巴塞尔协议三中英对照

巴塞尔协议3全文

巴塞尔协议3全文介绍巴塞尔协议3(Basel III)是一个国际上的银行监管规范,旨在增强银行的资本充足性和抵御金融风险的能力。

该协议于2010年12月由巴塞尔银行监管委员会发布,是对前两个巴塞尔协议(巴塞尔协议1和巴塞尔协议2)的进一步改进和完善。

背景巴塞尔协议3的制定是对全球金融危机的应对措施之一。

全球金融危机爆发后,许多银行陷入资本不足的困境,无法应对金融市场的风险。

因此,国际社会开始呼吁改革银行监管制度,以防范未来类似的金融危机。

巴塞尔协议3作为回应,采取了一系列措施来强化银行资本和风险管理。

核心要点1. 资本要求巴塞尔协议3规定了更严格的资本要求,以确保银行有足够的资本来应对损失。

首先,对风险加权资产计量的方法进行了改进,旨在更准确地反映银行资产的风险水平。

其次,规定了更高的最低资本要求,包括最低的核心一级资本比率和总资本比率。

2. 流动性风险管理巴塞尔协议3要求银行制定和实施更加严格的流动性风险管理政策。

银行需要具备足够的流动性资产,以应对紧急情况下的资金需求。

此外,银行还需要进行定期的压力测试,以确保其流动性风险管理措施的有效性。

3. 杠杆比率巴塞尔协议3引入了杠杆比率作为一种更简单的资本要求衡量指标。

杠杆比率是银行核心一级资本与风险敞口的比例。

该指标旨在衡量银行的杠杆风险水平,以防止过度借贷。

4. 缓冲储备巴塞尔协议3要求银行建立缓冲储备,以应对经济衰退期间的损失。

缓冲储备由国际流动性缓冲储备和资本缓冲储备两部分组成。

国际流动性缓冲储备用于应对流动性风险,而资本缓冲储备用于应对信用风险。

影响巴塞尔协议3的实施对金融体系和全球经济有着重要的影响。

首先,它有助于提高银行的资本充足性和稳定性,减少金融风险,防止金融危机的发生。

其次,巴塞尔协议3的推行可能会导致银行的成本上升,因为它要求银行持有更多的资本和流动性资产。

但与此同时,这也可以促使银行更加谨慎和适度的风险管理,从而提高整个金融体系的稳定性。

巴塞尔资本协议中英文完整版(首封)

概述导言1. 巴塞尔银行监管委员会(以下简称委员会)现公布巴塞尔新资本协议(BaselII,以下简称巴塞尔II)第三次征求意见稿(CP3,以下简称第三稿)。

第三稿的公布是构建新资本充足率框架的一项重大步骤。

委员会的目标仍然是在今年第四季度完成新协议,并于2006年底在成员国开始实施。

2. 委员会认为,完善资本充足率框架有两方面的公共政策利好。

一是建立不仅包括最低资本而且还包括监管当局的监督检查和市场纪律的资本管理规定。

二是大幅度提高最低资本要求的风险敏感度。

3. 完善的资本充足率框架,旨在促进鼓励银行强化风险管理能力,不断提高风险评估水平。

委员会认为,实现这一目标的途径是,将资本规定与当今的现代化风险管理作法紧密地结合起来,在监管实践中并通过有关风险和资本的信息披露,确保对风险的重视。

4. 委员会修改资本协议的一项重要内容,就是加强与业内人士和非成员国监管人员之间的对话。

通过多次征求意见,委员会认为,包括多项选择方案的新框架不仅适用于十国集团国家,而且也适用于世界各国的银行和银行体系。

5. 委员会另一项同等重要的工作,就是研究参加新协议定量测算影响分析各行提出的反馈意见。

这方面研究工作的目的,就是掌握各国银行提供的有关新协议各项建议对各行资产将产生何种影响。

特别要指出,委员会注意到,来自40多个国家规模及复杂程度各异的350多家银行参加了近期开展的定量影响分析(以下称简QIS3)。

正如另一份文件所指出,QIS3的结果表明,调整后新框架规定的资本要求总体上与委员会的既定目标相一致。

6. 本文由两部分内容组成。

第一部分简单介绍新资本充足框架的内容及有关实施方面的问题。

在此主要的考虑是,加深读者对新协议银行各项选择方案的认识。

第二部分技术性较强,大体描述了在2002年10月公布的QIS3技术指导文件之后对新协议有关规定所做的修改。

第一部分新协议的主要内容7. 新协议由三大支柱组成:一是最低资本要求,二是监管当局对资本充足率的监督检查,三是信息披露。

巴塞尔协议三中英对照

巴塞尔协议三中英对照本页仅作为文档页封面,使用时可以删除This document is for reference only-rar21year.MarchGroup of Governors and Heads of Supervision announces higher global minimum capital standards12 September 2010At its 12 September 2010 meeting, the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision, the oversight body of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, announced a substantial strengthening of existing capital requirements and fully endorsed the agreements it reached on 26 July 2010. These capital reforms, together with the introduction of a global liquidity standard, deliver on the core of the global financial reform agenda and will be presented to the Seoul G20 Leaders summit in November.The Committee's package of reforms will increase the minimum common equity requirement from 2% to 4.5%. In addition, banks will be required to hold a capital conservation buffer of 2.5% to withstand future periods of stress bringing the total common equity requirements to 7%. This reinforces the stronger definition of capital agreed by Governors and Heads of Supervision in July and the higher capital requirements for trading, derivative and securitisation activities to be introduced at the end of 2011.Mr Jean-Claude Trichet, President of the European Central Bank and Chairman of the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision, said that "the agreements reached today are a fundamental strengthening of global capital standards." He added that "their contribution to long term financial stability and growth will be substantial. The transition arrangements will enable banks to meet the new standards while supporting the economic recovery." Mr Nout Wellink, Chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and President of the Netherlands Bank, added that "the combination of a much stronger definition of capital, higher minimum requirements and the introduction of new capital buffers will ensure that banks are better able to withstand periods of economic and financial stress, therefore supporting economic growth."Increased capital requirementsUnder the agreements reached today, the minimum requirement for common equity, the highest form of loss absorbing capital, will be raised from the current 2% level, before the application of regulatory adjustments, to 4.5% after the application of stricter adjustments. This will be phased in by 1 January 2015. The Tier 1 capital requirement, which includes common equity and other qualifying financial instruments based on stricter criteria, will increase from 4% to 6% over the same period. (Annex 1 summarises the new capital requirements.)The Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision also agreed that the capital conservation buffer above the regulatory minimum requirement be calibrated at 2.5% and be met with common equity, after the application of deductions. The purpose of the conservation buffer is to ensure that banks maintain a buffer of capital that can be used to absorb losses during periods of financial and economic stress. While banks are allowed to draw on the buffer during such periods of stress, the closer their regulatory capital ratios approach the minimum requirement, the greater the constraints on earnings distributions. This framework will reinforce the objective of sound supervision and bank governance and address the collective action problem that has prevented some banks from curtailing distributions such as discretionary bonuses and high dividends, even in the face of deteriorating capital positions.A countercyclical buffer within a range of 0% - 2.5% of common equity or other fully loss absorbing capital will be implemented according to national circumstances. The purpose of the countercyclical buffer is to achieve the broader macroprudential goal of protecting the banking sector from periods of excess aggregate credit growth. For any given country, this buffer will only be in effect when there is excess credit growth that is resulting in a system wide build up of risk. The countercyclical buffer, when in effect, would be introduced as an extension of the conservation buffer range.These capital requirements are supplemented by a non-risk-based leverage ratio that will serve as a backstop to the risk-based measures described above. In July, Governors and Heads of Supervision agreed to test a minimum Tier 1 leverage ratio of 3% during the parallel run period. Based on the results of the parallel run period, any final adjustments would be carried out in the first half of 2017 with a view to migrating to a Pillar 1 treatment on 1 January 2018 based on appropriate review and calibration.Systemically important banks should have loss absorbing capacity beyond the standards announced today and work continues on this issue in the Financial Stability Board and relevant Basel Committee work streams. The Basel Committee and the FSB are developing a well integrated approach to systemically important financial institutions which could include combinations of capital surcharges, contingent capital and bail-in debt. In addition, work is continuing to strengthen resolution regimes. The Basel Committee also recently issued a consultative document Proposal to ensure the loss absorbency of regulatory capital at the point of non-viability. Governors and Heads of Supervision endorse the aim to strengthen the loss absorbency of non-common Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital instruments.Transition arrangementsSince the onset of the crisis, banks have already undertaken substantial efforts to raise their capital levels. However, preliminary results of the Committee's comprehensive quantitative impact study show that as of the end of 2009, large banks will need, in the aggregate, a significant amount of additional capital to meet these new requirements. Smaller banks, which are particularly important for lending to the SME sector, for the most part already meet these higher standards.The Governors and Heads of Supervision also agreed on transitional arrangements for implementing the new standards. These will help ensure that the banking sector can meet the higher capital standards through reasonable earnings retention and capital raising, while still supporting lending to the economy. The transitional arrangements, which are summarised in Annex 2, include:National implementation by member countries will begin on 1 January 2013. Member countries must translate the rules into national laws and regulations before this date. As of 1 January 2013, banks will be required to meet the following new minimum requirements in relation to risk-weighted assets (RWAs):3.5% common equity/RWAs;4.5% Tier 1 capital/RWAs, and8.0% total capital/RWAs.The minimum common equity and Tier 1 requirements will be phased in between 1 January 2013 and 1 January 2015. On 1 January 2013, the minimum common equity requirement will rise from the current 2% level to 3.5%. The Tier 1 capital requirement will rise from 4% to 4.5%. On 1 January 2014, banks will have to meeta 4% minimum common equity requirement and a Tier 1 requirement of 5.5%. On1 January 2015, banks will have to meet the 4.5% common equity and the 6% Tier 1 requirements. The total capital requirement remains at the existing level of 8.0% and so does not need to be phased in. The difference between the total capital requirement of 8.0% and the Tier 1 requirement can be met with Tier2 and higher forms of capital.The regulatory adjustments (ie deductions and prudential filters), including amounts above the aggregate 15% limit for investments in financial institutions, mortgage servicing rights, and deferred tax assets from timing differences, would be fully deducted from common equity by 1 January 2018.In particular, the regulatory adjustments will begin at 20% of the required deductions from common equity on 1 January 2014, 40% on 1 January 2015, 60% on 1 January 2016, 80% on 1 January 2017, and reach 100% on 1 January 2018. During this transition period, the remainder not deducted from common equity will continue to be subject to existing national treatments.The capital conservation buffer will be phased in between 1 January 2016 and year end 2018 becoming fully effective on 1 January 2019. It will begin at0.625% of RWAs on 1 January 2016 and increase each subsequent year by an additional 0.625 percentage points, to reach its final level of 2.5% of RWAs on 1 January 2019. Countries that experience excessive credit growth should consider accelerating the build up of the capital conservation buffer and the countercyclical buffer. National authorities have the discretion to impose shorter transition periods and should do so where appropriate.Banks that already meet the minimum ratio requirement during the transition period but remain below the 7% common equity target (minimum plus conservation buffer) should maintain prudent earnings retention policies with a view to meeting the conservation buffer as soon as reasonably possible.Existing public sector capital injections will be grandfathered until 1 January 2018. Capital instruments that no longer qualify as non-common equity Tier 1 capital or Tier 2 capital will be phased out over a 10 year horizon beginning 1 January 2013. Fixing the base at the nominal amount of such instruments outstanding on 1 January 2013, their recognition will be capped at 90% from 1 January 2013, with the cap reducing by 10 percentage points in each subsequent year. In addition, instruments with an incentive to be redeemed will be phased out at their effective maturity date.Capital instruments that no longer qualify as common equity Tier 1 will be excluded from common equity Tier 1 as of 1 January 2013. However, instruments meeting the following three conditions will be phased out over the same horizon described in the previous bullet point: (1) they are issued by a non-joint stock company 1 ; (2) they are treated as equity under the prevailing accounting standards; and (3) they receive unlimited recognition as part of Tier 1 capital under current national banking law.Only those instruments issued before the date of this press release should qualify for the above transition arrangements.Phase-in arrangements for the leverage ratio were announced in the 26 July 2010 press release of the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision. That is, the supervisory monitoring period will commence 1 January 2011; the parallel run period will commence 1 January 2013 and run until 1 January 2017; and disclosure of the leverage ratio and its components will start 1 January 2015. Based on the results of the parallel run period, any final adjustments will be carried out in the first half of 2017 with a view to migrating to a Pillar 1 treatment on 1 January 2018 based on appropriate review and calibration.After an observation period beginning in 2011, the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) will be introduced on 1 January 2015. The revised net stable funding ratio (NSFR) will move to a minimum standard by 1 January 2018. The Committee will put in place rigorous reporting processes to monitor the ratios during the transition period and will continue to review the implications of these standards for financial markets, credit extension and economic growth, addressing unintended consequences as necessary.The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision provides a forum for regular cooperation on banking supervisory matters. It seeks to promote and strengthen supervisory and risk management practices globally. The Committee comprises representatives from Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States.The Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision is the governing body of the Basel Committee and is comprised of central bank governors and (non-central bank) heads of supervision from member countries. The Committee's Secretariat is based at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland.Annex 1: Calibration of the Capital Framework (PDF 1 page, 19 kb)Annex 2: Phase-in arrangements (PDF 1 page, 27 kb)Full press release (PDF 7 pages, 56 kb)--------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 Non-joint stock companies were not addressed in the Basel Committee's 1998 agreement on instruments eligible for inclusion in Tier 1 capital as they do not issue voting common shares.最新巴塞尔协议3全文央行行长和监管当局负责人集团1宣布较高的全球最低资本标准国际银行资本监管改革是本轮金融危机以来全球金融监管改革的重要组成部分。

巴塞尔资本协议中英文完整版

巴塞尔资本协议中英文完整版导言1. 巴塞尔银行监管委员会〔以下简称委员会〕现公布巴塞尔新资本协议〔Basel II, 以下简称巴塞尔II〕第三次征求意见稿〔CP3,以下简称第三稿〕。

第三稿的公布是构建新资本充足率框架的一项重大步骤。

委员会的目标仍旧是在今年第四季度完成新协议,并于2006年底在成员国开始实施。

2. 委员会认为,完善资本充足率框架有两方面的公共政策利好。

一是建立不仅包括最低资本而且还包括监管当局的监督检查和市场纪律的资本治理规定。

二是大幅度提高最低资本要求的风险敏锐度。

3. 完善的资本充足率框架,旨在促进鼓舞银行强化风险治理能力,不断提高风险评估水平。

委员会认为,实现这一目标的途径是,将资本规定与当今的现代化风险治理作法紧密地结合起来,在监管实践中并通过有关风险和资本的信息披露,确保对风险的重视。

4. 委员会修改资本协议的一项重要内容,确实是加强与业内人士和非成员国监管人员之间的对话。

通过多次征求意见,委员会认为,包括多项选择方案的新框架不仅适用于十国集团国家,而且也适用于世界各国的银行和银行体系。

5. 委员会另一项同等重要的工作,确实是研究参加新协议定量测算阻碍分析各行提出的反馈意见。

这方面研究工作的目的,确实是把握各国银行提供的有关新协议各项建议对各行资产将产生何种阻碍。

专门要指出,委员会注意到,来自40多个国家规模及复杂程度各异的350多家银行参加了近期开展的定量阻碍分析〔以下称简QIS3〕。

正如另一份文件所指出,QIS3的结果说明,调整后新框架规定的资本要求总体上与委员会的既定目标相一致。

6. 本文由两部分内容组成。

第一部分简单介绍新资本充足框架的内容及有关实施方面的问题。

在此要紧的考虑是,加深读者对新协议银行各项选择方案的认识。

第二部分技术性较强,大体描述了在2002年10月公布的QIS3技术指导文件之后对新协议有关规定所做的修改。

第一部分新协议的要紧内容7. 新协议由三大支柱组成:一是最低资本要求,二是监管当局对资本充足率的监督检查,三是信息披露。

巴塞尔新资本协议第三版(中文版)-232页

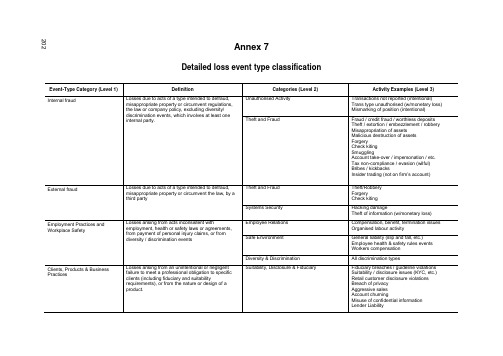

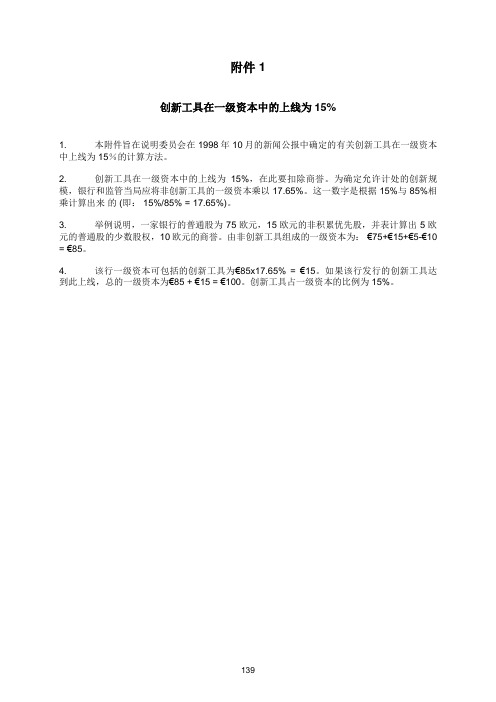

巴塞尔委员会Basel Committeeon Banking Supervision征求意见稿(第三稿)巴塞尔新资本协议The NewBasel Capital Accord 中国银行业监督管理委员会翻译目录概述 (10)导言 (10)第一部分新协议的主要内容 (11)第一支柱:最低资本要求 (11)信用风险标准法 (11)内部评级法(Internal ratings-based (IRB) approaches) (12)公司、银行和主权的风险暴露 (13)零售风险暴露 (14)专业贷款(Specialised lending) (14)股权风险暴露(Equity exposures) (14)IRB法的实施问题 (15)证券化 (15)操作风险 (16)第二支柱和第三支柱:监管当局的监督检查和市场纪律 (17)监管当局的监督检查 (17)市场纪律 (18)新协议的实施 (18)朝新协议过渡 (18)有关前瞻性问题 (19)跨境实施问题 (20)今后的工作 (20)第二部分: 对QIS3技术指导文件的修改 (21)导言 21允许使用准备 (21)合格的循环零售风险暴露(qualifying revolving retail exposures,QRRE)..22住房抵押贷款 (22)专业贷款(specialised lending, SL) (22)高波动性商业房地产(high volatility commercial real estate ,HVCRE).23信用衍生工具 (23)证券化 (23)操作风险 (24)缩写词 (26)第一部分:适用范围 (28)A.导言 (28)B.银行、证券公司和其他附属金融企业 (28)C.对银行、证券公司和其他金融企业的大额少数股权投资 (29)D.保险公司 (29)E.对商业企业的大额投资 (30)F.根据本部分的规定对投资的扣减 (31)第二部分:第一支柱-最低资本要求 (33)I. 最低资本要求的计算 (33)II.信用风险-标准法(Standardised Approach) (33)A.标准法 — 一般规则 (33)1.单笔债权的处理 (34)(i)对主权国家的债权 (34)(ii)对非中央政府公共部门实体(public sector entities)的债权 (35)(iii)对多边开发银行的债权 (35)(iv) 对银行的债权 (36)(v)对证券公司的债权 (37)(vi)对公司的债权 (37)(vii)包括在监管定义的零售资产中的债权 (37)(viii) 对居民房产抵押的债权 (38)(ix)对商业房地产抵押的债权 (38)(x)逾期贷款 (39)(xi)高风险的债权 (39)(xii)其他资产 (40)(xiii) 资产负债表外项目 (40)2.外部评级 (40)(i)认定程序 (40)(ii)资格标准 (40)3.实施中需考虑的问题 (41)(i)对应程序(mapping process) (41)(ii)多方评级结果的处理 (42)(iii)发行人评级和债项评级(issuer versus issues assessment) (42)(iv)本币和外币的评级 (42)(v)短期和长期评级 (43)(vi)评级的适用范围 (43)(vii)被动评级(unsolicited ratings) (43)B. 标准法—信用风险缓释(Credit risk mitigation) (44)1.主要问题 (44)(i)综述 (44)(ii) 一般性论述 (44)(iii)法律确定性 (45)2.信用风险缓释技术的综述 (45)(i)抵押交易 (45)(ii) 表内净扣(On-balance sheet netting) (47)(iii)担保和信用衍生工具 (47)(iv) 期限错配 (47)(v) 其他问题 (48)3.抵押品 (48)(i)合格的金融抵押品 (48)(ii) 综合方法 (49)(iii)简单方法 (56)(iv) 抵押的场外衍生工具交易 (57)4.表内净扣 (57)5.担保和信用衍生工具 (58)(i)操作要求 (58)(ii)合格的担保人/信用保护提供者的范围 (60)(iii)风险权重 (60)(iv)币种错配 (60)(v)主权担保 (61)6.期限错配 (61)7.与信用风险缓释相关的其他问题的处理 (62)(i)对信用风险缓释技术池(pools of CRM techniques)的处理 (62)(ii) 第一违约的信用衍生工具 (62)(iii)第二违约的信用衍生工具 (62)III. 信用风险——IRB法 (62)A.概述 (62)B.IRB法的具体要求 (63)1.风险暴露类别 (63)(i) 公司暴露的定义 (63)(ii) 主权暴露的定义 (65)(iii) 银行暴露的定义 (65)(iv) 零售暴露的定义 (65)(v)合格的循环零售暴露的定义 (66)(vi) 股权暴露的定义 (67)(vii)合格的购入应收账款的定义 (68)2.初级法和高级法 (69)(i)公司、主权和银行暴露 (69)(ii) 零售暴露 (70)(iii) 股权暴露 (70)(iv) 合格的购入应收账款 (70)3. 在不同资产类别中采用IRB法 (70)4.过渡期安排 (71)(i)采用高级法的银行平行计算资本充足率 (71)(ii) 公司、主权、银行和零售暴露 (72)(iii) 股权暴露 (72)C.公司、主权、及银行暴露的规定 (73)1.公司、主权和银行暴露的风险加权资产 (73)(i)风险加权资产的推导公式 (73)(ii) 中小企业的规模调整 (73)(iii) 专业贷款的风险权重 (74)2.风险要素 (75)(i)违约概率 (75)(iii)违约风险暴露 (79)(iv) 有效期限 (80)D.零售暴露规定 (82)1.零售暴露的风险加权资产 (82)(i) 住房抵押贷款 (82)(ii) 合格的循环零售贷款 (82)(iii) 其他零售暴露 (83)2.风险要素 (83)(i)违约概率和违约损失率 (83)(ii) 担保和信贷衍生产品的认定 (83)(iii) 违约风险暴露 (83)E.股权暴露的规则 (84)1.股权暴露的风险加权资产 (84)(i)市场法 (84)(ii) 违约概率/违约损失率方法 (85)(iii) 不采用市场法和违约概率/违约损失率法的情况 (86)2. 风险要素 (87)F. 购入应收账款的规则 (87)1.违约风险的风险加权资产 (87)(i)购入的零售应收账款 (87)(ii) 购入的公司应收账款 (87)2.稀释风险的风险加权资产 (89)(i)购入折扣的处理 (89)(ii) 担保的认定 (89)G. 准备的认定 (89)H.IRB法的最低要求 (90)1.最低要求的内容 (91)2.遵照最低要求 (91)3.评级体系设计 (91)(i)评级维度 (92)(ii) 评级结构 (93)(iv) 评估的时间 (94)(v)模型的使用 (95)(vi) 评级体系设计的记录 (95)4.风险评级体系运作 (96)(i) 评级的涵盖范围 (96)(ii) 评级过程的完整性 (96)(iii) 推翻评级的情况(Overrides) (97)(iv) 数据维护 (97)(v)评估资本充足率的压力测试 (98)5. 公司治理和监督 (98)(i)公司治理(Corporate governance) (98)(ii) 信用风险控制 (99)(iii) 内审和外审 (99)6. 内部评级的使用 (99)7.风险量化 (100)(i)估值的全面要求 (100)(ii) 违约的定义 (101)(iii) 重新确定帐龄(Re-ageing) (102)(iv) 对透支的处理 (102)(v) 所有资产类别损失的的定义 (102)(vi) 估计违约概率的要求 (102)(vii) 自行估计违约损失率的要求 (104)(viii) 自己估计违约风险暴露的要求 (104)(ix) 评估担保和信贷衍生产品成熟性效应的最低要求 (106)(x)估计合格的购入应收账款违约概率和违约损失率的要求 (107)8. 内部评估的验证 (109)9. 监管当局确定的违约损失率和违约风险暴露 (110)(i)商用房地产和居民住房作为抵押品资格的定义 (110)(ii) 合格的商用房地产/居民住房的操作要求 (110)(iii) 认定金融应收账款的要求 (111)10.认定租赁的要求 (113)11.股权暴露资本要求的计算 (114)(i)内部模型法下的市场法 (114)(ii) 资本要求和风险量化 (114)(iv) 验证和形成文件 (116)12.披露要求 (118)IV.信用风险--- 资产证券化框架 (119)A.资产证券化框架下所涉及交易的范围和定义 (119)B. 定义 (120)1. 银行所承担的不同角色 (120)(i)银行作为投资行 (120)(ii) 银行作为发起行 (120)2. 通用词汇 (120)(i) 清收式赎回(clean-up call) (120)(ii) 信用提升(credit enhancement) (120)(iii) 提前摊还(early amortisation) (120)(iv) 超额利差(excess spread) (121)(v)隐性支持(implicit support) (121)(vi) 特别目的机构(Special purpose entity (SPE)) (121)C. 确认风险转移的操作要求 (121)1.传统型资产证券化的操作要求 (121)2.对合成型资产证券化的操作要求 (122)3.清收式赎回的操作要求和处理 (123)D. 对资产证券化风险暴露的处理 (123)1.最低资本要求 (123)(i)扣减 (123)(ii) 隐性支持 (123)2. 使用外部信用评估的操作要求 (124)3. 资产证券化风险暴露的标准化方法 (124)(i) 范围 (124)(ii) 风险权重 (125)(iii) 对于未评级资产证券化风险暴露一般处理方法的例外情况 (125)(iv) 表外风险资产的信用转换系数 (126)(v)信用风险缓释的确认 (127)(vi) 提前摊还规定的资本要求 (128)(viii)对于非控制型具有提前摊还特征的风险暴露的信用风险转换系数的确定 (130)4.资产证券化的内部评级法 (131)(i)范围 (131)(ii) KIRB定义 (131)(iii) 各种不同的方法 (132)(iv) 所需资本最高限 (133)(v) 以评级为基础的方法 (133)(vi) 监管公式 (135)(vii)流动性便利 (137)(viii) 合格服务人现金透支便利 (138)(ix) 信用风险缓释的确认 (138)(x) 提前摊还的资本要求 (138)V. 操作风险 (139)A. 操作风险的定义 (139)B. 计量方法 (139)1.基本指标法 (139)2.标准法 (140)3.高级计量法(Advanced Measurement Approaches ,AMA) (141)C.资格标准 (142)1.一般标准 (142)2.标准法 (142)3. 高级计量法 (143)D.局部使用 (147)VI.交易账户 (148)A.交易账户的定义 (148)B.审慎评估标准 (149)1.评估系统和控制手段 (149)2.评估方法 (149)3.计值调整(储备) (150)C.交易账户对手信用风险的处理 (151)D.标准法对交易账户特定风险资本要求的处理 (152)1.政府债券的特定风险资本要求 (152)2.对未评级债券特定风险的处理原则 (152)3. 采用信用衍生工具套做保值头寸的专项资本要求 (152)4.信用衍生工具的附加系数 (153)第三部分:监督检查 (155)A.监督检查的重要性 (155)B.监督检查的四项主要原则 (155)C.监督检查的具体问题 (161)D:监管检查的其他问题 (167)第四部分:第三支柱——市场纪律 (169)A.总体考虑 (169)1.披露要求 (169)2.指导原则 (169)3.恰当的披露 (169)4. 与会计披露的相互关系 (169)5.重要性(Materiality) (170)6.频率 (170)B.披露要求 (171)1.总体披露原则 (171)2.适用范围 (171)3.资本 (173)4.风险暴露和评估 (175)(i)定性披露的总体要求 (175)(ii)信用风险 (175)(iii)市场风险 (183)(iv)操作风险 (184)(v)银行账户的利率风险 (184)附录1 创新工具在一级资本中的上线为15% (185)附录2 标准法-实施对应程序 (186)附录3 IRB法风险权重的实例 (190)附录4 监管当局对专业贷款设定的标准 (193)附录5 按照监管公式计算信用风险缓释的影响 (207)附录 6 (211)附录7 损失事件分类详表 (215)附录8 (220)概 述导言1.巴塞尔银行监管委员会(以下简称委员会)现公布巴塞尔新资本协议(Basel II, 以下简称巴塞尔II)第三次征求意见稿(CP3,以下简称第三稿)。

巴塞尔协议三

The Basel III Capital Framework:a decisive breakthroughHervé HannounDeputy General Manager, Bank for International Settlements1BoJ-BIS High Level Seminar onFinancial Regulatory Reform: Implications for Asia and the PacificHong Kong SAR, 22 November 2010IntroductionTen days ago, the Basel III framework was endorsed by the G20 leaders in South Korea. Basel III is the centrepiece of the financial reform programme coordinated by the Financial Stability Board.2 This endorsement represents a critical step in the process to strengthen the capital rules by which banks are required to operate. When the international rule-making process is completed and Basel III has been implemented domestically, we will have considerably reduced the probability and severity of a crisis in the banking sector, and by extension enhanced global financial stability.The title of my intervention, “The Basel III Capital Framework: a decisive breakthrough”, sounds like a military metaphor, which may be surprising in the context of a speech on banking regulation. But indeed, the supervisory community had to fight a fierce battle to require more capital and less leverage in the financial system in the face of significant resistance from some quarters of the banking industry.I will highlight nine key breakthroughs in Basel III, from a focus on tangible equity capital to a reduced reliance on banks’ internal models and a greater focus on stress testing, that will increase the safety and soundness of banks individually and the banking system more broadly.1This speech was prepared together with Jason George and Eli Remolona, and benefited from comments by Robert McCauley, Frank Packer, Ilhyock Shim, Bruno Tissot, Stefan Walter and Haibin Zhu.2Basel III: towards a safer financial system, speech by Mr Jaime Caruana, General Manager of the BIS, at the 3rd Santander International Banking Conference, Madrid, 15 September 2010Restricted3Thirty years of bank capital regulation11/2010G20 endorsement of Basel III06/2004Basel II issued 12/1996Market risk amendmentissued 07/1988Basel Iissued 01/2019Full implementation of Basel III12/1997 Market risk amendmentimplemented 12/1992Basel I fullyimplemented 12/2009Basel III consultative document issued 12/2006Basel II implemented 07/2009Revised securitisation & trading book rulesissued 12/2007Basel II advanced approaches implemented 01/2013Basel III implementation begins12/2011Trading book rules implementedTo understand the importance of the Basel III reforms and where we are headed in terms of capital regulation, I think it is instructive if we briefly look back to see where we have come from.Basel I, the first internationally agreed capital standard, was issued some 22 years ago in 1988. Although it only addressed credit risk, it reflected the thinking that we continue to subscribe to today, namely, that the amount of capital required to protect against losses in an asset should vary depending upon the riskiness of the asset. At the same time, it set 8% as the minimum level of capital to be held against the sum of all risk-weighted assets.Following Basel I, in 1996 market risk was added as an area for which capital was required. Then, in 2004, Basel II was issued, adding operational risk, as well as a supervisory review process and disclosure requirements. Basel II also updated and expanded upon the credit risk weighting scheme introduced in Basel I, not only to capture the risk in instruments and activities that had developed since 1988, but also to allow banks to use their internal risk rating systems and approaches to measure credit and operational risk for capital purposes. What could more broadly be referred to as Basel III began with the issuance of the revised securitisation and trading book rules in July 2009, and then the consultative document in December of that year. The trading book rules will be implemented at the end of next year and the new definition of capital and capital requirements in Basel III over a six-year period beginning in January 2013. This extended implementation period for Basel III is designed to give banks sufficient time to adjust through earnings retention and capital-raising efforts.Restricted5The Basel III reform of bank capital regulationCapital ratio =Capital Risk-weighted assets Enhancing risk coverage ●Securitisation products●Trading book●Counterparty credit riskNew capital ratios●Common equity●Tier 1●Total capital●Capital conservation buffer Raising the quality of capital ●Focus on common equity ●Stricter criteria for Tier 1●Harmonised deductions from capital Macroprudential overlay Mitigating procyclicality●Countercyclical bufferLeverage ratio Mitigating systemic risk(work in progress)●Systemic capitalsurcharge for SIFIs●Contingent capital●Bail-in debt●OTC derivativesIn my remarks today I will try to illustrate the fundamental change introduced by Basel III, that of marrying the microprudential and the macroprudential approaches to supervision. Basel III builds upon the firm-specific, risk based frameworks of Basel I and Basel II by introducing a system-wide approach. I will structure my remarks around these two approaches and, in so doing, will demonstrate how Basel III is BOTH a firm-specific, risk based framework and a system-wide, systemic risk-based framework.I. Basel III: a firm-specific, risk-based frameworkLet us look first at the microprudential, firm-specific approach, and consider in turn the three elements of the capital equation: the numerator of the new solvency ratios, ie capital, the denominator, ie risk-weighted assets, and finally the capital ratio itself.A. The numerator: a strict definition of capitalRegarding the numerator, the Basel III framework substantially raises the quality of capital. Basically, in the old definition of capital, a bank could report an apparently strong Tier 1 capital ratio while at the same time having a weak tangible common equity ratio. Prior to the crisis, the amount of tangible common equity of many banks, when measured against risk-weighted assets, was as low as 1 to 3%, net of regulatory deductions. That’s a risk-based leverage of between 33 to 1 and 100 to 1. Global banks further increased their leverage by infesting the Tier 1 part of their capital structure with hybrid “innovative” instruments with debt-like features.In the old definition, capital comprised various elements with a complex set of minimums and maximums for each element. We had Tier 1 capital, innovative Tier 1, upper and lower Tier 2, Tier 3 capital, each with their own limits which were sometimes a function of other capital elements. The complexity in the definition of capital made it difficult to determine what capital would be available should losses arise. This combination of weaknesses permitted tangible common equity capital, the best form of capital, to be as low as 1% of risk-weighted assets.In addition to complicated rules around what qualifies as capital, there was a lack of harmonisation of the various deductions and filters that are applied to the regulatory capital calculation. And finally there was a complete lack of transparency and disclosure on banks’ structure of capital, making it impossible to compare the capital adequacy of global banks.As we learned again during the crisis, credit losses and writedowns come directly out of retained earnings and therefore common equity. It is thus critical that banks’ risk exposures are backed by a high-quality capital base. This is why the new definition of capital properly focuses on common equity capital.The concept of Tier 1 that we are familiar with will continue to exist and will include common equity and other instruments that have a loss-absorbing capacity on a “going concern” basis,3 for example certain preference shares. Innovative capital instruments which were permitted in limited amount as part of Tier 1 capital will no longer be permitted and those currently in existence will be phased out.Tier 2 capital will continue to provide loss absorption on a “gone concern” basis1 and will typically consist of subordinated debt. Tier 3 capital, which was used to cover a portion of a bank’s market risk capital charge, will be eliminated and deductions from capital will be harmonised. With respect to transparency, banks will be required to provide full disclosure and reconciliation of all capital elements.The overarching point with respect to the numerator of the capital equation is the focus on tangible common equity, the highest-quality component of a bank’s capital base, and therefore, the component with the greatest loss-absorbing capacity. This is the first breakthrough in Basel III.B. The denominator: enhanced risk coverageRegarding the denominator, Basel III substantially improves the coverage of the risks, especially those related to capital market activities: trading book, securitisation products, counterparty credit risk on OTC derivatives and repos.In the period leading up to the crisis, when banks were focusing their business activities on these areas, we saw a significant increase in total assets. Yet under the Basel II rules, risk-weighted assets showed only a modest increase. This point is made clear in the following chart showing the increase in both total assets and risk-weighted assets for the 50 largest banks in the world from 2004 to 2010. This phenomenon was more pronounced for some countries and regions than for others.3Tier 1 capital is loss-absorbing on a “going concern” basis (ie the financial institution is solvent). Tier 2 capital absorbs losses on a “gone concern” basis (ie following insolvency and upon liquidation).Restricted9I. Firm specific framework (microprudential)B. The denominator: enhanced risk coverage1. From 2004 to 2009, total assets at the top 50 banks have increased at a more rapid pace than risk weighted assets2. The need to monitor the relationship between risk weighted assets and total assets which varies greatly across countriesand underscores the importance of consistent implementation of theglobal regulatory standards across jurisdictionsFor global banks the enhanced risk coverage under Basel III is expected to cause risk-weighted assets to increase substantially. This, combined with a tougher definition and level of capital, may tempt banks to understate their risk-weighted assets. This points to the need in future to monitor closely the relationship between risk-weighted assets and total assets with a view to promoting a consistent implementation of the global capital standards across jurisdictions.Risk weighting challengesLet me now focus for a moment on the challenges of getting the risk weights right in a risk-based framework.Many asset classes may appear to be low-risk when seen from a firm-specific perspective. But we have seen that the system-wide build-up of seemingly low-risk exposures can pose substantial threats to broader financial stability. Before the recent crisis, the list of apparently low-risk assets included highly rated sovereigns, tranches of AAA structured products, collateralised repos and derivative exposures, to name just a few. The leverage ratio will help ensure that we do not lose sight of the fact that there are system-wide risks that need to be underpinned by capital.The basic approach of the Basel capital standards has always been to attach higher risk weights to riskier assets. The risk weights themselves and the methodology were significantly enhanced as we moved from Basel I to Basel II, and they have now been further refined under Basel III. Nonetheless, as the crisis has made clear, what is not so risky in normal times may suddenly become very risky during a systemic crisis. Something that looks risk-free may turn out to have rather large tail risk.Focusing a bit more on exposures with low risk weights, let me cite a few examples to illustrate the difficulty of getting the risk weights correct.Sovereigns: the sovereign debt crisis of 2010 has shown that the zero risk weightassumption for AAA and AA-rated sovereigns under the standardised approach of Basel II did not account for the dramatic deterioration in the fiscal and debt positionsof major advanced economies. These exposures are still considered as low-risk but certainly not totally risk-free.∙ OTC derivatives (under CSAs) and repos: the Lehman and Bear Stearns failuresdemonstrated that the very low capital charge on OTC derivatives and repos did not capture the systemic risk associated with the interconnectedness and potential cascade effects in these markets.∙ Senior tranches of securitisation exposures: financial engineering produced AAA-rated tranches of complex products, such as the super-senior tranches of ABS CDOs. These proved much more risky than what would be expected from a AAA exposure. The preferential risk weight of 7% for those super-senior tranches was too low, and the risk weight has now been raised to 20%.For assets with medium risk weights, one could cite the following examples: ∙ Residential mortgages: 35% risk weight under the standardised approach. For highest-quality mortgages: 4.15% risk weight (IRB approach)∙ Highly rated corporates: 20% risk weight under the standardised approach. For best-quality corporates: 14.4% risk weight (IRB approach)∙ Highly rated banks: 20% risk weight (standardised approach)For assets with high risk weights, the following examples can be considered:∙ HVCRE (high volatility commercial real estate)∙ Mezzanine tranches of ABS/CDOs∙ Hedge fund equity stakes: 400% risk weight ∙ Claims on unrated corporates: 100% risk weight Restricted3I. Firm specific framework (microprudential)●●B. The denominator: risk weighting challengesWeak correlation between risk-weights and crisis-related losses Low risk-weights may have contributed to the build-up of system wide risksThe chart above shows how different asset classes fared during the crisis. Relative to their Basel II risk weights, equity stakes in hedge funds, claims on corporates and some retailexposures experienced modest losses during the crisis. By contrast, mortgages, highly rated banks, AAA-rated CDO tranches and sovereigns inflicted rather heavy losses on banks. These cases show that there is a rather weak correlation between risk weights and crisis-related losses during periods of system-wide stress. Moreover, we have also discovered that low risk weights can lead to an excessive build-up of system-wide risks. Recognising this problem, the Basel Committee has now introduced a backstop simple leverage ratio, which will require a minimum ratio of capital to total assets without any risk weights. I will come back to this later.The trading book and securitisationsTwo areas the crisis has revealed as needing enhanced risk coverage are the trading book and securitisations. Here capital charges fell short of risk exposures. Basel II focused primarily on the banking book, where traditional assets such as loans are held. But the major losses during the 2007–09 financial crisis came from the trading book, especially the complex securitisation exposures such as collateralised debt obligations. As shown in the table below, the capital requirements for trading assets were extremely low, even relative to banks’ own economic capital estimates. The Basel Committee has addressed this anomaly.Restricted15Trading assetsand marketriskcapitalrequirements¹The revised framework now requires the following:∙Introduction of a 12-month stressed VaR capital charge; ∙Incremental risk capital charge applied to the measurement of specific risk in credit sensitive positions when using VaR; ∙Similar treatment for trading and banking book securitisations; ∙Higher risk weights for resecuritisations (20% instead of 7% for AAA-rated tranches); ∙ Higher credit conversion factors for short-term liquidity facilities to off-balance sheetconduits and SIVs (the shadow banking system); andMore rigorous own credit analyses of externally rated securitisation exposures with less reliance on external ratings.As a result of this enhanced risk coverage, banks will now hold capital for trading book assets that, on average, is about four times greater than that required by the old capital requirements. The Basel Committee is also conducting a fundamental review of the market risk framework rules, including the rationale for the distinction between banking book and trading book. This is the second Basel III breakthrough: eradicate the trading book loophole, ie eliminate the possibility of regulatory arbitrage between the banking and trading books.Counterparty credit risk on derivatives and reposThe Basel Committee is also strengthening the capital requirements for counterparty credit risk on OTC derivatives and repos by requiring that these exposures be measured using stressed inputs. Banks also must hold capital for mark to market losses (credit valuation adjustments – CVA) associated with the deterioration of a counterparty’s credit quality. The Basel II framework addressed counterparty credit risk only in terms of defaults and credit migrations. But during the crisis, mark to market losses due to CVA (which actually represented two thirds of the losses from counterparty credit risk, only one third being due to actual defaults) were not directly capitalised.C. Capital ratios: calibration of the new requirementsWith a capital base whose quality has been enhanced, and an expanded coverage of risks both on- and off-balance sheet, the Basel Committee has made great strides in strengthening capital standards. But in addition to the quality of capital and risk coverage, it also calibrated the capital ratio such that it will now be able to absorb losses not only in normal times, but also during times of economic stress.To this end, banks will now be required to hold a minimum of 4.5% of risk-weighted assets in tangible common equity versus 2% under Basel II. In addition, the Basel Committee is requiring a capital conservation buffer – which I will discuss in just a moment – of 2.5%. Taken together, this means that banks will need to maintain a 7% common equity ratio. When one considers the tighter definition of capital and enhanced risk coverage, this translates into roughly a sevenfold increase in the common equity requirement for internationally active banks. This represents the third breakthrough.Restricted18I. Firm-specific framework (microprudential)C. Capital ratio: the new requirementsIncreases under Basel III are even greater when one considersthe stricter definition of capital and enhanced risk-weighting10.588.567.02.54.5Basel IIINewdefinition andcalibration Equivalent to around 2% for an average international bank underthe new definition Equivalent to around 1% for an averageinternational bank under the new definition Memo:842Basel II RequiredMinimum Required Minimum Required Conservationbuffer Minimum Total capital Tier 1 capital Common equityCapital requirementsAs a percentageof risk-weightedassets Third breakthrough: an average sevenfold increase in the common equityrequirements for global banksThis higher level of capital is calibrated to absorb the types of losses associated with crises like the previous one.The private sector has complained that these new requirements will cause them to curtail lending or increase the cost of borrowing. In an effort to address some of the industry’s concerns, the Basel Committee has agreed upon extended transitional arrangements that will allow the banking sector to meet the higher capital standards through earnings retention and capital-raising.The new standards will take effect on 1 January 2013 and for the most part will become fully effective by January 2019.D. Capital conservationA fourth key breakthrough of Basel III is that banks will no longer be able to pursue distribution policies that are inconsistent with sound capital conservation principles. We have learned from the crisis that it is prudent for banks to build capital buffers during times of economic growth. Then, as the economy begins to contract, banks may be forced to use these buffers to absorb losses. But to offset the contraction of the buffer, banks could have the ability to restrict discretionary payments such as dividends and bonuses to shareholders, employees and other capital providers. Of course they could also raise additional capital in the market.In fact, what we witnessed during the crisis was a practice by banks to continue making these payments even as their financial condition and capital levels deteriorated. This practice, in effect, puts the interest of the recipients of these payments above those of depositors, and this is simply not acceptable.To address the need to maintain a buffer to absorb losses and restrict the ability of banks to make inappropriate distributions as their capital strength declines, the Basel Committee will now require banks to maintain a buffer of 2.5% of risk-weighted assets. This buffer must be held in tangible common equity capital.As a bank’s capital ratio declines and it uses the conservation buffer to absorb losses, the framework will require banks to retain an increasingly higher percentage of their earnings and will impose restrictions on distributable items such as dividends, share buybacks and discretionary bonuses. Supervisors now have the power to enforce capital conservation discipline. This is a fundamental change.II. Basel III: A system-wide, systemic risk-based frameworkOverviewReturning to the theme of my discussion, Basel III is not only a firm-specific risk-based framework, it is also a system-wide, systemic risk-based framework. The so-called macroprudential overlay is designed to address systemic risk and is an entirely new way of thinking about capital.This new dimension of the capital framework consists of five elements. The first is a leverage ratio, a simple measure of capital that supplements the risk-based ratio and which constrains the build-up of leverage in the system. The second is steps taken to mitigate procyclicality, including a countercyclical capital buffer and, although outside a strict discussion of capital, efforts to promote a provisioning framework based upon expected losses rather than incurred losses. The third element of the macroprudential overlay is steps to address the externalities generated by systemically important financial institutions through higher loss-absorbing capacity. The fourth is a framework to address the risk arising from systemically important markets and infrastructures. In particular, I am referring to the OTC derivatives markets. And finally, the macroprudential overlay aims to better capture systemic risk and tail events in the banks’ own risk management framework, including through risk modelling, stress testing and scenario analysis.ratioA. LeverageIn the lead up to the crisis many banks reported strong Tier 1 risk based ratios while, at the same time, still being able to build up high levels of on and off balance sheet leverage.In response to this, the Basel Committee has introduced a simple, non-risk-based leverage ratio to supplement the risk-based capital requirements. The leverage ratio has the added benefit of serving as a safeguard against model risk and any attempts to circumvent the risk-based capital requirements.The leverage ratio will be a measure of a bank’s Tier 1 capital as a percentage of its assets plus off balance sheet exposures and derivatives.For derivatives, regulatory net exposure will be used plus an add-on for potential future exposure. Netting of all derivatives will be permitted. In so doing, the Basel Committee has successfully solved the difficulty resulting from the divergence between the main accounting frameworks. (Bank leverage is significantly lower under US GAAP than under IFRS due to the netting of OTC derivatives allowed under the former. Given that banks may hold offsetting contracts, US GAAP allows banks to report their net exposures while IFRS does not allow netting. As a result, the size of a bank‘s total assets can vary significantly based on the treatment of this one accounting item.)The leverage ratio will also include off-balance sheet items in the measure of total assets. These off-balance sheet items, including commitments, letters of credit and the like, unless they are unconditionally cancellable, will be converted using a flat 100% credit conversion factor.To highlight the importance of the leverage ratio we need look no further than the increase in total assets in the years leading up to the crisis versus the increase in risk-weighted assets. It is obvious that balance sheets were being leveraged, but the risk-based framework failed tocapture this dynamic, as suggested by the following chart depicting risk-weighted and totalassets for the top 50 banks.Restricted5II. System-wide approach (macroprudential)A. Leverage ratiothe importance of the banking sector building up additional capital defences in periods where the risks of system-wide stress are growing markedly.While some in the financial community are sceptical about the usefulness of a leverage ratio, the Basel Committee’s Top-down Capital Calibration Group recently completed a study that showed that the leverage ratio did the best job of differentiating between banks that ultimately required official sector support in the recent crisis and those that did not.This leads me to the fifth breakthrough: Basel III is a framework that remains risk-based but now includes – through the Tier 1 leverage ratio – a backstop approach that also captures risks arising from total assets. The risk-based and leverage ratios reinforce each other.For all of these reasons, public policymakers and legislators must resist the intense lobbying effort of the industry to water down the leverage ratio to merely a Pillar 2 instrument. Giving in to this lobbying would increase the exposure of taxpayers to future bank failures and hurt long-term growth over a full credit cycle since sustainable credit growth cannot be achieved through excessive leverage.B. Countercyclical capital bufferWe have learned that procyclicality, which is inherent in banking, has exacerbated the impact of the crisis. While we will not eliminate cyclicality, what we would like to do is prevent its amplification through the banking sector, particularly that caused by excessive credit growth. This can be achieved through the new countercyclical capital buffer.As the volume of loans grows, if asset price bubbles burst or the economy subsequently enters a downturn and loan quality begins to deteriorate, banks will adopt a very conservative stance when it comes to the granting of new credit. This lack of credit availability only serves to exacerbate the problem, pushing the real economy deeper into trouble with asset prices declining further and the level of non-performing loans increasing further. This in turn causes bank lending to become scarcer still. These interactions highlights of stress, but it helps to ensure that by leading to the build-up of ed in each of the jurisdictions in which the bank has credit exposures.th breakthrough in Basel III.As you know, there is considerable work being done by the Financial Stability Board on how tions, ework for identifying SIFIs and a study of the magnitude of se to the global financial ically infrastructures. This is clearly illustrated ring and trade reporting on OTC derivatives. Derivative counterparty credit exposures to central counterparty clearing The countercyclical capital buffer not only protects the banking sector from losses resulting from periods of excess credit growth followed by period credit remains available during this period of stress. Importantly, during the build-up phase, as credit is being granted at a rapid pace, the countercyclical capital buffer may cause the cost of credit to increase, acting as a brake on bank lending.Each jurisdiction will monitor credit growth in relation to measures such as GDP and, using judgment, assess whether such growth is excessive, there system-wide risk. Based on this assessment they may put in place a countercyclical buffer requirement ranging from 0 to 2.5%. This requirement will be released when system-wide risk dissipates.For banks that are operating in multiple jurisdictions, the buffer will be a weighted average of the buffers appli To give banks time to adjust to a buffer level, jurisdictions will preannounce their countercyclical buffer decisions by 12 months.The introduction of a countercyclical capital charge to mitigate the procyclicality caused by excessive credit growth is the six C. Systemically important financial institutions: additional loss-absorbing capacityto design the best framework for the oversight of systemically important financial institu or SIFIs.4 It is broadly recognised that systemically important banks should have loss-absorbing capacity beyond the basic Basel III standards. This can be achieved by a combination of a systemic capital charge, contingent bonds that convert to equity at a certain trigger point and bail-in debt.Although the work on SIFIs is incomplete at this time, the Basel Committee has committed to complete by mid-2011 a fram additional loss absorbency that global systemically important banks should have. Also by mid-2011, the Basel Committee will complete its assessment of going-concern loss absorbency in some of the various contingent capital structures.What is clear, and this is the seventh breakthrough, is that SIFIs need higher loss-absorbing capacity to reflect the greater risks that they po system. A systemic capital surcharge is the most straightforward, but not the only way to achieve this.D. Systemically important markets and infrastructures (SIMIs): the case of OTCderivativesJust as there are systemically important financial institutions, there are also system important markets and systemically important market by the case of OTC derivatives. In particular, the Lehman failure demonstrated that the very low capital charge on OTC derivatives did not capture the systemic risk associated with the interconnectedness and potential cascade effects in these markets.To address the problem of interconnectedness as it relates to derivatives, the Basel Committee and Financial Stability Board have endorsed central clea4 Reducing the moral hazard posed by systemically important financial institutions , FSB Recommendations and Time Lines, 20 October 2010.。

巴塞尔资本协议中英文完整版(13附录5)

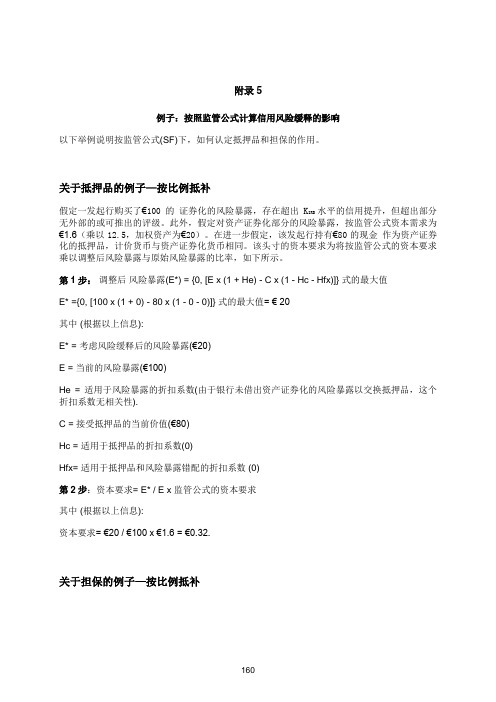

附录5例子:按照监管公式计算信用风险缓释的影响以下举例说明按监管公式(SF)下,如何认定抵押品和担保的作用。

关于抵押品的例子—按比例抵补假定一发起行购买了€100 的证券化的风险暴露,存在超出K IRB 水平的信用提升,但超出部分无外部的或可推出的评级。

此外,假定对资产证券化部分的风险暴露,按监管公式资本需求为€1.6(乘以12.5,加权资产为€20)。

在进一步假定,该发起行持有€80的现金作为资产证券化的抵押品,计价货币与资产证券化货币相同。

该头寸的资本要求为将按监管公式的资本要求乘以调整后风险暴露与原始风险暴露的比率,如下所示。

第1步:调整后风险暴露(E*) = {0, [E x (1 + He) - C x (1 - Hc - Hfx)]} 式的最大值E* ={0, [100 x (1 + 0) - 80 x (1 - 0 - 0)]} 式的最大值= € 20其中 (根据以上信息):E* = 考虑风险缓释后的风险暴露(€20)E = 当前的风险暴露(€100)He = 适用于风险暴露的折扣系数(由于银行未借出资产证券化的风险暴露以交换抵押品,这个折扣系数无相关性).C = 接受抵押品的当前价值(€80)Hc = 适用于抵押品的折扣系数(0)Hfx= 适用于抵押品和风险暴露错配的折扣系数 (0)第2步:资本要求= E* / E x 监管公式的资本要求其中 (根据以上信息):资本要求= €20 / €100 x €1.6 = €0.32.关于担保的例子—按比例抵补除信用风险缓释工具外,该例子中所有涉及抵押品的假设条件均适用。

假定发起行持有其他银行提供的合格,无抵押品的担保,金额为80€。

因此,货币错配的折扣系数不适用。

资本要求如下所示:∙ 资产证券化的保护部分(80€ )的风险权重为保护提供者的风险权重。

保护提供者的风险权重与提供给担保银行无担保贷款的风险权重相同,在内部评级法下也是如此。

假定风险权重是10%。

巴塞尔协议3

巴塞尔协议III巴塞尔协议III(The Basel III Accord)目录• 1 什么是巴塞尔协议III• 2 巴塞尔协议III的出台• 3 巴塞尔协议III的主要内容• 4 巴塞尔协议III对中国银行业的影响• 5 相关条目什么是巴塞尔协议III《巴塞尔协议》是国际清算银行(BIS)的巴塞尔银行业条例和监督委员会的常设委员会———“巴塞尔委员会”于1988年7月在瑞士的巴塞尔通过的“关于统一国际银行的资本计算和资本标准的协议”的简称。

该协议第一次建立了一套完整的国际通用的、以加权方式衡量表内与表外风险的资本充足率标准,有效地扼制了与债务危机有关的国际风险。

[编辑]巴塞尔协议III的出台巴塞尔协议一直都秉承稳健经营和公平竞争的理念,也正因为如此,巴塞尔协议对现代商业银行而言显得日益重要,已成为全球银行业最具有影响力的监管标准之一。

新巴塞尔协议也即巴塞尔协议II经过近十年的修订和磨合于2007年在全球范围内实施,但正是在这一年,爆发了次贷危机,这次席卷全球的次贷危机真正考验了巴塞尔新资本协议。

显然,巴塞尔新资本协议存在顺周期效应、对非正态分布复杂风险缺乏有效测量和监管、风险度量模型有内在局限性以及支持性数据可得性存在困难等固有问题,但我们不能将美国伞形监管模式的缺陷和不足致使次贷危机爆发统统归结于巴塞尔新资本协议。

其实,巴塞尔协议在危机中也得到了不断修订和完善。

经过修订,巴塞尔协议已显得更加完善,对银行业的监管要求也明显提高,如为增强银行非预期损失的抵御能力,要求银行增提缓冲资本,并严格监管资本抵扣项目,提高资本规模和质量;为防范出现类似贝尔斯登的流动性危机,设置了流动性覆盖率监管指标;为防范“大而不能倒”的系统性风险,从资产规模、相互关联性和可替代性评估大型复杂银行的资本需求。

如上所述,自巴塞尔委员会2007年颁布和修订一系列监管规则后,2010年9月12日,由27个国家银行业监管部门和中央银行高级代表组成的巴塞尔银行监管委员会就《巴塞尔协议Ⅲ》的内容达成一致,全球银行业正式步入巴塞尔协议III时代。

巴塞尔资本协议中英文完整版(10附录2(英文))

Annex 2Standardised Approach - Implementing the Mapping Process1. Because supervisors will be responsible for assigning eligible ECAI’s credit risk assessments to the risk weights available under the standardised approach, they will need to consider a variety of qualitative and quantitative factors to differentiate between the relative degrees of risk expressed by each assessment. Such qualitative factors could include the pool of issuers that each agency covers, the range of ratings that an agency assigns, each rating’s meaning, and each agency’s definition of default, among others.2. Quantifiable parameters may help to promote a more consistent mapping of credit risk assessments into the available risk weights under the standardised approach. This annex summarises the Committee’s proposals to help supervisors with mapping exercises. The parameters presented below are intended to provide guidance to supervisors and are not intended to establish new or complement existing eligibility requirements for ECAIs. Evaluating CDRs: two proposed measures3. To help ensure that a particular risk weight is appropriate for a particular credit risk assessment, the Committee recommends that supervisors evaluate the cumulative default rate (CDR) associated with all issues assigned the same credit risk rating. Supervisors would evaluate two separate measures of CDRs associated with each risk rating contained in the standardised approach, using in both cases the CDR measured over a three-year period.∙To ensure that supervisors have a sense of the long-run default experience over time, supervisors should evaluate the ten-year average of the three-year CDR when this depth of data is available.150 For new rating agencies or for those that have compiled less than ten years of default data, supervisors may wish to ask rating agencies what they believe the 10-year average of the three-year CDR would be for each risk rating and hold them accountable for such an evaluation thereafter for the purpose of risk weighting the claims they rate.∙The other measure that supervisors should consider is the most recent three-year CDR associated with each credit risk assessment of an ECAI4. Both measurements would be compared to aggregate, historical default rates of credit risk assessments compiled by the Committee that are believed to represent an equivalent level of credit risk.5. As three-year CDR data is expected to be available from ECAIs, supervisors should be able to compare the default experience of a particular ECAI’s assessments with t hose issued by other rating agencies, in particular major agencies rating a similar population.150 In 2002, for example, a supervisor would calculate the average of the three-year CDRs for issuers assigned to each rating grade (the “cohort”) for each of the ten years 1990-1999.170Mapping risk ratings to risk weights using CDRs6. To help supervisors determine the appropriate risk weights to which an ECAI’s risk ratings should be mapped, each of the CDR measures mentioned above could be compared to the following reference and benchmark values of CDRs:∙For each step in an ECAI’s rating scale, a ten-year average of the three-year CDR would be compared to a long run “reference” three-year CDR that would represent a sense of the long-run international default experience of risk assessments.∙Likewise, for each step in the ECAI’s rating scale, the two most recent three-year CDR would be compared to “benchmarks” for CDRs. This comparison would be intended to determine whether the ECAI’s most recent record of assessing credit risk remains within the CDR supervisory benchmarks.7. Table 1 below illustrates the overall framework for such comparisons.Table 1Comparisons of CDR Measures1511. Comparing an ECAI’s long-run average three-year CDR to a long-run“reference” CDR8. For each credit risk category used in the standardised approach of the New Accord, the corresponding long-run reference CDR would provide information to supervisors on what its default experience has been internationally. The ten-year average of an eligible ECAI’s particular assessment would not be expected to match exactly the long-run reference CDR. The long run CDRs are meant as guidance for supervisors, and not as “targets” that ECAIs would have to meet. The recommended long-run “reference” three-year CDRs for each of the Committee’s credit risk categories are presented in Table 2 below, based on the Committee’s observations of the default experience reported by major rating agencies internationally.151 It should be noted that each major rating agency would be subject to these comparisons as well, in which its individual experience would be compared to the aggregate international experience.171Table 2Proposed long run "reference" three-year CDRs2. Comparing an ECAI’s most recent three-year CDR to CDR Benchmarks9. Since an ECAI’s own CDRs are not intended to match the reference CDRs exactly, it is important to provide a better sense of what upper bounds of CDRs are acceptable for each assessment, and hence each risk weight, contained in the standardised approach. 10. It is the Committee’s general sense that the upper bounds for CDRs should serve as guidance for supervisors and not necessarily as mandatory requirements. Exceeding the upper bound for a CDR would therefore not necessarily require the supervisor to increase the risk weight associated with a particular assessment in all cases if the supervisor is convinced that the higher CDR results from some temporary cause other than weaker credit risk assessment standards.11. To assist supervisors in interpreting whether a CDR falls within an acceptable range for a risk rating to qualify for a particular risk weight, two benchmarks would be set for each assessment, namely a “monitoring” level benchmark and a “trigger” level benchmark.(a) “Monitoring” level benchmark12. Exceeding the “monitoring” level CDR benchmark implies that a rating agency’s current default experience for a particular credit risk-assessment grade is markedly higher than international default experience. Although such assessments would generally still be considered eligible for the associated risk weights, supervisors would be expected to consult with the relevant rating agency to understand why the default experience appears to be significantly worse. If supervisors determine that the higher default experience is attributable to weaker standards in assessing credit risk, they would be expected to assign a higher risk category to the agency’s credit risk assessment.(b) “Trigger” level13. Exceeding the “trigger” level benchmark implies that a rating agency’s default experience is considerably above the international historical default experience for a p articular assessment grade. Thus there is a presumption that the ECAI’s standards for assessing credit risk are either too weak or are not applied appropriately. If the observed three-year CDR exceeds the trigger level in two consecutive years, supervisors would be expected to move the risk assessment into a less favourable risk category. However, if supervisors determine that the higher observed CDR is not attributable to weaker 172assessment standards, then they may exercise judgement and retain the original risk weight.15214. In all cases where the supervisor decides to leave the risk category unchanged, it may wish to rely on Pillar 2 of the New Accord and encourage banks to hold more capital temporarily or to establish higher reserves.15. When the supervisor has increased the associated risk category, there would be the opportunity for the assessment to again map to the original risk category if the ECAI is able to demonstrate that its three-year CDR falls and remains below the monitoring level for two consecutive years.(c) Calibrating the benchmark CDRs16. After reviewing a variety of methodologies, the Committee decided to use Monte Carlo simulations to calibrate both the monitoring and trigger levels for each credit risk assessment category. In particular, the proposed monitoring levels were derived from the 99.0th percentile confidence interval and the trigger level benchmark from the 99.9th percentile confidence interval. The simulations relied on publicly available historical default data from major international rating agencies. The levels derived for each risk assessment category are presented in Table 3 below, rounded to the first decimal:Table 3Proposed three-year CDR benchmarks152 For example, if supervisors determine that the higher default experience is a temporary phenomenon, perhaps because it reflects a temporary or exogenous shock such as a natural disaster, then the risk weighting proposed in the standardised approach could still apply. Likewise, a breach of the trigger level by several ECAIs simultaneously may indicate a temporary market change or exogenous shock as opposed to a loosening of credit standards. In either scenario, supervisors would be expected to monitor the ECAI’s assessments to ensure that the higher default experience is not the result of a loosening of credit risk assessment standards.173。

Basel+III 巴塞尔协议3英文版

2. 3. 4. 5. B. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. III. A. B. C. IV. A. B. C. D. E. F. V. A. B.

Asset value correlation multiplier for large financial institutions ................. 39 Collateralised counterparties and margin period of risk ............................. 40 Central counterparties................................................................................ 46 Enhanced counterparty credit risk management requirements.................. 46 Standardised inferred rating treatment for long-term exposures................ 51 Incentive to avoid getting exposures rated................................................. 52 Incorporation of IOSCO’s Code of Conduct Fundamentals for Credit Rating Agencies .................................................................................................... 52 “Cliff effects” arising from guarantees and credit derivatives - Credit risk mitigation (CRM) ........................................................................................ 53 Unsolicited ratings and recognition of ECAIs ............................................. 54

巴塞尔协议三中英对照

Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision announces higher global minimum capital standards12 September 2010At its 12 September 2010 meeting, the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision, the oversight body of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, announced a substantial strengthening of existing capital requirements and fully endorsed the agreements it reached on 26 July 2010. These capital reforms, together with the introduction of a global liquidity standard, deliver on the core of the global financial reform agenda and will be presented to the Seoul G20 Leaders summit in November.The Committee's package of reforms will increase the minimum common equity requirement from 2% to %. In addition, banks will be required to hold a capital conservation buffer of % to withstand future periods of stress bringing the total common equity requirements to 7%. This reinforces the stronger definition of capital agreed by Governors and Heads of Supervision in July and the higher capital requirements fortrading, derivative and securitisation activities to be introduced at the end of 2011.Mr Jean-Claude Trichet, President of the European Central Bank and Chairman of the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision, said that "the agreements reached today are a fundamental strengthening of global capital standards." He added that "their contribution to long term financial stability and growth will be substantial. The transition arrangements will enable banks to meet the new standards while supporting the economic recovery." Mr Nout Wellink, Chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and President of the Netherlands Bank, added that "the combination of a much stronger definition of capital, higher minimum requirements and the introduction of new capital buffers will ensure that banks are better able to withstand periods of economic and financial stress, therefore supporting economic growth."Increased capital requirementsUnder the agreements reached today, the minimum requirement for common equity, the highest form of loss absorbing capital,will be raised from the current 2% level, before the application of regulatory adjustments, to % after the application of stricter adjustments. This will be phased in by 1 January 2015. The Tier 1 capital requirement, which includes common equity and other qualifying financial instruments based on stricter criteria, will increase from 4% to 6% over the same period. (Annex 1 summarises the new capital requirements.)The Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision also agreed that the capital conservation buffer above the regulatory minimum requirement be calibrated at % and be met with common equity, after the application of deductions. The purpose of the conservation buffer is to ensure that banks maintain a buffer of capital that can be used to absorb losses during periods of financial and economic stress. While banks are allowed to draw on the buffer during such periods of stress, the closer their regulatory capital ratios approach the minimum requirement, the greater the constraints on earnings distributions. This framework will reinforce the objective of sound supervision and bank governance and address the collective action problem that has prevented some banks fromcurtailing distributions such as discretionary bonuses and high dividends, even in the face of deteriorating capital positions.A countercyclical buffer within a range of 0% - % of common equity or other fully loss absorbing capital will be implemented according to national circumstances. The purpose of the countercyclical buffer is to achieve the broader macroprudential goal of protecting the banking sector from periods of excess aggregate credit growth. For any given country, this buffer will only be in effect when there is excess credit growth that is resulting in a system wide build up of risk. The countercyclical buffer, when in effect, would be introduced as an extension of the conservation buffer range.These capital requirements are supplemented by a non-risk-based leverage ratio that will serve as a backstop to the risk-based measures described above. In July, Governors and Heads of Supervision agreed to test a minimum Tier 1 leverage ratio of 3% during the parallel run period. Based on the results of the parallel run period, any final adjustmentswould be carried out in the first half of 2017 with a view to migrating to a Pillar 1 treatment on 1 January 2018 based on appropriate review and calibration.Systemically important banks should have loss absorbing capacity beyond the standards announced today and work continues on this issue in the Financial Stability Board and relevant Basel Committee work streams. The Basel Committee and the FSB are developing a well integrated approach to systemically important financial institutions which could include combinations of capital surcharges, contingent capital and bail-in debt. In addition, work is continuing to strengthen resolution regimes. The Basel Committee also recently issued a consultative document Proposal to ensure the loss absorbency of regulatory capital at the point of non-viability. Governors and Heads of Supervision endorse the aim to strengthen the loss absorbency of non-common Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital instruments.Transition arrangementsSince the onset of the crisis, banks have already undertakensubstantial efforts to raise their capital levels. However, preliminary results of the Committee's comprehensive quantitative impact study show that as of the end of 2009, large banks will need, in the aggregate, a significant amount of additional capital to meet these new requirements. Smaller banks, which are particularly important for lending to the SME sector, for the most part already meet these higher standards.The Governors and Heads of Supervision also agreed on transitional arrangements for implementing the new standards. These will help ensure that the banking sector can meet the higher capital standards through reasonable earnings retention and capital raising, while still supporting lending to the economy. The transitional arrangements, which are summarised in Annex 2, include:National implementation by member countries will begin on 1 January 2013. Member countries must translate the rules into national laws and regulations before this date. As of 1 January 2013, banks will be required to meet the following new minimum requirements in relation to risk-weighted assets (RWAs):% common equity/RWAs;% Tier 1 capital/RWAs, and% total capital/RWAs.The minimum common equity and Tier 1 requirements will be phased in between 1 January 2013 and 1 January 2015. On 1 January 2013, the minimum common equity requirement will rise from the current 2% level to %. The Tier 1 capital requirement will rise from 4% to %. On 1 January 2014, banks will have to meet a 4% minimum common equity requirement and a Tier 1 requirement of %. On 1 January 2015, banks will have to meet the % common equity and the 6% Tier 1 requirements. The total capital requirement remains at the existing level of % and so does not need to be phased in. The difference between the total capital requirement of % and the Tier 1 requirement can be met with Tier 2 and higher forms of capital.The regulatory adjustments (ie deductions and prudential filters), including amounts above the aggregate 15% limit for investments in financial institutions, mortgage servicing rights, and deferred tax assets from timing differences, would be fully deducted from common equity by 1 January 2018.In particular, the regulatory adjustments will begin at 20% of the required deductions from common equity on 1 January 2014, 40% on 1 January 2015, 60% on 1 January 2016, 80% on 1 January 2017, and reach 100% on 1 January 2018. During this transition period, the remainder not deducted from common equity will continue to be subject to existing national treatments.The capital conservation buffer will be phased in between 1 January 2016 and year end 2018 becoming fully effective on 1 January 2019. It will begin at % of RWAs on 1 January 2016 and increase each subsequent year by an additional percentage points, to reach its final level of % of RWAs on 1 January 2019. Countries that experience excessive credit growth should consider accelerating the build up of the capital conservation buffer and the countercyclical buffer. National authorities have the discretion to impose shorter transition periods and should do so where appropriate.Banks that already meet the minimum ratio requirement during the transition period but remain below the 7% common equity target (minimum plus conservation buffer) should maintain prudent earnings retention policies with a view to meeting the conservation buffer as soon as reasonably possible.Existing public sector capital injections will be grandfathered until 1 January 2018. Capital instruments that no longer qualify as non-common equity Tier 1 capital or Tier 2 capital will be phased out over a 10 year horizon beginning 1 January 2013. Fixing the base at the nominal amount of such instruments outstanding on 1 January 2013, their recognition will be capped at 90% from 1 January 2013, with the cap reducing by 10 percentage points in each subsequent year. In addition, instruments with an incentive to be redeemed will be phased out at their effective maturity date.Capital instruments that no longer qualify as common equity Tier 1 will be excluded from common equity Tier 1 as of 1 January 2013. However, instruments meeting the following three conditions will be phased out over the same horizon described in the previous bullet point: (1) they are issued by a non-joint stock company 1 ; (2) they are treated as equity under the prevailing accounting standards; and (3) they receive unlimited recognition as part of Tier 1 capital under current national banking law.Only those instruments issued before the date of this press release should qualify for the above transition arrangements.Phase-in arrangements for the leverage ratio were announced in the 26 July 2010 press release of the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision. That is, the supervisory monitoring period will commence 1 January 2011; the parallel run period will commence 1 January 2013 and run until 1 January 2017; and disclosure of the leverage ratio and its components will start 1 January 2015. Based on the results of the parallel run period, any final adjustments will be carried out in the first half of 2017 with a view to migrating to a Pillar 1 treatment on 1 January 2018 based on appropriate review and calibration.After an observation period beginning in 2011, the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) will be introduced on 1 January 2015. The revised net stable funding ratio (NSFR) will move to a minimum standard by 1 January 2018. The Committee will put in place rigorous reporting processes to monitor the ratios during the transition period and will continue to review the implications of these standards for financial markets, credit extension and economic growth, addressing unintended consequences as necessary.The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision provides a forum for regular cooperation on banking supervisory matters. It seeks to promote and strengthen supervisory and risk management practices globally. The Committee comprises representatives from Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States.The Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision is the governing body of the Basel Committee and is comprised of central bank governors and (non-central bank) heads of supervision from member countries. The Committee's Secretariat is based at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland.Annex 1: Calibration of the Capital Framework (PDF 1 page, 19 kb)Annex 2: Phase-in arrangements (PDF 1 page, 27 kb)Full press release (PDF 7 pages, 56 kb)--------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 Non-joint stock companies were not addressed in the Basel Committee's 1998 agreement on instruments eligible for inclusion in Tier 1 capital as they do not issue voting common shares.最新巴塞尔协议3全文央行行长和监管当局负责人集团1宣布较高的全球最低资本标准1央行行长和监管当局负责人集团是巴塞尔委员会中的监管机构,是由成员国央行行长和监管当局负责人组成的。

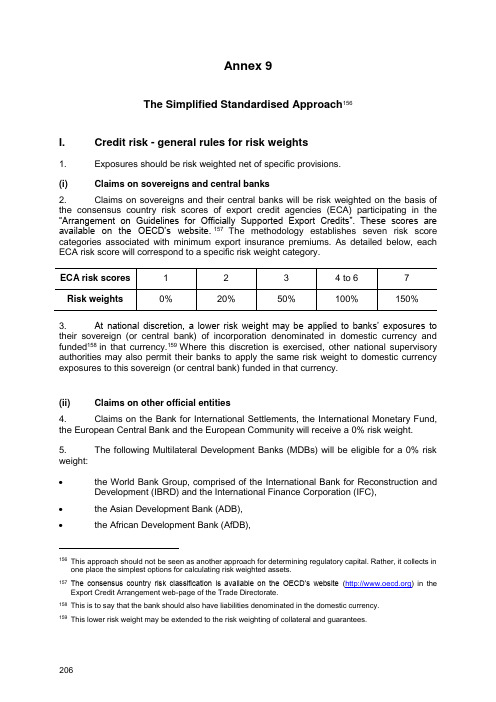

巴塞尔资本协议中英文完整版(17附录9(英文))