MS的经典调节治疗办法

多发性硬化症的治疗方法和注意事项

汇报人:XXX

2023-11-21

• 引言 • 治疗方法 • 注意事项 • 结论 • 参考文献

01

引言

定义和背景介绍

• 多发性硬化症(Multiple Sclerosis,简称MS)是一种慢性自身免疫性疾病,影响中枢神经系统,导致神经功能损害。该 病多发于年轻人,女性发病率略高于男性。MS的病因尚不明确,可能与遗传、环境、免疫系统异常等多种因素有关。

抗炎疗法

使用非甾体抗炎药、糖皮 质激素等,减轻炎症和疼 痛,改善症状。

神经保护疗法

使用一些药物如干扰素、 芬戈莫德等,保护神经元 免受炎症损害,延缓疾病 进展。

非药物治疗

物理治疗

包括康复训练、物理疗法等,帮 助患者恢复肌肉力量、协调性和

平衡感。

心理治疗

多发性硬化症患者可能出现焦虑、 抑郁等心理问题,心理治疗可以帮 助患者调整心态,提高生活质量。

参考文献3

物理治疗也是多发性硬化症的重要治 疗方法之一。包括理疗、按摩、运动 疗法等。这些方法可以改善肌肉力量 、减轻疼痛、提高运动协调能力等。

THANKS

感谢观看

避免感染

多发性硬化症患者在病毒感染后 容易诱发病情,因此Байду номын сангаас尽量避免

感冒、发热等感染情况发生。

避免过敏

过敏反应也可能诱发病情发作, 患者应尽量避免接触过敏原,如

花粉、尘螨等。

避免精神压力

长期的精神压力也可能导致病情 加重或复发,患者应学会调节情

绪,保持心情愉悦。

04

结论

结论

确诊后应尽早开始治疗,以减轻症状、延缓病情进展。

05

参考文献

参考文献

多发性硬化症的分类及治疗方案综述

多发性硬化症的分类及治疗方案综述多发性硬化症(Multiple Sclerosis,MS)是一种中枢神经系统疾病,主要特征是神经髓鞘(myelin)的破坏和神经纤维的损伤。

该病具有很高的年发病率,且大多数患者多在青壮年期间发病,对生命和健康造成重大影响。

目前,MS的分类和治疗方案已得到较为完善的研究和应用,本文将对其进行综述。

一、分类MS根据临床表现和病理生理学改变被分为下列类型:1. 核心型多发性硬化症(Relapsing-Remitting MS,RRMS)这是最常见的类型,约占MS患者的85%,特征是有明显的急性发作期,但在发病初期,患者往往可以出现症状消退期。

每次发作后,症状会有所缓解,但也可能存在残留症状。

2. 次级进行性多发性硬化症(Secondary-Progressive MS,SPMS)在RRMS的基础上发展而来,具有慢性和进行性的特征。

在这种情况下,治疗会相对困难。

3. 原发性进行性多发性硬化症(Primary-Progressive MS,PPMS)PPMS是RRMS和SPMS的特殊类型,它没有快速发展和期间停顿的情况,同时也没有再现性轮廓。

这是MS患者的15%的少见类型,在初次发作时就表现出来。

4. 可复发进行性多发性硬化症(Relapsing-Progressive MS,RPMS)这种类型的MS非常罕见,表现为在起初发作期间同时具有进行性的特征,病程是可重复性的。

二、治疗方案1. 免疫调节药物干扰素β、甲基泼尼松龙等唯一获得MS治疗免疫调节药物认证的激素,早期使用可以减缓病情恶化,但有一定的副作用,需要长时间使用。

其他免疫调节药物,如抗白细胞抗体、免疫抑制剂等,也可以缓解症状,但副作用也很明显。

2. 对症治疗针对不同的症状进行对症治疗,例如痉挛、抽搐、尿失禁等。

这种治疗方式可以通过改善患者的生活质量和加速康复进行治疗。

3. 维生素D长期缺乏维生素D与许多自身免疫疾病有关。

多发性硬化症患者症状缓解方法

多发性硬化症患者症状缓解方法多发性硬化症(Multiple Sclerosis,简称MS)是一种慢性进展性的自身免疫性疾病,主要影响中枢神经系统,导致神经元的破坏和功能损害。

该病的临床症状多样化,给患者的生活带来巨大的困扰与挑战。

然而,通过采取一系列综合的治疗措施,可以缓解患者的症状,提高生活质量。

本文将介绍一些多发性硬化症患者常用的症状缓解方法。

一、药物治疗目前,医学界广泛认可的多发性硬化症的标准治疗方法是疾病修饰性治疗(Disease-Modifying Therapies,简称DMTs)。

这些药物可以减少疾病复发的频率,延缓疾病的进展。

常用的DMTs药物包括干扰素β、甲基泼尼松龙、吗啡环酮、特比利肽等。

患者应在医生的指导下选用适合自身情况的药物,进行长期的维持治疗。

二、康复治疗康复治疗是多发性硬化症患者症状缓解的重要手段之一。

通过物理治疗、职业治疗、言语治疗等康复技术,可以改善患者的运动功能、日常生活能力和语言沟通能力。

康复治疗还可以提高患者对疾病的适应能力,减轻抑郁和焦虑的症状。

三、饮食调节合理的饮食对多发性硬化症患者的症状缓解具有积极作用。

患者应遵循均衡营养的原则,增加新鲜水果、蔬菜、全谷物、蛋白质等营养素的摄入。

此外,适量补充富含维生素D和ω-3脂肪酸的食物,如鱼肝油、深海鱼类等,也有助于缓解症状。

四、心理疏导多发性硬化症的患者常伴有情绪波动、焦虑和抑郁等心理问题。

因此,心理疏导对于缓解症状非常重要。

患者可以通过参加心理咨询、心理干预、心理支持小组等方式,倾诉内心的困扰,减轻心理负担,增强心理韧性。

五、适度运动适度的运动对多发性硬化症患者的身体康复和症状缓解有着明显的积极影响。

患者可以选择低强度、有氧、非负荷的运动方式,如散步、瑜伽、游泳等。

运动可以改善血液循环,增强肌肉的力量和灵活性,改善患者的平衡力和步态,缓解疲劳和压力。

六、中医中药作为传统医学的瑰宝,中医中药在多发性硬化症患者症状缓解上具有一定的疗效。

神经病学 名词解释及简答

1.上运动神经元锥体系:包括上、下两个运动神经元。

上运动神经元胞体主要位于大脑皮质躯体运动中枢的锥体细胞,这些细胞的轴突组成下行的锥体束,下行至脊髓的称皮质脊髓束,至脑干运动神经核的纤维为皮质核束。

上运动神经元损伤可引起痉挛性瘫痪,肌张力增高,深反射亢进,可出现病理反射,早期不出现肌萎缩。

2.下运动神经元:下运动神经元胞体位于脑干脑神经运动核和脊髓前角运动细胞,它们的轴突分别组成脑神经和脊神经,支配全身骨骼肌的随意运动。

下运动神经元受损时,出现弛缓性瘫痪,肌张力降低、肌萎缩,深反射消失。

3.视神经萎缩(optic atrophy):是指任何疾病引起视网膜神经节细胞和其轴突发生病变,致使视神经全部变细的一种形成学改变,为病理学通用的名词,一般发生于视网膜至外侧膝状体之间的神经节细胞轴突变性。

4.一个半综合征(one-and-a-half syndrome):又称脑桥麻痹性外斜视,若一侧桥脑侧视中枢(外展旁核)及双侧内侧纵束同时受到破坏,则出现同侧凝视麻痹(一个),对侧核间性眼肌麻痹(半个),即两眼向病灶侧注视时,同侧眼球不能外展,对侧眼球不能内收,向病灶对侧注视时,对侧眼球能外展,病灶侧眼球不能内收,两眼内聚运动仍正常。

5.帕里诺综合征(Parinaud综合征):又称上丘脑综合征、中脑顶盖综合征、上仰视性麻痹综合征。

由中脑上丘的眼球垂直同向运动皮质下中枢病变而导致的眼球垂直同向运动障碍,累及上丘的破坏性病灶可导致两眼向上同向运动不能。

6.阿-罗瞳孔(Argyell-Robertson瞳孔):发生在神经梅毒病人中,在半数左右的脊髓痨或者麻痹性痴呆病人中出现,主要是瞳孔缩小、光反射消失、而调节反射存在(调节反射是在看东西有远向近时,两眼向中间辐辏、瞳孔缩小)。

7.艾迪瞳孔:又称强直性瞳孔,其临床意义不明。

表现一侧瞳孔散大,只在暗处用强光持续照射时瞳孔缓慢收缩,停止光照后瞳孔缓慢散大。

调节反射也缓慢出现喝缓慢恢复。

代谢综合征(MS)解析

二、MS的诊断标准

2007年中国成人血脂异常防治指南

符合以下3项者即可诊断为代谢综合征。 1. 腹部肥胖:男性腰围>90 cm、女性腰围> 85cm。 2. TG≥1.7 mmol/L。 3. HDL-C<1.04 mmol/L。 4. 血压≥130/85 mmHg。 5. 空腹血糖≥6.1 mmol/L、餐后2h血糖≥7.8 mmol/L或有糖尿病史。

2型糖尿病 IGT

胰岛素抵抗 中心型肥胖 高VLDL甘油三脂

低HDL-胆固醇 高血压

微量白蛋白尿,等

心、脑血管疾病

一、MS的概述

(四)MS的发病机制

遗传因素

肥胖 全身性 中心性

环境因素

组织胰岛素抵抗

代谢综合征 糖尿病 血脂紊乱 高血压

动脉粥样硬化 冠状血管 脑血管 周围血管

一、MS的概述

(四)MS的发病机制

二、MS的诊断标准

2007年欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)指南:

符合以下3项者即可诊断为代谢综合征。 1. 血压≥130/85 mmHg。 2. HDL-C:男性<1.0 mmol/L、女性<1.2 mmol/L。 3. TG>1.7 mmol/L。 4. 空腹血糖>5.6 mmol/L。 5. 腹型肥胖:男性腰围>102 cm、女性腰围> 88 cm。

一、MS的概述

(三)MS的危害

➢ MS可明显增加心脑血管的患病率(5倍) ➢ MS可明显增加糖尿病的患病率(5倍) ➢ 增加心脑血管疾病和糖尿病的病死率,称为“死亡四重奏” ➢ 又称为CHAOS:C:冠心病;H:高血压、高Ins血症、高血

脂;A:成人DM;O:肥胖;S:综合征。

代谢综合征的冰山

MS调谐

什么是调谐?使用 LC/MSD 作为液相色谱检测器时,质谱将与 LC 色谱图中的每一数据点相关联。

要获得高质量且准确的质谱,必须优化 LC/MSD:∙使灵敏度达到最高∙保持可接受的分离度∙确保准确的质量指定调谐是指调整 LC/MSD 参数以达到这些目标的过程。

调整哪些参数?LC/MSD 有两组可以进行调整的参数。

其中一组参数与离子的形成相关。

这些参数控制雾化室(电喷雾或 APCI)和碰撞诱导解离。

另一组参数与离子的传输、过滤和检测相关。

这些参数控制锥孔体 2(仅 VL MSD)、八极杆、透镜、四极滤质器和 HED 电子倍增器(检测器)。

调谐主要是找到控制离子传输、过滤和检测的参数的正确设置。

通过将调谐液引入到 LC/MSD 并生成离子可以完成这一任务。

使用这些离子时,可以调整调谐参数,从而达到灵敏度、分离度和质量指定的目标。

在一些例外情况下,将不调整控制离子形成的参数。

这些参数将被设为有利于生成调谐液溶剂离子的固定值。

调谐的结果是什么?调谐的结果是一个调谐文件(实际上是一个目录),该文件包含两组参数设置:其中一组参数用于正极电离,另一组参数用于负极电离。

无论何时使用调谐文件,软件将自动调用适合方法指定的离子极性的设置。

自动调谐,自动调谐的程序,同时还生成一个报告。

如何使用调谐结果?在数据采集的过程中,与离子形成关联的参数由数据采集方法控制。

与离子传输关联的参数由指定给数据采集方法的调谐文件控制。

如何进行调谐?软件提供了两种方法来调谐 LC/MSD:∙自动调谐是一种在整个质量范围内对 LC/MSD 进行调谐以获得良好性能的自动调谐程序。

∙手动调谐使用户可以通过一次调整一个参数来调谐 LC/MSD,直到获得所需的性能。

当需要最大的灵敏度、针对受限的质量范围或需要调谐的化合物(标准调谐液除外)时,经常使用手动调谐。

快速扫描自动调谐要执行“快速扫描自动调谐”,请在启动“自动调谐”时选择一个快速扫描选项。

多发性硬化诊断和治疗中国专家共识

多发性硬化诊断和治疗中国专家共识多发性硬化(MS)是一种以中枢神经系统(CNS)白质炎症性脱髓鞘病变为主要特点的免疫介导性疾病。

其病因尚不明确,可能与遗传、环境、病毒感染等多种因素相关,MRI的影像学表现为CNS白质广泛髓鞘脱失并伴有少突胶质细胞坏变,也可伴有神经细胞及其轴索坏变。

MS病变具有时间多发和空间多发的特点。

MS的临床分型MS好发于青壮年,女性更多见,男女患病比率为1:1.5~1:2。

CNS各个部位均可受累,临床表现多样。

常见症状包括:视力下降、复视、肢体感觉障碍、肢体运动障碍、共济失调、膀胱或直肠功能障碍等。

一、复发缓解型MS(RRMS)疾病表现为明显的复发和缓解过程,每次发作后均基本恢复,不留或仅留下轻微后遗症。

80%~85%MS患者最初为本类型。

二、继发进展型MS(SPMS)约50%的RRMS患者在患病10~15年后疾病不再有复发缓解,呈缓慢进行性加重过程。

三、原发进展型MS(PPMS)病程大于1年,疾病呈缓慢进行性加重,无缓解复发过程。

约10%的MS患者表现为本类型。

四、进展复发型MS(PRMS)疾病最初呈缓慢进行性加重,病程中偶尔出现较明显的复发及部分缓解过程,约5%的MS患者表现为本类型。

五、其他类型根据MS的发病及预后情况,有以下2种少见临床类型作为补充,其与前面国际通用临床病程分型存在一定交叉:1.良性型MS(benign MS):少部分MS患者在发病15年内几乎不留任何神经系统残留症状及体征,日常生活和工作无明显影响。

目前对良性型无法做出早期预测。

2.恶性型MS(malignant MS):又名爆发型MS(fulminant MS)或Marburg变异型MS(Marburg variant MS),疾病呈爆发起病,短时间内迅速达到高峰,神经功能严重受损甚至死亡。

MS的诊断一、诊断原则首先,应以客观病史和临床体征为基本依据;其次,应充分结合辅助检查特别是MRI特点,寻找病变的时间多发及空间多发证据;再次,还需排除其他可能疾病。

外周神经系统的疾病发生机理

外周神经系统的疾病发生机理外周神经系统是人体中负责传递信息和控制身体肌肉的神经系统。

其主要由神经末梢、神经纤维、脊髓神经根和周围神经组成。

外周神经系统中的疾病,通常表现为运动或感觉方面的异常,例如肌肉无力、抽搐、疼痛或麻木。

这些异常常常由多种因素引起,包括遗传、环境因素和自身免疫反应等。

本文将对几种外周神经系统疾病的发生机理进行探讨,并讨论其治疗方法。

一、多发性神经病(MS)多发性神经病(MS)是一种自身免疫疾病,其主要特征为攻击外周神经系统中的髓鞘,导致神经冲动传递受到损害。

目前认为,MS可能是由多种因素引起的,包括遗传、环境和免疫系统等。

家族史和女性性别是患上MS的风险因素,而维生素D缺乏和吸烟等环境因素则被认为可以加重患者的病情。

MS的治疗目标是降低患者的症状,并尽可能减少发病的风险。

推荐的治疗包括抗炎药物、免疫抑制剂和激素替代疗法等。

然而,这些治疗方法的效果并不是每个患者都一样。

因此,定期进行随访和治疗方案调整是MS治疗的重要环节。

二、周围神经病(PN)周围神经病(PN)是外周神经系统中的神经损伤,通常由各种因素引起,包括毒素、感染、肿瘤和药物等。

PN的表现形式多种多样,包括肌肉无力、疼痛、麻木和感觉异常等。

PN的治疗首先应该针对其具体病因进行治疗。

例如,治疗由糖尿病引起的PN,需要控制患者的血糖水平,防止神经损伤的进一步发展。

另外,针对PN的症状进行治疗也是非常重要的。

例如,对于PN引起的疼痛,可以使用止痛药物、抗抑郁药物和局部应用药物等方法进行治疗。

三、帕金森综合征(PD)帕金森综合征(PD)是一种神经系统疾病,常导致外周神经系统中的运动异常。

PD通常由某些脑细胞的损伤导致,这些脑细胞含有一种神经递质-多巴胺。

多巴胺是一种调节我们的运动的物质。

缺乏多巴胺会导致肌肉僵硬、震颤和动作迟缓等症状。

PD的治疗主要侧重于缓解患者的症状。

目前可用的治疗手段包括多巴胺类药物、中枢神经系统兴奋剂和抗抑郁药物。

MS迈向治愈的努力—恢复功能与日常生活

MS迈向治愈的努力—恢复功能与日常生活【编者按】对多发性硬化(MS)患者的管理应该是全方位的,其中恢复患者的躯体和心理功能以及日常生活能力,往往需要非药物的康复治疗计划。

而对患者心理恢复能力的测试和干预,是其它促进康复措施获益的重要基础。

本文介绍了近期开展的一项旨在测试“复原力”的III期临床试验,这将为MS患者的全面管理提供非临床方面的探索经验。

近期一项“针对多发性硬化症患者的群体复原力训练计划:多中心集群随机对照试验(multi- READY for MS)的研究方案”的三期临床试验方案发表在 PLOS One 杂志上。

该试验将测试名为 READY 的团体复原力培训计划的能力,以提高多发性硬化症 (MS) 患者的生活质量和更好的心理社会结果。

该试验涉及200 多名MS 患者,将比较READY 训练与团体放松计划在恢复力和其他参数(如情绪和生活质量)方面的益处。

复原力 Resilience:从挑战中恢复或“反弹”的能力,在减轻心理压力所产生的不利影响方面发挥着重要作用。

预计[这项] 研究将通过将其与一线MS 康复和临床环境中的积极团体干预进行比较,为READY 的功效和有效性提供大量证据。

在应对疾病症状和进展、改变日常生活以及这些变化带来的不确定性时,许多MS 患者会出现焦虑、抑郁和生活质量下降。

反过来,这种心理困扰会影响 MS 症状和疾病复发。

READY 计划 - 每天的复原力和活动- 由澳大利亚团队开发,旨在提高复原力并恢复更积极的心理成果。

它旨在基于接受和承诺疗法(principles of acceptance and commitment therapy,ACT)的原则增强心理灵活性。

该计划靶向了五种有助于保护复原力的既定因素:认知灵活性、接受度、意义、社会联系和基于价值观的行动。

READY 最初是为工作场所开发的,后来被改编为多种其他用途,包括作为针对患有癌症、糖尿病和MS 等疾病的人的复原力培训计划。

中西医诊治老年代谢综合征研究近况

IDF(2004)

FBG≥5.6mmol/L,或已确诊IGR、DM正 在治疗者

SBP≥130和(或)DBP≥85 mm Hg,或已诊为 高血压

腰围 (华人):男性>90cm女性>80cm TG >1.7mmol/L,HDL-c <1.04mmol/L

(男)、< 1.3mmol/L (女) 腰围是必需因素, HDL-c和TG各为一项,

并具备任意2条或2条以上

国家/种族 性别 腰围

ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้

地区

男性腰围(cm) 女性腰围(cm)

欧洲

≥94CM

≥80CM

中国、马来西亚 ≥90CM

和亚洲的印第安 人

≥80CM

日本

≥85CM

≥90CM

在美国临床操作中仍会采用ATPⅢ的参考,腰围 男性≥102CM 女性 ≥88CM

同种族的中南部美国人 暂时参考南亚的推荐值

代谢综合征(MS) 老年MS的诊断标准、差异及临床意义 老年MS的治疗 前景与展望

代谢综合征(MS)

代谢综合征(MS)是一种以多种心血管和代 谢危险因素并存为特征的综合征,以胰岛 素抵抗(IR)为共同病理生理基础。

包括:中心型肥胖、收缩压和(或)舒张 压升高、糖脂代谢异常、促凝血状态、血 管异常、高胰岛素血症、高尿酸血症和炎 性标志物水平增高等。

情绪调整:避免情绪激动,保持放松、平和的 心态。

老年MS的治疗

二级干预

改善IR和降糖 调脂 减肥 降压 控制高凝状态 其他药物

老年MS的治疗

中医药治疗

老年MS中医概述

“脾瘅”、“痰浊”、“血瘀” MS患者属“膏人、肉人”范畴。 老年人病理特点:本虚标实 老年MS病因病机:本虚标实,虚实夹杂。 病因包括:先天禀赋,饮食不节,情志不遂,劳

《MS诊断治疗》课件

本课程将重点介绍多发性硬化的诊断和治疗,更深入地了解这种脑神经系统 疾病。

什么是多发性硬化?

概述

多发性硬化是一种常见的自身免疫疾病,导致 中枢神经系统功能障碍。

原因

科学家们相信多发性硬化是由环境和基因等多 种因素共同作用产生的。

症状

病人会经历多种不同的症状,包括视力问题, 肢体无力和感觉异常。

多发性硬化也可能会出现复发的情况。

有些药物可以减轻复发的次数。

3

复发治疗

如果复发发生了,治疗方法是使用激素 或静脉免疫球蛋白。

结语

求医问药

如果你或身边有人患有多发性硬化,请不要轻易放 弃。你可以在医生和亲朋好友的帮助下,渡过难关。

积极生活

虽然多发性硬化没有特效的治疗方法,但是采用健 康的饮食和生活方式可以缓解症状。

治疗

治疗的早期介入可以减轻病人的症状并缩短复 发时间。

神经系统症状

视力问题

双眼视力模糊或失明是多发性硬化最常见的症状之 一。

肌肉麻痹

多发性硬化会导致肢体无力或麻痹。

感觉异常

有时病人会感受到刺痛、针扎或麻痹的感觉。

其他症状

1

疲劳

疲劳是多发性硬化病人最常见的症状之一。它可能由于神经系统深层级别的原因 而产生。

2

抑郁

研究表明,抑郁症可以影响多发性硬化病人的认知和行为。

3

尿失禁

由于病人失去了对膀胱的控制,所以很多人在患上多发性硬化后会出现尿失禁的 症状。

诊断标准

1 神经学检查

医生会检查你的神经系统是否正常。这包括肌肉反应、视力、平衡和协调。

2 MRI检查

这种方法能够识别大多数多发性硬化的病人,它可以显示出不同颜色的病变。

MS诊断治疗解读

民到低发病区,其发病率仍高,在15岁以前 移居,其发病率低

发病机制

确切病因及发病机制不明

自身免疫介导的CNS脱髓鞘疾病

MS是自身免疫性疾病的证据

有特殊的人类白细胞抗原分型

硬化斑块区有淋巴细胞浸润 硬化斑块免疫荧光检查有IgG沉着

有些病人还可合并其它自身免疫性疾病

CSF中可测出MBP抗体

1.2次以上发作(复发) 2.1个临床病灶

不需附加证据,临床证据已足够 (可有附加证据但必须与MS相一致)

1.MRI显示病灶在空间上呈多发性 2.1个CSF 指标阳性及2个以上符合MS的MRI病灶 3.累及不同部位的再次临床发作 具备上述其中1项 1.MRI显示病灶在时间上呈多发性 2.第二次临床发作 具备上述其中1项

或1

1

或+ + +

临床可能

1. 2. 3.

1 + +

实验室可能

1. 2. 1

_______________________________________________________________

美国国立MS协会(NMSS)推荐的MS诊断标准(2001)

临床表现 所需的附加证据

1.2次以上发作(复发) 2.2个以上临床病灶

B

辅助检查

•MRI(cerebral/spinal)

•CSF(OB/IgG indexMBP)

•EP(VEP/BAEP/SSEP)

辅助检查

脑脊液检查

单个核细胞数:细胞数正常或轻度增高,不超过

50×106/L。40%患者蛋白轻度增高。

IgG 鞘内合成:① CSF-IgG 指数: >0.7 提示有 CNS 内的

MS诊断治疗

感觉障碍 视力障碍(单眼或双眼) 单肢或多肢无力 复视 共济失调 尿失禁 智能/情绪改变

受累结构

后索、脊丘束 视神经 锥体束 眼球运动神经 小脑及有关传导束、后索 脊髓 脑室周围、丘脑下部

MS主要症状

MS的典型及非典型症状

诊 断

MS诊断程序

建立MS诊断标准的意义

MS的基本诊断标准

推荐的治疗方法(美国MS临床指南推荐)

糖皮质激素 能促进急性发病的MS患者的神经功能恢复。急性发病的MS患者 可考虑用糖皮质激素治疗(A级推荐)。 短期使用糖皮质激素后对神经功能无长期效果(B级推荐)。 用药剂量或用药途径不会影响临床效果 (C级推荐)。 规律的激素冲击对复发缓解型MS患者的长期治疗有用(C级推荐) ( Goodin DS,Frohman EM,Garmany GP,et al.Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis.Neurology,2002,58:169-178 )

硫唑嘌呤

对于复发频繁的多发性硬化患者考虑使用。

可降低多发性硬化复发率,但不能影响残疾 的进展。 剂量为2~3 mg/kg/d,口服,可长期服用, 但应注意复查血象及肝肾功能。

环孢菌素A

3-8mg/kg /d ,连续用3-12 个月

复查肾功能及血药浓度

环磷酰胺

强烈的细胞毒和免疫抑制作用

-干扰素(Interferon-)

降低复发-缓解型MS的复发次数

降低复发后的严重程度 减少MRI上新病灶的形成

Copaxone

是合成的髓鞘碱性蛋白类似物

也称为Copolymer 1或glatiramer acetate 其免疫化学特性模拟髓鞘素碱性蛋白(MBP),

MS护理和治疗指导

MS患者日常注意事项及护理1、饮食均衡有益处:✓保持饮食均衡,让身体有所需的一切营养✓降低温度的方法:喝冷饮、吃冰淇淋等,但不要吃坏肚子;冷水淋浴、游泳✓控制体重:(1)减少摄取饮食之中的脂肪和糖份,减少热量的吸收(2)选择食用瘦肉、家禽和鱼类;切除可见脂肪和外皮(3)烹煮时少用油和脂肪,避免牛油、精炼奶油、猪油、乳脂和椰汁,采用不粘锅,以减少油量的使用(4)选择低脂烹饪,如蒸、烤、烘烤和微波烹调,避免油炸(5)避免食用加工肉类,如午餐肉、香肠(6)选择低脂乳品,如脱脂牛奶(7)减少食用糖类✓给难以吞咽者或咀嚼者的提示(1)食用松软和碎状食物,如粥和碎肉,容易吞咽(2)调节饮料,食物的浓稠性(3)小心薯片、饼干之类松脆的食物(4)少量多餐(5)早晨病人不疲劳时,增加进餐量2、坚持运动可增强体质✓运动给MS患者带来的益处:(1)保持肌肉弹性和平衡(2)加强反射动作和协调(3)提高体力和灵活性(4)减少意志消沉✓运动时的一些提示:(1)穿不会限制动作的衣着(2)确保室内温度偏冷而舒服(3)不要过份操劳。

若有疼痛,停止动作。

继续有关运动之前,询问专业医药人员(4)开始时慢慢来,所有动作必须轻轻进行,以便肌肉足以反应拉紧,动作太快,造成僵硬(5)感觉自己进行挑战性的动作。

增加动作幅度,让自己不再觉得一些动作会带来疼痛,记住,你固然可以感受动作的伸缩却不好让自己痛苦(6)如果(四肢)一边较弱,用较强的另一边来协助它,你的朋友或者孩子可以在边上进行帮助你。

(7)呼吸平均,放松脸部以配合每个动作。

进行特别动作时,不要一脸古怪的表情,也不要屏息。

3、化解工作生活的疲劳和压力✓化解疲劳初患MS时,患者主要的问题是面对突发的疲乏。

没有人清楚MS病容易疲乏的原因,可能感觉很难过,尤其是家人、朋友和同事误解患者的疲乏,认为是意志消沉或偷懒时。

化解疲乏并不容易,患者发觉药物和其他技巧可以控制。

倘若疲劳已经成为习惯,患者应该询问医生,医生将可以诊断疲乏的原因,并设法帮助患者。

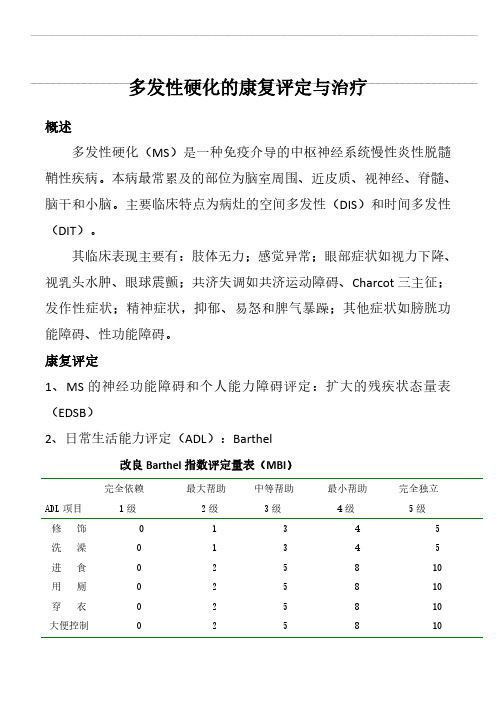

多发性硬化的康复评定与治疗

多发性硬化的康复评定与治疗概述多发性硬化(MS)是一种免疫介导的中枢神经系统慢性炎性脱髓鞘性疾病。

本病最常累及的部位为脑室周围、近皮质、视神经、脊髓、脑干和小脑。

主要临床特点为病灶的空间多发性(DIS)和时间多发性(DIT)。

其临床表现主要有:肢体无力;感觉异常;眼部症状如视力下降、视乳头水肿、眼球震颤;共济失调如共济运动障碍、Charcot三主征;发作性症状;精神症状,抑郁、易怒和脾气暴躁;其他症状如膀胱功能障碍、性功能障碍。

康复评定1、MS的神经功能障碍和个人能力障碍评定:扩大的残疾状态量表(EDSB)2、日常生活能力评定(ADL):Barthel改良Barthel指数评定量表(MBI)ADL项目完全依赖1级最大帮助2级中等帮助3级最小帮助4级完全独立5级修饰洗澡进食用厕穿衣大便控制1122223355554488885510101010小便控制上下楼梯床椅转移平地行走坐轮椅*22331558838812124101015155评定结果:正常100分;≥60分,生活基本自理41-59分,中度功能障碍,生活需要帮助21-40分,重度功能障碍,生活依赖明显≤20分,生活完全依赖2、认知功能评定:MMSE简易精神状态评价量表(MMSE)评分标准:每1项正确为1分,错误为0分。

总分范围为0~30分,正常与不正常的分界值与教育程度有关;文盲(未受教育)组≤17分,小学(受教育年限≤6年)组≤20分,中学或以上(受教育年限>6年)组≤24分。

分界值以下为有认知功能缺陷,以上为正常。

备注:评价项目6.重复:必须完全相同才算正确;评价项目7.阅读:有闭眼睛的动作才给分;评价项目10.绘图:图要有10个角和2条相交的直线。

评价项目1.定向力:现在我要问您一些问题,多数都很简单,请您认真回答。

1)现在是哪一年?2)现在是什么季节?3)现在是几月份?4)今天是几号?5)今天是星期几?6)这是什么城市(城市名)?7)这是什么区(城区名)?(如能回答出就诊医院在本地的哪个方位也可。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2011;69(3)537MS: immunomodulatory therapyMendes and SáMultiple sclerosis (MS), the most frequent primary demyelinating pathology of the central nervous system (CNS), is a chronic and progressive autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation, demyelination and axonal injury 1. The etiology of MS is ultimately unknown, al-though there is evidence that complex multifactorial fac-tors are implicated, in which environmental are hypothe-sized to interact with genetically susceptible individuals 2.The clinical hallmarks of MS may be summarized as follows 1: the disease typically begins in young adults and affects females more than males (1.77:1); most commonly, MS patients alternate relapses with remis-sion phases (relapsing-remitting MS or RRMS), some of them developing later on a secondary progressive course (SPMS), and in a fewer cases, the disease progresses ab initio without (progressive MS or PPMS) or with rare superimposed relapses (transitional or progressive re-lapsing MS-RPMS); the disease is heterogeneous as re-gards neurological manifestations, evolution and dis-ability; the diagnosis, based in international consensual criteria, depends strictly on clinical features and paraclin-ical exams, the most important of which is the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); these criteria turned feasible the identification of patients with a clinically isolated de-myelinating event or syndrome (CIS) that are at risk of conversion to a clinically definite disease (CDMS); finally, the progressive course and consequent neurological def-icits inflict a significant disabling condition to the patient and a major burden to relatives, caregivers and society.Although on the grounds of non-curative approaches, since the early nineties several pharmacological treat-ments with immunomodulatory properties were devel-oped to treat MS and modify its natural history, com-monly designated “disease modifying drugs” (DMD), which recognizably represented a major step in the con-trol of the disease.In this practical review we will focus on the classical immunomodulators specifically approved in MS - inter-feron beta (IFNβ) and glatiramer acetate (GA) - high-lighting their mechanisms of action (how they act) and their main clinical and imaging effects (how they work), based on the results of pivotal and comparative clinical trials. Despite the fast enlargement of the therapeutic ar-mamentarium for MS in the last years, with the approval of drugs with better efficacy yet potential limiting ad-verse effects, as mitoxantrone and natalizumab (usually indicated in more severe non-IFNβ-responder cases), and the development of oral drugs, exemplified by the recently FDA approved fingolimod, IFNβ and GA remain up to now the worldwide therapeutic mainstay of MS. INTERFERON BETAInterferons (IFNs) are proteins secreted by cells andare involved in self defense to viral infections, in the reg-ulation of cell growth and in the modulation of immune responses. Human IFNβ is a glycoprotein primarily pro-duced by fibroblasts with 166 amino acids and 22.5 kDa, which is encoded on chromosome 9 without introns 3. IFNβ was the first therapy to have proved beneficial ef-fects on the natural course of MS and has two molecules: IFNβ-1a and -1b.IFNβ-1a is obtained by eukaryote cell lines derived from a Chinese hamster ovary and, similarly to native human beta interferon, is glycosilated and has the com-plete 166 amino acid sequence; yet, the glycosylation pat-tern is not necessarily equal to the human 3. IFNβ-1b is a product of a bacterial (E. coli ) cell line and is not gly-cosilated because bacteria do not glycosylate proteins; additionally the cystein residue has been substituted by a serine at position 17, which prevents incorrect di-sulphide bond formation and minimizes the risk of im-paired folding of the molecules and the consequent re-duced activity; also, the methionine at position 1 has been deleted, so the final protein has one less amino acid than the natural IFNβ3. Glycosylation decreases aggregates formation and immunogenicity, which may give a lower potency of IFNβ-1a 4, but, on the other side, IFNβ-1b has a tight binding to human serum albumin, which may contribute to about 10% of IFNβ-1a potency 3. How it actsIFNβ binds to a high-affinity type-1 IFN transmem-brane receptors and induces a cascade of signaling path-ways. After binding to the receptor, phosphorylation and activation of two cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases occur. This leads to activation of latent transcription factors in cell cytoplasm that translocate to the nucleus 5. IFNβ has a role in the immune system by producing effects on T and B cells, and, additionally has influence in blood brain barrier (BBB) permeability 6.EFFECTS ON T CELLST cell activation – IFNβ is believed to reduce T cells activation, including myelin reactive T cells, because in-terferes with antigen processing and presentation by downregulating expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, and reduces the levels of co-stimulatory molecules 7 and other accessory molecules like intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and very late activation antigen-4 (VLA-4)8.T cell differentiation and proliferation – IFNβ inhibits the expansion of T cell clones, acting as an anti-proliferative agent. The exact mechanism for this anti-proliferative effect is unclear. Recently, it was dem-onstrated that type I IFNs, in which IFNβ is included,Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2011;69(3)538MS: immunomodulatory therapy Mendes and Sácould activate the Mnk/eIF4E kinase pathway that plays important roles in mRNA translation for IFN-stimu-lated genes and generation of IFN-inducible anti-prolif-erative responses 9. Previous studies have indicated that Th17 cells have a critical role in the development of the autoimmune response in MS 10. IFNβ-1a could induce an up-regulation of the TLR (toll-like receptors)-7 signaling pathway and inhibit multiple cytokines involved in Th17 cell differentiation. The authors propose that the exog-enously administered high-dose IFNβ-1a augments this naturally occurring regulatory mechanism and provides a therapeutic effect in patients with RRMS 11. Further-more, IFNβ inhibits the expression of FLIP , an anti-apop-totic protein, leading to an increased incidence of T cells death 12 and restores T-regulatory cell activity 6. EFFECTS ON CYTOKINES AND CHEMOKINESIt has been postulated that the modulation of the im-mune response by IFNβ may involve an immune devia-tion, consisting in a reduction of the expression of Th1 induced cytokines while enhancing Th2 responses 6. Ad-ditionally IFNβ has effects on chemokines: it could me-diate activity of the chemokine receptor CCR7 which is important to direct the entry of T lymphocytes to the peripheral lymph nodes rather than to the CNS 6. An-other chemokine, Regulated on Activation, Normal T Expressed and Secreted (RANTES), appears to play a role in the pathogenesis of RRMS and was observed a de-crease of its sera and peripheral blood adherent mono-nuclear cell levels triggered by IFNβ-1b 13. A recent study suggested that peripheral upregulation of the chemo-kines by IFNβ may reduce the chemoattraction of im-mune cells to the CNS 14.ANTIGEN PRESENTATIONFurthermore, IFNβ is postulated to inhibit antigen presentation to T cells in conjunction with MHC and co-stimulatory molecules as CD80 and CD86, which is a crucial event in the ensuing immune response 8. Another mechanism by which IFNβ can affect antigen presenta-tion is by counteracting the effect of IFNγ, because the latter cytokine is a potent promoter of MHC class II ex-pression on many cell types 8.EFFECTS ON B CELLSIFNβ upregulates a B-cell survival factor (BAAF) and for those patients in whom B cells play a major impor-tant role, this would be a quite undesirable consequence of IFNβ therapy. This might partially explain inter-indi-vidual differences in the therapeutic response. Other-wise, the systemic induction of BAFF by IFNβ therapy might facilitate the occurrence of various autoantibodies and IFN neutralizing antibodies (NAbs). The authorsconclude that individual MS patients with evidence for a significant role of B cells do not appear to be ideal can-didates for IFNβ therapy 15. However, B cells may trigger neurotrophic cytokines that exert positive effects on MS autoimmunity, which could outweigh the negative effects of IFNβ-induced BAAF responses 6.EFFECTS ON BBBIFNβ is able to inhibit the ability of T cells to get into the brain by interfering with the expression of sev-eral molecules. It was demonstrated that matrix metal-loproteinase type 9 (MMP-9) activity can be decreased by IFNβ-1b treatment in vitro 16, which could difficult the migration of lymphocytes across the fibronectin of ce-rebral endothelium. Another study did not find any dif-ference in the MMP-9 levels during the treatment with IFNβ17. Besides the role of the metalloproteinases, IFNβ can modulate the expression and traffic of other mol-ecules like cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules and integrins 16-18, improving endothelial barrier function and prevent the transmigration of leukocytes and other neurotoxic mediators across the BBB to sites of CNS inflammation 10. One example is the possible induction of an increase in CD73 expression. Additionally, Uhm and colleagues found that the decrease in cell migration seems to wane with time as patients who have been re-ceiving IFNβ-1b treatment for more than 3.5 years had high levels of T-cell migration that were indistinguishable from those of MS patients who have never been treated with IFNβ19. IFNβ may interfere with T-cell/endothelial cell adhesion by inhibiting MHC class II expression on endothelial cells, which can also function as ligands for T cells 20 and by decreasing the expression of VLA-48. IFNβ also increases serum concentrations of soluble VCAM1 (sVCAM1), which might block leukocyte adhesion to ac-tivated cerebral endothelium by binding competitively with the VLA-4 receptor 18. sVCAM1 had been correlated with a reduction in the number of MRI gadolinium-en-hancing lesions soon after the initiation of treatment 21. ANTIVIRAL EFFECTS Both formulations of IFNβ have antiviral properties, although IFNβ-1a seems to be more potent in this field 6. A group of investigators studied the relation of MS-as-sociated retrovirus (MSRV) in MS patients treated with IFNβ. They found that the viral load in the blood was directly related to MS duration and fell below detec-tion limits within 3 months of IFN therapy, suggesting that evaluation of plasmatic MSRV could be considered a prognostic marker for the individual patient to mon-itor disease progression and therapy outcome 22. Another group aimed to analyze IFNβ antiviral efficiency through the measurement of human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6)Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2011;69(3)539MS: immunomodulatory therapyMendes and Sáprevalence in MS patients and they noted a decreased number of reactivations of the virus associated with less relapses (42.8% of patients with viral reactivations ex-perienced at least one relapse versus 22.5% of patients without viral reactivations)23.NEUROPROTECTIVE EFFECTSSome studies issued potential neuroprotective effects of IFNβ, inducing release of nerve growth factor from astrocytes or stimulate the protection of neurons them-selves 6.Other investigators tried to measure the axonal in-jury in vivo using MRI spectroscopy to quantify the neu-ronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (NAA) and its relation with creatine (Cr) and found an increase in NAA/Cr in IFNβ-1b treated MS patients. Their data suggest that the axonal injury could be partially reversible with IFNβ-1b therapy 24. How it worksCLINICAL AND MRI OUTCOMES The first multicenter, randomized and placebo-con-trolled study in RRMS patients with IFNβ was pub-lished in 199325. This pivotal study demonstrated that IFNβ-1b 250 µg subcutaneous (SC) produced a 34% re-duction in the clinical relapse rate and in the confirmed 1-point EDSS progression rate after 2 years, better than a lower dose (50 µg), yet the latter was not statistically significant compared with the placebo group 25. Further-more, the number and frequency of T2 active lesions on brain MRI were decreased 26. Three years later, the results of a phase III trial with a similar design using IFNβ-1a 30 µg/week intramuscular (IM) showed a 37% reduction in the confirmed 1-point EDSS progres-sion rate. The median number of MRI-gadolinium en-hancing lesions in MS was 33% inferior comparatively to the placebo arm. This pivotal trial also showed that IFNβ-1a slowed the accumulation of disability 27. Since then, several trials confirmed these beneficial effects in RR form of MS 28,29 and in secondary progressive with relapses 30. The patients with CIS who are consid-ered with a high risk of CDMS have a proven benefit from early treatment with IFNβ to decrease clinical and MRI disease activity, as shown by specific studies con-ducted in CIS, either with IFNβ-1a 31 or with IFNβ-1b 32. As regards the route of administration, it does not seem to influence the biological effects of the IFNβ for-mulations 33. Similarly, a dose-dependent effect remains a controversial issue. Although the pivotal trials suggested a dose-response curve, i.e., clinical and MRI outcomes seem to be better with higher doses, the evidence pro-vided by them was considered somewhat equivocal 34. However, other studies pointed out a trend to the sameresult, in which higher dose and more frequently admin-istered IFNβ was favored 35,36, findings that were not cor-roborated by others 37.NEUTRALIZING ANTIBODIES (NABS)During treatment with IFNβ, a proportion of MS pa-tients develop NAbs. The potential impact of NAbs on the efficacy of IFN-β treatment in MS is an area of de-bate and controversy, although their presence has been associated with a significant hampering of the treatment effect on the relapse rate and both active lesions and burden of disease in MRI. In Europe it is recommended that the patients treated with IFNβ are tested for the presence of NAbs at 12 and 24 months of therapy. In pa-tients with NAbs, the measurement should be repeated at intervals of 3-6 months and if the titers continue el-evated, IFNβ might be discontinued 38. The American Academy of Neurology did not find enough evidence to make specific recommendations about when to test, which test to use, how many tests are necessary, and which cutoff titer to apply 39.Side effectsTherapy with IFNβ is usually well tolerated. The most frequent side effects are flu-like symptoms and injection-site reaction, which tend to reduce over time. Depres-sion, allergic reaction, haematologic and liver function abnormalities might also be observed 40. IFNβ is a safe treatment, but usually is not recommended during preg-nancy because of the higher risk of fetal loss and low birth weight 41.IFN formulations and indicationsThe actual commercially available formulations of IFNβ include IFNβ-1a and IFNβ-1b. IFNβ-1a is dosed in 30 µg (Avonex®), 22 or 44 µg (Rebif®). The first is ap-plied once a week by IM and the second three times a week with a SC injection. IFNβ-1b formulations have 250 µg (Betaferon® or Betaseron®, and Extavia®) and are ad-ministered by SC injection every other day. All formula-tions are indicated in RRMS, IFNβ-1a IM and IFNβ-1b are also approved in patients with CIS at risk of conver-sion to CDMS and IFNβ-1b is furthermore approved in Europe to treat patients with SPMS still with relapses.GLATIRAMER ACETATEGlatiramer acetate is a synthetic polypeptide com-posed of four amino acids (L-glutamic acid, L- lysine, L-alanine and L- tyrosine) with an average molecular mass of 4700-11.000 Da. It was discovered in the 1960’s, when studies to develop a polymer resembling myelin basic protein (MBP), a major component of myelin sheath, to the model of autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), wereArq Neuropsiquiatr 2011;69(3)540MS: immunomodulatory therapy Mendes and Sáperformed 42. One of them, called copolymer 1, demon-strated to decrease or prevent EAE, and was later re-named as GA 43.How it actsSeveral mechanisms of action have been proposed, yet the precise biological effects of GA are not fully un-derstood. We present the main effects on T and B lym-phocytes and on antigen presenting cells (APCs). EFFECTS ON T CELLSInhibition of myelin reactive T cells and immune deviation – GA binds directly to MHC class II, but also seems to be able to interact with MHC class I 44. GA in-terferes with the activation of myelin-specific T cells based on the observation that it acts as an antagonist to MBP/MHC at MBP-specific T cell receptor (TCR), op-erating as an altered peptide ligand to the 82-100 epitope of MBP in vitro 42, displacing MBP from the binding site on MHC II molecules. Some authors argued that this “TCR antagonism” is controversial and, whether it oc-curs, is not probably relevant in vivo because GA is un-likely to reach sites where it could compete with MBP. However, GA-reactive Th2 cells are able to cross the BBB and might be activated not only by MBP, but also by other cross-reactive antigens 44. Myelin reactive T cells exposed to increasing doses of GA manifest dose-de-pendent inhibition of proliferation and IFNγ production. That proliferative response of T cells to GA decreases with time. In addition, the observed decrease in GA-re-active T cells could be caused by the induction of T cell anergy and clonal elimination 45. This mechanism of T cell anergy can occur in the periphery at the injections sites or in their draining lymph nodes where the MBP specific cells might be confronted with GA. The used regimen of daily SC administration may favor the induction of an-ergy rather than a full immunization that requires longer intervals between doses 46. However, some clonal popula-tions of T cells could be expanded, since GA induced the conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25– to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells through the activation of transcrip-tion factor Foxp3 and lead to proliferation of these cells. However, this fact must be interpreted with caution be-cause almost all activated human T cells express Foxp342. Therapy with GA may improve the immune regulatory function of CD8+ T cells 42. These data suggest that the immunomodulatory effect of GA is attributed to the in-duction of a cytokine secretion pattern deviation from Th1 to Th2 cytokines, as happens with IFNβ43, which is the mechanism with the strongest experimental support. BYSTANDER SUPPRESSIONAnother potential mechanism of action is the socalled bystander suppression: a phenomenon of T cells specific to one antigen which suppress the immunolog-ical response induced by another antigen 46. This implies that GA-reactive Th2 cells are capable of entering the CNS and recognizing cross-reactive antigen(s), probably myelin antigen(s)44. It is characterized by the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines by GA-activated T cells after they cross the BBB and accumulate in the CNS 43. EFFECTS ON CELL-PRESENTING ANTIGENSAlthough the vast majority of evidence suggests that GA acts primarily at the level of T cells, additional ef-fects on other immune cells cannot be excluded. For ex-ample, GA was reported to inhibit a human monocytic cell line, THP-1. In THP-1 cells stimulated with lipopoly-saccharide or IFN-γ, GA reduced the percentage of cells expressing MHC-DR and DQ antigen and inhibited the production of TNF-α and cathepsin-B. In contrast, the production of interleukin(IL)-1β was increased 47. This could also indicate antigen-unspecific modes of action. A further study also demonstrated that GA affects mono-cytes/macrophages by inducing the production of an anti-inflammatory cytokine, the IL-1 receptor antago-nist (IL-1Ra), but diminishing the production of IL-1β in monocytes, activated by direct contact with stimulated T cells in MS patients and in the EAE model 48. IL-1Ra can be transported through the BBB and exert its immuno-modulatory effects in both systemic and CNS compart-ments. In addition to the modulation of the adaptive im-mune system, GA seems to affect significantly the innate immune system 48.GA may also affect the immune response through modifying APCs into anti-inflammatory type II cells. The process begins with the presentation of GA to CD8+ and CD4+ T cells by APCs. The final step is an alteration of cytokine environment that subsequently affect T-cell dif-ferentiation as far as concerned to further cytokine se-cretion. The T cell CD8+ response becomes oligoclonal with expansion and maintenance of CD8+ clone popu-lation over long periods of time, in contrast to what hap-pens to T cells CD4+ which may increase in number 42. NEUROPROTECTIVE EFFECTSFuthermore, GA specific T cells secrete neurotrophic factors as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuro-trophic growth factor, which might favor remyelination and axonal protection 42,43,49. A study with MRI spectros-copy showed a significant increase in NAA/Cr in a group of treatment naïve patients with RRMS, who received GA compared with untreated patients, suggesting the potential role of GA in axonal metabolic recovery and protection from sublethal injury 50. Another potential ef-fect of GA is the delivery of neuroprotective cytokinesArq Neuropsiquiatr 2011;69(3)541MS: immunomodulatory therapyMendes and Sáto the site of inflammation in patients with MS. So, the role of GA seems to be the creation of an anti-inflamm-matory and neuroprotective environment instead of sup-pression the immune activity 42. How it worksCLINICAL AND MRI OUTCOMESThe first studies on MS focusing treatment with co-polymer 1 were carried out in late 1970s and early 1980s. Ten years later, a phase III multicentre, double blind and placebo-controlled trial, performed in patients with RRMS, showed that 20 mg GA SC daily was effective in reducing the annualized relapse rate (ARR) by 29% over a 2-year period compared with the placebo 51. It also re-duced the disability progression in 12%, although this change was not statistically significant 51. After 10 years of open label extension of this pivotal trial, patients orig-inally randomized to GA were shown to maintain better outcomes than patients who were originally on placebo 52, although the high dropout rate raised some concerns about the power of the study.As the initial phase III trial did not include MRI end-points, a European/Canadian study was undertaken to address this specific issue in MS patients treated with GA versus placebo during 9 months 53. It was demonstrated a reduction in the frequency and volume of new enhancing lesions, such as a 35% and 8.3% decrease in the number of enhancing lesions and in the median change in T2 burden of disease, respectively, for the treatment arm, an effect that was delayed until 6 months after initia-tion of treatment 53. Later on, in various studies, ARR re-ductions with use of GA in RRMS patients were found to be much higher than those seen in its pivotal trial 51. Recently, the effect of GA on delaying conversion of pa-tients presenting with CIS to CDMS was evaluated in the PreCISe study, which showed that GA has a benefi-cial effect for the treatment of patients with this condi-tion 54. On the contrary, a large controlled trial with GA in PPMS failed to provide any evidence for benefit in this population 55.Side effectsThe results of the studies indicate that GA is gener-ally safe. The most common adverse reaction is a local reaction in the site of injection with erythema and indu-ration. GA is less frequently associated with a transient post-injection systemic reaction of flushing, chest tight-ness, dyspnea, chest palpitations, and anxiety. This self-limited systemic reaction may be experienced in 15% of the patients and typically resolve within 15-30 minutes without sequelae. No significant laboratory abnormal-ities have been found. According to the manufacturer, rare cases of non-fatal anaphylaxis have also been re-ported 49. Opportunistic infections, malignancies, and the development of autoimmune diseases are not risks asso-ciated with GA 52. Although its use is not recommended in pregnancy, there is no evidence to suggest increased risk of adverse fetal or pregnancy outcome 49,56.GA formulation and indicationsGlatiramer acetate (Copaxone®) is approved in a SC formulation of 20 mg to be administered once a day, to treat patients with RRMS and with CIS at risk of con-version to CDMS.Comparative studiesRecently, the results from three head-to-head trials (IFNβ and GA) were published and they did not find significant differences between the two molecules in the primary endpoints evaluating reduction in relapse rates 40,57,58. The REGARD study, a randomized, compar-ative, parallel-group, open-label trial, compared 44 µg of IFNβ-1a SC 3 times a week with 20 mg of GA SC once a day for 96 weeks. There was no significant difference between groups in the time to first relapse and ARR. Re-garding MRI outcomes, no significant differences were found in the number and change in volume of T2 ac-tive lesions. Patients treated with IFNβ-1a SC had sig-nificantly fewer gadolinium enhancing lesions and pa-tients treated with GA experienced significantly less brain atrophy 57. BEYOND study compared 3 groups for treatment-naïve early stages RRMS patients: 250 µg of IFNβ-1b, 500 µg IFNβ-1b, both SC dosed every other day and GA 20 mg SC daily over 2 years. No significant differences were found in time to first relapse, overall re-lapse rates and proportion of patients who remained re-lapse free during the study period. No differences were found in T1-hypointense lesion volume change among the groups when compared the baseline with the last MRI available or annual time points. Change in total MRI burden and T2 lesion volume was significantly lower in the patients in both IFNβ-1b compared with the patients who received GA. However, the differences in T2 lesion volume were noted during the first year but not in years 2 and 3. The overall median change in brain volume was similar in each group. MRI parameters did not differ between patients in either IFNβ-1b doses 40. The BECOME study was conducted to determine the ef-ficacy of treatment with IFNβ-1b 250 µg SC every other day versus GA 20 mg SC daily in RRMS or CIS patients, evaluating MRI outcomes (total number of contrast-en-hancing lesions plus new non-enhancing lesions on long repetition time scans). The results were similar, as there were no significant differences in the effects of the med-ications on relapse rates 58.Therefore, IFNβ and GA are both good options toArq Neuropsiquiatr 2011;69(3)542MS: immunomodulatory therapy Mendes and Sámodify the natural course of MS. The choice between them is usually a challenging issue in MS Clinics, which in our view must be centered on the patient informed deci-sion, after a thorough education about the disease and the real therapeutic expectations. However, the administra-tion routes are rather bothersome to the patients, which could contribute to a reduced therapeutic adherence 59. Pivotal studies of IFNβ and GA in MS demonstrated that they are efficacious, lowering the ARR in approxi-mately 30%, the lesion burden and their activity, as well as the brain atrophy as measured by MRI.Even though the mechanisms of action of these clas-sical immunomodulatory drugs are not completely un-derstood, there is sound evidence that they act on impor-tant steps of the inflammatory processes underpinning MS. The appearance of drugs with more specific targets, as monoclonals and orals, increasing therapeutic efficacy, albeit raising new safety and tolerability problems, as well as a better understanding of the immunogenetic profiles of MS patients, are altogether expected to permit a more advanced therapeutic choice in the future. Actually, IFNβ and GA are the better known DMD in MS, with proofs of their safety and tolerability, so the large clinical expe-rience in treating MS patients with them along almost two decades, deserves to be emphasized.REFERENCES1.Lublin FD, Miller AE. Multiple sclerosis and other inflammatory demyelin-ating diseases of the central nervous system. In Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (Eds). Neurology in clinical practice, 5th edition, Philadelphia: Butterworth Heinemann 2008:1588-1613.2.Ramagopalan SV, Dobson R, Meier UC, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis: risk factors, prodromes, and potential causal pathways. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9:727-739.3. Goodin DS. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with human beta interferon. Int MS J 2005;12:96-108.4. Markowitz CE. Interferon-beta: mechanism of action and dosing issues. Neurology 2007;68(Suppl):S8-S11.5. Rudick RA, Ransohoff RM. Biologic effects of interferons: relevance to multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 1995;1(Suppl 1):S12-S16.6. Dhib-Jalbut S, Marks S. Interferon beta mechanisms of action in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2010;74(Suppl 1):S17-S24.7.Jiang H, Milo R, Swoveland P, Johnson KP, Panitch H, Dhib-Jalbut S. In-terferon beta-1b reduces interferon gamma-induced antigen presenting capacity of human glial and B cells. J Neuroimmunol 1995;61:17-22.8. Yong VW, Chabot S, Stuve O, Williams G. Interferon beta in the treatment of multiple sclerosis-mechanisms of action. Neurology 1998;51:682-689.9.Joshi S, Kaur S, Redig AJ, et al. Type I interferon (IFN)-dependent activa-tion of Mnk1 and its role in the generation of growth inhibitory responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:12097-12102.10. Aranami T, Yamamura T. Th17 Cells and autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE/MS). Allergol Int 2008;57:115-120.11.Zhang X, Jin J, Tang Y, Speer D, Sujkowska D, Markovic-Plese S. IFN-beta1a inhibits the secretion of Th17-polarizing cytokines in human dendritic cells via TLR7 up-regulation. J Immunol 2009;182:3928-3936.12.Sharief MK, Semra YK, Seidi OA, Zoukos Y. Interferon-beta therapy down-regulates the anti-apoptosis protein FLIP in T cells from patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2001;120:199-207.13.Iarlori C, Reale M, Lugaresi A, et al. RANTES production and expression is reduced in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon-beta-1b. J Neuroimmunol 2000;107:100-107.14.Cepok S, Schreiber H, Hoffmann S, et al. Enhancement of chemokineexpression by interferon beta therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1216-1223.15.Krumbholz M, Faber H, Steinmeyer F, et al. Interferon-beta increases BAFF levels in multiple sclerosis: implications for B cell autoimmunity. Brain 2008;131:1455-1463.16.Ozenci V, Kouwenhoven M, Teleshova N, Pashenkov M, Fredrikson S, Link H. Multiple sclerosis: pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and metalloproteinases are affected differentially by treatment with IFN β. J Neuroimmunol 2000;108: 236-243.17.Karabudak R, Kurne G, Guc D, Sengelen M, Canpinar H, Kansu E. Effects of IFN β-1a on serum matrix MMP-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metallopro-teinase in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: one year follow-up results. J Neurol 2004;251:279-283.18.Graber J, Zhan M, Ford D, et al. IFN β-1a induces increases in vascular cell adhesion molecule: implications for its modes of action in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2005;161:169-176.19.Uhm JH, Dooley NP, Stuve O, et al. Migratory behavior of lymphocytes isolated from multiple sclerosis patients: effects of interferon b-1b therapy. Ann Neurol 1999;46:319-324.20.Huynh HK, Oger J, Dorovini-Zis K. Interferon beta downregulates inter-feron gamma-induced class II MHC molecule expression and morpholog-ical changes in primary cultures of human brain microvessel endothelial cells. J Neuroimmunol 1995;60:63-73.21.Calabresi PA, Tranquill LR, Dambrosia JM, et al. Increases in soluble VCAM-1 correlate with a decrease in MRI lesions in multiple sclerosis treated with interferon beta-1b. Ann Neurol 1997;41:669-674.22. Mameli G, Serra C, Astone V, et al. Inhibition of multiple-sclerosis-associated retrovirus as biomarker of interferon therapy. J Neurovirol 2008;14:73-77.23.Garcia-Montojo M, De Las Heras V, Bartolome M, Arroyo R, Alvarez-Lafuente R. Interferon beta treatment: bioavailability and antiviral activity in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurovirol 2007;13:504-512.24.Narayanan S, De Stefano N, Francis GS, et al. Axonal metabolic recovery in multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon beta-1b. J Neurol 2001; 248:979-986.25.IFN-β Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon beta-1b is effective in re-lapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. I. Clinical results of a multicenter, ran-domized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Neurology 1993;43:655-661.26.Paty DW, Li DKB, UBC MS/MRI Study Group, IFN-beta Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. II. MRI analysis results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Neurology 1993;43:662-667.27.Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group: intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 1996;39:285-294.28.PRISMS Study Group and the University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group. PRISMS-4: long-term efficacy of interferon-beta-1a in relapsing MS. Neurology 2001;56:1628-1636.29.Freedman MS, Francis GS, Sanders EA, et al. Once weekly interferon beta-1alpha for Multiple Sclerosis Study Group; University of British Columbia MS/MRI Research Group. Randomized study of once-weekly interferon beta-1la therapy in relapsing multiple sclerosis: three-year data from the OWIMS study. Mult Scler 2005;11:41-4530.European Study Group on interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS. Placebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial of interferon beta-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet 1998; 352:1491-1497.31.Jacobs LD, Beck RW, Simon JH, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. CHAMPS Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;343:898-904.32.Kappos L, Freedman MS, Polman CH, et al. Effect of early versus delayed interferon beta-1b treatment on disability after a first clinical event sugges-tive of multiple sclerosis: a 3-year follow-up analysis of the BENEFIT study. Lancet 2007;370:389-397.33.Stürzebecher S, Maibauer R, Heuner A, Beckmann K, Aufdembrinke B. Pharmacodynamic comparison of single doses of IFN-beta1a and IFN-beta1b in healthy volunteers. J Interferon Cytokine Res 1999;19:1257-1264.34.Goodin DS, Frohman EM, Garmany GP Jr, et al. Disease modifying ther-apies in multiple sclerosis: report of the Therapeutics and Technological Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Neurology 2002;58:169-178.35.Durelli L, Verdun E, Barbero P, et al. Independent Comparison of Inter-feron (INCOMIN) Trial Study Group. Every-other-day interferon beta-1b。