susan_bassnett

《西方翻译理论名著选读》 目录

刘军平、覃江华编著的《西方翻译理论名著选读》在皇皇卷帙的西方翻译理论的各种原典中,精选了52篇西方翻译理论家的代表性译论,“弱水三千我只取一瓢饮”,每位翻译理论家撷取的是最具代表性或最有影响的文章或代表作片段。

本书编排内容的时间顺序跨越古代、现代和当代,并按照西方翻译理论的发展特征和不同译论家的理论特色分为九大翻译理论流派,即语文学派、语言学派、功能学派、认知学派、描写学派、文化学派、后殖民及女性主义学派、哲学学派和中西比较诗学派。

全书基本按照这几大流派的思想背景和发展历程进行整理。

目录第一章语文学派圣·奥古斯丁(St.Augustine)/1The Use of Translations/2艾蒂安·多雷(Etienne Dolet)/10The Way to Translate Well from One Language into Another/10约翰·德莱顿(John Dryden)/14The Three Types of Translation/15亚历山大·弗雷泽·泰特勒(Alexander Fraser Tytler)/23The Proper Task of a Translator/24马修·阿诺德(Matthew Arnold)/30The Translator's Tribunal/3 1弗朗西斯·威廉·纽曼(Francis William Newman)/41The Unlearned Public Is the Rightful Judge of Taste/42第二章语言学派罗曼·雅各布逊(Roman Jakobson)/46On Linguistic Aspects of Translation/47约翰·坎尼森·卡特福德(John Cunnison Catford)/54 Translation Shifts/55尤金·阿尔伯特·奈达(Eugene Albert Nida)/63Principles of Correspondence/64彼得·纽马克(Peter Newmark)/81Communicative and Semantic Translation/82奥伯利奇·纽伯特(Albrecht Neubert)/101Translation,Text,Translation Studies/102巴兹尔·哈蒂姆和伊恩·梅森(Basil Hatim&Ian Mason)/130 Pofiteness in Screen Translating/131第三章功能学派卡特琳娜·赖斯(Katharina Reiss)/149Type, Kind and Individuality of Text:Decision-making in Translation/150汉斯·约瑟夫·弗米尔(Hans Josef Vermeer)/163Skopos and Commission in Translational Action/164克里斯蒂安·诺德(Christiane Nord)/178A Functional Typology of Translations/179第四章认知学派厄恩斯特-奥古斯特·格特(Ernst-August Gutt)/202 Translation and Relevance/203罗杰·贝尔(Roger T.Bell)/225Translating,the Model/226丹尼·吉尔(Daniel Gile)/242The Effort Models in Interpretation/243第五章描写学派詹姆斯·斯特拉顿·霍姆斯(James Stratton Holmes)/268The Name and Nature ofTranslation Studies/269伊塔玛·埃文-佐哈尔(Itamar Even-Zohar)/282The Position of Translated Literature within the Literary Polysystem/283吉迪恩·图里(Gideon Toury)/289The Nature and Role of Norms in Translation/290莫娜·贝克(Mona Baker)/306Narratives in and of Translation/307安德鲁·切斯特曼(Andrew Chesterman)/318Memes of Translation/3 19西奥·赫曼斯(Theo Hermans)/332Translation's Other/333第六章文化学派安德烈·勒费弗尔(Andre Lefevere)/353Mother Courage's Cucumbers:Text,System and Refraction in a Theory of Literature/354苏珊·巴斯内特(Susan Bassnett)/375The Translation Turn in Cultural Studies/376劳伦斯·韦努蒂(Lawrence Venuti)/392The Formation of Cultural Identities/393埃德温·根茨勒(Edwin Gentzler)/415Translation,Poststructuralism,and Power/416迈克尔·克罗宁(Michael Cronin)/436History,Translation,Postcolonialism/437霍米·巴巴(Homi Bhabha)/454How Newness Enters the World:Postmodern Space, Postcolonial Times and the ri ftals of Cuhural Translation/455第七章后殖民及女性主义学派加亚特里·查克拉沃蒂·斯皮瓦克(Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak)/482The Politics of Translation/483道格拉斯·罗宾逊(Douglas Robinson)/507Posteolonial Studies, Translation Studies/508玛丽亚·铁木志科(Mafia Tymoczko)/528Translations of Themselves: the Contours of Postcolonial Fiction/529罗莉·张伯伦(Lori Chamberlain)/543Gender and the Metaphorics of Translation/544露易丝·冯·弗洛托(Luise yon Flotow)/562Gender and the Practice of Translation/563雪莉·西蒙(Sherry Simon)/582Taking Gendered Positions in Translation Theory/583第八章哲学学派弗里德里希·施莱尔马赫(Friedrich Schleiermacher)/610On the Different Methods of Translating/611弗里德里希·威廉·尼采(Friedfieh Wilhelm Nietzsche)/635 Translation as Conquest/636瓦尔特·本雅明(Walter Benjamin)/638The Task of the Translator/639雅克·德里达(Jacques Derrida)/649Des Tours de Babel/650威拉德·冯·奥曼·奎因(Willard Van Orman Quine)/682 Meaning and Translation/683汉斯-格奥尔格·伽达默尔(Hans—Georg Gadamer)/704 Language as the Medium of Hermeneutic Experience/705 乔治·斯坦纳(George Steiner)/725The Hermeneutie Motion/726保罗·利科(Paul Ricoeur)/732The Paradigm of TrarMation/733安东尼·皮姆(Anthony Pyrn)/746Translation Studies avd Western Philosophy/747第九章中西比较诗学派刘若愚(James J.Y.Liu)/767The Critic as Translator/768叶维廉(Wai—lim Yip)/781Ezra Pound's Cathay/782欧阳桢(Eugene Chen Eqyang)/807“Aaifices of Eternity”:Audiences for Translations of Chinese Literature/808宇文所安(Stephen Owen)/822A Note on Translation/823厄内斯特·弗朗西斯科·费诺罗萨(Ernest Francisco Fenollosa)/830The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry/831 马悦然(Gfiran Malmqvist)/851On the R01e of the Translator/852葛浩文(Howard Goldblatt)/862Why I Hate Arthur Waley?Translating Chinese in aPost-Victorian Era/863参考文献。

关于巴斯奈特的介绍

关于巴斯奈特的介绍-社会科学论文关于巴斯奈特的介绍张莉苹(沈阳师范大学,辽宁沈阳110031)摘要:通过对巴斯奈特的“文化翻译观”进行了全面的介绍,目的是更深入地认识和理解该翻译理论,更加符合当代的翻译标准。

巴斯奈特的“文化翻译观”顺应全球经济一体化和文化多元化的潮流,因此在以后的翻译实践中具有重要的作用。

关键词:巴斯奈特;文化翻译观;介绍中图分类号:H059 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1673—2596(2015) 08—0238—02一、文化翻译观产生的历史随着全球科学研究关于人类中心范式”的树立与翻译理论研究中文化学派的崛起,翻译的文化价值观便逐步成为了翻译研究关注的重点之一。

苏珊·巴斯奈特(Susan Bassnett)是英国沃瑞克大学比较文学理论和翻译研究生院的教授、诗人、翻译家、和文学家。

作为翻译文化学派的代表人物之一,她的文化翻译观”对当代翻译研究和翻译实践都产生重大影响。

巴斯奈特在1980年出版了以《翻译研究》直接命名的专著,以回应翻译研究学派”创始人、荷兰著名翻译理论家霍尔姆斯提出的建立翻译研究独立学科的倡议。

在这本著作中,巴斯奈特勾勒了翻译研究的学科框架,回顾了翻译研宄已经取得的成绩,并为翻译研究未来的发展方向提出了建议。

《翻译研究》分别于1991年和2002年两次修订,并多次再版,现己成为翻译研究领域的重要文献。

1990年,巴斯奈特和美籍比利时学者勒菲弗尔(Andre Lefevere)编撰并出版了《翻译、历史与文化》论文集。

其中的《翻译研究》是巴斯奈特的代表性作品,此书在其出版的30多年内,逐渐成为了世界翻译研究者的必读书目。

20世纪20年代至60年代,语言学家们从语义学、描写语言学、符号学、以及应用语言学等方向来分析解释翻译问题,试图从语言学的角度找到解决翻译问题的方法。

语言学家们尝试把语言切分成许多基本的组成部分,来确定最基本的翻译单位。

从他们的视角来看,如果找到了语言和语言之间基本翻译单位的等值方法,就完全可以解决不同语言之间的翻译问题,在文化翻译学派诞生之前,西方翻译理论研究领域占统治地位的是语言派、功能学派和结构主义学派。

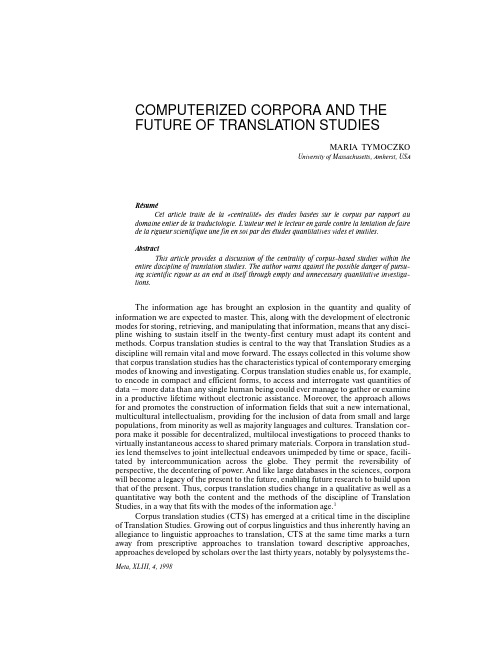

Computerized Corpora and the Future of Translation Studies

COMPUTERIZED CORPORA AND THEFUTURE OF TRANSLATION STUDIESMARIA TYMOCZKOUniversity of Massachusetts, Amherst, USARésuméCet article traite de la «centralité» des études basées sur le corpus par rapport au domaine entier de la traductologie. L'auteur met le lecteur en garde contre la tentation de faire de la rigueur scientifique une fin en soi par des études quantitatives vides et inutiles.AbstractThis article provides a discussion of the centrality of corpus-based studies within the entire discipline of translation studies. The author warns against the possible danger of pursu-ing scientific rigour as an end in itself through empty and unnecessary quantitative investiga-tions.The information age has brought an explosion in the quantity and quality of information we are expected to master. This, along with the development of electronic modes for storing, retrieving, and manipulating that information, means that any disci-pline wishing to sustain itself in the twenty-first century must adapt its content and methods. Corpus translation studies is central to the way that Translation Studies as a discipline will remain vital and move forward. The essays collected in this volume show that corpus translation studies has the characteristics typical of contemporary emerging modes of knowing and investigating. Corpus translation studies enable us, for example, to encode in compact and efficient forms, to access and interrogate vast quantities of data — more data than any single human being could ever manage to gather or examine in a productive lifetime without electronic assistance. Moreover, the approach allows for and promotes the construction of information fields that suit a new international, multicultural intellectualism, providing for the inclusion of data from small and large populations, from minority as well as majority languages and cultures. Translation cor-pora make it possible for decentralized, multilocal investigations to proceed thanks to virtually instantaneous access to shared primary materials. Corpora in translation stud-ies lend themselves to joint intellectual endeavors unimpeded by time or space, facili-tated by intercommunication across the globe. They permit the reversibility of perspective, the decentering of power. And like large databases in the sciences, corpora will become a legacy of the present to the future, enabling future research to build upon that of the present. Thus, corpus translation studies change in a qualitative as well as a quantitative way both the content and the methods of the discipline of Translation Studies, in a way that fits with the modes of the information age.1Corpus translation studies (CTS) has emerged at a critical time in the discipline of Translation Studies. Growing out of corpus linguistics and thus inherently having an allegiance to linguistic approaches to translation, CTS at the same time marks a turn away from prescriptive approaches to translation toward descriptive approaches, approaches developed by scholars over the last thirty years, notably by polysystems the-Meta, XLIII, 4, 19982Meta, XLIII, 4, 1998 orists such as Itamar Even-Zohar, Gideon Toury, and André Lefevere. CTS focuses on both the process of translation and the product of translation (cf. Holmes 1988: 67; Bassnett 1991: 7), and takes into account the smallest details of the text chosen by the individual translator, as well as the largest cultural patterns both internal and external to the text. It builds upon the studies of scholars working in the descriptive approach to Translation Studies, and those of scholars who have worked with corpora themselves, albeit corpora that have been manually assembled, examined, and analyzed.2 The essays collected here illustrate that, although the materials of corpora are based upon the language medium of translations, interrogation of corpora can nonetheless serve to address not simply questions of language or linguistics, but also questions of culture, ideology, and literary criticism. Modes of interrogation — as well as care in the encod-ing of metatextual information about translations and texts — allow researchers to move from text-based questions to context-based questions. The flexibility and adapt-ability of corpora, as well as the openendedness of the construction of corpora underlie the strength of the approach.Inevitably, as is to be expected, the debates of Translation Studies as a whole are mirrored in CTS. For some CTS writers, the notion of "a tertium comparationis" is central, for others the concept has implicitly been superseded (cf. Snell-Hornby 1990). Some writers see norms as one of the most pressing factors to be investigated, while for others the question of norms plays little or no role. Equivalence — a concept that to Jacobson (1959: 233) was "the cardinal problem of language and the pivotal concern of linguistics", but that more recently has fallen into discredit (Snell-Hornby 1988: 13; Van den Broeck 1978) — is still an important part of their discourse for some CTS scholars. The relationship of interpretation to Translation Studies, both theoretically and pragmatically, is addressed within CTS as it is elsewhere in the discipline. The types of literary questions addressed by the "manipulation" school of Translation Stud-ies (see Hermans 1985; cf. Snell-Hornby 1988: 22) motivate some CTS investigations, while literature as such is excluded from other corpora altogether and hence from research done with those corpora. For some CTS investigations, literary texts are seen as optimal, offering the most comprehensive information, while for others literary texts are seen as unrepresentative of natural language. The tendency toward segmentation of pedagogic, pragmatic, and theoretical studies is found in CTS, as it is in Translation Studies and intellectual endeavors altogether.One of the most important debates in intellectual domains has to do with the search for laws, both practical and theoretical. This debate is also conducted in Trans-lation Studies and mirrored in CTS. The interest in laws — promoted in Translation Studies by Even-Zohar and Toury, among others — follows the tradition of empirical research, behind which lies the presupposition of Western rationalism that science should be in the business of discovering natural laws and that "scientific" results have more value than others. In part a legacy of positivism, these predispositions are inti-mately connected with a tendency to polarize objectivity vs. subjectivity and privilege the former. A number of CTS scholars promote and justify corpus-based approaches on the grounds that such studies will uncover and establish universal laws of translation.By contrast, throughout the twentieth century the foundations of such objectivist research were repeatedly called into question. From the work of Einstein and Gödel and Heisenberg in physics and mathematics during the earliest decades of the twentieth century, to mid-century reconsiderations of objectivist premises about literature and history, to still later explorations of subjectivity in the social sciences, modern thought has increasingly come to understand the way that the perspective of the observer or the researcher is encoded in every investigation and impinges upon the object and theCOMPUTERIZED CORPORA AND THE FUTURE OF TRANSLATION STUDIES3 results of study. Such challenges to empiricist claims about objectivity and such asser-tions of subjectivity — and the large intellectual trajectory behind them — are echoed in some of the approaches represented in this collection and are germane to the devel-opment of CTS.In my view, the value of corpora in translation and of a CTS approach to transla-tion theory and practice does not rest on the claim to "objectivity" and the somewhat worn philosophical tradition claims of this type presuppose. Indeed, as a number of the authors here remind us, behind the establishment of corpora, as behind the design of any experiment or research program or survey, lie intuition and human judgement. Corpora in translation studies are products of human minds, of actual human beings, and, thus, inevitably reflect the views, presuppositions, and limitations of those human beings. Moreover, the scholars designing studies utilizing corpora are people operating in a particular time and place, working within a specific ideological and intellectual context. Thus, as with any scientific or humanistic area of research, the questions asked in CTS will inevitably determine the results obtained and the structure of the databases will determine what conclusions can be drawn. In that sense then, corpora are again to be seen as products of human sensibility, connected with human interests and self-interests.All the more reason, therefore, to consider the objects of study, the data gathered in the databases, and the parameters defining the corpora themselves very carefully. Central to this concern is the definition of translation, as Sandra Halverson argues. The nature and definition of the category "translation" have been notoriously contentious within the discourses of translation theory and practice. One man's translation is another man's adaptation. The favorite translations of one era are repudiated altogether by another. Like the category game discussed by Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Inves-tigations, there is no simple core identity for the cluster of objects identified as transla-tions by the many societies of human time and space. Rather, translations like games form a category linked by many partial and overlapping "family resemblances", as Wit-tgenstein called such commonalities. Ultimately the inability to define translation within bounded and finite characteristics and still include in the definition all the objects that human societies have identified as translations3 led Toury to define transla-tion in a pragmatic way as "any target language text which is presented or regarded as such within the target system itself, on whatever grounds" (Toury 1982: 27; cf. Toury 1980: 14, 37, 43-45). The family resemblances linking translations, like those linking games, have depended on the manifold factors of human culture, including, for exam-ple, characteristics of the culture's language, the conditions of "text" production, the role (if any) of literacy, the material culture, economics, social customs, social hierar-chies, values, and so forth. In the case of translation, moreover, the processes and prod-ucts of translation will be correlated not simply with the conditions of one culture, but with those of at least two cultures in interface. It is the very variety of human cultures that leads to the variety of translations and games, and it is that variety that prevents us both pragmatically and theoretically from drawing a neat line, as in classical set theory, around the category translation.4Although the theory of prototypes may ultimately offer some help in understand-ing how human beings learn and recognize and remember categories, including cluster concepts such as those of game and translation linked by loose family resemblances, prototypes do not necessarily offer a solution to the theoretical problem of constructing corpora that can be interrogated to reveal translation laws, should a scholar undertake such an exercise. Contrary to Halverson, I take the view that prototypes — including the proposed prototype of the professional translator5 — are themselves culturally4Meta, XLIII, 4, 1998 defined and culture bound, rather than universal. As Eleanor Rosch, the pioneer in prototype research, specifically stipulates, the theory of prototypes is intended to address issues in categorization that "have to do with explaining the categories found ina culture and coded by the language of that culture at a particular point in time" (1978:28); moreover, she acknowledges that "many categories may be culturally relative" (1975: 193). Thus, a prototype is hardly the point of departure for a search for general or universal laws of translation, for one would then immediately have to ask compro-mising questions about the results. For example, what language, what place, and what time were privileged in the selection of the prototype? Our own? If so, we consign our theoretical work to hopeless ethnocentrism and so doom it from the outset.To take as an analogue the well-discussed category chair, although we might dis-cover on the basis of research done with contemporary American subjects that the pro-totype of chair is a wooden, four-legged desk chair, the modern prototype is not necessarily a guide to the prototypical chair of other times and other cultures. In the case of chair, for example, there is good reason to believe that in the Renaissance and earlier, the prototypical chair would have been very different from the configuration of the modern prototype. In view of material evidence from the period, the prototype would perhaps have been a three-legged apurtenance, with a triangular seat and a rela-tively small back, chairs such as are common from the Renaissance period and earlier. Four-legged chairs are only practical if floors are level, whereas three-legged chairs, like three-legged stools, are more useful, more common, and, thus, presumably, more prototypical in cultures where floors are made of mud or uneven paving stones, as floors were in most houses in pre-modern conditions. Indeed such three-legged stools and chairs — if chairs and stools are used at all — continue to be the norm (and, hence, probably the prototype) in most peasant cultures today.The problems of beginning with a prototype in a search for general laws governing a cluster concept like translation are even more complex than those posed by implicit ethnocentrism. In the case of the would-be prototype of the professional translator sug-gested by Halverson, for example, we might go on to ask how one defines or picks out a professional translator now, leaving aside the question of the past or other cultures. Is a professional translator a translator trained in a translation school or program? (Even if that person never works as a translator or never is paid for translation?) At what point does the non-professional student translator make the transition to professional? (If a student translator publishes a translation, is that piece by a professional?) Or is a pro-fessional translator a translator whose work has been published or otherwise remuner-ated — hence an a posteriori determination which will include in many cases amateur translators who have "made good" or "become successful"? If one could resolve ques-tions such as these to the satisfaction of all, the question would still remain as to when the prototypical translator is translating prototypically, i.e. under what conditions pro-fessional translation is deemed to exist or to have taken place. Thus, are all translations of a professional translator prototypical, or only those produced in some stipulated professional context? Moreover, are all types of texts translated by a professional trans-lator prototypical, or only a limited subset? And so forth. The recursive nature of the stipulation required for defining a prototype in the case of the concept like translation illustrates the difficulty that follows from using prototypes as a foundation for the search for general laws of translation.Such issues can also be illustrated by questions related to Wittgenstein's category of game. What is the prototype of game in the modern period? The prototype of an abstract cluster concept like game is much harder to establish than that of a material category like chair.6 There may in fact not be any example of game that functions as aCOMPUTERIZED CORPORA AND THE FUTURE OF TRANSLATION STUDIES5 prototype for an entire culture as complex and differentiated as contemporary Western cultures are. It may be that there are several competing prototypes of game, each partic-ular to a specific subculture, for example, football, tennis, cards, video, and so forth. And again, as with categories like chair, a conceptual category like game or translation also changes through time. One might surmise, for example, on the basis of textual, artistic, and archaelogical evidence, that the prototypical game for many people in medieval France was dice gaming — a pastime that is currently unlikely to be prototyp-ical of game for very many people, if for anyone, in Europe or America. And once more the problem of establishing a prototype becomes recursive, for even if one could make allowances in research for multiple as well as ethnically decentered prototypes — say dice gaming as the medieval European prototype of game — what are the prototypes that are themselves in turn presupposed by the typical instance of game at any one cul-tural locus? In the case of the example under discussion, one should then ask, for instance, what is the prototype of dice. Almost invariably for a modern informant the term will suggest a pair of cubical objects (although other types of dice exist, as any player of Dungeons and Dragons can testify), while in medieval Europe oblong dice, made of bone and used in threes, were much more common and, thus, presumably more prototypical.These are some of the difficulties with basing the construction of translation cor-pora on a theory of prototypes. As Halverson proposes, translation corpora based on modern Western "prototypes" might be developed and interrogated so as to reveal gen-eral characteristics of contemporary translations done in circumstances and cultural settings congruent with the examples underlying the corpora. Such corpora will be enormously useful and valuable, but they will not yield general laws of translation applying to all times and all places and all languages. To discover general laws of trans-lation, if indeed such laws exist, a question that Wittgenstein's arguments about catego-ries should lead us to consider very seriously, at the very least what will be needed are corpora representing as many types of translations as are known from the whole of human history.7 It may be, however, that such a quest is a positivist chimera, the com-monalities so restricted for a category like translation that the effort is unlikely to pro-vide the field of Translation Studies with much information of lasting value or transferable worth and, therefore, would not be worth the effort.If the primary purpose of CTS is neither to be objective nor to uncover universal laws, what is the specific strength of descriptive studies of translation facilitated by computerized corpora that can be electronically searched and manipulated? Over and over again the essays collected in this volume speak to this question, offering many divergent and exciting new directions for Translation Studies. The multiple possibilities that can be foreseen even at this embryonic stage of CTS are welcome, suggesting that corpus translation studies will be an open rather than a convergent approach to the the-ory and practice of translation. One can project the construction of many different cor-pora for specialized, multifarious purposes, making room for the interests, inquiries, and perspectives of a diverse world.Comparison is always implicit or explicit in inquiries about translation, and there is often a tendency to focus on likeness rather than difference and to rest content with perceptions of similarity. Whether focused on linguistic or literary or cultural matters, comparative disciplines — among which Translation Studies takes its place (cf. Bassnett 1993) — all have a predilection for focusing on similarity or sameness, as Dwight Bolinger, writing about linguistic studies, observes (1977: 5):Always one's first impulse, on encountering two highly similar things, is to ignore their differences in order to get them into a system of relationships where they can be stored,6Meta, XLIII, 4, 1998 retrieved, and otherwise made manageable. The sin consists in stopping there. And also in creating an apparatus that depends on the signs of absolute equality and absolute inequality, and uses the latter only when the unlikeness that it represents is so gross that it bowls you over.This impulse, which partly drives the interest in laws of translation, could be a projection of the development of a narrow form of CTS, particularly at the beginning of the exploration of this approach to corpora of translations. Bolinger correctly sounds a cautionary note: like Translation Studies as a whole, CTS must find ways to move beyond systems of relationship that focus on likeness and to avoid being locked into a binary apparatus that acknowledges only perceptions of absolute equality and inequal-ity.One reason that CTS is likely to avoid the pitfall of fixation on similarity and remain open to difference, differentiation, and particularity, is the sheer variety in nat-ural languages themselves and the multiplicity of theoretical and practical conse-quences resulting from the manifold language pairings possible in translation. This "infinite variety", which CTS is more able to apprehend and include in its purview than traditional methods of Translation Studies, militates against universalist programs of research and universalist conclusions. From a positivist point of view, such variety and divergence might be seen in a negative light, but from most other perspectives, the potential of CTS to illuminate both similarity and difference and to investigate in a manageable form the particulars of language-specific phenomena of many different languages and cultures in translation constitutes the chief appeal of this new approach to Translation Studies. Particularly at this juncture of history, we need to know the spe-cifics of different languages in translation, the individual particularities of specific pair-ings of languages in translation exchanges, and the characteristics of translation as cultural interface at different times and places and under different cultural conditions. Such differences teach us as much as or more than commonalities of translation, and they contribute as much or more not only to our theoretical investigations of transla-tion phenomena but to the practical concerns of situating translation in a decentered, multicultural world.For a long time in the history of translation theory and practice, difference was perceived in a negative way, as a departure from fidelity, a sign of the loss inherent in the translation process. In very different ways, both Eugene Nida's school of "dynamic-equivalence" translation and more recent approaches to translation — from those of Philip Lewis (1985) to the feminist translation theorists (Bassnett 1992, 1993: ch. 7) to the Brazilian school promoting "cannibalism" (Vieira 1994) — have valorized differ-ence in translation. It is clear that CTS has the potential to be one means of challenging hegemonic, culture-bound views of texts, translations, and cultural transfer. It is a powerful tool for perceiving difference and for valorizing difference as well.What are the next steps in the development of corpus translation studies? As we have seen, there are many leading edges in this field, just as there are in the field of Translation Studies as a whole. Nonetheless, looking at the most exciting new work in Translation Studies, one notes certain common themes and common commitments. Thus, for example, there is an growing commitment to integrate linguistic approaches and cultural-studies approaches to translation, to explore their reciprocal relationship, thus turning away from the invidious competition and isolation that plagued these two branches of the discipline for some time (cf. Baker 1996). Second, the leading work in Translation Studies shows an ever more sophisticated awareness of the role of ideology as it affects text, context, and translation, and as it affects the theory, practice, and ped-agogy of translation as well. And, finally, as in other disciplines, the pioneering work inCOMPUTERIZED CORPORA AND THE FUTURE OF TRANSLATION STUDIES7 Translation Studies involves adapting modern technologies to the discipline's needs and purposes. The essays at hand illustrate that corpus translation studies is dead center on all of these developments, once again suggesting the leading role it will play in the discipline of Translation Studies in the coming decades.In building for the future, CTS must take care not to diminish itself, falling into the fetishistic search for quantification that plagues many "scientific studies" and makes them ridiculous, empty exercises. Researchers using CTS tools and methods must avoid the temptation to remain safe, exploiting corpora and powerful electronic capa-bilities merely to prove the obvious or give confirming quantification where none is really needed, in short, to engage in the type of exercise that after much expense of time and money ascertains what common sense knew anyway. As the dour Vermonter might put it, "Do bears sleep in the woods?" Researchers must take care to ask "the right questions": to pose questions and construct research programs that have as their goal substantive investigations that are worthy of the powerful means deployed by CTS.In building for the future, CTS must also recognize the imperatives and honour the claims of historicism. Within Translation Studies there have now been many case studies related to historical poetics, for example, amassing considerable data on the wide variation of the role of translation in culture and the range of the norms of transla-tion practice. The gains of such work must be incorporated into the design and con-struction of corpora. Researchers must of course avoid the obvious trap already discussed of being locked into the translation norms of the present, and of presuppos-ing such norms in the construction of corpora. But beyond that obvious weakness, ontological and epistemological commitments in the design of corpora must include dedication to the past and to other cultures as well.The development of corpora and CTS methods represents a long-term invest-ment for the field of Translation Studies. As we now set the foundation of a legacy that will come to fruition in the future, it is important to begin to envision the widest possi-ble range of corpora that can be established, the uses to which corpora can be put, of questions that can be asked solely of corpora, and of methods that can be utilized with corpora for both theoretical and practical results. From envisioning these things we must proceed to encourage their development and realization.Finally, CTS is once again an opportunity to reengage the theoretical and prag-matic branches of Translation Studies, branches which over and over again tend to dis-associate, developing slippage and even gulfs. One of the most encouraging aspects of the pioneering studies of CTS is the way that seemingly technical and theoretical inter-rogations come to have practical potential and immediate applicability, not only for the teaching of translation but for the work of the practising translator as well.Notes1. See T. Tymoczko (1979) for an example of the way that electronic capabilities change disciplines in a qualitative manner. The results of corpus translation studies may at times generate a scepticism similar to that which computer proofs initially raised among mathematicians.2. See for example the case studies in Even-Zohar (1990); Lefevere and Jackson (1982); and Hermans (1985). See also Brisset (1996).3. That is, to establish criteria that will individually be necessary and collectively be sufficient to pick out all translations and only translations.4. For a general discussion of the philosophical issues related to categories see Wittgenstein (1953); Rosch (1978); Gleitman, Armstrong, and Gleitman (1983); and Lakoff (1987).5. As a word of caution, one should note that a prototype is not defined by researchers a priori, but is derived from actual empirical research with actual subjects speaking a specific language. It is quite possible that research would show that a professional translator is not prototypical of the concept translator to most speakers of English.。

苏珊巴斯内特的翻译论及其翻译贡献

最后,她倡导翻译的伦理规范,认为翻译者应该遵循一定的伦理准则,对原 作者和目标读者负责。这种观点有助于提高翻译者的道德责任感和职业素养,确 保翻译的质量和社会效益。

3、苏珊巴斯内特翻译论的影响 和意义

苏珊巴斯内特的翻译论对当代翻译实践和翻译教育产生了深远的影响和意义。 首先,她提出的“翻译伦理”为翻译界提供了一种新的思考方式,引导翻译者遵 循职业道德,提高翻译质量。其次,她对翻译的文化差异性和客观性的强调,有 助于我们更加深入地理解翻译的本质和规律,推动翻译学科的发展。最后,她的 理论创新为翻译研究提供了新的视角和思路,引领了翻译理论研究的方向。

2、苏珊巴斯内特在翻译教育方 面的贡献

苏珊巴斯内特在翻译教育方面也做出了重要的贡献。她曾参与多所大学翻译 专业的课程设置和教学计划制定,强调跨文化交际能力和语言素养的培养。同时, 她还倡导在翻译教学中引入真实文本和实践教学相结合的方式,以提高学生的实 际操作能力和对翻译标准的理解。此外,她还重视翻译评估的作用,提出以客观、 全面的标准来衡量学生的翻译成果。

翻译论

1、苏珊巴斯内特翻译论的核心 观点和理论

苏珊巴斯内特认为翻译是一种复杂的文化活动,涉及两种语言和两种文化之 间的转换。她强调翻译中原语和目标语之间的文化差异,认为翻译应该忠实于原 作的整体意义,而不仅仅是字面上的对应。此外,巴斯内特还提出了“翻译伦理” 的概念,认为翻译者应该对原作者和目标读者负责,遵循一定的伦理规范。

谢谢观看

3、苏珊巴斯内特对翻译界的启 示和贡献

苏珊巴斯内特对翻译界的启示和贡献主要体现在以下几个方面:

首先,她强调了翻译的文化差异性和客观性,引导我们重新审视翻译的本质 和规律。这有助于我们提高对翻译复杂性和多元性的认识,更好地应对跨文化交 流中的挑战。

susan_bassnett

Part Two (4-7):

• This part exemplifies that language and culture are so closely interrelated and interprets and illustrates what “comprising” and “spread of English” mean.

Structural

Analysis

Part One (1-3):

• This part illustrates the fact we live in an era of easy access to the rest of the world, and clearly proves that this global communications revolution is also closely connected to the expansion of English.

Research interests: comparative and world literature, theatre history, English poetry.

Critical Ideas

• Foregrounding translation

• Comparative Literature as a literary strategy

Part Three(8):

• It points out the great function or the immense significance of intercultural understanding.

•Ted Hughes (Northcote Press, 2009)

三年级上册音乐课件噢苏珊娜人音版

跟着老师用“lu”音模唱旋律

歌曲的旋律同学们唱的真棒,接下来 让我们一起把歌词填上唱一唱吧!

11

范唱

伴奏

12

活泼欢快的歌曲同学们唱的很棒,但 你知道歌词中的“五弦琴”是什么琴吗?

13

点击播放视频,了解五弦琴

14

童年是难忘的,希望每一个同学在我 们这个大家庭里相亲相爱,快快乐乐,珍 惜我们度过的每一天。退出15噢!苏珊娜1

CONTENTS

感受歌曲 歌曲学唱

2

感受歌曲

欣赏歌曲,感受歌曲的 情感、旋律、内容

3

范唱 4

我问你答

这首歌曲的旋律是怎样的呢?它给你 带来什么样的感觉?

欢快的、活泼的旋律,听到这首歌曲, 有一种想跳舞的感觉……

这首歌曲的背后还有一个动人的故事, 跟随老师一起去看一看吧!

5

这首歌曲是美国著名的作曲家福斯特于1847年创作 完成的,歌词内容讲述了俩人之间的纯洁友谊,男主人 公的名字叫杰克,女主人公叫苏珊娜,俩人从小就结下 了深厚友谊,常常是杰克弹着他心爱的五弦琴,美丽迷 人、活泼开朗的苏珊娜伴随着琴声唱歌跳舞,他们就是 这样度过了快乐而令人难忘的童年生活。后来,俩人到 了美国两个不同的州生活,这首歌曲就唱的是住在美国 阿拉巴马州的杰克去探望他多年不见的、住在路易斯安 纳州的好朋友苏珊娜的一段动人的故事。

6

歌曲学唱

整体感知,掌握歌曲的 演唱

7

再次聆听音乐,找一找歌曲中相同的旋律部分 8

同学们观察的真仔细,歌曲中的第2 乐句和最后一个乐句它们的旋律完全相同, 而第1乐句和这两个乐句的旋律基本相同, 只是在尾音出有一些变化。接下来,就让 我们一起去唱一唱这些旋律吧!

9

同学们还记得这几个音吗?跟随琴声 一起唱一唱吧!

英语论文引言格式

英语论文引言格式第一篇:英语论文引言格式Idiom Translation under the Chinese and English Cultures Class XXX Number XXXName XXX Abstract: Nida, a famous translator, says, “For truly successful translation, it is much more important to familiarize two cultures than master two languages, because words are assigned meanings in its particular cultures.”(Background information)This is to say, translation is closely related with not only languages but also cultures.Studies of the cultural distinction in idiom translation are still relatively weak in the field of translation in China.Exclusive research on the translation of Chinese and English idioms is still incomplete.In the last twenty years, idiom translation has mostly emphasized the level of inter-lingual communication, but cultural differences were rarely involved in it.(Identify problem)This thesis analyses the cultural differences in Chinese and English idioms, then studies English-ChineseChinese-English idiom translation methods(Research subject)from the angle of culture(Method)and points out some warnings concerning idiom translation: pay attention to context and choose the right version in line with the style and meaning of the original passage(Results);culture is a whole way of life, when new culture emerges, new idioms also appear, therefore idiom translation should develop with the time.(Conclusion)Key Words: idioms;culture;translation论英汉文化背景下的习语翻译摘要:著名翻译学家奈达指出:“对于真正成功的翻译而言,熟悉两种文化甚至比掌握两种语言更为重要,因为词语只有在其作用的文化背景下才有意义。

翻译研究-Susan_Bassnett

翻译研究-获得和失去获得和失去(LOSS AND GAIN)一旦确立了两个语言中不可能完全一致的原则,那么在翻译的过程中处理获得和失去问题是合乎情理的。

翻译的低等地位表明了大量的时间都被花费在讨论从原语言向目标语言的传递过程中所失去的,然而,译者时常会丰富原语言作为翻译过程的直接结果,其中所获得的却被忽略了。

而且,在原语言语境中没有的可以在目标语言中被语境所代替。

就如Wyatt和Surrey翻译的彼特拉克(Petrarch)的情况。

Eugene Nida针对翻译的失去问题提供了大量信息,特别是译者面对原语言中的术语和概念而目标语言中却不存在的困难。

他引用了圭卡语(Guaica),在委内瑞拉(Venezuela)南部使用的一种语言为例,在这个语言里,不太容易找到英语中murder, stealing和lying等令人满意的替换项,然而,针对good, bad, ugly和beautiful的替换项却有着相当不同的词义。

比如,他指出,圭卡语并不遵循good和bad这样一分为二的范畴,圭卡语采用三分法:(1)Good包括合意的食物,杀死敌人,咀嚼适量大麻,用火烧妻子使其服从和偷窃其他团伙的东西。

(2)Bad包括腐烂的水果,有瑕疵的物品,谋杀了自己团队的成员,偷大家庭的东西和欺骗他人。

(3)Violating taboo包括乱伦,和岳母过于亲近,一个已婚女子在生第一个孩子之前吃貘还有孩子吃了啮齿类动物。

没有必要找离欧洲差别这么远的。

芬兰语中有大量表示雪的不同词汇,阿拉伯语有很多表示骆驼的习性的词,英语中对于光和水,法语中面包的类型,这些词在一定程度上对于译者是不可译的难题。

圣经译者声称另外的困难,比如,三位一体的概念和在特定文化中寓言的社会涵义。

另外还有词汇问题,当然还有不遵循印欧语系,没有时态体系或者时间概念的语言。

Whorf关于有时态语言(English)和无时态语言(Hopi)之间的比较列举了这方面。

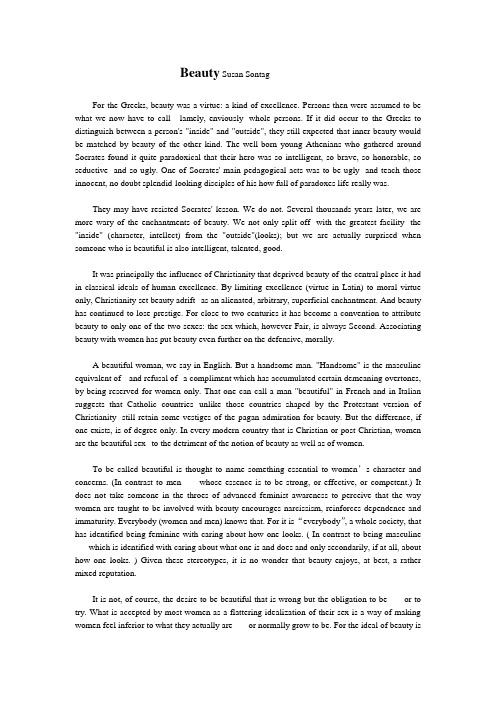

Beauty-Susan-Sontag优选全文

Beauty Susan SontagFor the Greeks, beauty was a virtue: a kind of excellence. Persons then were assumed to be what we now have to call-- lamely, enviously--whole persons. If it did occur to the Greeks to distinguish between a person's "inside" and "outside", they still expected that inner beauty would be matched by beauty of the other kind. The well-born young Athenians who gathered around Socrates found it quite paradoxical that their hero was so intelligent, so brave, so honorable, so seductive--and so ugly. One of Socrates' main pedagogical acts was to be ugly--and teach those innocent, no doubt splendid-looking disciples of his how full of paradoxes life really was.They may have resisted Socrates' lesson. We do not. Several thousands years later, we are more wary of the enchantments of beauty. We not only split off--with the greatest facility--the "inside" (character, intellect) from the "outside"(looks); but we are actually surprised when someone who is beautiful is also intelligent, talented, good.It was principally the influence of Christianity that deprived beauty of the central place it had in classical ideals of human excellence. By limiting excellence (virtue in Latin) to moral virtue only, Christianity set beauty adrift--as an alienated, arbitrary, superficial enchantment. And beauty has continued to lose prestige. For close to two centuries it has become a convention to attribute beauty to only one of the two sexes: the sex which, however Fair, is always Second. Associating beauty with women has put beauty even further on the defensive, morally.A beautiful woman, we say in English. But a handsome man. "Handsome" is the masculine equivalent of --and refusal of--a compliment which has accumulated certain demeaning overtones, by being reserved for women only. That one can call a man "beautiful" in French and in Italian suggests that Catholic countries--unlike those countries shaped by the Protestant version of Christianity--still retain some vestiges of the pagan admiration for beauty. But the difference, if one exists, is of degree only. In every modern country that is Christian or post-Christian, women are the beautiful sex--to the detriment of the notion of beauty as well as of women.To be called beautiful is thought to name something essential to women’s character and concerns. (In contrast to men ---- whose essence is to be strong, or effective, or competent.) It does not take someone in the throes of advanced feminist awareness to perceive that the way women are taught to be involved with beauty encourages narcissism, reinforces dependence and immaturity. Everybody (women and men) knows that. For it is “everybody”, a whole society, that has identified being feminine with caring about how one looks. ( In contrast to being masculine ---- which is identified with caring about what one is and does and only secondarily, if at all, about how one looks. ) Given these stereotypes, it is no wonder that beauty enjoys, at best, a rather mixed reputation.It is not, of course, the desire to be beautiful that is wrong but the obligation to be ---- or to try. What is accepted by most women as a flattering idealization of their sex is a way of making women feel inferior to what they actually are ---- or normally grow to be. For the ideal of beauty isadministered as a form of self-oppression. Women are taught to see their bodies in parts, and to evaluate each part separately. Breasts, feet, hips, waistline, neck, eyes, nose, complexion, hair, and so on ---- each in turn is submitted to an anxious, fretful, often despairing scrutiny. Even if some pass muster, some will always be found wanting. Nothing less than perfection will do.In men, good looks is a whole, something taken in at a glance. It does not need to be confirmed by giving measurements of different regions of the body, nobody encourages a man to dissect his appearance, feature by feature. As for perfection, that is considered trivial ---- almost unmanly. Indeed, in the ideally good-looking man a small perfection or blemish is considered positively desirable. According to one movie critic ( a woman ) who is declared Robert Redford fan, it is having that cluster of skin-colored moles on one neck that saves Redford from being merely a “pretty face.”Think of the depreciation of women ---- as well as of beauty ---- that is implied in that judgment.“The privileges of beauty are immense,”said Cocteau. To be sure, beauty is a form of power. And deservedly so. What is lamentable is that it is the only form of power that most women are encouraged to seek. This power is always conceived in relation to men; it is a power that negates itself. For this power is not one that can be chosen freely ---- at least, not by women ---- or renounced without social censure.To preen, for a woman, can never be just a pleasure. It is also a duty. It is her work. If a woman does real work ---- and even if she clambered up to a leading position in politics, law, medicine, business, or whatever ---- she is always under pressure to confess that she still works at being attractive. But in so far as she is keeping up as one of the Fair Sex, she brings under suspicion her very capacity to be objective, professional, authoritative, thoughtful. Damned if they do ---- women are. And damned if they do not.One could hardly ask for more important evidence of the dangers of considering persons a split between what is “inside”and what is “outside”than that interminable half-comic half-tragic tale, the oppression of women. How easy it is to start off by defining women as care-takers of their surfaces, and then disparage them (or find them adorable ) for being “superficial”. It is a crude trap, and it has worked for too long. But to get out of the trap requires that women get some critical distance from that excellence and privilege which is beauty, enough distance to see how much beauty itself has been abridged in order to prop up the mythology of the “feminine.”There should be a way of saving beauty from women ---- and for them.总之,在这一学年中,我不仅在业务能力上,还是在教育教学上都有了一定的提高。

苏珊·巴斯奈特翻译思想简述

苏珊·巴斯奈特翻译思想简述作者:高新宇来源:《青年时代》2018年第12期摘要:翻译学自20世纪70年代建立以来经历了蓬勃的发展,翻译研究领域的文化转向(cultural shift)把翻译推向一个崭新的台阶。

巴斯奈特的“文化翻译”思想既对应了文化功能对等论的内容,又和后殖民翻译观一脉相承。

文化研究学派的代表之一苏珊·巴斯奈特以其独特的视角和新颖的见解,在译坛上独树一帜。

从介绍其主要成果入手,简单归纳评述她的主要译学思想和贡献。

关键词:苏珊·巴斯奈特;翻译研究;文化研究一、宽广的学术研究视阀苏珊·巴斯奈特是活跃在当今英国甚至整个世界翻译界的著名翻译理论家和著名诗人,英国沃里克大学比较文学教授、校长。

她游历多国,有丰富的求学、教学经历,精通英、意、法、西等多种语言,对欧洲各国文学和文化有较深刻的研究,大量的翻译实践活动又使她在翻译研究方面建树颇多。

巴斯奈特笔耕不辍,其专著和编著多达40余部她不仅是位著名的翻译理论家,而且在教学、翻译中实践自己的理论,她把理论和实践结合起来,对翻译研究、文学和文化研究做出了巨大贡献,并且为这些领域提出了富有启发性的问题和建议。

巴斯奈特的学术研究视野极为宽广,除翻译研究以外,女性主义研究、后殖民主义研究、旅行文学研究、传媒研究等文化研究的诸多课题都在她的学术视野之内。

巴斯奈特翻译研究的特色在于将之与文化研究的诸多课题联姻,进而生发出新的学术增长点。

巴斯奈特在1980年出版了以《翻译研究》(Translation Studies)直接命名的专著,以回应“翻译研究学派”创始人、荷兰著名翻译理论家霍尔姆斯(James Holmes)提出的建立翻译研究独立学科的倡议。

在这本著作中,巴斯奈特勾勒了翻译研究的学科框架,回顾了翻译研究已经取得的成绩,并为翻译研究未来的发展方向提出了建议。

《翻译研究》分别于1991年和2002年两次修订,并多次再版,现已成为翻译研究领域的重要文献。

翻译研究-Susan Bassnett

E.V Rieu故意将《荷马》翻译成英文散文,因为古希腊史诗的意义等同于现代欧洲的散文,动态对等被应用到语篇的形式特征,这个例子显示Nida划分的范畴实际上会自相矛盾。

在翻译研究中确定的事实是,如果有一沓译者来翻译同一首诗,他们会翻译出一沓各不相同的译文。然而那些译文中都拥有Popovič所称的原诗的不变核心。他称,这个不变核心是由语篇中稳定的,基本的和恒定的语义成分为代表,由语义摘要证明的。转变或者变量,是那些不能改变核心意义的但是影响表达形式的变化。总之,不变的核心可以被看作共同存在于同一语篇的所有译文中。因此,不变核心是动态关系一部分,不应该被误认为语篇的本质(nature)、精神(spirit)、精髓(soul);它是译者很少能捕捉到的不能确定的特质。

John is beating about the bush.

(约翰说话拐弯抹角。)

英语和意大利语都有关于支支吾吾的习语表达方式,因此,在这个语言间的互译过程中,一个习语可以替代另一个习语。这种替换既不是以短语中的语言成分为基础也不是以句中相应的或相似的形象为基础,而是以习语的功能为基础的。在目标语言文化中,目标语言短语具有与原语言短语有着相同功能,这个过程包含原语言代替目标语言。Dagut关于翻译暗喻的问题的评论是有趣的,这个评论也适用于解决习语的翻译问题:

这两个产品在意大利的新闻周刊杂志的广告同样有两个形象。一个强调纯净、品质和社会地位;另一个强调迷人、刺激、时尚的生活和青春的气息。但是因为马提尼建立较早,苏格兰威士忌在众多市场中相对初来乍到,所以,产品所呈现的形象与英国的形象完全相反。相同的模式在两个社会的广告中,应用却不同。在两个社会的产品也许相同,但是他们却不同的价值标准。因此,就这两个产品通过广告所呈现出对等的社会功能,英国情境中苏格兰威士忌可以被定义为等同于意大利情境中的马提尼,反之亦然。

从Bassnett的“文化翻译理论”看西方诗歌英译汉的翻译策略

《从Bassnett的“文化翻译理论”看西方诗歌英译汉的翻译策略》摘要:摘要:随着文化翻译领域越来越受到学者们的关注,从Bassnett的“文化翻译理论”角度研究西方诗歌英译汉的翻译策略具有重要的学术意义,因此,本文试图以Sonnet18的汉译文本为例,探讨“文化翻译理论”在诗歌翻译中的体现和其对西方诗歌翻译的指导意义,lease hath all too short a date.”吴诚辉摘要:随着文化翻译领域越来越受到学者们的关注,从Bassnett的“文化翻译理论”角度研究西方诗歌英译汉的翻译策略具有重要的学术意义。

因此,本文试图以Sonnet18的汉译文本为例,探讨“文化翻译理论”在诗歌翻译中的体现和其对西方诗歌翻译的指导意义。

关键词:翻译策略;Sonnet18;文化翻译理论。

一、文化翻译理论概述谢天振(2014)在《隐身与现身》一书中指出,当代西方学者在翻译研究上最大的突破就是将翻译置于跨文化、跨学科的大背景下,即越来越多的学者从文化层面审视翻译,将文本作为一种跨文化的交际行为来分析。

20世纪90年代,Bassnett和Lefevere首次正式提出了“文化变迁”的概念形式(1991)。

[1]甚至有人认为,翻译单位已经开始从文字到文本、从文本到文化的转换。

Bassnett认为翻译不是一种纯粹的语言行为,而是深深植根于语言文化之中。

经过多年的翻译理论研究,Bassnett提出了“文化翻译理论”的观点:“首先,翻译应以文化为单位,文本不应仅仅停留在先前的文化语境中;其次,翻译不仅仅是一个简单的‘解码和重组过程,同时也是一种交际行为;第三,翻译不应局限于对原文的描述,而应在目的语文化中实现功能对等。

”[2]Bassnett将文化作为翻译的一个单元,无疑开辟了翻译研究的新视角。

二、文化翻译理论下的西方诗歌翻译诗歌翻译属于文学翻译,因此没有固定的评价标准。

但在世界文化一体化的时代,古代诗词中的文化因素如何翻译和传播显得尤为重要。

bassnett translation studies

bassnett translation studies

苏珊·巴斯内特(Susan Bassnett)的《翻译研究》(Translation Studies)是翻译研究的经典入门读物,介绍了翻译研究的核心概念、翻译理论历史,探讨了诗歌、散文、戏剧等各类翻译问题。

该书从古罗马时期开始,涵盖了20世纪关键的结构主义作品,探讨了翻译中的关键问题,并提供了一段翻译理论的历史。

作者通过对文本的仔细分析,探讨了文学翻译的具体问题,并在书末提供了大量延伸阅读的建议。

20多年来,翻译研究领域不断发展,但有一点始终未变:经过再次更新,苏珊·巴斯内特的《翻译研究》仍然是必读之书。

天津市滨海新区2023_2024学年高三上册第二次月考英语模拟测试卷(附答案)

天津市滨海新区2023_2024学年高三上册第二次月考英语模拟测试卷第一部分听力(共两节,满分20分)第一节(共5小题,每小题1分,共5分)听下面5段对话,选出最佳选项,每段对话读一遍。

1. Where is Mary now?A. At home.B. At school.C. In the office.2. When did the meeting start?A. 9:20.B. 9:00.C. 8:40.3. What are they probably going to do?A. Finish their homework.B. Do much housework.C. Enjoy the football match.4. How much will a boy and his girlfriend pay for their tickets?A. Two dollars.B. Three dollars.C. Four dollars.5. What does the man think Mark should do?A. Watch TV.B. Go on with the game.C. Prepare for the exam.第二节(共10小题,每小题1.5分,共15分)听下面3段对话,选出最佳选项,每段对话读两遍。

听第6段对话,回答第6至8小题。

6. Why does Susan think Peter might be interested in the theater group?A. Because he has a lot of free time.B. Because she knows he likes acting.C. Because he is looking for another job.7. How often does the group practice?A. Three times a week.B. Twice a week.C. Once a week.8. What does Peter worry about the most in joining the theater group?A. His school work takes much of his time.B. He has not been in a play for a long time.C. He might not like the way the group works.听第7段对话,回答第9至11小题。

影视毕业论文参考文献

影视毕业论文参考文献为撰写或编辑论文和著作而引用的有关文献信息资源,下面是搜集整理的影视参考文献,欢迎阅读参考。

参考文献一:[1]李和庆,薄振杰.规范与影视字幕翻译[J].中国科技翻译.2005(02)[2]钱绍昌.影视翻译──翻译园地中愈来愈重要的领域[J].中国翻译.2000(01)[3]陈莹.英汉节奏对比分析[J].西安外国语学院学报.2004(02)[4]余萍.论创造性叛逆视野下的《唐诗三百首》英译[D].安徽大学2011[5]尤杰.论网络盗版对电影产业收入流的影响[J].当代电影.2010(12)[6]肖维青.学术性·职业性·趣味性--“影视翻译”课程教学探索[J].外语教学理论与实践.2010(03)[7]龙千红.《花样年华》的英文字幕翻译策略研究--兼谈中国影片的对外译介[J].西安外国语学院学报.2006(01)[8]孙致礼.翻译与叛逆[J].中国翻译.2001(04)[9]胡心红.从孙致礼的《傲慢与偏见》译本看文学翻译中的创造性叛逆[D].湖南师范大学2008[10]赵菁婕.论文学翻译中的创造性叛逆[D].青岛大学2014[11]杨莎莎.亚瑟·韦利对《西游记》的创造性叛逆式翻译[D].首都师范大学2008[12]张锦兰.接受美学与复译[J].甘肃教育学院学报(社会科学版).2003(04)[13]麻争旗.翻译二度编码论--对媒介跨文化传播的理论与实践之思考[J].现代传播.2003(01)[14]钱梦妮.美剧字幕组的生存悖论[J].新闻世界.2011(01)[15]吴晓芳.字幕组:美剧“汉化”的背后[J].世界知识.2011(01)[16]麻争旗.影视对白中“节奏单位”的翻译探究[J].中国翻译.2011(06)[17]王平.“隐秘的流行”路在何方?--“字幕组”翻译面面观[J].电影评介.2009(17)[18]刘洪涛,刘倩.论林译小说《迦茵小传》中的创造性叛逆[J].北京师范大学学报(社会科学版).2008(03)[19]张春柏.影视翻译初探[J].中国翻译.1998(02)[20]麻争旗.论影视翻译的基本原则[J].现代传播-北京广播学院学报.1997(05)参考文献二:[1]王凯华.帕尔默文化语言学视角下的宋词英译意象传递研究[D].辽宁师范大学2014[2]高丽红.生态翻译学视角下《骆驼祥子》两个英译本对比研究[D].西北师范大学2014[3]吴十梅.“张掖大景区建设项目”翻译实践报告[D].西北师范大学2014[4]蔡莹莹.风景抒情唐诗英译的象似性研究[D].辽宁师范大学2014[5]赵菁婕.论文学翻译中的创造性叛逆[D].青岛大学2014[6]赵春梅.论译制片翻译中的四对主要矛盾[J].中国翻译.2002(04)[7]李运兴.字幕翻译的策略[J].中国翻译.2001(04)[8]李琼.《协商民主在中国》英译实践报告[D].西北师范大学2014[9]樊小花.“加拿大天然健康产品许可证申请指导文件”的翻译报告[D].西北师范大学2014[10]冉彤.二人互动模式下提示和重铸与二语发展[D].西北师范大学2012[11]赵爱仙.翻译美学视阈下陌生化在《围城》英译本中的再现与流失[D].西北师范大学2013[12]李文婧.基于功能派翻译理论的科技论文摘要的英译研究[D].西北师范大学2013[13]王番.概念隐喻理论视角下的情感隐喻翻译[D].南京工业大学2013[14]陈燕.互文视角下的诗歌翻译比较研究[D].南京工业大学2013[15]刘霖.基于构式语法的汉语明喻成语英译研究[D].辽宁师范大学2014[16]赵静.关联顺应模式下商标名称英译的文化缺省研究[D].西北师范大学2013[17]陆祖娟.语用翻译视角下《围城》中人物对话的汉英翻译研究[D].西北师范大学2014[18]王君.英语经济类语篇汉译实践报告[D].辽宁师范大学2014[19]姜姗.语境视域下的英语经济新闻文本汉译实践报告[D].辽宁师范大学2014[20]钱绍昌.影视翻译──翻译园地中愈来愈重要的领域[J].中国翻译.2000(01)[21]郭建中.翻译中的文化因素:异化与归化[J].外国语(上海外国语大学学报).1998(02)[22]王静.英语学习者词缀习得的实证研究及其启示[D].西北师范大学2012参考文献三:[1]张鑫.从关联理论视角看电影字幕翻译[D].内蒙古大学2010[2]熊婷.从关联理论角度看电影《赤壁》的字幕翻译[D].广东外语外贸大学2009[3]陈燕.字幕翻译的技巧研究[D].厦门大学2009[4]周昕.从功能主义的视角分析《老友记》字幕翻译的问题[D].苏州大学2010[5]唐立娟.场独立与场依存认知风格与大学生阅读附带词汇习得的相关性研究[D].西北师范大学2012[6]郭乔.关联理论指导下美剧字幕翻译的明示处理[D].上海外国语大学2009[7]李芸泽.南京沃蓝科技有限公司商务洽谈陪同口译实践报告[D].西北师范大学2014[8]马玉珍.认知语境视角下字幕翻译的“高效与经济”原则[D].中南大学2009[9]苏春梅.高中英语教师对教学研究的认知和理解[D].西北师范大学2014[10]姜泽宪.英语教师信念与职业认同的研究[D].西北师范大学2012[11]郭星余.字幕翻译的改写[D].中南大学2007[12]马子景.第三届中国河西走廊有机葡萄酒节陪同口译实践报告[D].西北师范大学2014[13]吴庆芳.大学英语精读课教师多模态话语分析[D].西北师范大学2013[14]Salvatore,Attardo.TranslationandHumor:AnApproachBasedontheGeneralTheoryofVer balHumor.TheTranslator.2002[15]杨帆.加拿大资助中国乡村女大学生基金会项目的口译实践报告[D].西北师范大学2014[16]王红霞.从关联理论视角研究影视剧字幕翻译[D].上海外国语大学2009[17]Bassnett-McGurie,Susan.TranslationStudies.JournalofWomensHealth.1980[18]李艳玲.基于Wiki的协作式写作教学对提高非英语专业学生写作水平的影响研究[D].西北师范大学2013[19]高东森.基于FIAS的新手-专家高中英语教师课堂言语行为对比研究[D].西北师范大学2013[20]程思.影视字幕翻译策略探究[D].上海外国语大学2009[21]费卫芝.韩国电影中文字幕翻译研究[D].湖南师范大学2010。

苏珊巴斯内特的文化翻译思想简述-精品文档资料

苏珊巴斯内特的文化翻译思想简述-精品文档资料-CAL-FENGHAI-(2020YEAR-YICAI)_JINGBIAN苏珊巴斯内特的文化翻译思想简述1、苏珊巴斯内特简介Susan Bassnett(1945--- )国际知名翻译理论学者、比较文学家和诗人,是英国沃里克大学(University of Warwick)资深教授,曾任该校副校长、“翻译与比较文化研究中心”主任。

早年在欧洲多国接受过教育,掌握多门语言并了解多种文化,在意大利开始其学术生涯,到沃里克大学任教前曾在美国短期工作。

现担任英国国家委员会英国研究咨询委员会主席、国际翻译理事会理事、欧洲翻译协会理事等学术团体职务。

巴斯内特教授学术兴趣广泛,从莎士比亚到西尔维亚普拉斯,从文艺复兴时期的意大利到后殖民时期的印度,都在她的视域之内。

她的研究范围包括:比较文学、翻译研究、英国文化、拉美文学、戏剧作品、女性作品和后殖民时期的翻译现象、旅行文学研究、传媒研究等等。

从1969年翻译出版意大利艺术评论家阿尔甘(G. C. Argan, 1909-1992)的《复兴之城》,到2009年出版与别尔萨博士合着的《全球化时代的新闻翻译》,巴斯内特已出版专着、编着和译着共30余种。

2、文化转向的历史背景20世纪五六十年代,语言学翻译观在翻译研究中占据了主导地位。

翻译被视为不同语言之间的转换。

60年代后期,西方翻译理论研究从字、词、句为单位过渡到以语篇为单位,翻译的功能学派大行其道。

70年代,以色列学者Even Zohar提出多元系统理论(poly-system theory),西方的翻译理论研究真正从文本转移到文本以外的文化、社会、历史及政治因素的相关研究。

这一时期的翻译研究虽然以不同的名称命名,“翻译研究”、“描述翻译学”、“多元系统理论”、“操纵学派”、“低地国家学派”等,但它们从事翻译研究的基本范式和方法却非常相近。

作为描述学派的前身,多元系统理论并没有将注意力集中在某种特殊的体裁(genre)上,而是着眼于各个民族不同的文化背景。

夜访吸血鬼中外电影经典欣赏之一

范海辛(2004)

主演:休·杰克曼, 凯特·贝金赛尔

小吸血鬼(2000)

描写了小吸血鬼们 天真烂漫、充满幻想 的世界,同时映射孩 子们的生活现实和心 理现实。

导演:尤里-艾德 尔(Uli Edel)

塞尔

原作作者:安妮•赖斯(Anne Rice, 1944 -)

赖斯的作品以生 动描写恐怖情节而著 称,小说的主题多为 历史背景下人的离群 索居及对自我的追求, 小说中的人物总是现 实社会或非现实社会 中孤立的群体。

导演Neil Jordan,1950 ——

爱尔兰导演与编剧。 曾经凭《哭泣游戏》

思考题

本片的主题是什么?

主题的探讨

生与死的关系 孤独; 自我身份的追寻。

吸血鬼的由来宗教 Biblioteka 病与迷信 现实原型该隐杀弟

亚当与夏娃之长子

现实原型

法国德莱斯男爵 罗马尼亚德古拉伯爵

匈牙利巴托里伯爵夫 人

德古拉伯爵的城堡

吸血鬼的特征

(一)早期故事中的吸血鬼——丑陋 1.长而尖利的犬牙。 2.吸血鬼有着冰冷苍白的皮肤。 3. 他们还能够变身为蝙蝠。 4.以坟墓和棺材作为栖息场所。

曾经获得奥斯卡最佳 男配角奖提名、金球 奖最佳男配角奖,并 于2007年凭《神枪手 之死》一片一举拿下 威尼斯电影节影帝。

2009年凭《本杰

明·巴顿》一片首次

提名奥斯卡最佳男主 角奖。

Kirsten Dunst (1982——)

3岁出道,11岁成名;

2011年因影片《忧郁症》 获第64届戛纳国际电影 节最佳女演员奖。

获得奥斯卡最佳原著 剧本奖。 1998年的《悲欢岁月》 获柏林影展最佳导演 奖。

Tom Cruise ,1962——

翻译方面的参考文献

1.Bassnett, Susan & Andre Lefevere. Constructing Cultures[M]. Shanghai:Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2001.2.Hatim, Basil. Communication across Cultures[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2001.3.Nord, Christiane. Translating as a Purposeful Activity[M]. Shanghai: ShanghaiForeign Language Education Press, 2001.4.Hickey, Leo(ed.). The Pragmatics of Translation[C]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2004.5.Newmark, Peter. Approaches to Translation[M].Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2001.6.Wilss, Wolfram. The Science of Translation[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2001.7.Newmark, Peter. A Textbook of Translation[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2001.8.Nida, A. Eugene. Language and Culture[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2001.9.Snell-Hornby, Mary. Translation Studies[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2001.10.Davis, Kathleen. Deconstruction and Translation[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2004.11.Katan, David. Translating Cultures[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign LanguageEducation Press, 2004.12.Gutt, Ernst-August. Translation and Relevance[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2004.13.Gentzler, Edwin. Contemporary Translation Theories[M]. Shanghai: ShanghaiForeign Language Education Press, 2004.14.Nida, A. Eugene. Toward a Science of Transalting. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2004.15.Nida, A. Eugene & Taber, R. Charles. The Theory and Practice of Translation[M].Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2004.16.Lefevere, Andre(ed.) Translation/History/Culture[C]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2004.17.Lefevere, Andre. Translation, Rewring and the Manipulation of Literary Fame[M].Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2004.18.Reiss, Katharina. Translation Criticism (Translated by Erroll F. Rhodes)[M].Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2004.19.Venuti, Lawrence. The Translator’s Invisibility[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2004.20.Bassnett, Susan. Translation Studies[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign LanguageEducation Press, 2004.21.Williams Jenny & Chesterman Andrew. The Map[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai ForeignLanguage Education Press, 2004.22.Lefevere, Andre. Translating Literature: Practice and Theory in a ComparativeLiterature Context[M]. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2006.23.Hermans, Theo(ed.). Crosscultural Transgressions: Research Models inTranslation Studies Ⅱ, Historical and Ideological Issues[C]. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2007.24.Rose, G. Marilyn. Translation and Literary Criticism: Translation as Analysis[M].Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2007.130. 罗新璋编. 翻译论集[C]. 北京:商务印书馆,1984.137. 思果. 翻译研究. [M] 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,2001.138. 刘重德. 文学翻译十讲[M]. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1998.139. 刘宓庆. 文体与翻译[M]. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1998.141. 许渊冲. 翻译的艺术[M]. 北京:五洲传播出版社,2006.2004.143. 刘宓庆. 中西翻译思想比较研究[M]. 北京: 中国对外翻译出版公司,2005. 144. 毛荣贵. 翻译美学. [M] 上海:上海交通大学出版社. 2005.145. 许渊冲. 中诗音韵探胜---从《诗经》到《西厢记》[M]. 北京:北京大学出版社,1992.146.《中国翻译》编辑部. 诗词翻译的艺术[C]. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1987.151. 思果. 翻译新究[M]. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,2001.19. 张南峰的书:中西译学批评,清华大学出版社,200420. 李文革《西方翻译理论流派研究》,中国社会科学出版社,2004。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Research interests: comparative and world literature, theatre history, English poetry.

Critical Ideas

• Foregrounding translation

• Comparative Literature as a literary strategy

Publications

Susan Bassnett is author of over 20 books,

and her Translation Studies, (3rd Ed. 2002) which first appeared in 1980, has remained consistently in print and has become the most important textbook around the world in the expanding field of Translation Studies. Recent publications include:

•Ted Hughes (Northcote Press, 2009)

•Translation in Global News, with Esperança Bielsa, (Routledge, 2008) •The Translator as Writer ed. Susan Bassnett and Peter Bush (London and New York; Continuum, 2006)

•Reflections on Translation, Clevedon (Multilingual Matters, 2011)

•Political Discourse, Media and Translation, ed. Cristina Schaeffner and Susan Bassnett (Newcastle upon Tyne; Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010)

Unit 4

CulturalEncounters

XXXXXXXXXXX

Susan Bassnett

-----a brief introduction

Position & Research Interests

Susan Bassnett is one of the leading

international figures and founding scholar in Translation Studies.

Part Two (4-7):

• This part exemplifies that language and culture are so closely interrelated and interprets and illustrates what “comprising” and “spread of English” mean.

Structural

Analysis

Part One (1-3):

• This part illustrates the fact we live in an era of easy access to the rest of the world, and clearly proves that this global communications revolution is also closely connected to the expant Three(8):

• It points out the great function or the immense significance of intercultural understanding.