航线安全审计

Info-Note-5-Doc9803alltext航线安全审计.en

Approved by the Secretary General and published under his authorityLine OperationsSafety Audit (LOSA)First Edition — 2002Doc 9803AN/761AMENDMENTSThe issue of amendments is announced regularly in the ICAO Journal and in the monthly Supplement to the Catalogue of ICAO Publications and Audio-visual Training Aids, which holders of this publication should consult. The space below is provided to keep a record of such amendments.RECORD OF AMENDMENTS AND CORRIGENDA AMENDMENTS CORRIGENDANo.DateapplicableDateenteredEnteredby No.Dateof issueDateenteredEnteredbyTABLE OF CONTENTSPage PageForeword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(v) Acronyms and Abbreviations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(vi) Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(vii) Chapter 1.Basic error management concepts. .1-11.1Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-11.2Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-2Reactive strategies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-2Combined reactive/proactive strategies. .1-2Proactive strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-41.3 A contemporary approach to operationalhuman performance and error. . . . . . . . . . .1-51.4The role of the organizational culture . . . .1-71.5Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-7 Chapter2.Implementing LOSA . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-12.1History of LOSA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-12.2The Threat and Error Management Model.2-1Threats and errors defined. . . . . . . . . . . .2-1Definitions of crew error response . . . . .2-4Definitions of error outcomes. . . . . . . . .2-4Undesired Aircraft States . . . . . . . . . . . .2-42.3LOSA operating characteristics . . . . . . . . .2-5Observer assignment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-7Flight crew participation. . . . . . . . . . . . .2-72.4How to determine the scope of a LOSA . .2-72.5Once the data is collected. . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-82.6Writing the report . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-82.7Success factors for LOSA. . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-8Chapter3.LOSA and the safety changeprocess (SCP) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3-13.1Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3-13.2 A constantly changing scene. . . . . . . . . . . .3-13.3One operator’s example of an SCP . . . . . .3-2 Chapter4.How to set up a LOSA —US Airways experience . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-14.1Gathering information. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-14.2Interdepartmental support . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-14.3LOSA steering committee. . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-1Safety department . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-1Flight operations and trainingdepartments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-2Pilots union . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-24.4The key steps of a LOSA. . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-2Goals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-2Action plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-24.5The keys to an effective LOSA . . . . . . . . .4-4Confidentiality and no-jeopardy. . . . . . .4-4The role of the observer . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-54.6Promoting LOSA for flight crews . . . . . . .4-5 Appendix A — Examples of the various forms utilized by LOSA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .A-1 Appendix B — Example of an introductory letterby an airline to its flight crews. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .B-1 Appendix C — List of recommended readingand reference material. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .C-1FOREWORDThe safety of civil aviation is the major objective of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Consider-able progress has been made in increasing safety, but additional improvements are needed and can be achieved. It has long been known that the majority of aviation accidents and incidents result from less than optimum human per-formance, indicating that any advance in this field can be expected to have a significant impact on the improvement of aviation safety.This was recognized by the ICAO Assembly, which in 1986 adopted Resolution A26-9 on Flight Safety and Human Factors. As a follow-up to the Assembly Resolution, the Air Navigation Commission formulated the following objective for the task:“To improve safety in aviation by making States more aware and responsive to the importance of Human Factors in civil aviation operations through the provision of practical Human Factors materials and measures, developed on the basis of experience in States, and by developing and recommending appropriate amendments to existing material in Annexes and other documents with regard to the role of Human Factors in the present and future operational environments. Special emphasis will be directed to the Human Factors issues that may influence the design, transition and in-service use of the future ICAO CNS/A TM systems.”One of the methods chosen to implement Assembly Resolution A26-9 is the publication of guidance materials, including manuals and a series of digests, that address various aspects of Human Factors and its impact on aviation safety. These documents are intended primarily for use by States to increase the awareness of their personnel of the influence of human performance on safety.The target audience of Human Factors manuals and digests are the managers of both civil aviation administrations and the airline industry, including airline safety, training and operational managers. The target audience also includes regulatory bodies, safety and investigation agencies and training establishments, as well as senior and middle non-operational airline management.This manual is an introduction to the latest information available to the international civil aviation community on the control of human error and the development of counter-measures to error in operational environments. Its target audience includes senior safety, training and operational personnel in industry and regulatory bodies.This manual is intended as a living document and will be kept up to date by periodic amendments. Subsequent editions will be published as new research results in increased knowledge on Human Factors strategies and more experience is gained regarding the control and management of human error in operational environments.ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADS Automatic Dependent SurveillanceA TC Air Traffic ControlCFIT Controlled Flight Into TerrainCNS/A TM Communications, Navigation and Surveillance/Air Traffic Management CPDLC Controller-Pilot Data Link CommunicationsCRM Crew Resource ManagementDFDR Digital Flight Data RecorderETOPS Extended Range Operations by Twin-engined AeroplanesFAA Federal Aviation AdministrationFDA Flight Data AnalysisFMS Flight Management SystemFOQA Flight Operations Quality AssuranceICAO International Civil Aviation OrganizationLOSA Line Operations Safety AuditMCP Mode Control PanelQAR Quick Access RecorderRTO Rejected Take-OffSCP Safety Change ProcessSOPs Standard Operating ProceduresTEM Threat and Error ManagementUTTEM University of Texas Threat and Error ManagementINTRODUCTION1.This manual describes a programme for the management of human error in aviation operations known as Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA). LOSA is proposed as a critical organizational strategy aimed at developing countermeasures to operational errors. It is an organizational tool used to identify threats to aviation safety, minimize the risks such threats may generate and implement measures to manage human error in operational contexts. LOSA enables operators to assess their level of resilience to systemic threats, operational risks and front-line personnel errors, thus providing a principled, data-driven approach to prioritize and implement actions to enhance safety.2.LOSA uses expert and highly trained observers to collect data about flight crew behaviour and situational factors on “normal” flights. The audits are conducted under strict no-jeopardy conditions; therefore, flight crews are not held accountable for their actions and errors that are observed. During flights that are being audited, observers record and code potential threats to safety; how the threats are addressed; the errors such threats generate; how flight crews manage these errors; and specific behaviours that have been known to be associated with accidents and incidents.3.LOSA is closely linked with Crew Resource Management (CRM) training. Since CRM is essentially error management training for operational personnel, data from LOSA form the basis for contemporary CRM training refocus and/or design known as Threat and Error Man-agement (TEM) training. Data from LOSA also provide a real-time picture of system operations that can guide organizational strategies in regard to safety, training and operations. A particular strength of LOSA is that it identifies examples of superior performance that can be reinforced and used as models for training. In this way, training inter-ventions can be reshaped and reinforced based on successful performance, that is to say, positive feedback. This is indeed a first in aviation, since the industry has traditionally collected information on failed human performance, such as in accidents and incidents. Data collected through LOSA are proactive and can be immediately used to prevent adverse events.4.LOSA is a mature concept, yet a young one. LOSA was first operationally deployed following the First LOSA Week, which was hosted by Cathay Pacific Airways in Cathay City, Hong Kong, from 12 to 14 March 2001. Although initially developed for the flight deck sector, there is no reason why the methodology could not be applied to other aviation operational sectors, including air traffic control, maintenance, cabin crew and dispatch.5.The initial research and project definition was a joint endeavour between The University of Texas at Austin Human Factors Research Project and Continental Airlines, with funding provided by the Federal Aviation Admin-istration (FAA). In 1999, ICAO endorsed LOSA as the primary tool to develop countermeasures to human error in aviation operations, developed an operational partnership with The University of Texas at Austin and Continental Airlines, and made LOSA the central focus of its Flight Safety and Human Factors Programme for the period 2000 to 2004.6.As of February 2002, the LOSA archives contained observations from over 2 000 flights. These observations were conducted within the United States and internationally and involved four United States and four non-United States operators. The number of operators joining LOSA has constantly increased since March 2001 and includes major international operators from different parts of the world and diverse cultures.7.ICAO acts as an enabling partner in the LOSA programme. ICAO’s role includes promoting the importance of LOSA to the international civil aviation community; facilitating research in order to collect necessary data; acting as a cultural mediator in the unavoidably sensitive aspects of data collection; and contributing multicultural obser-vations to the LOSA archives. In line with these objectives, the publication of this manual is a first step at providing information and, therefore, at increasing awareness within the international civil aviation community about LOSA.8.This manual is an introduction to the concept, methodology and tools of LOSA and to the potential remedial actions to be undertaken based on the data collected under LOSA. A very important caveat must be introduced at this point: this manual is not intended to convert readers into instant expert observers and/or LOSA auditors. In fact, it is strongly recommended that LOSA not be attempted without a formal introduction to it for the(viii)Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA)following reasons. First, the forms presented in Appendix A are for illustration purposes exclusively, since they are periodically amended on the basis of experience gained and feedback obtained from continuing audits. Second, formal training in the methodology, in the use of LOSA tools and, most important, in the handling of the highly sensitive data collected by the audits is absolutely essential. Third, the proper structuring of the data obtained from the audits is of paramount importance.9.Therefore, until extensive airline experience is accumulated, it is highly desirable that LOSA training be coordinated through ICAO or the founding partners of the LOSA project. As the methodology evolves and reaches full maturity and broader industry partnerships are developed, LOSA will be available without restrictions to the international civil aviation community.10.This manual is designed as follows:•Chapter 1 includes an overview on safety, and human error and its management in aviationoperations. It provides the necessary backgroundinformation to understand the rationale for LOSA.•Chapter 2 discusses the LOSA methodology and provides a guide to the implementation of LOSAwithin an airline. It also introduces a model of crewerror management and proposes the error classi-fication utilized by LOSA, which is essentiallyoperational and practical.•Chapter 3 discusses the safety change process that should take place following the implementation ofLOSA.•Chapter 4 introduces the example of one operator’s experience in starting a LOSA.•Appendix A provides examples of the various forms utilized by LOSA.•Appendix B provides an example of an introductory letter by an airline to its flight crews.•Appendix C provides a list of recommended reading and reference material.11.This manual is a companion document to the Human Factors Training Manual (Doc 9683). The cooperation of the following organizations in the production of this manual is acknowledged: The University of Texas at Austin Human Factors Research Project, Continental Airlines, US Airways and ALPA, International. Special recognition is given to Professor Robert L. Helmreich, James Klinect and John Wilhelm of The University of Texas at Austin Human Factors Research Project; Captains Bruce Tesmer and Donald Gunther of Continental Airlines; Captains Ron Thomas and Corkey Romeo of US Airways; and Captain Robert L. Sumwalt III of US Airways and of ALPA, International.Chapter 1BASIC ERROR MANAGEMENT CONCEPTS1.1INTRODUCTION1.1.1Historically, the way the aviation industry has investigated the impact of human performance on aviation safety has been through the retrospective analyses of those actions by operational personnel which led to rare and drastic failures. The conventional investigative approach is for investigators to trace back an event under consideration to a point where they discover particular actions or decisions by operational personnel that did not produce the intended results and, at such point, conclude human error as the cause. The weakness in this approach is that the conclusion is generally formulated with a focus on the outcome, with limited consideration of the processes that led up to it. When analysing accidents and incidents, investigators already know that the actions or decisions by operational personnel were “bad” or “inappropriate”, because the “bad” outcomes are a matter of record. In other words, investigators examining human performance in safety occurrences enjoy the benefit of hindsight. This is, however, a benefit that operational personnel involved in accidents and incidents did not have when they selected what they thought of as “good” or “appropriate” actions or decisions that would lead to “good” outcomes.1.1.2It is inherent to traditional approaches to safety to consider that, in aviation, safety comes first. In line with this, decision making in aviation operations is considered to be 100 per cent safety-oriented. While highly desirable, this is hardly realistic. Human decision making in operational contexts is a compromise between production and safety goals (see Figure 1-1). The optimum decisions to achieve the actual production demands of the operational task at hand may not always be fully compatible with the optimumFigure 1-1.Operational Behaviours — Accomplishing the system’s goals1-2Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA)decisions to achieve theoretical safety demands. All production systems — and aviation is no exception —generate a migration of behaviours: due to the need for economy and efficiency, people are forced to operate at the limits of the system’s safety space. Human decision making in operational contexts lies at the intersection of production and safety and is therefore a compromise. In fact, it might be argued that the trademark of experts is not years of experience and exposure to aviation operations, but rather how effectively they have mastered the necessary skills to manage the compromise between production and safety. Operational errors are not inherent in a person, although this is what conventional safety knowledge would have the aviation industry believe. Operational errors occur as a result of mismanaging or incorrectly assessing task and/or situ-ational factors in a specific context and thus cause a failed compromise between production and safety goals.1.1.3The compromise between production and safety is a complex and delicate balance. Humans are generally very effective in applying the right mechanisms to successfully achieve this balance, hence the extraordinary safety record of aviation. Humans do, however, occasionally mismanage or incorrectly assess task and/or situational factors and fail in balancing the compromise, thus contributing to safety breakdowns. Successful compromises far outnumber failed ones; therefore, in order to understand human performance in context, the industry needs to systematically capture the mechanisms underlying suc-cessful compromises when operating at the limits of the system, rather than those that failed. It is suggested that understanding the human contribution to successes and failures in aviation can be better achieved by monitoring normal operations, rather than accidents and incidents. The Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA) is the vehicle endorsed by ICAO to monitor normal operations.1.2BACKGROUNDReactive strategiesAccident investigation1.2.1The tool most often used in aviation to document and understand human performance and define remedial strategies is the investigation of accidents. However, in terms of human performance, accidents yield data that are mostly about actions and decisions that failed to achieve the successful compromise between production and safety discussed earlier in this chapter.1.2.2There are limitations to the lessons learned from accidents that might be applied to remedial strategies vis-à-vis human performance. For example, it might be possible to identify generic accident-inducing scenarios such as Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT), Rejected Take-Off (RTO), runway incursions and approach-and-landing acci-dents. Also, it might be possible to identify the type and frequency of external manifestations of errors in these generic accident-inducing scenarios or discover specific training deficiencies that are particularly related to identified errors. This, however, provides only a tip-of-the-iceberg perspective. Accident investigation, by definition, concen-trates on failures, and in following the rationale advocated by LOSA, it is necessary to better understand the success stories to see if they can be incorporated as part of remedial strategies.1.2.3This is not to say that there is no clear role for accident investigation within the safety process. Accident investigation remains the vehicle to uncover unanticipated failures in technology or bizarre events, rare as they may be. Accident investigation also provides a framework: if only normal operations were monitored, defining unsafe behaviours would be a task without a frame of reference. Therefore, properly focused accident investigation can reveal how specific behaviours can combine with specific circumstances to generate unstable and likely catastrophic scenarios. This requires a contemporary approach to the investigation: should accident investigation be restricted to the retrospective analyses discussed earlier, its contribution in terms of human error would be to increase existing industry databases, but its usefulness in regard to safety would be dubious. In addition, the information could possibly provide the foundations for legal action and the allocation of blame and punishment.Combined reactive/proactive strategies Incident investigation1.2.4 A tool that the aviation industry has increasingly used to obtain information on operational human perform-ance is incident reporting. Incidents tell a more complete story about system safety than accidents do because they signal weaknesses within the overall system before the system breaks down. In addition, it is accepted that incidents are precursors of accidents and that N-number of incidents of one kind take place before an accident of the same kind eventually occurs. The basis for this can be traced back almost 30 years to research on accidents from different industries, and there is ample practical evidence that supports this research. There are, nevertheless, limitationsChapter 1.Basic error management concepts1-3on the value of the information on operational human performance obtained from incident reporting.1.2.5First, reports of incidents are submitted in the jargon of aviation and, therefore, capture only the external manifestations of errors (for example, “misunderstood a frequency”, “busted an altitude”, and “misinterpreted a clearance”). Furthermore, incidents are reported by the individuals involved, and because of biases, the reported processes or mechanisms underlying errors may or may not reflect reality. This means that incident-reporting systems take human error at face value, and, therefore, analysts are left with two tasks. First, they must examine the reported processes or mechanisms leading up to the errors and establish whether such processes or mechanisms did indeed underlie the manifested errors. Then, based on this relatively weak basis, they must evaluate whether the error manage-ment techniques reportedly used by operational personnel did indeed prevent the escalation of errors into a system breakdown.1.2.6Second, and most important, incident reporting is vulnerable to what has been called “normalization of deviance”. Over time, operational personnel develop infor-mal and spontaneous group practices and shortcuts to circumvent deficiencies in equipment design, clumsy pro-cedures or policies that are incompatible with the realities of daily operations, all of which complicate operational tasks. These informal practices are the product of the collective know-how and hands-on expertise of a group, and they eventually become normal practices. This does not, however, negate the fact that they are deviations from procedures that are established and sanctioned by the organization, hence the term “normalization of deviance”. In most cases normalized deviance is effective, at least temporarily. However, it runs counter to the practices upon which system operation is predicated. In this sense, like any shortcut to standard procedures, normalized deviance carries the potential for unanticipated “downsides” that might unexpectedly trigger unsafe situations. However, since they are “normal”, it stands to reason that neither these practices nor their downsides will be recorded in incident reports.1.2.7Normalized deviance is further compounded by the fact that even the most willing reporters may not be able to fully appreciate what are indeed reportable events. If operational personnel are continuously exposed to sub-standard managerial practices, poor working conditions and/or flawed equipment, how could they recognize such factors as reportable problems?1.2.8Thus, incident reporting cannot completely reveal the human contribution to successes or failures in aviation and how remedial strategies can be improved to enhance human performance. Incident reporting systems are certainly better than accident investigations in understanding system performance, but the real challenge lies in taking the next step — understanding the processes underlying human error rather than taking errors at face value. It is essential to move beyond the visible manifestations of error when designing remedial strategies. If the aviation industry is to be successful in modifying system and individual per-formance, errors must be considered as symptoms that suggest where to look further. In order to understand the mechanisms underlying errors in operational environments, flaws in system performance captured through incident reporting should be considered as symptoms of mismatches at deeper layers of the system. These mismatches might be deficiencies in training systems, flawed person/technology interfaces, poorly designed procedures, corporate pressures, poor safety culture, etc. The value of the data generated by incident reporting systems lies in the early warning about areas of concern, but such data do not capture the concerns themselves.Training1.2.9The observation of training behaviours (during flight crew simulator training, for example) is another tool that is highly valued by the aviation industry to understand operational human performance. However, the “production”component of operational decision making does not exist under training conditions. While operational behaviours during line operations are a compromise between production and safety objectives, training behaviours are absolutely biased towards safety. In simpler terms, the compromise between production and safety is not a factor in decision making during training (see Figure 1-2). Training behaviours are “by the book”.1.2.10Therefore, behaviours under monitored conditions, such as during training or line checks, may provide an approximation to the way operational personnel behave when unmonitored. These observations may contribute to flesh out major operational questions such as significant procedural problems. However, it would be incorrect and perhaps risky to assume that observing personnel during training would provide the key to understanding human error and decision making in unmonitored operational contexts.Surveys1.2.11Surveys completed by operational personnel can also provide important diagnostic information about daily operations and, therefore, human error. Surveys1-4Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA)provide an inexpensive mechanism to obtain significant information regarding many aspects of the organization, including the perceptions and opinions of operational personnel; the relevance of training to line operations; the level of teamwork and cooperation among various employee groups; problem areas or bottlenecks in daily operations; and eventual areas of dissatisfaction. Surveys can also probe the safety culture; for example, do personnel know the proper channels for reporting safety concerns and are they confident that the organization will act on expressed concerns? Finally, surveys can identify areas of dissent or confusion, for example, diversity in beliefs among particular groups from the same organization regarding the appropriate use of procedures or tools. On the minus side, surveys largely reflect perceptions. Surveys can be likened to incident reporting and are therefore subject to the shortcomings inherent to reporting systems in terms of understanding operational human performance and error. Flight data recording1.2.12Digital Flight Data Recorder (DFDR) and Quick Access Recorder (QAR) information from normal flights is also a valuable diagnostic tool. There are, however, some limitations about the data acquired through these systems. DFDR/QAR readouts provide information on the frequency of exceedences and the locations where they occur, but the readouts do not provide information on the human behaviours that were precursors of the events. While DFDR/QAR data track potential systemic problems, pilot reports are still necessary to provide the context within which the problems can be fully diagnosed.1.2.13Nevertheless, DFDR/QAR data hold high cost/efficiency ratio potential. Although probably under-utilized because of cost considerations as well as cultural and legal reasons, DFDR/QAR data can assist in identifying operational contexts within which migration of behaviours towards the limits of the system takes place.Proactive strategiesNormal line operations monitoring1.2.14The approach proposed in this manual to identify the successful human performance mechanisms that contribute to aviation safety and, therefore, to the design of countermeasures against human error focuses on the monitoring of normal line operations.Figure 1-2.Training Behaviours — Accomplishing training goals。

中国民航安全审计 CASAP

中国民航安全审计CASAPPART 1 安全审计概述 (2)1.1背景 (2)1.2安全审计的目的 (2)1.3安全审计的定义 (2)1.4安全审计工作定位 (2)1.5安全审计组织实施和人员 (2)1.6安全审计员职责 (3)1.7安全审计的行为准则 (3)PART 2 航空公司安全审计依据 (3)PART 3 航空公司安全审计工具 (3)3.1《民用航空安全审计指南》 (3)3.2《航空公司安全审计手册》 (3)3.3航空公司安全审计检查单 (4)3.4安全审计信息管理系统 (4)PART 4 航空公司安全审计要素和范围 (4)4.1安全审计要素(七个要素) (4)4.2航空公司安全审计范围 (4)PART 5 航空公司航空公司安全审计程序 (4)5.1安全审计方法 (4)5.2安全审计原则 (4)5.3安全审计程序 (5)5.4审计各阶段的主要任务 (5)5.5审计检查单的使用 (6)5.6中止审计 (7)5.7整改跟踪 (7)5.8审计结果公布 (7)PART 6 航空公司安全审计分类 (7)6.1审计项分类 (7)6.2审计结果分类 (7)6.3航空公司审计要素综合评定原则 (8)6.4航空公司审计结果分类评定原则 (8)PART 7 航空公司安全审计文档和数据 (8)7.1安全审计文档 (8)7.2审计报告和整改跟踪报告 (8)7.3审计数据 (9)PART 8小结 (9)Part 1 安全审计概述1.1背景1、2006年全国民航安全会议首次提出2、安全生产十个专项整治取得了阶段性成果3、研究推广在民航企事业单位建立SMS体系4、安全监管能力还不能适应快速发展的需要1.2安全审计的目的1、全面掌握被审计方安全运行状况2、查找被审计方安全管理上存在的问题,督促并指导其进行安全整改3、督促并指导被审计方建立完善安全管理体系4、发现监管薄弱环节,完善民航规章标准,提高监管工作水平1.3安全审计的定义民航总局依据国际民航组织标准和建议措施、国家安全生产法律法规及民航规章、标准和规范性文件,对航空公司、机场、空管等单位进行的符合性检查,属政府安全监管行为。

航空航天行业审计指南了解航空企业的审计要点与特殊考虑

航空航天行业审计指南了解航空企业的审计要点与特殊考虑航空航天行业审计指南:了解航空企业的审计要点与特殊考虑航空航天行业是一个高度复杂和竞争激烈的行业,涵盖航空公司、航空器制造商、机场及相关服务供应商等多个领域。

对于审计师来说,了解航空企业的审计要点和特殊考虑至关重要,以保证审计过程的准确性和有效性。

本文将介绍航空企业审计的关键要点,以便审计师在开展审计工作时能够全面了解并有效应对。

一、航空企业的审计要点1.财务报表审核航空企业的财务报表审核是审计师最重要的任务之一。

审计师需对航空企业的资产负债表、利润表和现金流量表进行全面核查,确保其准确反映企业的财务状况和业绩。

此外,对于航空企业而言,客户预付款、航空器折旧和维护成本以及航空器租赁等相关交易也需要重点关注。

2.收入识别和成本核算航空企业的收入识别和成本核算是审计中的关键要点。

审计师需要仔细审查航空企业的收入来源,包括客票销售、货运和邮递服务、包机和其他服务等。

同时,审计师还需核实企业的成本核算是否准确,包括航空器的采购和维护成本、人工成本、燃料成本等。

3.运营性租赁合同审计在航空租赁中,运营性租赁合同是一种常见的合同形式。

审计师在审计过程中需要确认运营性租赁合同的有效性,并核实相关租赁收入和成本的准确性。

此外,还需要关注租赁合同的期限、租赁物的归还和维护责任等事项。

4.特许经营权和飞机技术服务审计对于航空企业而言,特许经营权和飞机技术服务是重要的商业模式。

审计师需要审核与特许经营权和飞机技术服务相关的合同条款,确保其合法有效。

同时,审计师还需核实特许经营权和技术服务所涉及的收入和成本,以及相应的运营指标和客户满意度。

二、航空企业审计的特殊考虑1.合规性审计航空企业在遵守航空法规和相关法律法规方面必须严格执行。

审计师在进行审计时需要重点关注企业的合规性,包括航空安全、环境保护等方面的合规性要求。

此外,还需要审查企业的内部控制制度,以确保公司运营符合规范和道德要求。

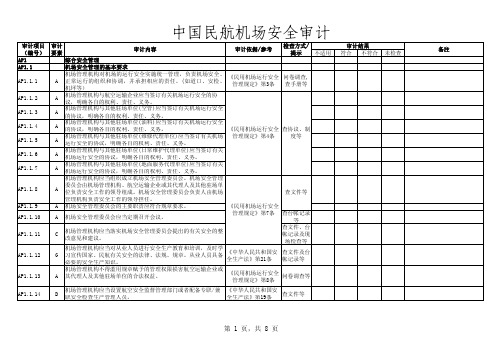

机场安全审计检查单

《中华人民共和国安 帐记录等 全生产法》第13条

A

机场管理机构应当至少每月召开一次安全生产例会,分析、研究 安全生产中的问题,部署安全生产工作;

A

机场管理机构每季度召开安全生产分析会,对前一阶段的工作进 行总结,对以后的工作进行部署;

A A

机场管理机构每半年召开安全生产分析会,对前一阶段的工作进 行总结,对以后的工作进行部署; 机场管理机构每年要召开安全生产分析会,对前一阶段的工作进 行总结,对以后的工作进行部署;

管理规定》第4条

度等

A

机场管理机构与其他驻场单位(日常维护代理单位)应当签订有关 机场运行安全的协议,明确各自的权利、责任、义务。

A

机场管理机构与其他驻场单位(地面服务代理单位)应当签订有关 机场运行安全的协议,明确各自的权利、责任、义务。

机场管理机构应当组织成立机场安全管理委员会。机场安全管理

A

委员会由机场管理导组成。机场安全管理委员会负责人由机场

查文件等

管理机构负责安全工作的领导担任。

A 机场安全管理委员会的主要职责应符合规章要求。

《民用机场运行安全

A 机场安全管理委员会应当定期召开会议。

管理规定》第7条 查台帐记录 等

C

机场管理机构应当落实机场安全管理委员会提出的有关安全的整 改意见和建议。

查文件、台 帐记录及现

场检查等

G

机场管理机构应当对从业人员进行安全生产教育和培训,及时学 习宣传国家、民航有关安全的法律、法规、规章。从业人员具备 必要的安全生产知识。

查文件等

审计结果 符合 不符合 未检查

第 1 页,共 8 页

备注

中国民航机场安全审计

审计项目 (编号) AP1.1.15 AP1.1.16 AP1.2 AP1.2.1 AP1.2.2 AP1.2.3 AP1.2.4 AP1.2.5 AP1.2.6 AP1.2.7 AP1.2.8 AP1.2.9 AP1.2.10 AP1.2.11

航空安保审计程序

航空安保审计程序一、目的1、全面掌握公司航空安保工作状况;2、查找被审计方航空安保管理工作中存在的问题,督促并指导其进行整改;3、督促并指导被审计方按照公司航空安保管理体系的要求开展工作;4、发现公司航空安保管理体系中的薄弱环节,完善公司各项规章制度,提高公司航空安保管理水平。

二、航空安保审计的定义及依据中国东方航空股份有限公司航空安保审计是公司根据国际民航组织、民航局、民航地区管理局的规章、标准和规范性文件,依据CCAR-121-R4《大型飞机公共航空运输承运人运行合格审定规则》、公司《航空保安手册》和《航空安保管理体系手册》的要求,对公司各单位进行的符合性检查。

三、职责(一)公司安全总监职责:1、审批公司航空安保审计年度计划。

2、监督公司航空安保审计年度计划的落实。

3、根据公司航空安保工作的要求,提出补充审计要求。

4、对公司航空安保审计检查员聘任、解聘的批准。

(二)公司保卫部职责:1、负责公司航空安保审计人员的管理和培训,确保航空安保审计按计划实施。

2、制定公司航空安保审计年度计划,报公司安全总监批准,并按经批准的计划实施航空安保审计。

3、根据公司组织机构调整、航线运行、内外部安全环境的变化情况,对航空安保审计的标准、范围、频次、时间及方法进行调整。

4、对审计组成员授权。

5、向公司各相关部门通报航空安保审计情况。

6、对航空安保审计的结果进行数据分析,通过统计分析、趋势分析、标准化比较、专家小组等工具和方法进行分析评估,并将分析情况报航空安保管理体系相关部门。

7、对责任部门航空安保审计中发现的问题所采取纠正预防措施的有效性实施评估,并对其落实情况进行监督。

8、编制、修订及更新公司航空安保审计程序及检查单等。

9、管理公司航空安保管理中各项措施的落实监督工作。

(三)航空安保审计员职责:1、参加审计准备,了解被审计方的航空安保管理状况和航空安保工作情况。

2、根据航空安保审计检查单开展航空安保审计工作。

航空安保审计介绍(机场类)

11

民航华北地区管理局

二、新一轮安保审计特点

12

民航华北地区管理局

2013年正式启动,华北地区天津航空、 国货航,鄂尔多斯、巴彦淖尔和阿尔 山机场5个单位于2013年接受并通过 了审计。 2014年审计国航、中联航、北京南苑、 二连浩特机场。 2015年审计吕梁机场、奥凯航空、张 家口机场、阿拉善机场,并对南苑机 场开展后续审计。

背景

▪航空安保审计是国际民航组织在 “9.11”事件后,综合衡量全球航空保 安形势,参照欧盟的做法提出的一项 旨在检测各缔约国执行《国际民用航 空公约》附件17有关标准和建议措施 执行情况的一项制度。

5

民航华北地区管理局目的来自1.通过定期对缔约国的审计,促进并加 强全球范围的航空安全保卫工作; 2.确定缔约国实施国际民航组织安全保 卫标准的水平; 3.找出被审计国航空安全保卫系统中不 符合标准之处并促进实施整改和补救计 划; 4.协调全球保安措施;

21

民航华北地区管理局

如何看手册是否符合规定:规章、公司 方案的要求是否在分公司的手册中体现 了,是否建立了相应的工作程序,程序 是否符合安保措施执行规范的要求。

22

民航华北地区管理局

人员访谈:是指通过与被审计单位人员 进行约谈、随机访谈、召开座谈会等形 式,核实被审计单位执行、掌握航空安 保程序、措施的情况。 向机长了解:机长作为航空器飞行中安 全保卫工作的负责人,承担的航空安保 方面的职责有哪些;航班起飞前发生扰 乱性的旅客如何处理等等。

13

民航华北地区管理局

(一)特点

1.加入了SeMS建设的内容,突出体系建设和 管理方面的内容。 2.新的航空安保规章、标准作为审计依据。 3.颁布了新版的《国家民用航空安保审计规 则》、国家民用航空安保审计指导手册》、 《国家民用航空安保审计检查单》、《公共 航空运输企业安保审计管理规定》。

国家民用航空安保审计规则

国家民用航空安保审计规则

国家民用航空安保审计规则是指对国家民用航空安全系统进行检查和评估的一套规则和程序。

该规则旨在确保国家民用航空系统的安全性和有效性,以保护旅客和航空运输设施免受恐怖袭击和其他威胁。

国家民用航空安保审计规则通常由相关国家民航安全机构或国际民用航空组织制定,并针对各个航空公司、机场、航空器等进行安全审计。

这些规则通常包括对安保措施和程序的评估、对人员培训和认证的审查、对设备和设施的检查,以及对安全管理系统的评估等。

国家民用航空安保审计规则的实施有助于发现潜在的安全风险和薄弱环节,并提供相应的改进建议。

通过定期的安保审计,可以确保国家民用航空系统的安全标准得到维护和提高,以适应不断变化的安全威胁。

同时,国家民用航空安保审计规则也有助于提高民航安全管理机构和从业人员的安全意识和能力,促进国际间的合作和信息共享,为旅客提供更安全和可靠的航空服务。

航空安保审计介绍机场类

航空安保审计介绍机场类航空安保在机场中扮演着至关重要的角色,确保航空运输的安全和顺畅进行。

为了确保机场安全体系的有效运作,航空安保审计成为不可或缺的环节。

本文将介绍航空安保审计及其在机场类中的应用。

一、航空安保审计的定义及目的航空安保审计是指对机场安保管理体系及其相关程序、政策和工作实施进行全面、系统的检查和评估的过程。

其目的是发现问题、提出改进建议,并确保机场安保工作符合国家法律法规和行业标准,以保障航空运输中的安全。

二、航空安保审计的内容1. 安保组织与管理:审查机场的安保管理机构、职责划分、人员配备、培训与考核等,确保安保工作的组织与管理符合要求。

2. 安保政策及程序:评估安保政策和程序的制定与实施情况,包括应急预案、安全检查流程、危险品管控等,确保程序的有效性和合规性。

3. 安保设备与技术:审查机场安保设备的选择、安装与维护情况,包括闭路电视监控、金属探测器、行李安检设备等,保证设备的正常运作。

4. 人员安全:评估机场安保人员的从业资质和工作纪律,检查执行情况与安保服务质量,确保人员安全工作的高效性和专业性。

5. 信息安全与网络安全:审查机场信息系统的安全性与保密性,包括数据库、网络通信、飞行数据等,保护机场信息资源的安全。

三、机场类中的航空安保审计应用在机场类中,航空安保审计扮演着重要的角色。

一方面,它可以确保机场安保工作的合规性,防范恐怖袭击和其他安全威胁。

另一方面,它可以为机场管理层提供审计报告和改进建议,提高安保工作的效率和质量。

1. 提高机场安全性:通过航空安保审计,机场可以及时发现安全管理体系中的不足和漏洞,采取相应的措施来加强安全防范,确保机场的安全运营。

2. 加强安保培训与管理:航空安保审计可以评估安保人员的从业资质和培训情况,发现人员素质的短板,并提出相应的培训和管理建议,提高安保人员的专业素质和工作质量。

3. 优化安保设备与技术:通过审查安保设备的选择与运行情况,机场可以发现设备存在的问题和短板,并及时更新和升级设备,提高安保设施的效能和运行质量。

国际航线安全风险评估

国际航线安全风险评估

国际航线的安全风险评估是评估在国际航线上飞行时可能面临的各种安全威胁和风险的过程。

这种评估通常由航空公司、民航管理机构和相关安全机构进行。

评估国际航线的安全风险可以包括以下几个方面:

1.飞行安全:评估飞行航线上可能遇到的天气条件、空中交通

管制、雷击、机械故障等因素对飞行安全的影响。

2.空中交通管理:评估不同国家和地区的空中交通管理体系和

程序,包括空中交通管制、通信、航路规划等方面的安全风险。

3.恐怖主义威胁:评估不同地区的恐怖主义威胁水平,包括航

空器遭劫持、爆炸袭击等可能的威胁。

4.地面安全:评估不同国家和机场的地面安全措施和程序,包

括机场安检、飞机停机坪安全、货物运输安全等方面的安全风险。

5.政治稳定性:评估不同国家和地区的政治稳定性,包括政变、战争、内乱等因素对航空运输的安全风险。

6.疾病和公共卫生:评估全球范围内疾病和公共卫生事件对航

空运输的安全风险,例如传染病的爆发、流行病控制等。

评估国际航线的安全风险是为了帮助航空公司和民航管理机构

制定有效的安全措施和应急计划,以确保乘客和机组人员的安全,并减少潜在的风险事件对航空业的影响。

同时,也有助于旅客做出明智的决策,选择相对安全的航线和航空公司进行旅行。

航线安全审计——驾驶舱安全的新突破

全程 序 , 待 取 得 飞 行 安 全 的 新 期 突破 。世 界 范 围 内 的 其 它 航 空 公 司也 已 开 始 着 手 整 理 和 研 究 航 线 安 全 审 计 (L S - Ln O A ie Oin tdSlr dt) 使 用 效 r te aa Aui 的 ea y s

加了会议。 然而 , 有 被 飞行 员 接 受 。 只 航线 安全审计 才会产 生效果 , 因

司。在南太 平洋地 区, 西兰航 新

维普资讯

中 田 民 兢 飞 行 学 院 学 报 1 4

Mae 212 rh ( 0

Ju a f h a il v in y g 姆 o m l C i C i 0 n v h ii n i c ao n

文献 标 识 码 : A

Байду номын сангаас机 组

中 圈分 类 号 : 3 83 V 2 .

为 了减 少 航 空 安 全 事 故 , 以

美 国大 陆 航 空 公 司 和 三 角 航 空

驾 驶 舱 的机 组 错 误 , 及 飞 行 安 危 全 的事 件 和 机 组 的 处 置 情 况。

航 线 安 全 审 计 是 由 德 克 萨 斯 大 学 ( T 人 的 因 素 研 究 项 目 组 开 U) 发 的 。 现 在 正 逐 步 得 到 推 广 和

空 公 司 , 日 空 航 空 公 司 和 中 国 全

际 民 航 组 织 (C O) 支 持 , 倡 IA 的 其 导 者 希 望 在 未 来 5年 里 。 将 成 它 为 全 世 界 各 航 空 公 司 标 准 工 作 程序 的 一 部 分 。 其 开 发 是 由 美 国 FA资助的。 A 2 0 年 3月 , 香 港 国泰 航 01 在 空 公 司 召 开 了 首 次 地 区 性 研 讨 会 以讨 论 航 线 安 全 审 计 问 题 。 5 月 国 泰 航 空 公 司 已 成 为 首 家 采 用 航 线 安 全 审 计 的 亚 洲 航 空 公

航线运行安全检查LOSA

第八章航线运行安全检查(LOSA)在航空科技高度发展的今天,大多数事故或事故征候都是由人为因素造成。

因此,识别人因失误、降低操作风险已经成为提高航空安全水平、预防事故或事故征候发生的重要手段。

航线运行安全检查(Line Operations Safety Audit,LOSA),是国外最近十年发展起来的一种控制人因失误的有效措施,可以协助航空公司发现安全隐患,确定飞机运营系统的优势和缺陷,同时,也能对机组的飞行技术和管理能力进行全面评估,从而提高整个系统安全的水平。

本章将介绍LOSA的有关涵义、发展过程、理论基础及其实施过程。

第一节航线运行安全检查(LOSA)概述1999年,国际民航组织(ICAO)正式承认并支持航线运行安全检查(LOSA),并把它作为预防飞行员人因失误的主要措施。

经过几年的发展和调整,LOSA已经成为获取航空公司飞行运行系统运作方式安全数据的一项系统性观察战略。

目前,LOSA收集的数据不仅可以了解飞行机组的飞行技术和管理能力、空中交通管理的指挥能力、驾驶舱机组与客舱机组的协调能力、地面支持能力,而且还可以对飞行运行中的组织性强项和弱点提供系统的诊断性指标1。

一、LOSA的涵义航线运行安全检查(LOSA)是一种实时观察数据的收集方式,指飞行专家和经过严格训练的观察员在日常定期航班飞行中,从备用位置(jump seat)观察航线飞行机组所遇到的与安全有关的各种潜在环境压力和机组操作失误。

从本质上来讲,LOSA完全等同于病人每年的体格检查。

人们希望通过定期体格检查来发现严重影响病人的潜在健康问题后,确立一套如针对血压,胆固醇和肝功等指标在内的诊断系统,从而给病人能够提供一些有效的治疗方案和改变生活习惯的建议。

LOSA的建立也具有相同的前提,目的也为航空公司提供一套航线安全运行系统的诊断方案和防御措施。

LOSA的核心原则是避免和杜绝各种形式的惩罚与责备,事先对飞行机组进行有关安全训练、安全文化及CRM等方面的访谈和问卷调查,试图从全方位、系统地评估航线飞行操作安全,观察的数据不仅记录了飞行情境中存在的外部威胁和机组操作的内部失误,同时也记录了机组如何处理和解决这些威胁和失误的操作方案,能够给航空安全管理部门提供现有的各种潜在威胁、机组的压力来源及容易疏忽和失误的地方,进而采取适当措施来消除这些潜在威胁。

航空安保审计个人总结

航空安保审计个人总结引言航空行业作为全球交通的重要组成部分,其安全问题一直是人们关注的焦点。

作为航空企业的一员,我有幸参与了航空安保审计的工作。

在此次审计过程中,我深入了解了航空安保措施的实施情况,并且对存在的问题提出了相应的建议。

通过这次审计,我深刻认识到航空安保的重要性以及审计工作对于保障航空安全的作用。

在本文中,我将总结个人在航空安保审计中的经验与收获。

审计目标航空安保审计的目标是确保航空公司在安全方面的各项措施符合相关法规和标准,有效保障乘客、机组人员和航空器的安全。

具体审计内容包括飞行员和空乘人员的背景调查、安全培训、机场安检、飞机机舱安全设备检查等。

审计方法为了顺利完成航空安保审计,我采用了以下方法:1. 预审阶段在正式开始审计前,我提前与相关部门进行沟通,并了解其安保制度、流程和工作目标。

通过预审,我获取了初步的信息,为后续的实地检查和信息收集做好了准备。

2. 实地检查实地检查是审计工作的重要环节。

我亲自参观了机场、飞机和训练场地,观察并比对实际情况与安保制度的一致性。

在实地检查中,我与责任人员进行了交流,详细了解他们对安保制度的理解和实施情况。

3. 文档分析审计工作不仅仅依赖于实地检查,还要对相关文档进行仔细的分析。

我仔细研读了相关的安保制度、安检记录、员工培训记录等文件,并与实际情况进行对比。

通过分析文档,我能够发现制度存在的不足和需完善的地方。

4. 数据统计和综合分析在审计过程中,我积极收集数据,并进行统计和分析。

通过数据的比对和整合,我能够更清晰地了解安保措施的实施情况和效果,并对存在的问题提出相应的改进措施。

审计结果与发现经过一段时间的审计工作,我得出了以下审计结果和发现:1. 安保制度健全,但部分操作流程存在不符合规定的情况,需要加强对员工的培训和监督。

2. 部分员工对安保制度的理解和执行不够到位,需要加强宣传和培训,提高员工的安全意识和责任心。

3. 设备维护不及时,存在一定的安全隐患,需要加强设备管理,定期检查和维修。

机场安全审计工作计划

机场安全审计工作计划一、背景介绍机场作为交通运输枢纽,安全问题一直备受关注。

为了确保机场安全运营,减少事故风险,机场安全审计工作显得尤为重要。

本文将从机场安全审计的目的、步骤、内容和方法等方面进行详细介绍,以期达到确保机场安全的目标。

二、目的机场安全审计的主要目的是评估机场运营安全管理体制的有效性和合规性,提出合理的建议和改进措施。

通过对安全管理人员、设施设备和安全管理程序的审查,发现潜在的安全风险,进一步提高机场的安全水平和应急响应能力,确保机场的安全运营。

三、步骤机场安全审计通常包括以下步骤:1. 确立审计目标和范围:明确审计的目标、范围和时间计划,以便组织和安排工作。

2. 收集相关数据:收集机场的安全管理文件、记录和数据,以便进行综合分析和评估。

3. 进行实地考察:实地考察机场的各个区域和设施,了解现场的情况和存在的问题。

4. 进行安全管理体制审查:审查机场的安全管理机构、职责分工、人员配备和工作流程等,评估其适应性和有效性。

5. 进行制度文件审查:审查机场的安全管理制度文件和政策,评估其合规性和完善性。

6. 进行设备设施审查:对机场的安全设备和设施进行审核,检查其运行和维护情况。

7. 进行安全培训审查:审查机场的安全培训计划和实施情况,评估培训的效果和合理性。

8. 完成报告和提出建议:根据审计结果,撰写审计报告,提出改进措施和建议,并进行汇报和解释。

四、内容机场安全审计主要包括以下内容:1. 机场安全管理体制的评估:评估机场的安全管理机构设置、职责分工和人员配备等,评估其合理性和有效性。

2. 安全制度和规章制度的审查:审查机场的安全管理制度文件和政策,评估其合规性和完善性。

3. 安全设备和设施审查:审查机场的安全设备和设施,评估其运行和维护情况。

4. 安全培训和演练的评估:评估机场的安全培训计划和实施情况,评估培训的效果和合理性。

5. 安全记录和报告分析:对机场的安全记录和报告进行综合分析,评估潜在的安全风险和问题。

航道工程船舶建造审计方案

航道工程船舶建造审计方案一、前言航道工程船舶建造审计是指对船舶建造过程中的设计、制造、监造、试航、交付等各个环节进行全面审计,以确定船舶建造是否符合相关法律法规、标准规范和合同要求,是否具备设计要求、建造质量、安全性和适航性等方面的保证。

审计结果将对航道工程船舶建造项目的合规性、合格性和合同履约情况进行评价,为相关各方提供可靠的参考依据。

本审计方案旨在规范和指导船舶建造审计工作,确保审计工作的科学性、客观性和公正性。

二、审计对象1.审计范围本次审计范围涵盖船舶建造全过程,包括设计、建材、制造、监造、试航、交付等环节。

2.审计对象本次审计对象为航道工程船舶建造项目的所有参与方,包括船舶建造企业、设计单位、监造单位、材料供应商等。

三、审计目的1.评价航道工程船舶建造项目的合规性和合格性,确定其安全、适航和质量风险,分析其合同履约情况。

2.发现并纠正船舶建造过程中存在的不合规、不合格、不符合要求的问题,提出改进建议,保障船舶建造质量和安全。

四、审计内容1.合规性审计审计船舶建造项目是否符合相关法律法规、标准规范和合同要求,包括建造工艺、建造工程技术方案、建造质量、建材供应等是否合规。

2.合格性审计审计船舶建造项目是否符合设计要求、适航标准、船舶检验检测标准等,包括船舶结构、防护设备、推进装置、电气设备等是否合格。

3.合同履约审计审计船舶建造项目双方是否按照合同要求履约,包括交付时间、质保期、保函要求等是否履约。

1.搜集资料收集船舶建造项目的相关资料和文件,包括设计文件、施工图纸、建造合同、监造记录、检测报告等。

2.实地检查对船舶建造项目进行实地检查,了解施工情况和建造质量,确认设计、建造、监造、试航等环节的工作情况。

3.抽样检测对船舶建造项目的关键部位和关键工艺进行抽样检测,确保其质量和安全性。

4.调查访谈与相关人员进行调查访谈,了解船舶建造项目的具体情况和存在的问题。

六、审计步骤1.准备工作确定审计范围、审计对象、审计目的和审计内容,组织审计团队,编制工作计划。

飞行审计实施方案

飞行审计实施方案一、背景介绍。

飞行审计是航空公司管理体系的重要组成部分,通过对飞行操作、飞行安全管理、飞行员培训等方面的审核,确保航空公司的运营符合国际民航组织(ICAO)的标准和要求。

为了有效实施飞行审计,制定飞行审计实施方案是至关重要的。

二、实施目标。

1. 确保飞行操作符合相关法规和标准。

2. 提高飞行安全管理水平。

3. 优化飞行员培训机制。

4. 提升航空公司整体运营水平。

三、实施步骤。

1. 制定审计计划。

首先,需要确定审计的范围和对象,包括飞行操作、飞行安全管理、飞行员培训等方面。

然后,制定详细的审计计划,包括时间安排、人员配置、审计内容等。

2. 实施前准备。

在实施审计前,需要进行充分的准备工作,包括准备审计所需的文件资料、制定审计程序和标准、培训审计人员等。

3. 进行审计工作。

审计工作包括实地考察、文件审核、访谈等方式,对飞行操作、飞行安全管理、飞行员培训等方面进行全面的审核和评估。

4. 形成审计报告。

根据审计结果,形成审计报告,包括发现的问题、改进建议、整改措施等内容,并提交给相关部门进行审阅和落实。

5. 落实改进建议。

相关部门根据审计报告中的改进建议,制定整改计划,并落实相关措施,确保问题得到有效解决。

四、实施要点。

1. 严格按照审计计划和程序进行实施,确保审计工作的全面性和客观性。

2. 加强对审计人员的培训和指导,提高其审计水平和专业能力。

3. 充分利用现代化的审计技术手段,提高审计效率和质量。

4. 积极借鉴国际先进经验,不断完善飞行审计实施方案,提高其适应性和实用性。

五、实施效果评估。

实施飞行审计后,需要对审计效果进行评估,包括问题整改情况、运营水平提升情况等,为下一阶段的审计工作提供经验和借鉴。

六、总结。

飞行审计实施方案的制定和落实,对于航空公司的健康发展和安全运营具有重要意义。

只有不断完善和提高飞行审计实施方案,才能更好地保障航空公司的飞行安全和运营质量。

希望全体员工能够积极配合,共同推动飞行审计工作的顺利实施。

民用航空安全审计指南

前 言安全是社会文明和进步的重要标志,是统筹经济社会健康、全面、可持续发展的重要内容,是实践邓小平理论和“三个代表”重要思想的具体体现。

民航是交通运输业的重要组成部分,具有技术密集、资金投入大、运营风险高的特点,安全是民航赖以生存和发展的重要基础。

近年来,中国民航安全管理正在向科学化、规范化、系统化转变,行业安全水平有了很大提高。

但从总体上看,中国民航的安全保障能力与行业快速发展还不相适应,安全基础相对薄弱,安全管理体系处在完善之中,传统的及新凸显的安全问题,使民航安全工作面临更为严峻的挑战。

为此,按照“安全第一、预防为主、综合治理”的方针和以人为本的科学发展观,结合中国民航长期积累的安全管理经验,借鉴国际民航相关做法,民航局决定从2006年起,对民航企事业单位实施安全审计,目的是掌握民航企事业单位安全运行状况,促进其建立和完善安全管理体系,提升行业安全运行整体水平。

为了规范安全审计工作,特编制本指南,对安全审计工作提供指导。

参与安全审计的单位和个人,应当按照本指南规定的程序和要求做好安全审计工作。

修订记录修订版本修订日期负责人第一版 2007年1月第二版 2008年3月目录第一章 总则.............................................................................................- 1 -1.1编制指南的目的.......................................................................- 1 -1.2适用范围...................................................................................- 1 -1.3依据...........................................................................................- 1 -1.4管理...........................................................................................- 1 -1.5修订...........................................................................................- 1 -1.6解释...........................................................................................- 1 -第二章 定义与术语..................................................................................- 2 -第三章 安全审计的一般规定..................................................................- 4 -3.1 审计目的....................................................................................- 4 -3.2 审计组织实施............................................................................- 4 -3.3 审计要素....................................................................................- 4 -3.4 审计方法....................................................................................- 5 -3.5 审计结果评分与分类................................................................- 5 -3.6 审计公布....................................................................................- 6 -3.7 审计周期和审计经费................................................................- 6 -3.8 审计行为准则............................................................................- 7 -3.9 中止审计....................................................................................- 7 -3.10 审计检查单..............................................................................- 7 -第四章 安全审计组织机构及职责........................................................- 11 -4.1 安全审计领导小组..................................................................- 11 -4.2 安全审计办公室......................................................................- 11 -4.3 安全审计组..............................................................................- 12 -4.4 安全审计观察员......................................................................- 13 -第五章 安全审计工作程序....................................................................- 14 -5.1 安全审计准备..........................................................................- 14 -5.2 安全审计启动会......................................................................- 15 -5.3 安全审计实施..........................................................................- 15 -5.4 安全审计情况通报会..............................................................- 15 -5.5 提交安全审计报告..................................................................- 16 -5.6 整改跟踪..................................................................................- 16 -5.7 安全审计公布..........................................................................- 17 -第六章 安全审计员资格与培训............................................................- 19 -6.1 安全审计员资格......................................................................- 19 -6.2 安全审计员培训......................................................................- 19 -6.3 安全审计员管理......................................................................- 19 -第七章 安全审计文档管理....................................................................- 20 -7.1 管理部门..................................................................................- 20 -7.2 安全审计文档..........................................................................- 20 -7.3 保存期限..................................................................................- 20 -7.4 文档格式..................................................................................- 20 -第一章 总则1.1编制指南的目的为规范民航局对国内航空运输承运人(航空公司)、机场、空管等单位的安全审计工作,特制定本指南。

航站楼审计报告

公司航站运行审计检查单课程航站运行安全审计4W+H WHAT WHY HOW WHO WHEN WHAT (什么是运行安全审计?)审计定义:为获得审计证据对组织进行客观的评价,以确定满足审计准则的程度所进行的系统的、独立的并形成文件的过程。

WHY 为什么要进行航站运行安全审计?东航安全管理体系东航安全管理体系IOSA 的审计要求——IOSA审计检查单中明确要求航空公司应对代理人(外部服务提供商)进行审计ORG3.5.3 The Operator should include auditing as a process for the monitoring of external service providers as specified in ORG3.5.2 ORG3.5.2 The Operator shall have processes to monitor external service providers that conduct outsourced operations,maintenance or security functions for the Operator to ensure requirements that affect the safety and/or security of operations are being fulfilled. WHO? 由谁来实施航站运行安全审计安监部每两年对全公司审计检查员进行培(复)训及聘用,由这些公司聘用的安全审计检查员开展实施航站安全运行审计。

航站安全运行审计组专业人员组成:机务维修、地面保障(客、货运)、签派、平衡、运行安全管理人员WHEN 航站运行安全审计的频次?航站运行安全审计检查的频次:由于公司航线站点多(100多家国内航站及50多家国外、地区航站),根据公司《运行手册》(第二章2.4 e款:对外站的审计检查,每3年覆盖一次),股份公司安监部在3年内对全部东航所属国内、外航站进行安全运行审计检查。

LOSA与飞行运行安全管理

LOSA and flight operation safety management 作者: 杨亚锋 徐远志

作者机构: 不详

出版物刊名: 民航管理

页码: 80-82页

年卷期: 2012年 第6期

主题词: 飞行技术 运行过程 安全管理 国际民航组织 运行系统 ICAO 安全审计 人为错误

摘要:LOSA(Line Operations Safety Audits)全称“航线运行安全审计”,是国际民航界最近十多年间发展起来的一种用于识别、分析和控制人为错误的安全管理方法。

利用它可以协助航空公司发现飞行运行过程中存在的安全隐患,确定飞行运行系统的优势和缺陷,同时也可以对飞行机组的飞行技术水平和管理能力进行全面评估,从而采取针对性的应对措施,借以提高运行系统的安全水平。

1999年,ICAO(国际民航组织)正式承认并支持了这一方法,并把它作为预防人为过失的主要措施。

LOSA因而成为ICAO飞行安全和人为因素计划的重点。

机场安全审计货物运输管理检查单

设备安全操作知识;

AP.9.3.4.9

G类

突发事件的处理程序;

AP.9.3.4.10

G类

货运操作的基础知识;

AP.9.3.4.11

G类

对危险品等特种货物运输的特殊要求;

AP.9.3.4.12

G类

相邻或相关岗位的必要的业务知识;

AP.9.3.4.13

G类

所代理航空公司的差异化内容。

AP.9.4.货物收运

AP.9.4.1

C类

查验托运人身份证件。

CCAR-275-R1

AP.9.4.2

C类

通过有效的方式告知托运人应如实填写托运单以及应承担的责任。

AP.9.4.3

C类

货运单各项内容的填写齐全、准确。

AP.9.4.4

C类

建立相应的检查机制,使货运单上填写的品名与托运人实际交运的货物相符。

AP.9.4.5

C类

AP.9.1.6.1

A类

有专门的监督检查部门或人员,有详细的货物运输安全检查计划和符合岗位安全要求的检查标准,并保障计划的实施。

AP.9.1.6.2

A类

进行定期和不定期的货物运输安全检查工作,及时纠正发现的问题,并做好相应记录。

AP.9.2.手册与文件

AP.9.2.1

B类

制订符合行业管理和所代理的航空公司运行要求的货运地面服务代理手册,包括与货物运输有关的现行政策、程序、标准和流程。

AP.9.3.4.1

G类

与各岗位相关的安全管理意识;

AP.9.3.4.2

G类

安全管理规则及规章;

AP.9.3.4.3

G类

货运操作的安全知识;

AP.9.3.4.4

航空航天行业审计了解航空航天行业中的审计要点和实践

航空航天行业审计了解航空航天行业中的审计要点和实践航空航天行业审计:了解航空航天行业中的审计要点和实践目录:1. 引言2. 航空航天行业审计概述3. 航空航天行业审计要点4. 航空航天行业审计实践案例5. 结论1. 引言航空航天行业作为高度复杂和风险严峻的行业,经常需要进行审计以确保运营和管理的有效性。

本文旨在探讨航空航天行业审计的重要性,并介绍相关要点和实践案例。

2. 航空航天行业审计概述航空航天行业审计是一项关键的管理工具,有助于监督和评估组织在运营过程中的合规性、效率和风险控制。

它旨在提供内部控制的保证,发现潜在的问题,并提供改进建议。

航空航天行业审计通常包括财务审计、合规性审计和运营审计。

财务审计主要关注财务报表和相关法规的遵守,合规性审计用于确保组织遵守适用法律法规,而运营审计则着眼于核实运营活动的效率和有效性。

3. 航空航天行业审计要点航空航天行业审计具有一些独特的要点,以下是其中几个重要的方面:3.1 风险管理:航空航天行业面临着许多风险,包括安全风险、运营风险和技术风险。

审计师需要关注组织对这些风险的管理和控制措施,并确保其有效性。

3.2 合同合规性:航空航天行业通常与多个供应商和承包商签订合同。

审计师需审查合同的合规性,包括履约义务、付款条款和知识产权等方面。

3.3 资产管理:航空航天行业的资产包括飞行器、维修设备和技术资产等。

审计师需要确保这些资产的准确记录、保护和有效利用,并发现潜在的盗窃和浪费问题。

3.4 内部控制:内部控制是防止失误和欺诈的关键。

审计师应评估组织内部控制的有效性,包括财务报告的准确性、数据的保密性和风险管理能力等方面。

4. 航空航天行业审计实践案例4.1 案例一:航空公司的财务审计在一家航空公司的财务审计中,审计师发现公司在财务报表中存在错误计算和偏差。

通过详细检查,审计师确认这些错误是由于某个部门的操作失误导致的。

审计师向管理层提出了改善建议,并协助他们实施了更严格的内部控制措施,以预防类似问题的再次发生。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

AN-Conf/11-WP/399/5/03第11次航行会议2003年9月22日至10月3日蒙特利尔议程项目2空中交通管理ATM的安全和保安2.1安全管理系统和方案空中交通服务ATS正常运行时的安全监测由秘书处提交摘要本文件主张作为系统安全管理方案的组成部分在正常航空运行中搜集安全数据的重要性本文件推出对A TS的正常运行进行监测的概念介绍航线运行安全审计LOSA作为达到这一目的的手段并讨论将LOSA扩大到ATS环境的问题会议的行动在第7段1. 引言1.1 附件11空中交通服务和空中航行服务程序空中交通管理PANS-A TM Doc 4444中要求为空中交通服务A TS制定系统的和适当的安全管理方案由于这些要求比较新许多A TS 组织仍在制定安全管理方案的过程中与此相反附件6航空器的运行则早从1990年起就要求航空公司制定事故预防和飞行安全方案航空公司在安全管理方案方面已经具有10多年的经验本文件介绍在航空公司环境下有关安全管理方案的最新发展并主张A TS安全管理方案的制定工作可以从航空公司的经验中吸取教益建立基础2. 航空公司安全数据的来源分析2.1 安全管理方案的数据来源因航空公司而异但有若干个来源是大多数方案所共有的其中每个来源都提供经验型安全数据对来自所有这些来源的数据进行综合则是系统安全管理方案具有的实际增值每一种来源也同时存在一些具体缺点AN-Conf/11-WP/39 - 2 -2.2 事故调查一直是航空安全资料的一个主要来源但是事故并不是经常发生的事情而且反映的通常仅是各种罕见因素并发的关系由于这种非经常性事故调查人员有时难以及时发现不安全的运行行为对其做出恰当处理2.3 事故征候报告提供的数据基础较大可以从中洞悉危险接近和救险的情况但事故征候报告也因其自愿性质而受到影响尽管已经努力说服驾驶员和其他航行人员做出报告并无危害的后果但这种保证并没有对做出完整报告起到推动作用这主要是因为担心会针对报告采取制裁措施尽管如此事故征候报告可以提供宝贵的资料帮助航空公司在事故和严重事故征候发生之前采取安全行动2.4 航线检查费用很高据一家主要的航空公司称每进行一次航线检查的费用为1 000美元而获得的资料基本上没有用处但其诊断价值却微乎其微行业统计数字表明航线检查结果被视为令人不满意的还不到1驾驶员在航线检查中表现出来的自然是他们最好的但并不一定是正常的即未受监测情况下的行为2.5 最后在不危害飞行机组的前提下对飞行数据加以监测以进行安全分析这种作法近来已经成为常规这些方案可以提供与组织预期发生偏差的情况的关键资料但这种数据本身无法揭示造成偏差发生的原因2.6 尽管将这些来源的安全数据进行综合后航空公司可以了解到自己运行的强项和弱点但上述来源还有另外一个缺点那就是有关的数据都是从已发事件中产生的而系统安全管理方案的基石则是从各种过程中各种常规运行中取得数据借以发现错误和故障在其酿成事件之前采取纠正行动这就要求在例行的飞行中对正常运行进行监测以便取得有关飞行机组和各种情景因素的安全数据为此航空公司方面已经开始实施一项从正常运行中获取安全数据的工具命名为航线运行安全审计LOSA3. 航线运行安全审计LOSA3.1 1999年11月空中航行委员会同意了2000年2004年飞行安全和人的因素5年行动计划这项行动计划特别提到作为航空公司的安全管理工具开发LOSA以搜集和分析取自正常运行的数据LOSA对于全球航空安全计划GASP继续将人的因素考虑纳入航空环境的目标也被认为是具有关键的作用3.2 LOSA是美国联邦航空局FAA出资由得克萨斯大学人的因素研究项目开发出来的经过几年的发展和细致调整LOSA现已成为获取航空公司飞行运行系统运作方式安全数据的一项系统性航线观察战略LOSA产生的数据可以对飞行运行中的组织性强项和弱点提供诊断性指标ICAO航线运行安全审计LOSA手册Doc 98034. 威胁和错误管理TEM模型4.1 LOSA以威胁和错误管理TEM模型为基础由10个运行特点加以界定参见附录TEM模型的出发点是威胁和错误是日常飞行运行的组成部分因此必须由飞行机组加以管理才能确保飞行结果的安全性- 3 - AN-Conf/11-WP/394.2 威胁是指在驾驶舱以外必须由飞行机组在正常的日常飞行中加以管理的事件这类事件使运行的复杂性增加对飞行构成潜在的安全风险威胁可以是在机组预料之中事先有估计和有情况介绍的也可以是在预料之外突然发生因而毫无警告或情况介绍的可能性威胁可以相对较小如签派文件中小的出入也可以很大如高度指定错误例如地勤人员发生加油错误被认为是一个威胁虽然机组不是这一事件的始作俑者但必须对其进行管理威胁的其他例子还有机组发现的A TC放行错误签派文件制作错误客舱乘务员数点登机旅客发生出入相似的呼号维修缺陷天气地形和陌生的机场等从系统安全管理的角度看威胁是错误的先兆4.3 错误是指造成与组织的或飞行机组的意图或预期发生偏差所采取的行动或未采取的行动运行上的错误往往会减少安全系数对飞行造成潜在的风险错误可以很小如在模式控制板上选错了高度但很快就察觉了也可以很大如忘记进行某项关键性检查单的检查4.4 TEM模型为搜集和分类整理安全数据提供了一个可以量化的框架在进行LOSA时经过训练的观察人员对潜在的安全威胁和飞行中对这些威胁的处理情况进行记录和编码进行记录和编码的还有这些威胁引起的错误和飞行机组对错误进行管理的情况4.5 TEM模型已被成功地纳入航空公司的培训方案并在某些情况下取代了机组资源管理CRM 训练A TS组织与CRM相当的培训叫做团队资源管理TRM训练将TEM模型纳入TRM训练计划可以为ATS未来对正常运行进行安全监测奠定基础5. 将LOSA扩大到空中交通服务ATS5.1 作为ATS安全管理数据的一个来源推出对正常运行的监测这是实际可行的另外空中航行委员会还要求秘书处在飞行安全和人的因素方案活动项下探讨将LOSA扩大到A TS的问题但是正如在航空公司环境下首创的其他安全行动一样LOSA也需要做出调整5.2 对航空公司安全数据的来源参见第2段与ATS进行比较后得出的异同情况如下a) 一般而言对ATS进行事故调查的方式与航空公司相同b) A TS事故征候报告具有与航空公司同样的局限性许多A TS组织的运行人员由于害怕受到制裁不愿意提出事故征候报告只有从自愿性报告方案得到充分保护的地方才能比较一贯地收到这种报告c) A TS根本不存在航线检查而且仅有少数A TS组织进行个人胜任能力检查产生不了什么系统的安全资料d) A TS没有与航空公司飞行数据监测方案相对应的办法有些A TS组织使用自动系统取得如有关间隔标准的正确运用等情况的统计反馈但这种监测的目的除收集安全数据外通常是为了提起行政程序因此组织上虽然知道发生了丧失间隔的事故征候但并不了解为什么间隔会低于预期的标准5.3 可以肯定A TS环境下可供使用的安全数据比航空公司环境下的数据要少第5.2段中的比较AN-Conf/11-WP/39 - 4 -不是对实行A TS正常运行监测唱反调而是主张以系统的方式探索A TS进一步落实安全数据来源的问题5.4 有些已经设置安全管理方案的A TS组织目前正处于根据A TS环境调整LOSA的早期阶段以便今后在正常的A TS运行中搜集安全数据为了区别A TS的工具参与制定从正常运行中搜集安全数据方案的A TS组织临时采用了NOSS正常运行安全考察这个缩略语其中考察survey一词与A TS组织安全监测方案中的用语是一致的预计NOSS在经过必要的调整后将具有与LOSA大致相同的运行特点参见附录6. 结论6.1 ATS的系统安全管理目前还不如航空公司那样发达和确定A TS组织在制定各自的安全管理方案时必须探索各种可以供其使用的安全数据的来源为此目的A TS组织可以有益地借鉴航空公司的经验6.2 监测正常的运行是对安全管理方案提供支持的一个正在形成的方法ICAO支持LOSA而且制定正常运行监测方案也是ICAO 2000年2004年飞行安全和人的因素方案的核心内容ICAO将致力于提高国际民用航空界对正常运行监测方案重要性的认识并尽可能鼓励和推动NOSS等方案的制定和进展6.3 ATS组织可能首先需要提出搜集安全数据的既定来源如事故征候报告然后再过渡到NOSS 等从正常运行中搜集数据的方案但增设这种方案应该是A TS组织在其安全管理方案范围内力求实现的一项目标而把TEM模型纳入TRM训练方案则被认为是逐步落实A TS正常运行监测方案的基石7. 会议的行动7.1 请会议注意本文件所载的信息并在讨论议程项目2时加以考虑――――――――――AN-Conf/11-WP/39附录附录航线运行安全审计LOSA运行特点LOSA由10个运行特点加以界定其作用在于确保这一方法及其数据的完好性这些特点是1. 在正常飞行运行中利用备用座位Jump-seat进行观察LOSA观察仅限于定期航班的正常飞行航线检查航线入门训练和其他训练飞行展现的行为缺乏现实性因此不属于观察之列2. 管理层/驾驶员协会联合推荐LOSA不仅需要得到管理层的支持而且必须得到驾驶员协会的支持才能作为一个可持续的安全项目获得成功联合推荐能够为项目提供分权制衡保证LOSA 的数据切实会带来变化最典型的作法是由两方面的代表组成一个指导委员会3. 机组自愿参与观察人员必须事先征得飞行机组同意对其进行观察如果机组谢绝观察员什么都不要问换一个航班即可如果被拒的次数很多说明存在重大的信任问题有待解决4. 不识别身份的保密的与执行纪律无关的数据搜集LOSA观察所用表格不记录姓名航班号码日期或任何其他可资识别机组身份的资料LOSA的目的是搜集安全数据不是处罚驾驶员航空公司不能因为造成驾驶员担心LOSA观察所得会被用作处罚他们的理由而坐失洞悉本公司运行情况的良机LOSA观察所得一旦被用来执行纪律航空公司内部接收LOSA的机会恐怕就会永远消失5. 有目标性的观察工具目前进行LOSA所使用的工具是得克萨斯大学人的因素研究项目制定的LOSA观察表该表是以TEM模型为基础的6. 经过训练的观察人员 LOSA由驾驶员执行观察小组的成员一般包括航线教练安全和管理驾驶员以及驾驶员组织的代表所选择的观察员必须是航空公司内受尊敬受信赖的人7. 可信赖的资料收集地点为保密起见航空公司必须选定一个可以信赖的资料收集地点目前所有的观察结果一概不予留置直接送到负责LOSA档案管理的得克萨斯大学人的因素研究项目这样做可以保证不会将任何观察结果放错地方或是在航空公司内部不当流传8. 数据核查圆桌会议象LOSA这种数据驱动的方案必须具有高质量的数据管理程序和一贯性检查对于LOSA这种检查是在数据核查圆桌会议上进行的圆桌会议由三至四个部门和驾驶员协会的代表组成负责对原始数据进行扫描以发现误差最后形成的产品是一个根据航空公司的标准和手册经过了一贯性和精确性验证的数据库然后再据此进行任何的统计分析9. 改进目标LOSA的终极产品是一个数据驱动的改进目标清单随着数据的搜集和分析会出现一些规律某些错误发生的频率比其他的错误高某些机场或事件显露的问题比其他的要严重某些标准操作程序SOPs一贯被忽略或改变等等这些规律就是LOSA为航空公司确定的改进目AN-Conf/11-WP/39附录 A-2标然后由航空公司根据这些目标制定行动计划动用本公司的专家实施恰当的改进策略10. 将结果反馈给航线驾驶员为了保证LOSA的长远成功航空公司必须把有关结果反馈给航线驾驶员驾驶员需要看到的不仅是审计的结果而且还有管理层的改进计划完。