斯蒂芬D威廉森宏观经济学第三版第十一章Stephen D. Williamson's Macroeconomics, Third Edition chapter11

威廉森《宏观经济学》笔记和课后习题详解(包含投资的实际跨期模型)【圣才出品】

1 / 205第11章 包含投资的实际跨期模型11.1 复习笔记一、典型消费者1.基本分析典型消费者在当期和未来的每一时期作出工作-闲暇决策,在当期作出消费-储蓄决策。

(1)典型消费者预算约束①基本假定a .典型消费者在每一时期有h 单位的时间,并在每一时期都将该时间划分为工作时间和闲暇时间;b .w 表示当期实际工资,w ′表示未来实际工资,r 表示实际利率,消费者当期和未来向政府缴纳的一次总付税,分别为T 和T ′;c .把w 、w ′和r 视为给定,该典型消费者是价格接受者。

从消费者的角度看,税收也是给定的。

2 / 205②预算约束a .当期预算约束当期,典型消费者挣得实际工资收入w (h -l ),从典型企业那里获得股息收入π,纳税T ,当期可支配收入是w (h -l )+π-T 。

当期可支配收入被划分为消费和储蓄,储蓄的表现形式是债券,获取的一时期实际利率为r 。

在这种情形下,消费者通过发行债券来借款。

于是,消费者的当期预算约束是:C +S P =w (h -l )+π-Tb .未来预算约束未来,典型消费者获取的实际工资收入w ′(h -l ′),从典型企业那里获得股息收入π′,向政府纳税T ′,并获得当期储蓄的本息(1+r )S p 。

由于未来是最后时期,又由于假定消费者没有留下遗产,因此未来消费者的全部财富都用于消费,于是,消费者的未来预算约束是:C ′=w′(h -l ′)+π′-T ′+(1+r )S pc .一生预算约束把S p 代入当期预算约束,可以得到典型消费者的一生预算约束3 / 205该预算约束表明,消费的现值(等式左边)等于一生可支配收入的现值(等式右边)。

(2)典型消费者的最优决策典型消费者的问题是,选择未来消费C ′、当期消费C 、当期闲暇时间l 和未来闲暇时间l ′,使其境况尽可能改善,同时又满足一生预算约束。

消费者的最优决策的三个边际条件:①消费者在当期作出工作—闲暇决策,因此,当消费者实现最优时,有: MRS l ,c =w亦即消费者通过选择当期闲暇和消费,使闲暇对消费的边际替代率等于当期实际工资,就可以实现最优。

罗默《高级宏观经济学》第3版课后习题详解(预算赤字与财政政策)【圣才出品】

的函数: r t r d t ,这里 r>0 ,

r>0 , lim r d g , lim r d g 。

d

d

①找出用 a 、 g 与 d t 表示的 d 的表达式。

②把

d t

刻画为

d t

的函数。在这种情形中

a

是充分小的,以至于对于一些

d

的值

d t 0 。这个体系的稳定性特性是什么呢?在 a 充分大,使得对于 d 的一切值 d t 0 的情

形,体系将是什么样的性质呢?

答:(a)①将等式 d t Dt /Y t 对时间求导得:

d

t

D

tY

t DtY Y t 2

t

1 / 41

(1)

圣才电子书 十万种考研考证电子书、题库视频学习平台

将预算赤字等于未清偿的债务量的变化率 D t t 和 Y t Y t g 代入方程(1)得:

及热尔兹,1986)。考虑这样一位个人,其生活在两个时期内,他无初始财富,只在两个时

期 内获 得 数量 为 Y1 与 Y2 的 劳动 收 入。 Y1 是 已知 的 ,但 Y2 是 随机 的 。为 了 简化 , 假设

E Y2 Y1 t 。政府在第一个时期征收的所得税税率为1 ,在第二个时期征收的所得税税率

d

t

Y

t t

Dt g Y t

(2)

假设赤字—产出比率不变, t /Y t a 和 d t Dt /Y t 两式代入方程(2)得:

d

t

a

gd

t

(3)

②图 11-1 画出了债务—产出比率。

图 11-1 债务—产出比率

在

d

,d

空间中,方程(3)是一条斜率为

宏观经济学-课后思考题答案_史蒂芬威廉森011

宏观经济学-课后思考题答案_史蒂芬威廉森011Chapter 11Market-Clearing Models of the Business CycleTeaching GoalsPhysics has so far failed to provide a unified theory to explain all physical phenomena. Economics is even further away from achieving such a goal. Keynesian models, while still popular among many policymakers, do not do a very good job of explaining the source and the mechanism by which the typical business cycle comes to pass. Although business cycles are remarkable similar, they are not identical, and they appear to have multiple causes.Equilibrium theorists have proposed a number of business cycle explanations that are based upon microeconomic principles and need not rely on markets failing to equilibrate. Interestingly, in contrastto the most basic of classical models, these models often admit a constructive role for macroeconomic policymaking.The real business cycle model emphasizes the point that shocks to total factor productivity are persistent, and that business cycles may represent the optimal response to such shocks. The segmentation markets model realizes that not everyone participates in financials markets and thus some agents are primarily effected by open market operations. The coordination failure model recognizes the possibility that strategic complementarities generate a kind of externality in production. While all of these considerations may, to a greater or less extent, be important factors in macroeconomic performance, a model that simultaneously considered all of these possibilitieswould be too unwieldy to provide coherent insights. Nevertheless, all of the possibilities of these models shed light on some causes and means of propagating business cycles.Classroom Discussion TopicsThe material in this chapter concludes the study of business cycle phenomena and macroeconomic stabilization policy. At this point it may be useful to revisit students’ original thoughts and prejudices about the proper role of government policy. With so many competing models, how would the students run monetary and fiscal policy if it were their job to do so? Does macroeconomics offer too many competing models and too many points of view? It can be helpful to point out that there is no consensus among macroeconomists on this issue. Should policy be used on a routine basis to fine-tune the economy? Should policymakers simply try to avoid significant fluctuations in the policy instruments? Should aggressive policy measures be employed against very serious shocks like the Great Depression?108 Williamson ? Macroeconomics, Third EditionOutlineI. The Real Business Cycle ModelA. The Workings of the Real Business Cycle Model1. Persistence of the Solow Residual2. Effects of a Persistent Change in Total Factor Productivity3. Qualitative and Quantitative Replication of the Business Cycle FactsB. Real Business Cycles and the Behavior of the Money Supply1. Cyclical Properties of the Money Supplya. Nominal Money Is Procyclicalb. Nominal Money Leads Real GDP2. Endogenous M oneya. Behavior of Bank Deposit Moneyb. Central Banks and Price-Level Stabilization3. Statistical Causality and True CausalityC. Implications of the Real Business Cycle Model for Government Policy1. Money Is Neutral2. Government Spending Based on Optimal Provision of Public Goods3. Other Policy Goalsa. The Friedman Ruleb. The Smoothing of Tax DistortionsD. Critique of the Real Business Cycle Model1. Measurement of Total Factor Productivity2. Labor Hoarding3. Real Business C ycle Theory and the “Volker Recession”II. The Segmented Markets ModelA. Limited Participation in Financial MarketsB. The Workings of the Model1. The Liquidity Effect2. Money Demand as a Function of the Expected Interest Rate3. Money Supply Surprises Are Not NeutralC. Implications1. Real Impact2. Money Injection Increases GDP and Components3. Average Labor Productivity Is Counterfactually Countercyclical4. Central Bank Can Be Welfare Improving: It Alleviates Cash ConstraintsD. Critique1. Relies on Central Bank Fooling Agents2. Relies on Firms Being Cash ConstraintChapter 11 Market-Clearing Models of the Business Cycle 109III. A Keynesian Coordination Failure ModelA. The Workings of the Model1. Coordination Failures2. Strategic Complementarities3.M ultiple Equilibria4. Increasing Returns to ScaleB. The Coordination Failure Model: An Example1. The Downward-Sloping Goods Supply Curve2. Multiple Intersections of Goods Supply and Goods Demand3. SunspotsC. Predictions of the Coordination Failure Model1. Properties of “Good” and “Bad” Equilibria2. The Coordination Failure Model and the Business Cycle FactsD. Policy Implications of the Coordination Failure Model1. Achieving a Single Equilibrium2. Does Policy Improve Performance?E. Critique of the Coordination Failure Model1. Evidence of Increasing Returns2. Unobservable ExpectationsTextbook Question SolutionsQuestions for Review1. Macroeconomic models should be based onmicroeconomic principles. Equilibrium models are the most productive vehicles for studying macroeconomic phenomena.2. Although business cycles are remarkably similar, they may have many causes. Alternative businesscycle models offer insights into one or more key features of the economy and some aspects of the e conomy’s response to macroeconomic shocks. Policymakers need as much insight as possible to guide their actions.3. In the real business cycle model, persistent shocks to total factor productivity cause output tofluctuate.4. Although changes in the money supply change nominal prices in the real business cycle, they changeneither perceived nor actual relative prices. There is therefore no reason for firms or consumers to change their behavior.5. In the real business cycle model, changes in the money supply may be endogenous. In particular,when output increases due to a total factor productivity shock, the banking system is likely toincrease the quantity of deposit money, and the Fed may increase the monetary base in order tostabilize the aggregate price level.6. In the real business cycle model, firms and consumers in the economy make optimal responses tochanges in total factor productivity. Therefore, policy cannot improve matters, and may actually make matters worse.110 Williamson ? Macroeconomics, Third Edition7. The real business cycle provides a good explanation of the business cycle facts, both qualitatively andquantitatively.8. There are some phenomena that the real business cycle model cannot adequately explain. As oneexample, there is good evidence that the U.S. recession of 1981–82 was due to a monetary policy shock. The real business cycle model has no explanation of monetary nonneutrality.9. It is because it affects agents after they have made their money choices and, in this model, allows thefirm to adjust its activities that are cash constrained.10. Only if it does that intelligently. Purely random policy would be detrimental, as it would throw agentsoff their plans. But if it helps them as they face shocks, for example by alleviating cash constraints, then it is good stabilization policy. The central bank, however, needs to have very good information and needs to act quickly.11. Remarkably well, except for the countercyclical average labor productivity.12. Parties are more fun when a lot of people attend. If everyone believes that others will attend,everyone goes to the party and has a good time. However, if most people think that others are not going, they will also choose not to go, few people will show up and the party will be much lesssuccessful. The coordination failure arises because people may not be able to jointly decide whether they will attend.13. In the coordination failure model, business cycles may occur if consumers and firms are alternativelyoptimistic and pessimistic. Aggregate-level increasing returns to scale then set in to amplify the effects of such changes in attitude.14. The coordination failure model is an equilibrium model. In the absence of any other changes inbehavior, changes in the money supply change the aggregate price level, but they do not change relative prices. Therefore, consumers and firms continue to make the same choices.15. The coordination failure model does a very good job in fitting the facts of the typical business cycle.16. The choice of which model is better depends on how we interpret some of the more detailedevidence. However, both models may shed some light on some features of different business cycle events, and both models may offer some insights that may be useful for policymakers.Problems1. The response to a temporary change in government spending in the real business cycle model is thesame as the response to such a disturbance in the monetary intertemporal model, as the two models are equivalent. Government spending shocks in this model wrongly predict that consumption,investment, and the real wage are countercyclical. In response to a temporary increase in government spending, output increases and the real interest rate increases. Because the net effect on moneydemand is ambiguous, the effect on the price level is also ambiguous. Therefore, there can be no contradiction of model’s predictions on the cyclical behavior of the price level.Chapter 11 Market-Clearing Models of the Business Cycle 111 2. We already know that persistent increases in total factorproductivity are consistent with all of thebusiness cycle facts. As developed in the answer to problem 4, above, we noted that temporaryincreases in government spending were not consistent with several of the business cycle facts. If both disturbances are combined, the ability to fit the facts depends on which of the parts of the disturbance are stronger. In particular, if the increase in government spending produces a small increase in total factor productivity, then this type of disturbance will not fit the facts very well. For this type ofdisturbance to fit the business cycle facts, a small increase in government spending would need to generate a large increase in total factor productivity.3. Business optimism about future total factor productivity.(a) First consider the fundamental effects of the increase in expected future total factor productivity.Such a disturbance shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right. In the coordination failuremodel, this results in an increase in output and employment in the good equilibrium and adecrease in output and employment in the bad equilibrium. The increased optimism might alsomove the economy from the original bad equilibrium to the new good equilibrium.(b) Let us focus on the effects of changes in future total factor productivity on the good equilibrium.This disturbance shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right. The good equilibrium is at higher levels of output and employment, and a lower real interest rate. In the labor market, the reduction in the real interest rate also increases the real wagerate. The decrease in the real interest rateincreases consumption spending. The increase in the real interest rate likely mitigates, but doesnot reverse, the direction of the effect of the disturbance on investment. All of these effects areconsistent with the business cycle facts. Finally, the increase in output and the reduction in thereal interest rate both work to increase money demand. The price level therefore decreases, which is also consistent with the business cycle facts.(c) The increased optimism decreases the price level in the good equilibrium. Therefore, themonetary authority should increase the money supply when firms become more optimistic andreduce the money supply when firms become more pessimistic. Note that if the money supply isa sunspot variable, there may be a difficulty with reducing the money supply when firms becomemore pessimistic. This policy response is therefore consistent with the nominal money supplybeing procyclical. Such a change in the money supply may also shift the economy from the good equilibrium to the bad equilibrium, and this factor obviously greatly complicates the analysis.4. Announced policies in the segmented markets model.(a) In this case, the expected real interest rate r e is unaffected, despite the announcement, and moneysupply M s is reduced. This is equivalent to an unexpected decrease of the money supply, and we have the exact opposite situation from what is described in Figure 11.5 of the textbook.Thus, the interest rate and the price level will increase; employment, output, consumption, and investment all decrease.(b) As this announcement is believed, all agents will be able to react to it and there is no marketsegmentation. We are thus back to the monetary model of Chapter 10. Real aggregates areunaffected, only the price level decreases.(c) The price level changes more in the second situation, as there is no real impact that wouldcounterbalance it. Now to make its policy announcements more credible, the central bank would need to show consistently that it is acting like it said it would. This can, for example, be attained by sticking to a well-publicized rule.112 Williamson ? Macroeconomics, Third Edition5. We want to compare here a positive money supply shock as it affects economies a and b that areinitially at steady state. The shock is larger in economy a. The figures below build on Figure 11.5 from the textbook, the only difference being the amplitude of the shocks. The steady states are the same for both countries, with one exception: money demand is lower in country a due to the higher uncertainty about prices. Indeed, households do not like variations, thus all agents will use more banking services to avoid the larger consequences from price variations. The consequence is that all aggregates fluctuate more in country a. While the price level is initially higher in country a, it may fall below the one in the other country, depending on the difference in money demands between the two countries. But the price level fluctuates more for sure in country a. The figures belowillustrate this.Chapter 11 Market-Clearing Models of the Business Cycle 1136. If the money supply were the only variable that shifts the economy between the bad and good states,the monetary authority would need to increase the money supply only if the economy starts out in the bad state. However, once the good state is reached, there is no further need to make any changes in the money supply. Both models are therefore consistent with a predictable money supply as the best way to make consumers better off.On the other hand, if there was a disturbance that shifted the economy into the bad state, it would be optimal for the monetary authority to increase the money supply when output falls. In the money surprise model, changes in the money supply in response to disturbances can only make consumers worse off.7. The reduction in the demand for leisure implies a rightward shift in labor supply. This shift in laborsupply implies an equilibrium in the labor market with less employment and a decreased real wage.The aggregate supply curve therefore shifts to the left. The increase in the demand for consumption goods shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right. Therefore, in the good state, output increases and the real interest rate decreases. In the bad state, output decreases and the real interest rate increases.114 Williamson ? Macroeconomics, Third Edition8. The permanent increase in government spending does not affect the aggregate demand curve, becausethe increase in government spending generates an approximately equal decrease in consumption. The implied increase in taxes shifts the labor supply curve to the right. In the coordination failure model this produces a leftward shift in aggregate supply. Recall that the labor demand curve is upward sloping and steeper than the labor supply curve. A leftward shift in aggregate supply is depicted in the figure below.In the “good” equilibrium, output increases and the real interest rate decreases. That output increases requires that employment increase. The increase in employment moves the economy along the labor demand curve, so that the real wage rate must also increase. Finally, the increase in output combined with the decrease in the real interest rate implies that money demand shifts to the right, and so the price level decreases.In the “bad” equilibrium, output decreases and the real interest rate increases. That output decreases requires that employment decrease. The decrease in employment moves theeconomy along the labor demand curve, so that the real wage rate must also decrease. Finally, the decrease in output combined with the decrease in the real interest rate implies that money demand shifts to the left, and so the price level increases.Chapter 11 Market-Clearing Models of the Business Cycle 115 9. The effects of the decrease in the capital stock depend on the specific model we are working with.The effect of the decrease in capital in the real business cycle is depicted in the figure below.116 Williamson ? Macroeconomics, Third EditionThe real interest rate unambiguously increases. The diagramdepicts a case in which real outputdecreases. In this case, the demand for money unambiguously decreases, and so a decrease in the money supply is required to maintain price stability. If, on the other hand, the increase in investment demand is strong enough, then the aggregate demand curve may shift to the right by more than the shift to the left in aggregate supply. In this case, real output increases. If real output increases enough, then the demand for money may increase. This case would require an increase in the money supply.In the coordination failure model, the situation is more complex. The decrease in the capital stock shifts the aggregate production function downward, as in the figure below. The new aggregateproduction function is flatter, so that the aggregate labor demand curve shifts downward. Employment would therefore increase. The increase in employment coupled with the decrease in the capital stock, may either increase or decrease the level of output. If, as depicted in the figure below, output on net decreases, then the aggregate supply curve shifts to the left.Chapter 11 Market-Clearing Models of the Business Cycle 117 The decrease in the capital stock also shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right. If the aggregate supply curve shiftsto the left, then the situation is as depicted in the figure below. In the bad equilibrium, output decreases and the real interest rate increases. Money demand would therefore decrease, and the money supply would need to decrease to maintain price stability. In the good equilibrium, output increases and the real interest rate decreases. Money demand would increase, and so the money supply would need to increase to maintain price stability.。

斯蒂芬D威廉森宏观经济学第三版第六章Stephen D. Williamson's Macroeconomics, Third Edition chapter6

6-25

Figure 6.10 Adjustment to the Steady State in the Malthusian Model When z Increases

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

6-26

6-21

Figure 6.7 The Per-Worker Production Function

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

6-22

Figure 6.8 Determination of the Steady State in the Malthusian Model

6-4

Real Per Capita Income and the Investment Rate

Across countries, real per capita income and the investment rate are positively correlated.

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

• There is no tendency for rich countries to grow faster than poor countries, and vice-versa. • Rich countries are more alike in terms of rates of growth than are poor countries.

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

宏观经济学第十一章-宏观经济政策和理论课件

宏观经济政策和理论

宏观经济学第十一章-宏观经济政 策和理论

1

第一节 主动性和被动性政策

➢一、政策效果滞后 ➢二、宏观经济的不确定性 ➢三、卢卡斯批判

宏观经济学第十一章-宏观经济政 策和理论

2

一、政策效果滞后

政策制定者会遇到的时滞有三种: ➢1、识别时滞 ➢2、行动时滞 ➢3、生效时滞

宏观经济学第十一章-宏观经济政 策和理论

25

反对实施严格的预算平衡策略的理由

➢ 首先,预算赤字或盈余可以对稳定经济有所帮助。 ➢ 其次,在税收体系的运作过程中常常会出现对经

济施加不当刺激的扭曲,而预算赤字或盈余则可 以用来消除这种扭曲。

➢ 此外,政府可以借助预算赤字将税收负担从当前 居民身上转移到下一代人,这在某些非常时期对 维护宏观经济的平稳运行是十分有益的。

P1

C

AD0

AD1

AD1

0

Y1 Y

Y2 Y 0

(a)货币主义周期

LAS SAS

C

A

B

AD2

AD0 AD1

Y1 Y

AD0

AD1

Y2

Y

(b)理性预期周期

图11.6

新古典的传统周期理论

宏观经济学第十一章-宏观经济政

策和理论

30

3、实际经济周期理论

实际经济周期理论(Real business cycle theory) 对传统总需求波动理论提出了修正。

3、麦卡伦姆规则代表了一种被动性政策的货币政策规则, 而泰勒规则体现了一种主动性政策的货币政策规则。

宏观经济学第十一章-宏观经济政 策和理论

24

财政政策规则

最突出的一条规则是预算平衡策略。所谓预算平 衡策略,顾名思义,就是政府的支出不得突破其 税收收入,进而维持财政收支的平衡。

西方经济学第三版第11-14 章课后习题答案

一、思考题 2.什么是总供给函数?说明总供给曲线的通常形状。

3.什么是总需求函数?怎么推导出总需求曲线?4.试比较"古典"AS —AD 模型和修正的凯恩斯的AS —AD 模型。

5.用图形说明短期均衡的三种状态。

(萧条、高涨和滞胀)6.说明完全凯恩斯模型的方程及其图像。

7.简述凯恩斯效应与庇古效应的含义及其比较。

8.叙述理性预期ES —AD 模型及政策含义。

9.评析宏观经济基本理论的演变。

二、计题1.有一古典的 AS-AD 模型,总供给函数 Y=Y f =1000, 求:( 1)均衡价格水平;( 2)如价格不变,总需求函数变为 P=1000-0.4Y 时,经济会怎样?( 3)如总需求函数为 P=1000-0.4Y ,价格可变动时,均衡价格变动多少?2.假定某经济社会的短期生产函数为 Y=14N-0.04N 2,劳动力需求为 N d =175-12.5(W/P ),劳动力供给函数 N s =70+5(W/P),求( 1)当 P=1和 P=1.25时,劳动力市场均衡的就业量和名义工资率分别是多 少?( 2)当 P=1和 P=1.25时,短期产出水平是多少?3.有一封闭经济,假定存在以下经济关系:在商品市场上,C=800+0.8Y D , T=t y =0.25y ,I=200-50r ,G=200。

在货币市场上,M d /P =0.4y-100r ,Ms=900。

试 求:(1)总需求函数;( 2)价格水平 P=1时的收入和利率;( 3)如总供给函数为 Y=2350+400P ,求 AS=AD 时的收入和价格水平。

参考答案:一、思考题1.答:在凯恩斯模型基础上,引入价格变量,和供给因素(即劳动市场),研 究产量(或国民收入)和价格水平的决定问题。

经济学家对总供给曲线形状的观点 不一致,因此存在许多不同形状和解释的总供给——总需求模型。

2.答:总供给函数中总产量与价格水平的对应关系可表示为总供给曲线。

黄亚钧《宏观经济学》第3版课后习题(宏观经济政策和理论)【圣才出品】

黄亚钧《宏观经济学》第3版课后习题第十一章宏观经济政策和理论1.为什么一些经济学家认为,被动性政策反而有助于经济的稳定?答:被动性政策有助于经济稳定的原因在于:(1)政策效果滞后。

政府在试图稳定宏观经济运行时,其采取行动的时机以及这些政策行动的最终生效,往往会滞后于实际经济的运行,因而常常带来适得其反的效果。

(2)宏观经济的不确定性。

由于时滞的存在,宏观经济政策要到实施后很久才会起效,这就要求政策制定者能精确地预测将来的经济情况。

但是,经济的发展趋势往往是难以预计的。

(3)卢卡斯批判。

卢卡斯认为,人们的预期会对经济政策的变动作出反应,并对经济政策形成反作用,从而抵消经济政策的效果。

2.卢卡斯批判的核心内容是什么?它对宏观经济政策之争产生了什么影响?答:从凯恩斯学派看来,总供给曲线是僵化的,没有生命力;而在卢卡斯眼中,总供给曲线是可变的,富有生命力的,它会对政府的宏观政策做出反应,政策制定者要了解和重视这种反应。

这就是“卢卡斯批判”的重点所在。

凭借对凯恩斯主义稳定性经济政策的批判,卢卡斯为新古典主义经济学提供了有力的理论支持。

3.什么是政策的“时间不一致性”,你能举出中国经济生活中的实例来说明这一点吗?答:政策制定者在特定时点上做出的相机抉择尽管在当时可能是理性选择,但从长期来看却不能取得良好的政策效果,这就是政策的“时间不一致性”。

宏观经济政策的作用过程实质上是政府与公众的博弈过程,政府开始时宣布一个规则,公众根据这一规则形成自己的预期;但一旦公众预期形成,政府就可能在这一预期下重新决策,从而违背自己开始时宣布的规则。

举例:中国在2009年大规模的信贷投放对经济率先走出金融危机起到十分重要的作用,但由此引发了未来发生通货膨胀的隐患,而收缩信贷却又担心经济是否会二次探底。

上述货币政策的困境在很大程度上表现为货币政策的时间不一致性问题。

4.为什么经济学家认为宏观经济政策应该是管理预期而不是调控经济?答:如果政策制定者采取的政策是时间不一致的,尽管有可能减少短期的社会损失,但由于政策制定者没有兑现承诺,从长期来看会付出更大的代价。

斯蒂芬D威廉森宏观经济学第三版第十五章Stephen-D

18

Equation 15.9

Pareto optimality requires that

19

Equation 15.10

wants. • The causes and effects of long-run inflation. • Financial intermediation and banking.

2

Alternative Forms of Money

• Commodity money • Circulating private bank notes • Commodity-backed paper currency • Fiat money • Transactions deposits at banks

26

Equation 15.12

• The marginal rate of substitution of early consumption for late consumption is

27

Equation 15.13

• First constraint that a deposit contract must satisfy is

9

Equation 15.1

Assume that the central bank causes the money supply to grow at a constant rate.

10

Equation 15.2

In equilibrium, money supply equals money demand.

威廉森《宏观经济学》笔记和课后习题详解(市场出清的经济周期模型)【圣才出品】

第11章市场出清的经济周期模型11.1 复习笔记一、经济周期理论概述1.经济周期理论的发展进程(1)凯恩斯的经济周期模型货币在短期不是中性的,这种非中性是由工资和价格的短期刚性引起的。

在凯恩斯模型中,价格和工资刚性以及由此造成的所有市场可能无法在每一时点上出清,是经济冲击造成总产出波动的形成机制的关键所在。

价格和工资缓慢向出清的市场变动的事实,意味着货币政策和财政政策在应对总冲击时可以发挥稳定经济的作用。

(2)货币主义的经济周期模型货币主义者往往认为,货币政策是比财政政策更有效的稳定工具,但他们对政府政策微调经济的能力持怀疑态度。

一些货币主义者认为,在短期,政策可能是有效的,但非常短。

(3)理性预期学派的经济周期模型理性预期革命提出的两大原则是:①宏观经济学模型应建立在微观经济学原理的基础上,即这些模型应以对消费者和企业的偏好、禀赋、技术和最优行为的描述为后盾;②均衡模型是研究宏观经济现象的最有成效的工具。

2.分析不同经济周期理论的必要性(1)财政政策和货币政策的决策者能够通过经济周期理论,了解左右经济的宏观经济冲击是什么,它对未来总体经济活动有什么影响。

(2)每一种经济周期模型都能确定经济的一个或几个特征及经济对宏观经济冲击作出反应的一些方面。

如果将所有这些特征纳入一个模型中,将无助于认识经济周期表现的基本规律和政府政策。

二、真实经济周期模型真实经济周期模型由芬恩·基德兰德和爱德华·普雷斯科特于20世纪80年代初首创。

1.全要素生产率持久提高的均衡效应假定货币跨期模型中的全要素生产率是持久提高,即z和z'分别提高。

(1)全要素生产率z提高的影响①当期z提高会增加每一数量劳动投入的边际劳动产出,劳动需求曲线右移,从而导致产出供给曲线右移。

如图11-1所示。

图11-1 真实经济周期模型中全要素生产率持久提高的影响②预期未来全要素生产率z'提高的影响:a .投资品需求会增加,因为典型企业预期未来边际资本产出会增加;b .典型消费者预期较高的未来全要素生产率会带来较高的未来收入,因此一生财富增加,消费品需求增加。

威廉森宏观经济学有投资的实际跨期模型PPT课件

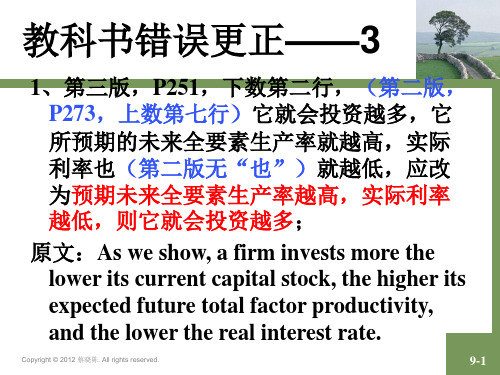

原文:As we show, a firm invests more the lower its current capital stock, the higher its expected future total factor productivity, and the lower the real interest rate.

9பைடு நூலகம்19

企业的劳动需求

Copyright © 2012 蔡晓陈. All rights reserved.

9-20

全要素生产率或资本存量变化时 的劳动需求需求移动

Copyright © 2012 蔡晓陈. All rights reserved.

9-21

Representative代表性企业投资决 策

9-11

实际利率提高对当期劳动供给 的影响(闲暇的跨期替代效应)

Copyright © 2012 蔡晓陈. All rights reserved.

9-12

一生财富增加对当期劳动供给 曲线的影响

Copyright © 2012 蔡晓陈. All rights reserved.

9-13

当前消费需求(参见第八章)

4、第三版,P300,式(10.15)应改为

A P Y P I P H ( X f) B f( 1 R ) B f

5、第三版,P300,式(10.16)应改为

A P Y P X f P H (X f)

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

9-26

第三节 政府

• 政府 ☆假设

1、当期购买G单位的消费品,未来购买G’单位的消费品; 2、当期的总税收是T,未来的总税收是T’; 3、政府当期发行B单位的政府债券;

宏观经济学-课后思考题答案_史蒂芬威廉森002

Chapter 2MeasurementTeaching GoalsStudents must understand the importance of measuring aggregate economic activity. Macroeconomics hopes to produce theories that provide useful insights and policy conclusions. To be credible, such theories must produce hypotheses that evidence could possibly refute. Macroeconomic measurement provides such evidence. Without macroeconomic measurements, macroeconomics could not be a social science, and would rather consist of philosophizing and pontificating. Market transactions provide the most simple and direct measurements. Macroeconomists’ most basic measurement is Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the value of final, domestically market output produced during a given period of time.In the United States, the Commerce Department’s National Income and Product Accounts provide official estimates of GDP. These accounts employ their own set of accounting rules to ensure internal consistency and to provide several separate estimates of GDP. These separate estimates are provided by the product accounts, the expenditure accounts, and the income accounts. The various accounting conventions may, at first glance, be rather dry and complicated. However, students can only easily digest the material in later chapters if they have a good grounding in the fundamentals.GDP changes through time because different amounts of goods and services are produced, and such goods and services are sold at different prices. Standards of living are determined by the amounts of goods and services produced, not by the prices they command in the market. While GDP is relatively easy to measure, the decomposition of changes in real GDP into quantity and price components is much more difficult. This kind of problem is less pressing for microeconomists. It is easy to separately measure the number of apples sold and the price of each apple. Because macroeconomics deals with aggregate output, the differentiation of price and quantity is much less easily apparent. It is important to emphasize that while there may be more or less reasonable approaches to this problem, there is no unambiguous best approach. Since many important policy discussions involve debates about output and price measurements, it is very important to understand exactly how such measurements are produced.Classroom Discussion TopicsAs the author demonstrates in presenting this chapter’s material, much of this material is best learned by example. Rather than simply working through the examples from the text or making up your own, the material may resonate better if the students come up with their own examples. They can start by picking a single good, and by the choice of their numbers they provide their own implied decomposition of output into wage and profit income. Later on, encourage them to suggest intermediate input production, inventory adjustments, international transactions, a government sector, and so on. Such an exercise may help assure them that the identities presented in the text are more than simply abstract constructions.If many of your students are familiar with accounting principles, it may also be useful to present the National Income and Product Account with the “T” accounts. Highlighting how every income is an expense elsewhere. Make one account for each of the firms, one for the household and one for the government. Add another account for the rest of the world when discussing the example with international trade. This procedure can highlight how some entities can be inferred from others because accounting10 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Editionidentities must hold. It makes it also easier to determine consumption for some student Social Security benefits are indexed to the Consumer Price Index. Explain with an example exactly how these adjustments are made. Ask the students if they think that this procedure is “fair.” Another topic for concern is the stagnation in the growth of measured real wages. Real wages are measured by dividing (for example) average hourly wages paid in manufacturing by the consumer price index. Ask students if measured changes in real wages confirm or conflict with their general beliefs about whether the typical worker is better or worse off than 10 or 20 years ago. How does possible mis-measurement of prices reconcile any apparent differences between casual impressions and statistical evidence?The text discusses why unemployment may or may not be a good measure of labor market tightness. Another interpretation of the unemployment rate is as a(n inverse) measure of economic welfare. Ask the students if they agree with this interpretation. Does the unemployment rate help factor in considerations like equal distribution of income? How can the unemployment rate factor in considerations like higher income per employed worker? Discuss possible pros and cons of using unemployment rather than per capita real GDP as a measure of well-being. Can unemployment be too low? Why or why not?OutlineI. Measuring GDP: The National Income and Product AccountsA. What Is GDP and How Do We Measure It?1. GDP: Value of Domestically Produced Output2. Commerce Department’s National Income and Product Accounts3. Business, Consumer, and Government AccountingB. The Product Approach1. Value Added2. Intermediate Good InputsC. The Expenditure Approach1. Consumption2. Investment3. Government Spending4. Net ExportsD. The Income Approach1. Wage Income2. After-Tax Profits3. Interest Income4. Taxes5. The Income-Expenditure IdentityE. Gross National Product (GNP)1. Treatment of Foreign Income2. GNP = GDP + Net Foreign IncomeF. What Does GDP Leave Out?1. GDP and Welfarea. Income Distributionb. Non-Market Production2. Measuring Market Productiona. The Underground Economyb. Valuing Government ProductionChapter 2 Measurement 11G. Expenditure Components1. Consumptiona. Durable Goodsb. Non-Durable Goodsc. Services2. Investmenta. Fixed Investment: Nonresidential and Residentialb. Inventory Investment3. Net Exportsa. Exportsb. Imports4. Government Expendituresa. Federal Defenseb. Federal Non-Defensec. State and Locald. Treatment of Transfer PaymentsII. Nominal and Real GDP and Price IndicesA. Real GDP1. Output Valued at Base Year Prices2 Chain Weighted Real GDPB. Measures of the Price Level1. Implicit GDP Price Deflator2. Consumer Price Index (CPI)C. Problems Measuring Real GDP and Prices1. Substitution Biases2. Accounting for Quality Changes3. Treatment of Newly Introduced GoodsIII. Savings, Wealth, and CapitalA. Stocks and FlowsB. Private Disposable Income and Private Sector Saving1.d Y Y NFP TR INT T =+++− 2.p d S Y C =− C. Government Surpluses, Deficits, and Government Saving1.g S T TR INT G =−−− 2. g D S =− D. National Saving: p g S S S Y NFP C G =+=+−−E. Saving, Investment, and the Current Account1. NFP NX I S ++=2. CA I S NFP NX CA +=⇒+=F. The Stock of Capital1. Wealth ΔS ⇒2. K I Δ⇒3. Claims on Foreigners CA ⇒12 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third EditionIV. Labor Market MeasurementA. BLS Categories1. Employed2. Unemployed3. Not in the Labor ForceB. The Unemployment RateNumber unemployed=Unemployment RateLabor forceC. The Participation RateLabor force=Participation RateTotal working age populationD. Unemployment and Labor Force Tightness1. Discouraged Workers2. Job Search IntensityTextbook Question SolutionsQuestions for Review1. Product, income, and expenditure approaches.2. For each producer, value added is equal to the value of total production minus the cost ofintermediate inputs.3. This identity emphasizes the point that all sales of output provide income somewhere in the economy.The identity also provides two separate ways of measuring total output in the economy.4. GNP is equal to GDP (domestic production) plus net factor payments from abroad. Net factorpayments represent income for domestic residents that are earned from production that takes place in foreign countries.5. GDP provides a reasonable approximation of economic welfare. However, GDP ignores the value ofnonmarket economic activity. GDP also measures only total income without reference to how that income is distributed.6. Measured GDP does not include production in the underground economy, which is difficult toestimate. GDP also measures the value of government spending at its cost of production, which may be greater or less than its true value.7. The largest component is consumption, which represents about 2/3 of GDP.8. Investment is equal to private, domestic expenditure on goods and services (Y − G − NX) minusconsumption. Investment includes residential investment, nonresidential investment, and inventory investment.9. National defense spending represents about 5% of GDP.Chapter 2 Measurement 13 10. GDP values production at market prices. Real GDP compares different years’ production at a specificset of prices. These prices are those that prevailed in the base year. Real GDP is therefore a weighted average of individual production levels. The weights are determined according to prevailing relative prices in the base year. Because relative prices change over time, comparisons of real GDP across time can differ according to the chosen base year.11. Chain weighting directly compares production levels only in adjacent years. The price weights aredetermined by averaging the prices of the individual goods and services over the two adjacent years.12. Real GDP is difficult to measure due to changes over time in relative prices, difficulties in estimatingthe extent of quality changes, and how one estimates the value of newly introduced goods.13. Private saving measures additions to private sector wealth. Government saving measures reductionsin government debt (increases in government wealth). National saving measures additions to national wealth. National saving is equal to private saving plus government saving.14. National wealth is accumulated as increases in the domestic stock of capital (domestic investment)and increases in claims against foreigners (the current account surplus).15. Measured unemployment excludes discouraged workers. Measured unemployment only accounts forthe number of individuals unemployed, without reference to how intensively they search for newjobs.Problems1. Product accounting adds up value added by all producers. The wheat producer has no intermediateinputs and produces 30 million bushels at $3/bu. for $90 million. The bread producer produces100 million loaves at $3.50/loaf for $350 million. The bread producer uses $75 million worth ofwheat as an input. Therefore, the bread producer’s value added is $275 million. Total GDP istherefore $90 million + $275 million = $365 million.Expenditure accounting adds up the value of expenditures on final output. Consumers buy100 million loaves at $3.50/loaf for $350 million. The wheat producer adds 5 million bushels ofwheat to inventory. Therefore, investment spending is equal to 5 million bushels of wheat valued at $3/bu., which costs $15 million. Total GDP is therefore $350 million + $15 million = $365 million.2. Coal producer, steel producer, and consumers.(a) (i) Product approach: Coal producer produces 15 million tons of coal at $5/ton, which adds$75 million to GDP. The steel producer produces 10 million tons of steel at $20/ton, whichis worth $200 million. The steel producer pays $125 million for 25 million tons of coal at$5/ton. The steel producer’s value added is therefore $75 million. GDP is equal to$75 million + $75 million = $150 million.(ii) Expenditure approach: Consumers buy 8 million tons of steel at $20/ton, so consumption is $160 million. There is no investment and no government spending. Exports are 2 milliontons of steel at $20/ton, which is worth $40 million. Imports are 10 million tons of coal at$5/ton, which is worth $50 million. Net exports are therefore equal to $40 million −$50 million =−$10 million. GDP is therefore equal to $160 million + (−$10 million) =$150 million.14 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Edition(iii) Income approach: The coal producer pays $50 million in wages and the steel producer pays $40 million in wages, so total wages in the economy equal $90 million. The coal producerreceives $75 million in revenue for selling 15 million tons at $15/ton. The coal producerpays $50 million in wages, so the coal producer’s profits are $25 million. The steel producerreceives $200 million in revenue for selling 10 million tons of steel at $20/ton. The steelproducer pays $40 million in wages and pays $125 million for the 25 million tons ofcoal that it needs to produce steel. The steel producer’s profits are therefore equal to$200 million − $40 million − $125 million = $35 million. Total profit income in theeconomy is therefore $25 million + $35 million = $60 million. GDP therefore is equal towage income ($90 million) plus profit income ($60 million). GDP is therefore $150 million.(b) There are no net factor payments from abroad in this example. Therefore, the current accountsurplus is equal to net exports, which is equal to (−$10 million).(c) As originally formulated, GNP is equal to GDP, which is equal to $150 million. Alternatively, ifforeigners receive $25 million in coal industry profits as income, then net factor payments from abroad are (−$25 million), so GNP is equal to $125 million.3. Wheat and Bread(a) Product approach: Firm A produces 50,000 bushels of wheat, with no intermediate goods inputs. At$3/bu., the value of Firm A’s production is equal to $150,000. Firm B produces 50,000 loaves ofbread at $2/loaf, which is valued at $100,000. Firm B pays $60,000 to firm A for 20,000 bushels of wheat, which is an intermediate input. Firm B’s value added is therefore $40,000. GDP is therefore equal to $190,000.(b) Expenditure approach: Consumers buy 50,000 loaves of domestically produced bread at $2/loafand 15,000 loaves of imported bread at $1/loaf. Consumption spending is therefore equal to$100,000 + $15,000 = $115,000. Firm A adds 5,000 bushels of wheat to inventory. Wheat isworth $3/bu., so investment is equal to $15,000. Firm A exports 25,000 bushels of wheat for$3/bu. Exports are $75,000. Consumers import 15,000 loaves of bread at $1/loaf. Imports are$15,000. Net exports are equal to $75,000 − $15,000 = $60,000. There is no governmentspending. GDP is equal to consumption ($115,000) plus investment ($15,000) plus net exports($60,000). GDP is therefore equal to $190,000.(c) Income approach: Firm A pays $50,000 in wages. Firm B pays $20,000 in wages. Total wagesare therefore $70,000. Firm A produces $150,000 worth of wheat and pays $50,000 in wages.Firm A’s profits are $100,000. Firm B produces $100,000 worth of bread. Firm B pays $20,000in wages and pays $60,000 to Firm A for wheat. Firm B’s profits are $100,000 − $20,000 −$60,000 = $20,000. Total profit income in the economy equals $100,000 + $20, 000 = $120,000.Total wage income ($70,000) plus profit income ($120,000) equals $190,000. GDP is therefore$190,000.Chapter 2 Measurement 15 4. Price and quantity data are given as the following.Year 1Good Quanti tyPri ceComputers 20$1,000 Bread 10,000$1.00Year 2Good Quanti tyPri ceComputers 25$1,500Bread 12,000$1.10(a) Year 1 nominal GDP =×+×=20$1,00010,000$1.00$30,000.Year 2 nominal GDP =×+×=25$1,50012,000$1.10$50,700.With year 1 as the base year, we need to value both years’ production at year 1 prices. In the base year, year 1, real GDP equals nominal GDP equals $30,000. In year 2, we need to value year 2’s output at year 1 prices. Year 2 real GDP =×+×=25$1,00012,000$1.00$37,000. The percentage change in real GDP equals ($37,000 − $30,000)/$30,000 = 23.33%.We next calculate chain-weighted real GDP. At year 1 prices, the ratio of year 2 real GDP to year1 real GDP equals g1= ($37,000/$30,000) = 1.2333. We must next compute real GDP using year2 prices. Year 2 GDP valued at year 2 prices equals year 2 nominal GDP = $50,700. Year 1 GDPvalued at year 2 prices equals (20 × $1,500 + 10,000 × $1.10) = $41,000. The ratio of year 2 GDP at year 2 prices to year 1 GDP at year 2 prices equals g2=chain-weighted ratio of real GDP in the two years therefore is equal to 1.23496cg==. The percentage change chain-weighted real GDP from year 1 to year 2 is therefore approximately23.5%.If we (arbitrarily) designate year 1 as the base year, then year 1 chain-weighted GDP equals nominal GDP equals $30,000. Year 2 chain-weighted real GDP is equal to (1.23496 × $30,000) = $37,048.75.(b) To calculate the implicit GDP deflator, we divide nominal GDP by real GDP, and then multiplyby 100 to express as an index number. With year 1 as the base year, base year nominal GDP equals base year real GDP, so the base year implicit GDP deflator is 100. For the year 2, the implicit GDP deflator is ($50,700/$37,000) × 100 = 137.0. The percentage change in the deflator is equal to 37.0%.With chain weighting, and the base year set at year 1, the year 1 GDP deflator equals($30,000/$30,000) × 100 = 100. The chain-weighted deflator for year 2 is now equal to($50,700/$37,048.75) × 100 = 136.85. The percentage change in the chain-weighted deflator equals 36.85%.16 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Edition(c) We next consider the possibility that year 2 computers are twice as productive as year1 computers. As one possibility, let us define a “computer” as a year 1 computer. In this case,the 25 computers produced in year 2 are the equivalent of 50 year 1 computers. Each year 1computer now sells for $750 in year 2. We now revise the original data as:Year 1Good Quanti tyPri ceYear 1 Computers 20 $1,000Bread 10,000$1.00Year 2Good Quanti tyPri ceYear 1 Computers 50 $750Bread 12,000$1.10First, note that the change in the definition of a “computer” does not affect the calculations of nominal GDP. We next compute real GDP with year 1 as the base year. Year 2 real GDP in year 1 prices is now ×+×=50$1,00012,000$1.00$62,000. The percentage change in real GDP is equal to ($62,000 − $30,000)/$30,000 = 106.7%.We next revise the calculation of chain-weighted real GDP. From above, g1 equals($62,000/$30,000) = 206.67. The value of year 1 GDP at year 2 prices equals $26,000. Therefore,g 2 equals ($50,700/$26,000) = 1.95. 200.75. The percentage change chain-weighted real GDPfrom year 1 to year 2 is therefore 100.75%.If we (arbitrarily) designate year 1 as the base year, then year 1 chain-weighted GDP equalsnominal GDP equals $30,000. Year 2 chain-weighted real GDP is equal to (2.0075 × $30,000) = $60,225. The chain-weighted deflator for year 1 is automatically 100. The chain-weighteddeflator for year 2 equals ($50,700/$60,225) × 100 = 84.18. The percentage rate of change of the chain-weighted deflator equals −15.8%.When there is no quality change, the difference between using year 1 as the base year and using chain weighting is relatively small. Factoring in the increased performance of year 2 computers, the production of computers rises dramatically while its relative price falls. Compared withearlier practices, chain weighting provides a smaller estimate of the increase in production and a smaller estimate of the reduction in prices. This difference is due to the fact that the relative price of the good that increases most in quantity (computers) is much higher in year 1. Therefore, the use of historical prices puts more weight on the increase in quality-adjusted computer output. 5. Price and quantity data are given as the following:Year 1GoodQuantity(million lbs.)Price(per lb.)Broccoli 1,500 $0.50 Cauliflower 300$0.80Year 2GoodQuantity(million lbs.)Price(per lb.)Broccoli 2,400 $0.60 Cauliflower 350$0.85Chapter 2 Measurement 17(a) Year 1 nominal GDP = Year 1 real GDP =×+×=1,500million$0.50300million$0.80 $990million.Year 2 nominal GDP=×+×=2,400million$0.60350million$0.85$1,730.5million Year 2 real GDP=×+×=2,400million$0.50350million$0.80$1,450million.Year 1 GDP deflator equals 100.Year 2 GDP deflator equals ($1,730.5/$1,450) × 100 = 119.3.The percentage change in the deflator equals 19.3%.(b) Year 1 production (market basket) at year 1 prices equals year 1 nominal GDP = $990 million.The value of the market basket at year 2 prices is equal to ×+×1,500million$0.60300million $0.85= $1,050 million.Year 1 CPI equals 100.Year 2 CPI equals ($1,050/$990) × 100 = 106.1.The percentage change in the CPI equals 6.1%.The relative price of broccoli has gone up. The relative quantity of broccoli has also gone up. The CPI attaches a smaller weight to the price of broccoli, and so the CPI shows less inflation.6. Corn producer, consumers, and government.(a) (i) Product approach: There are no intermediate goods inputs. The corn producer grows30 million bushels of corn. Each bushel of corn is worth $5. Therefore, GDP equals$150 million.(ii) Expenditure approach: Consumers buy 20 million bushels of corn, so consumption equals $100 million. The corn producer adds 5 million bushels to inventory, so investment equals$25 million. The government buys 5 million bushels of corn, so government spendingequals $25 million. GDP equals $150 million.(iii) Income approach: Wage income is $60 million, paid by the corn producer. The corn producer’s revenue equals $150 million, including the value of its addition to inventory. Additions toinventory are treated as purchasing one owns output. The corn producer’s costs includewages of $60 million and taxes of $20 million. Therefore, profit income equals $150 million −$60 million − $20 million = $70 million. Government income equals taxes paid by the cornproducer, which equals $20 million. Therefore, GDP by income equals $60 million +$70 million + $20 million = $150 million.(b) Private disposable income equals GDP ($150 million) plus net factor payments (0) plusgovernment transfers ($5 million is Social Security benefits) plus interest on the government debt ($10 million) minus total taxes ($30 million), which equals $135 million. Private saving equalsprivate disposable income ($135 million) minus consumption ($100 million), which equals$35 million. Government saving equals government tax income ($30 million) minus transferpayments ($5 million) minus interest on the government debt ($10 million) minus governmentspending ($5 million), which equals $10 million. National saving equals private saving($35 million) plus government saving ($10 million), which equals $45 million. The government budget surplus equals government savings ($10 million). Since the budget surplus is positive, the government budget is in surplus. The government deficit is therefore equal to (−$10 million).18 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Edition7. Price controls.Nominal GDP is calculated by measuring output at market prices. In the event of effective pricecontrols, measured prices equal the controlled prices. However, controlled prices reflect an inaccurate measure of scarcity values. Nominal GDP is therefore distorted. In addition to distortions in nominal GDP measures, price controls also inject an inaccuracy in attempts to decompose changes in nominal GDP into movements in real GDP and movements in prices. With price controls, there is typically little or no change in white market prices over time. Alternatively, black market or scarcity value prices typically increase, perhaps dramatically. Measures of prices (in terms of scarcity values) understate inflation. Whenever inflation measures are too low, changes in real GDP overstate the extent of increases in actual production.8. Underground economy.Transactions in underground economy are performed with cash exclusively, to exploit the anonymous nature of currency. Thus, once we have established the amount of currency held abroad, we know the portion of $2,474 that is held domestically. Remove from it what is used for recorded transactions, say by using some estimate of the proportion of transactions using cash and applying this to observed GDP. Finally apply a concept of velocity of money to the remaining amount of cash to obtain the size of the underground economy.9. S p– 1 = CA + D(a) By definition:p d S Y C Y NFP TR INT T C =−=+++−− Next, recall that .Y C I G NX =+++ Substitute into the equation above and subtract I to obtain:()()p S I C I G NX NFP INT T C INX NFP G INT TR T CA D −=+++++−−−=++++−=+(b) Private saving, which is not used to finance domestic investment, is either lent to the domesticgovernment to finance its deficit (D ), or is lent to foreigners (CA ).10. Computing capital with the perpetual inventory method.(a) First, use the formula recursively for each year:K 0 = 80K 1 = 0.9 × 80 + 10 = 82K 2 = 0.9 × 82 + 10 = 83.8K 3 = 0.9 × 83.8 + 10 = 85.42K 4 = 0.9 × 85.42 + 10 = 86.88K 5 = 0.9 × 86.88 + 10 = 88.19K 6 = 0.9 × 88.19 + 10 = 89.37K 7 = 0.9 × 89.37 + 10 = 90.43K 8 = 0.9 × 90.43 + 10 = 91.39K 9 = 0.9 × 91.39 + 10 = 92.25K 10 = 0.9 × 92.25 + 10 = 93.03(b) This time, capital stays constant at 100, as the yearly investment corresponds exactly to theamount of capital that is depreciated every year. In (a), we started with a lower level of capital, thus less depreciated than what was invested, as capital kept rising (until it would reach 100).Chapter 2 Measurement 19 11. Assume the following:10540308010520D INT T G C NFP CA S =======−= (a)201080110d p Y S C S D C =+=++=++= (b)103054015D G TR INT T TR D G INT T =++−=−−+=−−+= (c)208030130S GNP C G GNP S C G =−−=++=++= (d)13010120GDP GNP NFP =−=−= (e)Government Surplus 10g S D ==−=− (f)51015CA NX NFP NX CA NFP =+=−=−−=− (g)12080301525GDP C I G NXI GDP C G NX =+++=−−−=−−+=。

宏观经济学-课后思考题答案_史蒂芬威廉森004

Chapter 4Consumer and Firm Behavior: The Work-Leisure Decision and Profit MaximizationTeaching GoalsThe microeconomic approach to macroeconomics stresses the notion that economy-wide events are the result of decisions made by individuals. People work so that they may afford to buy market goods. On the other hand, people generally prefer to work less rather than working more. Although discussions in the popular press often refer to the idea that spending is what drives the economy, an economy cannot produce unless people are willing to work. Therefore, the most basic macroeconomic decision is the decision to choose whether, and how much, to work. Production and willingness to work are intrinsically interconnected.Students often believe that how much a person works is largely determined by the necessities of their circumstances. Students will report that they have to work to survive and pay tuition. Some might point out that some students need not work much or at all because their parents provide more support. However, circumstances need not dictate exactly how much they may choose to work. They may work less if they go to a less costly school. They may sometimes decide to switch to part-time student status and full-time work status if they find a high-paying job. A key message of this chapter is that choice is important and that choice is influenced by changes in circumstances.This chapter demands the mastery of a large body of structure and yet provides little in the way of immediate insights. Students may need frequent assurances that the mastery of this material eventually pays big dividends in providing hope of understanding the phenomenon of business cycles. This is particularly important as this chapter lays critical foundations for the rest of the book: the use of microfoundations in macroeconomics. Students need to be able to justify macroeconomic relationships with microeconomic arguments, like in this chapter. This requires to some extend some boring drills that they will come to appreciate only later. If for many textbooks the strategy is to teach one chapter a week, spend more time on this one, especially if students have not yet mastered intermediate microeconomics. Two key points of this chapter are the concepts of income and substitution effects. Often, students are perplexed at the amount of time spent on this material because nothing in practice is purely an income effect or a substitution effect. However, the two most basic insights of microeconomic analysis are that when we become more well-off we generally want more of everything and that we respond to price incentives at the margin.Classroom Discussion TopicsAsk the students about their work choices and the choices of their parents, friends, and relatives. Does everyone work? Does everyone work the same amount of hours? Then ask the students for examples of the kinds of factors that lead people to work more or less. Try to elicit very specific examples. Thenask the students to categorize these factors that lead to more or less work. Some of these factors are actually the by-products of more complex decision making. For example, if they say that they work more or less because they go to school, point out that going to school is a choice. They may also point to28 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Editioncircumstances like whether a married couple has children, and if so, their number and their ages. Point out that these events are also the results of other choices. Then ask the students to try to categorize the remaining factors as being primarily an income effect or a substitution effect. Compare also labor choices across countries, as the Macroeconomics in Action feature, new to the third edition, does.Ask the students to provide examples of factors other than more labor or capital that can allow some countries to be a lot more productive than others. What factors other than growth in capital and labor allow a given economy to produce more (or less) over time? Explain that these are the kinds of factors that we summarize by the concept of total factor productivity. Insist also on the concept of physical capital and what it measures and what it is not.OutlineI. The Representative ConsumerA. Preferences1. Goods: The Consumption Good and Leisure2. The Utility Functiona. More Preferred to Lessb. Preference for Diversityc. Normal Goods3. Indifference Curvesa Downward Slopingb. Convex to the Origin4. Marginal Rate of SubstitutionB. Budget Constraint1. Price-taking Behavior2. The Time Constraint3. Real Disposable Income4. A Graphical RepresentationC. Optimization1. Rational Behavior2. The Optimal Consumption Bundle3. Marginal Rate of Substitution = Relative Price4. A Graphical RepresentationD. Comparative Statics Experiments1. Changes in Dividends and Taxes: Pure Income Effect2. Changes in the Real Wage: Income and Substitution EffectsII. The Representative FirmA. The Production Function1. Constant Returns to Scale2. Monotonicity3. Declining MPN4. Declining MPK5. Changes in Capital and MPN6. Total Factor ProductivityChapter 4 Consumer and Firm Behavior: The Work-Leisure Decision and Profit Maximization 29B. Profit Maximization1. Profits = Total Revenue − Total Variable Costs2. Marginal Product of Labor = Real Wage3. Labor DemandTextbook Question SolutionsQuestions for Review1. Consumers consume an aggregate consumption good and leisure.2. Consumers’ preferences are summarized in a utility function.3. The first property is that more is always preferred to less. This property assures us that a consumptionbundle with more of one good and no less of the other good than any second bundle will always be preferred to the second bundle.The second property is that a consumer likes diversity in his or her consumption bundle. Thisproperty assures us that a linear combination of two consumption bundles will always be preferred to the two original bundles.The third property is that both consumption and leisure are normal goods. This property assures us that an increase in a consumer’s income will always induce the individual to consume more of both consumption and leisure.4. The first property of indifference curves is that they are downward sloping. This property is a directconsequence of the property that more is always preferred to less. The second property ofindifference curves is that they are bowed toward the origin. This property is a direct consequence of consumers’ preference for diversity.5. Consumers maximize the amount of utility they can derive from their given amount of availableresources.6. The optimal bundle has the property that it represents a point of tangency of the budget line with anindifference curve. An equivalent property is that the marginal rate of substitution of leisure forconsumption and leisure is equal to the real wage.7. In response to an increase in dividend income, the consumer will consume more goods and moreleisure.8. In response to an increase in the real value of a lump-sum tax, the consumer will consume less goodsand less leisure.9. An increase in the real wage makes the consumer more well off. As a result of this pure incomeeffect, the consumer wants more leisure. Alternatively, the increase in the real wage induces asubstitution effect in which the consumer is willing to consume less leisure in exchange for working more hours (consuming less leisure). The net effect of these two competing forces is theoretically ambiguous.10. The representative firm seeks to maximize profits.30 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Edition11. As the amount of labor is increased, holding the amount of capital constant, each worker gets asmaller share of the fixed amount of capital, and there is a reduction in each worker’s marginalproductivity.12. An increase in total factor productivity shifts the production function upward.13. The representative firm’s profit is equal to its production (revenue measured in units of goods) minusits variable labor costs (the real wage times the amount of labor input). A unit increase in labor input adds the marginal product of labor to revenue and adds the real wage to labor costs. The amount of labor demand is that amount of labor input that equates marginal revenue with marginal labor costs.This quantity of labor, labor demand, can simply be read off the marginal product of labor schedule.Problems1. Consider the two hypothetical indifference curves in the figure below. Point A is on both indifferencecurves, I1 and I2. By construction, the consumer is indifferent between A and B, as both points are onI 2. In like fashion, the consumer is indifferent between A and C, as both points are on I1. But atpoint C, the consumer has more consumption and more leisure than at point B. As long as the consumer prefers more to less, he or she must strictly prefer C to A. We therefore contradict the hypothesis that two indifference curves can cross.Chapter 4 Consumer and Firm Behavior: The Work-Leisure Decision and Profit Maximization 312. u al bC =+(a) To specify an indifference curve, we hold utility constant at u . Next rearrange in the form:u a C l b b=− Indifference curves are therefore linear with slope, −a /b , which represents the marginal rate ofsubstitution. There are two main cases, according to whether /a b w > or /.a b w < The top panelof the left figure below shows the case of /.a b w < In this case the indifference curves are flatterthan the budget line and the consumer picks point A, at which 0l = and .C wh T π=+− Theright figure shows the case of /.a b w > In this case the indifference curves are steeper than thebudget line, and the consumer picks point B, at which l h = and .C T π=− In the coincidentalcase in which /,a b w = the highest attainable indifference curve coincides with the indifference curve, and the consumer is indifferent among all possible amounts of leisure and hours worked.(b) The utility function in this problem does not obey the property that the consumer prefersdiversity, and is therefore not a likely possibility.(c) This utility function does have the property that more is preferred to less. However, the marginalrate of substitution is constant, and therefore this utility function does not satisfy the property ofdiminishing marginal rate of substitution.32 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Edition3. When the government imposes a proportional tax on wage income, the consumer’s budget constraintis now given by:(1)(),C w t h l T π=−−+−where t is the tax rate on wage income. In the figure below, the budget constraint for t = 0, is FGH.When t > 0, the budget constraint is EGH. The slope of the original budget line is –w , while the slope of the new budget line is –(1 – t )w . Initially the consumer picks the point A on the original budget line. After the tax has been imposed, the consumer picks point B. The substitution effect of theimposition of the tax is to move the consumer from point A to point D on the original indifference curve. The point D is at the tangent point of indifference curve, I 1, with a line segment that is parallel to EG. The pure substitution effect induces the consumer to reduce consumption and increase leisure (work less).The tax also makes the consumer worse off, in that he or she can no longer be on indifference curve,I 1, but must move to the less preferred indifference curve, I 2. This pure income effect moves the consumer to point B, which has less consumption and less leisure than point D, because bothconsumption and leisure are normal goods. The net effect of the tax is to reduce consumption, but the direction of the net effect on leisure is ambiguous. The figure shows the case in which the substitution effect on leisure dominates the income effect. In this case, leisure increases and hours worked fall. Although consumption must fall, hours worked may rise, fall, or remain the same.4. The increase in dividend income shifts the budget line upward. The reduction in the wage rate flattensthe budget line. One possibility is depicted in the figures below. The original budget constraint HGL shifts to HFE. There are two income effects in this case. The increase in dividend income is a positive income effect. The reduction in the wage rate is a negative income effect. The drawing in the topfigure shows the case where these two income effects exactly cancel out. In this case we are left with a pure substitution effect that moves the consumer from point A to point B. Therefore, consumption falls and leisure increases. As leisure increases, hours of work must fall. The middle figure shows a case in which the increase in dividend income, the distance GF, is larger and so the income effect is positive. The consumer winds up on a higher indifference curve, leisure unambiguously increases,Chapter 4 Consumer and Firm Behavior: The Work-Leisure Decision and Profit Maximization 33 and consumption may either increase or decrease. The bottom figure shows a case in which the increase in dividend income, the distance GF, is smaller and so the income effect is negative. The consumer winds up on a lower indifference curve, consumption unambiguously decreases, and leisure may either increase or decrease.34 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Edition5. This problem introduces a higher, overtime wage for hours worked above a threshold, q . Thisproblem also abstracts from any dividend income and taxes.(a) The budget constraint is now EJG in the figure below. The budget constraint is steeper for levels ofleisure less than h – q , because of the higher overtime wage. The figure depicts possible choices for two different consumers. Consumer #1 picks point A on her indifference curve, I 1. Consumer #2 picks point B on his indifference curve, I 2. Consumer #1 chooses to work overtime; consumer #2 does not.(b) The geometry of the figure above makes it clear that it would be very difficult to have anindifference curve tangent to EJG close to point J. In order for this to happen, an indifferencecurve would need to be close to right angled as in the case of pure complement. It is unlikely that consumers wish to consume goods and leisure in fixed proportions, and so points like A and Bare more typical. For any other allowable shape for the indifference curve, it is impossible forpoint J to be chosen.(c) An increase in the overtime wage steepens segment EJ of the budget constraint, but has no effecton the segment JG. For an individual like consumer #2, the increase in the overtime wage has no effect up until the point at which the increase is large enough to shift the individual to a point like point A. Consumer #2 receives no income effect because the income effect arises out of a higher wage rate on inframarginal units of work. An individual like consumer #1 has the traditionalincome and substitution effects of a wage increase. Consumer #1 increases her consumption, but may either increase or reduce hours of work according to whether the income effect outweighsthe substitution effect.Chapter 4 Consumer and Firm Behavior: The Work-Leisure Decision and Profit Maximization 356. Lump-sum Tax vs. Proportional Tax. Suppose that we start with a proportional tax. Under theproportional tax the consumer’s budget line is EFH in the figure below. The consumer choosesconsumption, *,C and leisure, *,l at point A on indifference curve I 1. A shift to a lump-sum tax steepens the budget line. The absolute value of the slope of the budget line is (1),t w − and t has fallen to zero. The imposition of the lump-sum tax shifts the budget line downward in a parallel fashion. By construction, the lump-sum tax must raise the same amount of revenue as the proportional tax. The consumer must therefore be able to continue to consume *C of the consumption good and *l ofleisure after the change in tax collection. Therefore, the new budget line must also pass through pointA. The new budget line is labeled LGH in the figure below. With the lump-sum tax, the consumer can do better by choosing point B, on the higher indifference curve, I 2. Therefore, the consumer is clearly better off. We are also assured that consumption will be greater at point B than at point A, and that leisure will be smaller at point B than at point A.7. Leisure represents all time used for nonmarket activities. If the government is now providing forsome of those, like providing free child care, households will take advantage of such a program,thereby allowing more time for other activities, including market work. Concretely, this translates in a change of preferences for households. For the same amount of consumption, they are now willing to work more, or in other words, they are willing to forego some additional leisure. On the figure below, the new indifference curve is labeled I 2. It can cross indifference curve I 1 because preferences, as we measure them here, have changed. The equilibrium basket of goods for the household now shifts from A to B. This leads to reduced leisure (from l *1 to l *2), and thus increased hours worked, and increased consumption (from C *1 to C *2) thanks to higher labor income at the fixed wage.36 Williamson • Macroeconomics, Third Edition8. The firm chooses its labor input, N d , so as to maximize profits. When there is no tax, profits for thefirm are given by(,).d d zF K N wN π=−That is, profits are the difference between revenue and costs. In the top figure on the following page,the revenue function is (,)d zF K N and the cost function is the straight line, wN d . The firm maximizes profits by choosing the quantity of labor where the slope of the revenue function equals the slope of the cost function:.N MP w =The firm’s demand for labor curve is the marginal product of labor schedule in the bottom figure on the following page.With a tax that is proportional to the firm’s output, the firm’s profits are given by:(,)(,)(1)(,),d d d d zF K N wN tzF K N t zF K N π=−−=−where the term (1)(,)d t zF K N − is the after-tax revenue function, and as before, wN d is the costfunction. In the top figure below, the tax acts to shift down the revenue function for the firm and reduces the slope of the revenue function. As before, the firm will maximize profits by choosing the quantity of labor input where the slope of the revenue function is equal to the slope of the cost function, but the slope of the revenue function is (1),N t MP − so the firm chooses the quantity of labor where(1).N t MP w −=In the bottom figure below, the labor demand curve is now (1),N t MP − and the labor demand curve has shifted down. The tax acts to reduce the after-tax marginal product of labor, and the firm will hire less labor at any given real wage.9. The firm chooses its labor input N dso as to maximize profits. When there is no subsidy, profits forthe firm are given by (,).d d zF K N wN π=−That is, profits are the difference between revenue and costs. In the top figure on the following page the revenue function is (,)d zF K N and the cost function is the straight line, wN d . The firm maximizes profits by choosing the quantity of labor where the slope of the revenue function equals the slope of the cost function:.N MP w =The firm’s demand for labor curve is the marginal product of labor schedule in the bottom figure below.With an employment subsidy, the firm’s profits are given by:(,)()d d zF K N w s N π=−−where the term (,)d zF K N is the unchanged revenue function, and (w – s )N d is the cost function. The subsidy acts to reduce the cost of each unit of labor by the amount of the subsidy, s . In the top figure below, the subsidy acts to shift down the cost function for the firm by reducing its slope. As before, the firm will maximize profits by choosing the quantity of labor input where the slope of the revenue function is equal to the slope of the cost function, (t – s ), so the firm chooses the quantity of labor where.N MP w s =−In the bottom figure below, the labor demand curve is now ,N MP s + and the labor demand curve has shifted up. The subsidy acts to reduce the marginal cost of labor, and the firm will hire more labor at any given real wage.10. Minimum Employment Requirement. Below *,N no output is produced. Thereafter, the production function has its usual properties. Such a production function is reproduced in the first two figures below. At high wages, the firm’s cost curve is entirely above the revenue curve, so the firm hires no labor, to prevent incurring losses. Only if the wage rate is less than ˆw will the firms choose to hire anyone. At ˆ,N just as it would in the absence of the constraint. Below ˆ,w w w=the firm chooses*,the labor demand curve is unaffected. The labor demand curve is reproduced in the bottom figure.11. The level of output produced by one worker who works h – l hours is given by(,).s Y zF K h l =−This equation is plotted in the figure below. The slope of this production possibilities frontier is simply .N MP −12. As the firm has to internalize the pollution, it realizes that labor is less effective than it previouslythought. It now needs to hire N (1 + x ) workers where N were previously sufficient. This is qualitatively equivalent to a reduction of z , total factor productivity. The figure below highlights the resulting outcome: the firm now hires fewer people for a given wage and thus its labor demand is reduced.13. 0.30.7Y zK n =(a) 0.7.Y n = See the top figure below. The marginal product of labor is positive and diminishing. (b) 0.72.Y n = See the figures below.(c) 0.30.70.72 1.23.Y n n =≈ See the figures below.(d) See the bottom figure below.−−−−==⇒===⇒===⇒=×≈0.30.30.30.30.31,10.72,1 1.41,220.70.86N N N z K MP n z K MP n z K MP n n。

【《宏观经济学》第三版精品讲义】第十一章 经济周期及其理论发展

• 加速程度取决于资本-产量比率,这一比率在技术不变时,就 是资本增量和产量增加量之比率,即加速数;

• 加速数同乘数一样,是双重的。

17

乘数-加速数模型

• 1.含义:

• 乘数原理反映投资增长对收入增长的作用,加速原理反 映收入增长对投资增长的作用。二者结合,可知投资是 收入变动的函数,收入又是投资变动的函数,静态分析 变成动态分析,这就是乘数-加速数模型。 • 2.机理:

26

(2)加速原理在实际经济中是发挥作用的,它可以解释 许多宏观经济现象,如:我国是在保持一定的经济增长率的 基础上,实现产业结构调整的。

加速原理在实际经济中是发挥作用的,它可以解释许多 宏观经济现象,如:我国是在保持一定的经济增长率的基础 上,实现产业结构调整的。

27

思考:政府一般采取什么措施对经济波动实现控制?1

12

投资过度理论

• 1、投资过度理论认为,资本品投资的波动造成了整个经济的波动。资本 生产过度发展促进经济进入繁荣阶段,资本品的过剩以及2个生产部门的 比例失调则导致经济进入萧条阶段。

• 2、三个派别: • (1)货币投资过度理论:哈耶克 • (2)非货币投资过度理论:施皮特霍夫与卡塞尔 • (3)加速度理论

我国的经济周期

每轮经济周期 的起止年份

1953-1957 1958-1962 1963-1968 1969-1972 1973-1976 1978-1981 1982-1986 1987-1990 1991-1998

1999-

峰尖及年份

18. 7 32. 7

19 25. 3 11. 6 11.7(1978) 15.2(1984) 11.6(1987) 14.2(1992)

31

斯蒂芬D威廉森宏观经济学第三版第九章Stephen D. Williamson's Macroeconomics, Third Edition chapter9

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

9-2

Real Intertemporal Model

• Current and future periods. • Representative Consumer – consumption/savings decision • Representative Firm – hires labor and invests in current period, hires labor in future • Government – spends and taxes in present and future, and borrows on the credit market.

9-22

The Representative Firm’s Investment Decision

The firm invests to the point where the marginal benefit from investment equals the marginal cost.

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

9-26

Equation 9.16

Simplified optimal investment rule:

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

宏观经济学第11章 短期国民收入的决定IS-LM模型

LS曲线的含义:

r

LS曲线,代表产品和服务市场

达到均衡状态时的一条线,它反映

某些相关经济变量(或指标)相互

联动的情况。I代表投资,S代表储

蓄。

r3

r2

r1

O

LS

y1

y2

LS曲线

y3

y

LS曲线的推导

✓ 两部门经济中总需求等于总供给是指 :

CI CS

✓ 经济均衡的条件是 : I=S

➢ 收入增加到Y2,实际货币需求曲线向右上方移位至L2, 产生新均衡点为E2。

针对所有收入水平,完成同样的操作,就会产生一系列的点,连接起来就形成了

LM 曲线。

令实际货币需求=实际货币供给:

可得到:

M

kY hr

P

1

M

r kY

h

P

LM曲线的斜率和变动

➢ LM曲线上的三个区域

✓ 假定消费函数为:C

Y

✓ 均衡收入决定的公式:Y

( I)(

/ 1 )

✓ 若计划投资与利率的线性函数关系为:

最终得到均衡收入的公式: Y

I e dr

e dr

1

LS曲线的推导

使用投资函数曲线和凯恩斯主义交叉图

来推导IS曲线

使用投资函数曲线和储蓄函数曲线图推

区域

产品市场

货币市场

Ⅰ

I S ,有超额产品供给

L M 有超额货币供给

Ⅱ

I S ,有超额产品供给

L M 有超额货币需求

Ⅲ

I S ,有超额产品需求

L M 有超额货币需求

Ⅳ

宏观经济学课件 第十一章

CHAPTER 10两条曲线的交点决定着Y 和r 的唯一组合点,该点表示产品市场与货币市场同时达到均衡。

LM 曲线表示货币市场的均衡。

IS 曲线表示产品市场的均衡。

()()Y C Y T I r G=−++(,)M P L r Y =r Y 1CHAPTER 10政策制定者能够借助以下两个方面影响宏观经济变量•财政政策:G 和/或T •货币政策:M可以利用IS-LM 模型分析这些政策的影响效果。

()()Y C Y T I r G=−++(,)M P L r Y =rCHAPTER 10导致产出和收入上升1.IS 曲线向右移动Δ−11MPCG2.进而增加了货币需求,导致利率上升…3.…结果导致投资减少,因此,Y 的最终增加量小于:11MPCG Δ−及其副产品CHAPTER 10 6CHAPTER 10Y 由于消费者将减税额的一部分(1−MPC)储蓄起来,因此初始产出的增加会小于ΔT ,同时小于支出ΔG 时引起的初始产出增长…此时,IS 曲线的移动量MPC 1MPCT−Δ−1.…因此,在同样的ΔT 和ΔG 变化量下,ΔT 对r 与Y 产生的影响要小于ΔG 。

2.CHAPTER 10 11.90%29.10%United States24.90%27.70%Japan27.10%33.50%United Kingdom35.20%45.40%Italy 42.70%42.70%Turkey 8.10%25.70%Ireland 18.60%29.50%Switzerland 11.00%29.00%Iceland 42.40%47.90%Sweden 39.90%50.50%Hungary 33.40%39.00%Spain 39.20%38.80%Greece 23.20%38.30%SlovakRepublic 26.60%36.20%Portugal 42.10%43.60%Poland 29.60%37.30%Norway 14.50%20.50%New Zealand 29.10%38.60%Netherlands 18.20%18.20%Mexico国会增加G ,IS 曲线将向右移动如果美联储保持M 不变,则LM 曲线不移动。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

11-4

Figure 11.2 Effects of a Persistent Increase in Total Factor Productivity in the Real Business Cycle Model

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

11-9

Segmented Markets Model

• Business cycles can be caused in this model by unanticipated shocks to the money supply. • Model exhibits a liquidity effect – the interest rate falls in the short run when the money supply increases. • Monetary policy can only improve the functioning of the economy if the central bank has an informational advantage over the private sector. • Fit to the data is not as good as with the real business cycle model.

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

11-10

Figure 11.5 Effects of an Unanticipated Increase in the Money Supply in the Segmented Markets Model

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

11-12

Figure 11.6 A Welfare-Improving Role for Active Monetary Policy

Copyright © 2008 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

11-16

Keynesian Coordination Failure Model