Lloyd's_Law_Reports-_BAYVIEW_MOTORS_LTD._v._MITSUI_MARINE_AND_FIRE_INSURANCE_CO._LTD._AND_OTHERS_[20

AvailabilityCascadesandRiskRegulation

315. Lior J. Strahilevitz, Wealth without Markets? (November 2006)

Timur Kuran

Follow this and additional works at:/

public_law_and_legal_theory

Part of the Law Commons

This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Working Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact

312. Dennis W. Carlton and Randal C. Picker, Antitrust and Regulation (October 2006)

313. Robert Cooter and Ariel Porat, Liability Externalities and Mandatory Choices: Should Doctors Pay Less? (November 2006)

University of Chicago Law School

会计信息质量外文文献及翻译

LNTU …Acc附录A会计信息质量在投资中的决策作用对私人信息和监测的影响安妮比蒂,美国俄亥俄州立大学瓦特史考特廖,多伦多大学约瑟夫韦伯,美国麻省理工学院1简介管理者与外部资本的供应商信息是不对称的在这种情况下企业是如何影响金融资本的投资的呢?越来越多的证据表明,会计质量越好,越可以减少信息的不对称和对融资成本的约束。

与此相一致的可能性是,减少了具有更高敏感性的会计质量的公司的投资对内部产生的现金流量。

威尔第和希拉里发现,对企业投资和与投资相关的会计质量容易不足,是容易引发过度投资的原因。

当投资效率低下时,会计的质量重要性可以减轻外部资本的影响,供应商有可能获得私人信息或可直接监测管理人员。

通过访问个人信息与控制管理行为,外部资本的供应商可以直接影响企业的投资,降低了会计质量的重要性。

符合这个想法的还有比德尔和希拉里的比较会计对不同国家的投资质量效益的影响。

他们发现,会计品质的影响在于美国投资效益,而不是在口本。

他们认为,一个可能的解释是不同的是债务和股权的美国版本的资本结构混合了SUS的日本企业。

我们研究如何通过会计质量灵敏度的重要性来延长不同资金来源对企业的投资现金流量的不同影响。

直接测试如何影响不同的融资来源会计,通过最近获得了债务融资的公司来投资敏感性现金流的质量的效果,债务融资的比较说明了对那些不能够通过他们的能力获得融资的没有影响。

为了缓解这一问题,我们限制我们的样本公司有所有最近获得的债务融资和利用访问的差异信息和监测通过公共私人债务获得连续贷款的建议。

我们承认,投资内部现金流敏感性叮能较低获得债务融资的可能性。

然而,这种町能性偏见拒绝了我们的假设。

具体来说,我们确定的数据样本证券公司有1163个采样公司(议会),通过发行资本公共债务或银团债务。

我们限制我们的样本公司最近获得的债务融资持有该公司不断融资与借款。

然而,在样本最近获得的债务融资的公司,也有可能是信号,在资本提供进入私人信息差异和约束他们放在管理中的行为。

Making the Connection in the Caribbean… to the Rest of the World

(Miss Universe participants at Trinidad and Tobago)

If You’re Not Sure Where to Begin…

Check to see what’s in your own library first Think globally, act locally…first

Making the Connection in the Caribbean…to the Rest of the World Lyonette Louis-Jacques University of Chicago Law Library llou@

ACURIL, San Juan, Puerto Rico, June 4, 2003

Standard Tools (Books)

Reynolds & Flores PIL Nutshell CIA World Factbook Treaty indexes (TIF) Martindale-Hubbell’s Law Digest The Bluebook Encyclopedia of Public International Law International Legal Materials (ILM)

BAILII (British and Irish Legal Information Institute)

Inner Temple Library’s AccessToLaw Page

eagle-i (e-access to global legal information)

Treaties

People Sources (Specialists in FCIL Research)

A Hybrid Algorithm for the Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Window

A Hybrid Algorithm for the Vehicle Routing Problem withTime WindowGuilherme Bastos Alvarenga, Ricardo Martins de Abreu Silva, Rudini Menezes SampaioDept. of Computer Science, Federal University of Lavras, Brazil{guilherme, rmas, rudini} @ dcc.ufla.brAbstract.The Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows (VRPTW) is a well-known and complex combinatorial problem, which has received considerable attention in recent years. The VRPTW benchmark problems of Solomon (1987) have been most commonly chosen to evaluate and compare all exact and heu-ristic algorithms. A genetic algorithm and a set partitioning two phases approach has obtained competitive results in terms of total travel distance minimization. However, a great number of heuristics has used the number of vehicles as the first objective and travel distance as the second, subject to the first. This paper proposes a three phases approach considering both objectives. Initially, a hierarchical tournament selection genetic algorithm is applied. It can reach all best results in number of vehicles of the 56 Solomon’s prob-lems explored in the literature. After then, the two phase approach, the genetic and the set partitioning, is applied to minimize the travel distance as the second objective.Keywords: vehicle routing, hybrid genetic algorithm, hierarchical tournament selection(Received April, 07, 2005 / Accepted July 15, 2005)1. IntroductionVehicle routing problems (VRP) have received considerable attention in recent years. The usual static version, namely Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows (VRPTW) includes capacity and time window constraints. In the VRPTW, a fleet of identical vehicles supplies goods to N customers. All vehicles have the same capacity Q. For each customer i, i = 1,…,N, the demand of goods, q i, the service time s i, and the time window [a i,b i] to meet the demand in i are known. The component s i represents the loading or unloading service time at the customer i, and a i describes the earliest time when it is possible to start the service. If any vehicle arrives at cus-tomer i before a i it must wait. The vehicle must start the customer service before b i. All vehicle routes start and finish at the central depot. Each customer must be visited once. The locations of the central depot and all customers, the minimal distance d ij and the travel time t ij between all locations are given. Different objectives have been proposed in the literature, including the minimal total travel distance, the minimal num-ber of vehicles used, the total wait time, the total time to complete the whole service and combina-tion of these.Alvarenga [1] and [11] has proposed a ge-netic and a set partitioning two phases approach for the VRPTW using travel distance as the unique objective. The tests were produced using both, real numbers and truncated data type, and the results were compared with previous pub-lished heuristic and exact methods. These results show that the heuristic CGH (Column Genera-tion Heuristic) proposed is very competitive in terms of travel distance (TD) minimization. In present paper, an extension of that approach is proposed to minimize the number of vehicles (NV) first and the total travel distance is mini-mized as a second objective.Berger [2] has improved some of the results of Solomon’s benchmark using parallel two-population co-evolution genetic algorithms, Pop1 and Pop2. The first population, Pop1, has the objective to minimize TD to a fixed number of vehicles. On the other hand, Pop2 works to minimize the violated time window, in order to find at least one feasible individual. In Pop2, NV is fixed as the number obtained by Pop1 minus one. The global objective is to minimize NV, and after that to minimize TD, in a second priority. Pop1 works to minimize TD over the population received from Pop2, where at least one feasible solution is known. Each time a feasible individ-ual is found the population Pop1 is substituted by Pop2 and the fixed number of vehicles consid-ered in both populations is decreased by one.Berger has also tested the algorithm in the 56 Solomon’s instances. Berger found 6 new results (for instances R108, R110, RC105, RC106, R210 and R211). Currently, three of them continue to be the best solutions known (R108, RC105 and RC106), considering NV as the first objectiveand TD as the second. One of the most important advantages of his work is the total NV for all 56 instances of Solomon, with 405 vehicles, one of the best results in the literature.Homberger [7] has also presented good re-sults for many Solomon’s benchmark problems using two evolutionary metaheuristic methods in a similar two-stage strategy. Two different heu-ristic methods were proposed, ES1 and ES2. Homberger emphasizes the importance of the evaluation criterion. The travel distance selection does not drive the search in the number of vehi-cles global minimum. Consequently, it is neces-sary to add new evaluation criteria. The first new criterion explored is the number of customers in the shortest route. The second criterion is namely the minimal delay D R . That is the sum of the minimal time violations caused by the forced elimination of the customers from the shortest route R , equation (1).∈=Rk kR DD(1) Where• D k = 0 if the customer k can be eliminated and inserted in any other route R’ R;• D k = ∞ if the insertion of k always results in a capacity violation to any route R’ R ; • D k = the minimal violated time , if the inser-tion of the customer k results in any time window violation. In this case, the minimal sum of time violations for the entirely route which received the customer k is assigned to D k .Both, ES1 and ES2 have considered two phase approach in the search. In the first step, the total travel distance is suppressed. In the second and last step, after the number of vehicle has been minimized, the search is redirected to minimize the total travel distance. The difference between ES1 and ES2 stay on the existence or not of the crossover to produce a new generation. In the ES1 the new generations are produced directly by mutations. These heuristic methods reduced the number of vehicles in two instances from the class R1 (R104 and R112). In the instance R109, the strategy ES1 still produced a new result, maintaining NV and reducing TD. In the same way, ES2 improved the results of TD in R105 and R107. In the class R2, five new results were produced by ES1 and three by ES2. The results in the classes, C1 and C2, were equivalent to the best known for all problems. ES2 still produced two new results for RC1 and two others for RC2, while ES1 produced two other new results for RC2. In summary, 20 new results were produced, where only 2 still continue undefeated.This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the first phase of the search (GA_NV), in order to minimize the number of vehicles. Section 3 describes how CGH is applied to minimize the second objective, travel distance, and the overall algorithm. The sections 4 and 5 describe the results and conclusions, respec-tively.2. Hierarchical Tournament Selection Genetic AlgorithmIn the first phase, an independently genetic algo-rithm is proposed to reduce the number of vehi-cles. Strategies exploring the number of vehicles (NV) and travel distance (TD) objectives in dis-tinguished phases have reached the best results at the moment in the literature. It’s possible to see the best results in [13] and their respective references.Although the number of vehicles is consid-ered as the first objective, the total travel dis-tance minimization continues to be very impor-tant, because it is the differentiate criterion as a second objective, once many algorithms have reached the same number of vehicles for many instances. By one side, the genetic algorithm and set partitioning two phase approach, composing the column generation heuristic CGH proposed by [1] showed to be competitive to minimize TD. Consequently, the main question is if the pro-posed CGH continues to be efficient when the NV is fixed in a minimized solution. However, an additional phase to minimize the NV is nec-essary. This is a second objective of this paper, because it’s very difficult for a robust algorithm to present good NV results to different instances. In this way, the fitness approach of Homberger evolution strategy, summarized in the previous section, was extended adding new criteria to evaluate how easy could be to eliminate one route from the individual solutions. The basic idea of the genetic algorithm GA_NV to mini-mize NV is the same utilized in [1]. However, new operators are necessary to change the search. The main characteristics of the algorithm are described bellow.Chromosome and Individual Representation The individual representation is the same util-ized in [1]. Each customer has a unique integer identifier i, i = 1,..,N, where N is the number of customers. The chromosome is defined as a string of integers, representing the customers to be served by only one vehicle. An individual, that represents a complete solution, and conse-quently many routes, is a set of chromosomes. The central depot is not considered in this repre-sentation, because all routes necessarily start and end on it.Initial PopulationTo start the first generation in the GA, the sto-chastic PFIH (Push Forward Insertion Heuristic) also proposed in [1] is utilized. It can produce quickly diversified individuals. In the original PFIH, see [14], the first customer in each new route is deterministically defined. Customers then are chosen one by one minimizing the travel distance. The original PFIH is determinis-tic, but differently, in the stochastic PFIH a ran-dom choice is used to define the first customer for each new route. That is necessary to produce distinguished individuals in the first GA genera-tion.FitnessThere are basically two main alternatives to evaluate individuals to the VRPTW in order to minimize the number of vehicles. In the first one the search occurs by the unfeasible region, and the evaluation is based on how much the time windows are violated. This option was adopted, for example in the genetic algorithm proposed by [2]. On the other hand, the second one treats only feasible individual solutions. This option needs the identification of characteristics in the individual solutions. They have hints of easiness to reduce routes, once the main objective NV is not sufficient to differentiate individuals and ensure the population evolution.In this paper, a k-way tournament selection method is used in the GA. In a k-way tourna-ment, k individuals are selected randomly. Then, the individual with the highest fitness is the winner. This process is repeated until the neces-sary number of selected individuals to the cross-over phase has been reached. Two individuals are selected for each crossover, which produces only one new offspring. As showed before, [7] propose some criteria of evaluation in a lexicog-raphy order. The first criterion is the number of vehicle by itself, followed by the number of cus-tomers in the shortest route and the minimal delay time D R, previously described. It’s possible to see that the minimal delay time resembles the idea of the search by the unfeasible time win-dows region.The strategy utilized in this paper to expand the fitness idea proposed by [7] evaluates how hard is to eliminate customers from the shortest route. However, it is possible to show that the use of all three criteria of evaluations from Homber-ger is not enough to differentiate the individuals. In other words, it’s possible to find different in-dividuals with the same value in all three crite-ria. Consequently, the idea is to use additional parameters to identify the easiest individual from the current tournament to eliminate a shortest route. Surprisingly, no less than nine additional criteria of evaluation can be useful in order to permit the identification and to eliminate one more route or a customer in the shortest route. These fitness criteria are presented bellow in their respective hierarchical order in the selec-tion algorithm:1st- Number of Routes (Fitness_NV): The main objective of the problem (NV) is the first criterion2nd- The Number of Customers in the Shortest Route (Fitness_NCSR): Naturally, the number of customers in the shortest route is the second criterion to identify the easiest individual solution to eliminate one more route.3rd - Difficulty to Eliminate One Customer from the Shortest Route (Fitness_1CSR): This criterion is very similar with the minimal delay time D k proposed by [7], but only one customer from the shortest route is considered (the mini-mal D k). The other difference is that no delay time is added in D k for subsequent not violated time windows. In contrast, Homberger considers all delay in any customer caused by a previous violated time window.4th- Difficulty to Eliminate All Customers from the Shortest Route (Fitness_AllCSR): This criterion (D R)is the sum of D k to all cus-tomers in the shortest route (equation (1)). This is the main additional criterion utilized by [7]. The difference mentioned above to calculate the delay persists.5th- Difficulty to Eliminate One Customer from the Taker Route(Fitness_1CTR): The taker route presents the minimal time window violation if receives a customer from the shortest route. Sometimes, it’s necessary to eliminate customers from this route, because inserting some customers in another route can make pos-sible the reception of others from the shortest route. Obviously the shortest route cannot be used as destination of these customers.6th- Difficulty to Eliminate All Customers from the Taker Route(Fitness_AllCTR): Again, the sum of the violated time for all cus-tomers from the taker route is considered to cal-culate the Fitness_AllCTR. The idea is the same applied to Fitness_AllCSR, but now the focus is the taker route and not the shortest route.7th- Total Travel Distance (Fitness_TD): The total travel distance (TD) minimization wasmentioned as a concurrent objective to the NV minimization. In fact, this can guide the search to a minimal TD with a bigger NV. However, when applied following all priority criteria above, it is verified to be useful to minimize NV. 8th - The number of customers in the taker route (Fitness_NCTR): This criterion is moti-vated by the fact that a short route has more probability to receive other customers without violated constraints.9th - Sum of Squares of the Number of Cus-tomers (Fitness_SSNC): The sum of squares of the number of customers is as large as the con-centration of customers in few routes. This crite-rion is interesting because has an effect over all routes together.10th - Total load in the Taker Route (Fit-ness_TLTR):Any route with few loads inside has more capacity to receive any other customer from the shortest route. This criterion is useful for instances where the capacity is more critical than the time window constraints.SelectionIn the k-way tournament selection method k in-dividuals are selected randomly. Then, the indi-vidual who presents the highest fitness is the winner and will participate of the crossover. In the hierarchical tournament there is not only one fitness value but many. Each fitness criterion is used to maintain in the tournament process only those individuals which present the highest val-ues. One or more individuals continue in the tournament selection considering the other hier-archical fitness criteria. The hierarchical criteria utilized, as showed in the previous section, can differentiate solution individuals with different number of vehicles, the main objective, but also identify those individuals, with the same number of vehicles, that are easier to eliminate customers in the last route and consequently to eliminate that route.CrossoverThe crossover algorithm is based on the cross-over operator proposed by [1] and [11]. In the first step, the algorithm select a route from each parent individual in turns, in order to inherit routes with maximum number of customers. Af-ter all feasible routes have been inserted in the offspring, the insertion of the remainder custom-ers is tested in the existing routes (second step). If some customers continue to be without any route there is no other option than to insert them in empty vehicles (new routes). In this case, the stochastic PFIH is again applied. MutationMany mutation operators in the GA proposed by [1] are not appropriated to minimize NV. Those operators give directions to minimize the total travel distance which can represent a local minimum in terms of NV. The new set of opera-tors is proposed, as explained below:Random Customer Migration (M_RCM): This operator chooses a vehicle randomly and a ran-dom customer associated to it; a migration of this customer to other non-empty vehicle is tried. If the insertion results a feasible route, then it is accepted independently of the new function cost. Simple Customer Exchange (M_SCE): This operator tries a random customer exchange be-tween two different routes. The unique require-ment to do the exchange is the feasibility of the resulted individual solution.Two Customers Swap (M_TCS): This operator is very similar with M_SCE, but the customers come from the same route.Customer Exchange with Gain in Fit-ness_1CSR, Fitness_AllCSR or Fitness_1CTR (M_CEGF1): Two routes are randomly selected. Every possible pair of customers, one from each route is candidate to exchange. The customer position in the target route is not necessarily the empty position. The exchange is performed only if there is gain in at least one of these fitness criteria: Fitness_1CSR, Fitness_AllCSR or Fit-ness_1CTR.Customer Exchange with Gain in Fit-ness_1CSR, Fitness_AllCSR (M_CEGF2): Two routes are randomly selected. Every possible pair of customers, one from each route is candi-date to exchange. The customer position in the target route have to be the empty position. The exchange is performed only if there is a gain in at least one of these fitness values: Fitness_1CSR or Fitness_AllCSR.Simple Customer Exchange with Travel Dis-tance Gain (M_SCETDG): This operator tries a random customer exchange between two differ-ent routes. Differently of the M_SCE this ex-change is performed only if the resulted solution presents a TD reduction.Customer Exchange with Travel Distance Gain (M_CETDG): This operator tries a ran-dom customer exchange between two different routes. Differently of the M_SCETDG the cus-tomer previous position does not necessarily need to be used. Again the exchange only is per-formed if the resulted solution presents a TDreduction.Taker Route Customer Migration (M_TRCM): This operator chooses a random customer from the taker route; a migration of this customer to another non-empty, different of the shortest route, and a random vehicle is tried. If the insertion results a feasible route, then it is accepted independently of the new function cost. If it is impossible to insert this customer in that vehicle, another one is randomly selected until all available vehicles have been tested. Customer Reinsertion with TD Gain (M_CRTDG):This mutation randomly choses customer in a route and try all position available. If there is another feasible position with travel distance reduction the position is changed.All Customers Reinsertion (M_AllCR): This mutation is very similar with M_CRTDG but this operation is repeated to every customer in a randomly selected route. Every new position with travel distance reduction is performed.Taker Route Elimination (M_TRE): This mu-tation tries to find a new feasible position for every customer of the taker route in another one. Obviously, the shortest route is not considered as destination once the objective is to improve the capacity to receive customers from that one. Last Customer Elimination from the Shortest Route including Customer Removal in the Destination (M_LCE1): This operator gets this last customer and tries to insert into other non-empty route. If necessary, a second customer in the destination route is removal to permit the insertion. In the last case, a new destination to the removed customer is tried, initially, in all nonempty route in the individual solution. If another feasible position to the removed cus-tomer is found, the shortest route has been eliminated. Otherwise the removed customer is inserted in an empty route and stays as the new shortest route.Last Customer Elimination from the Shortest Route including 2 Customers Removal in the Destination (M_LCE2): This operator is very similar to M_LCE1, but includes the possibility to remove 2 customers in order to permit the insertion of the last customer from the shortest route. If other feasible positions to the removed customers are found, the shortest route has been eliminated. Otherwise the remainder customers are inserted in an empty route and a different new shortest route has been established. Shortest Route Elimination (M_SRE): This mutation tries to find a new feasible position for every customer of the shortest route in another one.3. Second Phase and the Complete Algorithm In the previous sections, the new genetic algo-rithm GA_NV is proposed to minimize the num-ber of vehicles. The algorithm is applied for a fixed interval (15 min.) in order to find a solu-tion to the VRPTW with the minimal number of vehicles as possible. After that, the entire final population produced by GA_NV is used as the first population in the Column Generation Heu-ristic (CGH) proposed by [1] to minimize the second optimization criterion , the total travel distance.The result of GA_NV, block 1 in the 0 are 50 solution individuals containing the best solution in terms of NV. The CGH proposed by [1] gets this population many times to produce many local minima, while the TIME_LIMIT (block 3) permits. But now, the objective is to minimize TD after NV. Because there are many individu-als with the same NV and the operators utilized in CGH unlikely can reduce NV, actually TD is the practical objective to be reduced.The complete algorithm CGH_NV, described in Figure 1, is composed by the basic CGH algo-rithm (for details see [1] and [11]) joined with GA_NV. It’s important to emphasize the main aspects of that approach. The loop from the block 4 to 8 produces many different routes or local minima using the GA_TD (genetic algo-rithm wirh the criterion of travel distance mini-mization). The number of solutions, Max_Evol, generated is 10. The set partitioning problem SSP then is solved to obtain the optimal solution over this limited set of routes R, block 9. The solution then is applied to divide the whole prob-lem into many different sub-problems, solved again using the GA_TD, blocks 11 to 16. These 2 cycles are repeated until the TIME_LIMIT (60 min.) is reached. Finally, the SPP is solved over all previous routes generated and included in the set R GLOBAL.4. Computational ResultsThe GA_NV parameters were empirically ad-justed. A fixed period of 15 minutes has been used to run GA_NV. After that, as show the 0, the final population is passed to CGH in order to minimize TD. This phase has an additional pe-riod of 60 minutes to perform the search. In or-der to define the best hierarchical way to evalu-ate the individuals the GA_NV algorithm was tested with different options. The Fitness_NV isalways the first, because this is the main objec-tive. Again the number of customers in the shortest route (Fitness_NCSR) demonstrates clearly as the second fitness to be applied in the selection. Homberger [7] has used the difficulty to eliminate all customer from the shortest route as third criterion (Fitness_AllCSR) or delay time, but there was not information if the author has tried another criterion or comparisons. Also the GA_NV in this work has produced the best results considering the difficult to eliminate all customers in the shortest route (Fitness_AllCSR) in the third priority. The use of Fitness_1CSR has been used in forth priority. The use of Fit-ness_1CSR as the third criterion has produced fast customer elimination in the first phase but has increased the possibility to entrap in the local minima. The Fitness_TD produces better results only in seventh priority, but with substantial relevance in the search.Table 1 shows the main results from the lit-erature and the results from CGH_NV proposed. They are positioned in crescent order of NV, the main objective. The results of the CGH_NV are very expressive in NV, reaching the best known value for 100% of the problems. However, in the second objective TD, the results stay a bit above of the best known, produced by Berger.Figure 1:CGH_NV heuristic proposedNVReference R1 R2 C1 C2 RC1 RC2DT11.92 2.73 10.00 3.00 11.50 3.25 405Berger et al. (2003)1221 975.4 828.5 590 1390 1159 579511.92 2.73 10.00 3.00 11.50 3.25 405CGH_NV (this paper)1224.1012.828.4 590.9 1417.1195.589112.00 2.73 10.00 3.00 11.50 3.25 406Braysy et al. (2004)1220.970.4 828.4 589.9 1398.1139.577911.92 2.73 10.00 3.00 11.63 3.25 406Homberg et al. (1999)1228.970.0 828.4 589.9 1392.1144.578712.08 2.82 10.00 3.00 11.50 3.25 408Homberg et al (in press)1211.950.7 828.5 590.0 1395.1135.574212.08 2.91 10.00 3.00 11.75 3.25 411Liu et al. (1999)1215.953.4 828.4 589.9 1385.1142.574612.25 3.00 10.00 3.00 11.88 3.38 416Taillard et al. (1997)1216.995.4 828.5 590.3 1367.1165.579912.58 3.09 10.00 3.00 12.38 3.62 427Rochat et al. (1995)1197.954.4 828.5 590.3 1369.1139.5712Table 1: Best known results (july/04) GCH_NV5. ConclusionsIn the literature, the main results minimizing NV for Solomon’s test set have been compared with the results produced by CGH_NV. The pro-posed approach has produced the best NV results and a reasonable TD. The GA_NV proposed to minimize NV has produced the best results in NV using only 15 minutes of execution using a Pentium IV 2.4 GHz.The new hierarchical tournament selection proposed has been the main reason to the excel-lent performance of GA_NV in the NV minimi-zation. However the CGH proposed by [1] changed to minimize first NV and then TD as the second criterion seems to have difficulty to perform the search in narrow routes. Once the TD results from CGH without any NV restriction were very significantly [1], it’s interesting to extend this work producing new mutation opera-tors in the GA_TD to work with narrow routes found in the GA_NV.6. References[1] Alvarenga, G.B., Mateus, G.R. and Tomi, G.(2004), “A genetic and set partitioning two-phase approach for the vehicle routing prob-lem with time windows”. Proceedings of Fourth Intenational Conference on Hybrid Intelligent Systems, Kitakyushu, Japan, p.410-415.[2] Berger, J., Barkaoui, M. and Bräysy, O.,(2003), “A route-directed hybrid GA ap-proach for the VRPTW”, Information Sys-tems and Operational Research 41, 179-194. [3] Bräysy, O., Hasle G. and Dullaert W.,(2004), “A multi-start local search algorithm for the vehicle routing problem with time windows”. European Journal of Operational Research, 159, 586-605.[4] Corne, D., Dorigo, M. and Glover, F.,(1999), "New Ideas in Optimization".[5] Gambardella, L.M., Taillard, E. and Agazzi,G. (1999), "MACS-VRPTW: A multipe AntColony System for Vehicle Routing Problems with Time Windows", in Chap. 5 of [4]. [6] Homberger, J. and Gehring, H., (1999),“Two evolutionay metaheuristics for the ve-hicle routing problem with time windows. In-formation Systems and Operational Re-search, 37, 297-318.[7] Homberger, J. and Gehring, H., (2002) "Par-allelization of a two-phase metaheuristic for routing problems with time windows”. Jour-nal of Heuristics, 8, 251-276.[8] Homberger, J. and Gehring, H., (in press) "Atwo-phase hybrid metaheuristic for the vehi-cle routing problems with time windows”.European Journal of Operational Research.[9] Kohl N., Desrosiers J., Madsen O. B. G.,Solomon M. M. and Soumis F. (1997), "K-path Cuts for the Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows", Manuscript。

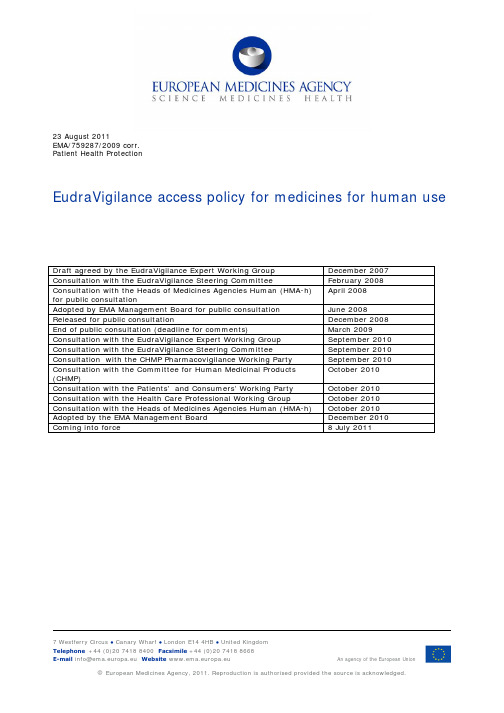

EudraVigilance

© European Medicines Agency, 2011. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

Table of contents

Executive summary ..................................................................................... 3 1. Background ............................................................................................. 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................ 5 3. Objectives of the EudraVigilance access policy........................................ 5 4. EudraVigilance and medicinal products for human use............................ 5 5. Access to data held in EudraVigilance...................................................... 7

5.1. Stakeholder groups ............................................................................................ 7 5.2. Overview .......................................................................................................... 7 5.3. General principles .............................................................................................. 9 5.3.1. ICSR types ................................................................................................... 10 5.3.2. Primary and secondary report sources .............................................................. 10 5.3.3. Individual cases, ICSRs and classification rules .................................................. 10 5.3.4. Access to EudraVigilance data and access tools.................................................. 11 5.4. Access by stakeholder group.............................................................................. 11 5.4.1. Group I: Medicines regulatory authorities in the EEA, the European Commission and the Agency ............................................................................................................ 11 5.4.2. Group II: Healthcare professionals and the general public ................................... 12 5.4.3. Group III: Marketing authorisation holders and sponsors..................................... 14 5.4.4. Group IV: Research organisations .................................................................... 15

怀念威廉·科恩劳尔的尼瓦达银腾打印目录与检查表

Las Vegas

Year Guide

MM .999 Released Price

CC Rim 1994 $22-$28

(V) Ali Baba (3 Dots)

Aladdin on Carpet

CC Rim 1994 $100-150

Sinbad

Aladdin on Carpet

$18.00 $15.60

$17.00

$22.75

Approx

2019

2020 Silver

Auction Auction Weight

$18-$25 $16-$20 .6010 Oz

.4898 Oz

$16.50 $25.00 .4948 Oz

$16-$20 $20.00 .5881 Oz

$15-$25

Monorail

Bally's (3 7s)

GDC Rim 1995 $22-$28

Running 7 (LV Top)

Bally's (3 7s) (LV Top)

GDC Rim 1995 $22-$28

(E) Running 7(WR)(LV NV.Bottom) Bally's (3 7s) (LV Top)

Reno

MM .999

G Rim

Year Guide Released Price

1996 $22-$28

Toucan/Angel Fish

Atlantis Hotel Tower

G Inner 1998 $22-$28

(E) Toucan/Angel Fish(50++)

Atlantis (Many Blds) (WL)

Barry Lloyd:Approaching the World

Germany

Search Engines

Total hold on German Search Market

100 90 Percentage of Total Market (%) 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Google t-online Search Engines Yahoo!

Preparing and the 3 Cs

Content

Connections

Compatibility

SEO and 3 Cs

Culture

Compatibility

t

Connections

Searching And Connecting Are Fundamental Human Needs Everywhere

Sources: http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/Internet/DE/Na vigation/Statistiken/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Bevoelkerungss tand.psml /top25.htm http://www.webhits.de/deutsch/index.shtml?webstats.html

Population: 82 million Est. Internet Users: 55.5 million Internet Penetration: 67.7% Language: German

Social Media

© WebCertain Publishing Ltd

Germany is the third largest social networking market in the world, trailing only the US and China. The most popular social network in the country is StudiVz with around 17 million users. Its main target audience is students. Facebook has around 11 million users in Germany, where it has taken longer to take hold than in other countries. Many German users have concerns over privacy on Facebook and German officials have recently begun legal proceedings against Facebook over its use of personal data.

关于自动驾驶汽车的看法英语作文

关于自动驾驶汽车的看法英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1Self-Driving Cars: A Road to the Future or a Crash Course?As a student trying to navigate the complexities of modern life, I can't help but be intrigued by the concept of self-driving cars. This cutting-edge technology promises to revolutionize the way we think about transportation, offering a tantalizing glimpse into a future where the drudgery of driving is a thing of the past. However, as with any paradigm shift, there are valid concerns and uncertainties that must be addressed. In this essay, I will explore the potential benefits and drawbacks of self-driving vehicles, and ultimately share my stance on whether they represent a road to the future or a crash course waiting to happen.Let's start with the potential advantages of self-driving cars, as there are many compelling reasons why this technology could be a game-changer. Firstly, the elimination of human error could lead to a significant reduction in traffic accidents, injuries, and fatalities. According to the National Highway Traffic SafetyAdministration, human error is responsible for a staggering 94% of all car crashes. With self-driving vehicles relying on advanced sensors, algorithms, and decision-making capabilities, the potential for mitigating these errors is immense. Additionally, self-driving cars could increase mobility for those who are unable to drive due to age, disability, or other factors, providing them with newfound independence and freedom.Another compelling benefit of self-driving cars is their potential to alleviate traffic congestion and improve efficiency on our roads. By communicating with one another and optimizing routes, these vehicles could significantly reduce the stop-and-go patterns that plague our cities, leading to smoother traffic flow and reduced emissions. Furthermore, the ability to summon a self-driving car on demand could potentially reduce the need for personal car ownership, freeing up valuable urban space currently occupied by parking lots and garages.However, despite these potential advantages, there are valid concerns and challenges that must be addressed. One of the most pressing issues is the question of liability in the event of an accident involving a self-driving car. Who would be held responsible – the manufacturer, the software developer, or theowner/operator? This legal quagmire could prove to be a significant hurdle in the widespread adoption of this technology.Furthermore, the issue of cybersecurity cannot be overlooked. As these vehicles become increasingly reliant on complex software and interconnected systems, the potential for hacking and malicious interference increases. A successful cyber attack could potentially wreak havoc, leading to disastrous consequences. Robust security measures and stringent safeguards must be implemented to mitigate these risks.Another concern that cannot be ignored is the potential impact on employment. Self-driving vehicles could potentially displace millions of workers in the transportation industry, from truck drivers to taxi operators. While new job opportunities may arise in fields such as software development and maintenance, the transition could be disruptive and challenging for many workers and their families.Moreover, the issue of public acceptance and trust is a significant barrier to overcome. Despite the potential benefits, many people may feel uneasy about relinquishing control to an autonomous system, particularly in high-risk situations. Building trust and confidence in the technology will be crucial for widespread adoption.As a student, I find myself torn between the excitement of embracing this technological marvel and the valid concerns that must be addressed. On one hand, the potential benefits ofself-driving cars are undeniably appealing. The prospect of safer roads, increased mobility, and reduced congestion and emissions is enticing, particularly in the face of our current transportation challenges. Additionally, the potential forself-driving vehicles to free up valuable time and mental resources, allowing me to study or work while commuting, is incredibly attractive.However, the potential risks and uncertainties cannot be ignored. The legal and ethical quandaries surrounding liability and accountability are complex and must be carefully navigated. The threat of cyber attacks and the potential for widespread job displacement are also valid concerns that require thoughtful solutions.Ultimately, my stance on self-driving cars is one of cautious optimism. I believe that this technology represents a road to the future, but one that must be approached with care and prudence. Rigorous testing, robust safety protocols, and a gradual, regulated rollout are essential to ensure that the transition is smooth and the benefits outweigh the risks.Additionally, I believe that public education and awareness campaigns will be crucial in addressing concerns and building trust in this technology. By openly addressing the challenges and uncertainties, and involving stakeholders from various sectors, we can work towards a future where self-driving cars are seamlessly integrated into our transportation landscape, improving safety, efficiency, and quality of life for all.In conclusion, self-driving cars are a fascinating and promising development that could reshape our relationship with transportation. While the potential benefits are substantial, the challenges and risks must be carefully navigated. As a student, I remain optimistic about the future of this technology, but I also recognize the need for a measured and responsible approach that prioritizes safety, security, and ethical considerations. Only by addressing these concerns head-on can we truly unleash the transformative potential of self-driving cars and pave the way for a safer, more efficient, and sustainable future of mobility.篇2The Future is Self-Driving CarsAs a student living in the modern world, I can't help but be fascinated by the rapid advancements in technology, particularlyin the field of transportation. One innovation that has captured my attention and sparked endless debates among my peers is the concept of self-driving cars, also known as autonomous vehicles.At first glance, the idea of a car that can navigate roads without human input might seem like something straight out of a science fiction movie. However, the reality is that self-driving technology is rapidly evolving, and major companies like Google, Tesla, and Uber are investing heavily in its development. The potential benefits of this technology are vast and could revolutionize the way we think about transportation.One of the most compelling arguments in favor ofself-driving cars is their potential to significantly reduce the number of road accidents caused by human error. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, human error is responsible for a staggering 94% of all traffic accidents. With self-driving cars eliminating the need for human drivers, the roads could become much safer. These vehicles are equipped with advanced sensors, cameras, and algorithms that can detect obstacles, predict potential hazards, and make split-second decisions far more accurately than humans.Moreover, self-driving cars could help alleviate traffic congestion, a major issue in most urban areas. By communicating with each other and optimizing routes, these vehicles could potentially reduce travel times and decrease the amount of time spent idling in traffic jams. This, in turn, would lead to lower greenhouse gas emissions and a more environmentally friendly transportation system.Another significant advantage of self-driving cars is their potential to increase mobility for individuals who are unable to drive due to age, disability, or other reasons. Imagine the freedom and independence that an elderly person or someone with a visual impairment could experience with access to a reliable self-driving vehicle. This technology could revolutionize their lives, allowing them to travel independently and maintain a sense of autonomy.Despite these potential benefits, there are valid concerns and challenges surrounding the implementation of self-driving cars. One of the primary concerns is the ethical dilemma of how these vehicles should be programmed to respond in emergency situations where harm is unavoidable. Should the car prioritize the safety of its occupants or minimize overall casualties? These are complex philosophical questions that require carefulconsideration and input from experts in various fields, including ethics, law, and technology.Another challenge is the potential impact on the job market, particularly for professions like taxi drivers, truckers, and delivery personnel. While some argue that new job opportunities will arise in the development and maintenance of self-driving technology, there is a valid concern about the potential displacement of workers and the need for retraining and transition assistance.Furthermore, there are technical challenges to overcome, such as ensuring the reliability and cybersecurity of these vehicles. As with any technology, self-driving cars could be vulnerable to hacking attempts or software glitches, which could have disastrous consequences. Rigorous testing, robust security measures, and ongoing maintenance will be crucial to ensuring the safe operation of these vehicles.As a student, I find the prospect of self-driving cars both exciting and daunting. On one hand, the potential benefits in terms of safety, efficiency, and accessibility are undeniable. The idea of being able to study or relax during my commute, rather than fighting traffic and navigating busy roads, is incredibly appealing. However, I also recognize the valid concerns andchallenges that need to be addressed before this technology can be fully embraced.Ultimately, I believe that self-driving cars represent the future of transportation, and their widespread adoption is inevitable. However, it is crucial that this technology is developed and implemented responsibly, with a focus on ensuring safety, addressing ethical concerns, and mitigating potential negative impacts on society.As students and future leaders, it is our responsibility to stay informed about these advancements, engage in thoughtful discussions, and contribute our perspectives to the ongoing debates surrounding self-driving cars. We must strive to strike a balance between embracing innovation and addressing legitimate concerns, so that we can shape a future where technology enhances our lives while respecting ethical principles and prioritizing the well-being of society as a whole.篇3The Driverless Revolution: A Student's Perspective on Autonomous VehiclesAs a student living in an era of rapid technological advancements, the concept of self-driving cars captivates myimagination and sparks a myriad of thoughts and emotions. On one hand, the idea of autonomous vehicles promises unprecedented convenience, safety, and efficiency on our roads. On the other hand, it raises concerns about job displacement, ethical dilemmas, and the potential for technology to outpace our ability to regulate it effectively. In this essay, I aim to explore both the potential benefits and drawbacks of self-driving cars, offering a balanced perspective on this groundbreaking innovation.The Promise of ConvenienceOne of the most alluring aspects of self-driving cars is the convenience they offer. Imagine being able to study, read, or even take a nap during your daily commute, while the vehicle navigates traffic and handles the tedious tasks of driving. For students juggling academics, extracurricular activities, and social lives, the ability to reclaim that time spent behind the wheel could be a game-changer. Additionally, self-driving cars could revolutionize transportation for those with disabilities or mobility challenges, providing them with newfound independence and accessibility.Increased Safety and EfficiencyAnother compelling argument in favor of autonomous vehicles is their potential to enhance road safety. Human error is a leading cause of traffic accidents, and self-driving cars, with their advanced sensors and algorithms, could significantly reduce the number of collisions caused by factors such as distracted driving, impaired driving, and poor decision-making. Furthermore, these vehicles could communicate with one another and optimize traffic flow, reducing congestion and improving overall efficiency on our roads.Environmental BenefitsSelf-driving cars also offer potential environmental benefits. By optimizing routes and driving patterns, these vehicles could reduce fuel consumption and emissions, contributing to a more sustainable future. Additionally, the rise of autonomous vehicles could encourage a shift towards shared mobility services, reducing the number of vehicles on the road and further minimizing their environmental impact.Job Displacement ConcernsHowever, the advent of self-driving cars is not without its challenges and drawbacks. One of the most significant concerns revolves around job displacement, particularly in the transportation and logistics sectors. Millions of individualsworldwide are employed as drivers, and the widespread adoption of autonomous vehicles could potentially lead to large-scale job losses. While new job opportunities may arise in the development and maintenance of these technologies, the transition could be disruptive and create economic hardships for many families.Ethical DilemmasSelf-driving cars also raise complex ethical dilemmas that must be addressed. For instance, how should these vehicles be programmed to respond in situations where a collision is unavoidable? Should they prioritize the safety of passengers over pedestrians, or vice versa? What about situations where the vehicle must choose between two suboptimal outcomes? These ethical quandaries highlight the need for robust legal and regulatory frameworks to govern the development and deployment of autonomous vehicles.Privacy and Cybersecurity ConcernsAdditionally, the widespread adoption of self-driving cars raises concerns about privacy and cybersecurity. These vehicles rely on a vast network of sensors and data-gathering technologies, which could potentially be exploited by malicious actors or misused by corporations or governments forsurveillance purposes. Ensuring the security and privacy of the data collected by these vehicles will be a critical challenge that must be addressed.Regulatory ChallengesFinally, the rapid pace of technological advancement in the field of autonomous vehicles presents regulatory challenges. Policymakers and lawmakers must work diligently to keep up with the evolution of these technologies, ensuring that appropriate safety standards, liability frameworks, and consumer protections are in place. The lack of a clear and consistent regulatory environment could hinder the widespread adoption of self-driving cars or lead to unintended consequences.ConclusionAs a student witnessing the dawn of the driverless revolution, I am both excited and apprehensive about the future of autonomous vehicles. While the potential benefits in terms of convenience, safety, and environmental sustainability are undeniable, the challenges posed by job displacement, ethical dilemmas, privacy concerns, and regulatory hurdles cannot be ignored.Ultimately, the successful integration of self-driving cars into our society will require a collaborative effort involving policymakers, industry leaders, ethicists, and the public. We must engage in open and honest dialogues, weighing the risks and rewards, and carefully navigating the complex landscape of this transformative technology.As students and the leaders of tomorrow, it is our responsibility to stay informed, ask critical questions, and actively participate in shaping the future of transportation. By embracing innovation while upholding our ethical principles and prioritizing the well-being of society, we can harness the potential of self-driving cars to create a safer, more efficient, and more sustainable world for generations to come.。

The Reputational Costs of Tax Avoidance

The Reputational Costs of Tax Avoidance*JOHN GALLEMORE,University of ChicagoEDWARD L.MAYDEW,University of North CarolinaJACOB R.THORNOCK,University of Washington1.IntroductionThis study investigates whetherfirms and their top executives bear reputational costs from engaging in aggressive tax avoidance activities.At least two decades of empirical tax research has shown thatfirms engage in a wide range of strategies for tax avoidance pur-poses.1Recent studies suggest that for manyfirms,tax avoidance appears to be highly effective at reducing thefirms’tax payments and increasing their after-tax earnings.For example,Dyreng,Hanlon,and Maydew(2008)find that more than a quarter of publicly traded U.S.firms are able to reduce their taxes to less than20percent of their pre-tax earnings,and are able to sustain such low rates of taxation over periods as long as ten years.Tax avoidance strategies are abundant and include a wide variety of activities such as shifting income into tax havens(Dyreng and Lindsey2009),using complex hybrid secu-rities(Engel,Erickson,and Maydew1999),and engaging in other tax shelters(Wilson 2009).While the evidence indicates there is wide variation in tax avoidance acrossfirms, the extant literature has a difficult time explaining this variation.What is puzzling is not that somefirms engage in tax avoidance,but rather why somefirms engage in it enthusiastically while others appear to shun it.For example,while showing that some firms engage in substantial tax avoidance,Dyreng et al.(2008)alsofind that approxi-mately one-fourth offirms pay taxes in excess of35percent of their pre-tax income over a ten-year period.Given a U.S.federal corporate tax rate of35percent,these firms appear to be engaging in little or no sustainable tax avoidance.The question of why so manyfirms do not avail themselves of tax avoidance opportunities has been coined the“under-sheltering puzzle”(Desai and Dharmapala2006;Hanlon and Heitz-man2010;Weisbach2002).*Accepted by Steve Salterio.The authors would like to thank Kathleen Andries,Darren Bernard,Jenny Brown,Nicole Cade,Charles Christian,Lisa De Simone,Katherine Drake,Don Goldman,Susan Gyeszly, Michelle Hanlon,Bradford Hepfer,JeffHoopes,Becky Lester,Kevin Markle,Zoe-Vonna Palmrose,Phil Quinn,Steven Savoy,Terry Shevlin,Michelle Shimek,Stephanie Sikes(Oxford discussant),Bridget Stom-berg,Laura Wellman,Brady Williams,Ryan Wilson,participants at the2012Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation annual conference,Vienna University of Economics and Business,and reading groups at Arizona State,Iowa,MIT,and University of Texas-Austin for helpful comments.They espe-cially thank Michelle Hanlon,Joel Slemrod,and Ryan Wilson for sharing tax shelter data and Bob Bo-wen,Andy Call,and Shiva Rajgopal for sharing Fortune Magazine reputation data.John Gallemore gratefully acknowledges thefinancial support of the Deloitte Foundation.1.For reviews of the literature on tax avoidance,see Hanlon,and Heitzman(2010),Maydew(2001),andShackelford and Shevlin(2001).Contemporary Accounting Research Vol.31No.4(Winter2014)pp.1103–1133©CAAAdoi:10.1111/1911-3846.120551104Contemporary Accounting ResearchReputational costs are often posited as an important factor that limits tax avoidance activities,particularly the most aggressive tax strategies.2For example,the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service(IRS)asserts that aggressive tax strategies can pose“a sig-nificant risk to corporate reputations”and“the general public has little tolerance for overly aggressive tax planning”(Shulman2009).However,empirical evidence on the repu-tational costs of tax avoidance is scarce.The most compelling evidence to date is Hanlon and Slemrod(2009)and Graham,Hanlon,Shevlin,and Shroff(2012).Hanlon and Slem-rod(2009)examine the stock price responses offirms accused of engaging in tax shelters. Theyfind evidence thatfirms suffer stock price declines following public revelation of tax shelter behavior.They are careful to acknowledge that there are many possible determi-nants of the negative returns,of which reputational costs are only one.With the exception of some tests on retailfirms,they leave extensive testing of reputational costs for future research.Graham et al.(2012)survey tax executives andfind that more than half agree that potential harm to theirfirm’s reputation is an important factor in deciding whether or not to implement a tax planning strategy.This evidence is consistent with managers perceiving that aggressive tax avoidance will subject them or theirfirms to reputational costs.Beyond this important initial evidence,we know very little about the reputational costs of tax shelters.In particular,we do not know iffirms that are publicly scrutinized for having engaged in tax shelters actually bear reputational costs,as might have been feared ex ante.In their review of tax research,Hanlon and Heitzman(2010)call for research on the under-sheltering puzzle,specifically posing the following questions:“Why do some corporations avoid more tax than others?How do investors,creditors,and con-sumers perceive corporate tax avoidance?...These are interesting questions worthy of study”(137,146).This study answers the call for research,focusing on the extent to which tax sheltering results in reputational costs.We analyze a sample offirms identified in prior studies as engaging in aggressive tax shelters.Our study combines the samples of several prior studies of tax shelter behavior; namely,Graham and Tucker(2006),Hanlon and Slemrod(2009),and Wilson(2009). After imposing data requirements,our sample constitutes118firms revealed during the period1995to2005as having engaged in tax shelters.To our knowledge,this is the larg-est sample of publicly identified corporate tax shelters analyzed to date.We maintain the assumption that managers act rationally in considering costs and benefits of a tax strategy for thefirm.When the managers decide to engage in tax avoid-ance,they weigh the expected benefits of tax avoidance against the expected costs and will not engage in tax avoidance unless the net benefits are positive in an expected value sense. Hence,for our sample of tax shelter users,our assumption is that managers expected the tax shelters to yield positive net benefits.However,we distinguish between the ex post cost of getting caught and the ex ante decision to engage in tax avoidance.While the probabil-ity of bearing reputational costs may be low ex ante,those costs will be realized ex post forfirms subject to scrutiny.Thus,a manager may rationally engage in tax sheltering even though doing so places thefirm at risk of bearing costs if it is later challenged;our objec-tive is to assess those potential ex post reputational costs.Reputation is a multifaceted construct associated with several parties,including the firm and its management,as well as shareholders,customers,and tax authorities.We begin by examining the reputational effects of tax sheltering exerted by shareholders.To provide some assurance that the sample and research design have sufficient power,we replicate Hanlon and Slemrod(2009)using our sample and design to test for capital 2.We define reputation as a general perception of thefirm by all interested stakeholders and further discussthis concept in section2.CAR Vol.31No.4(Winter2014)The Reputational Costs of Tax Avoidance1105 market reactions to tax shelter revelations.In the short window surrounding the revela-tion date,wefind that the stocks publicly revealed to have tax shelters exhibit signifi-cantly negative abnormal returns,consistent with thefindings in Hanlon and Slemrod (2009).We then expand the event period to30days past the revelation date to test whether the short-window effects on stock price are permanent or temporary.Wefind evidence that,although the immediate stock price response around the tax shelter is nega-tive,in the days that follow,the stock price systematically reverses back to its pre-event levels.Thus,we confirm that the Hanlon and Slemrod(2009)short-window effect on stock price is a robust result and at the same time,we alsofind that it is a temporary effect that reverses within30days.3Next,we examine the potential reputational effects on thefirms’managers,specifically those related to their employment.We do notfind evidence of increased chief executive officer(CEO),chieffinancial officer(CFO),or auditor turnover in the three years follow-ing tax shelter revelation relative to the turnover rates for matched controlfirms.Next,we assess whether customers exert a reputational cost on shelterfirms.Wefind no differential change in sales,sales growth,or advertising expense for revealed shelterfirms relative to that of controlfirms.We also examine how the revelation of a tax shelter influences the public media reputation of afirm,as measured by the Fortune magazine list for“Most Admired Companies,”following Bowen,Call,and Rajgopal(2010).Wefind no evidence that being caught in a tax shelter lowers the likelihood of making the Fortune list relative to the matched control sample.Firms also face potential reputational consequences with the tax authorities.When the IRS learns that afirm has engaged in what it considers a tax shelter,its policy allows it to expand the scope of information that it requests from thefirm,which can lead to the discovery of other aggressive tax avoidance.Accordingly,we examine whetherfirms accused of engaging in tax shelters become more conservative in the future regarding their tax avoidance,perhaps as a result of increased IRS scrutiny.If they do,we would expect to observe the effective tax rate(ETR)of tax shelterfirms to increase following scrutiny of their activities.The data,however,show that the ETR of tax shelterfirms remains approximately the same before and after discovery,and this is true regardless of whether ETRs are measured on a generally accepted accounting prin-ciples(GAAP)basis or on a cash basis.These results suggest thatfirms identified as tax shelter users may not suffer significant reputational costs even at the hands of the tax authorities.In summary,across a battery of tests,we do not observe a reputational effect of tax sheltering.We are careful to note,however,that such an effect may indeed exist;but we are simply unable tofind it empirically in our tests,perhaps because shelterfirms are peculiar or because we have a small sample and/or low power.For example,it is possi-ble thatfirms expecting nonzero reputational costs ex ante avoid tax shelter use com-pletely and that onlyfirms that are immune to reputational concerns engage in tax shelters.While we cannot rule out this possibility completely,it appears unlikely given the wide variety offirms we observe engaging in tax shelters.4Moreover,in logistic regressions of tax shelter usage on proxies for reputation and other factors known to be associated with tax shelter usage(Wilson2009),wefind no evidence that reputation sig-nificantly influences the likelihood of tax shelter participation.In summary,the absence of ex post reputational costs and the insignificance of reputation as a determinant of tax 3.By comparison,prior research shows that the stock price declines associated with corporate malfeasance arepermanent.For example,Hennes et al.(2008)show that the stock prices decline by nearly30percent following discovery offinancial irregularities and stay at reduced levels.4.For example,our sample of shelter users containsfirms from15of the17industries in the Fama-French17industry classification and has total assets ranging from$13million to$1.3billion.CAR Vol.31No.4(Winter2014)1106Contemporary Accounting Researchshelter use suggest that reputational costs are not likely to be responsible for the signifi-cant variation in tax sheltering.Thus,it appears that under-sheltering is more of a puz-zle than ever.52.Prior literature and research questionPrior literature on tax avoidance and tax sheltersThere is a vast and growing empirical literature on tax avoidance,dating back at least as far as Scholes,Wilson,and Wolfson(1990)and continuing to the present day,that pro-vides ample evidence that tax avoidance is pervasive and adaptable.Research has shown thatfirms engage in all manner of tax avoidance strategies,ranging from simple strategies like holding tax-exempt municipal bonds,to complex strategies such as debt–equity hybrid securities(Engel et al.1999),cross-border avoidance strategies(Dyreng and Lindsey 2009),intangible holding companies(Dyreng,Lindsey,and Thornock2013),and corpo-rate-owned life insurance(COLI)tax shelters(Brown2011).While prior research indicates that somefirms do not actively engage in tax avoidance (Dyreng et al.2008),the forces that are curtailing more widespread tax avoidance are not well understood.On average,it is reasonable to assume thatfirms are engaging in the optimal amount of tax avoidance.A maintained assumption in the literature,and in this paper,is that the presence of costs of tax avoidance at some point outweigh the benefits. However,such costs have been difficult to identify.6The lack of tax avoidance more gen-erally,especially in nonregulated settings and settings with nofinancial reporting trade-off, has been dubbed the“under-sheltering puzzle.”Essentially,the question is:what is hold-ing thosefirms back from taking advantage of known tax avoidance opportunities being used by otherfirms?Reputational costs are often conjectured to be an important factor constraining tax avoidance,particularly the more aggressive forms of tax avoidance.COLI shelters are a useful example of a tax avoidance strategy that many viewed as particularly aggressive and that resulted in adverse scrutiny forfirms that engaged in them.The COLI shelter involvedfirms taking out life insurance policies on their rank-and-file employees and then receiving the death benefits if the employee died(see Brown[2010]for a more detailed description).The COLI shelter was the subject of unflattering coverage in the media,including the Wall Street Journal,which identified the companies that engaged in COLI alongside pictures of their actual deceased employees(Schultz and Francis 2002).As noted in Hanlon and Slemrod(2009),there is anecdotal evidence that somefirms apply a“Wall Street Journal”test to their tax avoidance activities,whereby they forgo activities that would look unsavory if they were linked to thefirm on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.There is also anecdotal evidence that companies want to be perceived as being good corporate citizens that pay their“fair share”of taxes,although evidence on this is mixed(Davis,Guenther,Krull,and Williams2013;Watson2011).General Electric, for example,has been criticized by the New York Times for paying no taxes to the U.S. government in2011despite being one of the largest companies in the world by earnings 5.We test the robustness of our results using two different matching techniques(i.e.,a propensity scorematched control sample and an industry,size,and effective tax rate matched control sample),multiyear periods(i.e.,one,two,and three years following tax shelter revelation),and subsamples offirms for which the potential reputational effect of tax shelter involvement is likely to be higher.Throughout all of these dif-ferent specifications,we do notfind significant reputational costs from tax avoidance.6.The costs identified arefinancial reporting costs and regulatory costs,which apply to a subset of tax avoid-ance strategies and a subset offirms,respectively.See Frank,Lynch,and Rego(2009)and Badertscher,Phi-lips,Pincus,and Rego(2009)for examples offinancial reporting costs of tax avoidance and Mills,Nutter, and Schwab(2013)for an example of the regulatory costs of tax avoidance.CAR Vol.31No.4(Winter2014)The Reputational Costs of Tax Avoidance1107 and by market capitalization.7GE immediately responded by pointing out its other contri-butions to society,such as being a major employer and exporter,its prior tax payments, as well as tallying up a broader measure of its tax burden including payroll,property,and sales taxes paid.8These examples are consistent with the conjecture thatfirms perceive reputational costs from aggressive tax avoidance,especially when subjected to media scrutiny.To date, however,there is little in the way of empirical evidence on the validity of that claim.The closest evidence on the reputational effects of tax shelters is provided by Hanlon and Slemrod(2009),who examine the change infirms’market values following public revela-tion that thefirms engaged in tax sheltering,and by Graham et al.(2012),who survey tax executives in regard to their tax planning activities.Hanlon and Slemrod(2009)find that when tax shelter participation is revealed in the news media,the tax shelterfirms suffer a decline in market value.Graham et al.(2012)survey tax executives andfind that nearly 70percent respond that potential harm to theirfirm’s reputation is“very important”or “important”when deciding what tax planning strategies to implement.Moreover, responding to a question about tax disclosures,approximately half of executives surveyed responded that risk of adverse media attention was very important or important in reduc-ing theirfirm’s willingness to be tax aggressive.Other research examines the role of political costs in determining effective tax rates, where political costs can be viewed as a type of reputational cost or at least related to rep-utational costs.Zimmerman(1983)hypothesizes that accounting choices are often driven by political costs,such as taxation,andfinds that largefirms have higher effective taxes, which he asserts are a function of the higher political costs faced by thesefils et al.(2013)examine the influence of political costs on the tax avoidance in a sample of federal contractors.Theyfind that federal contractors that are highly sensitive to political costs have higher effective tax rates,consistent with political costs driving the tax strategy of federal contractors.Prior literature on corporate reputationMost of the prior research on corporate reputation focuses on nontax settings.In account-ing andfinance,the extant literature examines the reputational costs of malfeasance on bothfirms and their managers.For example,Karpoff,Lee,and Martin(2008a)track the careers of over2,000managers who allegedly engaged infinancial misrepresentation and find that93percent of these managers arefired and suffer a significant loss in personal wealth.Desai,Hogan,and Wilkins(2006)examine whether managers offirms suffer repu-tational costs following earnings restatements.Theyfind that top managers offirms that restate their earnings experience more turnover than managers at a control sample of firms.Bowen,Call,and Rajgopal(2010)find evidence of negative effects from whistle-blowing events,including significant negative abnormal returns,restatements,shareholder lawsuits,and negative future operating performance.Prior research has shown thatfirms accused of accounting improprieties(Karpoff,Lee,and Martin2008b;Dechow,Sloan, and Sweeney1996),defective products(Jarell and Peltzman1985),and violating environ-mental regulations(Karpoff,Lott,and Wehrly2005)are subject to adverse effects follow-ing revelation of the alleged misdeeds.However,there is also evidence that managers andfirms are not always severely pun-ished for improprieties.Beneish(1999)finds that managers offirms with extreme earnings overstatements do not have higher employment losses than managers of a matched sample offirms.Agrawal,Jaffe,and Karpoff(1999)find no evidence that managers and directors7./2011/03/25/business/economy/25tax.html?_r=1,accessed September30,2011.8./setting-the-record-straight-ge-and-taxes/,accessed September30,2011.CAR Vol.31No.4(Winter2014)1108Contemporary Accounting Researchoffirms charged with fraud have higher rates of turnover.Finally,Srinivasan(2005)finds that outside directors face labor market penalties following accounting restatements but not penalties through regulatory actions or litigation.In sum,there is evidence of significant reputational costs accruing to bothfirms and managers in a range of nontax settings.This evidence suggests that it is reasonable to expect that tax avoidance can be accompanied by adverse reputational costs if it is discov-ered and subject to outside scrutiny.However,some evidence suggests the opposite is the case,in which managers go unpunished following instances of inappropriate behavior. Moreover,tax avoidance may be viewed in a completely different light than other corpo-rate misdeeds because of the positive cashflow effects of such activity.Research question:Does tax sheltering affect corporate reputation?The reputation of thefirm is a multifaceted construct that results from the impressions and perceptions of numerous interested stakeholders.However,as Walker(2010)notes, the concept of corporate reputation is somewhat difficult to define because it means differ-ent things in different contexts.In this paper,we take a broad view of reputation,in which stakeholders form a perception of the corporation that influences the interactions between thefirm and stakeholders.The stakeholders of thefirm include any party with which the firm has a vested interest in maintaining a relationship,including equity-holders,debt-holders,customers,suppliers,and governments,among others.We follow Fombrun and Shanley(1990)in defining reputation as something that is both created and consumed as part of a corporate strategy.Hence,afirm’s reputation is an integral part of its compara-tive advantage,and as such,thefirm and its management will act to protect and grow the reputation of thefirm.To do so,it will strategically consider reputation in undergoing strategic initiatives and will make decisions,including tax decisions,based in part on the costs/benefits to its reputation.Accordingly,we are interested in those aspects of thefirm’s reputation that have real consequences for thefirm.This includes aspects of reputation that affect people’s percep-tions of thefirm and its managers for honesty and fair dealing,which could affect the firm’s brand values and sales,as well as scrutiny by parties thefirm deals with such as cus-tomers,suppliers,the IRS,and outside auditors.These costs may manifest as increased advertising costs to counter reputational damage,increased effective tax rates from height-ened IRS scrutiny,and increased auditor turnover.We are also interested in the reputation for competence and the effects on top execu-tives.Tax shelters that ultimately backfire and become the subject of intense IRS and media scrutiny may call into question the competence of thefirm’s managers.An impor-tant way that managers may internalize the reputational consequences of adverse scrutiny is through increased manager turnover following the tax shelter scrutiny,consistent with prior literature on nontax reputation-damaging events.However,as Hanlon and Slemrod(2009)discuss,some stakeholders may actually react positively to news of tax shelter involvement,or at least they will not react nega-tively.As a result,involvement in a tax shelter may affect afirm’s reputation differently than the corporate misdeeds listed above,for the following reasons.First,unlike account-ing fraud,corporate tax sheltering is usually legal or at least in an area of the tax law with substantial gray area.Second,tax sheltering can improve thefirm’s after-tax cashflow if the IRS ultimately agrees with thefirm’s interpretation of the tax law.Third,the risk involved in tax sheltering may not be the same(or even rank anywhere near the gravity) as other risk factors that thefirm faces,such as liquidity risk,competition,and going con-cern.Thus,the reputational risk of a tax shelter may not be of major importance to the firm or the parties with whom it does business.CAR Vol.31No.4(Winter2014)The Reputational Costs of Tax Avoidance11093.Data and SampleTo assessfirms’reputational costs of aggressive tax avoidance,we concentrate onfirms that were subjected to media scrutiny for having participated in a tax shelter.Tax avoid-ance activities range from mundane strategies that are unlikely to attract adverse attention to aggressive strategies that have little economic purpose other than to reduce taxes.Tax shelters tend to be at the extreme end of the tax avoidance spectrum.By focusing on tax shelters that attracted media scrutiny,we give the best chance for the public(including shareholders and governments)to form a negative opinion about thefirm.However,if we observe reputational costs in the sample of tax shelterfirms,we need to be careful about generalizing the results to less aggressive forms of tax avoidance.Conversely,if we do not observe reputational costs in this extreme sample,then it is unlikely that more mundane forms of tax avoidance result in significant reputational costs.Tax shelters are secretive by nature.As a result,it is difficult to identify a comprehen-sive sample offirms that are engaged in sheltering.Prior research has identified small sam-ples of public cases of tax sheltering.This research includes Graham and Tucker(2006), 44firm-year observations;Hanlon and Slemrod(2009),107firm-year observations;and Wilson(2009),33firm-year observations.To create a broad sample of tax shelter observa-tions,we combine the samples in these prior studies of tax sheltering with61additional observations of the COLI shelter(Sheppard1995),resulting in245tax shelter observa-tions.To the best of our knowledge,we have the largest public tax shelter database employed in current and past research.9To maximize power,we require the data to meet only minimal conditions to remain in the sample.Panel A of Table1presents the details of our sample composi-tion.From the combined245observations,we remove69observations that are dupli-cated across the databases.10We then remove foreignfirms(3observations),those for which the initial date of public scrutiny is unclear or missing(15),pre-1993tax shelters (10),those with insufficient data(17),and those that upon closer inspection are not clearly tax shelters(2).11,12Finally,we remove observations for which we cannot obtain a matched controlfirm(1observation),according to the matching process described below.In the end,we are left with118shelter observations from1995–2005.Panel B of Table1shows the number of tax shelter revelations in each year,from which we see that our shelter observations tend to cluster more in some time periods than others (e.g.,tax shelters made public in1995comprise about40percent of our sample).13The distribution of tax shelter revelations across time largely follows prior research that gave rise to the data(Graham and Tucker2006;Hanlon and Slemrod2009;and Wil-son2009).We perform sensitivity tests for the effects of temporal patterns in tax shel-tering in section5below.For the main tests,we match each revealed shelterfirm-years(i.e.,the treatment group)to a controlfirm from the same industry that is the closest infirm size(i.e.,assets) 9.Other researchers(e.g.,Lisowsky,Robinson,and Schmidt2012)have obtained larger samples of tax shel-ter transactions using confidential IRS data.Although that sample is useful for many research questions, the tax shelters in those studies are unobservable to the public and thus would not be suitable for tests of reputational penalties exerted by outside stakeholders.10.Since this study is conducted at thefirm-year level,if there is more than one tax shelter revelation in ayear,we count that as one observation.11.We begin our sample period in1993because SFAS109changed the rules regarding thefinancial reportingof taxes,and we want to maintain similar accounting treatment of income taxes for all our observations.12.Both incidents involved transfer pricing,which can be considered an aggressive form of tax planning.However,these observations are likely to be quite different from the other tax shelters,and hence we remove them from the sample.13.This time clustering results because the Tax Notes article identifying COLI users was published in1995.CAR Vol.31No.4(Winter2014)。

第5册--英国海上保险条款详论-第二版--Case table