语言学基础教程

语言学基础教程

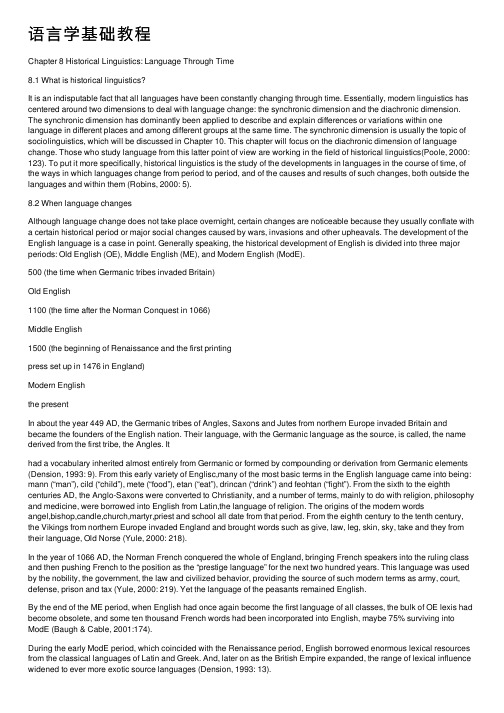

语⾔学基础教程Chapter 8 Historical Linguistics: Language Through Time8.1 What is historical linguistics?It is an indisputable fact that all languages have been constantly changing through time. Essentially, modern linguistics has centered around two dimensions to deal with language change: the synchronic dimension and the diachronic dimension. The synchronic dimension has dominantly been applied to describe and explain differences or variations within one language in different places and among different groups at the same time. The synchronic dimension is usually the topic of sociolinguistics, which will be discussed in Chapter 10. This chapter will focus on the diachronic dimension of language change. Those who study language from this latter point of view are working in the field of historical linguistics(Poole, 2000: 123). To put it more specifically, historical linguistics is the study of the developments in languages in the course of time, of the ways in which languages change from period to period, and of the causes and results of such changes, both outside the languages and within them (Robins, 2000: 5).8.2 When language changesAlthough language change does not take place overnight, certain changes are noticeable because they usually conflate with a certain historical period or major social changes caused by wars, invasions and other upheavals. The development of the English language is a case in point. Generally speaking, the historical development of English is divided into three major periods: Old English (OE), Middle English (ME), and Modern English (ModE).500 (the time when Germanic tribes invaded Britain)Old English1100 (the time after the Norman Conquest in 1066)Middle English1500 (the beginning of Renaissance and the first printingpress set up in 1476 in England)Modern Englishthe presentIn about the year 449 AD, the Germanic tribes of Angles, Saxons and Jutes from northern Europe invaded Britain and became the founders of the English nation. Their language, with the Germanic language as the source, is called, the name derived from the first tribe, the Angles. Ithad a vocabulary inherited almost entirely from Germanic or formed by compounding or derivation from Germanic elements (Dension, 1993: 9). From this early variety of Englisc,many of the most basic terms in the English language came into being: mann (“man”), cild (“child”), mete (“food”), etan (“eat”), drincan (“drink”) and feohtan (“fight”). From the sixth to the eighth centuries AD, the Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity, and a number of terms, mainly to do with religion, philosophy and medicine, were borrowed into English from Latin,the language of religion. The origins of the modern wordsangel,bishop,candle,church,martyr,priest and school all date from that period. From the eighth century to the tenth century, the Vikings from northern Europe invaded England and brought words such as give, law, leg, skin, sky, take and they from their language, Old Norse (Yule, 2000: 218).In the year of 1066 AD, the Norman French conquered the whole of England, bringing French speakers into the ruling class and then pushing French to the position as the “prestige language” for the next two hundred years. This language was used by the nobility, the government, the law and civilized behavior, providing the source of such modern terms as army, court, defense, prison and tax (Yule, 2000: 219). Yet the language of the peasants remained English.By the end of the ME period, when English had once again become the first language of all classes, the bulk of OE lexis had become obsolete, and some ten thousand French words had been incorporated into English, maybe 75% surviving into ModE (Baugh & Cable, 2001:174).During the early ModE period, which coincided with the Renaissance period, English borrowed enormous lexical resources from the classical languages of Latin and Greek. And, later on as the British Empire expanded, the range of lexical influence widened to ever more exotic source languages (Dension, 1993: 13).The types of borrowed words noted above are examples of external changes in English, and the internal changes overlap with the historical periods described above. According to Fennell (2005: 2), the year 500 AD marks the branching off of English from other Germanic dialects; the year 1100 AD marks the period in which English lost the vast majority of its inflections, signaling the change from a language that relied upon morphological marking of grammatical roles to one that relied on word order to maintain basic grammatical relations; and the year 1500 AD marks the end of major French influence on the language and the time when the use of English was established in all communicative contexts. Thus, those internal changes will be elaborated belowat the phonological, lexical, semantic and grammatical levels.8.3 How language changesThe change of the English language with the passage of time is so dramatic that today people hardly read OE or ME without special study. In general, the differences among OE, ME and ModE involve sound, lexicon and grammar, as discussed below.8.3.1 Phonological changeThe principle that sound change is normally regular is a very fruitful basis for examining the phonological history of a language. The majority of sound changes can be understood in terms of the movements of the vocal organs during speech, and sometimes more particularly in terms of a tendency to reduce articulatory effort (Trask, 2000: 70, 96).8.3.1.1 Phonemic change8.3.1.1.1 Vowel changeOne of the most obvious differences between ModE and the English spoken in earlier periods is in the quality of the vowel sounds (Yule, 2000: 219). Sometimes a language experiences a wholesale shift in a large part of its phonological system. This happened to the long vowels of English in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries AD, each vowel becoming closer, the highest becoming diphthongs as in the words wife and house (respectively changed from wayf /wi:f/ and haws /hu:s/ in OE). We call this shift the Great Vowel Shift (Poole, 2000: 127), and the specific changes may be diagrammed as follows (Robins, 2000: 342).In ME, the vowels in nearly all unstressed syllabic inflections were reduced to [?], spelled (Dension, 1993: 12). The general obscuring of unstressed syllables is a most significant sound change (to be elaborated further in 8.3.3 and 8.3.4), since it is one of the fundamental causes of the loss of inflections (Fennell, 2005: 99).8.3.1.1.2 Consonant changeConsonants are produced with an obstruction of the air-stream, and tend to be less stable over time than vowels in most languages. Two fairly common processes are assimilation and lenition.Assimilation is the process by which two sounds that occur close together in speech become more alike. This sort of change is easy to understand: moving the speech organs all over the place requires an effort, and making nearby sounds more similar reduces the amount of movement required, and hence the amount of effort (Trask, 2000: 53). Instances can be found in words such as irregular,impossible and illegal, in which the negative prefixes im-and il-should be “in-based” in accordance with etymology.Under the influence of neighboring vowels, consonants may also be weakened. This weakening or lenition, can change a voiceless consonant into a voiced one and a plosive into a fricative (Poole, 2000: 126). Instances of [h] in native English words generally derive from the lenition of an earlier *[k]: such words as head,heart,help,hill and he all began with [k] in a remote ancestral form of English, but this [k] was lenited first to [x] and then to [h], and the modern lenition of [h] to zero merely completes a process of lenition stretching over several thousand years (Trask, 2000: 59).8.3.1.2 Whole-segment changeCertain phonological changes are somewhat unusual in that they involve, not just changes in the nature of segments, but achange in the number or ordering of segments, and these are referred to as whole-segment processes (Trask, 2000: 66). The change known as metathesis involves a reversal in position of two adjoining sounds. The following are examples from the OE period: acsian → ask bridd → bird brinnan → beornan (burn)frist → first hros → horse waeps → wasp(Yule, 2000: 220).8.3.2 Lexical changeAs defined by Freeborn (2000: 23), lexical change refers to new words being needed in the vocabulary to refer to new things or concepts, with other words dropping out when they no longerhave any use in society. Lexical change may also involve semantic change, that is, change in the meaning of words. Thus, lexical change mainly consists of addition of new words, loss of words and change in the meaning of words.8.3.2.1 Addition of new wordsThe conditions of life for individuals in society, their artifacts, customs, and forms of organization are constantly changing. Accordingly, many words in languages and the situations in which they are employed are equally liable to change in the course of time (Robins, 2000: 343). Floods of new words constantly need to be added to the word-stock to reflect these developments.E tymology, which is the study of the history of individual words, shows that while the majority of words in a language are native words, there may also be loan words or borrowed words from another language. Native words are those that can be traced back to the earliest form of the language in question. In English, native words are words of Anglo-Saxon origin, such as full, hand, wind, red. Loan words are those that are borrowed or imported from another language, such as myth, career, formula, genius. Apart from borrowing, many new words are added to a language through word-formation. The following processes are quite pervasive in the addition of new words in the evolution of English.8.3.2.1.1 Compounding and affixingAccording to Fennell (2005: 77-8), new words in OE were mainly formed on the basis of compounding and affixing. Many words were formed through compounding, e.g. blod + read (“blood-red”); Engla (“Angles”) + land = England. Affixing covers suffixing and prefixing in OE, the former usually used to transform parts of speech while the latter generally used to change the semantic force. A suffix like -dom could create an abstract noun from another noun or adjective: wis + dom (“wisdom”). The perfective prefix ge- was most often used to form past participles: ceosan (“to choose), gecoren (“chosen”); findan (“to find”), gefunden (“found”). It could also be used to change the meaning of a word: hatan (“to call”), gehatan (“to promise”).In modern English, new words are added not only through compounding and affixing, but also by means of coinage, conversion, blending, backformation and abbreviation. All these word-formation processes are discussed in Chapter 3.8.3.2.1.2 Reanalysis and metanalysisReanalysis means that a word which historically has one particular morphological structure, is perceived by speakers as having a second, quite different structure. The Latin word minimum consisted in Latin of the morphemes min-(“little”, also found in minor and minus) and-im-(“most”), plus an inflectional ending; however, thanks to the influence of the unrelated miniature, English speakers have apparently reanalyzed both words as consisting of a prefix mini-(“very small”) plus something incomprehensible, leading to the creation of miniskirt and all the newer words which have followed it (Trask, 2000: 102).The history of English provides some nice examples of reanalysis involving nothing more than the movement of a morpheme boundary, a type of change impressively called metanalysis. Forms like a napron and an ewt were apparently misheard as an apron and a newt, producing the modern forms. Other similar instances are adder(the English former word: naddre), umpire (noumpere) and nickname (ekename) (Trask, 2000: 103).8.3.2.1.3 Analogical creationAnalogical creation is the replacement of an irregular or suppletive form within a grammatical paradigm by a new form modeled on the forms of the majority of members of the class to which the word in question belongs. The virtual replacement of kine by cows as the plural of cow is an example of analogical creation, and so are the more modern regular past tense forms helped, climbed, and snowed, for the earlier holp, clomb, and snew (Robins, 2000: 359). Analogical creation is quite persuasive in accounting for the process of cultural transmission to be discussed in 8.4.2.8.3.2.2 Loss of wordsIn the course of time, some words pass out of current vocabulary as the particular sorts of objects or ways of behaving to which they refer become obsolete. One need only think in English of the former specialized vocabulary, now largely vanished, which relates to obsolete sports such as falconry (Robins, 2000: 343). Such examples abound in almost every language.8.3.2.3 Semantic changeSemantic change refers to changes in the meanings of words. There are mainly three processes of semantic change: broadening, narrowing and meaning shifts (Fromkin & Rodman 1983: 297).Broadening and narrowing are changes in the scope of word meaning. That is, some words widen the range of their application or meaning, while other words have their contextual application reduced in scope. Broadening is a process by which a word with a specialized meaning is generalized to cover a broader or less definite concept or meaning. For example, the original meaning of carry is “transport by cart”, but now it means “transport by any means”. Narrowing is the opposite of broadening, a process by which words with a general meaning become restricted in use and express a narrow or specialized meaning. For example, the word girl used to mean “a young person”, but in modern English it refers to a young female person. More examples of broadening and narrowing are provided below:Broadening:dog (docga OE) one particular breed of dog →all breeds of dogsbird (brid ME) young bird →all birds irrespective of ageholiday (holy day) a religious feast →the very general break from workNarrowing:hound (hund OE) any kind of dog → a specific breed of dogmeat (mete OE) any kind of food →edible food from animalsdeer (dēor ME) any beast, animal →one species of animalMeaning shift is a process by which a word that used to denote one thing is used to mean something else. For example, the word coach, originally denoting a horse-drawn vehicle, now denotes a long-distance bus or a railway vehicle. Meaning shifts also include transference of meaning, that is, change from the literal meaning to the figurative meaning of words. For example, in expressions like the foot of a mountain, the bed of a river and the eye of a needle, we use foot, bed and eye in a metaphorical way. Other types of meaning shifts include elevation and degradation. Elevation of meaning is a process by which a word changes from a derogatory sense to an appreciative sense. For example, the word nice originally meant “ignorant” and fond simply meant “foolish”. Degradation of meaning is a process by which a word of appreciative meaning falls into pejorative use. For example, the word silly used to mean “happy” and cunning originally meant “skillful”.8.3.3 Grammatical changeThe most fundamental feature that distinguishes Old English from the language of today is its grammar (Baugh & Cable, 2001: 54). Modern English is an analytic language while Old English is a synthetic language. The major difference is that a synthetic language is one that indicates the relation of words in a sentence largely by means of inflections, but an analytic language makes extensive use of prepositions, auxiliary verbs, and depends on word order to show other relationships. In OE, the order of words in a clause was more variable than that of ModE, and there were many more inflections on nouns, adjectives and verbs (Freeborn, 2000: 66). The grammatical changes of English such as those in number, gender, case and tense mainly took place on its morphological level, while syntactic changes such as those in word order are the consequence of the loss of rich inflections in English. The most sweeping morphological change during the evolution of English is the progressive decay of inflections. OE, ME and ModE can be called the periods of full, reduced and zero inflections, respectively because, during most of the OE period the endings of the noun, the adjective, and the verb are preserved more or less unimpaired, while during the ME period the inflections become greatly reduced, and finally by the ModE period, a large part of the original inflectional system had disappeared entirely (Dension, 1993: 12; Baugh & Cable, 2001: 50).The loss of inflections in the case system of Old English is a good example of grammatical change. Case is the grammatical feature that marks functions of the subject, object, or possession in a clause. In OE, nouns showed a four-term case contrast, for which the Latinate terms nominative (subject), accusative (direct object), genitive (possessive) and dative (indirect object) are conventionally used, and the case-ending system can be illustrated by the following:CASE nominative genitive dative accusative MODERNENGLISHstone/stonesstone’s/stones’stone/stonesstone/stonesOESINGULARstānstānesstānestānOEPLURALstānasstānastānumstānas(Fromkin & Rodman, 1983: 290)The ME period is the beginning of the loss of most of the inflections of OE, mainly through the weakening and dropping of the final unstressed vowels. For example, when the vowel wasdropped in the plural form of stones[st :n?s], it became [st wnz], and when the “weak”syllables representing case endings in the forms of the singular, genitive plural, and dative plural were dropped, English lost much of its case system (ibid).The loss of inflections marks a transition of English from a synthetic to an analytic language, and thus led to a greater reliance on word order. Word order in OE was more variable than that of ModE: word order was not as fixed or rigid in OE as it is in ModE (Fennell, 2005: 59). Both the orders subject-object-verb (“hē hine geseah”: “he saw him”) and object-subject-verb (“him man ne sealde”: “no man gave [any] to him”) are possible (Yule, 2000: 221). Word order in an OE sentence was not so crucial because OE is so highly inflected. The doer of the action and the object of the action were revealed unambiguously by various case endings, which makes the sentence meaning perfectly clear.It can be said that changes in sound, lexicon and grammar do not operate separately or independently of each other, but they are interacting and interdependent. One change is often integrated or incorporated into the other changes. And, it is the complex interrelationships among them that have shaped the whole process of the language change. As is shown above, the dropping of the final unstressed vowels led to the loss of inflections of OE, and this in turn led to a greater reliance on word order.8.4 Why language changesNo change described above has happened overnight, but has constantly and gradually taken place. Many changes are difficult to discern while they are in progress. The causes of language change are many and various, and only some of them are reasonably well understood at present (Trask, 2000: 12). Two broad categories of factors contribute to language change: external and internal factors.8.4.1 External causesExternal causes of linguistic changes are the contacts between the speakers of different languages: the sort that occurs when a language is imposed on a people by conquest or political or cultural domination, or when cultural and other factors produce a high degree of bilingualism between adjacent speech areas (Robins, 2000: 340). The significant influence of Norman French on the English language from the eleventh century AD supports this proposition. It can be said thatany dramatic social change caused by wars, invasions and other upheavals can possibly bring about correspondent changes in language.8.4.2 Internal causesAccording to Yule (2000: 222), the most pervasive source of change seems to be in the continual process of cultural transmission (in particular, the transmission of speech habits from one generation to another). Each new generation has to find a way of using the language of the previous generation. In this unending process whereby each new language-user has to “recreate”for him-or herself the language of the community, there is an unavoidable propensity to pick up some elements exactly and others only approximately. There is also the occasional desire to be different.In the process of cultural transmission, some underlying physiological factors can also play a vital role, mainly marked by least effort. For sound change, one key motivator is ease of articulation. There is a tendency for intervocalic voiceless plosives to be subjected to lenition because producing a voiced fricative between vowels requires less physiological change than does the production of a voiceless plosive (Poole, 2000: 130). For grammatical change, it is not difficult to see that the principle of least effort works for widespread simplification of the grammatical categories in the English language, exemplified by substantial losses of gender, case and tense distinctions.8.5 SummaryIn this chapter we have focused on language change in the diachronic dimension, namely from the historical perspective of change. We draw the conclusion that English has gradually and continuously shifted from a synthetic language to an analytic language in the course of time, marked by interrelated and interdependent changes at all levels, including the general obscuring of unstressed syllables, the progressive decay of inflections and the rigidity of word order. And, this shift may be mainly caused by major social changes and contacts, and by cultural transmission and least effort.Questions and Exercises1. Define the following terms.historical linguistics Great V owel Shift lenitionmetathesis analogical creation etymologysynthetic languagereanalysisanalytic language2. How are the historical developments of the English language generally divided? What are the main features that characterize each period?3. Can you apply the theory of reanalysis to explain how cheeseburger, chickenburger andvegeburger are derived from the word hamburger? Can you find more examples of reanalysis in English?4. Use one or two examples to show how the grammatical case is changed in the course of the historical evolution of English.5. Use one or two examples to illustrate how changes in sound, lexicon and grammar areintegrated or interrelated.6. What are the semantic processes in the changes of word meanings?7. Among the phonological, lexical and grammatical levels of language change, which level do you believe undergoes the fastest change and which level the slowest change? Can you account for these changes?8. In the English language, some names of animals are generally known by the Germanic terms and the resultant meats by the French terms. Which of the following words are derived from OE and which from Norman French? Can you trace the reason for this differentiated origin?calf, pork, mutton, ox, veal, swine, beef, sheep9. Give examples to account for the causes for language change.。

《语言学教程》Chapter-2-ics

语法

语法

语法是语言中词和句子的结构规律和 规则,是语言的组织原则。语法包括 词法和句法两部分。词法研究词的内 部结构和变化规律;句法研究短语和 句子的结构规律和规则。

语法的特点

语法具有抽象性、生成性、层次性和 系统性等特点。抽象性是指语法规则 是对语言中具体实例的抽象概括;生 成性是指语法能够生成无限多的合乎 语法的句子;层次性是指语法结构分 为若干层次,不同层次之间存在递归 关系;系统性是指语法规则相互联系 、相互制约,形成一个完整的系统。

新的词汇、表达方式和语法结构等可能会随着时间的推移而出 现,丰富和发展语言的表达和沟通功能。

05

语言与社会文化的关系

语言与文化的关系

语言是文化的重要组成部分,是文化 传承和发展的载体。语言中蕴含着丰 富的文化信息,反映了特定民族的历 史、传统、信仰、价值观等。

语言与文化相互影响,语言使用中的 词汇、语法、表达方式等都受到文化 的影响,同时语言也影响了人们对世 界的认知和表达方式。

语音的生理属性

语音的生理属性包括发音机制和听觉机制。发音机制包括呼吸系统、声源系统、调制系统 和共鸣系统;听觉机制包括听觉接收器和大脑处理声音信息的过程。

词汇

词汇

词汇是语言中所有词的总和,是语言的建筑材料。词汇由词和固定词组构成,包括实词和虚词两大类。实词表示事物 、概念、动作等具体内容;虚词表示语法关系和语气等抽象内容。

语法的作用

语法在语言中起着非常重要的作用。 首先,语法保证语言的正确性和规范 性,使人们能够准确地表达思想、传 递信息。其次,语法使语言具有生成 性,能够生成无限多的合乎语法的句 子。最后,语法使语言具有开放性, 能够吸收外来文化和方言的影响,不 断丰富言演变的原因

语言学基础教程戴庆厦1-2章

第一章 导论

∆

第一节 语言学的性质及其任务

一、什么是语言学? 语言学:是关于语言的科学,是以人类语言为研究对象的一门独立科学。 语言学概论主要研究语言的基础理论,揭示人类语言的性质、功能、结构特点, 以及语言发展与变化的一般规律。

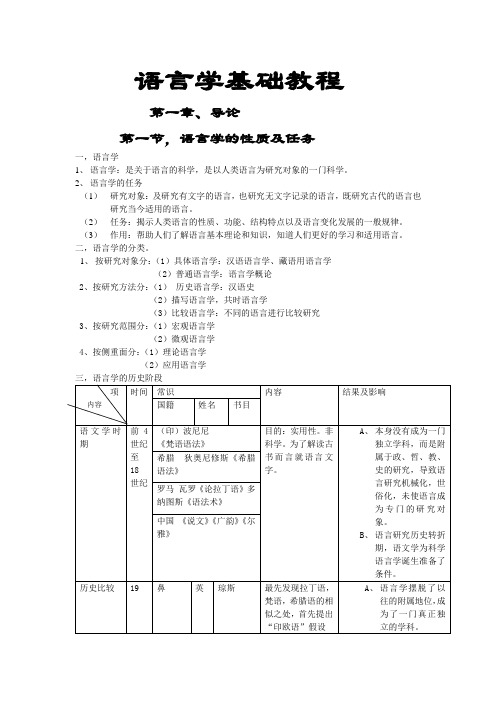

二、语言学的分类 1.从研究对象上,分为具体语言学和普通语言学(一般语言学)。 2.从研究方法上,分为历史语言学(历时),描写语言学(共时)、比较语言学(历史比 较语言学和对比语言学)等。 3.从研究范围上,分为宏观语言学和微观语言学。 4.从研究侧重面上,分为理论语言学和应用语言学。

第一章 导论

(3)结构语言学(20世纪20年代) 兴起于 20 世纪 20 年代的欧洲,基本理论源出于索绪尔的《普通语言学教 程》,反对对语言现象进行孤立的分析,主张系统的研究。结构语言学内 部又分为三大学派:布拉格学派(马泰修斯、特鲁别兹科依和雅各布逊)、 哥本哈根学派(布龙达尔、叶尔姆斯列夫)以及美国描写语言学(博厄斯、 萨丕尔、布龙菲尔德) 特点:重视系统性,重视共时的描写、重视口语,反对对语言现象进行孤 立的分析,主张系统的研究,影响深远,渗透到人文社会科学各个领域。

第一章 导论

(2)历史比较语言学(19世纪欧洲的语文学进入了一个新的时期) 英国的琼斯最先发现希腊语和拉丁语、梵语之间的相似之处,首先提出 “印欧语假设”。丹麦的拉斯克研究并论证了北欧诸语语欧洲其他语言的 地位。德国的葆朴在印欧语亲属关系的研究方面独树一帜。德国的格里姆 提出著名的“语音转变规律”(格里姆定律)。俄国的沃斯托克夫研究了 斯拉夫诸语言相互之间的发生学关系。 特点:摆脱了遗忘的附庸地位,促使语言成为了一门真正独立的学科,但 是仍具有局限性,认为只有研究语言历史的语言学才是科学,其他语言学 都不是科Байду номын сангаас。唯我独尊,只注重书面语的研究,忽视了口语研究和语言整 体的系统研究。

语言学基础教程

语言学基础教程

第一章、导论

第一节,语言学的性质及任务

一,语言学

1、语言学:是关于语言的科学,是以人类语言为研究对象的一门科学。

2、语言学的任务

(1)研究对象:及研究有文字的语言,也研究无文字记录的语言,既研究古代的语言也研究当今适用的语言。

(2)任务:揭示人类语言的性质、功能、结构特点以及语言变化发展的一般规律。

(3)作用:帮助人们了解语言基本理论和知识,知道人们更好的学习和适用语言。

二,语言学的分类。

1、按研究对象分:(1)具体语言学:汉语语言学、藏语用语言学

(2)普通语言学:语言学概论

2、按研究方法分:(1)历史语言学:汉语史

(2)描写语言学,共时语言学

(3)比较语言学:不同的语言进行比较研究

3、按研究范围分:(1)宏观语言学

(2)微观语言学

4、按侧重面分:(1)理论语言学

(2)应用语言学

四、名词解释

1.语言学:关于语言的科学,是以人类古今,书面和口头的语言为研究对象的一门科学。

2.语文学:广义,对文学和文化系统的研究;狭义,依据文献资料和文学作品作出的历史语

言分析。

此处偏重于从文献的角度研究语言,文学学科的总称,应属于语言科学

体系。

3.历史语言学:采用历史的方法

4.比较语言学:

5.描写语言学:

6.历史比较语言学:

7.结构语言学

8.转换生成语言学

9.历时语言学

10.共时语言学

11.一般语言学

12.具体语言学

13.理论语言学

14.应用语言学。

语言学教程

语言学教程语言学教程语言学是研究语言的科学,它关注的是语言的结构、使用和演变。

在本教程中,我们将介绍语言学的基本概念和主要研究领域,帮助读者了解语言学的基本原理和方法。

一、什么是语言学?语言学是研究语言的学科,它探究语言的本质、结构和使用。

语言是人类交流和表达思想的工具,它通过声音、符号和规则来构建意义。

语言学家研究语言的各个方面,包括语音学、语法学、语义学、语用学和历史比较语言学等。

二、语音学语音学是语言学的一个重要分支,研究语音的产生、传播和感知。

它涉及到语音的音素(语言中的基本音单位)和音位(音素在特定语言中的表现形式)。

语音学家使用声谱图、语音学家和实验方法来研究语音的特征和变化规律。

三、语法学语法学是研究语言的结构和组织的学科。

它研究语言的句子结构、词法和句法规则。

语法学家分析和描述语言中的句子成分和句法关系,并研究语言中的语法现象和规律。

四、语义学语义学是研究意义的学科。

它关注语言中的词汇和句子的意义。

语义学家研究词汇的意义和词义关系,分析句子的逻辑关系和语义关系。

通过语义学的研究,我们可以更好地理解语言中的意义和信息传递。

五、语用学语用学是研究语言使用的学科,它关注语言在特定情境下的使用和理解。

语用学家研究语言中的说话人意图、语体、修辞和隐喻等现象,研究语言在社交交流中的作用和效果。

六、历史比较语言学历史比较语言学是研究语言演变和语系关系的学科。

它比较不同语言间的相似性和差异性,通过语音、词汇和语法的比较,揭示语言的历史发展和变迁。

七、应用语言学应用语言学是语言学的一个重要分支,它将语言学理论和方法应用于实际问题的解决中。

应用语言学研究语言的教学、语言规划、翻译和语言治疗等领域,为语言相关的应用提供理论依据和实践指导。

结语语言学研究语言的各个方面,帮助我们更好地理解语言的本质和特点。

通过学习语言学,我们可以更好地掌握和应用语言,促进跨文化交流和理解。

以上就是本教程对语言学基本概念和主要研究领域的介绍。

普通语言学教程

第三章 语言学的对象

语言学的对象

语言; 它的定义 语言在言语活动事实中的地位 语言在人文事实中的地位: 符号学

第一节 语言; 它的定义

一 语言对象的复杂性 1 声音形象和发声动作 2 语音和语义 3 个人方面和社会方面 4 言语本身既是一种社会制度, 又是一个 演变过程

二 语言和言语活动的关系

索绪尔的设想

建立一门研究社会生活中符号生命的科 学 它的存在是预先确定了的 大家还不承认符号学是一门独立的科学 无法跳出的圈子

语言比任何东西更适宜了解符号学的性 质

要提出适当的问题,又必须研究语言本 身

大家不承认符号学是一门独立的学科 的原因

大众把语言看成分类命名集 心理学家的研究方法跨不出个人执行的 范围 大家忽略的问题和特征

第二节 语言在言语活动事实中的地位

一 索绪尔分析言语循环中的三个过程及 对该循环的另外分类 1 外面部分/里面部分 2 心理部分/非心理部分 3 主动部分/非主动部分 4 执行部分/接受部分 此外,还加上一个联合和配置机能

二 索绪尔在语言活动循环分析的基础 上关于语言特征的概括 三 索绪尔关于言语特征的概括 四 索绪尔关于语言和言语关系的概括

谢谢大家!

后人对索绪尔所做区分的看法与发展

叶尔姆斯列夫的观点 乔姆斯基的解释和修正 方光焘对它的评价

问题

言语活动的异质指的是什么?

语言的同质指的是什么?

第三节

语言在人文事实中的地位 符号学

语言

=>

人文事实

言语活动

≠>

人文事实

语言是一种社会制度 语言是一种表达观念的符号系统 亚里士多德: 最早提出: 英国的洛克 正式提出 《易经》详尽论述

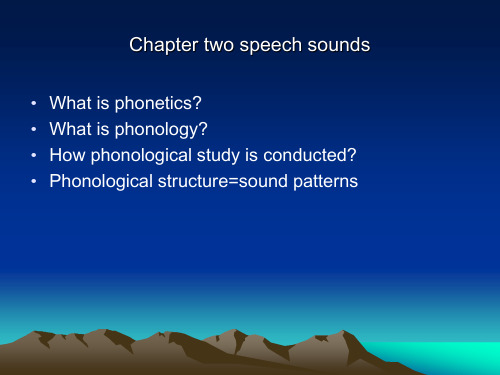

语言学教程Chapter 2 Speech Sounds

2.3.2 phonemes

• phonological study concerns the sounds which can cause the change of meaning of a word or a phrase. • Minimal pair is used to decide whether two sounds are two different sounds. • Phonemes are sounds which distinguish meaning. • A phoneme is a unit of explicit contrast. • Languages differ in the selection of contrastive sounds.

2.2.3 the sounds of English

• • • • What is RP? What is GA? The major differences of the two are? Two sounds are distinguished by VOICING when they share the same place and manner. • Symbols for vowels in this book are provided by Wells in 2000.

• Diacritics are used to record the variations of the same sound. This is called narrow transcription. It is put inside [ ]. Narrow transcription is used in phonetic transcription by phoneticians. • Broad transcription uses only symbols to record a sound. It is put inside / /. It is used in phonemic transcription by phonologists.

《英语语言学基础教程》评介

其中. 发音语音学研 究言语声音 的产生方式 , 编 者对此

进行 了重点介 绍 。 随后 。 编者在 两个 子章节里分别介绍 了元音 和辅音 的发音方式 。音标( p h o n e t i c t r a n s c r i p i t o n )

是 语 音 学 中极 为 重 要 的 内容 .也 是 学 生 考 核 的 重 点 项

第二 章介绍 了语 言学的定义 、 其 基本 研究 内容 、 语

言 学 中 一 些 基 本 概 念 的 区分 。 以及 语 言 学 和 语 言 教 学 。 通 过 对 上 一 章 内 容 的 回顾 .编 者 自然 过 渡 到 语 言 学 概

重庆 三峡学院外 国语 学院王扬教授 、杨清玉 副教授主 念 的引入 . 语言学就是对语 言的科 学系统 的研究 。 编者

系统 ” , 接 着 举 例 阐释 了 定 义 中 的系 统 性 、 任意性 、 符 号 性、 有声 、 人 类 交 际 等关 键 词 。随 之 , 编 者 由人 类 交 区别性特征. 并简要介

师资 、 资源等多种 因素 的影 响 . 国内各个 高校 的学 生水 绍 了语 言 功 能 的 主要 观 点 。 如语言 的人际功能 、 施 为 功 平参差 不齐 、 教学效果 高低不一 , 因此 有必要针 对不 同 能、 情感 功能 、 信息功 能 、 寒 喧功 能及 元语 言功 能。最

作者简介 : 王佳 ( 1 9 8 7 一 ) , 女, 甘 肃陇南人 , 硕士, 助教 , 研 究方 向 : 认 知语 言学。

1 4

一

三 峡 高 教 研 究

a )T h e ma n a n d w o ma n a r e b o t h o l d .

浅析索绪尔的《基础语言学教程》

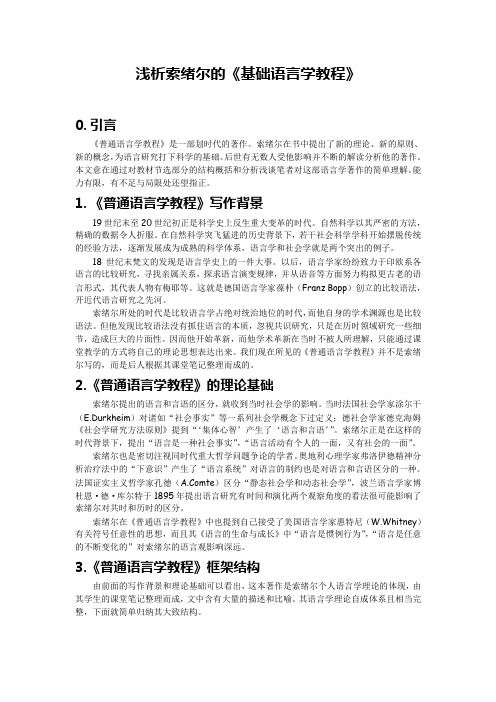

浅析索绪尔的《基础语言学教程》0.引言《普通语言学教程》是一部划时代的著作。

索绪尔在书中提出了新的理论、新的原则、新的概念,为语言研究打下科学的基础。

后世有无数人受他影响并不断的解读分析他的著作。

本文意在通过对教材节选部分的结构概括和分析浅谈笔者对这部语言学著作的简单理解。

能力有限,有不足与局限处还望指正。

1.《普通语言学教程》写作背景19世纪末至20世纪初正是科学史上反生重大变革的时代。

自然科学以其严密的方法,精确的数据令人折服。

在自然科学突飞猛进的历史背景下,若干社会科学学科开始摆脱传统的经验方法,逐渐发展成为成熟的科学体系,语言学和社会学就是两个突出的例子。

18世纪末梵文的发现是语言学史上的一件大事。

以后,语言学家纷纷致力于印欧系各语言的比较研究,寻找亲属关系,探求语言演变规律,并从语音等方面努力构拟更古老的语言形式,其代表人物有梅耶等。

这就是德国语言学家葆朴(Franz Bopp)创立的比较语法,开近代语言研究之先河。

索绪尔所处的时代是比较语言学占绝对统治地位的时代,而他自身的学术渊源也是比较语法。

但他发现比较语法没有抓住语言的本质,忽视共识研究,只是在历时领域研究一些细节,造成巨大的片面性。

因而他开始革新,而他学术革新在当时不被人所理解,只能通过课堂教学的方式将自己的理论思想表达出来。

我们现在所见的《普通语言学教程》并不是索绪尔写的,而是后人根据其课堂笔记整理而成的。

2.《普通语言学教程》的理论基础索绪尔提出的语言和言语的区分,就收到当时社会学的影响。

当时法国社会学家涂尔干(E.Durkheim)对诸如“社会事实”等一系列社会学概念下过定义;德社会学家德克海姆《社会学研究方法原则》提到“‘集体心智’产生了‘语言和言语’”。

索绪尔正是在这样的时代背景下,提出“语言是一种社会事实”,“语言活动有个人的一面,又有社会的一面”。

索绪尔也是密切注视同时代重大哲学问题争论的学者。

奥地利心理学家弗洛伊德精神分析治疗法中的“下意识”产生了“语言系统”对语言的制约也是对语言和言语区分的一种。

《英语语言学基础教程》述评

摘要: 《 英语语言学基础教程》是一部针对地方一般 高校 或西部边缘地区高校本科 生英语水平的实际情况所编写 的一本语言学基 础教材。该书能激发读者学习语 言学的兴趣 , 还能为今后进一步学习语言学打 下良好 的基础。 关键词: 语 言学 基本理论 述评

1 . 引言

借助理论强化英语单词理解 、 学习和记忆 。 第六章 的主要 内容是语言 的句子结构 ,涉及句法学方 而的

八十年代 以来 ,语 言学概论作 为一 门介绍语 言学 基本概念

和基 本理论 的学科已逐步在 各高校外语学院 、系作 为必修课程 内容 , 为传统语言学 的重点 , 也是相对 于前面章节关注词层 面而 为专业学 生所 开设 。为配合课程建 设 , 国内相继 出现 了约 5 0部 更 高一级 的研究 。作者 从介绍短语 , 句子 , 句法学概念人手 , 而后 对 句法分析 方面影响较 大的一些 方法 , 如 结构主 义 、 生成语 法、 语言学教材 , 大多教材定位对 象高 ; 内容多 ; 难度大 ; 课后练 习难

的语 言习得和学 习。

第九 、 十章都具有跨学科的性质 。第九章语言和文化审足于 萨丕尔——沃尔夫假设 ,反映川不 同的语 言会 给予人类不 同的

表现 自我 , 表达情绪 的方式 , 从而形成不 同的思维模式 和文化 背

景 。随后 , 作者重点讲解 了语言教学 中的语言与文化 , 翻译视角 下 的语 言和文化 , 强调文化在语言 学习中的重要地位 , 只有 了解 了 目的语 国家 的风土人情 才能在 国际交流 中运用 自如。第 十章

L e e c h 关 于对 “ 意义” 的七种分类进 行了说 明。对于语义学中意义

第一章从不 同角度介绍 了语 言的基本知识 ,如 “ 什么是语 分类标 准 、 语义成分分析 以ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้ 蕴涵 、 预设 、 命题等重要 内容 , 本章

语言学基础知识

语言学基础知识第一章语音学基础知识语音学是语言学中的一个重要分支,涉及了语音的基本概念和规律。

语音学的研究范围是语音的发音、分布、演变和分类等方面。

1. 语音的基本概念语音是语言中的基本音素,可以分为元音和辅音两类。

元音是由声门开放时,气流自由通过口腔腔面形成的音,例如/a/、/e/、/i/等。

辅音是由声音中气流在口腔腔面受阻而形成的音,例如/p/、/t/、/k/等。

2. 语音的分类语音的分类可以根据发音的方式、发音的部位和声音的调高低三个方面。

根据发音的方式,可以分为清音、浊音、摩擦音、塞音等四种。

根据发音的部位,可以分为唇音、齿音、舌音、软腭音、硬腭音、喉音等六种。

根据声音的调高低,可以分为高、低、中、升调和降调等五种。

3. 语音的演变语音的演变是指人类历史上语音系统的变化。

语音的演变可以分为语言演变和语音演变两种。

语言演变是指一个语言从古老的阶段到现代的阶段的演变。

语音演变是指一个语言在发音上的变化。

第二章词汇学基础知识词汇是一种语言的基本元素,是用来表达思想和意义的词语。

词汇有很多种类,包括独立词、依存词、派生词、合成词等。

1. 词汇的分类词汇可以按照词义、构词方式和语法功能进行分类。

按照词义,可以分为实义词和虚词两种。

实义词是有具体含义的单词,例如“桌子”、“衣服”等。

虚词则是语言中一些无实际含义,起到构词、语法等方面作用的词语,例如“的”、“是”等。

根据构词方式,可以分为派生词、合成词和构词词等。

根据语法功能,可以分为名词、动词、形容词、副词、代词、连词、介词等。

2. 词汇的记忆和运用词汇的记忆和运用是外语学习中的一大难点。

记忆词汇要注意搭配和应用场合,多做词汇扩展练习并巩固记忆。

在实际应用中,需要根据语境和情境进行运用。

第三章语法学基础知识语法学是语言学中的重要分支,主要研究语言的形式结构和规则。

语法学的研究内容包括词汇和句子两个层面。

1. 词类和语法关系词类是指单词属于哪一种语法类别,包括名词、动词、形容词等。

语言学基础教程知识点总结

语言学基础教程知识点总结语言学是研究语言的学科,它涉及语音、语法、语义、语用、语言变迁等多个方面。

在本文中,我们将对语言学的基础知识点进行总结,主要包括语音学、语法学、语义学和语用学四个方面。

希望通过本文的总结,读者能够对语言学有一个基本的了解,并能够在相关领域进行更深入的学习和研究。

一、语音学1. 语音学概述语音学是研究语音的学科,它主要涉及语音的产生、传播和接收等方面。

语音学包括音韵学和声学两个方面,音韵学主要研究语音的基本单位音素,声学则研究语音的物理和声学特性。

2. 语音的分类语音可以根据发音部位和发音方式进行分类。

根据发音部位可以分为唇音、齿音、舌音、软腭音和喉音等;根据发音方式可以分为清音、浊音、塞音、擦音、鼻音、侧音等。

3. 语音的产生机制语音的产生主要通过呼吸、发音器官和声带的协调完成。

呼吸提供气流,发音器官包括喉、嘴和鼻腔等,声带则通过震动产生声音。

4. 语音的变化规律语音的变化规律主要包括语音变调、重音位置和音位变异等方面。

语音的变化规律是语音学研究的一个重要内容,也是语言变迁的基础。

二、语法学1. 语法学概述语法学是研究语言结构和句子构成规律的学科,它包括句法学、词法学和形态学等内容。

语法学主要研究句子构成规律、词类和句法成分等方面。

2. 句子成分句子成分包括主语、谓语、宾语、定语、状语和补语等。

不同语言的句子成分可能存在差异,但大致都包括这几个方面。

3. 句子结构句子结构主要包括主谓结构、主谓宾结构、主系宾结构等。

句子结构是句法学的重要内容,也是句子的基本构成规律。

4. 语法规则语法规则是语言中的基本规律,它包括词汇、句法和语用等方面。

语法规则是语法学研究的核心内容,也是语言学习的重要内容。

三、语义学1. 语义学概述语义学是研究语言意义的学科,它主要包括词义学、句义学和话语义学等方面。

语义学主要研究词义、句义和话语意义的内在规律。

2. 词义及词义辨析词义是词语的意义,它包括词语的词义、义项和词义辨析等方面。

普通语言学教程知识点总结

普通语言学教程知识点总结第一部分:语言学概论1. 语言的定义语言是一种符号系统,通过语音或文字来传递意义,是人类思维和交流的重要工具。

2. 语言学的研究对象语言学研究语言的结构、形式、功能、发展以及语言在社会和文化中的作用。

3. 语言的基本特征语言的基本特征包括:任意性、符号性、交际性、复杂性、可变性、文化载体等。

4. 语言的层次结构语言的层次结构包括语音层、词汇层、词组层、句子层和语篇层。

第二部分:语言习得1. 语言的习得过程语言习得是指个体在学习自己的母语时所经历的过程,包括语音、词汇、语法和语用等方面的发展。

2. 语言习得的阶段语言习得包括婴儿期、幼儿期、儿童期、青少年期和成人期等不同阶段,每个阶段都有其特定的语言发展特点。

3. 习得语言与学习语言的区别习得语言是指自然而然地掌握母语的过程,而学习语言则是指通过学习来掌握一门语言。

第三部分:语音学1. 语音学的对象和内容语音学研究语音的发音、形成规律和分类,以及语音在语言中的功能。

2. 语音的分类语音可以分为辅音和元音,辅音可以再分为浊音和清音,元音可以分为前元音、中元音和后元音。

3. 语音的发音器官人类语音的发音器官包括声门、喉头、口腔、舌头、鼻腔等部位。

4. 语音的基本特征语音的基本特征包括调音的高低、音量的大小、音调的升降和语调的变化等。

第四部分:语音学1. 语法学的研究对象和内容语法学研究语言的结构和形式,包括词类、句子成分、句法关系等内容。

2. 词法和句法词法研究词汇的组成和形态变化规律,句法研究句子的结构和成分之间的关系。

3. 语法现象的分类语法现象可以分为形态学现象、句法现象和语义现象等。

4. 语法规则和规则性语法规则是语言使用中的规范,语法规则性是指语法现象的稳定性和规律性。

第五部分:语义学1. 语义学的研究对象和内容语义学研究语言中的词汇和句子的意义和语用规则。

2. 语义的分类语义可以分为词义和句义两个方面,词义是指词汇的意义,句义是指句子的意义。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Chapter 8 Historical Linguistics: Language Through Time8.1 What is historical linguistics?It is an indisputable fact that all languages have been constantly changing through time. Essentially, modern linguistics has centered around two dimensions to deal with language change: the synchronic dimension and the diachronic dimension. The synchronic dimension has dominantly been applied to describe and explain differences or variations within one language in different places and among different groups at the same time. The synchronic dimension is usually the topic of sociolinguistics, which will be discussed in Chapter 10. This chapter will focus on the diachronic dimension of language change. Those who study language from this latter point of view are working in the field of historical linguistics(Poole, 2000: 123). To put it more specifically, historical linguistics is the study of the developments in languages in the course of time, of the ways in which languages change from period to period, and of the causes and results of such changes, both outside the languages and within them (Robins, 2000: 5).8.2 When language changesAlthough language change does not take place overnight, certain changes are noticeable because they usually conflate with a certain historical period or major social changes caused by wars, invasions and other upheavals. The development of the English language is a case in point. Generally speaking, the historical development of English is divided into three major periods: Old English (OE), Middle English (ME), and Modern English (ModE).500 (the time when Germanic tribes invaded Britain)Old English1100 (the time after the Norman Conquest in 1066)Middle English1500 (the beginning of Renaissance and the first printingpress set up in 1476 in England)Modern Englishthe presentIn about the year 449 AD, the Germanic tribes of Angles, Saxons and Jutes from northern Europe invaded Britain and became the founders of the English nation. Their language, with the Germanic language as the source, is called, the name derived from the first tribe, the Angles. Ithad a vocabulary inherited almost entirely from Germanic or formed by compounding or derivation from Germanic elements (Dension, 1993: 9). From this early variety of Englisc,many of the most basic terms in the English language came into being: mann (“man”), cild (“child”), mete (“food”), etan (“eat”), drincan (“drink”) and feohtan (“fight”). From the sixth to the eighth centuries AD, the Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity, and a number of terms, mainly to do with religion, philosophy and medicine, were borrowed into English from Latin,the language of religion. The origins of the modern words angel,bishop,candle,church,martyr,priest and school all date from that period. From the eighth century to the tenth century, the Vikings from northern Europe invaded England and brought words such as give, law, leg, skin, sky, take and they from their language, Old Norse (Yule, 2000: 218).In the year of 1066 AD, the Norman French conquered the whole of England, bringing French speakers into the ruling class and then pushing French to the position as the “prestige language” for the next two hundred years. This language was used by the nobility, the government, the law and civilized behavior, providing the source of such modern terms as army, court, defense, prison and tax (Yule, 2000: 219). Yet the language of the peasants remained English.By the end of the ME period, when English had once again become the first language of all classes, the bulk of OE lexis had become obsolete, and some ten thousand French words had been incorporated into English, maybe 75% surviving into ModE (Baugh & Cable, 2001:174).During the early ModE period, which coincided with the Renaissance period, English borrowed enormous lexical resources from the classical languages of Latin and Greek. And, later on as the British Empire expanded, the range of lexical influence widened to ever more exotic source languages (Dension, 1993: 13).The types of borrowed words noted above are examples of external changes in English, and the internal changes overlap with the historical periods described above. According to Fennell (2005: 2), the year 500 AD marks the branching off of English from other Germanic dialects; the year 1100 AD marks the period in which English lost the vast majority of its inflections, signaling the change from a language that relied upon morphological marking of grammatical roles to one that relied on word order to maintain basic grammatical relations; and the year 1500 AD marks the end of major French influence on the language and the time when the use of English was established in all communicative contexts. Thus, those internal changes will be elaborated belowat the phonological, lexical, semantic and grammatical levels.8.3 How language changesThe change of the English language with the passage of time is so dramatic that today people hardly read OE or ME without special study. In general, the differences among OE, ME and ModE involve sound, lexicon and grammar, as discussed below.8.3.1 Phonological changeThe principle that sound change is normally regular is a very fruitful basis for examining the phonological history of a language. The majority of sound changes can be understood in terms of the movements of the vocal organs during speech, and sometimes more particularly in terms of a tendency to reduce articulatory effort (Trask, 2000: 70, 96).8.3.1.1 Phonemic change8.3.1.1.1 Vowel changeOne of the most obvious differences between ModE and the English spoken in earlier periods is in the quality of the vowel sounds (Yule, 2000: 219). Sometimes a language experiences a wholesale shift in a large part of its phonological system. This happened to the long vowels of English in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries AD, each vowel becoming closer, the highest becoming diphthongs as in the words wife and house (respectively changed from wayf /wi:f/ and haws /hu:s/ in OE). We call this shift the Great Vowel Shift (Poole, 2000: 127), and the specific changes may be diagrammed as follows (Robins, 2000: 342).In ME, the vowels in nearly all unstressed syllabic inflections were reduced to [ә], spelled <e> (Dension, 1993: 12). The general obscuring of unstressed syllables is a most significant sound change (to be elaborated further in 8.3.3 and 8.3.4), since it is one of the fundamental causes of the loss of inflections (Fennell, 2005: 99).8.3.1.1.2 Consonant changeConsonants are produced with an obstruction of the air-stream, and tend to be less stable over time than vowels in most languages. Two fairly common processes are assimilation and lenition.Assimilation is the process by which two sounds that occur close together in speech become more alike. This sort of change is easy to understand: moving the speech organs all over the place requires an effort, and making nearby sounds more similar reduces the amount of movement required, and hence the amount of effort (Trask, 2000: 53). Instances can be found in words such as irregular,impossible and illegal, in which the negative prefixes im-and il-should be “in-based” in accordance with etymology.Under the influence of neighboring vowels, consonants may also be weakened. This weakening or lenition, can change a voiceless consonant into a voiced one and a plosive into a fricative (Poole, 2000: 126). Instances of [h] in native English words generally derive from the lenition of an earlier *[k]: such words as head,heart,help,hill and he all began with [k] in a remote ancestral form of English, but this [k] was lenited first to [x] and then to [h], and the modern lenition of [h] to zero merely completes a process of lenition stretching over several thousand years (Trask, 2000: 59).8.3.1.2 Whole-segment changeCertain phonological changes are somewhat unusual in that they involve, not just changes in the nature of segments, but a change in the number or ordering of segments, and these are referred to as whole-segment processes (Trask, 2000: 66). The change known as metathesis involves a reversal in position of two adjoining sounds. The following are examples from the OE period: acsian → ask bridd → bird brinnan → beornan (burn)frist → first hros → horse waeps → wasp(Yule, 2000: 220).8.3.2 Lexical changeAs defined by Freeborn (2000: 23), lexical change refers to new words being needed in the vocabulary to refer to new things or concepts, with other words dropping out when they no longerhave any use in society. Lexical change may also involve semantic change, that is, change in the meaning of words. Thus, lexical change mainly consists of addition of new words, loss of words and change in the meaning of words.8.3.2.1 Addition of new wordsThe conditions of life for individuals in society, their artifacts, customs, and forms of organization are constantly changing. Accordingly, many words in languages and the situations in which they are employed are equally liable to change in the course of time (Robins, 2000: 343). Floods of new words constantly need to be added to the word-stock to reflect these developments.E tymology, which is the study of the history of individual words, shows that while the majority of words in a language are native words, there may also be loan words or borrowed words from another language. Native words are those that can be traced back to the earliest form of the language in question. In English, native words are words of Anglo-Saxon origin, such as full, hand, wind, red. Loan words are those that are borrowed or imported from another language, such as myth, career, formula, genius. Apart from borrowing, many new words are added to a language through word-formation. The following processes are quite pervasive in the addition of new words in the evolution of English.8.3.2.1.1 Compounding and affixingAccording to Fennell (2005: 77-8), new words in OE were mainly formed on the basis of compounding and affixing. Many words were formed through compounding, e.g. blod + read (“blood-red”); Engla (“Angles”) + land = England. Affixing covers suffixing and prefixing in OE, the former usually used to transform parts of speech while the latter generally used to change the semantic force. A suffix like -dom could create an abstract noun from another noun or adjective: wis + dom (“wisdom”). The perfective prefix ge- was most often used to form past participles: ceosan (“to choose), gecoren (“chosen”); findan (“to find”), gefunden (“found”). It could also be used to change the meaning of a word: hatan (“to call”), gehatan (“to promise”).In modern English, new words are added not only through compounding and affixing, but also by means of coinage, conversion, blending, backformation and abbreviation. All these word-formation processes are discussed in Chapter 3.8.3.2.1.2 Reanalysis and metanalysisReanalysis means that a word which historically has one particular morphological structure, is perceived by speakers as having a second, quite different structure. The Latin word minimum consisted in Latin of the morphemes min-(“little”, also found in minor and minus) and-im-(“most”), plus an inflectional ending; however, thanks to the influence of the unrelated miniature, English speakers have apparently reanalyzed both words as consisting of a prefix mini-(“very small”) plus something incomprehensible, leading to the creation of miniskirt and all the newer words which have followed it (Trask, 2000: 102).The history of English provides some nice examples of reanalysis involving nothing more than the movement of a morpheme boundary, a type of change impressively called metanalysis. Forms like a napron and an ewt were apparently misheard as an apron and a newt, producing the modern forms. Other similar instances are adder(the English former word: naddre), umpire (noumpere) and nickname (ekename) (Trask, 2000: 103).8.3.2.1.3 Analogical creationAnalogical creation is the replacement of an irregular or suppletive form within a grammatical paradigm by a new form modeled on the forms of the majority of members of the class to which the word in question belongs. The virtual replacement of kine by cows as the plural of cow is an example of analogical creation, and so are the more modern regular past tense forms helped, climbed, and snowed, for the earlier holp, clomb, and snew (Robins, 2000: 359). Analogical creation is quite persuasive in accounting for the process of cultural transmission to be discussed in 8.4.2.8.3.2.2 Loss of wordsIn the course of time, some words pass out of current vocabulary as the particular sorts of objects or ways of behaving to which they refer become obsolete. One need only think in English of the former specialized vocabulary, now largely vanished, which relates to obsolete sports such as falconry (Robins, 2000: 343). Such examples abound in almost every language.8.3.2.3 Semantic changeSemantic change refers to changes in the meanings of words. There are mainly three processes of semantic change: broadening, narrowing and meaning shifts (Fromkin & Rodman 1983: 297).Broadening and narrowing are changes in the scope of word meaning. That is, some words widen the range of their application or meaning, while other words have their contextual application reduced in scope. Broadening is a process by which a word with a specialized meaning is generalized to cover a broader or less definite concept or meaning. For example, the original meaning of carry is “transport by cart”, but now it means “transport by any means”. Narrowing is the opposite of broadening, a process by which words with a general meaning become restricted in use and express a narrow or specialized meaning. For example, the word girl used to mean “a young person”, but in modern English it refers to a young female person. More examples of broadening and narrowing are provided below:Broadening:dog (docga OE) one particular breed of dog →all breeds of dogsbird (brid ME) young bird →all birds irrespective of ageholiday (holy day) a religious feast →the very general break from workNarrowing:hound (hund OE) any kind of dog → a specific breed of dogmeat (mete OE) any kind of food →edible food from animalsdeer (dēor ME) any beast, animal →one species of animalMeaning shift is a process by which a word that used to denote one thing is used to mean something else. For example, the word coach, originally denoting a horse-drawn vehicle, now denotes a long-distance bus or a railway vehicle. Meaning shifts also include transference of meaning, that is, change from the literal meaning to the figurative meaning of words. For example, in expressions like the foot of a mountain, the bed of a river and the eye of a needle, we use foot, bed and eye in a metaphorical way. Other types of meaning shifts include elevation and degradation. Elevation of meaning is a process by which a word changes from a derogatory sense to an appreciative sense. For example, the word nice originally meant “ignorant” and fond simply meant “foolish”. Degradation of meaning is a process by which a word of appreciative meaning falls into pejorative use. For example, the word silly used to mean “happy” and cunning originally meant “skillful”.8.3.3 Grammatical changeThe most fundamental feature that distinguishes Old English from the language of today is its grammar (Baugh & Cable, 2001: 54). Modern English is an analytic language while Old English is a synthetic language. The major difference is that a synthetic language is one that indicates the relation of words in a sentence largely by means of inflections, but an analytic language makes extensive use of prepositions, auxiliary verbs, and depends on word order to show other relationships. In OE, the order of words in a clause was more variable than that of ModE, and there were many more inflections on nouns, adjectives and verbs (Freeborn, 2000: 66). The grammatical changes of English such as those in number, gender, case and tense mainly took place on its morphological level, while syntactic changes such as those in word order are the consequence of the loss of rich inflections in English. The most sweeping morphological change during the evolution of English is the progressive decay of inflections. OE, ME and ModE can be called the periods of full, reduced and zero inflections, respectively because, during most of the OE period the endings of the noun, the adjective, and the verb are preserved more or less unimpaired, while during the ME period the inflections become greatly reduced, and finally by the ModE period, a large part of the original inflectional system had disappeared entirely (Dension, 1993: 12; Baugh & Cable, 2001: 50).The loss of inflections in the case system of Old English is a good example of grammatical change. Case is the grammatical feature that marks functions of the subject, object, or possession in a clause. In OE, nouns showed a four-term case contrast, for which the Latinate terms nominative (subject), accusative (direct object), genitive (possessive) and dative (indirect object) are conventionally used, and the case-ending system can be illustrated by the following:CASE nominative genitive dative accusative MODERNENGLISHstone/stonesstone’s/stones’stone/stonesstone/stonesOESINGULARstānstānesstānestānOEPLURALstānasstānastānumstānas(Fromkin & Rodman, 1983: 290)The ME period is the beginning of the loss of most of the inflections of OE, mainly through the weakening and dropping of the final unstressed vowels. For example, when the vowel wasdropped in the plural form of stones[st :n☯s], it became [st wnz], and when the “weak”syllables representing case endings in the forms of the singular, genitive plural, and dative plural were dropped, English lost much of its case system (ibid).The loss of inflections marks a transition of English from a synthetic to an analytic language, and thus led to a greater reliance on word order. Word order in OE was more variable than that of ModE: word order was not as fixed or rigid in OE as it is in ModE (Fennell, 2005: 59). Both the orders subject-object-verb (“hē hine geseah”: “he saw him”) and object-subject-verb (“him man ne sealde”: “no man gave [any] to him”) are possible (Yule, 2000: 221). Word order in an OE sentence was not so crucial because OE is so highly inflected. The doer of the action and the object of the action were revealed unambiguously by various case endings, which makes the sentence meaning perfectly clear.It can be said that changes in sound, lexicon and grammar do not operate separately or independently of each other, but they are interacting and interdependent. One change is often integrated or incorporated into the other changes. And, it is the complex interrelationships among them that have shaped the whole process of the language change. As is shown above, the dropping of the final unstressed vowels led to the loss of inflections of OE, and this in turn led to a greater reliance on word order.8.4 Why language changesNo change described above has happened overnight, but has constantly and gradually taken place. Many changes are difficult to discern while they are in progress. The causes of language change are many and various, and only some of them are reasonably well understood at present (Trask, 2000: 12). Two broad categories of factors contribute to language change: external and internal factors.8.4.1 External causesExternal causes of linguistic changes are the contacts between the speakers of different languages: the sort that occurs when a language is imposed on a people by conquest or political or cultural domination, or when cultural and other factors produce a high degree of bilingualism between adjacent speech areas (Robins, 2000: 340). The significant influence of Norman French on the English language from the eleventh century AD supports this proposition. It can be said thatany dramatic social change caused by wars, invasions and other upheavals can possibly bring about correspondent changes in language.8.4.2 Internal causesAccording to Yule (2000: 222), the most pervasive source of change seems to be in the continual process of cultural transmission (in particular, the transmission of speech habits from one generation to another). Each new generation has to find a way of using the language of the previous generation. In this unending process whereby each new language-user has to “recreate”for him-or herself the language of the community, there is an unavoidable propensity to pick up some elements exactly and others only approximately. There is also the occasional desire to be different.In the process of cultural transmission, some underlying physiological factors can also play a vital role, mainly marked by least effort. For sound change, one key motivator is ease of articulation. There is a tendency for intervocalic voiceless plosives to be subjected to lenition because producing a voiced fricative between vowels requires less physiological change than does the production of a voiceless plosive (Poole, 2000: 130). For grammatical change, it is not difficult to see that the principle of least effort works for widespread simplification of the grammatical categories in the English language, exemplified by substantial losses of gender, case and tense distinctions.8.5 SummaryIn this chapter we have focused on language change in the diachronic dimension, namely from the historical perspective of change. We draw the conclusion that English has gradually and continuously shifted from a synthetic language to an analytic language in the course of time, marked by interrelated and interdependent changes at all levels, including the general obscuring of unstressed syllables, the progressive decay of inflections and the rigidity of word order. And, this shift may be mainly caused by major social changes and contacts, and by cultural transmission and least effort.Questions and Exercises1. Define the following terms.historical linguistics Great V owel Shift lenitionmetathesis analogical creation etymologysynthetic languagereanalysisanalytic language2. How are the historical developments of the English language generally divided? What are the main features that characterize each period?3. Can you apply the theory of reanalysis to explain how cheeseburger, chickenburger andvegeburger are derived from the word hamburger? Can you find more examples of reanalysis in English?4. Use one or two examples to show how the grammatical case is changed in the course of the historical evolution of English.5. Use one or two examples to illustrate how changes in sound, lexicon and grammar areintegrated or interrelated.6. What are the semantic processes in the changes of word meanings?7. Among the phonological, lexical and grammatical levels of language change, which level do you believe undergoes the fastest change and which level the slowest change? Can you account for these changes?8. In the English language, some names of animals are generally known by the Germanic terms and the resultant meats by the French terms. Which of the following words are derived from OE and which from Norman French? Can you trace the reason for this differentiated origin?calf, pork, mutton, ox, veal, swine, beef, sheep9. Give examples to account for the causes for language change.请浏览后下载,资料供参考,期待您的好评与关注!。