Soft Gamma Repeaters and Anomalous X-ray Pulsars Together Forever

科研Mol.Plant:拟南芥蛋白质组图谱的重塑与蛋白质在发育和免疫中共同调节

科研Mol.Plant:拟南芥蛋白质组图谱的重塑与蛋白质在发育和免疫中共同调节编译:东方不赢,编辑:Emma、江舜尧。

原创微文,欢迎转发转载。

导读蛋白质组重塑是一种基础适应性反应。

复合体蛋白质和功能性蛋白质通常是共表达的。

研究者使用深度采样策略,将拟南芥组织核心蛋白质组定义为每个组织中约10,000个蛋白质,且在整个植物生命周期中量化近16,000个蛋白质(单细胞的拷贝数)。

整体翻译后修饰蛋白质组学中发现了氨基酸的交换现象,说明了真核生物中可能存在翻译的不忠。

蛋白质丰度的相关性分析揭示了光合作用、种子发育以及衰老和脱落调节中,存在可能组织/年龄特异性转录信号传导模块。

另外,本研究数据表明RD26和其他NAC转录因子具有在种子发育中与耐干旱相关的潜在功能,富含半胱氨酸的受体激酶CRK可以作为衰老中ROS传感器。

核糖体生物发生因子(RBF)复合体的所有组分均以组织、年龄特异的方式共表达,表明拟南芥中这些研究较少的复合体蛋白质组装时功能混杂。

本研究用flg22处理了拟南芥幼苗16小时,分析鉴定了基础免疫反应中蛋白质组结构的特征。

在flg22处理后1、3和16小时,结合平行反应监测(PRM)靶向蛋白质组学,植物激素、氨基酸组分分析和转录本测量获取了一个全面的结果。

研究者发现, JA和JA-Ile水平抑制是通过MYC2(茉莉酸敏感物质1)控制下的IAR3(IAA-ALA抗体3)和JOX2(茉莉酸诱导的加氧酶2)的解共轭和羟基化作用。

这个JA触发的免疫反应调节机制从未被报道,尚未得到充分研究。

本研究生成的数据集广泛覆盖了不同条件中的拟南芥蛋白质组,为相关研究提供了丰富资源。

论文ID原名:Reshaping of the Arabidopsis thaliana proteome landscapeandco-regulation of proteins in development and immunity译名:拟南芥蛋白质组图谱的重塑与蛋白质在发育和免疫中共同调节期刊:Molecular PlantIF:12.084发表时间:2020.09通讯作者:Wolfgang Hoehenwarter通讯作者单位:莱布尼茨植物生物化学研究所实验设计实验结果1. 深度蛋白质组学研究方法因为要对拟南几种组织(组织分别为根,叶,茎生叶,茎,花和角果/种子以及7天至93天衰老的整株植物幼苗)的不同生命阶段进行蛋白质组学测量,及测量用肽flg22处理PTI诱导的蛋白质组。

霍格兰营养液配方

COMMENTS FOR THE AUTHOR:Reviewer #1: The manuscript CEMN-D-12-01363 by Chen and collaborators describes the expression and distribution of the transcription factor FOXO3a and the kinase inhibitor p27kip1 in the retina of the DBA/2J mouse relative o the C57/BL6 mice.The manuscript contains some original observations.SUMMARY:While Foxo3a inhibits cell cycle progression via control of p27kip1 (cyclin kinase inhibitor) during the G1-S phase transition in various cell lines, the authors believe these two genes/gene products are worthy candidates for study in differentiated neurons and glia in a mouse model for glaucoma.They looked for the spatial and temporal distributions in the retinas of the DBA/2J mice (D2) grouped by factors such as age, IOP, slit lamp and ophthalmoscope inspection to delineate non-glaucomatous,pre-glaucomatous and glaucomatous animal groups.The authors used light microscopy, RT-PCR, and immunocytochemistry to look at the spatial and temporal distributions and expression levels of foxo3a and p27kip1 and made use of TUNEL and antibodies to activated caspase-3 as measures of cell death.Their results indicated that - Westerns: foxo3a and p27kip proteins were reduced in time/condition relative to control mice retina; RT-PCR: p27kip mRNA may also be reduced with time/condition.Immuno-histology was used to show that - foxo3a and p27kip are diffusely expressed in retina of D2 and B6 mice and decreased in Muller (GS+) and astrocytes (GFAP+). However, foxo3a increased in RGCs (neuN+) of D2 mice and activated caspase 3 was evident in RGCs (NeuN+) of D2 mice. TUNEL was evident in RGC layer of D2 miceThe authors concluded that - foxo3a and p27kip1 are involved in neural cell loss in D2 miceCRITIQUE:INTRODUCTION:The experimental plan to group the animals into 3 groups is a good idea, although, it has been shown previously that there are changes the expression of some genes that occur prior to the full blown glaucomatous condition. In this case, it appears that FOXO3a and p27kip1 may be somewhat late and perhaps downstream to the primary signaling events leading to loss of vision."ubiquitously" seems to be redundant in first sentence of second paragraph. The listed citations do not give appropriate credit to many important studies. For example:1) The introduction to this paper needs additional references for the second sentence in the 1st paragraph, especially for each of themechanisms suggested as primary causes of RGC cell death. The author should add excitotoxicity as one of the postulated mechanisms here - especially as foxo3a has been implicated in apoptosis.2) Paragraph 4 of the introduction - the authors may want to cite the 2001 Nobel laureates for their discoveries of the role of cyclins and CDKs in cell cycle progression.3) The authors must cite Ophthalmol Eye Dis. 2010 March 11; 1: 23-41, a microarray study where up-regulation of GFAP (Muller cells and astrocytes) and Iba1 (microglia) were shown and where a CDI was also shown to be increased in the DBA/2J mouse retina. At the very least this should be in the last paragraph of the introduction, and probably, also used in the discussion.4) The authors should also cite Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:977-85 another important gene expression study. This should also go, at least in the last paragraph of the introduction.METHODS:Can the authors state how they determined an illumination level of 50-60 lux for housing the animals? Just curious.I would like to see a table for the 3 DBA/2J animal groups with the various factors used to assign animals to this or that group. This might be helpful to investigators who use these animals.Catalogue numbers should be used to identify the antibodies that were used. RESULTS:In second and fifth lines of the first paragraph, what is meant by the term "control group" here? Are these B6 or are they D2- non glaucomatous mice? You also use the term "control" for no-primary controls, for example, in the figure legends. So always be specific.The last sentence of the first paragraph states that neurodegeneration induced a decrease in foxo3a and p27kip1. The term "induced" may be inappropriate here.The second paragraph speaks of a decrease in immuno-staining. This is difficult to discern, perhaps due to the use of cresyl violet as a counterstain. It might be better to not use a nuclear counterstain. I cannot see the translocation from nucleus to cytoplasm. Again this might have been possible without the dark blue counterstain.I cannot see much overlap between foxo or p27 with the Muller cell glutamine synthase in figure3. While the author has boxed a possible example, there are many instances where the labeling is either red or green. There are hints of foxo and p27 in the middle layer of the INL and in the OPL, but the figure could be improved.There is some evidence in Figure 4 for double labeled cells containing both markers for GFAP and Foxo but all-GFAP or all-Foxo labeled cells are also to be seen. Can the authors explain this?The statement indicating a cause and effect relationship between FOXO andp27 may be misplaced, at least in this part of the results section. There does appear to be a correlation between the relative abundance of FOXO and p27 in the retina as judged from western blots of the whole retina, but you have also made a case for increased abundance of FOXO in RGCs. Thus, it is not clear that your argument is consistent at the cellular level, or at least, it is not made clear to this reviewer.It is not clear that figure 8 adds anything that has not already been reported and the data are not that convincing anyway. It might have been useful to show the presence of cleaved caspase or TUNEL in double labeled cells containing FOXO or p27 because the direct connection between FOXo and p27 with cell death is somewhat tenuous in this manuscript. DISCUSSION:Much is lost in translation and this is particularly true of the discussion section where misleading statements such as "The present data reveal that down-regulation of p27kip1 through FOXO transcriptional inhibition was associated with ----" and "our results demonstrated that Foxo3a as a positive regulator of p27kip1 was associated with ---" can be found. There is little integration with the existing data on the DBA/2J mouse or any other animal model of glaucoma.Reviewer #2: In this study the authors show that the transcription factor FOXO3a and its downstream gene p27kip1 are decreased in glaucomatous DBA/2J retinas. The decreased expression of these proteins was found in the Müller cells and astrocytes. The authors also found increased expression of FOXO3a in RGCs from glaucomatous retinas. The latter finding seems to be correlated with the apoptosis of RGCs, observed with TUNEL and Caspase3 staining in glaucomatous retinas.Major points:1) The authors were able to show that FOXO3a and p27kip1 expression levels are changing in glaucomatous retinas, however the study lacks a direct connection between their findings and the cellular processes in which these proteins are involved. Downregulation of FOXO3a and p27kip1 have been proposed to be involved in cell proliferation, while upregulation of FOXO3a in neurons is associated with apoptosis. It will be interesting if the authors are able to establish the connection between the expression of these proteins and the cellular events mentioned above. A previous study has shown the involvement of the PTEN-Akt-FOXO3a pathway in neuronal apoptosis in brain development after hypoxia-ischemia (Li et al., J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2009). In this study, the expression of Bim, an apoptosis related protein that is downstream of FOXO3a, is increased as a response of FOXO3a nuclear translocation. The authors could demonstrate the link between FOXO3a and apoptosis byshowing dephosphorylation in the PTEN-Akt-FOXO3a pathway and the consequent increased levels of Bim in glaucomatous RGCs. In this way the authors might propose a possible mechanism of apoptosis that could betargeted therapeutically in glaucoma.2) It is necessary to include an optic nerve assessment of degeneration for the establishment of glaucoma in these mice. The use of an axonal antibody in the optic nerve could be a good alternative.。

第六章 岛屿生物地理学理论与生物多样性保护

陆地植物

Galapagos 群岛

0 325 Preston(1962)

北方森林中的鸟

美国

0 165 Brown(1978)

北方森林中的哺乳动物

美国

0 326 Brown(1978)

浮游动物

美国纽约州湖泊

0 170 Browne(1981)

蜗牛

美国纽约州湖泊

0 230 Browne(1981)

4 库萨伊岛 Kusaie 5 图木图群岛 Tuamotu 6 马贵斯群岛 Marquesas 7 法属社会群

岛 Society lslands 8 波纳佩岛 Ponape 9 马里亚纳群岛 Marianas Islands 10 汤加岛

Tanga 11 加罗林群岛 Caroline Iqlands 12 卑硫群岛 Pelew Palau Islands 13 圣克

计算时所取单位为平方英里

动物或植物

岛屿

Байду номын сангаасz 值

来源

甲虫

西印度群岛

0 340 Darlingion(1943)

蚁类

美拉尼西亚群岛

0 300 Wilson(1992)

两栖和爬行动物

西印度群岛

0 301 Preston(1962)

繁殖的陆地和淡水鸟

西印度群岛

0 237 Hamilton 等 1964

斯群岛 New Hebrides 23 布鲁 Buru 24 希兰岛 Ceram 25 索罗门群岛 solomons

如果这一关系用一曲线表示 我们就可得到生态学中的所谓 物种 面积曲线

Species-Area curve 图 2

突变基因的拟南芥实验研究

突变基因的拟南芥实验研究拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)是一种模式植物,在生物学研究中发挥着重要的作用。

它的基因组序列已经被完整解读,并且其外观简单、生长周期短等特点,使得其成为基因功能研究的最佳实验材料。

突变基因是指由于DNA序列的变异,造成突变的基因。

拟南芥的突变基因贡献了大量关于植物发育与繁殖等方面的科学研究成果。

突变基因的发现突变基因的发现可以通过自然突变和诱导突变两种途径实现。

自然突变是指在自然条件下,由于DNA杂交、突变等自然因素,使得基因产生突变。

而诱导突变,则需要使用特殊的化学试剂或是电磁辐射等手段对DNA进行干预,从而获得突变基因。

诱导突变的方法目前,诱导突变的方法主要有以下几种:1. EMS法EMS是Ethyl methanesulfonate的缩写,是一种碱基化剂,能够导致DNA中的鸟嘌呤碱基突变。

通过对拟南芥幼苗进行EMS浸泡处理,可以获得大量的突变体。

2. Gamma射线法Gamma射线是一种高能辐射,能够直接影响DNA分子结构,从而导致基因突变。

使用Gamma射线进行诱导突变,可以获得不同类型的突变体,包括缺失、插入、点突变等。

3. T-DNA插入法T-DNA是一种细菌表现元(bacterial virulence factor),广泛存在于土壤中的根际细菌Agrobacterium tumefaciens中。

因为T-DNA能够与植物基因组发生同源重组,因此可以通过向植物中转化Agrobacterium,从而将T-DNA插入到植物基因组中,诱导基因突变。

突变基因的分析方法了解突变基因的表达情况,可以通过基因表达谱、荧光素酶检测、Northern blotting、Western blotting等多种方法实现。

其中基因表达谱是最常用的一种方法,能够快速、准确地检测基因的表达情况。

拟南芥突变基因的研究拟南芥作为模式植物,其突变基因的研究对于植物的发育和繁殖等方面具有重要的意义,以下是一些拟南芥突变基因的研究案例。

Neutron Stars, Pulsars and Supernova Remnants concluding remarks

a r X i v :a s t r o -p h /0208563v 1 30 A u g 2002Proceedings of the 270.WE-Heraeus Seminar on:“Neutron Stars,Pulsars and Supernova Remnants”Physikzentrum Bad Honnef,Germany,Jan.21-25,2002,eds.W.Becker,H.Lesch &J.Tr¨u mper,MPE Report 278,pp.300-302Neutron Stars,Pulsars and Supernova Remnants:concluding remarksF.Pacini 1,21Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory,L.go E.Fermi,5,I-50125Firenze,Italy2Dept.of Astronomy and Space Science,University of Florence,L.go E.Fermi,2,I-50125Firenze,Italy1.IntroductionMore than 30years have elapsed since the discovery of pul-sars (Hewish et al.1968)and the realization that they are connected with rotating magnetized neutron stars (Gold 1968;Pacini 1967,1968).It became soon clear that these objects are responsible for the production of the relativis-tic wind observed in some Supernovae remnants such as the Crab Nebula.For many years,the study of pulsars has been car-ried out mostly in the radio band.However,many recent results have come from observations at much higher fre-quencies (optical,X-rays,gamma rays).These observa-tions have been decisive in order to establish a realistic demography and have brought a better understanding of the relationship between neutron stars and SN remnants.The Proceedings of this Conference cover many aspects of this relationship (see also previous Conference Proceed-ings such as Bandiera et al.1998;Slane and Gaensler,2002).Because of this reason,my summary will not re-view all the very interesting results which have been pre-sented here and I shall address briefly just a few issues.The choice of these issues is largely personal:other col-leagues may have made a different selection.2.Demography of Neutron Stars:the role of the magnetic field For a long time it has been believed that only Crab-like remnants (plerions)contain a neutron star and that the typical field strength of neutron stars is 1012Gauss.The basis of this belief was the lack of pulsars associated with shell-type remnants or other manifestations of a relativis-tic wind.The justification given is that some SN explo-sions may blow apart the entire star.Alternatively,the central object may become a black hole.However,the number of shell remnants greatly exceeds that of pleri-ons:it becomes then difficult to invoke the formation of black holes,an event much more rare than the formation of neutron stars.The suggestion that shell remnants such as Cas A could be associated with neutron stars which have rapidly lost their initial rotational energy because of an ultra-strong magnetic field B ∼1014−1015Gauss (Cavaliere &Pacini,1970)did receive little attention.The observa-tional situation has now changed:a compact thermal X-ray source has been discovered close to the center of Cas A (Tananbaum,1999)and it could be the predicted ob-ject.Similar sources have been found in association with other remnants and are likely to be neutron stars.We have also heard during this Conference that some shell-type remnants (including Cas A)show evidence for a weak non-thermal X-ray emission superimposed on the thermal one:this may indicate the presence of a residual relativis-tic wind produced in the center.Another important result has been the discovery of neutron stars with ultra-strong magnetic fields,up to 1014−1015G.In this case the total magnetic energy could be larger than the rotational en-ergy (”magnetars”).This possibility had been suggested long time ago (Woltjer,1968).It should be noticed,how-ever,that the slowing down rate determines the strength of the field at the speed of light cylinder and that the usually quoted surface fields assume a dipolar geometry corresponding to a braking index n =3.Unfortunately the value of n has been measured only in a few cases and it ranges between 1.4−2.8(Lyne et al.,1996).The present evidence indicates that neutron stars man-ifest themselves in different ways:–Classical radio pulsars (with or without emission at higher frequencies)where the rotation is the energy source.–Compact X-ray sources where the energy is supplied by accretion (products of the evolution in binary sys-tems).–Compact X-ray sources due to the residual thermal emission from a hot surface.–Anomalous X-ray pulsars (AXP)with long periods and ultra strong fields (up to 1015Gauss).The power emit-ted by AXPs exceeds the energy loss inferred from the slowing down rate.It is possible that AXPs are asso-ciated with magnetized white dwarfs,rotating close to the shortest possible period (5−10s)or,alternatively,they could be neutron stars whose magnetic energy is dissipated by flares.–Soft gamma-ray repeaters.2 F.Pacini:Neutron Stars,Pulsars and Supernova Remnants:concluding remarks In addition it is possible that some of the unidentifiedgamma ray sources are related to neutron stars.Thepresent picture solves some previous inconsistencies.Forinstance,the estimate for the rate of core-collapse Super-novae(roughly one every30-50years)was about a factorof two larger than the birth-rate of radio pulsars,suggest-ing already that a large fraction of neutron stars does not appear as radio pulsars.The observational evidence supports the notion of a large spread in the magnetic strength of neutron stars and the hypothesis that this spread is an important factor in determining the morphology of Supernova remnants.A very strongfield would lead to the release of the bulk of the rotational energy during a short initial period(say, days up to a few years):at later times the remnant would appear as a shell-type.A more moderatefield(say1012 Gauss or so)would entail a long lasting energy loss and produce a plerion.3.Where are the pulses emitted?Despite the great wealth of data available,there is no gen-eral consensus about the radiation mechanism for pulsars. The location of the region where the pulses are emitted is also controversial:it could be located close to the stellar surface or,alternatively,in the proximity of the speed of light cylinder.The radio emission is certainly due to a coherent pro-cess because of the very high brightness temperatures(T b up to and above1030K have been observed).A possible model invokes the motion of bunches of charges sliding along the curvedfield lines with a relativistic Lorentz fac-torγsuch that the critical frequencyνc∼c2π:Ψ∼10−2;B⊥∼104G;γ∼102−103.The model leads to the expectation of a very fast de-crease of the synchrotron intensity with period because of the combination of two factors:a)the reduced particles flux when the period increases;b)the reduced efficiency of synchrotron losses(which scale∝B2∝R−6L∝P−6)at the speed of light cylinder(Pacini,1971;Pacini&Salvati 1983,1987).The predictionfits the observed secular de-crease of the optical emission from the Crab Nebula and the magnitude of the Vela pulsar.A recent re-examination of all available optical data confirms that this model can account for the luminosity of the known optical pulsars (Shearer and Golden,2001).If so,the optical radiation supports strongly the notion that the emitting region is located close to the speed of light cylinder.4.A speculation:can the thermal radiation fromyoung neutron stars quench the relativisticwind?Myfinal remarks concern the possible effect of the ther-mal radiation coming from the neutron star surface upon the acceleration of particles.This problem has been inves-tigated for the near magnetosphere(Supper&Truemper, 2000)and it has been found that the Inverse Compton Scattering(ICS)against the thermal photons is impor-tant only in marginal cases.However,if we assume that the acceleration of the relativistic wind and the radiation of pulses occur close to the speed of light cylinder,the sit-uation becomes different and the ICS can dominate over synchrotron losses for a variety of parameters.The basic reason is that the importance of ICS at the speed of light distance R L scales like the energy density of the thermal photons uγ∝R−2L∝P−2;on the other hand, the synchrotron losses are proportional to the magnetic energy density in the same region u B∝R−6L∝P−6.Numerically,onefinds that ICS losses dominate over synchrotron losses ifT6>0.4B1/2121012G; P s is the pulsar period in seconds).The corresponding upper limit for the energy of the electrons,assuming that the acceleration takes place for a length of order of the speed of light distance and that the gains are equal to the losses is given by:E max≃1.2×103T6−4P s GeV.F.Pacini:Neutron Stars,Pulsars and Supernova Remnants:concluding remarks3Provided that the particles are accelerated and radi-ate in proximity of the speed of light cylinder distance,weconclude that the thermal photons can limit the acceler-ation of particles,especially in the case of young and hotneutron stars.It becomes tempting to speculate that thismay postpone the beginning of the pulsar activity untilthe temperature of the star is sufficiently low.The mainmanifestation of neutron stars in this phase would be aflux of high energy photons in the gamma-ray band,dueto the interaction of the quenched wind with the thermalphotons from the stellar surface.This model and its ob-servational consequences are currently under investigation(Amato,Blasi,Pacini,work in progress).ReferencesAloisio,R.,&Blasi,P.2002,Astrop.Phys.,Bandiera,R.,et al.1998,Proc.Workshop”The Relationshipbetween Neutron Stars and Supernova Remnants”,Mem.Societ Astronomica Italiana,vol.69,n.4Cavaliere,A.,&Pacini,F.1970,ApJ,159,170Gold,T.1968,Nature,217,731Hewish A.,et al.1968,Nature217,709Lyne,G.,et al.1996,Nature,381,497Pacini,F.1967,Nature,216,567Pacini,F.1968,Nature,219,145Pacini,F.1971,ApJ,163,L17Pacini,F.,&Salvati,M.1983,ApJ,274,369Pacini F.,&Salvati,M.1987,ApJ.,321,447Shearer,A.,and Golden,A.2001,ApJ,547,967Slane,P.,Gaensler,B.2002,Proc.Workshop”Neutron Starsin Supernova Remnants”ASP Conference Proceedings(inpress)Supper,R.,&Trumper,J.2000,A&A,357,301Tananbaum,B,et al.1999,IAU Circular7246Thompson,C.,Duncan,R.C.1996,ApJ,473,322Woltjer,L.1968,ApJ,152,179。

两种星天牛嗅觉相关蛋白基因的鉴定及关键气味结合蛋白的功能分析

参考文献

参考文献1

标题:两种星天牛嗅觉相关蛋白基因的鉴定及关键气味结合蛋白的功能 分析

作者:张三、李四、王五

感谢您的观看

THANKS

功能验证

通过转录组分析等方法,了解这两种嗅觉相关蛋白基因在不同虫态和 组织中的表达情况,同时通过基因敲除等方法研究其对天牛寻找寄主 和逃避敌害等行为的影响。

03

实验结果

嗅觉相关蛋白基因的鉴定

鉴定了两种星天牛的嗅觉相关蛋白基因

通过基因组测序和生物信息学分析,鉴定了两种星天牛的嗅觉相关蛋白基因,这些基因可 能参与嗅觉信号转导。

农业害虫防治

研究结果为农业害虫防治提供了新 的潜在靶标,有助于开发更有效的 害虫防治策略和方法。

结论

揭示了关键气味结合蛋白在嗅觉过程中的作 用和重要性。

为农业害虫防治提供了新的潜在靶标。

成功鉴定两种星天牛的嗅觉相关蛋白基因, 并对其功能进行了初步分析。

为昆虫嗅觉机制的研究提供了新的思路和方 法。

05

嗅觉在星天牛的寻 找食物、繁殖和逃 逸等行为中发挥重 要作用。

研究目的

鉴定两种星天牛嗅觉相关蛋白基因,为研究其功能提供基础数据。

分析关键气味结合蛋白的功能,以期为开发新型防治策略提供理论依据。

02

材料与方法

材料

星天牛成虫

采集于北京市郊区,在实验室饲养至产卵 。

寄主植物

包括云杉、冷杉、红松等不同树种的叶片 和树皮。

发现基因的序列和结构

通过比对分析,发现这些基因的序列和结构与已知的嗅觉相关蛋白基因具有一定的相似性 ,暗示着它们可能具有相似的生物学功能。

表达模式分析

通过表达模式分析,发现这些基因在幼虫和成虫阶段的表达水平存在差异,暗示着它们在 不同生长阶段的生理功能可能有所不同。

遗传育种相关名词中英文对照

遗传育种相关名词中英文对照中英文对照的分子育种相关名词 3"untranslated region (3"UTR) 3"非翻译区 5"untranslated region (5; UTR) 5"非翻译区 A chromosome A 染色体 AATAAA 多腺苷酸化信号aberration 崎变 abiogenesis 非生源说 accessory chromosome 副染色体 accessory nucleus 副核 accessory protein 辅助蛋白 accident variance 偶然变异 Ac-Ds system Ac-Ds 系统 acentric chromosome 无着丝粒染色体acentric fragment 无着丝粒片段 acentric ring 无着丝粒环 achromatin 非染色质 acquired character 获得性状acrocentric chromosome 近端着丝粒染色体 acrosyndesis 端部联会 activating transcription factor 转录激活因子activator 激活剂 activator element 激活单元 activator protein( AP)激活蛋白 activator-dissociation system Ac-Ds 激活解离系统 active chromatin 活性染色质 activesite 活性部位 adaptation 适应 adaptive peak 适应高峰adaptive surface 适应面 addition 附加物 addition haploid 附加单倍体 addition line 附加系 additiveeffect 加性效应 additive gene 加性基因 additive genetic variance 加性遗传方差additive recombination 插人重组additive resistance 累加抗性 adenosine 腺昔adenosine diphosphate (ADP )腺昔二鱗酸adenosine triphosphate( ATP)腺昔三憐酸adjacent segregation 相邻分离A- form DNA A 型 DNAakinetic chromosome 无着丝粒染色体akinetic fragment 无着丝粒片断alien addition monosomic 外源单体生物alien chromosome substitution 外源染色体代换alien species 外源种 alien-addition cell hybrid 异源附加细胞杂种 alkylating agent 焼化剂 allele 等位基因allele center 等位基因中心 allele linkage analysis 等位基因连锁分析 allele specific oligonucleotide(ASO)等位基因特异的寡核苷酸 allelic complement 等位(基因)互补 allelic diversity 等位(基因)多样化 allelic exclusion 等位基因排斥 allelic inactivation 等位(基因)失活 allelic interaction 等位(基因)相互作用allelic recombination 等位(基因)重组 allelicreplacement 等位(基因)置换 allelic series 等位(基因)系列 allelic variation 等位(基因)变异 allelism 等位性 allelotype 等位(基因)型 allodiploid 异源二倍体 allohaploid 异源单倍体 allopatric speciation 异域种alloploidy 异源倍性 allopolyhaploid 异源多倍单倍体allopolyploid 异源多倍体 allosyndesis 异源联会allotetraploid 异源四倍体 alloheteroploid 异源异倍体alternation of generation 世代交替 alternative transcription 可变转录 alternative transcription initiation 可变转录起始 Alu repetitive sequence, Alu family Alu 重复序列,Alu 家族ambiguous codon 多义密码子 ambisense genome 双义基因组 ambisense RNA 双义 RNA aminoacyl-tRNA binding site 氨酰基 tRNA 接合位点 aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase 氨酰基 tRNA 连接酶 amixis 无融合amorph 无效等位基因amphidiploid 双二倍体amphipolyploid 双多倍体amplicon 扩增子amplification 扩增 amplification primer 扩增引物analysis of variance 方差分析 anaphase (分裂)后期anaphase bridge (分裂)后期桥anchor cell 锚状细胞 androgamete 雄配子aneuhaploid 非整倍单倍体aneuploid 非整倍体 animal genetics 动物遗传学annealing 复性 antibody 抗体anticoding strand 反编码链anticodon 反密码子anticodon arm 反密码子臂anticodon loop 反密码子环 antiparallel 反向平行antirepressor 抗阻抑物antisense RNA 反义 RNAantisense strand 反义链 apogamogony 无融合结实apogamy 无配子生殖apomixis 无融合生殖 arm ratio (染色体)臂比artificial gene 人工基因 artificial selection 人工选择 asexual hybridization 无性杂交 asexual propagation 无性繁殖 asexual reproduction 无性生殖assortative mating 选型交配 asynapsis 不联会 asynaptic gene 不联会基因atavism 返祖 atelocentric chromosome 非端着丝粒染色体 attached X chromosome 并连 X 染色体 attachmentsite 附着位点 attenuation 衰减 attenuator 衰减子autarchic gene 自效基因auto-alloploid 同源异源体 autoallopolyploid 同源异源多倍体 autobivalent 同源二阶染色体 auto-diploid 同源二倍体;自体融合二倍体 autodiploidization 同源二倍化autoduplication 自体复制 autogenesis 自然发生autogenomatic 同源染色体组 autoheteroploidy 同源异倍性autonomous transposable element 自主转座单元autonomously replicating sequence(ARS)自主复制序列autoparthenogenesis 自发单性生殖 autopolyhaploid 同源多倍单倍体 autopolyploid 同源多倍体 autoradiogram 放射自显影图 autosyndetic pairing 同源配对 autotetraploid 同源四倍体 autozygote 同合子 auxotroph 营养缺陷体 B chromosome B 染色体 B1,first backcross generation 回交第一代 B2,second backcross generation 回交第二代back mutation 回复突变 backcross 回交backcross hybrid 回交杂种 backcross parent 回交亲本 backcross ratio 回交比率 background genotype 背景基因型 bacterial artification chromosome( BAC )细菌人工染色体Bacterial genetics 细菌遗传学 Bacteriophage 噬菌体balanced lethal 平衡致死 balanced lethal gene 平衡致死基因 balanced linkage 平衡连锁 balanced load 平衡负荷balanced polymorphism 平衡多态现象 balanced rearrangements 平衡重组balanced tertiary trisomic 平衡三级三体balanced translocation 平衡异位balancing selection 平衡选择band analysis 谱带分析 banding pattern (染色体)带型basal transcription apparatus 基础转录装置 base analog 碱基类似物base analogue 类減基base content 减基含量base exchange 碱基交换 base pairing mistake 碱基配对错误 base pairing rules 碱基配对法则 base substitution 减基置换 base transition 减基转换 base transversion 减基颠换 base-pair region 碱基配对区base-pair substitution 碱基配对替换 basic number of chromosome 染色体基数 behavioral genetics 行为遗传学behavioral isolation 行为隔离 bidirectionalreplication 双向复制 bimodal distribution 双峰分布binary fission 二分裂binding protein 结合蛋白binding site 结合部位 binucleate phase 双核期biochemical genetics 生化遗传学 biochemical mutant 生化突变体biochemical polymorphism 生化多态性 bioethics 生物伦理学 biogenesis 生源说 bioinformatics 生物信息学biological diversity 生物多样性 biometrical genetics 生物统计遗传学(简称生统遗传学) bisexual reproduction 两性生殖 bisexuality 两性现象 bivalent 二价体 blending inheritance 混合遗传 blot transfer apparatus 印迹转移装置 blotting membrane 印迹膜 bottle neck effect 瓶颈效应 branch migration 分支迁移 breed variety 品种breeding 育种,培育;繁殖,生育 breeding by crossing 杂交育种法 breeding by separation 分隔育种法 breeding coefficient 繁殖率 breeding habit 繁殖习性 breeding migration 生殖回游,繁殖回游 breeding period 生殖期breeding place 繁殖地 breeding population 繁殖种群breeding potential 繁殖能力,育种潜能 breeding range繁殖幅度 breeding season 繁殖季节 breeding size 繁殖个体数 breeding system 繁殖系统 breeding true 纯育breeding value 育种值 broad heritability 广义遗传率bulk selection 集团选择 C0,acentric 无着丝粒的Cl,monocentric 单着丝粒 C2, dicentric 双着丝粒的C3,tricentric 三着丝粒的 candidate gene 候选基因candidate-gene approach 候选基因法 Canpbenmodel 坎贝尔模型carytype 染色体组型,核型 catabolite activator protein 分解活化蛋白catabolite repression 分解代谢产物阻遏catastrophism 灾变说 cell clone 细胞克隆 cell cycle 细胞周期 cell determination 细胞决定 cell division 细胞分裂 cell division cycle gene(CDC gene) 细胞分裂周期基因 ceU division lag 细胞分裂延迟 cell fate 细胞命运cell fusion 细胞融合 cell genetics 细胞的遗传学 cell hybridization 细胞杂交 cell sorter 细胞分类器 cell strain 细胞株 cell-cell communication 细胞间通信center of variation 变异中心 centimorgan(cM) 厘摩central dogma 中心法则 central tendency 集中趋势centromere DNA 着丝粒 DNA centromere interference 着丝粒干扰centromere 着丝粒 centromeric exchange ( CME)着丝粒交换centromeric inactivation 着丝粒失活 centromeric sequence( CEN sequence)中心粒序列 character divergence 性状趋异chemical genetics 化学遗传学chemigenomics 化学基因组学chiasma centralization 交叉中化chiasma terminalization 交叉端化chimera 异源嵌合体Chi-square (x2) test 卡方检验 chondriogene 线粒体基因 chorionic villus sampling 绒毛膜取样 chromatid abemition 染色单体畸变chromatid break 染色单体断裂chromatid bridge 染色单体桥chromatid interchange 染色单体互换 chromatid interference 染色单体干涉 chromatid segregation 染色单体分离chromatid tetrad 四分染色单体chromatid translocation 染色单体异位chromatin agglutination 染色质凝聚chromosomal aberration 染色体崎变chromosomal assignment 染色体定位chromosomal banding 染色体显带chromosomal disorder 染色体病chromosomal elimination 染色体消减 chromosomal inheritance 染色体遗传chromosomal interference 染色体干扰chromosomal location 染色体定位chromosomal locus 染色体位点 chromosomal mutation 染色体突变chromosomal pattern 染色体型chromosomal polymorphism 染色体多态性 chromosomal rearrangement 染色体质量排chromosomal reproduction 染色体增殖chromosomal RNA 染色体 RNAchromosomal shift 染色体变迁,染色体移位chromosome aberration 染色体畸变 chromosome arm 染色体臂chromosome association 染色体联合chromosome banding pattern 染色体带型chromosome behavior 染色体动态chromosome blotting 染色体印迹chromosome breakage 染色体断裂chromosome bridge 染色体桥 chromosome coiling 染色体螺旋chromosome condensation 染色体浓缩chromosome constriction 染色体缢痕chromosome cycle 染色体周期chromosome damage 染色体损伤chromosome deletion 染色体缺失chromosome disjunction 染色体分离chromosome doubling 染色体加倍chromosome duplication 染色体复制chromosome elimination 染色体丢失 chromosome engineering 染色体工程chromosome evolution 染色体进化 chromosome exchange 染色体交换chromosome fusion 染色体融合 chromosome gap 染色体间隙chromosome hopping 染色体跳移chromosome interchange 染色体交换chromosome interference 染色体干涉chromosome jumping 染色体跳查chromosome knob 染色体结 chromosome loop 染色体环chromosome lose 染色体丢失chromosome map 染色体图 chromosome mapping 染色体作图chromosome matrix 染色体基质chromosome mutation 染色体突变 chromosome non-disjunction 染色体不分离 chromosome paring 染色体配对chromosome polymorphism 染色体多态性 chromosome puff 染色体疏松 chromosome rearrangement 染色体质量排chromosome reduplication 染色体再加倍 chromosome repeat 染色体质量叠 chromosome scaffold 染色体支架chromosome segregation 染色体分离 chromosome set 染色体组chromosome stickiness 染色体粘性chromosome theory of heredity 染色体遗传学说chromosome theory of inheritance 染色体遗传学说chromosome thread 染色体丝chromosome walking 染色体步查chromosome-mediated gene transfer 染色体中介基因转移 chromosomology 染色体学 CIB method CIB 法;性连锁致死突变出现频率检测法 circular DNA 环林 DNA cis conformation 顺式构象 cis dominance 顺式显性 cis-heterogenote 顺式杂基因子 cis-regulatory element 顺式调节兀件 cis-trans test 顺反测验cladogram 进化树 cloning vector 克隆载体 C-meiosis C 减数分裂C-metaphase C 中期C-mitosis C 有丝分裂 code degeneracy 密码简并coding capacity 编码容量 coding ratio 密码比 coding recognition site 密码识别位置 coding region 编码区coding sequence 编码序列 coding site 编码位置 coding strand 密码链 coding triplet 编码三联体 codominance 共显性 codon bias 密码子偏倚 codon type 密码子型coefficient of consanguinity 近亲系数 coefficient of genetic determination 遗传决定系数 coefficient of hybridity 杂种系数 coefficient of inbreeding 近交系数coefficient of migration 迁移系数 coefficient of relationship 亲缘系数 coefficient of variability 变异系数 coevolution 协同进化 coinducer 协诱导物 cold sensitive mutant 冷敏感突变体colineartiy 共线性combining ability 配合力comparative genomics 比较基因组学competence 感受态competent cell 感受态细胞competing groups 竞争类群 competition advantage 竞争优势competitive exclusion principle 竞争排斥原理complementary DNA (cDNA)互补 DNAcomplementary gene 互补基因 complementation test 互补测验complete linkage 完全连锁 complete selection 完全选择 complotype 补体单元型 composite transposon 复合转座子 conditional gene 条件基因 conditional lethal 条件致死conditional mutation 条件突变 consanguinity 近亲consensus sequence 共有序列 conservative transposition 保守转座 constitutive heterochromatin 组成型染色质continuous variation 连续变异convergent evolution 趋同进化cooperativity 协同性 coordinately controlled genes 协同控制基因 core promoter element 核心启动子 core sequence 核心序列 co-repressor 协阻抑物correlation coefficient 相关系数 cosegregation 共分离 cosuppression 共抑制cotranfection 共转染cotranscript 共转录物 cotranscriptional processing 共转录过程 cotransduction 共转导cotransformation 共转化 cotranslational secrection 共翻译分泌counterselection 反选择coupling phase 互引相 covalently closed circular DNA(cccDNA)共价闭合环状 DNAcovariation 相关变异criss-cross inheritance 交叉遗传 cross 杂交crossability 杂交性crossbred 杂种cross-campatibility 杂交亲和性 cioss-infertility 杂交不育性 crossing over 交换crossing-over map 交换图crossing-over value 交换值crossover products 交换产物 crossover rates 交换率crossover reducer 交换抑制因子crossover suppressor 交换抑制因子crossover unit 交换单位 crossover value 值crossover-type gamete 交换型配子C-value paradox C 值悖论 cybrid 胞质杂种 cyclin 细胞周期蛋白cytidme 胞苷 cytochimera 细胞嵌合体cytogenetics 细胞遗传学 cytohet 胞质杂合子cytologic 细胞学的cytological map 细胞学图cytoplasm 细胞质cytoplasmic genome 胞质基因组 cytoplasmic heredity 细胞质遗传 cytqplasmic incompatibility 细胞质不亲和性cytoplasmic inheritance 细胞质遗传cytoplasmic male sterility 细胞质雄性不育cytoplasmic mutation 细胞质突变 cytofdasmic segregation 细胞质分离cytoskeleton 细胞骨架Darwin 达尔文 Darwinian fitness 达尔文适合度Darwinism 达尔文学说 daughter cell 子细胞 daughter chromatid 子染色体 daughter chromosome 子染色体deformylase 去甲酰酶 degenerate code 简并密码degenerate primer 简并引物 degenerate sequence 简并序列 degenerated codon 简并密码子degeneration 退化 degree of dominance 显性度delayed inheritance 延迟遗传 deletant 缺失体deletion 缺失。

拟南芥β-罗勒烯合成酶基因T-DNA插入突变体的鉴定

2 ‘ 置 2 n ,400rm 离 心 1 n 吹干 , 于 0C放 0mi)1 0 p 0mi, 溶

灭菌 的超 纯水 中后作 为 P R扩增 的 D C NA模 板 。

1 2 3 DNA 的 P R 扩 增 . . C

相 似 基 因组 成 的 家 族 命 名为 At P T S家 族 。 t PS 3 A T 0

1 2 2 单株 植物 总 DNA 提取 ..

类 化 合物 都 具 有 环状 结 构 。单 萜 合酶 分 布 于 TP — , Sb

TP — , P — 和 T S g4个 亚家 族 。单 萜 合酶 基 因表 Sd T Sf P — 达 受 生物 钟 调节 , 表达 量 随 昼 夜周 期 交替 变换 而 出现

f罗勒烯 (-cmee 是 近 年 来 发 现 的 , 植 物 防 } -  ̄oi n ) 与 御 相 关 的 植 物 通 讯 (ln—o pa tcmmu i t n) 号 分 nc i 信 ao 子 [, 自然 界 中包 括 两 个 同分 异 构 体 : 式一 勒 1在 ] 顺 罗

烯 ( i一 c n c  ̄o i e)和 反 式一- 勒 烯 ( rn — s me f罗 }  ̄a s o i n ) 罗勒 烯 是 一 种 单 萜 ( n tre e ) 合 c me e 。 mo oep n s 化

su yterl o  ̄o i n c a i td oe f c h me emeh ns h moy o smua t i -c n y tae e eepes nse c s b o . m・ o zg u tn t oi esnh s n x rsi i nemu t eg t w h ̄ me g o l

R 0 1 L, d H2 补 足至 1 L。 . 用 d O 5

薄壳山核桃ISSR—PCR反应体系的优化

( 江苏省 中国科学院植物研究 所 , 江苏南京 2 0 1 ) 104

摘要: 采用正交试验设计 , 薄壳 山核桃 IS 对 S R—P R反应 体 系的 主要影 响 因子 ( aD A聚合 酶 、N P、 C Tq N d T 引物 、 Mg 和模板 D A) N 进行 了优化 , 得到了适 合薄壳山核桃 的 IS 并 S R—P R扩增体 系。结果表 明 , 2 的 IS P R C 在 0 SR— C 反 应体系中 ,. 10U的 T q 、. m lL的 d T 、. m lL的引物 、. m lL的 M 和 4 g a 酶 0 4m o / N P 0 2 ̄ o / 20m o / g 0n 的模板 D A为适 N 合薄壳山核桃的最佳反应条件 。 关键词 : 薄壳 山核桃 ; 正交试验设计 ; S R—P R; 子标 记 IS C 分

[ ] h , h nB T, uSW,ta.Ta s rrs t c ob c rl 3 Z uY S C e Y e 1 rnf eia et at i e sn ea

la lg tfo Or z y ra a va a y e fb Jh r m y a me e i n i s mmer c s ma i y rd z t n t o t h b ia i i c i o

分布在美国和墨 西哥北 部 , 国、 法 西班牙 、 中国、 t E本等 国也 有, 但产量甚少。经过多年的培育 , 目前为止 已公开发表的 到 品种数 已逾 1 0 0个 。我国引种薄壳 山核 桃已有多年 的 0 历史 , 引种过程 中品种混 杂 , 以形成商业性 生产 , 但 难 因此迫

高。薄壳 山核桃还是优 良的材用 和庭 园绿化树种。其木材 纹 理细腻 , 质地坚韧 , 是建筑 、 军工 、 室内装饰和制作高档家具的 理想材料。其树形高大 , 树势挺拔 , 是深 受欢迎 的观 赏、 阳 遮 和行道树种 …。它 的起源可追 溯到遥远 的 白垩纪 时代 , 主要

ReX2(X=S,Se):二维各向异性材料发展的新机遇

ReX2(X=S,Se):二维各向异性材料发展的新机遇王人焱;甘霖;翟天佑【摘要】二维材料因其不同于体相的超薄原子结构、大的比表面积和量子限域效应等受到了人们的广泛关注.二维各向异性材料作为二维材料家族的一员,其取向依赖的物理和化学性质,使得对该类材料性能的选择性优化成为可能.过渡金属Re基硫属化合物作为各向异性材料的典型代表,具有可调的可见光波段吸收带隙,极弱的层间耦合作用力,以及各向异性的光学、电学性能,现已成为电子和光电子领域的研究热点之一.本文主要介绍了ReX2(X=S,Se)的晶体结构和基本性质,总结目前该材料体系主流的合成方法,研究其各向异性物理特性及优化的手段和条件,并对ReX2的制备和发展进行了展望.%Two dimensional (2D) materials have attracted wide attention due to their ultrathin atomic structure, large specific surface area and quantum confinement effect which are remarkably different from their bulk counterparts.Anisotropic materials are unique among reported 2D materials.Their orientation-dependent physical and chemical properties make it possible to selectively improve the performance of materials.As representative examples, Re-based transition metal dichalcogenides (Re-TMDs) have tunable bandgaps in visible spectrum, extremely weak interlayer coupling, and anisotropic properties in optics and electronics, which make them attractive in the application areas of electronics and optoelectronics.In this riviev, the unique crystal structures and intrinsic properties of the Re-based TMDs semiconductors are introduced firstly, and then the synthetic method is introduced, followed by discussion on the unique physical characterizations and optimized means.Finally,prospects and suggestions are put forward for the preparation and research of ReX2.【期刊名称】《无机材料学报》【年(卷),期】2019(034)001【总页数】16页(P1-16)【关键词】各向异性;ReS2;ReSe2;综述【作者】王人焱;甘霖;翟天佑【作者单位】华中科技大学材料科学与工程学院, 材料成型与模具技术国家重点实验室, 武汉 430074;华中科技大学材料科学与工程学院, 材料成型与模具技术国家重点实验室, 武汉 430074;华中科技大学材料科学与工程学院, 材料成型与模具技术国家重点实验室, 武汉 430074【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TQ174超薄的原子结构和巨大的比表面积赋予二维材料不同于体相的光学、电子学、磁学等方面独特的物理性质。

Anomaly Detection A Survey(综述)

A modified version of this technical report will appear in ACM Computing Surveys,September2009. Anomaly Detection:A SurveyVARUN CHANDOLAUniversity of MinnesotaARINDAM BANERJEEUniversity of MinnesotaandVIPIN KUMARUniversity of MinnesotaAnomaly detection is an important problem that has been researched within diverse research areas and application domains.Many anomaly detection techniques have been specifically developed for certain application domains,while others are more generic.This survey tries to provide a structured and comprehensive overview of the research on anomaly detection.We have grouped existing techniques into different categories based on the underlying approach adopted by each technique.For each category we have identified key assumptions,which are used by the techniques to differentiate between normal and anomalous behavior.When applying a given technique to a particular domain,these assumptions can be used as guidelines to assess the effectiveness of the technique in that domain.For each category,we provide a basic anomaly detection technique,and then show how the different existing techniques in that category are variants of the basic tech-nique.This template provides an easier and succinct understanding of the techniques belonging to each category.Further,for each category,we identify the advantages and disadvantages of the techniques in that category.We also provide a discussion on the computational complexity of the techniques since it is an important issue in real application domains.We hope that this survey will provide a better understanding of the different directions in which research has been done on this topic,and how techniques developed in one area can be applied in domains for which they were not intended to begin with.Categories and Subject Descriptors:H.2.8[Database Management]:Database Applications—Data MiningGeneral Terms:AlgorithmsAdditional Key Words and Phrases:Anomaly Detection,Outlier Detection1.INTRODUCTIONAnomaly detection refers to the problem offinding patterns in data that do not conform to expected behavior.These non-conforming patterns are often referred to as anomalies,outliers,discordant observations,exceptions,aberrations,surprises, peculiarities or contaminants in different application domains.Of these,anomalies and outliers are two terms used most commonly in the context of anomaly detection; sometimes interchangeably.Anomaly detectionfinds extensive use in a wide variety of applications such as fraud detection for credit cards,insurance or health care, intrusion detection for cyber-security,fault detection in safety critical systems,and military surveillance for enemy activities.The importance of anomaly detection is due to the fact that anomalies in data translate to significant(and often critical)actionable information in a wide variety of application domains.For example,an anomalous traffic pattern in a computerTo Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009,Pages1–72.2·Chandola,Banerjee and Kumarnetwork could mean that a hacked computer is sending out sensitive data to an unauthorized destination[Kumar2005].An anomalous MRI image may indicate presence of malignant tumors[Spence et al.2001].Anomalies in credit card trans-action data could indicate credit card or identity theft[Aleskerov et al.1997]or anomalous readings from a space craft sensor could signify a fault in some compo-nent of the space craft[Fujimaki et al.2005].Detecting outliers or anomalies in data has been studied in the statistics commu-nity as early as the19th century[Edgeworth1887].Over time,a variety of anomaly detection techniques have been developed in several research communities.Many of these techniques have been specifically developed for certain application domains, while others are more generic.This survey tries to provide a structured and comprehensive overview of the research on anomaly detection.We hope that it facilitates a better understanding of the different directions in which research has been done on this topic,and how techniques developed in one area can be applied in domains for which they were not intended to begin with.1.1What are anomalies?Anomalies are patterns in data that do not conform to a well defined notion of normal behavior.Figure1illustrates anomalies in a simple2-dimensional data set. The data has two normal regions,N1and N2,since most observations lie in these two regions.Points that are sufficiently far away from the regions,e.g.,points o1 and o2,and points in region O3,are anomalies.Fig.1.A simple example of anomalies in a2-dimensional data set. Anomalies might be induced in the data for a variety of reasons,such as malicious activity,e.g.,credit card fraud,cyber-intrusion,terrorist activity or breakdown of a system,but all of the reasons have a common characteristic that they are interesting to the analyst.The“interestingness”or real life relevance of anomalies is a key feature of anomaly detection.Anomaly detection is related to,but distinct from noise removal[Teng et al. 1990]and noise accommodation[Rousseeuw and Leroy1987],both of which deal To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.Anomaly Detection:A Survey·3 with unwanted noise in the data.Noise can be defined as a phenomenon in data which is not of interest to the analyst,but acts as a hindrance to data analysis. Noise removal is driven by the need to remove the unwanted objects before any data analysis is performed on the data.Noise accommodation refers to immunizing a statistical model estimation against anomalous observations[Huber1974]. Another topic related to anomaly detection is novelty detection[Markou and Singh2003a;2003b;Saunders and Gero2000]which aims at detecting previously unobserved(emergent,novel)patterns in the data,e.g.,a new topic of discussion in a news group.The distinction between novel patterns and anomalies is that the novel patterns are typically incorporated into the normal model after being detected.It should be noted that solutions for above mentioned related problems are often used for anomaly detection and vice-versa,and hence are discussed in this review as well.1.2ChallengesAt an abstract level,an anomaly is defined as a pattern that does not conform to expected normal behavior.A straightforward anomaly detection approach,there-fore,is to define a region representing normal behavior and declare any observation in the data which does not belong to this normal region as an anomaly.But several factors make this apparently simple approach very challenging:—Defining a normal region which encompasses every possible normal behavior is very difficult.In addition,the boundary between normal and anomalous behavior is often not precise.Thus an anomalous observation which lies close to the boundary can actually be normal,and vice-versa.—When anomalies are the result of malicious actions,the malicious adversaries often adapt themselves to make the anomalous observations appear like normal, thereby making the task of defining normal behavior more difficult.—In many domains normal behavior keeps evolving and a current notion of normal behavior might not be sufficiently representative in the future.—The exact notion of an anomaly is different for different application domains.For example,in the medical domain a small deviation from normal(e.g.,fluctuations in body temperature)might be an anomaly,while similar deviation in the stock market domain(e.g.,fluctuations in the value of a stock)might be considered as normal.Thus applying a technique developed in one domain to another is not straightforward.—Availability of labeled data for training/validation of models used by anomaly detection techniques is usually a major issue.—Often the data contains noise which tends to be similar to the actual anomalies and hence is difficult to distinguish and remove.Due to the above challenges,the anomaly detection problem,in its most general form,is not easy to solve.In fact,most of the existing anomaly detection techniques solve a specific formulation of the problem.The formulation is induced by various factors such as nature of the data,availability of labeled data,type of anomalies to be detected,etc.Often,these factors are determined by the application domain inTo Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.4·Chandola,Banerjee and Kumarwhich the anomalies need to be detected.Researchers have adopted concepts from diverse disciplines such as statistics ,machine learning ,data mining ,information theory ,spectral theory ,and have applied them to specific problem formulations.Figure 2shows the above mentioned key components associated with any anomaly detection technique.Anomaly DetectionTechniqueApplication DomainsMedical InformaticsIntrusion Detection...Fault/Damage DetectionFraud DetectionResearch AreasInformation TheoryMachine LearningSpectral TheoryStatisticsData Mining...Problem CharacteristicsLabels Anomaly Type Nature of Data OutputFig.2.Key components associated with an anomaly detection technique.1.3Related WorkAnomaly detection has been the topic of a number of surveys and review articles,as well as books.Hodge and Austin [2004]provide an extensive survey of anomaly detection techniques developed in machine learning and statistical domains.A broad review of anomaly detection techniques for numeric as well as symbolic data is presented by Agyemang et al.[2006].An extensive review of novelty detection techniques using neural networks and statistical approaches has been presented in Markou and Singh [2003a]and Markou and Singh [2003b],respectively.Patcha and Park [2007]and Snyder [2001]present a survey of anomaly detection techniques To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.Anomaly Detection:A Survey·5 used specifically for cyber-intrusion detection.A substantial amount of research on outlier detection has been done in statistics and has been reviewed in several books [Rousseeuw and Leroy1987;Barnett and Lewis1994;Hawkins1980]as well as other survey articles[Beckman and Cook1983;Bakar et al.2006].Table I shows the set of techniques and application domains covered by our survey and the various related survey articles mentioned above.12345678TechniquesClassification Based√√√√√Clustering Based√√√√Nearest Neighbor Based√√√√√Statistical√√√√√√√Information Theoretic√Spectral√ApplicationsCyber-Intrusion Detection√√Fraud Detection√Medical Anomaly Detection√Industrial Damage Detection√Image Processing√Textual Anomaly Detection√Sensor Networks√Table parison of our survey to other related survey articles.1-Our survey2-Hodge and Austin[2004],3-Agyemang et al.[2006],4-Markou and Singh[2003a],5-Markou and Singh [2003b],6-Patcha and Park[2007],7-Beckman and Cook[1983],8-Bakar et al[2006]1.4Our ContributionsThis survey is an attempt to provide a structured and a broad overview of extensive research on anomaly detection techniques spanning multiple research areas and application domains.Most of the existing surveys on anomaly detection either focus on a particular application domain or on a single research area.[Agyemang et al.2006]and[Hodge and Austin2004]are two related works that group anomaly detection into multiple categories and discuss techniques under each category.This survey builds upon these two works by significantly expanding the discussion in several directions. We add two more categories of anomaly detection techniques,viz.,information theoretic and spectral techniques,to the four categories discussed in[Agyemang et al.2006]and[Hodge and Austin2004].For each of the six categories,we not only discuss the techniques,but also identify unique assumptions regarding the nature of anomalies made by the techniques in that category.These assumptions are critical for determining when the techniques in that category would be able to detect anomalies,and when they would fail.For each category,we provide a basic anomaly detection technique,and then show how the different existing techniques in that category are variants of the basic technique.This template provides an easier and succinct understanding of the techniques belonging to each category.Further, for each category we identify the advantages and disadvantages of the techniques in that category.We also provide a discussion on the computational complexity of the techniques since it is an important issue in real application domains.To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.6·Chandola,Banerjee and KumarWhile some of the existing surveys mention the different applications of anomaly detection,we provide a detailed discussion of the application domains where anomaly detection techniques have been used.For each domain we discuss the notion of an anomaly,the different aspects of the anomaly detection problem,and the challenges faced by the anomaly detection techniques.We also provide a list of techniques that have been applied in each application domain.The existing surveys discuss anomaly detection techniques that detect the sim-plest form of anomalies.We distinguish the simple anomalies from complex anoma-lies.The discussion of applications of anomaly detection reveals that for most ap-plication domains,the interesting anomalies are complex in nature,while most of the algorithmic research has focussed on simple anomalies.1.5OrganizationThis survey is organized into three parts and its structure closely follows Figure 2.In Section2we identify the various aspects that determine the formulation of the problem and highlight the richness and complexity associated with anomaly detection.We distinguish simple anomalies from complex anomalies and define two types of complex anomalies,viz.,contextual and collective anomalies.In Section 3we briefly describe the different application domains where anomaly detection has been applied.In subsequent sections we provide a categorization of anomaly detection techniques based on the research area which they belong to.Majority of the techniques can be categorized into classification based(Section4),nearest neighbor based(Section5),clustering based(Section6),and statistical techniques (Section7).Some techniques belong to research areas such as information theory (Section8),and spectral theory(Section9).For each category of techniques we also discuss their computational complexity for training and testing phases.In Section 10we discuss various contextual anomaly detection techniques.We discuss various collective anomaly detection techniques in Section11.We present some discussion on the limitations and relative performance of various existing techniques in Section 12.Section13contains concluding remarks.2.DIFFERENT ASPECTS OF AN ANOMALY DETECTION PROBLEMThis section identifies and discusses the different aspects of anomaly detection.As mentioned earlier,a specific formulation of the problem is determined by several different factors such as the nature of the input data,the availability(or unavailabil-ity)of labels as well as the constraints and requirements induced by the application domain.This section brings forth the richness in the problem domain and justifies the need for the broad spectrum of anomaly detection techniques.2.1Nature of Input DataA key aspect of any anomaly detection technique is the nature of the input data. Input is generally a collection of data instances(also referred as object,record,point, vector,pattern,event,case,sample,observation,entity)[Tan et al.2005,Chapter 2].Each data instance can be described using a set of attributes(also referred to as variable,characteristic,feature,field,dimension).The attributes can be of different types such as binary,categorical or continuous.Each data instance might consist of only one attribute(univariate)or multiple attributes(multivariate).In To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.Anomaly Detection:A Survey·7 the case of multivariate data instances,all attributes might be of same type or might be a mixture of different data types.The nature of attributes determine the applicability of anomaly detection tech-niques.For example,for statistical techniques different statistical models have to be used for continuous and categorical data.Similarly,for nearest neighbor based techniques,the nature of attributes would determine the distance measure to be used.Often,instead of the actual data,the pairwise distance between instances might be provided in the form of a distance(or similarity)matrix.In such cases, techniques that require original data instances are not applicable,e.g.,many sta-tistical and classification based techniques.Input data can also be categorized based on the relationship present among data instances[Tan et al.2005].Most of the existing anomaly detection techniques deal with record data(or point data),in which no relationship is assumed among the data instances.In general,data instances can be related to each other.Some examples are sequence data,spatial data,and graph data.In sequence data,the data instances are linearly ordered,e.g.,time-series data,genome sequences,protein sequences.In spatial data,each data instance is related to its neighboring instances,e.g.,vehicular traffic data,ecological data.When the spatial data has a temporal(sequential) component it is referred to as spatio-temporal data,e.g.,climate data.In graph data,data instances are represented as vertices in a graph and are connected to other vertices with ter in this section we will discuss situations where such relationship among data instances become relevant for anomaly detection. 2.2Type of AnomalyAn important aspect of an anomaly detection technique is the nature of the desired anomaly.Anomalies can be classified into following three categories:2.2.1Point Anomalies.If an individual data instance can be considered as anomalous with respect to the rest of data,then the instance is termed as a point anomaly.This is the simplest type of anomaly and is the focus of majority of research on anomaly detection.For example,in Figure1,points o1and o2as well as points in region O3lie outside the boundary of the normal regions,and hence are point anomalies since they are different from normal data points.As a real life example,consider credit card fraud detection.Let the data set correspond to an individual’s credit card transactions.For the sake of simplicity, let us assume that the data is defined using only one feature:amount spent.A transaction for which the amount spent is very high compared to the normal range of expenditure for that person will be a point anomaly.2.2.2Contextual Anomalies.If a data instance is anomalous in a specific con-text(but not otherwise),then it is termed as a contextual anomaly(also referred to as conditional anomaly[Song et al.2007]).The notion of a context is induced by the structure in the data set and has to be specified as a part of the problem formulation.Each data instance is defined using following two sets of attributes:To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.8·Chandola,Banerjee and Kumar(1)Contextual attributes.The contextual attributes are used to determine thecontext(or neighborhood)for that instance.For example,in spatial data sets, the longitude and latitude of a location are the contextual attributes.In time-series data,time is a contextual attribute which determines the position of an instance on the entire sequence.(2)Behavioral attributes.The behavioral attributes define the non-contextual char-acteristics of an instance.For example,in a spatial data set describing the average rainfall of the entire world,the amount of rainfall at any location is a behavioral attribute.The anomalous behavior is determined using the values for the behavioral attributes within a specific context.A data instance might be a contextual anomaly in a given context,but an identical data instance(in terms of behavioral attributes)could be considered normal in a different context.This property is key in identifying contextual and behavioral attributes for a contextual anomaly detection technique.TimeFig.3.Contextual anomaly t2in a temperature time series.Note that the temperature at time t1is same as that at time t2but occurs in a different context and hence is not considered as an anomaly.Contextual anomalies have been most commonly explored in time-series data [Weigend et al.1995;Salvador and Chan2003]and spatial data[Kou et al.2006; Shekhar et al.2001].Figure3shows one such example for a temperature time series which shows the monthly temperature of an area over last few years.A temperature of35F might be normal during the winter(at time t1)at that place,but the same value during summer(at time t2)would be an anomaly.A similar example can be found in the credit card fraud detection domain.A contextual attribute in credit card domain can be the time of purchase.Suppose an individual usually has a weekly shopping bill of$100except during the Christmas week,when it reaches$1000.A new purchase of$1000in a week in July will be considered a contextual anomaly,since it does not conform to the normal behavior of the individual in the context of time(even though the same amount spent during Christmas week will be considered normal).The choice of applying a contextual anomaly detection technique is determined by the meaningfulness of the contextual anomalies in the target application domain. To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.Anomaly Detection:A Survey·9 Another key factor is the availability of contextual attributes.In several cases defining a context is straightforward,and hence applying a contextual anomaly detection technique makes sense.In other cases,defining a context is not easy, making it difficult to apply such techniques.2.2.3Collective Anomalies.If a collection of related data instances is anomalous with respect to the entire data set,it is termed as a collective anomaly.The indi-vidual data instances in a collective anomaly may not be anomalies by themselves, but their occurrence together as a collection is anomalous.Figure4illustrates an example which shows a human electrocardiogram output[Goldberger et al.2000]. The highlighted region denotes an anomaly because the same low value exists for an abnormally long time(corresponding to an Atrial Premature Contraction).Note that that low value by itself is not an anomaly.Fig.4.Collective anomaly corresponding to an Atrial Premature Contraction in an human elec-trocardiogram output.As an another illustrative example,consider a sequence of actions occurring in a computer as shown below:...http-web,buffer-overflow,http-web,http-web,smtp-mail,ftp,http-web,ssh,smtp-mail,http-web,ssh,buffer-overflow,ftp,http-web,ftp,smtp-mail,http-web...The highlighted sequence of events(buffer-overflow,ssh,ftp)correspond to a typical web based attack by a remote machine followed by copying of data from the host computer to remote destination via ftp.It should be noted that this collection of events is an anomaly but the individual events are not anomalies when they occur in other locations in the sequence.Collective anomalies have been explored for sequence data[Forrest et al.1999; Sun et al.2006],graph data[Noble and Cook2003],and spatial data[Shekhar et al. 2001].To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.10·Chandola,Banerjee and KumarIt should be noted that while point anomalies can occur in any data set,collective anomalies can occur only in data sets in which data instances are related.In contrast,occurrence of contextual anomalies depends on the availability of context attributes in the data.A point anomaly or a collective anomaly can also be a contextual anomaly if analyzed with respect to a context.Thus a point anomaly detection problem or collective anomaly detection problem can be transformed toa contextual anomaly detection problem by incorporating the context information.2.3Data LabelsThe labels associated with a data instance denote if that instance is normal or anomalous1.It should be noted that obtaining labeled data which is accurate as well as representative of all types of behaviors,is often prohibitively expensive. Labeling is often done manually by a human expert and hence requires substantial effort to obtain the labeled training data set.Typically,getting a labeled set of anomalous data instances which cover all possible type of anomalous behavior is more difficult than getting labels for normal behavior.Moreover,the anomalous behavior is often dynamic in nature,e.g.,new types of anomalies might arise,for which there is no labeled training data.In certain cases,such as air traffic safety, anomalous instances would translate to catastrophic events,and hence will be very rare.Based on the extent to which the labels are available,anomaly detection tech-niques can operate in one of the following three modes:2.3.1Supervised anomaly detection.Techniques trained in supervised mode as-sume the availability of a training data set which has labeled instances for normal as well as anomaly class.Typical approach in such cases is to build a predictive model for normal vs.anomaly classes.Any unseen data instance is compared against the model to determine which class it belongs to.There are two major is-sues that arise in supervised anomaly detection.First,the anomalous instances are far fewer compared to the normal instances in the training data.Issues that arise due to imbalanced class distributions have been addressed in the data mining and machine learning literature[Joshi et al.2001;2002;Chawla et al.2004;Phua et al. 2004;Weiss and Hirsh1998;Vilalta and Ma2002].Second,obtaining accurate and representative labels,especially for the anomaly class is usually challenging.A number of techniques have been proposed that inject artificial anomalies in a normal data set to obtain a labeled training data set[Theiler and Cai2003;Abe et al.2006;Steinwart et al.2005].Other than these two issues,the supervised anomaly detection problem is similar to building predictive models.Hence we will not address this category of techniques in this survey.2.3.2Semi-Supervised anomaly detection.Techniques that operate in a semi-supervised mode,assume that the training data has labeled instances for only the normal class.Since they do not require labels for the anomaly class,they are more widely applicable than supervised techniques.For example,in space craft fault detection[Fujimaki et al.2005],an anomaly scenario would signify an accident, which is not easy to model.The typical approach used in such techniques is to 1Also referred to as normal and anomalous classes.To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.Anomaly Detection:A Survey·11 build a model for the class corresponding to normal behavior,and use the model to identify anomalies in the test data.A limited set of anomaly detection techniques exist that assume availability of only the anomaly instances for training[Dasgupta and Nino2000;Dasgupta and Majumdar2002;Forrest et al.1996].Such techniques are not commonly used, primarily because it is difficult to obtain a training data set which covers every possible anomalous behavior that can occur in the data.2.3.3Unsupervised anomaly detection.Techniques that operate in unsupervised mode do not require training data,and thus are most widely applicable.The techniques in this category make the implicit assumption that normal instances are far more frequent than anomalies in the test data.If this assumption is not true then such techniques suffer from high false alarm rate.Many semi-supervised techniques can be adapted to operate in an unsupervised mode by using a sample of the unlabeled data set as training data.Such adaptation assumes that the test data contains very few anomalies and the model learnt during training is robust to these few anomalies.2.4Output of Anomaly DetectionAn important aspect for any anomaly detection technique is the manner in which the anomalies are reported.Typically,the outputs produced by anomaly detection techniques are one of the following two types:2.4.1Scores.Scoring techniques assign an anomaly score to each instance in the test data depending on the degree to which that instance is considered an anomaly. Thus the output of such techniques is a ranked list of anomalies.An analyst may choose to either analyze top few anomalies or use a cut-offthreshold to select the anomalies.2.4.2Labels.Techniques in this category assign a label(normal or anomalous) to each test instance.Scoring based anomaly detection techniques allow the analyst to use a domain-specific threshold to select the most relevant anomalies.Techniques that provide binary labels to the test instances do not directly allow the analysts to make such a choice,though this can be controlled indirectly through parameter choices within each technique.3.APPLICATIONS OF ANOMALY DETECTIONIn this section we discuss several applications of anomaly detection.For each ap-plication domain we discuss the following four aspects:—The notion of anomaly.—Nature of the data.—Challenges associated with detecting anomalies.—Existing anomaly detection techniques.To Appear in ACM Computing Surveys,092009.。

锰铝榴石的颜色三要素特征

2020年8月中国宝玉石16◦期Aug2020CHINA GEMS &JADES41-48页锰铝榴石的颜色三要素特征黎嘉宝中国地质大学(北京)珠宝学院,北京100083摘要:为促进锰铝榴石分级标准的建立和完善,本文从市场中选取38颗颜色由深橙红向浅橙色过渡的锰铝榴石样品,通过紫外一可见光分光光度计测试分析其光谱特征,利用X-Rite SP62积分球式分光光度计测量样品的颜色数据,并基 于CIE 1976 L W均匀色空间对样品颜色进行定量表征,分析其颜色特征,为锰铝榴石的颜色质量评价提供一定的理论 依据。

通过统计学分析,得出样品CT值与b’的相关系数r为0.927,说明锰铝榴石的彩度随黄色饱和度的增大而增大,样品K值与1/值的相关系数I•为0.896,说明锰铝榴石的色调角随黄色饱和度的增大而增大;样品I;值与IV值的相关 系数r为0.949,说明锰铝榴石的明度随色调角的增大而增大。

关键词:锰铝榴石;色度学;定量表征中图分类号:P574.1 + 1文献标识码:A文章编号:1002-1442(2020)04-0041-08The Characteristics of Three Elements of Spessartine ColorLI JiabaoSchool o f Gemmology,China University o f Geosciences(Beijing),Beijing 100083ABSTRACT:In order to promote the establishment and improvement o f the classification standard o f spessartine,this paper selected38 samples o f spessartine from market,whose colors vary from deep orange red to light orange.The experiment used ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy testing to analyze the optical spectra,and used X-Rite SP62 spectrophotometer to measure the color o f the samples.Quantitative characterization of the color of the samples based on the CIE 1976 L*a*b*uniform color space are used to analyze its color characteristics,so as to provide a certain theoretical basis for the color quality evaluation o f spessartine.According to statistical analysis,the Pearson correlation coefficient (r)between C*value and b*value o f samples is0.927, indicating that the chroma of spessartine increases as its yellow saturation increases.The r value between h value and b*value o f samples is 0.896, indicating that the hue angle o f spessartine increases as its yellow saturation increases.The r value between L*value and h value o f samples is0.949, indicating that the lightness o f spessartine increases as its hue angle increases. KEY W ORDS:spessartine;chromaticity;quantitative characterization引言锰铝榴石为石榴石族矿物中的重要品种之一,常见 橙一橙红色,其中具有明艳橙色者由于颜色接近芬达汽水 而被称为“芬达石”,颇受市场追捧。

【高中生物】Nature:蛋白表达,过犹不及

【高中生物】Nature:蛋白表达,过犹不及摘要:许多生物学过程都符合儒家“过犹不及”的规律:增之一分太多,减之一分太少,恰如其分刚刚好。

近日来自麻省理工学院的神经科学家们发现两种罕见的自闭症相关疾病是由大脑中的同一种神经传导受体mglur5以两种相反的机制引起。

这一研究发现在线发表在11月23日的《自然》(nature)杂志上。

生物通报导许多生物学过程都合乎儒家“过犹不及”的规律:减之一分太多,减至之一分太太少,恰如其分刚刚好。

近日源自麻省理工学院的神经科学家们辨认出两种少见的自闭症有关疾病就是由大脑中的同一种神经传导受体mglur5以两种恰好相反的机制引发。

这一研究辨认出在线刊登在11月23日的《自然》(nature)杂志上。

众所周知脆性x综合症(fragilexsyndrome)是由单个基因fmr1的突变引起的,当fmr1基因发生突变时会阻碍其编码蛋白fmrp表达,导致大脑中fmrp缺失。

几年前,麻省理工学院的神经学教授markbear发现在正常情况下fmrp蛋白可以控制或阻断大脑细胞中mglur5激活的信号途径。

fmrp缺失时,mglur5信号过度激活,促发过量突触蛋白合成,从而导致大脑神经元联系异常以及与脆性x综合症相关的行为及认知障碍。

mglur5就是一种在传输神经元之间信号上起至关键促进作用的受体。

当神经元前细胞放出神经递质,它将与神经元后神经元mglur5融合,引爆崭新突触蛋白的制备。

fmrp在这一过程中起至着蛋白制备制动器的功能。

通过调节mglur5提振和fmrp遏制之间的均衡,细胞制备适度水平的突触蛋白。

当fmrp出现缺位时,则可以引致过量分解成突触蛋白,引起脆性x综合症常用症状:自学障碍和自闭症犯罪行为等。

在过去的研究中,bear和其他研究人员证实切断mglur5即可爆冷小鼠的这些症状。

在确定了mglur5与脆性x综合症之间的联系后,bear和同事们开始进一步探究mglur5过度激活是否还可能引起了表现自闭症类似症状的其他单基因综合症。

斑马鱼松果体对视觉敏感性生物钟的维持作用及长时记忆缺陷突变体的筛选

记忆根据持续时间的长短分为长时记忆和短时记忆。

许多研究聚焦于学习和记忆如何进行的。

但是学习和记忆作为一种复杂的行为,仍然有许多问题需要去探索研究。

而在脊椎动物中发现学习和记忆的突变基因,对其机制的研究会有一定的贡献。

本实验中以斑马鱼为模式动物,经ENU诱变及大规模遗传筛选,利用抑制逃避反应的行为学方法获得一例学习记忆的斑马鱼突变体触。

这种fgt斑马鱼突变体的训练后24小时的长时记忆显著的低于野生型。

触突变体表现出正常的运动活性和正常的对黑色的倾向性。

该突变体的F2代在训练后的24小时的长时记忆中有将近一半(13/30)显著的低于野生型,而另一半则相对正常。

同时,在对一个新的环境的探索后,与学习记忆相关的即刻早期基因IEGsc-fos在该突变体将近一半F2代中的表达与野生型的对照有显著性的差异(13/30),另外一半相对正常,与行为学结果一致。

这些结果表明,该突变体触是一个学习和记忆缺陷的显性突变。

而该fgt突变体的发现对未来进一步学习和记忆相关的机制和信号通路提供了一种可能。

关键词:松果体,视觉敏感性,生物钟,学习和记忆,fgt突变体,c-los缩略词LLLDDDSCNGFPERGdpfhpfkK鼠§忒UASNTRMtzMOENUIEGsRTFsPVNFRAS符号说明英文名称Light-LightLight-DarkDark—DarkSupraChiasmaticNucleusGreenFluorescentProteinElectroretinogramsDaysPost-FertilizationHoursPost.FertilizationArylalkylamineN—acetyltransferaseUpstreamActivatingSequencesNitroreductaseMetronidazoteMorpho·linoN.-ethyl--N·-nitrosoureaImmediate-EarlyGenesRegulatoryTranscriptionFactorsParaventricularNucleusFos-relatedantigensV中文名称光照一光照光照一黑暗黑暗一黑暗视交叉上核绿色荧光蛋白视网膜电流图受精后N天受精后N小时芳烷基胺N一乙酰转移酶上游激活序列硝基还原酶甲硝唑吗啉代N.乙基一N一亚硝基脲即刻早期基因调节转录因子下丘脑室旁核Fos相关抗原目录帚一草闩U舌…………………………………………………………….1第一章前言…………………………………………………………….1第一节斑马鱼~脊椎动物模型………………………………………………一1第二节斑马鱼是研究昼夜节律的理想动物模型……………………………一31.2.1生物节律概述……………………………………………………………………31.2.2哺乳动物生物节律的分子机理…………………………………………………41.2.3斑马鱼的松果体…………………………………………………………………61.2.4斑马鱼是良好生物节律研究模型……………………………………………..I11.2.5生物节律在斑马鱼上的研究进展……………………………………………一12第三节转基因斑马鱼的研究与应用…………………………………………231.3.1T012转座技术…………………………………………………………………一241.3.2GAIA/UAS在斑马鱼中的应用…………………………………………………261.3.3NTR/Mtz系统在斑马鱼中的应用………………………………………………29第四节斑马鱼的ENU诱变…………………………………………………..31第五节学习和记忆相关的基因………………………………………………351.5.1即刻早期基因IEGs(immediate.earlygenes)的概述……………………….351.5.2IEG的细胞功能…………………………………………………………………381.5.3一个特别的IEG:c-fos…………………………………………………………38第二章斑马鱼松果体对维持视觉敏感性生物钟的作用……………43第一节材料和方法……………………………………………………………432.1.1实验动物………………………………………………………………………一432.1.2主要试剂………………………………………………………………………一432.1.3主要仪器……………………………………………..:…………………………442.1.4转基因载体pT2KXIG.gnat2一Gal4/VPl6的构建……………………………..442.1.5pCSTZ2.8转座酶mRNA的体外转录…………………………………………462.1.6显微注射………………………………………………………………………一482.1.7转基因斑马鱼的筛选和养殖…………………………………………………..49VI3.1.8诱导c-fos基因表达的行为学…………………………………………………793.1.9REAL—TIMEPCR…………………………………………………………………………………….793.1.10统计学分析……………………………………………………………………83第二节实验结果与分析………………………………………………………833.2.1野生型斑马鱼的黑色倾向性…………………………………………………..833.2.2斑马鱼在抑制逃避电击后形成稳定长时记忆………………………………..843.2.3学习和记忆突变体的筛选……………………………………………………一853.2.4基因表达水平鉴定突变体……………………………………………………一87第三节实验讨论与总结………………………………………………………89第四节实验结论与展望………………………………………………………94参考文献………………………………………………………………..95致谢……………………………………………………………………………………….107个人简历、在学期问发表的学术论文与研究成果…………………108个人简历………………………………………………………………………108在学期间发表的学术论文……………………………………………………108VII工第一章前言第一节斑马鱼一脊椎动物模型斑马鱼作为一种新的可以用于研究神经发育、功能和疾病的脊椎动物模型,已经吸引全世界大批实验室和科学家围绕其展丌了广泛的研究。

甘蔗二点螟性信息素地理变异假说

甘蔗二点螟性信息素地理变异假说胡玉伟;管楚雄;林明江;李继虎;温莉茵【摘要】甘蔗二点螟是严重为害我国甘蔗的钻蛀性害虫,化学防治效果不佳且污染环境.其性信息素防治技术早已开始,然而多年田间实验发现其在不同生态型蔗区活性差异很大,可能存在地理变异.本项目提出理论假说,认为二点螟性信息素可能因地理隔离存在组分或含量的地理变异,并给出该假说的理论依据,便于地理变异机制等实验的开展和实施,丰富此类昆虫的化学生态学理论.%Chilo infuscatellus is a very important pest in the sugarcane and it is not working to control it by pesticides.Researchers have paid close attention to the application of its sex pheromone.However,the effects of sex pheromone were found different in populations,which delayed the application of sex pheromone in field.One hypothesis is that there may be variation in composition of sex pheromone because of geographic isolation.This paper give the theory basis of this hypothesis to conduct the next experiment and to enrich the study of chemical biology of this species.【期刊名称】《甘蔗糖业》【年(卷),期】2013(000)003【总页数】4页(P15-18)【关键词】二点螟;信息素;变异【作者】胡玉伟;管楚雄;林明江;李继虎;温莉茵【作者单位】广州甘蔗糖业研究所广东省甘蔗改良与生物炼制重点实验室,广东广州510316;广州甘蔗糖业研究所广东省甘蔗改良与生物炼制重点实验室,广东广州510316;广州甘蔗糖业研究所广东省甘蔗改良与生物炼制重点实验室,广东广州510316;广州甘蔗糖业研究所广东省甘蔗改良与生物炼制重点实验室,广东广州510316;广州甘蔗糖业研究所广东省甘蔗改良与生物炼制重点实验室,广东广州510316【正文语种】中文【中图分类】S566.11 理论假说的提出及研究意义过度使用化学杀虫剂控制农业害虫,极大地影响着我国农业生产安全、农产品质量安全、农业生态安全和农业贸易安全。

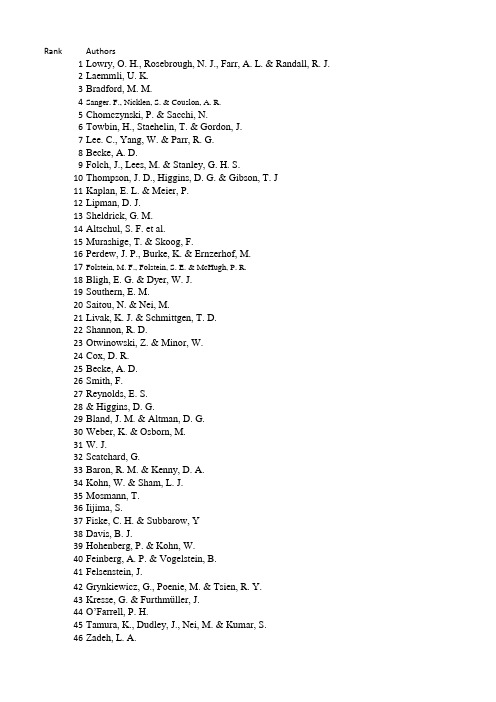

引用次数最多的100篇SCI文章