市场微结构Market Microstructure

拾穗多因子系列(20):市场微观结构研究:如何度量股市流动性?

拾穗多因子系列(20):市场微观结构研究:如何度量股市流动性?投资要点►引言该如何度量股市流动性?美国股票市场发生了“流动性危机”吗?A股市场的流动性情况如何?本期“拾穗”专题,我们从微观市场结构的研究视角出发,介绍几种度量市场流动性的指标,并对中美两市近期的流动性情况进行比较,以供投资者参考。

►“流动性是市场的一切”市场微观结构理论是研究交易价格的形成与发现过程与交易运作机制的一个金融分支,市场结构的研究主要包括流动性、透明性、有效性、稳定性、公平性、可靠性,而其中“流动性是市场的一切”。

流动性是在一定时间内完成交易所需的时间或成本,概括起来流动性包含速度(交易时间)、价格(交易成本)、交易数量和弹性四个方面。

►股市流动性度量指标介绍从市场流动性冲击出发,对Amihud非流动性指标、PastorGamma指标、LOT Zeros方法进行介绍。

从股票买卖价格出发,对采用日内高频交易数据构建的有效价差指标和采用日度低频价量指标的Roll价差,Corwin and Schultz指标进行介绍。

►实证检验通过对美股市场的整体流动性进行监测发现,近期美股市场的流动性冲击达到一个高峰,部分指标甚至高过2008年金融危机时刻。

近期美股市场确实承受了较大的卖压,由于投资者的恐慌性抛售导致的市场信心不足从多个流动性指标维度得到了验证。

相较之下,A股市场受近期全球波动影响虽然也出现了一定的波动放大情况,但总体而言A股市场流动性情况比较良好,并没有出现股市流动性紧张的情况。

►风险提示本报告统计结果基于历史数据,过去数据不代表未来,市场风格变化可能导致模型失效。

►更多交流,欢迎联系张宇,联系方式:176****8421(注明机构+姓名)欢迎在Wind研报平台中搜索关键字“星火“和”拾穗”,下载阅读专题报告的PDF版本。

本期是该系列报告的第20期,随着新冠疫情在全球范围内的扩散以及OPEC与俄罗斯之间的石油冲突爆发,近期外围市场出现了剧烈的波动,其中以美国市场的波动最为明显。

procast-初级教程

ProCAST软件综合培训教程 CopyRight cax2001@ ProCAST 3.20 简体中文基础应用教程版权所有:软件猎手cax2001@第一章 软件及基本操作介绍ProCAST软件是由美国UES公司开发的铸造过程模拟软件,采用基于有限元(FEM)的数值计算和综合求解的方法,对铸件充型、凝固和冷却过程中的流场、温度场、应力场、电磁场进行模拟分析。

一、软件模块:如图1所示,ProCAST软件包括8个模块:1、基本模块Base Module:基本模块包括温度场、凝固、材料数据库及前后处理。

2、剖分模块Meshing:产生输入模型的四面体体网格3、流动模块Fluid:对铸造过程中的流场进行模拟分析4、应力模块Stress:对铸造过程中的应力场进行模拟分析5、微结构模块Microstructure:对铸件的微观组织结构进行模拟分析6、电磁模块Electromagnetic:对铸造过程中的电磁场进行模拟分析7、辐射模块Radiation:对铸造过程中的辐射能量进行模拟分析8、逆运算模块Inverse:采用逆运算计算界面条件参数和边界条件参数二、模拟过程ProCAST软件的模拟流程包括:1、创建模型:可以分别用I-Deas、Pro/E、UG、Patran、Ansys 作为前处理软件创建模型,输出ProCAST可接受的模型或网格文件。

2、MeshCAST:对输入的模型或网格文件进行剖分,最终产生四面体体网格,生成xx.mesh文件,文件中包含节点数量、单元数量、材料数量等信息。

3、PreCAST:分配材料、设定界面条件、边界条件、初始条件、模拟参数,生成xxd.out和xxp.out文件,4、DataCAST:检查模型及PreCAST中对模型的定义是否有错误,如有错误,输出错误信息,如无错误,将所有的模型信息转换为二进制,生成xx.unf文件。

5、ProCAST:对铸造过程模拟分析计算,生成xx.unf文件。

无私奉献解构高考英语阅读试题

词·清平乐禁庭春昼,莺羽披新绣。

百草巧求花下斗,只赌珠玑满斗。

日晚却理残妆,御前闲舞霓裳。

谁道腰肢窈窕,折旋笑得君王。

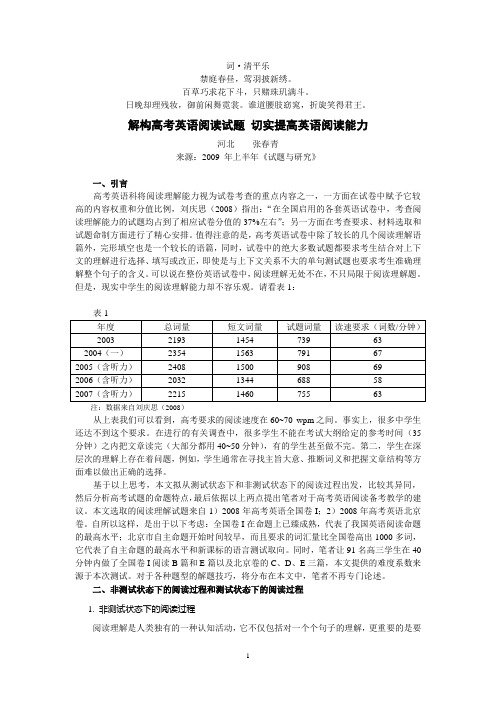

解构高考英语阅读试题切实提高英语阅读能力河北张春青来源:2009 年上半年《试题与研究》一、引言高考英语科将阅读理解能力视为试卷考查的重点内容之一,一方面在试卷中赋予它较高的内容权重和分值比例,刘庆思(2008)指出:“在全国启用的各套英语试卷中,考查阅读理解能力的试题均占到了相应试卷分值的37%左右”;另一方面在考查要求、材料选取和试题命制方面进行了精心安排。

值得注意的是,高考英语试卷中除了较长的几个阅读理解语篇外,完形填空也是一个较长的语篇,同时,试卷中的绝大多数试题都要求考生结合对上下文的理解进行选择、填写或改正,即使是与上下文关系不大的单句测试题也要求考生准确理解整个句子的含义。

可以说在整份英语试卷中,阅读理解无处不在,不只局限于阅读理解题。

但是,现实中学生的阅读理解能力却不容乐观。

请看表1:注:数据来自刘庆思(2008)从上表我们可以看到,高考要求的阅读速度在60~70 wpm之间。

事实上,很多中学生还达不到这个要求。

在进行的有关调查中,很多学生不能在考试大纲给定的参考时间(35分钟)之内把文章读完(大部分都用40~50分钟),有的学生甚至做不完。

第二,学生在深层次的理解上存在着问题,例如,学生通常在寻找主旨大意、推断词义和把握文章结构等方面难以做出正确的选择。

基于以上思考,本文拟从测试状态下和非测试状态下的阅读过程出发,比较其异同,然后分析高考试题的命题特点,最后依据以上两点提出笔者对于高考英语阅读备考教学的建议。

本文选取的阅读理解试题来自1)2008年高考英语全国卷I;2)2008年高考英语北京卷。

自所以这样,是出于以下考虑:全国卷I在命题上已臻成熟,代表了我国英语阅读命题的最高水平;北京市自主命题开始时间较早,而且要求的词汇量比全国卷高出1000多词,它代表了自主命题的最高水平和新课标的语言测试取向。

市场微观结构

组合收益率的矩

• 假设对所有证券按照不交易的概率来进 行分组,在此基础上组成等权重的证券 组合:组合A包含有 N a 个证券(不交易 概率均为 π a),组合B包含有 N b 个证券 0 0 π b )。定义 rat 和 rbt (不交易概率均为 为这两个组合在 t 时刻的观察收益率。 则

1 r ≈ Nk

• 三、不交易概率 • 假设在每一个t时期,证券i不交易的概 率为 π i ,证券交易与否独立于真实收益 率 {rit },且独立于任何其他随机变量。 这样,不同的证券有不同的不交易概率, 而每一种证券的不交易过程可以被视为 是一种抛硬币的独立同分布过程(IID)。

模型的推导

• 引入两个伯奴力(Bernoulli)指示变量:

k =1 j =1 ∞ k

• 则 kt 为 t 期前连续不交易的期数。

rit0 = ∑ rit − k

k =0

kt

(3)

rit0 = ∑ rit − k

k =0

kt

• 这说明观察收益率是所有过去真实收益 0 率的随机函数,即 rit 可以表示为随机 期数 (kt ) 的随机变量 ( rit ) 的和。 • 该等式概率为 (1 − π i )2 π ik = (1 − π i )π ik (1 − π i ) • 其中,第一个 (1 − π i ) 意味着第 t 期交易, 而后一个 (1 − π i ) 意味着第 kt −1 期交易, 而 π ikt 则意味着中间 kt 期均不交易。

• 3、真实收益过程的数字特征: • 根据假设,每一时期的真实收益率都是 随机的,并且反映消息到达和非系统噪 声。且有:

E[rit ] = µi (由于E ( ft ) = 0,且E (ε it ) = 0)

什么是电泳显示技术

什么是电泳显示技术(EPD)?电泳显示技术(EPD)又称电泳显示器,是类纸式显示器较早发展的显示技术,是利用有颜色的带电球,藉由外加电场,在液态环境中移动,呈现不同颜色的显示效果,其代表厂商包括E-Ink与Sipix。

日本Bridgestone所推出的高速响应液态显示器(QR-LPD),其工作原理与EPD 相似,只是其成像的物质不是使用带电球,而是由黑白2色的粉末在电场之间移动产生显示效果。

另外发展较早的胆固醇液晶(ChLC),是一种结构相似于胆固醇分子的液晶。

胆固醇反射式显示器在不加电压时,可存在两种稳定的状态,利用两个状态之间的转换,呈现亮暗态的显示效果。

其它还有强诱电性液晶(FerroelectricLiquid Crystal;FLC)等。

电泳显示(Electrophoretic,E-Paper)技术由于结合了普通纸张和电子显示器的优点,是最有可能实现电子纸张产业化的技术。

目前它已从众多显示技术中脱颖而出,成为极具发展潜力的柔性电子显示技术之一。

据iSuppli预测,电泳显示全球市场2006年仅仅900万美元,但是预计到2013年将增加到2.47亿美元,年均增长率高达60.5%。

该增长的大部分市场在指示标和新颖的直接驱动显示器,另外电子显示卡、柔性电子阅读器、电子纸张和数字签字等产品也将获得应用。

一、电泳技术及其优势何为电泳技术?照字面意味着“在一定的电压下可泳动”,其显示的工作原理是靠浸在透明或彩色液体之中的电离子移动,即通过翻转或流动的微粒子来使像素变亮或变暗,并可以被制作在玻璃、金属或塑料衬底上。

具体技术是将直径约为1mm的二氧化钛粒子被散布在碳氢油中,黑色染料、表面活性剂以及使粒子带电的电荷控制剂也被加到碳氢油中;这种混合物被放置在两块间距为10—100mm的平行导电板之间,当对两块导电板加电压时,这些粒子会以电泳的方式从所在的薄板迁移到带有相反电荷的薄板上。

当粒子位于显示器的正面(显示面)时,显示屏为白色,这是因为光通过二氧化钛粒子散射回阅读者一方;当粒子位于显示器背面时,显示器为黑色,这是因为彩色染料吸收了入射光。

triz理论的40个原理

triz理论的40个原理1. 1. 矛盾 (Contradiction)2. 2. 聚合 (Aggregation)3. 3. 优化传递 (Transferring)4. 4. 整合 (Integration)5. 5. 分离 (Separation)6. 6. 宇宙相似性 (Similarity)7. 7. 中介 (Mediator)8. 8. 统一 (Uniformity)9. 9. 反馈 (Feedback)10. 10. 副本 (Replication)11. 11. 增加热量、增加温度 (Increase heat, increase temperature)12. 12. 减少热量、减少温度 (Decrease heat, decrease temperature)13. 13. 分级 (Gradation)14. 14. 最大与最小 (Maximum and minimum)15. 15. 动态平衡 (Dynamic equilibrium)16. 16. 时空因果关系 (Cause and effect)17. 17. 薄层 (Thin layer)18. 18. 耐用与脆弱 (Durability and fragility)19. 19. 数量效应 (Quantity effect)20. 20. 助推 (Boost)21. 21. 过滤 (Filtering)22. 22. 倒置 (Inversion)23. 23. 反向 (Opposite)24. 24. 反馈优化 (Feedback optimization)25. 25. 极点 (Polarity)26. 26. 振动 (Vibration)27. 27. 安全储存 (Safe storage)28. 28. 光照、照明 (Lighting)29. 29. 引导 (Guiding)30. 30. 柔性 (Flexibility)31. 31. 过程偶然性 (Process randomness)32. 32. 多级反馈 (Multi-feedback)33. 33. 生物模仿 (Biomimicry)34. 34. 相变 (Phase change)35. 35. 传感器 (Sensor)36. 36. 微结构 (Microstructure)37. 37. 切割 (Cutting)38. 38. 扩展 (Expansion)39. 39. 孔洞、通道 (Holes, channels)40. 40. 精确度与精密度 (Accuracy and precision)。

第09章 市场微观结构与流动性建模

第九章市场微观结构与流动性建模[学习目标]掌握市场微观结构的基本理论;熟悉流动性的主要计量方法;掌握市场流动性的计量与实证分析;了解高频数据在金融计量中的的主要应用。

第一节市场微观结构理论的发展一、什么是市场微观结构市场微观结构的兴起,是近40年来金融经济学最具开创性的发展之一。

传统的金融市场理论中,一直将金融资产价格作为一个宏观变量加以考察。

但是,从Demsetz发表《交易成本》(Transaction Cost)之后,金融资产价格研究视角发生了重大变化——从研究宏观经济现象转而关注于金融市场内在的微观基础,金融资产价格行为被描述为经济主体最优化规划的结果。

这种转变包含两方面的含义:一是由于资产价格是由特定经济主体和交易机制决定,因而对经济主体行为或交易机制分析可以考察价格形成;二是这一分析可以将市场行为看作是个体交易行为的加总,这样从单个交易者的决策行为,可以预测金融资产价格的变化情况。

金融市场微观结构(market microstructure)的最主要功能是价格发现(price discovery),即如何利用公共信息和私有信息进行决定一种证券的价格。

在金融市场微观结构理论中,市场交易机制处于基础性作用,当前世界各交易所采用的交易方式大致可分为报价驱动(quote-driven)和指令驱动(order-driven)两大类。

美国的NASDAQ以及伦敦的国际证券交易所等都属于报价驱动交易机制。

在这种市场上,投资者在递交指令之前就能够从做市商那里得到证券价格的报价。

这种交易方式主要由做市商充当交易者的交易对手,主要适合于流动性较差的市场。

与此相反,在指令驱动制度下,投资者递交指令要通过一个竞价过程来执行。

我国各大证券交易所以及日本的东京证券交易所等都采用这种交易方式。

在指令驱动机制下,交易既可以连续地进行,又可以定期地进行。

前者主要指连续竞价(continuous auction),投资者递交指令可以通过早已由公众投资者或市商递交的限价指令立即执行。

高阶讲解:什么是SOIwafer?

高阶讲解:什么是SOIwafer?今天我们就讲讲衬底材料的SOI制程,到底它牛在哪里?在过去五十多年中,从肖克莱等人发明第一个晶体管到超大规模集成电路出现,硅半导体工艺取得了一系列重大突破,使得以硅材料为主体的CMOS集成电路制造技术为主流,逐渐成为性能价格比最优异、应用最广泛的集成电路产业。

如果说在亚微米/深亚微米(Sub-Micron)时代,器件的主要bottleneck在热载流子效应(HCE: Hot Carrier Effect)以及短沟道效应(SCE: Short Channel Effect)。

那么在纳米(or Sub-0.1um)时代,随着器件特征尺寸的缩小,器件内部pn结之间以及器件与器件之间通过衬底的相互作用愈来愈严重,出现了一系列材料、器件物理、器件结构和工艺技术等方面的新问题,使得亚0.1微米硅集成电路的集成度、可靠性以及电路的性能价格比受到影响。

这些问题主要包括:(1) 体硅CMOS电路的寄生可控硅闩锁效应以及体硅器件在宇宙射线辐照环境中出现的软失效效应等使电路的可靠性降低;(2) 随着器件尺寸的缩小,体硅CMOS器件的各种多维及非线性效应如表面能级量子化效应、隧穿效应、短沟道效应、窄沟道效应、漏感应势垒降低效应、热载流子效应、亚阈值电导效应、速度饱和效应、速度过冲效应等变得十分显著,影响了器件性能的进一步改善;(3) 器件之间隔离区所占的芯片面积随器件尺寸的减小相对增大,使得寄生电容增加,互连线延长,影响了集成度及速度的提高。

虽然深槽隔离(STI->DTI, Deep Trench Isolation)、电子束刻蚀、硅化物、中间禁带栅电极等工艺技术能够降低这种效应,但是只要PN 结存在就会有耗尽区,只要有Well就会有衬底漏电,所以根本无法解决。

所以绝缘衬底上硅(Silicon-On-Insulator,简称SOI)技术以其独特的材料结构有效地克服了体硅材料不足,以前最早是在well底部做一个oxide隔离层,业界称之为BOX (Buried OXide),隔离了well的bulk的漏电,但是这种PN结依然在well里面,所以PN结电容和结漏电还是无法解决,这种结构我们称之为部分耗尽型SOI (PD-SOI)。

市场微观结构研究

第三专题:市场微观结构研究(Market Microstructure)〖注:本专题主要参考资料有二:(1)“中国股票市场流动性理论与实证研究――市场微观结构分析”,博士论文,清华大学杨之曙。

(2)本课程指定教材的第三章:MarketMicrostructure〗第一章市场微观结构引论第一节市场微观结构的定义一、什么是市场微观结构(论文第7页)对市场微观结构的理解,不同的人有不同的定义。

1、O’Hara(1994)定义:市场微观结构包括一个具体的中介机构,如专业证券商,或者一个委托人;集中化的交易中心,如交易所或者期货交易场;或者是一个能够显示交易双方交易兴趣的简单的电子交易牌。

2、Aitken and Frino 1997的定义:对一个市场来说,其微观结构是由一下五个关键部分组成的,即:技术(technology)、规则(regulation)、信息(information)、市场参与者(participants)和金融工具(instruments)。

通过对一个市场的技术、规则、信息、参与者和工具等方面的研究,揭示该市场的质量和效率,当然研究市场微观结构的目的是采取必要的手段,提高市场的流动性、透明性、减小波动性和降低交易成本(手续费、印花税、买卖价差、市场影响成本及机会成本等)。

(见论文第8页)。

3、Harris(1999)的定义:把市场使用的交易规则和交易系统定义为市场结构。

市场结构决定了谁能交易,交易什么,什么时间交易,在哪儿交易,以及如何交易等。

是这些市场结构要素影响和决定了市场的流动性、价格的有效性、价格的波动性和交易利润。

4、Madhaven(2000)的定义:市场结构指的是一套保证交易过程的交易规则,由以下选择组成:(1)市场类型,包括是连续性交易市场还是间歇性交易市场;是依赖于做市商的报价驱动型市场还是不依赖于做市商的委托单驱动型市场;是基于大厅的手工交易市场还是基于计算机屏幕的自动交易市场;(2)价格发现功能;(3)委托单类型,包括是采用限价委托单还是市价委托单或止损单等;(4)交易规则,包括有关程序交易(programming trading),最小报价的选择,停止交易的规则,开盘、再开盘和收盘的交易规则;(5)透明性。

电工就业环境分析怎么写

电工就业环境分析怎么写自我评价:我于年出生在邵阳市的一个小农村里,从小接受正宗的农村教育,从小学到高中,一直是以学习为主。

性格比较内向,做事诚恳扎实,有农村人的纯朴之气,具有强烈的责任感和合作意识,能够真诚待人,为人诚实。

奠定目标:我设有短期,中期,长期以及人生目标。

我的短期目标是:在大一,大二,大三把专业知识学好,多出去实践,掌握本专业的实践能力,英语取得四,六级以及计算机取得国二。

中期目标是:在大四实践时找份好工作,在工作之余做好工作准备。

长期目标是:在电气这个专业以后不断破绽。

人生目标是:争取进入国家电网。

环境评价:电气工程及其自动化涉及电力电子技术,计算机技术,电机电器技术信息与网络控制技术,机电一体化技术等诸多领域,是一门综合性较强的学科,其主要特点是强弱电结合,机电结合,软硬件结合.该专业培养具有工程技术基础知识和相应的电气工程专业知识,受过电工电子,系统控制及计算机技术方面的基本训练,具有解决电气工程技术分析与控制问题基本能力的高级工程技术人才。

随着经济的发展,电气工程对于经济的发展有著举足轻重的促进作用。

该专业培育德、智、体、美全面发展,科学知识、能力、素质协同进步,能专门从事与电气工程有关的系统运转、自动控制、电力电子技术、信息处理、试验分析、研制开发、经济管理、电子与计算机技术应用领域等领域工作的“高素质、弱能力、应用型”高级工程技术人才。

培养要求:本专业学生主要学习电工技术、电子技术、信息控制、计算机技术、电气工程及自动化技术等方面较宽广的工程技术基础和一定的专业知识,使学生受到电工电子、信息控制及计算机技术方面的基本训练,以及电气工程及自动化领域的专业训练,具有解决电气工程技术与控制技术问题的基本能力。

职业定位:电气专业是一名具有发展前途的专业,电气技术是电气工程及其自动化专业的一个方向。

该专业是省级重点专业,具有电气工程一级学科博士学位授予权,电气工程领域拥有博士后流动站,在高电压与绝缘技术、电机与电气和电力电子与电力信息处理学科具有工学硕士授予权。

《微电子与集成电路设计导论》第六章 新型微电子技术

纳电子器件——Memristor忆阻器 ➢ 全称记忆电阻(Memristor),是表示磁通与电荷关系的电路器件。

特点

➢ 电阻取决于多少电荷经过了器件。 ➢ 若电荷以一个方向流过,电阻会增加;

如果让电荷以反向流动,电阻就会减小。 ➢ 具有记忆能力,断电后电阻值保持不变。

纳电子器件——石墨烯

➢ 它是已知材料中最薄的一种,且牢固坚硬; ➢ 优良的导电特性:它在室温下传递电子的速度比已知导体都快。

优势

➢ 碳纳米管FET沟道为一维结构,载流子 迁移率大大提高。

➢ 碳纳米管FET参与碳纳米管导电的是表 面。

➢ 碳纳米管FET通过选择源漏材料,可完 全消除源漏结势垒

图6.4.2 CNT-FET典型结构示意图

纳电子器件——有机分子场效应晶体管

该技术利用了分子之间可自由组合的化学特性,晶体管电极之间的距离仅为1纳米到2 个纳米,是目前世界最小的晶体管。同时具有制造简单,造价低廉的优点。

2006年3月, 佐治亚理工学院 (Georgia Institute of Technology) 的研究 员宣布,成功地制造了石墨烯平面场效应 晶体管并观测到了量子干涉效应。并基于 此研究出根据石墨烯为基础的电路。

6.4.2 纳电子材料

纳米材料一诞生,即以其异乎寻常的特性引起了材料界的广泛关注。这 是因为纳米材料具有与传统材料明显不同的一些特征。

人类社会是在不断征服自然和不断攀登科技顶 峰而前进的,纳米技术也是如此。

现在世纪纳米技术和纳米材料,正向新材料、 微电子、计算机、医学、航天、航空、环境、 能源、生物技术和农业等诸多领域渗透。

纳米打假

纳米技术并非高不可攀,但也决非人人都能“纳”一把, 因此,我们要提前做好纳米技术的打假工作,建立一套十分 严格的评审和考核制度,为纳米技术的发展创造良好的空间, 防止样样都要“纳”一把现象的发生,尽量避免恶意炒作 “伪纳米”,不能等到造成极其严重的恶果后,再去打与堵。

《计算材料学》结课复习

《计算材料学》结课复习《计算材料学》结课复习1. 根据模拟对象(空间)尺度和(时间)尺度的不同,我们可以选择相应的方法展开计算材料学模拟。

2.将多原子体系理解为电子和原子核组成的多粒子体系,并利用(绝热近似)将二者的行为区别对待,从而分别利用(量子力学)和(经典力学)进行处理。

3.材料的性质和行为取决于(组成材料的原子及其电子的运动状态),描述原子和电子的运动的物理基础是(量子力学)。

4.模拟原子实体系行为的主要方法是(分子动力学),其基本物理思想是求解一定物理条件下的多原子体系的(牛顿运动方程),给出原子运动随时间的演化,通过(统计力学方法)给出材料的相关性能。

5.描述微观粒子的运动行为采用的是(薛定谔方程),在(<10-13)的微观层次,方程放之四海而皆准。

方程建立容易,困难在于(求解)。

求解多粒子体系的(薛定谔方程)必须针对具体内容而进行必要的(简化)和(近似)。

6.离子实体系的(牛顿)方程决定着体系的(声波的传导、热膨胀、晶格比热、晶格热导率和结构缺陷等)性质。

7.电子体系的(薛定谔)方程决定着体系的(电导率、热导率、超导电性和磁学性能)等等。

8.对电子体系的(薛定谔方程)引入(单电子)近似、(自恰场)近似和(非均匀电子气)理论,建立了(hartree-fock理论)和(密度泛函理论),从而实现电子体系的方程(可解)。

9.(量子力学)使材料科学的体系和结构都了发生深刻的变化,使化学和物理学界限模糊理论上(趋于统一),带动材料科学进入(分子水平)。

10. 70余年,量子力学经受物质世界不同领域(原子、分子、各种凝聚态、基本粒子和宇宙物质等)实验事实的检验,其正确性无一例外。

任何(唯象理论)都不可与之同日而语。

11. 量子力学的第一原理方法只借助(5个基本物理常数):电子电量、电子,h, c和k),不依赖任何(经质量、普郎克常数、光速和玻耳兹曼常数 (e, me验参数)即可正确预测微观体系的状态和性质。

建筑专业英语词汇(M-N)

建筑专业英语词汇(M-N)macadam aggregate 锁结式集料machine 机械machine application 机械粉饰machine cavern 地下机械室machine made brick 机制砖machine mixed concrete 机拌混凝土machinery and equipment yard 机械设备堆集场地machinery foundation 机迄座machinery room 机房macrography 肉眼检查macrostructure 宏观结构made ground 填土magnesia brick 镁砖magnesia cement 镁氧水泥magnesia insulation 镁质绝缘材料magnesite brick 镁砖magnet 磁铁magnetic crack detection 磁力探伤magnetic separator 磁力分离器magnetism 磁力magnetization 磁化magnitude 大小main 干线main air duct 昼道main bar 种筋main beam 趾main bridge members 知桥梁杆件main canal 干渠main dike 痔main door 正门main drain 峙水沟main face 正面main girder 趾main pressure differential 周压差main rafter 知main reinforcement 种筋main runner 脂条main stair 芝梯main structural part 知结构配件main tie 值材main truss 朱架main valve 支main wall 纸mains distribution box 干线配电箱mains failure 电力网毁坏mains supply 干线供给mains water 自来水maintenance 维护maintenance cost 保养费maintenance hangar 修理棚maintenance overhaul 维修检查major axes of stress ellipse 应力椭圆的长径major axis 长径major overhaul 大修make up air 补偿空气make up pump 补充水泵make up water 补给水mall 木大锤mallet 木锤man 人man made stone 人造石management 管理manager program 操纵程序manhole 人孔manhole cover 检查井盖manhole rings 人孔环manhole step irons 人孔踏步铁manifold 集合管manilla rope 马尼拉麻绳索manometer 压力计manometric pressure 计示压力mansard 复折屋顶mansard dormer window 折线形屋顶窗mansard roof 折线形屋顶mansard roof construction 折线形屋顶结构mansion 住宅mantelpiece 壁炉台mantelshelf 壁炉台manual batcher 手动计量器manual cycling control 循环工程手动操纵manual damper 手动档板manual press 手压机manual proportioning control 手工称量控制manufacture 制造manufactured construction materials 人造建筑材料manufactured sand 人工砂manufacturing process 生产过程many roomed apartment 一套多房间公寓map 地图map cracking 网状裂缝marble 大理石marble gravel 大理石砾石marbling 仿制的大理石margin 边缘margin of safety 安全系数margin of stability 稳定性限marginal concrete strip finisher 混凝土边缘修整机marginal strip 路缘带marine clay 海成粘土marine construction 海洋建筑物marine glue 防水胶marine paint 海船油漆marine park 海蚀公园marine sand 海砂marine structures 海洋建筑物marine works 海洋建筑物mark 标记marker 标识器marker line 标志线marker post 标志杆market 市场market building 市场房屋marking 标识marking gauge 划线刀marl 泥灰岩marquee 雨罩marquetry 镶嵌装饰品marsh 沼泽地marshalling 砌体marshy ground 沼泽地mashroom valve 园锥形活门mason 石工mason's adjustable suspension scaffold 砖石工用可迭挂式脚手架mason's hammer 砖石工锤mason's mortar 圬工灰浆mason's scaffold 圬工脚手架masonry 砌石masonry anchor 圬工锚碇masonry arch 砌石拱masonry block 砌筑块masonry bridge 圬工桥masonry cement 砌切筑水泥masonry construction 砌筑结构masonry drill 圬工钻masonry mortar 圬工灰浆masonry nail 砖石钉masonry plate 座板masonry sand 圬工砂masonry veneer 表层砌体mass concrete 大块混凝土mass curve 土方曲线mass force 质量力mass foundation 块状基础mass haule curve 土方曲线mass produced structural units 成批生产的结构部件mass runoff 径量massive concrete structures 块状混凝土结构masstone 天然色调mast arm 灯具悬臂mast cap spider 紧桅箍星形轮mast with arm 带臂电杆master plan 总体规划mastic 玛脂mastic asphalt 石油沥青砂胶mastic cement 水泥砂胶mastic cooker 地沥青砂胶加热锅mat 底板mat coat 罩面mat foundation 板式基础mat reinforcement bender 钢筋网弯曲机match marking 装配标记match plane 开槽刨matchboarding 企口镶板matched ceiling 企口顶棚material 材料material aggressive to concrete 混凝土侵蚀材料material behavior 材料特性material debris chute 残渣滑槽material handling 材料装卸material handling bridge 材料转运桥material handling system 材料转运系统material hose 原料软管material list 材料酶表material retained on sieve 筛上筛余物material strength 材料强度material test 材料试验materials testing laboratory 材料试验室matt paint 无光泽涂料matte surface glass 毛面玻璃matted glass 毛面玻璃mattress 柴排mattress revetment 沉排铺面matured cement 长期贮存的老化水泥matured concrete 成熟混凝土maturing 老化maturing of concrete 混凝土的熟化maul 木大锤maximum 最大maximum allowable concentration 最大容许浓度maximum allowable emission 最大容许发散maximum capacity of well 井的最高容量maximum density grading 最大密度级配maximum density of soil 土壤的最大密度maximum dry density 最大干密度maximum flood discharge 最大洪水量maximum gradient 最大坡度maximum load 最大负荷maximum load design 最大荷载重设计法maximum rated load 最大额定荷载maximum safe load 最大安全载荷maximum simultaneous demand 最大同时需要量maximum size 最大尺寸maximum value 最大值meager lime 贫石灰mean cycle stress 循环应力的平均值mean depth 平均深度mean radiant temperature 平均辐射温度mean temperature difference 平均温差mean velocity of flow 平均临means of conveyance 传送工具means of egress 出口装置means of slinging 吊税置means of transportation 传送工具measure 尺寸measured drawing 实测图measurement 测定measurement data 测定资料measuring apparatus 测量仪器measuring chain 测量链measuring element 测定元件measuring frame 配料量斗measuring tank 计量槽measuring tape 卷尺measuring worm conveyor 测量螺旋输送机mechanical aeration 机械通风mechanical analysis 机械分析mechanical application 机械粉饰mechanical area 机械布置空间mechanical bond 机械结合mechanical calculation 力学计算mechanical classification 机械分级mechanical cooling 机械冷却mechanical core 技术设施中心带mechanical core wall 设有设施装置的心墙mechanical coupling link 机械轴节连杆mechanical draft cooling tower 机动气龄却塔mechanical dust collector 机械除尘器mechanical filter 机械滤器mechanical operator 机动装置mechanical rake 机械耙mechanical rammer 机械夯具mechanical refrigerating system 机械冷冻系统mechanical refrigeration 机械制冷mechanical stabilisation 机械稳定处理mechanical strength characteristics 力学强度特性mechanical testing 机械试验mechanical tooling of concrete 混凝土的机械加工mechanical treatment of sawage 污水的机械净化mechanical trowel 抹灰机mechanical ventilation 机械通风mechanics 力学mechanics of materials 材料力学mechanism 机构mechanization 机械化median barrier 路中护栏medium burned brick 标准烧成砖medium duty scaffold 中型脚手架medium grained asphalt concrete 中粒级配地沥青混凝土meeting rail 窗框的横挡meeting stile 连接板条member 构件membrane concrete curing 用膜混凝土养护membrane curing 薄膜养护法membrane filter 薄膜过滤器membrane fireproofing 隔膜防火层membrane forming type bond braker 粘结制止膜形成剂membrane theory 薄膜理论membrane waterproofing 薄膜防水memorial 纪念碑memorial architecture 纪念性建筑memorial table 纪念雕版menstruum 溶媒mercury arc lamp 汞弧灯meridian stress 经线应力mesh 筛目mesh analysis 筛分析mesh laying jumbo 钢筋网敷设设备mesh reinforced shotcrete 钢筋网加强喷射混凝土mesh reinforcement 钢筋网mesh series 筛一套mesh size 筛目大小metal 金属;铺路碎石metal clad cable 金属包皮电缆metal clad fire door 有金属包层的防火门metal construction 金属结构metal curtain wall 铁骨架悬挂壁metal door 金属门metal floor decking 金属楼板铺面metal form 金属模板metal furniture 金属家具metal gauze 金属网metal grating 金属栅板metal hose 金属蛇管metal lathing 钉钢丝网metal mesh fabric 金属网metal plate 金属板metal plating 镀metal runner 金属滑条metal sash putty 金属窗框油灰metal sheet 金属板metal sheet roof covering 金属薄板metal shingle 金属鱼鳞板metal stud 金属立杆metal tube 金属管metal valley 金属沟槽metal water stop 金属带密封metallic cement 熔渣硅酸盐水泥metallic sprayed coating 喷镀金属膜meteorological observation 气象观测meteorology 气象学meter 米methane tank 沼气桶method 方法method of curing 养护法method of elastic weights 弹性荷载法method of joint isolation 结点法method of least work 最小功法method of minimum strain energy 最小功法method of moment 力矩法method of redundant reactions 弯矩面积法method of sections 断面法method of the substitute redundant members 超静定构件取代法method of zero moment points 零点力矩法metro 地下铁道metropolitan area 大城市区域mezzanine 中二楼mica 云母micro crack 微细龟裂micro strainer 微孔滤网microclimate 小气候micrometer 微米microparticle 微粒micropolitan 居住区microscope 显微镜microstructure 微结构middle girder 中间梁middle strip 中间带middle surface 中面midget construction crane 小型建筑起重机midspan 中跨midspan deflection 中跨挠度midspan load 跨中荷载midwall 间隔墙mild steel reinforcement 低碳钢钢筋milk of lime 石灰乳mill 粉碎机mill construction 厂房结构millboard 麻丝板milled joint 研压接缝mineral aggregate 矿质骨料mineral dust 矿物粉末mineral fiber tiles 矿物纤维板mineral fibers 矿物纤维mineral filled asphalt 填充细矿料的沥青mineral filler 矿物质填料mineral pigment 矿物颜料mineral wool 矿物棉mineralogical composition of aggregates 集料的矿物的组成miniaturization 小型化mining shovel 采矿机铲mining town 矿业城镇mirror 镜mission tile 半圆形截面瓦mist 烟雾mist spraying 喷雾miter cut 斜切割miter gate 人字间门miter joint 斜角连接mitigation 水的软化mix 混合mix control 混合控制mix design 配合比设计mix in place machine 就地拌和机mix in place travel plant 就地拌和机mix ingredients 混合物成分mix proportions 混合比mixed cement 混合水泥mixed concrete 拌好的混凝土mixed construction 混合构造mixed greenery 混合式绿化区mixed in place construction of road 就地拌和法筑路mixed in place method 就地拌和法mixer 混合机mixer drum 混合圆筒mixer efficiency 混合机效率mixer skip 拌和机装料斗mixer trestle 混合机栈桥mixer truck 混凝土搅拌车mixing 混合mixing box 混合室mixing chamber 混合室mixing cycle 混合周期mixing damper 混合档板mixing drum 混合圆筒mixing of concrete 混凝土的搅拌mixing placing train 混合与灌筑综合装置mixing plant 搅拌装置mixing platform 拌和台mixing rate 混合物比率mixing ratio 混合比mixing screw 混合用螺旋mixing speed 拌和速度mixing tank 混合槽mixing temperature 混合温度mixing time 拌和时间mixing tower 混合塔mixing valve 混合阀mixing water 搅拌用水mixometer 拌和计时器mixture 混合mobile bituminous mixing plant 移动式沥青混合设备mobile crane 自行吊车mobile field office 移动式工地办公室mobile form 移动式模壳mobile hoist 移动式卷杨机mobile job crane 移动式起重机mobile load 活动荷载mobile scaffold tower 塔式机动脚手架mobile site office 移动式工地办公室mobile space heater 移动式空气加热器mobile tower crane 可移动塔式起重机mobile work platform 移动式工专mobility of concrete 混凝土怜性mode of buckling 压屈状态mode of failure 毁坏模式model 模型model testing 模型试验modern architecture 现代建筑modern city 现代城市modernization 现代化modification 更改modified i beam 改进的i型梁modified portland cement 改良硅酸盐水泥modular brick 符合模数尺寸的砖modular building 模数法建筑modular building unit 模数化建筑物单元modular constuction 模数化构造modular coordination 模数协调modular design 模数法设计modular dimension 模数尺寸modular ratio 模量化modular ratio method 模量比法modular size 标准化尺寸modular system 模数制modular unit 模数化构件modulator 爹器module 尺度modulus 系数modulus of creep 蠕变模量modulus of deformation 形变模量modulus of elasticity 弹性模量modulus of foundation support 地基反力系数modulus of resilience 回弹模量modulus of rigidity 抗剪模量modulus of rupture 挠折模量modulus of section 断面模量modulus of subgrade reaction 地基反力系数moist air cabinet 保湿箱moist room 湿气室moisture 湿气moisture barrier 防潮层moisture gradient 湿度梯度moisture laden air 潮湿空气moisture migration 水分移动moisture movement 水分移动moisture proof luminaire 防湿灯moisture resistant insulating material 耐湿性绝热材料moisture seal 防潮层moisture sensing probe 测湿器moisture tons 潜热冷冻负荷mold 模型mold oil 脱模油mold release 脱模剂molded brick 模制砖molded gutter 模制天沟molded insulation 模制塑料绝缘molded plywood 成型胶合板moldings 线脚molds reuseability 模重复使用能力mole 防波堤mole drain 地下排水沟mole drainage 地下排水工程moler brick 硅藻土砖moling 地下排水沟设置moment 力矩moment area 力矩面积moment area method 弯矩面积法moment at fixed end 支承挠矩moment at support 弯矩钢筋moment bar 弯矩杆moment buckling 力矩弯曲moment curvature law 力矩与曲率定律moment diagram 力矩分配法moment distribution 弯矩分配moment distribution method 力矩分配法moment equation 力矩方程moment influence line 力矩影响线图moment of couple 力偶矩moment of deflection 弯曲力矩moment of friction 摩擦力矩moment of inertia 惯性矩moment of load 负载矩moment of resistance 抗力矩moment of rupture 裂断力矩moment of span 跨矩moment of stiffness 刚性力矩moment reinforcement 弯曲钢筋moment resisting space frame 抗力矩空间构架moment resulting from sidesway 侧倾力矩moment splice 力矩的拼接moment zero point 零力矩点monastic building 寺院房屋monat cement 无熟料的矿渣水泥monitor 天窗monitor roof 通风的屋顶monitoring 监视monkey 起重机小车monkey wrench 螺丝板手monocable 单塑空死monolithic 整体式monolithic concrete 整体浇灌混凝土monolithic construction 整体式构造monolithic finish 整体修整monolithic grillage 整体式格床monolithic slab and foundation wall 整体式楼板与基础壁monolithic terrazzo 整块水磨石monolithic topping 整体式上部覆盖monopitch roof 单斜屋顶monorail 单轨道monorail system 单轨运输系统monorail transporter 单线运送机monorailway 单轨铁路monotower crane 单塔式起重机monsoon 季节风montage 装配monument 界标moon 月亮moor 沼泽地mooring accessories 系船设备mooring appurtenances 系船设备mooring dolphin 系船柱mooring ring 系船环mordant 腐蚀剂mortar 灰浆mortar additive 灰浆附加剂mortar admixture 灰浆附加剂mortar bar 灰浆棒mortar base 灰浆底座mortar bed 灰浆层mortar bond 灰浆砌筑mortar box 灰浆层mortar cube 灰浆立方块mortar fraction 灰浆部分mortar from chamotte 灰泥灰浆mortar from trass 火山灰灰浆mortar grouting 灌浆mortar gun 灰浆喷枪mortar mill 灰泥混合机mortar mixer 灰泥混合机mortar mixing machine 灰泥混合机mortar of dry consistency 干硬稠度灰浆mortar plasticizer 灰浆增塑剂mortar pump 灰浆泵mortar sand 灰浆用砂mortar spreader 灰浆撒布机mortar walling 灰浆砌筑mortarboard 灰板mortice 榫槽mortise 榫槽mortise chisel 錾mortise gauge 划榫器mortise joint 镶榫接头mortise lock 插锁mortise pin 梢子mosaic 镶嵌砖mosaic floor 镶嵌地板mosaic glass 嵌镶玻璃mosaic structure 镶嵌结构mosaic tile 镶嵌地砖moss 沼泽motel 汽车旅馆mother town 母域motion 运动motomixer 混凝土搅拌车motor 发动机motor bug 机动小车motor bus 公共汽车motor car 轿车motor damper 电动气邻器motor generator set 电动发电机motor grader 自行式平地机motor in head vibrator 电动振动棒motor operated valve 电动阀motor scraper 自动铲运机motorized solar control blinds 机动遮阳帘motorway 汽车路mottle effect 斑点样褪色mottled discoloration 斑点样褪色mottled surface 斑点样表面mould 型mould releasing agent 脱模剂moulded brick 模制砖moulded concrete 模制混凝土moulding plaster 模制用石膏moulding sand 型砂mound breakwater 堆石防波堤mounter 装配工mounting shop 装配车间mouthpiece 嘴子movable barrack 移动式工棚movable bridge 开合桥movable dam 活动堰movable distributor 活动配水器movable joint 活接头movable partition 可动间壁movable rocker bearing 活动振动机支承movable scaffolding 移动式脚手架movable span 可动桥跨movable tangential bearing 活动切线支承movable weir 活动堰moving form 移动式模壳moving form construction 活动模板建造moving load 活动荷载moving ramp 跳板moving staircase 自动升降梯moving walk 滑动步道muck loader 装渣机mucker 装渣机mucker belt 装岩机引带mucking 清理坍方mucosity 粘性mud 软泥mud box 泥渣分离箱mud outlet 污泥排泄口mud room 前厅mud soil 泥土mud trap 泥渣分离箱mudcapping 外部装药爆破mudsill 排架座木muffle furnace 高温烘炉muffler 消声器mullion 竖框mulseal 乳化沥青multi arch dam 连拱坝multi bucket dredger 多斗采砂船multi bucket excavator 多斗挖土机multi cell battery mould 多格仓式模板multi cell dust collector 多孔式积尘器multi compartment building 多户住宅multi compartment settling basin 多槽式沉淀池multi cored brick 多孔砖multi degree system 多自由度系multi lane roadway 多车道道路multi layer consolidation 多层固结multi legged sling 多支吊索multi point heater 多位置加热器multi purpose coating plant 多用途混合装置multi purpose scheme 综合利用设计multi rubber tire roller 多轴碾压机multi span structure 多跨结构multi wheel roller 多轴碾压机multi zone system 多区的空档统multiblade damper 多重叶瓣式节气闸multicolor brick 多色砖multicolor finish 多彩色终饰multideck screen 多层筛multielement member 多单元装配件multielement prestressing 多单元构件预加应力multifamily housing 多户住房multifolding door 卷折式门multilayer insulation 多层绝缘multilevel guyed tower 多位缆风拉紧的塔multimixer 通用混合器multipass aeration tank 多撂曝气池multiple 倍数multiple aeration tank 多撂曝气池multiple arch 连拱multiple arch bridge 连拱桥multiple bay frame 多跨框架multiple dome dam 弓顶连拱坝multiple dwelling 多户住房multiple dwelling building 多户住宅multiple flue chimney 多路烟囱multiple glass 多层玻璃multiple glazing 多层玻璃窗施工multiple leaf damper 多重叶瓣式节气闸multiple pipe inverted siphon 多管式倒虹吸管multiple purpose project 综合利用设计multiple purpose reservoir 综合利用水库multiple row heating coil 多行供热盘管multiple sedimentation tank 多路沉淀池multiple span bridge 多跨桥multiple span structure 多跨构造物multiple web systems 多肋式系统multiply plywood 多层夹板multiplying factor 倍加系数multistage construction 分阶段建筑multistage fan 多级风扇multistage gas supply system 多级供煤气系统multistage stressing 多级施加应力multistorey building 多层房屋;多层建筑物multistorey parking space 多层停车场multistoried building 多层房屋multistoried garage building 多层车库multiuse building 多用途建筑物multiway junction 复合交叉口municipal engineering 市政工程municipal facilities 市政工程设施municipal sanitary 城市卫生municipal sanitary engineering 城市卫生工程学municipal service 市政业务municipal sewage 城市污水municipal sewers 城市下水道网municipal treatment plant 城市污水处理场muntin 窗格条museum 博物馆mushroom construction 无粱板构造mushroom floor 环辐式楼板mushroom head column 无粱式楼板支承柱mushroom slab 无粱楼板mushy concrete 连混凝土mutual action of steel and concrete 钢筋和混凝土的共同酌n truss n字桁架n year flood n年周期洪水nail 钉nail claw 钉拔nail float 钉板抹子nail plate 钉接板nail puller 钉拔nailable concrete 受钉混凝土nailcrete 受钉混凝土nailed beam 钉梁nailed connection 钉结合nailed joint 钉结合nailed roof truss 钉固屋架nailer 可钉条nailing 打钉nailing block 可受钉块nailing marker 标记钉模naked flooring 毛面地板name block 名牌names of parts 部件品目narrow gauge 窄轨narrow gauge railway 窄轨铁路national architecture 民族建筑national highway 国道national style 民族形式natural adhesive 天然粘合剂natural aeration 自然通风natural aggregate 天然骨料natural angle of slope 自然倾斜角natural asphalt 天然沥青natural building sand 天然建筑砂natural cement 天然水泥natural circulation 自然循环natural color 天然色natural concrete aggregate 天然混凝土骨料natural convection 自然对流natural convector 自然对僚热器natural depth 天然深度natural draft 自然通风natural draft cooling tower 自然通风凉水塔natural drainage 自然排水natural finish 天然装饰natural flow 自然量natural foundation 天然地基natural grade 自然坡度natural ground 天然地基natural head 天然水头natural illumination factor 自然采光照玫数natural light 自然光natural lighting 天然照明natural mineral materials 天然矿物质材料natural pigment 天然颜料natural rock asphalt 沥青岩natural sand 天然砂natural sett 天然铺石natural slope 天然坡度natural stone 天然石natural stone slab 天然石板natural stone veneer 天然石表层natural stonework 天然石砌筑natural ventilation 自然通风natural water level 自然水位nature park 自然公园navier's hypothesis 纳维尔假说navigable canal 航行运河navigable construction 通航构造navigation canal 航行运河navigation facilities 通航设施navigation lock 通航船闸neat cement grout 净水泥浆neat cement mortar 净水泥灰浆neat cement paste 净水泥浆neat line 准线neat portland cement 纯波特兰水泥necking 颈缩现象needle 横撑杆needle beam 针梁needle beam scaffold 小梁托撑脚手架needle gate 针形闸门needle valve 针阀needle vibrator 针状振捣器needling 横撑杆negative friction 负摩擦negative moment 负力矩negative pressure 负压negative reaction 负反力negative reinforcement 负挠钢筋negative well 渗水井neighbourhood unit 近里单位neoprene paint 氯丁橡胶涂料nerve 交叉侧肋nervure 交叉侧肋nest of sieves 一套筛子net 网net area 净面积net cut 净挖方net duty of water 净用水量net fill 净填方net floor area 地板或楼层净面积net line 墙面交接线net load 净载荷net positive suction head 净吸引压头net residential area 居住净面积net room area 房间净面积net sectional area 净断面面积net settlement 净沉降net structure 网状结构netting 铁丝网network 格网络network of chains 三角测量网network of coordinates 坐标格网network of underground 地下管网neutral axis 中性轴neutral plane 中性面neutral pressure 中性压力neutral surface 中性面neutralisation tank 中和槽neutron shield 中子防护屏new construction 新建工程new town 新城市newel 螺旋楼梯中柱newel post 螺旋楼梯中柱newel stair 有中柱的螺旋楼梯newly placed concrete 新浇混凝土nibbed tile 有挂脚的瓦niche 壁龛nick break test 缺口冲辉验nidged ashlar 琢石nigged ashlar 琢石nigging 砍修石头night population 夜间人口night setback 夜间温度降低nippers 钳子nipple 短连接管nissen hut 金属结构掩蔽棚屋nitrogen 氮no bond prestressing 无粘结纲筋的后预应力no bond stretching 无粘结纲筋的后预应力no bond tensioning 无粘结纲筋的后预应力no fines concrete 无细集料混凝土no hinged frame 无铰的框架no slump concrete 干硬混凝土nodal forces 节点力node 节点nog 木栓nogging 填墙木砖;系柱横撑nogging piece 横撑noise 噪声noise abatement 减声noise abatement wall 减声壁noise absorption factor 噪声吸收系数noise attenuation 减声noise barrier 消音屏noise control 噪声控剂noise criteria curves 噪声标准曲线noise damper 消音器noise level 噪音级noise meter 噪声计noise nuisance 噪声危害noise rating 噪声评价noise rating curves 噪声评级曲线noise reduction coefficient 噪声降低系数nominal bore 公称直径nominal diameter 公称直径nominal dimension 标称尺寸nominal horsepower 标称马力nominal maximum size of aggregate 骨料的额定最大粒径nominal mix 标称配合比nominal size 公称尺寸nomogram 计算图表non air entrained concrete 非含气的混凝土non bonded joint 不粘着的楼缝non carbonate hardness 非碳酸盐硬度non clogging filter 不堵塞的过滤器non clogging screen 不堵塞的筛non concussive tap 无冲机头non fireproof construction 非防火建筑non load bearing partition 非承重隔墙non load bearing wall 非承重墙non pressure drain 无压排水渠non pressure pipe 无压管non redundant structure 静定结构non retern valve 逆止阀non scouring velocity 不冲刷临non shrinking cement 不收缩水泥non silting velocity 不淤临non slewing crane 非回转式吊机non slip floor 防滑楼板non structural component 非构造部件non tilting drum mixer 直卸料式拌合机nonagitating unit 途中不搅拌的混凝土运送车nonbearing partition 非承重隔墙nonbearing structure 非承压结构nonbearing wall 非承重墙nonbreakable glass 刚性玻璃noncohesive soil 不粘结的土质noncombustible construction 非燃结构noncombustible materials 非燃建筑材料noncreeping material 无蠕变材料nondestructive testing 非破坏性试验nondomestic building 非住宅楼nondomestic premises 非居住房产nonelastic deformation 非弹性变形nonelastic range 非弹性段nonhomogeneity of materials 材料的非均质性nonhomogeneous state of stress 不均等应力状况nonhydraulic lime 非水化石灰nonhydraulic mortar 非水硬性灰浆nonlinear distribution of stresses 应力的非线形分布nonlinear elastic behavior 非线性弹性状态nonlinear elasticity 非线性弹性nonlinear plastic theory 非线性塑性理论nonoverflow section 非溢水部分nonparallel chord truss 非平行弦杆桁架nonprestressed reinforcement 非预应力的钢筋nonresidential building 非居住建筑物nonrigid carriageway 非刚性车道nonrigid pavement 非刚性路面nonrotating rope 不旋转绳nonshrink concrete 抗缩混凝土nonsimultaneous prestressing 非同时预应力nonskid carpet 防滑毡层nonskid surfacing 防滑铺面nonstaining cement 无玷污水泥nonstaining mortar 不生锈的灰浆nonstandard component 非标准构件nonsticky soil 非粘结性土壤nonstorage calorifier 快速加热装置nonsymmetry 非对称nonvolatile matter 非挥发性物质nonvolatile vehicle 非挥发性媒液noon 正午noria 斗式提升机norm 标准norm of construction 建筑规范norm of material consumption 材料消耗定额norm of work 工专额normal concrete 普通混凝土normal consistency 正常稠度normal force 法向力normal force diagram 法向力图表normal heavy concrete 普通重混凝土normal portland cement 普通波特兰水泥normal section 正常断面normal weight concrete 正常重量混凝土normalization 标准化normalization of production 生产正规化normally hydrated cement 正常水化水泥north easter 东北风north light glazing 朝北锯齿形采光屋面装配玻璃north light gutter 朝北锯齿形屋顶边沟north wester 伪风northlight roof 朝北锯齿形屋面norton tube well 管井nose of groyne 丁顶前端noser 强迎面风nosing 梯级突边not water carriage toilet facility 非水冲厕notation 标记notch 切口notch board 梯级侧板notch fall 带缝隙的阶梯式构造notch impact strength 刻痕冲豢度notch shock test 刻痕冲辉验notch toughness 刻痕韧性notched bar test 切口试样冲辉验notched bars 变形钢筋notched specimen 切口试样notching 凹槽连结;刻痕notching machine 齿形刀片栽剪机novelty flooring 新颖花绞地板novelty siding 下垂坡叠板noxious fumes 有毒炮烟nozzle 喷嘴nozzle meter 管嘴式临计ntatorium 游泳池nuclear energy structures 原子力发电厂构造物nuclear reactor 核反应堆nursery 育儿室nursery garden 育苗区nut 螺母nut anchorage 带螺母锚nut runner 螺帽扳手nut socket driver 螺母扳手nut torque 拧螺母转矩nylon 尼龙nylon rope 尼龙绳。

材料科学与工程专业英语1-18单元课后翻译答案

Unit 1 Translation.1.“材料科学”涉及到研究材料的结构与性能的关系。

相反,材料工程是根据材料的结构与性质的关系来涉及或操控材料的结构以求制造出一系列可预定的性质。

2.实际上,所有固体材料的重要性质可以分为六类:机械、电学、热学、磁学、光学、腐蚀性。

3.除了结构与性质,材料科学与工程还有其他两个重要的组成部分,即加工与性能。

4.工程师或科学家越熟悉材料的各种性质、结构、性能之间的关系以及材料的加工技术,根据以上的原则,他或她就会越自信与熟练地对材料进行更明智的选择。

5.只有在少数情况下,材料才具有最优或最理想的综合性质。

因此,有时候有必要为某一性质而牺牲另一性能。

6.Interdisciplinary dielectric constantSolid material(s) heat capacityMechanical property electromagnetic radiationMaterial processing elastic modulus7.It was not until relatively recent times that scientists came to understand the relationships between the structural elements of materials and their properties.8. Materials engineering is to solve the problem during the manufacturing and application of materials.9.10.Mechanical properties relate deformation to an applied load or force.Unit 21.金属是电和热很好的导体,在可见光下不透明;擦亮的金属表面有金属光泽。

金融市场微观结构理论

金融市场微观结构理论金融市场微观结构理论(Financial Market Microstructure Theory)[编辑]金融市场微观结构理论的概述金融市场微观结构理论是现代金融学中一个重要的新兴分支。

它产生于20世纪60年代末,真正发展于20世纪80、90年代,至今依然方兴未艾。

并且它与金融学的其它分支,如行为金融学、实验金融学等有互相融合的发展趋势。

一般认为,金融市场微观结构理论的核心是要说明在既定的市场微观结构下,金融资产的定价过程及其结果,从而揭示市场微观结构在金融资产价格形成过程中的作用。

金融市场微观结构的概念有狭义与广义之分。

狭义的市场微观结构是仅指市场价格发现机制,广义的市场微观结构是各种交易制度的总称,包括价格发现机制、清算机制与信息传播机制等。

显然,期货市场的微观结构概念比一般广义的微观结构概念还要宽泛一些,因为期货市场所交易的“资产”是一份合约,而不是有价证券。

而合约中既包括了部分交易与清算机制的内容,也包括了影响其市场价格行为的其它条款。

因此合约设计本身也构成期货市场微观结构的一项重要内容。

金融市场微观结构理论研究的核心是金融资产交易及其价格形成过程和原因的分析,因此目前对该理论的应用主要集中在资产定价领域,拓展开去,该理论在公司财务和收入分配等方面也将有广泛的应用前景。

[编辑]金融市场微观结构理论的研究起源及对象金融市场微观结构理论是对金融市场上金融资产的交易机制及其价格形成过程和原因进行分析。

一般认为该理论产生于1960年代末,德姆塞茨1968年发表的论文《交易成本》奠定了其基础。

但真正引起人们重视源于1987年10月纽约股市暴跌。

这次事件使人们去思考股市的内在结构是否具有稳定性、股市运作的内在机理是如何的等有关股市微观结构问题。

从目前该领域的权威著作美国康奈尔大学奥哈拉教授(2002年美国金融学会主席)的”Market Microstructure Theory”来看,市场微观结构理论研究的主要领域包括:(1)证券价格决定理论:主要包括交易费用模型和信息模型。

【免费下载】材料专业翻译必备词汇

材料科学专业学术翻译必备词汇编号中文英文1合金alloy2材料material3复合材料properties4制备preparation5强度strength6力学mechanical7力学性能mechanical8复合composite9薄膜films10基体matrix11增强reinforced12非晶amorphous13基复合材料composites14纤维fiber15纳米nanometer16金属metal17合成synthesis18界面interface19颗粒particles20法制备prepared21尺寸size22形状shape23烧结sintering24磁性magnetic25断裂fracture26聚合物polymer27衍射diffraction28记忆memory29陶瓷ceramic30磨损wear31表征characterization 32拉伸tensile33形状记忆memory34摩擦friction35碳纤维carbon36粉末powder37溶胶sol-gel 38凝胶sol-gel39应变strain40性能研究properties41晶粒grain42粒径size43硬度hardness44粒子particles45涂层coating46氧化oxidation47疲劳fatigue48组织microstructure49石墨graphite50机械mechanical51相变phase52冲击impact53形貌morphology54有机organic55损伤damage56有限finite57粉体powder58无机inorganic59电化学electrochemical60梯度gradient61多孔porous62树脂resin63扫描电镜sem64晶化crystallization65记忆合金memory66玻璃glass67退火annealing68非晶态amorphous69溶胶-凝胶sol-gel70蒙脱土montmorillonite71样品samples72粒度size73耐磨wear74韧性toughness75介电dielectric76颗粒增强reinforced77溅射sputtering78环氧树脂epoxy79纳米tio80掺杂doped81拉伸强度strength82阻尼damping83微观结构microstructure84合金化alloying85制备方法preparation86沉积deposition87透射电镜tem88模量modulus89水热hydrothermal90磨损性wear91凝固solidification92贮氢hydrogen93磨损性能wear94球磨milling95分数fraction96剪切shear97氧化物oxide98直径diameter99蠕变creep100弹性模量modulus101储氢hydrogen102压电piezoelectric103电阻resistivity104纤维增强composites105纳米复合材料preparation106制备出prepared107磁性能magnetic108导电conductive109晶粒尺寸size110弯曲bending111光催化tio112非晶合金amorphous113铝基复合材料composites114金刚石diamond115沉淀precipitation116分散dispersion117电阻率resistivity 118显微组织microstructure 119复合材料sic120硬质合金cemented 121摩擦系数friction122吸波absorbing 123杂化hybrid124模板template125催化剂catalyst126塑性plastic127晶体crystal128颗粒sic129功能材料materials 130铝合金alloy131表面积surface132填充filled133电导率conductivity 134控溅射sputtering135金属基复合材料composites136磁控溅射sputtering137结晶crystallization 138磁控magnetron 139均匀uniform140弯曲强度strength141纳米碳carbon142偶联coupling143电化学性能electrochemical 144及性能properties145al复合材料composite146高分子polymer147本构constitutive 148晶格lattice149编织braided150断裂韧性toughness151尼龙nylon152摩擦磨损性friction153耐磨性wear154摩擦学tribological 155共晶eutectic 156聚丙烯polypropylene157半导体semiconductor158偶联剂coupling159泡沫foam160前驱precursor161高温合金superalloy162显微结构microstructure163氧化铝alumina164扫描电子显微镜sem165时效aging166熔体melt167凝胶法sol-gel168橡胶rubber169微结构microstructure170铸造casting171铝基aluminum172抗拉强度strength173导热thermal174透射电子显微镜tem175插层intercalation176冲击强度impact177超导superconducting178记忆效应memory179固化curing180晶须whisker181溶胶-凝胶法制sol-gel182催化catalytic183导电性conductivity184环氧epoxy185晶界grain186前驱体precursor187机械性能mechanical188抗弯strength189粘度viscosity190热力学thermodynamic191溶胶-凝胶法制备sol-gel192块体bulk193抗弯强度strength194粘土clay195微观组织microstructure196孔径pore197玻璃纤维glass198压缩compression199摩擦磨损wear200马氏体martensitic201制得prepared202复合材料性能composites203气氛atmosphere204制备工艺preparation205平均粒径size206衬底substrate207相组成phase208表面处理surface209杂化材料hybrid210材料中materials211断口fracture212增强复合材料composites213马氏体相变transformation214球形spherical215混杂hybrid216聚氨酯polyurethane217纳米材料nanometer218位错dislocation219纳米粒子particles220表面形貌surface221试样samples222电学properties223有序ordered224电压voltage225析出phase226拉伸性tensile227大块bulk228立方cubic229聚苯胺polyaniline230抗氧化性oxidation231增韧toughening232物相phase233表面改性modification 234拉伸性能tensile235相结构phase236优异excellent 237介电常数dielectric 238铁电ferroelectric239复合材料力学性能composites240碳化硅sic241共混blends 242炭纤维carbon 243复合材料层composite 244挤压extrusion 245表面活性剂surfactant 246阵列arrays 247高分子材料polymer 248应变率strain249短纤维fiber250摩擦学性能tribological 251浸渗infiltration 252阻尼性能damping 253室温下room254复合材料层合板composite255剪切强度strength256流变rheological 257磨损率wear258化学气相沉积deposition 259热膨胀thermal260屏蔽shielding 261发光luminescence 262功能梯度functionally 263层合板laminates 264器件devices265铁氧体ferrite266刚度stiffness 267介电性能dielectric 268xrd分析xrd269锐钛矿anatase270炭黑carbon271热应力thermal 272材料性能properties273溶胶-凝胶法sol-gel274单向unidirectional275衍射仪xrd276吸氢hydrogen277水泥cement278退火温度annealing279粉末冶金powder280溶胶凝胶sol-gel281熔融melt282钛酸titanate283磁合金magnetic284脆性brittle285金属间化合物intermetallic286非晶态合金amorphous287超细ultrafine288羟基磷灰石hydroxyapatite289各向异性anisotropy290镀层coating291颗粒尺寸size292拉曼raman293新材料materials294颗粒tic295孔隙率porosity296制备技术preparation297屈服强度strength298金红石rutile299采用溶胶-凝胶sol-gel300电容量capacity301热电thermoelectric302抗菌antibacterial303聚酰亚胺polyimide304二氧化硅silica305放电容量capacity306层板laminates307微球microspheres308熔点melting309屈曲buckling310包覆coated311致密化densification312磁化强度magnetization313疲劳寿命fatigue314本构关系constitutive315组织结构microstructure316综合性能properties317热塑性thermoplastic318形核nucleation319复合粒子composite320材料制备preparation321晶化过程crystallization322层间interlaminar323陶瓷基ceramic324多晶polycrystalline325纳米结构nanostructures326纳米复合composite327热导率conductivity328空心hollow329致密度density330x射线衍射仪xrd331层状layered332矫顽力coercivity333纳米粉体powder334界面结合interface335超导体superconductor336衍射分析diffraction337纳米粉powders338磨损机理wear339泡沫铝aluminum340进行表征characterized341梯度功能gradient342耐磨性能wear343平均粒particle344聚苯乙烯polystyrene345陶瓷基复合材料composites346陶瓷材料ceramics347石墨化graphitization348摩擦材料friction349熔化melting350多层multilayer 351及其性能properties 352酚醛树脂resin353电沉积electrodepositio n354分散剂dispersant 355相图phase356复合材料界面interface 357壳聚糖chitosan 358抗氧化性能oxidation 359钙钛矿perovskite 360分层delamination 361热循环thermal 362氢量hydrogen363蒙脱石montmorillonit e364接枝grafting365导率conductivity 366放氢hydrogen367微粒particles368伸长率elongation 369延伸率elongation 370烧结工艺sintering371层合laminated 372纳米级nanometer 373莫来石mullite374磁导率permeability 375填料filler376热电材料thermoelectric 377射线衍射ray378铸造法casting379粒度分布size380原子力afm381共沉淀coprecipitation 382水解hydrolysis 383抗热thermal384高能球ball385干摩擦friction386聚合物基polymer387疲劳裂纹fatigue388分散性dispersion 389硅烷silane390弛豫relaxation391物理性能properties392晶相phase393饱和磁化强度magnetization394凝固过程solidification395共聚物copolymer396光致发光photoluminescence397薄膜材料films398导热系数conductivity399居里curie400第二相phase401复合材料制备composites402多孔材料porous403水热法hydrothermal404原子力显微镜afm405压电复合材料piezoelectric406尼龙6nylon407高能球磨milling408显微硬度microhardness409基片substrate410纳米技术nanotechnology411直径为diameter412织构texture413氮化nitride414热性能properties415磁致伸缩magnetostriction416成核nucleation417老化aging418细化grain419压电材料piezoelectric420纳米晶amorphous421si合金si422复合镀层composite423缠绕winding424抗氧化oxidation425表观apparent426环氧复合材料epoxy427甲基methyl428聚乙烯polyethylene429复合膜composite430表面修饰surface431大块非晶amorphous432结构材料materials433表面能surface434材料表面surface435疲劳性能fatigue436粘弹性viscoelastic437基体合金alloy438单相phase439梯度材料material440六方hexagonal441四方tetragonal442蜂窝honeycomb443阳极氧化anodic444塑料plastics445超塑性superplastic446sem观察sem447烧蚀ablation448复合薄膜films449树脂基resin450高聚物polymer451气相vapor452电子能谱xps453硅烷偶联coupling454团聚particles455基底substrate456断口形貌fracture457抗压强度strength458储能storage459松弛relaxation460拉曼光谱raman461孔率porosity462沸石zeolite463熔炼melting464磁体magnet465sem分析sem466润湿性wettability467电磁屏蔽shielding468升温heating469致密dense470沉淀法precipitation 471差热分析dta472成功制备prepared 473复合体系composites 474浸渍impregnation 475力学行为behavior 476复合粉体powders 477沥青pitch478磁电阻magnetoresista nce479导电性能conductivity 480光电子能谱xps481材料力学mechanical 482夹层sandwich 483玻璃化glass484衬底上substrates 485原位复合材料composites 486智能材料materials 487碳化物carbide488复相composite 489氧化锆zirconia 490基体材料matrix491渗透infiltration 492退火处理annealing 493磨粒wear494氧化行为oxidation 495细小fine496基合金alloy497粒径分布size498润滑lubrication 499定向凝固solidification 500晶格常数lattice501晶粒度size502颗粒表面surface503吸收峰absorption 504磨损特性wear505水热合成hydrothermal 506薄膜表面films 507性质研究properties508试件specimen509结晶度crystallinity510聚四氟乙烯ptfe511硅烷偶联剂silane512碳化carbide513试验机tester514结合强度bonding515薄膜结构films516晶型crystal517介电损耗dielectric518复合涂层coating519压电陶瓷piezoelectric520磨损量wear521组织与性能microstructure522合成法synthesis523烧结过程sintering524金属材料materials525引发剂initiator526有机蒙脱土montmorillonite527水热法制hydrothermal528再结晶recrystallization529沉积速率deposition530非晶相amorphous531尖端tip532淬火quenching533亚稳metastable534穆斯mossbauer535穆斯堡尔mossbauer536偏析segregation537种材料materials538先驱precursor539物性properties540石墨化度graphitization541中空hollow542弥散particles543淀粉starch544水热法制备hydrothermal545涂料coating546复合粉末powder547晶粒长大grain548sem等sem549复合材料组织microstructure550界面结构interface551煅烧calcined552共混物blends553结晶行为crystallization554混杂复合材料hybrid555laves相laves556摩擦因数friction557钛基titanium558磁性材料magnetic559制备纳米nanometer560界面上interface561晶粒大小size562阻尼材料damping563热分析thermal564复合材料层板laminates565二氧化钛titanium566沉积法deposition567光催化剂tio568余辉afterglow569断裂行为fracture570颗粒大小size571合金组织alloy572非晶形成amorphous573杨氏模量modulus574前驱物precursor575过冷alloy576尖晶石spinel577化学镀electroless578溶胶凝胶法制备sol-gel579本构方程constitutive580磁学magnetic581气氛下atmosphere582钛合金titanium583微粉powder584压电性piezoelectric585sic晶须sic586应力应变strain587石英quartz588热电性thermoelectric 589相转变phase590合成方法synthesis591热学thermal592气孔率porosity593永磁magnetic594流变性能rheological 595压痕indentation 596热压烧结sintering597正硅酸乙酯teos598点阵lattice599梯度功能材料fgm600带材tapes601磨粒磨损wear602碳含量carbon603仿生biomimetic 604快速凝固solidification 605预制preform606差示dsc607发泡foaming608疲劳损伤fatigue609尺度size610镍基高温合金superalloy611透过率transmittance 612溅射法制sputtering613结构表征characterization 614差示扫描dsc615通过sem sem616水泥基cement617木材wood618tem分析tem619量热calorimetry 620复合物composites 621铁电薄膜ferroelectric 622共混体系blends623先驱体precursor624晶态crystalline 625冲击性能impact626离心centrifugal627断裂伸长率elongation628有机-无机organic-inorganic629块状bulk630相沉淀precipitation631织物fabric632因数coefficient633合成与表征synthesis634缺口notch635靶材target636弹性体elastomer637金属氧化物oxide638均匀化homogenization639吸收光谱absorption640磨损行为wear641高岭土kaolin642功能梯度材料fgm643滞后hysteresis644气凝胶aerogel645记忆性memory646磁流体magnetic647铁磁ferromagnetic648合金成分alloy649微米micron650蠕变性能creep651聚氯乙烯pvc652湮没annihilation653断裂力学fracture654滑移slip655差示扫描量热dsc656等温结晶crystallization657树脂基复合材料composite658阳极anodic659退火后annealing660发光性properties661木粉wood662交联crosslinking663过渡金属transition664无定形amorphous665拉伸试验tensile666溅射法sputtering667硅橡胶rubber668明胶gelatin669生物相容性biocompatibility670界面处interface671陶瓷复合材料composite672共沉淀法制coprecipitation673本构模型constitutive674合金材料alloy675磁矩magnetic676隐身stealth677比强度strength678改性研究modification679采用粉末powder680晶粒细化grain681抗磨wear682元合金alloy683剪切变形shear684高温超导superconducting685金红石型rutile686晶化行为crystallization687催化性能catalytic688热挤压extrusion689微观microstructure690tem观察tem691缺口冲击impact692生物材料biomaterials693涂覆coating694纳米氧化nanometer695x射线光电子能谱xps696硅灰石wollastonite697摩擦条件friction698衍射峰diffraction699块体材料bulk700溶质solute701冲击韧性impact702锐钛矿型anatase703凝固组织microstructure 704磨损试验机tester705丙烯酸甲酯pmma706raman光谱raman707减振damping708聚酯polyester709体材料materials710航空aerospace 711光吸收absorption 712韧化toughening 713疲劳裂纹扩展fatigue714超塑superplastic 715凝胶法制备gel716半导体材料semiconductor 717剪应力shear718发光材料luminescence 719凝胶法制gel720甲基丙烯酸甲酯pmma721硬质hard722摩擦性能friction723电致变色electrochromic 724超细粉powder725增强相reinforced 726薄带ribbons727结构弛豫relaxation 728光学材料materials729sic陶瓷sic730纤维含量fiber731高阻尼damping732镍基nickel733热导thermal734奥氏体austenite735单轴uniaxial736超导电性superconductivi ty737高温氧化oxidation 738树脂基体matrix 739含能energetic 740粘着adhesion 741穆斯堡尔谱mossbauer 742脱层delamination 743反射率reflectivity 744单晶高温合金superalloy 745粘结bonded746快淬quenching 747熔融插层intercalation 748外加applied749钙钛矿结构perovskite 750减摩friction751复合氧化物oxide752苯乙烯styrene753合金表面alloy754爆轰detonation 755长余辉afterglow 756断裂过程fracture 757纺织textile材料的类型Types of materials, metals, ceramics, polymers, composites, elastomer部分材料性质复习Review of selected properties of materials,电导率和电阻率conductivity and resistivity,热导率thermal conductivity,应力和应变stress and strain,弹性应变elastic strain,塑性应变plastic strain,屈服强度yield strength,最大抗拉强度ultimate tensile strength,最大强度ultimate strength,延展性ductility,伸长率elongation,断面收缩率reduction of area,颈缩necking,断裂强度breaking strength,韧性toughness,硬度hardness,疲劳强度fatigue strength,蜂窝honeycomb,热脆性heat shortness,晶胞中的原子数atoms per cell,点阵lattice, 阵点lattice point,点阵参数lattice parameter,密排六方hexagonal close-packed,六方晶胞hexagonal unit cell,体心立方body-centered cubic,面心立方face-centered cubic,弥勒指数Miller indices,晶面crystal plane,晶系crystal system,晶向crystal direction,相变机理Phase transformation mechanism:成核生长相变nucleation–growth transition,斯宾那多分解spinodal decomposition,有序无序转变disordered-order transition,马氏体相变martensite phase transformation,成核nucleation,成核机理nucleation mechanism, 成核势垒nucleation barrier,晶核,结晶中心nucleus of crystal,金属组织的)基体quay,基体,基块,基质,结合剂matrix,子晶,雏晶matted crystal,耔晶,晶种seed crystal,耔晶取向seed orientation,籽晶生长seeded growth,均质核化homogeneous nucleation,异质核化heterogeneous nucleation,均匀化热处理homogenization heattreatment,熟料grog,自恰场self-consistent field固溶体Solid solution:有序固溶体ordered solid solution,无序固溶体disordered solid solution,有序合金ordered alloy,无序合金disordered alloy.无序点阵disordered lattice,分散,扩散,弥散dispersal,分散剂dispersant,分散剂,添加剂dispersant additive,分散剂,弥散剂dispersant agent缺陷defect, imperfection,点缺陷point defect,线缺陷line defect, dislocation,面缺陷interface defect, surfacedefect,体缺陷volume defect,位错排列dislocation arrangement,位错阵列dislocation array,位错气团dislocation atmosphere,位错轴dislocation axis,位错胞dislocation cell,位错爬移dislocation climb,位错滑移dislocation slip, dislocationmovement by slip,位错聚结dislocation coalescence,位错核心能量dislocation coreenergy,位错裂纹dislocation crack,位错阻尼dislocation damping,位错密度dislocation density,体积膨胀volume dilation,体积收缩volume shrinkage,回火tempering,退火annealing,退火的,软化的softened,软化退火,软化(处理)softening,淬火quenching,淬火硬化quenching hardening,正火normalizing, normalization,退火织构annealing texture,人工时效artificial aging,细长比aspect ratio,形变热处理ausforming,等温退火austempering,奥氏体austenite,奥氏体化austenitizing,贝氏体bainite,马氏体martensite,马氏体淬火marquench,马氏体退火martemper,马氏体时效钢maraging steel,渗碳体cementite,固溶强化solid solutionstrengthening,钢屑混凝土steel chips concrete,水玻璃,硅酸钠sodium silicate,水玻璃粘结剂sodium silicate binder,硅酸钠类防水剂sodium silicatewaterproofing agent,扩散diffusion,扩散系数diffusivity,相变phase transition,烧结sintering,固相反应solid-phase reaction,相图与相结构phase diagrams andphase structures ,相phase,组分component,自由度freedom,相平衡phase equilibrium,吉布斯相律Gibbs phase rule,吉布斯自由能Gibbs free energy,吉布斯混合能Gibbs energy ofmixing,吉布斯熵Gibbs entropy,吉布斯函数Gibbs function,相平衡phase balance,相界phase boundary,相界线phase boundary line,相界交联phase boundarycrosslinking,相界有限交联phase boundary crosslinking,相界反应phase boundary reaction, 相变phase change,相组成phase composition,共格相phase-coherent,金相相组织phase constentuent,相衬phase contrast,相衬显微镜phase contrast microscope,相衬显微术phase contrast microscopy,相分布phase distribution,相平衡常数phase equilibrium constant,相平衡图phase equilibrium diagram, 相变滞后phase transition lag, Al-Si-O-N系统相关系phase relationships in the Al-Si-O-N system,相分离phase segregation, phase separation,玻璃分相phase separation in glasses,相序phase order, phase sequence,相稳定性phase stability,相态phase state,相稳定区phase stabile range,相变温度phase transition temperature,相变压力phase transition pressure, 同质多晶转变polymorphic transformation,相平衡条件phase equilibrium conditions,显微结构microstructures,不混溶固溶体immiscible solid solution,转熔型固溶体peritectic solid solution,低共熔体eutectoid,crystallization, 不混溶性immiscibility,固态反应solid state reaction,。

材料专业学术英文词汇

材料专业学术翻译必备词汇编中文英文号1合金alloy2材料material3复合材料properties4制备preparation5强度strength6力学mechanical7力学性能mechanical8复合composite9薄膜films10基体matrix11增强reinforced12非晶amorphouscomposites13基复合材料14纤维fiber15纳米nanometer16金属metal17合成synthesis18界面interface19颗粒particles20法制备prepared21尺寸size22形状shape23烧结sintering24磁性magnetic25断裂fracture26聚合物polymer27衍射diffraction28记忆memory29陶瓷ceramic30磨损wear31表征characterization 32拉伸tensile33形状记忆memory34摩擦friction35碳纤维carbon36粉末powder37溶胶sol-gel38凝胶sol-gel39应变strain40性能研究properties41晶粒grain42粒径size43硬度hardness44粒子particles45涂层coating46氧化oxidation47疲劳fatigue48组织microstructure 49石墨graphite50机械mechanical51相变phase52冲击impact53形貌morphology54有机organic55损伤damage56有限finite57粉体powder58无机inorganic59电化学electrochemical 60梯度gradient61多孔porous62树脂resin63扫描电镜sem64晶化crystallization 65记忆合金memory66玻璃glass67退火annealing68非晶态amorphous69溶胶-凝胶sol-gel70蒙脱土montmorillonite 71样品samples72粒度size73耐磨wear74韧性toughness75介电dielectric76颗粒增强reinforced77溅射sputtering78环氧树脂epoxy79纳米tio tio80掺杂doped81拉伸强度strength82阻尼damping83微观结构microstructure 84合金化alloying85制备方法preparation86沉积deposition87透射电镜tem88模量modulus89水热hydrothermal 90磨损性wear91凝固solidification 92贮氢hydrogen93磨损性能wear94球磨milling95分数fraction96剪切shear97氧化物oxide98直径diameter99蠕变creep100弹性模量modulus 101储氢hydrogen 102压电piezoelectric 103电阻resistivity 104纤维增强compositespreparation 105纳米复合材料106制备出prepared 107磁性能magnetic 108导电conductive 109晶粒尺寸size110弯曲bending111光催化tio112非晶合金amorphous113铝基复合composites 材料114金刚石diamond 115沉淀precipitation 116分散dispersion 117电阻率resistivity118显微组织microstructuresic119sic复合材料120硬质合金cemented121摩擦系数friction122吸波absorbing123杂化hybrid124模板template125催化剂catalyst126塑性plastic127晶体crystal128sic颗粒sic129功能材料materials130铝合金alloy131表面积surface132填充filled133电导率conductivity 134控溅射sputteringcomposites 135金属基复合材料136磁控溅射sputtering137结晶crystallization 138磁控magnetron 139均匀uniform140弯曲强度strength141纳米碳carbon142偶联couplingelectrochemical 143电化学性能144及性能properties145al复合材composite料146高分子polymer147本构constitutive 148晶格lattice149编织braided150断裂韧性toughness 151尼龙nylonfriction152摩擦磨损性153耐磨性wear154摩擦学tribological 155共晶eutectic156聚丙烯polypropylene 157半导体semiconductor 158偶联剂coupling159泡沫foam160前驱precursor161高温合金superalloy 162显微结构microstructure 163氧化铝aluminasem164扫描电子显微镜165时效aging166熔体melt167凝胶法sol-gel168橡胶rubber169微结构microstructure 170铸造casting171铝基aluminum 172抗拉强度strength173导热thermal174透射电子tem175插层intercalation 176冲击强度impact177超导superconducting 178记忆效应memory179固化curing180晶须whiskersol-gel181溶胶-凝胶法制182催化catalytic183导电性conductivity 184环氧epoxy185晶界grain186前驱体precursor187机械性能mechanical 188抗弯strength189粘度viscosity190热力学thermodynamicsol-gel191溶胶-凝胶法制备192块体bulk193抗弯强度strength194粘土clay195微观组织microstructure 196孔径pore197玻璃纤维glass198压缩compression 199摩擦磨损wear200马氏体martensitic201制得prepared202复合材料composites203气氛atmosphere 204制备工艺preparation 205平均粒径size206衬底substrate207相组成phase208表面处理surface209杂化材料hybrid210材料中materials211断口fracturecomposites 212增强复合材料transformation 213马氏体相变214球形spherical215混杂hybrid216聚氨酯polyurethane 217纳米材料nanometer 218位错dislocation 219纳米粒子particles220表面形貌surface221试样samples222电学properties 223有序ordered224电压voltage225析出phase226拉伸性tensile227大块bulk228立方cubic229聚苯胺polyaniline 230抗氧化性oxidation231增韧toughening 232物相phase233表面改性modification 234拉伸性能tensile235相结构phase236优异excellent 237介电常数dielectric 238铁电ferroelectriccomposites 239复合材料力学性能240碳化硅sic241共混blends242炭纤维carboncomposite 243复合材料层244挤压extrusionsurfactant 245表面活性剂246阵列arrayspolymer 247高分子材料248应变率strain249短纤维fibertribological 250摩擦学性能251浸渗infiltration 252阻尼性能damping 253室温下roomcomposite 254复合材料层合板255剪切强度strength 256流变rheological257磨损率weardeposition 258化学气相沉积259热膨胀thermal260屏蔽shielding 261发光luminescence 262功能梯度functionally 263层合板laminates 264器件devices265铁氧体ferrite266刚度stiffness267介电性能dielectric 268xrd分析xrd269锐钛矿anatase270炭黑carbon271热应力thermal272材料性能propertiessol-gel273溶胶-凝胶法274单向unidirectional 275衍射仪xrd276吸氢hydrogen 277水泥cement278退火温度annealing 279粉末冶金powder280溶胶凝胶sol-gel281熔融melt282钛酸titanate283磁合金magnetic 284脆性brittle285金属间化intermetallic合物286非晶态合amorphous金287超细ultrafinehydroxyapatite 288羟基磷灰石289各向异性anisotropy 290镀层coating291颗粒尺寸size292拉曼raman293新材料materials294tic颗粒tic295孔隙率porosity296制备技术preparation 297屈服强度strength298金红石rutilesol-gel299采用溶胶-凝胶300电容量capacity301热电thermoelectric 302抗菌antibacterial 303聚酰亚胺polyimide 304二氧化硅silica305放电容量capacity306层板laminates307微球microspheres 308熔点melting309屈曲buckling310包覆coated311致密化densification 312磁化强度magnetization313疲劳寿命fatigue314本构关系constitutive 315组织结构microstructure 316综合性能properties317热塑性thermoplastic 318形核nucleation 319复合粒子composite 320材料制备preparation 321晶化过程crystallization 322层间interlaminar 323陶瓷基ceramic324多晶polycrystalline 325纳米结构nanostructures 326纳米复合composite 327热导率conductivity 328空心hollow329致密度densityxrd330x射线衍射仪331层状layered332矫顽力coercivity333纳米粉体powder334界面结合interface335超导体superconductor 336衍射分析diffraction 337纳米粉powders338磨损机理wear339泡沫铝aluminum340进行表征characterized 341梯度功能gradient342耐磨性能wear343平均粒particle344聚苯乙烯polystyrenecomposites345陶瓷基复合材料346陶瓷材料ceramics347石墨化graphitization 348摩擦材料friction349熔化melting350多层multilayer351及其性能properties352酚醛树脂resin353电沉积electrodeposition 354分散剂dispersant355相图phaseinterface356复合材料界面357壳聚糖chitosanoxidation358抗氧化性能359钙钛矿perovskite360分层delamination 361热循环thermal362氢量hydrogen363蒙脱石montmorillonite 364接枝grafting365导率conductivity 366放氢hydrogen367微粒particles368伸长率elongation369延伸率elongation370烧结工艺sintering371层合laminated372纳米级nanometer373莫来石mullite374磁导率permeability375填料filler376热电材料thermoelectric 377射线衍射ray378铸造法casting379粒度分布size380原子力afm381共沉淀coprecipitation 382水解hydrolysis383抗热thermal384高能球ball385干摩擦friction386聚合物基polymer387疲劳裂纹fatigue388分散性dispersion389硅烷silane390弛豫relaxation391物理性能properties392晶相phasemagnetization 393饱和磁化强度394凝固过程solidification395共聚物copolymer396光致发光photoluminescence 397薄膜材料films398导热系数conductivity399居里curie400第二相phase401复合材料composites制备402多孔材料porous403水热法hydrothermal 404原子力显afm微镜piezoelectric 405压电复合材料406尼龙6nylon407高能球磨milling408显微硬度microhardness 409基片substrate410纳米技术nanotechnology 411直径为diameter412织构texture413氮化nitride414热性能properties415磁致伸缩magnetostriction 416成核nucleation417老化aging418细化grain419压电材料piezoelectric 420纳米晶amorphous421si合金si422复合镀层composite423缠绕winding424抗氧化oxidation425表观apparentepoxy426环氧复合材料427甲基methyl428聚乙烯polyethylene429复合膜composite 430表面修饰surface 431大块非晶amorphous 432结构材料materials 433表面能surface 434材料表面surface 435疲劳性能fatigue 436粘弹性viscoelastic 437基体合金alloy438单相phase439梯度材料material 440六方hexagonal 441四方tetragonal 442蜂窝honeycomb 443阳极氧化anodic444塑料plastics 445超塑性superplastic 446sem观察sem447烧蚀ablation 448复合薄膜films449树脂基resin450高聚物polymer 451气相vapor452电子能谱xps453硅烷偶联coupling 454团聚particles 455基底substrate 456断口形貌fracture 457抗压强度strength 458储能storage 459松弛relaxation460拉曼光谱raman461孔率porosity462沸石zeolite463熔炼melting464磁体magnet465sem分析sem466润湿性wettability467电磁屏蔽shielding468升温heating469致密dense470沉淀法precipitation471差热分析dta472成功制备prepared473复合体系composites474浸渍impregnation 475力学行为behavior476复合粉体powders477沥青pitch478磁电阻magnetoresistance 479导电性能conductivityxps480光电子能谱481材料力学mechanical482夹层sandwich483玻璃化glass484衬底上substratescomposites485原位复合材料486智能材料materials487碳化物carbide488复相composite489氧化锆zirconia490基体材料matrix491渗透infiltration 492退火处理annealing 493磨粒wear494氧化行为oxidation 495细小fine496基合金alloy497粒径分布size498润滑lubrication 499定向凝固solidification 500晶格常数lattice501晶粒度size502颗粒表面surface503吸收峰absorption 504磨损特性wear505水热合成hydrothermal 506薄膜表面films507性质研究properties 508试件specimen 509结晶度crystallinity510聚四氟乙ptfe烯silane511硅烷偶联剂512碳化carbide513试验机tester514结合强度bonding515薄膜结构films516晶型crystal517介电损耗dielectric518复合涂层coating519压电陶瓷piezoelectric 520磨损量wearmicrostructure 521组织与性能522合成法synthesis523烧结过程sintering524金属材料materials525引发剂initiatormontmorillonite 526有机蒙脱土527水热法制hydrothermal 528再结晶recrystallization 529沉积速率deposition530非晶相amorphous 531尖端tip532淬火quenching533亚稳metastable534穆斯mossbauer535穆斯堡尔mossbauer536偏析segregation 537种材料materials538先驱precursor539物性properties540石墨化度graphitization 541中空hollow542弥散particles543淀粉starch544水热法制hydrothermal 备545涂料coating546复合粉末powder547晶粒长大grain548sem等semmicrostructure 549复合材料组织550界面结构interface551煅烧calcined552共混物blends553结晶行为crystallizationhybrid554混杂复合材料555laves相laves556摩擦因数friction557钛基titanium558磁性材料magnetic559制备纳米nanometer 560界面上interface561晶粒大小size562阻尼材料damping563热分析thermallaminates 564复合材料层板565二氧化钛titanium566沉积法deposition 567光催化剂tio568余辉afterglow 569断裂行为fracture570颗粒大小size571合金组织alloy572非晶形成amorphous 573杨氏模量modulus574前驱物precursor 575过冷alloy576尖晶石spinel577化学镀electroless 578溶胶凝胶sol-gel法制备579本构方程constitutive 580磁学magnetic581气氛下atmosphere 582钛合金titanium583微粉powder584压电性piezoelectric 585sic晶须sic586应力应变strain587石英quartz588热电性thermoelectric 589相转变phase590合成方法synthesis 591热学thermal592气孔率porosity593永磁magnetic594流变性能rheological 595压痕indentation 596热压烧结sinteringteos597正硅酸乙酯598点阵latticefgm599梯度功能材料600带材tapes601磨粒磨损wear602碳含量carbon603仿生biomimetic604快速凝固solidification 605预制preform606差示dsc607发泡foaming608疲劳损伤fatigue609尺度size610镍基高温superalloy合金611透过率transmittance 612溅射法制sputtering613结构表征characterization 614差示扫描dsc615通过sem sem616水泥基cement617木材wood618tem分析tem619量热calorimetry620复合物composites621铁电薄膜ferroelectric622共混体系blends623先驱体precursor624晶态crystalline625冲击性能impact626离心centrifugalelongation627断裂伸长率628有机-无机organic-inorganic 629块状bulk630相沉淀precipitation631织物fabric632因数coefficientsynthesis633合成与表征634缺口notch635靶材target636弹性体elastomeroxide637金属氧化物638均匀化homogenization 639吸收光谱absorption640磨损行为wear641高岭土kaolinfgm642功能梯度材料643滞后hysteresis644气凝胶aerogel645记忆性memory646磁流体magnetic647铁磁ferromagnetic 648合金成分alloy649微米micron650蠕变性能creep651聚氯乙烯pvc652湮没annihilation 653断裂力学fracture654滑移slipdsc655差示扫描量热656等温结晶crystallization 657树脂基复composite合材料658阳极anodic659退火后annealing660发光性properties661木粉wood662交联crosslinking 663过渡金属transition664无定形amorphous665拉伸试验tensile666溅射法sputtering667硅橡胶rubber668明胶gelatinbiocompatibility 669生物相容性670界面处interfacecomposite671陶瓷复合材料672共沉淀法coprecipitation 制673本构模型constitutive 674合金材料alloy675磁矩magnetic676隐身stealth677比强度strength678改性研究modification 679采用粉末powder680晶粒细化grain681抗磨wear682元合金alloy683剪切变形shear684高温超导superconducting 685金红石型rutile686晶化行为crystallization 687催化性能catalytic688热挤压extrusion689微观microstructure 690tem观察tem691缺口冲击impact692生物材料biomaterials 693涂覆coating694纳米氧化nanometer 695x射线光电xps子能谱696硅灰石wollastonite 697摩擦条件friction698衍射峰diffraction 699块体材料bulk700溶质solute701冲击韧性impact702锐钛矿型anatase703凝固组织microstructuretester704磨损试验机705丙烯酸甲pmma酯706raman光谱raman707减振damping708聚酯polyester709体材料materials710航空aerospace 711光吸收absorption 712韧化tougheningfatigue713疲劳裂纹扩展714超塑superplasticgel715凝胶法制备semiconductor 716半导体材料717剪应力shear718发光材料luminescence 719凝胶法制gelpmma720甲基丙烯酸甲酯721硬质hard722摩擦性能friction723电致变色electrochromic 724超细粉powder725增强相reinforced726薄带ribbons727结构弛豫relaxation728光学材料materials729sic陶瓷sic730纤维含量fiber731高阻尼damping732镍基nickel733热导thermal734奥氏体austenite735单轴uniaxial736超导电性superconductivity 737高温氧化oxidation738树脂基体matrix739含能energetic740粘着adhesionmossbauer741穆斯堡尔谱742脱层delamination 743反射率reflectivitysuperalloy 744单晶高温合金745粘结bonded746快淬quenching 747熔融插层intercalation 748外加appliedperovskite 749钙钛矿结构750减摩frictionoxide751复合氧化物752苯乙烯styrene753合金表面alloy754爆轰detonation 755长余辉afterglow 756断裂过程fracture757纺织textile。

MS材料特性范文

MS材料特性范文MS材料(Microstructure material)是一种微结构材料,其特性主要由材料的结构和组织决定。

微结构是指材料的组成、晶粒尺寸、晶界以及其他相关微观结构的组合。

MS材料具有许多独特的特性,包括高强度、优异的机械性能、良好的疲劳寿命、良好的耐磨性、高抗腐蚀性等。

本文将对MS材料的特性进行详细介绍。

首先,MS材料具有高强度。

其高强度主要来自于材料的细晶粒结构和优化的晶粒配向。

晶粒尺寸越小,材料的强度就越高。

而MS材料经过特殊的处理得以获得细小的晶粒尺寸。

此外,MS材料采用了优化的晶粒配向方法,使晶界对应力的抵抗能力最大化,从而增强了材料的强度。

其次,MS材料具有优异的机械性能。

微结构的调控可以使材料具有很好的弹性模量、屈服强度和延展性等机械性能。

通过控制晶粒尺寸和晶界特性,可以实现对材料的机械性能进行调节。

此外,利用先进的成形加工方法,如等离子弧焊、高能电子束焊接等,可以进一步提高MS材料的机械性能。

再次,MS材料具有良好的疲劳寿命。

疲劳是材料在交变载荷作用下发生断裂的现象,而MS材料由于具有细小的晶粒尺寸和优化的晶粒配向,其抗疲劳性能得到了显著提高。

此外,MS材料在疲劳断裂后,由于晶界协同滑移的特性,疲劳断口并不容易扩展,从而延长了材料的疲劳寿命。

此外,MS材料具有良好的耐磨性。

由于微结构中的细小晶粒,MS材料具有更高的硬度和耐磨性。

细小的晶粒尺寸能够阻碍位错滑移的扩展,从而提高了材料的硬度。

同时,MS材料的晶界能够吸收冲击能量和分散应力,从而减小磨损。

最后,MS材料具有高抗腐蚀性。

微结构调控可以使晶界成为材料的阻氧层和屏蔽层,阻止金属和其他外界介质的相互作用。

此外,MS材料经过特殊防护处理可以形成一层致密的氧化层,进一步提高材料的抗腐蚀性。

因此,MS材料在各种恶劣的工作环境中具有较好的抗腐蚀性。

综上所述,MS材料具有高强度、优异的机械性能、良好的疲劳寿命、良好的耐磨性和高抗腐蚀性等特点。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。