Session 3 The psychology of SLA(1)

智慧树知到《人工智能基础》章节测试答案

鏅烘収鏍戠煡鍒般€婁汉宸ユ櫤鑳藉熀纭€銆嬬珷鑺傛祴璇曠瓟妗?绗竴绔?1銆? 绗竴涓嚮璐ヤ汉绫昏亴涓氬洿妫嬮€夋墜銆佺涓€涓垬鑳滀笘鐣屽洿妫嬪啝鍐涚殑浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鏈哄櫒浜烘槸鐢辫胺姝屽叕鍙稿紑鍙戠殑锛堬級銆?A.AlphaGoB.AlphaGoodC.AlphaFunD.Alpha绛旀: AlphaGo2銆?鏃犻渶妫嬭氨鍗冲彲鑷鍥存鐨勪汉宸ユ櫤鑳芥槸锛堬級A.AlphaGo FanB.AlphaGo LeeC.AlphaGo MasterD.AlphaGo Zero绛旀: AlphaGo Zero3銆?涓栫晫涓婄涓€娆℃寮忕殑AI浼氳浜庯紙锛夊勾鍙紑锛孞ohn McCarthy 姝e紡鎻愬嚭鈥淎rtificial Intelligence鈥濊繖涓€鏈A.1954B.1955C.1956D.1957绛旀: 19564銆? 浠ヤ笅鍝簺涓嶆槸浜哄伐鏅鸿兘姒傚康鐨勬纭〃杩帮紙锛?A.浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鏄负浜嗗紑鍙戜竴绫昏绠楁満浣夸箣鑳藉瀹屾垚閫氬父鐢变汉绫绘墍鑳藉仛鐨勪簨B.浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鏄爺绌跺拰鏋勫缓鍦ㄧ粰瀹氱幆澧冧笅琛ㄧ幇鑹ソ鐨勬櫤鑳戒綋绋嬪簭C.浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鏄€氳繃鏈哄櫒鎴栬蒋浠跺睍鐜扮殑鏅鸿兘D.浜哄伐鏅鸿兘灏嗗叾瀹氫箟涓轰汉绫绘櫤鑳戒綋鐨勭爺绌?绛旀: 浜哄伐鏅鸿兘灏嗗叾瀹氫箟涓轰汉绫绘櫤鑳戒綋鐨勭爺绌?5銆? 涓嬮潰涓嶅睘浜庝汉宸ユ櫤鑳界爺绌跺熀鏈唴瀹圭殑鏄紙锛夈€?A.鏈哄櫒鎰熺煡B.鏈哄櫒瀛︿範C.鑷姩鍖?D.鏈哄櫒鎬濈淮绛旀: 鑷姩鍖?6銆?浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鏄爺绌躲€佸紑鍙戠敤浜庢ā鎷熴€佸欢浼稿拰鎵╁睍浜虹殑锛? 锛夌殑鐞嗚銆佹柟娉曘€佹妧鏈強搴旂敤绯荤粺鐨勪竴闂ㄦ柊鐨勬妧鏈瀛︺€?A.鏅鸿兘B.琛屼负C.璇█D.璁$畻鑳藉姏绛旀: 鏅鸿兘7銆? 鍥剧伒娴嬭瘯鐨勫惈涔夋槸锛堬級A.鍥剧伒娴嬭瘯鏄祴璇曚汉鍦ㄤ笌琚祴璇曡€?涓€涓汉鍜屼竴鍙版満鍣?闅斿紑鐨勬儏鍐典笅锛岄€氳繃涓€浜涜缃紙濡傞敭鐩橈級鍚戣娴嬭瘯鑰呴殢鎰忔彁闂€傞棶杩囦竴浜涢棶棰樺悗锛屽鏋滆娴嬭瘯鑰呰秴杩?0%鐨勭瓟澶嶄笉鑳戒娇娴嬭瘯浜虹‘璁ゅ嚭鍝釜鏄汉銆佸摢涓槸鏈哄櫒鐨勫洖绛旓紝閭d箞杩欏彴鏈哄櫒灏遍€氳繃浜嗘祴璇曪紝骞惰璁や负鍏锋湁浜虹被鏅鸿兘銆?B.鎵€璋撶殑鍥剧伒娴嬭瘯灏辨槸鎸囦竴涓娊璞$殑鏈哄櫒锛屽畠鏈変竴鏉℃棤闄愰暱鐨勭焊甯︼紝绾稿甫鍒嗘垚浜嗕竴涓竴涓殑灏忔柟鏍硷紝姣忎釜鏂规牸鏈変笉鍚岀殑棰滆壊銆傛湁涓€涓満鍣ㄥご鍦ㄧ焊甯︿笂绉绘潵绉诲幓銆傛満鍣ㄥご鏈変竴缁勫唴閮ㄧ姸鎬侊紝杩樻湁涓€浜涘浐瀹氱殑绋嬪簭銆?C.鍥剧伒娴嬭瘯鏄竴绉嶇敤鏉ユ贩娣嗙殑鎶€鏈紝瀹冨笇鏈涘皢姝e父鐨勶紙鍙瘑鍒殑锛変俊鎭浆鍙樹负鏃犳硶璇嗗埆鐨勪俊鎭€?D.涓嶅瓨鍦ㄥ浘鐏垫祴璇曟蹇?绛旀: 鍥剧伒娴嬭瘯鏄祴璇曚汉鍦ㄤ笌琚祴璇曡€?涓€涓汉鍜屼竴鍙版満鍣?闅斿紑鐨勬儏鍐典笅锛岄€氳繃涓€浜涜缃紙濡傞敭鐩橈級鍚戣娴嬭瘯鑰呴殢鎰忔彁闂€傞棶杩囦竴浜涢棶棰樺悗锛屽鏋滆娴嬭瘯鑰呰秴杩?0%鐨勭瓟澶嶄笉鑳戒娇娴嬭瘯浜虹‘璁ゅ嚭鍝釜鏄汉銆佸摢涓槸鏈哄櫒鐨勫洖绛旓紝閭d箞杩欏彴鏈哄櫒灏遍€氳繃浜嗘祴璇曪紝骞惰璁や负鍏锋湁浜虹被鏅鸿兘銆?8銆? 涓嬪垪涓嶅睘浜庝汉宸ユ櫤鑳藉娲剧殑鏄紙锛夈€?A.绗﹀彿涓讳箟B.杩炴帴涓讳箟C.琛屼负涓讳箟D.鏈轰細涓讳箟绛旀: 鏈轰細涓讳箟9銆? 璁や负鏅鸿兘涓嶉渶瑕佺煡璇嗐€佷笉闇€瑕佽〃绀恒€佷笉闇€瑕佹帹鐞嗭紱浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鍙互鍍忎汉绫绘櫤鑳戒竴鏍烽€愭杩涘寲锛涙櫤鑳借涓哄彧鑳藉湪鐜板疄涓栫晫涓笌鍛ㄥ洿鐜浜や簰浣滅敤鑰岃〃鐜板嚭鏉ャ€傝繖鏄紙锛夊娲剧殑鍩烘湰鎬濇兂銆?A.杩炴帴涓讳箟B.绗﹀彿涓讳箟C.琛屼负涓讳箟D.閫昏緫涓讳箟绛旀: 琛屼负涓讳箟10銆?鍏充簬浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鐮旂┒鑼冨紡鐨勮繛鎺ヤ富涔夛紝鐩稿叧璁鸿堪涓嶆纭殑鏄紙锛?A.杩炴帴涓讳箟鍘熺悊鏄ā鎷熷ぇ鑴戠缁忕綉缁滃強绁炵粡缃戠粶闂寸殑杩炴帴鏈哄埗涓庡涔犵畻娉曘€?B.杩炴帴涓讳箟鐞嗚璁や负鎬濈淮鍩烘湰鏄缁忓厓銆佷汉鑴戜笉鍚屼簬鐢佃剳锛屽苟鎻愬嚭杩炴帴涓讳箟鐨勫ぇ鑴戝伐浣滄ā寮忋€?C.杩炴帴涓讳箟璧锋簮浜庝豢鐢熷鍜屼汉鑴戞ā鍨嬬殑鐮旂┒銆?D.杩炴帴涓讳箟瀛︽淳鐨勪唬琛ㄤ汉鐗╂湁鍗℃礇鍏?Warren S. McCulloch)銆佺毊鑼?Walter H. Pitts)銆丠opfield銆佸竷椴佸厠鏂?Brooks)銆佺航鍘勫皵(Newell)銆?绛旀: 杩炴帴涓讳箟瀛︽淳鐨勪唬琛ㄤ汉鐗╂湁鍗℃礇鍏?Warren S. McCulloch)銆佺毊鑼?Walter H. Pitts)銆丠opfield銆佸竷椴佸厠鏂?Brooks)銆佺航鍘勫皵(Newell)銆?11銆? 浜哄伐鏅鸿兘(AI)銆佹満鍣ㄥ涔犮€佹繁搴﹀涔犱笁鑰呭叧绯昏杩版纭殑鏄紙锛?A.浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鐮旂┒銆佸紑鍙戠敤浜庢ā鎷熴€佸欢浼稿拰鎵╁睍浜虹被鏅鸿兘鐨勭悊璁恒€佹柟娉曞強搴旂敤锛屽睘浜庝竴闂ㄧ嫭绔嬬殑鎶€鏈绉戙€?B.鏈哄櫒瀛︿範涓撻棬鐮旂┒璁$畻鏈烘€庢牱妯℃嫙浜虹被鐨勫涔犺涓猴紝浠ヨ幏鍙栨柊鐨勭煡璇嗗拰鎶€鑳斤紝閲嶆柊缁勭粐宸叉湁鐨勭煡璇嗙粨鏋勪互瀹屽杽鑷韩鐨勬€ц兘锛屼絾鏄満鍣ㄥ涔犺兘鍔涘苟闈濧I绯荤粺鎵€蹇呴』鐨勩€?C.浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鏄竴闂ㄧ爺绌躲€佸紑鍙戠敤浜庢ā鎷熴€佸欢浼稿拰鎵╁睍浜虹被鏅鸿兘鐨勭悊璁恒€佹柟娉曞強搴旂敤鐨勬柊鐨勪氦鍙夊绉戯紝鏈哄櫒瀛︿範鏄汉宸ユ櫤鑳界殑鏍稿績鐮旂┒閭诲煙涔嬩竴锛屾繁搴﹀涔犳槸鏈哄櫒瀛︿範鐨勬柊棰嗗煙锛岀爺绌跺闅愬眰澶氭劅鐭ュ櫒銆佹ā鎷熶汉鑴戣繘琛屽垎鏋愬涔犵殑浜哄伐绁炵粡缃戠粶銆?D.娣卞害瀛︿範鏂规硶鐮旂┒浜哄伐绁炵粡缃戠粶鐨勫崟灞傛劅鐭ュ櫒瀛︿範缁撴瀯銆?绛旀: 浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鏄竴闂ㄧ爺绌躲€佸紑鍙戠敤浜庢ā鎷熴€佸欢浼稿拰鎵╁睍浜虹被鏅鸿兘鐨勭悊璁恒€佹柟娉曞強搴旂敤鐨勬柊鐨勪氦鍙夊绉戯紝鏈哄櫒瀛︿範鏄汉宸ユ櫤鑳界殑鏍稿績鐮旂┒閭诲煙涔嬩竴锛屾繁搴﹀涔犳槸鏈哄櫒瀛︿範鐨勬柊棰嗗煙锛岀爺绌跺闅愬眰澶氭劅鐭ュ櫒銆佹ā鎷熶汉鑴戣繘琛屽垎鏋愬涔犵殑浜哄伐绁炵粡缃戠粶銆?12銆? 鏀寔鍚戦噺鏈哄彲浠ョ湅浣滄槸鍏锋湁涓€灞傞殣钘忓眰鐨勭缁忕綉缁溿€傛敮鎸佸悜閲忔満鐨勭悊璁哄熀纭€鏄紙锛?A.缁熻瀛?B.鐢熺墿绁炵粡瀛?C.瑙嗚鐢熺悊瀛?D.鎺у埗璁篠绛旀: 缁熻瀛?13銆? 娣卞害瀛︿範灞炰簬锛堬級A.绗﹀彿涓讳箟B.杩炴帴涓讳箟C.琛屼负涓讳箟D.閫昏緫涓讳箟绛旀: 杩炴帴涓讳箟14銆?璁$畻鏈鸿瑙夊彲搴旂敤浜庝笅鍒楀摢浜涢鍩燂紙锛夈€?A.瀹夐槻鍙婄洃鎺ч鍩?B.閲戣瀺棰嗗煙鐨勪汉鑴歌瘑鍒韩浠介獙璇?C.鍖荤枟棰嗗煙鐨勬櫤鑳藉奖鍍忚瘖鏂?D.鏈哄櫒浜?鏃犱汉杞︿笂浣滀负瑙嗚杈撳叆绯荤粺E.浠ヤ笂鍏ㄦ槸绛旀: 浠ヤ笂鍏ㄦ槸15銆? 涓嬪垪涓嶇鍚堢鍙蜂富涔夋€濇兂鐨勬槸锛堬級A.婧愪簬鏁扮悊閫昏緫B.璁や负浜虹殑璁ょ煡鍩哄厓鏄鍙?C.浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鐨勬牳蹇冮棶棰樻槸鐭ヨ瘑琛ㄧず銆佺煡璇嗘帹鐞?D.璁や负鏅鸿兘涓嶉渶瑕佺煡璇嗐€佷笉闇€瑕佽〃绀恒€佷笉闇€瑕佹帹鐞?绛旀: 璁や负鏅鸿兘涓嶉渶瑕佺煡璇嗐€佷笉闇€瑕佽〃绀恒€佷笉闇€瑕佹帹鐞?16銆? 涓嶅睘浜庤嚜鐒惰瑷€澶勭悊鐨勬牳蹇冪幆鑺傜殑鏄紙锛?A.鐭ヨ瘑鐨勮幏鍙栦笌琛ㄨ揪B.鑷劧璇█鐞嗚ВC.鑷劧璇█鐢熸垚D.璇煶璇箟璇嗗埆绛旀: 璇煶璇箟璇嗗埆17銆?浜哄伐鏅鸿兘鐨勮繎鏈熺洰鏍囧湪浜庣爺绌舵満鍣ㄦ潵锛? 锛夈€?A.瀹屽叏浠f浛浜虹被B.鍒堕€犳櫤鑳芥満鍣?C.妯′豢鍜屾墽琛屼汉鑴戠殑鏌愪簺鏅哄姏鍔熻兘D.浠f浛浜鸿剳绛旀: 妯′豢鍜屾墽琛屼汉鑴戠殑鏌愪簺鏅哄姏鍔熻兘绗簩绔?1銆?涓嬪垪鍝竴涓槸鈥滃垎绫烩€濅换鍔$殑鍑嗙‘鎻忚堪锛? 锛夈€?A.棰勬祴姣忎釜椤圭洰瀹為檯鐨勫€?B.瀵规瘡涓」鐩繘琛屾帓搴?C.涓烘瘡涓」鐩垎閰嶄竴涓被鍒?D.鍙戠幇姣忎釜绌洪棿涓緭鍏ョ殑鎺掑竷绛旀: 涓烘瘡涓」鐩垎閰嶄竴涓被鍒?2銆?涓嬪垪瀵逛簬鍒嗙被姒傚康鎻忚堪涓嶆纭殑鏄紙锛?A.鍒嗙被鐨勬蹇垫槸鍦ㄥ凡鏈夋暟鎹殑鍩虹涓婂浼氫竴涓垎绫诲嚱鏁版垨鏋勯€犲嚭涓€涓垎绫绘ā鍨嬶紙鍗虫垜浠€氬父鎵€璇寸殑鍒嗙被鍣?Classifier)锛夈€?B.鍒嗙被鐨勬柟娉曞寘鍚喅绛栨爲銆侀€昏緫鍥炲綊銆佹湸绱犺礉鍙舵柉銆佺缁忕綉缁滅瓑绠楁硶C.鍒嗙被鐨勬爣鍑嗙粺涓€D.鍒嗙被鐨勭粨鏋滄湁鍙兘閿欒銆?绛旀: 鍒嗙被鐨勬爣鍑嗙粺涓€3銆? 鍦ㄦ満鍣ㄥ涔犻鍩燂紝鍒嗙被鐨勭洰鏍囨槸鎸囷紙锛夈€?A.灏嗗叿鏈夌浉浼肩壒寰佺殑瀵硅薄鑱氶泦B.灏嗗叿鏈夌浉浼煎舰鐘剁殑瀵硅薄鑱氶泦C.灏嗗叿鏈夌浉浼煎€肩殑瀵硅薄鑱氶泦D.灏嗗叿鏈夌浉浼煎悕绉扮殑瀵硅薄鑱氶泦绛旀: 灏嗗叿鏈夌浉浼肩壒寰佺殑瀵硅薄鑱氶泦4銆? 涓ょ浠ヤ笂锛堜笉鍚袱绉嶏級鐨勫垎绫婚棶棰樿绉颁负锛堬級銆?A.浜屽垎绫?B.澶氬垎绫?C.鍒嗙被鍣?D.褰掍竴鍖?绛旀: 澶氬垎绫?5銆? 澶氬垎绫婚棶棰樺彲浠ユ媶鍒嗕负鑻ュ共涓€屽垎绫讳换鍔℃眰瑙o紝鍙噰鍙栫殑鎷嗗垎绛栫暐鍖呮嫭锛氾紙锛?A.涓€瀵逛竴B.涓€瀵瑰C.澶氬澶?D.浠ヤ笂鍧囧彲绛旀: 浠ヤ笂鍧囧彲6銆? 鏈夊叧鍒嗙被鍣ㄧ殑鏋勯€犲拰瀹炴柦姝ラ鎻忚堪閿欒鐨勬槸锛氾紙锛?A.閫夊畾鏍锋湰锛屽皢鎵€鏈夋牱鏈垎鎴愯缁冩牱鏈拰娴嬭瘯鏍锋湰涓ら儴鍒嗭紱B.鍦ㄨ缁冩牱鏈笂鎵ц鍒嗙被鍣ㄧ畻娉曪紝鐢熸垚鍒嗙被妯″瀷锛?C.鍦ㄨ缁冩牱鏈笂鎵ц鍒嗙被妯″瀷锛岀敓鎴愰娴嬬粨鏋滐紱D.鏍规嵁棰勬祴缁撴灉锛岃绠楀繀瑕佺殑璇勪及鎸囨爣锛岃瘎浼板垎绫绘ā鍨嬬殑鎬ц兘銆?绛旀: 鍦ㄨ缁冩牱鏈笂鎵ц鍒嗙被妯″瀷锛岀敓鎴愰娴嬬粨鏋滐紱7銆? 鍒嗙被鍣ㄦ槸鍩轰簬鐜版湁鏁版嵁鏋勯€犲嚭涓€涓ā鍨嬫垨鑰呭嚱鏁帮紝浠ュ皢鏁版嵁搴撲腑鐨勬暟鎹槧灏勫埌缁欏畾绫诲埆锛屼粠鑰屽彲浠ュ簲鐢ㄤ簬鏁版嵁棰勬祴銆傚父鍖呭惈浠ヤ笅姝ラ锛氣憼鍦ㄨ缁冩牱鏈笂鎵ц鍒嗙被鍣ㄧ畻娉曪紝鐢熸垚鍒嗙被妯″瀷銆? 鈶″湪娴嬭瘯鏍锋湰涓婃墽琛屽垎绫绘ā鍨嬶紝鐢熸垚棰勬祴缁撴灉銆? 鈶㈤€夊畾鏍锋湰锛堝寘鍚鏍锋湰鍜岃礋鏍锋湰锛夛紝灏嗘墍鏈夋牱鏈垎鎴愯缁冩牱鏈拰娴嬭瘯鏍锋湰銆傗懀鏍规嵁棰勬祴缁撴灉锛岃绠楀繀瑕佺殑璇勪及鎸囨爣锛岃瘎浼板垎绫绘ā鍨嬬殑鎬ц兘銆傛瀯閫犲拰瀹炴柦鍒嗙被鍣ㄧ殑姝g‘椤哄簭涓猴紙锛?A.鈶犫憽鈶⑩懀B.鈶⑩憼鈶♀懀C.鈶b憼鈶♀憿D.鈶♀憿鈶犫懀绛旀: 鈶⑩憼鈶♀懀8銆?涓嬪垪绠楁硶涓紝涓嶈兘澶熷缁欏畾鏍锋湰杩涜鍒嗙被鐨勬槸锛? 锛夈€?A.鍐崇瓥鏍戠畻娉?B.閫昏緫鍥炲綊绠楁硶C.姊害涓嬮檷绠楁硶D.绁炵粡缃戠粶绛旀: 姊害涓嬮檷绠楁硶9銆? 鍦ㄦ祴璇曟牱鏈笂鎵ц鍒嗙被妯″瀷锛屽彲浠ワ紙锛夈€?A.鍖哄垎姝f牱鏈?B.鍖哄垎璐熸牱鏈?C.鐢熸垚棰勬祴缁撴灉D.鐢熸垚鍒嗙被妯″瀷绛旀: 鐢熸垚棰勬祴缁撴灉10銆? SVM鏄竴绉嶅吀鍨嬬殑锛堬級妯″瀷A.鎰熺煡鏈?B.绁炵粡缃戠粶C.浜岀被鍒嗙被D.鑱氱被绛旀: 浜岀被鍒嗙被11銆? 鍏充簬鏍囨敞锛屼笅鍒楄娉曟纭殑鏄?A.鍦⊿VM涓紝璁粌闆嗙殑鏁版嵁鏄粡杩囨爣娉ㄧ殑B.鍦⊿VM涓紝娴嬭瘯闆嗙殑鏁版嵁涓嶇敤鏍囨敞C.鍦⊿VM涓紝璇嗗埆鐩爣鐨勬暟鎹槸缁忚繃鏍囨敞D.浠ヤ笂閮戒笉瀵?绛旀: 鍦⊿VM涓紝璁粌闆嗙殑鏁版嵁鏄粡杩囨爣娉ㄧ殑12銆? 澧炲姞鍒嗙被鍣ㄨ缁冮泦鐨勬璐熸牱鏈泦鏁伴噺锛堬級A.涓嶅ソ璇?B.浼氭彁楂樺垎绫诲櫒鏁堟灉C.杩橀渶瑕佸鍔犳祴璇曢泦鐨勬璐熸牱鏈泦鏁伴噺鎵嶈兘鎻愰珮鍒嗙被鍣ㄦ晥鏋?D.涓嶄細鎻愰珮鍒嗙被鍣ㄦ晥鏋?E.浠ヤ笂鍏ㄦ槸绛旀: 涓嶅ソ璇?13銆? 鎶婃牱鏈墍灞炵殑绫诲瀷鍜屾牱鏈疄鐜板搴旇捣鏉ヨ绉颁负()A.娴嬭瘯B.璁粌C.鏍囨敞D.鍒嗙被绛旀: 鏍囨敞14銆? 鍒嗙被鍣ㄦ祴璇曠殑浣滅敤鏄?A.鑾峰緱妫€娴嬬洰鏍囩殑鍒嗙被B.鍒ゆ柇娴嬭瘯闆嗘牱鏈€夋嫨鏄惁鍚堥€?C.鍒ゆ柇娴嬭瘯闆嗘牱鏈爣娉ㄦ槸鍚﹀悎閫?D.妫€楠屽垎绫诲櫒鐨勬晥鏋?绛旀: 妫€楠屽垎绫诲櫒鐨勬晥鏋?15銆? 涓嬪垪鍙欒堪涓叧浜庡綊涓€鍖栦笉姝g‘鐨勬槸锛堬級A.褰掍竴鍖栧悗锛屾墍鏈夊厓绱犲拰涓?B.褰掍竴鍖栧悗锛屾墍鏈夊厓绱犲€艰寖鍥村湪锛?,1锛?C.褰掍竴鍖栧悗锛屾墍鏈夊厓绱犲€艰寖鍥村湪[0,1]D.褰掍竴鍖栦篃琚О涓烘爣鍑嗗寲绛旀: 褰掍竴鍖栧悗锛屾墍鏈夊厓绱犲€艰寖鍥村湪锛?,1锛?16銆佹繁搴﹀涔犱腑锛屽父鐢ㄧ殑褰掍竴鍖栧嚱鏁版槸锛堬級鍑芥暟A.SoftMaxB.SoftMinC.MicroMaxD.MicroMin绛旀:SoftMax绗笁绔?1銆? 鏈夌壒寰侊紝鏃犳爣绛剧殑鏈哄櫒瀛︿範鏄紙锛?A.鐩戠潱瀛︿範B.鍗婄洃鐫e涔?C.鏃犵洃鐫e涔?D.寮哄寲瀛︿範绛旀:C2銆? 鏃犵洃鐫e涔犲彲瀹屾垚浠€涔堜换鍔★紙锛?A.鍒嗙被B.鍥炲綊C.鑱氱被D.鍒嗙被銆佸洖褰掋€佽仛绫?绛旀:C3銆? 瀵绘壘鏁版嵁涔嬮棿鐨勭浉浼兼€у苟灏嗕箣鍒掑垎缁勭殑鏂规硶绉颁负锛堬級A.鍒嗙粍B.鍒嗙被D.鑱氱被绛旀:D4銆? 鐢靛奖鎺ㄨ崘绯荤粺鏄互涓嬪摢浜涚殑搴旂敤瀹炰緥鈶犲垎绫烩憽鑱氱被鈶㈠己鍖栧涔犫懀鍥炲綊锛堬級A.鍙湁鈶?B.鍙湁鈶?C.闄や簡鈶?D.浠ヤ笂閮芥槸绛旀:D5銆? 涓嬪垪涓や釜鍙橀噺涔嬮棿鐨勫叧绯讳腑,鍝釜鏄嚱鏁板叧绯伙紙锛?A.瀛︾敓鐨勬€у埆鍜屼粬鐨勮嫳璇垚缁?B.浜虹殑宸ヤ綔鐜涓庡仴搴?C.瀛╁瓙鐨勮韩楂樺拰鐖朵翰鐨勮韩楂?D.姝f柟褰㈢殑杈归暱鍜岄潰绉?绛旀:D6銆? 鍒濆鍖栭噰鐢ㄩ殢鏈哄垎閰嶇殑K鍧囧€肩畻娉曪紝涓嬮潰鍝釜椤哄簭鏄纭殑锛堬級銆傗憼鎸囧畾绨囩殑鏁扮洰锛? 鈶¢殢鏈哄垎閰嶇皣鐨勮川蹇冿紱鈶㈠皢姣忎釜鏁版嵁鐐瑰垎閰嶇粰鏈€杩戠殑绨囪川蹇冿紱鈶e皢姣忎釜鐐归噸鏂板垎閰嶇粰鏈€杩戠殑绨囪川蹇冿紱鈶ら噸鏂拌绠楃皣鐨勮川蹇冿紱A.鈶犫憽鈶⑩懁鈶?B.鈶犫憿鈶♀懀鈶?C.鈶♀憼鈶⑩懀鈶?D.浠ヤ笂閮戒笉鏄?7銆佷粠鏌愪腑瀛﹂殢鏈洪€夊彇8鍚嶇敺鐢燂紝鍏惰韩楂榵(cm)鍜屼綋閲峺(kg)鐨勭嚎鎬у洖褰掓柟绋嬩负y=0.849x-85.712锛屽垯韬珮172cm鐨勭敺瀛︾敓锛屽張鍥炲綊鏂圭▼鍙互棰勬姤鍏朵綋閲嶏紙锛夈€?A.涓?0.316kgB.绾︿负60.316kgC.澶т簬60.316kgD.灏忎簬60.316kg绛旀:B8銆? 浠ヤ笅涓嶅睘浜庤仛绫荤畻娉曠殑鏄紙锛夈€?A.K鍧囧€肩畻娉?B.AGNES绠楁硶C.DIANA绠楁硶D.鏈寸礌璐濆彾鏂畻娉?绛旀:D9銆? Z绛変簬锛革紝鍒橺涓庯几涔嬮棿灞炰簬锛堬級A.瀹屽叏鐩稿叧B.涓嶅畬鍏ㄧ浉鍏?C.涓嶇浉鍏?D.瀹屽叏涓嶇浉鍏?绛旀:A10銆? 鍥狅細缁忓父鎸戦锛涙灉锛氳韩鏉愮煯灏忋€傝繖缁勫洜銆佹灉涔嬮棿灞炰簬锛堬級鍏崇郴銆?A.瀹屽叏鐩稿叧B.涓嶅畬鍏ㄧ浉鍏?C.涓嶇浉鍏?D.瀹屽叏涓嶇浉鍏?绛旀:B11銆? 锛堬級鏄寚鏍规嵁鈥滅墿浠ョ被鑱氣€濆師鐞嗭紝灏嗘湰韬病鏈夌被鍒殑鏍锋湰鑱氶泦鎴愪笉鍚岀殑缁勩€?A.鑱氱被B.鍥炲綊C.鍒嗙被D.闈炵洃鐫e涔?绛旀:A12銆佺幇娆插垎鏋愭€у埆銆佸勾榫勩€佽韩楂樸€侀ギ椋熶範鎯浜庝綋閲嶇殑褰卞搷锛屽鏋滆繖涓綋閲嶆槸灞炰簬瀹為檯鐨勯噸閲忥紝鏄繛缁€х殑鏁版嵁鍙橀噺锛岃繖鏃跺簲閲囩敤锛堬級锛涘鏋滃皢浣撻噸鍒嗙被锛屽垎鎴愰珮銆佷腑銆佷綆杩欎笁绉嶄綋閲嶇被鍨嬩綔涓哄洜鍙橀噺锛屽垯閲囩敤锛堬級銆?A.绾挎€у洖褰? 绾挎€у洖褰?B.閫昏緫鍥炲綊閫昏緫鍥炲綊C.閫昏緫鍥炲綊绾挎€у洖褰?D.绾挎€у洖褰? 閫昏緫鍥炲綊绛旀:D13銆? 鏈夌壒寰侊紝鏈夐儴鍒嗘爣绛剧殑鏈哄櫒瀛︿範灞炰簬锛堬級銆?A.鐩戠潱瀛︿範B.鍗婄洃鐫e涔?C.鏃犵洃鐫e涔?D.寮哄寲瀛︿範绛旀:B14銆? 涓嬮潰涓や釜涓ゅ畬鍏ㄧ浉鍏崇殑鏄紙锛夈€?A.鍦嗗舰鐨勯潰绉笌鐩村緞B.闀挎柟褰㈢殑闈㈢Н涓庤竟闀?C.瀛╁瓙鐨勮韩楂樹笌鐖朵翰韬珮D.姣忓ぉ鐨勬俯搴﹀拰瀛h妭绛旀:A15銆? 鏈哄櫒瀛︿範鍖呮嫭锛?A.鐩戠潱瀛︿範B.鍗婄洃鐫e涔?C.鏃犵洃鐫e涔?D.寮哄寲瀛︿範绛旀:16銆? 涓や釜鍙橀噺涔嬮棿鐨勫叧绯诲寘鎷細A.瀹屽叏鐩稿叧B.涓嶅畬鍏ㄧ浉鍏?C.涓嶇浉鍏?D.璐熺浉鍏?绛旀:ABC17銆? 涓嬮潰鍝竴涓笉鏄仛绫诲父鐢ㄧ殑绠楁硶锛堬級銆?A.K鍧囧€肩畻娉?B.AGNES绠楁硶C.DIANA绠楁硶D.SVM绠楁硶绛旀:D18銆? AGNES绠楁硶姝ラ姝g‘鐨勬槸锛堬級銆?鈶犲皢姣忎釜鏍锋湰鐗瑰緛鍚戦噺浣滀负涓€涓垵濮嬬皣锛涒憽鏍规嵁涓や釜绨囦腑鏈€杩戠殑鏁版嵁鐐瑰鎵炬渶杩戠殑涓や釜绨囷紱鈶㈤噸澶嶄互涓婄浜屻€佷笁姝ワ紝鐩村埌杈惧埌鎵€闇€瑕佺殑绨囩殑鏁伴噺锛涒懀鍚堝苟涓や釜绨囷紝鐢熸垚鏂扮殑绨囩殑闆嗗悎锛屽苟閲嶆柊璁$畻绨囩殑涓績鐐广€?A.鈶犫憽鈶⑩懀B.鈶犫憽鈶b憿C.鈶犫懀鈶⑩憽D.鈶犫懀鈶♀憿绛旀:B19銆? 涓嬮潰灞炰簬寮哄寲瀛︿範鐨勬槸锛堬級A.鐢ㄦ埛缁忓父闃呰鍐涗簨绫诲拰缁忔祹绫荤殑鏂囩珷锛岀畻娉曞氨鎶婂拰鐢ㄦ埛璇昏繃鐨勬枃绔犵浉绫讳技鐨勬枃绔犳帹鑽愮粰浣犮€?B.绠楁硶鍏堝皯閲忕粰鐢ㄦ埛鎺ㄨ崘鍚勭被鏂囩珷锛岀敤鎴蜂細閫夋嫨鍏舵劅鍏磋叮鐨勬枃绔犻槄璇伙紝杩欏氨鏄杩欑被鏂囩珷鐨勪竴绉嶅鍔憋紝绠楁硶浼氭牴鎹? 濂栧姳鎯呭喌鏋勫缓鐢ㄦ埛鍙兘浼氬枩娆㈢殑鏂囩珷鐨勨€滅煡璇嗗浘鈥濄€?C.鐢ㄦ埛姣忚涓€绡囨枃绔狅紝灏辩粰杩欑瘒鏂伴椈璐翠笂鍒嗙被鏍囩锛屼緥濡傝繖绡囨柊闂绘槸鍐涗簨鏂伴椈锛屼笅涓€绡囨柊闂绘槸缁忔祹鏂伴椈绛夛紱绠楁硶閫氳繃杩欎簺鍒嗙被鏍囩杩涜瀛︿範锛岃幏寰楀垎绫绘ā鍨嬶紱鍐? 鏈夋柊鐨勬枃绔犺繃鏉ョ殑鏃跺€欙紝绠楁硶閫氳繃鍒嗙被妯″瀷灏卞彲浠ョ粰鏂扮殑鏂囩珷鑷姩璐翠笂鏍囩浜嗐€?D.涓や釜鍙橀噺涔嬮棿鐨勫叧绯伙紝涓€涓彉閲忕殑鏁伴噺鍙樺寲鐢卞彟涓€涓彉閲忕殑鏁伴噺鍙樺寲鎵€鎯熶竴纭畾锛屽垯杩欎袱涓彉閲忎箣闂寸殑鍏崇郴绉颁负寮哄寲瀛︿範銆?绛旀:B绗洓绔?1銆佸湪涓€涓缁忕綉缁滈噷锛岀煡閬撴瘡涓€涓缁忓厓鐨勬潈閲嶅拰鍋忓樊鏄渶閲嶈鐨勪竴姝ャ€傚鏋滀互鏌愮鏂规硶鐭ラ亾浜嗙缁忓厓鍑嗙‘鐨勬潈閲嶅拰鍋忓樊锛屽氨鍙互杩戜技浠讳綍鍑芥暟銆傚疄鐜拌繖涓渶浣崇殑鍔炴硶鏄粈涔堬紵锛堬級A.闅忔満璧嬪€硷紝绁堢シ瀹冧滑鏄纭殑B.鎼滅储鎵€鏈夋潈閲嶅拰鍋忓樊鐨勭粍鍚堬紝鐩村埌寰楀埌鏈€浣冲€?C.璧嬩簣涓€涓垵濮嬪€硷紝閫氳繃妫€鏌ヨ窡鏈€浣冲€肩殑宸€硷紝鐒跺悗杩唬鏇存柊鏉冮噸D.浠ヤ笂閮戒笉姝g‘绛旀:C2銆? 1943骞达紝绁炵粡缃戠粶鐨勫紑灞变箣浣溿€夾 logical calculus of ideas immanent in nervous activity銆?鐢憋紙锛夊拰娌冨皵鐗?鐨尐瀹屾垚銆?A.娌冧鸡.楹﹀崱娲涘厠B.鏄庢柉鍩?C.鍞愮撼寰?璧竷D.缃楃礌绛旀:A3銆? 鎰熺煡鏈哄睘浜庯紙锛夈€?A.鐢熺墿绁炵粡缃戠粶B.BP绁炵粡缃戠粶C.鍓嶉绁炵粡缃戠粶D.鍙嶉绁炵粡缃戠粶绛旀:C4銆? 琚О涓衡€滅缁忕綉缁滀箣鐖垛€濆拰鈥滀汉宸ユ櫤鑳芥暀鐖垛€濈殑鏄紙锛夈€?A.杈涢】B.璧竷C.鏄庢柉鍩?D.椴佹灏斿搱鐗?绛旀:A5銆? 鍙嶉绁炵粡缃戠粶鍙堢О鍓嶉缃戠粶銆?A.瀵?B.閿?绛旀:B6銆? 涓嬪垪绁炵粡缃戠粶涓摢绉嶆灦鏋勬湁鍙嶉杩炴帴锛堬級銆?A.寰幆绁炵粡缃戠粶B.鍗风Н绁炵粡缃戠粶C.鎰熺煡鏈?D.閮戒笉鏄?绛旀:A7銆? 瀵逛簬鑷劧璇█澶勭悊闂锛屽摢绉嶇缁忕綉缁滄ā鍨嬬粨鏋勬洿閫傚悎锛燂紙锛夈€?A.澶氬眰鎰熺煡鍣?B.鍗风Н绁炵粡缃戠粶C.寰幆绁炵粡缃戠粶D.鎰熺煡鍣?绛旀:C8銆? 涓鸿В鍐冲崟涓緭鍑虹殑鎰熺煡鏈烘棤娉曡В鍐崇殑寮傛垨闂锛岄渶瑕佺敤鏈夎嚦灏戯紙锛変釜杈撳嚭鐨勬劅鐭ユ満锛?A.2涓?B.3涓?C.4涓?D.5涓?绛旀:A9銆? 浣跨敤鎰熺煡鏈烘ā鍨嬬殑鍓嶆彁鏄紙锛夈€?A.鏁版嵁鏍锋湰灏?B.鏁版嵁绾挎€у彲鍒?C.鏁版嵁绾挎€т笉鍙垎D.鏁版嵁鏍锋湰澶?绛旀:B10銆? 鏈夊叧娴呭眰绁炵粡缃戠粶鐨勮娉曟纭殑鏄紙锛夈€?A.鍚勭缁忓厓鍒嗗眰鎺掑垪B.绁炵粡鍏冧笌鍓嶄竴灞傚強鍚庝竴灞傜殑绁炵粡鍏冪浉杩?C.鏄竴绉嶅崟鍚戝灞傜粨鏋?D.鍚屼竴灞傜殑绁炵粡鍏冧箣闂存病鏈変簰鐩歌繛鎺?绛旀:ACD11銆? 瀵逛簬澶氬眰绁炵粡缃戠粶锛孊P锛堝弽鍚戜紶鎾級绠楁硶鐨勭洿鎺ヤ綔鐢ㄦ槸锛堬級銆?A.鎻愪緵璁粌闆嗐€佹祴璇曢泦鏍锋湰B.鍔犲揩璁粌鏉冨€煎弬鏁板拰鍋忕疆鍙傛暟C.鎻愰珮绁炵粡缃戠粶鐗瑰緛琛ㄧず绮剧‘搴?D.绉戝璇勪环璁粌妯″瀷绛旀:B12銆佹搴︿笅闄嶇畻娉曠殑姝g‘姝ラ鏄粈涔堬紵锛堬級(a)璁$畻棰勬祴鍊煎拰鐪熷疄鍊间箣闂寸殑璇樊銆?b)杩唬璺熸柊锛岀洿鍒版壘鍒版渶浣虫潈閲?c)鎶婅緭鍏ヤ紶鍏ョ綉缁滐紝寰楀埌杈撳嚭鍊?d)鍒濆鍖栭殢鏈烘潈閲嶅拰鍋忓樊(e)瀵规瘡涓€涓骇鐢熻宸殑绁炵粡鍏冿紝鏀瑰彉鐩稿簲鐨勶紙鏉冮噸锛夊€间互鍑忓皬璇樊A.a, b, c, d, eB.e, d, c,b , aC.c, b, a, e, dD.d, c, a, e, b绛旀:D13銆佹劅鐭ユ満鏄彧鍚緭鍏ュ眰鍜岃緭鍑哄眰鐨勪竴绉嶆祬灞傜缁忕綉缁滐紝涓や釜鎰熺煡鏈鸿緭鍑鸿В鍐充簡鈥濆紓鎴栤€濋棶棰橈紝杩涗竴姝ユ墿灞曞埌澶氭劅鐭ユ満杈撳嚭锛屽苟澧炲姞浜嗗亸缃崟鍏冦€傚叧浜庡亸缃崟鍏冪殑浣滅敤姝g‘鐨勬槸锛堬級銆?A.瑙e喅寮傛垨闂B.灞炰簬涓€绉嶅灞傞殣鍚眰C.鏂藉姞骞叉壈锛屾秷闄ょ綉缁滄寰幆锛屼互杈惧埌杈撳嚭鏀舵暃D.璁$畻缃戠粶浼犳挱鍋忓樊淇℃伅绛旀:C14銆佹繁搴﹀涔犳槸涓€绉嶅灞傜缁忕綉缁滅殑妯℃嫙璁ょ煡璁粌鏂规硶锛屽灞傜缁忕綉缁滃寘鍚涓殣鍚眰鎰熺煡灞傦紝涔熺О浣滃嵎绉缁忕綉缁?CNN)锛屽畠鐨勭爺绌剁儹娼叴璧蜂簬鏈笘绾垵鏈熴€?A.瀵?B.閿?绛旀:B15銆? 娣卞害瀛︿範鍙互鍏锋湁鍑犱釜闅愯棌灞傦紙锛夈€?A.1涓?B.2涓?C.3涓?D.4涓?绛旀:B16銆? 娣卞害瀛︿範涓父鐢ㄧ殑婵€娲诲嚱鏁颁笉鍖呮嫭锛堬級銆?A.sign鍑芥暟B.Sigmoid鍑芥暟C.ReLU鍑芥暟D.Sin鍑芥暟绛旀:D17銆? 鍦ㄤ綍绉嶆儏鍐典笅绁炵粡缃戠粶妯″瀷琚О涓烘繁搴﹀涔犳ā鍨嬶紙锛夈€?A.鍔犲叆鏇村灞傦紝浣跨缁忕綉缁滅殑灞傛暟澧炲姞B.鏈夌淮搴︽洿楂樼殑鏁版嵁C.褰撹繖鏄竴涓浘褰㈣瘑鍒棶棰樻椂D.浠ヤ笂閮戒笉姝g‘绛旀:A18銆? 娣卞害瀛︿範鏄惈鏈変竴涓殣鍚眰鐨勫灞傜缁忕綉缁滄ā鍨嬬殑寮哄寲瀛︿範锛岃缁冭繃绋嬪姞鍏ヤ簡婵€娲诲嚱鏁般€?A.瀵?B.閿?绛旀:B19銆? 绁炵粡缃戠粶涓紝绾挎€фā鍨嬬殑琛ㄨ揪鑳藉姏涓嶅鏃讹紝鍙紩鍏ワ紙锛夋潵娣诲姞闈炵嚎鎬у洜绱犮€?A.绾挎€у嚱鏁?B.婵€娲诲嚱鏁?C.鍒嗙被鍑芥暟D.鍋忕疆鍗曞厓绛旀:B20銆? 涓嬪垪鍏充簬绁炵粡缃戠粶璇存硶姝g‘鐨勬槸锛堬級銆?A.楂橀€熷鎵句紭鍖栬ВB.涓嶅鍐崇瓥鏍戠ǔ瀹?C.闈炵嚎鎬?D.鍏锋湁鑷涔犮€佽嚜缁勭粐銆佽嚜閫傚簲鎬?绛旀:ACD绗簲绔?1銆? 瑙嗙綉鑶滀笂瀵瑰急鍏夋晱鎰熺殑鏄?A.瑙嗘潌缁嗚優B.瑙嗛敟缁嗚優C.瑙嗙缁?D.鐬冲瓟绛旀:A。

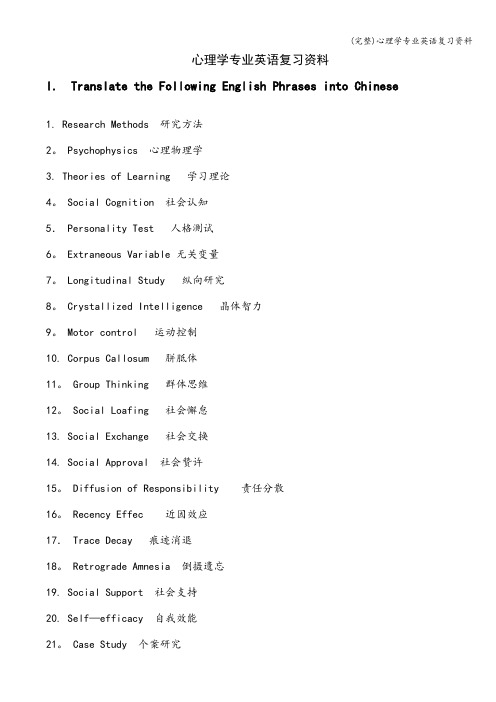

(完整)心理学专业英语复习资料

心理学专业英语复习资料I. Translate the Following English Phrases into Chinese1. Research Methods 研究方法2。

Psychophysics 心理物理学3. Theories of Learning 学习理论4。

Social Cognition 社会认知5. Personality Test 人格测试6。

Extraneous Variable 无关变量7。

Longitudinal Study 纵向研究8。

Crystallized Intelligence 晶体智力9。

Motor control 运动控制10. Corpus Callosum 胼胝体11。

Group Thinking 群体思维12。

Social Loafing 社会懈怠13. Social Exchange 社会交换14. Social Approval 社会赞许15。

Diffusion of Responsibility 责任分散16。

Recency Effec 近因效应17. Trace Decay 痕迹消退18。

Retrograde Amnesia 倒摄遗忘19. Social Support 社会支持20. Self—efficacy 自我效能21。

Case Study 个案研究II. Translate the Following Chinese Word Groups into English1。

机能主义 functionalism2。

自我实现 self—actualization3.一般规律研究法 nomothetic method4。

分层抽样 stratified sampling5. 外在信度 external reliability6. 选择性注意 selective attention7。

知觉恒常性 perceptual constancy8. 自我概念 self concept9. 液体智力 fluid intelligence10. 安全型依恋 secure attachment11. 性别图示 gender schema12。

二语习得教案

(a) 名词/代词做主语 (非标记主语)

• 他是我们班班长。 • 李明喜欢赵晶。

2020/9/28

(b) 不定式作主语

To keep healthy means you should do exercise regularly.

(c ) 现在分词作主语

Smoking is harmful.

2020/9/28

e.g. Don’t begin a sentence with a conjunction and do not end a sentence with a preposition.

4.2.2 descriptive grammar: the patterns underlying the actual use of languages by native speakers in communication

2020/9/28

2.3 题目: 中国英语学习者对英语主语 的习得研究

(1) 研究问题:

(a)中国英语学习者在习得英语标记性主语 和非标记性主语方面是否存在差异?

(b)不同的标记性主语是否对中国英语学习 者产生不同的难度?

2020/9/28

(C)中国英语学习者对英语主语的习得 是否会随着水平的提高而逐步增长?

2020/9/28

(2)定义: --词汇深度:学习者掌握一个词的全部 意义和用法的程度

--词汇广度(词汇量):阅读词汇量或 消极词汇量,反映的是了解一个词最常 用含义的能力。

2020/9/28

(3)结论:

词汇广度、深度知识均能有效预测语言 综合能力,其中词汇深度知识对语言综 合能力的预测力强于词汇广度知识,这 一优势体现在对完形填空及写作的预测 中;总体上,词汇广度与深度知识呈高 度正相关,但词汇深度知识的发展仍落 后与词汇广度知识。

What is SLA

1. Target language 2. Second language

3. First language

4. Foreign language

L1: First language, native language, mother tongue

Acquired before the age of three years as a

how and why questions, SLA has emerged as a field of study from within linguistics and psychology (and their subfields of applied linguistics, psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, and social psychology)

Why integrate these fields?

If not, you would end up like the 3 blind men of the

Asian Fable. While each perception is correct individually, they fail to provide an accurate picture of the total, because there is no integrated perspective.

The scope of SLA

The scope of SLA includes informal L2

learning that takes place in naturalistic contexts, fo in classrooms, and L2 learning that involves a mixture of these settings and circumstances.

second language acquisition简介

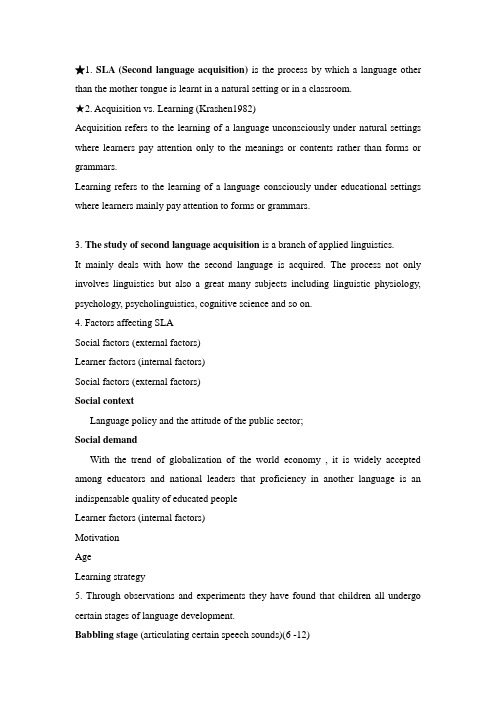

★1. SLA (Second language acquisition) is the process by which a language other than the mother tongue is learnt in a natural setting or in a classroom.★2. Acquisition vs. Learning (Krashen1982)Acquisition refers to the learning of a language unconsciously under natural settings where learners pay attention only to the meanings or contents rather than forms or grammars.Learning refers to the learning of a language consciously under educational settings where learners mainly pay attention to forms or grammars.3. The study of second language acquisition is a branch of applied linguistics.It mainly deals with how the second language is acquired. The process not only involves linguistics but also a great many subjects including linguistic physiology, psychology, psycholinguistics, cognitive science and so on.4. Factors affecting SLASocial factors (external factors)Learner factors (internal factors)Social factors (external factors)Social contextLanguage policy and the attitude of the public sector;Social demandWith the trend of globalization of the world economy , it is widely accepted among educators and national leaders that proficiency in another language is an indispensable quality of educated peopleLearner factors (internal factors)MotivationAgeLearning strategy5. Through observations and experiments they have found that children all undergo certain stages of language development.Babbling stage (articulating certain speech sounds)(6 -12)One word or Holophrastic stage (using single words to represent various meanings)(12-18 months)Two –word stage (18-20 months)Telegraphic speech stage (using phrase and sentences composed of only content words.)(2-3 years )。

消费者行为心理学中英文外文文献翻译

消费者行为心理学中英文外文文献翻译(含:英文原文及中文译文)英文原文Frontiers of Social PsychologyArie W. Kruglanski 、Joseph P. ForgasFrontiers of Social Psychology is a new series of domain-specific handbooks. The purpose of each volume is to provide readers with a cutting-edge overview of the most recent theoretical, methodological, and practical developments in a substantive area of social psychology, in greater depth than is possible in general social psychology handbooks. The editors and contributors are all internationally renowned scholars whose work is at the cutting-edge of research.Scholarly, yet accessible, the volumes in the Frontiers series are an essential resource for senior undergraduates, postgraduates, researchers, and practitioners, and are suitable as texts in advanced courses in specific subareas of social psychology.Some Social Asp ects of Living in a Consumer SocietyThe following sketches will illustrate that in a consumer society much of the behavior studied by social psychologists relates to consumer stimuli and consumer behavior. Thus, the consumer context provides a rich field for the study of social phenomena and behavior.Consumer Decisions Are UbiquitousWhether we are in the supermarket or not, we are constantly making consumer decisions. We enroll in gyms, use our frequent-flyer miles for a vacation resort, buy health care, choose a restaurant, skip dessert for a healthier lifestyle. In fact, most of our daily decisions do not involve existential decisions such as whom to marry or whether to have children or not, but whether to have tea or coffee, use our credit card or pay cash, or other seemingly trivial decisions. Moreover, many of our daily (consumer) behaviors do not even require intentional decisions. Rather, they may be habitual, such as switching to CNN to get the news or accessing Google when looking up some information. A typical day of a typical person is filled with countless minor consumer decisions or the consequences of previous decisions, starting with the brand of toothpaste in the morning to choosing a movie after work.Consumer Choices Fulfill a Social-Identity FunctionAlthough for most people being a consumer may not be central to their identity, many of their consumer decisions are nevertheless highly identity-relevant insofar as they correspond to a larger set of values and beliefs and express important aspects of the self. Eating a vegetarian diet because one does not want to endorse cruelty to animals and boycotting clothes potentially made by child laborers are some examples. Some people buy a Prius out of environmental concerns; others boycott Japanese cars —such as the Prius —in order to help the local carindustry. In this respect, even the choice between Coke and Pepsi is not necessarily trivial. People who cannot discriminate Coke from Pepsi in a blind test, or who prefer Pepsi, may nevertheless adhere to Coke as a cultural icon. Attempts to change the formula of Coke met with angry protests and opposition. Clearly, consumer products and brands do not only fulfill utilitarian needs (Olson & Mayo, 2000; Shavitt, 1990). In a world of oversupply and differentiating brands, many consumers choose brands in order to express their personality or to affiliate themselves with desired others. They do not simply use a Mac; they are Mac users, and switching to another brand of PC would be akin to treason. From soft drinks to computers, brands may become an ideology. People may also perceive of products as extended selves (Belk, 1988); for example, they may identify with their cars just as they do with pets. Likewise, brands may define social groups. The Harley-Davidson Club is a legendary example; an Internet search revealed clubs for almost every car brand and model. In my hometown, I found a V olkswagen New Beetle Club whose stated purpose is to cultivate contacts between New Beetle Drivers by organizing social events (among others, a visit to a car cemetery). On the road, drivers of the same car model often greet each other. Apparently, driving the same model is sufficient to establish social closeness. Brands, products, and consumption habits not only help to establish social connectivity but also serve as status symbols, defining vertical andhorizontal social boundaries. By using particular brands or consuming specific products, people can express a certain lifestyle or attempt to convey a particular social impression. Subscribing to the opera conveys one’s social position just as going to a monster truck race does. Whether your choice of drink is wine or beer, cappuccino or herbal tea, your order expresses more than merely your taste in beverages.Consumer Choices Affect Social PerceptionGiven that brands and products are part of social expression, it is not surprising that people are judged by the brands and products they use. In particular, products of a social-identity function are used as bases for inferences about a target’s personality traits (Shavitt & Nelson, 2000). Likewise, smoking, food choice and amount of food intake have all been shown to affect social impressions. Depending on the subculture of the perceiver (age, country), different personality traits are assumed in smokers compared with nonsmokers (e.g., Cooper & Kohn, 1989; Jones & Carroll, 1998). Various studies found that eaters of a healthier diet are perceived as more feminine and in general judged more favorably than eaters of unhealthy foods (for a review see V artanian, Herman, & Polivy, 2007). Arguing that a Pepsi drinker is to a Coke drinker what a Capulet was to a Montague is, of course, an exaggeration, but clearly brands may distinguish ingroup from out-group members. Possibly this is most extreme among teenagers, where the brand of jeans is perceived todetermine coolness and popularity. Nevertheless, the phenomenon is not limited to teen culture, as testified by the previous examples of social communities defined by shared brands. In sum, from wet versus dry shaving to driving a Porsche versus a Smart, consumer behavior is used as a cue in person perception. Most likely, such cues also manifest in behavior toward these consumers. Physical attacks on women who wear fur are a most extreme example.Affective Consequences of Consumer BehaviorObviously, consumption and the use of products and services may give pleasure and satisfaction or displeasure and dissatisfaction. People may experience joy from wearing a new sweater or suffer emotional consequences when products or services fail or cause inconvenience. Product use is only one source of affective consumer experiences. The mere act of choosing and acquisition is another. People enjoy or dislike the experience of shopping. They may take pleasure from the freedom of simply choosing between different options (e.g., Botti & Iyengar, 2004), feel overwhelmed and confused by an abundance of options (e.g., Huffman & Kahn, 1998), or feel frustrated by a limited assortment that does not meet their particular needs (e.g., Chernev, 2003). They may experience gratification and a boost in self-esteem from the fact that they can afford a particular consumer lifestyle or grudge the fact that they cannot. Many daily sources of affective experiences involve consumerbehavior in one way or another.The Consumer Context Provides Unique Social InteractionsGranted, we rarely form deep and meaningful relationships with our hairdressers and waiters. Still, the consumer context affords many social interactions over a day. Again, these interactions— even if brief— may constitute a source of affective experiences. The smile of the barista, the compliment from the shop-assistant, and the friendly help from the concierge are just a few examples of how such consumerrelated interactions may make us feel good, worthy, and valued, whereas snappy and rude responses have the opposite effect. Besides, the social roles defined by the consumer context may provide unique opportunities for particular behaviors, interactions, and experiences not inherent in other roles. Being a client or customer makes one expect respect, courtesy, and attendance to one’s needs. For some, this may be the only role in their life that gives them a limited sense of being in charge and having others meet their demands. To give another example, complaining is a form of social interaction that mostly takes place within the consumer context. A search for ―complaint behavior‖ in the PsycI NFO database found that 34 out of 50 entries were studies from the consumer context. (The rest mostly related to health care, which may to some extent also be viewed as consumer context.) Given the importance of the consumer context to social experiences and interactions, it provides a prime opportunity forstudying these social behaviors.•How consumers think, feel, reason, and the psychology of screening for different items (such as brands, products); • Consumer behavior when they shop or make other marketing decisions;•Limits in consumer knowledge or access to information affect decisions and marketing outcomes;•How can marketers adapt and improve their marketing competitiveness and marketing strategies to attract consumers more efficiently?Bergi gives an official definition of consumer behavior: the process and the activities people perform when they research, select, purchase, use, evaluate, and deal with products and services in order to meet their needs. The behavior occurs in a group or an organization where individuals or individuals appear in this context. Consumer behavior includes using and handling products and studying how products are bought. The use of products is generally of great interest to marketers because it may affect how a product is in the best position or how we can encourage increased consumption.The Nicosia model focuses on the relationship between the company and its potential customers. The company communicates with consumers through its marketing messages or advertisements and consumers' reactions to the information they want to buy. Seeing this pattern, we willfind that companies and consumers are interconnected. Companies want to influence consumers. Consumers influence company decisions through their decisions.Consumer sentiment refers to a unique set of emotional reactions to the use of or eliciting a consumer experience in the product, a unique class or relationship of the emotional experience described and expressed (such as joy, anger and fear), such as the structural dimensions of the emotional category or pleasant/unpleasant, Relax/action, or calm/excited. Goods and services are often accompanied by emotional reactions (such as the fear caused by watching a horror movie). Emotional values are often associated with aesthetic choices (such as religion, reason). However, more material and utilitarian products also seem to have emotional value. For example, some foods cause childhood experiences and feel comfortable with them. Izad (1977) developed a method of emotional experience and introduced basic emotions. He uses ten words to distinguish the basic types of emotions: interest, joy, surprise, sadness, anger, disgust, contempt, fear, shame, and guilt. This method has been widely used by consumer research.In order to implement the interpersonal and personal construction in this framework, we use the concept of self-awareness to express the influence of consumer response on society. Self-awareness is defined as the individual's consistent trend to focus directly on inward or outward.This theory identifies two different types of people with self-consciousness. The open self-conscious person pays special attention to other people's views on their outside. The private self-conscious person pays more attention to their inner thoughts and feelings. In this case, we assume that the reputation of consumption may be different based on sensitivity to other people. This proposal is also consistent with previous research. It shows that people with different personal behaviors depend on their sensitivity to interpersonal influences. Dubois and Dikena emphasized that "we believe that the analysis of the direct relationship between consumers and brands is a key to improving understanding of such a market." This original assumption is that of private or The value of the open superior product comes from the inherent social status of these objects. Many existing studies emphasize the role of the role played in the exchange of information about their owners and social relationships.中文译文社会心理学前沿艾瑞·克鲁格兰斯基,约瑟夫·弗加斯社会心理学的前沿是一个新的领域专用手册系列。

SLA余达(共27张PPT)

Session 1

Why are A case study

Are they interchangeable?

some

learners

more

successful

than

others?

languages acquired during early childhood (<3 yrs)

(in classrformance of learners

at various levels

Psychology

Mental/cognitive process; representation of language in

the brain

Sociology

group-related phenomena such as identity and social motivation and the interactional and social

contexts of learning

SLA as a field

Each discipline and subdiscipline uses different methods for gathering and analyzing data in research on SAL, employs different theoretical framewords, and reaches its interpretation of research findings and conclusions in different way.

What is a second language?

Questions about the process of SLA

Psychology-原文

Text A Discovering PsychologyScript:What makes us similar to other people and yet so uniquely different? Why do we think, feel, and behave as we do? Are we molded more by heredity or shaped by experience? How can the same brain that gives us the capacity for creativity, rationality, and love also become the crucible for mental illness?Psychology is formally defined as the scientific study of the behavior of individuals and of their mental processes. Psychologists then try to use their research to predict and in some cases control behavior. Ideally, out of their basic research will come solutions for the practical problems that plague individuals and society.Whatever type of behavior psychologists look at, whether it’s laughing, crying, making war, or making love, or anything else, they try to make sense of it by relating the observed behavior to certain aspects of the individual involved and the situation in which the behavior occurred. For example, my genetic makeup, personality traits, attitudes, and mental state are some of the personal factors involved in my behavior. They’re known as dispositional factors. They’re internal, characteristics and potentials inside me, while external things such as sensory stimulation, rewards, or the actions of other people are known as situational factors. They come from the outside, from the environment in which my behavior takes place.Modern psychology began in 1879 when Wilhelm Wundt founded the first experimental psychology laboratory in Germany. Wundt trained many young researchers who carried on the tradition of measuring reactions to experimental tasks such as reaction times to sensory stimuli, attention, judgment, and word associations. The first American psychological laboratory like Wundt’s was founded at the Johns Hopkins University in 1883 by G. Stanley Hall. Hall, the first president of the American Psychological Association, introduced Sigmund Freud to the American public by translating Freud’s General Introduction to Psychoanalysis(心理分析引论). But 1890 may stand as the most significant date in psychology’s youth. That’s when William James published what many consider to be the most important psychological text of all time, Principles of Psychology(心理学原理). James was a professor of psychology at Harvard University, where he also studied medicine and taught physiology. James was interested in all the ways in which people interact with and adapt to their environment, and so he found a place in psychology for human consciousness, emotions, the self, personal values, and religion. But the Wundtian psyc hologists like G. Stanley Hall rejected James’s ideas as unscientific and soft. They argued that psychology should be patterned after the model of the physical sciences, so they focused their study on topics like sensation and perception--on psychophysics, measuring mental reactions to physical stimuli. Later they added investigations of how animals acquire conditioned responses and how humans memorize new information. These differences among psychologists in what should be studied and how one should go about it are still with us a century later.Text B LiespottingScript:Trained liespotters get to the truth 90 percent of the time. The rest of us, we’re only 54 percent accurate. Why is it so easy to learn? There are good liars and there are bad liars. There are no real original liars. We all make the same mistakes. We all use the same techniques. So what I'm going to do is I’m going to show you two patterns of deception. And then we’re going to look at the hot spots and see if we can find them ourselves. We’re going to start with speech.Bill Clinton: I want you to listen to me. I'm going to say this again. I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky. I never told anybody to lie, not a single time, never. And these allegations are false. And I need to go back to work for the American people. Thank you.Pamela Meyer: Okay, what were the telltale signs? Well first we heard what’s known as a non-contracted denial. Studies show that people who are overdetermined in their denial will resort to formal rather than informal language. We also heard distancing language: “that woman”. We know that liars will unconsciously distance themselves from their subject using language as their tool. Now if Bill Clinton had said, “Well, to tell you the truth ...”or Richard Nixon’s favorite, “In all candor ...” he would have been a dead giveaway for any liespotter than knows that qualifying language, as it’s called, qualifying language like that, further discredits the subject. Now if he had repeated the question in its entirety, or if he had peppered his account with a little too much detail -- and we’re all really glad he didn’t do that -- he would have further discredited himself. Freud had it right. Freud said, look, there’s much more to it than speech: “No mortal can keep a secret. If his lips are silent, he chatters with his fingertips.” And we all do it no matter how powerful you are. We all chatter with our fingertips. I'm going to show you Dominique Strauss-Kahn with Obama who’s chattering with his fing ertips.Now this brings us to our next pattern, which is body language. With body language, here’s what you’ve got to do. You've really got to just throw your assumptions out the door. Let the science temper your knowledge a little bit. Because we think liars fidget all the time. Well guess what, they’re known to freeze their upper bodies when they’re lying. We think liars won't look you in the eyes. Well guess what, they look you in the eyes a little too much just to compensate for that myth. We think warmth and smiles convey honesty, sincerity. But a trained liespotter can spot a fake smile a mile away. Can you all spot the fake smile here? You can consciously contract the muscles in your cheeks. But the real smile’s in the eyes, the crow’s feet of the eye s. They cannot be consciously contracted, especially if you overdid the Botox. Don’t overdo the Botox; nobody will think you’re honest.Now we’re going to look at the hot spots. Can you tell what's happening in a conversation? Can you start to find the hot spots to see the discrepancies between someone’s words and someone’s actions? Now I know it seems really obvious, but when you’re having a conversation with someone you suspect of deception, attitude is by far the most overlooked but telling of indicators.An honest person is going to be cooperative. They’re going to show they’re on your side. They’re going to be enthusiastic.They’re going to be willing and helpful to getting you to the truth. They’re going to be willing to brainstorm, name suspects, provide details. They’re going to say, “Hey, maybe it was those guys in payroll that forged those checks.”They’re going to be infuriated if they sense they’re wrongly accused throughout the entire course of the interview, not just in flashes; they’ll be infur iated throughout the entire course of the interview. And if you ask someone honest what should happen to whomever did forge those checks, an honest person is much more likely to recommend strict rather than lenient punishment.Now let’s say you’re having t hat exact same conversation with someone deceptive. That person may be withdrawn, look down, lower their voice, pause, be kind of herky-jerky. Ask a deceptive person to tell their story, they’re going to pepper it with way too much detail in all kinds of irrelevant places. And then they’re going to tell their story in strict chronological order. And what a trained interrogator does is they come in and in very subtle ways over the course of several hours, they will ask that person to tell that story backwards, and then they’ll watch them squirm, and track which questions produce the highest volume of deceptive tells. Why do they do that? Well we all do the same thing. We rehearse our words, but we rarely rehearse our gestures. We say “yes”, we shake our heads“no”. We tell very convincing stories, we slightly shrug our shoulders. We commit terrible crimes, and we smile at the delight in getting away with it. Now that smile is known in the trade as “duping delight”. Part IV HomeworkSection A Listening Task.ExerciseListen to the passage and decide whether the sentences you hear are TRUE (T) or FALSE (F). Correct the sentence if it is false.1. People who lie will become nervous and their heart goes while people who are innocent will not have these reactions. ()2. Saxe’s experiment showed that lie detectors were valid only when the subjects believed so. ()3. If two things go together, most probably they are cause and effect. ()4. Seeing is always believing while what you hear about may be false. ()5. Scientific conclusions are not always accurate, and may be changed when better data appear.Script:People who lie are sometimes nervous and sometimes their heart goes faster and sometimes they sweat more. But it’s also true that people who are just c oncerned about an issue show the same reactions. Vice versa, it’s also true that people who liesometimes don’t sweat, don’t have their heart racing. And so there’s no direct connection and there’s no unequivocal connection between lying and these physiological states of arousal. Recently Congress asked Saxe and his colleagues to test the validity of lie detectors. Saxe set up an experiment where subjects were allowed to take money from a desk drawer. They were then given a lie-detector test. If they could pass the test, they could keep the money. (Do you have any money with you right now that you have taken from the desk? No. ) Some subjects were told that any lie detector can be deceived. Others were told that this lie detector was always accurate. The results were clear. Those who believed that the polygraph test did not work were able to deceive it. Those who believed it worked were, for the most part, caught, and some innocent subjects failed the test. (No. ) A polygraph is a prop. It’s a theatrical devi ce, if you will. If a polygrapher can convince the subject and they’re very good at convincing people, if they can convince the subject that the test works, if the subject is guilty, they are going to be nervous. They’re going to think that they can be detected. If, on the other hand, the subject knows that this is just theater that the polygrapher can’t really tell what they’re thinking they’re not going to be afraid. They’re not going to be nervous about being caught.Clearly getting at the truth is a difficult proposition, but fortunately there are a few guidelines we can follow to avoid the most common pitfalls. First, find out who the subjects were in any study, how many of them participated, and how they were selected. Avoid the assumption that two things that go together are cause and effect. Correlation is not necessarily causation. Remember that seeing isn’t believing if important information might be kept from you. Question any data that aren’t collected using the rigorous procedures of the scientific method. Any conclusion about human behavior is only as good as the data on which it is based. Keep in mind the power of placebos to alter reality. Restrain your enthusiasm for scientific breakthroughs until the results have been replicated by other researchers. And above all, beware of people claiming absolute truth and simple solutions for the many uncertainties and complexities of human nature. Scientific conclusions are always tentative, never absolute, and open to change should better data come along.。

二语习得(L1)

Course components

Lectures Discussions Assignments Research

Course assessment

Attendance and participation in class discussion (10%) Assignment (20%) Course paper (70%)

Course outline

L1 Introduction to SLA and SLA research L2 The role of the first language L3 The ‘natural’ route of development L4 Contextual variation in language-learner language L5 Individual learner differences L6 The role of the input L7 Learner processes(Learner strategies) L8 Learner processes(The universal hypothesis and SLA) L9 The role of formal instruction L10 Theories of second language acquisition

Students will be able to better describe the psychological and linguistic processes of second language acquisition Students will be able to better identify what internal and external factors help account for why learners do or do not acquire a second language Students will be able to better explain how such factors affect students' classroom performance Students will be able to have a greater understanding of the literature in the field of second language acquisition and develop greater skills in critically reading, understanding, and dissecting that literature Students will be able to relate issues discussed in class to past, current, and prospective learning/teaching experiences and to their future formal and informal research

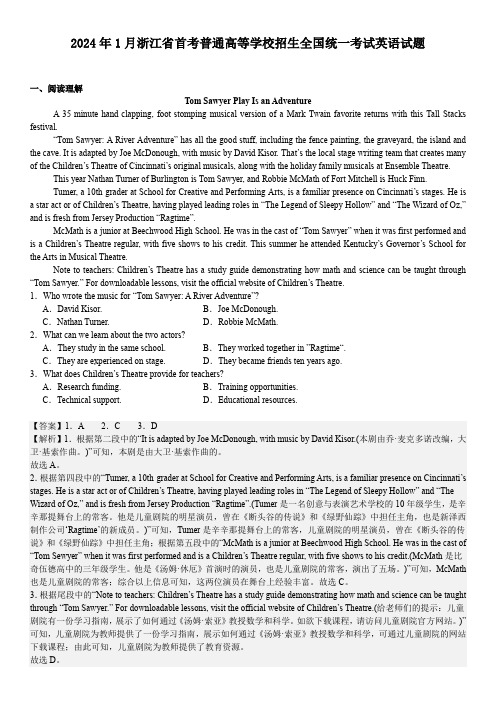

2024年1月浙江省首考普通高等学校招生全国统一考试英语试题

2024年1月浙江省首考普通高等学校招生全国统一考试英语试题一、阅读理解Tom Sawyer Play Is an AdventureA 35-minute hand-clapping, foot-stomping musical version of a Mark Twain favorite returns with this Tall Stacks festival.“Tom Sawyer: A River Adventure” has all the good stuff, including the fence painting, the graveyard, the island and the cave. It is adapted by Joe McDonough, with music by David Kisor. That’s the local stage writing team that creates many of the Children’s Theatre of Cincinnati’s original musicals, along with the holiday family musicals at Ensemble Theatre.This year Nathan Turner of Burlington is Tom Sawyer, and Robbie McMath of Fort Mitchell is Huck Finn.Tumer, a 10th-grader at School for Creative and Performing Arts, is a familiar presence on Cincinnati’s stages. He is a star act or of Children’s Theatre, having played leading roles in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “The Wizard of Oz,” and is fresh from Jersey Production “Ragtime”.McMath is a junior at Beechwood High School. He was in the cast of “Tom Sawyer” when it was first performed and is a Children’s Theatre regular, with five shows to his credit. This summer he attended Kentucky’s Governor’s School for the Arts in Musical Theatre.Note to teachers: Children’s Theatre has a study guide demonstrating how math and science can be taught through “Tom Sawyer.” For downloadable lessons, visit the official website of Children’s Theatre.1.Who wrote the music for “Tom Sawyer: A River Adventure”?A.David Kisor.B.Joe McDonough.C.Nathan Turner.D.Robbie McMath.2.What can we learn about the two actors?A.They study in the same school.B.They worked together in ”Ragtime“.C.They are experienced on stage.D.They became friends ten years ago.3.What does Children’s Theatre provide for teachers?A.Research funding.B.Training opportunities.C.Technical support.D.Educational resources.【答案】1.A 2.C 3.D【解析】1.根据第二段中的“It is adapted by Joe McDonough, with music by David Kisor.(本剧由乔·麦克多诺改编,大卫·基索作曲。

心理之战英语怎么说作文

The psychological battle, often referred to as psychological warfare, is a strategic approach used in various fields, including military, politics, and even personal relationships. It involves the use of psychological tactics to influence the thoughts, emotions, and behaviors of individuals or groups. In English, when writing about this concept, you might discuss several aspects:1. Definition: Begin by defining what psychological warfare is and its purpose. For example, Psychological warfare is the use of psychological tactics to demoralize, confuse, or otherwise influence the mindset of an adversary.2. Historical Context: Discuss how psychological warfare has been used throughout history. For instance, Throughout history, from the ancient Greeks to modern military campaigns, psychological warfare has played a crucial role in shaping the outcomes of conflicts.3. Tactics and Techniques: Explain the various tactics that can be employed, such as propaganda, misinformation, and fear. You might write, Tactics of psychological warfare include spreading propaganda to manipulate public opinion, using misinformation to sow doubt, and instilling fear to weaken resolve.4. Impact on Society: Reflect on the broader impact of psychological warfare on society and individuals. For example, The effects of psychological warfare can be farreaching, affecting not only the morale of soldiers but also the civilian populations perception of the conflict.5. Ethical Considerations: Address the ethical implications of using psychological warfare. You could say, While psychological warfare can be a powerful tool, it raises significant ethical concerns, as it often targets the most vulnerable aspects of human psychology.6. Modern Applications: Discuss how psychological warfare is applied in the modern world, including cyber warfare and social media manipulation. For instance, In the digital age, psychological warfare has taken on new forms, with cyber attacks and social media manipulation becoming prevalent tools in the arsenal of psychological operations.7. Case Studies: Provide specific examples or case studies to illustrate the concept. For example, The Vietnam War is a classic example of psychological warfare, where the U.S. militarys use of propaganda and fear tactics had a profound impact on both the enemy and the American public.8. Conclusion: Summarize the importance of understanding psychological warfare and its potential consequences. You might conclude with, Understanding the mechanisms of psychological warfare is essential for recognizing its influence in contemporary conflicts and for developing strategies to counter its effects.By structuring your essay around these points, you can provide a comprehensive overview of psychological warfare and its significance in various contexts.。

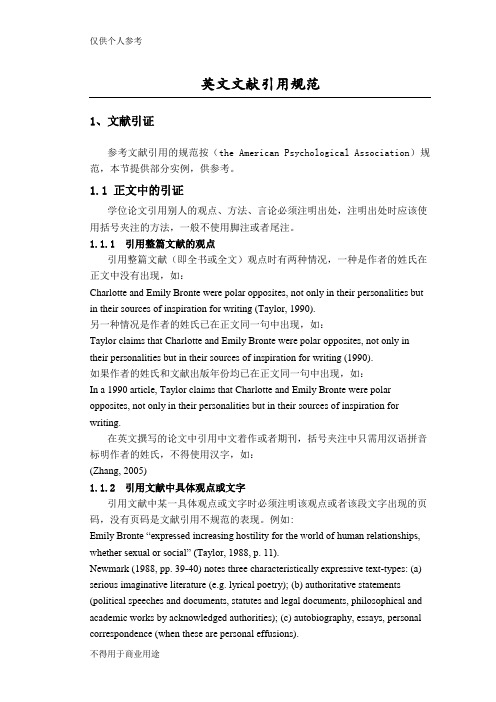

英文文献引用规范

英文文献引用规范1、文献引证参考文献引用的规范按(the American Psychological Association)规范,本节提供部分实例,供参考。

1.1 正文中的引证学位论文引用别人的观点、方法、言论必须注明出处,注明出处时应该使用括号夹注的方法,一般不使用脚注或者尾注。

1.1.1 引用整篇文献的观点引用整篇文献(即全书或全文)观点时有两种情况,一种是作者的姓氏在正文中没有出现,如:Charlotte and Emily Bronte were polar opposites, not only in their personalities but in their sources of inspiration for writing (Taylor, 1990).另一种情况是作者的姓氏已在正文同一句中出现,如:Taylor claims that Charlotte and Emily Bronte were polar opposites, not only in their personalities but in their sources of inspiration for writing (1990).如果作者的姓氏和文献出版年份均已在正文同一句中出现,如:In a 1990 article, Taylor claims that Charlotte and Emily Bronte were polar opposites, not only in their personalities but in their sources of inspiration for writing.在英文撰写的论文中引用中文着作或者期刊,括号夹注中只需用汉语拼音标明作者的姓氏,不得使用汉字,如:(Zhang, 2005)1.1.2 引用文献中具体观点或文字引用文献中某一具体观点或文字时必须注明该观点或者该段文字出现的页码,没有页码是文献引用不规范的表现。

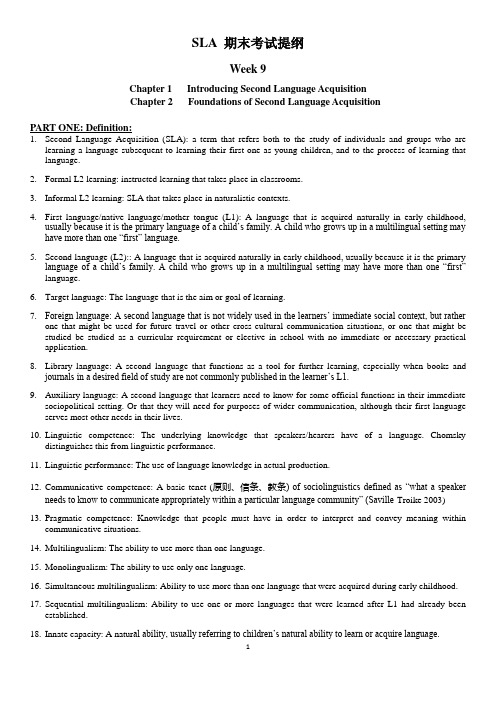

SLA_期末考试提纲(汇总版)

SLA 期末考试提纲Week 9Chapter 1 Introducing Second Language AcquisitionChapter 2 Foundations of Second Language AcquisitionPART ONE: Definition:1.Second Language Acquisition (SLA): a term that refers both to the study of individuals and groups who arelearning a language subsequent to learning their first one as young children, and to the process of learning that language.2.Formal L2 learning: instructed learning that takes place in classrooms.rmal L2 learning: SLA that takes place in naturalistic contexts.4.First language/native language/mother tongue (L1): A language that is acquired naturally in early childhood,usually because it is the primary language of a child‘s family. A child who grows up in a multilingual setting may have more than one ―first‖ language.5.Second language (L2):: A language that is acquired naturally in early childhood, usually because it is the primarylanguage of a child‘s family. A child who grows up in a multilingual setting may have more than one ―first‖ language.6.Target language: The language that is the aim or goal of learning.7.Foreign language: A second language that is not widely used in the learners‘ immediate social context, but ratherone that might be used for future travel or other cross-cultural communication situations, or one that might be studied be studied as a curricular requirement or elective in school with no immediate or necessary practical application.8.Library language: A second language that functions as a tool for further learning, especially when books andjournals in a desired field of study are not commonly published in the learner‘s L1.9.Auxiliary language: A second language that learners need to know for some official functions in their immediatesociopolitical setting. Or that they will need for purposes of wider communication, although their first language serves most other needs in their lives.10.Linguistic competence: The underlying knowledge that speakers/hearers have of a language. Chomskydistinguishes this from linguistic performance.11.Linguistic performance: The use of language knowledge in actual production.municative competence: A basic tenet (原则、信条、教条) of sociolinguistics defined as ―what a speakerneeds to know to communicate appropriately within a particular language community‖ (Saville-Troike 2003) 13.Pragmatic competence: Knowledge that people must have in order to interpret and convey meaning withincommunicative situations.14.Multilingualism: The ability to use more than one language.15.Monolingualism: The ability to use only one language.16.Simultaneous multilingualism: Ability to use more than one language that were acquired during early childhood.17.Sequential multilingualism: Ability to use one or more languages that were learned after L1 had already beenestablished.18.Innate capacity: A natur al ability, usually referring to children‘s natural ability to learn or acquire language.19.Child grammar: Grammar of children at different maturational levels that is systematic in terms of production andcomprehension.20.Initial state: The starting point for language acquisition; it is thought to include the underlying knowledge aboutlanguage structures and principles that are in learners‘ heads at the very start of L1 or L2 acquisition.21.Intermediate state: It includes the maturational changes which take pla ce in ―child grammar‖, and the L2developmental sequence which is known as learner language.22.Final state: The outcome of L1 and L2 leaning, also known as the stable state of adult grammar.23.Positive transfer: Appropriate incorporation of an L1 structure or rule in L2 structure.24.Negative transfer: Inappropriate influence of an L1 structure or rule on L2 use. Also called interference.25.Poverty-of-the-stimulus: The argument that because language input to children is impoverished and they stillacquire L1, there must be an innate capacity for L1 acquisition.26.Structuralism: The dominant linguistic model of the 1950s, which emphasized the description of different levels ofproduction in speech.27.Phonology: The sound systems of different languages and the study of such systems generally.28.Syntax: The linguistic system of grammatical relationships of words within sentences, such as ordering andagreement.29.Semantics: The linguistic study of meaning.30.Lexicon: The component of language that is concerned with words and their meanings.31.Behaviorism: The most influential cognitive framework applied to language learning in the 1950s. It claims thatlearning is the result of habit formation.32.Audiolingual method: An approach to language teaching that emphasizes repetition and habit formation. Thisapproach was widely practiced in much of the world until at least the 1980s.33.Transformational-Generative Grammar: The first linguistic framework with an internal focus, whichrevolutionized linguistic theory and had profound effect on both the study of first and second languages. Chomsky argued effectively that the behaviorist theory of language acquisition is wrong because it cannot explain the creative aspects of linguistic ability. Instead, humans must have some innate capacity for language.34.Principles and Parameters (model): The internally focused linguistic framework that followed Chomsky‘sTransformational-Generative Grammar. It revised specifications of what constitutes innate capacity to include more abstract notions of general principles and constraints common to human language as part of a Universal Grammar.35.Minimalist program: The internally focused linguistic framework that followed Chomsky‘s Principles andParameters model.This framework adds distinctions between lexical and functional category development, as well as more emphasis on the acquisition of feature specification as a part of lexical knowledge.36.Functionalism: A linguistic framework with an external focus that dates back to the early twentieth century andhas its roots in the Prague School (布拉格学派) of Eastern Europe. It emphasizes the information content of utterances and considers language primarily as a system of communication. Functionalist approaches have largely dominated European study of SLA and are widely followed elsewhere in the world.37.Neurolinguistics: The study of the location and representation of language in the brain, of interest to biologists andpsychologists since the nineteenth century and one of the first fields to influence cognitive perspectives on SLA when systematic study began in 1960s.38.Critical period: The limited number of years during which normal L1 acquisition is possible.39.Critical Period Hypothesis: The claim that children have only a limited number of years during which they canacquire their L1 flawlessly; if they suffered brain damage to the language areas, brain plasticity in childhood would allow other areas of the brain to take over the language functions of the damaged areas, but beyond a certain age, normal language development would not be possible. This concept is commonly extended to SLA as well, in the claim that only children are likely to achieve native or near-native proficiency in L2.rmation processing (IP): A cognitive framework which assumes that SLA (like learning of other complexdomains) proceeds from controlled to automatic processing and involves progressive reorganization of knowledge.41.Connectionism: A cognitive framework for explaining learning processes, beginning in the 1980s and becomingincreasingly influential. It assumes that SLA results from increasing strength of associations between stimuli and responses.42.Variation theory: A microsocial framework applied to SLA that explores systematic differences in learnerproduction which depend on contexts of use.43.Accommodation theory: A framework for study of SLA that is based on the notion that speakers usuallyunconsciously change their pronunciation and even the grammatical complexity of sentences they use to sound more like whomever they are talking to.44.Sociocultural theory (SCT): An approach established by Vygotsky which claims that interaction not onlyfacilitates language learning but is a causative force in acquisition. Further, all of learning is seen as essentially a social process which is grounded in sociocultural settings.45.Ethnography(人种论、民族志) of communication: A framework for analysis of language and its functions thatwas established by Hymes(1966). It relates language use to broader social and cultural contexts, and applies ethnographic methods of data collection and interpretation to study of language acquisition and use.46.Acculturation(文化适应): Learning the culture of the L2 community and adapting to those values and behaviorpatterns.47.Acculturation Model/Theory: Schumann‘s (1978) theory that identifies gro up factors such as identity and statuswhich determine social and psychological distance between learner and target language populations. He claims these influence outcomes of SLA.48.Social psychology: A societal approach in research and theory that allows exploration of issues such as howidentity, status, and values influence L2 outcomes and why. It has disciplinary ties to both psychological and social perspectives.PART TWO: Short & Long answers:Chapter 11.What are the similarities and differences between linguists, psycholinguist, sociolinguists and socialpsycholinguists? P3(1)Linguists emphasize the characteristics of the differences and similarities in the languages that are being learned, and the linguistic competence (underlying knowledge) and linguistic performance (actual production) of learners at various stages of acquisition.(2)Psychologists and psycholinguists emphasize the mental or cognitive processes involved in acquisition, and the representation of languages in the brain.(3)Sociolinguists emphasize variability in learner linguistic performance, and extend the scope of study to communicative competence (underlying knowledge that additionally accounts for language use, or pragmatic competence).(4)Social psychologists emphasize group-related phenomena, such as identity and social motivation, and the interactional and larger social contexts of learning.2.What are the differences between second language, foreign language, library language and auxiliarylanguage? P4(1)A second language is typically an official or societally dominant language needed for education, employment, and other basic purposes. It is often acquired by minority group members or immigrants who speak another language natively. In this more restricted sense, the term is contrasted with other terms in this list.(2)A foreign language is one not widely used in the learners' immediate social context which might be used for future travel or other cross-cultural communication situations, or studied as a curricular requirement or elective in school, but with no immediate or necessary practical application.(3)A library language is one which functions primarily as a tool for future learning through reading, especially when books or journals in a desired field of study are not commonly published in the learners' native tongue.(4)An auxiliary language is one which learners need to know for some official functions in their immediate political setting, or will need for purposes of wider communication, although their first language serves most other needs in their lives.3.Why are some learners more (or less) successful than other? P5The intriguing question of why some L2 learners are more successful than others requires us to unpack the broad label ―learners‖ for some dimensions of disc ussion. Linguistics may distinguish categories of learners defined by the identity and relationship of their L1 and L2; psycholinguists may make distinctions based on individual aptitude for L2 learning, personality factors, types and strength of motivation, and different learning strategies;sociolinguists may distinguish among learners with regard to social, economic, and political differences and learner experiences in negotiated interaction; and social psychologists may categorize learners according to aspects of their group identity and attitudes toward target language speakers or toward L2 learning itself.Chapter21.List at least five possible motivations for learning a second language at an older age. P10The motivation may arise from a variety of conditions, including the following:●Invasion or conquest of one‘s country by speakers of another language;● A need or desire to contact speakers of other languages in economic or other specific domains;●Immigration to a country where use of a language other than one's L1 is required;●Adoption of religious beliefs and practices which involve use of another language;● A need or desire to pursue educational experiences where access requires proficiency in another language;● A desire for occupational or social advancement which is furthered by knowledge of another language;●An interest in knowing more about peoples of other cultures and having access to their technologies orliteratures.2.What are the two main factors that influence the language learning? P13(1)The role of natural ability: Humans are born with a natural ability or innate capacity to learn language.(2)The role of social experience: Not all of L1 acquisition can be attributed to innate ability, for language-specific learning also plays a crucial role. Even if the universal properties of language arepreprogrammed in children, they must learn all of those features which distinguish their L1 from all other possible human languages. Children will never acquire such language-specific knowledge unless that language is used with them and around them, and they will learn to use only the language(s) used around them, no matter what their linguistic heritage. American-born children of Korean or Greek ancestry will never learn the language of their grandparents if only English surrounds them, for instance, and they will find their ancestral language just as hard to learn as any other English speakers do if they attempt to learn it as an adult. Appropriate social experience, including L1 input and interaction, is thus a necessary condition for acquisition.3.What is the initial state of language development for L1 and L2 respectively? P17-18The initial state of L1 learning is composed solely of an innate capacity for language acquisition which may or may not continue to be available for L2, or may be available only in some limited ways. The initial state for L2 learning, on the other hand, has resources of L1 competence, world knowledge, and established skills for interaction, which can be both an asset and an impediment.4.How does intermediate states process? P18-19The cross-linguistic influence, or transfer of prior knowledge from L1 to L2, is one of the processes that is involved in interlanguage development. Two major types of transfer which occur are: (1) positive transfer, when an L1 structure or rule is used in an L2 utterance and that use is appropriate or ―correct‖ in the L2; and (2) negative transfer (or interference), when an L1 structure or rule is used in an L2 utterance and that use is inappropriate and c onsidered an ―error‖.5.What is a necessary condition for language learning (L1 or L2)? P20Language input to the learner is absolutely necessary for either L1 or L2 learning to take place. Children additionally require interaction with other people for L1 learning to occur. It is possible for some individuals to reach a fairly high level of proficiency in L2 even if they have input only from such generally non-reciprocal sources as radio, television, or written text.6.What is a facilitating condition for language learning? P20While L1 learning by children occurs without instruction, and while the rate of L1 development is not significantly influenced by correction of immature forms or by degree of motivation to speak, both rate and ultimate level of development in L2 can be facilitated or inhabited by many social and individual factors, such as(1) feedback, including correction of L2 learners' errors; (2) aptitude, including memory capacity and analyticability; (3) motivation, or need and desire to learn; (4) instruction, or explicit teaching in school settings.7.Give at least 2 reasons that many scientists believe in some innate capacity for language. P21-24The notion that innate linguistic knowledge must underlie language acquisition was prominently espoused by Noam Chomsky. This view has been supported by arguments such as the following:(1)Children‘s knowledge of language goes beyond what could be learned from the input they receive: Childrenoften hear incomplete or ungrammatical utterances along with grammatical input, and yet they are somehow able to filter the language they hear so that the ungrammatical input is not incorporated into their L1 system.Further, children are commonly recipients of simplified input from adults, which does not include data for all of the complexities which are within their linguistic competence. In addition, children hear only a finite subset of possible grammatical sentences, and yet they are able to abstract general principles and constraints which allow them to interpret and produce an infinite number of sentences which they have never heard before.(2)Constraints and principles cannot be learned: Children‘s access to general constraints and principles whichgovern language could account for the relatively short time it takes for the L1 grammar to emerge, and for the fact that it does so systematically and without any ―wild‖ divergences. This could be so because innate principles lead children to organize the input they receive only in certain ways and not others. In addition to the lack of negative evidence , constraints and principles cannot be learnt in part because children acquire a first language at an age when such abstractions are beyond their comprehension; constraints and principles are thus outside the realm of learning process which are related to general intelligence.(3)Universal patterns of development cannot be explained by language-specific input: In spite of the surfacedifferences in input, there are similar patterns in child acquisition of any language in the world. The extent of this similarity suggests that language universals are not only constructs derived from sophisticated theories and analyses by linguists, but also innate representations in every young child‘s mind.8.Linguists have taken an internal and/or external focus to the study of language acquisition. What is thedifference between the two? P25-26Internal focus emphasizes that children begin with an innate capacity which is biologically endowed, as well as the acquisition of feature specification as a part of lexical knowledge; while external focus emphasizes the information content of utterances, and considers language primarily as a system of communication.9.What are the two main factors for learning process in the study of SLA from a psychological perspective?P26-27(1) Information Processing, which assumes that L2 is a highly complex skill, and that learning L2 is notessentially unlike learning other highly complex skills. Processing itself is believed to cause learning;(2) Connectionism, which does not consider language learning to involve either innate knowledge or abstractionof rules and principles, but rather to result from increasing strength of associations (connections) between stimuli and responses.10.What are the two foci for the study of SLA from the social perspective? P27(1) Microsocial focus: the concerns within the microsocial focus relate to language acquisition and use inimmediate social contexts of production, interpretation, and interaction. (2) Macrosocial focus: the concerns of the macrosocial focus relate language acquisition and use to broader ecological contexts, including cultural, political, and educational settings.Week10Chapter 5 Social contexts of Second Language AcquisitionPART ONE: Definitionmunicative compet ence: A basic tenet of sociolinguistics defined as ―what a speaker needs to know tocommunicate appropriately within a particular language community‖(Saville-Troike 2003)nguage community: A group of people who share knowledge of a common language to at least some extent.3.Foreigner talk: Speech from L1 speakers addressed to L2 learners that differs in systematic ways from languageaddressed to native or very fluent speakers.4.Direct Correction: Explicit statements about incorrect language use.5.Indirect correction: Implicit feedback about inappropriate language use, such as clarification requests when thelistener has actually understood an utterance.6.Interaction Hypothesis: The claim that modifications and collaborative efforts which take place in social interationfacilitate SLA because they contribute to the accessibility of input for mental processing.7.Symbolic mediation: A link between a person‘s current mental state and higher order functions that is providedprimarily by language; considered the usual route to learning (of language, and of learning in general). Part of Vygosky‘s Sociocultural Theory.8.Variable features: Multiple linguistic forms (vocabulary, phonology, morphology, syntax, discourse) that aresystematically or predictably used by different speakers of a language, or by the same speakers at different times, with the same meaning or function.9.Linguistic context: Elements of language form and function associated with the variable element.10.Psychological context: factors associated with the amount of attention which is being given to language formduring production, the level of automaticity versus control in processing, or the intellectual demands of a particular task.11.Microsocial context: features of setting/situation and interaction which relate to communicative events withinwhich language is being produced, interpreted, and negotiated.12.Accommodation theory: A framework for study of SLA that is based on the notion that speakers usuallyunconsciously change their pronunciation and even the grammatical complexity of sentences they use to sound more like whomever they are talking to .13.ZPD: Zone of Proximal Development, an area of potential development where the learner can only achieve thatpotential with assistance. Part of Vygosky‘s Sociocultur al Theory.14.Scaffolding: Verbal guidance which an expert provides to help a learner perform any specific task, or the verbalcollaboration of peers to perform a task which would be too difficult for any one of them in individual performance.15.Intrapersonal interaction: communication that occurs within an individual's own mind, viewed by Vygosky as asociocultural phenomen.16.Interpersonal interaction: Communicative events and situations that occur between people.17.Social institutions:The systems which are established by law, custom, or practice to regulate and organize the lifeof people in public domains: e.g. politics, religion, and education.18.Acculturation: learning the culture of the L2 community and adapting to those values and behavioral patterns.19.Additive bilingualism: The result of SLA in social contexts where members of a dominant group learn thelanguage of a minority without threat to their L1 competence or to their ethnic identity.20.Subtractive bilingualism: The result of SLA in social contexts where members of a minority group learn thedominant language as L2 and are more likely to experience some loss of ethnic identity and attrition of L1 skills—especially if they are children.21.Formal L2 learning: formal/instructed learning generally takes place in schools, which are social institutions thatare established in accord with the needs, beliefs, values, and customs of their cultural settings.rmal L2 learning: informal/naturalistic learning generally takes place in settings where people contact—andneed to interact with—speakers of another language.PART TWO: Short & Long answers1.what is the difference between monolingual and multilingual communicative competence?Differencese between monolingual and multilingual communicative competence are due in part to the different social functions of first and second language learning, and to the differences between learning language and learning culture. The differences of the competence between native speakers and nonative speakers include structural differences in the linguisitc system, different rules for usage in writing or conversation, and even somewhat divergent meanings for the ―same‖ lexical forms. Further, a multilingual speaker‘s total communicative competence differs from that of a monolingual in including knowledge of rules for the appropriate choice of language and for switching between languages, given a particular social context and communicative purpose.2.what are the microsocial factors that affect SLA? P101-102a) L2 variation b) input and interaction c) interaction as the genesis of language3.What is the difference between linguistic & communicative competence (CC)?Linguistic competence- It was defined in 1965 by Chomsky as a speaker's underlying ability to produce grammatically correct expressions. Linguistic competence refers to knowledge of language. Theoretical linguistics primarily studies linguistic competence: knowledge of a language possessed by ―an ideal speak-listener‖.Communicative competence- It is a term in linguistics which refers to ―what a speaker needs to know to communicate appropriately within a particular language community‖, such as a language user's grammatical knowledge of syntax ,morphology , phonology and the like, as well as social knowledge about how and when to use utterances appropriately.4.Why is CC in L1 different from L2?L1 learning for children is an integral part of their sociolization into their native language community. L2 learning may be part of second culture learning and adaptation, but the relationship of SLA to social and cultural learning differs greatly with circumstances.5.What is Accommodation Theory? How does this explain L2 variation?Accommodation theory: Speakers (usually unconsciously) change their pronunciation and even the grammatical complexity of sentences they use to sound more like whomever they are talking to. This accounts in part for why native speakers tend to simply their language when they are talking to a L2 learner who is not fluent, and why L2 learners may acquire somewhat different varieties of the target language when they have different friends.6.Discuss the importance of input & interaction for L2 learning. How could this affect the feedback providedto students?ⅰ. a) From the perspective of linguistic approaches: (1) behaviorist: they consider input to form the necessary stimuli and feedback which learners respond to and imitate; (2) Universal Grammar: they consider exposure to input a necessary trigger for activating internal mechanisms; (3) Monitor Model: consider comprehensible input not only necessary but sufficient in itself to account for SLA;b) From the perspective of psychological approaches: (1) IP framework: consider input which is attended to as essential data for all stages of language processing; (2) connectionist framework: consider the quantity or frequency of input structures to largely determine acquisitional sequencing;c) From the perspective of social approaches: interaction is generally seen as essential in providing learners with the quantity and quality of external linguistic input which is required for internal processing.ⅱ. Other types of interaction which can enhance SLA include feedback from NSs which makes NNs aware that their usage is not acceptable in some way, and which provides a model for ―correctness‖. Whil e children rarely receive such negative evidence in L1, and don‘t require it to achieve full native competence, corrective feedback is common in L2 and may indeed be necessary for most learners to ultimately reach native-like levels of proficiency when that is the desired goal.7.Explain ZPD. How would scaffolding put a student in ZPD?Zone of Proximal Development, this is an area of potential development, where the learner can achieve that potential only with assistance. Mental functions that are beyond an individual's current level must be performed in collaboration with other people before they are achieved independently. One way in which others help the learner in language development within the ZPD is through scaffolding. Scaffolding refers to verbal guidance which an expert provides to help a learner perform any specific task, or the verbal collaboration of peers to perform a task which would be too difficult for any one of them individually. It is not something that happens to learners as a passive recipient, but happens with a learner as an active participant.8.Think of a macrosocial factor that affects English learning in China. Which of does it fall under? What arethe effects? What are the results?The 5 topics are:●Global abd national status of L1 and L2●Boundaries and identities●Institutional forces and constraints●Social categories。

SLA_1_余达

immediate cocial context, but used for future travel or other crosscultural situations, or studied as a crurricular requiement or elective in school, but with no immediate or practical application

postgraduate schools(英语教学法方向)

Why SLA?

laying the foundation for your further academic research

being curious about SLA phenomenon

Q1: How do people manage to learn an L2?

"native language"?

Are they interchangeable?

A case study

My cousin was born in Korea and the very first language

she learned was obviously Korean; however, her whole family moved to the US when she was 7 and she grew up in New Jersey, USA. (She has been living in the US for nearly 20 years.) So she now speaks English much better than Korean. The language she speaks best, most comfortably and confidently is English. Is her first language still Korean? What about her native language? Her Korean became so rusty and she sounds like a brain-damaged person whenever she speaks Korean. Can we still call her a native speaker of Korean?

二语习得引论读书笔记chapter12