Generalized (s-Parameterized) Weyl Transformation

Discriminating large extra dimensions at the ILC with polarized beams

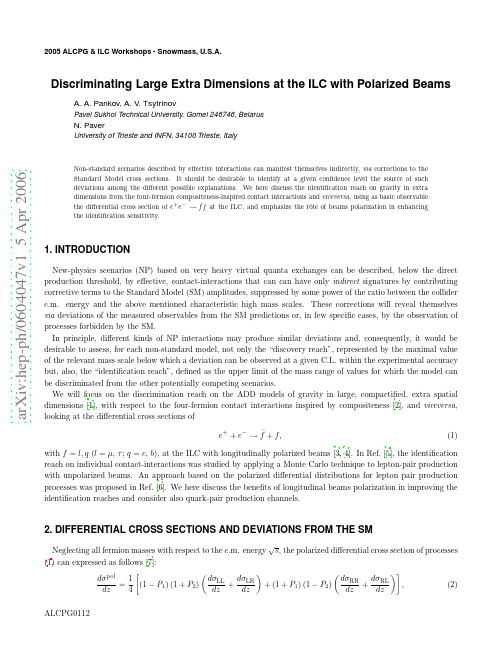

a r X i v :h e p -p h /0604047v 1 5 A p r 20062005ALCPG &ILC Workshops -Snowmass,U.S.A.Discriminating Large Extra Dimensions at the ILC with Polarized BeamsA.A.Pankov,A.V .TsytrinovPavel Sukhoi Technical University,Gomel 246746,BelarusN.PaverUniversity of Trieste and INFN,34100Trieste,ItalyNon-standard scenarios described by effective interactions can manifest themselves indirectly,via corrections to the Standard Model cross sections.It should be desirable to identify at a given confidence level the source of such deviations among the different possible explanations.We here discuss the identification reach on gravity in extra dimensions from the four-fermion compositeness-inspired contact interactions and viceversa ,using as basic observable the differential cross section of e +e −→¯ff at the ILC,and emphasize the rˆo le of beams polarization in enhancing the identification sensitivity.1.INTRODUCTION New-physics scenarios (NP)based on very heavy virtual quanta exchanges can be described,below the direct production threshold,by effective,contact-interactions that can can have only indirect signatures by contributing corrective terms to the Standard Model (SM)amplitudes,suppressed by some power of the ratio between the collider c.m.energy and the above mentioned characteristic high mass scales.These corrections will reveal themselves via deviations of the measured observables from the SM predictions or,in few specific cases,by the observation of processes forbidden by the SM.In principle,different kinds of NP interactions may produce similar deviations and,consequently,it would be desirable to assess,for each non-standard model,not only the “discovery reach”,represented by the maximal value of the relevant mass scale below which a deviation can be observed at a given C.L.within the experimental accuracy but,also,the “identification reach”,defined as the upper limit of the mass range of values for which the model can be discriminated from the other potentially competing scenarios.We will focus on the discrimination reach on the ADD models of gravity in large,compactified,extra spatial dimensions [1],with respect to the four-fermion contact interactions inspired by compositeness [2],and viceversa ,looking at the differential cross sections ofe ++e −→¯f +f,(1)with f =l,q (l =µ,τ;q =c,b ),at the ILC with longitudinally polarized beams [3,4].In Ref.[5],the identification reach on individual contact-interactions was studied by applying a Monte Carlo technique to lepton-pair production with unpolarized beams.An approach based on the polarized differential distributions for lepton pair production processes was proposed in Ref.[6].We here discuss the benefits of longitudinal beams polarization in improving the identification reaches and consider also quark-pair production channels.2.DIFFERENTIAL CROSS SECTIONS AND DEVIATIONS FROM THE SMNeglecting all fermion masses with respect to the c.m.energy√dz =1dz +dσLRdz +dσRLwhere z=cosθis the angle between the incoming and outgoing fermions in the c.m.frame and(α,β=L,R):dσαβσpt|Mαβ|2(1±z)2.(3)8P1and P2the degrees of longitudinal polarization of the electron and positron beams,respectively,and the‘±’signs apply to the cases LL,RR and LR,RL,respectively.According to sec.1,the reduced helicity amplitudes appearing in Eq.(3)can be expanded into the SM part represented byγand Z exchanges,plus corrections depending on the considered NP model:Mαβ=M SMαβ+∆αβ(NP).(4) The examples explicitly considered here are the following ones:a)The ADD large extra dimensions scenario[1],where only gravity can propagate in extra dimensions,and correspondingly a tower of graviton KK states occurs in the four-dimensional space[8,9].In the parameterization of Ref.[10],the(z-dependent)deviations can be expressed as[11]:∆LL(ADD)=∆RR(ADD)=f G(1−2z),∆LR(ADD)=∆RL(ADD)=−f G(1+2z),(5) where f G=λs2/(4παe.m.Λ4H),λ=±1,ΛH being a phenomenological cut-offon the integration on the KK spectrum.b)Gravity in TeV−1–scale extra dimensions,where also the SM gauge bosons can propagate there,parameterized by the“compactification scale”M C[12,13]:∆αβ(TeV)=− Q e Q f+g eαg fβ π2/(3M2C).(6) c)The four-fermion contact-interaction scenario(CI)[2]where,withΛαβthe“compositeness”mass scales(ηαβ=±1):∆αβ(CI)=ηαβs/(αe.m.Λ2αβ).(7) In cases b)and c)the deviations are z-independent,whereas in the case a)they introduce extra z-dependence in the angular distributions.The consequence is that the ADD contribution to the integrated cross sections is tiny, because the interference with the SM amplitudes vanishes in these observables.Current experimental lower bounds on the mass scales M H and M C are reviewed,e.g.,in Ref.[14](M H>1.1−1.3TeV,M C>6.8TeV),while those on Λs,of the order of10TeV,are detailed in Ref.[15].3.DERIVATION OF THE IDENTIFICATION REACHESLet us assume one of the models,for example the ADD model(5),to be the“true”one,i.e.,to be consistent with data for some value ofΛH.To estimate the level at which it may be discriminated from other,in principle competing NP scenarios(“tested”models),for any values of the relevant mass parameters,say example one of the four-fermion CI models(7),we introduce relative deviations of the differential cross section(denoted by O)from the ADD predictions due to the CI in each angular bin,and a correspondingχ2function:2.(8)∆(O)=O(CI)−O(ADD)δO binHere,δO s represent the expected relative uncertainties,which combine statistical and systematic ones,the former one being related to the ADD model prediction.Consequently,theχ2of Eq.(8)is a function ofλ/Λ4H and the considered η/Λ2,and we can determine the“confusion”region in this parameter plane where also the corresponding CI model may be considered as consistent with the ADD predictions at the chosen confidence level,so that an unambiguous identification of ADD cannot be made.We chooseχ2<3.84for95%C.L..ALCPG0112√For the numerical analysis,we consider an ILC withFigure 2:95%CL identification reach on the cutoffscale M C in the TeV model (left panel)and ΛVV in the VV model (right panel)as a function of the integrated luminosity obtained from the fermion pair production processes with unpolarized and both polarized beams at ILC(0.5TeV).References[1]N.Arkani-Hamed,S.Dimopoulos and G.R.Dvali,Phys.Lett.B 429,263(1998);N.Arkani-Hamed,S.Dimopoulos and G.R.Dvali,Phys.Rev.D 59,086004(1999);I.Antoniadis,N.Arkani-Hamed,S.Dimopoulos and G.R.Dvali,Phys.Lett.B 436,257(1998).[2]E.Eichten,ne and M.E.Peskin,Phys.Rev.Lett.50,811(1983);R.R¨u ckl,Phys.Lett.B 129,363(1983).[3]J.A.Aguilar-Saavedra et al.[ECFA/DESY LC Physics Working Group Collaboration],“TESLA TechnicalDesign Report Part III:Physics at an e +e −Linear Collider,”DESY-01-011,arXiv:hep-ph/0106315;T.Abe et al.[American Linear Collider Working Group Collaboration],“Linear collider physics resource book for Snowmass 2001.1:Introduction,”in Proc.of the APS/DPF/DPB Summer Study on the Future of Particle Physics (Snowmass 2001)SLAC-R-570,arXiv:hep-ex/0106055.[4]G.Moortgat-Pick et al.,arXiv:hep-ph/0507011.[5]G.Pasztor and M.Perelstein,in Proc.of the APS/DPF/DPB Summer Study on the Future of Particle Physics(Snowmass 2001)ed.N.Graf,arXiv:hep-ph/0111471.[6]A.A.Pankov,N.Paver and A.V.Tsytrinov,[arXiv:hep-ph/0512131].[7]B.Schrempp,F.Schrempp,N.Wermes and D.Zeppenfeld,Nucl.Phys.B 296,1(1988).[8]T.Han,J.D.Lykken and R.J.Zhang,Phys.Rev.D 59,105006(1999)[arXiv:hep-ph/9811350].[9]G.F.Giudice,R.Rattazzi and J.D.Wells,Nucl.Phys.B 544,3(1999)[arXiv:hep-ph/9811291].[10]J.L.Hewett,Phys.Rev.Lett.82,4765(1999)[arXiv:hep-ph/9811356].[11]S.Cullen,M.Perelstein and M.E.Peskin,Phys.Rev.D 62,055012(2000)[arXiv:hep-ph/0001166].[12]K.M.Cheung and ndsberg,Phys.Rev.D 65,076003(2002)[arXiv:hep-ph/0110346].[13]T.G.Rizzo and J.D.Wells,Phys.Rev.D 61,016007(2000)[arXiv:hep-ph/9906234].[14]For a review see,e.g.,K.Cheung,arXiv:hep-ph/0409028.[15]S.Eidelman et al.[Particle Data Group],Phys.Lett.B 502,1(2004).ALCPG0112。

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ROBUST AND NONLINEAR CONTROL

SUMMARY In this paper, a modular modification of the adaptive robust control (ARC) technique is presented. The modular design has all of the original ARC properties with an estimation-based update law instead of a Lyapunov-based update law. In this design, the controller is divided into two modules: a control module and an identification module. A key new idea is to set a priori bounds on the time derivatives of the estimates to be maintained by the update law. As a result, their effects on the system tracking accuracy can be dominated by the control law. A modification is proposed for the standard gradient and least-square update laws to guarantee the bounds. This modification also makes the controller robust against the generalized (unparameterized) uncertainties considered in the ARC formulation while allowing asymptotic output tracking without the generalized uncertainties. Both the ARC and the modular ARC techniques are applied to a force control problem for an active suspension system. Simulations and experimental results are provided to show that the update law of the modular design is less sensitive to measurement noise which results in smaller force tracking error and smaller control gain. Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Finding State Solutions to Temporal Logic Queries. www.cs.toronto.edumgstateqc.ps

Finding State Solutions to Temporal Logic QueriesMihaela Gheorghiu,Arie Gurfinkel,and Marsha ChechikDepartment of Computer Science,University of Toronto,Toronto,ON M5S3G4,Canada.Email:mg,arie,chechik@Abstract.Different analysis problems for state-transition models can be uni-formly treated as instances of temporal logic query-checking,where only statesare sought as solutions to the queries.In this paper,we propose a symbolic query-checking algorithm thatfinds exactly the state solutions to any query.We showthat our approach generalizes previous ad-hoc techniques,and this generality al-lows us tofind new and interesting applications,such asfinding stable states.Ouralgorithm is linear in the size of the state space and in the cost of model checking,and has been implemented on top of the model checker NuSMV,using the latteras a black box.We show the effectiveness of our approach by comparing it,on agene network example,to the naive algorithm in which all possible state solutionsare checked separately.1IntroductionIn the analysis of state-transition models,many problems reduce to questions of the type:“What are all the states that satisfy a property?”.Symbolic model checking can answer some of these questions,provided that the property can be formulated in an appropriate temporal logic.For example,suppose the erroneous states of a program are characterized by the program counter()being at a line labeled.Then the states that may lead to error can be discovered by model checking the property ,formalized in the branching temporal logic CTL[10].There are many interesting questions which are not readily expressed in temporal logic and require specialized algorithms.One example isfinding the reachable states, which is often needed in a pre-analysis step to restrict further analysis only to those states.These states are typically found by computing a forward transitive closure of the transition relation[8].Another example is the computation of“procedure summaries”.A procedure summary is a relation between states,representing the input/output behav-ior of a procedure.The summary answers the question of which inputs lead to which outputs as a result of executing the procedure.They are computed in the form of“sum-mary edges”in the control-flow graphs of programs[21,2].Yet another example is the algorithm forfinding dominators/postdominators in program analysis,proposed in[1].A state is a postdominator of a state if all paths from eventually reach,and is a dominator of if all paths to pass through.Although these problems are similar,their solutions are quite different.Unifying them into a common framework allows reuse of specific techniques proposed for each problem,and opens a way for creating efficient implementations to other problems ofa similar kind.We see all these problems as instances of model exploration,where properties of a model are discovered,rather than checked.A common framework for model exploration has been proposed under the name of query checking[5].Query checkingfinds which formulas hold in a model.For instance,a query is intended tofind all propositional formulas that hold in the reachable states.In general,a CTL query is a CTL formula with a missing propositional subformula,designated by a placeholder(“”).A solution to the query is any propositional formula that,when sub-stituted for the placeholder,makes a CTL formula that holds in the model.The general query checking problem is:given a CTL query on a model,find all of its propositional solutions.For example,consider the model in Figure1(a),where each state is labeled by the atomic propositions that hold in it.Here,some solutions to are, representing the reachable state,and,representing the set of states. On the other hand,is not a solution:does not hold,since no states whereis false are reachable.Query checking can be solved by repeatedly substituting each possible propositional formula for the placeholder,and returning those for which the resulting CTL formula holds.In the worst case,this approach is exponential in the size of the state space and linear in the cost of CTL model checking.Each of the analysis questions described above can be formulated as a query.Reach-able states are solutions to.Procedure summaries can be obtained by solvingholds in the return statement of the procedure.Dominators/postdominators are solutions to the query(i.e.,what propositional formulas eventually hold on all paths).This insight gives us a uniform formulation of these problems and allows for easy creation of solutions to other,sim-ilar,problems.For example,a problem reported in genetics research[4,12]called for finding stable states of a model,that are those states which,once reached,are never left by the system.This is easily formulated as,meaning“what are the reachable states in which the system will remain forever?”.These analysis problems further require that solutions to their queries be states of the model.For example,a query on the model in Figure1(a)has solutionsand.Thefirst corresponds to the state and is a state solution.The second cor-responds to a set of states but neither nor is a solution by itself.When only state solutions are needed,we can formulate a restricted state query-checking prob-lem by constraining the solutions to be single states,rather than arbitrary propositional formulas(that represent sets of states).A naive state query checking algorithm is to repeatedly substitute each state of the model for the placeholder,and return those for which the resulting CTL formula holds.This approach is linear in the size of the state space and in the cost of CTL model checking.While of significantly more efficient than general query checking,this approach is not“fully”symbolic,since it requires many runs of a model-checker.While several approaches have been proposed to solve general query checking,none are effective for solving the state query-checking problem.The original algorithm of Chan[5]was very efficient(same cost as CTL model checking),but was restricted to valid queries,i.e.,queries whose solutions can be characterized by a single propo-sitional formula.This is too restrictive for our purposes.For example,neither of the queries,,nor the stable states query are valid.Bruns and Gode-2froid[3]generalized query checking to all CTL queries by proposing an automata-basedCTL model checking algorithm over a lattice of sets of all possible solutions.This al-gorithm is exponential in the size of the state space.Gurfinkel and Chechik[15]havealso provided a symbolic algorithm for general query checking.The algorithm is basedon reducing query checking to multi-valued model checking and is implemented in atool TLQSolver[7].While empirically faster than the corresponding naive approach of substituting every propositional formula for the placeholder,this algorithm still has the same worst-case complexity as that in[3],and remains applicable only to modest-sized query-checking problems.An algorithm proposed by Hornus and Schnoebelen[17]finds solutions to any query,one by one,with increasing complexity:afirst solution is found in time linear in the size of the state space,a second,in quadratic time,and so on. However,since the search for solutions is not controlled by their shape,finding all state solutions can still take exponential time.Other query-checking work is not directly ap-plicable to our state query-checking problem,as it is exclusively concerned either with syntactic characterizations of queries,or with extensions,rather than restrictions,of query checking[23,25].In this paper,we provide a symbolic algorithm for solving the state query-checking problem,and describe an implementation using the state-of-the-art model-checker NuSMV[8]. The algorithm is formulated as model checking over a lattice of sets of states,but its implementation is done by modifying only the interface of NuSMV.Manipulation ofthe lattice sets is done directly by NuSMV.While the running time of this approach isthe same as in the corresponding naive approach,we show empirical evidence that our implementation can perform better than the naive,using a case study from genetics[12].The algorithms proposed for the program analysis problems described above are special cases of ours,that solve only and queries,whereas our algorithm solves any CTL query.We prove our algorithm correct by showing that it approximates general query checking,in the sense that it computes exactly those solutions,amongall given by general query checking,that are states.We also generalize our results toan approximation framework that can potentially apply to other extensions of model checking,e.g.,vacuity detection,and point to further applications of our technique,e.g.,to querying XML documents.There is a also a very close connection between query-checking and sanity checkssuch as vacuity and coverage[19].Both problems require checking several“mutants”ofthe property to obtain thefinal solution.In fact,the algorithm for solving state-queries presented in this paper bears many similarities to the coverage algorithms describedin[19].Since query-checking is a more general approach,we believe it can provide a uniform framework for studying all these problems.The rest of the paper is organized as follows.Section2provides the model checking background.Section3describes the general query-checking algorithm.We formallydefine the state query-checking problem and describe our implementation in Section4. Section5presents the general approximation technique for model checking over latticesof sets.We present our case study in Section6,and conclude in Section7.3(a)(b),for true false,for,forFig.1.(a)A simple Kripke structure;(b)CTL semantics.2BackgroundIn this section,we review some notions of lattice theory,minterms,CTL model check-ing,and multi-valued model checking.Lattice theory.Afinite lattice is a pair(,),where is afinite set and is a partial order on,such that everyfinite subset has a least upper bound(called join and written)and a greatest lower bound(called meet and written).Since the lattice isfinite,there exist and,that are the maximum and respectively minimum elements in the lattice.When the ordering is clear from the context,we simply refer to the lattice as.A lattice if distributive if meet and join distribute over each other.In this paper,we work with lattices of propositional formulas. For a set of atomic propositions,let be the set of propositional formulas over .For example,true false.This set forms afinite lattice ordered by implication(see Figure2(a)).Since true,is under true in this lattice.Meet and join in this lattice correspond to logical operators and,respectively.A subset is called upward closed or an upset,if for any,if and,then.In that case,can be identified by the set of its minimal elements(is minimal if),and we write.For example,for the lattice shown in Figure2(a),true. The set is not an upset,whereas true is.For singletons,we write for.We write for the set of all upsets of,i.e.,iff.is closed under union and intersection,and therefore forms a lattice ordered by set inclusion.We call the upset lattice of.The upset lattice of is shown in Figure2(b).An element in a lattice is join-irreducible if and cannot be decomposed as the join of other lattice elements,i.e.,for any and in,impliesor[11].For example,the join-irreducible elements of the lattice in Figure2(a) are and,and of the one in Figure2(b)—true,,,and false.4false(a)(b)(c)ttices for:(a);(b);(c). Minterms.In the lattice of propositional formulas,a join-irreducible element is aconjunction in which every atomic proposition of appears,positive or negated.Such conjunctions are called minterms and we denote their set by.For example,CTL Model Checking.CTL model checking is an automatic technique for verifying temporal properties of systems expressed in a propositional branching-time temporal logic called Computation Tree Logic(CTL)[9].A system model is a Kripke structure ,where is a set of states,is a(left-total)transition relation,is the initial state,is a set of atomic propositions,andis a labeling function,providing the set of atomic propositions that are true in each state.CTL formulas are evaluated in the states of.Their semantics can be described in terms of infinite execution paths of the model.For instance,a formula holds in a state if holds in every state,on every infinite execution path start-ing at;()holds in if holds in some state,on every(some)infi-nite execution path.The formal semantics of CTL is given in Figure1(b). Without loss of generality we consider only CTL formulas in negation normal form, where negation is applied only to atomic propositions[9].In Figure1(b),the function true false indicates the result of checking a formula in state;the set of successors for a state is;and are least and greatestfixpoints of,respectively,where false andtrue.Other temporal operators are derived from the given ones, for example:true,true.The operators in pairsare duals of each other.A formula holds in a Kripke structure,written,if it holds in the initial state,i.e.,true.For example,on the model in Figure1(a),where ,properties and are true,whereas is not.The complexity of model-checking a CTL formula on a Kripke structure is, where.Multi-valued model checking.Multi-valued CTL model checking[6]is a general-ization of model checking from a classical logic to an arbitrary De Morgan algebra ,where is afinite distributive lattice and is any operation that is an involution()and satisfies De Morgan laws.Conjunction and disjunction are the meet and join operations of,respectively.When the ordering and the negation5operation of an algebra are clear from the context,we refer to it as.In this paper,we only use a version of multi-valued model checking where the model remains classical,i.e.,both the transition relation and the atomic propositions are two-valued, but properties are specified in a multi-valued extension of CTL over a given De Morgan algebra,called CTL().The logic CTL()has the same syntax as CTL,except that the allowed constants are all.Boolean values true and false are replaced by the and of,respectively.The semantics of CTL()is the same as of CTL, except is extended to and the interpretation of constants is:for all ,.The other operations are defined as their CTL counterparts(see Fig-ure1(b)),where and are interpreted as lattice operators and,respectively.The complexity of model checking a CTL()formula on a Kripke structure is still ,provided that meet,join,and quantification can be computed in constant time[6],which depends on the lattice.3Query CheckingIn this section,we review the query-checking problem and a symbolic method for solv-ing it.Background.Let be a Kripke structure with a set of atomic propositions.A CTL query,denoted by,is a CTL formula containing a placeholder“”for a proposi-tional subformula(over the atomic propositions in).The CTL formula obtained by substituting the placeholder in by a formula is denoted by.A for-mula is a solution to a query if its substitution into the query results in a CTL formula that holds on,i.e.,if.For example,and are among the solutions to the query on the model of Figure1(a),whereas is not.In this paper,we consider queries in negation normal form where negation is ap-plied only to the atomic propositions,or to the placeholder.We further restrict our attention to queries with a single placeholder,although perhaps with multiple occur-rences.For a query,a substitution means that all occurrences of the place-holder are replaced by.For example,if,then.We assume that occurrences of the placeholder are ei-ther non-negated everywhere,or negated everywhere,i.e.,the query is either positive or negative,respectively.Here,we limit our presentation to positive queries;see Section5 for the treatment of negative queries.The general CTL query-checking problem is:given a CTL query on a model,find all its propositional solutions.For instance,the answer to the query on the model in Figure1(a)is the set consisting of,and every other formula implied by these,including,,and true.If is a solution to a query,then any such that(i.e.,any weaker)is also a solution,due to the monotonicity of positive queries[5].Thus,the set of all possible solutions is an upset;it is sufficient for the query-checker to output the strongest solutions,since the rest can be inferred from them.One can restrict a query to a subset[3].We then denote the query by, and its solutions become formulas in.For instance,checking on the model of Figure1(a)should result in and as the strongest solutions,together with all those implied by them.We write for.6If consists of atomic propositions,there are possible distinct solutions to .A“naive”method forfinding all solutions would model check for every possible propositional formula over,and collect all those’s for which holds in the model.The complexity of this naive approach is times that of usual model-checking.Symbolic Algorithm.A symbolic algorithm for solving the general query-checking problem was described in[15]and has been implemented in the TLQSolver tool[7]. We review this approach below.Since an answer to is an upset,the upset lattice is the space of all possible answers[3].For instance,the lattice for is shown in Figure2(b).In the model in Figure1(a),the answer to this query is true,encoded as,since is the strongest solution.Symbolic query checking is implemented by model checking over the upset lattice. The algorithm is based on a state semantics of the placeholder.Suppose query is evaluated in a state.Either holds in,in which case the answer to the query should be,or holds,in which case the answer is.Thus we have:if,if.This case analysis can be logically encoded by the formula.Let us now consider a general query in a state(where ranges over a set of atomic propositions).We note that the case analysis corresponding to the one above can be given in terms of minterms.Minterms are the strongest formulas that may hold in a state;they also are mutually exclusive and complete—exactly one minterm holds in any state,and then is the answer to at.This semantics is encoded in the following translation of the placeholder:The symbolic algorithm is defined as follows:given a query,first obtain ,which is a CTL formula(over the lattice),and then model check this formula.The semantics of the formula is given by a function from to, as described in Section 2.Thus model checking this formula results in a value from .That value was shown in[15]to represent all propositional solutions to .For example,the query on the model of Figure1(a)becomesThe result of model-checking this formula is.The complexity of this algorithm is the same as in the naive approach.In practice, however,TLQSolver was shown to perform better than the naive algorithm[15,7].74State Solutions to QueriesLet be a Kripke structure with a set of atomic propositions.In general query check-ing,solutions to queries are arbitrary propositional formulas.On the other hand,in state query checking,solutions are restricted to be single states.To represent a single state,a propositional formula needs to be a minterm over.In symbolic model checking,any state of is uniquely represented by the minterm that holds in.For example,in themodel of Figure1(a),state is represented by,by,etc.Thus,for state query checking,an answer to a query is a set of minterms,rather than an upset of propositional formulas.For instance,for the query,on the model of Figure1(a), the state query-checking answer is,whereas the general query checking one is.While it is still true that if is a solution,everything in is also a solution,we no longer view answers as upsets,since we are interested only in minterms,and is the only minterm in the set(minterms are incomparable by implication).We can thus formulate state query checking as minterm query checking: given a CTL query on a model,find all its minterm solutions.We show how to solve this for any query,and any subset.When,the minterms obtained are the state solutions.Given a query,a naive algorithm would model check for every minterm .If is the number of atomic propositions in,there are possible minterms, and this algorithm has complexity times that of model-checking.Minterm query checking is thus much easier to solve than general query checking.Of course,any algorithm solving general query checking,such as the symbolic approach described in Section3,solves minterm query checking as well:from all solu-tions,we can extract only those which are minterms.This approach,however,is much more expensive than needed.Below,we propose a method that is tailored to solve just minterm query checking,while remaining symbolic.4.1Solving minterm query checkingSince an answer to minterm query checking is a set of minterms,the space of all answers is the powerset that forms a lattice ordered by set inclusion.For example,the lattice is shown in Figure2(c).Our symbolic algorithm evaluates queries over this lattice.Wefirst adjust the semantics of the placeholder to minterms.Suppose we evaluate in a state.Either holds in,and then the answer should be,or holds,and then the answer is.Thus,we haveif,if.This is encoded by the formula.In general,for a query ,exactly one minterm holds in,and in that case is the answer to the query. This gives the following translation of placeholder:8Our minterm query-checking algorithm is now defined as follows:given a query on a model,compute,and then model check this over.For example,for,on the model of Figure1(a),we model checkand obtain the answer,that is indeed the only minterm solution for this model.To prove our algorithm correct,we need to show that its answer is the set of all minterm solutions.We prove this claim by relating our algorithm to the general al-gorithm in Section3.We show that,while the general algorithm computes the set of all solutions,ours results in the subset that consists of only the minterms from.Wefirst establish an“approximation”mapping fromto that,for any upset,returns the subset of minterms. Definition1(Minterm approximation).Let be a set of atomic propositions.Minterm approximation is,for any .With this definition,is obtained from by replacing with .The minterm approximation preserves set operations;this can be proven using the fact that any set of propositional formulas can be partitioned into minterms and non-minterms.Proposition1.The minterm approximation is a lattice ho-momorphism,i.e.,it preserves the set operations:for any,and.By Proposition1,and since model checking is performed using only set operations, we can show that the approximation preserves model-checking results.Model check-ing is the minterm approximation of checking.In other words, our algorithm results in set of all minterm solutions,which concludes the correctness argument.Theorem1(Correctness of minterm approximation).For any state of,In summary,for,we have the following correct symbolic state query-checking algorithm:given a query on a model,translate it to,and then model check this over.The worst-case complexity of our algorithm is the same as that of the naive ap-proach.With an efficient encoding of the approximate lattice,however,our approach can outperform the naive one in practice,as we show in Section6.94.2ImplementationAlthough our minterm query-checking algorithm is defined as model checking over a lattice,we can implement it using a classical symbolic model checker.This in done by encoding the lattice elements in such that lattice operations are already imple-mented by a symbolic model checker.The key observation is that the latticeis isomorphic to the lattice of propositional formulas.This can be seen, for instance,by comparing the lattices in Figures2(a)and2(c).Thus,the elements of can be encoded as propositional formulas,and the operations become proposi-tional disjunction and conjunction.A symbolic model checker,such as NuSMV[8], which we used in our implementation,already has data structures for representing propositional formulas and algorithms to compute their disjunction and conjunction —BDDs[24].The only modifications we made to NuSMV were parsing the input and reporting the result.While parsing the queries,we implemented the translation defined in Sec-tion4.1.In this translation,for every minterm,we give a propositional encoding to.We cannot simply use to encode.The lattice elements need to be con-stants with respect to the model,and is not a constant—it is a propositional formula that contains model variables.We can,however,obtain an encoding for,by renam-ing to a similar propositional formula over fresh variables.For instance,we encode as.Thus,our query translation results in a CTL formula with double the number of propositional variables compared to the model.For example,the translation of isWe input this formula into NuSMV,and obtain the set of minterm solutions as a propo-sitional formula over the encoding variables.For,on the model in Figure1(a),we obtain the result,corresponding to the only minterm solution .4.3Exactness of minterm approximationIn this section,we address the applicability of minterm query checking to general query checking.When the minterm solutions are the strongest solutions to a query,minterm query checking solves the general query-checking problem as well,as all solutions to that query can be inferred from the minterms.In that case,we say that the minterm approximation is exact.We would like to identify those CTL queries that admit exact minterm approximations,independently of the model.The following can be proven using the fact that any propositional formula is a disjunction of minterms. Proposition2.A positive query has an exact minterm approximation in any model iff is distributive over disjunction,i.e.,.10An example of a query that admits an exact approximation is;its strongest solu-tions are always minterms,representing the reachable states.In[5],Chan showed that deciding whether a query is distributive over conjunction is EXPTIME-complete.We obtain a similar result by duality.Theorem2.Deciding whether a CTL query is distributive over disjunction is EXPTIME-complete.Since the decision problem is hard,it would be useful to have a grammar that is guaran-teed to generate queries which distribute over disjunction.Chan defined a grammar for queries distributive over conjunction,that was later corrected by Samer and Veith[22]. We can obtain a grammar for queries distributive over disjunction,from the grammar in[22],by duality.5ApproximationsThe efficiency of model checking over a lattice is determined by the size of the lattice. In the case of query checking,by restricting the problem and approximating answers, we have obtained a more manageable lattice.In this section,we show that our minterm approximation is an instance of a more general approximation framework for reasoning over any lattice of sets.Having a more general framework makes it easier to accom-modate other approximations that may be needed in query checking.For example,we use it to derive an approximation to negative queries.This framework may also apply to other analysis problems that involve model checking over lattices of sets,such as vacuity detection[14].Wefirst define general approximations that map larger lattices into smaller ones. Let be anyfinite set.Its powerset lattice is.Let be any sublattice of the powerset lattice,i.e.,.Definition2(Approximation).A function is an approximation if:1.it satisfies for any(i.e.,is an under-approximation of),and2.it is a lattice homomorphism,i.e.,it respects the lattice operations:,and.From the definition of,the image of through is a sublattice of,having and as its maximum and minimum elements,respectively.We consider an approximation to be correct if it is preserved by model checking: reasoning over the smaller lattice is the approximation of reasoning over the larger one.Let be a CTL()formula.We define its translation into to be the CTL(formula obtained from by replacing any constant occurring in by.The following theorem simply states that the result of model checking is the approximation of the result of model checking.Its proof follows by structural induction from the semantics of CTL,and uses the fact that approximations are homomorphisms.[18]proves a similar result,albeit in a somewhat different context.11。

Ergodic solenoidal homology

arXiv:math/0702501v1 [math.DG] 16 Feb 2007

˜ ´ VICENTE MUNOZ AND RICARDO PEREZ MARCO Abstract. We define generalized currents associated with immersions of abstract solenoids with a transversal measure. We realize geometrically the full real homology of a compact manifold with these generalized currents, and more precisely with immersions of minimal uniquely ergodic solenoids. This makes precise and geometric De Rham’s realization of the real homology by only using a restricted geometric subclass of currents. These generalized currents do extend Ruelle-Sullivan and Schwartzman currents. We extend Schwartzman theory beyond dimension 1 and provide a unified treatment of Ruelle-Sullivan and Schwartzman theories via Birkhoff’s ergodic theorem for the class of immersions of controlled solenoids. We develop some intersection theory of these new generalized currents that explains why the realization theorem cannot be achieved only with Ruelle-Sullivan currents.

IMPLICATURE 语用学

A: Shall we hold the football match tomorrow?

B: It is raining.

Semantic and literal meaning: his answer unrelated to the question. Intended meaning: the football match will be canceled as ground is wet and slippery after the rain.

(c) Carmen: I hear you’ve invite Mat and Chris. Dave : I didn’t invite Mat. (Did Dave invite Chris?) →Dave invited Chris.

The notion of implicature provides some explicit account of how it is possible to mean more than what is actually “said” , or more than what is literally expressed.

a) Tom : Are you going to Mark‟s party tonight? Annie : My parents are in town. (No.) Shared knowledge : Annie‟s relation with her parents b) Tom : Where‟s the salad dressing? Gabriel : We‟ve run out of olive oil. (There isn‟t any salad dressing.) Shared knowledge : Oliver oil is a possible ingredient in salad dressing and they only use salad dressing made from olive oil.

generalized linear model结果解释-概述说明以及解释

generalized linear model结果解释-概述说明以及解释1.引言1.1 概述概述部分的内容可以包括对广义线性模型的简要介绍以及结果解释的重要性。

以下是一种可能的编写方式:在统计学和机器学习领域,广义线性模型(Generalized Linear Model,简称GLM)是一种常用的统计模型,用于建立因变量与自变量之间的关系。

与传统的线性回归模型不同,广义线性模型允许因变量(也称为响应变量)的分布不服从正态分布,从而更适用于处理非正态分布的数据。

广义线性模型的理论基础是广义线性方程(Generalized Linear Equation),它通过引入连接函数(Link Function)和系统误差分布(Error Distribution)的概念,从而使模型能够适应不同类型的数据。

结果解释是广义线性模型分析中的一项重要任务。

通过解释模型的结果,我们可以深入理解自变量与因变量之间的关系,并从中获取有关影响因素的信息。

结果解释能够帮助我们了解自变量的重要性、方向性及其对因变量的影响程度。

通过对结果进行解释,我们可以推断出哪些因素对于观察结果至关重要,从而对问题的本质有更深入的认识。

本文将重点讨论如何解释广义线性模型的结果。

我们将介绍广义线性模型的基本概念和原理,并指出结果解释中需要注意的要点。

此外,我们将提供实际案例和实例分析,以帮助读者更好地理解结果解释的方法和过程。

通过本文的阅读,读者将能够更全面地了解广义线性模型的结果解释,并掌握解释结果的相关技巧和方法。

本文的目的是帮助读者更好地理解和运用广义线性模型,从而提高统计分析和机器学习的能力。

在接下来的章节中,我们将详细介绍广义线性模型及其结果解释的要点,希望读者能够从中受益。

1.2文章结构文章结构部分的内容应该是对整篇文章的结构进行简要介绍和概述。

这个部分通常包括以下内容:文章结构部分的内容:本文共分为引言、正文和结论三个部分。

其中,引言部分主要概述了广义线性模型的背景和重要性,并介绍了文章的目的。

On the Interactions of Light Gravitinos

On the Interactions of Light GravitinosT.E.Clark1,Taekoon Lee2,S.T.Love3,Guo-Hong Wu4Department of PhysicsPurdue UniversityWest Lafayette,IN47907-1396AbstractIn models of spontaneously broken supersymmetry,certain light gravitino processes are governed by the coupling of its Goldstino components.The rules for constructing SUSY and gauge invariant actions involving the Gold-stino couplings to matter and gaugefields are presented.The explicit oper-ator construction is found to be at variance with some previously reported claims.A phenomenological consequence arising from light gravitino inter-actions in supernova is reexamined and scrutinized.1e-mail address:clark@2e-mail address:tlee@3e-mail address:love@4e-mail address:wu@1In the supergravity theories obtained from gauging a spontaneously bro-ken global N=1supersymmetry(SUSY),the Nambu-Goldstone fermion, the Goldstino[1,2],provides the helicity±1degrees of freedom needed to render the spin3gravitino massive through the super-Higgs mechanism.For a light gravitino,the high energy(well above the gravitino mass)interactions of these helicity±1modes with matter will be enhanced according to the su-persymmetric version of the equivalence theorem[3].The effective action de-scribing such interactions can then be constructed using the properties of the Goldstinofields.Currently studied gauge mediated supersymmetry breaking models[4]provide a realization of this scenario as do certain no-scale super-gravity models[5].In the gauge mediated case,the SUSY is dynamically broken in a hidden sector of the theory by means of gauge interactions re-sulting in a hidden sector Goldstinofield.The spontaneous breaking is then mediated to the minimal supersymmetric standard model(MSSM)via radia-tive corrections in the standard model gauge interactions involving messenger fields which carry standard model vector representations.In such models,the supergravity contributions to the SUSY breaking mass splittings are small compared to these gauge mediated contributions.Being a gauge singlet,the gravitino mass arises only from the gravitational interaction and is thus farsmaller than the scale √,where F is the Goldstino decay constant.More-2over,since the gravitino is the lightest of all hidden and messenger sector degrees of freedom,the spontaneously broken SUSY can be accurately de-scribed via a non-linear realization.Such a non-linear realization of SUSY on the Goldstinofields was originally constructed by Volkov and Akulov[1].The leading term in a momentum expansion of the effective action de-scribing the Goldstino self-dynamics at energy scales below √4πF is uniquelyfixed by the Volkov-Akulov effective Lagrangian[1]which takes the formL AV=−F 22det A.(1)Here the Volkov-Akulov vierbein is defined as Aµν=δνµ+iF2λ↔∂µσν¯λ,withλ(¯λ)the Goldstino Weyl spinorfield.This effective Lagrangian pro-vides a valid description of the Goldstino self interactions independent of the particular(non-perturbative)mechanism by which the SUSY is dynam-ically broken.The supersymmetry transformations are nonlinearly realized on the Goldstinofields asδQ(ξ,¯ξ)λα=Fξα+Λρ∂ρλα;δQ(ξ,¯ξ)¯λ˙α= F¯ξ˙α+Λρ∂ρ¯λ˙α,whereξα,¯ξ˙αare Weyl spinor SUSY transformation param-eters andΛρ≡−i Fλσρ¯ξ−ξσρ¯λis a Goldstinofield dependent translationvector.Since the Volkov-Akulov Lagrangian transforms as the total diver-genceδQ(ξ,¯ξ)L AV=∂ρ(ΛρL AV),the associated action I AV= d4x L AV is SUSY invariant.The supersymmetry algebra can also be nonlinearly realized on the matter3(non-Goldstino)fields,generically denoted byφi,where i can represent any Lorentz or internal symmetry labels,asδQ(ξ,¯ξ)φi=Λρ∂ρφi.(2) This is referred to as the standard realization[6]-[9].It can be used,along with space-time translations,to readily establish the SUSY algebra.Under the non-linear SUSY standard realization,the derivative of a matterfield transforms asδQ(ξ,¯ξ)(∂νφi)=Λρ∂ρ(∂νφi)+(∂νΛρ)(∂ρφi).In order to elim-inate the second term on the right hand side and thus restore the standard SUSY realization,a SUSY covariant derivative is introduced and defined so as to transform analogously toφi.To achieve this,we use the transformation property of the Volkov-Akulov vierbein and define the non-linearly realized SUSY covariant derivative[9]Dµφi=(A−1)µν∂νφi,(3) which varies according to the standard realization of SUSY:δQ(ξ,¯ξ)(Dµφi)=Λρ∂ρ(Dµφi).Any realization of the SUSY transformations can be converted to the standard realization.In particular,consider the gauge covariant derivative,(Dµφ)i≡∂µφi+T a ij A aµφj,(4)4with a=1,2,...,Dim G.We seek a SUSY and gauge covariant deriva-tive(Dµφ)i,which transforms as the SUSY standard ing the Volkov-Akulov vierbein,we define(Dµφ)i≡(A−1)µν(Dνφ)i,(5) which has the desired transformation property,δQ(ξ,¯ξ)(Dµφ)i=Λρ∂ρ(Dµφ)i, provided the vector potential has the SUSY transformationδQ(ξ,¯ξ)Aµ≡Λρ∂ρAµ+∂µΛρAρ.Alternatively,we can introduce a redefined gaugefieldV aµ≡(A−1)µνA aν,(6) which itself transforms as the standard realization,δQ(ξ,¯ξ)V aµ=Λρ∂ρV aµ, and in terms of which the standard realization SUSY and gauge covariant derivative then takes the form(Dµφ)i≡(A−1)µν∂νφi+T a ij V aµφj.(7) Under gauge transformations parameterized byωa,the original gaugefield varies asδG(ω)A aµ=(Dµω)a=∂µωa+gf abc A bµωc,while the redefinedgaugefield V aµhas the Goldstino dependent transformation:δG(ω)V aµ= (A−1)µν(Dνω)a.For all realizations,the gauge transformation and SUSY transformation commutator yields a gauge variation with a SUSY trans-formed value of the gauge transformation parameter,δG(ω),δQ(ξ,¯ξ)=δG(Λρ∂ρω−δQ(ξ,¯ξ)ω).(8) 5If we further require the local gauge transformation parameter to also trans-form under the standard realization so thatδQ(ξ,¯ξ)ωa=Λρ∂ρωa,then the gauge and SUSY transformations commute.In order to construct an invariant kinetic energy term for the gaugefields, it is convenient for the gauge covariant anti-symmetric tensorfield strength to also be brought into the standard realization.The usualfield strengthF a αβ=∂αA aβ−∂βA aα+if abc A bαA cβvaries under SUSY transformations asδQ(ξ,¯ξ)F aµν=Λρ∂ρF aµν+∂µΛρF aρν+∂νΛρF aµρ.A standard realization of thegauge covariantfield strength tensor,F aµν,can be then defined asF aµν=(A−1)µα(A−1)νβF aαβ,(9) so thatδQ(ξ,¯ξ)F aµν=Λρ∂ρF aµν.These standard realization building blocks consisting of the gauge singlet Goldstino SUSY covariant derivatives,Dµλ,Dµ¯λ,the matterfields,φi,their SUSY-gauge covariant derivatives,Dµφi,and thefield strength tensor,F aµν, along with their higher covariant derivatives can be combined to make SUSY and gauge invariant actions.These invariant action terms then dictate the couplings of the Goldstino which,in general,carries the residual consequences of the spontaneously broken supersymmetry.A generic SUSY and gauge invariant action can be constructed[9]asI eff=d4x detA L eff(Dµλ,Dµ¯λ,φi,Dµφi,Fµν)(10)6where L effis any gauge invariant function of the standard realization basic building ing the nonlinear SUSY transformationsδQ(ξ,¯ξ)detA=∂ρ(ΛρdetA)andδQ(ξ,¯ξ)L eff=Λρ∂ρL eff,it follows thatδQ(ξ,¯ξ)I eff=0.It proves convenient to catalog the terms in the effective Lagranian,L eff, by an expansion in the number of Goldstinofields which appear when covari-ant derivatives are replaced by ordinary derivatives and the Volkov-Akulov vierbein appearing in the standard realizationfield strengths are set to unity. So doing,we expandL eff=L(0)+L(1)+L(2)+···,(11)where the subscript n on L(n)denotes that each independent SUSY invariant operator in that set begins with n Goldstinofields.L(0)consists of all gauge and SUSY invariant operators made only from light matterfields and their SUSY covariant derivatives.Any Goldstinofield appearing in L(0)arises only from higher dimension terms in the matter covariant derivatives and/or thefield strength tensor.Taking the light non-Goldstinofields to be those of the MSSM and retaining terms through mass dimension4,then L(0)is well approximated by the Lagrangian of the mini-mal supersymmetric standard model which includes the soft SUSY breaking terms,but in which all derivatives have been replaced by SUSY covariant ones and thefield strength tensor replaced by the standard realizationfield7strength:L(0)=L MSSM(φ,Dµφ,Fµν).(12) Note that the coefficients of these terms arefixed by the normalization of the gauge and matterfields,their masses and self-couplings;that is,the normalization of the Goldstino independent Lagrangian.The L(1)terms in the effective Lagrangian begin with direct coupling of one Goldstino covariant derivative to the non-Goldstinofields.The general form of these terms,retaining operators through mass dimension6,is given byL(1)=1[DµλαQµMSSMα+¯QµMSSM˙αDµ¯λ˙α],(13)Fwhere QµMSSMαand¯QµMSSM˙αcontain the pure MSSMfield contributions to the conserved gauge invariant supersymmetry currents with once again all field derivatives being replaced by SUSY covariant derivatives and the vector field strengths in the standard realization.That is,it is this term in the effective Lagrangian which,using the Noether construction,produces the Goldstino independent piece of the conserved supersymmetry current.The Lagrangian L(1)describes processes involving the emission or absorption of a single helicity±1gravitino.Finally the remaining terms in the effective Lagrangian all contain two or more Goldstinofields.In particular,L(2)begins with the coupling of two8Goldstinofields to matter or gaugefields.Retaining terms through mass dimension8and focusing only on theλ−¯λterms,we can writeL(2)=1F2DµλαDν¯λ˙αMµν1α˙α+1F2Dµλα↔DρDν¯λ˙αMµνρ2α˙α+1F2DρDµλαDν¯λ˙αMµνρ3α˙α,(14)where the standard realization composite operators that contain matter and gaugefields are denoted by the M i.They can be enumerated by their oper-ator dimension,Lorentz structure andfield content.In the gauge mediated models,these terms are all generated by radiative corrections involving the standard model gauge coupling constants.Let us now focus on the pieces of L(2)which contribute to a local operator containing two gravitinofields and is bilinear in a Standard Model fermion (f,¯f).Those lowest dimension operators(which involve no derivatives on f or¯f)are all contained in the M1piece.After application of the Goldstino field equation(neglecting the gravitino mass)and making prodigious use of Fierz rearrangement identities,this set reduces to just1independent on-shell interaction term.In addition to this operator,there is also an operator bilinear in f and¯f and containing2gravitinos which arises from the product of det A with L(0).Combining the two independent on-shell interaction terms involving2gravitinos and2fermions,results in the effective actionIf¯f˜G˜G =d4x−12F2λ↔∂µσν¯λf↔∂νσµ¯f9+C ffF2(f∂µλ)¯f∂µ¯λ,(15)where C ff is a model dependent real coefficient.Note that the coefficient of thefirst operator isfixed by the normaliztion of the MSSM Lagrangian. This result is in accord with a recent analysis[10]where it was found that the fermion-Goldstino scattering amplitudes depend on only one parameter which corresponds to the coefficient C ff in our notation.In a similar manner,the lowest mass dimension operator contributing to the effective action describing the coupling of two on-shell gravitinos to a single photon arises from the M1and M3pieces of L(2)and has the formIγ˜G˜G =d4xCγF2∂µλσρ∂ν¯λ∂µFρν+h.c.,(16)with Cγa model dependent real coefficient and Fµνis the electromagnetic field strength.Note that the operator in the square bracket is odd under both parity(P)and charge conjugation(C).In fact any operator arising from a gauge and SUSY invariant structure which is bilinear in two on-shell gravitinos and contains only a single photon is necessarily odd in both P and C.Thus the generation of any such operator requires a violation of both P and ing the Goldstino equation of motion,the analogous term containing˜Fµνreduces to Eq.(16)with Cγ→−iCγ.Recently,there has appeared in the literature[11]the claim that there is a lower dimensional operator of the form˜M2F2∂νλσµ¯λFµνwhich contributes to the single photon-102gravitino interaction.Here˜M is a model dependent SUSY breaking massparameter which is roughly an order(s)of magnitude less than √.¿Fromour analysis,we do notfind such a term to be part of a SUSY invariant action piece and thus it should not be included in the effective action.Such a term is also absent if one employs the equivalent formalism of Wess and Samuel [6].We have also checked that such a term does not appear via radiative corrections by an explicit graphical calculation using the correct non-linearly realized SUSY invariant action.This is also contrary to the previous claim.There have been several recent attempts to extract a lower bound on the SUSY breaking scale using the supernova cooling rate[11,12,13].Unfortu-nately,some of these estimates[11,13]rely on the existence of the non-SUSY invariant dimension6operator referred to ing the correct low en-ergy effective lagrangian of gravitino interactions,the leading term coupling 2gravitinos to a single photon contains an additional supression factor ofroughly Cγs˜M .Taking√s 0.1GeV for the processes of interest and using˜M∼100GeV,this introduces an additional supression of at least10−12in the rate and obviates the previous estimates of a bound on F.Assuming that the mass scales of gauginos and the superpartners of light fermions are above the core temperature of supernova,the gravitino cooling of supernova occurs mainly via gravitino pair production.It is interesting to11compare the gravitino pair production cross section to that of the neutrino pair production,which is the main supernova cooling channel.We have seen that for low energy gravitino interactions with matter,the amplitudes for gravitino pair production is proportional to1/F2.A simple dimensional analysis then suggests the ratio of the cross sections is:σχχσνν∼s2F4G2F(17)where GF is the Fermi coupling and√s is the typical energy scale of theparticles in a supernova.Even with the most optimistic values for F,thegravitino production is too small to be relevant.For example,taking √F=100GeV,√s=.1GeV,the ratio is of O(10−11).It seems,therefore,thatsuch an astrophysical bound on the SUSY breaking scale is untenable in mod-els where the gravitino is the only superparticle below the scale of supernova core temperature.We thank T.K.Kuo for useful conversations.This work was supported in part by the U.S.Department of Energy under grant DE-FG02-91ER40681 (Task B).12References[1]D.V.Volkov and V.P.Akulov,Pis’ma Zh.Eksp.Teor.Fiz.16(1972)621[JETP Lett.16(1972)438].[2]P.Fayet and J.Iliopoulos,Phys.Lett.B51(1974)461.[3]R.Casalbuoni,S.De Curtis,D.Dominici,F.Feruglio and R.Gatto,Phys.Lett.B215(1988)313.[4]M.Dine and A.E.Nelson,Phys.Rev.D48(1993)1277;M.Dine,A.E.Nelson and Y.Shirman,Phys.Rev.D51(1995)1362;M.Dine,A.E.Nelson,Y.Nir and Y.Shirman,Phys.Rev.D53,2658(1996).[5]J.Ellis,K.Enqvist and D.V.Nanopoulos,Phys.Lett.B147(1984)99.[6]S.Samuel and J.Wess,Nucl.Phys.B221(1983)153.[7]J.Wess and J.Bagger,Supersymmetry and Supergravity,second edition,(Princeton University Press,Princeton,1992).[8]T.E.Clark and S.T.Love,Phys.Rev.D39(1989)2391.[9]T.E.Clark and S.T.Love,Phys.Rev.D54(1996)5723.[10]A.Brignole,F.Feruglio and F.Zwirner,hep-th/9709111.[11]M.A.Luty and E.Ponton,hep-ph/9706268.13[12]J.A.Grifols,R.N.Mohapatra and A.Riotto,Phys.Lett.B400,124(1997);J.A.Grifols,R.N.Mohapatra and A.Riotto,Phys.Lett.B401, 283(1997).[13]J.A.Grifols,E.Masso and R.Toldra,hep-ph/970753.D.S.Dicus,R.N.Mohapatra and V.L.Teplitz,hep-ph/9708369.14。

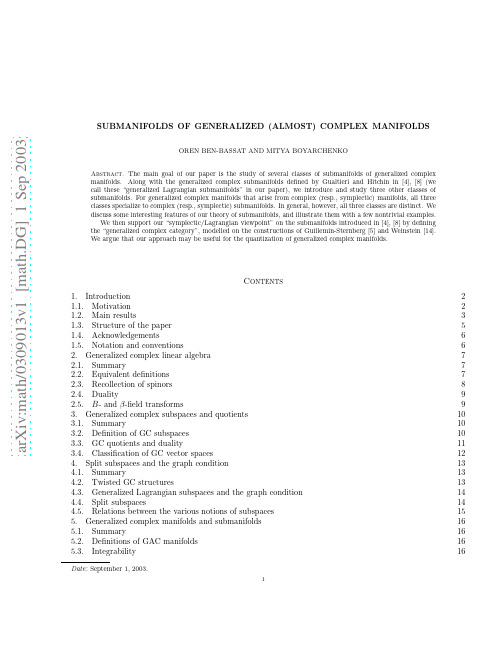

Submanifolds of generalized complex manifolds

arXiv:math/0309013v1 [math.DG] 1 Sep 2003

OREN BEN-BASSAT AND MITYA BOYARCHENKO Abstract. The main goal of our paper is the study of several classes of submanifolds of generalized complex manifolds. Along with the generalized complex submanifolds defined by Gualtieri and Hitchin in [4], [8] (we call these “generalized Lagrangian submanifolds” in our paper), we introduce and study three other classes of submanifolds. For generalized complex manifolds that arise from complex (resp., symplectic) manifolds, all three classes specialize to complex (resp., symplectic) submanifolds. In general, however, all three classes are distinct. We discuss some interesting features of our theory of submanifolds, and illustrate them with a few nontrivial examples. We then support our “symplectic/Lagrangian viewpoint” on the submanifolds introduced in [4], [8] by defining the “generalized complex category”, modelled on the constructions of Guillemin-Sternberg [5] and Weinstein [14]. We argue that our approach may be useful for the quantization of generalized complex manifolds.

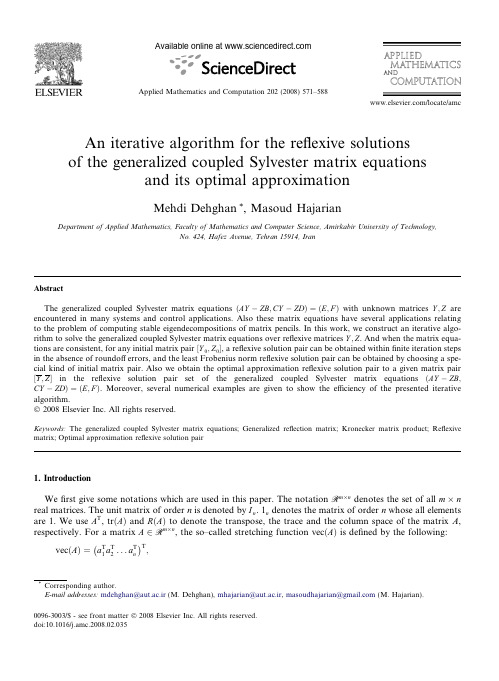

An-iterative-algorithm-for-the-reflexive-solutions-of-the-generalized-coupled-Sylvestermatrixequatio

An iterative algorithm for the reflexive solutions of the generalized coupled Sylvester matrix equationsand its optimal approximationMehdi Dehghan *,Masoud HajarianDepartment of Applied Mathematics,Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science,Amirkabir University of Technology,No.424,Hafez Avenue,Tehran 15914,IranAbstractThe generalized coupled Sylvester matrix equations ðAY ÀZB ;CY ÀZD Þ¼ðE ;F Þwith unknown matrices Y ;Z are encountered in many systems and control applications.Also these matrix equations have several applications relating to the problem of computing stable eigendecompositions of matrix pencils.In this work,we construct an iterative algo-rithm to solve the generalized coupled Sylvester matrix equations over reflexive matrices Y ;Z .And when the matrix equa-tions are consistent,for any initial matrix pair ½Y 0;Z 0 ,a reflexive solution pair can be obtained within finite iteration steps in the absence of roundofferrors,and the least Frobenius norm reflexive solution pair can be obtained by choosing a spe-cial kind of initial matrix pair.Also we obtain the optimal approximation reflexive solution pair to a given matrix pair ½Y ;Z in the reflexive solution pair set of the generalized coupled Sylvester matrix equations ðAY ÀZB ;CY ÀZD Þ¼ðE ;F Þ.Moreover,several numerical examples are given to show the efficiency of the presented iterative algorithm.Ó2008Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.Keywords:The generalized coupled Sylvester matrix equations;Generalized reflection matrix;Kronecker matrix product;Reflexive matrix;Optimal approximation reflexive solution pair1.IntroductionWe first give some notations which are used in this paper.The notation R m Ân denotes the set of all m Ân real matrices.The unit matrix of order n is denoted by I n .1n denotes the matrix of order n whose all elements are 1.We use A T ,tr ðA Þand R ðA Þto denote the transpose,the trace and the column space of the matrix A ,respectively.For a matrix A 2R m Ân ,the so–called stretching function vec ðA Þis defined by the following:vec ðA Þ¼a T 1a T 2...a T nÀÁT;0096-3003/$-see front matter Ó2008Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.amc.2008.02.035*Corresponding author.E-mail addresses:mdehghan@aut.ac.ir (M.Dehghan),mhajarian@aut.ac.ir ,masoudhajarian@ (M.Hajarian).Available online at Applied Mathematics and Computation 202(2008)571–588/locate/amcwhere a k is the k th column of A .A B stands for the Kronecker product of matrices A ¼ða ij Þm Ân and B which is defined asA B ¼a 11B a 12B ÁÁa 1n Ba 21B a 22B ÁÁa 2n B ÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁa m 1B a m 2B ÁÁa mn BBB BB BB@1C CC C C C A :In addition,h A ;B i ¼tr B T A ÀÁis defined as the inner product of the two matrices,which generates the Frobe-nius norm,i.e.h A ;A i ¼k A k 2[1,8,15].An n Ân real matrix P is said to be a real generalized reflection matrix if P T ¼P and P 2¼I n .An n Ân real matrix A is said to be a reflexive (anti-reflexive)matrix with respect to the generalized reflection matrix P ifA ¼PAP ðA ¼ÀPAP Þ.R n Ân r ðP ÞðR n Âna ðP ÞÞdenotes the subspace reflexive (anti-reflexive)matrices with respect to the n Ân generalized reflection matrix P .The reflexive and anti-reflexive matrices with respect to a general-ized reflection matrix P have applications in system and control theory,in engineering,in scientific computa-tions and various other fields [3–5].In this paper we consider the reflexive solutions of the linear matrix equationsAY ÀZB ¼E ;CY ÀZD ¼F ;ð1Þwhere A ;B ;C ;D ;E ;F 2R n Ân ,that is,we will find Y 2R n Ân r ðP Þand Z 2R n Ânr ðQ Þwhich satisfy in (1).Also we consider the reflexive solutions of the matrix pair nearness problemmin Y ;Z 2S YZfk Y ÀY k 2þk Z ÀZ k 2g ;ð2Þwhere Y 2R n Ân r ðP Þand Z 2R n Ânr ðQ Þare given reflexive matrices,and S YZ is the reflexive solution pair set of the generalized coupled Sylvester matrix equations (1).A large number of papers have been written for solving matrix equations [17,19,24,27,30–33].Chu [6]stud-ied the linear matrix equationAXB ¼C ;ð3Þwith an unknown symmetric matrix X .Peng and Hu in [26]established the necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of solution and the expressions for the reflexive and anti-reflexive with respect to a generalized reflection matrix P solutions of the matrix equationAX ¼B :In [7],the existence of a reflexive,with respect to the generalized reflection matrix P ,solution of the matrix equation (3)is presented.By extending the well-known Jacobi and Gauss–Seidel iterations for Ax ¼b ,Ding et al.in [14]derived iterative solutions of matrix equations AXB ¼F and generalized Sylvester matrix equa-tions AXB þCXD ¼F .Navarra et al.[25]studied a representation of the general common solution X to the matrix equationA 1XB 1¼C 1;A 2XB 2¼C 2:ð4ÞPeng et al.[29]presented an algorithm which is constructed to solve the reflexive with respect to the general-ized reflection matrix P solution of the minimum Frobenius norm residual problemA 1XB 1A 2XB 2 ÀC 1C 2 ¼min :In [28]an iterative algorithm is reported to solve the matrix equationAXB þCYD ¼E :572M.Dehghan,M.Hajarian /Applied Mathematics and Computation 202(2008)571–588We know the Sylvester matrix equations have a close relation with many problems in linear control theory of descriptor systems,and the matrix equations have important applications in stability analysis,in observers de-sign,in output regulation with internal stability,and in the eigenvalue assignment,and a large number of papers have presented several methods to solve these matrix equations[2,16,20–23].The generalized coupled Sylvester matrix equations(1)are very active research in the Sylvester matrix equations,and have been widely applied in various areas.In[23]Ka_gstro¨m and Poromaa introduced LAPACK–style error bounds for the generalized cou-pled Sylvester matrix equations,and presented their software that implement algorithms for solving this matrix equation.In[9,10,13,14],to solve(coupled)matrix equations,the iterative methods are given which are based on the hierarchical identification principle[11,12].The gradient-based iterative(GI)algorithms[9,14]and least squares based iterative algorithm[10]for solving(coupled)matrix equations are innovational and computa-tionally efficient numerical algorithms and were presented based on the hierarchical identification principle [11,12]which regards the unknown matrix as the system parameter matrix to be identified.Also Ding and Chen [13],applying the gradient search principle and the hierarchical identification principle,presented the gradient-based iterative algorithms for generalized Sylvester equation and general coupled matrix equations.This paper is organized as follows:In Section2,we propose an iterative algorithm and its properties to obtain the reflexive solutions of the generalized coupled Sylvester matrix equations(1).When the matrix equa-tions(1)are consistent over reflexive matrices,we show using the introduced iterative algorithm,for any(spa-cial)initial matrix pair½Y1;Z1 ,a reflexive solution pair(the minimal Frobenius normal reflexive solution pair) can be obtained withinfinite steps.Also the optimal approximation reflexive solution to a given matrix pair can be derived byfinding the least norm reflexive solution of new matrix equationsðA e YÀe ZB;C e YÀe ZDÞ¼ðe E;e FÞ.Several numerical examples are given in Section3to illustrate the application of the new iterative algorithm.2.Iterative algorithm to solve(1)and(2)In this section,wefirst introduce an iterative algorithm,then we propose some properties of this iterative algorithm which are essential tools forfinding the reflexive solution of matrix equations(1).Algorithm1step1.Input matrices A;B;C;D;E;F2R nÂn;step2.Chosen arbitrary Y12R nÂnr ðPÞ,Z12R nÂnrðQÞwhere P and Q are two nÂn arbitrary generalizedreflection matrices; step3.CalculateR1¼EÀAY1þZ1B00FÀCY1þZ1D;U1¼1A TðEÀAY1þZ1BÞþC TðFÀCY1þZ1DÞþPA TðEÀAY1þZ1BÞPþPC TðFÀCY1þZ1DÞP ÂÃ;V1¼12ÀðEÀAY1þZ1BÞB TÀðFÀCY1þZ1DÞD TÀQðEÀAY1þZ1BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY1þZ1DÞD T Q ÂÃ;k:¼1;step4.If R k¼0,then stop;Else go to step5; step5.CalculateY kþ1¼Y kþk R k k2k U k k2þk V k k2U k;Z kþ1¼Z kþk R k k2k U k kþk V k kV k;R kþ1¼EÀAY kþZ k B00FÀCY kþZ k D;¼R kÀk R k k2k U k k2þk V k k2AU kÀV k B00CU kÀV k D;M.Dehghan,M.Hajarian/Applied Mathematics and Computation202(2008)571–588573U k þ1¼12A TðE ÀAY k þ1þZ k þ1B ÞþC T ðF ÀCY k þ1þZ k þ1D ÞþPA T ðE ÀAY k þ1þZ k þ1B ÞP ÂþPC TðF ÀCY k þ1þZ k þ1D ÞP Ãþk R k þ1k 2k R k kU k ;V k þ1¼12ÀðE ÀAY k þ1þZ k þ1B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY k þ1þZ k þ1D ÞD TÂÀQ ðE ÀAY k þ1þZ k þ1B ÞB T Q ÀQ ðF ÀCY k þ1þZ k þ1D ÞD TQ Ãþk R k þ1k 2k R k k 2V k ;step 6.If R k þ1¼0,then stop;Else,let k :¼k þ1,go to step 5.Since the above algorithm,we can easily see that Y k ;U k 2R n Ân r ðP Þand Z k ;V k 2R n Ânr ðQ Þ.Now we intro-duce some properties of the above algorithm.Lemma 1.Assume that the sequences R i ,U i and V i (i ¼1;2;...;s ,R i ¼0)are generated by Algorithm 1,then we havetr R T j R i ¼0;and tr U T j U i þtr V Tj V i ¼0;i ;j ¼1;2;...;s ;i ¼j :ð5ÞProof.It is obvious that tr R T j R i ¼tr ðR T i R j Þ,tr U T j U i ¼tr U T i U j ÀÁand tr V Tj V i ¼tr V T iV j ÀÁ,hence we need only to show thattr R Tj R i ¼0;andtr U T j U i þtr V Tj V i ¼0for 16i <j 6s :ð6ÞWe use induction to prove (6),and also we do it in two steps.Step 1.We first showtr R T i þ1R i ÀÁ¼0;and tr U T i þ1U i ÀÁþtr V T i þ1V i ÀÁ¼0;i ¼1;2;...;s :ð7ÞWe also prove (7)by induction.Because all matrices in Algorithm 1are real for i ¼1,we can writetr R T 2R 1ÀÁ¼tr R 1Àk R 1k 2k U 1k þk V 1kAU 1ÀV 1B 00CU 1ÀV 1D "#T R 10@1A ¼k R 1k 2Àk R 1k 2k U 1k 2þk V 1k2tr AU 1ÀV 1B 00CU 1ÀV 1D T ÂE ÀAY 1þZ 1B 00F ÀCY 1þZ 1D¼k R 1k 2Àk R 1k 2k U 1k 2þk V 1k2tr AU 1ÀV 1B ðÞTE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ðÞh i þðCU 1ÀV 1D ÞTðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D Þh i¼k R 1k 2Àk R 1k2k U 1k þk V 1ktr U T 1A TðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞþU T 1C TðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞÀÀB T V T 1ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞÀD T V T1ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞÁ¼k R 1k 2Àk R 1k 2k U 1k 2þk V 1k 2tr U T 1A T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞþC TðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D Þ2 þA T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞþC T ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D Þ2574M.Dehghan,M.Hajarian /Applied Mathematics and Computation 202(2008)571–588þPA TðEÀAY1þZ1BÞPþPC TðFÀCY1þZ1DÞP2ÀPA TðEÀAY1þZ1BÞPþPC TðFÀCY1þZ1DÞP2!þV T1ÀðEÀAY1þZ1BÞB TÀðFÀCY1þZ1DÞD T2þÀðEÀAY1þZ1BÞB TÀðFÀCY1þZ1DÞD T2þÀQðEÀAY1þZ1BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY1þZ1DÞD T Q2ÀÀQðEÀAY1þZ1BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY1þZ1DÞD T Q!¼k R1k2Àk R1k2k U1kþk V1ktr U T1A TðEÀAY1þZ1BÞþC TðFÀCY1þZ1DÞ2þPA TðEÀAY1þZ1BÞPþPC TðFÀCY1þZ1DÞP2!þV T1ÀðEÀAY1þZ1BÞB TÀðFÀCY1þZ1DÞD T2þÀQðEÀAY1þZ1BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY1þZ1DÞD T Q2!¼k R1k2Àk R1k2k U1kþk V1ktr U T1U1þV T1V1ÀÁ¼0:ð8ÞAlso we havetr U T2U1ÀÁþtr V T2V1ÀÁ¼tr A TðEÀAY2þZ2BÞþC TðFÀCY2þZ2DÞ2þPA TðEÀAY2þZ2BÞPþPC TðFÀCY2þZ2DÞP2þk R2k2k R1k2U1#TU1!þtrÀðEÀAY2þZ2BÞB TÀðFÀCY2þZ2DÞD T2þÀQðEÀAY2þZ2BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY2þZ2DÞD T Q2þk R2k2k R1k2V1#TV11A¼tr A TðEÀAY2þZ2BÞþC TðFÀCY2þZ2DÞ2þA TðEÀAY2þZ2BÞþC TðFÀCY2þZ2DÞ2ÀPA TðEÀAY2þZ2BÞPþPC TðFÀCY2þZ2DÞP2þPA TðEÀAY2þZ2BÞPþPC TðFÀCY2þZ2DÞP2þk R2k2k R1kU1#TU1!þtrÀðEÀAY2þZ2BÞB TÀðFÀCY2þZ2DÞD T2þÀðEÀAY2þZ2BÞB TÀðFÀCY2þZ2DÞD T2ÀÀQðEÀAY2þZ2BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY2þZ2DÞD T Q2þÀQðEÀAY2þZ2BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY2þZ2DÞD T Q2þk R2k2k R1kV1#TV11AM.Dehghan,M.Hajarian/Applied Mathematics and Computation202(2008)571–588575¼tr U T 1A T ðE ÀAY 2þZ 2B ÞþC T ðF ÀCY 2þZ 2D ÞÂÃþV T 1ÀðE ÀAY 2þZ 2B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY 2þZ 2D ÞD TÂÃÀÁþk R 2k 2k R 1kðk V 1k 2þk U 1k 2Þ¼tr ððE ÀAY 2þZ 2B ÞT AU 1þðF ÀCY 2þZ 2D ÞT CU 1ÀðE ÀAY 2þZ 2B ÞT V 1B ÀðF ÀCY 2þZ 2D ÞT V 1D Þþk R 2k 2k R 1k2ðk V 1k 2þk U 1k 2Þ¼trðE ÀAY 2þZ 2B ÞT0ðF ÀCY 2þZ 2D ÞT!AU 1ÀV 1B0CU 1ÀV 1D! !þk R 2k 2k R 1kðk V 1k 2þk U 1k 2Þ¼k U 1k 2þk V 1k 2k R 1ktr ðR T 2ðR 1ÀR 2ÞÞþk R 2k 2k R 1kðk V 1k 2þk U 1k 2Þ¼0:ð9ÞAssume that (7)holds for i ¼d À1.Now let i ¼d .Similar to the proofs of (8)and (9),we can obtaintr R T d þ1R d ÀÁ¼k R d k 2Àk R d k 2k U d k þk V d ktr AU d ÀV d B 00CU d ÀV d D T ÂE ÀAY d þZ d B00F ÀCY d þZ d D¼k R d k 2Àk R d k 2k U d k 2þk V d k2tr U T d A T ðE ÀAY d þZ d B ÞþU T d C TðF ÀCY d þZ d D ÞÀÀB T V T d ðE ÀAY d þZ d B ÞÀD T V TdðF ÀCY d þZ d D ÞÁ¼k R d k 2Àk R d k 2k U d k 2þk V d k2tr U T d A T ðE ÀAY d þZ d B ÞþC TðF ÀCY d þZ d D Þ2 þPA T ðE ÀAY d þZ d B ÞP þPC T ðF ÀCY d þZ d D ÞP 2!þV T dÀðE ÀAY d þZ d B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY d þZ d D ÞD T 2þÀQ ðE ÀAY d þZ d B ÞB TQ ÀQ ðF ÀCY d þZ d D ÞD T Q 2! ¼k R d k 2Àk R d k 2k U d k þk V d k tr U T d U d Àk R d k 2k R d À1k U d À1 !þV Td V d Àk R d k 2k R d À1kV d À1! !¼k R d k 2Àk R d k 2k U d k þk V d kk U d k 2þk V d k 2 þk R d k 4k U d k 2þk V d k 2 k R d À1k 2tr U T d U d À1ÀÁþtr V T d V d À1ÀÁ1A ¼0ð10ÞAnd we havetr U T d þ1U d ÀÁþtr V T d þ1V d ÀÁ¼tr U T dA T ðE ÀAY d þ1þZ d þ1B ÞþC TðF ÀCY d þ1þZ d þ1D ÞÂÃÀþV Td ÀðE ÀAY d þ1þZ d þ1B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY d þ1þZ d þ1D ÞD TÂÃÁþk R d þ1k 2k R d k 2k V d k 2þk U d k 2¼tr E ÀAY d þ1þZ d þ1B ðÞT AU d þðF ÀCY d þ1þZ d þ1D ÞT CU dÀðE ÀAY d þ1þZ d þ1B ÞT V d B ÀðF ÀCY d þ1þZ d þ1D ÞTV d D576M.Dehghan,M.Hajarian /Applied Mathematics and Computation 202(2008)571–588þk R d þ1k2k R d k 2ðk V d k 2þk U d k 2Þ¼tr ðE ÀAY d þ1þZ d þ1B ÞT 0ðF ÀCY d þ1þZ d þ1D ÞT!ÂAU d ÀV d B00CU d ÀV d Dþk R d þ1k 2k R d k2ðk V d k 2þk U d k 2Þ¼k U d k 2þk V d k2k R d ktr ðR T d þ1ðR dÀR d þ1ÞÞþk R d þ1k 2k R d kðk V d k 2þk U d k 2Þ¼0:ð11ÞHence,(7)holds for i ¼d .Then since (8)–(11),(7)holds by principal of induction.Step 2.In this step,we assume tr R T i þt R i ÀÁ¼0,and tr ðU Ti þt U i Þþtr ðV T i þt V i Þ¼0for 16i 6t and 1<t <s .Now we show tr R T i þt þ1R i ÀÁ¼0,and tr U T i þt þ1U i ÀÁþtr ðV Ti þt þ1V i Þ¼0.By using step 1and similar to the proofs of (8)–(11),we can writetr R T i þt þ1R i ÀÁ¼tr R i þt Àk R i þt k 2k U i þt k þk V i þt kAU i þt ÀV i þt B 00CU i þt ÀV i þt D "#T R i 0@1A ¼tr R T i þt R i ÀÁÀk R i þt k 2k U i þt k 2þk V i þt k2tr AU i þt ÀV i þt B 00CU i þt ÀV i þt D T ÂE ÀAY i þZ i B 00F ÀCY i þZ i D¼Àk R i þt k 2k U i þt k þk V i þt ktr U T i þt A T ðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞþU T i þt C TðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞÀÀB T V T i þt ðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞÀD T V Ti þtðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞÁ¼Àk R i þt k 2k U i þt k 2þk V i þt k 2tr U Ti þt A T ðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞþC T ðF ÀCY i þZ i D Þ2 þA T ðE ÀAY i þZ iB ÞþC T ðF ÀCY i þZ iD Þ2þPA T ðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞP þPC T ðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞP 2ÀPA T ðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞP þPC T ðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞP 2!þV Ti þtÀðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞD T 2þÀðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞD T 2þÀQ ðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞB T Q ÀQ ðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞD T Q 2ÀÀQ ðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞB T Q ÀQ ðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞD T Q 2!¼Àk R i þt k 2k U i þt k 2þk V i þt k2tr U Ti þtA T ðE ÀAY i þZ iB ÞþC T ðF ÀCY i þZ iD Þ2 þPA T ðE ÀAY i þZ i B ÞP þPC T ðF ÀCY i þZ i D ÞP !M.Dehghan,M.Hajarian /Applied Mathematics and Computation 202(2008)571–588577þV Tiþt ÀðEÀAY iþZ i BÞB TÀðFÀCY iþZ i DÞD T2þÀQðEÀAY iþZ i BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY iþZ i DÞD T Q2!¼Àk R iþt k2k U iþt kþk V iþt ktr U TiþtU iÀk R i k2k R iÀ1kU iÀ1!þV TiþtV iÀk R i k2k R iÀ1kV iÀ1!!¼Àk R iþt k2k U iþt kþk V iþt ktr U TiþtU iÀÁþtr V TiþtV iÀÁÂÃþk R iþt k2k R i k2ðk U iþt kþk V iþt kÞk R iÀ1kþtr U Tiþt U iÀ1ÀÁþtr V Tiþt V iÀ1ÀÁÂü0:ð12ÞNothing that we have tr R Tiþtþ1R iÀÁ¼0,and tr R Tiþtþ1R iþ1ÀÁ¼0,hence we can obtaintr U Tiþtþ1U iÀÁþtr V Tiþtþ1V iÀÁ¼trA T EÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BðÞþC TðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞ2þPA TðEÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BÞPþPC TðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞP2þk R iþtþ1k2k R iþt k2U iþt#TU i!þtr ÀðEÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BÞB TÀðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞD T2þÀQðEÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BÞB T QÀQðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞD T Q2þk R iþtþ1k2k R iþt kV iþt#TV i1A¼tr U TiA T EÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BðÞþC TðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞÂÃþV TiÀðEÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BÞB TÂÀÀðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞD T ÃÁþk R iþtþ1k2k R iþt k2tr U TiþtU iÀÁþtr V TiþtV iÀÁÀÁ¼trðEÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BÞT AU iþðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞT CU iÀðEÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BÞT V i BÀðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞT V i Dþk R iþtþ1k2k R iþt k2tr U TiþtU iÀÁþtr V TiþtV iÀÁÀÁ¼tr ðEÀAY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1BÞT00ðFÀCY iþtþ1þZ iþtþ1DÞT!AU iÀV i B00CU iÀV i D!!þk R iþtþ1k2k R iþt k2tr U TiþtU iÀÁþtr V TiþtV iÀÁÀÁ¼k U i k2þk V i k2k R i k2tr R Tiþtþ1R iÀR iþ1ðÞÀÁþk R iþtþ1k2k R iþt k2tr U TiþtU iÀÁþtr V TiþtV iÀÁÀÁ¼0:ð13ÞBy steps1and2,the conclusion(5)holds by the principal of induction.hLemma2.Suppose that the matrix equations(1)are consistent over reflexive matrices,and½YÃ;Zà is an arbi-trary reflexive solution pair of the matrix equations(1).Then,for any initial reflexive matrix pair½Y1;Z1 trððYÃÀY iÞT U iþðZÃÀZ iÞT V iÞ¼k R i k2ð14Þfor i¼1;2;...,where the sequences f Y i g,f Z i g,f U i g,f V i g and f R i g are generated by Algorithm1.578M.Dehghan,M.Hajarian/Applied Mathematics and Computation202(2008)571–588Proof.We prove the conclusion (14)by induction.If i ¼1,we havetr ðY ÃÀY 1ÞT U 1þðZ ÃÀZ 1ÞTV 1¼tr Y ÃÀY 1ðÞT A T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞþC TðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D Þ2þPA T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞP þPC T ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞP 2!þðZ ÃÀZ 1ÞT ÀðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞD T 2þÀQ ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞB T Q ÀQ ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞD T Q 2!¼tr ðY ÃÀY 1ÞT A T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞþC TðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D Þ2þA T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞþC T ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞÀPA T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞP þPC T ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞP þPA T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞP þPC TðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞP 2!þðZ ÃÀZ 1ÞT ÀðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞD T 2 þÀðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞB T ÀðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞD T 2ÀÀQ ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞB T Q ÀQ ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞD T Q2þÀQ ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞB T Q ÀQ ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞD T Q2! ¼tr Y ÃÀY 1ðÞT A T ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞþC T ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞÂÃþðZ ÃÀZ 1ÞT ÀðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞB TÂÀðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞD TÃÁ¼tr ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞT A ðY ÃÀY 1ÞþðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞTC ðY ÃÀY 1ÞÀðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞT ðZ ÃÀZ 1ÞB ÀðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞT ðZ ÃÀZ 1ÞD¼tr ðE ÀAY 1þZ 1B ÞT0ðF ÀCY 1þZ 1D ÞT!ÂA ðY ÃÀY 1ÞÀðZ ÃÀZ 1ÞB00C ðY ÃÀY 1ÞÀðZ ÃÀZ 1ÞD0B @1C A 1C A¼trE ÀAY 1þZ 1B 00F ÀCY 1þZ 1D T E ÀAY 1þZ 1B 00F ÀCY 1þZ 1D!¼k R 1k 2:ð15ÞNow suppose the conclusion (14)holds for 16i 6d .Similar to the proof of (15),for i ¼d þ1we can obtaintr ðY ÃÀY d þ1ÞT U d þ1þðZ ÃÀZ d þ1ÞT V d þ1¼tr ðY ÃÀY d þ1ÞT A TðE ÀAY d þ1þZ d þ1B ÞþC T ðF ÀCY d þ1þZ d þ1D Þ2þPA T ðE ÀAY d þ1þZ d þ1B ÞP þPC TðF ÀCY d þ1þZ d þ1D ÞP 2þk R d þ1k2k R d k 2U d#M.Dehghan,M.Hajarian /Applied Mathematics and Computation 202(2008)571–588579。

A Review on Multi-Label Learning Algorithms

Index Terms Machine learning, multi-label learning, evaluation metrics, label correlations, problem transformation, algorithm adaptation.

I. I NTRODUCTION Traditional supervised learning is one of the mostly-studied machine learning paradigms, where each real-world object (example) is represented by a single instance (feature vector) and associated with a single label. Formally, let X denote the instance space and Y denote the label space, the task of traditional supervised learning is to learn a function f : X → Y from the training set {(xi , yi ) | 1 ≤ i ≤ m}. Here, xi ∈ X is an instance characterizing

Min-Ling Zhang is with the School of Computer Science and Engineering, and the MOE Key Laboratory of Computer Network and Information Integration, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, China. Email: zhangml@. Zhi-Hua Zhou is with the National Key Laboratory for Novel Software Technology, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China. Email: zhouzh@. (Corresponding author)

Generalized Quantifiers in Declarative and Interrogative Sentences