外文国外食品安全专题数据库

食品类30种SCI核心期刊附数据库源链接及文件下载链接

食品类30种SCI核心期刊附数据库源链接及文件下载链接【已搜索无重复】★★飘无影(金币+2,VIP+0):不错的资源,谢谢分享哦!!!5-19 16:06小弟不才,搜集到30种与"Food"相关的SCI核心期刊(不包括SCIE),不敢独享,斗胆发出来与广大食品虫友交流,希望对广大食品虫子有所帮助,希望你们多发PAPER,发好PAPER!1. CRITICAL REVIEWS IN FOOD SCIENCE AND NUTRITIONBimonthlyISSN: 1040-8398TAYLOR & FRANCIS INC, 325 CHESTNUT ST, SUITE 800, PHILADELPHIA, USA, PA, 19106 link: /smpp ... 6380~tab=issueslist2. ECOLOGY OF FOOD AND NUTRITIONBimonthlyISSN: 0367-0244TAYLOR & FRANCIS INC, 325 CHESTNUT ST, SUITE 800, PHILADELPHIA, USA, PA, 19106 link: /smpp/title~db=all~content=t7136411483. EUROPEAN FOOD RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGYMonthlyISSN: 1438-2377SPRINGER, 233 SPRING ST, NEW YORK, USA, NY, 10013link: /cont ... f26866c374&pi=04. FOOD ADDITIVES & CONTAMINANTS PART B-SURVEILLANCEISSN: 1939-3210TAYLOR & FRANCIS LTD, 4 PARK SQUARE, MILTON PARK, ABINGDON, ENGLAND, OXON, OX14 4RNlink: /smpp/title~db=all~content=t7834625965. FOOD ADDITIVES AND CONTAMINANTS PART A-CHEMISTRY ANALYSIS CONTROL EXPOSURE& RISK ASSESSMENTMonthlyISSN: 0265-203XTAYLOR & FRANCIS LTD, 4 PARK SQUARE, MILTON PARK, ABINGDON, ENGLAND, OXON, OX14 4RNlink: /smpp/title~db=all~content=t7135996616. FOOD AND CHEMICAL TOXICOLOGYMonthlyISSN: 0278-6915PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD, THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD, ENGLAND, OX5 1GBlink: /science/journal/027869157. FOOD CHEMISTRYMonthlyISSN: 0308-8146ELSEVIER SCI LTD, THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD, ENGLAND, OXON, OX5 1GBlink: /science/journal/030881468. FOOD CONTROLBimonthlyISSN: 0956-7135ELSEVIER SCI LTD, THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD, ENGLAND, OXON, OX5 1GBlink: /science/journal/095671359. FOOD HYDROCOLLOIDSBimonthlyISSN: 0268-005XELSEVIER SCI LTD, THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD, ENGLAND, OXON, OX5 1GBlink: /science/journal/0268005X10. FOOD MICROBIOLOGYBimonthlyISSN: 0740-0020ACADEMIC PRESS LTD ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD, 24-28 OVAL RD, LONDON, ENGLAND, NW1 7DXlink: /science/journal/0740002011. FOOD POLICYBimonthlyISSN: 0306-9192ELSEVIER SCI LTD, THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD, ENGLAND, OXON, OX5 1GBlink: /science/journal/0306919212. FOOD QUALITY AND PREFERENCEBimonthlyISSN: 0950-3293ELSEVIER SCI LTD, THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD, ENGLAND, OXON, OX5 1GBlink: /science/journal/0950329313. FOOD RESEARCH INTERNATIONALMonthlyISSN: 0963-9969ELSEVIER SCIENCE BV, PO BOX 211, AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS, 1000 AElink: /science/journal/0963996914. FOOD REVIEWS INTERNATIONALQuarterlyISSN: 8755-9129TAYLOR & FRANCIS INC, 325 CHESTNUT ST, SUITE 800, PHILADELPHIA, USA, PA, 19106 link: /smpp ... 13597252~link=cover15. FOOD TECHNOLOGYMonthlyISSN: 0015-6639INST FOOD TECHNOLOGISTS, 525 WEST VAN BUREN, STE 1000, CHICAGO, USA, IL, 60607-3814link: /IFT/Pubs/FoodTechnology/Archives/16. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FOOD MICROBIOLOGYSemimonthlyISSN: 0168-1605ELSEVIER SCIENCE BV, PO BOX 211, AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS, 1000 AElink: /science/journal/0168160517. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYBimonthlyISSN: 0950-5423WILEY-BLACKWELL PUBLISHING, INC, COMMERCE PLACE, 350 MAIN ST, MALDEN, USA, MA, 02148link: /journal/117988998/home18. JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD CHEMISTRYBiweeklyISSN: 0021-8561AMER CHEMICAL SOC, 1155 16TH ST, NW, WASHINGTON, USA, DC, 20036link: /journal/jafcau19. JOURNAL OF APPLIED BOTANY AND FOOD QUALITY-ANGEWANDTE BOTANIK SemiannualISSN: 1613-9216DRUCKEREI LIDDY HALM, BACKHAUSSTRASSE 9B, GOTTINGEN, GERMANY, 3708120. JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE AND HEALTH PART B-PESTICIDES FOOD CONTAMINANTS AND AGRICULTURAL WASTESBimonthlyISSN: 0360-1234TAYLOR & FRANCIS INC, 325 CHESTNUT ST, SUITE 800, PHILADELPHIA, USA, PA, 19106 link: /smpp/title~db=all~content=t71359726921. JOURNAL OF FOOD BIOCHEMISTRYBimonthlyISSN: 0145-8884WILEY-BLACKWELL PUBLISHING, INC, COMMERCE PLACE, 350 MAIN ST, MALDEN, USA, MA, 02148link: /journal/117997695/home22. JOURNAL OF FOOD ENGINEERINGSemimonthlyISSN: 0260-8774ELSEVIER SCI LTD, THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD, ENGLAND, OXON, OX5 1GBlink: /science/journal/0260877423. JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTIONMonthlyISSN: 0362-028XINT ASSOC FOOD PROTECTION, 6200 AURORA AVE SUITE 200W, DES MOINES, USA, IA, 50322-2863link: /content/iafp/jfp24. JOURNAL OF FOOD SAFETYQuarterlyISSN: 0149-6085WILEY-BLACKWELL PUBLISHING, INC, COMMERCE PLACE, 350 MAIN ST, MALDEN, USA, MA, 02148link: /journal/118494236/home25. JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCEBimonthlyISSN: 0022-1147WILEY-BLACKWELL PUBLISHING, INC, COMMERCE PLACE, 350 MAIN ST, MALDEN, USA, MA, 02148link: /journal/118509799/home26. JOURNAL OF MEDICINAL FOODQuarterlyISSN: 1096-620XMARY ANN LIEBERT INC, 140 HUGUENOT STREET, 3RD FL, NEW ROCHELLE, USA, NY, 10801link: /jmf27. JOURNAL OF THE SCIENCE OF FOOD AND AGRICULTUREMonthlyISSN: 0022-5142JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD, THE ATRIUM, SOUTHERN GATE, CHICHESTER, ENGLAND, W SUSSEX, PO19 8SQlink: /journal/1294/home28. LWT-FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYMonthlyISSN: 0023-6438ELSEVIER SCIENCE BV, PO BOX 211, AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS, 1000 AElink: /science/journal/0023643829. MOLECULAR NUTRITION & FOOD RESEARCHMonthlyISSN: 1613-4125WILEY-V C H VERLAG GMBH, PO BOX 10 11 61, WEINHEIM, GERMANY, D-69451link: /journal/117935711/grouphome30. TRENDS IN FOOD SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGYIrregularISSN: 0924-2244ELSEVIER SCIENCE LONDON, 84 THEOBALDS RD, LONDON, ENGLAND, WC1X 8RR link: /science/journal/09242244。

北美洲务各国家食品标准网址

细目/说明 联邦食品、药品与化妆品法 联邦肉检查法 公众健康服务法 禽产品检查法 蛋制品检查法 联邦杀虫剂、杀菌剂和杀鼠剂法 食品质量保护法

农药残留 基础条款(含豁免物质) 没有标准的农残(豁免的除外) 兽药残留 基础条款 新药 食品添加剂 色素规格与限量 调制色素用稀释剂规格与限量 豁免用色素规格 甜味剂与胶囊规格 直接添加物 间接添加物 纸与纸板 粘合剂与涂层材料 包装用聚合物 加工助剂与清洁消毒剂 GRAS 直接添加相当于GRAS 间接接添加相当于GRAS 禁止添加物 可以加入到食品中物质列表 化学污染物 再残留(含农药与部分重金属) PCB 三聚氰胺

一般食品(含代谢物) 婴儿配方奶粉(或代谢物) 针对中国(检测限:0.25ppm) 乳与乳制品、含乳食品(含代谢物) 法规要求 微生物 法定的肉和禽产品 禽肉 食品标签 辐照 电离辐射 紫外线 脉冲光 DAL 部分产品标准 水产品 瓶装水 冷冻 豌豆 人造黄油 婴儿配方奶粉营养规格 过敏原 动物食品 产品与包装中的污染物 GRAS 添加剂规格与限量 辐照 食物与饮用水中相当于GRAS 禁用物质 自动扣留通报 召回通报 扣留通报 审核报告 许可进口情报 新鲜水果和蔬菜进口手册 门户网站 法规搜索 FSIS审核国外肉禽蛋工厂报告 肉禽蛋及制品 含FDA与USDA两部门

联邦法规电子版 联邦法规正式版 食品药物管理局(FDA) 环境保护署(EPA) 动植物卫生检验署(APHIS) 食品安全检验署(FSIS) 农业部进口国相关信息

网址 /RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/FederalFoodDrugandCosmeticActFDCAct/default.htm /RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/ucm148693.htm /RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/ucm148717.htm /RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/ucm148721.htm /RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/ucm148752.htm /Legislation/Compilations/Fifra/FIFRA.pdf /pesticides/regulating/laws/fqpa/gpogate.pdf /Байду номын сангаасgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=863640f6ee7e6bb8715c0190bf6f51e1&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title40/40cfr180_main_02.tpl 不得检出 /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=edf74d1f0832f7928248a746a7c690e0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr556_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=6aaf29bb8b5f4f671ee33ec44dce89b9&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr556_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&rgn=div6&view=text&node=21:1.0.1.1.27.1&idno=21 /cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&rgn=div6&view=text&node=21:1.0.1.1.26.1&idno=21 /cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&rgn=div6&view=text&node=21:1.0.1.1.26.1&idno=21 /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=f0189619b0ca0efa2a333f8650bd2308&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr168_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=12c65284133bf0632612d0c0fa86bdc0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr172_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=12c65284133bf0632612d0c0fa86bdc0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr173_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=1d7fd632f347d6f7b7bff7dd4cceaffe&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr176_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=12c65284133bf0632612d0c0fa86bdc0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr175_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=12c65284133bf0632612d0c0fa86bdc0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr177_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=12c65284133bf0632612d0c0fa86bdc0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr178_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=12c65284133bf0632612d0c0fa86bdc0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr182_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=12c65284133bf0632612d0c0fa86bdc0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr184_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=12c65284133bf0632612d0c0fa86bdc0&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr186_main_02.tpl /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=e4a5161f44509f0234860f2a72526590&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr189_main_02.tpl /scripts/fcn/fcnNavigation.cfm?rpt=eafusListing&displayAll=true /Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocuments/ChemicalCont aminantsandPesticides/ucm077969.htm /cgi/t/text/textidx?c=ecfr&sid=e4a5161f44509f0234860f2a72526590&rgn=div8&view=text&node=21:2.0.1.1.9.2.1.1&i

【硕士论文】国外食品安全信息化管理体系研究及对我国的借鉴意义

需要整合相关的信息资源。信息化手段在食品相关专家系统开发和数据 管理方面能够起到非常重要的作用。 4)建立食品安全监控、预警和快速反应系统。食品安全管理除了对食品生 产和流通的监管之外,对食品相关疾病的监控、预警和快速反应也同样 重要。对食品相关疾病的信息化管理,主要体现在建立食品安全监控、 预警和快速反应系统。重点介绍了国外使用较广的PulseNet网络,美 国的食品网(FoodNet)和欧洲的RAsFF系统等。 在此基础上,以发达国家的成功经验为借鉴,并结合我国国情,为我国食品 安全信息化管理提出了具体的建议: 1)食品信息可追溯系统建设方面,建议推广卧N・ucc系统。针对我国经 济发展区域不平衡,监控条件还较为薄弱的国情,提出了“替代营销” 和“公司+农户(基地)”模式等特殊模式和手段,来完善我国的食品安 全信息可追溯管理体系。 2)食品安全信用体系建设方面,建立健全食品安全信息的交流和沟通机制, 食品及生产企业质量和信用档案管理和发布机制,食品相关数据管理和 共享机制,食品包装标识体系管理机制,专业信息教育机制等。 3)食品安全专家咨询体系和完善的数据库系统建设方面,使专家咨询工作 常态化制度化,开发应用于各种食品安全生产相关环节的的专家系统、 数据库、知识库和规则库等,替代专家为相关用户提供技术指导。 4)食品安全监控、预警和快速反应系统建设方面,构建一个包括疫情监测 系统、快速诊断系统、应急通信系统、预警和信息发布系统、疫情应急 预案、管理机构决策指挥系统、应急物品求援快速反应系统等子系统的 食品安全预警和应急指挥系统。并将其纳入全国突发公共卫生事件应急 指挥与决策系统的规划建设。 当前,对国内外食品安全信息化管理的研究还处于起步阶段,研究主题比较 分散,还很少有对食品安全信息化管理的系统研究,而且已有的研究成果,多是 从信息技术的角度展开的研究。本人认为,食品安全信息化管理工作是一项系统 工程,不仅仅是一个技术问题,还涉及管理学,社会学,经济学等内容,需要全 方位、多角度地开展研究工作,本文还在最后提出了我国食品信息可追溯系统和 食品安全信用体系建设的具体建议,建立了我国食品安全应急反应信息系统模 型,并提出关于食品安全信息化管理下一步目标的思考。

食品专业常用网站的介绍

中国面制品网址 /

中国乳业信息网址: /Index.asp

大食品网址 /

中国食品信息网 /index.aspx

中国农业信息网 /

食品营养与安全网址 /AMuseum/ foodnutri/index1.html

中国卫生标准管理网址: /index.asp

中国农药信息网 /

食品标准下载 /standard/

食品检测仪器及设备信息网 /dow nload/

我要找标准免费下载网 http://98.130.10.178/

餐饮管理资料下载网 /DataStore/

5强制性国家标准查询 /bzzyReadW ebApp/read.action;jsessionid=PdJHTP ZGn7XzBy4xqJ12pG12KGXLhySyKnhvk j8vl8VQJycm0BRF!288434931?m=fron tMain#

世界贸易组织(WTO):

世界卫生组织(WHO):

国际食品微生物标准委员会(ICMSF): /

北欧食品分析委员会(NMKL):

.欧盟标准:http://europa.eu.int

食品专业常用网站简介

食科081 王瑜

目录

• • • • • • 1.国内的一些关于食品的网站 2.国外的一些关于食品的网站 3.一些比较优秀的论坛 4.资料下载中心 5. 就业信息招聘网 6.专业的数据库

国家质检总局:

/business/ht mlfiles/foodaqxxw/s68/list.html

食品安全国家标准网 中国疾控中心 营养与食品安全所 /

食品科技在线/index.asp

英语听力论坛 /

可可英语学习论坛 /sp网 /app/my/doci n/event

faers类的文章

faers类的文章FAERS类的文章FAERS(美国食品和药物管理局不良事件报告系统)是美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)的一个数据库,用于收集和存储与使用药物相关的不良事件报告。

FAERS数据库中包含了大量的药物不良事件报告,这些报告来自医疗保健专业人员、消费者和制药公司等各个渠道。

FAERS的目标是监测并评估药物的安全性和有效性,以便及时采取必要的措施来保护公众的健康。

FAERS数据库的建立和维护对于监测药物的安全性至关重要。

通过收集和分析不良事件报告,可以发现药物的潜在风险和副作用,及时预警和采取措施,以保护患者的安全。

FAERS数据库中的不良事件报告包括但不限于药物副作用、药物滥用和误用、药物相互作用等情况。

这些报告对于制药公司、医疗保健专业人员和患者都具有重要的参考价值。

FAERS数据库的使用可以帮助制药公司评估其产品的安全性和有效性。

制药公司可以通过分析FAERS数据库中的不良事件报告,了解其产品在实际使用中可能存在的问题,并针对性地进行改进和优化。

此外,制药公司还可以通过FAERS数据库了解竞争对手的产品在市场上的表现和不良事件报告情况,从而指导其自身的产品策略和市场竞争。

医疗保健专业人员在临床实践中也可以利用FAERS数据库。

他们可以通过查询FAERS数据库,了解某种药物的不良事件报告情况,从而评估该药物的风险和安全性。

医疗保健专业人员还可以通过FAERS数据库了解某种药物的副作用和相互作用,以便在临床实践中更加谨慎地使用药物,并提供更好的药物治疗方案。

对于患者来说,FAERS数据库可以提供有关药物的不良事件报告信息,帮助他们更好地了解所用药物的安全性和副作用。

患者可以通过查询FAERS数据库,了解某种药物可能存在的风险和注意事项,从而更加理性地使用药物,并在必要时与医疗保健专业人员进行沟通和讨论。

然而,需要注意的是,FAERS数据库中的不良事件报告并不代表药物的绝对风险和安全性。

食品安全国内外文献综述.doc

国内外文献综述食品安全是一个与人类生存密切相关的问题,它涉及到资源配置与环境保护、需求的满足与社会福利的改善以及社会稳定等方面,也是农业持续发展的重要环节。

不同时期由于食品安全所面临的主要问题不同,研究的侧重点也不相同。

本章通过对食品安全相关文献的回顾与比较,以掌握对这一问题的研究脉络。

国外研究文献综述食品安全问题的提出食品安全是一个不断发展的概念。

国外对食品安全问题的认识经历了一个由侧重食品数量安全(food Sedcurity)到侧重食品质量安全的转变过程。

1974年,联合国粮农组织(FAO)等机构举行的世界粮食会议上,将食品安全定义为:所有人在任何情况下都能获得维持健康的生存所必需的足够食物。

1983年,FAO前总干事爱德华·萨乌马将食品安全最终目标解释为确保所有人在任何时候既能买得到又能买得起他们所需要的基本食品。

这一概念主要强调了一国的食品供给数量能否满足人口的基本需要,并且更关注社会弱势人群(如穷人、妇女和儿童等)的食品可获得性,以避免和减少饥荒和营养不良现象的发生,因而与缓解和消除贫困问题之间存在着紧密联系。

1984年,世界卫生组织(wHO)在题为《品安全在卫生和发展中的作用》的文件中,把“食品安全”与“食品卫生”作为同意语,定义为:“生产、加工、储存、分配和制作食品过程中确保食品安全可靠,有益于健康并且适合人消费的种种必要条件和措施”。

1996年,WHO在《加强国家级食品安全性计划指南》中,对食品安全与食品卫生这两个概念进行了区别,其中食品安全被解释为“对食品按其原定用途进行制作和或食用时不会使消费者受害的一种担保”,食品卫生则指“为确保食品安全性和适合性在食物链的所有阶段必须采取的一切条件和措施”。

食品安全规制主体食品安全规制的主体主要有规制机构、企业、用户(消费者)和非政府机构。

针对消费者在食品安全规制中的作用,不同学者有不同观点: May Aung(2004)在研究中表明,所有国家必须考虑消费者利益,使消费者能够参加培训、决策以及国家食品安全系统的发展、调整和实施活动; AndrewFearne,JulieA.Caswell和Spence Henson(2007)的研究表明:根据各国食品安全形势、食品行业特征、消费者消费行为模式的不同,各国对食品行业的规制模式也有很大差异。

国外产品质量、食品安全相关信息网址

常用国外信息网址1、加拿大边境服务局(署)http://cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/menu-eng.html2、加拿大食品检验局http://www.inspection.gc.ca/eng/1297964599443/1297965645317 3、美国环保局/4、美国能源部/5、欧盟官方网站http://europa.eu/index_en.htm6、欧盟委员会网站http://ec.europa.eu/index_en.htm7、食品导航网/8、加拿大卫生部http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/index-eng.php10、化学观察/9、英国食品标准局/10、澳新食品标准局.au/11、澳大利亚农渔林业部.au/12、美国动植物检疫局/13、新西兰生物安全局/14、美国农业部/wps/portal/usda/usdahome15、美国海关边境保护局/xp/cgov/home.xml16、美国食品药品管理局/17、新西兰食品安全局./18、北美植物保护组织的植物检疫警告系统/main.cfm19、爱尔兰食品安全局http://www.fsai.ie/20、香港贸发网/sc/21、欧洲食品安全局http://www.efsa.europa.eu/22、美国消费品安全委员会/23、美国食品安全检验局/Home/index.asp 24、美国合众国际社/25、澳大利亚产品安全局.au/26、国外网站大全/index.html27、日本厚生劳动省http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/。

FDA数据库2024

引言概述:FDA数据库是美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)建立和维护的一种重要的信息资源。

该数据库包含了与食品、药品、医疗器械、化妆品和其他相关产品相关的众多数据和信息。

通过对这些数据库的查询和分析,各利益相关者可以获得有关产品的安全性、有效性和合规性的重要信息。

本文将对FDA数据库进行详细的介绍和分析,并探讨其对不同领域的影响和价值。

正文内容:1.FDA数据库的类型及功能1.1药品数据库1.1.1药品注册数据库1.1.2药品副作用数据库1.1.3药品审批数据库1.1.4药品安全警报数据库1.1.5药品临床试验数据库1.2食品数据库1.2.1食品成分数据库1.2.2食品添加剂数据库1.2.3食品安全数据库1.2.4食品污染数据库1.2.5食品标签数据库2.FDA数据库在药品研发领域的应用2.1药物发现和开发2.1.1研究先前获批药物的数据库2.1.2分析临床试验数据2.1.3预测药物副作用2.2药物审批和监管2.2.1提供药物注册和批准指南2.2.2监测已上市药品安全性2.2.3分析药品安全警报3.FDA数据库在食品领域的应用3.1食品质量和安全监管3.1.1分析食品成分和添加剂3.1.2监测食品污染物3.1.3追踪食品召回和安全警报3.2食品标签规定和消费者教育3.2.1提供食品标签要求和规范3.2.2提供食品健康声明数据库3.2.3为消费者提供食品相关信息4.FDA数据库在医疗器械和化妆品领域的应用4.1医疗器械审批和监管4.1.1提供医疗器械注册和批准信息4.1.2分析医疗器械安全性和有效性4.1.3监测医疗器械事故和召回4.2化妆品安全监管4.2.1提供化妆品成分数据库4.2.2分析化妆品安全性评估4.2.3监测化妆品不良反应和召回5.FDA数据库的挑战和改进方向5.1数据库数据完整性和准确性5.2数据库隐私和安全保护5.3数据库的开放共享和数据访问5.4数据库查询和分析工具的改进5.5数据库与其他数据资源的整合与总结:FDA数据库是一个重要的信息资源,对食品、药品、医疗器械和化妆品的研发、审批和监管具有重要的意义。

faers 数据库 相关概念

faers 数据库相关概念

FAERS(美国食品药品监督管理局不良事件报告系统)是一个用于收集和分析药物和生物制品不良事件报告的数据库。

该数据库包含了来自医疗保健专业人员、患者和药品制造商的不良事件报告,这些报告包括药物的不良反应、药物错误使用、药物滥用和药物过量等信息。

FAERS数据库的目的是监测药物的安全性,识别潜在的风险和促进药物安全性信息的传播。

FAERS数据库中的数据包括报告的时间、报告者的身份、患者的特征(如年龄、性别等)、不良事件的描述、涉及的药物信息(如药品名称、剂量、使用途径等)以及不良事件的后果等。

这些数据可以帮助监管机构和药品制造商评估药物的安全性和有效性,并采取必要的措施来保护公众健康。

FAERS数据库的使用者包括监管机构、学术研究人员、医药公司和医疗保健专业人员等。

他们可以利用这些数据来进行药物安全性评估、发现药物的新的不良反应、评估药物之间的相互作用以及制定药物使用政策等。

总之,FAERS数据库是一个重要的药物安全监测工具,通过收

集和分析药物不良事件报告,有助于及时发现和评估药物的安全性问题,保障公众的用药安全。

FDA数据库 保障公众健康的信息宝库

FDA数据库: 保障公众健康的信息宝库简介:FDA数据库,即美国食品药品监督管理局数据库,是一个重要的信息资源库,旨在从食品、药品、医疗器械等多个方面收集、管理和共享数据,保障公众健康和建立科学决策的基础。

本文将介绍FDA数据库的基本信息、重要性以及其对公众健康的积极贡献。

正文:一、基本信息FDA数据库由美国食品药品监督管理局负责建设和维护,旨在为全球公众和科研人员提供各种食品、药品和医疗器械的相关信息。

该数据库包含了大量的数据和文献资料,被广泛用于食品安全评估、药物开发和监管、医疗设备审批等方面。

同时,FDA数据库还通过开放数据接口,供外部开发者和科学研究者使用,为保护公众健康提供了良好的技术支持。

二、重要性1. 保障食品安全FDA数据库收集了大量关于食品的数据,包括食品成分、添加剂、污染物等信息,为食品安全评估提供了科学依据。

通过检索和分析这些数据,可以帮助监管部门和食品行业预测和解决潜在的食品安全问题,保障公众健康。

2. 促进药物研发FDA数据库收录了各类药物的临床试验数据、副作用报告、生产质量检验等信息,为药物的研发和监管提供了重要的参考。

科研人员可以通过访问该数据库,获取关于药物的详细信息,并进行相应的分析和评估,从而加快药物研发周期、提高药物安全性和疗效。

3. 优化医疗设备管理FDA数据库还记录了医疗器械的注册和报告信息,包括产品说明书、使用说明、适应症等。

科研人员和医疗专业人员可以通过该数据库,了解到最新的医疗器械信息,并进行评估和选择,为患者提供更安全、有效的医疗设备。

三、对公众健康的贡献FDA数据库的建设和使用不仅为相关监管部门和行业提供了科学依据和决策支持,也对公众健康产生了积极的贡献。

首先,通过及时、频繁的数据更新,可以帮助公众了解食品、药物和医疗器械的相关信息,加强食品安全和健康教育。

其次,公众可以通过FDA数据库了解食品和药物的成分、剂量等信息,从而做出明智的消费和用药决策。

国外食品质量安全追溯系统情况分析

食品质量安全追溯系统作为保障食品安全的有效手段,在世界很多国家(特别是欧美等发达国家和部分发展中国家)受到了广泛的关注,欧盟、美国、日本等国纷纷建立食品质量安全追溯系统。

在调研江苏省食品安全追溯体系建设情况的同时,查阅了大量国外资料,现将有关情况报告如下:一、主要国家应用追溯系统概况(一)美国美国食物安全的监管特点是食物质量安全监督管理由多个部门负责,主要负责部门为农业部、卫生和公共事业部及环境保护署,分别负责农产品、葡萄酒和饮用水等不同产品。

此外,美国商业部、财政部和联邦贸易委员会也不同程度地承担了对食品安全的监管职能。

美国政府于2004年启动了国家动物标识系统(NAIS),通过对养殖场和动物个体或群体转移进行标识,确定其出生地和移动信息,最终保证在发现外来疫病的情况下,能够于48小时内确定所有与其有直接接触的企业。

(二)欧盟欧盟成立欧洲食品安全局对食物安全管理承担主要责任,成员国和欧盟共同执行食物安全管理政策。

食品产业受成员国有关机构的监督,这些机构同时受欧盟的管理,欧盟委员会也参与对欧盟的食物安全管理。

欧盟的畜产品可追溯系统主要应用在牛的生产和流通领域。

与一些价值较低、混合包装的产品只需追溯到生产批次不同,牛肉属于价值较高的产品,个体标记相对较为容易,其生产及包装特点决定了基本部位产品可以做到个体追溯,也因此欧盟在客观条件上能做到实行较严格、完善的追溯制度。

事实上,欧盟强制性要求入盟国家对家畜和肉制品开发和流通实施追溯制度,从2002年起所有店内销售的产品必须具有可追溯标签,该标签必须包含如下信息:出生国别、育肥国别及牛肉关联的其他畜体的引用数码标识、屠宰国别以及屠宰厂标识、分割包装国别、分割厂的批准号以及是否欧盟成员国生产等。

(三)澳大利亚澳大利亚70%的牛肉产品销往海外。

通过实行国家牲畜标识计划(NLIS),澳畜产品得以顺利出口欧盟,总值约每年5200万澳元。

NLIS是一个永久性的身份系统,能够全程追踪家畜的出生到屠宰。

外文数据库及学术搜索引擎

• 读秀学术搜索()

• BASE搜索引擎( 比勒菲尔德学术搜索 /)

是德国比勒菲尔德大学图书馆开发的

一个多学科的学术搜索引擎,采用挪威 公司的FAST搜索和传递技术,提供对全 球异构学术资源的及城建所服务。提供 160个开放资源(超过200万个文档)的 数据。

• Scitopia学术搜索引擎

A 共享参考文献

B

D

相关文献

进入现代社会,几乎所有的科学研究活动都是在前 人的基础上进行的发展,在撰写科技论文时也大多是参考 了他人的观点,或吸收了前人的概念、理论或方法而创作 的。因此,大多数文献在其发表时,文后都附有参考文献, 以便读者参考。反之,在实际的文献检索过程中,如果查 找到一篇文献与自己的研究课题相近或密切相关,那么这 篇文献所引用的参考文献一般与自己的研究课题也是密切 相关的。这样,找到这些参考文献也就变得很有意义与重 要了。

目前,《工程索引》的出版形式有:工程索引年刊本、 工程索引月刊本、工程索引缩微胶卷、工程索引机读磁带、 只读光盘以及网络版(EV平台)。

• 1992年,Ei公司中国信息部成立(设在 机械工业信息研究所)。

• 1998年11月Ei 公司在我国清华大学建立 Ei工程信息村中国镜像站正式对外服务;

• 2003年1月1日,设于辽宁大连市的Ei中 国网站正式开始运行;

美国《科学引文索引》 ( SCI )

一、引文索引概述

引文索引编制原理

“引文”

国内外食品法规标准数据库发展及现状_汤成正

1 概述长期以来,食品卫生安全一直是政府和社会普遍关注的问题。

特别是近几年来发生的一系列的重大蔬菜的农药残留、多宝鱼、有毒粉丝、塑化剂等在社会上引起了强烈的反响。

随着数字化时代的到来,一场以网络为载体、以数字信息为核心的数字浪潮正在到来。

在食品安全研究领域,通过不同专业的互联网资源数据库可以在线检索查询各种食品安全危害因子的基本情况、相关限量要求、分析方法、检验标准和法律法规等信息[1]。

随着信息量的急剧增加和网络规模的不断扩大,如何有效地获得网络信息是每一个网络用户面临的问题。

鉴于现阶段食品安全相关标准法规数据库存在零散性、重复性和封闭性等问题[2-4]。

本文将以网络资源数据库为着眼点,对部分实用性较强的与食品安全密切相关的法规标准数据库现有情况进行简要介绍,以期为广大食品安全从业人员提供更多的食品安全领域法规标准信息渠道,为相关研究的开展和应对措施的制定提供参考。

2 国外及发达地区食品法规标准数据库国外发达地区以及国际组织的食品安全综合型网络资源数据库的一个重要特色是规模较大,几乎涵盖与食品安全有关的各种信息,具体版块分类较细,而且有的数据库还具有搜索引擎功能,部分内容动态更新,可以方便快捷地为用户提供详实的实用信息。

本文介绍的国外及发达地区食品法规标准数据库主要有国际食品法典委员会CAC,欧盟农残标准体系及数据库查询MRLs,澳新食品标准局(FSANZ),东盟食品安全标准数据库,香港食品安全信息库,台湾食品标准数据库。

2.1 国际食品法典委员会CAC国际食品法典委员会(The codex alimentarius commission, CAC. http://www. /codex-home/zh/)1961国内外食品法规标准数据库发展及现状汤成正(深圳标准技术研究院)摘 要:在食品安全研究领域,通过不同专业的互联网资源数据库可以在线检索查询各种食品安全危害因子的基本情况、相关限量要求、分析方法、检验标准和法律法规等信息。

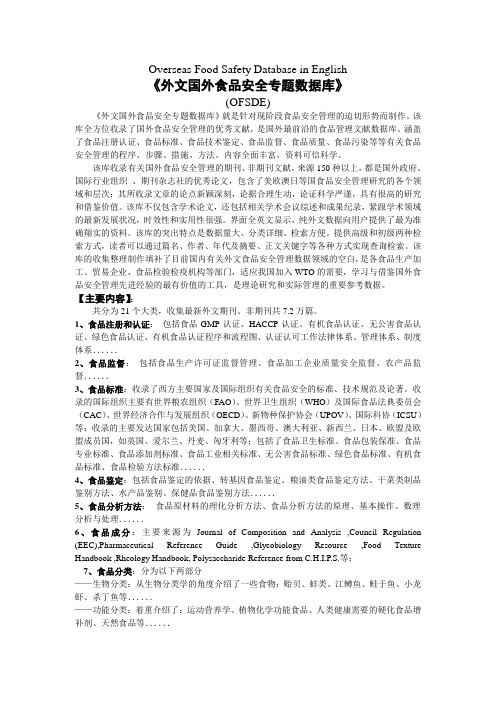

外文国外食品安全专题数据库

Overseas Food Safety Database in English《外文国外食品安全专题数据库》(OFSDE)《外文国外食品安全专题数据库》就是针对现阶段食品安全管理的迫切形势而制作。

该库全方位收录了国外食品安全管理的优秀文献,是国外最前沿的食品管理文献数据库。

涵盖了食品注册认证、食品标准、食品技术鉴定、食品监督、食品质量、食品污染等等有关食品安全管理的程序、步骤、措施、方法。

内容全面丰富,资料可信科学。

该库收录有关国外食品安全管理的期刊、非期刊文献,来源150种以上,都是国外政府、国际行业组织、期刊杂志社的优秀论文,包含了美欧澳日等国食品安全管理研究的各个领域和层次;其所收录文章的论点新颖深刻,论据合理生动,论证科学严谨,具有很高的研究和借鉴价值。

该库不仅包含学术论文,还包括相关学术会议综述和成果纪录,紧跟学术领域的最新发展状况,时效性和实用性很强。

界面全英文显示,纯外文数据向用户提供了最为准确翔实的资料。

该库的突出特点是数据量大、分类详细、检索方便。

提供高级和初级两种检索方式,读者可以通过篇名、作者、年代及摘要、正文关键字等各种方式实现查询检索。

该库的收集整理制作填补了目前国内有关外文食品安全管理数据领域的空白,是各食品生产加工、贸易企业、食品检验检疫机构等部门,适应我国加入WTO的需要,学习与借鉴国外食品安全管理先进经验的最有价值的工具,是理论研究和实际管理的重要参考数据。

【主要内容】:共分为21个大类,收集最新外文期刊、非期刊共7.2万篇。

1、食品注册和认证:包括食品GMP认证、HACCP认证、有机食品认证、无公害食品认证、绿色食品认证、有机食品认证程序和流程图、认证认可工作法律体系、管理体系、制度体系......2、食品监督:包括食品生产许可证监督管理、食品加工企业质量安全监督、农产品监督......3、食品标准:收录了西方主要国家及国际组织有关食品安全的标准、技术规范及论著。

食品安全外文文献翻译(适用于毕业论文外文翻译+中英文对照)

论食品供应链管理和食品质量安全上世纪90年代以来,供应链管理已成为学术界和实业界关注的热门话题,特别是供应链管理成功地应用于IBM、P&G、DELL 等公司的经营管理以后,食品和农产品行业也纷纷效仿并借助供应链管理这一工具来提高自身的竞争力。

1996年,Zuurbier等学者在一般供应链的基础上,首次提出了食品供应链概念,并认为食品供应链管理是农产品和食品生产销售等组织,为了降低食品和农产品物流成本、提高其质量安全和物流服务水平而进行的垂直一体化运作模式。

如今,在美国、英国、加拿大和荷兰等农业生产较为发达的国家,这一管理模式已经广为应用,并逐渐成为当今学术研究的重点课题。

对食品供应链管理的研究大致经历了三个阶段:第一阶段为商流管理阶段,研究范围包括农产品和食品加工企业的产出到消费者消费前的商流阶段,其研究内容通常被包含在营销范畴内;第二阶段为集成物流管理阶段,农产品的物流管理从市场营销中分离出来,且向上游扩展到农产品和食品生产企业的生产加工过程,强调生产应以市场需求为导向和对整个物流环节的成本控制;第三阶段为供应链一体化管理阶段,研究范围进一步向上游延伸到农产品的最上游企业(如种子供应商等),延伸的目的是为了跟踪和追溯农产品食品质量安全问题,以便快速和有效地发现并解决问题。

本文介绍了不同食品供应链的生产物流系统特点,并对食品供应链与食品质量安全管理的发展进行了分析和探讨。

一.食品供应链管理的产生原因近年来,食品供应链的产生和发展是人们对食品消费的要求不断提高的必然结果。

具体而言,产生的原因主要有:(1)消费者对食品和农产品的新鲜度要求越来越高,并要求食品和农产品交货期、生产期越短越好。

(2)消费者对食品和农产品的质量要求也越来越高,迫使食品生产企业实行食品供应链管理,以保证稳定的上游原料供应和下游的销售渠道畅通。

(3)消费者对食品的质量安全也越来越关注。

为了满足消费者对食品和农产品在种类和数量上的要求,企业不断寻求和研发新技术,而新技术和新方法的过度使用(如杀虫剂、激素、抗生素和转基因技术等),在满足了消费者需求的同时,也不可避免地对人体产生了危害从而引起食品质量安全问题。

食品安全外文文献

Food safety is affected by the decisions of producers, processors, distributors, food service operators, and consumers, as well as by government regulations. In developed countries, the demand for higher levels of food safety has led to the implementation of regulatory programs that address more types of safety-related attributes (such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), microbial pathogens, environmental contaminants, and animal drug and pesticide residues) and impose stricter standards for those attributes.They also further prescribe how safety is to be assured and communicated. Liability systems are another form of regulation that affect who bears responsibility when food safety breaks down.These regulatory programs are intended to improve public health by controlling the quality of the domestic food supply and the increasing flow of imported food products from countries around the world. Common to the adoption of new regulations by developed countries is the application of risk analysis principles. Under these principles, and in line with the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement), countries should base their regulatory actions on scientific risk assessment. In addition, a country should be able to clearly link its targeted level of protection, based on a scientifically assessed risk level, to its regulatory goals and, in turn, to its standards and inspection systems. Finally, the risk management options chosen should restrict trade as little as possible. Despite similarities in approach among developed countries, to date they have made only mixed progress toward aligning their regulatory requirements. Countries are struggling with the task of identifying key risk issues and choosing regulatory programs to control those risks.They emphasize different risks, apply different levels of precaution, and choose different regulatory approaches.The regulatory systems of countries are a mix of old laws and newer regulations that frequently do not apply consistent standards across products, risks, or countries of origin. Finally, countries may be tempted to use food safety regulations as a means of protecting domestic industries from foreign competition. These features of food safety regulation in developed countries have several implications for developing countries. First, they determine access to growing markets for food exports, particularly high-value fresh commodities such as those discussed in other briefs in this collection.When standards differ, this can create additional barriers for developingcountry exporters. Second, these features determine the issues that will be addressed in international forums, such as the Codex Alimentarius Commission.Third, they create expectations among developing-country consumers regarding acceptable levels of safety and set examples for emerging regulations in developing-country food systems. This brief reviews emerging regulatory approaches and the implications for developing countries. REGULATORY APPROACHES Countries regulate food safety through the use of process, product (performance), or information standards. Process standards specify how the product should be produced. For example, Good Manufacturing Practices specify in-plant design, sanitation, and operation standards. Product (performance) standards require that final products have specific characteristics. An example is the specification of a maximum microbial pathogen load for fresh meats and poultry. Finally, information standards specify the types of labeling or other communicationthat must accompany products. While these categories provide a neat breakdown, in practice most countries use a combination of approaches to regulate any particular food safety risk. For example, specifications for acceptable in-plant operations may be backed up with final product testing to monitor and verify the success of safety assurance programs. Labeling that instructs final consumers on proper food handling techniques may further back up these systems. MAJOR REGULATORY TRENDS IN DEVELOPED COUNTRIES • Stronger public health and consumer welfare emphasis in decisions by regulatory agencies. The increasing use of the risk analysis framework for regulatory decision-making focuses attention on the effective control of public health risks as the ultimate goal of regulations, rather than intermediate steps such as assuring that accepted practices are used in production.This in turn leads to a focus on the food supply chain, on identifying where hazards are introduced into it, and on determining where those hazards can be controlled most cost effectively in the chain.This approach is referred to as “farm to table” or “farm to fork” analysis.When the supply chain extends across international borders, risk analysis may encompass farm or processing practices in developing countries. • Adoption of more stringent safety standards, with a broader scope of standards. Food safety standards are becoming more stringent in developed countries on two fronts. First, in many cases food safety attributes that were previously regulated are being held to more precise and stringent standards. For example, rather than assuring meat product safety simply through process standards, those products may be required to meet specific pathogen load standards for E. coli or Salmonella. Similarly, tolerances for aflatoxin may be lowered as more information and better testing become readily available. Second, the scope of standards is broadening, as new risks become known. For example, the European Union, the United States, and other countries have instituted strict feeding restrictions to avoid the spread of BSE in cattle. In addition, the European Union has recently established a regulatory program to control human exposure to dioxins through the food supply.These evolving standards create continuing challenges for producers and regulatory agencies in exporting countries. • Adoption of the HACCP approach to assuring safety. During the 1990s, developed countries made a strong shift toward requiring the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) approach to assuring food safety. Under HACCP, companies are responsible for analyzing how hazards such as food-borne pathogens may enter the product, establishing effective control points for those hazards, and monitoring and updating the system to assure high levels of food safety.These HACCP systems are usually predicated on the processing plant having an adequate system of sanitary operating procedures already in place. HACCP does not prescribe specific actions to be taken in a plant: the company chooses its methods for controlling hazards. HACCP systems make clear that the central responsibility for assuring safety belongs to a company; the regulator’s job is often shifted from one of direct inspection to providing oversight for the company’s operation of its HACCP plan. Since HACCP is primarily a process standard for company-level activity, inspection to assure compliance is challenging for imported products coming from plants in other countries. Some countries, such as those in the European Union, have mandated HACCP for all levels of the food supplychain, while others such as the United States have mandated it for specific sectors (meat slaughter and processing, for example). • Adoption of hybrid regulatory systems. Mandatory HACCP may be combined with performance standards for finished products.The performance standards (a minimum incidence of Salmonella in finished products, for example) provide a check on whether the HACCP plan is performing adequately.The increased use of performance standards has been facilitated by the development of more accurate and speedier testing procedures, particularly for pathogens. Eventually such tests may make it easier for exporters to demonstrate and verify a particular level of safety.食品安全受生产者、加工者、经销商、餐饮服务经营者决策的影响,也受到消费者和政府法规的影响。

美国食品及饮料氟化物含量数据库

USDA National Fluoride Database of Selected Beverages and Foods, Release 2Prepared byNutrient Data LaboratoryBeltsville Human Nutrition Research CenterAgricultural Research ServiceU.S. Department of Agriculturein collaboration withUniversity of Minnesota, Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC)University of Iowa, College of DentistryVirginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Food AnalysisLaboratory Control CenterNational Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), CSREES, USDA and Food Composition Laboratory (FCL), Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of AgricultureDecember 2005U.S. Department of AgricultureAgricultural Research ServiceBeltsville Human Nutrition Research CenterNutrient Data Laboratory10300 Baltimore AvenueBuilding 005, Room 107, BARC-WestBeltsville, Maryland 20705Tel. 301-504-0630, FAX: 301-504-0632E-Mail: ndlinfo@Web site: http://www/nal/usda/gov/fnic/foodcompiTable of Contents Acknowledgements (i)Disclaimers (i)Introduction (1)Methods and procedures (2)Data Generation (2)Data evaluation (4)Format of the table (4)Data dissemination (6)References cited in the documentation (6)References cited in the database (8)USDA National Fluoride Database (10)AcknowledgementsThis study was conducted as part of an Interagency Agreement between the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Nutrient Data Laboratory and The National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, NIH Agreement No. Y3-HV-8839The authors wish to thank Dr. Nancy Miller-Ihli, FCL, USDA for her work on pilot studies with drinking water and brewed tea, and development of NFDIAS quality control materials. The authors also wish to thank the 144 participants nationwide who supplied residential drinking water samples for this study.DisclaimersMention of trade names, commercial products, or companies in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over others not mentioned.Documentation: USDA National Fluoride Database of SelectedBeverages and Foods, Release 2IntroductionAssessment of fluoride intake is paramount in understanding the mechanisms of fluoride metabolism specifically the prevention of dental caries, dental fluorosis, and skeletal fluorosis. The Institute of Medicine (IOM, 1997) specified Adequate Intakes (AI) of 0.01 mg/day for infants through 6 months, 0.05 mg/kg/day beyond 6 months of age, and 3 mg/day and 4 mg/day for adult women and men (respectively), to prevent dental caries. Upper limits (UL) of 0.10 mg/kg/day in children less than 8 years and 10 mg/day for those older than 8 years are recommended for prevention of dental fluorosis. Similar levels have been endorsed by the American Dental Association (ADA, 1994) and the American Dietetic Association (ADA, 2000). Fluoride works primarily via topical mechanisms to inhibit demineralization, to enhance remineralization, and to inhibit bacteria associated with tooth decay (Featherstone, 2000). Fluoride has an affinity for calcified tissues. Studies of exposure and bone mineral density, fractures and osteoporosis would benefit from a national fluoride database coupled with an intake assessment tool (Phipps, 1995; Phipps et al., 2000). Therefore, a database for fluoride is needed for epidemiologists and health researchers to estimate the intakes and to investigate the relationships between intakes and human health.The Nutrient Data Laboratory (NDL), Agriculture Research Service, USDA, coordinated the development of the USDA National Fluoride Database of Selected Beverages and Foods subsequently described as the National Fluoride Database--a critical element of the comprehensive multi-center National Fluoride Database and Intake Study (NFDIAS). This second release of the USDA National Fluoride Database includes a column with mean values reported in parts per million, some data changes, and some new data resulting from aggregations of the Jackson (Jackson et. al., 2002) data and new data from University of Minnesota(UMN), Nutrition Coordinating Center and University of Iowa (UIowa), College of Dentistry data (UMN-UIowa) along with data from other literature and unpublished sources. These new aggregations have resulted in increases in the number of data points and in the number of studies resulting in tighter minimum to maximum values ranges, tighter lower and upper Error Bounds, and in some cases improved confidence codes. The National Fluoride Database has been incorporated into a computer-based fluoride assessment tool being developed by the University of Minnesota, Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC), as a module of the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R) software.The National Fluoride Database is a comprehensive, nationally representative database of the fluoride concentration in foods and beverages consumed in the United States. It contains fluoride values for beverages, water, and foods that are major fluoride contributors. Water and water-based beverages are the chief source of dietary fluoride intake (Singer and Ophaug, 1984). Conventional estimates are that about 75% of dietary fluoride comes from water and water-based beverages. According to the Centers for Disease Control(CDC, 2000) , in 2000 about 66% of the population on U.S.public water systems are receiving water that is fluoridated naturally or by adding fluoride. Drinking water fluoride distributions may vary widely over geographical and geo-political boundaries (CDC, 1993). Variations occur with soil composition and with local political decisions to fluoridate water. The use of wells of varying depths, commercial water products, home water purifiers, and filtration systems also increase variability of fluoride in drinking water and complicate estimates of intake (Brown and Aaron, 1991; Robinson et al.1991; Van Winkle et al., 1995). These variations in fluoride in commercial foods and beverages have been addressed in this National Fluoride Database.Methods and proceduresData GenerationThe fluoride contents of the chief contributors to fluoride intake have been determined through a national sampling and analytical program developed by NDL under the National Food and Nutrient Analysis Program (NFNAP, Pehrsson et al., 2000). In this database, mean values for fluoride in a particular beverage or food come from different data sources. Analytical data for US samples from the scientific literature and unpublished analytical data from Jackson et al. (2002), Kingman (1984)- Levy et al. (1992-2003), and Ophaug (1983-1987) have been included as well as analytical data for 126 items developed specifically for this National Fluoride Database. NDL used the Key Foods approach (Haytowitz et al., 2000) giving consideration to the previously published fluoride data for foods, beverages, and drinking water as well as the respective patterns of consumption of these dietary items to identify and prioritize sampling and analysis of the key food and beverage contributors of dietary fluoride. Consumption data from the 1994-96 USDA Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals and a preliminary fluoride database developed by the NCC provided the values for the initial evaluation. Mean estimates of fluoride concentration and variability in drinking water, beverages and foods that are the chief contributors to dietary fluoride in the United States have been developed from analysis of representative samplings.High priority beverages which collectively contribute up to 80% of dietary fluoride consumed in the United States, including municipal (tap)/drinking and bottled waters, teas, carbonated beverages, beers, and ready-to drink juices and drinks were analyzed. Samples were collected according to a self-weighting, nationally representative sampling approach (Bellow et al., 2002). Samples were collected in up to 144 locations across the country, depending on the level of contribution to fluoride intake. Since drinking water accounts for approximately 75% of dietary fluoride intake, sampling of drinking water was conducted, with Office of Management and Budget approval, in 144 nationally representative private residential locations nationwide (Pehrsson et al., 2004). The distribution of fluoride does vary due to naturally occurring fluoride levels and local fluoridation practices. The use of well water, commercial bottled waters, home purifiers and filter systems also affects variability in fluoride content of drinking water and impacts on estimates of daily intakes for individuals. NDL contacted water suppliers about their fluoridation practices and these were compared to participant responses(Wilger et al., 2004). Differences in geographical location have been incorporated into the National Fluoride Database for drinking water, brewed tea, and carbonated sodas.Retail samples of fruit juices, fruit-flavored beverages, carbonated beverages, bottled water, and a limited number of foods were picked up in 12 to 36 locations. The authors’ assumption that the fluoride variability would be lower in processed beverages and foods than that of municipal water was made based on existing data and the results of the water pilot study (Miller-Ihli et al., 2003), and hence fewer samples.The procurement and sample preparation of the foods and beverages that are the chief contributors of fluoride were handled through NFNAP supervised contracts and agreements. Sample units were purchased at retail sites, following detailed instruction from NDL. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Food Analysis Laboratory Control Center (FALCC) handled sample preparation. A quality control (QC) oversight program was established by the NFDIAS Laboratory Methods/Quality Control Working Group with representation from NDL, the University of Iowa, and FALCC. NFDIAS quality control materials were prepared by the USDA, Food Composition Laboratory (FCL) and by the NDL and characterized by three cooperating laboratories.The University of Iowa, College of Dentistry, conducted the laboratory analysis of fluoride. Samples were analyzed using a fluoride ion-specific electrode direct read method for clear liquids and a micro-diffusion method for other food samples. The direct reading method was validated using Certified Reference Material (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), a Standard Reference Material (SRM) 2671a, Fluoride in Freeze-Dried Urine) and by a comparison of results for several beverage samples between University of Iowa and FCL (Patterson et al., 2004). The micro-diffusion method was validated by analysis of a Certified Reference Material (National Research Centre for Certified Reference Materials, Beijing, China, GBW 08572 Prawns) and other reference materials that have reference values for the fluoride content (for example: NIST, SRM 8436), prior to sample analysis. Methodological procedures for analyzing carbonated beverages were developed at the University of Iowa and presented at the March 2004 International Association for Dental Research (IADR) Meeting (Heilman et al., 2004).Values in the database are reported on a 100 gram and on a ppm basis on the edible portion of a food. For some foods, no standard error was available from the literature source. Much of the literature data as well as the analytical data reported by the University of Iowa were reported on a ppm basis. Specific gravities needed for fluoride data conversion and migrations were obtained from VPI. Specific gravities for literature data were based on the specific gravities obtained from VPI, from other sources (manufacturer), or were determined by NDL. Values for beverages other than water, coffee and tea were adjusted by their respective specific gravities and are reported as served.Fluoride analytical results were submitted to the NFDIAS Quality Control (QC) Panel for review. These data included beer, wine, drinking water, brewed tea (consideredsignificant contributors to total intake of fluoride) and miscellaneous lower priority foods. The fluoride value for unsweetened instant tea powder seems high when reported at 89,772 mcgs/100 grams or 897.72 ppm because this product is extremely concentrated. However when one teaspoon of the unsweetened tea powder weighing 0.7 gram is added to an eight ounce cup of tap water, the value for prepared instant tea is 335 mcgs/100 grams or 3.35 ppm. This prepared unsweetened instant tea value compares well with the analytical values reported for regular brewed tea.Data evaluationAnalytical data approved by the NFDIAS QC panel, unpublished data generated by the University of Iowa, and data gathered from the published literature by NCC and NDL were entered into the USDA National Nutrient Databank System (NDBS) for further evaluation and compilation. The data were evaluated for quality using procedures developed by scientists at the NDL as part of the NDBS (Holden, et al., 2002). These procedures were based on categories and criteria described earlier by Holden, et al. (1987) and Mangels, et al. (1993) with some modifications. Categories evaluated include: sampling plan, sample handling, number of samples, analytical method, and analytical quality control. The evaluation process was modified making it specific to fluoride analytical methods. Evaluation of the analytical method has two facets: the method itself (processing of samples, analysis and quantitation method) and validation and quality control of the method by the laboratory (accuracy and precision). Both the NFNAP analytical data and data from each manuscript were evaluated for each category, which then received a rating ranging from 0 to 20 points. The ratings for each of the five categories were summed to yield a Quality Index or QI-the maximum possible score is 100 points. The Confidence Code (CC) was derived from the QI and is an indicator of relative quality of the data and the reliability of a given mean. The CC is assigned as follows:QI CC75 -100 A74 - 50 B49 - 25 C< 25 DFormat of the tableThe table contains fluoride values for 427 foods across 23 food groups. The data were aggregated where possible to match the foods in the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (SR). Food groups are presented in alphabetical order with beverages and foods arranged in alphabetical order within a food group. Whenever possible, a NDB Number (No.) (a five digit numerical code used in the SR) is provided. This NDB No. provides the link between values for foods in this database and SR. As the data come from a variety of sources or are presented with specificity not used in SR, there are a number of beverages and foods, which do not have NDB Nos but do haveseparate identifiers. In these cases, we assigned a temporary NDB No. which begins with “975.” These temporary NDB Nos. are not unique to these beverages and foods and may be used in other special interest databases produced by NDL.The fields are as follows:Field Name DescriptionFood Group Description of food groupItem Description of food or beverageMean ppm Amount in parts per million.Mean mcg/100 g Amount in 100 grams, edible portionStd Error Standard error of the mean. Null, if could not becalculatedN Number of data points (samples analyzed). The N=1 onNFNAP data represents a composite of 12 samplesMin MinimumvalueMax MaximumvalueLower EB Lower 95% error boundUpper EB Upper 95% error boundCC Confidence code indicating data quality based onevaluations of sample plan, sample handling, analyticalmethod, analytical quality control, and number of samplesanalyzedDerivation Code Code giving specific information on how the value wasdetermined:A = Analytical dataRPA = Recipe; Known formulation; No adjustmentsapplied, combination of source codes 1, 12and/or 6RPI = Recipe; Known formulation; No adjustmentsapplied, combination of source codes whichincludes codes other than 1, 12 or 6Source Code Code indicating type of data1 = Analytical or derived from analytical6 = Aggregated data involving combinations of sourcecodes 1 & 1212 = Manufacturer's analytical; partial documentationStatistical Comments 1. The displayed summary statistics were computedfrom data containing some less-than values. Less-than, trace, and not detected values werecalculated2. The displayed degrees of freedom were computedusing Satterthwaite’s approximation (Korz andJohnson, 1988)3. The procedure used to estimate the reliability of thegeneric mean requires that the data associatedwith each study be a simple random sample fromall the products associated with the given datasource (for example, manufacturer, variety, cultivar,and species)4. For this nutrient, one or more data sources hadonly one observation. Therefore, the standarderrors, degrees of freedom and error bounds werecomputed from the between-group standarddeviation of the weighted groups having only onestudy observation.NDB No. 5-Digit Nutrient Databank number that uniquely identifiesa food item.No. of Studies Number of studiesReferences Unique descriptions of the references/sourcesData disseminationThe USDA National Fluoride Database of Selected Beverages and Foods, Release 2 is presented as a pdf file. Adobe Acrobat Reader® is needed to view the report of the database. A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet is also available (fluoride.xls). A compressed file (fluoride.zip) containing the complete database in the ASCII format and its documentation has also been prepared and is available for downloading from NDL’s Web site (/ba/bhnrc/ndl). The user can download the database, free of charge, onto his/her own computer for use with other programs.References cited in the documentationAmerican Dental Association (ADA). 1994. New fluoride schedule adopted. ADA News. 25: 12-14.American Dental Association (ADA). 2000. Position of the American Dietetic Association: The impact of fluoride on health. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 100: 1208-1213.Bellow ME, Perry CR, and Pehrsson PR. 2002. Sampling and Analysis Plan for a National Fluoride Study. 2002 Proceedings of the American Statistical Association, Section on Survey Research Methods [CD-ROM], Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association, Baltimore, MD, /sections/wrms/Proceedings/. (Presentation and publication)Brown MD and Aaron G. 1991. The effect of point-of-use conditioning systems on community fluoridated water. Pediatr. Dent. 13: 35-38.Centers for Disease Control (CDC). 2000. Populations Receiving Optimally Fluoridated Public Drinking Water --- United States, 2000. MMWR 51(07);144-147.Featherstone JD. 2000. The science and practice of caries prevention. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 131: 887-899.Haytowitz DB, Pehrsson PR, and Holden JM. 2002. Identification of Key Foods for Food Composition Research. J. Food Comp. Anal. 15(2): 183-194.Heilman JR, Levy SM, Wefel JS, Cutrufelli R, Pehrsson PR, Patterson KY, Phillips K, Razor AS, and Whalen AB. 2004. "Fluoride Levels of Carbonated Sodas and Beers" March 2004, International Association of Dental Research, Honolulu, HI. (Presentation)Holden JM, Bhagwat SA, and Patterson KY. 2002. Development of a Multi-Nutrient Data Quality Evaluation System. J. Food Comp. Anal. 15(4): 339-348.Holden JM, Schubert A, Wolf WR, and Beecher GR. 1987. A system for evaluating the quality of published nutrient data: selenium, a test case. Food Nutr. Bull. 9(Suppl.): 177-193.Institute of Medicine (IOM), Food and Nutrition Board, National Academy of Sciences. 1997. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.Jackson RD, Brizendine EJ, Kelly SA, Hinesley R, Stookey GK, Dunipace AJ. 2002.The fluoride content of foods and beverages from negligibly and optimally fluoridated communities. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 30: 382-391 and unpublished fluoride data.Kingman A. 1984. Unpublished data. NIDR/NIH.Korz S and Johnson NL. 1988. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. 8: 261-262, John Wiley and Son, New York, NY.Levy SM, Heilman JR, and Wefel JS. 1992-2003. Unpublished fluoride data.Mangels AR, Holden JM, Beecher GR, Forman MR, and Lanza E. 1993. Carotenoid content of fruits and vegetables: an evaluation of analytic data. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 93: 284-296.Miller-Ihli NJ, Pehrsson PR, Cutrufelli R, and Holden JM. 2003. Fluoride content of municipal water in the United States: What percentage is fluoridated? J. Food Comp. Anal. 16(5): 621-628.Ophaug RH. 1983-1987. Unpublished fluoride data.Patterson KY, Levy SM, Wefel JS, Heilman JR, Cutrufelli R, Pehrsson PR, Harnack L, and Holden JM. 2004. A Quality Assurance Program for the National Fluoride Database and Intake Assessment Study [Presentation abstract] 28th US National Databank Conference, June 24-26, 2004, Iowa City, Iowa.Pehrsson PR, Haytowitz DB, Holden JM, Perry CR, and Beckler DG. 2000. USDA’s National Food and Nutrient Analysis Program: Food Sampling. J. Food Comp. Anal. 12: 379-89.Pehrsson PR, Cutrufelli R, Patterson KY, Perry C, Holden JM, Banerjee S, Himes JH, Levy SM, and Heilman JR. 2004. Fluoride Concentration and Variability in U.S. Drinking Water [Presentation abstract] 28th US National Databank Conference, June24-26, 2004, Iowa City, Iowa.Phipps K. 1995. Fluoride and bone health. J. Public Health Dent. 55: 53-56.Phipps KR, Orwell ES, Mason JD, and Cauley JA. 2000. Community water fluoridation, bone mineral density, and fractures: Prospective study of effects in older women. B. M. J. 321: 860-864.Robinson SN, Davies EH, and Williams B. 1991. Domestic water treatment appliances and the fluoride ion. Br. Dent. J. 171: 91-93.Singer L and Ophaug RH. 1984. Present knowledge in nutrition: Fluoride. The Nutrition Foundation, Inc. Washington, D.C. 538-547.Van Winkle S, Levy SM, Kiritsy MC, Heilman JR, Wefel JS, and Marshall T. 1995. Water and formula fluoride concentrations: significance for infants fed formula. Pediatr. Dent. 17: 305-310.Wilger J, Cutrufelli R, Pehrsson PR, Patterson KY, and Holden JM. 2004. Participant Knowledge of Fluoride in Drinking Water Based on a National Survey [Poster abstract]37th Annual Meeting Society for Nutrition Education, July 17-21, 2004, Salt Lake City, Utah.References cited in the databaseAdair S, Leverett D, Shields C, and McKnight-Hanes C. 1991. Fluoride Content of School Lunches from an Optimally Fluoridated and a Fluoride-Deficient Community. J. Food Comp. Anal.4: 216-226.Chan JT and Koh SH. 1996. Fluoride Content in Caffeinated, Decaffeinated and Herbal Teas. Caries Research. 30: 88-92.Featherstone JDB and Shields CP. 1988. A study of fluoride intake in New York state residents. New York State Department of Health Report. December 1, 1988.9 Heilman JR, Kiritsy MC, Levy SM, Wefel JS, 1999. Assessing fluoride levels of carbonated soft drinks. JADA. 130: 1593-1599.Himes JH, Van Heel N , Harnack L, Levy SM, Heilman JR, and Wefel JS. 2004 -05. Unpublished fluoride data. UMN-UIowa.Jackson RD, Brizendine EJ, Kelly SA, Hinesley R, Stookey GK, Dunipace AJ. 2002. The fluoride content of foods and beverages from negligibly and optimally fluoridated communities. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 30: 382-391 and unpublished fluoride data.Kingman A. 1984. Unpublished data. NIDR/NIH.Kiritsy MC, Levy SM, Warren JJ, Guha Chowdhury N, Heilman JR, and Marshall T. 1996. Assessing Fluoride Concentrations of Juices and Juice Flavored Drinks. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 127: 895-902.Levy SM, Heilman JR, and Wefel JS. 1992-2003. Unpublished fluoride data. Ophaug RH. 1983-1987. Unpublished fluoride data.Shannon I. 1977. Fluoride in carbonated Drinks. Texas Dent. J. 95: 6-9.Schulz EM, Epstein JS, and Forrester DJ. 1976. Fluoride Content of Popular Carbonated Beverages, J. of Prev. Dent. 3(1): 27-29.Stannard J, Rovero J, Tsamtsouris A, and Gavris V. 1990. Fluoride content of some bottled waters and recommendations for fluoride supplementation. J. Pedodontics14(2): 103-107.Stannard JG, Shim YS, Kritsineli M, Labropoulou P, and Tsamtsouris A. 1991. Fluoride levels and fluoride contamination of fruit juices. J. of Clin. Pediatr. Dent.16(1): 38-40. Taves DR. (1983). 1983. Dietary intake of fluoride ashed (total fluoride) vs. unashed (inorganic fluoride) analysis of individual foods, Br. J. Nutr. 49: 295-301.。

外文国外食品安全专题数据库

Overseas Food Safety Database in English《外文国外食品安全专题数据库》(OFSDE)《外文国外食品安全专题数据库》就是针对现阶段食品安全管理的迫切形势而制作。

该库全方位收录了国外食品安全管理的优秀文献,是国外最前沿的食品管理文献数据库。

涵盖了食品注册认证、食品标准、食品技术鉴定、食品监督、食品质量、食品污染等等有关食品安全管理的程序、步骤、措施、方法。

内容全面丰富,资料可信科学。

该库收录有关国外食品安全管理的期刊、非期刊文献,来源150种以上,都是国外政府、国际行业组织、期刊杂志社的优秀论文,包含了美欧澳日等国食品安全管理研究的各个领域和层次;其所收录文章的论点新颖深刻,论据合理生动,论证科学严谨,具有很高的研究和借鉴价值。

该库不仅包含学术论文,还包括相关学术会议综述和成果纪录,紧跟学术领域的最新发展状况,时效性和实用性很强。

界面全英文显示,纯外文数据向用户提供了最为准确翔实的资料。

该库的突出特点是数据量大、分类详细、检索方便。

提供高级和初级两种检索方式,读者可以通过篇名、作者、年代及摘要、正文关键字等各种方式实现查询检索。

该库的收集整理制作填补了目前国内有关外文食品安全管理数据领域的空白,是各食品生产加工、贸易企业、食品检验检疫机构等部门,适应我国加入WTO的需要,学习与借鉴国外食品安全管理先进经验的最有价值的工具,是理论研究和实际管理的重要参考数据。

【主要内容】:共分为21个大类,收集最新外文期刊、非期刊共7.2万篇。

1、食品注册和认证:包括食品GMP认证、HACCP认证、有机食品认证、无公害食品认证、绿色食品认证、有机食品认证程序和流程图、认证认可工作法律体系、管理体系、制度体系......2、食品监督:包括食品生产许可证监督管理、食品加工企业质量安全监督、农产品监督......3、食品标准:收录了西方主要国家及国际组织有关食品安全的标准、技术规范及论著。

国内外食品安全风险监测数据需求概述

— 必须使 用 本 国 的 食 物 消 费 量 及 化 学 物 浓 度 。 必 须清晰表 达 所 使 用 的 方 法 学 以 及 暴 露 评 估 中 与 化 学物浓 度 相 关 联 的 假 设, 而且该方法学是可重复 局限性和不 的 。 有关使用的模 型 和 数 据 源 的 假 设 、 确定度也 应 记 录 。 必 须 清 晰 表 示 用 来 表 示 高 暴 露 人群的百分位数( 95 或 97. 5 百分位数) 及其偏差 。 1. 2 食品中化学物浓度数据 为使化 学 物 浓 度 数 据 最 大 程 度 地 为 膳 食 暴 露 评估服务, 在可能 的 情 况 下, 提 供 详 细 的 数 据 来 源、 LOD / 调查类型 / 计划 、 采样 、 样品处理 、 分析方法学 、 LOQ 和质 量 保 证 是 很 重 要 的 。 2010 年 WHO 有 关 食 品 中 出 现 的 危 害 物 ( hazard occurring in food , HOF ) 数据报告工作组对于 GEMS / Food 提出了更高 要求, 对采 用 数 据 电 子 提 交 系 统 ( OPAL ) 提 出 了 一 系列关键要 求 和 改 进 措 施, 希 望 有 助 于 WHO 和 成 员国工作人员减少报告 / 录入数据的工作负荷 。 在所有情况下, 食品化学数据中化学物浓度未 检出或不 能 定 量 值 的 指 定 可 能 会 显 著 地 影 响 膳 食 因 此, 应详细陈述这些结果的处理 暴露评估结 果, 方案 。 1. 3 食物消费量数据 无论 是 GEMS / Food 还 是 我 国 的 膳 食 消 费 量 数 其调查数据都应当包 据在应用于膳食暴 露 评 估 时, 括饮用水 、 饮料 消 费 和 膳 食 补 充 剂 。 GEMS / Food 已 经取得以下进展: ( 1 ) GEMS / Food 成功用于国际水平的慢性膳食 所用食物消费量已由 13 类聚类膳食取 暴露评估中, 代原来的 5 类区域膳食 。 ( 2 ) 在估计单个食物 商 品 及 其 化 学 残 留 的 急 性 膳食暴露时, 适当的 方 法 是 使 用 仅 消 费 这 个 单 一 食 物者的食 物 消 费 数 据 ( 仅 消 费 者 ) 。 用 多 种 食 物 商 品开展化学残留的 慢 性 膳 食 暴 露 估 计 时, 同时以仅 消费者 数 据 和 所 有 被 调 查 者 所 有 数 据 ( 调 查 全 人 群) 开展评估 。 ( 3 ) 理论上, GEMS / Food 食 物 消 费 大 份 ( LP ) 数 据库应以 成 员 国 所 开 展 国 家 调 查 结 果 的 个 体 消 费 天数 P97. 5 为基础 。 ( 4 ) CAC 通 过 GEMS / Food 收 集 有 关 国 家 基 于 个体膳食 记 录 产 生 的 消 费 量 P97. 5 的 数 据 。 要 求 有关国家的政 府 向 GEMS / Food 提 供 数 据 时 应 有 适 当的文件 。 中国作为重要 的 人 口 大 国, 并且由于膳食多样 性与发达国家在食 品 品 种 和 消 费 量 上 差 别 很 大, 应 该建立自己的 食 物 消 费 大 份 ( LP ) 。 应 定 期 开 展 食 物消费量调查, 最 好 是 基 于 个 体 的 膳 食 记 录。 食 物 消费量调查最好包 括 每 个 被 调 查 者 多 天 的 记 录, 并

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Overseas Food Safety Database in English《外文国外食品安全专题数据库》(OFSDE)《外文国外食品安全专题数据库》就是针对现阶段食品安全管理的迫切形势而制作。

该库全方位收录了国外食品安全管理的优秀文献,是国外最前沿的食品管理文献数据库。

涵盖了食品注册认证、食品标准、食品技术鉴定、食品监督、食品质量、食品污染等等有关食品安全管理的程序、步骤、措施、方法。

内容全面丰富,资料可信科学。

该库收录有关国外食品安全管理的期刊、非期刊文献,来源150种以上,都是国外政府、国际行业组织、期刊杂志社的优秀论文,包含了美欧澳日等国食品安全管理研究的各个领域和层次;其所收录文章的论点新颖深刻,论据合理生动,论证科学严谨,具有很高的研究和借鉴价值。

该库不仅包含学术论文,还包括相关学术会议综述和成果纪录,紧跟学术领域的最新发展状况,时效性和实用性很强。

界面全英文显示,纯外文数据向用户提供了最为准确翔实的资料。

该库的突出特点是数据量大、分类详细、检索方便。

提供高级和初级两种检索方式,读者可以通过篇名、作者、年代及摘要、正文关键字等各种方式实现查询检索。

该库的收集整理制作填补了目前国内有关外文食品安全管理数据领域的空白,是各食品生产加工、贸易企业、食品检验检疫机构等部门,适应我国加入WTO的需要,学习与借鉴国外食品安全管理先进经验的最有价值的工具,是理论研究和实际管理的重要参考数据。

【主要内容】:共分为21个大类,收集最新外文期刊、非期刊共7.2万篇。

1、食品注册和认证:包括食品GMP认证、HACCP认证、有机食品认证、无公害食品认证、绿色食品认证、有机食品认证程序和流程图、认证认可工作法律体系、管理体系、制度体系......2、食品监督:包括食品生产许可证监督管理、食品加工企业质量安全监督、农产品监督......3、食品标准:收录了西方主要国家及国际组织有关食品安全的标准、技术规范及论著。

收录的国际组织主要有世界粮农组织(FAO)、世界卫生组织(WHO)及国际食品法典委员会(CAC)、世界经济合作与发展组织(OECD)、新物种保护协会(UPOV)、国际科协(ICSU)等;收录的主要发达国家包括美国、加拿大、墨西哥、澳大利亚、新西兰、日本、欧盟及欧盟成员国,如英国、爱尔兰、丹麦、匈牙利等;包括了食品卫生标准、食品包装保准、食品专业标准、食品添加剂标准、食品工业相关标准、无公害食品标准、绿色食品标准、有机食品标准、食品检验方法标准......4、食品鉴定:包括食品鉴定的依据、转基因食品鉴定、粮油类食品鉴定方法、干菜类制品鉴别方法、水产品鉴别、保健品食品鉴别方法......5、食品分析方法:食品原材料的理化分析方法、食品分析方法的原理、基本操作、数理分析与处理......6、食品成分:主要来源为Journal of Composition and Analysis ,Council Regulation (EEC),Pharmaceutical Reference Guide ,Glycobiology Resource ,Food Texture Handbook ,Rheology Handbook, Polysaccharide Reference from C.H.I.P.S.等;7、食品分类:分为以下两部分——生物分类:从生物分类学的角度介绍了一些食物:贻贝、蚌类、江鳟鱼、鲑于鱼、小龙虾、杀丁鱼等......——功能分类:着重介绍了:运动营养学、植物化学功能食品、人类健康需要的硬化食品增补剂、天然食品等......8、功能食品:包括功能食品产业发展、功能食品功能因子研究、功能食品的研发、功能食品的功能学测定、功能性食品......9、食品添加剂:包括食品添加剂标准、食品添加剂的作用、食品添加剂分类、酸度调节剂、抗结剂、消泡剂、抗氧化剂、膨松剂、着色剂、护色剂、酶制剂、增味剂、营养强化剂、防腐剂、甜味剂、水分保持剂......10、动物饲料:包括动物饲料添加剂、微生物在动物饲料中的应用......11、特殊食用用途:包括动物饲料添加剂、微生物在动物饲料中的应用......12、食品质量:分为以下几部分——食品质量检验方法:包括食品质量检验的技术和方法、食品良好操作规范(GMP)、食品卫生标准操作规范(SSOP)、食品危害分析与关键点控制(HACCP)和ISO9000质量保证标准系列、质量管理体系标准与认证......——质量保证:包括食品质量控制;食品质量保持;食品从业人员健康检查、食品生产企业建筑设计卫生要求......——质量影响因素:包括蛋白质食品加工质量影响因素、食品质量决策、食品安全质量管理、食品工业全面质量管理......13、食品效应:分为以下几部分——经济效应:包括农业经济学中涉及的食品经济效应、印度谷类价格稳定性评估、采用更先进的农业技术提高食品产量、墨西哥乳汁品的需求等内容......——环境效益:化肥农药的大量投入,农业自身面临污染对环境的负面影响,阐述了美国、德国、挪威、意大利、委内瑞拉、尼日利亚等国家的情况......——健康效应:主要的文章包括木糖醇对II型糖尿病具有降糖作用、营养成分与机体免疫力密切相关等有关食品对健康的影响......——营养效应:波兰中东部补充维他命和矿物质的效果、科威特关于母奶和母奶替代品的比较研究等文章,包括美国、日本、法国等国的专家就食品补充营养的方面做阐述......14、食品污染:分为以下几部分——食品安全风险评估:日本、瑞士、挪威、阿根廷、美国、爱尔兰等国家的食品安全风险评估体系......——食品污染标准:包括细菌性污染标准、真菌毒素污染标准、病毒性污染标准、寄生虫标准、农药污染标准,涉及马来群岛、美国日本等国家和地区的分类标准......——食品污染防范和控制:包括食品环境污染防范、食品添加剂防范、食品中致癌防癌因素的防范和控制、食品污染分析的发展情况等方面......——食品安全能力建设:包括美国、英国等国家的有关食品安全能力建设方面的内容,比如:牛奶产品的安全、牛肉屠宰过程中的卫生安全等方面的建设......15、危害分析:分为以下几部分——化学危害:包括化学危害的控制、天然化学物质危害、有意加入的化学物质的危害、偶然加入的化学物质的危害、农用化学物质危害、公用化学物质危害......——食品相关疾病:包括不合理营养与疾病、食品结构与疾病、营养与食品卫生安全......——食品卫生和动物疾病:包括动物食品卫生检验、人畜共患疾病防治、动物疾病防治、动物保健食品......16、食品生产和消费:分为以下几部分——食品生产:介绍了非洲、美国、英国等国家和地区的玉米、水稻、马铃薯、蔬菜等的生产情况和技术情况......——食品消费:包括超市的食品供应、(日本、德国、美国)食品产业新动态、中国有关食品的消费等方面......——食品生产体系组成:美国、中国、加拿大等国家的有机食品、蔬菜生产、无污染绿色食品生产体系......——消费者教育:主要介绍了欧洲、日本、美国的一些情况......17、有害物防治:分为以下几部分——有害物报告:涉及二肽酶、氨基肽酶、磷酸化酶北美、欧洲的库蚊属类带的杆肠菌等......——有害物防治方法:农业防治措施、物理防治措施、生物防治措施等,涉及日本、美国、加拿大等国家......——有害物防治方法管理体系:杀虫剂控制的法律规定等,涉及的国家包括日本、美国等......18、生物技术:包括转基因生物技术、基因工程与食品产业、细胞工程与食品产业、酶工程与食品产业、蛋白质工程与食品产业、发酵工程与食品产业、食品生物工程下游技术以及现代生物技术与食品安全......19、食品技术法规:包括与国际接轨的技术法规、有机食品技术规范、蔬菜技术法规、保健食品技术工艺......20、与WTO有关的协议:主要涉及WTO成员国的一些国家,像美国、澳大利亚、墨西哥、日本等关于牛、柑橘、香蕉、蔬菜等方面的协议......【来源】:该库数据来源丰富,包括150多个国家级站点、电子期刊和一些大学的院系主页,都是研究了解食品安全的权威机构如下:Abg.at.au.sk.caAgri.ee .au Animal Feed Science and Technology.auBfr.bund.de.brBioresource Technology Canexplore.gc.caCao.go.jpCarbohydrate Polymers Efsa.eu.intEn.gmo.hrEuropa.eu.intFood and Chemical ToxicologyFood ControlFood MicrobiologyFood PolicyFood Quality and PreferenceFood Research InternationalFood Science and Technology.auFsai.ieFvm.huGrainscanada.gc.caIndustrial Crops & ProductsInnovative Food Science andEmerging TechnologiesInspection.gc.caInternational Dairy JournalInternational Journal of FoodMicrobiologyInternational Journal ofRefrigerationIso.chJapanfood.seJournal of Cereal ScienceJournal of Food Composition and AnalysisJournal of Food Engineering Journal of the American Dietetic Association Lst.min.dkMaff.go.jp.auMszt.huNlbc.go.jp Odin.dep.noOsec.chPostharvest Biology andTechnologyPwgsc.gc.ca.auSjv.seTeagasc.ieInternational Food andAgribusiness ManagementReviewTrends in Food Science &TechnologyUpov.intUsask.caWho.int【语种】英语(ENGLISH)【检索方式】分高级检索和初级检索两种方式。

读者可以通过标题、作者、篇名、年代及摘要、正文关键字等方式实现全文检索。