Hepatitis B Virus Infection — Natural History

丙酚替诺福韦用于范科尼综合征恩替卡韦治疗失败的慢性乙型肝炎患者挽救治疗个案报道并文献复习

【摘要】 慢性乙型肝炎治疗的关键是抗病毒治疗。

临床上长期使用阿德福韦酯或富马酸替诺福韦二吡呋酯抗病毒治疗的慢性乙型肝炎患者可发生范科尼综合征等罕见不良反应,临床上多采用恩替卡韦作为挽救治疗方案。

但对于恩替卡韦治疗失败的范科尼综合征患者,后续抗病毒治疗的证据尚不多见。

现报道1例恩替卡韦治疗失败的范科尼综合征患者,采用丙酚替诺福韦治疗有效,并对相关文献进行复习,为此类患者的治疗提供依据。

【关键词】 慢性乙型肝炎;丙酚替诺福韦;恩替卡韦;范科尼综合征;病毒学突破Tenofovir alafenamide as the rescue therapy for chronic hepatitis B patient with Fanconi syndrome and entecavir treatment failure: a case report and literature reviewWang Qian 1, Chang Chunyan 2, Yang Song 2 (1. Department of Pharmacy, the 960th Hospital of PLA Joint Service Support Force, Jinan 250031, China; 2. Center of Hepatology, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100015, China) Correspondingauthor:YangSong,E-mail:*******************【Abstract 】 Antiviral therapy is the key for management of chronic hepatitis B. Fanconi syndrome is a rare side effect in chronic hepatitis B patients who take long-term therapy of adefovir dipivoxil or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Usually entecavir is chosen as rescue therapy for these patients. There is little evidence for rescue therapy for chronic hepatitis B patients who comorbid with Fanconi syndrome and experienced entecavir treatment failure. We reported a case of Fanconi syndrome patient who underwent entecavir treatment failure and was rescued successfully with tenofovir alafenamide. Also, we reviewed related literatures. Our case might provide evidence for management of chronic hepatitis B patients who experienced entecavir treatment failure and comorbid with Fanconi syndrome.【Key words 】 Chronic hepatitis B; Tenofovir alafenamide; Entecavir; Fanconi syndrome; Virologic breakthrough丙酚替诺福韦用于范科尼综合征恩替卡韦治疗失败的慢性乙型肝炎患者挽救治疗:个案报道并文献复习王倩1,常春艳2,杨松2(1.中国人民解放军联勤保障部队第960医院 药学部,济南 250031;2.首都医科大学附属北京地坛医院 肝病中心,北京 100015)基金项目:传染病防治国家科技重大专项(2017ZX10202202;2018ZX10715-005);吴阶平医学基金会临床科研专项(No.LDWJPMF-105-201701)通信作者:杨松 E-mail :*******************慢性乙型肝炎(chronic hepatitis B ,CHB )治疗的关键是抗病毒治疗。

医院感染的常见病原体及其特点

医院感染的常见病原体及其特点医院感染(Hospital-acquired infection,HAI),也称为医疗保健相关感染(Healthcare-associated infection,HAI),是指在接受医疗保健服务期间感染的疾病,出现在住院期间或者出院后的一定时间内。

医院感染是全球范围内的公共卫生问题,给患者和医疗机构带来了巨大的负担。

本文将介绍医院感染的常见病原体及其特点。

一、细菌类病原体1. 铜绿假单胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa)铜绿假单胞菌是一种来源广泛、耐药性强的病原细菌,常引起尿路感染、呼吸道感染、创伤感染等。

它能够产生多种外毒素和酶,使得感染持续性强,且对多种抗生素表现出耐药性,给治疗带来一定困难。

2. 肺炎克雷伯菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae)肺炎克雷伯菌是一种常见的致病菌,尤其在医院环境中容易传播。

它的一大特点是产生广谱β-内酰胺酶,使其对多种常用抗生素表现出耐药性。

肺炎克雷伯菌常引发呼吸道感染、尿路感染等,严重时还可能导致败血症。

3. 金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus)金黄色葡萄球菌是一种常见的致病菌,分为甲型和非甲型两种。

其中,甲型金黄色葡萄球菌常常携带耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌(MRSA),对多种抗生素表现出耐药性。

该菌可引起皮肤软组织感染、呼吸道感染等,且在医院内广泛传播。

二、真菌类病原体1. 白色假丝酵母菌(Candida albicans)白色假丝酵母菌是一种最常见的致病真菌之一,在医院环境中容易生长繁殖。

它常引起口腔黏膜感染、阴道感染等,且还可能侵袭血液系统,造成严重的血液感染。

2. 隐球菌属(Cryptococcus)隐球菌属包括尖端隐球菌和广泛性隐球菌等多种类型。

这些真菌通常通过空气传播,而医院设施也是它们滋生的理想环境。

隐球菌感染一般发生在免疫系统受损的患者身上,尤其是艾滋病人。

该菌可引起肺部感染、脑膜炎等。

慢性乙型肝炎病毒感染的自然史

慢性乙型肝炎病毒感染的自然史首都医科大学附属北京友谊医院肝病中心吴鹏尤红编译自Brian J. McMahon, The Natural History of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection, HEPATOLOGY, S45-S55. Vol. 49, No. 5, Suppl., 2009摘要:慢性乙型肝炎病毒感染是个复杂的过程。

它包括三个阶段:(1)免疫耐受期,这一期HBV DNA高表达,谷丙转氨酶(ALT)水平正常,肝脏损伤程度最小;(2)免疫活动期,HBV DNA高表达,ALT水平升高,肝脏炎症活跃;(3)非活动期,HBV DNA<2000IU/ml,ALT水平正常,肝组织活检炎症和纤维化轻微。

感染者可以很快从一个阶段进展到另一个阶段但也可逆转。

HBV感染最主要的不良后果是肝细胞癌(HCC)和肝纤维化。

本文根据相关试验的证据强度对已发表的自然史研究进行评价和分级,通过最高证据等级的以人群为基础的前瞻性队列研究得出的HCC和肝硬化的危险因素包括男性、HCC的家族史、HBV DNA水平超过2000IU/ml、年龄大于40岁、HBV基因型为C型和F型,以及核心区启动子变异。

次最高证据等级的研究提示危险因素还包括暴露于黄曲霉素、大量饮酒和吸烟。

目前还需要改进研究方法以发现向HCC或肝硬化发展的高危病人,并在适当的人群中进行更早期的抗病毒治疗的干预。

未来的研究应包括对已经建立的、以人群为基础的、前瞻性队列研究进行随访,还应包括建立新的队列,即来自多中心而且根据不同HBV基因型/亚型和临床分期分层的队列,以判定HBV各期、HCC及肝硬化的发生率。

同时,在这些队列中应用巢式病例对照研究评价活动期或非活动期、HCC和肝硬化病人中免疫学的和宿主遗传学因素。

引言全世界有3.5至4亿人感染慢性乙肝病毒。

其两个主要不良后果是肝细胞癌(HCC)和肝硬化,均能导致肝病相关性死亡。

乙型肝炎

传播

乙型肝炎主要通过与被感染的人的血和其它体液的接触传染。通过血液、精液和阴道分泌液可以传染乙型肝炎。一般病毒 通过皮肤上的小伤口或者粘膜进入体内。危险因素包括:不安全的性交、静脉注射毒品(与其他人共用针头)、在卫生机 关工作日常接触大量乙型肝炎患者、获得没有检验乙型肝炎病毒的血制品、牙医和其它医学手术、美容手术(刺青、穿 孔)。幼儿可能通过抓挠和咬被感染。日常生活中容易造成伤口的物件比如刮胡刀、指甲刀等等也可能传染乙型肝 炎[16][17],但并非主要的传染途径。携带病毒的母亲在生育时感染给新生儿是最常见的传染途径之一。

流行病学分布

乙型肝炎尤其在东南亚和非洲热带地区流行。通过推进种疫苗的方法在北欧、西欧、美国、加拿大、墨西哥和 南美洲南部乙型肝炎的分布得以下降到所有慢性病毒病的0.1%以下。黄种人看起来比白种人对乙型肝炎病毒更 为易感染。阿拉斯加、加拿大、格陵兰的因纽特人,以及亚马逊丛林中的印第安人都是乙型肝炎显著高发,阿 拉斯加的爱斯基摩人的乙肝表面抗原阳性率为45%。

no data

100-125

<10

125-150

10-20

150-200

20-40

200-250

40-60

250-500

60-80

>500

80-100

病原体

乙型肝炎的病原体是一种属于肝病毒科的有外壳的双链脱氧核糖核酸病毒。它的直径为42纳米。它的脂蛋白外壳上携带乙型肝炎表面抗原HBsAg。近年的研究 证明这种病毒的基因的稳定性比过去想象的要差。现在也已经发现了数种不带乙型肝炎表面抗原的、但是仍然可以致病的病毒。

在大部分发达国家献血后的血液都要检查肝炎病毒,因此在这些地区通过受血感染肝炎的可能性几乎为零。

MyD88抑制乙型肝炎病毒复制依赖活化NF-κB信号通路

万方数据 万方数据 万方数据丝篁塑量壁鎏!Q堕堡i旦箜!鲞箜!塑』坐虫坐垡丛堡!虫望塑i!些!鱼塑:也堡!塑!!y堂!:盟!:;到显著抑制,而共转染RcCMV.1nBa.SR细胞内HBV复制中间体DNA的水平得到上调(图2A),检测细胞上清液中的HBeAg和HBsAg也得到了相同的结果(结果未在本文显示)。

免疫荧光结果也显示,单独表达MyD88可明显抑制HBVcore蛋白的合成;而kBa—SR与MyD88共表达后core蛋白在细胞中的表达量可显著增加(图2B)。

以上结果说明,NF.s:B活化被阻断后MyD88抑制HBV复制的效应也得到抑制,进一步提示MyD88抑制HBV复制中的作用依赖于NF—xB信号通路的活化。

A畿∞£确S《蠢6。

螂㈨j.芒羞4.00E+03£8蚕2.00E+03pemv3J(oatoM归∞(o.4t,O脑轴R蝴髑堆哼w蝌稍《卜D螃E乒毛吐(0.憾lqO+Bo-02图2阻断NF-r。

B信号通路对nyI粥8抑制HBV效应的影响rig2.BlockageofNF-r。

BactivationabolishesMyD68mediatedsuppressionofHBVA:BlockageofNF—KBactivationabolishesMyD88mediatedsuppressionofparticle—associatedHBVreplicativeintermediateDNA.B:BlockageofNF-·cBactivationabolishesMyD88mediatedsuppressionofprotein.3.活化NF.s:B信号通路可抑制HBV的复制和表达为进一步探讨单独活化NF.tcB信号通路对HBV复制的影响,将HBV的复制型质粒pHBV3.8与空载或不同剂量的NF.fcB激活剂pRc—G.actin.3HA.IⅪ血/IK邸共转染Huh7细胞,检测上清液中HBsAg和HBeAg的表达水平以及细胞内HBV复制中问体DNA的水平。

《慢性乙型肝炎防治指南(2022年版》解读

!()-.!DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.07.007《慢性乙型肝炎防治指南(2022年版)》解读谢艳迪,封 波,饶慧瑛北京大学人民医院,北京大学肝病研究所,北京100044通信作者:饶慧瑛,rao.huiying@163.com(ORCID:0000-0003-2431-3872)摘要:《慢性乙型肝炎防治指南(2022年版)》是以国内外慢性HBV感染的研究进展为依据,在既往多版指南基础上进行更新和修订而成。

本文介绍了新版指南在自然史、无创纤维化诊断、治疗等多方面的更新内容。

尤其是进一步扩大了慢性HBV感染者的治疗适应证,对干扰素的优势人群选择限定更清晰,对口服核苷(酸)类似物标准进行了更严格限制,对低病毒血症患者的处理更加积极,对免疫耐受期儿童的治疗也更积极。

新版指南将为我国扩大筛查HBV感染者、提高诊断率、优化治疗方案、规范临床管理提供重要依据。

关键词:乙型肝炎,慢性;乙型肝炎病毒;诊疗准则InterpretationofguidelinesforthepreventionandtreatmentofchronichepatitisB(2022edition)XIEYandi,FENGBo,RAOHuiying.(PekingUniversityPeople’sHospital,PekingUniversityHepatologyInstitute,Beijing100044,China)Correspondingauthor:RAOHuiying,rao.huiying@163.com(ORCID:0000-0003-2431-3872)Abstract:GuidelinesforthepreventionandtreatmentofchronichepatitisB(2022edition)areupdatedandrevisedbasedontheresearchadvancesinchronichepatitisBvirusinfectioninChinaandgloballyandthepreviouseditionsoftheguidelines.Thisarticleintroducestheupdatesinnaturalhistoryandthenoninvasivediagnosisandtreatmentoffibrosis.Inparticular,theguidelinesfurtherexpandtheindicationsforpatientswithchronichepatitisBvirusinfection,clearlydefinestheselectionofthepopulationbenefitingfrominterferontherapy,andstrictlylimitsthestandardoforalnucleos(t)ideanalogues.Meanwhile,theguidelinesalsorecommendmoreactivetreatmentofpatientswithlow-levelviremiaandchildrenintheimmune-tolerantphase.TheneweditionoftheguidelineswillprovideanimportantbasisforexpandingthescreeningforhepatitisBvirusinfec tion,improvingdiagnosticrate,optimizingtreatmentregimens,andstandardizingclinicalmanagementinChina.Keywords:HepatitisB,Chronic;HepatitisBvirus;PracticeGuidelines 自2005年起,至今历时18年,中华医学会感染病学分会和肝病学分会发布并更新《慢性乙型肝炎防治指南》(下称《指南》)共5版,在最新版的2022年《指南》[1]中,再次强调世界卫生组织提出的“2030年消除病毒性肝炎作为公共卫生危害”的目标,相较于2015年,2030年慢性乙型肝炎(CHB)新发感染率要减少90%,死亡率减少65%,诊断率达到90%和治疗率达到80%[2]。

中国知网为什么查不到近几年《国际医药卫生导报》发表的文章

国际医药卫生导报 2020年 第26卷 第12期 IMHGN,June 2020,Vol. 26 No. 123 讨论 慢性乙型肝炎是世界上最常见的传染病之一。

由于其难以治愈和容易传染的特性,目前对于使用单一药物进行抗病毒免疫治疗,无法达到彻底清除HBV的目的。

核苷酸类似物恩替卡韦作为治疗乙肝的指导用药,通过与患者体内HBV多聚酶的相互作用,干扰HBV-DNA的合成,从而达到抗病毒的效果,但在停药之后,易出现耐药性和复发的可能[5-6]。

长效干扰素派罗欣是一种多效性细胞因子,具有较强的抗病毒和免疫调节性能[7]。

派罗欣在临床上通过与细胞表面的特异性受体结合产生抗病毒蛋白抑制HBV复制,同时提高巨噬细胞、NK细胞和T细胞活力,增强患者的体内免疫调节功能。

二者临床效果明显,因为两种药物的作用机理有所区别,所以有研究提出联合用药可增强药物的协同效应,降低HBV耐药性,提高疗效[8]。

本研究结果表明,恩替卡韦与派罗欣联合用药在治疗的3、6、12个月后,随着疗程的增加,疗效显著。

联合用药后,患者ALT复常率得到明显提高。

观察组HBV-DNA复制水平下降,并显著低于对照组,证明联合用药对HBV的抑制具有增强的作用。

同时,HBV-DNA转阴率、HBe Ag转换率观察组明显高于对照组,说明联合用药明显提高了患者体内的免疫学应答,细胞免疫活性增强,抗病毒能力提高。

同时治疗过程中,观察组和对照组的不良反应发生率无明显差异,说明联合用药安全性较好,临床效果显著。

综上所述,核苷酸类似物联合派罗欣治疗慢性乙型肝炎在临床上疗效确切,安全性较好,值得推广。

利益冲突:作者已申明文章无相关利益冲突。

参考文献[1] Alonso S, Guerra AR, Carreira L, et al. Upcoming pharmacologicaldevelopments in chronic hepatitis B: can we glimpse a cure on the horizon [J].BMC Gastroenterol, 2017, 17(1): 168. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-017-0726-2.[2] Busch K, Thimme R. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virusinfection [J]. Med Microbiol Immunol, 2015, 204(1): 5-10. DOI: 10.1002/ hep.22898.[3] Su TH, Kao JH. Improving clinical outcomes of chronic hepatitis B virusinfection [J]. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015, 9(2): 141-154. DOI:10.1586/17474124.2015.960398.[4] 中华医学会肝病学分会, 中华医学会感染病学分会.慢性乙型肝炎防治指南(2015年更新版)[J].临床肝胆病杂志, 2015, 31(12): 1941-1960.DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2015.12.002.[5] Collo A, Belci P, Fagoonee S, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-termentecavir therapy in a European population [J]. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol, 2018, 64(3): 201-207. DOI: 10.23736/S1121-421X.18.02470-4. [6] 孟忠吉, 李新宇, 张永红, 等.核苷(酸)类药物治疗过程中发生病毒学突破的慢性乙型肝炎患者152例耐药分析[J].中华临床感染病杂志, 2013, 6(4): 234-236. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2013.04.011. [7] Swiecki M, Colonna M. Type I interferons: diversity of sources, productionpathways and effects on immune responses [J]. Curr Opin Virol, 2011, 1(6): 463-475. DOI: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.026.[8] Wang CT, Zhang YF, Sun BH, et al. Models for predicting hepatitis B eantigen seroconversion in response to interferon-alpha in chronic hepatitisB patients [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21(18): 5668-5676. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5668.(收稿日期:2019-12-17)(责任校对:成观星)·读者·作者·编者·中国知网为什么查不到近几年《国际医药卫生导报》发表的文章 有作者和读者询问:中国知网为什么查不到近几年《国际医药卫生导报》发表的文章? 原因是:中华医学会与北京万方数据股份有限公司,于2008年签署了“中华医学会系列杂志数据库”独家合作协议,《国际医药卫生导报》同其他中华医学会系列杂志一样,所发表的文章不再为中国知网收录。

隐匿性乙肝的最新研究进展

隐匿性HBV感染与血液安全—OBI与HBV血液

传播

许多实验及临床研究均证实HBsAg阴性、

HBV-DNA 阳性血液的传染性

用HBsAg 阴性HBV-DNA 阳性血清(HBV病毒载 量为3-169拷贝/ml)给猩猩注射, 结果猩猩感染了 HBV; 输HBsAg阴性的血和母亲为HBsAg 阴性结果发 生了输血后肝炎和母婴HBV-DNA的传染 。

HBV感染的转归

中国乙肝流行概况

中国各年龄人口中血清HBsAg阳性率

我国乙肝病毒的基因型分布

隐匿性HBV 感染 (Occult HBV infection)

历史: 1978年,美国学者首次报道了一起HBsAg(‐) /HBcAb(+)的血液导致的受血者HBV感染。 1991年, 法国学者用HBsAg(‐)/DNA(+) 的血浆接种大猩猩,观察到急性乙肝的发生。 1996年后,在全球献血员和各种肝脏疾病患 者中有越来越多的隐匿性HBV感染报道。

隐匿性HBV感染与血液安全—OBI的分类

根据抗-HBV模式,可将OBI分为: 血清阳性的OBI: 即抗-HBc和(或)抗-HBs阳性; 血清阴性的OBI: 即抗-HBc和(或)抗-HBs阴性。

临床类型(ISBT OBI研究国际协作组):

急性感染的“窗口期”; 慢性感染后期; 感染恢复期,体内存在抗-HBs,但病毒仍低水 平复制; 免疫逃逸突变株感染

隐匿性HBV感染的医学意义

公共卫生意义: 1、 输血后乙肝 2、HBV垂直传播 3、疫苗免疫失败的原因之一

隐匿性HBV感染的诊断

尚缺乏统一的、标准化的检测方法

1、核酸检测(NAT)。 是隐匿性HBV感染诊断的金 标准。但由于常规荧光定量PCR检测灵敏度不够高 且受引物或探针区序列变异影响,因此一般需用多 区段套式PCR辅以测序确认。 2、 HBcAb筛查。 HBcAb是HBV感染的间接指标, HBcAb单阳的人群中存在相对较高比例(~5%) 的OBI,部分发达国家用于血液筛查。 3、 新型试剂。 如超敏广谱表面抗原(HBsAgUltra), Dane Ag(联合检测前S1与核心抗原),HBcrAg, HBcAg等。

连花清瘟胶囊的功能主治英文翻译

连花清瘟胶囊的功能主治英文翻译1. 连花清瘟胶囊的介绍连花清瘟胶囊是一种传统中药制剂,由多种中药材精制而成。

它是一种口服胶囊剂,适用于治疗多种病症。

下面将介绍连花清瘟胶囊的主要功能和主治病症的英文翻译。

2. 连花清瘟胶囊的功能与主治病症2.1 功能 (Functions)•清热解毒 (Clearing heat and detoxifying)•解表散寒 (Dispelling exterior syndrome and dispersing cold)•活血化瘀 (Activating blood circulation and resolving stasis)•解毒黄胆 (Detoxifying and relieving jaundice)•解毒止痢 (Detoxifying and stopping diarrhea)2.2 主治病症 (Indications)以下是连花清瘟胶囊的主要主治病症及其英文翻译:•为风热袭表、症属于“感冒”的病症适应症的解表药 (Suitable for treating exterior syndrome caused by pathogenic wind and heat, used as amedicine for releasing exterior)•夏季流行性感冒 (Summer epidemic influenza)•青少年感冒(Teenagers’ cold)•疾病暴发期的感冒、上呼吸道感染 (Cold, upper respiratory tract infection during epidemic outbreak)•风寒袭表 (Exterior syndrome caused by pathogenic wind and cold)•风温袭表 (Exterior syndrome caused by pathogenic wind and warm)•扁桃体炎 (Tonsillitis)•咽炎 (Pharyngitis)•支气管炎 (Bronchitis)•肺炎 (Pneumonia)•溃疡性口腔炎 (Ulcerative stomatitis)•手足口病 (Hand, foot, and mouth disease)•肠道传染病、痢疾 (Acute infectious diarrhea, dysentery)•乙肝病毒感染 (Hepatitis B virus infection)•肝炎 (Hepatitis)2.3 用法用量 (Dosage and Administration)连花清瘟胶囊的用法用量如下:•成人每次2粒,每日3次 (Adult: take 2 capsules per time, 3 times daily)•18岁以下的未成年人按体重适量减量 (For individuals under 18 years old, dosage should be reduced according to body weight)注:请按照医生或药师的指导使用。

常见微生物拉丁学名(2024)

引言概述:微生物是指体积小、仅能在显微镜下观察到的生物体,包括细菌、真菌、病毒等。

拉丁学名(学名)是对生物分类学中各种生物的命名系统,它由拉丁或拉丁化的词汇组成,通过国际生物命名法规定的规则进行命名。

本文将继续介绍常见微生物的拉丁学名,帮助读者更好地了解这些微生物的科学分类。

正文内容:一、病毒类(Viruses)1.官病毒(InfluenzaVirus)学名:Influenzavirus病毒类型:Orthomyxoviridae科2.乙肝病毒(HepatitisBVirus)学名:HepatitisBvirus病毒类型:Hepadnaviridae科3.腺病毒(Adenovirus)学名:Adenovirus病毒类型:Adenoviridae科4.结核分枝杆菌病毒(Mycobacteriophagetuberculosis)学名:Mycobacteriophagetuberculosis病毒类型:Siphoviridae科5.人类免疫缺陷病毒(HumanImmunodeficiencyVirus)学名:HumanImmunodeficiencyVirus病毒类型:Retroviridae科二、细菌类(Bacteria)1.大肠杆菌(Escherichiacoli)学名:Escherichiacoli菌属:Escherichia2.铜绿假单胞菌(Pseudomonasaeruginosa)学名:Pseudomonasaeruginosa菌属:Pseudomonas3.葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus)学名:Staphylococcus菌属:Staphylococcus4.肺炎克雷伯菌(Klebsiellapneumoniae)学名:Klebsiellapneumoniae菌属:Klebsiella5.霍乱弧菌(Vibriocholerae)学名:Vibriocholerae菌属:Vibrio三、真菌类(Fungi)1.白色念珠菌(Candidaalbicans)学名:Candidaalbicans真菌属:Candida2.黄曲霉(Aspergillusflavus)学名:Aspergillusflavus真菌属:Aspergillus3.铜绿假丝酵母(Cryptococcusneoformans)学名:Cryptococcusneoformans真菌属:Cryptococcus4.念珠菌属(Candida)学名:Candida真菌属:Candida5.白色念珠菌属(Candidaalbicans)学名:Candidaalbicans真菌属:Candida四、藻类(Algae)1.石藻(Diatom)学名:Diatom尖角藻类(Bacillariophyta)的一种2.衣藻(Chlorella)学名:Chlorella碧藻门(Chlorophyta)的一种3.螺旋藻(Spirulina)学名:Spirulina蓝藻门(Cyanobacteria)的一种4.毛藻(Volvox)学名:Volvox珊瑚藻门(Chlorophyta)的一种5.日耳曼藻(Gymnodinium)学名:Gymnodinium浮游甲藻纲(Dinophyceae)的一种五、原虫类(Protozoa)1.锥虫(Trypanosome)学名:Trypanosome动结核虫目(Kinetoplastida)的一种2.疟原虫(Plasmodium)学名:Plasmodium引起疟疾的原虫属(Trypanosomatidae)的一种3.草履虫(Amoeba)学名:Amoeba盘古动物门(Amoebozoa)的一种4.草履虫动物门(Amoebozoa)学名:Amoebozoa草履虫纲(Amoebidia)的一种5.肠道滴虫(Giardialamblia)学名:Giardialamblia鞭毛虫门(Metamonada)的一种总结:通过本文详细介绍了常见微生物的拉丁学名及其科学分类。

《2024年世界卫生组织慢性乙型肝炎患者的预防、诊断、关怀和治疗指南》推荐意见要点

《2024年世界卫生组织慢性乙型肝炎患者的预防、诊断、关怀和治疗指南》推荐意见要点艾小委,张梦阳,孙亚朦,尤红首都医科大学附属北京友谊医院肝病中心,北京 100050通信作者:尤红,******************(ORCID:0000-0001-9409-1158)摘要:2024年3月世界卫生组织(WHO)发布了最新版《慢性乙型肝炎患者的预防、诊断、关怀和治疗指南》。

该指南在以下方面进行了更新:扩大并简化慢性乙型肝炎治疗适应证,增加可选的抗病毒治疗方案,扩大抗病毒治疗预防母婴传播的适应证,提高乙型肝炎病毒诊断,增加合并丁型肝炎病毒的检测等。

本文对指南中的推荐意见进行归纳及摘译。

关键词:乙型肝炎,慢性;预防;诊断;治疗学;世界卫生组织;诊疗准则Key recommendations in guidelines for the prevention,diagnosis,care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection released by the World Health Organization in 2024AI Xiaowei, ZHANG Mengyang, SUN Yameng, YOU Hong.(Liver Research Center, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100050, China)Corresponding author: YOU Hong,******************(ORCID: 0000-0001-9409-1158)Abstract:In March 2024, the World Health Organization released the latest version of guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis,care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection. The guidelines were updated in several aspects,including expanding and simplifying the indications for chronic hepatitis B treatment,adding alternative antiviral treatment regimens,broadening the indications for antiviral therapy to prevent mother-to-child transmission,improving the diagnosis of hepatitis B virus,and adding hepatitis D virus (HDV)testing. This article summarizes and gives an excerpt of the recommendations in the guidelines.Key words:Hepatitis B, Chronic; Prevention; Diagnosis; Therapeutics; World Health Organization; Practice Guideline近年来,慢性乙型肝炎(CHB)在预防、诊断、治疗等方面取得重要进展。

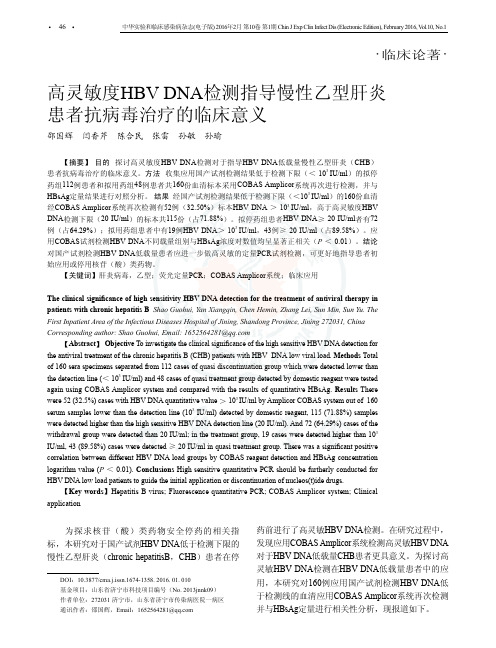

高灵敏乙肝病毒检测的临床意义

·临床论著·高灵敏度HBV DNA 检测指导慢性乙型肝炎患者抗病毒治疗的临床意义邵国辉 闫香芹 陈合民 张雷 孙敏 孙瑜【摘要】 目的 探讨高灵敏度HBV DNA 检测对于指导HBV DNA 低载量慢性乙型肝炎(CHB )患者抗病毒治疗的临床意义。

方法 收集应用国产试剂检测结果低于检测下限(< 103 IU/ml )的拟停药组112例患者和拟用药组48例患者共160份血清标本采用COBAS Amplicor 系统再次进行检测,并与HBsAg 定量结果进行对照分析。

结果 经国产试剂检测结果低于检测下限(<103 IU/ml )的160份血清经COBAS Amplicor 系统再次检测有52例(32.50%)标本HBV DNA > 103 IU/ml ,高于高灵敏度HBV DNA 检测下限(20 IU/ml )的标本共115份(占71.88%)。

拟停药组患者HBV DNA ≥ 20 IU/ml 者有72例(占64.29%);拟用药组患者中有19例HBV DNA > 103 IU/ml ,43例≥ 20 IU/ml (占89.58%)。

应用COBAS 试剂检测HBV DNA 不同载量组别与HBsAg 浓度对数值均呈显著正相关(P < 0.01)。

结论 对国产试剂检测HBV DNA 低载量患者应进一步做高灵敏的定量PCR 试剂检测,可更好地指导患者初始应用或停用核苷(酸)类药物。

【关键词】肝炎病毒,乙型;荧光定量PCR ;COBAS Amplicor 系统;临床应用The clinical significance of high sensitivity HBV DNA detection for the treatment of antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B Shao Guohui, Yan Xiangqin, Chen Hemin, Zhang Lei, Sun Min, Sun Yu. The First Inpatient Area of the Infectious Diseases Hospital of Jining, Shandong Province, Jining 272031, China Corresponding author: Shao Guohui, Email: 1652564281@【Abstract 】 Objective To investigate the clinical significance of the high sensitive HBV DNA detection for the antiviral treatment of the chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients with HBV DNA low viral load. Methods Total of 160 sera specimens separated from 112 cases of quasi discontinuation group which were detected lower than the detection line (< 103 IU/ml) and 48 cases of quasi treatment group detected by domestic reagent were tested again using COBAS Amplicor system and compared with the results of quantitative HBsAg. Results There were 52 (32.5%) cases with HBV DNA quantitative value > 103 IU/ml by Amplicor COBAS system out of 160 serum samples lower than the detection line (103 IU/ml) detected by domestic reagent, 115 (71.88%) samples were detected higher than the high sensitive HBV DNA detection line (20 IU/ml). And 72 (64.29%) cases of the withdrawal group were detected than 20 IU/ml; in the treatment group, 19 cases were detected higher than 103 IU/ml, 43 (89.58%) cases were detected ≥ 20 IU/ml in quasi treatment group. There was a significant positive correlation between different HBV DNA load groups by COBAS reagent detection and HBsAg concentration logarithm value (P < 0.01). Conclusions High sensitive quantitative PCR should be furtherly conducted for HBV DNA low load patients to guide the initial application or discontinuation of nucleos(t)ide drugs.【Key words 】Hepatitis B virus; Fluorescence quantitative PCR; COBAS Amplicor system; Clinical applicationDOI :10.3877/cma.j.issn.1674-1358. 2016. 01. 010基金项目:山东省济宁市科技项目编号(No. 2013jnnk09)作者单位:272031 济宁市,山东省济宁市传染病医院一病区通讯作者:邵国辉,Email :1652564281@ 为探求核苷(酸)类药物安全停药的相关指标,本研究对于国产试剂HBV DNA 低于检测下限的慢性乙型肝炎(chronic hepatitisB ,CHB )患者在停药前进行了高灵敏HBV DNA 检测。

乙型肝炎病毒核心抗体定量检测研究进展

乙型肝炎病毒核心抗体定量检测研究进展陈翔宇1,2综述张海峰1,3审校1.南通大学附属医院感染科,江苏南通226001;2.南通大学医学院,江苏南通226001;3.新疆克孜勒苏柯尔克孜自治州人民医院感染科,新疆阿图什845350【摘要】近年来多项研究发现乙型肝炎病毒核心抗体检测与抗病毒药物治疗应答、区分慢乙肝不同自然史时期、免疫抑制治疗后乙型肝炎病毒(HBV)再激活等相关,有望成为启动抗病毒治疗、预测疗效、判断预后的重要参考指标,具有巨大临床应用潜力。

本文就乙型肝炎病毒核心抗体(抗HBc)检测的最新研究进展和临床意义进行综述,为早日实现对慢性HBV 感染者的精准化、个体化治疗提供帮助。

【关键词】乙型肝炎病毒核心抗体;慢性HBV 感染自然史;疗效预测;隐匿性乙型肝炎病毒感染;HBV 再激活【中图分类号】R512.6+2【文献标识码】A【文章编号】1003—6350(2023)23—3492—05Clinical research advances in quantitative detection of core antibody of hepatitis B virus.CHEN Xiang-yu 1,2,ZHANG Hai-feng1,3.1.Department of Infectious Diseases,Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University,Nantong 226001,Jiangsu,CHINA;2.Medical College of Nantong University,Nantong 226001,Jiangsu,CHINA;3.Department of Infectious Diseases,Xinjiang Kyzylsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture People's Hospital,Atush 845350,Xinjiang,CHINA【Abstract 】In recent years,many studies have found that the core antibody detection of hepatitis B virus is relat-ed to the response to antiviral drug treatment,the differentiation of different natural history periods of chronic hepatitis B,and Hepatitis B (HBV)reactivation after immunosuppressive treatment.It is expected to become an important refer-ence index for initiating antiviral therapy,predicting efficacy and judging prognosis,and has great clinical application po-tential.This paper summarizes the latest research progress and clinical significance of the detection of hepatitis B virus core antibody (anti-HBc),so as to provide some help for the early realization of accurate and individualized treatment of chronic HBV infected patients.【Key words 】Core antibodies of hepatitis B virus;Natural history of chronic HBV infection;Prediction of effica-cy;Occult hepatitis B virus infection;HBV reactivation ·综述·doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-6350.2023.23.033基金项目:江苏省南通市科技计划项目(编号:MSZ2022002);新疆克州科研计划项目(编号:克科字[2022]13号)。

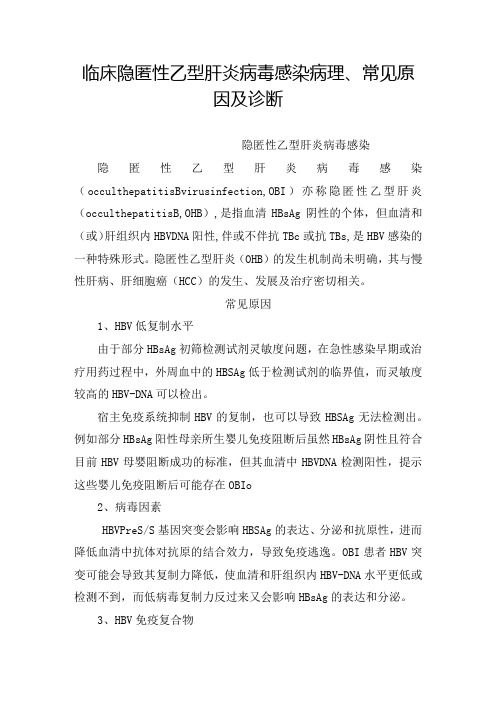

临床隐匿性乙型肝炎病毒感染病理、常见原因及诊断

临床隐匿性乙型肝炎病毒感染病理、常见原因及诊断隐匿性乙型肝炎病毒感染隐匿性乙型肝炎病毒感染(occulthepatitisBvirusinfection,OBI)亦称隐匿性乙型肝炎(occulthepatitisB,OHB),是指血清HBsAg阴性的个体,但血清和(或)肝组织内HBVDNA阳性,伴或不伴抗TBc或抗TBs,是HBV感染的一种特殊形式。

隐匿性乙型肝炎(OHB)的发生机制尚未明确,其与慢性肝病、肝细胞癌(HCC)的发生、发展及治疗密切相关。

常见原因1、HBV低复制水平由于部分HBsAg初筛检测试剂灵敏度问题,在急性感染早期或治疗用药过程中,外周血中的HBSAg低于检测试剂的临界值,而灵敏度较高的HBV-DNA可以检出。

宿主免疫系统抑制HBV的复制,也可以导致HBSAg无法检测出。

例如部分HBsAg阳性母亲所生婴儿免疫阻断后虽然HBsAg阴性且符合目前HBV母婴阻断成功的标准,但其血清中HBVDNA检测阳性,提示这些婴儿免疫阻断后可能存在OBIo2、病毒因素HBVPreS/S基因突变会影响HBSAg的表达、分泌和抗原性,进而降低血清中抗体对抗原的结合效力,导致免疫逃逸。

OBI患者HBV突变可能会导致其复制力降低,使血清和肝组织内HBV-DNA水平更低或检测不到,而低病毒复制力反过来又会影响HBsAg的表达和分泌。

3、HBV免疫复合物急性自限性HBV感染者恢复后,虽然血清中抗-HBs阳性,但仍能检测到HBVDNA颗粒,患者HBVDNA阳性率高达91%。

急性乙型肝炎早期HBV可以自由形式和免疫复合物(immunecomplex,IC)形式存在,在HBSAg转为抗TBs后就转化为以IC为主,这表明血清中的HBV-DNA与抗TBs形式的IC可能会促成OBI的发生。

4、其他因素对合并隐匿性乙肝病毒感染的HCV慢性感染者进行抗逆转录病毒治疗时,随着HeVRNA复制被抑制,HBV-DNA载量却在增加。

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B(乙型肝炎)Hepatitis B is an infectious(传染的)illness caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) which infects(感染)the liver(肝脏)of hominoidea(猿类), including humans, and causes an inflammation(炎症)called hepatitis. Originally (最初)known as "serum hepatitis{血清性肝炎)",[1] the disease has caused epidemics(蔓延;流行)in parts of Asia and Africa, and it is endemic(地方病)in China.[2] About a quarter of the world's population, more than 2 billion people, have been infected with the hepatitis B virus.[3] This includes 350 million chronic carriers(长期带菌者)of the virus.[4]Transmission (传播)of hepatitis B virus results from exposure(暴露)to infectious (传染性的)blood or body fluids(体液), saliva(唾液), tears (眼泪),and urine(小便)and so on. [3][5]The acute(急性的)illness causes liver inflammation(炎症), vomiting (呕吐), jaundice(黄疸)and rarely, death. Chronic hepatitis B may eventually(最后)cause liver cirrhosis (肝硬化)and liver cancer 肝癌)—a fatal(绝症)disease with very poor r esponse(响应,回应)to current chemotherapy(化疗).[6]The infection(感染)is preventable(可预防的)by vaccination(预防接种).[7] Hepatitis B virus has a circular genome(圆形的基因组)composed (组成)of partially double-stranded DNA(双链DNA). The viruses replicate (复制)through an RNA intermediate(起媒介作用)formby reverse transcription(逆转录), and in this aspect (方面)they are similar to retroviruses(逆转录病毒).[9] Although replication(复制)takes place(发生)in the liver, the virus spreads to the blood where virus-specific(病毒特异性的)proteins(蛋白)and their corresponding(相应的)antibodies (抗体)are found in infected people. Blood tests(验血)for these proteins and antibodies are used to diagnose(诊断)the infection.[10]Signs and symptoms(体征和症状)Acute infection with hepatitis B virus is associated with(与。

蔡后荣、李惠萍教授主编的《实用间质性肺疾病》出版

中华 医学会 传染病 与 寄生虫 病学 分会 、肝 脏病 学分 会 .病 毒 性肝 炎 防治方 案 . 中华肝 脏病 杂志 ,2000,8:324—329. 谢 庆元 .新 型抗病 毒药 物西 多福 韦和阿 德福 韦 的药动 学 [J1.国外 医学 药学分 册 ,2003,30:351-353.

出版 物查 询.网上 书店

M arcellin P’Chang TT,Lim SG, et a1.A def o vk dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen—positive chronic hepatitis B .N Engl J M ed,2003,348:808—816. Hadziyannis SJ,Tassopoulos NC ,Heathcote EJ,et a1.Long—term

HBeAg loss:a prospective study[J]J Hep ̄ol 2003,39:614—619. Lee HC,Suh DJ, Kyu SH,et a1.Quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay for serum hepatitis B virus DNA as a predictive factor

adefovir dipivoxil treatment induces regression of liver fibrosis in patients w ith H BeAg—negative chronic hepatitis B :results after 5

years oftherapy[abstract】【J1.Hepatology,2005,42:754A.

实时组织弹性成像检测正常成人肝脏肝纤维化指数正常值研究

实时组织弹性成像检测正常成人肝脏肝纤维化指数正常值研究李开林;农华斌;黄小平;吴向东;方北;朱学苹;徐云峰【摘要】目的:应用实时组织弹性成像(RTE)检测健康成人肝纤维化指数(LF index),分析年龄、性别和体重指数对测值的影响,计算正常参考值范围,为RTE 的临床应用提供参考。

方法应用RTE检测184例健康体检者的LF index,得到正常参考值范围。

根据年龄、性别、体重指数进行分组,采用单因素方差分析、独立样本t检验比较各组间的差异。

结果正常成人肝脏LF index均值为(1.67±0.33),95%可信区间为1.63~1.72。

不同年龄组间LF index比较差异均有统计学意义(F=5.981,P=0.001),40~49岁组、50岁及以上组检测值均大于18~29岁组(P=0.000、0.005)。

男性LF index高于女性(t=6.293,P=0.013)。

不同BMI组间LF index比较差异均有统计学意义(F=5.695,P=0.004),肥胖组检测值增大,与偏瘦组和正常组比较差异均有统计学意义(P=0.001、0.005)。

结论实时组织弹性成像在健康人群的LF index正常参考值范围为1.63~1.72。

年龄、性别和体重指数均对LF index的检测有一定的影响,临床应用中应注意合理解释。

%Objective To test the normal value of liver fibrosis index (LF index) in healthy liver with re-al-time tissue elastography (RTE) to analyze its influence on LF index by age, sex and Body Mass Index (BMI). Methods LF indexes of 184 patients with healthy liver were tested by RTE and a normal reference range was calcu-lated. They were divided into different groups according age, sex and BMI. One-way analysis of variance and indepen-dent sample t test were used to analyze the differences among groups. Results The mean value of LF index in healthy adults was (1.67±0.33) and 95%confidence interval was (1.63~1.72). The differences of LF index indifferent age groups were statistically significant (F=5.981,P=0.001). The LF indexes in 40~49 group and above 50 group were higher than that in18~29 group (P=0.000, 0.005). The LF indexes of male were higher than that of female (t=6.293, P=0.013). The differences were statistically significant in different BMI groups (F=5.695, P=0.004). The LF index of BMI≥25 kg/m2 was increased and the difference was statistically significant compared with that of BMI<18 kg/m2 and 18 kg/m2≤BMI<25 kg/m2 (P=0.001, 0.005). Conclusion The normal value of LF index in healthy people tested by RTE is 1.63~1.72. Age, Sex and BMI can be impact factors in the test of LF index, and reasonable explanations should be awared of in clinical application.【期刊名称】《海南医学》【年(卷),期】2015(000)010【总页数】3页(P1444-1446)【关键词】超声;肝脏;弹性成像技术;实时组织弹性成像;正常值【作者】李开林;农华斌;黄小平;吴向东;方北;朱学苹;徐云峰【作者单位】中山大学附属东华医院超声科,广东东莞 523110;中山大学附属东华医院超声科,广东东莞 523110;中山大学附属东华医院超声科,广东东莞523110;中山大学附属东华医院超声科,广东东莞 523110;中山大学附属东华医院超声科,广东东莞 523110;中山大学附属东华医院超声科,广东东莞 523110;中山大学附属东华医院超声科,广东东莞 523110【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R445肝纤维化是各种慢性肝病的共同病理过程,准确评估肝纤维化程度对于指导治疗和评估预后至关重要[1]。

慢性乙型肝炎疾病知识ID

P编码(biān mǎ)区

• P基因或聚合酶基因编码HBV聚合酶 • 是HBV最大的基因,大约横跨(hénɡ kuà)80%基因组 • 此酶功能众多,是病毒复制和组装中不可缺少的酶

第二十二页,共77页。

X编码(biān mǎ)区

• X基因编码一种能够增强HBV复制的蛋白 • 更常见于严重肝病的患者和肝癌患者 • 虽然迄今HBx蛋白的功能依然不清,但从土拨鼠肝炎 • 模型的研究(yánjiū)中可知 HBx 蛋白是病毒感染周期所必需的 • 蛋白质 • 与HBeAg和HBsAg不同 ,HBx蛋白几乎无任何诊断 • 价值。

组织学活动度(HAI) HAI评分的中位改善

血清HBV DNA水平与肝组织(zǔzhī)病变的相关性

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

0

对26个前瞻性研究的回顾

5

4

3

2

1

2

4

6

8 10 12

基线(jīxiàn) HBV DNA 水平, log10 copies/ml

0

–1

1

2

3

4

5

–2

log10 HBV DNA 中位数的降低(jiàngdī)

慢性(màn xìng)携带者

肝硬化

12-25%

30 – 50 年

肝癌 3-8%

死亡

死亡

第四页,共77页。

HBV和肝癌(ɡān ái)

• HBsAg阳性(yángxìng)的CHB患者发生肝癌的几率比一般人群 • 至少高100倍1,其中又以CHB和肝硬化同时存在的患 • 者最高2。 • CHB伴肝硬化的患者中每年有2%发生肝癌,病程超 • 过5年者肝癌发生率为15%-20%2。 • 肝癌的死亡率极高,在CHB高发区,是一种常见的致 • 死性病因3

需氧菌阴道炎/细菌性阴道病联合测定技术在Av诊断中的应用

Group on Quality Assurance[J].Vox Sang,2000,78(3):149~157. [8] Stramer SL,Glynn SA,Kleinman SH,et al.Detection of HIV-1 and HCV infections among antibody negative blood donors by nucleic acids amplification testing[J].N Engl J Med,2004,351(8):760~768. [9] S e e d C R , C h e n g A , I s m a y A L , e t al.Assessing the accuracy of three viral risk models in predicting the outcome of implementing HIV and HCV RNA donor screening in Austra1ia and the implications for future HBV NAT[J].Tran sfusion,2002,42(10):1365~1372. [10] Ofergeld R,Faensen D,Rit ter S,et al.Human immuno deficiency virus,hepatitis C and hepatilis B infections among blood donors in Germany 20002002:risk of virus transmission and the impact of nucleic aid amplification testing[J].Euro Surveill,2005,10(2):8~11. [11] Li L,Chen PJ,Chen MH,et al.A pilot study for screening blood donors in Taiwan by nucleic acid amplification technology:detecting occult hepatitis B virus infections and closing the serologic window period for hepatitis C virus[J].Tra nsfusion,2008,48(6):1198~1206.

乙肝【英文】 Hepatitis B Virus

Viral Hepatitis - Historical Perspectives

“Infectious”

A

NANB

Enterically E transmitted

Viral hepatitis“Serum”Fra bibliotekB D

Parenterally C transmitted F, G, TTV ? other

Hepatitis B In the United States

• 12 million Americans have been infected (1 out of 20 people). • More than one million people are chronically infected . • Up to 100,000 new people will become infected each year. • 5,000 people will die each year from hepatitis B and its complications. • Approximately 1 health care worker dies each day from hepatitis B.

Hepatitis B In the World

• 2 billion people have been infected (1 out of 3 people). • 400 million people are chronically infected. • 10-30 million will become infected each year. • An estimated 1 million people die each year from hepatitis B and its complications. • Approximately 2 people die each minute from hepatitis B.

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

The new england journal of medicinen engl j med 350;11 march 11, 20041118 mechanisms of diseaseHepatitis B Virus Infection — Natural Historyand Clinical ConsequencesDon Ganem, M.D., and Alfred M. Prince, M.D.From the Departments of Microbiologyand I mmunology and Medicine and theHoward Hughes Medical Institute, Univer-sity of California, San Francisco (D.G.); andthe Laboratory of Virology, Lindsley F. Kim-ball Research I nstitute, New York BloodCenter, and the Department of Pathology,New York University School of Medicine— both in New York (A.M.P.). Address re-print requests to Dr. Prince at the Laborato-ry of Virology, Lindsley F. Kimball ResearchInstitute, New York Blood Center, 310 E. 67thSt., New York, NY 10021, or at aprince@.N Engl J Med 2004;350:1118-29.Copyright © 2004 Massachusetts Medical Society. n the past 10 years, remarkable strides have been made in the understanding of the natural history and pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus (HBV)infection. In this article we will review these advances, with particular referencehepatitis in the decades after World War II. The groundbreaking studies of Krugmanand colleagues in 1967 firmly established the existence of at least two types of hepa-titis, 1 one of which (then called serum hepatitis, and now called hepatitis B) was parenter-ally transmitted. Links to the virus responsible for this form of hepatitis were derived by serologic studies conducted independently by Prince and colleagues 2-4 and byBlumberg and colleagues. 5 Blumberg and colleagues, searching for serum protein poly-morphisms linked to diseases, identified an antigen (termed Au) in serum from pa-tients with leukemia, leprosy, and hepatitis, though the relationship of this antigen tohepatitis was initially unclear. By systematically studying patients with transfusion-associated hepatitis, Prince and coworkers independently identified an antigen, termedSH, that appeared in the blood of these patients during the incubation period of thedisease, and further work established that Au and SH were identical. 6,7 The antigenrepresented the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). 8,9 These seminal studies madepossible the serologic diagnosis of hepatitis B and opened up the field to rigorous epi-Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the prototype member of the Hepadnaviridae (hepatotropicDNA virus) family. Hepadnaviruses have a strong preference for infecting liver cells, butsmall amounts of hepadnaviral DNA can be found in kidney, pancreas, and mononu-clear cells. However, infection at these sites is not linked to extrahepatic disease. 10-13HBV virions are double-shelled particles, 40 to 42 nm in diameter (Fig. 1A), 14 withan outer lipoprotein envelope that contains three related envelope glycoproteins (orsurface antigens). 15 Within the envelope is the viral nucleocapsid, or core. 16 The corecontains the viral genome, a relaxed-circular, partially duplex DNA of 3.2 kb, and a po-lymerase that is responsible for the synthesis of viral DNA in infected cells. 17 DNA se-quencing of many isolates of HBV has confirmed the existence of multiple viral geno-types, each with a characteristic geographic distribution. 18In addition to virions, HBV-infected cells produce two distinct subviral lipopro-tein particles: 20-nm spheres (Fig. 1B) and filamentous forms of similar diameteri The New England Journal of Medicine as published by New England Journal of Medicine.Downloaded from on July 29, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.mechanisms of disease(Fig. 1A).16 These HBsAg particles contain only en-ABFigure 1. Structure of HBsAg-Associated Particles(Phosphotungstic Acid–Negative Stain).Panel A shows HBV virions (Dane particles) and fila-ments. Panel B shows 20-nm HBsAg particles.n engl j med 350;11 march 11 , 2004 The new england journal of medicine1120 identity of which remains unknown. After mem-brane fusion, cores are presented to the cytosol andtransported to the nucleus. There, their DNA ge-nomes are converted to a covalently closed circular(ccc) form, 26 which serves as the transcriptionaltemplate for host RNA polymerase II. This enzymegenerates a series of genomic and subgenomictranscripts. 27All viral RNA is transported to the cytoplasm,where its translation yields the viral envelope, core,and polymerase proteins, as well as the X and preC polypeptides. Next, nucleocapsids are assembled in the cytosol, and during this process a single mol-ecule of genomic RNA is incorporated into the as-sembling viral core. 28 Once the viral RNA is en-capsidated, reverse transcription begins. 28 TheEntry of HBVinto cell Vesicular transportto cell membraneBudding intoendoplasmicreticulumCore assembly andRNA packaging Core particleCore particle plusstrand synthesisCore particle minus strand synthesisHBVTranslationTranscriptionNucleusCytoplasmcccDNARepairRecyclingThe New England Journal of Medicine as published by New England Journal of Medicine.Downloaded from on July 29, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.mechanisms of diseasesynthesis of the two viral DNA strands is sequential. The first DNA strand is made from the encapsi-dated RNA template; during or after the synthesis of this strand, the RNA template is degraded and the synthesis of the second DNA strand proceeds, with the use of the newly made first DNA strand as a template.25,27,29 Some cores bearing the mature genome are transported back to the nucleus, where their newly minted DNA genomes can be convert-ed to cccDNA to maintain a stable intranuclear pool of transcriptional templates.26 Most cores, how-ever, bud into regions of intracellular membranes bearing the viral envelope proteins. In so doing, they acquire lipoprotein envelopes containing the viral L, M, and S surface antigens and are then exported from the cell.pathogenesis of hepatitis bThe HBV replication cycle is not directly cytotoxic to cells. This fact accords well with the observation that many HBV carriers are asymptomatic and have minimal liver injury, despite extensive and ongo-ing intrahepatic replication of the virus.30 It is now thought that host immune responses to viral anti-gens displayed on infected hepatocytes are the prin-cipal determinants of hepatocellular injury. This no-tion is consistent with the clinical observation that patients with immune defects who are infected with HBV often have mild acute liver injury but high rates of chronic carriage.31The immune responses to HBV and their role in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B are incompletely understood. Correlative clinical studies show that in acute, self-limited hepatitis B, strong T-cell re-sponses to many HBV antigens are readily demon-strable in the peripheral blood.32 These responses involve both major-histocompatibility-complex (MHC) class II–restricted, CD4+ helper T cells and MHC class I–restricted, CD8+ cytotoxic T lympho-cytes. The antiviral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response is directed against multiple epitopes within the HBV core, polymerase, and envelope proteins; strong helper T-cell responses to C and P proteins have also been demonstrated in acute infection. By contrast, in chronic carriers of HBV, such virus-specific T-cell responses are greatly attenuated, at least as assayed in cells from the peripheral blood. However, anti-body responses are vigorous and sustained in both situations (although free antibodies against HBsAg [anti-HBs antibodies] are not detectable in carriers because of the excess of circulating HBsAg). This pattern strongly suggests that T-cell responses, es-pecially the responses of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, play a central role in viral clearance. Figure 3 sum-marizes the major types of cellular immune re-sponse to HBV.The mechanisms by which cytotoxic T lympho-cytes kill liver cells and cause viral clearance have been incisively investigated in transgenic mice that express viral antigens or contain replication-com-petent viral genomes in the liver.32,33 Because these mice harbor HBV genes in their germ-line DNA, they are largely tolerant to HBV proteins, and according-ly, clinically significant liver injury does not devel-op. However, if antiviral cytotoxic T lymphocytes of syngeneic animals are transferred into such mice, acute liver injury with many of the features of clini-cal hepatitis B develops.34 It is striking that, in this model, the number of hepatocytes killed by direct engagement between cytotoxic T lymphocytes and their targets is very small and clearly insufficient to account for most of the liver damage. This sug-gests that much of the injury is due to secondary antigen-nonspecific inflammatory responses that are set in motion by the response of the cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Presumably, much of the damage occurring in this context is due to cytotoxic by-prod-ucts of the inflammatory response, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), free radicals, and proteas-es. Other immune-cell populations, notably natu-ral killer T cells,35 probably also contribute to liver injury.Recent experiments suggest that some of the inflammatory by-products, notably interferon-g (IFN-g) and TNF-a, can have antiviral effects that do not involve killing the target cells. When cytotoxic T lymphocytes are transferred to mice that bear rep-licating HBV, viral DNA and RNA throughout the liver rapidly disappear, even from viable, uninjured hepatocytes — an effect that can be blocked by the administration of antibodies to TNF-a and IFN-g.34 Such noncytocidal antiviral effects may be impor-tant for viral clearance in natural infection. In fact, cytokine release triggered by unrelated hepatic in-fections in HBV-transgenic mice can have the same effect.36 This phenomenon may explain the sup-pression and occasional clearance of chronic HBV infection in patients with superimposed acute hep-atitis caused by unrelated viruses.natural historyPrimary HBV infection in susceptible (nonimmune) hosts can be either symptomatic or asymptomatic. The latter is more common than the former, espe-n engl j med 350;11 march 11 , 2004The new england journal of medicine1122 cially in young children. Most primary infections inadults, whether symptomatic or not, are self-lim-ited, with clearance of virus from blood and liverand the development of lasting immunity to rein-fection. 37,38 However, some primary infections inhealthy adults (generally less than 5 percent) do notresolve but develop into persistent infections. Insuch cases, viral replication continues in the liverand there is continual viremia, although the titersof virus in the liver and blood are variable. Persis-tent HBV infection may be symptomatic or asymp-tomatic. People with subclinical persistent infec-tion, normal serum aminotransferase levels, andnormal or nearly normal findings on liver biopsyare termed asymptomatic chronic H BV carriers;those with abnormal liver function and histologicfeatures are classified as having chronic hepatitis B.Cirrhosis, a condition in which regenerative nod-ules and fibrosis coexist with severe liver injury,develops in about 20 percent of people with chron-ic hepatitis B. The resulting hepatic insufficiency and portal hypertension make this process one of the most feared consequences of chronic HBV in-fection. Primary Infection In primary infection, HBsAg becomes detectable in the blood after an incubation period of 4 to 10weeks, followed shortly by antibodies against the HBV core antigen (anti-HBc antibodies), which ear-ly in infection are mainly of the IgM isotype. 38 Vire-mia is well established by the time HBsAg is detect-ed, and titers of virus in acute infection are very high — frequently 10 9 to 10 10 virions per milliliter. 39 Cir-culating HBeAg becomes detectable in most cases,and studies of chimpanzees and other animals with primary hepadnaviral infection show that 75 to 100percent of hepatocytes are infected when this anti-gen is evident. 40 Thus, it is not surprising that epi-demiologic studies consistently show high rates ofMHC class IMHCclass I Antigen-presenting cellMHCclass II Infected hepatocyte CD4+T cellCD8+T cell CD8+T cellHBVpeptidesHBVpeptidesHBV coresHBVantigens HBV DNAHBV RNA Down-regulation of viral replication TNF-aInterferon-g HBVHBsAgThe New England Journal of Medicine as published by New England Journal of Medicine.Downloaded from on July 29, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.mechanisms of diseaseboth vertical and horizontal transmissibility during acute HBV infection.41When liver injury does occur in primary infec-tion, alanine aminotransferase levels do not increase until after viral infection is well established, reflect-ing the time required to generate the T-cell–mediat-ed immune response that triggers liver injury. Once this response is under way, titers of virus in blood and liver begin to drop. The fact that infection can be cleared from virtually all hepatocytes without massive hepatic destruction (in most cases) is a tes-tament to the extraordinary power of the noncy-tolytic clearance mechanisms described above. With clearance of the infection, the viral antigens HBsAg and HBeAg disappear from the circulation, and free anti-HBs antibodies become detectable.Surprisingly, in self-limited infection, as defined by the disappearance of the viral antigens and the appearance of anti-H Bs antibodies, low levels of HBV DNA in the blood may persist for many years, if not for life.42 It is not known whether this DNA contains the entire HBV genome, or even whether it is contained in virions. However, inoculation of serum from three subjects with persistent H BV DNA into chimpanzees has not led to documented infectivity.42Persistent InfectionIn persistent HBV infection, the early events unfold as in self-limited infection, but HBsAg remains in the blood and virus production continues, often for life. However, levels of viremia in chronic infection are generally substantially lower than during pri-mary infection, although they can vary consider-ably from person to person. High titers of HBV in the blood are often indicated by the continued pres-ence of HBeAg. Typically, there are 107 to 109 virions per milliliter in the blood43 in such cases, which are highly infectious. But most people with persistent infection, especially those with anti-HBe antibod-ies, have somewhat lower levels of viremia.One feature of chronic HBV infection that is not widely appreciated is its dynamic natural history. Even though, in most cases, HBsAg remains detect-able for life, titers of viral DNA tend to decline over time. With the passage of time, there is also a ten-dency for HBeAg to disappear from the blood, along with seroconversion to positivity for anti-HBe anti-bodies — a progression that occurs at a rate of 5 to 10 percent per year in persistently infected peo-ple.39 Often, the disappearance of HBeAg is pre-ceded or accompanied by a transient rise in alanine aminotransferase levels, known as a flare, which suggests that the process reflects immune-mediat-ed destruction of infected hepatocytes. Reductions in the level of viremia as great as five orders of mag-nitude may accompany seroconversion to anti-HBe antibodies.44 Thus, the natural history of HBV per-sistence suggests that there is an ongoing immune attack on infected cells in the liver — an attack that is usually inadequate to eradicate infection alto-gether, but that does reduce the number of infected cells and thereby lowers the circulating viral load. Figure 4 shows typical patterns of serologic and molecular markers in both acute self-limited and chronic HBV infection.The widely held view that circulating viral DNA disappears when anti-HBe antibodies appear is in-correct; this idea reflects the fact that, for many years, HBV DNA was measured by relatively insen-sitive hybridization methods with a detection limit of 105 to 106 virions per milliliter. Thanks to the ad-vent of the polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) meth-od, we now know that at least 70 to 85 percent of people with anti-HBe antibodies have detectable viral DNA in the circulation, typically in the range of 103 to 105 molecules per milliliter, and some-times higher.44 Although these levels of HBV DNA are relatively low, they are hardly negligible. (For reference, they are similar to levels of human im-munodeficiency virus [HIV] and HCV DNA in many patients with symptomatic acquired immunodefi-ciency syndrome or hepatitis C.) Given the short half-life of HBV virions (approximately one day),39 such levels can be sustained only by ongoing viral replication; therefore, the claim that HBV enters a so-called nonreplicative phase later in its course is not correct. For this reason, anyone who has a pos-itive test for HBsAg should be presumed to have some level of ongoing viremia. For example, when a decision must be made about immunoprophy-laxis after a needle stick involving blood from an HBsAg-positive patient, prophylaxis should be of-fered irrespective of that patient’s HBeAg status.HBeAg-negative carriers are a heterogeneous group. Most such carriers have low levels of viral DNA, relatively normal levels of alanine amino-transferase, and a good prognosis.30 However, par-ticularly in southern Europe and in Asia, at least 15 to 20 percent of such carriers have elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase and viral DNA in the blood.45 The virus in many such carriers harbors mutations in the preC region that prevent the pro-duction of HBeAg.46 It has been suggested that per-n engl j med 350;11 march 11 , 2004The new england journal of medicine1124 sistently abnormal levels of alanine aminotransfer-ase and elevated levels of viral DNA may denote asubgroup of HBeAg-negative carriers who shouldreceive active antiviral therapy. 47Hepatocellular Carcinoma Another feature of the natural history of HBV infec-tion is its link to primary hepatocellular carcinoma.Chronically infected subjects have a risk of hepato-cellular carcinoma that is 100 times as high as thatfor noncarriers 48 ; within the HBsAg-positive group,HBeAg-positive carriers have the highest risk ofhepatocellular carcinoma, but even carriers withanti-HBe antibodies have a substantial risk of can-cer. 49 (Although the role of HBV in provoking hep-atocellular carcinoma is undisputed, its cellularand molecular mechanisms remain incompletelyunderstood. 50-54 ) Given these facts, twice-a-yearscreening of chronically infected patients with mea-surements of serum alpha fetoprotein or hepaticultrasonography, or both, is warranted. 47 However,there is debate as to when such screening shouldbegin. Furthermore, screening is imperfect — alpha fetoprotein screening, for example, has an excel-lent negative predictive value, but its positive pre-47are a reduction in the level of viremia and ameliora-tion of hepatic dysfunction. Most clinical studies have focused on chronically infected patients with elevated aminotransferase levels and circulating HBeAg, in whom viral loads can be readily mea-sured even with first-generation DNA tests. There are clear indications for therapy in HBeAg-positive patients. They have an increased risk of early pro-gression to chronic active hepatitis and cirrhosis, 55 and they have a risk of hepatocellular carcinoma that is substantially higher than that for other carri-ers. 49 By contrast, asymptomatic HBeAg-negative chronic carriers with viral loads below 10 5 genomes per milliliter and normal alanine aminotransferaseThe New England Journal of Medicine as published by New England Journal of Medicine.Downloaded from on July 29, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.mechanisms of diseasevalues tend to have a relatively stable course, with low rates of clinical or pathological progression.30 At present, therapy is usually not offered to such persons. As noted above, some HBeAg-negative pa-tients have liver dysfunction and substantial vire-mia (>105 molecules per milliliter). Discussions of the treatment of such patients are rare in the pub-lished literature, but results of a recent trial suggest that many of these patients would also benefit from effective antiviral therapy.56 A recent clinical prac-tice guideline47 includes this group in its discus-sion of treatment; clearly, future clinical investiga-tions should focus more attention on this group.The usual markers of successful therapy are the loss of H BeAg, seroconversion to anti-H Be anti-bodies, and reduction of the circulating viral load. These are useful indicators, since patients with sta-ble seroconversion to anti-HBe–positive status typ-ically have improved histologic findings in the liv-er, and this improvement tends to be maintained over the long term.57 True cure of infection (loss of HBsAg and complete disappearance of viremia, as measured by stringent PCR assays) is achieved only infrequently (in 1 to 5 percent of patients) with cur-rent regimens, although the increasing numbers of active antiviral drugs might lead to an upward revi-sion of this figure in the future. In the case of pa-tients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis, there is no information about which markers best mea-sure the response to therapy. Quantitation of vire-mia by PCR assays would seem a logical starting place, but there have been no systematic studies to guide the clinical interpretation of results. interferonFor many years, administration of interferon alfa (5 million to 10 million units subcutaneously three times per week, for at least three months) was the mainstay of therapy. About 30 percent of patients who tolerated this regimen had a successful re-sponse, defined as a loss of HBeAg, the develop-ment of anti-HBe antibodies, and a decline in se-rum alanine aminotransferase levels.58 With HBe seroconversion and normalization of alanine ami-notransferase levels, improvement is usually sus-tained well after therapy has been discontinued.58 Interferon alfa treatment of chronic HBV infections in patients with cirrhosis has even been reported to reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.59 However, the side effects of therapy with inter-feron alfa (fever, myalgias, thrombocytopenia, and depression) make it a difficult treatment for many patients. Moreover, in many patients a flare of liver injury occurs during administration of interferon alfa, often just before or during clearance of HBeAg. This phenomenon may reflect the immunomodu-latory activity of interferon alfa, which, in addition to impairing HBV replication, can also cause up-reg-ulation of MHC class I antigens on hepatocytes and thereby augment the recognition of infected cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Although sometimes disquieting to patients and physicians alike, these flares are intrinsic to the therapy and, as markers of enhanced antiviral immune responsiveness, often presage a successful outcome. However, treatment with interferon alfa is generally contraindicated in very advanced liver disease, since in such cases the flares may precipitate overt liver failure. Moreover, patients with advanced cirrhosis and splenomeg-aly usually have base-line leukopenia and throm-bocytopenia, which can be exacerbated by the drug. antiviral drugsLamivudineIn the past decade, therapy for HBV has been revo-lutionized by the advent of drugs that directly block replication of the HBV genome. All these drugs (to date) are nucleoside or nucleotide analogues that selectively target the viral reverse transcriptase. The first successful drug, lamivudine, emerged from screening for inhibitors of the HIV reverse trans-criptase and was introduced into clinical practice for the management of HIV infection. Carriers of HIV who are also infected with HBV had substan-tial declines in HBV viremia when treated with la-mivudine,60 and such declines were also observed in patients with chronic hepatitis B who did not have HIV infection.61 In general, treatment with la-mivudine results in a reduction of 3 to 4 log in circu-lating levels of HBV DNA in the first three months of therapy; this decline is associated with more rap-id loss of HBeAg, seroconversion to anti-HBe–pos-itive status, and improvement in serum aminotrans-ferase levels. The drug is usually well tolerated, a factor that has led to the rapid displacement of in-terferon alfa from the roster of first-line therapies for HBV. Lamivudine is not immunomodulatory and can be used in patients with decompensated cir-rhosis.62 Even polyarteritis nodosa associated with H BV has been shown to respond dramatically to treatment with lamivudine plus plasma exchange.63 Although lamivudine is not an immunomodu-lator, there is strong evidence that successful treat-ment with lamivudine relies to some extent on ann engl j med 350; march 11, 2004The new england journal of medicine1126adequate host immune response. This evidenceemerged from a retrospective examination of sub-groups of patients with optimal responses to ther-apy, which revealed a strong correlation betweenHBeAg clearance and elevated pretreatment val-ues for alanine aminotransferase.64 HBeAg sero-conversion occurred in 65 percent of cases in whichpretreatment values for alanine aminotransferasewere more than five times the upper limit of thenormal range, as compared with only 26 percentin patients with elevations in alanine aminotrans-ferase values that were two to five times the upperlimit of the normal range. Only 5 percent of pa-tients with pretreatment alanine aminotransferasevalues that were less than twice the upper limit ofthe normal range had clearance of H BeAg — arate similar to that for the spontaneous loss of thismarker. This finding suggests that by reducing theviral load, lamivudine allows the immune and in-flammatory responses to deal more effectively withthe remaining infected hepatocytes in the host.The principal limitation of lamivudine mono-therapy is the development of drug resistance,which is mediated largely by point mutations atthe YMDD motif at the catalytic center of the viralreverse transcriptase. The resulting mutants areslightly less fit than wild-type HBV in the absenceof the drug, but they are strongly selected for in itspresence.65 Viral resistance emerges much moreslowly in HBV infection than in HIV infection, forcomplex reasons beyond the scope of this review.By the end of one year of therapy, 15 to 20 percentof patients have resistant variants in the circula-tion; the figure rises to 40 percent by two years, andto 67 percent by the fourth year.66The clinical significance of the development ofresistance is still being debated. Clearly, in manypatients, resistance presages a return of higher-level viremia, and in some of these patients furtherliver injury develops. However, although the levelof viremia rises, in many patients it may still remainbelow pretreatment levels — perhaps as a resultof the reduced fitness of the variants. In addition,some patients continue to undergo conversion fromHBeAg-positive status to H BeAg-negative status,even after the appearance of lamivudine-resistantmutants in the circulation; by the end of four yearsof therapy, 40 to 50 percent of patients treated withlamivudine have undergone such conversion. There-fore, some experts favor the continuation of lamiv-udine therapy in patients with resistant variants but no evidence of overt clinical failure, especially since transient exacerbations of liver injury devel-op in some patients when antiviral therapy is with-drawn.67 (Such postwithdrawal flares are not lim-ited to lamivudine but have also been observed with other anti-H BV regimens.56,68) Now that newer anti-HBV drugs are available, additional options exist for patients with resistant strains of HBV .Other Nucleotide Analogues Recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)approved a second antiviral drug, adefovir, to treat HBV infection. Adefovir, a nucleotide (adenosine monophosphate) analogue, is a prodrug that un-dergoes two intracellular phosphorylations to yield the active drug, an inhibitor of the viral polymer-ase. Initially developed as an inhibitor of HIV re-verse transcriptase, it proved nephrotoxic in the dos-es that were required for effective inhibition of HIV replication. However, in lower doses (10 mg per day)it has shown little nephrotoxicity and retains good efficacy against HBV in HBeAg-positive patients,with a reduction of 3 to 4 log in viremia; the fre-quency of HBeAg seroconversion is enhanced, and there is histologic improvement in the liver.68 Simi-lar efficacy was documented in HBeAg-negative pa-tients with abnormal liver function and elevated lev-els of viral DNA.56 Moreover, the drug effectively inhibits the replication of lamivudine-resistant HBV mutants, both in vitro and in vivo.69,70 Clear evi-dence of the emergence of adefovir-resistant HBV mutants has not been found in the clinical trials performed to date,56,68,71 although this issue re-mains open now that large numbers of patients will be using the drug.Tenofovir, another adenine nucleotide analogue that was approved by the FDA for the treatment of HIV , also has activity against the HBV polymerase.In recent trials in HIV carriers who were positive for HBeAg, treatment with standard doses of tenofovir led to a reduction of 4 log in circulating HBV DNA levels, even in patients who had evidence of lamiv-udine-resistant virus.72,73 H owever, the FDA has not yet approved tenofovir for use in patients with HBV infection. Several investigational drugs are now in ad-vanced stages of clinical trials. Entecavir is a guan-osine analogue that, unlike the drugs discussed above, is highly selective for the HBV polymerase and has no activity against HIV . It is extremely po-tent on a molar basis, and doses as low as 0.1 mg perThe New England Journal of Medicine as published by New England Journal of Medicine.Downloaded from on July 29, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.。