but are foolish. There is a great danger in the tendency to suppose that opposition to authority is essentially meritorious and that unconventional opinions are bound to be correct: no useful purpose is served by smashing lamp-posts or maintaining Shakespeare to be no poet. Yet this excessive rebelliousness is often the effect that too much authority has on spirited pupils. And when rebels become educators, they sometimes encourage defiance in their pupils, for whom at the same time they are trying to produce a perfect environment, although these two aims are scarcely compatible.What is wanted is neither submissiveness nor rebellion, but good nature, and general friendliness both to people and to new ideas. These qualities are due in part to physical causes, to which old-fashioned educators paid too little attention; but they are due still more to freedom from the feeling of baffled impotencewhich arises when vital impulses are thwarted. If the young are to grow into friendly adults, it is necessary, in most cases, that they should feel their environment friendly. This requires that there should be a certain sympathy with the child's important desires, and not merely an attempt to use him for some abstract end such as the glory of God or the greatness of one's country. And, in teaching, every attempt should be made to cause the pupil to feel that it is worth his while to know what is being taught--at least when this is true. When the pupil cooperates willingly, he learns twice as fast and with half the fatigue. All these are valid reasons for a very great degree of freedom.It is easy, however, to carry the argument too far. It is not desirable that children, in avoiding the vices of the slave, should acquire those of the aristocrat. Consideration for others, not only in great matters, but also in little everyday things, is an essential element in civilization, without which social life would be intolerable. I am not thinking of mere forms of politeness, such as saying "please" and "thank you": formal manners are most fully developed among barbarians, and diminish with every advance in culture. I am thinking rather of willingness to take a fair share of necessary work, to be obliging in small ways that save trouble on the balance. It is not desirable to give a child a sense of omnipotence, or a belief that adults exist only to minister to the pleasures of the young. And those who disapprove of the existence of the idle rich are hardly consistent if they bring up their children without any sense that work is necessary, and without the habits that make continuous application possible.There is another consideration to which some advocates of freedom attach too little importance. In a community of children which is left without adult interference there is a tyranny of the stronger, which is likely to be far more brutal than most adult tyranny. If two children of two or three years old are left to play together, they will, after a few fights, discover which is bound to be the victor, and the other will then become a slave. Where the number of children is larger, one or two acquire complete mastery, and the others have far less liberty than they would have if the adults interfered to protect the weaker and less pugnacious. Consideration for others does not, with most children, arise spontaneously, but has to be taught, and can hardly be taught except by the exercise of authority. This is perhaps the most important argument against the abdication of the adults.I do not think that educators have yet solved the problem of combining the desirable forms of freedom with the necessary minimum of moral training. the right solution, it must be admitted, is often made impossible by parents before the child is brought to an enlightened school. Just as psychoanalysts, from their clinical experience, conclude that we are all mad, so the authorities in modern schools, from their contact with pupils whose parents have made them unmanageable, are disposed to conclude that all children are "difficult" and all parents utterly foolish. Children who have been driven wild by parental tyranny (which often takes the form of solicitous affection) may require a longer or shorter period of complete liberty before they can view any adult without suspicion. But children who have been sensibly handled at home can bear to be checked in minor ways, so long as they feel that they are being helped in the ways that they themselves regard as important. Adults who like children, and are not reduced to a condition of nervous exhaustion by their company, can achieve a great deal in the way of discipline without ceasing to be regarded with friendly feelings by their pupils.I think modern educational theorists are inclined to attach too much importance to the negative virtue of not interfering with children, and too little to the positive merit of enjoying their company. If you have the sort of liking for children that many people have for horse or dogs, they will be apt to respond to your suggestions, and to accept prohibitions, perhaps with some good-humoured grumbling, but without resentment. It is no use to have the sort of liking that consists in regarding them as a field for valuable social endeavor, or--what amounts to the same thing--as an outlet for power-impulses. No child will be grateful for an interest in him that springs from the thought that he will have a vote to be secured for your party or a body to be sacrificed to king and country. The desirable sort of interest is that which consists in spontaneous pleasure in the presence of children, without any ulterior purpose. Teachers who have this quality will seldom need to interfere with children's freedom, but will be able to do so, when necessary, without causing psychological damage. Unfortunately, it is utterly impossible for overworked teachers to preserve an instinctive liking for children; they are bound to come to feel towards them as the proverbial confectioner's apprentice does toward macaroons. I do not think that education ought to be any one's whole profession: it should be undertaken for at most two hours a day by people whose remaining hours are spent away with children. The society of the young is fatiguing, especially when strict discipline is avoided. Fatigue, in the end, produces irritation, which is likely to express itself somehow, whatever theories the harassed teacher may have taught himself or herself to believe. The necessary friendliness cannot be preserved by self-control alone. But where it exists, it should be unnecessary to have rules in advance as to how "naughty" children are to be treated, since impulse is likely to lead to the right decision, and almost any decision will be right if the child feels that you like him. No rules, however wise, are a substitute for affection and tact.。

罗素:我为何而活_教案参考(附原文及参考译文)

析罗素自传序言汉译中的问题李靖民[摘要] 伯特兰〃罗素自传的序言What I Have Lived For(我为何而活)文采横溢、意味深长,深受读者的喜爱。

这篇序言在国内已有多种版本的汉语译文,有的被刊登在各种杂志上,有的被附上英语原文上传至网络,广为流传。

而这些译文虽然各有所长,却大多存在一些翻译上的问题,要么对原文理解得不够准确,要么在译文的表达上有失妥当,要么忽略了历史背景,值得商榷。

(文后附原文及参考译文。

)[关键词] 罗素自传;序言;翻译英国哲学家、逻辑学家、诺贝尔文学奖获得者伯特兰·罗素的散文不仅文笔酣畅、优美动人,而且逻辑缜密、言简意赅,正如王佐良先生(1998: 202)在其《英国散文的流变》中所说:“他力求想得清楚,说得准确。

”罗素自传的序言What I Have Lived For堪称其散文的经典之作,短短三百余字,即高度概括了作者对主宰其一生的三种激情的执着和对人生的热爱,文采横溢、意味深长,深受读者的喜爱。

然而,目前国内一些杂志上刊登的罗素自传序言汉语译文,以及网络上广为流传的附有英语原文的汉语译文则大多存在一些翻译上问题。

这些问题不仅会造成普通读者对原文作者表达意图的误解,还会对希望通过英汉对比来提高翻译能力的读者产生负面影响。

本文拟就这些问题进行分析探讨。

(序言的英语全文及汉语参考译文附文后。

)一、Unbearable PityUnbearable pity出现在第一段第一句Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind。

在这句话里,罗素提到了主宰其一生的三种激情,而当他提到第三种激情时,特意在中心词之前加了一个修饰语,即unbearable + pity。

我为什么而活着课件

罗素生活的现实世界是怎样的?

饥饿中的孩子 被压迫被折磨者 孤苦无依的老人 全球性的孤独,贫穷和痛苦

这就 是生活在贫困山区的父子,他们一生别无所求。只求有一块属于自己的 土地。也许一辈子他们都不知道外面的世界是什么样子。他们没上过楼 梯,没打过“的士”,没进过电影院,可就是朴实勤劳的人们一代代的 供养着我们。皇天厚土无以回报。爱他们吧,至少在感情上尊重他们。 否则我们还谈什么人性??

3月27日,在伊拉克巴士拉城外,一名伊拉克女孩惊恐地注 视背枪的美军士兵。伊拉克战争是2003年国际社会最重大的 事件之一。战争给这个古老国度带来深重苦难

? 有多少孩子拿到这本书,能有这份兴奋

辍学后,12岁的杨荣在街头擦皮鞋为农村的弟弟挣 钱读书

同情人类不幸,保卫世界和平

他直接参加救弱扶困.第一次世界大战 间,他积极从事反战活动.1918年因给 反战报纸写社论被监禁6个月.1961年 为反对美国政府发展核武器,89岁高龄 的罗素偕夫人参与了伦敦游行示威.就 在他逝世的当天,还为中东战争给人民 带来的灾难忧心忡忡.

我为什么而活着

What I Have Lived For

作者简介

• 伯特兰· 罗素(1872—1970),出生于英 国,他2岁丧母,4岁丧父,由他的祖父 把他抚养成人。他一生坎坷,命运多舛, 但他始终坚强地生活。他后来成为一位 集众家于一身的伟人。他被称为“20世 纪最知名、最有影响力的哲学家”之一, 他还是著名的数学家、逻辑学家,社会 活动家。在1950年他又获得了诺贝尔文 学奖,被称为“百科全书式文学家”

只要每个人能够为我们的生活中任何一 片领域的进步而努力工作着,无论最终 他是否有成就,他的人生都是有意义的。 死只是终点,不是目标,进步的过程才 是我们每一个普通人共同的人生目标。

罗素-我为什么活着

罗素-我为什么而活(中英文)What I have Lived For——Bertrand RussellThree passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind. These passions, like great winds, have blown me hither and thither, in a wayward course, over a deep ocean of anguish, reaching to the very verge of despair. I have sought love, first, because it brings ecstasy--ecstasy so great that I would often have sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of this joy. I have sought it, next, because it relieves loneliness--that terrible loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss.I have sought it, finally, because in the union of love I have seen, In a mystic miniature, the prefiguring vision of the heaven that saints and poets have imagined. This is what I sought, and though it might seem too good for human life, this is what--at last--I have found.With equal passion I have sought knowledge. I have wished to understand the hearts of men. I have wished to know why the stars shine. And I have tried to apprehend the Pythagorean power by which number holds sway above the flux. A little of this, but not much, I have achieved.Love and knowledge, so far as they were possible, led upward toward the heavens. But always pity brought me back to earth. Echoes of cries of pain reverberate in my heart. Children in famine, victims tortured by oppressors, helpless old people a hated burden to their sons, and the whole world of loneliness, poverty, and pain make a mockery of what human life should be. I long to alleviate the evil, but I can’t , and I too suffer.This has been my life. I have found it worth living, and would gladly live it again if the chance were offered me.有三种简单然而无比强烈的激情左右了我的一生:对爱的渴望,对知识的探索和对人类苦难的难以忍受的怜悯。

我为什么而活着

我为什么而活着作者:饶莉来源:《高教学刊》2016年第07期摘要:通过从背景介绍,措辞表意,句子结构,句段大意,修辞手法,写作风格等几方面对《罗素自传》序言《我为什么而活着》的原文和译文进行详细的分析,从而更好地理解罗素作为一个思想家、哲学家的崇高人格和博大情怀,同时也对如何更好地进行翻译,传达原作内容和风格进行一些探索性研究。

关键词:我为什么而活着;《罗素自传》序言;译文赏析中图分类号:I106 文献标志码:A 文章编号:2096-000X(2016)07-0257-02Abstract: This paper is intended to analyze Russell's prologue What I Have livedfor and its translation through several aspects: its background, lexical choice, sentence structure,semantic, rhetorical devices, writing style, etc. so as to promote a better understanding of Russell's noble mind and greatness as a thinker and philosopher. Meanwhile, how to better convey the original content and style while translating is further explored.Keywords: what I have lived for; the prologue of The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell;translation appreciation一、概述爱因斯坦说:“阅读罗素的作品,是我一生中最快乐的时光之一。

我为什么而活着英语作文

我为什么而活着英语作文In the vast expanse of the universe, each life is a unique and precious spark. I, too, am one such spark,燃烧着with the intention to explore, understand, and contribute to the world. The question that has always perplexed me is: Why do I exist? What is the purpose of my life?Firstly, I live to pursue knowledge. Knowledge is the key to unlocking the mysteries of the universe and comprehending the complexities of life. It is the driving force that propels me to delve deeper into the sciences, arts, and humanities. Through learning, I seek to understand the principles that govern our world and the principles that shape our thoughts and actions. This quest for knowledge not only satisfies my intellectual curiosity but also equips me with the tools to make a positive impact in society.Secondly, I exist to foster relationships and connections. Life is a shared experience, and our interactions with others shape our identities and perspectives. I cherish the relationships I have with my family, friends, and community members. These relationshipsprovide me with a sense of belonging and purpose,激励我 to be a supportive and compassionate presence in their lives. Through fostering meaningful connections, I aim to create a web of mutual support and understanding that enriches our shared human experience.Lastly, I live to contribute to society. As an individual, I have a responsibility to make the world a better place. Whether it is through volunteer work, professional endeavors, or simple acts of kindness, Istrive to leave a positive impact on the world. My contributions may be small, but I believe that every effort counts in the grand scheme of human progress.In conclusion, the purpose of my existence is multifaceted and deeply personal. I live to pursue knowledge, foster relationships, and contribute to society. These reasons inform my decisions and actions, guiding me on my journey through life. While the path ahead may be uncertain, I am confident that my dedication to these purposes will lead me to a fulfilling and impactful existence.**我存在的意义**在宇宙的广阔无垠中,每一个生命都是独特而珍贵的火花。

我为什么而活着

渴望爱情

爱情带来狂喜 爱情解除孤寂 爱的结合能见到天堂的缩影 崇

追求知识

同情苦难

高 的 了解人类的心灵(人) 人 知道星星为何发光(自然) 格 理解毕达哥拉斯思想(社会) 博 大 饥饿中的孩子 的 被压迫被折磨者 胸 孤苦无依的老人 怀 ,

全球性的孤独、贫穷和痛苦

伯特兰· 罗素

• 一生经历过几次婚姻变故,但他始终是真诚的,一直在 努力追求爱。 “在我所爱的那些女人身上,我欠下了很大的人情,如 果不是她们,我的心地将偏狭得多。”——罗素 • 一生著书71种,论文几千篇,涉及哲学、数学、科学、 政治、宗教等诸方面,享有“百科全书”式思想家之称。 • 一生都在热诚地为公众的良知辩护。“对人类苦难的同 情”使得他坚决反对导致人类灾难的战争。1961年,因 反战静坐示威,89岁的罗素与他的妻子被判两个月监禁。

饥饿的侵袭

孤独、惊恐的儿童

死 于 流 弹 的 平 民

我只想要回我一年的 工钱而已 ..... 我只想要回我应得的 血汗钱...... 难道这就是你们给我 的报酬么?!

•

罗素一生积极参加社会政治活动, 为维护世界和平,多次发表声明和演讲, 反对侵略战争。二战期间,还因反战坐 了六个月牢。 • 1955年初,罗素、爱因斯坦和各国 科学家发起了禁核签名运动。 • 1961年,89岁高龄的罗素携夫人到 英国国防部门前静坐示威,被判两个月 监禁。 • 1964年创立罗素和平基金会。

《钢铁是怎样炼成的》描写保尔· 柯察金

人最宝贵的是生命。它给予我们只有 一次。人的一生应当这样度过:当他回首 往事时不因虚度年华而悔恨,也不因碌碌 无为而羞耻。这样在他临死的时侯就能够 说:“我已把我整个的生命和全部精力都 献给最壮丽的事业—为人类的解放而斗 争。”

我为什么而活着

英国.罗素《我为什么而活着》对爱情的渴望,对知识的追求,对人类苦难不可遏制的同情心,这三种纯洁而无比强烈的激情支配着我的一生。

这三种激情,就像飓风一样,在深深的苦海上,肆意地把我吹来吹去,吹到濒临绝望的边缘。

我寻求爱情,首先因为爱情给我带来狂喜,它如此强烈以致我经常愿意为了几小时的欢愉而牺牲生命中的其他一切。

我寻求爱情,其次是因为爱情可以解除孤寂一—那是一颗震颤的心,在世界的边缘,俯瞰那冰冷死寂、深不可测的深渊。

我寻求爱情,最后是因为在爱情的结合中,我看到圣徒和诗人们所想像的天堂景象的神秘缩影。

这就是我所寻求的,虽然它对人生似乎过于美好,然而最终我还是得到了它。

我以同样的热情寻求知识,我渴望了解人的心灵。

我渴望知道星星为什么闪闪发光,我试图理解毕达哥拉斯的思想威力,即数字支配着万物流转。

这方面我获得一些成就,然而并不多。

爱情和知识,尽其可能地把我引上天堂,但是同情心总把我带回尘世。

痛苦的呼唤经常在我心中回荡,饥饿的儿童,被压迫被折磨者,被儿女视为负担的无助的老人以及充满孤寂、贫穷和痛苦的整个世界,都是对人类应有生活的嘲讽。

我渴望减轻这些不幸,但是我无能为力,而且我自己也深受其害。

这就是我的一生,我觉得值得为它活着。

如果有机会的话,我还乐意再活一次。

What I Have Lived Forby Bertrand RussellThree passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind. These passions, like great winds, have blown me hither and thither, in a wayward course, over a great ocean of anguish, reaching to the very verge of despair.I have sought love, first, because it brings ecstasy - ecstasy so great that I would often have sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of this joy. I have sought it, next, because it relieves loneliness--that terrible loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss. I have sought it finally, because in the union of love I have seen, in a mystic miniature, the prefiguring vision of the heaven that saints and poets have imagined. This is what I sought, and though it might seem too good for human life, this is what--at last--I have found.With equal passion I have sought knowledge. I have wished to understand the hearts of men. I have wished to know why the stars shine. And I have tried to apprehend the Pythagorean power by which number holds sway above the flux. A little of this, but not much, I have achieved.Love and knowledge, so far as they were possible, led upward toward the heavens. But always pity brought me back to earth. Echoes of cries of pain reverberate in my heart. Children in famine, victims tortured by oppressors, helpless old people a burden to their sons, and the whole world of loneliness, poverty, and pain make a mockery of what human life should be. I long to alleviate this evil, but I cannot, and I too suffer.This has been my life. I have found it worth living, and would gladly live it again if the chance were offered me.。

罗素的名言英文版【三篇】

【导语】任何⼀种哲学思想只要是它能够⾃圆其说,它就具有某种真正的知识。

下⾯是整理发布的“罗素的名⾔英⽂版【三篇】”,欢迎阅读参考!更多相关讯息请关注! 【篇1】 ⾈以外,鄂河之波,鄂河之岸,皆静如死,诡如天。

The boat outside Hubei river waves, Hubei river shore, is as quiet as death, such as a day. 厌烦是⼀个极端重要的问题,因为⼈类的恶⾏中,⾄少有⼀半是由于对厌烦的恐惧引起的。

Boredom is an extremely important issue, because at least half of human's evil is caused by the fear of boredom. 幸福的秘诀是:尽量扩⼤你的兴趣范围,对感兴趣的⼈和物尽可能友善。

The secret of happiness is to expand your range of interests and to be as friendly to people as you are interested in. 伟⼤的事业是根源于坚韧不断的⼯作,以全付精神去从事,不避艰苦。

Great cause is the root of the tough work, to pay the spirit to engage in, not to avoid hard. 科学使我们为善或为恶的⼒量都有所提升。

Science gives us for good or evil forces have improved. 对于民主社会的公民来说,再没有什么⽐获得对⾼谈阔论的免疫⼒更加重要。

For the citizens of a democracy, no more than what to talk with eloquence immunity is more important. 惟有对外界事物抱有兴趣才能保持⼈们精神上的健康。

罗素名言英语版

罗素名言英语版1.求罗素的名言伯特兰·罗素(Bertrand Russell 1872-1970)罗素是20世纪声誉卓著、影响深远的思想家之一。

在其漫长的一生中,完成了40余部著作,涉及哲学、数学、科学、论理学、社会学、教育、历史、宗教及政治等各个领域,对西方哲学产生了深刻影响。

1950年获诺贝尔文学奖。

On Human Nature and Politics 论人性和政治 Undoubtedly the desire for food has been, and still is ,one of the main causes of great political events. But man differs from other animals in one very important respect, and that is that he has desires which are , so to speak, intimate, which can never be fully gratified, and which should keep him restless even in Paradise. The boa constrictor, when he had an adequate meal, goes to sleep, and does not wake until he needs another meal. Human beings, for the most not part are not like this. When the Arabs, who had been used to living sparingly on a few dates acquired the riches of the Eastern Roman Empire and dwelt in palaces of almost unbelievable luxury, they did not, on that account, become inactive. Hunger could no longer be a motive, for Greek slaves supplied them with exquisite viands at the slightest nod. But other desires kept them active; four in particular , which we can label acquisitiveness , rivalry, vanity and love of power.毫无疑问,占有食物的欲望过去一直是,而且现在也仍然是导致重大政治事件的主要原因之一。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

What I Have Lived For

——by Bertrand Russell Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind. These passions, like great winds, have blown me hither and thither, in a wayward course, over a great ocean of anguish, reaching to the very verge of despair.

I have sought love, first, because it brings ecstasy - ecstasy so great that I would often have sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of this joy. I have sought it, next, because it relieves loneliness--that terrible loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss. I have sought it finally, because in the union of love I have seen, in a mystic miniature, the prefiguring vision of the heaven that saints and poets have imagined. This is what I sought, and though it might seem too good for human life, this is what--at last--I have found.

With equal passion I have sought knowledge. I have wished to understand the hearts of men. I have wished to know why the stars shine. And I have tried to apprehend the Pythagorean power by which number holds sway above the flux. A little of this, but not much, I have achieved.

Love and knowledge, so far as they were possible, led upward toward the heavens. But always pity brought me back to earth. Echoes of cries of pain reverberate in my heart. Children in famine, victims tortured by oppressors, helpless old people a burden to their sons, and the whole world of loneliness, poverty, and pain make a mockery of what human life should be. I long to alleviate this evil, but I cannot, and I too suffer.

This has been my life. I have found it worth living, and would gladly live it again if the chance were offered me.。