Park_2007_Co-construction of Nonnative Speaker Identity in Cross-cultural Interaction

典型案例伯奈特公园

BG

8

BG

9

美国伯奈特公园 (burnett park)

彼得·沃克在追求极简的同时并没有淡漠景观的意 义,他没有像极少主义艺术家那样试图创造一种非 景观的作品,而是追求一种具有“可视品质”的场 所。他设计的伯奈特公园采用了网状主路与45°斜 交次路相叠合的规整布局结构,由方形水池拼成的 长方形水池带穿插在“米”字形图案中,产生了一 种强烈的抽象图案效果。

彼得·沃克

BG

2

设计师简介

彼得·沃克于1932年出生在美国加利福尼亚帕萨德纳

市。1955年在加州大学伯克利分校获得了他的风景园 林学士学位。上学期间,他曾经在当时著名的设计师 劳伦斯·海尔普林的事务所工作过一段时间。毋庸置 疑,这一切为他今后的成就打下了良好的基础。毕业 后,他去了哈佛大学研究生院攻读硕士学位。一年后, 他与另一位著名的设计师佐佐木·英夫(sas-aki)合 伙成立了事务所,这也就是现在著名的SWA集团的前身。 1976年,在完成了大量单一风格的作品后,感到有些 厌倦的彼得·沃克决定去哈佛大学教授风景园林设计 课程,并担任了系主任一职(1979-1981)。在那里, 他遇见了他后来的妻子玛萨·舒瓦茨(当时玛萨·舒 瓦茨还是他的学生)。由于有着共同的兴趣爱好,两 人结合并合作成立了彼得·沃克-玛萨·舒瓦茨事务 所。但是,数年后由于他们各自的设计思想存在着巨 大分歧,事务所宣告解散,沃克与其他人先后成立了 几家事务所,包括目前他与威廉·约翰逊合作的事务 所。

BG

3

极简主义

极简主义,又称最低限度艺术,它是在早期的结构主义的基础上 发展而来的一种艺术门类。最初,它主要通过一些绘画和雕塑作 品得以表现。很快,极简主义艺术就被彼得·沃克等先锋园林设 计师运用到他们的设计作品中去,并在当时社会引起了很大的反 响和争议。如今随着时间的推移,极简主义园林已经日益为人们 了解和认可。彼得·沃克是当今美国最具影响的园林设计师之一, 由于他的作品带有强烈的极简主义色彩,他也被人们认为极简主 义园林的代表者。不管是谁,当看到他的作品时,大都会被其简 洁现代的布置形式、古典的元素、浓重的原始气息、神秘的氛围 所打动,这也是彼得·沃克作品的过人之处——艺术与园林的无 声结合赋予了作品全新的含义。

狂犬病抗体检测实验室名单资料

600901 Yur'evets, Vladimir

Russia

21

法国

Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de l'Alimentation, de l'Environnement et du Travail

(Anses)

Laboratoire de la faune sauvage de Nancy

Russia

18

俄罗斯

The All Russian State Centre for Quality and Standardisation of Veterinary Drugs and Feed (VGNKI)

5 Zvenigorodskoe shosse

123022 Moscow

Russia

Schubertstraße 81

35392 Gießen

Germany

12

德国

Eurovir Hygiene-Labor GmbH

Im Biotechnologiepark 9(TGZ I)

14943 Luckenwalde

Germany

13

德国

Vet Med Labor GmbH

Mörikestraße 28/3

France

25

芬兰

Finnish Food Authority

Mustialankatu 3

FI-00790 Helsinki

Finland

26

韩国

Choong Ang Vaccine Laboratory

1476-37 Yuseong-daero Yuseong-gu,

纽顿轩公寓

纽顿轩公寓项目名称:纽顿轩公寓 新加坡项目地点:新加坡,牛顿路60号设计及建造时间:2003年12月~2007年6月项目造价:2350万新币建筑面积: 11 834.93m2用地面积: 3 842.5m2主要景观植被: 鸡蛋花、大邓伯花、黄菖蒲、波士顿蕨的另一层变化,而不是绝对清晰的语言,让建筑在一天的不同时间里呈现出不同的美感。

除此之外,这些网格也很好的与公寓的凸窗(凸窗在新加坡公寓里是一个标准的设计,因为它能为开发商增加可售面积带来更大的商业利益)结合起来,让凸窗在立面上变得更加统一且与众不同。

悬挑出的空中花园与阳台和遮阳网一起组成了塔楼的室外环境,这是一种有着充分遮阳和自然通风、非常适合热带居住的生活环境,而且由于基地地势较高的缘故,这种理念变得更加切合实际。

建筑的地面层是架空的,所有居住和辅助功能都被抬高,这样既避免了居民受周边街道的噪音烦扰,也避免了低楼层居民无法享受好景致的状况发生。

虽然楼层越高景致越好价格也越贵,但设计仍确保了楼层最低的居民也能看到远处的自然保护区并且能享受到小区内公共绿化的绿意,在保证品质的同时实现了开发商利益的最大化。

由于首层架空,居民楼的落客点也被设计得大方高挑。

同时因为建筑占地面积的减少,这里的公共区域得以做更多的绿化,让落客处等地面公共空间都被环绕在浓浓的绿意里。

公寓单元以每层两梯四户的格局垂直堆叠起来。

每个单元都有宽阔的室外生活阳台面向自然保护区和城市景观。

厨卫等功能区被安排在单元的后方,既能与室外通气又能被隐藏起来,不在立面上显露。

尽管公寓的布局紧凑,但前后的通风设计以及被动式环保节能外立面的采用,确保了每家每户都有良好的自然通风而不必过度依赖空调。

设计从项目一开始就将景观植栽如屋顶花园、空中花园和垂直绿墙当作是一种建筑材质来考虑。

在建筑外立面一般比较单调的位置设置了可供植被攀爬的屏障,形成了既可以创造视觉享受、又能吸收阳光和二氧化碳为高密度住宅制造氧分的垂直绿墙。

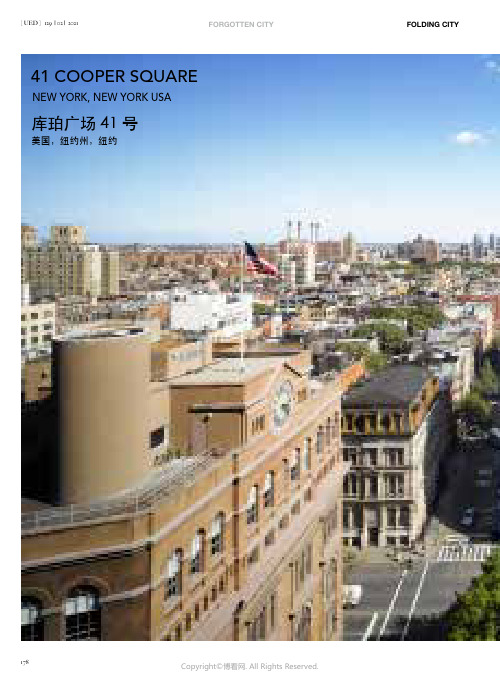

库珀广场41_号

41 COOPER SQUARE NEW YORK, NEW YORK USA库珀广场41号美国,纽约州,纽约项目地点:美国,纽约州,纽约,库珀广场41号委托客户:库珀高等科学艺术联盟学院建筑面积:175,000 平方英尺/ 16,258平方米用地面积:0.41 英亩 / 0.17公顷功能涵盖:带展览馆、礼堂、休息室和多用途空间以及零售空间的学术和实验室建筑设计时间:2004年至2006年施工时间:2006年至2009年项目类型:教育Location: 41 Cooper Square, New York City, New York, United States of America 10003 Client: The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and ArtSize: 175,000 gross sq ft / 16,258 gross sq mSite: 0.41 acres / 0.17 hectaresProgram: Academic and laboratory building with exhibition gallery, auditorium, lounge and multi-purpose space, and retail spaceDesign: 2004 – 2006Construction: 2006 – 2009Type: Educational巨人网络集团公司总部21世纪之交,中国创业活力的爆发带来了建筑业的相应热潮。

在谷歌(Google)和苹果(Apple)等科技巨头的引领下,中国的新兴企业正朝着创意办公空间的国际趋势发展,争先恐后地创造出与众不同的个性,这种个性由标志性的、设计大胆的办公楼所提供的优质工作环境所支撑。

正是基于这种背景,巨人网络集团作为一家领先的网络游戏开发商在上海市郊建立了一个新的公司总部。

普利茨克建筑奖0902

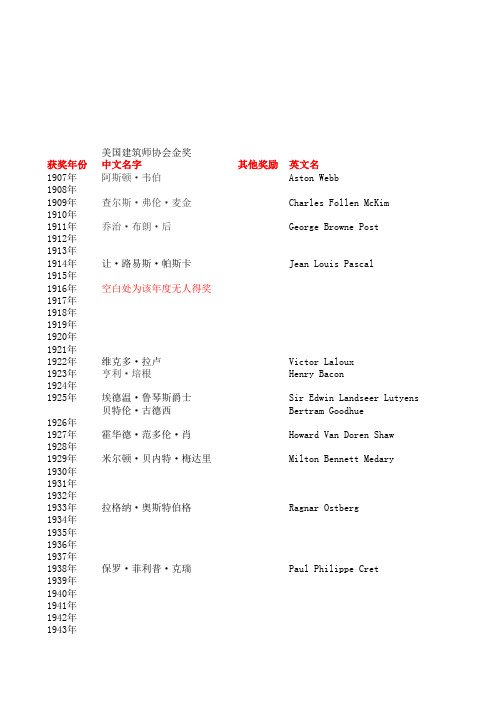

美国建筑师协会金奖获奖年份中文名字其他奖励英文名1907年阿斯顿·韦伯Aston Webb1908年1909年查尔斯·弗伦·麦金Charles Follen McKim1910年1911年乔治·布朗·后George Browne Post1912年1913年1914年让·路易斯·帕斯卡Jean Louis Pascal1915年1916年空白处为该年度无人得奖1917年1918年1919年1920年1921年1922年维克多·拉卢Victor Laloux1923年亨利·培根Henry Bacon1924年1925年埃德温·鲁琴斯爵士Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens 贝特伦·古德西Bertram Goodhue1926年1927年霍华德·范多伦·肖Howard Van Doren Shaw 1928年1929年米尔顿·贝内特·梅达里Milton Bennett Medary 1930年1931年1932年1933年拉格纳·奥斯特伯格Ragnar Ostberg1934年1935年1936年1937年1938年保罗·菲利普·克瑞Paul Philippe Cret1939年1940年1941年1942年1943年1944年路易斯·沙利文Louis Henri Sullivan1945年1946年1947年伊利尔·萨里南Eliel Saarinen1948年查尔斯·马基尼斯Charles Donagh Maginnis 1949年赖特Frank Lloyd Wright1950年帕德里克·艾伯克龙比爵士Sir Patrick Abercrombie1951年伯纳德·拉尔夫·梅贝克Bernard Ralph Maybeck 1952年奥格斯特·佩雷Auguste Perret1953年威廉·亚当斯·德拉诺William Adams Delano1954年1955年威廉·马里努斯·杜德克William Marinus Dudok 1956年克拉伦斯·斯坦Clarence Stein1957年拉尔夫·托马斯·沃克Ralph Thomas Walker 路易斯·斯基德莫尔Louis Skidmore1958年约翰·罗德John Wellborn Root1959年瓦尔特·格罗皮乌斯Walter Gropius1960年密斯·凡·德·罗Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe 1961年勒·柯布西耶Le Corbusier1962年埃罗·沙里宁Eero Saarinen1963年阿尔瓦·阿尔托Alvar Aalto1964年皮埃尔·路易吉·奈尔维Pier Luigi Nervi1965年1966年丹下健三Kenzo Tange1967年华莱士·哈里森Wallace Harrison1968年马塞尔·布劳耶Marcel Breuer1969年威廉·威尔逊·沃斯特William Wilson Wurster 1970年理查德·巴克明斯特·富勒Richard Buckminster Fuller 1971年路易斯·康Louis Isadore Kahn1972年皮耶特罗·贝鲁斯基Pietro Belluschi1973年1974年1975年1976年1977年查理德·诺伊特拉Richard Neutra1978年菲利普·约翰逊Philip Johnson1979年贝聿铭Ieoh Ming Pei1980年1981年约瑟夫·路易斯·塞特Joseph Luis Sert1982年罗马尔多·朱尔格拉Romaldo Giurgola1983年纳撒尼尔·奥因斯Nathaniel A. Owings1984年1985年威廉·韦恩·考迪尔William Wayne Caudill 1986年亚瑟·查尔斯·埃里克森Arthur Charles Erickson 1987年1988年1989年约瑟夫·埃谢瑞克Joseph Esherick1990年费依·琼斯 E. Fay Jones1991年查尔斯·威拉德·摩尔Charles Willard Moore 1992年本杰明·汤普森Benjamin Thompson1993年凯文·罗奇Kevin Roche托马斯·杰斐逊 Thomas Jefferson1994年诺曼·福斯特Norman Foster1995年西萨·佩里Cesar Pelli1996年1997年理查德·迈耶Richard Meier1998年1999年法兰克·盖瑞Frank Gehry2000年瑞卡多·雷可瑞塔Ricardo Legorreta 2001年迈克尔·格雷夫斯Michael Graves2002年安藤忠雄Tadao Ando2003年2004年塞缪尔·莫克比Samuel Mockbee2005年圣地亚哥·卡拉特拉瓦Santiago Calatrava 2006年安托尼·普里达克Antoine Predock2007年爱德华·拉华比·巴恩斯Edward Larrabee Barnes 2008年伦佐·皮亚诺Renzo Piano2009年2010年2011年/practicing/awards/AIAB025046国籍出生逝世评价代表作1英国1849-1930新古典主义白金汉宫美国1847-1909美术风格波斯顿公共图书馆美国1837-1913美术风格威廉斯堡储蓄银行法国1837-1920法国1850-1937美术风格图尔市政厅美国1866-1924美术风格林肯纪念堂英国1869-1944新古典主义海特拉巴住宅美国1869-1924内布拉斯加州议会大厦美国1869-1926第二长老会教堂美国1874-1929华盛顿纪念礼拜堂瑞典1866-1945浪漫主义斯德哥尔摩市政厅法国1876-1945古典主义泛美联盟大厦美国1856-1924早期现代主义芝加哥礼堂大楼芬兰1873-1950现代主义拉赫蒂市政厅美国1867-1955折衷主义圣帕特里克天主教会美国1869-1959现代主义芝加哥威利茨住宅英国1879-1957东北威尔士高等教育学院1862-1957折衷主义梅贝克工作室法国1874-1954新古典主义富兰克林街公寓美国1874-1960新古典主义新港艺术博物馆美国1882-1975菲普斯花园公寓美国1889–1973现代主义纽约电话公司大楼美国1897-1962现代主义林肯住宅美国1850-1891芝加哥学派风格Grannis街区德国1883-1969现代主义法古斯鞋楦厂(和A.迈耶合作设计)德国1886-1969现代主义白森毫夫公寓大楼法国1886-1965现代主义佛莱别墅美国1910-1961创造性建筑师圣路易市杰佛逊纪念碑芬兰1898-1976现代主义(地方风格)芬兰珊纳特赛罗市政中心意大利1891-1979罗马小体育宫日本1913-2005功能典型化代代木体育馆美国1895-1981现代主义联合国总部大楼美国1902-1981功能主义纽约萨拉·劳伦斯学院剧场美国1895-1973现代主义巴特勒众议院美国1895-1983未来主义节能多功能房美国1901-1974现代主义宾西法尼亚大学理查德医学研究中心意大利1899-1994现代主义中央路德教堂美国1892-1970现代主义罗维尔别墅美国1906-2005新古典主义与后现代休斯顿的潘索尔大厦美国1917-理性主义与几何构成东馆美国1902-1983现代主义米罗美术馆意大利1920-折衷主义朗音乐大楼美国1903-1984现代主义空军军官学校教堂美国1914-1983加拿大现代主义哥伦比亚大学人类学博物馆美国1914-1998美国1921-2004李奥纳多教堂美国1925-1993现代主义华盛顿历史博物馆美国1918-2002现代主义法纳维厅市场美国1922-现代传统主义奥克兰博物馆英国1935-高技派德国柏林国会大厦美国1920-实用主义马来西亚国家石油双子塔美国1935-白色派与典雅主义罗马千禧教堂美国1929-解构主义毕尔包古根汉美术馆分馆墨西哥1931-现代主义蒙特里中心图书馆美国1934-后现代主义波特兰市政厅日本1941-反现代机能主义光的教堂美国1944-2001当代现代主义布莱恩特住宅西班牙1951-结构形态主义雅典奥运主体育场美国1936-建筑诗人台湾故宫南院美国1915-2004朴素的现代主义干草堆山工艺学院意大利1937-现代主义巴黎蓬皮杜艺术中心代表作2代表作3圣巴塞洛缪教堂皇家瓦塞思中等学校哥伦比亚大学图书馆纽约大学俱乐部特洛伊储蓄银行布鲁克林历史协会鲁贝市政厅图尔Saint-Martin大教堂丹佛斯纪念图书馆康涅狄格火车站波克夏教区花园Tigbourne法院罗马众圣徒教堂新罕布什尔公共图书馆亨利·斯特德住宅尼·哈珀住宅湖鸟类保护区大钟楼海事历史博物馆施唐内利乌斯学校印第安纳波利斯公共图书馆底特律艺术研究所担保大厦伊利尔住宅约恩苏市政厅赫尔辛基火车站波斯顿学院新校园伊曼纽尔学院纽约州布法罗市拉金公司办公楼伊利诺州罗伯茨住宅伦敦规划(1943)大伦敦区域规划(1944)奇克住宅旧金山艺术宫勒兰西教堂嘉宫博物馆埃皮纳勒美国纪念馆尼克博克俱乐部恩光花园西联汇款大厦AT&T大厦美国空军军官学校纽约世界博览会展馆蒙托克大楼菲尼克斯大楼德意志制造联盟科隆展览会办公楼耶那市立剧场德国克雷费尔德朗格住宅西班牙巴塞罗那博览会德国馆国际联盟总部设计方案萨伏伊别墅耶鲁大学冰球馆纽约肯尼迪机场环球航空公司候机楼帕伊米奥结核病疗养院伊马特拉市教堂大体育宫皮瑞里大厦广岛和平公园原子弹爆炸纪念馆埃克森大厦大都会歌剧院巴黎的联合国教科文组织总部大厦鹿特丹比仁考夫百货商店格雷戈里农舍西贝特住宅大球形美国展览馆联合油槽汽车公司修理大厅耶鲁大学美术馆索克大学研究所费城罗姆和哈斯公司总部大楼加利福尼亚路555号大楼考夫曼住宅特里迈尼住宅加利福尼亚州加登格罗芙的“水晶教堂”纽约的AT&T大楼(美国电话电报大楼)卢浮宫金字塔肯尼迪图书馆哈佛大学霍利奥克中心波士顿大学中央校园Tredyffrin公共图书馆联合基金司令部大楼威尔斯学院图书馆约翰汉寇克中心温哥华省法院圣地亚哥会议中心克洛斯比植物园索恩克朗礼拜堂加利福尼亚艺术中心国立东华大学威廉斯学院布朗夫曼科学中心设计学院剑桥设计研究总部福特基金会大楼DEERE WEST办公大楼英国多克福德美国航空博物馆英国伦敦“千年大厦”太平洋设计中心圣贝纳迪诺市政厅美国洛杉矶格蒂中心克曼德威尔广场西雅图摇滚乐博物馆圣塔摩尼卡购物中心王者之道旅馆雷诺工厂佛罗里达天鹅饭店休曼纳大厦水的教堂风的教堂蝴蝶住宅燕西小教堂里昂国际机场里斯本东方火车站亚历桑纳科学中心加拿大人权博物馆纽约麦迪逊大街590号的IBM办公楼奥斯本住宅关西国际机场提巴欧文化中心代表作4维多利亚和阿尔伯特博物馆摩根图书馆纽约时报大厦图尔火车站卫斯理大学Olin图书馆伦敦不列颠之家华盛顿酒店霍姆伍德乡村俱乐部佐恩博物馆福尔杰·莎士比亚图书馆珠宝商大楼Kleinhans音乐厅三一学院礼拜堂芝加哥罗比住宅玫瑰道圣若瑟教会重建沃尔特斯艺术画廊纽约长岛电话公司总部纽约布鲁克林退伍军人管理处总医院蒙娜德诺克大厦丹默斯托克居住区捷克斯洛伐克布尔诺巴黎瑞士学生宿舍华盛顿杜勒斯机场候机楼卡雷住宅都灵展览馆B厅东京都厅舍第一长老会教堂法国戛得国际商用机器公司研究中心大厦詹森之家美国圣路易斯植物园热带植物展厅爱塞特图书馆俄勒冈的维拉米特大学德莱塞大楼劳维尔住宅与路德维西·密斯·凡·德·罗合作设计的西格莱姆大厦香山饭店在蓬塔马丁内特的住宅哥伦布市高中惠好公司总部鲍德温公园医疗中心库珀教堂贝亚维斯塔密西根大学卢里塔楼南街海港联邦广场饭店上海久事大厦华盛顿国家机场海滨别墅迪士尼音乐厅创新技术博物馆阿维亭中心泰特现代美术展览馆阿克伦男孩女孩俱乐部巴塞罗那聚光塔巴黎迪斯尼乐园中的圣塔菲饭店巴恩斯住宅梅尼博物馆代表作5代表作6大不列颠皇家海军学院南肯辛顿皇家科学学院宾夕法尼亚车站美国艺术学院纽约物产交易所世界大楼奥赛火车站奥斯博物馆卫斯理大学天文台卫斯理大学宿舍楼米德兰银行特拉法加广场加利福尼亚海军训练中心克兰布鲁克基督教堂湖畔新闻大楼普尔曼信托储蓄银行Nedre马尼拉Ekarne别墅家政大厦(现玛丽齿轮厅)建筑大厦(现戈德史密斯厅)考夫曼商店与公寓圣三一俄国东正教堂哥伦布第一基督教教会波赫尤拉保险大厦圣母大学法学院波士顿学院Gasson塔东京帝国饭店流水别墅督科学第一教堂安德鲁·劳森住宅香榭丽舍剧院巴黎高等师范学院音乐厅赖特纪念馆圣伯纳德学校时代广场大厦欧文信托大厦米度湖住宅发展小区Inland钢铁大厦北密西根333大厦芝加哥交易所大楼德国柏林西门子住宅区英国英平顿地方乡村学校密斯•凡•德•罗住宅范士沃斯住宅巴西里约热内卢教育卫生部大楼马赛公寓大楼底特律市通用汽车公司技术中心麻省理工学院礼堂奥尔夫斯贝格文化中心欧塔尼米技术学院礼堂纽约乔治·华盛顿桥汽车站梵蒂冈教皇大厅香川县厅舍山梨文化会馆斯图书馆拉瓜迪亚国际机场布劳耶住宅克拉克海滨别墅教皇楼网格穹顶孟加拉国达卡国民议会厅艾哈迈德巴德的印度管理学院佛蒙特州本宁顿大学图书馆俄勒冈州立大学布列腾布什大楼塞尔鲁尼别墅洛杉矶市考罗那初级小学达拉斯感恩广场德克萨斯州休斯顿美国银行美秀美术馆苏州博物馆已婚学生公寓哈佛大学科学中心堪培拉议会大厦费城INA塔楼威斯康辛第一广场希尔斯大厦瀑布大楼科威特石油大厦自然之家加利福尼亚大学附校哈斯商业学校迈阿密海边市场杰克逊维尔码头杜勒斯国际机场香港汇丰银行总部大厦英国伦敦千年桥世界金融中心冬季花园莱斯大学青鱼大厅深圳华侨城欢乐海岸“OCT会所”艾佛利费舍尔音乐厅盖瑞自宅跃鲤餐厅市政府电视广播中心视觉艺术中心纽瓦克博物馆布赖恩学院教学楼韩国国立博物馆新笛洋美术馆布莱恩特熏制室梅森本德社区中心巴伦西亚科学城密尔沃基美术馆亚历桑那州州立大学尼尔森美术中心加州史丹福大学帕洛奥托巴克住宅马斯特斯住宅日本大阪工业亭木棚状文化中心代表作7代表作8金钟拱 阿斯顿·韦伯大厦哈佛大学约翰逊门纽波特赌场纽约棉花交易所布利夫兰信托公司里昂信贷总部美国驻法大使馆联盟广场储蓄银行安布罗斯Swasey大帐蓬林迪斯法城堡爱尔兰国家战争纪念馆火奴鲁鲁艺术学院内布拉斯加国会大厦古德曼纪念剧院基督门徒教会德克萨斯州联盟大厦美国法院大楼克劳兹音乐店范爱伦大厦芬兰国家博物馆帕德里克大教堂罗马天主教堂约翰逊公司总部亚利桑那州斯科茨代尔博克住宅奇克院亚眠火车站蓬蒂厄车库斯特林化学实验室日本大使馆密歇根福特汽车总部大楼利华公司办公大厦芝加哥每日新闻报大楼克莱斯勒大厦格罗皮乌斯自用住宅哈佛大学研究生中心湖滨公寓美国伊利诺工学院建筑及设计系馆郎香教堂哈佛大学卡本特视觉艺术中心华沙学院诺埃宿舍莫尔斯学院赫尔辛基芬兰地亚会议厅伊马特拉附近的伏克塞涅斯卡教堂巴黎联合国教科文组织大楼米兰派拉里大楼仓敷县厅舍Mary圣大教堂洛克菲勒中心康宁玻璃中心道波楼吉拉德里广场费城市规划设计米尔溪公建住宅布克住宅乔治·福克斯大学千禧年塔和体育中心梅列海滨的汽车旅馆美国驻巴基斯坦大使馆俄亥俄州克里夫兰雕刻中心美国康涅狄格州纽卡纳安玻璃住宅中银大厦约翰逊艺术馆琼·米罗画室琼·米罗基金会当代艺术研究中心麦克米兰•布隆德尔大厦洛杉矶加利佛尼亚广场克雷斯基学院日本东京千年塔日本东京世纪大厦哥伦布公众广场圣卢克诊所塔楼Jesolo丽都酒店及住宅区皮克&克洛彭堡百货大楼辛辛那提大学分子研究中心Conde Nast咖啡厅卡隆实验室瑞诺住宅滨港公寓塔楼奥兰多的迪斯尼世界旅馆苏菲亚王妃艺术中心布利码头博物馆学生小窝毕尔巴鄂步行桥毕尔巴鄂机场航楼佛罗里达州科学与工艺博物馆加州圣地亚哥教士队棒球场沃克艺术中心堪萨斯市皇冠中心休斯顿menil博物馆贝耶勒基金会博物馆代表作9伯明翰维多利亚法院香港立法会大楼维拉德住房威斯康辛国会大厦蒙特利尔证券交易所大楼切尔西储蓄银Halle兄弟百货公司凤凰公园美国国家科学院大楼四方俱乐部费城联邦储备银行联合信托大厦古根海姆博物馆泛美航空公司系统终端大楼马萨诸塞州西水桥小学何塞·昆西公立学校美国伊利诺理工学院皇冠厅纽约西格拉姆大厦印度昌迪加尔城市规划斯特尔斯学院联邦德国沃耳夫斯堡的沃尔斯瓦根文化中心不来梅市的高层公寓大楼罗马奥运会运动场馆阿尔及尔国际机场草月会馆霍普金斯中心莱曼住宅奥瑟住宅美国联邦储备银行大楼纽约林肯中心朱丽娅音乐学院洛杉矶鹰石俱乐部洛杉矶唱片名人堂JP摩根大楼华盛顿特区加拿大总理府西班牙巴伦西亚会议中心法国加里艺术中心米林·贝拉塔楼俄亥俄州艺术中心布尔达收藏馆波士顿儿童博物馆科尔多巴住宅汉诺威世博会墨西哥馆安特卫普市立美术馆姬路文学馆坦纳利佛音乐厅马德里巴伦西亚科学城德州奥斯汀市政厅纽约列克星敦大街599号达拉斯艺术博物馆罗马音乐厅琦玉广场梅隆科技馆德国柏林新国家美术馆贝克大楼维堡图书馆王子饭店波特兰博物馆旧金山圣玛丽大教堂皮诺基金会美术馆希腊Mimico Bridge斯达德霍芬火车站罗达高架桥瓦伦西亚的艺术科学城。

公园道路设计国际奖的翻译

形式与功能:走线amrish穆克,妮可斯塔尔,塔伦电影2008年11月18日1摘要艺术四是一个空间,是受几个相互竞争的利益。

它的设计是期望提供的机会,为个人移动方便从一头到另一头,保持一般维修费用是可行的和允许的活动范围从讲座,打雪仗。

本文提出了一个数学模型,提供了一种智能设计四路网络。

我们的核心模型是一个成本函数,其中评价可行性的一个给定的路径配置。

探索一套可行的路径配置我们写一个算法,随机生成样品本集。

然后在此基础上改进的搜索通过构建一个优化算法灵感来自马尔可夫链蒙特卡洛方法。

我们相信,这一改进的搜索找到一个地方最小路径配置,因为它似乎稳定摄动下。

2内容我问题的声明4二艺术四边形为图4三路径长度6四非正式路径诱导人的行为7五成本函数8六假设:9七算法寻找最优路径配置9八结果:10九推荐方案11未来工作15×西安书目163第一部分问题陈述我们的任务是重新设计艺术四通道使用一个数学模型,将帮助我们确定一个首选的设计。

除了一般的事实,尽量减少总长度的路径和最大限度的地区连续的草坪是可取的,我们要求道路维修成本是成正比的,道路总长度。

_美化成本取决于一些连续的草坪,创造了非官方的路径(因行人离开铺设路径到达目的地迅速)和几何连续的草坪。

_如果两点之间的路径是15%长于直线的点线连接,一行人离开道路,跨越四。

_平均步行可能离开的路径,如果它意味着节省10%以上的总长度的路径。

第二部分艺术作为一个图图论是一个重要的工具,在探索的问题,尽量减少总长度的路径和最大限度的地区连续的草坪是可取的,我们要求其范围从确定神经网络的线虫线虫发现失败的原因在电力grids1。

通过制定我们的走道设计问题的语言,我们可以很容易地提取关键结构和功能之间的关系。

我们描述的艺术四边形(现称为艺术四或简单的四)作为一个图的10个节点,这是最常见的入境和出境点的四(见下面的图1)。

看[ 1 ]4图1:康奈尔艺术四让节点集是一个=集合的。

屋顶绿化与墙体绿化是复兴城市与建筑剩余空间的工具

屋顶绿化与墙体绿化是复兴城市与建筑剩余空间的工具Monica Perez Baez1,Katsuhiko Suzuki2日本京都606-8585,京都市左京区松ヶ崎桥上町,京都工艺纤维大学,工程与技术研究生院,建筑设计系1博士研究生(mopearch@yahoo.co.jp),2教授(suzuki28@kit.ac.jp)范洪伟译摘要:多年来,随着城市的加速发展,城市中绿色空间大大减少。

热岛效应和全球变暖等环境问题明显恶化,在城市里增加或建设绿色空间的可能性减少。

为了缓和这种现象,建筑和城市绿化作为一种方法成为关注的焦点。

这篇文章分析了不同的屋顶绿化和墙体绿化的设计方法,有助于现有建筑和城市剩余空间的复兴和重复应用。

并演示了如何通过城市与自然的和谐共生来实现生活条件的改善以及环境的恢复。

在一个绿化提案前后,日本关西地区实施了三个绿化项目,其结果被广泛的谈论。

此外,为了了解人们对城市绿化的态度,对京都、大阪和名古屋的10个现存地区进行调查,并利用有铃木教授实验室所提出可持续环境的评估方法(SEAM)进行信息的分析和比较。

最后基于调查的结果,给城市绿化以及未来应用给出一些建议。

关键词:绿化方式、城市绿化、屋顶花园、墙面绿化、剩余空间、复兴简介工业污染,过度使用的交通手段和城市硬灰色空间的加速增长,是造成当今环境问题的主要根源。

因此,增加城市绿色空间的必要性和结合自然来创造更加健康愉快的城市空间的理念已开始被许多国家所接受。

应对能源减少和自然资源过渡消耗的方法也在发展。

此外,同过利用绿色技术和环境友好型材料来设计高效能建筑的实践也正在进行。

然而,许多情况下这些解决方案被认为是只适用于新建地区,因为他们可以在一定程度上减少对环境的破坏。

在建成的城市里增加绿色空间的可能性很小,因为可利用的区域已逐渐被占领。

另一方面,现有建筑物和与之相关的空间(如墙壁,屋顶,阳台等)以及未使用的或被遗弃的城市空间所代表的宝贵机会都被低估了。

“城村架构”中的一个砖墙原型——林君翰先生访谈

“城村架构”中的一个砖墙原型——林君翰先生访谈范路【期刊名称】《世界建筑》【年(卷),期】2014(000)007【总页数】4页(P22-25)【作者】范路【作者单位】清华大学建筑学院【正文语种】中文林君翰先生是香港大学建筑系的副教授和“城村架构”(RUF)工作团队的创始人。

“城村架构”成立于2005年,是一个非盈利机构。

它以建筑项目、学术研究、展览和写作等方式,积极介入中国大陆的乡村向城市转变的过程。

到目前为止,该机构团队已经在中国大陆完成了至少15个项目。

这些项目位于大陆不同地区的乡村,包括学校、社区中心、医院、乡村住宅、桥梁及增量规划策略等(图1、2)。

在这些项目中,坐落于陕西省石家村的“四季”住宅(2009-2012)格外引人注目。

它获得了2014年维纳博艮砖筑奖、2012年WA中国建筑奖优胜奖和2012年《建筑评论》杂志住宅奖。

林君翰先生通过设计这座乡村砖墙住宅,尝试发展一种关于中国传统合院住宅的可持续发展的现代原型。

他还试图通过使用当地已有建筑材料和工序,来沟通传统和现代。

本访谈旨在呈现石家村住宅中所运用的创新性设计策略,以及建筑师对项目背后社会问题的批判性思考。

范路:您为何想要于2005年成立“城村架构”?该组织的建筑学目标又是什么?林君翰:“城村架构”是我和约书亚·鲍乔弗(Joshua Bolchover)一起成立的,目的是探究中国的城市化问题。

我们认为,城市化会导致积极或消极的后果,而城市化的过程对于决定结果非常重要。

我们通过合作,试图找到将学术研究与实际项目相结合的方式。

我们的一个方法就是在项目进行过程中开展研究。

这不同于纯粹的分析性研究,还是对建筑项目所产生影响的检验。

我们常常会想,对一个单独的项目来说,它能否在乡村或更大的尺度上解决更多的问题?范路:在您看来,中国乡村向城市转变过程中的主要社会问题是什么?建筑又能以何种方式来应对这些问题?林君翰:在这一过程中有许多问题,也有许多可能。

基坑规范英文版

基坑规范英文版篇一:行业标准中英对照44项工程建设标准(英文版)目录123篇二:地下室设计深基坑中英文对照外文翻译文献中英文对照外文翻译(文档含英文原文和中文翻译)Deep ExcavationsABSTRACT :All major topics in the design of in-situ retaining systems for deep excavations in urban areas are outlined. Type of wall, water related problems and water pressures, lateral earth pressures, type of support, solution to earth retaining walls, types of failure, internal and external stability problems.KEYWORDS: deep excavation; retaining wall; earth pressure;INTRODUCTIONNumbers of deep excavation pits in city centers are increasing every year. Buildings, streets surroundingexcavation locations and design of very deep basements make excavations formidable projects. This chapter has been organized in such a way that subjects related to deep excavation projects are summarized in several sections in the order of design routine. These are types of in-situ walls, water pressures and water related problems. Earth pressures in cohesionless and cohesive soils are presented in two different categories. Ground anchors, struts and nails as supporting elements are explained. Anchors are given more emphasis pared to others due to widespread use observed in the recent years. Stability of retaining systems are discussed as internal and external stability. Solution of walls for shears, moments, displacements and support reactions under earth and water pressures are obtained making use of different methods of analysis. A pile wall supported by anchors is solved by three methods and the results are pared. Type of wall failures, observed wall movements and instrumentation of deep excavation projects are summarized.1. TYPES OF EARTH RETAINING WALLS1.1 IntroductionMore than several types of in-situ walls are used to support excavations. The criteria for the selection of type of wall are size of excavation, ground conditions, groundwater level, vertical and horizontal displacements of adjacent ground and limitations of various structures, availability of construction, cost,speed of work and others. One of the main decisions is the water-tightness of wall. The following types ofin-situ walls will be summarized below;1. Braced walls, soldier pile and lagging walls2. Sheet-piling or sheet pile walls3. Pile walls (contiguous, secant)4. Diaphragm walls or slurry trench walls5. Reinforced concrete (cast-in-situ or prefabricated) retaining walls6. Soil nail walls7. Cofferdams8. Jet-grout and deep mixed walls9. Top-down construction10. Partial excavation or island method1.1.1 Braced WallsExcavation proceeds step by step after placement of soldier piles or so called king posts around the excavation at about 2 to 3 m intervals. These may be steel H, I or WF sections. Rail sections and timber are also used. At each level horizontal waling beams and supporting elements (struts, anchors,nails) are constructed. Soldier piles are driven or monly placed in bored holes in urban areas, and timberlagging is placed between soldier piles during the excavation. Various details of placement of lagging are available, however(来自: 小龙文档网:基坑规范英文版), precast units, in-situ concrete or shotcrete may also be used as alternative to timber. Depending on ground conditions no lagging may be provided in relatively shallow pits.Historically braced walls are strut supported. They had been used extensively before the ground anchor technology was developed in 1970?s. Soils with some cohesion and without water table are usually suitable for this type of construction or dewatering is acpanied if required and allowed. Strut support is monly preferred in narrow excavations for pipe laying or similar works but also used in deep and large excavations (See Fig 1.1). Ground anchor support is increasingly used and preferred due to access for construction works and machinery. Waling beams may be used or anchors may be placed directly on soldierpiles without any beams.1.1.2 Sheet-piling or Sheet Pile WallsSheet pile is a thin steel section (7-30 mm thick)400-500 mm wide. It is manufactured in different lengths and shapes like U, Z and straight line sections (Fig. 1.2). There are interlocking watertight grooves at the sides, and they are driven into soil by hammering or vibrating. Their use is often restricted in urbanized areas due to environmental problems likenoise and vibrations. New generation hammers generate minimum vibration anddisturbance, and static pushing of sections have been recently possible. In soft ground several sections may be driven using a template. The end product is a watertight steel wall in soil. One side (inner) of wall is excavated step by step and support is given by struts or anchor. Waling beams (walers) are frequently used. They are usually constructed in water bearing soils.Steel sheet piles are the most mon but sometimes reinforced concrete precast sheet pile sections are preferred in soft soils if driving difficulties are not expected. Steel piles may also encounter driving difficulties in very dense, stiff soils or in soils with boulders. Jetting may be acpanied during the process to ease penetration. Steel sheet pile sections used in such difficult driving conditions are selected according to the driving resistance rather than the design moments in the project. Another frequently faced problem is the flaws in interlocking during driving which result in leakages under water table. Sheet pile walls are monly used for temporary purposes but permanent cases are also abundant. In temporary works sections are extracted after their service is over, and they are reused after maintenance. This process may not be suitable in dense urban environment.1.1.3 Pile WallsIn-situ pile retaining walls are very popular due to their availability and practicability. There are different types of pile walls (Fig. 1.3). In contiguous (intermittent) bored pile construction, spacing between the piles is greater篇三:基坑开挖换填施工方案英文版Sokoto Cement Factory Project of the 17 Bureau, Chinese Railway ConstructionCompanythConstruction Schemes for Foundation pit ExcavationAnd ReplacementComposed by:Editor:Chief editor:Fifth division of 17th Bureau of CRCC, manager department of theSokoto Cement Factory Project, Nigeria23th November 2104Contents1Introduction ......................................... ...................................................... ............................. 11.1 Basis for theposition ............................................. ............................................... 11.2 Principles for theposition ............................................. ........................................ 12.1Location ............................................. ...................................................... .................... 12.2 Geographicreport ............................................... ...................................................... ... 22.3 Ground water and undergroundwater. ............................................... ......................... 2 Construction techniques andmethods .............................................. ...................................... 23.1 Excavation of the foundationpit .................................................. ................................ 23.1.13.1.23.1.33.1.43.1.53.1.63.23.2.13.2.23.2.33.2.44 Gradient of the foundationpit .................................................. ......................... 3 The stability of the side slope ................................................ ............................ 3 The form ofexcavation ........................................... .......................................... 4Preparation for theexcavation ........................................... ................................ 5 Construction procedures ........................................... ......................................... 6Methods .............................................. ...................................................... ......... 6 Constructionmaterial ............................................. ........................................... 7Constructionpreparation .......................................... ......................................... 8Techniques and constructionalprocedure. ........................................... ............. 8Methods .............................................. ...................................................... ......... 9 3 Gravelreplacement .......................................... ...................................................... ...... 7 Organization of construction and logistic work ................................................. ................ 114.1 The managing system for construction organization. ........................................ ...... 114.2 Human resources for theconstruction ......................................... ............................ 114.3 Logisticwork ................................................. ...................................................... .... 124.4 Technicalguarantee ............................................ ..................................................... 124.5 Quality and techniques standard andregulation ........................................... ........... 124.5.14.5.24.5.34.5.44.64.6.14.6.24.6.34.74.8 Qualitystandard ............................................. ............................................... 12Quality monitoringorganization ......................................... .......................... 13 Raising awareness for the importance of quality and professional skills. .... 13 Establishing quality managementcode. ................................................ ........ 13 Safety regulations for mechanical construction ......................................... ... 14 Trafficregulations ......................................................................................... 15Safety regulations for fillingconstruction. ........................................ ............ 15 Safety techniquesmeasures ............................................. ........................................ 14Environment protectionmeasures ............................................. .............................. 16 Construction during the rainseason ............................................... ......................... 164.8.14.8.2 Collecting weatherdata ................................................. ................................ 16 Technical measures fordrainage ............................................. ...................... 164.9 Technical measures for sandstorm ................................................ .......................... 174.10 Contingencyplan ................................................. .................................................... 17Construction Schemes for Foundation pitExcavation And Replacement1 Introduction1.1 Basis for the position1.1.1 1.1.21.1.3 Drawings submitted by the Owner (GB50300-2001)。

1-2007_-_Y_F_Han_-_PreparationofnanosizedMn3O4SBA15catalystforcomplet[retrieved-2016-11-15]

![1-2007_-_Y_F_Han_-_PreparationofnanosizedMn3O4SBA15catalystforcomplet[retrieved-2016-11-15]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/9d89122483c4bb4cf7ecd13a.png)

Preparation of nanosized Mn 3O 4/SBA-15catalyst for complete oxidation of low concentration EtOH in aqueous solution with H 2O 2Yi-Fan Han *,Fengxi Chen,Kanaparthi Ramesh,Ziyi Zhong,Effendi Widjaja,Luwei ChenInstitute of Chemical and Engineering Sciences,1Pesek Road,Jurong Island 627833,Singapore Received 11May 2006;received in revised form 18December 2006;accepted 29May 2007Available online 2June 2007AbstractA new heterogeneous Fenton-like system consisting of nano-composite Mn 3O 4/SBA-15catalyst has been developed for the complete oxidation of low concentration ethanol (100ppm)by H 2O 2in aqueous solution.A novel preparation method has been developed to synthesize nanoparticles of Mn 3O 4by thermolysis of manganese (II)acetylacetonate on SBA-15.Mn 3O 4/SBA-15was characterized by various techniques like TEM,XRD,Raman spectroscopy and N 2adsorption isotherms.TEM images demonstrate that Mn 3O 4nanocrystals located mainly inside the SBA-15pores.The reaction rate for ethanol oxidation can be strongly affected by several factors,including reaction temperature,pH value,catalyst/solution ratio and concentration of ethanol.A plausible reaction mechanism has been proposed in order to explain the kinetic data.The rate for the reaction is supposed to associate with the concentration of intermediates (radicals: OH,O 2Àand HO 2)that are derived from the decomposition of H 2O 2during reaction.The complete oxidation of ethanol can be remarkably improved only under the circumstances:(i)the intermediates are stabilized,such as stronger acidic conditions and high temperature or (ii)scavenging those radicals is reduced,such as less amount of catalyst and high concentration of reactant.Nevertheless,the reactivity of the presented catalytic system is still lower comparing to the conventional homogenous Fenton process,Fe 2+/H 2O 2.A possible reason is that the concentration of intermediates in the latter is relatively high.#2007Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.Keywords:Hydrogen peroxide;Fenton catalyst;Complete oxidation of ethanol;Mn 3O 4/SBA-151.IntroductionRemediation of wastewater containing organic constitutes is of great importance because organic substances,such as benzene,phenol and other alcohols may impose toxic effects on human and animal anic effluents from pharmaceu-tical,chemical and petrochemical industry usually contaminate water system by dissolving into groundwater.Up to date,several processes have been developed for treating wastewater that contains toxic organic compounds,such as wet oxidation with or without solid catalysts [1–4],biological oxidation,supercritical oxidation and adsorption [5,6],etc.Among them,catalytic oxidation is a promising alternative,since it avoids the problem of the adsorbent regeneration in the adsorption process,decreases significantly the temperature and pressure in non-catalytic oxidation techniques [7].Generally,the disposalof wastewater containing low concentration organic pollutants (e.g.<100ppm)can be more costly through all aforementioned processes.Thus,catalytic oxidation found to be the most economical way for this purpose with considering its low cost and high efficiency.Currently,a Fenton reagent that consists of homogenous iron ions (Fe 2+)and hydrogen peroxide (H 2O 2)is an effective oxidant and widely applied for treating industrial effluents,especially at low concentrations in the range of 10À2to 10À3M organic compounds [8].However,several problems raised by the homogenous Fenton system are still unsolved,e.g.disposing the iron-containing waste sludge,limiting the pH range (2.0–5.0)of the aqueous solution,and importantly irreversible loss of activity of the reagent.To overcome these drawbacks raised from the homogenous Fenton system,since 1995,a heterogeneous Fenton reagent using metal ions exchanged zeolites,i.e.Fe/ZSM-5has proved to be an interesting alternative catalytic system for treating wastewater,and showed a comparable activity with the homogenous Fenton system [9].However,most reported heterogeneous Fenton reagents still need UV radiation during/locate/apcatbApplied Catalysis B:Environmental 76(2007)227–234*Corresponding author.Tel.:+6567963806.E-mail address:han_yi_fan@.sg (Y .-F.Han).0926-3373/$–see front matter #2007Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.05.031oxidation of organic compounds.This might limit the application of homogeneous Fenton system.Exploring other heterogeneous catalytic system considering the above disadvantages,is still desirable for this purpose.Here,we present an alternative catalytic system for the complete oxidation of organic com-pounds in aqueous solution using supported manganese oxide as catalyst under mild conditions,which has rarely been addressed.Mn-containing oxide catalysts have been found to be very active for the catalytic wet oxidation of organic effluents (CWO)[10–14],which is operated at high air pressures(1–22MPa)and at high temperatures(423–643K)[15].On the other hand,manganese oxide,e.g.MnO2[16],is well known to be active for the decomposition of H2O2in aqueous solution to produce hydroxyl radical( OH),which is considered to be the most robust oxidant so far.The organic constitutes can be deeply oxidized by those radicals rapidly[17].The only by-product is H2O from decomposing H2O2.Therefore,H2O2is a suitable oxidant for treating the wastewater containing organic compounds.Due to the recent progress in the synthesis of H2O2 directly from H2and O2[18,19],H2O2is believed to be produced through more economical process in the coming future.So,the heterogeneous Fenton system is economically acceptable.In this study,nano-crystalline Mn3O4highly dispersed inside the mesoporous silica,SBA-15,has been prepared by thermolysis of organic manganese(II)acetylacetonate in air. We expect the unique mesoporous structure may provide add-itional function(confinement effect)to the catalytic reaction, i.e.occluding/entrapping large organic molecules inside pores. The catalyst as prepared has been examined for the complete oxidation of ethanol in aqueous solution with H2O2,or to say, wet peroxide oxidation.Ethanol was selected as a model organic compound because(i)it is one of the simplest organic compounds and can be easily analyzed,(ii)it has high solu-bility in water due to its strong hydrogen bond with water molecule and(iii)the structure of ethanol is quite stable and only changed through catalytic reaction.Presently,for thefirst time by using the Mn3O4/SBA-15catalyst,we investigated the peroxide ethanol oxidation affected by factors such as temperature,pH value,ratio of catalyst(g)and volume of solution(L),and concentration of ethanol in aqueous solution. In addition,plausible reaction mechanisms are established to explain the peroxidation of ethanol determined by the H2O2 decomposition.2.Experimental2.1.Preparation and characterization of Mn3O4/SBA-15 catalystSynthesis of SBA-15is similar to the previous reported method[20]by using Pluronic P123(BASF)surfactant as template and tetraethyl orthosilicate(TEOS,98%)as silica source.Manganese(II)acetylacetonate([CH3COCH C(O)CH3]2Mn,Aldrich)by a ratio of2.5mmol/gram(SBA-15)werefirst dissolved in acetone(C.P.)at room temperature, corresponding to ca.13wt.%of Mn3O4with respect to SBA-15.The preparation method in detail can be seen in our recent publications[21,22].X-ray diffraction profiles were obtained with a Bruker D8 diffractometer using Cu K a radiation(l=1.540589A˚).The diffraction pattern was taken in the Bragg angle(2u)range at low angles from0.68to58and at high angles from308to608at room temperature.The XRD patterns were obtained by scanning overnight with a step size:0.028per step,8s per step.The dispersive Raman microscope employed in this study was a JY Horiba LabRAM HR equipped with three laser sources(UV,visible and NIR),a confocal microscope,and a liquid nitrogen cooled charge-coupled device(CCD)multi-channel detector(256pixelsÂ1024pixels).The visible 514.5nm argon ion laser was selected to excite the Raman scattering.The laser power from the source is around20MW, but when it reached the samples,the laser output was reduced to around6–7MW after passing throughfiltering optics and microscope objective.A100Âobjective lens was used and the acquisition time for each Raman spectrum was approximately 60–120s depending on the sample.The Raman shift range acquired was in the range of50–1200cmÀ1with spectral resolution1.7–2cmÀ1.Adsorption and desorption isotherms were collected on Autosorb-6at77K.Prior to the measurement,all samples were degassed at573K until a stable vacuum of ca.5m Torr was reached.The pore size distribution curves were calculated from the adsorption branch using Barrett–Joyner–Halenda(BJH) method.The specific surface area was assessed using the BET method from adsorption data in a relative pressure range from 0.06to0.10.The total pore volume,V t,was assessed from the adsorbed amount of nitrogen at a relative pressure of0.99by converting it to the corresponding volume of liquid adsorbate. The conversion factor between the volume of gas and liquid adsorbate is0.0,015,468for N2at77K when they are expressed in cm3/g and cm3STP/g,respectively.The measurements of transmission electron microscopy (TEM)were performed at Tecnai TF20S-twin with Lorentz Lens.The samples were ultrasonically dispersed in ethanol solvent,and then dried over a carbon grid.2.2.Kinetic measurement and analysisThe experiment for the wet peroxide oxidation of ethanol was carried out in a glass batch reactor connected to a condenser with continuous stirring(400rpm).Typically,20ml of aqueous ethanol solution(initial concentration of ethanol: 100ppm)wasfirst taken in the round bottomflask(reactor) together with5mg of catalyst,corresponding to ca.1(g Mn)/30 (L)ratio of catalyst/solution.Then,1ml of30%H2O2solution was introduced into the reactor at different time intervals (0.5ml at$0min,0.25ml at32min and0.25ml at62min). The total molar ratio of H2O2/ethanol is about400/1. Hydrochloric acid(HCl,0.01M)was used to acidify the solution if necessary.NH4OH(0.1M)solution was used to adjust pH to9.0when investigating the effect of pH.The pH for the deionized water is ca.7.0(Oakton pH meter)and decreased to 6.7after adding ethanol.All the measurements wereY.-F.Han et al./Applied Catalysis B:Environmental76(2007)227–234 228performed under the similar conditions described above if without any special mention.For comparison,the reaction was also carried out with a typical homogenous Fenton reagent[17], FeSO4(5ppm)–H2O2,under the similar reaction conditions.The conversion of ethanol during reaction was detected using gas chromatography(GC:Agilent Technologies,6890N), equipped with HP-5capillary column connecting to a thermal conductive detector(TCD).There is no other species but ethanol determined in the reaction system as evidenced by the GC–MS. Ethanol is supposed to be completely oxidized into CO2and H2O.The variation of H2O2concentration during reaction was analyzed colorimetrically using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Epp2000,StellarNet Inc.)after complexation with a TiOSO4/ H2SO4reagent[18].Note that there was almost no measurable leaching of Mn ion during reaction analyzed by ICP(Vista-Mpx, Varian).3.Results and discussion3.1.Characterization of Mn3O4/SBA-15catalystThe structure of as-synthesized Mn3O4inside SBA-15has beenfirst investigated with powder XRD(PXRD),and the profiles are shown in Fig.1.The profile at low angles(Fig.1a) suggests that SBA-15still has a high degree of hexagonal mesoscopic organization even after forming Mn3O4nanocrys-tals[23].Several peaks at high angles of XRD(Fig.1b)indicate the formation of a well-crystallized Mn3O4.All the major diffraction peaks can be assigned to hausmannite Mn3O4 structure(JCPDS80-0382).By N2adsorption measurements shown in Fig.2,the pore volume and specific surface areas(S BET)decrease from 1.27cm3/g and937m2/g for bare SBA-15to0.49cm3/g and 299m2/g for the Mn3O4/SBA-15,respectively.About7.7nm of mesoporous diameter for SBA-15decreases to ca.6.3nm for Mn3O4/SBA-15.The decrease of the mesopore dimension suggests the uniform coating of Mn3O4on the inner walls of SBA-15.This nano-composite was further characterized by TEM. Obviously,the SBA-15employed has typical p6mm hex-agonal morphology with the well-ordered1D array(Fig.3a). The average pore size of SBA-15is ca.8.0nm,which is very close to the value(ca.7.7nm)determined by N2adsorption. Along[001]orientation,Fig.3b shows that the some pores arefilled with Mn3O4nanocrystals.From the pore A to D marked in Fig.3b correspond to the pores from empty to partially and fullyfilled;while the features for the SBA-15 nanostructure remains even after forming Mn3O4nanocrys-tals.Nevertheless,further evidences for the location of Mn3O4inside the SBA-15channels are still undergoing in our group.Raman spectra obtained for Mn3O4/SBA-15is presented in Fig.4a.For comparison the Raman spectrum was also recorded for the bulk Mn3O4(97.0%,Aldrich)under the similar conditions(Fig.4b).For the bulk Mn3O4,the bands at310,365, 472and655cmÀ1correspond to the bending modes of Mn3O4, asymmetric stretch of Mn–O–Mn,symmetric stretch of Mn3O4Fig.1.XRD patterns of the bare SBA-15and the Mn3O4/SBA-15nano-composite catalyst.(a)At low angles:(A)Mn3O4/SBA-15,(B)SBA-15;and (b)at high angles of Mn3O4/SBA-15.Fig.2.N2adsorption–desorption isotherms:(!)SBA-15,(~)Mn3O4/SBA-15.Y.-F.Han et al./Applied Catalysis B:Environmental76(2007)227–234229groups,respectively [24–26].However,a downward shift ($D n 7cm À1)of the peaks accompanying with a broadening of the bands was observed for Mn 3O 4/SBA-15.For instance,the distinct feature at 655cm À1for the bulk Mn 3O 4shifted to 648cm À1for the nanocrystals.The Raman bands broadened and shifted were observed for the nanocrystals due to the effect of phonon confinement as suggested previously in the literature [27,28].Furthermore,a weak band at 940cm À1,which should associate with the stretch of terminal Mn O,is an indicative of the existence of the isolated Mn 3O 4group [26].The assignment of this unique band has been discussed in our previous publication [22].3.2.Kinetic study3.2.1.Blank testsUnder a typical reaction conditions,that is,20ml of 100ppm ethanol aqueous solution (pH 6.7)mixed with 1ml of 30%H 2O 2,at 343K,there is no conversion of ethanol was observed after running for 120min in the absence of catalyst or in the presence of bare SBA-15(5mg).Also,under the similar conditions in H 2O 2-free solution,ethanol was not converted for all blank tests even with Mn 3O 4/SBA-15catalyst (5mg)in the reactor.It suggests that a trace amount of oxygen dissolved in water or potential dissociation of adsorbed ethanol does not have any contribution to the conversion of ethanol under reaction conditions.To study the effect of low temperature evaporation of ethanol during reaction,we further examined the concentration of ethanol (100ppm)versus time at different temperatures in the absence of catalyst and H 2O 2.Loss of ca.5%ethanol was observed only at 363K after running for 120min.Hence,to avoid the loss of ethanol through evaporation at high temperatures,which may lead to a higher conversion of ethanol than the real value,the kinetic experiments in this study were performed at or below 343K.The results from blank tests confirm clearly that ethanol can be transformed only by catalytic oxidation during reaction.3.2.2.Effect of amount of catalystThe effect of amount of catalyst on ethanol oxidation is presented in Fig.5.Different amounts of catalyst ranging from 2to 10mg were taken for the same concentration of ethanol (100ppm)in aqueous solution under the standard conditions.It can be observed that the conversion of ethanol increases monotonically within 120min,reaching 15,20and 12%for 2,5and 10mg catalysts,respectively.On the other hand,Fig.5shows that the relative reaction rates (30min)decreased from 0.7to ca 0.1mmol/g Mn min with the rise of catalyst amount from 2to 10mg.Apparently,more catalyst in the system may decrease the rate for ethanol peroxidation,and a proper ratio of catalyst (g)/solution (L)is required for acquiring a balance between the overall conversion of ethanol and reaction rate.In order to investigate the effects from other factors,5mg (catalyst)/20ml (solution),corresponding to 1(g Mn )/30(L)ratio of catalyst/solution,has been selected for the followedexperiments.Fig.4.Raman spectroscopy of the Mn 3O 4/SBA-15(a)and bulk Mn 3O 4(b).Fig.3.TEM images recorded along the [001]of SBA-15(a),Mn 3O 4/SBA-15(b):pore A unfilled with hexagonal structure,pores B and C partially filled and pore D completely filled.Y.-F .Han et al./Applied Catalysis B:Environmental 76(2007)227–2342303.2.3.Effect of temperatureAs shown in Fig.6,the reaction rate increases with increasing the reaction temperature.After 120min,the conversion of ethanol increases from 12.5to 20%when varying the temp-erature from 298to 343K.Further increasing the temperature was not performed in order to avoid the loss of ethanol by evaporation.Interestingly,the relative reaction rate increased with time within initial 60min at 298and 313K,but upward tendency was observed above 333K.3.2.4.Effect of pHIn the pH range from 2.0to 9.0,as illustrated in Fig.7,the reaction rate drops down with the rise of pH.It indicates that acidic environment,or to say,proton concentration ([H +])in the solution is essential for this reaction.With considering our target for this study:purifying water,pH approaching to 7.0in the reaction system is preferred.Because acidifying the solution with organic/inorganic acids may potentially causea second time pollution and result in surplus cost.Actually,there is almost no effect on ethanol conversion with changing pH from 5.5to 6.7in this system.It is really a merit comparing with the conventional homogenous Fenton system,by which the catalyst works only in the pH range of 2.0–5.0.3.2.5.Effect of ethanol concentrationThe investigation of the effect of ethanol concentration on the reaction rate was carried out in the ethanol ranging from 50to 500ppm.The results in Fig.8show that the relative reaction rate increased from 0.07to 2.37mmol/g Mn min after 120min with increasing the concentration of ethanol from 50to 500ppm.It is worth to note that the pH value of the solution slightly decreased from 6.7to 6.5when raising the ethanol concentration from 100to 500ppm.paring to a typical homogenous Fenton reagent For comparison,under the similar reaction conditions ethanol oxidation was performed using aconventionalFig.5.The ethanol oxidation as a function of time with different amount of catalyst.Conversion of ethanol vs.time (solid line)on 2mg (&),5mg (*)and 10mg (~)Mn 3O 4/SBA-15catalyst,the relative reaction rate vs.time (dash line)on 2mg (&),5mg (*)and 10mg (~)Mn 3O 4/SBA-15catalyst.Rest conditions:20ml of ethanol (100ppm),1ml of 30%H 2O 2,708C and pH of6.7.Fig.6.The ethanol oxidation as a function of temperature.Conversion of ethanol vs.time (solid line)at 258C (&),408C (*),608C (~)and 708C (!),the relative reaction rate vs.time (dash line)at 258C (&),408C (*),608C (~)and 708C (5).Rest conditions:20ml of ethanol (100ppm),1ml of 30%H 2O 2,pH of 6.7,5mg ofcatalyst.Fig.7.The ethanol oxidation as a function of pH value.Conversion of ethanol vs.time (solid line)at pH value of 2.0(&),3.5(*),4.5(~),5.5(!),6.7(^)and 9.0("),the relative reaction rate vs.time (dash line)at pH value of 2.0(&),3.5(*),4.5(~),5.5(5),6.7(^)and 9.0(").Rest conditions:20ml of ethanol (100ppm),1ml of 30%H 2O 2,708C,5mg ofcatalyst.Fig.8.The ethanol oxidation as a function of ethanol concentration.Conver-sion of ethanol vs.time (solid line)for ethanol concentration (ppm)of 50(&),100(*),300(~),500(!),the relative reaction rate vs.time (dash line)for ethanol concentration (ppm)of 50(&),100(*),300(~),500(5).Condi-tions:20ml of ethanol,pH of 6.7,1ml of 30%H 2O 2,708C,5mg of catalyst.Y.-F .Han et al./Applied Catalysis B:Environmental 76(2007)227–234231homogenous reagent,Fe 2+(5ppm)–H 2O 2(1ml)at pH of 5.0.It has been reported to be an optimum condition for this system [17].As shown in Fig.9,the reaction in both catalytic systems exhibits a similar behavior,that is,the conversion of ethanol increases with extending the reaction time.Varying reaction temperature from 298to 343K seems not to impact the conversion of ethanol when using the homogenous Fenton reagent.Furthermore,the conversion of ethanol (defining at 120min)in the system of Mn 3O 4/SBA-15–H 2O 2is about 60%of that obtained from the conventional Fenton reagent.There are no other organic compounds observed in the reaction mixture other than ethanol suggesting that ethanol directly decomposing to CO 2and H 2O.3.2.7.Decomposition of H 2O 2In the aqueous solution,the capability of metal ions such as Fe 2+and Mn 2+has long been evidenced to be effective on the decomposition of H 2O 2to produce the hydroxyl radical ( OH),which is oxidant for the complete oxidation/degrading of organic compounds [9,17].Therefore,ethanol oxidation is supposed to be associated with H 2O 2decomposition.The investigation of H 2O 2decomposition has been performed under the reaction conditions (in an ethanol-free solution)with different amounts of catalyst.H 2O 2was introduced into the reaction system by three steps,initially 0.5ml followed by twice 0.25ml at 32and 62min,the pH of 6.7is set for all experiments except pH of 5.0for Fe 2+.As shown in Fig.10,H 2O 2was not converted in the absence of catalyst or presence of bare SBA-15(5mg);in contrast,by using the Mn 3O 4/SBA-15catalyst we observed that ca.Ninety percent of total H 2O 2was decomposed in the whole experiment.It can be concluded that that dissociation of H 2O 2is mainly caused by Mn 3O paratively,the rate of H 2O 2decomposition is relatively low with the homogenous Fenton reagent,total conversion of H 2O 2,was ca.50%after runningfor 120min.Considering the fact that H 2O 2decomposition can be significantly enhanced with the rise of Fe 2+concentration,however,it seems not to have the influence on the reaction rate for ethanol oxidation simultaneously.The similar behavior of H 2O 2decomposition was also observed during ethanol oxidation.The rate for ethanol oxidation is lower for Mn 3O 4/SBA-15comparing to the conventional Fenton reagent.The possible reasons will be discussed in the proceeding section.3.3.Plausible reaction mechanism for ethanol oxidation with H 2O 2In general,the wet peroxide oxidation of organic constitutes has been suggested to proceed via four steps [15]:activation of H 2O 2to produce OH,oxidation of organic compounds withOH,recombination of OH to form O 2and wet oxidation of organic compounds with O 2.It can be further described by Eqs.(1)–(4):H 2O 2À!Catalyst =temperture 2OH(1)OH þorganic compoundsÀ!Temperatureproduct(2)2 OHÀ!Temperature 12O 2þH 2O(3)O 2þorganic compoundsÀ!Temperature =pressureproduct(4)The reactive intermediates produced from step 1(Eq.(1))participate in the oxidation through step 2(Eq.(2)).In fact,several kinds of radical including OH,perhydroxyl radicals ( HO 2)and superoxide anions (O 2À)may be created during reaction.Previous studies [29–33]suggested that the process for producing radicals could be expressed by Eqs.(5)–(7)when H 2O 2was catalytically decomposed by metal ions,such asFeparison of ethanol oxidation in systems of typical homogenous Fenton catalyst (5ppm of Fe 2+,20ml of ethanol (100ppm),1ml of 30%H 2O 2,pH of 5.0acidified with HCl)at room temperature (~)and 708C (!),and Mn 3O 4/SBA-15catalyst (&)under conditions of 20ml of ethanol (100ppm),pH of 6.7,1ml of 30%H 2O 2,708C,5mg ofcatalyst.Fig.10.An investigation of H 2O 2decomposition under different conditions.One milliliter of 30%H 2O 2was dropped into the 20ml deionized water by three intervals,initial 0.5ml followed by twice 0.25ml at 32and 62min.H 2O 2concentration vs.time:by calculation (&),without catalyst (*),SBA-15(~),5ppm of Fe 2+(!)and Mn 3O 4/SBA-15(^).Rest conditions:5mg of solid catalyst,pH of 7.0(5.0for Fe 2+),708C.Y.-F .Han et al./Applied Catalysis B:Environmental 76(2007)227–234232and Mn,S þH 2O 2!S þþOH Àþ OH (5)S þþH 2O 2!S þ HO 2þH þ(6)H 2O $H þþO 2À(7)where S and S +represent reduced and oxidized metal ions,both the HO 2and O 2Àare not stable and react further with H 2O 2to form OH through Eqs.(8)and (9):HO 2þH 2O 2! OH þH 2O þO 2(8)O 2ÀþH 2O 2! OH þOH ÀþO 2(9)Presently, OH radical has been suggested to be the main intermediate responsible for oxidation/degradation of organic compounds.Therefore,the rate for ethanol oxidation in the studied system is supposed to be dependent on the concentra-tion of OH.Note that the oxidation may proceed via step four (Eq.(4))in the presence of high pressure O 2,which is so-called ‘‘wet oxidation’’and usually occurs at air pressures (1–22MPa)and at high temperatures (423–643K)[15].However,it is unlikely to happen in the present reaction conditions.According to Wolfenden’s study [34],we envisaged that the complete oxidation of ethanol may proceed through a route like Eq.(10):C 2H 5OH þ OH À!ÀH 2OC 2H 4O À! OHCO 2þH 2O(10)Whereby,it is believed that organic radicals containing hydroxy-groups a and b to carbon radicals centre can eliminate water to form oxidizing species.With the degrading of organic intermediates step by step as the way described in Eq.(10),the final products should be CO 2and H 2O.However,no other species but ethanol was detected by GC and GC–MS in the present study possibly due to the rapid of the reaction that leads to unstable intermediate.Fig.5indicates that a proper ratio of catalyst/solution is a necessary factor to attain the high conversion of ethanol.It can be understood that over exposure of H 2O 2to catalyst will increase the rate of H 2O 2decomposition;but on the other hand,more OH radical produced may be scavenged by catalyst with increasing the amount of catalyst and transformed into O 2and H 2O as expressed in Eq.(3),instead of participating the oxidation reaction.In terms of Eq.(10),stoichiometric ethanol/H 2O 2should be 1/6for the complete oxidation of ethanol;however,in the present system the total molar ratio is 1/400.In other words,most intermediates were extinguished through scavenging during reaction.This may explain well that the decrease of reaction rate with the rise of ratio of catalyst/solution in the system.The same reason may also explain the decrease of reaction rate with prolonging the time.Actually,H 2O 2decomposition (ca.90%)may be completed within a few minutes over the Mn 3O 4/SBA-15catalyst as illustrated in Fig.10,irrespective of amount of catalyst (not shown for the sake of brevity);in contrast,the rate for H 2O 2decomposition became dawdling for Fe 2+catalyst.As a result,presumably,the homogenous system has relatively high concentration ofradicals.It may explain the superior reactivity of the conventional Fenton reagent to the presented system as depicted in Fig.9.Therefore,how to reduce scavenging,especially in the heterogeneous Fenton system [29],is crucial for enhancing the reaction rate.C 2H 5OH þ6H 2O 2!2CO 2þ9H 2O(11)On the other hand,as illustrated by Eqs.(1)–(4),all steps in the oxidation process are affected by the reaction temperature.Fig.6demonstrates that increasing temperature remarkably boosts the reactivity of ethanol oxidation in the system of Mn 3O 4/SBA-15–H 2O 2possibly,due to the improvement of the reactions in Eqs.(2)and (4)at elevated temperatures.In terms of Eqs.(6)and (7),acidic conditions may delay the H 2O 2decomposition but enhance the formation of OH (Eqs.(5),(8)and (9)).This ‘‘delay’’is supposed to reduce the chance of the scavenging of radicals and improve the efficiency of H 2O 2in the reaction.The protons are believed to have capability for stabilizing H 2O 2,which has been elucidated well previously [18,19].Consequently,it is understandable that the reaction is favored in the strong acidic environment.Fig.7shows a maximum reactivity at pH of 2.0and the lowest at pH of 9.0.As depicted in Fig.8,the reaction rate for ethanol oxidation is proportional to the concentration of ethanol in the range of 50–500ppm.It suggests that at low concentration of ethanol (100ppm)most of the radicals might not take part in the reaction before scavenged by catalyst.With increasing the ethanol concentration,the possibility of the collision between ethanol and radicals can be increased significantly.As a result,the rate of scavenging radicals is reduced relatively.Thus,it is reasonable for the faster rate observed at higher concentration of ethanol.Finally,it is noteworthy that as compared to the bulk Mn 3O 4(Aldrich,98.0%of purity),the reactivity of the nano-crystalline Mn 3O 4on SBA-15is increased by factor of 20under the same typical reaction conditions.Obviously,Mn 3O 4nanocrystal is an effective alternative for this catalytic system.The present study has evidenced that the unique structure of SBA-15can act as a special ‘‘nanoreactor’’for synthesizing Mn 3O 4nanocrystals.Interestingly,a latest study has revealed that iron oxide nanoparticles could be immobilized on alumina coated SBA-15,which also showed excellent performance as a Fenton catalyst [35].However,the role of the pore structure of SBA-15in this reaction is still unclear.We do expect that during reaction SBA-15may have additional function to trap larger organic molecules by adsorption.Thus,it may broaden its application in this field.So,relevant study on the structure of nano-composites of various MnO x and its role in the Fenton-like reaction for remediation of organic compounds in aqueous solution is undergoing in our group.4.ConclusionsIn the present study,we have addressed a new catalytic system suitable for remediation of trivial organic compound from contaminated water through a Fenton-like reaction withY.-F .Han et al./Applied Catalysis B:Environmental 76(2007)227–234233。

美国纽约时代大厦

美国纽约时代大厦■ 伦佐 · 皮亚诺建筑工作室 ■ Renzo Piano Building Workshop作者单位:伦佐 · 皮亚诺建筑工作室收稿日期:2009-08-05The New York Times Building, USA纽约时代公司和地产开发商森林城市拉特纳公司(Forest City Ratner)宣布了他们的一项计划,即在纽约市第八大道的第四十和四十一街区之间建造一座大厦,服务于纽约时代公司及其他世界级的商户。

在该项目的竞标过程中,伦佐·皮亚诺和森林城市拉特纳公司一同被选中,该建筑于2007年竣工11月盛大开幕。

纽约时代大厦的基本外观简洁大气,52层高的玻璃维护体系配合钢筋支撑结构,既保证了大厦的稳固性与实用性,又增强了其通透感,以彰显建筑自身的文化特征,与曼哈顿的城市风尚浑然天成。

虽然时代大厦高耸入云,但却没有采用镀色玻璃凸显其神秘色彩,相反地,它使用了18.6万根陶杆悬挂起双层幔墙阻隔热量,建筑外层如同防晒霜一样,而建筑内层则是由从地面一直延伸到天花板的透明玻璃构成,使大厦能与外界环境色融为一体,雨后的时代大厦变成与环境一致的淡蓝色,而在夕阳西下时则闪烁出绯红的光芒。

纽约时代公司占据了这幢大楼的1层~28层,每层都有很高的举架,其上的24层是地产开发商和律师事务所。

新闻工作室集中设在中央庭院的花园附近,处于较低的楼层,这3层楼被戏称为“面包房”,因为记者经常在办公室熬夜来“烹制”第二天的新闻。

在时代大厦底层建有一座大花园,种植着桦树,还有蕨类、苔藓类植物。

人们从街道上就可以观赏到这个内部花园,并可在其中自由通行,由此为第40和第41大街之间的区域营造出极富层次的通透感。

这座大厦底层还拥有可容纳378人的会场,为举办各种演出及报告会、舞台剧、展示会等活动提供了场地。

在这个会场旁还设有一个可容纳400人的宴会厅。

另外,此处还有一些与周边街区环境氛围契合的店铺和办公空间。

彼得沃克与伯纳特公园案例分析

著名设计项目

伯纳特公园

哈佛大学谭纳喷泉

柏林索尼中心

哈佛大学唐纳喷泉

柏林索尼中心

德国勒沃库森拜耳制药公司总部

美国波特兰公园和杰米森广场

日本幕张IBM公司大楼庭园

日本播磨科学花园城

美国德克萨斯州雕塑中心

日本欧亚玛市欧亚玛培训中心

日本埼玉广场

丸龟火车站

加利福尼亚州赫尔曼 米勒公司庭园

四、个人感悟

在伯纳特公园的设计中,较为传统的造景元素在沃克的手中 对于传统和过去,我们既不应该毫无取舍的盲目。同时, 焕发了新的艺术活力,成为其设计中不可获缺的一部分 继承,也不宜过于激进的割裂与抛弃,而是尽量客观的看待和面 沃克的极简主义构图表现了一种纯净的简洁,这种简洁极富时 对。既学习也批判,无论如何都是要和当下的背景和谐共生,透 代精神和进步精神。通过沃克的设计,伯纳特公园巧妙地将公 过春夏秋冬里那似乎早已远去的阳光, 我们不仅应该只看到历史, 园艺术性与功能价值相结合,并与周边环境很好的融合。 也应借其预见未来。

主入口活动 区

公 共 活 场 私密休息区

伯纳特公园周围的环境十分复杂,怎样在这个繁华的商业 中心创造出一片流连忘返的绿洲呢?

人流分析:

主要人流 分布

次要人流分 布

构图:

步道构成矩形和成对角线的网格。最高层是 稍许高出地面的粉红色花岗岩步道。下陷的草 地成了场地的基底,最底层是拼接的水池。

道路在公园平面上形成了一张网,把影子投射到下一层的绿色草地上。 下陷的草地成了场地的基底,同相互交叉的花岗岩步道构成不断变化的 图案。坚硬与柔和,素净与繁茂,正统与乡土之间的对比又被最低的第 三层所强化。

极简主义(Minimalist),又称最低 限度艺术,它是在早期结构主义的基 础上发展而来的一种艺术门类。最初 在20世纪60年代,它主要通过一些绘 画和雕塑作品得以表现。很快,极简 主义艺术就被彼得·沃克(Peter Walker)、玛萨·舒瓦茨(Martha Schwartz)等先锋园林设计师运用到 他们的设计作品中去,并在当时社会 引起了很大的反响和争议。彼得沃克 将极简主义解释为:物即其本身。 (The object is the thing itself)。

《中国近零排放建筑案例汇编》(中英文版)出版发行

王磊,等:徐州地区农村居住建筑节能状况调查与分析缺失或设置不当都会造成室内热舒适性差的状况。

夏、冬两季的空调制冷或采暖消耗的电能较高,炊事、生活用水等也在增加农村电能的消耗。

根据以上的调查分析,后续研究工作将以此为依据进行新农村建设中居住建筑的节能设计。

参考文献:[1]赵岩,叶建东,邢永杰.北方农村既有居住建筑节能改造[J ].建设科技,2010,(5):43-46.[2]黄志甲,许凯睿,张婷,等.马鞍山农村居住建筑能耗现状调查及分析[J ].小城镇建设,2011,(8):92-94.[3]张忠扩.寒冷地区农村居住建筑太阳能应用模式研究[D ].西安:西安建筑科技大学,2009.[4]陈国杰.衡阳农村居住建筑舒适性调查与能耗模拟分析[D ].衡阳:南华大学,2007.[5]GB 50176—2016,民用建筑热工设计规范[S ].北京:中国建筑工业出版社,2016.[6]张洪波,王磊.建筑节能技术[M ].北京:高等教育出版社,2016.[7]高倩,徐学东.北方寒冷地区农村住房节能现状分析与节能改造措施[J ].施工技术,2011,40(20):98-101.[8]谭志明.北方农村既有建筑节能改造经济分析[D ].青岛:中国海洋大学,2012.[9]田国华,季翔,刘伟,等.徐州地区既有居住建筑能耗调查与节能改造分析[J ].建筑节能,2018,46(6):79-84.[10]辛伟宁.新农村住房节能现状及节能改造措施[J ].节能,2017,36(10):64-66.[11]郭春梅,张志刚,张丽璐,等.中国寒冷地区农村居住建筑现状调查与能耗分析[J ].中国建设信息,2011,(5):49-51.作者简介:王磊(1981),男,江苏徐州人,硕士,研究方向:建筑节能、公路养护(602000595@qq.com )。

《建筑节能》期刊编委会林波荣教授、朱颖心教授团队项目荣获2019年度国家科技进步二等奖2020年1月10日,2019年度国家科学技术奖励大会在北京隆重举行。

机制设计理论及其应用

18

航空旅行: 各旅行者收益

旅行者

Maria Robin

区隔

商务 休闲

不受限旅行($)

1000 500

旅行者 Maria Robin

区隔 商务 休闲

不受限旅行($) 1000 500

受限旅行 ($)

500 400

受限旅行 ($) 950 400

招标:直接机制

1

支付额p需要不小于150,这 样的机制才能是激励相容的。

2

最优的机制

3

使用最优机制时政府的购买成 本

4

两阶段: ○ 报价阶段 ○ 交割阶段

12

机制设计及其应用

机制设计理论要回答的问题是: 什么时候一个集体(或某个交易 方)的目标可以实现?如何实现?

实现这样目标的难点在于: ○ 集体(或交易)中各个成员的个人目标往往和集体目 标不一致。 ○ 集体(或交易)中各个成员的特性不同,而且往往每 个成员的特性并不为所有人所知。(信息不对称)

可能 四种可能:

○ 甲乙成本均为1 ○ 甲乙成本均为2 ○ 甲成本为1,乙成本为2 ○ 乙成本为1,甲成本为2

2

招标问题的难点

政府和生产商之间信息不对称

生产商明确地知道他自己的成本,而政 府不明确知道生产商的成本

与不确定性有区别

政府和生产商利益不完全一致

政府希望以最低成本购买 生产商希望以最高的价格出售

机制设计中的两个重要原 则

○ 激励相容:当 面临机制设计 主体所提供的 几个方案时, 每个人都更愿 意选择机制设 计主体针对他 设计的方案

○ 自愿参与

住房问题的机 制设计体现了 这两个原则

重构建筑学

重构建筑学

凯瑟琳·波尔扎克

【期刊名称】《科技创业》

【年(卷),期】2011(000)002

【摘要】纽约瑞泽+梅车彻建筑事务所(Reuser+Umemoto)参与竞标广东深圳宝安国际机场新3号候机楼的设计方案是2007年设计的,虽然最后未被采用,但它那一体成形的扭曲网格式天窗给人印象深刻.这是渲染生成的效果图,从中可以看到事务所使用参数化设计软件计算出每个窗格的不同角度,让自然光以非常柔和的方式射入而保证照明,而多余的光线则被有意遮挡以免整个空调系统太耗电.如果没有这种新的软件,要设计出这样复杂多变的建筑简直是不可能的.

【总页数】8页(P78-85)

【作者】凯瑟琳·波尔扎克

【作者单位】

【正文语种】中文

【相关文献】

1.认知与重构——中国古典园林空间在建筑学类本科设计初步课程中的引入

2.“新三届”华南建筑人与他们的时代兼论华南工学院建筑学科的调适与重构

3.关联·集成·拓展——以学为中心的建筑学课程教学机制重构

4.重构课程体系,培养建筑学专业应用型创新人才——德国应用科技大学模式的借鉴与启示

5.建筑学语境下电影《山河故人》的空间再现与重构

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

建设_理想城市_需要更科学更务实的城市规划_省略_7版纽约城市规划的经验借鉴及其

建设“理想城市”需要更科学更务实的城市规划2007版纽约城市规划的经验借鉴及其对我们的启示The Construction of Ideal City Needs a More Scientific and Practical Urban PlanningSome Inspirations from the New York City Planning (2007 Version)蔡瀛CAI Ying 中图分类号:TU986文献标识码:A文章编号:1673-1530(2011)06-0031-04收稿日期:2011-10-13修回日期:2011-11-12摘要:面临城市化进程不断加快、人口持续增长和资源短缺日益严重等一系列严峻挑战,通过空间规划建设可持续发展的“理想城市”已成为当前备受关注的问题。

以纽约2007年版城市规划为研究范例,其科学的编制过程、务实的实施措施,在引领城市发展成功转型中起到了重要的作用。

纽约规划的经验,对于致力于建设“理想城市”的广东具有十分重要的启示。

要以全世界最先进的规划实践为标杆,把不断提高规划的科学性和操作性作为贯穿规划工作始终的最重要环节。

关键词:风景园林;城市规划;评论;可持续发展Abstract: The fast urbanization, expanding population and serious resource shortage have brought great challenges to our living environment. The construction of a sustainable ideal city through space planning has become a hot issue at present. The New York City Plan (2007 Version) played an important role in the successful transformation of urban development. The urban planning experience of New York is encouraging for Guangdong who endeavors to build an Ideal City. We should set the most advanced planning practice as the example and improve our urban planning.Key words: Landscape Architecture; Urban Planning; Review; Sustainable Development 快,人口持续增长,水、土地、能源等资源短缺日益严重等一系列严峻挑战,如何通过空间规划引导广东的城市实现建设文明、宜居、承载力强、可持续发展的“理想城市”的目标①②,已成为当前必须高度关注的关键问题。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。