MOT Discussion Result-Stakeholder Exercise Workshop_PA Minerals_Apr24.2011

具体实施方案 英文

具体实施方案英文Specific Implementation PlanThe specific implementation plan is a crucial step in turning ideas and strategies into action. It provides a detailed roadmap for executing a project or initiative, ensuring that all necessary steps are taken in the right order and with the right resources. In this document, we will outline the key components of a successful specific implementation plan and provide guidance on how to create one.1. Clearly Define the ObjectivesThe first step in creating a specific implementation plan is to clearly define the objectives of the project or initiative. What are the desired outcomes? What problem are we trying to solve? By clearly articulating the objectives, we can ensure that all subsequent actions are aligned with the overall goals.2. Identify Key StakeholdersNext, it is important to identify the key stakeholders who will beinvolved in the implementation process. This may include internal team members, external partners, and other relevant parties. Understanding the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder is essential for effective coordination and communication.3. Develop a Detailed TimelineA detailed timeline is essential for ensuring that the implementation process stays on track. This should include specific milestones, deadlines, and dependencies between different tasks. By breaking down the project into smaller, manageable steps, we can ensure that progress is being made and identify any potential bottlenecks.4. Allocate ResourcesIn order to successfully implement a project, it is important to allocate the necessary resources, including budget, personnel, and materials. This may involve securing funding, hiring additional staff, or procuring equipment. By ensuring that the right resources are in place, we can avoid delays and setbacks during the implementation process.5. Establish Clear Communication ChannelsEffective communication is critical for successful implementation. It is important to establish clear communication channels and protocols for sharing information, reporting progress, and addressing any issues that may arise. This may involve regular meetings, status updates, and other forms of communication.6. Monitor and Evaluate ProgressThroughout the implementation process, it is important to monitor and evaluate progress against the established objectives and timeline. This may involve tracking key performance indicators, conducting regular reviews, and making adjustments as needed. By staying vigilant, we can identify any potential problems early and take corrective action.7. Adapt and IterateFinally, it is important to recognize that implementation plans are not set in stone. As circumstances change and new information becomes available, it may be necessary to adapt and iterate the plan. Thisflexibility is essential for ensuring that the project stays aligned with the overall objectives and remains responsive to changing conditions.In conclusion, a specific implementation plan is a critical tool for turning ideas into action. By clearly defining objectives, identifying key stakeholders, developing a detailed timeline, allocating resources, establishing clear communication channels, monitoring progress,and remaining adaptable, we can ensure that our projects and initiatives are implemented successfully. With careful planning and execution, we can turn our vision into reality.。

Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice

JPART18:543–571 Collaborative Governance in Theoryand PracticeChris AnsellAlison GashUniversity of California,BerkeleyABSTRACTOver the past few decades,a new form of governance has emerged to replace adversarial and managerial modes of policy making and implementation.Collaborative governance,as it has come to be known,brings public and private stakeholders together in collective forums with public agencies to engage in consensus-oriented decision making.In this article, we conduct a meta-analytical study of the existing literature on collaborative governance with the goal of elaborating a contingency model of collaborative governance.After review-ing137cases of collaborative governance across a range of policy sectors,we identify critical variables that will influence whether or not this mode of governance will produce successful collaboration.These variables include the prior history of conflict or cooperation, the incentives for stakeholders to participate,power and resources imbalances,leadership, and institutional design.We also identify a series of factors that are crucial within the collaborative process itself.These factors include face-to-face dialogue,trust building,and the development of commitment and shared understanding.We found that a virtuous cycle of collaboration tends to develop when collaborative forums focus on‘‘small wins’’that deepen trust,commitment,and shared understanding.The article concludes with a discus-sion of the implications of our contingency model for practitioners and for future research on collaborative governance.Over the last two decades,a new strategy of governing called‘‘collaborative governance’’has developed.This mode of governance brings multiple stakeholders together in common forums with public agencies to engage in consensus-oriented decision making.In this article,we conduct a meta-analytical study of the existing literature on collaborative governance with the goal of elaborating a general model of collaborative governance. The ultimate goal is to develop a contingency approach to collaboration that can highlight conditions under which collaborative governance will be more or less effective as an Early versions of this article were presented at the Conference on Democratic Network Governance,Copenhagen,the Interdisciplinary Committee on Organizations at the University of California,Irvine,and the Berkeley graduate seminar Perspectives on Governance.We thank the participants of these events for their useful suggestions and Martha Feldman,in particular,for her encouragement.We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and useful comments.Address correspondence to the author at cansell@ or aligash@.doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032Advance Access publication on November13,2007ªThe Author2007.Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Journal of Public Administration Researchand Theory,Inc.All rights reserved.For permissions,please e-mail:journals.permissions@approach to policy making and public management.1In conducting this meta-analytic study,we adopted a strategy we call ‘‘successive approximation’’:we used a sample of the literature to develop a common language for analyzing collaborative governance and then successively ‘‘tested’’this language against additional cases,refining and elaborating our model of collaborative governance as we evaluated additional cases.Although collaborative governance may now have a fashionable management cache´,the untidy character of the literature on collaboration reflects the way it has bubbled up from many local experiments,often in reaction to previous governance failures.Collabo-rative governance has emerged as a response to the failures of downstream implementation and to the high cost and politicization of regulation.It has developed as an alternative to the adversarialism of interest group pluralism and to the accountability failures of manageri-alism (especially as the authority of experts is challenged).More positively,one might argue that trends toward collaboration also arise from the growth of knowledge and in-stitutional capacity.As knowledge becomes increasingly specialized and distributed and as institutional infrastructures become more complex and interdependent,the demand for collaboration increases.The common metric for all these factors may be,as Gray (1989)has pointed out,the increasing ‘‘turbulence’’faced by policy makers and managers.Although Susskind and Cruikshank (1987),Gray (1989),and Fung and Wright (2001,2003)have suggested more general theoretical accounts of collaborative governance,much of the literature is focused on the species rather than the genus .The bulk of the collaborative governance literature is composed of single-case case studies focused on sector-specific governance issues like site-based management of schools,community po-licing,watershed councils,regulatory negotiation,collaborative planning,community health partnerships,and natural resource comanagement (the species).2Moreover,a num-ber of the most influential theoretical accounts of this phenomenon are focused on specific types of collaborative governance.Healey (1996,2003)and Innes and Booher (1999a,1999b),for example,provide foundational accounts of collaborative planning,as Freeman (1997)does for regulation and administrative law and Wondolleck and Yaffee (2000)do for natural resources management.Our goal is to build on the findings of this rich literature,but also to derive theoretical and empirical claims about the genus of collaborative governance—about the common mode of governing.DEFINING COLLABORATIVE GOVERNANCEWe define collaborative governance as follows:A governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collective decision-making process that is formal,consensus-oriented,and deliberative and that aims to make or implement public policy or manage publicprograms or assets.This definition stresses six important criteria:(1)the forum is initiated by public agencies or institutions,(2)participants in the forum include nonstate actors,(3)participants engage directly in decision making and are not merely ‘‘consulted’’by public agencies,(4)the 1Thomas (1995)develops a contingency perspective on public participation,though it aims more broadly and is developed from the perspective of public managers.2A smaller group of studies evaluates specific types of collaborative governance at a more aggregated level (for example,see Beierle [2000],Langbein [2002],and Leach,Pelkey,and Sabatier [2002]).Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory544Ansell and Gash Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice545 forum is formally organized and meets collectively,(5)the forum aims to make decisionsby consensus(even if consensus is not achieved in practice),and(6)the focus of collab-oration is on public policy or public management.This is a more restrictive definition thanis sometimes found in the literature.However,the wide-ranging use of the term has,as Imperial notes,been a barrier to theory building(Imperial2005,286).Since our goal is to compare apples with apples(to the extent possible),we have defined the term restrictivelyso as to increase the comparability of our cases.One critical component of the term collaborative governance is‘‘governance.’’Much research has been devoted to establishing a workable definition of governance that is bounded and falsifiable,yet comprehensive.For instance,Lynn,Heinrich,and Hill (2001,7)construe governance broadly as‘‘regimes of laws,rules,judicial decisions,and administrative practices that constrain,prescribe,and enable the provision of publicly supported goods and services.’’This definition provides room for traditional governmental structures as well as emerging forms of public/private decision-making bodies.Stoker,onthe other hand,argues:As a baseline definition it can be taken that governance refers to the rules and forms that guidecollective decision-making.That the focus is on decision-making in the collective impliesthat governance is not about one individual making a decision but rather about groups ofindividuals or organisations or systems of organisations making decisions(2004,3).He also suggests that among the various interpretations of the term,there is‘‘baseline agreement that governance refers to the development of governing styles in which bound-aries between and within public and private sectors have become blurred’’(Stoker1998, 17).We opt for a combined approach to conceptualize governance.We agree with Lynn, Heinrich,and Hill that governance applies to laws and rules that pertain to the provision ofpublic goods.However,we adopt Stoker’s claim that governance is also about collective decision making—and specifically about collective decision making that includes bothpublic and private actors.Collaborative governance is therefore a type of governance inwhich public and private actors work collectively in distinctive ways,using particular processes,to establish laws and rules for the provision of public goods.Although there are many forms of collaboration involving strictly nonstate actors,ourdefinition stipulates a specific role for public agencies.By using the term‘‘public agency,’’our intention is to include public institutions such as bureaucracies,courts,legislatures,andother governmental bodies at the local,state,or federal level.But the typical public in-stitution among our cases is,in fact,an executive branch agency,and therefore,the term‘‘public agency’’is apt.Such public agencies may initiate collaborative forums either tofulfill their own purposes or to comply with a mandate,including court orders,legislation,or rules governing the allocation of federal funds.For example,the Workforce InvestmentAct of1998stipulates that all states and localities receiving federal workforce develop-ment funds must convene a workforce investment board that comprised public and privateactors in order to develop and oversee policies at the state and local level concerning job training,under-and unemployment.According to our definition,these workforce invest-ments boards are mandated to engage in collaborative governance.Although public agencies are typically the initiators or instigators of collaborative governance,our definition requires participation by nonstate stakeholders.Some scholars describe interagency coordination as collaborative governance.Although there is nothing inherently wrong with using the term in this way,much of the literature on collaborativegovernance uses this term to signal a different kind of relationship between public agencies and nonstate stakeholders.Smith (1998,61),for example,argues that collaboratives in-volve ‘‘representation by key interest groups.’’Connick and Innes (2003,180)define collaborative governance as including ‘‘representatives of all relevant interests.’’Reilly (1998,115)describes collaborative efforts as a type of problem solving that involves the ‘‘shared pursuit of government agencies and concerned citizens.’’We use the term ‘‘stakeholder’’to refer both to the participation of citizens as indi-viduals and to the participation of organized groups.For convenience,we will also here-after use the term ‘‘stakeholder’’to refer to both public agencies and nonstate stakeholders,though we believe that public agencies have a distinctive leadership role in collaborative governance.Our definition of collaborative governance also sets standards for the type of participation of nonstate stakeholders.We believe that collaborative governance is never merely consultative.3Collaboration implies two-way communication and influence be-tween agencies and stakeholders and also opportunities for stakeholders to talk with each other.Agencies and stakeholders must meet together in a deliberative and multilateral process.In other words,as described above,the process must be collective .Consultative techniques,such as stakeholder surveys or focus groups,although possibly very useful management tools,are not collaborative in the sense implied here because they do not permit two-way flows of communication or multilateral deliberation.Collaboration also implies that nonstate stakeholders will have real responsibility for policy outcomes.Therefore,we impose the condition that stakeholders must be directly engaged in decision making.This criterion is implicit in much of the collaborative gov-ernance literature.Freeman (1997,22),for example,argues that stakeholders participate ‘‘in all stages of the decisionmaking process.’’The watershed partnerships studied by Leach,Pelkey,and Sabatier (2002,648)make policy and implementation decisions on a range of ongoing water management issues regarding streams,rivers,and watersheds.Ultimate authority may lie with the public agency (as with regulatory negotiation),but stakeholders must directly participate in the decision-making process.Thus,advisory committees may be a form of collaborative governance if their advice is closely linked to decision-making outcomes.In practice (and by design),however,advisory committees are often far removed from actual decision making.We impose the criteria of formal collaboration to distinguish collaborative gover-nance from more casual and conventional forms of agency-interest group interaction.For example,the term collaborative governance might be thought to describe the informal relationships that agencies and interest groups have always cultivated.Surely,interest groups and public agencies have always engaged in two-way flows of influence.The difference between our definition of collaborative governance and conventional interest group influence is that the former implies an explicit and public strategy of organizing this influence.Walter and Petr (2000,495),for example,describe collaborative governance as a formal activity that ‘‘involves joint activities,joint structures and shared resources,’’and Padilla and Daigle (1998,74)prescribe the development of a ‘‘structured arrangement.’’This formal arrangement implies organization and structure.Decisions in collaborative forums are consensus oriented (Connick and Innes 2003;Seidenfeld 2000).Although public agencies may have the ultimate authority to make 3See Beierle and Long (1999)for an example of collaboration as consultation.Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory546Ansell and Gash Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice547 a decision,the goal of collaboration is typically to achieve some degree of consensus among stakeholders.We use the term consensus oriented because collaborative forumsoften do not succeed in reaching consensus.However,the premise of meeting together ina deliberative,multilateral,and formal forum is to strive toward consensus or,at least,tostrive to discover areas of agreement.Finally,collaborative governance focuses on public policies and issues.The focuson public issues distinguishes collaborative governance from other forms of consensus decision making,such as alternative dispute resolution or transformative mediation. Although agencies may pursue dispute resolution or mediation to reduce social or politicalconflict,these techniques are often used to deal with strictly private conflicts.Moreover,public dispute resolution or mediation may be designed merely to resolve private disputes.While acknowledging the ambiguity of the boundary between public and private,we restrict the use of the term‘‘collaborative governance’’to the governance of public affairs.Our definition of collaborative governance is meant to distinguish collaborative gov-ernance from two alternative patterns of policy making:adversarialism and managerialism (Busenberg1999;Futrell2003;Williams and Matheny1995).By contrast with decisionsmade adversarially,collaborative governance is not a‘‘winner-take-all’’form of interest intermediation.In collaborative governance,stakeholders will often have an adversarial relationship to one another,but the goal is to transform adversarial relationships into more cooperative ones.In adversarial politics,groups may engage in positive-sum bargainingand develop cooperative alliances.However,this cooperation is ad hoc,and adversarial politics does not explicitly seek to transform conflict into cooperation.In managerialism,public agencies make decisions unilaterally or through closed de-cision processes,typically relying on agency experts to make decisions(Futrell2003; Williams and Matheny1995).Although managerial agencies may take account of stake-holder perspectives in their decision making and may even go so far as to consult directlywith stakeholders,collaborative governance requires that stakeholders be directly includedin the decision-making process.A number of synonyms for collaborative governance may cause confusion.For ex-ample,‘‘corporatism’’is certainly a form of collaborative governance as we define it. Classic definitions of corporatism(like Schmitter’s)emphasize tripartite bargaining be-tween peak associations of labor and capital and the state.Typically,these peak associa-tions have a representational monopoly in their sector(they are‘‘encompassing’’).If westart with this narrower definition of corporatism,collaborative governance is the broader term.Collaborative governance often implies the inclusion of a broader range of stake-holders than corporatism,and the stakeholders often lack a representational monopoly overtheir sector.The term‘‘associational governance’’is sometimes used to refer to the more generic mode of governing with associations,but collaborative governance may not even include formal associations.The Porte Alegre project,for example,is a form of collabo-rative governance that includes individual citizens in budgetary decision making(Fung and Wright2001).Sometimes the term‘‘policy network’’is used to describe more pluralistic forms ofstate-society cooperation.A policy network may include both public agencies and stake-holder groups.Moreover,policy networks typically imply cooperative modes of deliber-ation or decision making among actors within the network.Thus,the terms policy networkand collaborative governance can refer to similar phenomena.However,collaborative governance refers to an explicit and formal strategy of incorporating stakeholders intomultilateral and consensus-oriented decision-making processes.By contrast,the co-operation inherent in policy networks may be informal and remain largely implicit (e.g.,unacknowledged,unstated,nondesigned).Moreover,it may operate through infor-mal patterns of brokerage and shuttle diplomacy rather than through formal multilateral processes.Collaborative governance and public-private partnership can also sometimes refer to the same phenomenon.Public-private partnerships typically require collaboration to func-tion,but their goal is often to achieve coordination rather than to achieve decision-making consensus per se.A public-private partnership may simply represent an agreement between public and private actors to deliver certain services or perform certain tasks.Collective decision making is therefore secondary to the definition of public-private partnership.By contrast,the institutionalization of a collective decision-making process is central to the definition of collaborative governance.Finally,a range of terms are often used interchangeably with collaborative gover-nance.Such terms include participatory management,interactive policy making,stake-holder governance,and collaborative management.We prefer the term governance to management because it is broader and encompasses various aspects of the governing process,including planning,policy making,and management.The term collaborative is also more indicative of the deliberative and consensus-oriented approach that we contrast with adversarialism or managerialism than terms like participatory or interactive.A MODEL OF COLLABORATIVE GOVERNANCEArmed with a working definition of collaborative governance,we collected a wide range of case studies from the literature.We did this in the typical fashion:we systematically reviewed journals across a wide range of disciplines,including specialist journals in public health,education,social welfare,international relations,etc.We also conducted key word electronic searches using a wide variety of search terms,including those described above and many more (e.g.,‘‘comanagement,’’‘‘public participation,’’‘‘alternative dispute res-olution’’).Of course,we also followed up on the literature cited in the cases we discovered.Ultimately,our model is built on an analysis of 137cases.Although international in scope,our search was restricted to literature in English,and thus,American cases are overrepre-sented.Even a cursory examination of our cases also suggests that natural resource man-agement cases are overrepresented.This is not due to any sampling bias on our part but rather reflects the importance of collaborative strategies for managing contentious local resource disputes.Most of the studies we reviewed were case studies of an attempt to implement collaborative governance in a particular sector.As you might imagine,the universe of cases we collected was quite diverse and the cases differed in quality,methodology,and intent.Although our definition was restrictive so as to facilitate comparison of apples with apples,representing this diversity was also one of our goals.We perceived experiments with collaborative governance bubbling up in many different policy sectors,with little sense that they were engaged in a similar governance strategy.Surely,we felt,these diverse experiments could learn from each other.Yet this diversity proved a challenge.Our original intention to treat these cases as a large-N data set subject to quasi-experimental statistical evaluation was not successful.Since it is useful for both scholarsJournal of Public Administration Research and Theory548Ansell and Gash Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice549 and practitioners to understand how we arrived at our conclusions,we briefly report on the problems we encountered in conducting our meta-analysis.Early attempts at systematic coding were frustrating,and we soon developed an understanding of our dilemma.Although scholars studying collaborative governancehad already made some important theoretical statements,the language used to describewhat was happening was far from standardized.We found ourselves groping tofinda common language of description and evaluation even as we were trying to‘‘code’’studies.Add to this challenge a severe problem of‘‘missing data’’—a reflection of thehighly varied motivations of the researchers—and we concluded that a quasi-experimental approach was ill advised.Ultimately,we moved toward a meta-analytic strategy that wecall successive approximation.We selected a subset of our cases and used them to developa common‘‘model’’of collaborative governance.4We then randomly selected additional subsets of case studies.The second subset was used to‘‘test’’the model developed in thefirst round and then to further‘‘refine’’the model.A third sample of cases was used to testthe second-round model,and so on.The appendix provides a list of the studies evaluated ineach of four successive rounds of evaluation.Successive approximation has the advantage of both refining the conceptual modelwhile providing some of the evaluative‘‘discipline’’of a quasi-experimental study.How-ever,we are under no illusion that this process yielded‘‘the one’’model of collaborative governance.There was a large element of art involved in both specifying and evaluatingour model.As we proceeded,we were overwhelmed by the complexity of the collaborative process.Variables and causal relationships proliferated beyond what we felt would ulti-mately be useful for policy makers and practitioners.Therefore,our model representsa conscious attempt to simplify as much as possible the representation of key variablesand their relationships.This goal of simplification led us to stress common and frequentfindings across cases.This approach strengthens the generality of ourfindings but dis-counts less universal or frequently mentionedfindings from the literature.Toward the endof our analysis,we were ourselves in disagreement about how to represent key relations.We used thefinal round of case analysis to settle these differences.One other important clarification needs to be made before we introduce ourfindings.Our survey of the cases quickly disabused us of the notion that we could use our analysis to answer the question:‘‘Is collaborative governance more effective than adversarial or managerial governance?’’Very few of the studies we reviewed actually evaluated gover-nance outcomes.This is not to say that the comparison between collaborative,adversarial,and managerial governance is not relevant to these studies.Experiments with collaborative governance were typically driven by earlier failures with adversarial or managerial approaches.But systematic comparisons were rarely explicitly made.What most studiesdid try to do was understand the conditions under which stakeholders acted collaboratively.Did they engage in good faith negotiation?Did they pursue mutual gains?Did they achieve consensus?Were they satisfied with the process?In other words,most studies in the collaborative governance literature evaluate‘‘process outcomes’’rather than policy or management outcomes.Figure1provides a visual representation of our centralfindings.The model has fourbroad variables—starting conditions,institutional design,leadership,and collaborative4To avoid recreating the wheel,ourfirst subset was not randomly selected but included many of the most prominent theoretical statements about collaborative governance.process.Each of these broad variables can be disaggregated into more fine-grained vari-ables.Collaborative process variables are treated as the core of our model,with starting conditions,institutional design,and leadership variables represented as either critical contributions to or context for the collaborative process.Starting conditions set the basic level of trust,conflict,and social capital that become resources or liabilities during col-laboration.Institutional design sets the basic ground rules under which collaboration takes place.And,leadership provides essential mediation and facilitation for the collaborative process.The collaborative process itself is highly iterative and nonlinear,and thus,we represent it (with considerable simplification)as a cycle.The remainder of the article describes each of these variables in more detail and draws out their implications for a contingency model of collaborative governance.STARTING CONDITIONSThe literature is clear that conditions present at the outset of collaboration can either facilitate or discourage cooperation among stakeholders and between agencies and stake-holders.Imagine two very different starting points.In one,the stakeholders have a history of bitter division over some emotionally charged local issue and have come to regard each other as unscrupulous enemies.In the other,the stakeholders have a shared vision for what they would like to achieve through collaboration and a history of past cooperation and mutual respect.In both cases,collaboration may be difficult,but the first case must over-come problems of distrust,disrespect,and outright antagonism.We narrowed the critical starting conditions down to three broad variables:imbalances between the resources orFigure 1A Model of Collaborative GovernanceJournal of Public Administration Research and Theory550。

软件项目管理案例分析考核试卷

9.项目沟通管理包括以下哪些关键活动?()

A.沟通计划

B.信息分发

C.绩效报告

D.项目收尾

10.敏捷项目管理的核心价值观包括以下哪些?()

A.个体和互动高于流程和工具

B.工作软件高于详尽的文档

C.客户合作高于合同谈判

D.响应变化高于遵循计划

11.以下哪些角色在敏捷开发团队中常见?()

A.产品负责人

五、主观题(本题共4小题,每题10分,共40分)

1.描述软件项目管理中项目范围的定义过程,并解释为什么控制项目范围是项目成功的关键因素。

答案:____

2.以一个实际项目为例,说明如何使用风险管理计划来识别和应对项目风险。

答案:____

3.阐述敏捷项目管理和传统瀑布模型在软件项目开发中的主要区别,并讨论敏捷方法在哪些情况下更为适用。

A.风险避免

B.风险减轻

C.风险转移

D.风险接受

6.以下哪些活动属于软件质量保证的工作?()

A.质量计划

B.质量审计

C.过程改进

D.错误跟踪

7.软件测试的类型包括以下哪些?()

A.单元测试

B.集成测试

C.系统测试

D.性能测试

8.以下哪些是配置管理的主要活动?()

A.配置项识别

B.配置状态记录

C.配置审核

2.在项目中,通过风险登记册记录已识别的风险,评估风险概率和影响,制定风险应对策略,如避免、转移、减轻或接受,以减轻对项目的不利影响。

3.敏捷项目管理强调快速迭代、客户合作和响应变化,而瀑布模型是顺序开发过程。敏捷适用于需求不明确、需快速响应变化的场景。

4.项目收尾阶段确保项目目标达成,完成产品交付、财务结算、资源遣散和项目总结,为组织提供经验和教训。

参考方案的英文

Reference Scheme: A Complete GuideIntroductionThe reference scheme is a crucial aspect of any project or initiative. It provides a framework for others to follow and learn from, ensuring consistency and efficiency. In this guide, we will explore the various components of a reference scheme and how it contributes to the success of a project.What is a Reference Scheme?A reference scheme is a set of guidelines, instructions, and standards that serves as a reference for the project team. It provides a basis for decision-making, ensuring that all project stakeholders follow a consistent approach. A well-defined reference scheme saves time and effort by providing a roadmap for tackling challenges and achieving project goals.Components of a Reference SchemeA comprehensive reference scheme consists of the following components:1. Project GoalsAt the core of the reference scheme lies the project goals. Clearly defining the objectives and desired outcomes of the project is essential for success. This section should provide a concise and measurable description of the project’s scope and purpose.2. Stakeholder AnalysisUnderstanding the project’s stakeholders and their respective roles is crucial for effective decision-making and communication. This section should identify key stakeholders, their interests, and their level of influence. It should also outline strategies for engaging and involving stakeholders throughout the project’s lifecycle.3. Project TimelineA well-defined timeline is essential for managing project activities and resources effectively. Thi s section should outline the project’s major milestones and deliverables, along with their expected completion dates. Consider incorporating Gantt charts or other visual tools to enhance clarity and ease of understanding.4. Budget and Resource AllocationManaging project resources, including budget and personnel, is a critical aspect of any project. This section should outline the project’s budget allocation, including any specific funding sources. It should also identify key resource requirements and how they will be allocated throughout the project.5. Risk ManagementEvery project comes with inherent risks. Identifying and managing these risks is crucial for project success. This section should outline thepotential risks associated with the project, along with mitigation strategies. Consider including a risk assessment matrix or other visual tools to d in risk prioritization and mitigation planning.6. Communication PlanEffective communication is essential for project success. This section should outlin e the project’s communication channels, protocols, and stakeholders, along with their respective roles and responsibilities. Consider utilizing a communication matrix to track and manage project communications effectively.7. Quality AssuranceEnsuring quality throughout the project lifecycle is critical for achieving project goals. This section should outline the project’s quality assurance processes, including any relevant standards or benchmarks. Consider incorporating quality control checklists or other tools to measure and track project quality.ConclusionA well-defined reference scheme is a valuable asset for any project or initiative. It provides a roadmap for success, ensuring that all project stakeholders are aligned and working towards a common goal. By incorporating the components outlined in this guide, you can create a comprehensive and effective reference scheme for your project.。

英语初级商务英语(集锦5篇)

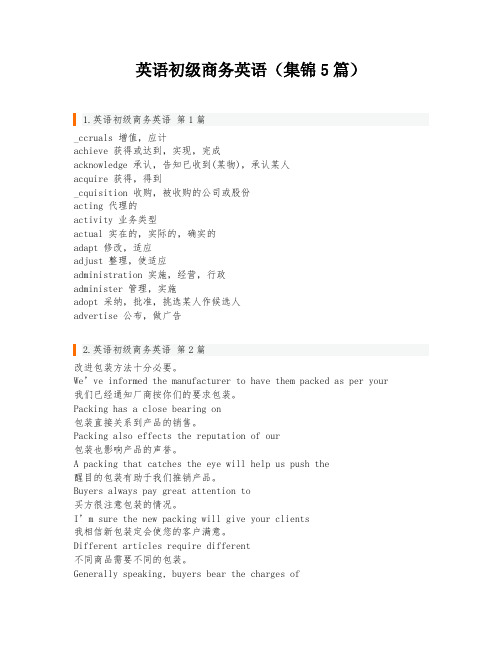

英语初级商务英语(集锦5篇)1.英语初级商务英语第1篇_ccruals 增值,应计achieve 获得或达到,实现,完成acknowledge 承认,告知已收到(某物),承认某人acquire 获得,得到_cquisition 收购,被收购的公司或股份acting 代理的activity 业务类型actual 实在的,实际的,确实的adapt 修改,适应adjust 整理,使适应administration 实施,经营,行政administer 管理,实施adopt 采纳,批准,挑选某人作候选人advertise 公布,做广告2.英语初级商务英语第2篇改进包装方法十分必要。

We’ve informed the manufacturer to have them packed as per your 我们已经通知厂商按你们的要求包装。

Packing has a close bearing on包装直接关系到产品的销售。

Packing also effects the reputation of our包装也影响产品的声誉。

A packing that catches the eye will help us push the醒目的包装有助于我们推销产品。

Buyers always pay great attention to买方很注意包装的情况。

I’m sure the new packing will give your clients我相信新包装定会使您的客户满意。

Different articles require different不同商品需要不同的包装。

Generally speaking, buyers bear the charges of包装费用一般由买方负担。

Packing charge is about 3% of the total cost of the3.英语初级商务英语第3篇完整拼出下列句中空格处的单词(注意是完整拼出):Although he was a f( )e at school, he became a successful man 失败者He was so c( )s to know what was in the letter that he opened it ,even though it was addressed to his 好奇的Will you be quite f( )k with me about this matter? 坦白的In their school they have an i( )l of ten minutes for 间隔的时间The police watched the cafe to which the robber was known to r( ) 常去答案及解析:正确答案:failure 题目翻译:尽管他在学校是个失败者,最后他还是成了一个成功的人.正确答案:curious 题目翻译:他太好奇信里是什么,就打开了,尽管是寄给他姐姐的.正确答案:frank 题目翻译:你能非常坦白的告诉我这件事吗?正确答案:interval 题目翻译:在学校里,有十分钟的休息时间.正确答案:resort 题目翻译:警察们监视了强盗们常去的咖啡馆.4.英语初级商务英语第4篇找出与中括号内单词意义相近的单词:Steam can [generate] electricity by turning an electricHe earned high [commendation] from the people for hisThe policeman [halted] the speeding car to see if the driver wasI have a [sore] throat fromI will show you the [magnificent] palace of the答案及解析:正确答案:b题目翻译:发电机可以转化让水蒸汽产生电. 选项翻译改变产生停止覆盖正确答案:c题目翻译:他的勇敢赢得了人们很高的赞扬选项翻译报答自毫表扬考虑正确答案:a题目翻译:警察让超速的车停下检查司机是否喝酒. 选项翻译停止发现追捕拿正确答案:d题目翻译:我感冒喉咙痛. 选项翻译强壮微弱干净痛正确答案:a题目翻译:我带你去看国王华丽的宫殿. 选项翻译伟大的古代的钝的彩色的5.英语初级商务英语第5篇Achieving a successful mergerHowever attractive the figures may look on paper, in thelong run the success or failure of a merger depends on thehuman When the agreement has been signed and theaccountants have departed, the real problems may only just If there is a culture clash between the two companiesin the way their people work, then all the efforts of the financiersand lawyers to strike a deal may have been inAccording to Chris Bolton of KS Management Consultants, 70% of mergers fail to live up totheir promise of shareholder value, riot through any failure in economic terms but because theintegration of people is Corporates, he explains, concentrate their efforts before amerger on legal, technical and financial They employ a range of experts to obtain themost favourable contract But even at these early stages, people issues must be takeninto The strengths and weaknesses of both organisations should be assessed and, ifit is a merger of equals, then careful thought should be given to which personnel, from whichside,should take on the keyThis was the issue in 20XX when the proposed merger between two pharmaceuticalcompanies promised to create one of the largest players in the For both companies themerger was intended to reverse falling market share and shareholder However, although thecompanies' skill bases were compatible, the chief executives of the two companies could not agreewhich of them was to head up the new This illustrates the need to compromise if amerger is to takeBut even in mergers that do go ahead, there can be culture One way to avoid this isto work with focus groups to see how employees view the existing culture of their Inone example, where two global organisations in the food sector were planning to merge, focusgroups discovered that the companies displayed very different One was sales-focused,knew exactly what it wanted to achieve and pushed initiatives The other got involved inlengthy discussions, trying out options methodically and making contingency The firstresponded quickly to changes in the marketplace; the second took longer, but the option iteventually chose was usually the correct Neither company's approach would have worked fortheThe answer is not to adopt one company's approach, or even to try to incorporate everyaspect of both organisations, but to create a totally new This means taking the best fromboth sides and making a new organisation that everyone can Or almost there will be those who cannotadapt to a different Research into the impact ofmergers has found that companies with differing management styles are the ones that need towork hardest at creating a newAnother tool that can help to get the right cultural mix isintercultural This involvescarrying out research that looks at the culture of a company and the business culture of thecountry in which it is It identifies how people, money and time are managed in a company,and investigates the business customs of the country and how its politics, economics and historyimpact on the way business is13 According to the text, mergers can encounter problems whenA contracts are signed tooB experts cannot predict accurateC conflicting attitudes cannot beD staff are opposed to the terms of the14 According to Chris Bolton, what do many organisations do in preparation for a merger?A ensure their interests are representedB give reassurances to shareholdersC consider the effect of a merger on employeesD analyse the varying strengths of their staff15 The proposed merger of two pharmaceutical groups failed becauseA major shareholders wereB there was a fall in the demand for theirC there were problems combining their areas ofD an issue of personal rivalry could not be16 According to the text, focus groups can help companies toA develop newB adopt contingencyC be decisive and reactD evaluate how well matched they17 Creating a new culture in a newly merged organisation means thatA management styles become moreB there is more chance of the merger 中华考试网C staff will find it more difficult to adapt to theD successful elements of the original organisations are18 According to the text, intercultural analysis will showA what kind of benefits a merger can leadB how the national context affects the way a company isC how long it will take for a company culture toD what changes companies should make before a merger takes参考答案接解析《Achieving a successful merger》,实现一个成功的并购。

如何进行利益相关者分析(以福特中国为例)

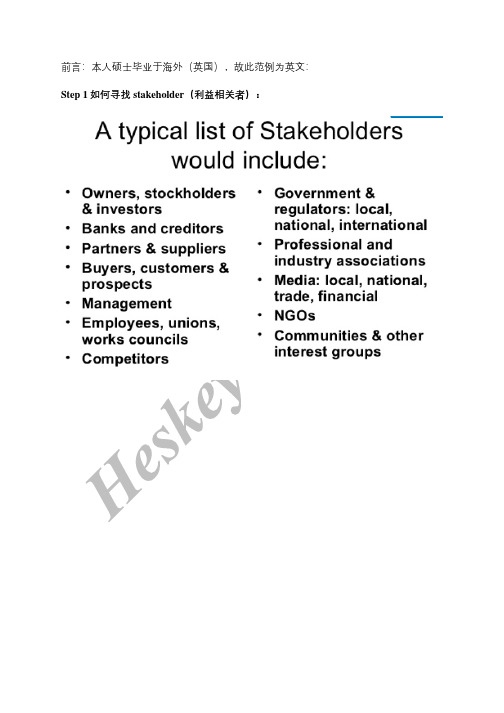

前言:本人硕士毕业于海外(英国),故此范例为英文:Step 1如何寻找stakeholder(利益相关者):Step 2建立stakeholder analysis matrix(根据利益interest和影响influence去考虑):Key stakeholders of Ford China AnalysisStep 3根据上述matrix,寻找key stakeholder:Step 4 相关阐释(为什么那些利益相关者是key——不要你觉得,一定要拿出你的道理说服别人,这点很关键):1.1 Ford Motor CompanyFord Motor company makes an effort on its strategy in Asian Pacific Region and established Ford China as a crucial subsidiary in this area. As the parent company, it enjoys the final decision on all the activities Ford China plans to conduct. Therefore, its goal is the supreme target of Ford China’s Strategy.1.2 Changan Motor Company, Jiangling Motor Company & Mazda Motor CompanyAll Changan, Jiangling and Mazda have a strategic partnership with Ford China. According to Ford China (2016), Changan, Ford, and Mazda commonly aim at constructing a “world-class engine base” and corporately built up Changan Ford Mazda Automobile (shareholding situation: Changan 50%, Ford 35%, and Mazda 15%). Besides, to dominate a SUV (sports utility vehicle) market in China, Ford China collaborates with Jiangling to set up a joint venture (shareholding position: Jiangling 64% and Ford 32%). All Changan, Jiangling and Mazda are essential shareholders of the companies cooperating with Ford China, thereby, their every determination on the joint venture will considerably influence Ford China. Therefore, the strategic themes of Ford China are closely related to them.1.3 4S shopsIn China, 4S (Sale, Sparepart, Service, and Survey) shops are the dealers of Ford vehicles. They are the formal sales channel of Ford motors. If their relationship with Ford has several barriers, a problem of Ford motors selling might emerge in China. Hence, financially, it affects the in come/sales volume of Ford China’s strategy.1.4 CustomersAs a customer-centralised company, Ford China takes a tremendous consideration on Chinese customers to optimise their services to be customer-oriented. In a competitive market, if the quality of Ford China productions and/or its aftersales are not relatively high, fewer originalowners will re-purchase a second Ford vehicle when their primary motors meet the expiration. In addition, if the word of mouth is not sufficiently excellent, a smaller number of potential customers will reveal. They are the objectives in Ford China’s strategy on customer perspective.1.5 EmployeesAs a company in second-tier industry and focusing on aftersales services, Ford China has hired exceeding 20,000 employees (Ford China, 2016). They all are important components in Ford China’s strategy on learning & growth perspective, without which the strategy cannot be achievable ultimately.1.6 Buick Motor Company & Chevrolet Motor CompanyIn China motor indust ry, Buick and Chevrolet are Ford’s two main competitors. Their marketing activities are considerably concerned by Ford China on account of maintaining competitiveness in the motor industry. They are significant benchmarking objectives of Ford China on internal perspective.1.7 China Association of Automobile ManufacturesChina Association of Automobile Manufactures (CAAM) supervises all the issues in terms of motor industry in China. Therefore, Ford China and all its activities are taken into CAAM’s consideration. All activities Ford China undertakes and participates in are monitored by CAAM and should be under its regulation, and every dispute Ford China is involved in will be c oordinated by CAAM. Thus, it externally impacts on Ford China’s strategy on all perspectives.。

Stakeholder利益相关者阐述

• Business is not equipped to handle social activities.

• It dilutes the primary purpose of business. • Businesses have too much power already . • It limits the ability to compete in a global marketplace.

Ch2 Corporate Citizenship

Starting questions

1. What is the most concerned issue in the eyes of corporate decision-makers? Maximization of profits or commitment to social responsibility

Ethical Responsibilities

=

+ Philanthropic Responsibilities

Total Corporate CSR

A stakeholder perspective focuses on the CSR pyramid as a unified whole.

Arguments Against CSR

Corporate social responsibility emphasizes:

a. obligation and accountability. b. action and activity. c. outcomes and results. d. socially responsible investing.

Meshfree and particle methods and their applications

Meshfree and particle methods and their applicationsShaofan LiDepartment of Civil&Environmental Engineering,University of California,Berkeley CA94720;li@Wing Kam LiuDepartment of Mechanical Engineering,Northwestern University,2145Sheridan Rd,Evanston IL60208;w-liu@Recent developments of meshfree and particle methods and their applications in applied mechan-ics are surveyed.Three major methodologies have been reviewed.First,smoothed particlehydrodynamics͑SPH͒is discussed as a representative of a non-local kernel,strong form collo-cation approach.Second,mesh-free Galerkin methods,which have been an active researcharea in recent years,are reviewed.Third,some applications of molecular dynamics͑MD͒inapplied mechanics are discussed.The emphases of this survey are placed on simulations offinite deformations,fracture,strain localization of solids;incompressible as well as compress-ibleflows;and applications of multiscale methods and nano-scale mechanics.This review ar-ticle includes397references.͓DOI:10.1115/1.1431547͔1INTRODUCTIONSince the invention of thefinite element method͑FEM͒in the1950s,FEM has become the most popular and widely used method in engineering computations.A salient feature of the FEM is that it divides a continuum into discrete ele-ments.This subdivision is called discretization.In FEM,the individual elements are connected together by a topological map,which is usually called a mesh.Thefinite element in-terpolation functions are then built upon the mesh,which ensures the compatibility of the interpolation.However,this procedure is not always advantageous,because the numerical compatibility condition is not the same as the physical com-patibility condition of a continuum.For instance,in a La-grangian type of computations,one may experience mesh distortion,which can either end the computation altogether or result in drastic deterioration of accuracy.In addition, FEM often requires a veryfine mesh in problems with high gradients or a distinct local character,which can be compu-tationally expensive.For this reason,adaptive FEM has be-come a necessity.Today,adaptive remeshing procedures for simulations of impact/penetration problems,explosion/fragmentation prob-lems,flow pass obstacles,andfluid-structure interaction problems etc have become formidable tasks to undertake. The difficulties involved are not only remeshing,but also mapping the state variables from the old mesh to the new mesh.This process often introduces numerical errors,and frequent remeshing is thus not desirable.Therefore,the so called Arbitrary Lagrangian Eulerian͑ALE͒formulations have been developed͑see,eg͓1–4͔͒.For a complete descrip-tion on this subject,readers may consult Chapter7of the book by Belytschko,Liu,and Moran͓5͔.The objective of the ALE formulation is to make the mesh independent of the material so that the mesh distortion can be minimized.Un-fortunately,in computer simulations of very large deforma-tion and/or high-speed mechanical and structural systems, even with the ALE formulation,a distorted mesh introduces severe errors in numerical computations.Furthermore,the convective transport effects in ALE often lead to spurious oscillation that needs to be stabilized by artificial diffusion or a Petrov-Galerkin stabilization.In other cases,a mesh may carry inherent bias in numerical simulations,and its presence becomes a nuisance in computations.A well known example is the simulation of the strain localization problem,which is notorious for its mesh alignment sensitivity͓6,7͔.Therefore, it would be computationally efficacious to discretize a con-tinuum by only a set of nodal points,or particles,without mesh constraints.This is the leitmotif of contemporary mesh-free Galerkin methods.The advantages of the meshfree particle methods may be summarized as follows:1͒They can easily handle very large deformations,since the connectivity among nodes is generated as part of the computation and can change with time;2͒The methodology can be linked more easily with a CAD database thanfinite elements,since it is not necessary to generate an element mesh;3͒The method can easily handle damage of the components, such as fracture,which should prove very useful in mod-elings of material failure;Transmitted by Associate Editor JN ReddyASME Reprint No AMR319$26.00Appl Mech Rev vol55,no1,January2002©2002American Society of Mechanical Engineers14͒Accuracy can be controlled more easily,since in areas where more refinement is needed,nodes can be added quite easily͑h-adaptivity͒;5͒The continuum meshfree methods can be used to model large deformations of thin shell structures,such as nano-tubes;6͒The method can incorporate an enrichment offine scale solutions of features,such as discontinuities as a function of current stress states,into the coarse scale;and7͒Meshfree discretization can provide accurate representa-tion of geometric object.In general,particle methods can be classified based on two different criteria:physical principles,or computational formulations.According to the physical modeling,they may be categorized into two classes:those based on deterministic models,and those based on probabilistic models.On the other hand,according to computational modelings,they may be categorized into two different types as well:those serving as approximations of the strong forms of partial differential equations͑PDEs͒,and those serving as approximations of the weak forms of PDEs.In this survey,the classification based on computational strategies is adopted.To approximate the strong form of a PDE using a particle method,the partial differential equation is usually discretized by a specific collocation technique.Examples are smoothed particle hydrodynamics͑SPH͓͒8–12͔,the vortex method ͓13–18͔,the generalizedfinite difference method͓19,20͔, and many others.It is worth mentioning that some particle methods,such as SPH and vortex methods,were initially developed as probabilistic methods͓10,14͔,and it turns out that both SPH and the vortex method are most frequently used as deterministic methods today.Nevertheless,the ma-jority of particle methods in this category are based on probabilistic principles,or used as probabilistic simulation tools.There are three major methods in this category:1͒molecular dynamics͑both quantum molecular dynamics ͓21–26͔and classical molecular dynamics͓27–32͔͒;2͒di-rect simulation Monte Carlo͑DSMC͒,or Monte Carlo method based molecular dynamics,such as quantum Monte Carlo methods͓33–41͔͒͑It is noted that not all the Monte Carlo methods are meshfree methods,for instance,a proba-bilisticfinite element method is a mesh-based method͓42–44͔͒;and3͒the lattice gas automaton͑LGA͒,or lattice gas cellular automaton͓45–49͔and its later derivative,the Lat-tice Boltzmann Equation method͑LBE͓͒50–54͔.It may be pointed out that the Lattice Boltzmann Equation method is not a meshfree method,and it requires a grid;this example shows that particle methods are not always meshfree.The second class of particle methods is used with various Galerkin weak formulations,which are called meshfree Galerkin methods.Examples in this class are Diffuse Ele-ment Method͑DEM͓͒55–58͔,Element Free Galerkin Method͑EFGM͓͒59–63͔,Reproducing Kernel Particle Method͑RKPM͓͒64–72͔,h-p Cloud Method͓73–76͔,Par-tition of Unity Method͓77–79͔,Meshless Local Petrov-Galerkin Method͑MLPG͓͒80–83͔,Free Mesh Method͓84–88͔,and others.There are exceptions to this classification,because someparticle methods can be used in both strong form collocationas well as weak form discretization.The particle-in-cell ͑PIC͒method is such an exception.The strong form colloca-tion PIC is often called thefinite-volume particle-in-cellmethod͓89–91͔,and the weak form PIC is often called thematerial point method͓92͔,or simply particle-in-cell method ͓93–95͔.RKPM also has two versions as well:a collocation version͓96͔and a Galerkin weak form version͓66͔.In areas such as astrophysics,solid state physics,biophys-ics,biochemistry and biomedical research,one may encoun-ter situations where the object under consideration is not acontinuum,but a set of particles.There is no need for dis-cretization to begin with.A particle method is the naturalchoice in numerical simulations.Relevant examples are thesimulation of formation of a star system,the nano-scalemovement of millions of atoms in a non-equilibrium state,folding and unfolding of DNA,and dynamic interactions ofvarious molecules,etc.In fact,the current trend is not onlyto use particle methods as discretization tools to solve con-tinuum problems͑such as SPH,vortex method͓14,15,97͔and meshfree Galerkin methods͒,but also to use particlemethods as a physical model͑statistical model,or atomisticmodel͒to simulate continuum behavior of physics.The latestexamples are using the Lattice Boltzmann method to solvefluid mechanics problems,and using molecular dynamics tosolve fracture mechanics problems in solid mechanics͓98–103͔.This survey is organized as follows:Thefirst part is acritical review of smoothed particle hydrodynamics͑SPH͒.The emphasis is placed on the recent development of correc-tive SPH.The second part is a summary of meshfree Galer-kin methods,which includes DEM,EFGM,RKPM,hp-Cloud method,partition of unity method,MLPGM,andmeshfree nodal integration methods.The third part reviewsrecent applications of molecular dynamics in fracture me-chanics as well as nanomechanics.The last part is a surveyon some other meshfree/particle methods,such as vortexmethods,the Lattice Boltzmann method,the natural elementmethod,the particle-in-cell method,etc.The survey is con-cluded with the discussions of some emerging meshfree/particle methods.2SMOOTHED PARTICLE HYDRODYNAMICS2.1OverviewSmoothed Particle Hydrodynamics is one of the earliest par-ticle methods in computational mechanics.Early contribu-tions have been reviewed in several articles͓8,12,104͔.In1977,Lucy͓10͔and Gingold and Monaghan͓9͔simulta-neously formulated the so-called Smoothed Particle Hydro-dynamics,which is known today as SPH.Both of them wereinterested in the astrophysical problems,such as the forma-tion and evolution of proto-stars or galaxies.The collectivemovement of those particles is similar to the movement of aliquid,or gasflow,and it may be modeled by the governingequations of classical Newtonian hydrodynamics.Today,SPH is being used in simulations of supernovas͓105͔,col-2Li and Liu:Meshfree and particle methods and applications Appl Mech Rev vol55,no1,January2002lapse as well as formation of galaxies͓106–109͔,coales-cence of black holes with neutron stars͓110,111͔,single and multiple detonations in white dwarfs͓112͔,and even in ‘‘Modeling the Universe’’͓113͔.Because of the distinct ad-vantages of the particle method,soon after its debut,the SPH method was widely adopted as one of the efficient computa-tional techniques to solve applied mechanics problems. Therefore,the term hydrodynamics really should be inter-preted as mechanics in general,if the methodology is applied to other branches of mechanics rather than classical hydro-dynamics.To make distinction with the classical hydrody-namics,some authors,eg Kum et al͓114,115͔,called it Smoothed Particle Applied Mechanics.This idea of the method is somewhat contrary to the con-cepts of the conventional discretization methods,which dis-cretize a continuum system into a discrete algebraic system. In astrophysical applications,the real physical system is dis-crete;in order to avoid singularity,a local continuousfield is generated by introducing a localized kernel function,which can serve as a smoothing interpolationfield.If one wishes to interpret the physical meaning of the kernel function as the probability of a particle’s position,one is dealing with a probabilistic method.Otherwise,it is only a smoothing tech-nique.Thus,the essence of the method is to choose a smooth kernel,W(x,h)͑h is the smoothing length͒,and to use it to localize the strong form of a partial differential equation through a convoluted integration.Define SPH averaging/ localization operator asA k͑x͒ϭ͗A͑x͒͘ϭ͵R n W͑xϪxЈ,h͒A͑xЈ͒d⍀xЈϷ͚Iϭ1N W͑xϪx I,h͒A͑x I͒⌬V I(1) One may derive a SPH discrete equation of motion from its continuous counterpart͓12,116͔,ͳd v dtʹI ϭϪٌ͗•͘I⇒Id v IdtϷϪ͚Jϭ1N͑IϩJ͒•ٌW͑x IϪx J,h͒⌬V J(2)whereis Cauchy stress,is density,v is velocity,and⌬V J is the volume element carried by the particle J.Usually a positive function,such as the Gaussian func-tion,is chosen as the kernel functionW͑x,h͒ϭ1͑h2͒n/2expͫϪx2h2ͬ,1рnр3(3)where the parameter h is the smoothing length.In general, the kernel function has to satisfy the following conditions:i)W͑x,h͒у0(4) ii)͵R n W͑u,h͒d⍀uϭ1(5) iii)W͑u,h͒→␦͑u͒,h→0(6) i v)W͑u,h͒C p͑R n͒,pу1(7)The third property ensures the convergence,and the last property comes from the requirement that the smoothing ker-nel must be differentiable at least once.This is because the derivative of the kernel function should be continuous to prevent a largefluctuation in the force felt by the particle. The latter feature gives rise to the name smoothed particle hydrodynamics.In computations,compact supported kernel functions such as spline functions are usually employed͓117͔.In this case, the smoothing length becomes the radius of the compact sup-port.Two examples of smooth kernel functions are depicted in Fig.1.The advantage of using an analytical kernel is that one can evaluate a kernel function at any spatial point without knowing the local particle distribution.This is no longer true for the latest corrective smoothed particle hydrodynamics methods͓66,118͔,because the corrective kernel function de-pends on the local particle distribution.The kernel representation is not only an instrument that can smoothly discretize a partial differential equation,but it also furnishes an interpolant scheme on a set of moving par-ticles.By utilizing this property,SPH can serve as a La-grangian type method to solve problems in continuum me-chanics.Libersky and his co-workers apply the method to solid mechanics͓117,119,120͔,and they successfully simu-late3D thick-wall bomb explosion/fragmentation problem, tungsten/plate impact/penetration problem,etc.The impact and penetration simulation has also been conducted by Johnson and his co-workers͓121–123͔,and an SPH option is implemented in EPIC code for modeling inelastic,dam-age,large deformation problems.Attaway et al͓124͔devel-oped a coupling technique to combine SPH with thefinite element method,and an SPH option is also included in PR-ONTO2D͑Taylor and Flanagan͓125͔͒.SPH technology has been employed to solve problems of both compressibleflow͓126͔and incompressibleflow Fig.1Examples of kernel functionsAppl Mech Rev vol55,no1,January2002Li and Liu:Meshfree and particle methods and applications3͓116,127–129͔,multiple phaseflow and surface tension ͓114,115,129,130,131,132,133͔,heat conduction͓134͔, electro-magnetic͑Maxwell equations͓͒90,104,135͔,plasma/fluid motion͓135͔,general relativistic hydrodynamics͓136–138͔,heat conduction͓134,139͔,and nonlinear dynamics ͓140͔.2.2Corrective SPH and other improvementsin SPH formulationsVarious improvements of SPH have been developed through the years͓104,141–149͔.Most of these improvement are aimed at the following shortcomings,or pathologies,in nu-merical computations:•tensile instability͓150–154͔;•lack of interpolation consistency,or completeness ͓66,155,156͔;•zero-energy mode͓157͔;•difficulty in enforcing essential boundary condition ͓120,128,131͔.2.2.1Tensile instabilitySo-called tensile instability is the situation where particles are under a certain tensile͑hydrostatic͒stress state,and the motion of the particles become unstable.To identify the cul-prit,a von Neumann stability analysis was carried out by Swegle et al͓150͔,and by Balsara͓158͔.Swegle and his co-workers have identified and explained the source of the tensile instability.Recently,by using von Neumann and Cou-rant stability criterion,Belytschko et al͓151͔revisited the problem in the general framework of meshfree particle meth-ods.In their analysis,finite deformation effects are also con-sidered.Several remedies have been proposed to avoid such ten-sile instability.Morris proposed using special kernel func-tions.While successful in some cases,they do not always yield satisfactory results͓152͔.Randles and Libersky͓120͔proposed adding dissipative terms,which is related to con-servative smoothing.Notably,Dyka et al͓153,154͔proposed a so-called stress point method.The essential idea of this approach is to add additional points other than SPH particles when evaluating,or sampling,stress and other state vari-ables.Whereas the kinematic variables such as displacement,velocity,and acceleration are still sampled at particle points.In fact,the stress point plays a similar role as the‘‘Gaussquadrature point’’does in the numerical integration of theGalerkin weak form.This analogy wasfirst pointed out byLiu et al͓66͔.This problem was revisited again recently byChen et al͓159͔as well as Monaghan͓148͔.The formerproposes a special corrective smoothed-particle method ͑CSPM͒to address the tensile instability problem by enforc-ing the higher order consistency,and the latter proposes toadd an artificial force to stabilize the computation.Randlesand Libersky͓160͔combined normalization with the usualstress point approach to achieve better stability as well aslinear consistency.Apparently,the SPH tensile instability isrelated to the lack of consistency of the SPH interpolant.A2D stress point deployment is shown in Fig.2.2.2.2Zero-energy modeThe zero energy mode has been discovered in bothfinitedifference andfinite element computations.A comprehensivediscussion of the subject can be found in the book by Be-lytschko et al͓5͔.The reason that SPH suffers similar zeroenergy mode deficiency is due to the fact that the derivativesof kinematic variables are evaluated at particle points by ana-lytical differentiation rather than by differentiation of inter-polants.In many cases,the kernel function reaches a maxi-mum at its nodal position,and its spatial derivatives becomezero.To avoid a zero-energy mode,or spurious stress oscil-lation,an efficient remedy is to adopt the stress point ap-proach͓157͔.2.2.3Corrective SPHAs an interpolation among moving particles,SPH is not apartition of unity,which means that SPH interpolants cannotrepresent rigid body motion correctly.This problem wasfirstnoticed by Liu et al͓64–66͔.They then set forth a key no-tion,a correction function,which has become the centraltheme of the so-called corrective SPH.The idea of a correc-tive SPH is to construct a corrective kernel,a product of thecorrection function with the original kernel.By doing so,theconsistency,or completeness,of the SPH interpolant can beenforced.This new interpolant is named the reproducing ker-nel particle method͓64–66͔.SPH kernel functions satisfy zero-th order moment condi-tion͑5͒.Most kernel functions satisfy higher order momentcondition as well͓104͔,for instance͵R xW͑x,h͒dxϭ0.(8)These conditions only hold in the continuous form.In gen-eral they are not valid after discretization,ie͚Iϭ1NPW͑xϪx I,h͒⌬x I 1(9)͚Iϭ1NP͑xϪx I͒W͑xϪx I,h͒⌬x I 0(10)where NP is the total number of the particles.Note that con-dition͑9͒is the condition of partition of unity.Sincethe Fig.2A2D Stress point distribution4Li and Liu:Meshfree and particle methods and applications Appl Mech Rev vol55,no1,January2002kernel function can not satisfy the discrete moment condi-tions,a modified kernel function is introduced to enforce the discrete consistency conditionsW˜h ͑x Ϫx I ;x ͒ϭC h ͑x Ϫx I ;x ͒W ͑x Ϫx I ,h ͒(11)where C h (x ;x Ϫx I )is the correction function,which can be expressed asC h ͑x ;x Ϫx I ͒ϭb 0͑x ,h ͒ϩb 1͑x ,h ͒x Ϫx Ihϩb 2͑x ,h ͒ϫͩx Ϫx I hͪ2ϩ¯¯(12)where b 0(x ),b 1(x ),¯.,b n (x )are unknown functions.Wecan determine them to correct the original kernel function.Suppose f (x )is a sufficiently smooth function.By Taylor expansion,f I ϭf ͑x I ͒ϭf ͑x ͒ϩf Ј͑x ͒ͩx I Ϫxhͪh ϩf Љ͑x ͒2!ͩx I Ϫx hͪ2h 2ϩ¯¯(13)the modified kernel approximation can be written as,f h ͑x ͒ϭ͚I ϭ1NPW˜h ͑x Ϫx I ;x ͒f I ⌬x I ϭ͚ͩI ϭ1NP W˜h ͑x Ϫx I ,x ͒⌬x I ͪf ͑x ͒h 0Ϫ͚ͩI ϭ1NP ͩx Ϫx IhͪW ˜h ͑x Ϫx I ,x ͒⌬x I ͪf Ј͑x ͒h ϩ¯¯ϩ͚ͩI ϭ1NP ͑Ϫ1͒nͩx Ϫx I hͪnW˜h ϫ͑x Ϫx I ,x ͒⌬x Iͪf n ͑x ͒n !h nϩO ͑h n ϩ1͒.(14)To obtain an n -th order reproducing condition,the moments of the modified kernel function must satisfy the following conditions:M 0͑x ͒ϭ͚I ϭ1NPW ˜h ͑x Ϫx I ,x ͒⌬x I ϭ1;M 1͑x ͒ϭ͚I ϭ1NPͩx Ϫx IhͪW ˜h ͑x Ϫx I ,x ͒⌬x I ϭ0;ӇM n ͑x ͒ϭ͚I ϭ1NPͩx Ϫx IhͪnW˜h ͑x Ϫx I ,x ͒⌬x I ϭ0;·(15)Substituting the modified kernel expressions,͑11͒and ͑12͒into Eq.͑15͒,we can determine the n ϩ1coefficients,b i (x ),by solving the following moment equations :ͩm 0͑x ͒m 1͑x ͒¯m n ͑x ͒m 1͑x ͒m 2͑x ͒¯m n ϩ1͑x ͒ӇӇӇӇm n ͑x ͒m n ϩ1͑x ͒¯m 2n ͑x ͒ͪͩb 0͑x ,h ͒b 1͑x ,h ͒Ӈb n ͑x ,h ͒ͪϭͩ10Ӈ0ͪ(16)It is worth mentioning that after introducing the correction function,the modified kernel function may not be a positive function anymore,K ͑x Ϫx I ͒у”0.(17)Within the compact support,K (x Ϫx I )may become negative.This is the reason why Duarte and Oden refer to it as the signed partition of unity ͓73,74,76͔.There are other approaches to restoring completeness of the SPH approximation.Their emphases are not only consis-tency,but also on cost ing RKPM,or a moving-least-squares interpolant ͓155,156͔to construct modified kernels,one has to know all the neighboring par-ticles that are adjacent to a spatial point where the kernel function is in evaluation.This will require an additional CPU to search,update the connectivity array,and calculate the modified kernel function pointwise.It should be noted that the calculation of the modified kernel function requires pointwise matrix inversions at each time step,since particles are moving and the connectivity map is changing as well.Thus,using a moving least square interpolant as the kernel function may not be cost-effective,and it destroys the sim-plicity of SPH formulation.Several compromises have been proposed throughout the years,which are listed as follows:1͒Monaghan’s symmetrization on derivative approximation ͓104,145͔;2͒Johnson-Beissel correction ͓123͔;3͒Randles-Libersky correction ͓120͔;4͒Krongauz-Belytschko correction ͓61͔;5͒Chen-Beraun correction ͓139,140,161͔;6͒Bonet-Kulasegaram integration correction ͓118͔;7͒Aluru’s collocation RKPM ͓96͔.Since the linear reproducing condition in the interpolation is equivalent to the constant reproducing condition in the de-rivative of the interpolant,some of the algorithms directly correct derivatives instead of the interpolant.The Chen-Beraun correction corrects even higher order derivatives,but it may require more computational effort in multi-dimensions.Completeness,or consistency,closely relates to conver-gence.There are two types of error estimates:interpolation error and the error between exact solution and the numerical solution.The former usually dictates the latter.In conven-tional SPH formulations,there is no requirement for the completeness of interpolation.The particle distribution is as-sumed to be randomly distributed and the summations areAppl Mech Rev vol 55,no 1,January 2002Li and Liu:Meshfree and particle methods and applications5Monte Carlo estimates of integral interpolants.The error of random interpolation wasfirst estimated by Niedereiter͓162͔as beingϰNϪ1log N nϪ1where N is total particle number and n is the dimension of space.This result was further improved by Wozniakowski͓163͔as beingϰNϪ1log N nϪ1/2.Accord-ing to reference͓104͔,‘‘this remarkable result was produced by a challenge with a payoff of sixty-four dollars!’’Twenty-one years after its invention,in1998Di Lisio et al͓164͔gave a convergence proof of smoothed particle hydrodynam-ics method for regularized Eulerflow equations.Besides consistency conditions,the conservation proper-ties of a SPH formulation also strongly influence its perfor-mance.This has been a critical theme throughout SPH re-search,see͓12,104,120,145,155,165͔.It is well known that classical SPH enjoys Galilean invariance,and if certain de-rivative approximations,or Golden rules as Monaghan puts it,are chosen,the corresponding SPH formulations can pre-serve some discrete conservation laws.This issue was re-cently revisited by Bonet et al͓166͔,and they set forth a discrete variational SPH formulation,which can automati-cally satisfy the balance of linear momentum and balance of angular momentum conservation laws.Here is the basic idea. Assume the discrete potential energy in a SPH system is ⌸͑x͒ϭ͚I V I0U͑J I͒(18) where V I0is the initial volume element,and U(J I)is the internal energy density,which is assumed to be the function of determinant of the Jacobian—ratio between the initial and current volume element,JϭV IV I0ϭI0I(19)whereI0andI are pointwise density in initial configuration and in current configuration.For adiabatic processes,the pressure can be obtained from ץU I/ץJϭp I.Thus,the stationary condition of potential en-ergy gives␦⌸ϭD⌸͓␦v͔ϭ͚I V I0DU I͓␦v͔ϭ͚I͚ͭJ m I m Jͩp II2ϩp JJ2ٌͪW I͑x J͒ͮ␦v I(20)where m I is the mass associated with particle I.On the other hand,D⌸͓␦v͔ϭ͚Iץ⌸ץx I␦v Iϭ͚I T I•␦v I(21)where T is the internal force͑summation of stress͒.Then through the variational principle,one can identify,T Iϭ͚I m I m Jͩp II2ϩp JJ2ٌͪW I͑x J͒(22)and establish the discrete SPH equation of motion͑balance of linear momentum͒,m Id v IdtϭϪ͚I m I m Jͩp II2ϩp JJ2ٌͪW I͑x J͒.(23)2.2.4Boundary conditionsSPH,and in fact particle methods in general,have difficulties in enforcing essential boundary condition.For SPH,some effort has been devoted to address the issue.Takeda’s image particle method͓131͔is designed to satisfy the no-slip boundary condition;it is further generalized by Morris et al ͓128͔to satisfy boundary conditions along a curved bound-ary.Based on the same philosophy,Randles and Libersky ͓120͔proposed a so-called ghost particle approach,which is outlined as follows:Suppose particle i is a boundary particle. All the other particles within its support,N(i),can be di-vided into three subsets:1͒I(i):all the interior points that are the neighbors of i;2͒B(i):all the boundary points that are the neighbors of i; 3͒G(i):all the exterior points that are the neighbors of i,ie, all the ghost particles.Therefore N(i)ϭI(i)ഫB(i)ഫG(i).Figure3illustrates such an arrangement.In the ghost particle approach,the boundary correction formula for general scalarfield f is given as followsf iϭf bcϩ͚jI…i…͑f jϪf bc͒⌬V j W i jͩ1Ϫ͚jB…i…⌬V j W i jͪ(24)where f bc is the prescribed boundary value at xϭx i.One of the advantages of the above formula is that the sampling formula only depends on interior particles.2.3Other related issues and applicationsBesides resolving the above fundamental issues,there have been some other progresses in improving the performance of SPH,which have focused on applications as well as algorith-mic efficiency.How to choose an interpolation kernel to en-sure successful simulations is discussed in͓167͔;how to modify the kernel functions without correction isdiscussed Fig.3The Ghost particle approach for boundary treatment6Li and Liu:Meshfree and particle methods and applications Appl Mech Rev vol55,no1,January2002。

Undefined

01

Introduction

Background of the report

The report was commissioned to investigate a specific issue or problem

It provides an overview of the current situation and identifies key trends and

05

Suggested undefined coping strategies

Government level response strategies

03

Exploration of undefined solutions

Plan 1: Improve laws and regulations

Establish comprehensive laws and regulations

Develop comprehensive laws and regulations to define and regulate undefined behaviors, covering various aspects such as data privacy, cybersecurity, and AI ethics

In mathematics, undefined values may vary from division by zero, taking the logarithm of a negative number, or other operations that are not defined for central inputs

开启片剂完整性的窗户(中英文对照)

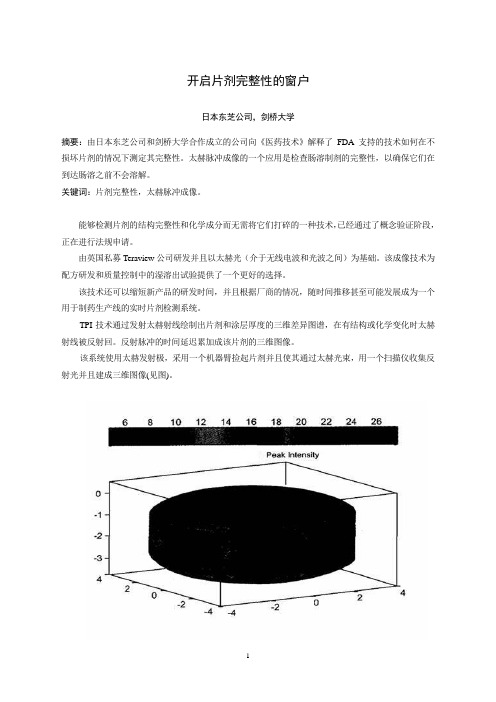

开启片剂完整性的窗户日本东芝公司,剑桥大学摘要:由日本东芝公司和剑桥大学合作成立的公司向《医药技术》解释了FDA支持的技术如何在不损坏片剂的情况下测定其完整性。

太赫脉冲成像的一个应用是检查肠溶制剂的完整性,以确保它们在到达肠溶之前不会溶解。

关键词:片剂完整性,太赫脉冲成像。

能够检测片剂的结构完整性和化学成分而无需将它们打碎的一种技术,已经通过了概念验证阶段,正在进行法规申请。

由英国私募Teraview公司研发并且以太赫光(介于无线电波和光波之间)为基础。

该成像技术为配方研发和质量控制中的湿溶出试验提供了一个更好的选择。

该技术还可以缩短新产品的研发时间,并且根据厂商的情况,随时间推移甚至可能发展成为一个用于制药生产线的实时片剂检测系统。

TPI技术通过发射太赫射线绘制出片剂和涂层厚度的三维差异图谱,在有结构或化学变化时太赫射线被反射回。

反射脉冲的时间延迟累加成该片剂的三维图像。

该系统使用太赫发射极,采用一个机器臂捡起片剂并且使其通过太赫光束,用一个扫描仪收集反射光并且建成三维图像(见图)。

技术研发太赫技术发源于二十世纪九十年代中期13本东芝公司位于英国的东芝欧洲研究中心,该中心与剑桥大学的物理学系有着密切的联系。

日本东芝公司当时正在研究新一代的半导体,研究的副产品是发现了这些半导体实际上是太赫光非常好的发射源和检测器。

二十世纪九十年代后期,日本东芝公司授权研究小组寻求该技术可能的应用,包括成像和化学传感光谱学,并与葛兰素史克和辉瑞以及其它公司建立了关系,以探讨其在制药业的应用。

虽然早期的结果表明该技术有前景,但日本东芝公司却不愿深入研究下去,原因是此应用与日本东芝公司在消费电子行业的任何业务兴趣都没有交叉。

这一决定的结果是研究中心的首席执行官DonArnone和剑桥桥大学物理学系的教授Michael Pepper先生于2001年成立了Teraview公司一作为研究中心的子公司。

TPI imaga 2000是第一个商品化太赫成像系统,该系统经优化用于成品片剂及其核心完整性和性能的无破坏检测。

Topological Hunds rules and the electronic properties of a triple lateral quantum dot molec