Performance-Based Logistics — Next Big Thing

电商运营英语试题及答案

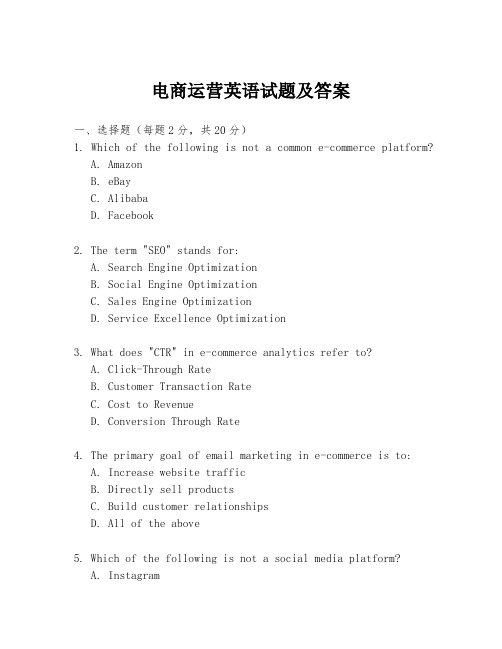

电商运营英语试题及答案一、选择题(每题2分,共20分)1. Which of the following is not a common e-commerce platform?A. AmazonB. eBayC. AlibabaD. Facebook2. The term "SEO" stands for:A. Search Engine OptimizationB. Social Engine OptimizationC. Sales Engine OptimizationD. Service Excellence Optimization3. What does "CTR" in e-commerce analytics refer to?A. Click-Through RateB. Customer Transaction RateC. Cost to RevenueD. Conversion Through Rate4. The primary goal of email marketing in e-commerce is to:A. Increase website trafficB. Directly sell productsC. Build customer relationshipsD. All of the above5. Which of the following is not a social media platform?A. InstagramB. LinkedInC. TwitterD. Shopify二、填空题(每题1分,共10分)6. The process of increasing the visibility of a website or a web page in a search engine's unpaid results is known as_________.7. In e-commerce, the term "dropshipping" refers to a retail fulfillment method where a store does not keep the _________ it sells in stock.8. A/B testing is a method used to compare the performance of two versions of a webpage, email, or _________ to determine which one performs better.9. The acronym "ROI" stands for _________, which is a measure used to evaluate the efficiency of an investment.10. The term "affiliate marketing" refers to a performance-based marketing in which a business rewards one or more_________ for each customer brought about by the affiliate's own marketing efforts.三、简答题(每题5分,共30分)11. Explain the importance of product listing optimization in e-commerce.12. Describe the role of customer reviews in influencing purchasing decisions.13. What are the key components of a successful e-commerce website?14. Discuss the impact of mobile commerce on the e-commerce industry.四、论述题(每题15分,共30分)15. Discuss the challenges and opportunities of international e-commerce.16. Analyze the role of data analytics in driving e-commerce business decisions.五、案例分析题(10分)17. Given a scenario where an e-commerce company is experiencing a high bounce rate, suggest possible reasons and solutions to improve the situation.参考答案:一、选择题1. D. Facebook2. A. Search Engine Optimization3. A. Click-Through Rate4. D. All of the above5. D. Shopify二、填空题6. SEO (Search Engine Optimization)7. products8. landing page9. Return on Investment10. affiliates三、简答题11. Product listing optimization is crucial in e-commerce as it helps to improve product visibility, increase search engine rankings, and enhance user experience, thereby driving more traffic and sales.12. Customer reviews play a significant role in influencing purchasing decisions as they provide social proof, build trust, and offer insights into the quality and performance of products.13. Key components of a successful e-commerce website includea user-friendly interface, secure payment options, fast loading speed, clear product descriptions, and effective search and filter functions.14. Mobile commerce has had a profound impact on the e-commerce industry, driving sales, enhancing customer engagement through mobile apps, and necessitating responsive design for a seamless shopping experience across devices.四、论述题15. International e-commerce presents challenges such as cultural differences, varying regulations, and logistics complexities, but also offers opportunities for market expansion, increased revenue, and access to a global customer base.16. Data analytics is instrumental in driving e-commerce business decisions by providing insights into customer behavior, optimizing marketing strategies, personalizing customer experiences, and improving inventory management.五、案例分析题17. High bounce rates could be due to irrelevant traffic, slow page loading, or poor user experience. Solutions include improving SEO to attract relevant visitors, optimizing website speed, and enhancing the site's design and content to engage users.。

物流英语课本翻译和单词

39迷你型,袖珍型mini

40取最小值minimize

41替代replacement

42一票(货物)shipment

43多变的volatile

44浪费的,不经济的wasteful

45装满。收费charge

46方式mode

47定价过高overprice

95制造manufacture

96少数民族minority

97工厂plant

98集中地pool

99有潜力的potential

1资格qualification

2招募resource

3零售reta

4专业于specialize

5供应商supplier

6受训者trainee

7喜好weakness

79使迷惑,使为难,迷惑不解puzzle

80比,比率ration

81合理的,有理的reasonable

82残余,剩余物remainder

83表现,象征,代表represent

84计划,方案scheme

85对待,处理treatment

86倾向,趋势trend

87充分的adequately

6延长extend

7幸运地fortunately

8货运,运费freight

9货运代理freght forwarder

10基金fund

11租(船等)hire

12按照in terms of

13 内在的inherent

14劳动,努力,工作labor

15责任,义务,倾向,债务liability

54是与销售的sellable

《物流成本管理》课件6 项目六 物流成本绩效评价

(一)财务指标 2.作业指标

(1)进出货作业评价指标

常用指标:

(一)财务指标 2.作业指标

(2)仓储评价指标

常用指标:

(一)财务指标 1.作业指标

(3)盘点作业评价指标

常用指标:

(一)财务指标 2.作业指标

(4)物流订单作业评价指标 常用指标--订单基本指标

652万元,计算该企业的单位物流成本率。 根据单位物流成本率的计算公式,力航物流公司2019年的单位物流

成本率如下: 单位物流成本率=物流成本/企业总成本 = 652/812×100%=77%

思考:如何评价计算结果?

(一)财务指标

1.效率指标

(3)单位营业费用物流成本率 【例6-3】 2020力航物流公司的物流成本为652万元,销售费用为

➢ 绩效管理的指标和标准难以确定,不能确定到底应该 从哪些方面来考核员工,考核指标到底要怎样设计, 考核的标准的高低也难以衡量。

学 习 目 标

素养目标

1.践行社会主义核心价值观 2.倡导自由、平等、公正、法制,确保成本考核的公正性学 3.立足岗位,客观评价业绩

知识目标

1.了解物流绩效评价的基本知识 2.熟练掌握物流绩效评价的方法 3.灵活用运综合绩效评价体系

任务三 物流成本绩效综合评价

CONTENTS

➢ 一、平衡计分卡法 ➢ 二、关键绩效指标法

《物流成本管理》(王桂花等编写,高等教育出版社,9787040549201)

一、平衡计分卡法

平衡记分卡法(简称BSC)是以公司的战略目标和竞争需要为基础,将财务测评指 标、客户满意度、内部流程,以及公司的创新与学习能力结合起来,进行综合评价 的管理方法。

绿色物流可持续发展外文翻译(节选)

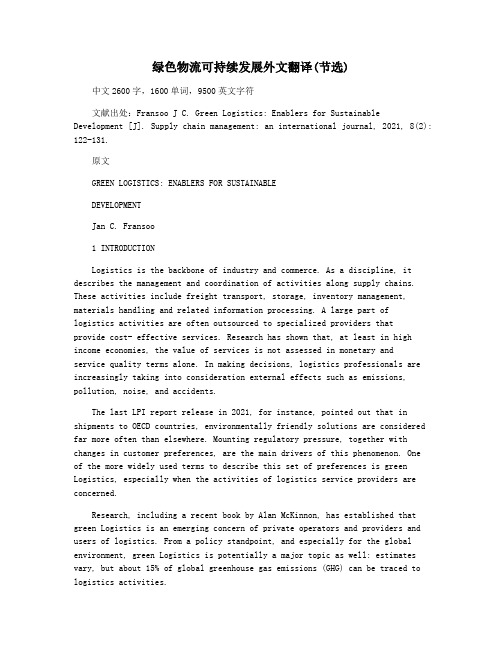

绿色物流可持续发展外文翻译(节选)中文2600字,1600单词,9500英文字符文献出处:Fransoo J C. Green Logistics: Enablers for Sustainable Development [J]. Supply chain management: an international journal, 2021, 8(2): 122-131.原文GREEN LOGISTICS: ENABLERS FOR SUSTAINABLEDEVELOPMENTJan C. Fransoo1 INTRODUCTIONLogistics is the backbone of industry and commerce. As a discipline, it describes the management and coordination of activities along supply chains. These activities include freight transport, storage, inventory management, materials handling and related information processing. A large part oflogistics activities are often outsourced to specialized providers thatprovide cost- effective services. Research has shown that, at least in high income economies, the value of services is not assessed in monetary andservice quality terms alone. In making decisions, logistics professionals are increasingly taking into consideration external effects such as emissions, pollution, noise, and accidents.The last LPI report release in 2021, for instance, pointed out that in shipments to OECD countries, environmentally friendly solutions are considered far more often than elsewhere. Mounting regulatory pressure, together with changes in customer preferences, are the main drivers of this phenomenon. Oneof the more widely used terms to describe this set of preferences is green Logistics, especially when the activities of logistics service providers are concerned.Research, including a recent book by Alan McKinnon, has established that green Logistics is an emerging concern of private operators and providers and users of logistics. From a policy standpoint, and especially for the global environment, green Logistics is potentially a major topic as well: estimates vary, but about 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) can be traced to logistics activities.Green Logistics may not be an independent policy area. Rather, the supply chain perspective provides a framework to understand and deal with issues that are separate.but ultimately interrelated. Importantly, looking at supply chains helps policy makers understand the interests and actions of private sector operators. Green Logistics may therefore propose a number of tools and identify emerging sustainable solutions contributing to the overarching objective of green Growth.From a policy perspective, logistics cut across several areas and sectors. The performance of supply chains depends on areas or activities where government as regulator or catalyst of investment is critical, such as:Transport infrastructure: road and rail corridors, ports and airportsThe efficiencies of logistics services: services include not only modal freight transport, but also warehousing and intermediary services, such as brokers and forwarders, and related information-flow management. In modern economies, the trend is towards integration in multi-activity logistics providers (3PLs, 4PLs) to which industrial and commercial firms outsourcetheir supply chain activities. Understanding the regulatory dimension of services is becoming increasingly critical to the development of effective policies in areas such as:professional and operational standards, regulation of entry in market and professions, competition, enforcement.Procedures applying to the merchandise, such as trade procedures (customs and other controls).The soft infrastructure that supports information or financial flow associated with the physical movements along supply chains: IT infrastructure, payment systems.The concept of national logistics performance capturing the outcome of these policies is widely recognized by policy makers and the private sector worldwide as a critical contribution to national competitiveness. A key question for sustainable development is how to integrate supply chain participants concern with environmental sustainability with the concept of national logistics performance.Within logistics, transport creates the largest environmental footprint. But the volume of emissions can vary greatly, depending on the mode oftransport. The volume of emission per ton per km increases by an order of magnitude from maritime to land transportation and to air transportation. This is a key environmental aspect of logistics that is not taken into consideration by most supply chain operators. Logisticsexperts typically integrate freight modes and other related activities so that the transport and distribution network is used in the most efficient manner, which is important for keeping emissions in check, as well. Depending on the type of industry and geographical region, supply chain operators can place varying emphasis on the reliability of supply chains, as well. In summary, supply chain choices typically include multiple criteria and trade-offs, and this makes an analysis of their environmental impact complex; the most environmentally friendly choices do not only depend on mode of transportation, but also on other elements, such as efficiency and reliability.To reduce the environmental footprint of a supply chain, the focus should be on several dimensions and should select the best mode of transport,efficient movements, and innovation. Comprehensive work on greening individual modes of transportation is already available. Here, the key drivers have been energy efficiency and the urge to diminish various types of emission. Given the integrated nature of supply chains, however, the manner in which price signals and incentives catalyze supply chain structure is a rather intricate problem: lower- emission modes of transport (maritime, e.g.) are typically also less reliable or have other limitations (such as maritime access to a landlocked country). Such limitations may include the cost of such technologies, the temperature range within which they can be used or the availability of certain types of fuel. It is therefore critical to complement the current knowledge about emissions produced by different modes of transportation with an understanding of what drives the demand for Green Logistics within supply chains.The emerging response is likely to take the form of top-down policy, such as measures in the form of standards or taxes addressing emissions (GHG, SO2, NOx) by mode of freight. For instance, a cap on SO2 emissions on major maritime routes will go into effect at the end of 20212. At least as important is the response from the bottom up. These are supply-chain strategies coming from the private sector in response to policy or price changes, but also demand from consumers, clients and stake-holders. Green Supply Chain management has to be taken seriously by policy makers.An exclusive focus on price mechanism (including taxes), as is the current tendency, may miss some of the major driver of changes in supply chain management. Another complication, at least in the context of international trade, is that the focus on the impact on international logistics does not capture the footprint of production processes. These processes may have different impact than the supply chain itself, as in the case of food production.There is also evidence that much of the environmental footprint of logistics operations is tied to short distances and distribution. Green Logistics is intimately linked with concerns such as urban congestion, and innovations in Logistics are critical to sustainable supply chains. Grassroots innovations in Logistics have recently flourished, often producing win-win solutions in terms of jobs and the environment. More generally, there is increasing awareness that green supply chains can be also competitive, either because the awareness of the environment helps productivity or because consumers expect it, particularly in wealthy countries.A concrete case in point is also the so-called sculpture emission regulation by IMO that enters into force on January 1, 2021 in most of North Sea, Baltic Sea and along west and east coasts of US & Canada (bar Alaska). Ships have to go over from fuel with 1.5 % sculpture to 0.1 % sculpture or invest in so-called scrubbers, that absorb the sculpture from exhaust gases; technology that is still nascent in the maritime context. Scrubber investment per cargo ship is USD 2 million and no with multiples as the ship engine size increases, with annual maintenance cost approx..7-10 % of investment. This seemingly innocent and rather technical change is going to have a huge impact on shipping and the spillover effect to other modes & Supply chains are going to be significant Green Logistics also encompasses potentially longer-term concerns. A green focus within logistics analysis could examine a supply chain vulnerability to climate events or to large swings in the price of transport inputs, for instance. A recent volcanic episode in Iceland showed the vulnerability of one specific supply chain that relies heavily on air freight fresh produce coming from Africa spoiled when flights were cancelled because of the volcanic ash. Resilience concerns and other form of uncertainty are likely to shape supply chain choices by regional and global operators.Given the importance of trade in components and intra-firm trade, how large operators develop green supply chain strategies will have profound economic impact. Resilient and greener supply chains are likely to be lessextended and leaner, for example, though the consequences for trade and integration of low income economies cannot be treated fully here.Policy makers should be concerned by both the supply and demand aspects of logistics environmental dimensions. So far, the policy focus has been on modal footprint and has not taken into account a supply chain perspective. There have not been major initiatives in Green Logistics, even in the countries most sensitive to the issue, such as those in Northern Europe. Rather the most important changes have occurred as a combination of largely uncoordinated public and private initiatives: voluntary behavior by shippers, innovation in terms of technology, information (environmental logistics dashboard) or services, or common public-private objectives such as in modal shifts.2 DEFINING GREEN LOGISTICS AND GREEN SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENTThere are many variations in the terminology regarding green logistics and green supply chain management. This section aims at providing a brief overview on some of the key terms used in the literature.Green logistics refers mainly to environmental issues related to transportation, material handling and storage, inventory control, warehousing, packaging, and facility location allocation decisions (Min & Kim, 2021). Gonzalez-Benito and Gonzalez-Benito (2021) use the term environmentallogistics to describe logistics practices that are divided intosupply/purchasing, transportation, warehousing and distribution, and reverse logistics and waste management. Although distribution is considered to be one of the interrelated areas of supply chain management, the term green distribution has also been used to describe the whole process of integrating environmental concerns into transportation, packaging, labeling and reverse logistics (Shi et al., 2021).Reverse logistics is often used as a synonym to efforts to reduce the environmental impact of the supply chain by recycling, reusing and remanufacturing.译文绿色物流:促进可持续发展贾恩. 法兰斯1. 引言物流是工商业的支柱。

后勤人员提成分配方案

后勤人员提成分配方案英文回答:Performance-Based Commission Allocation Plan for Logistics Personnel.A performance-based commission allocation plan for logistics personnel is a system that rewards employeesbased on their individual performance and the overall performance of the logistics department. This type of plan can help to motivate employees to perform at a high level and to contribute to the success of the department.There are a number of different factors that can be considered when developing a performance-based commission allocation plan. These factors include:Individual performance: This can be measured based ona number of different metrics, such as sales, profitability, and customer satisfaction.Departmental performance: This can be measured based on factors such as overall sales, profitability, and customer satisfaction.Company performance: This can be measured based on factors such as overall revenue, profitability, and market share.The weight given to each of these factors will vary depending on the specific goals of the organization. For example, a company that is focused on growth may place a greater weight on sales, while a company that is focused on profitability may place a greater weight on profitability.Once the factors have been determined, the next step is to develop a formula for calculating commissions. The formula should be fair and equitable, and it should take into account the different levels of performance that can be achieved.The following is an example of a performance-basedcommission allocation plan:Individual performance: 50%。

常用英文缩写

QM质量手册-Quality Manual

QMS质量管理体系-Quality Management System

MRB质量例会-Material Review Board

CQE注册质量工程师-Certified Quality Engineer

STEPS解决问题团队卓越系统-System for Team Excellence in Problem Solving

物流

SCM供应链管理-Supply Chain Management

PPAP生产件批准程序-Production Part Approval Process

FIFOቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ进先出-First in,First out

纠正措施程序-Corrective Action Processes

设备校准Equipment Calibration

纠正预防措施Corrective and Preventive Action Processes

SPC统计过程控制-Statistical Process Control

TOPS解决问题小组-Team Oriented Problem Solving

SUR快速换活-Set up Reduction

CFM连续流动-Continuous Flow Manufacturing

差错预防Error Proofing

拉动生产Pull System

EQS 16个方针-Management Review、Quality Training、Change Control Process、Processes to ID Special Characteristics、Eaton Internal Supplier PPAP/FAI、Supplier Quality Mgmt.、(P)FMEA、Process Control、MSA、Fresh Eyes Audit、Common Mfg. & Special Processes Audit、Process Capability Methods & Requirements、Control of Nonconforming Material、Performance Analysis and Improvement Process、Corrective and Preventive Action、Quality Alert System

常见的物流专业术语

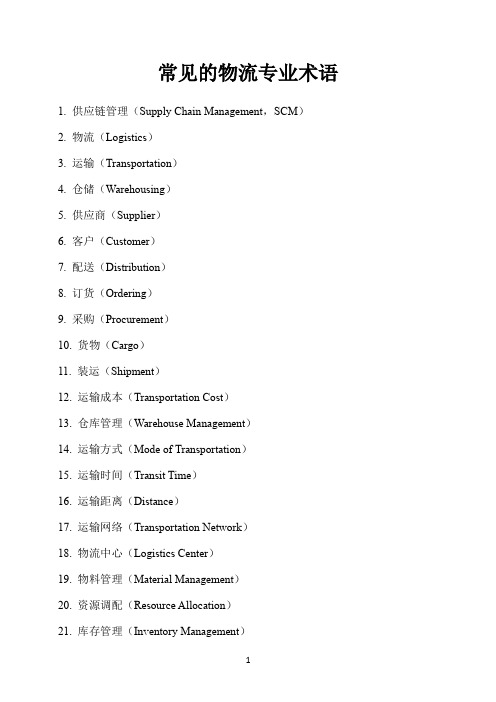

常见的物流专业术语1. 供应链管理(Supply Chain Management,SCM)2. 物流(Logistics)3. 运输(Transportation)4. 仓储(Warehousing)5. 供应商(Supplier)6. 客户(Customer)7. 配送(Distribution)8. 订货(Ordering)9. 采购(Procurement)10. 货物(Cargo)11. 装运(Shipment)12. 运输成本(Transportation Cost)13. 仓库管理(Warehouse Management)14. 运输方式(Mode of Transportation)15. 运输时间(Transit Time)16. 运输距离(Distance)17. 运输网络(Transportation Network)18. 物流中心(Logistics Center)19. 物料管理(Material Management)20. 资源调配(Resource Allocation)21. 库存管理(Inventory Management)22. 供应链协同(Supply Chain Collaboration)23. 海关(Customs)24. 清关(Customs Clearance)25. 国际贸易(International Trade)26. 出口(Export)27. 进口(Import)28. 海运(Ocean Freight)29. 空运(Air Freight)30. 铁路运输(Rail Transportation)31. 公路运输(Road Transportation)32. 仓储设施(Warehousing Facility)33. 仓储系统(Warehousing System)34. 包装(Packaging)35. 集装箱(Container)36. 货运代理(Freight Forwarder)37. 物流服务商(Logistics Service Provider)38. 运输安全(Transportation Security)39. 危险品运输(Hazardous Materials Transportation)40. 配送中心(Distribution Center)41. 装卸设备(Material Handling Equipment)42. 拣货(Picking)43. 装载(Loading)44. 卸货(Unloading)45. 中转(Transshipment)46. 运输保险(Transportation Insurance)47. 供应链可视化(Supply Chain Visibility)48. 物流效率(Logistics Efficiency)49. 物流成本(Logistics Cost)50. 逆物流(Reverse Logistics)51. 供应链优化(Supply Chain Optimization)52. 库存周转率(Inventory Turnover)53. 入库(Receiving)54. 出库(Shipping)55. 货运费用(Freight Charges)56. 运输路线(Transportation Route)57. 运输计划(Transportation Plan)58. 交付时间(Delivery Time)59. 运输管理系统(Transportation Management System,TMS)60. 仓储管理系统(Warehouse Management System,WMS)61. 托盘(Pallet)62. 货架(Rack)63. 供应商管理(Supplier Management)64. 货主(Shipper)65. 分销中心(Distribution Center)66. 订购点(Order Point)67. 定期订购(Regular Order)68. 经济订购数量(Economic Order Quantity,EOQ)69. 货运成本(Freight Cost)70. 运输效率(Transportation Efficiency)71. 供应链合作伙伴(Supply Chain Partner)72. 物流战略(Logistics Strategy)73. 货物跟踪(Cargo Tracking)74. 物流网络设计(Logistics Network Design)75. 全球物流(Global Logistics)76. 城市物流(Urban Logistics)77. 网络优化(Network Optimization)78. 成本控制(Cost Control)79. 风险管理(Risk Management)80. 总部仓库(Central Warehouse)81. 分布式仓库(Decentralized Warehouse)82. 跨境电商(Cross-border E-commerce)83. 供应商评估(Supplier Evaluation)84. 交货期(Delivery Date)85. 物流流程(Logistics Process)86. 物流组织(Logistics Organization)87. 物流规划(Logistics Planning)88. 跟踪系统(Tracking System)89. 订单处理(Order Processing)90. 门到门服务(Door-to-Door Service)91. 配送路线优化(Route Optimization)92. 冷链物流(Cold Chain Logistics)93. 单一窗口(Single Window)94. 联合运输(Intermodal Transportation)95. 快递(Express Delivery)96. 无人机配送(Drone Delivery)97. 末端配送(Last Mile Delivery)98. 供应链可持续性(Supply Chain Sustainability)99. 供应链风险(Supply Chain Risk)100. 货运容量(Freight Capacity)101. 系统集成(System Integration)102. 自动化仓库(Automated Warehouse)103. 运输需求管理(Transportation Demand Management)104. 配送计划(Distribution Plan)105. 订货周期(Order Cycle)106. 供应商协调(Supplier Coordination)107. 物流监控(Logistics Monitoring)108. 物流协同(Logistics Collaboration)109. 物流效益(Logistics Performance)110. 包装材料(Packaging Material)111. 拖车(Trailer)112. 仓储面积(Warehousing Space)113. 库存周转时间(Inventory Turnaround Time)114. 批次(Batch)115. 供应商评估指标(Supplier Evaluation Metrics)116. 运输分析(Transportation Analysis)117. 订单管理(Order Management)118. 运输优化(Transportation Optimization)119. 分销网络(Distribution Network)120. 多式联运(Multimodal Transportation)121. 物流策略(Logistics Strategy)122. 库存控制(Inventory Control)123. 物流信息系统(Logistics Information System)124. 运输监控(Transportation Monitoring)125. 物流效果评估(Logistics Performance Evaluation)126. 运输管理(Transportation Management)127. 收货确认(Receipt Confirmation)128. 配送时间窗口(Delivery Time Window)129. 物流外包(Logistics Outsourcing)130. 货运合同(Freight Contract)131. 运输文件(Transportation Documents)132. 物流安全(Logistics Security)133. 运输节点(Transportation Node)134. 物流地图(Logistics Map)135. 托运人(Consignor)136. 承运人(Carrier)137. 运输协议(Transportation Agreement)138. 物流审计(Logistics Audit)139. 运输成本分摊(Transportation Cost Allocation)140. 供应链可控性(Supply Chain Controllability)141. 仓储设备(Warehousing Equipment)142. 仓库布局(Warehouse Layout)143. 库位管理(Location Management)144. 入库管理(Receiving Management)145. 出库管理(Shipping Management)146. 发货通知(Shipment Notification)147. 配送费用(Distribution Costs)148. 运输分配(Transportation Allocation)149. 手工作业(Manual Operation)150. 电子商务物流(E-commerce Logistics)151. 航空货运(Air Cargo)152. 陆运(Land Transportation)153. 运输容量(Transportation Capacity)154. 环保物流(Green Logistics)155. 同城配送(Same-day Delivery)156. 订购量(Order Quantity)157. 装载率(Loading Rate)158. 卸载率(Unloading Rate)159. 损耗率(Loss Rate)160. 物流效能(Logistics Effectiveness)161. 供应链可靠性(Supply Chain Reliability)162. 物流合同(Logistics Contract)163. 仓库效率(Warehouse Efficiency)164. 计划运输(Planned Transportation)165. 非计划运输(Unplanned Transportation)166. 运输提单(Transportation Bill of Lading)167. 全程运输(Door-to-Door Transportation)168. 物流优化模型(Logistics Optimization Model)169. 仓储操作(Warehousing Operation)170. 运输过程(Transportation Process)171. 分销商(Distributor)172. 发货人(Consignor)173. 制造商(Manufacturer)174. 销售商(Retailer)175. 中转仓(Transit Warehouse)176. 集配中心(Consolidation and Distribution Center)177. 多渠道物流(Multichannel Logistics)178. 供应链整合(Supply Chain Integration)179. 物流服务水平(Logistics Service Level)180. 交货条件(Delivery Terms)181. 出口商(Exporter)182. 进口商(Importer)183. 港口(Port)184. 集装箱码头(Container Terminal)185. 干线运输(Trunk Transportation)186. 短途运输(Short-haul Transportation)187. 跨境物流(Cross-border Logistics)188. 拼箱(Less than Container Load,LCL)189. 整箱(Full Container Load,FCL)190. 物流外包商(Logistics Outsourcer)191. 物流执行系统(Logistics Execution System,LES)192. 物流规模化(Logistics Scaling)193. 货运管理(Freight Management)194. 物流数据分析(Logistics Data Analysis)195. 供应商协同计划(Supplier Collaboration Planning)196. 仓储容量规划(Warehousing Capacity Planning)197. 配送路线规划(Distribution Route Planning)198. 供应链网络优化(Supply Chain Network Optimization)199. 应急物流(Emergency Logistics)200. 满足率(Fill Rate)201. 物料需求计划(Material Requirements Planning,MRP)202. 运输订单(Transportation Order)203. 运输跟踪(Transportation Tracking)204. 物流成本分析(Logistics Cost Analysis)205. 运输报告(Transportation Report)206. 供应商评估体系(Supplier Evaluation System)207. 客户满意度(Customer Satisfaction)208. 采购管理(Procurement Management)209. 配送点(Delivery Point)210. 订购周期(Ordering Cycle)211. 缺货(Stockout)212. 外包物流(Outsourced Logistics)213. 物流效益评估(Logistics Performance Assessment)214. 境内物流(Domestic Logistics)215. 全球供应链(Global Supply Chain)216. 供应链整合技术(Supply Chain Integration Technology)217. 库存周转率指标(Inventory Turnover Ratio)218. 可追溯性(Traceability)219. 销售预测(Sales Forecast)220. 仓储费用(Warehousing Cost)221. 运输费率(Freight Rate)222. 物流信息共享(Logistics Information Sharing)223. 配送中心管理(Distribution Center Management)224. 入库检验(Receiving Inspection)225. 出库检验(Shipping Inspection)226. 货运监控(Cargo Monitoring)227. 物流执行(Logistics Execution)228. 物流路线规划(Logistics Route Planning)229. 城市配送(Urban Distribution)230. 物流模拟(Logistics Simulation)231. 系统优化(System Optimization)232. 运输效益评估(Transportation Efficiency Assessment)233. 运输需求预测(Transportation Demand Forecasting)234. 物流合作关系(Logistics Cooperation)235. 物流可靠性评估(Logistics Reliability Evaluation)236. 运输成本优化(Transportation Cost Optimization)237. 物流资金流转(Logistics Fund Flow)238. 供应链协同计划(Supply Chain Collaboration Planning)239. 仓库布局优化(Warehouse Layout Optimization)240. 运输容量规划(Transportation Capacity Planning)241. 物料流动(Material Flow)242. 运输效果分析(Transportation Effectiveness Analysis)243. 物流决策支持系统(Logistics Decision Support System)244. 供应链整合管理(Supply Chain Integration Management)245. 仓库操作规范(Warehouse Operation Specification)246. 订单处理时间(Order Processing Time)247. 运输效果评估(Transportation Effectiveness Evaluation)248. 物流网络优化(Logistics Network Optimization)249. 供应链风险管理(Supply Chain Risk Management)250. 货物追踪系统(Cargo Tracking System)251. 仓储容量规划(Warehousing Capacity Planning)252. 配送中心运作(Distribution Center Operation)253. 运输需求管理系统(Transportation Demand Management System)254. 运输过程监控(Transportation Process Monitoring)255. 物流信息共享平台(Logistics Information Sharing Platform)256. 库存周转率分析(Inventory Turnover Analysis)257. 批发物流(Wholesale Logistics)258. 城市配送中心(Urban Distribution Center)259. 货物跟踪技术(Cargo Tracking Technology)260. 物流供应商选择(Logistics Supplier Selection)261. 物流运营管理(Logistics Operations Management)262. 运输效能评估(Transportation Effectiveness Assessment)263. 物流执行管理(Logistics Execution Management)264. 物流路线优化(Logistics Route Optimization)265. 物流成本控制(Logistics Cost Control)266. 物流质量管理(Logistics Quality Management)267. 运输可行性分析(Transportation Feasibility Analysis)268. 物流人力资源管理(Logistics Human Resource Management)269. 物流合作模式(Logistics Cooperation Mode)270. 供应链服务水平(Supply Chain Service Level)271. 仓库容量规划(Warehousing Capacity Planning)272. 配送中心布局优化(Distribution Center Layout Optimization)273. 运输需求预测系统(Transportation Demand Forecasting System)274. 物流过程监控系统(Logistics Process Monitoring System)275. 供应链协同管理平台(Supply Chain Collaboration Management Platform)276. 仓储操作效率评估(Warehouse Operation Efficiency Assessment)277. 订单处理周期(Order Processing Cycle)278. 运输成本效益分析(Transportation Cost Benefit Analysis)279. 物流网络可达性(Logistics Network Accessibility)280. 供应链整合策略(Supply Chain Integration Strategy)281. 物料需求计划系统(Material Requirements Planning System)282. 运输订单管理系统(Transportation Order Management System)283. 运输跟踪技术(Transportation Tracking Technology)284. 物流成本分析系统(Logistics Cost Analysis System)285. 运输报告生成系统(Transportation Report Generation System)286. 供应商评估体系建立(Supplier Evaluation System Establishment)287. 客户满意度调查(Customer Satisfaction Survey)288. 采购管理系统(Procurement Management System)289. 配送点优化(Delivery Point Optimization)290. 订购周期缩短(Ordering Cycle Reduction)291. 运输安全管理(Transportation Security Management)292. 物流执行系统优化(Logistics Execution System Optimization)293. 物流路线规划系统(Logistics Route Planning System)294. 城市配送管理(Urban Distribution Management)295. 物流模拟系统(Logistics Simulation System)296. 系统优化方法(System Optimization Method)297. 运输效益评估指标(Transportation Effectiveness Evaluation Metrics)298. 物流协同计划系统(Logistics Collaboration Planning System)299. 仓库布局规划技术(Warehouse Layout Planning Technology)300. 运输容量规划系统(Transportation Capacity Planning System)这是一个包含常见物流专业术语的列表,覆盖了供应链管理、运输、仓储、供应商管理等多个方面。

外企公司常用英文缩写

:: 外企日常工作中常用的英语术语和缩写语 ::办公室职员(Office Clerk)加入公司的整个过程为例,引出在跨国公司(MNC-Multi-National Company) 工作中,日常人们喜欢经常使用的术语(Terminology)和缩写语(Abbreviation)。

[找工作Job Searching]我立志大学毕业后加入一家跨国公司。

我制作了精美的个人简历(Resume, cv)。

我参加了校园招聘(Campus Recruitment)。

我关注报纸招聘广告(Recruiting Ads)。

我也经常浏览招聘网站(Recruiting Website)。

我还参加人才招聘会(Job Fair)。

[参加面试Be invited for Interview] 我选择了几家中意的公司,投出了简历。

终于接到了人力资源部(Human Resources Department)邀请面试的通知。

经过几轮面试(Interview)和笔试(Written Test)我终于接到了XXXX公司的聘用书(Offer Letter)。

这是一家独资/合资企业(Wholly Foreign-Owned Company/Joint-Venture)。

[录用条件Employment Terms] 我隶属XX部门(Department)。

我的职位(Position)是XXXX。

我的工作职责(Job Responsibilities)是XXXX。

我的直接上司(Direct Supervisor)是XXX。

我的起点工资(Starting Salary)是XXXX。

我的入职日期(Join-Date)是XXXX。

我的试用期(Probation)是3个月。

首期劳动合同(Labor Contract/Employment Contract)的期限(Term)是3年。

[第一天上班 First day of join] 我乘坐公司班车(Shuttle Bus/Commuting Bus)来到公司。

墨菲物流学英文版第12版课后习题答案第6章

PART IIANSWERS TO END-OF-CHAPTER QUESTIONSCHAPTER 6: PROCUREMENT6-1. What is procurement? What is its relevance to logistics?Procurement refers to the raw materials, component parts, and supplies bought from outside organizations to support a company’s operations. It is closely related to logistics because acquired goods and services must be entered into the supply chain in the exact quantities and at the precise time they are needed. Procurement is also important because its costs often range between 60 and 80 percent of an organization’s revenues.6-2. Contrast procurement’s historical focus to its more strategic orientation today. Procurement’s historical focus in many organizations was to achieve the lowest possible cost from potential suppliers. Oftentimes these suppliers were pitted against each other in “cutthroat” competition involving three- or six-month arm’s-length contracts awarded to the lowest bidder. Once this lowest bidder was chosen, the billing cycle would almost immediately start again and another low bidder would get the contract for the next several months. Today procurement has a much more strategic orientation in many organizations, and a contemporary procurement manager might have responsibility for reducing cycle times, playing an integral role in product development, or generating additional revenues by collaborating with the marketing department.6-3. Discuss the benefits and potential challenges of using electronic procurement cards. Electronic procurement cards (p-cards) can benefit organizations in several ways, one of which is a reduction in the number of invoices. In addition, these p-cards allow employees to make purchases in a matter of minutes, as opposed to days, and p-cards generally allow suppliers to be paid in a more timely fashion. As for challenges, p-cards may require control processes that measure usage and identify procurement trends, limit spending during the appropriate procurement cycle, and block unauthorized expenditures at gaming casinos or massage parlors. In addition, using p-cards beyond the domestic market can be challenge because of currency differences, availability of technology, difference in card acceptance, and cultural issues.6-4. Discuss three potential procurement objectives.The text provides five potential procurement objectives that could be discussed. They are supporting organizational goals and objectives; managing the purchasing process effectively and efficiently; managing the supply base; developing strong relationships with other functional groups; and supporting operational requirements.6-5. Name and describe the steps in the supplier selection and evaluation process.Identify the need for supply can arise from the end of an existing supply agreement or the development of a new product. →Situation analysis looks at both the internal and external environment within which the supply decision is to be made. →Identify and evaluate potential suppliers delineates sources of potential information, establishes selection criteria, and assigns weights to selection criteria. →Select supplier(s) is where an organization chooses one or more companies to supply the relevant products. →Evaluate the decision involves comparison of expected supplier performance to actual supplier performance.6-6. Distinguish between a single sourcing approach and a multiple sourcing approach.A single sourcing approach consolidates purchase volume with a single supplier in the hopes of enjoying lower costs per unit and increased cooperation and communication in the supply relationship. Multiple sourcing proponents argue that using more than one supplier can lead to increased amounts of competition, greater supply risk mitigation, and improved market intelligence.6-7. What are the two primary approaches for evaluating suppliers? How do they differ?There are two primary approaches for evaluating suppliers: process based and performance based. A process-based evaluatio n is an assessment of the supplier’s service and/or production process (typically involving an audit). The performance-based evaluation is focused on the supplier’s actual performance on a variety of criteria, such as cost and quality.6-8. Discuss the factors that make supplier selection and evaluation difficult.First, supplier selection and evaluation generally involve multiple criteria, and these criteria can vary both in number and importance depending on the particular situation. Second, because some vendor selection may be contradictory, it is important to understand trade-offs between them. Third, the evolution of business practices and philosophies, such as just-in-time and supply chain management, may require new selection criteria or the reprioritization of existing criteria.6-9. Distinguish between supplier audits and supplier scorecards. When should each be used?A supplier audit usually involves an onsite visit to a supplier’s facility, with the goal being to gain a deeper knowledge of the supplier. By contrast, supplier scorecards report information about a supplier’s performance on certain criteria. Both supplier audits and supplier scorecards are associated with evaluating the supplier selection decision; supplier audits focus on process evaluation whereas supplier scorecards focus on performance evaluation.6-10. Describe Kraljic’s Portfolio Matrix. What are the four categories of this segmentation approach?Kraljic’s Portfolio Matrix is used by many managers to classify corpora te purchases in terms of their importance and supply complexity, with the goal of minimizing supply vulnerability and getting the most out of the firm’s purchasing power. The matrix delineates four categories: noncritical (low importance, low complexity), leverage (high importance, low complexity), strategic (high importance, high complexity), and bottleneck (low importance, high complexity).6-11. Define supplier development, and explain why it is becoming more prominent in some organizations.Supplier development (reverse marketing) refers to aggressive procurement not normally encountered in supplier selection and can include a purchaser initiating contact with a supplier, as well as a purchaser establishing prices, terms, and conditions. One reason for its growing prominence is the myriad inefficiencies associated with suppliers initiating marketing efforts toward purchasers. A second reason is that the purchaser may be aware of important events that are unknown to the supplier. Moreover, achieving competitive advantage in the supply chain is predicated on purchasers adopting a more aggressive approach so as to compel suppliers to meet the necessary requirements.6-12. What are the components of the global sourcing development model presented in this chapter?Planning, specification, evaluation, relationship management, transportation and holding costs, implementation, and monitoring and improvements make up the components of the global sourcing development model presented in this chapter.6-13. What are some of the challenges of implementing a global sourcing strategy?In terms of the challenges of implementing a global sourcing strategy, as organizations continue to expand their supply bases, many are realizing that hidden cost factors are affecting the level of benefits that were projected to be achieved through this approach. Some of these hidden costs include increased costs of dealing with suppliers outside the domestic market, and duty and tariff charges that occur over the life of a supply agreement.6-14. Pick, and discuss, two components of the global sourcing development model presented in this chapter.Any two components listed in the answer to Question 6-12 could be discussed.6-15. What is total cost of ownership and why is it important to consider?When taking a total cost of ownership (TCO) approach, firms consider all the costs that can be assigned to the acquisition, use, and maintenance of a purchase. With respect to global sourcing, the logistics costs related to the typically longer delivery lead times associated with global shipments are a key consideration.6-16. Why are some firms considering near-sourcing?Near-sourcing refers to procuring products from supplier s closer to one’s own facilities. Firms are considering near-sourcing because of rising transportation and energy costs, growing desires to be able to quickly adapt to changing market trends, and risk and sustainability concerns.6-17. Name, and give an example of, the five dimensions of socially responsible purchasing.•Diversity includes procurement activities associated with minority or women-owned organizations.•The environment includes considerations such as waste reduction and the design of products for reuse or recycling.•Human rights includes child labor laws as well as sweatshop labor.•Philanthropy focuses on employee volunteer efforts and philanthropic contributions.•Safety is concerned with the safe transportation of purchased products as well as the safe operation of relevant facilities.6-18. Discuss some of the ethical issues that are associated with procurement.Areas of ethical concern in procurement include gift giving and receiving; bribes (money paid before an exchange) and kickbacks (money paid after an exchange); misuse of information; improper methods of knowledge acquisition; lying or misrepresentation of the truth; product quality (lack thereof); misuse of company assets, to include abuse of expense accounts; and conflicts of interest, or activity that creates a potential conflict between one’s personal interest and her or his employer’s interests.6-19. Distinguish between excess, obsolete, scrap, and waste materials.Excess (surplus) materials refer to stock that exceeds the reasonable requirements of an organization, perhaps because of an overly optimistic demand forecast. Obsolete materials, unlike excess materials, are not likely to ever be used by the organization that purchased them. Scrap materials refer to materials that are no longer serviceable, have been discarded, or are a by-product of the production process. Waste materials refer to those that have been spoiled, broken, or otherwise rendered unfit for reuse or reclamation. Unlike scrap materials, waste materials have no economic value.6-20. How can supply chain finance help procurement drive value for its firm?Supply chain finance is a set of technology and finance-based processes that strives to optimize cash flow by allowing businesses to extend their payment terms to their suppliers while simultaneously allowing suppliers to get paid early. Procurement would negotiate extended payment terms with their suppliers by using technology to enable the supplier to choose and receive their money early (minus a service fee for this convenience). The advantage for the selling firm is the ability to decide when they receive payment, while the buying firm receives the benefits of longer payables.PART IIICASE SOLUTIONSCASE 6-1: TEMPO LTD.Question 1: Should Terim let somebody else complete the transaction because he knows that if he doesn’t sell to the North Koreans, somebody else will?This question may stimulate a great deal of discussion among students. On the one hand, Terim is contemplating a transaction involving commodities (chemicals and lumber) as well as with a country (North Korea) with which he is not all that familiar. These aspects might argue against completing the transaction. Moreover, in light of certain events involving North Korea—specifically, admitting that the country possesses nuclear capabilities—Terim might pull back from the proposed transaction because of uncertainty as to exactly how the chemicals will be used by the North Koreans (e.g., might the chemicals actually be used to make weapons?). On the other hand, even though the case indicates that the Turkish have imposed trade sanctions against North Korea, trade involving banned partners is periodically achieved by routing the products through other countries.Question 2: What are the total costs given in the case for the option of moving via Romania?Question 3: What are the total costs given in the case for the option of moving via Syria?Question 4: Which option should Terim recommend? Why?Either option can be supported. For example, the Romanian option is nearly $30,000 cheaper than the Syrian option—thus, solely from the perspective of cost, the Romanian option might be preferred. However, the Romanian option takes three weeks longer to complete than does the Syrian option. Moreover, the Romanian option appears to be riskier than the Syrian one in the sense that things might go awry in the redocumentation process.Question 5: What other costs and risks are involved in these proposed transactions, including some not mentioned in the case?The entertainment of the North Korean officials can be viewed as both a cost and a risk. At minimum, luxurious hotel accommodations as well as business-related dinners and receptions will not come cheaply. From a risk perspective, there is a chance that the entertainment could get out of hand and generate embarrassing publicity.There is also a chance that some of the rusvet“fees” might unexpectedly increase, particularly those associated with generating the false documents. If providers of the documentation understand the “captive” nature of the lumber shipment from Romania to Turkey, then it is possible that these providers could leverage their position to increase their income.A more general risk for these proposed transactions is the volatile political situation in the Middle East. One manifestation of this volatility is through disruptions in transportation routes; traffic through the Suez Canal has periodically been influenced by the region’s political volatility—an important consideration given that the proposed lumber shipments will need to move through the Suez Canal.Students are likely to identify other costs and risks.Question 6: Regarding the supply chain, how—if at all—should bribes be included? What functions do they serve?From a broad perspective, the purpose of bribes should be to facilitate the completion of international transactions. At least two perspectives must be considered when analyzing the first part of the question. One is the legal perspective; quite simply, in some countries (such as the United States), bribes are theoretically illegal—regardless of the circumstances. Under this scenario, bribes would not be included in the supply chain.A second perspective, practicality, understands that bribes are essential for the completion of international transactions. Under this scenario, supply chains would need the flexibility to accommodate situations that require a bribe. One manifestation of this flexibility could be the name assigned to a “bribe.” For example, one of the authors of this text was not allowed to board an airplane flight to Katmandu, Nepal until all four members of his traveling party (each a U.S. reside nt) paid what was called a “weightpenalty.” This weight penalty appears to have been bribe-like in the sense that none of the other passengers, several of whom clearly had weight problems, were assessed weight penalties.Question 7: If Terim puts together this transaction, is he acting ethically? Discuss.The answer to this question could depend on one’s definition of ethical actions. One definition, for example, focuses on a personal code of conduct to guide one’s actions. Another definition suggests that anything that is not illegal is ethical. Having said this, the Romanian routing appears questionable because of the document alterations associated with it. These document alterations are probably illegal, regardless of the country in question.Alternatively, because the Syrian routing does not appear to include any overtly illegal activities, some might view it as ethical. Even though it includes rusvets, Terim merely would be following accepted protocol for many international transactions. Moreover, the use of Syria is smart in the sense that Terim is avoiding a Turkish port where the chances of getting caught, and the associated penalties, are much higher.From another perspective, the case suggests that Terim is struggling with the decision to do business with the North Koreans, in part because of concerns about their communist regime and support of terrorist policies. Because this may indicate that Terim has a conscience, any transaction involving the North Koreans could be viewed as unethical in the sense that Terim is violating his personal code of conduct.Question 8: What do you suggest should be done to bring moral values into the situation so that the developing countries are somewhat in accordance with Western standards? Keep in mind that the risks involved in such environments are much higher than the risks of conducting business in Western markets. Also note that some cultures see bribery as a way to better distribute wealth among their citizens.Because this case involves organizations located in two non-Western countries, it might be culturally insensitive to bring in moral values that are more in accordance with Western standards.。

译文 《商务英语》UNIT1 LOGISTICS(物流)

UNIT I LOGISTICS第一单元物流PART ⅠThe Definition of LogisticsPART Ⅰ物流的定义The introduction of Logistics物流简介[Para1]“Logistics” is a term, which originates from both the army an d French. According to the French, the Baron of Jomini, who of Swiss origin who had served in Napoleon’s army before joining the Russians and who later founded the Military Academy of St. Petersburg, first used the term in the early 19th century. So in a m ilitary sense, the term ‘logistics’ encompasses transport organization, army replenishments and material maintenance.“物流”或“后勤”一词其实源于军队,对其词义解释亦有多个不同版本,根据法国人阐述之词义,该词早于十九世纪初被祖文尼男爵率先采用。

祖文尼是一名原藉瑞士的军官,他在投奔俄罗斯军队之前在拿破伦军中服役,其后一手创立“圣彼得堡军事学院”。

就军事意识而言,物流管理―词意即运输编制、军队补给和物料保养。

[Para2] In the business world however, the concept of “logistics” was applied solely to “Material Replenishment Programs” (MRP) and was confined to the manufacturing sector at the beginning. Therefore the extension of the concept to involve company operations is a relatively new one and the earliest usage dates back to the 1950s in the USA.然而在商务界中,“物流管理”的概念仅仅用于“物料需求计划”,并且最初是在制造业的部门开始使用。

物流企业总体绩效评估研究综述陈玲玲高新阳张媛媛

物流企业总体绩效评估研究综述陈玲玲高新阳张媛媛发布时间:2021-10-07T04:52:10.077Z 来源:《基层建设》2021年第18期作者:陈玲玲高新阳张媛媛[导读] 本文介绍了物流企业总体绩效评估的意义,并总结了物流企业总体绩效评估国内外研究现状华北科技学院经济管理学院河北廊坊 065201摘要:本文介绍了物流企业总体绩效评估的意义,并总结了物流企业总体绩效评估国内外研究现状,最后总结物流企业总体绩效评估国内外研究主要方面及存在问题,以期能为从事相关领域的研究者提供借鉴。

关键词:物流企业;绩效评估;研究综述1引言随着全球经济的快速发展,世界范围内的经营活动和资源配置已经成为经济全球化最为显著的特点。

物流链条和贸易链条的持续优化,使得物流经济迎来发展新气象,在经济全球化的发展中发挥着举足轻重的作用[1]。

可见,物流在我国经济发展和资源配置中承担着重要角色,已成为国民经济新的增长点,更是经济发展的重要支撑。

现代物流作为一种崭新的经济组织模式,已经从传统的产品供给和资源流通环节中分离出来,逐渐走向独立化和专业化。

随着物流企业在国民经济发展中的地位日渐突出,众多研究学者和行业内部管理者更加青睐于相关理论和实践经验的探寻。

物流企业的绩效评价对提高物流运输质量和效益十分重要,更是实现物流企业市场竞争地位提升的关键。

2 物流企业总体绩效评估国内外研究现状竞争激烈的环境中,许多公司都致力于利用更高的生产和采购效率获得全球市场份额,如今,业务绩效作为企业重点关注的方面突显出来,并被认为是竞争优势的关键因素。

国外发展水平较高的国家,早已经关注物流企业的经营发展状况,物流企业的绩效评价更是由来已久。

美国物流协会曾委托A.T科尔尼公司对物流企业评价系统展开研究,并且构建完成基于行政管理指标、仓储指标、运输指标和采购指标为一体的评价指标体系[2]。

YY Komarovskaya(2019)在《Optimization Of Knowledge And Information Exchange In Research On Performance Of Quality Management System》中通过对科学知识体系的分析研究,模拟知识监控、评价和共享过程之间的相互关系,以及它们在各种能力形成中的作用,可以实现这种优化,提出了一个知识评价与管理相互关系的模型,以提高组织从过去的经验教训中获益的重要能力[3]。

供应链物流管理第二章

What is malfunction ?

• Malfunction is concerned with the probability of logistical performance failure, such as damaged products, incorrect assortment, or inaccurate documentation.

• 避免为那些次要的、非关键客户购买的、 盈利能力较弱的产品提供高质量的服务。

没有竞争真空的环境

• It may be necessary to position inventory specific warehouse to gain competitive advantage even if such commitment increases total cost.

• The objective of information management is to reconcile these differentials to improve overall supply chain pe之间的差异,从 而提高供应链绩效。

• The benefit of fast information flow is directly related to work balancing.

• (信息流的快速传递有利于实现各运作环节 之间的平衡)

• ——对客户需求的承诺,从成本结构上来讲, 就是物流价值观。

• Customer requirements are transmitted in the form of orders.

麦肯锡供应链管理-流程与绩效(英文原版)

McKinsey • Proprietary and Confidential

LShop/Ldn/22Oct97Rp-fc/kf

-2-

We used information from several sources during our project

– Supply chain benchmarks and best practice (Dow Polyurethane & Epoxy April 1995). – Supply Chain Benchmark Assessment (March 1997). – Supply chain appraisal and benchmarks: (client X September 1997).

• Internal and external documents:

– High level benchmarking framework for supply chain performance (H .Cook): • Shop Study (March 1997) accessing information from available experts and past projects.

LShop/Ldn/22Oct97Rp-fc/kf

-6-

. . . and concluded there are three strategic objectives we should focus on when analysing the supply chain

物流术语中英文

物流术语基础术语物品 goods物流 logistics物流活动 logistics activity物流管理 logistics management供应链 supply chain供应链管理 supply chain management服务 service物流服务 logistics service一体化物流服务 integrated logistics service物流系统logistics system第三方物流 the third party logistics物流设施 logistics establishment物流中心 logistics center配送中心 distribution center分拨中心 distribution center物流园区 logistics park物流企业 logistics enterprise物流作业 logistics operation物流模数 logistics modulus物流技术 logistics technology物流成本 logistics cost物流网络 logistics network物流信息 logistics information物流单证 logistics documents物流联盟 logistics alliance物流作业流程 logistics operation process企业物流 internal logistics供应物流supply logistics生产物流production logistics销售物流 distribution logistics社会物流 external logistics军事物流 military logistics项目物流 project logistics国际物流 International logistics虚拟物流 virtual logistics精益物流 lean logistics反向物流reverse logistics回收物流 return logistics废弃物物流 waste material logistics货物运输量 freight volume货物周转量 turnover volume of freight transport军事物资 military material筹措 raise军事供应链 military supply chain军地供应链管理 military supply chain management军事物流一体化 integration of military logistics and civil logistics 物流场 logistics field战备物资储备 military repertory of combat readiness全资产可见性 total asset visibility配送式保障 distribution-mode support作业服务术语托运 consignment承运 carriage承运人 carrier运输 transportation道路运输 road transport水路运输 waterway transport铁路运输 railway transport航空运输 air transport管道运输 pipeline transport门到门服务 door to door service直达运输 through transportation中转运输 transfer transportation甩挂运输 drop and pull transport整车运输 transportation of truck-load零担运输 sporadic freight transportation联合运输 combined transport联合费率 joint rate联合成本 joint cost仓储 warehousing储存 storing库存 inventory库存成本 inventory cost保管 storage仓单 storage invoice仓单质押融资 Warehouse receipt hypothecating/ Depot bill pledge 库存商品融资Inventory Financing仓储费用 warehousing fee订单满足率 fill rate货垛 goods stack堆码 stacking?配送 distribution拣选 order picking分类 sorting集货 goods consolidation共同配送 joint distribution装卸 loading and unloading搬运 handling carrying包装 package/packaging销售包装 sales package运输包装 transport package流通加工 distribution processing检验inspection增值物流服务 value-added logistics service定制物流customized logistics物流客户服务 logistics customer service物流运营服务 logistics operation service物流服务质量 logistics service quality?物品储备 goods reserves缺货率 stock-out rate货损率 cargo damages rate商品完好率 rate of the goods in good condition 基本运价freight unit price理货 tally组配 assembly订货周期 order cycle time库存周期 inventory cycle time技术与设施设备术语标准箱 twenty-feet equivalent unit (TEU)集装运输 containerized transport托盘运输 pallet transport货物编码 goods coding四号定位 four number location零库存技术 zero-inventory technology单元装卸 unit loading & unloading气力输送法 pneumatic conveying system生产输送系统 production line system分拣输送系统 sorting & picking system自动补货 automatic replenishment自动存储取货系统 automated storage & retrieval system (AS/RS) 集装化 containerization?散装化 in bulk托盘包装 palletizing直接换装 cross docking物流系统仿真 logistics system simulation冷链cold chain自营仓库 private warehouse公共仓库 public warehouse自动仓库 automated storage & retrieval system 立体仓库 stereoscopic warehouse交割仓库 transaction warehouse交通枢纽 traffic hinge集装箱货运站container freight station (CFS)?集装箱码头 container terminal控湿储存区 humidity controlled space?冷藏区 chill space冷冻区 freeze space收货区 receiving space区域配送中心 regional distribution center (RDC) 公路集装箱中转站 inland container depot?铁路集装箱场 railway container yard专用线 special railway line基本港口 base port周转箱 container叉车 fork lift truck?叉车属具 attachments of fork lift trucks托盘 pallet?称量装置 load weighing devices工业用门 industrial door货架 goods shelf重力货架系统 live pallet rack system移动货架系统 mobile rack system驶入货架系统 drive-in rack system集装袋 flexible freight bags集装箱 container特种货物集装箱 specific cargo container 集装单元器具 palletized unit implants全集装箱船 full container ship码垛机器人 robot palletizer起重机械 hoisting machinery牵引车 tow tractor升降台 lift table (LT)输送机 conveyors箱式车 box car自动导引车 automatic guided vehicle (AGV) 自动化元器件 element of automation手动液压升降平台车scissor lift table零件盒 working accessories条码打印机 bar code printer站台登车桥 dock levelers信息术语条码 bar code商品标识代码 identification code for commodity产品电子编码 Electronic Product Code (EPC)EPC序列号 serial number对象名称解析服务 object name service (ONS)对象分类 object class位置码 location number (LN)?贸易项目 trade item物流单元 logistics unit全球贸易项目标识代码 global trade item number应用标识符 application identifier (AI)物流信息编码 logistics information code自动数据采集 automatic data capture (ADC)自动识别技术auto identification条码标签 bar code tag条码识读器 bar code reader条码检测仪 bar code verifier条码系统 bar code system条码自动识别技术 bar code auto ID射频标签 RFID tag射频识读器 RFID reader射频识别 radio frequency identification (RFID)射频识别系统 RFID systemEPC系统 EPC system数据元 metadata报文 message实体标记语言 Physical Markup Language (PML)电子数据交换 electronic data interchange (EDI)电子通关 electronic clearance电子认证 electronic authentication电子报表 e-report电子采购 e-procurement电子合同 e-contract电子商务 e-commerce (EC)电子支付 e-payment地理信息系统 geographical information system (GIS) 全球定位系统global positioning system (GPS)智能交通系统 intelligent transportation system (ITS) 货物跟踪系统 goods-tracked system仓库管理系统 warehouse management system (WMS)销售时点系统point of sale (POS)电子订货系统 electronic order system (EOS)计算机辅助订货系统 computer assisted ordering (CAO)拉式订货系统 pull order system永续存货系统 perpetual inventory system虚拟仓库 virtual warehouse物流信息系统 logistics information system (LIS)物流信息技术 logistics information technology物流信息分类 logistics information sorting分布式的网络软件 savant管理术语仓库布局 warehouse layoutABC分类管理 ABC classification安全库存 safety stock经常库存 cycle stock库存管理 inventory management库存控制 inventory control供应商管理库存 vendor managed inventory (VMI)定量订货制 fixed-quantity system (FQS)定期订货制 fixed-interval system (FIS)经济订货批量 economic order quantity (EOQ)连续补货计划 continuous replenishment program (CRP)联合库存管理 joint managed inventory (JMI)前置期 lead time?物流成本管理 logistics cost control物流绩效管理 logistics performance management物流战略 logistics strategy物流战略管理 logistics strategy management物流质量管理 logistics quality management物流资源计划 logistics resource planning (LRP)供应链联盟 supply chain alliance供应商关系管理 supplier relationships management (SRM)准时制 just in time (JIT)?准时制物流 just-in-time logistics?有效客户反应 efficient customer response (ECR)快速反应 quick response (QR)?物料需求计划 material requirements planning (MRP)制造资源计划 manufacturing r esource planning (MRPⅡ)配送需求计划 distribution requirements planning (DRP)配送资源计划distribution resource planning (DRPⅡ)企业资源计划 enterprise resource planning (ERP)协同计划、预测与补货collaborative planning,forecasting and replenishment (CPFR) 服务成本定价法 cost-of-service pricing服务价值定价法 value-of-service pricing业务外包 outsourcing流程分析法 process analysis延迟策略 postponement strategy业务流程重组 business process reengineering(BPR)物流流程重组 logistics process reengineering有形损耗 tangible loss无形损耗 intangible loss?总成本分析 total cost analysis物流作业成本法 logistics activity-based costing效益悖反 trade off国际物流术语多式联运 multimodal transport国际多式联运 international multimodal transport国际航空货物运输 international airline transport国际铁路联运 international through railway transport班轮运输liner transport?租船运输 shipping by chartering大陆桥运输 land bridge transport保税运输 bonded transport转关运输Tran-customs transportation报关 customs declaration报关行 customs broker不可抗力 accident beyond control保税货物 bonded goods海关监管货物cargo under custom’s supervision拼箱货 less than container load (LCL)整箱货 full container load (FCL)通运货物 through goods转运货物 transit cargo自备箱shipper’s own container到货价格 delivered price出厂价 factory price成本加运费cost and freight (CFR)出口退税 drawback过境税 transit duty海关估价 customs ratable price等级标签 grade labeling等级费率 class rate船务代理 shipping agency国际货运代理 international freight forwarding agent无船承运业务 non vessel operating common carrier business 无船承运人 NVOCC non vessel operating、common carrier索赔 claim for damages理赔 settlement of claim国际货物运输保险 international transportation cargo insurance 原产地证明 certificate of origin进出口商品检验 commodity inspection清关 clearance滞报金 fee for delayed declaration装运港船上交货 free on board (FOB)进料加工 processing with imported materials来料加工 processing with supplied materials保税仓库 boned warehouse保税工厂 bonded factory保税区 bonded area保税物流中心 bonded logistics center保税物流中心A型 bonded logistics center of A type保税物流中心B型 bonded logistics center of B type融通仓 financing warehouse出口监管仓库 export supervised warehouse出口加工区 export processing zone定牌包装 packing of nominated brand中性包装 neutral packing提单(海运提单) bill of lading。

现代物流管理第四章(英文版)

4-14

Supplier operational integration

• Primary objective of operational integration is to cut waste, reduce cost, and develop a relationship that allows both buyer and seller to achieve mutual improvements • Integration can take many forms

• Access technology and innovation • Lowest total cost of ownership

4-6

Lowest total cost of ownership

Although the purchase price of a material or item remains important, it is only one part of the total cost for their organization. Service costs and life cycle costs must be considered. Purchase price price and discounts lowest TCO

• Procurement is an organizational capability that ensures the firm is positioned to implement its strategies with support from its supply base

– Procurement looks up and down the entire supply chain for impacts and opportunities

供应链专业术语缩写及含义

供应链专业术语缩写及含义1. SCM -供应链管理(Supply Chain Management)供应链管理是指在产品或服务从原始材料生产到最终用户使用的整个过程中,协调和管理各个环节,以实现高效的运作和最大程度的客户满意度。

2. ERP -企业资源规划(Enterprise Resource Planning)企业资源规划是一种集成管理系统,通过整合企业内部的各个部门和业务流程,提高资源利用效率,优化供应链流程。

3. WMS -仓储管理系统(Warehouse Management System)仓储管理系统是一种用于管理和优化仓库操作的软件系统,包括入库、出库、库存管理、订单处理等功能。

4. TMS -运输管理系统(Transportation Management System)运输管理系统是一种用于优化货物运输和配送过程的软件系统,包括路线规划、运输成本管理、运输跟踪等功能。

5. GPS -全球定位系统(Global Positioning System)全球定位系统是一种卫星导航系统,用于确定物品或车辆的精确位置,提高运输过程的可视化和管理效率。

6. RFID -射频识别技术(Radio Frequency Identification)射频识别技术是一种利用无线电信号来识别和跟踪物品或货物的技术,可以实现物流信息的实时采集和监控。

7. JIT -及时制(Just-In-Time)及时制是一种生产和库存管理方法,通过在需要时准确生产所需数量的产品,以减少库存和提高效率。

8. SLA -服务水平协议(Service Level Agreement)服务水平协议是一种合同或协议,规定供应商或物流服务提供商应达到的服务水平标准和指标。

9. KPI -关键绩效指标(Key Performance Indicator)关键绩效指标是用于衡量供应链绩效的重要指标,可以是成本、交货准时率、库存周转率等。

performance-based