威尔逊《行政学之研究》(中英对照)

《行政学之研究》读书报告

《行政学之争辩》读书报告一、作者简介伍德罗・威尔逊(1856. 12. 28—1924. 2. 3)是美国第28任总统。

诞生于弗吉尼亚州。

父亲约瑟夫•威尔逊是大学教授。

威尔逊毕业于普林斯顿大学,毕业后任教多年。

1910年中选为泽西州州长。

1912年获民主党总统候选人提名,击败西奥多•罗斯福获胜。

执政期间推行改革.取代罗斯福为进步主义改革旗手。

1916 年连任。

当时,正值第一次世界大战,开头,威尔逊政府避战,后参战,于1918年1月提出《公正与和平》为14点方案。

南北战斗完毕后,美国确立了北方大资产阶级在全国的统治地位。

内战消灭了奴隶制,为美国资本主义的进展扫清了障碍;而随之对西部的开发,促进农业资本主义在美国的成功进展,为美国资本主义加速进展扫清道路,也为美国跻身于世界强国之列奠定了根底。

而在此背景下,美国政府职能日益变得更加简单和更困难,行政部门的职能范围扩大,美国必定查找一种更更好的行政制度来为资本主义的进展效劳。

二、主要内容分析(一)行政学争辩的必要性威尔逊认为,任何实践性科学在没有必要了解它的地方是不会有人去争辩它的。

行政科学具有明显实践性特,是争辩政府行政治理的科学。

他首先说明白进展行政学的必要性,即现阶段美国的政治环境和遇到的困难。

威尔逊认为美国现在正处于这样一个时刻:“在以往很多世纪中可以看到政府活动方面的困难在不断聚拢起来,那么在我们所处的世纪则可以看到这些困难正在积存到顶点。

”同时“政府的职能日益变得更加简单和更加困难,在数量上也同样大大增加。

行政治理部门将手伸向每一处地方以执行的任务。

”而且在19世纪下半叶,美国市政府中气氛污浊、州行政当局幕后交易的流行,以及在华盛顿政府机构中屡见不鲜的杂乱无章、人浮于事和贪污腐化,都使得有必要消灭一门特地争辩行政学的科学。

“它将力求使政府不走弯路,使政府认真处理公务削减闲杂事务,加强和纯洁政府的组织机构,为政府的尽职尽责带来美誉。

”当前美国需要对行政有更多的了解。

《行政学之研究》

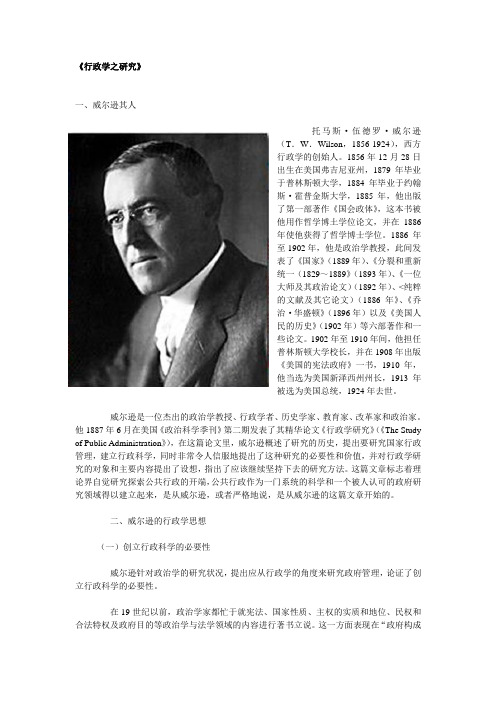

《行政学之研究》一、威尔逊其人托马斯·伍德罗·威尔逊(T.W.Wilson,1856-1924),西方行政学的创始人。

1856年12月28日出生在美国弗吉尼亚州,1879年毕业于普林斯顿大学,1884年毕业于约翰斯·霍普金斯大学,1885年,他出版了第一部著作《国会政体》,这本书被他用作哲学博土学位论文,并在1886年使他获得了哲学博士学位。

1886年至1902年,他是政治学教授,此间发表了《国家》(1889年)、《分裂和重新统一(1829~1889》(1893年)、《一位大师及其政治论文)(1892年)、<纯粹的文献及其它论文)(1886年》、《乔治·华盛顿》(1896年)以及《美国人民的历史》(1902年)等六部著作和一些论文。

1902年至1910年间,他担任普林斯顿大学校长,并在1908年出版《美国的宪法政府》一书,1910年,他当选为美国新泽西州州长,1913年被选为美国总统,1924年去世。

威尔逊是一位杰出的政治学教授、行政学者、历史学家、教育家、改革家和政治家。

他1887年6月在美国《政治科学季刊》第二期发表了其精华论文《行政学研究》(《The Study of Public Administration》),在这篇论文里,威尔逊概述了研究的历史,提出要研究国家行政管理,建立行政科学,同时非常令人信服地提出了这种研究的必要性和价值,并对行政学研究的对象和主要内容提出了设想,指出了应该继续坚持下去的研究方法。

这篇文章标志着理论界自觉研究探索公共行政的开端,公共行政作为一门系统的科学和一个被人认可的政府研究领域得以建立起来,是从威尔逊,或者严格地说,是从威尔逊的这篇文章开始的。

二、威尔逊的行政学思想(一)创立行政科学的必要性威尔逊针对政治学的研究状况,提出应从行政学的角度来研究政府管理,论证了创立行政科学的必要性。

在19世纪以前,政治学家都忙于就宪法、国家性质、主权的实质和地位、民权和合法特权及政府目的等政治学与法学领域的内容进行著书立说。

威尔逊行政学研究原文

对威尔逊行政学说的批评与反思

对威尔逊行政学说的批评

对威尔逊行政学说的反思

• 威尔逊行政学说受到一些学者的批评,认为其过于强调

• 对威尔逊行政学说的反思有助于我们发现其理论观点的

政治与行政的分离

局限性,为理论创新提供空间

• 威尔逊行政学说受到一些学者的批评,认为其过于强调

• 对威尔逊行政学说的反思有助于我们发现其理论观点的

S M A RT C R E AT E

威尔逊行政学研究原文解析

CREATE TOGETHER

01

威尔逊行政学说的背景及影响

威尔逊行政学说的产生背景

19世纪末20世纪初的美国政治变革

• 罗斯福新政的实施,政府职能的扩大

• 进步主义运动的兴起,对政府管理的关注

• 美国政治学的兴起,对政治与行政关系的探讨

02

行政管理的艺术性

• 行政管理需要发挥管理者的创造性,实现管理创新

• 行政管理需要关注人的因素,提高管理效果

03

行政管理的科学性与艺术性的关系

• 行政管理的科学性与艺术性相辅相成,共同推动行政管

理的发展

• 行政管理的科学性与艺术性相互补充,提高政府治理能

力

民主与行政的关联

民主与行政的关系

• 民主为行政提供合法性,保障行政的有效性

• 美国联邦政府遵循民主原则,实现政治与行政的平衡

• 美国联邦政府实行公众参与,提高政府决策的民主性

威尔逊行政学说在其他国家的应用

威尔逊行政学说在欧洲国家的应用

• 欧洲国家借鉴威尔逊行政学说,进行政府改革

• 欧洲国家按照威尔逊行政学说进行政府职能划分,

提高政府治理能力

威尔逊行政学说在亚洲国家的应用

《行政学研究》威尔逊

行政学研究威尔逊我认为任何一门实用科学,在没有必要了解它时,不会有人去研究它。

因此,如果我们需要以某种事实来论证这种情况的话;著名的行政学实用科学正在进入我国高等学校课程的事实本身;则证明我们国家需要更多地了解行政学。

然而,在此无需说明,我们并非要调查高校教学计划来证明这一事实。

目前人们称为文官制度改革的运动在实现了它的第一个目标之后,不仅在人事方面,而且在政府机构的组织和方法方面都必须为继续扩大改革努力,这是我们大家几乎都承认的事实,因为政府机构的组织和方法同其人事问题一样需要进行改进,这一点已经十分明显。

行政学研究的目标在于了解:首先,政府能够适当地和成功地进行什么工作。

其次,政府怎样才能以尽可能高的效率及在费用或能源方面用尽可能少的成本完成这些适当的工作。

在这两个问题上,我们显然更需要得到启示,只有认真进行研究才能提供这种启示。

但是,我们在进入这种研究之前,需要做到下列几点:l.考虑其他人在此领域中所做过的研究。

即是说,考虑这种研究的历史。

2.确定这种研究的课题是什么。

3.断定发展这种研究所需要的最佳方法以及我们用来进行这种研究所需要的最清楚的政治概念。

如果不了解这些问题,不解决这些问题,我们就好像是离开了图表或指南针而去出发远航。

行政科学是已在两千两百年前开始出现的政治科学研究的最新成果。

它是本世纪,几乎就是我们这一代的产物。

它为什么姗姗来迟?它为什么直到我们这个忙的几乎注意不到它的世纪才出现?行政机关是政府最明显的部分,它是行动中的政府;它是政府的执行者,是政府的操作者,是政府的最显露的方面,当然,它的历程也和政府一样悠久。

它是行动中的政府,人们很自然地希望看到政治学的论著者在系统思想史的很早时期即已引起对行动中的政府的注意,并激发他们进行仔细的研究。

但是,事与愿违。

直到本世纪已经度过了它的最初的青春时期,并且已经开始长出独具特色的系统知识之花的时候,才有人将行政机关作为政府科学的一个分支系统地进行论述。

威尔逊《行政学之研究》(中英对照)

行政学之研究威尔逊我认为任何一门实用科学,在没有必要了解它时,不会有人去研究它。

因此,如果我们需要以某种事实来论证这种情况的话;著名的行政学实用科学正在进入我国高等学校课程的事实本身;则证明我们国家需要更多地了解行政学。

然而,在此无需说明,我们并非要调查高校教学计划来证明这一事实。

目前人们称为文官制度改革的运动在实现了它的第一个目标之后,不仅在人事方面,而且在政府机构的组织和方法方面都必须为继续扩大改革努力,这是我们大家几乎都承认的事实,因为政府机构的组织和方法同其人事问题一样需要进行改进,这一点已经十分明显。

行政学研究的目标在于了解:首先,政府能够适当地和成功地进行什么工作。

其次,政府怎样才能以尽可能高的效率及在费用或能源方面用尽可能少的成本完成这些适当的工作。

在这两个问题上,我们显然更需要得到启示,只有认真进行研究才能提供这种启示。

但是,我们在进入这种研究之前,需要做到下列几点:l.考虑其他人在此领域中所做过的研究。

即是说,考虑这种研究的历史。

2.确定这种研究的课题是什么。

3.断定发展这种研究所需要的最佳方法以及我们用来进行这种研究所需要的最清楚的政治概念。

如果不了解这些问题,不解决这些问题,我们就好像离开了图表或指南针而去出发远航。

一、行政科学是已在两手两百年前开始出现的政治科学研究的最新成果。

它是本世纪,几乎就是我们这一代的产物。

它为什么姗姗来迟?它为什么直到我们这个忙的几乎注意不到它的世纪才出现?行政机关是政府最明显的部分,它是行动中的政府;它是政府的执行者,是政府的操作者,是政府的最显露的方面,当然,它的历程也和政府一样悠久。

它是行动中的政府,人们很自然地希望看到政治学的论著者在系统思想史的很早时期即已引起对行动中的政府的注意,并激发他们进行仔细的研究。

但是,事与愿违。

直到本世纪已经度过了它的最初的青春时期,并且已经开始长出独具特色的系统知识之花的时候,才有人将行政机关作为政府科学的一个分支系统地进行论述。

第一讲威尔逊-行政学之研究-文档资料19页

Questions

3.The reason why there should be a science of administration

To seek to straighten the paths of government

To make its business less unbusinesslike To strengthen and purify its organization To crown its duties with dutifulness.

第一讲

行政学之研究 The Study of Administration

——伍德罗·威尔逊 Woodrow Wilson

I. An introduction of Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson(1856-1924):The son of a priest's family in Virginia. In 1883, Wilson entered Johns Hopkins University, and get history and political science phd 3 years later.

2.Administration in UK

The English race, consequently, has long and successfully studied the art of curbing executive power to the constant neglect of the art of perfecting executive methods. It has exercised itself much more in controlling than in energizing government.

第一讲威尔逊-行政学之研究-19页PPT精选文档

President of Princeton University(19021910) Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics(Doctoral Dissertation) Princeton in the Nation's Service and in the Service of All Nations.(School running concept) Turn the man who can only do homework foolishly to a man who can think problems. The academic department system and A core requirement system.

1. A Scholar Academic research in Bryn Mawr Institute ( 1885-1888 ) and Wesley University ( 1888-1890 ) . Law and political economics professor in Princeton University(18901910).

Questions

3.The reason why there should be a science of administration

行政学研究威尔逊

行政学研究威尔逊伍德罗·威尔逊我以为任何一门适用迷信,在没有必要了解它时,不会有人去研讨它。

因此,假设我们需求以某种理想来论证这种状况的话;著名的行政学适用迷信正在进入我国初等学校课程的理想自身;那么证明我们国度需求更多地了解行政学。

但是,在此无需说明,我们并非要调查高校教学方案来证明这一理想。

目先人们称为文官制度革新的运动在完成了它的第一个目的之后,不只在人事方面,而且在政府机构的组织和方法方面都必需为继续扩展革新努力,这是我们大家简直都供认的理想,由于政府机构的组织和方法同其人事效果一样需求停止改良,这一点曾经十分清楚。

行政学研讨的目的在于了解:首先,政府可以适外地和成功地停止什么任务。

其次,政府怎样才干以尽能够高的效率及在费用或动力方面用尽能够少的本钱完成这些适当的任务。

在这两个效果上,我们显然更需求失掉启示,只要仔细停止研讨才干提供这种启示。

但是,我们在进入这种研讨之前,需求做到以下几点:l.思索其他人在此范围中所做过的研讨。

即是说,思索这种研讨的历史。

2.确定这种研讨的课题是什么。

3.判定开展这种研讨所需求的最正确方法以及我们用来停止这种研讨所需求的最清楚的政治概念。

假设不了解这些效果,不处置这些效果,我们就似乎是分开了图表或指南针而去动身远航。

一行政迷信是已在两千两百年前末尾出现的政治迷信研讨的最新效果。

它是本世纪,简直就是我们这一代的产物。

它为什么姗姗来迟?它为什么直到我们这个忙的简直留意不到它的世纪才出现?行政机关是政府最清楚的局部,它是举动中的政府;它是政府的执行者,是政府的操作者,是政府的最显露的方面,当然,它的历程也和政府一样悠久。

它是举动中的政府,人们很自然地希望看到政治学的论著者在系统思想史的很早时期即已惹起对举动中的政府的留意,并激起他们停止细心的研讨。

但是,适得其反。

直到本世纪曾经渡过了它的最后的青春时期,并且曾经末尾长出独具特征的系统知识之花的时分,才有人将行政机关作为政府迷信的一个分支系统地停止论述。

初读《行政学之研究》

初读《行政学之研究》王魁1887年伍德罗·威尔逊发表了文章<行政学研究>,开创了行政学的开端,此后行政学成为独立的学科逐渐发展起来.在《行政学研究》中围绕着在美国创立行政科学的必要性及如何创立这门学科的目标,采用了逻辑思辨法、历史研究法、比较研究法和例证法等研究方法,对行政学研究的必要性、行政学美国化、行政学研究的题材、目的和方法等问题做了深入阐述,从而实现了对美国的其他法学和政治学研究者的理论研究之超越,并由此成为美国行政学研究的拓荒者。

他对行政学这一新领域的发现和倡导、对创立美国行政科学的原则与研究方法以及这一学科研究的主题与目的等问题的理论阐发均具有独特贡献和启发价值,当然亦有值得商榷或深化的方面。

作者在开篇便提出了行政学的研究的目的,即在于了解政府能够适当的做什么工作和高效率或者低成本的完成这些工作。

并在该研究的历史、课题和该研究所需的最佳方法和政治概念三个方面对此做了较为精炼的阐述。

在行政学研究的历史方面,作者有较清晰的解读。

政府和行政机关有着同样悠久的历史,但前者有着博大而广泛的研究,行政机关作为行动中的政府却久久未闻其名。

千年来,在政府机构方面出现的麻烦不胜枚举,为此哲学家们的眼光集中于此表现其时代的精神。

究其源头在于:早期时代统治者以高度的权威而驱使人们从事劳动,低下的生产力水平造成较少种类的财产,“牲口远比集团的数目多”。

到了相对较晚的时期,集团的数目激增多于牲口了,庞大的垄断资本造成了资本持有者和工人之间的长期冲突。

冲突的不断积累,造成国家机构的升级,而升级后的模式却带来了沉重的行政工作,需要经过长期训练和持久勤奋的专业人员才能完成这些工作。

为此,实用性问题的不断积累产生行政学来来解决。

有大批支配着的政府由原来的驱变为被驱使,地位的转换使政府责能的复杂化,遍布每一个地方。

庞大的政府机构不得不借靠行政学来科学的规范处理方式和加强运作效率。

究其源头,作者又把视角转向欧洲——最先重视行政的地域。

威尔逊行政学研究

威尔逊行政学研究威尔逊在行政学领域的研究主要体现在他的著作《行政学(TheStudy of Administration)》中。

这本书是威尔逊于1887年在约翰·霍普金斯大学教授一门政治学课时,所撰写的一本重要论文,也是他在行政学领域中的代表作。

全书共分为12章,详细讨论了行政学的概念、范围以及行政机构的功能等诸多内容。

威尔逊在《行政学》一书中阐述了他对于行政学的理解。

在威尔逊看来,行政学是一门独立的学科,其研究的是政府机构的组织和运作方式,以及公共行政的各个方面。

他认为行政学的核心是研究政府如何通过行政组织来实现公共利益,以及如何提高行政效率和公共服务质量。

威尔逊强调行政学应该以实证研究为基础,通过观察和研究现实中的行政实践,以提出改进行政机构和行政管理的方法和建议。

威尔逊在《行政学》一书中还提出了一些行政学的基本原则和观点。

首先,他强调行政学的研究对象应该是政府机构而不是个别行政官员。

其次,他主张行政应该是一门贯彻法律的活动,行政官员应该秉持公正和法律精神来履行职责。

此外,威尔逊还提出了“政府应该像企业一样运作”的观点,认为政府应该像经营企业一样高效、经济地运行,并提供高质量的公共服务。

威尔逊的行政学研究对于美国政府行政产生了深远影响。

他的观点和理论为美国政府行政机构的发展和提供了指导,也为后来的行政学研究奠定了基础。

在威尔逊的影响下,美国政府行政的特点之一就是注重专业化和科学化,提倡正式的行政程序和规范的行政决策。

威尔逊的行政学研究也对其他国家的行政产生了一定影响,促使了行政学在全球范围内的发展。

然而,威尔逊的行政学研究也存在一些争议。

一方面,他强调行政应该是一门技术性的活动,忽视了行政的政治性和价值性。

另一方面,有学者认为威尔逊过于理想化地将行政和企业管理相提并论,并未充分考虑政府行政与市场机制的差异性。

综上所述,威尔逊行政学研究对于行政学领域的发展和政府行政产生了深远影响。

他通过《行政学》一书提出了行政学的核心概念和基本原则,并将其应用到美国政府行政机构的发展和中。

威尔逊-行政学研究

行政学研究1[1][1]伍德罗·威尔逊我认为任何一门实用科学,在没有必要了解它时,不会有人去研究它。

因此,如果我们需要以某种事实来论证这种情况的话;著名的行政学实用科学正在进入我国高等学校课程的事实本身;则证明我们国家需要更多地了解行政学。

然而,在此无需说明,我们并非要调查高校教学计划来证明这一事实。

目前人们称为文官制度改革的运动在实现了它的第一个目标之后,不仅在人事方面,而且在政府机构的组织和方法方面都必须为继续扩大改革努力,这是我们大家几乎都承认的事实,因为政府机构的组织和方法同其人事问题一样需要进行改进,这一点已经十分明显。

行政学研究的目标在于了解:首先,政府能够适当地和成功地进行什么工作。

其次,政府怎样才能以尽可能高的效率及在费用或能源方面用尽可能少的成本完成这些适当的工作。

在这两个问题上,我们显然更需要得到启示,只有认真进行研究才能提供这种启示。

但是,我们在进入这种研究之前,需要做到下列几点:l.考虑其他人在此领域中所做过的研究。

即是说,考虑这种研究的历史。

2.确定这种研究的课题是什么。

3.断定发展这种研究所需要的最佳方法以及我们用来进行这种研究所需要的最清楚的政治概念。

如果不了解这些问题,不解决这些问题,我们就好像是离开了图表或指南针而去出发远航。

一行政科学是已在两手两百年前开始出现的政治科学研究的最新成果。

它是本世纪,几乎就是我们这一代的产物。

它为什么姗姗来迟?它为什么直到我们这个忙的几乎注意不到它的世纪才出现?行政机关是政府最明显的部分,它是行动中的政府;它是政府的执行者,是政府的操作者,是政府的最显露的方面,当然,它的历程也和政府一样悠久。

它是行动中的政府,人们很自然地希望看到政治学的论著者在系统思想史的很早时期即已引起对行动中的政府的注意,并激发他们进行仔细的研究。

但是,事与愿违。

直到本世纪已经度过了它的最初的青春时期,并且已经开始长出独具特色的系统知识之花的时候,才有人将行政机关作为政府科学的一个分支系统地进行论述。

行政学研究 威尔逊(英文版)(The Study of Administration)

The Study of AdministrationWoodrow WilsonNovember 1, 1886An EssayPrinter-Friendly VersionI suppose that no practical science is ever studied where there is no need to know it. The very fact, therefore, that the eminently practical science of administration is finding its way into college courses in this country would prove that this country needs to know more about administration, were such proof of the fact required to make out a case. It need not be said, however, that we do not look into college programmes for proof of this fact. It is a thing almost taken for granted among us, that the present movement called civil service reform must, after the accomplishment of its first purpose, expand into efforts to improve, not the personnel only, but also the organization and methods of our government offices: because it is plain that their organizations and methods need improvement only less than their personnel. It is the object of administrative study to discover, first, what government can properly and successfully do, and, secondly, how it can do these proper things with the utmost possible efficiency and at the least possible cost either of money or of energy. On both these points there is obviously much need of light among us; and only careful study can supply that light.Before entering on that study, however, it is needful:I. To take some account of what others have done in the same line; that is to say, of the history of the study.II. To ascertain just what is its subject-matter.III. To determine just what are the best methods by which to develop it, and the most clarifying political conceptions to carry with us into it.Unless we know and settle these things, we shall set out without chart or compass. I.The science of administration is the latest fruit of that study of the science of politics which was begun some twenty-two hundred years ago. It is a birth of our own century, almost of our own generation.Why was it so late in coming? Why did it wait till this too busy century of ours to demand attention for itself? Administration is the most obvious part of government; it is government in action; it is the executive, the operative, the most visible side of government, and is of course as old as government itself. It is government in action, and one might very naturally expect to find that government in action had arrested the attention and provoked the scrutiny of writers of politics very early in the history of systematic thought.But such was not the case. No one wrote systematically of administration as a branch of the science of government until the present century had passed its first youth and had begun to put forth its characteristic flower of the systematic knowledge. Up to our own day all the political writers whom we now read had thought, argued, dogmatized only about the constitution of government; about the nature of the state, the essence and seat of sovereignty, popular power and kingly prerogative; about the greatest meanings lying at the heart of government, and the high ends set before the purpose of government by man’s nature and man’s aims. The central field of controversy was that great field of theory in which monarchy rode tilt against democracy, in which oligarchy would have built for itself strongholds of privilege, and in which tyranny sought opportunity to make good its claim to receive submission from all competitors. Amidst this high warfare of principles, administration could command no pause for its own consideration. The question was always: Who shall make law, and what shall thatlaw be? The other question, how law should be administered with enlightenment, with equity, with speed, and without friction, was put aside as "practical detail" which clerks could arrange after doctors had agreed upon principles.That political philosophy took this direction was of course no accident, no chance preference or perverse whim of political philosophers. The philosophy of any time is, as Hegel says, "nothing but the spirit of that time expressed in abstract thought"; and political philosophy, like philosophy of every other kind, has only held up the mirror to contemporary affairs. The trouble in early times was almost altogether about the constitution of government; and consequently that was what engrossed men’s thoughts. There was little or no trouble about administration,-at least little that was heeded by administrators. The functions of government were simple, because life itself was simple. Government went about imperatively and compelled men, without thought of consulting their wishes. There was no complex system of public revenues and public debts to puzzle financiers; there were, consequently, no financiers to be puzzled. No one who possessed power was long at a loss how to use it. The great and only question was: Who shall possess it? Populations were of manageable numbers; property was of simple sorts. There were plenty of farms, but no stocks and bonds: more cattle than vested interests.I have said that all this was true of "early times"; but it was substantially true also of comparatively late times. One does not have to look back of the last century for the beginnings of the present complexities of trade and perplexities of commercial speculation, nor for the portentous birth of national debts. Good Queen Bess, doubtless, thought that the monopolies of the sixteenth century were hard enough to handle without burning her hands; but they are not remembered in the presence of the giant monopolies of the nineteenth century. When Blackstone lamented that corporations had no bodies to be kicked and no souls to be damned, he was anticipating the proper time for such regrets by a full century. The perennial discords between master and workmen which now so often disturb industrial society began before the Black Death and the Statute of Laborers; but never before our own day did they assume such ominous proportions as they wear now. In brief, if difficulties of governmental action are to be seen gathering in other centuries, they are to be seen culminating in our own.This is the reason why administrative tasks have nowadays to be so studiously and systematically adjusted to carefully tested standards of policy, the reason why we are having now what we never had before, a science of administration. The weightier debates of constitutional principle are even yet by no means concluded; but they are no longer of more immediate practical moment than questions of administration. It is getting to be harder to run a constitution than to frame one.Here is Mr. Bagehot’s graphic, whi msical way of depicting the difference between the old and the new in administration:In early times, when a despot wishes to govern a distant province, he sends down a satrap on a grand horse, and other people on little horses; and very little is heard of the satrap again unless he send back some of the little people to tell what he has been doing. No great labour of superintendence is possible. Common rumour and casual report are the sources of intelligence. If it seems certain that the province is in a bad state, satrap No. I is recalled, and satrap No. 2 sent out in his stead. In civilized countries the process is different. You erect a bureau in the province you want to govern; you make it write letters and copy letters; it sends home eight reports per diem to the head bureau in St. Petersburg. Nobody does a sum in the province without some one doing the same sum in the capital, to "check" him, and see that he does it correctly. The consequence of this is, to throw on the heads of departments an amount of reading and labour which can only be accomplished by the greatest natural aptitude, the most efficient training, the most firm and regular industry.(Essay on Sir William Pitt. [All footnotes WW’s.])There is scarcely a single duty of government which was once simple which is not now complex; government once had but a few masters; it now has scores of masters. Majorities formerly only underwent government; they now conduct government. Where government once might follow the whims of a court, it must now follow the views of a nation.And those views are steadily widening to new conceptions of state duty; so that, at the same time that the functions of government are everyday becoming more complex and difficult, they are also vastly multiplying in number. Administration is everywhere putting its hands to new undertakings. The utility, cheapness, and success of the government’s postal service, for instance, point towards the early establishment of governmental control of the telegraph system. Or, even if our government is not to follow the lead of the governments of Europe in buying or building both telegraph and railroad lines, no one can doubt that in some way it must make itself master of masterful corporations. The creation of national commissioners of railroads, in addition to the older state commissions, involves a very important and delicate extension of administrative functions. Whatever hold of authority state or federal governments are to take upon corporations, there must follow cares and responsibilities which will require not a little wisdom, knowledge, and experience. Such things must be studied in order to be well done. And these, as I have said, are only a few of the doors which are being opened to offices of government. The idea of the state and the consequent ideal of its duty are undergoing noteworthy change; and "the idea of the state is the conscience of administration." Seeing every day new things which the state ought to do, the next thing is to see clearly how it ought to do them.This is why there should be a science of administration which shall seek to straighten the paths of government, to make its business less unbusinesslike, to strengthen and purify its organization, and to crown its duties with dutifulness. This is one reason why there is such a science. But where has this science grown up? Surely not on this side the sea. Not much impartial scientific method is to be discerned in our administrative practices. The poisonous atmosphere of city government, the crooked secrets of state administration, the confusion, sinecurism, and corruption ever and again discovered in the bureaux at Washington forbid us to believe that any clear conceptions of what constitutes good administration are as yet very widely current in the United States. No; American writers have hitherto taken no very important part in the advancement of this science. It has found its doctors in Europe. It is not of our making; it is a foreign science, speaking very little of the language of English or American principle. It employs only foreign tongues; it utters none but what are to our minds alien ideas. Its aims, its examples, its conditions, are almost exclusively grounded in the histories of foreign races, in the precedents of foreign systems, in the lessons of foreign revolutions. It has been developed by French and German professors, and is consequently in all parts adapted to the needs of a compact state, and made to fit highly centralized forms of government; whereas, to answer our purposes, it must be adapted, not to a simple and compact, but to a complex and multiform state, and made to fit highly decentralized forms of government. If we would employ it, we must Americanize it, and that not formally, in language merely, but radically, in thought, principle, and aim as well. It must learn our constitutions by heart; must get the bureaucratic fever out of its veins; must inhale much free American air.If an explanation be sought why a science manifestly so susceptible of being made useful to all governments alike should have received attention first in Europe, where government has long been a monopoly, rather than in England or the United States, where government has long been a common franchise, the reason will doubtless be found to be twofold: first, that in Europe, just because government was independent of popular assent, there was more governing to be done; and, second, that the desire to keep government a monopoly made the monopolists interested in discovering the least irritating means of governing. They were, besides, few enough to adopt means promptly.It will be instructive to look into this matter a little more closely. In speaking of European governments I do not, of course, include England. She has not refused to change with the times. She has simply tempered the severity of the transition from a polity of aristocratic privilege to a system of democratic power by slow measures of constitutional reform which, without preventing revolution, has confined it to paths of peace. But the countries of the continent for a long time desperately struggled against all change, and would have diverted revolution by softening the asperities of absolute government. They sought so to perfect their machinery as to destroy all wearing friction, so to sweeten their methods with consideration for the interests of the governed as to placate all hindering hatred, and so assiduously and opportunely to offer their aid to all classes of undertakings as to render themselves indispensable to the industrious. They did at last give the people constitutions and the franchise; but even after that they obtained leave to continue despotic by becoming paternal. They made themselves too efficient to be dispensed with, too smoothly operative to be noticed, too enlightened to be inconsiderately questioned, too benevolent to be suspected, too powerful to be coped with. All this has required study; and they have closely studied it.On this side the sea we, the while, had known no great difficulties of government. With a new country in which there was room and remunerative employment for everybody, with liberal principles of government and unlimited skill in practical politics, we were long exempted from the need of being anxiously careful about plans and methods of administration. We have naturally been slow to see the use or significance of those many volumes of learned research and painstaking examination into the ways and means of conducting government which the presses of Europe have been sending to our libraries. Like a lusty child, government with us has expanded in nature and grown great in stature, but has also become awkward in movement. The vigor and increase of its life has been altogether out of proportion to its skill in living. It has gained strength, but it has not acquired deportment. Great, therefore, as has been our advantage over the countries of Europe in point of ease and health of constitutional development, now that the time for more careful administrative adjustments and larger administrative knowledge has come to us, we are at a signal disadvantage as compared with the transatlantic nations; and this for reasons which I shall try to make clear.Judging by the constitutional histories of the chief nations of the modern world, there may be said to be three periods of growth through which government has passed in all the most highly developed of existing systems, and through which it promises to pass in all the rest. The first of these periods is that of absolute rulers, and of an administrative system adapted to absolute rule; the second is that in which constitutions are framed to do away with absolute rulers and substitute popular control, and in which administration is neglected for these higher concerns; and the third is that in which the sovereign people undertake to develop administration under this new constitution which has brought them into power.Those governments are now in the lead in administrative practice which had rulers still absolute but also enlightened when those modern days of political illumination came in which it was made evident to all but the blind that governors are properly only the servants of the governed. In such governments administration has been organized to subserve the general weal with the simplicity and effectiveness vouchsafed only to the undertakings of a single will.Such was the case in Prussia, for instance, where administration has been most studied and most nearly perfected. Frederic the Great, stern and masterful as was his rule, still sincerely professed to regard himself as only the chief servant of the state, to consider his great office a public trust; and it was he who, building upon the foundations laid by his father, began to organize the public service of Prussia as in very earnest a service of the public. His no less absolute successor, Frederic William III, under the inspiration of Stein, again, in his turn, advanced the work still further, planning many of the broader structural features which give firmness and form to Prussianadministration to-day. Almost the whole of the admirable system has been developed by kingly initiative.Of similar origin was the practice, if not the plan, of modern French administration, with its symmetrical divisions of territory and its orderly gradations of office. The days of the Revolution—of the Constituent Assembly—were days of constitution-writing, but they can hardly be called days of constitution-making. The revolution heralded a period of constitutional development,-the entrance of France upon the second of those periods which I have enumerated,-but it did not itself inaugurate such a period. It interrupted and unsettled absolutism, but it did not destroy it. Napoleon succeeded the monarchs of France, to exercise a power as unrestricted as they had ever possessed.The recasting of French administration by Napoleon is, therefore, my second example of the perfecting of civil machinery by the single will of an absolute ruler before the dawn of a constitutional era. No corporate, popular will could ever have effected arrangements such as those which Napoleon commanded. Arrangements so simple at the expense of local prejudice, so logical in their indifference to popular choice, might be decreed by a Constituent Assembly, but could be established only by the unlimited authority of a despot. The system of the year VIII was ruthlessly thorough and heartlessly perfect. It was, besides, in large part, a return to the despotism that had been overthrown.Among those nations, on the other hand, which entered upon a season of constitution-making and popular reform before administration had received the impress of liberal principle, administrative improvement has been tardy and half-done. Once a nation has embarked in the business of manufacturing constitutions, it finds it exceedingly difficult to close out that business and open for the public a bureau of skilled, economical administration. There seems to be no end to the tinkering of constitutions. Your ordinary constitution will last you hardly ten years without repairs or additions; and the time for administrative detail comes late.Here, of course, our examples are England and our own country. In the days of the Angevin kings, before constitutional life had taken root in the Great Charter, legal and administrative reforms began to proceed with sense an d vigor under the impulse of Henry II’s shrewd, busy, pushing, indomitable spirit and purpose; and kingly initiative seemed destined in England, as elsewhere, to shape governmental growth at its will. But impulsive, errant Richard and weak, despicable John were not the men to carry out such schemes as their father’s. Administrative development gave place in their reigns to constitutional struggles; and Parliament became king before any English monarch had had the practical genius or the enlightened conscience to devise just and lasting forms for the civil service of the state.The English race, consequently, has long and successfully studied the art of curbing executive power to the constant neglect of the art of perfecting executive methods. It has exercised itself much more in controlling than in energizing government. It has been more concerned to render government just and moderate than to make it facile, well-ordered, and effective. English and American political history has been a history, not of administrative development, but of legislative oversight,-not of progress in governmental organization, but of advance in law-making and political criticism. Consequently, we have reached a time when administrative study and creation are imperatively necessary to the well-being of our governments saddled with the habits of a long period of constitution-making. That period has practically closed, so far as the establishment of essential principles is concerned, but we cannot shake off its atmosphere. We go on criticizing when we ought to be creating. We have reached the third of the periods I have mentioned,-the period, namely, when the people have to develop administration in accordance with the constitutions they won for themselves in a previous period of struggle with absolute power; but we are not prepared for the tasks of the new period. Such an explanation seems to afford the only escape from blank astonishment at the fact that, in spite of our vast advantages in point of political liberty,and above all in point of practical political skill and sagacity, so many nations are ahead of us in administrative organization and administrative skill. Why, for instance, have we but just begun purifying a civil service which was rotten full fifty years ago? To say that slavery diverted us is but to repeat what I have said—that flaws in our constitution delayed us.Of course all reasonable preference would declare for this English and American course of politics rather than for that of any European country. We should not like to have had Prussia’s history for the sake of having Prussia’s administrative skill; and Prussia’s particular system of administration would quite suffocate us. It is better to be untrained and free than to be servile and systematic. Still there is no denying that it would be better yet to be both free in spirit and proficient in practice. It is this even more reasonable preference which impels us to discover what there may be to hinder or delay us in naturalizing this much-to-be-desired science of administration.What, then, is there to prevent?Well, principally, popular sovereignty. It is harder for democracy to organize administration than for monarchy. The very completeness of our most cherished political successes in the past embarrasses us. We have enthroned public opinion; and it is forbidden us to hope during its reign for any quick schooling of the sovereign in executive expertness or in the conditions of perfect functional balance in government. The very fact that we have realized popular rule in its fullness has made the task of organizaing that rule just so much the more difficult. In order to make any advance at all we must instruct and persuade a multitudinous monarch called public opinion,-a much less feasible undertaking than to influence a single monarch called a king. An individual sovereign will adopt a simple plan and carry it out directly: he will have but one opinion, and he will embody that one opinion in one command. But this other sovereign, the people, will have a score of differing opinions. They can agree upon nothing simple: advance must be made through compromise, by a compounding of differences, by a trimming of plans and a suppression of too straightforward principles. There will be a succession of resolves running through a course of years, a dropping fire of commands running through the whole gamut of modifications.In government, as in virtue, the hardest of things is to make progress. Formerly the reason for this was that the single person who was sovereign was generally either selfish, ignorant, timid, or a fool,-albeit there was now and again one who was wise. Nowadays the reason is that the many, the people, who are sovereign have no single ear which one can approach, and are selfish, ignorant, timid, stubborn, or foolish with the selfishness, the ignorances, the stubbornnesses, the timidities, or the follies of several thousand persons,-albeit there are hundreds who are wise. Once the advantage of the reformer was that the sovereign’s mind had a definite locality, t hat it was contained in one man’s head, and that consequently it could be gotten at; though it was his disadvantage that the mind learned only reluctantly or only in small quantities, or was under the influence of some one who let it learn only the wrong t hings. Now, on the contrary, the reformer is bewildered by the fact that the sovereign’s mind has no definite locality, but is contained in a voting majority of several million heads; and embarrassed by the fact that the mind of this sovereign also is under the influence of favorites, who are none the less favorites in a good old-fashioned sense of the word because they are not persons by preconceived opinions; i.e., prejudices which are not to be reasoned with because they are not the children of reason.Wherever regard for public opinion is a first principle of government, practical reform must be slow and all reform must be full of compromises. For wherever public opinion exists it must rule. This is now an axiom half the world over, and will presently come to be believed even in Russia. Whoever would effect a change in a modern constitutional government must first educate his fellow-citizens to want some change. That done, he must persuade them to want the particular change he wants. He must first make public opinion willing to listen and then see to it that it listen to the right things. He must stir it up to search for an opinion, and then manage to put theright opinion in its way.The first step is not less difficult than the second. With opinions, possession is more than nine points of the law. It is next to impossible to dislodge them. Institutions which one generation regards as only a makeshift approximation to the realization of a principle, the next generation honors as the nearest possible approximation to that principle, and the next worships the principle itself. It takes scarcely three generations for the apotheosis. The grandson accepts his grandfather’s hesitating experiment as an integral part of the fixed constitution of nature.Even if we had clear insight into all the political past, and could form out of perfectly instructed heads a few steady, infallible, placidly wise maxims of government into which all sound political doctrine would be ultimately resolvable, would the country act on them? That is the question. The bulk of mankind is rigidly unphilosophical, and nowadays the bulk of mankind votes. A truth must become not only plain but also commonplace before it will be seen by the people who go to their work very early in the morning; and not to act upon it must involve great and pinching inconveniences before these same people will make up their minds to act upon it.And where is this unphilosophical bulk of mankind more multifarious in its composition than in the United States? To know the public mind of this country, one must know the mind, not of Americans of the older stocks only, but also of Irishmen, of Germans, of negroes. In order to get a footing for new doctrine, one must influence minds cast in every mould of race, minds inheriting every bias of environment, warped by the histories of a score of different nations, warmed or chilled, closed or expanded by almost every climate of the globe.So much, then, for the history of the study of administration, and the peculiarly difficult conditions under which, entering upon it when we do, we must undertake it. What, now, is the subject-matter of this study, and what are its characteristic objects? II.The field of administration is a field of business. It is removed from the hurry and strife of politics; it at most points stands apart even from the debatable ground of constitutional study. It is a part of political life only as the methods of the counting house are a part of the life of society; only as machinery is part of the manufactured product. But it is, at the same time, raised very far above the dull level of mere technical detail by the fact that through its greater principles it is directly connected with the lasting maxims of political wisdom, the permanent truths of political progress.The object of administrative study is to rescue executive methods from the confusion and costliness of empirical experiment and set them upon foundations laid deep in stable principle.It is for this reason that we must regard civil-service reform in its present stages as but a prelude to a fuller administrative reform. We are now rectifying methods of appointment; we must go on to adjust executive functions more fitly and to prescribe better methods of executive organization and action. Civil-service reform is thus but a moral preparation for what is to follow. It is clearing the moral atmosphere of official life by establishing the sanctity of public office as a public trust, and, by making service unpartisan, it is opening the way for making it businesslike. By sweetening its motives it is rendering it capable of improving its methods of work.Let me expand a little what I have said of the province of administration. Most important to be observed is the truth already so much and so fortunately insisted upon by our civil-service reformers; namely, that administration lies outside the proper sphere of politics. Administrative questions are not political questions. Although politics sets the tasks for administration, it should not be suffered to manipulate its offices.。

行政学之研究读书笔记

行政学之研究读书笔记《行政学之研究》是一部关于行政学的经典之作,作者威尔逊经过在美国、欧洲等地广泛而深入的实地考察,对行政学的历史和现状进行了全面而深入的研究。

通过阅读这本书,我对行政学有了更深入的认识,并对行政管理的实践有了更深刻的理解。

我认识到行政学是一门独立的学科。

在阅读这本书之前,我一直将行政学视为管理学科的一个分支,但威尔逊却明确提出,行政学是一门独立的学科。

他强调,行政学的研究对象是政府机构的运行和行政管理活动,这些活动是政府机构的基本职能,也是政府机构存在的基础。

因此,行政学的研究对象具有独立性和特殊性,它与经济学、社会学等其他学科的研究对象有明显的区别。

我认识到行政管理的实践与理论是密不可分的。

威尔逊在书中强调了行政管理实践的重要性,他认为理论如果不与实践相结合,就会变得空洞和无用。

因此,他主张行政学的研究应该从实践中来,到实践中去,只有通过对实践的深入研究和总结,才能形成具有指导意义的理论。

同时,他也认为理论对实践具有指导作用,只有通过理论的指导,才能更好地进行行政管理实践。

我认识到行政学的发展需要不断的创新和变革。

威尔逊认为行政学的发展是一个不断探索和创新的过程,只有不断地进行创新和变革,才能适应社会发展的需要。

他认为行政学的创新和变革应该从以下几个方面入手:一是加强学科建设,完善学科体系;二是加强理论与实践的结合,推动理论创新;三是加强国际交流与合作,推动行政学的国际化发展。

我认为《行政学之研究》是一本极具价值的著作,它不仅让我对行政学有了更深入的了解,也让我对行政管理的实践有了更深刻的认识。

在未来的学习和工作中,我将继续深入学习行政学的相关知识,不断提高自己的理论素养和实践能力,为行政管理事业的发展贡献自己的力量。

通过对《行政学之研究》的阅读,我对行政学的基本概念、研究领域、发展历程以及实践与理论的关系有了更全面、更深入的理解。

这不仅丰富了我的行政学知识,也使我更加明确地在行政管理的实践中找到理论依据,从而提高自己的实践能力。

威尔逊:行政学研究

行政学研究[1]伍德罗·威尔逊我认为任何一门实用科学,在没有必要了解它时,不会有人去研究它。

因此,如果我们需要以某种事实来论证这种情况的话;著名的行政学实用科学正在进入我国高等学校课程的事实本身;则证明我们国家需要更多地了解行政学。

然而,在此无需说明,我们并非要调查高校教学计划来证明这一事实。

目前人们称为文官制度改革的运动在实现了它的第一个目标之后,不仅在人事方面,而且在政府机构的组织和方法方面都必须为继续扩大改革努力,这是我们大家几乎都承认的事实,因为政府机构的组织和方法同其人事问题一样需要进行改进,这一点已经十分明显。

行政学研究的目标在于了解:首先,政府能够适当地和成功地进行什么工作。

其次,政府怎样才能以尽可能高的效率及在费用或能源方面用尽可能少的成本完成这些适当的工作。

在这两个问题上,我们显然更需要得到启示,只有认真进行研究才能提供这种启示。

但是,我们在进入这种研究之前,需要做到下列几点:l.考虑其他人在此领域中所做过的研究。

即是说,考虑这种研究的历史。

2.确定这种研究的课题是什么。

3.断定发展这种研究所需要的最佳方法以及我们用来进行这种研究所需要的最清楚的政治概念。

如果不了解这些问题,不解决这些问题,我们就好像是离开了图表或指南针而去出发远航。

一行政科学是已在两手两百年前开始出现的政治科学研究的最新成果。

它是本世纪,几乎就是我们这一代的产物。

它为什么姗姗来迟?它为什么直到我们这个忙的几乎注意不到它的世纪才出现?行政机关是政府最明显的部分,它是行动中的政府;它是政府的执行者,是政府的操作者,是政府的最显露的方面,当然,它的历程也和政府一样悠久。

它是行动中的政府,人们很自然地希望看到政治学的论著者在系统思想史的很早时期即已引起对行动中的政府的注意,并激发他们进行仔细的研究。

但是,事与愿违。

直到本世纪已经度过了它的最初的青春时期,并且已经开始长出独具特色的系统知识之花的时候,才有人将行政机关作为政府科学的一个分支系统地进行论述。

行政之研究全文翻译

行政之研究伍德罗·威尔逊1886.11.1我认为在没有必要了解它的地方实践科学从未被研究过。

因此,非常真实的是关于行政的实践科学正在寻找一个方法进入国家的大学课程,这将会证明这个国家需要去对行政了解地更多,这是如此有证明力的关于这个事实。

然而没有必要用研究大学课程来证明这个事实。

在我们当中这件事几乎被认为是一件理所当然的事情,现在被称为公务员改革的运动在达到首要目标后必须要扩展提高,不仅是人员,还包括我们政府办公处的组织与方法:因为他们的组织和方法比他们的人员更需要改进。

要发现行政研究对象。

首先,政府能够正确和成功地做什么,其次,它如何能够以尽可能高的效率和最低的成本无论是金钱还是能源来做这些正确的事情。

在这些点上我们显然非常需要光,并且只有仔细研究才能提供这种光。

然而,在进入这项研究之前,它是有必要的:1.思考其他人在同一条线上己经做的,也就是说,关于历史的研究。

2.去确定它的主题是什么。

3.确定什么是发展它的最好的模式和最明确的政治概念带着我们进入它。

除非我们知道并解决这些问题,否则我们将不带图表或比较。

行政学是在两百年前开始的政治学研究的最新成果。

这是在我们这个世纪的诞生,几乎是我们自己的诞生地。

为什么它来得这么晚?为何它要等到我们这个繁忙的世纪才要求关注呢?行政是政府中最明显的部分,它是政府的行动;它是政府的行政部门、执行者、最显眼的一面,当然,它与政府本身一样古老。

这是一种政府的行动,人们会很自然地发现在系统思想史的早期,政府行动就引起了政界作家们的关注。

但事实并非如此。

行政学作为政府科学的一个分支,直到现代社会度过了它的第一个青年时期,开始呈现出系统知识较低的特点,才有人对其进行系统的论述。

到今天为止,我们所读到的所有政治作家都在思考、争论、教条地谈论政府的组成;关于国家的性质、主权的本质和地位、人民的权力和国王的特权;关于政府的最重要的意义,以及以人的本性和人的目标为政府目的而设定的最高的目的。

《行政学之研究》的启示

《行政学之研究》的启示威尔逊的《行政学之研究》被视为政治学发展史上最具意义的里程碑。

托马斯·伍德罗·威尔逊,在系统的研究了行政学理论与美国的具体国情后,在1887年的《政治科学》季刊上发表了《行政学研究》,这标志着行政管理学概念上的行政学正式产生,威尔逊也因此成为传统公共行政学说的早期理论奠基人。

该书系统的阐述了行政学的重要性,以及在美国发展行政学的必要性与现状,对后世学者在行政学研究方面产生了深远持久的影响。

威尔逊在开篇深刻地分析了将行政学引入美国的历史背景与现实背景。

他指出此时的美国政府在政策活动方面遇到许多困难,因此,对于行政政策系统的调节,使其适应时代的变化,是必须进行的。

另外,19世纪晚期美国文官制度改革将人事方面、政府机构的组织和方法方面改革扩大化。

随着时代的变化,全民的政治意识也逐渐加深,国家职责的观念也深入人心,因此,为了让人民更加透彻地了解政府行政,行政学的学习是十分有必要的。

正如威尔逊所说,“政府的职能日益变得更加复杂和更加困难,在数量上也同样大大增加”,政府的职能越来越广泛越来越复杂,因此需要更多的智慧和经验来协调政府的工作,在美国引入完整系统的行政学理论。

在这篇文章中,威尔逊直接明了的表达了自己的观点与见解,一是政府通过研究学习行政学,能够在如何高效完成工作、尽量减少成本与资源方面获得启发和认真思考的动力;二是它将力求使政府不走弯路,使政府专心处理公务减少闲杂事务,加强和纯洁政府的组织机构,为政府的尽职尽责带来美誉;三是把行政方法从经验性实验的混乱和浪费中拯救出来,并使它们深深植根于稳定的原则之上。

综上可见,威尔逊认为行政学的主要目的是帮助美国政府,在19世纪晚期逐渐接受理论基础的系统化,使得政府在愈发复杂的时代更加适应时代潮流,提高工作效率,更加正确的处理政府在国家的位置、人民与社会的相关问题。

威尔逊的这些主要观点有着极大的影响力,同时对中国也有深远意义。

行政学研究-威尔逊

行政学研究伍德罗·威尔逊我认为任何一门实用科学,在没有必要了解它时,不会有人去研究它。

因此,如果我们需要以某种事实来论证这种情况的话;著名的行政学实用科学正在进入我国高等学校课程的事实本身;则证明我们国家需要更多地了解行政学。

然而,在此无需说明,我们并非要调查高校教学计划来证明这一事实。

目前人们称为文官制度改革的运动在实现了它的第一个目标之后,不仅在人事方面,而且在政府机构的组织和方法方面都必须为继续扩大改革努力,这是我们大家几乎都承认的事实,因为政府机构的组织和方法同其人事问题一样需要进行改进,这一点已经十分明显。

行政学研究的目标在于了解:首先,政府能够适当地和成功地进行什么工作。

其次,政府怎样才能以尽可能高的效率及在费用或能源方面用尽可能少的成本完成这些适当的工作。

在这两个问题上,我们显然更需要得到启示,只有认真进行研究才能提供这种启示。

但是,我们在进入这种研究之前,需要做到下列几点:l.考虑其他人在此领域中所做过的研究。

即是说,考虑这种研究的历史。

2.确定这种研究的课题是什么。

3.断定发展这种研究所需要的最佳方法以及我们用来进行这种研究所需要的最清楚的政治概念。

如果不了解这些问题,不解决这些问题,我们就好像是离开了图表或指南针而去出发远航。

一行政科学是已在两千两百年前开始出现的政治科学研究的最新成果。

它是本世纪,几乎就是我们这一代的产物。

它为什么姗姗来迟?它为什么直到我们这个忙的几乎注意不到它的世纪才出现?行政机关是政府最明显的部分,它是行动中的政府;它是政府的执行者,是政府的操作者,是政府的最显露的方面,当然,它的历程也和政府一样悠久。

它是行动中的政府,人们很自然地希望看到政治学的论著者在系统思想史的很早时期即已引起对行动中的政府的注意,并激发他们进行仔细的研究。

但是,事与愿违。

直到本世纪已经度过了它的最初的青春时期,并且已经开始长出独具特色的系统知识之花的时候,才有人将行政机关作为政府科学的一个分支系统地进行论述。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

行政学之研究威尔逊我认为任何一门实用科学,在没有必要了解它时,不会有人去研究它。

因此,如果我们需要以某种事实来论证这种情况的话;著名的行政学实用科学正在进入我国高等学校课程的事实本身;则证明我们国家需要更多地了解行政学。

然而,在此无需说明,我们并非要调查高校教学计划来证明这一事实。

目前人们称为文官制度改革的运动在实现了它的第一个目标之后,不仅在人事方面,而且在政府机构的组织和方法方面都必须为继续扩大改革努力,这是我们大家几乎都承认的事实,因为政府机构的组织和方法同其人事问题一样需要进行改进,这一点已经十分明显。

行政学研究的目标在于了解:首先,政府能够适当地和成功地进行什么工作。

其次,政府怎样才能以尽可能高的效率及在费用或能源方面用尽可能少的成本完成这些适当的工作。

在这两个问题上,我们显然更需要得到启示,只有认真进行研究才能提供这种启示。

但是,我们在进入这种研究之前,需要做到下列几点:l.考虑其他人在此领域中所做过的研究。

即是说,考虑这种研究的历史。

2.确定这种研究的课题是什么。

3.断定发展这种研究所需要的最佳方法以及我们用来进行这种研究所需要的最清楚的政治概念。

如果不了解这些问题,不解决这些问题,我们就好像离开了图表或指南针而去出发远航。

一、行政科学是已在两手两百年前开始出现的政治科学研究的最新成果。

它是本世纪,几乎就是我们这一代的产物。

它为什么姗姗来迟?它为什么直到我们这个忙的几乎注意不到它的世纪才出现?行政机关是政府最明显的部分,它是行动中的政府;它是政府的执行者,是政府的操作者,是政府的最显露的方面,当然,它的历程也和政府一样悠久。

它是行动中的政府,人们很自然地希望看到政治学的论著者在系统思想史的很早时期即已引起对行动中的政府的注意,并激发他们进行仔细的研究。

但是,事与愿违。

直到本世纪已经度过了它的最初的青春时期,并且已经开始长出独具特色的系统知识之花的时候,才有人将行政机关作为政府科学的一个分支系统地进行论述。

直到今天,我们所拜读的所有的政治学论著者都仅仅围绕下列问题进行思考、争辩和论证:政府“构成方式”;国家性质,主权的本质和地位,人民的权力和君主的特权;属于政府核心内容的最深的含义及根据人性和人的目的摆在政府目标之前的更高目标。

下列范围广泛的理论领域是存在激烈论战的中心地区:君主制对民主制进行攻击,寡头政治力图建立特权的堡垒,专制制度寻求使其所有竞争者投降的要求得以实现的机会。

在这些理论原则的激烈斗争中,行政机关不能中断其自身的思考。

经常出现的问题是:由谁制定法律以及制定什么法律?另一个问题是如何有启发性的、公平的、迅速而又没有摩擦地实施法律。

这一问题被看做是“实际工作中的细节问题”,在专家学者们就理论原则取得一致意见后由办事人员进行处理。

政治哲学采取这种方向,当然不是一种意外现象,不是出于政治哲学家的偶然性偏爱或反常行为。

正如黑格尔所说的,任何时代的哲学“都只不过是抽象思维所表现的那个时代的精神。

”而政治哲学也和其它任何种类的哲学一样,只不过是举起了反映当代事务的一面镜子。

在很早的时代,麻烦的事情几乎都出在政府结构方面。

因此,结构问题就成为吸引人们思考的焦点。

当时,在行政管理方面很少或完全没有遇到麻烦问题,至少没有引起行政官员注意的问题。

那时候政府的职能很简单,因为生活本身就很简单。

政府靠行政命令行事,驱使着人们,从来没有想到过要征询人们的意见。

那时候没有使财政人员感到麻烦的公共收入和公债的复杂制度,因此也并不存在感到此种麻烦的财政人员。

所有掌握权力的人员都不会对怎样运用权力长期茫然不解。

唯一重大的问题是:谁将掌握权力?全体居民只不过是处于管辖之下的人群;财产的种类很少,当时农庄很多,但却没有股票和债券;牲口远比既得利益集团的数目多。

我曾经说过,这一切都是“早期时代”的真实情况。

在相对较晚的时期,这些情况也基本上是真实的。

人样做来了解国家公债是怎样奇异地诞生的。

毫无疑问,仁慈的贝斯女王曾经认为16世纪的垄断资本极难驾驭,要想不烫伤她的手指是不可能的。

但是在19世纪庞大的垄断资本面前,已不再有人记得这些话了。

当布莱克斯通“哀叹地说,公司企业既无躯体可让你敲打,又无灵魂可供你谴责时,他早在整整一个世纪之前就预见到了这种令人遗憾现象的准确时间。

经常扰乱工业社会的老板和工人之间的长期冲突,在黑死病和劳工法出现之前就已开始存在了。

但是在我们的这个时代到来之前,它们从来没有像今天这样显示不祥之兆。

简言之,如果在以往许多世纪中可以看到政府活动方面的困难在不断聚集起来,那么在我们所处的世纪则可以看到这些困难正在累积到顶点。

这就是当前必须认真和系统地调整行政工作使之适合于仔细试验过的政策标准的原因。

我们现在所以正产生一种前所未有的行政科学,原因也在这里。

关于宪政原则的重要论战甚至到现在还远没有得出结论,但是在实用性方面它们已不再比行政管理问题更突出。

执行一部宪法变得比制定一部宪法更要困难得多。

下面是巴奇霍特先生对于行政管理中新旧方式之间的差别所做的生动而独辟蹊径径的描述:“从前,当一个专制君主想统治一个边远省份时,他便派出一名骑着高头大马的总督,其他人则骑在矮小的马匹上;如果这位总督不派某些人回来汇报他正在作些什么,君主便很少听到这位总督的信息,不可能采取重大的监督措施,信息的来源是普通的谣传和临时性的报告。

如果可以肯定这个省份管理得不好,将前一任总督召回,另派一位总督接替他的职位。

在文明国家,程序则与此不同:人们在想要进行统治的省份中建立一个机构,要求该机构书写和抄录文件,每天向圣彼得堡的首脑机关递交八份报告。

如果在首都没有人进行汇总工作,对省里人的工作进行“检查”,看他是否作得正确,在省里也不可能有人作汇总工作。

这种作法的后果是加给各种首脑机构大量的阅读资料和繁重的工作。

只有具备最大的先天能力,经过最有效的训练,具有最坚决、最有持久性的勤奋精神的人才有可能完成这些工作。

”没有任何一种政府职责现在没有变得复杂起来,它们当初曾经是很简单的,政府曾经只有少数支配者,而现在却有大批的支配者。

大多数人以前仅仅听命于政府,现在他们却指导着政府。

在有些国家,政府曾经对朝廷唯命是从,而现在却必须遵从全民的意见。

并且全民的意见正在稳步地扩展成为一种关于国家职责的新观念。

与此同时,政府的职能日益变得更加复杂和更加困难,在数量上也同样大大增加。

行政管理部门将手伸向每一处地方以执行新的任务。

例如政府在邮政事务方面的效用、廉价服务和成就,使政府较早地实现了对电报系统的控制。

或者说,在收购或建造电报和火车路线方面,即使我们的政府并不遵循欧洲各国政府走过的道路,但却没有任何人会怀疑我们的政府必须采取某种方式,使自己能够支配各种有支配力的公司。

除旧有的国家铁路委员会之外,政府又新设立了全国铁路特派员,这意味着行政管理职能的一种非常重要而巧妙的扩充。

不管州政府或联邦政府决定对各大公司有什么样的权力,都必须小心谨慎和承担责任,这样做会需要许多智慧、知识和经验。

为了很好完成这些事情必须对其认真研究。

而这一切,正如我所说过的那样,还仅仅是那正向政府机构敞开着的许多大门中的一小部分。

关于国家以及随之而来的关于国家职责的观念正在发生引人注目的变化,而“关于国家的观念正式行政管理的灵魂”。

当你了解国家每天应该作的新事情之后,紧接着就应该了解国家应该如何去做这些事情。

这就是为什么应该有一门行政科学的原因,它将力求使政府不走弯路,使政府专心处理公务减少闲杂事务,加强和纯洁政府的组织机构,为政府的尽职尽责带来美誉。

这就是为什么会有这一门科学的原因之一。

但是这门科学是在什么地方成长起来的呢?肯定不是在海洋的这一边。

在我们的行政实践中不可能发现很多公平的科学方法。

市政府中的污浊气氛、州行政当局的幕后交易,以及在华盛顿政府机构中屡见不鲜的杂乱无章、人浮于事和贪污腐化,都使我们决不相信到目前为止,关于建立良好行政管理的任何明确观念已在美国广泛流行。

没有,美国的学者们迄今为止并没有在这门科学的发展中发挥很重要的作用。

行政学言规则。

它所使用的仅仅是外国腔调。

它表述的只是与我们的思想迥然不同的观念。

它的目标、事例和条件,几乎都是以外国民族的历史、外国制度的惯例和外国革命的教训为根据的。

它是由法国和德国的教授们发展起来的,因此,其各个组成部分是与一个组织严密的国家的需要相适应的,并且是为了适应高度集权的政府形式而建立起来的。

因此,为了与我们的目的相符,对它必须进行调整,使之适合于权力高度分散的政府形式建立起来。

如果我们要应用这种科学,我们必须使之美国化,不只是从形式上或仅仅从语言上美国化,而是必须在思想、原则和目标方面从根本上加以美国化。

它必须从内心深处认识我们的制度,必须把官僚主义的热病从血管中加以排除,必须多多吸入美国的自由空气。

这一显然如此容易使一切政府都能得到好处的科学,为什么首先是在欧洲受到重视呢?在欧洲跟在英国和美国不同,其政府长期以来属于垄断性;而在美国,其政府长期以来只是享有一种公共性质的授权。

如果有人想要找到一种解释,他毫无疑问将会发现其原因是双重的:首先,在欧洲,正因为政府不依赖国民的同意,它所要做的更多的工作是统治;其次,想使政府保持垄断地位的愿望,使那些垄断者对于发现尽可能不激怒民众的统治方法深感兴趣。

此外,这些垄断者人数甚少,便于迅速采取各种手段。

对于这种情况稍做较深入的观察将会是很有教益的。

当然,在提到欧洲政府时,我并没有把英国包括在内。

英国并没有拒绝随着时代潮流进行改革。

英国只不过是通过程度缓慢的宪政改革,缓和了从一个贵族享有特权的政体演化成具有民主权力的体制这种转变的严厉程度。

这种改革并没有阻碍革命,而是把它限制在采取和平途径的范围之内。

然而大陆各国长期以来拼命反抗一切改革,他们希望通过缓和专制政府的粗暴程度改变革命的方向。

他们希望通过这种作法来完善他们的国家机器,从而消灭一切令人讨厌的摩擦;通过这种作法,以及对被统治者利益的关心,来使政府的措施变得温和,从而使一切起阻碍作用的仇恨得到和解;他们还殷勤而及时通过这种作法来向一切经营事业的阶层提供帮助,从而使国家本身变成一切勤劳人民所不可缺少的东西。

最后,他们还给予人民以宪法和公民权利。

但是,即使在这些措施之后,他们还是得到许可,以变成家长的身分继续行使其专制权力。

他们使自己变得极有效率,从而变得不可缺少;工作极其稳妥,从而不引人注意;极端开明,从而不会受到轻率的质询;极端仁慈,从而不会引起怀疑;极端强大,从而难以对付。

所有这一切都需要进行研究,而他们已对此作了认真的研究。

当时,在大洋的这边,我们在政府工作方面却没有碰到重大的困难。

作为一个新的国家,并且在其中每一个人都有住房并可找到有报酬的工作,加之政府奉行自由主义原则和在实际的政治活动中运用不受限制的技能。